Protein Molecular Weight Validation: A Comprehensive Guide to SDS-PAGE and Mass Spectrometry

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for validating protein molecular weight, critically comparing the established technique of SDS-PAGE with modern mass spectrometry (MS).

Protein Molecular Weight Validation: A Comprehensive Guide to SDS-PAGE and Mass Spectrometry

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for validating protein molecular weight, critically comparing the established technique of SDS-PAGE with modern mass spectrometry (MS). It covers foundational principles, detailed methodologies, troubleshooting for common pitfalls, and integrated validation strategies. By synthesizing insights from foundational and application-focused perspectives, this guide aims to enhance analytical accuracy, improve reproducibility, and support robust protein characterization in biomedical research and biopharmaceutical development.

Core Principles: Understanding How SDS-PAGE and Mass Spectrometry Determine Molecular Weight

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) remains a foundational technique in biochemical research for separating proteins based on their molecular weight. The method, largely developed by Ulrich Laemmli in 1970, leverages two core principles to achieve this separation: charge uniformity, imparted by the anionic detergent SDS, and molecular sieving, provided by the polyacrylamide gel matrix [1] [2]. Within the context of modern proteomics, SDS-PAGE serves as a crucial first-step tool for protein analysis, often preceding more advanced techniques like mass spectrometry for comprehensive molecular weight validation and structural characterization. This guide objectively examines the principles, performance, and limitations of SDS-PAGE, providing a direct comparison with mass spectrometry to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Principles of SDS-PAGE

The efficacy of SDS-PAGE relies on two synergistic principles that work to separate proteins exclusively by molecular weight.

Charge Uniformity: The Role of SDS

The first principle involves masking the inherent chemical heterogeneity of proteins. Native proteins possess unique three-dimensional structures and variable net charges determined by their amino acid composition, which would cause them to migrate at different speeds in an electric field based on both size and charge [3]. SDS-PAGE overcomes this by using the anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS).

- Protein Denaturation and Linearization: SDS disrupts nearly all non-covalent bonds (e.g., hydrogen, hydrophobic, and ionic bonds) that maintain secondary and tertiary protein structures [1] [4]. This process unfolds and denatures the proteins.

- Uniform Negative Charge: SDS binds to the unfolded polypeptide backbone at a constant ratio of approximately 1.4 g of SDS per 1 g of protein [5] [2]. This abundant coating confers a uniform negative charge per unit mass, effectively swamping the protein's intrinsic charge [3] [5]. Consequently, all SDS-coated proteins possess a nearly identical charge-to-mass ratio [1] [3].

- Elimination of Shape Anomalies: Reducing agents like dithiothreitol (DTT) or β-mercaptoethanol are often added to the sample buffer to break disulfide bonds, ensuring multi-subunit proteins dissociate into individual polypeptides and all proteins are linearized [4] [6]. The result is that all proteins become linear, negatively charged molecules whose migration in an electric field will be determined solely by their molecular size, not their original charge or conformation [1].

Molecular Sieving: The Gel Matrix

The second principle governs the separation of these uniformly charged molecules. The polyacrylamide gel, created by polymerizing acrylamide and a cross-linker (usually N,N'-methylenebisacrylamide, or Bis), forms a porous, three-dimensional mesh that acts as a molecular sieve [4] [2].

- Size-Dependent Migration: When an electric field is applied, the negatively charged, SDS-coated proteins migrate toward the positive anode. Smaller proteins can navigate the pores of the gel matrix more easily and thus migrate faster and farther. Larger proteins encounter greater resistance and are retarded [1] [3].

- Pore Size Control: The pore size of the gel can be precisely controlled by varying the concentrations of acrylamide and bisacrylamide. Higher acrylamide concentrations create smaller pores, providing better resolution for lower molecular weight proteins, while lower percentages create larger pores more suitable for separating high molecular weight proteins [1] [4].

Table 1: Selecting Gel Percentage Based on Protein Size

| Acrylamide Percentage (%) | Effective Separation Range (kDa) |

|---|---|

| 7-8% | 25 - 200 [1] |

| 10% | 15 - 100 [1] |

| 12% | 10 - 200 [3] |

| 15% | 3 - 100 [3] |

The Discontinuous Buffer System

A key innovation in modern SDS-PAGE is the use of a discontinuous (or disc) buffer system, which incorporates a stacking gel layered on top of the resolving gel. This system sharpens the protein bands before they enter the separating gel, dramatically improving resolution [3] [5].

- Sample Stacking: The stacking gel has a low acrylamide concentration and is buffered to pH 6.8. The electrode buffer (pH ~8.3) contains glycine. When power is applied, the glycine ions entering the low-pH stacking gel become zwitterions (neutrally charged), slowing their mobility. Chloride ions from the Tris-HCl buffer in the gel move ahead rapidly. This sets up a narrow zone of high voltage gradient that sweeps through the sample, compressing all proteins into a very tight band between the leading chloride and trailing glycine ions [3] [5].

- Separation: This procession continues until it reaches the separating gel, which is buffered at a higher pH (8.8). Here, the glycine molecules become deprotonated and gain negative charge, allowing them to migrate past the proteins. The proteins, now in a gel with a higher acrylamide concentration and smaller pores, are left behind and begin to separate based on size [3].

The following diagram illustrates this workflow:

SDS-PAGE vs. Mass Spectrometry for Molecular Weight Validation

While SDS-PAGE is a cornerstone technique, its performance must be compared to mass spectrometry (MS), the gold standard for accurate molecular weight determination, especially in a research context focused on validation.

Table 2: SDS-PAGE vs. Mass Spectrometry for Molecular Weight Determination

| Parameter | SDS-PAGE | Mass Spectrometry |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Size-based migration through a gel matrix [1] | Mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of gas-phase ions [7] |

| Sample State | Denatured, linearized proteins [1] | Can analyze intact proteins (Top-Down) or digested peptides (Bottom-Up) [7] |

| Accuracy | Moderate (~±10%) [8] [2]; can be skewed by PTMs or anomalous migration [9] | High (often <0.01%); provides exact mass [7] |

| Information | Apparent molecular weight; purity assessment [4] | Exact molecular weight; identification; PTM mapping [7] |

| Throughput | High; multiple samples per gel | Lower; typically sequential analysis |

| Cost & Accessibility | Low cost; widely accessible | High cost; requires specialized equipment and expertise |

| Key Limitation | Cannot distinguish proteins of identical size; poor resolution for very large/small proteins [9] | Complex data analysis; can be biased towards abundant proteins without pre-fractionation [7] |

Supporting Experimental Data

The limitations of SDS-PAGE are evident in integrated workflows. For instance, a 2020 study developed PEPPI-MS, a method to efficiently extract intact proteins from polyacrylamide gels for subsequent top-down mass spectrometry analysis [7]. This approach was necessary because traditional in-gel digestion for bottom-up MS loses information about intact protein forms and their modifications. The study highlighted that while SDS-PAGE is excellent for fractionating complex mixtures, the recovery of intact proteins, particularly those over 50 kDa, for precise MS analysis has been a major challenge [7]. This demonstrates a key scenario where SDS-PAGE provides the separation power, but MS is required for validation and detailed characterization.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A successful SDS-PAGE experiment depends on a suite of key reagents, each with a critical function.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for SDS-PAGE

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge [1] [4] | Must be present in excess; critical for charge uniformity. |

| Reducing Agents (DTT, β-ME) | Breaks disulfide bonds to fully linearize proteins [4] [6] | Essential for accurate MW determination of multi-subunit proteins. |

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms the cross-linked polyacrylamide gel matrix for molecular sieving [4] [2] | Concentration determines gel pore size and resolution range. |

| Molecular Weight Markers | Standard ladder for estimating sample protein size [4] [8] | Crucial for reliable molecular weight estimation. |

| Coomassie/Silver Stains | Visualizes separated protein bands after electrophoresis [1] | Coomassie for general use; silver for high sensitivity. |

| Optiblot SDS-PAGE Kit (ab133414) | Quick preparation and concentration of protein samples [1] | Removes interfering buffers, improves band clarity. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for SDS-PAGE

This protocol summarizes the standard methodology for reducing SDS-PAGE, as used for molecular weight validation [1] [6] [9].

1. Gel Preparation:

- Separating Gel: Mix acrylamide/bis-acrylamide solution, Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.8), and SDS. Initiate polymerization with ammonium persulfate (APS) and TEMED. Pour the gel and overlay with isopropanol or water for a flat surface.

- Stacking Gel: After the separating gel polymerizes, pour off the overlay. Prepare a low-concentration acrylamide solution with Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), SDS, APS, and TEMED. Pour on top of the separating gel and insert a comb to create wells.

2. Sample Preparation:

- Dilute protein samples with SDS-PAGE Sample Buffer (typically containing Tris-HCl, glycerol, SDS, bromophenol blue, and a reducing agent like DTT or β-mercaptoethanol).

- Heat the samples at 95°C for 5 minutes to ensure complete denaturation [2] [9].

- Centrifuge briefly to collect condensation.

3. Electrophoresis:

- Assemble the gel in the electrophoresis tank filled with running buffer (e.g., Tris-Glycine-SDS buffer, pH ~8.3).

- Load prepared samples and molecular weight markers into the wells.

- Apply a constant voltage (100-150 V) until the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel [1].

4. Post-Electrophoresis Analysis:

- Staining: Carefully remove the gel and stain with Coomassie Brilliant Blue or a more sensitive silver stain to visualize protein bands [1] [9].

- Destaining: For Coomassie, destain with a methanol-acetic acid solution to remove background dye [1].

- Analysis: Compare the migration distance of sample bands to the standard curve generated from the marker to estimate apparent molecular weight [8].

SDS-PAGE remains an indispensable, accessible, and high-throughput method for protein separation based on the robust principles of charge uniformity and molecular sieving. Its strength lies in providing a rapid assessment of protein molecular weight, purity, and integrity. However, for rigorous molecular weight validation, especially where high accuracy or detection of subtle mass changes from post-translational modifications is required, mass spectrometry is unequivocally superior. The most powerful modern proteomics workflows often integrate both techniques, using SDS-PAGE for initial fractionation and MS for definitive identification and characterization, thereby leveraging the complementary strengths of each method to achieve in-depth protein analysis.

The Role of SDS and Reducing Agents in Protein Denaturation and Linearization

Within the context of protein research and drug development, the accurate determination of molecular weight is a fundamental step in characterizing protein therapeutics. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) has served as a cornerstone technique for this purpose for decades, reliant on the denaturing action of SDS and reducing agents to linearize proteins. However, the emergence of mass spectrometry (MS) as a high-precision alternative has necessitated a critical comparison of these methods. This guide objectively evaluates the performance of SDS-PAGE against MS, framing the discussion within a broader thesis on molecular weight validation. The denaturation and linearization of proteins by SDS and reagents like dithiothreitol (DTT) are not merely sample preparation steps; they are foundational processes that directly impact the accuracy, reliability, and interpretation of data in biochemical analysis [10] [11]. Understanding their mechanism is crucial for researchers and scientists to correctly appraise the capabilities and limitations of SDS-PAGE in protein characterization.

The Fundamental Mechanisms of Denaturation and Linearization

The Action of Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS)

SDS is an anionic detergent that plays a dual role in protein denaturation. First, it disrupts the native structure of proteins by breaking non-covalent bonds, including hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and ionic bonds [11]. Second, and most critically, SDS binds to the unfolded polypeptide chains at a nearly constant ratio of approximately 1.4 grams of SDS per gram of protein [12] [11]. This extensive binding coats the protein, imparting a uniform negative charge that masks the protein's intrinsic charge. Consequently, all proteins in a sample attain a consistent charge-to-mass ratio, which is the fundamental principle enabling separation by molecular weight during electrophoresis [11]. The protein's migration through the polyacrylamide gel matrix then becomes a function of size alone, with smaller proteins moving faster than larger ones [11].

The prevailing model for the final SDS-protein complex, supported by calorimetric and small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) studies, is the core-shell model (also known as protein-decorated micelles) [13]. This model depicts the denatured protein enveloping a micelle of SDS, forming a complex that migrates through the gel. The earlier "beads-on-a-string" model, which suggested micelles forming along an unfolded polypeptide chain, is now considered inappropriate based on recent evidence [13]. The process is highly pH-dependent, and at low pH, charge neutralization can lead to the formation of large, super-clustered protein-SDS complexes [13].

The Role of Reducing Agents

While SDS effectively disrupts non-covalent interactions, many proteins possess disulfide bonds (-S-S-) that are covalent and thus resistant to SDS alone [10]. These bonds can tether polypeptide chains together, preserving quaternary structure or key elements of tertiary structure even in the presence of SDS. To achieve complete linearization, a reducing agent is essential.

Reducing agents such as dithiothreitol (DTT) or 2-mercaptoethanol (BME) specifically target these disulfide bonds [14] [10]. They work by reducing the disulfide bonds to sulfhydryl groups (-SH), thereby liberating individual polypeptide subunits [11]. This action "removes the last bit of tertiary and quaternary structure," ensuring that multi-subunit proteins dissociate into their individual components and that proteins with internal disulfide bonds are fully unfolded [10]. The combination of heat, SDS, and a reducing agent provides a robust system for the complete denaturation and linearization of a vast majority of proteins, rendering them suitable for molecular weight estimation via SDS-PAGE.

Experimental Protocols for Protein Denaturation and Analysis

Standard Sample Preparation for SDS-PAGE

A reliable protocol is critical for reproducible and accurate SDS-PAGE results. The following methodology, adapted from established laboratory practices, details the key steps [10].

Step 1: Preparation of Sample Buffer. A common 2X concentrated sample buffer consists of the following components:

- 2% SDS: To denature proteins and confer negative charge.

- 20% Glycerol: To increase the density of the sample solution, allowing it to sink to the bottom of the gel well during loading.

- 20 mM Tris-Cl, pH 6.8: To provide a buffering environment at the correct pH for the stacking gel.

- 2 mM EDTA: To chelate divalent cations (e.g., Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺), reducing the activity of metal-dependent proteolytic enzymes that could degrade the sample.

- 160 mM DTT: A reducing agent to break disulfide bonds. DTT is often preferred over 2-mercaptoethanol due to its lower odor [10].

- 0.1 mg/ml Bromophenol Blue: A tracking dye to monitor the progress of electrophoresis.

Step 2: Mixing and Denaturation. The protein sample is mixed with an equal volume of the 2X sample buffer. This mixture is then heated, typically in a steaming water bath or heating block at 60-100°C for 10 minutes [10]. Heating agitates the molecules, facilitating the penetration of SDS into hydrophobic regions and ensuring complete denaturation. It is crucial to avoid boiling the sample, as this can cause protein aggregation [10].

Step 3: Loading and Electrophoresis. After heating and brief centrifugation (if necessary), the denatured sample is loaded into the wells of a polyacrylamide gel. The gel electrophoresis is then carried out using an appropriate running buffer, such as Tris-Glycine buffer containing SDS [11].

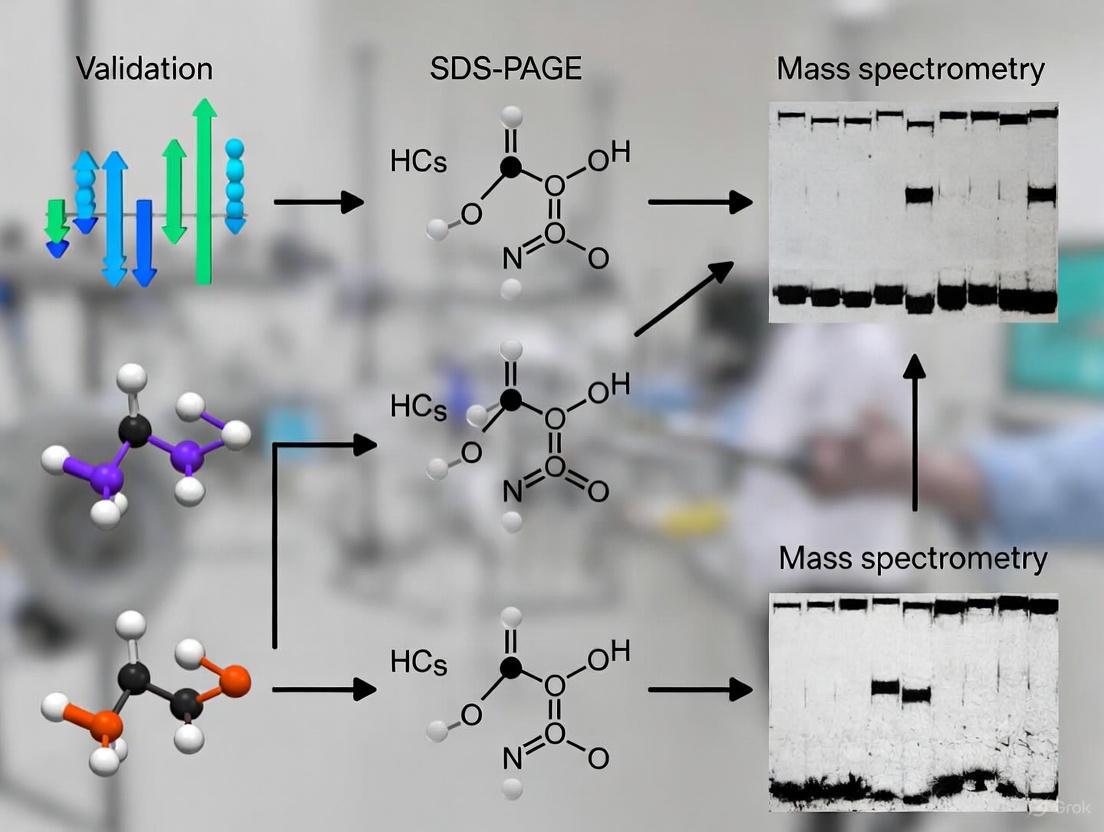

Workflow for Comparative Analysis via SDS-PAGE and Mass Spectrometry

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for preparing and analyzing protein samples using both SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry, highlighting the critical denaturation step.

Diagram 1: Workflow for protein analysis using SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry.

Comparative Data: SDS-PAGE vs. Mass Spectrometry

Quantitative Comparison of Method Performance

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of SDS-PAGE and Mass Spectrometry for protein molecular weight determination, providing a basis for objective comparison.

| Feature | SDS-PAGE | Mass Spectrometry (e.g., MALDI-TOF, ESI) |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Size-based separation in a gel matrix [11] | Mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) measurement of ions [15] |

| Sample State | Denatured and linearized [11] | Can be analyzed intact or digested (BUP) [16] |

| Molecular Weight Estimation | Relative, by comparison to standards [11] | Direct and precise measurement [15] |

| Accuracy | Moderate; can be skewed by amino acid composition (e.g., acidic residues) [17] | High (within 1 Da or less) [15] |

| Key Limitation | Poor resolution for proteins with extreme pI or post-translational modifications [12] [17] | Lower sensitivity for large, intact proteoforms; complex data analysis [16] |

| Proteoform Analysis | Cannot distinguish proteoforms with similar mass but different PTMs [16] | Capable of identifying specific proteoforms and PTM combinations (TDP) [16] |

| Throughput | Medium to High | Medium (TDP) to High (BUP) [16] |

Impact of Protein Composition on SDS-PAGE Accuracy

A significant limitation of SDS-PAGE is its deviation from ideal behavior for certain proteins. Research has established a linear correlation between the percentage of acidic amino acids (aspartate (D) and glutamate (E)) in a protein and the discrepancy between its predicted molecular weight and its apparent molecular weight on an SDS-PAGE gel [17]. The derived equation, y = 276.5x − 31.33 (where 'x' is the percentage of D+E, and 'y' is the average ΔMW per amino acid residue), allows researchers to predict the gel mobility shift for acidic proteins [17]. For example, the zebrafish protein Def, with a high acidic amino acid content in its N-terminal region, displayed an apparent molecular weight ~13 kDa larger than its predicted size, a phenomenon not attributable to post-translational modifications like glycosylation [17]. This systematic error underscores the need for caution when interpreting SDS-PAGE data for proteins with unusual sequence compositions.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for experiments involving protein denaturation and SDS-PAGE analysis.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Denaturation & Analysis |

|---|---|

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Anionic detergent that denatures proteins and imparts uniform negative charge for size-based separation [10] [11]. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Reducing agent that breaks disulfide bonds to ensure complete protein unfolding and subunit dissociation [10]. |

| Polyacrylamide Gel | Sieving matrix composed of acrylamide and bis-acrylamide that separates proteins by size during electrophoresis [11]. |

| Tris-Glycine Buffer | A common running buffer that maintains pH and ionic strength during electrophoresis [12] [11]. |

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue | A dye used to stain and visualize protein bands on the gel after electrophoresis [14] [18]. |

| Molecular Weight Standards | A mixture of proteins of known molecular weights run alongside samples to create a calibration curve for size estimation [11]. |

SDS and reducing agents are indispensable for protein denaturation and linearization, enabling the widespread use of SDS-PAGE as an accessible and effective tool for protein analysis. Within a framework of validating protein molecular weight, SDS-PAGE provides a robust, first-line method for assessing purity, subunit composition, and approximate size. However, the comparative data clearly shows that its accuracy is not absolute and can be influenced by protein composition. Mass spectrometry emerges as a superior technique for obtaining precise molecular weight data and for characterizing proteoforms, albeit with requirements for more sophisticated instrumentation and data analysis. Therefore, the choice between these techniques is not one of outright replacement but of strategic application. For researchers and drug development professionals, a synergistic approach—using SDS-PAGE for initial, rapid characterization and MS for definitive, high-resolution validation—represents the most powerful strategy for comprehensive protein analysis.

In the field of protein science, accurately determining molecular weight and characterizing proteoforms—defined as all the different molecular forms in which a protein can be found, including genetic variants, and post-translational modifications (PTMs)—is fundamental to understanding protein function in health and disease [19]. Two cornerstone techniques for this analysis are SDS-PAGE (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis) and mass spectrometry (MS)-based intact mass analysis. While SDS-PAGE is a ubiquitous, low-cost method for estimating molecular weight, mass spectrometry offers unparalleled precision for identifying and characterizing proteoforms. This guide objectively compares the performance of these techniques within the broader thesis of validating protein molecular weight, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the data and protocols needed to inform their experimental strategies.

Core Principles and Technical Comparison

SDS-PAGE separates proteins based on their molecular weight by using the anionic detergent SDS to denature proteins and impart a uniform negative charge, allowing migration through a polyacrylamide gel matrix to be determined primarily by size [11] [4]. In contrast, intact mass analysis via mass spectrometry involves ionizing proteins and measuring their mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio, enabling the precise determination of a protein's molecular weight and the identification of proteoforms that differ due to PTMs, alternative splicing, or genetic variation [20].

The table below summarizes the fundamental differences between these two approaches:

| Feature | SDS-PAGE | Intact Mass Spectrometry |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Principle | Size-based separation in a gel matrix [11] | Measurement of mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio of ions [20] |

| Measured Output | Migration distance (Rf) relative to standards | Mass spectrum (intensity vs. m/z) |

| Key Instrumentation | Gel tank, power supply [11] | Mass spectrometer (ion source, analyzer, detector) [20] |

| Typical Sample Input | Micrograms (µg) | Nanograms (ng) to micrograms (µg) |

| Key Limitation | Indirect measurement; accuracy affected by protein composition [21] | Requires sample purification; can be hindered by complex mixtures |

Performance and Capability Comparison

When evaluating the two techniques for specific analytical tasks, their performance diverges significantly, particularly in accuracy, proteoform characterization, and sensitivity.

Molecular Weight Determination Accuracy

SDS-PAGE provides a reasonable estimate but is known to produce inaccuracies, especially for acidic proteins. A key study demonstrated that the discrepancy between the predicted and SDS PAGE-displayed molecular weight has a linear correlation with the percentage of acidic amino acids (glutamate and aspartate), following the equation: ΔMW per residue = 276.5 * (% Acidic AA) - 31.33 [21]. This means an acidic protein with 30% D/E content would display an apparent mass approximately 52 kDa larger than its true mass for a 100 kDa protein. Mass spectrometry directly measures mass with high precision and accuracy, typically within a few Daltons, unaffected by amino acid composition [20].

Proteoform Characterization

SDS-PAGE has limited capability to resolve proteoforms. Different proteoforms of a similar mass may co-migrate as a single or smeared band, providing no specific information on the type of modification [11]. Intact mass spectrometry excels at this task, capable of identifying and quantifying multiple proteoforms in a single analysis by detecting small mass shifts caused by PTMs like phosphorylation (+80 Da) or oxidation (+16 Da) [22] [19]. Advanced "top-down" MS workflows can further fragment intact proteoforms inside the mass spectrometer to localize the modification sites [22].

Sensitivity and Dynamic Range

SDS-PAGE sensitivity depends on the staining method. Coomassie blue staining detects tens of nanograms of protein, while silver staining can detect down to nanogram levels [11]. Mass spectrometry is exceptionally sensitive, capable of detecting proteins and peptides at attomolar (10⁻¹⁸) concentrations, offering a much wider dynamic range for detecting low-abundance species in complex mixtures [20].

The table below provides a direct comparison of their performance across key metrics:

| Performance Metric | SDS-PAGE | Intact Mass Spectrometry |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight Accuracy | Low to Moderate (highly sequence-dependent) [21] | High (within a few Daltons) [20] |

| Resolution | Low (cannot resolve small mass differences) | High (can resolve small mass differences from PTMs) |

| Proteoform Identification | Limited (cannot identify modification type) [11] | High (can identify and quantify multiple proteoforms) [22] [19] |

| Sensitivity | ~1-10 ng (with silver staining) [11] | Attomole (10⁻¹⁸) range [20] |

| Throughput | Moderate (several hours per run) | High (minutes per run with direct infusion) |

| Quantitation | Semi-quantitative (based on band intensity) [11] | Quantitative (with stable isotope labels or label-free methods) [20] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Molecular Weight Validation via SDS-PAGE and In-Gel Recovery for MS

This protocol is adapted for downstream mass spectrometry analysis, using the PEPPI-MS method for efficient protein recovery [7].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Dilute protein samples in SDS-PAGE loading buffer (e.g., Laemmli buffer) containing a reducing agent like 50 mM DTT or β-mercaptoethanol to break disulfide bonds [11].

- Heat denature samples at 70-95°C for 5-10 minutes.

2. Gel Electrophoresis:

- Use a discontinuous gel system with a stacking gel (e.g., 4-5% acrylamide, pH 6.8) and a separating gel (e.g., 8-16% acrylamide, pH 8.8) [23].

- Load samples alongside pre-stained and unstained protein molecular weight standards.

- Run gel in Tris-Glycine-SDS running buffer at constant voltage (e.g., 120-150V) until the dye front reaches the bottom.

3. Protein Visualization and Band Excision:

- Stain the gel with a compatible stain, such as Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) [7].

- Destain as needed and excise gel bands corresponding to protein(s) of interest with a clean scalpel.

4. In-Gel Protein Recovery via PEPPI-MS:

- Place the gel piece in a disposable plastic homogenizer.

- Homogenize the gel thoroughly with a pestle to facilitate extraction.

- Add 0.05% SDS/100 mM ammonium bicarbonate solution and shake for 10 minutes to passively elute the protein. The CBB acts as an extraction enhancer [7].

- Transfer the supernatant containing the recovered protein to a new tube.

5. Clean-up for Mass Spectrometry:

- Remove SDS, which interferes with MS analysis, using a clean-up method. Alternatives to traditional methanol-chloroform-water (MCW) precipitation include commercial kits like DetergentOUT or HiPPR, which show improved recovery of small and acidic proteoforms [24].

- The cleaned protein is now ready for intact mass analysis.

Protocol 2: Intact Mass Analysis by LC-MS

This protocol describes the basic workflow for analyzing an intact protein by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS).

1. Sample Preparation:

- The protein sample should be in a volatile buffer compatible with MS (e.g., ammonium bicarbonate, ammonium acetate). Desalt if necessary using spin columns or dialysis.

- Determine protein concentration.

2. Liquid Chromatography (LC) Separation:

- Inject the sample onto a reversed-phase UHPLC (e.g., C4 or C8 column) using an in-line system.

- Use a gradient of increasing organic solvent (e.g., acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid) to separate proteins by hydrophobicity. This step reduces sample complexity and removes salts [20].

3. Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

- The LC eluent is directly ionized using Electrospray Ionization (ESI), which produces gas-phase ions [20].

- Intact masses are measured with a high-resolution mass analyzer such as an Orbitrap or Time-of-Flight (TOF) detector [20].

- For proteoform characterization, Tandem MS (MS/MS) can be performed. Selected precursor ions are fragmented using methods like Higher-Energy Collisional Dissociation (HCD) to obtain sequence and modification-site information [22] [20].

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the key steps involved in a comparative workflow for protein molecular weight validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful protein characterization relies on a suite of specialized reagents and instruments. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experiments.

| Research Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Anionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge, enabling size-based separation in SDS-PAGE [11]. |

| Polyacrylamide Gel | A cross-linked polymer matrix that acts as a molecular sieve during electrophoresis. Pore size is adjusted via acrylamide concentration to separate different protein sizes [11]. |

| DTT (Dithiothreitol) | A reducing agent that breaks disulfide bonds in proteins, ensuring complete denaturation and linearization for accurate SDS-PAGE migration [11] [4]. |

| Mass Spectrometry Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents (e.g., water, acetonitrile) with minimal contaminants to prevent ion suppression and background noise during LC-MS analysis [20]. |

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) | A protein stain used to visualize bands after SDS-PAGE. In the PEPPI-MS workflow, it also enhances passive extraction of proteins from the gel matrix [7]. |

| SDS Removal Kits (e.g., DetergentOUT) | Resin-based kits for efficiently removing SDS from protein samples after gel extraction, which is critical for subsequent mass spectrometry analysis [24]. |

| Molecular Weight Standards | A mixture of proteins of known molecular weights, run alongside samples on a gel to create a standard curve for estimating the size of unknown proteins [11]. |

SDS-PAGE remains a foundational, accessible technique for initial protein separation and purity assessment. However, for the precise validation of protein molecular weight and in-depth characterization of proteoforms, intact mass spectrometry is the unequivocally superior technology. Mass spectrometry provides exact mass measurements, identifies specific PTMs, and can resolve complex mixtures of proteoforms that are invisible to SDS-PAGE. For the most rigorous research and drug development applications, an integrated approach—using SDS-PAGE for initial fractionation and MS for definitive analysis—represents the gold standard, unlocking a deeper understanding of protein structure and function.

In the field of protein science, accurately determining molecular weight and characterizing proteoforms are fundamental tasks. Two principal methodologies dominate this landscape: gel-based electrophoresis, notably SDS-PAGE, and mass spectrometry (MS)-based approaches. Within the broader context of validating protein molecular weight, these techniques offer complementary strengths and limitations. SDS-PAGE provides high-resolution separation of intact proteins and their modified forms, while mass spectrometry delivers unparalleled precision in mass determination and identification. This guide objectively compares the performance of these methodologies, supported by experimental data, to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the appropriate analytical strategy for their specific needs.

Fundamental Principles and Technical Comparison

The core distinction between these techniques lies in their operational principle: SDS-PAGE separates proteins based on their hydrodynamic size under denaturing conditions, whereas MS separates and detects ions based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z).

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) is a bedrock method in biochemistry. Proteins are denatured and coated with the anionic detergent SDS, conferring a uniform negative charge. During electrophoresis, proteins migrate through a polyacrylamide gel matrix primarily according to their molecular weight, with smaller proteins migrating faster. The resulting separation can be visualized using various staining techniques, and molecular weight is estimated by comparison with standard protein ladders [25] [26].

Mass Spectrometry (MS) for proteins involves ionizing intact proteins (top-down MS) or their enzymatically digested peptides (bottom-up or shotgun proteomics) and measuring their m/z. Techniques like Electrospray Ionization (ESI) and Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI-TOF) are commonly used. MS provides exceptional mass accuracy, often within a few parts per million, allowing for precise molecular weight determination and detailed characterization of post-translational modifications (PTMs) [27] [7].

Table 1: Core Principle Comparison of SDS-PAGE and Mass Spectrometry

| Feature | SDS-PAGE | Mass Spectrometry |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Principle | Molecular size (hydrodynamic radius) in a gel matrix | Mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) in the gas phase |

| Typical Sample Input | Microgram (µg) quantities | Nanogram (ng) to microgram (µg) quantities |

| Key Readout | Band/spot position relative to standards | Mass spectrum (intensity vs. m/z) |

| Information Obtained | Apparent molecular weight, integrity, purity | Accurate mass, amino acid sequence, PTM identification |

Performance Data: Analytical Strengths and Limitations

A direct comparative study of 2D-DIGE (a gel-based top-down method) and label-free shotgun proteomics (a bottom-up MS method) revealed distinct performance characteristics. The study analyzed technical and biological replicates of a human cell line, providing quantitative data on robustness and proteoform resolution [27].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Gel-Based vs. Shotgun Proteomics

| Performance Metric | 2D-DIGE (Gel-Based Top-Down) | Label-Free Shotgun (Bottom-Up MS) | Context from Experiments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technical Variation (CV) | Lower (approx. 3x lower than shotgun) | Higher (approx. 3x higher than 2D-DIGE) | Indicates superior quantitative robustness for gel-based methods [27] |

| Proteoform Resolution | Excellent - Direct visualization of proteoforms | Poor - Loss of proteoform information during digestion | 2D-DIGE can detect PTMs and cleavage products; shotgun infers proteins from peptides [27] |

| Analysis Time per Protein | ~20x more time required | Faster and more automated | Gel-based methods involve more manual work and processing time [27] |

| Profiling Sensitivity | Limited for extreme MW/pI, hydrophobic proteins | High, especially when coupled with LC fractionation | GeLC-MS/MS (combining both) enhances sensitivity for low-abundance components [23] [7] |

The study concluded that while shotgun proteomics rapidly provides an annotated proteome, it suffers from reduced robustness and loses essential information about proteoforms—the different molecular forms in which a protein can exist, arising from genetic variation, alternative splicing, or PTMs. In contrast, 2D-DIGE top-down analysis directly provides stoichiometric qualitative and quantitative information on intact proteoforms, even revealing unexpected modifications, albeit with a significant time investment [27].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility, below are detailed protocols for key experiments cited in this comparison.

Protocol: GeLC-MS/MS for Bottom-Up Proteomics

This workflow combines the separation power of SDS-PAGE with the identification power of MS.

- Protein Separation: Separate the protein complex mixture using 1D SDS-PAGE. A precast gradient gel (e.g., 4-12% Bis-Tris) is typically used. Load micrograms of total protein alongside a pre-stained molecular weight marker [23] [7].

- In-Gel Digestion: The entire lane is excised and subjected to in-gel tryptic digestion.

- Fix and stain the gel with Coomassie or compatible fluorescent stain.

- Destain the gel pieces.

- Reduce disulfide bonds with dithiothreitol (DTT) and alkylate with iodoacetamide.

- Digest proteins with sequencing-grade trypsin overnight at 37°C.

- Peptide Extraction: Peptides are extracted from the gel pieces using solutions such as 50% acetonitrile/5% formic acid.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: The extracted peptides are separated by nanoflow reversed-phase liquid chromatography (LC) and directly introduced into a tandem mass spectrometer (MS/MS). The instrument cycles between full MS scans and data-dependent MS/MS scans on the most intense ions.

- Data Analysis: MS/MS spectra are searched against a protein database to identify the peptides and infer the proteins present in the original sample [28].

Protocol: PEPPI-MS for Top-Down Proteomics

The "Passively Eluting Proteins from Polyacrylamide Gels as Intact Species for MS" method enables efficient recovery of intact proteins from gels for top-down MS.

- SDS-PAGE Separation: Separate proteins using standard SDS-PAGE and stain with an aqueous Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) solution (e.g., EzStain AQua) [7].

- Gel Fractionation: Excise the entire lane and slice it into multiple molecular weight regions based on the marker.

- Protein Recovery (PEPPI):

- Place each gel slice in a disposable plastic homogenizer.

- Homogenize the gel thoroughly with a pestle.

- Add an extraction solution (0.05% SDS in 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate).

- Shake the homogenate for 10 minutes to passively elute the proteins. The CBB dye acts as an extraction enhancer, achieving a mean recovery rate of ~68% for proteins under 100 kDa.

- Purification and MS Analysis: Recovered proteins are purified (e.g., via organic solvent precipitation) and analyzed by LC-MS systems compatible with intact proteins, such as reversed-phase LC coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometers (e.g., Orbitrap or FT-ICR) [7].

Workflow and Decision Pathway Visualization

The following diagrams illustrate a standard GeLC-MS/MS workflow and a logical framework for selecting the appropriate analytical method.

GeLC-MS/MS Workflow for Bottom-Up Proteomics

Method Selection for Protein Analysis

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for performing the described protein analysis techniques.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Protein Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) | Protein stain for visualization in gels; enhances passive protein elution in PEPPI-MS. | Staining proteins after SDS-PAGE; used as an extraction enhancer in PEPPI-MS workflow [7]. |

| Cyanine Fluorescent Dyes (CyDyes) | Fluorescent labels for differential gel electrophoresis (2D-DIGE). | Labeling different protein samples for multiplexed, quantitative comparison within a single 2D gel [27]. |

| Trypsin (Sequencing Grade) | Proteolytic enzyme that cleaves peptide bonds at the C-terminal side of lysine and arginine. | In-gel digestion of proteins into peptides for bottom-up LC-MS/MS analysis [28]. |

| Carrier Ampholytes | Create a stable pH gradient for isoelectric focusing (IEF). | Used in the first dimension of 2D-PAGE and in solution-phase IEF fractionation devices [29] [23]. |

| Non-Ionic Detergents (e.g., DDM) | Solubilize membrane proteins while preserving native protein complexes. | Solubilization buffer for native membrane protein complexes in Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) [30]. |

| Stable Isotope Labels (e.g., Dimethyl Labeling) | Introduce mass tags for accurate relative quantification in MS. | Chemically labeling peptides from different samples for precise quantitative comparison in shotgun proteomics [28]. |

SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry are not mutually exclusive but are powerful orthogonal techniques in the protein scientist's toolkit. SDS-PAGE and its advanced forms like 2D-DIGE offer superior resolution for directly visualizing intact proteoforms and provide more robust quantitative data with lower technical variation, making them ideal for assessing protein integrity, purity, and complex modification patterns. In contrast, mass spectrometry delivers unmatched precision in molecular weight determination and sequence-level characterization, excelling in high-throughput proteome profiling and detailed PTM mapping, albeit with a loss of direct proteoform context in bottom-up modes.

The choice between them hinges on the specific analytical question. For routine molecular weight checks, purity assessment, and initial proteoform screening, SDS-PAGE remains a robust, accessible, and cost-effective choice. For precise mass measurement, deep proteome mining, and detailed structural characterization, mass spectrometry is indispensable. As demonstrated by integrated workflows like GeLC-MS/MS and PEPPI-MS, the most powerful strategy often lies in synergistically combining the high-resolution separation of gels with the precise identification and quantification capabilities of mass spectrometry.

Practical Protocols: Executing SDS-PAGE and MS for Accurate Protein Analysis

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) remains a cornerstone technique in biochemistry and molecular biology laboratories for separating proteins based on their molecular weight. First established in the 1970s through the work of Ulrich Laemmli, who refined the method by incorporating SDS, this technique has maintained its relevance for over half a century due to its simplicity, reliability, and cost-effectiveness [8] [1]. SDS-PAGE serves as a critical step in Western blot analysis and plays an indispensable role in protein characterization, purity assessment, and molecular weight estimation across diverse fields including pharmaceutical development, clinical diagnostics, and nutritional research [31] [32].

Within the context of validating protein molecular weight, SDS-PAGE provides an apparent molecular weight based on a protein's migration distance through a polyacrylamide gel matrix. However, this observed molecular weight can sometimes deviate from the actual molecular mass determined through more advanced techniques like mass spectrometry, particularly when proteins undergo post-translational modifications (PTMs), alternative splicing, or endoproteolytic processing [8] [33]. This guide explores the optimized SDS-PAGE workflow within this validation framework, comparing its performance with mass spectrometric approaches and providing detailed methodologies to enhance accuracy, resolution, and reproducibility for research and drug development professionals.

SDS-PAGE vs. Mass Spectrometry: A Comparative Analysis for Molecular Weight Determination

Fundamental Principles and Technical Comparison

SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry (MS) represent complementary approaches for protein molecular weight assessment, each with distinct advantages and limitations. SDS-PAGE separates proteins based on their hydrodynamic size in a denatured state. The anionic detergent SDS binds to proteins at a constant ratio of approximately 1.4 g SDS per 1 g protein, unfolding tertiary structures and imparting a uniform negative charge. This charge-to-mass uniformity ensures that separation occurs primarily based on polypeptide chain length rather than inherent charge or shape [1] [34]. In contrast, mass spectrometry measures the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of ionized molecules in the gas phase, providing precise molecular mass determination with accuracy often within 1-100 ppm, depending on the instrument [16] [33].

The table below summarizes the key methodological differences between these approaches:

Table 1: Technical Comparison of SDS-PAGE and Mass Spectrometry for Molecular Weight Determination

| Parameter | SDS-PAGE | Mass Spectrometry |

|---|---|---|

| Separation/Mass Principle | Size-based migration through gel matrix | Mass-to-charge ratio of ionized species |

| Sample State | Denatured, reduced proteins | Intact proteoforms (TDP) or peptides (BUP) |

| Molecular Weight Information | Apparent MW relative to standards | Precise mass measurement |

| Throughput | Moderate (hours to overnight) | Low to moderate (minutes to hours per sample) |

| Proteoform Characterization | Limited (band shifts indicate possible modifications) | Comprehensive (can identify PTM combinations) |

| Typical Mass Range | 3-600 kDa [34] | < 30 kDa for Top-Down Proteomics [16] |

| Detection Sensitivity | 5-30 ng (Coomassie) [35] | High (femtomole to attomole range) |

Concordance and Discordance in Molecular Weight Data

Studies comparing SDS-PAGE observations with mass spectrometric data reveal important patterns in molecular weight validation. Research on human lymphoblastoid cell lines demonstrated that approximately 80% of proteins show agreement between their SDS-PAGE migration and predicted full-length molecular weight. However, a significant minority (20%) exhibit discrepancies where the observed molecular weight differs from that predicted by the amino acid sequence [33]. These discrepancies often provide valuable biological insights, potentially indicating:

- Post-translational modifications (phosphorylation, glycosylation, ubiquitination)

- Alternative splicing events generating different protein isoforms

- Endoproteolytic processing or protein cleavage

- Genetic variations or mutations affecting protein size

- Abnormal migration due to unusual amino acid composition [8] [33]

Mass spectrometry approaches provide different levels of information depending on the methodology. Bottom-up proteomics (BUP), which involves enzymatic digestion of proteins into peptides before analysis, offers broad proteome coverage and high sensitivity but cannot provide intact protein molecular weight or characterize combinations of PTMs on single proteoforms [16]. In contrast, top-down proteomics (TDP) analyzes intact proteins without digestion, preserving comprehensive proteoform information including PTMs, splice variants, and sequence variations. However, TDP currently faces challenges with lower sensitivity, throughput, and difficulties analyzing proteins larger than 30 kDa [16].

Optimized SDS-PAGE Workflow: Detailed Methodologies

Gel Casting: Optimization for Resolution and Reproducibility

The foundation of successful SDS-PAGE begins with proper gel preparation. The acrylamide concentration directly determines the pore size of the gel matrix and must be optimized based on the target protein's molecular weight. The bisacrylamide-to-acrylamide ratio (typically 1:29 to 1:37) controls crosslinking density and affects gel clarity and mechanical properties [34].

Table 2: Recommended Acrylamide Concentrations for Optimal Protein Separation

| Protein Molecular Weight Range | Optimal Gel Percentage |

|---|---|

| 100-600 kDa | 4% |

| 50-500 kDa | 7% |

| 30-300 kDa | 10% |

| 10-200 kDa | 12% |

| 3-100 kDa | 15% |

For complex samples containing proteins of widely varying sizes, gradient gels (e.g., 4-20% acrylamide) provide enhanced resolution across a broad molecular weight range in a single gel. The increasing acrylamide concentration creates a pore size gradient that sharpens protein bands as they migrate, with smaller proteins eventually encountering restrictive pore sizes while larger proteins remain in more open regions [1] [36].

The discontinuous buffer system pioneered by Laemmli employs a stacking gel (pH ~6.8) and a resolving gel (pH ~8.8). This system creates sharp protein bands by leveraging differences in electrophoretic mobility between leading ions (chloride) and trailing ions (glycinate) at the stacking stage, concentrating proteins into a thin zone before they enter the resolving gel [1]. Modern innovations include precast gel systems that offer superior consistency compared to hand-cast gels, reducing variability and improving reproducibility across experiments [36].

Sample Preparation: Critical Steps for Accurate Representation

Proper sample preparation is crucial for obtaining reliable SDS-PAGE results. Proteins must be denatured, reduced, and uniformly coated with SDS to ensure migration proportional to molecular weight. Key steps include:

Protein Extraction and Solubilization: Use lysis buffers containing 1-2% SDS to effectively solubilize proteins and disrupt non-covalent interactions. For difficult-to-solubilize proteins (e.g., membrane proteins), additional strategies such as mechanical disruption, sonication, or alternative detergents may be necessary [1] [34].

Reduction of Disulfide Bonds: Include 1-5% β-mercaptoethanol or 1-10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) in the sample buffer to reduce disulfide bonds, ensuring complete protein unfolding. Incubate at 95-100°C for 5-10 minutes for optimal denaturation [1].

Sample Buffer Composition: Standard Laemmli buffer contains 62.5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, and 0.01% bromophenol blue. The glycerol adds density for sample loading, while the tracking dye monitors migration progress [1].

Protein Quantification: Precisely quantify protein concentration using compatible methods (e.g., BCA assay) to ensure equal loading across gel lanes. Typical loading amounts range from 10-100 μg for complex mixtures when using Coomassie staining, with lower amounts (1-10 μg) sufficient for Western blotting [35] [1].

Commercial sample preparation kits, such as the Optiblot SDS-PAGE Sample Preparation Kit, can efficiently concentrate protein samples and remove interfering substances like salts or detergents that might affect electrophoresis [1].

Electrophoresis Conditions: Optimizing Separation Parameters

Proper electrophoresis conditions are essential for achieving high-resolution protein separation. Key parameters to optimize include:

Voltage and Run Time: Standard practice involves running gels at 100-150 volts for 40-60 minutes, or until the dye front reaches the gel bottom. Excessive voltage can generate heat causing band distortion ("smiling"), while insufficient voltage prolongs run time and may cause band diffusion [1]. For precast gradient gels, follow manufacturer recommendations as these systems often tolerate higher voltages.

Buffer System: The running buffer typically contains 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, and 0.1% SDS (pH ~8.3). Maintain consistent buffer ionic strength and pH across runs. For high-throughput applications, concentrated buffer stocks can be diluted as needed [1] [34].

Temperature Control: Excessive heat during electrophoresis can affect protein mobility and gel structure. For high-voltage runs, use cooling systems or run in a cold room to prevent heat-related artifacts [1].

Troubleshooting common electrophoresis issues:

- Smiling bands: Often caused by uneven heating; ensure proper buffer circulation and consider reducing voltage

- Uneven band spreading: May result from improper buffer levels or uneven gel polymerization

- Vertical streaking: Frequently indicates protein aggregation or insufficient denaturation [35] [1]

Staining Protocols: Balancing Sensitivity and Compatibility

Protein visualization after electrophoresis requires careful selection of staining methods based on sensitivity requirements, downstream applications, and equipment availability.

Coomassie Brilliant Blue Staining offers an optimal balance of simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and compatibility with mass spectrometry. The protocol involves:

- Fixation: Incubate gel in solution containing 50% ethanol and 10% acetic acid for 10 minutes to 1 hour to precipitate proteins and prevent diffusion [35].

- Staining: Use 0.1% Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 in 20% methanol and 10% acetic acid with gentle agitation for at least 3 hours (or overnight for enhanced sensitivity) [35].

- Destaining: Remove background stain with multiple changes of 20% methanol/10% acetic acid solution until bands are clear against a light background. Alternatively, for Coomassie G-250, water alone can be used for destaining [35].

- Preservation: Incubate gel in 5% acetic acid for at least 1 hour before sealing in polyethylene bags to prevent dehydration [35].

Table 3: Comparison of Protein Staining Methods for SDS-PAGE

| Staining Method | Detection Sensitivity | Compatibility with MS | Procedure Complexity | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue | 5-30 ng [35] | High [35] | Low | Low |

| Silver Staining | 0.1-1 ng | Variable (MS-compatible versions available) | High | Moderate |

| Fluorescent Stains | 1-5 ng | High | Moderate | High |

| Zinc/Reverse Staining | 1-10 ng | High | Moderate | Low |

For mass spectrometry compatibility, minimize formaldehyde and glutaraldehyde cross-linking in silver staining protocols, and use high-purity reagents to reduce chemical modifications that might interfere with protein identification [35] [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Equipment

Successful implementation of optimized SDS-PAGE workflows requires access to specific laboratory reagents and equipment. The following table outlines essential solutions and materials:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SDS-PAGE Workflow

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms cross-linked gel matrix | Typically 29:1 or 37:1 ratio; neurotoxin in monomer form |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins and confers negative charge | High purity; working concentration 0.1-0.5% |

| Tris Buffers | Maintain pH during electrophoresis and gel polymerization | Tris-HCl pH 6.8 (stacking), pH 8.8 (resolving) |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | Initiates free radical polymerization | Fresh preparation recommended |

| TEMED | Catalyzes acrylamide polymerization | Accelerates reaction; store tightly sealed |

| Glycine | Leading ion in discontinuous buffer system | Electrophoresis grade for consistency |

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue | Protein staining | R-250 for gels; G-250 for Bradford assay |

| β-Mercaptoethanol or DTT | Reducing agent for disulfide bond cleavage | DTT preferred for stronger reducing capability |

| Molecular Weight Standards | Calibration for molecular weight determination | Pre-stained markers available for transfer monitoring |

| Precast Gels | Ready-to-use gel cassettes | Enhance reproducibility; save preparation time |

Leading companies providing SDS-PAGE equipment and reagents include Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Merck KGaA, and Danaher Corporation, offering systems ranging from traditional gel tanks to advanced precast gel systems with integrated digital imaging capabilities [37] [36].

Integrated Workflow for Molecular Weight Validation

The complete optimized SDS-PAGE workflow integrates each component into a cohesive process for protein molecular weight validation, with potential integration points for mass spectrometric analysis:

This integrated approach enables researchers to efficiently validate protein molecular weight while identifying candidates for further characterization. When discrepancies between observed and predicted molecular weights occur, subsequent analysis by top-down mass spectrometry can characterize specific proteoforms, including post-translational modifications and sequence variants that account for these differences [16] [33].

The optimized SDS-PAGE workflow detailed in this guide provides a robust framework for protein molecular weight assessment that remains relevant in modern proteomics and drug development. While mass spectrometry offers superior precision for molecular weight determination and proteoform characterization, SDS-PAGE maintains its position as an accessible, cost-effective technique that provides valuable preliminary data and guides further analysis. The integration of these complementary methodologies creates a powerful approach for comprehensive protein characterization in basic research, biomarker discovery, and biopharmaceutical development.

Advances in SDS-PAGE technology, including precast gradient gels, digital imaging systems, and automated analysis software, continue to enhance the technique's reproducibility and throughput. These innovations ensure that SDS-PAGE will remain an essential component of the protein researcher's toolkit, particularly when implemented within validated workflows that acknowledge both its capabilities and limitations for molecular weight determination.

Mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics has become an indispensable technology in modern biological research and drug development, enabling the large-scale study of proteins' identities, quantities, structures, and functions. Within this field, three principal methodologies—bottom-up proteomics, top-down proteomics, and LC-MS/MS—provide complementary approaches for probing the proteome. These techniques offer distinct advantages and limitations, making them suitable for different research objectives within pharmaceutical development and basic science.

The validation of protein molecular weight represents a fundamental application where these techniques demonstrate their respective capabilities. While SDS-PAGE (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis) has long served as the traditional workhorse for estimating molecular weight and assessing purity, MS-based methods provide superior accuracy, resolution, and additional layers of information including sequence verification and post-translational modification (PTM) characterization [4]. This guide provides a detailed technical comparison of these advanced MS techniques, framed within the context of protein characterization and validation, to assist researchers in selecting the most appropriate methodology for their specific applications in drug development and biomedical research.

Core Principles and Technical Differentiation

Bottom-Up Proteomics (BUP)

Bottom-up proteomics (also called "shotgun proteomics") is the most widely adopted MS-based strategy. This approach involves enzymatically digesting proteins into peptides followed by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis [38]. The process begins with protein extraction and denaturation, followed by proteolytic digestion (typically with trypsin) to generate peptides. These peptides are then separated by liquid chromatography and introduced into the mass spectrometer, where they are ionized, measured, and selectively fragmented to produce MS/MS spectra. These spectra are subsequently matched to theoretical spectra from protein databases to identify peptide sequences and infer protein identities [39] [38].

The primary advantage of bottom-up proteomics lies in its high sensitivity and broad proteome coverage, routinely identifying and quantifying thousands of proteins in a single analysis from complex mixtures like cell lysates or tissue extracts [38]. This makes it particularly powerful for discovery-phase studies aiming to comprehensively profile protein expression changes. However, a significant limitation is the "protein inference problem," where multiple proteins may share peptides, complicating unambiguous protein identification and making it difficult to distinguish between specific protein isoforms and proteoforms [38]. Additionally, because proteins are digested prior to analysis, information about the combination of post-translational modifications (PTMs) on a single protein molecule is lost.

Top-Down Proteomics (TDP)

In contrast, top-down proteomics analyzes intact proteins without enzymatic digestion, preserving comprehensive proteoform information [16]. This approach involves separating intact proteins using chromatographic or electrophoretic methods followed by MS analysis where the entire protein ions are fragmented within the mass spectrometer (gas-phase fragmentation) [16].

The key strength of TDP is its ability to characterize specific proteoforms—defined as all the different molecular forms in which a protein product can exist, including those arising from genetic variation, alternative splicing, and post-translational modifications [16]. This provides a "bird's-eye view" of proteoforms with combinations of various PTMs, which is crucial for understanding protein function in many biological contexts [16]. For example, in the characterization of protein coronas on nanoparticles, TDP can identify specific proteoforms that influence cellular uptake and immune responses, information that BUP cannot provide [16]. The main challenges for TDP include lower sensitivity, reduced proteome coverage, and limitations in analyzing large proteins (typically above 30-50 kDa), though technological advances are gradually mitigating these constraints [16].

LC-MS/MS in Proteomics Workflows

LC-MS/MS represents the instrumental backbone for both bottom-up and top-down approaches, integrating liquid chromatography for biomolecule separation with tandem mass spectrometry for structural characterization [40]. In this platform, LC efficiently separates peptides or proteins based on their chemical properties, reducing sample complexity before MS analysis. The mass spectrometer then performs two stages of mass analysis: the first (MS1) measures the mass-to-charge ratios of intact ions, while the second (MS2) fragments selected ions to generate structural information [40].

Recent advancements in LC-MS/MS technology have dramatically improved the sensitivity, resolution, and speed of proteomic analyses. Techniques such as Orbitrap mass analyzers, ion mobility separation, and data-independent acquisition (DIA) methods have enhanced the depth and reproducibility of proteomic measurements [41] [40]. The application of artificial intelligence and machine learning in data processing has further accelerated protein identification and quantification, making LC-MS/MS an increasingly powerful tool for both basic research and pharmaceutical applications [41].

Comparative Technical Performance Analysis

Table 1: Technical comparison of bottom-up versus top-down proteomics approaches

| Parameter | Bottom-Up Proteomics | Top-Down Proteomics |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Multi-step enzymatic digestion (typically 1 day) [16] | Minimal steps without digestion (several hours) [16] |

| Analytical Target | Peptides [38] | Intact proteoforms [16] |

| Typical Proteome Coverage | Thousands of proteins per experiment [16] | Hundreds of proteins per experiment [16] |

| Sensitivity | High [16] | Relatively lower [16] |

| Throughput | High (minutes per sample) [16] | Lower (∼1 hour per sample) [16] |

| Molecular Weight Range | Essentially unlimited (analyzes peptides) [16] | Typically <30 kDa (difficulties with larger proteoforms) [16] |

| PTM Characterization | Identifies PTM types and locations but cannot determine combinations on single molecules [16] | Provides complete PTM mapping including combinations on individual proteoforms [16] |

| Protein Inference | Protein inference problem: cannot always distinguish between isoforms [38] | Direct proteoform identification without inference problems [16] |

| Instrument Requirements | Standard commercial Orbitrap and TOF instruments [16] | Advanced high-sensitivity, high-resolution instruments with gas-phase fragmentation [16] |

| Informatics Maturity | Mature bioinformatics tools [16] | Less established bioinformatic tools [16] |

Table 2: Comparison of protein characterization capabilities across techniques

| Characterization Capability | SDS-PAGE | Bottom-Up Proteomics | Top-Down Proteomics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight Determination | Estimated with 5-10% accuracy [4] | Precise (from peptide data) | Highly precise (intact mass) |

| Proteoform Resolution | Limited (same MW proteoforms co-migrate) | Cannot distinguish proteoforms | High (distinguishes proteoforms) |

| PTM Detection | Indirect (band shifts) [4] | Yes, but loses PTM connectivity [16] | Comprehensive PTM characterization [16] |

| Sequence Coverage | None | High (from peptides) | Complete (intact protein) |

| Multi-Subunit Analysis | Under reducing conditions [4] | Indirect inference | Direct analysis |

| Sample Throughput | High | Medium to High | Low to Medium |

| Technical Reproducibility | Moderate | High | Medium |

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Bottom-Up Proteomics Workflow for Protein Mixture Characterization

The standard bottom-up protocol begins with protein extraction and denaturation using buffers containing detergents or chaotropes. Proteins are then reduced (e.g., with dithiothreitol) and alkylated (e.g., with iodoacetamide) to break disulfide bonds and prevent their reformation. Next, proteolytic digestion with trypsin is performed for 4-18 hours, typically at 37°C, followed by peptide purification and concentration [38]. The resulting peptides are separated using reversed-phase nano-LC with acetonitrile gradients and analyzed by MS/MS with collision-induced dissociation (CID) or higher-energy collisional dissociation (HECD) [38]. Data analysis involves database search algorithms (MaxQuant, FragPipe, Spectronaut) for protein identification and quantification [38].

Top-Down Proteomics Workflow for Proteoform Characterization

For top-down analysis, proteins are extracted under non-denaturing conditions to preserve native proteoforms. The extract is then subjected to intact protein separation using techniques like reversed-phase LC, capillary zone electrophoresis, or gel filtration [16]. The separated proteins are introduced into the mass spectrometer via electrospray ionization, and intact protein masses are measured with high resolution and accuracy. Gas-phase fragmentation techniques like electron-transfer dissociation (ETD) or electron-capture dissociation (ECD) are applied to preserve labile PTMs [16]. Data processing involves deconvolution of protein mass spectra and database matching for proteoform identification using specialized software (TopPIC, ProSightPC) [16].

LC-MS/MS Protocol for Therapeutic Antibody Characterization

For biopharmaceutical applications like monoclonal antibody characterization, a combined approach is often optimal. Intact antibody analysis by LC-MS provides information about overall molecular weight and major glycoforms. Middle-down analysis after limited proteolysis (e.g., with IdeS enzyme) characterizes larger fragments. Finally, bottom-up analysis after tryptic digestion provides detailed sequence coverage and PTM localization [41]. The recent introduction of instruments like the Thermo Orbitrap Excedion Pro MS, which combines Orbitrap technology with alternative fragmentation technologies, has proven particularly effective for such comprehensive analysis of complex biotherapeutics [41].

Workflow Visualization

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential research reagents for advanced proteomics workflows

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Separation Media | Polyacrylamide gels (SDS-PAGE) [4], CZE capillaries [16], LC columns (C18, C8) [40] | Separate proteins or peptides based on size, charge, or hydrophobicity |

| Digestion Enzymes | Trypsin, Lys-C, Asp-N [38] | Proteolytically cleave proteins into peptides for bottom-up analysis |

| Chemical Reagents | SDS [4], DTT/β-mercaptoethanol [4], iodoacetamide [38] | Denature proteins, reduce disulfide bonds, alkylate cysteine residues |

| Molecular Weight Standards | Precision Plus Protein Standards [42], unstained protein ladders | Provide reference for molecular weight calibration in gels and MS |

| Cross-linking Reagents | DSSO, BS3 [38] | Stabilize protein-protein interactions for structural MS (XL-MS) |

| Chromatography Solvents | Water, acetonitrile, methanol, formic acid [40] | Mobile phases for LC separation of proteins/peptides |

| Ionization Sources | Electrospray ionization (ESI) [40], Atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) [40] | Generate gas-phase ions from liquid samples for MS analysis |

| Mass Analyzers | Orbitrap [41], Q-TOF [41], Time-of-Flight (TOF) [40] | Separate ions based on mass-to-charge ratio with high resolution and accuracy |

Application Contexts in Drug Development and Research

Biopharmaceutical Characterization

In therapeutic protein and monoclonal antibody development, top-down proteomics provides critical advantages for characterizing lot-to-l consistency, post-translational modifications, and higher-order structure [41]. The technology's ability to identify specific proteoforms helps ensure product quality and consistency, particularly for biosimilar development. Meanwhile, bottom-up approaches deliver comprehensive sequence coverage and can detect low-abundance impurities or degradation products [41].

Biomarker Discovery and Validation

For biomarker discovery, bottom-up proteomics excels at screening large sample sets to identify potential protein signatures associated with disease states or treatment responses [39] [43]. The high throughput and sensitivity enable profiling of hundreds to thousands of proteins across numerous clinical samples. Once candidate biomarkers are identified, targeted LC-MS/MS methods can be developed for precise validation in independent cohorts [43].

Structural Proteomics and Protein-Protein Interactions

Cross-linking mass spectrometry (XL-MS), which typically employs bottom-up workflows, provides structural information by identifying spatially proximal amino acids within protein complexes [38]. This approach, combined with hydrogen-deuterium exchange (HDX-MS) and limited proteolysis (LiP-MS), enables the mapping of protein interaction interfaces and conformational changes, offering insights into mechanism of action for drug targets [38].

The choice between bottom-up, top-down, and LC-MS/MS approaches depends heavily on the specific research questions and analytical requirements. Bottom-up proteomics remains the preferred method for comprehensive proteome profiling, offering exceptional sensitivity and throughput for discovery-phase studies. Top-down proteomics provides unparalleled ability to characterize specific proteoforms, making it invaluable for applications requiring complete PTM characterization or analysis of protein isoforms. LC-MS/MS serves as the foundational technology enabling both approaches, with continuous advancements in instrumentation expanding the capabilities of each methodology.

For protein molecular weight validation, MS-based techniques provide significant advantages over traditional SDS-PAGE in terms of accuracy, resolution, and additional characterization capabilities. However, SDS-PAGE maintains utility for rapid assessment of protein purity and integrity, particularly in resource-limited settings [4]. As the proteomics field continues to evolve, the integration of multiple approaches—leveraging the complementary strengths of each methodology—will provide the most comprehensive understanding of protein structure and function, ultimately accelerating drug development and biomedical research.

The integration of sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) with mass spectrometry (MS) represents a cornerstone approach in modern proteomics, enabling researchers to decipher protein complexity with high resolution and sensitivity. This integration addresses a critical challenge in structural biology: obtaining comprehensive structural information on cellular proteomes with sufficient depth to cover both abundant and low-abundance components [7]. For decades, the GeLC-MS workflow (gel electrophoresis followed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry) has served as a fundamental method for in-depth proteome analysis by reducing sample complexity prior to MS analysis [7]. However, traditional GeLC-MS approaches have faced significant limitations in recovering intact proteins from polyacrylamide gels, particularly for high molecular weight species [44].

The recent development of PEPPI-MS (Passively Eluting Proteins from Polyacrylamide gels as Intact species for Mass Spectrometry) has revolutionized this field by overcoming longstanding protein recovery challenges [44]. This innovative approach enables highly efficient extraction of intact proteins across a wide molecular weight range, making it particularly valuable for top-down proteomics where maintaining protein intactness is essential [45]. As proteomics continues to evolve toward characterizing complete proteoforms (all molecular forms of proteins derived from a single gene), the integration of SDS-PAGE with advanced MS techniques becomes increasingly important for understanding protein function in health and disease [46].

This comparison guide examines both traditional GeLC-MS and innovative PEPPI-MS workflows within the context of validating protein molecular weight measurements across techniques. We provide experimental data, detailed methodologies, and practical considerations to help researchers select appropriate integration strategies for their specific research objectives in basic science and drug development.

Background: Structural Proteomics and Technological Evolution

Mass Spectrometry Approaches in Structural Proteomics

Structural proteomics aims to comprehensively characterize protein structures and interactions on a proteome-wide scale. Several MS-based methodologies have emerged to address this challenge:

Top-down MS: This approach ionizes proteins in their intact form and fragments them inside the MS instrument to obtain comprehensive chemical structural information, including amino acid sequences and post-translational modifications (PTMs) [7] [47]. It enables highly accurate identification of proteoforms, which are diverse protein chemical structures produced from a single gene in vivo [47].

Native MS: This technique analyzes non-denatured proteins and protein complexes, maintaining higher-order structure by suppressing structural destruction during ionization [7] [47]. It provides mass information on intact complexes and can be combined with fragmentation for structural analysis of subunits [47].

Cross-linking MS (XL-MS): This method chemically cross-links protein molecules in solution and identifies cross-linking sites through bottom-up MS, enabling analysis of protein-protein interactions and spatial relationships [7].

A significant challenge common to all these structural MS methods, as well as conventional bottom-up proteomics, is the need for effective sample preparation to enhance detection of low-abundance components [7]. Even with advanced LC-MS systems, the separation of complex proteome samples often requires additional fractionation to achieve sufficient depth of analysis [7].

SDS-PAGE as a Separation Tool