Tissue-Resident Memory B Cells: Decoding Their Critical Role in Mucosal vs. Systemic Vaccination

This review synthesizes current knowledge on tissue-resident memory B cells (BRM), a specialized lymphocyte subset residing in mucosal tissues that provides localized, rapid-response defense against pathogens.

Tissue-Resident Memory B Cells: Decoding Their Critical Role in Mucosal vs. Systemic Vaccination

Abstract

This review synthesizes current knowledge on tissue-resident memory B cells (BRM), a specialized lymphocyte subset residing in mucosal tissues that provides localized, rapid-response defense against pathogens. We explore the fundamental biology of BRM, including their generation through CD40-dependent germinal center responses and their role as frontline defenders in the airways and other mucosal surfaces. The article contrasts the potent, localized antibody responses elicited by mucosal vaccination with the predominantly systemic immunity induced by traditional parenteral vaccines. We detail cutting-edge methodological approaches for studying BRM, address key challenges in vaccine design such as durability and adjuvant selection, and present comparative evidence validating the superior ability of mucosal vaccines to establish protective tissue-resident memory. This resource is intended to guide researchers and drug development professionals in the rational design of next-generation vaccines that leverage BRM for enhanced protection against respiratory and other mucosal pathogens.

Frontline Defenders: Unraveling the Biology and Generation of Tissue-Resident Memory B Cells

Within the intricate landscape of adaptive immunity, a specialized sentinel has emerged as a critical mediator of localized protection: the tissue-resident memory B cell (BRM). These cells are a distinct subset of memory B cells that take up long-term residence in tissues without recirculating, providing a first line of defense against pathogen re-exposure at mucosal surfaces and other barrier sites [1] [2]. Unlike their circulating counterparts, BRM cells are strategically positioned at common sites of pathogen entry, enabling them to mount rapid, localized antibody responses during secondary challenges [1]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of BRM phenotypic and functional characteristics, situating their role within the broader context of mucosal versus systemic vaccination strategies. We synthesize current experimental data and methodologies to offer researchers a foundational resource for investigating these crucial cellular sentinels.

Phenotypic Profile and Tissue Distribution of BRM

BRM cells are defined by their long-term persistence in tissues and a characteristic molecular profile that distinguishes them from circulating memory B cells. A core set of surface markers facilitates their identification and isolation from tissue samples, though their specific phenotype can exhibit notable heterogeneity across different tissue environments [2].

Table 1: Core Phenotypic Markers of Tissue-Resident Memory B Cells (BRM)

| Marker | Expression Status | Function and Significance |

|---|---|---|

| CD69 | Consistently expressed | A canonical tissue-residency marker; inhibits the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1P1), thereby preventing egress from tissues [2]. |

| CD49a (VLA-1) | Variably expressed | An integrin that facilitates adhesion to collagen in the extracellular matrix; more commonly expressed in non-mucosal tissues [2]. |

| CD103 (αE integrin) | Variably expressed | Binds to E-cadherin on epithelial cells; predominantly expressed by BRM in mucosal tissues [2]. |

The anatomic distribution of BRM cells is a key determinant of their sentinel function. They have been identified in multiple mucosal tissues, including the lung and airways, where they are derived from CD40-dependent germinal center responses [1]. The inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) is a specific site that contributes to the formation and maintenance of BRM populations in the lung [2]. Their presence has been confirmed through advanced techniques such as parabiosis surgery and intravascular staining, which definitively distinguish tissue-resident from circulating cell populations [2].

Functional Capacities and Role in Protective Immunity

The functional specialization of BRM cells is directly linked to their tissue-resident nature, enabling a unique mode of immune defense.

Primary Functions and Mechanisms

- Rapid Plasma Cell Differentiation: Upon re-encounter with their cognate antigen, BRM cells swiftly differentiate into antibody-secreting plasma cells. This provides a robust and localized source of antibodies directly at the site of pathogen entry, a critical advantage over the slower recall response from circulating memory B cells [1].

- Localized Antibody Production: The antibodies produced by BRM-derived plasma cells can include all major isotypes, such as IgG and IgA. This local production creates a specific immune environment at mucosal surfaces, neutralizing pathogens before they can establish a systemic infection [1] [2].

Comparative Functional Output

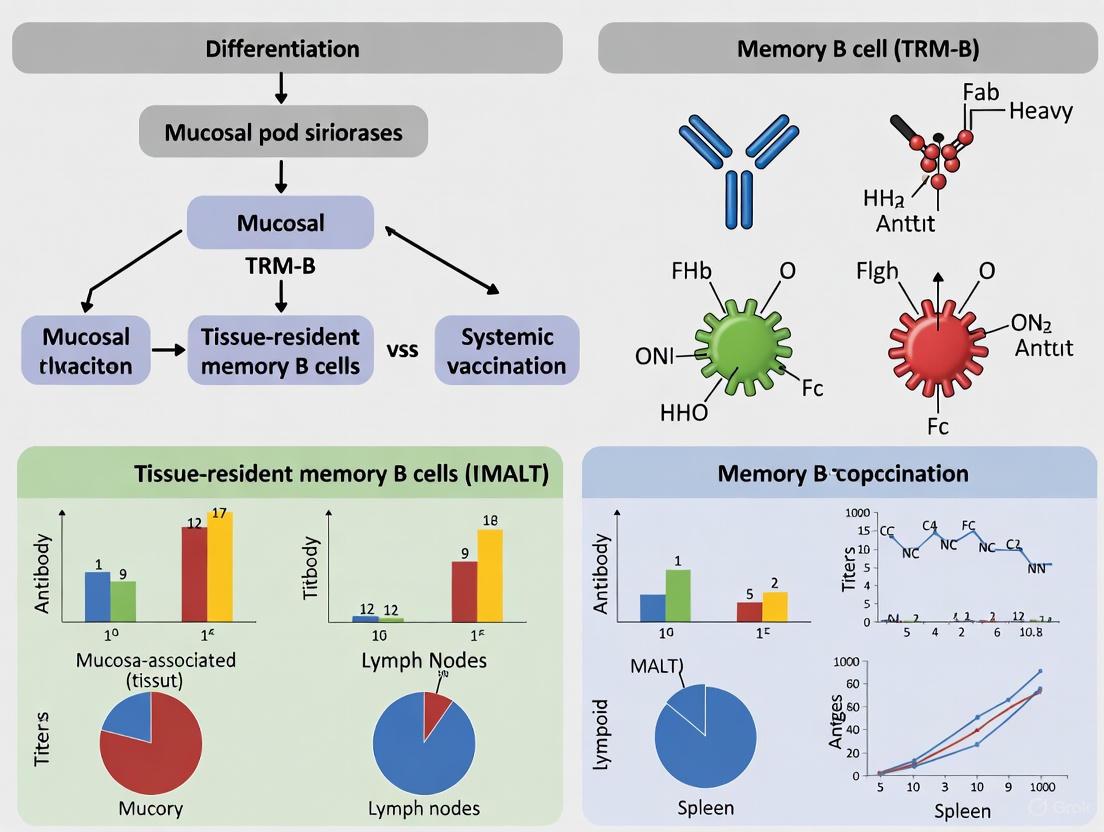

The functional profile of BRM cells can be contrasted with other B cell subsets to highlight their unique role. The following diagram illustrates the core functional characteristics and protective mechanisms of BRM cells.

Methodologies for BRM Research: A Toolkit for the Scientist

Studying BRM cells requires a combination of established immunological techniques and advanced technologies to confirm their tissue residency and elucidate their unique biology.

Core Experimental Protocols

Confirming Tissue Residency:

- Parabiosis Surgery: This gold-standard method involves surgically joining two mice to create a shared circulatory system. Circulating cells equilibrate between both partners, while true tissue-resident cells (like BRM) remain in the host tissue and are not found in the partner's tissues [2].

- Intravascular Staining: An intravenous injection of a fluorescently-labeled antibody is administered moments before euthanasia. This antibody labels all cells within the blood vasculature. During subsequent flow cytometry, true tissue-resident cells are identified as the population that is not labeled by the intravascular dye [2].

Profiling and Phenotyping:

- High-Parameter Flow Cytometry: This is essential for identifying the complex surface phenotype of BRM cells (e.g., CD19⁺, CD69⁺, CD49a⁺/CD103⁺) and for isolating pure populations via Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) for functional assays [2].

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq): This powerful technology reveals the complete transcriptional landscape of BRM cells, uncovering heterogeneity, developmental pathways, and functional states by analyzing gene expression cell-by-cell [2].

Functional Assays:

- B Cell Receptor (BCR) Sequencing: This technique sequences the variable regions of the BCRs of BRM cells, providing insights into clonality, antigenic experience, and affinity maturation [2].

- In Vitro Re-stimulation and Differentiation Assays: Isolated BRM cells can be stimulated with antigens or mitogens in vitro to measure their proliferation, differentiation into plasma cells, and antibody secretion, directly quantifying their functional capacity [1].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for BRM Cell Research

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-CD69 Antibody | Blocking/Saturation | Used in intravascular staining protocols to discriminate resident vs. circulating cells; critical for flow cytometry panels to identify BRM. |

| Anti-CD49a & Anti-CD103 Antibodies | Phenotypic Identification | Key for defining the BRM population via flow cytometry, especially to distinguish subsets in mucosal vs. non-mucosal sites. |

| Recombinant Cytokines | Cell Culture & Differentiation | IL-4, IL-5, IL-21, and BAFF are used in in vitro cultures to support B cell survival and promote plasma cell differentiation. |

| TaqMan Assays for BCR/Expression | Genotyping & Gene Expression | Custom TaqMan assays (as used in genotyping studies) can be adapted for quantifying BCR clonotypes or BRM-specific gene expression [3]. |

BRM in Mucosal vs. Systemic Vaccination: A Comparative Analysis

The differential induction of BRM cells is a fundamental consideration when comparing mucosal and systemic vaccination routes. The following workflow diagram outlines the key experimental and analytical steps for characterizing BRM cells in vaccination studies.

Table 3: Comparison of BRM Induction by Vaccination Route

| Characteristic | Mucosal Vaccination | Systemic Vaccination |

|---|---|---|

| BRM Induction Efficiency | High; directly targets immune induction at mucosal sites. | Typically low; primarily generates circulating memory and plasma cells that home to bone marrow. |

| Location of Induced BRM | Local mucosal tissues (e.g., lung airways, iBALT) [2]. | Largely absent from mucosal sites; may induce some populations in secondary lymphoid organs. |

| Functional Outcome | Elicits strong local antibody secretion at the portal of entry for many pathogens, providing immediate sterilizing immunity. | Elicits strong systemic antibody titers but poor mucosal immunity, potentially allowing initial infection at mucosae. |

| Protective Efficacy | Superior for preventing initial infection at mucosal surfaces (e.g., against influenza, SARS-CoV-2). | Superior for controlling pathogens after they have entered the systemic circulation. |

BRM cells represent a critical axis of adaptive immunity, defined by their non-recirculating nature, canonical marker expression (CD69, often with CD49a or CD103), and function as rapid local responders. A clear understanding of their phenotypic and functional characteristics, as detailed in this guide, is paramount for the rational design of next-generation vaccines. The current data strongly indicates that mucosal vaccination strategies are the most effective means to generate these sentinel cells at relevant portals of pathogen entry. Future research should focus on optimizing delivery platforms and adjuvants that robustly induce durable BRM populations, thereby bridging the gap between systemic immunity and true mucosal protection.

Tissue-resident memory B cells (BRM cells) represent a specialized subset of memory B cells that reside within mucosal tissues and play a critical role in frontline defense against respiratory pathogens. Unlike their circulating counterparts, BRM cells establish permanent residence in barrier tissues, particularly the airways, where they provide rapid, localized immune protection against reinfection. The strategic positioning of these cells at common sites of pathogen entry enables immediate response capabilities that far exceed those of systemically generated memory responses. This review examines the precise anatomical localization of BRM cells within mucosal tissues and the airways, comparing the effectiveness of mucosal versus systemic vaccination strategies in establishing these sentinel populations. Understanding the factors governing BRM cell development, maintenance, and function provides crucial insights for designing next-generation vaccines capable of eliciting robust tissue-localized immunity against respiratory pathogens.

Biological Basis of BRM Localization

Definition and Key Characteristics

BRM cells are a distinct population of non-recirculating memory B cells that persist long-term in mucosal tissues after antigen exposure. These cells are strategically positioned at barrier surfaces where they interface directly with the external environment [1]. Unlike circulating memory B cells that survey the body through lymphoid organs, BRM cells remain sessile within peripheral tissues, forming a network of antigen-experienced sentinels [4]. Their presence has been most comprehensively characterized in the respiratory tract, though evidence suggests similar populations may exist in other mucosal sites.

Key identifying features of BRM cells include their non-recirculating nature, demonstrated through parabiosis experiments and intravenous antibody labeling techniques [4]. These cells typically display surface markers associated with tissue residency, such as CD69, and often express CXCR3, a chemokine receptor guiding migration to inflammatory sites [4]. Functionally, BRM cells maintain the capacity to rapidly differentiate into antibody-secreting plasma cells upon re-encounter with cognate antigen, providing immediate local antibody production at the infection site [1].

Mechanisms of Tissue Entry and Retention

The establishment of BRM populations in mucosal tissues follows a coordinated sequence of trafficking, retention, and local maintenance. The process begins when antigen-activated B cells are recruited to peripheral tissues through tissue-specific homing signals. In the respiratory tract, this recruitment is driven by inflammatory cytokines and chemokines upregulated during local infection [5].

Once within the tissue, developing BRM cells undergo a program of * tissue residency differentiation, mediated by microenvironmental cues including cytokines and cellular interactions. The *upregulation of CD69 contributes to retention by countering S1P1-mediated egress signals [4]. Local survival factors, including BAFF (B cell-activating factor) and interactions with tissue-resident stromal cells, support the long-term maintenance of BRM populations without requiring continuous replenishment from circulation [4].

Critical to BRM development is the requirement for local antigen encounter. Systemic immunization typically fails to generate substantial BRM populations in mucosal tissues, whereas localized infection or mucosal vaccination efficiently establishes these resident sentinels [5] [6]. This highlights the importance of tissue context in instructing the residency program and ensuring BRM cells are positioned at sites of potential pathogen rechallenge.

Comparative Analysis of BRM in Mucosal vs. Systemic Vaccination

Formation and Maintenance

The differentiation of BRM cells follows distinct pathways depending on the route of antigen encounter, with significant implications for the quality, quantity, and durability of local immune protection.

Table 1: BRM Formation and Maintenance Characteristics

| Aspect | Mucosal Vaccination/Infection | Systemic Vaccination |

|---|---|---|

| Induction Requirement | Local antigen exposure in mucosal tissue | Primarily systemic immune activation |

| Primary Induction Site | Local germinal centers (e.g., iBALT) | Draining lymph nodes, spleen |

| Tissue Homing | Efficient migration to and retention in mucosal sites | Limited mucosal homing capacity |

| Persistence | Long-term residence (≥6 months documented) | Typically transient in peripheral tissues |

| Maintenance Mechanism | Local survival signals, tissue niche support | Continuous replenishment from circulation (limited) |

Mucosal vaccination or natural infection establishes BRM populations through local germinal center reactions occurring in inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) and other mucosal-associated lymphoid structures [5]. These tissue-based germinal centers generate BRM cells specifically imprinted for residence in the local mucosal environment. Once established, BRM cells can persist for extended periods, with studies documenting their presence in lungs for at least six months post-infection [6]. This persistence occurs independently of continuous replenishment from circulation, as demonstrated by FTY720 treatment experiments that block lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs without depleting lung BRM populations [4].

In contrast, systemic vaccination primarily generates circulating memory B cells with limited capacity to establish resident populations in mucosal tissues [5]. While some circulating cells may be recruited to tissues during subsequent inflammatory events, they typically fail to undergo the full differentiation program required for long-term residence. The few memory B cells that do enter tissues following systemic immunization often display transient persistence and may lack the optimal positioning and functional programming of bona fide BRM cells generated via mucosal routes.

Functional Efficacy in Protection

The strategic positioning of BRM cells within mucosal tissues confers significant functional advantages for rapid pathogen control, particularly against respiratory infections.

Table 2: Functional Characteristics of BRM Cells in Protection

| Functional Aspect | Mucosal-Derived BRM | Systemically Primed Memory B Cells |

|---|---|---|

| Response Kinetics | Rapid differentiation (within days) | Delayed response (≥7 days) |

| Antibody Production Site | Directly in infected alveoli | Primarily in iBALT structures |

| Spatial Organization | Distributed network throughout parenchyma | Confined to lymphoid aggregates |

| Early Protection | Significantly reduces early viral loads | Limited impact on early replication |

| Response to Heterologous Strains | Cross-reactive potential documented | Varies depending on immunization |

During secondary challenge, mucosally-established BRM cells demonstrate superior response kinetics, differentiating into antibody-secreting plasma cells within days of reinfection [1]. This rapid response occurs directly at sites of viral replication in the alveolar space, where BRM cells interface with infected cells [5]. The spatial organization of BRM cells throughout the lung parenchyma creates a network of sentinels that collectively surveil large tissue volumes, enabling detection and response to infection even in areas distant from organized lymphoid structures [5].

The functional superiority of mucosally-primed BRM responses was clearly demonstrated in influenza challenge experiments. Mice primed intranasally developed BRM cells that, upon rechallenge, rapidly differentiated into alveolar plasma cells and accumulated at infection sites within four days [5]. In contrast, systemically primed mice lacked this early response wave, with plasma cell development confined to iBALT structures and delayed until seven days post-challenge [5]. This temporal advantage translates to significantly enhanced early viral control, potentially limiting both disease severity and transmission.

Furthermore, evidence suggests that BRM cells generated through mucosal routes may exhibit broader reactivity against heterologous viral strains compared to systemically induced memory B cells [4]. This cross-reactive potential, likely shaped by local germinal center reactions in mucosal tissues, represents a significant advantage against rapidly evolving respiratory pathogens.

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Key Experimental Models for BRM Research

Investigating BRM cells requires specialized experimental approaches capable of distinguishing tissue-resident from circulating populations and assessing their functional capabilities.

Table 3: Key Experimental Models for BRM Research

| Model Type | Methodology | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Parabiosis | Surgical joining of two mice with shared circulation | Demonstration of non-recirculating nature |

| IV Antibody Labeling | Intravenous antibody administration prior to tissue collection | Distinguishing circulating versus tissue-resident cells |

| Adoptive Transfer | Transfer of labeled cells into recipient animals | Tracking migration and tissue integration |

| FTY720 Treatment | Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulator blocking egress | Assessing independence from circulating precursors |

| Tissue Transplantation | Transfer of infected tissue to naïve recipients | Demonstrating autonomous local memory |

The parabiosis model has been instrumental in establishing the sessile nature of BRM cells. In this approach, two mice are surgically joined, developing a shared circulatory system over several weeks. While circulating lymphocytes reach equilibrium between partners, tissue-resident cells remain confined to their host of origin [4]. Research using this model has demonstrated that lung BRM cells do not equilibrate between parabionts, confirming their non-recirculating nature [4].

Intravenous antibody labeling provides a rapid method for distinguishing tissue-resident from circulating cells. Minutes before tissue collection, mice receive intravenous anti-CD45 or other lymphocyte surface antibodies, which label cells within the circulation but cannot penetrate tissues. During subsequent flow cytometry, unlabeled cells are identified as tissue-resident, while labeled cells are classified as circulating [4]. This technique has revealed that a significant proportion of memory B cells in previously infected lungs are protected from labeling, confirming their tissue-resident status.

For functional studies, adoptive transfer experiments have elucidated the requirements for BRM establishment. When memory B cells from systemically immunized donors are transferred to naïve recipients, they show limited capacity to establish resident populations in mucosal tissues unless the recipients have previously experienced local infection [5]. This highlights the importance of both cellular intrinsic programming and permissive tissue environments in BRM development.

Methodologies for Assessing BRM Localization and Function

Advanced imaging and analytical techniques have provided unprecedented insights into the spatial organization and functional dynamics of BRM populations.

Two-photon microscopy of lung tissues has revealed that BRM cells form a homogeneously distributed network throughout the parenchyma in close association with alveoli [5]. This strategic positioning enables comprehensive tissue surveillance. During rechallenge, BRM cells increase their migration speeds and accumulate within infected foci before differentiating into plasma cells directly at sites of viral replication [5].

For molecular characterization, single-cell RNA sequencing has identified distinct transcriptional profiles distinguishing lung BRM cells from their circulating counterparts or memory B cells in lung-draining lymph nodes [4]. These analyses have revealed upregulated expression of tissue retention genes and chemokine receptors guiding positioning within mucosal environments.

Functional assessments often employ secondary challenge models comparing viral loads and immune responses between animals with and without established BRM populations. Such experiments consistently demonstrate that BRM cells confer superior protection against respiratory pathogens compared to systemic memory alone [5] [4]. Protection correlates with rapid local antibody production and significantly reduced early viral replication.

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Regulation

Diagram 1: Molecular regulation of BRM differentiation and activation. BRM development depends on CD40-mediated germinal center responses following initial antigen recognition. During secondary challenge, chemokine signaling (CXCL9/10-CXCR3 axis) guides BRM migration to infection sites where they differentiate into antibody-producing plasma cells.

The establishment and function of BRM cells are regulated by coordinated molecular signals that program their tissue residency and rapid response capabilities. Key pathways include:

CD40-Mediated Germinal Center Formation: BRM cells originate from CD40-dependent germinal center responses within mucosal tissues [1]. This T cell-dependent pathway ensures the generation of high-affinity, class-switched memory B cells equipped for tissue residence.

Chemokine-Mediated Positioning and Recruitment: The CXCL9/CXCL10-CXCR3 axis plays a critical role in BRM mobilization during secondary challenge. Alveolar macrophages produce these chemokines in response to viral detection, creating gradients that guide CXCR3-expressing BRM cells to sites of infection [4]. This chemotactic response ensures rapid accumulation of BRM cells precisely where their effector functions are required.

Tissue Residency Program: The upregulation of CD69 promotes tissue retention by antagonizing sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1P1), a key mediator of lymphocyte egress from tissues [4]. Additional transcription factors, including BATF and T-bet, contribute to the tissue residency program and functional specialization of BRM populations.

Innate-Like Activation Pathways: BRM cells exhibit a low activation threshold, responding to innate stimuli even in the absence of cognate antigen. Experimental evidence demonstrates that virus-like particles containing ssRNA can trigger BRM cell differentiation through innate pattern recognition, suggesting T cell-independent activation potential under certain conditions [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for BRM Investigation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse Models | BAT reporter mice (BLIMP1mVenus AIDCre/+ Rosa26tdTomato), ChAT-GFP reporter mice, mb-1Cre+/−ChATfl/fl (ChatBKO) | Lineage tracing, cell fate mapping, conditional gene deletion |

| Antibodies for Flow Cytometry | Anti-CD45 (IV labeling), anti-CD69, anti-CXCR3, anti-CD19, anti-B220, anti-IgM, anti-IgD | Cell phenotyping, identification of tissue-resident populations |

| Cell Isolation Kits | Lung dissociation kits, magnetic bead-based B cell isolation | Preparation of single-cell suspensions from tissues |

| Cytokines/Chemokines | Recombinant CXCL9, CXCL10 | Chemotaxis assays, migration studies |

| Viral Strains | Influenza A/PR8, CFP-S-flu reporter strain | Infection models, tracking viral replication foci |

| Activation Reagents | LPS, anti-IgM, CD40L, TLR agonists (CL097, poly(I:C)) | B cell stimulation, in vitro differentiation assays |

The investigation of BRM cells relies on specialized reagents and model systems that enable precise identification, isolation, and functional characterization of these tissue-resident populations. Critical tools include:

Reporter Mouse Models: Genetically engineered mice expressing fluorescent proteins under the control of B cell-specific promoters permit real-time tracking of BRM differentiation and localization. The BAT reporter system (BLIMP1mVenus AIDCre/+ Rosa26tdTomato) has been particularly valuable for tracing memory B cell and plasma cell differentiation during influenza infection [5]. Similarly, ChAT-GFP reporter mice have identified acetylcholine-producing B cell subsets in the respiratory tract, revealing novel immunoregulatory functions [7].

Isolation and Phenotyping Reagents: Comprehensive BRM characterization requires antibodies against surface markers including CD19, CD69, CXCR3, and various immunoglobulin isotypes. Intravenous anti-CD45 antibody labeling is essential for distinguishing tissue-resident from circulating populations during flow cytometric analysis [4]. Specialized tissue dissociation protocols preserve cell surface markers while generating single-cell suspensions from complex organs like lungs.

Challenge Strains and Immunogens: Pathogen-specific BRM responses are often studied using influenza virus strains (e.g., A/PR8) or engineered reporter viruses (e.g., CFP-S-flu) that enable visualization of infection foci [5]. For vaccination studies, mucosal vaccine candidates employing viral vectors, outer membrane vesicles, or minicell technologies provide platforms for comparing mucosal versus systemic immunization strategies [6] [8].

The strategic localization of BRM cells within mucosal tissues and airways represents a critical determinant of protective immunity against respiratory pathogens. Evidence consistently demonstrates that mucosal vaccination or infection establishes resident populations that confer superior protection compared to systemically generated memory responses. The functional advantages of BRM cells include their strategic positioning at potential sites of infection, rapid response kinetics, and capacity for local antibody production directly at replication sites. Future vaccine development should prioritize strategies that effectively engage these tissue-resident mechanisms, particularly through mucosal immunization routes that recapitulate the natural signals guiding BRM development and maintenance. As our understanding of BRM biology continues to evolve, so too will opportunities to design next-generation vaccines that leverage these sentinel cells for enhanced protection against respiratory infections.

The generation of long-lasting, high-affinity antibody responses and memory B cells constitutes a cornerstone of adaptive immunity. This process, essential for effective vaccination and pathogen clearance, occurs primarily within specialized structures called germinal centers (GCs) and is fundamentally regulated by CD40-CD40 ligand (CD40L) interactions. This review compares the cellular and molecular mechanisms governing GC responses, detailing how CD40 signaling orchestrates B cell fate. Furthermore, we frame this molecular machinery within the modern paradigm of mucosal immunity, contrasting how systemic versus mucosal vaccination strategies engage these pathways to generate protective tissue-resident memory B cells ((B_{RM})).

The germinal center reaction represents a critical phase of the T cell-dependent humoral immune response. These transient structures form in secondary lymphoid organs and serve as central factories for the production of high-affinity antibodies, long-lived plasma cells, and memory B cells [9]. The GC response is absolutely dependent on costimulatory signals, among which the interaction between the CD40 receptor (on B cells) and its CD40 ligand (CD40L, primarily on T cells) is one of the best-characterized and most essential [10].

CD40 is a 48-kDa type I transmembrane protein belonging to the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) superfamily. Its ligand, CD40L (CD154), is a type II transmembrane protein expressed mainly on activated T cells. The engagement of CD40 by CD40L promotes the recruitment of adapter proteins known as TNFR-associated factors (TRAFs) to the cytoplasmic domain of CD40, initiating a complex signaling cascade that is indispensable for an effective adaptive immune response [10].

The Germinal Center: A Structured Microenvironment for B Cell Maturation

The germinal center is a highly organized and dynamic microenvironment, physically partitioned into two distinct zones that facilitate a cyclic process of mutation and selection.

Dark Zone: Proliferation and Somatic Hypermutation

In the dark zone (DZ), B cells, known as centroblasts, undergo rapid proliferation and somatic hypermutation (SHM) [9] [11]. SHM is a process mediated by the activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) enzyme, which introduces pseudo-random mutations into the variable regions of the antibody genes. This mutative process generates a diverse repertoire of B cell clones with varying affinities for the antigen [9].

Light Zone: Selection and Differentiation

Following mutation, B cells migrate to the light zone (LZ), where they are called centrocytes. Here, they encounter antigen presented as immune complexes by follicular dendritic cells (FDCs) and compete for survival signals from T follicular helper ((T{FH})) cells [9] [11]. Centrocytes that have gained B cell receptors (BCRs) with higher affinity for the antigen are more effective at internalizing and presenting it to (T{FH}) cells. This interaction, which includes CD40L on (T_{FH}) cells engaging CD40 on B cells, provides a critical survival signal. Positively selected B cells can then re-enter the DZ for further rounds of mutation, differentiate into antibody-secreting plasma cells, or become memory B cells [9].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Germinal Center Zones

| Feature | Dark Zone (DZ) | Light Zone (LZ) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary B Cell Type | Centroblasts | Centrocytes |

| Proliferative Activity | High | Low |

| Key Processes | Somatic hypermutation, clonal expansion | Antigen presentation, positive selection, differentiation |

| Critical Interacting Cells | - | Follicular Dendritic Cells (FDCs), T Follicular Helper ((T_{FH})) Cells |

| Master Regulator | BCL6 | BCL6 |

The following diagram illustrates the cyclical process of germinal center B cell maturation:

CD40 Signaling: The Molecular Engine of the GC Reaction

CD40 engagement acts as a master regulator of the GC response, triggering multiple downstream signaling pathways that determine B cell fate.

TRAF-Dependent Signaling Pathways

Upon CD40L binding, CD40 clusters and recruits TNFR-associated factor (TRAF) proteins (TRAF1, 2, 3, 5, 6) to its cytoplasmic tail. This recruitment activates several key pathways [10]:

- Canonical NF-κB Pathway: Leads to the degradation of the IκB complex and translocation of NF-κB heterodimers (e.g., p50/p65) to the nucleus, promoting cell survival and proliferation.

- Non-Canonical NF-κB Pathway: Involves the processing of p100 to p52, which complexes with RelB and translocates to the nucleus to regulate specific target genes.

- MAPK Pathways: Including Jnk and p38, which are involved in cellular stress responses and differentiation.

TRAF-Independent and Other Signaling

CD40 can also signal through TRAF-independent mechanisms. For instance, it can bind directly to Janus family kinase 3 (Jak3), leading to the phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5) [10]. Furthermore, CD40 ligation on T cells can stimulate a signaling cascade involving p56lck, Rac1, and the activation of Jun-N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38-K [12].

The complexity of CD40 signaling is depicted in the following pathway diagram:

Comparative Analysis: Mucosal vs. Systemic Vaccination

The route of vaccine administration significantly influences the engagement of GC and CD40-dependent pathways, ultimately shaping the quality, duration, and anatomical localization of protective immunity. This is particularly relevant for the generation of tissue-resident memory B cells ((B_{RM})), which are crucial for frontline defense at mucosal surfaces.

Table 2: Comparison of Mucosal vs. Systemic Vaccination Strategies

| Parameter | Systemic Vaccination (e.g., Intramuscular) | Mucosal Vaccination (e.g., Intranasal, Intravaginal) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary GC/Immune Induction Site | Draining lymph nodes (e.g., axillary, inguinal) | Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) and regional lymph nodes |

| Strength of Systemic Immunity | Strong systemic antibody and CD8 T cell responses [13] | Variable, often lower systemic antibody titers [13] |

| Strength of Mucosal Immunity | Weaker mucosal T and B cell responses [13] | Stronger local CD4 T cell central memory responses and tissue-resident memory [1] [13] |

| Generation of Mucosal (B_{RM}) | Limited | Robust, derived from CD40-dependent GC responses in mucosal sites [1] [14] |

| Protection against Mucosal Challenge | Partial control of viral load [13] [15] | Enhanced control; lower viral set points in some studies [13] |

| Practical Advantages | Standardized, well-established delivery | Non-invasive, potential for mass administration (e.g., in aquaculture [16]) |

Evidence from Preclinical Models

- Primate SHIV Model: A comparative study in rhesus macaques immunized with helper-dependent adenoviral (HD-Ad) vectors expressing HIV-1 envelope found that intramuscular (i.m.) immunization generated stronger systemic CD8 T cell responses in PBMCs, but weaker mucosal responses. Conversely, intravaginal (ivag.) mucosal immunization generated stronger CD4 T cell central memory responses in the colon. After rectal SHIV challenge, both groups controlled the virus better than controls, but a greater number of animals in the mucosally immunized group had lower viral set points, suggesting improved protection against sexually-transmitted virus [13].

- SIV Challenge Model: Another study comparing aerosol (AE) vaccination with intramuscular (IM) delivery found that both routes controlled acute viremia in an intravenous challenge model. However, after an intrarectal challenge, only peak viremia was reduced by immunization, with no significant effect on the acquisition rate. This underscores the difficulty in achieving sterile immunity against mucosal challenge but also highlights that aerosol delivery induced strong mucosal cellular responses and systemic humoral responses equivalent to the intramuscular route [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Models

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying GC and CD40 Pathways

| Reagent / Model | Function / Application | Key Insight from Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-CD40L Antibody | Blocks CD40-CD40L interaction in vivo | Abrogates GC formation, Ig isotype switching, and affinity maturation, confirming pathway necessity [10]. |

| CD40 or CD40L KO Mice | Genetic models to study loss of function | Demonstrate defective GC formation, humoral immunity, and failure to generate long-lived plasma cells and memory B cells [10]. |

| BCL6 Reporter Mice | Fate-mapping of GC B cells and (T_{FH}) cells | Identified BCL6 as the master transcriptional regulator of GC B and (T_{FH}) cell differentiation [9]. |

| c-Myc Reporter Mice | Tracking positively selected GC B cells | Revealed that CD40 signaling from (T_{FH}) cells induces c-Myc in LZ B cells in proportion to antigen amount, licensing them for DZ re-entry [11]. |

| Metabolic Inhibitors (e.g., 2-DG, DON) | Inhibit glycolysis (2-DG) and glutaminolysis (DON) | Uncovered distinct metabolic dependencies; glutamine is crucial for GC development, while autoreactive GC B cells may be uniquely glucose-dependent [11]. |

| Adenovirus Vectors (HD-Ad) | Vaccine vectors for immunization studies | Used in primate models to compare immunization routes; effective for serotype-switching to overcome pre-existing immunity [13]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To provide context for the data discussed, here are detailed methodologies for key experiments cited.

This protocol outlines the method used to compare intramuscular (i.m.) and intravaginal (ivag.) vaccination.

- Priming: Rhesus macaques are first immunized intranasally with 1x10^11 virus particles (vp) of first-generation adenovirus serotype 5 (FG-Ad5) expressing a marker gene (e.g., β-galactosidase) to establish anti-vector immunity.

- Serotype-Switch Vaccination:

- Group 1 (Systemic): Immunized by i.m. injection with 1x10^11 vp of HD-Ad6 expressing the antigen of interest (e.g., HIV-1 Env gp140).

- Group 2 (Mucosal): Immunized by intravaginal (ivag.) lavage with the same dose of HD-Ad6-Env.

- Boosting: Both groups are boosted at 3-week intervals using the same routes but switching the adenovirus serotype (e.g., to HD-Ad1-Env, then HD-Ad5-Env, then HD-Ad2-Env) to evade neutralizing antibodies.

- Immune Monitoring:

- T cell responses: Measured by IFN-γ ELISPOT on PBMCs stimulated with peptide pools spanning the antigen.

- Mucosal T cells: Isolated from biopsies (e.g., colon) and analyzed by flow cytometry for central memory markers.

- Antibody responses: Quantified by ELISA for antigen-binding antibodies.

- Challenge: At week 32, animals are challenged rectally with a pathogenic virus (e.g., 1000 TCID50 of SHIV-SF162P3) and monitored for viral load (plasma viremia) and disease progression.

- Cell Isolation: Collect PBMCs from vaccinated subjects via density gradient centrifugation.

- Peptide Stimulation: Plate 1x10^5 PBMCs per well in an ELISPOT plate pre-coated with an IFN-γ capture antibody. Stimulate cells with 3 pools of 15-mer peptides (50-70 peptides per pool) overlapping the sequence of the vaccine antigen. Include negative (medium only) and positive (mitogen) control wells.

- Incubation: Incubate plates for 36 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2.

- Detection: After incubation, discard cells and add a biotinylated detection antibody against IFN-γ, followed by enzyme-conjugated streptavidin.

- Development: Add a precipitating substrate to develop spots. Each spot represents a single IFN-γ-secreting T cell.

- Analysis: Enumerate spot-forming units (SFU) using an automated ELISPOT reader. Data are expressed as SFU per 10^6 input cells after subtracting background from negative control wells.

The germinal center, powered by CD40 signaling, is the essential crucible for the birth of protective, high-affinity B cell responses. The CD40-CD40L axis is non-redundant in initiating the signaling cascades that drive B cell proliferation, SHM, and differentiation into plasma cells and memory B cells. The choice between systemic and mucosal vaccination represents a critical strategic decision. While systemic vaccination robustly engages GC pathways in draining lymph nodes, mucosal vaccination uniquely leverages these pathways within mucosal tissues to generate frontline defenders—tissue-resident memory B cells. A deep understanding of these intertwined cellular, molecular, and spatial relationships is fundamental for advancing novel vaccine strategies against pathogens that enter through mucosal surfaces.

In the defense against recurrent pathogens, the speed and location of the immune response are paramount. The "recall advantage" refers to the unique capacity of antigen-experienced memory B cells to rapidly differentiate into antibody-secreting cells (ASCs) upon reinfection, a cornerstone of protective immunity. This process is markedly different from the primary response, which requires days to weeks to generate specific antibodies, whereas memory responses can be mounted within hours to days. Within this paradigm, tissue-resident memory B cells (Brm) situated at mucosal surfaces have emerged as crucial frontline defenders, particularly against respiratory pathogens. Their strategic positioning at sites of pathogen entry enables immediate reaction, bypassing the time required for recruitment from circulation [17] [1]. Understanding the mechanisms governing this rapid differentiation is not merely an academic exercise but a critical endeavor for developing next-generation vaccines, especially mucosal vaccines that can establish these localized sentinels [6].

The broader thesis of modern vaccinology is increasingly shifting toward strategies that leverage these tissue-resident responses. While conventional systemic vaccination excels at generating circulating antibodies and protection against severe disease, it often fails to induce robust mucosal immunity, creating a potential gap in sterilizing immunity that prevents initial infection and transmission [6]. This review objectively compares the performance of mucosal versus systemic vaccination strategies in generating Brm and eliciting rapid ASC differentiation upon reinfection, providing experimental data and methodologies central to this evolving field.

Comparative Performance: Mucosal vs. Systemic Vaccination

The route of vaccine administration fundamentally shapes the quality, location, and kinetics of the resulting B cell memory. The table below synthesizes key performance characteristics based on current research.

Table 1: Comparison of Immune Responses Following Mucosal vs. Systemic Vaccination

| Parameter | Mucosal Vaccination (e.g., Intranasal) | Systemic Vaccination (e.g., Intramuscular) |

|---|---|---|

| Induction of Tissue-Resident Memory B Cells (Brm) | Directly induces Brm in respiratory mucosa [17] [1] | Fails to generate pulmonary Brm; memory B cells are primarily circulating [17] |

| Antibody Secreting Cell (ASC) Kinetics | Brm rapidly differentiate into ASCs upon challenge, providing local antibody [1] | Recall responses involve activation of circulating memory B cells, with a potential delay in local antibody production |

| Key Signaling for Brm Formation | CD40-dependent germinal center responses in local mucosal tissues [1] | Germinal center responses in systemic lymphoid organs (e.g., spleen, lymph nodes) |

| Local Secretory IgA (SIgA) | Robust induction of SIgA at the site of pathogen entry [6] | Ineffective induction of mucosal SIgA; primarily induces serum IgG [6] |

| Protection against Infection & Transmission | Potently blocks initial infection and reduces viral transmission [6] | Primarily protects against severe disease but may be less effective at blocking initial infection [6] |

Quantitative data further underscores this comparison. A study on SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections in vaccinated individuals revealed that Spike-specific CD4 T cells and plasmablasts expanded, and CD8 T cells were robustly activated during the first week of infection. In contrast, memory B cell activation and the production of potent neutralizing antibodies were features of the second week, highlighting the coordinated, multi-layered nature of the recall response [18]. Furthermore, intranasal vaccination in mice with a chimpanzee adenoviral-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccine induced CD103+CD69+CD8 T cells in the lungs, a hallmark of tissue-resident memory T cells (Trm), while intramuscular vaccination failed to do so [17]. This principle extends to B cells, where local antigen encounter is a known requirement for establishing a tissue-resident population [17].

Decoding the Experiments: Key Methodologies and Findings

The conclusions drawn in the previous section are supported by rigorous experimental models. Below is a summary of foundational protocols used to investigate Brm and recall responses.

Table 2: Key Experimental Models and Methodologies for Studying Brm and Recall Responses

| Experimental Approach | Key Methodology | Primary Readout / Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Parabiosis / Adoptive Transfer | Surgically connecting two mice or transferring cells from a donor to a recipient mouse, often followed by intravenous labeling to distinguish circulating vs. resident cells [17]. | Confirms the non-circulating, tissue-resident nature of Brm populations in mucosal tissues like the lung [17]. |

| In Vivo Challenge Models | Immunizing mice via different routes (e.g., intranasal vs. intramuscular) and later challenging with a pathogen to assess protection and immune kinetics [17]. | Demonstrates that mucosal vaccination leads to superior local protection and faster ASC responses upon rechallenge compared to systemic vaccination [17]. |

| Longitudinal BCR Repertoire Sequencing | Using high-throughput sequencing to track B cell receptor (BCR) clonotypes in memory B cells and ASCs over time in humans or model systems [19]. | Reveals clonal persistence and reactivation of memory B cells, showing they can undergo new rounds of affinity maturation when differentiating into ASCs upon antigen re-encounter [19]. |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq) | Profiling the transcriptome of individual B cells during activation and differentiation in vivo [20]. | Identified an early cell fate bifurcation upon B cell activation; ASC-destined cells downregulate CD62L and induce IRF4, MYC-target genes, and oxidative phosphorylation [20]. |

| Flow Cytometry / FACS Panels | Using multicolor antibody panels to identify and isolate specific B cell subsets (e.g., Brm: CD19+ CD69+; Plasmablasts: CD19low CD20- CD27high CD138-) [21] [19]. | Allows for phenotypic characterization and functional assessment of B cell populations, defining ASCs as CD27high CD38high among CD3- CD20- cells [21]. |

A critical study elucidating the requirements for ASC differentiation used an adoptive transfer model where labeled B cells were tracked in vivo. This research found that a minimum of eight cell divisions were required for ASC formation in response to T-cell independent antigens like LPS. The transcription factor BLIMP-1 was essential for this differentiation at division eight, underscoring the link between cellular proliferation and fate determination [20].

Molecular Mechanisms: From Memory B Cell to Antibody Factory

The rapid differentiation of Brm into ASCs is governed by a well-orchestrated molecular program. The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways and transcriptional regulators involved in this process.

Diagram Title: Signaling Pathway for Brm to ASC Differentiation

The journey begins when a tissue-resident memory B cell (Brm) re-encounters its cognate antigen. B cell receptor (BCR) engagement, coupled with CD40 signaling (recapitulating T cell help) and cytokine signals (such as IL-21), triggers a pivotal early event: the rapid upregulation of the transcription factor IRF4 [20]. IRF4 initiates a cascade of changes that commit the cell to the ASC fate, including the induction of MYC-target genes to sustain proliferation and a metabolic shift toward oxidative phosphorylation to meet energy demands [20]. A key downstream effector is BLIMP-1 (encoded by Prdm1), a master regulator that extinguishes the B cell gene expression program and drives the expression of XBP1, facilitating the expansion of the endoplasmic reticulum necessary for massive antibody production [20]. This pathway enables the swift conversion of a quiescent Brm into a dedicated antibody factory.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Brm and ASC Research

Progress in this field relies on a specific set of research tools and reagents that allow for the identification, isolation, and functional characterization of memory B cells and ASCs.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Brm and ASC Studies

| Research Reagent / Tool | Primary Function | Key Application in the Field |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescently-Labeled Antigen Probes | To identify antigen-specific B cells via flow cytometry. | Critical for tracking pathogen-specific B cell responses (e.g., using SARS-CoV-2 Spike probes) without relying on phenotypic markers alone [18]. |

| Multicolor Flow Cytometry Antibody Panels | To phenotype and isolate distinct B cell subsets based on surface and intracellular markers. | Panels including CD19, CD20, CD27, CD38, CD138, CD69, CD103 are used to define human ASCs (CD19low CD20- CD27high CD38high) and tissue-resident cells (CD69+) [21] [19]. |

| ELISpot/Fluorospot Assays | To enumerate and characterize functional antibody-secreting cells (ASCs) at a single-cell level. | Measures the prevalence and antigen-specificity of ASCs from tissues or blood; robust for quantifying recall responses [21]. |

| BCR Sequencing Kits | For high-throughput sequencing of B cell receptor repertoires. | Enables clonal tracking, analysis of somatic hypermutation, and understanding of B cell lineage relationships over time and between subsets [19]. |

| Recombinant Cytokines & Signaling Agonists/Antagonists | To modulate specific signaling pathways in vitro and in vivo. | Used to dissect the role of pathways like CD40 (agonistic antibodies), IL-21, and BCR signaling in Brm reactivation and ASC differentiation. |

The workflow for a typical deep immune profiling experiment might involve using fluorescent antigen probes and flow cytometry to sort specific B cell populations (e.g., Brm, plasmablasts), followed by single-cell RNA sequencing to understand their transcriptional state and BCR sequencing to track their clonal history [18] [21] [19]. This integrated approach provides an unprecedented view of the immune response at the clonal level.

The evidence unequivocally demonstrates that the "recall advantage"—the rapid differentiation of memory B cells into ASCs—is profoundly enhanced when the memory pool is strategically positioned at the site of potential infection. Tissue-resident memory B cells (Brm), induced most effectively by mucosal vaccination or infection, represent a key mediator of this frontline defense [17] [1]. Their ability to swiftly produce local antibody upon rechallenge provides a kinetic and spatial advantage that systemic memory responses cannot match.

The current data underscores a clear performance dichotomy: mucosal vaccines excel at inducing local immunity that can block infection and transmission, while systemic vaccines are highly effective at preventing severe disease but less so at providing sterilizing mucosal immunity [6]. This is not a failure of systemic vaccination but rather a reflection of compartmentalized immunity. The future of vaccine development, particularly against respiratory pathogens, therefore lies in the strategic combination of both approaches or the optimization of mucosal platforms to reliably generate robust and durable Brm populations. Key challenges remain, including the identification of definitive correlates of protection for mucosal immunity and the development of safe and effective adjuvants for human mucosal vaccines [17] [6]. As these hurdles are overcome, leveraging the full potential of the recall advantage offered by tissue-resident memory B cells will be fundamental to achieving next-generation protective immunity.

From Bench to Barrier: Techniques and Strategies for Inducing and Analyzing BRM Responses

While peripheral blood is the most common source for human immunology studies, a growing body of evidence reveals that B cells in tissues are not in homeostasis with circulatory compartments. Advanced profiling technologies now enable direct investigation of tissue-localized B cell repertoires, revealing specialized tissue-resident memory B cells (Brm) with unique phenotypic signatures and functional capabilities. This guide compares methodological approaches for tissue-based B cell repertoire analysis and synthesizes recent findings on tissue-specific B cell compartments, providing researchers with frameworks for selecting appropriate profiling strategies based on research objectives and tissue accessibility.

The conventional reliance on peripheral blood for B cell analysis presents a fundamental limitation in understanding adaptive immunity, as blood B cells are not in homeostasis with tissue compartments [22]. Studies utilizing tissues from organ donors have demonstrated striking differences in B cell subset distribution, isotype usage, and functional capabilities between mucosal tissues, lymphoid organs, and circulatory compartments [22] [23]. This compartmentalization is particularly relevant in vaccine research, where successful mucosal vaccination strategies must induce not only systemic immunity but also tissue-localized Brm cells that provide frontline defense at pathogen entry sites [17] [1].

The development of tissue-resident memory B cells represents a critical adaptation for localized protection. These non-circulating cells persist in tissues long after antigen clearance and mount rapid, robust responses upon re-exposure to pathogens [17]. Their induction requires local antigen encounter and is influenced by vaccination route, with mucosal vaccination strategies demonstrating superior ability to generate these tissue-localized protective populations [17] [6].

Methodological Approaches for Tissue-Based B Cell Repertoire Analysis

Comparative Analysis of Profiling Technologies

| Technology | Key Applications | Sample Requirements | Output Data | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCR-Seq (Bulk) | Repertoire diversity, clonality, V(D)J usage [24] | Tissue DNA/RNA (120ng for library prep) [24] | Clonotype frequencies, V/D/J gene usage, SHM analysis [24] | Loses cellular resolution, cannot pair heavy/light chains |

| CITE-seq (Single-Cell) | Multimodal analysis of phenotype + BCR [23] | Viable single-cell suspensions from tissues [23] | Paired BCR sequences + surface protein expression (127+ parameters) [23] | Higher cost, complex computational analysis |

| Multicolor Flow Cytometry | B cell subset identification and sorting [22] | Fresh or cryopreserved tissue single-cell suspensions [22] | Surface marker expression (CD19, CD27, CD45RB, CD69, etc.) [22] | Limited to pre-defined marker panels, no sequence information |

| ViCloD Web Server | Clonality and intraclonal diversity analysis [25] | Preprocessed AIRR-seq data (e.g., IMGT/HighV-QUEST) [25] | Clonal abundance, lineage trees, SHM patterns [25] | Dependent on quality of input sequencing data |

Experimental Workflow for Tissue B Cell Repertoire Profiling

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive workflow for profiling tissue-localized B cell repertoires, integrating both phenotypic and sequencing approaches:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Tissue Processing | Collagenase/DNase cocktails, mechanical dissociation systems | Isolation of viable lymphocytes from solid tissues |

| Cell Staining Panels | CD19, CD27, CD45RB, CD69, CD38, IgD, IgM, IgA [22] | Identification of B cell subsets and tissue-resident populations |

| Library Prep Kits | 7genes DNA multiplexing kits (MiLaboratories) [24] | Simultaneous profiling of T and B cell repertoires from same sample |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq 6000 (150bp paired-end) [24] | High-throughput immune repertoire sequencing |

| Analysis Tools | MiXCR, ViCloD, Immcantation framework [24] [25] | Clonotype identification, lineage tree reconstruction, diversity analysis |

Tissue-Specific B Cell Signatures: Key Findings from Multi-Tissue Studies

Comparative Distribution of B Cell Subsets Across Tissues

Comprehensive analysis of B lineage cells across multiple tissues from the same donors has revealed striking tissue-specific distributions that are not reflected in peripheral blood [22] [23]. The table below summarizes key quantitative differences in B cell subsets across major tissue compartments:

| Tissue Site | CD27+ Memory B Cells | Naive B Cells | Plasma Cells/Plasmablasts | Tissue-Resident (CD69+) B Cells | Dominant Isotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peripheral Blood | 20.37% [22] | 79.63% [22] | 0.24% [22] | Absent/Low [22] | IgG [23] |

| Spleen | 70.39% [22] | 29.61% [22] | 1.00% [22] | Moderate [22] | IgG [23] |

| Gut (Jejunum) | 86.44% [22] | 13.56% [22] | 1.92% [22] | High (CD69+CD45RB+) [22] | IgA [23] |

| Bone Marrow | 46.00% [22] | 54.00% [22] | 0.51% [22] | Low [22] | IgG [23] |

| Lymph Nodes | Variable (LN-dependent) [23] | Variable [23] | 0.42% [22] | Moderate (CD69+) [23] | IgG [23] |

Identification and Characterization of Tissue-Resident Memory B Cells

Tissue-resident memory B cells (Brm) represent a distinct B cell subset characterized by their non-circulating nature and tissue-localized persistence. The following diagram illustrates the phenotypic markers and differentiation pathways of Brm cells:

The generation of Brm cells occurs through both germinal center (GC)-dependent and GC-independent pathways [26]. GC-independent Brm development is driven by CD40 signaling and occurs with relatively brief T follicular helper (Tfh) cell contact, while GC-dependent development involves sustained Tfh help and cytokine signaling (particularly IL-21), which upregulates BCL-6 and promotes GC formation [26]. These developmental pathways converge on the establishment of CD69+ Brm populations that persist in tissues.

Implications for Mucosal Versus Systemic Vaccination Research

Differential Immune Responses by Vaccination Route

The route of vaccine administration dramatically influences the generation of tissue-localized B cell memory. Studies comparing mucosal versus parenteral vaccination have revealed fundamental differences in the quality, location, and durability of B cell responses [17] [6]. The table below compares key features of B cell responses induced by different vaccination routes:

| Vaccination Parameter | Mucosal Vaccination | Systemic Vaccination |

|---|---|---|

| Tissue Brm Induction | Robust generation of Brm at site of administration [17] [1] | Limited tissue Brm generation [17] |

| Secretory Antibody Production | Induces secretory IgA (SIgA) at mucosal surfaces [6] | Minimal SIgA production [6] |

| Systemic Antibody Response | Variable, often lower systemic IgG [6] | Strong systemic IgG response [6] |

| Germinal Center Reactions | Local GC formation in mucosal tissues [6] | Primarily systemic GC in spleen/LNs [6] |

| Protection Against Infection | Blocks initial infection/colonization [6] | Reduces severe disease but limited blocking of initial infection [6] |

| Durability of Response | May wane faster for mucosal IgA [6] | Often longer-lasting systemic immunity [6] |

Mucosal Vaccination Strategies for Optimal Brm Induction

Successful mucosal vaccine strategies leverage specific mechanisms to induce tissue-resident memory. Intranasal administration of live-attenuated influenza virus induces development of CD4+ and CD8+ Trm cells in lungs, whereas systemic immunization fails to generate similar Trm responses [17]. The "prime and pull" strategy, involving systemic priming followed by local mucosal recruitment through chemokine application, has proven effective for generating tissue-resident memory in vaginal tract and respiratory mucosa [17].

For Brm induction, local antigen encounter is essential [17]. This requirement makes mucosal vaccination particularly advantageous, as it ensures direct antigen presentation to tissue-localized B cells. The local microenvironment, including cytokine signals from innate lymphoid cells and stromal elements, further supports Brm differentiation and maintenance [6].

Technical Considerations and Protocol Details

Detailed Methodology for Simultaneous T and B Cell Repertoire Profiling

The protocol below, adapted from PMC12447526 [24], enables comprehensive profiling of adaptive immune repertoires from limited tissue samples:

Sample Preparation:

- Collect tissues (e.g., colon biopsies) during diagnostic procedures and immerse in Allprotect reagent overnight at 2-8°C before freezing at -80°C

- Extract DNA using automated systems (e.g., Chemagic STAR or QIAcube Connect with DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit)

- Perform quality control using Agilent TapeStation Systems (acceptable DIN score: 6.5-9.7)

- Quantify DNA using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit dsDNA-BR assay)

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Use 120ng of DNA as input for library preparation with 7genes DNA multiplexing kits (MiLaboratories)

- Follow manufacturer's instructions for simultaneous T and B cell repertoire amplification

- Pool libraries and clean with magnetic beads (AMPure XP Beads, 1:0.8 sample:beads ratio)

- Dilute to ~2nM final concentration and sequence on Illumina NovaSeq 6000 using paired 150bp x 2 approach

- Include ~10% PhiX control to improve base calling accuracy

Data Processing and Analysis:

- Process raw sequencing data using MiXCR with "milab-human-dna-xcr-7genes-multiplex" preset

- Expect approximately 45-48% of reads to align successfully to immune receptor loci

- Typical distribution of aligned reads: TRA (~10.9%), TRB (~3.43%), TRG (~52.2%), TRD (~11.55%), IGH (~4.93%), IGK (~5.37%), IGL (~2.28%)

- Remove samples with initial low-quality input DNA from downstream analysis

Analysis of Intracional Diversity and Lineage Relationships

Tools like ViCloD provide specialized functionality for analyzing B cell intraclonal diversity and evolutionary relationships [25]. The web server:

- Accepts preprocessed data in Adaptive Immune Receptor Repertoire (AIRR) Community format

- Performs clonal grouping based on shared IGHV, IGHD, IGHJ genes and identical CDR3 amino acid sequences

- Reconstructs intraclonal evolutionary trees to visualize somatic hypermutation patterns

- Enables navigation of repertoire clonality and identification of expanded clones

- Generates downloadable tables and publication-quality plots of lineage relationships

Advanced profiling of tissue-localized B cell repertoires has fundamentally transformed our understanding of adaptive immunity, revealing specialized tissue-resident populations that are not reflected in circulatory compartments. The methodologies and findings summarized in this guide provide researchers with frameworks for investigating these localized immune responses, with significant implications for vaccine development, particularly in the context of mucosal protection. As tissue-based immunology continues to advance, integrating multimodal single-cell technologies with functional assays will further elucidate the unique biology of tissue-resident B cells and their role in protective immunity.

Respiratory infections remain a major global public health threat, as demonstrated by the COVID-19 pandemic [27]. While traditional intramuscular vaccines have proven effective at reducing severe disease and hospitalization, they primarily elicit systemic IgG responses and are limited in their ability to induce robust immunity at mucosal surfaces—the primary site of pathogen entry for many viruses [27] [28]. This immunological gap has accelerated development of mucosal vaccine platforms designed to stimulate localized responses at pathogen entry points. Mucosal vaccines, administered via intranasal, oral, or sublingual routes, aim to induce secretory IgA (SIgA) production and establish tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM) and B cells within mucosal tissues, providing a critical first line of defense against infection and potentially reducing viral transmission [27] [28].

The fundamental advantage of mucosal vaccination lies in its capacity to establish protective immunity at the site of pathogen invasion. Unlike intramuscular vaccines, which rely on circulatory antibodies and cells migrating to infection sites, mucosal vaccines stimulate the common mucosal immune system, enabling activated immune cells to home to distant mucosal tissues [27]. Intranasal vaccination, in particular, induces the formation of CD69⁺CD103⁺ TRM cells, germinal center reactions, and memory B cells that persist locally in the respiratory tract for at least six months, playing a pivotal role in limiting viral replication and transmission [27]. This review comprehensively compares three prominent mucosal delivery platforms—intranasal, oral, and sublingual—focusing on their immunological mechanisms, current developmental status, and relative advantages and challenges within the context of establishing protective tissue-resident memory responses.

Comparative Analysis of Mucosal Vaccine Platforms

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and challenges of the three primary mucosal vaccine delivery platforms.

Table 1: Comparison of Mucosal Vaccine Delivery Platforms

| Feature | Intranasal | Oral | Sublingual |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immune Induction Site | Nasal-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT) [27] | Gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) [29] | Mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue [30] |

| Primary Antibody Response | Secretory IgA (SIgA) in upper and lower respiratory tract [27] [28] | Secretory IgA (SIgA) in gut mucosa and other mucosal sites [29] | Secretory IgA (SIgA) in respiratory and other mucosal tissues [30] |

| Cellular Immunity | Strong tissue-resident memory T cell (TRM) formation in respiratory tract [27] | Systemic and mucosal T cell responses [29] | Mucosal and systemic T cell responses [30] |

| Key Advantages | Directly targets respiratory pathogen entry point; potential to block transmission [28] [31] | Non-invasive, high patient compliance, ease of distribution [29] | Avoids gastric degradation; favorable safety profile vs. intranasal [30] |

| Major Challenges | Potential safety concerns regarding brain access via olfactory bulb; mucosal barriers [28] [30] | Degradation in GI tract; variable efficacy influenced by gut microbiota [29] [32] | Mucin barrier and saliva dilution require formulation solutions [30] |

| Authorized Examples | FluMist (USA), COVID-19 vaccines in China, India, Iran, Russia [33] [28] | Oral polio, cholera, rotavirus, and typhoid vaccines [29] | None widely authorized to date (still in development) [30] |

| Clinical Trial Progress | 36 mucosal COVID-19 vaccines in clinical trials as of late 2025 [34] | Vaxart's oral COVID-19 vaccine in Project NextGen-funded trial [33] | Primarily in preclinical and early clinical development stages [30] |

Immunological Mechanisms and Key Research Methodologies

Immune Mechanisms of Mucosal Vaccination

The following diagram illustrates the general immunological mechanisms shared by mucosal vaccines, which lead to the generation of tissue-resident memory and secretory IgA responses.

The diagram above outlines the core adaptive immune mechanism leading to protective mucosal immunity. Upon administration, mucosal vaccines are sampled by specialized microfold (M) cells that transport antigens across the epithelial barrier to underlying antigen-presenting cells, particularly dendritic cells (DCs) [27] [29]. These DCs then migrate to mucosal-associated lymphoid tissues (MALT) such as nasal-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT) for intranasal vaccines or gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) for oral vaccines, where they present antigens to naïve T cells [27] [29].

Activated T follicular helper (Tfh) cells are crucial for supporting B cell maturation and antibody class switching in germinal centers [27]. This process leads to the generation of plasma cells that produce dimeric IgA, which is transported across the epithelium as secretory IgA (SIgA) by the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (pIgR) [27]. SIgA acts to neutralize and clear pathogens directly at the mucosal surface. Concurrently, antigen-specific tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM), characterized by surface expression of CD69 and CD103, are established in the mucosal tissue [27]. These non-circulating cells provide rapid, localized protection upon subsequent pathogen exposure and are a key correlate of protection for mucosal vaccines [27].

Experimental Workflow for Mucosal Vaccine Evaluation

The diagram below illustrates a standard experimental workflow used in preclinical studies to evaluate the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of mucosal vaccine candidates.

The experimental workflow for evaluating mucosal vaccines involves multiple coordinated steps. Following vaccine administration to animal models (typically mice or non-human primates), researchers collect mucosal samples such as nasal washes, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid, and saliva, alongside systemic samples like blood and spleen tissue [27] [30]. These samples are analyzed for antigen-specific SIgA and IgG antibodies using ELISA and neutralization assays, while flow cytometry characterizes cellular immune populations, particularly TRM cells (CD69⁺CD103⁺) and memory B cells [27].

A critical component of mucosal vaccine assessment involves live pathogen challenge studies. Vaccinated and control animals are exposed to the target pathogen (e.g., SARS-CoV-2), and researchers monitor viral loads in respiratory tissues, clinical signs of disease, and tissue histopathology [31]. Some studies also incorporate transmission models where vaccinated animals are co-housed with naïve counterparts to assess the vaccine's ability to prevent viral spread [33] [31]. Additionally, safety evaluations include monitoring inflammatory gene expression in tissues like the olfactory bulb and lungs using RT-qPCR, especially for intranasal vaccines [30].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Mucosal Vaccine Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(I:C) HMW | TLR3 agonist adjuvant that stimulates proinflammatory cytokine production and enhances vaccine immunogenicity [30]. | Used in sublingual and intranasal vaccine formulations to boost immune responses [30]. |

| N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) | Mucolytic agent that disrupts the mucin barrier, improving antigen access to underlying immune cells [30]. | Pre-treatment of sublingual mucosa before vaccine application to enhance delivery [30]. |

| Recombinant Trimeric Proteins | Stabilized antigen forms that mimic native viral structures, improving antibody recognition and immunogenicity [31]. | Key component in two-component intranasal vaccines (e.g., RBDXBB.1.5-HR) [31]. |

| Adenovirus Vectors | Vaccine delivery platform that also functions as a natural adjuvant by activating STING and TLR pathways [31]. | Used in intranasal vaccines (e.g., Ad5XBB.1.5) to deliver antigen genes and enhance immunity [31]. |

| Fluorescence-Labeled Antibodies | Cell population characterization via flow cytometry to identify TRM (CD69, CD103) and other immune cells [27]. | Phenotyping tissue-resident memory T cells in mucosal tissues and BAL fluid [27]. |

| ELISA Kits (SIgA, IgG) | Quantification of antibody responses in mucosal secretions and serum to assess immunogenicity [27] [29]. | Measuring antigen-specific SIgA in nasal washes and saliva post-vaccination [27]. |

Current Status and Future Directions in Mucosal Vaccine Development

Clinical Development Progress

The mucosal vaccine field has expanded rapidly, with 36 mucosal COVID-19 vaccines having reached clinical trials as of late 2025 [34]. Currently, five mucosal COVID-19 vaccines are authorized for use in at least six countries, though none have yet received WHO approval for global use [33]. The most advanced platforms include viral-vectored (adenovirus, Newcastle disease virus), live-attenuated, and protein-subunit formulations [33] [31].

Recent clinical advances include the progression of Vaxart's oral vaccine into a Project NextGen-funded 10,000-participant trial in the US and the initiation of a phase 2a trial for Castlevax's intranasal Newcastle virus-based vaccine in high-risk individuals [33] [34]. Additionally, a novel two-component intranasal vaccine combining an adenovirus vector (Ad5XBB.1.5) with a trimeric protein (RBDXBB.1.5-HR) has demonstrated superior immunogenicity and protective efficacy in preclinical models and early human trials [31].

Key Research Findings and Experimental Data

Recent studies have provided compelling evidence for the potential of mucosal vaccines. The following table summarizes quantitative results from key preclinical and clinical studies, highlighting the immune responses and protective efficacy elicited by different mucosal vaccine platforms.

Table 3: Experimental Data from Mucosal Vaccine Studies

| Vaccine Platform | Immune Response Findings | Protection/Transmission Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Two-Component Intranasal (Ad5XBB.1.5 + RBDXBB.1.5-HR) | Superior humoral and cellular immunity vs. single components; induced high levels of neutralizing antibodies in all human participants [31]. | Protected against live XBB.1.16 virus in mice; prevented XBB.1.5 virus transmission in hamster model [31]. | [31] |

| Intranasal DNA Vaccine (GLS-5310) | Phase 1 trial: Reduced rate of COVID-19 after nasal booster (1/17 infected vs. 16/53 in control groups) [33]. | Preclinical study in rabbits showed increased mucosal immunity after intranasal vaccination [33]. | [33] |

| Sublingual vs. Intranasal (Poly(I:C)-adjuvanted influenza) | No adverse effects on olfactory bulb or pons in mice/macaques with sublingual route [30]. | Intranasal vaccination upregulated inflammatory genes (Saa3, Tnf, IL6) in olfactory bulb 1 & 7 days post-vaccination [30]. | [30] |

| Oral Vaccine (Convidecia Air platform) | In mice: Intramuscular version immunity waned, but oral version effects were more durable up to 250 days [34]. | Both versions induced similar peak immune responses [34]. | [34] |

Future Research Directions

Future development of mucosal vaccines faces several key challenges and opportunities. Safety optimization remains paramount, particularly for intranasal vaccines where potential neurological effects must be carefully evaluated [30]. The promising safety profile of sublingual administration suggests it may offer a favorable alternative, though technical challenges like saliva dilution and the mucin barrier require innovative formulation solutions [30].

Durability of protection represents another critical research frontier. While mucosal vaccines can induce TRM cells that persist for at least six months [27], the factors governing their long-term maintenance are not fully understood. Additionally, the impact of prior immunity on mucosal vaccine performance is significant, with studies showing stronger nasal IgA and IgG responses in previously exposed individuals compared to naïve subjects [27].

The emerging strategy of heterologous prime-boost regimens—combining intramuscular priming with mucosal boosting—shows particular promise for enhancing mucosal immunity in previously vaccinated populations [28]. Furthermore, antigen design continues to evolve, with multivalent approaches (e.g., three-component vaccines incorporating antigens from multiple variants) demonstrating enhanced breadth of protection against diverse viral variants [31].

As the field advances, validating reliable correlates of protection for mucosal vaccines will be essential for accelerating their clinical development and regulatory approval [27]. While systemic neutralizing antibodies serve as established correlates for intramuscular vaccines, SIgA levels in upper airways and TRM cells in respiratory tissues are emerging as key potential correlates for mucosal protection [27].

The pursuit of next-generation vaccines has increasingly focused on the mucosal immune system, which serves as the body's first line of defense at barrier surfaces such as the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. Comprising a surface area approximately 200 times greater than the skin, mucosal tissues represent a critical interface where most pathogens initially encounter host immunity [35]. While traditional intramuscular vaccines effectively induce systemic IgG responses, they often fail to elicit robust protection at mucosal entry points, limiting their ability to prevent initial infection and transmission [6]. This recognition has catalyzed the development of mucosal vaccination strategies designed to induce localized immune responses, including the production of secretory IgA (SIgA) and the establishment of tissue-resident memory lymphocytes [35] [6].