Troubleshooting STAT Dimerization Assays: A Comprehensive Guide for Cellular Systems Research

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for understanding, performing, and troubleshooting STAT protein dimerization assays in cellular systems.

Troubleshooting STAT Dimerization Assays: A Comprehensive Guide for Cellular Systems Research

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for understanding, performing, and troubleshooting STAT protein dimerization assays in cellular systems. Covering foundational biology, established and emerging methodologies, common pitfalls with solutions, and validation strategies, it addresses critical challenges such as differentiating dimer conformations, detecting phosphorylation-independent activity, and interpreting disease-associated mutations. The content synthesizes recent advances, including genetically encoded biosensors and structural insights, to enhance assay reliability and translational relevance for both basic research and therapeutic discovery.

Understanding STAT Biology: From Structure to Dimerization Dynamics

STAT Protein Domains and Their Functional Roles in Dimerization

Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STAT) proteins are intracellular transcription factors that mediate cellular immunity, proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation. These proteins share a conserved multi-domain architecture that enables their dual functionality as signal transducers and transcription factors. Understanding these domains is crucial for troubleshooting dimerization assays in cellular systems research.

All seven mammalian STAT proteins (STAT1, STAT2, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5A, STAT5B, and STAT6) share a common structural organization consisting of six functional domains:

- N-terminal domain (NTD): Facilitates interactions between STAT molecules and enables dimerization even in the absence of phosphorylation [1] [2].

- Coiled-coil domain (CCD): Binds to other transcription factors and co-activators; contains nuclear localization signal (NLS) motifs [3] [1].

- DNA-binding domain (DBD): Recognizes and binds specific DNA target sequences, typically variations of the gamma-activated sequence (GAS) motif [1] [4].

- Linker domain: Provides structural support during activation and DNA binding [1].

- Src homology 2 (SH2) domain: Binds phosphotyrosine-containing motifs; critical for receptor docking and STAT dimerization [3] [1].

- C-terminal transactivation domain (TAD): Interacts with transcriptional co-activators to regulate gene expression [3] [1].

Table 1: Core Domains of STAT Proteins and Their Functions

| Domain | Primary Function | Key Structural Features |

|---|---|---|

| N-terminal domain (NTD) | Mediates STAT-STAT interactions; facilitates latent dimerization | Hook-like structure of multiple alpha-helices [1] |

| Coiled-coil domain (CCD) | Binds transcription factors and co-activators; nuclear translocation | Several alpha-helices in ropelike structure; contains NLS [1] |

| DNA-binding domain (DBD) | Recognizes and binds specific DNA sequences | Immunoglobin-like structure [1] |

| Linker domain | Structural support during activation and DNA binding | Short connecting region [1] |

| SH2 domain | Binds phosphotyrosine motifs; enables receptor docking and dimerization | Highly conserved structural module [1] |

| C-terminal transactivation domain (TAD) | Interacts with transcriptional co-activators | Diverse, poorly defined sequence [1] |

Troubleshooting STAT Dimerization Assays: FAQs

FAQ 1: Why is my STAT dimerization assay showing weak or no signal despite cytokine stimulation?

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Verify tyrosine phosphorylation status: STAT dimerization requires phosphorylation of a conserved tyrosine residue (e.g., Y705 in STAT3). Confirm phosphorylation using phospho-specific antibodies [5]. Inadequate cytokine stimulation or inhibited JAK activity can prevent phosphorylation.

Check SH2 domain integrity: The SH2 domain must be intact for phosphotyrosine recognition and dimerization. Mutations in this domain disrupt reciprocal phosphotyrosine-SH2 interactions essential for dimer formation [5] [1].

Validate nuclear translocation: Phosphorylated STAT dimers translocate to the nucleus. Use controls to confirm proper nuclear import machinery function [3] [1].

Optimize cytokine concentrations and timing: Different STATs have varying activation kinetics. Perform time-course and dose-response experiments to establish optimal conditions for your specific STAT protein [5].

FAQ 2: How can I distinguish between latent (unphosphorylated) and active (phosphorylated) STAT dimers in my assays?

Methodological Approaches:

Employ phosphorylation-deficient mutants: Use STAT mutants where the critical tyrosine residue is mutated to phenylalanine (e.g., STAT3 Y705F) to differentiate phosphorylation-dependent dimerization [5].

Utilize N-domain targeting: Latent STAT dimers are stabilized by N-terminal domain interactions, while active dimers rely on SH2 domain-phosphotyrosine interactions [2]. Mutations in N-domain dimerization hotspots (e.g., F77A in STAT1, L78R in STAT3) disrupt latent but not active dimers [2].

Implement specialized detection systems: The homoFluoppi system allows detection of dynamic STAT dimerization in living cells and can differentiate between phosphorylation-dependent and latent dimers [5].

FAQ 3: What could cause constitutive STAT dimerization independent of cytokine stimulation in my experiments?

Troubleshooting Guide:

Investigate pathological STAT mutations: Certain disease-associated STAT mutants exhibit constitutive dimerization. For example, some STAT3 mutants identified in inflammatory hepatocellular adenoma form dimers independently of cytokine stimulation [5].

Check for upstream pathway activation: Oncogenic mutations in JAKs or receptors can lead to persistent STAT activation [6] [7].

Verify experimental conditions: Overexpression artifacts can sometimes cause non-physiological dimerization. Include proper controls with endogenous STAT proteins.

FAQ 4: Why do my STAT proteins show aberrant subcellular localization in dimerization experiments?

Resolution Strategies:

Assess nuclear import/export machinery: STATs continuously shuttle between cytoplasm and nucleus via direct interaction with nucleoporins and importin complexes [1] [2]. Disruption of this machinery affects localization.

Evaluate NLS and NES functionality: The coiled-coil domain contains NLS motifs, while other regions may contain nuclear export signals (NES) [3] [1]. Mutations in these signals alter localization patterns.

Monitor dephosphorylation events: Nuclear phosphatases dephosphorylate STATs, leading to inactivation and nuclear export [3] [1]. Inhibit phosphatases if studying nuclear dimers.

Experimental Protocols for STAT Dimerization Analysis

Protocol 1: Detecting Dynamic STAT Dimerization in Living Cells Using HomoFluoppi

The homoFluoppi system enables real-time visualization of STAT dimerization in living cells, providing significant advantages over traditional endpoint assays like co-immunoprecipitation [5].

Methodology:

Construct Preparation:

Cell Transfection and Treatment:

- Transfect constructs into appropriate cell lines (HEK293 cells recommended for STAT3 studies due to low endogenous expression) [5].

- Stimulate with cytokines (oncostatin M, IL-6, or IFN-α) at varying concentrations and durations to establish activation kinetics.

Image Acquisition and Analysis:

- Use automated microscopy systems (e.g., ArrayScan) with Spot Detector Bioapplication protocol.

- Quantify punctate signal (fluorescent punctate intensity per cell) as a measure of dimer formation.

- For reversibility studies, wash out cytokine and monitor puncta dissolution [5].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for STAT Dimerization Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| HomoFluoppi System | Live-cell visualization of STAT dimerization | PB1 and mAG1 tags form condensed phase-separated droplets upon interaction; reversible detection [5] |

| Phospho-specific STAT Antibodies | Detection of activated, phosphorylated STATs | Target phosphorylated tyrosine residues (e.g., STAT3 pY705) [5] |

| JAK Inhibitors (Jakinibs) | Block upstream STAT activation | Inhibit JAK kinase activity; examples: ruxolitinib (JAK1/JAK2), tofacitinib (JAK1/JAK3) [6] [7] |

| STAT SH2 Domain Inhibitors | Directly target STAT dimerization | Small molecules competing with phosphotyrosine binding (e.g., 3,4-methylenedioxy-β-nitrostyrene for STAT3) [5] [8] |

| N-domain Mutants | Study latent vs. active dimerization | Point mutations (e.g., STAT1-F77A, STAT3-L78R) disrupt latent dimerization [2] |

Protocol 2: Systematic Analysis of Latent STAT Dimerization Using Co-localization Assay

This approach comprehensively assesses both homo- and heterodimeric interactions among unphosphorylated STATs (U-STATs) [2].

Methodology:

Construct Design:

- Generate STAT variants with transferable nuclear localization (NLS) or nuclear export (NES) signals.

- Create wild-type and dimerization-deficient mutants (e.g., N-domain mutants) as controls.

Transfection and Compartmental Shift Assay:

- Co-express bait (NES- or NLS-tagged) and test (untagged) STAT constructs.

- For homodimerization assessment: Express STAT-NES with wild-type STAT and monitor cytoplasmic co-localization.

- For heterodimerization assessment: Express different STAT family members with compartment-targeted baits.

Quantitative Imaging and Validation:

- Acquire fluorescence images and quantify co-localization coefficients.

- Ensure bait protein expression levels are within 1-4-fold of test protein concentration.

- Validate interactions with orthogonal methods (FRET, biochemical assays).

STAT Dimerization: Canonical and Non-Canonical Pathways

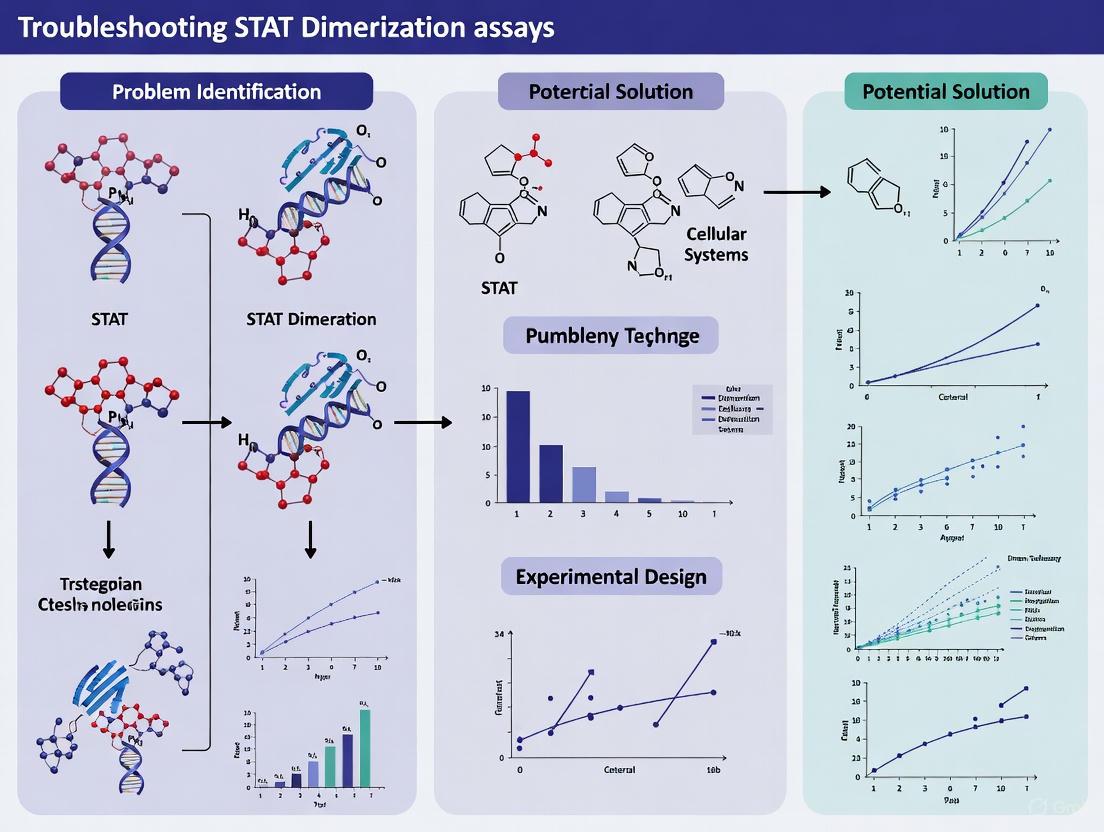

The following diagrams illustrate key pathways and experimental workflows for studying STAT dimerization:

Diagram 1: Canonical STAT Activation and Dimerization Pathway

Diagram 2: Latent STAT Dimerization and Nuclear Shuttling

Advanced Technical Considerations

STAT-Specific Dimerization Patterns

Recent systematic analyses have revealed distinct dimerization preferences across the STAT family [2]:

- Homodimer-forming STATs: STAT1, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5A, and STAT5B

- Heterodimer-forming STATs: STAT1:STAT2 and STAT5A:STAT5B

- Monomeric STAT: STAT6 under unphosphorylated conditions

Targeting STAT Dimerization for Therapeutic Intervention

The development of STAT-specific inhibitors faces challenges due to high homology among STAT family members, particularly in the SH2 domains [8]. Current strategies include:

- Comparative screening approaches: Using 3D structure models of all human STAT-SH2 domains for virtual screening of compound libraries [8].

- SH2 domain-targeting compounds: Small molecules that compete with phosphotyrosine binding to prevent dimerization [5] [8].

- Novel inhibitor identification: High-throughput screening using living cell systems like homoFluoppi has identified compounds such as 3,4-methylenedioxy-β-nitrostyrene (MNS) as STAT3 dimerization inhibitors [5].

In cellular signaling, the canonical pathway for Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STAT) protein activation follows a precise sequence: phosphorylation initiates a conformational change that enables parallel dimer formation and subsequent nuclear translocation. This process is fundamental to gene regulation in response to extracellular cues, and its disruption can lead to experimental pitfalls in research and drug development. This guide addresses the core mechanisms and common challenges in studying this critical pathway.

The Core Mechanism: From Cytokine to Dimer

The following diagram illustrates the canonical JAK-STAT activation pathway, from the initial cytokine signal to the formation of a transcriptionally active parallel STAT dimer.

Troubleshooting FAQs and Guides

FAQ: Core Concepts and Mechanisms

Q1: What defines "canonical" STAT activation? Canonical STAT activation is a membrane-to-nucleus signaling module initiated by cytokine binding to its transmembrane receptor. This event brings receptor-associated Janus kinases (JAKs) into proximity, triggering their trans-autophosphorylation and activation [9] [6]. The activated JAKs then phosphorylate a single conserved tyrosine residue on STAT monomers. This phosphorylation induces a conformational change that enables STATs to form parallel, transcriptionally active dimers via reciprocal phosphotyrosine-SH2 domain interactions [9].

Q2: Why is phosphorylation insufficient for full STAT activity? Phosphorylation is necessary but not always sufficient for robust activity. Research on related dimeric systems, such as IRE1α, reveals that dimerization alone may not trigger full phosphorylation or activity; instead, the congregation of multiple dimers is often needed for efficient cross-phosphorylation and full enzymatic activation [10]. This principle suggests that achieving a critical local concentration of STAT dimers may be essential for a potent transcriptional response in your cellular systems.

Troubleshooting Guide: Experimental Pitfalls in Dimerization Assays

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphorylation | Weak or no phospho-STAT signal. | Inefficient JAK activation; overly rapid dephosphorylation by phosphatases. | Include phosphatase inhibitors (e.g., sodium orthovanadate) in lysis buffer. Confirm JAK activation by checking its phosphorylation status [6]. |

| Dimerization | Failure to detect dimers in native gels or cross-linking assays. | Low phosphorylation efficiency; STAT protein degradation; suboptimal assay conditions. | Ensure fresh, high-quality reagents. Use a positive control (e.g., cell line with constitutive pathway activation). Verify antibody specificity for phosphorylated STAT. |

| Nuclear Localization | Poor nuclear accumulation despite phosphorylation. | Damaged nuclear import machinery; incorrect cell fractionation. | Include importin α/β in cell-free systems. Validate fractionation protocol with nuclear markers (e.g., Lamin A/C). Use immunofluorescence as a complementary method. |

| Non-Specific Results | High background noise in Western blots. | Antibody cross-reactivity; incomplete blocking. | Optimize antibody dilution. Use phospho-specific antibodies. Include a non-phosphorylatable STAT mutant (Y->F) as a negative control. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol 1: Detecting STAT Phosphorylation and Dimerization via Western Blot

This protocol is foundational for assessing the initial steps of canonical activation.

Methodology:

- Cell Stimulation & Lysis: Stimulate cells with the appropriate cytokine (e.g., IFN-γ for STAT1) for 15-30 minutes. Lyse cells using a RIPA buffer supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitors.

- Electrophoresis:

- For total protein and phosphorylation analysis, use standard SDS-PAGE.

- For detecting dimerization, use non-denaturing (native) PAGE without SDS in the gel or sample buffer to preserve protein complexes.

- Western Blotting: Transfer proteins to a PVDF membrane. Probe sequentially with:

- Primary antibody against the phosphorylated tyrosine of your STAT (e.g., anti-pSTAT1 (Y701)).

- A secondary antibody conjugated to HRP.

- After imaging, strip the membrane and re-probe with an antibody against total STAT protein to normalize for loading.

Troubleshooting Tip: A smear or high molecular weight band on a native gel may indicate higher-order oligomer formation, which can occur under intense signaling conditions [10].

Protocol 2: Analyzing STAT Dimer-DNA Binding via Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

This assay assesses the functional outcome of dimerization: the ability to bind DNA.

Methodology:

- Prepare Nuclear Extract: Harvest cytokine-stimulated cells and isolate nuclear proteins using a commercial kit or differential centrifugation.

- Prepare Labeled Probe: Design a double-stranded DNA oligonucleotide containing the consensus STAT binding sequence (e.g., GAS element: TTCCNGGAA). Label it with a fluorophore or biotin for detection.

- Binding Reaction: Incubate the nuclear extract with the labeled probe in a binding buffer. To confirm specificity, include a reaction with a 100-fold excess of unlabeled (cold) probe as a competitor.

- Electrophoresis & Detection: Run the reaction mixture on a non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The protein-DNA complex (STAT dimer bound to DNA) will migrate more slowly than the free probe. Visualize using a gel imager.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Phospho-specific STAT Antibodies | Detect activated, tyrosine-phosphorylated STATs in Western blot, EMSA, and immunofluorescence. | Anti-pSTAT1 (Y701), Anti-pSTAT3 (Y705). Critical for distinguishing active from total STAT pools. |

| Recombinant Cytokines | Specific agonists to activate the JAK-STAT pathway in cellular assays. | IFN-γ (for STAT1), IL-6 (for STAT3). Use at validated concentrations to avoid off-target effects. |

| JAK Inhibitors | Pharmacological tools to inhibit pathway activation upstream of STATs; used for control experiments. | Tofacitinib (pan-JAK), Ruxolitinib (JAK1/2). Essential for confirming the specificity of an observed phenotype [11] [12]. |

| Phosphatase Inhibitors | Prevent dephosphorylation of STATs during cell lysis and protein preparation, preserving signal. | Sodium orthovanadate, Sodium fluoride. Must be added fresh to lysis buffers. |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevent degradation of STAT proteins and other pathway components during processing. | EDTA, PMSF, commercial protease inhibitor cocktails. |

| STAT Mutant Constructs | Key controls for mechanistic studies (e.g., phosphorylation-deficient, constitutively active). | STAT-YF (tyrosine to phenylalanine), STAT-CA (constitutive dimer). Validate functionality in your system [6]. |

Advanced Considerations and Pathway Cross-Talk

The following workflow diagram integrates core concepts and troubleshooting steps for a robust dimerization assay, highlighting critical checkpoints.

Integrated Analysis is Key: Always correlate dimerization data with functional readouts. For instance, in cancer research, overactive JAK-STAT signaling drives immune escape by upregulating PD-L1 [12]. Combining dimerization assays with PD-L1 expression analysis provides a more comprehensive view of pathway biology and therapeutic intervention points.

Core Concepts: STAT Protein Fundamentals

What are the core structural domains of STAT proteins and their functions? STAT proteins share a conserved multi-domain structure that dictates their function. The key domains include:

- N-terminal domain (NTD): Facilitates interactions between STAT molecules, enabling dimerization even without phosphorylation. [1]

- Coiled-coil domain (CCD): Binds to other transcription factors and co-activators; contains nuclear localization signals for nuclear import. [1]

- DNA-binding domain (DBD): Recognizes and binds specific DNA target sequences, typically variations of the gamma-activated sequence (GAS). [1]

- Linker domain (LD): Provides structural support during activation and DNA binding. [1]

- SH2 domain: Binds phosphotyrosine motifs, crucial for receptor docking and STAT dimerization. [1]

- C-terminal transactivation domain (TAD): Interacts with transcriptional co-activators to regulate gene expression. [1]

How does "canonical" STAT signaling differ from "non-canonical" functions? The table below summarizes the key distinctions:

| Feature | Canonical Signaling | Non-Canonical Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Activation Trigger | Cytokine/Growth Factor stimulation [6] | Various, including basal cellular processes [13] |

| Phosphorylation State | Tyrosine-phosphorylated (pSTAT) [1] | Primarily unphosphorylated (uSTAT) [14] [1] |

| Dimerization State | Parallel dimers via SH2-pTyr [15] [1] | Antiparallel dimers, monomers, or other complexes [15] |

| Primary Localization | Nucleus [1] | Nucleus and cytoplasm [13] [1] |

| Main Function | Transcriptional activation [1] | Transcriptional repression, heterochromatin stabilization, mitochondrial modulation [13] [14] [1] |

What are the specific dimerization states of unphosphorylated STATs? Unphosphorylated STATs exist in a dynamic equilibrium of different states, a key concept for troubleshooting dimerization assays.

Unphosphorylated STAT proteins can exist in a concentration-dependent equilibrium between monomers and antiparallel dimers. For STAT5a, this equilibrium is governed by a moderate dissociation constant (Kd ~90 µM). [15] These antiparallel dimers are structurally distinct from the parallel dimers formed by phosphorylated STATs and are considered inactive in the canonical sense. [15] [16] Interactions via the N-terminal domains can further stabilize these complexes or enable the formation of tetramers. [15] [1]

Troubleshooting Guide: Dimerization Assays

FAQ: My dimerization assays show inconsistent results. What could be affecting the monomer-dimer equilibrium? The dynamic nature of uSTAT dimerization makes it sensitive to several experimental conditions. Consider the following common issues and solutions:

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Variable dimer detection in native gels | Protein concentration is near the Kd, causing shifts in equilibrium. [15] | Standardize protein concentration across experiments. Use crosslinking to "trap" the dimer state for analysis. [17] |

| Low signal in FRET-based biosensors | Fluorophores positioned suboptimally; low expression of biosensor. [16] | Use biosensors with fluorophores fused C-terminally to the SH2 domain. [16] Validate expression levels via Western blot. |

| Unexpected nuclear localization without stimulation | Unphosphorylated STATs can shuttle to the nucleus. [14] | Do not use nuclear localization alone as proof of canonical activation. Corroborate with phosphorylation-specific antibodies. |

| Discrepancy between crystallography and solution data | Crystallography may capture one state; solution methods reflect dynamic equilibrium. [15] | Use complementary techniques (e.g., SAXS, analytical ultracentrifugation) to study STATs in solution. [15] |

FAQ: How can I specifically track the active, parallel dimerization of STATs in live cells? Genetically encoded biosensors, such as STATeLights, are powerful tools for this purpose. [16] The optimal design involves C-terminal fusion of fluorescent proteins (e.g., mNeonGreen and mScarlet-I) to the STAT monomer, as this position shows a large change in distance and orientation upon the antiparallel-to-parallel conformational shift during activation. [16] This setup can be read out using Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy-Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FLIM-FRET), which is less susceptible to expression level variability and photobleaching. [16]

Essential Reagents and Protocols

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents for studying unphosphorylated STAT dimerization.

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Feature / Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| STATeLight Biosensors [16] | Real-time detection of STAT conformational changes in live cells. | C-terminal FP fusions to STAT core; readout via FLIM-FRET. |

| Crosslinkers (e.g., DSG) [17] | Stabilize transient protein complexes for analysis. | Use in combination with non-reducing electrophoresis to trap dimer states. |

| SAXS (Solution Analysis) [15] | Study oligomeric states and low-resolution structure in solution. | Characterizes dynamic equilibria (e.g., monomer-dimer) under near-native conditions. [15] |

| AlphaFold-Multimer [16] | Computational prediction of full-length STAT dimer structures. | Provides models for rational biosensor design, though low-confidence flexible regions exist. [16] |

Protocol: Validating Dimerization with Crosslinking and Electrophoresis

This protocol is adapted from methods used in recent studies. [17]

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells in a non-denaturing lysis buffer (e.g., without SDS) to preserve native protein complexes.

- Protein Quantification: Precisely quantify total protein concentration. Remember that dimerization is concentration-dependent. [15]

- Crosslinking: Treat equal amounts of protein lysate with a range of disuccinimidyl glutarate (DSG) concentrations (e.g., 0, 0.5, 1, 2 mM). Incubate at room temperature for 30 minutes.

- Quenching: Stop the reaction by adding Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) to a final concentration of 20-50 mM and incubate for 15 minutes.

- Non-Reducing Electrophoresis: Prepare samples without β-mercaptoethanol or DTT (reducing agents). Load and run on a standard SDS-PAGE gel. The absence of reducing agents allows disulfide-independent dimers stabilized by crosslinking to be visualized.

- Western Blotting: Transfer proteins to a membrane and probe with an antibody specific to your STAT of interest. The appearance of a higher molecular weight band corresponding to twice the monomeric size indicates successful dimer crosslinking. [17]

Protocol: Core Workflow for a STAT Dimerization Study

This workflow integrates multiple techniques to provide a comprehensive analysis.

The Src Homology 2 (SH2) domain is a protein interaction module of approximately 100 amino acids that specifically recognizes and binds to phosphorylated tyrosine (pY) residues within peptide motifs [18]. In the context of STAT (Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription) proteins, the SH2 domain performs an indispensable function: it facilitates the reciprocal phosphotyrosine-mediated dimerization that is essential for STAT activation and nuclear translocation [5] [19]. This interaction is a critical decision point in signal transduction, and its dysregulation is implicated in numerous disease states, including cancers and immunodeficiencies [20] [5]. Troubleshooting STAT dimerization assays requires a deep understanding of the SH2 domain's structure, its specificity determinants, and the key residues that govern its function. This guide addresses common experimental challenges by providing targeted FAQs and troubleshooting advice grounded in the molecular mechanics of SH2-pY interactions.

SH2 Domain Structure & Function: A Primer

Core Structural Architecture

All SH2 domains share a highly conserved fold, despite variations in amino acid sequence. The core structure consists of a central three-stranded antiparallel beta-sheet flanked by two alpha helices, forming a compact α-β-α sandwich [18]. A deep pocket within the βB strand binds the phosphate moiety of the phosphotyrosine. This pocket contains a nearly invariant arginine residue at position βB5 (part of the FLVR motif), which forms a critical salt bridge with the phosphate group [18].

Structural Classification of SH2 Domains

| Structural Feature | SRC-Type SH2 Domains | STAT-Type SH2 Domains |

|---|---|---|

| Beta-Sheet Composition | Contains βE and βF strands | Lacks βE and βF strands |

| Alpha-Helix B | Single continuous helix | Split into two helices |

| C-Terminal Loops | Has adjoining loops after βF | Lacks these loops |

| Primary Function | Substrate recruitment | Facilitates dimerization |

Mechanism of Phosphopeptide Recognition

SH2 domain binding is characterized by high specificity for cognate pY ligands with moderate binding affinity, typically in the 0.1–10 µM range [18]. The interaction involves a two-pronged binding mechanism:

- Phosphotyrosine Binding: The invariant arginine in the FLVR motif anchors the phosphorylated tyrosine.

- Specificity Pocket Engagement: Residues C-terminal to the pY (primarily at positions +1 to +3) engage in complementary pockets on the SH2 domain surface, conferring sequence-specific recognition [21] [22].

Beyond simple motif recognition, SH2 domains achieve remarkable selectivity by integrating contextual peptide sequence information. This includes recognizing both permissive residues that enhance binding and non-permissive residues that oppose it due to steric clash or charge repulsion [21]. The local sequence context matters, as neighboring positions can affect one another, allowing SH2 domains to distinguish subtle differences in peptide ligands [21].

Figure 1. SH2 Domain Binding Mechanism. The diagram illustrates the two-pronged binding mechanism of an SH2 domain (yellow) to a phosphopeptide. The interaction is anchored by the invariant arginine (RβB5) of the FLVR motif binding the phosphotyrosine (pY, green). Specificity is determined by additional contacts with residues C-terminal to the pY, such as the +1 (blue) and +3 (red) positions.

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for STAT Dimerization Assays

FAQ 1: My dimerization assay shows weak or no signal. What are the key residues to check for proper SH2 domain function?

Weak dimerization signal is one of the most common problems. The issue often lies in the integrity of the SH2 domain or its phosphorylation-dependent activation mechanism.

Key Residues and Functional Motifs to Validate:

| Component | Key Residue/Motif | Functional Role | Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphotyrosine (Ligand) | Tyrosine (e.g., STAT3 Y705) | Phosphorylation creates SH2 binding site | Phospho-specific Western Blot |

| SH2 Domain (Receptor) | Arginine in FLVR motif (βB5) | Essential for pY binding; mutation abrogates all binding | Sequencing, Functional Assay |

| SH2 Domain (Receptor) | Specificity-determining residues (e.g., in EF/BG loops) | Recognize residues C-terminal to pY (e.g., +1, +3) | Sequencing, Peptide Binding Assay |

| Dimer Interface | SH2 domain surface | Binds reciprocal pY-peptide; distinct from pY-binding pocket | Mutagenesis (e.g., R609Q in STAT3) [5] |

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Confirm Phosphorylation: Verify phosphorylation of the critical tyrosine (e.g., STAT3-Y705) using phospho-specific antibodies. Without phosphorylation, SH2-mediated dimerization cannot occur [5].

- Check SH2 Domain Integrity: Ensure the SH2 domain is correctly folded. The FLVR motif arginine is absolutely essential. Mutations in this residue will completely disrupt phosphopeptide binding [18].

- Verify Specificity Pocket: For STAT proteins, the SH2 domain must also be available for the reciprocal interaction. Mutations like STAT3 R609Q, located within the SH2 domain, can disrupt phosphotyrosine binding and dimerization without affecting phosphorylation [5].

FAQ 2: How can I distinguish between specific and non-specific binding in my SH2 domain interaction assays?

Non-specific binding can lead to false positives. Specificity is governed by the contextual peptide sequence recognized by the SH2 domain [21].

Strategies to Confirm Specificity:

- Use Validated Positive Controls: Include peptides with known high-affinity interactions for your SH2 domain. For example, the SH2 domain of SH2D1A (SAP) binds to a specific motif [TIpYxx(V/I)] [23].

- Employ Non-Permissive Residues: Design mutant peptide controls where key residues C-terminal to the pY (e.g., at +1, +2, or +3) are replaced with non-permissive residues. Non-permissive residues inhibit binding through steric clash or charge repulsion, providing strong evidence for the specificity of the wild-type interaction [21].

- Competition with Free Phosphotyrosine: An excess of free phosphotyrosine should compete for binding to the primary pY pocket, significantly reducing the signal. A lack of competition suggests non-specific binding.

FAQ 3: I observe constitutive dimerization in my negative controls. What could be causing this?

Constitutive, ligand-independent dimerization suggests a breakdown in the normal regulatory mechanisms of the SH2 domain.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Description | Experimental Check |

|---|---|---|

| Activating Mutations | Mutations in the SH2 domain (e.g., in its surface or loops) can lead to cytokine-independent, constitutive dimerization. Such mutations have been found in inflammatory hepatocellular adenoma (IHCA) [5]. | Sequence the SH2 domain to rule out gain-of-function mutations. |

| Latent Dimer/Oligomer Formation | STAT3 can form latent dimers or oligomers independent of tyrosine phosphorylation [5]. This baseline signal may be normal but can be exaggerated by protein overexpression. | Compare to untransfected/low-expression cells. Use functional assays (e.g., reporter gene) to confirm if dimers are active. |

| Overexpression Artifacts | High concentrations of STAT and SH2 domain proteins can drive dimerization through mass action, even without stimulation. | Titrate protein expression to the minimum level required for detection. |

FAQ 4: What are the best practices for detecting dynamic STAT-SH2 dimerization in living cells?

Traditional methods like co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) are endpoint assays that cannot capture rapid, reversible dimerization kinetics [5].

Recommended Methodologies:

- homoFluoppi Assay: This system uses a single fusion construct (PB1-mAG1-STAT3) to detect homodimerization reversibly and quantitatively in living cells. Upon dimerization, the proteins form fluorescent puncta, allowing real-time monitoring of dimer dynamics, including formation and dissociation [5].

- FRET/BRET: While powerful, these resonance energy transfer techniques can be time-consuming to optimize (e.g., linker lengths) and may not be ideal for high-throughput screening [5].

- Avoid BiFC (Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation): While BiFC can detect dimers, the fluorescent complex is often irreversible, making it unsuitable for studying the dynamic dimerization process [5].

Workflow for Dynamic Dimerization Analysis:

Figure 2. Workflow for Dynamic Dimerization Assay. The recommended workflow for detecting reversible STAT dimerization in living cells using the homoFluoppi system, from construct design to kinetic analysis [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Reagents for SH2 Domain and STAT Dimerization Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Features / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| homoFluoppi System | Detects protein homodimerization reversibly and quantitatively in living cells. | PB1-mAG1-STAT3 construct; forms puncta upon dimerization; ideal for kinetic studies and HTS [5]. |

| Phospho-specific STAT Antibodies | Detects phosphorylation of critical tyrosine residues (e.g., STAT3 Y705). | Essential validation tool; confirms upstream activation is intact. |

| Addressable Peptide Arrays (SPOT) | Semiquantitative profiling of SH2 domain specificity against hundreds of pY peptides. | Identifies physiological ligands; confirms specificity; reveals permissive/non-permissive residues [21] [22]. |

| Small-Molecule SH2 Inhibitors | Inhibits STAT3 activation and dimerization by targeting its SH2 domain. | Stattic: Inhibits STAT3 SH2 domain function [19]. MNS: Novel inhibitor identified via homoFluoppi HTS [5]. |

| High-Affinity Control Peptides | Positive controls for specific SH2 domains. | e.g., CD150-derived pTyr peptide (TIpYxxV/I) for SH2D1A/SAP and EAT-2 SH2 domains [23]. |

Advanced Concepts: Lipid Binding and Phase Separation

Emerging research reveals that SH2 domain function extends beyond simple peptide binding. Understanding these concepts is crucial for advanced troubleshooting.

- Lipid Binding: Nearly 75% of SH2 domains can interact with membrane lipids like PIP2 and PIP3 via cationic regions near the pY-binding pocket. This interaction is vital for membrane recruitment and the full activation of proteins like SYK, ZAP70, and LCK [18]. Disease-causing mutations can occur in these lipid-binding pockets.

- Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation (LLPS): Multivalent interactions, including those mediated by SH2 domains, can drive the formation of biomolecular condensates via LLPS. For example, interactions among GRB2, Gads, and the LAT receptor contribute to LLPS that enhances T-cell receptor signaling [18]. This concentrates signaling components and can profoundly impact signal amplitude and kinetics.

How Oncogenic Mutations Disrupt Dimer Equilibrium

Troubleshooting STAT Dimerization Assays: A Technical Support Guide

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the primary causes of nonspecific background signal in my STAT dimerization assay? Nonspecific background often stems from antibody cross-reactivity, over-expression artifacts, or incomplete blocking. To mitigate this, ensure you use validated, phospho-specific antibodies and include appropriate controls (e.g., cells expressing a dimerization-deficient STAT mutant). The STATeLight biosensor, which uses FLIM-FRET to directly detect conformational changes, offers a highly specific alternative by bypassing issues related solely to phosphorylation detection [16].

My assay shows successful STAT phosphorylation but no nuclear translocation. What could be wrong? This indicates a potential disruption in the nuclear import process. While phosphorylation is necessary, it is not always sufficient for dimerization and nuclear translocation. Verify the functionality of your importin system and check for disease-associated STAT mutations, particularly in the SH2 or DNA-binding domains, which can impair the conformational shift from inactive antiparallel to active parallel dimers, even in the presence of phosphorylation [16].

How can I distinguish between STAT homo-dimers and hetero-dimers in a cellular system? Traditional co-immunoprecipitation can be inconclusive. For live-cell analysis, the STATeLight biosensor platform is engineered to detect specific dimeric conformations. Furthermore, techniques like bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) can be used, though they may have lower time resolution compared to FRET-based methods [16].

Why do I get inconsistent results between my reporter gene assay and my phospho-STAT western blot? These assays measure different endpoints of the pathway. Inconsistencies can arise if the STAT dimers are phosphorylated but fail to bind DNA or activate transcription due to mutations in the DNA-binding domain. A counter-screen with a reporter for a different transcription factor (e.g., NF-κB) can help exclude non-specific effects on general transcription or translation [24].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Problems and Solutions

Table: Common issues, their causes, and recommended solutions in STAT dimerization studies.

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No Dimerization Signal | Defective cytokine stimulus, JAK inhibitor present, non-functional STAT mutant, insufficient assay sensitivity. | Titrate cytokine concentration (e.g., IL-2, IL-6); verify JAK/STAT pathway functionality; use a positive control (e.g., wild-type STAT); employ more sensitive biosensors like STATeLights [16] [6]. |

| High Non-Specific Background | Antibody cross-reactivity, over-expression artifacts, auto-fluorescent compounds in drug screens. | Include a dimerization-deficient STAT mutant control; use hot-start enzymes in PCR-based detection; implement a counter-screen (e.g., NF-κB reporter) to rule out general transcription effects [25] [24]. |

| Inconsistent Results Between Assays | Assays measure different endpoints (phosphorylation vs. dimerization vs. transcription); STAT mutations affect specific steps. | Correlate phospho-STAT blots with DNA-binding or transcriptional reporter assays; use biosensors that directly report on dimer conformation, such as FRET-based systems [24] [16]. |

| Poor Assay Reproducibility | Variable cell health, passage number, or transfection efficiency; inconsistent reagent quality. | Standardize cell culture and transfection protocols; use low-passage-number cells; aliquot and quality-control all critical reagents (e.g., cytokines, ligands) [25]. |

| Inconclusive Results with Mutant STATs | Mutation causes complex, multi-faceted defects not captured by a single assay. | Characterize mutants with a multi-assay workflow: check phosphorylation, use conformational biosensors (STATeLights), and test transcriptional activity [16]. |

Quantitative Data Reference

Table: Key quantitative parameters for STAT dimerization assays and biosensors.

| Parameter | Typical Range / Value | Notes / Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| FRET Efficiency (STATeLight Biosensor) | Up to 12% change | Observed upon IL-2 stimulation in optimized C-terminal tagged biosensor; indicates conformational shift to parallel dimer [16]. |

| STAT-SH2 Domain Distance (Parallel Dimer) | ~105 Å (Modeled) | Based on AlphaFold-multimer simulations; proximity allows for FRET detection upon activation [16]. |

| STAT-SH2 Domain Distance (Antiparallel Dimer) | ~50 Å (Modeled) | Based on available crystal structures; represents the inactive state conformation [16]. |

| High-Throughput Screening Yield (VNp system) | 40 - 600 µg (96-well plate) | Typical yield of exported, >80% pure recombinant protein from a 100-µl culture, suitable for downstream assays [26]. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating STAT Dimerization with a Luciferase Reporter Gene Assay This cell-based assay is suitable for high-throughput screening of inhibitors or activators of STAT-dependent transcription.

- Cell Line Preparation: Stably transduce your cell line with a luciferase reporter gene under the control of a STAT-responsive promoter (e.g., from the M67 SIE element for STAT3).

- Counter-Screen Cell Line: Develop a second cell line with a luciferase reporter dependent on a different transcription factor (e.g., NF-κB) to exclude non-specific hits [24].

- Assay Execution: Seed cells in multi-well plates. Pre-treat with compounds or vehicles, then stimulate with the appropriate cytokine (e.g., IL-6 for STAT3) for a predetermined time.

- Lysis and Measurement: Lyse cells and measure luciferase activity using a luminometer.

- Data Analysis: Normalize data to untreated controls. A true STAT-specific hit will show significant inhibition in the STAT reporter line but minimal effect in the counter-screen line [24].

Protocol 2: Utilizing STATeLight Biosensors for Real-Time Dimerization Kinetics This protocol uses fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) to detect FRET as a direct readout of STAT conformational change.

- Biosensor Selection: Use a STATeLight biosensor with fluorescent proteins (e.g., mNeonGreen donor and mScarlet-I acceptor) fused C-terminally to the STAT's SH2 domain (Variant 4 from the primary research) for optimal FRET signal upon activation [16].

- Cell Transfection: Transfect the biosensor construct into a relevant cell line (e.g., HEK-Blue IL-2 cells for STAT5 studies).

- FLIM Imaging: Place cells on a confocal microscope equipped with FLIM capability. Acquire a baseline fluorescence lifetime measurement of the donor (mNeonGreen).

- Stimulation and Measurement: Stimulate cells with ligand (e.g., IL-2) and continuously monitor the fluorescence lifetime of the donor. A decrease in lifetime indicates FRET and, therefore, STAT dimerization and activation.

- Data Interpretation: Calculate FRET efficiency based on the change in donor lifetime. This system allows for direct, real-time observation of dimerization without the need for cell lysis or fixation [16].

Key Signaling Pathways and Workflows

STAT Activation and Dimerization Pathway

HTS Workflow for STAT Inhibitors

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential reagents and their functions for STAT dimerization studies.

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Assay | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| STATeLight Biosensors [16] | Genetically encoded FRET-based biosensors for real-time detection of STAT conformational changes in live cells. | High spatiotemporal resolution; specific for active dimer conformation; compatible with FLIM. |

| VNp Technology [26] | A peptide tag that promotes high-yield vesicular export of functional recombinant proteins from E. coli. | Enables production of 40-600 µg of >80% pure protein in a 96-well plate format for HTS. |

| Luciferase Reporter Cell Lines [24] | Stably transfected cells with a luciferase gene under a STAT-responsive promoter for functional transcriptional output. | Amenable to HTS; requires a counter-screen (e.g., NF-κB) to ensure specificity. |

| Phospho-Specific STAT Antibodies | Detect tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT (e.g., pY694-STAT5A) via Western blot or flow cytometry. | Standard method but requires cell fixation/permeabilization; does not directly prove dimerization. |

| JAK Inhibitors (e.g., Tofacitinib, Ruxolitinib) [27] [6] | Small molecule inhibitors of upstream JAK kinases; used as pathway controls. | Validates that STAT activation is dependent on canonical JAK activity. |

| Natural Product Inhibitors (e.g., Curcumin, EGCG) [28] | Phytochemicals that can inhibit STAT phosphorylation, dimerization, or DNA binding. | Useful as tool compounds; often have multiple cellular targets. |

Methodological Toolkit: From Classic to Cutting-Edge Dimerization Assays

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guide

This section addresses common challenges researchers face when developing and using FRET/FLIM-based biosensors for studying STAT dimerization in cellular systems.

Q1: Our FRET biosensor shows a very small dynamic range. What are the primary strategies to improve the FRET change?

A: A small dynamic range is a common hurdle. You can address it through several engineering and optimization strategies:

- Linker Optimization: The flexible linkers between the fluorescent proteins (FPs) and the sensing domain (e.g., STAT) are critical. Diversifying the length and composition of these linkers can optimize the distance and orientation of the FPs in the active vs. inactive state. One effective method is to create libraries with randomized N- and C-terminal linkers flanking the sensing domain and screen for variants with improved responses [29].

- FRET Pair Selection: The classic CFP-YFP pair, while widely used, may not be optimal for all sensors. Consider pairs with higher quantum yield (donor) and extinction coefficient (acceptor), such as mTurquoise2/mVenus or mCerulean/mVenus, which can offer larger Förster radii (r0) and thus improved FRET efficiency [30] [31].

- Spectral Overlap: Ensure sufficient overlap (>30%) between the donor's emission spectrum and the acceptor's absorption spectrum. A red-shifted FRET pair with improved optical properties can maximize the r0, which is the distance at which FRET efficiency is 50% [30].

Q2: Why did we choose FLIM over ratiometric FRET for our STATeLight biosensors?

A: Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM) provides several distinct advantages for quantifying FRET in live cells, which is why it was selected for the STATeLight biosensors [16]:

- Independence from Concentration: FLIM measures the donor's fluorescence lifetime, which is an intrinsic property. This makes the measurement independent of the biosensor's expression level, a significant source of artifact in intensity-based ratiometric methods [32] [16].

- Robustness to Photobleaching: While the fluorescence intensity decays with photobleaching, the fluorescence lifetime typically remains unchanged. This makes FLIM-FRET more reliable for long-term time-lapse experiments [32].

- Specificity: FLIM-FRET directly monitors the quenching of the donor fluorescence lifetime, providing an unambiguous measurement of FRET efficiency that is less susceptible to spectral bleed-through and autofluorescence artifacts [32] [16].

Q3: What are the key limitations of FLIM-FRET, and how can we mitigate them?

A: Despite its strengths, FLIM-FRET has drawbacks that must be planned for [33]:

- Speed and Cost: FLIM is a slower imaging technique, often requiring several minutes per image, and the instrumentation is costly and not universally available [33].

- Environmental Sensitivity: The measured fluorescence lifetime can be influenced by local environmental factors like pH or autofluorescence, potentially leading to inaccuracies. It is crucial to run proper controls and be aware of the cellular conditions [33].

- Complex Data Analysis: The multi-exponential lifetimes of fluorescent proteins in live cells demand comprehensive data collection and more complex analysis, which can further slow down the process [33].

Q4: Our biosensor shows high FRET in the unstimulated state. Is this a problem?

A: Not necessarily. For single-chain biosensors, an inherent residual FRET signal in the "off" state is common because the donor and acceptor are tethered in close proximity [32]. This is actually a feature of the design for STATeLights, as the inactive STAT5A antiparallel dimer exhibits FRET, and the conformational change to the active parallel dimer alters this FRET efficiency [16]. The critical parameter is the change in FRET (or lifetime) upon stimulation, not the absolute starting value.

Key Quantitative Data for FRET Pairs and Biosensor Design

The following tables summarize critical parameters for selecting FRET pairs and understanding biosensor performance.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Fluorescent Protein FRET Pairs

| FRET Pair (Donor/Acceptor) | Key Characteristics | Typical FRET Efficiency | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| CFP / YFP [30] [31] | The first and most classic pair. Good spectral overlap, but CFP has lower brightness. | Varies by specific variant (e.g., Cerulean/Venus). | General purpose; a reliable starting point for many biosensors. |

| mTurquoise2 / mVenus [31] | mTurquoise2 is a superior CFP variant with higher quantum yield and mono-exponential decay. | High | An excellent upgrade from the CFP/YFP pair for improved dynamic range. |

| mNeonGreen / mScarlet-I [16] | A modern, bright pair with favorable properties for FLIM-FRET. | Up to ~20% (in a direct fusion construct) [16] | Ideal for sensitive detection of protein-protein interactions, as in STATeLights. |

| Clover / mRuby2 [31] | A green-red pair, reducing cross-talk and cellular autofluorescence. | High | When spectral separation is a priority, or for multiplexing with other green probes. |

Table 2: Critical Parameters for FRET Biosensor Performance

| Parameter | Description | Impact on Biosensor | Optimization Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Förster Radius (r₀) [30] | The distance at which FRET efficiency is 50%. | A larger r₀ increases the working distance and potential dynamic range. | Select a pair with high donor QY, high acceptor EC, and strong spectral overlap. |

| FRET Dynamic Range [30] | The range of FRET efficiency change (Emax - Emin)/Emin. | Determines the sensitivity and signal-to-noise ratio of the biosensor. | Engineer linkers and sensing domain to maximize conformational change; screen linker libraries [29]. |

| Dipole Orientation (κ²) [30] | The spatial relationship between donor and acceptor transition dipoles. | Assumed to be 2/3 for dynamic random orientation, but can vary and affect r₀. | Difficult to control, but using flexible linkers can help average out orientation. |

Experimental Protocol: Developing a STATeLight Biosensor with FLIM-FRET

This protocol outlines the key steps for creating and validating a FRET/FLIM biosensor similar to the STATeLight biosensor for STAT5 activation [16].

Objective: To engineer a genetically encoded biosensor for real-time, quantitative monitoring of STAT dimerization in live cells using FLIM-FRET.

Materials:

- Plasmids: Vectors for mammalian expression of FP fusions (e.g., mNeonGreen-N1, mScarlet-I-C1).

- Cell Line: A signaling-competent cell line (e.g., HEK-Blue IL-2 cells for STAT5 studies [16]).

- Microscope: A confocal or widefield microscope equipped with FLIM capability (time-domain or frequency-domain).

- Ligand: The specific cytokine or agonist to activate the STAT pathway (e.g., IL-2).

Procedure:

Step 1: Molecular Design and Cloning

- Identify Fusion Sites: Use structural modeling (e.g., AlphaFold-multimer) to predict full-length STAT dimer conformations. Identify N- or C-terminal sites where FP fusion will yield the largest distance/orientation change between antiparallel (inactive) and parallel (active) dimers. For STAT5, C-terminal fusion to the SH2 domain was optimal [16].

- Clone Biosensor Variants: Genetically fuse the donor FP (e.g., mNeonGreen) and acceptor FP (e.g., mScarlet-I) to the selected sites on the STAT protein via flexible linkers. Create both full-length and core fragment (CF) truncated variants for screening [16].

Step 2: Initial Screening in Cell Culture

- Transfect Cells: Co-transfect different combinations of donor- and acceptor-tagged STAT constructs into your chosen cell line.

- Stimulate and Image: Acquire fluorescence lifetime images of the donor (mNeonGreen) before and after stimulation with the ligand (e.g., IL-2).

- Identify Lead Candidate: Calculate the FRET efficiency from the change in donor fluorescence lifetime. Select the construct that shows the most significant and reliable decrease in lifetime (increase in FRET) upon activation [16].

Step 3: FLIM-FRET Data Acquisition and Analysis

- Measure Donor-Only Lifetime: Transfert cells with the donor-FP-STAT construct alone. Measure the fluorescence lifetime (τD)—this is your reference for 0% FRET.

- Measure Biosensor Lifetime: Image cells expressing the full biosensor (donor- and acceptor-FP-STAT) in both unstimulated and stimulated states. The lifetime in these conditions is τDA.

- Calculate FRET Efficiency: For each pixel or cell, calculate FRET efficiency (E) using the formula:

Step 4: Biosensor Validation

- Specificity Test: Confirm that the FRET response is specific to the intended pathway by using pharmacological inhibitors (e.g., JAK inhibitors for STAT5) or mutating critical residues in the STAT protein.

- Functional Validation: Compare the activation kinetics and localization of your biosensor with traditional methods like immunofluorescence for phosphorylated STAT.

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the core principle of the STATeLight biosensor and the experimental workflow for its use.

STAT Activation & Experimental Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential materials and reagents used in the development and application of FRET/FLIM biosensors like the STATeLights.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for FRET/FLIM Biosensor Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example(s) from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Protein Plasmids [31] | To genetically encode the donor and acceptor fluorophores fused to your protein of interest. | mNeonGreen-N1, mScarlet-I-C1, mTurquoise2, mVenus vectors. |

| Signaling-Competent Cell Line [16] | A cellular system with an intact pathway for the target being studied (e.g., STAT5). | HEK-Blue IL-2 cells (for IL-2/JAK/STAT5 pathway). |

| Pathway Agonists / Antagonists [16] | To activate or inhibit the target pathway for biosensor validation and experimental use. | IL-2 cytokine (agonist); JAK inhibitors (e.g., Tofacitinib). |

| FLIM-Compatible Microscope [32] [16] | To measure the fluorescence lifetime of the donor fluorophore with high spatiotemporal resolution. | Time-domain or frequency-domain FLIM systems. |

| Library Cloning Reagents [29] | For generating diversified biosensor libraries to screen for optimized variants. | Seamless ligation kits (e.g., SLiCE) and primers with degenerated codons (NNB). |

DNA-Binding ELISA and Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays (EMSAs)

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are the primary applications of DNA-Binding ELISA and EMSA? Both techniques are used to study protein-DNA interactions, particularly the binding of transcription factors like STATs to specific DNA sequences. EMSA separates complexes based on size and charge in a gel, while DNA-Binding ELISA provides a colorimetric, plate-based readout of binding events, often offering higher throughput [34].

2. My EMSA shows a band in the negative control lane (no protein). What is happening? A nonspecific shift band in the negative control lane is a known issue, particularly in non-radioactive EMSA using digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled probes. This can be caused by the labeling enzyme, terminal transferase (TdT), remaining bound to the DNA probe. A simple solution is to heat the DIG-labeled probe at 95°C for 5 minutes after the labeling reaction and then allow it to slowly cool to re-anneal before use. This denaturation step separates TdT from the probe and eliminates the nonspecific band [35].

3. How can I reduce high background in my DNA-Binding ELISA? High background is often a result of insufficient washing, non-specific antibody binding, or contamination. Ensure you perform adequate washing steps, use a suitable blocking buffer (e.g., BSA, casein), and read the plate immediately after adding the stop solution. Preparing fresh buffers and using fresh plate sealers for each step can also prevent contamination that leads to high background [36] [37] [38].

4. What causes weak or no signal in a DNA-Binding ELISA? Weak signal can stem from multiple factors, including reagents not being at room temperature, incorrect reagent dilutions, expired reagents, or using an inappropriate plate (e.g., a tissue culture plate instead of an ELISA plate). Ensure all reagents are prepared according to the protocol and that the capture antibody has properly adhered to the plate surface [37] [38] [39].

5. Why do I see high variation between replicates? High variation is commonly due to pipetting errors, insufficient mixing of reagents, inadequate washing, or bubbles in the wells before reading. Ensure all solutions are homogenous, use proper pipetting technique, and confirm that no residual fluid remains in wells between wash steps. Using fresh buffers and plate sealers can also improve consistency [36] [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

DNA-Binding ELISA Troubleshooting

The following table summarizes common issues, their potential causes, and solutions for DNA-Binding ELISA experiments.

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Signal | Reagents not at room temperature [37]. | Allow all reagents to sit on the bench for 15-20 minutes before starting the assay. |

| Incorrect storage or expired reagents [37]. | Double-check storage conditions and expiration dates. | |

| Using a tissue culture plate instead of an ELISA plate [37] [38]. | Use a plate specifically designed and validated for ELISA. | |

| Inadequate capture antibody binding [38]. | Ensure the antibody is diluted in an appropriate coating buffer like PBS and optimize coating incubation time/temperature. | |

| High Background | Insufficient washing [37] [38]. | Increase the number or duration of washes. Add a 30-second soak step between washes. |

| Delay in reading after stop solution [36] [38]. | Read the plate immediately after adding the stop solution. | |

| Substrate exposure to light [37]. | Store substrate in the dark and limit exposure during the assay. | |

| High Variation Between Replicates | Pipetting or mixing errors [36] [38]. | Double-check calculations and ensure reagents are mixed thoroughly. |

| Inconsistent incubation temperature or time [36] [38]. | Use a consistent incubation temperature and adhere strictly to recommended times. | |

| Bubbles in wells [36]. | Centrifuge the plate or carefully remove bubbles before reading. | |

| Poor Standard Curve | Improper dilution of standards [36] [37]. | Check calculations and pipetting technique; prepare a new standard curve. |

| Degraded standard [38]. | Use a new vial of standard and avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles. | |

| Edge Effects | Uneven temperature across the plate [36] [37]. | Do not stack plates during incubation; use a uniform temperature environment. |

| Evaporation [37] [38]. | Always cover the plate with a new, high-quality sealer during incubations. |

EMSA Troubleshooting

The table below addresses specific challenges encountered in Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays.

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Nonspecific Shift Bands | TdT enzyme bound to DIG-labeled probe [35]. | Heat the labeled probe at 95°C for 5 min and re-anneal before use. |

| Insufficient non-specific competitor [40]. | Optimize the type and concentration of competitor DNA (e.g., poly d(I-C) for GC-rich sequences). | |

| Smear Formation | Non-specific protein binding [40]. | Include poly d(I-C) or poly d(A-T) in the binding reaction to prevent smear formation. |

| Protease activity in extracts [40]. | Add BSA (250 µg/mL) to the binding reaction to stabilize specific DNA-binding factors. | |

| DNA/Protein Complexes Do Not Enter Gel | Large DNA fragment with multiple binding sites [40]. | Reduce the size of the DNA fragment or use a single oligonucleotide. |

| Using an SDS gel [40]. | Always use a native polyacrylamide gel for EMSA. | |

| Low Signal Intensity | Poor labeling efficiency of the probe [40]. | Determine the labeling efficiency of your DIG-labeled oligonucleotide. |

| Suboptimal salt conditions [40]. | Modify the binding buffer conditions (salt concentration) to suit the specific DNA-binding protein. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents are essential for robust and reliable DNA-binding assays.

| Reagent | Function |

|---|---|

| Protein Stabilizers & Blockers (e.g., StabilCoat, StabilGuard) | Minimize non-specific binding interactions with the assay surface and stabilize dried capture proteins, thereby increasing signal-to-noise ratios and assay shelf life [36] [41]. |

| Sample/Assay Diluents (e.g., MatrixGuard) | Help significantly reduce matrix interferences (e.g., HAMA, Rheumatoid Factor), thereby lowering the risk of false positives [36] [41]. |

| Colorimetric TMB Substrates | Used for detection in ELISA, offering a combination of stability, low background, and high sensitivity [36]. |

| Non-specific Competitor DNA (poly d(I-C) / poly d(A-T)) | Prevents nonspecific binding of proteins to the DNA probe in EMSA. The choice depends on the GC or AT richness of the binding sequence [40] [35]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | When added to EMSA binding reactions (e.g., at 250 µg/mL), it can yield higher signals by stabilizing specific DNA-binding factors and buffering against protease activity in extracts [40]. |

STAT3 Dimerization and DNA Binding Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the process of STAT3 activation, dimerization, and subsequent DNA binding, which is the central biological process studied by the techniques in this guide.

Experimental Protocol: DNA-Binding ELISA for STAT Dimers

This protocol provides a general framework for a sandwich ELISA to detect transcription factor dimers, such as phosphorylated STAT3, based on common practices in the field [36] [38] [39].

Key Steps:

- Coating: Dilute a capture antibody specific to the transcription factor (e.g., STAT3) in PBS and add it to an ELISA plate. Incubate overnight at 4°C or for 1-2 hours at room temperature.

- Blocking: Discard the coating solution and block the plate with a protein-based blocking buffer (e.g., BSA or a commercial stabilizer/blocker) for 1-2 hours to prevent non-specific binding.

- Sample Incubation: Add your cell lysates or nuclear extracts (containing the target transcription factor) to the wells. Incubate for 2 hours at room temperature. Include a standard curve if available.

- Detection Antibody Incubation: Add a biotinylated detection antibody specific to the transcription factor. Incubate for 1-2 hours.

- Streptavidin-Enzyme Conjugate: Add Streptavidin conjugated to Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP). Incubate for 30 minutes.

- Washing: Perform thorough washing steps (3-5 times) with a wash buffer containing a detergent like Tween-20 after steps 3, 4, and 5.

- Signal Detection: Add a colorimetric TMB substrate. Incubate in the dark for 15-30 minutes.

- Stop and Read: Add a stop solution (e.g., acid) and immediately read the absorbance on a plate reader at the appropriate wavelength (e.g., 450 nm).

EMSA Workflow for Analyzing STAT-DNA Complexes

This workflow outlines the key steps for performing an EMSA to study STAT protein binding to DNA, integrating troubleshooting tips directly into the protocol.

Native PAGE for Detecting Dimer-Monomer Equilibrium Shifts

Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Native PAGE) is a fundamental tool for studying protein complexes, such as dimers and monomers, in their biologically active states. Unlike denaturing gel systems, Native PAGE preserves protein structure and interactions, making it indispensable for analyzing dimer-monomer equilibria. This technique is particularly valuable in cellular systems research, including studies of STAT protein dimerization, where equilibrium shifts can have significant functional consequences. This technical support center provides comprehensive troubleshooting and methodological guidance to ensure reliable detection of these critical molecular events.

Troubleshooting Common Native PAGE Issues

Poor Protein Migration into the Gel

Problem: Proteins do not enter the gel sufficiently or remain stuck in the wells, preventing analysis of dimer-monomer equilibrium.

Solutions:

- Adjust buffer pH: The standard Tris-glycine electrode buffer (pH ~8.3) may be too close to the isoelectric point (pI) of your protein. For proteins with pI between 7-8, increasing the electrode buffer pH to 9.5 can improve migration [42].

- Optimize gel concentration: High percentage gels can restrict migration of larger complexes. For proteins around 12-25 kDa, use 10% gels instead of 15% to improve separation [42].

- Check sample ionic strength: High ionic strength in samples can cause band deformation. Ensure your sample ionic strength does not exceed 0.1 mmol/L [43].

- Extended running time: Run the gel for a longer duration at appropriate voltage (100-200V) to improve migration, but monitor temperature to prevent overheating [42].

Insufficient Separation Between Dimer and Monomer Bands

Problem: Dimer and monomer bands appear too close together or poorly resolved.

Solutions:

- Optimize gel percentage: Use gradient gels (e.g., 4-20%) for better separation of complexes with different molecular weights [42].

- Implement gel pre-running: Pre-run the gel for 30-60 minutes before sample application to establish stable pH conditions [43].

- Control voltage: Maintain voltage between 100-200V; too low voltage reduces separation, while too high generates excessive heat [43].

- Verify buffer composition: Ensure running buffers are prepared correctly at the proper concentration and pH [44].

Power Supply and Electrical Issues

Problem: Gel run stops prematurely or current drops unexpectedly.

Solutions:

- Disable "No Load" detection: Many power supplies automatically shut off when current drops below 1 mA, which is common in Native PAGE. Disable the "Load Check" feature if your power supply has this function [44].

- Check for leaks: Ensure the upper buffer chamber is properly sealed with intact gaskets to maintain electrical continuity [44].

- Verify connections: Inspect all electrodes and connections for proper contact [44].

- Confirm tape removal: Ensure plastic tape has been removed from the bottom of pre-cast gel cassettes [44].

Quantitative Data on Dimer-Monomer Equilibria

The following table summarizes dissociation constants (Kd) for various protein systems determined through different biophysical methods, providing reference values for interpreting Native PAGE results:

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Dimer-Monomer Dissociation Constants

| Protein System | Kd Value | Measurement Technique | Experimental Conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| αβ-Tubulin heterodimer (porcine brain) | 8.48 ± 1.22 nM | Mass photometry | BRB80 buffer, no added GTP | [45] |

| αβ-Tubulin heterodimer (porcine brain) | 3.69 ± 0.65 nM | Mass photometry | BRB80 buffer with 1 mM GTP | [45] |

| SARS-CoV-2 Mpro | ~2.5 μM | Analytical ultracentrifugation | Not specified | [46] |

| SARS-CoV-2 Mpro | 0.14 ± 0.03 μM | Mass spectrometry | Not specified | [46] |

| Mammalian brain tubulin (general) | 3-10 nM | Multiple techniques | Various | [45] |

Table 2: Comparison of Techniques for Studying Dimer-Monomer Equilibria

| Technique | Affinity Range | Sample Requirements | Key Advantages | Limitations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native PAGE | μM-mM | Moderate concentration, small volume | Preserves native structure, equipment accessible | Semi-quantitative, potential migration artifacts | |

| Mass photometry | <μM (nM range) | Low concentration (0.1-100 nM) | Label-free, single-molecule sensitivity, quantitative Kd measurement | Specialized equipment required | [45] |

| Analytical ultracentrifugation | nM-μM | Various concentrations | Absolute measurement, solution-based | Equipment intensive, longer analysis time | [46] |

| SAXS | μM range | Higher concentrations | Structural information in solution | Limited to higher concentrations | [46] |

| Single-molecule fluorescence | nM range | Requires fluorescent labeling | Single-molecule sensitivity, dynamic information | Potential labeling artifacts | [47] |

Experimental Protocols

Optimized Native PAGE Protocol for Dimer-Monomer Analysis

Materials:

- Pre-cast gradient gels (4-20%) or self-cast gels at appropriate percentage

- Running buffer: Tris-glycine, pH 8.3-9.5 (adjust based on protein pI)

- Sample buffer: Commercial native sample buffer or 50 mM Tris-HCl, 10% glycerol, pH 6.8

- Power supply capable of constant voltage

- Cooling apparatus (if running at higher voltages)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Dialyze samples into low-ionic strength buffer (<0.1 mmol/L)

- Mix sample with native sample buffer (avoid SDS or reducing agents)

- Centrifuge briefly before loading to remove aggregates

Gel Setup:

- Pre-run gel for 30-60 minutes at 100V to establish pH gradient

- Load samples (10-20 μg per lane for detection)

- Include appropriate controls (known monomers/dimers if available)

Electrophoresis:

- Run at constant voltage (100-150V) for 1-2 hours

- Maintain temperature between 4-10°C if possible

- Monitor dye front migration

Detection and Analysis:

- Use compatible staining methods (Coomassie, silver stain, or native-compatible fluorescent dyes)

- Compare band migration to high-molecular weight native markers

- Quantify band intensities for equilibrium analysis

Protocol for Detecting Equilibrium Shifts

To detect ligand-induced or condition-dependent shifts in dimer-monomer equilibrium:

- Prepare identical protein samples under different conditions (e.g., ± ligand, different concentrations)

- Incubate samples for equilibrium establishment (typically 15-30 minutes at room temperature)

- Load and run samples on the same gel to enable direct comparison

- Quantify band intensities using densitometry

- Calculate dimer:monomer ratios for each condition

- Plot ratio changes against condition variables (e.g., ligand concentration)

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Native PAGE Dimer-Monomer Assays

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrophoresis Systems | XCell SureLock Mini-Cell, Mini Gel Tank | Housing for gel electrophoresis | Ensure proper sealing and electrical connections | [44] |

| Gel Systems | Tris-HCl gradient gels (4-20%), Self-cast Tris-glycine gels | Separation matrix | Gradient gels improve resolution of different oligomeric states | [42] |

| Buffer Systems | Tris-glycine (pH 8.3-9.5), High-pH system for acidic proteins, Low-pH system for basic proteins | Create electrophoresis pH environment | Match buffer pH to protein pI for optimal migration | [43] [42] |

| Detection Reagents | Coomassie R-250, Sypro Orange, Silver stain reagents | Visualize separated protein bands | Ensure compatibility with native conditions | |

| Reference Standards | NativeMark unstained protein standard, High molecular weight native markers | Size estimation of complexes | Use native markers for accurate size determination | [43] |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Native PAGE Experimental Workflow for Dimer-Monomer Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My protein has a pI of 7.5 and doesn't migrate well in standard Native PAGE. What should I do?

A1: This is a common issue when the protein's pI is close to the buffer pH. Switch to a high-pH buffer system (pH 9.0-9.5) to increase the net negative charge on your protein and improve migration. The Ornstein-Davis buffer system is recommended for this purpose [42].

Q2: How can I distinguish between true dimers and non-specific aggregates in Native PAGE?

A2: True dimers will show a concentration-dependent equilibrium, while aggregates typically do not. Perform a dilution series - true dimers will show increasing monomer bands at lower concentrations, while aggregates remain constant. You can also compare migration to known standards and check for specific biological effects (e.g., ligand-induced shifts).

Q3: What are the key considerations for quantitative analysis of dimer-monomer equilibria using Native PAGE?

A3: Ensure that (1) the system has reached equilibrium before loading, (2) staining is quantitative and within linear range, (3) you include appropriate controls for migration artifacts, and (4) you account for potential staining efficiency differences between monomers and dimers. For precise quantification, combine with other techniques like mass photometry or analytical ultracentrifugation [45].

Q4: Can I use Native PAGE to study membrane protein dimerization?

A4: While possible, membrane proteins require special handling. You must use compatible detergents that maintain native structure without disrupting interactions. Mild detergents like digitonin are often preferred over harsh detergents like SDS. However, alternative methods such as single-molecule fluorescence in lipid bilayers may provide more reliable data for membrane proteins [47].

Q5: Why does my Native PAGE show smeared bands instead of sharp dimer and monomer bands?

A5: Sample smearing can result from several factors: (1) excessive ionic strength in the sample buffer, (2) protein degradation, (3) incomplete equilibration, or (4) inappropriate running conditions. Ensure proper dialysis into low-ionic strength buffer, use fresh protease inhibitors, and optimize running temperature and voltage.

Co-Immunoprecipitation and Pull-Down Assays for Protein Interactions

FAQs: Core Principles and Method Selection

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and pull-down assays?

- Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) is used to isolate a native protein complex directly from a cell lysate using a specific antibody immobilized on beads. The antibody targets the "bait" protein, which co-precipitates its binding partners ("prey") from the lysate. It is ideal for studying stable or strong protein interactions that occur under physiological conditions [48].

- Pull-Down Assays use an immobilized bait protein (e.g., a GST- or polyHis-tagged fusion protein) to purify binding partners from a lysate. This method is ideal for studying strong interactions or for situations where no suitable antibody is available for the target protein [48].

Q2: Under what circumstances should I choose a pull-down assay over a Co-IP?

A pull-down assay is the preferred method in the following scenarios [48]:

- When a high-quality, specific antibody for your bait protein is not commercially available.

- When you need to study the interaction between a recombinant protein and its potential partners from a complex lysate.

- When you want to map specific interaction domains by using truncated versions of your bait protein.

Q3: What types of protein interactions can these methods capture?

The following table summarizes the suitability of different methods for various interaction types:

| Method | Protein-Protein Interaction Types | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) | Stable or strong [48] | Captures native complexes from cell lysates; requires a specific antibody. |

| Pull-Down Assay | Stable or strong [48] | Uses a recombinant tagged bait protein; no antibody needed. |

| Crosslinking | Transient or weak [48] | Stabilizes temporary interactions covalently before lysis. |

| Far-Western Blotting | Moderately stable [48] | Identifies direct protein-binding partners on a membrane. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Issues and Solutions in Co-IP and Pull-Down Assays

The table below outlines frequent problems, their potential causes, and expert-recommended solutions.

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|