Protein Ladder Migration: A Comprehensive Guide to Denaturing vs. Native Gel Analysis

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical differences in protein ladder migration between denaturing (SDS-PAGE) and native gel electrophoresis.

Protein Ladder Migration: A Comprehensive Guide to Denaturing vs. Native Gel Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical differences in protein ladder migration between denaturing (SDS-PAGE) and native gel electrophoresis. It covers the foundational principles of each method, their specific applications in experimental design, and practical troubleshooting for common issues like smearing and incorrect band sizing. By offering a direct comparative analysis, the content equips scientists with the knowledge to accurately select the appropriate gel system, interpret protein ladder migration patterns, and validate their protein analysis results, thereby enhancing the reliability of data in downstream biomedical and clinical research.

Core Principles: How Gel Chemistry Dictates Protein Ladder Migration

In the realm of protein biochemistry, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) serves as a fundamental analytical technique for separating protein mixtures based on their physicochemical properties. Two principal methodologies dominate this field: denaturing SDS-PAGE and native PAGE. These systems employ distinct mechanisms to achieve separation, each offering unique advantages and limitations for specific research applications. The critical distinction lies in their treatment of protein structure—while SDS-PAGE dismantles proteins to their primary structure using the powerful denaturant sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), often coupled with reducing agents, native PAGE preserves the intricate three-dimensional architecture and biological activity of proteins [1] [2]. This comprehensive guide examines the molecular mechanisms, experimental parameters, and practical applications of these complementary techniques, with particular focus on the definitive roles of SDS and reducing agents in denaturing gel systems.

The selection between denaturing and native gel systems carries significant implications for protein analysis. Denaturing SDS-PAGE provides unparalleled resolution based primarily on molecular mass, making it indispensable for determining protein purity, subunit composition, and molecular weight [2]. In contrast, native PAGE separates proteins according to their combined charge, size, and shape under non-denaturing conditions, enabling researchers to study functional protein complexes, oligomerization states, and enzymatic activities [1] [3]. Understanding the fundamental principles governing each system is essential for designing appropriate experiments and accurately interpreting results in both basic research and drug development contexts.

Core Principles: Denaturing vs. Native Gel Systems

Mechanism of SDS-PAGE (Denaturing Conditions)

SDS-PAGE operates on the principle of complete protein denaturation to achieve separation primarily by molecular mass. The ionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) plays the pivotal role in this process by binding uniformly to denatured polypeptides in a constant weight ratio of approximately 1.4 g SDS per 1 g of polypeptide [1]. This uniform SDS coating masks the proteins' intrinsic charges, imparting a relatively consistent negative charge density across all polypeptides. Consequently, the SDS-polypeptide complexes migrate through the polyacrylamide gel matrix strictly according to polypeptide size, with minimal influence from compositional or charge differences [1].

The denaturation process in SDS-PAGE typically involves heating protein samples to 70-100°C in sample buffer containing excess SDS and reducing agents. This heat-denaturation step ensures complete unfolding of protein structures and facilitates thorough SDS binding [1]. The resulting linearized polypeptides then experience a sieving effect as they migrate through the gel matrix under an electric field, with smaller polypeptides moving more rapidly than larger ones. This predictable relationship between migration distance and molecular size enables accurate molecular weight estimation when appropriate standards are included [1] [4].

Diagram: Protein Denaturation and Migration in SDS-PAGE

Mechanism of Native PAGE

In stark contrast to SDS-PAGE, native PAGE maintains proteins in their natural, folded state throughout the separation process. Without denaturants or reducing agents, proteins retain their secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures, including subunit interactions in multimeric complexes [2]. This preservation of native structure allows separation based on the combined effects of intrinsic charge, hydrodynamic size, and three-dimensional conformation [1].

The migration of native proteins through the gel matrix depends on their net charge at the running buffer pH and the frictional forces they encounter. The gel matrix creates a sieving effect that regulates protein movement according to size and shape, with smaller, more compact proteins migrating faster than larger, bulkier proteins with equivalent charge [1]. This complex interplay of charge and size means that molecular weight determination is less straightforward than in SDS-PAGE, but the preservation of biological activity enables functional assays directly from gel fractions [2].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Denaturing vs. Native Gel Systems

| Parameter | SDS-PAGE (Denaturing) | Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Protein State | Denatured to primary structure | Native, folded conformation |

| Separation Basis | Primarily molecular mass | Charge, size, and shape |

| Sample Treatment | Heating with SDS ± reducing agents | No denaturation; minimal disruption |

| Detergent | SDS present | No SDS |

| Reducing Agents | Often used (DTT, β-mercaptoethanol) | Not used |

| Molecular Weight Determination | Direct estimation possible | Not reliable |

| Biological Activity | Lost | Preserved |

| Protein Complexes | Dissociated | Maintained |

| Typical Applications | Purity assessment, subunit analysis, western blot | Enzyme activity assays, protein-protein interactions |

The Denaturing System: Components and Mechanisms

Role of SDS in Protein Denaturation

Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) serves as the cornerstone of denaturing gel electrophoresis, performing two critical functions in protein sample preparation. First, SDS acts as a powerful denaturant by wrapping around the polypeptide backbone, disrupting hydrophobic interactions, and effectively unraveling the tertiary and secondary structures of proteins [1]. This denaturation process results in fully unfolded polypeptide chains with minimal residual structure.

Second, SDS provides a uniform negative charge to the denatured polypeptides through its sulfate head groups, which bind to proteins at a consistent ratio regardless of amino acid composition. This SDS coating confers a relatively uniform charge-to-mass ratio across different polypeptides, ensuring that separation occurs primarily according to molecular size rather than intrinsic charge differences [1] [4]. The anionic character of the SDS-protein complexes drives their electrophoretic migration toward the anode when an electric field is applied.

Role of Reducing Agents

While SDS effectively denatures most protein structures, additional agents are often required to completely reduce proteins to their monomeric subunits. Reducing agents such as dithiothreitol (DTT) or 2-mercaptoethanol (β-ME) serve this essential function by breaking disulfide bonds that covalently link cysteine residues within or between polypeptide chains [5].

The distinction between reducing and non-reducing SDS-PAGE lies in the inclusion of these agents. In reducing SDS-PAGE, disulfide-cross-linked subunits are fully dissociated, allowing analysis of individual polypeptide chains [5]. This is particularly important for proteins with complex quaternary structures or multiple subunits connected by disulfide bridges. In contrast, non-reducing SDS-PAGE omits reducing agents, preserving disulfide-linked complexes, which can provide information about protein oligomerization and covalent interactions [5].

Table 2: Key Reagents in Denaturing Gel Electrophoresis

| Reagent | Function | Mechanism of Action | Typical Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denaturant and charge provider | Binds polypeptide backbone, masks intrinsic charge, unfolds proteins | 1-2% in sample buffer |

| DTT (Dithiothreitol) | Reducing agent | Cleaves disulfide bonds through thiol-disulfide exchange | 10-100 mM |

| 2-Mercaptoethanol | Reducing agent | Reduces disulfide bonds via thiol group | 0.1-1% |

| Tris-HCl Buffer | pH control | Maintains optimal pH for electrophoresis | 50-200 mM, pH 6.8-8.8 |

| Glycerol | Density agent | Increases sample density for gel loading | 5-20% |

| Bromophenol Blue | Tracking dye | Visualizes migration front during electrophoresis | 0.001-0.01% |

Experimental Design and Protocols

Standard SDS-PAGE Protocol

The following protocol outlines the fundamental steps for performing denaturing SDS-PAGE, adapted from established methodologies [1] [5] [4]:

Sample Preparation:

- Combine protein sample with SDS-PAGE sample buffer (typically containing 62.5 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 0.01% bromophenol blue)

- Add fresh reducing agent (50-100 mM DTT or 5% 2-mercaptoethanol)

- Heat denature at 70-100°C for 5-10 minutes

- Centrifuge briefly to collect condensed sample

Gel Preparation:

- Prepare resolving gel solution (e.g., 10% acrylamide for 40-100 kDa proteins)

- Add polymerization catalysts (APS and TEMED)

- Cast gel between glass plates, overlay with water-saturated butanol

- After polymerization, prepare and cast stacking gel (lower acrylamide concentration, typically 4-5%)

- Insert well-forming comb

Electrophoresis:

- Assemble gel in electrophoresis apparatus

- Fill buffer chambers with running buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.3)

- Load samples and molecular weight markers (10-50 μg total protein per lane)

- Apply constant voltage (100-150 V for mini-gels) until dye front reaches bottom

- Terminate electrophoresis

Optimal protein separation requires appropriate gel composition selection based on target protein size. Lower percentage acrylamide gels (e.g., 8-10%) provide better resolution for high molecular weight proteins, while higher percentage gels (12-15%) are optimal for smaller proteins [4]. Gradient gels with increasing acrylamide concentration (e.g., 4-20%) offer broad separation ranges for complex mixtures.

Critical Factors Affecting Separation Quality

Several technical factors significantly impact the resolution and accuracy of SDS-PAGE separation:

Gel Composition: The acrylamide-to-bisacrylamide ratio determines gel pore size, directly affecting protein mobility and resolution [1]. Inappropriate acrylamide concentration for the target protein size range can result in poor separation.

Buffer System: The discontinuous Tris-glycine buffer system (stacking gel at pH 6.8, resolving gel at pH 8.8, running buffer at pH 8.3) creates ion fronts that concentrate proteins into sharp bands before entering the resolving gel [1] [4].

Electrophoresis Conditions: Excessive voltage generates heat, causing band distortion ("smiling effect"), while insufficient voltage prolongs runs and increases diffusion-related band broadening [6]. Optimal separation typically occurs at 10-15 volts per cm of gel length.

Sample Integrity: Incomplete denaturation or reduction results in anomalous migration, while protein degradation produces multiple bands or smearing [4]. Fresh reducing agents and proper heating are essential for reproducible results.

Applications and Data Interpretation

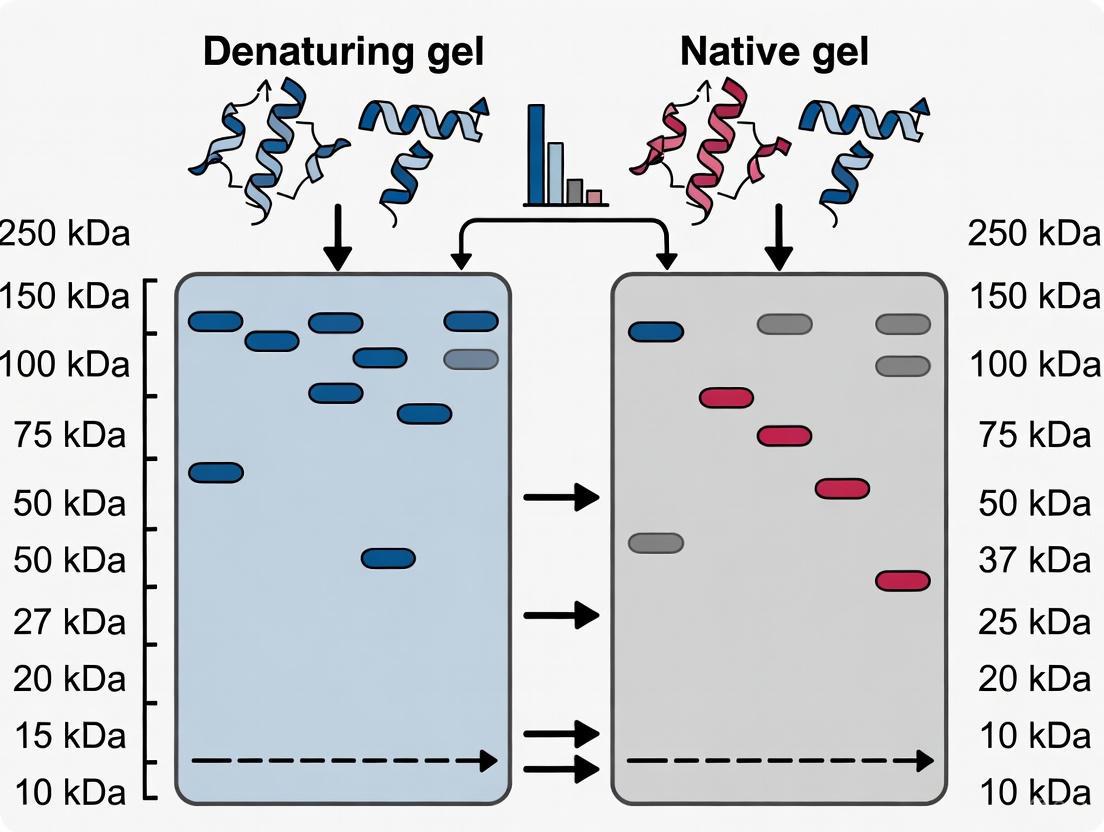

Comparative Analysis of Separation Outcomes

The distinct separation mechanisms of denaturing and native gel systems produce characteristically different protein migration patterns with unique interpretive value:

Molecular Weight Determination: SDS-PAGE enables direct molecular weight estimation by comparing protein migration distances to those of standard markers [1]. This relationship follows a logarithmic function, with smaller proteins migrating farther than larger ones. In native PAGE, migration depends on both size and charge, preventing reliable molecular weight determination without additional experimental parameters.

Complexity Analysis: SDS-PAGE reveals the subunit composition of protein complexes, with each polypeptide chain appearing as a distinct band [2]. This enables assessment of sample purity and identification of individual protein components. Native PAGE preserves protein complexes, displaying them as single entities with migration characteristics reflecting their oligomeric state [3].

Western Blotting Compatibility: Denatured proteins from SDS-PAGE gels transfer efficiently to membranes for immunodetection, making SDS-PAGE the preferred method for western blotting [4]. The linearized polypeptides expose epitopes for antibody binding and facilitate uniform transfer. Native proteins from native PAGE may transfer less efficiently and exhibit variable antibody recognition due to conformational epitopes.

Table 3: Applications and Data Interpretation in Different Gel Systems

| Application | SDS-PAGE Approach | Native PAGE Approach | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight Estimation | Direct comparison to standards | Not reliable | SDS-PAGE provides mass of subunits; native PAGE reflects complex size |

| Purity Assessment | Bands represent polypeptide chains | Bands may represent complexes | Contaminants easily identified in SDS-PAGE; co-migrating proteins possible in native PAGE |

| Western Blotting | Standard method; efficient transfer | Possible but challenging | Denaturation in SDS-PAGE exposes linear epitopes |

| Activity Assays | Not possible (proteins denatured) | Direct in-gel activity staining possible | Enzymatic function preserved only in native PAGE |

| Complex Analysis | Identifies subunit composition | Reveals oligomeric states | Reducing vs. non-reducing SDS-PAGE shows disulfide-linked complexes |

| Post-translational Modifications | May cause mobility shifts | Affect charge and/or size | Phosphorylation, glycosylation alter migration differently in each system |

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Several common electrophoretic anomalies provide diagnostic information about experimental conditions:

Smeared Bands: Often result from incomplete denaturation, insufficient reduction, protein overloading, or inappropriate gel percentage [6] [4]. Solution: Ensure fresh reducing agents, adequate heating, and optimal protein loading.

"Smiling" Bands (curved bands): Caused by excessive heat during electrophoresis [6]. Solution: Reduce voltage, implement cooling, or run in a cold room.

Atypical Migration: Post-translational modifications (e.g., glycosylation, phosphorylation) or unusual amino acid composition can alter SDS binding and mobility [7]. Solution: Confirm results with alternative methods like mass spectrometry.

Poor Resolution: Insufficient running time, improper buffer pH, or incorrect gel composition [6]. Solution: Optimize run duration, verify buffer preparation, and select appropriate gel percentage.

Edge Effects: Distorted lanes at gel periphery caused by empty wells [6]. Solution: Load reference samples or buffer in unused wells.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful gel electrophoresis requires specific reagents and equipment designed to support the distinct mechanisms of denaturing and native systems. The following research reagent solutions represent essential components for protein separation experiments:

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Gel Electrophoresis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Gel matrix formation | 30% acrylamide: 0.8% bis-acrylamide for standard gels |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Protein denaturation and charging | 10-20% stock solution for sample buffer and running buffer |

| Reducing Agents | Disulfide bond reduction | DTT (1M stock), 2-mercaptoethanol (14M stock) |

| Tris-based Buffers | pH maintenance | Tris-HCl for gels (pH 6.8, 8.8), Tris-glycine for running buffer |

| Polymerization Initiators | Gel polymerization | Ammonium persulfate (10% fresh solution), TEMED |

| Protein Molecular Weight Markers | Size calibration | Prestained and unstained standards covering 10-250 kDa range |

| Tracking Dye | Migration monitoring | Bromophenol blue (0.25%) in sample buffer |

| Protein Stains | Visualization | Coomassie Blue, Silver Stain, SYPRO Ruby, SimplyBlue SafeStain |

Denaturing SDS-PAGE and native PAGE represent complementary approaches to protein separation, each with distinctive advantages for specific research applications. The denaturing system, driven by the combined action of SDS and reducing agents, provides unparalleled resolution based primarily on molecular mass, making it indispensable for determining subunit composition, assessing purity, and facilitating immunoblotting techniques. In contrast, native PAGE preserves protein structure and function, enabling the study of protein complexes, oligomeric states, and biological activities under conditions that mimic the cellular environment.

The selection between these systems fundamentally depends on the research objectives: SDS-PAGE delivers precise molecular weight information and simplified banding patterns ideal for analytical applications, while native PAGE maintains structural integrity and biological function essential for physiological studies. For comprehensive protein characterization, researchers often employ both techniques in tandem to obtain complementary data regarding both structural and functional properties. As electrophoretic methodologies continue to evolve alongside advanced detection and analysis technologies, both denaturing and native gel systems remain cornerstone techniques in the molecular biologist's toolkit, providing fundamental insights into protein structure, function, and interactions in both basic research and drug development contexts.

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) is a foundational technique in molecular biology for separating protein mixtures, yet the choice between native and denaturing conditions fundamentally dictates the type of information obtained. Native PAGE operates without denaturants to preserve proteins in their biologically active state, maintaining complex quaternary structures, enzymatic activity, and protein-protein interactions [8]. In contrast, denaturing PAGE, typically SDS-PAGE, employs strong detergents and reducing agents to unfold proteins into linear polypeptides, separating them almost exclusively by molecular weight [9]. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these techniques, focusing on their mechanistic differences and practical applications in research and drug development, with special attention to the critical implications for protein ladder migration and interpretation.

Table 1: Core Principles of Native PAGE vs. Denaturing SDS-PAGE

| Feature | Native PAGE | Denaturing SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Separation Basis | Size, shape, and intrinsic charge of the native structure [9] | Molecular mass of polypeptide chains [9] |

| Protein Conformation | Native (folded, 3D structure preserved) [8] | Denatured (unfolded, linear chains) [9] |

| Key Reagents | Coomassie G-250 (in some systems), mild detergents [10] [11] | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS), DTT or β-mercaptoethanol [9] [5] |

| Treatment of Protein Complexes | Preserves oligomeric states and quaternary structure [3] [9] | Disassembles complexes into individual subunits [3] [12] |

| Biological Activity Post-Electrophoresis | Often retained (enzymatic assays possible) [10] [8] | Destroyed [8] [11] |

Experimental Protocols: A Side-by-Side Comparison

Standard Native PAGE Protocol for Protein Complexes

The following protocol, adapted from studies on epichaperome identification, is designed to preserve high-order protein assemblies [13].

- Sample Preparation: Cells are lysed using a cold, mild non-ionic detergent (e.g., 0.01% NP-40) in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris pH 7.4, 20 mM KCl, and 5 mM MgCl2. Protease and phosphatase inhibitors are essential. Crucially, samples are not boiled and are kept on ice throughout to prevent denaturation [13].

- Gel Chemistry & Buffer Selection: The choice of native gel system depends on the experimental goal. Tris-Glycine systems (pH 8.3-9.5) are traditional and preserve the native net charge of proteins. NativePAGE Bis-Tris systems (pH ~7.5) use Coomassie G-250 dye in the cathode buffer to impart a uniform negative charge, allowing even basic proteins to migrate toward the anode and improving resolution for membrane proteins [10].

- Electrophoresis Conditions: Run pre-cast 3-12% or 4-16% Bis-Tris gradient gels at 4°C to maintain protein stability. Use a constant voltage of 150V for approximately 90 minutes using an appropriate anode and cathode buffer system [13] [10].

- Post-Electrophoresis Analysis: Proteins can be transferred to PVDF (not nitrocellulose) for western blotting [10]. Alternatively, complexes can be recovered via diffusion or electroelution for functional studies or examined via in-gel activity assays [13].

Standard Denaturing SDS-PAGE Protocol

This protocol, fundamental to proteomics, ensures complete protein denaturation for separation by mass.

- Sample Preparation: Mix protein samples with an SDS-based sample buffer (e.g., Laemmli buffer) containing a reducing agent like dithiothreitol (DTT) or β-mercaptoethanol. Heat samples at 70-100°C for 10 minutes to fully denature proteins and break disulfide bonds [9] [5].

- Gel Chemistry & Buffer Selection: Use Tris-Glycine or Bis-Tris gels with SDS incorporated into both the gel and the running buffer. A standard running buffer is 25 mM Tris, 192 mM Glycine, 0.1% SDS [9].

- Electrophoresis Conditions: Load samples onto a polyacrylamide gel (e.g., 12%) with a stacking gel. Run at a constant voltage (e.g., 200V) for 30-45 minutes at room temperature until the dye front reaches the bottom [11].

- Post-Electrophoresis Analysis: Proteins are typically stained (e.g., Coomassie, silver stain) or transferred for western blotting. The migration distance is compared to a denatured protein ladder to estimate molecular weight [9].

Performance and Data Comparison

Quantitative Analysis of Separation Characteristics

The presence or absence of denaturants creates starkly different separation profiles and functional outcomes, as quantified in various studies.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance and Outcome Comparison

| Parameter | Native PAGE | Denaturing SDS-PAGE | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Ion Retention | 98% Zn²⁺ retained | 26% Zn²⁺ retained | Analysis of Zn-proteome after electrophoresis [11] |

| Enzymatic Activity Retention | 7 out of 9 model enzymes active | 0 out of 9 model enzymes active | In-gel activity assay post-electrophoresis [11] |

| Key Resolvable Targets | Protein complexes, oligomers, supercomplexes, active enzymes [3] [14] | Individual subunits, purity, molecular weight [3] [5] | Applicability for different analytical goals |

| Impact on Protein Ladder Migration | Migration depends on mass, charge, and shape; not reliable for mass determination alone [8] | Migration proportional to log(MW); reliable for mass determination [9] | Interpretation of protein standard bands |

Case Study: NSDS-PAGE as an Intermediate Method

Research has explored hybrid methods to balance resolution and native-state preservation. Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE) modifies traditional SDS-PAGE by removing EDTA from buffers, drastically reducing SDS concentration (from 0.1% to 0.0375%), and eliminating the sample heating step [11]. This protocol achieves high-resolution separation similar to denaturing SDS-PAGE while allowing 98% of zinc ions to remain bound to metalloproteins and preserving the activity of most enzymes tested [11]. This demonstrates that the denaturants themselves, rather than the electrophoretic process, are primarily responsible for the loss of native structure and function.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Successful experimentation requires careful selection of reagents tailored to the chosen method.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Native and Denaturing Electrophoresis

| Reagent / Material | Function | Native PAGE Application | Denaturing SDS-PAGE Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Ionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers uniform charge. | Absent or minimal (e.g., 0.0375% in NSDS-PAGE) [11] | Present (e.g., 0.1-0.5%) in sample and running buffers [9] |

| Coomassie G-250 Dye | Imparts negative charge to proteins for migration at neutral pH. | Key component in BN-PAGE and NativePAGE Bis-Tris systems [10] [14] | Not used in standard protocols. |

| DTT / β-mercaptoethanol | Reducing agent that breaks disulfide bonds. | Typically omitted to preserve structure. | Essential component for full denaturation [5]. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Prevents protein degradation during sample prep. | Critical, as samples are not denatured [13]. | Often used, but less critical due to denaturation. |

| Mild Detergent (e.g., NP-40, DDM) | Solubilizes membranes while preserving protein complexes. | Used in lysis buffer (e.g., 0.01% NP-40) [13]. | Not typically used; SDS is the primary detergent. |

| PVDF Membrane | Substrate for western blotting after electrophoresis. | Recommended for NativePAGE transfers [10]. | Compatible with standard western blotting. |

Application Scenarios and Decision Guide

The choice between native and denaturing gels is dictated by the biological question. The diagram below outlines the decision-making workflow for selecting the appropriate method.

Use Native PAGE when your objective is to study the architecture and function of proteins in their biologically relevant form. This includes identifying specific protein complexes like epichaperomes in disease models [13], analyzing the oligomeric state of a protein, resolving different conformational states (e.g., circular vs. linear DNA) [3], or performing in-gel enzymatic activity assays [14]. It is the preferred method for any application where the preservation of protein-protein interactions or biological function is paramount.

Use Denaturing SDS-PAGE when the goal is to determine the molecular weight of polypeptide chains, establish the purity of a protein sample, analyze complex protein mixtures like cell lysates with high resolution, or prepare samples for downstream techniques like western blotting or protein sequencing [3] [8] [9]. It is the standard workhorse for most analytical and preparative protein biochemistry tasks where functional integrity is not required.

In conclusion, the absence of denaturants in Native PAGE is not merely a technical omission but a fundamental design feature that enables the study of proteins as dynamic, functional macromolecular machines. While SDS-PAGE provides unparalleled resolution for determining molecular weight, Native PAGE and its derivatives offer a unique window into the structural and functional biology that underpins both basic research and drug development efforts.

Protein gel electrophoresis serves as a fundamental technique in molecular biology, biochemistry, and drug development for separating and analyzing proteins. The core principle of this technique involves the migration of charged protein molecules through a gel matrix under the influence of an electrical field [9] [15]. However, the specific mechanism governing this separation varies dramatically depending on whether the experimental conditions preserve or disrupt the native structure of proteins. This creates a critical dichotomy in separation principles: denaturing techniques separate proteins primarily by molecular weight, while native techniques separate proteins based on a combination of size, shape, and intrinsic charge [3] [9].

Understanding this distinction is paramount for researchers interpreting protein ladder migration patterns, as the same protein can migrate to different positions under denaturing versus native conditions. The choice between these systems directly impacts the resolution, sensitivity, and analytical outcomes of experiments, particularly in pharmaceutical development where characterizing protein complexes, enzyme activity, and protein-protein interactions is routine [16] [3]. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these separation mechanisms, supported by experimental data and protocols, to inform method selection for specific research objectives.

Fundamental Principles of Electrophoretic Separation

Core Factors Influencing Protein Mobility

The mobility of a molecule through an electric field depends on several factors: field strength, the net charge on the molecule, its size and shape, the ionic strength of the buffer, and the properties of the matrix through which the molecule migrates (e.g., viscosity, pore size) [9] [15]. The support matrix, such as polyacrylamide or agarose, acts as a porous molecular sieve. Polyacrylamide, with its smaller pore size, is ideal for separating most proteins, while agarose, with larger pores, is suitable for very large protein complexes [9] [15].

The fundamental relationship can be summarized as: mobility is inversely proportional to the size of the molecule and directly proportional to its net charge [15]. The conformation also plays a critical role; globular proteins, with their compact structures, exhibit faster mobility than fibrous proteins of similar molecular weight [15]. The separation mechanism an experimenter chooses—either denaturing or native—determines which of these factors become the primary determinant of mobility.

A Tale of Two Techniques: Denaturing vs. Native Conditions

The following workflow illustrates the fundamental procedural and mechanistic differences between denaturing (SDS-PAGE) and native PAGE, guiding researchers on the critical choice points in experimental design.

Denaturing Gel Electrophoresis: Separation by Molecular Weight

The SDS-PAGE Mechanism

In denaturing gel electrophoresis, specifically SDS-PAGE (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate - Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis), the ionic detergent SDS plays the pivotal role. When a protein sample is heated (typically between 70-100°C) in the presence of excess SDS and a reducing agent (like β-mercaptoethanol), the protein undergoes complete denaturation [9]. SDS binds to the polypeptide backbone in a constant weight ratio (approximately 1.4 g SDS per 1 g of polypeptide), which masks the protein's intrinsic charge [9]. The reducing agent cleaves disulfide bonds, ensuring the protein is fully dissociated into its subunits [9].

The result is that all SDS-polypeptide complexes adopt a similar rod-like shape and possess a uniform negative charge. This means the charge-to-mass ratio is essentially identical for all proteins. Consequently, when an electric field is applied, separation occurs strictly based on polypeptide size, as the proteins are sieved through the pores of the polyacrylamide gel [9]. Smaller polypeptides migrate more quickly through the gel matrix than larger ones, allowing for molecular weight determination when compared to a protein ladder of known molecular weights [9].

Experimental Protocol for SDS-PAGE

Detailed Methodology for Denaturing SDS-PAGE:

- Sample Preparation: Dilute protein samples in a Laemmli buffer containing SDS, a reducing agent (e.g., DTT or β-mercaptoethanol), and a tracking dye (e.g., bromophenol blue). Heat the samples at 70-100°C for 5-10 minutes to ensure complete denaturation and reduction [9].

- Gel Casting: Polyacrylamide gels are formed by polymerizing acrylamide and bisacrylamide (a cross-linker) in the presence of a catalyst such as ammonium persulfate (APS) and a stabilizer TEMED [9]. A resolving gel (e.g., 10-12% acrylamide) at an alkaline pH (e.g., Tris-HCl, pH 8.8) is poured first and is responsible for separation. A lower-concentration stacking gel (e.g., 4-5% acrylamide) at a lower pH (e.g., Tris-HCl, pH 6.8) is poured on top to concentrate all proteins into a sharp band before they enter the resolving gel, enhancing resolution [9].

- Electrophoresis: Load the denatured samples and a pre-stained protein molecular weight ladder into the wells. Submerge the gel cassette in a running buffer containing Tris, glycine, and SDS. Apply a constant voltage (e.g., 150-200 V) until the tracking dye front reaches the bottom of the gel [9].

- Visualization & Analysis: After electrophoresis, proteins are visualized using stains like Coomassie Brilliant Blue, silver stain, or fluorescent dyes. The distance migrated by sample proteins is compared to the protein ladder to estimate molecular weight [9].

Advantages, Limitations, and Key Data

Table 1: Characteristics of Denaturing SDS-PAGE

| Aspect | Description | Supporting Experimental Data |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Primarily molecular weight of polypeptide chains [9]. | Mass spectrometry coupled with SDS-PAGE has validated migration patterns for ~10,000 human proteins, confirming MW as the primary factor [7]. |

| Key Reagents | SDS (denaturant), reducing agents (DTT/β-Me), Tris-Glycine buffer [9]. | Consistent migration patterns across five different cell lines demonstrate high reproducibility of this method [7]. |

| Protein State | Denatured, linearized, and reduced; subunits dissociated [3] [9]. | SDS binding in a constant ratio (1.4:1) confirmed through quantitative analysis, ensuring uniform charge [9]. |

| Molecular Weight Resolution | Effective for a broad range, typically from small peptides to large complexes >100 kDa [16]. | Tris-Glycine gels resolve 10-250 kDa; Bis-Tris gels offer a wider range (15-1,000 kDa) with higher resolution [16]. |

| Applications | Molecular weight estimation, purity assessment, Western blotting, protein quantitation [3] [9]. | Critical for antibody validation and reliable Western blot data, as highlighted by databases of reference MWs [7]. |

Native Gel Electrophoresis: Separation by Size, Shape, and Charge

The Native-PAGE Mechanism

In contrast, Native-PAGE (or non-denaturing PAGE) is performed without denaturing agents like SDS. This technique preserves the protein's native, three-dimensional structure, its enzymatic activity, and its interactions within multimeric complexes [3] [9]. Under these conditions, a protein's migration through the gel is a complex function of its inherent net charge, size, and shape [9].

In an alkaline running buffer, most proteins carry a net negative charge and migrate toward the anode. The higher the charge density (more charges per molecular mass), the faster a protein will migrate. Simultaneously, the frictional force of the gel matrix creates a sieving effect, regulating movement according to the protein's size and three-dimensional shape [9]. A small, highly charged, globular protein will migrate rapidly, while a large, less charged, or fibrous protein will migrate slowly. This multi-parameter separation can provide superior resolution for certain applications but does not allow for direct determination of molecular weight without additional controls.

Experimental Protocol for Native-PAGE

Detailed Methodology for Native-PAGE:

- Sample Preparation: Protein samples are mixed with a non-denaturing loading buffer that lacks SDS and reducing agents. The buffer may contain glycerol to aid in well loading and a tracking dye. The sample is typically not heated to prevent denaturation [17].

- Gel Casting: Polyacrylamide gels are cast similarly to SDS-PAGE but without SDS in any of the components. Both the stacking and resolving gels use compatible non-denaturing buffer systems, such as Bis-Tris at neutral pH, which helps maintain protein stability and native state [16].

- Electrophoresis: The running buffer also lacks SDS. The apparatus is often run in a cold room or with a cooling unit to minimize denaturation and proteolysis during the run, as the native structure is more sensitive to heat. The electrical current is applied, and proteins migrate according to their native properties [9].

- Visualization & Analysis: Proteins can be detected using standard staining methods. A key advantage is that enzymatic activity can often be detected after electrophoresis using specific activity stains (zymography). Proteins can also be recovered from native gels in their active form via passive diffusion or electro-elution [9].

Advantages, Limitations, and Key Data

Table 2: Characteristics of Native PAGE

| Aspect | Description | Supporting Experimental Data |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Net charge, size, and shape of the native structure [9]. | Used to study protein complexes and ligand-binding, where changes in migration indicate altered stability or assembly [17]. |

| Key Reagents | Non-denaturing buffers (e.g., Bis-Tris, pH-neutral), no SDS/reducing agents [16]. | Bis-Tris gels maintain a neutral pH, better preserving the native state of protein complexes compared to alkaline Tris-Glycine [16]. |

| Protein State | Native, folded; multimers, complexes, and enzymatic activity retained [3] [9]. | Semi-native PAGE (with SDS but no heat) separates based on differences in protein structural stability [17]. |

| Applications | Analysis of protein complexes, enzyme activity assays, protein-protein interactions, studying binding events [16] [3]. | Essential for screening protein-transition metal complex interactions while maintaining the integrity of the complex [17]. |

| Key Consideration | pH extremes and heat must be avoided to prevent irreversible protein damage [9]. | Maintaining cool temperatures during the run is critical for preserving native structure and function [9]. |

Direct Comparative Analysis: Denaturing vs. Native PAGE

The following table provides a consolidated, direct comparison of the two techniques, highlighting their performance and suitability for different experimental goals.

Table 3: Direct Comparison of Denaturing (SDS-PAGE) and Native PAGE

| Parameter | Denaturing (SDS-PAGE) | Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Separation Mechanism | Molecular weight of polypeptide subunits [9]. | Net charge, size, and 3D shape of the native protein [9]. |

| Protein State | Denatured, linearized, subunits dissociated [3]. | Native, folded, complexes intact [3]. |

| Key Reagents | SDS, reducing agents, Tris-Glycine/SDS buffer [16] [9]. | Non-denaturing buffers (e.g., Bis-Tris), no SDS [16]. |

| Effect on Activity | Enzymatic activity destroyed [3]. | Enzymatic activity often retained [9]. |

| Molecular Weight Determination | Yes, straightforward via comparison to ladder [9]. | No, not directly possible due to influence of charge and shape. |

| Information on Quaternary Structure | No, complexes are disrupted [9]. | Yes, multimeric state is preserved and can be analyzed [9]. |

| Typical Applications | - MW estimation [9]- Purity assessment [3]- Western blotting [3]- Protein sequencing prep [3] | - Protein-complex analysis [16]- Enzyme activity assays [9]- Protein-protein/ligand interactions [16] [17] |

| Optimal Gel Type | Tris-Glycine (routine), Bis-Tris (high-resolution) [16]. | Bis-Tris (neutral pH), other non-denaturing buffer systems [16]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the appropriate reagents is critical for successful electrophoresis. The table below details key materials and their functions, drawing from the compared methodologies.

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Protein Gel Electrophoresis

| Reagent/Category | Function | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gel Matrices | Forms the porous sieve for separation. | Polyacrylamide: Standard for most proteins [9]. Agarose: For very large protein complexes [9]. |

| Gel Chemistry Kits | Pre-mixed solutions for specific needs. | Bis-Tris Gels: High-resolution, neutral pH, superior for native and stable gels [16]. Tris-Glycine Gels: Cost-effective, routine SDS-PAGE, broad MW range [16]. Gradient Gels: Linear or gradient (e.g., 4-20%) for resolving proteins over a wider MW range [16] [9]. |

| Denaturing Agents | Disrupts protein structure, confers uniform charge. | SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate): Primary denaturant for SDS-PAGE [9]. Urea/DMSO/Glyoxal: Alternative denaturants for nucleic acids or specific applications [3]. |

| Reducing Agents | Cleaves disulfide bonds. | DTT (Dithiothreitol) or β-Mercaptoethanol: Added to sample buffer for complete denaturation [9]. |

| Buffers | Carries current, maintains pH. | Tris-Glycine-SDS: Standard running buffer for denaturing gels [9]. Bis-Tris, Native Buffer Systems: For native PAGE, no SDS [16]. |

| Molecular Weight Standards | Reference for size estimation. | Pre-stained Protein Ladders: Visualize migration during run. Unstained Protein Ladders: Higher accuracy for MW determination post-staining [9]. |

| Visualization Dyes | Detect separated proteins. | Coomassie Brilliant Blue: Standard, moderate sensitivity [16]. Silver Stain: High sensitivity [16]. Fluorescent Stains: High sensitivity, quantitative potential [16]. |

The choice between denaturing and native gel electrophoresis is not a matter of one technique being superior to the other, but rather of selecting the right tool for the specific biological question. SDS-PAGE is the unrivaled method for determining polypeptide molecular weight, assessing sample purity, and preparing for techniques like Western blotting, as it simplifies separation to a single parameter: size [9]. In contrast, Native-PAGE is indispensable when the goal is to understand a protein's functional state, revealing insights into its quaternary structure, complex formation, and enzymatic activity by leveraging the combined effects of size, shape, and native charge on migration [3] [9].

For researchers in drug development and basic science, this comparison underscores that data from one system cannot be directly transposed to the other. The migration of a protein ladder, and indeed any protein sample, is governed by fundamentally different rules in each environment. A comprehensive analysis of an unknown protein, particularly in the context of therapeutic antibody validation or characterizing biomolecular condensates [18], may even require the sequential application of both techniques to build a complete picture of both its composition and its native functional architecture.

Protein function is intrinsically linked to its structure, which is organized into four hierarchical levels. The primary structure is the linear sequence of amino acids, while secondary structure refers to localized folding into patterns such as alpha-helices and beta-sheets. The tertiary structure describes the overall three-dimensional conformation of a single polypeptide chain, and the quaternary structure arises when multiple folded polypeptide chains (subunits) assemble into a multi-subunit complex [19] [20]. Not all proteins possess quaternary structure; however, for those that do, this level of organization is critical for their biological activity, enabling complex functions such as cooperativity (exemplified by hemoglobin) and allosteric regulation [21] [20].

Understanding these structures, particularly the intact quaternary complexes, is essential in biomedical research and drug development. This guide objectively compares two fundamental electrophoretic techniques—denaturing and native gel electrophoresis—for analyzing proteins across these structural levels, providing researchers with data to inform their methodological choices.

Fundamental Principles: Denaturing vs. Native Gel Electrophoresis

Gel electrophoresis separates macromolecules based on their size and charge as they migrate through a gel matrix under an electric field. The choice between denaturing and native conditions profoundly impacts the level of protein structure that can be analyzed.

Denaturing gels, such as SDS-PAGE (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis), use the ionic detergent SDS to unfold proteins. SDS coats the polypeptide backbone with a uniform negative charge, overpowering the protein's intrinsic charge, and heat treatment disrupts non-covalent interactions. This process reduces the protein to a linear chain, meaning separation occurs almost exclusively based on molecular mass rather than shape or charge [3] [22]. Recent advancements in SDS capillary gel electrophoresis (SDS-CGE) further optimize this for high-throughput analysis of biopharmaceuticals, with studies highlighting the significant effects of operational parameters like temperature and electric field strength on resolution [22].

In contrast, native gels maintain the protein's higher-order structure during separation. Without denaturing agents, proteins remain in their folded state, retaining their secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures. Consequently, separation depends on a combination of the protein's intrinsic charge, molecular mass, and overall three-dimensional shape (cross-sectional area) [3]. This technique, including variants like Blue Native (BN)-PAGE and Clear Native (CN)-PAGE, is indispensable for studying functional protein complexes, oligomeric states, and protein-protein interactions [23] [24].

Table 1: Core Principles of Denaturing vs. Native Gel Electrophoresis.

| Feature | Denaturing Gels (e.g., SDS-PAGE) | Native Gels (e.g., BN-/CN-PAGE) |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Condition | Proteins unfolded and linearized | Proteins in folded, native state |

| Key Reagents | SDS, reducing agents (e.g., DTT) | No denaturants; often Coomassie G-250 (BN-PAGE) |

| Separation Basis | Primarily molecular mass | Size, intrinsic charge, and 3D shape |

| Quaternary Structure | Disassembled into subunits | Preserved intact |

| Key Applications | Determining polypeptide molecular weight, purity checks, western blotting | Studying oligomeric state, protein complexes, in-gel enzymatic activity |

Experimental Data and Comparative Analysis

Case Study: Analyzing a Mitochondrial Enzyme Complex

A 2025 study on Medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) provides a compelling quantitative comparison. MCAD is a mitochondrial homotetramer with a theoretical mass of ~178 kDa for the intact complex [23]. Researchers employed a high-resolution clear native PAGE (hrCN-PAGE) in-gel activity assay to investigate pathogenic variants.

When analyzed under native conditions, the wild-type MCAD showed a major active band migrating between 240 and 480 kDa, consistent with its tetrameric form. A second, less intense active band at a lower molecular mass suggested the presence of an alternative, active oligomeric species. Crucially, the in-gel enzymatic activity demonstrated a linear correlation with the amount of protein loaded, confirming the assay's quantitative nature for the functional tetramer [23].

When the same MCAD variants were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, the monomers of all variants migrated identically, confirming identical polypeptide chain molecular weights. However, this technique was blind to the critical structural differences between the variants [23]. This case underscores that while SDS-PAGE is excellent for analyzing primary structure (sequence), native gels are required to understand the functional quaternary structure.

Comparative Migration Patterns of Protein Ladders

Protein ladders migrate differently under denaturing and native conditions, which must be considered for accurate size interpretation.

Table 2: Comparative Migration of Protein Ladders and Complexes.

| Protein/Complex | Structure & Theoretical Mass | Migration in Denaturing Gel (SDS-PAGE) | Migration in Native Gel | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCAD (Wild-Type) | Homotetramer (~178 kDa) | Single band at ~44 kDa (monomer mass) [23] | Major band at 240-480 kDa (intact tetramer) [23] | Native gels preserve the functional oligomeric state. |

| MCAD Variant (R206C) | Disrupted tetramer (same monomer mass) | Single band at ~44 kDa (identical to WT) [23] | Altered migration; shifted band and inactive lower-mass fragments [23] | Reveals structural instability invisible to SDS-PAGE. |

| General Oligomers | Dimers, Trimers, etc. | All dissociate to monomers. Migration reflects monomeric mass. | Migration is a function of mass, charge, and shape, not mass alone [3]. | Calibration requires native protein standards of known oligomeric state. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: In-Gel Activity Assay for a Quaternary Enzyme Complex

This protocol, adapted from a 2025 study, allows simultaneous assessment of a protein's oligomeric state and enzymatic function [23].

1. Sample Preparation:

- For recombinant proteins: Purify using standard methods (e.g., affinity chromatography). Keep buffers free of denaturing agents.

- For cell lysates: Prepare mitochondrial-enriched fractions via differential centrifugation to concentrate the complex of interest.

2. High-Resolution Clear Native Electrophoresis (hrCN-PAGE):

- Cast a 4-16% gradient polyacrylamide gel to resolve a broad size range of complexes.

- Prepare the anode (lower chamber) buffer: 25 mM Imidazole/HCl, pH 7.0.

- Prepare the cathode (upper chamber) buffer: 50 mM Tricine, 7.5 mM Imidazole, pH ~7.0 (note: no SDS or other denaturants).

- Mix protein samples with a native loading dye (e.g., containing 5% Coomassie G-250). Load 1-10 µg of protein per lane.

- Run electrophoresis at 4°C to maintain complex stability. Start at 100 V, then increase to 200 V once the sample has entered the gel, until the dye front reaches the bottom.

3. In-Gel Activity Staining:

- Prepare a reaction mixture containing:

- 100 µM Octanoyl-CoA (physiological substrate)

- 200 µM Nitro Blue Tetrazolium (NBT, electron acceptor)

- 100 µM Phenazine Methosulfate (PMS, electron carrier)

- in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.0.

- Incubate the gel in the staining solution in the dark at room temperature with gentle agitation.

- Active enzyme complexes will reduce NBT, producing an insoluble purple formazan precipitate. Monitor band development (typically 10-30 minutes).

- Stop the reaction by rinsing the gel with water.

4. Data Analysis:

- Capture gel images and use densitometry software to quantify band intensity. The linear correlation between protein amount and activity can be established as in [23].

Protocol B: Sequential BN-PAGE and SDS-PAGE for Complex Composition

This two-dimensional method first separates complexes natively, then denatures them to analyze subunit composition [24].

1. First Dimension: Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE)

- Cast a 4-12% gradient polyacrylamide gel.

- Add Coomassie Blue G-250 (0.02%) to the cathode buffer, which confers a negative charge to the protein complexes.

- Solubilize protein samples (e.g., membrane complexes) with a mild non-ionic detergent (e.g., Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside).

- Load and run the gel at 4°C. The blue dye allows visual tracking of migration.

2. Gel Strip Excission and Denaturation

- After BN-PAGE, excise a single lane from the gel.

- Equilibrate the gel strip for 15-20 minutes in a solution containing 1% SDS and 1% β-mercaptoethanol to unfold proteins and reduce disulfide bonds.

3. Second Dimension: SDS-PAGE

- Place the equilibrated gel strip horizontally on top of a standard SDS-polyacrylamide gel.

- Seal it in place with agarose.

- Perform standard SDS-PAGE. Protein complexes separated in the first dimension (by native size) are now dissociated, and their subunits are separated in the second dimension by molecular mass.

- Visualize proteins by Coomassie staining, fluorescent staining, or western blotting.

Diagram 1: 2D BN-PAGE/SDS-PAGE workflow for analyzing complex composition.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Protein Electrophoresis Studies.

| Reagent / Solution | Critical Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge. | Core component of denaturing gels; final conc. ~0.1% in gels, 1-2% in sample buffer. |

| DTT or β-Mercaptoethanol | Reduces disulfide bonds, fully linearizing polypeptides. | Essential for complete denaturation in SDS-PAGE; typically 50-100 mM in sample buffer. |

| Coomassie G-250 | Imparts negative charge to protein complexes. | Used in BN-PAGE cathode buffer; critical for native separation. |

| Nitro Blue Tetrazolium (NBT) | Electron acceptor that forms purple precipitate upon reduction. | Key component of in-gel activity assays for oxidoreductases like MCAD [23]. |

| Polyacrylamide Gel Matrix | Sieving medium for size-based separation. | Gradient gels (e.g., 4-16%) offer superior resolution for diverse complex sizes. |

| Crosslinking Reagents (e.g., DSS) | Stabilizes transient protein-protein interactions. | Used in TX-MS workflows to capture quaternary structures in complex samples [25]. |

Advanced and Emerging Techniques

While traditional gels are powerful, emerging technologies are pushing the boundaries of quaternary structure analysis. Targeted Cross-Linking Mass Spectrometry (TX-MS) combines chemical cross-linking with high-resolution MS and computational modeling to determine quaternary structures directly in complex biological samples, such as a host-pathogen complex in human plasma [25]. This method generates dense networks of distance constraints that guide high-resolution protein docking algorithms.

Furthermore, computational methods are rapidly advancing. AlphaFold-Multimer extends the revolutionary AlphaFold model to predict the structures of multimeric protein complexes [21]. Simultaneously, Protein Language Models (PLMs) fine-tuned on mutational datasets show great promise in predicting the thermodynamic stability of both tertiary and quaternary structures directly from sequence information, a significant advantage when structural data is unavailable [26].

The choice between denaturing and native gel electrophoresis is not a matter of which is superior, but which is appropriate for the biological question at hand.

Use Denaturing Gels (SDS-PAGE) when: Your goal is to verify the molecular weight of a polypeptide chain, assess sample purity, check protein expression levels, or prepare samples for western blotting or protein sequencing [3]. It is the standard for analyzing the primary structure level.

Use Native Gels (BN-/CN-PAGE) when: Your goal is to study the intact quaternary structure, identify the native oligomeric state (e.g., dimer vs. tetramer), investigate protein-protein interactions, monitor complex assembly/disassembly, or perform in-gel functional assays [23] [3] [24]. This is the definitive method for analyzing functional, higher-order structures.

For the most comprehensive structural insights, these techniques are often used in concert, as demonstrated by the 2D BN-/SDS-PAGE protocol. Furthermore, integrating these classical methods with emerging cross-linking MS and computational approaches provides a powerful, multi-faceted strategy for elucidating the architecture of protein complexes from linear chains to intact quaternary structures.

In molecular biology, the separation of proteins using gel electrophoresis is a foundational technique, and the choice between denaturing and native systems fundamentally dictates the outcome and interpretation of the experiment. Denaturing gel electrophoresis, most commonly Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), unravels protein complexes and coats them with a negative charge, allowing separation based almost exclusively on polypeptide chain mass. In contrast, native gel electrophoresis separates proteins based on a combination of their intrinsic charge, shape, and size, preserving complex quaternary structures and enzymatic activity. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding the distinct band patterns produced by a protein ladder in these two systems is critical for accurate analysis. This guide provides a detailed, evidence-based comparison of the expected migration patterns, empowering you to troubleshoot your experiments and correctly interpret the resulting data.

Core Principles of Separation

The migration of a protein ladder—a set of proteins of known molecular weights used for calibration—looks dramatically different between denaturing and native systems because the underlying principles of separation are fundamentally distinct.

Denaturing SDS-PAGE Systems

In SDS-PAGE, the treatment of proteins with the anionic detergent SDS and a reducing agent like β-mercaptoethanol has two critical effects. First, it disrupts all non-covalent interactions and reduces disulfide bonds, effectively unfolding the proteins into linear polypeptide chains. Second, SDS binds to the proteins at a relatively constant ratio, imparting a uniform negative charge per unit mass. This means the charge-to-mass ratio is essentially identical for all proteins. When an electric field is applied, the proteins migrate through the polyacrylamide gel matrix, which acts as a molecular sieve. Under these conditions, separation is determined primarily by molecular size (length of the polypeptide chain), with smaller proteins migrating faster than larger ones. The polyacrylamide gel's tunable pore size (typically 5-100 nm) allows for high-resolution separation of proteins in the 10-250 kDa range [27]. The resulting protein ladder displays bands that correlate directly with the molecular weights of its constituent polypeptides, creating a reliable standard curve when migration distance is plotted against the logarithm of the molecular weight [7].

Native Gel Systems

Native gel electrophoresis is performed without denaturing agents, preserving the protein's higher-order structure—its secondary, tertiary, and quaternary conformation. Consequently, a protein's migration is influenced by three interdependent factors: its inherent net charge (determined by the pH of the running buffer), its size and shape (compact globular proteins vs. extended fibrous proteins), and its native molecular mass as a functional complex [28]. For example, a homotetrameric protein like Medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD), with a theoretical mass of 177.7 kDa, will migrate at a position corresponding to its tetrameric mass, not the 43.6 kDa of its monomeric subunit [28]. This means a protein ladder on a native gel will produce a band pattern that reflects the native masses and shapes of the standard proteins, which may not align with the simple linear relationship seen in SDS-PAGE. Furthermore, active enzymes can be detected within the gel using specific substrates, a technique known as in-gel activity assay, which is impossible in denatured systems [28].

Comparative Analysis of Band Patterns

The following table summarizes the key differences in how a protein ladder migrates and appears in denaturing versus native gel systems.

| Feature | Denaturing (SDS-PAGE) System | Native Gel System |

|---|---|---|

| Basis of Separation | Molecular mass of polypeptide chains [29] | Combined effect of native mass, intrinsic charge, and 3D shape [28] |

| Protein State | Denatured, linearized, and uniformly negatively charged by SDS [29] | Native, folded, with intact secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structure |

| Expected Ladder Pattern | Bands form a smooth, predictable standard curve when log(MW) is plotted vs. migration distance [7] | Band pattern is less predictable; may not follow a simple log-linear relationship due to variable charge and shape |

| Key Visual Cues | Sharp, well-defined bands; relative spacing consistent with polypeptide mass | Potential for multiple active forms (e.g., tetramers, aggregates); bands may be diffuse due to charge heterogeneity |

| Impact on Mass Estimation | Provides accurate estimation of polypeptide chain mass [30] | Provides an "apparent native mass"; requires careful interpretation and specific native standards |

Table 1: Comparative analysis of protein ladder band patterns in denaturing vs. native gel electrophoresis.

The visual representation of these core separation principles and their outcomes can be summarized in the following workflow.

Experimental Protocols and Data

To illustrate these concepts with concrete examples, here are outlines of key experimental protocols from recent research that highlight the distinct outcomes in each system.

Protocol for Accurate MW Determination Using SDS-PAGE and Mass Spectrometry

This methodology, used to create a database of accurate electrophoretic migration patterns for human proteins, underscores the precision achievable in denaturing conditions [7].

- Sample Preparation: Proteins from human cell lines are solubilized in a buffer containing SDS and a reducing agent (e.g., DTT) to fully denature and linearize them. The sample is then heated to ensure complete disruption of protein structure.

- Gel Electrophoresis: Denatured samples are loaded onto a polyacrylamide gel (typically a gradient gel for a broader separation range). The gel is run under constant voltage until the dye front approaches the bottom. Internal calibration standards are run alongside to correct for gel-to-gel variability.

- In-Gel Digestion and Mass Spectrometry: Protein bands of interest are excised from the gel. Proteins within the gel pieces are subjected to enzymatic digestion (e.g., with trypsin). The resulting peptides are extracted and analyzed by tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) to identify the protein and confirm its theoretical molecular weight.

- Data Analysis: The migration distance of each identified protein is plotted against the logarithm of its known molecular weight to create a highly accurate standard curve. This large-scale approach allows for the identification of proteoforms and splicing events that cause minor mass shifts [7].

Protocol for In-Gel Activity Assay of a Native Tetrameric Protein

This protocol for analyzing MCAD activity directly within a native gel demonstrates the power of native systems for studying functional oligomers [28].

- Sample Preparation: Mitochondrial fractions or purified recombinant MCAD protein are prepared in a non-denaturing lysis buffer that lacks SDS or reducing agents. This preserves the homotetrameric structure of the enzyme.

- High-Resolution Clear Native PAGE (hrCN-PAGE): Samples are loaded onto a native polyacrylamide gel (e.g., 4-16% gradient). The gel is run in a cold room or with cooling to prevent heat-induced denaturation during electrophoresis.

- In-Gel Activity Staining: After electrophoresis, the gel is incubated in a reaction mixture containing the physiological substrate octanoyl-CoA, the electron acceptor nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT), and the catalyst phenazine methosulfate. Active MCAD tetramers oxidize the substrate, reducing NBT to an insoluble purple formazan precipitate at the site of the enzyme.

- Data Analysis: The formation of purple bands indicates the presence and location of active MCAD. Multiple bands can reveal different active oligomeric states (e.g., tetramers vs. higher-order aggregates), and their enzymatic activity can be quantified via densitometry, providing insights into how pathogenic variants affect structure and function [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of these electrophoretic techniques requires specific reagents. The following table details key materials and their functions.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Denaturing (SDS-PAGE) | Function in Native Gel Electrophoresis |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge [29] | Typically omitted to preserve native structure |

| Reducing Agents (DTT, β-Mercaptoethanol) | Breaks disulfide bonds for complete linearization [31] | Omitted to maintain native quaternary structure |

| Polyacrylamide Gel | Acts as a molecular sieve; pore size determines resolution range [27] | Same function, but proteins migrate based on native size/shape/charge |

| Coomassie/Silver Stain | Detects denatured protein bands post-electrophoresis | Detects native protein bands; compatible with subsequent activity assays |

| Protein Ladder | Provides standards of known polypeptide mass for calibration [30] | Ideally, provides standards of known native mass and charge |

| Substrate for Activity Stain | Not applicable | Used to detect functional enzymes in-gel (e.g., NBT for dehydrogenases) [28] |

Table 2: Essential reagents for denaturing and native gel electrophoresis and their respective functions.

Choosing Your Method: A Practical Guide to Gel Selection and Ladder Usage

In the realm of protein analysis, selecting the appropriate electrophoretic method is fundamental to obtaining accurate, reproducible results. Denaturing gel electrophoresis, specifically sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), serves as a cornerstone technique for molecular weight determination and western blotting. This guide provides an objective comparison between denaturing and native gel systems, focusing on their performance characteristics, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies. Within the broader context of protein ladder migration research, understanding the distinct separation profiles generated by each system enables researchers to select the optimal approach for their specific application, thereby enhancing the reliability of protein analysis in drug development and basic research.

Denaturing vs. Native Gels: A Fundamental Comparison

Denaturing gels utilize chemical treatments to unfold proteins into linear chains, while native gels preserve the protein's higher-order structure and activity. The table below summarizes the core differences, helping you select the appropriate system for your experimental goals.

Table 1: Core Differences Between Denaturing and Native Gel Electrophoresis

| Parameter | Denaturing Gels (SDS-PAGE) | Native Gels |

|---|---|---|

| Key Components | SDS, reducing agent (DTT/β-Me), heat [32] [8] | No SDS, no reducing agent, no heat [32] [8] |

| Protein State | Linearized, denatured [3] [8] | Native conformation preserved [3] [8] |

| Separation Basis | Molecular mass (almost exclusively) [32] [8] | Size, shape, and intrinsic charge [3] [8] |

| Molecular Weight Determination | Accurate and straightforward [8] | Not suitable due to charge/shape influence [8] |

| Key Applications | - Estimating molecular weight [3] [8]- Western blotting [3] [32]- Establishing sample purity [3] [8]- Protein sequencing preparation [3] [32] | - Isolating active enzymes [3] [32]- Determining protein aggregation state [32] [8]- Analyzing protein complexes and quaternary structure [3] [8]- Studying protein-binding interactions [3] |

The Mechanism of Denaturing Gels: How SDS-PAGE Works

The power of denaturing gels for molecular weight determination lies in their ability to negate the influence of a protein's inherent charge and three-dimensional shape. This is achieved through a sample preparation process that linearizes and uniformly charges all proteins in the mixture [32] [8].

- Reduction of Disulfide Bonds: A reducing agent like dithiothreitol (DTT) breaks disulfide bonds, disrupting tertiary and quaternary structures [32] [8].

- Denaturation and Charge Uniformity: The strong anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) binds to the protein backbone at a constant ratio of approximately 1.4 g SDS per 1.0 g of protein. This coats the protein with negative charges, overwhelming any charge the protein naturally possesses [32] [8].

- Heat-Assisted Unfolding: Heating the sample (typically to 95°C) further aids in denaturation, ensuring proteins are fully unfolded into rod-like chains [32].

The result is that all proteins become linear, negatively charged chains with a nearly identical charge-to-mass ratio. During electrophoresis, separation occurs almost exclusively based on molecular size, as smaller proteins migrate more easily through the pores of the polyacrylamide gel than larger ones [8]. This allows for accurate molecular weight estimation by comparing migration distances to a standardized protein ladder.

Diagram: SDS-PAGE Workflow for Protein Separation

This workflow illustrates the process of transforming complex protein structures into linearized molecules that can be separated by size.

Denaturing Gels in Western Blotting: A Synergistic Workflow

Western blotting is a quintessential application for denaturing gels. The SDS-PAGE workflow is perfectly suited for the initial separation step in immunoblotting, as it provides a reliable method to resolve complex protein mixtures before transfer and antibody detection [33] [34].

The transfer of proteins from the gel to a solid membrane is a critical step. The efficiency of this transfer can vary significantly based on the method used and the molecular weight of the target protein. The following table compares common transfer methods and their performance, based on optimization studies.

Table 2: Comparison of Western Blot Protein Transfer Methods [33] [35]

| Transfer Method | Typical Transfer Time | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Recommended Protein Size Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wet (Tank) Transfer | 30 min - overnight | High transfer efficiency; consistent performance for a wide size range [33] | Time-consuming; requires large buffer volumes; extensive cleanup [33] [35] | 14 - 116 kDa (80-100% efficiency) [33] |

| Semi-Dry Transfer | 7 - 60 min | Faster; uses less buffer; light cleanup [33] [35] | Can be less efficient for high MW proteins (>300 kDa) [33] | Best for small to medium proteins [36] |

| Dry (Electroblotting) Transfer | As few as 3 - 10 min | Fastest; no transfer buffers needed; minimal cleanup [33] | Requires proprietary, pre-assembled transfer stacks [33] | 10 - 300 kDa [33] |

Optimization Insight: Research shows that transfer time must be optimized for the protein of interest. For instance, while a 35-minute transfer may be suitable for a 70 kDa protein, it can lead to the complete loss ("blow-through") of a 15 kDa protein from the membrane. Recommendations suggest 15 minutes for 10-25 kDa proteins and 30-35 minutes for 70-130 kDa proteins [35].

Membrane Selection: The membrane pore size is another critical factor. A 0.45 µm pore size is standard for larger proteins, but a 0.22 µm pore size PVDF membrane is significantly more effective at retaining small-molecular-weight proteins (<30 kDa) and preventing over-transfer [35].

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Standard SDS-PAGE Protocol for Molecular Weight Determination

This is a foundational protocol for separating proteins by size, adapted from common laboratory practices [32] [8] [34].

Sample Preparation:

- Mix protein sample with 2X or 4X SDS-PAGE loading buffer (containing SDS and DTT or β-mercaptoethanol).

- Heat the mixture at 95°C for 5 minutes to fully denature proteins. For heat-sensitive proteins, alternatives include 70°C for 10-20 minutes or 37°C for 30-60 minutes [36].

- Centrifuge briefly to bring down condensation.

Gel Electrophoresis:

- Load denatured samples and a pre-stained protein ladder onto a polyacrylamide gel (e.g., 4-20% gradient gel for a broad separation range).

- Run the gel using a standard Tris-glycine-SDS running buffer. A modified running buffer (e.g., with added HEPES) can enable faster run times (e.g., 35 minutes at 200V) [35].

- Monitor the migration of the dye front (usually bromophenol blue) to prevent proteins from running off the gel.

Detection and Analysis:

- After electrophoresis, stain the gel with Coomassie Blue or a more sensitive fluorescent stain to visualize the protein bands.

- Plot the log(MW) of the protein ladder standards against their migration distance (Rf value) to generate a standard curve.

- Use this curve to interpolate the molecular weight of unknown protein bands based on their migration.

Denaturing Mass Photometry (dMP) Protocol for Cross-linking Analysis

A novel denaturing method, dMP, has been developed as a faster, more accurate alternative to SDS-PAGE for optimizing chemical cross-linking (XL) reactions. It showcases the evolution of denaturing techniques beyond traditional gels [37].

Denaturation:

- Incubate cross-linked protein samples in a high concentration of denaturant (5.4 M urea or 6 M guanidine hydrochloride) at room temperature for 5 minutes to achieve >95% denaturation [37].

Dilution and Measurement:

Analysis:

- The dMP method provides accurate mass identification across a broad range (30 kDa to 5 MDa) and directly quantifies all coexisting cross-linked species (sub-complexes and aggregates) at the single-molecule level [37].

Performance Data: When benchmarked against SDS-PAGE, dMP was found to be time-efficient (3 min/triplicate), required 20–100 times less material, and offered single-molecule sensitivity, making it highly suitable for rapid screening of XL conditions [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Denaturing Gel Electrophoresis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Anionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge [32] [8]. | Critical for masking intrinsic protein charge. Purity is essential for consistent results. |

| DTT or β-Mercaptoethanol | Reducing agent that breaks disulfide bonds [32] [8]. | Must be added fresh to the loading buffer as it oxidizes over time. |

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms the cross-linked gel matrix for size-based separation [35]. | Concentration (%T) determines pore size and resolution range. Pre-mixed reagents can save time [35]. |

| Tris-Glycine-SDS Buffer | Standard running buffer for SDS-PAGE. | Can be modified with HEPES to allow higher voltage and faster run times [35]. |

| PVDF or Nitrocellulose Membrane | Solid support for protein immobilization after transfer [33] [35]. | 0.45 µm for standard proteins; 0.22 µm for proteins <30 kDa to prevent blow-through [35] [36]. |

| Methanol or Ethanol in Transfer Buffer | Promotes protein adhesion to the membrane [33] [35]. | Ethanol is a less toxic alternative to methanol with comparable efficiency for many proteins [35]. |

Troubleshooting Common Issues in Denaturing Gels and Western Blotting

- Protein Aggregation During Prep: If proteins aggregate at 95°C, try longer incubation at 70°C or 37°C [36].

- Smiling Bands or Smearing: Caused by overheating; reduce voltage, run in a cold room, or use ice packs [36].

- Poor Transfer Efficiency: For large proteins (>100 kDa), use wet transfer with extended time. For small proteins (<20 kDa), use a 0.22 µm membrane and shorter semi-dry transfer to prevent over-transfer [35] [36].

- High Background in Western Blot: Ensure sufficient blocking time (at least 60 minutes) with milk or BSA. Check antibody specifications for recommended blocking buffers [36].

Gel electrophoresis is a fundamental tool in protein research, but the choice between native and denaturing systems is critical and application-dependent. While denaturing SDS-PAGE separates proteins based primarily on molecular mass, native PAGE preserves protein complexes in their functional state, enabling analysis of oligomeric structure and biological activity [8] [38]. This guide provides a comparative framework for researchers needing to characterize protein quaternary structure and enzymatic function within the broader context of protein ladder migration studies.

Key Differences: Native vs. Denaturing Gels

The table below summarizes the fundamental distinctions between these electrophoretic techniques:

| Parameter | Native-PAGE | Denaturing SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Net charge, size, and shape of native structure [8] [38] | Molecular mass of polypeptide subunits [8] [38] |

| Protein Structure | Maintains native conformation, quaternary structure, and subunit interactions [8] [38] | Denatures proteins into linear polypeptides; disrupts quaternary and tertiary structures [3] [8] |

| Typical Applications | Analyzing oligomeric state, isolating active enzymes, studying protein complexes [3] [8] | Determining polypeptide molecular weight, assessing sample purity, Western blotting [3] [8] |

| Enzymatic Activity | Often retained after separation, enabling in-gel activity assays [23] [8] | Destroyed due to denaturation [8] |

| Migration Direction | Can be toward either anode or cathode depending on protein's native charge [8] | Always toward the anode due to SDS coating [38] |

Experimental Applications and Protocols

Analyzing Oligomeric State

Native gels, particularly Blue Native (BN)-PAGE and Clear Native (CN)-PAGE, are indispensable for determining the oligomeric state of protein complexes, as they separate proteins based on both size and shape under non-denaturing conditions [39] [40].

Protocol: Oligomeric State Analysis via BN-PAGE/CN-PAGE

- Sample Preparation: Solubilize proteins in a non-denaturing, non-reducing buffer. For membrane proteins, use mild detergents like dodecyl maltoside to maintain solubility without disrupting complexes [41] [39]. Avoid SDS and boiling.