Primer Self-Complementarity Tools: A Guide to Minimizing Dimerization for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on utilizing in-silico tools to analyze and minimize primer self-complementarity and dimer formation.

Primer Self-Complementarity Tools: A Guide to Minimizing Dimerization for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on utilizing in-silico tools to analyze and minimize primer self-complementarity and dimer formation. It covers foundational concepts of thermodynamic parameters like ΔG and self-complementarity scores, offers a methodological walkthrough of major tools including Primer-BLAST, IDT OligoAnalyzer, and Eurofins Oligo Analysis Tool, and presents advanced troubleshooting and optimization strategies. The content also explores validation techniques using tools like PrimerEvalPy and IsoPrimer for specificity checking and application in complex scenarios such as degenerate primer design and highly divergent viral genomes, aiming to improve PCR efficiency and specificity in biomedical research.

Understanding Primer Self-Complementarity: Why It's Critical for PCR Success

In molecular biology, the success of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and related amplification techniques depends critically on the specific binding of primers to their target DNA sequences. This specificity is governed by the thermodynamic properties of the nucleic acids involved. Self-dimers, cross-dimers, and hairpins represent three classes of aberrant secondary structures that can form spontaneously, compromising reaction efficiency and specificity. These structures arise from the innate tendency of single-stranded nucleic acids to form stable duplexes or internal loops through complementary base pairing. Understanding the thermodynamic principles underlying their formation is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who rely on precise molecular assays. This application note examines the thermodynamic characterization of these structures and provides detailed protocols for their analysis within the broader context of primer design research.

Defining the Structures and Their Thermodynamic Basis

Structural Definitions and Functional Impact

The table below defines the three primary secondary structures and their consequences in molecular assays.

Table 1: Characteristics and Impacts of Primer Secondary Structures

| Structure Type | Definition | Key Thermodynamic Parameters | Impact on Assays |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Dimer | Intermolecular hybridization between two identical primers, making them unavailable for target binding [1] [2]. | ΔG (Gibbs Free Energy); More negative values indicate more stable, undesirable dimers [1]. | Reduces effective primer concentration and product yield; can lead to primer-dimer artifacts in electrophoresis [3]. |

| Cross-Dimer | Intermolecular hybridization between the forward and reverse primers in a pair [1] [2]. | ΔG of dimer formation; Stability is calculated using the nearest-neighbor model [3] [4]. | Sequesters primer pairs, severely inhibiting or preventing amplification of the target amplicon [3]. |

| Hairpin (or Self-Complementarity) | Intramolecular folding of a single primer, creating a stem-loop structure [1]. | ΔG; Stability depends on stem length/GC content and loop size (typically 4 bases) [1] [5]. | Prevents primer from annealing to the template; particularly detrimental when the 3' end is involved in the structure [6] [1]. |

Thermodynamic Principles of Formation

The formation of self-dimers, cross-dimers, and hairpins is a spontaneous process governed by a negative change in the Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG), according to the fundamental equation ΔG = ΔH – TΔS [1]. In this context, ΔH represents the enthalpy change (primarily from the energy of hydrogen bonds formed between base pairs), T is the temperature, and ΔS is the entropy change (related to the loss of disorder as single strands become ordered duplexes or structures) [1] [4].

The stability of these secondary structures is most accurately predicted using the nearest-neighbor model [3] [4]. This model calculates the overall stability of a nucleic acid duplex by summing the contributions of all adjacent base pairs, accounting for the stacking interactions between them, rather than considering base pairs in isolation [4]. Sophisticated algorithms use this model, along with thermodynamic parameters for base pairing, stacking, and loop penalties, to compute the overall ΔG for potential dimers and hairpins [4].

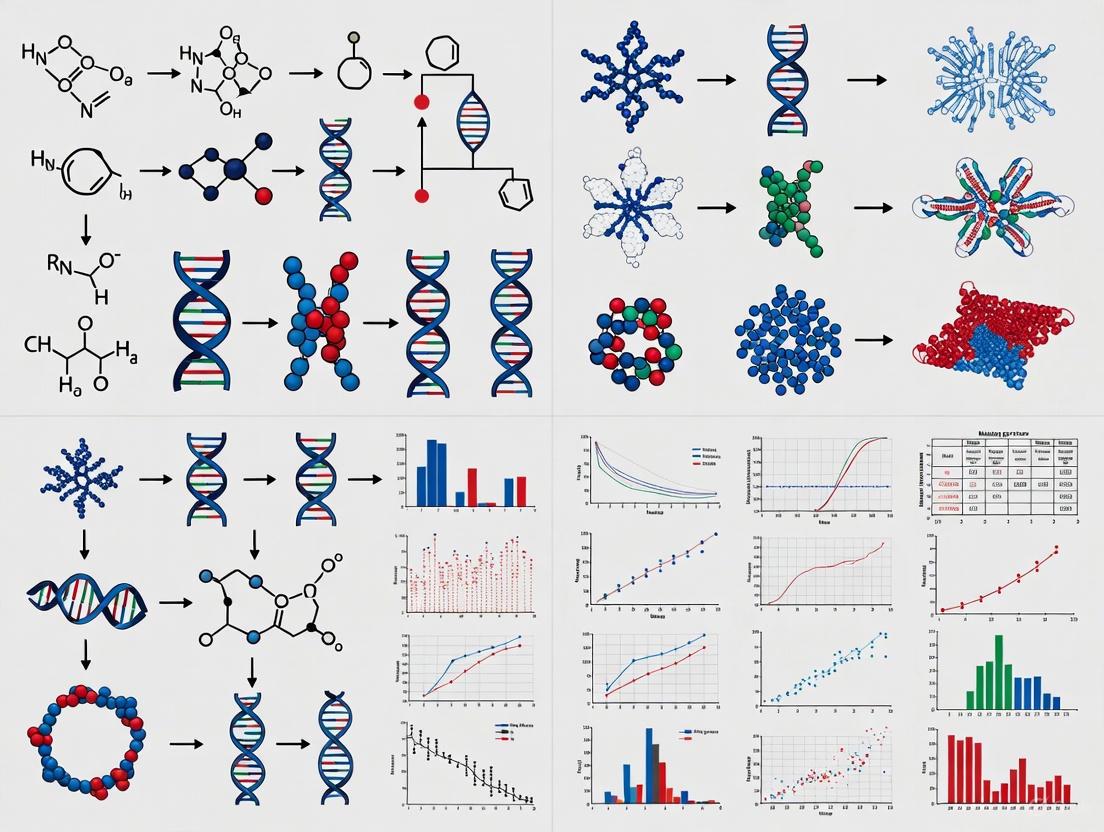

Diagram: Thermodynamic Formation Pathways

Quantitative Stability Thresholds and Analytical Tools

Acceptable Thermodynamic Parameters

For a PCR primer to function optimally, its propensity to form secondary structures must fall below specific thermodynamic thresholds. The following table summarizes the generally accepted stability limits for these structures.

Table 2: Thermodynamic Stability Thresholds for Primer Secondary Structures

| Structure | Location | Maximum Tolerated ΔG (kcal/mol) | Calculation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hairpin | 3' End | ≥ -2.0 | mFold or IDT OligoAnalyzer [1] |

| Hairpin | Internal | ≥ -3.0 | mFold or IDT OligoAnalyzer [1] |

| Self-Dimer | 3' End | ≥ -5.0 | Multiple Primer Analyzer [1] [7] |

| Self-Dimer | Internal | ≥ -6.0 | Multiple Primer Analyzer [1] [7] |

| Cross-Dimer | 3' End | ≥ -5.0 | Multiple Primer Analyzer [1] [7] |

| Cross-Dimer | Internal | ≥ -6.0 | Multiple Primer Analyzer [1] [7] |

The 3' end of the primer is particularly critical because it is where the DNA polymerase initiates synthesis. A stable secondary structure at the 3' end, sometimes called a "rattle snake structure," will severely interfere with the enzyme's ability to extend the primer [6]. Ideally, the 3' complementarity score should be 0 for maximum performance [6].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Tools for Secondary Structure Analysis

| Tool or Reagent | Category | Primary Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bst 2.0 WarmStart Polymerase | Enzyme | Isothermal DNA amplification for LAMP/RT-LAMP assays [3]. | Tolerant of some primer secondary structures but requires high-fidelity primer design for optimal results [3]. |

| SYTO 9 / SYTO 82 Dyes | Fluorescent Probe | Intercalating dye for real-time monitoring of DNA amplification [3]. | Binds non-specifically to dsDNA, allowing detection of both specific amplicons and non-specific primer-dimer products [3]. |

| PrimerChecker | Web Tool | Visualizes multiple thermodynamic parameters of primers against optimal/suboptimal ranges [6]. | Provides a holistic, visual plot of Tm, ΔTm, GC%, ΔG, and self-complementarity scores for rapid analysis [6]. |

| Multiple Primer Analyzer (Thermo Fisher) | Web Tool | Analyzes potential dimer formation between multiple primer sequences [7]. | Useful for preliminary screening of primer pairs; reports possible dimers based on user-defined detection parameters [7]. |

| Eurofins Oligo Analysis Tool | Web Tool | Calculates physical properties and checks for self-dimers and cross-dimers [2]. | Provides a multi-functional analysis of a single oligo's properties and its interactions with a partner [2]. |

| NCBI Primer-Blast | Web Tool | Designs primers and checks specificity against a selected database [6]. | Retrieves parameters like Tm, GC%, and self-complementarity scores; does not calculate ΔG [6]. |

| IDT OligoAnalyzer / mFold | Web Tool | Calculates the ΔG of secondary structures like hairpins [6] [1]. | Uses an implementation of the nearest-neighbor model to predict the most stable secondary structures and their free energies [6]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Silico Analysis of Primer Secondary Structures

This protocol details the use of computational tools to predict and evaluate the thermodynamic stability of self-dimers, cross-dimers, and hairpins.

Materials:

- Primer sequences in FASTA or plain text format.

- Computer with internet access.

Procedure:

- Retrieve Thermodynamic Parameters:

- Navigate to NCBI Primer-Blast [6].

- Input your forward and reverse primer sequences into the respective 'Primer Parameter' boxes.

- Select the appropriate organism and database under 'Primer Pair Specificity Checking Parameters'.

- Run the tool. From the results, record the Tm, GC%, and self-complementarity scores (ANY and 3') [6].

Calculate Hairpin Stability (ΔG):

- Go to the IDT OligoAnalyzer tool [6].

- Enter one primer sequence and click 'Hairpin'.

- Under the generated energy dot plot, locate the ΔG value in the 'General Information' section [6].

- Repeat for the second primer.

- Alternative: Use the mFold web server. Input the primer sequence, set the folding temperature to your PCR annealing temperature (e.g., 60°C), and adjust the ionic conditions (e.g., [Na+] = 50 mM, [Mg++] = 1.5-3.0 mM). The ΔG will be displayed at the top of the output plot [6].

Check for Primer-Dimer Formation:

- Access the Thermo Fisher Multiple Primer Analyzer [7].

- Input both primer sequences in the text box, ensuring each is on a new line with a name (e.g., "Fwd ACGTACGT...").

- The tool will instantly analyze and report possible dimer pairs and their estimated stability.

- Alternative: Use the Eurofins Oligo Analysis Tool. Use the "Self-Dimer" tab for individual primers and the "Cross-Dimer" tab to check interactions between the forward and reverse primer [2].

Holistic Visualization:

- Use PrimerChecker to generate a unified visual profile [6].

- Input the thermodynamic parameters obtained in the previous steps (Tm, GC%, ΔG, ANY, 3').

- The tool will generate a radial plot, visually indicating which parameters fall within optimal, good, or suboptimal ranges, facilitating comprehensive analysis and decision-making [6].

Diagram: In Silico Analysis Workflow

Protocol 2: Empirical Validation of Primer-Dimer Artifacts

This protocol uses RT-LAMP to empirically observe the impact of amplifiable primer dimers and hairpins by monitoring reaction kinetics with intercalating dyes.

Materials:

- Purified primer sets (original and modified).

- Bst 2.0 WarmStart DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs).

- SYTO 9 or SYTO 82 fluorescent dye (Thermo Fisher).

- Isothermal Amplification Buffer (New England Biolabs).

- dNTPs, Betaine, MgSO4.

- AMV Reverse Transcriptase (for RT-LAMP).

- Real-time PCR instrument (e.g., Bio-Rad CFX 96).

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup:

- Prepare a master mix for at least one no-template control (NTC) reaction containing [3]:

- 1x Isothermal Amplification Buffer.

- 8 mM MgSO₄ (final concentration).

- 1.4 mM of each dNTP.

- 0.8 M Betaine.

- Primers at specified concentrations (e.g., 0.2 µM F3/B3, 1.6 µM FIP/BIP, 0.8 µM LoopF/LoopB).

- 3.2 Units Bst 2.0 WarmStart Polymerase.

- 2.0 Units AMV Reverse Transcriptase (for RNA targets).

- 1-2 µM SYTO 9, SYTO 82, or SYTO 62 dye.

- Aliquot the master mix into reaction tubes.

- Prepare a master mix for at least one no-template control (NTC) reaction containing [3]:

Amplification and Data Acquisition:

- Place the reactions in a real-time thermocycler and incubate at 63°C for 60-90 minutes [3].

- Monitor fluorescence continuously in the appropriate channel (e.g., FAM for SYTO 9).

Data Analysis:

- Observe the amplification curves. A slowly rising baseline in the NTC, rather than a flat line, indicates the non-specific synthesis of double-stranded DNA from amplifiable primer-dimers or self-amplifying hairpins [3].

- Compare the baseline slope and the time-to-threshold between the original primer set and a modified set where problematic structures have been thermodynamically destabilized.

Troubleshooting:

- High Background in NTC: Redesign primers by making minor adjustments (e.g., shifting bases upstream/downstream or adding non-complementary 5' extensions) to disrupt stable secondary structures, and re-evaluate their ΔG values [6] [3].

- No Amplification in Positive Control: Ensure the primer concentrations and Mg++ concentration are optimized. The inner primers (FIP/BIP) are particularly prone to stable hairpins due to their length [3].

The formation of self-dimers, cross-dimers, and hairpins is a fundamental thermodynamic problem that directly impacts the sensitivity and specificity of nucleic acid amplification assays. The spontaneous formation of these structures is dictated by a negative change in Gibbs Free Energy, which can be accurately predicted using the nearest-neighbor model. By integrating in silico thermodynamic analyses—focusing on key parameters like ΔG, self-complementarity, and 3' stability—with empirical validation in experimental protocols, researchers can proactively identify and eliminate problematic primers. This rigorous, thermodynamics-guided approach to primer design is essential for developing robust molecular diagnostics, ensuring reliable results in research, clinical testing, and drug development.

In molecular biology and drug development research, the efficacy of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays is fundamentally dependent on primer specificity. Self-complementarity parameters—specifically ΔG (delta G), self-complementarity (ANY), and 3'-complementarity scores—provide critical thermodynamic and structural insights that predict primer behavior in solution. These parameters help researchers identify primers prone to forming intramolecular hairpins or intermolecular dimers, which compete with target binding and severely compromise assay efficiency, specificity, and reliability. Proper interpretation of these scores allows for the selection of optimal primers before synthesis, reducing experimental failure and conserving valuable research resources. This application note details the theoretical foundation, quantitative assessment protocols, and practical implementation of these key parameters within a comprehensive primer design workflow.

Theoretical Foundation and Parameter Definitions

Thermodynamic Basis of Primer Interactions

The interactions governing primer self-complementarity are rooted in nucleic acid thermodynamics, which describes the stability of double-stranded DNA through non-covalent interactions. The most significant stabilizing factor in the DNA double helix is base stacking, the attractive interactions between the flat surfaces of adjacent bases [8]. During annealing, primers form duplexes with their targets or with themselves through hybridization, a process driven by the formation of hydrogen bonds between complementary bases (A=T and G≡C) and stabilized by stacking interactions [8]. The stability of these structures is sequence-dependent; G/C base pairs contribute three hydrogen bonds and thus confer greater stability than A/T pairs, which form only two hydrogen bonds [9]. The nearest-neighbor model provides the most accurate method for calculating duplex stability by considering the free energy contribution of each base pair and its immediate neighbor, rather than treating the helix as a simple string of independent base pairs [8].

Definition of Key Parameters

ΔG (Gibbs Free Energy Change): ΔG represents the net change in free energy during the formation of a secondary structure, such as a hairpin or dimer. It is expressed in kcal/mol. A negative ΔG value indicates a spontaneous, energetically favorable process. In primer design, strongly negative ΔG values for secondary structures are undesirable as they signify stable, non-productive primer conformations that will outcompete target binding [10] [11]. The numerical value quantifies the stability of the unwanted structure.

Self-Complementarity (ANY): This score evaluates the potential for a single primer molecule to bind to itself in an intermolecular reaction, forming a "self-dimer." It assesses complementarity between any two regions within the same primer sequence, indicating the likelihood of primer-dimer artifacts that consume primers and reduce amplification efficiency [9] [11].

3'-Complementarity: This parameter specifically examines the complementarity at the 3' end of the primer. Strong complementarity at the 3' end is particularly detrimental because DNA polymerases initiate extension from this point. If the 3' end is engaged in a dimer or hairpin, it can be efficiently extended, leading to prominent primer-dimer artifacts in PCR products. It is therefore critical to ensure the 3' end lacks self-complementarity [12] [11].

Table 1: Key Parameters for Assessing Primer Secondary Structures

| Parameter | Structural Association | Thermodynamic Principle | Impact on PCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔG (kcal/mol) | Stability of hairpins, self-dimers, and cross-dimers | Free energy change of duplex formation/disruption | Stable structures (highly negative ΔG) reduce primer availability for target binding |

| Self-Complementarity (ANY) | Intermolecular dimerization between two identical primers | Measures enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS) of dimerization | Primer-dimer formation consumes primers, generates spurious products, reduces yield |

| 3'-Complementarity | Dimerization or hairpin formation involving the 3' terminus | Terminal base pairing stability and polymerase initiation efficiency | 3' structures can be extended by polymerase, amplifying non-specific products |

Quantitative Assessment and Thresholds

Accepted Values and Interpretation

Adherence to established quantitative thresholds for self-complementarity parameters is essential for robust experimental design. The following values represent the consensus from industry and academic guidelines:

ΔG Threshold: The ΔG value for any potential secondary structure (hairpin, self-dimer, or hetero-dimer) should be weaker (more positive) than -9.0 kcal/mol [10] [11]. Positive ΔG values indicate the structure is unlikely to form spontaneously. Structures with ΔG more negative than this threshold are considered too stable and pose a significant risk to assay performance.

Self-Complementarity (ANY) and 3'-Complementarity Scores: While these are often reported as numerical scores or alignment patterns, the fundamental guideline is that lower scores are superior [9]. These scores typically represent the number of contiguous complementary bases or the strength of the interaction. For 3'-complementarity, a critical rule is to avoid more than 3 G or C bases in the last five nucleotides at the 3' end, as this promotes non-specific binding through strong GC interactions [13] [9]. Furthermore, any complementarity at the very 3' end should be avoided, as it can lead to primer multimerization [12].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide Based on Parameter Analysis

| Parameter Issue | Observed Experimental Consequence | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| ΔG < -9.0 kcal/mol for hairpin | Poor amplification efficiency; low yield | Redesign primer to eliminate regions of intramolecular complementarity |

| ΔG < -9.0 kcal/mol for self-dimer | Multiple bands or smearing on a gel; primer-dimer formation | Shift primer sequence; avoid palindromic sequences; increase annealing temperature |

| High 3'-Complementarity | Strong primer-dimer band (~50-100 bp) on gel | Redesign to avoid complementarity in the last 3-4 bases at the 3' end |

| High Self-Complementarity (ANY) | Reduced overall product yield; complex dimer artifacts | Select a new primer pair with lower self-complementarity scores |

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Analysis

In Silico Analysis Using OligoAnalyzer Tool

This protocol details the use of the IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool to comprehensively assess primer sequences for potential secondary structures [14] [11].

Methodology:

- Access the Tool: Navigate to the IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool web interface.

- Input Sequence: Enter your oligonucleotide sequence (DNA) in the input field. Ensure the sequence is 5' to 3'.

- Set Reaction Conditions: Adjust the calculation options to reflect your specific PCR buffer conditions, including:

- Oligo concentration (typical range: 0.1-0.5 µM)

- Na+ concentration (e.g., 50 mM)

- Mg2+ concentration (a critical variable, often 1.5-3 mM)

- dNTP concentration (e.g., 0.8 mM)

- Secondary Structure Analysis:

- Select the "Hairpin" function to analyze intramolecular folding. Examine the reported ΔG value and ensure it is > -9.0 kcal/mol.

- Select the "Self-Dimer" function to check for interactions between two identical primers. Confirm the ΔG value meets the > -9.0 kcal/mol threshold.

- For a primer pair, use the "Hetero-Dimer" function to analyze interactions between the forward and reverse primers. Again, validate that the ΔG is acceptable.

- Interpretation: The tool will visualize potential structures. Pay close attention to any interactions involving the 3' end. Even if the overall ΔG is acceptable, significant 3'-complementarity should be avoided.

Workflow for Integrated Primer Design and Validation

The following diagram outlines the logical sequence for incorporating self-complementarity checks into a standard primer design pipeline.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential In Silico Tools for Primer Analysis and Design

| Tool Name | Provider | Primary Function | Application in Complementarity Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| OligoAnalyzer | IDT [14] [11] | Tm calculation, secondary structure prediction | Calculates ΔG for hairpins and dimers; visualizes interaction sites |

| Primer-BLAST | NCBI [15] | Integrated primer design and specificity checking | Designs primers and checks for off-target binding; incorporates Primer3 engine |

| Oligo Analysis Tool | Eurofins Genomics [2] | Physical property calculation, dimer analysis | Checks for self-dimer and cross-dimer formation in primer pairs |

| PrimerQuest Tool | IDT [11] | Custom assay and primer design | Generates primer designs with optimized properties, including minimized secondary structure |

| UNAFold Tool | IDT [11] | oligonucleotide secondary structure analysis | Provides advanced analysis of folding pathways and stability |

Rigorous assessment of ΔG, self-complementarity (ANY), and 3'-complementarity scores is a non-negotiable step in the design of functional primers for advanced research and drug development applications. By applying the quantitative thresholds and standardized protocols outlined in this document—specifically, a ΔG threshold of > -9.0 kcal/mol for secondary structures and minimal 3'-end complementarity—researchers can proactively eliminate a major source of PCR failure. The integration of these in silico analyses into a systematic workflow, leveraging the sophisticated tools described, ensures the selection of high-quality primers, thereby enhancing the reliability, specificity, and efficiency of genetic analyses and diagnostic assays.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a foundational technique in molecular biology, but its efficiency and accuracy are frequently compromised by the formation of primer-dimers. These nonspecific amplification artifacts occur when primers anneal to each other rather than to the intended target DNA template [16] [17]. Primer-dimer formation represents a significant challenge in molecular diagnostics, genetic research, and drug development, where amplification fidelity is paramount. This application note examines the mechanistic basis of dimer formation, its detrimental effects on PCR performance, and provides validated experimental protocols for its detection and prevention, framed within the context of primer self-complementarity research.

The impact of dimers extends beyond mere anecdotal troubleshooting; quantitative studies demonstrate that dimerization directly correlates with failed reactions and compromised data integrity [18]. Understanding the biophysical parameters governing primer-interactions enables researchers to design more robust assays, particularly for sensitive applications including low-abundance target detection, quantitative PCR, and next-generation sequencing library preparation where dimer competition can invalidate results.

Mechanisms and Consequences of Primer-Dimer Formation

Formation Mechanisms

Primer-dimers form through two primary mechanisms: self-dimerization, where a single primer contains regions complementary to itself, and cross-dimerization, where forward and reverse primers exhibit mutual complementarity [17]. These processes are facilitated by residual polymerase activity during reaction setup at non-stringent temperatures, allowing primers with partially complementary regions to anneal and become extended [19]. The resulting short DNA fragments contain binding sites for both primers, creating templates that amplify with high efficiency and compete with the target amplicon for reaction resources.

Early initiation of nonspecific amplification is particularly problematic in reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) where extended low-temperature conditions are often employed [19]. Sequencing of primer-dimers reveals they frequently consist of two primer sequences connected by a short intervening sequence of unknown origin, sometimes with homology to human genomic DNA or included oligonucleotides [19].

Impact on PCR Performance

The consequences of primer-dimer formation manifest across multiple aspects of PCR performance:

Reduced Yield: Dimers compete with target amplicons for essential reaction components including primers, dNTPs, and polymerase enzymes [19] [16]. This resource partitioning diminishes the amplification efficiency of the desired product, particularly for low-copy targets where reaction resources are limiting.

Compromised Sensitivity: The presence of amplification artifacts reduces the detection sensitivity for intended targets, potentially leading to false negatives in diagnostic applications [19] [20]. This effect is most pronounced when amplifying rare targets from complex biological matrices.

Assay Interpretation Challenges: In quantitative PCR, dimer formation generates fluorescence signal that does not correlate with target abundance, distorting amplification curves and compromising quantification accuracy [18]. Electrophoresis analysis reveals problematic patterns including smears, unexpected bands, and primer multimers that obscure results [16].

Table 1: Characterization of Common Non-Specific Amplification Artifacts

| Artifact Type | Typical Size Range | Visual Appearance on Gel | Primary Cause |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primer-dimer | 20-60 bp | Bright discrete band at gel bottom | Primer self-complementarity or inter-primer complementarity |

| Primer multimer | 100 bp, 200 bp, or more | Ladder-like pattern | Primer dimers joining with other dimers |

| Non-specific amplification | Variable | One or more unexpected bands | Primers binding to unintended template regions |

| Smear | Variable range | Continuous spread of DNA | Random DNA amplification from fragmented templates or degraded primers |

Quantitative Experimental Analysis

Empirical studies have quantitatively defined the parameters governing primer-dimer stability. Systematic investigation using free-solution conjugate electrophoresis (FSCE) with drag-tagged DNA primers revealed precise conditions under which dimerization occurs [21].

Critical findings from controlled experiments include:

Base Pairing Threshold: Dimerization occurs when more than 15 consecutive base pairs form between primers. Notably, non-consecutive base pairing did not create stable dimers even when 20 out of 30 possible base pairs bonded [21].

Temperature Dependence: When less than 30 out of 30 base pairs were bonded, dimerization was inversely correlated with temperature, with significant reduction observed at elevated temperatures [21].

Structural Determinants: The spatial arrangement of complementary regions significantly influences dimer stability, with contiguous complementary segments having substantially greater impact on dimer formation than distributed complementarity [21].

Table 2: Experimental Parameters for Dimerization Analysis Using Free-Solution Conjugate Electrophoresis

| Experimental Parameter | Conditions/Values | Experimental Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Capillary temperature | 18, 25, 40, 55, 62°C | Assess dimer stability across temperatures |

| Separation matrix | Free-solution (no sieving polymer) | Eliminate matrix interaction effects |

| Drag-tag | Poly-N-methoxyethylglycine (NMEG) | Modulate electrophoretic mobility for ssDNA vs dsDNA separation |

| DNA labeling | 5'-ROX and internal FAM | Enable multiplex detection and peak assignment |

| Buffer system | 1× TTE (89 mM Tris, 89 mM TAPS, 2 mM EDTA) | Provide consistent ionic strength and pH |

| Analysis duration | <10 minutes per sample | Enable rapid assessment of dimerization risk |

These quantitative findings provide researchers with empirically validated thresholds for evaluating primer compatibility and predicting dimerization risk during assay design.

Detection and Visualization Methods

Electrophoretic Analysis

Agarose gel electrophoresis remains the most accessible method for detecting primer-dimer artifacts. Primer-dimers typically appear as bright bands of 20-60 bp in size, often with a smeary appearance, migrating near the dye front of the gel [16] [17]. Distinctive electrophoretic patterns associated with dimerization include:

- Residual Primers: Unincorporated primers appear as a diffuse hazy band at the gel bottom (approximately 21-30 bp) [16].

- Primer Multimers: Repeated dimerization events produce ladder-like patterns with bands at 100 bp, 200 bp, or larger intervals [16].

- Smears: Random DNA amplification creates continuous distributions of fragment sizes, often resulting from highly fragmented templates or degraded primers [16].

No-Template Controls

Inclusion of no-template controls (NTCs) represents a critical diagnostic approach. Because primer-dimers form independently of template DNA, their presence in NTC reactions confirms their origin through primer self-interaction rather than template-directed amplification [17]. This simple validation step should be incorporated in all PCR optimization workflows.

Melting Curve Analysis

In quantitative PCR applications, melting curve analysis following amplification provides a powerful tool for distinguishing specific products from primer-dimers. Artifacts typically exhibit lower melting temperatures (Tm) than specific amplicons, enabling their discrimination through post-amplification thermal ramping and fluorescence monitoring [18].

Diagram: PCR Dimer Impact Pathway. Primer-dimer formation initiates a cascade of detrimental effects that ultimately compromise assay performance.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Covalent Modification of Primers to Suppress Dimerization

The covalent attachment of alkyl groups to exocyclic amines of deoxyadenosine or cytosine residues at primer 3'-ends represents an advanced strategy for enhancing PCR specificity by sterically interfering with dimer propagation [19].

Materials:

- Controlled pore glass (CPG) substrates with protected nucleosides

- Appropriate phosphoramidites for standard DNA synthesis

- Anhydrous acetonitrile for reagent dissolution

- Alkylating reagents (specific compositions described in patent literature)

- Standard deprotection reagents (ammonium hydroxide, methylamine)

- Purification columns or cartridges

Method:

- Synthesize modified nucleotides and corresponding phosphoramidites as described in supplementary materials of [19].

- Incorporate modified nucleotides during automated oligonucleotide synthesis at strategic positions:

- 3'-terminal nucleotides only

- Internal positions only

- Both 3'-terminal and penultimate nucleotides for maximum effect

- Use standard phosphoramidite chemistry with extended coupling times for modified residues.

- Deprotect oligonucleotides using standard ammonium hydroxide/methylamine treatment at 65°C for 30 minutes.

- Purify modified primers using reversed-phase or anion-exchange HPLC.

- Verify primer quality and concentration using UV spectrophotometry.

Application Notes:

- Primers modified at both 3'-termini show maximum suppression of dimer formation [19].

- Thermal stability of primers is only minimally affected by inclusion of these modifiers.

- The principal mode of action involves poor enzyme extension of substrates with closely juxtaposed bulky alkyl groups that would result from replication of primer-dimer artifacts.

Protocol: Free-Solution Conjugate Electrophoresis for Dimerization Assessment

This specialized capillary electrophoresis method provides quantitative analysis of dimerization risk between primer pairs, offering superior resolution for short DNA fragments [21].

Materials:

- ABI 3100 capillary electrophoresis system or equivalent

- 47 cm length capillary array (36 cm effective length)

- PolyDuramide polymer (poly-N-hydroxyethylacrylamide) for dynamic coating

- DNA oligomers with 5'-thiol modification and 3'-rhodamine (ROX)

- NMEG drag-tags of length 12, 20, 28, or 36 monomers

- Sulfo-SMCC crosslinker

- Tris-TAPS-EDTA (TTE) buffer

- Temperature-controlled thermocycler

Method:

- Conjugate drag-tags to thiolated DNA oligomers using Sulfo-SMCC chemistry:

- Reduce DNA oligos with 100:1 molar excess TCEP

- Incubate with 40:1 molar excess NMEG drag-tag overnight at room temperature

- Prepare control samples by denaturing at 95°C for 5 minutes followed by snap-cooling

- Anneal test samples by mixing drag-tagged and non-drag-tagged primers:

- Heat denature at 95°C for 5 minutes

- Anneal at 62°C for 10 minutes

- Cool to 25°C

- Dilute samples to 16 pM final concentration

- Load samples into capillary array using 1 kV (21 V/cm) for 20 seconds

- Electrophorese under free-solution conditions at 15 kV (320 V/cm) at temperatures ranging from 18-62°C

- Analyze electropherograms to quantify dimer vs. monomer peaks

Application Notes:

- Analysis at multiple temperatures provides insight into dimer stability

- The method enables precise determination of complementarity thresholds for dimer formation

- Results serve as quantitatively precise input data for computational models of dimerization risk

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Dimer Investigation and Prevention

| Reagent / Tool | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-start DNA polymerase | Suppresses pre-amplification activity | Activated only at high temperatures; reduces primer extension during reaction setup |

| Primer design software (Primer-Blast) | In silico primer evaluation | Checks specificity against database; calculates Tm and secondary structure |

| OligoAnalyzer (IDT) | Primer parameter calculation | Determines Tm, GC%, hairpin formation, and self-dimerization potential |

| Covalently modified primers | Steric hindrance of dimer extension | Alkyl groups at 3'-terminal bases interfere with polymerase extension on dimer templates |

| Free-solution CE system | Quantitative dimer assessment | Precisely measures dimerization propensity between primer pairs |

| No-template controls | Diagnostic for dimer formation | Identifies primer-self interactions independent of template |

| Checkerboard titration | Optimization of primer concentration | Identifies optimal primer ratios that minimize inter-primer annealing |

Computational Tools for Primer Analysis

Robust primer design represents the most effective strategy for preventing dimer-related amplification issues. Computational tools provide critical pre-screening of potential dimerization risks:

NCBI Primer-BLAST: Combos primer design with specificity checking against database sequences to identify potential off-target binding sites [15]. Key parameters include primer length (19-22 bp), Tm (60±1°C), and limited 3'-end complementarity [18].

OligoAnalyzer Tool: Calculates thermodynamic parameters including hairpin formation, self-dimerization, and hetero-dimerization potential [22]. Researchers should aim for dimer strengths of ΔG ≤ -9 kcal/mol and ensure no extendable 3' ends in dimer configurations [18].

PrimerChecker: Provides holistic visualization of multiple primer parameters including Tm differences, self-complementarity scores, and secondary structure potential [6]. This facilitates rapid assessment of primer pair compatibility.

These tools enable researchers to identify problematic complementarity regions before synthesizing primers, significantly reducing optimization time and reagent costs while improving assay robustness.

Primer-dimer formation remains a significant challenge in PCR-based applications, with demonstrated impacts on assay yield, sensitivity, and reliability. Through understanding of dimerization mechanisms, implementation of appropriate detection methods, and application of targeted prevention strategies, researchers can significantly improve PCR performance. The integration of computational design tools with empirical validation approaches provides a robust framework for developing dimer-resistant assays. Particularly for sensitive applications including diagnostic testing and low-copy target detection, proactive dimer management represents an essential component of rigorous experimental design.

The Role of Melting Temperature (Tm) and GC Content in Dimer Formation

Primer-dimer formation represents a significant challenge in polymerase chain reaction (PCR) efficiency, often leading to reduced target amplification yield and false results. This application note examines two critical factors governing dimerization: melting temperature (Tm) and guanine-cytosine (GC) content. Understanding the interplay between these parameters enables researchers to design more specific and efficient primers, particularly crucial for diagnostic assays, gene expression studies, and next-generation sequencing applications where multiplexing increases dimerization risk [21]. We frame this discussion within broader research on tools for checking primer self-complementarity, providing both theoretical principles and practical protocols.

Theoretical Foundations

Fundamental Principles of Primer Thermodynamics

Primer-dimer formation occurs when primers anneal to themselves or each other instead of the target template, primarily driven by complementary base pairing and stabilization through hydrogen bonds. Guanine and cytosine bases form three hydrogen bonds, while adenine and thymine form only two, making GC-rich sequences thermodynamically more stable [9]. This fundamental difference directly influences both the melting temperature of primer-template complexes and their propensity for off-target dimerization.

The stability of primer-dimers depends on the spatial arrangement and consecutive length of complementary regions. Experimental evidence indicates that more than 15 consecutive complementary base pairs can create stable dimers, while non-consecutive base pairs (even when 20 out of 30 possible base pairs bond) do not necessarily form stable dimers [21]. This understanding is crucial for predicting and preventing dimer formation through careful primer design.

Interrelationship Between Tm and GC Content

Melting temperature and GC content share a direct relationship in oligonucleotide design. The GC content significantly influences Tm because G-C base pairs contribute more to duplex stability than A-T pairs due to their additional hydrogen bond [9] [23]. This relationship is formally expressed through the formula:

Tm = 81.5 + 16.6(log[Na+]) + 0.41(%GC) – 675/primer length [9]

This equation demonstrates that as GC percentage increases, melting temperature rises correspondingly, assuming other factors remain constant. Consequently, primers with elevated GC content not only exhibit higher melting temperatures but also increased potential for stable dimer formation through enhanced intermolecular binding.

Table 1: Key Parameters Influencing Primer-Dimer Formation

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Effect on Dimer Formation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| GC Content | 40-60% [24] [9] [11] | >60% increases dimer risk [23] | GC bonds form 3 hydrogen bonds vs AT's 2, increasing stability of misfolded structures [9] |

| Tm | 60-75°C [24] [11] | Excessive Tm promotes secondary annealing [9] | High Tm indicates stronger binding capacity for both target and non-target sequences |

| 3'-End GC Clamp | 1-3 G/C bases [24] [23] | >3 consecutive G/C bases promotes dimerization [24] | 3' end is critical for polymerase extension; stable mismatches here amplify efficiently |

| Primer Length | 18-30 bases [24] [9] | Shorter primers increase mishybridization risk | Shorter sequences have higher probability of random complementarity |

Quantitative Data Analysis

Experimental Measurements of Dimerization Thresholds

Capillary electrophoresis studies utilizing drag-tag DNA conjugates have quantitatively demonstrated that dimerization occurs inversely with temperature and requires specific minimum complementary regions. The research revealed that primer-dimer formation becomes significant when more than 15 consecutive base pairs form between primers, while non-consecutive complementary regions demonstrated markedly reduced dimer stability even with up to 20 out of 30 potential base pairs bonded [21].

These findings establish clear operational thresholds for predicting dimerization risk. Specifically, the number of consecutive complementary bases at the 3' end serves as a more reliable predictor than total complementary bases distributed throughout the primer sequence. This understanding directly informs the design rules implemented in primer analysis software.

Impact of GC Distribution on Dimer Stability

The localization of GC-rich regions significantly influences dimer stability. Experimental data confirms that sequences containing more than three repeats of G or C bases at the 3' end should be avoided due to substantially increased probability of primer-dimer formation [23]. This effect stems from the stronger hydrogen bonding of G and C bases, particularly problematic when concentrated at the 3' terminus where polymerase extension initiates.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for GC-Rich Primer Design

| Problem | Cause | Solution | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| No amplification | Stable secondary structures in GC-rich templates | Codon optimization at wobble positions; Add 5% DMSO [25] | Successfully amplified 66% GC-content Mycobacterium genes [25] |

| Primer-dimer artifacts | Excessive 3' complementarity; High GC content | Redesign to minimize 3' self-complementarity; Avoid >3 consecutive G/C at 3' end [24] [23] | CE studies showing >15 consecutive bp causes stable dimers [21] |

| Non-specific amplification | Tm too low; Secondary structures | Increase Tm to 60-64°C; Screen for hairpins [9] [11] | ΔG values more positive than -9.0 kcal/mol reduce artifacts [11] |

| Differential primer efficiency | Tm mismatch between forward/reverse primers | Balance Tm within 2°C; Add 5' non-complementary bases to lower Tm primer [11] [6] | Adding G/C nucleotides to 5' end raises Tm without affecting specificity [6] |

Experimental Protocols

Computational Primer Analysis Protocol

Purpose: To identify potential dimer formation and optimize Tm/GC parameters before oligonucleotide synthesis.

Materials:

- Primer sequences (18-30 bases)

- Computer with internet access

- IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool [22]

- NCBI Primer-BLAST [15]

- Primer3 software [26]

Procedure:

- Initial Sequence Input: Enter candidate primer sequences into OligoAnalyzer Tool using the "Analyze" function to determine baseline Tm, GC content, and molecular weight [22].

Secondary Structure Screening:

- Select the "Hairpin" function to identify self-folding structures with ΔG values.

- Use "Self-Dimer" and "Hetero-Dimer" functions to check for inter-primer interactions.

- Record ΔG values for all structures, aiming for values more positive than -9.0 kcal/mol [11].

Specificity Verification:

- Submit sequences to NCBI Primer-BLAST with organism specification.

- Select appropriate database (e.g., Refseq mRNA, nr) for your application.

- Check that primers demonstrate specificity to intended target [15].

Parameter Optimization:

Iterative Redesign: Reposition primers along template sequence if parameters fall outside optimal ranges or significant dimerization potential is detected.

Empirical Dimer Validation Protocol

Purpose: To experimentally verify primer-dimer formation predicted by computational analysis.

Materials:

- Synthesized primers (desalted minimum, cartridge purified for cloning) [24]

- Free-solution conjugate electrophoresis (FSCE) system with drag-tag modification [21]

- Temperature gradient thermal cycler

- Standard PCR reagents (polymerase, buffer, dNTPs, Mg2+)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Conjugate one primer with neutral polyamide "drag-tag" to modify electrophoretic mobility [21].

- Prepare primer mixtures: (1) Forward primer only, (2) Reverse primer only, (3) Both primers combined.

Annealing Reaction:

- Denature samples at 95°C for 5 minutes.

- Anneal using temperature gradient from 40°C to 65°C for 10 minutes.

- Cool to 25°C to allow dimer stabilization [21].

Capillary Electrophoresis:

- Load samples using 21 V/cm for 20 seconds.

- Electrophorese under free-solution conditions (no sieving matrix) at 320 V/cm.

- Perform separations at multiple temperatures (18°C, 25°C, 40°C, 55°C, 62°C) to assess temperature-dependent dimerization [21].

Data Analysis:

- Compare electrophoregram peaks of individual primers versus primer mixtures.

- Identify new peaks corresponding to dimer formations.

- Calculate percentage dimerization based on peak areas.

- Correlate dimer abundance with annealing temperature and computational predictions.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Primer Design and Dimer Analysis

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| IDT OligoAnalyzer [22] | Calculates Tm, GC%, screens for secondary structures | Use hairpin and self-dimer functions with specific buffer conditions for accurate predictions |

| NCBI Primer-BLAST [15] | Verifies primer specificity against database sequences | Always specify organism to limit search and improve speed/accuracy |

| Primer3 [26] | Automated primer design with parameter constraints | Adjust objective function weights to prioritize dimer prevention |

| DMSO (5-10%) [25] | PCR additive for GC-rich templates | Reduces secondary structure formation; decreases effective Tm |

| Modified Nucleotides | Adjust Tm without changing length | Incorporate at wobble positions to disrupt GC stretches while maintaining amino acid sequence [25] |

| Drag-tag Conjugates [21] | Mobility modifiers for dimer detection | Enable separation of ssDNA and dsDNA species in free-solution electrophoresis |

The strategic management of melting temperature and GC content represents a critical frontier in the broader context of primer self-complementarity research. Through understanding the quantitative relationships between these parameters and dimer formation, researchers can leverage both computational tools and experimental methods to design highly specific amplification systems. The integration of these approaches—from in silico prediction to empirical validation—enables the development of robust PCR assays even for challenging templates, advancing diagnostic and research applications across molecular biology.

A Practical Workflow: Using Top Tools to Check Your Primers

In molecular biology, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a foundational technique whose success critically depends on the design of specific primers that efficiently and exclusively amplify the intended target DNA region [27]. Poor primer design can lead to issues such as non-specific amplification, primer-dimer formation, and weak or failed reactions, ultimately compromising experimental results and wasting valuable resources [13]. The process of designing specific primers traditionally involves two distinct stages: initial primer generation followed by specificity verification against nucleotide databases—a complex and time-consuming task, especially when dealing with numerous potential off-target hits [28].

To address this challenge, the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) developed Primer-BLAST, a powerful tool that integrates the primer design capabilities of Primer3 with a rigorous specificity check using the BLAST algorithm and a global alignment strategy [28]. This combination allows researchers to design target-specific primers in a single step, significantly streamlining the workflow for applications ranging from gene cloning and variant analysis to diagnostic assay development [29]. For researchers focused on primer self-complementarity—a key factor in primer efficacy—Primer-BLAST provides built-in analysis of parameters such as self-complementarity and 3' self-complementarity, enabling the selection of primers less likely to form secondary structures or primer-dimers that interfere with amplification [30]. This integrated approach makes Primer-BLAST an indispensable component of the modern molecular biologist's toolkit, ensuring that primers meet both thermodynamic and specificity requirements from the outset.

Primer-BLAST Fundamentals: How Integration Enhances Specificity

Primer-BLAST distinguishes itself from standalone primer design tools by its unique two-module architecture that seamlessly combines design and validation. The first module leverages the well-established Primer3 engine to generate candidate primer pairs based on a wide array of user-definable parameters, including melting temperature (Tm), primer length, GC content, and amplicon size [28]. This design phase incorporates template-specific features such as exon-intron boundaries and SNP locations, which is particularly valuable when designing primers to distinguish between genomic DNA and cDNA in reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) applications [28].

The second module performs a comprehensive specificity check that goes beyond simple BLAST searches. While BLAST uses a local alignment algorithm that might miss partial matches at primer ends, Primer-BLAST enhances this approach by incorporating a global alignment algorithm (Needleman-Wunsch) to ensure complete alignment across the entire primer sequence [28]. This hybrid approach is notably more sensitive, capable of detecting potential amplification targets that contain up to 35% mismatches to the primer sequences—significantly expanding the range of detectable off-target effects [15] [28]. This sensitivity is crucial because studies have consistently demonstrated that a target can still be amplified even with several mismatches, particularly when these mismatches are located toward the 5' end rather than the critical 3' end where extension initiates [28].

The specificity checking process evaluates all possible primer combinations—not only forward-reverse pairs but also forward-forward and reverse-reverse pairs—to identify potential amplification products that could arise from any primer configuration [15] [30]. To maximize efficiency, when a user submits a template sequence for new primer design, Primer-BLAST performs a single BLAST search using the entire template, then uses this result to assess all candidate primer pairs, significantly reducing computational time compared to individual BLAST searches for each primer [28].

Table 1: Key Specificity Parameters in Primer-BLAST

| Parameter | Function | Impact on Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Database Selection | Determines the sequence database for specificity checking | Using organism-specific databases increases relevance and speed [15] [31] |

| Exon-Exon Junction Span | Requires primers to span exon boundaries | Limits amplification to spliced mRNA, not genomic DNA [15] [28] |

| Mismatch Sensitivity | Controls the number of mismatches allowed between primers and off-targets | Higher mismatch requirements increase specificity but may reduce viable primer options [15] |

| Max Product Size | Sets maximum amplicon size for potential off-targets | Larger non-specific products are less concerning due to lower PCR efficiency [15] |

Core Analytical Features: Self-Complementarity and Dimer Analysis

A critical aspect of primer design that Primer-BLAST directly addresses is the analysis of self-complementarity and primer-dimer potential—key factors that significantly impact primer performance by competing with target template binding [13] [30]. Primer-BLAST evaluates and reports two specific metrics to help researchers avoid these problematic interactions.

Self-complementarity quantifies the tendency of a single primer molecule to bind to itself through intramolecular base pairing, which can create hairpin structures that interfere with proper template binding [30]. This parameter is calculated using local alignment across the entire primer sequence, with lower scores indicating reduced self-binding propensity [30].

Perhaps even more critical is the 3' self-complementarity score, which specifically examines the tendency of the primer to bind to itself at the 3' end—the region where DNA polymerase initiates extension [30]. This parameter is calculated using global alignment rather than local alignment, providing a more stringent assessment of complementarity at the functionally crucial 3' terminus [30]. A high 3' self-complementarity value can severely compromise amplification efficiency, as the polymerase may extend from the misfolded 3' end rather than from the correct template-bound conformation.

In addition to self-complementarity, Primer-BLAST inherently addresses primer-dimer potential through its comprehensive specificity check that evaluates all possible primer combinations. The tool examines not only the intended forward-reverse pairings but also forward-forward and reverse-reverse combinations, identifying potential inter-primer interactions that could lead to dimer formation [15] [30]. This thorough analysis is vital because primer-dimers consume reaction reagents and can amplify efficiently, competing with the target amplicon and potentially generating false-positive signals in quantitative applications [13].

Table 2: Critical Primer Design Parameters for Optimal Performance

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Rationale | Tool for Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primer Length | 18-24 nucleotides | Balances specificity with binding efficiency [13] | Primer3 within Primer-BLAST |

| GC Content | 40%-60% | Ensures stable priming without excessive stability [13] | Primer3 within Primer-BLAST |

| Melting Temperature (Tₘ) | 50-65°C (within 2°C for pair) | Enables synchronous binding of both primers [13] | Primer3 within Primer-BLAST |

| Self-Complementarity | Lower values preferred | Minimizes hairpin formation [30] | Primer-BLAST |

| 3' Self-Complementarity | Lower values critical | Prevents extension from misfolded 3' ends [30] | Primer-BLAST |

Application Notes: Experimental Protocol for Specific Primer Design

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for using NCBI Primer-BLAST to design target-specific primers with optimized characteristics, including minimal self-complementarity. The workflow is presented in the diagram below, followed by a comprehensive explanation of each step.

Diagram 1: Primer design and analysis workflow

Template Input and Parameter Configuration

Access Primer-BLAST: Navigate to the NCBI Primer-BLAST tool at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/ [15].

Input Template Sequence: In the "PCR Template" field, enter your target sequence using either a FASTA format sequence or a valid accession number (e.g., RefSeq mRNA accession). For precise amplification of specific regions, use the "Range" fields to define the target boundaries. For instance, to amplify a region between positions 100 and 1000, set "Forward Primer To" to 100 and "Reverse Primer From" to 1000 [15] [31].

Configure Basic Primer Parameters: In the "Primer Parameters" section, set the following key criteria:

- Product Size Ranges: Define appropriate size ranges for your application. For qPCR primers, target 50-200 bp; for cloning and gene knockout constructs, consider 800-1200 bp [31].

- Melting Temperature (Tₘ): Set "Opt" to 60°C with "Min" and "Max" values typically spanning 57-63°C. Maintain a maximum Tₘ difference of ≤2°C between forward and reverse primers [13].

- Primer Length: Specify 18-24 nucleotides as the optimal range [13].

Specificity and Advanced Settings

Configure Specificity Checking Parameters: This critical step ensures primer specificity:

- Database Selection: Choose an appropriate database for your application. "Refseq mRNA" is suitable for cDNA targets, while "Refseq representative genomes" offers comprehensive genomic coverage with minimal redundancy [15].

- Organism Specification: Always specify the target organism to limit searches and improve performance. This restricts off-target checking to relevant sequences and significantly accelerates the search process [15] [31].

Adjust Advanced Parameters (Optional): For specialized applications:

- Exon-Exon Junction Spanning: Select "Primer must span an exon-exon junction" when designing RT-PCR primers to ensure amplification only from spliced mRNA, not genomic DNA [15] [28].

- SNP Avoidance: Enable SNP exclusion to avoid placing primers over known polymorphic sites that could affect binding efficiency [28].

Results Analysis and Primer Selection

Execute Search and Select Targets: Click "Get Primers" to initiate the design process. Primer-BLAST may prompt you to select highly similar sequences from the database that should be considered "intended targets," which is particularly important when working with raw sequences rather than accessions [30].

Analyze and Select Primer Pairs: Primer-BLAST returns a results page with candidate primer pairs. Systematically evaluate each suggestion:

- Review Specificity: Examine the "Graphical view of primer pairs" to verify primers only hit your intended target. Investigate any non-specific hits, preferring those that produce much larger amplicons that may be minimized by optimizing PCR extension times [31].

- Check Self-Complementarity Scores: Prioritize primers with low "Self complementarity" and "Self 3' complementarity" values (preferably ≤4) to minimize hairpin formation and primer-dimer potential [31] [30].

- Verify Other Parameters: Ensure GC content (40%-60%), Tₘ values, and absence of repetitive sequences align with best practices [13].

Experimental Validation: Always validate selected primers experimentally. While CREPE, a computational pipeline combining Primer3 with in-silico PCR, demonstrated >90% amplification success for primers deemed acceptable by its evaluation script [27], laboratory verification under specific experimental conditions remains essential.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Primer Design and Validation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Primer Design

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Design Tools | Primer-BLAST, Primer3, CREPE pipeline | Automated primer design and specificity checking [27] [28] |

| Specificity Databases | RefSeq mRNA, RefSeq representative genomes, core_nt | Background databases for specificity verification [15] |

| Secondary Structure Analysis | OligoAnalyzer Tool, RNAfold | Predict hairpin formation and dimer potential [13] |

| Sequence Alignment | MAFFT, Geneious, BLAST | Multiple sequence alignment and homology checking [32] |

| In-Silico PCR Tools | ISPCR (BLAT-based), UCSC in-silico PCR | Simulate PCR amplification from primer pairs [27] |

NCBI Primer-BLAST represents a significant advancement in primer design methodology by seamlessly integrating the primer generation capabilities of Primer3 with rigorous specificity checking using BLAST and global alignment algorithms. This integrated approach effectively addresses two critical aspects of primer design: ensuring specificity to the intended target through comprehensive off-target detection, and evaluating primer quality through self-complementarity and dimer formation analysis. The tool's ability to incorporate additional constraints such as exon-intron boundaries and SNP locations further enhances its utility for complex experimental designs.

For the research community focused on primer self-complementarity and optimization, Primer-BLAST provides essential analytical capabilities that help minimize problematic secondary structures and primer interactions. The continued development of complementary tools like CREPE for large-scale primer design [27] underscores the ongoing evolution of this field toward more automated, reliable, and scalable solutions. As molecular techniques continue to advance, with increasing applications in diagnostics [32], functional genomics, and synthetic biology, the role of robust computational primer design tools becomes increasingly vital for generating reliable, reproducible results across diverse scientific disciplines.

Within the field of molecular biology, the success of techniques such as PCR, qPCR, and next-generation sequencing is fundamentally dependent on the specific and efficient hybridization of oligonucleotide primers. A significant challenge in assay design involves mitigating adverse secondary structures, including hairpins, self-dimers, and hetero-dimers, which can drastically reduce amplification efficiency and specificity. This application note provides a detailed, protocol-driven guide for using the IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool—a central component of a broader research thesis on primer self-complementarity—to identify and evaluate these problematic structures. By integrating quantitative biophysical parameters such as Gibbs free energy (ΔG) and melting temperature (Tm), researchers and drug development professionals can preemptively optimize oligo designs, thereby saving valuable time and resources.

Essential Concepts and Problematic Structures

Oligonucleotides can form several types of secondary structures that interfere with their intended function. The table below summarizes the key structures analyzed in this document.

Table 1: Problematic Oligonucleotide Secondary Structures

| Structure Type | Description | Primary Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Hairpin | An oligo folds back on itself, forming an intra-molecular duplex with a loop region. | Blocks binding to the target sequence [33]. |

| Self-Dimer (Homodimer) | An oligo molecule hybridizes to another identical molecule via intermolecular base pairing [33]. | Consumes primers, can lead to nonspecific amplification products. |

| Hetero-Dimer | The forward primer hybridizes to the reverse primer (or another different oligo) instead of the target [34]. | Causes primer-dimer artifacts, severely reducing PCR yield and specificity [34]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful oligonucleotide analysis and experimental performance depend on accurately replicating reaction conditions in silico. The following table details key reagents and their functions in the context of the OligoAnalyzer Tool and downstream applications.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Analysis & Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Oligonucleotides | The core molecule under analysis; its sequence dictates potential for secondary structure formation. |

| Magnesium Ions (Mg²⁺) | A critical divalent cation that stabilizes nucleic acid duplexes; its concentration significantly impacts Tm calculations and must be specified in the tool [35] [36]. |

| Deoxynucleoside Triphosphates (dNTPs) | Essential components for PCR; their concentration is required by the OligoAnalyzer for accurate Tm prediction as they chelate free Mg²⁺ [36]. |

| Sodium Ions (Na⁺) | Monovalent cations that influence duplex stability; the tool uses an improved correction model for their effect on melting temperature [36]. |

| Modified Bases (e.g., LNA, RNA) | Chemically altered nucleotides that can enhance binding affinity and nuclease resistance; the tool can account for many of these modifications in its calculations [22] [36]. |

Analysis Workflow and Interpretation Criteria

The process for comprehensive oligonucleotide analysis follows a logical sequence to diagnose and troubleshoot potential issues. The workflow below outlines the key steps from sequence input to final interpretation.

Diagram 1: Oligo Analysis Workflow

Protocol 1: Initial Setup and Basic Oligo Analysis

- Access the Tool: Navigate to the IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool online [22].

- Input Sequence: Enter your oligonucleotide sequence in the 5' to 3' orientation into the "Sequence" box. Select the correct nucleic acid type (DNA, RNA) and add any modifications from the provided menus [22] [35].

- Define Reaction Conditions: Adjust the Oligo concentration, Na⁺ concentration, Mg²⁺ concentration, and dNTP concentration to match your intended experimental conditions. Note: The default Tm on the IDT spec sheet uses 0 mM Mg²⁺ and will differ from your experimental Tm [35].

- Run Standard Analysis: Click the "Analyze" button. The tool will return fundamental properties including the complementary sequence, GC content, melting temperature (Tm), molecular weight (MW), and extinction coefficient (ε) [35] [36]. The extinction coefficient is calculated using a nearest-neighbor method for high accuracy, which is crucial for precise quantification [37].

Protocol 2: Hairpin Analysis

- Initiate Analysis: With your sequence entered, click the "Hairpin" button to the right of the interface [34].

- Review Structures: The tool will display predicted secondary structures, starting with the most stable [36].

- Interpret Results:

- Key Parameter: Evaluate the reported Tm for each hairpin structure.

- Acceptance Criterion: The hairpin Tm should be lower than the temperature at which the oligo will be used (e.g., the annealing temperature in PCR). If the hairpin Tm is higher than your reaction temperature, the oligo may be problematic and should be redesigned [34] [35].

Protocol 3: Self-Dimer Analysis

- Initiate Analysis: Click the "Self-Dimer" button [34].

- Review Output: The tool will generate a list of all possible dimer structures your oligo can form, ranked from most to least stable [34] [36].

- Interpret Results:

- Key Parameter: Identify the calculated delta G (ΔG) value for the strongest dimer. ΔG represents the Gibbs free energy; a more negative value indicates a more stable, and therefore more problematic, interaction.

- Acceptance Criterion: IDT recommends that an oligo with a ΔG of –9 kcal/mol or more negative is likely to be problematic and should be considered for redesign [34] [35].

Protocol 4: Hetero-Dimer Analysis

- Initiate Analysis: Click the "Hetero-Dimer" button. This will open a second sequence input box below the first [34].

- Input Partner Oligo: Enter the sequence of the second oligonucleotide (e.g., the reverse primer for a forward primer analysis) into the new box [34].

- Run Calculation: Click the "Calculate" button below the second sequence box.

- Interpret Results:

- Key Parameter: As with self-dimers, identify the delta G (ΔG) for the most stable hetero-dimer complex.

- Acceptance Criterion: A primer pair with a ΔG of –9 kcal/mol or more negative will likely form a stable primer-dimer and be problematic in assays [34].

Table 3: Summary of Interpretation Criteria and Thresholds

| Analysis Type | Key Parameter | Interpretation Threshold | Recommended Action if Threshold is Exceeded |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hairpin | Melting Temperature (Tm) | Tm < Assay Temperature | Structure is stable; oligo is acceptable. |

| Tm ≥ Assay Temperature | Structure is stable; consider redesigning oligo [34] [35]. | ||

| Self-Dimer | Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG) | ΔG > –9 kcal/mol | Interaction is weak; oligo is acceptable. |

| ΔG ≤ –9 kcal/mol | Interaction is strong; redesign oligo [34] [35]. | ||

| Hetero-Dimer | Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG) | ΔG > –9 kcal/mol | Interaction is weak; primer pair is acceptable. |

| ΔG ≤ –9 kcal/mol | Strong primer-dimer likely; redesign one or both primers [34]. |

Advanced Analysis and Quality Control Integration

For researchers requiring the highest level of confidence, in-silico analysis should be complemented by physical quality control (QC) data. IDT provides optional QC services that offer deep insights into oligo purity and sequence accuracy.

- Capillary Electrophoresis (CE): This service provides a quantitative analysis of micropurity, showing the percentage of full-length product versus truncated sequences in your sample. CE traces are provided free for purified oligos under 60 bases [38].

- Electrospray Ionization (ESI) Mass Spectrometry: This is provided as a standard service for every oligo and confirms the molecular weight of the full-length product, thereby verifying sequence accuracy [38].

The IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool is an indispensable resource for the modern molecular biologist. By following the detailed protocols outlined in this application note—systematically analyzing hairpins, self-dimers, and hetero-dimers against well-defined thermodynamic thresholds—researchers can proactively identify and eliminate oligonucleotides prone to forming adverse secondary structures. This rigorous, pre-emptive screening, framed within the broader context of primer self-complementarity research, ensures the design of robust and highly specific assays, ultimately accelerating the pace of scientific discovery and therapeutic development.

Within primer self-complementarity research, in-silico analysis is a critical first step to prevent experimental failure. The Eurofins Oligo Analysis Tool is a multifunctional web-based platform that enables researchers to theoretically calculate several physicochemical properties of nucleic acids. A key function for assay development is its ability to check for self-dimer and cross-dimer formation, which are intermolecular interactions that can severely compromise PCR efficiency and specificity. By identifying these problematic secondary structures beforehand, scientists can streamline their experimental workflow, saving valuable time and resources in drug development and diagnostic applications [2] [39].

The tool provides an integrated environment where users can select the oligo type (DNA or RNA), input a sequence, and initiate various calculations. For dimer analysis, it specifically evaluates the potential for primers to form non-productive hybrids with themselves or a partner primer, providing critical information to guide the selection of optimal primers for PCR and qPCR assays [2] [39].

Theoretical Background and Definitions

Types of Problematic Dimer Structures

- Self-Dimers: These are formed by intermolecular interactions between two identical primer molecules, where the primer is homologous to itself. This occurs when regions within the same primer sequence are complementary, allowing them to hybridize to each other instead of to the target template. Self-dimerization can lead to the amplification of primer artifacts instead of the intended amplicon [2] [9].

- Cross-Dimers (Hetero-Dimers): These structures result from intermolecular interaction between the sense (forward) and antisense (reverse) primers in a PCR pair. Cross-dimers form when the two primers share homologous regions, causing them to anneal to each other. This prevents them from binding to their respective target sites on the DNA template, drastically reducing amplification efficiency [2] [39].

- Hairpin Structures: While not a dimer, hairpin formation is another critical secondary structure to avoid. It involves intramolecular interaction within a single primer, where two regions of three or more nucleotides within the same molecule are complementary. This causes the primer to fold back on itself, forming a stem-loop structure that interferes with its ability to bind to the template DNA [9].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for identifying and resolving these dimerization issues using the Eurofins Oligo Analysis Tool:

Experimental Protocol for Dimer Analysis

Step-by-Step Workflow

Step 1: Access the Tool and Input Basic Parameters Navigate to the Eurofins Genomics Oligo Analysis Tool online. Select the oligo type—DNA or RNA—to be analyzed. DNA sequences should use A, C, G, and T, while RNA sequences should use A, C, G, and U. The tool also accepts IUB codes for wobble bases. Enter a name for the oligo using only alphanumeric characters, underscores, or hyphens [2] [39].

Step 2: Initiate Primary Sequence Analysis After entering the sequence, click on the "Analysis" or "Oligo Properties" tab to initiate the calculation of fundamental physical properties. This includes the melting temperature (Tm), GC content, molecular weight, and extinction coefficient. These parameters provide a baseline assessment of your primer's suitability. The Tm is calculated using the nearest-neighbor model with thermodynamic parameters determined by SantaLucia, providing a highly accurate prediction [40] [41] [42].

Step 3: Perform Self-Dimer Analysis Click on the "Self-Dimer" tab to check if your primer sequence can form dimers with itself. The tool will evaluate intermolecular interactions by scanning for complementary regions within the same primer sequence. The output will indicate the potential for self-dimer formation and typically display the predicted structure if one is likely [2] [39].

Step 4: Perform Cross-Dimer Analysis For cross-dimer analysis, click on the "Cross-Dimer" or "Hetero-Dimer" tab. In the field provided, enter the sequence of the other primer in your PCR pair (e.g., if you analyzed the forward primer, now enter the reverse primer sequence). The tool will evaluate intermolecular homology between the two primers and determine if they can form a stable hetero-dimer. The output will advise whether the primer pair can be used effectively in PCR or if redesign is necessary [2] [39].

Step 5: Interpret Results and Iterate If the tool indicates significant potential for self-dimer or cross-dimer formation, it is recommended to redesign the primer(s). The parameters "self-complementarity" and "self 3'-complementarity" should be kept as low as possible. After modifying the sequence, repeat the analysis until the tool indicates minimal dimerization risk [9].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions relevant to oligonucleotide analysis and application in PCR experiments:

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Oligonucleotide Analysis and PCR

| Reagent/Material | Function in Analysis/Experiment |

|---|---|

| Custom DNA Oligos | Serve as the primary primers or probes under analysis; the starting material for all in-silico and physical testing [2]. |

| Buffer/Water for Dilution | Used to resuspend or dilute the oligo stock solution to a desired working concentration for experimental use [2] [39]. |

| Salt Solutions (Na+, Mg2+) | Critical components of PCR buffers; their concentration directly influences the melting temperature (Tm) of primers and must be specified in the analysis tool for accurate calculations [40] [41]. |

| qPCR Probes (Dual-Labeled) | Fluorophore-labeled DNA sequences, such as TaqMan probes, used for quantification in qPCR assays; their design requires careful analysis of secondary structure and specificity similar to primers [9]. |

Data Interpretation and Key Parameters

Quantitative Guidelines for Optimal Primer Design

Successful primer design relies on balancing multiple physicochemical parameters to ensure high specificity and efficiency. The following table summarizes the optimal ranges for key properties as recommended by industry experts and implemented in design tools like those from Eurofins Genomics [9].

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters for Optimal Primer and Probe Design

| Parameter | Optimal Range for Primers | Optimal Range for Probes | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length | 18 - 24 nucleotides | 15 - 30 nucleotides | Ensures specificity and efficient hybridization [9]. |

| Melting Temp (Tm) | 54°C - 65°C (Pair Tm difference < 2°C) | N/A | Ensures synchronized primer binding during annealing [9]. |

| GC Content | 40% - 60% | 35% - 60% | Balances binding strength and specificity; prevents mismatches [9]. |

| GC Clamp | 1-3 G/Cs in last 5 bases | Avoid G at 5' end | Promotes specific binding at the 3' end; prevents fluorescence quenching in probes [9]. |

| Self-Complementarity | As low as possible | As low as possible | Minimizes primer-dimer and hairpin formation [9]. |

Advanced Specificity Controls