Why Do Primers Form Secondary Structures? Causes, Consequences, and Solutions for Molecular Assays

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of primer secondary structure formation, a critical challenge in molecular biology that impacts PCR, qPCR, and sequencing efficiency.

Why Do Primers Form Secondary Structures? Causes, Consequences, and Solutions for Molecular Assays

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of primer secondary structure formation, a critical challenge in molecular biology that impacts PCR, qPCR, and sequencing efficiency. We explore the fundamental thermodynamic and sequence-based causes of structures like hairpins and primer-dimers. The content details practical design strategies to prevent these issues, advanced troubleshooting methods for problematic templates, and validation techniques using both in silico tools and novel biochemical reagents. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this guide bridges theoretical principles with actionable protocols to enhance assay reliability and data integrity in biomedical research.

The Fundamental Science: Unraveling Why Primer Secondary Structures Form

Within the broader context of research into why primers form secondary structures, it is essential to recognize that these structures represent a fundamental challenge in molecular biology, significantly impacting the efficacy of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays [1]. Primer secondary structures are undesirable conformations that primers can adopt, which interfere with their primary function: to anneal specifically and efficiently to the target DNA template [2]. The formation of these structures is driven by the innate tendency of single-stranded nucleic acids to maximize stability through intramolecular and intermolecular base pairing, a principle grounded in thermodynamic spontaneity [3]. When primers form secondary structures, they become unavailable for the amplification reaction, leading to poor or failed experiments, reduced product yield, and inaccurate quantification in qPCR applications [1] [4]. Understanding the defining characteristics, formation mechanisms, and experimental consequences of hairpins, self-dimers, and cross-dimers is therefore not merely a procedural formality but a critical determinant of success in genetic research, diagnostics, and drug development [2].

Defining Core Concepts: Types of Primer Secondary Structures

Hairpins

Hairpins, also known as stem-loops, are formed by intramolecular interactions within a single primer molecule [4]. This occurs when a region of three or more nucleotides within the primer is complementary to another region within the same primer, causing the molecule to fold back on itself [2] [3]. The stability of a hairpin is commonly represented by its Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG) value, which indicates the energy required to break the secondary structure [1]. A more negative ΔG value indicates a more stable, and therefore more problematic, hairpin structure [1]. Hairpins are particularly detrimental when they form at the 3' end of the primer, as this is where DNA polymerase initiates synthesis, and their presence can block the enzyme from binding and extending [1].

Self-Dimers

Self-dimers are formed by intermolecular interactions between two identical primers (e.g., two forward primers or two reverse primers) [5]. This happens when a primer sequence has complementarity to itself, allowing two molecules to anneal to each other instead of to the template DNA [3]. The formation of self-dimers reduces the effective concentration of functional primers available for the intended reaction [1]. In a typical PCR, where primer concentrations are high relative to the target DNA, this can lead to a significant reduction in product yield as primers preferentially form dimers with each other rather than hybridizing with the target DNA [1].

Cross-Dimers

Cross-dimers, a specific type of heterodimer, are formed by intermolecular interactions between the forward and reverse primers of a primer pair due to inter-primer homology [1] [4]. When the sense and antisense primers have complementary sequences, they can anneal to each other, forming a primer-duplex that is unusable for amplification of the target template [1] [3]. Like self-dimers, cross-dimers sequester primers from the reaction, but they pose the additional risk of being efficiently extended by DNA polymerase since both primers provide free 3'-OH groups, leading to the amplification of short, primer-derived artifacts that compete with the target amplicon [3].

Table 1: Summary of Primer Secondary Structure Types

| Structure Type | Cause | Key Characteristic | Primary Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hairpin | Intra-primer homology [4] | Primer folds back on itself [3] | Blocks polymerase binding and extension [1] |

| Self-Dimer | Inter-primer homology (identical primers) [5] | Two copies of the same primer anneal [1] | Reduces available primer concentration [1] |

| Cross-Dimer | Inter-primer homology (F & R primers) [4] | Forward and reverse primers anneal [3] | Produces non-specific artifacts and reduces yield [3] |

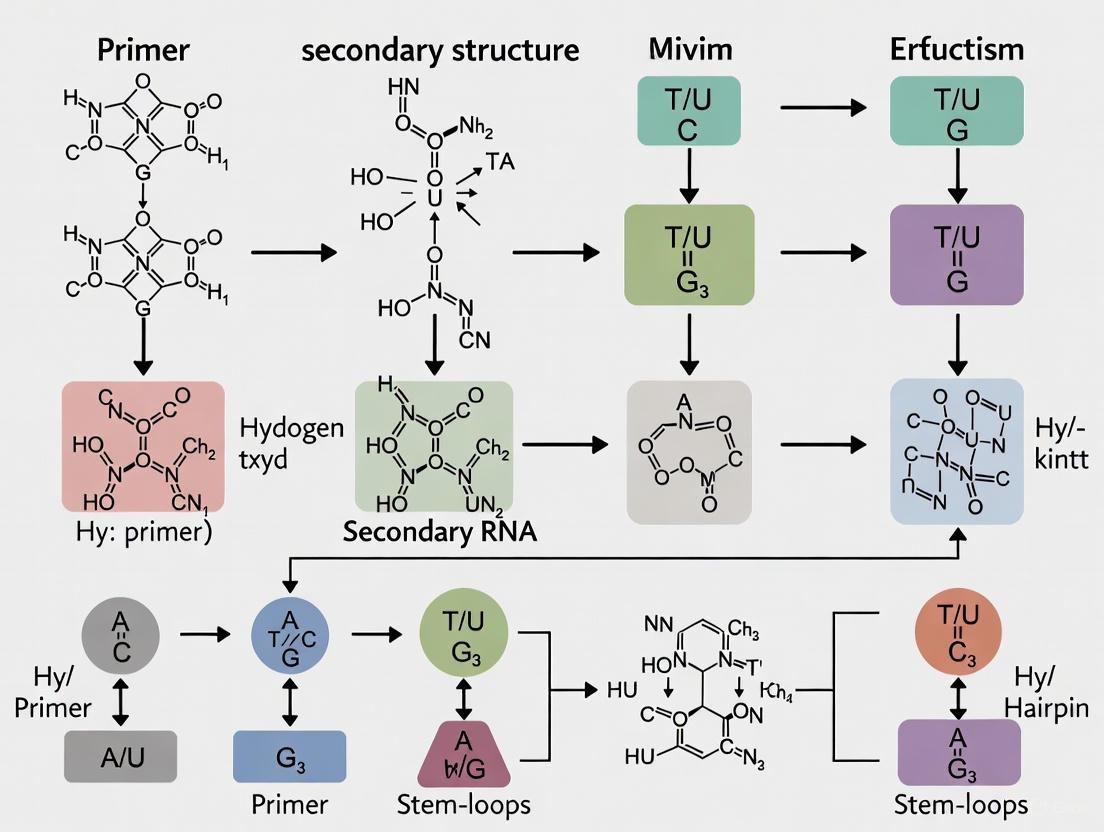

Figure 1: Schematic of secondary structure formation pathways from different primer starting states.

Thermodynamic Stability and Quantitative Design Parameters

The formation and stability of secondary structures are governed by thermodynamics. The key parameter is the Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG), which measures the spontaneity of a reaction—in this case, the formation of a secondary structure [1] [3]. A negative ΔG value indicates that the structure forms spontaneously and is stable, with larger negative values representing more stable, and therefore more problematic, structures [1] [3]. The ΔG is calculated as ΔG = ΔH – TΔS, where ΔH represents the change in enthalpy (energy from base-pair bonds) and ΔS represents the change in entropy (disorder) [1].

Researchers have established generally tolerated thresholds for the ΔG values of different secondary structures to guide primer design [1] [6]. These thresholds represent a balance; structures with ΔG values more negative than these are likely to be too stable to be easily denatured under standard PCR annealing conditions, thereby interfering with the reaction.

Table 2: Generally Tolerated ΔG Thresholds for Primer Secondary Structures [1] [6]

| Secondary Structure | Location | Generally Tolerated ΔG Threshold (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Hairpin | 3' End | ≥ -2.0 |

| Hairpin | Internal | ≥ -3.0 |

| Self-Dimer | 3' End | ≥ -5.0 |

| Self-Dimer | Internal | ≥ -6.0 |

| Cross-Dimer | 3' End | ≥ -5.0 |

| Cross-Dimer | Internal | ≥ -6.0 |

Beyond ΔG, other sequence characteristics heavily influence a primer's propensity to form secondary structures. A GC content between 40% and 60% is recommended, as G and C bases form three hydrogen bonds, creating more stable duplexes than A and T bases, which form only two [2] [5] [3]. While a "GC clamp" (one or two G or C bases at the 3' end) is beneficial for specific binding, more than three G/C bases in the last five bases at the 3' end should be avoided, as this can promote non-specific priming [1] [7]. Furthermore, runs of a single base (e.g., "AAAA") and di-nucleotide repeats (e.g., "ATATAT") can cause mispriming and should be avoided [1] [4] [3].

Experimental Consequences and Broader Research Implications

The practical consequences of primer secondary structures in the laboratory are severe and multifaceted. The most common outcome is a significant reduction in PCR product yield [1] [4]. This occurs because primers engaged in hairpins or dimers are functionally unavailable to anneal to the template DNA [1]. In quantitative applications like qPCR, this reduction in efficiency directly compromises data accuracy, leading to incorrect quantification of gene expression levels [8]. Furthermore, the formation of primer-dimers, especially cross-dimers, can lead to non-specific amplification, generating unwanted artifacts that compete for reaction components and can be mistaken for true amplification products in gel electrophoresis [2] [3]. In worst-case scenarios, typically when stable secondary structures form at the primers' 3' ends, the reaction can fail completely, yielding no amplification at all [1] [4].

Understanding why primers form these structures extends beyond troubleshooting failed experiments. It is a fundamental aspect of nucleic acid biochemistry with broad implications for research. The principles of intra- and intermolecular base pairing that govern primer behavior are the same ones that drive the formation of complex secondary and tertiary structures in functional RNAs, such as riboswitches, microRNAs, and ribosomal RNAs [9]. Misfolding in these molecules can disrupt critical regulatory functions and is implicated in various diseases [9]. Consequently, the tools and knowledge used to predict and avoid secondary structures in primers are directly applicable to predicting and understanding the function of natural RNA molecules. This knowledge is also leveraged in the design of therapeutic oligonucleotides and in forced evolution experiments to select for RNA aptamers with desired binding properties, making it highly relevant for drug development professionals [9].

Methodologies for Analysis and Validation

In Silico Analysis and Screening Protocols

The first and most crucial line of defense against secondary structures is computational analysis using specialized software tools.

- Screening with OligoAnalyzer Tool: Tools like the IDT OligoAnalyzer allow for thorough thermodynamic analysis [5] [6]. The procedure involves entering the primer sequence into the tool and using its functions to analyze for hairpins and self-dimers/homodimers. For cross-dimer analysis, both the forward and reverse sequences must be entered to check for heterodimers. The key output to evaluate is the ΔG value for any predicted structure, which should be compared against the tolerated thresholds (see Table 2) [5] [6]. IDT recommends that the ΔG of any self-dimers, hairpins, and heterodimers should be weaker (more positive) than -9.0 kcal/mol [5].

- Specificity Checking with BLAST: After designing primers, it is critical to check their specificity by performing a BLAST search against the appropriate genomic database (e.g., the non-redundant database for the target organism) [1] [7]. This identifies regions with significant cross-homology, which should be avoided during primer design to ensure amplification of only the intended target [1].

Figure 2: A recommended workflow for the analysis and validation of primers to avoid secondary structures.

Experimental Validation Techniques

After in silico screening, experimental validation is essential to confirm primer performance.

- Gel Electrophoresis for Specificity: After PCR amplification, the product should be analyzed by electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel [8]. A single, sharp band at the expected amplicon size confirms specific amplification and the absence of significant primer-dimer artifacts, which typically appear as a fuzzy band around 50 bp or lower [8].

- Melt Curve Analysis for qPCR: In qPCR experiments, performing a melt curve analysis is a critical step post-amplification [8]. The reaction is slowly heated while fluorescence is continuously measured. A single, sharp peak in the melt curve indicates that a single, specific PCR product has been amplified. The presence of multiple peaks or a broad peak suggests non-specific amplification or primer-dimer formation, indicating problematic primers [8].

- Empirical Determination of Annealing Temperature (Tₐ): Even with well-designed primers, the annealing temperature must be optimized. A gradient PCR is performed by setting a thermal cycler to a range of annealing temperatures (e.g., from 5°C below to 5°C above the calculated Tₐ) [4]. The resulting products are analyzed by gel electrophoresis. The highest temperature that produces the strongest, most specific band is the optimal Tₐ, as it maximizes stringency and minimizes non-specific binding and secondary structure stability [4].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Tools for Primer Analysis

| Tool or Reagent | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| OligoAnalyzer (IDT) | Thermodynamic analysis of hairpins, dimers, and Tm [5] | In silico primer screening and design |

| Primer-BLAST (NCBI) | Integrated primer design and specificity checking [8] [10] | In silico design of target-specific primers |

| UNAFold Tool | Analysis of oligonucleotide secondary structure [5] | Advanced in silico folding prediction |

| SYBR Green Master Mix | Fluorescent dye for detecting double-stranded DNA in qPCR [8] | Experimental validation via qPCR and melt curve analysis |

| Agarose | Matrix for gel electrophoresis to separate DNA by size [8] | Experimental validation of amplicon specificity and size |

| Thermal Cycler with Gradient | Instrument for PCR that allows temperature optimization across blocks [4] | Empirical determination of optimal annealing temperature (Tₐ) |

In the context of a broader thesis investigating why primers form secondary structures, understanding the governing thermodynamic principles is paramount. Nucleic acid primers do not exist as simple, linear single strands; they spontaneously fold into complex secondary structures—such as hairpins, self-dimers, and cross-dimers—through intramolecular and intermolecular base pairing [3] [11] [12]. The formation and stability of these structures are dictated by the fundamental laws of thermodynamics, primarily the Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG) and the Melting Temperature (Tm). These parameters are not merely abstract concepts but are critical, predictable forces that determine a primer's availability for binding to its target template. Failure to account for them during experimental design can lead to primer-dimer artifacts, non-specific amplification, and complete PCR failure [3] [11]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide on how ΔG and Tm govern the folding of primer secondary structures, equipping researchers with the knowledge to design more effective primers and oligonucleotide-based therapeutics.

Core Thermodynamic Principles

Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG) and Spontaneity

The Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG) is a measure of the spontaneity of a chemical reaction, in this case, the folding of a nucleic acid strand into a secondary structure. The stability of any secondary structure is commonly represented by its ΔG value, which is the energy required to break it [12].

- Negative ΔG (ΔG < 0): A spontaneous, exothermic reaction. Structures with large negative ΔG values (e.g., -5 kcal/mol) are stable and undesirable in primers, as they form easily and require significant energy (heat) to reverse [3].

- Positive ΔG (ΔG > 0): A non-spontaneous, endothermic reaction. Recent research demonstrates that even structures with positive ΔG° can form and exist at appreciable concentrations, significantly impacting hybridization kinetics. These "thermodynamically unfavorable" structures can change hybridization rates by two orders of magnitude and lead to non-Arrhenius behavior [13].

Table 1: Stability and Implications of Common Primer Secondary Structures

| Structure Type | Description | Stability (ΔG) | Impact on PCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hairpin | Intramolecular binding within a single primer, forming a loop [3] [12]. | 3' end: > -2 kcal/molInternal: > -3 kcal/mol [12] | Reduces primer availability; 3' end hairpins are most detrimental [12]. |

| Self-Dimer | Intermolecular binding between two identical primers [11] [12]. | 3' end: > -5 kcal/molInternal: > -6 kcal/mol [12] | Consumes primers, leading to low product yield or primer-dimer artifacts [11]. |

| Cross-Dimer | Intermolecular binding between forward and reverse primers [11] [12]. | 3' end: > -5 kcal/molInternal: > -6 kcal/mol [12] | Can cause catastrophic reaction failure by preventing target binding [11]. |

Melting Temperature (Tm) and Duplex Stability

The Melting Temperature (Tm) is defined as the temperature at which half of the DNA duplexes dissociate into single strands [12]. For secondary structures, the Tm indicates the thermal stability of these unintended conformations.

- Calculation: The most accurate method for calculating Tm is the nearest neighbor thermodynamic model, which accounts for the sequence-dependent stacking energies of dinucleotide pairs [12]. Simpler formulas, such as

Tm = 4°C x (G+C) + 2°C x (A+T), provide a rough estimate but are less reliable [11]. - Experimental Relevance: If the Tm of a primer's secondary structure is higher than the reaction's annealing temperature (Ta), the structure will not unfold, and the primer will be unavailable for binding [12]. This is a common cause of PCR failure. Optimal primer Tm generally falls between 52°C and 65°C, with primer pairs having Tms within 5°C of each other [11] [12] [14].

Experimental Protocols for Characterization

Accurately characterizing the thermodynamic properties of primers requires a combination of experimental techniques. The following protocols are standard in the field for validating primer behavior and verifying in silico predictions.

Stopped-Flow Fluorescence Kinetics

This method is used to measure the hybridization kinetics of oligonucleotides and is particularly effective for quantifying the influence of positive ΔG° secondary structures [13].

- Objective: To determine the second-order rate constant of DNA hybridization and observe non-Arrhenius behavior caused by nucleation-limited folding [13].

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dilute two complementary oligonucleotide strands in an appropriate buffer. One strand is typically fluorescently labeled.

- Rapid Mixing: The two strands are rapidly mixed in the stopped-flow instrument, initiating the hybridization reaction.

- Data Acquisition: Fluorescence change (e.g., from a dye like FRET pair) is monitored in real-time as a function of time after mixing.

- Data Analysis: The resulting kinetic trace is fitted to a second-order reaction model to obtain the rate constant (k). Experiments are repeated at various temperatures to study temperature dependence [13].

Thermal Melting Analysis

This protocol determines the melting temperature (Tm) and thermodynamic parameters (ΔH, ΔS, ΔG) of DNA duplexes and secondary structures.

- Objective: To experimentally determine the Tm and stability of primer secondary structures and primer-template duplexes [13] [12].

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a solution containing the oligonucleotide at a defined concentration in a standardized buffer.

- Spectrophotometer Setup: Load the sample into a UV-Vis spectrophotometer equipped with a temperature-controlled cell holder.

- Denaturation-Renaturation Cycle: Slowly heat the sample (e.g., from 20°C to 95°C) while monitoring the absorbance at 260 nm. Then, cool the sample back to the starting temperature.

- Data Analysis: Plot the absorbance versus temperature to generate a melting curve. The Tm is the point of the maximum first derivative of this curve. The thermodynamic parameters ΔH and ΔS can be calculated from a van't Hoff analysis of the melting curve [12].

Gradient PCR for Empirical Validation

This method empirically determines the optimal annealing temperature (Ta) for a PCR primer pair, which is directly influenced by the Tm of both the primer-template duplex and any primer secondary structures [11].

- Objective: To find the Ta that maximizes specific product yield while minimizing non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation.

- Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Set up a standard PCR master mix and aliquot it into multiple tubes or wells.

- Thermal Cycler Programming: Program a thermal cycler with a gradient across the blocks, typically spanning a range of 5-10°C below to above the calculated Ta.

- Amplification: Run the PCR protocol.

- Analysis: Analyze the PCR products using agarose gel electrophoresis. The well with the strongest band of the correct size and the least non-specific product indicates the optimal Ta [11].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for primer design and validation.

Advanced Considerations and Computational Design

The Challenge of "Unfavorable" Structures and Kinetics

The classical view that only stable (negative ΔG) secondary structures impact hybridization is incomplete. Groundbreaking research has shown that even thermodynamically unfavorable secondary structures (positive ΔG°) can alter hybridization kinetics by two orders of magnitude [13]. These structures exist in a dynamic equilibrium with the unfolded state, especially when |ΔG°| is small. Under isothermal conditions common in biosensors and DNA nanotechnology, these structures can trap oligonucleotides in a non-functional state, making hybridization nucleation-limited and leading to observed non-Arrhenius kinetics [13]. This necessitates kinetic models, not just thermodynamic equilibrium models, for accurate prediction in these contexts.

Integrated Thermodynamic Models in Primer Design

Modern primer design software has moved beyond simple rules-of-thumb to integrate sophisticated thermodynamic models.

- Pythia: This advanced method uses statistical mechanical models to compute the binding affinity between all relevant DNA dimers and the folding energy of individual nucleic acids. It then employs chemical reaction equilibrium analysis to model 11 competing reactions in a PCR (e.g., primer folding, dimerization, correct binding). The equilibrium concentrations of all species are calculated, and primer quality is assessed by the fraction of primers bound to their correct sites [15].

- Specificity Heuristics: Tools like Pythia also use thermodynamics to assess specificity, identifying the shortest stable suffix at the 3'-end of a primer and searching for exact matches in the background genome to predict off-target binding [15].

Diagram 2: Thermodynamic competition model in PCR.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Thermodynamic Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Stopped-Flow Spectrofluorometer | Measures rapid kinetics of nucleic acid hybridization [13]. | Essential for characterizing the influence of unstable secondary structures on hybridization rates [13]. |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer with Peltier | Measures thermal melting curves (Tm) of oligonucleotides [12]. | Data is used for van't Hoff analysis to determine ΔH and ΔS [12]. |

| Thermal Cycler with Gradient Function | Empirically determines optimal primer annealing temperature (Ta) [11]. | Critical for bridging in silico predictions with experimental reality [11] [14]. |

| DNA Polymerase Master Mix | Enzymatic amplification of the target DNA [14]. | Proofreading polymerases may degrade primers; this can be inhibited by phosphorothioate linkages at the 3' end [14]. |

| In Silico Design Software | Predicts secondary structures, ΔG, Tm, and specificity [15] [12]. | Tools include Primer3, Pythia, and commercial suites. They implement nearest-neighbor thermodynamics [15] [12]. |

The folding of primers into secondary structures is a direct physical consequence of the thermodynamic landscape, governed by ΔG and Tm. A deep understanding of these principles—including the nuanced role of kinetically significant, positive ΔG° structures—is fundamental to the "why" behind primer folding. Moving beyond basic design rules and leveraging integrated thermodynamic models and empirical validation allows researchers to proactively manage these forces. This approach is crucial for advancing robust PCR assay development, enhancing the efficacy of oligonucleotide therapeutics, and pushing the boundaries of DNA nanotechnology.

The formation of secondary structures in primers is not a random occurrence but a direct consequence of specific sequence determinants that dictate intermolecular and intramolecular interactions. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of how GC content, palindromic sequences, and base repeats fundamentally influence primer folding and dimerization. Within the broader thesis of why primers form secondary structures, we examine the biophysical principles governing these interactions, present optimized experimental protocols for mitigating structural issues, and provide a curated research toolkit. By understanding these sequence-based determinants, researchers can design more effective oligonucleotides, thereby enhancing the specificity and efficiency of molecular assays critical to diagnostic and therapeutic development.

In polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays, primers are the cornerstone of specificity and sensitivity. However, their performance is critically dependent on their linearity and ability to hybridize exclusively to the intended target sequence. The propensity of primers to form secondary structures—such as hairpins, self-dimers, and cross-dimers—is primarily encoded within their own nucleotide sequence [16]. These structures, which include intra-primer homology (complementarity within a single primer) and inter-primer homology (complementarity between forward and reverse primers), compete with target binding and can lead to failed amplification, reduced yield, and inaccurate quantification [17] [3].

This guide explores the core sequence determinants that predispose oligonucleotides to these problematic conformations: GC content, palindromic sequences, and base repeats. A deep understanding of these elements is not merely a design consideration but a fundamental prerequisite for reliable assay development in research and drug discovery contexts. The following sections detail the mechanisms, quantitative impacts, and practical strategies for managing these determinants.

GC Content: A Primary Driver of Stability and Structure

The Biophysical Basis of GC Influence

The guanine-cytosine (GC) pair is stabilized by three hydrogen bonds, compared to the two hydrogen bonds that stabilize adenine-thymine (AT) pairs [2] [18]. This difference in bond strength means that regions with high GC content exhibit significantly greater thermodynamic stability. This stability directly increases the primer's melting temperature (Tm), which is the temperature at which 50% of the DNA duplex is in a single-stranded state [17] [3]. While stable binding to the target is desired, this same principle facilitates unwanted intramolecular and intermolecular interactions when the primer is in a single-stranded state, leading to secondary structure formation.

GC-rich regions (typically defined as >60%) are particularly problematic because they are "bendable" and readily form stable secondary structures like hairpins that can block polymerase binding and extension [18]. Conversely, primers with very low GC content may lack the binding stability required for specific amplification.

Optimal GC Content and the GC Clamp

The consensus across multiple sources is that primers should have a GC content between 40% and 60% [17] [2] [5]. This range provides a balance between specificity and the avoidance of excessive stability that promotes secondary structures.

A critical design feature is the GC clamp. This refers to the presence of one or more G or C bases at the 3' end of the primer. The stronger hydrogen bonding of a GC clamp promotes more efficient binding by the DNA polymerase [17] [3]. However, caution is advised: more than three G or C bases at the 3' end can promote non-specific binding and false-positive results [2].

Table 1: Guidelines for Managing GC Content in Primer Design

| Parameter | Recommended Value | Rationale | Consequence of Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall GC Content | 40–60% [17] [5] | Balances specificity and binding stability without promoting excessive structure. | Low: Reduced Tm, poor binding. High: Increased secondary structure, non-specific binding. |

| GC Clamp | 1–2 G/C bases in the last 5 nucleotides at the 3' end [17] [3] | Stabilizes the critical polymerase binding site. | Too many (>3): Increases risk of primer-dimer and non-specific amplification [2]. |

| Consecutive Gs | Avoid runs of 4 or more [5] | Reduces complexity of synthesis and potential for non-standard structures. | Can lead to mispriming and difficult-to-denature quadruplex structures. |

Experimental Solutions for GC-Rich Target Amplification

Amplifying GC-rich templates (≥60% GC) requires specialized reagents and conditions to counteract their high stability and secondary structure formation.

- Polymerase and Buffer Systems: Use polymerases specifically optimized for GC-rich templates, such as OneTaq or Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase. These are often supplied with specialized GC Buffers and GC Enhancers [18]. These enhancers typically contain additives like betaine, DMSO, or glycerol, which help denature stable secondary structures by reducing the melting temperature of GC-rich DNA [19] [18].

- Mg²⁺ Concentration Optimization: Magnesium is a critical cofactor for polymerase activity. While standard reactions use 1.5–2 mM MgCl₂, GC-rich PCR may require fine-tuning. A gradient from 1.0 to 4.0 mM in 0.5 mM increments can help find the optimal concentration for specific amplification [18].

- Thermal Cycling Parameters: Using a higher denaturation temperature (e.g., 98°C instead of 95°C) or a longer denaturation time can help melt stubborn secondary structures. A touchdown PCR protocol, starting with an annealing temperature higher than the calculated Tm and gradually decreasing it over subsequent cycles, can improve specificity [18].

Palindromic Sequences and Primer Self-Complementarity

Defining the Problem: Hairpins and Dimers

Palindromic sequences, which read the same in the 5' to 3' direction on one strand as their complementary sequence does on the opposite strand, are a major source of secondary structures. When these sequences occur within a single primer, they enable intra-primer homology, leading to the formation of hairpin loops [3] [2]. When complementary sequences exist between two primers (or two copies of the same primer), they enable inter-primer homology, leading to the formation of self-dimers or cross-dimers [17] [3].

These structures are problematic because they consume primers that would otherwise be available for target amplification. Furthermore, if a primer's 3' end is involved in dimer formation, it can be extended by the polymerase, efficiently amplifying the dimer and competing with the desired product.

Quantifying and Evaluating Self-Complementarity

The stability of secondary structures is measured by their Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG). More negative ΔG values indicate a more stable, and therefore more problematic, structure [3]. IDT recommends that the ΔG of any predicted self-dimer, heterodimer, or hairpin should be weaker (more positive) than –9.0 kcal/mol [5].

Tools like the IDT OligoAnalyzer or Beacon Designer can be used to calculate ΔG and visualize potential secondary structures. It is critical to check for 3' end complementarity, as dimers or hairpins involving the 3' end are far more detrimental to PCR efficiency than those involving the 5' end [3].

Table 2: Types of Primer Secondary Structures and Their Characteristics

| Structure Type | Cause | Description | Key Design Check |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hairpin Loop | Intra-primer homology [3] | A single primer folds back on itself to form a stem-loop structure. | Avoid regions of ≥3 bases that are complementary within the primer [17]. |

| Self-Dimer | Inter-primer homology (identical primers) [3] | Two identical primers (e.g., two forward primers) anneal to each other. | Check for complementarity between copies of the same primer sequence. |

| Cross-Dimer | Inter-primer homology (different primers) [17] | The forward and reverse primers anneal to each other instead of the template. | Check for complementarity between the forward and reverse primer sequences. |

PST-PCR: An Advanced Application of Palindromic Sequences

Interestingly, palindromic sequences can be harnessed for specific experimental goals. The Palindromic Sequence-Targeted (PST) PCR method uses walking primers (PST primers) whose 3'-ends are designed to be complementary to short, naturally occurring palindromic sequences (PST sites) in the genome [20] [21]. This method, used for genome walking and transposon display, demonstrates a controlled application where knowledge of palindrome behavior is leveraged for specific annealing, avoiding the random priming that plagues other methods like TAIL-PCR [20]. The PST-PCR v.2 method is rapid (2–3 hours) and efficient, requiring only one or two PCR rounds due to its specific primer design that minimizes off-target annealing and RAPD-like amplification [21].

The Problem of Mononucleotide and Dinucleotide Repeats

Mechanisms of Mispriming

Runs of identical bases (homopolymers, e.g., AAAA) or dinucleotide repeats (e.g., ATATAT) are another significant sequence determinant of poor primer performance [17] [3]. These repetitive sequences increase the likelihood of the primer binding to non-target sites in the template genome that feature similar short repeats—a phenomenon known as mispriming. This occurs because the primer does not require perfect complementarity over its entire length to initiate polymerization; a repetitive sequence can find multiple partially complementary sites to bind to, especially at lower annealing temperatures.

Design Rules for Avoiding Repeats

The universal recommendation is to avoid runs of four or more of a single base (e.g., ACCCC) and dinucleotide repeats of four or more (e.g., ATATATAT) [17] [3]. Oligonucleotides containing these sequences are often more difficult to synthesize and may form non-Watson-Crick secondary structures that interfere with their intended function [17]. During the design process, the primer sequence should be visually inspected for such repeats, a check that is also a standard feature of most modern primer design software.

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: PCR Amplification of GC-Rich Targets

This protocol is adapted from recommendations for challenging GC-rich amplicons [19] [18].

Reaction Setup:

- Polymerase: Use a polymerase optimized for GC-rich templates (e.g., Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase, OneTaq DNA Polymerase).

- Buffer: Use the accompanying GC Buffer.

- Additives: Add 1x final concentration of the supplied GC Enhancer.

- Template: 75 ng genomic DNA or equivalent.

- Primers: 1.0 µM each, designed with a GC clamp and checked for secondary structures.

- dNTPs: 2.5 mM mix.

- Mg²⁺: The buffer typically contains Mg²⁺, but optimization from 1.0–4.0 mM may be required.

Thermal Cycling Conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 98°C for 4 minutes.

- Amplification (30 cycles):

- Denaturation: 94°C for 50 seconds.

- Annealing: Optimize using a temperature gradient, starting ~5°C above the calculated Tm.

- Extension: 72°C for 2 minutes.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 7 minutes.

Analysis: Analyze 5 µL of the PCR product on a 1.5% agarose gel.

Protocol 2: Primer Validation and Specificity Check

Ensuring primer specificity is a critical step before experimental use [16] [5].

In Silico Analysis:

- Secondary Structures: Analyze primers using tools like OligoAnalyzer to check for hairpins and self-dimers (ΔG > -9.0 kcal/mol).

- Specificity Check: Perform an NCBI Primer-BLAST analysis. This tool checks the specificity of the primer pair against the entire nucleotide database to ensure it will only amplify the intended target [22].

- Cross-Homology: Verify that primers are unique to the desired target sequence and do not have significant homology to other genes or regions.

Wet-Lab Validation:

- Perform a temperature gradient PCR to empirically determine the optimal annealing temperature.

- Include a no-template control (NTC) to check for primer-dimer formation.

- Sequence the PCR product to confirm amplification of the correct target.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Managing Primer Secondary Structures

| Tool / Reagent | Category | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| OligoAnalyzer Tool (IDT) | In Silico Tool | Analyzes Tm, hairpins, dimers, and ΔG values for oligonucleotides [5]. | Pre-design validation to screen out primers with stable secondary structures (ΔG < -9.0 kcal/mol). |

| NCBI Primer-BLAST | In Silico Tool | Designs primers and checks their specificity against the NCBI database to avoid off-target binding [22]. | Ensuring primers are unique to the target gene and do not have cross-homology. |

| Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase with GC Enhancer | Wet-Lab Reagent | High-fidelity enzyme with additives to denature GC-rich secondary structures [18]. | Amplifying targets with >70% GC content or persistent hairpins. |

| OneTaq GC Enhancer | Wet-Lab Reagent | Additive containing betaine/DMSO that reduces DNA secondary structure stability [18]. | Added to the PCR mix to improve yield and specificity for GC-rich templates. |

| DMSO / Betaine / Formamide | Wet-Lab Additive | Additives that lower DNA Tm, disrupt hydrogen bonding, and increase primer stringency [19] [18]. | Empirical testing to overcome amplification failure due to template or primer structure. |

The formation of secondary structures in primers is a direct and predictable result of specific sequence elements: high GC content provides the thermodynamic stability for structure formation, palindromic sequences provide the complementary geometry for intra- and intermolecular binding, and base repeats increase the probability of mispriming. Within the broader thesis of why primers form secondary structures, this guide establishes that these determinants are not independent but often interact, compounding their negative effects on PCR efficacy. By applying the design rules, experimental protocols, and toolkit resources outlined herein, researchers and drug developers can proactively diagnose and prevent these issues. This leads to more robust, reproducible, and specific molecular assays, accelerating the pace of scientific discovery and diagnostic innovation.

The kinetic competition between intramolecular and intermolecular interactions is a fundamental determinant of macromolecular behavior, influencing processes from protein folding to the self-assembly of amyloid fibrils. This interplay is of paramount importance in molecular biology, dictating whether a polypeptide chain adopts a functional native structure or progresses toward pathological aggregation. Within the context of primer design for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methodologies, this same competition determines whether a single-stranded DNA oligonucleotide remains available for hybridization with its target template or forms stable, non-productive secondary structures. Such primer dimerization and self-folding are a significant source of experimental artifact, reducing assay specificity, sensitivity, and robustness. This whitepaper explores the governing principles of this kinetic competition, drawing upon quantitative studies of protein aggregation to illuminate the analogous challenges in nucleic acid research. We provide a structured analysis of key quantitative parameters, detailed experimental protocols for characterizing these interactions, and strategic guidance for mitigating their adverse effects in scientific and diagnostic applications.

The fate of a polymeric molecule, be it a protein or a single-stranded DNA primer, is often decided by a kinetic race between two types of interactions. Intramolecular interactions occur between different parts of the same molecule, promoting its collapse into a stable, defined structure, such as a globular protein fold or a primer hairpin loop. In contrast, intermolecular interactions occur between two or more separate molecules, driving their association into larger complexes, such as amyloid fibrils or primer dimers [23] [24].

The outcome of this competition has profound consequences. In proteins, a shift in favor of intermolecular interactions can lead to aggregation diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's [23] [25]. In PCR, the formation of intramolecular (secondary structures) or intermolecular (primer-dimer) complexes directly competes with the desired intermolecular hybridization between the primer and the target DNA template [16]. This results in failed amplification, reduced yield, and inaccurate quantification. The principles governing this competition are universal, revolving around the relative strengths, dynamics, and accessibility of these interaction networks.

Quantitative Data and Comparative Analysis

The kinetic parameters of folding and aggregation reveal the core of the competition. The following table summarizes key quantitative data from protein aggregation studies, which provide a conceptual framework for understanding similar processes in nucleic acids.

Table 1: Quantitative Parameters in Protein Folding and Aggregation Kinetics

| Parameter | Description | Impact on Competition | Typical Range/Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lag Time | The initial slow phase in aggregation, often involving nucleation. | A longer lag time indicates a higher kinetic barrier to intermolecular association, favoring intramolecular folding. | Minutes to hours, highly sequence-dependent [23] |

| Elongation Rate | The apparent rate constant for fibril growth after nucleation. | A faster elongation rate favors intermolecular aggregation once nucleation has occurred. | Measured by Thioflavin T fluorescence kinetics [25] |

| Aggregation Propensity | The intrinsic tendency of a sequence segment to form intermolecular β-sheets. | Modulated by residual structure in the precursor state [23] | Calculated by algorithms like Zyggregator [23] [25] |

| Intramolecular Bond Strength | Energy required to break internal bonds (e.g., H-bonds in a folded protein or primer hairpin). | Stronger intramolecular bonds protect against intermolecular aggregation [24] | ~464 kJ/mol for covalent H-O bonds (intramolecular) [24] |

| Intermolecular Bond Strength | Energy of bonds formed between molecules (e.g., in a fibril or primer dimer). | Stronger intermolecular bonds drive aggregation. | ~19 kJ/mol for water-water bonds (intermolecular) [24] |

For PCR primers, the competition is similarly quantifiable. The annealing temperature (Ta) of a primer to its target is a critical variable, rather than its theoretical melting temperature (Tm). The optimal Ta must be determined experimentally, as it defines the temperature at which the maximum amount of primer is bound to its target, thereby outcompeting intramolecular folding or primer-dimer formation [16]. Furthermore, the efficiency of the PCR reaction, ideally close to 100%, is a direct measure of successful intermolecular priming; reduced efficiency often signals competition from non-productive structures.

Case Study: Amyloid Formation in β₂-Microglobulin

A seminal study on human β₂-microglobulin (β₂m) provides a powerful illustration of this kinetic competition. At low pH, β₂m exists in an acid-denatured state that lacks persistent tertiary structure but contains significant non-random hydrophobic interactions (intramolecular) [23] [25].

Experimental Protocol and Workflow

The investigation employed a multi-faceted approach to dissect the aggregation mechanism:

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Key regions of the β₂m sequence were altered to perturb specific intramolecular interactions and assess their impact on aggregation kinetics.

- Quantitative Kinetic Analysis: The kinetics of fibril formation were monitored using thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence, which binds specifically to amyloid structures. The output of this assay provides two critical kinetic parameters: the length of the lag phase and the apparent elongation rate [25].

- NMR Spectroscopy: Used to characterize the residual structure and conformational properties of the acid-unfolded monomeric precursor state.

- Computational Prediction: The experimental data from NMR was incorporated into the Zyggregator algorithm to predict aggregation-prone regions and rationalize the kinetic data [23].

Despite the presence of multiple regions with a significant intrinsic propensity for aggregation, the study revealed that only a single region of about 10 residues in length was the primary determinant of the fibril formation rate. This key region was shielded by residual intramolecular interactions in the denatured state. Mutations that disrupted these protective intramolecular contacts significantly accelerated the aggregation kinetics by exposing this aggregation-prone "hot spot" [23] [25]. This demonstrates that the intrinsic aggregation propensity of a sequence is powerfully modulated by the conformational properties of its precursor state.

Visualizing the Kinetic Competition Pathway

The pathway of this competition, from functional monomer to pathological aggregate, can be summarized in the following workflow. The central decision point is the kinetic competition between intramolecular folding and intermolecular association.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimental analysis of intramolecular and intermolecular interactions requires a suite of specific reagents and tools. The following table details key materials used in the featured β₂m study and their analogous applications in nucleic acid research.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Molecular Interactions

| Reagent/Material | Function in Protein Studies | Analogous Tool in Nucleic Acid Research |

|---|---|---|

| Thioflavin T (ThT) | A fluorescent dye that binds specifically to amyloid fibrils, allowing quantitative kinetic analysis of aggregation [25]. | SYBR Green I; a fluorescent dye that intercalates into double-stranded DNA, enabling real-time monitoring of PCR amplification. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | To systematically alter protein sequence and probe the role of specific residues in intramolecular vs. intermolecular interactions [23]. | Oligonucleotide Synthesis Services; for custom-designing and ordering primer variants with modified sequences to avoid secondary structures. |

| NMR Spectroscopy | To characterize residual structure and dynamics in denatured monomeric states at atomic resolution [23] [25]. | Thermal Denaturation (Tm) Analysis; using UV spectrophotometry to assess the stability and melting profile of primer secondary structures. |

| Zyggregator Algorithm | A computational prediction algorithm that identifies aggregation-prone regions in protein sequences [23] [25]. | Primer Design Software (e.g., mFold, OligoAnalyzer); in silico tools to predict primer secondary structures, dimer formation, and annealing properties [16]. |

| qPCR Master Mixes | Not applicable to protein studies. | Optimized Buffers; commercial master mixes containing optimized salts, buffers, and enzymes to promote specific primer-template binding over non-productive interactions [16]. |

Connecting the Principles to Primer Secondary Structure Research

The principles elucidated in the β₂m case study translate directly to the challenge of why primers form secondary structures. A single-stranded DNA primer, much like an unfolded polypeptide, is a flexible chain with competing internal and external interaction potentials.

Residual Structure and "Hot Spots": Just as residual structure in the acid-denatured β₂m masked its primary aggregation "hot spot," a primer's sequence can contain self-complementary regions that act as nucleation points for intramolecular folding (e.g., hairpin loops) or intermolecular dimerization with another primer [16]. These structures are often stable and can outcompete the desired binding to the target template, especially under suboptimal reaction conditions.

Kinetics and Experimental Robustness: The competition is governed by kinetics. A robust PCR assay is one where the rate of correct primer-template hybridization is vastly favored. This is achieved by careful primer design to avoid stable intramolecular structures and by empirical optimization of the annealing temperature (Ta) [16]. A primer that only functions within a narrow Ta range is inherently non-robust, indicating a precarious balance where slight perturbations can tip the scales in favor of non-productive interactions.

Visualizing Primer Competitive Pathways

The fate of a primer in a PCR reaction is determined by a kinetic competition analogous to that of proteins, as shown in the following pathway.

Experimental Protocol: A Standardized Workflow for Primer Validation

To mitigate the risks posed by secondary structures, a rigorous and standardized experimental workflow is essential. The following protocol, aligned with systems biology best practices for generating reproducible quantitative data [26], ensures robust PCR assay design and validation.

Objective: To empirically validate primer specificity and optimize reaction conditions to minimize the impact of intramolecular and intermolecular competition.

Materials:

- Purified template DNA (concentration accurately quantified)

- Designed forward and reverse primers

- qPCR master mix (commercial, from a defined lot)

- Nuclease-free water

- Thermal cycler (calibrated)

Procedure:

In Silico Analysis:

- Target Identification: Acquire the correct target sequence from a curated database (e.g., NCBI RefSeq) and always refer to its accession number [16].

- Primer Characterization: Use oligonucleotide analysis software to check for self-complementarity, hairpin formation, and potential for primer-dimer artifacts. Calculate theoretical Tm values.

Empirical Optimization:

- Annealing Temperature Gradient: Run a thermal gradient PCR, typically spanning 3-5°C below and above the calculated average Tm of the primer pair. The goal is to identify the temperature that yields the lowest Cq (quantification cycle) value with the highest fluorescence (ΔRn) and no non-specific amplification [16].

- Specificity Verification: Analyze the amplification products from the gradient run using gel electrophoresis. A single band of the expected size confirms specific amplification. Alternatively, analyze the melt curve for a single, sharp peak.

Validation and Data Processing:

- Efficiency Calculation: Perform a serial dilution (at least 5 points) of the template and run qPCR at the optimized Ta. The slope of the log (template concentration) versus Cq plot is used to calculate amplification efficiency (E) using the formula: E = 10^(-1/slope) - 1. Ideal efficiency is 100% (slope = -3.32) [16].

- Data Documentation: Report all critical information, including primer sequences, accession number of the target, optimized Ta, calculated efficiency, and the master mix used, as per the MIQE guidelines [16].

The kinetic competition between intramolecular and intermolecular interactions is a unifying principle across macromolecular biochemistry. The detailed study of amyloid-forming proteins like β₂-microglobulin provides a quantitative and mechanistic framework for understanding this contest, revealing that the intrinsic propensity of a chain to self-associate is powerfully modulated by the structural dynamics of its monomeric state. In the realm of molecular biology, this same competition underpins the critical challenge of primer secondary structure formation, which can subvert the accuracy and efficiency of PCR-based assays. By applying the lessons from protein biophysics—emphasizing rigorous in silico design, empirical optimization, and standardized validation—researchers can effectively steer the kinetic competition toward the desired intermolecular outcome, ensuring the generation of specific, reliable, and reproducible data.

Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) intermediates, essential during DNA replication, recombination, and repair, remain vulnerable to enzymatic degradation and secondary structure formation. These structures, including hairpins and loops, pose a significant biochemical challenge by impeding the progression of replicative enzymes like DNA polymerase (DNAp). Single-stranded DNA-binding proteins (SSBs) protect these transiently exposed regions by coating ssDNA, preventing hairpin formation, and recruiting replication machinery. However, this protective mechanism creates a paradox: given SSBs' high affinity for ssDNA, how do replicative enzymes efficiently navigate these potential barriers during DNA synthesis? The mechanism by which polymerases overcome or displace SSB-DNA complexes without hindering replication remains a fundamental yet incompletely resolved question in molecular biology [27].

This whitepaper explores the biochemical consequences of secondary structures and protein-bound DNA on polymerase function, framed within the broader thesis of primer secondary structure research. We examine how these structures mechanically hinder polymerase binding and primer extension, detailing the experimental approaches used to quantify these effects at the single-molecule level. Understanding these dynamics is critical for drug development professionals targeting DNA replication processes in therapeutic interventions.

Quantitative Effects of Structural Obstacles on Polymerization

Single-molecule studies reveal that structural obstacles on the DNA template, including bound SSB proteins and intrinsic secondary structures, modulate DNA replication rates in a force-dependent manner. This relationship highlights the direct mechanical challenge these structures pose to the polymerase.

Table 1: Force-Dependent Replication Rates With and Without SSB Proteins

| Template Tension | Experimental Condition | Replication Rate (bp/s, mean ± SEM) | Probability of Exonuclease (backtracking) Events | Key Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 pN | No SSB | 180 ± 10 (N=67) | Higher | Secondary structures impede replication; SSB prevents these, enhancing rate. |

| 10 pN | With SSB | 230 ± 20 (N=72) | Lower | SSB coating prevents secondary structure formation, accelerating replication by ~20% (p=0.0467). |

| 20 pN | No SSB | 130 ± 10 (N=63) | Lower | Minimal secondary structure exists; replication proceeds without major hindrance. |

| 20 pN | With SSB | 80 ± 5 (N=81) | Lower | SSB proteins become unnecessary obstacles, reducing replication efficiency (p<0.0001). |

The data in Table 1, derived from high-resolution optical tweezers studies, demonstrate SSB's dual role. At lower tension (10 pN), conducive to secondary structure formation, SSB binding is beneficial, enhancing the replication rate by approximately 20%. In contrast, at higher tension (20 pN), which inherently disrupts secondary structures, SSB proteins impede replication, reducing the rate by nearly 40%. This force-dependent modulation provides direct evidence of how physical obstructions on the template strand biochemically consequence polymerase progression [27].

Experimental Methodologies for Investigating Polymerase Obstruction

Investigating the dynamic interplay between DNA polymerase and template obstacles requires methodologies capable of capturing real-time, high-resolution biomolecular processes. The following protocols outline key experimental approaches.

Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy with Optical Tweezers

This technique measures DNA length changes catalyzed by DNA polymerase under controlled template tension [27].

- 1. Experimental Setup: A DNA template is tethered between two optically trapped beads, allowing precise application and measurement of force on the DNA molecule. The end-to-end distance (EED) between the beads is monitored in real-time.

- 2. Interpreting EED Changes:

- Polymerase Activity: At lower tensions (e.g., 10-20 pN), DNA synthesis converts ssDNA to double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), shortening the EED.

- Exonuclease Activity: At higher tensions (e.g., 50 pN), the polymerase preferentially switches to its exonuclease mode, digesting DNA and increasing the ssDNA fraction, thereby lengthening the EED.

- 3. Data Analysis:

- Replication Kinetics: The number of base pairs synthesized over time is calculated from the EED, accounting for SSB-induced compaction of ssDNA.

- Activity Transition Points: A change-point detection algorithm is applied to base pair-time traces to identify shifts between polymerase and exonuclease activities, quantifying the enzyme's binding preference and backtracking frequency.

Dual-Color Single-Molecule Imaging

This approach visualizes the spatial and temporal dynamics between polymerase and SSBs directly [27].

- 1. Fluorescent Labeling: T7 SSB and T7 DNA polymerase are labeled with distinct fluorescent tags (e.g., different fluorophores for dual-color imaging).

- 2. Imaging and Tracking: The co-localization and movement of these labeled proteins on the DNA template are observed using fluorescence microscopy.

- Key Finding: SSBs remain stationary as the DNA polymerase advances, supporting a sequential displacement model rather than a cooperative pushing mechanism.

- 3. FRET Analysis: Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) is used to detect close spatial proximity (typically <10nm) between the polymerase and SSB during encounters, indicating direct physical interaction or "collision."

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

MD simulations provide atomic-level insights into the transient events of SSB displacement, which are challenging to capture experimentally [27].

- 1. Model System: A coarse-grained protein model like AWSEM is employed, which has been benchmarked for simulating protein-DNA interactions and large-scale motions.

- 2. Simulation of Encounter: The simulation models the approach of DNA polymerase towards an SSB-ssDNA complex.

- 3. Energy Analysis:

- The binding energy of the SSB-ssDNA complex is calculated in the presence and absence of DNA polymerase.

- A reduction in the dissociation energy barrier in the polymerase's presence indicates an active, facilitative displacement mechanism.

- Analysis of electrostatic interactions reveals the role of specific protein domains, such as the SSB's C-terminal tail.

Visualizing the Mechanistic Workflow and Key Findings

The following diagrams, created using Graphviz and adhering to the specified color and contrast guidelines, illustrate the core experimental workflow and the mechanistic findings.

Polymerase-SSB Interplay Workflow

Sequential Displacement Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Polymerase Obstruction Studies

| Item | Function in Research | Technical Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteriophage T7 Replication System | A well-characterized model system for studying polymerase-SSB interactions. | Includes T7 SSB (binds as a monomer) and T7 DNA polymerase. Mechanistically similar to more complex organisms [27]. |

| T7 SSB with C-terminal Tail | Critical for efficient polymerase-mediated displacement. The acidic tail interacts with polymerase. | The C-terminal truncated mutant (mut T7 SSB) shows reduced replication efficiency, validating its functional role [27]. |

| Optical Tweezers Setup | Applies controlled tension to a single DNA molecule to study replication mechanics. | Enables precise measurement of replication rates and enzyme mode switching (polymerase vs. exonuclease) under force [27]. |

| Fluorophore-labeled Proteins | Enables visualization of protein dynamics via dual-color imaging and FRET. | Used to track SSB and polymerase positions in real-time and confirm their close spatial proximity during collisions [27]. |

| Coarse-Grained MD Simulation (AWSEM) | Provides atomic-level insights into SSB displacement mechanics and energy landscapes. | Models the reduction in SSB-ssDNA binding energy facilitated by polymerase interaction, predicting mechanistic steps [27]. |

The journey of DNA polymerase along its template is fraught with structural impediments, from intrinsic secondary structures to protective SSB proteins. The biochemical consequence is a force-dependent modulation of replication efficiency, where these structures can either facilitate or hinder polymerase binding and extension depending on the template's conformational state. The mechanistic model that emerges is one of active, sequential displacement of SSBs, critically dependent on specific protein-protein interactions mediated by the SSB's C-terminal tail.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings highlight the delicate balance the replication machinery must maintain between DNA protection and synthesis efficiency. Targeting the interaction interfaces identified in these studies—such as the SSB C-terminal tail or the polymerase's basic patch region—offers a potential avenue for novel therapeutic interventions. Disrupting this precise spatiotemporal coordination could provide a powerful mechanism for controlling cellular replication in diseases like cancer, underscoring why research into primer secondary structures and their consequences remains a critical frontier in molecular biology.

Strategic Primer Design: Methodologies to Prevent Secondary Structures

In molecular biology, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) serves as a fundamental technique for DNA amplification, with its success critically dependent on the design of oligonucleotide primers. Primer secondary structures such as hairpins and primer-dimers represent a significant challenge in assay development, directly impacting efficiency, specificity, and sensitivity. These structures form due to inherent complementarity within a single primer or between primer pairs, leading to unintended amplification events that compete with the target sequence [28] [29]. Within the context of a broader thesis on why primers form secondary structures, this guide establishes the core design rules—optimizing length, GC content, and melting temperature (Tm)—as the primary strategy for enhancing primer stability and assay performance. Understanding the thermodynamic principles governing these parameters enables researchers to proactively minimize non-specific interactions, thereby ensuring the accuracy and reliability of results in applications ranging from basic research to clinical diagnostics and drug development [2] [19].

Core Principles of Primer Design

The stability and specificity of a primer are governed by three interdependent physicochemical properties: its length, guanine-cytosine (GC) content, and melting temperature (Tm). Adherence to established ranges for these parameters reduces the potential for secondary structure formation by minimizing regions of self-complementarity and ensuring balanced binding energy.

Primer Length

Primer length directly influences both specificity and hybridization efficiency. Excessively short primers risk non-specific binding, while overly long primers hybridize more slowly and can form complex secondary structures [2].

- Optimal Range: 18–30 nucleotides is the generally recommended length for PCR primers [17] [30] [2]. This range provides a sufficient sequence for specific binding while maintaining efficient annealing.

- Mechanism: Shorter primers within this range (e.g., 18–24 bases) anneal more efficiently to the target sequence, requiring fewer PCR cycles for amplicon generation [2]. Specificity is sufficiently maintained because the probability of a unique sequence of 18 bases or longer occurring by chance in a complex genome is very low.

GC Content

The GC content, which is the percentage of guanine (G) and cytosine (C) bases in the primer, dictates the strength of the primer-template binding due to the three hydrogen bonds formed in a GC base pair compared to the two in an AT base pair [2].

- Optimal Range: A GC content of 40–60% is considered ideal for most applications [17] [30] [2].

- GC Clamp: The presence of one or two G or C bases in the last five nucleotides at the 3' end of the primer is known as a GC clamp. This promotes stronger binding at the terminus where DNA polymerase initiates synthesis. However, more than three G or C bases at the 3' end should be avoided, as this can promote non-specific binding [17] [2].

Melting Temperature (T~m~)

The melting temperature (Tm) is the temperature at which 50% of the DNA duplex dissociates into single strands. It is a critical parameter for determining the optimal annealing temperature in a PCR protocol [2].

- Optimal Range: Primers should have a Tm between 54°C and 65°C, with many protocols recommending an optimal Tm around 60°C [17] [30] [2].

- Primer Pair Matching: The Tm of the forward and reverse primers should be within 1–5°C of each other to ensure both primers anneal to their target sequences simultaneously and with similar efficiency [17] [30]. A maximum difference of 4°C is often stipulated [30].

The following table summarizes these core design parameters:

Table 1: Core Design Parameters for Primer Optimization

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Rationale | Consequence of Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length | 18–30 nucleotides [17] [2] | Balances specificity with efficient hybridization. | Short: Non-specific binding; Long: Slower hybridization, increased secondary structure risk [2]. |

| GC Content | 40–60% [17] [30] | Ensures stable yet not overly strong binding. | Low: Weak binding; High: Mismatches, primer-dimer formation [2]. |

| Melting Temp (T~m~) | 54–65°C [30] [2] | Allows for specific annealing at a practicable temperature. | Low: Non-specific amplification; High: Reduced efficiency or no yield [28]. |

| T~m~ Difference (Pair) | ≤ 4°C [30] | Ensures synchronized annealing of both primers. | Large difference: One primer anneals inefficiently, reducing yield [30]. |

The Structural Biology of Primer Defects

When core design rules are neglected, primers become prone to forming stable secondary structures that severely compromise PCR efficiency. These defects arise from predictable thermodynamic interactions and can be visualized as specific structural entities.

Primer-Dimers

Primer-dimers are short, unintended DNA fragments formed when primers anneal to each other instead of the target template. This occurs through two primary mechanisms [28]:

- Self-Dimerization: A single primer contains regions complementary to itself, allowing two copies to hybridize.

- Cross-Dimerization: The forward and reverse primers have complementary regions, causing them to bind together.

In both cases, the hybridized primers create a free 3' end that DNA polymerase can extend, effectively amplifying the primer dimer itself. This consumes reaction components and competes with the amplification of the desired target [28] [29]. In quantitative PCR (qPCR), this non-specific amplification can lead to false-positive signals and inaccurate quantification [29].

Hairpin Structures

Hairpins (or stem-loops) are intramolecular structures that form when two regions within a single primer are complementary, causing the molecule to fold back on itself [2] [19]. This is particularly problematic in longer primers, such as the 40–45 base inner primers used in loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) [29].

- Formation Mechanism: The complementary regions form a stable double-stranded "stem," while the non-complementary loop region remains single-stranded.

- Impact on PCR: Hairpins can prevent the primer from binding to its template sequence. If the hairpin structure has complementarity at the 3' end, it can become a self-amplifying structure, leading to non-specific background amplification and consuming reagents [29].

Table 2: Characteristics and Impacts of Common Primer Secondary Structures

| Structure | Formation Mechanism | Key Impact on PCR | Identification Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primer-Dimer | Inter-primer complementarity [28]. | Consumes primers/dNTPs; competes with target; causes smears on gels [28] [29]. | No-template control (NTC) shows amplification; fuzzy bands below 100 bp [28]. |

| Hairpin | Intra-primer complementarity [2]. | Blocks template binding; can self-amplify; reduces efficiency [29] [19]. | Primer design software (e.g., calculates self 3'-complementarity) [30] [2]. |

| Self-Amplifying Hairpin | Hairpin with a free, complementary 3' end [29]. | Causes exponential non-specific amplification in negative controls. | Real-time monitoring shows rising baseline in NTC [29]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between poor design, the formation of these structural defects, and their ultimate negative consequences in the PCR process.

Diagram 1: Primer Defect Formation and Consequences

Experimental Protocols for Optimization and Troubleshooting

In Silico Design and Validation Workflow

A rigorous computational workflow is essential for designing robust primers and identifying potential structural defects before synthesis.

- Step 1: Sequence Retrieval and Preparation. Retrieve the target gene sequence from a curated database like NCBI. For genes with unknown sequences in the target organism, use sequences from closely related organisms and perform multiple sequence alignment using tools like CLUSTALW to identify conserved regions [31].

- Step 2: Primer Design with Primer3. Use Primer3 with the parameters outlined in Table 1. Key settings include: Primer Size: Min=18, Opt=20, Max=27; Tm: Min=62°C, Opt=64°C, Max=66°C; GC%: Min=40, Opt=50, Max=60 [31].

- Step 3: Specificity Check with BLAST. Run the designed primer sequences through the NCBI Primer-BLAST tool to ensure they are unique to the intended target and do not bind off-target to other genes or homologous sequences [32] [31].

- Step 4: Secondary Structure Analysis. Use tools like OligoAnalyzer (IDT) or the Multiple Prime Analyzer (Thermo Fisher) to check for self-dimers, cross-dimers, and hairpins. The parameters "self-complementarity" and "self 3'-complementarity" should be as low as possible [2] [29]. The stability of any predicted hairpin, particularly near the 3' end, is a critical factor for potential self-amplification [29].

Wet-Lab Optimization of Problematic Primers

When secondary structures persist or amplification fails, empirical optimization is required.

Protocol 1: Tackling Primer-Dimers.

- Lower Primer Concentration: Reducing primer concentration (a common working stock is 10–100 µM) gives primers fewer opportunities to interact with each other [28] [33].

- Increase Annealing Temperature: Incrementally raise the annealing temperature by 2–5°C above the calculated Tm to disrupt nonspecific interactions [28].

- Use Hot-Start Polymerase: Hot-start polymerases remain inactive until a high-temperature denaturation step, preventing polymerase activity during reaction setup and reducing primer-dimer formation [28].

Protocol 2: Amplifying GC-Rich Targets. Genes with high GC content (e.g., >70%) are prone to forming stable secondary structures that halt polymerase progression [19].

- Primer Redesign via Codon Optimization: For protein-coding sequences, modify the primer sequence by substituting bases at the wobble position of codons. This changes the DNA sequence without altering the amino acid sequence, effectively breaking up long GC stretches and disrupting stable secondary structures [19].

- Add PCR Enhancers: Include additives like 3–6% DMSO or glycerol in the reaction mix. These reduce the melting temperature of DNA and help denature stubborn secondary structures [19].

- Adjust Thermocycling Parameters: Increase the denaturation temperature and/or time to ensure the GC-rich template is fully melted at each cycle [19].

Protocol 3: Empirical Determination of Annealing Temperature.

- Use a Tm Calculator: Input primer sequences and concentration into a calculator to get a recommended Tm and a starting annealing temperature [34].

- Run a Temperature Gradient PCR: Using the calculated annealing temperature as a midpoint, set a thermal gradient that spans a range of 6–10°C to empirically determine the ideal temperature for specificity and yield [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and tools are essential for implementing the protocols described in this guide and for achieving successful, specific amplification.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Primer Design and Optimization

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Description | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | An enzyme inactive at room temperature, activated only at high temperatures (~95°C). | Minimizes primer-dimer formation and non-specific amplification during reaction setup [28]. |

| Primer Design Software (Primer3) | A freely available online tool for designing primers based on user-defined parameters. | The primary tool for generating candidate primer pairs with optimal length, Tm, and GC content [30] [31]. |

| Secondary Structure Analysis Tool (OligoAnalyzer) | A tool for calculating Tm, GC%, and analyzing potential for dimers and hairpins. | Used to screen and reject primers with high self-complementarity or stable 3' hairpins [2] [19]. |

| DMSO (Dimethyl Sulfoxide) | A PCR additive that reduces nucleic acid melting temperature. | Added to PCR mixes (e.g., 5% v/v) to assist in denaturing templates and primers with high GC content or secondary structure [19]. |

| No-Template Control (NTC) | A control reaction containing all PCR components except the template DNA. | Critical for identifying contamination and confirming that amplification signals (e.g., in qPCR) are not from primer-dimers [28]. |

| T~m~ Calculator | A tool for calculating primer melting temperature and recommending annealing temperature. | Provides a data-driven starting point for setting annealing temperature, especially for novel polymerases [34]. |

In polymerase chain reaction (PCR) experiments, the success of the entire amplification process hinges on the precise molecular events occurring at the 3' end of oligonucleotide primers. This region serves as the initiation point for DNA synthesis by thermostable DNA polymerase. Incomplete binding or mispriming at the 3' end frequently results in inefficient PCR or complete amplification failure [35]. This guide examines two fundamental principles governing 3' end functionality: the implementation of a GC clamp to stabilize primer-template binding and the avoidance of complementarity patterns that lead to secondary structures. These considerations are not merely theoretical recommendations but are empirically derived from analyses of thousands of successful PCR experiments across diverse template types and experimental conditions [35]. Understanding these principles provides critical insight into the broader question of why primers form secondary structures and how these structures interfere with experimental outcomes.

The GC Clamp: Biochemical Principles and Implementation

The Molecular Basis of the GC Clamp

The GC clamp refers to the strategic placement of guanine (G) or cytosine (C) bases within the last five nucleotides from the 3' end of a primer. This design principle leverages the stronger bonding stability of G-C base pairs compared to A-T base pairs. While A-T pairs form two hydrogen bonds, G-C pairs form three hydrogen bonds, creating a more thermodynamically stable interaction [36] [37]. This enhanced stability at the 3' terminus promotes specific binding and facilitates the initiation of polymerase extension [12]. The 3' end of a primer is particularly critical because thermostable DNA polymerase begins nucleotide attachment precisely from this point during the extension step of PCR [35].

Empirical Evidence and Optimal Configuration

Analysis of over 2,000 primer sequences from successful PCR experiments reveals that while all 64 possible 3'-end triplets can yield successful amplification, certain triplets appear with significantly higher frequency [35]. The most successful triplets (AGG, TGG, CTG, TCC, ACC, CAG, AGC, TTC, GTG, CAC, and TGC) share a common characteristic: they typically contain 2-3 G or C bases, effectively creating a GC clamp without exceeding the recommended limit [35].

Table 1: Optimal and Non-Preferred 3'-End Triplets Based on Empirical Analysis

| Category | Triplet Examples | Frequency in Successful PCR | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Most Preferred | AGG, TGG, CTG, TCC, ACC | >2.34% (Mean + SD) | Typically 2-3 G/C bases; strong terminal stability |

| Neutral | AAA, CCA, GCA, TCA | 1.0-2.0% | Mixed G/C and A/T content; moderate stability |

| Least Preferred | TTA, TAA, CGA, ATT, CGT, GGG | <0.93% (Mean - SD) | Low G/C content or excessive G repeats |

The recommendation for a GC clamp specifically suggests including at least 2 G or C bases within the final five bases at the 3' end [3]. However, designers should avoid incorporating more than 3 G or C bases in this region, as excessively stable clamps can promote primer-dimer formation and other non-specific artifacts [36] [12]. The undesirable performance of the GGG triplet, despite its high GC content, underscores the importance of balanced distribution rather than maximal GC content [35].

Complementarity and Primer Secondary Structures

Patterns of Problematic Complementarity

Complementarity in molecular biology describes the relationship between nucleotide sequences that allows them to bind through specific hydrogen bonding [37]. While this principle enables specific primer-template binding, problematic complementarity occurs when primers interact with themselves or each other instead of the target template. Three primary forms of detrimental complementarity require consideration during primer design: