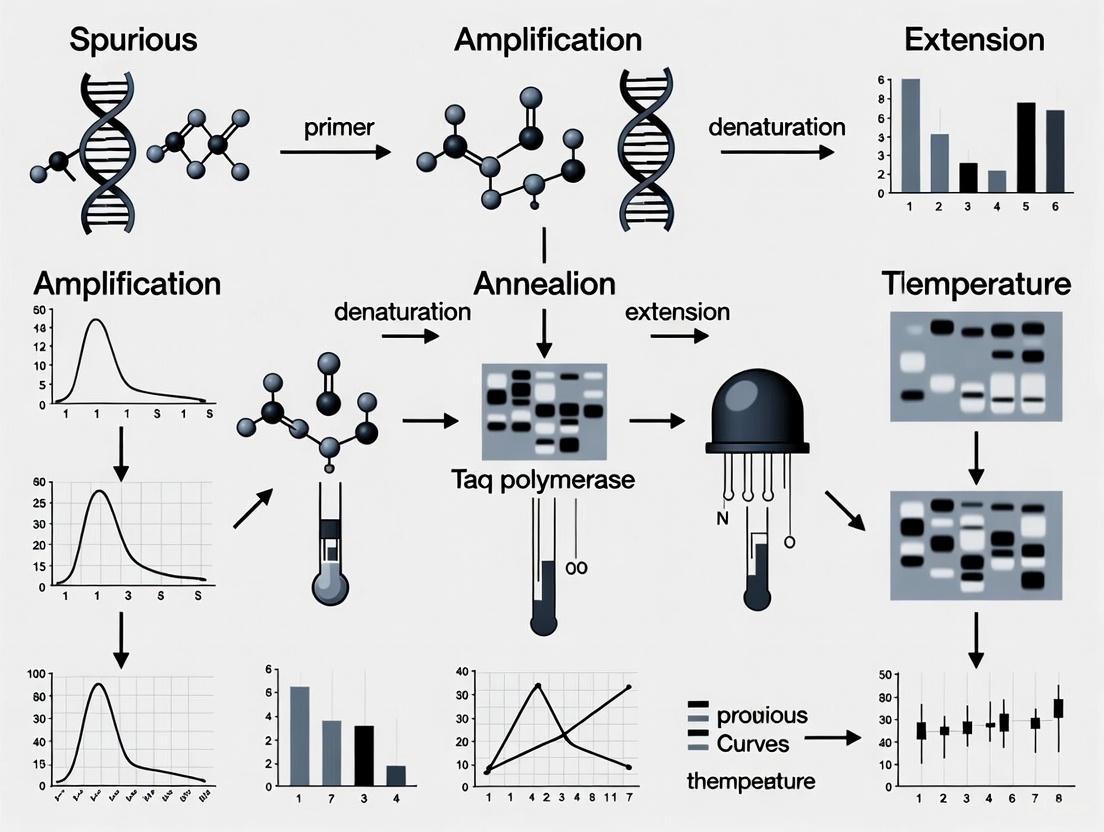

PCR Troubleshooting Guide: Solving Spurious Results and Product Smearing

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals facing the common yet frustrating challenges of spurious results and product smearing in PCR.

PCR Troubleshooting Guide: Solving Spurious Results and Product Smearing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals facing the common yet frustrating challenges of spurious results and product smearing in PCR. It covers the foundational science behind these issues, outlines robust methodological setups for various applications, delivers a step-by-step, evidence-based troubleshooting and optimization protocol, and discusses validation techniques to ensure result reliability. By integrating proven strategies for primer design, reaction condition calibration, and inhibitor management, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to achieve specific, efficient, and reproducible amplification crucial for biomedical and clinical research.

Understanding Spurious Results and Smearing: A Deep Dive into PCR Failure Modes

Frequently Asked Questions

What are spurious bands in PCR? Spurious bands, also known as non-specific products, are DNA fragments amplified by PCR that are not the intended target sequence. They occur when primers bind to unintended, partially complementary regions on the DNA template and are extended by the polymerase. These unwanted products appear as extra bands on an agarose gel, often at unexpected sizes, and can complicate the interpretation of results [1] [2] [3].

What is a primer dimer? A primer dimer (PD) is a common PCR by-product formed when two primer molecules hybridize to each other via complementary bases, particularly at their 3' ends, instead of binding to the template DNA. The DNA polymerase then amplifies this short duplex, leading to a short product, typically visible as a band around 30-50 base pairs on an agarose gel. Primer dimers consume PCR reagents, potentially inhibiting the amplification of the desired target sequence [4] [2] [5].

What causes smearing in PCR results? PCR smearing appears as a continuous ladder or smear of DNA fragments of varying sizes on an agarose gel, rather than as sharp, distinct bands. Common causes include:

- Too much template DNA [6] [7] [8].

- Too many PCR cycles, leading to over-amplification and accumulation of artifacts [6] [7] [9].

- Suboptimal cycling conditions, such as an annealing temperature that is too low, which permits non-specific binding [6] [2] [8].

- Degraded DNA template or contaminants in the reaction [6] [2].

- Gradual accumulation of amplifiable DNA contaminants that interact with the primers over time [2].

A Troubleshooting Guide to Common PCR Artifacts

The table below summarizes the characteristics and primary causes of spurious bands, primer dimers, and smearing.

| Artifact | What It Looks Like on a Gel | Primary Causes |

|---|---|---|

| Spurious Bands | One or more discrete bands at incorrect sizes [1] [3] | - Low annealing temperature [2] [8] [9]- Poor primer design/specificity [8] [9]- Excessive Mg2+ concentration [2] [9]- High enzyme concentration [7] |

| Primer Dimer | A sharp band or smear near 30-50 bp [4] | - Complementary sequences, especially at the 3' ends of primers [4] [5] [9]- High primer concentration [5]- Low-temperature annealing during reaction setup [4] |

| Smearing | A continuous ladder or smear of DNA [6] | - Excessive template DNA [6] [7] [8]- Too many PCR cycles [6] [7]- Long extension times [8] [3]- DNA degradation or contaminants [6] [2] |

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key reagents and methods that can help prevent or mitigate these common PCR artifacts.

| Solution / Reagent | Function in Preventing Artifacts |

|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Inhibits polymerase activity at low temperatures (e.g., during reaction setup), preventing primer-dimer formation and non-specific priming before the PCR begins [4] [2] [9]. |

| Betaine & DMSO | Additives used to destabilize DNA secondary structure, particularly helpful for amplifying GC-rich templates and reducing spurious bands and smearing [2] [9]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Binds to and neutralizes common PCR inhibitors present in sample preparations (e.g., phenols, polysaccharides), which can cause smearing or amplification failure [2] [9]. |

| Magnesium (Mg2+) Optimization | Mg2+ concentration is critical for polymerase activity and specificity; optimizing it (typically 1.5-5.0 mM) is a primary strategy to resolve spurious bands, primer dimers, and smearing [2] [7] [8]. |

| SAMRS-Containing Primers | Primers incorporating Self-Avoiding Molecular Recognition Systems (SAMRS) nucleotides bind to natural DNA but not to other SAMRS primers, thereby avoiding primer-dimer formation [4] [10]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Systematic Approach to Troubleshooting

The following workflow provides a logical method for diagnosing and resolving issues with spurious bands, primer dimers, and smearing.

Detailed Optimization Steps

Based on the workflow above, if contamination is ruled out, the following specific optimizations are recommended.

| Parameter to Optimize | Specific Action for Spurious Bands | Specific Action for Primer Dimer | Specific Action for Smearing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Cycling | Increase annealing temperature in 2°C increments [8] [9]. Use touchdown PCR [8]. | Increase annealing temperature [2] [9]. | Reduce number of cycles (e.g., 20-35) [6] [7]. Reduce extension time [6] [3]. |

| Reagent Concentration | Lower Mg2+ concentration [2] [9]. Use minimum necessary enzyme [7]. | Reduce primer concentration using a gradient (e.g., 0.1-0.5 µM) [5] [7]. | Reduce template DNA amount [6] [7] [8]. Optimize Mg2+ concentration [7]. |

| Primer Design & Quality | Redesign primers to be longer and avoid 3' end complementarity [9]. Check for degraded primers [7]. | Redesign primers to avoid 3' end complementarity (≥2-3 bases) [5] [9]. Use design software [4]. | Redesign primers [7] [8]. Use nested primers for re-amplification [8]. |

| Enzyme & Additives | Use a hot-start polymerase [4] [2] [9]. | Use a hot-start polymerase [4] [2]. Consider SAMRS primers [4] [10]. | Use additives like BSA to counteract inhibitors [2]. |

What is Non-Specific Amplification?

In a Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), non-specific amplification occurs when primers bind to unintended regions of the template DNA, leading to the amplification of incorrect DNA fragments [11]. This results in PCR products that are not the intended target, which can be observed on an agarose gel as multiple bands, smears, or bands of an unexpected size [12] [11]. This phenomenon compromises the integrity of experimental data, leading to wasted reagents, time, and potential misinterpretation of results [13].

Non-specific amplification can manifest in several ways [12]:

- Multiple Bands: Several discrete bands appear instead of a single, clean band at the expected size.

- Primer Dimers: Short, amplifiable products formed by two primers hybridizing to each other, typically visible as a bright band around 20-60 bp [12].

- Smears: A broad, diffuse spread of DNA fragments of varying sizes, often indicating random, non-targeted amplification [12] [2].

- Single Incorrect Amplicon: A single, discrete band at an unexpected size [11].

How Suboptimal Conditions Cause Non-Specificity

Suboptimal PCR conditions reduce the stringency of the reaction, which is the requirement for perfect complementarity between the primer and the template for binding to occur. When stringency is low, primers can bind to sequences with partial homology, and the polymerase enzyme can extend these mismatched primers, leading to spurious products [2]. The table below summarizes the primary causes.

| Root Cause | Mechanism of Non-Specificity | Optimal Range / Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Low Annealing Temperature [11] | Reduces stringency, allowing primers to bind to sites with partial complementarity. | Typically 55–65°C; optimize using a gradient PCR [11] [14]. |

| Poor Primer Design [15] [11] | Primers with self-complementarity form hairpins; complementary 3' ends form primer-dimers; low complexity leads to binding at multiple genomic sites. | Use design software (e.g., Primer3); length 18-30 nt; GC content 40-60%; check for secondary structures [15] [14]. |

| Excessive Primer Concentration [11] [14] | High concentration promotes primer-dimer formation and off-target binding, especially during temperature transitions. | 0.1–1.0 µM (typically 0.2–0.5 µM); avoid excess [14] [16]. |

| High Magnesium Chloride (MgCl₂) Concentration [17] [11] | Mg²⁺ is a cofactor for DNA polymerase; high concentrations increase enzyme processivity and stabilize primer-template duplexes, even mismatched ones. | 1.5–3.0 mM; optimize in 0.5 mM increments [17] [15] [11]. |

| High Template DNA Concentration [11] [8] | Excess template increases the chance of non-specific priming and can introduce more PCR inhibitors. | 10–100 ng per standard reaction; use the minimum amount required [11] [8]. |

| Too Many PCR Cycles [11] | In later cycles, target amplicons plateau, but non-specific artifacts (which may be shorter and amplify more efficiently) can continue to accumulate. | 25–35 cycles; avoid unnecessary cycles [11]. |

| Contamination [8] [2] | Foreign DNA (e.g., from previous PCR products, lab environment) provides unintended templates for amplification. | Use separate pre- and post-PCR work areas; include a negative control; use sterile techniques [8]. |

| Non-Hot-Start DNA Polymerase [18] [2] | Standard polymerases have residual activity at room temperature, enabling primer-dimer formation and mispriming during reaction setup. | Use a hot-start polymerase (antibody, aptamer, or chemically modified) that activates only at high temperatures [18] [2]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between suboptimal conditions and the resulting types of non-specific amplification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Protocols and Reagents for Troubleshooting

This section provides actionable methods and reagents to diagnose and resolve non-specific amplification.

Experimental Protocol 1: Optimize Annealing Temperature via Gradient PCR

A gradient PCR is the most effective method to empirically determine the optimal annealing temperature for a primer pair [11].

Materials:

- Thermal cycler with gradient functionality

- Standard PCR reagents: DNA polymerase, buffer, dNTPs, primers, template

- Gel electrophoresis equipment

Method:

- Prepare a master mix containing all PCR components except the template. Aliquot the mix into several PCR tubes.

- Add the template to each tube.

- Place the tubes in the thermal cycler and set the annealing step to a temperature gradient (e.g., from 55°C to 70°C). The cycler will run identical reactions at different annealing temperatures simultaneously.

- Run the PCR program.

- Analyze the products using agarose gel electrophoresis.

Expected Outcome: At lower temperatures, you may observe multiple bands or smears. As the temperature increases, non-specific bands should disappear, leaving a single, bright band of the expected size. The optimal annealing temperature is the highest temperature that yields a strong, specific product [16].

Experimental Protocol 2: Optimize MgCl₂ Concentration

Mg²⁺ concentration is critical and often requires optimization, especially for new primer sets [17] [2].

Materials:

- PCR buffer without MgCl₂

- MgCl₂ stock solution (e.g., 25 mM)

Method:

- Set up a series of PCR reactions with identical components.

- Vary the MgCl₂ concentration in each reaction, typically in the range of 0.5 mM to 5.0 mM, in increments of 0.5 mM [15] [14].

- Run the PCR and analyze the products by gel electrophoresis.

- Select the concentration that produces the highest yield of the specific product with the least background.

Expected Outcome: Low Mg²⁺ may result in no amplification, while very high Mg²⁺ often causes non-specific bands and smears. The goal is to find the concentration that balances efficiency with specificity [17].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Troubleshooting Non-Specificity |

|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase [18] [2] | Prevents polymerase activity during reaction setup at room temperature, drastically reducing primer-dimer formation and mispriming. |

| PCR Additives (DMSO, BSA, Betaine) [14] | DMSO helps denature GC-rich secondary structures. BSA can bind inhibitors. Betaine equalizes DNA melting temperatures, aiding in specific amplification of difficult templates. |

| Nested Primers [18] | A second set of primers that bind within the first PCR product. Used in a second round of PCR to specifically amplify the correct target, eliminating background from non-specific products from the first round. |

| Primer Design Software (e.g., Primer3, NCBI Primer-BLAST) [15] [16] | Automates the design of high-specificity primers by checking for self-complementarity, dimer potential, and off-target binding sites within a genome. |

| qPCR with Melt Curve Analysis [16] | Post-amplification, the temperature is gradually increased while fluorescence is measured. A single, sharp peak indicates a single, specific product; multiple or broad peaks indicate non-specific amplification or primer dimers. |

The workflow below outlines a systematic approach to troubleshooting non-specific amplification in the lab.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My negative control shows a smear. What does this mean? A smear in your negative control is a clear indicator of contamination, most likely from previous PCR products (carryover contamination) or contaminated reagents [8] [2]. You must decontaminate your workspace and equipment with 10% bleach or UV irradiation, prepare fresh reagents, and ensure your pre- and post-PCR work areas are strictly separated [8].

Q2: I see a bright band at the very bottom of my gel. What is it? This is most likely a primer dimer [12]. To resolve this, use a hot-start polymerase, lower your primer concentration, ensure you are setting up reactions on ice, and consider increasing your annealing temperature [12] [18].

Q3: How can I quickly check if my primers are the problem? Use in silico PCR tools available online. These tools simulate PCR using your primer sequences and the target genome, predicting potential off-target binding sites and helping you assess primer specificity before you begin wet-lab work [11].

Q4: What is the single most impactful change I can make to prevent non-specific amplification? Implementing hot-start PCR is highly effective, as it prevents non-specific amplification during the reaction setup phase [18]. Coupled with setting up reactions on ice, this can dramatically improve specificity. Following this, optimizing the annealing temperature via a gradient PCR is the next critical step [11].

The Critical Role of Primer Design in Amplification Specificity

Core Principles of Specific Primer Design

Effective primer design is the most critical factor in determining the success of a Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) experiment. Primers that are poorly designed can lead to a complete failure of amplification or, more commonly, the generation of non-specific products that compromise experimental results. The following guidelines represent the fundamental principles for creating specific and efficient primers.

What are the essential characteristics of a well-designed primer?

- Length: Primers should typically be 18-30 nucleotides long. This length provides sufficient sequence for specific binding while maintaining practical melting temperatures [19] [20].

- GC Content: Maintain a GC content between 40-60%. This ensures balanced binding strength without promoting non-specific interactions [20] [19].

- Melting Temperature (Tm): The Tm for both forward and reverse primers should be similar, ideally within 2°C of each other. This allows both primers to bind to their target sequences simultaneously during the annealing step [20].

- 3'-End Stability: The 3' end of the primer is crucial for initiation. It should not be complementary to other sequences within the primer or to the other primer in the pair, as this promotes primer-dimer formation. Avoid runs of 3 or more G/C bases at the 3' end, as their strong binding can facilitate mispriming [19] [21].

- Sequence Uniqueness: Primer sequences must be unique to the intended target. Use tools like NCBI BLAST to verify specificity and ensure primers do not bind to non-target regions, including homologous genes or pseudogenes [20] [21].

How do I calculate the annealing temperature? The annealing temperature (Ta) is typically set at 3-5°C below the calculated Tm of the primers [20]. The Tm can be approximated using the formula: Tm = 2°C × (A + T) + 4°C × (G + C) [19].

Table 1: Essential Primer Design Parameters

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 18–30 nucleotides | Balances specificity with practical melting temperature [19] [20]. |

| GC Content | 40–60% | Provides stable yet specific hybridization; avoids extreme AT- or GC-richness [20] [19]. |

| Melting Temp (Tm) | 52–65°C; primers within 2°C | Ensures simultaneous binding of both primers to the template [20] [21]. |

| 3' End Rule | No complementarity; avoid G/C runs | Prevents primer-dimer formation and non-specific initiation [19] [21]. |

Troubleshooting Common Amplification Problems

Despite careful design, amplification issues can occur. The table below links common problems directly to their potential primer-related causes and solutions.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Primer-Related Issues

| Problem | Potential Primer-Related Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No Amplification or Low Yield | Primer contains mismatches, especially at the 3' end; Tm too high [22] [2]. | Verify sequence specificity; lower annealing temperature in 1–2°C increments; check for secondary structures [22]. |

| Non-Specific Bands/Smears | Low annealing temperature; primers bind to multiple sites; self-complementarity [2] [22]. | Increase annealing temperature; use hot-start polymerase; check for unique sequence with BLAST [2] [22]. |

| Primer-Dimer Formation | High primer concentration; complementary 3' ends between primers [2] [21]. | Lower primer concentration (0.1–0.5 µM); redesign primers to remove 3' complementarity [2] [19]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for diagnosing and resolving the most common primer-related issues:

Advanced Strategies for Challenging Applications

For specialized PCR applications, standard primer design rules require specific modifications to account for template alterations or increased sensitivity requirements.

How does primer design differ for bisulfite PCR? Bisulfite conversion treatment, used in DNA methylation analysis, reduces sequence complexity by converting unmethylated cytosine to uracil. This requires specific design considerations [20]:

- Longer Primers: Design primers 26-30 base pairs long to compensate for the reduced sequence complexity and achieve adequate specificity [20].

- Avoid CpG Sites: Primers should not contain CpG sites in their sequence. If unavoidable, place the CpG at the 5' end and use a degenerate base (Y) [20].

- Amplicon Length: Keep amplicons short, between 70-300 base pairs, as the bisulfite treatment fragments DNA [20].

What are the key considerations for dPCR primer and probe design? Digital PCR (dPCR), due to its absolute quantification nature and partitioning of the reaction, has specific requirements [23]:

- Higher Concentrations: Use higher primer and probe concentrations compared to qPCR. Optimal results are often achieved with a final primer concentration of 0.5–0.9 µM and a probe concentration of 0.25 µM per reaction. This increases fluorescence amplitude for better separation of positive and negative partitions [23].

- Probe Validation: Carefully check that the fluorophore and quencher combination does not create background noise due to emission spectrum overlap, which can impair cluster separation during analysis [23].

Can covalent modification of primers improve specificity? Yes, advanced chemical modifications offer a robust solution. Research shows that introducing thermally stable alkyl groups to the exocyclic amines of deoxyadenosine or cytosine residues at the 3'-ends of primers can significantly enhance PCR specificity [24]. Unlike traditional "hot-start" methods that temporarily inactivate the polymerase, this modification is stable and works throughout the PCR process by interfering with the extension of misprimed products like primer-dimers, thereby increasing the yield of the intended amplicon [24].

Successful PCR troubleshooting and optimization rely on having the right reagents and tools. The following table details key resources for overcoming primer-related challenges.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for PCR Specificity

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Enzyme remains inactive at room temperature, preventing non-specific priming and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup [2] [22]. | Critical for high-specificity applications; available as antibody-inhibited or chemically modified [2]. |

| PCR Additives (BSA, Betaine, DMSO) | Co-solvents that reduce secondary structures in template/primers; BSA can bind inhibitors [21] [22]. | Use at optimized concentrations (e.g., DMSO at 1-10%); betaine helps with GC-rich templates [21]. |

| NCBI Primer-BLAST | A free online tool that combines primer design with specificity verification by searching against a database [21] [20]. | Essential first step to ensure primers are unique and do not bind to non-target sequences [21]. |

| Covalently Modified Primers | Primers with stable modifications (e.g., alkyl groups) at the 3'-end that intrinsically block extension from misprimed sites [24]. | An advanced solution to persistently reduce non-specific amplification and primer-dimer propagation [24]. |

| Nuclease-Free TE Buffer (pH 8.0) | Optimal solution for resuspending and storing primers and probes; maintains stability and prevents degradation [23] [22]. | Avoid using water, especially for fluorescently labeled probes, as it can affect solubility and long-term stability [23]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My primers worked perfectly last month, but now I get smeared bands. What happened? This is a common issue often caused by the gradual accumulation of "amplifiable DNA contaminants" in the laboratory environment that are specific to your primer sequences. As these contaminants build up, they interfere with the reaction. The most efficient solution is to switch to a new set of primers designed to a different region of your target, as the new sequences will not interact with the accumulated contaminants. General lab cleanliness and having separate pre- and post-PCR areas can help slow this contamination buildup [2].

Q2: How can I prevent amplification of genomic DNA in RT-qPCR? To ensure your RT-qPCR assay is specific for mRNA, design your primers to span an exon-exon junction. This means the sequence of at least one primer should bridge the boundary between two exons. Since genomic DNA contains introns, the primer will not bind efficiently to the genomic template, while it will bind perfectly to the cDNA derived from spliced mRNA. If possible, design the primer so that the 3' end has 3-4 bases in the adjacent exon, increasing specificity [20].

Q3: What is the ideal amplicon length for a standard qPCR assay? For optimal efficiency in qPCR, it is recommended to keep the amplicon length between 70 and 140 base pairs. Shorter amplicons amplify with higher efficiency and are also more tolerant if your starting DNA or RNA template is fragmented, which is common in samples like FFPE tissue or cell-free DNA [20].

Q4: My target is GC-rich. What specific primer design strategies can help? For GC-rich targets (>60%), consider using PCR additives like betaine, DMSO, or formamide, which can help denature stable secondary structures. Also, ensure your primers themselves do not have very high GC content, and avoid long stretches of G or C bases. Using a DNA polymerase with high processivity, which has a stronger ability to unwind tough structures, can also be beneficial [22].

In polymerase chain reaction (PCR) experiments, the quality and quantity of template DNA are foundational to success. Poor template DNA is a frequent cause of amplification issues, including spurious results, smeared bands on gels, and complete amplification failure [2] [25]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding how to assess, troubleshoot, and optimize template DNA is crucial for generating reliable and reproducible data. This guide addresses the common template-related problems that can derail PCR experiments and provides targeted solutions.

FAQs on Template DNA Issues

What are the signs that my PCR failure is due to template DNA?

Several symptoms in your PCR results can point directly to template DNA issues:

- No amplification or low yield: The most direct sign is a lack of product or a very faint band on an agarose gel [2].

- Smearing or ladder-like patterns: Degraded template DNA can produce a smear of various-sized fragments instead of a clean, discrete band [26] [12].

- Complete PCR failure: This can occur if the template contains potent PCR inhibitors [8].

How does poor-quality template DNA lead to smeared bands?

Smeared bands on an agarose gel indicate a heterogeneous mixture of DNA fragments of varying sizes. When the template DNA is degraded, it becomes fragmented. During PCR, these fragments can act as unintended starting points for DNA synthesis if the primers bind non-specifically, leading to the random amplification of many different DNA segments instead of a single, specific target [12].

What are common PCR inhibitors, and how do they enter my sample?

PCR inhibitors are diverse compounds that can interfere with the DNA polymerase or the template itself. They are often co-purified with the DNA during extraction from complex samples [8].

The table below lists common inhibitors and their sources:

| Inhibitor Category | Specific Examples | Common Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Organic Compounds | Phenol, Heparin, Hemoglobin, Humic acids | Blood, serum, plasma; plant and soil samples; residual extraction chemicals [8] [27] |

| Inorganic Ions | EDTA, Calcium | EDTA from lysis or storage buffers; other metal ions that compete with Magnesium [8] |

| Other Substances | Polysaccharides, Proteins, Detergents (SDS) | Tissue samples (e.g., plants); carryover from incomplete purification [25] [8] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing and Solving Template Problems

Step 1: Assess Template DNA Quantity and Purity

The first step is to verify the amount and purity of your template using spectrophotometry or fluorometry [2].

Quantitative Guidelines for Template DNA: The following table summarizes recommended template amounts for a standard 50 µL PCR reaction [26] [8].

| Template Type | Recommended Quantity | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic DNA | 1 - 1000 ng [26] | ~100 ng is a common starting point for human genomic DNA [8] |

| Plasmid DNA | ||

| cDNA |

Step 2: Identify the Specific Problem and Apply Solutions

Based on your assessment and PCR results, use the following flowchart to diagnose and address the issue.

Experimental Protocols for Troubleshooting

Protocol 1: Purifying Template DNA via Ethanol Precipitation

This protocol is effective for removing salts, detergents, and other soluble inhibitors [27].

- Add Components: To your DNA sample, add 1/10 volume of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2) and 2-2.5 volumes of ice-cold 100% ethanol.

- Precipitate: Incubate at -20°C for 30 minutes to overnight to precipitate the DNA.

- Pellet DNA: Centrifuge at >12,000 x g for 15 minutes at 4°C. A visible pellet should form.

- Wash Pellet: Carefully remove the supernatant. Wash the pellet with 500 µL of ice-cold 70% ethanol to remove residual salts. Centrifuge again for 5 minutes and remove all supernatant.

- Resuspend: Air-dry the pellet for 5-10 minutes, then resuspend in molecular-grade water or TE buffer (pH 8.0) [25].

Protocol 2: Performing a Template Dilution Series

A dilution series helps determine if inhibitors are present or if the template concentration is suboptimal [8].

- Prepare Dilutions: Serially dilute your template DNA in molecular-grade water (e.g., 1:10, 1:100, 1:1000).

- Set Up PCRs: Use the same PCR master mix to set up reactions with each dilution as the template.

- Run and Analyze PCR: Perform amplification and analyze the products via gel electrophoresis.

- Interpret Results:

- If a higher dilution (e.g., 1:100) yields a strong specific product where the neat template failed, inhibitors are likely present and were diluted to a less active concentration.

- If product yield increases with higher template concentration, the original amount was likely too low.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents are essential for preventing and overcoming template-related PCR issues.

| Reagent or Tool | Function in Troubleshooting Template Issues |

|---|---|

| Spectrophotometer/Fluorometer | Accurately measures DNA concentration and assesses purity (A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios) [2]. |

| Inhibitor-Tolerant DNA Polymerases | Engineered enzymes that maintain activity in the presence of common inhibitors found in blood, plants, or soil [25] [8]. |

| PCR Additives (e.g., BSA, Betaine) | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) can bind to and neutralize inhibitors [2]. Betaine can help denature complex secondary structures in GC-rich templates [26] [2]. |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Reduces non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation at room temperature, improving specificity and yield, especially with suboptimal templates [2] [25]. |

| DNA Clean-up Kits | Silica-membrane based kits for rapid removal of salts, proteins, and other contaminants from DNA samples [8]. |

Polymerase fidelity refers to the accuracy with which a DNA polymerase incorporates nucleotides during DNA replication, defined by its error rate—the frequency of misincorporated nucleotides per base synthesized [28]. In practical terms, this translates to the number of errors a polymerase introduces during PCR amplification. Maintaining high fidelity is critical for applications where sequence integrity directly impacts results, including cloning, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis, and next-generation sequencing (NGS) library preparation [28] [29]. Errors introduced during amplification can lead to erroneous conclusions, particularly in sensitive applications like liquid biopsy, where detecting low-frequency variants is essential [29].

The biochemical foundation of fidelity rests on two primary mechanisms: nucleotide selectivity and proofreading activity. Nucleotide selectivity involves the polymerase's ability to choose the correct nucleotide through geometric constraints and hydrogen bonding in its active site. Proofreading is a separate 3'→5' exonuclease activity that identifies and excises misincorporated nucleotides before elongation continues [28]. Understanding how to leverage these mechanisms through polymerase selection and reaction optimization is fundamental to troubleshooting spurious results and product smears in PCR experiments.

Mechanisms of Polymerase Fidelity

The Dual Mechanisms of Accuracy

DNA polymerases achieve remarkable accuracy through a two-tiered system that ensures faithful DNA replication.

Nucleotide Selectivity: The polymerase active site is structured to favor Watson-Crick base pairing. Correct nucleotides form an optimal geometric fit, aligning catalytic groups for efficient incorporation. When an incorrect nucleotide binds, the suboptimal architecture of the active site complex slows incorporation, increasing the chance that the incorrect nucleotide will dissociate before being permanently added to the chain [28]. This initial selectivity provides the first layer of error prevention.

Proofreading Activity (3'→5' Exonuclease): Many high-fidelity polymerases possess an additional domain that confers proofreading capability. When a mispaired base is incorporated, it creates a perturbation that the polymerase detects. The growing DNA chain is then translocated from the polymerase active site to the exonuclease domain, where the incorrect nucleotide is excised. The chain subsequently returns to the polymerase active site for continued synthesis with the correct nucleotide [28]. This proofreading function can improve fidelity by up to 125-fold compared to non-proofreading versions of the same polymerase [28].

Diagram: The dual biochemical mechanisms—nucleotide selectivity and proofreading activity—that polymerases use to achieve high-fidelity DNA amplification.

Quantitative Comparison of Polymerase Fidelity

Error Rates Across Polymerase Types

Direct comparisons of polymerase fidelity reveal significant differences that directly impact experimental outcomes. These error rates are typically measured using specialized assays and expressed as errors per base per duplication.

Table 1: Polymerase Fidelity Measurements and Error Rates

| Polymerase | Error Rate (errors/bp/duplication) | Fidelity Relative to Taq | Proofreading Activity | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taq | 1.0-2.0 × 10⁻⁴ [28] to 1-20 × 10⁻⁵ [30] | 1X [28] | No | Standard for routine PCR; lowest fidelity |

| AccuPrime-Taq HF | ~1.0 × 10⁻⁵ [30] | ~9X [30] | No | Optimized Taq formulation |

| KOD | ~1.2 × 10⁻⁵ [28] | ~12X [28] | Yes | Thermophilic polymerase with high processivity |

| Pfu | 1.0-5.1 × 10⁻⁶ [30] [28] | 6-30X [30] [28] | Yes | Archetypal proofreading polymerase |

| Phusion HF (HF Buffer) | 3.9 × 10⁻⁶ [28] to 4.0 × 10⁻⁷ [30] | 39X [28] to >50X [30] | Yes | Engineered high-fidelity enzyme |

| Pwo | >10X lower than Taq [30] | >10X [30] | Yes | Similar fidelity to Pfu |

| Q5 | ~5.3 × 10⁻⁷ [28] | 280X [28] | Yes | Ultra-high fidelity engineered polymerase |

Practical Impact on Experimental Outcomes

The error rates in Table 1 translate directly into practical consequences for PCR experiments. After 30 cycles of PCR amplification of a 3 kb template:

- Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase generates products where only 3.96% of molecules contain an error, meaning 96.04% of product molecules are entirely error-free [31].

- Taq DNA Polymerase produces a situation where every product molecule contains an average of 2 errors, with 205.2% of molecules containing errors (indicating multiple errors per molecule) [31].

- Pfu DNA Polymerase results in approximately 25.2% of product molecules containing errors [31].

These differences become critically important in applications like cloning, where a single mutation can disrupt protein function, or in next-generation sequencing, where polymerase errors contribute significantly to background noise, especially when detecting low-frequency variants [29].

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on PCR Fidelity

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My PCR produces no amplification product after using a high-fidelity polymerase. What should I check first?

- Verify reaction components: Ensure all PCR components were included, and always run a positive control to confirm component functionality [8].

- Adjust thermal cycling parameters: Increase PCR cycles by 3-5 cycles at a time (up to 40 cycles) for low-abundance templates. Lower annealing temperature in 2°C increments if conditions are too stringent. Increase extension time, as high-fidelity polymerases often require longer extension times than Taq [8].

- Check template quality: Dilute or purify template if PCR inhibitors are present. For difficult templates (>65% GC content), use a polymerase specifically formulated for such templates [8].

- Optimize primer design: Check primers for secondary structures and redesign if necessary. Consider using nested primers with diluted primary PCR product (1:100 to 1:10,000) [8].

Q2: My high-fidelity PCR generates nonspecific bands or smears. How can I improve specificity?

- Increase stringency: Raise annealing temperature in 2°C increments. Use touchdown PCR or a two-step PCR protocol. Reduce the number of PCR cycles to minimize late-cycle artifacts [8] [2].

- Optimize primer design: Use BLAST alignment to verify primer specificity, especially at the 3' ends. Redesign primers if they complement non-target sites [8].

- Adjust template amount: Reduce template amount by 2-5 fold, as excess template can promote nonspecific amplification [8].

- Use hot-start enzymes: Employ hot-start polymerases to prevent primer dimer formation and nonspecific amplification during reaction setup [2].

- Optimize Mg²⁺ concentration: Titrate Mg²⁺ concentration, as excessive Mg²⁺ can decrease specificity and fidelity [2] [32].

Q3: How does polymerase fidelity affect next-generation sequencing results, particularly for low-frequency variant detection?

- Background error contribution: Polymerase errors during library amplification contribute significantly to background noise in NGS, challenging detection of variants below ~1% allele frequency [29].

- Barcoding impact: Unique molecular identifiers (UMIs/barcodes) correct most errors, with barcoding itself having the largest impact on error reduction [29].

- Fidelity improvement: High-fidelity polymerases in the barcoding step further suppress errors, enabling detection below 0.1% allele frequency. However, this improvement is modest compared to the barcoding effect alone [29].

- Practical considerations: For NGS applications, polymerase characteristics like multiplexing capacity, PCR efficiency, and GC-rich amplification capability may outweigh small fidelity differences between high-fidelity enzymes [29].

Q4: What specific reaction conditions can introduce errors even with high-fidelity polymerases?

- Overcycling: Excessive PCR cycles can change reaction pH, reduce polymerase efficiency, deplete dNTPs (increasing misincorporation), and cause accumulation of single-stranded and double-stranded DNA artifacts [8].

- High Mg²⁺ concentration: Elevated Mg²⁺ (typically 1-5 mM) may increase yield but can impair proofreading activity and decrease specificity. Mg²⁺ concentration should always exceed dNTP concentration but be optimized for each reaction [8] [32].

- Template DNA damage: Limit UV exposure during gel analysis/excision, as DNA damage can introduce errors during amplification [8].

- Unbalanced dNTP concentrations: Ensure equivalent concentrations of all four dNTPs ([A] = [T] = [C] = [G]) to prevent misincorporation due to unbalanced nucleotide pools [32].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Fidelity

Direct Sequencing Approach for Fidelity Determination

Principle: This method involves direct sequencing of cloned PCR products to identify and quantify mutations across a large DNA sequence space [30].

Protocol:

- Template Preparation: Select a diverse set of plasmid templates (e.g., 94 unique targets as used in one study) with size range from 360 bp to 3.1 kb and varying GC content (e.g., 35% to 52%) [30].

- PCR Amplification: Use minimal template DNA (e.g., 25 pg/reaction) to maximize the number of doublings. Apply standardized thermocycling conditions: 30 cycles with extension time of 2 minutes/cycle for targets ≤2 kb and 4 minutes/cycle for targets >2 kb [30].

- Cloning and Sequencing: Clone purified PCR products using a system such as Gateway cloning. Sequence sufficient clones to achieve statistical significance (e.g., 8.8 × 10⁴ to 1.0 × 10⁵ total bp sequenced per enzyme) [30].

- Error Rate Calculation: Calculate error rate using the formula: Error Rate = Number of mutations observed / Total bp sequenced. Account for the number of template doublings in the PCR reaction [30].

Applications: This approach allows interrogation of error rates across diverse sequence contexts, making it particularly relevant for large-scale cloning projects where targets span extensive DNA sequence space [30].

Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) Sequencing Fidelity Assay

Principle: PacBio SMRT sequencing directly sequences PCR products without molecular indexing or intermediary amplification, enabling highly accurate consensus sequencing that identifies true replication errors [28].

Protocol:

- Amplicon Selection: Choose an appropriate amplicon (e.g., LacZ gene segment) of sufficient length for meaningful error detection.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify target using polymerase of interest under optimized conditions.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare SMRTbell libraries without amplification steps. Sequence on PacBio platform to generate circular consensus sequences.

- Data Analysis: Derive highly accurate consensus sequences for each read by sequencing the same molecule multiple times. Identify true replication errors by comparing to known template sequence. Calculate errors per base per doubling event [28].

Advantages: This method has an extremely low background error rate (~9.6 × 10⁻⁸ errors/base), making it suitable for quantifying the fidelity of proofreading polymerases. It captures all error types, including substitutions, indels, template switching, and PCR-mediated sequence recombination [28].

Diagram: Experimental workflow for assessing polymerase fidelity through direct sequencing of cloned PCR products.

Buffer Chemistry and Additives for Optimizing Fidelity

Key Buffer Components and Their Effects

The buffer system plays a crucial role in polymerase fidelity, influencing both enzyme activity and template structure.

Table 2: Buffer Components, Additives, and Their Impact on Fidelity

| Component/Additive | Typical Concentration | Effect on PCR | Impact on Fidelity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Magnesium Salt (MgCl₂) | 0.5 - 5.0 mM [32] | Essential cofactor for polymerase activity | Critical: Excessive Mg²⁺ decreases specificity and fidelity [32] |

| Potassium Salt (KCl) | 35 - 100 mM [32] | Stabilizes DNA-DNA hybrids; enhances longer product amplification | Moderate: Affects stringency; typically used with DMSO/glycerol |

| dNTPs | 20 - 200 μM of each [32] | Nucleotide substrates for DNA synthesis | High: Unbalanced concentrations increase misincorporation; low concentrations increase specificity [32] |

| DMSO | 1-10% (often <2%) [32] | Disrupts base pairing; reduces secondary structures | Moderate: Enhances GC-rich amplification but >2% may inhibit polymerase [32] |

| Formamide | 1-10% (often <5%) [32] | Destabilizes DNA duplex; lowers Tm | Moderate: Increases stringency of primer annealing |

| Betaine | 0.5 - 2.5 M [32] | Reduces secondary structures; enhances GC-rich amplification | Moderate: Reduces DNA Tm dependence on dNTP concentration |

| BSA | Up to 0.8 mg/ml [32] | Binds inhibitors; stabilizes enzymes | High: Eliminates effect of PCR inhibitors in difficult samples |

| Nonionic Detergents | 0.1 - 1% [32] | Reduces secondary structures; neutralizes SDS | Moderate: Stabilizes polymerase; prevents secondary structure formation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for High-Fidelity PCR

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Fidelity Optimization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in High-Fidelity PCR |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Polymerases | Q5, Phusion, Pfu, KOD [30] [28] | Provide high nucleotide selectivity and proofreading activity for accurate amplification |

| Proofreading Polymerases | Pfu, Deep Vent, Q5 [28] | Contain 3'→5' exonuclease activity to excise misincorporated nucleotides |

| Hot-Start Enzymes | Antibody-mediated or chemically modified polymerases [2] | Prevent nonspecific amplification and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup |

| GC-Rich Enhancers | Betaine, DMSO, 7-deaza-dGTP [32] | Disrupt secondary structures in GC-rich templates that promote polymerase errors |

| Inhibitor Neutralizers | BSA, Nonionic detergents [32] | Bind contaminants that interfere with polymerase activity or cause errors |

| dNTP Solutions | Balanced dNTP mixes at 10 mM each [32] | Provide equimolar nucleotides to prevent misincorporation from unbalanced pools |

| Optimized Buffers | HF buffers, GC buffers [30] [31] | Provide optimal pH and cofactor concentrations for specific polymerase formulations |

Achieving high fidelity in PCR requires a comprehensive strategy that addresses both polymerase selection and reaction biochemistry. The evidence demonstrates that polymerase choice alone can create up to 280-fold differences in error rates [28], but this inherent fidelity can be compromised by suboptimal reaction conditions. Researchers facing spurious results or product smears should implement a systematic approach: (1) select a polymerase with appropriate fidelity characteristics and proofreading capability for the application; (2) optimize Mg²⁺ concentration and buffer composition specifically for the target template; (3) utilize fidelity-enhancing additives like DMSO or betaine for difficult templates; and (4) establish thermal cycling conditions that balance yield with accuracy. By understanding and manipulating the biochemical foundations of polymerase fidelity, researchers can significantly reduce artifacts and errors, producing more reliable and reproducible results across molecular biology applications.

Building a Robust PCR: Methodologies for Clean and Specific Amplification

Core Principles of Primer Design

This section outlines the fundamental parameters for designing effective PCR primers. Adherence to these guidelines is critical for maximizing specificity and yield, thereby reducing spurious results and product smears in your research.

Table: Key Parameters for Effective Primer Design

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Rationale & Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Length | 18–30 bases (18–25 is common) [33] [26] [34] | Balances specificity (long enough) with efficient binding (short enough) [34]. |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | 55–65°C [34] [35]; 52–58°C [26]; 65–75°C [33] | Primer pair Tm should be within 5°C of each other [33] [26]. |

| GC Content | 40–60% [33] [26] [34] | Provides primer stability; content outside this range can hinder binding [35]. |

| GC Clamp | At least 2 G/C bases in the last 5 bases at the 3' end [34] | Stronger hydrogen bonding of G/C bases stabilizes binding at the critical priming site [33] [34]. |

| 3'-End Stability | Avoid stable secondary structures (very negative ΔG) at the 3' end [34] [36] | An unstable 3' end (less negative ΔG) reduces false priming [36]. |

Design Elements to Avoid

- Repeats and Runs: Avoid runs of 4 or more of a single base (e.g.,

AAAA) or dinucleotide repeats (e.g.,ATATAT), as they can cause mispriming [33] [34] [36]. - Secondary Structures: Check for intra-primer homology (hairpins) and inter-primer homology (self-dimers and cross-dimers), which can reduce product yield [33] [34] [36].

- Cross Homology: Verify primer specificity using tools like NCBI BLAST to ensure primers only bind to the intended target sequence [26] [34].

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for Experimental Issues

FAQ 1: What should I do if I get no amplification or a very low yield?

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Verify Reaction Components: Ensure all PCR components were included. Always include a positive control to confirm reagent functionality [8].

- Increase Cycle Number: Gradually increase the number of PCR cycles by 3–5 cycles at a time, up to 40 cycles, especially for low-abundance templates [8].

- Lower Stringency: If increasing cycles doesn't work, the conditions may be too stringent.

- Check Primer Design: Ensure primers meet all optimal design parameters and are specific to the target. Consider using nested primers for difficult templates [8].

FAQ 2: How can I eliminate non-specific bands and smearing on my gel?

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Increase Specificity:

- Optimize Reaction Components:

- Address Contamination: If a negative control (no template) also shows smearing, contamination is likely. Replace all reagents, use aerosol-filter pipette tips, and decontaminate workspaces and equipment with UV light or 10% bleach [8].

FAQ 3: Why do I see primer-dimer formation, and how can I prevent it?

Primer-dimer occurs when primers anneal to each other instead of the template DNA, producing a short, unwanted product [2].

Prevention Strategies:

- Careful Primer Design: Check for and avoid complementarity between the 3' ends of the forward and reverse primers [26] [34].

- Optimize Reaction Conditions:

- Use Hot-Start Polymerases: These enzymes remain inactive until a high-temperature activation step, preventing polymerase activity during reaction setup that can extend primer-dimers [2].

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Primer Design and Optimization

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for designing and validating primers, integral to a thesis focused on eliminating spurious PCR results.

Step 1: In Silico Primer Design

- Sequence Acquisition: Obtain the target DNA sequence from a reliable database (e.g., NCBI).

- Parameter Setting: Use primer design software (e.g., Primer3, Primer-BLAST [26] [35]) with the following inputs:

- Product Size: Specify the desired amplicon length.

- Primer Length: Set to 18–30 bp.

- Tm: Set optimum to 60°C with a maximum difference of 5°C between primers.

- GC Content: Set between 40–60%.

- Specificity Check: Analyze the proposed primer sequences using NCBI Primer-BLAST to ensure they are unique to your target gene [26] [34].

- Secondary Structure Analysis: Use software (e.g., Benchling) to check for hairpins and self-dimers. Avoid primers with stable 3' end structures [34] [36].

Step 2: Laboratory Validation and Optimization

- Prepare Reaction Mixture:

- Set up a standard 50 µL PCR reaction on ice [26] [22].

- Template DNA: 1–1000 ng (104–107 molecules) [26].

- Primers: 20–50 pmol each (e.g., 1 µL of 20 µM stock) [26].

- dNTPs: 200 µM (e.g., 1 µL of 10 mM dNTP mix) [26].

- PCR Buffer: 1X concentration (e.g., 5 µL of 10X buffer) [26].

- MgCl2: 1.5 mM final concentration (adjust if not in buffer) [26].

- DNA Polymerase: 0.5–2.5 units per 50 µL reaction [26].

- Nuclease-free Water: to 50 µL.

- Thermal Cycling (Initial Run):

- Initial Denaturation: 94–95°C for 2–5 minutes.

- Amplification (25–35 cycles):

- Denature: 94–95°C for 30 seconds.

- Anneal: Use a gradient cycler from 5°C below to 5°C above the calculated primer Tm for 30 seconds.

- Extend: 72°C for 1 minute per kb of product.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5–10 minutes [22].

- Analyze Results:

- Run PCR products on an agarose gel.

- A single, sharp band at the expected size indicates success.

- If results are suboptimal (no band, smearing, multiple bands), proceed to Step 3.

Step 3: Troubleshooting and Optimization Workflow

Follow this logical pathway to diagnose and resolve common PCR problems.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PCR Troubleshooting

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Application in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Prevents non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation by remaining inactive until a high-temperature activation step [2] [22]. |

| MgCl2 Solution | Critical cofactor for DNA polymerase. Concentration must be optimized (1.5–5.0 mM); excess can cause non-specific products, while too little reduces yield [26] [7] [22]. |

| PCR Additives (BSA, Betaine, DMSO) | Help amplify difficult templates (e.g., GC-rich sequences) by reducing secondary structure or binding inhibitors [26] [2] [22]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Ensures reactions are not degraded by environmental nucleases, a critical factor for reproducibility [8] [22]. |

| Primer Design Software (e.g., Primer-BLAST) | Designs primers based on key parameters and checks for specificity against genomic databases to avoid off-target binding [26] [34] [35]. |

| Gradient Thermal Cycler | Empirically determines the optimal annealing temperature for a primer set in a single run, a cornerstone of efficient optimization [22]. |

A PCR master mix is a pre-mixed, optimized solution containing all the essential components required to execute a Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), except for the template DNA and gene-specific primers [37] [38]. This premixed formulation typically includes a thermostable DNA polymerase (such as Taq polymerase), deoxynucleotides (dNTPs), magnesium ions (MgCl₂ or MgSO₄), and a proprietary reaction buffer [37] [38]. The fundamental purpose of the master mix is to streamline reaction setup, enhance experimental consistency, and significantly reduce the risk of contamination [37].

The adoption of a master mix approach directly addresses two critical challenges in molecular biology: reproducibility and contamination. By providing a consistent baseline of reagents across all reaction tubes, it minimizes pipetting variations and prevents the omission of critical components, thereby ensuring greater experimental reproducibility [37]. Furthermore, by reducing the number of pipetting steps and tube openings required, it directly lowers the opportunity for introducing contaminants into the reactions [37] [38]. This is particularly crucial for sensitive applications like diagnostic PCR and high-throughput screening, where false positives can have significant consequences [39].

Understanding and Preventing Contamination

Contamination is one of the most persistent challenges in PCR laboratories, potentially leading to false-positive results and jeopardizing experimental integrity. The extreme sensitivity of PCR, which allows for the amplification of a few DNA molecules, also makes it vulnerable to amplification of contaminating DNA [40] [39]. The primary sources of contamination include carryover contamination from previous PCR amplifications (amplicons), cross-contamination between samples, and contamination from laboratory reagents and environments [41] [39].

Laboratory Setup and Workflow

A properly designed laboratory workflow is the first line of defense against PCR contamination. The following diagram illustrates the essential principle of a unidirectional workflow that must be maintained to prevent amplicon contamination.

This physical separation should be reinforced with dedicated equipment, supplies, and personal protective equipment (PPE) for each area [41]. Movement of personnel should follow the workflow direction, and those who have entered post-amplification areas should not return to pre-amplification areas on the same day without thorough decontamination [40] [41].

Practical Contamination Control Measures

| Control Measure | Description | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| No-Template Controls (NTC) | Reaction containing all components except DNA template [40] | Detects contamination in reagents or environment [40] |

| Aerosol-Barrier Tips | Pipette tips with internal filters [41] | Prevents aerosol contamination from entering pipettors |

| Surface Decontamination | Cleaning with 10-15% bleach (freshly diluted) followed by 70% ethanol and UV irradiation [40] [41] | Destroys contaminating DNA on surfaces and equipment |

| Enzymatic Control (UNG) | Using uracil-N-glycosylase with dUTP instead of dTTP in PCR [40] [39] | Selectively degrades contaminating amplicons from previous reactions |

| Reagent Aliquoting | Dividing bulk reagents into single-use aliquots [40] | Prevents widespread contamination of stock reagents |

Uracil-N-Glycosylase (UNG) is particularly effective against carryover contamination. This method involves incorporating dUTP instead of dTTP during PCR, making all newly synthesized amplicons susceptible to degradation by UNG enzyme. Before the next PCR experiment, UNG treatment cleaves any contaminating uracil-containing amplicons, while native thymine-containing template DNA remains unaffected. The UNG is then inactivated during the initial denaturation step of the PCR cycle [40] [39].

Master Mix Protocols and Formulations

Standard Master Mix Protocol

The following table outlines a standard protocol for setting up a PCR reaction using a commercial 2X master mix:

| Component | Volume for 50 µL Reaction | Final Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| 2X PCR Master Mix | 25 µL | 1X |

| Forward Primer (10 µM) | 2 µL | 400 nM |

| Reverse Primer (10 µM) | 2 µL | 400 nM |

| Template DNA | Variable (e.g., 0.5-2 µL) | 10 pg-1 µg |

| Nuclease-Free Water | To 50 µL | - |

Note: Component volumes may vary slightly depending on the specific commercial master mix used. Always refer to the manufacturer's instructions [42] [43] [44].

Specialized Master Mix Formulations

Different PCR applications require specifically optimized master mixes. The table below summarizes common types and their applications:

| Master Mix Type | Key Components | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Routine PCR | Taq DNA Polymerase, buffer, dNTPs, MgCl₂ [37] | Standard amplification of DNA fragments up to ~5 kb [37] [44] |

| Hot-Start PCR | Antibody-mediated or chemically modified polymerase activated at high temperature [42] | Multiplex PCR, reduction of primer-dimers, high-specificity applications [37] [2] |

| High-Fidelity PCR | Polymerase with proofreading activity (e.g., KOD, Pfu) [37] | Cloning, sequencing, and applications requiring low error rates [37] |

| Long-Range PCR | Blend of polymerases optimized for long extensions [43] | Amplification of targets up to 40 kb [43] |

| Multiplex PCR | Optimized buffer with enhanced salt concentrations and stabilizers [42] | Simultaneous amplification of multiple targets in a single tube [42] |

| qPCR/SYBR Green | Hot-start Taq, SYBR Green dye, passive reference dye (e.g., ROX) [37] [38] | Quantitative gene expression analysis, melting curve analysis [37] |

Troubleshooting Common PCR Issues

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: I see no amplification or very low yield in my PCR. What should I check first? A: Begin by verifying the quality and concentration of your DNA template using spectrophotometry or fluorometry [2]. Ensure all reaction components were added correctly, and consider running a positive control. Optimization may involve adjusting the annealing temperature (typically 5°C below the primer Tm), Mg²⁺ concentration (0.5-5.0 mM), or the amount of DNA polymerase [26] [2].

Q: My agarose gel shows multiple non-specific bands instead of a single clean product. How can I improve specificity? A: Non-specific amplification is often due to low reaction stringency [2]. Try: 1) Increasing the annealing temperature in 2°C increments, 2) Using a hot-start master mix to prevent primer extension during reaction setup [2], 3) Optimizing Mg²⁺ concentration (reduce if too high), 4) Ensuring primers are specific and do not form secondary structures [26] [2].

Q: What causes primer-dimer formation, and how can I prevent it? A: Primer-dimer occurs when primers anneal to each other due to complementary 3' ends [26] [2]. Prevention strategies include: 1) Careful primer design to avoid 3' complementarity, 2) Reducing primer concentration (typically 0.2-1 µM final), 3) Using a hot-start enzyme, 4) Increasing annealing temperature, and 5) Optimizing cycling conditions to reduce time at low temperatures [26] [2].

Q: I observe smeared bands on my agarose gel. What does this indicate? A: Smeared bands can result from several issues: 1) Degraded DNA template - check template quality, 2) Excessive cycle numbers leading to accumulated non-specific products - reduce cycle number, 3) Contamination with amplifiable DNA from previous experiments - implement strict laboratory separation and use a new primer set if needed [2], 4) Too much template DNA - titrate template amount [2].

Q: How can I overcome PCR inhibition from my sample? A: Inhibitors can be present in biological samples or from purification reagents [2]. Solutions include: 1) Diluting the template sample, 2) Using additives like BSA (10-100 µg/mL) or betaine (0.5-2.5 M) [26] [2], 3) Purifying the template DNA again, preferably with a method designed for PCR, 4) Using a master mix specifically formulated for inhibited samples [2].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for successful PCR experiments using the master mix method:

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| PCR Master Mix (2X) | Premixed solution of polymerase, dNTPs, Mg²⁺, and buffer [37] | Choose type (standard, hot-start, high-fidelity) based on application [37] |

| Primers (Oligonucleotides) | Sequence-specific initiation of DNA synthesis [26] | Design for 18-30 bp length, 40-60% GC content, and similar Tm (52-65°C) [26] |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Solvent for reactions and dilutions | Essential to avoid degradation of reagents and templates by nucleases |

| Aerosol-Barrier Pipette Tips | Precise liquid handling while preventing contamination [41] | Critical for preventing cross-contamination between samples |

| Positive Control Template | DNA known to amplify with your primers | Verifies reaction efficiency and helps troubleshoot failed experiments |

| DNA Molecular Weight Marker | Size standard for agarose gel electrophoresis | Essential for confirming the expected size of amplification products |

| PCR Tubes/Plates | Reaction vessels compatible with thermal cyclers | Thin-walled materials ensure optimal thermal conductivity |

| Agarose | Matrix for gel electrophoresis | Standard agarose (1-2%) for resolving most PCR products (100-3000 bp) |

The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a foundational technique in molecular biology, yet its success is highly dependent on the meticulousness of the initial setup. Spurious results, such as product smears or complete amplification failure, are often traceable to suboptimal practices during the pre-amplification stages. This guide provides a systematic protocol for reagent thawing, pipetting, and reaction assembly, forming the first line of defense against common PCR artifacts and ensuring reproducible, high-quality results for research and drug development.

Pre-Assembly Preparations

Laboratory Setup and Contamination Control

A controlled environment is non-negotiable for successful PCR assembly.

- Dedicated Work Areas: Establish physically separated pre-PCR and post-PCR areas. Equipment, lab coats, pipettes, and waste containers should not be moved between these areas [8].

- Workstation Decontamination: Before beginning, clear the laminar flow hood or workbench and thoroughly wipe all surfaces with 70% alcohol. If available, expose the workspace and equipment to UV light for at least 10 minutes [45].

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Always wear gloves throughout the entire setup procedure to prevent contamination from nucleases or previously amplified DNA [21] [8].

Reagent Thawing and Preparation

Proper handling of reagents is critical for maintaining enzyme activity and reaction consistency.

- Systematic Thawing: Retrieve all necessary PCR reagents from the freezer and organize them. Thaw all components except the DNA polymerase on ice. The polymerase should be kept in a cooling block or ice bucket until the moment of use, as it is often stored in a glycerol solution that maintains its liquid state even at -20°C [46] [45].

- Homogenization and Centrifugation: Once thawed, vortex each reagent for approximately 5 seconds. Subsequently, spin them down in a mini-centrifuge to ensure all liquid is collected at the bottom of the tube. Keep all reagents on ice throughout the experiment [21] [45].

Table: Recommended Reagent Storage and Handling Practices

| Reagent | Storage | Thawing Method | Post-Thaw Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10X Buffer | -20°C | On ice | Vortex & brief centrifugation |

| dNTPs | -20°C | On ice | Vortex & brief centrifugation |

| Primers | -20°C | On ice | Vortex & brief centrifugation |

| DNA Template | -20°C or 4°C | On ice or at room temperature | Vortex & brief centrifugation if necessary |

| Taq Polymerase | -20°C | Place directly on ice; remains liquid | Mix gently by pipetting; do not vortex |

Reaction Assembly Protocol

Master Mix Formulation

The use of a Master Mix is highly recommended to minimize pipetting errors, tube-to-tube variation, and contamination risk [21].

- Label a sterile 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube for the Master Mix and place it on ice [45].

- Calculate the required volumes for your experiment. It is standard practice to prepare a Master Mix for (n + 1) reactions, where 'n' is the number of planned reactions, to account for pipetting tolerance and ensure sufficient volume [46].

- Add components to the Master Mix tube in the following order: sterile water, 10X PCR buffer, dNTPs, MgCl₂ (if not in the buffer), and primers [21]. Using a barrier pipette tip for each ingredient is advised to prevent aerosol contamination [45].

- Mix the contents gently by vortexing and then centrifuge briefly [45].

- Add the DNA polymerase last. Mix the complete Master Mix gently by pipetting up and down at least 20 times. Avoid introducing bubbles. The micropipettor should be set to about half the reaction volume during this mixing step [21].

Table: Example of a 25 µL Reaction Master Mix

| Component | Example Concentration | Volume per 25 µL Reaction | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sterile dH₂O | - | 20 µl | Q.S. to final volume |

| 10X Buffer | 1X | 2.5 µl | Optimal enzymatic conditions |

| dNTPs | 200 µM | 0.5 µl | DNA building blocks |

| Primer #1 | 0.5 µM | 0.25 µl | Forward binding site |

| Primer #2 | 0.5 µM | 0.25 µl | Reverse binding site |

| DNA Polymerase | 0.05 U/µl | 0.25 µl | Enzymatic amplification |

| DNA Template | Variable | 1 µl | Target sequence |

Aliquotting and Template Addition

This step finalizes the reaction setup before thermal cycling.

- Label individual PCR tubes or a 96-well plate to match your samples and include a negative control [21] [45].

- Dispense the appropriate volume of Master Mix into each labeled tube [45].

- Add template DNA. Using a new barrier pipette tip for each sample, pipette the required volume of DNA into the individual tubes. Visually confirm that the DNA has been delivered into the Master Mix and not remained on the tube wall [45].

- Prepare a negative control. One tube should contain all Master Mix ingredients but no template DNA. Increase the volume of water to compensate for the missing DNA volume [21].

- Cap the tubes securely and load them into the thermocycler. Briefly spin all tubes in a mini-centrifuge to collect all liquid at the bottom before starting the run [45].

Systematic PCR Assembly Workflow

Troubleshooting Common Setup Issues

FAQ: What should I do if I get no amplification product?

- First, verify all components were added. A positive control using known functional reagents and template is essential for this check [8].

- Check the systematic setup. Ensure reagents were thawed completely and mixed properly before use. Non-homogeneous reagents can create density gradients that lead to reaction failure [22].

- Consider template quality and quantity. Inhibitors from the sample preparation can be co-purified with DNA. Diluting the template or purifying it further can help. Also, verify the DNA concentration and integrity [8] [22].

- Troubleshoot the reaction mix. If the problem persists, systematically add fresh working stocks of each reagent one at a time to identify if a specific component has degraded or is inhibitory [2].

FAQ: How can I prevent nonspecific bands and smears in my gel?

- Optimize annealing temperature. A temperature that is too low is a common cause of nonspecific binding. Increase the temperature in 2°C increments or use a gradient PCR block to find the optimal temperature [8] [47].

- Use a hot-start polymerase. These enzymes remain inactive until a high-temperature activation step, preventing primer-dimer formation and nonspecific extension during reaction setup [2] [22].

- Reduce template or primer amount. Too much template or primer can promote mispriming. Reduce the template amount by 2–5 fold and ensure primer concentrations are typically between 0.1–1 µM [8] [22].

- Check for contamination. If a smear appears in the negative control, the reaction is contaminated with exogenous DNA. Replace reagents and decontaminate the workspace [8].

FAQ: Why did my previously working PCR assay suddenly fail?

- Test reagent batches. On rare occasions, a new batch of a core reagent (e.g., polymerase buffer) may be incompatible with a specific assay, even if it passes the manufacturer's quality control. Test the assay with an old batch or a different manufacturer [48].

- Verify thermal cycler calibration. An inconsistent block temperature can cause failure. Test the calibration of the heating block [47].

- Check for primer degradation. Over time, primers can degrade, especially after multiple freeze-thaw cycles. Use fresh primer aliquots [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents for PCR Setup and Troubleshooting

| Reagent/Solution | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Prevents enzymatic activity until initial denaturation, reducing primer-dimer and non-specific amplification [2]. | Essential for complex templates and high-specificity assays. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Binds to PCR inhibitors present in the template DNA, neutralizing their effects [21] [2]. | Use at 10–100 µg/ml final concentration when impurities are suspected. |

| DMSO (Dimethylsulfoxide) | A co-solvent that aids in denaturing DNA with high GC-content or complex secondary structures [21] [22]. | Typical final concentration is 1–10%. Use the lowest effective concentration. |

| Betaine | Reduces the melting temperature of DNA strands, aiding in the uniform denaturation of GC-rich templates [21]. | Can be used at 0.5 M to 2.5 M final concentration. |

| Magnesium Chloride (MgCl₂) | Cofactor for DNA polymerase; concentration directly affects primer annealing, enzyme fidelity, and yield [21] [47]. | Optimize between 1–5 mM; concentration must exceed total dNTP concentration. |

| Agencourt AMPure XP Beads | Solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) beads for post-amplification purification and size selection [49]. | Critical for cleaning up PCR products before downstream applications like sequencing. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary mechanism by which Touchdown PCR increases specificity?

Touchdown PCR enhances specificity by systematically varying the annealing temperature during the cycling program. The process begins with an annealing temperature set 5–10°C above the calculated melting temperature (Tm) of the primers [50] [51]. This high initial temperature favors only the most specific primer-template binding, minimizing off-target priming. The annealing temperature is then gradually decreased in steps of 1–2°C per cycle until it reaches a temperature 2–5°C below the primers' Tm [50] [52]. This method ensures that specific amplicons, amplified in the initial stringent cycles, become the dominant products and outcompete any non-specific sequences in later cycles [53].

2. When should I consider using Touchdown PCR?

You should consider Touchdown PCR in the following scenarios:

- When you observe non-specific amplification bands or smearing on your agarose gel [8].

- When amplifying templates with high GC content or complex secondary structures [54] [55].

- When the primer sequence is not perfectly complementary to the template, such as when primers are designed from amino acid sequences or when amplifying across species boundaries [51].

- In multiplex PCR assays to reduce cross-binding and non-specific amplification from multiple primer sets [55].

3. Why is Hot-Start Polymerase recommended for use with Touchdown PCR?

Hot-start polymerases are recommended because they remain inactive until a high-temperature step (usually the initial denaturation) is applied [52]. This prevents enzymatic activity during reaction setup on the bench or during the initial, high-temperature annealing cycles of Touchdown PCR. By inhibiting polymerase activity at lower temperatures, hot-start enzymes further reduce the formation of primer-dimers and non-specific products that can occur before cycling begins, thereby complementing the specificity gains of the Touchdown protocol [8] [52].

4. What are the most common causes of smearing in PCR, and how can these be addressed?

A smear on an agarose gel indicates a heterogeneous mixture of DNA fragments. Common causes and solutions include:

- Non-specific primer annealing: Increase annealing temperature, use Touchdown PCR, or redesign primers [8].

- Too many cycles: Reduce the number of PCR cycles, as overcycling can lead to smearing [8].

- Excess template: Reduce the amount of template DNA by 2–5 fold [8].

- Contamination: Always include a negative control (no template). If the control is smeared, decontaminate your workspace and reagents, and use separate pre- and post-PCR areas [8].

- Long extension times: For some high-speed polymerases, excessively long extension times can cause smearing; follow manufacturer guidelines [8].

5. My PCR shows no product. What are the first parameters to check?

If you get no amplification, first verify the following:

- All reaction components: Ensure all PCR components were added, and always include a positive control [8].

- Number of cycles: Increase the number of cycles by 3–5 at a time, up to 40 cycles, to account for low-abundance templates [8].

- Stringency: Lower the annealing temperature in increments of 2°C if conditions are too stringent [8].

- Extension time: Increase the extension time, especially for longer amplicons [8].

- Template quality: Check for PCR inhibitors; dilute or purify the template if necessary [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Non-Specific Bands or Multiple Bands

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Primers annealing non-specifically.

- Cause: PCR conditions are not stringent enough.

- Solution: Use a two-step PCR protocol (combining annealing and extension). Reduce the number of PCR cycles [8].

- Cause: Too much template DNA.

- Solution: Reduce the amount of template by 2–5 fold [8].

- Cause: Suboptimal primer design.

Problem 2: Faint or No Bands (PCR Failure)

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Insufficient number of cycles for low-abundance template.

- Solution: Increase the number of cycles by 3–5, up to 40 cycles [8].

- Cause: Annealing temperature is too high.

- Solution: Lower the annealing temperature in increments of 2°C [8].

- Cause: Presence of PCR inhibitors in the template.

- Solution: Dilute the template 100-fold or purify it using a PCR clean-up kit. Use a polymerase tolerant to impurities [8].

- Cause: Inefficient priming or extension.

- Solution: Increase primer concentration. Increase extension time, particularly for long amplicons or complex templates like genomic DNA [8].

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: Touchdown PCR

This protocol is designed to be used with a hot-start DNA polymerase.

1. Reagent Setup: Prepare a master mix on ice. The following table summarizes the reagents and their typical final concentrations for a 50 µl reaction [15] [26].

Table 1: Reaction Mixture for Touchdown PCR

| Component | Final Concentration/Amount | Volume per 50 µl Reaction | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10X PCR Buffer | 1X | 5 µl | Supplied with polymerase; may contain Mg²⁺ |

| dNTP Mix | 200 µM (each) | 1 µl (of 10 mM total) | |

| MgCl₂ | 1.5 - 4.0 mM | Variable | Add only if not in buffer; concentration requires optimization [15]. |

| Forward Primer | 0.2 - 0.5 µM | 1 µl (of 20 µM stock) | |

| Reverse Primer | 0.2 - 0.5 µM | 1 µl (of 20 µM stock) | |

| Template DNA | 1 - 1000 ng | Variable | 10^4 - 10^7 molecules [15]. |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | 0.5 - 2.5 units | Variable | Follow manufacturer's recommendation. |

| Sterile Water | - | To 50 µl |

2. Thermal Cycling Conditions: The cycling program is divided into two main phases. The example below assumes a primer Tm of 57°C [52].

Table 2: Touchdown PCR Thermal Cycler Program

| Step | Temperature | Time | Cycles | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Denaturation | 95°C | 3 min | 1 | Activates hot-start polymerase, fully denatures template. |

| Touchdown Phase | 10 cycles | |||

| › Denaturation | 95°C | 30 sec | ||

| › Annealing | 67°C (-1°C/cycle) | 45 sec | Starts at Tm+10°C, decreases by 1°C per cycle. | |

| › Extension | 72°C | 45 sec/kb | ||

| Amplification Phase | 20-25 cycles | |||

| › Denaturation | 95°C | 30 sec | ||

| › Annealing | 57°C (constant) | 45 sec | Uses final, lower annealing temperature. | |