Preventing Primer-Dimer: A Strategic Guide to Annealing Temperature Optimization for Reliable PCR

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing annealing temperature to prevent primer-dimer formation in PCR.

Preventing Primer-Dimer: A Strategic Guide to Annealing Temperature Optimization for Reliable PCR

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing annealing temperature to prevent primer-dimer formation in PCR. It covers the fundamental principles of how primer-dimers compromise assay sensitivity and specificity, details systematic methodologies for calculating and validating the correct annealing temperature, presents advanced troubleshooting protocols for recalcitrant reactions, and explores modern validation techniques using digital PCR and in silico analysis. By integrating foundational knowledge with practical application, this resource enables scientists to achieve highly specific amplification, crucial for accurate diagnostic assay development and robust research outcomes.

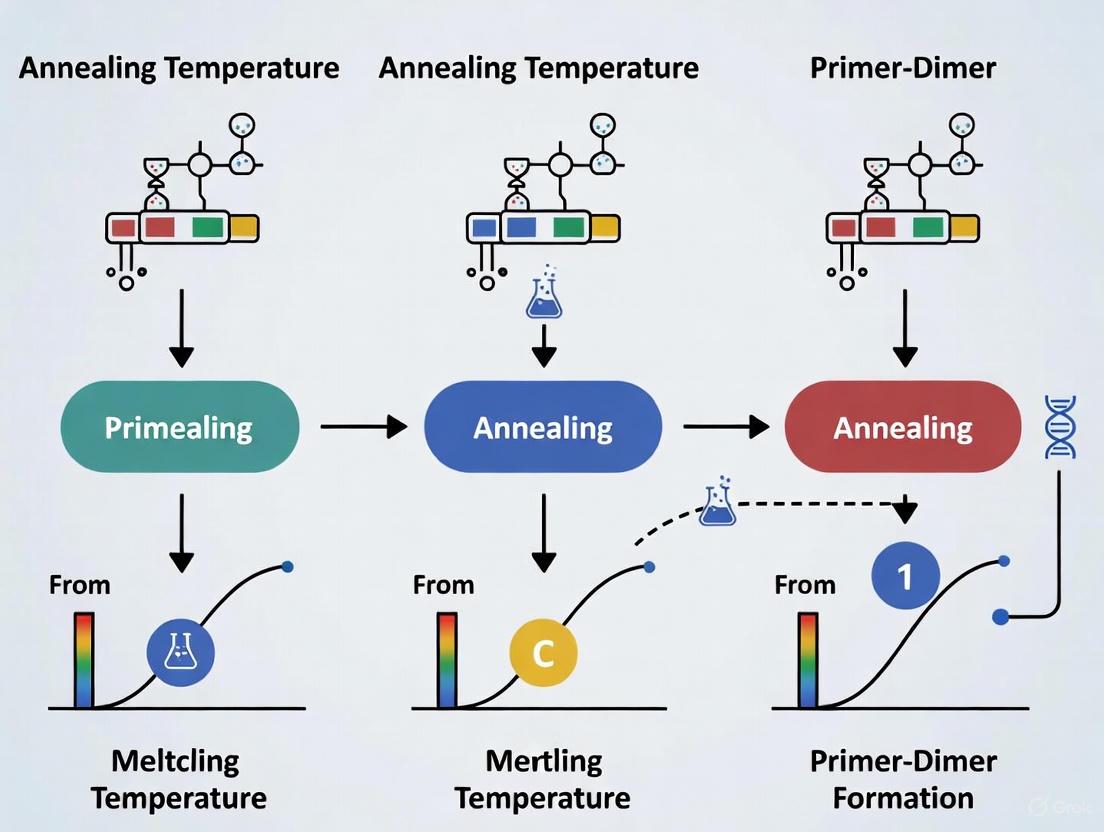

Understanding Primer-Dimer: How It Forms and Why Temperature is Key

In polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and quantitative PCR (qPCR), primer-dimer formation is a prevalent cause of assay failure, resulting in reduced efficiency, false positives, and inaccurate quantification [1] [2]. This artifact occurs when primers anneal to each other or themselves instead of the target DNA template, becoming unintended substrates for DNA polymerase [3]. Understanding the structural and thermodynamic distinctions between self-dimers and cross-dimers is fundamental to designing robust amplification assays. This guide defines these dimer types, details their mechanisms of formation and consequences, and provides experimentally validated protocols to identify and prevent them, with particular emphasis on the critical role of annealing temperature optimization.

Defining Primer-Dimer Species

Primer-dimers are classified based on the interacting oligonucleotides. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the two primary types.

Table 1: Characteristics of Primer-Dimer Species

| Dimer Type | Interacting Primers | Formation Mechanism | Key Structural Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Dimer | Two identical primers [4] | Intra-primer homology enables a single primer sequence to anneal to itself [5]. | Homodimer |

| Cross-Dimer | Forward and reverse primers (non-identical) [4] | Inter-primer homology enables the forward primer to anneal to the reverse primer [5]. | Heterodimer |

The formation of both types follows a three-step mechanism [1]:

- Annealing: Two primers anneal at their 3' ends via complementary bases.

- Extension: DNA polymerase binds and extends one or both primers, synthesizing a short, double-stranded DNA product.

- Amplification: The newly synthesized dimer strand serves as a template in subsequent PCR cycles, leading to exponential amplification of the dimer artifact.

The following diagram illustrates the structural formation and amplification pathway for cross-dimers.

Consequences of Primer-Dimer Formation

The formation and amplification of primer-dimers have significant negative impacts on PCR efficiency and data integrity, which are often exacerbated in complex multiplex assays [2].

- Consumption of Reaction Resources: Primer-dimers compete with the target amplicon for essential reaction components, including primers, DNA polymerase, and dNTPs [2]. This resource sequestration reduces the available reagents for target amplification, leading to poorer yield of the desired product.

- Inhibition of Target Amplification: When primers are sequestered in dimer complexes, they are unavailable for binding to the target template [6] [2]. This can lead to a complete failure of amplification or, more commonly, a reduction in amplification efficiency. In qPCR, this manifests as a higher Ct (cycle threshold) value, potentially leading to false negatives, especially with low-copy-number targets [2].

- Generation of False-Positive Signals: In assays that use non-specific detection dyes like SYBR Green, the amplification of primer-dimers generates a fluorescent signal indistinguishable from the target amplicon [1] [3]. In a no-template control (NTC), this produces a false-positive result. Even with specific probes, the formation of dimers can deplete reagents and inhibit the reaction [2].

Table 2: Impact of Primer-Dimers on PCR and qPCR Results

| Assay Type | Primary Impact | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Standard PCR | Reduced target yield; presence of a low molecular weight band on a gel [3]. | Failed cloning or sequencing; inaccurate genotyping. |

| qPCR (SYBR Green) | False-positive signal from NTC amplification; inaccurate melting curve [1] [2]. | Overestimation of target quantity; misidentification of amplicon identity. |

| qPCR (TaqMan Probe) | Consumption of reagents leading to higher Ct values and reduced sensitivity [2]. | Underestimation of target quantity; potential false negatives. |

Experimental Detection and Validation

Detecting primer-dimers is a critical step in assay validation. The following protocols outline standard methodologies for their identification.

Gel Electrophoresis Detection

This classical method is most suitable for endpoint analysis of standard PCR reactions [3].

- Procedure:

- Execute the PCR amplification protocol.

- Separate the PCR products using agarose gel electrophoresis (e.g., 2-4% agarose).

- Stain the gel with an intercalating dye like ethidium bromide or SYBR Safe and visualize under UV light.

- Interpretation: Primer-dimers appear as a diffuse smear or band between 30–50 base pairs (bp) [1] [3]. This band is distinctly smaller and often fuzzier than the specific target amplicon. Running the gel for a longer duration can help separate these small fragments from the desired products.

- Critical Control: Always include a no-template control (NTC). The presence of the low molecular weight band in the NTC confirms it is a primer-derived artifact and not a specific product [3].

Melting Curve Analysis

This is the standard method for detecting dimers in qPCR assays that use intercalating dyes [1].

- Procedure:

- Perform qPCR with continuous fluorescence acquisition at the end of each cycle.

- After amplification, slowly heat the products from a low temperature (e.g., 60°C) to a high temperature (e.g., 95°C) while continuously monitoring fluorescence.

- Plot the negative derivative of fluorescence over temperature (-dF/dT vs. T) to generate the melting curve.

- Interpretation: Primer-dimers, being short and often AT-rich, denature at a lower temperature than the specific target amplicon [1]. A distinct peak at a lower melting temperature (Tm) indicates primer-dimer formation. A single, sharp peak at a higher Tm indicates specific amplification.

Capillary Electrophoresis for Quantitative Analysis

For precise, quantitative analysis of dimerization risk, particularly with modified primers, capillary electrophoresis offers high resolution [7].

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Anneal primer pairs with complementary regions of varying lengths. One primer may be conjugated to a neutral "drag-tag" (e.g., a synthetic polyamide) to alter its electrophoretic mobility and enable clear separation from non-tagged strands [7].

- Separation: Load samples into a capillary electrophoresis system under free-solution conditions (no sieving matrix) at a range of temperatures (e.g., 18°C, 25°C, 40°C, 55°C, 62°C) [7].

- Detection: Use laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) for detection with fluorophore-labeled primers.

- Interpretation: The proportion of single-stranded primer vs. double-stranded dimer is quantitated from the electropherogram peaks. This method allows for empirical determination of dimer stability under different thermodynamic conditions [7].

Strategic Prevention and Optimization

Preventing primer-dimer formation requires a multi-faceted approach combining rational primer design, precise reaction conditions, and specialized biochemical reagents.

In Silico Primer Design and Screening

The first line of defense is careful primer design using thermodynamic principles.

- Guidelines for Design:

- Length: 18–24 nucleotides [6] [8] [9].

- Melting Temperature (Tm): 60–64°C for both primers, with a difference of ≤ 2°C between the pair [9].

- GC Content: 40–60%, avoiding long runs of a single nucleotide (e.g., GGGG) [6] [5] [8].

- 3'-End Stability: Avoid more than 2 G/C bases in the last 5 nucleotides to prevent stable non-specific initiation [6] [5].

- Specificity: Use tools like NCBI Primer-BLAST to ensure sequences are unique to the intended target [8].

- Screening for Secondary Structures: Utilize software (e.g., IDT OligoAnalyzer) to calculate the Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG) of potential dimers and hairpins. The ΔG of any self-dimers, hairpins, and heterodimers should be weaker (more positive) than –9.0 kcal/mol to be tolerated [9]. Stable, undesirable structures have larger negative ΔG values [6].

Wet-Lab Optimization Techniques

Even well-designed primers may require experimental optimization.

- Annealing Temperature (Ta): This is the most critical parameter. The optimal Ta is typically 2–5°C below the Tm of the primers [9]. A temperature that is too low permits annealing of primers with partial complementarity, while a temperature that is too high reduces yield. A temperature gradient PCR is recommended to determine the highest Ta that still provides robust target amplification.

- Primer Concentration: Lowering primer concentration reduces the opportunity for primer-primer interactions [3]. A typical starting concentration is 0.2–0.5 µM for each primer, which can be titrated down.

- Hot-Start DNA Polymerase: Use hot-start polymerases to prevent activity at low temperatures (e.g., during reaction setup) where primer-dimer formation is most likely [1] [3]. These enzymes are activated only after a high-temperature incubation step (e.g., 95°C for several minutes).

- Reagent Additives: For problematic templates or primers, additives like betaine (0.8 M) or DMSO (1–5%) can help disrupt secondary structures and improve specificity [10].

The following workflow integrates these strategies into a logical troubleshooting protocol.

Successful prevention and troubleshooting of primer-dimers rely on key reagents and software tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Primer-Dimer Management

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Enzyme inactive at room temperature; prevents pre-PCR mis-priming and dimer extension during reaction setup [1] [3]. | Essential for all diagnostic and multiplex qPCR assays to reduce background. |

| IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool | Free online software for calculating Tm, hairpins, and dimer ΔG values under user-defined buffer conditions [9]. | Initial screening of candidate primer sequences for self- and cross-complementarity. |

| NCBI Primer-BLAST | Integrates primer design with specificity checking against genomic databases to avoid off-target binding [8]. | Ensuring primer pairs are unique to the target gene before synthesis. |

| SYBR Green Dye | Intercalating dye that fluoresces upon binding double-stranded DNA; allows detection of both target and non-specific products like primer-dimers [1]. | Ideal for initial assay development and optimization to visualize non-specific amplification in NTCs. |

| Betaine | PCR additive that reduces secondary structure in the template and primers, and can equalize the stability of AT and GC base pairs [10]. | Useful for amplifying GC-rich regions or when primer sequences are suboptimal. |

| No-Template Control (NTC) | A control reaction containing all PCR components except the template DNA; critical for identifying reagent contamination and primer-dimer artifacts [3]. | A mandatory control in every qPCR run to distinguish true amplification from artifact. |

Primer-dimer formation, whether through self- or cross-dimerization, presents a formidable challenge in molecular assay development. Its impact ranges from reduced amplification efficiency to catastrophic false results. A rigorous approach combining strategic in silico design, meticulous thermodynamic screening using ΔG thresholds, and empirical optimization of annealing temperature and reagent concentrations is paramount. The integration of hot-start enzymes and systematic validation via no-template controls and melting curve analysis forms the cornerstone of robust, reliable PCR and qPCR protocols. By adhering to these detailed application notes, researchers can effectively mitigate the risk of primer-dimers, thereby ensuring the accuracy and reproducibility of their genetic analyses.

Primer-dimer formation represents a significant challenge in molecular biology, adversely impacting the accuracy and reliability of PCR-based research and diagnostic assays. This artifact, resulting from nonspecific primer-primer interactions, can lead to false negative results and inaccurate quantification, particularly in quantitative PCR (qPCR) and low-copy-number target amplification. The mechanisms underlying these inaccuracies involve competitive inhibition of target amplification, resource depletion, and signal interference. This application note details the consequences of primer-dimer formation, provides validated methodologies for its detection and prevention, and introduces advanced computational tools for predictive analysis. By integrating strategic primer design, optimized thermal cycling parameters, and specialized biochemical reagents, researchers can effectively mitigate these detrimental effects, thereby enhancing experimental validity across various applications including gene expression studies, clinical diagnostics, and drug development pipelines.

Primer-dimers are short, unintended DNA fragments that form during polymerase chain reaction (PCR) when primers anneal to each other instead of binding to their intended target DNA sequence [3]. These artifacts typically manifest as smeary bands below 100 bp in gel electrophoresis and can substantially compromise PCR efficiency and accuracy [3]. In research settings, particularly those involving quantitative PCR (qPCR), primer-dimer formation presents a formidable obstacle to data integrity, potentially leading to both false positive and, more insidiously, false negative results [2]. The broader thesis of optimizing annealing temperature to prevent primer-dimer formation provides a critical framework for understanding how these artifacts undermine experimental outcomes. This application note examines the specific mechanisms through which primer-dimers generate false negatives and impede accurate quantification, thereby providing researchers with strategic approaches to safeguard their findings against these detrimental effects.

Mechanisms and Consequences of Primer-Dimer Formation

Formation Pathways

Primer-dimers form primarily through two distinct molecular pathways:

- Self-dimerization: Occurs when a single primer contains regions complementary to itself, creating a free 3' end that DNA polymerase can extend [3].

- Cross-dimerization: Involves two or more primers with complementary regions binding together, again creating extendable 3' ends [3].

These interactions are facilitated by low annealing temperatures that allow weak complementary regions to hybridize, and are particularly problematic during reaction setup before thermal cycling begins, when components are at permissive temperatures for nonspecific binding [2].

Consequences for PCR Efficiency and Accuracy

The diagram below illustrates how primer-dimer formation competes with and inhibits target amplification, leading to false negatives and inaccurate quantification.

Figure 1: Mechanism of primer-dimer interference in PCR amplification

The consequences of primer-dimer formation extend beyond mere nuisance, significantly impacting experimental outcomes through several distinct mechanisms:

Competitive Resource Depletion: Primer-dimers competitively consume essential PCR reagents including primers, DNA polymerase, and dNTPs, thereby reducing the resources available for legitimate target amplification [2]. This resource competition directly diminishes amplification efficiency of the intended target.

Direct Amplification Inhibition: Contamination with minute quantities of primer-dimers from previous PCR reactions can completely inhibit amplification of legitimate target DNA, even when present at high copy numbers (up to 60 ng) [11]. This effect occurs regardless of whether uracil-DNA-glycosylase (UNG) is present in the reaction mix.

qPCR Signal Interference: In quantitative PCR, primer-dimers can be recognized and amplified by DNA polymerases, generating nonspecific fluorescence signals that interfere with accurate quantification of the target sequence [2]. This is particularly problematic in SYBR Green-based detection systems, where any double-stranded DNA product generates signal.

Quantitative Impact on PCR Sensitivity

Table 1: Experimental demonstration of primer-dimer inhibition effects

| Target Copy Number | Primer-Dimer Contamination | Amplification Efficiency | Observed Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 × 10^6 copies | None (Clean Reaction) | 100% | Normal amplification |

| 2 × 10^6 copies | 10^-5 dilution of Gag PCR primer-dimers | Complete inhibition (0%) | False negative |

| 200,000 copies | None (Clean Reaction) | 100% | Normal amplification |

| 200,000 copies | 10^-7 dilution of Gag PCR primer-dimers | >90% inhibition | False negative |

| High template (60 ng) | 10 picoliters PCR product | Significant inhibition | Reduced yield |

Research demonstrates that primer-dimer contamination with extremely small quantities (dilutions as low as 10^-7) from previous PCR reactions can almost completely inhibit PCR product formation when targets are present at low copy numbers (200,000 copies or less) [11]. This effect explains the occurrence of false negatives in sensitive detection applications, particularly when amplifying low-abundance targets such as potentially novel viral sequences or weakly expressed genes.

Detection and Diagnostic Methodologies

Gel Electrophoresis Detection

Conventional PCR products can be analyzed for primer-dimer formation using gel electrophoresis with the following protocol:

- Procedure: Prepare a 2-4% agarose gel in 1X TAE or TBE buffer containing an intercalating DNA stain. Mix 5-10 μL of PCR product with loading dye and load alongside an appropriate DNA ladder (e.g., 50-1000 bp range). Run at 80-100V until sufficient separation is achieved, then visualize under UV light [3].

- Interpretation: Primer-dimers typically appear as fuzzy, smeary bands below 100 bp, often running below the last band of the DNA ladder [3]. These differ from specific amplicons, which appear as crisp, well-defined bands at expected sizes.

- Troubleshooting: Running the gel longer ensures small primer-dimer fragments migrate past the desired PCR products, which are usually larger and run more slowly [3].

No-Template Controls (NTC)

Incorporating no-template controls (NTCs) in every run is essential for identifying primer-dimer formation:

- Procedure: Prepare reaction mixtures identical to test samples but replacing template DNA with nuclease-free water. Subject NTCs to the same thermal cycling conditions as experimental samples [3].

- Interpretation: Because primer-dimers do not require template DNA for formation, they will be the only amplification product present in NTCs. Amplification in NTCs indicates primer-dimer formation independent of template [3].

- qPCR Application: In SYBR Green qPCR, NTCs typically show late amplification curves (high Ct values) compared to template-containing samples, but early amplification in NTCs indicates significant primer-dimer problems [2].

Advanced Computational Detection

For sequencing-based assays and multiplex PCR applications, advanced computational tools enable sophisticated primer-dimer detection:

- URAdime Analysis: This tool analyzes primer sequences in sequencing data to identify dimers and super-amplicons. It processes BAM files and searches for input primers in the 5'-ends of sequences through a Levenshtein distance-based matching algorithm, providing detailed classification of primer-primer interactions [12].

- PrimerROC: Using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, this tool assesses dimer prediction accuracy with greater than 92% demonstrated efficacy. It provides condition-independent prediction of dimer formation likelihood based on Gibbs free energy (ΔG) calculations [13].

Table 2: Comparison of primer-dimer detection methodologies

| Method | Sensitivity | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gel Electrophoresis | Moderate | Conventional PCR, endpoint analysis | Simple, low-cost, visual confirmation | Low resolution, not quantitative |

| No-Template Controls | High | qPCR, conventional PCR | Easy implementation, identifies template-independent artifacts | Does not prevent dimers, only detects them |

| URAdime Computational Analysis | Very High | Sequencing assays, multiplex PCR | Detailed classification, works with empirical data | Requires sequencing data, computational resources |

| PrimerROC Prediction | High (92% accuracy) | Assay design phase | Preemptive, condition-independent | Predictive only, requires validation |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents for primer-dimer prevention

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Remains inactive until activated at high temperatures (≥90°C), preventing enzymatic activity during reaction setup [3]. | Critical for reducing pre-cycling primer-dimer formation; multiple commercial variants available. |

| UNG Treatment with dUTP | Degrades uracil-containing contaminants from previous reactions while leaving thymine-containing target DNA intact [11]. | Prevents carryover contamination but does not inhibit primer-dimer formation from current reaction primers. |

| Co-Primers Technology | Patented primers with two target recognition sequences linked together, reducing off-target interactions [14]. | Particularly valuable for multiplexed assays; requires specialized synthesis. |

| Primer Design Software | Identifies potential self-complementarity and heterodimers during assay design phase [9] [13]. | Tools include IDT OligoAnalyzer, PrimerROC; essential for preemptive dimer prevention. |

| Modified Nucleotides (LNA, PNA) | Enhance primer specificity and reduce self-complementarity through altered binding properties [15]. | Increase Tm allowing shorter, more specific primers; useful for problematic sequences. |

Experimental Protocols for Primer-Dimer Prevention

Optimized Primer Design Protocol

Effective primer design represents the first line of defense against primer-dimer formation:

- Step 1: Establish Basic Parameters: Design primers 18-30 nucleotides in length with a GC content between 40-60% [9]. Aim for melting temperatures (Tm) between 60-64°C, with forward and reverse primer Tms differing by no more than 2°C [9].

- Step 2: Avoid Complementarity: Screen primers for self-complementarity and 3'-end complementarity using tools like IDT OligoAnalyzer [9]. Avoid complementarity of 4 or more consecutive bases, particularly at the 3' ends where extension initiates [3].

- Step 3: Implement GC Clamps: Include 1-3 G or C residues in the last five nucleotides at the 3' end of primers to promote specific binding, but avoid more than 3 G/C residues which can promote nonspecific amplification [5].

- Step 4: Computational Validation: Utilize dimer prediction tools such as PrimerROC to assess potential primer-primer interactions before synthesis [13]. For multiplex assays, evaluate all possible primer pair combinations following the formula (n² + n)/2, where n represents the number of primers [13].

PCR Optimization Protocol

Reaction condition optimization can substantially reduce primer-dimer formation:

- Step 1: Optimize Primer Concentration: Titrate primer concentrations (typically 50-900 nM) to find the lowest concentration that provides robust amplification of the target. Lower primer concentrations reduce opportunities for primer-primer interactions [3] [15].

- Step 2: Implement Touchdown PCR: Begin with an annealing temperature 5-10°C above the calculated Tm, then decrease by 0.5-1°C per cycle until the optimal Tm is reached. This approach favors specific amplification in early cycles when primer-dimers are most likely to form [16].

- Step 3: Adjust Thermal Cycling Parameters: Increase denaturation times to ensure complete separation of DNA strands and disrupt weak primer-primer interactions [3]. Implement a two-step PCR protocol with combined annealing/extension at 68-72°C for assays where primers permit.

- Step 4: Validate with Controls: Always include no-template controls to monitor primer-dimer formation and internal amplification controls to detect inhibition that could lead to false negatives [11].

Advanced Multiplex PCR Strategy

For complex multiplex assays requiring numerous primer pairs, the following protocol minimizes dimer formation:

- Step 1: Primer Group Design: Divide primers into groups based on Tm, ensuring intra-group primers have similar melting temperatures (±2°C). Design primers with similar characteristics within each group [13].

- Step 2: In Silico Validation: Use URAdime or similar tools to analyze potential primer-primer interactions across all primer combinations [12]. This post-hoc analysis complements a priori optimization tools by providing insights into specific primers' performance under particular reaction conditions.

- Step 3: Empirical Testing: Test primer pairs in sub-pools before combining into full multiplex reactions. Analyze products by gel electrophoresis and sequencing to confirm specific amplification without dimer artifacts.

- Step 4: Reaction Optimization: Employ hot-start polymerase and optimize Mg²⁺ concentration (typically 1.5-3.0 mM) to enhance specificity. Consider additive agents such as DMSO (1-3%) or betaine (0.5-1.2 M) for difficult templates [5].

Primer-dimer formation presents a multifaceted challenge to molecular biology research, with demonstrated potential to generate false negative results and compromise quantitative accuracy in PCR-based assays. The consequences extend beyond mere reaction inefficiency to include complete amplification failure in sensitive detection applications, particularly when targeting low-abundance sequences. Through strategic primer design, reaction optimization, appropriate reagent selection, and robust control strategies, researchers can effectively mitigate these detrimental effects. The integration of computational prediction tools such as PrimerROC and URAdime with empirical validation provides a powerful framework for ensuring assay reliability. As molecular diagnostics and research applications continue to demand greater sensitivity and multiplexing capability, vigilant attention to primer-dimer prevention remains essential for generating accurate, reproducible scientific data.

The annealing temperature (Ta) is a critical parameter in the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) that dictates the specificity of primer binding to the intended target DNA sequence. When the annealing temperature is set too low, it promotes non-specific primer annealing, where primers bind to partially complementary or non-intended sites on the DNA template. This leads to the amplification of non-target DNA fragments, including primer-dimers, smears, and amplicons of unexpected sizes, which can severely compromise the efficiency, accuracy, and reliability of PCR results [17] [3] [18]. This application note, framed within a broader thesis on preventing primer-dimer formation, details the mechanistic link between low Ta and non-specific amplification and provides researchers and drug development professionals with optimized protocols to identify and establish the correct annealing temperature for specific, high-yield PCR.

The Mechanism: How Low Annealing Temperature Drives Non-Specificity

Thermodynamic Principles of Primer Binding

The annealing step in PCR is governed by the thermodynamic principle of hybridization, where primers seek out and bind to their complementary sequences. The melting temperature (Tm) of a primer is defined as the temperature at which 50% of the primer-DNA duplexes are dissociated. At a temperature significantly below the Tm, the reaction provides sufficient energy to stabilize even weak, incorrect bonds. A low Ta reduces the stringency of this binding event, allowing primers to remain stably bound to target sites even with one or more mismatched base pairs [9] [18]. This tolerance for mismatches is the fundamental cause of non-specific amplification.

Consequences of Reduced Stringency

- Amplification of Non-Target Sequences: With low stringency, primers can anneal to sequences other than the intended target that have regions of partial complementarity. These non-specific products then compete with the target amplicon for polymerase and nucleotides, often reducing the yield of the desired product [17] [15].

- Formation of Primer-Dimers: A low Ta dramatically increases the opportunity for primer-dimer formation. Primer-dimers are short, artifactual products formed when primers anneal to each other via complementary regions, particularly at their 3' ends, rather than to the template DNA. These can be extended by the DNA polymerase, creating a product that amplifies efficiently and depletes reagents [3] [15].

- Generation of Smears and Multiple Bands: Non-specific annealing can occur at many different sites across the complex DNA template, leading to the simultaneous amplification of numerous DNA fragments of varying lengths. This appears as a smear or multiple unexpected bands on an agarose gel, obscuring the target amplicon [17].

The following diagram illustrates the causal relationship between low annealing temperature and its detrimental effects on PCR outcomes.

Experimental Protocol: A Stepwise Guide to Optimize Annealing Temperature

Preliminary Primer Design and Tm Calculation

The optimization process begins with prudent primer design. Adhere to the following general guidelines to enhance initial specificity [9] [19]:

- Primer Length: 18–30 bases.

- GC Content: 40–60%.

- GC Clamp: The 3' end should end in G or C to strengthen binding.

- Melting Temperature (Tm): Aim for a Tm between 60–75°C for both primers, with the Tm of each primer in a pair within 2°C of each other.

- Avoid self-complementarity, long runs of a single base, and inter-primer complementarity to minimize dimerization.

Utilize free online tools, such as the IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool, to calculate the Tm of your primers based on your specific reaction conditions, as Tm is influenced by buffer components like salt concentration [9].

Determining and Testing the Annealing Temperature

The optimal annealing temperature (Ta Opt) is typically lower than the Tm of the primers. A standard starting point is to set the Ta at 3–5°C below the calculated Tm of the less stable primer [20]. For a more precise calculation, the following formula is recommended [20]: Ta Opt = 0.3 x (Tm of primer) + 0.7 x (Tm of product) – 14.9

A robust method for empirical determination is to perform a temperature gradient PCR. Set up a single master mix containing all reaction components and aliquot it into multiple PCR tubes. Run the PCR with the annealing step set to a gradient of temperatures, for example, from 50°C to 70°C. This allows you to test a range of annealing temperatures in a single experiment.

Analyzing Results and Selecting the Optimal Ta

After the gradient PCR, analyze the products using agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Identify the Specific Product: The correct annealing temperature will produce a single, bright band of the expected size.

- Identify Non-Specific Products: Lower temperatures in the gradient will typically show multiple bands, smears, or a prominent primer-dimer band at the bottom of the gel (~20-100 bp) [3].

- Select the Optimal Ta: The optimal annealing temperature is the highest temperature that still produces a robust yield of your specific amplicon. This maximizes stringency and minimizes non-specific products [18].

The following workflow provides a visual summary of the stepwise optimization protocol.

Data Presentation: Quantitative Parameters for PCR Optimization

Table 1: Key Primer Design Parameters and Their Impact on Specificity

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Rationale for Specificity | Consequence of Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primer Length | 18–30 bases [9] [19] | Balances specificity and efficient binding. | Shorter primers reduce specificity; longer primers may bind less efficiently. |

| GC Content | 40–60% [9] [19] | Provides balanced binding strength. | Low GC: weak binding; High GC: non-specific binding and secondary structures. |

| Melting Temp (Tm) | 60–75°C [9] [19] | Allows for a sufficiently high, specific Ta. | Low Tm forces use of a low Ta, promoting non-specific binding. |

| Tm Difference | ≤ 2°C between primer pairs [9] | Ensures both primers anneal efficiently at the same Ta. | One primer may anneal poorly, reducing yield and efficiency. |

| Annealing Temp (Ta) | Tm of lower primer - (2–5°C) [20] | Maximizes specific primer-template binding. | Ta too low: non-specific binding; Ta too high: reduced or no yield. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Non-Specific Amplification

| Observed Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Primer-dimer bands | Low Ta, high primer concentration, primers with 3' complementarity [3] [15]. | Increase Ta, lower primer concentration, use hot-start polymerase, re-design primers. |

| Smears on gel | Excessively low Ta, too much template DNA, degraded primers [17]. | Increase Ta, titrate template DNA concentration, use fresh primers. |

| Multiple non-specific bands | Low Ta, primers binding to multiple genomic sites [17] [18]. | Increase Ta, use touchdown PCR, check primer specificity via BLAST. |

| No product | Ta too high, poor primer design, inefficient lysis [20]. | Perform a Ta gradient, verify primer design and template quality. |

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Optimizing Annealing Temperature

| Reagent / Tool | Function and Role in Optimization | Example / Vendor |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Remains inactive at room temperature, preventing non-specific priming and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup. Critical for low-Ta protocols [3] [15]. | Various suppliers (e.g., NEB, Thermo Fisher, IDT). |

| Gradient Thermal Cycler | Allows a single PCR run to test a range of annealing temperatures simultaneously, drastically accelerating the optimization process. | Various manufacturers. |

| Primer Design Software | Computational tools that assess Tm, GC content, secondary structures, self-dimers, and specificity to facilitate optimal primer design [9]. | IDT PrimerQuest, Primer3Plus, Primer-BLAST. |

| Tm Calculator | Accurately calculates primer melting temperature based on sequence and reaction buffer conditions, which is essential for determining the starting Ta [9]. | IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool. |

| No-Template Control (NTC) | A control reaction containing all components except template DNA. Essential for identifying contamination and confirming that primer-dimer bands are not specific amplicons [3] [18]. | N/A (Standard practice). |

Within the broader context of optimizing annealing temperature to prevent primer-dimer formation, accurate identification of these artifacts is a critical first step in troubleshooting polymerase chain reaction (PCR) efficiency. Primer-dimers are short, unintended DNA fragments that form when PCR primers anneal to each other rather than to the intended target DNA template, leading to competition for reagents and potentially inhibiting the amplification of the desired product [15] [1]. This application note provides detailed methodologies for characterizing primer-dimer bands in agarose gels, enabling researchers to distinguish these nonspecific amplification products from target amplicons and to refine their experimental protocols accordingly.

Understanding Primer-Dimer Formation

Mechanism of Formation

Primer-dimer formation occurs through a three-step process [1]. First, two primers anneal at their respective 3' ends due to regions of complementarity. If this hybridized construct is sufficiently stable, DNA polymerase binds and extends the primers, synthesizing a complementary strand. In subsequent PCR cycles, this newly synthesized short duplex DNA itself serves as a template for further primer binding and extension, leading to exponential amplification of the primer-dimer artifact. The stability of the initial primer-primer interaction is heavily influenced by a high GC-content at the 3' ends and the length of the complementary overlap [1].

Impact on PCR Efficiency

The formation and amplification of primer-dimers competitively inhibits target amplification by consuming available primers, nucleotides, and polymerase activity [13] [15]. This resource diversion results in reduced amplification efficiency and yield of the specific target product, which is particularly problematic in applications requiring accurate quantification, such as real-time PCR [1]. In multiplex PCR applications, where numerous primers are present simultaneously, the potential for dimer formation increases polynomially, making effective identification and prevention crucial for assay success [13].

Characteristic Band Patterns in Gel Electrophoresis

Visual Identification Criteria

When analyzing PCR products via agarose gel electrophoresis, primer-dimers exhibit distinctive characteristics that allow them to be differentiated from specific amplification products, as illustrated in the workflow below.

The diagram above outlines the systematic approach for identifying primer-dimer bands in gel electrophoresis. The following table summarizes the key distinguishing features between primer-dimers and target amplicons based on visual inspection of stained agarose gels.

Table 1: Characteristic Features of Primer-Dimers vs. Target Amplicons in Gel Electrophoresis

| Feature | Primer-Dimer | Target Amplicon |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 30-50 base pairs [1] | Typically >50 bp (often 80-200 bp) [21] |

| Band Appearance | Fuzzy smear or diffuse band [3] | Sharp, well-defined band [22] |

| Position on Gel | Runs far from well, near dye front [3] | Position varies based on expected amplicon size |

| Presence in NTC | Appears in no-template control [3] | Absent in no-template control |

| Intensity | May appear with moderate to high intensity [1] | Intensity correlates with amplification success |

Experimental Confirmation Using Controls

The use of appropriate controls is essential for unambiguous identification of primer-dimer artifacts. A no-template control (NTC) reaction, containing all PCR components except the DNA template, serves as a critical diagnostic tool [3]. Since primer-dimers form independently of template DNA, they will appear as bands or smears in the NTC lane, typically in the 30-50 bp range [1]. In contrast, specific target amplicons will be absent from the NTC lane. When the NTC shows amplification products while test samples show similar low molecular weight bands, this confirms primer-dimer formation rather than specific amplification of target sequences.

Optimization Strategies to Minimize Primer-Dimer Formation

Primer Design Considerations

Strategic primer design represents the most effective approach for preventing primer-dimer formation. The following experimental protocol outlines a comprehensive method for designing primers with minimal dimerization potential.

Table 2: Optimal Primer Design Parameters to Minimize Dimer Formation

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 18-30 nucleotides [23] | Balances specificity and binding efficiency |

| GC Content | 40-60% [24] | Provides appropriate binding stability |

| 3' End Complementarity | ≤3 contiguous complementary bases [23] | Minimizes primer-primer annealing |

| Self-Complementarity | ≤3 contiguous bases [23] | Reduces hairpin structure formation |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | 55-72°C [23] | Ensures primers have similar annealing properties |

Experimental Protocol: Primer Design and Evaluation

- Sequence Selection: Identify template-specific binding sites with minimal homology to non-target sequences [21].

- In Silico Analysis: Utilize primer design software (e.g., Primer3, Primer-BLAST) to generate candidate primers meeting the parameters in Table 2 [23].

- Dimer Prediction: Employ computational tools such as PrimerROC to assess dimer formation potential through Gibbs free energy (ΔG) calculations [13].

- Specificity Verification: Conduct BLAST analysis to confirm primer specificity to the target sequence [23].

- Experimental Validation: Test selected primers empirically with appropriate controls.

Advanced dimer prediction algorithms like PrimerROC use receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to assess the predictive accuracy of Gibbs free energy calculations for dimer formation, achieving greater than 92% accuracy in identifying dimer-forming primer pairs [13]. This computational approach provides a condition-independent prediction of dimerization likelihood before experimental validation.

PCR Condition Optimization

When primer-dimer formation persists despite careful primer design, optimization of reaction conditions often mitigates the problem. The systematic workflow below outlines this optimization process, with annealing temperature adjustment being particularly critical within the thesis context.

Detailed Protocol: Annealing Temperature Optimization

Gradient PCR Setup:

Product Analysis:

- Separate PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis (2-3% agarose depending on expected product size) [22].

- Visualize using intercalating dyes (ethidium bromide, SYBR Safe, or GelRed).

- Identify the highest annealing temperature that yields strong target amplification without primer-dimer formation.

Secondary Condition Optimization:

- Primer Concentration: Titrate primer concentrations from 0.1-0.5 μM in 0.1 μM increments [3].

- Magnesium Concentration: Test Mg2+ concentrations from 1.5-4.0 mM, as Mg2+ stabilizes DNA duplexes and affects polymerase fidelity [24].

- Buffer Additives: Include DMSO (2-10%) or betaine (1-2 M) for templates with high GC-content or secondary structure [24].

Validation:

- Confirm optimal conditions with no-template controls to ensure primer-dimer elimination.

- Verify specificity of amplification through melt curve analysis (for qPCR) or restriction digest.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Primer-Dimer Prevention and Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Reduces non-specific amplification at low temperatures; requires heat activation | Antibody-mediated, aptamer-based, or chemically modified forms [15] |

| Agarose | Matrix for electrophoretic separation of DNA fragments by size | Standard agarose (1-3%) for resolving 50-2000 bp fragments [22] |

| DNA Intercalating Dyes | Visualization of DNA bands after electrophoresis | Ethidium bromide, SYBR Green, GelRed; varies in sensitivity and safety [1] |

| Primer Design Software | In silico primer evaluation and dimer prediction | Primer3, Primer-BLAST, Oligo 7, PrimerROC [13] [23] |

| DNA Ladder | Molecular weight standard for size determination of amplified products | Should include low molecular weight references (50-100 bp) [22] |

| Buffer Additives | Enhance specificity for challenging templates | DMSO (2-10%), betaine (1-2 M) for GC-rich templates [24] |

Accurate identification of primer-dimer artifacts through their characteristic band patterns in gel electrophoresis is an essential skill for molecular biologists. The systematic approach outlined in this application note—encompassing visual identification criteria, strategic controls, and optimized experimental design—enables researchers to confidently distinguish these nonspecific products from target amplicons. Within the broader context of annealing temperature optimization, the protocols provided here offer a pathway to significantly reduce primer-dimer formation, thereby enhancing PCR specificity and efficiency. By implementing these evidence-based strategies and utilizing appropriate reagent solutions, researchers can overcome the challenge of primer-dimer formation and improve the reliability of their molecular analyses.

A Step-by-Step Protocol for Determining the Optimal Annealing Temperature

In the context of optimizing annealing temperature to prevent primer-dimer formation, meticulous primer design serves as the foundational defense. Primer-dimers are short, unintended amplification artifacts that form when primers anneal to each other instead of the target DNA template, primarily due to complementary regions, especially at the 3' ends [3] [2]. These artifacts consume reaction resources, reduce amplification efficiency, and can lead to both false-positive and false-negative results in Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) [2]. Effective primer design, focusing on optimal length, GC content, and stringent avoidance of 3' complementarity, establishes the preconditions for a successful assay with a high specific annealing temperature, thereby forming the first and most crucial line of defense against these detrimental structures.

Core Principles of Defensive Primer Design

A robust primer design strategy is built on controlling specific physicochemical parameters to ensure primers bind efficiently and exclusively to their intended target sequence.

Optimal Primer Length

Primer length is a primary determinant of specificity and hybridization efficiency.

- Recommended Range: 18–30 nucleotides [19] [5]. A length of 18–24 bases is often ideal for standard PCR [5].

- Rationale: Shorter primers (<18 bases) risk reduced specificity, while longer primers (>30 bases) can exhibit slower hybridization rates and reduced annealing efficiency [5]. The shorter the primers, the more efficiently they will bind to the target [19].

Melting Temperature (Tm)

The melting temperature (Tm) is the temperature at which 50% of the DNA duplex dissociates into single strands and is critical for determining the annealing temperature (Ta) [5].

- Recommended

Tm: 65°C–75°C for each primer, with theTm for both forward and reverse primers within 5°C of each other [19]. An optimalTm for specificity is 54°C or higher [5]. - Relationship to

Ta: The annealing temperature (Ta) is often set 2°C–5°C above theTm of the primers for maximum specificity [5]. - Calculation: A common formula for estimating

Tm is:Tm = 4(G + C) + 2(A + T) [5].

GC Content and the GC Clamp

GC content influences primer stability due to the stronger hydrogen bonding of G-C base pairs (three bonds) compared to A-T base pairs (two bonds) [5].

- Recommended GC Content: 40%–60% [19] [5].

- GC Clamp: The presence of G or C bases at the 3' end of the primer promotes specific binding [19]. However, the 3' end should not contain more than three consecutive G or C bases, as this can promote non-specific binding [19] [5].

Avoiding Secondary Structures and 3' Complementarity

Unwanted secondary structures are a major source of primer-dimer formation and amplification failure.

- Self-Dimerization: Occurs when a single primer has regions complementary to itself [3] [2].

- Cross-Dimerization: Occurs when the forward and reverse primers have complementary sequences [3] [2].

- 3' Complementarity: Complementarity at the 3' ends of primers is particularly detrimental because DNA polymerases extend from the 3' end. Even a few complementary nucleotides can lead to extension and primer-dimer amplification [2].

- Prevention: Utilize primer design software to analyze and minimize "self-complementarity" and "self 3'-complementarity" parameters. The lower these values, the better [5].

Table 1: Summary of Key Primer Design Parameters for Preventing Primer-Dimer Formation

| Parameter | Optimal Value / Condition | Rationale & Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 18–30 nucleotides (18–24 ideal) [19] [5] | Balances hybridization efficiency with sufficient specificity for unique targeting. |

Melting Temperature (Tm) |

65°C–75°C; primers within 5°C of each other [19] | Ensures both primers anneal efficiently at the same temperature, enabling synchronized amplification. |

| GC Content | 40%–60% [19] [5] | Provides thermodynamic stability without promoting mispriming due to excessively strong binding. |

| GC Clamp | 1–2 G or C bases at the 3'-end [19] | Stabilizes the priming site for polymerase initiation. Avoid >3 consecutive G/C bases [5]. |

| 3' Complementarity | Avoid complementarity >3 bases [19] | Precludes primer-dimer and hairpin formation by minimizing unintended self- and cross-annealing. |

| Repeat Sequences | Avoid runs of 4 or more identical bases; avoid dinucleotide repeats [19] | Reduces chances of slippage and misalignment on the template or another primer. |

Experimental Protocols for Design and Verification

Protocol 1:In SilicoPrimer Design and Screening Workflow

This protocol outlines the computational design and validation steps to select candidate primer pairs before laboratory testing.

Methodology:

- Sequence Retrieval: Obtain the target DNA sequence from a trusted database (e.g., NCBI). Identify the precise region to be amplified.

- Initial Parameter Setting: Using primer design software (e.g., Primer-BLAST, Eurofins Genomics tools), set the selection criteria to the values specified in Table 1.

- Candidate Selection: The software will generate multiple candidate primer pairs. Select pairs that fulfill all baseline criteria.

- Specificity Check: Perform an in silico PCR or BLAST analysis to ensure the primers are unique to the target sequence and do not bind to other non-target regions in the relevant genome.

- Secondary Structure Analysis: Use the software's analysis tools to evaluate "self-complementarity" and "self 3'-complementarity" scores. Reject any primer pairs with high scores indicating potential for dimer or hairpin formation.

- Final Selection: Choose the top 2-3 candidate primer pairs for empirical testing.

The following workflow visualizes this multi-step design and screening process:

Protocol 2: Empirical Verification and Primer-Dimer Troubleshooting

This protocol describes the experimental verification of candidate primers and steps to mitigate primer-dimer formation if observed.

Materials:

- Candidate primer pairs

- Target DNA template

- Hot-Start DNA Polymerase Master Mix [3] [2]

- dNTPs

- Appropriate buffer system

- Thermocycler

- Gel electrophoresis equipment or qPCR instrument

Methodology:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare PCR reactions for each candidate primer pair. It is critical to include a No-Template Control (NTC) containing all reaction components except the DNA template, replaced with nuclease-free water [3].

- Thermocycling: Use a thermocycling protocol with an initial activation step for the hot-start polymerase (e.g., 95°C for 2 min), followed by 30-40 cycles of denaturation, annealing, and extension. For the first run, use the calculated

Ta based on theTm. - Analysis:

- Gel Electrophoresis: Analyze the PCR products and NTC on an agarose gel. Primer-dimers typically appear as a fuzzy smear or band below 100 bp [3]. Run the gel long enough to separate small primer-dimers from the desired amplicon.

- qPCR Analysis: In qPCR using intercalating dyes like SYBR Green, primer-dimers in the NTC will cause an amplification curve with a late cycle threshold (Ct) value [2].

- Troubleshooting: If primer-dimers are detected in the NTC:

- Increase Annealing Temperature: Systematically increase the

Ta by 2°C increments to disrupt the weak bonds forming primer-dimers [3]. - Optimize Primer Concentration: Lower the primer concentration (e.g., 50-300 nM final concentration) to reduce the likelihood of primer-primer interactions [3].

- Use Hot-Start Polymerase: Ensure a hot-start polymerase is used to prevent activity during reaction setup at low temperatures, a common period for dimer formation [3] [2].

- Redesign Primers: If optimization fails, redesign the primers, paying utmost attention to 3' complementarity.

- Increase Annealing Temperature: Systematically increase the

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Robust PCR Assay Development

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Application in Primer-Dimer Prevention |

|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Enzyme engineered to be inactive at room temperature. Critical for preventing non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup [3] [2]. |

| dNTP Mix | Deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP). The building blocks for DNA synthesis. Consumed by primer-dimer extension, reducing target amplification efficiency [2]. |

| Primer Design Software | Computational tools (e.g., Primer-BLAST, Eurofins Genomics Tool) to calculate Tm, GC%, and check for self-/cross-complementarity, enabling predictive avoidance of problematic primers [5]. |

| SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix | Contains all components for qPCR, including SYBR Green dye. Essential for empirical testing as it binds to any double-stranded DNA, allowing detection of primer-dimer products in No-Template Controls [2]. |

| Agarose Gel Electrophoresis System | Standard method for post-PCR visualization. Used to distinguish the size of the desired amplicon from the characteristic small, smeary band of primer-dimers [3]. |

Within the context of optimizing annealing temperature to prevent primer-dimer formation, the accurate calculation of primer melting temperature (Tm) stands as a critical first step. Tm is defined as the temperature at which 50% of DNA duplexes dissociate into single strands and serves as the foundational reference for establishing the optimal annealing temperature (Ta) in polymerase chain reaction (PCR) experiments [25]. miscalculations in Tm can directly lead to suboptimal annealing conditions, a primary contributor to the formation of primer-dimers—spurious amplification products where primers anneal to each other instead of the target template [15]. These byproducts compete for precious reaction reagents, thereby reducing the yield and specificity of the desired amplicon [15] [26]. This application note provides a detailed comparison of formula-based methods for calculating theoretical Tm, equipping researchers with the knowledge to select the appropriate methodology for robust assay design and effective primer-dimer minimization.

Tm Calculation Methods: A Comparative Analysis

The evolution of Tm calculation methods has progressed from simple GC-counting rules to sophisticated thermodynamic models. The choice of method is dictated by the required precision, the length of the oligonucleotide, and the specific reaction conditions.

Historical and Basic Formula-Based Approaches

Early and basic methods rely on simple formulas derived from the base composition of the oligonucleotide. These are useful for quick estimates but lack the accuracy of more advanced models.

- The Wallace Rule: This is one of the simplest methods, intended for short primers of less than 20 nucleotides [27]. The formula is:

Tm = 2°C × (A + T) + 4°C × (G + C), where A, T, G, and C represent the count of each respective base in the sequence [27]. It provides a rough approximation but ignores several critical factors that influence DNA duplex stability. - The GC% Method for Longer Sequences: For sequences longer than 13-14 nucleotides, a more general formula can be applied:

Tm = 64.9 + 41 × (number of Gs + number of Cs - 16.4) / total number of bases[28] [29]. This equation, like the Wallace Rule, assumes standard conditions of 50 nM primer and 50 mM Na⁺ concentration [28] [29].

Table 1: Summary of Basic Formula-Based Tm Calculation Methods

| Method Name | Formula | Optimal Sequence Length | Key Assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wallace Rule | Tm = 2°C × (A + T) + 4°C × (G + C) | < 20 nucleotides [27] | Standard salt conditions; ignores sequence context. |

| Basic GC% Formula | Tm = 64.9 + 41 × (G + C - 16.4) / N Where N = total bases [28] [29] | > 13 nucleotides [28] | 50 nM primer, 50 mM Na⁺, pH 7.0 [28]. |

Advanced Thermodynamic Models

For high-fidelity applications, particularly in complex genomic studies or multiplex PCR, advanced models that account for the nuanced thermodynamics of DNA hybridization are essential.

- Nearest-Neighbor Method: This is the current gold-standard for Tm prediction. Instead of treating each base pair independently, this method considers the sequence context by accounting for the stability of each dinucleotide (nearest-neighbor) pair [25] [30]. It uses well-established thermodynamic parameters for enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS) derived from empirical data. The SantaLucia model is a widely recognized implementation of this method, reportedly achieving an accuracy within ±1-2°C of experimental values [25]. This method directly incorporates the effects of salt concentrations, oligonucleotide concentration, and additives like DMSO into its calculations [25] [31].

Table 2: Comparison of Tm Calculation Method Accuracies and Applications

| Method | Reported Accuracy | Key Factors Considered | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple GC% Formula | ±5-10°C error [25] | GC content only [25] | Rough estimates only. |

| Basic Nearest-Neighbor | ±3-5°C error [25] | Sequence context [25] | General use with simple templates. |

| SantaLucia Nearest-Neighbor | ±1-2°C error [25] | Sequence context, terminal effects, salt corrections [25] | PCR, qPCR, multiplex assays, difficult templates (e.g., GC-rich). |

Experimental Protocols for Tm Determination and Verification

Protocol A: Applying Basic Formulas for Initial Primer Screening

This protocol is suitable for high-throughput initial screening of primer candidates where extreme accuracy is not yet required.

- Sequence Preparation: Obtain the nucleotide sequence of the primer in the 5' to 3' direction. Remove any non-base characters (spaces, numbers).

- Base Count: Tally the number of Adenine (A), Thymine (T), Guanine (G), and Cytosine (C) bases.

- Formula Application:

- For primers shorter than 14 nucleotides, apply the Wallace Rule:

Tm = (wA + xT) * 2 + (yG + zC) * 4, where w, x, y, z are the counts of A, T, G, and C, respectively [28]. - For primers of 14 nucleotides or longer, apply the GC% method:

Tm = 64.9 + 41 * (yG + zC - 16.4) / (wA + xT + yG + zC)[28] [29].

- For primers shorter than 14 nucleotides, apply the Wallace Rule:

- Result Interpretation: Use the calculated Tm to quickly compare a large set of primers and shortlist those with Tm values in the optimal 55-65°C range [25] for further, more precise analysis.

Protocol B: Using a Nearest-Neighbor Calculator for Robust Assay Design

This protocol outlines the use of sophisticated online calculators (e.g., OligoPool, IDT OligoAnalyzer, NEB Tm Calculator) that implement the nearest-neighbor method for highly accurate Tm determination [25] [31] [26].

- Tool Access: Navigate to a trusted Tm calculator.

- Sequence Input: Paste the primer sequence into the input field. The sequence can be DNA or RNA and is typically case-insensitive. The tool will automatically calculate the GC content and length [25].

- Parameter Setting: Accurately input the specific reaction conditions, as these critically impact the result:

- Oligo Concentration: Set between 0.1-0.5 µM (0.25 µM is standard for PCR primers) [25].

- Salt Concentration: Input monovalent (Na⁺/K⁺) and divalent (Mg²⁺) cation concentrations. Standard PCR often uses 50 mM Na⁺ and 1.5-2.5 mM Mg²⁺ [25]. Note: Mg²⁺ has a disproportionately strong stabilizing effect and must be accounted for [31].

- Additives: If using DMSO, input the percentage. DMSO reduces Tm by approximately 0.5-0.6°C per 1% concentration [25].

- Calculation and Analysis: Execute the calculation. The tool will return the Tm and often thermodynamic parameters (ΔH, ΔS). For primer pairs, ensure the Tms are within 5°C of each other to ensure balanced amplification [26].

Protocol C: Empirical Validation and Primer-Dimer Check

Theoretical calculations must be validated experimentally, especially when designing primers for novel or challenging templates.

- Annealing Temperature Gradient PCR: Set up a series of identical PCR reactions and run them with an annealing temperature gradient, typically spanning 5-10°C below the calculated lower Tm.

- Product Analysis: Analyze the PCR products using gel electrophoresis. The optimal annealing temperature produces a strong, specific band of the correct size with minimal to no primer-dimer smearing at lower molecular weights.

- Primer-Dimer Assessment: Inspect the gel for a low molecular weight smear or band, particularly in the no-template control (NTC) lane. The presence of primer-dimer in the NTC confirms that the signal is a reagent-derived artifact and not specific amplification [15].

- Optimization Iteration: If primer-dimer is observed, incrementally increase the annealing temperature by 1-2°C in subsequent runs until the dimer is eliminated or minimized without significant loss of the target product yield.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Tm-Centric PCR Setup

| Item | Function/Benefit | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Reduces non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation by remaining inactive until initial high-temperature denaturation step [15]. | Critical for assays prone to primer-dimer or with low-copy targets. |

| High-Purity, Desalted Primers | Ensures accurate concentration and removes synthesis byproducts that can inhibit polymerization or lead to spurious results [26]. | Essential for quantitative applications like qPCR. |

| PCR Buffers with [Mg²⁺] | Provides the optimal ionic environment and co-factor (Mg²⁺) for polymerase activity and primer-template binding [25]. | The concentration of free Mg²⁺ is a critical variable; use the value specified by the buffer manufacturer for Tm calculations [31]. |

| DMSO | A common additive that disrupts secondary structures in GC-rich templates, facilitating primer binding [25]. | Reduces calculated Tm by ~0.6°C per 1% added; must be factored into Tm calculations [25]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | The solvent for primer resuspension and reaction setup; ensures no enzymatic degradation of primers or template. | Prevents loss of reagents and maintains reaction integrity. |

Discussion: Integrating Tm Calculation into Primer-Dimer Prevention Strategy

The accurate prediction of Tm is not an isolated calculation but an integral component of a holistic strategy to prevent primer-dimer formation. The relationship is direct: an annealing temperature set too low facilitates transient hybridization between primers via complementary regions, especially at their 3' ends, which DNA polymerase can then extend [15] [5]. Therefore, an accurately determined Tm is the most important factor in setting a Ta high enough to promote specific binding while still allowing efficient amplification.

While advanced nearest-neighbor calculators are highly accurate, they are not infallible. Researchers must be aware of their limitations. The presence of mismatches or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) under the primer binding site can significantly alter the experimental Tm, sometimes by up to 18°C for a single base mismatch, depending on the type and context of the mismatch [31]. Furthermore, the calculations assume idealized reaction conditions. Variations in template quality or the presence of inhibitors in the sample can create a discrepancy between the theoretical and practical Tm. Consequently, the final validation must always be empirical, using a temperature gradient PCR to fine-tune the annealing conditions for the specific experimental setup [26]. By combining precise in silico Tm prediction with empirical validation, researchers can effectively minimize primer-dimer formation, thereby enhancing the specificity, efficiency, and reliability of their PCR assays.

The annealing temperature (Ta) is a critical parameter in the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) that determines the specificity and efficiency of primer binding to the target DNA sequence. Setting the correct annealing temperature is fundamental to the success of any PCR experiment, particularly in diagnostic and drug development contexts where precision is paramount. The widely cited rule of thumb is to set the annealing temperature 3–5°C below the melting temperature (Tm) of the primers [32] [33]. This application note details the theoretical basis for this rule, provides explicit protocols for its application, and outlines necessary adjustments to mitigate a common and critical issue in PCR: primer-dimer formation.

The Rule of Thumb: Theoretical Basis and Calculation

The Principle Behind Tm -5°C

The melting temperature (Tm) of a primer is defined as the temperature at which 50% of the primer-DNA duplexes are dissociated [34]. Using an annealing temperature exactly at the Tm is suboptimal because, at this point, only half of the primers are bound to the template. An annealing temperature about 5°C below the Tm shifts the equilibrium, ensuring a significantly higher proportion of primers are bound (e.g., 70-80%), thereby facilitating efficient initiation of DNA synthesis by the polymerase [34]. Conversely, an excessively low Ta permits toleration of partial annealing and internal base mismatches, leading to nonspecific amplification, while a Ta that is too high drastically reduces priming efficiency and can yield no product [32] [33].

Calculating Primer Melting Temperature (Tm)

Accurate Tm calculation is the foundation for applying the rule of thumb. The simplest formula considers base composition:

Tm = 4(G + C) + 2(A + T)

This basic calculation provides an initial estimate. For greater accuracy, especially for longer primers, more sophisticated methods that account for salt concentrations are required. The following formula incorporates this effect:

Tm = 81.5 + 16.6(log[Na+]) + 0.41(%GC) – 675/primer length [32]

The most accurate method is the Nearest Neighbor method, which uses thermodynamic parameters to calculate the stability of every adjacent nucleotide pair in the duplex [32] [35]. This method is the basis for most modern online Tm calculators and is highly recommended for critical applications. Furthermore, the optimal annealing temperature (Ta Opt) can be calculated more precisely using the formula: Ta Opt = 0.3 x (Tm of primer) + 0.7 x (Tm of product) – 14.9, where Tm of primer is the melting temperature of the less stable primer-template pair [33].

Table 1: Methods for Calculating Tm and Ta

| Method | Formula / Approach | When to Use | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Rule of Thumb | Ta = Tm - 5°C | Initial experiment setup | Quick estimate; requires prior accurate Tm calculation. |

| Base Composition | Tm = 4(G + C) + 2(A + T) | Initial primer design screening | Less accurate; does not account for sequence context or salt. |

| Salt-Adjusted | Tm = 81.5 + 16.6(log[Na+]) + 0.41(%GC) – 675/length | Standard PCR design | More accurate than basic method; requires knowledge of buffer. |

| Nearest Neighbor | Computational, uses thermodynamic stability | Critical applications, problematic templates (e.g., high GC) | Gold standard; used by most online calculator tools. |

| Full Optimization | Ta Opt = 0.3 x Tm(primer) + 0.7 x Tm(product) - 14.9 | High-fidelity requirements, long products | Considers the stability of the entire PCR product [33]. |

Adjustments to Prevent Primer-Dimer Formation

What is Primer-Dimer?

Primer-dimer is a small, unintended amplification artifact that forms when primers anneal to each other via complementary regions instead of binding to the target DNA template [3] [2]. This can occur as self-dimerization (one primer folding on itself) or cross-dimerization (forward and reverse primers binding to each other) [3]. The DNA polymerase can extend these bound primers, consuming reaction resources (dNTPs, enzymes, primers) and potentially leading to false-positive signals in quantitative PCR (qPCR) or reduced target amplification efficiency [2] [4].

Optimizing Annealing Temperature to Suppress Primer-Dimer

The rule of thumb Ta is a starting point that often requires adjustment to suppress primer-dimer. The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for this optimization.

The following strategies are central to this optimization process:

- Increase Annealing Temperature: If primer-dimer or nonspecific products are observed, incrementally increase the annealing temperature by 2–3°C [32] [3]. A higher Ta stringently enforces correct primer-template binding and disrupts the weaker bonds formed between primers.

- Apply a Temperature Gradient: For systematic optimization, use a thermal cycler with a gradient function to test a range of annealing temperatures simultaneously (e.g., from the calculated Tm down to the extension temperature) [32] [36].

- Employ Two-Step PCR: If the annealing temperature is within 3°C of the extension temperature (typically 68-72°C), combine the annealing and extension steps into a single two-step PCR protocol. This reduces the time spent at permissive temperatures where primer-dimer can form [32].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Initial Setup and Ta Determination

This protocol outlines the steps for a standard PCR setup using the rule of thumb.

Materials:

- Template DNA (e.g., genomic DNA, plasmid)

- Forward and Reverse Primers

- Taq DNA Polymerase (standard or hot-start)

- 10X PCR Buffer (with MgCl₂)

- dNTP Mix

- Nuclease-free water

Procedure:

- Calculate Tm: Determine the Tm for both forward and reverse primers using the Nearest Neighbor method via a reliable online calculator.

- Set Ta: Calculate the initial annealing temperature:

Ta = (Lower Tm of the two primers) - 5°C. - Prepare Master Mix: On ice, assemble a 50 µL reaction as shown in the table below.

- Thermal Cycling: Program the thermal cycler with the following parameters:

Table 2: PCR Reaction Setup

| Component | Final Concentration | Volume for 50 µL Reaction |

|---|---|---|

| 10X PCR Buffer | 1X | 5 µL |

| MgCl₂ (if not in buffer) | 1.5 - 2.0 mM | Varies |

| dNTP Mix (10 mM each) | 200 µM each | 1 µL |

| Forward Primer (10 µM) | 0.5 µM | 2.5 µL |

| Reverse Primer (10 µM) | 0.5 µM | 2.5 µL |

| Template DNA | Variable (e.g., 1 ng - 1 µg genomic) | Variable |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | 1.25 units | 0.25 µL (e.g., 5 U/µL) |

| Nuclease-free Water | - | To 50 µL |

Protocol 2: Optimization via Annealing Temperature Gradient

This protocol is used to empirically determine the optimal Ta when the theoretical value is insufficient.

Procedure:

- Calculate Range: Based on the results from Protocol 1, define a temperature gradient. For example, if primer-dimer was observed at a Ta of 55°C, set a gradient from 55°C to 65°C across the thermal cycler block.

- Prepare Reactions: Prepare a single master mix sufficient for all gradient reactions plus one extra. Aliquot equal volumes into multiple PCR tubes.

- Run Gradient PCR: Place the tubes in the pre-defined gradient positions in the thermal cycler and run the cycling program from Protocol 1.

- Analyze Results: Resolve the PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis. Identify the annealing temperature that produces the strongest specific band with the absence of primer-dimer (a smeary band typically below 100 bp) [3].

Protocol 3: Using a No-Template Control (NTC) to Diagnose Primer-Dimer

An NTC is essential for identifying primer-dimer derived from the primers themselves, independent of the template.

Procedure:

- Include NTC: During reaction setup (Protocol 1 or 2), include a control reaction where the template DNA is replaced with nuclease-free water.

- Run Concurrently: Subject the NTC to the same PCR cycling conditions as the test samples.

- Interpret Results: After gel electrophoresis, any amplification product in the NTC lane is a result of primer-dimer or contamination. A clear NTC lane confirms that amplification in the test samples is derived from the template [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Optimization

The following reagents are critical for successful PCR setup and troubleshooting primer-dimer issues.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Optimization |

|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Critical. Remains inactive until the initial high-temperature denaturation step, dramatically reducing primer-dimer formation that occurs during reaction setup at lower temperatures [3] [2]. |

| Gradient Thermal Cycler | Allows for the empirical testing of a range of annealing temperatures in a single run, drastically speeding up the optimization process [32]. |

| Primer Design Software | Identifies primers with low self-complementarity and 3'-end complementarity to minimize the intrinsic tendency for dimer formation [3]. |

| Betaine, DMSO, Formamide | PCR additives that can help denature templates with high GC content or strong secondary structure, which can indirectly influence effective annealing [32]. Note: DMSO lowers the effective Tm of primers, requiring a corresponding decrease in Ta [32] [36]. |

| dNTPs | The building blocks for DNA synthesis. Consistent quality and correct concentration (typically 200 µM each) are vital for efficient amplification and fidelity [37]. |

| MgCl₂ Solution | Mg²⁺ is a cofactor for DNA polymerase. Its concentration (typically 1.5-2.0 mM) can be optimized; slightly lower concentrations can sometimes increase specificity and reduce primer-dimer [37]. |

The annealing temperature (Ta) is a critical determinant in the success of the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), directly influencing specificity, yield, and the formation of unwanted by-products such as primer-dimers [5] [38]. Setting the Ta based solely on calculated melting temperatures (Tm) can be insufficient, as the theoretical Tm is affected by the specific reaction buffer, salts, and additives present in the PCR mix [39]. Temperature gradient PCR is an empirical method that allows researchers to rapidly identify the optimal Ta for a given primer-template system by testing a range of temperatures in a single run. This protocol details the application of a temperature gradient PCR to optimize annealing conditions, providing a robust methodology to suppress primer-dimer formation and enhance amplification specificity within the broader context of primer-dimer research.

Key Principles and Rationale

The Critical Role of Annealing Temperature

The annealing step is where primers bind to their complementary sequences on the DNA template. If the Ta is too low, primers can bind non-specifically to partially matched sequences, leading to off-target amplification. More critically, low temperatures facilitate primer-dimer formation, where the primers anneal to themselves or each other via a few complementary bases, particularly at their 3' ends [5] [38]. Primer-dimers are a major side product that consumes reaction reagents and can outcompete the amplification of the desired target, drastically reducing PCR efficiency and yield. Conversely, a Ta that is too high reduces hybridization efficiency, as the primers cannot bind stably to the template, resulting in low or no amplification product [39].

Advantages of a Temperature Gradient

While the Tm of a primer can be calculated using standard formulas (e.g., Tm = 4(G + C) + 2(A + T)), the in silico prediction is an approximation [5]. The actual optimal Ta in a specific laboratory setup is influenced by the precise composition of the PCR buffer, including Mg2+ concentration and the presence of additives like DMSO [38] [39]. A temperature gradient experiment circumvents this uncertainty by physically testing a spectrum of annealing temperatures simultaneously. This not only identifies the Ta that provides the highest yield of the specific product but also reveals the temperature range where specific amplification occurs, providing robustness for future reproductions of the assay.

Experimental Protocol: Temperature Gradient PCR

Primer Design and Preparation

Proper primer design is the foundation for a successful PCR.

- Length: Design primers to be 18-24 nucleotides long [5] [38].

- GC Content: Maintain a GC content of 40-60%. Avoid long stretches of a single nucleotide [5] [38].