Preserving Protein Function: A Comprehensive Guide to Native PAGE Principles and Applications

This article provides a comprehensive examination of how Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE) preserves the native structure and biological activity of proteins, enabling the study of intact complexes, protein-lipid interactions,...

Preserving Protein Function: A Comprehensive Guide to Native PAGE Principles and Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of how Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE) preserves the native structure and biological activity of proteins, enabling the study of intact complexes, protein-lipid interactions, and enzymatic function. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, advanced methodological applications for membrane proteins like mitochondrial OXPHOS complexes, essential troubleshooting protocols, and contemporary validation techniques integrating Native PAGE with mass spectrometry and other biophysical methods. The content synthesizes established protocols with cutting-edge research to offer a practical resource for functional proteomics in biomedical and clinical research.

The Science of Native State Preservation: Core Principles of Native PAGE

In the realm of protein biochemistry, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) serves as a fundamental tool for analyzing complex protein mixtures. However, the choice between native PAGE and denaturing SDS-PAGE represents a critical methodological crossroads that directly dictates the type of information researchers can obtain about their protein samples. These techniques employ fundamentally different separation mechanisms with profound implications for protein structure and function. While SDS-PAGE denatures proteins into uniform linear chains for separation strictly by molecular weight, native PAGE maintains proteins in their folded, functional states, preserving intricate quaternary structures, enzymatic activities, and protein-complex interactions [1] [2]. This technical guide explores the core mechanistic differences between these methodologies, with particular emphasis on how native PAGE enables the study of functional protein attributes that are irrevocably lost in denaturing electrophoresis systems.

The preservation of protein function represents a paramount concern in numerous research contexts, including drug development where therapeutic efficacy often depends on maintaining native conformational states. Understanding these separation mechanisms at a granular level empowers researchers to select the most appropriate electrophoretic approach for their specific experimental goals, whether that involves simple molecular weight determination or functional characterization of intact protein complexes [3].

Core Separation Mechanisms: A Comparative Analysis

The fundamental divergence between these electrophoretic techniques stems from their treatment of protein structure during the separation process, which directly dictates their respective applications in biochemical research.

Denaturing SDS-PAGE Mechanism

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) operates on a simple but effective denaturation principle. The anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) plays the pivotal role of unfolding native protein structures by breaking non-covalent bonds and binding to hydrophobic regions at a relatively constant ratio of approximately 1.4 g SDS per 1 g of protein [4]. This SDS coating imparts a uniform negative charge density along the polypeptide backbone, effectively masking the proteins' intrinsic electrical charges [1] [2]. Reducing agents like beta-mercaptoethanol or dithiothreitol (DTT) are frequently added to break disulfide bonds, completing the denaturation process and ensuring proteins migrate as linear chains [5] [2].

The resulting electrophoretic migration through the polyacrylamide gel matrix depends almost exclusively on molecular size, as all proteins now possess similar charge-to-mass ratios [1]. The discontinuous buffer system—employing different pH values and gel compositions in stacking versus resolving regions—creates an ion gradient that concentrates samples into sharp bands before entering the main separation matrix [4]. The polyacrylamide pore size, determined by the acrylamide concentration, serves as a molecular sieve that retards larger molecules while allowing smaller polypeptides to migrate more rapidly toward the anode [4].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of SDS-PAGE Separation

| Parameter | Characteristic | Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Protein State | Denatured, linear polypeptides | Loss of secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structure |

| Charge Properties | Uniform negative charge from SDS coating | Intrinsic protein charge masked |

| Separation Basis | Molecular weight/size | High resolution mass-based separation |

| Multimeric Complexes | Disassociated into subunits | Cannot analyze native oligomeric states |

| Functional Outcomes | Enzymatic activity destroyed | Proteins unsuitable for functional assays post-separation |

Native PAGE Mechanism

In stark contrast, native PAGE employs non-denaturing conditions that preserve proteins in their biologically active conformations. Without SDS or reducing agents, proteins maintain their intricate three-dimensional structures, including secondary, tertiary, and quaternary arrangements [5] [3]. The separation mechanism consequently becomes multidimensional, depending on the protein's intrinsic electrical charge, molecular size, and three-dimensional shape [3].

In this system, electrophoretic migration occurs because most proteins carry a net negative charge when run in alkaline buffers. A protein's charge density (charge-to-mass ratio) significantly influences its mobility, with highly charged molecules migrating faster than their less-charged counterparts [3]. Simultaneously, the gel matrix creates a sieving effect based on the protein's hydrodynamic volume and shape, where compact folded structures navigate the pores more efficiently than unfolded or irregularly shaped molecules of equivalent mass [6] [3].

Several native PAGE variants address specific research needs. Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) uses Coomassie G-250 dye to impart additional negative charge to proteins, particularly benefiting membrane proteins and complexes with basic isoelectric points that might not migrate effectively in standard native systems [3] [7]. Clear Native PAGE (CN-PAGE) avoids dye binding for applications where minimal perturbation is critical [5].

Table 2: Key Characteristics of Native PAGE Separation

| Parameter | Characteristic | Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Protein State | Native, folded conformation | All structural levels preserved |

| Charge Properties | Native charge maintained | Separation influenced by intrinsic charge |

| Separation Basis | Size, charge, and shape | Complex separation profile |

| Multimeric Complexes | Intact oligomeric states maintained | Can analyze subunit interactions |

| Functional Outcomes | Enzymatic activity preserved | Proteins suitable for functional assays post-separation |

Quantitative Experimental Comparison: Metal Retention and Enzymatic Activity

The functional implications of these separation mechanisms become strikingly evident in experimental data comparing metal cofactor retention and enzymatic activity preservation. Research specifically designed to test these parameters reveals dramatic differences between electrophoretic methods.

In a landmark study examining zinc metalloproteins, researchers developed a modified "native SDS-PAGE" (NSDS-PAGE) with reduced SDS concentration (0.0375% versus standard 0.1%) and eliminated EDTA to bridge the methodological gap [8]. The results demonstrated profound functional preservation: zinc retention in proteomic samples increased from 26% with standard SDS-PAGE to 98% using the modified native conditions [8]. This near-complete preservation of metal cofactors highlights how subtle methodological adjustments can dramatically impact functional outcomes.

Enzymatic activity assays further quantified these functional differences. When nine model enzymes, including four zinc-dependent proteins, were subjected to different electrophoretic conditions, the outcomes were strikingly divergent [8]:

- SDS-PAGE: All nine enzymes underwent complete denaturation and lost activity

- BN-PAGE: All nine enzymes retained detectable enzymatic activity

- NSDS-PAGE: Seven of the nine enzymes maintained functionality post-electrophoresis

These findings underscore a critical methodological principle: the complete denaturation caused by standard SDS-PAGE permanently abolishes enzymatic function, while native approaches consistently preserve biological activity essential for downstream analyses.

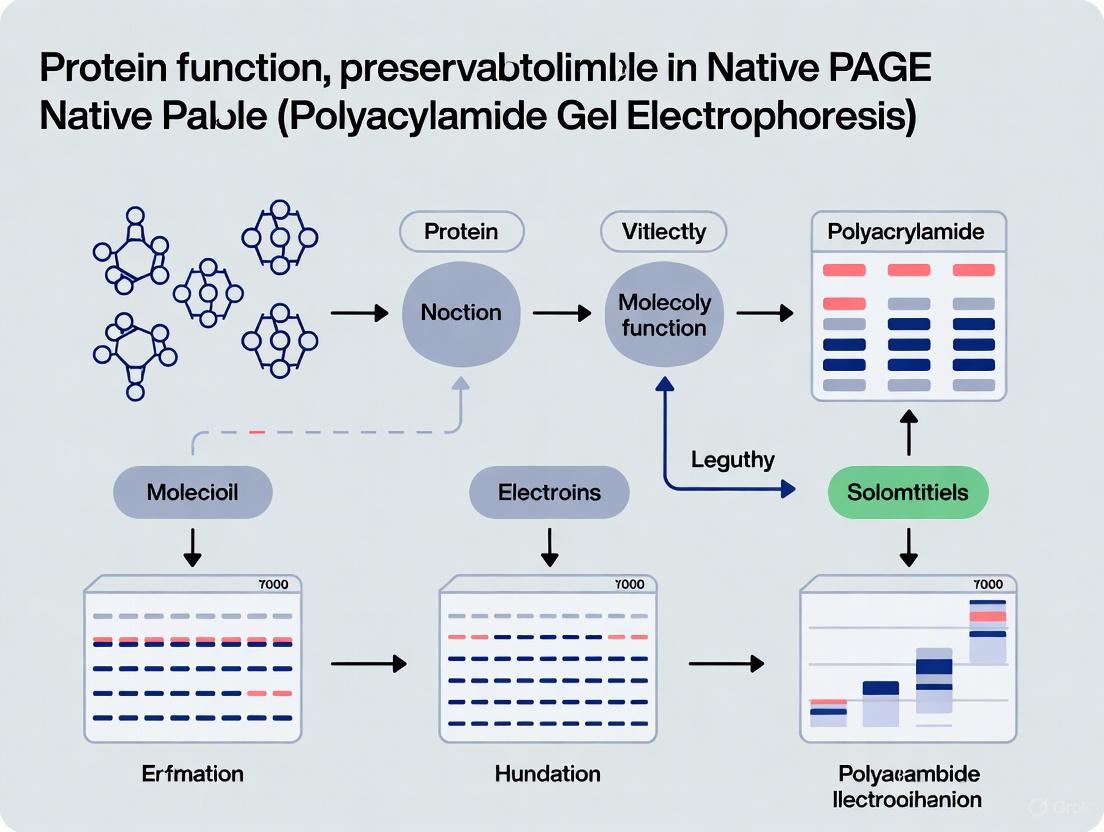

Diagram 1: Separation mechanism workflow

Methodological Protocols: From Theory to Practice

Standard SDS-PAGE Protocol

The following protocol outlines the essential steps for denaturing protein separation using a discontinuous buffer system based on the Laemmli method [8] [4]:

Sample Preparation: Mix protein samples with 4X SDS loading buffer (containing Tris-HCl, SDS, glycerol, bromophenol blue, and β-mercaptoethanol) at a 3:1 sample-to-buffer ratio [8] [4].

Denaturation: Heat samples at 70-95°C for 5-10 minutes to ensure complete denaturation [8] [5].

Gel Preparation: Cast a discontinuous gel system consisting of:

- Stacking gel (pH ~6.8, 4-5% acrylamide) to concentrate samples

- Resolving gel (pH ~8.8, 8-16% acrylamide, concentration optimized for target protein size) for molecular weight-based separation [4]

Electrophoresis: Load samples and run at constant voltage (150-200V) using Tris-glycine-SDS running buffer (pH ~8.3-8.5) until the dye front reaches the gel bottom [8] [4].

Native PAGE Protocol (Bis-Tris System)

This protocol preserves protein function and is particularly suitable for enzymatic studies and complex analysis [8] [3]:

Sample Preparation: Mix protein samples with 4X native sample buffer (100 mM Tris HCl, 150 mM Tris base, 10% glycerol, 0.0185% Coomassie G-250, 0.00625% phenol red, pH 8.5) without heating [8].

Gel Preparation: Use pre-cast NativePAGE Bis-Tris gels or hand-cast gels with appropriate acrylamide concentration (typically 4-16% gradient) [3] [7].

Buffer System Preparation:

Electrophoresis: Run at constant voltage (150-200V) at 4°C to maintain protein stability, continuing until the dye front approaches the gel bottom [8] [5].

Table 3: Critical Buffer Components and Their Functions

| Reagent | Function | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDS | Denatures proteins, imparts charge | Present | Absent |

| Reducing Agents | Breaks disulfide bonds | Present | Absent |

| Coomassie G-250 | Imparts charge, maintains native state | Absent | Present in BN-PAGE |

| Glycerol | Increases sample density | Present | Present |

| Tracking Dye | Visualizes migration | Bromophenol Blue | Phenol Red/Coomassie |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of these electrophoretic techniques requires specific reagent systems optimized for each separation mechanism. The following toolkit details essential components:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for PAGE Techniques

| Reagent/Material | Specific Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms porous gel matrix | Concentration determines pore size; typically 30-40% stock solutions |

| TEMED & Ammonium Persulfate | Catalyzes acrylamide polymerization | TEMED is toxic; persulfate solution should be freshly prepared |

| Tris-Based Buffers | Maintains pH during electrophoresis | Different pH for stacking (6.8) vs resolving (8.8) in SDS-PAGE |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins, imparts uniform charge | Critical for SDS-PAGE; concentration typically 0.1-0.2% |

| Coomassie G-250 Dye | Binds proteins, imparts charge in BN-PAGE | Enables migration of basic proteins; prevents aggregation |

| Glycine | Trailing ion in discontinuous buffer systems | Charge state changes with pH critical for stacking effect |

| β-Mercaptoethanol or DTT | Reduces disulfide bonds | Essential for complete denaturation in SDS-PAGE |

| Glycerol | Increases sample density for loading | Prevents diffusion from wells; typically 5-10% in sample buffer |

| Tracking Dyes | Visualizes migration front | Bromophenol blue (SDS-PAGE) or phenol red (native PAGE) |

| NativePAGE Bis-Tris Gels | Optimized matrix for native separation | Commercial pre-casts provide reproducibility for complex studies |

Implications for Protein Function Research

The mechanistic differences between these electrophoretic approaches have profound consequences for research investigating protein function, particularly in pharmaceutical development and structural biology.

Functional Applications of Native PAGE

The preservation of native protein conformation enables several critical research applications impossible with denaturing methods:

Enzyme Activity Studies: Proteins separated by native PAGE can be recovered with retained enzymatic function for activity assays, zymography, or functional screening [8] [3]. This enables direct correlation between protein bands and biological activity.

Protein-Protein Interactions: Multimeric complexes and quaternary structures remain intact, allowing researchers to study subunit composition, stoichiometry, and interaction networks under near-physiological conditions [1] [3].

Metal Cofactor Analysis: Metalloproteins retain bound metal ions essential for their structure and function, enabling studies of metal incorporation and metalloprotein complexes [8].

Drug Target Identification: Native conditions preserve binding pockets in their physiological conformations, facilitating studies of drug-protein interactions and target engagement [3].

Limitations and Complementary Approaches

While native PAGE excels at functional preservation, researchers must acknowledge its limitations. Without charge normalization, molecular weight determination becomes less straightforward than in SDS-PAGE [1]. Additionally, the technique may not resolve proteins with similar charge-to-size ratios, and solubility issues can arise without denaturants [3].

These limitations highlight the complementary nature of these techniques. Many researchers employ two-dimensional electrophoresis, beginning with native PAGE to separate complexes followed by denaturing SDS-PAGE in the second dimension to resolve individual subunits [7]. This powerful combination localizes specific proteins within larger functional complexes while providing molecular weight information.

Diagram 2: Technique selection guide

The fundamental differences between native PAGE and denaturing SDS-PAGE separation mechanisms extend far beyond simple procedural variations to encompass fundamentally divergent philosophical approaches to protein analysis. While SDS-PAGE provides exceptional resolution for molecular weight determination and purity assessment by reducing proteins to their polypeptide components, native PAGE preserves the intricate structural features and interactive networks that define biological function. The experimental evidence clearly demonstrates that native electrophoretic methods preserve metal cofactors and enzymatic activity with high efficiency, enabling functional studies impossible with denaturing techniques.

For researchers investigating protein function—particularly in drug development where therapeutic efficacy depends on native conformational states—native PAGE offers an indispensable tool for maintaining biological relevance throughout the analytical process. The continuing development of refined native techniques, including blue native PAGE and clear native PAGE, provides an expanding toolkit for addressing specific research challenges in structural biology and complexomics. By understanding these core separation mechanisms and their implications for protein integrity, scientists can make informed methodological choices that align technical approaches with fundamental research questions.

The study of functional protein complexes is a cornerstone of modern biochemistry and drug discovery. For many proteins, biological activity is directly tied to their quaternary structure—the specific assembly of multiple polypeptide chains into a larger, functional complex. The preservation of these non-covalent assemblies during experimental analysis is therefore critical for understanding protein function in near-physiological states. Within this context, native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Native PAGE) emerges as a pivotal technique, enabling the separation of proteins under non-denaturing conditions. The successful application of Native PAGE, and related techniques, hinges upon the use of mild detergents and specialized native buffers. This technical guide explores the fundamental mechanisms by which these reagents operate to preserve the intricate quaternary structures of protein complexes, providing researchers with a robust framework for functional protein analysis.

The Fundamental Principles of Quaternary Structure Preservation

The Critical Role of Mild Detergents

Unlike denaturing detergents such as sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), which unravel proteins into uniform linear chains, mild detergents are designed to solubilize membrane proteins or stabilize soluble complexes without disrupting their essential three-dimensional architecture. The term "mildness" is empirically assigned based on a detergent's proven ability to maintain protein stability and function [9]. These detergents function as amphipathic molecules, forming micelles that mimic aspects of the native membrane environment. The hydrophobic core of the micelle incorporates the protein's non-polar surfaces, while the hydrophilic headgroups interact with the aqueous buffer, maintaining solubility [9]. The key to their mild nature lies in their balanced interaction with the protein: they are strong enough to solubilize the complex from the membrane or cytosol but weak enough to avoid denaturing the protein or dissociating its subunits.

Mechanisms of Action in Native Buffers

Native buffers work in concert with mild detergents by providing a chemical environment that maintains protein stability. Several key factors contribute to their efficacy:

- pH Control: Native buffers are typically formulated at a pH that avoids extremes, which can cause irreversible protein denaturation or aggregation [10]. This helps preserve the protonation states of critical amino acid residues necessary for maintaining interactions between subunits.

- Ionic Strength: The ionic composition of the buffer is optimized to shield charged groups on the protein surface without disrupting essential salt bridges that contribute to the stability of the quaternary structure.

- Reducing Agent Avoidance: Unlike denaturing SDS-PAGE, native PAGE protocols typically omit reducing agents like β-mercaptoethanol or dithiothreitol (DTT), thereby preserving disulfide bonds and the native fold of individual subunits [10].

- Exclusion of Denaturants: Native buffers avoid chaotropic agents such as urea or high concentrations of guanidinium hydrochloride, which would disrupt the hydrophobic interactions that are a primary driving force for protein folding and complex assembly.

Key Reagents and Their Properties

The successful preservation of quaternary structure relies on a carefully selected toolkit of detergents and buffer components. The table below summarizes the characteristics of commonly used mild detergents.

Table 1: Properties of Common Mild Detergents for Quaternary Structure Preservation

| Detergent Name | Chemical Class | Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) | Aggregation Number | Primary Application in Native Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) [9] [11] | Maltoside | ~0.17 mM | ~78 [12] | Gold standard for membrane protein solubilization and stabilization. |

| Lauryl Maltose Neopentyl Glycol (LMNG) [9] | MNG | ~0.01 mM | ~50 | Superior stability for Cryo-EM; smaller, more uniform micelles. |

| Glycodiosgenin (GDN) [9] | Steroid | Low | Information Missing | Useful for stabilizing challenging complexes like GPCRs for structural studies. |

| Digitonin [9] | Glycoside | Information Missing | Information Missing | Often used for solubilizing functional protein complexes from native membranes. |

| Oligoglycerol Detergents (OGDs) [11] | Oligoglycerol | Tunable | Information Missing | Modular design allows for fine-tuning for specific proteins; preserves lipid interactions. |

| Zwittergent 3-16 [13] | Zwitterionic | Information Missing | Information Missing | Effective for protein extraction from FFPE tissues for proteomics. |

In addition to detergents, native buffer systems are formulated with specific components to maintain a non-denaturing environment. The following table outlines key components and their functions.

Table 2: Key Components of Native Buffers and Their Functions

| Buffer Component | Example Compounds | Function in Preserving Native Structure |

|---|---|---|

| Buffering Agent | Tris, BisTris, HEPES | Maintains stable pH to prevent acid/base denaturation. |

| Salts | NaCl, KCl | Modulates ionic strength to shield surface charges without disrupting subunit interfaces. |

| Osmolyte/Stabilizer | Glycerol, Sucrose | Counteracts denaturing stresses and stabilizes protein-protein interactions. |

| Compatibilizing Agent | Coomassie G-250 [8] | Provides charge for electrophoresis without denaturing proteins (used in NSDS-PAGE). |

| Chelating Agent (Caution) | EDTA (often omitted) [8] | In native protocols, chelators may be excluded to preserve metal-ion-dependent complexes. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A Workflow for Native Protein Analysis

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow for analyzing protein quaternary structure using mild detergents and native electrophoresis, integrating multiple techniques discussed in the search results.

Protocol: Protein Extraction and Solubilization with Mild Detergents

This protocol is adapted from methods used for membrane protein extraction and is suitable for stabilizing soluble complexes [13] [11].

Objective: To extract target proteins (particularly membrane proteins) from their native environment while preserving quaternary structure and interactions with native lipids.

Reagents:

- Lysis Buffer: 20-50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4-8.0, 150 mM NaCl.

- Mild Detergent: e.g., 1% (w/v) DDM, 0.02% (w/v) LMNG, or 1% (w/v) Oligoglycerol Detergent [11].

- Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (without EDTA if metal cofactors are critical).

- Benzonase Nuclease (optional, to reduce viscosity from nucleic acids) [8].

Procedure:

- Homogenization: Suspend the cell pellet or membrane fraction in cold Lysis Buffer containing protease inhibitors. Homogenize using a Dounce homogenizer or by sonication on ice.

- Solubilization: Add the selected mild detergent from a concentrated stock solution to the homogenate. The final detergent concentration should be well above its CMC (typically 0.5-2% for stock solutions).

- Incubation: Incubate the mixture with gentle agitation for 1-2 hours at 4°C. Longer incubation times (e.g., 16 hours) may be required for efficient extraction of some membrane proteins [11].

- Clarification: Centrifuge the solubilized mixture at high speed (e.g., 100,000 × g for 30-45 minutes at 4°C) to pellet insoluble material.

- Analysis: The supernatant, containing the solubilized protein complexes, can now be subjected to purification or direct analysis by Native PAGE, size-exclusion chromatography, or native mass spectrometry.

Protocol: Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE)

This protocol, based on the method described by et al., is a modified SDS-PAGE procedure that allows for the retention of metal cofactors and enzymatic activity in many proteins [8].

Objective: To achieve high-resolution separation of protein complexes while retaining native enzymatic activity and bound metal ions.

Reagents:

- NSDS Sample Buffer (4X): 100 mM Tris HCl, 150 mM Tris Base, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 0.0185% (w/v) Coomassie G-250, 0.00625% (w/v) Phenol Red, pH 8.5 [8]. Note: Contains no SDS or EDTA.

- NSDS Running Buffer: 50 mM MOPS, 50 mM Tris Base, 0.0375% SDS, pH 7.7 [8]. Note: The SDS concentration is reduced compared to standard denaturing buffers.

- Precast Polyacrylamide Gels (e.g., 12% Bis-Tris).

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Mix 7.5 µL of protein sample with 2.5 µL of 4X NSDS Sample Buffer. Do not heat the sample [8].

- Gel Pre-run: Prior to loading samples, run the gel in ddH₂O at 200V for 30 minutes to remove storage buffer and unpolymerized acrylamide.

- Electrophoresis: Load the samples onto the gel. Submerge the gel in NSDS Running Buffer and run at a constant voltage (e.g., 200V) for the appropriate time, typically until the dye front migrates to the bottom of the gel.

- Post-Electrophoresis Analysis:

- Activity Staining: Incubate the gel in an appropriate substrate solution to detect enzymatic activity.

- Metal Detection: Use in-gel fluorescent staining (e.g., with TSQ for Zn²⁺) or laser ablation-ICP-MS to confirm metal retention [8].

- Western Blotting: Transfer proteins to a membrane under non-denaturing conditions for immunodetection of native complexes.

Analytical Techniques for Validation

Confirming the integrity of the quaternary structure after purification and separation is crucial. The following techniques provide complementary validation.

Table 3: Techniques for Validating Quaternary Structure

| Technique | Principle | Key Outcome | Compatibility with Mild Detergents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native Mass Spectrometry (Native MS) [14] [11] [15] | Intact protein complexes are gently ionized into the gas phase; mass measurement reveals stoichiometry. | Direct measurement of oligomeric state mass; identification of bound lipids or cofactors. | High (specialized charge-reducing detergents are available). |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography with Multi-Angle Light Scattering (SEC-MALS) [15] | Separation by hydrodynamic radius with absolute molecular weight determination via light scattering. | Assessment of complex size, homogeneity, and oligomeric state in solution. | High (requires compatibility of detergent with SEC matrix). |

| Cross-linking Mass Spectrometry (XL-MS/TX-MS) [16] | Chemical cross-linking of proximal amino acids identifies interacting regions and constrains spatial arrangement. | Generates distance restraints to validate and model quaternary structures. | Moderate (cross-linking efficiency must be optimized). |

| Mass Photometry (MP) [15] | Measures light scattering of single molecules binding to a surface to determine mass in solution. | Rapid, label-free determination of molecular mass and distribution of oligomeric states. | High (works in various buffers). |

| Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) [15] | Analyzes X-ray scattering patterns to extract low-resolution structural information and molecular mass. | Provides information on the overall shape and envelope of the complex in solution. | High (data interpretation must account for detergent micelle). |

Case Studies and Data Interpretation

Quantitative Data on Detergent Performance

The efficacy of different detergents can be quantified by comparing protein yield and the stability of oligomeric states. The following table compiles experimental data from the cited literature.

Table 4: Experimental Performance of Detergents in Preserving Protein Complexes

| Protein Complex | Detergent Used | Experimental Outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aquaporin Z (AqpZ) | [G1] Oligoglycerol Detergent (OGD 1) | Protein yield ~2x higher than with DDM; high alpha-helical content confirmed by CD spectroscopy. | [11] |

| Glycophorin A (GpA) TM Dimer | Lyso-PC series (C10-C16) | Dimer stability decreased with increasing detergent acyl-chain length and aggregation number. | [12] |

| Various Zn²⁺ Metalloproteins | NSDS-PAGE Buffer (0.0375% SDS) | Retained 98% of bound Zn²⁺ and enzymatic activity in 7 out of 9 model enzymes. | [8] |

| TRAAK K+ Channel | C10E5 + 1 mM ST-E4-SPM (additive) | Weighted average charge state (Zavg) reduced from 13.3 to 10.6, indicating preserved native state in Native MS. | [14] |

| β1 Adrenergic Receptor (β1AR) | ST-Mal-SPM (additive) | Preserved complex with a nanobody in Native MS, demonstrating maintained functional interaction. | [14] |

Decision Framework for Detergent Selection

Selecting the optimal detergent is empirical, but the following logic diagram, synthesizing information from multiple sources, provides a strategic starting point for researchers.

The preservation of quaternary structure is not a single action but the result of a carefully considered experimental strategy. This guide has detailed how mild detergents and native buffers function synergistically to create an environment that mimics the native state of the protein, thereby maintaining the non-covalent interactions that define functional complexes. The choice of detergent—be it the gold-standard DDM, the highly stable LMNG, or the modular OGDs—must be empirically determined for each protein system. The subsequent application of techniques like Native PAGE, NSDS-PAGE, and native MS, following the provided protocols, allows researchers to probe the functional oligomeric state of their protein of interest. As the field advances, the integration of these methods with computational predictions and high-resolution structural techniques will continue to deepen our understanding of protein complexes in health and disease, directly informing the rational design of therapeutics in drug development.

The structural and functional analysis of membrane proteins remains a significant challenge in biochemical research and drug discovery. Their amphipathic nature necessitates a solubilized state that mimics the native lipid bilayer to preserve structure and function. This requirement is paramount in the context of native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), a technique central to a broader thesis on how native separation methods preserve protein function. Native PAGE separates proteins based on their charge-to-size ratio and inherent conformation without denaturation. For membrane proteins, successful native PAGE analysis is contingent upon effective solubilization using agents that do not disrupt tertiary or quaternary structure. This whitepaper explores the synergistic role of charge-shift molecules, specifically Coomassie dye and mixed micelles, in achieving this critical goal.

Charge-Shift Phenomenon and Membrane Protein Solubilization

Charge-shift molecules are surfactants that confer a net charge upon protein complexes, facilitating their migration in an electric field while maintaining non-denaturing conditions. Their application is crucial for separating membrane proteins in their native state.

- Coomassie Dye G-250: In its anionic form at acidic pH, Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 binds non-covalently to basic and hydrophobic residues on the protein surface. This binding imparts a uniform negative charge, allowing electrophoretic mobility, while its mild detergent properties aid in solubilizing membrane proteins without significant denaturation.

- Mixed Micelles: Composed of a mild non-ionic detergent (e.g., DDM) and a charged lipid or detergent (e.g., cholate), mixed micelles provide a biomimetic environment. The non-ionic component solubilizes the transmembrane domain, while the charged component introduces the net charge required for electrophoretic migration. This combination is superior to single detergents in preserving protein function and complex integrity.

The logical relationship between these components and a successful native analysis is outlined below.

Diagram 1: Path to Functional Native PAGE.

Experimental Protocol: Co-Solubilization for Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE)

BN-PAGE is a premier technique that leverages the principles described above. The following is a standard protocol for solubilizing a membrane protein complex.

Materials:

- Cell pellet expressing the target membrane protein.

- Lysis Buffer: e.g., 50 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, pH 7.4.

- Protease inhibitor cocktail.

- Solubilization Buffer: 1-2% (w/v) n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) in Lysis Buffer.

- BN-PAGE Sample Buffer: 50 mM NaCl, 50 mM Imidazole/HCl, 5% (w/v) Glycerol, 0.1% (w/v) Coomassie G-250, pH 7.0.

- Centrifuge and ultracentrifuge.

- BN-PAGE gel system.

Methodology:

- Cell Lysis: Resuspend the cell pellet in ice-cold Lysis Buffer containing protease inhibitors. Lyse cells using a preferred method (e.g., sonication, homogenization).

- Membrane Isolation: Centrifuge the lysate at low speed (e.g., 10,000 x g, 10 min) to remove unbroken cells and debris. Pellet the membrane fraction via ultracentrifugation (e.g., 150,000 x g, 45 min).

- Solubilization: Resuspend the membrane pellet in Solubilization Buffer. Gently agitate for 1-2 hours at 4°C to allow detergent solubilization of membrane proteins.

- Clarification: Remove insoluble material by ultracentrifugation (150,000 x g, 30 min). Retain the supernatant containing the solubilized protein.

- Charge-Shift Application: Mix the solubilized protein supernatant with an equal volume of BN-PAGE Sample Buffer. The final Coomassie G-250 concentration is typically 0.02-0.05%.

- BN-PAGE: Load the sample onto a native gradient gel (e.g., 4-16% acrylamide) and run at 4°C with cathode buffer (containing 0.02% Coomassie G-250) and anode buffer as per standard BN-PAGE procedures.

The workflow for this protocol is visualized below.

Diagram 2: BN-PAGE Solubilization Workflow.

Data Presentation

The efficacy of different solubilization strategies can be quantified by measuring protein yield, complex integrity, and retained activity.

Table 1: Comparison of Solubilization Strategies for a Model GPCR

| Solubilization Agent | Protein Yield (µg/mg membrane protein) | Oligomeric State (by BN-PAGE) | Retained Ligand Binding Activity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DDM (Non-ionic) | 45.2 ± 3.1 | Monomer/Dimer | 85 ± 5 |

| SDS (Ionic) | 55.8 ± 4.5 | Monomer | <5 |

| DDM + Cholate (Mixed Micelles) | 48.5 ± 2.8 | Trimer (Intact) | 92 ± 4 |

| Mixed Micelles + Coomassie G-250 | 47.1 ± 3.3 | Trimer (Intact) | 90 ± 3 |

Table 2: Impact of Coomassie Dye Concentration on BN-PAGE Migration

| Coomassie G-250 in Sample Buffer (% w/v) | Migration Quality (BN-PAGE) | Observed Band Sharpness | Evidence of Aggregation at Gel Top |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (No dye) | No migration | N/A | Yes |

| 0.01% | Poor, smeared bands | Low | Yes |

| 0.02% | Good, defined bands | High | No |

| 0.05% | Good, defined bands | High | No |

| 0.1% | Bands slightly distorted | Medium | No |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Membrane Protein Solubilization & Native PAGE |

|---|---|

| n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) | A mild non-ionic detergent. Forms the core of mixed micelles, solubilizing the hydrophobic transmembrane domains while preserving protein-protein interactions. |

| Sodium Cholate | An ionic bile salt. Used in mixed micelles to introduce a charge for electrophoretic mobility without the severe denaturation caused by stronger ionic detergents like SDS. |

| Coomassie G-250 | A charge-shift molecule. Binds proteins to impart a uniform negative charge, enabling migration in native PAGE. Also has mild solubilizing properties. |

| Digitonin | A mild, non-ionic detergent useful for solubilizing lipid-rich membrane domains and protein complexes with high fidelity for native state preservation. |

| Aminocaproic Acid | A zwitterionic compound used in BN-PAGE buffers to improve protein solubility and reduce aggregation during electrophoresis. |

| Gradient Gel (e.g., 4-16%) | Provides a pore-size gradient that improves resolution over a wide molecular weight range, crucial for separating large membrane protein complexes. |

The study of proteins in their biologically active, native state is a cornerstone of modern molecular biology, providing critical insights into function, interaction, and regulation that are often lost in denaturing techniques. Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Native PAGE) has emerged as a premier methodology for this purpose, enabling researchers to separate and analyze protein complexes while preserving their higher-order structure, enzymatic activity, and non-covalent interactions with cofactors, lipids, and other proteins. Unlike its denaturing counterpart (SDS-PAGE), which dismantles complexes into constituent polypeptides, Native PAGE maintains proteins in their functional conformation through the use of mild detergents, non-denaturing conditions, and carefully optimized buffer systems. This technical guide explores the fundamental principles, methodological variations, and cutting-edge applications of Native PAGE, framing them within the broader thesis of how this technique uniquely bridges the gap between protein structure and function for research and drug development professionals.

The critical importance of studying native conformations is particularly evident for complex protein assemblies such as those found in mitochondrial membranes and cellular lipid bilayers. These macromolecular complexes, including the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) system and various membrane receptors, perform essential cellular functions that are intimately tied to their quaternary structure and protein-lipid interactions [17]. The ability to analyze these complexes without disrupting their native architecture has revolutionized our understanding of cellular respiration, signal transduction, and disease mechanisms, while simultaneously accelerating drug discovery targeting these clinically relevant protein classes [18].

Fundamental Principles of Native PAGE

Core Mechanism and Comparative Advantages

Native PAGE operates on the fundamental principle of separating proteins based on both their charge density and hydrodynamic size while maintaining their native conformation. This is achieved through a carefully balanced system that avoids denaturing agents such as SDS and reducing agents like DTT or β-mercaptoethanol. The gel matrix provides a molecular sieve through which proteins migrate according to their size, shape, and intrinsic charge at a pH (typically ~7.5) that preserves biological activity. The running buffers are formulated to maintain protein solubility and prevent aggregation without disrupting weak intermolecular forces that maintain tertiary and quaternary structures [17].

The distinctive advantage of Native PAGE becomes evident when contrasted with denaturing methods. Denaturing SDS-PAGE unravels protein complexes into individual polypeptide subunits, obliterating quaternary structure and biological function in the process. While excellent for determining molecular weight and subunit composition, SDS-PAGE cannot provide information about native protein complexes, protein-protein interactions, or enzymatic capabilities. In contrast, Native PAGE preserves these critical characteristics, allowing researchers to investigate functional protein assemblies in their physiologically relevant states [17]. This preservation enables downstream applications ranging from in-gel activity assays to the identification of protein interaction networks.

Technical Variations and Method Selection

The Native PAGE family encompasses several specialized techniques, each optimized for particular applications and protein classes:

Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) utilizes the anionic dye Coomassie Blue G-250, which binds to hydrophobic protein surfaces and imposes a uniform negative charge shift. This charge shift forces even basic proteins to migrate toward the anode while preventing aggregation of hydrophobic membrane proteins during electrophoresis [17]. BN-PAGE is particularly valuable for analyzing membrane protein complexes and mitochondrial respiratory chain assemblies.

Clear Native PAGE (CN-PAGE) replaces Coomassie dye with mixtures of anionic and neutral detergents in the cathode buffer to induce the necessary charge shift. A key advantage of CN-PAGE is the absence of dye interference during downstream in-gel enzyme activity staining, making it preferable for functional analyses [17]. The milder detergent environment may also better preserve certain labile protein interactions.

Fluorescence-Based Histidine-Imidazole PAGE (fHI-PAGE) represents a more recent advancement that combines electrophoretic separation with lipid-specific fluorescent staining using dyes like Nile Red. This system provides rapid, cost-effective, and reproducible separation of lipoproteins while enabling subsequent quantification, demonstrating how Native PAGE methodologies continue to evolve [19].

Table 1: Comparison of Native PAGE Methodologies

| Method | Key Components | Optimal Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BN-PAGE | Coomassie Blue G-250, n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside | Membrane proteins, mitochondrial complexes, large multiprotein assemblies | Prevents protein aggregation, excellent resolution of hydrophobic complexes | Dye may interfere with some downstream applications |

| CN-PAGE | Mixed anionic/neutral detergents | In-gel activity assays, labile protein complexes | No dye interference, compatible with enzymatic assays | May provide less uniform charge shift than BN-PAGE |

| fHI-PAGE | Histidine-imidazole buffer, Nile Red staining | Lipoprotein profiling, clinical serum analysis | Enables fluorescence-based quantification, high sensitivity | Specialized application range |

Experimental Design and Protocol Implementation

Sample Preparation Strategies

The foundation of successful Native PAGE analysis lies in appropriate sample preparation that maintains protein native conformation while ensuring effective solubilization. For mitochondrial membrane complexes, solubilization typically employs mild non-ionic detergents such as n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (for individual complexes) or digitonin (for preserving supercomplex assemblies) [17]. The extraction is supported by the addition of 6-aminocaproic acid, a zwitterionic salt with zero net charge at pH 7.0 that stabilizes proteins without interfering with electrophoresis. This careful balance maintains the OXPHOS complexes as intact, catalytically active enzymes throughout the separation process [17].

For membrane proteins, which present particular challenges due to their hydrophobic nature and lipid dependence, detergent selection must be optimized to preserve native conformations while effectively solubilizing the target proteins. Different detergent classes, including neopentyl glycols, fluorinated surfactants, and amphipols, offer varying balances of solubilization efficiency and structure preservation [18] [20]. Recent advancements in detergent systems and lipid-based approaches have significantly improved membrane protein characterization, with newer formulations offering improved stability and reduced interference with protein function compared to traditional detergents [18].

Electrophoresis and Detection Workflow

The Native PAGE process follows a systematic workflow from gel casting through detection, with each step optimized to preserve protein function:

Gel Casting: Linear gradient polyacrylamide gels are typically cast manually using systems like the Mini-Protean Tetra Vertical Electrophoresis Cell. Gradient gels (e.g., 3-13% acrylamide) provide optimal resolution across a broad molecular weight range, effectively separating both small proteins and large macromolecular complexes [17].

Electrophoresis Conditions: Running buffers for Native PAGE are specifically formulated to maintain native conformations. For example, the HI-PAGE system employs a Tris-histidine running buffer at approximately pH 8.4 without requiring adjustment [19]. Electrophoresis is typically performed at 4°C to maintain protein stability throughout the separation process.

Detection Methods: A key advantage of Native PAGE is the diversity of detection options available:

- In-gel enzyme activity staining allows direct visualization of catalytic function for complexes such as mitochondrial respiratory enzymes [17].

- Fluorescence detection enables sensitive quantification, as demonstrated in fHI-PAGE where Nile Red staining provides more sensitive detection of lipoproteins compared to conventional Sudan Black B staining [19].

- Western blot analysis following Native PAGE permits specific identification of complex components using antibodies against target proteins [17].

The following diagram illustrates the core Native PAGE workflow and its functional advantages:

Research Reagent Solutions for Native PAGE

Successful implementation of Native PAGE requires specific reagents optimized for preserving protein structure and function. The following table details essential materials and their functions in native electrophoresis workflows:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Native PAGE

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Mild Detergents | n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside, Digitonin | Solubilize membrane proteins while preserving native complexes and supercomplexes [17] |

| Charge Shift Agents | Coomassie Blue G-250, Anionic detergents | Impose negative charge on proteins, prevent aggregation, ensure migration toward anode [17] |

| Stabilizing Additives | 6-Aminocaproic acid, Histidine-imidazole buffer | Enhance protein stability, maintain native pH environment, support electrophoretic separation [19] [17] |

| Fluorescent Stains | Nile Red | Enable sensitive detection and quantification of specific protein classes like lipoproteins [19] |

| Gel Matrix Components | Acrylamide-bisacrylamide mixtures, Ammonium persulfate (APS), TEMED | Form porous polyacrylamide networks for size-based separation of native complexes [19] [17] |

Applications in Protein Complex Analysis

Mitochondrial Respiratory Chain Complexes

Native PAGE has proven exceptionally valuable for characterizing the mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) system, which consists of five multimeric complexes critical to cellular energy production. BN-PAGE enables resolution of individual OXPHOS complexes (I-V) as well as higher-order supercomplexes (respirasomes) when the mild detergent digitonin is used for membrane solubilization [17]. This application provides insights into assembly pathways, compositional changes in disease states, and the functional organization of respiratory enzymes within cristae membranes.

A particularly powerful application is the combination of BN-PAGE with in-gel enzyme activity staining, which demonstrates the preservation of biological function following electrophoretic separation. Established histochemical methods can detect catalytic activity for Complexes I, II, IV, and V directly in the gel matrix, confirming that these enzymes remain fully functional throughout the Native PAGE process [17]. For example, Complex V (F1Fo-ATP synthase) activity can be visualized with a simple enhancement step that markedly improves staining sensitivity, enabling semi-quantitative assessment of functional capacity in patient samples and experimental models [17].

Clinical and Diagnostic Applications

The preservation of native conformation and function makes Native PAGE particularly suitable for clinical applications where accurate assessment of protein behavior is essential for diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring. The fluorescence-based HI-PAGE system has been validated for lipoprotein analysis in human serum, providing rapid separation and profiling of lipoprotein fractions such as LDL and HDL within one hour without band distortion [19]. This method enables direct comparison of multiple clinical samples under identical conditions, with LDL-cholesterol estimates that show concordance with values calculated by the Friedewald formula while offering advantages in cases of hypertriglyceridemia where conventional calculations are unreliable [19].

For drug development professionals, Native PAGE offers a robust platform for evaluating compound effects on protein complexes in their native states. The technique can detect changes in complex assembly, stability, and interactions that might be missed by denaturing methods, providing more physiologically relevant information for target validation and mechanism-of-action studies. This is particularly valuable for membrane proteins, which represent over 60% of current drug targets yet present significant technical challenges for structural and functional analysis [20].

Technical Considerations and Limitations

Methodological Challenges and Optimization

While Native PAGE offers significant advantages for studying biologically active proteins, researchers must consider several technical challenges to ensure successful implementation:

Protein Solubilization Balance: Achieving complete solubilization while preserving native complexes requires careful optimization of detergent type and concentration. Insufficient solubilization yields poor protein recovery, while excessive detergent conditions can disrupt native interactions [17]. Empirical testing is often necessary to establish ideal conditions for specific protein systems.

Molecular Weight Determination Limitations: Unlike SDS-PAGE, where migration distance correlates directly with polypeptide size, Native PAGE separation depends on multiple factors including size, shape, and intrinsic charge. While native molecular weights can be estimated using appropriate standards, determinations are less straightforward than in denaturing systems [17].

Detection Sensitivity Constraints: While fluorescent staining methods have improved detection sensitivity, Native PAGE may still require larger protein amounts compared to denaturing Western blot techniques. The maintenance of native structure can limit epitope accessibility for some antibodies, potentially affecting immunodetection efficiency [21].

Complementary and Emerging Technologies

Native PAGE should be viewed as part of an integrated structural biology toolkit rather than a standalone solution. The technique complements other biophysical methods such as:

Native Mass Spectrometry (nMS): This emerging technique analyzes membrane proteins under nondenaturing ionization conditions that preserve noncovalent interactions and quaternary structure [18]. While nMS provides superior mass determination accuracy, it requires extensive optimization and specialized instrumentation not needed for Native PAGE.

Expansion Microscopy (ExM): Techniques like protein retention expansion microscopy (proExM) enable super-resolution analysis of cellular structures using conventional confocal microscopy, providing spatial context that complements biochemical analyses [22].

Fluorescent Protein Tags: The inherent stability of fluorescent proteins like GFP allows their direct detection in SDS-PAGE with only minor protocol adaptations, bridging conventional denaturing methods with native analysis [21].

The continuing development of customized detergents, stabilizing additives, and detection methodologies promises to further enhance the capabilities of Native PAGE for studying proteins in their biologically active conformations, solidifying its role as an essential tool for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to understand protein function in physiologically relevant contexts.

From Theory to Bench: Practical Protocols for Functional Protein Analysis

Within the broader context of research on how native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) preserves protein function, Blue Native (BN)-PAGE and Clear Native (CN)-PAGE stand as pivotal techniques. Unlike denaturing methods such as SDS-PAGE, which dismantles protein complexes into individual polypeptides, native PAGE maintains proteins in their folded state, preserving post-translational modifications, enzymatic activity, and most importantly, the intricate quaternary structures of multi-protein complexes [23] [24]. This capability is fundamental for studying the actual functional units of the cell. Most proteins operate as part of larger multiprotein complexes, and understanding these interactions is crucial in fields from mitochondrial research to drug development [7] [23]. BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE both serve this goal but differ in their mechanisms and optimal applications, making the choice between them a critical strategic decision for researchers.

Core Principles and Mechanistic Differences

The fundamental difference between these techniques lies in the use of a charged dye. BN-PAGE uses the anionic dye Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250, which binds to protein surfaces, imparting a strong negative charge shift. This masks the proteins' intrinsic charge, allowing them to separate primarily by size and shape in a gradient gel [7] [23] [24]. CN-PAGE, in contrast, is performed without Coomassie dye or with a much lower concentration in a modified version (pCN-PAGE). Consequently, separation depends on the protein's intrinsic charge, its size, and the gel's pore size [24] [25].

This mechanistic distinction has direct practical consequences. The Coomassie dye in BN-PAGE provides a uniform charge density, which often leads to a higher resolution of protein complexes and allows for a more reliable estimation of native molecular weights [26] [24]. However, the dye can sometimes act as a detergent, disrupting weak protein-protein interactions or labile supramolecular assemblies. In rare cases, it may also quench the fluorescence of prosthetic groups or interfere with certain activity assays [24]. CN-PAGE is considered a milder technique. The absence of Coomassie dye helps preserve very delicate and transient interactions, such as those in photosynthetic megacomplexes or certain oligomeric states of enzymes like mitochondrial ATP synthase, which might dissociate under BN-PAGE conditions [26] [24].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE

| Feature | BN-PAGE | CN-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Key Principle | Charge shift via Coomassie dye binding | Relies on protein's intrinsic charge |

| Primary Separation Basis | Native mass and molecular shape | Intrinsic charge, size, and gel porosity |

| Resolution | Typically higher | Typically lower |

| Gentleness | Harsher; dye may disrupt weak interactions | Milder; preserves labile complexes |

| Molecular Weight Estimation | More reliable | Less reliable |

| Downstream Compatibility | May interfere with fluorescence and some activity assays | Better suited for fluorescence (FRET) and in-gel activity assays |

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Core BN-PAGE Protocol

The following protocol, adapted from key methodological sources, outlines the standard BN-PAGE procedure for isolating mitochondrial protein complexes [27] [7].

- Sample Preparation: Isolate mitochondria from tissue or cells. Resuspend the mitochondrial pellet (0.4 mg) in 40 μL of solubilization buffer containing 50 mM Bis-Tris (pH 7.0), 750 mM ε-amino-N-caproic acid, and 1% n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (or a mixture of 1% dodecyl maltoside and 1% digitonin for better preservation of supercomplexes). Incubate on ice for 30-60 minutes to solubilize membranes [27] [7] [28].

- Clarification: Centrifuge the lysate at high speed (e.g., 20,000 × g to 72,000 × g) for 30 minutes to remove insoluble material. Collect the supernatant [27] [7].

- Dye Addition: Add a 5% solution of Coomassie Blue G-250 (e.g., 2.5 μL) to the supernatant to impart the necessary charge for electrophoresis [7].

- Gel Casting and Electrophoresis:

- Use a gradient gel (e.g., 4–13% or 6–13% acrylamide) for optimal separation across a wide molecular weight range. A large-pore gel (e.g., 4.3–8% gradient) is recommended for resolving very large mega- and supercomplexes [7] [28].

- The gel and electrophoresis buffers are typically based on Bis-Tris and ε-amino-N-caproic acid or Tricine at pH 7.0 [27] [7].

- Load the prepared samples (20–30 μg protein) and run the gel at 4°C. Start with a cathode buffer containing 0.02% Coomassie dye. Once the sample has entered the gel, the cathode buffer can be replaced with a dye-free version to prevent excessive dye from interfering with downstream analysis. Run the gel at 100-150 V until the dye front migrates off the gel [27] [7].

Core CN-PAGE Protocol

The CN-PAGE protocol shares similarities with BN-PAGE but omits the key dye component [24].

- Sample Solubilization: Solubilize the sample as for BN-PAGE, using mild detergents like dodecyl maltoside or digitonin. The goal is to preserve native interactions without the stabilizing charge from Coomassie dye.

- Electrophoresis: Load the solubilized sample onto a native gradient gel. The key difference is that the cathode buffer does not contain Coomassie Blue G-250. The entire run is performed under "clear" conditions [26] [24].

- Modified CN-PAGE (pCN-PAGE): A modified pseudo-CN-PAGE (pCN-PAGE) method has been developed for analyzing the oligomeric state of purified soluble proteins. This method allows for the assessment of diverse dye-to-protein ratios on a single gel, providing unambiguous results for oligomeric state determination without specialized equipment [25].

The workflow below illustrates the key procedural differences and outcomes for these methods.

Application Scenarios and Decision Framework

The choice between BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE is dictated by the biological question and the nature of the protein complexes under investigation.

BN-PAGE is the preferred method for most standard applications, especially when the goal is to determine the native mass, oligomeric state, and subunit composition of stable protein complexes. Its high resolution makes it ideal for proteomic studies of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complexes (I-V) [27] [23], analysis of whole cellular lysates [29], and immunodetection studies where sharp band separation is paramount.

CN-PAGE should be selected when studying exceptionally labile supramolecular assemblies that are disrupted by Coomassie dye. This is often the case for photosynthetic mega- and supercomplexes in thylakoid membranes [28] [26] and for certain oligomeric states of enzymes. It is also the method of choice when planning downstream in-gel activity assays that are sensitive to Coomassie dye or when using techniques like fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) [24] [25].

For a comprehensive analysis, a powerful strategy is to use both methods in tandem or to employ a two-dimensional (2D) electrophoresis approach. In 2D electrophoresis, protein complexes are first separated by BN-PAGE or CN-PAGE, and then a single lane is excised, soaked in SDS buffer, and placed on an SDS-PAGE gel. This second dimension denatures the complexes and separates their individual protein subunits by molecular weight, providing detailed information about the composition of each native complex [7] [23] [29].

Table 2: Application-Based Method Selection Guide

| Research Goal | Recommended Method | Rationale and Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight / Oligomeric State Determination | BN-PAGE | Coomassie dye provides a uniform charge-to-mass ratio, enabling more accurate size estimation [26] [23]. |

| Analysis of Stable Complexes (e.g., Mitochondrial Complexes I-V) | BN-PAGE | Standard method offering high-resolution separation and identification of these well-characterized complexes [27]. |

| Identification of Novel Interacting Partners (Proteomics) | BN-PAGE | Superior resolution for analyzing complex mixtures from whole cell lysates, ideal for subsequent mass spectrometry [29]. |

| Preservation of Labile Supercomplexes | CN-PAGE | Milder conditions preserve weak interactions in assemblies like PSI-NDH megacomplexes in photosynthesis [28] [26]. |

| In-Gel Enzymatic Activity Assays | CN-PAGE | Avoids potential quenching or inhibition of enzyme activity by Coomassie dye [24]. |

| FRET or Fluorescence-Based Detection | CN-PAGE | Prevents interference and quenching of fluorophores by the blue dye [24] [25]. |

Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents required for successful BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE experiments.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Native PAGE

| Reagent | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 | Imparts negative charge to proteins in BN-PAGE; prevents aggregation. | Use Serva Blue G for best results; critical for BN-PAGE, omitted in CN-PAGE [27] [7]. |

| n-Dodecyl-β-D-Maltoside (DDM) | Mild non-ionic detergent for solubilizing membrane proteins. | Preserves protein-protein interactions; typical working concentration is 1% (w/V) [7] [28]. |

| Digitonin | Mild non-ionic detergent for gentle solubilization. | Often used in mixtures (e.g., with DDM) to preserve very labile supercomplexes [28]. |

| ε-Amino-N-Caproic Acid (6- Aminocaproic Acid) | Provides a conductive medium in gels and buffers; improves membrane protein solubilization. | Acts as a protease inhibitor; a key component of the gel buffer system [27] [7]. |

| Bis-Tris | pH-buffering agent for gels and buffers. | Standard buffer for native PAGE, typically at pH 7.0 [27] [7]. |

| Tricine | Buffer for cathode chamber. | Used in the cathode running buffer [7]. |

| Acrylamide/Bis-Acrylamide | Forms the porous gel matrix. | Gradient gels (e.g., 4-13%, 6-13%) are recommended for optimal separation [27] [7]. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (e.g., PMSF, Leupeptin, Pepstatin) | Prevents proteolytic degradation of protein complexes during isolation. | Essential for maintaining complex integrity during sample preparation [7]. |

Advanced Applications and Integrated Workflows

The true power of native electrophoresis is realized when it is integrated into broader analytical workflows. A prime example is its use in "complexome profiling," where BN-PAGE is combined with large-scale mass spectrometry to comprehensively characterize the protein composition of bands excised from a native gel, leading to the discovery of new complexes and proteins [28].

Furthermore, the sequential use of native and denaturing electrophoresis remains a cornerstone for analyzing multi-protein complexes. The following diagram illustrates a standard 2D approach that leverages the strengths of both BN-PAGE and SDS-PAGE.

This 2D approach allows researchers to not only see the intact complexes but also to resolve their constituent subunits, providing a map of complex composition. This has been successfully applied to study dynamics, such as changes in the proteasome complex after γ-interferon stimulation of cells, and to identify novel protein-protein interactions using antibody shift assays within the BN-PAGE system [29].

BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE are complementary, not competing, techniques in the functional proteomics toolkit. BN-PAGE, with its high resolution and reliability, is the workhorse for standard characterization of protein complexes. CN-PAGE serves as a specialized, milder alternative for preserving the most delicate biological assemblies and for specific downstream applications. The decision framework and detailed protocols provided in this guide are designed to empower researchers and drug development professionals to make an informed choice, ensuring their experimental design optimally aligns with their goal of preserving and understanding protein function in its native context. By integrating these electrophoretic methods with mass spectrometry and other analytical techniques, scientists can continue to unravel the complex protein interaction networks that underlie cellular function and dysfunction.

The efficacy of native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Native PAGE) in preserving native protein function is critically dependent on the initial sample preparation, particularly the choice of solubilizing detergents. This technical guide elucidates the optimized use of two non-ionic detergents, n-Dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (β-DM) and Digitonin, for the extraction of membrane and soluble protein complexes. Within the context of a broader thesis on how Native PAGE preserves protein function, this whitepaper establishes that the gentle solubilization properties of these detergents are foundational to maintaining native conformational states, oligomeric assemblies, and biological activities throughout the electrophoretic process. We provide a comparative analysis of detergent properties, detailed protocols for their application, and data demonstrating their success in preserving functional protein complexes for researchers and drug development professionals.

Native PAGE is a powerful, non-denaturing electrophoretic technique that separates proteins based on their size, charge, and shape, all while preserving their native conformation and, crucially, their biological function [5] [2]. Unlike SDS-PAGE, which denatures proteins into uniform charge-mass-ratio polypeptides, Native PAGE maintains the protein's folded structure, its oligomeric state, and its interactions with cofactors, lipids, and other proteins [5]. This preservation is paramount for downstream functional assays, activity measurements, and the study of protein-protein interactions.

The integrity of any Native PAGE analysis, however, is only as good as the initial sample preparation. For membrane proteins—which constitute over 60% of drug targets—and for delicate multi-subunit complexes, the extraction and solubilization step is the most critical determinant of success. Harsh ionic detergents like SDS will denature proteins, strip associated factors, and irrevocably destroy function [5]. Therefore, the use of mild, non-ionic detergents is indispensable for isolating intact complexes from their biological membranes [30] [18].

This guide focuses on two exemplary detergents for this purpose: n-Dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (β-DM) and Digitonin. Both are non-ionic surfactants, but their distinct chemical structures and physicochemical properties lend themselves to specific applications. By optimizing their use, researchers can solubilize target proteins while maintaining a native lipid environment and preserving supramolecular assemblies that are often disrupted by other detergents [31] [32].

Detergent Fundamentals and Properties

n-Dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (β-DM)

β-DM is a glucoside-based surfactant featuring a dodecyl alkyl chain attached to a maltose head group. The "β" designation refers to the equatorial configuration of the alkyl chain around the anomeric center of the carbohydrate [30]. This structure confers a bulky hydrophilic head group and a non-charged alkyl glycoside chain, making it a mild and effective detergent for solubilizing membrane proteins.

Table 1: Key Physicochemical Properties of β-DM and Digitonin

| Property | n-Dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (β-DM) | Digitonin |

|---|---|---|

| Classification | Non-ionic detergent | Non-ionic, steroidglycoside detergent [32] |

| Molecular Formula | C₂₄H₄₆O₁₃ (for α/β-DM) | C₅₆H₉₂O₂₉ [33] |

| Molecular Weight | ~510.6 g/mol | 1229.3 g/mol [32] |

| Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) | ~0.1-0.2 mM (approx.) | 0.67 – 0.73 mM [32] |

| Typical Use Concentration | 5–100 mM for membrane solubilization [30] | 0.2–2% (w/v) [33]; 1–2X CMC for sample prep [33] |

| Micelle Size | Information not specified in results | ~70 kDa [33] |

| Key Feature | Effective for solubilizing photosynthetic complexes [30] | Preserves native lipid environment and labile supercomplexes [32] |

Digitonin

Digitonin is a naturally occurring, non-ionic surfactant with a cholesterol-like structure [33]. This unique structure allows it to interact favorably with cholesterol-rich membrane domains and to solubilize membrane proteins in an extremely gentle fashion, often preserving their function and their interaction with native lipids [32]. Its mildness makes it the detergent of choice for studying labile supramolecular assemblies, such as mitochondrial respiratory supercomplexes, which are dissociated under the conditions of other detergents like Triton X-100 [34] [31].

Experimental Protocols: Optimized Extraction and Solubilization

Protocol 1: Extraction of Photosynthetic Complexes from Pea Thylakoid Membranes using β-DM

This protocol is adapted from comparative studies on the solubilizing properties of DM isomers [30].

Materials:

- Pea thylakoid membranes maintaining native architecture of stacked grana and stroma lamellae.

- n-Dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (β-DM) stock solution.

- Appropriate isolation buffer (e.g., containing HEPES, MES, and osmoticum).

Method:

- Membrane Preparation: Isolate intact pea thylakoids using standard differential centrifugation techniques. Resuspend the membrane pellet to a desired chlorophyll concentration in a suitable isolation buffer.

- Detergent Titration: Expose the stacked thylakoid membranes to a single-step treatment with increasing concentrations of β-DM (ranging from 5 mM to 100 mM).

- Solubilization: Incubate the detergent-membrane mixture on ice for 5-10 minutes with gentle agitation.

- Separation of Solubilized Material: Centrifuge the mixture at high speed (e.g., 100,000 × g) for 30 minutes at 4°C to pellet insoluble material.

- Analysis: Collect the supernatant, which contains the solubilized protein complexes. These can now be analyzed by Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) or Clear Native PAGE (CN-PAGE).

Key Observations from this Protocol [30]:

- At low β-DM concentrations (e.g., 5 mM), only partial solubilization occurs, releasing small protein complexes and membrane fragments enriched in Photosystem I (PSI) from stroma lamellae.

- At concentrations above 30 mM, complete solubilization is achieved, releasing high molecular weight complexes including dimeric Photosystem II (PSII), PSI-LHCI, and PSII–LHCII supercomplexes.

Protocol 2: Preservation of Mitochondrial Supercomplexes using Digitonin

This protocol is critical for studying the native organization of the mitochondrial electron transport chain [31].

Materials:

- Isolated mitochondrial preparation.

- Digitonin stock solution (e.g., 5% solution in ultrapure water). Note: If a precipitate forms, warm the solution to 95°C for 5 minutes and vortex to dissolve before use [33].

- Native-specific buffers.

Method:

- Mitochondrial Isolation: Purify mitochondria from the desired tissue (e.g., liver, heart) using differential centrifugation.

- Critical Digitonin Optimization: Solubilize the mitochondrial pellet using a carefully titrated concentration of digitonin. The digitonin-to-protein ratio (e.g., g/g) is a critical determinant for the preservation of supercomplexes. For example, a specific study found that 4-6 g digitonin per g of protein was optimal for visualizing respiratory supercomplexes [31].

- Gentle Solubilization: Incubate the mixture on ice for 10-30 minutes with gentle agitation. Avoid vigorous mixing to prevent shearing of labile complexes.

- Clarification: Centrifuge the solubilized mixture at high speed (e.g., 20,000 × g) for 20-30 minutes at 4°C to remove insoluble debris.

- Native PAGE Analysis: Load the resulting supernatant directly onto a BN-PAGE or CN-PAGE gel.

Key Observations from this Protocol [34] [31]:

- The combination of digitonin and CN-PAGE is exceptionally mild and can retain labile supramolecular assemblies that are dissociated under the conditions of BN-PAGE.

- Enzymatically active oligomeric states of mitochondrial ATP synthase, previously undetected using other detergents, have been identified using this approach [34].

- Digitonin concentration is determinant for distinguishing genuine associations of complexes from proteins being randomly trapped in the same micelle [31].

Data Presentation and Analysis

The effectiveness of optimized detergent extraction is quantifiable through the analysis of resolved protein complexes on Native PAGE.

Table 2: Separation Profile of Photosynthetic Complexes from Pea Thylakoids Solubilized with β-DM [30]

| β-DM Concentration | Solubilization Efficiency | Major Complexes Released |

|---|---|---|

| Low (e.g., 5 mM) | Partial solubilization | Small protein complexes; Membrane fragments enriched in PSI from stroma lamellae |

| High (> 30 mM) | Complete solubilization | Dimeric PSII, PSI-LHCI, and PSII–LHCII supercomplexes |

Furthermore, the choice between CN-PAGE and BN-PAGE after solubilization offers different advantages for functional studies, as summarized below.

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of CN-PAGE vs. BN-PAGE for Functional Studies

| Criteria | Clear-Native PAGE (CN-PAGE) | Blue-Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Lower resolution than BN-PAGE [34] | High resolution [34] |

| Migrational Basis | Protein intrinsic charge and pore size of gradient gel [34] | Charge shift imposed by Coomassie dye [34] |

| Compatibility with Activity Assays | Excellent; Coomassie dye can interfere with catalytic activities [34] | Poor; Coomassie dye often inhibits enzyme function [34] |

| Mildness | Milder than BN-PAGE; better preserves labile assemblies [34] | Stronger; may dissociate very weak interactions [34] |

| Ideal Application | In-gel functional assays (e.g., ATP synthase activity), FRET analyses [34] | Standard analysis for determining native mass and oligomeric state [34] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents essential for successful sample preparation for native electrophoresis.

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Optimized Native Protein Extraction

| Reagent | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| n-Dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (β-DM) | A mild, non-ionic detergent effective for the solubilization of a wide range of membrane protein complexes, including photosynthetic supercomplexes [30]. |

| Digitonin (5% Solution) | A non-ionic, steroid-based detergent used for gentle permeabilization and solubilization that preserves the native lipid environment and labile supercomplexes [32] [33]. |

| NativePAGE Sample Prep Kit | A commercial kit that includes digitonin and is optimized to improve solubility of hydrophobic proteins, reduce streaking, and increase resolution in native gels [33]. |

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue Dye (for BN-PAGE) | Provides the necessary charge shift for protein migration in BN-PAGE, enabling high-resolution separation but potentially interfering with enzyme function [34]. |

| HEPES/MES Buffers | Standard buffering agents used in isolation and solubilization buffers to maintain a stable pH during the extraction process, crucial for protein stability [30]. |

| DTT/BME (Excluded from Native Lysis) | Reducing agents used in SDS-PAGE to break disulfide bonds. They are typically omitted from native sample prep to preserve all non-covalent interactions and native quaternary structure [5]. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

The following diagrams illustrate the core logical relationships and experimental workflows described in this guide.

Diagram 1: Core workflow for native protein extraction.

Diagram 2: Analysis paths after Native PAGE.

The mastery of sample preparation, specifically through the optimized application of detergents like n-Dodecyl-β-d-maltoside and Digitonin, is the cornerstone of successful Native PAGE analysis aimed at preserving protein function. β-DM serves as a robust and effective agent for solubilizing a broad range of stable membrane complexes, while Digitonin is unparalleled in its ability to maintain the integrity of the most labile supramolecular assemblies and their enzymatic activities. The protocols and data presented herein provide a clear framework for researchers to make informed decisions on detergent selection and application. When integrated with the appropriate Native PAGE system (BN-PAGE for high-resolution mass analysis or CN-PAGE for in-gel functional studies), these optimized extraction methods empower scientists in basic research and drug development to probe the authentic structure, interactions, and function of the proteome in its native state.

The inner mitochondrial membrane hosts the respiratory chain, a critical system for cellular energy conversion composed of four multi-subunit complexes (CI-CIV). For decades, biochemical and structural evidence has demonstrated that these complexes do not operate in isolation but can organize into higher-order assemblies known as supercomplexes [35] [36]. The most recent and advanced structural work has revealed a 5.8-MDa supercomplex from Tetrahymena thermophila containing CI, CII, CIII₂, and CIV₂, comprising 150 different proteins and 311 bound lipids [35]. This I–II–III₂–IV₂ supercomplex represents the most complete respiratory chain assembly characterized to date and exhibits a pronounced membrane curvature, suggesting an active role in shaping the bioenergetic membrane architecture [35].