PCR Mastery: A Comprehensive Guide from Basic Protocol to Advanced Troubleshooting

This article provides a complete guide to the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for researchers and drug development professionals.

PCR Mastery: A Comprehensive Guide from Basic Protocol to Advanced Troubleshooting

Abstract

This article provides a complete guide to the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles and the revolutionary history of PCR, detailed step-by-step protocols and diverse clinical applications, systematic troubleshooting for common pitfalls like low yield and nonspecific products, and a comparative analysis with other nucleic acid amplification techniques. The content integrates the most current validation standards and innovative optimization strategies, including the use of universal annealing temperatures and specialized polymerases, to empower scientists in achieving robust, reproducible, and highly specific amplification for both research and diagnostic purposes.

The Foundations of PCR: From Theoretical Concept to Revolutionary Tool

The Polymerase Chain Reaction: Basic Principles and Protocol

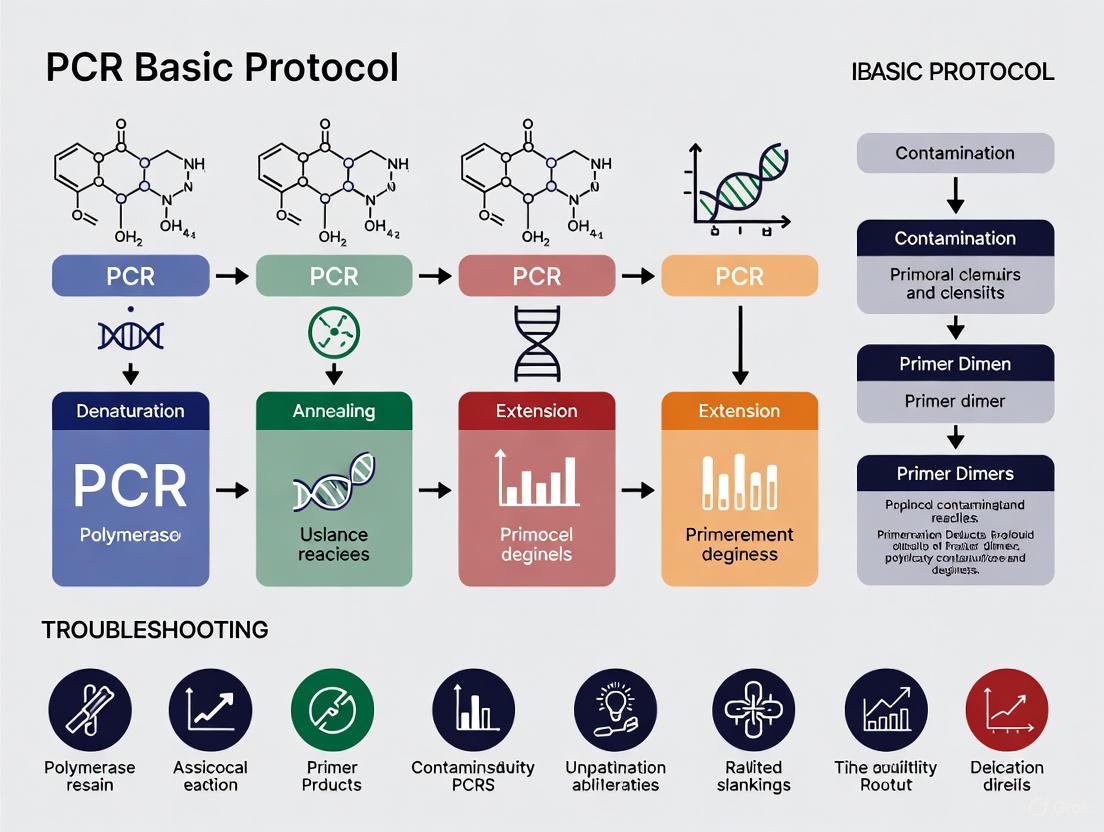

The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a foundational enzymatic assay that revolutionized biological science by enabling the rapid amplification of specific DNA fragments from a complex pool of genetic material [1]. First discovered by Kary Mullis in the 1980s, this technique allows researchers to selectively amplify millions to billions of copies of a targeted DNA segment, making it possible to study minute quantities of DNA in great detail [2] [3]. PCR works by repeating cycles of DNA denaturation, primer annealing, and primer extension using a thermostable DNA polymerase, facilitating the exponential amplification of the target sequence [1].

Core Components of a PCR Reaction

A standard PCR reaction requires several key components, each playing a critical role in the amplification process. The precise assembly of these components is crucial for successful DNA amplification.

- Template DNA: The DNA sample containing the target sequence to be amplified. Only trace amounts are needed, as PCR is highly sensitive [1].

- Primers: Short, synthetic DNA fragments (typically 20-25 nucleotides) that are complementary to the sequences flanking the target DNA. They define the specific region to be amplified [1] [2].

- DNA Polymerase: A thermostable enzyme, most commonly Taq polymerase isolated from Thermus aquaticus, that synthesizes new DNA strands by adding nucleotides to the primers. Its heat stability allows it to withstand the high denaturation temperatures of each cycle [2].

- Deoxynucleotides (dNTPs): The building blocks of DNA, consisting of adenine (A), thymine (T), cytosine (C), and guanine (G). The DNA polymerase uses these to build the new DNA strands [1].

- Reaction Buffer: Provides the optimal chemical environment (pH and ionic strength) for the DNA polymerase to function efficiently [4].

- Divalent Cations (Mg²⁺): Magnesium ions (Mg²⁺) are a critical cofactor for DNA polymerase activity. Its concentration often requires optimization for specific primer-template systems [5] [6].

Table 1: Standard PCR Reaction Setup (50 µL Volume)

| Component | Final Concentration/Amount | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Water | To 50 µL | Solvent and volume adjuster |

| Buffer (10X) | 1X | Provides optimal reaction conditions (pH, salts) |

| dNTP Mix | 200 µM | Building blocks for new DNA strands |

| MgCl₂ | 0.1-0.5 mM | Essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity |

| Forward Primer | 0.1-0.5 µM | Binds to the complementary strand to define the 5' end of the amplicon |

| Reverse Primer | 0.1-0.5 µM | Binds to the opposite strand to define the 3' end of the amplicon |

| Template DNA | ~200 pg/µL (varies by complexity) | The source DNA containing the target sequence to be copied |

| DNA Polymerase (e.g., Taq) | 0.05 units/µL | Enzyme that catalyzes the synthesis of new DNA strands |

| DMSO (optional) | 1-10% | Additive to help denature GC-rich templates with secondary structures |

Standard PCR Protocol and Thermal Cycling Conditions

The PCR process is carried out in a thermal cycler, which is programmed to rapidly change temperatures for precise time intervals. The following protocol outlines the standard steps for a traditional PCR amplification [4].

- Reaction Assembly: Thaw all reagents on ice. Assemble the reaction mix in a thin-walled 0.2 mL PCR tube in the order listed in Table 1. Gently mix by tapping the tube and briefly centrifuge to collect all contents at the bottom. Include negative (no template) and positive (template of known size) controls.

- Thermal Cycling: Place the reaction tubes in the thermal cycler and run the program with the following steps:

Table 2: Standard PCR Thermal Cycling Conditions

| Step | Temperature | Time | Cycles | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Denaturation | 94°C | 5 minutes | 1 | Completely denature complex DNA and activate hot-start enzymes |

| Denaturation | 94°C | 30 seconds | 25-35 | Separate double-stranded DNA templates before each cycle |

| Annealing | (Tm of primers) - 5°C | 45 seconds | 25-35 | Allow primers to bind to their complementary sequences on the single-stranded DNA |

| Extension | 72°C | 1 minute per kb | 25-35 | Synthesize new DNA strands from the 3' end of the primers |

| Final Extension | 72°C | 5-10 minutes | 1 | Ensure all PCR products are fully extended |

- Post-Amplification Analysis: After cycling, hold the reactions at 4°C. Analyze the PCR products by loading an aliquot onto an agarose gel for electrophoresis. The DNA can be visualized by staining with intercalating dyes like ethidium bromide and examining under UV light [1].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The reliability of PCR results is contingent upon the quality and appropriateness of the reagents used. The following table details key reagent solutions and their critical functions in a PCR experiment [5] [6] [7].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PCR

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Polymerases | Standard Taq, Hot-Start Taq, High-Fidelity (e.g., Q5, Phusion) | Catalyzes DNA synthesis. Hot-Start reduces pre-amplification mis-priming. High-Fidelity polymerases have proofreading to reduce errors [5] [6]. |

| Specialized Buffers & Enhancers | GC Enhancer, Mg²⁺ Solution (MgCl₂ or MgSO₄), DMSO | Optimizes reaction conditions. Mg²⁺ is a crucial cofactor. GC enhancers and DMSO help denature difficult templates with high GC-content or secondary structures [5]. |

| Primer Design Tools | Online algorithms (e.g., NCBI Primer-BLAST), Commercial assay design tools | Ensures primers are specific to the target, have appropriate melting temperatures (Tm), and minimize self-complementarity to avoid primer-dimer artifacts [5] [7]. |

| Quantification Chemistry | SYBR Green dye, TaqMan probes | For real-time PCR (qPCR). SYBR Green binds dsDNA non-specifically. TaqMan probes provide target-specific detection through a fluorogenic probe [7]. |

| Nucleic Acid Purification Kits | Silica-column based kits, Alcohol precipitation kits, Monophasic lysis reagents | Isolves high-quality, inhibitor-free template DNA/RNA. Essential for removing contaminants like phenol, EDTA, or heparin that can inhibit polymerase activity [5] [2]. |

Advanced PCR Applications: Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR)

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), also known as real-time PCR, represents a significant technological advancement over traditional PCR. It allows for the accurate quantification of DNA (or RNA, when combined with reverse transcription in RT-qPCR) as the amplification occurs, rather than at the end of the process [7]. This is achieved by incorporating fluorescent reporters into the reaction, with the signal intensity being proportional to the amount of amplified product [2] [8].

Key Concepts in qPCR Data Interpretation

Understanding the output of a qPCR run is critical for accurate gene expression analysis or quantification.

- Amplification Curve: This sigmoidal plot represents the accumulation of fluorescence (DNA product) over the course of cycling. It consists of three phases: the baseline (initial cycles with background fluorescence), the exponential phase (where reliable quantification occurs), and the plateau (where reagents are depleted) [8] [7].

- Threshold: A fluorescence level set within the exponential phase, sufficiently above the baseline, used to define a point of detection that is common to all samples in the run [8].

- Quantification Cycle (Cq): Formerly known as Ct, this is the PCR cycle number at which the sample's amplification curve intersects the threshold. The Cq value is inversely proportional to the starting quantity of the target nucleic acid; a lower Cq indicates a higher initial amount of target [2] [8].

- PCR Efficiency: A measure of how effectively the target is being amplified in each cycle. Ideal efficiency is 100%, meaning the product doubles every cycle. Efficiency between 90-110% is generally acceptable and is calculated from the slope of a standard curve generated from serial dilutions: Efficiency (%) = (10^(-1/slope) - 1) × 100 [8].

One-Step vs. Two-Step RT-qPCR

For gene expression analysis, RT-qPCR is the standard method. The process can be performed in one or two steps, each with distinct advantages.

- One-Step RT-qPCR: The reverse transcription (RT) and PCR amplification are performed sequentially in a single tube. This method is faster, reduces pipetting steps and contamination risk, and is ideal for high-throughput analysis of a single target [7].

- Two-Step RT-qPCR: The RT reaction is performed first to generate complementary DNA (cDNA) from all RNA in a sample. An aliquot of this cDNA is then used in subsequent qPCR reactions. This method offers flexibility, as the cDNA can be stored and used to assay multiple different targets over time [7].

Comprehensive PCR Troubleshooting Guide

Despite its robustness, PCR can encounter issues. Systematic troubleshooting is essential to resolve common problems related to yield, specificity, and fidelity.

Common PCR Problems and Solutions

Table 4: Troubleshooting Common PCR Issues

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No Product | Poor template quality or quantityIncorrect annealing temperatureMissing reaction componentInsufficient Mg²⁺ | Repurify template; assess integrity and concentration by gel electrophoresis and spectrophotometry [5] [6].Use a gradient thermal cycler to optimize annealing temperature; recalculate primer Tm [6].Check reagent addition; include positive control [6].Optimize Mg²⁺ concentration in 0.2-1 mM increments [5] [6]. |

| Multiple or Non-Specific Bands | Low annealing temperatureExcess primers, enzyme, or Mg²⁺Primers binding non-specifically | Increase annealing temperature stepwise (1-2°C increments) [5].Optimize concentrations of primers (0.1-1 µM), enzyme, and Mg²⁺ [5] [6].Use hot-start DNA polymerase to prevent mis-priming at low temperatures; redesign primers for better specificity [5] [6]. |

| Faint or Low Yield | Too few cyclesInsufficient template or reagentsSuboptimal extension time/temperaturePCR inhibitors present | Increase cycle number (up to 40 for low copy number targets) [5].Check template amount and increase if necessary; ensure fresh, fully-concentrated dNTPs and enzyme are used [5].Increase extension time (1 min/kb); ensure extension temperature is correct (usually 68-72°C) [5] [4].Further purify template DNA via ethanol precipitation or column purification [5] [6]. |

| Smear or High Background | Excessive template DNADegraded templateNon-specific primingToo many cycles | Reduce the amount of input template DNA [5].Run intact, high-quality template on a gel to check for degradation [5].Increase annealing temperature; optimize Mg²⁺ concentration [5] [6].Reduce the number of amplification cycles [5]. |

| Sequence Errors (Low Fidelity) | Low-fidelity DNA polymeraseUnbalanced dNTP concentrationsExcessive Mg²⁺Too many cycles | Use a high-fidelity polymerase with proofreading activity (e.g., Q5, Phusion) [5] [6].Use fresh, equimolar dNTP mix [5] [6].Reduce Mg²⁺ concentration, as excess Mg²⁺ can increase misincorporation [5].Reduce cycle number and increase input DNA if possible [5]. |

The development of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) represents a transformative milestone in molecular biology, enabled by critical contributions from multiple scientists across decades. This application note details the key historical breakthroughs, from Kjell Kleppe's initial theoretical concept to Kary Mullis's practical implementation and the pivotal incorporation of Taq polymerase. Within the context of PCR research and troubleshooting, we provide standardized protocols for conventional PCR, guidelines for reagent preparation, and strategies for optimizing amplification efficiency. The integration of thermostable Taq polymerase solved the fundamental limitation of enzyme thermolability, revolutionizing genetic analysis and enabling applications across diagnostics, forensics, and biomedical research.

The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) has fundamentally transformed molecular biology since its widespread adoption in the 1980s, providing researchers with an unprecedented ability to exponentially amplify specific DNA sequences. This technique leverages the natural process of DNA replication in a controlled, automated in vitro environment. The core principle involves repeated thermal cycling to separate DNA strands, allow primers to anneal to complementary sequences, and extend these primers using a DNA polymerase enzyme, effectively doubling the amount of target DNA with each cycle [2]. What began as a theoretical concept evolved into a core technology driving advances in genetics, medicine, and biotechnology. The complete PCR process relies on precise reagent formulation, temperature control, and protocol optimization to achieve specific and efficient amplification of target sequences from minimal starting material [9]. This document traces the critical historical path of PCR's development and provides detailed methodological guidance for its effective application in research settings.

Historical Timeline and Key Discoveries

The evolution of PCR was not a single discovery but a series of interconnected breakthroughs spanning several decades. The foundational work began with the elucidation of DNA's structure by Watson and Crick in 1953, followed by Arthur Kornberg's isolation of DNA polymerase in 1956 [10]. However, the direct lineage to modern PCR began in the early 1970s and culminated in a practical, automated methodology in the 1980s.

Kjell Kleppe's Pioneering Concept

The earliest conceptual precursor to PCR was described by Kjell Kleppe and colleagues in the laboratory of H. Gobind Khorana. In a 1971 paper, Kleppe envisioned a process for amplifying DNA using two primers and DNA polymerase [11] [10]. He described the core concept: DNA denaturation to form single strands, followed by cooling in the presence of an excess of two specific primers, and finally the addition of DNA polymerase to complete "repair replication," theoretically resulting in two molecules of the original duplex [11] [10]. Despite this prescient theoretical framework, the technique was not successfully implemented at the time due to significant technical limitations, including the laborious manual synthesis of oligonucleotides and the lack of a thermostable enzyme, which made the process impractical and inefficient [11] [10].

Kary Mullis and the Practical Realization of PCR

The practical invention of PCR as we know it is credited to Kary Mullis in 1983 while he was working at Cetus Corporation [12]. Mullis conceived of using two primers targeting opposite strands of DNA and a repetitive cycling process to achieve exponential amplification [11]. His key insight was that this cyclic process could generate billions of copies of a specific DNA segment in just a few hours. The first successful experiment demonstrating specific genomic DNA amplification via PCR was completed in 1984, with results confirmed by Southern blot analysis [11]. For this groundbreaking work, which "changed DNA chemistry forever," Kary Mullis was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993 [10] [12].

The Discovery and Integration of Taq Polymerase

A pivotal breakthrough in PCR technology came with the introduction of a thermostable DNA polymerase. The initial PCR protocol used the Klenow fragment from E. coli, which was heat-sensitive and required the addition of fresh enzyme after each denaturation cycle, making the process tedious and costly [11] [13].

The solution was found in a microorganism from a extreme environment. Thomas Brock had discovered the bacterium Thermus aquaticus (Taq) in the hot springs of Yellowstone National Park in 1969 [11] [14]. This thermophile thrived at temperatures near 75°C, implying its enzymes were naturally heat-stable. In 1976, Alice Chien and colleagues isolated the DNA polymerase from T. aquaticus [13] [15]. Years later, when Mullis and his team at Cetus searched for a solution to the enzyme stability problem, they identified and began using Taq polymerase [11] [14].

The incorporation of Taq polymerase revolutionized PCR. Its thermostability (with a half-life of over 2 hours at 92.5°C and 9 minutes at 97.5°C) allowed it to withstand the repeated high-temperature denaturation steps without being inactivated [13]. This enabled the automation of the entire PCR process within a single tube in a thermal cycler, dramatically improving efficiency, specificity, and ease of use [13] [16]. The use of Taq polymerase, commercialized by Cetus in 1988, was the final key development that propelled PCR to become a ubiquitous tool in laboratories worldwide [16].

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in the Development of PCR

| Year | Scientist(s) | Discovery/Contribution | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1953 | Watson & Crick | Elucidation of DNA double-helix structure [11] | Provided the fundamental understanding of DNA replication. |

| 1956 | Arthur Kornberg | Discovery of DNA polymerase [10] | Identified the enzyme critical for DNA synthesis. |

| 1969 | Thomas Brock | Discovery of Thermus aquaticus [11] | Isolated the source organism for Taq polymerase. |

| 1971 | Kjell Kleppe | Theoretical description of a PCR-like process [11] [10] | First published concept of gene amplification using two primers and DNA polymerase. |

| 1976 | Alice Chien et al. | Isolation of Taq polymerase [13] [15] | Obtained the thermostable enzyme from T. aquaticus. |

| 1983 | Kary Mullis | Conceptualization and proof-of-principle of PCR [11] [12] | Invented the practical method for exponential DNA amplification. |

| 1985 | Mullis, Saiki, et al. | First publication of PCR [11] [10] | Introduced the technique to the scientific community. |

| 1986-88 | Cetus Corporation | Introduction of Taq polymerase in PCR [11] [16] | Automated PCR, greatly improving specificity, yield, and efficiency. |

| 1993 | Kary Mullis | Awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry [12] | Recognized for the invention of the PCR method. |

Diagram 1: PCR Development Timeline

Essential PCR Protocols and Workflows

Basic PCR Protocol

The following standard protocol is designed for a 50 µL reaction volume and uses Taq DNA polymerase. It serves as a robust starting point for amplifying most target sequences from a genomic DNA template [9].

Materials and Reagents

- Template DNA: 1–1000 ng (typically 10^4 to 10^7 molecules) of genomic DNA [9].

- Primers: 20–50 pmol of each oligonucleotide primer [9].

- 10X PCR Buffer: Supplied by the polymerase manufacturer, often containing MgCl₂ [9].

- dNTPs: 200 µM final concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) [9].

- MgCl₂: 1.5 mM final concentration (adjust if not present in the buffer) [9].

- Taq DNA Polymerase: 0.5–2.5 units per 50 µL reaction [9].

- Sterile Water: Nuclease-free water to bring the reaction to the final volume.

Methodology

- Reaction Setup: Thaw all reagents on ice and mix thoroughly. Assemble the reaction mixture in a sterile, thin-walled 0.2 mL PCR tube in the following order:

- Sterile Water (Q.S. to 50 µL)

- 10X PCR Buffer (5 µL)

- dNTP Mix (10 mM total, 1 µL)

- MgCl₂ (25 mM, variable µL - if needed)

- Primer 1 (20 µM, 1 µL)

- Primer 2 (20 µM, 1 µL)

- Template DNA (variable µL)

- Taq DNA Polymerase (0.5–2.5 Units, e.g., 0.5 µL) [9]

- Thermal Cycling: Place the tubes in a thermal cycler and run the following standard program:

- Post-Amplification Analysis: Analyze PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis. Load 5–10 µL of the reaction product alongside an appropriate DNA molecular weight size standard to confirm the presence and size of the expected amplicon [9].

Diagram 2: Standard PCR Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

A successful PCR experiment depends on the quality and precise formulation of its core reagents. The table below details the function and critical considerations for each essential component.

Table 2: Essential PCR Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent | Function | Key Considerations & Optimization Tips |

|---|---|---|

| Template DNA | Provides the target sequence to be amplified. | Purity is critical; avoid contaminants like phenol, EDTA, or heparin which inhibit Taq [2]. Use 1–1000 ng genomic DNA. |

| Primers | Short, single-stranded DNA sequences that define the start and end points of amplification. | Design primers 15–30 bases long with 40–60% GC content. Tm should be 52–68°C and differ by ≤5°C for the pair. Avoid self-complementarity and dimerization [9]. |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Thermostable enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands by adding dNTPs to the primers. | Thermostable; optimal activity at 75–80°C. Lacks 3'→5' proofreading activity (error rate ~1 in 9,000 bases) [13]. |

| dNTPs | Deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP); the building blocks for new DNA. | Use balanced 200 µM concentration of each dNTP. Higher concentrations can increase error rate and inhibit the polymerase [9]. |

| MgCl₂ | Cofactor for Taq polymerase; its concentration profoundly affects enzyme activity and fidelity. | Optimal concentration is typically 1.5–2.5 mM. Titrate (0.5–5.0 mM) to optimize specificity and yield [9] [13]. |

| PCR Buffer | Provides the optimal ionic environment and pH for Taq polymerase activity. | Typically contains Tris-HCl (pH 8.3–8.8) and KCl. KCl promotes activity at ~50 mM, while higher levels can be inhibitory [9] [13]. |

Advanced PCR Optimization and Troubleshooting

Even with a sound basic protocol, PCR experiments can fail due to suboptimal conditions. A systematic approach to troubleshooting is essential for resolving common issues such as nonspecific amplification, primer-dimer formation, or complete absence of a product.

Optimization of Critical Parameters

- Annealing Temperature: This is the most critical variable for specificity. If spurious bands appear, empirically determine the optimal annealing temperature by running a gradient PCR across a range of 3–5°C below and above the calculated primer Tm [9].

- Magnesium Concentration: Mg²⁺ concentration influences enzyme activity, primer annealing, and product specificity. If amplification is weak or absent, titrate MgCl₂ in increments of 0.5 mM from 1.0 to 5.0 mM [9].

- Thermal Cycling Conditions: Adjusting cycle numbers can improve yield or reduce background. For abundant targets, 25–30 cycles may suffice. For low-copy targets, up to 40 cycles may be needed, though efficiency declines in later cycles due to reagent depletion [2].

- Additives and Enhancers: For difficult templates (e.g., high GC content, complex secondary structure), include enhancers in the reaction mix:

- DMSO (1–10%)

- Formamide (1.25–10%)

- Betaine (0.5 M to 2.5 M) [9]. These compounds help lower the melting temperature of the template and disrupt secondary structures.

Troubleshooting Common PCR Problems

Table 3: PCR Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No Product | - Inactive enzyme - Insufficient template - Denaturation temperature too low - Primers poor quality or mismatched | - Check enzyme activity and storage conditions. - Titrate template amount (1 pg–1 µg). - Ensure denaturation step is at 94–95°C. - Re-synthesize or re-design primers [9]. |

| Non-specific Bands or Smearing | - Annealing temperature too low - Excess Mg²⁺ - Too many cycles - Enzyme activity too high | - Increase annealing temperature in 2°C increments. - Titrate Mg²⁺ to lower concentration. - Reduce cycle number to 25–30. - Use a "Hot-Start" Taq polymerase [9] [16]. |

| Primer-Dimer | - Excess primers - 3' end complementarity between primers - Low annealing temperature | - Redesign primers to avoid 3' complementarity. - Increase annealing temperature. - Optimize primer concentration [9]. |

| Low Yield | - Poor primer design - Suboptimal Mg²⁺ - Inefficient denaturation - Low dNTP concentration | - Verify primer Tm and specificity. - Optimize Mg²⁺ concentration. - Ensure denaturation time and temperature are sufficient. - Check dNTP concentration and quality [9]. |

The journey of PCR from Kjell Kleppe's theoretical proposal to Kary Mullis's practical implementation and its refinement with Taq polymerase stands as a powerful example of how foundational science and technological innovation intertwine to create transformative tools. The historical development of PCR underlines the importance of both conceptual insight and practical problem-solving in scientific progress. The protocols and troubleshooting guidelines provided here are built upon this legacy, offering researchers a robust framework for applying PCR in diverse experimental contexts. Mastery of both the theoretical underpinnings and practical nuances of this technique, from reagent selection to cycle optimization, remains essential for generating reliable, reproducible data that drives discovery in genomics, molecular diagnostics, and drug development.

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a foundational technique in molecular biology that allows for the exponential amplification of specific DNA sequences. Since its introduction by Kary Mullis in the 1980s, PCR has become an indispensable tool across diverse fields, from clinical diagnostics to pharmaceutical development [2]. The core mechanism of PCR relies on the precise repetition of three fundamental steps—DNA denaturation, primer annealing, and extension—facilitated by a thermostable DNA polymerase. This protocol details the principles and methodologies of these core steps, providing researchers and drug development professionals with optimized application notes and a comprehensive troubleshooting framework to ensure experimental success.

The Core Principles of PCR

DNA Denaturation

Denaturation is the process by which double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) is separated into single strands, making the template sequence accessible for primer binding. This is achieved by heating the reaction mixture to a high temperature, typically between 94°C and 98°C, which breaks the hydrogen bonds between complementary base pairs [17] [18]. An initial, prolonged denaturation step (often 1-3 minutes) is critical to ensure complete separation of complex genomic DNA at the start of the reaction. In subsequent cycles, shorter denaturation periods (20-30 seconds) are sufficient [18] [19]. For templates with high GC content (>65%), which form stronger secondary structures, longer denaturation times or slightly higher temperatures may be necessary for efficient strand separation [5] [17].

Primer Annealing

Following denaturation, the reaction temperature is rapidly lowered to a defined annealing temperature, which typically ranges from 50°C to 65°C [18]. During this step, short, synthetic oligonucleotide primers bind (or "anneal") to their complementary sequences on the single-stranded DNA templates [2]. The forward primer anneals to the 3'-5' strand, and the reverse primer anneals to the 5'-3' strand, thereby flanking the target region to be amplified [19]. The annealing temperature is a critical parameter determined by the melting temperature (Tm) of the primers, often calculated as 3-5°C below the lowest Tm of the primer pair [17]. Optimal annealing ensures specific primer binding and minimizes non-target amplification.

Extension

During the extension (or elongation) step, the temperature is raised to the optimal working temperature for the DNA polymerase, commonly 72°C for Taq DNA polymerase [18]. The enzyme synthesizes a new DNA strand by adding deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs) to the 3' end of the annealed primer, creating a complementary copy of the DNA template [20] [2]. The extension time required depends on the length of the amplicon and the synthesis speed of the polymerase (e.g., 1 minute per kilobase for Taq polymerase) [17]. A final, prolonged extension step after the last cycle ensures that all amplicons are fully synthesized.

The following diagram illustrates the cyclic nature of PCR, showing how the three core steps are repeated to exponentially amplify the target DNA sequence:

Quantitative Data and Cycling Parameters

Efficient PCR amplification requires careful optimization of thermal cycling parameters. The tables below summarize standard and optimized conditions for the core PCR steps.

Table 1: Standard PCR Cycling Parameters for a Three-Step Protocol

| Step | Typical Temperature Range | Typical Time Range | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Denaturation | 94-98°C | 1-5 minutes | Complete separation of complex DNA and activation of hot-start polymerases [17] [19]. |

| Denaturation (per cycle) | 94-98°C | 20-30 seconds | Separation of the newly synthesized DNA strands for the next cycle [18]. |

| Annealing (per cycle) | 50-65°C | 20-40 seconds | Specific binding of primers to the single-stranded template [18]. |

| Extension (per cycle) | 70-75°C (often 72°C) | 30-60 seconds per kb | Synthesis of new DNA strands by the DNA polymerase [17] [18]. |

| Final Extension | 70-75°C (often 72°C) | 5-10 minutes | Completion of any partial DNA strands [17] [19]. |

| Hold | 4-10°C | Indefinite | Short-term storage of the product [18]. |

Table 2: Optimization Guidelines for Challenging Templates

| Template Type | Challenge | Recommended Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| GC-Rich Sequences | Strong secondary structures impede denaturation; primers may bind non-specifically. | - Increase denaturation temperature (to 98°C) and/or time [5] [17]. - Use PCR additives like DMSO, betaine, or GC enhancers [5] [21]. - Use polymerases designed for high GC content [21]. |

| Long Targets (>5 kb) | Polymerase may not complete synthesis within standard extension time. | - Increase extension time (e.g., 2 min/kb for Pfu polymerase) [17]. - Use a polymerase blend formulated for long-range PCR [5] [21]. - Reduce annealing and extension temperatures to maintain enzyme stability [5]. |

| Low Abundance Targets | Signal is too weak for detection. | - Increase the number of cycles up to 40 (but generally not beyond 45) [5] [17]. - Use a high-sensitivity DNA polymerase [5]. - Ensure primer concentration is optimized (typically 0.1-1 μM) [5]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Standard PCR

| Reagent/Material | Function | Typical Concentration/Final Volume |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Template | Contains the target sequence to be amplified. | 1 pg–1 µg per 50 µL reaction, depending on complexity [21] [19]. |

| Forward & Reverse Primers | Short, single-stranded DNA sequences that define the start and end of the target region. | 0.1–1 µM each primer [5] [19]. |

| DNA Polymerase (e.g., Taq) | Thermostable enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands. | 0.5–2.5 units per 50 µL reaction [20] [19]. |

| dNTPs (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) | The building blocks for new DNA synthesis. | 200 µM of each dNTP [19]. |

| Reaction Buffer (with MgCl₂/MgSO₄) | Provides optimal chemical environment (pH, salts); Mg²⁺ is a crucial cofactor for the polymerase. | 1X concentration; Mg²⁺ typically 1.5–2.5 mM, may require optimization [21] [18]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Solvent to bring the reaction to the final volume. | To a final volume of 20–50 µL [18]. |

| PCR Tubes & Thermal Cycler | Reaction vessel and instrument that rapidly changes temperature for the cycling steps. | - |

Step-by-Step Standard PCR Workflow

1. Reaction Setup (on Ice) - Prepare a Master Mix: In a sterile, nuclease-free tube, combine the following components in the listed order for a 50 µL reaction. Preparing a master mix for multiple reactions minimizes pipetting errors and ensures consistency [18]. - Nuclease-Free Water: to a final volume of 50 µL - 10X Reaction Buffer (with MgCl₂): 5 µL - dNTP Mix (10 mM): 1 µL - Forward Primer (10 µM): 2 µL - Reverse Primer (10 µM): 2 µL - DNA Template: 1 µL (e.g., 100 ng/µL) - DNA Polymerase (e.g., 0.5 U/µL): 1 µL - Mix and Centrifuge: Gently pipette the entire mixture up and down to ensure homogeneity. Briefly centrifuge the tube to collect all liquid at the bottom [19]. - Controls: Always include a negative control (replace DNA template with nuclease-free water) to check for contamination, and a positive control if available [18] [19].

2. Thermal Cycling - Transfer the PCR tubes to a pre-programmed thermal cycler and run the following standard three-step protocol, adapted from multiple sources [20] [18] [19]: - Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 3 minutes (1 cycle). - Amplification Cycles (25-35 cycles): - Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds. - Annealing: 55-65°C (optimize based on primer Tm) for 30 seconds. - Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per kilobase of expected product length. - Final Extension: 72°C for 7 minutes (1 cycle). - Hold: 4°C forever.

3. Post-PCR Analysis: Agarose Gel Electrophoresis - Prepare a 1-2% agarose gel in 1X TAE or TBE buffer, incorporating a DNA-safe stain [20] [19]. - Mix 5 µL of the PCR product with 1 µL of 6X DNA loading dye and load into the gel wells. Include an appropriate DNA molecular weight marker (ladder) in one well [19]. - Run the gel at 5-10 V/cm until the dye front has migrated adequately. - Visualize the gel under a UV transilluminator. A single, sharp band at the expected size indicates successful and specific amplification.

Comprehensive PCR Troubleshooting Guide

Despite its robustness, PCR can fail due to various factors. The table below outlines common problems, their causes, and evidence-based solutions.

Table 4: Common PCR Problems and Troubleshooting Strategies

| Observation | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No or Low Yield | • Poor template quality/degradation [5] [21] • Incorrect annealing temperature [21] [22] • Insufficient Mg²⁺ concentration [23] [21] • Reagents omitted or compromised [22] | • Repurify DNA template; check A260/280 ratio [5] [22]. • Optimize annealing temperature using a gradient cycler [5] [17]. • Titrate MgCl₂ in 0.2–1 mM increments [21]. • Check reagent integrity; prepare fresh master mix [22]. |

| Non-Specific Bands / Smearing | • Annealing temperature too low [21] [22] • Excess primers, template, or enzyme [5] [21] • Excessive cycle number [17] • Primer-dimer formation [23] | • Increase annealing temperature in 2-3°C increments [5] [17]. • Optimize reagent concentrations [5]. • Reduce cycles to 25-35 [17]. • Redesign primers to avoid 3' complementarity; use hot-start polymerase [23] [5]. |

| Primer-Dimer Formation | • High primer concentration [23] [5] • Low annealing temperature [23] • Primers with complementary 3' ends [23] [5] | • Lower primer concentration (e.g., to 0.1-0.5 µM) [5]. • Increase annealing temperature [23]. • Re-design primers using specialized software [23] [19]. |

| Sequence Errors (Low Fidelity) | • Low-fidelity polymerase [21] [22] • Unbalanced dNTP concentrations [5] [21] • Excess Mg²⁺ [5] [21] | • Use a high-fidelity polymerase (e.g., Q5, Phusion) [21]. • Use fresh, equimolar dNTP stock [5] [22]. • Optimize and/or reduce Mg²⁺ concentration [21]. |

The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a foundational technology in molecular biology, enabling the exponential amplification of specific DNA sequences from minimal starting material. Its development revolutionized fields from basic research to clinical diagnostics and drug development. The power of PCR hinges on a finely tuned biochemical reaction, the success of which is entirely dependent on the precise interplay of its core components. This article deconstructs the essential elements of the PCR reaction mixture—template DNA, primers, deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), DNA polymerase, and buffer/Mg2+—providing detailed application notes, optimized protocols, and targeted troubleshooting strategies for scientific professionals. A thorough understanding of each component's function and optimal parameters is critical for developing robust, reproducible assays, particularly in a drug development context where reliability and accuracy are paramount.

The Core Components of PCR

Template DNA

The template DNA is the target sequence that will be amplified. It can originate from various sources, including genomic DNA (gDNA), complementary DNA (cDNA), plasmid DNA, or previously amplified PCR products [24] [25]. The quality, quantity, and complexity of the template are primary determinants of PCR success.

Key Considerations:

- Purity: Template DNA must be free of contaminants that inhibit DNA polymerase, such as phenol, EDTA, heparin, salts, or proteins [5] [26]. Impurities can be removed by ethanol precipitation, column-based purification kits, or drop dialysis [27] [5].

- Quantity: Optimal input amounts vary significantly with template complexity. Using too much DNA can lead to nonspecific amplification, while too little can result in low or no yield [24].

- Integrity: For gDNA, minimize shearing during isolation. Degraded template may appear as a smear on an agarose gel or cause high background [5]. DNA should be stored in molecular-grade water or TE buffer (pH 8.0) to prevent nuclease degradation [5].

Table 1: Recommended Template DNA Input for a 50 µL PCR

| Template Type | Recommended Amount | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmid DNA | 0.1–1 ng | Low complexity; requires minimal input [24] [28]. |

| Genomic DNA (gDNA) | 5–50 ng [24] / 1 ng–1 µg [27] | High complexity; requires more input. Amount depends on genome size. |

| cDNA | 1–10 ng | Based on the original RNA input; may require optimization [24]. |

| PCR Amplicon (re-amplification) | 1–5% of reaction volume | Best purified first; unpurified products can inhibit the new reaction [24]. |

Primers

PCR primers are short, single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides (typically 15–30 bases) that define the start and end points of the amplification target [24] [9]. They are complementary to the 3' ends of the target sequence and provide the free 3'-OH group required for DNA polymerase to initiate synthesis [25].

Guidelines for Primer Design:

- Length: 15–30 nucleotides [24] [9].

- Melting Temperature (Tm): 55–70°C, with the Tm for each primer in a pair within 5°C of each other [24] [9].

- GC Content: 40–60%, with a uniform distribution of G and C bases [24].

- 3' End: Should not contain more than three G or C bases to minimize nonspecific priming. Including a single G or C base (a "G/C clamp") can enhance priming efficiency [24] [9].

- Specificity: Avoid self-complementarity (hairpins), complementarity between primers (primer-dimers), and direct repeats [24] [9]. Use tools like NCBI Primer-BLAST to ensure target specificity.

- Concentration: Typically 0.1–1.0 µM in the final reaction. Excess primer can promote mispriming and primer-dimer formation, while insufficient primer yields low product [24] [5].

Deoxynucleoside Triphosphates (dNTPs)

dNTPs (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) are the building blocks from which DNA polymerase synthesizes new DNA strands [24] [25]. They are typically provided in an equimolar mixture to ensure balanced and accurate incorporation.

Key Considerations:

- Concentration: A final concentration of 0.2 mM for each dNTP is standard for most applications [24] [9]. Higher concentrations can be inhibitory, while concentrations below the estimated Km (0.010–0.015 mM) can lead to premature cessation of polymerization [24].

- Quality and Storage: dNTPs are labile and should be stored at -20°C in small, single-use aliquots to avoid degradation from repeated freeze-thaw cycles. The solution should be neutral (pH 7.0–7.5) to prevent hydrolysis [28].

- Fidelity: For high-fidelity PCR, use lower dNTP concentrations (0.01–0.05 mM) to reduce misincorporation rates, especially with non-proofreading enzymes [24] [28].

- Modifications: dNTPs can be partially or fully substituted with modified nucleotides (e.g., dUTP, biotin- or fluorescein-labeled dNTPs) for specialized applications. The DNA polymerase must be compatible with these analogs [24] [5].

DNA Polymerase

DNA polymerase is the enzyme that catalyzes the template-directed synthesis of new DNA strands. Taq DNA polymerase, isolated from Thermus aquaticus, is the most well-known due to its thermostability, with a half-life of >40 minutes at 95°C [24] [9]. It polymerizes at a rate of approximately 60 bases/second at 70°C [24].

Types and Selection:

- Standard PCR: Taq DNA polymerase is suitable for routine amplification of fragments up to ~5 kb [24].

- High-Fidelity PCR: For cloning, sequencing, and mutagenesis, use proofreading polymerases (e.g., Pfu, Q5). These enzymes possess 3'→5' exonuclease activity to correct misincorporated nucleotides, resulting in lower error rates [27] [25].

- Long-Range PCR: Specialized enzyme blends (e.g., Takara LA Taq) are engineered for efficient amplification of long targets (>10 kb) [5] [26].

- Hot-Start PCR: Hot-start polymerases remain inactive until a high-temperature activation step, preventing nonspecific amplification and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup [5] [26].

Usage:

- Amount: 1–2.5 units per 50-100 µL reaction is standard [24] [28] [9]. Excessive enzyme can increase nonspecific products, while too little will reduce yield.

Buffer and Magnesium Ions (Mg²⁺)

The reaction buffer provides the optimal chemical environment for DNA polymerase activity and specificity. Its most critical component is Mg²⁺.

Role of Mg²⁺:

- Acts as an essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity [24] [28].

- Facilitates primer binding to the template by stabilizing the negative charges on the DNA backbone [24].

- Forms a soluble complex with dNTPs to facilitate their incorporation [24] [28].

Optimization:

- Concentration: The optimal final concentration is typically 1.5–2.5 mM, but it must be determined empirically for each primer-template system [9]. Mg²⁺ is often supplied as MgCl₂ or MgSO₄ in the 10X buffer.

- Balance: Excessive Mg²⁺ promotes nonspecific binding and increases the error rate of non-proofreading enzymes. Insufficient Mg²⁺ reduces polymerase activity and yield [27] [5].

- Interactions: The free Mg²⁺ concentration is critical because dNTPs chelate Mg²⁺ ions. Therefore, if dNTP concentrations are increased, the Mg²⁺ concentration may need to be increased proportionally [24] [26].

Table 2: Summary of Core PCR Components and Their Optimization

| Component | Standard Concentration/Range | Primary Function | Common Issues & Fixes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Template DNA | 0.1–1000 ng (varies by type) | Provides the target sequence for amplification | Inhibition: Further purify template. No product: Increase amount. Smearing: Reduce amount or improve integrity. |

| Primers | 0.1–1 µM each | Defines the region to be amplified | No product: Check design, increase concentration. Nonspecific bands: Increase annealing T°, reduce concentration. Primer-dimers: Improve design, use hot-start enzyme. |

| dNTPs | 0.2 mM each | Building blocks for new DNA strands | Low yield: Ensure fresh, high-quality stock. High error rate: Use balanced, equimolar mix; lower concentration. |

| DNA Polymerase | 1–2.5 U/50 µL | Synthesizes new DNA strands | Nonspecific bands: Use hot-start enzyme; reduce amount. No product: Increase amount; check enzyme compatibility with template. |

| Mg²⁺ | 1.5–2.5 mM (often requires titration) | Essential DNA polymerase cofactor | Nonspecific bands: Lower concentration. No/low yield: Increase concentration. |

Advanced Protocol and Workflow

Master Mix Setup and Thermal Cycling

A standardized protocol ensures consistency, especially when running multiple reactions.

Materials and Reagents:

- Template DNA: Prepared and quantified.

- Primers: Resuspended in sterile water or TE buffer to a stock concentration (e.g., 10–100 µM).

- 10X PCR Buffer: Often supplied with the enzyme, with or without Mg²⁺.

- dNTP Mix: 10 mM total dNTPs (2.5 mM of each).

- MgCl₂ (or MgSO₄): 25 mM stock, if not included in the buffer.

- DNA Polymerase: e.g., Taq DNA polymerase.

- Nuclease-free Water.

Procedure:

- Thaw all reagents on ice and mix thoroughly by gentle vortexing before use.

- Prepare a Master Mix for all common components to minimize pipetting errors and ensure uniformity between samples. For a single 50 µL reaction, assemble as shown in the table below. Scale accordingly for multiple reactions.

- Aliquot the Master Mix into individual PCR tubes.

- Add template DNA to each tube. Include a negative control (no template DNA) to check for contamination.

- Mix gently by pipetting up and down or brief pulsing in a microcentrifuge.

- Load the thermal cycler and run the following standard program:

Table 3: Standard 50 µL Reaction Setup

| Component | Stock Concentration | Volume per 50 µL Reaction | Final Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclease-free Water | - | Variable (to 50 µL) | - |

| 10X PCR Buffer | 10X | 5 µL | 1X |

| MgCl₂ | 25 mM | 3 µL (variable) | 1.5 mM (variable) |

| dNTP Mix | 10 mM (total) | 1 µL | 0.2 mM each |

| Forward Primer | 20 µM | 1 µL | 0.4 µM |

| Reverse Primer | 20 µM | 1 µL | 0.4 µM |

| Template DNA | Variable | Variable | 1–1000 ng |

| DNA Polymerase | 5 U/µL | 0.5 µL | 2.5 U |

| Total Volume | 50 µL |

Standard Thermal Cycler Program:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2–5 minutes (1 cycle).

- Amplification (25–35 cycles):

- Denaturation: 95°C for 20–30 seconds.

- Annealing: 5°C below the lower primer Tm (45–65°C) for 20–30 seconds.

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per kb of amplicon.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5–15 minutes (1 cycle).

- Hold: 4–10°C.

Diagram 1: Standard PCR Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PCR

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Enzyme remains inactive until heated, reducing nonspecific amplification during setup. | Essential for high-specificity assays and multiplex PCR where primer-dimer formation is a concern [5] [26]. |

| Proofreading DNA Polymerase (e.g., Pfu, Q5) | Possesses 3'→5' exonuclease activity to correct misincorporated bases, providing high fidelity. | Critical for cloning, sequencing, and site-directed mutagenesis where low error rates are required [27] [25]. |

| PCR Clean-up Kit | Purifies amplicons from reaction components like primers, dNTPs, and enzymes. | Required for downstream applications such as sequencing, cloning, or re-amplification [24] [27]. |

| dNTP Mix, PCR Grade | Provides a balanced, equimolar solution of high-purity nucleotides. | Ensures efficient and accurate DNA synthesis; preferred over homemade mixes for reproducibility [28]. |

| GC Enhancer / PCR Additives | Chemical additives (e.g., DMSO, Betaine, BSA) that destabilize DNA secondary structures. | Used to amplify difficult templates such as GC-rich regions (>65% GC) or sequences with stable secondary structures [5] [9]. |

| UDG (Uracil-DNA Glycosylase) | Enzyme that cleaves uracil-containing DNA, preventing carryover contamination from previous PCRs. | Used in diagnostic and qPCR assays where dUTP is substituted for dTTP to control contamination [24]. |

Troubleshooting and Optimization Strategies

Even well-designed PCRs can fail. A systematic approach to troubleshooting is vital.

Common Problems and Solutions:

No Product:

- Cause: Incorrect annealing temperature, missing component, poor template quality/quantity, or inefficient denaturation.

- Solution: Run a positive control. Lower the annealing temperature in 2°C increments. Verify template integrity and concentration. Check the thermal cycler calibration. Increase the number of cycles (up to 40) for low-copy templates [27] [5] [26].

Nonspecific Bands/Smearing:

- Cause: Annealing temperature too low, excess Mg²⁺, primer concentration too high, too many cycles, or enzyme activity too high.

- Solution: Increase the annealing temperature. Use a gradient thermal cycler for optimization. Titrate Mg²⁺ downward. Reduce primer and/or enzyme concentration. Use a hot-start polymerase. Reduce the number of cycles [27] [5] [26].

Primer-Dimer Formation:

Low Yield:

- Cause: Insfficient number of cycles, poor primer design, low dNTPs, suboptimal Mg²⁺, or inefficient extension.

- Solution: Increase the number of cycles (cautiously). Check primer Tm and specificity. Ensure dNTPs are fresh and at correct concentration. Optimize Mg²⁺ concentration. Increase extension time [5] [26].

High Error Rate (Mutation Incorporation):

Diagram 2: Logical Troubleshooting Guide for Common PCR Issues

A deep and practical understanding of the five essential components of the PCR reaction mixture is non-negotiable for success in modern molecular biology and drug development. As this application note demonstrates, the process extends beyond simply mixing reagents. It requires careful consideration of template integrity, precise primer design, balanced nucleotide concentrations, appropriate enzyme selection, and meticulous optimization of the buffer system, particularly Mg²⁺. By adhering to the detailed protocols, utilizing the structured troubleshooting guide, and leveraging the recommended reagent toolkit, researchers can deconstruct and master their PCR experiments. This systematic approach ensures the development of robust, specific, and efficient amplification assays, thereby providing a reliable foundation for critical downstream applications in research and diagnostics.

The thermal cycler, also known as a PCR machine or thermocycler, is a fundamental instrument in molecular biology laboratories that automates the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) process [29]. This apparatus revolutionized molecular biology by replacing the labor-intensive manual transfer of samples among water baths set at different temperatures [30] [31]. Thermal cyclers precisely control temperature cycles to facilitate the amplification of specific DNA sequences, enabling the generation of millions of copies from a minimal starting template [30] [31].

The core function of a thermal cycler is to regulate the three essential temperature stages required for PCR: denaturation, primer annealing, and extension [32] [33]. By automating these temperature transitions, thermal cyclers ensure experimental reproducibility, significantly reduce hands-on time, and improve amplification efficiency [30] [31]. Modern instruments have evolved to include sophisticated features such as gradient temperature control, heated lids, rapid ramp rates, and connectivity options that enhance experimental outcomes and workflow efficiency [30].

Technical Specifications and Performance Metrics

Selecting an appropriate thermal cycler requires careful evaluation of key performance metrics that directly impact PCR results and laboratory throughput. The technical specifications determine the instrument's capability to deliver consistent, reliable amplification across various applications.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Thermal Cyclers

| Performance Metric | Technical Specification | Impact on PCR Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature Accuracy | Typically within ±0.1°C to ±0.5°C of setpoint [33] | Ensures each reaction step occurs at optimal temperature for enzyme activity and specificity [33] |

| Temperature Uniformity | Variance <0.5°C across the block (ideally <0.2°C) [29] [33] | Prevents well-to-well variation in amplification efficiency and yield [33] |

| Ramp Rate | 1-6°C/second (standard); >10°C/second (fast cyclers) [30] [33] | Determines transition speed between steps; faster rates reduce overall run time [30] [33] |

| Block Capacity | 96-well (standard), 384-well (high-throughput), interchangeable blocks [30] | Defines sample processing capability per run; affects laboratory throughput [30] |

| Gradient Functionality | Temperature range across different block zones [30] [33] | Enables simultaneous testing of different annealing temperatures for optimization [30] [33] |

The operational performance of a thermal cycler depends on several integrated components. Peltier elements serve as solid-state heat pumps that provide both heating and cooling functionality by reversing electrical current direction [30] [31]. The thermal block, typically constructed from high thermal conductivity metals like aluminum or silver, holds reaction vessels and transfers temperature to samples [31] [33]. A heated lid maintains temperature above the reaction mixture to prevent evaporation and condensation, eliminating the need for mineral oil overlays [30] [29]. Modern interfaces and software allow programming of complex protocols with storage capabilities for repeated use [30] [31].

Thermal Cycler Protocol for Standard PCR Amplification

Reagent Preparation and Setup

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for PCR

| Reagent/Material | Function in PCR Protocol | Optimization Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Polymerase | Enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands during extension [30] [32] | Selection of thermostable enzyme (e.g., Taq) affects yield and specificity; high-processivity enzymes enable fast PCR [30] |

| Primers | Short oligonucleotides that define target sequence for amplification [32] | Design specificity and annealing temperature (Tm) critical; optimize using gradient thermal cycler function [34] [33] |

| dNTPs | Deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) as DNA building blocks [32] | Balanced concentrations required; quality affects fidelity and efficiency of amplification |

| Reaction Buffer | Provides optimal chemical environment (pH, ionic strength) for enzyme activity [32] | Often includes magnesium chloride (MgCl₂), which co-factors the DNA polymerase [34] |

| Magnesium Chloride (MgCl₂) | Essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity [34] | Concentration must be optimized empirically for each primer-template combination [34] |

| Template DNA | Source DNA containing target sequence to be amplified [32] | Quality and quantity affect amplification success; minimal inhibitors required |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Solvent for reaction components; free of contaminating nucleases | Ensures reaction integrity and prevents degradation of nucleic acids |

Instrument Operation and Workflow

The standard PCR protocol consists of three fundamental steps repeated for 25-40 cycles, preceded by an initial denaturation and followed by a final extension. The thermal cycler automates this entire process once programmed.

Diagram 1: Standard PCR Thermal Cycling Workflow

Initial Denaturation: A single prolonged denaturation step (typically 95°C for 2-5 minutes) ensures complete separation of double-stranded DNA templates before cycling begins. This step also activates hot-start DNA polymerases if used [32] [33].

Cycling Parameters (25-40 cycles):

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15-30 seconds. This high temperature breaks hydrogen bonds between complementary DNA strands, creating single-stranded templates for primer binding [32] [33].

- Annealing: 50-65°C for 15-60 seconds. Primers bind to complementary sequences on the template DNA. The optimal temperature is primer-specific and often requires optimization using the thermal cycler's gradient function [34] [33].

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per kilobase of target DNA. The DNA polymerase synthesizes new DNA strands by adding nucleotides to the 3' ends of the annealed primers [32] [33].

Final Extension: A single prolonged extension (72°C for 5-10 minutes) ensures all PCR products are fully synthesized and any partial extension products are completed [32] [33].

Hold: 4-10°C indefinitely stabilizes the amplified products until they can be removed from the thermal cycler for analysis or storage [32].

Advanced Applications and Modifications

Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Quantitative PCR, also known as real-time PCR, expands upon standard PCR by enabling detection and quantification of amplified DNA during the cycling process rather than at the endpoint [32]. This method utilizes fluorescent reporters (dyes or sequence-specific probes) that generate increasing fluorescence signals proportional to the amount of amplified DNA [35] [32]. The thermal cycler requirements for qPCR are more stringent, as the instrument must integrate precise temperature control with optical detection systems to monitor fluorescence at each cycle [35] [33]. The cycle threshold (Ct), the point at which fluorescence crosses a threshold above background, is used for quantification relative to standards of known concentration [35] [33].

Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR)

RT-PCR combines reverse transcription of RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) followed by standard PCR amplification [33]. This application requires the thermal cycler to program an initial, lower-temperature step (typically 37-55°C for 30-60 minutes) where reverse transcriptase synthesizes cDNA from RNA templates before transitioning to the standard three-step PCR cycling [33]. Modern thermal cyclers must accommodate this extended temperature profile while maintaining stability during the reverse transcription phase [33].

Digital PCR (dPCR)

Digital PCR represents a advanced approach that provides absolute quantification of nucleic acids without requiring standard curves [35] [33]. This method involves partitioning a PCR reaction into thousands of individual reactions, each containing zero, one, or several target molecules [35]. After amplification, the thermal cycler or associated reader counts the positive and negative partitions to determine the original target concentration using Poisson statistics [35] [33]. Digital PCR systems like the Bio-Rad QX200 AutoDG Droplet Digital PCR System offer exceptional sensitivity for applications including rare mutation detection, copy number variation analysis, and minimal residual disease monitoring [35].

Troubleshooting and Optimization Strategies

PCR optimization is critical for achieving specific and efficient amplification. Several common issues can be addressed through systematic troubleshooting of both reaction components and thermal cycler performance.

Non-specific Amplification: This manifests as multiple bands or smearing on gels and often results from suboptimal annealing temperatures or excessive enzyme activity [34] [33]. Implement a temperature gradient across the thermal block to empirically determine the optimal annealing temperature [30] [33]. Increase annealing temperature incrementally by 2-3°C and reduce magnesium concentration if necessary [34].

Low Yield or No Product: This failure can stem from insufficient primer concentration, incorrect denaturation temperatures, or enzyme inhibition [34]. Verify thermal cycler calibration using a temperature verification kit to ensure the block reaches the programmed denaturation temperature [31] [33]. Check primer concentrations and increase cycle numbers if amplifying low-copy targets [34].

Well-to-Well Variation: Inconsistent results across the thermal block typically indicate poor temperature uniformity or improper plate sealing [33]. Regularly maintain and calibrate the thermal cycler according to manufacturer specifications [31] [33]. Use appropriate tray/retainer sets to ensure even pressure distribution from the heated lid and prevent tube deformation [34].

Evaporation and Condensation Issues: Sample loss during cycling compromises reaction efficiency and can lead to complete failure [30] [34]. Ensure the heated lid is properly set to a temperature 5-10°C above the maximum reaction temperature and is making even contact with all tube lids [30] [34]. Use the recommended tray/retainer sets for specific thermal cycler models to optimize lid pressure [34].

Future Perspectives and Technological Advances

Thermal cycler technology continues to evolve with emerging trends focusing on miniaturization, speed, and integration. The global PCR machine market is projected to grow from USD 1813 million in 2025 to USD 2539 million by 2032, exhibiting a compound annual growth rate of 6.0% [36]. This growth is driven by rising demand for molecular diagnostics, increasing investments in genomics research, and expanding applications in infectious disease testing [36] [37].

Miniaturization and microfluidics represent a significant trend, with systems utilizing reduced reaction volumes (down to nanoliters) and achieving faster ramp rates through decreased thermal mass [33]. These advancements enable higher throughput while lowering consumables costs [33]. Integration with laboratory automation systems is another key development, with next-generation thermal cyclers designed with robotic plate handling features and standardized communication protocols for seamless workflow integration [33].

Connectivity enhancements continue to transform thermal cycler operation, with cloud-enabled platforms allowing remote monitoring, protocol sharing, and data management via mobile devices and desktop computers [30] [34]. These innovations provide researchers with unprecedented flexibility and accessibility in PCR experimentation [30]. As molecular biology continues to advance, thermal cycler technology will undoubtedly evolve to meet the changing demands of research, clinical diagnostics, and emerging applications in personalized medicine.

The invention of the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) in 1986 revolutionized molecular biology by providing a method for the exponential amplification of specific DNA sequences [38]. This foundational technique leverages a thermostable DNA-replicative enzyme, target-specific oligonucleotide primers, and deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate monomers to selectively copy DNA fragments across multiple thermal cycles [38]. PCR's core utility lies in its ability to generate millions of copies of a target DNA sequence from a minimal starting sample, enabling detailed analysis and detection.

The technology has evolved significantly from its first generation, which used gel electrophoresis for semi-quantitative analysis, to its second generation, quantitative PCR (qPCR), which enables real-time reaction monitoring via fluorescent dyes or probes [38]. The latest evolution, digital PCR (dPCR), provides absolute nucleic acid quantification without a standard curve by partitioning a sample into thousands of individual reactions [38]. This progression has cemented PCR's role as an indispensable tool in research, clinical diagnostics, and biotechnology, with the global biological PCR technology market projected to grow from USD 14.65 billion in 2024 to USD 28.93 billion by 2034 [39].

Impact on Genomics and Biomedical Research

Advancements in Genomic Medicine

PCR technologies are central to large-scale genomic medicine initiatives, facilitating the integration of genome sequencing into routine clinical practice. The 2025 French Genomic Medicine Initiative (PFMG2025), a nationwide program with €239 million in government funding, exemplifies this trend [40]. This initiative utilizes genome sequencing (GS) for patients with rare diseases (RD), cancer genetic predisposition (CGP), and cancers, moving beyond exome sequencing for more comprehensive clinical and research exploration [40].

As of December 2023, this program had delivered 12,737 results for RD/CGP patients (30.6% diagnostic yield) and 3,109 for cancer patients, demonstrating PCR's substantial impact on diagnostic precision and patient management [40]. The organizational framework involves a network of clinical laboratories (FMGlabs), multidisciplinary meetings for prescription validation, and a national data facility, creating a robust research-care continuum [40].

Enabling Precision Oncology

PCR, particularly dPCR, has transformed cancer monitoring through liquid biopsy applications. Its exceptional sensitivity allows for the detection of rare tumor DNA variants in blood, enabling early cancer diagnosis, monitoring of minimal residual disease, and detection of treatment resistance [41]. dPCR's ability to detect variant allele frequencies below 0.01% allows clinicians to identify cancer relapse months earlier than traditional imaging methods [41]. This precision is critical for personalized treatment approaches and tailored therapeutic interventions, representing a significant advancement in precision medicine [42].

Table 1: PCR Applications in Genomics and Biomedical Research

| Application Area | PCR Technology Used | Key Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Rare Disease Diagnosis | Genome Sequencing (GS) | 30.6% diagnostic yield for French genomic medicine initiative [40] |

| Cancer Monitoring | Digital PCR (dPCR) | Detection of variant allele frequencies <0.01% in liquid biopsies [41] |

| Infectious Disease Surveillance | dPCR, qPCR | Wastewater monitoring for pathogens (influenza, RSV, norovirus) [41] |

| Agricultural & Environmental Testing | dPCR | Pathogen monitoring, microplastic DNA markers, invasive species detection [41] |

PCR in Diagnostic Applications

Infectious Disease Detection and Public Health

The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically highlighted PCR's critical role in public health, establishing PCR-based tests as the gold standard for SARS-CoV-2 detection globally [42]. This widespread adoption propelled market growth and demonstrated PCR's utility in large-scale screening programs. Beyond pandemic response, PCR technologies are increasingly employed in wastewater surveillance to track community transmission of pathogens like influenza, RSV, norovirus, and antimicrobial resistance genes [41]. dPCR is particularly valuable in this context due to its resilience to common inhibitors and ability to provide accurate quantification even at extremely low viral concentrations [41].

Market Expansion and Point-of-Care Testing

The Diagnostics PCR Market is expected to grow from US$6.21 billion in 2024 to USD 10.87 billion by 2032, reflecting expanding clinical applications [42]. Key growth drivers include the rising prevalence of infectious diseases and genetic disorders, necessitating accurate and rapid diagnostic solutions [42]. A significant market trend is the growing demand for point-of-care PCR testing, enabled by compact, user-friendly devices that facilitate testing at the bedside or in resource-limited environments [42]. This expansion parallels advancements in multiplex PCR assays, which allow simultaneous detection of multiple targets cost-effectively, and continued improvements in sample preparation techniques [42].

Essential PCR Protocols

Standard PCR Protocol

The following workflow details a fundamental protocol for a standard PCR amplification reaction. This methodology forms the basis for most PCR-based applications, with specific modifications possible for specialized requirements.

Procedure Notes:

- Template Quantity: Use 1 pg–10 ng for low-complexity templates (plasmid DNA) or 1 ng–1 µg for high-complexity templates (genomic DNA) per 50 µL reaction [43].

- Primer Concentration: Optimize within 0.1–1 µM range; high concentrations promote primer-dimer formation [5].

- Mg²⁺ Concentration: Optimize between 1–5 mM, always exceeding dNTP concentration [44].

- Cycle Number: Typically 25–35 cycles; increase to 40 for low-copy targets, but avoid overcycling to prevent errors [5] [44].

Digital PCR Protocol

Digital PCR provides absolute quantification of nucleic acids by partitioning samples into numerous individual reactions. The workflow below outlines the key steps in this process, which offers enhanced sensitivity and precision for demanding applications.

Procedure Notes:

- Partitioning: Modern dPCR systems generate thousands to millions of partitions (droplets or microchambers) for statistical robustness [38].

- Amplification: Endpoint PCR amplification occurs within each partition, with fluorescent probes indicating target presence [38].

- Quantification: The fraction of positive partitions is used in Poisson statistics to calculate absolute target concentration without standard curves [38].

- Applications: Ideal for detecting rare mutations, copy number variations, and viral load quantification where highest sensitivity is required [41].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PCR Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Optimization Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Polymerase | Enzymatic amplification of DNA | Choose fidelity/speed: High-fidelity (Q5) for cloning; hot-start for specificity [43] [23] |

| Primers | Target sequence recognition | Design specificity; avoid complementarity; optimize concentration (0.1-1 µM) [5] [45] |

| dNTPs | DNA synthesis building blocks | Use balanced equimolar concentrations (200 µM each); unbalanced increases error rate [43] [44] |

| Mg²⁺ Solution | Polymerase cofactor | Critical parameter: optimize between 1-5 mM in 0.2-1 mM increments [43] [23] |

| Buffer System | Optimal reaction environment | Provides pH stability, salt concentrations; often includes additives for GC-rich targets [5] |

| Template DNA | Target nucleic acid for amplification | Quality check via electrophoresis/spectroscopy; avoid inhibitors; optimize amount [5] [23] |

| PCR Additives | Enhance specificity/yield | BSA (inhibitor binding), betaine (destabilize secondary structure), DMSO [5] [23] |

Comprehensive PCR Troubleshooting Guide

Despite its established methodology, PCR experiments can encounter various challenges. The following table systematically addresses common issues, their potential causes, and evidence-based solutions to guide optimization.

Table 3: Comprehensive PCR Troubleshooting Guide

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No Amplification or Low Yield | ||

| Incorrect annealing temperature | Recalculate primer Tm; test gradient starting 5°C below lower Tm [43] | |

| Poor template quality or inhibitors | Analyze DNA integrity (gel electrophoresis); purify template; use inhibitor-tolerant enzymes [43] [5] | |

| Missing reaction component or enzyme | Include positive control; verify all components added; ensure fresh reagents [44] [45] | |

| Insufficient number of cycles | Increase cycles (3-5 at a time up to 40) for low-abundance targets [44] | |

| Multiple or Non-Specific Bands | ||

| Primer annealing temperature too low | Increase annealing temperature in 2°C increments [43] [44] | |

| Non-hot-start polymerase activity | Use hot-start polymerase; set up reactions on ice [43] [23] | |

| Excess primer or template | Optimize primer concentration (0.1-1 µM); reduce template amount 2-5 fold [43] [44] | |

| High Mg²⁺ concentration | Optimize Mg²⁺ concentration in 0.2-1 mM increments [43] | |

| Primer-Dimer Formation | ||

| Primer complementarity | Redesign primers with minimal 3' complementarity; use software tools [5] [23] | |

| High primer concentration | Reduce primer concentration within 0.1-1 µM range [5] [23] | |

| Low annealing temperature | Increase annealing temperature; reduce annealing time [23] | |

| Smear on Gel | ||

| Contamination with previous PCR products | Use separate pre- and post-PCR areas; UV-irradiate equipment; use aerosol-filter tips [44] | |

| Excessive cycle number | Reduce number of cycles; avoid overcycling [44] | |

| Non-specific priming | Increase annealing temperature; use touchdown PCR; redesign primers [44] [23] | |

| Sequence Errors | ||

| Low-fidelity polymerase | Switch to high-fidelity polymerase (e.g., Q5, Phusion) [43] | |

| Unbalanced dNTP concentrations | Use fresh, equimolar dNTP mixes [43] [44] | |

| Too many cycles | Reduce number of cycles; increase input DNA [5] | |

| Template DNA damage | Limit UV exposure during gel extraction; use PreCR Repair Mix [43] |

The future of PCR technology is characterized by several convergent trends. Miniaturization of PCR devices aims to reduce costs and improve data quality, with some studies reporting potential cost reductions of up to 75% while providing enhanced sensitivity and efficiency [39]. Advancements in microfluidic technology are creating opportunities for developing compact, portable PCR devices that expedite DNA amplification through high surface-to-volume ratios and improved heat transfer [39].

The integration of artificial intelligence with PCR technologies, particularly dPCR, is expected to enhance data analytics and interpretation [41]. Furthermore, automation and connectivity features in newer instruments, including cartridge-based workflows and cloud-connected analytics, are streamlining laboratory workflows and data management [41]. Regulatory frameworks are also evolving, with the recent ISO 20395:2025 establishing best practices for dPCR assay design, data reporting, and statistical analysis [41].

In conclusion, PCR maintains its fundamental role in genomics, diagnostics, and biomedical research while continuously evolving to meet emerging challenges. From its basic form to advanced dPCR applications, this technology remains indispensable for detecting pathogens, genetic mutations, and biomarkers across diverse fields. As PCR technologies become more accessible, sensitive, and integrated with complementary platforms, their impact on personalized medicine, public health surveillance, and basic research will continue to expand, solidifying their position as cornerstone methodologies in the life sciences for the foreseeable future.

Precision in Practice: A Step-by-Step PCR Protocol and Its Clinical Applications

In the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), primer design represents one of the most critical determinants of success, directly influencing the specificity, yield, and reliability of amplification [46]. Poorly designed primers can lead to a complete absence of product, low yields, amplification of non-target sequences, or the formation of primer-dimers and other artifacts that compromise experimental results [46] [47]. Within the broader context of PCR protocol establishment and troubleshooting, mastering primer design is paramount for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who require robust and reproducible molecular assays. This application note provides a comprehensive guide to the fundamental rules of primer design, complete with structured protocols for optimization and visualization of key concepts.

Core Principles of Primer Design

The design of effective PCR primers requires careful consideration of several interdependent physicochemical properties. The following parameters must be optimized to work harmoniously under a single set of cycling conditions.

Primer Length

The length of a primer directly balances specificity with binding efficiency. Short primers (less than 18 nucleotides) anneal very efficiently but are more likely to bind to multiple, non-specific sites on a complex template. Excessively long primers (greater than 30 nucleotides) bind more specifically but with reduced hybridization kinetics, leading to lower amplification efficiency [48] [49] [47].

- Optimal Range: The consensus for optimal PCR primers is 18 to 30 nucleotides, with 18-24 bases being the sweet spot for standard applications [46] [49] [47]. This range provides a high probability of being unique within a genome while maintaining efficient annealing.

Melting Temperature (Tm)

The melting temperature (Tm) is the temperature at which 50% of the primer-DNA duplexes dissociate into single strands and is a cornerstone for determining the PCR annealing temperature [48]. The forward and reverse primers must have closely matched Tms to anneal to their respective targets simultaneously during the cycling protocol.

- Optimal Tm Range: Primers should have a Tm between 55°C and 70°C [50] [24]. A higher Tm (e.g., >65°C) is often recommended to enhance specificity [49].

- Pair Compatibility: The Tms for a primer pair should be within 2-5°C of each other [51] [48] [47]. A larger difference will prevent finding an annealing temperature that works for both primers.

- Calculation Methods: Simple formulas provide an estimate. The "Wall Rule" (Tm = 4(G+C) + 2(A+T)) is a basic method [47]. For more accurate results, the modified Allawi & SantaLucia's thermodynamics method (the nearest-neighbor method) is used by modern online calculators and is considered the gold standard [52] [47].

GC Content and Clamp