Primer Melting Temperature (Tm) Calculation: A 2025 Guide for Accurate PCR Optimization

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on calculating and applying primer melting temperature (Tm) for optimal PCR and qPCR results.

Primer Melting Temperature (Tm) Calculation: A 2025 Guide for Accurate PCR Optimization

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on calculating and applying primer melting temperature (Tm) for optimal PCR and qPCR results. It covers foundational thermodynamic principles, modern calculation methodologies including the SantaLucia nearest-neighbor method, practical troubleshooting for common experimental challenges, and advanced validation techniques for ensuring primer specificity and accuracy in biomedical applications.

Understanding Tm: The Fundamental Principles of DNA Melting Temperature

What is Tm? Defining the Melting Temperature in Molecular Biology

In molecular biology, the melting temperature (Tm) is a fundamental thermodynamic property defined as the temperature at which 50% of DNA duplexes are in a double-stranded state and 50% are dissociated into single strands [1] [2] [3]. This parameter serves as a critical predictor for the stability of nucleic acid hybrids, enabling researchers to optimize the specificity and efficiency of experimental techniques reliant on hybridization, such as PCR, quantitative PCR (qPCR), Southern blotting, and next-generation sequencing (NGS) [1] [4].

Understanding Tm is not merely an academic exercise; it is a practical necessity for successful experimental design. The Tm of an oligonucleotide dictates the conditions under which it will bind to its complementary sequence. An inaccurate Tm prediction can lead to experimental failures, including non-specific amplification, primer-dimer formation, or complete absence of product in PCR [5] [6]. As noted by Dr. Richard Owczarzy, a principal scientist and nucleic acid thermodynamics expert at Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT), "Tm is not a constant value, but is dependent on the conditions of the experiment" [1]. This underscores the importance of using sophisticated calculation methods that account for the full spectrum of variables influencing duplex stability.

Fundamental Principles of Tm Calculation

The transition from double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) to single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) is a cooperative process that can be measured experimentally by monitoring UV absorbance at 260 nm. As the temperature increases, the hydrogen bonds and base-stacking interactions that stabilize the double helix are disrupted, leading to a sharp increase in UV absorbance as the bases unstack—a phenomenon known as hyperchromicity [4]. The Tm is identified as the midpoint of the transition curve between the double-stranded and single-stranded states (Figure 1).

Key Calculation Methods

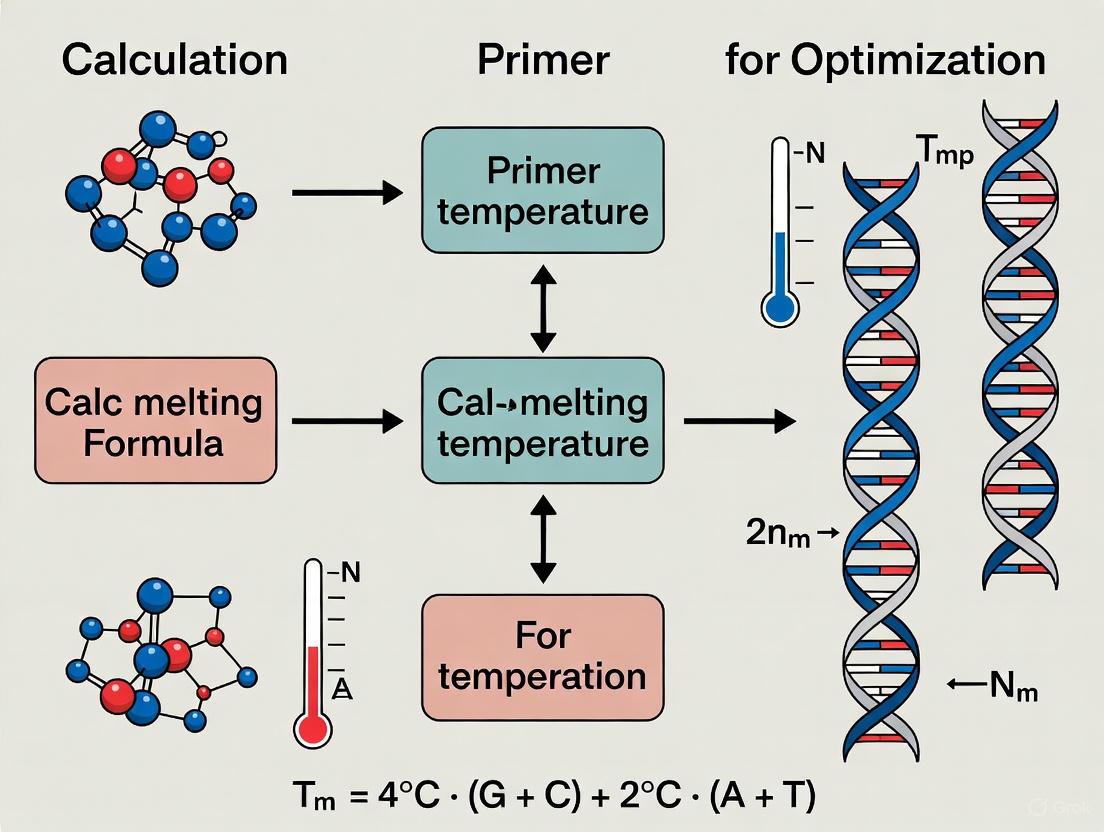

Two primary mathematical approaches are used to predict Tm: the basic method (or Wallace rule) and the more sophisticated nearest-neighbor method.

Basic Method (Wallace Rule): This is a simple, length-dependent formula often used for short oligonucleotides (approximately 14-20 nucleotides) [4] [5]. It provides a quick estimate but lacks accuracy as it does not account for sequence context or solution conditions. The standard formula is: Tm = 2 °C × (A + T) + 4 °C × (G + C) [5]. For example, for a primer with 6 A, 6 T, 3 G, and 3 C bases: Tm = 2°C × (6+6) + 4°C × (3+3) = 24 + 24 = 52°C [5].

Nearest-Neighbor Method: This is the gold standard for accurate Tm prediction, especially for longer oligonucleotides (up to 120 bases) [1] [4]. It is a thermodynamic model that considers the sequence dependence of duplex stability by summing the free energy contributions (ΔH, enthalpy; ΔS, entropy) of all adjacent base pairs (nearest neighbors) in the sequence [4]. This method can explicitly incorporate experimental conditions like salt and oligonucleotide concentration into its calculations. The complex formula is: Tm = [ΔH / (A + ΔS + R ln(C))] - 273.15 [4] Where:

- ΔH = total enthalpy change (kcal/mol)

- ΔS = total entropy change (kcal/K·mol)

- A = helix initiation constant (-0.0108 kcal/K·mol)

- R = gas constant (0.00199 kcal/K·mol)

- C = molar concentration of the oligonucleotide [4]

Table 1: Comparison of DNA Melting Temperature (Tm) Calculation Methods

| Feature | Basic Method (Wallace Rule) | Nearest-Neighbor Method |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Use Case | Quick estimates for short primers (14-20 nt) | High-accuracy predictions for assay design |

| Formula | Tm = 2°C(A+T) + 4°C(G+C) | Tm = [ΔH / (A + ΔS + R ln(C))] - 273.15 |

| Sequence Context | Not considered | Accounted for via nearest-neighbor thermodynamics |

| Solution Conditions | Not considered | Explicitly accounts for salt, oligo concentration, etc. |

| Accuracy | Lower | Higher |

Online Tm Calculation Tools

Given the complexity of the nearest-neighbor calculations, researchers typically rely on web-based calculators. Major suppliers provide these tools, which use advanced algorithms and are regularly updated.

- IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool: Part of the SciTools suite, this tool uses sophisticated models that account for sodium and magnesium ion concentrations [1].

- Thermo Fisher Tm Calculator: Calculates Tm and suggests annealing temperatures for specific DNA polymerases like Platinum SuperFi and Phusion [7].

- Tm Tool (University of Utah): A web-based application that predicts Tm using the nearest-neighbor method with adjustments for laboratory conditions [3].

Critical Factors Influencing Tm

The Tm of an oligonucleotide is not an intrinsic property; it is highly dependent on several experimental variables. Optimizing an assay requires a clear understanding of how these factors influence hybridization stability.

Oligonucleotide Sequence Characteristics:

- GC Content: Guanine-cytosine (GC) base pairs, stabilized by three hydrogen bonds, confer greater stability to a duplex than adenine-thymine (AT) pairs, which have only two. Consequently, a higher GC content results in a higher Tm [5]. primers should generally have a GC content between 40–60% for optimal performance [6].

- Length: Longer oligonucleotides have more stabilizing base-pair interactions and therefore a higher Tm [5].

- Sequence Context: The identity of adjacent base pairs (e.g., stacking a G-C pair next to an A-T pair) affects stability, a factor considered in the nearest-neighbor model [4].

Experimental Conditions:

- Oligo Concentration: Tm varies with the total concentration of the interacting strands. In PCR, where the primer is in excess, the primer concentration determines the Tm. Concentration alone can cause Tm to vary by about ±10°C [1].

- Salt and Ion Concentration: Cations in solution neutralize the negative charges on the DNA phosphate backbone, stabilizing the duplex. Monovalent ions (e.g., Na⁺, K⁺) and divalent ions (e.g., Mg²⁺) both raise the Tm, with divalent cations like Mg²⁺ having a more profound effect. A shift from 20-30 mM Na⁺ to 1 M Na⁺ can increase Tm by as much as 20°C [1] [8]. It is crucial to note that it is the concentration of free Mg²⁺ that is relevant, as it can be bound by dNTPs and other solution components [1].

- Mismatches and SNPs: A single base mismatch between a primer and its template can reduce the Tm by anywhere from 1°C to 18°C, depending on the identity of the mismatch, its sequence context, and the solution composition. For instance, A-A and A-C mismatches are among the least stable, while G-T mismatches are more stable [1].

- Chemical Additives: Reagents like dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and urea destabilize duplexes and lower the Tm. It has been reported that 10% DMSO decreases the Tm by 5.5–6.0°C [9].

Table 2: Factors Affecting DNA Melting Temperature (Tm)

| Factor | Effect on Tm | Practical Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| GC Content | Higher GC content increases Tm. | Aim for 40-60% GC in primer design [6]. |

| Length | Longer sequences increase Tm. | Design primers 18-25 nucleotides long [6]. |

| Oligo Concentration | Higher concentration increases Tm. | In PCR, the primer in excess dictates Tm [1]. |

| Divalent Cations (Mg²⁺) | Increase Tm significantly. | Optimize Mg²⁺ concentration; 1.5-2.0 mM is typical for Taq [6]. |

| Monovalent Cations (Na⁺/K⁺) | Increase Tm. | Standard PCR buffers often contain 50 mM KCl [8]. |

| Mismatches | Decrease Tm. | Check for SNPs in primer binding sites [1]. |

| DMSO | Decreases Tm. | Lower annealing temperature if using DMSO for GC-rich templates [9]. |

Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol 1: Calculating Tm and Annealing Temperature for PCR

This protocol outlines the steps for determining the Tm of PCR primers and selecting an optimal annealing temperature using online tools, a critical step for assay specificity and yield [7] [9].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- DNA Polymerase: Select a polymerase (e.g., Platinum SuperFi, Phusion, Taq) based on fidelity, speed, and template requirements [7] [6].

- Primers: Forward and reverse oligonucleotides, typically 18-25 nucleotides in length, with balanced GC content (40-60%) and closely matched Tms [6].

- dNTPs: Deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP), typically used at 200 µM each. Higher concentrations can reduce fidelity [6].

- MgCl₂ or MgSO₄: A required cofactor for DNA polymerases. The free concentration must be optimized, as it is chelated by dNTPs and the DNA template [8] [6].

- Reaction Buffer: Provides optimal pH, salt (e.g., 50 mM KCl), and stabilizers for the polymerase [6].

Procedure:

- Design Primers: Follow standard design rules: length of 18-25 nt, GC content of 40-60%, and avoidance of self-complementarity or primer-dimer formation [6].

- Calculate Tm: Use an online calculator like the IDT OligoAnalyzer or Thermo Fisher Tm Calculator [1] [7].

- Select Annealing Temperature (Ta): The annealing temperature is typically set 3–5°C below the calculated Tm of the lower-melting primer for standard polymerases like Taq [6]. For high-fidelity polymerases like Phusion or Phire, follow specific guidelines:

- For primers ≤20 nt, use the lower Tm given by the calculator.

- For primers >20 nt, use an annealing temperature 3°C higher than the lower Tm [9].

- Empirical Optimization: If amplification fails or is non-specific, perform a temperature gradient PCR. Test a range of annealing temperatures from 5–10°C below to 2–5°C above the calculated Ta to empirically determine the optimal condition [7] [9].

Protocol 2: Designing Probes for Mismatch Discrimination

The ability to distinguish a single nucleotide difference (e.g., a SNP) is crucial for genotyping, mutation detection, and diagnostic assays. This is achieved by designing probes where the mismatch has a maximal destabilizing effect [1].

Procedure:

- Identify the Target SNP: Verify the SNP and its context using databases like NCBI's dbSNP [1].

- Design Shorter Probes: Shorter probes are more sensitive to the destabilizing effect of a mismatch, providing better discrimination. However, this also lowers the overall Tm [1].

- Check Both Strands: The type of mismatch formed depends on which DNA strand (sense or antisense) the probe binds. Calculate the Tm for both scenarios using an online tool that allows for mismatch input, such as the IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool [1].

- Position the Mismatch Centrally: The destabilizing effect of a mismatch is greatest when it is located in the central region of the probe, rather than near the ends [1].

- Consider Stabilizing Modifications: If shorter probes result in a Tm that is too low for the assay, incorporate modified bases such as Locked Nucleic Acids (LNAs, e.g., Affinity Plus bases). These modifications increase the probe's Tm and stability, allowing for the use of shorter, more discriminatory sequences without sacrificing hybridization energy [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Tm-Based Experiments

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Nucleic Acid Hybridization Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Enzymes with proofreading activity for high-accuracy amplification. | Phusion or PrimeSTAR polymerases for cloning and sequencing applications [9] [8]. |

| Hot Start DNA Polymerase | Polymerase activated only at high temperatures, reducing non-specific amplification. | Phire Hot Start DNA Polymerase for improved PCR specificity [9]. |

| dNTP Mix | Equimolar mixture of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP; the building blocks for DNA synthesis. | Standard PCR amplification; use 200 µM of each dNTP for balance of yield and fidelity [6]. |

| MgCl₂ Solution | Source of Mg²⁺ ions, an essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity. | Optimization of PCR; titrate from 1.5 to 4.0 mM for specific primer-template systems [6]. |

| PCR Buffer with KCl | Provides optimal ionic strength and pH for polymerase activity and primer-template hybridization. | Standard PCR with Taq polymerase; typically contains 50 mM KCl [8] [6]. |

| DMSO (Dimethyl Sulfoxide) | Additive that destabilizes DNA duplexes, aiding in the amplification of GC-rich templates. | Add at 2.5-5% to improve amplification of difficult, GC-rich templates [8]. |

| Online Tm Calculator | Web tool for predicting oligonucleotide Tm using thermodynamic models. | IDT OligoAnalyzer or Thermo Fisher Tm Calculator for primer and probe design [1] [7]. |

| Locked Nucleic Acids (LNA) | Modified nucleotide analogs that increase duplex stability and Tm. | Incorporating into short probes to enhance mismatch discrimination while maintaining a workable Tm [1]. |

The melting temperature (Tm) is a cornerstone parameter in molecular biology that bridges the gap between theoretical oligonucleotide design and successful experimental execution. A deep understanding of its definition, the factors that influence it, and the methods for its accurate calculation is non-negotiable for researchers aiming to develop robust and specific hybridization-based assays. While simple formulas offer a starting point, the use of sophisticated online calculators based on the nearest-neighbor thermodynamic method is strongly recommended for critical applications. By systematically applying the principles and protocols outlined in this article—from calculating Tm and selecting annealing temperatures to designing probes for SNP discrimination—scientists can significantly enhance the reliability and efficiency of their work in PCR, diagnostics, and genetic research.

The Melting Temperature (Tm) of a primer is a fundamental physicochemical property defined as the temperature at which 50% of the DNA duplex remains hybridized with its complementary sequence and 50% dissociates into single strands [3]. In the context of the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), precise knowledge and calculation of primer Tm is not merely a theoretical exercise but a critical prerequisite for experimental success. It serves as the primary determinant for setting the annealing temperature (Ta), which directly controls the stringency of primer-binding to the template DNA [10] [11]. An accurately optimized Ta, derived from a correctly calculated Tm, ensures that primers bind specifically to their intended target sequences, thereby maximizing amplification yield and specificity while minimizing non-specific products such as primer-dimers and spurious amplicons [11].

The critical relationship between Tm and the overall PCR process is outlined below, showing how Tm calculation influences experimental setup and outcomes.

Calculating Primer Melting Temperature

Fundamental Calculation Methods

Several mathematical approaches exist for calculating Tm, ranging from simple empirical formulas to complex thermodynamic models. The choice of method depends on primer length, sequence composition, and the required level of precision [12] [10].

Basic Rule-of-Thumb Method: For a quick estimate, the simplest formula is

Tm = 4(G + C) + 2(A + T), where G, C, A, and T represent the number of respective nucleotides in the primer sequence [10]. This method provides a rough approximation but does not account for critical factors like salt concentration, which can significantly alter actual Tm values.Salt-Adjusted Calculation: For greater accuracy, a formula that incorporates salt concentration is recommended:

Tm = 81.5 + 16.6(log[Na+]) + 0.41(%GC) - 675/primer length[10]. This calculation accounts for the stabilizing effect of monovalent cations on DNA duplex formation.Nearest-Neighbor Method: Recognized as the most accurate approach, this thermodynamic model considers the stability of every adjacent dinucleotide pair in the oligo sequence, along with precise concentrations of salts and primers [10] [7]. The modified Allawi & SantaLucia's thermodynamics method, used in sophisticated online calculators, applies this principle with parameters specifically adjusted to maximize PCR specificity and yield [7].

Comparison of Tm Calculation Methods

Table 1: Key methods for calculating primer melting temperature (Tm).

| Method | Formula | Best For | Key Assumptions/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Rule-of-Thumb | Tm = 4(G+C) + 2(A+T) |

Quick estimates, initial design | Assumes standard conditions; less accurate [12] [10]. |

| Salt-Adjusted | Tm = 81.5 + 16.6(log[Na+]) + 0.41(%GC) - 675/length |

General laboratory use | Accounts for [Na+]; assumes pH ~7 [10]. |

| Nearest-Neighbor | Complex; based on ΔG of dinucleotide pairs | High-fidelity applications, critical assays | Requires software; accounts for sequence, [salts], and [primer] [7] [10]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting the appropriate Tm calculation method based on experimental requirements.

Experimental Protocols for Tm-Dependent PCR Optimization

Protocol 1: Gradient PCR for Empirical Annealing Temperature Determination

This protocol provides a systematic method for determining the optimal annealing temperature (Ta) for a primer pair, which is typically 3–5°C below the calculated Tm [10].

Materials:

- Thermostable DNA polymerase and its compatible reaction buffer

- dNTP mix

- Template DNA

- Forward and reverse primers

- Thermal cycler with gradient functionality

Procedure:

- Calculate Tm: Determine the Tm for both forward and reverse primers using the nearest-neighbor method via a reliable online calculator [7].

- Prepare Master Mix: Create a PCR master mix containing all reaction components except template DNA, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Aliquot and Add Template: Distribute the master mix into individual PCR tubes, then add template DNA to each.

- Set Gradient: Program the thermal cycler with a gradient across the block that spans a temperature range from 5°C below the lowest primer Tm to 5°C above it [10].

- Run PCR: Initiate the cycling protocol, which typically includes: initial denaturation (94–98°C for 1–3 min); 25–35 cycles of denaturation (94–98°C for 15–30 s), gradient annealing (30 s), and extension (68–72°C for 1 min/kb); final extension (72°C for 5–10 min) [10].

- Analyze Results: Separate PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis. The optimal Ta produces a single, intense band of the expected size with minimal to no non-specific amplification.

Protocol 2: MgCl₂ Concentration Optimization Based on Tm and Primer Properties

Mg²⁺ is an essential cofactor for DNA polymerase, and its optimal concentration is influenced by primer characteristics and Tm. Recent research has enabled predictive modeling of MgCl₂ requirements with high accuracy (R² = 0.9942) [13].

Materials:

- MgCl₂ stock solution (typically 25–50 mM)

- PCR components as listed in Protocol 1

Procedure:

- Prepare Mg²⁺ Titration Series: Create a series of PCR master mixes with MgCl₂ concentrations ranging from 1.0 to 4.0 mM in 0.5 mM increments.

- Utilize Predictive Modeling (Optional): For a theoretically informed starting point, apply the predictive equation from recent research:

(MgCl₂) ≈ 1.5625 + (-0.0073 × Tm) + (-0.0629 × GC) + (0.0273 × L) + (0.0013 × dNTP) + (-0.0120 × Primers) + (0.0007 × Polymerase) + (0.0012 × log(L)) + (0.0016 × Tm_GC) + (0.0639 × dNTP_Primers) + (0.0056 × pH_Polymerase)[13]. - Run PCR: Amplify using the established Ta from Protocol 1.

- Analyze Results: Identify the MgCl₂ concentration that yields the highest quantity of specific product with minimal background.

Table 2: Relative importance of variables in predicting optimal MgCl₂ concentration [13].

| Variable | Relative Importance (%) |

|---|---|

| dNTP_Primers Interaction | 28.5% |

| GC Content | 22.1% |

| Amplicon Length (L) | 15.7% |

| Primer Tm | 12.3% |

| Primer Concentration | 8.9% |

| pH_Polymerase Interaction | 5.6% |

| Tm_GC Interaction | 3.2% |

| log(Amplicon Length) | 2.1% |

| dNTP Concentration | 1.1% |

| Polymerase Concentration | 0.5% |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for PCR Optimization

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions for enhancing PCR specificity and efficiency.

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Purpose | Optimal Concentration | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| TMA Oxalate | Novel enhancer that increases specificity and yield of specific PCR products [14]. | 2 mM | Maximum specificity (1.0) and efficiency (2.2) observed at this concentration [14]. |

| DMSO (Dimethyl Sulfoxide) | Disrupts secondary structures; lowers effective Tm particularly for GC-rich templates (>65%) [11]. | 2–10% | 10% DMSO decreases annealing temperature by 5.5–6.0°C [10]. |

| Betaine | Homogenizes thermodynamic stability of DNA; reduces the dependence of duplex stability on base composition [11]. | 1–2 M | Especially useful for long-range PCR and GC-rich templates [11]. |

| Formamide | Increases specificity of amplification; can improve efficiency [14]. | 0.5 M | Maximal efficiency of 1.4 observed at this concentration [14]. |

| MgCl₂ | Essential cofactor for DNA polymerase; stabilizes primer-template duplex [11]. | 1.5–2.5 mM (typical) | Concentration must be optimized; significantly affects fidelity and specificity [13] [11]. |

| High-Fidelity Polymerase Blends | Enzyme mixtures providing proofreading (3'→5' exonuclease) activity for accurate DNA replication [11]. | Manufacturer specified | Reduces error rates from ~1 x 10⁻⁵ (Taq) to as low as ~3 x 10⁻⁶ [11]. |

Advanced Considerations and Troubleshooting

Impact of PCR Additives on Tm Calculation

The presence of enhancers and cosolvents in PCR reactions necessitates adjustments to calculated Tm values. For instance, the addition of 10% DMSO typically lowers the effective annealing temperature by 5.5–6.0°C [10]. Similarly, substitution of dGTP with 7-deaza-dGTP also decreases Tm. When using these additives, the annealing temperature should be adjusted empirically, starting with a temperature 3–5°C lower than the calculated Tm and optimizing from there. This is particularly crucial when amplifying challenging templates such as those with high GC content (>65%), where additives like DMSO or betaine are commonly employed to improve yield [11].

Universal Annealing Temperature Systems

Recent advancements in PCR buffer formulation have led to the development of specialized systems that enable a universal annealing temperature (e.g., 60°C) regardless of primer Tm variations [7]. These systems incorporate isostabilizing components that increase the stability of primer-template duplexes during the annealing step [10]. For DNA polymerases such as Platinum II Taq, Platinum SuperFi II, and Phusion Plus, specially formulated buffers eliminate the need for Tm calculation and individual annealing temperature optimization, streamlining experimental workflow [7]. These developments are particularly valuable in high-throughput settings where multiple primer pairs with different Tm values are used simultaneously.

Troubleshooting Common Tm-Related PCR Issues

- No/Low Amplification: This often results from an annealing temperature that is too high. Lower the Ta in increments of 2–3°C, ensuring it does not fall more than 5°C below the primer Tm [10]. Also verify Mg²⁺ concentration and primer design.

- Non-Specific Bands/Multiple Bands: Typically caused by an annealing temperature that is too low. Increase Ta in increments of 2–3°C up to the extension temperature [10] [11]. Alternatively, use a hot-start polymerase or optimize Mg²⁺ concentration.

- PCR Efficiency in qPCR: For accurate quantification in real-time PCR, assays should be designed to achieve 100% geometric efficiency, where the amount of product doubles each cycle [15]. Assays with efficiencies significantly different from 100% complicate data analysis, particularly when using the ΔΔCt method for quantification [15] [16].

The accurate prediction of primer melting temperature (Tm) is a cornerstone of successful molecular biology research, directly impacting the specificity and efficiency of techniques such as PCR, qPCR, and next-generation sequencing. This application note details the core biochemical factors governing Tm—sequence composition, length, and GC content—and provides validated protocols for their precise calculation and application. By integrating thermodynamic models and modern computational tools, researchers can standardize assay design, thereby enhancing reproducibility and reliability in diagnostic and therapeutic development pipelines.

In polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and its derivatives, the melting temperature (Tm) of an oligonucleotide is the temperature at which 50% of the DNA duplex dissociates into single strands. This parameter fundamentally controls the annealing step, where primers bind to the template DNA. An inaccurately predicted Tm can lead to assay failure through non-specific amplification, primer-dimer formation, or complete absence of product, compromising data integrity in fields from basic research to clinical diagnostics [17] [18]. The shift from simple, rule-based Tm calculations to sophisticated thermodynamic models has been driven by the demanding precision required in modern applications, including single-cell sequencing and CRISPR-based editing, where even minor Tm inconsistencies can cause significant sequence dropouts or biased results [19]. This document delineates the key factors influencing Tm and provides a rigorous framework for its determination.

Core Factors Influencing Melting Temperature

The stability of a DNA duplex, and consequently its Tm, is governed by the sum of the energetic contributions of its constituent nucleotides and their interactions with the reaction environment.

Sequence Composition and Nearest-Neighbor Thermodynamics

The sequence composition's impact on Tm is most accurately captured by the nearest-neighbor model, the current gold standard in Tm prediction. Unlike simplistic methods that consider only base composition, this model accounts for the sequence context by quantifying the stacking energy between adjacent base pairs.

- Thermodynamic Basis: The model sums the enthalpy (ΔH°) and entropy (ΔS°) changes for the ten possible dinucleotide pairs. For instance, a 5'-GC-3' pair, with its three hydrogen bonds, contributes more stability than a 5'-AT-3' pair, which has only two [19].

- Accuracy: This method achieves precision within 1-2°C of experimental values, a significant improvement over the ±5-10°C error of basic GC% formulas [20] [19].

Calculation Foundation: The fundamental Tm calculation formula for a monovalent salt solution is:

Tm = (ΔH° / (ΔS° + R × ln(Ct/4))) - 273.15 + 16.6 × log₁₀[Na⁺]

Where ΔH° and ΔS° are the sum of the nearest-neighbor values, R is the gas constant, and Ct is the total oligonucleotide concentration [19].

Oligonucleotide Length

The length of the oligonucleotide directly influences the total stabilizing energy of the duplex. Longer primers have more dinucleotide stacking interactions, leading to a higher Tm.

- Optimal Range: For most PCR applications, an optimal primer length is between 18 and 24 nucleotides [11]. This provides sufficient sequence for specific binding while avoiding overly high Tm that could reduce annealing efficiency.

- Diminishing Returns: The relationship between length and Tm is not linear. The incremental stability added by each base pair decreases with increasing length, causing Tm to plateau.

GC Content

GC content is a primary, though incomplete, indicator of duplex stability. The proportion of guanine (G) and cytosine (C) bases in a sequence is critical because GC base pairs form three hydrogen bonds, making them more thermally stable than AT base pairs, which form only two.

- Optimal Range: The ideal GC content for primers is between 40% and 60% [19] [11].

- Low GC Content (<30%): Results in unstable priming and low reaction yield due to weak binding [19].

- High GC Content (>70%): Promotes the formation of stable secondary structures (e.g., hairpins) and increases the risk of non-specific binding, challenging assay specificity [19] [11].

Table 1: Summary of Core Factors Influencing Tm

| Factor | Mechanism of Influence | Optimal Range | Impact on Tm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Composition | Sum of dinucleotide stacking energies (nearest-neighbor model) | N/A | High predictive accuracy (±1-2°C); core to modern calculation |

| Oligonucleotide Length | Total number of stabilizing base-pair interactions | 18-24 nucleotides | Longer sequences have higher Tm; effect plateaus |

| GC Content | Proportion of strong 3-hydrogen-bond GC pairs | 40-60% | Higher GC content significantly increases Tm and stability |

Experimental Protocols for Tm Determination and Verification

Protocol: In-silico Tm Calculation Using the Nearest-Neighbor Method

This protocol outlines the steps for obtaining a theoretically accurate Tm using a SantaLucia-based online calculator, suitable for designing individual primers or small sets.

1. Access the Tool: Navigate to a publicly available Tm calculator that implements the SantaLucia nearest-neighbor method with Owczarzy salt corrections, such as the OligoPool tool [20].

2. Enter Sequence: Paste the oligonucleotide sequence (DNA or RNA) into the input field. The sequence can include spaces and line breaks; the tool will automatically sanitize the input. Example: ATCGATCGATCGATCGATCG [20].

3. Set Reaction Conditions: Input the specific chemical conditions of your assay [20] [19]:

- Na⁺ Concentration: 50 mM for standard PCR.

- Mg²⁺ Concentration: 1.5-2.5 mM for standard PCR. *Note: Mg²⁺ has a stronger stabilizing effect than Na⁺ and must be accounted for using specific correction formulas [19].

- Oligonucleotide Concentration: 0.25 µM is a standard default for primers.

- DMSO: If used, input the percentage (e.g., 5%). DMSO reduces Tm by ~0.5-0.7°C per 1% [20] [19]. 4. Calculate and Interpret: Execute the calculation. The tool will return the Tm, thermodynamic parameters (ΔH, ΔS), GC%, and length. For PCR, the annealing temperature (Ta) is typically set 3-5°C below the calculated Tm [20].

Protocol: Empirical Validation of Tm via Gradient PCR

Theoretical Tm values should be empirically verified, especially for critical assays. Gradient PCR is the standard method for this.

1. Primer-Template System: Prepare a standard PCR mixture containing your target template and the designed primer pair. 2. Thermal Cycler Setup: Program the thermal cycler with a gradient across the annealing step, spanning a range of at least 5°C above and below the predicted Tm. 3. Amplification and Analysis: Run the PCR and analyze the products using gel electrophoresis. 4. Determine Optimal Ta: Identify the annealing temperature that produces the highest yield of the specific target product with minimal non-specific amplification or primer-dimer. This empirically determined Ta validates the accuracy of the theoretical Tm and refines the assay conditions [11].

Table 2: Comparison of Tm Calculation Software

| Software Tool | Calculation Method | Reported Accuracy | Key Features | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OligoPool Calculator | SantaLucia Nearest-Neighbor | ±1-2°C [20] | Owczarzy Mg²⁺ correction, batch processing | General PCR, high-accuracy research |

| Primer3 Plus | Nearest-Neighbor | Best-in-class per study [17] | Integrated primer design & analysis | Holistic PCR assay design |

| Primer-BLAST | Nearest-Neighbor | Best-in-class per study [17] | Combines design with specificity check | Ensuring primer specificity |

| NEB Tm Calculator | Proprietary Nearest-Neighbor | ±2-3°C [20] | Optimized for NEB polymerases | Using NEB enzyme/buffer systems |

| IDT OligoAnalyzer | Nearest-Neighbor | ±2-3°C [20] | User-friendly, additional analysis | Quick checks, secondary structure |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PCR and Tm-Dependent Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Polymerase (e.g., Pfu, KOD) | DNA polymerase with 3'→5' exonuclease (proofreading) activity. | Reduces error rate to ~1 x 10⁻⁶ for cloning and sequencing [11]. |

| Hot-Start Taq Polymerase | Enzyme engineered for inactivity at room temperature. | Prevents non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation prior to thermal cycling [11]. |

| DMSO (Dimethyl Sulfoxide) | A chemical additive that disrupts secondary structures. | Use at 2-10% to lower Tm and improve amplification of GC-rich templates (>65% GC) [19] [11]. |

| Betaine | A chemical additive that homogenizes DNA duplex stability. | Use at 1-2 M to improve the amplification of long or complex templates [11]. |

| MgCl₂ Solution | Source of Mg²⁺, an essential cofactor for polymerase activity. | Concentration must be optimized (typically 1.5-2.5 mM); significantly affects Tm, fidelity, and yield [19] [11]. |

| Synthetic Oligo Pool | Defined mixtures of oligonucleotides synthesized in parallel. | Essential for screening applications (e.g., CRISPR); require uniform Tm (±5°C) for consistent performance [21] [19]. |

Workflow and Relationship Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for designing and validating primers, integrating the key factors influencing Tm and the experimental protocols for verification.

Tm Determination and Primer Validation Workflow

Precision in Tm prediction is not merely a theoretical exercise but a practical necessity for robust and reproducible molecular assays. By understanding and applying the principles of sequence composition, length, and GC content through the framework of nearest-neighbor thermodynamics, researchers can systematically eliminate a major source of experimental variability. The integration of reliable in-silico tools with empirical validation, as outlined in these protocols, provides a clear path to optimizing PCR conditions, ultimately enhancing the fidelity of results in genomics, diagnostics, and drug development.

The Evolution from Simple Formulas to Advanced Thermodynamic Models

The accurate prediction of primer melting temperature (Tm) is a cornerstone of molecular biology, directly influencing the success of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and related techniques. The evolution from simple, rule-based formulas to sophisticated thermodynamic models represents a significant advancement in the field of assay design and optimization. This evolution has been driven by the growing demand for precision in diagnostic applications, high-throughput genomic studies, and genetic engineering. Early methods provided rough approximations sufficient for basic applications, while modern approaches incorporate comprehensive thermodynamic parameters that more accurately reflect the complex biochemical reality of nucleic acid hybridization. This application note traces this technological journey, detailing the underlying principles, practical methodologies, and reagent solutions that empower researchers to achieve superior experimental outcomes through thermodynamically-informed primer design.

From Rule-Based Calculations to Thermodynamic Predictions

Historical Foundations and Simple Formulas

The initial methods for Tm calculation relied on simple formulas derived from empirical observations. The most iconic among these is the Wallace rule, which states that Tm ≈ 2°C × (A+T) + 4°C × (G+C) for primers shorter than 20 nucleotides. Similarly, the %GC method estimated Tm as the sum of the product of GC percentage and a constant factor, often Tm = 81.5 + 0.41(%GC) - (675/length). These heuristic approaches provided a starting point but suffered from significant limitations. They largely ignored the sequence context of the nucleotides, treating all base pairs as contributing independently to duplex stability, which fails to capture the nuanced energetics of DNA hybridization. Consequently, these methods often resulted in discrepancies between predicted and experimental Tm values, leading to suboptimal PCR conditions and failed experiments [17].

The Advent of the Nearest-Neighbor Model

The development of the nearest-neighbor model marked a paradigm shift in Tm prediction. This model is grounded in the understanding that the stability of a DNA duplex depends not only on its base composition but also critically on the sequence context—specifically, how each base pair stacks upon its neighboring base pairs. The model assigns thermodynamic parameters (ΔH°: enthalpy change; ΔS°: entropy change) for all ten possible combinations of neighboring base pairs (AA/TT, AT/TA, TA/AT, CA/GT, GT/CA, CT/GA, GA/CT, CG/GC, GC/CG, GG/CC). The total free energy change (ΔG°) for duplex formation is calculated by summing these individual nearest-neighbor contributions along with initiation and symmetry terms. The Tm is then derived from the relationship Tm = ΔH°/(ΔS° + R ln(Ct)) - 273.15 + 16.6 log10([Na+]), where R is the gas constant and Ct is the total strand concentration [17].

This approach was significantly refined through the extensive experimental work of SantaLucia and colleagues, who provided a unified set of thermodynamic parameters that have become the standard for accurate Tm calculation [17] [22]. The superiority of the nearest-neighbor model lies in its ability to account for the fact that the stability of a duplex can vary dramatically depending on the order of its nucleotides, even for sequences with identical length and GC content.

Integration of Reaction Conditions and Modern Computational Tools

Modern Tm prediction has evolved further by integrating the nearest-neighbor model with detailed considerations of the reaction environment. Key factors such as monovalent (e.g., Na+) and divalent (e.g., Mg2+) cation concentrations, which stabilize the duplex by shielding the negatively charged phosphate backbone, are now routinely incorporated into calculations [13]. The critical influence of MgCl2 concentration on amplification specificity and primer annealing has been formally modeled using multivariate Taylor series expansions and thermodynamic functions, achieving remarkable predictive accuracy (R² = 0.9942) [13].

This advanced understanding is embedded in contemporary primer design software. A comparative study of 22 Tm calculator tools demonstrated that programs implementing the full nearest-neighbor model with salt correction, notably Primer3 Plus and Primer-BLAST, provide Tm predictions closest to experimentally determined values [17]. These tools have become indispensable for researchers, moving beyond simple Tm calculation to evaluate primer specificity, secondary structure formation, and potential off-target binding, thereby ensuring robust assay design [22].

Table 1: Comparison of Tm Calculation Methods

| Method | Underlying Principle | Key Input Parameters | Accuracy & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wallace Rule (Simple Formula) | Empirical; linear combination of A-T and G-C counts. | Primer length, base count. | Low accuracy; only suitable for very short primers. |

| %GC Method (Simple Formula) | Linear relationship with GC content. | Primer length, GC percentage. | Low accuracy; ignores sequence context and reaction conditions. |

| Nearest-Neighbor Model | Thermodynamic sum of base-pair stacking energies. | Primer sequence, oligonucleotide concentration, salt concentration. | High accuracy; accounts for sequence context; basis for modern software. |

Advanced Thermodynamic Integration in Primer Design

The progression of thermodynamic models has enabled the development of sophisticated primer design tools that transcend mere Tm calculation. These tools leverage state-of-the-art DNA binding affinity computations and chemical reaction equilibrium analysis to predict overall PCR efficiency and specificity.

The Pythia Algorithm: A Thermodynamic Framework

The Pythia primer design method exemplifies this advanced approach. It directly integrates DNA binding affinity and folding stability computations into the design process. Pythia employs statistical mechanical models to calculate the binding affinity between all relevant DNA dimers (e.g., primer-template, primer-primer) and the folding energy of individual nucleic acid molecules to predict structures like hairpins. These energetic calculations are then fed into a chemical reaction equilibrium analysis [23].

This analysis considers a system of 11 competing simultaneous reactions that can occur in a PCR mix, including primer folding, primer dimerization, primers binding to off-target template regions, and the desired priming reaction. By minimizing the Gibbs energy of the system, the model determines the equilibrium concentrations of all chemical species. The primer pair quality is then characterized by the minimum of the fractions of left and right primers binding to their correct binding sites under idealized late-stage PCR conditions. This provides a physically meaningful, conservative measure of PCR efficiency derived from first principles, moving beyond arbitrary weighted scoring metrics [23].

Thermodynamic Specificity Assessment

Beyond efficiency, thermodynamic principles are crucial for assessing primer specificity. Following the heuristic proposed by Miura et al. and used in Pythia, the shortest suffix (3'-end sequence) of a primer that would bind stably at equilibrium is determined. This sequence is then used to search for exact matches within a precomputed genomic index. This method leverages the thermodynamic stability of the 3'-terminal region, which is critical for polymerase extension, to predict and minimize off-target amplification [23].

Experimental Protocols for Validation and Optimization

While computational design has become highly sophisticated, empirical validation and optimization remain essential. The following protocols provide a systematic framework for this process.

Protocol 1: In Silico Primer Design with Thermodynamic Parameters

This protocol leverages modern software to design primers based on advanced thermodynamic models.

- Sequence Acquisition and Alignment: Obtain the complete target sequence. If working with a gene family or in a species with a sequenced genome, retrieve all homologous sequences and perform a multiple sequence alignment to identify unique single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) for designing sequence-specific primers [24].

- Software Selection and Parameter Setting: Use a tool with robust thermodynamic prediction, such as Primer3 Plus or Primer-BLAST [17]. For Primer-BLAST, the default thermodynamic parameters are "SantaLucia 1998" for both the thermodynamic table and salt correction [22].

- Constraint Definition:

- Set the product size range (e.g., 85-125 bp for qPCR).

- Define the primer length (typically 18-25 bases).

- Set the Tm range for both forward and reverse primers to be within 5°C of each other, ideally between 50-72°C [25].

- Set the GC content to 40-60%.

- Avoid repeats and stable secondary structures at the 3'-end.

- Specificity Check: In Primer-BLAST, select the appropriate organism database (e.g., "Refseq mRNA" or "Refseq representative genomes") to ensure primers are specific to the intended target and do not amplify unintended genomic regions [22].

- Output Analysis: Select candidate primer pairs from the output. Manually verify the absence of stable hairpins or significant self-complementarity, especially at the 3'-ends, which can lead to primer-dimer artifacts.

Protocol 2: Stepwise Optimization of Real-Time PCR Assays

Computational design must be followed by wet-lab optimization to account for the complex biological reality [24] [25].

- Primer Preparation: Resuspend desalted or HPLC-purified primers in nuclease-free water to a stock concentration (e.g., 100 µM). Determine the exact concentration spectrophotometrically and dilute to a working concentration (e.g., 10 µM). Aliquot to prevent degradation from freeze-thaw cycles [25].

- Annealing Temperature (Ta) Optimization: Perform a temperature gradient PCR. Center the gradient around the predicted Tm (e.g., Tm ± 5°C). Analyze the PCR products using gel electrophoresis. The optimal Ta is the highest temperature that yields a single, strong band of the expected size.

- Primer Concentration Optimization: Using the optimal Ta, test a range of final primer concentrations (e.g., 0.05 - 1.0 µM) in a standard qPCR reaction [25]. The ideal concentration produces the lowest Cq value without increasing non-specific background.

- Efficiency and Standard Curve Validation: Prepare a serial dilution (at least 5 points) of the target cDNA or DNA template. Run qPCR with the optimized conditions. Generate a standard curve by plotting the Cq values against the log of the template concentration.

- The amplification efficiency (E) is calculated as E = (10^(-1/slope) - 1) × 100%.

- The ideal efficiency is 100% (slope = -3.32), with an acceptable range of 90-110% (R² ≥ 0.99) [24].

- Final Validation: Use the optimized protocol to run experimental samples and confirm specificity through melt curve analysis, showing a single, sharp peak.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Thermodynamic Optimization

| Reagent/Material | Function in Optimization | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Catalyzes DNA synthesis from primers. | Proofreading activity reduces errors; different polymerases may have varying buffer formulations. |

| MgCl₂ Solution | Essential co-factor for polymerase activity; influences Tm and specificity. | Concentration is critical; optimal level is often determined empirically (e.g., 1.5-3.5 mM) [13]. |

| dNTP Mix | Building blocks for new DNA strands. | Balanced concentration is necessary to prevent misincorporation; competes with primers for Mg²⁺. |

| Thermostable Buffer | Provides optimal chemical environment (pH, salts) for polymerization. | Buffer composition (e.g., KCl, (NH₄)₂SO₄) affects primer Tm and should match calculator assumptions. |

| Template DNA/cDNA | The target sequence to be amplified. | Quality and quantity must be high; serial dilutions for standard curves must be accurate. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental workflow for advanced, thermodynamically-driven primer design and validation.

The evolution of primer melting temperature prediction from simple formulas to advanced thermodynamic models has fundamentally transformed molecular assay design. This journey reflects a broader shift in biology towards quantitative, physics-based approaches that offer greater predictive power and experimental robustness. Modern tools, grounded in the nearest-neighbor model and integrated with chemical equilibrium analysis, allow researchers to design primers with high efficiency and specificity, even in challenging genomic contexts. However, the most successful protocols combine these powerful in silico predictions with rigorous empirical validation, creating a feedback loop that further refines our theoretical understanding. As thermodynamic models continue to incorporate more variables and machine-learning approaches enhance their accuracy, the future promises even more precise and reliable design capabilities, accelerating discovery and diagnostics across the life sciences.

DNA melting temperature (Tm) is a fundamental thermodynamic property critical for optimizing molecular biology techniques such as PCR, hybridization probes, and genotyping assays. This application note details experimental protocols for visualizing and quantifying the DNA melting process, framed within the context of primer Tm calculation for optimization research. We provide methodologies for both ultraviolet (UV) absorbance and fluorescence-based melting analysis, enabling researchers to accurately determine Tm values essential for experimental design. The protocols include detailed workflows, reagent specifications, and data analysis procedures to ensure reproducible results across applications from basic research to drug development.

DNA melting, or denaturation, describes the temperature-dependent separation of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) into single-stranded DNA (ssDNA). This process is central to many molecular techniques, particularly polymerase chain reaction (PCR), where the accuracy of primer melting temperature (Tm) calculation directly impacts amplification specificity, sensitivity, and efficiency [17] [26]. The Tm is formally defined as the temperature at which half of the DNA duplexes are in a single-stranded state [27].

The thermal stability of DNA duplexes depends on several sequence-specific and environmental factors. GC content significantly influences Tm due to the three hydrogen bonds in G≡C base pairs compared to two in A=T pairs, making GC-rich sequences more stable [27] [28]. DNA length affects stability, with longer fragments generally exhibiting higher Tm values [28]. Sequence composition beyond simple GC content, including nearest-neighbor interactions, plays a crucial role in duplex stability [29] [27]. Environmental factors such as salt concentration stabilize DNA duplexes by neutralizing the negatively charged phosphate backbone, while pH extremes can destabilize the double helix [13] [28].

Accurate Tm prediction enables researchers to optimize annealing temperatures in PCR, design specific hybridization probes, and detect genetic variations through melt curve analysis [26] [28]. This note provides standardized protocols for experimental Tm determination, bridging theoretical calculations with empirical validation for robust experimental design in research and diagnostic applications.

Theoretical Foundations of DNA Melting

Thermodynamic Principles

DNA melting follows a two-state model transitioning from duplex to random coil configurations. The thermodynamics are governed by the Gibbs free energy equation:

ΔG = ΔH - TΔS

Where ΔG is the change in free energy, ΔH is the enthalpy change (primarily from hydrogen bonding and base stacking), ΔS is the entropy change, and T is the temperature in Kelvin [27] [13]. At Tm, ΔG = 0, leading to the relationship:

Tm = ΔH/ΔS

For short oligonucleotides, Tm can be calculated using the nearest-neighbor model, which considers the sequence dependence of stability by summing the free energy contributions of adjacent base pairs [27]. The free energy of forming a nucleic acid duplex is expressed as:

ΔG°₃₇(total) = ΔG°₃₇(initiation) + ΣnᵢΔG°₃₇(i)

Where nᵢ is the number of occurrences of nearest-neighbor i, and ΔG°₃₇(i) is its free energy contribution [27].

Calculation Methods and Tools

Several computational approaches exist for Tm prediction, with varying levels of accuracy:

Table 1: Comparison of DNA Melting Temperature Prediction Tools

| Method/Software | Basis of Calculation | Sequence Length Applicability | Reported Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primer3 Plus [17] | Nearest-neighbor model | Oligonucleotides (typically 15-30 bp) | Best prediction performance in comparative studies |

| Primer-BLAST [17] | Nearest-neighbor model | Oligonucleotides (typically 15-30 bp) | Best prediction performance in comparative studies |

| Nearest-neighbor model [27] | Sum of dimer free energies | Short oligonucleotides | High accuracy for short sequences |

| Empirical formula (GC 40-60%) [30] | Tm = ΔH/ΔS–0.27GC%–(150+2n)/n–273.15 | PCR products | Average error <1°C within specified GC range |

| Empirical formula (GC <40%) [30] | Tm = ΔH/ΔS–GC%/3–(150+2n)/n–273.15 | PCR products | Average error <1°C within specified GC range |

| Linear regression model [13] | Multivariate Taylor series expansion | Various lengths | R² = 0.9942 for MgCl₂; 0.9600 for Tm |

Comparative studies evaluating 22 different primer design tools revealed significant variation in Tm prediction accuracy, with Primer3 Plus and Primer-BLAST demonstrating the best performance when benchmarked against experimentally determined Tm values [17]. Recent advances incorporate machine learning and high-throughput experimental data to improve prediction accuracy for diverse structural motifs including mismatches, bulges, and hairpin loops [29] [13].

Experimental Visualization Methodologies

UV-Visible Spectroscopy-Based Melting Analysis

Ultraviolet (UV) absorbance monitoring at 260 nm represents the classical approach for DNA melting analysis, leveraging the hyperchromic effect where single-stranded DNA exhibits approximately 30-40% greater absorbance than double-stranded DNA [26] [28].

Protocol: UV-Vis DNA Melting Analysis

Sample Preparation

- Prepare DNA sample in appropriate buffer (typically 10-50 μM DNA concentration in duplex)

- Common buffers: 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5-8.0, with 50-100 mM NaCl

- Use quartz cuvette with 1 cm path length

Instrument Setup

- Set spectrophotometer to monitor absorbance at 260 nm

- Program temperature controller for gradual heating (0.5-1.0°C per minute)

- Set temperature range to encompass complete transition (typically 20-95°C)

- Equilibrate at each temperature point for 30-60 seconds before measurement

Data Collection

- Record absorbance values at each temperature increment

- Ensure sufficient data points (≥1 per °C) for accurate curve fitting

Data Analysis

This method requires relatively pure DNA samples without significant contaminating absorbance at 260 nm and is ideal for fundamental thermodynamic studies [28].

Fluorescence-Based Melting Analysis

Fluorescence monitoring using DNA-intercalating dyes offers enhanced sensitivity and compatibility with complex samples, making it particularly suitable for post-PCR melting analysis [26] [31].

Protocol: Fluorescence-Based HRM Analysis

Reaction Setup

- Prepare PCR reaction mix containing:

- DNA template (genomic DNA, plasmid, or PCR product)

- Primers (0.1-0.5 μM each)

- DNA-binding dye (SYBR Green I, EvaGreen, or LCGreen)

- Reaction buffer with Mg²⁺

- dNTPs

- DNA polymerase

- Prepare PCR reaction mix containing:

Amplification and Melting

- Perform PCR amplification if analyzing amplicons:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 2 minutes

- 35-45 cycles: 95°C for 15s, annealing for 20s, 72°C for 20s

- Execute high-resolution melting protocol:

- Temperature range: 5-10°C below expected Tm to 10-15°C above

- Temperature increment: 0.1-0.3°C per step

- Equilibration time: 2-15 seconds per step depending on instrument

- Perform PCR amplification if analyzing amplicons:

Data Processing

Variant Detection

- Compare melting curve shapes and Tm values between samples

- Normalize curves to identical temperature scales for shape comparison

- Use difference plots to enhance detection of subtle variants [26]

Fluorescence-based methods enable analysis of complex mixtures and are compatible with high-throughput formats, including digital HRM in picoliter-scale reactions for absolute quantification of sequence variants [32].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for DNA Melting Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA-Binding Dyes | SYBR Green I, EvaGreen, LCGreen | Fluorescent intercalation for real-time monitoring; saturating dyes preferred for HRM [26] |

| Buffer Components | Tris-HCl, NaCl, MgCl₂ | Stabilize pH and ionic strength; Mg²⁺ critical for polymerase activity in PCR [13] |

| Enzymes | Thermostable DNA polymerases | Catalyze DNA amplification; choice affects fidelity and processivity |

| Universal Primers | 16S rRNA gene primers | Enable broad detection of bacterial sequences in digital HRM applications [32] |

| Quantification Standards | Known Tm control DNA | Validate instrument calibration and enable cross-run comparisons [31] |

| Microfluidic Chips | Digitizing chips (20,000 reactions) | Enable massively parallel digital HRM for absolute quantification [32] |

Advanced Applications and Methodologies

High-Resolution Melting (HRM) for Genotyping

High-resolution melting analysis enables sensitive detection of single nucleotide variants (SNVs), small insertions/deletions, and methylation status without sequencing [26]. The precise monitoring of fluorescence loss during DNA melting can distinguish sequences differing by as little as a single base pair.

Protocol: HRM for SNV Detection

Amplicon Design

- Design PCR amplicons of 50-300 bp encompassing the variant of interest

- Avoid repetitive sequences and extreme GC content (>80% or <20%)

PCR Amplification

- Use saturating DNA dyes such as LCGreen or EvaGreen for enhanced resolution

- Optimize primer concentrations to minimize primer-dimer formation

- Include control samples with known genotypes in each run

High-Resolution Melting

- Use instrument capable of temperature precision ≤0.1°C

- Set temperature ramp rate to 0.1-0.3°C per second for optimal resolution

- Ensure sufficient data acquisition (10-25 acquisitions/°C)

Data Analysis

Digital High-Resolution Melting (dHRM)

Digital HRM combines limiting dilution digital PCR with high-resolution melting to achieve absolute quantification of multiple sequence variants in complex samples [32].

Protocol: Digital HRM for Quantitative Profiling

Sample Digitization

- Dilute sample to achieve approximately 0.1-0.01 molecules per reaction

- Partition across 20,000 picoliter-scale reactions using microfluidic chip

Universal Amplification

- Use conserved primers targeting genetic regions of interest (e.g., bacterial 16S gene)

- Perform amplification with intercalating dye (e.g., 2.5X EvaGreen)

Massively Parallel Melting

- Implement precise temperature control with thermoelectric heater/cooler

- Acquire fluorescence images at each temperature point across all reactions

- Use automated image analysis to extract raw fluorescence data

Machine Learning Classification

- Train Support Vector Machine (SVM) algorithm with known melt curve signatures

- Classify individual reaction curves to identify sequence variants

- Quantify variant abundances based on Poisson statistics of positive reactions [32]

This approach reduces reaction volumes by 99.995% and achieves a greater than 200-fold increase in dynamic range compared to traditional PCR-HRM methods [32].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Melting Curve Processing

Proper data analysis is essential for accurate Tm determination and sequence variant detection:

Normalization Procedures

- For UV data: Normalize absorbance between minimum (double-stranded) and maximum (single-stranded) values

- For fluorescence data: Apply similar normalization, adjusting for dye-specific fluorescence loss independent of melting

Derivative Plot Generation

- Calculate first derivative of normalized melting curve

- Apply smoothing algorithms to reduce noise while preserving signal

- Identify Tm as temperature at derivative peak maximum

Multicomponent Analysis

Quality Control Parameters

Implement rigorous quality control to ensure reliable melting data:

- Replicate Consistency: Tm values should vary by <0.5°C between technical replicates

- Curve Shape: Smooth, sigmoidal melting curves indicate homogeneous samples

- Peak Sharpness: Sharp derivative peaks suggest cooperative melting of uniform duplexes

- Baseline Stability: Stable pre- and post-melt baselines ensure accurate normalization [31]

Advanced analysis tools like web-based LinRegPCR provide automated processing of amplification and melting data, highlighting deviant reactions for exclusion from analysis [31].

Experimental visualization of the DNA melting process provides critical validation for computational Tm predictions, enabling robust optimization of molecular biology applications. The protocols detailed in this application note—spanning traditional UV spectroscopy to advanced digital HRM—offer researchers comprehensive methodologies for accurate Tm determination. By integrating these experimental approaches with theoretical calculations, scientists can enhance the precision of PCR optimization, probe design, and genotyping assays, ultimately advancing research and diagnostic applications in drug development and biomedical science.

Practical Tm Calculation: Methods, Tools, and Laboratory Application

In molecular biology techniques, the melting temperature (Tm) is a fundamental thermodynamic property defined as the temperature at which 50% of DNA duplexes dissociate into single strands and 50% remain hybridized [33]. Accurate Tm prediction is critical for experimental success across numerous applications including PCR, quantitative PCR, site-directed mutagenesis, hybridization-based techniques, and next-generation sequencing library preparation [33] [17]. Errors in Tm estimation directly impact annealing temperature selection, which can lead to failed amplification, reduced product yield, or nonspecific products that compromise experimental results [17].

The selection of an appropriate Tm calculation method depends on multiple factors including oligonucleotide length, sequence composition, and experimental conditions. This application note provides a comprehensive comparison of three predominant calculation methods: the SantaLucia nearest-neighbor method, basic nearest-neighbor approach, and simple GC percentage formula. Understanding the strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications of each method enables researchers to optimize molecular biology assays for improved specificity and efficiency.

Theoretical Foundations of TmCalculation Methods

SantaLucia Nearest-Neighbor Method (1998)

The SantaLucia nearest-neighbor method represents the current gold standard for Tm prediction, incorporating comprehensive thermodynamic parameters derived from experimental data [34] [35]. This method calculates duplex stability by considering the sequence-dependent stacking interactions between adjacent nucleotide pairs, accounting for the fact that DNA stability depends not only on base composition but also on sequence context [35]. The model uses the following thermodynamic equation:

Tm = ΔH° / (ΔS° + R ln(Ct)) - 273.15

Where ΔH° represents the enthalpy change, ΔS° represents the entropy change, R is the gas constant, and Ct is the total oligonucleotide concentration [33]. The SantaLucia method incorporates salt concentration corrections and provides specific thermodynamic parameters for all ten possible Watson-Crick nearest-neighbor pairs, enabling highly accurate predictions across diverse sequence contexts and experimental conditions [34] [35]. This method is particularly valuable for designing critical experiments where precision is paramount, such as quantitative PCR assays or multiplex PCR systems [17].

Basic Nearest-Neighbor Method (1986)

The basic nearest-neighbor method represents an earlier thermodynamic approach that also considers base stacking interactions but with less comprehensive parameterization than the SantaLucia method [33] [35]. Developed based on work by Breslauer et al. (1986) and Freier et al. (1986), this method uses a similar mathematical framework but with different thermodynamic values for the nearest-neighbor pairs [33]. The basic formula is:

Tm = ΔH / (ΔS + R ln(C)) + 16.6 log[Na+] - 272.3

Where ΔH is the sum of enthalpy changes for all nearest-neighbor pairs, ΔS is the sum of entropy changes, R is the gas constant, C is the oligo concentration, and [Na+] is the sodium ion concentration [33]. While this method represents a significant improvement over simplistic formulas, studies have demonstrated that it provides less accurate predictions compared to the updated SantaLucia parameters, particularly for sequences with unusual stacking interactions or complex secondary structures [35].

Simple GC Percentage Method

The simple GC percentage method provides a rudimentary approach to Tm estimation based primarily on base composition rather than sequence arrangement. This method uses the formula:

Tm = 4(G + C) + 2(A + T)

Where G, C, A, and T represent the counts of respective nucleotides in the sequence [36]. This calculation assumes standard conditions of 50 nM primer concentration and 50 mM sodium ion concentration at neutral pH [36]. A common alternative formulation for slightly longer oligonucleotides is:

Tm = 64.9 + 41(G + C - 16.4)/N

Where N represents the total number of bases in the oligonucleotide [36]. The primary limitation of this approach is its failure to account for sequence context, stacking interactions, or precise environmental conditions, potentially leading to errors exceeding 15°C in some cases [37]. Despite its limitations, this method remains in use for quick estimations and educational purposes due to its computational simplicity.

Comparative Analysis of TmCalculation Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Key Features of Tm Calculation Methods

| Feature | SantaLucia (1998) | Basic Nearest-Neighbor | Simple GC% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Nearest-neighbor thermodynamics with updated parameters | Nearest-neighbor thermodynamics with 1986 parameters | Base counting without sequence context |

| Key Parameters | ΔH, ΔS, oligonucleotide concentration, salt correction | ΔH, ΔS, oligonucleotide concentration, salt correction | G+C count, total length |

| Sequence Consideration | Full sequence context including all stacking interactions | Stacking interactions with less accurate parameters | Only base composition |

| Accuracy | Highest (89% predictions within 5°C of experimental Tm) [35] | Moderate | Low (errors can exceed 15°C) [37] |

| Optimal Length Range | 15-120 bases [33] | 15-120 bases | <14 bases: 2(A+T)+4(G+C) [36] |

| Salt Correction | Comprehensive including [Na+] and [Mg2+] | [Na+] correction | No correction |

| Computational Complexity | High | Moderate | Low |

Table 2: Typical Calculation Deviations from Experimental Tm Values

| Method | Average Deviation | Recommended Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| SantaLucia (1998) | 1.6-5.0°C [35] | Critical applications (qPCR, multiplex PCR), high-throughput studies |

| Basic Nearest-Neighbor | 5.0-10.0°C [35] | Routine PCR when SantaLucia unavailable, educational purposes |

| Simple GC% | 10.0-15.0°C+ [37] | Initial estimations, educational demonstrations |

The comparative analysis reveals significant differences in the theoretical foundations and predictive accuracy of these three methods. The SantaLucia method provides superior accuracy due to its comprehensive parameter set derived from extensive experimental data [35]. Studies comparing calculated versus experimental Tm values across hundreds of oligonucleotides demonstrate that the SantaLucia method consistently outperforms both earlier nearest-neighbor approaches and simplistic formulas [35]. The basic nearest-neighbor method, while representing a substantial improvement over GC-based calculations, shows significantly higher deviations from experimental values, particularly for sequences with complex stacking interactions or unusual distributions of nucleotides [35]. The simple GC percentage method shows the highest variability and largest average errors, limiting its utility in precision applications [37].

Decision Framework for Method Selection

The following workflow diagram illustrates the systematic process for selecting the appropriate Tm calculation method based on experimental requirements:

Figure 1: Decision workflow for selecting appropriate Tm calculation method. The SantaLucia method is recommended for most research applications where accuracy is critical, particularly for oligonucleotides longer than 14 bases.

Experimental Protocols for TmDetermination and Validation

Protocol 1: Computational TmDetermination Using SantaLucia Method

Purpose: To accurately determine primer Tm using the SantaLucia nearest-neighbor method for PCR optimization.

Materials:

- Oligonucleotide sequences (forward and reverse primers)

- Computer with internet access

- Tm calculation software (Primer3Plus, Primer-BLAST, or ThermoFisher Tm Calculator)

Procedure:

- Input Preparation: Obtain purified oligonucleotide sequences in 5' to 3' orientation. Verify sequence accuracy and purity.

- Parameter Specification:

- Set oligonucleotide concentration to 50-500 nM (typical range for PCR)

- Specify monovalent ion concentration (typically 50 mM for Na+)

- For buffers containing Mg2+, input concentration (typically 1.5-3.0 mM)

- Select the appropriate DNA polymerase (influences buffer composition)

- Calculation: Input sequences into preferred software. For manual calculation using thermodynamic parameters, sum ΔH and ΔS values for all nearest-neighbor pairs and apply the thermodynamic formula.

- Validation: Cross-verify Tm using multiple tools (e.g., Primer3Plus and OligoCalc) to ensure consistency.

- Annealing Temperature Determination: Calculate optimal annealing temperature (Ta) as Tm - 5°C for initial testing.

Notes: Empirical validation through temperature gradient PCR is recommended for critical applications. Studies indicate Primer3Plus and Primer-BLAST implement the most accurate Tm prediction models based on the SantaLucia method [17].

Protocol 2: Empirical TmValidation Using Temperature Gradient PCR

Purpose: To experimentally validate calculated Tm values and optimize annealing conditions.

Materials:

- Purified DNA template

- Forward and reverse primers with calculated Tm

- PCR master mix with DNA polymerase

- Thermal cycler with temperature gradient capability

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare PCR reactions according to manufacturer recommendations with final primer concentration of 0.1-0.5 µM.

- Gradient Programming: Set annealing temperature gradient spanning ±10°C of calculated Tm.

- PCR Amplification: Run amplification protocol with 30-35 cycles.

- Product Analysis: Separate PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis and visualize.

- Optimal Ta Determination: Identify the highest annealing temperature that produces strong, specific amplification.

Notes: The optimal annealing temperature can be more accurately calculated as Ta = 0.3 × Tm,primer + 0.7 × Tm,product - 14.9, where Tm,primer is the Tm of the less stable primer-template pair [37].

Research Reagent Solutions for TmDetermination

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Melting Temperature Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Products |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Polymerases | PCR amplification with specific buffer systems | Platinum SuperFi, Phusion, Phire DNA polymerases [7] |

| Tm Calculation Software | Computational Tm prediction | Primer3 Plus, Primer-BLAST, ThermoFisher Tm Calculator [7] [17] |

| Online Tm Tools | Web-based Tm calculation | OligoCalc, Tm Tool, OLV Tm Calculator [38] [3] |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Specialized primer design applications | QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit [39] |

| Buffer Systems | Control ionic environment affecting Tm | Various salt solutions (Na+, K+, Mg2+) |

The selection of an appropriate Tm calculation method significantly impacts the success of molecular biology experiments. The SantaLucia nearest-neighbor method (1998) provides the highest accuracy and is recommended for critical applications such as quantitative PCR, multiplex PCR, and next-generation sequencing library preparation. The basic nearest-neighbor method offers moderate accuracy and may be suitable for routine applications when SantaLucia parameters are unavailable. The simple GC percentage method, while computationally straightforward, demonstrates significant limitations in predictive accuracy and should be reserved for initial estimations or educational purposes. For optimal results, researchers should combine computational Tm predictions with empirical validation through temperature gradient PCR, particularly when working with novel sequences or non-standard reaction conditions. As molecular techniques continue to evolve, accurate Tm prediction remains fundamental to experimental design across diverse applications in biomedical research, diagnostics, and biotechnology.

Step-by-Step Guide to Using Online Tm Calculators (OligoPool, IDT, NEB, Thermo Fisher)

This application note provides a detailed protocol for researchers and scientists on the use of four major online melting temperature (Tm) calculators. Accurate Tm calculation is foundational to the success of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and other molecular biology techniques, directly impacting the specificity and yield of experiments in drug development and diagnostic research.

Calculator Selection and Key Parameters

The choice of a Tm calculator can influence the accuracy of your predictions. The table below compares the core features of four widely used tools.

Table 1: Comparison of Online Tm Calculators

| Calculator Provider | Primary Calculation Method | Key Salt & Buffer Corrections | Special Features | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OligoPool [20] [40] | SantaLucia nearest-neighbor | Na⁺, Mg²⁺, dNTPs, DMSO | Batch processing (up to 1000 sequences); transparent thermodynamic data | High-throughput primer design; general PCR optimization |

| IDT OligoAnalyzer [41] [1] | Nearest-neighbor thermodynamic | Na⁺, Mg²⁺ | Integrated secondary structure analysis (hairpin, dimer); BLAST functionality | Detailed oligonucleotide analysis, especially for qPCR probes |

| Thermo Fisher [7] [9] | Modified Breslauer's/SantaLucia's method | Polymerase-specific buffer formulations | Annealing temperature calculation for specific Thermo Scientific polymerases | Users of Phusion, Phire, or Platinum SuperFi DNA polymerases |

| NEB Tm Calculator [42] | Nearest-neighbor | Proprietary buffer component adjustments | Optimized for NEB's polymerases, particularly high-fidelity enzymes like Q5 | Users of New England Biolabs' DNA polymerases |

Several physical and chemical parameters significantly impact Tm calculations and must be accounted for [1]:

- Oligo Concentration: Tm can vary by up to ±10°C depending on which nucleic acid strand is in excess [1].

- Salt Ions: Divalent cations (Mg²⁺) have a more profound effect than monovalent cations (Na⁺, K⁺). The free Mg²⁺ concentration is critical, as it can be chelated by dNTPs [1] [42].

- Additives: DMSO reduces Tm by approximately 0.5–0.6°C per 1% concentration [20] [9].

Step-by-Step Protocols

OligoPool Tm Calculator

The OligoPool calculator is designed for high accuracy and batch processing, utilizing the SantaLucia nearest-neighbor method [20] [40].

Protocol:

- Access the Tool: Navigate to the OligoPool Tm Calculator [40].

- Enter Sequence: Input your DNA or RNA sequence (10–500 nt) in the input field. The tool automatically handles spaces and case variations [40].

- Set Reaction Conditions:

- Salt Conditions: Input the concentrations of Na⁺ (typically 50 mM for standard PCR) and Mg²⁺ (typically 1.5–3 mM). Input dNTP concentration if applicable, as it chelates Mg²⁺ [20] [40].

- Oligo Concentration: Set the total oligonucleotide concentration (typically 250–500 nM for PCR primers) [20].

- DMSO: Enter the percentage if used (e.g., 5% DMSO reduces Tm by ~2.5–3°C) [20].

- Calculate: Click "Calculate Tm." The results will display the salt-corrected Tm, thermodynamic parameters (ΔH, ΔS), GC content, and a recommended annealing temperature (Tm - 5°C) [40].

- (Optional) Batch Processing: Switch to "Batch Processing" mode to paste and analyze up to 1000 sequences simultaneously using the same set parameters [40].

IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool

The IDT OligoAnalyzer offers comprehensive oligonucleotide analysis, including Tm calculation and secondary structure prediction [41].

Protocol:

- Access the Tool: Go to the IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool [41].

- Enter Sequence & Adjust Parameters:

- Select Function: For standard analysis, ensure "Analyze" is selected. This provides Tm, GC%, molecular weight, and extinction coefficient [41].

- Analyze Secondary Structures: Use the "Hairpin," "Self-Dimer," and "Hetero-Dimer" functions to screen for potential structures that could interfere with PCR efficiency [41].

- Interpret Results: The calculated Tm is displayed prominently. Use the "Tm Mismatch" function to evaluate how specific sequence variations might impact the hybridization temperature [1].

Thermo Fisher Tm Calculator