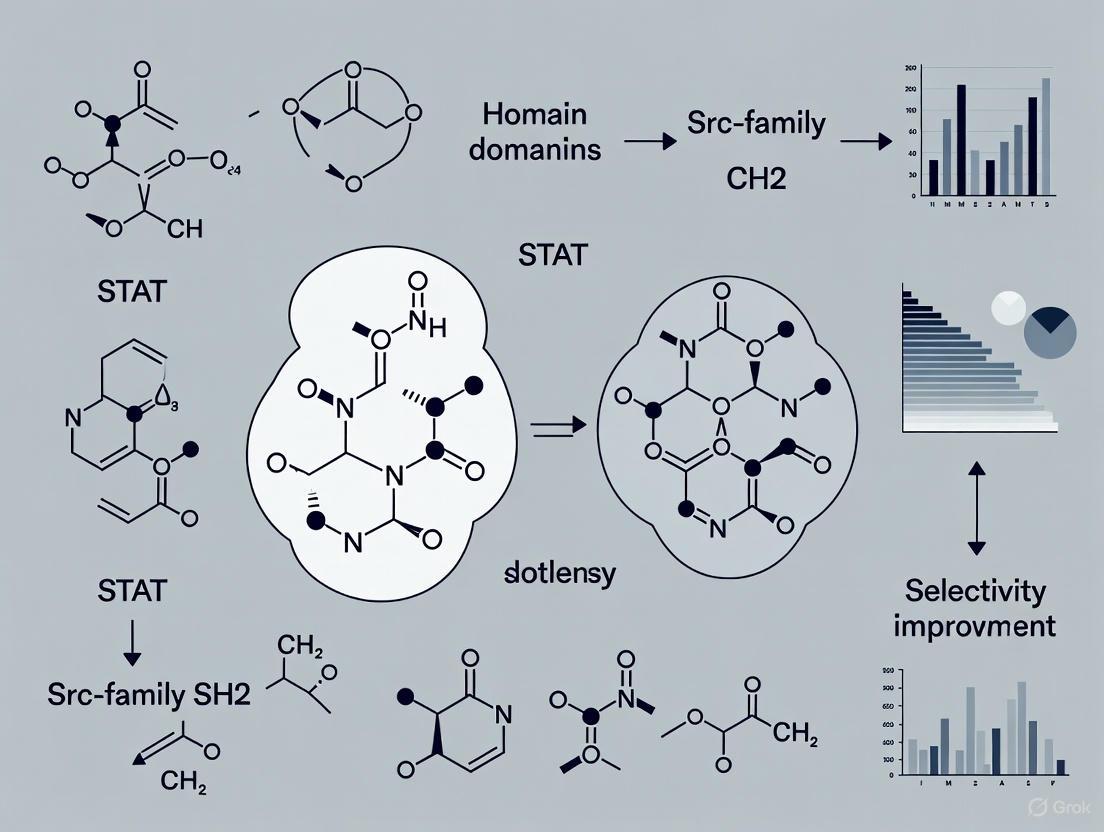

Targeting the Distinction: Strategies for Achieving Selectivity Between STAT and Src-Family SH2 Domains in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the strategies and challenges in achieving high selectivity between the SH2 domains of STAT and Src-family kinases (SFKs), a critical goal for developing...

Targeting the Distinction: Strategies for Achieving Selectivity Between STAT and Src-Family SH2 Domains in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the strategies and challenges in achieving high selectivity between the SH2 domains of STAT and Src-family kinases (SFKs), a critical goal for developing targeted therapeutics with reduced off-target effects. We first explore the foundational structural biology, contrasting the conserved pTyr-binding mechanism with the key sequence and architectural differences that distinguish STAT-type and SRC-type SH2 domains. The review then surveys cutting-edge methodological approaches, including the development of synthetic binding proteins and small-molecule inhibitors that exploit these structural distinctions. We further delve into troubleshooting common pitfalls in selectivity profiling and present a framework for the rigorous validation and comparative analysis of novel inhibitors. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this synthesis of established knowledge and emerging trends offers a roadmap for the rational design of next-generation, selective SH2 domain inhibitors.

Decoding the Blueprint: Structural and Functional Divergence Between STAT and Src SH2 Domains

Src Homology 2 (SH2) domains are approximately 100-amino-acid protein modules that serve as crucial "readers" of tyrosine phosphorylation, a key post-translational modification in eukaryotic cellular signaling [1] [2]. These domains specifically recognize and bind to sequences containing phosphorylated tyrosine (pTyr), thereby facilitating the assembly of signaling complexes downstream of protein tyrosine kinases [1]. The human genome encodes 120 SH2 domains distributed across 110 proteins, including kinases, phosphatases, adaptor proteins, and transcription factors [1] [3]. This extensive family mediates critical signaling events that govern cell proliferation, differentiation, survival, and immune responses, with dysregulation contributing to various pathologies, including cancer and developmental disorders [1] [4]. Understanding the structural basis of SH2 domain function is fundamental to developing selective inhibitors for therapeutic applications.

Table 1: Major Categories of SH2 Domain-Containing Proteins

| Category | Example Proteins | Molecular Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Kinases | Src, Abl, Fyn, JAK | Enzyme (Tyrosine kinase) |

| Phosphatases | Shp2 (PTPN11) | Enzyme (Tyrosine phosphatase) |

| Adaptor Proteins | Grb2, Crk, NCK, SHC | Scaffolding, protein recruitment |

| Transcription Factors | STAT1, STAT3, STAT5 | Gene expression regulation |

| Ubiquitin Ligases | Cbl, Cbl-b | Enzyme (E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase) |

The Conserved Structural Architecture of SH2 Domains

Core Folding Motif

All SH2 domains share a highly conserved structural fold despite significant sequence variation among family members [4]. The canonical architecture consists of a central anti-parallel β-sheet flanked by two α-helices [2] [5]. Specifically, the core structure is organized as αA-βB-βC-βD-αB, with most SH2 domains containing additional β-strands (A, E, F, and G) for a total of seven β-strands [4]. This structural conservation across the family highlights that the SH2 fold has evolved primarily to recognize pTyr motifs while allowing for specificity variations [4].

The Phosphotyrosine-Binding Pocket

The N-terminal region of the SH2 domain contains a deeply conserved pTyr-binding pocket located within the βB strand [2] [6]. This pocket features a strictly conserved arginine residue (Arg βB5) that is part of the FLVR motif found in nearly all SH2 domains [6] [4]. Structural studies reveal that Arg βB5 forms crucial bidentate hydrogen bonds with the phosphate moiety of pTyr, serving as the primary interaction that drives phosphopeptide binding [6]. This interaction contributes approximately 50% of the total binding free energy for a high-affinity tyrosyl phosphopeptide [6]. The pTyr-binding pocket also contains other positively charged residues, including Lys βD6 and Arg αA2, which form a clamp around the phenol ring of the pTyr [6].

Specificity-Determining Regions

While the pTyr-binding pocket is highly conserved, regions determining ligand specificity are predominantly located in the C-terminal half of the domain [2] [5]. The EF loop (connecting β-strands E and F) and the BG loop (connecting the αB helix and βG strand) play particularly important roles in defining specificity by controlling access to surface pockets that engage residues C-terminal to the pTyr [5] [4]. These loops vary in length, sequence, and conformation across different SH2 domains, creating distinct binding surfaces that recognize specific peptide sequences [5]. Structural analyses have identified three primary binding pockets that exhibit selectivity for the three positions immediately C-terminal to the pTyr in a peptide ligand [5].

Diagram: The conserved architecture of SH2 domains showing the N-terminal pTyr-binding pocket and C-terminal specificity-determining regions.

Molecular Determinants of SH2 Domain Specificity

Loop-Controlled Access to Binding Pockets

The remarkable specificity diversity among SH2 domains arises primarily from combinatorial loop variations that control access to binding pockets [5]. Research has revealed that the EF and BG loops function as "gates" that can either permit or block ligand access to key binding subsites [5]. For instance, in SH2 domains that recognize hydrophobic residues at the P+3 position (third residue C-terminal to pTyr), these loops maintain an open conformation allowing access to the P+3 binding pocket [5]. Conversely, in Grb2 SH2 domains that prefer asparagine at P+2, a bulky tryptophan residue in the EF loop physically occupies the P+3 pocket, forcing the peptide ligand to adopt a β-turn conformation and creating a new P+2 binding subsite [5] [4].

Recognition of Distinct Sequence Motifs

Systematic profiling of SH2 domain binding specificities using oriented peptide array libraries (OPAL) has categorized SH2 domains into groups based on their preferred recognition motifs [5] [7]. The majority of SH2 domains recognize hydrophobic residues at either the P+3 or P+4 positions relative to the pTyr [5]. A significant subset of approximately 20 SH2 domains (classified as Group IC), including Grb2, instead recognize an asparagine residue at the P+2 position [5]. This specificity is enabled by a network of hydrogen bonds between the asparagine side chain and residues βD6 and βE4 of the SH2 domain [5]. The BRDG1 SH2 domain exemplifies another specificity class, recognizing bulky hydrophobic residues at P+4 through a unique "pentagon basket" hydrophobic pocket formed by five conserved hydrophobic residues [5] [7].

Table 2: SH2 Domain Specificity Groups and Their Recognition Motifs

| Specificity Group | Representative SH2 Domains | Preferred Motif | Key Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| P+3 Hydrophobic | Src, Fyn, Abl1, NCK1 | pY-x-x-ψ* | Open P+3 pocket; accessible EF/BG loops |

| P+2 Asn | Grb2, GADS, GRB7, FES | pY-x-N | EF loop Trp blocks P+3 pocket; β-turn conformation |

| P+4 Hydrophobic | BRDG1, BKS, CBL | pY-x-x-x-ψ | Extended binding surface; open P+4 pocket |

| STAT-type | STAT1, STAT3, STAT5 | pY-x-x-Q | Lack βE/βF strands; split αB helix |

ψ represents hydrophobic residues

Thermodynamics of SH2 Domain-Peptide Interactions

SH2 domains typically bind their cognate pTyr-containing peptides with moderate affinity, with dissociation constants (Kd) generally ranging from 0.1 to 10 μM [2] [4]. This affinity range is considered optimal for enabling transient interactions necessary for dynamic signaling processes [2]. The pTyr residue itself contributes approximately 50% of the total binding free energy, with the conserved Arg βB5 interaction accounting for the majority of this contribution [6]. The residues C-terminal to pTyr provide the remaining binding energy and confer specificity [6]. Artificially increasing binding affinity can disrupt normal cellular signaling, as demonstrated by engineered "superbinder" SH2 domains that cause cellular dysfunction by perturbing normal signal transduction dynamics [2].

Distinguishing STAT and Src-Family SH2 Domains

Structural Classification: STAT-type vs. Src-type SH2 Domains

SH2 domains can be broadly classified into two major structural subgroups: STAT-type and Src-type [4]. This classification reflects fundamental structural differences that underlie their distinct functions in cellular signaling. Src-type SH2 domains represent the canonical architecture with all seven β-strands and two α-helices, while STAT-type SH2 domains lack the βE and βF strands and feature a split αB helix [4]. This structural divergence likely represents an adaptation for STAT dimerization, which is essential for STAT transcriptional activity [4].

Functional Implications for Signaling

The structural differences between STAT and Src-family SH2 domains correlate with their distinct biological roles. Src-family SH2 domains primarily facilitate intracellular signaling cascades by recruiting specific proteins to activated receptors or scaffolding complexes [3]. They also play critical roles in autoinhibition, as exemplified by the intramolecular interaction between the SH2 domain and phosphorylated C-terminal tail in Src kinases that maintains the kinase in an inactive state [3]. In contrast, STAT SH2 domains are specialized for mediating tyrosine phosphorylation-dependent dimerization, nuclear translocation, and DNA binding in response to cytokine and growth factor signaling [4]. These functional specializations make selective targeting of these SH2 subfamilies a promising therapeutic strategy.

Diagram: Structural and functional differences between Src-type and STAT-type SH2 domains with implications for therapeutic targeting.

Technical Support: Troubleshooting SH2 Domain Experiments

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why is my SH2 domain exhibiting non-specific binding in pull-down assays? A: Non-specific binding often results from incomplete blocking or improperly optimized binding conditions. Ensure your binding buffer contains sufficient concentrations of non-ionic detergents (e.g., 0.1% Triton X-100) and carrier proteins (e.g., 1-2% BSA). Include control experiments with non-phosphorylated peptides and consider using competitive elution with high concentrations of soluble phosphorylated peptides (100-500 μM) to confirm specificity [7] [8].

Q2: How can I improve the weak binding affinity observed in my SH2 domain interaction studies? A: Weak binding (Kd > 10 μM) may reflect non-optimal peptide sequence or incorrect phosphorylation status. Verify the phosphorylation of your tyrosine residue by mass spectrometry or phospho-specific antibodies. Design peptides with appropriate residues C-terminal to pTyr based on known specificity profiles for your SH2 domain [5] [7]. Consider extending your peptide length to include more distal residues that may contribute to binding affinity through secondary interactions.

Q3: What causes SH2 domain instability during recombinant expression and purification? A: SH2 domains can be unstable when expressed in isolation. Include flanking sequences from the native protein context, as these may contribute to stability. Use lower induction temperatures (18-25°C) during protein expression and add stabilizing agents (e.g., 5-10% glycerol, 0.5-1 M NaCl) in purification buffers. For problematic domains, consider generating fusion proteins with solubility-enhancing tags (e.g., MBP, GST) that can be cleaved after purification [3].

Q4: How can I achieve selective inhibition of specific SH2 domains given their high conservation? A: Focus on the specificity-determining regions rather than the conserved pTyr pocket. Structure-based design targeting the less conserved EF and BG loops can yield selective inhibitors. Alternative approaches include developing monobodies or other synthetic binding proteins that achieve remarkable selectivity by engaging unique surface features, as demonstrated by monobodies that distinguish between even highly similar SrcA and SrcB subfamily SH2 domains [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for SH2 Domain Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Applications | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monobodies | Mb(Src2), Mb(Lck1) | Selective SH2 domain inhibition | Nanomolar affinity; discriminate SrcA vs. SrcB subgroups [3] |

| Peptide Libraries | Oriented Peptide Array Library (OPAL) | Specificity profiling | High-density peptide chips for proteome-wide screening [7] [8] |

| Computational Tools | SMALI, ProBound | Binding partner prediction | Quantitative sequence-to-affinity modeling [9] [7] |

| Expression Systems | Yeast surface display, Bacterial expression | SH2 domain production | Yeast display enables Kd estimation during selection [3] [9] |

Advanced Methodologies for Specificity Profiling

Next-Generation Sequencing-Enhanced Peptide Display Recent advances combine bacterial display of genetically-encoded peptide libraries with enzymatic phosphorylation and next-generation sequencing (NGS) to comprehensively profile SH2 domain specificity [9]. This approach involves:

- Library Construction: Creating highly diverse random peptide libraries (10^6-10^7 sequences) with degenerate sequences flanking a central tyrosine residue

- Enzymatic Phosphorylation: Using specific tyrosine kinases to phosphorylate displayed peptides

- Affinity Selection: Performing multiple rounds of selection against purified SH2 domains

- NGS Analysis: Sequencing selected pools and analyzing with computational tools like ProBound to generate quantitative sequence-to-affinity models [9]

This methodology enables accurate prediction of binding free energies across the complete theoretical ligand sequence space and can identify the impact of phosphosite variants on SH2 domain binding [9].

Structural Workflow for Specificity Analysis

Diagram: Structural workflow for analyzing SH2 domain specificity and developing selective inhibitors.

The canonical SH2 domain fold represents a remarkable example of evolutionary conservation coupled with functional diversification. While the fundamental architecture remains constant across the family, nature has employed combinatorial loop variations to generate an extensive repertoire of specificities from this conserved scaffold [5] [4]. This understanding provides a robust foundation for developing selective therapeutic agents that target specific SH2 domains in pathological conditions.

The distinct structural features of STAT-type versus Src-type SH2 domains create unique opportunities for selective inhibition strategies. Rather than targeting the highly conserved pTyr-binding pocket, successful therapeutic development should focus on the specificity-determining regions, particularly the EF and BG loops, and the unique binding pockets that engage residues C-terminal to the pTyr [5] [4]. Emerging approaches including monobodies, computational design, and structure-based small molecule development offer promising paths to achieve the selectivity required for effective therapeutics with minimal off-target effects [3] [9] [4]. As our understanding of SH2 domain biology continues to advance, so too will our ability to precisely manipulate these critical signaling modules for therapeutic benefit.

SH2 domains are modular protein domains approximately 100 amino acids in length that specifically recognize and bind to phosphorylated tyrosine (pTyr) motifs. These domains are crucial for signal transduction in multicellular organisms, mediating protein-protein interactions in response to tyrosine phosphorylation. All SH2 domains share a conserved core fold consisting of a central anti-parallel β-sheet flanked by two α-helices, forming what is known as an αβββα motif [10] [11]. Despite this common framework, significant structural and functional distinctions exist between different SH2 classes, particularly between STAT-type and Src-type SH2 domains.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of SH2 Domains

| Feature | STAT-type SH2 Domains | Src-type SH2 Domains |

|---|---|---|

| C-terminal Structure | Features an additional α-helix (αB') | Contains an extra β-sheet (βE or βE-βF motif) |

| Classification Basis | Based on C-terminal secondary structure | Distinguished by β-sheet C-terminal structure |

| Evolutionary Origin | More ancient form; template for SH2 evolution | More recently evolved variant |

| Representative Proteins | STAT family transcription factors | Src family kinases, Abl, Grb2, PI3K |

Structural Differences: STAT-type vs. Src-type SH2 Domains

Core Structural Architecture

The primary structural distinction between STAT-type and Src-type SH2 domains lies in their C-terminal regions. STAT-type SH2 domains contain an additional α-helix (αB') in what is known as the evolutionary active region (EAR). In contrast, Src-type SH2 domains harbor an extra β-sheet (βE and βF, though each strand is not always observed) in this same region [10] [12]. This fundamental architectural difference influences how these domains interact with binding partners and function within cellular signaling pathways.

Binding Pocket Organization

Both STAT-type and Src-type SH2 domains contain two primary binding subpockets: the pY (phosphate-binding) pocket and the pY+3 (specificity) pocket [10]. The pY pocket is formed by the αA helix, the BC loop, and one face of the central β-sheet, while the pY+3 pocket is created by the opposite face of the β-sheet along with residues from the αB helix and CD and BC* loops [10]. Despite these similarities, the precise geometry and chemical environment of these pockets differ between STAT-type and Src-type SH2 domains, contributing to their distinct binding preferences.

Functional Implications

The structural differences between STAT-type and Src-type SH2 domains directly impact their cellular functions. STAT-type SH2 domains are critical for STAT protein activation, facilitating receptor recruitment, phosphorylation, and subsequent dimerization through reciprocal SH2-pTyr interactions [10]. This dimerization is essential for nuclear translocation and transcriptional activation. Src-type SH2 domains, in contrast, often participate in autoinhibitory intramolecular interactions or mediate the assembly of multiprotein signaling complexes [3] [13]. For example, SFK SH2 domains maintain kinase autoinhibition by engaging phosphorylated C-terminal tails, while adaptor proteins like Grb2 use their SH2 domains to recruit specific signaling effectors to activated receptors [3] [13].

Experimental Characterization Methodologies

Structural Biology Approaches

X-ray Crystallography: This technique provides high-resolution structures of SH2 domains in complex with their phosphopeptide ligands. Researchers have successfully crystallized various SH2 domains to reveal atomic-level details of their binding interactions. For STAT proteins, crystallization has revealed the distinctive orientation of the αB' helix and its role in dimer stabilization [10]. For Src-family SH2 domains, structures have illuminated the precise geometry of the pY+3 hydrophobic pocket that accommod specific residues like isoleucine in pYEEI motifs [13].

Experimental Protocol:

- Express and purify recombinant SH2 domains using affinity chromatography

- Co-crystallize with high-affinity phosphopeptide ligands

- Collect diffraction data at synchrotron facilities

- Solve structures using molecular replacement or experimental phasing

- Analyze binding interfaces and conformational features

Biophysical Binding assays

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC): ITC directly measures the thermodynamic parameters of SH2 domain-phosphopeptide interactions, providing quantitative data on binding affinity (Kd), stoichiometry (n), enthalpy (ΔH), and entropy (ΔS). This technique is particularly valuable for comparing the binding preferences of STAT-type versus Src-type SH2 domains and for characterizing the effects of mutations on ligand recognition [3].

Experimental Protocol:

- Prepare purified SH2 domain protein in appropriate buffer

- Synthesize or purchase high-purity phosphopeptides

- Perform titrations at constant temperature (typically 25°C)

- Inject aliquots of peptide solution into protein cell while measuring heat changes

- Analyze data using appropriate binding models to extract thermodynamic parameters

Yeast Surface Display for Affinity Measurements

Yeast surface display enables rapid determination of binding affinities for SH2 domain-ligand interactions. This method is particularly useful for screening multiple binding pairs and for characterizing the specificity profiles of engineered binding proteins like monobodies [3].

Experimental Workflow for SH2 Domain Characterization

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Low Binding Affinity in SH2 Domain Interactions

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Phosphopeptide Quality: Ensure synthetic peptides are properly phosphorylated and purified. Verify phosphorylation status using mass spectrometry.

- Buffer Conditions: Optimize buffer composition, particularly ionic strength and pH, as SH2 domain binding can be sensitive to electrostatic interactions.

- Oxidation Issues: Include reducing agents like DTT (1-2 mM) in buffers to prevent cysteine oxidation in SH2 domains [14].

- Temperature Effects: Perform binding assays at multiple temperatures, as some SH2-phosphopeptide interactions show significant temperature dependence.

Problem: Poor Specificity in SH2 Domain Targeting

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Ligand Design: Optimize phosphopeptide length and flanking residues based on known specificity determinants for each SH2 domain class.

- Competition Assays: Include control experiments with unphosphorylated peptides and peptides with scrambled sequences to verify specificity.

- Domain Context Effects: Consider testing binding in the context of full-length proteins or protein fragments, as adjacent domains can influence SH2 domain specificity [14].

Problem: Difficulty in Discriminating Between STAT and Src SH2 Domains

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Structural Analysis: Focus on the C-terminal regions using limited proteolysis or hydrogen-deuterium exchange to detect structural differences.

- Mutagenesis Studies: Introduce mutations at key specificity-determining residues, such as those in the pY+3 pocket [15].

- Computational Docking: Utilize molecular modeling to predict how ligands interact with the distinct structural features of each SH2 type.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for SH2 Domain Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Systems | E. coli expression vectors (pET, GST-tag) | Recombinant SH2 domain production |

| Purification Tools | Nickel-NTA resin (His-tag), Glutathione Sepharose (GST-tag) | Affinity purification of recombinant domains |

| Binding Assay Reagents | Phosphorylated peptides, ITC instrument, SPR chips | Quantitative binding measurements |

| Structural Biology | Crystallization screens (Hampton Research), cryoprotectants | Structure determination of SH2 domains |

| Cellular Studies | Monobodies [3], cell lines (HEK293, Jurkat) | Intracellular inhibition and pathway analysis |

Advanced Technical Considerations

Engineering SH2 Domain Specificity

Research has demonstrated that SH2 domain specificity can be engineered through targeted mutations. A seminal study showed that a single Thr to Trp mutation in the Src SH2 domain (ThrEF1Trp) switched its binding preference from pYEEI motifs to pYVNV motifs, effectively converting its specificity to resemble that of Grb2 SH2 domain [15]. This finding highlights how minimal structural changes can dramatically alter SH2 domain function and suggests how new signaling specificities might evolve naturally.

Dynamic Behavior and Allostery

SH2 domains exhibit considerable structural flexibility that impacts their function. Molecular dynamics simulations and kinetic studies have revealed that STAT SH2 domains display particularly flexible behavior even on sub-microsecond timescales [10]. The accessible volume of the pY pocket can vary dramatically, and crystal structures do not always preserve targetable pockets in accessible states [10]. This dynamic behavior underscores the importance of accounting for protein flexibility in drug discovery efforts targeting SH2 domains.

Structural Determinants of SH2 Domain Function

The structural divide between STAT-type and Src-type SH2 domains represents a fundamental evolutionary adaptation that enables these domains to serve distinct functions in cellular signaling. While they share a common core fold, their divergent C-terminal structures—α-helical in STAT-type versus β-sheet in Src-type—underpin their specialized roles in transcription factor activation versus kinase regulation and scaffold assembly. Understanding these architectural differences is crucial for developing selective inhibitors that can discriminate between these domain classes, potentially leading to more targeted therapeutic interventions in cancer and other diseases driven by aberrant tyrosine kinase signaling. As structural biology techniques continue to advance, particularly in capturing dynamic states and transient interactions, our understanding of how these architectural differences translate to functional specialization will continue to deepen.

Src Homology 2 (SH2) domains are crucial protein interaction modules that specifically recognize phosphotyrosine (pTyr) sequences, playing pivotal roles in cellular signal transduction immediately downstream of tyrosine kinases. The human genome encodes approximately 110 SH2-containing proteins, which are critical for fidelity in phosphotyrosine signaling networks. These domains fulfill their function by recruiting host polypeptides to ligand proteins harboring phosphorylated tyrosine residues. However, a fundamental challenge in the field has been understanding how SH2 domains achieve sufficient selectivity to maintain signaling specificity given that they share a highly conserved structural fold and recognize similar pTyr-containing motifs. Recent research has revealed that SH2 domains possess a remarkable ability to discriminate among physiological peptide ligands through contextual sequence information that extends beyond previously described binding motifs. This technical resource addresses the experimental approaches and troubleshooting strategies for investigating the nuanced mechanisms underlying SH2 domain selectivity, with particular emphasis on distinguishing between STAT and Src-family SH2 domains—a crucial consideration for therapeutic development in cancer and other diseases.

Understanding SH2 Domain Structure and Function

Fundamental SH2 Domain Architecture

SH2 domains are approximately 100 amino acids in length and share a highly conserved structural fold despite sequence variation. The core structure consists of a central three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet flanked by two α-helices, forming a characteristic "sandwich" structure. The phosphotyrosine-binding pocket is located in the N-terminal region, featuring a highly conserved arginine residue (at position βB5) that forms a critical salt bridge with the phosphate moiety of phosphotyrosine. The C-terminal region contains specificity-determining elements that recognize residues C-terminal to the phosphotyrosine, particularly at the pY+3 position, though additional contextual recognition occurs at other flanking positions.

Key Structural Differences: STAT vs. Src-Family SH2 Domains

Understanding the structural distinctions between STAT and Src-family SH2 domains is essential for designing selective experiments and interpreting results accurately.

| Structural Feature | STAT-Type SH2 Domains | Src-Type SH2 Domains |

|---|---|---|

| βE and βF strands | Absent | Present |

| C-terminal adjoining loop | Simplified or absent | Well-developed |

| αB helix configuration | Split into two helices | Single continuous helix |

| Dimerization capability | Adapted for dimerization (critical for function) | Primarily mediates intra- and intermolecular interactions |

| Ancestral function | Transcriptional regulation | Diverse signaling adaptor functions |

Table 1: Structural comparison between STAT-type and Src-type SH2 domains. STAT-type domains lack certain structural elements found in Src-type domains, reflecting their adaptation for dimerization and transcriptional regulation [4].

Core Mechanisms of SH2 Domain Selectivity

Contextual Peptide Recognition: Beyond Simple Binding Motifs

Traditional models of SH2 domain specificity emphasized position-independent contributions of residues, particularly at the pY+3 position. However, contemporary research reveals that SH2 domains employ a more sophisticated "linguistic" approach to peptide recognition, where contextual sequence information significantly influences binding affinity and specificity.

Key Conceptual Advances:

- Permissive vs. Non-permissive Residues: SH2 domains recognize both permissive residues that enhance binding and non-permissive residues that oppose binding through mechanisms like steric clash or charge-based repulsion [16].

- Contextual Dependencies: Neighboring positions affect one another, meaning that local sequence context matters significantly to SH2 domain recognition [16].

- Integrated Information Processing: SH2 domains integrate various permissive and non-permissive factors in a context-dependent manner to produce sophisticated recognition profiles [16] [17].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Specificity Problems

- Problem: Unexpected cross-reactivity in pull-down assays.

Solution: Analyze peptide sequences for potential non-permissive residues that might inhibit binding to your target SH2 domain while permitting binding to off-target domains.

Problem: Inconsistent binding affinity measurements.

Solution: Ensure peptide context is consistent across experiments, as neighboring residue effects can significantly impact binding measurements.

Problem: Failure to recapitulate physiological interactions with minimal peptides.

- Solution: Consider potential secondary interaction sites or avidity effects that may contribute to physiological specificity but are absent in reduced experimental systems.

Quantitative Binding Profiles for SH2 Domains

Understanding typical binding affinities and specificity determinants provides essential context for experimental design and interpretation.

| SH2 Domain | Preferred Motif | Typical Kd Range (μM) | Key Specificity Determinants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lck | pYEEI | 0.1-1.0 | pY+3 hydrophobic residue |

| Grb2 | pYVNV | 0.1-1.0 | pY+2 Asn, pY+3 Val |

| STAT1 | pYDKP | 0.1-1.0 | Contextual sequence dependence |

| p85αN | pYMDM | 0.1-1.0 | pY+1 Met |

| BRDG1 | pY----(pY+4 hydrophobic) | ~1.0 | Bulky hydrophobic residue at pY+4 |

Table 2: Binding characteristics of representative SH2 domains. Note that while motifs provide general guidance, contextual sequence information significantly refines specificity [16] [18] [7].

Essential Methodologies for SH2 Domain Specificity Profiling

SPOT Peptide Array Analysis

The SPOT peptide array method provides a semiquantitative approach for high-throughput assessment of SH2 domain binding specificity.

Experimental Protocol:

- Membrane Preparation: Synthesize peptides directly onto acid-hardened nitrocellulose membranes using automated SPOT synthesis. Each peptide typically yields approximately 5 nmol.

- Library Design: Create arrays representing physiological peptides of interest (typically 11 amino acids with phosphotyrosine at the central position). Include both known binding motifs and variant sequences to assess contextual effects.

- Binding Assay:

- Block membrane with 5% non-fat dry milk in TBST

- Incubate with purified GST-tagged SH2 domains (10-100 nM) for 2 hours at room temperature

- Wash with TBST (3 × 10 minutes)

- Detect binding with anti-GST antibodies and appropriate detection reagents

- Data Analysis: Quantify binding signals and normalize to positive controls. Identify both permissive and non-permissive sequence contexts [16].

Troubleshooting Guide: SPOT Array Challenges

- Problem: High background signal across entire membrane.

Solution: Optimize blocking conditions—try different blocking agents (BSA, non-fat dry milk) or increase blocking time. Ensure thorough washing between steps.

Problem: Weak or absent binding signals.

Solution: Verify phosphotyrosine incorporation using anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies. Confirm SH2 domain integrity and concentration. Consider increasing incubation time or protein concentration.

Problem: Inconsistent peptide synthesis.

- Solution: Monitor synthesis with ninhydrin reaction and bromphenol blue staining. Consider Cys to Ala/Ser substitutions to prevent oxidation issues [16].

Fluorescence Polarization Binding Assays

Fluorescence polarization provides quantitative binding affinity measurements in solution, complementing array-based approaches.

Experimental Protocol:

- Peptide Labeling: Synthesize phosphopeptides with N- or C-terminal fluorescent tags (FITC, TAMRA, or similar).

- Binding Reactions: Incubate fixed concentration of fluorescent peptide with varying concentrations of purified SH2 domain (typically 1 nM - 100 μM range).

- Measurement: Read polarization values using a fluorescence plate reader with appropriate filters.

- Data Analysis: Fit binding isotherms to determine Kd values using nonlinear regression.

Troubleshooting Guide: Fluorescence Polarization Issues

- Problem: Poor signal-to-noise ratio.

Solution: Optimize peptide concentration—typically 1-10 nM for high-affinity interactions. Verify peptide purity and labeling efficiency.

Problem: Non-specific binding.

Solution: Include control proteins (BSA, GST alone) to assess specificity. Adjust salt concentration or add mild detergents to reduce non-specific interactions.

Problem: Curved or irregular binding isotherms.

- Solution: Check for protein aggregation at higher concentrations. Ensure proper temperature equilibration before measurements.

Free Energy Calculations and Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Computational approaches provide atomic-level insights into SH2 domain specificity and can rationalize experimental observations.

Methodology Overview:

- System Preparation: Build SH2 domain-phosphopeptide complexes based on crystal structures or homology models.

- Molecular Dynamics: Perform simulations using implicit or explicit solvent models to sample conformational space.

- Free Energy Calculations: Apply potential of mean force (PMF) methods with restraining potentials to calculate absolute binding free energies.

- Specificity Analysis: Compare computed affinities across peptide sequences to identify preferred binding motifs and contextual effects [18].

Workflow Application:

Advanced Targeting Strategies for SH2 Domains

Monobody Technology for Selective SH2 Domain Targeting

Monobodies are synthetic binding proteins developed as high-specificity inhibitors of SH2 domain function, particularly valuable for discriminating among highly similar SH2 domains such as those in the Src family.

Key Advances:

- Subfamily Selectivity: Monobodies have been developed that discriminate between SrcA (Yes, Src, Fyn, Fgr) and SrcB (Lck, Lyn, Blk, Hck) subgroups, achieving nanomolar affinity with strong selectivity [3] [19].

- Diverse Binding Modes: Crystallography reveals that monobodies employ distinct and only partly overlapping binding modes to achieve specificity, enabling structure-based engineering to modulate inhibition properties [3].

- Functional Perturbation: Monobodies binding the Src and Hck SH2 domains selectively activate recombinant kinases, while Lck SH2-binding monobodies inhibit proximal signaling downstream of the T-cell receptor complex [3].

Experimental Protocol: Monobody Selection

- Library Construction: Generate monobody libraries using phage or yeast display with diversification in FG loops (and optionally CD loops).

- Selection: Perform 2-3 rounds of selection against target SH2 domains under stringent conditions.

- Characterization: Screen clones for binding affinity and selectivity across related SH2 domains.

- Validation: Test functional effects in cellular systems and determine complex structures to understand binding mechanisms [3].

Emerging Targeting Modalities

Beyond monobodies, several innovative approaches are being explored to target SH2 domains with improved selectivity:

- Lipid-Binding Inhibition: Approximately 75% of SH2 domains interact with membrane lipids (particularly PIP2 and PIP3). Targeting lipid-binding interfaces represents an alternative strategy for selective inhibition [4] [20].

- Phase Separation Modulation: SH2 domain-containing proteins participate in liquid-liquid phase separation. Small molecules that modulate these interactions offer potential therapeutic avenues [4].

- Context-Based Peptidomimetics: Designing inhibitors that incorporate both permissive and non-permissive elements based on contextual recognition principles.

Research Reagent Solutions

A carefully selected toolkit of reagents and methodologies is essential for successful investigation of SH2 domain specificity.

| Reagent/Method | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| SPOT Peptide Arrays | High-throughput specificity profiling | Requires specialized synthesis equipment; semiquantitative |

| Fluorescence Polarization | Quantitative binding affinity measurement | Solution-based; requires fluorescently labeled peptides |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Thermodynamic characterization of binding | Requires substantial protein; provides complete thermodynamic profile |

| Monobody Libraries | Generation of selective SH2 domain inhibitors | Yeast/phage display infrastructure needed |

| Molecular Dynamics Simulations | Atomic-level understanding of specificity | Computationally intensive; provides mechanistic insights |

| PepMapViz Software | Peptide mapping and visualization | Compatible with multiple mass spectrometry platforms [21] |

Table 3: Essential research tools for investigating SH2 domain specificity. Selection should be guided by specific research questions and available resources.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do my minimal phosphopeptides show different binding specificity compared to full-length proteins in cellular contexts?

A1: This common issue arises because cellular contexts provide additional specificity mechanisms beyond primary sequence recognition, including avidity effects from multiple binding sites, membrane localization through lipid interactions, and potential allosteric regulation. To address this discrepancy, consider using longer peptide sequences that include secondary interaction sites or employing full-length protein constructs in validation experiments.

Q2: How can I improve selectivity when targeting highly similar SH2 domains like those in the Src family?

A2: Several strategies can enhance selectivity: 1) Focus on targeting the less conserved surfaces outside the primary pTyr-binding pocket; 2) Exploit differences in lipid-binding properties between similar SH2 domains; 3) Utilize monobody technology or other synthetic binding proteins that can achieve subfamily selectivity; 4) Design inhibitors that incorporate non-permissive elements for off-target domains.

Q3: What are the most critical controls for SH2 domain binding experiments?

A3: Essential controls include: 1) Non-phosphorylated peptide variants to confirm phosphorylation dependence; 2) SH2 domains with point mutations in conserved arginine residues (e.g., βB5) to verify specific binding; 3) Competition with known high-affinity ligands; 4) Unrelated SH2 domains to assess specificity; 5) Binding to scrambled or irrelevant phosphopeptides.

Q4: How does contextual sequence information actually influence binding at a structural level?

A4: Contextual influences operate through several mechanisms: 1) Non-permissive residues may cause steric clashes with specific SH2 domain surfaces; 2) Neighboring residues can influence peptide backbone conformation and presentation to the binding pocket; 3) Charge distributions across the peptide sequence can create favorable or unfavorable electrostatic interactions; 4) Secondary interactions with surfaces outside the primary binding pocket can contribute to affinity and specificity.

Q5: What emerging technologies show promise for selective SH2 domain targeting in therapeutic applications?

A5: Promising approaches include: 1) Monobodies and other synthetic binding proteins with engineered specificity; 2) Small molecules targeting lipid-binding interfaces rather than the pTyr pocket; 3) Bivalent inhibitors that engage both SH2 and adjacent domains; 4) Proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) that leverage SH2 domains for targeted protein degradation; 5) Compounds that modulate phase separation behavior of SH2-containing proteins.

FAQs: Core Concepts and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental functional difference between an SH2 domain in a STAT protein versus one in an Src-family kinase (SFK)?

The core difference lies in their ultimate functional output:

- STAT SH2 Domain: Its primary role is in signal transduction and transcriptional regulation. It facilitates the recruitment of STATs to activated cytokine receptors, leading to their own phosphorylation, dimerization with another STAT protein, and translocation to the nucleus to act as a transcription factor [22] [23].

- SFK SH2 Domain: Its primary role is in kinase autoinhibition and substrate recruitment. In the inactive state, it intramolecularly binds the phosphorylated C-terminal tail of its own kinase, repressing activity. Upon activation, it recruits specific phosphorylated substrates for the kinase to act upon [3] [24].

FAQ 2: Why is achieving selectivity when targeting SFK SH2 domains so challenging?

The primary challenge is the high degree of structural conservation among the roughly 120 human SH2 domains, particularly within the 8 highly homologous SFK members [3] [7]. The phosphotyrosine (pY) binding pocket is especially conserved, making it difficult to develop inhibitors that can discriminate between closely related SFK SH2 domains, such as those in the SrcA (Yes, Src, Fyn, Fgr) and SrcB (Lck, Lyn, Blk, Hck) subfamilies [3].

FAQ 3: During my experiments, my SFK construct shows high background activity. How can I better stabilize its autoinhibited state?

High background activity often indicates a failure to maintain the repressed kinase conformation. The autoinhibited state is stabilized by two key intramolecular interactions:

- The SH2 domain binds to a phosphotyrosine in the C-terminal tail (e.g., pY527 in Src) [24].

- The SH3 domain binds to a polyproline type II helix in the SH2-kinase linker region [24]. Ensure that your purification protocol preserves these interactions. Using a construct that includes both the SH3 and SH2 domains along with the kinase domain, and confirming that the C-terminal tail tyrosine is phosphorylated, is critical for maintaining low basal activity.

FAQ 4: My STAT dimerization assay is inconsistent. What are the critical checkpoints for successful STAT activation?

For consistent STAT dimerization, ensure these key steps are optimized:

- Receptor Activation: Confirm that the upstream cytokine receptor is properly dimerized and that its cytoplasmic tyrosines are phosphorylated by JAK kinases. This creates the docking sites for the STAT SH2 domain [22] [23].

- STAT Phosphorylation: Verify that the recruited STAT is phosphorylated on its conserved tyrosine residue by JAK. This phosphorylation is absolutely required for dimerization [23].

- Dimerization Specificity: Remember that STAT dimers form through a reciprocal interaction where the SH2 domain of one STAT molecule binds the phosphorylated tyrosine of its partner [23]. Use phospho-specific antibodies to confirm successful phosphorylation.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Poor Selectivity of SH2 Domain Inhibitors

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Experimental Verification & Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor affects off-target SFKs or other SH2 proteins. | The inhibitor's chemical scaffold targets the highly conserved pY-binding pocket. | Verify: Perform a binding affinity assay (e.g., ITC, SPR) against a panel of purified SH2 domains [3].Solve: Explore inhibitors that engage less conserved regions outside the pY pocket, such as the hydrophobic selectivity pocket for residues C-terminal to the pY [7]. |

| Inhibitor is ineffective against a specific SFK subfamily (SrcA vs. SrcB). | The inhibitor lacks motifs to discriminate between subfamily-specific structural variations. | Verify: Use yeast display or phage display to map binding specificity across the SFK family [3].Solve: Employ engineered synthetic binding proteins (e.g., monobodies) selected for high specificity towards your target SH2 domain, which have been shown to achieve subfamily-level discrimination [3]. |

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Issues in SFK Activation Assays

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Experimental Verification & Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Ligand peptide fails to activate the SFK effectively. | Using only a single SH3 or SH2 ligand, providing insufficient stimulus to disrupt autoinhibition. | Verify: Titrate the ligand and measure the activation constant (Kact). Compare with known values (e.g., Kact for SH2 ligand ~18μM; for SH3 ligand ~159μM) [24].Solve: Utilize a combined activator with both SH3 and SH2 binding motifs, as they act cooperatively. The presence of one ligand lowers the Kact required for the second, leading to synergistic activation [24]. |

| Inability to recapitulate signaling complex formation in cells. | Not accounting for the role of SH2 domains in binding membrane lipids or forming phase-separated condensates. | Verify: Check if your SFK localizes to the plasma membrane. Perform experiments to detect liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) in signaling complexes [4].Solve: Ensure experimental conditions support lipid interactions. Consider that multivalent SH2-SH3 interactions can drive LLPS to enhance signaling output [4]. |

Key Data and Experimental Parameters

Table 1: Quantitative Parameters for SFK Activation by Domain Ligands

The following data, obtained from in vitro kinetic studies with purified, downregulated Hck, demonstrates the cooperative activation by SH3 and SH2 ligands [24].

| Ligand Type | Activation Constant (Kact) Alone | Kact in Presence of Cooperating Ligand* | Key Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| SH2 Ligand (pYEEI peptide) | 18 μM | Reduced (Cooperative effect) | Displaces phospho-C-terminal tail, partially relieving autoinhibition. |

| SH3 Ligand (polyproline peptide) | 159 μM | Reduced (Cooperative effect) | Displaces SH2-kinase linker, partially relieving autoinhibition. |

| Combined SH3 + SH2 Ligands | N/A | Strong synergistic activation | Cooperatively disrupts the "snap lock" mechanism, fully activating the kinase [24]. |

*Note: The presence of one ligand lowers the concentration of the second required for half-maximal activation.

Table 2: Binding Affinities of Selective Monobodies for SFK SH2 Domains

Engineered monobodies can achieve high selectivity within the challenging SFK SH2 family. The data below exemplifies their binding performance [3].

| Monobody Target | Dissociation Constant (Kd) | Selectivity Profile | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lck SH2 | 10-20 nM | Binds Lck with high affinity; selective for SrcB subfamily (Lck, Lyn, Hck). | Potent tool to dissect Lck-specific functions in T-cell receptor signaling [3]. |

| Lyn SH2 | 10-20 nM | Binds Lyn with high affinity; selective for SrcB subfamily. | Useful for probing Lyn-specific roles in B-cell receptor signaling. |

| Src SH2 | 150-420 nM | Binds Src with good affinity; selective for SrcA subfamily (Src, Yes, Fyn). | Can be used to activate recombinant Src kinase by disrupting autoinhibition [3]. |

Core Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) for SH2 Domain Binding Affinity

Purpose: To accurately determine the thermodynamic parameters (Kd, ΔH, ΔG, ΔS) of the interaction between an SH2 domain and a phosphopeptide or inhibitor [3].

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Purify the SH2 domain protein and the ligand (e.g., phosphopeptide) in the same buffer (e.g., 25mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150mM NaCl). Ensure exhaustive dialysis to match buffer components perfectly.

- Instrument Setup: Load the SH2 domain solution into the sample cell. Load the ligand solution into the syringe.

- Titration: Program the instrument to perform a series of injections (e.g., 19 injections of 2 μL each) of the ligand into the protein solution, with constant stirring.

- Data Collection: The instrument measures the heat released or absorbed (microcalories per second) after each injection.

- Data Analysis: Fit the raw data (plot of heat vs. molar ratio) to a suitable binding model (e.g., one-set-of-sites model) using the instrument's software to obtain the Kd, stoichiometry (N), and enthalpy change (ΔH).

Protocol 2:In VitroKinase Assay for Cooperative SFK Activation

Purpose: To quantitatively measure the cooperative activation of a purified, downregulated SFK (e.g., Hck) by SH3 and SH2 ligand peptides [24].

Method:

- Kinase Preparation: Purify the full-length, downregulated SFK from an expression system like Sf9 insect cells. Pre-phosphorylate the activation loop tyrosine in vitro with ATP to generate a constitutively active kinase domain conformation.

- Assay Setup: Use a continuous spectrophotometric kinase assay that couples ADP production to the oxidation of NADH, measured as a decrease in absorbance at 340 nm.

- Ligand Titration:

- Single Ligand: Pre-incubate the kinase with varying concentrations of a single ligand (SH3 or SH2 peptide) and measure the initial reaction velocity.

- Cooperative Ligand: Pre-incubate the kinase with a fixed concentration of one ligand (e.g., SH3 ligand), then add varying concentrations of the second ligand (e.g., SH2 ligand) during the assay.

- Data Analysis: For each titration, plot the activation velocity (Va) against the ligand concentration ([L]). Determine the activation constant (Kact), the concentration of ligand required for half-maximal activation, by fitting the data to the equation: Va = Vact[L] / (Kact + [L]).

Research Reagent Solutions

A curated list of essential tools for investigating STAT and SFK SH2 domains.

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Application | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Engineered Monobodies | High-affinity, selective synthetic binding proteins that target specific SFK SH2 domains [3]. | Nanomolar affinity; can discriminate between SrcA and SrcB subfamilies; useful as intracellular perturbation tools. |

| Oriented Peptide Array Library (OPAL) | Defines the binding specificity and consensus motif for a given SH2 domain by screening against a vast library of pY peptides [7]. | Provides a comprehensive map of potential binding partners in the proteome. |

| SH2 Domain Cooperativity Peptides | Synthetic peptides containing optimal SH3-binding (e.g., SPPTPKPRPPRP) and/or SH2-binding (e.g., EPQpYEEIPIKQ) sequences [24]. | Enable the study of cooperative kinase activation in in vitro assays. |

| Scoring Matrix-Assisted Ligand ID (SMALI) | A web-based bioinformatics program for predicting in vivo binding partners for SH2-containing proteins based on OPAL data [7]. | Helps transition from in vitro specificity to potential cellular functions. |

Signaling Pathway Diagrams

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the primary source of the selectivity challenge between Src-family and STAT SH2 domains? The core challenge arises from the high degree of structural conservation across all SH2 domains. Despite variations in the amino acids they recognize, all SH2 domains share a nearly identical three-dimensional fold consisting of a central β-sheet flanked by two α-helices [25] [4]. The most conserved feature is the deep, positively charged pocket that binds the phosphotyrosine (pTyr). This pocket almost always contains a critical arginine residue (at position βB5) as part of a highly conserved "FLVR" motif, which forms a salt bridge with the phosphate moiety of the pTyr [25] [4]. This fundamental similarity makes it difficult to design inhibitors that can distinguish between different SH2 domains.

Beyond the pTyr pocket, where can selectivity be achieved? Selectivity is primarily determined by the regions that recognize the amino acids C-terminal to the phosphotyrosine. Key among these are the EF and BG loops [5] [26]. These surface loops act as "gates" or "plugs," controlling access to secondary binding pockets (like those for the +2, +3, or +4 positions) [5]. Variations in the sequence, length, and conformation of these loops differ between SH2 domain families (such as Src-family vs. STAT) and are a major determinant of their distinct peptide-binding preferences [26]. Targeting these less-conserved loop regions and their adjacent pockets is the most promising strategy for achieving selectivity.

Our experimental monobody binds to the SrcA subgroup but shows cross-reactivity with SrcB. What could be the reason? This is consistent with the natural phylogenetic grouping of Src-family kinases. The eight SFK members are divided into the SrcA subgroup (Src, Yes, Fyn, Fgr) and the SrcB subgroup (Hck, Lyn, Lck, Blk) [3]. Monobodies developed to target one subgroup often show strong selectivity for that subgroup over the other, but may bind less specifically within the subgroup [3]. To improve intra-subgroup selectivity, you may need to perform further structure-based mutagenesis. Analyzing crystal structures of your monobody bound to on- and off-target SH2 domains can reveal the specific contact residues responsible for the cross-reactivity, enabling you to rationally design more selective variants [3].

We are seeing unexpected binding kinetics in live-cell assays compared to in vitro measurements. Is this normal? Yes, this is a recognized phenomenon. The cellular environment introduces complexities not present in purified protein systems. Research using live-cell single-molecule imaging has shown that the recruitment of SH2 domains to the membrane in vivo can be much slower than predicted from in vitro affinity measurements [27]. This delay is correlated with the clustering of SH2 domain binding sites on the membrane after receptor activation. This clustering allows for repeated rebinding events, which prolongs the membrane dwell time of SH2 domain-containing proteins and suppresses the apparent off-rate [27]. Therefore, your live-cell data may be reflecting the true spatio-temporal dynamics of SH2 domain interactions.

Quantitative Comparison of Src-Family Kinase SH2 Domain Binding

The following table summarizes quantitative binding data for engineered monobodies targeting different SFK SH2 domains, illustrating the selectivity challenge and the distinction between SrcA and SrcB subgroups [3].

| Monobody Target | SFK Subgroup | Dissociation Constant (Kd) for On-target | Representative On-target Affinity | Representative Off-target Affinity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lck, Lyn | SrcB | 10 - 20 nM [3] | High (Lck, Lyn) | ~5-10 fold lower for other SrcB members [3] |

| Src, Hck, Fgr, Yes | SrcA / SrcB | 150 - 420 nM [3] | Medium (Src, Hck, Fgr, Yes) | Weak or no binding to the opposite subgroup (SrcA vs. SrcB) [3] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Selectivity of a Novel SH2 Domain Inhibitor

Symptoms: Your small-molecule inhibitor or binding protein (e.g., monobody) shows potent binding to the intended SH2 domain but also interacts with several off-target SH2 domains.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Targeting overly conserved regions. The inhibitor might be engaging primarily with the highly conserved pTyr-binding pocket.

- Solution: Refocus your design strategy on the specificity pockets. Use structural information (e.g., from X-ray crystallography or homology models) to identify less-conserved residues in the +3 or +4 binding pockets, which are often defined by the variable EF and BG loops [5] [26]. Engineer your inhibitor to form critical hydrogen bonds or van der Waals contacts with these unique residues.

- Cause: Insufficient exploitation of non-permissive residues.

- Solution: Incorporate features that create steric clashes or charge repulsion with off-target SH2 domains. Analyze the sequences of your top off-targets; if they contain bulky residues near the binding pocket, design your inhibitor to sterically clash with them. Conversely, if your on-target has a unique charged residue, design a complementary charged group on your inhibitor to create a favorable interaction that is absent (or repulsive) in off-targets [16].

- Cause: Rigid inhibitor scaffold.

- Solution: Explore more flexible chemical scaffolds or loop regions in your binding protein that can better conform to the unique topography of your on-target SH2 domain, while being unable to adapt to off-targets.

Problem: Discrepancy Between Affinity Measurements and Cellular Activity

Symptoms: Your inhibitor shows excellent affinity (low nM Kd) in surface plasmon resonance (SPR) or isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) assays, but fails to effectively disrupt signaling in cellular or functional assays.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Differences between in vitro and cellular binding contexts.

- Solution: Validate binding in a cellular context. Use techniques like far-Western blotting to confirm your inhibitor can bind to the SH2 domain within a complex cellular lysate [27]. Employ live-cell imaging (e.g., sptPALM) to visually monitor the inhibitor's ability to displace the native SH2 domain from membrane clusters [27].

- Cause: The targeted SH2 domain engages in liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS).

- Solution: Investigate the role of multivalency and condensation. Some SH2 domain-containing proteins, like GRB2 and NCK, form signaling condensates via multivalent interactions [4]. An inhibitor designed to block a single pTyr-binding event might be insufficient to disrupt these dense clusters. Consider if a multivalent inhibitor strategy is required.

- Cause: Off-target effects disrupting the assay.

- Solution: Perform a comprehensive selectivity screen. Use a platform like SH2 domain reverse-phase protein array to profile your inhibitor against a wide panel of SH2 domains [27]. This can identify unexpected off-target interactions that might be causing confounding effects in your cellular model.

Core Experimental Protocols for Assessing SH2 Selectivity

Yeast Surface Display for Affinity and Specificity Screening

This protocol is ideal for the initial characterization and engineering of binding proteins like monobodies or scFvs against SH2 domains [3].

- Principle: The SH2 domain of interest is displayed on the surface of yeast cells. A library of potential binding proteins (e.g., monobodies) is also displayed. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) is used to select and enrich for binders.

- Procedure:

- Clone your SH2 domain gene into a yeast display vector to express it as a fusion protein with an epitope tag.

- Induce expression in a suitable yeast strain (e.g., Saccharomyces cerevisiae EBY100).

- Incubate the yeast cells expressing the SH2 domain with your library of potential binding proteins (also displayed on yeast or in soluble form).

- Use fluorescently-labeled antibodies against the epitope tag (to label the SH2 domain) and against the binding protein to detect interactions via flow cytometry.

- Sort double-positive cells by FACS and collect the selected population.

- For specificity screening, the selected binders can be incubated with off-target SH2 domains displayed on yeast, and binders with weak cross-reactivity are isolated.

- Application: This method allows for high-throughput screening and quantitative estimation of dissociation constants (Kd) directly on the yeast cell surface [3].

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) for Thermodynamic Profiling

ITC is the gold standard for determining the binding affinity and stoichiometry of SH2 domain interactions in solution [3].

- Principle: ITC directly measures the heat released or absorbed during a binding event. By titrating one binding partner into the other, it provides a full thermodynamic profile, including the dissociation constant (Kd), enthalpy change (ΔH), entropy change (ΔS), and binding stoichiometry (N).

- Procedure:

- Purify the SH2 domain and its binding partner (e.g., inhibitor, phosphopeptide, monobody) to homogeneity using recombinant expression (e.g., in E. coli) and affinity chromatography.

- Thoroughly dialyze both proteins into an identical buffer to avoid heat effects from buffer mismatch.

- Load the SH2 domain solution into the sample cell of the calorimeter. Load the binding partner into the syringe.

- Program the instrument to perform a series of automated injections of the titrant into the sample cell.

- The instrument software fits the data from the resulting thermogram to a binding model to extract the Kd, ΔH, ΔS, and N.

- Application: Use ITC to obtain precise, label-free affinity measurements for your lead compounds against both the on-target and key off-target SH2 domains to quantitatively assess selectivity [3].

Key Signaling Pathway: SH2 Domain Role in JAK/STAT and SFK Signaling

The diagram below illustrates the critical role of SH2 domains in the JAK/STAT pathway, a key area for therapeutic intervention, and contrasts it with Src-family kinase (SFK) autoinhibition.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table lists essential reagents and their applications for studying SH2 domain selectivity.

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function and Application in Selectivity Research |

|---|---|

| Monobodies | Engineered synthetic binding proteins that can achieve high affinity and unprecedented selectivity for specific SH2 domain subgroups (e.g., distinguishing SrcA from SrcB) [3]. |

| Phage & Yeast Display Libraries | Platforms for displaying vast libraries of peptides or proteins (like monobodies) to select for high-affinity binders against a specific SH2 domain. Yeast display allows for direct on-cell Kd estimation [3] [26]. |

| Oriented Peptide Array Library (OPAL) | A method to determine the binding motif of an SH2 domain by screening it against a library of immobilized phosphopeptides with defined positional amino acid variations [5] [16]. |

| Recombinant SH2 Domains (GST-tagged) | Purified, isolated SH2 domains used as probes in far-Western blotting to identify binding partners in complex cell lysates and study binding dynamics over time [16] [27]. |

| Structure-Guided Mutagenesis | Using high-resolution structures from X-ray crystallography to identify key residues responsible for binding and selectivity, enabling rational design of more specific inhibitors or binding proteins [3]. |

Exploiting Structural Nuances: Emerging Strategies for Selective Targeting

High-Affinity Synthetic Binding Proteins (Monobodies) as Selective Probes and Inhibitors

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues in Monobody Experiments

Q1: My monobody shows weak or no binding to the intended SH2 domain target. What could be wrong?

- Verify Protein Folding and Stability: Ensure both your monobody and the target SH2 domain are properly folded and stable under your experimental conditions. Check for aggregation via size-exclusion chromatography or dynamic light scattering [3] [28].

- Confirm Epitope Accessibility: The target epitope on the SH2 domain might be sterically hindered. Consult existing structural data if available. Consider using a different monobody library (e.g., switching from a "loop" to a "side" library) designed to bind different types of surfaces [29].

- Check Experimental Conditions: Binding affinity can be influenced by buffer composition, pH, and temperature. Include positive controls, such as a known phosphotyrosine peptide ligand for SFK SH2 domains, to verify the SH2 domain is functional [3] [30].

Q2: How can I improve the selectivity of my monobody for a specific SFK SH2 domain over its close paralogs?

- Leverage Diverse Library Designs: Utilize monobody libraries that present diversity on different surfaces (e.g., loops vs. β-sheet surfaces) to access a wider range of epitopes and enhance selectivity [29] [3].

- Employ Counter-Selection During Screening: During the phage or yeast display selection process, include off-target SH2 domains (e.g., from other SFK members or the broader SH2 family) in the selection buffer to deplete binders that cross-react [3].

- Characterize Binding Mode via Structural Analysis: If possible, determine the crystal structure of the monobody-SH2 complex. This can reveal the molecular basis of selectivity and guide structure-based mutagenesis to fine-tune it, as demonstrated with SFK SH2 domains [3] [30].

Q3: My intracellularly expressed monobody is not producing the expected phenotypic effect (e.g., inhibition of STAT3 signaling). How should I proceed?

- Verify Intracellular Engagement: Confirm that the monobody is binding to its endogenous target inside cells. This can be done by co-immunoprecipitation or using a degradation-based assay (e.g., by fusing the monobody to an E3 ubiquitin ligase subunit like VHL and monitoring target protein levels) [28].

- Check Expression and Solubility: Ensure the monobody is expressed at sufficient levels and remains soluble in the cellular compartment where the target resides. Fusion to solubility tags (e.g., GST, MBP) can sometimes help [29] [31].

- Confirm the Mechanism of Action: Understand your monobody's intended effect. Does it block a protein-protein interaction, inhibit enzymatic activity, or induce degradation? Use appropriate functional assays (e.g., reporter gene assays for STAT3, phosphorylation assays for kinases) to test the specific pathway [28].

Q4: Can I engineer temporal control over monobody binding?

- Yes, using optogenetics. The AsLOV2 domain can be fused to a monobody to create a light-controlled tool (OptoMB). In the dark, the monobody binds its target; blue light illumination causes a conformational change in AsLOV2 that reversibly inhibits binding. This has been demonstrated for an SH2-domain-binding monobody, achieving a 330-fold change in affinity [32].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What are the key advantages of monobodies over traditional antibodies for intracellular targeting? A: Monobodies are small (~10 kDa), stable, lack disulfide bonds (allowing correct folding in the reducing cytoplasm), and can be easily genetically encoded for intracellular expression. They can be engineered for high affinity and exceptional selectivity, even between highly similar protein domains like those in the STAT family or Src-family kinases [29] [28] [31].

Q: What types of libraries are used to generate monobodies? A: Two primary library types are commonly used:

- Loop Libraries: Diversity is introduced in the BC and FG loops, mimicking the antigen-binding loops of antibodies. These often prefer concave epitopes [29] [3].

- Side-and-Loop Libraries: Diversity is introduced on a β-sheet face ("side") in addition to loops, expanding the range of recognizable epitopes to include flat surfaces [29] [3]. Most selective monobodies against SFK SH2 domains were derived from the side-and-loop library [3].

Q: Is it feasible to target protein-protein interactions (PPIs) with monobodies? A: Absolutely. Monobodies are exceptionally well-suited for inhibiting PPIs. They have been successfully developed to target the challenging PPI interfaces of STAT3 and the SH2 domains of Src-family kinases, disrupting both intramolecular autoinhibition and intermolecular signaling interactions [3] [28].

Q: How can monobodies be used beyond simple inhibition? A: Monobodies are highly versatile tool biologics. They can be fused to effector domains to create multi-functional proteins. A prominent example is the creation of "bio-PROTACs" by fusing a target-binding monobody to an E3 ubiquitin ligase subunit (e.g., VHL), leading to targeted degradation of the protein of interest, as shown for STAT3 [28] [31].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Example Monobody Affinities and Selectivity for Src-Family Kinase (SFK) SH2 Domains

Data derived from yeast surface display and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) [3].

| Monobody Target | Monobody Name | Apparent Kd (Yeast Display) | Kd by ITC | Key Selectivity Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lck SH2 | Mb(Lck_1) | 10-20 nM | Not Specified | Selective for SrcB subgroup (Lck, Lyn, Hck, Blk) |

| Lyn SH2 | Mb(Lyn_2) | 10-20 nM | Not Specified | Selective for SrcB subgroup |

| Src SH2 | Mb(Src_2) | 150-420 nM | Low nanomolar | Selective for SrcA subgroup (Src, Yes, Fyn, Fgr) |

| Hck SH2 | Mb(Hck_2) | Not Specified | Low nanomolar | Selective for SrcB subgroup |

Table 2: Example Monobodies Targeting STAT3

Data on monobodies binding to the STAT3 core fragment (CF) and N-terminal domain (NTD) [28].

| Monobody Name | Target Domain | Apparent Kd (Yeast Display) | Kd by ITC | Application & Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS3-6 | STAT3 Coiled-Coil | 31 ± 6 nM | 7.6 ± 4.5 nM | Inhibits transcriptional activation; degrades STAT3 as VHL fusion. |

| MS3-N3 | STAT3 N-Terminal | 40 ± 4 nM | Not Specified | Binds STAT3-NTD; partial degradation as VHL fusion. |

Detailed Protocol: Yeast Surface Display for Monobody Affinity Measurement

This protocol is used for determining apparent binding affinities of monobodies for their targets, as employed in characterizing SFK SH2 and STAT3 binders [3] [28].

- Monobody Display: Express the monobody library on the surface of yeast cells as a fusion to a yeast cell wall protein (e.g., Aga2p).

- Target Labeling: Label the purified, recombinant target protein (e.g., an SH2 domain or STAT3-CF) with a fluorescent tag, such as biin for detection with fluorescently labeled streptavidin.

- Binding Titration: Incubate a fixed concentration of yeast cells displaying the monobody with a series of increasing concentrations of the labeled target protein.

- Flow Cytometry Analysis: Analyze the yeast cells by flow cytometry. The fluorescence intensity of the cell population is proportional to the amount of bound target.

- Kd Calculation: Plot the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) against the target protein concentration. Fit the binding curve (e.g., with a one-site binding model) to determine the apparent dissociation constant (Kd).

Detailed Protocol: Intracellular Target Validation using Monobody-VHL Fusions

This protocol describes a method to degrade an endogenous target protein and validate on-target engagement in cells, as demonstrated for STAT3 [28].

- Construct Generation: Clone the gene encoding your monobody (e.g., MS3-6) in-frame with the coding sequence for the VHL protein (residues 54-213) into an appropriate mammalian expression vector.

- Cell Transfection: Transfect the constructed plasmid into a relevant cell line (e.g., NPM-ALK+ thymoma cells for STAT3 studies).

- Induction and Degradation Monitoring: Induce expression of the monobody-VHL fusion (if using an inducible system) and harvest cells at various time points post-induction.

- Western Blot Analysis: Lyse the cells and perform Western blotting to monitor the protein levels of the target (STAT3) and a loading control (e.g., GAPDH or Actin).

- Proteasome Dependence Check (Optional): Treat cells with a proteasome inhibitor (e.g., MG132). If degradation is inhibited, it confirms the mechanism is proteasomal.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Monobody Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| FN3 Scaffold Libraries | Provides the foundational framework for engineering binders. Diversified loops or sheets serve as the paratope. | Loop library; Side-and-loop library [29] [3]. |

| Phage & Yeast Display Systems | High-throughput platforms for selecting high-affinity monobodies from combinatorial libraries. | Used for selecting monobodies against SFK SH2 and STAT3 [3] [28]. |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Label-free method for determining binding affinity (Kd), stoichiometry (N), and thermodynamics (ΔH, ΔS). | Used to characterize binding of MS3-6 to STAT3-CF [28]. |

| Crystallography Tools | Reveals atomic-level structure of monobody-target complexes, guiding selectivity understanding and engineering. | Structures of monobodies bound to SFK SH2 and STAT3 CC domain [3] [28]. |

| VHL (Von Hippel-Lindau) Fusion | Creates a "bio-PROTAC" to induce targeted degradation of the monobody-bound protein for functional validation. | MS3-6-VHL fusion used to degrade endogenous STAT3 [28]. |

| AsLOV2 Domain | Confers light-sensitive, reversible control over monobody binding activity when fused to the scaffold. | Creation of αSH2 OptoMonobody for light-controlled affinity chromatography [32]. |

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow Diagrams

STAT3 Pathway and Monobody Inhibition

SFK SH2 Domain Roles and Monobody Targeting

Monobody Development and Validation Workflow

FAQs: Troubleshooting Guide for SH2 Domain Selectivity Experiments

FAQ 1: Our inhibitors show poor selectivity between Src-family and STAT SH2 domains. What structural features should we target to improve specificity?

The primary feature to target is the divergent architecture of their C-terminal regions, which creates distinct specificity pockets. While all SH2 domains share a conserved phosphotyrosine (pY)-binding pocket, selectivity is determined by pockets that recognize residues C-terminal to the pY [5] [4].

The table below summarizes the key comparative features:

| Structural Feature | Src-Family SH2 Domains | STAT Family SH2 Domains |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Architecture | Src-type; contains βE and βF strands, and BG loop [4]. | STAT-type; lacks the βE and βF strands and the C-terminal adjoining loop [4]. |

| Key Specificity Pocket | Typically a hydrophobic P+3 pocket, formed by the EF and BG loops, which selects for a hydrophobic residue at the third position C-terminal to pY [5]. | Lacks a conventional P+3 pocket due to the absence of the EF loop and an open BG loop [5]. |

| Defining Loops | EF and BG loops control access to the P+3 binding pocket [5]. | Lacks the EF loop; the BG loop is open, which precludes formation of the classic P+3 pocket [5] [4]. |

| αB Helix | Single, continuous αB helix [4]. | Split into two separate helices [4]. |

To achieve selectivity, design strategies should exploit these structural differences. For Src-family inhibitors, target the well-defined, loop-controlled P+3 pocket. For STAT inhibitors, focus on alternative pockets or surface features unique to its simplified, dimerization-adapted fold [5] [4].

FAQ 2: Our binding assays are inconsistent with published affinity values. What could be causing this, and how can we improve accuracy?

Discrepancies in binding affinity measurements are a recognized challenge in the field, often stemming from protein concentration errors and incorrect model fitting [33].

- Problem: Inaccurate Protein Concentration. Using protein concentration measurements that do not account for impurities, degradation, or protein inactivity leads to overestimation of active protein, directly causing errors in calculated affinity (Kd) [33].

- Solution: Implement controls to determine the degree of protein functionality before affinity measurements. Consider alternative methods to quantify active protein concentration rather than relying solely on absorbance [33].

- Problem: Improper Model Fitting. Using the coefficient of determination (r²) to evaluate the fit of nonlinear models (like the receptor occupancy model) is a statistically poor indicator and can lead to a high rate of false negatives and inaccurate affinities [33].

- Solution: Refine model-fitting techniques by using statistically robust methods for model selection instead of r². Fit multiple models to each measurement dataset to improve accuracy [33].

FAQ 3: We are exploring non-peptide inhibitors. Are there successful examples of highly selective SH2 domain targeting?

Yes, synthetic binding proteins known as monobodies have been developed with unprecedented selectivity for Src-family kinase (SFK) SH2 domains. Key lessons from this success include:

- High Selectivity is Achievable: Monobodies have been generated that can discriminate between even the highly homologous SrcA (Yes, Src, Fyn, Fgr) and SrcB (Lck, Lyn, Blk, Hck) subgroups of SFKs [3].