SDS-PAGE vs Native-PAGE: A Comprehensive Guide to Choosing the Right Protein Separation Technique

This article provides a definitive comparison of SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

SDS-PAGE vs Native-PAGE: A Comprehensive Guide to Choosing the Right Protein Separation Technique

Abstract

This article provides a definitive comparison of SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the core principles, separation mechanisms, and underlying biochemistry of each technique. A detailed methodological guide explains sample preparation, buffer composition, and gel selection for specific applications such as molecular weight determination, activity assays, and protein complex analysis. The content includes practical troubleshooting for common issues like smeared bands and incomplete separation, alongside optimization strategies for resolution and reproducibility. Finally, it explores advanced validation methods and emerging hybrid techniques like Native SDS-PAGE, synthesizing key takeaways to guide experimental design in biomedical and clinical research.

Core Principles of Protein Electrophoresis: Understanding SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE

In protein analysis research, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) serves as a fundamental technique for separating and characterizing proteins. The choice between denaturing (SDS-PAGE) and non-denaturing (Native-PAGE) separation methods represents a critical branching point in experimental design, each pathway preserving or eliminating different protein features to serve distinct analytical purposes [1] [2]. This comparison guide objectively examines the performance of these two foundational techniques against key parameters relevant to researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. While SDS-PAGE dominates routine molecular weight determination due to its simplicity and reproducibility, Native-PAGE provides unique capabilities for functional analysis that make it indispensable for studying native protein complexes, interactions, and enzymatic activity [3]. Understanding the precise applications, limitations, and experimental requirements of each method enables researchers to select the optimal approach for their specific protein characterization needs.

Core Principles and Separation Mechanisms

The fundamental distinction between these techniques lies in their treatment of protein structure during separation. SDS-PAGE employs denaturing agents to unfold proteins, while Native-PAGE maintains proteins in their native, functional state throughout the separation process [1] [2].

SDS-PAGE: Separation by Molecular Weight Alone

In SDS-PAGE, the anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) binds uniformly to proteins in a constant weight ratio (approximately 1.4g SDS per 1g of protein) [2]. This SDS-binding process, coupled with heating and reducing agents like dithiothreitol (DTT) or β-mercaptoethanol, effectively denatures proteins by disrupting their secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures [1] [4]. The bound SDS masks the proteins' intrinsic charges and confers a uniform negative charge density, linearizing the polypeptides into rod-like shapes [1]. Consequently, separation occurs primarily according to molecular weight as these SDS-polypeptide complexes migrate through the polyacrylamide gel matrix, with smaller proteins moving faster than larger ones [2]. This singular focus on molecular weight makes SDS-PAGE exceptionally reliable for mass determination and purity assessment.

Native-PAGE: Separation by Charge, Size, and Shape

In contrast, Native-PAGE preserves proteins in their folded, functional conformations by eliminating denaturing agents from all gel and buffer components [1] [5]. Without SDS to normalize charge, proteins separate according to their intrinsic charge density, molecular size, and three-dimensional shape [2]. In the slightly basic pH conditions typically employed, most proteins carry a net negative charge and migrate toward the anode, with higher charge density correlating with faster migration [1]. Simultaneously, the gel matrix exerts a sieving effect, creating frictional forces that regulate movement according to protein size and shape—smaller, more compact proteins migrate faster than larger, more complex structures [1] [2]. This multi-parameter separation preserves protein complexes, subunit interactions, and biological activity, enabling functional studies impossible with denaturing methods.

Table 1: Fundamental Principles and Separation Characteristics

| Characteristic | SDS-PAGE | Native-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Molecular weight primarily | Size, charge, and shape |

| Protein State | Denatured and linearized | Native, folded conformation |

| Quaternary Structure | Disrupted; subunits separate | Preserved; complexes remain intact |

| Net Charge on Proteins | Uniformly negative due to SDS | Intrinsic charge (positive or negative) |

| Key Reagents | SDS, reducing agents (DTT, β-mercaptoethanol) | No denaturants; may use Coomassie in BN-PAGE |

| Typical Buffer Systems | Tris-glycine-SDS, Bis-Tris-MOPS-SDS | Tris-glycine (pH 8.8 for acidic proteins) |

Comparative Experimental Performance Data

When evaluating technique performance for specific applications, SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE demonstrate complementary strengths. The selection between them involves trade-offs between resolution, structural preservation, and functional retention.

Resolution and Molecular Weight Determination

SDS-PAGE provides superior resolution for molecular weight determination, typically resolving proteins from 6-200 kDa in Tris-Glycine systems [6]. The denaturation and charge normalization process creates a linear relationship between migration distance and log molecular weight, enabling accurate mass estimation when appropriate standards are used [2]. Native-PAGE offers poorer molecular weight accuracy because a protein's migration depends on multiple factors beyond size [1] [5]. While specialized approaches like plotting Rf values at different gel concentrations can provide molecular weight estimates in Native-PAGE, these require additional experimental steps and offer less precision than SDS-PAGE [5].

Structural and Functional Preservation

Native-PAGE excels in preserving protein structure and function, with research demonstrating that seven of nine model enzymes retained activity after separation using modified native conditions, compared to complete denaturation in standard SDS-PAGE [7]. This structural preservation extends to metal cofactors, with one study reporting 98% zinc retention in metalloproteins using Native-SDS-PAGE versus only 26% with denaturing SDS-PAGE [7]. This capability makes Native-PAGE indispensable for studying metal-binding proteins, enzymatic function, and protein complexes in their biologically active states.

Applicability to Downstream Analyses

The techniques differ significantly in their compatibility with downstream applications. Proteins separated by SDS-PAGE are ideal for western blotting, mass spectrometry analysis, and protein sequencing because the denatured, reduced state facilitates transfer to membranes and peptide digestion [1] [2]. Conversely, proteins separated by Native-PAGE can be recovered in active form for functional assays, enzymatic studies, and interaction analyses through techniques like passive diffusion or electro-elution from gels [2]. This functional preservation enables researchers to correlate separation patterns with biological activity.

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Key Applications

| Performance Metric | SDS-PAGE | Native-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight Determination | Accurate and straightforward | Indirect and less accurate |

| Protein Complex Analysis | Disassembles complexes; analyzes subunits | Preserves oligomeric states and complexes |

| Functional Activity Post-Separation | Typically lost | Typically retained |

| Metal Cofactor Retention | Poor (26% in one study) | Excellent (98% in one study) |

| Detection Limit | Microgram quantities sufficient | May require more protein for activity assays |

| Downstream Western Blotting | Excellent compatibility | Possible with caution |

| Enzymatic Activity Assays | Not possible | Directly possible after separation |

Detailed Methodologies and Protocols

Standardized protocols for both techniques ensure reproducible results. The following sections detail established methodologies from commercial and research sources.

SDS-PAGE Protocol

The denaturing SDS-PAGE procedure follows a well-established workflow centered on complete protein denaturation [6]:

Sample Preparation:

- Mix protein sample with 2X Tris-Glycine SDS Sample Buffer containing SDS and reducing agent [6].

- For reduced samples, add DTT to a final concentration of 1X immediately before electrophoresis [6].

- Heat samples at 85°C for 2-5 minutes to ensure complete denaturation [6]. Avoid 100°C heating to prevent proteolysis [6].

Gel Electrophoresis:

- Use pre-cast or freshly poured polyacrylamide gels with appropriate percentage for target protein size [2].

- Assemble gel cassette in electrophoresis chamber with Tris-Glycine SDS Running Buffer [6].

- Load samples and molecular weight markers (e.g., 5-25μg protein per lane) [7].

- Run at constant voltage (125V for mini-gels) for approximately 90 minutes or until dye front reaches bottom [6].

- Typical current ranges from 30-40mA start to 8-12mA end for single mini-gels [6].

Post-Electrophoresis Analysis:

- After separation, proteins can be stained (Coomassie, silver stain), transferred for western blotting, or excised for mass spectrometry [2].

Native-PAGE Protocol

The non-denaturing PAGE method requires modifications to preserve protein structure [6] [5]:

Sample Preparation:

- Mix protein sample with Tris-Glycine Native Sample Buffer (without SDS or reducing agents) [6].

- Do not heat samples to prevent denaturation [6] [5].

- Keep samples at 4°C to maintain stability [8].

Gel Electrophoresis:

- Use polyacrylamide gels cast without SDS or other denaturants [5].

- For basic proteins, adjust buffer pH or reverse electrode configuration [5].

- Assemble gel cassette with Tris-Glycine Native Running Buffer [6].

- Load samples and appropriate native markers.

- Run at constant voltage (125V) for 1-12 hours depending on protein size and complex [6].

- Maintain cooler temperatures (4°C recommended) during extended runs to prevent denaturation [8] [5].

- Expected current: 6-12mA start to 3-6mA end for single mini-gels [6].

Post-Electrophoresis Analysis:

- Detect proteins with Coomassie Brilliant Blue or silver staining [5].

- For functional recovery, passively diffuse or electro-elute proteins from gel slices [2].

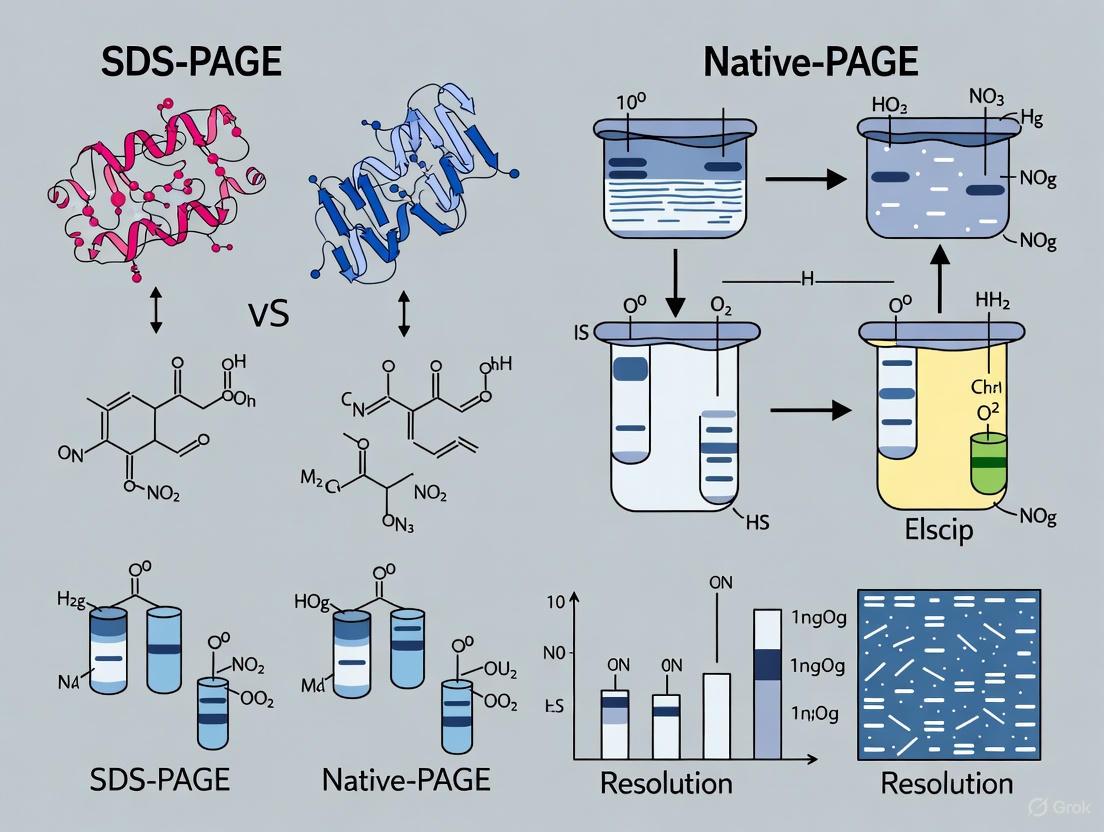

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following workflow diagrams illustrate the key procedural differences between SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE, highlighting critical branching points that determine experimental outcomes.

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of either technique requires specific reagent systems tailored to each method's requirements. The following table outlines essential solutions for both SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Protein Electrophoresis

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Buffers | Tris-Glycine SDS Sample Buffer (2X) [6] | Denatures proteins and provides charge for SDS-PAGE |

| Tris-Glycine Native Sample Buffer (2X) [6] | Maintains native state without denaturation for Native-PAGE | |

| Reducing Agents | NuPAGE Reducing Agent (10X DTT) [6] | Breaks disulfide bonds in reducing SDS-PAGE |

| β-mercaptoethanol [6] | Alternative reducing agent for SDS-PAGE | |

| Running Buffers | Tris-Glycine SDS Running Buffer (10X) [6] | Provides conducting ions and SDS for denaturing separation |

| Tris-Glycine Native Running Buffer (10X) [6] | Conducting buffer without denaturants for native separation | |

| Gel Matrices | Pre-cast Tris-Glycine Gels [6] | Ready-to-use polyacrylamide gels of various percentages |

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide solutions [5] | For casting custom polyacrylamide gels | |

| Detection Reagents | Coomassie Brilliant Blue Staining Kits [5] | Protein visualization in both denaturing and native gels |

| Silver Staining Kits [5] | Higher sensitivity protein detection |

SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE offer complementary approaches to protein separation, each with distinct advantages for specific research goals. SDS-PAGE provides high-resolution separation based primarily on molecular weight, making it ideal for determining protein size, assessing purity, and preparing samples for western blotting or mass spectrometry [1] [2]. Its standardized protocol, simplicity, and reproducibility explain its widespread adoption in molecular biology laboratories [4]. Conversely, Native-PAGE preserves native protein structure and function, enabling researchers to study protein complexes, oligomeric states, enzymatic activity, and protein-metal interactions [7] [2]. While more technically challenging and providing less precise molecular weight information, Native-PAGE offers unique capabilities for functional proteomics that denaturing methods cannot replicate.

For drug development professionals and researchers designing protein characterization strategies, the choice between these techniques should be driven by specific experimental questions. When determining molecular weight, purity, or subunit composition is paramount, SDS-PAGE delivers superior performance. When investigating biological function, protein-protein interactions, or native structural properties, Native-PAGE provides the necessary preservation of protein activity. In advanced proteomic approaches, these techniques can be combined—using Native-PAGE for first-dimension separation followed by denaturing SDS-PAGE in the second dimension—to leverage the strengths of both methods [2]. Understanding these performance characteristics enables researchers to strategically implement the most appropriate separation technology for their specific protein analysis requirements.

In the field of protein research, the choice of electrophoretic technique fundamentally shapes the experimental outcome. Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and native PAGE represent two foundational approaches with distinct philosophies and applications [8] [3]. SDS-PAGE employs a powerful detergent to dismantle protein structures, creating a uniform population of polypeptides separated strictly by molecular weight [9] [2]. In contrast, native PAGE preserves the delicate, functional architecture of proteins, enabling separation based on the combined interplay of charge, size, and shape [10] [2]. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these techniques, focusing on the transformative role of SDS in denaturation, charge manipulation, and molecular weight-based separation, supported by experimental data and protocols for life science researchers and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Principles and the Defining Role of SDS

The Mechanism of SDS in Protein Denaturation and Charge Conferral

The resolving power of SDS-PAGE hinges on the action of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). This anionic detergent performs two critical functions: it denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge [11].

- Protein Denaturation: SDS disrupts the hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions that maintain a protein's secondary and tertiary structure [11]. Its hydrophobic tail interacts with hydrophobic regions of the protein, while its ionic head group disrupts non-covalent interactions. This unfolds the protein into a linear polypeptide chain [11].

- Charge Conferral: SDS binds to the protein backbone at a nearly constant ratio of approximately 1.4 g SDS per 1.0 g of protein [9] [2]. This extensive, uniform binding masks the protein's intrinsic charge, creating a cloud of negative charge around the polypeptide. The result is that all SDS-bound proteins carry a similar charge-to-mass ratio and a nearly identical conformation, transforming a complex mixture of unique proteins into a population that varies primarily in polypeptide chain length [9] [11].

Sample preparation for SDS-PAGE involves heating the protein sample (typically at 95°C for 3-5 minutes) in a buffer containing SDS and a reducing agent like beta-mercaptoethanol (BME) or dithiothreitol (DTT) [8] [9]. Heating further denatures the proteins by breaking hydrogen bonds, while the reducing agents cleave disulfide bridges, ensuring complete unfolding into monomeric subunits [11].

Separation Principles in Native PAGE

Native PAGE operates on a different premise: the preservation of the protein's native state. No denaturing agents are used, so proteins remain in their folded, functional conformation [8] [2]. Consequently, separation depends on three intrinsic properties of the protein within the gel matrix and the alkaline running buffer:

- Net Charge: The protein's inherent charge at the running buffer's pH.

- Size: The molecular weight of the native protein or protein complex.

- Shape: The three-dimensional structure, which affects frictional drag through the gel matrix [10] [2].

This technique is ideal for studying functional properties, protein-protein interactions, and oligomeric states, as the biological activity is often retained post-separation [8] [3]. Some native PAGE systems, such as Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE), use Coomassie G-250 dye to impart a slight negative charge to proteins, which helps prevent aggregation and allows even basic proteins to migrate toward the anode [10].

Direct Technique Comparison: SDS-PAGE vs. Native PAGE

The core differences between these two techniques are systematic and impact every aspect of experimental design and outcome.

Table 1: Core Differences Between SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE

| Criteria | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Molecular weight (polypeptide chain length) [8] [9] | Native size, overall charge, and 3D shape [8] [10] |

| Gel Type | Denaturing [8] | Non-denaturing [8] |

| SDS Presence | Present in gel and buffer [8] | Absent [8] |

| Reducing Agent | Present (e.g., DTT, BME) [8] | Absent [8] |

| Sample Prep | Heating required [8] [9] | No heating [8] |

| Protein State | Denatured and linearized [8] [11] | Native, folded conformation [8] |

| Protein Function | Function lost [8] | Function often retained [8] |

| Protein Recovery | Typically not recoverable in functional form [8] | Can be recovered for functional studies [8] |

| Primary Applications | Molecular weight determination, purity checks, Western blotting [8] [7] | Studying oligomeric state, protein complexes, enzymatic activity [8] [12] |

Experimental Data and Methodologies

Quantitative Comparison of Protein and Metal Retention

Recent research has explored hybrid approaches, such as native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE), which modifies standard SDS-PAGE conditions to preserve some native properties while maintaining high resolution. The following data illustrates the functional consequences of choosing different electrophoretic methods.

Table 2: Experimental Comparison of Standard and Modified PAGE Techniques

| Parameter | SDS-PAGE | BN-PAGE | NSDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zn²⁺ Retention in Proteomic Samples | 26% | Not Specified | 98% [7] |

| Enzymatic Activity Retention | 0 out of 9 model enzymes | 9 out of 9 model enzymes | 7 out of 9 model enzymes [7] |

| Key Modification | Sample heated with SDS and reducing agent; running buffer contains SDS and EDTA [7] | No SDS; uses Coomassie G-250 dye in cathode buffer [7] [10] | No heating, no EDTA; reduced SDS in running buffer (0.0375%) [7] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard SDS-PAGE [9] [11]

- Gel Casting: Assemble gel cassette. Prepare the resolving gel (e.g., 12% acrylamide, pH ~8.8) by mixing acrylamide/bis-acrylamide, Tris-HCl buffer, SDS, and ammonium persulfate (APS), and catalyzing polymerization with TEMED. Pour the gel and overlay with water or isopropanol for a flat surface. Once polymerized, pour the stacking gel (e.g., 4% acrylamide, pH ~6.8) on top and insert a comb to create wells.

- Sample Preparation: Mix protein sample with SDS-PAGE sample buffer (containing SDS, glycerol, a tracking dye like Bromophenol Blue, and a reducing agent like DTT or BME). Heat the mixture at 95°C for 3-5 minutes to denature proteins. Centrifuge briefly to collect condensate.

- Electrophoresis: Mount the gel cassette in the electrophoresis tank filled with running buffer (e.g., Tris-Glycine with 0.1% SDS). Load denatured samples and molecular weight markers into the wells. Apply a constant voltage (e.g., 200V for a mini-gel) until the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel.

- Post-Electrophoresis Analysis: Proteins can be visualized by staining (e.g., Coomassie Brilliant Blue, silver stain), or transferred to a membrane for Western blotting.

Protocol 2: Native PAGE for GPCR-mini-G Protein Coupling [12]

- Sample Preparation (Screening Format): Solubilize adherent mammalian cells (e.g., HEK293S) transiently expressing a fluorescently tagged GPCR (e.g., EGFP-tagged) directly in a detergent solution containing Lauryl Maltose Neopentyl Glycol (LMNG) and Cholesteryl Hemisuccinate (CHS). Centrifuge to remove insoluble debris.

- Complex Formation: Incubate the solubilized supernatant with agonist peptides and purified mini-G protein to allow complex formation.

- Electrophoresis: Prepare a native polyacrylamide gel (e.g., hrCNE gel). Load the samples without heating. Run electrophoresis under native conditions (e.g., 150V, room temperature) using an appropriate anode and cathode buffer (without SDS or other denaturants).

- Detection: Visualize the receptor and receptor-mini-G complexes directly in the gel using in-gel fluorescence imaging. A mobility shift indicates successful complex formation.

Visualization of Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical and procedural relationships in the two primary electrophoretic methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful electrophoresis relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions for both SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PAGE Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge [11]. | SDS-PAGE |

| DTT (Dithiothreitol) / BME (Beta-Mercaptoethanol) | Reducing agents that break disulfide bonds to ensure complete unfolding [11]. | SDS-PAGE |

| Coomassie G-250 Dye | Binds hydrophobically to proteins, imparting negative charge without denaturation [10]. | BN-PAGE / Native PAGE |

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Monomer and crosslinker that polymerize to form the porous gel matrix [2] [11]. | SDS-PAGE & Native PAGE |

| APS & TEMED | Ammonium persulfate (APS) and TEMED catalyze the polymerization of the polyacrylamide gel [11]. | SDS-PAGE & Native PAGE |

| Tris-based Buffers | Provide the conductive ionic medium and maintain stable pH during electrophoresis [9] [10]. | SDS-PAGE & Native PAGE |

| Molecular Weight Markers | Pre-stained or unstained protein ladders for estimating the molecular weight of unknown proteins [2]. | SDS-PAGE & Native PAGE |

| LMNG / CHS Detergents | Mild detergents for solubilizing membrane proteins while maintaining native structure and interactions [12]. | Native PAGE (Membrane Proteins) |

SDS-PAGE and native PAGE are complementary, not competing, techniques in the protein scientist's arsenal. The role of SDS is definitive: it creates a universal system for separating polypeptides by molecular weight, invaluable for analytical and preparative workflows like Western blotting. In contrast, native PAGE preserves the intricate and functionally crucial world of protein structures, complexes, and activities. The choice between them is not a matter of which is superior, but which is appropriate for the biological question at hand. By understanding their fundamental principles—centered on the role of SDS—and leveraging their distinct capabilities, researchers can design more effective experiments to advance protein science and drug discovery.

In the realm of protein research, the choice of analytical technique is pivotal, dictating the type and quality of information that can be extracted. Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Native-PAGE) stands as a fundamental method for separating proteins in their folded, functional state. Unlike its denaturing counterpart, SDS-PAGE, Native-PAGE preserves the intricate three-dimensional structure of proteins, allowing researchers to probe characteristics lost in fully denatured systems. This guide provides a detailed objective comparison between Native-PAGE and SDS-PAGE, framing them as complementary tools within a comprehensive protein analysis strategy. The core distinction lies in what property drives the separation: Native-PAGE separates proteins based on a combination of their native charge, size, and shape, whereas SDS-PAGE separates primarily by molecular weight after denaturation [3] [13] [14].

This capability makes Native-PAGE indispensable for experiments where maintaining biological activity is paramount, such as studying enzyme function, protein-protein interactions within complexes, and oligomeric states [10] [3]. The following sections will dissect the principles, methodologies, and applications of Native-PAGE, providing direct comparisons with SDS-PAGE through structured data, experimental protocols, and visual workflows to equip researchers with the knowledge to select the optimal technique for their scientific inquiries.

Fundamental Principles of Separation

The separation mechanism in Native-PAGE is multifaceted, relying on the innate physical properties of proteins in their native conformation. Understanding these principles is key to interpreting experimental results and designing effective protocols.

A Multi-Factor Separation Mechanism

In Native-PAGE, a protein's migration through the polyacrylamide gel matrix is simultaneously influenced by three key factors [15]:

- Charge: The net charge of a protein at the buffer's pH determines its direction and rate of migration. Positively charged proteins (cations) move toward the negative electrode (cathode), while negatively charged proteins (anions) move toward the positive electrode (anode) [16] [15]. This net charge is dictated by the protein's isoelectric point (pI) relative to the pH of the running buffer [17].

- Size: The molecular weight of the protein affects its mobility, with larger proteins generally migrating more slowly than smaller ones due to greater frictional forces [10].

- Shape: The three-dimensional conformation of the native protein influences how easily it navigates the pores of the gel. A compact, globular protein will migrate differently than an elongated fibrous protein of the same molecular weight [15].

This triad of influences contrasts sharply with SDS-PAGE, where the denaturing agent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and a reducing agent linearize the proteins and confer a uniform negative charge. This simplification means separation in SDS-PAGE occurs almost exclusively based on polypeptide chain length and molecular weight [3] [13] [18].

The Critical Influence of Buffer pH

The buffer pH is a critical experimental parameter in Native-PAGE because it directly determines the net charge of a protein [17]. A protein's net charge is zero at its isoelectric point (pI). In a buffer with a pH below the protein's pI, the protein gains a net positive charge and will migrate toward the cathode. Conversely, in a buffer with a pH above the pI, the protein gains a net negative charge and will migrate toward the anode [17]. This principle allows researchers to manipulate migration direction and separation efficiency simply by selecting an appropriate buffer system.

Direct Technique Comparison: Native-PAGE vs. SDS-PAGE

The choice between Native-PAGE and SDS-PAGE is fundamental to experimental design. The table below provides a systematic, point-by-point comparison of the two techniques, highlighting their optimal applications and limitations.

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of Native-PAGE and SDS-PAGE characteristics and applications.

| Feature | Native-PAGE | SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Native charge, size, and 3D shape [10] [3] [15] | Molecular weight of polypeptide chains [3] [13] [18] |

| Protein State | Native, folded; multimers intact [10] [3] | Denatured, linearized; subunits dissociated [3] [18] |

| Biological Activity | Retained (enzymatic activity, etc.) [10] [3] | Lost [3] [7] |

| Key Reagents | No SDS or reducing agents; may use Coomassie G-250 (BN-PAGE) [10] [7] | SDS, reducing agents (e.g., β-mercaptoethanol, DTT) [13] [18] |

| Sample Preparation | Non-denaturing buffers; no heating [13] | Boiling in SDS and reducing agent [13] [18] |

| Information Gained | Oligomeric state, protein complexes, native charge [10] [3] | Subunit molecular weight, protein purity, number of subunits [3] [18] |

| Optimal For | Studying functional complexes, enzyme assays, interaction studies [10] [3] | Determining molecular weight, assessing purity, western blotting [3] [4] [18] |

| Limitations | Complex migration interpretation; not universal for all proteins [10] [3] | Loss of functional and structural data; not for native complexes [3] [7] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

A successful Native-PAGE experiment requires careful attention to protocol details, from buffer selection to sample preparation. Below is a detailed methodology for a standard Native-PAGE setup and a specialized variant.

Standard Native-PAGE Protocol Using Tris-Glycine

This protocol is adapted from common laboratory practices and commercial system guidelines [10] [13].

Gel Composition:

- Resolving Gel: Typically 7-12% acrylamide, pH ~8.8. The exact percentage is chosen based on the target protein size.

- Stacking Gel: 4-5% acrylamide, pH ~6.8. This layer concentrates the protein samples into sharp bands before they enter the resolving gel [13].

Buffers and Reagents:

- Running Buffer: Tris-Glycine, pH ~8.3-9.5 [10]. This alkaline buffer ensures most proteins carry a net negative charge and migrate towards the anode [10].

- Sample Buffer: Tris-Glycine Native Sample Buffer, containing glycerol and a tracking dye (e.g., Bromophenol Blue), but no SDS or reducing agents [10] [13].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Gel Casting: Prepare and pour the resolving gel. Once polymerized, pour the stacking gel and insert the well comb.

- Sample Preparation: Mix the protein sample with native sample buffer. Do not boil the samples. Centrifuge to remove insoluble debris [13].

- Loading and Running: Load the prepared samples and molecular weight standards into the wells. Run the gel at a constant voltage (e.g., 100-150V) in a cooled tank to minimize heat-induced denaturation [13].

- Visualization: After electrophoresis, proteins can be visualized using Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining or other compatible methods [14].

Specialized Protocol: Blue Native (BN)-PAGE

BN-PAGE is a powerful variant for analyzing membrane protein complexes and proteins with basic pI values.

Key Differentiating Reagent:

- Coomassie G-250 Dye: This anionic dye is added to the cathode buffer and sample. It binds non-specifically to proteins, conferring a negative charge and allowing even basic proteins to migrate towards the anode [10] [7]. It also helps solubilize membrane proteins [10].

Workflow and Data Interpretation: The general workflow is similar to standard Native-PAGE but uses Bis-Tris gels at a near-neutral pH (~7.5) and specific BN-PAGE buffers [10]. The Coomassie dye provides a "charge shift" mechanism, simplifying the separation by ensuring all proteins move in the same direction, but it can sometimes dissociate weakly bound complexes [10] [14].

Quantitative Data from Comparative Studies

Modified electrophoresis methods have been developed to bridge the gap between the high resolution of SDS-PAGE and the native-state preservation of BN-PAGE. One study, as detailed in Metallomics, developed a "Native SDS-PAGE" (NSDS-PAGE) method by drastically reducing SDS concentration and eliminating heating and reducing agents [7]. The quantitative outcomes from this comparative study are summarized below.

Table 2: Quantitative comparison of protein activity and metal retention across PAGE methods.

| Analysis Metric | SDS-PAGE | BN-PAGE | NSDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retention of Zn²⁺ in Proteome | 26% | Data not provided | 98% |

| Active Enzymes (from 9 tested) | 0 | 9 | 7 |

| Protein Resolution | High | Lower than SDS-PAGE | High, comparable to SDS-PAGE |

This data demonstrates that protocol modifications can significantly impact functional outcomes, such as metal retention and enzymatic activity, while maintaining high-resolution separation [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Selecting the correct reagents is fundamental to the success of any Native-PAGE experiment. The table below lists key solutions and materials, along with their critical functions.

Table 3: Essential reagents and materials for Native-PAGE experiments.

| Reagent/Material | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Polyacrylamide Gel | A matrix of cross-linked acrylamide and bis-acrylamide that acts as a molecular sieve. Pore size is adjusted via concentration to separate proteins by size and shape [13] [16]. |

| Tris-Glycine Buffer | A common discontinuous buffer system for Native-PAGE. The pH (8.3-9.5) influences protein charge and mobility [10] [13]. |

| Coomassie G-250 Dye | Key component of BN-PAGE. Binds to proteins, imparting negative charge and aiding in the solubilization of membrane proteins [10] [7]. |

| Native Sample Buffer | Contains glycerol to densify the sample for well loading and a tracking dye (e.g., Bromophenol Blue) to monitor migration. Crucially lacks SDS and denaturants [10] [13]. |

| Molecular Weight Standards | A mixture of native proteins with known molecular weights and characteristics, used to estimate the size and oligomeric state of sample proteins [13]. |

| Coomassie Staining Solution | A standard protein stain (e.g., Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250) for visualizing separated protein bands post-electrophoresis [14]. |

Native-PAGE and SDS-PAGE are not competing techniques but rather complementary pillars of protein analysis. The decision to use one over the other must be strategically aligned with the specific research question. Native-PAGE is the unequivocal choice when the experimental goal involves probing the native state—whether it be to visualize active protein complexes, measure enzymatic function after separation, or determine the oligomeric status of a purified protein [10] [3]. Its power lies in preserving the delicate, non-covalent interactions that define protein function in the cellular environment.

Conversely, SDS-PAGE provides unparalleled simplicity and resolution for questions related to polypeptide molecular weight, subunit composition, and sample purity [3] [18]. Its ability to denature and linearize proteins removes the confounding variables of native charge and shape, creating a one-dimensional separation that is straightforward to interpret. For a complete picture, researchers often employ these techniques in tandem; for example, by using BN-PAGE in the first dimension to isolate a complex, followed by SDS-PAGE in the second dimension to identify its constituent subunits [7]. By understanding the fundamental principles and practical considerations outlined in this guide, researchers can effectively leverage the strengths of each method to advance their investigations in biochemistry, structural biology, and drug development.

Protein electrophoresis is a fundamental laboratory technique in which charged protein molecules are transported through a solvent by an electrical field, enabling the separation and analysis of complex protein mixtures. [2] This methodology serves as an indispensable tool for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who require precise protein characterization. Among the various electrophoretic techniques, Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Native-PAGE have emerged as cornerstone methods with complementary applications. SDS-PAGE separates proteins primarily by molecular weight under denaturing conditions, while Native-PAGE separates proteins based on both size and charge while preserving their native conformation and biological activity. [3] [2] [8] The evolution of these techniques from their initial development to modern methodologies represents a critical historical progression in protein science, facilitating advances across diverse fields including proteomics, drug discovery, and diagnostic development.

The significance of these methods extends throughout the biopharmaceutical industry, where they are employed for quality control, purity assessment, and characterization of therapeutic proteins. [19] Understanding the historical context and technical evolution of SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE provides researchers with a foundation for selecting appropriate methodologies for specific applications and appreciating the limitations and advantages inherent in each approach. This comparative guide examines the key historical developments, methodological refinements, and contemporary applications of these essential protein separation techniques, providing objective performance comparisons and supporting experimental data to inform research decisions.

Historical Timeline: From Laemmli to Contemporary Innovations

The development of polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) methodologies represents a series of strategic innovations that have progressively enhanced researchers' ability to characterize proteins. The historical trajectory from initial methodologies to contemporary refinements illustrates how technical challenges have been systematically addressed through scientific ingenuity.

The Laemmli Breakthrough: Standardizing SDS-PAGE

The modern era of protein electrophoresis began with the groundbreaking work of Ulrich K. Laemmli, who in 1970 developed the discontinuous SDS-PAGE system that remains the foundation for most contemporary protein separation protocols. [4] [8] Laemmli's critical insight was incorporating the anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) into the electrophoretic system, which fundamentally transformed protein separation by denaturing proteins and conferring a uniform negative charge proportional to their molecular weight. [4] [2] This innovation effectively eliminated the influence of protein shape and intrinsic charge on migration through the polyacrylamide gel matrix, enabling separation based primarily on molecular mass.

The Laemmli method established several foundational components that remain central to SDS-PAGE protocols today. The technique introduced a discontinuous buffer system with stacking and resolving gel phases, dramatically improving band sharpness and resolution compared to previous continuous systems. [2] The stacking gel, with its lower acrylamide concentration and different pH, concentrates protein samples into tight bands before they enter the resolving gel, where separation based on size occurs. This concentration effect allows researchers to load larger sample volumes without sacrificing resolution, significantly enhancing the practical utility of the technique. Additionally, the standardization of sample preparation involving SDS and reducing agents like β-mercaptoethanol or dithiothreitol (DTT) to break disulfide bonds established a reproducible framework for protein denaturation prior to separation. [4]

Native-PAGE: Preserving Native Conformation

While SDS-PAGE was revolutionizing molecular weight determination, the parallel development of Native-PAGE (non-denaturing PAGE) by Ornstein and Davis addressed the complementary need for analyzing proteins in their biologically active state. [8] Unlike SDS-PAGE, Native-PAGE avoids denaturing agents, preserving protein complexes in their native conformation and maintaining enzymatic activity and binding capabilities. [3] [2] This preservation enables researchers to study functional properties, protein-protein interactions, oligomeric states, and enzymatic activities directly following electrophoretic separation.

The methodological framework for Native-PAGE presented distinct technical challenges compared to SDS-PAGE. Without the charge-masking effect of SDS, separation in Native-PAGE depends on both the intrinsic charge of the protein at the running pH and the molecular size and shape, creating a more complex separation profile. [2] [8] The requirement for milder electrophoretic conditions, often including lower temperatures (4°C) and careful buffer formulation, became essential to maintain protein stability and function throughout the separation process. [8] These methodological considerations established Native-PAGE as a more specialized but invaluable technique for functional protein analysis.

Methodological Refinements and Hybrid Approaches

Following these foundational developments, subsequent innovations have refined and expanded the capabilities of both SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE. The introduction of Blue Native-PAGE (BN-PAGE) by Schägger and von Jagow in 1991 represented a significant advancement for analyzing native protein complexes, particularly membrane protein complexes. [7] This technique incorporates Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250, which confers negative charge to native protein complexes while maintaining their structure, enabling separation by molecular size under non-denaturing conditions. [7] [8]

More recently, researchers have developed hybrid approaches that seek to balance the high resolution of denaturing methods with the functional preservation of native techniques. A notable innovation is Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE), which modifies traditional SDS-PAGE conditions by reducing SDS concentration, eliminating EDTA from buffers, and omitting the heating step during sample preparation. [7] This approach represents a convergence of methodological principles, attempting to maintain certain functional properties while retaining the separation resolution characteristic of traditional SDS-PAGE. Experimental data demonstrates that this modified approach significantly improves metal retention in metalloproteins (from 26% to 98%) and preserves enzymatic activity in seven of nine model enzymes tested. [7]

Table 1: Key Historical Developments in PAGE Methodologies

| Year | Development | Key Innovators | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1959 | Starch Gel Electrophoresis | Smithies | Early electrophoretic separation method [4] |

| 1970 | Discontinuous SDS-PAGE | Laemmli | Standardized denaturing protein separation by molecular weight [4] |

| 1960s | Native-PAGE | Ornstein and Davis | Enabled separation of native, functional proteins [8] |

| 1991 | Blue Native-PAGE (BN-PAGE) | Schägger and von Jagow | Allowed high-resolution separation of membrane protein complexes [7] |

| 2014 | Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE) | PMC Research | Balanced resolution with functional preservation for metalloproteins [7] |

Methodological Comparison: Principles and Procedures

Understanding the fundamental principles and detailed procedures governing SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE is essential for researchers to select the appropriate technique for specific experimental objectives. While both methods share the common foundation of polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, their implementation and outcomes differ significantly due to their distinct approaches to protein structure.

Fundamental Separation Principles

SDS-PAGE operates on the principle of molecular weight-based separation under denaturing conditions. The anionic detergent SDS binds to proteins in a constant weight ratio (approximately 1.4 g SDS per 1 g of protein), unfolding them into linear chains and masking their intrinsic charge. [2] [20] This SDS-protein complex migrates through the polyacrylamide gel matrix toward the anode, with separation determined primarily by molecular size due to the sieving effect of the gel pores. [2] Smaller proteins migrate more rapidly through the matrix, while larger proteins experience greater frictional resistance, resulting in band separation correlated with molecular weight.

In contrast, Native-PAGE separates proteins based on both charge and size while maintaining their native conformation. Without denaturing agents, proteins retain their tertiary and quaternary structures, and their migration depends on the net charge at the gel running pH, molecular size, and three-dimensional shape. [3] [2] This multi-parameter separation mechanism provides information about native protein properties but presents greater challenges for molecular weight determination due to the influence of charge and conformation on migration distance.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

SDS-PAGE Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Protein samples are mixed with SDS-containing sample buffer (typically including Tris-HCl, glycerol, SDS, and bromophenol blue) with or without reducing agents like DTT or β-mercaptoethanol. [4] [2] The mixture is heated at 70-100°C for 5-10 minutes to denature proteins and ensure complete SDS binding. [2] [8]

Gel Preparation: Polyacrylamide gels are cast in two layers: a stacking gel (typically 4-5% acrylamide, pH ~6.8) and a resolving gel (typically 8-15% acrylamide, pH ~8.8), with the appropriate acrylamide concentration selected based on the molecular weight range of target proteins. [2] Lower percentage gels (e.g., 8-10%) resolve higher molecular weight proteins, while higher percentages (e.g., 12-15%) provide better resolution for smaller proteins.

Electrophoresis: Prepared samples and molecular weight markers are loaded into wells, and electrophoresis is performed at constant voltage (typically 100-200V) using running buffers such as Tris-glycine or Tris-acetate containing 0.1% SDS until the dye front approaches the gel bottom. [7] [2]

Protein Visualization: Separated proteins are visualized using staining methods including Coomassie Brilliant Blue (detecting ~50 ng/band), silver staining (detecting 2-5 ng/band), or fluorescent stains, followed by destaining to reduce background. [21]

Native-PAGE Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Protein samples are mixed with non-denaturing sample buffer (typically containing Tris-HCl, glycerol, and tracking dye) without SDS or reducing agents. [2] [8] Samples are not heated to preserve native structure.

Gel Preparation: Polyacrylamide gels are cast without SDS in the resolving gel, often using the same acrylamide percentages as SDS-PAGE but with different buffer systems optimized for maintaining protein stability. [2] The pH of the running buffer is critical as it determines the net charge on the proteins.

Electrophoresis: Prepared samples are loaded, and electrophoresis is performed at constant voltage, typically at 4°C to maintain protein stability and prevent denaturation during separation. [8] The running buffer lacks SDS and may have different ionic compositions compared to SDS-PAGE buffers.

Protein Detection: Similar staining methods are used, with the additional possibility of activity staining (zymography) for enzymes to detect functional proteins directly in the gel. [2]

Diagram 1: Decision workflow for selecting between SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE methodologies

Comparative Performance Analysis

Objective evaluation of SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE performance characteristics reveals distinct advantages and limitations for each technique, guiding researchers in selecting the appropriate method for specific experimental requirements. The following comparative analysis examines resolution capability, functional preservation, and practical considerations based on experimental data and established protocols.

Resolution and Separation Characteristics

SDS-PAGE provides exceptional resolution for separating proteins by molecular weight, effectively resolving complex protein mixtures with small size differences. [22] [20] The denaturing conditions eliminate influences from protein shape and charge heterogeneity, creating a linear relationship between migration distance and logarithm of molecular weight. [2] This high resolution makes SDS-PAGE particularly valuable for assessing protein purity, determining molecular weights, and analyzing subunit composition. The technique demonstrates high sensitivity, detecting trace protein amounts down to nanogram levels when combined with sensitive staining methods like silver staining. [22] [21]

Native-PAGE typically offers lower resolution for complex protein mixtures due to the multi-parameter nature of separation (size, charge, shape). [7] Without the charge uniformity provided by SDS, proteins with similar molecular weights but different charge characteristics may co-migrate or show anomalous migration patterns. However, Native-PAGE provides superior capability for resolving native protein complexes and oligomeric forms, preserving the quaternary structure that would be disrupted in SDS-PAGE. [3] [2] This makes it indispensable for studying protein-protein interactions and complex assembly states.

Functional Preservation and Downstream Applications

A fundamental distinction between these techniques lies in their impact on protein structure and function. SDS-PAGE completely denatures proteins, stripping non-covalently bound cofactors and rendering proteins inactive. [3] [22] While this enables accurate molecular weight determination, it eliminates the possibility of functional analysis following separation. Proteins separated by SDS-PAGE are typically used for immunoblotting, mass spectrometry analysis, or amino acid sequencing rather than activity assays. [3]

In contrast, Native-PAGE preserves biological activity, allowing researchers to recover functional proteins from the gel for enzymatic assays, ligand binding studies, or interaction analyses. [3] [2] [8] This functional preservation enables direct investigation of structure-function relationships and is particularly valuable for characterizing enzymes, multiprotein complexes, and metalloproteins that require non-covalently bound cofactors for activity. Experimental data demonstrates that most enzymes retain activity following Native-PAGE separation, while all are denatured during SDS-PAGE. [7]

Table 2: Performance Comparison Between SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE

| Performance Characteristic | SDS-PAGE | Native-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Molecular weight primarily [2] [20] | Size, charge, and shape [3] [2] |

| Structural Preservation | Denatured, linearized polypeptides [3] [22] | Native conformation maintained [3] [8] |

| Functional Activity Post-Separation | Lost [3] [7] | Preserved [3] [2] |

| Molecular Weight Determination | Accurate with appropriate standards [2] | Approximate, influenced by charge and shape [3] |

| Resolution of Complex Mixtures | High [22] [20] | Moderate [7] |

| Protein Recovery for Further Analysis | Limited to denatured forms [8] | Functional proteins can be recovered [2] [8] |

| Typical Run Temperature | Room temperature [8] | 4°C [8] |

| Detection Sensitivity | High (ng level with silver staining) [22] [21] | Variable, depends on native structure |

Quantitative Experimental Data

Recent methodological innovations have generated quantitative data highlighting the performance characteristics of various PAGE techniques. Comparative studies of standard SDS-PAGE, Blue Native-PAGE (BN-PAGE), and the hybrid Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE) provide insight into their relative capabilities for maintaining protein function while achieving adequate separation.

Research examining zinc metalloproteins demonstrated that standard SDS-PAGE resulted in only 26% retention of bound Zn²⁺, while NSDS-PAGE improved metal retention to 98%. [7] Similarly, enzymatic activity assays following electrophoretic separation revealed that all nine model enzymes tested were denatured during standard SDS-PAGE, while seven of nine retained activity following NSDS-PAGE separation, and all nine remained active after BN-PAGE. [7] These quantitative findings illustrate the functional trade-offs between resolution and activity preservation across different methodological approaches.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE methodologies requires specific reagent systems optimized for each technique's distinct requirements. The following research reagent solutions represent essential components for electrophoretic protein separation, with formulations tailored to preserve denatured or native protein states as required by the specific application.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for PAGE Methodologies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in SDS-PAGE | Function in Native-PAGE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Denaturing Agents | SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) [2] [20] | Denatures proteins, confers uniform negative charge [2] | Not typically used [8] |

| Reducing Agents | DTT (Dithiothreitol), β-mercaptoethanol [4] | Reduces disulfide bonds [4] | Not typically used [8] |

| Gel Buffers | Tris-glycine, Tris-acetate, Bis-Tris [7] [2] | Provides appropriate pH and conductivity [2] | Maintains native protein structure and activity [2] |

| Tracking Dyes | Bromophenol blue [2] | Visualizes migration front [2] | Visualizes migration front [2] |

| Staining Solutions | Coomassie Brilliant Blue, silver stain [21] | Visualizes separated protein bands [21] | Visualizes separated protein bands [21] |

| Molecular Weight Standards | Pre-stained or unstained protein ladders [2] | Molecular weight calibration [2] | Approximate molecular size estimation [3] |

Contemporary Applications and Methodological Evolution

The ongoing utility of SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE in contemporary research reflects their adaptability to evolving scientific questions and technological landscapes. Both techniques continue to find diverse applications across multiple disciplines while undergoing methodological refinements that enhance their capabilities and address their limitations.

Current Research Applications

SDS-PAGE Applications:

- Protein Purity Assessment: SDS-PAGE remains a standard method for evaluating purification efficiency and assessing sample homogeneity in protein isolation protocols. [22] [4]

- Molecular Weight Determination: The technique provides reliable molecular weight estimates for unknown proteins when calibrated with appropriate standards. [2] [20]

- Western Blotting: SDS-PAGE serves as the first dimension for immunoblotting analyses, enabling detection of specific proteins with antibodies. [3] [2]

- Expression Analysis: Researchers routinely use SDS-PAGE to monitor protein expression levels in recombinant systems and native tissues. [4] [20]

- Food Science: SDS-PAGE is extensively applied in food protein characterization, species identification, adulteration detection, and monitoring processing-induced changes. [4]

Native-PAGE Applications:

- Protein Complex Analysis: Native-PAGE preserves oligomeric structures, enabling study of multiprotein complexes and quaternary organization. [3] [2]

- Enzymatic Activity Studies: Zymography techniques coupled with Native-PAGE allow direct detection of enzyme activity in gels. [2]

- Protein-Protein Interactions: The technique facilitates investigation of interacting protein partners under non-denaturing conditions. [3]

- Metalloprotein Characterization: Native-PAGE preserves non-covalent metal cofactor binding, enabling analysis of metalloenzymes. [7]

Technological Innovations and Future Directions

The evolution of PAGE methodologies continues through technological innovations that enhance performance, throughput, and compatibility with downstream analytical techniques. Several significant trends are shaping contemporary electrophoretic practices:

Miniaturization and Automation: The development of microfluidic platforms and chip-based electrophoresis systems has reduced sample volume requirements while accelerating run times and improving reproducibility. [19] These systems increasingly interface with digital data capture tools, enabling real-time analysis and automated reporting that align with regulatory requirements in pharmaceutical and diagnostic applications. [19]

Advanced Buffer Formulations: Continued refinement of buffer systems has yielded specialized formulations with enhanced resolution capabilities and application-specific optimizations. [23] Ready-to-use, pre-mixed buffers reduce preparation time and potential errors while improving inter-laboratory reproducibility. [23] The development of environmentally friendly and sustainable buffer options addresses growing concerns about laboratory waste streams. [23]

Integrated Analytical Workflows: PAGE techniques increasingly function as components within integrated analytical pipelines, particularly in proteomic research. Two-dimensional electrophoresis, combining isoelectric focusing (IEF) with SDS-PAGE, provides exceptionally high resolution for complex protein mixtures. [2] Similarly, Native-PAGE followed by denaturing SDS-PAGE enables detailed characterization of complex subunit composition. [7]

The commercial electrophoresis market reflects these technological trends, with growing emphasis on precast gradient gels, specialized staining kits, and integrated imaging systems. [19] [23] As proteomic research becomes increasingly central to pharmaceutical development and clinical diagnostics, both SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE continue to evolve, maintaining their relevance through adaptation to contemporary research requirements.

Diagram 2: Comparative workflow for SDS-PAGE versus Native-PAGE methodologies

The historical development of protein electrophoresis from Laemmli's foundational SDS-PAGE methodology to contemporary Native-PAGE approaches represents a continuous refinement of tools for protein analysis. Each technique offers distinct advantages: SDS-PAGE provides high-resolution separation by molecular weight under denaturing conditions, while Native-PAGE preserves native structure and function at the cost of some resolution. The choice between these methodologies depends fundamentally on research objectives—whether molecular characterization or functional analysis takes priority.

Recent innovations such as NSDS-PAGE demonstrate ongoing efforts to balance the resolution advantages of denaturing methods with the functional preservation of native techniques. As proteomic research continues to advance, both SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE maintain their essential roles in protein characterization workflows, adapted through miniaturization, automation, and enhanced buffer formulations to meet contemporary research demands. For drug development professionals and researchers, understanding the historical context, methodological principles, and performance characteristics of these techniques ensures appropriate application selection and optimal experimental design for protein analysis requirements.

Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE) is a cornerstone technique in biochemistry and molecular biology laboratories, enabling the separation of macromolecules based on their electrophoretic mobility [13]. For protein analysis, PAGE is often the technique of choice, with its effectiveness hinging on three core components: the polyacrylamide matrix, the buffer systems, and the electrophoresis setup [2]. The polyacrylamide gel serves as a porous sieve, while the buffers establish the pH and ionic environment necessary for controlled protein migration. The electrophoresis apparatus provides the electric field that drives this separation. The specific configuration of these components varies significantly between the two primary PAGE methodologies: SDS-PAGE (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-PAGE) and Native-PAGE [3] [8]. SDS-PAGE denatures proteins, separating them primarily by molecular weight, whereas Native-PAGE maintains proteins in their native, folded state, separating them based on a combination of size, charge, and shape [13]. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these essential components, equipping researchers with the knowledge to select and optimize the appropriate system for their specific protein analysis needs.

Core Principles: SDS-PAGE vs. Native-PAGE

The fundamental difference between SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE lies in the state of the protein during separation. SDS-PAGE is a denaturing technique. The anionic detergent SDS binds uniformly to the protein backbone, masking the protein's intrinsic charge and unfolding it into a linear form [3] [13]. This process, aided by heat and reducing agents like DTT, ensures that separation occurs almost exclusively based on polypeptide size [2] [8]. In contrast, Native-PAGE is a non-denaturing technique. It omits SDS and reducing agents, and samples are not heated [8] [5]. This preserves the protein's higher-order structure, quaternary interactions, and biological activity [3]. Consequently, separation depends on the protein's intrinsic charge, size, and three-dimensional shape [2]. The choice between these methods is dictated by the experimental goal: SDS-PAGE is ideal for determining molecular weight and subunit composition, while Native-PAGE is essential for studying protein function, oligomeric state, and native protein complexes [8].

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE

| Criteria | SDS-PAGE | Native-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Protein State | Denatured and linearized [3] | Native, folded conformation [3] |

| Separation Basis | Primarily molecular weight [2] | Size, intrinsic charge, and shape [2] |

| Key Reagents | SDS, reducing agents (e.g., DTT, BME) [8] | No denaturants; may use Coomassie dye (BN-PAGE) [24] [8] |

| Sample Preparation | Heating step required [8] | No heating; kept at low temperatures (often 4°C) [8] [5] |

| Protein Function | Biological activity is destroyed [3] | Biological activity is typically retained [3] |

| Primary Applications | Molecular weight determination, purity check, Western blot [8] [7] | Enzyme activity assays, protein-protein interactions, oligomerization studies [3] [8] |

The Polyacrylamide Matrix: A Tunable Molecular Sieve

The separation medium for both SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE is a cross-linked polyacrylamide gel. This matrix is formed through the co-polymerization of acrylamide monomers and N,N'-methylenebisacrylamide (Bis) cross-linker, a reaction catalyzed by ammonium persulfate (APS) and TEMED (N,N,N',N'-Tetramethylethylenediamine) [2] [13]. The resulting gel is a three-dimensional network whose pore size is critical for separation resolution.

The pore size is precisely controlled by two factors: the total acrylamide concentration (%T) and the cross-linker ratio (%C) [25]. A higher %T creates a denser matrix with smaller pores, providing better resolution for lower molecular weight proteins. Conversely, a lower %T creates larger pores, suitable for separating higher molecular weight proteins [2]. This principle allows for the creation of gels tailored to specific protein size ranges. Furthermore, gradient gels, which have a continuously varying acrylamide concentration (e.g., from 4% to 16%), are highly effective for separating complex protein mixtures with a broad molecular weight range, as the increasing density sieves proteins across a wide spectrum [2] [13].

The gel is cast in two distinct layers: the stacking gel and the resolving gel (or separating gel) [13]. The stacking gel, with a lower acrylamide concentration (typically ~4-5%) and a different pH (e.g., 6.8), acts to concentrate all protein samples into a sharp, unified band before they enter the resolving gel. The resolving gel, with a higher, optimized acrylamide concentration (typically 7-20%) and a higher pH (e.g., 8.8), is where the actual separation of proteins occurs based on their size (SDS-PAGE) or charge-to-size ratio (Native-PAGE) [2] [13]. While the basic composition of the polyacrylamide matrix is similar for both techniques, the use of detergents or dyes in the gel itself differs, as detailed in the buffer section.

Diagram 1: Polyacrylamide Gel Fabrication Workflow. The process begins with an acrylamide mixture whose polymerization is catalyzed by APS and TEMED. The pore size of the resulting gel matrix is controlled by the total acrylamide concentration (%T) and cross-linker ratio (%C), forming a two-layer structure with distinct functions.

Buffer Systems: Establishing the Electrophoretic Environment

The buffer system is a critical component that dictates the success of the electrophoretic separation. PAGE typically employs a discontinuous buffer system (also known as the Ornstein-Davis system) to achieve high-resolution bands [13]. This system utilizes different buffers for the gel and the electrode tanks, creating discontinuities in pH and ionic strength that stack proteins into sharp lines before separation.

Buffer Systems for SDS-PAGE

For SDS-PAGE, the buffers contain the denaturing agent SDS to maintain protein denaturation.

- Gel Buffer: Tris-HCl at different pHs for the stacking gel (e.g., pH 6.8) and resolving gel (e.g., pH 8.8) [13].

- Running Buffer: Tris-Glycine with SDS (typically 0.1%) is most common, providing the ions to carry current and maintain the denaturing environment during electrophoresis [2] [7].

- Sample Buffer: Contains SDS, a reducing agent (DTT or β-mercaptoethanol), glycerol, and a tracking dye (e.g., Bromophenol Blue). The sample is heated (70-100°C) before loading to ensure complete denaturation [8] [7].

Buffer Systems for Native-PAGE

For Native-PAGE, all buffers omit SDS and reducing agents to preserve protein structure and activity.

- Gel and Running Buffers: Tris-based buffers without SDS are common. For basic proteins, the buffer system may require a slightly acidic environment, and the cathode/anode may need to be reversed [5].

- Sample Buffer: Lacks SDS and reducing agents. The sample is not heated to prevent denaturation [8] [5].

- Variants: Specialized Native-PAGE techniques use unique buffers. Blue Native (BN)-PAGE uses Coomassie G-250 dye in the cathode buffer, which confers a negative charge on proteins, aiding in their separation and solubility [24]. Clear Native (CN)-PAGE replaces the dye with mixtures of anionic and neutral detergents to avoid dye interference in downstream activity assays [24]. A hybrid method, Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE), uses minimal SDS (e.g., 0.0375%) in the running buffer but no heating or reducing agents, aiming to balance resolution with the retention of some native properties like bound metal ions [7].

Table 2: Comparison of Standard Buffer Compositions

| Buffer Component | SDS-PAGE | Native-PAGE | Blue Native (BN)-PAGE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Buffer | Tris-HCl, SDS, reducing agent (DTT/BME), glycerol, tracking dye [7] [13] | Tris-HCl, glycerol, tracking dye (no denaturants) [5] | 50 mM BisTris, 50 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol [7] |

| Stacking Gel | Low % acrylamide, Tris-HCl (pH ~6.8) [13] | Low % acrylamide, buffer without SDS | Not typically used; single gradient gel common [24] |

| Resolving Gel | Higher % acrylamide, Tris-HCl (pH ~8.8), can contain SDS [13] | Higher % acrylamide, buffer without SDS | Linear gradient gel (e.g., 4-16%), BisTris [24] |

| Running Buffer (Cathode) | Tris-Glycine, 0.1% SDS [7] | Tris-Glycine or TBE, no SDS [13] | BisTris, Tricine, 0.02% Coomassie G-250 [7] |

| Running Buffer (Anode) | Same as cathode buffer | Same as cathode buffer | BisTris, Tricine [7] |

| Key Additive Role | SDS denatures proteins and imparts uniform charge [3] | No denaturants preserve native structure [3] | Coomassie dye charges proteins for migration [24] |

Electrophoresis Setup and Workflow

The physical setup for PAGE is consistent across techniques, comprising a gel cassette, buffer tanks, and a power supply [13]. However, the specific running conditions differ to accommodate the sensitivity of native proteins.

Apparatus and Setup

- Gel Cassette: The polymerized gel is housed between two glass or plastic plates sealed with spacers [2].

- Electrophoresis Tank: The cassette is mounted vertically in a tank filled with running buffer. The tank contains electrodes (cathode and anode) that connect to a power supply [13].

- Temperature Control: This is a critical differentiator. SDS-PAGE is typically run at room temperature [8]. Native-PAGE, however, is often performed at 4°C to minimize protein denaturation and proteolytic activity during the extended run time [8] [5]. An ice bath or a cooled electrophoresis unit may be used.

Standard Experimental Protocols

The following protocols outline the core steps for SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE.

Protocol 1: SDS-PAGE for Molecular Weight Determination

- Sample Preparation: Mix protein sample with 2X SDS-PAGE loading buffer (e.g., 106 mM Tris HCl, 2% LDS, 10% glycerol, 0.22 mM Phenol Red) [7]. Heat at 70-100°C for 10 minutes [7]. Centrifuge to pellet debris.

- Gel Preparation: Cast or obtain a discontinuous gel (e.g., 4% stacking gel, 12% resolving gel). Ensure running buffer (e.g., 50 mM MOPS, 50 mM Tris Base, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.7) contains SDS [7].

- Loading and Run: Load samples and molecular weight markers into wells. Run gel at constant voltage (e.g., 200V for ~45 minutes for a mini-gel) at room temperature until dye front reaches the bottom [7].

- Downstream Analysis: Proceed to stain with Coomassie Blue or Sypro Ruby, or transfer to membrane for Western blotting [2].

Protocol 2: Native-PAGE for Protein Functionality Studies

- Sample Preparation: Mix protein sample with non-denaturing loading buffer (e.g., Tris-HCl, glycerol, tracking dye) [5]. Do not heat. Keep samples on ice. Centrifuge to remove debris.

- Gel Preparation: Cast or obtain a gel without SDS in both stacking and resolving layers. Use a running buffer without SDS (e.g., Tris-Glycine) [13].

- Loading and Run: Load samples on ice. Run gel at a constant voltage (e.g., 150V) in a cold room (4°C) or with a cooling apparatus [24] [5]. Run time may be longer than for SDS-PAGE.

- Downstream Analysis: For activity assays, incub gel in appropriate substrate solution [24] [3]. For further analysis, proteins can be recovered from the gel by passive diffusion or electro-elution for functional studies [2].

Diagram 2: Comparative Workflow for SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE. The workflows diverge immediately at sample preparation, with SDS-PAGE using denaturing conditions and heat, while Native-PAGE avoids them. Temperature control is a critical differentiator throughout the process.

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful PAGE experiments require a suite of reliable reagents. The following table details essential materials and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PAGE Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms the cross-linked polymer network of the gel matrix [2]. | Unpolymerized acrylamide is a neurotoxin; handle with gloves [25]. |

| APS (Ammonium Persulfate) | Initiates the polymerization reaction as a free-radical source [2]. | Prepare fresh solutions for consistent polymerization. |

| TEMED | Catalyzes the polymerization reaction by accelerating radical formation from APS [2]. | Essential for gel formation; add last. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge density [3] [13]. | Critical for SDS-PAGE; must be omitted for Native-PAGE. |

| DTT or β-Mercaptoethanol | Reducing agents that break disulfide bonds to fully denature proteins [13]. | Used in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. |

| Coomassie G-250 Dye | Used in BN-PAGE to charge proteins; also used for staining post-electrophoresis [24]. | In BN-PAGE, it's part of the running buffer; in staining, it detects proteins. |

| Tris-based Buffers | Provides the pH and ionic environment for electrophoresis and protein stability [13]. | Different pHs and compositions are used for stacking vs. resolving gels. |

| Molecular Weight Markers | A set of proteins of known size run alongside samples to estimate molecular weight [2]. | Essential for SDS-PAGE; available in pre-stained and unstained formats. |

| Coomassie Staining Kit | A set of reagents (fixative, stain, destain) for visualizing protein bands in the gel [5]. | Standard method for detecting proteins post-electrophoresis. |

Practical Protocols and Application-Based Selection Guide

In protein analysis, the journey from a complex cellular mixture to interpretable data begins with sample preparation. This initial step is not merely procedural; it is a decisive factor that determines the success of all subsequent analysis. For researchers choosing between SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE, the preparation protocol dictates whether proteins will be studied in their denatured, linearized forms or their native, functionally active states. The core differentiator lies in the use of denaturing agents, particularly sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and the application of heat [3] [26]. These treatments fundamentally alter protein structure, thereby defining the type of information—size, purity, or functional activity—that can be gleaned from the experiment. This guide provides a detailed, evidence-based comparison of these critical sample preparation methodologies to inform experimental design in research and drug development.

SDS-PAGE Sample Preparation: Complete Denaturation for Molecular Weight Separation

The goal of SDS-PAGE sample preparation is the complete dismantling of a protein's higher-order structure to ensure separation occurs strictly as a function of polypeptide chain length [26]. This is achieved through a combination of chemical and physical treatments.

Key Denaturing Reagents and Their Roles

- SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate): This anionic detergent is the primary denaturant. It binds to the hydrophobic regions of proteins in a constant weight ratio (approximately 1.4 g SDS per 1 g of protein), effectively masking the protein's intrinsic charge and imparting a uniform negative charge [27] [26]. Simultaneously, it disrupts nearly all non-covalent interactions, unfolding the protein into a linear chain.

- Reducing Agents (DTT or β-mercaptoethanol): These compounds are added to break covalent disulfide bonds that link cysteine residues within or between polypeptide chains [26] [5]. This is essential for fully dissociating protein subunits and achieving complete unfolding.

- Sample Buffer: The sample is mixed with a loading buffer containing SDS, a reducing agent, glycerol (to increase density for gel loading), and a tracking dye [26] [28].

The Critical Heating Step

After mixing with the sample buffer, the protein solution is heated at 95–100°C for 5–10 minutes [26] [8]. This heating step is non-negotiable; the application of high temperature provides the kinetic energy required to fully disrupt stable secondary and tertiary structures, allowing SDS to bind uniformly and ensuring complete denaturation and reduction of disulfide bonds [26]. The final result is a solution of protein-SDS complexes that are linearly structured and uniformly charged, ready for separation based solely on molecular weight.

Native-PAGE Sample Preparation: Preserving Native Structure for Functional Analysis

In direct contrast, the objective of Native-PAGE sample preparation is to maintain the protein's native conformation, thereby preserving its biological activity, subunit interactions, and bound cofactors [3] [5]. The protocol is designed to avoid any disruption of the protein's structure.

The Absence of Denaturants

The most defining feature of Native-PAGE sample preparation is the omission of SDS and reducing agents [8] [29]. The sample buffer is typically composed of a mild, non-denaturing buffer, glycerol, and a tracking dye. Without SDS, proteins retain their intrinsic three-dimensional shape, their natural charge, and their interactions with other subunits or molecules [27].

The Omission of Heating and Emphasis on Cold Temperatures

Crucially, the heating step is entirely omitted [8]. The protein sample is simply mixed with the non-denaturing sample buffer and kept cold to maintain stability. Furthermore, the entire electrophoresis process is often performed at 4°C to prevent heat-induced denaturation during the run and to minimize proteolytic activity [8] [5]. The outcome is a sample where proteins remain in their native, functionally intact state, allowing for separation based on a combination of size, charge, and shape.

Direct Comparison: Denaturation and Heating Protocols

Table 1: A direct comparison of the critical sample preparation parameters for SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE.

| Parameter | SDS-PAGE | Native-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Denaturing Agent (SDS) | Present | Absent [8] [29] |

| Reducing Agent (DTT/β-ME) | Present | Absent [8] |

| Heating Step | Required (typically 95-100°C for 5-10 min) [26] [8] | Not Performed [8] [5] |

| Separation Basis | Molecular weight [3] [27] | Size, charge, and shape [3] [27] |

| Protein State Post-Prep | Denatured, linearized, inactive [3] [26] | Native, folded, potentially active [3] [5] |