Strategic Approaches to Enhance Cost-Effectiveness in B-Cell Receptor Repertoire Sequencing

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to optimize B-cell receptor (BCR) repertoire sequencing for maximum cost-effectiveness without compromising data quality.

Strategic Approaches to Enhance Cost-Effectiveness in B-Cell Receptor Repertoire Sequencing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to optimize B-cell receptor (BCR) repertoire sequencing for maximum cost-effectiveness without compromising data quality. It explores the foundational principles of BCR sequencing, compares established and emerging methodological approaches, details practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies, and discusses validation frameworks for technology selection. By synthesizing current research and benchmarking studies, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to design efficient sequencing projects, crucial for advancing immunology research, vaccine development, and therapeutic antibody discovery in an era of increasing budgetary constraints.

Understanding BCR Sequencing Fundamentals and Cost Drivers

The Critical Role of BCR Repertoire Diversity in Adaptive Immunity and Disease Research

B-cell receptor (BCR) repertoire sequencing (Rep-seq) is a powerful high-throughput method for profiling the diversity of B-cell receptors within an individual's adaptive immune system. Each B cell expresses a unique BCR, generated through somatic recombination of variable (V), diversity (D), and joining (J) gene segments. The resulting diversity, concentrated in the complementarity-determining regions (CDRs)—particularly CDR3—enables the recognition of a vast array of pathogens [1]. Profiling this repertoire provides crucial insights into immune responses in health, disease, and following vaccination.

This technical support center addresses common challenges in BCR Rep-seq experiments, with a specific focus on improving cost-effectiveness without compromising data quality—a key consideration for research and drug development.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: How do I choose between bulk and single-cell BCR sequencing?

The choice between bulk and single-cell BCR sequencing depends on your research goals, budget, and required data resolution. The table below compares their key characteristics [2] [3].

Table 1: Comparison of Bulk vs. Single-Cell BCR Sequencing

| Feature | Bulk BCR Sequencing | Single-Cell BCR Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput & Cost | High sequencing depth; lower cost per sequence [3] | Lower throughput (100-1000x less than bulk); higher cost per cell [3] |

| Primary Advantage | Excellent for assessing overall repertoire diversity and clonal expansion | Enables native pairing of heavy and light chains [3] |

| Key Limitation | Loses paired-chain information and cellular context [2] | Lower repertoire coverage due to limited cell input [3] |

| Ideal Application | Large-scale diversity studies, tracking clonal dynamics over time | Studying antibody function, discovering therapeutic antibodies, characterizing rare B-cell subsets [2] [3] |

Cost-Effectiveness Tip: For large-scale diversity studies, bulk sequencing provides superior depth per dollar. If chain pairing is essential, consider targeted single-cell sequencing on specific B-cell populations of interest to manage costs.

Sequencing errors artificially inflate repertoire diversity, leading to false conclusions. The primary sources are errors during PCR amplification and errors from the sequencing process itself [4]. The Illumina MiSeq platform, for example, has an average base error rate of ~1% [4].

Troubleshooting Guide: Error Correction Methods

- Problem: Artificially high diversity due to sequencing errors.

- Symptoms: An overabundance of unique sequences, particularly singletons.

- Solutions:

- Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): Short random oligonucleotide tags are added to each original mRNA molecule during library prep. Reads sharing the same UMI are considered PCR descendants of the same original molecule, and a consensus sequence is built to correct for errors [5] [4].

- Computational Error Correction (e.g., Hamming Graph Clustering): This method clusters highly similar sequencing reads (e.g., within a Hamming distance of ≤5) and generates a consensus sequence for each cluster, effectively removing errors without the need for UMIs [4].

Cost-Effectiveness Tip: While UMIs require specialized library kits, purely computational error correction can be applied to existing datasets, making it a cost-saving alternative for labs re-analyzing data or working with limited budgets.

FAQ 3: My CDR-H3 structural coverage is low. What could be the cause?

Low coverage for CDR-H3, the most variable loop, can occur for several reasons. The SAAB+ pipeline, which annotates CDR structures, achieves different coverages for human (~48%) versus mouse (~88%) data [6].

Troubleshooting Guide: Low Structural Coverage

- Primary Cause: CDR-H3 Length. Longer CDR-H3 loops are inherently more difficult to model structurally. The most common CDR-H3 lengths in mouse data are 11-12 residues, whereas in human data it is 15 residues, which is a major factor in the lower human coverage [6].

- Solution: If your research specifically requires structural annotations, consider that your species of interest and the natural length distribution of its CDR-H3s will impact coverage. There is no simple fix, but being aware of this limitation is key for data interpretation.

FAQ 4: How much sequencing depth is sufficient for my experiment?

Oversequencing wastes resources, while undersequencing misses diversity. The optimal depth depends on your sample type and complexity.

Troubleshooting Guide: Determining Sequencing Saturation

- Use UMIs to Assess Saturation: As shown in the diagram and supported by experimental data, the number of corrected clonotypes plateaus after a certain sequencing depth. Continuing to sequence past this point yields diminishing returns [5].

- General Guideline: For libraries made from 10 ng of PBMC RNA using a UMI-based method, a depth of ~100,000 reads per library may be sufficient to capture the majority of clones, as clonotype counts plateau beyond this point [5].

Diagram 1: Sequencing Depth Saturation Curve

Cost-Effectiveness Tip: Always perform a pilot saturation analysis. Sequence a single library at high depth, then computationally downsample the reads to find the point where clonotype discovery plateaus. Use this depth for your remaining samples to avoid overspending on sequencing.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Standardized Workflow for BCR Rep-seq

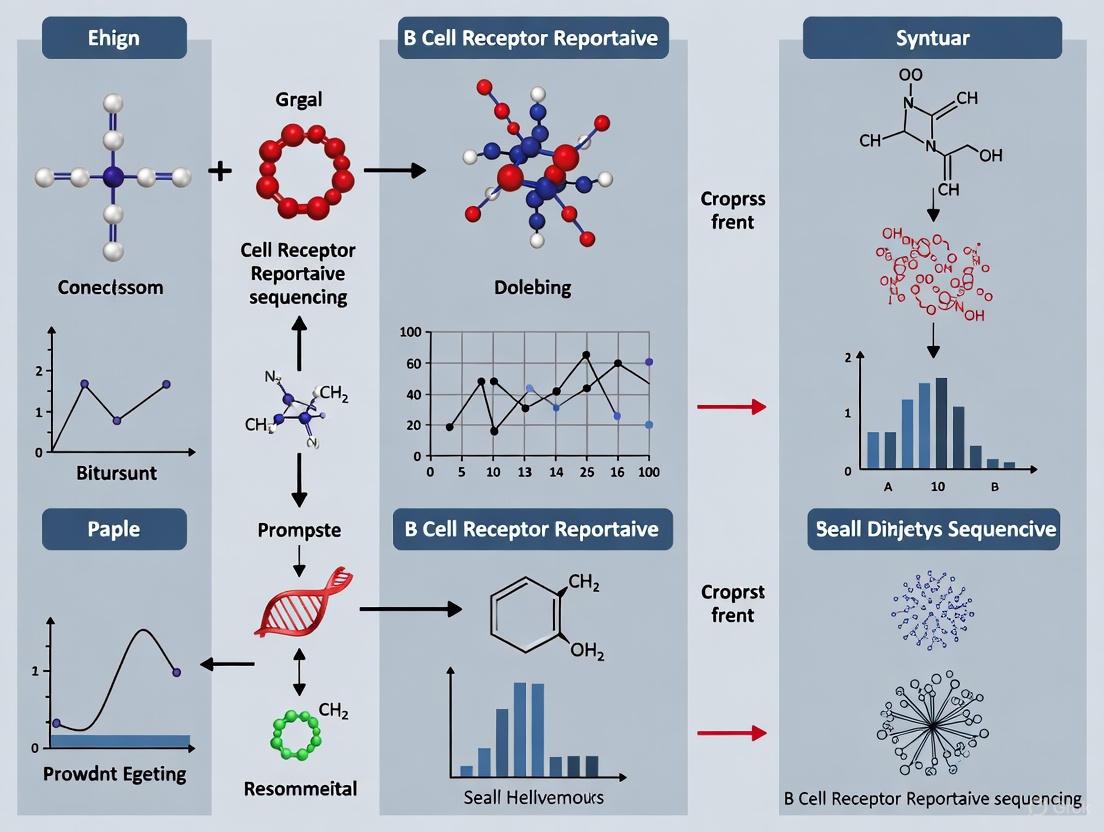

A robust BCR Rep-seq pipeline involves multiple critical steps, from sample preparation to data analysis. The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow that incorporates best practices for cost-effective and accurate profiling [7] [5].

Diagram 2: BCR Rep-seq Analysis Workflow

Key Methodology: Structural Annotation of BCR Repertoires (SAAB+)

For studies where CDR loop structure is relevant, the SAAB+ pipeline provides a rapid method for structural annotation.

- Objective: To annotate BCR repertoire sequences with structural information on their CDR loops, enabling insights into structural predetermination and dynamics [6].

- Procedure:

- Input: BCR repertoire amino acid sequences.

- Structural Filtering: Sequences are filtered for structural viability using alignment to Hidden Markov Models (HMMs), indel checks, and verification of conserved residues and CDR loops.

- Canonical Class Identification: SCALOP is used for rapid identification of canonical classes for CDR-H1 and CDR-H2.

- CDR-H3 Prediction: FREAD is employed to find structurally similar crystallographically-solved templates for the CDR-H3 loops.

- Output: A file compatible with the AIRR-seq standard, listing structural templates for each CDR [6].

- Performance: The pipeline can process approximately 4.5 million sequences per day on a 40-core computing cluster [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the right reagents and tools is fundamental to a successful and cost-effective experiment. The following table details essential materials and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for BCR Rep-seq

| Item | Function / Description | Cost-Efficiency Note |

|---|---|---|

| SMARTer Human BCR Kit | Uses 5' RACE and template-switching for sensitive, unbiased amplification of BCR transcripts from RNA. Reduces amplification bias compared to multiplex PCR [5]. | The high sensitivity allows for lower RNA input, preserving precious samples. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide tags added to each mRNA molecule during cDNA synthesis to correct for PCR and sequencing errors [5] [4]. | Reduces artifactual diversity, preventing costly misinterpretations and the need for follow-up experiments. |

| SCALOP | A computational tool for rapid canonical class identification of CDR-H1 and CDR-H2 loops [6]. | Freely available software that adds structural dimension to sequence data without wet-lab costs. |

| FREAD | A computational tool for predicting CDR-H3 loop structure by homology to solved crystal structures [6]. | As above, provides structural insights from standard sequencing data. |

| pRESTO/Change-O Suite | A comprehensive set of bioinformatics tools for processing raw reads, error correction, V(D)J assignment, and clonal analysis [7]. | An open-source suite that standardizes analysis, improving reproducibility and reducing reliance on commercial software. |

To aid in experimental planning and benchmarking, the table below consolidates key quantitative metrics from published studies and technical specifications.

Table 3: Key Quantitative Metrics in BCR Rep-seq

| Metric | Typical Range / Value | Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical BCR Diversity | >10^14 [7] | The potential diversity generated by V(D)J recombination. |

| Human B Cells per Adult | 10^10 - 10^11 [7] | Highlights the challenge of comprehensive sampling. |

| SAAB+ CDR-H3 Coverage (Human) | 48.1% [6] | Highly dependent on CDR-H3 length distribution. |

| SAAB+ CDR-H3 Coverage (Mouse) | 88.1% [6] | Higher due to shorter average CDR-H3 length. |

| Recommended RNA Input (PBMC) | 10 ng - 1 μg [5] | Lower inputs possible with highly sensitive kits. |

| Expected Clonotypes (10 ng PBMC RNA) | 50 - 2,000 [5] | Varies significantly by donor and health status. |

| Illumina MiSeq Error Rate | ~1% per base [4] | Drives the need for error correction. |

| Global IRS Market Size (2024) | USD 334.2 Million [8] | Indicates a growing field with increasing adoption. |

Technology Comparison Tables

Core Sequencing Technology Specifications

| Technology | Sequencing Method | Read Length | Single-Read Accuracy | Primary Error Type | Sensitivity (VAF) | Time per Run |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanger | Dideoxy chain termination | 400–900 bp | >99% | N/A | 15–20% | 20 min–3 h |

| NGS | Massively parallel sequencing | 50–500 bp | >99% | Substitution | ~1% | ~48 h |

| Oxford Nanopore (MinION) | Nanopore sequencing | Up to megabase scales | >99% | Insertion/Deletion (~5%) | <1% | 1 min–48 h (real-time) |

| Single-Cell RNA-Seq | Barcoded reverse transcription | Varies by platform | Dependent on downstream sequencing | Droplet-based omission | N/A | Includes cell processing + sequencing |

bp: base pairs; VAF: Variant Allele Frequency [9]

Immune Repertoire Sequencing Applications and Costs

| Application | Relevant Technology | Key Metric | Impact on Cost-Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCR Repertoire for HIV Vaccine Design | NGS, Single-Cell BCR-seq | Precursor B cell rarity: ~1-2 specific lineages per person [10] | High-depth sequencing required; justifies targeted approaches |

| TCR Repertoire Analysis (TIRTL-seq) | High-throughput TCR-seq | Cost: ~$200 for 10 million cells [11] | 90% cost reduction vs. conventional methods ($2000 for 20k cells) |

| Clinical Oncohematology | MinION, Sanger | Turnaround Time (TAT): <24h for MinION vs. 3-4 days for Sanger [9] | Faster TAT enables quicker clinical decisions, improving resource utilization |

| Bulk vs. Single-Cell BCR Analysis | Bulk RNA-Seq vs. scRNA-seq/BCR-seq | Input: 300–20,000 sorted cells for bulk [12] | Bulk is lower cost but misses cellular heterogeneity; scRNA-seq reveals subset-specific responses [13] |

| Immune Repertoire Market Growth | Integrated NGS platforms | Market CAGR: 9.6% (2025-2030) [14] | Growing competition and adoption drive innovation and lower costs |

CAGR: Compound Annual Growth Rate; BCR: B Cell Receptor; TCR: T Cell Receptor

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Sanger Sequencing Troubleshooting

Q: What are the common causes of a noisy baseline or shoulder peaks in my Sanger data?

- Excess dye terminators (dye blobs): These appear as broad C, G, or T peaks within the first 100 bp and can impact basecalling. Ensure proper purification to remove unincorporated dyes. If using the BigDye XTerminator Kit, ensure sufficient vortexing with a qualified vortexer and use the correct reagent-to-reaction volume ratio [15].

- Multiple priming sites or secondary amplification: Redesign primers to ensure a single, specific annealing site. For PCR products, gel purification is recommended to isolate a single product [15].

- Capillary array deterioration: Replace the capillary array if shouldering is observed on all peaks [15].

- Primer impurities: Primers containing n+1 or n-1 synthesis products can cause shouldering. Use HPLC-purified primers [15].

Q: How can I resolve off-scale or flat peaks that are difficult to analyze?

- Cause: Excessive template or primer in the sequencing reaction, leading to signal oversaturation.

- Solution: Re-do the reaction using a lower amount of template DNA. The recommended amount for a PCR product of 500–1000 bp is 5–20 ng. You can also reduce the injection time and voltage if re-injecting the same sample [15].

Next-Generation and Single-Cell Sequencing Troubleshooting

Q: How can I overcome the challenge of a limited number of primary cells for B cell receptor RNA sequencing?

- Challenge: Isolating sufficient high-quality RNA from rare cell populations, such as sorted B cell subsets or very small embryonic-like stem cells (VSELs).

- Solution: Specialized low-input RNA-Seq kits are essential. For example, the Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep Ligation with Ribo-Zero Plus Kit has been used successfully with sorted cell populations. Preserving RNA quality during cell sorting is critical; keep samples constantly at 4°C and avoid cell disruption. Even with low RNA concentration (as low as 0.17 ng/μL), libraries can be prepared and meet sequencing quality criteria [12].

Q: Our lab wants to study full-length BCR repertoires but finds long-read sequencing cost-prohibitive. Are there any efficient alternatives?

- Solution: Yes, a method called Full-Length Immune Repertoire sequencing (FLIRseq) integrates linear rolling circle amplification (RCA) with Oxford Nanopore techniques. This method allows for quantitative, full-length immune repertoire reconstruction at the transcriptome level using long-read sequencing, making comprehensive profiling more accessible [14].

Q: In single-cell RNA-seq data from B cells, how do we accurately link BCR sequence to cell phenotype?

- Technology: Use integrated single-cell RNA sequencing coupled with B cell receptor sequencing (scRNA-seq/BCR-seq). This allows you to simultaneously capture the transcriptional state (cell type, activation, and signaling pathways) and the paired heavy- and light-chain BCR sequence from the same cell [13].

- Application: This integrated approach is powerful for tracking clonal expansion, somatic hypermutation, and lineage relationships within B cell populations in response to infection[vaccination [13], providing direct insight into the cost-effectiveness of sequencing by maximizing data per cell.

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: Bulk BCR Repertoire Sequencing from Sorted B Cells

This protocol is adapted from a study isolating very small embryonic-like stem cells and hematopoietic stem cells for RNA-seq, demonstrating its applicability for low-input samples [12].

1. Sample Collection and Cell Sorting

- Sample Source: Collect peripheral blood or bone marrow. For the referenced study, blood was obtained from patients, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated using Ficoll separation [12].

- Cell Staining and Sorting: Stain mononuclear cells with antibodies. A typical panel includes:

- A Lineage (Lin) cocktail of FITC-conjugated antibodies (e.g., CD235a, CD2, CD3, CD14, CD16, CD19, CD24, CD56, CD66b).

- PE-Cy7-conjugated anti-CD45.

- PE-conjugated anti-CD34.

- Sorting Strategy: Use a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (e.g., MoFlo Astrios EQ). First, gate small events (2–15 μm). Then, sort target populations. For example:

- B cell progenitors/HSC example: CD34+lin-CD45+.

- VSEL example: CD34+lin-CD45-.

- Critical Note: Keep samples constantly at 4°C during sorting to preserve RNA integrity and avoid cell disruption [12].

2. RNA Isolation and Quality Control

- Isolation Kit: Use an RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen) for low cell numbers, incorporating a DNase digestion step.

- Quality Assessment: Assess RNA quantity using a fluorometer (e.g., Quantus Fluorometer). Assess RNA quality (e.g., RNA Integrity Number) using a TapeStation 4100. Universal Human RNA Standard can be used as an internal control. Even with low concentrations (e.g., 0.17 ng/μL), sequencing may be feasible, but quality is paramount [12].

3. Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Library Prep Kit: For bulk RNA-seq including BCR transcriptome, use the Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep Ligation with Ribo-Zero Plus Kit to remove ribosomal RNA.

- Sequencing: Pool libraries and run on an Illumina NextSeq 1000/2000 system using a P2 flow cell (200 cycles) in paired-end mode, aiming for at least 30 million reads per sample [12].

Detailed Protocol: Integrated scRNA-seq and BCR-seq of Splenic B Cells

This protocol is based on a study investigating T and B cell responses to viral infection in a mouse model [16].

1. Animal Infection and Sample Preparation

- Model: Use an immunocompetent mouse model suitable for the pathogen of interest (e.g., Ifnar−/− C57BL/6 mice for FMDV studies).

- Infection: Infect mice subcutaneously with the pathogen (e.g., 4.7 log₁₀ PFUs of virus in 100 μL). Mock-infected controls receive an equal volume of medium.

- Tissue Collection: At the desired time post-infection, harvest the spleen and prepare a single-cell suspension under sterile conditions [16].

2. Single-Cell Partitioning and Library Construction

- Platform: Use a platform like the 10X Genomics Chromium, which partitions single cells into droplets with barcoded beads.

- Library Types: Prepare two libraries in parallel from the same cell suspension:

- Gene Expression Library: Captures the full transcriptome of each cell.

- BCR V(D)J Library: Enriches for B cell receptor transcripts using targeted amplification.

- Sequencing: Combine libraries and sequence on an Illumina system to sufficient depth [16].

3. Data Analysis Workflow

- Cell Ranger: Use 10X Genomics' Cell Ranger pipeline to perform sample demultiplexing, barcode processing, and alignment. The

cellranger countfunction is used for gene expression, andcellranger vdjfor BCR assembly. - Clustering and Annotation: Import expression matrices into R (Seurat) or Python (Scanpy) for dimensionality reduction, clustering, and cell-type annotation based on canonical markers.

- Integration: Overlay the clonotype information from the BCR analysis onto the UMAP clusters to correlate BCR sequences with B cell subtypes and states [16].

Workflow and Signaling Pathway Diagrams

BCR Repertoire Sequencing Experimental Workflow

B Cell Activation and Sequencing Data Integration Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Key Research Reagents for BCR Repertoire Sequencing

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Ficoll-Paque PREMIUM | Density gradient medium for isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from whole blood. | Initial sample preparation for both bulk and single-cell BCR sequencing [12] [9]. |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) | High-speed sorting of specific B cell populations (e.g., naive, memory, plasma cells) using surface markers. | Enriching rare B cell subsets for targeted repertoire analysis, improving cost-effectiveness by sequencing only relevant cells [12]. |

| RNeasy Micro Kit | Isolation of high-quality total RNA from small numbers of sorted cells (as low as 300 cells). | RNA extraction for bulk BCR transcriptome sequencing from limited clinical samples [12]. |

| Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep with Ribo-Zero | Library preparation kit that removes ribosomal RNA, enriching for mRNA including BCR transcripts. | Construction of sequencing libraries for bulk RNA-seq to assess overall BCR repertoire [12]. |

| 10X Genomics Chromium Single Cell BCR Solution | Integrated kit for partitioning single cells and preparing both 5' gene expression and V(D)J libraries. | Simultaneous capture of B cell phenotype and paired BCR sequence from the same cell [13] [16]. |

| BigDye XTerminator Purification Kit | Purification of Sanger sequencing reactions to remove unincorporated dye terminators and salts. | Cleanup step for Sanger sequencing of cloned BCR variable regions; critical for reducing dye blob artifacts [15]. |

| Oxford Nanopore Barcoding Kits | Multiplexing of samples for long-read sequencing, enabling full-length BCR sequencing. | Obtaining complete V(D)J sequences in a single read, resolving allelic ambiguity and complex haplotypes [9] [14]. |

For researchers focusing on B cell receptor (BCR) repertoire sequencing, understanding and managing the key cost components—library preparation, sequencing, and data analysis—is fundamental to conducting cost-effective research. This guide provides a detailed breakdown of these costs, along with targeted troubleshooting advice, to help you optimize your experimental workflow and budget.

Cost Component Breakdown

The total cost of a BCR sequencing project is primarily driven by three stages. The table below summarizes the key cost elements and typical price ranges.

Table 1: Key Cost Components in BCR Repertoire Sequencing

| Cost Component | Key Elements | Typical Cost Range | Notes & Impact on Cost-Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library Preparation | - Input nucleic acid (DNA/RNA) extraction & QC [17]- Reverse transcription (for RNA input) [18]- Primer panels for multiplex PCR [18]- Library construction reagents [18] [19] | - DNA/RNA Extraction: \$39 - \$57/sample [17]- Library Prep Kits: \$115 - \$250/sample [17]- Specialized BCR Kit: ~\$165/sample (e.g., SMARTer kit) [17] | - Input quality directly affects success; poor quality leads to costly re-runs [20].- Low input requirements can reduce upstream sample processing costs [18].- Automated protocols can reduce hands-on time and errors [21]. |

| Sequencing | - Sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina MiSeq, NextSeq) [18]- Sequencing kit/flow cell- Read length & depth | - MiSeq Run: \$740 - \$2,650/run [17]- NextSeq P2 Kit: ~\$3,105/run [17]- NovaSeq X Lane: \$15,000 - \$48,000/run [22] | - Required read depth depends on the diversity of the BCR repertoire [23].- Longer reads (e.g., for full-length BCRs) cost more but provide richer data (e.g., chain pairing, somatic hypermutation) [23] [19].- Multiplexing samples per run significantly reduces cost per sample [21]. |

| Data Analysis | - Bioinformatics pipeline operation- Specialist time for analysis & interpretation- Data visualization & storage | - Basic Service Rate: \$70 - \$76/hour [17] | - Complexity increases with full-length vs. CDR3-only sequencing [23].- In-house pipeline development has high initial cost but may be cheaper long-term for high-volume projects.Core facilities often provide analysis packages [19]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

1. Our BCR library yields are consistently low. What are the primary causes and how can we fix this?

Low library yield is a common issue that wastes reagents and sequencing capacity. The causes and solutions are often found in the early stages of preparation.

- Primary Causes & Solutions:

- Poor Input Sample Quality: Degraded RNA/DNA or contaminants (e.g., salts, phenol) inhibit enzymes. Solution: Re-purify input samples and always use fluorometric quantification (e.g., Qubit) over absorbance alone to ensure accurate measurement of usable material [20].

- Inefficient Fragmentation or Ligation: Over- or under-fragmentation reduces ligation efficiency. Solution: Optimize fragmentation parameters for your sample type (e.g., FFPE vs. fresh tissue) and titrate the adapter-to-insert molar ratio [20].

- Overly Aggressive Purification: Sample loss during clean-up and size selection. Solution: Avoid over-drying magnetic beads and use the correct bead-to-sample ratio during clean-up steps [20].

2. Our sequencing runs show a high rate of PCR duplicates and artifacts. How can we improve data quality?

This problem is frequently due to suboptimal amplification during library prep and directly compromises data quality.

- Root Cause: Traditional fixed-cycle PCR often leads to overamplification (too many cycles) or underamplification (too few cycles). Overamplification is a major source of PCR duplicates, chimeric sequences, and artifacts that consume sequencing reads without providing useful data [22].

- Solutions:

- Optimize PCR Cycles: Avoid overcycling. If a weak product is observed, it is better to repeat the amplification from leftover ligation product than to overamplify [20].

- Adopt Advanced Methods: Consider technologies that move away from fixed-cycle PCR. For example, some systems use real-time fluorescence monitoring to dynamically determine the optimal number of cycles for each sample individually, normalizing output and preventing overamplification [22].

3. What is the cost-benefit of CDR3-only sequencing versus full-length BCR sequencing?

The choice depends entirely on the research question and has significant cost implications.

- CDR3-Only Sequencing: Focuses on the most variable region.

- Pros: Lower sequencing costs, simpler bioinformatics, sufficient for clonotype profiling and diversity analysis [23].

- Cons: Lacks information on the complete variable region, making it impossible to reconstruct full antibody sequences for functional studies or to analyze somatic hypermutation in detail [23].

- Full-Length BCR Sequencing: Captures the entire variable region of the heavy and light chains.

4. How can we reduce costs through multiplexing without introducing errors?

Multiplexing is essential for cost-effectiveness but must be implemented carefully.

- Best Practices:

- Use High-Quality Indexes: Employ dual-indexing strategies to minimize index misassignment (cross-talk between samples) [21] [24].

- Automate Normalization: Use library prep kits that feature built-in normalization to achieve consistent read depths across samples, reducing the need for manual quantification and normalization steps [21].

- Automate Pipetting: Using liquid handling robots for library preparation can significantly reduce pipetting errors and improve consistency, especially when processing large numbers of samples [21].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Bulk BCR Sequencing from RNA (Core Protocol)

This protocol outlines the key steps for preparing BCR sequencing libraries from RNA samples, such as sorted B cells or tissue extracts [19].

Workflow Diagram: Bulk BCR Sequencing from RNA

Key Steps:

- Step 1: Cell Sorting. Sort B cells directly into an appropriate lysis buffer (e.g., RLT plus) to stabilize RNA. For low cell numbers (e.g., <50,000), sort into a small volume of buffer [19].

- Step 2: RNA Extraction & QC. Extract total RNA using a column- or bead-based kit. Assess RNA quality and quantity using methods like Agilent TapeStation and Qubit [17] [19].

- Step 3: cDNA Synthesis. Convert RNA to cDNA using a reverse transcriptase. For BCR sequencing, using a gene-specific primer or a kit designed for immune repertoire profiling (e.g., SMARTer technology) is recommended [18] [19].

- Step 4: Multiplex PCR. Amplify BCR regions using a multiplex primer panel targeting the variable regions of the immunoglobulin genes (e.g., AmpliSeq for Illumina TCR/BCR panels or similar) [18]. Carefully optimize cycle numbers to avoid overamplification [22] [20].

- Step 5: Library Purification & Size Selection. Clean up the PCR product using magnetic beads to remove primers, dimers, and non-specific products. Adjust bead ratios to select for the desired fragment size [20].

- Step 6: Library QC & Quantification. Accurately quantify the final library using qPCR or fluorometry. Check the library size distribution using a TapeStation or BioAnalyzer [17].

- Step 7: Multiplexing & Sequencing. Pool (multiplex) individually indexed libraries at equimolar concentrations and load onto the sequencer. Standard Illumina platforms like MiSeq or NextSeq are commonly used [18] [17].

Troubleshooting Low Yield and Quality

This workflow helps diagnose and resolve the most common issues leading to failed library preparations.

Workflow Diagram: BCR Library Prep Troubleshooting

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Kits for BCR Repertoire Sequencing

| Item | Function | Example Products / Kits |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit | Isolates high-quality DNA or RNA from various sample types (tissue, blood, FFPE, sorted cells). | Qiagen RNeasy Mini/Micro kits [19], Gentra Puregene for DNA [19], AmpliSeq for Illumina Direct FFPE DNA [18] |

| cDNA Synthesis Kit | Converts RNA into stable cDNA for subsequent PCR amplification; critical for RNA-based BCR sequencing. | AmpliSeq cDNA Synthesis for Illumina [18], SMARTer technology kits [19] |

| BCR-Specific Primer Panel | Multiplex PCR primers designed to comprehensively amplify the highly variable V(D)J regions of BCR genes. | AmpliSeq for Illumina Immune Repertoire Plus, BCR Panel [18], SMARTer Human BCR IgG IgM H/κ/λ Profiling Kit [19] |

| Library Construction Kit | Provides enzymes and buffers for attaching sequencing adapters and sample indexes (barcodes) to amplified BCR fragments. | AmpliSeq Library PLUS [18], Illumina DNA Prep [17] |

| Library Normalization Reagent | Simplifies and automates the process of pooling libraries at equal concentrations for balanced sequencing depth. | AmpliSeq Library Equalizer for Illumina [18], ExpressPlex Library Prep Kit [21] |

| Sequence Analysis Pipeline | Bioinformatics software to process raw sequencing data, identify V(D)J genes, assemble CDR3 sequences, and perform clonal analysis. | ImmuneDB [19], MiXCR [19], 10x Genomics Cell Ranger [24] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Concepts

Q1: What is the fundamental difference in throughput between bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing? Bulk and single-cell RNA-seq represent two different approaches to throughput. The key differences are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Throughput Comparison: Bulk vs. Single-Cell RNA-Seq

| Feature | Bulk RNA-Seq | Single-Cell RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Throughput | Population-level (millions of cells pooled) | Individual cell level (hundreds to millions of cells assayed individually) [25] [26] |

| Sequencing Depth | High sequencing depth per sample [25] | Lower sequencing depth per cell [27] |

| Data Output | Average gene expression for the entire cell population [25] | Gene expression profile for every single cell, revealing heterogeneity [25] [26] |

| Primary Trade-off | Provides depth of coverage for transcripts but misses cellular heterogeneity. | Provides breadth of cellular information but with less depth per cell due to budget constraints [27]. |

Q2: For B cell receptor repertoire sequencing, should I prioritize sequencing depth (bulk) or cellular breadth (single-cell)? The choice depends entirely on your research goal.

- Use Bulk RNA-seq if your primary goal is to deeply sequence the BCR repertoire from a large population of B cells to identify the most abundant clonotypes or to perform high-throughput screening across many patient samples cost-effectively [28] [29].

- Use Single-Cell RNA-seq if your goal is to link BCR sequence to the transcriptional identity of the individual B cell that produced it. This is essential for understanding which B cell clones (e.g., those producing broadly neutralizing antibodies against HIV) are derived from which B cell subsets (e.g., memory B cells, plasma cells) and to study the clonal diversity and evolution of the B cell response [28] [29].

Experimental Design & Cost-Effectiveness

Q3: How can I make my single-cell BCR sequencing more cost-effective without sacrificing critical information? A key strategy is optimal sequencing budget allocation. A mathematical framework suggests that for estimating many important gene properties, the optimal allocation is to sequence at a depth of around one read per cell per gene, and to maximize the number of cells within a fixed total budget [27].

Table 2: Strategies for Cost-Effective Single-Cell BCR Sequencing

| Strategy | Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Read Depth | General scRNA-seq/BCR-seq experiments [27]. | Allocate your budget for more cells sequenced at a lower depth per cell (~1 UMI/cell/gene for genes of interest). |

| Targeted Assays | Focusing on specific B cell lineages or predefined subsets. | Use antibody-based pre-enrichment (e.g., FACS) for B cells or antigen-specific B cells to reduce sequencing costs on irrelevant cells [29]. |

| Multiplexing | Large cohort studies or multiple condition comparisons. | Use sample multiplexing (e.g., cell hashing) to pool samples, reducing per-sample library preparation costs and batch effects [25]. |

| Pilot Studies | Any new project or sample type. | Use bulk sequencing or a small-scale scRNA-seq run to estimate the abundance of your B cell population of interest and inform the scale of the main experiment [28]. |

Q4: What are the key experimental bottlenecks in single-cell BCR repertoire analysis? Characterizing vaccine-induced HIV-specific B cell repertoires is labor-intensive. Bottlenecks include [29]:

- The Rarity of Target B Cells: Naive B cell lineages capable of producing broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) are exceptionally rare in the human repertoire.

- Data Depth and Labor: Isolating and sequencing a sufficient number of these rare B cells across multiple subjects to achieve statistical power is challenging.

- Bioinformatics Complexity: Analyzing the data to reconstruct B cell lineages and identify key somatic hypermutations requires specialized computational pipelines.

Technical Troubleshooting

Q5: I am not detecting my rare B cell population of interest in my single-cell data. What could be wrong?

- Sample Preparation: Ensure your tissue dissociation protocol is optimized to preserve the viability and integrity of your target B cells. Dissociation can induce artificial stress responses that alter transcription [26].

- Cell Viability: Low cell viability can lead to the loss of rare populations. Aim for high viability (>90%) in your single-cell suspension.

- Enrichment Strategy: If the population is extremely rare (e.g., bNAb precursors), consider using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) with specific antibodies to pre-enrich for these cells before loading them onto the single-cell platform [29].

- Cell Number Loaded: You may not have loaded enough cells to capture the rare population. Use the following formula as a starting point for estimation: Number of cells to load = (1 / Estimated frequency of rare population) * Capture efficiency of your platform.

Q6: My single-cell data is very sparse with many dropouts (genes with zero counts). How does this impact BCR analysis? Sparsity, or "dropouts," is a common challenge in scRNA-seq due to the low starting RNA material [30]. For BCR analysis:

- Impact: It can make it difficult to accurately assemble the full-length paired heavy and light chain sequences for each B cell.

- Mitigation:

- Use protocols and platforms that incorporate Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs). UMIs tag each original mRNA molecule, allowing for accurate counting of transcripts and correcting for amplification biases, which improves the quantitative accuracy of your BCR data [26].

- Ensure you are using a dedicated BCR analysis toolkit that is designed to handle the inherent noise and sparsity in single-cell data.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Suboptimal Single-Cell Sequencing Depth for Target Genes

Problem: The sequencing depth for your single-cell experiment is not sufficient to reliably detect expression of key B cell marker genes or to assemble BCR sequences.

Solution: Follow this workflow to determine the optimal sequencing budget allocation.

Issue: Choosing Between Bulk and Single-Cell BCR Sequencing

Problem: Uncertainty about whether to use bulk or single-cell sequencing for a B cell receptor study.

Solution: Use this decision diagram to guide your experimental design based on your primary research question.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for B Cell Receptor Repertoire Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Single Cell Immune Profiling | A commercial solution that simultaneously profiles the transcriptome and paired V(D)J sequences (BCR/TCR) from single cells [25]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide sequences that label each individual mRNA molecule before amplification. This allows for accurate digital counting of transcripts and eliminates PCR amplification bias, which is critical for quantitative BCR analysis [26]. |

| Cell Hashing Antibodies | Antibodies conjugated to oligonucleotide "barcodes" that uniquely label cells from different samples. This allows for sample multiplexing, reducing costs and technical variability by pooling samples before single-cell library preparation [25]. |

| VRC01-Class Germline Targeting Immunogen (e.g., eOD-GT8 60mer) | An example of an engineered immunogen used in vaccine trials to specifically prime and expand rare naive B cell precursors with the potential to develop into broadly neutralizing antibodies [29]. |

| FACS Antibodies for B Cell Enrichment | Fluorescently-labeled antibodies against surface markers (e.g., CD19, CD20, CD27) used to isolate specific B cell subsets (e.g., naive, memory) via Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting, enabling targeted sequencing of populations of interest [29]. |

| BG505 SOSIP GT1.1 Trimer | A native-like HIV Env trimer immunogen engineered to bind and activate precursors for multiple classes of bNAbs, used in sequential immunization strategies to guide B cell maturation [29]. |

In B cell receptor (BCR) repertoire sequencing, the choice of starting template—genomic DNA (gDNA) or RNA/complementary DNA (cDNA)—is a critical initial decision that fundamentally shapes the scope, sensitivity, and biological interpretation of your research data. This choice represents a balance between capturing the complete, naive diversity of the B cell population and profiling the actively expressed, functional immune response. Within the context of improving cost-effectiveness in sequencing research, aligning your template selection with primary experimental objectives prevents costly missteps and ensures efficient resource allocation. This guide provides troubleshooting and methodological support for this essential step.

Core Concepts: gDNA and RNA/cDNA Compared

The table below summarizes the fundamental characteristics and appropriate applications of gDNA and RNA/cDNA templates.

| Feature | Genomic DNA (gDNA) | RNA / Complementary DNA (cDNA) |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Source | Cell nucleus; one copy per cell [31] | Messenger RNA (mRNA); copy number correlates with expression level [31] |

| Represents | Total B cell diversity, including non-productive rearrangements [23] [31] | Actively expressed, functional BCR repertoire [23] |

| Ideal Application | Quantifying clonal diversity and B cell abundance [23] [32] | Studying active immune responses, antibody isotypes, and functional clonotypes [23] |

| Stability | Highly stable; suitable for archival specimens [32] | RNA is labile; cDNA is stable for experimental workflows [23] [33] |

| Quantitative Output | Enables absolute cell counting and precise clonal frequency [32] | Provides relative abundance, confounded by variable BCR expression levels [32] |

Template Selection Decision Tree

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the single most important factor in choosing a template?

The most critical factor is your primary research question. If you need to measure the total number of B cell clones (including non-functional ones), gDNA is the quantitatively accurate choice [23] [32]. If your goal is to understand the current functional immune response, RNA/cDNA, which reflects actively transcribed BCRs, is the appropriate template [23].

Can I use cDNA if I want information on antibody isotypes?

Yes, cDNA is the required template for isotype analysis. Because mRNA has already undergone class-switch recombination, cDNA synthesized with constant region-specific primers can directly reveal the isotype distribution of the antibody response [31].

Why is gDNA considered more quantitatively accurate for clonal frequency?

gDNA has one template per cell, allowing sequencing read counts to directly correspond to B cell numbers [31] [32]. In contrast, mRNA expression levels can vary significantly between individual B cells, meaning a highly active plasma cell might contribute thousands more cDNA transcripts than a naive B cell, skewing the perceived clonal frequency [32].

Our lab has archived tissue samples. Which template is more reliable?

gDNA is generally more stable over time and is less degraded in archival specimens compared to RNA [32]. For such samples, gDNA is the more reliable and robust choice for repertoire analysis.

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inability to detect rare B cell clones | Insufficient sequencing depth for template used. | Increase sequencing depth. For rare functional clones, use cDNA with Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) to correct for amplification bias [31]. |

| Skewed or biased repertoire | gDNA: Degraded sample. RNA/cDNA: RNA degradation or inefficient reverse transcription. | gDNA: Check sample quality. RNA/cDNA: Use fresh samples, rigorous RNase-free techniques, and include high-quality controls for reverse transcription [33]. |

| No isotype information | Used gDNA template, where constant regions are far from V(D)J segments. | Switch to RNA/cDNA template and employ isotype-specific reverse primers during cDNA synthesis [31]. |

| Poor correlation between technical replicates | Stochastic sampling of low-frequency clones, especially in diverse repertoires. | Increase biological replicates and perform deeper sequencing to overcome natural sampling variation [34]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: gDNA Extraction for BCR Repertoire Diversity Studies

This protocol is optimized for quantifying the total B cell repertoire from patient peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs).

- Key Materials: QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen), Proteinase K, Ethanol.

- Procedure:

- Cell Lysis: Resuspend up to 5 million PBMCs in 200 µL PBS. Add 20 µL Proteinase K and 200 µL Buffer AL. Mix thoroughly and incubate at 56°C for 10 minutes.

- Precipitation: Add 200 µL of 96-100% ethanol to the mixture and vortex.

- Binding: Transfer the mixture to the QIAamp Mini spin column and centrifuge at 6,000 x g for 1 minute. Discard flow-through.

- Washing: Wash the column with 500 µL Buffer AW1, centrifuge, and discard flow-through. Wash again with 500 µL Buffer AW2, centrifuge at full speed for 3 minutes to dry the membrane.

- Elution: Place the column in a clean microcentrifuge tube. Apply 50-200 µL Buffer AE or nuclease-free water to the center of the membrane. Incubate for 5 minutes at room temperature, then centrifuge at 6,000 x g for 1 minute to elute the high-quality gDNA.

- Technical Note: For absolute quantification, use a fluorometric method (e.g., Qubit) to measure gDNA concentration, which directly relates to cell number [32].

Protocol 2: RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis for Functional BCR Profiling

This protocol focuses on generating a faithful cDNA representation of the expressed BCR repertoire, suitable for subsequent 5' RACE library construction.

- Key Materials: TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen), SMARTer RACE cDNA Amplification Kit (Clontech), SuperScript IV Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen).

- Procedure:

- RNA Extraction (TRIzol Method):

- Lyse up to 10 million PBMCs in 1 mL TRIzol. Incubate for 5 minutes.

- Add 0.2 mL chloroform, shake vigorously, and centrifuge at 12,000 x g for 15 minutes at 4°C.

- Transfer the colorless upper aqueous phase to a new tube. Precipitate RNA with 0.5 mL isopropyl alcohol. Centrifuge and wash the pellet with 75% ethanol.

- Air-dry the RNA pellet and dissolve in nuclease-free water.

- cDNA Synthesis (5' RACE-ready):

- Use 1 µg of total RNA as template. Combine with a gene-specific primer (e.g., targeting the IgH constant region) and the SMARTer oligonucleotide.

- Add reverse transcriptase and buffer. Incubate according to the manufacturer's instructions (typically 90 minutes at 42°C).

- The resulting cDNA includes universal priming sites at the 5' ends, enabling amplification of the entire variable region with a single primer pair, thereby minimizing primer bias [31].

- RNA Extraction (TRIzol Method):

- Technical Note: Always include UMI adapters during cDNA synthesis. UMIs are short random nucleotide sequences that tag individual mRNA molecules, allowing bioinformatic correction of PCR amplification errors and duplicates, leading to more accurate quantitative data [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Consideration for Cost-Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|

| QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) | Reliable gDNA purification from cells and tissues. | High yield and purity reduce downstream assay failures, offering good long-term value. |

| TRIzol Reagent | Monophasic RNA isolation reagent that maintains RNA integrity. | A versatile and established method; suitable for processing multiple sample types simultaneously. |

| SMARTer RACE Kit | Generates high-quality, full-length cDNA with universal primer sites. | Reduces primer bias, increasing the efficiency of capturing true repertoire diversity and minimizing wasted sequencing on non-informative amplicons. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide sequences that label individual mRNA molecules. | Critical for accurate quantification; prevents overestimation of diversity from PCR errors, making sequencing spending more efficient [31]. |

| Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | High-fidelity PCR enzyme for library amplification. | Low error rate ensures sequence accuracy, reducing the need for costly validation of false-positive variants. |

cDNA Synthesis Workflow

Selecting and Applying Cost-Effective BCR Sequencing Methods

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of bulk BCR-seq over single-cell BCR-seq for repertoire diversity studies?

Bulk BCR-seq provides a significantly higher sampling depth, allowing researchers to profile a much larger number of B cells, which is crucial for capturing the full diversity of the immune repertoire. While single-cell methods typically sequence 10³–10⁵ cells, bulk sequencing can analyze 10⁵ to 10⁹ cells, making it far superior for covering the immense theoretical diversity of BCRs, estimated at over 10¹⁴ unique receptors [23] [3]. This high throughput makes bulk BCR-seq both more cost-effective and better suited for detecting rare clonotypes in highly diverse samples [35] [3].

Q2: When studying functional immune responses, should I use genomic DNA (gDNA) or RNA as my starting template?

For studies focused on the functional immune repertoire—i.e., the receptors that are actively being expressed—RNA (converted to cDNA for sequencing) is the recommended template. Unlike gDNA, which captures all rearrangements including non-productive ones, cDNA represents the actively transcribed BCR repertoire, providing a direct view of the immune system's functional response [23] [36]. However, gDNA is more stable and is ideal for quantifying the absolute number of B cell clones, as each cell contributes a single template [23].

Q3: What are the key trade-offs between CDR3-only sequencing and full-length BCR sequencing?

The choice involves a balance between depth of analysis and functional insight, as summarized in the table below.

Table: Comparison of CDR3-only and Full-Length BCR Sequencing Approaches

| Feature | CDR3-Only Sequencing | Full-Length Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3) | Entire variable region (CDR1, CDR2, CDR3, FWR) |

| Cost & Complexity | Lower cost; simpler bioinformatics | Higher cost; more complex data analysis [23] |

| Primary Application | Clonotype profiling, diversity estimation, tracking clonal expansions [23] | Understanding structural function, MHC-binding, paired-chain analysis, therapeutic antibody development [23] |

| Key Limitation | Limited functional/structural insight; no chain pairing information [23] | Lower read coverage per clonotype for the same sequencing depth [23] |

Q4: My bulk BCR-seq library yield is unexpectedly low. What are the most common causes?

Low library yield is a common issue, often stemming from problems at the initial stages of the workflow. Key causes and solutions include:

- Poor Input Sample Quality: Degraded RNA or DNA and contaminants like phenol or salts can inhibit enzymatic reactions. Always check RNA Integrity Numbers (RIN) for RNA and use fluorometric quantification (e.g., Qubit) instead of just absorbance to ensure accurate measurement of usable material [20].

- Inefficient Reverse Transcription or Adapter Ligation: Suboptimal reaction conditions, inactive enzymes, or incorrect adapter-to-insert ratios can drastically reduce yield. Titrate adapter concentrations and ensure fresh, properly stored reagents are used [36] [20].

- Overly Aggressive Purification: Excessive cleanup and size selection steps can lead to significant sample loss. Precisely follow recommended bead-to-sample ratios and avoid over-drying magnetic beads during cleanups [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Library Diversity and High Duplicate Read Rates

Symptoms: The final sequencing data has a low number of unique clonotypes relative to the number of sequenced reads, with a high proportion of PCR duplicates.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Insufficient Input Material or B-Cell Count.

- Solution: Ensure an adequate number of B cells are used as starting material. For rare B cell populations, consider increasing the scale of cell sorting or using amplification protocols designed for low inputs [37].

- Cause 2: PCR Over-Amplification.

- Cause 3: Inefficient Fragmentation or Tagmentation.

- Solution: Optimize fragmentation conditions (time, energy, or enzyme concentration) to generate a balanced distribution of fragment sizes. Verify the fragmentation profile using an instrument like the BioAnalyzer before proceeding [20].

Problem: High Background of Adapter-Dimer Contamination

Symptoms: BioAnalyzer traces show a sharp peak around 70-90 bp, indicating ligated adapters without a DNA insert. This consumes sequencing capacity and reduces useful data yield.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Overabundance of Adapters.

- Solution: Precisely titrate the adapter-to-insert molar ratio. An excess of adapters promotes adapter-dimer formation. Use fluorometric quantification for both adapters and the insert DNA [20].

- Cause 2: Inefficient Ligation or Purification.

- Solution: Ensure the ligation reaction is set up with fresh, active ligase and correct buffer conditions. Optimize post-ligation cleanup protocols, such as using a higher bead-to-sample ratio to more effectively remove short, adapter-only fragments [20].

- Cause 3: Low Input DNA.

- Solution: Increase the amount of input cDNA/gDNA to improve the likelihood of adapter-insert ligation over adapter-adapter ligation [20].

Problem: Inaccurate V(D)J Gene Assignment

Symptoms: A high proportion of sequences cannot be aligned to germline V, D, or J genes, or the assignments have low confidence.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: High Somatic Hypermutation (SHM).

- Cause 2: Incomplete or Incorrect Reference Germline Database.

- Cause 3: Sequencing Errors in the Key V(D)J Regions.

- Solution: Implement a pre-processing workflow that includes quality trimming and error correction. Using Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) is highly recommended, as they allow for the consensus-based correction of PCR and sequencing errors, providing a true representation of the original BCR sequence [36] [37].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standardized Bulk BCR-Seq Wet-Lab Protocol

This protocol outlines a cost-effective and robust workflow for generating bulk BCR-seq libraries from purified B cells.

1. B Cell Isolation and Lysis

- Isulate B cells from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or tissue using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) with CD19+ or CD20+ markers [37].

- Lyse cells in a mild lysis buffer (e.g., containing 0.3% IGEPAL CA-630) to release RNA. Centrifuge to remove debris.

2. Reverse Transcription (RT) to cDNA

- Use gene-specific primers targeting the constant region of the immunoglobulin heavy chain (e.g., for IgM, IgG, IgA) to initiate reverse transcription. This ensures only productive BCR transcripts are converted to cDNA.

- Cost-Saving Tip: Incorporate Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) during the RT step. This allows for bioinformatic error correction and accurate clonal quantification, mitigating the impact of PCR duplicates [36].

3. Targeted PCR Amplification

- Perform the first PCR amplification using a multiplex of primers targeting the variable (V) gene regions and a primer for the constant (C) region.

- Keep PCR cycles to the minimum necessary to avoid over-amplification bias. Typically, 18-22 cycles are sufficient [36] [20].

4. Library Construction and Indexing

- Perform a second, shorter PCR to add platform-specific sequencing adapters and dual indices (barcodes). This allows for pooling and multiplexing of multiple samples in a single sequencing run.

- Cost-Saving Tip: Using in-house purified Tn5 transposase and homemade reagents, as in methods like BOLT-seq or BRB-seq, can reduce costs to under a few dollars per sample [39].

5. Library Purification and Quantification

- Purify the final library using double-sided size selection with magnetic beads to remove primer dimers and large contaminants.

- Quantify the library accurately using fluorometry (e.g., Qubit) and qualify it by fragment analysis (e.g., BioAnalyzer) to confirm the expected size distribution and absence of adapter dimers.

Core Bioinformatic Analysis Pipeline with Immcantation

The following workflow processes raw bulk BCR-seq data into analyzable clonotypes. The diagram below illustrates the key steps of this computational pipeline.

Diagram: Computational Pipeline for Bulk BCR-Seq Data

1. Pre-processing and V(D)J Assignment

- Quality Control: Assess raw FASTQ files with tools like FastQC. Trim low-quality bases and remove reads with average quality scores below a threshold (e.g., Phred score < 20) [36].

- V(D)J Assignment: Use

AssignGenes.pyfrom the Change-O suite to run IgBLAST. This aligns each sequence to a database of germline V, D, and J genes, identifying the best match and locating the CDR3 region [38].

2. Clonal Inference and Population Structure

- Error Correction: If UMIs were used, generate a consensus sequence for each unique UMI group to correct for PCR and sequencing errors [36].

- Clonal Grouping: Define clonotypes using the

DefineClones.pytool. Sequences are typically grouped based on shared V and J genes and similar CDR3 nucleotide sequence lengths. A hierarchical clustering model can account for somatic hypermutation within clones [38].

3. Advanced Repertoire Analysis

- Lineage Tree Reconstruction: For each clonal family, build a phylogenetic tree (

BuildTreescommand) to visualize the evolutionary relationships between sequences and infer the unmutated common ancestor [38]. - Selection Pressure Analysis: Use the

shazampackage to calculate selection pressure metrics, such as the Focused and Replacement Mutation (FWR)/CDR model, to identify if mutations are likely driven by antigen selection [38]. - Diversity Analysis: Calculate clonal diversity indices (e.g., ShannonWiener, Simpson) using the

alakazampackage to compare repertoire richness and evenness across samples [38].

Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key reagents and materials essential for a cost-effective bulk BCR-seq workflow.

Table: Essential Reagents for Bulk BCR-Seq Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function / Rationale for Cost-Effectiveness |

|---|---|

| M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase | Enzyme for synthesizing cDNA from BCR mRNA. In-house purification of this enzyme, as done in BOLT-seq, can drastically reduce costs compared to commercial kits [39]. |

| Tn5 Transposase | Enzyme used in "tagmentation" to fragment DNA and simultaneously ligate adapters. In-house production is a major cost-saving strategy for high-throughput library prep [39]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide sequences added during reverse transcription. While adding a small initial cost, UMIs are critical for accurate error correction and clonal quantification, preventing costly resequencing of biased libraries [36]. |

| Magnetic Beads (SPRI) | Used for DNA purification and size selection. They are a versatile and affordable alternative to column-based kits, especially when bought in bulk [20]. |

| In-House Prepared Buffers | Reaction buffers for RT, PCR, and tagmentation. Preparing common buffers (e.g., Tris-HCl, PEG) in-house from raw materials significantly cuts down per-sample costs [39]. |

Quantitative Data for Experimental Design

To aid in planning and benchmarking experiments, the table below consolidates key quantitative metrics from the literature.

Table: Benchmarking Data for Bulk and Single-Cell BCR-Seq

| Metric | Bulk BCR-Seq | Single-Cell BCR-Seq | Source / Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Sampling Depth (No. of Cells) | 10⁵ to 10⁹ cells | 10³ to 10⁵ cells | [3] |

| Typical Unique CDRH3s (per sample) | ~2,900 to ~223,000 | ~85 to ~9,300 | Dataset 2 in [3] |

| Relative Cost per Sample | Lower (~1/10th of scBCR-seq) | Higher | [35] |

| Clonal Expansion (Evenness) | Higher | Lower | Dataset 1 & 2 in [3] |

| Ability to Resolve Chain Pairing | No | Yes (native pairing) | [23] [3] |

| Error Correction with UMIs | Possible and recommended | Inherent to most protocols | [36] [3] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is preserving the native heavy-light (H-L) chain pairing so critical in antibody discovery?

The native pairing between antibody heavy and light chains is essential for forming a stable, functional antigen-binding site. Correct pairing ensures the proper structural conformation for antigen recognition and binding affinity. Preserving these natural pairs allows researchers to directly clone and express antibodies with the desired specificity, which is vital for developing therapeutic antibodies. Inferring pairs from bulk sequencing data is unreliable, making single-cell approaches that capture both chains from the same cell indispensable for discovering functional antibodies [40] [41].

Q2: What are the main technical challenges when attempting to recover full-length BCR sequences from single-cell RNA-seq data?

A primary challenge, especially with widely used 3'-barcoded scRNA-seq libraries (e.g., 10x Genomics 3' GEX), is that the BCR variable region is located on the 5'-end of the transcript. Standard library preparation fragments the transcripts, preventing the simultaneous sequencing of the single-cell barcode (on the 3' end) and the full-length BCR variable region [41]. Specialized wet-lab methods and bioinformatic tools are required to overcome this orientation issue and accurately reconstruct the full, paired sequence [41] [42].

Q3: How does single-cell BCR-Seq improve cost-effectiveness in repertoire sequencing research?

While single-cell methods have a higher per-cell cost, they provide a much richer dataset that can be more cost-effective overall for antibody discovery. By directly providing the correct H-L pair, it eliminates the need for expensive and time-consuming de novo pairing efforts through methods like phage display or computational inference. Furthermore, it concurrently provides transcriptomic data from the same cell, enabling deep phenotypic analysis without the need for separate assays [43] [41].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Single-Cell BCR-Seq Experimental Issues

The table below outlines common problems, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

| Problem | Symptoms | Possible Causes | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Cell Viability [20] | Low cell recovery, high cell death rate post-thaw. | Improper sample handling, freeze-thaw cycles, prolonged storage. | Use fresh cells when possible; optimize freezing medium and thawing protocol; minimize processing delays. |

| Low BCR Recovery Rate [41] | A low percentage of B cells yield paired H-L chain sequences. | Inefficient BCR transcript capture or amplification; suboptimal primer design. | Validate and optimize primer sets for constant/leader regions; use probe-based enrichment (e.g., B3E-seq) [41]; check RNA quality. |

| High Contamination or Adapter Dimers [20] | Sharp peaks at ~70-90 bp in Bioanalyzer traces. | Contaminated reagents; overamplification; inefficient purification. | Use fresh, filtered reagents; optimize PCR cycles; perform rigorous size selection and clean-up (e.g., adjust bead-to-sample ratio). |

| Lack of Full-Length Sequences [23] | Inability to assemble sequences covering CDR1, CDR2, and framework regions. | Using CDR3-only sequencing methods; short-read sequencing limitations. | Employ full-length targeted protocols (e.g., B3E-seq, 5'-barcoded kits); use primer sets targeting leader/Framework 1 regions [41]. |

| Inconsistent Results Between Operators [20] | Sporadic failures not linked to a specific reagent batch. | Manual pipetting errors; protocol deviations; reagent degradation. | Implement detailed SOPs with highlighted critical steps; use master mixes; introduce technician checklists and "waste plates" to catch pipetting mistakes. |

Bioinformatics Analysis Challenges

The table below summarizes common issues encountered during the computational analysis of single-cell BCR-Seq data.

| Problem | Description | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Inaccurate V(D)J Assignment | Failure to correctly identify V, D, and J gene segments. | Use specialized tools designed for single-cell data (e.g., VDJPuzzle [42]); ensure the reference database is comprehensive and up-to-date. |

| Poor Consensus Sequence Quality | Noisy or unproductive reconstructed BCR sequences. | Group reads by cellular barcode and UMI to build molecular consensus sequences; apply quality filters during assembly [41]. |

| Difficulty with Somatically Hypermutated Sequences | Alignment tools fail to map highly mutated reads to germline V genes. | Use algorithms tolerant of high mutation rates; manually inspect alignments for clonally related, hypermutated sequences. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol: Recovering Full-Length BCRs from 3'-Barcoded scRNA-seq Libraries (B3E-Seq)

This protocol adapts the B3E-seq method [41] for cost-effective recovery of paired, full-length BCR variable regions from pre-existing 3'-barcoded libraries, maximizing data yield from valuable samples.

- Step 1: BCR Transcript Enrichment. Use a portion of the whole-transcriptome amplification (WTA) product from your 3'-barcoded library (e.g., from 10x Genomics or Seq-Well). Perform a probe-based hybridization capture using biotinylated oligonucleotides that target the constant regions of IgG, IgM, IgD, IgA, IgE, and IgK/IgL.

- Step 2: Primer Extension. Reamplify the enriched product using the universal primer site (UPS) from the original WTA. Then, perform a primer extension using a pool of oligonucleotides containing a new universal primer site (UPS2) linked to sequences specific to the leader or framework 1 (FR1) region of BCR heavy and light chain V segments.

- Step 3: Library Construction for Sequencing. Amplify the primer extension product with primers containing platform-specific adapters linked to the UPS2 (forward) and the original UPS (reverse). This creates a sequencing library where the full-length V region is adjacent to the UPS2.

- Step 4: Multiplex Sequencing. Sequence the library using a custom run. Key reads include:

- Read 1: Sequences from the UPS2 primer through the V region (5' to 3').

- Read 2: A custom read using a primer targeting the BCR constant region to sequence back towards the V region (3' to 5').

- Index Read: To obtain the cellular barcode and UMI.

- Step 5: In Silico Assembly. Process the data using a dedicated pipeline (you can adapt the principles from the VDJPuzzle tool [42]):

- Group reads by cellular barcode and UMI.

- Generate a high-quality consensus sequence for each molecule.

- Assemble the forward and reverse reads to reconstruct a full-length BCR sequence.

- Establish a single-cell consensus by collapsing sequences for heavy and light chains under each cellular barcode.

BCR Reconstruction from 3' Libraries

Protocol: Validating Reconstructed BCR Sequences with Sanger Sequencing

This validation protocol is crucial for confirming the accuracy of your NGS-based BCR reconstructions before proceeding to antibody expression [42].

- Step 1: Single-Cell Sorting. Sort single B cells of interest (e.g., antigen-specific B cells) into a 96-well or 384-well PCR plate containing a lysis buffer.

- Step 2: Reverse Transcription and Nested PCR. Perform reverse transcription followed by a nested PCR using primers specific for the heavy and light chain constant regions and variable region leader sequences.

- Step 3: Sanger Sequencing. Purify the PCR products and submit them for Sanger sequencing using the PCR primers or internal sequencing primers.

- Step 4: Sequence Alignment and Validation. Align the Sanger-derived sequences with the computationally reconstructed BCR sequences from your single-cell BCR-Seq data. A high degree of identity validates the accuracy of your reconstruction pipeline.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The table below lists key reagents and tools for a successful single-cell BCR-Seq workflow.

| Category | Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Biotinylated Oligos (anti-BCR constant regions) | Enriching BCR transcripts from complex WTA products for full-length sequencing [41]. |

| V-region Primers (targeting Leader/FR1) | Primer extension to append new universal primers for sequencing the 5' end of BCR transcripts [41]. | |

| Single-Cell Barcoding Beads (e.g., from 10x Genomics, Seq-Well) | Uniquely labeling mRNA from individual cells during library preparation [41]. | |

| Software & Databases | VDJPuzzle | A bioinformatic tool specifically designed to reconstruct productive, full-length BCR sequences from scRNA-seq data [42]. |

| IMGT/V-QUEST | A comprehensive database and tool for annotating immunoglobulin gene segments and analyzing mutations [23]. | |

| ImmunoMatch | A machine-learning framework used to identify and validate cognate heavy-light chain pairing from sequence data [40]. | |

| Experimental Platforms | Droplet-Based scRNA-seq (e.g., 10x Genomics) | High-throughput platform for simultaneously capturing transcriptomes and paired BCRs from thousands of cells [41]. |

| Microfluidic scRNA-seq (e.g., Seq-Well) | A portable, low-cost platform for single-cell RNA sequencing, compatible with BCR recovery methods [41]. |

Technical FAQs: Choosing and Troubleshooting Your Sequencing Approach

Q1: What is the core difference between CDR3-only and full-length V(D)J sequencing, and why does it matter for B cell research?

CDR3-only sequencing targets the Complementarity Determining Region 3, the most diverse part of the BCR, which primarily determines antigen specificity. In contrast, full-length sequencing captures the entire variable region of the receptor, including CDR1, CDR2, framework regions, and the constant region [23].

The choice matters because:

- CDR3-Focused: Ideal for tracking clonal dynamics, repertoire diversity studies, and large cohort screenings where cost-effectiveness is paramount. It provides high-depth coverage of the most variable region but does not give a complete picture of the antigen-binding site [23] [44].

- Full-Length: Essential for studies requiring a deep understanding of antibody function, including detailed analysis of somatic hypermutation (SHM), class-switch recombination, and the structural basis of antigen binding. This approach is critical for therapeutic antibody discovery and functional immune response studies [23] [45].

Q2: My BCR sequencing data shows low library diversity and high duplicate read rates. What are the potential causes and solutions?

This is a common issue often stemming from preparation and amplification. The table below outlines major failure signals and their fixes [20].

| Failure Signal | Potential Root Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Low library yield & high duplication | Over-amplification during PCR; too many cycles for the input material. | Reduce the number of PCR cycles; use unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to distinguish true biological duplicates from PCR duplicates [20]. |

| Poor input sample quality (degraded RNA/DNA) or contaminants inhibiting enzymes. | Re-purify input nucleic acids; use fluorometric quantification (e.g., Qubit) instead of absorbance alone to ensure accurate measurement of usable material [20]. | |

| Adapter-dimer peaks (~70-90 bp) in electrophoresis | Inefficient ligation or overly aggressive purification leading to loss of target fragments. | Titrate adapter-to-insert molar ratios; optimize bead-based cleanup ratios to avoid discarding library fragments of the desired size [20]. |

| Inefficient V gene recovery / Bias | Primer bias in multiplex PCR (mPCR) assays. | Consider switching to a 5' RACE (Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends)-based library construction method, which uses a single primer and demonstrates lower bias compared to mPCR [44]. |

Q3: When should I use genomic DNA (gDNA) versus RNA as my starting template for BCR-seq?

The choice of template is a critical decision that impacts the quantitative and functional interpretation of your data [23] [32].

- Genomic DNA (gDNA): More stable and is ideal for quantifying clonal abundance and diversity, as each cell contains a single template for the rearranged receptor. This makes gDNA-based assays highly accurate for estimating the absolute number of B cells and tracking clonal expansion over time [23] [32].

- RNA / cDNA: Reflects the actively expressed repertoire and is more sensitive for detecting receptors with high transcriptional activity. However, quantification can be confounded by varying expression levels across B cell subsets (e.g., plasma cells have very high BCR expression). RNA is essential for studying class-switch recombination, as it captures the constant region transcript [23] [44].

Q4: For a large-scale cohort study aimed at identifying cost-effective biomarkers, should I choose bulk or single-cell BCR sequencing?

This decision balances cost, scale, and informational depth [23] [45] [46].

- Bulk Sequencing (CDR3 or full-length): The default choice for large cohort studies. It is highly scalable and cost-effective for profiling repertoire diversity and identifying clonal expansions across hundreds of samples. The key limitation is the loss of native heavy and light chain pairing information [23] [47].

- Single-Cell Sequencing: Necessary when paired heavy-light chain information and B cell phenotype are critical to the research question. It allows you to link a specific BCR sequence to the transcriptional state of the same cell (e.g., memory cell, plasma cell). However, it is significantly more expensive per cell and has lower throughput, making it less suitable for initial large-scale biomarker screening [45] [46].

The following decision pathway visualizes the key questions that guide the selection of the appropriate sequencing modality.

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol: Cost-Effective BCR Repertoire Profiling for Large Cohorts

Objective: To achieve broad, quantitative profiling of the BCR repertoire across many samples for biomarker discovery, minimizing cost per sample while maintaining robust data on clonality and diversity [44] [47].

Materials:

- Input: 100 ng total RNA or 2 µg genomic DNA (from PBMCs, tissue) [44].

- Library Prep Kit: A commercially available bulk BCR-seq kit or a custom 5' RACE-based protocol to reduce primer bias [44].

- Primers: Gene-specific primers for the immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGH) constant region (for 5' RACE) or a multiplex primer set for the IGH V genes [44].

- Sequencing Platform: Illumina MiSeq or HiSeq for short-read sequencing (e.g., PE150 or PE300 for full-length) [44].

Method:

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Isolate high-quality RNA or DNA. Verify integrity and quantity using a fluorometer.

- Library Construction:

- For RNA inputs, use a 5' RACE approach with a single primer pair to minimize bias. Reverse transcribe RNA to cDNA using a constant region primer.

- For DNA inputs, use a multiplex PCR with primers targeting the IGH V and J genes.

- Incorporate Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) during reverse transcription or the first-strand synthesis to correct for PCR amplification bias and sequencing errors.

- Amplification: Perform a limited number of PCR cycles (e.g., 12-18) to add sequencing adapters and sample indices. Avoid over-amplification.

- Library Clean-up: Purify the library using bead-based size selection to remove adapter dimers and fragments that are too short or long.

- Sequencing: Pool libraries and sequence on an Illumina platform. Aim for 50,000-100,000 reads per sample for diversity estimates, and 10-20 million reads for tracking rare clones [44].

Data Analysis:

- Process raw reads using a standardized pipeline (e.g., MiXCR, pRESTO) for quality control, UMI consensus building, V(D)J alignment, and CDR3 extraction [45].

- Generate output metrics including clonality, Shannon diversity, V/J gene usage, and CDR3 length distribution [44].

Protocol: Full-Length Paired BCR Sequencing with TIRTL-Seq Inspiration

Objective: To obtain quantitative, full-length, and paired heavy-light chain BCR sequences from a large number of B cells at a reasonable cost, enabling functional studies and antibody discovery [46].

Materials:

- Input: PBMCs or purified B cells.

- Plates: 384-well PCR plates.

- Lysis/RT Mix: Triton-X-100, Maxima H Minus Reverse Transcriptase, dNTPs, constant region-specific primers.

- First-PCR Primers: A mix of forward primers for IGH V genes and reverse primers for the constant region, with plate-specific barcodes.

- Second-PCR Primers: Primers to add full Illumina sequencing adapters and unique dual indices (UDIs).

Method:

- Cell Partitioning: Dilute and distribute B cells into a 384-well plate, aiming for thousands of cells per well. Use a non-contact liquid dispenser for accuracy and miniaturization.

- Lysis and Reverse Transcription: Perform simultaneous cell lysis and reverse transcription in each well. This step converts BCR mRNA into cDNA without the need for RNA purification.

- Targeted Amplification (PCR I): In each well, perform a multiplex PCR to amplify the full-length V(D)J region of the BCR from the cDNA. The reverse primers contain a well-specific barcode, labeling all transcripts from the same well.