Preventing Hairpins in PCR Primer Design: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Assay Development

This article provides a complete framework for researchers and drug development professionals to understand, prevent, and troubleshoot hairpin structures in PCR primer design.

Preventing Hairpins in PCR Primer Design: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Assay Development

Abstract

This article provides a complete framework for researchers and drug development professionals to understand, prevent, and troubleshoot hairpin structures in PCR primer design. Covering foundational concepts to advanced validation techniques, it details the mechanisms by which hairpins compromise assay specificity and efficiency. The guide offers practical design rules, in silico tools for screening, and optimization strategies for challenging templates. It further emphasizes the critical role of rigorous in silico and experimental validation in developing reliable PCR-based diagnostics and research assays, ensuring high-fidelity results in biomedical applications.

Understanding Hairpin Structures: The Hidden Enemy of PCR Specificity

What Are Primer Hairpins? Defining Intramolecular Secondary Structures

Primer hairpins are intramolecular secondary structures formed when a single primer oligonucleotide folds back upon itself, creating a stem-loop configuration. These structures are a critical consideration in molecular assay design, as they can sequester the primer's 3' end, reduce amplification efficiency, and lead to assay failure. This application note details the thermodynamic principles underlying hairpin formation, provides validated protocols for their computational prediction and empirical identification, and presents design strategies to minimize their impact within the broader context of PCR primer design guidelines for hairpin prevention research. Implementation of these guidelines is essential for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to optimize assay robustness in diagnostic and therapeutic applications.

In nucleic acid chemistry, secondary structures refer to stable, predictable conformations that primers and probes can adopt through intramolecular base pairing. Among these, primer hairpins (or hairpin loops) occur when two regions within a single primer are complementary, causing the molecule to fold and form a double-stranded stem with an unpaired loop region [1]. This folding is driven by the same thermodynamic forces that govern DNA duplex formation, primarily hydrogen bonding and base stacking interactions [2].

The formation of hairpin structures is particularly problematic in polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays. When a primer forms a stable hairpin, especially one involving its 3' end, it becomes unavailable for binding to the template DNA. The DNA polymerase may also extend the folded 3' end, leading to self-amplification and generating non-specific products that deplete reaction reagents and create background noise [3]. In advanced techniques like loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), which utilizes long inner primers (40–45 bases), the propensity for hairpin formation is even greater, making systematic prevention strategies essential for successful assay development [3].

Thermodynamic Stability and Quantitative Analysis

The stability of a primer hairpin is quantitatively determined by its Gibbs Free Energy change (ΔG). The ΔG value represents the spontaneity of the folding process; a more negative ΔG indicates a more stable, readily formed structure [4]. The probability of hairpin interference is directly correlated with this thermodynamic parameter [3].

Table 1: Hairpin Stability Thresholds and Impact on PCR

| Structural Parameter | Acceptable Threshold | Impact if Threshold is Exceeded |

|---|---|---|

| ΔG of Hairpin Formation | > -3 kcal/mol (internal); > -2 kcal/mol (3' end) [4] | Primer fails to linearize during annealing, preventing template binding. |

| Hairpin Melting Temperature (Tm) | >10°C below primer annealing temperature (Ta) [5] | Hairpin remains stable during annealing phase, sequestering primer. |

| Stem Length | Avoid >3 complementary bases [6] | Formation of excessively stable stems that are difficult to denature. |

| 3'-End Complementarity | Avoid complementarity in final 3-4 bases [3] [6] | Polymerase extends the self-annealed end, causing self-amplification. |

Research on reverse transcription LAMP (RT-LAMP) assays for viral detection has demonstrated that even primers with hairpins possessing 3' complementarity one or two bases away from the terminus can still self-amplify, generating a slowly rising fluorescent baseline in real-time monitoring and depleting primer concentrations [3]. This underscores the necessity of rigorous in silico checks.

Computational Prediction and Analysis Workflow

A multi-step computational workflow is recommended to identify primers with a high risk of forming stable secondary structures.

Protocol: In Silico Hairpin Analysis

Objective: To identify and thermodynamically characterize potential hairpin structures within a candidate primer sequence.

Materials:

- Software Tools: OligoAnalyzer Tool (IDT), mFold (Unafold), or equivalent secondary structure predictor [3] [5].

- Input: Candidate primer sequence in FASTA or plain text format.

- Reaction Conditions: Assay parameters including monovalent (Na⁺) and divalent (Mg²⁺) cation concentrations, and oligonucleotide concentration [7].

Method:

- Input Sequence: Enter the candidate primer sequence into the prediction tool.

- Set Conditions: Input the specific buffer conditions (e.g., 50 mM Na⁺, 1.5-2.5 mM Mg²⁺ for standard PCR) to ensure accurate thermodynamic calculations [7]. The stability of base pair interactions is strongly dependent on salt concentration and identity [3].

- Run Analysis: Execute the secondary structure prediction algorithm.

- Interpret Results:

- Examine all predicted folded conformations.

- Record the ΔG value for the most stable structure.

- Note the location of the hairpin—specifically, whether the 3' end is involved in the stem.

- Check the calculated melting temperature (Tm) of the hairpin structure itself.

Validation Criterion: A primer is considered suitable for experimental testing if the most stable hairpin has a ΔG > -3 kcal/mol (internal) or > -2 kcal/mol (for 3' end hairpins) and its Tm is at least 10°C below the intended assay annealing temperature [5] [4]. Primers failing these criteria should be redesigned.

Experimental Validation and Troubleshooting

While in silico design is the first line of defense, empirical validation is crucial for confirming primer performance, especially in complex, multiplexed, or diagnostically critical applications.

Protocol: Empirical Identification via Melt Curve Analysis

Objective: To detect the presence of primer dimer and self-amplifying hairpins in a no-template control (NTC) qPCR reaction.

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- qPCR Master Mix: Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and optimized buffer [8].

- Intercalating Dye: SYBR Green or similar LAMP-compatible dyes like SYTO 9 [3].

- Nuclease-Free Water: Serves as the no-template control.

- Candidate Primers: Forward and reverse primers at working concentration (typically 0.05–1.0 µM) [9].

- Equipment: Real-time PCR instrument capable of melt curve analysis.

Method:

- Prepare NTC Reaction: Combine qPCR master mix, primers, and nuclease-free water in place of template DNA.

- Run qPCR Protocol: Execute a standard qPCR cycling program.

- Perform Melt Curve Analysis: After amplification, slowly ramp the temperature from 60°C to 95°C while continuously monitoring fluorescence.

- Analyze Results: In the absence of template, a peak in the melt curve derivative indicates the dissociation of a specific double-stranded DNA product. A peak at a lower temperature than the expected amplicon confirms the formation of primer-dimers or self-amplified hairpin products [8]. A slowly rising baseline during the real-time run can also indicate non-specific amplification [3].

Troubleshooting and Primer Redesign Strategies

If hairpin-related amplification is detected, the following redesign strategies should be employed:

- Shift Primer Binding Site: Move the primer sequence a few nucleotides upstream or downstream to avoid self-complementary regions [3].

- Trim the 5' End: If complementarity exists between the 5' and 3' ends, shortening the primer can sometimes break the stem, provided specificity and Tm are maintained.

- Adjust Annealing Temperature: If the hairpin Tm is only slightly above the annealing temperature, increasing Ta may help, but risks reducing specific amplification efficiency [1] [5].

- Use Additives: For primers that are difficult to redesign, additives like DMSO (5-10%) can be incorporated to destabilize secondary structures [7]. DMSO lowers the melting temperature of DNA duplexes by approximately 0.5–0.7°C per 1% [7].

Research Reagent Solutions for Hairpin Prevention

The following table details key reagents and tools essential for the analysis and mitigation of primer hairpins.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Hairpin Prevention | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Secondary Structure Prediction Software (e.g., mFold, OligoAnalyzer) | Predicts stable hairpin conformations and calculates their ΔG and Tm [3] [5]. | First-pass screening of candidate primers during the design phase. |

| Thermostable DNA Polymerase (e.g., Bst 2.0, Taq) | Extends primers from the 3' end. Its activity is inhibited if the 3' end is sequestered in a hairpin [3] [9]. | Core enzyme in PCR, qPCR, and LAMP amplification reactions. |

| Intercalating Dye (e.g., SYBR Green, SYTO 9) | Binds double-stranded DNA, allowing detection of non-specific products from self-amplifying hairpins in real-time [3] [8]. | Enables melt curve analysis and monitoring of amplification baseline. |

| Additives (e.g., DMSO, Betaine) | Destabilizes secondary structures by interfering with base pairing, facilitating primer linearization [3] [7]. | Added to PCR mixes for GC-rich templates or primers prone to folding. |

| Nearest-Neighbor Tm Calculator | Accurately calculates primer Tm using SantaLucia's parameters and salt corrections (Owczarzy 2008), informing optimal Ta [7]. | Ensures annealing temperature is set to maximize specific binding and minimize hairpin stability. |

Primer hairpins represent a significant risk to the specificity and efficiency of nucleic acid amplification assays. Their impact is quantifiable through thermodynamic parameters like ΔG and hairpin Tm, which can be leveraged during in silico design to predict and prevent failure. For researchers in drug development and diagnostics, adhering to a rigorous workflow that integrates computational prediction using modern tools, careful attention to reaction conditions, and empirical validation is non-negotiable for developing robust, reproducible molecular assays. By treating primer hairpins as a definable and manageable variable, scientists can significantly enhance the success rate of their PCR-based experiments and diagnostic applications.

In polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and related amplification techniques, the exquisite specificity of the assay is critically dependent on the unimpeded binding of primers to their complementary target sequences. The formation of stable intramolecular secondary structures, known as hairpins, within oligonucleotide primers represents a significant molecular challenge that can severely compromise assay performance. Hairpins occur when two regions within a single primer are complementary, causing the molecule to fold onto itself and form a double-stranded stem with a single-stranded loop. This paper examines the precise molecular mechanisms by which these structures inhibit both primer binding and enzymatic elongation, provides validated experimental protocols for their detection and quantification, and presents strategic solutions for their mitigation within the broader context of PCR primer design guidelines for hairpin prevention research.

Molecular Mechanisms of Inhibition

Steric Hindrance of Target Binding

The fundamental mechanism by which hairpins impair PCR efficiency is through steric hindrance. When a primer forms a stable hairpin, the sequence involved in the stem structure becomes physically occupied with intramolecular binding and is therefore unavailable for intermolecular hybridization with the template DNA. The folded conformation creates a kinetic barrier that must be overcome for productive template binding to occur. Research demonstrates that this is particularly problematic when the hairpin structure involves the 3'-end of the primer, as this region is critical for the initiation of polymerase-mediated elongation [1]. The equilibrium between the folded (hairpin) and unfolded (functional) states of the primer determines the proportion of molecules capable of target binding at any given time during the annealing phase of the PCR cycle.

Impediment of Polymerase Processivity

Even if partial binding to the template occurs, hairpin structures can significantly impede the processivity of DNA polymerase. Thermostable DNA polymerases are molecular motors that require single-stranded templates for efficient 5' to 3' nucleic acid synthesis. Stable secondary structures in the template can cause polymerase stalling or dissociation, leading to truncated extension products [10] [1]. In the case of hairpin-forming primers, the polymerase must either denature the stable secondary structure during elongation—a process requiring energy and time—or terminate synthesis prematurely. This effect is particularly pronounced in isothermal amplification methods (e.g., LAMP, HAIR) where reaction temperatures are constant and often lower than those used for PCR denaturation steps, making spontaneous hairpin resolution less probable [11] [3].

Quantitative Impact on Assay Performance

The consequences of hairpin formation are not merely theoretical but produce quantitatively measurable detrimental effects on amplification assays. The table below summarizes key performance parameters affected by primer hairpins and their practical consequences.

Table 1: Quantitative Impacts of Primer Hairpins on Amplification Assays

| Performance Parameter | Impact of Hairpins | Experimental Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Amplification Efficiency | Significant reduction (>50% in severe cases) [3] | Higher Cq values, reduced sensitivity |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Increased background, rising baseline [3] | Poor discrimination between positive and negative samples |

| Reaction Velocity | Slower amplification kinetics [11] | Increased time to threshold in real-time monitoring |

| Effective Primer Concentration | Sequestration into inactive forms [1] | Apparent requirement for higher primer concentrations |

| Specificity | Promotion of non-specific amplification [3] | Spurious bands, primer-dimer artifacts |

Studies on Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) have demonstrated that primers with stable hairpins, particularly those with 3' complementarity, can lead to self-amplifying structures that generate false-positive signals even in no-template controls [3]. This non-specific amplification depletes reaction components and can completely obscure target-specific amplification, rendering assays unreliable for diagnostic applications. In quantitative PCR, hairpin formation causes a rightward shift in amplification curves (higher Cq values) and reduces the efficiency of the reaction, thereby compromising accurate nucleic acid quantification [12].

Experimental Detection and Analysis Protocols

In Silico Hairpin Analysis Using MFEprimer

Computational prediction represents the first line of defense against hairpin-related issues in primer design. The MFEprimer platform provides a robust algorithm for evaluating the thermodynamic stability of potential secondary structures.

Table 2: Key Parameters for In Silico Hairpin Analysis

| Parameter | Recommended Threshold | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Min Loop Size | 3-4 bases | Smaller loops create steric strain |

| Max Loop Size | 7-8 bases | Larger loops indicate distant complementarity |

| ΔG (Free Energy) | > -3 kcal/mol | More negative values indicate greater stability |

| Tm (Melting Temp) | < Primer Annealing Temp | Prefers hairpin denaturation at reaction temperature |

| 3'-Complementarity | Absolutely avoid | Critical for polymerization initiation |

Protocol:

- Access the MFEprimer-3.1 hairpin analysis tool at https://mfeprimer3.igenetech.com/hairpin [13]

- Input primer sequence in FASTA format or plain text

- Set parameters according to Table 2 above

- Execute analysis and review all predicted hairpins with ΔG values more negative than -3 kcal/mol

- Particularly flag any hairpins involving the 3'-terminal region (last 5 bases)

- Redesign primers that form stable secondary structures exceeding thresholds

Empirical Validation by Electrophoretic Mobility Shift

Bioinformatic predictions require experimental validation. Non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) can resolve structural conformations of oligonucleotides based on their migration characteristics.

Protocol:

- Oligo Preparation: Dilute the primer to 10 µM in nuclease-free water containing 1× Isothermal Amplification Buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM (NH₄)₂SO₄, 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgSO₄, 0.1% Tween 20, pH 8.8) [3]

- Folding Reaction: Heat the mixture to 95°C for 2 minutes, then cool gradually to annealing temperature (typically 25°C) over 30 minutes to allow secondary structure formation

- Gel Preparation: Prepare a 12% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel in 0.5× TBE buffer

- Electrophoresis: Load samples alongside a linear molecular weight marker and run at 100V for 60-90 minutes at a constant temperature of 25°C

- Visualization: Stain with SYBR Gold or ethidium bromide and image using a gel documentation system

- Interpretation: Primers with stable hairpins will demonstrate altered mobility compared to unstructured controls, appearing as multiple bands or smears due to structural heterogeneity

Thermodynamic Stability Assessment

The propensity for hairpin formation can be quantified thermodynamically using the nearest-neighbor model, which accounts for the sequence-dependent stability of nucleic acid duplexes.

Protocol:

- Parameter Calculation: Determine the Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of predicted hairpins using the nearest-neighbor model with SantaLucia parameters [14] [3]

- Concentration Adjustment: Account for monovalent ion concentration (typically 50 mM KCl) and divalent ion concentration (typically 2-8 mM MgCl₂) in the reaction buffer

- Stability Threshold: Flag any hairpin with ΔG < -5 kcal/mol as high risk for PCR interference

- Competitive Binding Assessment: Compare the ΔG of the primer-template hybrid with the ΔG of the hairpin structure—the former should be significantly more favorable (at least 3-4 kcal/mol more negative) to ensure efficient binding

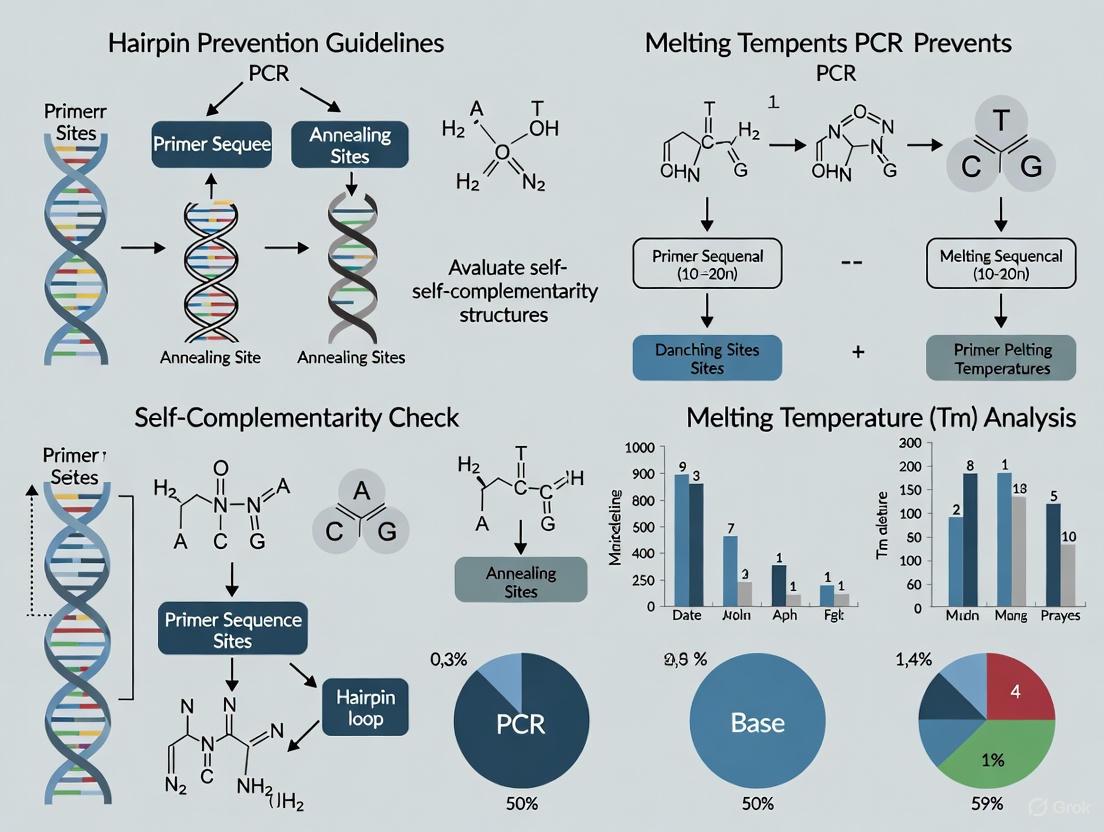

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for hairpin analysis from in silico prediction to empirical validation:

Diagram 1: Hairpin analysis workflow from prediction to validation.

Strategic Solutions and Reagent Toolkit

Primer Design Guidelines for Hairpin Prevention

Based on empirical evidence from multiple studies, the following design strategies effectively minimize hairpin formation:

- Terminal Sequence Management: Avoid complementarity in the 3'-terminal region, particularly within the last 5 nucleotides, as this region is critical for polymerization initiation [1] [3]

- GC Content Distribution: Maintain GC content between 40-60% and distribute GC residues evenly throughout the sequence rather than clustering them [10] [1]

- Length Optimization: Design primers between 18-30 nucleotides; longer primers have increased propensity for secondary structure formation [10] [1]

- Sequence Complexity: Incorporate residues that disrupt potential stem structures; AT-rich segments can serve as "breakers" between complementary regions [1]

Reaction Condition Optimization

When primer redesign is not feasible, strategic modification of reaction conditions can help mitigate hairpin effects:

- Increased Annealing Temperature: Implement touchdown PCR starting 5-10°C above the calculated Tm and gradually decreasing to the optimal annealing temperature [10]

- Additive Incorporation: Include betaine (0.8-1.0 M) or DMSO (2-10%) to destabilize secondary structures without compromising enzyme activity [3]

- Enzyme Selection: Utilize polymerases with enhanced strand displacement activity (e.g., Bst 2.0 WarmStart) for applications requiring resolution of stable secondary structures [11] [3]

Alternative Approaches: Hairpin-Assisted Amplification

Paradoxically, some innovative methods strategically employ hairpin structures for advantageous purposes. Hairpin-PCR deliberately converts DNA sequences to hairpin configurations following ligation of oligonucleotide caps, enabling complete separation of genuine mutations from polymerase misincorporations by converting errors into mismatches [15]. Similarly, the Hairpin-Assisted Isothermal Reaction (HAIR) utilizes terminal hairpins to facilitate primer-free amplification once initiated, demonstrating amplification rates more than five times faster than LAMP [11].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Hairpin Mitigation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Polymerases | Bst 2.0 WarmStart, Titanium Taq, Pfu Turbo | Enhanced strand displacement activity for secondary structure resolution |

| Buffer Additives | Betaine, DMSO, Formamide | Destabilize secondary structures by reducing base stacking interactions |

| Computational Tools | MFEprimer-3.1, mFold, Primer-BLAST | Predict thermodynamic stability of secondary structures before synthesis |

| Modified Primers | Hairpin-forming primers (Hairpin-PCR) | Intentional hairpin formation for error reduction in mutation detection |

| Blocking Oligos | C3-spacer modified primers | Competitively bind to predator DNA in mixed samples to enhance rare template amplification |

Hairpin structures in PCR primers represent a significant molecular challenge with clearly defined consequences for amplification efficiency and specificity. Through steric hindrance of target binding and impediment of polymerase processivity, these secondary structures can compromise even carefully designed assays. The integration of robust in silico prediction tools with empirical validation methods provides a systematic approach for identifying and quantifying hairpin formation, while strategic primer design principles and reaction optimization techniques offer effective mitigation strategies. For researchers developing diagnostic assays or conducting sensitive detection of rare targets, comprehensive hairpin analysis should be considered an essential component of the primer validation workflow, ensuring the reliability and accuracy of molecular amplification in both research and clinical applications.

Within the broader research on PCR primer design guidelines for hairpin prevention, this application note addresses the critical impact of suboptimal conditions on three common experimental outcomes: reduced yield, non-specific amplification, and complete assay failure. The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a foundational technique in molecular biology, yet its success hinges on the precise optimization of multiple interdependent parameters [16]. Even a single poorly designed primer can compromise years of research, particularly in sensitive applications like drug development and diagnostic assay validation [6].

Achieving robust, reproducible amplification requires a systematic understanding of how reaction components and thermal cycling conditions influence product specificity, yield, and fidelity [17] [18]. This document provides researchers with a detailed framework for diagnosing and resolving common PCR pathologies, with a special emphasis on the role of primer secondary structures—a key focus of our ongoing thesis research. The protocols and data analysis methods outlined herein are designed to integrate seamlessly into quality-controlled workflows for pharmaceutical and clinical research settings.

Critical Factors Affecting PCR Performance

Primer Design Parameters

Primer design is the most significant determinant of PCR success, directly controlling the specificity and efficiency of amplification [17] [1]. The following table summarizes the optimal design parameters to prevent common failure modes, including those caused by hairpin formation.

Table 1: Optimal Primer Design Parameters to Prevent PCR Failures

| Parameter | Optimal Range/Value | Impact of Deviation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length | 18-24 nucleotides [17] [1] [19] | Short: Reduced specificity.Long: Slower hybridization, inefficient annealing [1]. | Provides a balance between specificity and binding efficiency. |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | 55-65°C [17] [19]; Ideally 52-58°C for primers [16]. | Low Tm: Non-specific binding.High Tm: Secondary annealing, reduced yield [17]. | Ensures stringent and synchronous annealing of both primers. |

| Tm Difference (Primer Pair) | ≤ 2-5°C [1] [16] | Asymmetric amplification, low yield of the desired product. | Allows both primers to bind with similar efficiency during the annealing step. |

| GC Content | 40-60% [17] [1] [6] | Low: Weak binding, nonspecific products.High: Stable mismatches, primer-dimer formation [1]. | Balances duplex stability and minimizes mis-priming. |

| GC Clamp | Presence of 1-2 G/C bases in the last 5 bases at the 3' end [6]. Avoid >3 G/C in last 5 bases [19]. | Absence: Reduced priming efficiency, "breathing" of ends.Excess: Non-specific binding [6] [19]. | Stabilizes the primer-template hybrid at the critical point of polymerase initiation. |

| Self-Complementarity | Low scores for "self-complementarity" and "self 3'-complementarity" [1]. Avoid hairpins with ΔG ≤ -2 kcal/mol and dimers with ΔG ≤ -5 kcal/mol [19]. | Hairpins: Render primer unavailable.Primer-dimers: Consume reagents, produce artifacts [17] [19]. | Prevents intramolecular and intermolecular structures that compete with target binding. |

Reaction Components and Cycling Conditions

Beyond primer design, the meticulous preparation of the reaction mixture is crucial. The following table outlines the function and optimal concentration of key PCR components, the miscalibration of which directly leads to reduced yield or non-specific amplification.

Table 2: Optimization of Key PCR Reaction Components

| Component | Function | Typical Concentration | Optimization Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mg2+ | Essential cofactor for DNA polymerase; stabilizes primer-template duplex [17] [18]. | 1.5 - 2.5 mM [16]; can be titrated from 0.5 - 5.0 mM [20] [18]. | Too low: Reduced enzyme activity, low yield.Too high: Non-specific amplification, reduced fidelity [17]. |

| dNTPs | Building blocks for DNA synthesis. | 40 - 200 µM of each dNTP [20] [16]. | Must be balanced with Mg2+ concentration, as dNTPs chelate Mg2+ [18]. |

| DNA Polymerase | Catalyzes DNA synthesis. | 0.5 - 2.5 units/50 µL reaction [16]. | Standard Taq: Fast, robust for screening.High-Fidelity (e.g., Pfu): Possesses 3'→5' proofreading for cloning/sequencing [17]. |

| Template DNA | The target sequence to be amplified. | Plasmid: ~1 ng; Genomic DNA: ~100 ng [20]. | Must be free of inhibitors (e.g., phenol, heparin, EDTA). Purity is often more critical than quantity [17]. |

| Primers | Provide the initial point for DNA synthesis. | 0.1 - 1.0 µM each primer [20] [18]. | Lower concentrations can reduce primer-dimer and non-specific products [20]. |

Thermal cycler conditions must be tailored to the specific primer-template system. The denaturation temperature is typically 94-98°C for 20-30 seconds [20]. The annealing temperature (Ta) is the most critical variable and is best determined empirically via gradient PCR [17]. A good starting point is 3-5°C below the calculated primer Tm [20], though more precise formulas exist (e.g., Ta = 0.3 x Tm(primer) + 0.7 x Tm(product) – 14.9) [19]. The extension time at 70-74°C depends on amplicon length, generally 1 minute per 1 kb [21] [20].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Gradient PCR for Annealing Temperature Optimization

This protocol is the primary method for identifying the optimal annealing temperature to maximize specificity and yield [17] [20].

Materials:

- Thermal cycler with gradient functionality

- Designed primer pair

- DNA template

- PCR master mix (containing buffer, Mg2+, dNTPs, polymerase)

- Sterile nuclease-free water

Procedure:

- Prepare Master Mix: Combine the following components in a sterile microcentrifuge tube on ice. Multiply volumes by the number of reactions (n) plus ~10% to account for pipetting error.

- Sterile H2O: Q.S. to 50 µL

- 10X PCR Buffer: 5 µL

- dNTP Mix (10 mM): 1 µL

- MgCl2 (25 mM, if not in buffer): Variable (e.g., 2-4 µL)

- Forward Primer (20 µM): 1 µL

- Reverse Primer (20 µM): 1 µL

- DNA Polymerase (e.g., 1 U/µL): 0.5-1 µL

- Template DNA: X µL (e.g., 1 µL of ~10-100 ng/µL)

Aliquot: Mix the master mix thoroughly by pipetting. Dispense equal volumes (e.g., 49 µL) into each PCR tube.

Add Template: Add 1 µL of template DNA to each tube. Include a negative control (NTC) by adding 1 µL of sterile water to one tube.

Thermal Cycling: Place tubes in the thermal cycler and run the following program, setting a gradient across the block for the annealing step based on the primers' calculated Tm (e.g., 50°C to 65°C).

- Initial Denaturation: 94-98°C for 2-5 minutes.

- Amplification (30-35 cycles):

- Denaturation: 94-98°C for 20-30 seconds.

- Annealing: [Gradient from Tm -10°C to Tm +5°C] for 30 seconds.

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per 1 kb.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes.

- Hold: 4-10°C.

Analysis: Analyze the PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis. The optimal Ta is the highest temperature that produces a single, intense band of the expected size.

Protocol 2: Magnesium Titration for Reaction Efficiency and Fidelity

This protocol systematically optimizes Mg2+ concentration, which is critical for polymerase activity and primer annealing [17] [18].

Procedure:

- Prepare a master mix as in Protocol 1, but omit MgCl2 if it is not already included in the 10X buffer.

Aliquot the master mix into a series of tubes (e.g., 6-8 tubes).

Add MgCl2 (e.g., 25 mM stock) to each tube to create a concentration series across the range of 0.5 mM to 5.0 mM (e.g., 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0 mM final concentration).

Run the PCR using the optimal annealing temperature determined from Protocol 1 or a standard Ta.

Analyze the products by gel electrophoresis. Identify the Mg2+ concentration that yields the strongest specific band with the least background smearing or non-specific bands.

Troubleshooting and Data Analysis

Diagnostic Workflow for Common PCR Problems

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for diagnosing the root causes of the three main PCR failure modes based on experimental observations.

Advanced Data Analysis for qPCR

For quantitative PCR (qPCR), adherence to the MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines ensures robust and reproducible data [22]. Key metrics include:

- PCR Efficiency: Calculated from a standard curve (Efficiency = 10-1/slope – 1). Ideal efficiency is 90-110% (slope of -3.1 to -3.6) [22].

- Dynamic Range: The range of template concentrations over which the assay is linear (preferably 5-6 orders of magnitude) [22].

- Specificity: Assessed through melt curve analysis (for SYBR Green assays) or probe validation, and confirmed by the absence of amplification in no-template controls (NTCs) [22].

The "dots in boxes" method provides a high-throughput visualization for comparing multiple qPCR assays. It plots PCR Efficiency (Y-axis) against ΔCq (X-axis), where ΔCq = Cq(NTC) - Cq(Lowest Template Concentration). High-quality assays (efficiency 90-110%, ΔCq ≥ 3) fall within the "box," with dot size and opacity representing an overall quality score based on linearity, reproducibility, and curve shape [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and tools are essential for implementing the protocols and troubleshooting strategies outlined in this document.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for PCR Optimization and Hairpin Prevention Research

| Category | Item | Specific Function / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Polymerases | Standard Taq Polymerase | Fast and robust for routine amplification and screening [17]. |

| High-Fidelity Polymerase (e.g., Pfu, KOD) | Contains 3'→5' proofreading activity for high-fidelity amplification essential for cloning and sequencing; significantly lowers error rate [17] [18]. | |

| Hot-Start Taq | Activated only at high temperatures to prevent non-specific priming and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup [17] [21]. | |

| Buffer Additives | DMSO (2-10%) | Disrupts secondary structures in the DNA template, particularly beneficial for GC-rich targets (>65%) [17] [16]. |

| Betaine (0.5-2.5 M) | Homogenizes the stability of DNA duplexes, improving the amplification of GC-rich regions and long templates [17] [16]. | |

| Primer Design & Validation | Primer Design Software (e.g., Primer-BLAST, Primer3) | Automates the design process while enforcing parameters for length, Tm, GC content, and avoidance of secondary structures [6] [16]. |

| Oligo Analyzer Tools | Calculates thermodynamic properties (ΔG) to screen for stable hairpins and primer-dimers that hinder amplification [6] [19]. | |

| BLAST/In Silico PCR | Validates primer specificity against genomic databases to prevent off-target amplification [6] [16]. |

Polymersse Chain Reaction (PCR) is a foundational technique in molecular biology, and its success critically depends on the effective design of oligonucleotide primers. PCR amplification fails if primers form intra- or intermolecular secondary structures, such as hairpins, instead of binding to the template DNA. This application note examines the key factors influencing hairpin formation—sequence composition, GC content, and thermodynamic stability—within the broader context of PCR primer design guidelines for hairpin prevention research. We provide detailed protocols and analytical frameworks to enable researchers to design highly specific and efficient primers, minimizing secondary structure formation and maximizing assay robustness for critical applications in drug development and diagnostic testing.

Key Factor Analysis and Data Presentation

Primary Sequence Composition

The nucleotide sequence of a primer is the primary determinant of its propensity to form secondary structures. Specific sequence patterns must be avoided to prevent misfolding and mispriming.

Table 1: Sequence Composition Guidelines for Hairpin Prevention

| Parameter | Optimal Value/Range | Undesirable Pattern | Impact on PCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primer Length [4] [23] [24] | 18–25 nucleotides (bp) | < 18 bp or > 30 bp | Short primers cause nonspecific binding; long primers hybridize slowly. |

| Runs (Homopolymers) [4] [24] | Maximum of 4 consecutive identical bases | e.g., AAAAA or GGGG |

Promotes mispriming and can stabilize hairpin loops. |

| Di-nucleotide Repeats [4] [24] | Maximum of 4 di-nucleotide repeats | e.g., ATATATAT |

Causes mispriming due to repetitive alignment. |

| 3'-End Stability [4] [24] | Low stability (less negative ΔG) | A stable (highly negative ΔG) 3' end | Increases the likelihood of false priming and hairpin initiation. |

GC Content and Distribution

GC content refers to the percentage of guanine (G) and cytosine (C) bases within the primer. GC base pairs form three hydrogen bonds, conferring greater stability to the DNA duplex than AT base pairs, which form only two [1]. This differential stability makes GC content and its distribution critical for controlling primer behavior.

Table 2: GC Content and Clamp Specifications

| Parameter | Recommended Guideline | Rationale | Hairpin/Specificity Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall GC Content [4] [23] [24] | 40%–60% | Balances duplex stability and specificity. | Content >60% increases intra-strand binding; <40% can necessitate overly long primers. |

| GC Clamp [4] [24] [25] | 1-2 G or C bases in the last 5 nucleotides at the 3' end. | Promotes specific binding at the critical point for polymerase extension. | More than 3 G/C bases at the 3' end can promote non-specific binding and hairpin stabilization [24] [1]. |

Thermodynamic Principles

The formation of secondary structures is a spontaneous process governed by thermodynamics. The Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG) quantifies this spontaneity, where a more negative ΔG indicates a more stable and favorable reaction [4] [24]. For hairpins, a negative ΔG value signifies a stable, undesirable structure. Analyzing the ΔG of potential secondary structures is therefore essential for predicting primer behavior.

Table 3: Thermodynamic Stability Thresholds for Primer Structures

| Secondary Structure Type | Description | Tolerable ΔG Threshold (kcal/mol) | Energetic Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hairpin (3' end) [4] [24] [25] | Primer folds back on itself, with the 3' end involved in the duplex. | > -2.0 | The 3' end must remain available for extension; stable 3' hairpins are highly detrimental. |

| Hairpin (Internal) [4] [24] | Primer folds back on itself, but the 3' end is not part of the duplex. | > -3.0 | Internal hairpins are slightly easier to break than 3' end hairpins but still hinder annealing. |

| Self-Dimer [24] | Two identical primers (e.g., two forward primers) bind to each other. | > -5.0 (3' end) | Depletes primer availability and can be extended by polymerase, competing with the target. |

| Cross-Dimer [24] | Forward and reverse primers bind to each other. | > -5.0 (3' end) | Prevents primers from annealing to the template and can lead to primer-dimer artifacts. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Silico Primer Design and Hairpin Analysis

This protocol uses bioinformatics tools to design primers and rigorously check for potential secondary structures before synthesis.

I. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Tools for Computational Primer Design

| Item | Function/Description | Example Tools/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Editing & Analysis Software | Platform for visualizing template sequence, selecting target regions, and integrating design parameters. | Benchling, Vector NTI [4] [25] |

| Primer Design Algorithm | Core engine that generates candidate primer pairs based on user-defined constraints. | Primer3 (integrated in many platforms) [26] |

| BLAST Search Database | Public database for checking primer specificity against known sequences to avoid cross-homology. | NCBI Nucleotide BLAST [4] [14] |

| Thermodynamic Prediction Tool | Software feature that calculates Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG) for potential secondary structures. | Integrated in Primer Premier, Beacon Designer, and other advanced tools [24] |

II. Methodology

- Template Preparation: Obtain the pure, accurate DNA template sequence in FASTA format. Annotate the exact genomic coordinates of the region you wish to amplify [14].

- Parameter Initialization: Input the following design parameters into your chosen software [4] [23] [24]:

- Primer Length: 18-25 bp

- Melting Temperature (Tm): 55-65°C for each primer, with Tm between primer pairs within 2°C.

- GC Content: 40-60%

- Amplicon Length: Define based on experimental need (e.g., ~100 bp for qPCR, ~500 bp for standard PCR).

- Generate Candidate Primers: Run the primer design algorithm. The software will return a list of ranked primer pairs.

- Secondary Structure Analysis: For the top candidate primers, run the software's secondary structure analysis function [4] [24].

- Inspect the reported ΔG values for hairpins, self-dimers, and cross-dimers.

- Reject any primer with a 3' end hairpin ΔG ≤ -2.0 kcal/mol or an internal hairpin ΔG ≤ -3.0 kcal/mol.

- Reject any primer pair with a 3' end cross-dimer ΔG ≤ -5.0 kcal/mol.

- Specificity Validation: Perform an in silico PCR check using a tool like NCBI's Primer-BLAST [14]. This step verifies that the primers are unique to your target sequence and will not amplify unintended genomic regions.

The following workflow summarizes the computational design and validation process:

Protocol 2: Empirical Validation and Annealing Temperature Optimization

Even well-designed primers require experimental optimization. This protocol uses a temperature gradient PCR to determine the optimal annealing temperature (Ta) that maximizes specific product yield while minimizing artifacts from secondary structures.

I. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Key Reagents for Empirical PCR Optimization

| Item | Function/Description | Example Product |

|---|---|---|

| Thermostable DNA Polymerase | Enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands. Use hot-start versions to reduce non-specific amplification. | Taq DNA Polymerase, Pfu DNA Polymerase [27] |

| PCR Buffer with Additives | Provides optimal pH and salt conditions. May include isostabilizing agents or co-solvents that help with complex templates. | Buffers with betaine, DMSO [27] |

| dNTP Mix | Building blocks (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) for DNA synthesis. | |

| Template DNA | The target DNA to be amplified (e.g., genomic DNA, plasmid). | |

| Gradient Thermal Cycler | Instrument that allows a range of annealing temperatures to be tested in a single run. | "Better-than-gradient" thermal cyclers [27] |

II. Methodology

Reaction Setup:

- Prepare a master mix containing nuclease-free water, PCR buffer, dNTPs, DNA polymerase, and the forward and reverse primers (typically 0.1–1.0 µM each).

- Aliquot the master mix into PCR tubes and add an identical amount of template DNA to each.

- For a 50 µL final reaction volume, use 10–100 ng of genomic DNA or 1–10 pg of plasmid DNA [27].

Thermal Cycling with Gradient:

- Initial Denaturation: 94–98°C for 1–3 minutes [27].

- Amplification (25–35 cycles):

- Denaturation: 94–98°C for 15–30 seconds.

- Annealing: Set a gradient across the thermal cycler block from 5°C below to 5°C above the calculated Tm of your primers. Use an incubation time of 15–60 seconds [27].

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per kilobase of expected product length.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5–10 minutes.

Product Analysis:

- Run the PCR products on an agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide or a comparable DNA stain.

- Visualize under UV light. The optimal annealing temperature (Ta) is the highest temperature that produces a strong, specific band of the expected size with minimal to no non-specific products or primer-dimer smears [27].

The relationship between annealing temperature and PCR outcomes is visualized below:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 6: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Hairpin Prevention

| Category | Item | Specific Function in Hairpin Prevention |

|---|---|---|

| Software & Bioinformatics | Primer Design Suites (e.g., Primer Premier, Beacon Designer) [24] | Incorporates thermodynamic algorithms (Nearest Neighbor model) to calculate ΔG of secondary structures during the design phase. |

| Specificity Check Tools (e.g., NCBI Primer-BLAST) [14] | Identifies unique template regions for primer binding, avoiding cross-homology that can complicate secondary structure landscapes. | |

| PCR Enzymes & Buffers | Hot-Start DNA Polymerase [27] | Reduces non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation by remaining inactive until high temperatures are reached. |

| PCR Additives (e.g., DMSO, Betaine) [27] | Acts as a destabilizing agent, lowering the Tm and helping to denature stable GC-rich secondary structures in both primers and template. | |

| Laboratory Equipment | High-Precision Gradient Thermal Cycler [27] | Enables fine-tuning of the annealing temperature, which is critical for disrupting stable hairpins without compromising specific yield. |

Proactive Design Strategies: Building Hairpin-Free Primers from the Ground Up

Within the broader scope of establishing robust PCR primer design guidelines for hairpin prevention research, mastering three core parameters is non-negotiable: primer length, GC content, and melting temperature (Tm). These interdependent factors form the foundational triad that dictates primer specificity, efficiency, and most critically, the minimization of deleterious secondary structures like hairpins. Hairpin formation, a form of intramolecular base-pairing, can sequester the 3' end of a primer, preventing it from annealing to the template DNA and leading to PCR failure or spurious amplification [16] [28]. For researchers and drug development professionals, a meticulous and quantitative approach to optimizing these parameters is essential for developing reliable genetic assays, diagnostic tests, and biopharmaceutical products. This application note provides detailed protocols and structured data to guide this optimization process, framed within the context of systematic hairpin prevention.

Quantitative Design Parameter Tables

Core Parameter Specifications

The following table summarizes the consensus optimal ranges and critical constraints for the three core design parameters, as established by industry leaders and peer-reviewed protocols [29] [1] [30].

Table 1: Core Primer Design Parameters and Specifications

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Critical Constraints | Primary Impact on Hairpin Prevention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length | 18–30 nucleotides [29] [31] | Most specific: 20–24 bases [1] [6] | Longer primers increase risk of self-complementarity. |

| GC Content | 40–60% [29] [16] [30] | Ideal target: ~50% [31] | High GC content promotes stable hairpin structures. |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | 60–75°C [30] [31] | Primer pair Tm difference: ≤2–5°C [16] [31] [6] | High Tm can stabilize misfolded secondary structures. |

| GC Clamp | G or C at 3'-end [16] [30] | Max 2-3 G/C in last 5 bases [1] [6] | Prevents "breathing" but excessive G/C causes non-specific binding. |

Troubleshooting and Parameter Adjustment

When standard conditions fail, particularly with challenging templates, strategic parameter adjustment is required. The following table outlines common problems and evidence-based solutions.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Suboptimal Parameters

| Problem | Potential Cause | Corrective Action | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Amplification | Hairpin stable at annealing temperature [28] | Increase Ta in 2°C increments; redesign primer to avoid internal complementarity [31] | Check for product with gradient PCR. |

| Primer-Dimer Formation | 3'-end complementarity between primers [16] | Redesign primers to minimize ΔG of heterodimer (aim > -9.0 kcal/mol) [31] | Analyze reaction on high-% agarose gel. |

| Non-Specific Bands | Low annealing temperature; short primer length [1] | Increase Ta; lengthen primer to 25-30 nt for complexity [29] | Use touchdown PCR; optimize Mg2+ concentration. |

| GC-Rich Target Failure | Stable secondary structures in template/primer [28] | Use 3–10% DMSO or 1–10% glycerol as additive [16] [28]; employ high-fidelity polymerases [32] | Test additives in a matrix optimization experiment. |

Experimental Protocols

Core Protocol: Primer Design and In Silico Validation

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for designing primers with optimized parameters and validating them computationally to prevent hairpins and other secondary structures.

1. Define Target Region and Retrieve Sequence

- Action: Obtain the precise target genomic or cDNA sequence from a curated database like NCBI Nucleotide or Ensembl using the FASTA format or accession number [6].

- Rationale: Using a RefSeq entry reduces sequence ambiguity, which is critical for specificity analysis.

2. Design Primers Using Specialized Software

- Action: Input the target sequence into a reliable primer design tool such as NCBI Primer-BLAST or Primer3 [16] [6].

- Parameter Settings: Constrain the search to the following specifications [31] [6]:

- Product Size: 70–500 bp (150 bp ideal for qPCR)

- Primer Length: 18–24 bases

- Tm Optimum: 60°C (set range 58–62°C)

- Max Tm Difference: 2°C

- GC%: 40–60%

- Rationale: These constraints ensure the design engine returns primers with balanced thermodynamics.

3. Screen for Secondary Structures

- Action: Analyze each candidate primer sequence using an oligonucleotide analysis tool like the IDT OligoAnalyzer [33] [31].

- Procedure:

- Select the "Hairpin" function.

- Input the primer sequence and the recommended buffer conditions (e.g., 50 mM K+, 3 mM Mg2+).

- Examine the results. Reject any primer with a predicted hairpin ΔG value more negative than -9.0 kcal/mol [31].

- Rationale: This step identifies and eliminates primers with a strong tendency to form stable intramolecular structures.

4. Validate Specificity

- Action: Use the integrated BLAST function in Primer-BLAST or OligoAnalyzer to check for off-target binding sites in the appropriate organismal genome [33] [6].

- Rationale: Ensures the primer pair will amplify only the intended target, reducing non-specific amplification.

5. Final Selection

- Action: From the candidate list, select the primer pair that best fulfills all optimal parameters and shows the cleanest in silico profile for hairpins, self-dimers, and cross-dimers [31].

Advanced Protocol: Amplification of GC-Rich Targets

Genes with high GC content (>65%) present a significant challenge for amplification and are prone to forming stable secondary structures. This protocol adapts the core principles to overcome these hurdles [28].

1. Primer Redesign via Codon Optimization

- Principle: For GC-rich gene sequences, modify the primer sequence at the wobble position of codons without altering the encoded amino acid sequence [28].

- Action:

- Identify tracts of G or C residues longer than 3 bases in the original primer sequence.

- Substitute a G with an A, or a C with a T, at the third (wobble) position of a codon to reduce local GC content.

- Use OligoAnalyzer to re-check the Tm and hairpin potential of the modified primer. The goal is to disrupt stable secondary structures while maintaining the target amino acid sequence.

2. Prepare Reaction Mixture

- Reagents:

- Procedure:

- Assemble the 25 µL reaction on ice, adding DMSO last.

- Mix components gently by pipetting.

3. Execute Thermal Cycling

- Cycle Conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 98°C for 2–4 minutes.

- 30–35 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 98°C for 20–30 seconds.

- Annealing: Test a gradient from 60°C to 72°C for 30–40 seconds. For modified primers, start 2–5°C below the calculated Tm [28].

- Extension: 72°C for 1–2 minutes per kb.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5–7 minutes.

- Rationale: The combination of codon-optimized primers, DMSO, and a higher annealing temperature disrupts the stable secondary structures of GC-rich templates.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for designing primers with an emphasis on preventing secondary structures, integrating both core and advanced protocols.

Primer Design and Validation Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents are essential for implementing the protocols described in this document and for ensuring successful, reproducible PCR amplification while mitigating hairpin formation.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PCR Primer Design and Optimization

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Purpose | Specific Recommendation / Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Amplifies target with high accuracy; essential for cloning. | CloneAmp HiFi, PrimeSTAR Max; avoid error-prone polymerases like Taq for cloning [32]. |

| IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool | In silico analysis of Tm, hairpins, self-dimers, and hetero-dimers. | Critical for screening designs; reject primers with hairpin ΔG < -9.0 kcal/mol [33] [31]. |

| NCBI Primer-BLAST | Integrated primer design and specificity validation. | Ensures primers are unique to the intended target sequence [16] [6]. |

| DMSO (Dimethyl Sulfoxide) | PCR additive that reduces secondary structure stability. | Use at 3–10% (v/v) for GC-rich targets (>65% GC) to improve yield [16] [28]. |

| HPLC or PAGE Purified Primers | Removes truncated oligonucleotide synthesis byproducts. | Essential for long primers (>45 nt) and critical applications like cloning to ensure efficiency [29] [32]. |

| Mg2+ Solution | Cofactor for DNA polymerase; concentration affects specificity and yield. | Optimize concentration (1.5–5.0 mM); included in many buffers but may require titration [16]. |

In polymerase chain reaction (PCR) experiments, the design of primers is a fundamental determinant of success. Among the critical design parameters, the prevention of self-complementarity at the 3' end stands out as particularly crucial for ensuring specific and efficient DNA amplification. Self-complementarity in primers leads to the formation of secondary structures such as hairpins and primer-dimers, which directly compete with the intended template binding and can severely compromise amplification efficiency [31] [1]. This application note details the underlying principles, quantitative guidelines, and practical methodologies for designing primers with optimal 3' end characteristics, framed within broader research on PCR primer design guidelines for hairpin prevention.

The 3' end of a PCR primer serves as the initiation point for DNA polymerase activity. Any mispriming due to self-complementarity at this critical location can result in false amplification products, reduced target yield, and ultimately, experimental failure [34]. This document provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with structured protocols and analytical frameworks to identify and eliminate 3' self-complementarity during primer design and validation.

Principles of 3' End Complementarity

Structural Consequences of 3' End Self-Complementarity

The 3' hydroxyl group of PCR primers provides the essential substrate for DNA polymerase-mediated extension. When regions within a single primer are complementary, particularly at the 3' end, they can form stable secondary structures that prevent proper annealing to the template DNA [1]. The most common problematic structures include:

- Hairpins: Formed when two regions within the same primer are complementary, causing the primer to fold onto itself [34].

- Self-dimers: Occur when multiple copies of the same primer anneal to each other through complementary regions [31].

- Cross-dimers: Formed when forward and reverse primers interact through complementary sequences [1].

These aberrant structures are particularly detrimental when they involve the 3' terminus, as they provide alternative substrates for DNA polymerase activity, redirecting enzymatic extension away from the target template [34].

Energetic Considerations of Primer-Template Interactions

The stability of primer-template interactions is governed by Gibbs free energy (ΔG), with more negative values indicating thermodynamically favorable spontaneous reactions [35]. Self-complementary structures with strongly negative ΔG values at the 3' end effectively compete with proper template binding. The binding strength of G and C nucleotides versus A and T nucleotides further influences this balance, with GC base pairs forming three hydrogen bonds compared to the two formed by AT base pairs [1]. This fundamental difference explains why GC-rich regions at the 3' end pose particular challenges for specificity.

Quantitative Design Parameters

Critical Threshold Values for 3' End Design

Adherence to specific thermodynamic parameters ensures primers remain free of problematic secondary structures. The following table summarizes the key quantitative guidelines for preventing 3' end self-complementarity:

Table 1: Quantitative Design Parameters for Preventing 3' End Self-Complementarity

| Parameter | Optimal Value/Range | Critical Threshold | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3' End Self-Complementarity Score [35] | 0 | ≤3 | Maximizes sensitivity; higher values interfere with polymerase progression |

| ΔG of Secondary Structures [31] | > -9.0 kcal/mol | -9.0 kcal/mol | Weaker (more positive) ΔG prevents stable secondary structure formation |

| Consecutive G/C Residues at 3' End [34] | ≤2 bases | 3 bases | Prevents excessively stable non-specific binding |

| GC Clamp (G/C in last 5 bases) [1] | 1-2 bases | 3+ bases | Balances specific binding without promoting mispriming |

| Terminal 3' Base [34] | T (Thymidine) | Avoid A (Adenine) | Reduces extension likelihood in mismatch events |

Comprehensive Primer Design Specifications

While focusing on the 3' end, successful primer design requires adherence to multiple interdependent parameters. The following table provides complete specifications for designing primers that minimize secondary structures while maintaining amplification efficiency:

Table 2: Comprehensive Primer Design Guidelines to Prevent Secondary Structures

| Parameter | Recommended Range | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Length [31] [36] | 18-30 nucleotides | Balance between specificity (longer) and hybridization efficiency (shorter) |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) [31] [37] | 55-65°C; ≤2°C difference between primers | Enables simultaneous primer annealing |

| GC Content [31] [36] | 40-60% | Provides sequence complexity while maintaining specificity |

| Self-Complementarity (Any) [35] | Low score; avoid regions of ≥4 complementary bases | Preforms intramolecular hairpin structures |

| Cross-Complementarity (Primer Pair) [38] | No significant complementarity | Prevents primer-dimer formation between forward and reverse primers |

| Free Energy (ΔG) Distribution [34] | High ΔG at 5' end and middle; low ΔG at 3' end | Promotes specific binding and reduces non-specific interactions |

Experimental Protocols

Computational Validation Workflow

Prior to laboratory experimentation, comprehensive in silico analysis provides a cost-effective approach to identify primers with optimal 3' end characteristics. The following diagram illustrates the sequential validation workflow:

Protocol 1: In Silico Primer Validation

Primary Parameter Validation

- Input candidate primer sequences into analysis software (e.g., IDT OligoAnalyzer, Primer3) [31] [14].

- Verify length (18-30 nt), GC content (40-60%), and Tm (55-65°C) compliance.

- Specifically check for ≤2 consecutive G/C residues at the 3' terminus [34].

- Expected Outcome: Primers passing initial screening proceed to secondary structure analysis.

Secondary Structure Analysis

- Analyze self-complementarity using "Hairpin" function in OligoAnalyzer [35].

- Record ΔG values for all predicted secondary structures.

- Reject primers with ΔG < -9.0 kcal/mol, particularly for structures involving the 3' end [31].

- Check 3' end self-complementarity score, prioritizing values of 0 [35].

- Expected Outcome: Identification of primers with minimal propensity for secondary structure formation.

Specificity Verification

- Perform BLAST analysis against appropriate genome databases [34].

- Verify primer specificity to intended target, especially at 3' terminal region.

- Use "Primer must span an exon-exon junction" option when working with mRNA templates [14].

- Expected Outcome: Confirmation of target-specific binding without significant off-target matches.

Thermodynamic Scoring

- Utilize PrimerChecker or similar tools to generate holistic quality plots [35].

- Evaluate multiple parameters simultaneously (Tm difference, 3' complementarity, ΔG).

- Assign overall quality score based on composite assessment.

- Expected Outcome: Primers ranked by probability of successful amplification.

Laboratory Verification Protocol

Following computational validation, laboratory testing provides essential empirical confirmation of primer performance.

Protocol 2: Empirical Validation of Primer Specificity

Reaction Setup

- Prepare PCR master mix according to manufacturer's recommendations.

- Use high-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., CloneAmp HiFi, PrimeSTAR Max) for superior accuracy [39].

- Include appropriate positive and negative controls.

- Materials: Template DNA (5-50 ng genomic DNA or 0.1-1 ng plasmid), primers (0.1-1 μM each), dNTPs (0.2 mM each), MgCl₂ (1.5-3.5 mM), reaction buffer.

Thermal Cycling Conditions

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 2 minutes

- 30-35 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds

- Annealing: Temperature gradient (50-65°C) for 30 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per kb

- Final extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes

- Note: Include annealing temperature gradient to empirically determine optimal Ta [31].

Product Analysis

- Separate PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis (1.5-2% agarose).

- Visualize with appropriate DNA stain (ethidium bromide, SYBR Safe).

- Analyze for single, discrete bands of expected size.

- Expected Results: Specific amplification manifested as a single band of expected size; non-specific amplification appears as multiple bands; primer-dimer formation visible as low molecular weight smear [1].

Troubleshooting Problematic Primers

- If non-specific products observed: Increase annealing temperature in 2°C increments [31].

- If primer-dimer present: Reduce primer concentration to 0.1-0.3 μM [36].

- If no product formed: Verify 3' end sequence specificity and check for secondary structures.

- Consider adding 5' non-complementary G/C nucleotides to balance Tm between primer pairs if sequence constraints prevent modification of core binding region [35].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and tools are essential for implementing the protocols described in this application note:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Primer Design and Validation

| Reagent/Tool | Specific Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| IDT OligoAnalyzer [31] | Analyzes Tm, hairpins, dimers, and mismatches | Provides ΔG values for secondary structures; includes BLAST functionality |

| NCBI Primer-BLAST [14] | Designs primers and checks specificity against database | Ensures primers are unique to intended target sequence |

| PrimerChecker [35] | Generates holistic quality plots of thermodynamic parameters | Facilitates visual interpretation of multiple parameters simultaneously |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase [39] | PCR amplification with minimal error introduction | Essential for cloning applications; superior to Taq for accuracy |

| Double-Quenched Probes [31] | qPCR detection with low background fluorescence | Recommended over single-quenched for higher signal-to-noise ratios |

| PCR-Grade Water [39] | Reconstitution of primers and reaction components | Prevents contamination from nucleases or inhibitors |

The critical importance of the 3' end in PCR primer design cannot be overstated. Through careful attention to self-complementarity parameters, researchers can significantly improve amplification specificity and efficiency. The quantitative thresholds and experimental protocols provided herein offer a structured approach to primer design that minimizes secondary structure formation while maximizing target-specific binding. As PCR methodologies continue to evolve in diagnostic and therapeutic development contexts, these fundamental principles remain essential for generating reliable, reproducible results in molecular biology research.

The precision of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) experiments is fundamentally dependent on the quality of the oligonucleotides used. Secondary structures, particularly hairpins, are a major source of experimental failure, leading to reduced amplification efficiency, non-specific products, or complete reaction failure. Specialized software tools are indispensable for predicting and preventing these issues in silico, saving valuable time and resources. These tools leverage sophisticated thermodynamic models, such as the nearest-neighbor method developed by SantaLucia (1998) and the salt correction algorithms from Owczarzy (2008), to provide accurate predictions of oligonucleotide behavior under specific experimental conditions [7]. This application note details the use of these tools, with a focus on the IDT OligoAnalyzer platform, to design primers and probes devoid of problematic secondary structures, thereby enhancing the reliability of data generated for hairpin prevention research.

The Critical Role of In-Silico Hairpin Prevention

Hairpins are intramolecular base-pairing events that occur when a single oligonucleotide strand folds back on itself, forming a stem-loop structure. During PCR, a primer or probe locked in a hairpin conformation is unable to bind efficiently to its target DNA template. This can prevent the DNA polymerase from initiating synthesis, drastically reducing yield or causing false-negative results in qPCR assays [1] [6].

The stability of a hairpin is quantitatively expressed by its Gibbs free energy value (ΔG). A more negative ΔG indicates a more stable, and therefore more problematic, secondary structure. IDT recommends that the ΔG of any predicted hairpin should be weaker (more positive) than –9.0 kcal/mol to ensure it does not interfere with the reaction [31] [40]. Preventing these structures at the design stage is a more robust strategy than attempting to resolve them through post-hoc reaction optimization.

A suite of free, online tools is available to researchers for comprehensive oligonucleotide analysis and design. The following table summarizes the primary tools and their applications.

Table 1: Key Oligonucleotide Design and Analysis Software Tools

| Tool Name | Provider | Primary Function | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| OligoAnalyzer Tool | IDT | Analyzes individual oligonucleotides for Tm, hairpins, dimers, and mismatches [31]. | Integrated BLAST analysis for specificity checking [31]. |

| PrimerQuest Tool | IDT | Generates customized designs for qPCR assays and PCR primers [31]. | Design engines use nearest-neighbor analysis for high accuracy [31]. |

| Primer-BLAST | NCBI | Designs primers and checks their specificity against a selected organism database [6]. | Combines Primer3's design engine with NCBI's BLAST for specificity [6]. |

| UNAFold Tool | IDT | Analyzes oligonucleotide secondary structure formation [31]. | Specialized in predicting complex folding patterns. |

| RealTime qPCR Design Tool | IDT | Designs primers, probes, and assays across exon boundaries for various species [31]. | Ideal for ensuring RNA-specific amplification in gene expression studies. |

Step-by-Step Protocol: Using OligoAnalyzer for Hairpin Analysis

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for screening a single primer or probe sequence for hairpin structures using the IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for In-Silico and Experimental Validation

| Item | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool | Free online software for analyzing oligonucleotide thermodynamics and secondary structures [31]. |

| Desalted Oligonucleotides | Standard purification method; sufficient for most routine PCR applications [41]. |

| DNA Polymerase | Enzyme for PCR amplification; choice should be compatible with reaction additives if needed (e.g., DMSO) [41]. |

| DMSO (Dimethyl Sulfoxide) | Additive used to reduce secondary structure formation in GC-rich templates, though it lowers Tm [7]. |

Workflow for Hairpin Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for analyzing a primer sequence and interpreting the results.

Detailed Methodology

- Access the Tool: Navigate to the IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool online.

- Input Sequence: Enter your oligonucleotide sequence (primer or probe) in the 5' to 3' direction. Ensure the sequence is correct and free of ambiguous bases for an accurate analysis.

- Set Reaction Parameters: To obtain the most accurate results, input your specific experimental conditions in the provided fields [31]:

- Oligo Concentration: Typically 0.1–0.5 µM for PCR primers [41].

- Na⁺ Concentration: Often set at 50 mM for standard PCR conditions [7].

- Mg²⁺ Concentration: A critical parameter; typically 1.5–3.0 mM in PCR buffers. Mg²⁺ has a stronger stabilizing effect on DNA duplexes than Na⁺ and must be accounted for [31] [7].

- dNTP Concentration: Usually 0.8 mM; note that dNTPs chelate Mg²⁺, reducing its effective concentration.

- Analyze Hairpin Formation:

- Select the "Hairpin" analysis option.

- Execute the analysis. The tool will compute and display any potential hairpin structures.

- Interpret Results:

- Examine the predicted secondary structure diagram.

- Locate the ΔG value. As per IDT guidelines, the ΔG should be weaker (more positive) than –9.0 kcal/mol [31] [40].

- A ΔG value more positive than -9.0 kcal/mol indicates a low-risk, unstable hairpin. A value more negative than -9.0 kcal/mol indicates a stable hairpin that requires sequence redesign.

- Iterate and Redesign: If the hairpin is stable, modify the sequence by shifting the binding site a few nucleotides upstream or downstream and repeat the analysis until a suitable candidate is found.

Experimental Validation and Troubleshooting

Experimental Validation Protocol

After in-silico design, wet-lab validation is essential.

- Primer Reconstitution and Dilution: Resuspend synthesized primers in TE buffer or nuclease-free water to create a concentrated stock (e.g., 100 µM). Prepare a working dilution (e.g., 10 µM) as recommended by the polymerase manufacturer [41].

- PCR Setup and Cycling:

- Analysis and Interpretation:

- Analyze the PCR products using agarose gel electrophoresis.

- A single, sharp band of the expected size indicates specific amplification with minimal secondary structure interference.

- Weak or absent bands may suggest issues like hairpin formation preventing primer annealing.

- Non-specific bands or primer-dimer indicate off-target binding or self-complementarity.

Troubleshooting Common Hairpin-Related Issues

- Problem: Low or no amplification yield despite good in-silico parameters.

- Solution: Visually check the OligoAnalyzer output for the location of the hairpin. A stable hairpin at the 3'-end is particularly detrimental. Redesign the primer to eliminate 3' self-complementarity. Empirically optimize the annealing temperature, increasing it in 1–2°C increments to enhance stringency [1].

- Problem: PCR works but qPCR efficiency is poor or quantification is inaccurate.

- Solution: For qPCR probes, ensure their Tm is 5–10°C higher than the primers to promote specific binding before amplification [31]. Re-analyze the probe for hairpins that might quench the fluorophore or prevent hybridization.

Advanced Design Strategies for Complex Applications

For challenging applications, additional strategies can be employed:

- Multi-Template PCR and Deep Learning: Newer deep learning models (1D-CNNs) are being developed to predict sequence-specific amplification efficiencies in complex pools, identifying motifs that lead to poor amplification beyond traditional parameters like GC content [42].

- GC-Rich Templates: For sequences with high GC content (which promotes stable hairpins), the use of additives is recommended. DMSO at 5-10% can help disrupt secondary structures. When using DMSO, remember to adjust the Tm calculation, as it lowers the melting temperature by approximately 0.5–0.7°C per 1% [7].

- qPCR Probe Design: Opt for double-quenched probes (e.g., using ZEN or TAO internal quenchers) to lower background fluorescence, which allows for the use of longer probes without sacrificing signal-to-noise ratio [31]. This provides more flexibility in finding a probe sequence without secondary structures.

In polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays, the Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG) is a fundamental thermodynamic parameter that quantifies the stability of nucleic acid secondary structures. ΔG values predict the spontaneity of molecular interactions; a negative ΔG indicates a favorable, spontaneous reaction. In primer design, this translates to the likelihood of primers forming unwanted secondary structures, such as hairpins and primer-dimers, which can severely compromise assay efficiency and specificity [19] [3]. A key guideline is to ensure that the calculated ΔG for any potential self-dimers, cross-dimers, or hairpins is weaker (more positive) than -9 kcal/mol [31]. Adhering to this threshold is a critical risk minimization strategy, preventing issues like nonspecific amplification, reduced product yield, and false-positive signals, thereby ensuring robust and reliable experimental results.

Quantitative Data and Risk Thresholds

The following table summarizes the key ΔG thresholds and their implications for PCR specificity and yield.

Table 1: ΔG Thresholds for Primer Secondary Structures and Associated Risks

| Structure Type | Recommended ΔG Threshold (kcal/mol) | Primary Risk if Threshold is Exceeded | Impact on Assay Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Dimers & Cross-Dimers | > -9.0 [31] | Primer-dimer formation | Depletes primer concentration; leads to amplification of primer artifacts instead of target amplicon [3] [31]. |

| Hairpins (Internal) | > -6.0 [19] | Intramolecular folding | Reduces primer availability for template binding; can cause no yield or non-specific products [19] [1]. |

| Hairpins (3' End) | > -5.0 [19] | Self-amplifying structure | Can cause exponential amplification from the primer itself, even in no-template controls [3]. |

| 3' End Stability (General) | Less negative ΔG preferred [19] | False priming | Reduces the likelihood of the primer initiating DNA synthesis from non-target sites [19]. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol: In Silico Analysis of Primer Secondary Structures

This protocol details the use of online tools to calculate ΔG values and identify risky secondary structures in primer sequences.

1. Materials and Reagents

- Oligonucleotide Sequences: Forward and reverse primer sequences in text format.

- Software Tools:

- OligoAnalyzer Tool (IDT): For calculating Tm, analyzing dimers, and hairpins [31].

- UNAFold Tool (IDT): For detailed oligonucleotide secondary structure analysis [31].

- mFold Tool (IDT): An alternative for hairpin analysis [3].

- Multiple Prime Analyzer (Thermo Fisher): For analyzing potential dimer interactions between multiple primers [3].

2. Procedure 1. Input Sequence: Enter a single primer sequence into the analysis tool (e.g., OligoAnalyzer). 2. Set Reaction Conditions: Input your specific PCR buffer conditions, particularly Mg²⁺ concentration, as it significantly impacts ΔG calculations [31]. 3. Analyze Self-Dimerization: Run the "Self-Dimer" analysis. Examine the output for any predicted duplex formation and note the associated ΔG value. 4. Analyze Hairpin Formation: Run the "Hairpin" analysis. Check for stable structures, paying special attention to any complementarity at the 3' end. 5. Analyze Cross-Dimerization: Input both forward and reverse primer sequences and run a "Hetero-Dimer" analysis. 6. Interpret Results: Compare all calculated ΔG values against the thresholds in Table 1. Primers with ΔG values more negative than -9 kcal/mol for dimers or -5 kcal/mol for 3' end hairpins should be redesigned.

3. Troubleshooting

- If a primer fails the ΔG threshold, consider adjusting the annealing temperature as an initial optimization step, though redesign is often more effective [1].

- For problematic hairpins in long primers (e.g., LAMP inner primers), consider "bumping" the priming site—making minor sequence adjustments to break complementarity while maintaining target specificity [3].

Protocol: Empirical Validation by RT-LAMP

This protocol, adapted from a study on dengue and yellow fever virus detection, validates the impact of primer dimers and self-amplifying hairpins in an isothermal amplification context [3].

1. Materials and Reagents

- Primer Sets: Original set with amplifiable secondary structures and a modified set designed to eliminate them.

- Enzymes: Bst 2.0 WarmStart DNA polymerase and AMV Reverse Transcriptase.

- Buffer: Isothermal amplification buffer supplemented with MgSO₄ (to 8 mM Mg²⁺ final), dNTPs, and betaine.

- Detection Reagent: A LAMP-compatible intercalating dye (e.g., SYTO 9, SYTO 82).