The STAT-SH2 Domain: Master Regulator of Dimerization in Health and Disease

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical role played by the Src Homology 2 (SH2) domain in Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STAT) protein dimerization—a pivotal event...

The STAT-SH2 Domain: Master Regulator of Dimerization in Health and Disease

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical role played by the Src Homology 2 (SH2) domain in Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STAT) protein dimerization—a pivotal event in cellular signaling. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the unique structural features of STAT-type SH2 domains that facilitate both canonical phosphotyrosine-mediated dimerization and non-canonical interactions. The scope extends from foundational mechanisms and advanced research methodologies to the functional consequences of disease-associated mutations and emerging therapeutic strategies targeting the SH2 domain. By integrating foundational knowledge with current research and clinical implications, this review serves as a valuable resource for understanding and manipulating this crucial signaling node in cancer, immunology, and beyond.

The Structural Blueprint: Understanding the STAT-SH2 Domain Architecture

The Src Homology 2 (SH2) domain is a modular protein unit of approximately 100 amino acids that functions as a critical reader in phosphotyrosine-based signal transduction [1] [2]. Its primary function is to mediate specific protein-protein interactions by recognizing and binding to phosphorylated tyrosine (pTyr) containing peptide sequences on partner proteins [3]. This ability allows SH2 domain-containing proteins to participate in the assembly of multiprotein signaling complexes immediately downstream of protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs), thereby determining the specificity of cellular signaling pathways [3] [2]. In the context of STAT (Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription) proteins, the SH2 domain plays an indispensable role in their activation cycle. It facilitates recruitment to activated cytokine receptors, mediates phosphorylation-dependent dimerization through reciprocal pTyr-SH2 domain interactions, and is essential for the nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity of STAT dimers [4] [5] [6]. Understanding the canonical structure of the SH2 domain, particularly its core αβββα motif and key sub-pockets, is therefore foundational to research focused on targeting STAT dimerization for therapeutic purposes.

The Canonical SH2 Domain Architecture

The Conserved αβββα Structural Core

All SH2 domains share a highly conserved tertiary structure despite significant sequence variation. The centerpiece of this structure is the αβββα motif, which forms a compact molecular scaffold [1] [7] [8]. This core fold consists of a central anti-parallel β-sheet (composed of three β-strands conventionally labeled βB, βC, and βD) that is flanked on both sides by two α-helices (αA and αB) [1] [7]. This arrangement creates a "sandwich"-like structure where the β-sheet partitions the ligand-binding surface of the domain into two functionally distinct sub-pockets [1]. The remarkable conservation of this three-dimensional fold across diverse proteins underscores its evolutionary optimization for recognizing phosphotyrosine motifs [8].

Generic Residue Numbering and Structural Nomenclature

To enhance comparability across different SH2 domains, a generic residue numbering scheme has been developed, inspired by similar systems in other protein families like GPCRs [1] [7]. In this scheme:

- Secondary structural elements are denoted by lowercase letters (a for α-helix, b for β-strand) with capital letters indicating their order in the N- to C-terminal direction [1].

- Within each structural element, the most conserved residue is assigned position 50 [1] [7].

- Residue numbers increase in the C-terminal direction and decrease in the N-terminal direction from this central point [1].

- Loops are named by combining the labels of the structural elements they connect (e.g., loop aAbB connects α-helix A to β-strand B) [1].

This nomenclature provides a unified framework for discussing and comparing structural features across the diverse SH2 domain family, which includes 120 distinct domains in the human proteome [7] [8].

Key Functional Sub-pockets and Their Molecular Anatomy

The central β-sheet strategically divides the SH2 domain's binding surface into two primary sub-pockets that jointly determine phosphopeptide recognition [1] [7].

Table 1: Key Functional Sub-pockets of the Canonical SH2 Domain

| Sub-pocket | Structural Components | Key Conserved Residues | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphotyrosine (pY) Pocket | αA helix, BC loop, one face of central β-sheet [5] | Sheinerman residues, including invariant Arg βB5 [1] [7] [8] | Anchors phosphorylated tyrosine via electrostatic interactions with phosphate moiety [1] [2] |

| Specificity (pY+3) Pocket | Opposite face of β-sheet, αB helix, CD and BC* loops [5] | Variable residues defining pocket chemistry and accessibility [9] [5] | Recognizes 3-5 amino acids C-terminal to pTyr, conferring binding specificity [9] [2] |

The Phosphotyrosine (pY) Binding Pocket

The pY pocket is a deeply buried, positively charged cavity that serves as the primary anchor for ligand binding. Its architecture features several highly conserved residues, most notably an invariant arginine at position βB5 (Arg175 in v-Src), which forms a critical salt bridge with the phosphate moiety of the phosphotyrosine [1] [2] [8]. This arginine is part of the FLXRXS signature motif (also known as the FLVR motif) found in the βB strand of nearly all SH2 domains [1] [7]. A group of eight conserved residues, collectively termed the Sheinerman residues, create the precise electrostatic environment necessary for high-affinity phosphate binding [1] [7]. The exceptional conservation of these residues highlights their fundamental role in the SH2 domain's function as a phosphorylation-dependent switch.

The Specificity (pY+3) Pocket

The pY+3 pocket, also referred to as the specificity-determining region, is more variable in sequence and structure across different SH2 domains [9] [5]. This pocket is responsible for recognizing specific amino acids at the +1 to +5 positions C-terminal to the phosphotyrosine, thereby conferring selectivity for distinct physiological ligands [3] [2]. The EF and BG loops play a particularly important role in defining the accessibility and shape of this pocket by either plugging or exposing key binding subsites [9]. For instance, in Grb2 SH2, a bulky tryptophan in the EF loop occupies the P+3 binding pocket, forcing the bound peptide to adopt a β-turn conformation and selecting for asparagine at the P+2 position [9] [2]. This loop-controlled access to binding pockets represents a fundamental mechanism for generating functional diversity within the conserved SH2 structural fold.

STAT-Type SH2 Domains: Specialization for Dimerization

STAT proteins feature a distinct subclass of SH2 domains that are structurally specialized for their unique role in transcription factor activation. STAT-type SH2 domains exhibit several characteristic features that distinguish them from Src-type SH2 domains [5] [8]:

- C-terminal Architecture: Instead of the βE and βF strands found in Src-type SH2 domains, STAT-type domains possess an additional α-helix (αB') in what is known as the evolutionary active region (EAR) [5] [8].

- Dimerization Interface: Residues in the αB, αB', and BC* loop participate in SH2-mediated STAT dimerization, forming critical cross-domain interactions that stabilize the parallel dimer configuration required for nuclear translocation [5].

- Flexibility: STAT SH2 domains exhibit significant structural flexibility, particularly in the pY pocket, which may facilitate their dual functions in phosphopeptide binding and dimer stabilization [5].

Table 2: Comparative Features of STAT-type versus Src-type SH2 Domains

| Feature | STAT-type SH2 Domains | Src-type SH2 Domains |

|---|---|---|

| C-terminal Structure | Additional α-helix (αB') [5] [8] | βE and βF strands with adjoining loop [8] |

| Primary Function | Receptor recruitment & STAT dimerization [5] | Signal relay & complex assembly [2] |

| Dimerization Role | Direct participation in parallel dimer formation [5] | Typically intramolecular autoinhibition [2] |

| Loop Characteristics | Shorter CD loops [8] | Variable, often longer loops [8] |

The critical importance of the STAT3 SH2 domain is highlighted by the numerous disease-associated mutations identified in patient sequencing studies. These mutations cluster in functionally significant regions and can result in either hyperactivated or loss-of-function STAT3 variants, underscoring the delicate balance required for proper SH2 domain function [5].

Experimental Approaches for Studying SH2 Domain Structure and Function

Methodologies for Mapping SH2 Domain Specificity

Understanding SH2 domain function requires precise characterization of their binding specificity and affinity. Several well-established experimental approaches are routinely employed:

Fluorescence Polarization (FP) Assays: This solution-based technique measures the change in polarization of fluorescently labeled phosphopeptides upon binding to SH2 domains. It provides quantitative data on binding affinity (Kd) and is particularly useful for competitive inhibition studies, such as those used to characterize STAT3 SH2 domain inhibitors [6]. The assay involves incubating purified SH2 domains with a fixed concentration of fluorescent tracer peptide and measuring polarization values across a range of protein concentrations or in the presence of potential inhibitors [6].

SPOT Peptide Array Analysis: This semiquantitative method involves synthesizing arrays of phosphorylated peptides on nitrocellulose membranes and probing them with recombinant SH2 domains [3]. The relative binding intensity to each peptide spot provides information about sequence preferences. This technique was instrumental in identifying the contextual dependence of SH2 domain recognition, including the role of both permissive and non-permissive residues in determining binding selectivity [3].

Oriented Peptide Array Library (OPAL) Screening: This approach uses degenerate phosphopeptide libraries to comprehensively map the binding preferences of SH2 domains [9]. The resulting specificity profiles have enabled the classification of SH2 domains into groups based on their preference for specific residues at the P+2, P+3, or P+4 positions C-terminal to the phosphotyrosine [9].

Structural Biology Techniques

- X-ray Crystallography: This remains the gold standard for determining high-resolution structures of SH2 domains in complex with phosphopeptide ligands. It has revealed diverse binding modes, including the classic two-pronged plug-and-socket model observed in Src family SH2 domains and the β-turn conformation seen in Grb2 SH2-peptide complexes [2].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: NMR provides insights into the dynamics and conformational flexibility of SH2 domains in solution, complementing the static snapshots provided by crystallography [5].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for SH2 domain research, from initial database mining to therapeutic development.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Tools for SH2 Domain Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| GST-tagged SH2 Domains | Recombinant protein production for binding assays [3] | Purification via glutathione-Sepharose; FP and SPOT assays [3] |

| Phosphotyrosine Peptide Libraries | Mapping binding specificity and motifs [3] [9] | OPAL screening; SPOT array synthesis; competitive FP [3] [6] |

| STATeLight Biosensors | Real-time monitoring of STAT activation in live cells [10] | FLIM-FRET detection of STAT conformational changes [10] |

| SH2 Domain Inhibitors | Probing function and therapeutic development [6] | S3I-201, delavatine A derivatives for STAT3 dimer disruption [6] |

| Structural Biology Resources | Molecular visualization and analysis [1] [7] | SH2db database; PDB structures; AlphaFold models [1] [7] |

The canonical αβββα structure of the SH2 domain, with its bipartite organization into pY and pY+3 sub-pockets, represents an elegant evolutionary solution for achieving specific, phosphorylation-dependent protein-protein interactions. In STAT proteins, this conserved architecture has been specially adapted to facilitate the reciprocal SH2-phosphotyrosine interactions that underlie STAT dimerization and activation. The structural insights into these domains provide a crucial foundation for ongoing drug discovery efforts aimed at modulating STAT signaling in cancer and other diseases. Particularly promising are approaches that target the STAT3 SH2 domain to prevent dimerization, as demonstrated by inhibitors like S3I-201 and the delavatine A derivatives 323-1 and 323-2, which directly bind the SH2 domain and disrupt STAT3 dimer formation [6]. As structural databases like SH2db continue to expand and new methodologies such as genetically encoded biosensors enable real-time monitoring of STAT activation in live cells [10], our understanding of STAT-SH2 domain structure and function will continue to deepen, opening new avenues for therapeutic intervention in STAT-driven pathologies.

The Src Homology 2 (SH2) domain is a approximately 100-amino-acid modular unit that specifically recognizes and binds to phosphorylated tyrosine (pY) motifs, serving as a critical component in intracellular signal transduction [11] [12] [2]. Within the human proteome, SH2 domains are found in roughly 110 proteins involved in diverse cellular functions, including enzymes, adapters, and transcription factors [11] [8]. Despite a conserved core function of pY-recognition, SH2 domains have evolved structural variations that define their specific biological roles. STAT-type SH2 domains, found in Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription (STAT) proteins, exhibit distinctive structural features that set them apart from the more common Src-type SH2 domains [5]. These differences are not merely structural curiosities; they are fundamental adaptations that enable the unique dimerization-dependent transcriptional functions of STAT proteins. Within the context of STAT dimerization research, understanding these structural distinctions is paramount, as the STAT SH2 domain is indispensable for mediating the reciprocal phosphotyrosine-SH2 interactions that form active dimers capable of nuclear translocation and DNA binding [4] [5]. This review delineates the unique structural, functional, and biophysical characteristics of STAT-type SH2 domains, contrasting them with Src-type domains, and explores the implications for experimental research and therapeutic intervention.

Structural Comparison: STAT-type vs. Src-type SH2 Domains

Consensus Fold and Fundamental Architecture

All SH2 domains share a conserved central αβββα structural motif, comprising a central anti-parallel β-sheet (βB-βD) flanked by two α-helices (αA and αB) [5]. This core scaffold creates two primary ligand-binding subpockets: the phosphotyrosine (pY) pocket, which binds the phosphate group of the phosphorylated tyrosine, and the pY+3 pocket, which confers binding specificity by interacting with residues C-terminal to the pY [5]. The pY pocket is highly conserved and features an invariant arginine residue (at position βB5) that forms a critical salt bridge with the phosphate moiety [11] [8]. Despite this common blueprint, STAT-type and Src-type SH2 domains diverge significantly in their C-terminal architectures and loop configurations, which directly influence their dimerization functions and ligand selectivity.

Table 1: Core Structural Features of SH2 Domain Types

| Feature | STAT-type SH2 Domains | Src-type SH2 Domains |

|---|---|---|

| C-terminal Structure | Features additional αB' helix [8] [5] | Contains βE and βF strands forming a small β-sheet [8] [5] |

| BC* Loop | Present; involved in dimerization interfaces [5] | Present; role primarily in ligand binding |

| Representative Proteins | STAT1, STAT3, STAT5 [5] | Src, Abl, Lck, Fyn [2] |

| Primary Functional Role | Mediate STAT dimerization for nuclear translocation and transcription [5] | Recruit signaling proteins to membranes and receptors; regulate catalytic activity [2] |

Determinants of Specificity and Binding

The specificity of SH2 domains is governed by interactions with amino acids flanking the phosphotyrosine, typically positions C-terminal to the pY [2]. While Src-type domains often recognize specific motifs extending from the pY (e.g., the Src SH2 domain prefers pYEEI), STAT-type SH2 domains are optimized for a unique function: they directly bind to phosphotyrosine motifs on other STAT monomers during activation-induced dimerization [5]. This reciprocal interaction creates a stable dimer that is essential for STAT function. The pY+3 pocket in STAT SH2 domains is therefore a critical determinant of dimerization specificity. Furthermore, the architecture of the STAT SH2 domain, particularly the presence of the αB' helix and the configuration of the BC* loop, creates a surface that facilitates specific cross-domain interactions between two STAT monomers, a feature not required in most Src-type domains [5].

Functional Implications for STAT Dimerization and Signaling

The unique structural features of STAT-type SH2 domains are direct adaptations for their non-redundant role in JAK-STAT signaling pathways. Upon activation by extracellular cytokines or growth factors, receptor-associated Janus Kinases (JAKs) phosphorylate specific tyrosine residues on the receptor's cytoplasmic tail. This creates docking sites for STAT proteins, which are subsequently recruited via their SH2 domains. Following recruitment, JAKs phosphorylate a single conserved tyrosine residue in the C-terminal transactivation domain of the STAT protein. This phosphorylation event triggers a profound conformational change: latent STAT monomers form active dimers via reciprocal phosphotyrosine-SH2 domain interactions [4] [5].

In this dimeric complex, the SH2 domain of one STAT monomer binds the phosphorylated tyrosine of its partner, and vice versa. The distinct structure of the STAT SH2 domain, especially the αB' helix and its surrounding regions, is crucial for stabilizing this dimeric interface. Once formed, the phosphorylated STAT dimer translocates to the nucleus, where it binds to gamma-activated sequence (GAS) elements in the promoters of target genes to regulate transcription [4] [5]. This entire process is dependent on the precise molecular architecture of the STAT SH2 domain. Disease-causing mutations frequently localize to this domain, disrupting dimerization and nuclear translocation, which underscores its functional importance [5]. For instance, germline heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in the STAT3 SH2 domain cause Autosomal-Dominant Hyper IgE Syndrome (AD-HIES), characterized by impaired Th17 T-cell responses [5].

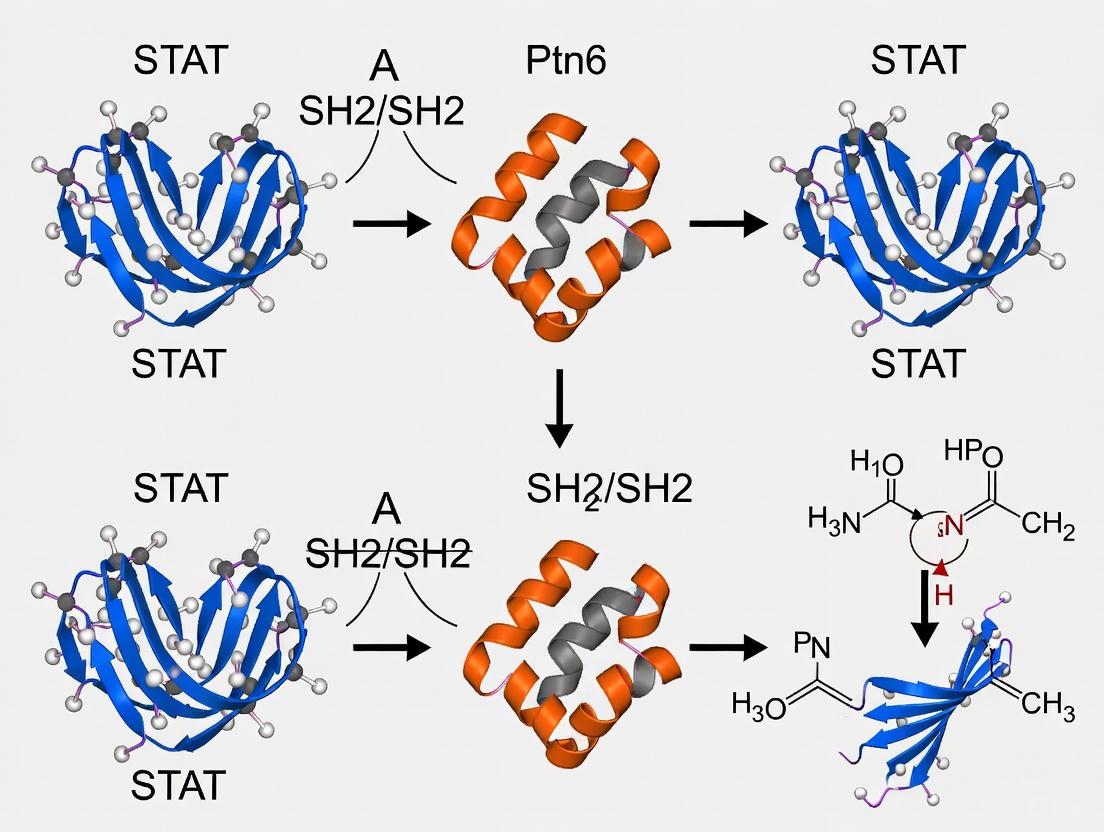

The following diagram illustrates the central role of the SH2 domain in the canonical STAT activation and dimerization pathway.

Experimental Analysis of STAT-type SH2 Domains

Key Methodologies and Workflows

Deciphering the unique properties of STAT-type SH2 domains requires a multidisciplinary approach. The following experimental protocols are fundamental to probing their structure, dynamics, and function.

Protocol 1: Mapping SH2 Domain Specificity Using Peptide Array Libraries Objective: To define the phosphotyrosine-containing peptide sequence motif that a STAT SH2 domain recognizes with highest affinity [13].

- Clone and Express: Clone the cDNA encoding the STAT SH2 domain of interest into an expression vector. Express and purify the recombinant SH2 domain protein, often with an affinity tag (e.g., GST, His-tag) [13].

- Generate Peptide Library: Synthesize an oriented peptide array library (OPAL) on cellulose membranes. The library consists of thousands of spot-synthesized peptides, each containing a central phosphotyrosine flanked by degenerate amino acid sequences [13].

- Binding Assay: Incubate the purified SH2 domain with the peptide array membrane under controlled buffer conditions.

- Detection: Wash away unbound protein and detect the bound SH2 domain using a tag-specific antibody conjugated to a reporter enzyme (e.g., horseradish peroxidase) for chemiluminescent detection [13].

- Data Analysis: Identify the spots with the strongest signal intensity. Align the peptide sequences of the high-affinity binders to deduce the consensus binding motif (e.g., pY-X-X-Z, where X and Z are specific amino acids) [13].

Protocol 2: Characterizing Folding and Stability via Kinetic Analysis Objective: To determine the thermodynamic stability and folding pathway of a STAT SH2 domain, which can inform on the functional consequences of disease-associated mutations [12].

- Protein Purification: Purify the recombinant SH2 domain to homogeneity, ensuring it is suitable for biophysical analysis.

- Equilibrium Denaturation: Use a chemical denaturant like urea or guanidinium hydrochloride. Prepare a series of samples with increasing denaturant concentration. Monitor the unfolding transition using a spectroscopic signal intrinsic to the protein (e.g., fluorescence emission of tryptophan residues) or circular dichroism (CD) at 222 nm to track secondary structure loss [12].

- Stopped-Flow Kinetics: For folding/unfolding kinetics, use a stopped-flow instrument to rapidly mix the native or denatured protein with refolding or unfolding buffer, respectively. Monitor the change in fluorescence or CD signal over time (from milliseconds to seconds) [12].

- Data Modeling: Plot the observed rate constants against denaturant concentration to generate a "chevron plot." Analyze the plot to determine if folding follows a simple two-state model or involves populated intermediates. Extract thermodynamic parameters like the free energy of unfolding (ΔG) and the kinetic rate constants [12].

Protocol 3: Structural Workflow for SH2 Domain-Ligand Complexes Objective: To obtain high-resolution atomic-level structures of STAT SH2 domains, often in complex with phosphopeptide ligands, to visualize the dimerization interface and guide drug discovery [5].

- Crystallization: Crystallize the purified STAT SH2 domain, typically in the presence of a high-affinity phosphopeptide mimicking the binding partner. Optimization of crystallization conditions is critical.

- X-ray Diffraction: Flash-cool the crystal in liquid nitrogen and collect X-ray diffraction data at a synchrotron facility.

- Structure Determination: Solve the phase problem by molecular replacement using a known SH2 domain structure as a search model. Build and refine the atomic model into the electron density map.

- Analysis: Analyze the refined structure to identify key residues in the pY and pY+3 pockets, hydrogen bonding networks, and the conformational changes induced by peptide binding. Compare with known Src-type SH2 structures to highlight STAT-specific features [5].

The workflow for structural and biophysical characterization is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Investigating STAT-type SH2 Domains

| Reagent / Tool | Function and Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Oriented Peptide Array Library (OPAL) | Defines the binding specificity and consensus motif of an SH2 domain [13]. | High-throughput; allows for screening of thousands of peptide sequences in parallel. |

| Phosphotyrosine Mimetic Peptides | Used in binding assays and crystallography to mimic the natural ligand and stabilize the SH2 domain structure [5]. | Often contain non-hydrolyzable pY mimetics like phosphonofluorophenylalanine (F2Pmp). |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Generates point mutations in the SH2 domain to probe the function of specific residues (e.g., in pY pocket) [12] [5]. | Critical for establishing structure-function relationships and validating disease mutations. |

| Recombinant SH2 Domain Proteins | Purified, often tagged (GST, His), proteins for in vitro binding, structural, and biophysical studies [13] [12]. | Essential for all downstream biochemical and structural analyses. |

| Denaturants (Urea, GdnHCl) | Used in equilibrium and kinetic folding experiments to unfold the SH2 domain and measure its stability [12]. | Allows for the determination of free energy of unfolding (ΔG) and identification of folding intermediates. |

Therapeutic Targeting and Research Perspectives

The STAT SH2 domain is a hotspot for mutations in diseases like cancer and immunodeficiencies, making it a prime target for therapeutic intervention [5]. Mutations can be either gain-of-function (GOF), leading to constitutive dimerization and oncogenic signaling (e.g., in T-cell leukemias), or loss-of-function (LOF), causing immunological deficiencies like AD-HIES [5]. The table below summarizes key disease-associated mutations.

Table 3: Exemplary Disease-Associated Mutations in the STAT3 SH2 Domain

| Mutation | Location/Region | Pathology | Functional Type | Molecular Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S614R | BC Loop / pY Pocket | T-LGLL, NK-LGLL, ALCL [5] | Somatic GOF | Enhances phosphopeptide binding affinity, promoting constitutive activation. |

| E616K | BC Loop / pY Pocket | NKTL [5] | Somatic GOF | Disrupts autoinhibitory interactions, facilitating dimerization. |

| R609G | βB5 / pY Pocket | AD-HIES [5] | Germline LOF | Impairs phosphate coordination, crippling phosphotyrosine binding and dimerization. |

| S611I/N/G | βB7 / pY Pocket | AD-HIES [5] | Germline LOF | Disrupts the conserved SH2 fold, reducing stability and ligand binding. |

Targeting the STAT SH2 domain with small-molecule inhibitors presents a formidable challenge. The pY pocket is highly polar and charged, making it difficult to develop drug-like molecules with sufficient affinity and cell permeability [2] [5]. Furthermore, STAT SH2 domains exhibit significant conformational flexibility, with the pY pocket's accessible volume varying dramatically, complicating structure-based drug design [5]. Current strategies are exploring allosteric pockets, such as the evolutionary active region (EAR) in the pY+3 pocket, and developing non-peptidic, non-phosphorylated inhibitors that can disrupt the protein-protein interaction interface [11] [5]. The continued structural and biophysical dissection of STAT-type SH2 domains, particularly in the context of disease mutations, remains essential for unlocking their full potential as therapeutic targets.

The Src Homology 2 (SH2) domain serves as a fundamental modular component in intracellular signaling, specifically mediating protein-protein interactions through recognition of phosphorylated tyrosine (pTyr) residues. This in-depth technical guide examines the atomic-level mechanism of pTyr recognition by the conserved SH2 domain pocket, with particular emphasis on its indispensable role in STAT protein dimerization and signal transduction. We synthesize structural biology data, quantitative binding affinity measurements, and recent advances in specificity profiling to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for understanding this critical biological mechanism. The content further explores experimental methodologies for investigating SH2 domain interactions and discusses emerging therapeutic strategies targeting these interfaces.

Intracellular communication in metazoans relies heavily on tyrosine phosphorylation, a post-translational modification that creates docking sites for signaling proteins. The SH2 domain, a conserved protein module of approximately 100 amino acids, serves as the primary "reader" of these phosphotyrosine signals [14]. First identified in the v-Fps/Fes oncoprotein, SH2 domains have since been found in over 100 human proteins, including kinases, phosphatases, adaptor proteins, and transcription factors such as STATs (Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription) [15]. These domains function as critical regulatory elements by directing the formation of transient protein complexes in response to tyrosine phosphorylation events. The specificity of SH2 domain-pTyr interactions ensures proper signal transmission from activated receptors to downstream pathways, including the canonical JAK-STAT signaling cascade [16]. In the context of STAT proteins, the SH2 domain performs a dual function: it mediates recruitment to phosphorylated receptor cytoplasmic tails and facilitates STAT dimerization through reciprocal SH2-pTyr interactions [17] [18]. This review comprehensively examines the structural mechanism of pTyr recognition by SH2 domains, with specific emphasis on its fundamental role in STAT biology and dimerization.

Structural Architecture of the SH2 Domain

Conserved SH2 Domain Fold

All SH2 domains adopt a conserved structural fold despite sequence variation, consisting of a central antiparallel β-sheet flanked by two α-helices [15]. The core structure comprises three or four β-strands forming the central sheet, surrounded by two α-helices (αA and αB) positioned on either side [16]. This conserved architecture creates a binding interface specifically designed for phosphopeptide recognition. The N-terminal region of the SH2 domain (from αA to βD) forms a highly conserved phosphotyrosine-binding pocket, while the C-terminal half (from βD to βG) exhibits greater structural variability that confers sequence specificity [14]. The most conserved residues cluster primarily on the βB strand, which contains the critical arginine residue responsible for coordinating the phosphate moiety of pTyr [14].

The Phosphotyrosine Binding Pocket

The pTyr binding pocket is a positively charged cleft on the SH2 domain surface that recognizes the phosphate group of phosphorylated tyrosine. A strictly conserved arginine residue (located within the highly conserved FLVR sequence motif on the βB strand) serves as the anchor point, forming bidentate hydrogen bonds with the phosphate moiety [15] [14]. This arginine-phosphate interaction provides approximately half of the total binding free energy for SH2 domain-phosphopeptide interactions [14]. The pocket is further defined by other positively charged and polar residues that stabilize the phosphate group through additional hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions. The depth and charge complementarity of this pocket explain the strong preference for phosphotyrosine over unmodified tyrosine or phosphoserine/threonine, ensuring specificity in signaling fidelity.

Table 1: Key Structural Elements of the SH2 Domain Fold

| Structural Element | Position in Fold | Functional Role | Conservation Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central β-sheet | Core domain | Provides structural scaffold | High |

| αA helix | N-terminal region | Flanks binding pocket | Medium-High |

| αB helix | C-terminal region | Contributes to specificity | Medium |

| βB strand | N-terminal half | Contains conserved Arg for pTyr binding | Very High |

| EF loop | Connects βE-βF | Determines specificity pocket access | Low (Variable) |

| BG loop | Connects βG-αB | Determines specificity pocket access | Low (Variable) |

Molecular Mechanism of pTyr Recognition

Canonical Binding Mode

In the canonical binding mode, phosphotyrosine-containing peptides bind to SH2 domains in an extended conformation, positioning perpendicular to the central β-strands of the domain [14]. The interaction involves two distinct binding pockets: (1) the conserved pTyr pocket that engages the phosphate group, and (2) a specificity pocket that recognizes residues C-terminal to the pTyr [16]. The pTyr residue inserts into the deep, basic pocket where the conserved arginine forms crucial hydrogen bonds with the phosphate group. The peptide backbone then extends across the SH2 domain surface, allowing the C-terminal flanking residues (typically positions +1 to +6 relative to pTyr) to interact with the specificity-determining region of the domain [16]. This two-pocket mechanism enables SH2 domains to achieve both high affinity (through phosphate coordination) and specificity (through interactions with flanking residues).

Specificity Determinants

SH2 domain specificity is primarily determined by interactions with amino acids at positions C-terminal to the phosphotyrosine residue. Structural studies reveal that the hydrophobic pocket located in the C-terminal half of the SH2 domain engages these flanking residues [14]. The EF and BG loops, which connect secondary structure elements, play a particularly important role in controlling access to this specificity pocket and thus dictate peptide selectivity [19] [14]. Different SH2 domains recognize distinct sequence motifs based on their unique complementarity-determining regions. For example, Src family kinases preferentially bind to pYEEI motifs, while the SH2 domains of PI3K or PLC-γ favor pYφXφ motifs (where φ represents a hydrophobic residue) [16]. This specificity allows different SH2 domain-containing proteins to engage distinct subsets of the phosphoproteome, enabling precise signaling pathway activation.

Table 2: SH2 Domain Specificity Profiles and Representative Binding Motifs

| SH2 Domain | Preferred Recognition Motif | Representative Binding Proteins | Affinity Range (K_D) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Src Family | pYEEI | Src, Fyn, Lck | 0.1-0.5 μM |

| Grb2 | pYXNX | Growth factor receptors | 0.2-5 μM |

| PI3K | pYφXM | PDGFR, IRS-1 | 0.5-5 μM |

| STAT1 | pYXPQ | IFN-γ receptor | 0.1-1 μM |

| ZAP70 | pYφXφ | T-cell receptor ζ-chain | 0.2-2 μM |

| PLC-γ | pYφXφ | PDGFR, FGFR | 0.3-3 μM |

SH2 Domains in STAT Dimerization and Activation

Dual Roles in STAT Signaling

STAT proteins exemplify the critical functional importance of SH2 domains in transcription factor regulation. The STAT SH2 domain performs two essential functions in JAK-STAT signaling: first, it mediates recruitment to phosphorylated cytokine receptors; second, it facilitates STAT dimerization through reciprocal SH2-pTyr interactions [17] [18]. In the canonical pathway, cytokine binding induces receptor dimerization and activation of associated JAK kinases, which phosphorylate tyrosine residues on the receptor cytoplasmic tails. STAT proteins are then recruited to these phosphotyrosine motifs via their SH2 domains [18]. Once bound, JAKs phosphorylate a conserved tyrosine residue in the STAT C-terminus, inducing a conformational change that enables STAT dimerization.

STAT Dimerization Mechanism

STAT dimerization occurs through reciprocal SH2-phosphotyrosine interactions between two STAT monomers [17]. Specifically, the SH2 domain of one STAT molecule binds to the phosphorylated tyrosine residue (pTyr) of its dimerization partner. This interaction forms stable STAT homo- or heterodimers that translocate to the nucleus and bind target DNA sequences [18]. Research on Stat1 and Stat2 has demonstrated that their SH2 domains mediate both homo- and heterodimerization, with evidence suggesting that a single SH2-phosphotyrosyl interaction is sufficient for dimer formation [17]. The crystal structures of STAT SH2 domains in complex with phosphopeptides reveal similar binding modes to other SH2 domains, with the conserved arginine coordinating the phosphate moiety and specificity pockets engaging residues C-terminal to the pTyr. This dimerization mechanism is conserved across STAT family members and is essential for their transcriptional activity.

Figure 1: STAT Activation Pathway via SH2-Mediated Dimerization. This diagram illustrates the sequential process from cytokine binding to STAT-mediated gene transcription, highlighting the critical SH2-pTyr interaction step.

Quantitative Analysis of SH2-pTyr Interactions

Binding Affinity and Kinetics

SH2 domain interactions with phosphotyrosine motifs are characterized by moderate affinity and specific kinetic parameters that enable dynamic signaling responses. Typical dissociation constants (K_D) for SH2 domain-phosphopeptide interactions range from 0.1 to 10 μM, with most physiological interactions falling between 0.2-5 μM [16] [14]. This moderate affinity is crucial for allowing transient association and dissociation events necessary for reversible signal transduction. Artificially increasing affinity through engineered "superbinder" SH2 domains has been shown to cause detrimental consequences to cells, demonstrating the physiological importance of this affinity range [14]. Kinetic studies reveal that SH2 domain interactions exhibit rapid association and dissociation rates, enabling responsive signaling systems. Comparative analysis with phosphotyrosine-binding (PTB) domains shows that PTB domain-mediated interactions can display similar overall affinity but slower exchange kinetics than SH2 domains, suggesting that PTB domains may not rapidly exchange among associated proteins [20].

Lipid Binding and Membrane Localization

Recent research has revealed an additional layer of complexity in SH2 domain function: approximately 90% of human SH2 domains can bind plasma membrane lipids independently of their phosphotyrosine recognition capability [21]. These lipid interactions occur through surface cationic patches separate from the pTyr-binding pocket, allowing simultaneous binding to both membranes and pTyr motifs [21]. The lipid-binding sites adopt two distinct configurations: grooves for specific phosphoinositide headgroup recognition or flat surfaces for non-specific membrane binding. Cellular studies with ZAP70 demonstrated that multiple lipids bind its C-terminal SH2 domain in a spatiotemporally specific manner, exerting exquisite control over its protein binding and signaling activities in T cells [21]. This dual-binding capability suggests that membrane localization may work in concert with pTyr recognition to enhance specificity and efficiency in signal transduction.

Experimental Methods for Profiling SH2-pTyr Interactions

High-Throughput Specificity Profiling

Advancements in peptide display technologies have enabled comprehensive profiling of SH2 domain specificity landscapes. A recently developed platform combines bacterial surface display of genetically encoded peptide libraries with deep sequencing to quantitatively analyze SH2 domain binding specificities [22]. This method involves displaying peptide libraries on the surface of E. coli cells as fusions to an engineered bacterial surface-display protein (eCPX). The libraries can include fully random sequences (X5-Y-X5 libraries) or defined sequences derived from human proteome phosphorylation sites (pTyr-Var libraries) [22]. SH2 domains of interest are used as baits to isolate binding peptides through magnetic bead-based separation, followed by deep sequencing of bound peptides to determine enrichment patterns. This approach allows for simultaneous processing of multiple samples and can profile specificity against libraries containing millions of peptide sequences, providing unprecedented resolution of SH2 domain recognition rules.

Figure 2: High-Throughput SH2 Specificity Profiling Workflow. This experimental pipeline illustrates the process from library generation to specificity analysis using bacterial peptide display and deep sequencing.

Structural and Biophysical Approaches

X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy have been instrumental in elucidating the atomic-level details of SH2 domain-pTyr interactions. Crystallographic analyses of SH2 domain-phosphopeptide complexes have revealed the conserved binding mode and specific variations that account for differential specificity across the SH2 domain family [14]. NMR techniques provide complementary information about binding kinetics and dynamics under physiological conditions. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) offer quantitative measurements of binding affinity and thermodynamics, enabling researchers to determine the energetic contributions of specific residues to the interaction [20]. These biophysical approaches are particularly valuable for characterizing the effects of disease-associated mutations and for evaluating potential therapeutic compounds that target SH2 domain interfaces.

Table 3: Experimental Methods for Studying SH2-pTyr Interactions

| Method | Key Output Parameters | Throughput | Information Gained |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Peptide Display | Specificity profiles, enrichment scores | High | Comprehensive recognition motifs |

| X-ray Crystallography | Atomic coordinates, binding interfaces | Low | Detailed molecular interactions |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Chemical shifts, dynamics, weak affinities | Medium | Solution-state structure and dynamics |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance | KD, kon, k_off | Medium | Binding kinetics and affinity |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry | K_D, ΔG, ΔH, ΔS | Low | Thermodynamic parameters |

| Oriented Peptide Libraries | Positional scanning data | Medium | Amino acid preferences at each position |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for SH2 Domain Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function/Application | Key Features | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| SH2 Domain Superbinders | High-affinity pTyr capture | Mutated pTyr pocket for enhanced affinity | Proteomic studies, detection assays |

| Phosphopeptide Libraries | Specificity profiling | X5-Y-X5 or proteome-derived sequences | High-throughput specificity screens |

| Bacterial Display Systems | Peptide library screening | eCPX-based display platform | SH2 ligand identification |

| Recombinant SH2 Domains | Biophysical characterization | Tagged purification (GST, His) | Structural studies, in vitro binding |

| JAK-STAT Reporter Cells | Functional signaling assays | STAT-responsive luciferase reporters | Pathway activation studies |

| Phosphospecific Antibodies | Detection of STAT phosphorylation | pY701-STAT1, pY705-STAT3 specific | Western blot, immunofluorescence |

The phosphotyrosine pocket of SH2 domains represents a remarkable example of evolutionary optimization for specific molecular recognition. The conserved structural framework coupled with variable specificity determinants enables these domains to mediate precise interactions in complex signaling networks. In STAT proteins, the SH2 domain plays an especially critical role in both receptor recruitment and dimerization, making it a central player in JAK-STAT signal transduction. Recent advances in understanding lipid binding by SH2 domains and high-throughput specificity profiling have expanded our appreciation of the regulatory complexity of these interactions. The experimental methodologies outlined here provide powerful approaches for investigating SH2 domain function and characterizing potential therapeutic interventions. As structural information grows and profiling technologies continue to advance, our understanding of the subtleties of SH2 domain specificity will further improve, facilitating the development of targeted therapies for diseases involving aberrant tyrosine kinase signaling, including cancer, immunodeficiencies, and inflammatory disorders.

The Specificity (pY+3) Pocket and Evolutionary Active Region (EAR)

The Src Homology 2 (SH2) domain is a critical modular unit found in numerous signaling proteins, including the Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STAT) family. Its primary function is to recognize and bind phosphorylated tyrosine (pY) residues, thereby facilitating specific protein-protein interactions essential for cellular signaling [8]. Within the STAT protein structure, the SH2 domain serves a dual purpose: it mediates recruitment to activated cytokine receptors and is indispensable for the dimerization of STAT monomers through reciprocal phosphotyrosine-SH2 domain interactions [23]. This dimerization is a fundamental step in the canonical STAT activation pathway, enabling nuclear translocation and regulation of target genes.

This whitepaper focuses on two specialized structural regions within the STAT-SH2 domain: the specificity pocket (pY+3) and the Evolutionary Active Region (EAR). These regions are crucial for determining binding selectivity and facilitating the structural adaptations necessary for STAT dimerization. Understanding their precise mechanisms provides a foundation for targeted therapeutic interventions aimed at modulating pathological STAT signaling in cancer and inflammatory diseases [23].

Structural Anatomy of the STAT-SH2 Domain

The STAT-SH2 domain shares a conserved fold but possesses distinct features that differentiate it from other SH2 domains, such as those in the Src kinase family.

Core SH2 Domain Architecture

The fundamental structure of an SH2 domain consists of a central anti-parallel β-sheet (comprising strands βB, βC, and βD) flanked by two α-helices (αA and αB), forming an αβββα motif [23]. This core structure creates two primary ligand-binding pockets:

- The pY pocket: A deep pocket that binds the phosphate moiety of the phosphorylated tyrosine residue. It contains a highly conserved arginine residue (from the FLVR motif) that forms a salt bridge with the phosphotyrosine [8] [23].

- The pY+3 pocket: Located adjacent to the pY pocket, it accommodates the amino acid residue at the +3 position relative to the phosphotyrosine in the peptide ligand. This pocket is the primary determinant of binding specificity [23].

Unique Characteristics of the STAT-Type SH2 Domain

STAT-type SH2 domains are characterized by specific structural deviations from the Src-type [8] [24]:

- They lack the C-terminal βE and βF strands typically found in Src-type SH2 domains.

- The αB helix is split into two helices, designated as αB and αB'.

- The region encompassing the αB' helix and the adjacent BC* loop (connecting the αB and αC helices) constitutes the Evolutionary Active Region (EAR) [23]. This area is a hotspot for structural variation and disease-associated mutations.

Table 1: Key Structural Regions of the STAT-SH2 Domain

| Structural Region | Key Components | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| pY Pocket | αA helix, BC loop, βB strand, conserved Arg | High-affinity binding to phosphotyrosine |

| pY+3 Pocket | Opposite face of central β-sheet, αB helix, CD loop | Determines ligand-binding specificity |

| Evolutionary Active Region (EAR) | αB' helix, BC* loop | Facilitates STAT dimerization and cross-domain interactions |

The pY+3 Pocket: Determining Specificity

The pY+3 pocket is a specificity-determining cavity within the SH2 domain that engages residues C-terminal to the phosphotyrosine. Its chemical and physical properties dictate which peptide sequences the SH2 domain can recognize with high affinity.

Mechanism of Specificity Determination

The binding of a phosphopeptide to an SH2 domain occurs perpendicular to the central β-sheet. While the pY residue anchors the interaction, the amino acids at the +1, +2, and especially the +3 position relative to the pY extend into the pY+3 pocket. The physicochemical environment of this pocket—dictated by the side chains of the surrounding SH2 domain residues—selectively favors certain amino acids over others, enabling the discrimination between different STAT proteins and other SH2-containing signaling molecules [23]. This ensures the fidelity of downstream signaling cascades.

Role in STAT Dimerization

In the context of STAT activation, the pY+3 pocket is critical for reciprocal SH2-phosphotyrosine interaction that forms active STAT dimers. One STAT monomer presents its phosphorylated tyrosine, while the other monomer's SH2 domain binds to it, with the pY+3 pocket playing a key role in stabilizing this interaction. This dimerization is a prerequisite for the nuclear accumulation of STATs and their function as transcription factors [23].

The Evolutionary Active Region (EAR): A Hub for Regulation and Mutation

The Evolutionary Active Region is a defining feature of STAT-type SH2 domains and represents a critical functional and evolutionary module.

Structural Composition of the EAR

The EAR is located at the C-terminal end of the pY+3 pocket and includes two key elements:

- The αB' Helix: An additional α-helix not found in Src-type SH2 domains.

- The BC* Loop: The loop connecting the αB and αC helices [23].

This region participates in cross-domain interactions that stabilize the dimeric structure of activated, phosphorylated STATs. Its evolutionary conservation underscores its fundamental role in STAT protein function.

The EAR as a Mutational Hotspot

Sequencing of patient samples has identified the SH2 domain, and the EAR in particular, as a hotspot for disease-associated mutations [23]. These mutations can have either gain-of-function (GOF) or loss-of-function (LOF) consequences, disrupting the delicate balance of cellular signaling.

Table 2: Selected Disease-Associated Mutations in the STAT3/STAT5 SH2 Domain

| STAT Protein | Mutation | Location | Functional Impact | Associated Disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAT3 | Various point mutations | SH2 domain (incl. EAR) | Loss-of-Function (LOF) | Autosomal-Dominant Hyper IgE Syndrome (AD-HIES) [23] |

| STAT3 | Various point mutations | SH2 domain (incl. EAR) | Gain-of-Function (GOF) | Autoimmune disorders, lymphoproliferative disease [23] |

| STAT5B | Various point mutations | SH2 domain (incl. EAR) | Loss-of-Function (LOF) | Growth hormone insensitivity syndrome (GHIS) [23] |

The genetic volatility of the EAR highlights its evolutionary active nature. Even single amino acid changes can alter dimerization stability, DNA-binding affinity, and transcriptional output, making it a compelling target for drug discovery.

Experimental Analysis of the pY+3 Pocket and EAR

Investigating the structure and function of these regions requires a combination of biophysical, computational, and cell-based assays.

Structural Methodologies

X-ray Crystallography and NMR Spectroscopy: These high-resolution techniques are fundamental for determining the three-dimensional structures of STAT-SH2 domains, both alone and in complex with phosphopeptide ligands. They allow for the precise mapping of the pY+3 pocket and visualization of the EAR's role in dimer interface formation [23].

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) and Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): These methods are used to quantitatively measure the binding affinity (Kd) and thermodynamics of interactions between SH2 domains and their target phosphopeptides. They are essential for characterizing how mutations in the pY+3 pocket or EAR affect ligand binding [8] [23].

Functional and Cellular Assays

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA): This assay assesses the DNA-binding capability of STAT dimers. Mutations that impair dimerization via the SH2 domain will result in reduced DNA binding activity [4].

Luciferase Reporter Assays: To functionally validate the impact of SH2 domain mutations, a luciferase gene under the control of a STAT-responsive promoter is transfected into cells. Changes in luciferase activity upon cytokine stimulation directly report on the transcriptional activity of the STAT pathway [23].

CoDIAC Analysis: A comprehensive computational approach for domain interface analysis. As detailed in a 2025 study, CoDIAC is a structure-based interface analysis tool that can map domain interfaces from experimental and predicted structures. It can identify conserved post-translational modifications (PTMs) relative to interaction interfaces, enabling researchers to infer the specific effects of mutations or PTMs on SH2 domain function and regulation [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Progress in STAT-SH2 domain research relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for STAT-SH2 Domain Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant STAT-SH2 Proteins | In vitro binding assays, structural studies, inhibitor screening. | Wild-type and mutant variants; full-length or truncated domains. |

| Phosphopeptide Ligands | Mapping binding specificity, competition assays, SPR/ITC experiments. | Sequences derived from native STATs or receptors; pY at defined position. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Introducing disease-associated or rational mutations into the pY+3 pocket or EAR. | Essential for establishing structure-function relationships. |

| STAT-Luciferase Reporter Constructs | Cellular functional assays to measure pathway activity. | Reporter gene under control of STAT-responsive promoter. |

| CoDIAC Python Package | Computational analysis of SH2 domain interfaces, interactions, and regulation. | Reveals coordinated regulation by PTMs; infers effects of mutations [25]. |

Therapeutic Targeting and Future Directions

The critical role of the STAT-SH2 domain in dimerization makes it a high-priority target for therapeutic intervention, particularly in cancers driven by constitutive STAT signaling.

Drug discovery efforts have focused on developing small-molecule inhibitors that disrupt the protein-protein interactions mediated by the SH2 domain. The pY+3 pocket and the adjacent EAR are attractive targets due to their role in determining specificity and dimerization. However, the flexibility of the STAT SH2 domain and the relatively shallow nature of its binding surfaces have posed significant challenges [23]. Emerging strategies include:

- Targeting allosteric sites that indirectly affect the pY+3 pocket.

- Developing stapled peptides that mimic the native phosphopeptide and competitively inhibit dimerization.

- Exploiting insights from the CoDIAC framework to understand how post-translational modifications like acetylation or serine phosphorylation might regulate SH2 domain function and offer new avenues for intervention [25].

The specificity (pY+3) pocket and the Evolutionary Active Region (EAR) are integral components of the STAT-SH2 domain, jointly governing phosphopeptide recognition selectivity and STAT dimerization stability. Their distinct structural features within the STAT family and their propensity for disease-driving mutations underscore their biological and clinical significance. Continued research using integrated structural, biophysical, and computational methods will be essential to fully elucidate their mechanisms and to translate this knowledge into novel therapeutics for STAT-driven diseases.

The Src Homology 2 (SH2) domain is a approximately 100-amino-acid protein module that serves as a crucial recognition domain in tyrosine kinase signaling pathways by specifically binding to phosphorylated tyrosine (pY) residues [26] [2]. These domains are fundamental components of eukaryotic cellular communication, enabling the assembly of multiprotein signaling complexes in response to tyrosine phosphorylation events [2] [8]. While the canonical function of SH2 domains involves phosphotyrosine recognition, emerging research highlights the critical importance of SH2 domain flexibility and structural dynamics in regulating their biological functions [27] [28] [29]. This review explores the structural plasticity of SH2 domains, with particular emphasis on the STAT-SH2 domain, examining how conformational dynamics influence dimerization mechanisms and create novel opportunities for therapeutic intervention in disease states, particularly cancer and immune disorders.

Structural Fundamentals of SH2 Domains

Conserved Architecture with Adaptive Features

SH2 domains maintain a highly conserved structural fold despite sequence diversity across family members [8]. The core structure consists of a central anti-parallel β-sheet flanked by two α-helices, forming a compact globular domain [2] [8]. This scaffold creates two functionally critical binding pockets: a highly conserved phosphotyrosine (pY) binding pocket that engages the phosphorylated tyrosine residue, and a specificity-determining pocket that recognizes residues C-terminal to the phosphotyrosine, typically at the pY+3 position [2] [8].

The N-terminal region of SH2 domains is particularly conserved, featuring a deep pocket within the βB strand that contains an invariant arginine residue (at position βB5) responsible for coordinating the phosphate moiety of phosphotyrosine [8]. In contrast, the C-terminal region displays greater variability, contributing to ligand specificity diversity among different SH2 domains [8]. Structural variations in loop regions between secondary elements, particularly the EF loop and BG loop, further modulate binding specificity by controlling access to ligand-binding pockets [8].

Table 1: Key Structural Elements of SH2 Domains and Their Functional Roles

| Structural Element | Location | Primary Function | Conservation |

|---|---|---|---|

| βB strand & FLVR motif | pY binding pocket | Phosphate group coordination via invariant arginine | High across family |

| Specificity pocket | Adjacent to pY site | Recognition of C-terminal residues (e.g., pY+3) | Variable |

| EF & BG loops | Surface accessibility | Control ligand access to binding pockets | Moderate to variable |

| CD loop | Distal surface | Allosteric regulation, interdomain communication | Variable |

| Central β-sheet | Structural core | Domain stability, conformational transmission | High |

STAT-SH2 Domain Distinctiveness

STAT (Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription) proteins feature a distinct subclass of SH2 domains classified as the "STAT-type," which differs structurally from the "Src-type" SH2 domains [8]. STAT-SH2 domains lack the βE and βF strands present in Src-type domains and feature a split αB helix [8]. This structural adaptation appears specialized to facilitate the reciprocal phosphotyrosine-SH2 domain interactions that underlie STAT dimerization and nuclear translocation following activation [4] [30].

The STAT-SH2 domain is essential for the canonical activation mechanism of STAT proteins [4]. Upon tyrosine phosphorylation by Janus kinases (JAKs) or receptor tyrosine kinases, STAT proteins form parallel dimers through reciprocal phosphotyrosine-SH2 domain interactions between two monomers [4] [30]. These dimers then translocate to the nucleus and bind specific DNA elements to regulate target gene expression [4]. Recent evidence indicates that unphosphorylated STAT (U-STAT) proteins can also form dimers and regulate gene expression through distinct mechanisms, expanding the functional repertoire of STAT-SH2 domains beyond canonical signaling [4].

Flexibility and Dynamics of SH2 Domains

Allosteric Communication Networks

SH2 domains function not as static binding modules but as dynamic structures with internal allosteric communication networks. Research on the Fyn SH2 domain demonstrates that information transfer occurs between the phosphopeptide binding site and distal regions of the domain via a contiguous pathway of residues that crosses the protein core [27]. This communication channel enables binding events at one site to trigger conformational changes at distal locations, facilitating coordination with other protein domains.

Molecular dynamics simulations and mutual information analysis of the Fyn SH2 domain have quantified these allosteric networks, revealing that the SH2 domain forms a "noisy communication channel" that couples residues in the phosphopeptide binding site with residues near the linkers connecting the SH2 domain to SH3 and kinase domains [27]. This connectivity allows ligand binding to influence domain orientation and interdomain relationships, effectively transmitting biological information across the protein structure.

Figure 1: Allosteric Communication in SH2 Domains. Ligand binding triggers information flow through internal networks to distal functional sites.

Loop Dynamics and Functional Regulation

Surface loops connecting secondary structural elements serve as critical mediators of SH2 domain flexibility and function. The CD loop, in particular, exemplifies how structural dynamics can influence signaling outcomes. Comparative studies between Csk and Src SH2 domains reveal that natural variations in CD loop length and flexibility significantly impact protein dynamics and catalytic efficiency, despite preservation of the global domain fold [28].

In Csk, engineering a more flexible CD loop through insertion of two glycine residues (to mimic the longer loop found in Src) resulted in reduced catalytic activity without affecting global domain folding or phosphopeptide binding capability [28]. This demonstrates that subtle modifications to flexible loop regions can alter allosteric communication pathways and functional output. Molecular dynamics simulations identified specific signal transduction routes from the distal CD loop to the active site, underscoring how surface loops can serve as tunable modulators of SH2 domain function [28].

STAT-SH2 Domain in STAT Dimerization

Molecular Determinants of STAT Dimerization

The STAT-SH2 domain mediates dimerization through a sophisticated interface involving multiple interaction types. Molecular dynamics simulations of STAT5A have revealed three distinct interfaces in the active dimer [30]:

- Reciprocal intermolecular PTM-SH2 domain interactions: The classical phosphotyrosine-SH2 domain interaction present in all activated STAT dimers

- Intermolecular PTM-PTM interactions: Interactions between C-terminal tail segments of opposing monomers

- Intramolecular PTM-SH2 domain interactions: Interactions within individual monomers that stabilize the dimer configuration

The phosphorylated tyrosine (pY694 in STAT5A) forms salt bridges with the invariant arginine (R618) in the βB strand of the opposing monomer's SH2 domain [30]. This primary interaction is supplemented by additional contacts involving residues K600, S620, S622, and T628, which form transient hydrogen bonds with the phosphotyrosine [30]. STAT5-specific hydrophobic interactions further stabilize this interface, with residues N642 and K644 engaging the aromatic ring of phosphotyrosine, and V695 (pY+1) packing into a hydrophobic pocket containing W631, W641, and L643 [30].

Novel Intramolecular Interface in STAT5

A distinctive feature of STAT5 dimerization is the presence of a novel intramolecular interaction mediated by F706, located adjacent to the phosphotyrosine motif, and a unique hydrophobic interface on the SH2 domain surface [30]. This interaction is dispensable for receptor-mediated phosphorylation of STAT5 but essential for dimer formation and subsequent nuclear accumulation [30]. Mutational analysis confirms that disruption of this hydrophobic interface abolishes STAT5 dimerization without affecting phosphorylation, highlighting its specific role in stabilizing the dimeric state.

This intramolecular interface differs significantly from corresponding regions in STAT1 and STAT3, which utilize flexible loop structures to stabilize dimerization [30]. The absence of conservation in these structural elements between STAT family members suggests distinct evolutionary solutions to the challenge of stable dimer formation, with implications for selective therapeutic targeting.

Table 2: Key Interactions in STAT-SH2 Domain Dimerization

| Interaction Type | Key Residues | Functional Role | Conservation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphotyrosine coordination | pY694, R618, K600, S620, S622, T628 | Primary dimer interface formation | High across STATs |

| Hydrophobic packing | V695, W631, W641, L643 | Stabilization of pY positioning | Moderate |

| STAT5-specific hydrophobic | N642, K644 | Enhanced pY binding stability | STAT5-specific |

| Intramolecular interface | F706, hydrophobic surface | Dimer stabilization post-phosphorylation | STAT5-specific |

| PTM-PTM interface | Q698, I699, K700, Q701, E705 | Intermonomer contacts in C-terminal tails | Variable |

Methodological Approaches for Studying SH2 Dynamics

Computational and Theoretical Frameworks

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have proven invaluable for characterizing SH2 domain flexibility and allosteric communication. MD simulations of STAT5A, spanning 2000 nanoseconds, have enabled detailed analysis of dimer interface stability and identification of key interacting residues [30]. Similarly, enhanced sampling MD combined with small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) has successfully mapped allosteric interfaces between SH2 and kinase domains in Btk [29].

Information theory approaches provide complementary insights into SH2 domain dynamics. By applying mutual information analysis to SH2 domains, researchers can quantify conformational correlations between residues and map information exchange pathways across the protein structure [27]. This method treats the SH2 domain as a communication channel, quantifying how binding-induced conformational changes propagate through the structure to distal functional sites.

Experimental Techniques for Dynamics Analysis

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy offers powerful approaches for characterizing SH2 domain dynamics at atomic resolution. Backbone dynamics studies using 15N relaxation experiments can probe changes in molecular motions upon ligand binding [31]. NMR-based hydrogen-deuterium exchange (HDx) experiments provide site-specific information on protein stability and dynamics by monitoring the exchange rates of backbone amide protons [28].

Biophysical and biochemical approaches further illuminate SH2 domain function. Fluorescence polarization assays quantitatively measure phosphopeptide binding affinities [29], while circular dichroism spectroscopy and thermal shift assays assess domain folding and stability [29]. Enzyme kinetic assays complement these approaches by quantifying the functional consequences of structural perturbations on catalytic activity [28] [29].

Table 3: Experimental Methods for Analyzing SH2 Domain Flexibility and Function

| Method | Application | Key Information | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Simulations | Conformational sampling, allosteric pathways | Residue correlations, dynamic interfaces | [27] [30] [29] |

| Mutual Information Analysis | Information transfer mapping | Communication pathways, allosteric networks | [27] |

| NMR Relaxation | Backbone dynamics | Ps-ns timescale motions, binding effects | [31] |

| Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange | Stability and dynamics | Structural flexibility, stabilization effects | [28] |

| Fluorescence Polarization | Binding affinity | Ligand binding constants, specificity | [29] |

| Circular Dichroism | Secondary structure | Folding state, stability | [29] |

| Enzyme Kinetics | Functional output | Catalytic efficiency, allosteric effects | [28] [29] |

Therapeutic Targeting of SH2 Domains

Allosteric Targeting Strategies

The critical role of SH2 domains in signaling pathways and their involvement in disease states makes them attractive therapeutic targets. Traditional approaches focused on developing phosphotyrosine mimetics to compete with native ligands for the pY binding pocket, but these faced challenges due to poor pharmacological properties [2] [8]. Emerging strategies now target allosteric sites and dynamic interfaces, offering potentially more selective interventions.

Research on Btk exemplifies the therapeutic potential of allosteric SH2 domain targeting. A engineered repebody protein that binds the Btk SH2 domain and disrupts its interface with the kinase domain effectively prevents Btk activation in cells, inhibiting signaling and proliferation in malignant B-cells [29]. This approach remains effective against Btk with the C481S mutation that confers resistance to covalent ATP-competitive inhibitors, highlighting the value of allosteric targeting for overcoming drug resistance [29].

Targeting STAT-SH2 Dimerization Interfaces

The STAT-SH2 dimerization interface represents a promising target for therapeutic intervention in cancers and immune disorders driven by constitutive STAT signaling. The identification of a novel intramolecular interface in STAT5, mediated by F706 and a unique hydrophobic surface on the SH2 domain, provides a potential target for disrupting STAT5 dimerization [30]. This interface is particularly significant as it is dispensable for phosphorylation but essential for dimer formation, offering opportunity for selective inhibition without affecting upstream signaling events.

Several leukemic STAT5 mutants map to the SH2 domain and C-terminal tail segment, including T628S, N642H, Y665F, I699L, and Q701L [30]. These mutations promote constitutive STAT5 activation through various mechanisms, often by enhancing dimer stability or facilitating phosphorylation-independent activation. Understanding how these mutations alter SH2 domain dynamics and dimer interface stability provides insights for developing targeted inhibitors that specifically counteract pathogenic signaling.

Figure 2: SH2 Domain Therapeutic Targeting Approaches. Multiple strategies exploit different aspects of SH2 domain structure and function.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for SH2 Domain Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Application | Key Function in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant SH2 Domains | Wild-type and mutant SH2 domains (Btk, Fyn, STAT5) | Biophysical and biochemical studies | Folding, stability, and binding assays |

| Phosphopeptide Libraries | Combinatorial pY peptide libraries | Specificity profiling | Mapping SH2 domain binding preferences |

| NMR Isotope Labeling | 15N, 13C-labeled SH2 domains | NMR dynamics studies | Backbone and sidechain dynamics analysis |

| MD Simulation Software | GROMACS, AMBER, CHARMM | Molecular dynamics | Conformational sampling, allosteric pathways |

| Binding Assay Systems | Fluorescence polarization, SPR, ITC | Affinity and kinetics | Quantitative binding measurements |

| Engineered Protein Binders | Repebodies, monobodies, nanobodies | Allosteric inhibition | Targeting specific conformational states |

| Disease-Associated Mutants | XLA (Btk), leukemic (STAT5) mutants | Pathophysiological mechanisms | Linking dynamics to disease phenotypes |

SH2 domains exemplify how protein flexibility and dynamics enable sophisticated regulation of cellular signaling pathways. The STAT-SH2 domain in particular demonstrates how specialized structural adaptations facilitate controlled dimerization through a complex interface involving reciprocal phosphotyrosine recognition, hydrophobic packing, and unique intramolecular interactions. The dynamic nature of SH2 domains, mediated through flexible loops and internal allosteric networks, allows integration of multiple regulatory inputs and coordination with neighboring domains.

Understanding SH2 domain dynamics opens new avenues for therapeutic intervention, particularly through allosteric targeting and interface disruption strategies. As research methodologies continue to advance, particularly in molecular simulations and dynamics measurements, our ability to correlate SH2 domain flexibility with biological function will further improve. This knowledge will accelerate the development of novel therapeutics that selectively modulate SH2 domain interactions in disease states, offering promising approaches for targeting challenging pathologies driven by aberrant tyrosine kinase signaling.

Research Tools and Techniques: Probing SH2 Domain Dimerization Mechanisms

The Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STAT) family of proteins represents a critical signaling node in cellular communication, directly influencing gene expression in response to cytokine and growth factor stimulation. Among the most critical steps in STAT protein activation is dimerization, which is essential for nuclear translocation and DNA binding. This process is mediated by the Src Homology 2 (SH2) domain, which recognizes and binds to phosphorylated tyrosine residues on a reciprocal STAT monomer. The structural basis for this interaction was revealed in the crystal structure of a tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT-1 dimer bound to DNA, which demonstrates how the dimer forms a C-shaped clamp around DNA, stabilized by specific interactions between the SH2 domain of one monomer and the phosphotyrosine-containing C-terminal segment of the other [32].

Understanding STAT dimerization is not merely of academic interest but has direct clinical implications. Dysregulation of JAK/STAT signaling is associated with various cancers and autoimmune diseases, making the protein-protein interactions mediated by the SH2 domain a promising therapeutic target [33]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of three principal methodologies used to characterize STAT dimerization: fluorescence co-localization, Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET), and Analytical Ultracentrifugation (AUC). By framing these techniques within the context of STAT-SH2 domain research, this review serves as an essential resource for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to quantify and interrogate these critical interactions.

The STAT-SH2 Domain: Structure and Function

The SH2 domain is a modular protein interaction domain that arose within metazoan signaling pathways approximately 600 million years ago. In STAT proteins, it plays two non-redundant critical roles: it mediates the initial recruitment of STATs to activated cytokine receptors and facilitates the subsequent reciprocal dimerization of phosphorylated STAT proteins [5].

Structurally, STAT-type SH2 domains possess a central anti-parallel β-sheet (βB-βD strands) flanked by two α-helices (αA and αB), forming a characteristic αβββα motif. This structure creates two key binding pockets [5]:

- The pY (phosphate-binding) pocket: Formed by the αA helix, BC loop, and one face of the central β-sheet, this pocket engages the phosphotyrosine residue.

- The pY+3 (specificity) pocket: Created by the opposite face of the β-sheet, the αB helix, and adjacent loops, this pocket accommodates residues C-terminal to the phosphotyrosine, conferring binding specificity.

A unique feature of STAT-type SH2 domains is the presence of an additional α-helix (αB') in the C-terminal region of the pY+3 pocket, known as the evolutionary active region (EAR), which distinguishes them from Src-type SH2 domains that harbor a β-sheet in this region [5]. The integrity of the SH2 domain is maintained by a hydrophobic system of non-polar residues at the base of the pY+3 pocket, which stabilizes the β-sheet structure. The critical nature of this domain is highlighted by patient sequencing data, which identifies the SH2 domain as a hotspot for mutations in STAT3 and STAT5B, leading to either hyperactivated or refractory STAT mutants associated with various pathologies [5].

The following diagram illustrates the key structural features of the STAT SH2 domain and its role in dimerization:

Figure 1: STAT Dimerization Mechanism. The SH2 domain of one STAT monomer recognizes and binds to the phosphorylated tyrosine motif of a reciprocal STAT monomer, forming an active dimer capable of nuclear translocation.

Methodological Approaches for Assessing Dimerization

Fluorescence Co-localization

Principle and Application to STAT Dimerization

Fluorescence co-localization is a microscopy-based technique used to determine if two fluorescently labeled molecules occupy the same subcellular structures. While it lacks the resolution to directly prove molecular interaction, it can indicate association with common cellular compartments. In the context of STAT dimerization, co-localization can demonstrate that two differentially labeled STAT proteins converge in the cytoplasm upon pathway activation or co-accumulate in the nucleus following dimerization [34].

The fundamental approach involves labeling STAT proteins with distinct fluorophores (e.g., GFP and RFP) and visualizing their distribution in fixed or live cells via fluorescence microscopy. Co-localization is subjectively identified in merged images as structures whose color represents the combined contribution of both probes (e.g., yellow from red and green). However, this visual assessment is qualitative and can be ambiguous, as the combined color is highly dependent on the relative intensity and concentration of the two probes [34].

Quantitative Analysis and Key Considerations

For robust quantification, co-localization analysis must move beyond simple image merging. The recommended workflow involves:

- Image Acquisition: Collecting images with signals sufficient to distinguish from noise and background, and free of bleed-through between channels [34].

- Scatterplot Analysis: Plotting the intensity of each pixel in the red channel against its intensity in the green channel. Proportional co-distribution produces a scatterplot where points cluster around a straight line, whereas non-colocalizing probes form two separate clusters [34].

- Pearson's Correlation Coefficient (PCC): A statistical measure that quantifies the degree of linear correlation between pixel intensities in two channels. The formula is: ( PCC = \frac{\sum (Ri - \langle R \rangle)(Gi - \langle G \rangle)}{\sqrt{\sum (Ri - \langle R \rangle)^2 \sum (Gi - \langle G \rangle)^2}} ) where ( Ri ) and ( Gi ) are the intensity values of the red and green channels, respectively, and ( \langle R \rangle ) and ( \langle G \rangle ) are their mean values. A PCC value close to +1 indicates strong positive correlation, while values near 0 or negative indicate no or inverse correlation [34].