Small Molecule vs. Peptidomimetic SH2 Domain Inhibitors: A Strategic Comparison for Targeted Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive comparison for researchers and drug development professionals on two primary strategies for inhibiting SH2 domain-mediated protein-protein interactions: small molecules and peptidomimetics.

Small Molecule vs. Peptidomimetic SH2 Domain Inhibitors: A Strategic Comparison for Targeted Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison for researchers and drug development professionals on two primary strategies for inhibiting SH2 domain-mediated protein-protein interactions: small molecules and peptidomimetics. We explore the foundational principles of SH2 domain structure and function, detail modern design and screening methodologies, analyze challenges in achieving potency and selectivity, and present a direct comparative analysis of both approaches. Drawing on recent advances, including the application of molecular dynamics and novel screening platforms, this review synthesizes key considerations for selecting the optimal inhibitor modality based on specific therapeutic objectives, from overcoming bioavailability hurdles to targeting challenging interfaces like STAT3 and SHP2.

SH2 Domains as Therapeutic Targets: Structure, Function, and Inhibition Rationale

Src Homology 2 (SH2) domains are approximately 100 amino acid modular protein domains that serve as critical "readers" of phosphotyrosine (pTyr) signals within cellular signaling networks [1]. The human genome encodes 120 SH2 domains distributed across 110 proteins, forming one of the largest families of specialized protein-protein interaction modules [2] [1]. These domains function within a sophisticated phosphorylation-dependent signaling system where protein tyrosine kinases act as "writers" that install phosphate groups, and protein tyrosine phosphatases serve as "erasers" that remove them [1]. SH2 domains recognize and bind to specific pTyr-containing sequences, thereby enabling the formation of transient signaling complexes that drive fundamental cellular processes including differentiation, proliferation, motility, and apoptosis [1].

Proteins containing SH2 domains exhibit remarkable functional diversity, encompassing enzymes, adaptors, regulators, docking proteins, transcription factors, and cytoskeletal proteins [3]. This functional versatility, combined with precise phosphotyrosine recognition, positions SH2 domains as crucial mediators of signal transduction with significant implications for human disease. Notably, mutations and aberrant expression within SH2-containing proteins are frequently associated with tumorigenesis and other pathological conditions, making these domains attractive therapeutic targets [1] [4].

The Conserved Structural Architecture of SH2 Domains

The Canonical SH2 Fold

Despite substantial sequence variation among family members, all SH2 domains share a highly conserved tertiary structure that forms the structural blueprint for phosphotyrosine recognition. The canonical SH2 fold features a central anti-parallel β-sheet consisting of seven strands (βA-βG) flanked by two α-helices (αA and αB) [1] [3]. This characteristic "sandwich" architecture creates a stable scaffold that supports the specific phosphotyrosine-binding functionality while allowing for sequence diversification at key positions to enable recognition diversity [3].

The N-terminal region of the SH2 domain (from αA to βD) is particularly well-conserved and contains the phosphotyrosine-binding pocket, while the C-terminal region (βD to βG) exhibits greater structural variability and contributes primarily to specificity determination [1]. Structural studies have revealed that the majority of SH2 domain-ligand complexes feature bound pTyr-peptides adopting an extended conformation that binds perpendicular to the central β-strands of the domain [1].

Molecular Determinants of Phosphotyrosine Recognition

The molecular mechanism of phosphotyrosine recognition involves highly conserved structural elements within the SH2 fold:

The pTyr-Binding Pocket: A deep, positively charged pocket formed by residues in the N-terminal region specifically accommodates the phosphorylated tyrosine residue [2] [1]. This pocket contains a critical arginine residue (Arg βB5) located on the βB strand that forms bidentate hydrogen bonds with the phosphate moiety of pTyr [1] [4]. This arginine is part of a conserved FLVR sequence motif (G(S/T)FLVR(E/D)S) found in most SH2 domains [4].

Specificity Pockets: Additional binding pockets that engage residues C-terminal to the phosphotyrosine confer sequence specificity to different SH2 domains [2] [1]. Most SH2 domains contain hydrophobic pockets that recognize specific amino acids at the P+2, P+3, or P+4 positions (the second, third, or fourth residues C-terminal to the pTyr) [2].

Loop-Mediated Specificity Determinants: The loops connecting secondary structure elements, particularly the EF and BG loops, control access to binding pockets and define specificity by either plugging (making inaccessible) or opening (making accessible) these pockets to ligand recognition [2]. This combinatorial use of loops represents a fundamental mechanism for generating specificity diversity across the SH2 domain family while maintaining the conserved structural fold.

Table 1: Key Structural Elements of the SH2 Domain Fold

| Structural Element | Location | Functional Role | Conservation |

|---|---|---|---|

| βB strand | N-terminal region | Contains critical Arg βB5 for pTyr binding | Highly conserved |

| pTyr-binding pocket | N-terminal region | Binds phosphate moiety of pTyr | Highly conserved |

| Specificity pockets | C-terminal region | Recognize residues C-terminal to pTyr | Variable |

| EF and BG loops | Connector regions | Control access to binding pockets | Variable |

| Central β-sheet | Core domain | Structural scaffold | Conserved fold |

| Flanking α-helices | Core domain | Structural stability | Conserved fold |

Diagram 1: The conserved structural architecture of SH2 domains, highlighting core elements, binding regions, and specificity determinants.

Targeting SH2 Domains: Small Molecules vs. Peptidomimetics

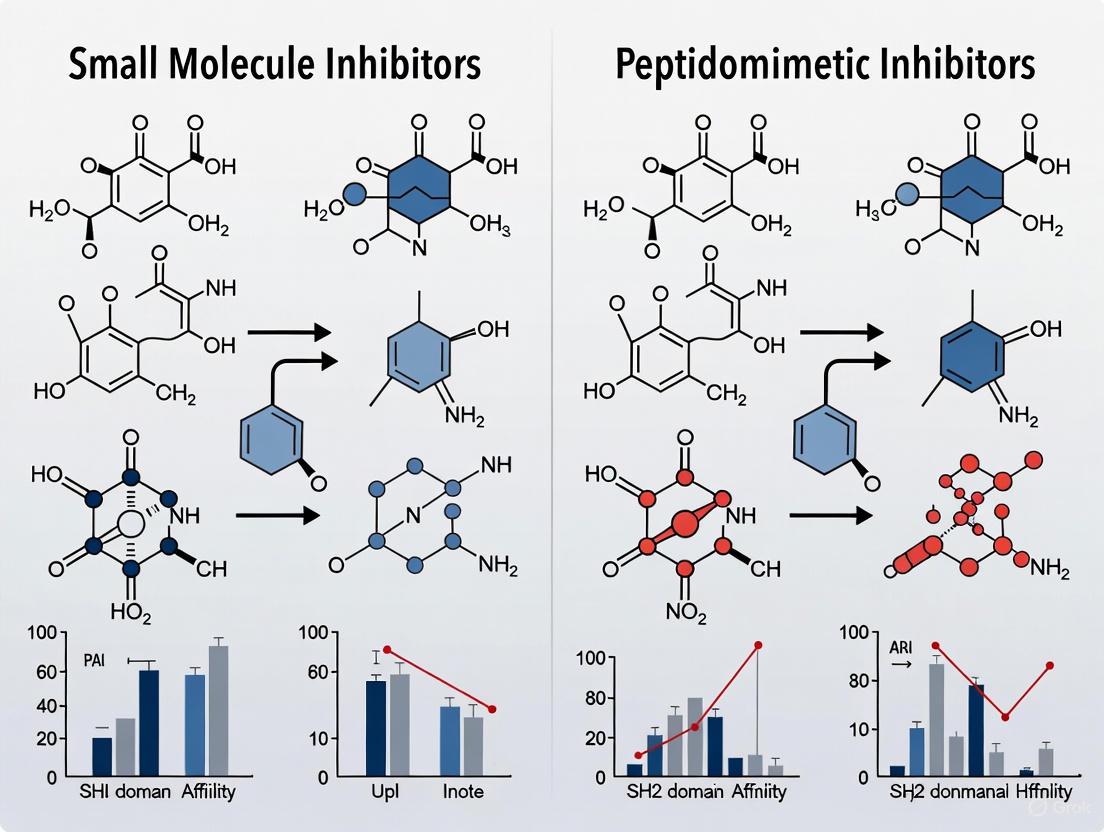

The strategic importance of SH2 domains in disease pathology has motivated extensive drug discovery campaigns targeting these domains. Two primary therapeutic strategies have emerged: small molecule inhibitors and peptidomimetic approaches, each with distinct advantages and challenges.

Small Molecule SH2 Domain Inhibitors

Small molecule inhibitors represent a promising therapeutic approach for targeting SH2 domains, with several candidates demonstrating impressive preclinical results:

BTK SH2 Domain Inhibitors: Recludix Pharma has pioneered the development of small molecule inhibitors targeting the SH2 domain of Bruton's Tyrosine Kinase (BTK), demonstrating an alternative to traditional kinase domain inhibition [5]. Their lead compound exhibits exceptional biochemical potency (Kd = 0.055 nM) and remarkable selectivity, showing >8,000-fold selectivity over off-target SH2 domains and minimal cytotoxicity (EC50 > 10,000 nM in Jurkat cells) [5]. Unlike conventional BTK inhibitors that target the kinase domain, the SH2-targeted approach avoids off-target inhibition of TEC kinase, potentially reducing adverse effects such as platelet dysfunction associated with current therapies [5].

SHP2 N-SH2 Domain Inhibitors: Computational drug discovery approaches have identified promising small molecule inhibitors for the N-SH2 domain of SHP2 tyrosine phosphatase. Through virtual screening of repurposing libraries followed by molecular dynamics simulations and MM/PBSA calculations, Irinotecan (CID 60838) emerged as a potential candidate with a favorable binding free energy value of -64.45 kcal/mol and significant interactions with key residues including the critical Arg32 in the phosphotyrosine-binding pocket [4].

Table 2: Small Molecule SH2 Domain Inhibitors in Development

| Target | Compound | Potency | Selectivity | Development Stage | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BTK SH2 | Recludix BTK SH2i | Kd = 0.055 nM | >8,000-fold SH2ome selectivity | Preclinical | Avoids TEC kinase inhibition; prodrug delivery |

| SHP2 N-SH2 | Irinotecan (CID 60838) | ΔG = -64.45 kcal/mol | N/A | Computational discovery | Targets Arg32 in pTyr pocket |

| STAT SH2 | Various | Variable | Variable | Early research | Targets STAT dimerization |

Peptidomimetic SH2 Domain Inhibitors

Peptidomimetics offer an alternative strategy that mimics natural peptide ligands while addressing limitations of native peptides:

STAT NTD-Targeting Peptidomimetics: Research has focused on developing β³-peptidomimetic foldamers targeting the N-terminal domain (NTD) of STAT3 and STAT4 proteins to disrupt dimerization [6]. These rationally designed foldamers incorporate β³-amino acids with side chains that mimic residues within interface II of the STAT NTD dimeric structures. Computational studies including molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and binding free energy calculations have demonstrated that these peptidomimetics (Peptide-A, Peptide-B, and Peptide-C) effectively bind to and inhibit the dimerization process of STAT3 and STAT4 NTDs [6]. The use of β-peptides enhances proteolytic stability and bioavailability compared to natural peptides, overcoming significant limitations of peptide-based therapeutics [6].

Comparative Analysis of Therapeutic Approaches

Table 3: Comparison of Small Molecule vs. Peptidomimetic SH2 Domain Inhibitors

| Characteristic | Small Molecule Inhibitors | Peptidomimetic Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | Typically <500 Da | Larger (peptide-like) |

| Oral Bioavailability | Generally favorable | Often challenging |

| Proteolytic Stability | High | Moderate to high (β-peptides) |

| Target Specificity | Can be exceptional | Potentially high |

| Development Approach | Structure-based design, HTS | Rational design, computational modeling |

| Manufacturing Complexity | Generally lower | Generally higher |

| Cell Permeability | Typically good | Variable |

| Clinical Validation | Emerging (BTK SH2i) | Preclinical stage |

Experimental Approaches in SH2 Domain Research

Methodologies for Inhibitor Development

Small Molecule Discovery Platforms: The development of small molecule SH2 inhibitors employs integrated platforms combining custom DNA-encoded libraries (DELs), SH2-targeted crystallographic structure-guided design, proprietary biochemical screening assays, and prodrug delivery modalities to enhance intracellular exposure [5]. These comprehensive approaches enable the identification of compounds with exceptional potency and selectivity profiles.

Computational Peptidomimetic Design: The development of peptidomimetic inhibitors relies heavily on computational methodologies including molecular docking techniques to assess binding affinity, molecular dynamics simulations to evaluate complex stability and conformational changes, and MM/PBSA calculations to compute binding free energies [6]. These in silico approaches facilitate rational design and optimization before synthetic and experimental validation.

High-Throughput Functional Assays: Advanced cellular assays enable high-throughput assessment of SH2 domain function and inhibition. For BTK research, fitness measurements employ Jurkat T cells or BTK-deficient Ramos B cells, monitoring CD69 upregulation as a functional readout [7]. Cells expressing SH2 domain variants are sorted based on CD69 expression, with RNA sequencing used to measure relative abundances of each variant in selected versus input libraries [7]. Fitness values are calculated as: Fitnessᵢ = log₁₀(SortCountᵢ/InputCountᵢ) - log₁₀(SortCountwildtype/InputCountwildtype) [7].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for SH2 domain inhibitor development, showing parallel approaches for small molecule and peptidomimetic strategies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SH2 Domain Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| DNA-encoded libraries (DELs) | Large-scale compound screening | BTK SH2 inhibitor discovery [5] |

| SH2-targeted crystallography | Structure-guided inhibitor design | BTK SH2i optimization [5] |

| Custom biochemical assays | Potency and selectivity assessment | Kd determination, kinome profiling [5] |

| Molecular docking software | Binding pose prediction | STAT NTD peptidomimetic design [6] |

| Molecular dynamics simulations | Complex stability assessment | Peptidomimetic-STAT NTD interactions [6] |

| MM/PBSA calculations | Binding free energy estimation | SHP2 N-SH2 inhibitor ranking [4] |

| Cellular fitness assays | Functional activity measurement | BTK SH2 chimera evaluation [7] |

| Phosphospecific antibodies | Pathway activation monitoring | pERK signaling in B cells [5] |

The structural blueprint of SH2 domains—characterized by a conserved fold with variable specificity determinants—continues to inspire innovative therapeutic strategies. Both small molecule and peptidomimetic approaches show significant promise, with small molecules potentially offering superior pharmacokinetic properties while peptidomimetics may provide enhanced specificity through more natural target engagement. The ongoing elucidation of SH2 domain structures and mechanisms, including their roles in autoinhibition [7] and non-canonical functions such as lipid binding [3] and participation in liquid-liquid phase separation [3], continues to reveal new opportunities for therapeutic intervention. As targeting strategies evolve to address the challenges of selectivity and efficacy, SH2 domains remain compelling targets for treating malignancies, inflammatory diseases, and immune disorders driven by aberrant phosphotyrosine signaling.

Src homology 2 (SH2) domains are protein modules approximately 100 amino acids in length that specialize in recognizing and binding phosphorylated tyrosine (pY) motifs [8]. They form a crucial component of the protein-protein interaction network involved in diverse cellular processes, including development, homeostasis, cytoskeletal rearrangement, and immune responses [8]. The primary function of SH2 domains in phosphotyrosine signaling networks is to induce proximity of protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs) and protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) to specific substrates and signaling effectors [8]. The human proteome contains roughly 110 SH2 domain-containing proteins, which can be broadly classified into enzymes, signaling regulators, adapter proteins, docking proteins, transcription factors, and cytoskeleton proteins [8].

Beyond their canonical role in phosphotyrosine recognition, recent research has revealed that nearly 75% of SH2 domains interact with lipid molecules in the membrane, particularly phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) and phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3) [8]. These lipid-SH2 domain interactions modulate cell signaling, with examples including the PIP3 binding activity of the TNS2 SH2 domain that regulates phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) in insulin signaling pathways [8]. Additionally, proteins with SH2 domains have been linked to the formation of intracellular condensates via protein phase separation, driven by multivalent interactions between modules such as SH2 and SH3 domains [8]. This mechanism enhances signaling capacity, as demonstrated by interactions among GRB2, Gads, and the LAT receptor that contribute to liquid-liquid phase separation formation and enhanced T-cell receptor signaling [8].

Structural Mechanisms of SH2 Domain Function

SH2 Domain Architecture and Ligand Recognition

The structure of SH2 domains has been intensely studied since their discovery in 1986, with approximately 70 SH2 domain structures experimentally solved to date [8]. Despite having some family members with as little as ~15% pairwise sequence identity, all SH2 domains assume nearly identical folds with very little three-dimensional divergence, suggesting these folds have evolved almost exclusively to bind pY-peptide motifs [8]. The conserved structure consists of a "sandwich" comprising a three-stranded antiparallel beta-sheet flanked on each side by an alpha helix, following the pattern αA-βB-βC-βD-αB [8].

The N-terminal region of the SH2 domain contains a deep pocket within the βB strand that binds the phosphate moiety, harboring an invariable arginine at position βB5 that is part of the FLVR motif found in most SH2 domains [8]. This arginine directly binds to the pY residue within peptide ligands through a salt bridge [8]. The C-terminal region contains additional structural elements that contribute to binding specificity, particularly the EF loop (joining β-strands E and F) and the BG loop (joining α-helix B and β-strand G), which control access to ligand specificity pockets [8].

Structurally, SH2 domains can be divided into two major subgroups: the STAT type and SRC type [8]. STAT-type SH2 domains are distinct in that they lack the βE and βF strands as well as the C-terminal adjoining loop, with the αB helix split into two helices—an adaptation that facilitates dimerization, a critical step in STAT-mediated transcriptional regulation [8].

Specificity Determinants and Binding Affinity

SH2 domain binding is characterized by a combination of high specificity toward cognate pY ligands with moderate binding affinity (Kd typically ranging from 0.1–10 μM) [8]. This affinity range allows for specific but short-lived interactions, a defining characteristic of most cell signaling mediator interactions [8]. Approximately 40% of protein interactions involve proteins bound to peptide-like sequences located within unstructured regions of other proteins, facilitating rapid off-rates necessary for dynamic signaling responses [8].

Recent advances have enabled more precise quantification of SH2 domain binding specificities. An integrated experimental-computational framework combining bacterial peptide display, next-generation sequencing, and ProBound statistical learning has allowed researchers to build accurate sequence-to-affinity models that predict binding free energy across the full theoretical ligand sequence space [9]. This approach updates specificity profiling from simple classification to quantitative prediction, enabling researchers to predict novel phosphosite targets or the impact of phosphosite variants on binding [9].

Figure 1: Structural Organization and Functional Determinants of SH2 Domains. SH2 domains feature a conserved core structure with specialized binding pockets that determine phosphotyrosine recognition specificity and additional lipid-binding capabilities.

SH2 Domains in Oncogenesis: SHP2 as a Case Study

SHP2 Structure and Regulatory Mechanisms in Colorectal Cancer

SHP2, encoded by the PTPN11 gene, is the first validated proto-oncogenic phosphatase and represents a compelling case study of SH2 domain involvement in oncogenesis [10]. SHP2 is a non-receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase characterized by three domains: tandem N-terminal SH2 domains (N-SH2 and C-SH2) and a C-terminal catalytic (PTP) domain, along with a regulatory tail containing tyrosine phosphorylation sites (Y542/Y580) [10]. In the resting state, SHP2 exists in an auto-inhibited conformation through interactions between N-SH2 and the PTP domain that suppress catalytic activity [10]. Ligand-induced activation of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) triggers phosphorylation of specific intracellular tyrosine residues, which bind to the SH2 domains, inducing conformational changes that expose the catalytic site of SHP2 [10].

In colorectal cancer (CRC), SHP2 is consistently overexpressed and facilitates oncogenesis by mediating downstream signaling cascades of receptor tyrosine kinases, including the RAS/ERK, JAK/STAT, and PI3K/AKT pathways [10]. Clinicopathological analyses demonstrate that decreased SHP2 expression is significantly associated with poor differentiation, lymph node metastasis, and advanced TNM stage, suggesting its potential as an independent prognostic biomarker in CRC [10].

SHP2 Signaling Pathways in Colorectal Cancer

SHP2 plays a dual regulatory role in the PI3K/AKT pathway in CRC. SHP2 depletion demonstrates potent antitumor effects through dual suppression of cellular proliferation and induction of apoptosis [10]. It is upregulated in oxaliplatin-resistant cells, where it drives chemoresistance via AKT hyperphosphorylation [10]. Additionally, SHP2 plays a critical role in ferroptosis regulatory networks by orchestrating the PI3K/BRD4/TFEB axis to inhibit ferritinophagy, thereby attenuating ROS generation and blocking iron-dependent cell death mechanisms essential for tumor survival [10].

In the JAK/STAT pathway, SHP2 expression exhibits a negative correlation with nuclear STAT3 expression in CRC [10]. Patients with elevated SHP2 expression and diminished nuclear STAT3 levels experience significantly longer disease-specific survival and disease-free survival [10]. SHP2 inhibits CRC cell proliferation by dephosphorylating STAT3 at Tyr705, although mutant p53 can reverse this suppression through competitive binding to STAT3 [10].

Within the RAS/MAPK pathway, SHP2-IL-22R1 binding is essential for IL-22-mediated ERK activation, which drives downstream MAPK signaling to promote cell proliferation [10]. Additionally, MUC1-C interacts with SHP2 to enhance RTK-mediated RAS/ERK signaling, making it a potential therapeutic target in BRAFV600E-mutant CRC [10].

SHP2 in Tumor Microenvironment Remodeling

SHP2 has emerged as a critical regulator of the tumor microenvironment (TME) in CRC. In tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), targeting SHP2 with PHPS1 attenuates its expression, activating the PI3K/AKT pathway to induce M2-polarized TAMs and exosome secretion that foster CRC metastasis [10]. Genetic ablation of SHP2 in macrophages exacerbates CRC hepatic metastasis through the Tie2-PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling axis, upregulating pro-metastatic mediators including VEGF, COX-2, and MMP2/MMP9 that collectively foster a metastasis-permissive niche [10].

In T-cells, CD4+ T cell-specific SHP2 deficiency results in reduced tumor volume, accompanied by elevated IFN-γ expression and amplified cytotoxic CD8+ T cell activity [10]. Inhibition of SHP2 using the allosteric inhibitor SHP099 potentiates antitumor immunity, evidenced by STAT1 hyperphosphorylation, an elevated proportion of CD8+IFN-γ+ T cells, and marked reduction in tumor burden [10].

Figure 2: SHP2-Mediated Signaling Networks in Colorectal Cancer Oncogenesis. SHP2 integrates signals from multiple pathways to drive tumor progression, metastasis, and immune evasion through its SH2 domain-mediated protein interactions.

Therapeutic Targeting of SH2 Domains: Small Molecules vs. Peptidomimetics

Allosteric SHP2 Inhibitors as Small Molecule Therapeutics

Significant progress has been made in developing small molecule inhibitors targeting SH2 domains, particularly against SHP2. A recent study published in the Journal of Medicinal Chemistry explored the development of allosteric inhibitors targeting SH2 domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase-2 (SHP2) for cancer therapy [11]. These allosteric inhibitors constitute a class of compounds designed to modulate SHP2 activity by interfering with its signaling pathways, potentially thwarting oncogenic functions [11].

Among synthesized compounds, compound 28 exhibited potent inhibitory activity and selectivity against SHP2, warranting further investigation into its therapeutic potential [11]. permeability studies using CacoReady plates revealed varying degrees of cell membrane permeability among the SHP2 inhibitors, highlighting the need for refining chemical properties to balance potency and permeability for optimal therapeutic outcomes [11]. Allosteric SHP2 inhibitors characterized by high oral bioavailability and potent target specificity are currently under evaluation in multicenter phase I/II trials [10].

BTK SH2 Domain Inhibitors: Achieving Exceptional Selectivity

A groundbreaking approach in SH2 domain targeting comes from Recludix Pharma's development of first-in-class Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) SH2 domain inhibitors [12]. Preclinical data demonstrates that BTK inhibition through the SH2 domain results in greater selectivity compared to BTK tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) or degraders [12]. The company's BTK SH2 inhibitor demonstrated best-in-class selectivity for BTK far greater than even the most selective BTK TKIs, with broader off-target profiling across the kinome confirming no off-target inhibition of TEC, which is associated with platelet dysfunction—a limitation of current BTK TKIs and degraders [12].

In preclinical models, the BTK SH2 inhibitor robustly inhibited proximal SH2-dependent phosphorylation (pERK) signaling and downstream immune cell activation (B cell CD69 expression) [12]. In an in vivo model of chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU), dose-dependent reduction in skin inflammation was observed following a single dose of the BTK SH2 inhibitor [12]. This highly selective BTK SH2 inhibitor has the potential to provide maximal efficacy through deep and durable inhibition of the BTK pathway while minimizing off-target safety risks associated with kinase-targeted agents [12].

STAT SH2 Domain Targeting and Biosensor Development

STAT proteins represent another important therapeutic target class dependent on SH2 domain function. STAT proteins are structurally composed of six domains, including the N-terminal domain (NTD), coiled-coil domain (CCD), DNA-binding domain (DBD), linker domain (LD), SH2 domain, and C-terminal transactivation domain (TAD) [13]. The SH2 domain plays a critical role in STAT activation, facilitating dimerization through reciprocal phosphotyrosine-SH2 domain interactions between STAT monomers [13].

Recent technological advances have enabled better monitoring of STAT activation, crucial for drug development. Researchers have developed a class of highly sensitive genetically encoded STAT biosensors termed STATeLights, which allow direct and continuous detection of STAT activity in live cells with high spatiotemporal resolution [13]. These biosensors open up unprecedented possibilities for studying STAT biology and druggability in various cellular contexts, facilitating real-time tracking of STAT5 activation in human primary CD4+ T cells and precise selection of compounds targeting the STAT5 signaling pathway [13].

Table 1: Comparison of SH2 Domain-Targeted Therapeutic Approaches

| Therapeutic Approach | Molecular Target | Key Characteristics | Development Stage | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allosteric SHP2 Inhibitors [10] [11] | SHP2 (N-SH2 domain) | • Allosteric modulation• High oral bioavailability• Potent target specificity | Phase I/II clinical trials | • Overcomes autoinhibition• Favorable pharmacokinetics | • Acquired resistance• Complex pathway interactions |

| BTK SH2 Inhibitors [12] | BTK SH2 domain | • Exceptional selectivity• No TEC kinase inhibition• Durable pathway inhibition | Preclinical development | • Minimal platelet toxicity• Deep pathway inhibition | • Early development stage• Limited clinical data |

| STAT-Targeting Approaches [13] | STAT SH2 domains | • Blocks dimerization• Transcriptional inhibition• Biosensor-monitored | Research phase | • Direct nuclear signaling blockade• Real-time activity monitoring | • Delivery challenges• Compensatory pathway activation |

| Peptidomimetic Inhibitors [8] | Various SH2 domains | • High specificity• Phosphotyrosine mimicry | Early research | • Direct competition• Rational design | • Poor bioavailability• Metabolic instability |

Experimental Approaches and Research Tools

Methodologies for SH2 Domain Binding Characterization

Advanced methodologies have been developed to characterize SH2 domain binding specificities and affinities. A concerted experimental and computational strategy updates specificity profiling from classification to quantification [9]. Multi-round affinity selection on random phosphopeptide libraries yields next-generation sequencing data suitable for training additive models that accurately predict binding free energy across the full theoretical ligand sequence space [9].

This integrated approach employs bacterial display of genetically-encoded peptide libraries, enzymatic phosphorylation of displayed peptides, affinity-based selection, and NGS, followed by ProBound analysis—a statistical learning method that generates quantitative sequence-to-affinity models covering the full theoretical sequence space independent of library format [9]. For SH2 domains profiled using this method, the sequence-to-affinity model can predict novel phosphosite targets or the impact of phosphosite variants on binding [9].

Biosensor Engineering for Real-Time Monitoring

Innovative biosensor technology has been developed to monitor STAT activation in real-time, providing valuable tools for drug discovery. STATeLights employ fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy-Förster resonance energy transfer (FLIM-FRET) to directly monitor conformational rearrangement of STAT dimers rather than just phosphorylation events [13]. This approach is not susceptible to potential adverse signals stemming from inactive phosphorylated monomers or truncated STAT variants, allowing specific observation of STAT activation [13].

The biosensor engineering process involved comprehensive screening of various STAT5A constructs tagged with fluorescent proteins, identifying optimal fusion sites that maximize FRET efficiency changes upon activation [13]. The selected biosensor variant exhibited up to 12% FRET efficiency upon IL-2 stimulation, consistent with predicted close distances between SH2 domains in the parallel conformation [13].

Figure 3: Experimental Workflows for SH2 Domain Research. Integrated approaches combining peptide display, sequencing, and computational modeling enable comprehensive binding characterization, while biosensor engineering facilitates real-time monitoring of SH2-dependent signaling.

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for SH2 Domain Investigation

| Research Tool | Application | Key Features | Experimental Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Peptide Display [9] | SH2 binding specificity profiling | • Random peptide libraries• Enzymatic phosphorylation• High diversity (10⁶-10⁷ sequences) | Multi-round affinity selection with NGS readout for comprehensive specificity mapping |

| ProBound Analysis [9] | Binding affinity prediction | • Free energy regression• Additive binding models• Library format independence | Builds sequence-to-affinity models predicting ∆∆G for any ligand sequence |

| STATeLight Biosensors [13] | Real-time STAT activation monitoring | • FLIM-FRET detection• Conformational change sensing• Live cell compatibility | Continuous tracking of STAT activation dynamics in primary cells and drug screening |

| CacoReady Assay Systems [11] | Inhibitor permeability assessment | • In vitro permeability model• Bioavailability prediction• High-throughput capability | Evaluates membrane permeability of SH2 inhibitors during optimization |

| X-ray Crystallography [8] | SH2 structure determination | • High-resolution structures• Ligand binding visualization• Conformational analysis | Solved 70+ SH2 domain structures to inform rational inhibitor design |

Clinical Implications and Future Directions

Therapeutic Challenges and Combination Strategies

Targeting SHP2 in colorectal cancer has entered a transformative phase, though limitations of monotherapy have emerged [10]. Therapeutic challenges include compensatory AKT reactivation through PDGFRβ-PI3K signaling during SHP2 monotherapy, which can be circumvented by combining SHP2 inhibitors with AKT/FAK inhibitors to achieve synergistic pathway blockade [10]. Resistance mechanisms involving WWP1-mediated AKT resilience can be addressed through dual SHP2/WWP1 inhibition using agents like I3C [10].

Emerging therapeutic agents, such as metallocene-curcumin hybrid derivatives (e.g., compound 3f), show dual efficacy by directly suppressing PI3K-AKT signaling while modulating the tumor immune microenvironment, highlighting the multifaceted potential of SHP2-PI3K axis modulation in precision CRC therapeutics [10]. Similarly, HPK1 inhibitors represent another SH2 domain-related target showing promise in cancer immunotherapy, with compound 34 demonstrating 1257-fold selectivity over GLK and significant anti-tumor effects when combined with anti-PD-1 treatment [14].

Targeting SH2 Domain-Lipid Interactions

Emerging research on SH2 domain-lipid interactions opens new therapeutic avenues. Studies have identified cationic regions in SH2 domains close to the pY-binding pocket as lipid-binding sites, usually flanked by aromatic or hydrophobic amino acid side chains [8]. Many disease-causing mutations in SH2 domains are localized within these lipid-binding pockets [8]. Research indicates that targeting lipid binding in SH2 domain-containing kinases may offer promising avenues for new small-molecule drugs [8].

Cologna and colleagues have successfully developed nonlipidic inhibitors of Syk kinase, demonstrating that nonlipidic small molecules are capable of specific and potent inhibition of lipid protein interactions [8]. This approach could produce potent, selective, and resistance-resistant inhibitors for various other kinases possessing the SH2 domain [8].

SH2 domains represent critical hubs in cellular signaling networks, with their dysfunction strongly linked to oncogenesis through multiple mechanisms. The structural conservation of these domains across diverse proteins highlights their fundamental importance in phosphotyrosine-dependent signaling, while variations in specificity determinants enable precise signaling circuit control. Therapeutic targeting of SH2 domains has evolved from basic research to clinical development, with allosteric SHP2 inhibitors and selective BTK SH2 inhibitors demonstrating the feasibility of targeting these domains. Advanced experimental approaches, including comprehensive binding affinity profiling and real-time biosensor monitoring, provide powerful tools for both basic research and drug discovery. As our understanding of non-canonical SH2 functions—including lipid binding and phase separation roles—continues to expand, new therapeutic opportunities will likely emerge, offering potential for more effective and selective interventions in cancer and other diseases driven by aberrant SH2 domain-mediated signaling.

Src Homology 2 (SH2) domains are protein interaction modules, approximately 100 amino acids in length, that specifically recognize and bind to phosphorylated tyrosine (pTyr) motifs on partner proteins [8] [15]. They are fundamental components of intracellular signaling networks, governing critical cellular processes such as proliferation, differentiation, and survival by transducing signals from activated receptor tyrosine kinases [16]. The human proteome encodes approximately 110 proteins containing SH2 domains, making them one of the most prominent families of phosphorylation-dependent signaling domains [8] [15]. Their direct involvement in dysregulated signaling pathways driving diseases like cancer, immune disorders, and developmental syndromes has established them as highly attractive therapeutic targets [15] [17].

However, the very features that define their biological function have also classified them as "undruggable" [18]. The primary challenge lies in targeting their large, polar, and shallow pTyr-binding pocket, which has a high affinity for negatively charged phosphate groups [16] [18]. Developing small molecules that can compete with native phosphopeptide ligands without inheriting poor drug-like properties—such as low cell permeability, rapid proteolytic degradation, and enzymatic lability of the phosphate group—has represented a formidable hurdle for drug developers [19] [18]. This review will objectively compare the two predominant strategies to overcome this challenge: small molecule inhibitors and peptidomimetic approaches, providing a structured analysis of their performance and underlying experimental data.

SH2 Domain Structure and Function: The Basis for Inhibitor Design

Conserved Architecture and Mechanism

All SH2 domains share a highly conserved fold, described as a "sandwich" consisting of a central anti-parallel β-sheet flanked by two α-helices [8] [3]. The key to their function is a deep, positively charged pocket that binds the phosphate moiety of the pTyr residue. This pocket contains a nearly invariant arginine residue (from the FLVR motif) that forms a salt bridge with the phosphate, constituting the primary anchor point for binding [8] [20]. Specificity for distinct physiological targets is determined by additional interactions between residues C-terminal to the pTyr and so-called "specificity-determining" regions of the SH2 domain, which can include variable loops and secondary structural elements [8] [16]. This combination of a universal phosphotyrosine anchor and variable specificity pockets provides the structural blueprint for inhibitor design.

Diverse Biological Roles in Signaling

SH2 domain-containing proteins are functionally diverse, encompassing enzymes, adaptors, docking proteins, and transcription factors [8] [3]. A critical non-canonical function that expands their therapeutic relevance is their interaction with membrane lipids. Recent research indicates nearly 75% of SH2 domains interact with lipid molecules, particularly phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) or phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3), which can modulate their signaling activity [8] [3]. Furthermore, SH2 domains contribute to the formation of intracellular condensates via liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS), a process that enhances signaling efficiency in pathways such as T-cell receptor activation [8] [3]. This functional versatility underscores their broad influence on cellular physiology and the potential impact of their pharmacological inhibition.

Figure 1: SH2 Domain-Mediated Signal Transduction. SH2 domains are recruited to phosphorylated tyrosine motifs on activated receptors, initiating downstream signaling cascades.

Comparative Analysis of Inhibitor Strategies

The pursuit of SH2 domain inhibitors has followed two primary trajectories: the development of non-peptidic small molecules and the rational design of modified peptides, or peptidomimetics. The table below provides a direct, data-driven comparison of these core strategies based on key performance metrics.

Table 1: Strategic Comparison of SH2 Domain Inhibitor Platforms

| Feature | Small Molecule Inhibitors | Peptidomimetic Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|

| Core Design Principle | Target allosteric sites or develop non-charged pTyr mimics; high chemical diversity. | Retain pTyr anchor but incorporate non-natural amino acids (e.g., β-amino acids) to enhance stability. |

| Representative Example | SHP099 (Allosteric SHP2 inhibitor) [17]. | Mixed α,β-phosphopeptides targeting SAP SH2 domain [19]. |

| Binding Affinity | SHP099 IC~50~ = 71 nM [17]. | K~d~ range: ~120 nM to 10 μM [19] [18]. |

| Selectivity Profile | Potentially high for allosteric sites; can be engineered for multi-target (dual) inhibition. | Moderate to high; driven by sequence mimicking native peptide ligand. |

| Cell Permeability | Good; enabled by optimized logP and low molecular weight. | Poor for naked pTyr; requires prodrug strategies (e.g., POM-capping) [18]. |

| Metabolic Stability | Generally high; resistant to proteolysis. | Improved over native peptides, but susceptibility depends on modifications. |

| Primary Challenge | Identifying novel, druggable pockets outside the conserved pTyr site. | Achieving oral bioavailability and balancing affinity with drug-like properties. |

| Therapeutic Validation | Multiple candidates in clinical trials (e.g., SHP2 allosteric inhibitors) [17]. | Largely pre-clinical; valued as high-quality chemical probes. |

Analysis of Comparative Data

The data in Table 1 reveals a strategic trade-off. Small molecule inhibitors targeting allosteric sites, such as SHP099, demonstrate superior drug-like properties, including excellent cell permeability and metabolic stability, which has facilitated their advancement into clinical trials [17]. In contrast, peptidomimetic inhibitors can achieve high affinity and selectivity by closely mimicking the natural ligand but incur significant penalties in permeability and stability, often requiring sophisticated prodrug technologies to become functionally useful in cellular systems [19] [18].

Experimental Protocols for Inhibitor Discovery and Validation

The development of both small molecule and peptidomimetic inhibitors relies on a suite of sophisticated biochemical, biophysical, and computational techniques. The workflows below detail the standard protocols for identifying and characterizing these inhibitors.

Protocol for Small Molecule Inhibitor Discovery

This pathway is exemplified by the discovery of allosteric SHP2 inhibitors [20] [17].

- Target Identification and Validation: A target SH2 domain-containing protein (e.g., SHP2 phosphatase) is selected based on its genetic and functional link to disease. The autoinhibited structure of SHP2 (PDB: 2SHP) provides a blueprint for targeting its closed conformation [17] [21].

- Virtual Screening: Large compound libraries (e.g., Broad Repurposing Hub, ZINC15) are computationally docked against a defined allosteric pocket (e.g., the "tunnel" site at the C-SH2/PTP interface). Docking software like Smina/Autodock Vina is used with a defined grid box to rank compounds by predicted binding score [20].

- Hit Validation and Optimization: Top-ranking hits are subjected to biochemical assays to determine IC~50~ values. Co-crystal structures of protein-ligand complexes are solved to guide medicinal chemistry for structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies and optimization of potency and pharmacokinetics [17].

- Cellular and In Vivo Evaluation: The inhibitory activity of lead compounds is tested in cellular models (e.g., inhibition of SHP2-dependent RAS-ERK signaling) and, subsequently, in animal models of cancer to demonstrate efficacy and acceptable pharmacokinetic profiles [17].

Protocol for Peptidomimetic Inhibitor Discovery

This pathway is exemplified by the development of SAP SH2 domain inhibitors using the Integrated Chemical Biophysics (ICB) platform [19].

- Library Design and Synthesis: Combinatorial one-bead-one-compound (OBOC) libraries of mixed α/β-phosphopeptides are designed. The pTyr residue is often retained as an anchor, while flanking residues are systematically replaced with β-amino acids to enhance metabolic stability and explore new chemical space [19].

- On-Bead Screening (CONA): The library is incubated with a fluorescently labeled SH2 domain (e.g., Cy5-labelled SAP). Beads displaying high-affinity ligands are identified quantitatively using confocal nanoscanning (CONA) [19].

- Hit Confirmation in Solution: Compounds from hit beads are re-synthesized and their binding affinity (K~d~) and kinetics are rigorously characterized in homogeneous solution using techniques like fluorescence polarization (FP) or isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) [19] [18].

- Binding Mode Rationalization: Computational docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are performed to understand the binding mode of hit compounds and rationalize the structure-activity relationship (SAR) to inform the design of subsequent, optimized libraries [19].

Figure 2: Workflow comparison of small molecule (top) and peptidomimetic (bottom) SH2 inhibitor discovery.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Advancing SH2 domain research and drug discovery requires a specialized set of reagents and tools. The following table catalogs key solutions utilized in the experiments and methodologies cited throughout this review.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SH2 Domain Drug Discovery

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function and Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant SH2 Domains & Proteins | Purified proteins for biophysical binding assays (SPR, ITC, FP), structural studies, and high-throughput screening. | SHP2 protein (PDB: 2SHP) for crystallography and enzymatic assays [20] [17]. |

| Phosphopeptide Microarrays (Pepspot Chips) | High-density peptide chips to probe the binding specificity and affinity of SH2 domains against thousands of tyrosine phosphopeptides from the human proteome. | Mapping the SH2 domain interaction landscape [22]. |

| Covalent Probe MN551 / Prodrug MN714 | A covalent inhibitor (MN551) targeting Cys111 of SOCS2 and its prodrug (MN714) with a POM group to mask the phosphate charge for cell permeability. | Validating cellular target engagement of the SOCS2 SH2 domain [18]. |

| Allosteric SHP2 Inhibitor SHP099 | A first-in-class, tool compound that stabilizes SHP2 in an autoinhibited conformation by binding the "tunnel" allosteric site. | Proof-of-concept for SHP2 allosteric inhibition and combination therapy studies [17]. |

| Split-NanoLuc-based Assay | A cellular assay system used to demonstrate intracellular target engagement of a drug with its protein target. | Confirming cellular activity of the SOCS2 prodrug MN714 [18]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Software (e.g., GROMACS) | Software for simulating the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time to study protein-ligand interactions and stability. | Analyzing the binding stability of hit compounds with the target SH2 domain [20]. |

The druggability challenge of SH2 domains is being systematically overcome through innovative chemical and biological strategies. The comparative data indicates that small molecule allosteric inhibitors currently lead in the transition to clinically viable therapeutics, as evidenced by multiple SHP2 inhibitors in clinical trials [17]. Conversely, peptidomimetic approaches provide powerful tools for validating targets and generating highly selective chemical probes, though their development as drugs remains complex [19] [18].

Future directions are likely to focus on combination therapies to overcome resistance, the development of bifunctional molecules such as PROTACs to degrade SH2-containing proteins, and the continued expansion of E3 ligase ligands for targeted protein degradation, as demonstrated by the recent targeting of SOCS2 [17] [18]. The integration of high-throughput interaction data [22], advanced computational screening [20], and sophisticated prodrug technologies [18] will continue to drive the field forward, transforming SH2 domains from "undruggable" targets into a new frontier for precision medicine.

Src homology 2 (SH2) domains are protein modules approximately 100 amino acids in length that specifically recognize and bind to phosphorylated tyrosine (pTyr) residues, playing a fundamental role in intracellular signal transduction [3]. These domains are found in approximately 110 human proteins and function as critical components in phosphotyrosine-mediated signaling networks immediately downstream of protein tyrosine kinases [23] [3]. By facilitating the recruitment of specific effector proteins to activated receptor complexes, SH2 domains help determine signaling specificity in crucial cellular processes including proliferation, survival, and differentiation [23] [24]. The structured binding mechanism of SH2 domains involves a conserved "two-pronged plug" interaction, where a deep basic pocket binds the phosphotyrosine residue while an adjacent specificity pocket recognizes residues C-terminal to the pTyr, typically at the +3 position [24]. Among SH2 domain-containing proteins, Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (STAT3) has emerged as a particularly compelling therapeutic target. STAT3 drives oncogenic progression through constitutive activation in many cancers, regulating the expression of genes involved in cell survival, proliferation, and angiogenesis [25]. This central role in malignancy has made the STAT3 SH2 domain a focus for drug discovery efforts, primarily aiming to disrupt the phosphotyrosine-SH2 interactions necessary for STAT3 dimerization and activation [25] [26]. Two distinct yet complementary therapeutic approaches have emerged: peptidomimetics and small molecules, each with characteristic advantages and challenges that define their application in biomedical research and drug development.

Core Characteristics at a Glance

The table below summarizes the fundamental properties that distinguish peptidomimetic inhibitors from small-molecule inhibitors, with a specific focus on their application against SH2 domains.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Peptidomimetic and Small-Molecule SH2 Domain Inhibitors

| Characteristic | Peptidomimetics | Small Molecules |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Origin | Derived from native peptide sequences of SH2 domain ligands [25] [27] | Identified via screening of synthetic chemical libraries [26] |

| Molecular Weight | Moderate to High (e.g., ~500-800 Da) [27] | Low (often <500 Da) [26] |

| Key Structural Features | Incorporates non-hydrolysable pTyr mimetics and conformational constraints [28] [27] | Often neutral, drug-like scaffolds; may lack phosphate groups [26] |

| Binding Affinity | High to very high (e.g., IC₅₀: 150 nM to 162 nM) [25] [27] | Variable, can be highly potent (low µM range) [26] |

| Selectivity | High, due to targeted design from native interaction sequences [25] | Can be challenging; must be engineered [26] |

| Cell Permeability | Often limited, may require cell-penetrating sequences [25] | Generally favorable, a key design advantage [26] |

| Oral Bioavailability | Low, due to peptidic nature and susceptibility to proteolysis [26] | High, a primary objective in their development [29] |

| Primary Development Challenge | Optimizing drug-like properties while maintaining high affinity [27] | Achieving high affinity against a large, flexible protein-protein interface [26] |

Peptidomimetic Inhibitors: Rational Design from Native Ligands

Design Philosophy and Evolution from Peptide Leads

Peptidomimetics are sophisticated compounds designed to retain the high affinity and specificity of native peptide ligands while overcoming their inherent pharmacological limitations. The development journey typically begins with the identification of high-affinity phosphopeptide sequences derived from physiological SH2 domain-binding partners. For the STAT3 SH2 domain, early work identified the native peptide sequence Pro-pTyr-Leu-Lys-Thr-Lys as a starting point, demonstrating that disruption of Stat3 dimerization was a viable therapeutic strategy [25]. A significant breakthrough came from screening receptor docking sites, which identified the hexapeptide Ac-pTyr-Leu-Pro-Gln-Thr-Val-NH₂ from the gp130 receptor as a high-affinity ligand with an IC₅₀ of 150 nM [25] [27]. This peptide provided the essential pharmacophore blueprint for subsequent mimetic development.

Key Structural Engineering Strategies

The transformation of a lead peptide into a potent peptidomimetic involves several strategic modifications aimed at enhancing stability, affinity, and drug-like properties.

Phosphotyrosine Mimetics: Replacement of the labile phosphate ester with non-hydrolysable, isosteric substitutes is crucial for metabolic stability. Examples include 4-phosphoryloxycinnamate (pCinn) and L-O-malonyltyrosine (L-OMT) [28] [27]. This modification challenges the notion that all SH2 domains tolerate the same pTyr mimetics, as some, like phosphonodifluoromethyl phenylalanine (F2Pmp), can abolish binding to certain SH2 domains [28].

Conformational Constraint: Incorporation of rigid structural elements pre-organizes the inhibitor into its bioactive conformation, reducing the entropy penalty upon binding. For instance, replacing the proline at position pY+2 with a rigid (2S,5S)-5-amino-1,2,4,5,6,7-hexahydro-4-oxo-azepino[3,2,1-hi]indole-2-carboxylic acid (Haic) scaffold significantly enhanced affinity, leading to the potent peptidomimetic pCinn-Haic-Gln-NHBn (IC₅₀ = 162 nM) [27].

Terminal Modifications: The C-terminal dipeptide (Thr-Val) can be effectively replaced by a simple benzyl group, reducing peptide character and molecular weight while maintaining key hydrophobic interactions [27].

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow for developing a peptidomimetic SH2 domain inhibitor, from lead identification to optimized compound.

Small-Molecule Inhibitors: Targeting Druggability and Cellular Permeability

Discovery Methodologies and Design Challenges

In contrast to the rational design of peptidomimetics, small-molecule inhibitors are typically identified through systematic screening of diverse chemical libraries. Structure-based virtual ligand screening (SB-VLS) has emerged as a powerful technique, where compound libraries are computationally docked into the three-dimensional structure of the target SH2 domain [26]. A significant challenge in this approach is the inherent flexibility of the SH2 domain, which can lead to the identification of low-affinity hits. Advanced methods now incorporate molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to account for this flexibility, creating "induced-active site" receptor models that more accurately represent the conformational landscape of the target and improve screening outcomes [26].

A primary objective in small-molecule design is to eliminate charged groups, particularly phosphate mimics, which often impair cell permeability. Successful campaigns have identified neutral, low-molecular-weight compounds that fulfill Lipinski's rule-of-five and possess favorable drug-like properties, making them superior candidates for further development [26].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Rigorous biochemical and cellular assays are essential to validate and characterize potential inhibitors.

Binding Affinity Measurement (Fluorescence Polarization, FP): This solution-based assay quantifies the direct interaction between the inhibitor and the purified SH2 domain. A fluorescently labeled phosphopeptide probe is incubated with the SH2 domain, causing high polarization due to slow molecular tumbling. Test compounds displace the probe, leading to a decrease in polarization that is quantified to determine IC₅₀ values [27].

Cellular Target Engagement (Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay, EMSA): This assay assesses the functional consequence of inhibition by measuring the disruption of STAT3:STAT3-DNA binding in nuclear extracts. Inhibitors that prevent STAT3 dimerization reduce the formation of the protein-DNA complex, visible as a decrease in a shifted band on a gel [25].

Cellular Signaling Inhibition (Western Blot): To confirm on-target activity in cells, the levels of phosphorylated Tyr705-STAT3 are measured via immunoblotting following cytokine stimulation. A reduction in pY-STAT3 signals effective pathway inhibition [26].

The following diagram outlines a representative screening workflow for identifying small-molecule SH2 domain inhibitors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogues key reagents and their applications in the development and characterization of SH2 domain inhibitors.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for SH2 Domain Inhibitor Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function and Application | Reference / Example |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant SH2 Domains (GST-tagged) | Purified protein for in vitro binding assays (FP, SPR) and structural studies. | Expressed in E. coli; purified via glutathione-Sepharose [23]. |

| Fluorescent Phosphopeptide Probes | Tracer molecules for Fluorescence Polarization (FP) competition assays. | Derived from native sequences (e.g., gp130 pY905LPQTV) [26] [27]. |

| Phosphotyrosine Mimetics (e.g., pCinn, L-OMT) | Stable, non-hydrolysable chemical substitutes for phosphotyrosine in inhibitor design. | pCinn incorporated via solid-phase peptide synthesis [28] [27]. |

| Constrained Scaffolds (e.g., Haic) | Rigid amino acid analogs to pre-organize peptidomimetics into bioactive conformations. | Synthesized as Fmoc-protected building blocks for SPPS [27]. |

| Cell Lines with Constitutive pY-STAT3 | Cellular models for testing inhibitor efficacy (e.g., MDA-MB-231, NIH3T3/v-Src). | Used to assess inhibition of STAT3 phosphorylation and downstream effects [25] [26]. |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies (e.g., pY705-STAT3) | Essential tools for Western Blot and ELISA to monitor target engagement in cells. | Used to detect levels of activated STAT3 in treated vs. untreated cells [26]. |

The strategic choice between peptidomimetic and small-molecule modalities for targeting SH2 domains involves a fundamental trade-off between affinity/selectivity and druggability/permeability. Peptidomimetics, born from native ligand structures, offer a rational path to high-potency, selective inhibitors but require intensive chemical optimization to overcome poor pharmacokinetic properties. Small molecules, while more amenable to oral administration and favorable physicochemical properties, face the significant hurdle of achieving high affinity against challenging, flexible protein-protein interaction interfaces like the SH2 domain. The future of SH2-directed therapeutics lies in the continued refinement of both approaches: leveraging advanced structural insights and dynamics for smarter small-molecule design, while applying innovative chemistry to further minimize the peptide character of peptidomimetics. This dual-track strategy maximizes the chances of delivering viable clinical candidates for cancer and other diseases driven by aberrant SH2 domain-mediated signaling.

Design and Discovery: Modern Strategies for Developing SH2 Inhibitors

Src Homology 2 (SH2) domains are protein modules comprising approximately 100 amino acids that specifically recognize and bind to phosphorylated tyrosine (pTyr) residues, thereby facilitating critical protein-protein interactions (PPIs) in cellular signaling networks [15] [3]. These domains are found in 111 human proteins, with roles ranging from enzyme activation to adaptor functions, and are fundamental to signaling pathways that regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival [15] [3]. Their central role in signal transduction, coupled with their dysregulation in diseases like cancer and autoimmune disorders, makes them attractive therapeutic targets [15] [30]. However, targeting the large, relatively shallow, and conserved pTyr-binding pocket of SH2 domains presents a significant drug design challenge [31] [3]. This has spurred the development of peptidomimetics—molecules that mimic the structure and function of native peptide ligands but are engineered with improved drug-like properties, such as enhanced metabolic stability, cell permeability, and binding affinity [31].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of two central strategies in peptidomimetic design: (1) the constraint of peptide conformations to pre-organize the binding structure and (2) the specific mimicry of key recognition motifs, with a focus on the Stat3-specific pY-X-X-Q motif. We objectively evaluate these approaches by comparing experimental data on their binding affinity, selectivity, and functional activity, providing researchers with a structured framework for inhibitor selection and design.

Structural Basis of SH2 Domain Recognition

Canonical SH2-pTyr Peptide Binding Mechanism

SH2 domains share a conserved architectural fold featuring a central antiparallel β-sheet flanked by two α-helices [3] [4]. The binding event is anchored by a deep pocket within the βB strand that accommodates the phosphotyrosine residue. A nearly invariant arginine residue (Arg βB5) within the FLVR motif forms a critical salt bridge with the phosphate moiety of pTyr, contributing a substantial portion of the total binding energy [3] [4]. The specificity of the interaction is further determined by residues in the peptide sequence C-terminal to the pTyr, which bind to secondary pockets on the SH2 domain surface labeled as +1, +2, +3, etc. [3] [32]. This two-tiered mechanism—conserved pTyr anchoring and sequence-specific side-chain recognition—provides the blueprint for rational peptidomimetic design.

The Stat3 and pY-X-X-Q Motif: A Case Study in Specificity

The Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (Stat3) is an SH2-containing protein constitutively activated in many cancers [32] [30]. Its recruitment and dimerization depend on binding to phosphopeptides containing the signature pY-X-X-Q motif [32]. Structural and mutational studies have elucidated that this high specificity is achieved through a unique β-turn conformation in the peptide backbone, which positions the glutamine residue at the +3 position for optimal interaction [32]. The side chain of Glu-638 on the Stat3 SH2 domain hydrogen-bonds with the amide of the +3 Gln, a interaction crucial for binding [32]. Disrupting this specific interaction, for instance by mutating Glu-638 or substituting Gln with other residues, drastically reduces binding affinity, highlighting the critical nature of this motif [32]. Consequently, accurately mimicking the pY-X-X-Q motif and its associated backbone structure is a primary objective for designing specific Stat3 inhibitors.

The diagram below illustrates the key steps and decision points in the rational design of peptidomimetics targeting SH2 domains.

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for the rational design of SH2 domain-targeting peptidomimetics, beginning with target identification and culminating in experimental validation.

Comparative Analysis of Peptidomimetic Design Strategies

Strategy 1: Constraining Peptide Conformations

A primary limitation of native peptides is their conformational flexibility in solution, which results in a significant entropy penalty upon binding to their target. Constraining peptides aims to pre-organize the ligand into its bioactive conformation, thereby minimizing this entropy cost and improving binding affinity and metabolic stability [31]. This is often achieved through macrocyclization, stapling, or the introduction of rigid scaffolds that lock the peptide into a specific secondary structure, such as a β-turn or α-helix.

Table 1: Experimental Data from the Development of a Constrained C-SH2 Inhibitor Peptide (CSIP) for SHP2

| Parameter | Unmodified ITSM(pTyr) Peptide | Constrained/Optimized CSIP (Peptide 21) | Experimental Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence | EQTE(pY)ATIVFP-NH₂ | -QTE(pY)ATIKHP-NH₂ | Peptide Synthesis [33] |

| Binding Affinity (K_D) to C-SH2 | 48.9 nM | 88.16 nM | Fluorescence Polarization (FP) [33] |

| Binding Affinity (K_D) to N-SH2 | 164.0 nM | >3000 nM | Fluorescence Polarization (FP) [33] |

| Inhibitory Potency (IC₅₀) | Not Applicable | 1.054 µM | Competitive FP Assay [33] |

| Selectivity (C-SH2 vs. N-SH2) | Low (Binds both domains) | High (>34-fold preference for C-SH2) | Calculated from K_D ratios [33] |

| Cellular Permeability | Presumed Low | Demonstrated as Cell-Permeable | Live-Cell Assay [33] |

| Cytotoxicity | Not Reported | Non-cytotoxic (up to 100 µM) | Cell Viability Assay [33] |

The data in Table 1 demonstrates the success of a rational optimization process. While the constrained CSIP experienced a slight decrease in absolute affinity for the C-SH2 domain compared to the native peptide, this was traded for a dramatic improvement in domain selectivity and the acquisition of favorable drug-like properties, including cell permeability and lack of cytotoxicity [33]. This trade-off is often desirable in drug development, as a highly selective inhibitor can more precisely probe biological function with fewer off-target effects.

Strategy 2: Mimicking the pY-X-X-Q Motif for Stat3 Inhibition

For targets like Stat3, where specificity is governed by a well-defined motif like pY-X-X-Q, the design focus shifts to accurately replicating these key interactions. This involves not only presenting the correct side chains but also mimicking the backbone conformation that optimally orients them. A critical component of this strategy is the use of non-hydrolysable pTyr mimetics to overcome the metabolic instability of phosphotyrosine.

Table 2: Comparison of pTyr Mimetics in Peptide Inhibitors

| pTyr Mimetic | Chemical Structure | Binding Affinity to SHP2 C-SH2 | Key Advantages & Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphotyrosine (pTyr) | -PO₃²⁻ | K_D = 48.9 - 58.8 nM (from ITSM peptide) | Native residue; high affinity but poor metabolic stability and cell permeability [33] |

| L-O-malonyltyrosine (l-OMT) | -O-CO-CH₂-COO⁻ | IC₅₀ = 7.8 µM (in peptide sequence) | Non-hydrolysable, stable; confers cell permeability; moderate affinity [33] |

| Phosphonodifluoromethyl phenylalanine (F₂Pmp) | -PO₃H-CF₂ | No binding detected | Widely assumed to be a general pTyr mimetic; can abolish binding to specific SH2 domains like SHP2's C-SH2 [33] |

The data in Table 2 underscores that the choice of pTyr mimetic is not one-size-fits-all. The failure of F₂Pmp to bind the C-SH2 domain of SHP2, in contrast to its success in other contexts, challenges existing notions and highlights the necessity of empirical testing for each specific SH2 target [33]. For Stat3, research has shown that beyond the pTyr mimetic, preserving the β-turn structure that presents the +3 Gln is paramount. Mutagenesis studies confirm that mutation of key Stat3 residues like Lys-591, Arg-609 (which contact the pTyr), or Glu-638 (which hydrogen-bonds with the +3 Gln) leads to a complete loss of binding to pYXXQ-containing peptides [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Protocols

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Peptidomimetic Research on SH2 Domains

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant SH2 Domains | In vitro binding and inhibition assays (FP, ITC, SPR). | Purified N-SH2 and C-SH2 domains of SHP2 [33]; Stat3 SH2 domain [32]. |

| Fluorescent Peptide Probes | Tracer molecules for Fluorescence Polarization (FP) competition assays. | FAM-labeled ITSM(pTyr) peptide (FAM-EQTE(pY)ATIVFP-NH₂) [33]. |

| Non-hydrolysable pTyr Mimetics | Incorporating stability into peptide designs for cellular assays. | l-O-malonyltyrosine (l-OMT), Phosphonodifluoromethyl phenylalanine (F₂Pmp) [33]. |

| Structure-Based Design Software | Visualizing binding pockets, docking, and optimizing designs. | Pymol (visualization); Molecular docking (Smina/AutoDock Vina [4]); MD simulations (GROMACS [4]). |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Fluorescence Polarization Competition Assay

This protocol is adapted from the methodology used to characterize the C-SH2 inhibitor peptide (CSIP) [33] and is a cornerstone for quantifying inhibitor potency.

- Prepare the Assay Mixture: In a buffer-compatible format (e.g., 384-well plate), create a solution containing a fixed, low concentration (e.g., 10-50 nM) of the fluorescent tracer peptide (e.g., FAM-ITSM(pTyr)) and a fixed concentration of the target SH2 domain at or near its K_D for the tracer to ensure a robust signal window.

- Titrate the Inhibitor: Add the unlabeled inhibitor peptide (or peptidomimetic) across a series of wells in a concentration gradient, typically spanning several orders of magnitude (e.g., 1 nM to 100 µM).

- Incubate and Measure: Allow the plate to incubate in the dark to reach binding equilibrium. Then, measure the fluorescence polarization (mP units) for each well using a plate reader.

- Data Analysis: The decrease in polarization as a function of increasing inhibitor concentration is fit to a sigmoidal dose-response curve. The concentration that displaces 50% of the tracer (IC₅₀) is calculated from this curve and serves as the primary measure of inhibitory potency.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation and Binding Free Energy Calculation

This in silico protocol, as employed in the identification of SHP2 N-SH2 inhibitors [4], provides atomic-level insights into binding stability and energetics.

- System Preparation: Obtain the crystal structure of the target SH2 domain (e.g., PDB ID: 2SHP). Prepare it by adding missing hydrogen atoms and residues using a tool like PDBFixer. The ligand topology is generated using a service like LigParGen.

- Simulation Setup: Solvate the protein-ligand complex in an explicit water model (e.g., SPC216) within a defined periodic box. Add ions to neutralize the system's charge.

- MD Simulation Run: Perform the simulation using software like GROMACS [4]. This involves energy minimization, equilibration under constant number, volume, and temperature (NVT) and constant number, pressure, and temperature (NPT) ensembles, followed by a production run (typically 100 ns or more).

- MM/PBSA Calculation: To estimate binding free energy (ΔG_bind), extract multiple snapshots from the stable trajectory. Use a tool like

g_mmpbsato perform Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area calculations, which sum the gas-phase energy, solvation energy, and surface area terms [4].

The diagram below maps the key signaling pathways discussed, highlighting the points of therapeutic intervention.

Figure 2: Key cellular signaling pathways regulated by SH2 domains and the points of inhibition by different peptidomimetic strategies. The diagram shows how inhibitors like CSIP, Stat3-targeting mimetics, and allosteric inhibitors like SHP099 intervene at specific points to modulate signaling output.

The objective comparison of experimental data reveals that the choice between constraining peptides and mimicking specific motifs is not mutually exclusive and is often guided by the target biology and desired therapeutic outcome.

- Constraining Peptides is a powerful strategy for enhancing selectivity and improving drug-like properties, as evidenced by the development of CSIP. It is particularly valuable when targeting specific isoforms or domains within a family of highly related proteins (e.g., the C-SH2 vs. N-SH2 domain of SHP2).

- Mimicking the pY-X-X-Q Motif is essential for achieving high specificity against targets like Stat3, where the binding motif is well-defined. The success of this approach hinges on the dual challenge of selecting an appropriate pTyr mimetic and engineering the peptidomimetic scaffold to faithfully reproduce the bioactive conformation of the native peptide.

The future of peptidomimetic design lies in the intelligent integration of these strategies. Advances in structural biology, computational chemistry, and synthetic methodology will enable the creation of next-generation inhibitors that are not only highly potent and selective but also possess optimal pharmacokinetic properties for in vivo efficacy. The continued refinement of these approaches promises to deliver valuable chemical probes and novel therapeutics targeting the biologically rich but challenging landscape of SH2 domain-mediated interactions.

This guide provides an objective comparison of current virtual screening and molecular docking methodologies, contextualized within research focused on discovering inhibitors of Src Homology 2 (SH2) domains—a prominent target in oncology for its role in signal transduction. Performance data and protocols for various software platforms are detailed to inform selection for small molecule and peptidomimetic drug discovery projects.

Biological Context: SH2 Domains as Therapeutic Targets

SH2 domains are protein modules approximately 100 amino acids long that specifically recognize and bind to phosphorylated tyrosine (pY) residues on their partner proteins. [3] [34] This ability makes them critical "readers" in intracellular signaling networks, regulating key cellular processes such as proliferation, survival, and differentiation. [3] [34] The human proteome contains roughly 110 proteins with SH2 domains, which can be enzymes, adaptors, or transcription factors. [3]

Dysregulation of SH2-mediated interactions is strongly implicated in disease, particularly cancer. For example, the transcription factor STAT3 must dimerize via its SH2 domain to translocate to the nucleus and activate genes that promote cell survival and proliferation. [35] Consequently, inhibiting the SH2 domain of STAT3 to prevent its dimerization is a validated strategy for anticancer drug development. [35] [6] Both small molecules and peptidomimetics are being explored to block these critical protein-protein interactions (PPIs). [6]

The following diagram illustrates the central role of SH2 domains in the JAK-STAT signaling pathway and the strategic point for inhibitory intervention.

Comparative Performance of Docking and Virtual Screening Methods

The core task of virtual screening is to accurately predict how a small molecule binds to a target (pose prediction) and to rank compounds by their predicted affinity (virtual screening enrichment). The table below summarizes the performance of leading methods across standardized benchmarks.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of State-of-the-Art Virtual Screening Tools

| Method / Platform | Type | Key Feature | Pose Prediction Success (RMSD ≤ 2 Å) | Virtual Screening Enrichment (Top 1%) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glide SP [36] [37] | Traditional Physics-Based | Robust scoring function & sampling | ~80% (Astex Diverse Set) [36] | Not Specified | High physical validity & reliability [36] |

| Glide WS [37] | Traditional Physics-Based (New) | Explicit water modeling | 92% (Self-docking, 2.5 Å criterion) [37] | Significant improvement over Glide SP [37] | Superior docking accuracy & enrichment [37] |

| RosettaVS [38] | Physics-Based with AI | Models receptor flexibility & entropy | High performance on CASF2016 [38] | EF1~1%~ = 16.72 (Top on CASF2016) [38] | Best-in-class affinity ranking [38] |

| OpenVS [38] | AI-Accelerated Platform | Integrated active learning | Dependent on docking engine (e.g., RosettaVS) | High hit rates (14-44% in prospective studies) [38] | Speed for ultra-large libraries [38] |

| SurfDock [36] | Deep Learning (Generative) | Diffusion model for pose generation | >75% across benchmarks [36] | Not Specified | High pose prediction accuracy [36] |

| CryoXKit + AutoDock [39] | Data-Guided Docking | Uses experimental density maps | Significant improvement in cross-docking [39] | Better discriminatory power [39] | Leverages experimental structural data [39] |

EF~1%~ = Enrichment Factor at the top 1% of the screened library. A higher value indicates better ability to identify true binders early. [38]

Performance Trends: Traditional vs. Deep Learning Methods

A comprehensive 2025 study reveals a clear stratification of docking methods. [36]

- Traditional physics-based methods like Glide SP consistently achieve high physical validity (e.g., correct bond lengths, no steric clashes), with success rates above 94% in generating chemically plausible structures. [36]

- Deep learning generative models (e.g., SurfDock) excel in raw pose prediction accuracy (RMSD ≤ 2 Å), often exceeding 70-90% on standard benchmarks. [36]

- A significant caveat for many deep learning methods is that they can produce physically invalid poses or fail to recover critical molecular interactions despite having a good RMSD, limiting their direct application in lead optimization. [36]

- Hybrid methods that combine traditional conformational sampling with AI-driven scoring offer a balanced approach, though they may not surpass the performance of top-tier traditional methods like Glide. [36]

Experimental Protocols for Virtual Screening

Successful virtual screening campaigns follow a structured workflow. The diagram below outlines the key stages, from target preparation to experimental validation.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Stages

1. Target Preparation

- Structure Selection: For targets with multiple structures, select the receptor from a co-crystal structure with a ligand most similar to the compounds being screened ("dock-close" strategy). This often outperforms using multiple structures. [40]

- Binding Site Definition: Clearly define the coordinates of the binding site. For SH2 domains, this is the conserved pY-binding pocket. [3] [34]

- Receptor Flexibility: Incorporate flexibility where critical. RosettaVS allows for full side-chain and limited backbone flexibility in its high-precision mode. [38] Ensemble docking is an alternative, but can introduce noise. [40]

2. Library Preparation

- Library Curation: Use focused libraries for specific targets. For PPIs like SH2 domain inhibition, libraries rich in peptidomimetics or multicomponent reaction (MCR)-derived compounds are advantageous. [40]

- Compound Preprocessing: Generate realistic, low-energy 3D conformers for each compound. Tools like Open Babel or OMEGA are standard for this step. [40]

3. Virtual Screening Execution

- Docking Protocol: A tiered approach is computationally efficient.

- Active Learning: Platforms like OpenVS integrate active learning, where a target-specific neural network is trained during docking to intelligently select promising compounds for more expensive calculations, dramatically speeding up the screening of billion-member libraries. [38]

4. Post-Docking Analysis

- Consensus Scoring: Rank compounds using multiple scoring functions or more computationally intensive methods like Molecular Mechanics with Generalized Born and Surface Area Solvation (MM/GBSA) to improve hit rates. [40] [6]

- Interaction Analysis: Manually inspect top-ranked poses to ensure they form key interactions with the target. For STAT3 SH2 domain inhibitors, this involves verifying interactions with the critical arginine residue in the pY-binding pocket. [35]

5. Experimental Validation