The Charge Effect: How Protein Net Charge Governs Migration and Resolution in Native PAGE

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of how a protein's intrinsic net charge dictates its electrophoretic mobility in Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE).

The Charge Effect: How Protein Net Charge Governs Migration and Resolution in Native PAGE

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of how a protein's intrinsic net charge dictates its electrophoretic mobility in Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE). Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the fundamental principles of charge-based separation, detail methodological setups for different protein types, address common troubleshooting scenarios related to charge, and validate findings through comparative analysis with denaturing techniques. The guide synthesizes foundational knowledge with advanced applications to empower the study of native protein complexes, enzyme activity, and protein-protein interactions.

The Core Principles: Understanding the Interplay of Charge, Size, and Shape in Native PAGE

Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Native PAGE) is a powerful analytical technique that separates proteins based on their net charge, size, and three-dimensional shape while maintaining their native conformation [1] [2]. Unlike denaturing SDS-PAGE, which disrupts protein structure and renders proteins inactive, Native PAGE preserves protein complexes in their functional state, allowing researchers to study quaternary structure, enzymatic activity, and protein-protein interactions under non-denaturing conditions [1] [3]. This technique is particularly valuable for investigating membrane proteins, protein complexes, and enzymes whose functional properties must be retained for subsequent analysis.

The fundamental principle of Native PAGE relies on the fact that most proteins carry a net negative charge in alkaline running buffers, causing them to migrate toward the anode when an electric field is applied [1]. The rate of migration is determined by the protein's charge density (number of charges per molecular mass) and the frictional force exerted by the gel matrix, which creates a molecular sieving effect [2]. Proteins with higher negative charge density migrate faster, while larger proteins experience greater frictional forces that slow their progression through the gel [1]. This dual dependence on both charge and physical dimensions makes Native PAGE uniquely suited for analyzing proteins in their biologically active states.

Fundamental Principles of Protein Separation in Native PAGE

The Role of Protein Charge in Electrophoretic Migration

In Native PAGE, protein migration is governed primarily by the protein's intrinsic charge at the pH of the running buffer [2] [4]. Unlike SDS-PAGE, where SDS confers a uniform negative charge to all proteins, Native PAGE preserves the protein's native charge distribution, making separation dependent on the protein's isoelectric point (pI) relative to the buffer pH [5]. Proteins with pI values below the buffer pH become negatively charged and migrate toward the anode, while proteins with pI values above the buffer pH carry a positive charge and would theoretically migrate toward the cathode [6]. However, in standard Native PAGE systems using alkaline buffers, most proteins exhibit a net negative charge and migrate toward the anode [1].

The relationship between protein charge and migration can be described by the equation for electrophoretic mobility (μ): μ = ZeffQp/6πRsη where Zeff represents the effective valence (unitless ratio of Coulombic charge to elementary proton charge), Qp is the proton fundamental charge, Rs is the Stokes radius of the protein, and η is the solvent viscosity [5]. This equation highlights how both charge (Zeff) and size (Rs) jointly determine a protein's migration rate through the gel matrix.

Research has demonstrated significant disparities between theoretically calculated protein charges and experimentally measured values. For cytochrome c, the measured valence at pH 7.0 was approximately 2-fold lower than predicted from primary structure analysis, highlighting the complex nature of charge-charge interactions on polyelectrolyte surfaces [5]. These interactions are influenced by buffer composition, ionic strength, and preferential binding of specific ions to the protein surface [5].

Molecular Sieving and the Influence of Protein Size and Shape

The polyacrylamide gel matrix creates a porous network that acts as a molecular sieve, imparting size-dependent frictional resistance to migrating proteins [2] [4]. Smaller proteins navigate the pores more easily and migrate farther, while larger proteins are impeded by the gel matrix [7]. The pore size of the gel is controlled by the acrylamide concentration, with lower percentages (e.g., 6-8%) creating larger pores suitable for high molecular weight complexes, and higher percentages (12-16%) creating smaller pores for better resolution of lower molecular weight proteins [1].

A protein's three-dimensional shape further influences its migration by affecting its hydrodynamic size [7]. A compact, globular protein will migrate faster than an elongated protein of the same molecular weight due to differences in frictional drag [7]. This shape sensitivity enables Native PAGE to detect conformational changes in proteins that alter their hydrodynamic properties without affecting their molecular weight.

Buffer Systems and pH Considerations

The choice of buffer system and pH is critical in Native PAGE as it determines the net charge on proteins and their direction of migration [1] [4]. Different buffer systems operate at specific pH ranges:

Table 1: Native PAGE Buffer Systems and Their Characteristics

| Gel System | Operating pH Range | Key Features | Recommended Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tris-Glycine | 8.3-9.5 | Traditional Laemmle system; preserves native net charge | Studying smaller molecular weight proteins (20-500 kDa) [1] |

| Tris-Acetate | 7.2-8.5 | Better resolution of larger molecular weight proteins | Analyzing proteins >150 kDa [1] |

| NativePAGE Bis-Tris | ~7.5 | Uses Coomassie G-250 to impart negative charge; enables separation regardless of pI | Membrane proteins, hydrophobic proteins, or when separation by molecular weight is desired [1] |

For basic proteins with high pI values, the standard alkaline buffer systems may cause these proteins to carry a net positive charge and migrate toward the cathode, potentially being lost from the gel [6] [4]. Specialized protocols using low pH gel systems or charge-shifting molecules like Coomassie G-250 are employed to ensure anodic migration of basic proteins [1] [4].

Native PAGE Methodologies and Technical Approaches

Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE)

Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) is a specialized variant that uses the anionic dye Coomassie Blue G-250 to bind to protein surfaces and confer a net negative charge while maintaining proteins in their native state [1] [6]. This technique, developed by Schägger and von Jagow, overcomes the limitation of traditional native gel electrophoresis by providing a near-neutral operating pH and detergent compatibility [1]. In BN-PAGE, Coomassie G-250 is present in the cathode buffer, providing a continuous flow of dye into the gel during electrophoresis [1].

The binding of Coomassie G-250 offers two significant advantages: (1) it converts basic proteins (pI >7.5) to a net negative charge, allowing them to migrate toward the anode, and (2) it reduces aggregation of membrane proteins and proteins with significant surface-exposed hydrophobic areas by binding nonspecifically to hydrophobic sites and converting them to negatively charged sites [1]. BN-PAGE is particularly valuable for studying membrane protein complexes and mitochondrial complexes, with a separation range from 10 kDa to 10 MDa [6].

Clear Native PAGE (CN-PAGE) and High-Resolution Clear Native PAGE (hrCNE)

Clear Native PAGE (CN-PAGE) and its high-resolution variant (hrCNE) are non-colored alternatives to BN-PAGE that differ primarily in cathode buffer composition [6]. In CN-PAGE, proteins migrate according to their intrinsic isoelectric point without charged compounds that could bind and cause a charge shift [6]. However, CN-PAGE is limited to acidic soluble proteins (pI <7.5), as basic proteins migrate toward the cathode and are lost [6].

High-Resolution Clear Native PAGE (hrCNE) represents an improvement over traditional CN-PAGE. The cathode buffer for hrCNE contains mixed anionic micelles formed from a neutral and an anionic detergent that can bind to hydrophobic proteins and some soluble proteins, similar to Coomassie dye in BN-PAGE [6]. This charge-shift technique makes hrCNE particularly suitable for analyzing fluorescently labeled proteins or conducting in-gel catalytic activity assays where dye interference would be problematic [6].

Comparative Analysis of Native PAGE Variants

Table 2: Comparison of Native PAGE Methodologies

| Method | Charge Modification | Resolution | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Native PAGE | None; relies on intrinsic protein charge | Moderate | Preserves native charge; simple protocol | Limited to acidic proteins in standard alkaline buffers [6] |

| BN-PAGE | Coomassie Blue G-250 binding | High | Compatible with membrane proteins; separates basic and acidic proteins | Dye may interfere with some downstream applications [1] [6] |

| hrCNE | Mixed anionic micelles | High | No dye interference; ideal for fluorescent tags and activity assays | Less robust than BN-PAGE [6] |

Native PAGE separation principles determine the optimal choice of methodology for different protein types and research applications.

Experimental Protocol for Native PAGE

Gel Preparation

The following protocol describes the preparation of a basic non-denatured discontinuous gel for separating acidic proteins [4]:

Separating Gel (17%, 10 mL):

- 4.25 mL 40% Acr-Bis solution (Acr:Bis = 19:1)

- 2.5 mL 4× Separating Gel Buffer (1.5 mol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.8)

- 3.2 mL Deionized Water

- 35 μL 10% Ammonium Persulfate (APS)

- 15 μL TEMED

Stacking Gel (4%, 5 mL):

- 0.5 mL 40% Acr-Bis solution (Acr:Bis = 19:1)

- 1.25 mL 4× Stacking Gel Buffer (0.5 mol/L Tris-HCl, pH 6.8)

- 3.2 mL Deionized Water

- 35 μL 10% APS

- 15 μL TEMED

The separating gel components (except APS and TEMED) are mixed and degassed before adding polymerization catalysts. After adding APS and TEMED, the solution is poured to about 3/4 of the gel cassette height and overlaid with isopropanol or water to create a flat interface. Once polymerized (approximately 30 minutes), the stacking gel is prepared similarly and poured over the polymerized separating gel. A sample comb is inserted, and polymerization proceeds for another 30 minutes [4].

Sample Preparation

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful Native PAGE separation. For standard Native PAGE, samples are typically mixed with Native Sample Buffer (e.g., Tris-Glycine Native Sample Buffer) containing glycerol to increase density and a tracking dye [1]. It is essential to avoid denaturing agents such as SDS, urea, or reducing agents like β-mercaptoethanol [7].

For BN-PAGE, samples are mixed with NativePAGE Sample Buffer and NativePAGE 5% G-250 Sample Additive [1]. The Coomassie G-250 dye in the sample additive binds to proteins prior to electrophoresis, initiating the charge-shift process. For membrane proteins, solubilization with appropriate detergents (dodecylmaltoside, Triton X-100, or digitonin) is necessary to extract protein complexes while preserving native structure [6].

Electrophoresis Conditions

The polymerized gel is placed in an electrophoresis chamber filled with appropriate running buffer. For Tris-Glycine gels, the running buffer typically consists of 25 mM Tris and 192 mM glycine at pH 8.3-9.5 [1]. For BN-PAGE, specialized cathode and anode buffers are used, with Coomassie G-250 included in the cathode buffer [1] [3].

Samples are loaded into wells, and electrophoresis is performed at constant voltage or current. Typical conditions for a mini-gel system are 100 V constant voltage for approximately 20 minutes until the tracking dye enters the separation gel, then increased to 160 V constant voltage for the remainder of the separation (approximately 60-80 minutes total) [4]. It is crucial to maintain cool temperatures during electrophoresis, often by using a cooling system or performing the run in a cold room, as heating can denature proteins and alter migration patterns [4].

Research Reagent Solutions for Native PAGE

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Native PAGE Experiments

| Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide-Bis Solution | Forms the porous gel matrix | Total concentration (T%) determines pore size; crosslinker ratio (C%) affects gel elasticity [4] |

| Tris-HCl Buffers | Maintains pH during electrophoresis | Different pH for stacking (pH 6.8) and separating (pH 8.8) gels in discontinuous systems [4] |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | Polymerization initiator | Provides free radicals for acrylamide polymerization [4] |

| TEMED | Polymerization catalyst | Accelerates the polymerization reaction initiated by APS [4] |

| Coomassie G-250 | Charge-shift molecule in BN-PAGE | Binds to proteins imparting negative charge without denaturation [1] |

| Glycine | Leading ion in discontinuous systems | Facilitizes stacking of proteins at the stack-separating gel interface [1] |

| Non-ionic Detergents | Solubilizes membrane proteins | Dodecylmaltoside, Triton X-100, or digitonin used for extracting membrane complexes [6] |

| Glycerol | Increases sample density | Added to sample buffer to prevent diffusion from wells during loading [4] |

| Tracking Dyes | Visualize migration progress | Bromophenol blue or Ponceau S used to monitor electrophoresis progression [6] [4] |

Troubleshooting and Optimization Strategies

Common Issues and Solutions

Poor Resolution: Optimize acrylamide concentration gradient for the protein size range of interest. For broad molecular weight ranges, use gradient gels (e.g., 4-16% or 3-12%) [1] [7].

Protein Aggregation: For membrane or hydrophobic proteins, increase detergent concentration or use charge-shift methods like BN-PAGE to reduce aggregation [1] [6].

Altered Migration Patterns: Ensure consistent buffer pH and ionic strength between experiments. Check for proteolysis by including protease inhibitors in sample preparation [7].

In-Gel Artifacts: Run electrophoresis at 4°C to minimize heating effects that can denature proteins. Use fresh ammonium persulfate solutions to ensure complete gel polymerization [4].

Method Selection Guidelines

Choosing the appropriate Native PAGE variant depends on the protein properties and research objectives:

For acidic soluble proteins with pI <7.0: Traditional Native PAGE with Tris-Glycine or Tris-Acetate systems [1]

For basic proteins with pI >7.5: BN-PAGE or specialized low-pH systems with reversed electrode configuration [6] [4]

For membrane protein complexes: BN-PAGE with appropriate detergents (dodecylmaltoside for individual complexes, digitonin for supercomplexes) [6]

For enzymatic activity assays: hrCNE to avoid dye interference with activity measurements [6]

For maximum resolution of complex mixtures: 2D-PAGE combining Native PAGE in the first dimension with SDS-PAGE in the second dimension [8]

Native PAGE remains an indispensable technique in the protein researcher's toolkit, offering unique capabilities for analyzing proteins in their native, functional states. The separation mechanism, dependent on both protein charge and size/shape, provides information complementary to denaturing electrophoretic methods. Through various methodological adaptations—including BN-PAGE, CN-PAGE, and hrCNE—researchers can tailor the technique to diverse protein types and experimental goals.

Understanding how protein charge affects migration in Native PAGE is fundamental to proper experimental design and data interpretation. The effective valence of proteins in electrophoretic conditions often differs significantly from theoretical predictions due to ion-binding and charge-shift phenomena [5]. By selecting appropriate buffer systems, pH conditions, and potential charge-modifying agents, researchers can optimize separation for their specific protein systems, advancing our understanding of protein structure-function relationships in both basic research and drug development applications.

In the realm of protein analysis, gel electrophoresis stands as a fundamental technique for separating complex protein mixtures. At its core, this technique relies on a simple yet powerful principle: charged molecules migrate when subjected to an electric field. Proteins, as amphoteric molecules containing both positively and negatively charged amino acid residues, possess a net charge that varies with their environment. This net charge constitutes the primary driving force behind their electrophoretic mobility in native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Unlike denaturing techniques such as SDS-PAGE that obscure intrinsic charge characteristics, native PAGE preserves proteins in their natural conformation, enabling separation based on the combined effects of charge, size, and shape [2] [9]. For researchers in drug development and proteomics, understanding the precise role of net charge is essential for interpreting experimental results, optimizing separation conditions, and studying protein function in near-physiological states.

The direction and speed of a protein's migration in native PAGE are direct reflections of its electrostatic properties at a given pH. When an electric field is applied, proteins with a net negative charge migrate toward the positively charged anode, while those with a net positive charge move toward the negatively charged cathode [10] [2]. The magnitude of this net charge determines the protein's mobility through the gel matrix—proteins with higher charge density experience greater electrostatic pull and migrate faster, assuming similar sizes and shapes. This fundamental relationship between charge and mobility provides the theoretical foundation for native PAGE and forms the basis for its application in characterizing native protein complexes, studying protein-protein interactions, and analyzing functional enzymatic activity [2] [9].

The Biochemical Basis of Protein Charge

Amino Acid Composition and Ionizable Groups

A protein's net charge originates from the ionizable side chains of its constituent amino acids. The specific combination of acidic residues (aspartic acid and glutamic acid), which carry negatively charged carboxylate groups (-COO⁻) at neutral pH, and basic residues (lysine, arginine, and histidine), which carry positively charged groups (-NH₃⁺ for lysine, guanidinium for arginine, and imidazolium for histidine) at neutral pH, determines its overall charge signature [10]. At any given pH, the protein's net charge represents the sum of all these positive and negative charges. Each ionizable group has a characteristic acid dissociation constant (pKₐ) that influences its protonation state across the pH spectrum. Understanding this biochemical foundation is crucial for predicting electrophoretic behavior and designing appropriate buffer systems for separation.

The relationship between a protein's net charge and the surrounding pH is quantified by its isoelectric point (pI), defined as the specific pH at which the protein carries no net electrical charge [10]. This fundamental property serves as a critical predictor of electrophoretic behavior:

- Below its pI: A protein exists in an environment where the pH is lower than its pI, resulting in protonation of basic groups and the protein carrying a net positive charge [10]

- Above its pI: A protein exists in an environment where the pH is higher than its pI, resulting in deprotonation of acidic groups and the protein carrying a net negative charge [10]

Table 1: Relationship Between Buffer pH, Protein Charge, and Migration Direction

| Buffer pH Relative to Protein pI | Net Protein Charge | Migration Direction |

|---|---|---|

| pH < pI | Positive | Toward cathode (-) |

| pH = pI | Zero | No migration |

| pH > pI | Negative | Toward anode (+) |

The Role of Buffer pH in Determining Net Charge

In native PAGE, the buffer pH is the critical experimental parameter that determines a protein's net charge by establishing the protonation state of its ionizable groups [10]. This relationship makes electrophoresis a powerful tool for characterizing protein properties, as researchers can manipulate separation outcomes by simply adjusting the buffer conditions. For example, a protein with a pI of 5.5 will carry a net negative charge in a Tris-glycine buffer at pH 8.3 and migrate toward the anode, whereas the same protein would carry a net positive charge and migrate toward the cathode in a citrate buffer at pH 4.5.

The buffer pH not only determines the direction of migration but also affects its rate. According to Ohm's law, the electrophoretic mobility (μ) of a protein is proportional to its net charge (Q) and inversely proportional to the frictional coefficient (f), which relates to the protein's size and shape: μ = Q/f [2]. Thus, at a constant pH, proteins with higher net charge will migrate faster through the gel matrix than those with lower net charge, assuming similar sizes and shapes. This charge-based separation is the hallmark of native PAGE and distinguishes it from SDS-PAGE, where the uniform charge imparted by SDS binding makes separation primarily dependent on molecular size [2] [9].

Native PAGE: Separation Based on Native Charge Properties

Fundamental Principles and Comparison with SDS-PAGE

Native PAGE represents a fundamental approach in protein separation that preserves the protein's higher-order structure and biological activity. Unlike denaturing electrophoresis methods, native PAGE employs non-denaturing buffers without SDS or reducing agents, maintaining the protein's native conformation, quaternary structure, and post-translational modifications [9]. This preservation enables researchers to study proteins in a state that closely resembles their physiological condition, providing unique insights into functional properties that would be lost under denaturing conditions.

The separation mechanism in native PAGE is multifaceted, depending on the protein's intrinsic charge, molecular size, and three-dimensional shape [2] [9]. The intrinsic charge dictates the electrostatic driving force, while the size and shape collectively determine the frictional resistance experienced as the protein migrates through the porous gel matrix. This complex interplay of factors means that native PAGE can resolve protein species that would co-migrate in SDS-PAGE, such as different oligomeric states of the same polypeptide or proteins with similar mass but different charge characteristics.

Table 2: Key Differences Between Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE

| Feature | Native PAGE | SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Size, shape, and intrinsic charge | Molecular weight (polypeptide chain length) |

| SDS | Absent | Present (denatures and imparts uniform charge) |

| Protein State | Native conformation | Denatured, unfolded |

| Protein Complexes | Preserved | Dissociated |

| Biological Activity | Often retained | Lost |

| Resolution | Lower, more complex interpretation | Higher, simpler interpretation |

| Typical Uses | Studying protein complexes, enzyme activity, interactions | Determining molecular weight, analyzing purity |

Experimental Considerations for Native PAGE

Successful implementation of native PAGE requires careful attention to several experimental parameters. The buffer system must maintain a pH that preserves protein structure while promoting optimal separation. Common buffer systems include Tris-glycine (pH 8.3-8.8) for basic separations and other specialized formulations for specific applications [11]. The polyacrylamide concentration determines the gel pore size and thus the separation range—lower percentages (e.g., 7-10%) are suitable for higher molecular weight proteins, while higher percentages (12-20%) provide better resolution for smaller proteins [2].

Temperature control is another critical factor, as the absence of denaturants makes proteins more vulnerable to heat-induced aggregation or conformational changes. Running native PAGE at 4°C is a common practice to minimize these effects [9]. Additionally, the ionic strength of the buffer must be optimized—too low and proteins may not solubilize properly; too high and excessive current and heating may occur during electrophoresis. Sample preparation is also crucial, requiring gentle lysis conditions with appropriate protease and phosphatase inhibitors to prevent degradation while maintaining native structure [12].

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Standard Native PAGE Protocol

The following protocol provides a standardized approach for native PAGE separation, optimized for preserving protein structure and function while achieving high-resolution separation based on native charge properties:

Gel Preparation: Prepare a non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel (typically 6-10% acrylamide depending on protein size) using Tris-HCl or Tris-glycine buffer at the desired pH (commonly pH 8.8 for the resolving gel). Omit SDS from all solutions. Add ammonium persulfate (APS) and TEMED to initiate polymerization. Pour the gel between glass plates and allow it to polymerize completely (approximately 30 minutes) [2] [13].

Sample Preparation: Lyse cells or tissues using a non-denaturing lysis buffer (e.g., Tris-HCl, NP-40, or CHAPS-based buffers) containing protease inhibitors. Maintain samples at 4°C throughout preparation. Centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove insoluble debris. Determine protein concentration using a compatible assay (Bradford or BCA). Mix protein sample with native sample buffer (typically containing glycerol, Tris-HCl, and tracking dye) without heating [12].

Electrophoresis: Assemble the gel apparatus and fill both chambers with native running buffer (e.g., Tris-glycine, pH 8.3). Load samples into wells alongside native molecular weight markers. Run electrophoresis at constant voltage (typically 100-150 V for mini-gels) at 4°C until the tracking dye reaches the bottom of the gel [2].

Post-Electrophoresis Analysis: Following separation, proteins can be visualized using compatible staining methods (Coomassie Blue, Silver Stain) or transferred to membranes for western blotting. For functional assays, proteins can be eluted from excised gel bands using appropriate buffers [2] [12].

Specialized Native Electrophoresis Techniques

Beyond standard native PAGE, several specialized techniques offer unique advantages for specific applications:

Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE): This technique utilizes Coomassie G-250 dye, which binds to proteins and confers additional negative charges, allowing the separation of membrane protein complexes and high molecular weight assemblies. BN-PAGE is particularly valuable for studying mitochondrial complexes, nuclear pore complexes, and other large macromolecular assemblies [11].

Semi-Native PAGE: This hybrid approach involves separating partially denatured protein samples in gels containing low concentrations of SDS. It enables separation based on differences in structural stability and can be used to screen protein-ligand interactions, particularly with metallocomplexes, as it preserves some native structure while allowing for size-based separation [14].

Isoelectric Focusing (IEF): While not strictly a native technique, IEF separates proteins based solely on their isoelectric points in a pH gradient, providing high-resolution charge-based separation. IEF is often used as the first dimension in two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2D-PAGE), where proteins are subsequently separated by SDS-PAGE in the second dimension [2] [11].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful native PAGE experimentation requires specific reagents and materials optimized for preserving protein structure and function while enabling charge-based separation. The following table details essential components for native PAGE workflows:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Native PAGE

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms the porous gel matrix for molecular sieving; concentration determines pore size |

| Tris-based Buffers | Maintains stable pH during electrophoresis; different formulations (Tris-glycine, Bis-Tris) available |

| TEMED and Ammonium Persulfate | Catalyzes acrylamide polymerization to form the polyacrylamide gel matrix |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Prevents protein degradation during sample preparation, crucial for maintaining native structure |

| Non-ionic Detergents | (e.g., NP-40, Triton X-100) Solubilizes membrane proteins while maintaining native conformation |

| Glycerol | Increases density of protein samples for easier loading into gel wells |

| Native Marker Standards | Proteins of known molecular weight and charge for comparison and calibration |

| Coomassie Blue Stain | Visualizes separated protein bands after electrophoresis; compatible with native structures |

Commercial precast native gels offer convenience and reproducibility for researchers. Companies such as Thermo Fisher Scientific provide specialized native gel systems including NativePAGE Bis-Tris gels, Novex Tris-Glycine gels, and NuPAGE Tris-Acetate gels, each optimized for specific separation needs and protein characteristics [11]. These pre-cast systems eliminate gel-to-gel variability and are particularly valuable for comparative studies and high-throughput applications.

Current Research Applications and Case Study

Investigation of PSME3 in Myoblast Differentiation

A 2025 study investigating the role of the proteasome regulator PSME3 in myoblast differentiation provides an excellent example of native PAGE application in contemporary research [15]. Researchers employed native electrophoresis techniques to characterize PSME3-containing protein complexes and their dynamics during muscle cell differentiation. This approach was crucial for maintaining the native interactions between PSME3 and its binding partners, which would have been disrupted under denaturing conditions.

The study revealed that PSME3 forms specific complexes with proteins including RPRD1A and NUDC, interactions that regulate the levels of adhesion-related proteins and influence cell migration and differentiation [15]. By using co-immunoprecipitation followed by native PAGE analysis, researchers could demonstrate that these complexes remain stable under native conditions, providing evidence for their physiological relevance. This research highlights how charge-based separation techniques continue to enable discoveries in cell biology, particularly in understanding the macromolecular complexes that govern cellular processes.

Technical Workflow for Protein Complex Analysis

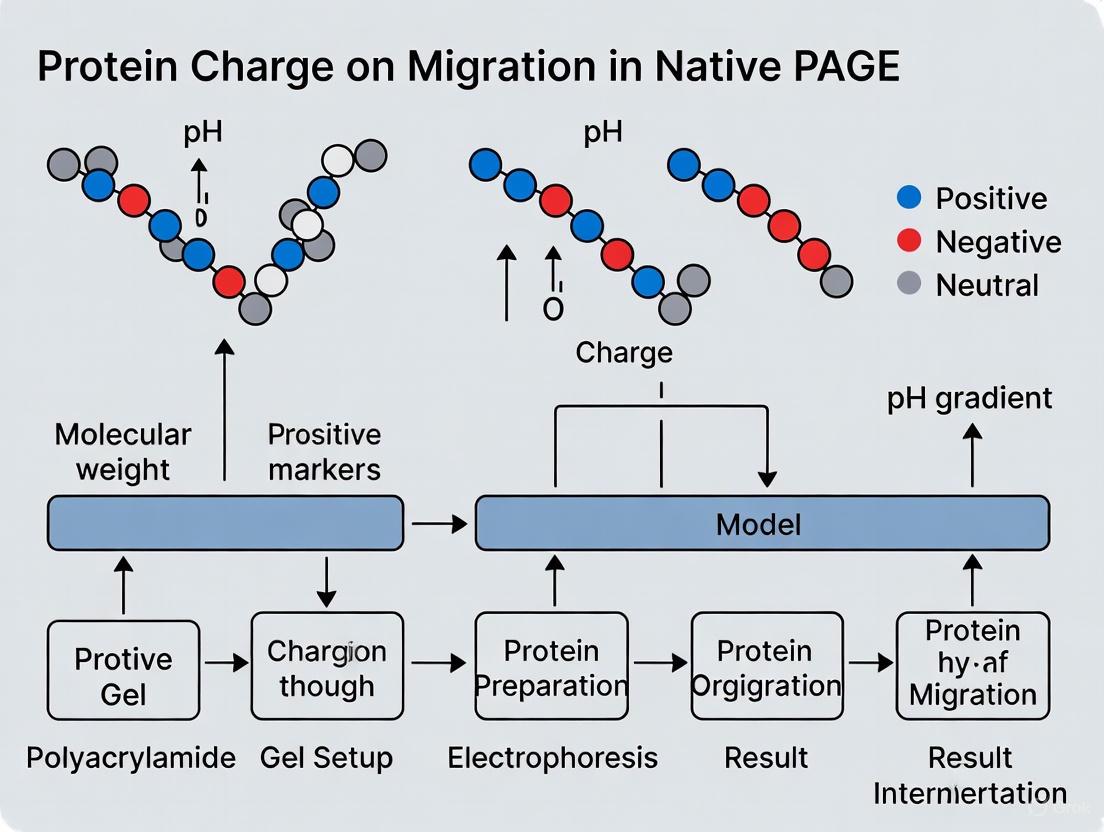

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow for analyzing protein complexes using native PAGE, as applied in current research:

The migration of proteins in an electric field represents a fundamental phenomenon with profound implications for protein research and biotechnology applications. The net charge of a protein, determined by its amino acid composition and the buffer pH, serves as the primary driver of electrophoretic mobility in native PAGE systems. This charge-based separation principle enables researchers to study proteins in their native, functional states—preserving complex quaternary structures, enzymatic activities, and protein-protein interactions that would be lost under denaturing conditions.

For drug development professionals and research scientists, understanding the role of net charge in protein migration is not merely academic; it provides a practical foundation for experimental design, result interpretation, and method selection. The continuing development of specialized native electrophoresis techniques, including Blue Native PAGE and semi-native approaches, expands the toolbox available for characterizing challenging protein samples. As proteomics research increasingly focuses on macromolecular complexes and functional interactions, charge-based separation methods will remain indispensable for elucidating the complex machinery of biological systems.

Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) is a fundamental technique in protein research that separates proteins under non-denaturing conditions, preserving their higher-order structure and biological activity. Unlike denaturing SDS-PAGE, which separates proteins primarily by mass, native PAGE resolves protein mixtures based on the complex interplay of three intrinsic properties: net charge, size, and three-dimensional shape [1]. This multi-parameter separation is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals studying native protein complexes, oligomeric states, and functional proteoforms, as it provides information that is lost in denaturing techniques.

In native PAGE, electrophoretic migration occurs because most proteins carry a net negative charge in alkaline running buffers. The rate of migration is governed by both the protein's charge density and the frictional force imposed by the gel matrix [1]. Proteins with higher negative charge density migrate more rapidly toward the anode, while the gel matrix creates a sieving effect that retards movement according to the protein's size and three-dimensional structure [1]. This dual mechanism enables the separation of complex protein mixtures while maintaining their native conformations, subunit interactions, and enzymatic activities—critical considerations for drug development where functional protein characterization is essential.

Core Separation Mechanisms in Native PAGE

The Interplay of Charge, Size, and Shape

The fundamental separation mechanism in native PAGE relies on three interdependent factors that collectively determine a protein's electrophoretic mobility:

Net Charge and Charge Density: A protein's net charge, determined by the ionization state of its surface amino acid residues at the running buffer pH, creates the electrophoretic driving force. However, charge density—the number of charges per unit mass—is often more significant than absolute charge, as it determines how effectively the electric field propels the molecule through the gel matrix [1]. Proteins with higher negative charge density migrate faster toward the anode.

Molecular Size and Mass: The polyacrylamide gel acts as a molecular sieve, creating frictional resistance that opposes protein migration. Larger proteins experience greater frictional forces and therefore migrate more slowly than smaller proteins with similar charge characteristics [1].

Three-Dimensional Shape and Conformation: A protein's native conformation significantly impacts its mobility through the gel matrix. Compact, globular proteins encounter less resistance than extended or irregularly shaped proteins of equivalent molecular weight, leading to different migration patterns despite similar mass and charge [1].

Because no denaturants are used in native PAGE, subunit interactions within multimeric proteins are generally preserved, allowing researchers to gain information about quaternary structure and complex formation [1]. This preservation of native structure also enables the recovery of enzymatically active proteins following separation, making the technique invaluable for functional studies and preparative applications.

Comparative Analysis of Native PAGE Gel Systems

Three primary gel chemistry systems are available for native PAGE separation, each with distinct operational characteristics and applications. The selection of an appropriate system depends on protein properties and research objectives, as no universal chemistry is ideal for all proteins in their native state [1].

Table 1: Native PAGE Gel Chemistry Systems and Their Applications

| Gel System | Operating pH Range | Key Features | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Novex Tris-Glycine | 8.3 - 9.5 | Traditional Laemmle system; preserves native net charge | Studying smaller MW proteins (20-500 kDa); when maintaining native charge is critical [1] |

| NuPAGE Tris-Acetate | 7.2 - 8.5 | Enhanced resolution for larger molecular weight proteins | Analyzing proteins >150 kDa; maintaining native charge structure [1] |

| NativePAGE Bis-Tris | ~7.5 | Uses Coomassie G-250 dye for charge shifting; resolves proteins by MW regardless of pI | Membrane proteins, hydrophobic proteins, separation primarily by molecular weight [1] |

The Tris-Glycine and Tris-Acetate systems maintain proteins' native net charges, while the Bis-Tris system employs a different mechanism based on the blue native PAGE (BN-PAGE) technique developed by Schägger and von Jagow [1]. This system uses Coomassie G-250 dye to bind proteins and confer a net negative charge while maintaining native conformation, overcoming limitations of traditional native gel electrophoresis through near-neutral pH operation and detergent compatibility [1].

Table 2: Technical Specifications of Native PAGE Systems

| Parameter | Tris-Glycine Gels | Tris-Acetate Gels | NativePAGE Bis-Tris Gels |

|---|---|---|---|

| Available Gel Concentrations | 6%, 8%, 10%, 12%, 14%, 16%, 4–12%, 4–20%, 8–16%, 10–20% | 7%*, 3–8% | 3–12%, 4–16% |

| Recommended Sample Buffer | Tris-Glycine Native Sample Buffer | Tris-Glycine Native Sample Buffer | NativePAGE Sample Buffer, NativePAGE 5% G-250 Sample Additive |

| Recommended Running Buffer | Tris-Glycine Native Running Buffer | Tris-Glycine Native Running Buffer | NativePAGE Running Buffer, NativePAGE Cathode Buffer Additive |

| Shelf Life | Up to 12 months | Up to 8 months | Up to 6 months |

| Storage Conditions | 2-8°C | Room temperature | Room temperature |

*7% polyacrylamide is only available in the mini size [1]

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Standard Native PAGE Procedure Using Tris-Glycine System

Sample Preparation:

- Dilute protein samples in Tris-Glycine Native Sample Buffer to desired concentration [1].

- Avoid denaturing agents (SDS, urea, β-mercaptoethanol) and reducing agents that disrupt disulfide bonds.

- Centrifuge at 10,000-15,000 × g for 5-10 minutes to remove insoluble material.

- Maintain samples at 4°C until loading to preserve native state.

Gel Electrophoresis:

- Select appropriate polyacrylamide concentration based on target protein size (refer to Table 2).

- Pre-run gel for 15-30 minutes at constant voltage (recommended: 125V) to establish pH gradient.

- Load samples (typically 10-60 μL per well) alongside native protein standards.

- Run at constant voltage (125V for mini-gels) for approximately 90 minutes or until dye front reaches bottom [1].

- Maintain temperature at 4°C during run using cooling apparatus if necessary.

Post-Electrophoresis Analysis:

- Proteins may be visualized using Coomassie Blue, silver stain, or specialized activity stains.

- For western blotting, use PVDF membranes with Tris-Glycine Transfer Buffer [1].

- Nitrocellulose membranes are not recommended due to poor compatibility with native conditions [1].

Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) Protocol

Based on the technique developed by Schägger and von Jagow, BN-PAGE has become instrumental for analyzing membrane protein complexes and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) systems [16]:

Membrane Protein Solubilization:

- Solubilize membrane proteins using mild, nonionic detergents such as n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside [16].

- Include zwitterionic salt 6-aminocaproic acid in extraction buffer to support solubilization without affecting electrophoresis [16].

- Add Coomassie blue G-250 to extracted samples prior to electrophoresis and to cathode buffer [16].

Electrophoresis Conditions:

- Use linear gradient polyacrylamide gels (typically 3-12% or 4-16%) [16].

- The anionic blue dye binds to hydrophobic protein surfaces, imposing a negative charge shift that forces even basic proteins to migrate toward the anode at pH 7.0 [16].

- The induced negative surface charge prevents aggregation of hydrophobic proteins and maintains solubility during electrophoresis [16].

Downstream Applications:

- For supercomplex analysis (e.g., respiratory chain complexes), use digitonin instead of n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside for milder solubilization [16].

- Combine with second dimension SDS-PAGE for comprehensive complex analysis (BN/SDS-PAGE) [16].

- Perform in-gel enzyme activity staining for functional assessment [16].

- Use clear-native PAGE (CN-PAGE) with mixed detergents instead of Coomassie dye when residual dye interferes with activity staining [16].

Critical Parameter Optimization

pH Considerations:

- Select running pH based on protein stability and isoelectric point (pI).

- Proteins with pI below running buffer pH will carry negative charge and migrate toward anode.

- Proteins with pI above running buffer pH may require charge-shifting systems like BN-PAGE.

Detergent Selection:

- For membrane proteins, choose detergents that maintain native structure without disrupting protein complexes.

- n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside provides balanced solubilization for many membrane proteins [16].

- Digitonin offers milder solubilization for preserving supercomplexes [16].

Gel Concentration:

- Lower percentage gels (4-8%) better resolve high molecular weight complexes (>500 kDa).

- Higher percentage gels (10-20%) optimal for smaller proteins and subunits (<100 kDa).

- Gradient gels (e.g., 4-16%) provide broad separation range for complex mixtures.

Visualization of Native PAGE Separation Mechanisms

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key separation principles and experimental considerations in native PAGE:

Native PAGE Separation Workflow and Key Parameters

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful native PAGE experimentation requires careful selection of reagents and materials that preserve protein native structure while enabling effective separation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Native PAGE

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| NativePAGE Bis-Tris Gels (3-12%, 4-16%) | Provides polyacrylamide matrix for separation | Commercial pre-cast gels; compatible with BN-PAGE; room temperature storage [1] |

| Coomassie G-250 Dye | Charge-shifting agent for BN-PAGE | Binds hydrophobic protein surfaces; confers negative charge; prevents aggregation [1] [16] |

| n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside | Nonionic detergent for membrane protein solubilization | Maintains native protein complexes; compatible with activity assays [16] |

| Digitonin | Mild detergent for supercomplex analysis | Preserves labile protein interactions; used for respiratory chain complexes [16] |

| 6-aminocaproic acid | Zwitterionic solubilization aid | Supports membrane protein extraction; zero net charge at pH 7.0 [16] |

| NativeMark Unstained Protein Standard | Native molecular weight standards | Essential for accurate size estimation under native conditions |

| PVDF Membrane | Western blot transfer membrane | Required for NativePAGE gels; nitrocellulose incompatible due to G-250 binding [1] |

| NativePAGE Running Buffer | Electrolyte system for BN-PAGE | Maintains near-neutral pH (7.5); contains cathode buffer additive [1] |

Advanced Applications and Research Implications

The unique ability of native PAGE to separate proteins based on charge, size, and shape simultaneously makes it invaluable for advanced research applications, particularly in drug development and structural proteomics. The technique provides critical insights into protein complex stoichiometry, assembly pathways, and higher-order structures that are often disrupted under denaturing conditions [16].

For researchers studying mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) systems, BN-PAGE has become an indispensable tool for analyzing respiratory supercomplexes and assembly intermediates [16]. The combination of one-dimensional BN-PAGE with second-dimension denaturing electrophoresis (BN/SDS-PAGE) enables comprehensive mapping of complex subunits and identification of assembly defects in metabolic disorders [16]. Furthermore, the preservation of enzymatic activity following native PAGE separation allows direct functional assessment through in-gel activity staining for Complexes I, II, IV, and V [16].

In biopharmaceutical development, native PAGE techniques support characterization of therapeutic proteins, including monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), by monitoring charge heterogeneity and aggregation states—Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) mandated by regulatory authorities [17]. The technique's compatibility with downstream mass spectrometry analysis further enhances its utility for comprehensive biotherapeutic characterization [18].

Native PAGE represents a powerful separation methodology that extends beyond simple charge-based separation to incorporate the sieving effects of protein size and three-dimensional shape. The technique's ability to preserve native protein structure and activity provides researchers with unique insights into protein complexes, oligomeric states, and functional characteristics that are essential for both basic research and drug development applications. Through appropriate selection of gel chemistry, buffer systems, and experimental parameters, scientists can leverage the full potential of native PAGE to address complex questions in structural biology and biopharmaceutical analysis.

In native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), a protein's migration is not solely dictated by its mass but by the complex interplay between its intrinsic isoelectric point (pI) and the pH of the electrophoresis buffer. This relationship directly determines the protein's net charge at run time, thereby influencing its electrophoretic mobility. This technical guide delves into the core principles of how protein charge governs migration in native PAGE. We provide a detailed framework for predicting migration behavior, summarize key native PAGE systems, and present established and novel experimental protocols for the charge-based analysis of proteins, including the determination of pI and the characterization of membrane protein complexes.

Core Principles: pI, Buffer pH, and Net Charge

The fundamental parameter governing protein migration in native PAGE is the net charge the molecule carries during electrophoresis. This net charge is not a fixed property but is dynamically determined by the buffer environment.

- The Isoelectric Point (pI): The pI is the specific pH at which a protein carries no net electrical charge. At this pH, the number of positively charged groups (e.g., from lysine and arginine) equals the number of negatively charged groups (e.g., from aspartic acid and glutamic acid). [19]

- Net Charge in a Running Buffer: When the same protein is placed in an electrophoresis buffer with a pH different from its pI, it will possess a net charge. In a buffer with a pH below the protein's pI, the protein's basic groups become protonated, resulting in a net positive charge. Conversely, in a buffer with a pH above the protein's pI, the protein's acidic groups are deprotonated, resulting in a net negative charge. [20]

The following diagram illustrates this deterministic relationship:

Diagram 1: The relationship between pI, buffer pH, and net charge.

In native PAGE, the applied electric field causes charged proteins to migrate through the porous gel matrix. The direction of migration is determined by the sign of the net charge: positively charged proteins (cationic) migrate toward the cathode (negative electrode), while negatively charged proteins (anionic) migrate toward the anode (positive electrode). The speed of migration is influenced by the charge density (net charge relative to size and shape) and the frictional force imposed by the gel. A protein with a high charge density and compact structure will migrate faster than a large, low-charge protein. [1]

Native PAGE Systems and Their Operational pH

There is no universal native PAGE system ideal for all proteins. The choice of gel chemistry and buffer system is critical and depends on the protein's stability, isoelectric point, and molecular weight. The table below summarizes the characteristics of three common commercial systems.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Native PAGE Gel Chemistries and Their Properties [1]

| Gel System | Operating pH Range | Key Features | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Novex Tris-Glycine | 8.3 - 9.5 | Traditional Laemmle system; proteins retain their native charge. | Studying smaller proteins (20-500 kDa); general native analysis. |

| NuPAGE Tris-Acetate | 7.2 - 8.5 | Provides better resolution for larger molecular weight proteins. | Analyzing large proteins (>150 kDa). |

| NativePAGE Bis-Tris | ~7.5 | Uses Coomassie G-250 dye to impart negative charge; resolves proteins by molecular weight regardless of intrinsic pI. | Membrane proteins, hydrophobic proteins, or when separation by molecular weight is desired in a native state. |

The NativePAGE Bis-Tris system deserves special attention as it uses a unique mechanism to overcome the limitations of intrinsic protein charge. In this system, the anionic Coomassie G-250 dye binds non-specifically to hydrophobic patches on proteins, conferring a relatively uniform negative charge density. This allows even basic proteins (pI > buffer pH) to migrate consistently toward the anode, enabling separation primarily by size and shape. [1]

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining the pI of a Native Protein

This protocol outlines the use of vertical isoelectrofocusing (IEF) under non-denaturing conditions to determine the isoelectric point of a native protein from a biological sample, followed by immunoblotting for identification. [19] [21]

Workflow Overview:

Diagram 2: Workflow for native protein pI determination.

Detailed Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare the biological sample (e.g., cell lysate, tissue homogenate) in a non-denaturing lysis buffer without SDS, reducing agents, or urea to preserve the native state of the proteins. [19]

- Gel Equilibration: Rehydrate a commercial immobilized pH gradient (IPG) strip with the appropriate pH range (e.g., 3-10, 5-8) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Sample Loading: Load the prepared native protein sample onto the IPG strip.

- Isoelectrofocusing (IEF): Perform IEF using a vertical electrophoresis unit under pre-optimized conditions (e.g., stepwise increasing voltage). During IEF, a protein with a net charge will migrate through the pH gradient. It will stop migrating at the point in the gradient where the pH equals its pI and it becomes neutrally charged. [19]

- Immunoblotting: Following IEF, proteins are transferred from the IPG gel to a membrane (e.g., PVDF or nitrocellulose) via western blotting under non-denaturing conditions.

- pI Determination: Identify the protein of interest using a specific antibody. The pI is determined by correlating the band's position on the membrane with the known pH gradient of the IPG strip. [19] [21]

Protocol 2: Native PAGE for GPCR-Mini-G Protein Coupling

This membrane protein native PAGE assay is a powerful method to visualize and biochemically characterize agonist-dependent coupling of detergent-solubilized G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) to purified mini-G proteins. [22]

Workflow Overview:

Diagram 3: Workflow for GPCR-mini-G protein coupling assay.

Detailed Methodology:

- Receptor Expression and Preparation: Transiently express an EGFP-tagged GPCR in a mammalian cell line (e.g., HEK293S GnT1-). Prepare crude membranes from the harvested cells and solubilize the membrane proteins using a suitable detergent, such as lauryl maltose neopentyl glycol (LMNG), to extract the GPCR while maintaining its native conformation. [22]

- Complex Formation: Incubate the solubilized receptor with the agonist of interest and a purified mini-G protein. Mini-G proteins are engineered, minimal Gα subunits that stabilize the active state of the GPCR. [22]

- High-Resolution Clear Native Electrophoresis (hrCNE): Load the samples onto a native polyacrylamide gel. The hrCNE method is compatible with fluorescently-labeled proteins and detergents. Electrophoresis is then carried out.

- Detection and Analysis: Visualize the EGFP-tagged receptor using in-gel fluorescence imaging. The formation of a stable GPCR-mini-G protein complex will result in a distinct upward mobility shift (slower migration) compared to the receptor alone, due to the increased size and potential alteration in charge of the complex. This assay can be adapted to a quantitative format to determine apparent binding affinities. [22]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of native electrophoresis experiments requires specific reagents. The following table details key solutions and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Native Electrophoresis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Coomassie G-250 | Charge-shift molecule in NativePAGE Bis-Tris gels; binds proteins to confer net negative charge while maintaining native state. [1] [3] | Added to cathode buffer and sample; enables analysis of basic proteins. Preferable to SDS for native conditions. |

| Mild Detergents (e.g., LMNG) | Solubilizes membrane proteins while preserving native protein-protein interactions and functional state. [22] | Critical for studying membrane protein complexes like GPCRs; choice of detergent is experiment-dependent. |

| Native Sample Buffer | Prepares protein sample for loading without denaturation; typically contains glycerol, tracking dye, and a compatible buffer. | Lacks SDS and reducing agents (DTT, β-mercaptoethanol). May include Coomassie G-250 for certain systems. [1] |

| PVDF Membrane | Recommended blotting membrane for western blotting following NativePAGE. [1] | Binds Coomassie G-250 less tightly than nitrocellulose, making it compatible with the destaining and fixing steps required. |

| Mini-G Proteins | Surrogate, engineered G protein alpha subunits used to trap and stabilize active-state GPCRs for biochemical studies. [22] | Enhance stability of GPCR complexes in detergent solution; available for different G protein families (Gs, Gi/o, Gq). |

| Tris-Based Buffers | Form the basis of most running and sample buffers; provide a constant pH in the continuous buffer system. [20] | Effective pH range can be shifted to ~10.0; high buffering capacity is essential for stable pH during runs. |

In native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Native PAGE), proteins are separated in their folded, functional state, allowing for the analysis of complex quaternary structures, enzymatic activity, and protein-protein interactions. Unlike denaturing SDS-PAGE, which separates proteins primarily by mass, Native PAGE separates proteins according to their charge-to-size ratio within a gel matrix. This technique is indispensable for researchers studying multimeric protein complexes, such as those involved in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and fatty acid metabolism, as it preserves native structural and functional characteristics [16].

The fundamental parameter governing migration in Native PAGE is a protein's intrinsic charge, which is determined by its amino acid composition and the pH of the running buffer. In the absence of denaturing detergents like SDS, a protein's surface charge dictates its electrophoretic mobility. When an electric field is applied, negatively charged proteins migrate toward the anode, while positively charged proteins move toward the cathode. The porous gel matrix then acts as a molecular sieve, allowing smaller proteins to migrate faster than larger ones. Consequently, the final position of a protein band reflects a combination of its inherent charge and its hydrodynamic size—the compactness of its three-dimensional structure [3].

Key Methodological Variations in Native Electrophoresis

Several variants of Native PAGE have been developed to optimize separation for different applications. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of the three main techniques.

Table 1: Core Native Electrophoresis Techniques Compared

| Technique | Separation Principle | Key Feature | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blue-Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) | Charge & Size | Uses Coomassie G-250 dye to impart negative charge [16] | Analysis of membrane protein complexes and supercomplexes [16] |

| Clear-Native PAGE (CN-PAGE) | Charge & Size | Uses mixed micelles of detergents instead of dye for charge shift [23] [16] | In-gel enzyme activity assays without dye interference [23] |

| Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE) | Size (Minimal Denaturation) | Uses greatly reduced SDS concentration and no heating [3] | Retaining enzymatic activity and metal cofactors while achieving high resolution [3] |

BN-PAGE is particularly powerful for membrane proteins. The anionic Coomassie blue dye binds to hydrophobic protein surfaces, conferring a uniform negative charge that drives electrophoretic migration and prevents protein aggregation [16]. In contrast, CN-PAGE, which replaces the dye with mild detergents, is advantageous for subsequent in-gel activity assays because the absence of blue dye eliminates potential interference with colorimetric detection [23] [16]. The NSDS-PAGE method offers a hybrid approach, providing the high resolution接近SDS-PAGE while maintaining protein function for many enzymes [3].

Experimental Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide

This section provides a detailed methodology for conducting a high-resolution clear-native PAGE (hrCN-PAGE), adapted for analyzing the medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) enzyme, a homotetrameric flavoprotein [23].

Sample Preparation

- Protein Extraction: Solubilize mitochondrial or cellular membrane proteins using a mild, non-ionic detergent such as n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside or digitonin. The choice and concentration of detergent are critical for maintaining the integrity of protein complexes while ensuring sufficient solubilization [16]. The addition of 6-aminocaproic acid, a zwitterionic salt, helps stabilize proteins and prevents aggregation during extraction [16].

- Sample Buffer Preparation: Mix the solubilized protein sample with a native sample buffer. For the hrCN-PAGE method used for MCAD, this buffer typically contains 100 mM Tris HCl, 150 mM Tris base, 10% glycerol, and tracking dyes, with a final pH of 8.5 [23] [3]. Crucially, the sample is not heated to preserve native structure.

Gel Electrophoresis

- Gel Casting: Manually cast or use commercial linear gradient gels, typically between 4-16% acrylamide, to achieve optimal separation across a broad molecular weight range [23] [16]. A gradient gel allows smaller proteins to migrate freely in the lower-percentage regions while effectively resolving larger complexes in the higher-percentage regions.

- Electrophoresis Conditions:

- Running Buffer: For CN-PAGE, the cathode buffer contains a mixture of anionic and neutral detergents to induce the necessary charge shift on proteins, replacing Coomassie blue [23] [16].

- Running Conditions: Load the prepared samples onto the gel. Run electrophoresis at a constant voltage (e.g., 150-200V) at 4°C to prevent heat-induced denaturation, until the dye front migrates to the bottom of the gel [23] [3].

Downstream Applications: In-Gel Activity Assay

A significant advantage of native electrophoresis is the ability to detect enzymatic activity directly within the gel.

- Activity Staining: After electrophoresis, incubate the gel in a reaction mixture specific to the enzyme of interest.

- For MCAD, the gel is stained in a solution containing its physiological substrate, octanoyl-CoA, and an electron acceptor, nitro blue tetrazolium chloride (NBT). MCAD activity oxidizes the substrate, leading to the reduction of NBT and the formation of an insoluble, purple-colored diformazan precipitate at the location of the active enzyme band [23].

- Quantification: The intensity of the resulting activity bands can be quantified using densitometry. This assay has been shown to be sensitive enough to quantify the activity of less than 1 µg of protein and can linearly correlate with the amount of protein and its FAD cofactor content [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful native PAGE requires specific reagents designed to maintain protein structure and function. The following table details key materials and their roles.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Native PAGE Experiments

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Purpose | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| n-Dodecyl-β-d-maltoside | Mild, non-ionic detergent for solubilizing membrane proteins without dissociating complexes [16]. | Used to extract intact OXPHOS complexes from mitochondrial membranes [16]. |

| Digitonin | Very mild, non-ionic detergent used to preserve weak protein-protein interactions in supercomplexes [16]. | Used for the analysis of respiratory chain supercomplexes (respirasomes) [16]. |

| Coomassie Blue G-250 | Anionic dye that binds protein surfaces, imparting negative charge and enhancing solubility during BN-PAGE [16]. | A key component in the cathode buffer and sample mix for BN-PAGE [16]. |

| 6-Aminocaproic Acid | Zwitterionic salt used as a stabilizing agent in extraction buffers; prevents protein aggregation [16]. | Included in the sample extraction buffer to support protein solubilization [16]. |

| Nitro Blue Tetrazolium (NBT) | Colorimetric electron acceptor; reduces to an insoluble purple formazan precipitate upon enzyme activity [23]. | Used in the in-gel activity stain to visualize active MCAD tetramers [23]. |

| Octanoyl-CoA | Physiological substrate for the MCAD enzyme; acts as an electron donor in the activity assay [23]. | The reductant in the in-gel activity stain, enabling specific detection of MCAD function [23]. |

Data Interpretation and the Impact of Protein Charge

Interpreting native PAGE results requires understanding how protein properties influence migration. A protein with a higher negative surface charge will migrate faster toward the anode. However, a larger hydrodynamic size (or molecular mass) will retard migration. The quaternary structure profoundly impacts this balance. For example, a compact tetramer might migrate faster than a more loosely structured dimer of similar mass due to its smaller effective size.

Pathogenic mutations offer a clear view of charge and structure effects. Research on MCAD deficiency (MCADD) reveals that some missense variants (e.g., p.R206C) do not significantly alter the monomer's molecular weight on denaturing gels but cause a measurable shift in migration on native gels [23]. This shift indicates a change in the protein's global conformation or surface charge, which can destabilize the homotetramer, leading to fragmentation into inactive, lower-mass species or formation of aggregates, all of which are separable and identifiable via native PAGE [23].

Workflow for Native PAGE and In-Gel Activity Assay

Factors Influencing Protein Migration in Native PAGE

Native PAGE is a powerful and versatile technique that provides unique insights into the functional state of proteins and their complexes. By separating proteins based on their intrinsic charge, size, and quaternary structure, it allows researchers to move beyond simple molecular weight determination to analyze enzymatic activity, protein-protein interactions, and the structural consequences of genetic variations. The continued refinement of methods like BN-PAGE, CN-PAGE, and NSDS-PAGE ensures that this foundational technology will remain a cornerstone of biochemical and biomedical research, directly contributing to our understanding of cellular mechanisms and the molecular basis of disease.

Practical Applications: Method Design and Buffer Selection for Charge-Based Separation

In native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), a protein's migration behavior is fundamentally governed by its intrinsic charge, size, and three-dimensional structure, unlike denaturing SDS-PAGE where charge differences are masked by SDS. The separation occurs because most proteins carry a net negative charge in alkaline running buffers, causing them to migrate toward the anode. A protein's charge density (the number of charges per unit mass) directly determines its electrophoretic mobility—the higher the negative charge density, the faster a protein migrates. Simultaneously, the gel matrix creates a sieving effect that retards movement according to proteins' size and shape [24].

The choice of gel chemistry—Tris-Glycine, Bis-Tris, or Tris-Acetate—directly manipulates the electrostatic environment, profoundly impacting which protein properties dominate the separation and ultimately determining the success of the experiment [24]. This technical guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for selecting the optimal native PAGE system based on their specific experimental requirements.

Comparative Analysis of Native PAGE Gel Systems

Technical Specifications and Operating Parameters

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Native PAGE Gel Systems

| Parameter | Tris-Glycine Gels | Tris-Acetate Gels | Bis-Tris Gels (NativePAGE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating pH Range | 8.3 - 9.5 [24] | 7.2 - 8.5 [24] | ~7.5 [24] |

| Key Separation Basis | Net charge, size, & shape [24] | Net charge, size, & shape [24] | Molecular weight (using Coomassie G-250) [24] |

| Optimal Protein Size Range | 20 - 500 kDa [24] | >150 kDa [24] | 15 - 10,000 kDa [25] |

| Key Features | Traditional Laemmli system [24] | Better resolution of high molecular weight proteins [24] | Near-neutral pH; detergent compatible; overcomes pI limitations [24] |

| Recommended Sample Buffer | Tris-Glycine Native Sample Buffer [24] | Tris-Glycine Native Sample Buffer [24] | NativePAGE Sample Buffer + 5% G-250 Additive [24] |

| Recommended Running Buffer | Tris-Glycine Native Running Buffer [24] | Tris-Glycine Native Running Buffer [24] | NativePAGE Running Buffer + Cathode Buffer Additive [24] |

| Shelf Life & Storage | Up to 12 months at 2-8°C [24] | Up to 8 months at room temperature [24] | Up to 6 months at room temperature [24] |

Mechanism of Protein Separation and Charge Manipulation

Figure 1: Mechanism of Protein Separation in Native PAGE Systems

The fundamental separation mechanisms differ significantly between the systems, particularly in how they handle protein charge:

Tris-Glycine & Tris-Acetate Systems: These systems rely on the protein's intrinsic net charge at the operating pH. In the alkaline environment of Tris-Glycine gels (pH 8.3-9.5), most proteins carry a net negative charge and migrate toward the anode. However, proteins with basic isoelectric points (pI >9.5) may carry a net positive charge and migrate in the opposite direction or not enter the gel, making them unsuitable for these systems [24].

Bis-Tris (NativePAGE) System: This system uses Coomassie G-250 dye as a charge-shift molecule, fundamentally altering the separation paradigm. The dye binds non-specifically to proteins, conferring a net negative charge on all proteins regardless of their intrinsic pI. This allows even basic proteins to migrate toward the anode and enables separation primarily by molecular weight and shape, similar to SDS-PAGE but without denaturation [24]. This mechanism is particularly valuable for membrane proteins and complexes with significant hydrophobic surfaces, as the dye binding reduces aggregation by converting hydrophobic sites to negatively charged sites [24].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

NativePAGE Bis-Tris Gel Electrophoresis Protocol

The NativePAGE Bis-Tris system, based on blue native PAGE (BN-PAGE) technology, provides a robust method for analyzing membrane protein complexes and soluble native proteins [25].

Sample Preparation:

- Dilute protein samples with NativePAGE Sample Buffer.

- Add NativePAGE 5% G-250 Sample Additive to the samples prior to loading [24]. This additive provides the Coomassie dye necessary for imparting charge.

Gel Electrophoresis:

- Prepare anode (clear) and cathode (dark blue) buffers according to manufacturer instructions [24].

- Load samples onto a NativePAGE 3-12% Bis-Tris gel [25].

- Assemble the gel in the Mini Gel Tank, filling the front cathode chamber with dark blue cathode buffer and the back anode chamber with clear anode buffer [25].

- Run at constant voltage until the dye front has migrated appropriately (typically ~1/3 of the way through the gel for transfer applications).

- For western transfer applications: Pause the run, replace the cathode buffer with light blue cathode buffer, and resume electrophoresis [25].

Critical Considerations:

- Membrane Selection: PVDF membranes are required for western blotting with NativePAGE gels. Nitrocellulose is incompatible as it tightly binds the Coomassie G-250 dye [24].

- Power Supply Settings: During NativePAGE runs, current may drop below 1 mA, triggering "No Load" errors on some power supplies. Disable the load check feature to prevent automatic shutdown [25].

- Protein Standards: Use NativeMark Unstained Protein Standard (Cat. No. LC0725) for accurate molecular weight estimation under native conditions [25].

Tris-Glycine and Tris-Acetate Native Electrophoresis

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare protein samples in Tris-Glycine Native Sample Buffer [24].

- Avoid reducing agents unless specifically required, as they may disrupt native structure.

Gel Electrophoresis:

- Use the appropriate gel percentage based on target protein size (refer to Table 1).

- Prepare Tris-Glycine Native Running Buffer [24].

- Load samples and run at constant voltage recommended by the manufacturer.

- For Tris-Acetate gels, follow similar procedures but use the specified buffers and conditions for that system [24].

Transfer Considerations for Basic Proteins: Proteins with pI higher than the transfer buffer pH may require modified transfer conditions:

- Increase Tris-Glycine transfer buffer pH to 9.2 to transfer proteins with pI up to 9.2 [26].

- Place a membrane on both sides of the gel to capture proteins migrating in either direction [26].

- Pre-incubate the gel in transfer buffer containing 0.1% SDS to provide additional charge for transfer, though this may cause partial denaturation [26].

Advanced Applications and Integrative Techniques

SMA-PAGE: A Novel Approach for Membrane Protein Complexes

Recent advancements have integrated native PAGE with novel encapsulation technologies for studying membrane protein complexes. The SMA-PAGE method combines styrene maleic acid lipid particles (SMALPs) with native gel electrophoresis to separate membrane proteins in their native state while maintaining their lipid environment [27].

Key Advantages:

- Preserved Quaternary Structure: SMA-PAGE provides an excellent measure of protein quaternary structure within the membrane [27].

- Lipid Environment Analysis: The surrounding lipid environment can be probed using mass spectrometry [27].

- Compatibility with Downstream Techniques: Intact membrane protein-SMALPs extracted from gels can be visualized using electron microscopy [27].

- Immunoblotting Compatibility: The method complements traditional immunoblotting techniques [27].

This innovative approach demonstrates how native PAGE systems continue to evolve, particularly for challenging targets like membrane protein complexes that are crucial in drug development research.

Troubleshooting Common Native PAGE Issues

Poor Resolution or Smearing:

- Cause: Protein aggregation, especially common with hydrophobic or membrane proteins.

- Solution: Use NativePAGE Bis-Tris system with Coomassie G-250, which reduces aggregation by binding to hydrophobic sites [24].

Gel Run Stops Prematurely:

- Cause: Current drops below 1 mA in NativePAGE, triggering power supply safety features.

- Solution: Disable the "Load Check" feature on the power supply [25].

Bands Appear Narrowed or "Funneled":

- Cause: Excessive reducing agent (BME, DTT) in samples, causing over-reduction and charge repulsion.

- Solution: Optimize reducing agent concentration or omit unless essential for native structure [26] [25].

High Background in Western Blotting:

- Cause: Membrane contamination or insufficient blocking.

- Solution: Wear gloves, handle membranes carefully, optimize blocking conditions, and ensure proper antibody concentrations [25].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for Native PAGE Experiments

| Reagent/Catalog Item | Function/Application | Compatible System(s) |

|---|---|---|

| NativePAGE Bis-Tris Gels (3-12%, 4-16%) | High-resolution separation of native proteins & membrane complexes | NativePAGE Bis-Tris [24] |

| NativePAGE Sample Buffer & 5% G-250 Additive | Provides charge shift for proteins via Coomassie binding | NativePAGE Bis-Tris [24] |

| Tris-Glycine Native Sample Buffer | Maintains proteins in native state without charge modification | Tris-Glycine, Tris-Acetate [24] |

| NativeMark Unstained Protein Standard (LC0725) | Accurate molecular weight estimation under native conditions | All native systems [25] |

| HiMark Prestained/Unstained Standards (LC5699/LC5688) | Molecular weight standards for high molecular weight proteins | Tris-Acetate [26] |

| PVDF Transfer Membrane | Required for blotting with NativePAGE systems; compatible with Coomassie dye | NativePAGE Bis-Tris [24] |

Choosing between Tris-Glycine, Tris-Acetate, and Bis-Tris native PAGE systems requires careful consideration of experimental goals and protein properties:

- Select Tris-Glycine when studying smaller proteins (20-500 kDa) and maintaining native charge is essential for interpretation [24].

- Choose Tris-Acetate for superior resolution of large protein complexes (>150 kDa) while preserving native charge states [24].

- Opt for NativePAGE Bis-Tris when working with membrane proteins, hydrophobic proteins, basic proteins (high pI), or when molecular weight estimation is desired under native conditions [24].

The integration of native PAGE with emerging technologies like SMA-PAGE demonstrates the continued evolution of these separation systems, offering researchers powerful tools for probing protein complex structure and function in drug development and basic research.

Blue Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) represents a powerful technique for separating native protein complexes according to their molecular mass while maintaining their structural integrity and enzymatic activity. Unlike denaturing SDS-PAGE, which disrupts protein-protein interactions, BN-PAGE preserves the quaternary structure of protein assemblies, enabling researchers to study intact complexes and supercomplexes. The core innovation enabling this technique lies in the strategic use of the dye Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250, which imposes a uniform negative charge shift upon proteins, facilitating their migration under native conditions. This charge-shift mechanism is particularly crucial for investigating how intrinsic protein charge influences electrophoretic mobility in native systems, revealing that migration depends not merely on innate charge but on a dye-imposed uniform charge density that enables separation primarily by size and shape.

The fundamental challenge in native electrophoresis of membrane proteins stems from their hydrophobic nature and varying intrinsic charges. Without a standardized charge carrier, these proteins would migrate unpredictably based on their inherent charge properties rather than their molecular dimensions. Coomassie G-250 resolves this limitation by binding nonspecifically to protein surfaces, converting diverse protein charge profiles into a uniformly negative state [1]. This transformation allows even basic proteins to migrate toward the anode at near-neutral pH (approximately 7.5) [28], enabling separation based primarily on molecular size and structural conformation rather than intrinsic charge characteristics.

The Biochemical Mechanism of Coomassie G-250 Binding

Chemical Properties and Molecular Interactions

Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 is an anionic synthetic dye belonging to the triphenylmethane family, characterized by its three phenyl rings [29]. The dye exists in different ionic forms depending on pH conditions, which directly influences its coloring and binding behavior. Critically for BN-PAGE applications, at the operating pH of approximately 7.5 used in NativePAGE Bis-Tris systems, Coomassie G-250 forms an anion and appears blue (590 nm absorption) [29]. This anionic form is essential for its function in BN-PAGE, as the negatively charged sulfonic acid groups of the dye molecule facilitate binding to protein surfaces.