Protein Gel Electrophoresis: Principles, Methods, and Advanced Applications for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to gel electrophoresis for protein separation, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Protein Gel Electrophoresis: Principles, Methods, and Advanced Applications for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to gel electrophoresis for protein separation, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, including the core mechanisms of separation based on size and charge. The article details established and emerging methodologies like SDS-PAGE and capillary gel electrophoresis, alongside their critical applications in biopharmaceutical quality control and proteomics. A dedicated troubleshooting section addresses common challenges to ensure reproducible results, and a final section validates the technique through performance comparisons with other separation technologies and explores future trends, including automation and integration with mass spectrometry.

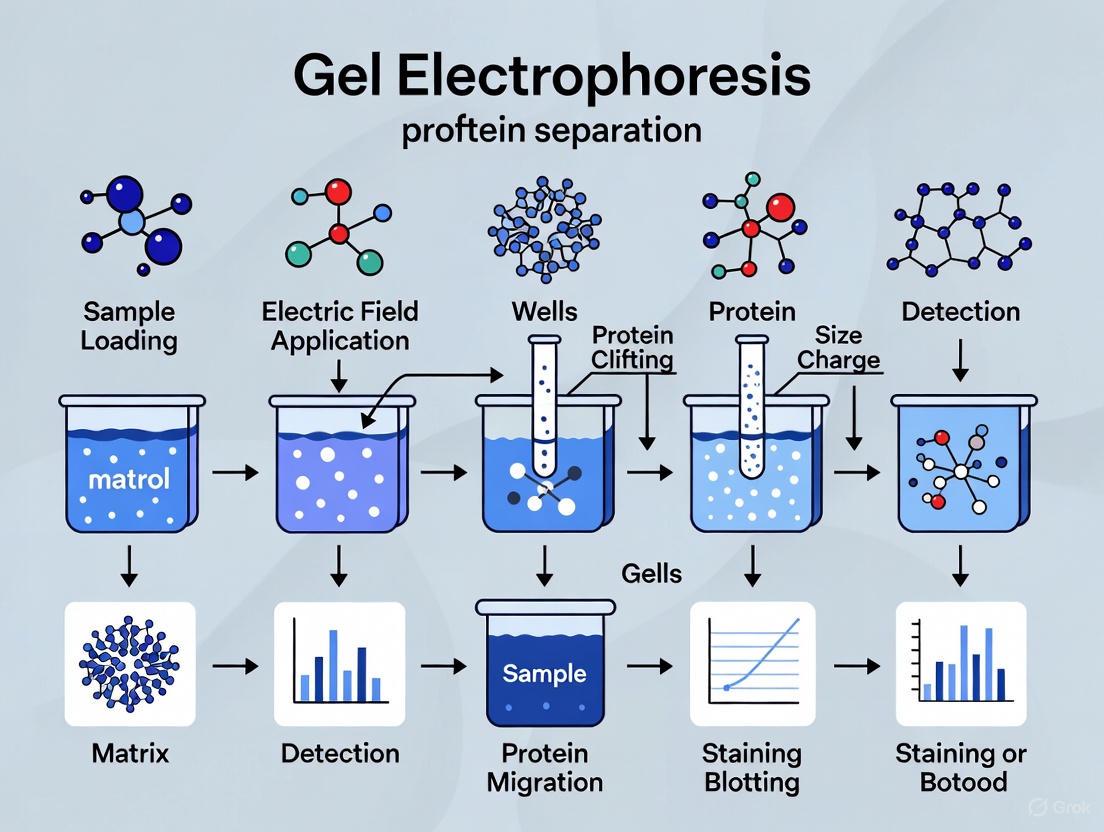

The Core Principles of Protein Separation: Understanding Gel Electrophoresis Fundamentals

Electrophoresis is a standard laboratory technique in which charged protein molecules are transported through a solvent by an electrical field [1]. First demonstrated by Swedish biochemist Arne Tiselius in 1937, this method exploits the fundamental property that biomolecules, including proteins, peptides, and nucleic acids, possess electrical charges and will migrate toward either the anode or cathode based on their net charge when placed in an electric field [2]. This technique provides a simple, rapid, and sensitive analytical tool for separating macromolecules based on their size, charge, and shape [1] [3].

In the context of protein research, electrophoresis serves as a fundamental step in many proteomics analyses, enabling researchers to separate complex protein mixtures, determine molecular weights, analyze protein purity, and investigate post-translational modifications [1]. The technique has evolved significantly since its inception, with modern implementations offering high-resolution separation of thousands of proteins in a single run, making it indispensable for drug development professionals seeking to understand disease mechanisms and identify novel therapeutic targets [1] [4].

Core Principles of Separation

The fundamental principle of electrophoresis relies on the phenomenon that charged particles experience a force and move through a medium when subjected to an electrical field. The direction and speed of this migration depend on the molecule's net charge, with positively charged molecules (cations) migrating toward the negative electrode (cathode) and negatively charged molecules (anions) moving toward the positive electrode (anode) [2]. For protein separation, this principle is harnessed using gel-based matrices that serve as molecular sieves, adding a size-based separation dimension to the charge-based migration.

Factors Governing Electrophoretic Mobility

The mobility of a molecule through an electric field during electrophoresis depends on several key factors that researchers must optimize for effective separation [1]:

- Field Strength: Mobility is proportional to the potential gradient (voltage). Higher voltages generally increase migration rates but can generate excessive heat if not properly controlled [2].

- Net Charge on the Molecule: Mobility is directly proportional to the net charge of the molecule. Higher charge density results in faster migration [2].

- Size and Shape of the Molecule: Mobility is inversely proportional to molecular size. Smaller, more compact molecules migrate faster than larger ones through the gel matrix [2].

- Buffer Ionic Strength: The optimum ionic strength is necessary as higher ionic strength increases the share of current carried by buffer ions, slowing sample migration and generating heat. Lower ionic strength reduces resolution due to reduced overall current [2].

- Matrix Properties: The viscosity and pore size of the gel matrix significantly affect separation. Matrices with smaller pores provide better resolution for smaller molecules but restrict the movement of larger molecules [1].

Table 1: Key Factors Affecting Electrophoretic Mobility

| Factor | Effect on Mobility | Practical Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Size | Inversely proportional | Larger molecules migrate slower |

| Net Charge | Directly proportional | Higher charge increases migration rate |

| Field Strength | Proportional | Higher voltage speeds separation but increases heat |

| Buffer Ionic Strength | Complex effect | Optimal strength needed; too high causes overheating |

| Matrix Pore Size | Inversely related | Smaller pores provide better resolution for small molecules |

Mathematical Relationship of Separation

The electrophoretic mobility (μ) of a molecule can be described by the following relationship:

μ = q / (6πηr)

Where:

- q = net charge on the molecule

- η = viscosity of the medium

- r = molecular radius

This equation illustrates that mobility is directly proportional to net charge and inversely proportional to molecular size and medium viscosity. In practical terms, this means that under constant experimental conditions, small, highly charged molecules will migrate fastest, while large molecules with low charge will migrate slowest [2].

Support Matrices and Their Properties

The support matrix serves as a critical component in gel electrophoresis, providing a porous medium that acts as a molecular sieve to separate molecules based on size as they migrate under the influence of the electric field. The choice of matrix significantly impacts resolution and separation efficiency [1] [2].

Polyacrylamide Gel Matrix

Polyacrylamide gel is formed by polymerizing acrylamide monomers in the presence of a crosslinking agent, typically N,N'-methylenebisacrylamide (bis-acrylamide) [1]. The polymerization reaction is initiated by ammonium persulfate (APS) and catalyzed by N,N,N',N'-tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED) [1] [5]. The resulting gel forms a three-dimensional network with pore sizes that can be precisely controlled by adjusting the concentrations of acrylamide and bis-acrylamide, typically ranging between 20 and 150 nm in diameter [5].

Polyacrylamide gels are particularly favored for protein separation due to their smaller pore sizes, which provide superior resolution for most proteins and smaller nucleic acids [1]. The total concentration of acrylamide plus bis-acrylamide (expressed as %T) determines the pore size, with higher percentages creating smaller pores better suited for separating smaller molecules [5].

Table 2: Polyacrylamide Gel Concentrations for Optimal Separation

| Gel Percentage | Separation Range for Proteins | Application Focus |

|---|---|---|

| 7-8% | 50-150 kDa | Large proteins |

| 10% | 20-100 kDa | Standard separation |

| 12% | 15-70 kDa | Standard separation |

| 15% | 10-50 kDa | Small proteins |

Agarose Gel Matrix

Agarose, a polysaccharide polymer derived from red algae, forms gels with larger pore sizes suitable for separating larger molecules and protein complexes [1] [6]. When heated and cooled, agarose forms a gel matrix with pore sizes ranging from 50 to 200 nm in diameter, governed by gel concentration [5]. Agarose gels are typically used for separating nucleic acids and large protein complexes but have limited application for standard protein separation due to their larger pore size [1].

Buffer Systems

The buffer in electrophoresis serves two critical functions: carrying the electric current and maintaining stable pH to ensure molecules retain their charge throughout separation [2]. The discontinuous buffer system used in SDS-PAGE incorporates two different buffers: one for the stacking gel and another for the resolving gel, which concentrates proteins into sharp bands before separation by size [1].

Methodologies and Experimental Approaches

SDS-PAGE (Denaturing Electrophoresis)

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) represents the most widely used electrophoresis technique for protein separation, employing a discontinuous buffer system that separates proteins primarily by mass [1]. The methodology involves several critical steps:

Sample Preparation: Protein samples are heated between 70-100°C in the presence of excess SDS and a reducing agent (β-mercaptoethanol or dithiothreitol) [1]. SDS denatures proteins by wrapping around the polypeptide backbone while the reducing agent cleaves disulfide bonds, fully dissociating proteins into their subunits [1]. Most polypeptides bind SDS in a constant weight ratio (approximately 1.4 g SDS per 1 g polypeptide), masking intrinsic charges and creating uniformly negatively charged complexes [1].

Gel Preparation: SDS-PAGE uses a discontinuous gel system consisting of:

- Stacking Gel: A lower concentration gel (typically 4-5% acrylamide) with a different pH (e.g., 6.8) that concentrates proteins into a sharp band before entering the resolving gel [1].

- Resolving Gel: A higher concentration gel (typically 7-15% acrylamide, depending on target protein sizes) with higher pH (e.g., 8.8) where actual separation occurs [1].

Example Traditional Polyacrylamide Gel Formulation [1]:

- 7.5 mL 40% acrylamide solution

- 3.9 mL 1% bisacrylamide solution

- 7.5 mL 1.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.7

- Water to 30 mL total volume

- 0.3 mL 10% APS

- 0.3 mL 10% SDS

- 0.03 mL TEMED

Electrophoretic Run: Prepared samples are loaded into wells, and current is applied (typically 100-200 V for 30-90 minutes, depending on gel size). Proteins migrate toward the anode, with smaller polypeptides moving faster through the gel matrix [1].

Visualization: Separated proteins are typically visualized using stains such as Coomassie Blue, silver stain, or fluorescent dyes [7]. For specific detection, proteins can be transferred to membranes for Western blotting with antibody probes [1] [7].

Diagram 1: SDS-PAGE Workflow

Native-PAGE

Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Native-PAGE) separates proteins according to their net charge, size, and shape while maintaining their native structure [1]. Unlike SDS-PAGE, no denaturants are used, allowing multimeric proteins to retain subunit interactions and enzymatic activity [1]. This technique is particularly valuable for studying protein complexes, oligomeric states, and functional analyses where maintaining native conformation is essential [1].

Two-Dimensional Electrophoresis

Two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2D-PAGE) provides the highest resolution for protein analysis by separating proteins based on two distinct properties in sequential steps [1]:

First Dimension - Isoelectric Focusing (IEF): Proteins are separated according to their native isoelectric point (pI) using immobilized pH gradient (IPG) strips that establish a pH gradient [1]. Proteins migrate until they reach their isoelectric point (pI), where their net charge becomes zero [2].

Second Dimension - SDS-PAGE: The IPG strip is then applied to an SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and proteins are separated by mass at a 90° angle to the first dimension run [1]. This orthogonal separation approach can resolve thousands of proteins in a single gel, making it invaluable for proteomic research [1].

Capillary Electrophoresis

Capillary electrophoresis (CE) represents an advanced format where separation occurs in narrow-bore capillaries filled with separation matrix [8] [2]. This format offers several advantages over traditional gel-based methods, including automation, higher resolution, superior reproducibility, quantitative precision, and reduced consumption of samples and reagents [8]. For SDS-based separations, CE-SDS (capillary electrophoresis-sodium dodecyl sulfate) provides an automated, quantitative alternative to traditional SDS-PAGE with minimal hands-on time [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful protein electrophoresis requires specific reagents and materials, each serving a distinct function in the separation process. The following table details key components essential for electrophoretic experiments:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Electrophoresis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms polyacrylamide gel matrix | Neurotoxic; handle with protective equipment [5] |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | Initiates polymerization | Free radical source for acrylamide polymerization [1] |

| TEMED | Catalyzes polymerization | Promotes free radical production by APS [1] |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins, confers uniform charge | Critical for SDS-PAGE; masks intrinsic protein charges [1] |

| Reducing Agents (β-mercaptoethanol, DTT) | Cleaves disulfide bonds | Ensures complete protein denaturation into subunits [1] |

| Tris Buffers | Maintains pH during electrophoresis | Different pH for stacking (6.8) and resolving (8.8) gels [1] |

| Molecular Weight Markers | Size reference for separated proteins | Pre-stained or unstained protein ladders [1] |

| Tracking Dye | Visualizes migration front | Bromophenol blue or xylene cyanol in sample buffer [7] |

| Protein Stains (Coomassie, Silver, Fluorescent) | Visualizes separated proteins | Different sensitivity levels; Coomassie most common [7] |

Factors Affecting Resolution and Performance

Several technical factors must be optimized to achieve high-resolution protein separation by electrophoresis:

Gel Percentage Selection: The appropriate acrylamide concentration must be matched to the target protein size range. Lower percentage gels (7-10%) are optimal for high molecular weight proteins, while higher percentages (12-15%) provide better resolution for smaller proteins [1]. Gradient gels, with increasing acrylamide concentration from top to bottom, can separate a broader range of protein sizes in a single run [1].

Buffer Composition and Ionic Strength: Buffer ionic strength affects both migration rate and resolution. Higher ionic strength increases current sharing with buffer ions, slowing protein migration and generating excessive heat that can cause band diffusion and distortion [2]. Lower ionic strength reduces overall current and may decrease resolution [2].

Voltage and Run Conditions: Applied voltage must be balanced against gel size and cooling capacity. Higher voltages reduce run time but can generate heat that melts gels or creates smiling bands [7]. Standard SDS-PAGE runs typically use 100-200 V constant voltage for mini-gels [1].

Electroendosmosis: This phenomenon occurs when fixed charged groups on the support matrix (such as sulfate groups in agarose) become ionized and migrate, creating a counterflow that can impede sample movement and reduce resolution [2]. Using ultrapure agarose with low sulfate content minimizes this effect [2].

Diagram 2: Separation Principle in Gel Matrix

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Protein electrophoresis continues to evolve with technological advancements that enhance its utility in research and drug development:

Biopharmaceutical Applications: Electrophoresis techniques, particularly CE-SDS, have become critical analytical tools in biopharmaceutical development and quality control [8]. Regulatory filings for commercial biotherapeutics frequently include CE-SDS data to characterize protein therapeutics, including monoclonal antibodies, bispecific antibodies, antibody-drug conjugates, fusion proteins, and viral vectors [8].

Diagnostic Applications: Clinical diagnostics employs protein electrophoresis for detecting and monitoring various conditions. Immunoelectrophoresis and immunofixation electrophoresis are used to identify abnormal gamma-globulin fractions and free light chains in patients with monoclonal or polyclonal gammopathy [2]. High-resolution techniques like isoelectric focusing can fractionate hemoglobin variants for diagnosing hemoglobinopathies [2].

Proteomics Research: Two-dimensional electrophoresis remains a cornerstone of proteomic research, enabling comprehensive analysis of complex protein mixtures from cells, tissues, or biological fluids [1]. When combined with mass spectrometry, 2D-PAGE facilitates protein identification, quantification of expression changes, and detection of post-translational modifications [1].

Technology Advancements: The field continues to advance with trends toward miniaturization, automation, and integration of digital technologies [9]. Automated systems with integrated software for gel visualization, analysis, and data management are becoming standard, enhancing reproducibility and throughput while reducing manual errors [9]. These advancements align with the growing emphasis on precision, efficiency, and data integrity in both research and clinical applications.

This technical guide explores the fundamental physical and chemical factors governing protein migration in gel electrophoresis, a cornerstone technique in biochemical research and drug development. The separation of proteins in an electric field is a complex process dictated by an interplay of intrinsic molecular properties and extrinsic buffer conditions. A deep understanding of these factors—protein charge, size, and shape, combined with buffer pH, ionic strength, and composition—is essential for optimizing experimental design, improving resolution, and generating reproducible, high-quality data in applications ranging from proteomics to pharmaceutical quality control.

Gel electrophoresis is a foundational technique in molecular biology and biochemistry for the separation and analysis of complex protein mixtures. The general principle involves applying an electric field to drive the migration of charged protein molecules through a porous gel matrix [10]. The differential mobility of proteins through this matrix allows for their separation based on key physical characteristics.

The effectiveness of this separation, or electrophoretic mobility (μ), is described by the fundamental equation μ = v/E = q/f, where v is the velocity of the molecule, E is the electric field strength, q is the net charge of the molecule, and f is the frictional coefficient, which is influenced by the molecule's size and shape and the viscosity of the medium [11]. This review provides an in-depth examination of the core factors in this equation—charge, size, shape, and buffer conditions—framing them within the practical context of designing and interpreting protein electrophoresis experiments.

Intrinsic Factors Governing Protein Migration

Molecular Charge

The net charge of a protein is a primary determinant of its direction and speed of migration. Unlike nucleic acids, which possess a uniform negative charge, a protein's charge is determined by the ionizable groups on its constituent amino acids and is highly dependent on the pH of the surrounding buffer [10] [12].

- Isoelectric Point (pI): The pH at which a protein has a net charge of zero is its isoelectric point. When the buffer pH is less than the protein's pI, the protein carries a net positive charge and migrates toward the cathode. Conversely, when the buffer pH is greater than the pI, the protein is negatively charged and migrates toward the anode [10] [13]. At its pI, a protein's mobility ceases.

- Charge in SDS-PAGE: The use of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) fundamentally alters protein charge. SDS is an anionic detergent that binds to hydrophobic regions of proteins, coating them in a uniform negative charge. This masks the protein's intrinsic charge, resulting in an approximately uniform charge-to-mass ratio for all SDS-protein complexes [11] [14]. This allows separation to proceed primarily based on molecular weight rather than native charge.

Molecular Size and Shape

The frictional coefficient (f) in the mobility equation represents the drag a molecule experiences as it moves through the gel matrix. This is profoundly affected by both the size and three-dimensional structure of the protein.

- Molecular Sieving: The gel matrix (e.g., polyacrylamide or agarose) acts as a molecular sieve. Smaller proteins can navigate the pores of the gel more easily, experiencing less friction and migrating faster, while larger proteins are more hindered and migrate more slowly [11] [12].

- Role in Native vs. Denaturing Electrophoresis: Under native conditions, without denaturants, a protein's shape and quaternary structure significantly influence its mobility. Compact, globular proteins will migrate faster than elongated, fibrous proteins of the same molecular weight [12]. In denaturing SDS-PAGE, reducing agents and heat disrupt disulfide bonds, and SDS linearizes the polypeptide chain, minimizing the influence of shape. Proteins thus migrate primarily as linear chains, with mobility being inversely proportional to the logarithm of their molecular weight [15] [14].

Table 1: Impact of Intrinsic Protein Properties on Electrophoretic Mobility

| Factor | Description | Impact on Migration | Technique for Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Net Charge | Determined by amino acid composition and buffer pH. | Higher net charge increases mobility; direction depends on charge polarity. | Isoelectric focusing (IEF); manipulation of buffer pH. |

| Isoelectric Point (pI) | The pH where net charge is zero. | Defines the charge state and direction of migration at a given pH. | Key parameter for 2D-PAGE and native PAGE. |

| Molecular Size | Mass or number of amino acids. | Larger size increases frictional drag, decreasing mobility. | SDS-PAGE to separate by molecular weight. |

| Molecular Shape | Three-dimensional conformation (globular, fibrous). | Compact shapes migrate faster than extended shapes of similar mass. | Use of denaturants (SDS) to linearize proteins. |

| Quaternary Structure | Assembly of multiple polypeptide subunits. | Complexes have lower mobility than individual subunits. | Use of reducing agents (DTT, β-mercaptoethanol) to disrupt disulfide bonds. |

Extrinsic Buffer and Gel Conditions

The environment in which electrophoresis occurs is as critical as the properties of the proteins themselves. Buffer conditions and gel composition must be carefully controlled to ensure reproducible and accurate separations.

Buffer pH and Ionic Strength

The electrophoresis buffer provides the ions necessary for electrical conductivity and establishes the pH environment that dictates protein charge [16].

- pH Stability: The buffer must maintain a stable pH throughout the run. Changes in pH can alter the charge states of proteins mid-experiment, leading to distorted migration patterns, band broadening, and loss of resolution [10] [16].

- Ionic Strength: This measures the concentration of ions in the buffer. High ionic strength increases current and can lead to excessive Joule heating, which may denature proteins and cause gel smearing. Low ionic strength results in poor conductivity, slow migration, and band diffusion due to a weak electric field [10] [16]. An optimal ionic strength ensures efficient separation without overheating.

Table 2: Key Buffer Conditions and Their Electrophoretic Effects

| Buffer Parameter | Optimal Condition | Effect of High Value | Effect of Low Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | Chosen based on protein pI or technique (e.g., Tris-HCl ~pH 8.8 for SDS-PAGE). | Alters protein charge; can cause protein deamidation or degradation. | Alters protein charge; may reduce stability. |

| Ionic Strength | Balanced to provide conductivity without excessive heat. | Excessive heat generation, gel smearing, and longer run times. | Poor separation, band diffusion, and slow migration. |

| Buffer Capacity | Sufficient to maintain stable pH for the duration of the run. | Can contribute to high ionic strength effects. | pH shifts during run, leading to unreliable migration. |

Gel Matrix Properties

The choice and composition of the gel matrix define the sieving properties that separate proteins by size.

- Gel Type: Agarose gels have larger pores and are typically used for separating large protein complexes or nucleic acids. Polyacrylamide gels offer a more uniform and smaller pore structure, providing superior resolution for most proteins [12]. The pore size in polyacrylamide is determined by the total concentration of acrylamide (%T) and the cross-linker bisacrylamide (%C) [13].

- Gel Concentration: The percentage of acrylamide dictates the effective separation range. Lower percentages (e.g., 8-10%) are optimal for high molecular weight proteins, while higher percentages (e.g., 12-15%) provide better resolution for low molecular weight proteins [15].

Experimental Protocols for Key Techniques

SDS-PAGE for Molecular Weight Determination

The Laemmli method of discontinuous SDS-PAGE is the gold standard for determining protein molecular weight and analyzing purity [15] [14].

Detailed Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Protein samples are mixed with a sample buffer containing SDS (typically 1-2%), a reducing agent (β-mercaptoethanol or DTT), glycerol, and a tracking dye. The mixture is heated at 95-100°C for 5-10 minutes to ensure complete denaturation and linearization [15] [14].

- Gel Casting: A polyacrylamide gel is cast in two layers:

- Resolving Gel: The lower gel (e.g., 12% acrylamide, Tris-HCl pH 8.8) where size-based separation occurs.

- Stacking Gel: The upper gel (e.g., 4% acrylamide, Tris-HCl pH 6.8) that concentrates all proteins into a sharp band before they enter the resolving gel, improving resolution [14].

- Electrophoresis Run: The gel is mounted in a vertical tank, submerged in running buffer (e.g., Tris-Glycine-SDS). Samples and a pre-stained protein ladder are loaded. A constant voltage (e.g., 100-150V) is applied until the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel [15].

- Visualization and Analysis: The gel is stained with Coomassie Blue, silver stain, or fluorescent dyes. The migration distance of unknown proteins is compared to the standard curve generated from the molecular weight marker to estimate size [11] [17].

Native PAGE for Studying Protein Complexes

Native PAGE is performed without denaturants to preserve protein structure, activity, and non-covalent interactions [12].

Detailed Methodology:

- Sample and Buffer Preparation: Samples are prepared in a non-denaturing buffer without SDS or reducing agents. The pH of the gel and running buffer is carefully selected to maintain protein solubility and native charge. Common systems include Tris-Glycine at pH 8.8 or Tris-Borate at various pHs [12].

- Gel Casting and Run: A polyacrylamide or agarose gel is cast without SDS. The sample is loaded, and electrophoresis is performed, typically at 4°C to maintain stability. Since proteins retain their native charge, they can migrate toward either the anode or cathode depending on their pI and the buffer pH.

- Activity Staining: Following electrophoresis, proteins can be detected through activity assays (e.g., zymography for enzymes) or general protein stains, allowing for the analysis of functional complexes [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Protein Gel Electrophoresis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge. | Critical for SDS-PAGE; disrupts most non-covalent interactions. |

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Monomer and cross-linker for forming the polyacrylamide gel matrix. | Polymerized gels act as a molecular sieve; concentration determines pore size. |

| Tris-based Buffers | Provides stable pH and ionic strength for gel polymerization and running. | Common formulations include Tris-HCl for gel casting and Tris-Glycine for running buffer. |

| DTT or β-Mercaptoethanol | Reducing agents that break disulfide bonds. | Ensures complete denaturation and subunit separation in reducing SDS-PAGE. |

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue | A dye that binds non-specifically to proteins for visualization. | Standard for general protein detection; sensitivity in the ~10-100 ng range. |

| SYBR-based Dyes | Fluorescent nucleic acid stains; used in EMSA protocols. | Safer alternative to ethidium bromide; high sensitivity for detecting DNA in gels [18]. |

| Agarose | Polysaccharide for making gels with larger pore sizes. | Ideal for native analysis of large protein complexes or nucleic acids [12]. |

| Molecular Weight Markers | Pre-stained or unstained protein standards of known molecular weight. | Essential for estimating the size of unknown proteins and monitoring run progress. |

Advanced Applications and Considerations

Understanding the core factors of protein migration enables more sophisticated techniques. Affinity Gel Electrophoresis (AGE) investigates specific protein-ligand interactions. In AGE, a ligand is immobilized within the gel matrix. A specific interaction between the protein and the ligand causes a decrease in electrophoretic mobility. The presence of a free, competing ligand in the buffer restores mobility, allowing for the quantification of dissociation constants (KD) [19]. This technique is powerful for studying enzyme-substrate, antibody-antigen, and protein-carbohydrate interactions.

Furthermore, two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2D-PAGE) separates proteins based on two independent properties in sequential steps: first by their isoelectric point (pI) using isoelectric focusing, and then by molecular weight using SDS-PAGE [11]. This orthogonal separation provides extremely high resolution for analyzing complex protein mixtures, such as entire proteomes, and is capable of resolving thousands of proteins in a single experiment.

The migration of proteins in gel electrophoresis is a predictable phenomenon governed by the precise interplay of intrinsic molecular properties—charge, size, and shape—and carefully controlled extrinsic buffer conditions. Mastery of these factors is not merely academic; it is a practical necessity for researchers and drug development professionals. A deep understanding allows for the rational selection of the appropriate electrophoretic technique, optimization of protocols for maximum resolution and reproducibility, and, most importantly, the correct interpretation of experimental data. As electrophoresis continues to be a foundational tool in biochemistry and molecular biology, a firm grasp of these key influencing factors remains indispensable for advancing scientific discovery and ensuring the rigor of analytical data.

Gel electrophoresis remains a cornerstone technique in molecular biology and biochemistry laboratories worldwide, enabling the separation of charged macromolecules based on their size and charge. The technique's fundamental principle involves applying an electric field to move molecules through a porous gel matrix, which acts as a molecular sieve. Among the various matrices available, agarose and polyacrylamide represent the two primary support media, each with distinct properties that dictate their application scope and separation efficacy. The selection between these matrices is critical for researchers, particularly in protein separation research, where resolution, molecular size range, and downstream applications must be carefully considered. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of agarose and polyacrylamide as molecular sieves, detailing their structural characteristics, separation mechanisms, and optimal applications within protein research and drug development contexts.

The sieving properties of these matrices originate from their nanoporous structures, which retard the movement of molecules in a size-dependent manner. When an electric field is applied, charged molecules migrate through this porous network, with smaller molecules navigating the pores more readily than larger counterparts, resulting in differential migration distances. This molecular sieving effect forms the basis for size-based separations critical for protein characterization, purity assessment, and functional analysis in both academic research and pharmaceutical development pipelines. Understanding the nuanced interplay between gel matrix structure and separation performance empowers researchers to select optimal conditions for their specific experimental requirements, thereby enhancing data quality and experimental throughput.

Fundamental Properties and Separation Mechanisms

Structural Composition and Pore Formation

The structural foundations of agarose and polyacrylamide gels dictate their fundamental sieving properties. Agarose, a natural polysaccharide derived from seaweed, forms a gel through hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions that create a three-dimensional network with large, non-uniform pores [20] [21]. This matrix is characterized by its mechanical stability and thermal reversibility, allowing gels to be remelted if necessary. The pore size in agarose gels is primarily controlled by adjusting the agarose concentration, with lower concentrations (0.5-1%) generating larger pores suitable for big macromolecules, and higher concentrations (2-3%) creating smaller pores for improved separation of smaller species [21].

In contrast, polyacrylamide gels are synthetic polymers formed through a chemical polymerization reaction between acrylamide monomers and a cross-linking agent, typically N,N'-methylenebisacrylamide (bis-acrylamide) [22] [1]. This covalent cross-linking creates a uniform mesh with precisely controllable pore sizes. The polymerization is catalyzed by ammonium persulfate (APS) and tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED), which generate free radicals to initiate the chain reaction [1]. The pore dimensions in polyacrylamide gels are determined by both the total acrylamide concentration (%T) and the cross-linker ratio (%C), enabling exquisite control over the sieving properties for high-resolution separations [22].

Table 1: Fundamental Structural Properties of Agarose and Polyacrylamide Gels

| Property | Agarose Gel | Polyacrylamide Gel |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Nature | Natural polysaccharide from seaweed | Synthetic polymer of acrylamide and bis-acrylamide |

| Gel Formation Mechanism | Physical gelation via hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions | Chemical polymerization via free radical reaction |

| Polymerization Trigger | Cooling of heated solution | Chemical catalysts (APS/TEMED) |

| Pore Size Distribution | Large, non-uniform pores | Small, highly uniform pores |

| Primary Pore Control | Agarose concentration | Total acrylamide concentration and cross-linker ratio |

| Mechanical Strength | High, forms robust gels | Brittle, requires glass plates for support |

| Thermal Properties | Thermoreversible (can be remelted) | Thermally stable (irreversible formation) |

Molecular Sieving Mechanisms

The molecular sieving mechanisms in both gel types operate on the principle of size-based separation, but their specific interactions with migrating molecules differ significantly. In agarose gels, the large, random pore structure functions as a obstacle course where smaller molecules navigate through the matrix more rapidly than larger molecules that experience greater frictional resistance and more frequent collisions with the gel fibers [20] [21]. This sieving mechanism is particularly effective for large DNA fragments and big protein complexes, where the resolution, while lower than polyacrylamide, remains sufficient for many applications including DNA fragment analysis and protein complex separation [23].

Polyacrylamide gels provide a more refined sieving action due to their homogeneous, well-defined pore structure that creates a more predictable migration environment [22]. For protein separations, the system is often enhanced with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in SDS-PAGE, where the detergent denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge, ensuring separation occurs primarily based on molecular mass rather than charge or shape [22] [1]. In native PAGE, however, proteins retain their higher-order structure, and separation depends on both intrinsic charge and molecular dimensions, enabling functional analysis of proteins in their native state [24] [1]. The discontinuous buffer system commonly used in polyacrylamide electrophoresis further enhances resolution by stacking proteins into tight bands before they enter the separating gel, sharpening the resulting bands [22].

Comparative Performance and Applications

Separation Range and Resolution Characteristics

The separation ranges of agarose and polyacrylamide gels complement each other, covering the full spectrum of biomolecule sizes encountered in research. Agarose gels excel in separating large DNA fragments from 100 base pairs to over 20 kilobases, with optimal resolution achieved by modulating agarose concentration [20] [23]. For protein applications, agarose is suitable for large protein complexes and can separate hyaluronan in the range of approximately 5-500 kDa, with excellent linear calibration obtained for molecular masses as low as 9 kDa in specific formulations [25]. The resolution offered by agarose, while sufficient for many applications, remains lower than polyacrylamide, making it ideal for analytical separations where extreme resolution is not required.

Polyacrylamide gels provide superior resolution for smaller molecules, capable of separating proteins from 5-250 kDa in standard SDS-PAGE systems [22]. Gradient polyacrylamide gels extend this range further, offering enhanced resolution for complex protein mixtures by continuously varying pore sizes throughout the gel [25] [1]. The high resolution of polyacrylamide enables discrimination of proteins differing by just a few thousand Daltons, and for nucleic acids, can resolve fragments differing by a single base pair [20] [23]. This exceptional resolving power makes polyacrylamide indispensable for proteomic research, protein purity assessment, and detailed characterization of therapeutic proteins in drug development.

Table 2: Performance Characteristics and Optimal Applications

| Parameter | Agarose Gel | Polyacrylamide Gel |

|---|---|---|

| Effective Separation Range | DNA: 100 bp - 20 kbpProteins: 5-500 kDa (specialized) | Proteins: 5-250 kDa (standard SDS-PAGE)Small nucleic acids: <1000 bp |

| Resolution Capability | Lower resolution, suitable for larger fragments | High resolution, can distinguish <1 kDa differences for proteins |

| Optimal Gel Concentrations | 0.5% (large DNA), 1.5-2% (small DNA), 2-4% (proteins) | 6-8% (large proteins), 10-12% (standard proteins), 15-20% (small proteins/peptides) |

| Primary Applications | DNA analysis, RNA integrity checking, large protein complexes | Protein analysis (SDS-PAGE, native PAGE), western blotting, protein complex studies |

| Detection Sensitivity | Moderate (typically requires 0.5-2.5 μg nucleic acid) | High (can detect <0.5 μg protein with silver staining) |

| Quantitation Capability | Good for relative quantitation of nucleic acids | Excellent for protein quantitation with appropriate standards |

Application-Specific Considerations for Protein Research

The selection between agarose and polyacrylamide for protein research depends heavily on the experimental objectives, target protein characteristics, and downstream applications. Agarose gels find specialized utility in separating very large protein complexes and specific glycoconjugates like hyaluronan, where their large pore structure permits migration of macromolecular assemblies that would be excluded from polyacrylamide matrices [25]. Recent innovations in capillary agarose gel electrophoresis have demonstrated its value for therapeutic protein analysis, offering rapid, baseline hump-free separation of monoclonal antibodies and fusion proteins across a wide molecular weight range [26].

Polyacrylamide gels remain the gold standard for most protein electrophoresis applications due to their superior resolving power and versatility. SDS-PAGE provides reliable molecular mass estimation under denaturing conditions and is fundamental for protein purity assessment, western blotting, and mass spectrometry sample preparation [22] [1]. Native PAGE preserves protein structure and function, enabling the study of protein complexes, enzyme activity after separation, and metal-binding properties [24]. Two-dimensional PAGE combining isoelectric focusing with SDS-PAGE represents the highest resolution method for complex protein mixtures, capable of resolving thousands of proteins in proteomic studies [1]. For drug development professionals, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis provides critical quality control capabilities for biopharmaceutical characterization, including assessment of protein aggregation, degradation, and post-translational modifications.

Experimental Methodologies

Agarose Gel Electrophoresis for Macromolecular Separation

The preparation and execution of agarose gel electrophoresis for protein and large biomolecule separation follows a standardized methodology with specific modifications for different analyte classes. For separation of hyaluronan samples in the 5-500 kDa range, researchers have developed optimized protocols using both Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE) and Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer systems [25]. The gel concentration typically ranges from 0.5% to 4.0% agarose, with higher concentrations providing better resolution for lower molecular weight species.

Detailed Protocol for Protein Separation in Agarose Gels:

- Gel Preparation: Select appropriate agarose type (standard or high-resolution) and concentration based on target protein size. For most protein applications, 1-3% gels provide optimal separation. Dissolve agarose in appropriate buffer (TAE: 40 mM Tris, 5 mM CH₃COONa, 0.9 mM EDTA, pH 7.9; or TBE: 100 mM Tris-borate, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.3) using heating and mixing until completely dissolved [25].

- Casting: Cool agarose solution to 50-60°C, then pour into casting tray with well comb in place. Allow to solidify completely at room temperature (20-30 minutes).

- Sample Preparation: Mix protein samples with loading buffer (typically containing glycerol for density and tracking dyes). For quantitative analysis, include appropriate protein standards.

- Electrophoresis Conditions: Place gel in electrophoresis chamber filled with running buffer. Apply samples to wells. Run at constant voltage (typically 80-120 V) for 45-90 minutes, depending on gel size and separation requirements.

- Detection: Stain with appropriate protein stains (Stains-All, Coomassie Blue, or silver stain) followed by destaining in water. For hyaluronan detection, Stains-All dye (3,3'-dimethyl-9-methyl-4,5,4',5'-dibenzothiacarbocyanine) provides sensitive detection [25].

- Analysis: Document separation using densitometric scanning and calculate molecular mass averages using appropriate standards for calibration.

For high-percentage agarose gels (3.0-4.0%), a modified preparation protocol is recommended to ensure complete dissolution and proper gelling. The agarose powder is slowly sprinkled into chilled buffer while stirring, followed by controlled heating with intermittent swirling to achieve complete dissolution without excessive evaporation [25]. The final gel concentration should be verified by weight, replacing any evaporated water with hot deionized water to maintain accurate matrix density.

Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis for High-Resolution Protein Separation

SDS-PAGE represents the most widely used protein electrophoresis technique, providing reliable size-based separation under denaturing conditions. The discontinuous buffer system, initially described by Laemmli, employs stacking and resolving gels with different pore sizes and pH to achieve high-resolution separation [22].

Detailed Protocol for SDS-PAGE:

- Gel Preparation: Prepare resolving gel solution appropriate for target protein size (7-12% acrylamide for most applications). The solution contains acrylamide/bis-acrylamide, Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.8), SDS, and polymerization initiators (APS and TEMED). Pour between glass plates, overlay with isopropanol or water to create flat interface, and allow to polymerize (15-30 minutes) [1].

- Stacking Gel Preparation: After resolving gel polymerization, remove overlay liquid and add stacking gel solution (lower acrylamide concentration, typically 4-5%, with Tris-HCl buffer pH 6.8). Insert well comb and allow to polymerize.

- Sample Preparation: Mix protein samples with SDS-PAGE loading buffer (containing SDS, reducing agent such as β-mercaptoethanol, glycerol, and tracking dye). Heat at 70-100°C for 3-5 minutes to denature proteins [22] [1].

- Electrophoresis: Assemble gel in electrophoresis apparatus filled with running buffer (typically Tris-glycine with SDS). Load samples and molecular weight markers. Run at constant voltage (100-200 V) until tracking dye reaches gel bottom (typically 40-60 minutes).

- Detection: Stain with Coomassie Blue, silver stain, or fluorescent stains according to required sensitivity. For western blotting, transfer proteins to membrane after electrophoresis.

Native PAGE Protocol for Functional Protein Analysis: Native PAGE preserves protein structure and function by omitting denaturants from all buffers. The protocol follows similar steps to SDS-PAGE with key modifications:

- Sample Preparation: Mix protein samples with native loading buffer (containing glycerol and tracking dye but no SDS or reducing agents). Do not heat samples [24] [1].

- Gel and Buffer Composition: Prepare gels without SDS. Use running buffers without SDS, typically Tris-glycine or TBE at pH 8.3-8.8 [24].

- Electrophoresis Conditions: Run at constant voltage (100-150 V) at 4°C to maintain protein stability. Higher voltages may generate excessive heat that denatures proteins.

- Activity Staining: For enzyme detection, use specific activity stains instead of general protein stains.

A specialized variant called NSDS-PAGE (native SDS-PAGE) employs reduced SDS concentration (0.0375% in running buffer) and eliminates EDTA and heating steps, resulting in retention of Zn²⁺ in metalloproteins and preservation of activity for seven of nine model enzymes tested [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of gel electrophoresis experiments requires specific reagents and materials optimized for each matrix type. The following research reagent solutions represent essential components for protein separation workflows using both agarose and polyacrylamide gel systems.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Gel Electrophoresis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| Agarose (Various Types) | Matrix formation for large pore gels | Standard agarose for routine separations; low-melting point for fragment recovery; high-resolution for improved band sharpness [21] |

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Matrix formation for polyacrylamide gels | 29:1 or 37.5:1 acrylamide:bis ratio common; concentration determines pore size; neurotoxic monomer requires careful handling [22] [1] |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Protein denaturation and charge uniformity | Anionic detergent that binds proteins at ~1.4g SDS per 1g protein; masks intrinsic charge [22] [1] |

| APS (Ammonium Persulfate) and TEMED | Polyacrylamide gel polymerization | Free radical initiators catalyze acrylamide polymerization; fresh preparation required for consistent results [1] |

| Tris-Based Buffers | pH maintenance and current conduction | Discontinuous system: Tris-HCl pH 6.8 (stacking) and pH 8.8 (resolving); continuous systems also available [22] |

| Tracking Dyes | Migration monitoring | Bromophenol blue (migrates at ~4 kDa) and xylene cyanol (~20 kDa) common in SDS-PAGE [22] |

| Reducing Agents | Disulfide bond reduction | β-mercaptoethanol or DTT breaks disulfide linkages for complete denaturation [22] |

| Protein Molecular Weight Markers | Size calibration and estimation | Pre-stained or unstained standards covering specific size ranges (e.g., 10-250 kDa) [1] |

| Staining Solutions | Protein detection | Coomassie Blue (moderate sensitivity), silver stain (high sensitivity), fluorescent stains (quantitative) [25] [1] |

The selection between agarose and polyacrylamide as molecular sieves represents a critical decision point in experimental design for protein separation research. Each matrix offers distinct advantages that make it suitable for specific applications: agarose with its large pore structure accommodates massive protein complexes and specialized macromolecules, while polyacrylamide provides unparalleled resolution for standard protein analyses. Understanding the fundamental principles underlying their molecular sieving mechanisms enables researchers to make informed decisions that optimize separation efficiency and data quality.

Recent methodological advances continue to expand the applications of both matrix types. Innovations in agarose gel formulations, including tetrahydroxyborate-stabilized matrices for capillary electrophoresis, enable rapid, hump-free analysis of therapeutic proteins [26]. Modifications to traditional polyacrylamide protocols, such as NSDS-PAGE, preserve metal binding and enzymatic activity while maintaining high resolution [24]. These developments underscore the dynamic nature of electrophoretic separation technologies and their continued relevance in modern biological research and drug development. As protein therapeutics increase in complexity, with emerging modalities including multispecific antibodies, antibody-drug conjugates, and fusion proteins, the role of appropriate gel matrix selection becomes increasingly critical for accurate characterization and quality assurance in pharmaceutical development pipelines.

Electrophoresis, a cornerstone technique in analytical biochemistry, has fundamentally shaped the field of protein separation research. The principle, first proposed in the 1930s, involves the migration of charged particles through a medium under the influence of an electric field [10]. For proteins, this technique leverages their inherent charge properties, which vary based on their amino acid composition and the pH of their environment. The rate of migration is influenced by multiple factors including the protein's net charge, size and shape, the composition of the separation medium, and the buffer conditions such as pH and ionic strength [10]. This foundational principle has been implemented in increasingly sophisticated formats over the decades, driving progress in proteomics, drug development, and clinical diagnostics. The evolution from slab gels to capillary and microchip systems represents a continuous pursuit of higher resolution, faster analysis, and greater automation, enabling researchers to address increasingly complex biological questions.

The Evolution of Electrophoresis Formats

Slab Gel Electrophoresis: The Foundational Tool

The 1950s and 1960s saw the establishment of slab gel electrophoresis as a standard laboratory technique, particularly with the introduction of polyacrylamide gels which allowed for improved differentiation of proteins and nucleic acids [10]. In this format, samples are loaded into wells at one end of a gel slab, and an electric field is applied, causing charged molecules to migrate through the porous matrix. The gel acts as a molecular sieve, separating proteins primarily by size in denaturing conditions (SDS-PAGE) or by both size and charge in native conditions [1]. The polyacrylamide matrix is created by polymerizing acrylamide with bisacrylamide, forming a cross-linked network whose pore size can be precisely controlled by adjusting the concentration of acrylamide and the cross-linking ratio [1]. This allows researchers to tailor the separation for specific protein size ranges. Slab gel electrophoresis remains a fundamental tool due to its simplicity, low cost, and ability to analyze multiple samples simultaneously on a single gel [27]. Its visual, post-stain readout provides intuitive qualitative data, and separated proteins can be excised for downstream analysis, making it a versatile preparatory and analytical tool [27].

Capillary Electrophoresis: The Shift to Automation

The 1980s and 1990s marked a significant transition with the advent of capillary electrophoresis (CE), which offered higher resolution and longer analysis times due to reduced particle diffusion in narrow capillaries [10]. CE miniaturizes the separation path into a fused-silica capillary typically 25-75 µm in diameter and up to 100 cm long [27]. This format enables the application of very high electric field strengths (300-600 V/cm) because the high surface-to-volume ratio efficiently dissipates Joule heat, preventing sample degradation [27]. Separation in CE is governed by the combination of electrophoretic mobility (the movement of charged species in an electric field) and electroosmotic flow (the bulk flow of buffer solution caused by the charged capillary wall) [28]. Detection occurs in real-time through on-capillary detection systems such as UV absorbance or laser-induced fluorescence (LIF), providing quantitative digital data in the form of electropherograms [27]. The automation of sample injection, separation, and capillary rinsing makes CE highly reproducible and suitable for high-throughput applications, while its minimal sample volume requirements (nanoliters) conserve precious biological samples [27] [28].

Microchip Electrophoresis: The Dawn of Miniaturization

In 2008, a new era began with the development of microchip electrophoresis (MCE), which integrated electrophoresis with microfluidics to enable high-throughput analysis and rapid results [10]. MCE is a miniaturized form of capillary electrophoresis performed on stamp-sized chips containing networks of microchannels [29]. The working principle is based on the movement of charged analytes under an electric field, with separations often occurring in seconds to minutes due to short separation distances and the ability to apply very high field strengths [29]. These devices can integrate multiple laboratory functions onto a single chip, including sample preparation, separation, and detection, creating "lab-on-a-chip" systems [10] [29]. The dramatically reduced consumption of samples and reagents, combined with the potential for portability and point-of-care diagnostics, makes MCE a transformative technology [29]. Recent research has even demonstrated on-chip protein separation with single-molecule resolution, highlighting the advanced capabilities of this format [30].

Comparative Analysis of Electrophoresis Techniques

Table 1: Performance comparison of different electrophoresis formats for protein analysis.

| Feature | Slab Gel Electrophoresis | Capillary Electrophoresis (CE) | Microchip Electrophoresis (MCE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Separation Medium | Polyacrylamide or agarose slab gel [27] | Fused-silica capillary filled with buffer or polymer matrix [27] | Microfabricated chip with integrated channels [29] |

| Typical Field Strength | 4–10 V/cm [27] | 300-600 V/cm [27] | Up to 1000 V/cm and higher [29] |

| Analysis Time | Tens of minutes to hours [27] | Minutes to tens of minutes [27] [28] | Seconds to a few minutes [29] |

| Sample Volume | Microliters [27] | Nanoliters [27] [28] | Picoliters to nanoliters [29] |

| Detection Method | Post-run staining (e.g., Coomassie Blue, silver stain) [31] [1] | On-capillary UV or Laser-Induced Fluorescence (LIF) [27] | On-chip detection (e.g., LIF, electrochemical) [29] |

| Resolution | Good for routine analysis; distinguishes proteins with mass differences of a few percent [27] | High; can resolve single-amino-acid differences and protein isoforms [27] | Very high; capable of single-molecule resolution under optimized conditions [30] |

| Throughput | Multiple samples per gel, but largely manual [27] | Sequential analysis, but fully automated with autosamplers [27] | High-throughput potential with parallel channels and integrated automation [10] |

| Key Advantage | Low cost, visual confirmation, preparative use [27] | High resolution, automation, quantitative data [27] [28] | Extreme speed, minimal reagent use, portability [10] [29] |

Table 2: Summary of key applications and limitations for each electrophoresis format.

| Format | Primary Applications in Protein Research | Common Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Slab Gel | Protein purity checks, Western blotting, molecular weight determination, protein expression analysis [27] [1] | Manual, labor-intensive, semi-quantitative, lower resolution [27] [28] |

| Capillary (CE) | High-resolution profiling of complex protein mixtures, glycoform analysis, pharmacokinetic studies, quality control of biopharmaceuticals [27] | Higher instrument cost, capillary clogging, specialized training required [27] |

| Microchip (MCE) | Rapid clinical diagnostics, single-cell proteomics, point-of-care testing, environmental monitoring [10] [30] [29] | Emerging technology, can require complex chip fabrication and integration [29] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: SDS-PAGE Using Slab Gel Electrophoresis

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) is the most widely used electrophoresis technique for separating proteins primarily by mass [1]. The following protocol details a standard procedure for a discontinuous SDS-PAGE system.

Principle: Proteins are denatured and linearized by heating in the presence of SDS and a reducing agent (e.g., β-mercaptoethanol or DTT). SDS binds to the polypeptide backbone in a constant mass ratio, imparting a uniform negative charge that masks the protein's intrinsic charge. This allows separation to occur based almost exclusively on polypeptide size as molecules migrate through the polyacrylamide gel matrix [1].

Reagents and Solutions:

- Resolving Gel Buffer: 1.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.8

- Stacking Gel Buffer: 0.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8

- 30% Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide Solution (37.5:1 ratio)

- 10% Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS)

- 10% Ammonium Persulfate (APS)

- TEMED (N,N,N',N'-Tetramethylethylenediamine)

- Running Buffer: 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS, pH ~8.3

- 5X Sample Loading Buffer: 250 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 10% SDS, 0.5% Bromophenol Blue, 50% Glycerol, 5% β-mercaptoethanol

- Protein Stain: Coomassie Brilliant Blue or similar

Procedure:

- Gel Casting:

- Assemble glass plates in a casting cassette.

- For a 10% resolving gel, mix 4.0 mL of 30% acrylamide solution, 3.0 mL of resolving gel buffer, 4.9 mL of water, 0.1 mL of 10% SDS, 0.1 mL of 10% APS, and 0.01 mL of TEMED. Pour between the plates, overlay with water-saturated butanol or water, and allow to polymerize for 15-30 minutes [1].

- Prepare the stacking gel (e.g., 5% acrylamide) using stacking gel buffer. Pour off the overlay, add the stacking gel mixture, and insert a well-forming comb. Allow to polymerize.

Sample Preparation:

- Mix the protein sample with an appropriate volume of 5X sample loading buffer (e.g., 4:1 sample to buffer ratio).

- Heat the samples at 70-100°C for 5-10 minutes to denature the proteins [1].

Electrophoresis:

- Place the polymerized gel into the electrophoresis chamber and fill the upper and lower chambers with running buffer.

- Load the prepared samples and molecular weight markers into the wells.

- Connect the power supply and run at a constant voltage of 80-150 V until the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel [1].

Detection:

- Carefully disassemble the gel cassette.

- Stain the gel with Coomassie Blue or a fluorescent protein stain to visualize the separated protein bands [31]. Destain if necessary.

Protocol 2: Capillary Electrophoresis-Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (CE-SDS)

CE-SDS is an automated, capillary-based version of SDS-PAGE that provides quantitative data with high resolution.

Principle: Similar to SDS-PAGE, proteins are complexed with SDS and denatured. They are then electrokinetically injected into a capillary filled with a sieving polymer matrix. Under an applied high-voltage field, proteins are separated by size. Real-time detection via UV absorbance or laser-induced fluorescence at the end of the capillary generates an electropherogram with peaks corresponding to separated proteins [27].

Reagents and Equipment:

- CE Instrument with UV or LIF detector

- Fused-silica capillary (e.g., 50 µm inner diameter, 30-40 cm length)

- SDS-MW Gel Buffer (commercial sieving matrix with SDS)

- CE-SDS Sample Buffer (containing SDS)

- Iodoacetamide (for optional alkylation)

- Running Buffer (typically provided with the kit)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Dilute the protein sample (0.5-2 mg/mL) in CE-SDS sample buffer containing SDS and a fluorescent dye (for LIF detection) or leave unlabeled for UV detection.

- Denature the samples by heating at 70-100°C for 5-10 minutes [27].

Instrument Setup:

- Install the capillary in the instrument according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Prime the capillary with fresh SDS-MW gel buffer.

Separation:

- Inject the sample hydrodynamically or electrokinetically (e.g., 5-10 kV for 10-30 seconds).

- Apply the separation voltage (typically 10-15 kV) with reversed polarity (anode at the detector side) [27].

- Monitor the separation in real-time; total run time is typically less than 30 minutes.

Data Analysis:

- The software generates an electropherogram. Peak areas are used for quantification, and migration times are compared to a protein ladder (size standards) to determine molecular weights.

Protocol 3: On-Chip Protein Separation (Microchip SDS-PAGE)

This protocol is adapted from a research study demonstrating protein separation with single-molecule resolution on a microfluidic device [30].

Principle: The protocol scales down SDS-PAGE to a microchip. Proteins are driven electrokinetically through a photopolymerized polyacrylamide gel within a shallow (~0.6 µm deep) microchannel. The restricted depth keeps the proteins in focus for widefield fluorescence microscopy, allowing video-rate monitoring of single-protein migration [30].

Reagents and Specialized Equipment:

- Microchip with offset double T-junctions for sample injection and a separation channel [30].

- Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide Solution (e.g., 5-10% concentration)

- Photoinitiator (e.g., VA-086)

- SDS and Tris-Glycine Buffer

- Fluorescently Labeled Protein Sample

- Widefield Fluorescence Microscope with high NA objective and EM-CCD camera.

- Digital Lithography System for selective gel polymerization.

Procedure:

- Chip Preparation and Gel Polymerization:

- Coat the microchannels with linear polyacrylamide to prevent protein adsorption [30].

- Fill the channels with an unpolymerized acrylamide solution containing SDS, Tris-Glycine buffer, and a photoinitiator.

- Use a digital lithography system with 365 nm light to selectively photopolymerize the gel only in the separation channel region [30].

Sample Loading and Separation:

- Load the fluorescently labeled protein sample into the sample port.

- Apply a vacuum or electric field to load the sample into the injection arm.

- Switch the electric field to the separation channel to inject a precise plug of sample into the separation gel.

- Apply a separation voltage (e.g., up to 30 V across a 5 mm channel) [30].

Detection and Imaging:

- Image the protein migration in real-time using video-rate (e.g., 19.31 frames per second) widefield fluorescence microscopy [30].

- Use single-particle image analysis software to track the mobility of individual proteins and create separation profiles.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key reagents and materials for electrophoresis-based protein separation.

| Item | Function/Description | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Polyacrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms the cross-linked polymer network that acts as a molecular sieve. Pore size is controlled by the total percentage and cross-linking ratio [1]. | Used for slab gels, capillary sieving matrices, and microchip gels. Lower percentages (e.g., 8%) separate larger proteins; higher percentages (e.g., 15%) separate smaller proteins. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Anionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge, allowing separation primarily by molecular weight [1]. | Essential for SDS-PAGE and CE-SDS. Typically used at a concentration of 0.1-1% in buffers and samples. |

| TEMED & APS | Catalytic system for gel polymerization. APS provides free radicals, and TEMED accelerates the polymerization reaction [1]. | TEMED is hygroscopic and should be stored under nitrogen. Fresh APS solution should be prepared regularly. |

| Tris-Glycine Buffer | A common discontinuous buffer system for SDS-PAGE. The stacking gel (low pH, Tris-HCl) concentrates proteins before they enter the resolving gel (high pH, Tris-HCl) [1]. | The standard running buffer is 25 mM Tris, 192 mM Glycine, 0.1% SDS. |

| Molecular Weight Markers | A mixture of proteins of known molecular weights, run alongside samples to calibrate the gel/capillary and estimate the size of unknown proteins [1]. | Available in pre-stained, unstained, and fluorescent formats for different detection needs. |

| Coomassie Blue Stain | A colorimetric dye that binds nonspecifically to proteins through ionic and van der Waals interactions, enabling visualization of separated bands on a slab gel [31] [1]. | A workhorse stain for slab gels; sensitivity is typically in the 10-100 ng range. Requires destaining. |

| Sypro Ruby / Fluorescent Dyes | Fluorescent stains that offer higher sensitivity than Coomassie Blue and are compatible with subsequent mass spectrometry analysis [1]. | Used for both slab gels and for labeling proteins in capillary and microchip electrophoresis with LIF detection. |

| Fused-Silica Capillary | The separation conduit for CE. Its inner wall possesses silanol groups that generate electroosmotic flow (EOF) at neutral to basic pH [27] [29]. | Capillaries are often coated with polymers (e.g., linear polyacrylamide) to suppress EOF and protein adsorption for protein separations. |

| Replaceable Sieving Matrix | A polymer solution (e.g., linear polyacrylamide, dextran) used in CE-SDS and some MCE applications to mimic the sieving properties of a cross-linked gel [27] [29]. | Allows for automatic capillary rinsing and refilling between runs, enabling high-throughput automation. |

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the historical and technical progression of electrophoresis formats, highlighting their interrelationships and key technological drivers.

Evolution of Electrophoresis Formats

The journey of protein electrophoresis from traditional slab gels to sophisticated capillary and microchip systems illustrates a consistent trajectory toward higher performance, automation, and integration. While slab gel electrophoresis remains an indispensable tool for its simplicity and preparative capabilities, capillary electrophoresis has set a new standard for quantitative, high-resolution analysis in regulated environments. Microchip electrophoresis, now pushing the boundaries toward single-molecule resolution, promises to further transform biomedical analysis through point-of-care diagnostics and massive parallelization [30] [29]. For today's researcher, this historical context provides not just a timeline of technological advancement, but a strategic framework for selecting the appropriate separation platform. The choice hinges on the specific analytical requirements: slab gels for visual confirmation and low-cost screening, capillary systems for automated quantification and high-resolution analytics, and microchips for ultimate speed and minimal sample consumption. As these technologies continue to converge and evolve, they will undoubtedly unlock new frontiers in proteomics and personalized medicine.

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) is a foundational technique in biochemistry and molecular biology that allows for the separation of proteins based solely on their molecular weight. The method was developed by Ulrich K. Laemmli in 1970 and has since become one of the most cited scientific techniques, with the original paper accumulating over 259,000 citations by 2025 [32]. The power of SDS-PAGE lies in its ability to negate the influence of a protein's inherent charge and three-dimensional structure, ensuring that separation occurs exclusively by molecular size. This technique is indispensable for a wide range of applications, from initial protein characterization and purity assessment in academic research to quality control in pharmaceutical development [33] [34].

The core principle of SDS-PAGE involves the use of an anionic detergent, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), which binds to and denatures proteins, conferring upon them a uniform negative charge. When these denatured proteins are subjected to an electric field within a polyacrylamide gel matrix, they migrate toward the anode at rates inversely proportional to their molecular weights. This process provides researchers with a reliable method for estimating protein size, assessing sample purity, analyzing subunit composition, and preparing samples for downstream applications such as Western blotting or mass spectrometry [33] [34].

The Fundamental Role of SDS in Charge Unification

Mechanism of Protein Denaturation and Linearization

The effectiveness of SDS-PAGE hinges on the complete denaturation of proteins into their linear form, thereby eliminating the influence of secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures on their electrophoretic mobility. SDS plays a pivotal role in this process through its unique chemical properties as an anionic surfactant [35] [36]. The SDS molecule consists of a hydrophobic hydrocarbon tail (a 12-carbon chain) and a hydrophilic sulfate head group [35]. This amphipathic nature allows SDS to interact extensively with protein molecules.

The denaturation process involves two key mechanisms. First, the hydrophobic tails of SDS molecules interact with and disrupt the hydrophobic regions within the protein's core. Second, the ionic sulfate heads disrupt non-covalent interactions, including hydrogen bonds and ionic attractions, that stabilize secondary and tertiary structures [35]. This combined action unfolds the protein, transforming it from a compact, folded structure into an extended, linear polypeptide chain coated with SDS molecules. For complete linearization, especially for proteins with disulfide bridges, reducing agents such as β-mercaptoethanol (BME) or dithiothreitol (DTT) are added to break these covalent bonds, ensuring the protein is fully denatured to its primary structure [35] [32].

Charge Masking and Uniform Charge-to-Mass Ratio

The second critical function of SDS is to mask the protein's intrinsic charge and confer a uniform negative charge. In their native state, proteins possess variable net charges depending on their amino acid composition and the pH of their environment. This inherent charge heterogeneity would cause proteins to migrate at different speeds and even in different directions during electrophoresis, preventing separation based solely on size [35] [33].

SDS binds to proteins with high affinity and in large quantities—approximately 1.4 grams of SDS per 1 gram of protein, which corresponds to roughly one SDS molecule for every two amino acids [32]. This extensive binding creates a uniform "coat" of negative charges along the entire polypeptide backbone. Consequently, the intrinsic charges of the amino acid side chains become negligible compared to the overwhelming negative charge provided by SDS [35] [36] [33]. This results in all proteins achieving a similar charge-to-mass ratio, a fundamental prerequisite for size-based separation. Under an electric field, all SDS-bound protein complexes will now migrate toward the positive electrode (anode) at speeds determined only by their ability to navigate the pores of the polyacrylamide gel [35] [33].

Table 1: Key Steps in Protein Sample Preparation for SDS-PAGE

| Step | Reagents | Purpose | Typical Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Denaturation | SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Unfolds protein; confers uniform negative charge | ~1.4g SDS / 1g protein [33] [32] |

| Reduction | β-mercaptoethanol (BME) or Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Breaks disulfide bonds for complete linearization | 5% BME or 10-100 mM DTT [35] [32] |

| Heating | Heat | Disrupts hydrogen bonds, ensures complete denaturation | 95°C for 5 minutes [35] [32] |

The Polyacrylamide Gel Matrix as a Molecular Sieve

Gel Composition and Polymerization Chemistry

The polyacrylamide gel serves as a molecular sieve that separates linearized proteins based on their size. This three-dimensional network is created through the polymerization of acrylamide monomers cross-linked by N,N'-methylenebisacrylamide (Bis) [35] [33]. The pore size of the gel, which dictates its sieving properties, is determined by the concentrations of these two components. A higher total percentage of acrylamide results in a smaller pore size, which is more effective at separating lower molecular weight proteins. Conversely, a lower percentage creates larger pores, better suited for resolving higher molecular weight proteins [36] [37].

The polymerization reaction is a free-radical process catalyzed by a pair of initiators: ammonium persulfate (APS) and N,N,N',N'-Tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED) [35] [37]. APS provides the persulfate free radicals that initiate the chain reaction, while TEMED acts as a catalyst that accelerates the formation of these free radicals. When added to a solution of acrylamide and bisacrylamide, these catalysts trigger a rapid polymerization, forming a solid gel with a consistent, mesh-like structure. The entire process of preparing and pouring the gel is known as "casting" [35].

Table 2: Polyacrylamide Gel Formulations for Different Protein Size Ranges

| Protein Size Range | Recommended Acrylamide % | Purpose and Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Very Large Proteins (>150 kDa) | 5-8% | Larger pores allow big proteins to enter and migrate through the gel [37]. |

| Standard Range (10-250 kDa) | 10-15% (or 8-15% gradient) | Standard pore size for resolving most common proteins [33] [32]. |

| Small Proteins/Peptides (<30 kDa) | 15-20% | Smaller pores provide better resolution and prevent small proteins from running off the gel [36] [37]. |

The Discontinuous Buffer System: Stacking and Resolving Gels

A key innovation in modern SDS-PAGE is the use of a discontinuous buffer system employing two distinct gel layers with different pore sizes, pH, and ionic compositions: the stacking gel and the resolving (or separating) gel [35] [36] [32]. This system is critical for achieving sharp, well-defined protein bands.

The Resolving Gel: This is the lower portion of the gel, typically comprising a higher percentage of acrylamide (e.g., 10-15%) and buffered at a higher pH (pH ~8.8). It is here that the actual separation of proteins by molecular weight occurs. The smaller pore size presents a sieving effect that differentially retards the progress of larger proteins [35] [37].

The Stacking Gel: Positioned above the resolving gel, this layer has a lower acrylamide concentration (~4-5%) and a lower pH (pH ~6.8). Its primary function is to "stack" or concentrate all protein samples into extremely narrow, well-defined bands before they enter the resolving gel. This stacking effect ensures that proteins begin their size-based separation from an identical starting line, dramatically improving resolution [35] [36].

The mechanism behind the stacking effect relies on the differential mobility of ions in the discontinuous system. The running buffer contains glycine ions. At the pH of the stacking gel (6.8), glycine exists predominantly as a zwitterion with minimal net charge and thus low mobility. Chloride ions (from Tris-HCl in the gel) are highly mobile "leading ions," while the glycine zwitterions act as slow "trailing ions." Sandwiched between these two ion fronts, the proteins—whose mobility is intermediate—are compressed into a very narrow zone as they move through the stacking gel. When this protein zone reaches the resolving gel with its higher pH (8.8), the glycine ions lose a proton, become negatively charged glycinate ions, and overtake the proteins. The proteins are then deposited as a tight band at the top of the resolving gel, where their size-based separation begins [36] [32].

SDS-PAGE Gel Separation Process: Illustrates protein stacking and separation mechanism across gel layers.

Experimental Protocol for SDS-PAGE

Reagent Preparation and Gel Casting

A successful SDS-PAGE experiment begins with the careful preparation of reagents and the casting of the polyacrylamide gel. The following protocol outlines a standard method for preparing a mini-gel system [34] [37].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

Table 3: Essential Reagents for SDS-PAGE

| Reagent | Function | Critical Details |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis Solution | Forms the gel matrix; pore size determines resolution. | Neurotoxic; handle with gloves [37]. |

| Tris-HCl Buffer (pH 6.8 & 8.8) | Maintains pH for stacking and resolving gels. | Different pH values are crucial for discontinuous system [37]. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins and provides uniform charge. | Typically used as a 10% solution [34]. |