SDS-PAGE Master Guide: Principles, Protocol, and Troubleshooting for Precise Protein Separation

This comprehensive guide details the SDS-PAGE protocol for separating proteins by molecular weight, a foundational technique in molecular biology and biopharmaceutical development.

SDS-PAGE Master Guide: Principles, Protocol, and Troubleshooting for Precise Protein Separation

Abstract

This comprehensive guide details the SDS-PAGE protocol for separating proteins by molecular weight, a foundational technique in molecular biology and biopharmaceutical development. It covers core principles of protein denaturation and electrophoretic separation, provides a step-by-step methodological protocol, addresses common troubleshooting scenarios, and explores advanced applications and comparative technologies. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this article synthesizes foundational knowledge with practical optimization strategies to ensure high-resolution, reproducible results in both research and quality control contexts.

The Science of SDS-PAGE: Unraveling How Proteins Separate by Size

Sodium Dodecyl Sulphate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) is a foundational technique in biochemistry and molecular biology that enables researchers to separate proteins based almost exclusively on their molecular weight [1]. This method resolves protein mixtures into discrete bands, providing critical information for analyzing protein purity, composition, and size. The technique's ability to deliver precise, reproducible results has made it indispensable in research laboratories and essential for diagnostic applications, including western blotting for disease markers such as HIV [1] [2].

The development of SDS-PAGE represents a significant advancement in protein analytics. While initial work on polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis began in the 1960s, the breakthrough came in 1970 when Ulrich Laemmli refined the method by incorporating SDS, creating a system that dramatically improved the resolution of protein bands by ensuring separation occurred primarily according to molecular weight [2].

Core Principle of Molecular Weight-Based Separation

The fundamental principle of SDS-PAGE is that proteins are separated based solely on their molecular mass, independent of their native charge or three-dimensional structure [1]. This is achieved through a two-component system that standardizes protein physical properties before separation occurs.

Role of Sodium Dodecyl Sulphate (SDS)

SDS, an anionic detergent, serves two critical functions in the denaturation process:

- Protein Denaturation: SDS disrupts and unfolds the secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures of proteins by breaking non-covalent bonds, converting them into linear polypeptide chains [1] [3].

- Charge Standardization: SDS binds to the polypeptide backbone in a constant ratio of approximately 1.4g SDS per 1.0g protein [1]. This binding imparts a uniform negative charge to all proteins proportional to their molecular mass, effectively masking the proteins' intrinsic electrical charges [2].

Polyacrylamide Gel as a Molecular Sieve

The polyacrylamide gel matrix creates a three-dimensional network with pores of defined sizes through which proteins migrate [1]. When an electric field is applied, the negatively charged SDS-protein complexes migrate toward the positive anode, with smaller proteins moving faster through the pores while larger proteins are retarded [2]. This molecular sieving effect results in the separation of polypeptides according to their molecular weights rather than their chemical properties [3].

Table 1: Key Components and Their Functions in SDS-PAGE

| Component | Function | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulphate) | Denatures proteins and standardizes charge | Binds to protein backbone, disrupting non-covalent bonds and imparting negative charge |

| Reducing Agents (β-mercaptoethanol/DTT) | Breaks disulfide bonds | Reduces covalent linkages between cysteine residues, ensuring complete denaturation |

| Polyacrylamide Gel | Acts as molecular sieve | Creates pore network that separates proteins based on size |

| Tris Buffers | Maintain pH environment | Provides optimal pH for electrophoresis and protein stability |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful SDS-PAGE requires precise preparation and quality reagents. The following components are essential for the procedure:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SDS-PAGE

| Reagent/Solution | Composition/Preparation | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis Solution | 30% acrylamide, 0.8% bis-acrylamide in water [3] | Forms the cross-linked gel matrix for protein separation |

| Separating Gel Buffer | 1.5M Tris-HCl, pH 8.8 [3] | Creates high pH environment for optimal separation |

| Stacking Gel Buffer | 1.0M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8 [3] | Creates lower pH for sample stacking before separation |

| Electrophoresis Buffer | 25mM Tris, 250mM glycine, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.3 [3] | Conducts current and maintains buffer conditions during run |

| SDS-PAGE Sample Buffer | Tris-HCl, SDS, glycerol, β-mercaptoethanol, bromophenol blue [4] | Denatures proteins, adds density for loading, provides tracking dye |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | 10% solution in water [4] | Free radical source initiates acrylamide polymerization |

| TEMED | N,N,N',N'-Tetramethylethylenediamine [4] | Catalyst that accelerates acrylamide polymerization |

Experimental Protocol

Gel Preparation

Step 1: Assembling Glass Plates Clean glass plates thoroughly with warm detergent, rinse sequentially with tap water, deionized water, and ethanol [3]. Assemble the plates with spacer strips, ensuring edges are properly sealed to prevent leakage [3].

Step 2: Preparing the Separating Gel The separating gel concentration should be selected based on the molecular weight range of the target proteins, as detailed in Table 3. Combine components in the order listed, adding TEMED and ammonium persulfate last to initiate polymerization [4]. Pour the gel mixture immediately between the glass plates, leaving appropriate space for the stacking gel, and overlay with water-saturated butanol or isopropanol to create a flat interface [4] [5]. Allow complete polymerization for approximately 30-45 minutes [5].

Table 3: Optimal Acrylamide Concentrations for Protein Separation [4] [5]

| Acrylamide Concentration (%) | Effective Separation Range (kDa) | Applications |

|---|---|---|

| 8% | 25-200 | Large proteins and protein complexes |

| 10% | 15-100 | Standard mixture of proteins |

| 12.5% | 10-70 | Intermediate size range proteins |

| 15% | 12-45 | Smaller proteins and peptides |

Step 3: Preparing the Stacking Gel After polymerization of the separating gel, pour off the overlay solution and rinse the gel surface. Prepare the stacking gel solution (typically 4-5% acrylamide) [1], add polymerization initiators, and pour immediately over the separating gel. Insert the sample comb carefully to avoid air bubbles and allow to polymerize for 20-30 minutes [4].

Sample Preparation

Protein Denaturation Mix protein samples with SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing SDS and reducing agents [1]. The typical sample buffer composition includes Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 0.1% bromophenol blue, and 5% β-mercaptoethanol or DTT [3]. Heat samples at 95-100°C for 5 minutes to ensure complete denaturation [4]. Centrifuge briefly to collect condensation before loading.

Handling Difficult Samples For dilute protein samples or samples containing high salt concentrations, precipitate proteins first using trichloroacetic acid (TCA) [4]. Add TCA to a final concentration of 10%, incubate on ice for 20 minutes, then centrifuge. Wash the pellet with ice-cold ethanol, dry, and resuspend in SDS-PAGE sample buffer [4].

Electrophoresis

Setup and Loading Mount the polymerized gel in the electrophoresis chamber and fill with running buffer [1]. Carefully rinse wells with buffer to remove unpolymerized acrylamide. Load protein samples and molecular weight markers into the wells using a micropipette [4]. Include a prestained protein ladder in at least one well for molecular weight estimation.

Running Conditions Connect the chamber to the power supply with correct polarity (proteins migrate toward the positive anode) [4]. Run the gel at constant voltage: 80-100V through the stacking gel, then 120-150V through the separating gel until the dye front reaches the bottom [2] [4]. For standard mini-gels, running time is typically 60-90 minutes; for larger formats, 4-6 hours may be required [3].

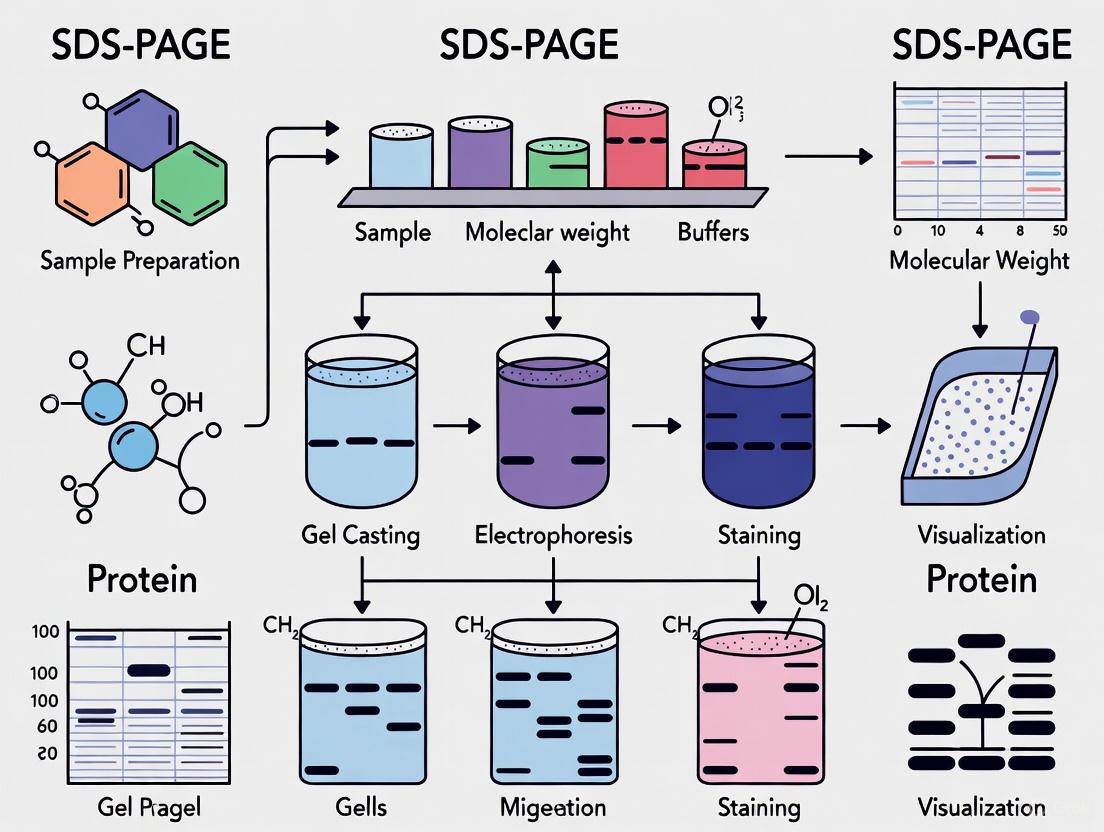

SDS-PAGE Experimental Workflow

Protein Visualization

Coomassie Staining After electrophoresis, carefully remove the gel from the plates and immerse in Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining solution (0.25% Coomassie in 40% ethanol, 10% acetic acid) [3] [4]. Stain with gentle agitation for 30 minutes to several hours. Destain with multiple changes of destaining solution (40% ethanol, 10% acetic acid) until protein bands are clear against a light background [4]. Adding a paper towel to the destaining solution can help absorb excess stain [4].

Alternative Staining Methods For increased sensitivity, silver staining can detect 2-5 ng of protein per band, approximately 50 times more sensitive than Coomassie staining [4]. Fluorescent stains offer broad dynamic range and are ideal for proteomics applications and quantification [2].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Molecular Weight Determination

To estimate the molecular weight of unknown proteins, compare their migration distances to those of standard protein markers [1]. Create a semi-logarithmic plot of the log molecular weight versus migration distance for the standard proteins, which typically produces a linear relationship through which unknown molecular weights can be extrapolated [2].

Assessing Sample Purity

Homogeneous protein samples appear as single, sharp bands after staining, while heterogeneous samples or those containing contaminants show multiple bands [3]. The relative intensity of bands corresponds to protein abundance, with densitometric analysis enabling semi-quantitative comparisons [2].

Molecular Sieving Principle in SDS-PAGE

Advanced Applications and Modifications

Gradient Gels

Gradient gels containing a varying concentration of acrylamide (e.g., 5-20%) provide enhanced resolution for separating proteins across a wide molecular weight range in a single run [2]. The decreasing pore size creates a sieving effect that sharpens protein bands, particularly beneficial for complex samples.

Two-Dimensional Electrophoresis

Two-dimensional electrophoresis combines isoelectric focusing (separation by charge) with SDS-PAGE (separation by molecular weight), enabling the resolution of thousands of proteins in a single analysis [2]. This powerful technique is essential for proteomics research, biomarker discovery, and analysis of post-translational modifications [2].

Western Blotting

SDS-PAGE is frequently coupled with western blotting, where separated proteins are transferred to a membrane and probed with specific antibodies for targeted detection [1] [2]. This combination allows for identification of specific proteins within complex mixtures with high specificity.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Table 4: Troubleshooting Guide for SDS-PAGE

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Smiling or frowning bands | Uneven heating, improper buffer composition, excessive voltage [2] | Ensure even current distribution, check buffer composition, reduce voltage |

| Poor resolution | Incorrect acrylamide percentage, insufficient run time, improper buffer pH [2] | Select appropriate gel percentage, allow complete run, verify buffer preparation |

| Diffuse bands | Incomplete denaturation, protein aggregation, sample overload [2] | Ensure proper heating with reducing agents, centrifuge samples before loading, reduce sample amount |

| Gel polymerization issues | Old reagents, oxygen inhibition, improper TEMED/APS amounts [2] | Use fresh ammonium persulfate, degas solutions, optimize catalyst concentrations |

Comparison with Alternative Techniques

SDS-PAGE vs. Native PAGE

While SDS-PAGE separates denatured proteins solely by molecular weight, Native PAGE maintains proteins in their folded, native state, with separation depending on a combination of size, shape, and intrinsic charge [1] [2]. Native PAGE preserves protein function and biological activity but provides less predictable migration behavior compared to SDS-PAGE.

Other Electrophoretic Techniques

Other protein separation methods include isoelectric focusing (IEF), which separates proteins based on their isoelectric points, and blue native PAGE (BN-PAGE), used for separating intact protein complexes under non-denaturing conditions [2]. Each technique offers unique advantages depending on the research objectives.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) represents a foundational methodology in biochemical research for separating proteins based on their molecular weight. The technique's resolution and reliability hinge critically on the action of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), which transforms native proteins into linearized polypeptides with uniform charge characteristics [6] [7]. This application note delineates the molecular mechanisms by which SDS unfolds proteins and confers negative charge, details experimental protocols for effective implementation, and provides practical considerations for researchers employing this technique in drug development and basic research contexts. Within the broader thesis on SDS-PAGE protocol for protein separation, understanding SDS's fundamental role is paramount for proper experimental design and accurate interpretation of results.

Molecular Mechanisms of SDS-Protein Interactions

Protein Denaturation and Linearization

SDS operates as a strong anionic detergent that fundamentally disrupts the native structure of proteins. It effectively dismantles the secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures of proteins by breaking non-covalent bonds, including hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions [1] [7]. This denaturation process unfolds the compact three-dimensional structure of native proteins, converting them into linear polypeptide chains. The extent of denaturation is concentration-dependent, with unfolding beginning at SDS concentrations above 0.1 mM and most proteins becoming fully denatured above 1 mM [7]. For complete denaturation, samples are typically heated to 95°C for 5 minutes in the presence of SDS-containing buffer to ensure thorough linearization [8] [7].

Table 1: SDS Denaturation Conditions and Effects on Protein Structure

| SDS Concentration | Effect on Protein Structure | Experimental Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| >0.1 mM | Initiation of protein unfolding | Partial denaturation begins |

| >1 mM | Denaturation of most proteins | Loss of secondary/tertiary structure |

| 1-2% (w/v) | Complete denaturation and charge masking | Full linearization for accurate MW separation |

Charge Equilibration and SDS Binding

The binding of SDS to proteins represents a critical aspect of the technique's functionality. SDS molecules bind to the protein backbone via hydrophobic interactions at a relatively constant ratio of approximately 1.4 grams of SDS per 1 gram of protein [7]. This corresponds to approximately one SDS molecule per two amino acid residues in the polypeptide chain [7]. This uniform binding pattern confers a strong negative charge to the protein complex that is directly proportional to the polypeptide chain length [6] [1]. Consequently, the intrinsic charge of the native protein becomes negligible compared to the overwhelming negative charge contributed by SDS, resulting in a consistent charge-to-mass ratio across different protein species [7].

Molecular Dynamics of Unfolding

Recent molecular dynamics simulations have elucidated the microscopic mechanisms of SDS-induced protein unfolding. All-atom simulations conducted at boiling water temperature (373 K) with SDS concentrations of 110-165 mM revealed that SDS induces spontaneous protein unfolding on the microsecond timescale [9] [10]. The unfolding process occurs through two distinct mechanisms: (1) specific interactions of individual SDS molecules with protein structures that disrupt secondary elements, and (2) the formation of protein-SDS complexes in a fluid "necklace-and-beads" configuration where the protein wraps around dynamically changing SDS micelles [9]. The global conformation of the unfolded protein correlates with the number of SDS micelles bound, while the number of directly bound SDS molecules determines the relaxation time scale of the unfolded polypeptide [9] [10].

Figure 1: Molecular Mechanism of SDS-Induced Protein Unfolding. The process involves initial SDS monomer binding, protein linearization, and final complex formation with SDS micelles.

Experimental Protocols for SDS-PAGE

Sample Preparation Protocol

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful protein separation by SDS-PAGE. The following detailed protocol ensures complete protein denaturation and reduction:

Prepare Sample Buffer: Use 2X Laemmli sample buffer containing 4% SDS, 10% glycerol, 0.125 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), and 0.002% bromophenol blue [6] [8].

Add Reducing Agent: Incorporate β-mercaptoethanol (BME) to a final concentration of 0.55 M (1 μL stock BME per 25 μL lysate) or dithiothreitol (DTT) to 10-100 mM final concentration [8] [7]. These reducing agents cleave disulfide bonds critical for proper folding [6] [1].

Mix Samples: Combine protein sample with an equal volume of 2X sample buffer containing reducing agent [8]. Mix thoroughly by flicking the tube or pipetting [6].

Denature Proteins: Heat samples at 95°C for 5 minutes in a heat block or water bath [8] [7]. Alternative protocol: 70°C for 10 minutes [7].

Clarify Samples: Centrifuge at 15,000 rpm for 1-3 minutes at 4°C to pellet any debris [6] [8]. Use the supernatant for SDS-PAGE.

Gel Electrophoresis Procedure

The discontinuous gel electrophoresis system provides superior resolution for protein separation:

- Gel Selection: Choose appropriate acrylamide concentration based on target protein size (Table 2) [6] [8].

Table 2: Polyacrylamide Gel Concentration Guidelines for Optimal Separation

| Acrylamide Concentration | Effective Separation Range | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 6-8% | 50-200 kDa | Suitable for large proteins |

| 10% | 30-100 kDa | Standard separation range |

| 12-15% | 10-60 kDa | Optimal for small proteins |

| 4-20% gradient | 10-200 kDa | Extended separation range |

Electrophoresis Setup:

Post-Electrophoresis Analysis:

Figure 2: SDS-PAGE Experimental Workflow. Key steps include sample denaturation, gel electrophoresis, and post-separation analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of SDS-PAGE requires specific reagents, each performing critical functions in the separation process:

Table 3: Essential Reagents for SDS-PAGE Experimentation

| Reagent | Function | Working Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge [6] [7] | 0.1-0.5% in buffer; 1-2% in sample buffer |

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms polyacrylamide gel matrix that acts as molecular sieve [6] [7] | 5-15% depending on target protein size |

| TEMED and APS | Catalyzes acrylamide polymerization (TEMED) and initiates free radical formation (APS) [1] [7] | 0.1% TEMED; 0.1-0.5% APS |

| Tris-Glycine Buffer | Provides conducting medium and maintains pH during electrophoresis [6] [7] | 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS |

| β-Mercaptoethanol or DTT | Reducing agent that breaks disulfide bonds [1] [8] | 0.55 M BME or 10-100 mM DTT |

| Molecular Weight Markers | Proteins of known size for molecular weight estimation [12] [11] | Varies by manufacturer |

Technical Considerations and Limitations

While SDS-PAGE provides robust protein separation for most applications, researchers should be aware of several technical considerations. Proteins with extensive post-translational modifications, particularly glycosylation, may exhibit anomalous migration due to altered SDS binding capacity [12]. Similarly, membrane proteins with substantial hydrophobic domains or proteins with extreme pI values may not bind SDS in the typical 1.4:1 ratio, leading to deviations in expected mobility [8] [7]. The apparent molecular weight determined by SDS-PAGE typically has an accuracy of ±10% when compared to known standards [12] [7]. For proteins with known deviations from typical SDS binding, complementary methods such as mass spectrometry should be employed for precise molecular weight determination [12].

The critical micelle concentration of SDS (7-10 mM in aqueous solutions) represents another important consideration, as only SDS monomers bind to proteins while micelles remain anionic on the outside and do not adsorb protein [7]. At typical working concentrations of 0.1-0.5% in running buffer (approximately 3.5-17 mM), SDS occurs as both monomers and micelles, ensuring a continuous supply of SDS monomers for protein binding during electrophoresis [7].

Advanced Applications in Research and Drug Development

The fundamental principles of SDS-protein interactions extend beyond basic molecular weight determination to numerous advanced applications. In western blotting, the uniform negative charge imparted by SDS enables efficient protein transfer from gels to membranes for subsequent antibody probing [1] [11]. The denaturing conditions of SDS-PAGE make it indispensable for studying post-translational modifications, where shifts in apparent molecular weight can indicate phosphorylation, glycosylation, or ubiquitination [1]. In drug development contexts, SDS-PAGE provides critical quality control for recombinant protein therapeutics by verifying molecular weight and assessing sample purity [12] [13]. Recent innovations have explored SDS-unfolded proteins for nanopore protein sequencing, where the linearized polypeptide chains translocate through nanopores for amino acid sequence determination [9] [10].

The role of SDS in unfolding proteins and imparting uniform negative charge remains the cornerstone of reliable protein separation by molecular weight. Through its dual mechanisms of protein denaturation and charge equilibration, SDS enables researchers to separate complex protein mixtures with consistent reproducibility. The detailed protocols and technical considerations outlined in this application note provide researchers with the foundational knowledge to implement SDS-PAGE effectively in diverse research settings. As protein analysis continues to evolve in pharmaceutical and academic contexts, understanding these fundamental principles ensures proper experimental design and accurate interpretation of results, forming an essential component of the broader thesis on SDS-PAGE methodology for protein separation.

In the realm of protein biochemistry, the polyacrylamide gel matrix stands as a fundamental tool for achieving high-resolution separation of complex protein mixtures. This matrix serves as the core component of Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), a technique that has become indispensable in molecular biology and biotechnology laboratories worldwide [1]. The gel functions as a molecular sieve, enabling the separation of proteins primarily based on their molecular weight by creating a porous network through which proteins migrate under the influence of an electric field [14]. The development of SDS-PAGE in 1970 by Ulrich Laemmli, who incorporated the anionic detergent SDS into a discontinuous gel electrophoresis system, significantly improved the resolution of protein separation and revolutionized protein analysis [2]. This system remains a cornerstone technique in modern research, particularly valued for its reproducibility, versatility, and ability to provide reliable protein characterization.

The significance of the polyacrylamide gel matrix extends beyond mere separation; it provides the structural framework that permits precise discrimination between proteins of subtly different sizes. When combined with SDS, which denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge, the polyacrylamide gel matrix ensures that separation occurs almost exclusively based on polypeptide chain length rather than native charge or protein shape [6]. This powerful combination has established SDS-PAGE as an essential methodology for various applications, including protein purity assessment, molecular weight estimation, subunit composition analysis, and as a prerequisite technique for western blotting and mass spectrometry [2] [14] [15].

Principles of Molecular Sieving in Polyacrylamide Gels

Gel Composition and Pore Formation

The molecular sieving properties of polyacrylamide gels originate from their precise chemical composition and polymerization process. The gel matrix is formed through the copolymerization of acrylamide monomers and a cross-linking agent, most commonly N,N'-methylenebisacrylamide (Bis) [15]. This polymerization reaction, typically initiated by ammonium persulfate (APS) and catalyzed by N,N,N',N'-tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED), creates a three-dimensional mesh-like network with pores of defined sizes [14] [7]. The relative concentrations of acrylamide and bisacrylamide determine the porosity of the resulting gel, which directly governs its sieving properties and separation capabilities [14].

The pore size within the gel matrix is inversely proportional to the total acrylamide concentration, allowing researchers to tailor the gel composition to separate proteins within specific molecular weight ranges [15]. This tunable porosity is fundamental to the gel's function as a molecular sieve, as it creates a path through which smaller proteins can navigate more easily than larger ones [1]. When an electric field is applied, SDS-coated proteins with uniform charge-to-mass ratios migrate toward the anode, with their movement impeded by the gel matrix in a size-dependent manner [2] [14]. Smaller proteins experience less resistance and migrate faster through the pores, while larger proteins encounter greater frictional forces and migrate more slowly, resulting in distinct separation based on molecular size [14].

Table 1: Relationship Between Gel Percentage and Effective Separation Range

| Acrylamide Concentration (%) | Effective Separation Range (kDa) | Optimal For Proteins |

|---|---|---|

| 6-8% | 50-250 | High molecular weight |

| 10% | 15-100 | Medium molecular weight |

| 12-15% | 5-60 | Low molecular weight |

| 5-20% (Gradient) | 5-250 | Broad molecular weight range |

The Discontinuous Buffer System

SDS-PAGE employs a sophisticated discontinuous buffer system that significantly enhances separation resolution compared to continuous systems [15]. This system utilizes two distinct gel layers with different pore sizes, pH values, and ionic compositions: the stacking gel and the separating (or resolving) gel [14]. The stacking gel, with a lower acrylamide concentration (typically 4-5%) and pH (approximately 6.8), serves to concentrate the protein samples into sharp, narrow bands before they enter the separating gel [1] [14]. This concentration occurs due to differential migration velocities of ions in the discontinuous buffer system, creating a boundary that compresses the protein into thin zones [7].

The separating gel contains a higher acrylamide concentration (typically 7.5-20%) and operates at a higher pH (approximately 8.8) [14]. When proteins transition from the stacking gel to the separating gel, they encounter both a change in pH and a decrease in pore size [15]. The increased pH alters the electrophoretic mobility of glycine ions in the running buffer, which then overtake the proteins and eliminate the stacking effect [7]. As the now-unstacked proteins enter the finer pores of the separating gel, their migration becomes governed solely by molecular sieving, where size-dependent separation occurs [14]. This two-stage process of initial concentration followed by resolution is critical for achieving the high level of separation that makes SDS-PAGE so valuable for protein analysis.

Diagram 1: SDS-PAGE Workflow - Visualization of the protein separation process in discontinuous gel electrophoresis.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for SDS-PAGE

Successful execution of SDS-PAGE requires precise preparation and utilization of specific reagents, each serving a critical function in the separation process. The following table catalogues the essential materials and their roles in the SDS-PAGE methodology.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for SDS-PAGE

| Reagent/Chemical | Function/Purpose | Critical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms the porous gel matrix; bisacrylamide acts as a crosslinker [14] | Ratio typically 37.5:1 or 29:1 (acrylamide:bis); concentration determines pore size |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Anionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge [1] [2] | Binds at ~1.4g per 1g protein; masks intrinsic charge; ensures separation by size only |

| TEMED | Catalyst that accelerates polymerization of acrylamide gel [7] | Used with APS to initiate free radical polymerization; concentration affects gelation time |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | Free radical initiator for acrylamide polymerization [14] | Fresh preparation recommended; decomposes in aqueous solution |

| Tris-HCl Buffer | Maintains pH during electrophoresis; different concentrations for stacking and separating gels [14] | Stacking gel: pH ~6.8; Separating gel: pH ~8.8 |

| Glycine | Component of running buffer; migrates behind proteins in stacking gel, then overtakes in separating gel [7] | Zwitterionic nature crucial for discontinuous buffer system |

| β-mercaptoethanol or DTT | Reducing agent that breaks disulfide bonds [1] [14] | Ensures complete protein denaturation and linearization |

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue | Protein stain for visualization post-electrophoresis [1] | Binds nonspecifically to proteins; detects ~100ng protein |

| Molecular Weight Markers | Prestained or unstained proteins of known size for molecular weight calibration [14] | Enables estimation of unknown protein sizes |

Detailed SDS-PAGE Protocol

Gel Preparation and Casting

The preparation of polyacrylamide gels requires precision and careful handling to ensure reproducible results. The process involves creating two distinct gel layers within a sealed glass plate cassette.

Separating Gel Preparation:

- Assemble Glass Plates: Clean glass plates thoroughly with ethanol and assemble the gel casting cassette using spacers to define gel thickness (typically 0.75mm or 1.5mm) [6].

- Mix Separating Gel Solution: Combine appropriate volumes of acrylamide/bis-acrylamide solution, Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.8), SDS, and deionized water in a flask. The acrylamide concentration should be selected based on the target protein size range (refer to Table 1) [16] [14].

- Initiate Polymerization: Add ammonium persulfate (APS) and TEMED to the solution, mix gently to avoid introducing air bubbles, and immediately pour the solution between the glass plates, leaving space for the stacking gel [7].

- Overlay with Solvent: Carefully layer a small amount of water-saturated butanol or isopropanol over the gel solution to exclude oxygen and create a flat meniscus. Allow polymerization to proceed for 20-30 minutes [7].

- Remove Overlay: After polymerization is complete, pour off the overlay solution and rinse the top of the gel with deionized water to remove any unpolymerized acrylamide [6].

Stacking Gel Preparation:

- Prepare Stacking Gel Solution: Mix acrylamide/bis-acrylamide (typically 4-5%), Tris-HCl buffer (pH 6.8), SDS, and deionized water [14].

- Complete Gel Assembly: Add APS and TEMED to the stacking gel solution, pour over the polymerized separating gel, and immediately insert a clean sample comb without introducing air bubbles. Allow to polymerize for 20-30 minutes [6].

- Final Preparation: Once polymerized, carefully remove the comb and rinse wells with running buffer to remove any unpolymerized acrylamide and gel debris [6].

Table 3: Standard Gel Formulations for Different Protein Size Ranges

| Component | 15% Separating Gel (10 mL) | 10% Separating Gel (10 mL) | Stacking Gel (5 mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide (30%) | 5.0 mL | 3.3 mL | 0.83 mL |

| Tris-HCl (1.5M, pH 8.8) | 2.5 mL | 2.5 mL | - |

| Tris-HCl (0.5M, pH 6.8) | - | - | 1.25 mL |

| 10% SDS | 100 µL | 100 µL | 50 µL |

| Deionized Water | 2.3 mL | 4.0 mL | 2.8 mL |

| 10% APS | 100 µL | 100 µL | 50 µL |

| TEMED | 10 µL | 10 µL | 10 µL |

| Effective Range | 5-60 kDa | 15-100 kDa | N/A |

Sample Preparation and Electrophoresis

Proper sample preparation is critical for achieving accurate separation in SDS-PAGE, as incomplete denaturation can lead to aberrant migration.

Sample Preparation Protocol:

- Combine with Sample Buffer: Mix protein sample with 2X or 5X SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing Tris-HCl, SDS, glycerol, bromophenol blue, and a reducing agent (β-mercaptoethanol or DTT) [2] [14]. Typical ratio is 1:1 for 2X buffer.

- Denature Proteins: Heat samples at 95-100°C for 5 minutes in a heat block to ensure complete denaturation [7]. For temperature-sensitive proteins, 70°C for 10 minutes may be used as an alternative [7].

- Brief Centrifugation: Centrifuge heated samples at 15,000 rpm for 1 minute to collect condensation and any insoluble material [6].

Electrophoresis Execution:

- Assemble Apparatus: Place the polymerized gel in the electrophoresis chamber and fill both upper and lower chambers with running buffer (typically Tris-glycine-SDS buffer) [1] [14].

- Load Samples: Carefully load prepared protein samples and molecular weight markers into wells using a micropipette [6]. Include appropriate positive controls and molecular weight standards.

- Apply Electric Field: Connect the chamber to a power supply and run at constant voltage. For mini-gels, 80-100 V through the stacking gel and 120-150 V through the separating gel is typical [2]. Run until the bromophenol blue tracking dye reaches the bottom of the gel (approximately 1-1.5 hours) [1].

- Terminate Electrophoresis: Turn off power supply once separation is complete. Proceed to protein visualization or transfer for western blotting.

Advanced Applications and Modifications

Gradient Gels and Two-Dimensional Electrophoresis

For complex protein mixtures or samples containing proteins with widely varying molecular weights, gradient gels provide superior resolution across a broad size range [2]. These gels contain an increasing concentration of acrylamide from top to bottom (typically 5-20% gradients), creating a pore size gradient that simultaneously resolves both high and low molecular weight proteins [15]. As proteins migrate through gradient gels, they progressively encounter smaller pores, causing each protein to migrate until it reaches a pore size that restricts further movement, resulting in sharp, well-defined bands across the entire molecular weight spectrum [2].

For even higher resolution analysis of complex protein samples, two-dimensional electrophoresis combines isoelectric focusing (IEF) with SDS-PAGE [17]. In this technique, proteins are first separated based on their isoelectric point in a pH gradient, then subsequently separated by molecular weight in the second dimension using SDS-PAGE [2]. This orthogonal separation approach can resolve thousands of protein isoforms in a single gel, making it particularly valuable for proteomic studies, analysis of post-translational modifications, and biomarker discovery [2].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Even with careful execution, various issues can arise during SDS-PAGE that affect result quality. The following flowchart outlines common problems and their solutions.

Diagram 2: SDS-PAGE Troubleshooting Guide - Diagnostic flowchart for common electrophoresis issues.

The polyacrylamide gel matrix remains an indispensable tool in modern biological research, providing the molecular sieving properties necessary for high-resolution protein separation by size. Through its tunable porosity, customizable composition, and compatibility with denaturing agents like SDS, this matrix enables precise characterization of protein samples across diverse applications from basic research to clinical diagnostics. The well-established protocols for gel preparation, sample processing, and electrophoresis continue to make SDS-PAGE an accessible yet powerful technique for researchers studying protein structure, function, and expression.

While emerging technologies like capillary electrophoresis offer advantages in automation and quantification, the visual clarity, simplicity, and cost-effectiveness of traditional SDS-PAGE ensure its continued relevance in laboratory workflows [18]. Furthermore, the integration of SDS-PAGE with downstream applications such as western blotting, mass spectrometry, and protein sequencing underscores its foundational role in comprehensive protein analysis pipelines [1] [14]. As protein science advances, the polyacrylamide gel matrix will undoubtedly continue to serve as a critical platform for separation and analysis, adapting to new research needs while maintaining its core principle of molecular sieving for size-based separation.

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) is a foundational technique in biochemistry and molecular biology for separating proteins based on their molecular weight [7] [15]. The robustness and reproducibility of this method stem from three core components that work in concert: the anionic detergent SDS, reducing agents, and a discontinuous buffer system. Together, these elements denature proteins, mask their intrinsic charges, and orchestrate their migration through a polyacrylamide gel matrix under an electric field, enabling precise separation by size [19] [20]. This application note details the principles, protocols, and practical considerations for employing these key components effectively within the context of protein separation research for drug development and other scientific applications.

Core Principles and Components

The efficacy of SDS-PAGE relies on the specific functions of its core components, which together ensure that protein migration is dependent solely on polypeptide chain length.

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS)

SDS is an anionic detergent that serves two critical functions in protein denaturation. Firstly, it disrupts nearly all non-covalent interactions—including hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and ionic bonds—thereby unraveling the secondary and tertiary structures of proteins [15] [20]. Secondly, SDS binds uniformly to the unfolded polypeptide chains at an approximate ratio of 1.4 g of SDS per 1 g of protein [19] [7] [15]. This extensive binding confers a uniform negative charge density along the protein backbone, effectively masking the proteins' intrinsic charges [19]. The resulting SDS-protein complexes are linear molecules, all with similar charge-to-mass ratios, ensuring that their electrophoretic mobility is determined primarily by molecular size [19].

Reducing Agents

To achieve complete denaturation and linearization, reducing agents are essential for cleaving disulfide bonds, which are covalent linkages that stabilize tertiary and quaternary structures. Common reducing agents include:

- β-Mercaptoethanol (β-ME) at concentrations of 4-5% [20] or Dithiothreitol (DTT) at 10-100 mM [7]. These compounds break disulfide bridges, ensuring that multi-subunit proteins are dissociated into their individual polypeptides [15] [21]. The inclusion of a reducing agent is a critical step, as without it, proteins may not fully unfold, leading to anomalous migration and inaccurate molecular weight estimation [20].

The Discontinuous Buffer System

The discontinuous (or disc) buffer system, pioneered by Laemmli, is a key innovation that sharpens protein bands at the start of electrophoresis, greatly enhancing resolution [19] [7]. This system employs buffers of different pH and composition in the stacking gel, separating gel, and electrode chambers.

The mechanism hinges on the differential mobility of ions. In the stacking gel (pH ~6.8), the glycine ions from the Tris-glycine running buffer exist predominantly in a zwitterionic state, migrating slowly [19] [20]. Chloride ions (Cl⁻) from Tris-HCl move rapidly, while the SDS-coated proteins possess an intermediate mobility. This setup creates a narrow, high-voltage gradient zone that forces all protein species to focus into a sharp band before they enter the separating gel [19]. Upon reaching the separating gel (pH ~8.8), the glycine ions become predominantly negatively charged, overtake the proteins, and leave them to separate by molecular weight as they migrate through the sieving matrix of the polyacrylamide gel [19] [20].

Table 1: Composition of the Discontinuous Buffer System

| Component | Buffer & pH | Key Ions & Their Role | Gel Pore Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stacking Gel | Tris-HCl, pH ~6.8 [19] [20] | Cl⁻ (leading ion), glycine (trailing ion) [19] | Large pores, no sieving [19] |

| Separating Gel | Tris-HCl, pH ~8.8 [19] [20] | Glycine now mobile; proteins separate by size [19] | Small pores, molecular sieving [19] [15] |

| Running Buffer | Tris-glycine, pH ~8.3 [7] [20] | Provides glycine and completes circuit [19] | N/A |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the process of protein separation using SDS-PAGE, from sample preparation to final analysis:

Diagram 1: SDS-PAGE Experimental Workflow

Detailed Protocols and Methodologies

Sample Preparation Protocol

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful protein separation.

- Sample Dilution: Mix the protein sample with an equal volume of 2X SDS-PAGE sample loading buffer. A typical 2X loading buffer contains:

- SDS: 2-4% (w/v) for denaturation and charge masking [8] [20].

- Reducing Agent: 5% β-mercaptoethanol or 100 mM DTT to reduce disulfide bonds [8] [21].

- Glycerol: 10% (v/v) to add density for gel loading [20] [21].

- Bromophenol Blue: A tracking dye to monitor electrophoresis progress [20] [21].

- Tris-HCl Buffer: ~62.5 mM, pH ~6.8 [20].

- Denaturation: Heat the mixture at 95°C for 5 minutes (or 70°C for 10 minutes) to ensure complete denaturation and disruption of protein complexes [7] [8].

- Clarification: Centrifuge the heated samples briefly (e.g., 3 minutes in a microcentrifuge) to pellet any insoluble debris [8].

- Loading: Load the supernatant into the wells of the polyacrylamide gel. For a standard mini-gel, loading volumes typically range from 5–35 µL per lane [8].

Gel Preparation and Electrophoresis

Polyacrylamide gels are formed by the polymerization of acrylamide and a cross-linker, N,N'-methylenebisacrylamide (Bis), catalyzed by ammonium persulfate (APS) and TEMED [7] [15]. The gel percentage must be chosen based on the target protein's size.

Table 2: Recommended Acrylamide Concentrations for Target Protein Sizes

| Acrylamide Concentration (%) | Effective Separation Range (kDa) | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 5% | 100 - 500 [8] | For very high molecular weight proteins |

| 7.5% | 50 - 250 [19] | Broad range separation |

| 10% | 20 - 300 [19] | Standard range for many proteins |

| 12% | 10 - 200 [19] | Standard range for many proteins |

| 15% | 3 - 100 [19] | For low molecular weight proteins and peptides |

Gel Casting and Running Procedure:

- Assemble the gel cassette according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Prepare the separating gel by mixing components as detailed in the table below. Pour the solution into the cassette, leaving space for the stacking gel. Layer with isopropanol or water to create a flat interface and wait for polymerization (~30 minutes) [20].

- Prepare the stacking gel after discarding the sealing layer. Pour it on top of the polymerized separating gel and immediately insert a sample comb. Allow it to polymerize fully (~30 minutes) [20].

- Assemble the electrophoresis unit and fill the inner and outer chambers with 1X running buffer (e.g., Tris-glycine with 0.1% SDS) [8] [20].

- Load prepared samples and molecular weight standards into the wells.

- Run the gel by applying a constant voltage: 60-80V through the stacking gel, then increase to 120-200V for the separating gel. Run until the dye front reaches the bottom [8] [21].

- Post-processing: After electrophoresis, proteins can be visualized by staining (e.g., Coomassie Blue, silver stain) or transferred to a membrane for western blotting [21].

Table 3: Example Gel Formulations for Discontinuous SDS-PAGE

| Reagent | 10% Separating Gel (20 mL) | 15% Separating Gel (20 mL) | 3% Stacking Gel (10 mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30% Acrylamide-Bis Solution | 6.66 mL [20] | 10 mL [20] | 1 mL [20] |

| Separating Gel Buffer (Tris-HCl, pH 8.8) | 2.5 mL [20] | 2.5 mL [20] | - |

| Stacking Gel Buffer (Tris-HCl, pH 6.8) | - | - | 1.25 mL [20] |

| 10% SDS | 0.2 mL [20] | 0.2 mL [20] | 0.1 mL [20] |

| Deionized Water | 8.54 mL [20] | 5.2 mL [20] | 5.6 mL [20] |

| 10% Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | 0.1 mL [20] | 0.1 mL [20] | 0.05 mL [20] |

| TEMED | 2 µL [20] | 2 µL [20] | 2 µL [20] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogs the essential materials required for executing a successful SDS-PAGE experiment.

Table 4: Essential Reagents for SDS-PAGE

| Reagent/Material | Function & Role in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Anionic detergent; denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge [19] [15]. |

| Reducing Agents (DTT, β-ME) | Cleaves disulfide bonds to fully linearize proteins [15] [20]. |

| Acrylamide / Bis-Acrylamide | Monomer and cross-linker that polymerize to form the sieving gel matrix [7] [15]. |

| Tris Buffers | Provides the buffering environment at different pHs (6.8 and 8.8) for the discontinuous system [19] [20]. |

| Glycine | Component of the running buffer; its charge-state change is key to the stacking effect [19] [7]. |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) & TEMED | Catalyst and stabilizer for the free-radical polymerization of acrylamide [7] [20]. |

| Molecular Weight Markers | Pre-stained or unstained proteins of known sizes for estimating sample protein molecular weights [8] [21]. |

The precise interplay of SDS, reducing agents, and the discontinuous buffer system is what makes SDS-PAGE a uniquely powerful and enduring technique for protein analysis. Mastery of these components—understanding their specific roles, optimal concentrations, and handling protocols—is fundamental for obtaining reliable, high-resolution separation of proteins by molecular weight. This knowledge forms the bedrock for countless downstream applications in research and drug development, from western blotting and protein purification to expression profiling and purity assessment.

The Laemmli system of sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) represents a foundational methodology in biochemical research, enabling precise protein separation by molecular weight. This discontinuous electrophoretic system, developed by Ulrich K. Laemmli, employs a sophisticated buffer and pH configuration to concentrate protein samples before separation, significantly enhancing resolution. Within the context of molecular weight determination for drug development and basic research, understanding the distinct yet complementary functions of the stacking and resolving gel components remains critical for experimental success. This application note delineates the theoretical principles underpinning the Laemmli system, provides detailed protocols for its implementation, and discusses key considerations for researchers employing this technique in protein characterization.

SDS-PAGE is an indispensable technique that allows protein separation by molecular mass, typically in the range of 5 to 250 kDa [7]. The method relies on the anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), which binds to proteins at approximately 1.4 grams SDS per gram of protein, effectively masking their intrinsic charge and conferring a uniform negative charge density [7]. This process, combined with protein denaturation, ensures that separation occurs primarily based on molecular size rather than charge or structural characteristics. The Laemmli system, introduced in 1970, implements a discontinuous buffer system that significantly improves resolution compared to continuous electrophoresis methods. This system's elegant exploitation of differences in pore size, ionic strength, and pH values between gel regions enables the precise analysis of complex protein mixtures, making it the standard approach for protein separation in most molecular biology and biochemistry laboratories [7] [22].

Theoretical Framework: The Discontinuous System

Principles of Operation

The hallmark of the Laemmli system is its discontinuous nature, employing different buffer compositions and pH levels in the stacking versus resolving gel regions. This configuration creates a dramatic stacking effect at the interface between the two gels, resulting in the concentration of protein samples into extremely sharp bands before they enter the separating gel. The system operates through the strategic use of three ions: chloride (Cl⁻) from the gel buffer, glycine (Gly⁻) from the running buffer, and the common Tris⁺ cation present throughout the system [22]. During electrophoresis, the highly mobile chloride ions migrate rapidly toward the anode, forming the "leading" ion front. The glycine ions, which exist in a zwitterionic form with a net charge that varies with pH, initially migrate more slowly as the "trailing" ions. The proteins, with their intermediate mobility under the stacking gel conditions, become compressed between these two ion fronts, resulting in the concentration of dilute protein samples into sharp, well-defined zones.

The Role of pH in Ion Mobility

The discontinuous pH environment is fundamental to the stacking phenomenon. The stacking gel typically maintains a neutral pH (approximately pH 6.8), while the separating gel operates at a basic pH (approximately pH 8.8) [7]. At the neutral pH of the stacking gel, glycine molecules predominantly exist as zwitterions with a net charge接近 zero, resulting in low electrophoretic mobility. In contrast, upon reaching the basic pH of the separating gel, glycine molecules lose positive charges and become predominantly anionic, significantly increasing their mobility. This transition causes the former trailing ions (glycinate) to overtake the proteins, eliminating the stacking effect and allowing molecular sieving to become the dominant separation mechanism in the resolving gel [7].

Visualization of the Stacking Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates the stepwise process of protein stacking and separation in the Laemmli system:

Materials and Reagent Solutions

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents required for implementing the Laemmli SDS-PAGE system, along with their specific functions in the electrophoretic process:

| Reagent | Composition/Concentration | Function in Laemmli System |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | 30% (w/w), typically 37.5:1 or 29:1 ratio | Forms polyacrylamide gel matrix; concentration determines pore size for molecular sieving [23] [5] |

| Tris-HCl Buffers | 1.5 M pH 8.8 (resolving), 0.5 M pH 6.8 (stacking) | Establishes pH discontinuity; primary buffer component for both gel types [23] |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | 10-20% (w/v) stock solution, 0.1% in gels | Denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge; critical for separation by size [7] |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | 10% (w/v) aqueous solution | Free radical initiator for acrylamide polymerization [23] |

| TEMED | N,N,N',N'-Tetramethylethylenediamine | Catalyzes polymerization by generating free radicals from APS [23] |

| Glycine | 0.96 M in 5X running buffer | Trailing ion in stacking gel; mobility changes with pH transition [23] [22] |

| Sample Buffer | Tris-HCl, glycerol, SDS, bromophenol blue, ß-mercaptoethanol or DTT | Denatures proteins, provides density for loading, and visual tracking [23] |

Gel Percentage Selection Guide

The appropriate acrylamide concentration in the resolving gel must be selected based on the molecular weights of the target proteins, as detailed in the following table:

| Protein Size Range (kDa) | Recommended Acrylamide Percentage | Separation Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| 4-40 | 20% | Optimal for very low molecular weight proteins and peptides |

| 12-45 | 15% | High resolution for small to medium proteins |

| 10-70 | 12.5% | Broad range for routine applications |

| 15-100 | 10% | Standard range for most research applications |

| 25-200 | 8% | Suitable for high molecular weight proteins [5] |

For proteins falling outside these standard ranges, gradient gels (e.g., 4-20% acrylamide) provide an extended separation range and are particularly valuable for complex samples with diverse molecular weights [7].

Experimental Protocol: Laemmli SDS-PAGE

Gel Preparation Protocol

Resolving Gel Solution

The following protocol is adapted for preparing four 0.75-mm thick mini-gels, with adjustments provided for different percentages and formats [23] [5]:

- Assemble glass plates in casting apparatus, ensuring a tight seal to prevent leakage.

- Prepare resolving gel mixture according to the table below, adding TEMED and APS last to initiate polymerization:

| Component | 8% Gel | 10% Gel | 12% Gel | 15% Gel |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30% Acrylamide/Bis | 4.0 mL | 5.0 mL | 6.0 mL | 7.5 mL |

| 1.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.8) | 3.75 mL | 3.75 mL | 3.75 mL | 3.75 mL |

| 10% SDS | 150 µL | 150 µL | 150 µL | 150 µL |

| H₂O | 7.0 mL | 5.9 mL | 4.9 mL | 3.4 mL |

| 10% APS | 75 µL | 75 µL | 75 µL | 75 µL |

| TEMED | 7.5 µL | 7.5 µL | 7.5 µL | 7.5 µL |

| Total Volume | 15 mL | 15 mL | 15 mL | 15 mL |

- Pour resolving gel immediately after adding TEMED and APS, leaving approximately 2.5 cm below the top of the plates for the stacking gel.

- Overlay with isopropanol or water-saturated butanol to exclude oxygen and create a flat meniscus.

- Allow polymerization for 30-45 minutes at room temperature until a distinct interface forms.

Stacking Gel Solution

After resolving gel polymerization:

- Decant and rinse the isopropanol overlay with deionized water; remove residual liquid completely.

- Prepare stacking gel solution using the following formulation for four mini-gels:

| Component | Volume |

|---|---|

| 0.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8) | 3.78 mL |

| 30% Acrylamide/Bis | 1.98 mL |

| 10% SDS | 150 µL |

| H₂O | 9 mL |

| 10% APS | 75 µL |

| TEMED | 15 µL |

| Total Volume | 15 mL |

- Pour stacking gel immediately over the resolving gel.

- Insert sample comb carefully, avoiding bubble formation beneath the teeth.

- Allow complete polymerization for 30-45 minutes before use [23] [5].

Sample Preparation and Electrophoresis

Protein Sample Denaturation

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful separation:

- Mix protein sample with an equal volume of 2X SDS sample buffer (typically containing: 0.5 M Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 10% glycerol, 2% SDS, 5% β-mercaptoethanol or 100 mM DTT, and 0.01% bromophenol blue) [23].

- Denature samples by heating at 95-100°C for 3-5 minutes, or alternatively at 70°C for 10 minutes [7] [23].

- Cool samples to room temperature and briefly centrifuge to collect condensation.

Critical Considerations:

- For membrane proteins or difficult-to-solubilize samples, include 8M urea in the sample buffer [23].

- Avoid heating samples containing certain membrane proteins that may aggregate at high temperatures; instead, incubate at 40°C for 30 minutes [23].

- Remove potassium ions from samples, as they can precipitate SDS [23].

Electrophoresis Conditions

- Assemble gel apparatus according to manufacturer's instructions, ensuring proper orientation.

- Load samples alongside appropriate molecular weight markers in adjacent lanes.

- Fill electrode chambers with Tris-glycine-SDS running buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.3) [23].

- Apply constant voltage: 125 V for mini-gels (approximately 90 minutes runtime) until the bromophenol blue tracking dye reaches the gel bottom [22].

- Terminate electrophoresis and process gel for staining or western blotting.

Technical Variations and Modifications

Alternative Buffer Systems

While the Tris-glycine buffer system remains standard for Laemmli SDS-PAGE, several modifications have been developed for specialized applications:

- Tris-Tricine System: Developed by Schägger and von Jagow for improved resolution of low molecular weight proteins (0.5-50 kDa) [7] [24]. This system substitutes glycine with tricine as the trailing ion, which does not interfere with protein sequencing and provides better separation of small peptides.

- Bis-Tris System: Used in commercial pre-cast gels with a nearly neutral pH (6.4-7.2), offering enhanced stability and reduced protein modification, particularly for cysteine residues [7].

- Continuous Systems: Simplified systems using the same buffer throughout the gel and electrode chambers, though with reduced resolution compared to discontinuous systems [25].

Gel Staining and Visualization

Following electrophoresis, multiple protein detection methods are available:

- Coomassie Brilliant Blue Staining: Standard method with detection limits of approximately 10-100 ng/protein band. Typical protocols involve fixing (50% methanol, 10% acetic acid), staining (0.25% Coomassie R-250 in 50% methanol, 10% acetic acid), and destaining (15% methanol, 10% acetic acid) [23].

- Silver Staining: 10-100 times more sensitive than Coomassie staining, capable of detecting 0.1-1.0 ng protein per band.

- Specialized Stains: Fluorescent dyes, zinc-reverse staining, and specific glycoprotein or phosphoprotein detection methods.

- Western Blotting: Transfer to membranes for immunodetection with specific antibodies.

Applications in Research and Drug Development

The Laemmli SDS-PAGE system serves as a fundamental tool across multiple research domains, providing critical protein characterization data. In drug development, the technique enables assessment of protein drug purity, stability, and integrity throughout purification and formulation processes. The method's ability to detect protein degradation, aggregation, or post-translational modifications makes it invaluable for quality control of biopharmaceuticals. In basic research, SDS-PAGE facilitates protein expression analysis, subunit composition determination, verification of homogeneity in purified samples, and preparation for downstream applications including protein sequencing, mass spectrometry, and antibody production [12] [25]. The technique's robust nature, reproducibility, and relative simplicity have maintained its position as an essential methodology in life science research for over five decades, despite the development of more sophisticated analytical technologies.

Executing the Perfect Run: A Step-by-Step SDS-PAGE Protocol

In the molecular biology laboratory, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) stands as a fundamental technique for separating protein mixtures according to their molecular weights. The success of this separation hinges on the precise casting of polyacrylamide gels with well-defined structural and electrical properties. This process relies on a sophisticated polymerization reaction catalyzed by the critical pair of tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED) and ammonium persulfate (APS). These catalysts drive the formation of the mesh-like matrix that separates proteins based on size. This application note provides detailed protocols and formulations for the consistent preparation of stacking and resolving gels, focusing specifically on the optimal use of TEMED and APS to achieve reliable, reproducible results for research and drug development applications. Mastery of this fundamental technique ensures the generation of high-quality data in downstream analyses such as western blotting and protein characterization.

Background Principles

The Chemistry of SDS-PAGE Gel Polymerization

The formation of a polyacrylamide gel is a process of free radical-induced polymerization, creating a cross-linked matrix with predictable pore sizes. Acrylamide monomers form the linear backbone of the polymer, while bis-acrylamide crosslinks these chains, creating a three-dimensional network. The pore size of this network is determined by the ratio and total concentration of these two components; higher percentages of acrylamide create smaller pores, ideal for resolving lower molecular weight proteins.

The polymerization reaction is initiated by a pair of catalysts: Ammonium persulfate (APS) and Tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED). APS, when dissolved in water, decomposes to produce sulfate free radicals. TEMED functions as a chemical accelerator by catalyzing the decomposition of the persulfate radical, thereby dramatically increasing the rate of radical generation. These free radicals then activate the acrylamide monomers, initiating a chain reaction that propagates until the gel is fully polymerized. The concentrations of APS and TEMED are critical parameters that must be optimized; excessive amounts can lead to rapid, inefficient polymerization and distorted gel structures, while insufficient amounts result in delayed or incomplete gel formation [5] [26].

The Function of Stacking versus Resolving Gels

SDS-PAGE employs a discontinuous gel system to achieve sharp, well-resolved protein bands. This system consists of two distinct layers:

The Resolving Gel (also called the separating gel): This lower portion of the gel contains a higher percentage of acrylamide (typically between 8% and 15%) and is buffered at Tris-HCl, pH 8.8. Its function is to separate denatured proteins based solely on their molecular weight as they migrate through the sieving matrix. The appropriate acrylamide percentage is selected based on the molecular weight range of the target proteins, as detailed in Table 1 [5] [27].

The Stacking Gel: This upper portion is composed of a low-percentage acrylamide (usually 4% or 5%) and is buffered at a lower pH (Tris-HCl, pH 6.8). Its primary purpose is not to separate, but to concentrate all protein samples into a sharp, unified band before they enter the resolving gel. This "stacking" effect, achieved through differences in ion mobility and buffer pH, ensures that all proteins enter the resolving gel at the same time, leading to sharper bands and higher resolution [5].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete process of hand-casting an SDS-PAGE gel, from preparation to the final polymerized product:

Reagents and Materials

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful gel casting requires precise preparation and understanding of all component solutions. The following table details the essential reagents, their standard formulations, and their critical functions within the SDS-PAGE gel system.

Table 1: Essential Reagents for SDS-PAGE Gel Casting

| Reagent | Standard Composition / Concentration | Primary Function in Gel Formulation |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | 30% or 40% (w/v) solution; common bis ratio 37.5:1 or 29:1 [5] [27] | Forms the backbone of the polyacrylamide matrix. The total concentration (%) determines pore size and resolving range. |

| Tris-HCl Buffer | 1.5 M, pH 8.8 (Resolving Gel)0.5 M, pH 6.8 (Stacking Gel) [5] [26] | Provides the appropriate pH environment for electrophoresis and is critical for the discontinuous buffer system. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | 10% (w/v) solution [5] [26] | Imparts uniform negative charge to proteins, masking their intrinsic charge and allowing separation by size. |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | 10% (w/v) solution in water [5] [28] | Initiator. Decomposes to provide sulfate free radicals required to begin the polymerization chain reaction. |

| TEMED | Liquid, 99% purity [5] [26] | Catalyst. Accelerates the decomposition of APS into free radicals, controlling the rate of polymerization. |

| Isopropanol | >99% purity [5] [26] | Used to overlay the resolving gel to exclude oxygen and ensure a flat, even polymerization surface. |

Key Considerations for Reagent Preparation

- Acrylamide Toxicity: Acrylamide monomer is a potent neurotoxin and suspected carcinogen. Always wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) including gloves and safety goggles when handling, and dispose of waste according to institutional safety guidelines [28].

- APS Solution Stability: A 10% (w/v) APS solution must be prepared fresh daily for consistent and reliable polymerization performance. The accumulation of water in stored liquid APS causes a rapid loss of reactivity, leading to failed or inconsistent gel polymerization [26].

- TEMED Handling: TEMED is volatile and has a strong, unpleasant odor. It should be handled in a fume hood and the bottle tightly sealed after use [26]. It is highly hygroscopic, so drawing it up quickly is advised.

Detailed Protocols and Formulations

Formulating the Resolving Gel

The resolving gel is the workhorse of the separation. The appropriate acrylamide percentage must be selected based on the molecular weight of the target proteins to achieve optimal resolution. The table below provides a standardized recipe and serves as a guide for selecting the correct gel percentage.

Table 2: Resolving Gel Formulation for a 15 mL Gel (Adaptable for 4 mini-gels, ~0.75 mm thick) [5] [26] [27]

| Component | Final Acrylamide Percentage in Resolving Gel | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8% | 10% | 12% | 15% | |

| 30% or 40% Acrylamide/Bis | 4.0 mL [30%] | 5.0 mL [30%] | 6.0 mL [30%] | 7.5 mL [30%] |

| or 3.0 mL [40%] | or 3.75 mL [40%] | or 4.5 mL [40%] | or 5.63 mL [40%] | |

| 1.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.8 | 3.75 mL | 3.75 mL | 3.75 mL | 3.75 mL |

| 10% (w/v) SDS | 150 µL | 150 µL | 150 µL | 150 µL |

| Deionized H(_2)O | 7.0 mL | 5.95 mL | 4.95 mL | 3.45 mL |

| 10% APS (Fresh) | 75 µL | 75 µL | 75 µL | 75 µL |

| TEMED | 7.5 µL | 7.5 µL | 7.5 µL | 7.5 µL |

Table 3: Guide for Selecting Resolving Gel Percentage Based on Protein Size [5] [27]

| Target Protein Size (kDa) | Recommended Acrylamide Percentage |

|---|---|

| 4 - 40 | 20% |

| 12 - 45 | 15% |

| 10 - 70 | 12.5% |

| 15 - 100 | 10% |

| 25 - 200 | 8% |

Protocol: Casting the Resolving Gel

- Clean and Assemble: Thoroughly clean the short and spacer glass plates with a laboratory detergent, rinse with deionized water, and wipe with 70% ethanol. Assemble the glass plate sandwich securely within the casting module according to the manufacturer's instructions, ensuring a leak-proof seal [28] [26].

- Mix Base Solution: In a clean 15 mL conical tube, combine all the reagents for the chosen resolving gel percentage except for APS and TEMED. Mix the solution gently by inverting the tube to avoid introducing air bubbles, which can inhibit polymerization [5].

- Add Polymerization Catalysts: Immediately before pouring, add the freshly prepared 10% APS to the mixture, followed immediately by TEMED. Mix gently but swiftly. Critical Step: Once APS and TEMED are added, polymerization begins rapidly; work efficiently [26].

- Pour the Gel: Using a serological pipette or plastic Pasteur pipette, transfer the resolving gel solution into the gap between the glass plates. Fill to a level that leaves approximately 2.5 cm (or the height of the comb's teeth) below the top of the shorter plate [5].

- Overlay and Polymerize: Gently layer isopropanol or water-saturated butanol on top of the unpolymerized gel solution to exclude air and create a flat, even surface. Allow the gel to polymerize completely for 30-45 minutes at room temperature. Polymerization is complete when a distinct schlieren line is visible between the polymerized gel and the overlay [5] [27].

- Remove Overlay: After polymerization, pour off the isopropanol overlay. Rinse the top of the gel thoroughly with deionized water to remove any residual alcohol. Wick away the excess water completely using a lint-free tissue or filter paper [5] [28].

Formulating and Casting the Stacking Gel

The stacking gel is poured immediately after the resolving gel has been prepared. The following table provides a standard 4% or 5% stacking gel recipe.

Table 4: Stacking Gel Formulation for a 5 mL Gel (Sufficient for 2-4 mini-gels) [5] [26] [27]

| Component | 4% Stacking Gel | 5% Stacking Gel |

|---|---|---|

| 30% or 40% Acrylamide/Bis | 0.67 mL [30%] | 0.83 mL [30%] |

| or 0.5 mL [40%] | or 0.625 mL [40%] | |

| 0.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8 | 1.25 mL | 1.25 mL |

| 10% (w/v) SDS | 50 µL | 50 µL |

| Deionized H(_2)O | 3.0 mL | 2.84 mL |

| 10% APS (Fresh) | 25 µL | 25 µL |

| TEMED | 5 µL | 5 µL |

Protocol: Casting the Stacking Gel

- Prepare Stacking Gel Solution: In a clean tube, combine all stacking gel reagents except APS and TEMED. This can be done while the resolving gel is polymerizing to save time [5].

- Add Catalysts and Pour: Once the resolving gel is ready and the overlay has been removed and dried, add 10% APS and TEMED to the stacking gel solution. Mix quickly and pour the solution directly onto the top of the polymerized resolving gel. Fill the cassette completely [28].

- Insert the Comb: Carefully insert a clean, dry comb into the liquid stacking gel, ensuring that no air bubbles are trapped under the teeth. The comb should be inserted at a slight angle to minimize bubbles. The stacking gel will polymerize in 20-30 minutes [5] [26].

- Final Preparation: Once polymerized, carefully remove the comb by pulling it straight up in a slow, steady motion. Immediately rinse the resulting wells with deionized water or running buffer to remove any unpolymerized acrylamide and debris [26]. The gel is now ready for immediate use or can be stored appropriately.

Critical Factors for Success and Troubleshooting

Optimization of TEMED and APS

The polymerization process is highly dependent on the correct use of APS and TEMED. An experiment testing the feasibility of creating a pre-mixed APS/TEMED aliquot demonstrated that gels only polymerized successfully when APS and TEMED were added separately to the gel solution just before casting. The pre-mixed aliquot failed to initiate polymerization, indicating that the reactive species required for initiation are short-lived [29]. This underscores the importance of the standard protocol.

- Catalyst Addition Order: Always add APS first, followed immediately by TEMED. This sequence ensures the efficient generation of free radicals.

- Freshness of APS: As emphasized, always use a freshly prepared 10% APS solution. Older solutions lose potency and are a primary cause of failed or delayed polymerization [26].

- Adjusting Polymerization Speed: The gel polymerization rate is temperature-dependent and can be controlled by the amount of TEMED and APS. To slow polymerization (e.g., for handling multiple gels or complex setups), reduce the amount of TEMED. To accelerate it (e.g., in cold rooms), slightly increase the amounts of both catalysts.

Gel Storage and Stability

Hand-cast gels can be stored for short periods. To store gels, wrap the polymerized gel (still in its cassette) in moistened tissue paper that has been soaked in deionized water and squeezed out. Then, seal the entire package in cling film to prevent dehydration. Label the package with the gel percentage, date, and thickness, and store it at 4°C. It is not recommended to store hand-cast gels for more than one week, as the gel matrix may deteriorate and affect electrophoretic performance [5] [26].

Troubleshooting Common Polymerization Issues

- Gel does not polymerize or polymerizes too slowly: The most common cause is degraded APS. Prepare a fresh 10% APS solution. Also, ensure TEMED has not been stored improperly and is not old.

- Gel polymerizes too quickly, leading to streaks or distortions: This is often due to excessive amounts of TEMED and/or APS, or a high ambient temperature. Pre-chill the gel solutions on ice before adding catalysts and/or slightly reduce the volume of TEMED added.

- Wavy or uneven gel surface: This can result from improper mixing of the gel solution after adding APS/TEMED, or from failing to overlay the resolving gel with a smoothing solvent like isopropanol [5].

- Leaking wells or collapsed wells: Leaking wells can occur if the gel cassette was not assembled tightly. Collapsed wells often result from using an old or damaged comb, or from removing the comb too forcefully or at an angle. Always remove the comb slowly and vertically [5].

In molecular biology and biochemistry, the accurate separation and analysis of proteins is a foundational technique. Sodium Dodecyl Sulphate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) stands as the cornerstone method for separating proteins based primarily on their molecular weight [1] [30]. The reliability and resolution of this technique are critically dependent on the complete denaturation of protein samples into their constituent polypeptide chains prior to electrophoresis [31] [2]. Inadequate sample preparation can lead to anomalous migration, poor resolution, and incorrect molecular weight estimations, thereby compromising experimental results.

This application note details a robust and standardized protocol for the denaturation of protein samples using a combination of heat, the anionic detergent SDS, and reducing agents such as Dithiothreitol (DTT) or 2-Mercaptoethanol (BME). Proper execution of this procedure ensures that proteins are unfolded, linearized, and uniformly charged, allowing for true size-based separation during SDS-PAGE [1] [4]. The information presented herein is designed to support researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in achieving highly reproducible and reliable protein analysis within the broader context of SDS-PAGE-based research.

Principles of Protein Denaturation for SDS-PAGE

The native structure of a protein, maintained by secondary, tertiary, and quaternary interactions, presents a complex challenge for electrophoresis. The goal of sample denaturation for SDS-PAGE is to dismantle these intricate structures to create linear polypeptide chains whose migration through a polyacrylamide gel is dependent solely on molecular weight [31] [2]. This is achieved through the synergistic action of three key components: SDS, reducing agents, and heat.

Role of SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulphate): SDS is a strong anionic detergent that plays a dual role. First, it disrupts nearly all non-covalent interactions—including hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic forces—that maintain the secondary and tertiary structures of a protein [1] [32]. This causes the protein to unfold. Second, SDS binds to the denatured polypeptide backbone at a relatively constant ratio of approximately 1.4 g SDS per 1.0 g of protein [32]. This binding imparts a uniform negative charge density along the entire length of the polypeptide chain, effectively masking the protein's intrinsic charge [1] [2]. Consequently, the charge-to-mass ratio becomes nearly identical for all proteins, eliminating charge as a variable during electrophoresis.

Role of Reducing Agents (DTT/BME): While SDS disrupts non-covalent bonds, it cannot break covalent disulfide (-S-S-) linkages that stabilize tertiary and quaternary structures [31] [33]. Reducing agents such as Dithiothreitol (DTT) or 2-Mercaptoethanol (BME) are essential for reducing these disulfide bonds. They work by undergoing a thiol-disulfide exchange reaction, converting cystine (the oxidized, disulfide-linked form) into two cysteine residues (the reduced, sulfhydryl form) [33]. This action ensures that multi-subunit proteins are dissociated into individual polypeptides and that the internal loops within a single polypeptide are fully linearized [1] [31]. DTT is often preferred over BME due to its lower odor and higher efficiency under some conditions [31] [34].

Role of Heat: The application of heat, typically between 70°C and 100°C, provides the kinetic energy necessary to accelerate the denaturation process [31] [34]. Heating "shakes up" the protein molecules, facilitating the penetration of SDS and reducing agents into hydrophobic core regions, thereby ensuring complete and uniform denaturation and linearization [31].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the transformative process proteins undergo during sample denaturation.

Reagent Formulations and Functions

A typical sample buffer for denaturing SDS-PAGE is a composite solution where each component serves a specific function to ensure effective denaturation, stability, and visualization during electrophoresis. The table below summarizes the common components of a 2X Laemmli sample buffer and their roles [31] [4].

Table 1: Composition and function of a standard 2X SDS-PAGE sample buffer.

| Component | Final Concentration (in 1X buffer) | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|