Western Blotting: A Comprehensive Guide for Accurate Protein Detection in Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Western blotting, a cornerstone technique for specific protein detection.

Western Blotting: A Comprehensive Guide for Accurate Protein Detection in Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Western blotting, a cornerstone technique for specific protein detection. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, detailed methodological protocols, advanced troubleshooting strategies, and rigorous validation approaches. The scope includes emerging trends such as total protein normalization for superior quantification, automation for enhanced reproducibility, and the technique's pivotal role in proteomics, biomarker discovery, and clinical diagnostics, offering a complete resource for optimizing accuracy and reliability in protein analysis.

Western Blot Fundamentals: Principles, History, and Core Components

The History and Evolution of Western Blotting from the 1970s to Modern Day

The western blot, sometimes called the protein immunoblot, is a widely used analytical technique in molecular biology and immunogenetics to detect specific proteins in a sample of tissue homogenate or extract [1]. Its core task is to separate a specific protein from a complex mixture using a three-element process: separation by size, transfer to a solid support, and marking the target protein using a primary and secondary antibody for visualization [1]. Since its inception in the late 1970s, western blotting has become a fundamental tool, with one analysis suggesting it has been mentioned in "the titles, abstracts, and keywords of more than 400,000 PubMed-listed publications" and may still be the most-used protein-analytical technique [1]. This application note traces its evolution from a qualitative technique to a modern quantitative method, detailing key protocols and applications for today's researchers.

Historical Development: From Conception to Commonplace

The late 1970s saw the first publicly reported use of the western blot [2]. The method was independently invented in 1979 by Jaime Renart, Jakob Reiser, and George Stark, and by Harry Towbin, Theophil Staehelin, and Julian Gordon at the Friedrich Miescher Institute in Basel, Switzerland [1]. The term "western blot" itself was given by W. Neal Burnette in 1981 [1]. The name is a playful reference to the Southern blot, a technique for DNA detection developed by Edwin Southern. By analogy, the detection of RNA is termed northern blotting [1] [3].

The original purpose of the technique was to determine the presence or absence of a protein of interest in a complex biological sample [2]. The Towbin group's implementation notably used secondary antibodies for detection, thus resembling the actual method that is almost universally used today [1]. Visualization methods have evolved significantly over time, starting with radio-labeled tags for detection, which then progressed to colorimetric and later to the more widely used chemiluminescent (ECL) methods [2].

Methodological Evolution and Quantitative Advancements

The journey of western blotting from a qualitative to a quantitative technique has been driven by advancements in detection technologies and a refined understanding of the methodology.

The Shift from Film to Digital Imaging

A significant breakthrough came with the advancement of western blotting using fluorescence, which allowed for the detection of subtle changes in protein expression, enabling true quantitative analyses [2]. Table 1 summarizes the core differences between film-based chemiluminescence and modern digital detection.

Table 1: Comparison of Historical Film-Based and Modern Digital Detection Methods

| Feature | Traditional Film-Based Chemiluminescence | Modern Digital Detection (Fluorescence & Digital Chemiluminescence) |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Enzymatic (HRP) reaction producing light captured on X-ray film [2] | Fluorescence emission or CCD/CMOS capture of chemiluminescence [4] |

| Dynamic Range | Low (~1 order of magnitude); signal saturates quickly [4] [5] | High (3-4 orders of magnitude); maintains linearity [4] [5] |

| Quantitative Capability | Semi-quantitative at best; approximation due to saturation [2] [5] | Truly quantitative; linear detection profile directly related to protein quantity [2] [4] |

| Multiplexing | Difficult; requires stripping and reprobing, which can damage the membrane [4] | Native; multiple targets can be detected simultaneously from the same blot [4] |

The limitations of film are a key reason why early western blotting was considered only semi-quantitative. The linear quantitative range of film is narrow and challenging to assess by eye, making reproducible results difficult [4] [5]. Camera-based imaging systems extended the linear dynamic range to about three to four orders of magnitude, permitting the generation of semi-quantitative data from chemiluminescence [4]. However, the development of sensitive fluorescent labels truly enabled the Quantifiable Fluorescence-based Western Blot (QFWB), which allows biologists to carry out comparative expression analysis with greater sensitivity and accuracy [2]. A direct comparison revealed that fluorescence detection could quantify a target over a 128-fold range, compared to only a 16-fold range for film [5].

Fluorescence vs. Chemiluminescence: A Modern Comparison

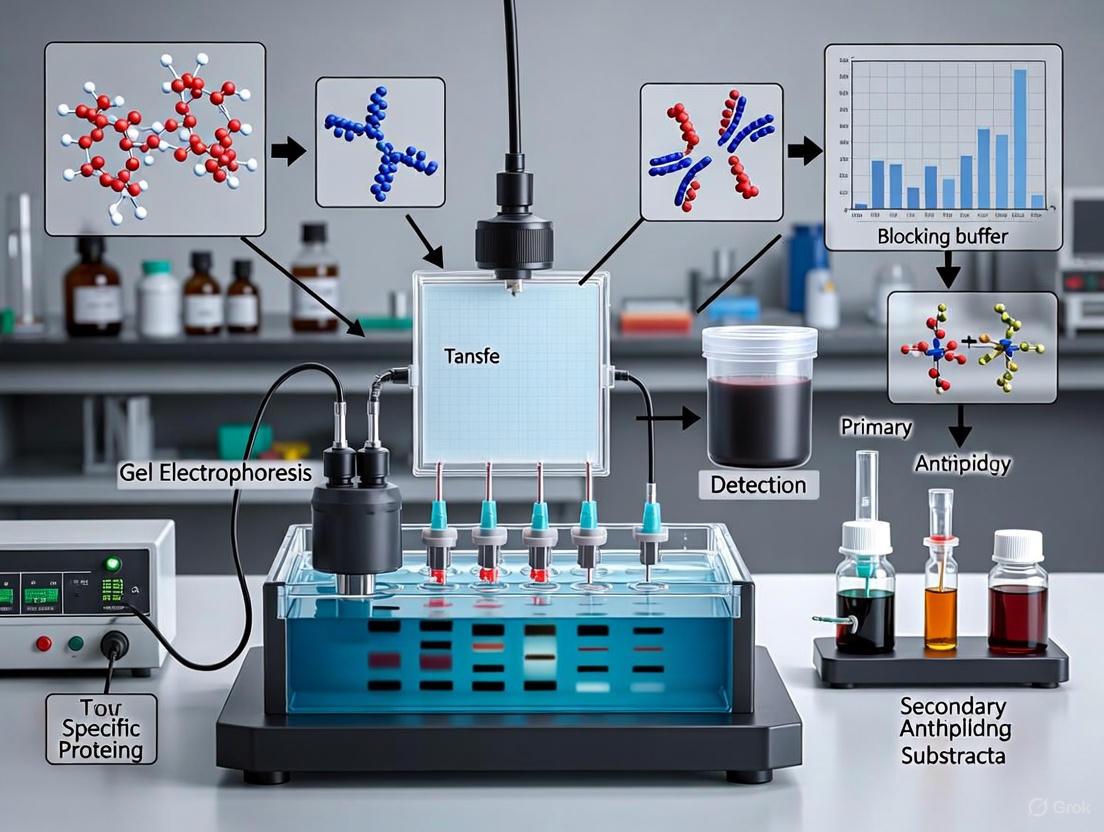

The choice between fluorescence and chemiluminescence remains relevant. Fluorescent western blotting uses a fluorescently labeled secondary antibody, generating a linear detection profile that is directly related to the quantity of protein [2]. In contrast, traditional ECL techniques can suffer from signal saturation, especially with highly expressed proteins [2]. Figure 1 illustrates the modern workflow that incorporates both detection methods.

Figure 1. Modern western blot workflow, highlighting the divergence at the detection stage for fluorescence and chemiluminescence methods. Fluorescence enables direct digital capture and multiplexing, while chemiluminescence requires an extra enzymatic step and carries a risk of signal saturation.

Fluorescence offers several key advantages, particularly for multiplexing. It permits the interrogation of multiple targets from the same sample without the need for stripping and reprobing the membrane, a process that can be time-consuming and can remove variable amounts of protein, leading to artefactual data [4]. A 2022 study directly comparing the two methods on identical membranes found that fluorescence provided a broader linear dynamic range and higher precision and accuracy between replicate data [4].

Essential Protocols for Modern Western Blotting

Standard Fluorescent Western Blot Protocol

This protocol is optimized for quantitative results using fluorescent secondary antibodies and a digital imager (e.g., LI-COR Odyssey) [2] [6].

Sample Preparation:

- Homogenization: Manually macerate tissue and homogenize in an appropriate extraction buffer (e.g., RIPA buffer) at approximately 1:10 w/v (tissue weight/buffer volume) until a smooth homogenate is produced [2].

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge samples at 20,000 x g for 20 min at 4°C. Collect the supernatant containing solubilized proteins [2].

- Protein Determination: Determine protein concentration using a BCA or Bradford assay. Ensure the standard curve has an R-squared value ≥ 0.99 for accurate determination [2].

- Sample Loading: Prepare samples by mixing protein (e.g., 15 µg for neuronal isolates) with loading buffer. Heat at 98°C for 2 minutes [2].

Electrophoresis and Transfer:

- Gel Electrophoresis: Load samples onto a 4-12% Bis-Tris gradient gel for broad molecular weight separation. Use MES or MOPS running buffer [2].

- Protein Transfer: Transfer proteins to a nitrocellulose or PVDF membrane. For PVDF, pre-wet in 100% methanol for 30 seconds, rinse in deionized water, and equilibrate in transfer buffer before use [6].

Immunodetection:

- Blocking: Incubate the membrane with a sufficient volume of filtered fluorescent-compatible blocking buffer (e.g., Blocker FL) for 30-60 minutes at room temperature with agitation. Do not add detergent, as this may increase background fluorescence [6].

- Primary Antibody: Dilute the primary antibody per supplier recommendations in blocking buffer. Incubate the membrane protein-side up in the primary antibody solution for 1 hour at room temperature or overnight at 2-8°C with agitation [6].

- Washing: Wash the membrane 3 times for 10 minutes each with Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween 20 (TBST) with agitation [6].

- Secondary Antibody: Dilute the fluorescently labeled secondary antibody to 0.4 - 0.1 µg/mL (typically a 1:5,000 to 1:20,000 dilution) in wash buffer or blocking buffer. Incubate the membrane protein-side up in the secondary antibody solution for 1 hour at room temperature with agitation. Protect the membrane from bright light to prevent photobleaching [6].

- Final Washing: Wash the membrane 6 times for 5 minutes each in wash buffer to remove any unbound secondary antibodies. This step is crucial for reducing background [6].

Imaging:

- Image the blot using an appropriate imaging system with fluorescence detection mode. The blot can be imaged while still wet or after drying [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential materials and reagents for a successful fluorescent western blot

| Item | Function / Rationale | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lysis Buffer | Solubilizes proteins and prevents degradation during extraction. | RIPA buffer (whole cell, mitochondrial, nuclear); NP-40 (whole cell, membrane bound). Must be compatible with protein assay [2]. |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevents proteolytic degradation of the target protein during and after extraction. | Added to the lysis buffer prior to sample isolation [2]. |

| Protein Assay | Accurately determines protein concentration for equal loading. | BCA or Bradford assay. All samples must be assayed against the same standard curve with R² ≥ 0.99 [2]. |

| Fluorescent Blocking Buffer | Blocks nonspecific binding sites on the membrane to reduce background. | Filtered, specialized buffers (e.g., Blocker FL). Avoid detergents in blocking buffer for fluorescence [6]. |

| Validated Primary Antibodies | Specifically binds to the protein of interest. | Critical for specificity. Validate using knockout controls if possible [3] [7]. Report supplier, catalog number, and RRID [7]. |

| Fluorescent Secondary Antibodies | Binds to the primary antibody and provides the signal for detection. | Highly cross-absorbed antibodies conjugated to fluorescent dyes (e.g., IRDye). Dilute to 0.1-0.4 µg/mL [6] [4]. |

| Digital Imaging System | Captures the fluorescent signal over a wide linear dynamic range for quantification. | Camera-based systems (e.g., LI-COR Odyssey). Avoids saturation issues of film [2] [4] [5]. |

Applications in Research and Diagnostics

Western blotting has maintained its relevance through diverse applications in both basic research and clinical diagnostics.

In basic research, it is a cornerstone for verifying protein production after cloning, assessing protein expression levels, and understanding post-translational modifications [1]. It is also essential for subcellular localization studies, aided by fractionation techniques [1]. Furthermore, it plays a role in epitope mapping, helping to identify the binding sites of antibodies on their target proteins, which is crucial for vaccine and therapeutic development [1].

In medical diagnostics, the western blot is used as a confirmatory test for several diseases. It is part of the confirmatory HIV test, the definitive test for variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, and a key tool in the diagnosis of Lyme disease and tularemia [1]. It is also used to confirm Hepatitis B and Herpes Simplex Virus-2 (HSV-2) infections [1] [8].

In the pharmaceutical sector, western blotting is used to understand the molecular consequences of drug administration, such as measuring biomarker levels and validating the mechanism of action of new therapeutics [3]. For example, it has been used in clinical trials to demonstrate target inhibition by a drug in leukemia patients [3].

Current Challenges and Best Practices for Reporting

Despite its long history, western blotting faces ongoing challenges related to reproducibility and reporting. A systematic assessment of over 500 articles revealed that western blot figures and methods often omit essential details [7]. Common problems include:

- Excessive Cropping: Over 90% of published blots are cropped, and most do not provide source data, depriving readers of information on protein multiplicity or antibody specificity [7].

- Missing Molecular Weight Markers: More than 95% of published blots lack visible molecular weight markers, and many lack molecular weight labels, making it impossible to confirm the size of the detected protein [7].

- Incomplete Methods Reporting: Critical details are often omitted, including the amount of protein loaded (55-78% of papers), blocking duration, and detailed antibody identifiers (especially for secondary antibodies) [7].

To ensure the production of high-quality, reproducible data, researchers should adhere to the following best practices:

- Perform a Linear Dynamic Range Test: Load a dilution series of a representative sample to determine the protein load that yields a linear signal, avoiding saturation [4] [5].

- Use Total Protein Normalization: Normalize target protein signal to the total protein loaded in each lane, as this is more reliable than using a single housekeeping protein [4] [3].

- Report Completely: Provide full-length, uncropped blot images in supplements. Always include molecular weight markers and labels. In the methods, report the amount of protein loaded, detailed blocking conditions, and complete antibody information (supplier, catalog number, RRID, and dilution) for both primary and secondary antibodies [7].

From its inception in 1979 to the present day, western blotting has evolved from a qualitative technique for detecting proteins into a robust, quantitative tool capable of measuring subtle changes in protein expression. The advent of fluorescence-based detection and digital imaging has been pivotal in this transformation, offering greater sensitivity, a wider dynamic range, and multiplexing capabilities that were not possible with traditional film-based chemiluminescence. As the technique continues to be a cornerstone of protein research and diagnostics, a commitment to rigorous methodology and transparent reporting is essential to ensure the reliability and reproducibility of the data it generates.

Western blotting is a cornerstone technique in molecular biology and biochemistry for the specific detection and analysis of proteins within a complex mixture [9]. The method combines the resolving power of gel electrophoresis with the specificity of antibody-based immunodetection, allowing researchers to confirm the presence, relative abundance, and molecular weight of a target protein [7] [9]. This protocol is indispensable in diverse settings, from academic research and biomarker validation to drug development and clinical diagnostics [10]. The core principle hinges on a series of interrelated steps: protein separation by size via SDS-PAGE, transfer of the separated proteins to a solid membrane support, and subsequent detection of a specific protein using a primary antibody and an enzyme- or fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody [7] [9].

Core Procedural Workflow

The Western blotting procedure is a comprehensive process that can be divided into three major stages. The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and key relationships between these critical stages.

Stage 1: SDS-PAGE (Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis)

Principle and Objective

The primary objective of this stage is to separate denatured proteins based solely on their molecular weight [9]. SDS (sodium dodecyl sulfate) is a key reagent that denatures the proteins and confers a uniform negative charge along the polypeptide backbone. When an electric field is applied, these negatively charged proteins migrate through the polyacrylamide gel matrix towards the positive anode, with smaller proteins moving faster and thus farther than larger ones [9].

Detailed Protocol: Sample Preparation and Gel Loading

A. Materials Required

- Your protein sample (cell culture or tissue lysate) [9]

- Lysis Buffer (e.g., RIPA or non-denaturing buffer) [9]

- Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (to prevent protein degradation) [9]

- Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (essential for preserving phosphorylated epitopes) [9]

- Loading Buffer (contains SDS and tracking dye) [9]

- Dithiothreitol (DTT) (a reducing agent to break disulfide bonds) [9]

- Protein Quantification Assay Kit (e.g., BCA or Bradford assay) [9]

- SDS-PAGE Gel (commercial or hand-cast) [9]

- Molecular Weight Ladder [9]

- Gel Running Apparatus and Power Supply [9]

- Running Buffer (e.g., Tris-Glycine, MES, MOPS) [9]

B. Step-by-Step Method

- Prepare Lysate: Lyse cells or tissue in an appropriate ice-cold lysis buffer supplemented with protease (and phosphatase) inhibitors. Keep samples on ice throughout to minimize degradation [9].

- Clarify Lysate: Centrifuge the lysate at 14,000–17,000 x g for 5-10 minutes at 4°C. Transfer the supernatant (which contains the soluble proteins) to a fresh tube and discard the pellet [9].

- Determine Protein Concentration: Use a BCA or Bradford assay to determine the precise protein concentration of the lysate. This is a critical step for ensuring equal loading across gel lanes [9].

- Prepare Samples for Loading: Dilute lysate aliquots in loading buffer containing DTT. A final protein concentration of 1–2 mg/mL is often suitable. Boil the samples at 100°C for 10 minutes to fully denature the proteins [9].

- Load the Gel: Load an equal amount of total protein (typically 10–40 µg for a lysate) into each well of the gel. Include a well for the molecular weight ladder [9].

- Run the Gel: Assemble the gel apparatus filled with running buffer and apply a constant voltage (e.g., 120-200V) until the dye front has migrated to the bottom of the gel. Running time and voltage should be optimized for the specific gel and protein size [9].

Gel Selection Guide

The choice of gel system depends on the molecular weight of your target protein, as detailed in the table below.

Table 1: Recommended SDS-PAGE Gel Conditions for Different Protein Sizes [9]

| Protein Size Range | Recommended Gel Chemistry | Recommended Running Buffer |

|---|---|---|

| 10 – 30 kDa | 4-12% acrylamide gradient Bis-Tris gel | MES |

| 31 – 150 kDa | 4-12% acrylamide gradient Bis-Tris gel | MOPS |

| > 150 kDa | 3-8% acrylamide gradient Tris-Acetate gel | Tris-Acetate |

Stage 2: Protein Transfer

Principle and Objective

After separation by SDS-PAGE, the proteins must be transferred from the gel onto a solid membrane support, creating the "blot." This step makes the proteins accessible for antibody probing. The most common method is electrotransfer, where an electric field drives the negatively charged proteins from the gel onto the membrane [9].

Detailed Protocol: Western Blot Transfer

A. Materials Required

- Transfer Buffer (typically Tris-Glycine with methanol)

- Membrane (Nitrocellulose or PVDF)

- Filter Paper

- Transfer Apparatus (wet or semi-dry system)

B. Step-by-Step Method

- Equilibrate: Following electrophoresis, briefly equilibrate the gel in transfer buffer.

- Prepare Membrane: If using PVDF membrane, activate it by briefly soaking in 100% methanol, then rinse in transfer buffer. Nitrocellulose can be placed directly into buffer.

- Assemble Transfer Stack: In a tray of transfer buffer, assemble the "transfer sandwich" in the following order: cathode (negative electrode), sponge, filter paper, gel, membrane, filter paper, sponge, anode (positive electrode). Ensure no air bubbles are trapped between the gel and membrane.

- Execute Transfer: Place the cassette into the transfer tank filled with cold buffer and apply a constant current (e.g., 300-400 mA) for 60-90 minutes. The system should be kept cool (in an ice bath or cold room) to prevent overheating.

- Verify Transfer: After transfer, proteins can be visualized on the membrane using reversible stains like Ponceau S to confirm successful and even transfer.

Stage 3: Immunodetection

Principle and Objective

This final stage utilizes the specificity of antibodies to detect the protein of interest immobilized on the membrane. The process involves blocking non-specific binding sites on the membrane, followed by sequential incubation with a primary antibody that recognizes the target protein, and a conjugated secondary antibody that recognizes the primary antibody. The signal from the secondary antibody is then detected, revealing the location and intensity of the target protein band [9].

Detailed Protocol: Blocking, Antibody Incubation, and Detection

A. Materials Required

- Blocking Buffer (e.g., 5% non-fat dry milk or BSA in TBST)

- Primary Antibody (specific for your target protein)

- Secondary Antibody (conjugated to HRP or a fluorophore, specific for the host species of the primary antibody)

- Wash Buffer (e.g., TBST or PBST)

- Detection Reagents (e.g., chemiluminescent substrate for HRP)

B. Step-by-Step Method

- Block the Membrane: Incubate the membrane in an ample volume of blocking buffer for 1 hour at room temperature with gentle agitation. This step saturates non-specific protein-binding sites on the membrane to minimize background [11].

- Incubate with Primary Antibody: Dilute the primary antibody to the appropriate concentration in blocking buffer or a dedicated antibody diluent. Incubate the membrane with the primary antibody solution for 1 hour at room temperature or overnight at 4°C with agitation [9].

- Wash the Membrane: Remove the primary antibody and wash the membrane 3-5 times for 5 minutes each with a large volume of wash buffer (e.g., TBST) to remove unbound antibody.

- Incubate with Secondary Antibody: Dilute the HRP- or fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody in blocking buffer. Incubate the membrane with the secondary antibody solution for 1 hour at room temperature, protected from light if using a fluorescent dye.

- Wash the Membrane: Perform a second series of washes as in Step 3 to remove any unbound secondary antibody.

- Detect Signal:

- For Chemiluminescence: Mix the chemiluminescent substrate reagents according to the manufacturer's instructions. Incubate the membrane with the substrate and visualize using a CCD camera-based imaging system. Ensure the signal is within the linear dynamic range for quantification [12] [13].

- For Fluorescence: Image the membrane using a compatible fluorescence imager at the appropriate excitation/emission wavelengths [11].

Common Pitfalls and Data Reporting Standards

A systematic assessment of publications reveals that Western blot figures and methods often omit essential details, which limits reproducibility [7]. The table below summarizes frequent issues and current reporting standards.

Table 2: Common Western Blotting Pitfalls and Journal Publication Guidelines [7] [13]

| Aspect | Common Pitfall (Prevalence) | Recommended Practice for Publication |

|---|---|---|

| Image Cropping | Over 90% of published blots are tightly cropped [7]. | Provide full, uncropped images of the entire membrane and gel as supplemental data [7]. |

| Molecular Weight Markers | >95% of blots lack visible molecular weight markers; 30-38% lack any molecular weight labels [7]. | Always include visible molecular weight markers with clear labels on the blot image to confirm expected protein size [7]. |

| Antibody Reporting | Catalog numbers missing for 20-32% of primary and 66-75% of secondary antibodies; RRIDs rarely reported [7]. | Report supplier, catalog number, lot number, and RRID (Research Resource Identifier) for all antibodies [7]. |

| Protein Loading | 55-78% of papers omit the amount of protein loaded per lane [7]. | Always state the exact amount of total protein loaded per lane in the figure legend or methods [7]. |

| Normalization | Over-reliance on variable housekeeping proteins (HKPs) like GAPDH and β-actin [13]. | Use Total Protein Normalization (TPN) as the gold standard for more accurate quantification, as it is increasingly required by top journals [13]. |

| Image Manipulation | Use of editing tools that obscure original data. | Avoid any editing that misrepresents data (e.g., improper cloning, healing tools). Only adjust contrast/brightness uniformly across the entire image, as per journal policies [13]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful Western blotting relies on a suite of reliable reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions and their critical functions in the workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Western Blotting

| Reagent / Material | Critical Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| Protease/Phosphatase Inhibitors | Preserves protein integrity by preventing proteolytic degradation and maintaining post-translational modifications during lysate preparation [9]. |

| SDS-PAGE Gel Systems | Provides the matrix for size-based separation of denatured proteins. Gradient gels offer a broader separation range [9]. |

| Nitrocellulose or PVDF Membrane | Serves as the solid support for immobilized proteins after transfer, enabling subsequent antibody probing [11]. |

| Blocking Buffer (e.g., BSA, Milk) | Reduces nonspecific antibody binding to the membrane, a crucial step for minimizing background noise [11]. |

| Validated Primary Antibodies | The key to specificity; binds selectively to the target protein of interest. Proper validation is essential for reliable results [7] [11]. |

| HRP- or Fluorophore-conjugated Secondary Antibodies | Enables detection by binding to the primary antibody. Conjugates generate a measurable signal (chemiluminescent or fluorescent) [11]. |

| Total Protein Normalization (TPN) Reagents | Provides a superior method for normalization by staining the total protein in each lane, correcting for loading errors more reliably than housekeeping proteins [13]. |

Within the framework of research dedicated to detecting specific proteins, the Western blot remains an indispensable technique. Its reliability hinges on the precise selection and application of its core components: gels for separation, membranes for immobilization, and buffers for maintaining the biochemical environment. This guide details the essential characteristics, selection criteria, and protocols for these components, providing a foundation for robust, reproducible, and publication-ready protein analysis in research and drug development.

Protein Separation: Polyacrylamide Gels

The first critical step in Western blotting is the electrophoretic separation of proteins based on molecular weight using polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Proteins are denatured and linearized, and their migration through the gel matrix is inversely proportional to the logarithm of their molecular mass [14]. The choice of gel composition directly impacts resolution.

Table 1: Gel Percentage Recommendations for Optimal Protein Separation

| Gel Percentage (% Acrylamide) | Optimal Molecular Weight Separation Range |

|---|---|

| 4-20% Gradient Gel | Broad range: 10 - 300 kDa |

| 6% Gel | High molecular weight: 50 - 300 kDa |

| 8% Gel | Medium-high molecular weight: 30 - 200 kDa |

| 10% Gel | Medium molecular weight: 20 - 100 kDa |

| 12% Gel | Medium-low molecular weight: 15 - 70 kDa |

| 15% Gel | Low molecular weight: 5 - 50 kDa |

For most applications, precast gradient gels (e.g., 4-20%) are recommended as they provide superior resolution across a wide mass range, simplify protocol optimization, and enhance reproducibility [14]. The following workflow diagram outlines the core steps of the Western blot process, from sample preparation to detection.

Membrane Selection: PVDF vs. Nitrocellulose

Following separation, proteins are transferred from the gel onto a solid support membrane. The two primary options are nitrocellulose and polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF), each with distinct properties that influence protein binding, background signal, and detection performance [15] [16].

Table 2: Comprehensive Comparison of PVDF and Nitrocellulose Membranes

| Feature | PVDF Membrane | Nitrocellulose Membrane |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Binding Capacity | 150–300 µg/cm² [15] | 80–100 µg/cm² [15] |

| Binding Mechanism | Hydrophobic interactions [16] | Hydrophobic, H-bond, and ionic interactions [16] |

| Durability & Chemical Resistance | High; withstands stripping/re-probing [15] | Low; fragile and brittle [15] [16] |

| Pre-wetting Requirement | Requires activation in 100% methanol or ethanol [15] [16] | Ready to use; do not wet with methanol [15] |

| Background Noise | Can be high with standard PVDF [15] | Generally low [15] |

| Autofluorescence | High for standard PVDF; low for low-fluorescence PVDF [15] [16] | Low [16] |

| Optimal Detection Method | Chemiluminescence; low-fluorescence PVDF for fluorescence [15] [16] | Chemiluminescence and fluorescence [15] |

| Cost | High [15] | Low [15] |

| Pore Size (Common) | 0.2 µm (proteins <20 kDa), 0.45 µm (proteins >20 kDa) [15] | 0.2 µm (proteins <20 kDa), 0.45 µm (proteins >20 kDa) [15] |

Application-Based Membrane Selection Guide

- Choose a PVDF membrane when: Detecting low-abundance or high molecular weight proteins, multiple stripping and re-probing are required, or superior mechanical strength is needed for rigorous protocols [15] [16].

- Choose a nitrocellulose membrane when: Working with medium-to-low molecular weight proteins, minimizing background noise is a priority, or a cost-effective solution for routine detection is desired [15].

- Choose a low-fluorescence PVDF membrane when: Performing fluorescent Western blotting or total protein normalization with fluorescent labels, as it offers the lowest autofluorescence and highest signal-to-noise ratio [16].

Essential Buffers: Recipes and Protocols

The buffers used throughout the Western blot process are critical for success. Below are standard recipes and protocols for key steps [17].

Lysis Buffers for Protein Extraction

Choice of lysis buffer depends on protein localization and the need for denaturation.

Table 3: Lysis Buffer Selection Guide and Compositions

| Buffer Type | Target Protein Location | Key Components |

|---|---|---|

| RIPA Buffer | Membrane-bound, nuclear, whole-cell extracts [17] | 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 [17] |

| NP-40 Buffer | Cytoplasmic, membrane-bound, whole-cell extracts [17] | 150 mM NaCl, 1.0% NP-40, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 [17] |

| Tris-HCl Buffer | Soluble cytoplasmic proteins [17] | 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 [17] |

| Tris-Triton Buffer | Cytoskeletal-bound proteins [17] | 100 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 10 mM Tris, 0.1% SDS, 10% glycerol [17] |

Protocol: Protein Extraction with RIPA Buffer

- Prepare Lysis Buffer: Add fresh protease and/or phosphatase inhibitors to chilled RIPA buffer [17].

- Lyse Cells/Tissue: Add cold buffer to your sample (e.g., 500 µL per 5x10⁶ cells). Incubate on ice for 30 minutes with gentle vortexing every 5-10 minutes [17].

- Clarify Lysate: Centrifuge at 12,000-16,000 x g for 15-20 minutes at 4°C.

- Collect Supernatant: Transfer the supernatant (containing solubilized protein) to a new tube. Store at -80°C if not used immediately.

Electrophoresis and Transfer Buffers

- 2X Laemmli Loading Buffer: 4% SDS, 10% 2-mercaptoethanol, 20% glycerol, 0.004% bromophenol blue, 0.125 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8 [17]. Mix 1:1 with protein lysate and denature at 95°C for 5 minutes.

- Running Buffer (10X Stock): 250 mM Tris base, 1.9 M glycine, 1% SDS. Dilute to 1X for use [17].

- Wet Transfer Buffer: 25 mM Tris base, 190 mM glycine, 20% methanol. For proteins >80 kDa, include SDS to 0.1% final concentration [17].

Blocking and Incubation Buffers

Blocking is crucial to prevent nonspecific antibody binding. A 5% solution of Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) in TBST is often preferred for its low background, especially with phospho-specific antibodies [14].

- 10X Tris-Buffered Saline (TBS): 240 mM Tris base, 88 g/L NaCl, pH to 7.6 [17].

- TBST (1X): 1X TBS with 0.1% Tween-20 [17].

- Blocking Buffer: 3-5% BSA or non-fat dry milk in TBST [14] [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials and Reagents for Western Blotting

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Precast SDS-PAGE Gels | Provide consistent, reproducible protein separation without the need to pour gels, saving time and reducing variability. |

| PVDF/Nitrocellulose Membranes | Serve as a stable matrix to immobilize proteins after transfer, enabling subsequent probing with antibodies. |

| Enhanced Chemiluminescent (ECL) Substrate | A sensitive detection reagent that produces light upon reaction with HRP-conjugated antibodies, captured on film or digital imagers. |

| Primary Antibodies | Immunoglobulins that specifically bind to the protein of interest. Critical for assay specificity. |

| HRP- or Fluorophore-conjugated Secondary Antibodies | Bind the primary antibody and carry the label (enzyme or fluorophore) for detection, providing signal amplification. |

| Protein Ladder (Molecular Weight Marker) | A mixture of proteins of known sizes run alongside samples to estimate the molecular weight of the target protein. |

| Protease/Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktails | Added to lysis buffers to prevent the degradation and dephosphorylation of proteins during and after extraction. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | A high-quality blocking agent that minimizes nonspecific binding, leading to lower background noise. |

| Methanol & Transfer Buffers | Methanol activates PVDF membranes and is a component of transfer buffers, facilitating protein movement and binding. |

| Digital Imaging System (CCD-based) | For capturing chemiluminescent or fluorescent signals; superior to film for quantitative analysis due to a wider linear dynamic range [13]. |

Advanced Quantitative Analysis and Publication Standards

For quantitative Western blotting, normalization is essential to distinguish true biological change from technical variability [13] [12]. The traditional method of using Housekeeping Proteins (HKPs) like GAPDH or β-actin is falling out of favor due to documented expression variability under different experimental conditions [13]. Total Protein Normalization (TPN) is now considered the gold standard, as it normalizes the target protein signal to the total protein loaded in each lane, providing a more accurate and reliable quantification [13].

Adherence to journal publication guidelines is critical. Key requirements often include [13]:

- Providing original, uncropped blot images in the supplemental information.

- Including molecular weight markers and labels on all blot images.

- Avoiding excessive image manipulation and brightness/contrast adjustments that misrepresent data.

- Clearly indicating where lanes have been spliced or rearranged from different parts of the same gel.

- Reporting antibodies with complete identifiers (company, catalog number, RRID).

In the realm of protein research, the western blot remains a cornerstone technique for the specific detection and analysis of proteins within complex biological samples [9] [18]. The core of this method's exceptional specificity and sensitivity lies in the strategic use of antibody-antigen interactions. The critical partnership between primary and secondary antibodies forms the backbone of immunodetection, enabling researchers to visualize and quantify specific proteins with precision [19]. This application note details the fundamental principles, selection criteria, and optimized protocols essential for leveraging antibodies to generate reproducible, high-quality data in western blotting, framed within the broader context of thesis research on specific protein detection.

Antibody Fundamentals and Selection Criteria

Primary Antibodies: Specificity and Types

Primary antibodies are immunoglobulins that bind directly to a unique epitope on the target protein. The choice of primary antibody is the primary determinant of specificity in a western blot [19].

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Antibody Types

| Feature | Polyclonal | Monoclonal | Recombinant |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | A collection of antibodies from different B cells that recognize multiple epitopes | A single antibody type produced by identical B cell clones that recognize one epitope | A single antibody derived from recombinant DNA |

| Key Advantages | High sensitivity; multiple epitope recognition can compensate for slight epitope masking | Superior lot-to-lot consistency; often well-characterized with extensive publication history | Superior long-term supply consistency; not susceptible to cell-line drift; defined sequence |

| Key Disadvantages | Potential for lot-to-lot variability; higher risk of non-specific bands | Sensitivity depends on a single epitope; potential for subtle cell-line drift over time | Specialized and epitope-dependent; longer development time; usually higher cost |

The selection of a primary antibody must be guided by validation for western blotting. Crucially, researchers must confirm that the antibody is specific towards the denatured protein, as the SDS-PAGE process unfolds proteins, potentially destroying conformation-dependent epitopes [19].

Secondary Antibodies: Signal Amplification and Detection

Secondary antibodies are directed against the immunoglobulins of the species in which the primary antibody was raised. They are typically conjugated to enzymes or fluorophores for detection and are responsible for signal generation [19]. The indirect detection method—using an unlabeled primary followed by a labeled secondary—offers significant signal amplification as multiple secondary antibodies can bind to a single primary antibody [19].

Table 2: Secondary Antibody Target Specificity

| Secondary Antibody Target | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Heavy and Light Chain (H+L) | Most versatile; high signal amplification; recommended for most chemiluminescent and fluorescent applications [19]. | Possible cross-reactivity with light chains of other immunoglobulins; may saturate for highly abundant targets [19]. |

| Fc Fragment Specific | Binds only to the heavy chain; good for detecting mouse monoclonal primaries; useful after immunoprecipitation or for specific isotype detection [19]. | Generally less sensitive than H+L specific secondaries; potential for interference [19]. |

Experimental Design for Quantitative Western Blotting

Producing quantitative data requires a fundamental shift from simple detection to a rigorous, validated methodology [18]. Key considerations include:

Determining Linear Dynamic Range

A critical, often overlooked step is determining the linear dynamic range for each antibody-target pair. Loading a random amount of protein (e.g., 10-100 µg) often leads to overloading and saturation, producing non-linear, unreliable data [18]. To establish the optimal loading concentration:

- Create a 1:2 dilution series of a pooled sample, spanning at least 12 dilutions from a high starting concentration (e.g., 100 µg).

- Run, transfer, and blot the series.

- Plot the relative signal density against the protein load.

- Select the protein load that corresponds to the middle of the linear dynamic range for subsequent experiments [18].

Appropriate Normalization Strategies

Normalization corrects for minor variations in protein loading and transfer efficiency. While housekeeping proteins (HKPs) like GAPDH, actin, and tubulin are traditional choices, they can be unreliable as they are often overloaded and their expression can vary with experimental conditions [18]. Total protein normalization (TPN), which uses a stain to measure the total protein in each lane, has been shown to provide excellent data for quantitative analyses [18].

Multiplex Fluorescent Western Blotting

For multiplexing, where multiple targets are detected on the same blot, use primary antibodies raised in distantly related host species (e.g., rabbit and mouse, or rat and rabbit). This enables the use of species-specific secondary antibodies conjugated to different fluorophores, minimizing cross-reactivity and yielding clean, multi-target data from a single sample [19] [4]. Fluorescent detection avoids the need for stripping and reprobing, a process that can damage proteins and lead to artefacts [4].

The following diagram illustrates the critical decision points and workflow for a successful quantitative western blot experiment.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation and Gel Electrophoresis

Materials & Reagents:

- Lysis Buffer (e.g., RIPA buffer: 1% NP-40 or Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 1 mM EDTA) [18].

- Protease Inhibitor Cocktail [9].

- Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (for phosphorylated proteins) [9].

- Loading Buffer (with SDS and reducing agent like DTT or β-mercaptoethanol) [9] [20].

- BCA or Bradford Protein Assay Kit [9].

Protocol:

- Cell Lysis: Wash cells with PBS. Lyse cells in ice-cold RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors. Scrape adherent cells and transfer the lysate to a microcentrifuge tube. Sonicate briefly (10-15 seconds) to complete lysis and shear DNA [18] [21].

- Clarification: Centrifuge the lysate at 14,000–17,000 x g for 5-10 minutes at 4°C. Transfer the supernatant (containing soluble proteins) to a new tube [9].

- Protein Quantification: Determine the protein concentration using a detergent-compatible assay (e.g., BCA or Bradford) [9] [18].

- Sample Denaturation: Dilute lysates in loading buffer containing a reducing agent (e.g., DTT). Heat samples at 95-100°C for 5 minutes to fully denature proteins [9] [21].

- Gel Electrophoresis: Load an equal amount of protein (the predetermined optimal mass) into each well of an SDS-PAGE gel. Include a prestained protein ladder.

- Run the gel at 100-150 V for 40-60 minutes in the appropriate running buffer until the dye front nears the bottom [22].

Protein Transfer, Blocking, and Immunoblotting

Materials & Reagents:

- Transfer Buffer (e.g., Tris-Glycine with methanol) [21].

- Membrane (Nitrocellulose or PVDF). Note: Pre-wet PVDF in 100% methanol. [20].

- Filter Paper and Sponges.

- Blocking Agent (5% w/v Non-fat Dry Milk or BSA in TBST) [21].

- Primary Antibody (validated for western blotting).

- HRP-conjugated or Fluorescent-conjugated Secondary Antibody.

- Wash Buffer (TBST or TBST) [21].

Protocol:

- Electrotransfer: Assemble the "transfer stack" in the following order (from anode to cathode): sponge, filter paper, gel, membrane, filter paper, sponge. Ensure no air bubbles are trapped. Perform wet transfer at constant voltage (e.g., 100V for 60-90 minutes) on ice [22].

- Blocking: Incubate the membrane in 25 mL of blocking buffer (e.g., 5% non-fat dry milk in TBST) for 1 hour at room temperature with gentle agitation [21].

- Primary Antibody Incubation:

- Dilute the primary antibody in the recommended buffer (often 5% BSA or milk in TBST) as specified on the product datasheet.

- Incubate the membrane with the primary antibody solution (e.g., 10 mL) with gentle agitation overnight at 4°C [21].

- Washing: Wash the membrane three times for 5 minutes each with 15 mL of TBST [21].

- Secondary Antibody Incubation:

- Dilute the HRP-conjugated or fluorescent-conjugated secondary antibody in blocking buffer (e.g., 1:2000-1:10000 for HRP).

- Incubate the membrane with the secondary antibody solution for 1 hour at room temperature with gentle agitation [21].

- Washing: Repeat the wash step three times for 5 minutes each with TBST [21].

Detection and Analysis

Materials & Reagents:

- Chemiluminescent Substrate (e.g., LumiGLO, SignalFire, Clarity) [21] [18].

- Fluorescent Imager or CCD-based Chemiluminescence Imager.

Protocol:

- Chemiluminescent Detection: For HRP-conjugated antibodies, mix the chemiluminescent substrate reagents as per manufacturer instructions. Incubate the membrane with the substrate for ~1 minute. Drain excess liquid and image using a CCD-based imager capable of capturing a digital image within the linear dynamic range [21] [4]. Avoid using film, which has a narrow linear range and saturates easily [18].

- Fluorescent Detection: For fluorescently conjugated antibodies, image the membrane directly using a compatible laser-based scanner with appropriate excitation/emission filters [4].

- Data Analysis:

- Use imaging software to perform background subtraction and quantify the densitometry of the bands.

- Normalize the target protein signal to the corresponding total protein or housekeeping protein signal in each lane.

- Perform statistical analysis on the normalized data from biological replicates.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Western Blotting

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Lysis Buffer (RIPA) | Extracts soluble proteins from cells/tissues while maintaining integrity. | Must include protease inhibitors; ionic vs. non-ionic detergent choice impacts stringency [18]. |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevents proteolytic degradation of target protein during extraction. | Essential for all sample preparation; use a broad-spectrum cocktail [9]. |

| BCA/Bradford Assay | Quantifies total protein concentration in lysates for equal loading. | Must be detergent-compatible [9] [18]. |

| SDS-PAGE Gels | Separates proteins by molecular weight under denaturing conditions. | Gel percentage must be matched to target protein size for optimal resolution [20]. |

| Transfer Buffer | Medium for electrophoretic transfer of proteins from gel to membrane. | Typically Tris-Glycine with methanol; composition affects efficiency [21]. |

| Blocking Agent (BSA/Milk) | Covers unused membrane binding sites to reduce non-specific antibody binding. | BSA is preferred for phospho-specific antibodies or biotin-streptavidin systems; milk is economical [20] [21]. |

| Validated Primary Antibody | Binds specifically to the target protein of interest. | Must be validated for western blot and for detection of denatured protein [19]. |

| Conjugated Secondary Antibody | Binds to the primary antibody and generates a detectable signal. | Host species must be matched to primary antibody; conjugate (HRP/fluor) determines detection method [19]. |

| Chemiluminescent Substrate | Generates light upon reaction with HRP enzyme for signal detection. | Sensitivity and signal duration vary between substrates [21]. |

Troubleshooting and Best Practices

- High Background: Ensure the membrane is fully blocked and that antibody concentrations are optimized. Increase the number and duration of washes. Consider using a different blocking agent (e.g., switch from milk to BSA) [20].

- Non-specific Bands: Confirm antibody specificity. These bands may indicate suboptimal blocking or antibody concentration but could also represent protein isoforms or degradation products. Optimize conditions and run appropriate controls [23].

- No Signal/Weak Signal: Confirm that the primary antibody recognizes the denatured epitope. Check antigen integrity and increase protein load (within the linear range). Ensure the detection substrate is active [20].

- Publication-Quality Data: Journals are increasingly stringent. Always save original, unprocessed images. Minimize cropping of blots to show relevant molecular weight markers and important lanes. Adjustments to brightness/contrast must be applied evenly across the entire image and must not alter the data interpretation [23]. Many journals now require full, uncropped blot images as supplementary information [23].

The critical role of antibodies in western blotting cannot be overstated. A deep understanding of primary and secondary antibody characteristics, coupled with a rigorously optimized and quantitative experimental workflow, is fundamental to achieving specific, sensitive, and reproducible results. By adhering to the principles and detailed protocols outlined in this application note—particularly the determination of the linear dynamic range and appropriate normalization—researchers can elevate western blotting from a simple qualitative tool to a robust quantitative method, thereby generating reliable data capable of supporting high-impact thesis research and drug development.

The Ubiquitous Role of Western Blotting in Biomedical Research and Diagnostics

Western blotting, also known as immunoblotting, is a cornerstone technique in molecular biology and biochemistry for identifying specific proteins in complex biological samples and analyzing their expression levels [8] [24]. This method combines the size-based separation of proteins with the specificity of antibody-antigen interactions, allowing researchers to determine the presence, absence, and relative abundance of a target protein, as well as its molecular weight [8] [25]. Its robustness and specificity have cemented its role as an indispensable tool in basic scientific research, drug development, and clinical diagnostics.

Principles of Western Blotting

The western blot technique operates on the principle of separating proteins by size through gel electrophoresis and then using antibodies for specific detection [25]. The process can be broken down into three core stages: separation by size, transfer to a solid support, and immunodetection [25].

The first step typically involves SDS-PAGE (sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis). SDS denatures the proteins and imparts a uniform negative charge, ensuring that separation occurs based almost exclusively on molecular weight rather than native charge or structure [8] [9]. An electrical current applied across the gel causes the proteins to migrate, with smaller proteins moving faster through the gel matrix than larger ones [9].

Following separation, the proteins are transferred from the gel onto a solid membrane, usually nitrocellulose or PVDF (polyvinylidene fluoride), creating a replica of the gel's protein pattern [8] [6]. This transfer is essential because the gel matrix is poorly suited for the antibody incubations required for detection [25]. An electric current is applied again to drive the proteins from the gel onto the membrane [8].

The final stage, immunodetection, involves probing the membrane with antibodies to visualize the protein of interest. The membrane is first treated with a blocking agent like non-fat dry milk or bovine serum albumin (BSA) to prevent antibodies from binding non-specifically to the membrane [21] [26]. The membrane is then incubated with a primary antibody that is specific to the target protein. After washing, a secondary antibody that recognizes the primary antibody is applied. This secondary antibody is conjugated to a reporter enzyme, such as horseradish peroxidase (HRP), or a fluorophore, which enables detection [21] [25]. Alternatively, directly conjugated primary antibodies can be used to simplify the protocol by eliminating the secondary antibody step [25].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

A successful western blot requires meticulous attention to each step of the procedure. The following protocol, synthesized from industry leaders, provides a comprehensive guide for chemiluminescent detection, one of the most common methods [21] [9] [6].

Sample Preparation

Proper sample preparation is a crucial first step for an accurate western blot [8].

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells or tissues in an appropriate ice-cold lysis buffer (e.g., RIPA buffer) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors to prevent degradation [9]. Keep samples on ice throughout.

- Protein Quantification: Determine the protein concentration of each lysate using an assay such as Bradford or BCA [8] [9]. This is critical for loading equal amounts of protein across samples for quantitative comparisons.

- Denaturation: Dilute lysates in SDS sample buffer containing a reducing agent like DTT. Heat samples at 95–100°C for 5 minutes to fully denature the proteins [21] [9].

- Storage: Aliquots can be stored at -80°C until use [9].

Gel Electrophoresis and Protein Transfer

- Gel Selection: Choose an appropriate SDS-PAGE gel based on the molecular weight of your target protein (see Table 1) [9]. Pre-cast gradient gels (e.g., 4-12% Bis-Tris) are suitable for a wide range of protein sizes.

- Loading and Running: Load an equal mass of total protein (typically 10-40 µg for cell lysates) per lane alongside a pre-stained protein molecular weight marker [21] [9]. Apply a constant voltage (e.g., 120-150V for mini-gels) until the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel.

- Membrane Preparation:

- Transfer: Assemble the "sandwich" in the order of sponge, filter paper, gel, membrane, filter paper, sponge. Remove all air bubbles by rolling a tube over the sandwich. Perform wet or semi-dry transfer according to the manufacturer's instructions [6].

Immunoblotting

- Blocking: Incubate the membrane in 25 mL of blocking buffer (e.g., 5% non-fat dry milk in TBST) for 1 hour at room temperature with gentle agitation to prevent nonspecific antibody binding [21] [26].

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Dilute the primary antibody in the recommended buffer (often 5% BSA or milk in TBST) [21]. Incubate the membrane with the primary antibody solution with gentle agitation, overnight at 4°C for optimal sensitivity [21].

- Washing: Wash the membrane three times for 5-10 minutes each with a large volume (e.g., 15 mL) of wash buffer (TBST or PBST) to remove unbound antibody [21] [6].

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: Dilute the HRP-conjugated secondary antibody in blocking or wash buffer (typical dilutions range from 1:2,000 to 1:100,000) [21] [6]. Incubate the membrane for 1 hour at room temperature with agitation [21].

- Final Washes: Wash the membrane six times for 5 minutes each with wash buffer to thoroughly remove any unbound secondary antibody, which is crucial for minimizing background [6].

Detection

For chemiluminescent detection, incubate the membrane with the working solution of an ECL substrate for approximately 1 minute [21] [6]. Drain excess reagent, wrap the membrane in plastic, and image using a system capable of detecting the emitted light, such as a digital imager or X-ray film [21]. The signal is most intense immediately following incubation and declines over the following few hours [21].

Table 1: Recommended Gel and Buffer Systems for Protein Separation [9]

| Protein Size Range | Recommended Gel Chemistry | Recommended Running Buffer |

|---|---|---|

| 10 - 30 kDa | 4-12% acrylamide gradient Bis-Tris gel | MES |

| 31 - 150 kDa | 4-12% acrylamide gradient Bis-Tris gel | MOPS |

| > 150 kDa | 3-8% acrylamide gradient Tris-Acetate gel | Tris-Acetate |

Table 2: Key Solutions and Reagents for Western Blotting [21] [9] [6]

| Solution/Reagent | Function | Example Composition |

|---|---|---|

| Lysis Buffer (e.g., RIPA) | Extracts and solubilizes proteins from cells or tissues. | Detergent, salt, buffer, protease inhibitors. |

| SDS Sample Buffer | Denatures proteins and confers negative charge for electrophoresis. | Tris buffer, SDS, glycerol, bromophenol blue, DTT. |

| Running Buffer | Conducts current and maintains pH during electrophoresis. | Tris, glycine, SDS. |

| Transfer Buffer | Conducts current and facilitates protein migration from gel to membrane. | Tris, glycine, methanol. |

| Blocking Buffer | Covers membrane surface to prevent non-specific antibody binding. | 5% non-fat dry milk or BSA in TBST. |

| Wash Buffer (e.g., TBST) | Removes unbound antibodies and reagents between steps. | Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20. |

Detection Methods and Analysis

The choice of detection method depends on the required sensitivity, available equipment, and whether the goal is qualitative or quantitative analysis.

Detection Modalities

- Chemiluminescent Detection: This is the most common method [8]. An enzyme-linked secondary antibody (e.g., HRP) catalyzes a substrate, producing light as a by-product. The light signal can be captured on X-ray film or with a CCD camera. It offers high sensitivity and a dynamic range suitable for many applications [25].

- Fluorescent Detection: This method uses secondary antibodies conjugated to fluorophores. The fluorophore is excited by a light source, and the emitted light is detected with a specialized scanner. Fluorescent detection is gaining popularity for quantitative work as it provides a stable signal, allows for multiplexing (detecting multiple proteins on the same blot), and has a wide linear dynamic range [12] [25].

- Colorimetric Detection: Enzyme-conjugated antibodies convert a chromogenic substrate into an insoluble colored precipitate on the membrane. While less sensitive and not quantitative, it is simple and requires no specialized equipment for visualization [25].

Qualitative vs. Quantitative Analysis

The analytical goal dictates the stringency of the experimental workflow.

- Qualitative Western Blotting: The primary objective is to answer a binary question: "Is the target protein present or absent?" [12]. This approach is used for verifying protein expression, confirming gene knockdown, or simple screening. The key concern is ensuring band specificity to avoid false positives, and normalization is not required [12].

- Quantitative Western Blotting: The goal is to measure and compare the relative abundance of a target protein across different samples [12]. This demands a more rigorous approach. The most critical principle is normalization using a loading control, typically a housekeeping protein (e.g., GAPDH, β-actin) that is constitutively expressed. The signal intensity of the target band is divided by that of the loading control to correct for variations in protein loading and transfer efficiency [12]. For accurate quantification, it is essential that the signal for both the target and control proteins falls within the linear dynamic range of the detection system to avoid saturation [12].

Current Standards and Publication Guidelines

A systematic assessment of over 500 scientific publications revealed that western blot figures and methods often omit essential details, limiting a reader's ability to evaluate or reproduce the results [7]. Adhering to best practices is therefore critical for scientific integrity.

Common Pitfalls in Reporting

An analysis of neuroscience and cell biology journals found that [7]:

- Over 90% of published western blots are cropped, and most do not provide source data in the supplement.

- Over 95% of blots lack a visible molecular weight marker.

- Approximately 30% of blots lack any molecular weight labels.

- Methods sections frequently omit the amount of protein loaded (55-78% of papers), blocking duration, and detailed antibody information (especially for secondary antibodies) [7].

Recommendations for Reproducible Western Blots

To ensure transparency and reproducibility, researchers should [7] [23]:

- Minimize Cropping: Provide uncropped images, preferably full-length, in the supplementary information to show the entire lane and any potential non-specific bands or protein multiplicity [7].

- Include Molecular Weight Markers: Always include the molecular weight marker in the blot image and label the key weights adjacent to the blot to confirm the target protein is at the expected size [7].

- Report Key Methodological Details: The methods section must include:

- The amount of protein loaded per lane [7].

- The blocking reagent, concentration, and duration [7].

- Complete antibody information: supplier, catalog number, RRID (Research Resource Identifier), and lot number if possible for both primary and secondary antibodies [7].

- Antibody dilution and incubation conditions [7].

- Provide Original Images: Many journals, including those in the Nature portfolio, now require unprocessed images of blots and gels to be published as Supplementary Information [23].

Table 3: Journal-Specific Publication Guidelines for Western Blots (2024) [23]

| Journal/Publisher | Key Image Requirements | Data Submission Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Press | Color images: 300 DPI at final print size. Fluorescent blots in RGB. | Western blots should be submitted as separate files, not embedded in text. |

| Nature Portfolio | Requires original, unprocessed images of all gels and blots. | Unprocessed images must be published as Supplementary Information. |

| Science | Follows general guidelines for file type and resolution. | Avoids excessive cropping and manipulation; adjustments must be documented. |

| Wiley | Specific requirements for resolution and color mode vary by journal. | Check individual journal guidelines for accepted file formats and sizes. |

Applications in Research and Diagnostics

The western blot assay has a multitude of applications, from basic research to applied clinical diagnostics [8].

Research Applications

In basic and translational research, western blotting is used for:

- Measuring Protein Expression: Comparing relative protein levels between different samples, such as treated vs. untreated cells or diseased vs. healthy tissues [8] [12].

- Analyzing Post-Translational Modifications: Detecting specific modifications like phosphorylation, glycosylation, or cleavage using modification-specific antibodies.

- Verifying RNAi or CRISPR Results: Confirming the successful knockdown or knockout of a target protein at the protein level.

- Biomarker Measurement: Used in the drug development process to measure potential biomarkers [8].

Diagnostic Applications

Western blotting's high specificity makes it a valuable confirmatory diagnostic tool. Notable examples include:

- Lyme Disease Diagnosis: The CDC recommends a two-tiered testing protocol where a positive or equivocal ELISA is followed by a western blot test to detect antibodies against Borrelia burgdorferi proteins, which improves diagnostic specificity [8].

- HIV Confirmation: The western blot was historically used as a confirmatory test after a positive HIV screening to detect antibodies to specific viral antigens, though it has largely been replaced by other methods.

- Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) Typing: Researchers have developed an HSV western blot test to determine the presence of antibodies against herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2), which is considered a gold standard [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Western Blotting

| Reagent/Material | Critical Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevents proteolytic degradation of target proteins during sample preparation. | Added fresh to lysis buffer. Essential for preserving protein integrity. |

| Pre-cast Gels | Provides consistent, reproducible protein separation without the need to pour gels. | Available in various percentages and gradients (e.g., 4-12% Bis-Tris). |

| Nitrocellulose/PVDF Membrane | Serves as the solid support for immobilized proteins during immunodetection. | PVDF requires pre-wetting in methanol. Nitrocellulose is more common. |

| Validated Primary Antibodies | Binds specifically to the protein of interest. The key determinant of specificity. | Knockout (KO)-validated antibodies are ideal to confirm specificity [25]. |

| HRP-Conjugated Secondary Antibodies | Binds to the primary antibody and produces an amplifiable signal for detection. | Species-specific. Cross-adsorbed antibodies reduce background. |

| Chemiluminescent Substrate | Generates light signal upon reaction with the enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody. | Choice of substrate (e.g., Pico vs. Femto) depends on target abundance. |

Mastering the Western Blot Protocol: A Step-by-Step Workflow from Sample to Signal

Within the framework of western blotting for detecting specific proteins, sample preparation is the foundational step upon which all subsequent results depend. The quality of protein extraction and preservation directly dictates the accuracy, reproducibility, and interpretability of data related to protein expression, post-translational modifications, and protein-protein interactions [27]. Effective preparation involves the strategic disruption of cellular membranes to release proteins while simultaneously mitigating the immediate and relentless activity of endogenous enzymes. Upon cell lysis, compartmentally contained proteases and phosphatases are unleashed, capable of mass protein degradation and dephosphorylation, which can rapidly obliterate experimental results [28]. Therefore, the dual strategy of selecting an appropriate lysis buffer and employing a robust regimen of enzyme inhibitors is not merely a recommendation but a critical requirement for successful western blot analysis, particularly in drug development where quantifying specific protein targets or their phosphorylated states is essential [29].

Core Components of a Lysis Buffer

A lysis buffer is a chemically engineered solution designed to disrupt cell membranes and solubilize proteins while maintaining their integrity for analysis. Its composition is a careful balance of components, each serving a specific function.

- Buffer System: Compounds like Tris-HCl or HEPES maintain a stable physiological pH (typically 7.0-7.6), preventing protein precipitation and instability that can occur outside this range [30] [17].

- Salts: Ionic salts such as Sodium Chloride (NaCl) maintain the ionic strength of the solution, which is necessary to disrupt molecular interactions within the cell membrane. However, excessively high salt concentrations can cause protein precipitation or electrophoresis artifacts [30].

- Chaotropic Agents/Detergents: These surfactants are pivotal for solubilizing proteins by binding to their hydrophobic regions. Detergents are categorized based on their properties [30]:

- Ionic (e.g., SDS, Sodium Deoxycholate): Strong, anionic detergents that efficiently solubilize membranes but denature proteins and disrupt protein-protein interactions.

- Non-ionic (e.g., Triton X-100, NP-40): Milder detergents that solubilize membranes while preserving native protein structures and interactions.

- Zwitterionic (e.g., CHAPS): Exhibit properties of both ionic and non-ionic detergents and are useful for preserving protein function.

- Reducing Agents: Chemicals like Dithiothreitol (DTT) or β-Mercaptoethanol (BME) disrupt disulfide bonds, ensuring proteins are in their monomeric form and preventing oxidation damage caused by cysteine residues [30] [31].

Table 1: Common Detergents Used in Lysis Buffers and Their Properties

| Detergent | Type | Strength | Key Applications and Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Ionic | Harsh | Excellent for solubilizing difficult proteins (e.g., membrane-bound, nuclear); fully denatures proteins [27] [30]. |

| Sodium Deoxycholate | Ionic | Harsh | Often used in RIPA buffer; helps disrupt protein-protein interactions [32] [30]. |

| Triton X-100 / NP-40 | Non-ionic | Mild | Ideal for whole-cell extracts and membrane-bound proteins; preserves protein-protein interactions [32] [33] [17]. |

| CHAPS | Zwitterionic | Mild | Useful for extracting functional proteins with minimal denaturation [33]. |

| Tween-20 | Non-ionic | Mild | More commonly used in washing buffers, but can be found in some mild lysis formulations [30]. |

Selecting the Optimal Lysis Buffer

The selection of a lysis buffer is primarily guided by the subcellular location of the target protein and the required state of the protein (native or denatured) for downstream analysis.

Buffer Selection Based on Protein Localization

The following workflow diagram outlines the decision-making process for selecting the most appropriate lysis buffer based on the protein of interest's subcellular location and the experimental requirements.

The logic presented in the workflow is supported by consistent recommendations across multiple technical resources [32] [31] [17]. RIPA buffer, with its combination of non-ionic and ionic detergents (NP-40, deoxycholate, and SDS), is particularly effective for hard-to-solubilize proteins found in the nucleus, mitochondria, or membrane compartments [32] [30]. For cytoplasmic proteins, the milder Tris-HCl buffer may be sufficient, while NP-40 is an excellent all-rounder for whole-cell extracts and membrane proteins when a non-denaturing environment is desired [32] [17].

Comparison of Common Lysis Buffers

Table 2: Common Lysis Buffer Compositions and Applications

| Buffer | Key Components | Best For | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| RIPA Buffer [32] [30] | 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40/Triton X-100, 0.5% Sodium Deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA | Nuclear, mitochondrial, and membrane-bound proteins; difficult-to-solubilize targets. | Harsh; can disrupt some protein-protein interactions. The gold standard for many western blotting applications [30]. |

| NP-40 Buffer [32] [17] | 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4-8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40 | Whole-cell extracts, membrane-bound proteins (under mild conditions). | Milder than RIPA; better for preserving protein-protein interactions. |

| Tris-HCl Buffer [31] [17] | 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) | Cytoplasmic, soluble proteins. | Very mild; no detergents, so it will not solubilize membrane-bound proteins without mechanical disruption. |

| 1% SDS Buffer [27] | 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1% SDS | Strong solubilization of all proteins, including complexes and aggregates. | Highly denaturing; not suitable for studies of native protein interactions. |

The Critical Role of Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitors

Cell lysis disrupts the careful compartmentalization of enzymes, leading to the unregulated activity of proteases and phosphatases. This can cause rapid protein degradation, altered protein function, and a misrepresentation of protein activation states (e.g., phosphorylation levels), ultimately compromising data integrity [28] [29]. Therefore, the use of inhibitors is not optional but essential.

- Proteases are hydrolase enzymes that cleave peptide bonds. They are categorized into serine, cysteine, aspartic, and metalloproteases based on their catalytic mechanism [28] [29].

- Phosphatases remove phosphate groups from serine, threonine, or tyrosine residues, reversing kinase activity. This dephosphorylation is a rapid and dominant process upon cell lysis, making phosphatase inhibitors absolutely critical for phosphoprotein analysis [28] [29].

Classes of Inhibitors and Their Use

Effective inhibition requires a cocktail of compounds targeting different enzyme classes. Inhibitors can be reversible (forming temporary bonds) or irreversible (forming permanent covalent bonds) [29].

Table 3: Essential Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitors

| Inhibitor | Target Enzyme(s) | Mechanism | Recommended Working Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| AEBSF [28] [29] | Serine Proteases | Irreversible | 0.2 - 1.0 mM |

| PMSF [31] [17] | Serine, Cysteine Proteases | Irreversible | 0.1 - 1.0 mM (1 mM is common) |

| Aprotinin [28] [17] | Serine Proteases | Reversible | 2 µg/mL (or 100-200 nM) |

| Leupeptin [28] [31] | Serine & Cysteine Proteases | Reversible | 5 - 100 µM |

| E-64 [28] | Cysteine Proteases | Irreversible | 1 - 20 µM |

| Pepstatin A [28] [31] | Aspartic Proteases | Reversible | 1 - 20 µM |

| EDTA [28] [17] | Metalloproteases | Reversible (Chelator) | 1 - 5 mM |

| Sodium Fluoride [32] [17] | Serine/Threonine Phosphatases, Acidic Phosphatases | Irreversible | 5 - 20 mM |

| Sodium Orthovanadate [32] [17] | Tyrosine Phosphatases, Alkaline Phosphatases | Irreversible | 1 - 100 mM |

| β-Glycerophosphate [28] | Serine/Threonine Phosphatases | Reversible | 1 - 100 mM |

Practical Application of Inhibitors

- Preparation and Storage: Most inhibitors are supplied as powders or stock solutions. They should be reconstituted according to the manufacturer's instructions or standard protocols [17]. Stock solutions should be aliquoted and stored at -20°C. PMSF is unstable in aqueous solutions and must be added fresh from an ethanol or methanol stock [31] [17].

- Creating a Cocktail: For comprehensive protection, a broad-spectrum cocktail is necessary. This can be achieved by using commercial tablets or ready-made cocktails (e.g., Thermo Fisher Pierce tablets [28] [34]) or by preparing a homemade mix. A typical homemade cocktail might include PMSF (1 mM), Leupeptin (5-10 µg/mL), Aprotinin (2 µg/mL), Pepstatin A (1 µg/mL), and EDTA (1-5 mM), along with phosphatase inhibitors like Sodium Fluoride (10 mM) and activated Sodium Orthovanadate (1 mM) for phosphoprotein studies [31] [17].

- Addition to Lysis Buffer: Inhibitors must be added to the ice-cold lysis buffer immediately before use to ensure maximum effectiveness [32] [34].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Workflow for Cell Lysate Preparation

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for preparing protein lysates from adherent cell culture, incorporating the critical steps for maintaining sample integrity.

Protocol: Lysate Preparation from Adherent Cell Culture

Materials:

- Ice-cold Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Lysis Buffer (e.g., RIPA Buffer) [32] [30]

- Freshly added protease and phosphatase inhibitors [34]

- Cell scraper

- Refrigerated microcentrifuge

- BCA or Bradford Protein Assay Kit

Method:

- Preparation: Place the cell culture dish on ice. Prepare lysis buffer and add protease and phosphatase inhibitors immediately before use [34].

- Washing: Aspirate the culture medium and wash the cells gently but thoroughly with ice-cold PBS to remove residual serum and media proteins [27] [34].

- Lysis: Aspirate the PBS. Add ice-cold lysis buffer (e.g., ~1 mL per 10⁷ cells or a 100 mm plate) [34]. Scrape the cells adherent cells swiftly and transfer the cell suspension to a pre-cooled microcentrifuge tube.

- Incubation: Agitate the lysate gently for 30 minutes on ice to ensure complete lysis. Vortex the tube occasionally [31].

- Sonication (Optional but Recommended): Sonicate the lysate on ice using short bursts (e.g., 3-5 seconds) with intervals to prevent heating. This shears genomic DNA and reduces sample viscosity [32] [27].

- Clarification: Centrifuge the lysate at approximately 14,000 x g for 15 minutes at 4°C to pellet insoluble cell debris, lipids, and nuclei [34].

- Collection: Carefully transfer the supernatant (the clarified protein lysate) to a new, pre-chilled tube. Avoid disturbing the pellet.

- Quantification: Determine the protein concentration of the lysate using a compatible protein assay (e.g., BCA assay) following the manufacturer's protocol. The BCA assay is often preferred over Bradford as it is less affected by detergents common in lysis buffers [34].

- Preparation for Electrophoresis: Mix the lysate with an equal volume of 2X Laemmli sample buffer [31] [17]. For denatured SDS-PAGE, boil the samples at 95-100°C for 5 minutes [31]. Cool briefly, centrifuge, and load onto the gel.

Protocol: Lysate Preparation from Tissue Samples

Materials:

- Liquid nitrogen and mortar & pestle or electric homogenizer

- Lysis Buffer (e.g., RIPA or T-PER Reagent) with fresh inhibitors [34]

Method:

- Dissection and Homogenization: Dissect the tissue of interest on ice and quickly wash with ice-cold PBS to remove excess blood. Weigh the tissue.

- For tough tissues, flash-freeze the tissue in liquid nitrogen and pulverize it to a fine powder using a mortar and pestle pre-cooled with liquid nitrogen [27]. Transfer the powder to a tube containing ice-cold lysis buffer (~500 μL to 1 mL per 10 mg tissue) [32].

- Alternatively, for softer tissues, add the tissue directly to lysis buffer in a tube and homogenize thoroughly using an electric homogenizer (e.g., Polytron) on ice [32] [27].

- Incubation and Clarification: Incubate the homogenate on ice for 30 minutes with occasional vortexing. Centrifuge at 10,000 - 15,000 x g for 15-20 minutes at 4°C [32] [34].

- Collection and Storage: Transfer the supernatant to a new tube. Quantify the protein concentration, aliquot, and store at -80°C or prepare for immediate electrophoresis [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for Western Blot Sample Preparation

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application | Example Products / Components |

|---|---|---|

| RIPA Lysis Buffer [30] [34] | Gold-standard buffer for total protein extraction, especially for nuclear, mitochondrial, and membrane-bound proteins. | 25-50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% Deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS. |