Primer Dimer Prevention in Sanger Sequencing: A Complete Guide for Reliable Results

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on designing Sanger sequencing primers to prevent dimer formation and secondary structures, which are common causes of sequencing...

Primer Dimer Prevention in Sanger Sequencing: A Complete Guide for Reliable Results

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on designing Sanger sequencing primers to prevent dimer formation and secondary structures, which are common causes of sequencing failure. It covers foundational principles of primer thermodynamics, step-by-step methodological design using modern bioinformatics tools, practical troubleshooting for problematic templates, and the role of validated Sanger sequencing in orthogonal confirmation of NGS variants. By synthesizing established guidelines with advanced optimization techniques, this resource aims to enhance sequencing success rates, save critical research time, and ensure data reliability in clinical and biomedical research applications.

Understanding Primer Dimers and Secondary Structures: The Root Cause of Sequencing Failure

What Are Primer Dimers? Defining Self-Dimers and Cross-Dimers

In the context of Sanger sequencing research, primer design is a foundational step that directly determines the success and accuracy of data generation. A predominant challenge in this process is the formation of primer dimers, aberrant structures that consume reaction resources and compromise data quality. Primer dimers are short, unintended amplification artifacts generated when primers anneal to each other rather than to the intended template DNA [1] [2]. For scientists and drug development professionals, recognizing and eliminating these artifacts is crucial for obtaining clean sequencing chromatograms and ensuring the reliability of genetic data used in diagnostic and therapeutic development. This application note delineates the types of primer dimers, their consequences on Sanger sequencing, and provides detailed protocols for their identification and prevention.

Defining Primer Dimers: Self-Dimers and Cross-Dimers

Primer dimers are primarily classified into two categories based on the primers involved in their formation. The following table summarizes their key characteristics:

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Primer Dimers

| Dimer Type | Alternative Name | Definition | Primary Cause | Impact on Amplification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Dimer | Homodimer | Formed when two identical primers (e.g., two forward primers) bind to each other due to regions of internal complementarity [2]. | Complementarity within a single primer sequence [3] [1]. | Directly interferes as one primer type is unavailable for target amplification [2]. |

| Cross-Dimer | Heterodimer | Formed when the forward and reverse primers bind to each other because of shared complementary regions [3] [2]. | Complementarity between the two different primer sequences [1]. | Reduces amplification efficiency and yield by consuming both primers [2]. |

The formation process initiates during reaction preparation. If primers contain complementary sequences, they can anneal to each other. The DNA polymerase then extends these annealed primers, creating short, double-stranded fragments [2]. Studies indicate that some DNA polymerases possess activity at room temperature, allowing this dimerization process to begin before the thermal cycling even starts [2].

Consequences of Primer Dimers in Molecular Applications

Impact on Sanger Sequencing

In Sanger sequencing, primer dimers have particularly detrimental effects. A primer dimer can itself become a template for the sequencing reaction, leading to extension from the dimerized primer. This produces a sequencing read that contains a short, intense region of non-specific sequence at the beginning of the chromatogram, which often overwhelms the signal from the intended template [4]. This background "noise" can obscure the target sequence, result in poor-quality reads with early termination, and complicate base calling, thereby wasting valuable sequencing resources [2] [4].

Impact on PCR and qPCR

In conventional PCR, primer dimers are visible on an agarose gel as a fuzzy smear or a low molecular weight band typically below 100 base pairs, which runs ahead of the desired amplicon [1]. They consume primers, nucleotides, and enzyme, thereby reducing the efficiency and yield of the target amplification [5]. In quantitative PCR (qPCR), the problem is exacerbated because the fluorescent DNA-binding dyes cannot distinguish between specific amplicons and primer dimers. The amplification of primer dimers leads to false-positive fluorescence signals and inaccurate quantification [2]. Their early amplification curves can appear before the target amplicon, complicating data interpretation [2].

Detection and Analysis of Primer Dimers

Experimental Detection Methods

Researchers can employ several laboratory techniques to identify the presence of primer dimers:

- Agarose Gel Electrophoresis: Primer dimers appear as a diffuse smear or a sharp band near the bottom of the gel (generally in the 20-100 bp range), well below the expected product size [1] [2]. Running the gel for a longer duration can help separate these small fragments from the desired amplicons.

- No-Template Control (NTC): This is a critical control. An NTC reaction contains all PCR components except the DNA template. If amplification occurs in the NTC, it is almost certainly due to primer-dimer formation or other non-specific amplification, confirming that the primers themselves are the source of the artifact [1].

- Melting Curve Analysis (for qPCR): Following a qPCR run, a gradual increase in temperature causes DNA duplexes to denature. Primer dimers, being shorter and often having a different GC content, will typically melt at a lower temperature than the specific amplicon, producing a distinct, earlier peak in the melting curve [2].

- Sanger Sequencing Chromatograms: As previously mentioned, primer dimers manifest as overlapping peaks and a high-intensity, unreadable sequence region at the start of the chromatogram (see Figure 1) [4].

In silico Analysis Tools

Preventing primer dimers begins at the design stage using sophisticated bioinformatics tools. These tools analyze primer sequences for potential self-complementarity and cross-complementarity:

- Self-Complementarity Analysis: Checks for regions within a single primer that can bind to itself, potentially forming hairpin structures [3] [6].

- Hetero-Dimer Analysis: Evaluates the potential for the forward and reverse primers to bind to each other [6].

Table 2: Common Primer Analysis Tools and Their Functions

| Tool Name | Key Functions | Dimer Analysis Features | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| OligoAnalyzer (IDT) | Tm calculator, GC%, molecular weight, extinction coefficient. | Hairpin, Self-Dimer, and Hetero-Dimer prediction [6]. | Web-based |

| Multiple Primer Analyzer (Thermo Fisher) | Compares multiple primers simultaneously for Tm, GC%. | Reports possible primer-dimers based on user-defined parameters [7]. | Web-based |

| PrimerAnalyser (PrimerDigital) | Analyzes standard and degenerate bases; calculates physical properties. | Self-dimer and G-quadruplex detection [8]. | Web-based |

| Primer3 & Primer-BLAST | Designs primers and checks for specificity. | Checks for secondary structure and primer dimer formation during design [9]. | Web-based |

Protocols for Preventing and Troubleshooting Primer Dimers

Primer Design Protocol to Avoid Dimer Formation

Objective: To design specific primers with minimal potential for self-dimer and cross-dimer formation. Materials: Template DNA sequence, computer with internet access, primer design software (e.g., Primer3, OligoAnalyzer).

- Define Target Region: Identify the specific sequence to be amplified or sequenced.

- Set Primer Parameters: Design primers to be 18-30 nucleotides in length [9] [3].

- Calculate Melting Temperature (Tm): Ensure both forward and reverse primers have a Tm within 2-5°C of each other, ideally between 55-72°C [9].

- Optimize GC Content: Design primers with a GC content between 40-60%. Avoid long stretches of a single nucleotide [9] [3].

- Check for GC Clamp: Include a G or C base at the 3'-end (GC clamp) to promote specific binding, but avoid more than 3 G or C bases in the last five nucleotides to prevent non-specific binding [3].

- Perform In silico Analysis:

- Analyze each primer for self-complementarity (hairpins). The parameter "self 3'-complementarity" should be low [3].

- Analyze the primer pair for cross-complementarity, especially at the 3' ends. Most tools flag dimers based on the number of contiguous complementary bases; ≤3 contiguous bases is a common threshold [9] [10].

- Use BLAST to check primer specificity to the intended target [9].

Experimental Protocol to Minimize Dimer Formation in PCR

Objective: To optimize PCR conditions to suppress primer dimer amplification even if primers have some complementarity. Materials: High-quality primers, hot-start DNA polymerase, thermal cycler, PCR reagents.

- Use a Hot-Start DNA Polymerase: This enzyme is inactive until a high-temperature step, preventing primer dimer formation during reaction setup and the initial thermal cycle [1] [5].

- Optimize Primer Concentration: Perform a primer titration. Reduce the primer concentration to the lowest level that still yields robust amplification of the target product, typically between 0.1-0.5 µM [10].

- Increase Annealing Temperature: Use the highest possible annealing temperature that allows for specific primer binding. A temperature 2-5°C above the Tm of the primers is often effective [3] [1].

- Increase Denaturation Time: Lengthening the denaturation time can help ensure primers are fully dissociated and available to bind the template [1].

- Optimize Mg2+ Concentration: As Mg2+ is a cofactor for polymerase and stabilizes DNA duplexes, high concentrations can promote non-specific binding. Titrate Mg2+ to find the optimal concentration [9].

Troubleshooting Protocol for Sanger Sequencing Affected by Primer Dimers

Objective: To resolve poor-quality sequencing data caused by primer dimers. Materials: Sanger sequencing setup, new primer designs, analysis software.

- Inspect the Chromatogram: Look for a region of high-intensity, overlapping peaks within the first 20-50 bases of the sequence [4].

- Analyze the Primer Sequence: Use an oligo analyzer tool to check the offending primer for self-complementarity, as demonstrated in Figure 2 [4].

- Redesign the Primer: If self- or cross-complementarity is found, design a new primer following the protocol in Section 5.1. The new primer should be checked in silico before ordering.

- Validate with New Primer: Repeat the sequencing reaction with the newly designed primer. A successful result will show strong, well-resolved peaks without the initial high-intensity noise (see Figure 4) [4].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Primer Dimer Management

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Remains inactive until a high-temperature activation step, preventing enzymatic activity during reaction setup [1]. | Critical for minimizing primer-dimer formation in both PCR and sequencing sample preparation. |

| In Silico Design Tools (e.g., OligoAnalyzer, Primer3) | Predicts potential secondary structures and primer-primer interactions before synthesis [9] [7] [6]. | The first line of defense; use to screen all primer designs for self- and cross-dimers. |

| No-Template Control (NTC) | A diagnostic control containing all reaction components except the DNA template. | Confirms that amplification or sequencing artifacts are due to primer interactions rather than the template. |

| High-Purity Oligonucleotides | Primers synthesized with high fidelity and purified (e.g., HPLC purification) to remove truncated sequences. | Reduces the chance of short, faulty primers that are more prone to non-specific binding and dimer formation. |

| Self-Avoiding Molecular Recognition Systems (SAMRS) | Modified nucleobases that pair with natural bases but not with other SAMRS bases [5]. | An advanced strategy for demanding applications like highly multiplexed PCR or SNP detection to virtually eliminate primer dimer. |

Primer dimers, encompassing both self-dimers and cross-dimers, represent a significant impediment to obtaining high-quality data in Sanger sequencing and PCR-based applications. Their formation depletes critical reaction resources and generates artifacts that can lead to misinterpretation of results. Through rigorous in silico primer design, adherence to established primer design parameters, and the implementation of optimized experimental protocols—such as the use of hot-start polymerases and no-template controls—researchers can effectively mitigate this risk. For scientists engaged in drug development and genetic research, where data accuracy is non-negotiable, mastering the prevention and troubleshooting of primer dimers is an essential laboratory competency.

The Impact of Hairpins and Loops on Primer Binding Efficiency

In Sanger sequencing and PCR-based diagnostics, the binding efficiency of primers is paramount for obtaining high-quality, reliable results. Among the various factors that can compromise this efficiency, the formation of intramolecular secondary structures—specifically hairpins and loops—within the primers themselves presents a significant challenge. These structures occur when regions within a single primer are complementary and can hybridize, causing the primer to fold back on itself. This folding can prevent the primer from binding to its target template DNA, leading to failed reactions, reduced signal strength, non-specific amplification, and misinterpreted data [3] [11]. This application note details the quantitative impact of these structures, provides protocols for their identification, and offers validated strategies for designing robust primers, thereby supporting the broader objective of achieving dimer-free Sanger sequencing primer design.

Quantitative Impact of Secondary Structures

The formation of hairpin structures within a primer can critically impair its function. The thermodynamic stability of a hairpin, quantified by its change in Gibbs free energy (ΔG), determines the likelihood of its formation and its detrimental impact on amplification assays.

Table 1: Thermodynamic Impact of Hairpin Structures on Assay Performance

| Hairpin Characteristic | Impact on Primer | Experimental Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Stable hairpin with 3' complementarity | Forms a self-amplifying structure [12] | Exponential amplification in no-template controls; high background fluorescence [12] |

| ΔG of potential dimer/hairpin < -9 kcal/mol | Strong, stable secondary structure formation [11] | Primer fails to bind to the template; failed or weak sequencing reaction [11] |

| Hairpin with complementarity 1-2 bases from 3' end | Can still self-amplify in techniques like LAMP [12] | Slowly rising baseline in real-time monitoring; poor discrimination between positive and negative reactions [12] |

Research on Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP), which uses long primers (~40-45 bases) particularly prone to hairpins, has demonstrated that even minor modifications to eliminate these structures can dramatically reduce non-specific background amplification and improve assay performance [12]. While LAMP primers are more complex, the fundamental principle that stable secondary structures inhibit primer binding is universal and applies directly to Sanger sequencing primers.

Experimental Detection and Analysis Protocols

In silico Analysis of Primer Secondary Structures

Purpose: To computationally predict and evaluate the potential for hairpin and loop formation in primer sequences before synthesis.

Materials:

- Computer with internet access

- Candidate primer sequence(s) in FASTA or plain text format

Methodology:

- Sequence Input: Access a reputable oligonucleotide analysis tool, such as OligoAnalyzer (Integrated DNA Technologies) or similar software [12] [13] [11].

- Hairpin Analysis: Input your primer sequence and initiate a secondary structure analysis. The tool will calculate and display potential hairpin formations.

- Thermodynamic Evaluation: Examine the calculated ΔG (change in Gibbs free energy) for any predicted hairpins. A more negative ΔG indicates a more stable, and therefore more problematic, structure [11].

- Dimer Analysis: Use the tool's "Self-Dimer" or "Hetero-Dimer" analysis function to check for interactions between forward and reverse primers.

- Parameter Assessment: Confirm that the primer meets standard design criteria: length of 18-24 bases, GC content of 40-60%, and a melting temperature (Tm) between 50-65°C [14] [3] [11].

Interpretation: Primers with predicted hairpins that have a ΔG more negative than -9 kcal/mol should be flagged and redesigned. Similarly, primers with high self-complementarity scores should be avoided [11].

Empirical Validation by Gel Electrophoresis

Purpose: To experimentally confirm the specificity of a PCR product that will serve as the template for Sanger sequencing.

Materials:

- Purified PCR product

- Agarose gel

- Gel electrophoresis system

- DNA staining dye and visualization system

Methodology:

- PCR Amplification: Perform PCR using the primers in question.

- Gel Analysis: Separate the PCR products on an agarose gel. A successful, specific reaction should show a single, sharp band at the expected amplicon size [15].

- Control Check: Verify that a negative control (no DNA template) reaction is blank. A band in the negative control indicates primer-dimer formation or non-specific amplification, often exacerbated by secondary structures in the primers [15].

Interpretation: The presence of multiple bands or a smear suggests non-specific priming, which can be caused by hairpins forcing the primer to bind to unintended sites. A single clean band indicates specific amplification and that the primers are functioning adequately for subsequent sequencing.

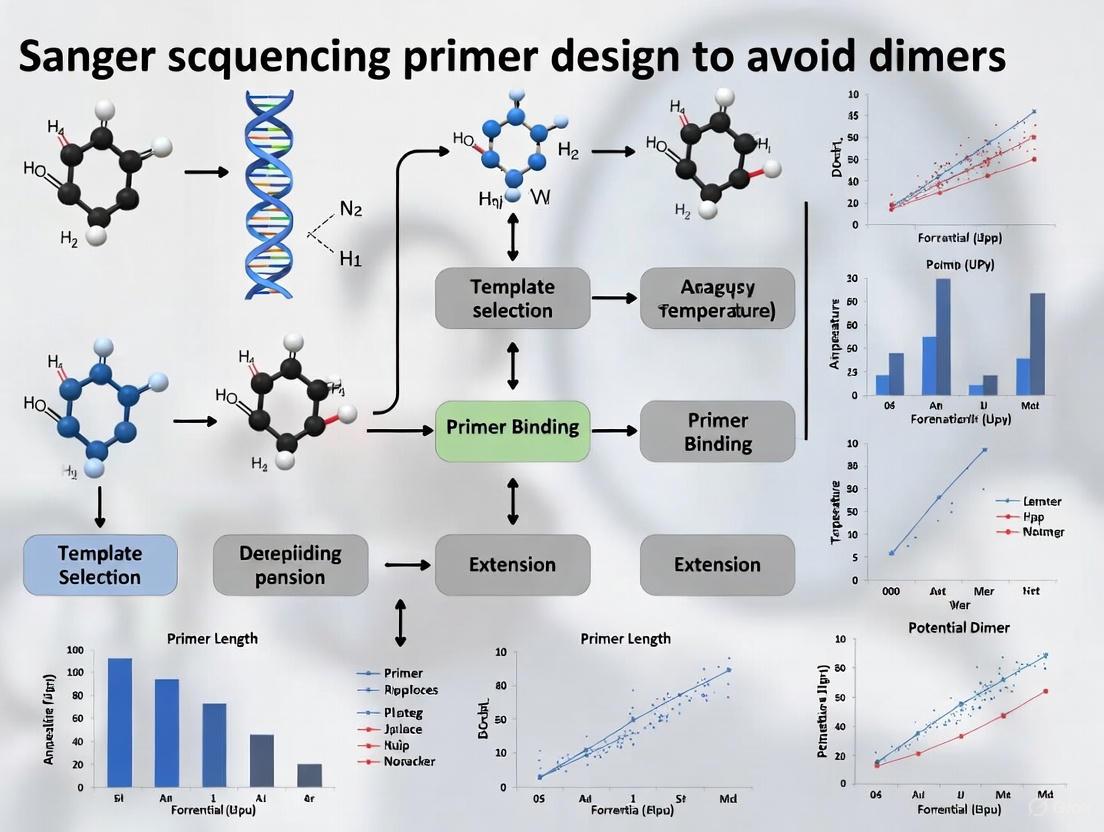

Visualization of Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for identifying and resolving hairpin-related issues in primer design and application.

Title: Workflow for Managing Primer Hairpins

Mitigation Strategies and Alternative Primer Designs

When standard primers are found to form stable secondary structures, the following advanced strategies can be employed:

- Primer Redesign with Thermodynamic Checks: The primary strategy is to redesign the primer, shifting its position slightly along the template. Use the nearest-neighbor model to estimate the stability of all possible secondary structures in the new candidate primers, aiming for a less negative ΔG [12].

- Utilization of "Loop-Out" Primers: For persistent problematic sequences (e.g., hairpin-prone regions or GC-rich stretches), a innovative solution is the use of noncontinuously binding "loop-out" primers [16]. This design involves creating a single oligonucleotide in two segments that flank, but do not include, the problematic sequence. During annealing, the problematic region is looped-out, bypassing the interference.

- Reaction Optimization: Adjusting reaction components can help mitigate minor secondary structures. The addition of DMSO or adjusting Mg²⁺ concentration can destabilize weak hairpins and improve binding specificity [11].

- Stringency Control: Increasing the annealing temperature (Tₐ) by 2-5°C can prevent the primer from folding on itself or binding to off-target sites, as the higher energy prevents stabilization of the hairpin structure [3] [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Analysis

| Item | Function/Description | Application in This Context |

|---|---|---|

| OligoAnalyzer Tool (IDT) | Online software for predicting hairpin formation, dimerization, and Tm. | Critical first step for in-silico validation of primer sequences and thermodynamic stability [12] [13]. |

| Bst 2.0 WarmStart Polymerase | DNA polymerase with hot-start capability for high-specificity amplification. | Reduces non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation during PCR assay setup [12] [13]. |

| QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) | System for cleaning PCR products by removing primers, enzymes, and salts. | Essential for preparing pure template for Sanger sequencing, preventing carryover of faulty primers [15]. |

| DMSO (Dimethyl Sulfoxide) | A chemical additive that destabilizes secondary structures in DNA. | Can be added to PCR or sequencing mixes to help unwind stable hairpins in primers or templates [11]. |

| SYTO 9 Green Fluorescent Nucleic Acid Stain | An intercalating dye for real-time fluorescence detection of DNA amplification. | Used in research settings to monitor amplification kinetics and detect rising baselines from non-specific amplification [12]. |

In the context of Sanger sequencing primer design, the formation of primer-dimers represents a significant thermodynamic challenge that can compromise data quality. Primer-dimers are spurious amplification artefacts formed by primer-primer interactions, leading to their extension by DNA polymerase. Within sequencing workflows, these artefacts competitively consume essential reaction reagents—including primers, nucleotides, and polymerase—thereby reducing the efficiency and sensitivity of the target sequencing reaction [17]. The formation of stable primer-dimers is governed by the principles of Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG), a thermodynamic quantity that predicts the spontaneity and stability of the dimerization reaction. A more negative ΔG value indicates a more stable dimer complex, which is more likely to form and persist under standard reaction conditions [18]. Understanding and applying ΔG calculations is therefore a critical step in designing dimer-free primers, ensuring the high-quality, reliable data required by researchers and drug development professionals in their genomic analyses.

Thermodynamic Foundations of ΔG and Dimer Stability

The Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG) of a system quantifies the maximum amount of reversible work that may be performed at a constant temperature and pressure. In molecular biology, it is used to describe the spontaneity of a reaction, such as the hybridization of two oligonucleotide primers. A negative ΔG value indicates an exergonic (energy-releasing) reaction that proceeds spontaneously, whereas a positive ΔG value signifies an endergonic (energy-absorbing) reaction that is non-spontaneous [18].

When two primers interact, the overall ΔG of dimer formation is a composite value derived from the sum of energetic contributions from base pairing (hydrogen bonds) and base stacking (van der Waals forces), minus penalties associated with structural disruptions like loops or mismatches. The stability of the resulting duplex is not uniform; it is profoundly influenced by the sequence and context of the 3' ends. Stable complementarity at the 3' termini is particularly detrimental because DNA polymerase requires a stable double-stranded structure to initiate extension [17]. Experimental studies have confirmed that interactions allowing for more than 15 consecutive base pairs reliably form stable dimers, while those with non-consecutive bonding, even with up to 20 potential base pairs, do not form stable structures that amplify efficiently [19].

Quantitative Data on ΔG Thresholds for Dimer Prediction

Empirical research has established quantitative thresholds for ΔG values to classify the risk of primer-dimer formation. These values serve as critical benchmarks during the in silico design phase of Sanger sequencing primers. The following table consolidates key stability thresholds and their practical interpretations for experimentalists.

Table 1: ΔG Value Thresholds and Their Experimental Implications

| ΔG Value (kcal/mol) | Dimer Formation Risk | Experimental Implication |

|---|---|---|

| > -9.0 | Low | Dimer formation is unlikely; primers are generally safe to use [11]. |

| ≤ -9.0 | High | Indicates a stable, extensible dimer that can significantly compete with target amplification [17]. |

| 3' End Hairpins > -2.0 | Tolerable | Hairpin structures at the 3' end with ΔG > -2 kcal/mol are typically tolerated in PCR [18]. |

| Internal Hairpins > -3.0 | Tolerable | Internal hairpin structures with ΔG > -3 kcal/mol are generally tolerated [18]. |

The predictive power of ΔG is not merely binary. Advanced algorithms, such as the one powering the PrimerDimer software, analyze all possible alignments between two primers, calculating a dimer score based on the most negative ΔG value among all possible hetero- and homo-dimer pairs. This analysis incorporates nearest-neighbour parameters for duplexes, mismatches, and overhangs [17]. The accuracy of this ΔG-based prediction has been validated through epidemiological Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis, achieving greater than 92% predictive accuracy when distinguishing dimer-forming from dimer-free primer pairs [17].

Protocol for Computational Prediction and Validation of Primer-Dimers

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for leveraging thermodynamic principles to predict and prevent primer-dimer formation during the design of Sanger sequencing primers.

Computational Screening Using Primer Design Tools

Objective: To identify primer pairs with a high risk of forming stable primer-dimers prior to synthesis and wet-lab experimentation. Reagents & Equipment: Sequence of the target amplicon, computer with internet access, primer design software (e.g., Primer-BLAST, Primer3, or commercial platforms). Procedure:

- Define Target: Input your target DNA sequence into the primer design software. Set appropriate parameters for Sanger sequencing, typically yielding a product size of 200–500 bp [11].

- Generate Candidates: Use the software to generate candidate primer pairs. Constrain the design with standard parameters: primer length of 18–24 nucleotides, melting temperature (Tm) of 58–64°C, and GC content of 40–60% [11].

- Screen for Dimers: For each candidate pair, utilize the software's built-in dimer analysis function (or a dedicated tool like PrimerDimer) to calculate the ΔG of the most stable potential dimer structure.

- The algorithm will typically slide the shorter primer along the longer one, calculating ΔG for all structures with 5' overhangs [17].

- Apply Threshold: Reject any primer pair for which the returned dimer score (most negative ΔG) is ≤ -9.0 kcal/mol [11] [17].

- Specificity Check: Perform a final specificity validation using a tool like NCBI Primer-BLAST to ensure the selected primers bind uniquely to the intended target, minimizing off-target amplification [11].

The workflow for this computational screening process is summarized in the following diagram:

Experimental Validation via Capillary Electrophoresis

Objective: To empirically confirm the absence of extensible primer-dimers in a simulated PCR environment. Reagents & Equipment:

- Oligonucleotide Primers: Forward and reverse primers, resuspended in nuclease-free water.

- DNA Polymerase & Master Mix: A hot-start PCR master mix to prevent nonspecific interactions during reaction setup.

- Thermal Cycler: For precise control of annealing temperatures.

- Capillary Electrophoresis System: Equipped with a fluorescence detector (e.g., ABI 3100). A drag-tag (e.g., synthetic poly-N-methoxyethylglycine) is required for free-solution conjugate electrophoresis (FSCE) to resolve short DNA fragments [19].

- Analysis Software: For quantifying electropherogram peaks.

Procedure:

- Primer Modification: Conjugate one primer (e.g., the forward primer) at its 5' end with a neutral, hydrophilic drag-tag and a fluorophore (e.g., ROX). Label the other primer (e.g., the reverse) with a different fluorophore (e.g., FAM) [19].

- Reaction Setup: In a PCR tube, mix the labeled primers in a standard PCR buffer. Omit the DNA template. This no-template control is essential for isolating primer-dimer artefacts.

- Thermal Cycling: Run a limited number of PCR cycles (e.g., 10-15 cycles) using an annealing temperature suitable for your primers (e.g., 55–65°C).

- Capillary Electrophoresis:

- Prepare samples by diluting the PCR reaction.

- Load samples into the capillary array and run under free-solution conditions (no sieving matrix) at a controlled temperature (e.g., 25°C).

- The drag-tag alters the mobility of the conjugated primer, allowing clear separation of single-stranded primers from double-stranded primer-dimer products [19].

- Analysis:

- Examine the electropherogram for the presence of new peaks corresponding to dimer products.

- The absence of such peaks confirms the success of the computational design and the lack of extensible dimers.

- The presence of peaks indicates dimer formation, and the primers should be redesigned.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Dimer Analysis

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Dimer Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function in Dimer Analysis |

|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Remains inactive until high temperatures are reached, preventing primer-dimer formation during reaction setup [20]. |

| NMEG Drag-Tag | A neutral, synthetic polyamide conjugated to primers to alter their hydrodynamic drag for separation in free-solution capillary electrophoresis [19]. |

| Fluorophore-Labeled dNTPs | Enable real-time monitoring of amplification; unexpected early amplification signals can indicate primer-dimer formation. |

| Primer Design Software (e.g., PrimerDimer) | Utilizes thermodynamic parameters and ΔG calculations to predict the stability of primer-primer interactions in silico [17]. |

| Capillary Electrophoresis System | Provides a high-resolution platform for detecting and quantifying primer-dimer artefacts post-amplification [19]. |

Advanced Strategies: SAMRS and Modified Bases

For particularly challenging applications, such as highly multiplexed sequencing or SNP detection, advanced chemical solutions can be employed. Self-Avoiding Molecular Recognition Systems (SAMRS) incorporate modified nucleobases that pair strongly with natural DNA but weakly with other SAMRS nucleotides [5]. By strategically substituting standard bases with SAMRS components in a primer sequence, primer-primer interactions are significantly reduced without compromising the primer's ability to bind to the natural DNA template. This approach directly alters the underlying thermodynamics of dimerization, making ΔG values for unwanted interactions less negative and thus less favourable. Other advanced strategies include the use of locked nucleic acids (LNAs) or peptide nucleic acids (PNAs), which enhance primer specificity and reduce self-complementarity through altered backbone structures [20].

Primer design is a critical step in molecular biology workflows, serving as the foundation for successful polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and Sanger sequencing experiments. Within the broader context of Sanger sequencing primer design research aimed at avoiding dimer formation, three parameters emerge as fundamentally important: primer length, melting temperature (Tm), and GC content. Proper optimization of these parameters ensures high specificity, efficient amplification, and minimizes the formation of non-specific products like primer-dimers that compromise sequencing results [3] [21]. This application note details the established protocols and quantitative guidelines for designing effective primers, with a specific focus on preventing dimerization artifacts.

Critical Design Parameters

The success of a Sanger sequencing reaction is profoundly influenced by the physicochemical properties of the primer itself. The following parameters must be carefully balanced to achieve optimal performance.

Primer Length

Primer length directly determines the specificity of binding to the target DNA sequence. Excessively short primers risk binding to non-target sites, while excessively long primers can reduce hybridization efficiency and amplicon yield [3].

Table 1: Optimal Primer Length Guidelines

| Parameter | Recommended Range | Rationale & Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Length | 18 - 24 nucleotides [22] [3] [21] | Provides a balance of high specificity, efficient binding, and sufficient sequence uniqueness. |

| Shorter Primers | < 18 nucleotides | Higher risk of non-specific binding and second-site hybridization [23]. |

| Longer Primers | > 30 nucleotides | Slower hybridization rate, reduced annealing efficiency, and potentially less amplicon yield [3]. |

Melting Temperature (Tm)

The melting temperature (Tm) is the temperature at which 50% of the DNA duplex dissociates into single strands. It is a critical factor for determining the optimal annealing temperature (Ta) during the thermal cycling process [3].

Table 2: Melting Temperature (Tm) Specifications

| Parameter | Recommended Range | Calculation & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Tm | 50°C - 65°C [22] [3] [23] | Essential for maintaining primer specificity. A Tm of at least 54°C is recommended [3]. |

| Annealing Temperature (Ta) | Typically 2-5°C above Tm [3] | The actual temperature used in the PCR cycle for primer binding. |

| Primer Pair Matching | Tm should not differ by more than 2°C [3] | Ensures both primers in a PCR pair bind to their targets synchronously and with similar efficiency. |

| Key Consideration | Avoid Tm > 65°C | Higher temperatures increase the risk of secondary, non-specific annealing events [3]. |

The following equations are commonly used for Tm calculation. The "Salt Concentration" method is generally more accurate as it accounts for more variables:

- Basic Method: Tm = 4(G + C) + 2(A + T) [3]

- Salt Concentration Method: Tm = 81.5 + 16.6(log[Na+]) + 0.41(%GC) – 675/primer length [3]

GC Content

GC content refers to the percentage of nitrogenous bases in the primer that are either Guanine (G) or Cytosine (C). Since G-C base pairs form three hydrogen bonds (as opposed to two in A-T pairs), the GC content directly affects the primer's binding strength and stability [3].

Table 3: GC Content Guidelines

| Parameter | Recommended Range | Impact on Primer Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Ideal GC Content | 40% - 60% [3], ideally 50% - 55% [23] [21] | Provides stable binding without promoting mispriming. |

| GC Clamp | Presence of G or C at the 3' end [3] | Promotes specific binding at the 3' terminus, which is critical for polymerase initiation. |

| Low GC Content | < 40% | May require increasing primer length to achieve the necessary Tm [3] [23]. |

| High GC Content | > 60% | Can lead to non-specific binding and primer-dimer formation due to excessively strong, non-discriminative interactions [3]. |

| Consecutive Bases | Avoid runs of 4 or more identical nucleotides, particularly G's [23] | Prevents the formation of stable but non-specific secondary structures. |

Experimental Protocol for Primer Design and Validation

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for designing, in silico validating, and empirically testing sequencing primers to minimize dimer formation.

In Silico Primer Design

- Sequence Input: Obtain the pure target DNA sequence in FASTA format or as a raw sequence. The design tool will not select primers complementary to ambiguous bases (e.g., N, R, Y) [24].

- Parameter Setting: In your selected primer design software, set the search parameters to the optimal ranges defined in Section 2:

- Length: 18-24 nt.

- Tm: 50-65°C, with a maximum difference of 2°C between forward and reverse primers.

- GC Content: 40-60%.

- Primer Selection: Execute the design algorithm. The tool will output a list of candidate primers ranked by a composite score that typically incorporates all set parameters and checks for secondary structures [24].

- Secondary Structure Analysis: Manually inspect the top candidate primers for:

- Self-Complementarity: The propensity of a single primer to bind to itself (self-dimer) [3] [1].

- 3'-Complementarity: The potential for the 3' end of a primer to bind to itself or to the 3' end of the paired primer (cross-dimer). This is a critical parameter for preventing primer-dimer formation [3] [10]. For both parameters, a lower score is better.

- Specificity Check: Verify that the primer sequence does not span known single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) locations, as this can lead to failed sequencing reactions [23].

Wet-Lab Validation and Troubleshooting

- Primer Reconstitution: Resuspend the synthesized, HPLC-purified primer [23] in nuclease-free water or TE buffer to a standardized stock concentration (e.g., 100 µM).

- PCR Amplification:

- Use a hot-start DNA polymerase to minimize primer-dimer formation during reaction setup [1].

- Set up a no-template control (NTC) containing all PCR components except the DNA template. The appearance of a product in the NTC indicates primer-dimer formation [1].

- Thermal Cycling Conditions: If non-specific amplification or dimers are observed, increase the annealing temperature in 2°C increments. Alternatively, implement a temperature gradient to empirically determine the optimal Ta [1].

- Product Analysis: Analyze the PCR products using gel electrophoresis.

- Primer-dimer artifacts typically appear as a fuzzy smear or a sharp band below 100 bp [1].

- To better separate dimers from the target amplicon, run the gel for a longer duration.

- Sequencing Reaction Setup:

- Template Quality: Ensure PCR products are purified via gel extraction or enzymatic treatment to remove primers, salts, and enzymes [22].

- Template Quantity:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Primer Design and Sequencing

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| In Silico Design Tools | |

| Primer Designer Tool (Thermo Fisher) | Online tool to search a database of ~650,000 pre-designed, validated primer pairs for human exome and mitochondrial genome resequencing [25]. |

| Sequencing Primer Design Tool (Eurofins Genomics) | Analyzes an input DNA sequence to select optimum forward or reverse sequencing primers based on standard parameters [24]. |

| Geneious Bioinformatics Software | A comprehensive software suite that includes industry-leading molecular biology and sequence analysis tools for primer design [26]. |

| Wet-Lab Reagents | |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | A modified enzyme inactive at room temperature, preventing primer-dimer formation during reaction setup [1]. |

| ExoSAP-IT Kit (USB) | An enzymatic PCR clean-up method to degrade excess primers and nucleotides prior to Sanger sequencing [22]. |

| HPLC-Purified Primers | Purification method that ensures primers are free of truncated sequences, resulting in higher quality sequencing data [25] [23]. |

In Sanger sequencing, the primer serves as the foundation for DNA polymerase to initiate the synthesis of a new DNA strand. The 3' end of the primer is particularly crucial because this is where enzyme-mediated extension begins. A poorly designed 3' end can lead to two major failure modes: mispriming (binding to incorrect template sites) and slippage (improper alignment with the template), which consume sequencing resources and compromise data quality [27] [5]. Research indicates that the last 3-4 bases at the 3' end are essential for successful polymerase initiation, with even single mismatches in this region critically reducing extension efficiency [11]. This application note details the biochemical principles behind 3' end functionality and provides validated protocols to design primers that minimize artifacts, thereby enhancing sequencing success rates for research and diagnostic applications.

Key Principles of 3' End Design

Biochemical Basis of 3' End Specificity

DNA polymerase requires a stable, correctly base-paired 3' hydroxyl group from which to extend a new DNA strand. The stability of the primer-template hybrid is governed by the hydrogen bonding between base pairs: G-C pairs form three hydrogen bonds, while A-T pairs form two [3]. The terminal bases of the primer must form a stable duplex with the template to initiate synthesis efficiently. The presence of mismatches, weak bonding, or secondary structures at the 3' end disrupts this process, leading to failed or erroneous sequencing reactions [11].

The most problematic artifacts stemming from poor 3' end design are:

- Mispriming: Occurs when the 3' end anneals to an off-target site with partial complementarity, producing sequence data from incorrect loci [11].

- Slippage: Happens when the 3' end contains homopolymeric runs or repetitive sequences, allowing the primer to shift position on the template during extension and generating ambiguous or out-of-frame sequences [27].

- Primer-Dimer Formation: Results when the 3' ends of primers are complementary to each other, enabling them to hybridize and be extended as if they were legitimate templates. This consumes reaction resources and generates short, nonspecific products [1] [10].

Essential Design Parameters for the 3' End

The following parameters are critical for ensuring proper 3' end function and should be verified for every sequencing primer.

Table 1: Critical 3' End Design Parameters and Their Specifications

| Design Parameter | Optimal Specification | Rationale | Consequences of Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| GC Clamp | 1-2 G or C bases in last 5 nucleotides [11] [14] | Promotes stable binding due to stronger GC bonding [3] | >3 G/C bases: increases non-specific binding [3] [11] |

| Terminal Base | C or G preferred at ultimate 3' base [14] | Provides strong anchoring for polymerase | A or T at end: weaker binding, potential initiation failure |

| Complementarity | Avoid >4 contiguous complementary bases between primers [28] | Precludes primer-dimer formation | Primer-dimer artifacts consume reagents [1] [10] |

| Self-Complementarity | Avoid complementarity in final 3-4 bases [11] | Prevents hairpin formation | Hairpins block primer binding sites [3] [11] |

| Homopolymeric Runs | Avoid >3-4 identical consecutive bases [27] [28] | Prevents primer slippage on template | Slippage causes ambiguous or out-of-frame sequences [27] |

| Di-nucleotide Repeats | Maximum of 4 repeats [28] | Minimizes misalignment potential | Mispriming and smeared sequencing reads |

Experimental Protocols for Primer Design and Validation

In Silico Primer Design Workflow

This protocol ensures systematic design of sequencing primers with optimized 3' end characteristics, leveraging tools like NCBI Primer-BLAST [11] [29].

Step 1: Define Target Region and Obtain Sequence

- Input the precise genomic or plasmid DNA coordinates for your region of interest.

- Retrieve the FASTA format sequence from a curated database (e.g., NCBI RefSeq, Ensembl).

- For Sanger sequencing, design primers to be 50-600 bp upstream of the target region to ensure the region of interest falls within the high-quality portion of the sequence trace [29].

Step 2: Set Primer Design Parameters in Software

- Use NCBI Primer-BLAST or Primer3 with the following specific constraints [11] [29]:

- Primer Length: 18-24 nucleotides [27] [21] [14]

- Melting Temperature (Tm): 60-65°C for both forward and reverse primers (max ΔTm ≤ 2°C) [29]

- GC Content: 40-60% [11] [28]

- Product Size: 200-500 bp for optimal amplification and sequencing

- 3' End Constraints: Disallow G/C clamps with >3 bases, exclude primers with homopolymeric runs >3 bases, and set maximum self-complementarity score to prevent hairpins.

Step 3: Evaluate and Select Candidate Primers

- Screen all candidate primers for:

- Specificity: Use the integrated BLAST function to verify a single binding site in the target genome [29].

- Secondary Structures: Analyze potential hairpin formation using tools like OligoAnalyzer; discard primers with stable secondary structures (ΔG < -9 kcal/mol) [11].

- Dimer Formation: Check for self-dimers and cross-dimers, paying particular attention to 3' end complementarity between forward and reverse primers [11] [1].

- Select the primer pair with the most balanced properties and absence of 3' end red flags.

Wet-Lab Validation Protocol

Even well-designed primers require experimental validation. This protocol confirms primer performance before full-scale sequencing.

Materials:

- High-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., Hot Start varieties to reduce primer-dimer formation) [1] [5]

- Purified template DNA (plasmid or genomic)

- Designed forward and reverse primers

- Appropriate PCR reagents (buffer, dNTPs, Mg²⁺)

- Agarose gel electrophoresis equipment

Procedure:

- Prepare PCR Reactions:

- Set up a 25 μL reaction containing:

- Include a no-template control (NTC) containing all components except template DNA to detect primer-dimer formation or contamination [1].

Thermocycling Conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 2-5 minutes

- 30-35 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds

- Annealing: Use temperature 2-5°C below the calculated Tm for 30 seconds [11]

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per 1 kb of product

- Final extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes

Analysis:

- Separate PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis (1-2% agarose).

- Visualize with DNA staining dye.

- Interpretation:

- Successful validation: A single, sharp band at the expected amplicon size in the sample lane, with no bands in the NTC lane.

- Primer-dimer detection: A smeary band below 100 bp, present in both sample and NTC lanes [1].

- Non-specific amplification: Multiple bands in sample lane, clear NTC.

Troubleshooting 3' End Issues:

- If primer-dimers persist:

- If amplification is weak despite good in silico design:

Advanced Strategy: SAMRS Nucleotides for Challenging Targets

For multiplex reactions or templates with high secondary structure, consider Self-Avoiding Molecular Recognition Systems (SAMRS) nucleotides [5]. These modified bases pair with natural complements but not with other SAMRS bases, virtually eliminating primer-dimer formation.

Implementation:

- Replace standard nucleotides with SAMRS analogs (a, t, g, c) at positions prone to dimerization, particularly near the 3' end.

- Limit SAMRS components to 3-5 bases per primer to maintain adequate binding strength.

- Position SAMRS modifications at the 5' end and middle of the primer rather than the critical 3' terminal base to preserve extension efficiency.

Visualization of 3' End Effects and Design Workflow

Diagram 1: Consequences of 3' End Design Choices. Proper design leads to efficient sequencing, while problematic 3' ends cause various failure modes that compromise data quality.

Diagram 2: Primer Design and Validation Workflow. A systematic approach to designing and validating primers with emphasis on 3' end parameters to ensure sequencing success.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Primer Design and Validation

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Usage Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Reduces primer-dimer formation by inhibiting polymerase activity at low temperatures | Essential for primers with slight complementarity; activates only at high temperatures [1] |

| NCBI Primer-BLAST | Integrated primer design and specificity checking tool | Verifies single binding site in target genome; combines Primer3 with BLAST [11] [29] |

| OligoAnalyzer Tool | Analyzes secondary structures, hairpins, and primer-dimer potential | Check ΔG values for dimers (prefer > -9 kcal/mol) [11] |

| Betaine Additive | Stabilizes DNA duplexes and improves amplification of GC-rich targets | Added to sequencing reactions to lower Tm and improve annealing [27] |

| DMSO Additive | Reduces secondary structure in templates and primers | Helps with difficult templates; typically used at 2-5% concentration [11] |

| SAMRS Phosphoramidites | Special nucleotides for primer synthesis that prevent primer-primer interactions | Virtually eliminates primer-dimer formation in multiplex applications [5] |

| No-Template Control (NTC) | Diagnostic for contamination and primer-dimer formation | Essential validation step; reveals primer-dimer issues before sequencing [1] |

Meticulous attention to the 3' end of sequencing primers is not merely a theoretical consideration but a practical necessity for obtaining high-quality Sanger sequencing data. By adhering to the design parameters outlined in this document—particularly regarding GC clamps, avoidance of self-complementarity and repetitive sequences, and thorough in silico and wet-lab validation—researchers can significantly reduce artifacts like mispriming and slippage. Implementation of these protocols within a broader Sanger sequencing primer design strategy will enhance experimental efficiency, reduce costs associated with failed reactions, and improve the reliability of generated data for both research and drug development applications.

Step-by-Step Primer Design: A Methodological Framework for Success

Within molecular biology research and drug development, the Sanger sequencing method remains a gold standard for validating genetic sequences, detecting mutations, and confirming genotypes. Its success is fundamentally reliant on the precise design of sequencing primers. This application note details the optimal specifications for Sanger sequencing primers, focusing on a length of 18-25 bases and a GC content of 50-55%, framed within a broader research context of minimizing primer-dimer formation and other non-specific interactions. Adherence to these parameters ensures high specificity, robust amplification, and clean, reliable sequencing data, which is critical for research and diagnostic applications.

Core Primer Specifications and Rationale

The following table summarizes the critical quantitative parameters for designing optimal Sanger sequencing primers. These criteria are collectively aimed at maximizing primer specificity and binding efficiency while minimizing secondary structures such as dimers and hairpins.

Table 1: Optimal Specifications for Sanger Sequencing Primers

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Rationale and Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Length | 18 - 25 nucleotides [14] [30] [31] | Balances specificity (longer primers) with efficient hybridization and amplicon yield (shorter primers). Primers shorter than 18 bases may lack specificity, while those longer than 30 bases are prone to secondary structures [3] [31]. |

| GC Content | 50% - 55% [14] [21] [31] | Provides balanced binding strength. GC pairs form three hydrogen bonds, enhancing stability, but content >60% promotes non-specific binding, while <40% results in weak annealing [3] [31]. |

| GC Clamp | Presence of 1-2 G or C bases at the 3' end [14] [31] | Stabilizes the binding of the 3' terminus, which is crucial for polymerase initiation. However, more than 3 G/C bases at the 3' end can cause non-specific binding [3]. |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | 55°C - 65°C [14] [27] [32] | Ensures specific and efficient annealing. The Tms of primer pairs should be within 2-5°C of each other for synchronized binding [27] [3] [31]. |

| Homopolymer Runs | Avoid >3-4 identical consecutive bases [14] [32] [31] | Prevents primer slippage during annealing and polymerization, which can lead to sequencing errors and ambiguous results [27] [31]. |

The Critical Role of the 3' End in Preventing Dimers

A primary focus in dimer research is the management of complementarity at the 3' end of primers. The 3' end is the site of DNA polymerase extension; if two primers (or one primer with itself) pair at their 3' ends, they can be extended, forming primer-dimers [31]. These non-functional duplexes compete with the target template for reagents, leading to reduced yield and non-specific products [3] [31]. To prevent this, primers must be designed with minimal self-complementarity and 3'-complementarity. Analysis tools should be used to ensure that the free energy (ΔG) of such structures is not significantly negative (e.g., > -5 kcal/mol), indicating stable, problematic binding [31].

Experimental Protocols for Primer Design and Validation

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for designing, validating, and applying primers that meet the optimal specifications to prevent dimerization in Sanger sequencing.

Protocol: In Silico Primer Design and Dimer Analysis

Purpose: To computationally design a target-specific sequencing primer and evaluate its potential for forming secondary structures. Reagents & Software: Sequence analysis software (e.g., Geneious, SnapGene), Oligo analyzer tool (e.g., IDT OligoAnalyzer), NCBI BLAST or Primer-BLAST.

- Define Target Region: Identify the precise DNA sequence to be sequenced. Position the primer start site at least 30-40 bases upstream of the region of interest to ensure the target falls within the high-quality portion of the sequencing read [14] [31].

- Select Primer Sequence: From the template, select a contiguous 18-25 base sequence that fulfills the criteria in Table 1.

- Analyze Secondary Structures:

- Input the primer sequence into an oligo analyzer.

- Check for hairpin formation: intramolecular folding where regions within the primer are complementary.

- Check for self-dimerization: hybridization of the primer to another copy of itself.

- Check for cross-dimerization (if a pair is being designed): hybridization between the forward and reverse primers.

- Acceptance Criterion: The analysis should report no stable secondary structures, particularly those involving the 3' end [31].

- Validate Specificity: Perform a BLAST search against the relevant genome database (e.g., human, mouse) to confirm the primer binds uniquely to the intended target site and does not amplify unintended sequences [33] [31].

Protocol: Laboratory Workflow for Sequencing Template Preparation

Purpose: To prepare a high-quality DNA template for the Sanger sequencing reaction, which is crucial for obtaining clean data when using optimized primers.

Research Reagent Solutions:

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Sequencing Template Preparation

| Item | Function in Protocol | Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Amplifies target region via PCR prior to sequencing. | Reduces non-specific amplification during reaction setup [33]. |

| PCR Cleanup Kit | Removes excess primers, dNTPs, and enzyme post-amplification. | Critical to prevent residual PCR primers from acting in sequencing reaction [15]. |

| Nanodrop Spectrophotometer | Accurately measures DNA concentration and purity. | Ensures A260 reading is between 0.1-0.8 for accuracy; OD260/280 ~1.8 indicates pure DNA [15] [34]. |

Procedure:

- Amplify Target (if using PCR template): Perform PCR with optimized primers and a hot-start DNA polymerase to minimize non-specific products [33].

- Verify Amplicon: Analyze the PCR product on an agarose gel. A single, sharp band of the expected size must be present. Multiple bands indicate multiple templates, which will lead to mixed sequencing signals [15].

- Purify Template: Use a commercial PCR cleanup kit (e.g., Qiaquick) to remove all reaction components, especially the unused PCR primers. This step is vital; failure to purify will result in the sequencing reaction primed by both the sequencing primer and the residual PCR primers, producing a mixed and unreadable sequence [15].

- Quantify and Dilute:

- Quantify the purified DNA using a Nanodrop. If the A260 reading is above 0.8, dilute the sample and re-measure for accuracy [15].

- Dilute the template to the required concentration in nuclease-free water. Do not use TE or Tris buffer, as EDTA in TE can inhibit the sequencing reaction [34].

- Guideline Concentrations:

Troubleshooting Common Primer-Related Issues

Even with careful design, issues can arise. The following table connects common sequencing problems to potential primer-related causes and solutions.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Primer-Related Sequencing Failures

| Problem | Potential Primer-Related Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Failed or weak sequence signal | Primer Tm too low; primer concentration too low. | Redesign primer with higher Tm (lengthen or increase GC%). Supply primer at 10 μM concentration [27] [34]. |

| Noisy, mixed sequence baseline | Non-specific priming due to low primer specificity or multiple templates. | Use Primer-BLAST to check specificity. Re-run PCR gel to ensure a single product is being sequenced [15] [31]. |

| Poor sequence quality after ~500 bases | Primer designed too close to region of interest. | Redesign primer to be located 50-60 bases upstream of the target [14] [27]. |

| Secondary sequence peaks (double sequence) | Primer dimerization or self-annealing; contaminated PCR primers in template. | Re-analyze primer for self-complementarity. Re-purify PCR product before sequencing [15] [31]. |

The meticulous design of sequencing primers according to the specifications of 18-25 bases and 50-55% GC content is a foundational element for successful Sanger sequencing. By integrating these parameters with a rigorous in silico analysis of secondary structures and a robust laboratory protocol for template preparation, researchers can effectively mitigate the risk of primer-dimer formation and other artifacts. This structured approach ensures the generation of high-fidelity sequencing data, thereby accelerating research and development in genomics and drug discovery.

In the context of Sanger sequencing primer design, the melting temperature (Tm) is a critical thermodynamic parameter defined as the temperature at which 50% of DNA duplexes dissociate into single strands and 50% remain hybridized [35] [36]. Accurate Tm determination is fundamental to designing specific primers that effectively avoid dimer formation, a key research focus in developing robust sequencing assays. Proper Tm calculation ensures precise annealing conditions during the sequencing reaction, which directly impacts primer specificity, signal strength, and data quality by minimizing non-specific binding and primer-dimer artifacts that can compromise sequencing chromatograms [30] [11].

The selection of an appropriate Tm range (55-65°C) provides the thermodynamic stability necessary for specific primer-template interactions while maintaining the reaction conditions optimal for DNA polymerase activity in Sanger sequencing workflows [30] [37]. This balance is particularly crucial when designing primers for mutation detection or genotype confirmation, where even minor non-specific amplification can lead to misinterpretation of results.

Tm Calculation Methods and Formulas

Thermodynamic Foundations

Tm calculation methods range from simple empirical formulas to sophisticated algorithms based on nearest-neighbor thermodynamics. The nearest-neighbor method, considered the gold standard, accounts for the sequence-dependent stability of DNA duplexes by considering the enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS) contributions of adjacent base pairs, rather than treating each base pair in isolation [35] [38]. This method incorporates the understanding that the stability of a DNA duplex depends on the specific neighboring nucleotides, with different base pair combinations contributing differently to overall duplex stability.

The fundamental thermodynamic equation for Tm calculation using the nearest-neighbor method is:

[ T_m = \frac{\Delta H}{\Delta S + R \ln(C)} - 273.15 ]

Where ΔH is the enthalpy change, ΔS is the entropy change, R is the gas constant (0.00199 kcal·K⁻¹·mol⁻¹), and C is the oligo concentration [38]. This formula demonstrates how Tm is influenced by both the sequence composition through ΔH and ΔS, and the experimental conditions through C.

Calculation Methods Comparison

Table 1: Comparison of Tm Calculation Methods

| Method | Accuracy | Key Parameters | Best Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple GC% Formula (Tm = 4°C × GC% + 2°C × AT%) | ±5-10°C error [35] | GC content only | Rough estimates, manual calculations | Ignores sequence context and salt effects |

| Basic Nearest-Neighbor | ±3-5°C error [35] | Sequence context, basic salt correction | General PCR applications | Limited consideration of experimental conditions |

| SantaLucia Method (Full nearest-neighbor) | ±1-2°C error [35] | Sequence context, terminal effects, accurate salt corrections [35] [38] | PCR, qPCR, Sanger sequencing research | Requires specialized software |

The traditional basic formula (Tm = 4°C × [G+C] + 2°C × [A+T]) provides a quick estimate but fails to account for sequence context, often resulting in significant errors of 5-10°C [35] [31]. This method is particularly unreliable for primers with unusual sequence characteristics or when used under non-standard buffer conditions.

For research-grade applications like Sanger sequencing primer design, the SantaLucia nearest-neighbor method provides superior accuracy by incorporating dimeric thermodynamic parameters that account for the stacking interactions between adjacent base pairs [35] [38]. This method uses experimentally determined values for each of the ten possible nucleotide neighbor pairs, providing a more realistic model of DNA duplex stability.

Salt and Additive Corrections

The presence of monovalent and divalent cations significantly stabilizes nucleic acid duplexes by shielding the negative charges on the phosphate backbone. The Tm increases by approximately 16-21°C as Na⁺ concentration rises from 20 mM to 1 M [36]. Divalent cations like Mg²⁺ have an even more pronounced effect, with changes in the millimolar range causing significant Tm variations [36].

Common PCR additives also affect Tm calculations:

- DMSO: Reduces Tm by ~0.5-0.6°C per 1% concentration [35]

- Formamide: Reduces Tm by ~0.6-0.7°C per 1% concentration

- Betaine: Can help neutralize GC-content effects on Tm

These effects must be incorporated into accurate Tm predictions for sequencing primers, especially when amplifying difficult templates with high GC content that require such additives.

Experimental Protocols for Tm Determination

Computational Tm Determination Protocol

Protocol 1: Using Online Tm Calculators for Primer Design

This protocol describes the use of web-based tools for accurate Tm calculation, essential for designing sequencing primers that minimize dimer formation.

Access the Tool: Navigate to a reliable Tm calculator such as OligoPool, IDT OligoAnalyzer, or NEB Tm Calculator [35] [36] [37].

Enter Primer Sequence: Input the DNA sequence (5' to 3') without spaces or special characters. Most tools accept both DNA and RNA sequences.

Set Reaction Conditions:

Calculate and Interpret Results:

Compare Primer Pairs:

Application Notes: For Sanger sequencing primer design, always use the same calculator consistently throughout a project to maintain comparative results. Verify calculator accuracy by comparing results from multiple tools when designing critical primers.

Empirical Tm Validation Protocol

Protocol 2: Gradient PCR for Experimental Tm Verification

While computational methods provide excellent predictions, experimental validation is recommended for critical applications to account for specific reaction conditions and template characteristics.

Primer Design:

- Design primers according to standard guidelines (18-25 bp, 40-60% GC content)

- Include a GC clamp (1-2 G/C bases at the 3' end) but avoid more than 3 G/Cs

- Calculate theoretical Tm using nearest-neighbor method

Gradient PCR Setup:

- Prepare master mix containing template, polymerase, dNTPs, and buffer

- Aliquot into tubes or plate wells

- Set thermal cycler with a gradient spanning at least ±10°C around the predicted Tm

- Include appropriate controls (no template, no primer)

Analysis:

- Run PCR products on agarose gel

- Identify temperature range producing single, specific amplicon

- Determine optimal annealing temperature as highest temperature yielding strong specific amplification

Sequencing Verification:

- Purify PCR products from optimal annealing temperatures

- Perform Sanger sequencing with the same primers

- Assess sequencing quality and absence of secondary peaks indicating non-specific binding

Troubleshooting: If no amplification occurs, extend the gradient range or redesign primers. If multiple bands persist, increase annealing temperature or optimize Mg²⁺ concentration. For sequencing primers, purity of the PCR product is essential, so gel extraction may be necessary before sequencing.

Tm Calculation Workflow for Sequencing Primer Design

The following workflow illustrates the systematic process for calculating Tm and designing effective primers for Sanger sequencing applications, with particular emphasis on avoiding dimer formation:

Diagram Title: Tm Calculation and Primer Design Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for Tm Analysis

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Tm Determination and Primer Design

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Tm Analysis | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Online Tm Calculators | OligoPool Calculator, IDT OligoAnalyzer, NEB Tm Calculator [35] [36] | Accurate Tm prediction using nearest-neighbor algorithms | Compare multiple tools; OligoPool uses SantaLucia method (±1-2°C accuracy) [35] |

| Primer Design Software | Primer3, NCBI Primer-BLAST, OligoPerfect [11] [33] | Automated primer design with Tm calculation and specificity checking | Primer-BLAST combines design with specificity analysis against genomic databases |

| Salt Solutions | MgCl₂, KCl, (NH₄)₂SO₄ [35] [36] | Adjust cation concentration that significantly affects Tm | Mg²⁺ has stronger effect than monovalent ions; dNTPs chelate Mg²⁺ [36] |

| Polymerase Systems | Hot-start Taq polymerases, high-fidelity enzymes [30] [33] | Provide optimal buffer systems with characterized salt conditions | Hot-start enzymes prevent nonspecific amplification during reaction setup |

| Additives for Difficult Templates | DMSO, betaine, formamide, GC enhancers [35] [33] | Modify Tm for GC-rich or complex templates | DMSO reduces Tm by ~0.6°C per 1%; essential for high-GC targets [35] |

Accurate melting temperature calculation within the 55-65°C range represents a fundamental aspect of Sanger sequencing primer design that directly impacts experimental success. The implementation of nearest-neighbor computational methods, coupled with empirical validation through gradient PCR, provides researchers with a robust framework for developing specific primers that minimize dimer formation and maximize sequencing quality. By adhering to the detailed protocols and utilizing the recommended reagent solutions outlined in this document, scientists can systematically address the thermodynamic challenges inherent in primer design, thereby enhancing the reliability of sequencing data for critical applications in genetic analysis and drug development.

Using Primer-BLAST and Primer3 for Automated Design and Specificity Checking

In the context of a broader thesis on Sanger sequencing primer design to avoid dimers, the integration of automated bioinformatics tools has become indispensable for research and drug development. Primer dimers and non-specific amplification constitute major failure points in sequencing workflows, potentially compromising data quality and leading to misinterpretation of results. The combined use of Primer3 and Primer-BLAST, developed and maintained by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), provides a powerful solution to these challenges by enabling systematic design of target-specific primers while minimizing self-complementarity [39] [40].

Primer3 serves as the foundational engine for calculating optimal primer sequences based on thermodynamic properties, while Primer-BLAST adds a critical layer of validation by screening these candidates against extensive sequence databases to ensure specificity [39] [40]. This integrated approach is particularly valuable for applications requiring high fidelity, such as mutation detection in clinical diagnostics or verification of cloning experiments in pharmaceutical development. The protocol outlined in this application note provides researchers with a standardized methodology for designing primers that not only amplify the target region efficiently but also generate clean, interpretable sequencing data by avoiding secondary structures and off-target binding.

Theoretical Foundations and Design Parameters

Core Primer Design Principles

Effective primer design balances multiple thermodynamic and sequence-based parameters to ensure robust amplification and sequencing performance. The following criteria represent consensus recommendations from leading scientific resources and instrumentation providers:

Primer Length: Optimal primers typically range from 18-30 nucleotides, with 18-25 bases being ideal for most Sanger sequencing applications [30] [21] [32]. Shorter primers may lack specificity, while longer primers can increase costs and potentially form secondary structures.

Melting Temperature (Tm): Primer pairs should have compatible Tm values, ideally within 5°C of each other, with an optimal range of 50-65°C [41] [21] [32]. Tm calculation using the SantaLucia 1998 thermodynamic parameters is recommended as the default in Primer3 [39].

GC Content: Ideally 40-60%, with approximately 50% being optimal for most applications [41] [21] [32]. GC content outside this range can significantly impact Tm and hybridization efficiency.

GC Clamp: The 3' end should contain 1-3 G or C bases to enhance specific annealing, but should not exceed 3 Gs or Cs [41] [32]. This practice strengthens binding at the critical extension point while minimizing mispriming.

Sequence Composition: Avoid polybase sequences (e.g., poly(dG)), repeating motifs, and long runs (≥4) of a single base [41] [32]. These sequences can promote nonspecific hybridization and primer-dimer formation.

Avoiding Primer Dimers and Secondary Structures

The minimization of self-complementarity is crucial for successful Sanger sequencing. Primer-dimers occur when primers hybridize to themselves or each other rather than to the template DNA, while secondary structures such as hairpins can interfere with proper annealing [41] [30]. Both phenomena reduce amplification efficiency and sequencing quality. Automated tools evaluate these parameters by analyzing complementarity within and between primers. Researchers should specifically avoid primers with four or more complementary bases at the 3' ends, as this dramatically increases the likelihood of dimer formation [21]. The 3' end sequence is particularly critical, as it serves as the initiation point for DNA polymerase during extension.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Primer Design Workflow Using Primer3 and Primer-BLAST

The following protocol describes a standardized methodology for designing and validating Sanger sequencing primers using the combined capabilities of Primer3 and Primer-BLAST.

Template Preparation and Parameter Configuration

Template Input: Begin by obtaining your target sequence in FASTA format or as an NCBI accession number [40] [42]. For sequencing specific genomic regions like SNPs, use the chromosomal coordinate system (e.g., NC_000012.12 for human chromosome 12) rather than gene-specific accessions to ensure primers can be designed outside the immediate gene locus [42].

Product Size Determination: For Sanger sequencing, optimal amplicon size typically ranges from 400-800 base pairs [40] [42]. This size range supports efficient amplification while providing adequate coverage for sequencing applications. When designing primers for SNP detection, ensure the variant is positioned centrally with at least 100-150 bases of flanking sequence on either side to facilitate high-quality sequencing reads [42].

Primer Positioning Parameters: In Primer-BLAST, specify primer location ranges using the "From" and "To" fields for both forward and reverse primers [39]. This is particularly important when targeting specific regions or avoiding problematic sequences. For SNP detection, position primers 300-500 bases upstream and downstream of the variant to ensure complete coverage [42].

Primer3 Core Parameter Configuration

Table 1: Essential Primer Parameters for Primer3 Configuration

| Parameter | Recommended Value | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Length | 18-25 bases | 20 bases optimal for most applications [30] [21] |

| Melting Temperature | 50-65°C | Keep pairs within 5°C difference [41] [32] |

| GC Content | 40-60% | Approximately 50% ideal [41] [21] |

| Product Size | 400-800 bp | Optimal for Sanger sequencing [40] [42] |

| 3' End Stability | 1-3 G/C bases | GC clamp enhances specificity [41] [32] |

Configure these parameters in Primer3 with the following specific values:

- Set PRIMEROPTSIZE to 20

- Set PRIMERMINSIZE to 18

- Set PRIMERMAXSIZE to 25

- Set PRIMEROPTTM to 60.0°C

- Set PRIMERMINTM to 55.0°C

- Set PRIMERMAXTM to 65.0°C

- Set PRIMERMINGC to 40.0%

- Set PRIMEROPTGC_PERCENT to 50.0%

- Set PRIMERMAXGC to 60.0%

- Set PRIMERPRODUCTSIZE_RANGE to 400-800

Specificity Validation with Primer-BLAST

Database Selection and Organism Specification

After obtaining candidate primers from Primer3, submit them to Primer-BLAST for specificity validation [39] [40]. Proper configuration of database parameters is essential for accurate specificity assessment:

Database Selection: Choose "RefSeq mRNA" as your primary database for most applications involving coding regions [40]. This database contains naturally occurring sequences without plasmid or vector constructs. For whole-genome applications, select "RefSeq representative genomes" for comprehensive coverage with minimal redundancy [39].

Organism Specification: Always specify the target organism to limit specificity checking to relevant sequences [39] [40]. This significantly reduces processing time and improves result relevance. For cell line studies, use the appropriate species designation (e.g., Rattus norvegicus for PC12 cells) [40].

Exon-Exon Junction Spanning: When working with mRNA templates, select "Primer must span an exon-exon junction" to ensure amplification specifically targets cDNA rather than contaminating genomic DNA [39] [40]. This option requires primers to anneal across splice junctions, with default settings requiring minimal annealing to both exons (typically 3-5 bases on each side of the junction).

Advanced Specificity Parameters

Table 2: Primer-BLAST Specificity Checking Parameters

| Parameter | Setting | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity Check | Enabled | Checks primers against selected database [39] |

| Max Target Mismatches | 0-1 | Requires exact or near-exact matching [39] |

| Exon Junction | Enabled for cDNA | Avoids genomic DNA amplification [39] [40] |

| Organism | User-specified | Limits off-target detection [39] [40] |

| Intron Inclusion | Optional | Helps distinguish mRNA vs. genomic products [39] |

Configure these advanced parameters for optimal specificity:

- Set "Primer specificity stringency" to "Automatic" unless working with polymorphic templates

- Enable "Check primer pairs for mispriming against intended genome"

- Set "Max number of mismatches in the primer" to 0 for maximum stringency

- For quantitative applications, set "Primer must span an exon-exon junction"

- Adjust "Minimal and maximal number of bases that must anneal to exons" to default values (typically 3-7 bases)

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Successful implementation of the primer design and validation workflow requires specific reagents and computational resources. The following table details essential materials and their functions within the experimental protocol.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Primer Design and Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Template DNA | Provides target for amplification | High purity (OD260/OD280: 1.8-2.0); Plasmid, genomic DNA, or PCR product [30] |

| DNA Polymerase | Catalyzes DNA synthesis | Hot-start enzyme recommended to prevent mispriming [41] |

| MgCl₂ | Cofactor for polymerase | Concentration varies with dNTP levels; typically 1.5-2.5mM [41] |

| dNTPs | Building blocks for synthesis | Balanced solution of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP [41] |

| Buffer System | Maintains optimal reaction conditions | Typically supplied with polymerase; may require optimization [41] |

| Primer Pairs | Sequence-specific amplification | 18-25 nucleotides; HPLC-purified for sequencing [30] [25] |

Results Interpretation and Troubleshooting

Analyzing Primer-BLAST Output

After completing the Primer-BLAST analysis, carefully evaluate the results to select optimal primer pairs: