Protein Gel Electrophoresis: Principles, Protocols, and Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to protein gel electrophoresis, a foundational technique in molecular biology and proteomics.

Protein Gel Electrophoresis: Principles, Protocols, and Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to protein gel electrophoresis, a foundational technique in molecular biology and proteomics. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the core principles of electrophoretic separation, detailed methodologies including SDS-PAGE and native-PAGE, and advanced techniques like 2D electrophoresis. It also offers practical troubleshooting for common issues and a comparative analysis of traditional gel-based versus emerging capillary electrophoresis for clinical diagnostics, particularly in monitoring conditions like multiple myeloma.

The Core Principles of Protein Electrophoresis: How an Electric Field Separates Complex Protein Mixtures

Protein gel electrophoresis serves as a fundamental analytical tool in biochemical research and clinical diagnostics, enabling the separation of complex protein mixtures based on their physicochemical properties. This technical guide examines the core principle of charged molecule migration under an electrical field, detailing how variables including molecular weight, net charge, and gel matrix properties collectively govern electrophoretic mobility. The discourse encompasses both theoretical foundations and practical methodologies, with particular emphasis on SDS-PAGE and native-PAGE systems. Within the broader context of proteomic research, this technique provides indispensable capabilities for protein characterization, purity assessment, and biomarker discovery, forming the cornerstone of experimental workflows in basic science and drug development.

Protein electrophoresis is a standard laboratory technique by which charged protein molecules are transported through a solvent by an electrical field [1]. This method leverages the fundamental physical principle that charged particles migrate toward oppositely charged electrodes when subjected to an electrical potential. The rate and direction of migration, known as electrophoretic mobility, depend on multiple factors intrinsic to both the protein molecules and the electrophoretic system [2].

At any pH other than their isoelectric point, proteins carry a net positive or negative charge due to the ionization of their amino acid side chains [1]. In an alkaline buffer environment, such as that used in most electrophoretic procedures, most proteins acquire a net negative charge and consequently migrate toward the positively charged anode [3]. The electrophoretic mobility of a protein is determined by the interplay between the electrical force driving its migration and the frictional forces resisting its movement through the matrix [2]. This relationship means that under controlled conditions, proteins with different physical properties will migrate at different rates, resulting in their physical separation within the gel matrix [1].

The support matrix, typically polyacrylamide or agarose, serves as a porous medium that functions as a molecular sieve [1]. Polyacrylamide gels, formed through the polymerization of acrylamide and bisacrylamide, create a cross-linked network with precisely controllable pore sizes [1] [4]. This matrix is particularly suitable for separating most proteins and smaller nucleic acids, while agarose gels with larger pore sizes are preferred for separating large protein complexes and nucleic acids [1]. The selection of an appropriate matrix and buffer system allows researchers to tailor separations for specific applications, from analytical procedures requiring high resolution to preparative techniques designed for protein recovery.

Core Factors Governing Electrophoretic Mobility

The migration of proteins during electrophoresis is governed by a complex interplay of factors that collectively determine the efficiency and resolution of separation. Understanding these variables is essential for both experimental design and accurate interpretation of results.

Properties of the Molecule: The size, shape, and net charge of a protein directly influence its mobility through the gel matrix [2]. Mobility is inversely proportional to molecular size and directly proportional to net charge [2]. Globular proteins typically demonstrate faster mobility than fibrous proteins of similar molecular weight due to their more compact structures [2]. In SDS-PAGE, the binding of sodium dodecyl sulfate masks the intrinsic charge of proteins, creating a uniform charge-to-mass ratio and ensuring separation occurs primarily based on molecular weight [1] [4].

Electrical Field Parameters: The strength of the electrical field, determined by the voltage applied, directly affects migration rate [2]. Higher voltage increases the speed of separation but generates more heat, which can cause diffusion of protein bands and reduce resolution [2]. Optimal voltage settings balance separation efficiency with band sharpness, with high-voltage electrophoresis (400-2000V) sometimes employed for rapid separation with minimal diffusion [2].

Buffer System Characteristics: The buffer serves dual purposes of carrying electrical current and maintaining stable pH throughout the electrophoresis run [2]. Buffer ionic strength critically affects resolution; higher ionic strength increases current sharing by buffer ions, slowing protein migration and generating excessive heat, while low ionic strength reduces overall current and resolution [2]. The pH determines the ionization state of protein functional groups, potentially altering both direction and velocity of migration if not properly controlled [2].

Support Medium Properties: The matrix through which proteins migrate creates a sieving effect that significantly influences separation [2]. The pore size of polyacrylamide gels is inversely proportional to the acrylamide concentration [1]. Low-percentage gels (e.g., 6-8%) with larger pores facilitate the separation of high molecular weight proteins, while high-percentage gels (e.g., 12-15%) with smaller pores provide better resolution for lower molecular weight proteins [1]. The phenomenon of electroendosmosis, caused by fixed charged groups on the support medium, can also affect resolution by generating counterflow of buffer ions [2].

Table 1: Key Factors Affecting Protein Electrophoretic Mobility

| Factor | Effect on Mobility | Practical Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | Inversely proportional | Smaller proteins migrate faster than larger ones [5] |

| Net Charge | Directly proportional | Higher charge density increases migration rate [1] |

| Molecular Shape | Compact shapes migrate faster | Globular proteins move more readily than fibrous proteins [2] |

| Field Strength | Proportional to voltage | Higher voltage speeds migration but generates more heat [2] |

| Buffer Ionic Strength | Complex effect | Optimal strength needed; too high causes heat, too low reduces resolution [2] |

| Gel Pore Size | Inversely related | Larger pores (low % acrylamide) for large proteins; smaller pores for small proteins [1] |

Methodological Approaches in Protein Electrophoresis

SDS-PAGE (Denaturing Electrophoresis)

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) represents the most widely employed electrophoresis technique for separating proteins primarily by molecular mass [1]. The method relies on the ionic detergent SDS, which denatures proteins by wrapping around the polypeptide backbone and confers a uniform negative charge that masks the proteins' intrinsic charge [1] [4]. When protein samples are heated to 70-100°C in buffer containing excess SDS and a reducing agent such as beta-mercaptoethanol or dithiothreitol (DTT), disulfide bonds are cleaved and proteins fully dissociate into their subunits [1] [4]. Under these conditions, most polypeptides bind SDS in a constant weight ratio of approximately 1.4 g SDS per 1 g of polypeptide [1]. The resulting SDS-polypeptide complexes assume a rod-like shape with essentially identical charge density, ensuring migration through the gel occurs strictly according to polypeptide chain length with minimal influence from compositional differences [1].

The discontinuous buffer system employed in SDS-PAGE enhances resolution through two distinct gel phases [1] [4]. The stacking gel, with lower acrylamide concentration (typically 4-5%) and pH (~6.8), concentrates protein samples into tight bands before they enter the resolving gel [4]. The resolving gel, with higher acrylamide concentration (variable based on target protein size) and pH (~8.8), performs the actual separation based on molecular size [4]. Gradient gels with increasing acrylamide concentration from top to bottom provide an alternative approach, enabling separation of a broader range of protein sizes without a discrete stacking phase [1].

Native-PAGE

Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (native-PAGE) separates proteins according to their net charge, size, and shape while maintaining their native conformation [1]. Without denaturing agents, subunit interactions within multimeric proteins are generally preserved, allowing researchers to gain information about quaternary structure and, in many cases, retain enzymatic activity following separation [1]. In this technique, proteins migrate at rates proportional to their charge density (more charges per molecule mass migrate faster) while simultaneously experiencing the sieving effect of the gel matrix, which regulates movement according to size and three-dimensional structure [1]. Several variants exist, including blue native-PAGE (using Coomassie dye to provide charge to native complexes) and clear native-PAGE (utilizing intrinsic protein charge) [6]. Maintaining cool temperatures during electrophoresis and avoiding pH extremes is crucial for preserving protein integrity in native systems [1].

Two-Dimensional Electrophoresis

Two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2D-PAGE) provides the highest resolution for protein analysis by separating compounds based on two independent properties in sequential procedures [1]. The first dimension employs isoelectric focusing (IEF), where proteins migrate through a pH gradient until they reach their isoelectric point (pI), the pH at which their net charge becomes zero [1]. The second dimension then separates the same proteins by mass using standard SDS-PAGE oriented at a 90-degree angle to the first separation [1]. This orthogonal approach can resolve thousands of proteins on a single gel, making it an invaluable technique in proteomic research where comprehensive protein profiling is required [1].

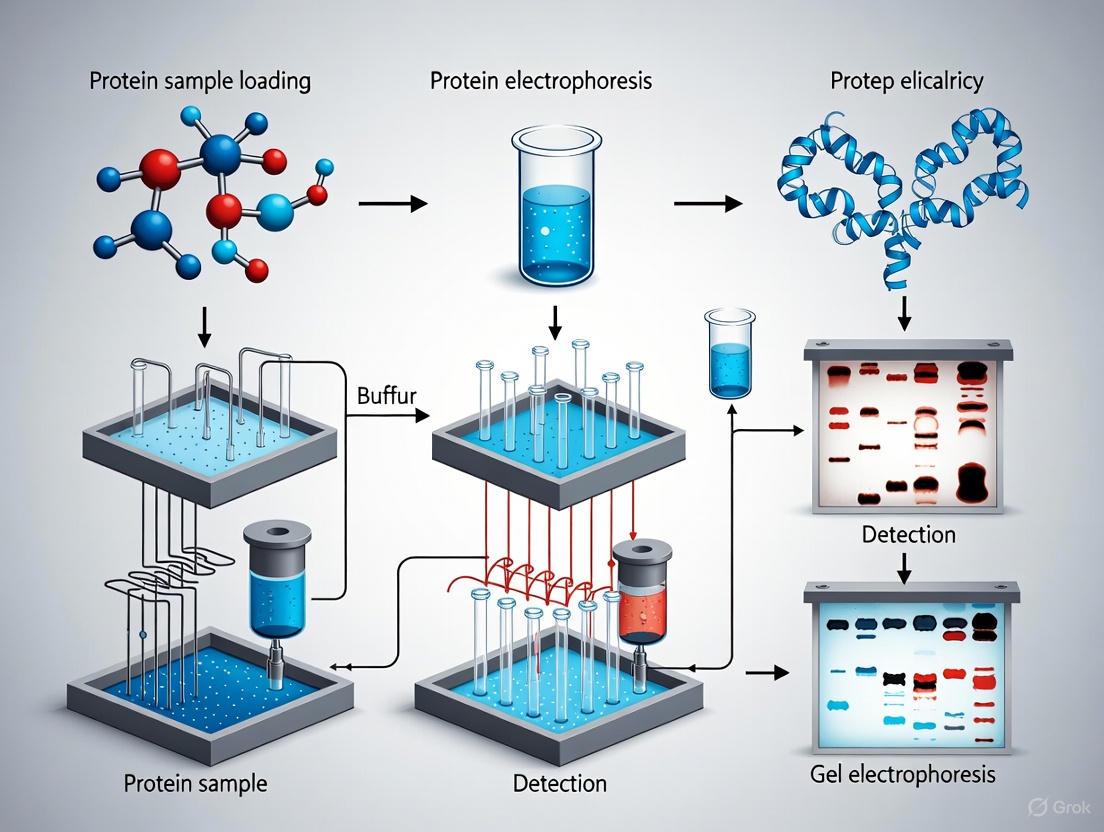

Diagram 1: Protein Electrophoresis Experimental Workflow

Experimental Protocol: SDS-PAGE Procedure

Gel Preparation and Casting

Polyacrylamide gels are formed through the polymerization of acrylamide and bis-acrylamide, a cross-linking agent, in the presence of catalytic compounds [1] [4]. The polymerization reaction is initiated by ammonium persulfate (APS), which generates free radicals, and tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED), which catalyzes the formation of these free radicals [1] [4]. The resulting cross-linked polymer network creates a porous matrix with pore size determined by the ratio of bis-acrylamide to acrylamide and the total concentration of both components [1].

Step-by-step procedure for traditional discontinuous gel casting [5] [4]:

- Assemble casting apparatus: Thoroughly clean glass plates with ethanol and assemble with spacers to form a water-tight cassette [5].

- Prepare resolving gel: Mix acrylamide solution, bis-acrylamide, Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.8), SDS, and water. Add TEMED and APS last to initiate polymerization and immediately pour the solution between the glass plates [1] [4].

- Overlay with solvent: Carefully layer water-saturated butanol or isopropanol over the resolving gel to exclude oxygen and create a flat interface [5] [4].

- Polymerize resolving gel: Allow the gel to polymerize completely (typically 20-30 minutes), then remove the overlay solvent and rinse the gel surface [5].

- Prepare stacking gel: Mix acrylamide solution with Tris-HCl buffer (pH 6.8), SDS, and water. Add TEMED and APS, then pour over the polymerized resolving gel [1] [4].

- Insert comb: Place a sample well comb into the stacking gel without introducing air bubbles and allow polymerization to complete [5] [4].

Table 2: Example Traditional Polyacrylamide Gel Formulation [1]

| Component | Resolving Gel (10%) | Stacking Gel (~4%) | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide Solution | 7.5 mL (40%) | Variable lower concentration | Polymer matrix formation |

| Bis-acrylamide | 3.9 mL (1%) | Variable lower concentration | Cross-linking agent |

| Tris-HCl Buffer | 7.5 mL (1.5 M, pH 8.8) | Different volume (pH 6.8) | Maintains pH during run |

| SDS | 0.3 mL (10%) | Small amount | Uniform negative charge |

| APS | 0.3 mL (10%) | Small amount | Polymerization initiator |

| TEMED | 0.03 mL | Small amount | Polymerization catalyst |

| Water | To 30 mL final volume | To final volume | Solvent |

Sample Preparation and Electrophoresis

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful protein separation. The protocol involves both denaturation and reduction steps to ensure complete unfolding of protein structures [4].

Sample preparation procedure [5] [4]:

- Mix sample with buffer: Combine protein sample with SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing SDS, reducing agent (DTT or beta-mercaptoethanol), glycerol, tracking dye (bromophenol blue), and Tris-HCl buffer [5].

- Denature proteins: Heat the sample mixture at 95-100°C for 3-5 minutes in a heat block to disrupt hydrogen bonds and ensure complete denaturation [5] [4].

- Centrifuge: Briefly centrifuge at high speed (e.g., 15,000 rpm for 1 minute) to collect condensation and particulate matter [5].

- Load gel: Using a micropipette, load samples and molecular weight markers into wells of the polymerized gel [5].

- Run electrophoresis: Assemble the gel cassette in the electrophoresis apparatus, fill buffer chambers, connect to power supply, and run at constant voltage until the tracking dye approaches the gel bottom [5]. Typical conditions for a mini-gel are 150-200 V for 30-50 minutes [1].

- Post-processing: Disassemble apparatus, remove gel from plates, and proceed with staining, western blotting, or other analytical techniques [5].

Visualization, Analysis, and Data Interpretation

Protein Detection Methods

Following electrophoretic separation, proteins immobilized within the gel matrix must be visualized for analysis. Multiple staining techniques offer different levels of sensitivity and compatibility with downstream applications.

Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining provides a reliable and relatively sensitive method for protein detection, binding strongly to proteins to produce deep blue bands against a colorless background [6]. This stain is compatible with protein extraction for further analysis and is commonly used in both analytical and preparative applications. Silver staining offers significantly higher sensitivity, capable of detecting trace amounts of proteins in the nanogram range, but can be more technically challenging and may not be compatible with subsequent protein sequencing or mass spectrometry analysis [6]. Fluorescent stains including SYPRO Ruby and others provide alternative detection methods with broad linear dynamic ranges, though they require appropriate imaging equipment for visualization.

Quantitative Analysis and Uncertainty Estimation

Following staining and imaging, densitometric analysis quantifies protein abundance by measuring the optical density of separated bands, which is directly proportional to the concentration of stained protein [2]. This approach enables semi-quantitative comparison of protein levels between samples when appropriate controls and standards are included.

Advanced computational methods have been developed to improve the accuracy and efficiency of gel image analysis. Traditional approaches involve converting lane images to one-dimensional intensity profiles and applying peak-finding algorithms to identify and quantify bands [7]. More recently, artificial intelligence-based systems have demonstrated capability to automatically identify bands through segmentation, classifying pixels as 'band' or 'background' with accuracy matching or exceeding conventional methods [7]. These AI-powered frameworks can extract bands from diverse gel images in seconds without requiring expert knowledge, potentially revolutionizing this aspect of electrophoretic analysis [7].

Uncertainty in quantitative electrophoresis arises from multiple sources, including sample preparation variability, electrophoretic conditions, staining efficiency, and image analysis methodologies [8]. Studies indicate that methodological errors in band identification and integration can reach up to 10%, while baseline noise may contribute up to 5% uncertainty [8]. Proper experimental design with replication, inclusion of standards, and consistent processing protocols helps minimize these uncertainties and improve data reliability.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful protein electrophoresis requires precise formulation of reagents and appropriate selection of materials. The following table catalogizes essential components for standard procedures.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Electrophoresis

| Reagent/Material | Composition/Type | Function in Procedure |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | 29:1 or 37:1 ratio mixtures | Forms cross-linked polymer matrix for molecular sieving [1] [4] |

| Tris-HCl Buffers | Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane + HCl | Maintains pH in stacking (pH 6.8) and resolving (pH 8.8) gels [1] |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Anionic detergent | Denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge [1] [4] |

| APS (Ammonium Persulfate) | Free radical source | Initiates acrylamide polymerization reaction [1] [4] |

| TEMED | N,N,N',N'-Tetramethylethylenediamine | Catalyzes free radical formation from APS, accelerating polymerization [1] [4] |

| DTT/BME | Dithiothreitol/Beta-mercaptoethanol | Reducing agents that break disulfide bonds [4] |

| Protein Molecular Weight Markers | Prestained or unstained protein ladders | Reference standards for molecular mass determination [1] |

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue | Triphenylmethane dye | Protein stain for visualization after separation [6] |

| Tracking Dye | Bromophenol Blue in glycerol | Visualizes migration front during electrophoresis [6] |

Applications in Research and Drug Development

Protein electrophoresis serves as a foundational analytical technique with diverse applications across biological research and pharmaceutical development. In basic research, it provides critical information about protein purity, integrity, subunit composition, and molecular weight [6] [9]. The technique is routinely employed to monitor protein purification processes, assess recombinant protein expression, and verify antibody specificity. As a preliminary step in proteomic workflows, electrophoresis enables fractionation of complex protein mixtures prior to analysis by mass spectrometry or other advanced analytical techniques [1] [9].

In clinical diagnostics and drug development, serum protein electrophoresis (SPE) represents a cornerstone technique for identifying dysproteinemias associated with various disease states [3]. Electrophoretic patterns of serum proteins facilitate diagnosis of conditions such as multiple myeloma through detection of monoclonal gammopathies, characterized by discrete, narrow bands in the gamma region [3]. Similarly, polyclonal gammopathies, appearing as broad increases in gamma globulins, indicate inflammatory or infectious processes [3]. Acute phase responses manifest as elevated alpha globulins, providing valuable diagnostic information for monitoring disease progression and therapeutic response [3].

The pharmaceutical industry relies heavily on electrophoresis for biopharmaceutical characterization, including assessment of therapeutic protein purity, detection of degradation products, and verification of monoclonal antibody integrity [9]. These applications ensure product quality and consistency throughout development and manufacturing processes. Additionally, specialized electrophoretic techniques including capillary electrophoresis and two-dimensional electrophoresis continue to expand the utility of this fundamental separation principle in increasingly sophisticated analytical contexts.

Electrophoresis is a foundational technique in biochemistry and molecular biology for separating charged molecules based on their differential migration in an electric field. The principle of protein gel electrophoresis research hinges on understanding and manipulating the factors that govern this migration, known as electrophoretic mobility. For researchers and drug development professionals, optimizing these parameters is crucial for obtaining high-resolution data in applications ranging from purity assessment of biopharmaceuticals to biomarker discovery. Electrophoretic mobility (μ) is defined by the relationship μ = v/E, where v is the velocity of the molecule and E is the electric field strength [10]. This review provides an in-depth technical examination of the key factors—molecular properties (charge, size, shape) and buffer conditions—that determine electrophoretic mobility, equipping scientists with the knowledge to design and interpret protein separation experiments effectively.

Fundamental Principles and Mathematical Relationship of Electrophoretic Mobility

The electrophoretic mobility of a molecule determines its velocity within an electric field and is the ultimate factor defining its position after separation. The overall mobility is governed by a balance between the driving force of the electric field and the retarding frictional forces of the medium.

The fundamental equation for electrophoretic mobility (μ) is [10]: μ = v/E = q/f Where:

- v is the velocity of the molecule

- E is the electric field strength (voltage/distance)

- q is the net charge of the molecule

- f is the frictional coefficient, representing the molecule's resistance to movement through the medium

The frictional coefficient f is itself influenced by the molecule's size, shape, and the viscosity of the medium. This core relationship illustrates that mobility is directly proportional to the molecule's net charge and inversely proportional to the factors that increase frictional drag [2] [10].

The following diagram illustrates the core relationship between a protein's properties and its electrophoretic mobility.

Core Factors Governing Electrophoretic Mobility

Molecular Charge

The net charge of a protein is the primary driver of its electrophoretic mobility and is influenced by the pH of the buffer relative to the protein's isoelectric point (pI).

- Charge and Migration Direction: Particles with a negative charge (anions) migrate toward the positive electrode (anode), while positively charged particles (cations) migrate toward the negative electrode (cathode) [2].

- Dependence on pH: Proteins contain ionizable groups on their amino acid side chains. The net charge of a protein is determined by the pH of the buffer relative to the protein's pI. When the buffer pH is less than the protein's pI, the protein carries a net positive charge and migrates toward the cathode. When the pH is greater than the pI, the protein carries a net negative charge and migrates toward the anode [11].

- Charge-to-Mass Ratio: In techniques like SDS-PAGE, the binding of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) imparts a uniform negative charge density, masking the protein's intrinsic charge. This creates a constant charge-to-mass ratio, allowing separation to proceed primarily based on size [12] [13].

Molecular Size and Shape

The size and three-dimensional structure of a protein determine the frictional resistance it experiences when moving through the gel matrix.

- Molecular Size: Mobility is inversely proportional to the size of the molecule [2] [13]. Larger molecules experience greater frictional drag and migrate more slowly through the porous gel matrix, which acts as a molecular sieve [10] [14].

- Molecular Shape: The three-dimensional conformation of a protein significantly impacts its mobility. Globular proteins, with their compact structures, typically experience less drag and have faster mobility compared to fibrous proteins of a similar molecular weight [2]. The shape influences the effective hydrodynamic volume and thus the frictional coefficient

fin the mobility equation.

Buffer Conditions

The buffer system is not merely a conductor of current; it creates the chemical environment that dictates the behavior of the molecules being separated.

- Buffer pH: The pH is critical as it determines the ionization state of the protein and thus its net charge [2] [11]. It also affects the charge of the gel matrix itself (e.g., ionized sulfate groups in agarose), which can lead to electroendosmotic flow [2].

- Ionic Strength: The concentration of ions in the buffer has a dual effect. Higher ionic strength increases the current carried by the buffer ions, which can slow sample migration and generate excessive heat, leading to band diffusion. Conversely, low ionic strength reduces the overall current and can diminish resolution [2] [11].

- Buffer Composition: Discontinuous buffer systems (e.g., Tris-Glycine in the Laemmli method) use different pH and composition in the gel and tank buffer to create a stacking effect. This concentrates the protein samples into sharp bands before they enter the resolving gel, greatly enhancing resolution [12].

Table 1: Summary of Core Factors Affecting Electrophoretic Mobility

| Factor | Effect on Mobility | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Net Charge (q) | Directly Proportional | Higher net charge increases the driving force in the electric field [2] [10]. |

| Molecular Size | Inversely Proportional | Larger size increases frictional drag (f) through the gel pores [2] [13]. |

| Molecular Shape | Variable (Globular > Fibrous) | Compact shapes present a smaller hydrodynamic radius, reducing friction [2]. |

| Buffer pH | Determines charge sign/magnitude | pH relative to pI controls the ionization state of protein side chains [2] [11]. |

| Buffer Ionic Strength | High: Decreases; Low: Can decrease resolution | High ionic strength shares current, generates heat; low ionic strength reduces conductivity [2]. |

Experimental Control and Optimization

Standardization via SDS-PAGE

The SDS-PAGE (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis) protocol is a quintessential example of how to control for multiple factors to achieve separation based on a single variable—molecular weight.

Sample Preparation:

- Proteins are denatured by heating (typically 95-100°C) in a sample buffer containing SDS (an anionic detergent) and a reducing agent (e.g., β-mercaptoethanol or DTT) [12] [13].

- SDS binds uniformly to the polypeptide backbone, imparting a large negative charge that masks the protein's intrinsic charge.

- The reducing agent breaks disulfide bonds, ensuring complete unfolding into individual polypeptides.

- The result is a solution of linear polypeptide chains with a uniform charge-to-mass ratio and a consistent, rod-like shape [12] [13].

Gel Preparation:

- Polyacrylamide gels are formed by polymerizing acrylamide and a cross-linker (bis-acrylamide). The gel pore size is controlled by the total percentage of acrylamide (%T). Higher %T creates smaller pores, providing better resolution for lower molecular weight proteins [12] [14] [13].

- Discontinuous systems use a low-percentage stacking gel (large pores) and a higher-percentage resolving gel (smaller pores). The different pH and acrylamide concentrations work together to stack proteins into sharp bands before separation in the resolving gel [12].

Electrophoresis and Visualization:

- The denatured, SDS-coated proteins are loaded onto the gel, and an electric field is applied. Due to their negative charge, they migrate towards the anode.

- Separation occurs in the resolving gel primarily based on molecular weight, as smaller polypeptides navigate the pores more easily than larger ones [13].

- Post-electrophoresis, proteins are visualized using stains like Coomassie Brilliant Blue or more sensitive options like silver stain or fluorescent dyes [12].

Advanced Techniques for Specific Applications

- Native PAGE: This technique is performed without denaturants, preserving the protein's native charge, shape, and functional state. Separation depends on the complex interplay of the protein's intrinsic charge, size, and shape [12].

- Isoelectric Focusing (IEF): This method separates proteins based solely on their isoelectric point (pI). Proteins migrate through a stable pH gradient until they reach the pH where their net charge is zero (their pI), at which point they focus into sharp bands [2].

- Two-Dimensional Gel Electrophoresis: This powerful combination first separates proteins by their pI using IEF, followed by a second dimension where the strip is placed on an SDS-PAGE gel to separate by molecular weight. This allows for the high-resolution separation of complex protein mixtures [2].

Table 2: Optimizing Electrophoretic Conditions for Different Goals

| Analytical Goal | Recommended Technique | Key Controlled Factors | Typical Buffer/Gel System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight Determination | SDS-PAGE | Denatures proteins; masks intrinsic charge with SDS; reduces disulfide bonds [12] [13]. | Discontinuous Tris-Glycine or Bis-Tris systems [12]. |

| Analysis of Native Structure/Complexes | Native PAGE / BN-PAGE | No denaturants; preserves native charge, shape, and protein-protein interactions [12]. | Tris-Glycine, often with Coomassie G-250 (BN-PAGE) [12]. |

| Separation by Isoelectric Point | Isoelectric Focusing (IEF) | Uses a pH gradient; proteins migrate to their pI (net charge = 0) [2]. | Polyacrylamide or agarose gel with immobilized ampholytes. |

| High-Resolution Proteomics | Two-Dimensional (2D) PAGE | 1st Dimension: pI (IEF); 2nd Dimension: Mass (SDS-PAGE) [2]. | Combination of IEF and SDS-PAGE systems. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Gel Electrophoresis

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Strong anionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge, enabling separation by size [12] [13]. | Purity is critical for consistent binding and migration. |

| Acrylamide/Bis-Acrylamide | Monomer and cross-linker that polymerize to form the porous polyacrylamide gel matrix, which acts as a molecular sieve [2] [13]. | Concentration determines pore size; a neurotoxin in its unpolymerized form. |

| Reducing Agent (e.g., DTT, β-mercaptoethanol) | Breaks disulfide bonds within and between polypeptide chains, ensuring complete denaturation and linearization of proteins [12] [13]. | Must be fresh; included in the sample loading buffer. |

| Tris-based Buffers | Provides the conductive medium and maintains a stable pH during electrophoresis [12]. | Discontinuous systems use different buffers (e.g., Tris-HCl for gel, Tris-Glycine for tank) [12]. |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) & TEMED | Catalysts for the free-radical polymerization of acrylamide to form a polyacrylamide gel [2] [13]. | Fresh APS is required for efficient and timely gel polymerization. |

| Protein Stain (Coomassie, Silver, Fluorescent Dyes) | Binds to proteins to visualize separated bands after electrophoresis [12]. | Coomassie is routine; silver is more sensitive; fluorescent dyes offer wide dynamic range. |

| Tracking Dye (Bromophenol Blue) | A low-molecular-weight colored compound mixed with the sample to visually monitor the progress of the electrophoretic run [12]. | Migrates ahead of most proteins, indicating the leading edge of separation. |

A deep understanding of the factors governing electrophoretic mobility—charge, size, shape, and buffer conditions—is fundamental to the principle of protein gel electrophoresis research. By systematically controlling these variables through techniques like SDS-PAGE, researchers can transform a complex mixture of proteins into a clear, interpretable pattern of bands. This capability is indispensable in modern life sciences, underpinning critical endeavors in drug development, such as assessing the purity and integrity of recombinant protein therapeutics, analyzing differential protein expression in disease states, and validating target engagement. As electrophoretic techniques continue to evolve, particularly in areas of microchip integration and enhanced detection sensitivity, their role in accelerating scientific discovery and biopharmaceutical innovation remains as vital as ever.

Within the framework of protein gel electrophoresis research, the fundamental principle is the separation of macromolecules based on their physical characteristics to facilitate analysis of complex biological mixtures. The core of this principle lies in the ability to resolve proteins into discrete bands, allowing researchers to determine purity, estimate molecular weight, and identify components. The support matrix is the critical component that makes this separation possible, acting as a molecular sieve to differentially retard the migration of molecules based on their size. Polyacrylamide gel has emerged as the matrix of choice for protein separation due to its highly tunable pore structure, which can be precisely engineered to separate molecules across a wide size range. This technical guide explores the fundamental mechanisms, composition, and practical implementation of polyacrylamide gels as molecular sieves in electrophoretic separations, providing researchers with both theoretical understanding and practical methodologies.

The Molecular Sieve Mechanism in Polyacrylamide Gels

Fundamental Principles of Molecular Sieving

The molecular sieve effect in polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis operates on the principle that molecules moving through a gel matrix under the influence of an electric field will encounter resistance from the gel structure. The polyacrylamide gel forms a three-dimensional mesh-like network with pores of defined sizes through which molecules must travel [15]. Smaller molecules navigate these pores with relative ease, while larger molecules are progressively more hindered, resulting in separation by size [16] [17].

This molecular sieving process is governed by the electrophoretic mobility (μ) of proteins, which is determined by the formula: μ = q/E, where q represents the charge of the molecule and E represents the frictional coefficient. In native PAGE, both charge and shape influence mobility, but in SDS-PAGE, the use of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) largely eliminates the influence of structure and charge by linearizing proteins and conferring a uniform negative charge [16] [15]. This results in proteins being separated solely based on polypeptide chain length [16], as the SDS-bound proteins all have a similar mass-to-charge ratio [17].

The frictional coefficient E is directly influenced by the gel concentration, with higher acrylamide concentrations creating smaller pores that exert greater frictional forces on migrating molecules [15] [17]. The pore size distribution within the gel is not uniform but forms a statistical array that creates a sieving effect, with the average pore diameter determined by the total concentration of acrylamides (%T) and the concentration of the cross-linker bisacrylamide (%C) [17].

Gel Composition and Pore Structure

The structure of polyacrylamide gels has been examined through transmission-electron microscopy of freeze-etched specimens, revealing structural details that correlate with empirical findings concerning the molecular sieving effect [18]. The gel is created through the polymerization of acrylamide monomers cross-linked by N,N'-methylene bisacrylamide [15] [19]. This reaction is initiated by ammonium persulfate (APS) and catalyzed by tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED) [15] [17].

The resulting gel structure possesses several electrophoretically desirable features that make it a versatile medium [17]. The pore size can be precisely controlled by adjusting the concentration of acrylamide and bisacrylamide, with the average pore diameter reduced reciprocally as the total acrylamide concentration increases [17]. The cross-linking ratio also influences pore size, with a concentration of approximately 5% bisacrylamide producing the smallest pores [17].

Table 1: Influence of Acrylamide Concentration on Separation Range

| Acrylamide Concentration (%) | Effective Separation Range (kDa) | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|

| 4-8% | Large proteins (>100 kDa) | Separation of high molecular weight complexes |

| 8-12% | 30-100 kDa | Standard protein separation, routine analysis |

| 12-20% | <30 kDa | Small proteins, peptides, high-resolution separation |

| Gradient (e.g., 4-20%) | Broad range (10-300 kDa) | Complex mixtures with diverse protein sizes |

Practical Implementation and Methodologies

Gel Preparation and Optimization

The preparation of polyacrylamide gels with consistent molecular sieving properties requires careful attention to composition and polymerization conditions. The process begins with assembling a gel casting system consisting of glass plates, spacers, and a comb to create sample wells [16]. The gel is typically formed in two distinct sections: a stacking gel (usually around 4% acrylamide) with a pH of approximately 6.8, and a resolving gel (typically between 6-15% acrylamide) with a pH of about 8.8 [15].

The resolving gel, which performs the actual molecular sieving, is poured first. The acrylamide solution for this gel contains acrylamide monomer, bisacrylamide cross-linker, buffer (typically Tris-HCl at pH 8.8 for SDS-PAGE), and SDS for denaturing electrophoresis [16] [15]. After adding APS and TEMED to initiate polymerization, the solution is pipetted between the glass plates, and a layer of hydrated isopropyl alcohol is often added on top to create a crisp edge and prevent oxygen inhibition of polymerization [16] [15]. Once polymerized (20-30 minutes), the isopropyl alcohol is removed, and the stacking gel is added with the comb inserted to create sample wells [16].

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis

| Reagent | Function | Typical Concentrations/Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide | Main gel matrix component | Varies from 5% to 20% total concentration depending on target protein size |

| Bisacrylamide | Cross-linking agent | Generally 1:35 to 1:40 ratio with acrylamide |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | Free radical initiator for polymerization | 0.1% final concentration |

| TEMED | Polymerization catalyst | 0.1% final concentration |

| Tris-HCl Buffer | Maintains pH during electrophoresis | Resolving gel: 1.5 M Tris, pH 8.8; Stacking gel: 0.5 M Tris, pH 6.8 |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins and confers negative charge | 0.1% in gels and running buffers |

| Running Buffer | Conducts current and maintains pH | Typically Tris-glycine with 0.1% SDS |

Electrophoresis Procedure

The electrophoresis process begins with sample preparation. For SDS-PAGE, protein samples are mixed with loading buffer containing SDS, a reducing agent (such as β-mercaptoethanol or DTT), glycerol, and a tracking dye (typically bromophenol blue) [16] [15]. The samples are then heated at 95-100°C for 3-5 minutes to ensure complete denaturation [16] [17]. For native PAGE, SDS and reducing agents are omitted, and no heating step is performed to maintain proteins in their native conformation [15].

After loading samples and molecular weight markers into the wells, an electric current is applied (typically 100-200 V for mini-gel systems) [16] [15]. The discontinuous buffer system creates a stacking effect at the interface between the stacking and resolving gels, concentrating the proteins into a tight band before they enter the resolving gel where separation based on size occurs [15]. Electrophoresis continues until the tracking dye front reaches the bottom of the gel, indicating completion.

Visualization and Analysis

Following electrophoresis, separated proteins are visualized using various staining techniques. Coomassie Brilliant Blue is the most commonly used non-covalent stain for proteins, creating blue bands that can be detected visually, though with limited sensitivity [20]. Silver staining offers higher sensitivity, where soluble silver ions permanently mark proteins and are reduced by formaldehyde to form a brown precipitate [20]. For specialized applications, fluorescent dyes may be incorporated for enhanced sensitivity [21].

Advanced analysis techniques include digital image acquisition with mathematical processing of electropherograms for protein quantification [22]. Specialized software such as Chrom & Spec can be used to convert gel images to densitograms, with peak areas corresponding to protein content [22]. For two-dimensional gels, sophisticated image analysis software (Delta2D, PDQuest, Progenesis) employs image warping and consensus spot patterns to overcome variations between gels and enable accurate quantification [23].

Advanced Applications and Current Developments

Quantitative Electrophoresis

While traditionally considered a qualitative technique, PAGE can be adapted for protein quantification through careful implementation of digital imaging and mathematical processing [22]. This approach involves acquiring high-resolution images of stained gels under uniform illumination conditions, followed by software-based analysis to generate densitograms where peak areas correlate with protein concentration [22]. This methodology has been successfully applied to both purified protein systems (e.g., bovine serum albumin) and complex protein mixtures (e.g., casein-containing sports nutrition supplements) [22].

The global protein gel market, valued at approximately $2.5 billion in 2024, reflects the continued importance of these techniques, with innovations focusing on miniaturization of gels for high-throughput analysis, development of pre-cast gels with improved resolution and reproducibility, and incorporation of fluorescent dyes for enhanced sensitivity [21].

Two-Dimensional Electrophoresis

For complex protein mixtures, two-dimensional gel electrophoresis combines isoelectric focusing (first dimension) with SDS-PAGE (second dimension) to separate proteins based on both charge and molecular weight [23]. This technique can resolve up to 10,000 protein spots on a single gel, providing a powerful tool for proteomic analysis [23]. Software-based image analysis is crucial for interpreting 2D gel experiments, with recent advances including image warping methods that correct for positional variations between gels and consensus spot patterns that enable more reliable matching and quantification [23].

Experimental Workflow and Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, highlighting the role of the gel as a molecular sieve:

Diagram 1: Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis Workflow. This diagram illustrates the complete experimental process, highlighting the molecular sieve mechanism where smaller proteins migrate faster through the gel matrix than larger proteins.

The selection of appropriate gel concentration is critical for optimal separation. The following decision guide illustrates the relationship between gel percentage and protein separation:

Diagram 2: Gel Concentration Selection Guide. This diagram provides guidance for selecting appropriate acrylamide concentrations based on target protein size, illustrating the inverse relationship between acrylamide percentage and pore size.

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis remains a cornerstone technique in biochemical research and biotechnology, with its effectiveness fundamentally rooted in the molecular sieving properties of the polyacrylamide matrix. The ability to precisely control pore size by adjusting acrylamide concentration enables researchers to separate proteins across a wide size range with high resolution. While traditional PAGE is primarily qualitative, advances in digital imaging and analysis software have expanded its capabilities to include reliable protein quantification. The continued evolution of the technique, including miniaturization, improved sensitivity, and integration with downstream analysis methods, ensures that PAGE will remain an essential tool in proteomic research and biopharmaceutical development. Understanding the fundamental role of the support matrix as a molecular sieve allows researchers to optimize experimental conditions and correctly interpret separation results within the broader context of protein analysis.

Protein gel electrophoresis is a foundational technique in biochemical research and drug development, enabling the separation of complex protein mixtures based on their molecular size. The core principle hinges on applying an electric field to drive charged proteins through a porous polyacrylamide gel matrix. In the most common variant, SDS-PAGE (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate–Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis), proteins are denatured and uniformly coated with the negatively charged SDS detergent, rendering them a consistent charge-to-mass ratio [24] [25]. Consequently, separation occurs primarily by molecular weight, with smaller proteins migrating faster through the gel's molecular sieve than larger ones [26]. This methodology provides researchers with a powerful tool for analyzing protein purity, estimating molecular weight, and preparing samples for downstream applications like western blotting or mass spectrometry.

Core Components of the Electrophoresis Apparatus

A standard SDS-PAGE setup is an integrated system composed of several key components, each fulfilling a critical function for successful protein separation.

The Gel Matrix: Polyacrylamide

The polyacrylamide gel is the central separation medium, formed through the polymerization of acrylamide and a cross-linker, typically N,N'-methylenebisacrylamide [25]. This creates a three-dimensional network whose pore size is determined by the concentrations of these components; higher percentages of acrylamide create smaller pores, providing better resolution for lower molecular weight proteins [26]. The gel is structurally divided into two distinct layers:

- Stacking Gel: A large-pore gel (typically 4-5% acrylamide) at a neutral pH (~6.8) where protein samples are concentrated into a sharp starting zone before entering the resolving gel [25].

- Resolving Gel (Separating Gel): A small-pore gel (typically 8-15% acrylamide) at a basic pH (~8.8) where the actual size-based separation of proteins occurs [24]. The appropriate percentage is chosen based on the target protein's molecular weight.

The Electrophoresis Module

This module houses the gel and provides the environment for electrophoresis.

- Gel Cassette: Comprises two glass plates separated by thin spacers, which form the mold in which the gel is cast and define the gel's thickness (commonly 0.75 mm or 1.5 mm) [24].

- Buffer Chambers: The apparatus contains two buffer chambers filled with a running buffer (e.g., Tris-glycine-SDS).

- Upper Chamber (Cathode): Houses the gel cassette and interfaces with the top of the gel where the wells are located.

- Lower Chamber (Anode): Interfaces with the bottom of the gel.

- Electrodes and Power Supply: Platinum or wire electrodes are immersed in each buffer chamber and connected to a high-voltage power supply. The power supply delivers a constant voltage (typically 100-200 V) to drive the migration of proteins toward the anode (positive electrode) [24] [25].

Critical Reagents and Chemical Components

The successful execution of SDS-PAGE relies on a suite of specialized reagents [24] [25].

Table 1: Essential Reagent Solutions for SDS-PAGE

| Reagent Solution | Function |

|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Anionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge, negating the influence of intrinsic protein charge [25]. |

| Reducing Agents (DTT, β-Mercaptoethanol) | Break disulfide bonds in proteins by reducing them, ensuring complete unfolding into linear polypeptides [24] [25]. |

| Tris-based Buffers | Maintain a stable pH throughout the electrophoresis process. Different pH levels in the stacking (pH 6.8) and resolving (pH 8.8) gels enable the discontinuous system [24]. |

| APS & TEMED | Ammonium Persulfate (APS) and Tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED) are catalysts that initiate and drive the free-radical polymerization of acrylamide to form the polyacrylamide gel [25]. |

| Tracking Dye (Bromophenol Blue) | A small, colored molecule added to the sample buffer to visually monitor the progress of electrophoresis [24]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for SDS-PAGE

The following is a standardized methodology for performing SDS-PAGE.

Gel Casting Procedure

- Assemble Gel Cassette: Clean and dry the glass plates and spacers. Assemble the cassette and clamp it securely in a casting stand to create a water-tight mold [25].

- Prepare and Pour Resolving Gel: Mix the resolving gel solution containing acrylamide/bis-acrylamide, Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), SDS, and water. Add catalysts APS and TEMED to initiate polymerization and immediately pipette the solution into the gel cassette. Layer the top with isopropanol or water-saturated butanol to create a flat, oxygen-free interface, which ensures even polymerization [24] [25].

- Prepare and Pour Stacking Gel: After the resolving gel has polymerized (∼15-30 minutes), pour off the overlay. Prepare the stacking gel solution with acrylamide, Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), SDS, APS, and TEMED. Pour it onto the resolving gel and immediately insert a sample comb without introducing air bubbles [25].

- Polymerize: Allow the stacking gel to polymerize completely (∼15-30 minutes). The gel can be used immediately or stored refrigerated for a short period.

Sample Preparation

- Mix with Sample Buffer: Combine the protein sample with a 2X or 5X SDS-PAGE sample buffer. This buffer contains SDS for denaturation and charge, a reducing agent (DTT or β-mercaptoethanol) to break disulfide bonds, Tris for pH, glycerol for density, and bromophenol blue as the tracking dye [24] [25].

- Denature: Heat the sample mixture at 95°C for 5 minutes (or 70°C for 10 minutes). This heat treatment disrupts hydrogen bonds and secondary structures, ensuring proteins are fully denatured and linearized [24] [25].

- Cool and Centrifuge: Briefly cool the sample to room temperature and centrifuge to consolidate condensation.

Electrophoresis Execution

- Assemble Apparatus: Place the polymerized gel cassette into the electrophoresis chamber. Fill the inner (upper) and outer (lower) chambers with running buffer (e.g., Tris-glycine-SDS) [24].

- Load Samples: Carefully remove the sample comb. Using a microsyringe, load equal amounts of prepared protein samples and a molecular weight size marker into individual wells [25].

- Run Gel: Connect the chamber to the power supply. Apply a constant voltage of ~100-150 V for a mini-gel system. Run the gel until the bromophenol blue tracking dye front has migrated to the bottom of the gel (∼1-1.5 hours) [24].

- Terminate and Analyze: Turn off the power supply. Disassemble the apparatus and carefully pry open the glass plates to retrieve the gel. The gel is then stained (e.g., with Coomassie Blue or silver stain) or processed for western blotting to visualize the separated protein bands [9].

Workflow and Data Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of a standard SDS-PAGE experiment, from setup to analysis.

Quantitative Analysis and Molecular Weight Determination

Following electrophoresis, quantitative data is derived by comparing the migration of unknown proteins to a molecular weight marker loaded on the same gel [24]. The relative mobility (Rf) of each band is calculated as the migration distance of the protein divided by the migration distance of the dye front. A semi-log plot of the molecular weights of the marker proteins versus their Rf values produces a standard curve, which is used to estimate the molecular weight of unknown proteins with an accuracy of approximately ±10% [24]. For precise quantification of band intensities—such as in purity assessment or titration experiments—advanced software like GelExplorer can be employed. These tools use curve-fitting algorithms (e.g., Lorentzian lineshapes) to deconvolute and quantify even overlapping bands, providing robust quantitative data for rigorous analysis [27].

Table 2: Recommended Polyacrylamide Concentrations for Protein Separation

| % Acrylamide (Resolving Gel) | Effective Separation Range (kDa) |

|---|---|

| 8% | 30 - 200 |

| 10% | 20 - 150 |

| 12% | 15 - 100 |

| 15% | 5 - 70 |

Note: Effective range estimates based on standard Tris-glycine SDS-PAGE systems [24] [26].

From Theory to Bench: A Practical Guide to SDS-PAGE, Native-PAGE, and 2D Electrophoresis

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) stands as a cornerstone methodology in protein science, providing researchers with a robust, reproducible, and relatively simple means to separate complex protein mixtures. As a form of polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, its development represented a pivotal advancement by standardizing protein separation primarily on the basis of molecular weight, largely independent of innate protein charge or three-dimensional structure [1] [28]. This technique is indispensable in molecular biology, genetics, forensics, and biotechnology for characterizing protein samples, determining molecular weights, and assessing sample purity [29] [30]. The core achievement of SDS-PAGE lies in its use of a denaturing detergent system to unravel proteins and impose a uniform charge density, thereby transforming the unpredictable process of native protein electrophoresis into a standardized analytical tool grounded in polypeptide chain length [16] [31]. This whitepaper explores the fundamental principles, detailed methodologies, and critical applications of SDS-PAGE, framing it within the broader context of protein gel electrophoresis research essential for modern scientific inquiry and drug development.

The Fundamental Principle of SDS-PAGE

The principle of SDS-PAGE is elegantly simple: charged molecules migrate toward an oppositely charged electrode when placed in an electric field, and their separation depends on their relative mobility through a sieving matrix [29] [30]. In the case of proteins, which possess varying native charges and complex structures, this process is standardized through a denaturation step.

Protein Denaturation and Uniform Charge Conferral: The ionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) plays the central role. When a protein sample is heated (typically to 95°C for several minutes) in the presence of SDS and a reducing agent like β-mercaptoethanol or dithiothreitol (DTT), several key events occur [31] [32]. The reducing agent cleaves disulfide bonds critical for tertiary and quaternary structure, while SDS disrupts hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions [31]. Most critically, SDS binds to the hydrophobic regions of the denatured polypeptide backbone in a constant weight ratio of approximately 1.4 g of SDS per 1 g of protein [1] [28]. This SDS-polypeptide complex forms a rod-like structure, effectively masking the protein's intrinsic charge. Because the SDS coating is uniformly negative, all proteins in the mixture acquire a net negative charge proportional to their polypeptide chain length [16] [1] [31].

Molecular Sieving in the Gel Matrix: The polyacrylamide gel acts as a molecular sieve. Polymerized acrylamide, cross-linked by bisacrylamide, forms a porous, mesh-like matrix [16] [1]. When an electric field is applied, the negatively charged SDS-protein complexes migrate toward the positively charged anode (the positive electrode) [31]. Their rate of migration is inversely proportional to their molecular size; smaller proteins navigate the pores of the gel matrix more easily and thus migrate faster and farther, while larger proteins are impeded and migrate more slowly [16] [1]. Consequently, separation occurs almost exclusively based on polypeptide length, enabling accurate molecular weight estimation [1].

The SDS-PAGE System: Components and Setup

A successful SDS-PAGE experiment relies on a discontinuous buffer system and a layered gel structure to achieve high-resolution separation.

Key Chemical Components and Reagents

The following table details the essential reagents and their specific functions in the SDS-PAGE process.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SDS-PAGE

| Reagent | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Anionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge [31]. |

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Monomer and cross-linker that polymerize to form the porous gel matrix [1] [32]. |

| TEMED (N,N,N',N'-Tetramethylethylenediamine) | Catalyst that promotes the production of free radicals to initiate gel polymerization [1] [32]. |

| APS (Ammonium Persulfate) | Polymerizing agent that, with TEMED, generates free radicals to catalyze acrylamide polymerization [1] [32]. |

| Tris-based Buffers | Provides the appropriate pH environment for electrophoresis (e.g., pH 6.8 for stacking gel, pH 8.8 for resolving gel) [32]. |

| Glycine | A key component of the running buffer; its charge state is manipulated in the discontinuous system to stack proteins [32]. |

| Reducing Agents (DTT/BME) | Dithiothreitol (DTT) or β-mercaptoethanol (BME) break disulfide bonds to fully denature proteins [31] [32]. |

| Tracking Dye (Bromophenol Blue) | A small, colored molecule that migrates ahead of the proteins, allowing visual tracking of the electrophoresis progress [16] [32]. |

The Discontinuous Gel System

SDS-PAGE typically employs a two-layer gel cast between two glass plates:

- Resolving Gel (Separating Gel): This is the lower, main part of the gel, usually with a higher percentage of acrylamide (e.g., 10-15%) and a pH of about 8.8 [32]. Its specific pore size is responsible for the final separation of proteins by molecular weight [1]. The appropriate acrylamide concentration depends on the size of the target proteins, with higher percentages providing better resolution for smaller proteins [16] [32].

- Stacking Gel: Poured on top of the polymerized resolving gel, this upper layer has a lower acrylamide concentration (e.g., 4-5%) and a lower pH (~6.8) [32]. Its purpose is to concentrate all the protein samples into a sharp, unified band before they enter the resolving gel. This is achieved through a phenomenon known as isotachophoresis, which creates a steep voltage gradient that forces all proteins to migrate at the same speed and stack into a tight zone, regardless of their size [1] [31]. This process ensures that proteins enter the resolving gel simultaneously, leading to sharper bands and better resolution.

Table 2: Recommended Acrylamide Concentrations for Protein Separation

| Gel Acrylamide Concentration (%) | Linear Separation Range (kDa)* |

|---|---|

| 5.0 | 57 - 212 [32] |

| 7.5 | 36 - 94 [32] |

| 10.0 | 16 - 68 [32] |

| 12.0 | Not specified in results |

| 15.0 | 12 - 43 [32] |

*Values are approximate and can vary based on specific gel formulations.

The workflow below illustrates the core process and underlying principles of SDS-PAGE.

SDS-PAGE Principle and Process Flow

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The following section provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for performing SDS-PAGE, from gel preparation to visualization.

Gel Preparation and Casting

Materials Needed: Gel apparatus (glass plates, spacers, comb), acrylamide/bis-acrylamide stock solution (typically 30%), separating gel buffer (e.g., 1.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.8), stacking gel buffer (e.g., 0.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8), 10% SDS, 10% Ammonium Persulfate (APS), TEMED, water-saturated butanol or isopropanol, electrophoresis running buffer (e.g., Tris-Glycine buffer with 0.1% SDS) [16] [32].

Safety Note: Acrylamide monomer is a potent neurotoxin. Wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) including gloves when handling solutions and gels [32].

- Assemble the Gel Cassette: Thoroughly clean and dry the glass plates and spacers. Assemble the plates according to the manufacturer's instructions to form a water-tight cassette [16] [32].

- Prepare and Pour the Resolving Gel: In a beaker, mix the components for the resolving gel in the order listed, adding TEMED and APS last. The table below provides an example recipe for a 10% mini-gel [32].

- Pour the mixture immediately into the gap between the glass plates. Leave space for the stacking gel.

- Overlay the gel carefully with water-saturated butanol or isopropanol to exclude air (oxygen inhibits polymerization) and ensure a flat gel surface [16] [32].

- Allow polymerization to proceed for 20-30 minutes. A distinct schlieren line will appear between the gel and the overlay once polymerization is complete.

- Prepare and Pour the Stacking Gel: Pour off the overlay liquid and rinse the top of the gel with water. Dry the area with filter paper. Mix the stacking gel components, again adding TEMED and APS last.

- Pour the stacking gel solution on top of the resolving gel and immediately insert a clean comb, avoiding air bubbles [16] [32].

- Allow polymerization for about 10-15 minutes. The polymerized gel can be used immediately or stored wrapped in moist paper towel and plastic film at 4°C for a short period.

Table 3: Example Gel Formulations for a Mini-Gel

| Component | 10% Resolving Gel (for ~8x10 cm gel) | 5% Stacking Gel (for ~8x10 cm gel) |

|---|---|---|

| Water | 1.1 mL | 1.0 mL |

| 30% Acrylamide/Bis Mix | 2.2 mL | 0.28 mL |

| Separating Gel Buffer (1.5M Tris, pH8.8) | 2.2 mL | - |

| Stacking Gel Buffer (0.5M Tris, pH6.8) | - | 0.33 mL |

| 10% SDS | 0.3 mL (if not in buffer) | 15 µL (if not in buffer) |

| 10% APS | 50 µL | 15 µL |

| TEMED | 5 µL | 2 µL |

Sample Preparation

- Dilute Protein Sample: Mix the protein sample with an appropriate volume of 5X SDS-PAGE sample buffer (final concentration 1X). A typical 5X sample buffer contains: 250 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 10% SDS, 30% glycerol, 0.02% Bromophenol Blue, and 5% β-mercaptoethanol or DTT [32].

- Denature the Proteins: Heat the sample at 95°C for 3-5 minutes in a heat block or boiling water bath [16] [32]. This ensures complete denaturation and SDS binding.

- Briefly Centrifuge: Spin down the condensed sample to the bottom of the tube.

Electrophoretic Run

- Set Up the Electrophoresis Unit: Remove the comb from the polymerized gel cassette and mount the cassette in the electrophoresis chamber [16].

- Fill with Running Buffer: Fill the inner and outer chambers of the electrophoresis apparatus with running buffer (e.g., Tris-Glycine-SDS buffer) to submerge the gel. Remove any air bubbles from the bottom of the gel and flush out the wells with buffer using a syringe [16] [32].

- Load Samples: Carefully load the denatured protein samples and a molecular weight marker (protein ladder) into individual wells using a micropipette [16].

- Run the Gel: Connect the electrodes to the power supply (cathode, negative/black, at the top; anode, positive/red, at the bottom). Apply a constant voltage. For a mini-gel, 80-120 V through the stacking gel and 120-150 V through the resolving gel is common. Run the gel until the bromophenol blue tracking dye reaches the bottom of the gel [16] [32].

Protein Visualization

- Staining: After electrophoresis, carefully open the gel cassette and remove the gel. Immerse the gel in Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining solution (e.g., 0.05% Coomassie R-250, 40% methanol, 10% acetic acid) and agitate gently for at least 30 minutes to several hours [32].

- Destaining: Transfer the gel to a destaining solution (e.g., 40% methanol, 10% acetic acid) to remove excess stain from the gel background. Agitate until protein bands are clear and the background is light. A folded paper towel can be added to the destaining bath to absorb excess stain [32].

- Analysis: The stained gel can be imaged. The molecular weight of unknown proteins can be estimated by comparing their migration distance to that of the protein ladder bands of known molecular weight [32].

Applications and Variations in Research

SDS-PAGE is not merely a standalone technique but a fundamental tool that integrates into broader research workflows.

- Molecular Weight Determination: By comparing the migration distance of an unknown protein to a standard curve generated from a protein ladder, researchers can estimate its molecular weight with reasonable accuracy [32] [30].

- Purity Analysis and Quality Control: SDS-PAGE is used to assess the homogeneity of protein samples during purification processes. A pure protein will typically appear as a single band on the gel [32] [30].

- Western Blotting (Immunoblotting): Proteins separated by SDS-PAGE are transferred onto a membrane (e.g., nitrocellulose or PVDF) and probed with specific antibodies to detect and characterize a protein of interest [1] [32] [30].

- Peptide Mapping and Proteomic Analysis: Excised protein bands from SDS-PAGE gels can be subjected to proteolytic digestion (e.g., with trypsin) and subsequent analysis by mass spectrometry for protein identification [33].

- Post-Translational Modification Analysis: While SDS-PAGE separates denatured proteins, shifts in apparent molecular weight can sometimes indicate modifications like glycosylation or phosphorylation [30].

- Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE): A variation of the standard method where the heating step is omitted, and lower concentrations of SDS are used. This allows for partial retention of protein structure and function, including enzymatic activity and non-covalently bound metal ions, while still providing separation primarily based on mass [34]. This technique bridges the gap between fully denaturing SDS-PAGE and non-denaturing Native-PAGE.

SDS-PAGE remains an indispensable and foundational technique in the life sciences. Its power lies in its ability to standardize protein separation by exploiting the simple relationship between polypeptide chain length and electrophoretic mobility in a sieving matrix, a relationship made possible by the effective denaturing action of SDS. From its role in routine quality control to its critical position in complex workflows like western blotting and proteomics, SDS-PAGE provides a reliable, relatively inexpensive, and highly informative window into the protein composition of a sample. While newer technologies continue to emerge, the principles and practice of SDS-PAGE continue to underpin a vast array of research and development activities, solidifying its status as an essential tool for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to understand and manipulate the molecular machinery of the cell.

Protein gel electrophoresis is a fundamental laboratory technique for separating complex protein mixtures based on their physicochemical properties. While denaturing methods like SDS-PAGE separate proteins primarily by molecular weight, Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (Native-PAGE) operates on a different principle—preserving protein structure and function throughout the separation process. This technique allows researchers to separate proteins according to their net charge, size, and shape while maintaining their native conformation, enzymatic activity, and subunit interactions [1] [35]. Within the broader thesis of protein electrophoresis research, Native-PAGE represents a crucial methodological approach for functional proteomics, enabling the study of proteins in their biologically active states, which is essential for understanding protein function in basic research and drug development.

The significance of Native-PAGE extends across multiple scientific domains. In enzymology, it facilitates the isolation of active enzymes for kinetic studies. In pharmaceutical development, it enables the analysis of protein-drug interactions under non-denaturing conditions. For structural biologists, it provides insights into quaternary protein structures and complexes [1]. This technical guide explores the principles, methodologies, and applications of Native-PAGE, providing researchers with a comprehensive resource for implementing this powerful technique in their functional protein studies.

Fundamental Principles of Native-PAGE

Separation Mechanisms in Non-Denaturing Conditions

Unlike SDS-PAGE, which uses sodium dodecyl sulfate to denature proteins and confer uniform negative charge, Native-PAGE relies on the intrinsic electrical properties of proteins under non-denaturing conditions. In this system, proteins maintain their folded conformation, and their migration through the polyacrylamide gel matrix depends on multiple factors including their net charge, hydrodynamic size, and three-dimensional structure [1]. The porous nature of the polyacrylamide gel creates a molecular sieve effect, regulating protein movement according to size and shape—smaller proteins encounter less frictional resistance and migrate faster, while larger proteins face greater resistance [35].

The electrophoretic mobility in Native-PAGE follows the principle that most proteins carry a net negative charge in alkaline running buffers and migrate toward the anode. The higher the negative charge density (more charges per molecular mass), the faster a protein will migrate [1]. This combination of charge-based separation and molecular sieving allows Native-PAGE to resolve protein complexes in their functional states, making it indispensable for studying multi-subunit proteins, protein-protein interactions, and enzymatic activities.

Buffer System Considerations and pH Optimization

The buffer system is critical in Native-PAGE as it determines the charge characteristics of the proteins being separated. For optimal results, the pH of the running buffer must be carefully selected based on the isoelectric points (pI) of the target proteins. Acidic proteins are typically separated using high pH buffer systems (e.g., pH 8.8), where they carry net negative charges and migrate toward the anode. Conversely, basic proteins require low pH buffer systems, where they maintain positive charges; in this case, the electrode polarity must be reversed during electrophoresis [35].

The discontinuous buffer system employed in Native-PAGE consists of two components: a stacking gel with lower acrylamide concentration (typically 4%) and pH ~6.8, and a resolving gel with higher acrylamide concentration (up to 17%) and pH ~8.8 [35]. This configuration creates an environment where proteins are initially concentrated into a tight band before entering the resolving region, enhancing separation resolution. The ionic strength and composition of the buffer also influence protein stability and migration, requiring optimization for different protein systems.

Table 1: Key Differences Between Native-PAGE and SDS-PAGE

| Parameter | Native-PAGE | SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Protein State | Native, folded | Denatured, unfolded |

| Separation Basis | Charge, size, shape | Molecular weight |

| Detergent | None (non-denaturing) | SDS (denaturing) |

| Sample Treatment | No heating, no reducing agents | Heating with SDS and DTT/β-mercaptoethanol |

| Protein Activity | Preserved after separation | Destroyed after separation |

| Molecular Weight Determination | Not accurate due to native conformation | Accurate for polypeptide chains |

| Applications | Functional studies, enzyme assays, oligomerization | Purity analysis, molecular weight estimation |

Experimental Design and Protocol

Gel Composition and Formulation

The polyacrylamide gel matrix for Native-PAGE consists of acrylamide and a crosslinking agent (typically N,N'-methylenebisacrylamide) polymerized with ammonium persulfate (APS) and catalyzed by TEMED (N,N,N',N'-tetramethylethylenediamine) [1]. The pore size and sieving properties are controlled by the total acrylamide concentration (%T) and the crosslinker ratio (%C), which must be optimized based on the size range of target proteins. Lower percentage gels (e.g., 7-10%) are suitable for high molecular weight proteins and complexes, while higher percentages (12-17%) provide better resolution for smaller proteins [35].

Table 2: Basic Native-PAGE Gel Formulation for Acidic Proteins

| Reagent | Separating Gel (17%) 10 mL | Stacking Gel (4%) 5 mL |

|---|---|---|

| 40% Acr-Bis (Acr:Bis=19:1) | 4.25 mL | 0.5 mL |

| 4× Separating Gel Buffer (1.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.8) | 2.5 mL | - |

| 4× Stacking Gel Buffer (0.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8) | - | 1.25 mL |

| Deionized Water | 3.2 mL | 3.2 mL |

| 10% APS | 35 μL | 35 μL |

| TEMED | 15 μL | 15 μL |

The gel polymerization process requires careful timing—the separating gel is first poured to approximately 3/4 of the cassette height and overlayered with isopropanol or water to create a flat interface. After polymerization (approximately 30 minutes), the stacking gel is added, and a sample comb is inserted to create wells for protein loading [35]. Proper degassing of solutions before polymerization minimizes oxygen inhibition and ensures consistent gel formation.

Sample Preparation and Electrophoresis Conditions

Sample preparation for Native-PAGE requires gentle handling to maintain protein integrity. Proteins should be dissolved in non-denaturing buffers compatible with the electrophoresis system, avoiding strong detergents, high salts, or reducing agents that might disrupt native structure. A native-compatible loading buffer containing glycerol (for density) and a tracking dye (e.g., Bromophenol Blue) is typically mixed with the protein sample before loading [35] [6].

Electrophoresis is performed under constant voltage conditions, typically starting at 100V until samples enter the resolving gel, then increasing to 150-200V for the remainder of the run [35]. To prevent heat-induced denaturation, the electrophoresis apparatus should be maintained at 4°C or placed on ice, particularly for extended run times [35]. The progress is monitored by the migration of the tracking dye, with electrophoresis stopped before the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel to prevent loss of small proteins.

Diagram 1: Native-PAGE Experimental Workflow

Advanced Applications and Methodological Variations

Quantitative Analysis and Detection Methods

While traditionally considered a qualitative technique, Native-PAGE can be adapted for quantitative analysis through digital imaging and mathematical processing of electropherograms [22]. Advanced staining and detection methods enable researchers to extract both qualitative and quantitative information about protein composition and abundance:

Activity Staining: For enzymes, specific activity stains can be applied after electrophoresis to identify functional proteins based on their catalytic capabilities, providing a direct link between protein bands and biological function [35].

Fluorescence Detection: Sensitive fluorescent dyes like SYBR Green or specialized fluorophores (e.g., TSQ for zinc-containing proteins) enable detection of low-abundance proteins while maintaining protein function for downstream analysis [34].

Digital Imaging and Densitometry: High-resolution digital photography with uniform illumination, coupled with specialized software (e.g., Chrom & Spec), allows conversion of gel images to densitograms for quantitative analysis of band intensity, enabling protein quantification similar to chromatographic techniques [22].

Methodological Variations and Hybrid Approaches

Several specialized forms of Native-PAGE have been developed to address specific research needs:

Blue Native-PAGE (BN-PAGE): Utilizes Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 to confer additional negative charge to native protein complexes, enabling the separation of large membrane protein complexes while maintaining protein-protein interactions [34]. The dye can sometimes act as a detergent, potentially causing partial denaturation.

Clear Native-PAGE (CN-PAGE): Relies solely on the intrinsic charge of proteins for separation, making it suitable for acidic membrane proteins and water-soluble proteins where dye-induced artifacts are a concern [6].

Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE): A hybrid approach that reduces SDS concentration in running buffers (to 0.0375%) and eliminates heating steps, achieving high resolution while retaining enzymatic activity and metal cofactors in many proteins [34]. This method represents a promising compromise between resolution and native state preservation.

Table 3: Comparison of Native Electrophoresis Methods

| Method | Resolution | Protein State | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native-PAGE | Moderate | Fully native | Enzyme analysis, protein-protein interactions |

| BN-PAGE | Moderate-high | Mostly native | Membrane protein complexes, oligomeric states |

| CN-PAGE | Low-moderate | Fully native | Acidic proteins, metal-binding proteins |