The Critical Role of the Stacking Gel in Protein Electrophoresis: A Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the stacking gel's purpose in protein electrophoresis, a foundational technique in molecular biology and proteomics.

The Critical Role of the Stacking Gel in Protein Electrophoresis: A Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the stacking gel's purpose in protein electrophoresis, a foundational technique in molecular biology and proteomics. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it details the foundational principles of the discontinuous buffer system, offers methodological guidance for robust SDS-PAGE, presents troubleshooting strategies for common issues like smearing and poor resolution, and validates the technique through comparisons with alternative methods. The synthesis of these four intents serves as a definitive resource for optimizing protein separation, ensuring reliable and reproducible results in downstream applications like Western blotting.

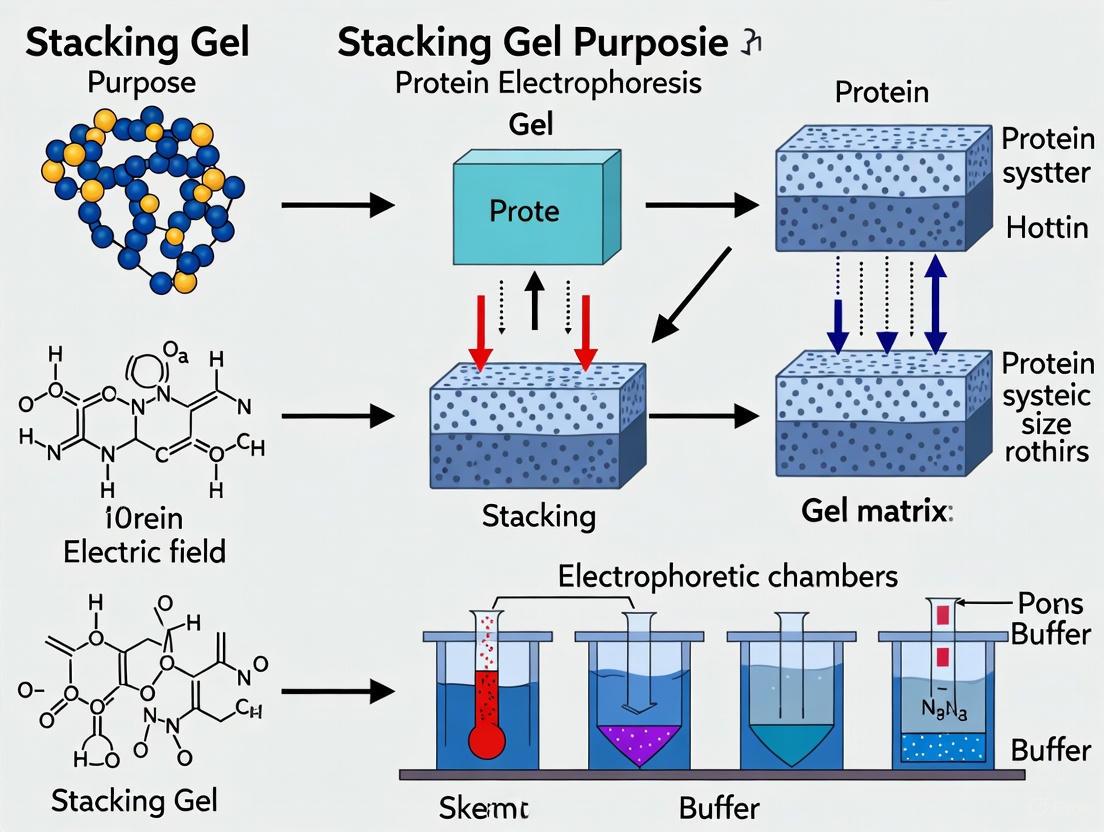

Understanding the Stacking Gel: Principles of the Discontinuous Buffer System

Defining Protein Electrophoresis and the Role of Gel Layers

Protein electrophoresis is a fundamental analytical technique used in biochemistry and molecular biology to separate complex protein mixtures based on their physicochemical properties. This method relies on an electrical field to transport charged protein molecules through a porous gel matrix, effectively separating them according to their size, charge, or both [1]. The technique serves as a cornerstone for proteomic research, enabling scientists to analyze protein expression, purity, and molecular weight across diverse applications from basic research to drug development [1] [2].

The historical development of electrophoresis spans nearly a century, beginning with Aronovich's initial concept in 1937 and Tiselius's first instrumental application in the 1930s [2]. The introduction of polyacrylamide gel in the 1960s revolutionized the field by enabling precise separation of biological molecules that were previously difficult to resolve [2]. Subsequent technological advancements, including capillary electrophoresis in the 1980s-1990s and microchip electrophoresis in 2008, have progressively enhanced the technique's resolution, speed, and application scope [2].

The separation principle relies on multiple factors influencing protein migration: the net charge of the molecule determined by buffer pH, the size and three-dimensional shape of the protein, the pore size of the gel matrix, the ionic strength of the buffer, and the strength of the applied electrical field [1] [2]. These parameters collectively determine electrophoretic mobility, allowing researchers to optimize conditions for specific separation goals.

Fundamentals of Gel Electrophoresis Systems

Polyacrylamide Gel Composition

Polyacrylamide gels form through the polymerization reaction between acrylamide and bisacrylamide, cross-linking to create a three-dimensional matrix with tunable pore sizes [1]. This reaction is catalyzed by ammonium persulfate (APS) and TEMED (N,N,N',N'-tetramethylenediamine), which generates free radicals to initiate polymerization [1]. The resulting gel serves as a molecular sieve, selectively retarding the movement of proteins based on their size [1].

The gel porosity is precisely controlled by adjusting the acrylamide concentration, typically ranging from 4% to 20% [1]. Lower percentage gels (e.g., 7%) feature larger pores ideal for separating high molecular weight proteins, while higher percentage gels (e.g., 15%) with smaller pores provide better resolution for lower molecular weight proteins [1]. For separating proteins across a broad molecular weight range, gradient gels with increasing acrylamide concentration from top to bottom offer superior resolution [1].

Table: Standard Polyacrylamide Gel Formulations for Protein Separation

| Gel Type | Total Acrylamide (%) | Primary Separation Basis | Optimal Protein Size Range | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDS-PAGE | 8-20% | Molecular weight | 5-250 kDa | Routine protein analysis, molecular weight determination |

| Native PAGE | 6-12% | Charge-to-mass ratio | Variable | Native protein analysis, enzyme activity assays |

| Gradient Gel | 4-20% | Molecular weight | 10-500 kDa | Broad-range separation, complex mixtures |

| Stacking Gel | 4-5% | Stacking effect | N/A | Sample concentration |

Discontinuous Gel Systems: The Stacking and Resolving Layers

Standard protein electrophoresis employs a discontinuous buffer system with two distinct gel layers stacked vertically within the same cassette [1] [3]. This configuration creates different environments optimized for sequential stages of the separation process.

The upper stacking gel features a large-pore structure with lower acrylamide concentration (typically 4-5%) and lower pH (approximately 6.8) [3]. Its primary function is to concentrate disparate protein samples from the relatively large volume of the loading wells into sharp, defined bands before they enter the separating region of the gel [1]. This concentration step occurs within the first few minutes of electrophoresis and is critical for achieving high-resolution separation [1].

The lower resolving gel (or separating gel) contains a higher acrylamide concentration (typically 8-20%) with higher pH (approximately 8.8) [3]. This region serves as the molecular sieving matrix where proteins separate according to their molecular weights (in SDS-PAGE) or combined charge-to-mass ratios (in native PAGE) [1]. The restrictive pore size of this gel layer creates a frictional force that differentially retards protein migration based on size and shape [1].

Electrophoresis Workflow: From Sample Loading to Separation

The Stacking Gel Mechanism

Principles of Stacking Gel Operation

The stacking gel achieves protein concentration through a sophisticated discontinuous buffer system that creates a sharp boundary between leading and trailing ions [3]. This system exploits differences in electrophoretic mobility across the different pH environments of the stacking and resolving gels [3].

The key mechanism involves glycine ionization states that change dramatically between the different pH regions [3]. In the running buffer (pH 8.3), glycine exists primarily as glycinate anions carrying a slight negative charge [3]. When these anions enter the stacking gel (pH 6.8), the lower pH causes most glycine molecules to adopt a zwitterionic form with no net charge, dramatically reducing their electrophoretic mobility [3].

This creates an ion mobility gradient where highly mobile chloride ions (from Tris-HCl in the gel) migrate rapidly toward the anode, while the relatively immobile glycine zwitterions lag behind [3]. The proteins, with mobilities intermediate between chloride and glycine, become compressed into a narrow zone between these two fronts [3]. This concentrating effect continues until the proteins reach the interface with the resolving gel.

Transition to the Resolving Gel

When the concentrated protein stack reaches the resolving gel boundary, the sharp increase to pH 8.8 triggers a critical transition [3]. At this elevated pH, glycine zwitterions rapidly lose protons and convert back to highly mobile glycinate anions [3]. These anions quickly migrate past the protein zone, eliminating the trailing ion front and depositing the proteins as a sharp band at the top of the resolving gel [3].

Once in the resolving gel, proteins encounter increased resistance from the higher acrylamide concentration, which slows their migration and enables separation based on molecular size [1] [3]. Without the concentrating effect of the stacking process, proteins would enter the resolving gel as diffuse bands, resulting in poor resolution and overlapping bands [1]. The stacking gel therefore serves the essential function of ensuring that all proteins begin their molecular weight-based separation simultaneously from a unified starting point.

Protein Electrophoresis Methodologies

SDS-PAGE: Denaturing Electrophoresis

SDS-PAGE (sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) represents the most widely used electrophoresis format for protein analysis [1]. This technique employs the ionic detergent SDS to denature proteins and impart a uniform negative charge density [1] [3]. Sample preparation involves heating proteins at 70-100°C in buffer containing excess SDS and a reducing agent (e.g., beta-mercaptoethanol) to cleave disulfide bonds [1] [3].

The SDS binding mechanism unfolds proteins and coats the polypeptide backbone at a constant weight ratio (approximately 1.4 g SDS per 1 g protein) [1]. This SDS coating masks the proteins' intrinsic charges, creating complexes with similar charge-to-mass ratios that migrate through the gel strictly according to molecular size rather than native charge [1]. The relationship between migration distance and molecular weight is semi-logarithmic, enabling molecular weight estimation by comparison with protein standards [1].

Limitations of SDS-PAGE include potential anomalous migration of heavily glycosylated or membrane proteins, which may bind SDS unevenly [3]. Additionally, the denaturing conditions destroy native protein structure and function, including enzymatic activity and non-covalently bound cofactors [4].

Native PAGE: Non-Denaturing Electrophoresis

Native PAGE separates proteins in their biologically active conformations without denaturing agents [1]. Separation depends on the combined influence of the protein's intrinsic charge, molecular size, and three-dimensional shape [1]. In this method, proteins migrate toward the electrode of opposite charge at rates proportional to their charge density while being retarded by the sieving effect of the gel matrix [1].

The primary advantage of native PAGE is preservation of function - proteins retain enzymatic activity and multimeric quaternary structures following separation [1]. This enables direct activity assays and analysis of protein complexes [1]. However, resolution is generally lower than with SDS-PAGE, and interpretation is more complex due to multiple factors influencing migration [1].

Two-Dimensional Electrophoresis

Two-dimensional (2D) PAGE provides the highest resolution separation of complex protein mixtures by combining two orthogonal separation techniques [1]. The first dimension separates proteins by their isoelectric point using isoelectric focusing (IEF) in a pH gradient [1]. The second dimension then resolves these focused proteins by molecular weight using standard SDS-PAGE [1].

This technique can resolve thousands of proteins simultaneously, making it invaluable for proteomic applications where comprehensive protein profiling is required [1]. Specialized immobilized pH gradient (IPG) strips have standardized the first dimension separation, improving reproducibility across experiments [1].

Emerging Techniques: Native SDS-PAGE

Recent methodological developments include native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE), which modifies standard SDS-PAGE conditions to preserve certain functional properties while maintaining high resolution [4]. This approach eliminates or reduces SDS concentration, removes EDTA from buffers, and omits the heating step during sample preparation [4].

Studies demonstrate that NSDS-PAGE retains metal cofactors in metalloproteins and preserves enzymatic activity in many cases, addressing a significant limitation of conventional denaturing electrophoresis [4]. For example, Zn²⁺ retention increased from 26% with standard SDS-PAGE to 98% with NSDS-PAGE, and seven of nine model enzymes remained active following separation [4].

Table: Comparative Analysis of Electrophoresis Techniques

| Parameter | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE | 2D-PAGE | NSDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Molecular weight | Size, charge, shape | pI then molecular weight | Molecular weight with native features |

| Protein State | Denatured | Native | Denatured in 2nd dimension | Partially native |

| Resolution | High | Moderate | Very high | High |

| Functional Retention | No | Yes | No | Partial |

| Typical Run Time | 30-60 minutes | 60-90 minutes | 5-8 hours | 30-60 minutes |

| Metal Cofactor Retention | Minimal | High | Minimal | High (98% Zn²⁺) |

Experimental Protocols and Reagent Systems

Standard SDS-PAGE Protocol

Gel Preparation: Traditional polyacrylamide gels are cast between glass plates using a recipe such as: 7.5 mL 40% acrylamide solution, 3.9 mL 1% bisacrylamide solution, 7.5 mL 1.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.7), water to 30 mL total volume, 0.3 mL 10% APS, 0.3 mL 10% SDS, and 0.03 mL TEMED [1]. The stacking gel uses lower acrylamide concentration (typically 4%) and lower pH Tris-HCl (pH 6.8) [1] [3].

Sample Preparation: Protein samples are diluted in loading buffer containing Tris-HCl, SDS, glycerol, bromophenol blue tracking dye, and beta-mercaptoethanol [3]. Samples are heated at 70-100°C for 5-10 minutes to ensure complete denaturation [1].

Electrophoresis Conditions: Prepared gel cassettes are mounted vertically in an electrophoresis tank filled with running buffer (typically Tris-glycine-SDS, pH 8.3) [1] [3]. Samples are loaded into wells, and constant voltage (150-200V for mini-gels) is applied until the dye front reaches the gel bottom (typically 30-45 minutes) [1].

Protein Detection Methods

Following electrophoresis, separated proteins are visualized using various staining techniques with different sensitivity ranges and compatibilities with downstream applications [5].

Coomassie Staining: The most common method uses Coomassie Brilliant Blue dye, which binds to basic and hydrophobic protein residues in acidic conditions, changing from reddish-brown to intense blue [5]. Detection sensitivity ranges from 5-25 ng per protein band, with protocols typically requiring 10-135 minutes [5]. Coomassie staining is fully compatible with mass spectrometry and protein sequencing applications [5].

Silver Staining: This highly sensitive method (0.25-0.5 ng detection limit) deposits metallic silver onto protein bands [5]. Silver ions interact with functional groups including carboxylic acids (Asp, Glu), imidazole (His), sulfhydryls (Cys), and amines (Lys) [5]. Protocol times range from 30-120 minutes, with variable compatibility for mass spectrometry depending on the specific formulation [5].

Fluorescent Staining: Modern fluorescent dyes provide exceptional sensitivity (0.25-0.5 ng) with broad linear dynamic ranges and minimal protein modification [5]. These stains typically require 60-minute protocols and are compatible with most downstream applications including western blotting and mass spectrometry [5].

Zinc Staining: This unique reverse-staining method stains the gel background with zinc-imidazole complex, leaving proteins as transparent bands against an opaque background [5]. With 15-minute protocol times and 0.25-0.5 ng sensitivity, zinc staining offers rapid, sensitive detection with excellent compatibility for protein recovery [5].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Protein Electrophoresis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gel Matrix Components | Acrylamide, bisacrylamide | Forms porous polyacrylamide gel matrix | Concentration determines pore size; typically 4-20% total acrylamide |

| Polymerization Initiators | Ammonium persulfate (APS), TEMED | Catalyzes acrylamide polymerization | TEMED stabilizes free radicals generated by APS |

| Buffers | Tris-HCl, Tris-Glycine, MOPS, Bis-Tris | Maintains pH and conducts current | Discontinuous systems use different buffers in stacking/resolving gels |

| Denaturing Agents | SDS, LDS, β-mercaptoethanol | Denatures proteins, disrupts disulfide bonds | SDS binds proteins at constant ratio (1.4g SDS:1g protein) |

| Tracking Dyes | Bromophenol Blue, Coomassie G-250 | Visualizes migration front | Mobility varies with gel percentage; may affect protein migration |

| Protein Standards | PageRuler, Spectra, SeeBlue, MagicMark | Molecular weight calibration | Prestained for process monitoring; unstained for accurate size determination |

Advanced Applications and Research Implications

Drug Development and Biomarker Discovery

In pharmaceutical research, protein electrophoresis provides critical analytical capabilities throughout drug development pipelines [2]. The technique enables assessment of protein drug purity, stability testing, and detection of degradation products [2]. Electrophoresis methods are routinely employed in quality control processes for biologics manufacturing, ensuring batch-to-batch consistency of protein-based therapeutics [2].

Biomarker discovery represents another major application, particularly using high-resolution 2D-PAGE to identify disease-associated protein patterns in clinical samples [2]. Comparative analysis of protein expression in healthy versus diseased tissues facilitates identification of potential diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets [2]. These applications leverage the technique's ability to resolve complex mixtures into individual components for subsequent identification, typically by mass spectrometry [1] [5].

Environmental and Clinical Monitoring

Electrophoresis techniques increasingly support environmental monitoring applications, analyzing pollutants and studying toxin effects on biological systems [2]. Slab gel electrophoresis facilitates assessment of heavy metals, pesticides, and organic pollutants in environmental samples, while also enabling analysis of microbial population genetics in ecosystems [2].

In clinical diagnostics, electrophoresis remains a standard tool for analyzing serum proteins, detecting immunoglobulin abnormalities, and diagnosing various disease states [2]. The combination of high resolution, sensitivity, and relatively simple implementation makes these methods accessible to clinical laboratories worldwide [2]. Automation and standardization continue to improve the reliability and throughput of clinical electrophoresis applications [2].

Publication Guidelines and Data Integrity

As protein electrophoresis data frequently supports scientific publications, researchers must adhere to evolving journal requirements for gel and western blot images [6]. Recent guidelines emphasize minimal image manipulation, with acceptable adjustments limited to uniform changes in brightness, contrast, or color balance applied across the entire image [6].

Best practices include preserving original images, including molecular weight markers in all published images, minimizing cropping, and providing full gel images as supplementary materials when required [6]. Journals increasingly request original, unprocessed images during manuscript review, with some requiring publication of unprocessed images as supplementary information [6]. These standards ensure data integrity and enhance research reproducibility in the scientific literature.

Method Selection Workflow for Protein Electrophoresis

Protein electrophoresis remains an indispensable tool in modern biological research, with the stacking gel serving a critical role in ensuring high-resolution separations. The fundamental principles of discontinuous buffer systems continue to support both routine analyses and advanced proteomic applications. Ongoing methodological developments, including native SDS-PAGE and improved detection chemistries, continue to expand the technique's capabilities while addressing historical limitations. As electrophoresis technologies evolve toward higher sensitivity, miniaturization, and integration with complementary analytical platforms, researchers across basic science, drug development, and clinical diagnostics will continue to rely on these separation methods for protein characterization and biomarker discovery.

In the realm of protein biochemistry and proteomic research, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) is a foundational analytical technique for separating complex protein mixtures by their molecular weight [7]. The resolution of this separation—the ability to distinguish individual protein bands as sharp, distinct entities—is paramount for accurate analysis. However, a significant technical challenge arises from the initial physical loading of samples into the gel. When a protein sample is loaded into a well, it can occupy a volume several millimeters deep, creating a diffuse starting zone. If this diffuse zone were to enter the main separating (resolving) gel directly, the resulting separated proteins would appear as broad, overlapping smears rather than sharp bands, severely compromising resolution and interpretability [8]. The stacking gel, a distinct layer cast on top of the resolving gel, is an ingenious biochemical solution to this problem. Its core function is to concentrate all protein molecules from the relatively large sample volume into an extremely narrow, unified band before they enter the resolving gel, thereby ensuring that separation begins from a fine, well-defined starting point and dramatically enhancing the final resolution [7] [9].

The Fundamental Principles of the Stacking Gel

The stacking gel operates on the principle of a discontinuous buffer system, utilizing differences in pH, gel porosity, and ionic composition to create a transient state that focuses the proteins [10]. This system comprises three key elements: the stacking gel, the resolving gel, and the running buffer. Each is engineered with specific properties that work in concert to achieve sample concentration.

- pH Discontinuity: The stacking gel is polymerized at a lower pH (~6.8) compared to the resolving gel (~8.8) [10]. This pH difference is critical for modulating the charge state of key ions, as detailed below.

- Porosity Difference: The stacking gel has a lower percentage of polyacrylamide (e.g., 4-5%) than the resolving gel, creating larger pores. This low-density matrix allows proteins to move freely and quickly without significant separation based on size, fulfilling the sole purpose of stacking [7] [10].

- Ionic Discontinuity: The running buffer contains Tris and glycine, while the gel matrices contain Tris and Cl⁻ ions (from Tris-HCl) [10]. The behavior of glycine is the cornerstone of the entire stacking mechanism.

The following diagram illustrates the orchestrated interplay of these components during the stacking process.

The Key Role of Glycine and the Discontinuous System

As illustrated above, the stacking mechanism is a dynamic process driven by glycine's charge state. In the running buffer (pH 8.3), glycine exists predominantly as a glycinate anion, carrying a negative charge and possessing relatively high electrophoretic mobility [10]. However, when these glycinate ions enter the low-pH environment of the stacking gel (pH 6.8), their charge environment changes dramatically. At this pH, the majority of glycine molecules enter a zwitterionic state, possessing both a positive and a negative charge and resulting in a net charge close to zero [10] [9]. Consequently, their electrophoretic mobility drops severely.

This creates a fundamental ion mobility gradient:

- Leading Ion: The Cl⁻ ions from the Tris-HCl in the gel, which are highly mobile and move rapidly toward the anode.

- Trailing Ion: The glycine zwitterions, which move much more slowly due to their lack of net charge.

A steep voltage gradient forms between these two ion fronts. The SDS-coated proteins, which have an intermediate mobility greater than the trailing glycine but less than the leading Cl⁻, become compressed into a micrometer-thick zone between them. This phenomenon effectively "herds" all protein species into a single, extremely tight band [10] [9]. When this stacked band reaches the interface with the resolving gel (pH 8.8), the glycine molecules are re-ionized to the fully negative glycinate form. They suddenly regain high mobility, overtake the proteins, and dissipate the voltage gradient. The proteins, now deposited as a sharp band at the top of the resolving gel, begin the separation phase based solely on molecular weight [10].

Experimental Protocol: SDS-PAGE with a Stacking Gel

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for performing SDS-PAGE utilizing a standard two-layer gel system to achieve sample stacking [7] [8].

Materials and Reagents

Table 1: Essential Reagents for SDS-PAGE with Stacking Gel

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Key Components & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms the cross-linked polyacrylamide gel matrix that acts as a molecular sieve. | Ratio determines pore size. Caution: Neurotoxin in its monomeric form. [7] |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | Polymerizing agent; generates free radicals to initiate acrylamide cross-linking [7]. | Freshly prepared solution is recommended. |

| TEMED | Catalyst; stabilizes free radicals and accelerates the polymerization process [7]. | |

| Tris-HCl Buffers | Provides the buffering capacity and pH for both stacking and resolving gels [10]. | Resolving gel buffer: pH 8.8. Stacking gel buffer: pH 6.8. |

| SDS Solution | Ionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge [7]. | Added to both gel solutions and running buffer. |

| Running Buffer | Conducts current and provides ions (Tris, glycine) for the discontinuous buffer system [10]. | Tris, glycine, SDS, pH ~8.3. |

| Laemmli Sample Buffer | Prepares protein samples for electrophoresis [10]. | Contains Tris-HCl, SDS, glycerol, Bromophenol Blue, and a reducing agent like β-mercaptoethanol (BME). |

| Protein Molecular Weight Markers | Provides standards of known molecular weight for estimating sample protein sizes [7]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Cast the Resolving Gel:

- Prepare the resolving gel solution according to the desired percentage (e.g., 10%, 12%) using Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), acrylamide/bis-acrylamide, SDS, APS, and TEMED [7].

- Piper the solution into a gel cassette, leaving space for the stacking gel. Carefully overlay with isopropanol or water to create a flat, smooth interface.

- Allow the gel to polymerize completely (typically 20-30 minutes).

Cast the Stacking Gel:

- Pour off the overlay liquid from the polymerized resolving gel.

- Prepare the stacking gel solution (typically 4-5% acrylamide) using Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), acrylamide, SDS, APS, and TEMED [7] [8].

- Piper the stacking gel solution onto the top of the resolving gel and immediately insert a well comb, avoiding bubbles.

- Allow the stacking gel to polymerize fully.

Prepare Protein Samples:

Run the Electrophoresis:

- Assemble the gel cassette in the electrophoresis tank and fill the chambers with running buffer.

- Carefully load the denatured samples and protein markers into the wells.

- Connect the power supply and run the gel at a constant voltage. For a mini-gel system, 80-150V is typical [11]. The run should be stopped once the dye front (Bromophenol Blue) reaches the bottom of the gel.

The workflow below summarizes the key stages of the protocol, from gel preparation to final analysis.

Technical Data and Optimization

Successful execution and interpretation of SDS-PAGE rely on understanding the quantitative relationships between gel composition, protein size, and migration.

Table 2: Optimizing Gel Composition for Target Protein Sizes

| Gel Type | Acrylamide Concentration (%) | Effective Separation Range (kDa) | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stacking Gel | 4 - 5 | Not Applicable | Concentrates all protein samples into a sharp band; no size-based separation [10]. |

| Resolving Gel | 7.5 | 40 - 200 | Optimal for resolving high molecular weight proteins [7]. |

| 10 | 20 - 100 | Standard range for most routine protein analyses [8]. | |

| 12 | 10 - 60 | Optimal for resolving low molecular weight proteins [7]. | |

| Gradient Gel | e.g., 4-20% | 10 - 300 | Broad-range separation; the gradient itself can perform a stacking function [7]. |

Advanced Applications and Integration with Downstream Analyses

The stacking gel is not an end point but a critical first step in a pipeline of sophisticated protein analysis. The high-resolution separation it enables is a prerequisite for numerous downstream techniques.

- Western Blotting (Immunoblotting): The sharp protein bands produced by a properly stacked gel are essential for effective transfer to a membrane and subsequent detection with specific antibodies. Poor stacking leading to diffuse bands results in low-sensitivity detection and high background [7].

- Mass Spectrometric Analysis: For protein identification and characterization, individual bands of interest can be excised from the gel. The proteins are then digested with trypsin within the gel piece, and the resulting peptides are extracted for mass spectrometry. High resolution, enabled by effective stacking, is critical for isolating a single protein species for pure analysis [7].

- Two-Dimensional Gel Electrophoresis (2D-PAGE): In 2D-PAGE, proteins are first separated by their isoelectric point and then, in the second dimension, by their molecular weight using SDS-PAGE [7] [12]. The stacking gel is therefore integral to the second dimension, ensuring that the complex mixture of proteins from the first dimension is focused into sharp spots rather than smears, allowing for the resolution of thousands of proteins on a single gel.

This technical guide examines the fundamental role of Tris, glycine, and pH discontinuity in establishing the discontinuous buffer system central to protein electrophoresis. Within the context of stacking gel function, these components create a moving boundary that concentrates protein samples into sharp bands prior to separation, significantly enhancing resolution. The precise interplay of these chemicals establishes ionic conditions that dictate electrophoretic mobility, forming the biochemical foundation for high-resolution protein analysis critical to proteomic research and drug development.

The resolution achieved in modern protein electrophoresis relies heavily on the sophisticated principle of discontinuous buffer systems. This methodology utilizes differences in pH and buffer ion composition between the stacking and resolving gels to concentrate proteins into infinitesimally thin starting zones before separation occurs. The core chemical components enabling this process are Tris (a buffering agent), glycine (a trailing ion), and chloride (a leading ion), operating within a precisely engineered pH gradient [13] [14]. The primary function of the stacking gel is to leverage this chemical discontinuity to compress the protein sample, which may be distributed across a millimeter-deep well, into a micron-scale band at the interface of the stacking and resolving gels. This compression is paramount for achieving the sharp, distinct bands that enable accurate analysis of complex protein mixtures, a non-negotiable requirement in both basic research and biopharmaceutical characterization [15].

The Core Chemical Components

Tris: The Common Buffering Ion

Tris (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane) serves as the foundational buffering agent throughout the system. Its consistent presence in the gel buffers and running buffer provides a uniform counter-ion (Tris+) environment [13]. The critical property of Tris is its pKa of approximately 8.1, which makes it an effective buffer in the pH range of 7 to 9, perfectly spanning the different pH conditions required in the various gel phases [15]. In the Laemmli system, the stacking gel is buffered to pH 6.8, while the resolving gel is at pH 8.8 [14]. During electrophoresis, the actual operating pH in the separation region rises to approximately 9.5 [13]. Tris is responsible for maintaining the structural integrity of this pH gradient, which is essential for modulating the charge of glycine, as detailed in Section 2.2.

Glycine: The Trailing Ion

Glycine, an amino acid with the chemical formula NH₂-CH₂-COOH, is the primary anion supplied by the running buffer and functions as the "trailing ion" [13]. Its role is defined by its zwitterionic nature, meaning its net charge is highly dependent on the ambient pH [15]. This pH-dependent charge switching is the central mechanism enabling the stacking phenomenon:

- In the Stacking Gel (pH ~6.8): At this pH, which is near glycine's pKa₂ (carboxyl group), a significant proportion of glycine molecules exist as zwitterions, possessing both a positive and a negative charge and thus a net electrophoretic mobility that is very low [15]. They trail behind the more mobile ions.

- In the Resolving Gel (pH ~8.8): Upon entering the higher pH of the resolving gel, the amino group of glycine becomes deprotonated. Glycine molecules become predominantly negatively charged glycinate anions, acquiring high electrophoretic mobility and overtaking the proteins [13] [15].

Chloride: The Leading Ion

Chloride ions (Cl⁻), supplied by Tris-HCl in the gel buffers, act as the "leading ion" [13]. As a small, highly mobile anion with a high electrophoretic affinity for the anode, chloride migrates rapidly through both the stacking and resolving gels, establishing the ion front [16].

The pH Discontinuity

The engineered difference in pH between the stacking gel (pH 6.8) and the resolving gel (pH 8.8) is not arbitrary. This discontinuity is the critical external control that governs the charge state and, consequently, the mobility of glycine. It acts as a switch, ensuring glycine functions as a trailing ion in the stacking phase and a fast-moving ion in the resolving phase, thereby depositing the proteins at the top of the resolving gel in a finely focused band [15].

Table 1: Summary of Key Chemical Components and Their Roles

| Component | Chemical Nature | Primary Role | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tris | Buffering agent (pKa ~8.1) | Maintains pH gradient; common cation | Gel buffers & running buffer |

| Glycine | Zwitterionic amino acid | Trailing ion (stacking); fast ion (resolving) | Running buffer |

| Chloride | Small, mobile anion | Leading ion | Gel buffers (Tris-HCl) |

The Mechanism of Stacking: A Synergistic Interaction

The stacking process is a dynamic consequence of the interplay between the components described above. The following diagram illustrates the ionic dynamics and protein focusing that occur when the electric field is applied.

The process unfolds in two distinct phases, as visualized above:

- Formation of the Moving Boundary and Voltage Gradient: When the electric field is applied, the highly mobile chloride ions (leading ions) from the stacking gel rush ahead toward the anode. The glycinate ions from the running buffer enter the low-pH stacking gel and convert to slow-moving zwitterions. This creates a sharp moving boundary between the fast Cl⁻ front and the slow glycine front [13] [15].

- Protein Compression and Stacking: The SDS-coated proteins possess an electrophoretic mobility that is intermediate between the leading Cl⁻ ions and the trailing glycine zwitterions. Consequently, the proteins are "swept" and concentrated into an extremely narrow zone within this moving boundary, effectively "stacking" them into a sharp band before they enter the resolving gel [16].

- Destacking in the Resolving Gel: When this ionic front encounters the high-pH environment of the resolving gel, the glycine zwitterions rapidly deprotonate to become fast-moving glycinate anions. These anions overtake the proteins, depositing the now-concentrated protein band at the top of the resolving gel. Freed from the voltage gradient, the proteins then migrate based on their size through the sieving matrix of the resolving gel [15].

Experimental Protocol: Tris-Glycine SDS-PAGE

The following methodology, adapted from standard protocols for pre-cast gels, outlines the procedure for utilizing the Tris-Glycine discontinuous system [13].

Materials and Reagent Preparation

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Purpose | Key Components |

|---|---|---|

| Tris-Glycine SDS Running Buffer (1X) | Conducts current; provides trailing ion (glycine) and maintains pH for migration [13] [17]. | 25 mM Tris, 192 mM Glycine, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.3 [13] [17]. |

| Tris-Glycine SDS Sample Buffer (2X) | Denatures proteins; provides negative charge (SDS) and density for loading. | Tris-HCl, SDS, Glycerol, Bromophenol Blue, ß-mercaptoethanol or DTT [13]. |

| NuPAGE Reducing Agent (10X) | Reduces disulfide bonds to fully denature proteins. | Dithiothreitol (DTT) in stabilized liquid form [13]. |

| Pre-Cast Gel (Tris-Glycine) | Provides the pre-formed matrix for separation, with built-in pH discontinuity. | Stacking gel: ~5% acrylamide, pH 6.8. Resolving gel: Variable % acrylamide, pH 8.8 [13]. |

| Protein Molecular Weight Markers | Reference standards for estimating the molecular weight of unknown proteins. | Mixture of purified proteins of known molecular weight. |

Running Buffer Preparation: Dilute the 10X Tris-Glycine SDS Running Buffer to a 1X working concentration. For a standard mini-gel apparatus, prepare 800 mL by adding 80 mL of 10X buffer to 720 mL of deionized water [13].

Step-by-Step Electrophoresis Procedure

Sample Preparation:

- Mix the protein sample with an equal volume of 2X Tris-Glycine SDS Sample Buffer.

- For reduced samples, add reducing agent (e.g., DTT) to a final 1X concentration.

- Heat the samples at 85°C for 2 minutes to denature proteins. Avoid boiling (100°C) to minimize acid-hydrolysis of Asp-Pro bonds [13].

- Centrifuge briefly to collect condensation.

Gel Apparatus Setup:

- Remove the pre-cast gel from its pouch and rinse the cassette with deionized water.

- Remove the comb and thoroughly rinse the sample wells with 1X running buffer.

- Place the gel cassette into the electrophoresis chamber according to the manufacturer's instructions (e.g., using the XCell SureLock Mini-Cell) [13].

- Fill the inner (upper) and outer (lower) buffer chambers with the prepared 1X running buffer.

Sample Loading and Electrophoresis Run:

- Load the prepared samples and protein molecular weight markers into the wells.

- Secure the lid and connect the electrodes to the power supply (red to +, black to -).

- Run the gel at a constant voltage of 125 V.

- The run should take approximately 90 minutes, or until the bromophenol blue tracking dye front reaches the bottom of the gel. The initial current for a single mini-gel will be ~30-40 mA, dropping to ~8-12 mA by the end of the run [13].

Post-Electrophoresis Analysis:

- After the run, turn off the power supply.

- Carefully open the gel cassette using a specialized gel knife or tool, avoiding damage to the gel.

- Proceed with the desired downstream application, such as staining with Coomassie Blue or Silver Stain, or transfer to a membrane for western blotting [13].

Advanced Buffer Systems and Considerations

While the Tris-Glycine system is the historical standard, alternative buffer systems have been developed to address specific limitations.

- Tris-Tricine-HEPES Buffer: Recent research has developed a "fast-running buffer" (FRB) combining Tris, Tricine, and HEPES. This system creates multiple ionic boundaries, which reportedly improves resolving power and allows for a significantly reduced run time of 35 minutes under optimized conditions (150 V for 15 min, then 200 V for 20 min) while maintaining compatibility with western blotting [16].

- Bis-Tris Gel Technology: Bis-Tris gels, used with MOPS or MES running buffer, operate at a neutral pH (e.g., ~7.0) instead of the highly alkaline conditions of Tris-Glycine gels. This minimizes protein modifications like deamination and alkylation, leading to sharper band resolution and greater stability. MES buffer is optimal for proteins <50 kDa, while MOPS is better for mid-to-large-sized proteins [18].

- Tris-Taurine System: For high-resolution analysis across a very broad molecular weight range (6-200 kDa), a system using taurine as the trailing ion and chloride as the leading ion has been described. This multiphasic buffer system is particularly useful for proteomic applications where simultaneous analysis of high and low molecular weight proteins is necessary [19].

Table 3: Comparison of Electrophoresis Buffer Systems

| Buffer System | Optimal Separation Range | Key Feature | Typical Running Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tris-Glycine (Laemmli) | 6 - 200 kDa [13] | Historical standard; cost-effective. | ~90 minutes [13] |

| Tris-Tricine | < 15 kDa [16] | Superior resolution of small polypeptides. | Up to 5 hours [16] |

| Tris-Tricine-HEPES (FRB) | Broad range [16] | Fast run time; good for high-throughput. | ~35 minutes [16] |

| Bis-Tris / MOPS or MES | Wide range, tunable [18] | Neutral pH; sharper bands; longer gel shelf life. | Varies, often faster |

The chemical triad of Tris, glycine, and the engineered pH discontinuity forms the cornerstone of the discontinuous electrophoresis system. Their synergistic interaction creates the dynamic conditions necessary for the stacking phenomenon, which is the very purpose of the stacking gel. By concentrating disparate protein samples into a unified, sharp starting zone, this system overcomes the fundamental limit of resolution imposed by diffuse sample application. A deep understanding of this core biochemistry empowers researchers to select and optimize electrophoresis conditions, troubleshoot anomalies, and leverage newer buffer technologies. This knowledge is indispensable for achieving the high-quality, reproducible protein separation required to advance discovery in proteomics and therapeutic development.

In protein electrophoresis research, the primary purpose of the stacking gel is to concentrate protein samples into sharp, tight bands before they enter the resolving gel, thereby dramatically improving resolution [20]. This process is achieved through a sophisticated physicochemical mechanism known as a discontinuous buffer system, which exploits differential mobility of leading and trailing ions [21]. The fundamental principle hinges on creating a steep voltage gradient that compresses protein molecules into a microscopic zone, ensuring all proteins enter the resolving matrix simultaneously regardless of initial loading volume [20]. This review examines the precise physics governing leading and trailing ions in SDS-PAGE and its critical importance in modern proteomics and drug development.

The Core Mechanism: Leading Ions, Trailing Ions, and the Voltage Gradient

The Key Players: Chloride and Glycine Ions

The discontinuous system employs three distinct buffer zones with different pH values and ionic compositions: the running buffer (pH ≈ 8.3), the stacking gel (pH ≈ 6.8), and the resolving gel (pH ≈ 8.8) [21] [20]. Within this framework, specific ions perform specialized functions:

- Leading Ions: Chloride ions (Cl⁻) from Tris-HCl in the gel buffers serve as the leading ions [21]. These highly mobile, small anions form a front that moves rapidly toward the anode when current is applied.

- Trailing Ions: Glycine molecules from the running buffer function as the trailing ions [20]. Their mobility is critically dependent on the local pH environment.

- Proteins: SDS-coated proteins possess an intermediate mobility between the leading and trailing ions [21].

Table 1: Ionic Composition and Roles in Discontinuous Electrophoresis

| Component | Chemical Identity | Primary Function | Electrophoretic Mobility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leading Ion | Chloride (Cl⁻) | Establish fast-moving front ahead of proteins | High |

| Trailing Ion | Glycine (Glycinate) | Create slow-moving boundary behind proteins | pH-dependent |

| Protein Stack | SDS-coated polypeptides | Focus between ion fronts for concentration | Intermediate |

| Buffer System | Tris-HCl/Tris-Glycine | Maintain pH discontinuities between zones | N/A |

The Physics of Stacking: A Three-Stage Process

The stacking mechanism unfolds through a precise sequence of events driven by pH-dependent charge transitions:

In the Stacking Gel (pH 6.8): Glycine enters the acidic stacking gel environment where its amino group becomes protonated, resulting in a zwitterionic form with no net charge (NH₃⁺-CH₂-COO⁻) [21]. This neutral state dramatically reduces glycine's electrophoretic mobility, creating a slow-moving trailing ion front.

Formation of the Voltage Gradient: The highly mobile chloride ions surge ahead toward the anode, while the virtually immobile glycine zwitterions lag behind [20]. This separation creates a narrow zone with a steep voltage gradient between the two ion fronts.

Protein Concentration: SDS-coated proteins, with their uniform negative charge and intermediate mobility, become compressed into a thin disk within this high-voltage gradient zone [21]. The proteins stack according to their electrophoretic mobilities, with fastest-migrating species positioned immediately behind the chloride front.

Table 2: pH-Dependent Charge States and Mobilities of Key Ions

| Ion Species | Stacking Gel (pH 6.8) | Resolving Gel (pH 8.8) | Mobility in Stacking Gel |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chloride (Cl⁻) | Fully negative | Fully negative | High |

| Glycine | Zwitterion (net neutral) | Anionic (Glycinate) | Very Low |

| SDS-Proteins | Uniformly negative | Uniformly negative | Intermediate |

Experimental Protocols for Studying Stacking Dynamics

Gel Preparation Methodology

The Laemmli method remains the gold standard for preparing discontinuous SDS-PAGE gels [20]. The following protocol details the preparation of a standard mini-gel system:

Stacking Gel Formulation (5 mL, 4% Acrylamide):

- 1.0 mL of 20% acrylamide/bis solution

- 1.25 mL of 0.5M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8

- 2.65 mL deionized water

- 50 μL of 10% SDS

- 25 μL of 10% ammonium persulfate (APS)

- 5 μL TEMED

Resolving Gel Formulation (10 mL, 12% Acrylamide):

- 4.0 mL of 30% acrylamide/bis solution

- 3.75 mL of 1.5M Tris-HCl, pH 8.8

- 2.15 mL deionized water

- 100 μL of 10% SDS

- 50 μL of 10% APS

- 10 μL TEMED

Critical Procedural Steps:

- Prepare resolving gel solution first, excluding TEMED

- Add TEMED last, mix thoroughly, and pipette between glass plates

- Overlay with isopropanol to ensure a level interface

- After polymerization (20-30 minutes), remove isopropanol and rinse

- Prepare stacking gel solution, add TEMED, and layer over resolving gel

- Immediately insert well-forming comb avoiding bubbles

Electrophoresis Running Conditions

Sample Preparation:

- Dilute protein extracts in lysis buffer to equalize concentrations (typically 1-5 μg/μL)

- Mix 1:1 with Laemmli buffer (60 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 20% glycerol, 2% SDS, 4% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.01% bromophenol blue) [20]

- Heat samples at 70-100°C for 5 minutes to ensure complete denaturation [21]

Electrophoresis Parameters:

- Running buffer: 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.3 [20]

- Initial voltage: 80-100V constant through stacking phase

- Increase to 120-150V after dye front enters resolving gel

- Run until bromophenol blue tracking dye reaches bottom of gel (approximately 45-60 minutes for mini-gels)

Visualization of the Stacking Process

The following diagram illustrates the stepwise process of protein stacking in SDS-PAGE:

The transition to the resolving gel triggers the final phase of the process. As the ion fronts encounter the higher pH (8.8) environment of the resolving gel, glycine molecules lose protons from their amino groups and become negatively charged glycinate anions [21]. This transformation dramatically increases their electrophoretic mobility, allowing them to rapidly migrate past the stacked proteins. With the dissolution of the voltage gradient, proteins are deposited as an extremely thin band at the top of the resolving gel, where molecular sieving based on size commences [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Stacking Gel Electrophoresis

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Discontinuous Electrophoresis

| Reagent | Composition | Primary Function | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laemmli Sample Buffer | 60 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 2% SDS, 20% glycerol, 4% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.01% bromophenol blue [20] | Denatures proteins, provides density for loading, includes tracking dye | β-mercaptoethanol reduces disulfide bonds; must be heated for full denaturation |

| Running Buffer | 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.3 [20] | Conducts current, provides trailing ions (glycine) | Glycine charge state critical for stacking mechanism |

| Stacking Gel Buffer | 0.5M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8 [20] | Creates acidic environment for glycine zwitterion formation | Lower pH essential for reducing glycine mobility |

| Resolving Gel Buffer | 1.5M Tris-HCl, pH 8.8 [20] | Creates basic environment for glycine deprotonation | Higher pH essential for protein separation by size |

| Acrylamide/Bis Solution | 30% acrylamide, 0.8% bis-acrylamide | Forms porous polyacrylamide matrix | Concentration determines pore size and resolution range |

| Polymerization System | Ammonium persulfate (APS) and TEMED | Catalyzes acrylamide polymerization | TEMED stabilizes free radicals generated by APS |

Implications for Research and Drug Development

The physics of leading and trailing ions has profound implications for biomedical research and pharmaceutical development. The stacking mechanism enables detection of low-abundance proteins that would otherwise be invisible in crude mixtures—a critical capability for biomarker discovery [20]. In drug development, the ability to resolve proteins with similar molecular weights is essential for analyzing post-translational modifications, proteolytic processing, and protein-drug interactions [21]. The discontinuous buffer system provides the foundation for western blotting, the premier technique for protein detection and quantification in complex biological samples [20]. Recent methodological innovations, including colored stacking gels for visual validation of gel integrity, build upon these fundamental principles while enhancing experimental reliability [22]. Understanding the precise physics of stacking gels remains essential for optimizing electrophoretic separations and interpreting resulting data in both basic research and applied pharmaceutical contexts.

In protein electrophoresis, the stacking gel serves a critical, non-negotiable purpose: it acts as a molecular compression chamber that transforms a diffuse, heterogeneous protein sample loaded from a well into a sharp, unified stack before it enters the resolving gel. This initial focusing is the fundamental prerequisite for achieving high-resolution separation based on molecular weight in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The process is governed by well-defined principles of buffer chemistry and electrophoretic mobility, which this whitepaper elucidates through detailed protocols, quantitative data, and mechanistic diagrams. Understanding this transition is not merely academic; it is essential for any researcher aiming to optimize protein separation for applications ranging from western blotting to proteomic analysis and drug development.

The central challenge in protein electrophoresis is the physical reality of the sample well. When a protein sample is pipetted into a well, it occupies a relatively large, diffuse volume. If this sample were to enter the resolving gel directly, the resulting protein bands would be broad, poorly separated, and unsuitable for accurate analysis [7]. The stacking gel, a distinct region cast on top of the resolving gel, is engineered specifically to overcome this limitation.

Its purpose within the broader context of protein research is to ensure the maximum resolution and sensitivity of the technique. A sharp, concentrated stack of proteins entering the resolving dimension allows for the clear distinction between proteins of similar sizes, enhances detection limits for low-abundance proteins, and ensures the reproducibility and reliability of quantitative analyses [7] [23]. This foundational step is what makes SDS-PAGE a cornerstone of modern biochemistry and molecular biology.

The Core Mechanism: Principles of Discontinuous Buffer Electrophoresis

The "stacking" phenomenon is achieved through a clever manipulation of buffer systems, known as discontinuous electrophoresis. It relies on creating two key disparities between the stacking and resolving gels: a difference in pore size and, more importantly, a difference in pH and ionic composition [7] [23].

Key Disparities Enabling Stacking

- Gel Porosity and pH: The stacking gel is typically composed of a low percentage of acrylamide (e.g., 4-5%), creating larger pores that offer minimal sieving effect. Its pH is buffered to approximately 6.8. In contrast, the resolving gel has a higher acrylamide concentration (e.g., 10-12%) for molecular sieving and a higher pH of about 8.8 [23].

- Ionic Environment: The running buffer contains glycine ions. At the stacking gel's pH of 6.8, a significant fraction of glycine exists in a neutral, zwitterionic form (H3N+CH2COO–), with a low electrophoretic mobility. The chloride ions (Cl-) from Tris-HCl in the gel buffer have a high mobility. The protein-SDS complexes, due to the bound SDS, have a net negative charge and an intermediate mobility, slower than Cl- but faster than glycine at this pH [7].

The Transient Stacking Process

The following diagram visualizes the stepwise process of protein stacking, from the initial state in the sample well to the focused stack entering the resolving gel.

When the electrical current is applied, the highly mobile chloride ions rush ahead, followed by the stacked protein-SDS complexes, which are confined in a narrow zone between the leading chloride and the trailing glycine ions. This process concentrates the proteins from a diffuse volume spanning several millimeters in the well into a sharp stack only tens of micrometers thick. Upon reaching the resolving gel at pH 8.8, the glycine ions become predominantly negatively charged (H2NCH2COO–), gain mobility, and overtake the proteins. Freed from the stacking boundary, the proteins then enter the resolving gel as a sharp, concentrated band where separation based on molecular weight begins in earnest [7] [23].

Experimental Protocols for Visualization and Optimization

Standard SDS-PAGE Gel Casting with a Stacking Gel

Objective: To prepare a discontinuous polyacrylamide gel system for the separation of proteins based on molecular weight.

Materials:

- Resolving Gel Solution: Acrylamide/bis-acrylamide (e.g., 30% stock, 29:1), 1.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 10% Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 10% Ammonium persulfate (APS), N,N,N',N'-Tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED), deionized water.

- Stacking Gel Solution: Acrylamide/bis-acrylamide, 0.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 10% SDS, 10% APS, TEMED, deionized water.

- Equipment: Gel cassette, comb, gel casting stand.

Methodology:

- Prepare the Resolving Gel: Combine acrylamide, Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), SDS, and water in a flask. To initiate polymerization, add TEMED and APS last, swirl gently to mix, and immediately pipette the solution into the gel cassette. Layer with isopropanol or water to create a flat, seamless interface. Allow complete polymerization (approx. 15-30 minutes) [23].

- Prepare the Stacking Gel: After removing the overlay liquid, combine acrylamide, Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), SDS, and water. Add TEMED and APS, mix, and pipette onto the polymerized resolving gel.

- Insert the Comb: Immediately insert a clean comb into the stacking gel solution, ensuring no air bubbles are trapped in the wells. Allow to polymerize fully [23].

- Sample Preparation: Mix protein samples with SDS-PAGE sample buffer (containing SDS, a reducing agent like DTT, and glycerol). Heat the samples at 70-100°C for 3-5 minutes to ensure complete denaturation [7] [23].

Protocol for Visualizing Wells with Colored Stacking Gels

Objective: To enhance the visualization of sample wells for more accurate and straightforward sample loading.

Materials: Standard SDS-PAGE materials, plus an acidic dye (e.g., tartrazine, brilliant blue FCF, or new coccine) [24].

Methodology:

- Add Dye to Stacking Gel: During the preparation of the stacking gel solution, include a low concentration of an acidic dye (e.g., 0.001% brilliant blue FCF) before adding TEMED and APS.

- Polymerize: Complete the polymerization as described in the standard protocol. The resulting stacking gel will be tinted, making the wells clearly visible against the colorless resolving gel.

- Load and Run: Load protein samples as usual. The performance of the colored gel in protein separation and western blotting is comparable to that of a non-colored standard gel [24].

Quantitative Data and Reagent Specifications

Comparative Buffer Formulations for Electrophoresis

Table 1: Composition of sample and running buffers for different PAGE methodologies. Adapted from [4].

| Method / Component | SDS-PAGE (Standard Denaturing) | BN-PAGE (Native) | NSDS-PAGE (Partial Denaturing) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Buffer | 106 mM Tris HCl, 141 mM Tris Base, 0.51 mM EDTA, 2% LDS, 10% Glycerol, pH 8.5 | 50 mM BisTris, 50 mM NaCl, 10% Glycerol, 0.001% Ponceau S, pH 7.2 | 100 mM Tris HCl, 150 mM Tris Base, 0.01875% Coomassie G-250, 10% Glycerol, pH 8.5 |

| Running Buffer | 50 mM MOPS, 50 mM Tris Base, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, pH 7.7 | Cathode: 50 mM BisTris, 50 mM Tricine, 0.02% Coomassie G-250, pH 6.8Anode: 50 mM BisTris, 50 mM Tricine, pH 6.8 | 50 mM MOPS, 50 mM Tris Base, 0.0375% SDS, pH 7.7 |

| Key Characteristic | Fully denaturing; separates by mass | Native; separates by mass/charge/size | Partial denaturation; retains some activity & metal cofactors |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Stacking Gel Electrophoresis

Table 2: Key reagents and materials used in stacking gel electrophoresis, with their specific functions in the process.

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Acrylamide / Bis-acrylamide | Forms the cross-linked polymer matrix that creates the porous gel structure for molecular sieving [7]. |

| Tris-HCl Buffers | Provides the appropriate pH for the stacking (pH ~6.8) and resolving (pH ~8.8) gels, critical for the discontinuous buffer system [7] [23]. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | An ionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge, allowing separation based primarily on molecular weight [7] [23]. |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) & TEMED | Catalytic system that generates free radicals to initiate and accelerate the polymerization of acrylamide [7] [23]. |

| Glycine | Key component of the running buffer; its pH-dependent mobility is the driving force behind the stacking process [7]. |

| DTT or BME (Beta-Mercaptoethanol) | Reducing agents that break disulfide bonds in proteins, ensuring complete unfolding and accurate molecular weight determination [23]. |

| Tartrazine / Brilliant Blue FCF | Acidic dyes that can be incorporated into the stacking gel to visually demarcate wells without interfering with separation [24]. |

Advanced Techniques and Future Directions

While the principle of the stacking gel remains constant, innovations continue to emerge. The development of Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE) modifies standard conditions by reducing SDS concentration and omitting heating and reducing agents. This allows for high-resolution separation while retaining native enzymatic activity and metal cofactors in many proteins, bridging the gap between denaturing SDS-PAGE and native PAGE [4].

Furthermore, the field of detection is advancing. Online Intrinsic Fluorescence Imaging techniques are being developed to allow for real-time, label-free monitoring of protein migration during electrophoresis, providing immediate data without the need for post-run staining [25]. Finally, the integration of artificial intelligence, as seen in tools like GelGenie, is beginning to revolutionize gel image analysis by using AI-powered segmentation to identify bands with high accuracy and consistency, surpassing the capabilities of traditional software [26].

The journey from a diffuse well to a sharp protein stack is a beautifully orchestrated physicochemical process that lies at the very heart of reliable protein electrophoresis. The stacking gel is not a mere preliminary step but an essential molecular focusing device. Its discontinuous design, leveraging differences in pH, ionic strength, and gel porosity, ensures that proteins enter the resolving dimension as a unified, concentrated band. This is the non-negotiable foundation for achieving the high-resolution separation that drives discovery in proteomics, diagnostics, and therapeutic development. A deep understanding of this process empowers researchers to troubleshoot issues, optimize protocols, and fully leverage the power of electrophoresis in their scientific pursuits.

Implementing Stacking Gels in SDS-PAGE: Protocols and Best Practices

Standard Protocol for Casting a Two-Layer Polyacrylamide Gel

This technical guide details the standard protocol for casting a two-layer polyacrylamide gel, a foundational technique in protein electrophoresis. The two-layer gel system, comprising a stacking gel and a resolving gel, is engineered to leverage principles of isotachophoresis to concentrate protein samples into sharp bands before their separation by molecular weight. This process is critical for achieving high-resolution analysis of complex protein mixtures, which is indispensable in modern biochemical research, proteomics, and drug development. The protocol outlined herein provides researchers with a reliable methodology to prepare gels that deliver consistent, reproducible results for applications ranging from routine protein analysis to advanced proteoform characterization [27] [8] [7].

The discontinuous buffer system of a two-layer polyacrylamide gel is the cornerstone of its high resolving power. In the presence of the ionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), proteins denature into linear polypeptides with a uniform negative charge-to-mass ratio [27] [7]. When an electric field is applied, these SDS-protein complexes migrate through two distinct gel phases.

- The Resolving Gel: This lower layer contains a higher concentration of polyacrylamide (typically 6-15%), creating a smaller pore size that acts as a molecular sieve. Proteins are separated based on their polypeptide chain length, with smaller proteins migrating faster than larger ones [27] [8].

- The Stacking Gel: This upper layer has a lower acrylamide concentration (e.g., 4-5%), larger pores, and a different pH (6.8) compared to the resolving gel (pH 8.8). The purpose of the stacking gel is to concentrate all protein samples from the relatively large volume of the well into a single, sharp band before they enter the resolving gel. This concentration occurs due to the differential mobility of glycine ions, chloride ions, and the protein-SDS complexes in the discontinuous pH environment, creating a phenomenon that focuses the proteins [8] [7].

This two-stage process ensures that proteins enter the resolving gel simultaneously as tight bands, which is essential for achieving clear separation and high resolution, even for proteins of similar molecular weight [27] [7].

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists the essential materials and reagents required for casting a two-layer polyacrylamide gel.

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Glass Plates, Spacers, and Combs | Form the cassette or mold in which the gel is polymerized. The comb creates wells for sample loading [27]. |

| 40% Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide Stock Solution | Pre-mixed solution of acrylamide and crosslinker (bis-acrylamide). The ratio (e.g., 29:1, 37.5:1) and final concentration determine gel pore size [28] [7]. |

| 1.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.8 (Resolving Gel Buffer) | Provides the appropriate alkaline pH and ionic environment for the resolving gel [7]. |

| 0.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8 (Stacking Gel Buffer) | Provides the lower pH environment critical for the stacking phenomenon in the upper gel [7]. |

| 10% Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Anionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge [27] [7]. |

| 10% Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | Initiates the free-radical polymerization of acrylamide and bis-acrylamide. A fresh solution is recommended [28] [7]. |

| N,N,N',N'-Tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED) | Catalyst that stabilizes free radicals and accelerates the polymerization process [7]. |

| Water-Saturated Butanol or Isopropanol | layered over the resolving gel solution to exclude oxygen, which inhibits polymerization, resulting in a flat gel surface [27]. |

| Electrophoresis Running Buffer | Typically Tris-Glycine-SDS buffer, which conducts current and provides the ions necessary for the discontinuous buffer system [8]. |

Safety Considerations

Warning: Acrylamide and bis-acrylamide monomers are potent neurotoxins and are suspected carcinogens. Always wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), including gloves and safety glasses, when handling these chemicals, whether in powder or liquid form. Handle all solutions in a fume hood whenever possible and dispose of waste according to institutional safety guidelines [29].

Detailed Step-by-Step Protocol

Gel Casting Setup and Preparation

- Assemble the Gel Cassette: Thoroughly clean two glass plates and spacers with ethanol or a laboratory detergent. Assemble the plates with the spacers in between, secured firmly with binder clips or a casting frame to create a leak-proof cassette [27].

- Prepare the Resolving Gel Solution: In a clean beaker or conical flask, mix the components for the resolving gel in the order listed in the table below. Gently swirl to mix after adding each component. Do not add TEMED until you are ready to pour the gel, as polymerization will begin immediately.

Table: Example Resolving Gel Formulations for Different Protein Separation Ranges. Volumes are for one mini-gel (~8-10 mL).

| Component | 7% Gel (High MW: 50-150 kDa) | 10% Gel (Mid MW: 20-100 kDa) | 12% Gel (Low MW: 10-60 kDa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 4.88 mL | 3.88 mL | 2.88 mL |

| 1.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.8 | 2.50 mL | 2.50 mL | 2.50 mL |

| 40% Acrylamide/Bis Solution (29:1) | 1.75 mL | 2.50 mL | 3.00 mL |

| 10% SDS | 0.10 mL | 0.10 mL | 0.10 mL |

| 10% APS | 0.10 mL | 0.10 mL | 0.10 mL |

| TEMED | 0.01 mL | 0.01 mL | 0.01 mL |

- Pour the Resolving Gel: Immediately after adding TEMED, pipette the resolving gel solution into the assembled cassette, leaving space for the stacking gel (typically to about 1-1.5 cm below the top of the shorter plate).

- Overlay with Solvent: Carefully add a layer of water-saturated butanol or isopropanol on top of the gel solution. This layer flattens the gel surface and creates an airtight seal to prevent inhibition of polymerization. Allow the gel to polymerize completely for 20-30 minutes. A distinct schlieren line will appear at the gel-solvent interface once polymerization is complete [27].

- Prepare and Pour the Stacking Gel: Once the resolving gel has set, pour off the overlay solution and rinse the top of the gel with distilled water to remove any residual solvent or unpolymerized acrylamide. In a separate tube, prepare the stacking gel solution as per the table below. Add TEMED last, mix, and pour the solution onto the resolving gel.

Table: Standard 4-5% Stacking Gel Formulation.

| Component | Volume for 1-2 mini-gels |

|---|---|

| Water | 3.05 mL |

| 0.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8 | 1.25 mL |

| 40% Acrylamide/Bis Solution (29:1) | 0.50 mL |

| 10% SDS | 0.05 mL |

| 10% APS | 0.05 mL |

| TEMED | 0.005 mL |

- Insert the Comb: Immediately after pouring the stacking gel, carefully insert a clean comb into the cassette, avoiding air bubbles in the wells. Allow the stacking gel to polymerize for 15-20 minutes [27].

Post-Casting and Electrophoresis Setup

- After polymerization, remove the comb and binder clips/spacers used for casting. Rinse the wells gently with running buffer to remove any unpolymerized acrylamide.

- Mount the gel cassette into the electrophoresis chamber according to the manufacturer's instructions. Fill the upper and lower chambers with running buffer, ensuring that the wells in the upper chamber are completely submerged [27] [8].

- Prepare protein samples by mixing them with 2X Laemmli sample buffer (containing SDS and a reducing agent like β-mercaptoethanol) and heating at 95-100°C for 3-5 minutes to fully denature the proteins [27] [8].

- Load the denatured samples and an appropriate protein molecular weight marker into the wells.

- Connect the electrodes and apply a constant voltage to run the gel. A common strategy is to start at a lower voltage (e.g., 80 V) through the stacking gel, then increase to 120-150 V once the dye front has entered the resolving gel. The run is complete when the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel [8] [30].

Optimization and Troubleshooting

Optimizing Electrophoresis Conditions

Managing heat is critical for obtaining straight, well-resolved protein bands. The relationship between electrical settings and heat production is governed by Joule's Law (Heat ∝ Power = V * I) [30].

- Constant Voltage vs. Constant Current: Running at constant voltage is common, as the current and heat production will naturally decrease during the run. Constant current maintains a consistent run time but can cause increased voltage and heat later, leading to "smiling" bands (warmer in the center). For constant current, running the gel in a cold room or with a cooling unit is advised [30].

- General Guidelines: Start the run at a lower voltage (50-80 V) to allow proteins to stack properly in the stacking gel. After 20-30 minutes, increase the voltage (e.g., 100-150 V for mini-gels) to complete the run. A rule of thumb is 5-15 V per cm of gel length [30].

Common Issues and Resolutions

- Poor Polymerization: Ensure APS and TEMED are fresh and have been added. Inadequate mixing can also cause uneven polymerization.

- Smiling Bands: This is typically caused by excessive heat. Reduce the voltage/current or implement active cooling [30].

- Diffuse or Streaked Bands: The sample may not have been fully denatured. Ensure the sample buffer contains sufficient SDS and reducing agent, and that the heating step was performed correctly. Overloading the well can also cause this issue.

- Vertical Streaks: Air bubbles trapped under the gel or between the glass plates can cause distortions.

Advanced Applications and Downstream Analysis

The two-layer polyacrylamide gel is not an endpoint but a gateway to advanced analytical techniques. Following electrophoresis, the separated proteins can be processed in several ways:

- Protein Visualization: Gels can be stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue for general protein detection (sensitivity in the microgram range) or with silver stain for high-sensitivity detection (nanogram range) [31].

- Western Blotting (Immunoblotting): Proteins are transferred from the gel onto a membrane for specific detection using antibodies [7].

- Mass Spectrometry (MS) Analysis: Protein bands or spots of interest can be excised from the gel, digested with trypsin, and identified by MS. Recent advances, such as the PEPPI-MS protocol, use high-resolution SDS-PAGE as a pre-fractionation step for intact proteoforms (top-down proteomics) before MS analysis, significantly increasing proteome coverage [32].

- Two-Dimensional Electrophoresis (2D-PAGE): The SDS-PAGE protocol described here serves as the second dimension in 2D-PAGE, where proteins are first separated by their isoelectric point and then by molecular weight, providing the highest resolution for analyzing complex protein mixtures [33] [34].

Workflow and Principle Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the key stages and underlying principles of the two-layer gel system, from casting to separation.

Figure 1: Workflow for casting a two-layer polyacrylamide gel and the fundamental principle of stacking.

In the realm of protein electrophoresis research, the stacking gel serves a critical, though often underappreciated, function within the discontinuous buffer system of SDS-PAGE. Its primary purpose is not to separate proteins by size, but to concentrate and align all sample components into a sharp, unified band before they enter the resolving gel, thereby guaranteeing the high-resolution separation that is fundamental to accurate protein analysis [35] [36]. This technical guide delves into the core formulation parameters—specifically, the low acrylamide percentage and the distinct acidic pH—that enable this stacking phenomenon. We provide a detailed examination of the underlying mechanisms, standardized formulations, and practical protocols to empower researchers and drug development professionals to optimize this crucial first step in protein characterization.

The pursuit of optimal protein separation is a cornerstone of modern biochemical and proteomic research. Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE), particularly in its denaturing SDS-PAGE form, is a ubiquitous technique for achieving this separation based on molecular weight [35] [37]. The most common implementation of this technique employs a discontinuous buffer system using a gel composed of two distinct parts: the resolving gel (or separating gel) and the stacking gel [36] [38].

While the resolving gel is responsible for the final separation of proteins by size, the stacking gel acts as a crucial preparatory phase. When a protein sample is loaded into the wells of a gel, it occupies a volume that is relatively deep. If this diffuse sample were to enter the resolving gel directly, it would result in smeared and poorly resolved bands [36]. The stacking gel eliminates this issue by leveraging differences in pH and gel porosity to focus the proteins into a narrow, sharp band. This process ensures that all proteins begin their journey through the resolving gel at the same starting point, which is a prerequisite for precise separation and reliable molecular weight determination [35] [38]. Understanding and correctly formulating the stacking gel is therefore not a mere procedural step, but a fundamental aspect of producing publication-quality and analytically sound data.

Core Formulation Parameters

The stacking effect is engineered through a specific combination of chemical parameters that create a transient state of highly regulated protein mobility. The key variables are the acrylamide concentration and the pH of the gel buffer.

Acrylamide Percentage

The stacking gel features a low percentage of acrylamide, typically between 4% and 5% [35] [39] [38]. This low concentration creates a gel matrix with large pores, offering minimal resistance to the migrating proteins [36]. The primary function of this large-pore environment is not to sieve proteins by size, but to allow them to move freely and quickly under the influence of the electric field, facilitating their concentration into a single, tight band before they encounter the sieving matrix of the resolving gel.

Buffer and pH

The pH of the stacking gel buffer is its most distinctive feature. It is formulated at an acidic pH, typically 6.8, which is significantly lower than the pH of the resolving gel (usually 8.8) and the running buffer (typically 8.3) [35] [36] [38]. This pH differential is the engine of the stacking mechanism. It directly governs the ionic state of key molecules in the system, particularly the glycine from the running buffer, to create a sharp boundary that confines and stacks the proteins.

Table 1: Standard Formulation for a Stacking Gel (for a 5 mL gel)

| Reagent | Order | Volume | Final Concentration/Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| dH₂O | 1 | 3.05 mL | Solvent |

| 0.5M or 1.0M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8 | 2 | 1.25 mL | Buffer (est. 125-250 mM) |

| 10% SDS | 3 | 50 µL | 0.1% (w/v), maintains protein charge |

| 30% Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide (29.2:0.8) | 4 | 650 µL | ~4% (w/v), creates large-pore matrix |

| 10% Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | 5 | 25 µL | Radical initiator for polymerization |

| TEMED | 6 | 10 µL | Catalyst for polymerization |

Source: Adapted from [39]. Reagents should be added in the specified order, with APS and TEMED added last to initiate polymerization immediately.

The Science Behind the Stacking Mechanism

The discontinuous buffer system relies on the manipulation of ion mobility to achieve stacking. The key players in this process are the leading ions (chloride, Cl⁻ from Tris-HCl in the gel), the trailing ions (glycine from the running buffer), and the proteins (coated with SDS).

In the running buffer at pH 8.3, glycine exists primarily as a glycinate anion, carrying a negative charge [36] [37]. However, when this glycinate enters the low-pH (6.8) environment of the stacking gel, its amino group becomes protonated, shifting its equilibrium overwhelmingly towards a zwitterionic form with no net charge [36]. This has a profound effect on its electrophoretic mobility: the zwitterionic glycine moves through the gel much more slowly than the fully charged chloride ions.