Primer Length and Dimer Formation: A Research Guide for Optimized PCR and qPCR

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical relationship between primer length and the formation of primer dimers, a common obstacle in PCR and qPCR that compromises assay efficiency...

Primer Length and Dimer Formation: A Research Guide for Optimized PCR and qPCR

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical relationship between primer length and the formation of primer dimers, a common obstacle in PCR and qPCR that compromises assay efficiency and specificity. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of primer dimer formation, detail methodological strategies for designing primers of optimal length, present advanced troubleshooting and optimization techniques to minimize nonspecific amplification, and review validation and comparative approaches for primer selection. By synthesizing current research and best practices, this guide aims to equip practitioners with the knowledge to enhance the accuracy and reliability of their molecular diagnostics and research applications.

The Primer Dimer Problem: Understanding the Basics and Impact on Assay Efficiency

What Are Primer Dimers? Defining Self-Dimers and Cross-Dimers

Primer dimers are short, unintended DNA fragments that can form during the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) when primers anneal to each other instead of to the intended target sequence in the template DNA [1] [2]. This artifact formation is a significant challenge in molecular biology, capable of compromising assay efficiency and leading to false results. The relationship between primer design, particularly primer length, and the propensity for dimer formation is a critical area of research, with recent studies advocating for energy-based design principles over traditional fixed-length approaches to achieve more uniform amplification [3].

This guide details the definitions, formation mechanisms, and experimental impacts of primer dimers, providing researchers with strategies for their identification and prevention.

Types and Mechanisms of Primer Dimer Formation

Primer dimers are primarily classified into two types based on the primers involved in the aberrant pairing.

- Self-Dimer (Homodimer): A self-dimer is formed through the intermolecular interaction between two identical primers. For example, one forward primer anneals to another forward primer via regions of self-complementarity [2] [4] [5].

- Cross-Dimer (Heterodimer): A cross-dimer is formed through the intermolecular interaction between the forward and reverse primers due to inter-primer homology, particularly at their 3' ends [1] [2] [4].

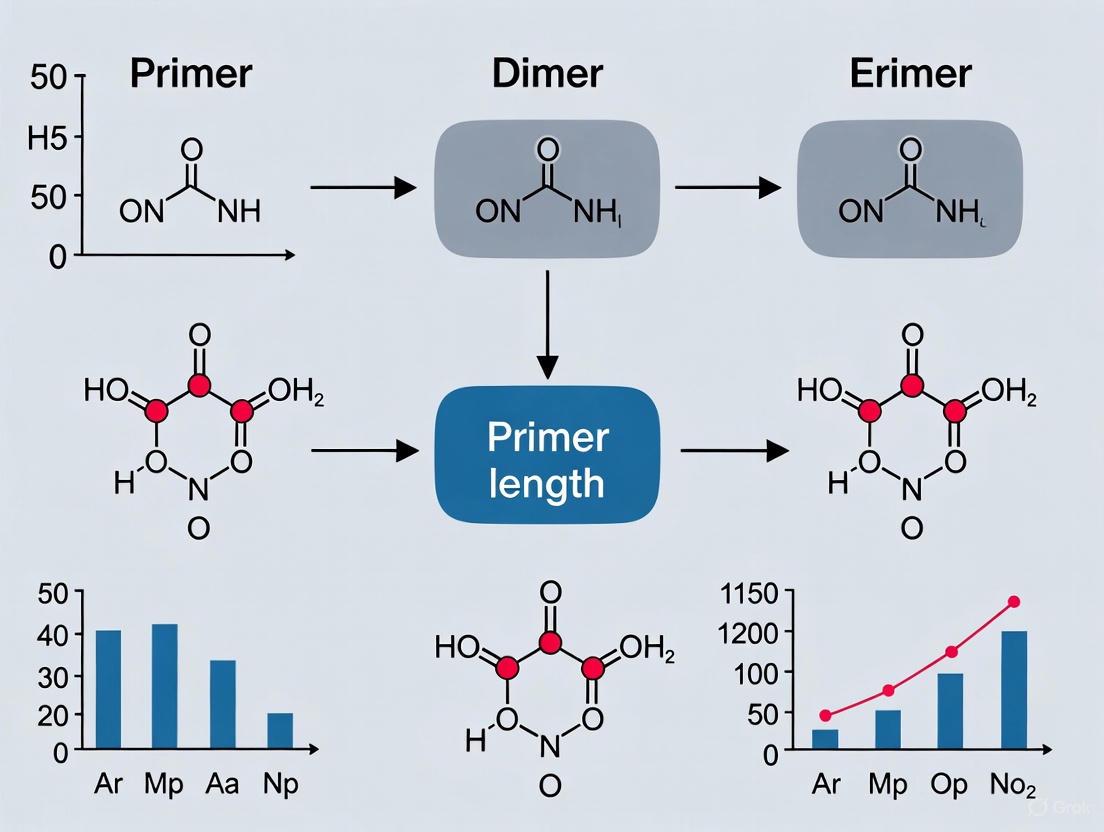

The following diagram illustrates the molecular structure and formation process of both self-dimers and cross-dimers.

Formation occurs when primers contain regions of complementarity—as few as 3-4 complementary bases, especially at the 3' end, can be sufficient for annealing [4] [5]. Once primers anneal to each other, DNA polymerase recognizes the duplex and, crucially, the free 3' hydroxyl ends, treating them as legitimate starting points for DNA synthesis [1] [2]. The enzyme extends the primers, thereby amplifying the short, unintended dimer into a stable artifact.

This process is most likely to occur during reaction setup at room temperature, before PCR begins, and is exacerbated by high primer concentrations and low annealing temperatures during cycling [2] [5].

Experimental Consequences of Primer Dimers

Primer dimers have significant downstream effects that can compromise experimental results and diagnostic accuracy.

- Reduced Amplification Efficiency and False Negatives: Primer dimers consume reaction resources, including primers, dNTPs, and polymerase activity [5]. This competition reduces the availability of these components for the intended target, leading to inefficient amplification of the true target. In quantitative PCR (qPCR), this manifests as a higher cycle threshold (Ct) value, potentially leading to false negatives or significant underestimation of the target's initial concentration [5].

- False Positives and Misinterpretation: In assays that use non-specific detection dyes like SYBR Green, the amplification of primer dimers generates a fluorescent signal indistinguishable from that of the target amplicon [5]. This is particularly problematic in no-template control (NTC) reactions, where any amplification signal is by definition a false positive [1] [5].

- Compromised Data in Complex Applications: In multiplex PCR, where multiple primer sets are used simultaneously, and in high-throughput applications like DNA data storage, primer dimer formation becomes a major barrier to success. Dimers can cause imbalances in amplification efficiency between different targets, leading to the complete loss of some sequences from the library and distorted data representation [3].

Detection and Identification Methods

Accurately identifying primer dimers is a crucial skill for troubleshooting PCR experiments. The table below summarizes the common techniques.

Table 1: Methods for Detecting Primer Dimers

| Method | Protocol Description | Key Identifier for Primer Dimers |

|---|---|---|

| Agarose Gel Electrophoresis | Standard protocol: Run PCR products on an agarose gel (e.g., 2-3%) alongside a DNA ladder for size reference. Run the gel longer to improve separation of small fragments [1]. | A fuzzy, smeary band (not sharp) at a low molecular weight, typically below 100 bp, often near the 20-50 bp region [1] [2]. |

| qPCR with Melting Curve Analysis | Standard qPCR protocol: After amplification, gradually increase the temperature from ~60°C to 95°C while continuously monitoring fluorescence. | A distinct, lower temperature peak in the melting curve derivative plot, separate from the main amplicon peak, indicating a product with a lower melting temperature (Tm) [2]. |

| No-Template Control (NTC) | A crucial control reaction: Prepare the PCR master mix identically but omit the DNA template. | Amplification signal in the NTC (e.g., a band on a gel or a curve in qPCR) confirms the artifact is primer-derived, as it forms without a template [1] [5]. |

The following workflow outlines a recommended experimental approach for systematic detection and validation of primer dimers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Methods

Successful experimentation requires specific reagents and methodologies tailored to prevent and analyze primer dimers.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Reagent | Primary Function in Primer Dimer Context |

|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Remains inactive at room temperature during reaction setup, preventing polymerase-mediated extension of primed dimers before PCR begins. Critical for dimer reduction [1] [5]. |

| Primer Design Software (e.g., Primer3, Primer-BLAST) | In-silico tools that automate the design of specific primers and analyze potential secondary structures like self-dimers, cross-dimers, and hairpins [6] [7]. |

| SYBR Green Master Mix | A fluorescent dye that binds double-stranded DNA. Essential for detecting primer dimer formation in qPCR and in No-Template Controls (NTCs), as it will bind to and report amplification of any dsDNA product [5]. |

| CertPrime / Fixed-Energy Design | An advanced oligonucleotide design tool that minimizes spurious dimer formation and melting-temperature deviations by fixing the hybridization energy (ΔG°) of primers rather than their length, leading to more uniform amplification [8] [3]. |

Strategies for Preventing Primer Dimer Formation

The most effective approach to primer dimers is proactive prevention through optimized experimental design.

- Optimal Primer Design: The first and most crucial line of defense. Design primers 18-25 nucleotides in length with a GC content between 40-60% [6] [9] [7]. Ensure they have low self-complementarity and minimal 3'-end complementarity to other primers [6] [9]. Using a GC clamp (1-2 G/C bases at the 3' end) can enhance specific binding but avoid more than 3 G/Cs, which can promote non-specific binding [9] [7].

- Wet-Lab Optimization: If dimer formation persists, optimize reaction conditions. Lower primer concentrations reduce opportunities for primers to encounter each other [1]. Increase the annealing temperature to discourage the weak bonds that form dimers [1] [5]. Using a hot-start polymerase is highly recommended to prevent pre-PCR amplification [1].

- Advanced Fixed-Energy Design: Recent research highlights a paradigm shift from fixed-length to fixed-energy primer design. A 2024 study demonstrates that primers designed to have a uniform hybridization thermodynamic energy (ΔG°) around -11.5 kcal/mol achieve dramatically more uniform amplification compared to traditional fixed-length primers [3]. This approach minimizes bias, which is critical for complex applications like DNA data storage and multiplex PCR.

Primer dimers, comprising self-dimers and cross-dimers, are consequential artifacts that arise from unintended primer interactions. Their formation depletes critical PCR resources, leading to false results and reduced assay robustness. Ongoing research into the thermodynamics of primer binding, especially the shift from fixed-length to fixed-energy design, is providing powerful new strategies to suppress dimer formation. By integrating rigorous in-silico design, wet-lab optimization, and modern energy-based principles, researchers can effectively mitigate this pervasive challenge, ensuring the accuracy and efficiency of their molecular assays.

Within polymerase chain reaction (PCR) dynamics, the unintended formation of primer-dimers (PDs) represents a significant inefficiency, directly competing with the amplification of the desired DNA target. This whitepaper delineates the molecular mechanism by which primers anneal to each other rather than the template DNA, a process exacerbated by suboptimal primer design and reaction conditions. Framed within broader research on the relationship between primer length and dimer formation, this guide synthesizes quantitative experimental data to outline precise protocols for detecting and preventing this parasitic byproduct. The insights provided are essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals aiming to optimize assay sensitivity and reliability in molecular diagnostics and multiplexed sequencing applications.

Primer annealing is a fundamental process in PCR where short, single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides (primers) bind to complementary sequences flanking the target DNA region, providing a starting point for DNA polymerase to initiate synthesis [10]. The specificity of this process is governed by thermodynamic principles and precise reaction conditions. However, under suboptimal conditions, primers can bypass the intended template and anneal to themselves or each other, leading to the formation of primer-dimers [11].

Primer-dimers are potential by-products in PCR that consist of two primer molecules which have hybridized because of strings of complementary bases in the primers [11]. The formation of these structures is not merely a theoretical concern; it leads to direct competition for essential PCR reagents such as nucleotides and DNA polymerase, thereby potentially inhibiting the amplification of the target sequence and reducing the overall sensitivity and accuracy of the assay, particularly in quantitative PCR [11]. Understanding the mechanistic pathway of dimer formation is therefore a critical prerequisite for developing effective countermeasures, especially in the context of advanced research focusing on how primer physical characteristics, such as length and sequence, influence dimerization risk.

The Stepwise Mechanism of Primer-Dimer Formation

The formation and amplification of a primer-dimer occur through a series of distinct, sequential steps. This process is facilitated when primers contain regions of complementarity, particularly at their 3' ends, which can form stable duplexes.

The following diagram illustrates the three-step mechanism of primer-dimer formation and amplification:

Molecular Drivers of Dimerization

The initial annealing step is highly dependent on several key factors that influence the stability of the primer-primer duplex:

- 3' End Complementarity: Strings of complementary bases, particularly at the 3' ends of the primers, are the primary driver for dimer formation. A high GC-content at the 3' ends contributes significantly to duplex stability due to the stronger hydrogen bonding of G-C base pairs compared to A-T base pairs [11] [12].

- Low-Temperature Activity of Polymerase: DNA polymerases retain some polymerizing activity even at lower temperatures (e.g., during reaction setup at room temperature). If primers anneal during this stage, the polymerase can extend them, committing the reaction to dimer amplification [11].

- Physical-Chemical Parameters: Elevated primer concentrations, high magnesium chloride (MgCl₂) concentrations, and suboptimal ionic strength can all favor non-specific annealing and extension, thereby increasing the risk of PD formation [11] [13].

Quantitative Experimental Analysis of Dimer Formation

Empirical research has been critical in quantifying the biophysical parameters that govern primer-dimer formation. A seminal study utilized free-solution conjugate electrophoresis (FSCE) with drag-tagged DNA to precisely investigate dimerization between primer-barcode pairs [14].

Key Experimental Findings

The FSCE study provided the following critical quantitative insights, which are summarized in the table below:

Table 1: Quantitative Parameters for Stable Primer-Dimer Formation

| Experimental Parameter | Quantitative Finding | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum Consecutive Base Pairs | >15 consecutive base pairs [14] | Required for stable dimer formation. |

| Effect of Non-consecutive Bases | 20/30 non-consecutive base pairs did not form stable dimers [14] | Highlights the importance of contiguous complementarity. |

| Temperature Correlation | Dimerization was inversely correlated with temperature for imperfect matches [14] | Study temperatures: 18, 25, 40, 55, 62°C. |

| Critical Dimerization Region | 3' ends of the primers [11] | Initial binding occurs at the 3' ends. |

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying Dimerization via FSCE

The following workflow outlines the key steps of the capillary electrophoresis method used to generate the quantitative data on dimer formation [14]:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Dimerization Analysis

The following table catalogues key reagents and their functions as used in the cited experimental protocol for analyzing primer-dimer formation [14].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Primer-Dimer Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| 30-mer Oligonucleotides | Model primer-barcode conjugates with designed complementary regions. |

| Poly-N-methoxyethylglycine (NMEG) Drag-tags | Chemically synthesized, neutral polymers conjugated to primers to alter hydrodynamic drag and enable separation of ssDNA and dsDNA species by FSCE. |

| Sulfo-SMCC (Crosslinker) | Covalently links the drag-tag to the thiolated 5'-end of the DNA oligomer. |

| Tris-TAPS-EDTA (TTE) Buffer | Running buffer for free-solution capillary electrophoresis. |

| PolyDuramide Polymer (pHEA) | Dynamic capillary coating to suppress electroosmotic flow and sample interactions with the capillary interior. |

| Fluorophores (e.g., ROX, FAM) | Fluorescent labels for laser-induced fluorescence detection, allowing unambiguous peak assignment. |

Detection and Prevention of Primer-Dimers

Detection Methodologies

Accurate detection is crucial for diagnosing and troubleshooting primer-dimer issues. The two primary methods are:

- Gel Electrophoresis: After PCR, primer-dimers may be visible on an ethidium bromide-stained gel as a moderate to high intensity band or smear in the 30-50 base-pair range, which is distinguishable from the typically longer target amplicon [11].

- Melting Curve Analysis: In quantitative PCR using intercalating dyes like SYBR Green I, primer-dimers can be identified by their characteristic melting temperature, which is lower than that of the specific target amplicon due to their shorter length [11].

Strategic Prevention and Optimization

Preventing primer-dimer formation is multi-faceted, involving strategic primer design, reaction optimization, and specialized enzymatic systems.

Table 3: Strategies for Preventing Primer-Dimer Formation and Impact

| Strategy Category | Specific Method | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Design | Optimal Length (18-30 bp) & GC Content (40-60%) [13] [15] [12] | Balances specificity and binding efficiency; avoids overly stable mispriming. |

| Primer Design | Avoid 3' End Complementarity & Secondary Structures [15] [12] | Prevents initial stable annealing between primers. |

| Reaction Chemistry | Hot-Start PCR [11] | Inhibits polymerase activity at low temperatures until the first high-temperature denaturation step. |

| Reaction Chemistry | Optimize Mg²⁺ and Primer Concentration [13] [16] | Reduces components that favor non-specific interactions. |

| Structural Modification | SAMRS (Self-Avoiding Molecular Recognition Systems) [11] | Incorporates nucleotide analogues that bind to natural DNA but not to other SAMRS-containing primers. |

| Structural Modification | Blocked-Cleavable Primers (rhPCR) [11] | Uses a blocking group removed only by RNase HII at high temperature, preventing extension of mis-annealed primers. |

The molecular mechanism of primer-dimer formation is a deterministic process initiated by the annealing of complementary 3' ends between primers, followed by enzymatic extension and exponential amplification. This guide has elaborated on this mechanism within the critical context of primer length and sequence composition, demonstrating that stable dimerization requires contiguous complementary regions and is favored by suboptimal reaction conditions. The quantitative data and experimental methodologies presented provide a framework for researchers to systematically diagnose, quantify, and prevent this pervasive issue. As molecular techniques evolve towards higher multiplexing and sensitivity, such as in next-generation sequencing and low-copy-number detection in drug development, a foundational and practical understanding of primer-dimer dynamics becomes indispensable for ensuring data integrity and experimental success.

In molecular biology and diagnostic development, the unintended formation of dimeric structures presents a significant challenge to experimental accuracy and product efficacy. This whitepaper examines the consequences of dimer formation across two key domains: primer dimers in polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and its derivatives, and heterodimers in co-formulated monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapeutic cocktails. Within the context of ongoing research into the relationship between primer length and dimer formation, we explore how these aberrant products compromise experimental results and therapeutic quality.

Dimer formation fundamentally represents a failure of specificity. In PCR, primers anneal to each other rather than the target template, while in mAb cocktails, different therapeutic antibodies interact instead of functioning independently. The consequences permeate multiple levels, from reduced amplification yield and false positive signals in diagnostics to altered therapeutic profiles and potential immunogenicity in biopharmaceuticals. Understanding these consequences is critical for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to develop robust assays and stable biotherapeutic formulations.

Mechanisms and Types of Dimer Formation

Primer Dimers in Nucleic Acid Amplification

Primer dimers are short, unintended DNA fragments generated during PCR when primers anneal to one another instead of the target DNA sequence [1]. The formation occurs primarily through two mechanisms:

- Self-dimerization: A single primer molecule contains regions that are self-complementary, allowing it to fold and create a free 3' end that DNA polymerase can extend.

- Cross-dimerization: The forward and reverse primers possess complementary regions, enabling them to hybridize together. The DNA polymerase then extends the annealed primers, producing a short double-stranded DNA product [1] [17].

These dimers typically appear below 100 base pairs in gel electrophoresis and often present a "smeary" appearance rather than a well-defined band [1]. The following diagram illustrates the formation mechanism and key identification features.

Heterodimers in Monoclonal Antibody Cocktails

In biopharmaceuticals, heterodimers represent a distinct challenge for co-formulated therapeutic mAbs. These are high molecular weight (HMW) species formed through intermolecular interactions between different mAbs in a cocktail formulation [18]. Unlike homodimers (formed by identical mAbs), heterodimers are unique to co-formulated products and are considered a potential critical quality attribute that must be rigorously monitored throughout product development [18]. The following table summarizes key characteristics of both dimer types.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Dimer Types

| Feature | Primer Dimers | mAb Heterodimers |

|---|---|---|

| Composition | Short DNA fragments from primers | Non-covalent complexes of different mAbs |

| Formation Cause | Complementary primer regions; suboptimal conditions | Intermolecular interactions between co-formulated mAbs |

| Primary Impact | Reduced PCR efficiency; false positives | Potential immunogenicity; reduced efficacy |

| Detection Methods | Gel electrophoresis, qPCR curve analysis | Native SEC-MS, AF4, SV-AUC |

| Prevention Strategies | Optimized primer design, hot-start polymerases | Formulation optimization, screening |

Consequences of Dimer Formation

Impact on PCR Efficiency and Diagnostic Accuracy

The consequences of primer dimer formation extend beyond mere nuisance, significantly compromising experimental outcomes:

Reduced Amplification Yield: Primer dimers compete with the target DNA for essential reaction components, including polymerase enzymes, dNTPs, and primers. This resource partitioning results in decreased amplification of the desired product, potentially leading to false negatives in low-template reactions [17].

False Positive Results: In quantitative PCR (qPCR) and reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR), fluorescent DNA-binding dyes like SYBR Green cannot distinguish between specific amplicons and primer dimers. The nonspecific fluorescence from dimer formation generates false positive signals that compromise data interpretation [19]. This is particularly problematic in diagnostic applications where result accuracy directly impacts clinical decision-making.

Inaccurate Quantification: The presence of primer dimers distorts the quantification cycle (Cq) values in qPCR, leading to imprecise measurement of target abundance. This inaccuracy renders gene expression studies unreliable and can invalidate viral load testing in clinical diagnostics [17].

Consequences for Therapeutic Antibody Development

In co-formulated mAb products, heterodimer formation presents distinct challenges for biopharmaceutical development:

Altered Efficacy and Safety Profiles: Heterodimer formation may modify the binding affinity and pharmacokinetics of therapeutic mAbs by blocking paratopes or creating new epitopes. These changes can reduce therapeutic efficacy or, in worst-case scenarios, lead to increased immunogenicity [18].

Analytical Complexity: The similar biophysical properties of heterodimers and homodimers complicate their separation and individual quantification using conventional techniques like SEC-UV. This analytical challenge impedes accurate monitoring of product stability and consistency [18].

Regulatory and Manufacturing Hurdles: As potential critical quality attributes, heterodimers require extensive characterization and control strategies throughout product development. Failure to adequately monitor and control these species can lead to batch rejection and regulatory delays [18].

The Primer Length-Dimer Formation Relationship

Fundamental Thermodynamic Principles

The relationship between primer length and dimer formation is governed by the thermodynamics of nucleic acid hybridization. Longer primers generally have:

- Higher Melting Temperatures (Tm): Tm increases with primer length due to additional stabilizing hydrogen bonds between complementary bases.

- Reduced ΔG° Variability: Fixed-length primers exhibit wide variations in standard Gibbs free energy change (ΔG°), leading to inconsistent hybridization efficiencies across different sequences [3].

Recent research has challenged the conventional fixed-length approach to primer design. A 2025 study demonstrated that fixed-length 20 nt primers without GC content control exhibited a broad ΔG° range from 0 to -24 kcal mol⁻¹ and hybridization yields from 0% to 100% [3]. This heterogeneity in thermodynamic properties directly contributes to variable dimer formation tendencies.

Fixed-Length vs. Fixed-Energy Primer Design

The traditional approach of using fixed-length primers simplifies data processing but introduces significant amplification bias. Research comparing fixed-length (20 nt) primers with fixed-energy primers (maintaining ΔG° around -11.5 kcal mol⁻¹) revealed striking differences:

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Fixed-Length vs. Fixed-Energy Primers

| Parameter | Fixed-Length Primers (20 nt) | Fixed-Energy Primers |

|---|---|---|

| ΔG° Range | 0 to -24 kcal mol⁻¹ | Tightly controlled around -11.5 kcal mol⁻¹ |

| Hybridization Yield Range | 0% to 100% | More consistent across sequences |

| Amplification Uniformity (fold-80) | 3.2 | 1.0 |

| Additional Sequencing Cost | 11,643-fold increase at 30x coverage | Baseline |

| Primer Dimer Propensity | Higher with longer primers | Controlled through design constraints |

Fixed-energy design achieves superior uniformity by harmonizing the thermodynamic driving force for hybridization, thereby reducing the exponential amplification of small efficiency differences across PCR cycles [3]. This approach represents a paradigm shift in primer design strategy, directly addressing the relationship between primer characteristics and dimer formation.

Experimental Protocols for Dimer Analysis

Protocol 1: Native SEC-MS for mAb Heterodimer Analysis

This protocol enables identification and quantitation of various hetero- and homodimer species in co-formulated mAb cocktails [18].

Materials:

- Analytical SEC column (e.g., AdvanceBio SEC 300Å, 2.7µm)

- Mass spectrometer with nanospray ionization capability

- 150 mM ammonium acetate, pH 6.8 (MS-compatible mobile phase)

- mAb cocktail samples

- PNGase F for deglycosylation (optional)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: If needed, treat samples with PNGase F to remove N-linked glycans, reducing mass heterogeneity and simplifying spectra.

- SEC Method Setup: Equilibrate the SEC column with 150 mM ammonium acetate (pH 6.8) at a flow rate of 0.2-0.4 mL/min.

- MS Parameter Optimization: Set MS resolution to low (LR) setting if sensitivity is prioritized over resolution. Adjust cone voltage and source temperature for optimal detection.

- Sample Injection: Inject 5-10 µg of mAb cocktail sample onto the SEC column.

- Data Acquisition: Monitor UV absorbance at 280 nm while simultaneously acquiring mass spectra in the m/z range of 2000-8000.

- Data Analysis: Identify heterodimer and homodimer peaks by their distinct masses. Quantitate individual species based on UV peak areas after mass-based identification.

Troubleshooting Tip: For three-mAb cocktails where mass detection alone is insufficient, implement an immunodepletion strategy to remove specific mAbs, simplifying the remaining dimer spectrum for interpretation [18].

Protocol 2: Primer Dimer Detection and Mitigation in PCR

This protocol provides a comprehensive approach to detect, identify, and minimize primer dimer formation in conventional PCR [1].

Materials:

- Thermostable DNA polymerase (preferably hot-start)

- Optimized primer set

- DNA template

- dNTP mix

- Appropriate reaction buffer

- Agarose gel electrophoresis equipment

- DNA ladder (covering 50-1000 bp range)

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare PCR master mix on ice, including hot-start polymerase, according to manufacturer's instructions.

- No-Template Control (NTC): Always include an NTC reaction containing all components except template DNA to specifically identify primer-derived artifacts.

- Thermal Cycling:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 2-5 minutes

- 30-35 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 20-30 seconds

- Annealing: Temperature optimized for specific primer set (often 3-5°C above calculated Tm) for 20-30 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for appropriate time based on target length

- Final extension: 72°C for 5 minutes

- Analysis:

- Separate PCR products on 2-3% agarose gel

- Run gel until primer dimers (typically <100 bp) have migrated sufficiently from main products

- Identify primer dimers as fuzzy, smeary bands below the last ladder band

- Interpretation: Compare test reactions with NTC to confirm primer dimer identity.

Optimization Steps: If dimers persist:

- Redesign primers using tools like Primer3 or NCBI Primer-BLAST to minimize complementarity

- Increase annealing temperature in 2°C increments

- Reduce primer concentration (typically 0.1-0.5 µM final concentration)

- Implement touchdown PCR protocols

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and their specific functions in managing dimer formation across applications.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Dimer Management

| Reagent/Category | Specific Function in Dimer Management | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Prevents enzymatic activity during reaction setup, reducing pre-amplification dimer formation | PCR, qPCR |

| Fixed-Energy Primers | Maintains consistent ΔG° (-10.5 to -12.5 kcal mol⁻¹) for uniform hybridization, reducing amplification bias | DNA information storage, NGS |

| Ammonium Acetate Buffer | MS-compatible volatile salt enabling native SEC-MS analysis of non-covalent mAb dimers | mAb cocktail characterization |

| SYBR Green I | Fluorescent DNA dye requiring careful primer design to avoid dimer-derived false signals | qPCR |

| Locked Nucleic Acids (LNAs) | Modified bases enhancing primer specificity and reducing self-complementarity | Allele-specific PCR |

| Native Deglycosylation Enzymes | Reduces mAb mass heterogeneity, simplifying dimer mass spectra | SEC-MS of mAbs |

| Silica Immobilization Matrix | Provides purification and stabilization platform for recombinant enzymes in diagnostics | LAMP-based diagnostics |

Advanced Analytical Strategies

Technological Solutions for Dimer Analysis

Advanced analytical techniques have emerged to address the challenges of dimer characterization:

Native SEC-MS (nSEC-MS): This hyphenated technique combines the separation power of size-exclusion chromatography with the identification capability of mass spectrometry under native conditions. Using MS-compatible mobile phases (e.g., ammonium acetate), nSEC-MS preserves non-covalent interactions while enabling accurate mass determination of heterodimers and homodimers in mAb cocktails [18].

High-Resolution Melting (HRM) Analysis: For nucleic acid applications, HRM differentiates specific amplicons from primer dimers by monitoring the precise melting behavior of DNA duplexes. This post-PCR analysis detects sequence differences based on subtle melting temperature variations [17].

Immunodepletion-Assisted SEC-MS: For complex three-mAb cocktails where mass differences are insufficient for dimer discrimination, selective immunodepletion of individual mAbs simplifies the sample matrix. This strategic pre-treatment enables identification of all six possible hetero- and homodimers by systematically reducing sample complexity [18].

Computational Tools for Dimer Prevention

Bioinformatics approaches play a crucial role in preventing dimer formation at the design stage:

Primer Design Algorithms: Tools like Primer3 and NCBI Primer-BLAST incorporate checks for self-complementarity and cross-dimer formation during primer selection. These programs evaluate potential intermolecular interactions to minimize dimer-prone designs [6].

Fixed-Energy Primer Design Platforms: Innovative tools like CertPrime represent the next generation of oligonucleotide design, specifically addressing the limitations of fixed-length approaches. By minimizing melting-temperature deviations and spurious dimer formation, these platforms enhance gene-synthesis efficiency and amplification uniformity [8] [3].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and computational workflow for managing dimer formation in diagnostic and therapeutic development.

Dimer formation represents a critical challenge with far-reaching consequences across molecular biology and biopharmaceutical development. The relationship between primer length and dimer formation exemplifies how fundamental molecular interactions impact practical applications, from diagnostic accuracy to therapeutic efficacy. Through advanced design strategies like fixed-energy primers and sophisticated analytical techniques such as nSEC-MS, researchers can effectively mitigate these challenges. The continued refinement of computational tools and experimental protocols will further enhance our ability to control dimer formation, ultimately strengthening the reliability of molecular diagnostics and the quality of biotherapeutic products.

In the realm of molecular biology, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a cornerstone technique for nucleic acid amplification. The success and fidelity of this process are critically dependent on the oligonucleotide primers, which are designed to flank and define the target sequence. A pervasive challenge in this domain is the formation of primer dimers (PDs), unintended amplification artifacts that arise when primers anneal to each other rather than to the template DNA. PDs compete with the target amplification for essential reagents, such as nucleotides and polymerase, thereby reducing assay efficiency, sensitivity, and reliability [1] [11]. While multiple factors contribute to PD formation, including primer sequence and reaction conditions, primer length is a fundamental and primary determinant. This whitepaper examines the mechanistic relationship between primer length and dimerization potential, framing it within the broader context of assay optimization for research and diagnostic applications.

The Mechanistic Basis of Primer Dimer Formation

Understanding how primer dimers form is essential to appreciating why primer length is so critical. The process is a sequence of molecular events that can be catalyzed by the DNA polymerase itself.

A Three-Step Process

The formation of a stable primer dimer follows a defined pathway [11]:

- Initial Annealing (Step I): Two primers anneal at their 3' ends via short regions of complementary bases. The stability of this initial duplex is heavily influenced by the GC content and the length of the complementary overlap.

- Polymerase Extension (Step II): If the initial duplex is stable, DNA polymerase binds and extends the primers, using each as a template for the other. This synthesizes a short, double-stranded DNA fragment.

- Template Amplification (Step III): In subsequent PCR cycles, the newly synthesized PD strand acts as a template for fresh primers, leading to exponential amplification of the dimer product, which competes directly with the intended target.

The Critical Role of the 3' End

The 3' end of the primer is particularly crucial for dimerization. Because DNA synthesis proceeds from the 3' end, any complementarity in this region is a significant risk factor. Mismatches in the 3' end region have a disproportionately large effect on priming efficiency, as they can disrupt the polymerase active site [20]. Consequently, even a short stretch of complementarity at the 3' ends—a scenario more probable with shorter primers—can provide a sufficient foothold for polymerase binding and extension, initiating the dimerization cascade [11].

The following diagram illustrates this multi-step process of primer dimer formation:

Primer Length: A Primary Determinant of Dimerization

Primer length directly influences two key properties that govern dimerization potential: specificity and thermal stability.

The Specificity Paradox of Short Primers

Shorter primers, typically defined as those below 18 nucleotides, are inherently less specific. The statistical probability of a short sequence finding a complementary match by random chance elsewhere in the reaction mixture—including on another primer molecule—is significantly higher than for a longer sequence [12]. While this can be advantageous in some applications, such as random amplification in next-generation sequencing library preparation [21], it is a major liability in targeted PCR. A random 6mer, for instance, has a high probability of finding a near-complementary sequence on another primer, leading to dimer formation. In contrast, an 18mer or longer primer is far less likely to randomly encounter a perfectly complementary sequence, thereby drastically reducing the potential for nonspecific annealing [21] [12].

Melting Temperature (T~m~) and Stability

The melting temperature (T~m~) of a primer, the temperature at which half of the DNA duplex dissociates, is directly proportional to its length and its GC content [6] [12]. Shorter primers have a lower T~m~. If the annealing temperature of the PCR is set higher than the T~m~ of the intended, specific primer-template duplex, amplification may fail. However, if the annealing temperature is too low, it permits the stabilization of short, imperfect primer-primer duplexes, facilitating dimerization [11]. Longer primers, with their inherently higher T~m~, allow the use of higher, more stringent annealing temperatures that prevent the transient primer-primer interactions from stabilizing, thus suppressing PD formation.

Table 1: General Primer Design Guidelines to Minimize Dimerization [6] [12]

| Parameter | Recommended Optimal Value | Impact on Dimerization |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Length | 18–30 nucleotides | Increases specificity and T~m~, reducing chance random complementarity. |

| GC Content | 40–60% | Balanced GC prevents overly low or high T~m~; a 3' GC clamp enhances specificity. |

| 3' End Complementarity | ≤3 contiguous bases between primers | Minimizes the risk of stable cross-dimer initiation by polymerase. |

| Self-Complementarity | ≤3 contiguous bases within a primer | Prevents hairpin structures and self-dimerization. |

| Melting Temperature (T~m~) | 65–75°C for both primers | Enables use of high annealing temperatures to discourage nonspecific binding. |

Experimental Evidence and Protocol for Assessing Dimerization

Systematic investigation is required to unequivocally link primer length to dimerization potential and to optimize assay conditions.

Key Experimental Methodology

A robust approach to study this involves designing a series of primers of varying lengths (e.g., 6mers, 12mers, 18mers, and 24mers) targeting the same genomic locus and comparing their performance in controlled PCR experiments [21].

Protocol: Evaluating Primer Length and Dimerization [21] [22]

- Primer Design: Design forward and reverse primers of different lengths (e.g., 12nt, 18nt, 24nt) for the same target. Use primer analysis software (e.g., Primer3, Oligo) to check for self-complementarity and inter-primer complementarity for all sets.

- Reaction Setup: Prepare separate PCR mixtures for each primer set. The reaction should include:

- DNA template (including a no-template control, NTC)

- Forward and reverse primers (e.g., 0.1–0.5 µM each)

- Master mix (polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl₂ buffer)

- Thermal Cycling: Run the PCR with a standardized protocol, including an initial denaturation (95°C for 2–5 min), followed by 30–40 cycles of denaturation (95°C for 15–30 s), annealing (a temperature gradient from 50–68°C for 30 s), and extension (72°C for 1 min/kb).

- Analysis by Gel Electrophoresis:

- Analyze the PCR products and NTCs on a 2–3% agarose gel.

- Target Amplicon: Should appear as a sharp, discrete band at the expected size.

- Primer Dimers: Typically appear as a fuzzy smear or band between 30–100 bp, notably in the NTC lanes where no true target exists [1].

- Analysis by Melting Curve (for qPCR): If using SYBR Green chemistry in quantitative PCR, perform a melting curve analysis post-amplification. Primer dimers will manifest as a distinct, lower temperature peak separate from the higher temperature peak of the specific product [11].

The workflow for this experimental approach is summarized below:

Quantitative Data and Observations

While direct comparative studies on dimerization frequency across different primer lengths are less common in the literature, related research provides strong indirect evidence. A landmark 2024 study in Nature Communications systematically investigated the impact of random primer length (6mer, 12mer, 18mer, 24mer) on RNA-seq library generation [21]. They found that the 18mer random primer demonstrated superior efficiency in overall transcript detection compared to the commonly used 6mer. Although the primary focus was on detection sensitivity, the improved performance of the 18mer is consistent with reduced nonspecific interactions and dimerization, which would otherwise deplete reagents and compromise library complexity. This underscores that moving away from very short primers can yield substantial gains in assay performance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Practical Reagents and Solutions

Success in preventing primer dimers relies on a combination of intelligent primer design and the use of specialized biochemical reagents.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Mitigating Primer Dimerization

| Reagent / Method | Function / Principle | Practical Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Inhibits polymerase activity at room temperature, preventing dimer formation during reaction setup. Activated only at high initial denaturation temperature [1] [11]. | A critical first-line defense. Available in antibody-based, chemical modification, or aptamer-based formats. |

| Optimized Buffer Systems | Provides optimal MgCl₂ and salt concentrations. Mg²⁺ is a cofactor for polymerase; its precise concentration is vital for specificity [6]. | Too much Mg²⁺ promotes nonspecific binding; too little reduces efficiency. Must be empirically optimized. |

| dNTP Mix | The building blocks for DNA synthesis. | Balanced concentrations are necessary; imbalances can promote mispriming. |

| Primer Design Software (e.g., Primer3, Primer-BLAST) | Algorithms check for self-dimers, cross-dimers, secondary structure, and calculate accurate T~m~ [6]. | Essential for the in-silico phase of assay development to flag problematic primers before synthesis. |

| Blocked-Cleavable Primers (e.g., for rhPCR) | Primers are chemically blocked at the 3' end, preventing extension until a specific enzyme cleaves the block upon specific binding to the true target [11]. | Highly effective at eliminating primer dimer formation but can be more complex and costly to implement. |

The body of evidence firmly establishes primer length as a critical and primary factor in dimerization potential. Short primers, while sometimes necessary for specific applications, carry an inherent and significantly higher risk of forming primer dimers due to their reduced sequence specificity and lower thermal stability. Adhering to design principles that utilize longer primers (18–30 nucleotides) and employing strategic experimental protocols—including rigorous in-silico design, the use of hot-start enzymes, and careful optimization of reaction conditions—constitutes a robust defense against this pervasive technical artifact. For researchers and drug development professionals, a deep understanding of this critical link is indispensable for developing robust, sensitive, and reliable molecular assays, from basic research to clinical diagnostics.

Exploring the Role of Complementary Regions and Free 3' Ends in Dimer Initiation

Dimer formation represents a critical challenge in molecular biology, particularly in polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and oligonucleotide-based applications. This technical review examines the fundamental mechanisms through which complementary regions and free 3' hydroxyl ends initiate and facilitate dimerization processes. Through systematic analysis of experimental data and mechanistic studies, we elucidate how sequence complementarity, primer length, and structural dynamics contribute to dimer formation. The findings presented herein inform the development of robust experimental design principles that minimize spurious dimerization while maintaining amplification efficiency, thereby advancing diagnostic and synthetic biology applications.

Dimer initiation constitutes a significant impediment to reaction specificity across molecular biology, disproportionately impacting PCR fidelity and gene synthesis efficiency. The phenomenon arises primarily through two interconnected mechanisms: inter-molecular complementarity between oligonucleotide sequences and the enzymatic exploitation of free 3' hydroxyl ends. Within PCR, for instance, primer-dimer artifacts can consume reaction components, thereby competing with target amplification and reducing sensitivity [1]. Similarly, in gene synthesis applications, spurious dimer formation between overlapping oligonucleotides compromises assembly efficiency and accuracy [8].

This review contextualizes dimer initiation mechanisms within broader research on primer length relationships, examining how thermodynamic parameters and structural constraints govern unwanted oligonucleotide interactions. For research scientists and drug development professionals, understanding these principles is paramount for designing robust assays and synthetic constructs. We present quantitative analyses of dimerization parameters, detailed experimental methodologies for characterization, and evidence-based strategies for mitigation, providing a comprehensive toolkit for optimizing molecular protocols.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Dimer Initiation

Structural Bases of Dimer Formation

Dimer initiation proceeds through defined molecular mechanisms wherein complementary nucleic acid sequences undergo hybridization, creating substrates for polymerase extension. The process requires two fundamental components: sequence complementarity that enables strand association, and free 3' OH ends that provide priming sites for enzymatic elongation [1]. These interactions manifest as either self-dimerization (involving a single primer species) or cross-dimerization (between distinct primers).

The initial interaction depends on transient base pairing between complementary regions, typically involving 3-5 nucleotide stretches with significant complementarity [23]. Once stabilized, these duplexes present free 3' hydroxyl groups that DNA polymerase recognizes as legitimate priming sites, instating enzymatic extension that covalently stabilizes the dimeric complex. The resulting products are short, doublestranded DNA fragments approximately twice the primer length, often appearing as smeared bands below 100 bp during gel electrophoresis [1].

The Critical Role of Free 3' OH Ends

The free 3' hydroxyl group serves as an absolute prerequisite for dimer stabilization through polymerase-mediated extension. This chemical moiety provides the necessary substrate for DNA polymerase to catalyze phosphodiester bond formation using incoming deoxynucleoside triphosphates [24]. Without this reactive group, transient dimer complexes would dissociate rather than become stabilized through elongation.

In PCR applications, the problem exacerbates during reaction setup stages when reagents are at room temperature, allowing primers increased opportunity for nonspecific interactions before thermal cycling commences. This explains the efficacy of hot-start DNA polymerases, which remain inactive until elevated temperatures denature incidental duplexes, thereby preventing extension of primerdimers during reaction preparation [1].

Table 1: Characteristics of Primer-Dimer Formation Mechanisms

| Mechanism Type | Complementarity Requirement | Free 3' OH Utilization | Resulting Product |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Dimerization | Internal regions of single primer species | 3' end of same primer | Hairpin-like structures or homodimers |

| Cross-Dimerization | Complementary regions between different primers | 3' ends of either or both primers | Heterodimers of varying lengths |

| Polymerase Extension | Minimal (2-3 bp can initiate) | Required for stabilization | Elongated dsDNA fragments |

Quantitative Analysis of Dimerization Parameters

Impact of Primer Length and Design

Recent investigations reveal complex relationships between primer length, binding energy, and dimerization propensity. While traditional primer design often employs fixed-length oligonucleotides (typically 18-25 nucleotides), emerging research demonstrates that binding energy optimization more effectively minimizes spurious interactions than length standardization alone [3].

In a comprehensive analysis of 2 million primer candidates, only 8.3% satisfied optimal free energy change (ΔG°) criteria (-10.5 to -12.5 kcal/mol) when screened across lengths of 15-30 nucleotides. A mere 2% simultaneously met GC content requirements (40-60%), highlighting the challenge of designing primers that balance specificity with minimized dimerization potential [3]. Fixed-length primers exhibited substantial variation in hybridization efficiency (ΔG° range: 0 to -24 kcal/mol), whereas fixed-energy designs demonstrated uniform amplification behavior with significantly reduced dimer formation [3].

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters Influencing Dimer Formation

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Dimerization Risk | Experimental Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primer Length | 18-25 nucleotides | Short primers: Increased risk Long primers: Secondary structure risk | Non-specific amplification Reduced yield |

| GC Content | 40-60% (ideal: 45-50%) | High GC: Stronger unintended bonds Low GC: Reduced specificity | False positives Primer-dimer artifacts |

| Annealing Temperature | 5°C below Tm | Low temperature: Increased mishybridization | Spurious amplification Reduced target amplicons |

| 3' End Complementarity | ≤3 complementary bases | >4 bases: Significant dimer risk | Primer-dimer accumulation Reaction failure |

| Free Energy (ΔG°) | -10.5 to -12.5 kcal/mol | Wider ranges: Inconsistent hybridization | Amplification bias Selective template loss |

Complementary Region Characteristics

The arrangement and extent of complementary regions fundamentally dictate dimerization probability. Computational and empirical analyses demonstrate that ≥4 complementary bases between primer 3' ends substantially increase dimer formation, particularly when complementarity involves the 3'-terminal nucleotides [23]. The GC content within these complementary regions further modulates interaction stability, with GC-rich stretches forming more stable dimers due to additional hydrogen bonding.

Notably, dimerization exhibits concentration dependence, with higher primer concentrations accelerating kinetics. This relationship underscores the importance of optimizing primer concentrations to achieve favorable primer-to-template ratios, typically through empirical titration between 0.1-0.5 μM [1]. The use of bioinformatic tools like CertPrime facilitates preemptive identification of problematic complementarity during oligonucleotide design, enabling selection of sequences with minimized interaction potential [8].

Experimental Protocols for Dimer Analysis

Gel Electrophoresis Detection Method

Purpose: To separate and visualize primer-dimer artifacts from target amplicons via agarose gel electrophoresis.

Materials:

- Nucleic acid samples (PCR products)

- Agarose powder

- Electrophoresis buffer (TAE or TBE)

- DNA staining solution (e.g., ethidium bromide, SYBR Safe)

- DNA molecular weight ladder (50-1000 bp range)

- Gel electrophoresis apparatus

- UV transilluminator or blue light imager

Procedure:

- Prepare a 2-4% agarose gel by dissolving agarose in electrophoresis buffer, melting via heating, and adding nucleic acid stain before solidification.

- Load 5-10 μL of PCR product mixed with loading dye into gel wells alongside appropriate DNA size standards.

- Conduct electrophoresis at 5-8 V/cm for 30-45 minutes sufficient to separate fragments below 100 bp.

- Visualize using UV or blue light illumination.

Interpretation: Primer-dimers manifest as diffuse, smeared bands typically below 100 bp, distinct from the discrete, larger bands of specific amplicons. Extended electrophoresis times improve resolution of small dimer products [1].

No-Template Control (NTC) Implementation

Purpose: To distinguish primer-derived artifacts from target-specific amplification products.

Materials:

- All standard PCR reagents excluding template DNA

- Nuclease-free water (template substitute)

Procedure:

- Prepare identical reaction mixtures alongside experimental samples, replacing template DNA with nuclease-free water.

- Subject NTC to identical thermal cycling conditions as experimental reactions.

- Analyze results alongside test samples using gel electrophoresis or other detection methods.

Interpretation: Amplification products in NTC reactions indicate primer-dimer formation or contaminating nucleic acids, as these reactions lack specific template [1]. This control is essential for validating reaction specificity.

Melting Temperature Analysis for Dimer Prediction

Purpose: To computationally predict dimerization potential during primer design.

Materials:

- Oligonucleotide sequences

- Primer design software (e.g., Primer3, CertPrime)

Procedure:

- Input candidate primer sequences into analysis software.

- Execute self-complementarity and cross-dimerization algorithms.

- Review output reports highlighting complementary regions and predicted interaction strengths.

- Select primer pairs with minimal 3' complementarity (<4 consecutive bases) and stable hybridization to target sequences.

Interpretation: Software tools identify problematic complementarity, particularly at 3' ends, allowing redesign before synthesis. CertPrime specifically minimizes Tm deviations and spurious dimer formation for gene synthesis applications [8].

Visualization of Dimer Initiation Pathways

Dimer Initiation and Stabilization Pathway

This diagram illustrates the sequential molecular events in dimer formation, highlighting the critical roles of complementary regions and free 3' OH ends in initiating and stabilizing dimer artifacts through polymerase-mediated extension.

Research Reagent Solutions for Dimer Prevention

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Dimer Investigation and Prevention

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Dimer Prevention |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start Polymerases | Hot-start Taq, Phusion | Prevents enzymatic activity during reaction setup, minimizing extension of transient dimers |

| Optimized Buffer Systems | Mg²⁺-free formulations, additive-enhanced | Modifies hybridization kinetics to favor specific annealing |

| Computational Design Tools | CertPrime, Primer3 | Identifies and eliminates sequences with high dimerization potential pre-synthesis |

| dNTP Formulations | Balanced dNTP mixes, concentration-optimized | Prevents preferential extension of mismatched termini |

| Template Enhancers | Betaine, DMSO, PEG | Reduces secondary structure and minimizes mishybridization |

| Negative Controls | No-template controls (NTC) | Detects primer-dimer formation in absence of target |

Discussion and Research Implications

The empirical data and mechanistic analyses presented substantiate the critical relationship between complementary regions, free 3' ends, and dimer initiation. This understanding directly informs primer design strategies within broader research on primer length optimization. Specifically, the demonstrated efficacy of fixed-energy primer designs over fixed-length approaches underscores the importance of thermodynamic predictability in controlling dimerization [3].

For research and diagnostic applications, these findings enable development of more robust nucleic acid amplification systems with reduced false-positive rates and improved quantification accuracy. In gene synthesis, implementing dimer-minimized oligonucleotide designs significantly enhances assembly efficiency, particularly for complex constructs [8]. Future research directions should explore polymerase engineering to enhance discrimination against dimer templates and develop machine learning algorithms for improved dimer prediction.

The strategic integration of computational design, empirical validation, and enzymatic control methods outlined herein provides researchers with a comprehensive framework for managing dimerization across diverse molecular biology applications.

Strategic Primer Design: Leveraging Length and Other Parameters for Success

In polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology, primer design stands as a critical determinant of experimental success. Among the various parameters, primer length emerges as a fundamental factor directly influencing amplification specificity, efficiency, and the propensity for primer-dimer formation. This technical guide examines the scientific rationale underpinning the established "Goldilocks zone" of 18-25 nucleotides for primer design, framing it within broader research on dimer formation. Through systematic analysis of quantitative data, experimental protocols, and molecular interactions, we demonstrate how this optimal length range balances the competing demands of specificity, annealing kinetics, and structural stability, thereby minimizing aberrant primer interactions while maximizing target amplification efficiency for research and diagnostic applications.

Primer design represents a cornerstone of molecular biology, enabling countless applications in gene expression analysis, cloning, mutagenesis, and diagnostic testing. At its core, PCR requires oligonucleotide primers that provide a starting point for DNA synthesis by DNA polymerase. These primers must be complementary to the template DNA strand to facilitate specific amplification [25]. The concept of a "Goldilocks zone" – where conditions are neither too extreme nor too mild but perfectly suited for the intended purpose – aptly describes the delicate balance required in primer length optimization. This principle resonates with recent findings in cellular biochemistry, where specific concentration ranges of components like magnesium and polyphosphate form condensates with DNA that exhibit optimal functionality [26].

The length of a primer directly governs its binding behavior through well-established principles of molecular hybridization kinetics and thermodynamics. Excessively short primers (<18 nucleotides) demonstrate reduced specificity due to a higher statistical probability of encountering complementary sequences at multiple genomic locations, while overly long primers (>30 nucleotides) suffer from slower hybridization rates and increased likelihood of secondary structure formation [27] [25]. The 18-25 nucleotide range establishes an equilibrium where primers are long enough for unique recognition of target sequences yet short enough to anneal efficiently without problematic self-interactions. This review systematically explores the relationship between primer length and dimer formation, providing researchers with evidence-based protocols for designing and validating primers that operate within this optimal range.

Quantitative Analysis of Primer Design Parameters

Core Primer Design Specifications

The established guidelines for effective primer design incorporate several interdependent parameters that collectively determine PCR success. The following table summarizes the optimal ranges for key primer characteristics as established across multiple technical resources:

Table 1: Optimal Parameters for Standard PCR Primer Design

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Technical Rationale | Consequences of Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primer Length | 18-25 nucleotides [27] [25] [28] | Balances specificity with efficient annealing [27] | Short primers: nonspecific binding; Long primers: slow hybridization [25] |

| GC Content | 40-60% [12] [25] [28] | Ensures stable primer-template duplex without excessive strength [12] | Low GC: unstable binding; High GC: nonspecific amplification [12] |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | 55-65°C [27] [28] | Compatible with standard PCR cycling conditions | Low Tm: poor annealing; High Tm: secondary annealing [27] |

| 3'-End GC Clamp | 1-2 G/C bases [12] [28] | Strong hydrogen bonding for polymerase initiation [12] | A/T-rich 3' end: inefficient extension [28] |

| Tm Difference Between Primer Pair | ≤5°C [27] [25] | Enables simultaneous annealing of both primers | Differential annealing efficiencies reduces yield [27] |

Primer Length Impact on Experimental Outcomes

The relationship between primer length and experimental success extends beyond simple base count, influencing multiple aspects of PCR performance. Research indicates that primers shorter than 18 bases produce "inaccurate, nonspecific DNA amplification product," while those longer than 30 nucleotides result in "slower hybridizing rate" [25]. Computational design tools like CREPE (CREate Primers and Evaluate), which integrate Primer3 and In-Silico PCR functionality, demonstrate successful amplification for more than 90% of primers deemed acceptable by their evaluation criteria, with most falling within the 18-25 nucleotide range [29].

Table 2: Application-Specific Primer Length Recommendations

| Application | Recommended Length | Technical Justification | Additional Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard PCR | 18-24 bases [27] | Sequence-specific with efficient binding [27] | Balance specificity and annealing stability |

| qPCR Assays | 18-25 bases [30] | Optimized for real-time detection efficiency | Shorter amplicons (70-200 bp) preferred [30] |

| Genome Mapping | ~15 bases [27] | Sufficient for simple genome identification | Reduced specificity acceptable for intended use |

| Heterogeneous Sequences | 28-35 bases [27] | Accommodates sequence variability | Longer length compensates for mismatch tolerance |

| Cloning with Restriction Sites | 18-25 bases + 3-6 base "clamp" [25] | Maintains core functionality with enzyme efficiency | Length calculation excludes added cloning sequences |

Molecular Mechanisms of Primer-Dimer Formation

Thermodynamic Basis for Primer Self-Interactions

Primer-dimer formation represents a significant challenge in PCR optimization, occurring when primers anneal to each other instead of the target DNA template [17]. These aberrant interactions are classified as either homodimers (between two identical primers) or heterodimers (between forward and reverse primers with complementary sequences) [31]. The formation of primer dimers follows predictable thermodynamic principles influenced by primer length, sequence composition, and concentration. Shorter primers exhibit increased mobility and higher likelihood of transient interactions, particularly when containing complementary regions at their 3' ends where DNA polymerase can initiate extension, thereby generating undesired amplification products [31].

The 18-25 nucleotide range establishes a thermodynamic "sweet spot" that minimizes dimer formation through several mechanisms. Firstly, longer primers within this range possess greater sequence complexity, reducing the statistical probability of extensive complementarity between primer pairs. Research indicates that "repeated patterns can result in primers that form hairpin loops or self-dimers" [27], a problem exacerbated in shorter sequences with limited design flexibility. Secondly, the optimal length supports stable binding to the intended target without excessive strength that might promote off-target interactions. As noted in technical literature, primers should avoid "runs of 4 or more of one base, or dinucleotide repeats (for example, ACCCC or ATATATAT)" [12] as these motifs increase dimerization potential regardless of length, though their impact is more pronounced in shorter primers.

Experimental Evidence Linking Length to Dimerization

Advanced analytical techniques have quantified the relationship between primer length and dimer formation. Studies utilizing high-resolution melting analysis (HRM) demonstrate that primer dimers exhibit distinct melting profiles from specific amplification products, enabling researchers to differentiate and quantify these aberrant interactions [17]. The findings consistently reveal that primers shorter than 18 nucleotides show markedly increased dimer formation, particularly under suboptimal cycling conditions. This phenomenon is compounded by the fact that "LAMP primers at higher concentrations can form primer dimers and other mismatched hybridizations" more readily than standard PCR primers [31], highlighting the concentration-dependent nature of the problem.

The mechanistic progression of dimer formation follows a predictable pathway that initiates with transient hybridization between complementary regions, particularly at the 3' ends where extension can commence. The diagram below illustrates this molecular process and its experimental consequences:

Figure 1: Molecular pathway of primer-dimer formation and its experimental consequences. Characteristics including short length (<18 bp), high concentration, and self-complementary sequences promote transient binding that progresses to stable dimer formation through polymerase extension, ultimately yielding nonspecific amplification and reduced target yield.

Experimental Protocols for Primer Design and Validation

Computational Design and Specificity Verification

Large-scale primer design projects benefit from integrated computational pipelines that streamline the design and validation process. The CREPE (CREate Primers and Evaluate) pipeline represents one such approach, combining Primer3 for initial design with In-Silico PCR (ISPCR) for specificity analysis [29]. The following protocol outlines the key steps for implementing this validated methodology:

Input Preparation: Prepare an input file containing the required columns 'CHROM', 'POS', and 'PROJ' compatible with the reference genome (UCSC's GRCh38.p14 as default) [29].

Primer Design Execution: Process input files using Primer3 with standardized parameters: product size range of 70-200 bp for qPCR applications [30], primer length of 18-25 bases, Tm between 55-65°C, and GC content of 40-60% [29].

Specificity Analysis: Format resulting primer pairs for ISPCR analysis using algorithm parameters including -minPerfect = 1 (minimum size of perfect match at 3′ end of primer), -minGood = 15 (minimum size where there must be two matches for each mismatch), -tileSize = 11 (the size of match that triggers an alignment), and -maxSize = 800 (maximum size of PCR product) [29].

Off-Target Assessment: Execute custom evaluation script to identify concerning off-target amplicons. Filter primer pairs aligning to decoy contigs and eliminate those with ISPCR scores less than 750. Calculate normalized percent match for off-target amplicons, considering those with 80-100% match to on-target amplicon as high-quality concerning off-targets (HQ-Off) [29].

Output Generation: Generate final tab-delimited output file containing variant_ID, Primer3 success Boolean, ISPCR acceptance Boolean, primer names, sequences, melting temperatures, and off-target annotations [29].

Empirical Validation and Optimization

While computational prediction provides robust primer selection, empirical validation remains essential for protocol confirmation. The following experimental workflow details the laboratory validation process:

Primer Quality Assessment: Utilize cartridge purification as a minimum purification level for standard PCR applications, with HPLC purification recommended for demanding applications or longer primers [12].

Annealing Temperature Optimization: Perform gradient PCR with annealing temperature range spanning 5°C below to 5°C above the calculated Tm to establish optimal annealing conditions [27]. For primers with Tm of 56-62°C, this typically corresponds to an annealing temperature range of 51-67°C [27].

Specificity Verification: Analyze PCR products using gel electrophoresis to confirm single band amplification at expected size. For qPCR applications, perform melt curve analysis to detect primer-dimer formations which typically demonstrate lower melting temperatures than specific products [17].

Efficiency Calculation: For qPCR applications, generate standard curve with serial dilutions of template DNA. Calculate efficiency using the formula E = 10^(-1/slope) - 1, with optimal efficiency ranging from 90-110% [30].

Cross-Validation: Compare performance of multiple primer pairs designed for the same target to identify optimal candidates based on amplification efficiency, specificity, and minimal dimer formation [28].

The experimental workflow below illustrates the integrated computational and empirical validation process:

Figure 2: Integrated workflow for computational primer design and empirical validation. The process begins with target sequence input, progresses through bioinformatic design and specificity analysis, and concludes with laboratory-based optimization and efficiency verification.

Successful primer design and implementation requires both computational tools and laboratory reagents. The following table catalogues essential resources for effective PCR experimentation:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Primer Design and Validation

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Design Tools | Primer3 [29], NCBI Primer-BLAST [27], SnapGene [28] | Automated primer design with parameter optimization | Length 18-25 bp, Tm 55-65°C, GC 40-60% [28] |

| Specificity Analysis Platforms | In-Silico PCR (ISPCR) [29], BLAST-Like Alignment Tool (BLAT) [29] | Genome-wide off-target binding prediction | -minPerfect=1, -minGood=15, -tileSize=11 parameters [29] |

| DNA Polymerases | Hot-start polymerases [17] | Reduce primer-dimer formation during reaction setup | Thermoactivated or antibody-mediated inhibition |

| Primer Purification Methods | Cartridge purification [12], HPLC purification [12] | Remove truncated synthesis products | Cartridge: standard applications; HPLC: demanding applications |

| Specialized Chemistries | Locked Nucleic Acids (LNAs) [17], Peptide Nucleic Acids (PNAs) [17] | Enhance primer specificity and reduce self-complementarity | Modified bases with higher binding affinity |

| Validation Instruments | High-Resolution Melting (HRM) analysis [17], Gel electrophoresis systems | Differentiate specific amplification from primer-dimer products | Melt curve analysis for qPCR applications |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The established 18-25 nucleotide "Goldilocks zone" for primer length represents more than a historical convention—it embodies a thermodynamic optimum validated through decades of molecular experimentation. This length range successfully balances the competing demands of hybridization kinetics, specificity requirements, and practical synthetic considerations. The relationship between primer length and dimer formation exemplifies how molecular systems often exhibit optimal zones of operation, a concept observed elsewhere in biochemistry as noted in recent research on biomolecular condensates where "a delicate 'Goldilocks' zone - a specific magnesium concentration range" governs DNA wrapping around polyP-magnesium ion condensates [26].

Future directions in primer design will likely incorporate increasingly sophisticated computational modeling that accounts for chromatin architecture and epigenetic modifications when predicting binding efficiency. The development of bifunctional synthetic molecules like SynGRs (synthetic genome readers/regulators), which must navigate structural constraints to engage target domains effectively [32], highlights the growing importance of spatial considerations in nucleic acid recognition. Similarly, advances in polymerase engineering may relax some current constraints, potentially expanding the operable range of primer lengths for specialized applications. However, the fundamental thermodynamic principles underlying the 18-25 nucleotide optimum will continue to inform basic primer design strategies for standard PCR applications.

For research and drug development professionals, adherence to these established parameters provides a robust foundation for experimental success while minimizing resource expenditure on optimization. By recognizing the scientific rationale behind the Goldilocks zone and implementing the validated protocols outlined in this review, researchers can systematically reduce primer-dimer formation while maximizing amplification specificity and efficiency across diverse molecular applications.

The design of oligonucleotide primers is a foundational step in the success of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and other molecular biology applications. The relationship between primer length, melting temperature (Tm), and specificity is a tightly coupled system where altering one parameter inevitably affects the others. This interplay is not merely a theoretical concern; it has direct and profound implications for experimental outcomes, particularly in the prevention of primer-dimer artifacts and non-specific amplification. Primer-dimer formation, an off-target amplification event where primers anneal to each other instead of the template DNA, competitively inhibits binding to the target, removes primers from the reaction pool, and exhausts reagents, ultimately leading to reduced amplification efficiency and suboptimal product yields [33]. Within the context of dimer formation research, understanding the biophysical parameters that govern primer-primer interactions is essential for designing robust assays. This guide provides an in-depth examination of these core principles, supported by experimental data and methodologies, to empower researchers in making informed design choices.

Core Principles and Quantitative Relationships

Primer Length: The Foundation of Specificity and Efficiency

Primer length is the primary determinant of its specificity. The challenge lies in balancing a length sufficient for unique targeting against the annealing efficiency.

- Optimal Range: The widely accepted optimal length for PCR primers is 18 to 24 nucleotides [27] [34] [12]. This range provides a high probability of being unique within a complex genome while still allowing for efficient annealing.

- The Specificity Dilemma: Shorter primers (e.g., 15-17 bases) anneal more rapidly but have a significantly higher risk of binding to multiple, non-target sites, leading to non-specific amplification [27] [34]. Conversely, longer primers (> 30 bases) are more specific but can anneal less efficiently, potentially reducing PCR yield [34]. In microbial ecology or for amplifying sequences with high heterogeneity, longer primers in the 28-35 base range are sometimes employed [27].

Table 1: Impact of Primer Length on Key Parameters

| Primer Length | Specificity | Annealing Efficiency | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short (15-17 bp) | Lower | Higher | Mapping simple genomes |

| Standard (18-24 bp) | High | High | Standard PCR, qPCR |

| Long (28-35 bp) | Very High | Lower | High-heterogeneity sequences |

Melting Temperature (Tm): The Thermodynamic Keystone

The melting temperature (Tm) is the temperature at which 50% of the primer-DNA duplex dissociates and 50% remains bound [35]. It is a critical parameter for determining the annealing temperature (Ta) of the PCR cycle.

- Optimal Tm Range: For standard PCR, a Tm between 56°C and 65°C is recommended [27] [36]. For cycle sequencing, the ideal Tm is between 55°C and 65°C [36]. It is crucial that the forward and reverse primers have Tms within 2°C to 5°C of each other to ensure both anneal efficiently at the same reaction temperature [27] [34].

- Calculating Tm: Several formulas exist. The Wallace Rule, ( T_d = 2(A+T) + 4(G+C) ), provides a quick estimate but is less accurate for longer primers [36]. The nearest-neighbor method is considered the most accurate and is used by modern primer design software [34]. A simple approximation is ( Tm = 4°C \times (G+C) + 2°C \times (A+T) ), which highlights that G and C bases (linked by three hydrogen bonds) contribute more significantly to duplex stability than A and T bases (two hydrogen bonds) [34] [12].