SDS-PAGE vs Native PAGE: A Comprehensive Guide to Choosing the Right Protein Separation Method

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a definitive comparison of SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE, two foundational protein electrophoresis techniques.

SDS-PAGE vs Native PAGE: A Comprehensive Guide to Choosing the Right Protein Separation Method

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a definitive comparison of SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE, two foundational protein electrophoresis techniques. We explore the core principles governing each method, from the denaturing action of SDS to the native state preservation in non-denaturing gels. The scope extends to detailed methodological protocols, diverse applications in protein characterization and functional studies, troubleshooting for common experimental challenges, and strategic guidance for method selection and validation. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with practical optimization strategies, this guide empowers professionals to make informed decisions that enhance the accuracy and efficiency of their protein analysis workflows in biomedical and clinical research.

Core Principles of Protein Electrophoresis: Understanding SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE Fundamentals

Electrophoresis is a fundamental laboratory technique in which charged molecules, such as proteins, are transported through a solvent by an electrical field [1]. It is a simple, rapid, and sensitive analytical tool that leverages the fact that most biological molecules carry a net charge at any pH other than their isoelectric point (pI), the pH at which a molecule has no net charge [2] [1]. The mobility of a molecule through an electric field depends on several factors: the field strength, the net charge on the molecule, its size and shape, the ionic strength of the buffer, and the properties of the support matrix through which the molecule migrates [1].

This guide focuses on the application of this core principle in two dominant protein separation methods: SDS-PAGE (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis) and Native PAGE. While both techniques use an electric field to drive separation, their methodologies and outcomes differ profoundly, making each suitable for distinct research objectives in biochemistry and drug development.

Core Principles of Electrophoretic Separation

At its heart, electrophoresis relies on the movement of charged particles in an electric field. Molecules with a net positive charge (cations) migrate toward the cathode (negative electrode), while molecules with a net negative charge (anions) migrate toward the anode (positive electrode) [1]. The support matrix, typically a polyacrylamide gel, acts as a molecular sieve, regulating the movement of molecules based on their size and three-dimensional structure [1].

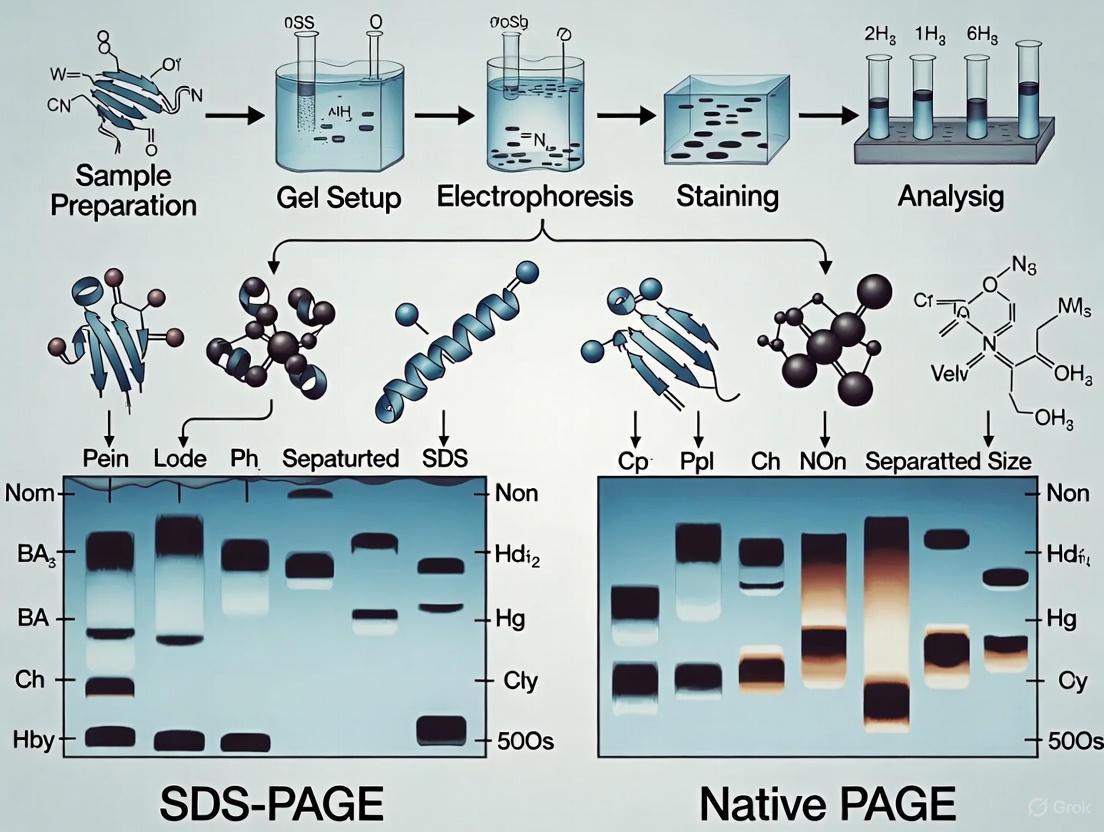

The following diagram illustrates the foundational workflow of a protein electrophoresis experiment, from sample preparation to analysis.

SDS-PAGE vs. Native PAGE: A Direct Comparison

The choice between SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE dictates the type of information gleaned from an experiment. The key distinction lies in whether proteins are denatured and uniformly charged, or kept in their native, functional state.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE

| Feature | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Principle of Separation | Primarily by molecular mass (size) [3] [1]. | By net charge, size, and 3D shape of the native protein [3] [1]. |

| Protein State | Denatured; secondary and higher structures are disrupted [4]. | Native; folded, functional structure is preserved [4]. |

| Key Reagents | SDS (denaturant/detergent), reducing agents (e.g., β-mercaptoethanol) [5]. | Native buffers, often without detergents or reducing agents [6]. |

| Molecular Weight Determination | Excellent; provides accurate estimates [1]. | Poor; migration is influenced by charge and shape, not just size [7]. |

| Preservation of Activity | No; enzymatic and functional activity is destroyed [3] [6]. | Yes; proteins often retain enzymatic and binding activity [3] [1]. |

| Ideal Applications | Assessing protein purity, subunit composition, and molecular weight [3] [5]. | Studying protein-protein interactions, oligomeric state, and enzymatic function [3] [8]. |

The fundamental difference in how proteins are prepared and separated in these two techniques is summarized in the workflow below.

Supporting Experimental Data and Protocols

The theoretical differences between these techniques are demonstrated by concrete experimental data. The following table summarizes quantitative findings from a study that modified standard SDS-PAGE to create "Native SDS-PAGE" (NSDS-PAGE), which aims to balance high resolution with the retention of functional properties [6].

Table 2: Experimental Comparison of PAGE Method Performance

| Method | Key Buffer Modifications | Impact on Protein Function | Metal Retention (Zn²⁺) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDS-PAGE [6] | Sample buffer: Contains SDS and EDTA. Sample heated. Running buffer: 0.1% SDS, 1mM EDTA. | All nine model enzymes denatured and inactivated. | 26% |

| BN-PAGE [6] | Sample buffer: No SDS, contains Coomassie G-250. Running buffer: Cathode and anode buffers without SDS. | All nine model enzymes retained activity. | Not Specified |

| NSDS-PAGE [6] | Sample buffer: No SDS or EDTA, no heating step. Running buffer: Reduced SDS (0.0375%), no EDTA. | Seven of nine model enzymes retained activity, including four Zn²⁺ proteins. | 98% |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: NSDS-PAGE

The following methodology, adapted from a metallomics study, outlines the steps for performing NSDS-PAGE to separate proteins while preserving metal ions and enzymatic activity [6].

- Gel Pre-run: Precast NuPAGE Novex 12% Bis-Tris 1.0 mm mini-gels are run at 200V for 30 minutes in double-distilled H₂O to remove the storage buffer and any unpolymerized acrylamide.

- Sample Preparation: 7.5 μL of protein sample (e.g., partially purified proteome fractions) is added to 2.5 μL of 4X NSDS sample buffer (100 mM Tris HCl, 150 mM Tris base, 10% v/v glycerol, 0.0185% w/v Coomassie G-250, 0.00625% w/v Phenol Red, pH 8.5). Crucially, the sample is not heated.

- Electrophoresis: The prepared samples are loaded onto the pre-run gel. Electrophoresis is carried out at a constant voltage (200V) for approximately 45 minutes using the modified NSDS-PAGE running buffer (50 mM MOPS, 50 mM Tris Base, 0.0375% SDS, pH 7.7).

- Post-Electrophoresis Analysis:

- Activity Staining: The gel can be incubated in a specific substrate solution to detect enzymatic activity.

- Metal Detection: Retained metal ions (e.g., Zn²⁺) can be confirmed using techniques like laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) or in-gel staining with a metal-binding fluorophore like TSQ [6].

Advanced Two-Dimensional (2D) Electrophoresis Applications

To gain deeper insights into complex protein systems, researchers often combine the strengths of native and denaturing electrophoresis in two-dimensional (2D) separations. A powerful combination is Blue Native (BN)-PAGE in the first dimension, followed by SDS-PAGE in the second dimension [9].

In this technique, protein complexes are first separated intact based on their native charge and size in a BN-PAGE gel. A single lane is then excised from the first-dimension gel, placed horizontally on a second gel, and subjected to SDS-PAGE. This second dimension denatures the complexes and separates their individual protein subunits by molecular weight [9]. This method is exceptionally valuable for characterizing multiprotein complexes, studying host-virus interactions, and identifying changes in protein complex composition in disease states [9].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents required for performing SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE, based on protocols from the cited literature.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Protein Gel Electrophoresis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example from Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide / Bis-acrylamide | Forms the cross-linked polyacrylamide gel matrix that acts as a molecular sieve [1]. | Precast NuPAGE Novex 12% Bis-Tris gels [6]. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Ionic detergent that denatures proteins and imparts a uniform negative charge [3] [5]. | Component of SDS-PAGE sample and running buffers [6]. |

| Reducing Agent (e.g., β-mercaptoethanol) | Breaks disulfide bonds between cysteine residues to fully denature protein subunits [5]. | Used in denaturing SDS-PAGE sample prep [5]. |

| Coomassie Blue G-250 | Negatively charged dye used in BN-PAGE and NSDS-PAGE to confer charge on protein complexes without significant denaturation [6]. | 0.02% in BN-PAGE cathode buffer; 0.01875% in NSDS-PAGE sample buffer [6]. |

| Tris-based Buffers (Bis-Tris, MOPS, Tricine) | Maintain stable pH during electrophoresis to ensure consistent protein charge and migration [6] [1]. | MOPS/SDS running buffer; BisTris ACA native anode buffer [6]. |

| Molecular Weight Markers | A set of proteins of known mass that provide a reference for estimating sample protein molecular weights [1]. | Prestained SDS-PAGE Standards; NativeMark unstained standards [6]. |

The basic principle of electrophoresis—the movement of charged molecules in an electric field—is powerfully applied in both SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE. The choice between them is not a matter of which is superior, but which is appropriate for the specific research question. SDS-PAGE is the unrivaled method for determining molecular weight and analyzing subunit composition under denaturing conditions. In contrast, Native PAGE is the definitive technique for probing the functional intricacies of proteins in their native state, including their interactions, oligomeric structures, and enzymatic activities. Advanced techniques like 2D BN/SDS-PAGE further combine these strengths, enabling researchers to deconstruct complex protein assemblies and gain a more holistic understanding of cellular machinery, which is paramount in fundamental research and drug development.

In the realm of protein analysis, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) serves as a foundational technique for separating and characterizing proteins. Two primary methodologies dominate this field: SDS-PAGE (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate–Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis) and Native PAGE. While both techniques separate proteins using an electric field through a polyacrylamide gel matrix, their philosophical approaches and outcomes are fundamentally different. The core distinction lies in the role of the denaturing detergent Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS), which transforms proteins into uniformly charged, linear molecules, enabling separation strictly by molecular weight. This guide objectively compares SDS-PAGE against Native PAGE, detailing their mechanisms, experimental protocols, and applications to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the appropriate method for their analytical needs.

The Fundamental Role of SDS in Protein Denaturation

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) is a powerful anionic detergent that performs two critical, simultaneous functions on protein structure, fundamentally enabling the SDS-PAGE technique.

Protein Denaturation and Linearization: SDS molecules possess a hydrophobic hydrocarbon tail and a hydrophilic sulfate head group. The hydrophobic tails interact strongly with the non-polar regions of a protein, disrupting hydrogen bonds and van der Waals forces that maintain secondary and tertiary structures. This interaction unfolds the protein, destroying its native conformation and converting it into a random, linear coil [10]. The biological activity of the protein is lost in this process.

Charge Masking and Uniform Negative Charge Impartation: As SDS binds to the unfolded polypeptide chain, it coats the protein in a uniform layer of negative charge. SDS binds to proteins in high concentrations—approximately 1.4 grams of SDS per gram of protein—which translates to roughly one SDS molecule for every two amino acids [11]. This massive, uniform negative charge overwhelms the protein's intrinsic charge, meaning a protein's own positively or negatively charged amino acids no longer influence its movement. Consequently, all proteins in the mixture attain a similar charge-to-mass ratio [11] [10].

The combined effect of these actions is that the factors of native charge and three-dimensional shape are eliminated. The sole determinant of a protein's migration speed through the gel sieve becomes its molecular weight (size). Smaller proteins migrate faster, while larger ones migrate more slowly, allowing for precise size-based separation [12] [3].

SDS-PAGE Experimental Protocol: A Detailed Methodology

The following section provides a standardized, step-by-step protocol for conducting a reducing SDS-PAGE analysis, as developed by Laemmli [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents are essential for performing SDS-PAGE.

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Denaturing Detergent | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Unfolds proteins and imparts uniform negative charge [10]. |

| Reducing Agents | β-mercaptoethanol (BME), Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Breaks disulfide bonds to fully dissociate protein subunits [12] [11]. |

| Gel Matrix Components | Acrylamide, Bis-acrylamide | Forms cross-linked polyacrylamide gel matrix that acts as a molecular sieve [11]. |

| Polymerization Initiators | Ammonium Persulfate (APS), TEMED | Catalyzes the free-radical polymerization of acrylamide [10]. |

| Buffers | Tris-HCl | Maintains stable pH in stacking gel (pH 6.8) and resolving gel (pH 8.8) [10]. |

| Tracking Dye | Bromophenol Blue | Visualizes sample migration during electrophoresis [10]. |

| Running Buffer | Tris-Glycine, SDS | Provides ions to carry current and maintains denaturing conditions during run [11] [10]. |

| Staining Solutions | Coomassie Brilliant Blue | Visualizes separated protein bands post-electrophoresis [12] [11]. |

Step-by-Step Workflow

Gel Preparation: A discontinuous gel system is used, comprising two distinct layers:

- Separating (Resolving) Gel: This lower layer has a higher percentage of acrylamide (e.g., 10-12%) and a pH of 8.8. Its pore size is designed to separate proteins by size [11] [10].

- Stacking Gel: This upper layer has a lower percentage of acrylamide (4-6%) and a pH of 6.8. It serves to concentrate all protein samples into a sharp, unified band before they enter the separating gel, vastly improving resolution [10]. The gel is cast between two glass plates, and a comb is inserted to create sample wells.

Sample Preparation: Protein samples are mixed with Laemmli sample buffer, which contains SDS, a reducing agent (like DTT or BME), glycerol, and tracking dye [10]. This mixture is then heated to 95 °C for 5 minutes. Heating provides the energy required to fully denature the proteins and ensure complete binding of SDS [12] [11].

Electrophoresis: The prepared samples and a molecular weight size marker are loaded into the wells. The gel apparatus is filled with a Tris-glycine-SDS running buffer, and an electric current (∼100-200V) is applied. The negatively charged proteins migrate toward the positive anode. The stacking gel mechanism, driven by the unique charge states of glycine in the different pH environments, focuses the proteins into thin lines. Once they enter the resolving gel, proteins are separated based on their molecular weight [11] [10].

Post-Run Analysis: After electrophoresis, the gel is stained (e.g., with Coomassie Blue) to visualize the protein bands. The distance migrated by unknown proteins is compared to the standard curve generated by the molecular weight marker to estimate their size [11].

Figure 1: SDS-PAGE Experimental Workflow. The process involves parallel sample and gel preparation steps, followed by loading, electrophoresis, and analysis.

SDS-PAGE vs. Native PAGE: A Direct Comparison

The addition of SDS creates a fundamental divergence from Native PAGE. The table below provides a direct, objective comparison of the two techniques based on key experimental and analytical parameters [12].

| Criterion | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Molecular weight only [12] [3] | Size, intrinsic charge, and 3D shape [12] [3] |

| Protein State | Denatured and linearized [12] | Native, folded conformation [12] |

| SDS Presence | Present (critical for function) [12] | Absent [12] |

| Reducing Agents | Often used (e.g., DTT, BME) [12] | Not used [12] |

| Sample Preparation | Heated to 95°C in SDS buffer [12] | Not heated; mixed in non-denaturing buffer [12] |

| Protein Function Post-Run | Lost [12] | Retained [12] |

| Protein Recovery | Not recoverable in functional form [12] | Can be recovered for activity assays [12] |

| Information Obtained | Subunit molecular weight, purity [12] | Oligomeric state, protein-protein interactions [12] |

| Primary Applications | Molecular weight determination, purity checks, Western blotting [12] [3] | Studying native function, enzyme activity, protein complexes [12] [3] |

Figure 2: Separation Logic Comparison. SDS-PAGE simplifies separation to molecular weight, while Native PAGE separates based on multiple native properties.

Applications in Research and Biopharmaceutical Development

The distinct principles of SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE make them suitable for different applications in life sciences and drug development.

Applications of SDS-PAGE

Molecular Weight Determination and Purity Analysis: SDS-PAGE is the standard method for estimating protein molecular weight and assessing sample purity. By comparing the migration distance of an unknown protein to a standard curve of proteins with known molecular weights, researchers can determine the approximate size of the protein subunit with an error of about ±10% [11]. It is routinely used to check the purity of protein samples after purification steps [3].

Food Science and Quality Control: In the food industry, SDS-PAGE is used extensively for protein profiling to assess the integrity and quality of proteins in raw materials and finished products. It can detect adulteration, monitor changes induced by processing (e.g., heat or enzymatic hydrolysis), and identify specific proteins in complex matrices like cereals, pulses, dairy, and meat products [13] [5].

Therapeutic Protein Characterization: In biopharmaceutical development, SDS-PAGE is critical for analyzing therapeutic proteins like monoclonal antibodies. It is used to monitor subunit integrity, check for the presence of aggregates or fragments, and ensure batch-to-batch consistency. Recent advancements, such as capillary SDS gel electrophoresis, aim to improve the efficiency and precision of these analyses for next-generation biologic drugs [14].

Applications of Native PAGE

Analysis of Protein Complexes and Oligomeric State: Native PAGE is indispensable for studying proteins in their functional, multi-subunit forms. It allows researchers to determine the stoichiometry and quaternary structure of complexes without dissociation into subunits. For example, a protein that runs as a 120 kDa complex on Native PAGE but as a 60 kDa band on non-reducing SDS-PAGE can be inferred to be a non-covalent dimer of 60 kDa subunits [7].

Functional and Enzymatic Studies: Because native PAGE preserves protein activity, it can be coupled with in-gel activity assays (zymography) to detect enzymes like proteases or dehydrogenases based on their biological function. Proteins separated by Native PAGE can also be eluted from the gel for further functional studies [12] [3].

Advanced Techniques and Future Directions

The core principles of SDS-PAGE continue to be refined and integrated with advanced analytical platforms.

Alternative Gel and Buffer Systems: For specific needs, variations of the standard SDS-PAGE exist. Tricine-SDS-PAGE is preferred for the separation of lower molecular weight proteins (< 30 kDa) and peptides, offering better resolution in this range than the traditional glycine-based system [13] [11]. Furthermore, the use of pre-cast gels with Bis-tris buffers at a near-neutral pH enhances gel stability and reduces protein modifications, such as cysteine adduct formation with unpolymerized acrylamide [11].

Integration with Mass Spectrometry: SDS-PAGE is a key front-end separation technique for mass spectrometric analysis. After separation, protein bands can be excised, digested with trypsin, and the resulting peptides analyzed by MS for protein identification and characterization of post-translational modifications. This powerful combination is a cornerstone of modern proteomics [3].

Innovations in Capillary Electrophoresis: Recent research focuses on translating slab gel SDS-PAGE to capillary formats (CE-SDS) for automated, quantitative analysis. A 2025 study highlighted a novel baseline hump-free SDS capillary agarose gel electrophoresis (SDS-CAGE) method. This advancement enables rapid (~5 minutes), high-resolution purity testing and subunit integrity analysis of therapeutic proteins, such as antibodies and highly glycosylated fusion proteins, addressing long-standing challenges with baseline disturbances in traditional CE-SDS methods [14].

SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE are powerful, complementary techniques in the protein scientist's toolkit. The inclusion of the denaturing detergent Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate is the defining feature of SDS-PAGE, enabling robust and reproducible separation of proteins based solely on subunit molecular weight. This makes it ideal for determining molecular weight, assessing purity, and analyzing protein composition in complex mixtures. In contrast, Native PAGE preserves the native structure and function of proteins, making it the method of choice for studying oligomerization, protein-protein interactions, and enzymatic activity. The choice between these techniques is not a matter of superiority but of strategic alignment with research goals. For characterizing the intrinsic properties of polypeptide chains, SDS-PAGE is unparalleled. For probing the functional architecture of native protein complexes, Native PAGE is indispensable. A comprehensive protein analysis strategy often leverages the strengths of both methodologies to build a complete picture of protein identity, structure, and function.

Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE) is a powerful protein separation technique that resolves proteins in their folded, native conformation. Unlike its denaturing counterpart, SDS-PAGE, Native PAGE operates under non-denaturing conditions that preserve protein structure, biological activity, and complex interactions [12] [3]. This makes it an indispensable tool for researchers studying functional protein characteristics, including enzymatic activity, protein-protein interactions, and oligomerization states [3] [15]. The technique was developed by Ornstein and Davis and separates proteins based on their combined size, charge, and shape as they migrate through a porous polyacrylamide gel matrix under the influence of an electric field [12] [16]. By maintaining the native state of proteins, this method allows scientists to extract proteins post-separation for further functional assays, providing insights that are often lost in denaturing methods [3].

Native PAGE vs. SDS-PAGE: A Fundamental Comparison

The core distinction between Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE lies in their treatment of protein structure. The table below summarizes the key differences:

Table 1: Key Differences Between Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE

| Criteria | Native PAGE | SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Gel State | Non-denaturing [12] [15] | Denaturing [12] [15] |

| SDS Presence | Absent [12] | Present [12] |

| Sample Preparation | Not heated [12] | Heated [12] |

| Separation Basis | Size, charge, and shape [12] [3] | Molecular weight only [12] [16] |

| Protein State | Native, folded conformation [3] | Denatured, linearized [3] |

| Biological Activity | Retained [3] | Lost [3] |

| Protein Recovery | Possible post-separation [12] [15] | Not possible in functional form [12] |

| Primary Application | Studying structure, composition, and function [12] [3] | Determining molecular weight, checking purity/expression [12] [3] |

In SDS-PAGE, the anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) denatures proteins and coats them with a uniform negative charge, ensuring separation is based almost exclusively on molecular weight [3] [16]. Conversely, Native PAGE uses no denaturing agents, allowing proteins to retain their intrinsic charge and complex three-dimensional structure [3]. Consequently, a protein's migration in Native PAGE depends on its native charge-to-mass ratio and the physical obstruction of its folded shape as it moves through the gel [3] [16]. This fundamental difference dictates their application: use SDS-PAGE for analyzing protein purity and subunit molecular weight, and Native PAGE for investigating protein function, interactions, and native architecture [3].

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Comparative studies highlight how the choice of electrophoresis method impacts experimental outcomes, particularly in protein identification and the retention of functional properties.

Table 2: Comparative Experimental Data from Proteomic Studies

| Analysis Method | Proteins Identified (HBSMC Supernatant) | Key Functional Findings |

|---|---|---|

| 1D SDS-PAGE-MS | 2,552 proteins [17] | Advantageous for comparative quantitation of individual proteins [17]. |

| Native 2DE-MS | 4,323 proteins [17] | Advantageous for visualizing protein interactions in cells; higher sensitivity for certain membrane proteins [17]. |

| BN-PAGE | N/A | All nine model enzymes retained activity [6]. |

| Standard SDS-PAGE | N/A | All nine model enzymes underwent denaturation and lost activity [6]. |

| NSDS-PAGE | N/A | Seven of nine model enzymes, including four Zn²⁺ proteins, retained activity; 98% Zn²⁺ retention in proteomic samples [6]. |

A study analyzing human bronchial smooth muscle cells (HBSMC) found that SDS-PAGE and native 2DE provide complementary information [17]. While SDS-PAGE was superior for comparative quantification, native 2DE enabled the analysis of a larger number of proteins and was particularly effective for revealing protein interactions [17]. Furthermore, research into metalloproteins demonstrated the critical importance of native conditions. A modified method called Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE), which uses reduced SDS and omits EDTA and a heating step, showed a dramatic increase in the retention of bound metal ions—from 26% in standard SDS-PAGE to 98% in NSDS-PAGE [6]. This protocol also allowed most model enzymes to remain active post-electrophoresis, whereas they were completely inactivated by standard SDS-PAGE [6].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Standard Native PAGE Protocol

The following workflow outlines a typical Native PAGE experiment, from sample preparation to analysis:

1. Sample Preparation: Protein samples are prepared in a non-denaturing loading buffer that typically contains glycerol to increase density for gel loading, and a tracking dye like phenol red or Coomassie G-250 [6]. Crucially, this buffer contains no SDS, urea, or reducing agents like β-mercaptoethanol [12]. The sample is not heated prior to loading to prevent denaturation [12].

2. Gel Composition and Running Buffer: A standard polyacrylamide gel is used, but it is cast and run without SDS or other denaturing agents [12] [15]. The running buffer is also free of SDS. Common buffers include Tris-Glycine or Tris-BisTris systems at a neutral pH to help maintain protein stability [6].

3. Electrophoresis Conditions: The gel run is typically performed at 4°C to dissipate heat and protect proteins from thermal denaturation during the run, which can take 90-95 minutes [12] [6].

4. Post-Electrophoresis Analysis: After separation, proteins can be visualized using stains like Coomassie Blue or Silver Stain [18]. Because proteins are native, they can be electroeluted from gel slices or diffused out into an appropriate buffer for downstream functional assays, such as activity tests for enzymes or interaction studies [3] [15].

To experimentally verify the retention of biological activity after Native PAGE, the following methodology can be employed:

- Select Model Enzymes: Choose a set of diverse enzymes, such as alcohol dehydrogenase (Zn-ADH), alkaline phosphatase (Zn-AP), and carbonic anhydrase (Zn-CA).

- Run Parallel Gels: Subject identical aliquots of each enzyme to three parallel electrophoresis methods: Standard Denaturing SDS-PAGE, BN-PAGE, and Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE).

- In-Gel Activity Assay: Following electrophoresis, incubate the gel in a substrate solution specific to each enzyme. For example, for alkaline phosphatase, use a solution containing a chromogenic substrate like BCIP/NBT.

- Quantify Activity: The development of a colored precipitate band on the gel indicates the location of the active enzyme. Compare the intensity and clarity of the activity bands between the different PAGE methods. As demonstrated in research, all nine model enzymes were active after BN-PAGE, seven were active after NSDS-PAGE, and none were active after standard SDS-PAGE [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful Native PAGE experiments require specific reagents tailored to preserve protein native state. The following table lists key solutions and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Native PAGE Research

| Research Reagent | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Non-Denaturing Lysis Buffers | Extracts proteins from cells or tissues without disrupting non-covalent interactions, maintaining protein complexes. |

| Tris-Based Running Buffers | Provides the necessary ionic environment and pH control (typically near pH 7-8) for protein migration without denaturation. |

| Native-Compatible Stains (Coomassie G-250) | Visualizes protein bands without the use of harsh denaturing fixatives. Coomassie G-250 is used in techniques like BN-PAGE [6]. |

| Coomassie-Based Sample Buffer | Used in methods like NSDS-PAGE, it provides density for loading and a faint dye front without significant denaturation [6]. |

| Native Molecular Weight Standards | A mixture of intact, native proteins of known mass and charge used for calibration; essential for accurate analysis under non-denaturing conditions. |

| 4°C Electrophoresis Unit | A cooling system or dedicated cold room is crucial to run the gel at 4°C, preventing heat-induced denaturation during the run [12]. |

Advanced Techniques: Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) and NSDS-PAGE

Beyond standard Native PAGE, advanced variants have been developed for specific applications:

Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE): This technique uses Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 dye, which binds to proteins and confers a negative charge, improving solubility and resolution during electrophoresis [12] [6]. BN-PAGE is particularly powerful for studying native membrane protein complexes and determining the oligomeric state of proteins [12]. It retains functional properties but may have lower resolution for complex proteomic mixtures compared to SDS-PAGE [6].

Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE): This is a hybrid approach designed to bridge the gap between high resolution and function retention. It involves removing SDS and EDTA from the sample buffer, omitting the heating step, and significantly reducing the SDS concentration in the running buffer (e.g., to 0.0375%) [6]. This method results in high-resolution separation while retaining metal cofactors and enzymatic activity in most proteins, making it excellent for metalloprotein analysis [6].

Native PAGE is a cornerstone technique for functional proteomics, offering the unique advantage of preserving the native structure and biological activity of proteins. While SDS-PAGE remains the go-to method for determining molecular weight and analyzing purity, Native PAGE and its advanced derivatives like BN-PAGE and NSDS-PAGE are indispensable for interrogating protein function, characterizing complexes, and studying interactions in a state that closely mirrors their physiological environment. The choice between these techniques should be guided by the research question—whether the goal is to dissect protein composition or to understand its biological activity.

In polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), the gel matrix serves as a sophisticated molecular sieve that physically separates protein molecules based on their ability to navigate through its porous network. The polyacrylamide gel is formed by polymerizing acrylamide and bisacrylamide, creating a crosslinked polymer network whose pore size is precisely determined by the ratio and total concentration of these components [1]. This fundamental principle underpins both SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE techniques, though how proteins interact with the matrix differs significantly between these methods. Understanding and controlling polyacrylamide pore size is essential for optimizing protein separation efficiency, whether determining molecular weight under denaturing conditions or studying native protein complexes in their functional state.

Fundamentals of Polyacrylamide Gel Matrix

Gel Composition and Pore Formation

The polyacrylamide gel matrix is created through the copolymerization of acrylamide monomers and bisacrylamide (N,N'-methylenediacrylamide) crosslinkers. When ammonium persulfate (APS) is added as a polymerizing agent along with the catalyst TEMED (N,N,N',N'-tetramethylenediamine), a three-dimensional network forms with pores of defined sizes [1]. The pore size characteristics are determined by two key factors: the total acrylamide concentration (%T) and the degree of crosslinking (%C), which represents the proportion of bisacrylamide relative to the total acrylamide. This precise control over the gel's physical structure enables researchers to tailor separation conditions for different protein size ranges.

The Inverse Relationship Between Gel Percentage and Pore Size

The porosity of polyacrylamide gels exhibits an inverse relationship with the total acrylamide percentage. Lower-percentage gels (e.g., 7-8%) feature larger pores and are optimal for separating high molecular weight proteins, while higher-percentage gels (e.g., 12-15%) with smaller pores provide better resolution for lower molecular weight proteins [1]. This principle is exploited in gradient gels, which contain a low percentage of polyacrylamide at the top and a high percentage at the bottom, enabling a broader range of protein sizes to be separated effectively within a single gel [1]. The gradient design allows proteins to encounter progressively smaller pores during migration, sharpening bands and improving resolution across diverse molecular weight ranges.

Comparative Separation Mechanisms: SDS-PAGE vs. Native PAGE

Separation by Molecular Weight in SDS-PAGE

In SDS-PAGE, the anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) denatures proteins and binds to polypeptide chains in a constant weight ratio (approximately 1.4 g SDS per 1 g of protein) [1]. This SDS coating masks the proteins' intrinsic charge and confers a uniform negative charge density, transforming them into unstructured linear chains whose migration through the gel matrix depends primarily on molecular weight [12] [1]. Smaller proteins navigate the porous network more easily and migrate faster, while larger proteins encounter greater frictional resistance and migrate more slowly. This predictable relationship enables accurate molecular weight estimation when protein standards of known sizes are run in parallel.

Multidimensional Separation in Native PAGE

Native PAGE employs a non-denaturing approach that preserves proteins in their folded, functional state. Without SDS to normalize charge and disrupt structure, separation depends on a combination of size, intrinsic charge, and three-dimensional shape [12] [1] [3]. The gel pore size governs the sieving effect based on the hydrodynamic volume of native proteins, while charge dictates their electrophoretic mobility. This multidimensional separation mechanism allows Native PAGE to resolve protein complexes, study oligomerization states, and investigate protein-protein interactions under conditions that maintain biological activity [12] [3].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of SDS-PAGE vs. Native PAGE Separation Characteristics

| Parameter | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Molecular weight only [12] | Size, charge, and shape [12] [1] |

| Protein State | Denatured, linearized polypeptides [12] [1] | Native, folded conformation [12] [3] |

| Gel Pore Size Role | Molecular sieving based on polypeptide chain length | Molecular sieving based on hydrodynamic volume |

| Charge Characteristics | Uniform negative charge from SDS [1] | Intrinsic charge determined by protein sequence and buffer pH |

| Functional Preservation | Enzymatic activity destroyed [12] [6] | Biological activity typically retained [12] [3] |

| Optimal Applications | Molecular weight determination, purity assessment [12] [1] | Protein complexes, oligomeric states, functional studies [12] [3] |

Experimental Data and Methodologies

Gel Percentage Selection for Target Protein Separation

The appropriate polyacrylamide percentage must be carefully matched to the molecular weight range of target proteins to achieve optimal separation. Experimental data demonstrate that different gel percentages provide resolution across distinct molecular weight windows, with lower percentages (8-10%) optimal for high molecular weight proteins and higher percentages (12-15%) providing superior resolution for smaller proteins [1]. Gradient gels (e.g., 4-20% or 8-16%) effectively separate broad molecular weight ranges by continuously varying pore sizes, allowing all proteins to encounter their optimal sieving environment during electrophoresis [1] [19].

Table 2: Optimal Gel Percentages for Protein Separation by Molecular Weight Range

| Gel Percentage | Effective Separation Range (kDa) | Optimal Resolution (kDa) | Pore Size Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6-8% | 50-500 | 100-300 | Large pores, minimal sieving of high MW proteins |

| 10% | 20-300 | 40-150 | Moderate pores, standard analytical range |

| 12% | 15-200 | 30-100 | Moderately small pores, common for proteomics |

| 15% | 5-100 | 10-50 | Small pores, optimal for low MW proteins |

| 4-20% Gradient | 10-500 | 15-200 | Continuously variable pores, broadest range |

Experimental Protocol: Standard SDS-PAGE Setup

The following methodology outlines a standard SDS-PAGE procedure for protein separation based on molecular weight, with particular attention to gel matrix preparation [1]:

Gel Solution Preparation: Combine 7.5 mL of 40% acrylamide solution, 3.9 mL of 1% bisacrylamide solution, 7.5 mL of 1.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.7 for resolving gel), and water to 30 mL total volume for a 10% Tris-glycine mini gel.

Polymerization Initiation: Add 0.3 mL of 10% ammonium persulfate (APS), 0.3 mL of 10% SDS, and 0.03 mL TEMED to catalyze the polymerization reaction. Pour immediately between glass plates and overlay with water or isopropanol to ensure even formation.

Stacking Gel Addition: Once polymerized, prepare stacking gel with lower acrylamide concentration (typically 4-5%) at pH 6.8 and pour over the resolving gel, inserting well combs immediately.

Sample Preparation: Mix protein samples with SDS-containing sample buffer, often including reducing agents like DTT or β-mercaptoethanol, and heat at 70-100°C for 5-10 minutes to ensure complete denaturation [12] [1].

Electrophoresis Conditions: Load samples into wells and run at constant voltage (typically 150-200V) using MOPS or Tris-glycine-SDS running buffer until the dye front approaches the gel bottom [6] [1].

Modified Electrophoresis Conditions: NSDS-PAGE Protocol

Recent methodological advances have led to the development of Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE), which modifies traditional SDS-PAGE conditions to retain protein function while maintaining high resolution [6]. The experimental protocol involves:

Sample Buffer Modification: Omit SDS and EDTA from the sample buffer and eliminate the heating step to preserve native protein structure and metal cofactors [6].

Running Buffer Adjustment: Reduce SDS concentration in the running buffer from the standard 0.1% to 0.0375% and remove EDTA to maintain protein-metal interactions [6].

Electrophoresis Conditions: Perform electrophoresis using standard equipment but maintain lower temperatures (4°C) to further preserve protein native state during separation [6].

Functional Analysis: Recover proteins from gels for activity assays, with experimental data showing seven of nine model enzymes, including four Zn²⁺ proteins, retained activity after NSDS-PAGE compared to complete denaturation in standard SDS-PAGE [6].

Visualization of Separation Mechanisms

The following workflow diagrams illustrate how polyacrylamide pore size governs protein separation in SDS-PAGE versus Native PAGE systems.

Diagram 1: Workflow comparison of SDS-PAGE versus Native PAGE separation mechanisms.

Diagram 2: Impact of gel percentage and pore size on protein separation efficiency.

Research Reagent Solutions for Gel-Based Protein Separation

Successful protein separation using polyacrylamide gels requires specific reagents and materials optimized for electrophoretic applications. The following table details essential components and their functions in gel-based protein separation protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide-Bis Solution | Forms the crosslinked polymer network that creates the sieving matrix [1] | Typically used at 30-40% stock solutions; concentration determines pore size |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | Free radical initiator for acrylamide polymerization [1] | Fresh preparation recommended; concentration affects polymerization rate |

| TEMED | Catalyst that promotes free radical formation from APS to accelerate polymerization [1] | Added last; quantity controls gel setting time |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Anionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers uniform charge [12] [1] | Critical for SDS-PAGE; omitted in Native PAGE |

| Tris Buffers | Provides appropriate pH environment for electrophoresis and protein stability [6] [1] | Different pH for stacking (pH 6.8) and resolving (pH 8.8) gels in discontinuous systems |

| DTT or β-Mercaptoethanol | Reducing agents that break disulfide bonds for complete denaturation [12] | Used in SDS-PAGE; typically omitted in Native PAGE to preserve structure |

| Coomassie Blue/SERVAL Blue | Anionic dyes for visualizing protein bands post-electrophoresis [12] [6] | Can be incorporated in Native PAGE buffer systems (BN-PAGE) |

| Molecular Weight Standards | Reference proteins of known size for molecular weight calibration [1] | Essential for accurate MW determination in SDS-PAGE |

Discussion and Technical Considerations

Strategic Selection of Electrophoresis Conditions

The choice between SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE hinges on experimental objectives, with each technique offering distinct advantages and limitations. SDS-PAGE provides superior resolution for molecular weight determination and protein purity assessment but destroys native structure and function [12] [1]. Native PAGE preserves biological activity and protein complexes but offers more complex separation patterns influenced by multiple protein properties [12] [3]. Recent methodological developments like NSDS-PAGE attempt to bridge this gap by maintaining high resolution while preserving some functional characteristics, demonstrating that 98% of Zn²⁺ remained bound to metalloproteins compared to only 26% in standard SDS-PAGE [6].

Gel Matrix Optimization Strategies

Effective protein separation requires careful optimization of gel matrix parameters. For routine analytical applications, 10-12% gels provide satisfactory resolution for most protein mixtures, while gradient gels (e.g., 4-20% or 8-16%) offer superior performance for complex samples with broad molecular weight distributions [1] [19]. The incorporation of specialized buffer systems, such as the use of Coomassie G-250 in Native PAGE, can enhance resolution while maintaining protein function [6]. For specialized applications like metalloprotein analysis, modified protocols that reduce denaturant concentrations while maintaining adequate separation efficiency present promising alternatives to traditional methods [6].

The polyacrylamide gel matrix, with its precisely controllable pore size, remains the cornerstone of protein separation technologies. The critical role of this molecular sieve in governing protein migration cannot be overstated, as it directly determines the resolution and efficacy of both SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE methodologies. By understanding the fundamental relationship between gel composition, pore size, and protein separation mechanisms, researchers can strategically select and optimize electrophoretic conditions to address specific experimental questions. The continuing evolution of gel-based separation techniques, including hybrid approaches that balance resolution with native structure preservation, ensures that polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis will maintain its essential role in protein analysis and biopharmaceutical development.

In the field of protein analysis, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) serves as a fundamental technique for separating and characterizing complex protein mixtures. Among the various PAGE methodologies, SDS-PAGE (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-PAGE) and Native PAGE represent two fundamentally different approaches distinguished primarily by their chemical components. These techniques offer complementary insights—SDS-PAGE denatures proteins to separate them by molecular weight, while Native PAGE preserves native protein structure and function. The distinction between these methods lies substantially in their use of specific buffers, reducing agents, and additives, which directly dictate the type of information that can be obtained from an experiment. This comparison guide provides an objective analysis of the key chemical components in both methods, supported by experimental data, to assist researchers in selecting the appropriate technique for their specific protein analysis requirements within drug development and basic research contexts.

Core Principles and Separation Mechanisms

The fundamental difference between SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE lies in their treatment of protein structure during separation. SDS-PAGE employs the anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) to denature proteins and impart a uniform negative charge, resulting in separation based primarily on molecular weight [12] [3] [1]. In contrast, Native PAGE avoids denaturing agents, preserving proteins in their native, folded state, which enables separation based on the protein's intrinsic charge, size, and three-dimensional shape [12] [1]. This critical distinction in approach directly impacts the choice of buffers, additives, and experimental procedures for each method.

The preservation of protein structure in Native PAGE allows for the analysis of functional properties, including enzymatic activity, protein-protein interactions, and quaternary structure [12] [1]. Meanwhile, SDS-PAGE provides superior resolution for molecular weight determination and analysis of protein subunit composition [6] [1]. A hybrid approach, termed NSDS-PAGE (Native SDS-PAGE), has been developed to balance the high resolution of traditional SDS-PAGE with the functional preservation of Native PAGE by significantly modifying standard SDS-PAGE conditions [6].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE

| Characteristic | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Molecular weight | Size, charge, and shape |

| Protein State | Denatured | Native/folded |

| Functional Preservation | No | Yes |

| Post-Separation Recovery | Not functional | Functional proteins can be recovered |

| Primary Applications | Molecular weight determination, protein detection, purity assessment | Protein-protein interactions, enzymatic activity studies, oligomeric state analysis |

Comparative Analysis of Chemical Components

The chemical environment defining each electrophoretic method is created through specific combinations of buffers, detergents, and additives. These components work in concert to either denature and uniformly charge proteins (SDS-PAGE) or maintain their native conformation and intrinsic charge (Native PAGE).

Buffer Systems and Composition

Buffer systems in electrophoresis serve to maintain stable pH conditions and provide the ionic environment necessary for protein migration under an electric field. SDS-PAGE typically utilizes Tris-based running buffers, often with MOPS or MES, containing SDS to maintain protein denaturation and charging during separation [6] [1]. For example, a standard SDS-PAGE running buffer contains 50 mM MOPS, 50 mM Tris Base, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1% SDS at pH 7.7 [6]. Native PAGE employs different buffer systems, such as Bis-Tris and Tricine, without SDS, to preserve protein structure and function [6].

The modified NSDS-PAGE method utilizes a running buffer with significantly reduced SDS content (0.0375% instead of 0.1%) and omits EDTA, creating conditions that maintain protein function while still providing high-resolution separation [6]. Sample buffer composition also differs substantially, with SDS-PAGE sample buffers containing denaturing agents like LDS (lithium dodecyl sulfate) and EDTA, while Native PAGE sample buffers lack these components [6].

Table 2: Buffer Composition Comparison Between Electrophoresis Methods

| Component | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE | NSDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Running Buffer | 50 mM MOPS, 50 mM Tris Base, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, pH 7.7 [6] | Cathode: 50 mM BisTris, 50 mM Tricine, 0.02% Coomassie G-250, pH 6.8; Anode: 50 mM BisTris, 50 mM Tricine, pH 6.8 [6] | 50 mM MOPS, 50 mM Tris Base, 0.0375% SDS, pH 7.7 [6] |

| Sample Buffer | 106 mM Tris HCl, 141 mM Tris Base, 0.51 mM EDTA, 0.22 mM SERVA Blue G-250, 0.175 mM Phenol Red, 2% LDS, 10% Glycerol, pH 8.5 [6] | 50 mM BisTris, 50 mM NaCl, 16 mM HCl, 10% Glycerol, 0.001% Ponceau S, pH 7.2 [6] | 100 mM Tris HCl, 150 mM Tris Base, 10% Glycerol, 0.01875% Coomassie G-250, 0.00625% Phenol Red, pH 8.5 [6] |

| Detergent Content | High (SDS or LDS) | None | Low (SDS omitted from sample buffer, reduced in running buffer) |

Detergents and Denaturing Agents

Detergents represent the most distinctive differentiating component between these methods. SDS-PAGE utilizes the anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), which binds to proteins in a constant weight ratio (approximately 1.4 g SDS per 1 g of protein) [1]. This SDS coating denatures proteins by disrupting non-covalent bonds and confers a uniform negative charge that overwhelms the protein's intrinsic charge [12] [1]. The result is that all proteins migrate toward the anode with mobility determined primarily by molecular weight rather than native charge.

Native PAGE intentionally omits denaturing detergents like SDS to preserve protein structure and function [12]. Some Native PAGE variants, particularly Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE), use Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250, which confers a slight negative charge to proteins without causing significant denaturation [12] [6]. Clear Native PAGE (CN-PAGE) avoids dyes altogether, separating proteins based solely on their intrinsic charge in a gradient gel [12].

Reducing Agents and Additives

Reducing agents play a critical role in SDS-PAGE by breaking disulfide bonds to fully denature proteins into their constituent polypeptides. Common reducing agents include β-mercaptoethanol or dithiothreitol (DTT), which are typically added to the sample buffer [12] [5]. The sample preparation process for SDS-PAGE usually involves heating samples to 70-100°C in the presence of these reducing agents to ensure complete denaturation [12] [1].

In contrast, Native PAGE buffers specifically exclude reducing agents to maintain the native protein structure, including disulfide bonds that may be essential for structural integrity [12]. The non-reducing environment preserves non-covalent interactions that maintain protein quaternary structure and complexes [7]. Additives in Native PAGE are limited to those that stabilize native conformations, such as glycerol in sample buffers, which helps maintain protein stability and improve sample loading [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard SDS-PAGE Protocol

Sample Preparation: Mix protein samples with SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing reducing agents (DTT or β-mercaptoethanol) and denaturing agents (SDS or LDS) [6]. Heat samples at 70-100°C for 10 minutes to ensure complete denaturation [12] [1].

Gel Preparation: Cast polyacrylamide gels with appropriate acrylamide concentration for target protein size range. Lower percentage gels (e.g., 7-10%) separate higher molecular weight proteins better, while higher percentages (e.g., 12-15%) provide better resolution for smaller proteins [1]. Include a stacking gel with lower acrylamide concentration and pH to concentrate proteins before entering the resolving gel.

Electrophoresis: Load prepared samples into wells alongside molecular weight markers. Run gels at constant voltage (typically 150-200V) for 30-60 minutes using MOPS/Tris/SDS running buffer until dye front reaches gel bottom [6].

Post-Electrophoresis Analysis: Visualize proteins using stains (Coomassie, silver stain) or transfer to membranes for western blotting [1]. Proteins can be excised for mass spectrometry analysis but are not functionally active [12].

Standard Native PAGE Protocol

Sample Preparation: Mix protein samples with Native PAGE sample buffer containing no denaturing or reducing agents [6]. Do not heat samples to preserve native structure [12].

Gel Preparation: Cast polyacrylamide gels without SDS or other denaturants. Gradient gels (e.g., 4-16%) are often used to separate protein complexes of varying sizes [6].

Electrophoresis: Load prepared samples into wells. Run gels at constant voltage (typically 150V) for 90-95 minutes using appropriate anode and cathode buffers [6]. Maintain cool temperatures (often 4°C) during separation to prevent denaturation [12].

Post-Electrophoresis Analysis: Visualize proteins using non-denaturing stains. Proteins can be recovered from gels through passive diffusion or electro-elution while retaining function [1]. Activity assays can be performed directly on gel sections [12].

NSDS-PAGE Modified Protocol

Sample Preparation: Mix protein samples with NSDS sample buffer (100 mM Tris HCl, 150 mM Tris base, 10% glycerol, 0.01875% Coomassie G-250, 0.00625% Phenol Red, pH 8.5) without heating [6].

Gel Preparation: Use standard precast Bis-Tris gels but pre-run in double distilled H₂O for 30 minutes to remove storage buffer and unpolymerized acrylamide [6].

Electrophoresis: Run gels at 200V for approximately 45 minutes using NSDS running buffer (50 mM MOPS, 50 mM Tris Base, 0.0375% SDS, pH 7.7) [6].

Post-Electrophoresis Analysis: Proteins can be analyzed for metal content using techniques like laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry or for function using activity assays [6].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and materials required for implementing each electrophoretic method, along with their specific functions in the experimental process.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Electrophoresis Methods

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Method Application |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins and imparts uniform negative charge | SDS-PAGE |

| DTT (Dithiothreitol) or β-mercaptoethanol | Reduces disulfide bonds | SDS-PAGE |

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 | Imparts slight negative charge without complete denaturation | BN-PAGE (Native PAGE variant) |

| Polyacrylamide | Forms porous gel matrix for molecular sieving | All PAGE methods |

| Bis-acrylamide | Cross-linking agent for polyacrylamide gel formation | All PAGE methods |

| TEMED | Catalyzes acrylamide polymerization | All PAGE methods |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | Initiates acrylamide polymerization | All PAGE methods |

| Tris-based Buffers | Maintain stable pH during electrophoresis | All PAGE methods |

| Molecular Weight Markers | Reference standards for size determination | Primarily SDS-PAGE |

| Glycerol | Increases sample density for well loading; stabilizes proteins | All PAGE methods (sample buffer) |

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Comparative studies provide quantitative data on the performance characteristics of different electrophoretic methods. Research comparing 1D SDS-PAGE with nondenaturing 2DE for analyzing proteins from human bronchial smooth muscle cells revealed that SDS-PAGE of the supernatant fraction enabled identification of 2552 proteins with percent abundance ranging from 3.5% to 2×10⁻⁴% [20]. Under similar conditions, nondenaturing 2DE identified 4323 proteins with percent abundance ranging from 3.6% to 1×10⁻⁵%, suggesting enhanced sensitivity with the native isoelectric focusing step [20].

The functional preservation achieved through Native PAGE and modified SDS-PAGE methods is substantiated by experimental data. In studies comparing standard SDS-PAGE with NSDS-PAGE, retention of Zn²⁺ bound in proteomic samples increased from 26% to 98% when shifting from standard to modified conditions [6]. Furthermore, seven of nine model enzymes, including four Zn²⁺ proteins subjected to NSDS-PAGE, retained activity, while all nine enzymes were inactive following standard SDS-PAGE [6].

Analysis of protein migration patterns has revealed systematic discrepancies between theoretical molecular weights and observed migration in SDS-PAGE. Large-scale studies creating databases of electrophoretic migration patterns for approximately 10,000 human proteins have highlighted how post-translational modifications and structural features affect protein migration, providing crucial reference data for troubleshooting western blot experiments and characterizing proteoforms [21].

Application Workflows and Decision Pathways

The selection between SDS-PAGE, Native PAGE, or hybrid approaches depends on research objectives, protein characteristics, and desired analytical outcomes. The following diagram illustrates the decision pathway for selecting the appropriate electrophoretic method based on experimental goals:

The comparative analysis of key chemical components in SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE reveals how specific buffers, detergents, and additives fundamentally direct experimental outcomes in protein separation. SDS-PAGE, with its denaturing conditions created by SDS and reducing agents, provides high-resolution separation based primarily on molecular weight, making it ideal for analytical applications requiring precise size determination. Native PAGE, through the omission of denaturants, preserves protein structure and function, enabling the study of protein complexes, interactions, and enzymatic activities. The development of modified methods like NSDS-PAGE demonstrates that the boundary between these approaches is not rigid but can be strategically manipulated to balance resolution with functional preservation. Understanding these chemical foundations allows researchers to make informed decisions about method selection based on their specific protein analysis requirements, ultimately enhancing the reliability and relevance of experimental results in both basic research and drug development applications.

Protocols and Applications: Step-by-Step Methods and Real-World Use Cases

In protein analysis, the choice of electrophoresis method dictates the type of information obtained, with sample preparation being the most critical determinant of success. SDS-PAGE (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis) and Native PAGE represent two fundamental approaches: one denatures proteins to separate them purely by molecular weight, while the preserves their native structure to study function and complexes [3] [22]. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of their sample preparation protocols, enabling researchers to select and optimize the correct method for their specific application, whether it involves determining molecular weight, analyzing purity, or investigating active protein complexes and interactions.

Core Principles and Objectives

The underlying principles of SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE are diametrically opposed, leading to their distinct applications in research and drug development.

SDS-PAGE: Separation by Molecular Weight

In SDS-PAGE, the anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) plays a pivotal role. It denatures proteins by binding to the polypeptide backbone and confers a uniform negative charge, effectively masking the protein's intrinsic charge [23] [22]. The addition of reducing agents like β-mercaptoethanol or DTT breaks disulfide bonds, fully dissociating protein subunits [23] [24]. This process ensures that the charge-to-mass ratio is nearly identical for all proteins, resulting in separation based almost exclusively on polypeptide chain length and molecular weight [23] [22]. Consequently, SDS-PAGE is the method of choice for determining protein purity, estimating molecular weight, and analyzing subunit composition in a denatured state.

Native PAGE: Preservation of Native Structure

Native PAGE is a non-denaturing technique. Proteins are prepared in buffers without SDS or reducing agents, allowing them to maintain their secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures, as well as their intrinsic biological activity [25] [12] [22]. Separation depends on the protein's native charge, size, and three-dimensional shape as it migrates through the gel matrix [22] [26]. This preservation enables the study of functional properties, making Native PAGE ideal for investigating protein-protein interactions, oligomerization states, enzymatic activity, and the composition of native protein complexes [3] [27].

Detailed Sample Preparation Protocols

The following section outlines the specific, step-by-step protocols for preparing protein samples for each method. Adherence to these protocols is essential for generating reliable and reproducible results.

SDS-PAGE Sample Preparation Protocol

The goal of SDS-PAGE sample prep is complete denaturation and linearization of proteins.

Step 1: Prepare Sample Buffer. The loading buffer is typically a 2X or 5X concentrated solution. A common 5X formulation contains: 10% (w/v) SDS for denaturation and charge masking, 10 mM Dithiothreitol (DTT) or β-mercaptoethanol (e.g., 1 µL per 25 µL lysate) to reduce disulfide bonds, 20% (v/v) Glycerol to add density for gel loading, 0.2 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8 to maintain pH, and 0.05% (w/v) Bromophenol Blue as a tracking dye [23] [24] [28].

Step 2: Mix Sample with Buffer. The protein sample should be mixed with an equal volume of 2X sample buffer [23]. The final protein concentration should be sufficiently high for detection, typically resulting in a load of 0.5 µg to 20 µg per lane, depending on gel size and detection method [23] [28].

Step 3: Denature by Heating. A critical denaturation step involves heating the samples at 95-100°C for 5-10 minutes in a heating block or boiling water bath [23] [24] [28]. This heat treatment ensures complete unfolding and SDS binding.

Step 4: Clarify by Centrifugation. After heating, samples should be briefly centrifuged (e.g., 3 minutes in a microcentrifuge) to pellet any insoluble debris, and the supernatant is loaded into the gel [23].

Native PAGE Sample Preparation Protocol

The goal of Native PAGE sample prep is to maintain the protein's native conformation.

Step 1: Prepare Non-Denaturing Sample Buffer. A typical 2X native sample buffer contains: 62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 25% Glycerol for density, and 1% Bromophenol Blue as a tracking dye [25]. Crucially, it lacks SDS, DTT, and other reducing agents [25] [12].

Step 2: Mix Sample with Buffer Gently. The protein sample is mixed with an equal volume of the native sample buffer. This step should be performed gently to minimize shear forces and avoid foaming, which could denature the protein [25].

Step 3: Omit Heating. Do not heat the samples [25]. Heating is a denaturing step and would defeat the purpose of Native PAGE. Samples are kept on ice or at 4°C to preserve activity.

Step 4: Load and Run at Cool Temperatures. To further prevent denaturation during electrophoresis, the gel apparatus is often run at 4°C and at lower voltages to minimize heat generation [12] [26].

Comparative Analysis: Key Differences at a Glance

The table below provides a consolidated, direct comparison of the critical parameters differentiating SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE sample preparation.

Table 1: Direct Comparison of SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE Sample Preparation

| Parameter | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Detergent | SDS present (0.1-2%) [24] [22] | No SDS [12] |

| Reducing Agent | DTT or β-mercaptoethanol present [23] [24] | No reducing agent [12] |

| Heating Step | Required (95-100°C for 5-10 min) [23] [28] | Not performed [25] [12] |

| Separation Basis | Molecular weight [23] [22] | Size, charge, and shape [12] [22] |

| Protein State | Denatured and linearized [22] | Native, folded conformation [22] |

| Protein Function | Lost [3] [12] | Retained [3] [22] |

| Typical Running Temperature | Room Temperature [12] | 4°C [12] [26] |

| Post-Electrophoresis Protein Recovery | Not feasible in functional form [12] | Possible, proteins can be electro-eluted for activity assays [22] |

Supporting Experimental Data and Hybrid Approaches

Experimental data underscores the functional consequences of these preparation methods. A study comparing standard SDS-PAGE with a modified "Native SDS-PAGE" (NSDS-PAGE) demonstrated that by removing SDS and EDTA from the sample buffer and omitting the heating step, retention of bound metal ions in zinc proteins increased dramatically from 26% to 98% [6]. Furthermore, enzymatic activity assays showed that seven out of nine model enzymes remained active after NSDS-PAGE, whereas all nine were denatured and inactivated by standard SDS-PAGE conditions [6]. This highlights the direct impact of sample preparation on functional preservation.

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Sample Preparation on Protein Functionality

| Electrophoresis Method | Sample Preparation Key Features | Zinc Retention in Proteome | Enzymatic Activity Retention |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDS-PAGE | SDS, EDTA, Heating | ~26% | 0/9 Model Enzymes |

| BN-PAGE | No SDS, Coomassie Dye, No Heat | Not Specified | 9/9 Model Enzymes |

| NSDS-PAGE | No SDS/EDTA in Sample, No Heat | ~98% | 7/9 Model Enzymes |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of these protocols requires specific reagents. The following table lists key solutions and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for PAGE Sample Preparation

| Reagent Solution | Core Function | Key Components |

|---|---|---|

| SDS-PAGE Sample Buffer (2X/5X) | Denatures proteins, imparts uniform charge, allows visualization [23] [24] | SDS, Reducing Agent (DTT/BME), Glycerol, Tris-HCl, Bromophenol Blue |

| Native PAGE Sample Buffer (2X) | Maintains native state, provides density for loading [25] | Tris-HCl, Glycerol, Bromophenol Blue |

| SDS-PAGE Running Buffer | Conducts current, maintains SDS saturation [23] [24] | Tris, Glycine, SDS (0.1%) |

| Native PAGE Running Buffer | Conducts current in non-denaturing conditions [25] | Tris, Glycine |

| Blue Native (BN) PAGE Sample Buffer | Solubilizes protein complexes, imparts negative charge with dye [6] [27] | Aminocaproic Acid, Bis-Tris, Detergent (e.g., Lauryl Maltoside), Coomassie Blue G-250 |

Workflow and Decision Pathway

The following diagram summarizes the critical decision points in sample preparation, leading to the appropriate protocol for either SDS-PAGE or Native PAGE.

The choice between denaturation for SDS-PAGE and native state preservation is fundamental and dictated by the scientific question. SDS-PAGE, with its stringent denaturation and reduction, is an unparalleled tool for determining molecular weight and assessing sample homogeneity. In contrast, Native PAGE provides a unique window into the functional proteome, enabling the study of proteins in their biologically active state. By understanding and meticulously applying the distinct sample preparation protocols outlined in this guide, researchers can effectively harness the power of each technique to advance their research in biochemistry, molecular biology, and drug development.

In protein analysis, the resolution and reliability of results are fundamentally rooted in the initial gel casting process. The meticulous formulation of resolving and stacking gels within polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) is not merely a preparatory step but a critical determinant of experimental success. Within the broader context of comparing SDS-PAGE and native PAGE, the design of the gel matrix dictates the physical principle upon which separation occurs—either purely by molecular weight or by a complex interplay of charge, size, and shape. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of gel casting procedures, delivering the protocols and data necessary for researchers and drug development professionals to optimize protein separation for their specific analytical needs.

Core Principles: SDS-PAGE vs. Native PAGE

The choice between SDS-PAGE and native PAGE dictates every subsequent decision in gel formulation, as each technique operates on a different separation principle.

SDS-PAGE (Denaturing Conditions): This method separates proteins based almost exclusively on molecular weight. The anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) denatures proteins and binds to the polypeptide backbone in a constant weight ratio, imparting a uniform negative charge density. A reducing agent, such as dithiothreitol (DTT) or β-mercaptoethanol, is added to break disulfide bonds, ensuring complete denaturation into individual subunits. Consequently, the intrinsic charge of the polypeptide becomes insignificant, and all SDS-bound proteins migrate through the gel toward the anode, with smaller proteins moving faster than larger ones [1] [29] [30].

Native-PAGE (Non-Denaturing Conditions): This technique separates proteins according to the net charge, size, and shape of their native structure. Without denaturants, proteins retain their higher-order structure (quaternary and tertiary). In alkaline running buffers, most proteins carry a net negative charge and migrate toward the anode. The gel matrix creates a sieving effect, where the frictional force regulates movement based on the protein's size and three-dimensional shape [1]. This method is ideal for studying functional protein complexes, enzymatic activity, and protein-protein interactions, as native structure is preserved [1].

The following workflow outlines the key decision points and procedures for casting gels for both techniques:

Gel Formulation and Experimental Protocols

The physical structure of the gel, defined by the concentrations of acrylamide and bisacrylamide, is the primary factor controlling pore size and thus resolving power.

SDS-PAGE Gel Recipe and Casting Protocol

A standard protocol for casting a discontinuous SDS-PAGE gel for four 0.75-mm thick gels is detailed below [31].

Table 1: SDS-PAGE Gel Recipe for Four 0.75-mm Gels

| Component | Amount for X % Resolving Gel | Amount for Stacking Gel |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide, 30% | (0.5 x X) mL | 1.98 mL |

| Tris, 1.5 M, pH 8.8 | 3.75 mL | 0 mL |

| Tris, 0.5 M, pH 6.8 | 0 mL | 3.78 mL |

| SDS, 10% w/v | 150 µL | 150 µL |

| H₂O | (11.02 – (0.5 x X)) mL | 9 mL |

| TEMED | 7.5 µL | 15 µL |

| APS, 10% w/v | 75 µL | 75 µL |

| Total Volume | 15 mL | 15 mL |

10-Step Gel Casting Protocol [31]:

- Assemble Equipment: Clean glass plates and assemble the casting cassette.

- Prepare Gel Solutions: Mix resolving and stacking gel components in separate beakers, omitting APS and TEMED initially.

- Initiate Resolving Gel Polymerization: Add APS and TEMED to the resolving gel mixture and mix gently.

- Pour Resolving Gel: Immediately pour the mixture into the cassette, leaving space for the stacking gel.

- Overlay with Isopropanol: Gently add isopropanol on top to create a flat, smooth interface. Polymerize for 30-45 minutes.

- Remove Overlay: Pour off isopropanol and wipe residual liquid with a lint-free tissue.

- Initiate Stacking Gel Polymerization: Add APS and TEMED to the stacking gel mixture and mix.

- Pour Stacking Gel: Pour the stacking gel on top of the polymerized resolving gel.

- Insert Comb: Place the comb into the stacking gel, avoiding bubbles. Allow to polymerize fully.

- Remove Comb: Carefully remove the comb vertically to prevent well distortion.

The percentage of the resolving gel must be matched to the molecular weight of the target proteins for optimal resolution.

Table 2: Resolving Gel Percentage for Target Protein Sizes [31]

| Size of Protein (kDa) | % Acrylamide in Resolving Gel |

|---|---|

| 4 - 40 | 20% |

| 12 - 45 | 15% |

| 10 - 70 | 12.5% |

| 15 - 100 | 10% |

| 25 - 200 | 8% |

Native PAGE Gel Formulation

For native PAGE, the gel formulation is typically simpler, often consisting of a single resolving gel without a stacking gel, though discontinuous systems can be used [1]. The key difference is the absence of SDS in both the gel matrix and the running buffer. The gel percentage is chosen based on the size of the native protein or complex, as shown below. It is crucial to avoid pH extremes and keep the apparatus cool to maintain protein integrity and activity [1].

Table 3: Recommended Polyacrylamide Percentages for Non-Denaturing Gels (for double-stranded nucleic acids or native proteins) [32]

| Polyacrylamide Gel % (bis, 19:1) | Range of Efficient Separation (bp for DNA) |

|---|---|

| 3.5 | 100 - 1,000 |

| 5.0 | 80 - 500 |

| 8.0 | 60 - 400 |

| 12.0 | 50 - 200 |

| 15.0 | 25 - 150 |

| 20.0 | 5 - 100 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful gel casting and electrophoresis rely on a specific set of high-quality reagents and equipment.

Table 4: Essential Materials for Gel Casting and Electrophoresis

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms the cross-linked polymer network (gel matrix) that acts as a molecular sieve. The ratio and total concentration determine pore size [1] [32]. |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | Initiator that provides free radicals to catalyze the polymerization of acrylamide and bis-acrylamide [1] [31]. |

| TEMED | Catalyst that accelerates the polymerization reaction by promoting free radical production from APS [1] [31]. |

| Tris-HCl Buffer | Maintains a stable pH during electrophoresis. Different pH levels (8.8 for resolving, 6.8 for stacking) are critical for the discontinuous buffer system [31]. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Ionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge, allowing separation by mass alone in SDS-PAGE [1] [30]. |

| Vertical Gel Electrophoresis System | Apparatus that holds the gel cassette vertically in buffer tanks and allows application of an electrical current [33] [30]. |

| Power Supply | Provides the controlled electrical current (constant voltage/current/power) required to drive protein migration through the gel [33]. |

Troubleshooting Common Gel Casting and Running Issues

Even with precise protocols, issues can arise. The table below outlines common problems and their solutions.

Table 5: Troubleshooting Common SDS-PAGE Issues [34]

| Issue | Possible Explanation | Troubleshooting Suggestion |

|---|---|---|

| Smeared Bands | Voltage too high. | Run gel at 10-15 V/cm; use lower voltage for a longer time. |

| "Smiling" Bands | Excessive heat generation during run. | Run gel in a cold room, use ice packs, or lower the voltage. |

| Poor Resolution | Gel run time too short; uneven gel concentration; improper buffer. | Run until dye front nears bottom; ensure proper gel mixing and buffer preparation. |

| Edge Effect | Empty wells at the periphery of the gel. | Load ladders or dummy samples in empty edge wells. |

| Diffused Samples | Lag between loading and running. | Start electrophoresis immediately after loading the last sample. |

Advances in Gel Casting Technology

Innovation in gel casting technology focuses on improving efficiency, safety, and consistency. Traditional hand-casting, while cost-effective, is time-consuming (up to 90 minutes) and involves handling neurotoxic monomers [31] [35].