PCR Efficiency Optimization: A Comprehensive Comparison of Commercial Buffers and Magnesium Chloride Concentrations

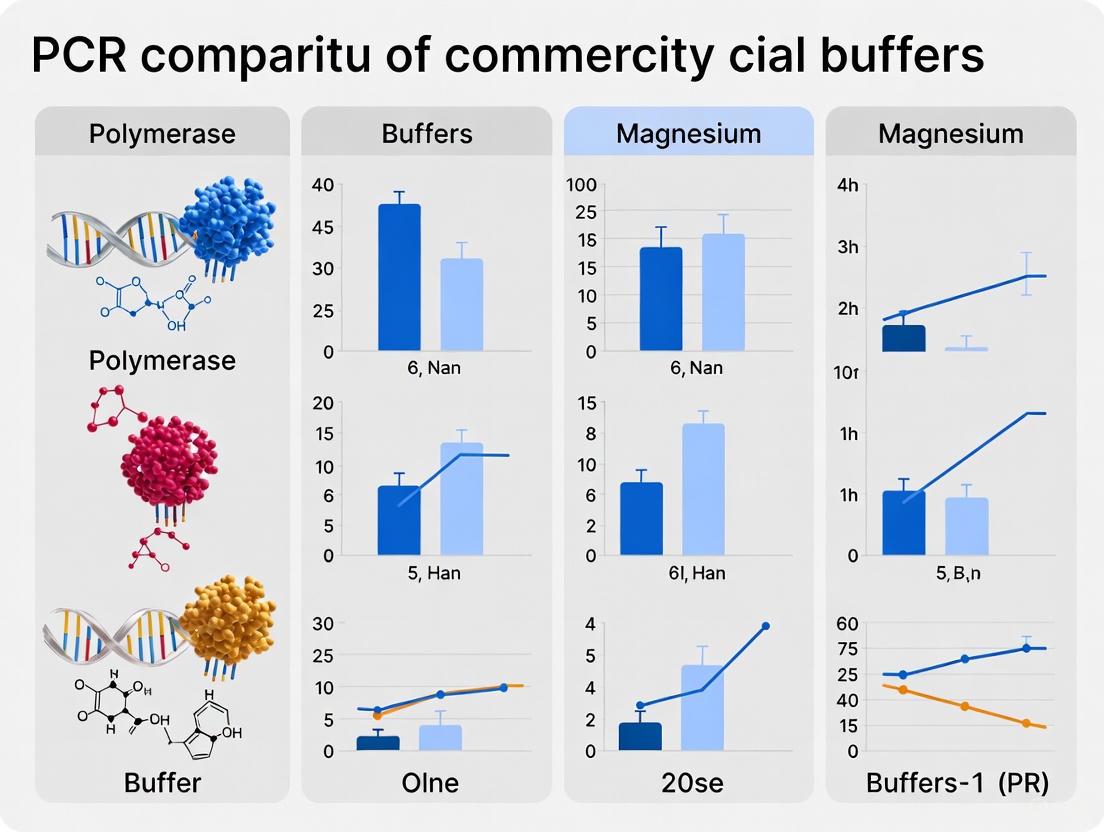

This article provides a systematic analysis of how commercial PCR buffers and magnesium chloride (MgCl2) concentration jointly influence polymerase chain reaction efficiency, specificity, and yield.

PCR Efficiency Optimization: A Comprehensive Comparison of Commercial Buffers and Magnesium Chloride Concentrations

Abstract

This article provides a systematic analysis of how commercial PCR buffers and magnesium chloride (MgCl2) concentration jointly influence polymerase chain reaction efficiency, specificity, and yield. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we synthesize foundational principles with applied methodologies, offering evidence-based guidelines for buffer selection and magnesium optimization across diverse template types, including challenging GC-rich targets. The content explores troubleshooting common amplification failures, presents validation strategies for protocol comparison, and delivers a practical framework for selecting optimal reaction conditions to enhance reproducibility and success in genetic analysis, diagnostic testing, and clinical research.

The Fundamental Role of Magnesium and Buffer Components in PCR Thermodynamics

In the realm of molecular biology, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) stands as a foundational technique, and at the heart of its enzymatic machinery lies an essential inorganic cofactor: the magnesium ion (Mg²⁺). This review delves into the critical mechanisms by which Mg²⁺ activates DNA polymerases and facilitates deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) incorporation, framing this discussion within practical optimization contexts familiar to researchers and drug development professionals. The concentration of Mg²⁺ is not merely a component to be added; it is a central determinant of PCR efficiency, specificity, and fidelity, influencing everything from enzyme kinetics to product yield [1] [2].

The success of PCR amplification depends on a delicate balance of reaction components, with Mg²⁺ playing a uniquely multifaceted role. It functions as a cofactor for DNA polymerase activity, stabilizes nucleic acid-template interactions, and directly influences the fidelity of the amplification process [1]. Understanding its mechanisms is therefore not just of academic interest but is crucial for any experimental workflow relying on PCR, from basic cloning to advanced diagnostic assay development.

Molecular Mechanisms: The Two-Metal Ion Catalysis

Extensive structural and kinetic studies have elucidated that DNA polymerases primarily utilize a two-metal ion mechanism to catalyze the nucleotidyl transfer reaction—the fundamental step of DNA synthesis. This conserved mechanism is critical for the formation of phosphodiester bonds between the incoming dNTP and the 3'-OH terminus of the growing DNA chain [3] [4].

Atomic-Level Coordination and Function

High-resolution crystal structures of DNA polymerase β, among other enzymes, have captured pre-catalytic complexes that reveal the precise geometry of these metal ions. The two ions, often referred to as Metal A (catalytic metal) and Metal B (nucleotide-binding metal), are coordinated by two invariant aspartate residues within the enzyme's active site [3] [5].

- Metal A (Catalytic Mg²⁺): This ion directly coordinates the 3'-OH group of the primer terminus, facilitating the deprotonation of the oxygen and enabling its nucleophilic attack on the α-phosphate of the incoming dNTP [3] [4]. Its binding induces subtle conformational rearrangements that position the O3' for an in-line nucleophilic attack, a prerequisite for catalysis [3].

- Metal B (Nucleotide-Binding Mg²⁺): This ion enters the complex bound to the dNTP substrate. It coordinates the β- and γ-phosphate oxygens of the dNTP, stabilizing the negative charge and assisting in the departure of the pyrophosphate leaving group [4] [5].

The following diagram illustrates this sophisticated catalytic mechanism:

Kinetic and Thermodynamic Roles

Recent kinetic analyses have further defined the distinct roles of these two ions at various stages of the catalytic cycle. Studies on HIV reverse transcriptase demonstrate that the Mg²⁺-dNTP complex binding induces an enzyme conformational change at a rate independent of free Mg²⁺ concentration. Subsequently, the second catalytic Mg²⁺ binds to the closed state of the enzyme–DNA–Mg.dNTP complex with a dissociation constant (Kd) of approximately 3.7 mM to facilitate catalysis [4].

This weak binding of the catalytic Mg²⁺ is, in fact, a crucial contributor to fidelity. It allows the enzyme to sample the correctly aligned substrate without significantly perturbing the equilibrium for nucleotide binding at physiological Mg²⁺ concentrations. Specificity (kcat/Km) can increase significantly—up to 12-fold as Mg²⁺ concentration rises from 0.25 to 10 mM—largely by enhancing the rate of the chemical step relative to the rate of nucleotide release [4].

Experimental Optimization: Magnesium Concentration and PCR Efficiency

The Critical Balance of Magnesium Concentration

The concentration of free Mg²⁺ available in the reaction mix is a pivotal variable that requires empirical optimization for each primer-template system. As a cofactor for DNA polymerases like Taq, Mg²⁺ is indispensable for enzyme activity, but its concentration must be carefully titrated [1] [2] [6].

- Low Mg²⁺ Concentrations (≤ 1.0 mM): Under these conditions, polymerase activity is suboptimal due to insufficient cofactor availability. This can lead to low product yield or complete PCR failure as the enzyme cannot function efficiently [2] [6].

- High Mg²⁺ Concentrations (≥ 4.0 mM): Excessive Mg²⁺ stabilizes double-stranded DNA, preventing complete denaturation during the PCR cycle and reducing product yield. It also decreases reaction specificity by stabilizing primer binding to incorrect template sites, leading to nonspecific amplification [1] [6].

- Optimal Range (1.5 - 2.5 mM): While system-dependent, most PCRs perform optimally within this range, balancing enzyme activity with reaction specificity [2].

It is important to note that the "free" concentration of Mg²⁺ is what ultimately matters, as various reaction components can chelate or otherwise bind Mg²⁺. dNTPs, in particular, bind Mg²⁺ ions and can significantly reduce the amount of free magnesium available for the polymerase [2] [6]. EDTA, if present in template or primer stocks, is a potent chelator of Mg²⁺ and can inhibit the reaction entirely if not accounted for [6].

Magnesium-DNTP Stoichiometry and Buffer Composition

The interaction between Mg²⁺ and dNTPs is both stoichiometric and dynamic. Each dNTP molecule can bind one Mg²⁺ ion, meaning that the total dNTP concentration in the reaction directly affects Mg²⁺ availability [1]. The recommended final concentration of each dNTP is typically 0.2 mM, requiring a minimum of 0.8 mM Mg²⁺ just for dNTP complexation before any is available for the polymerase [1] [2].

Table 1: Effects of Magnesium Ion Concentration on PCR Performance

| Mg²⁺ Concentration | Polymerase Activity | Reaction Specificity | Common Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (0.1-1.0 mM) | Significantly reduced | High but with low yield | Faint or absent bands; incomplete amplification |

| Optimal (1.5-2.5 mM) | High | High | Strong specific product; minimal nonspecific bands |

| High (3.0-4.0 mM) | High | Reduced | Multiple bands; smearing; primer-dimer formation |

| Very High (>4.0 mM) | Potentially inhibited | Very low | Heavy smearing; possible reaction failure |

Beyond concentration, the specific buffer formulation can dramatically impact PCR outcomes. Commercial polymerase manufacturers often provide proprietary buffers that are optimized for their specific enzymes. For instance, Phusion Hot Start polymerase demonstrates different error rates in different buffers—4 × 10⁻⁷ in HF buffer versus 9.5 × 10⁻⁷ in GC buffer [7]. This highlights how the ionic environment, of which Mg²⁺ is a central component, interacts with other factors to determine overall PCR performance.

Comparative Analysis: Magnesium Interactions with Different DNA Polymerases

Fidelity Variations Across Polymerase Families

DNA polymerases exhibit varying degrees of fidelity, largely influenced by their structural attributes and metal ion coordination. Comparative studies have quantified these differences by measuring error rates across multiple enzymes.

Table 2: DNA Polymerase Fidelity Comparison and Magnesium Dependence

| DNA Polymerase | Source Organism/Family | Published Error Rate (errors/bp/duplication) | Fidelity Relative to Taq | Key Magnesium-Related Properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taq | Thermus aquaticus (A) | 1–20 × 10⁻⁵ | 1x | Standard Mg²⁺ dependence; no proofreading |

| Pfu | Pyrococcus furiosus (B) | 1-2 × 10⁻⁶ | 6–10x better | Tight metal coordination; proofreading activity |

| Phusion Hot Start | Engineered chimeric | 4 × 10⁻⁷ (HF buffer) | >50x better | Optimized buffer systems for fidelity |

| KOD Hot Start | Thermococcus kodakaraensis (B) | N/A | 4-50x better (varies by study) | High processivity; strong Mg²⁺ coordination |

| Pwo | Pyrococcus woesii (B) | >10x lower than Taq | >10x better | Proofreading activity; similar to Pfu |

The data reveal that proofreading enzymes (those with 3'→5' exonuclease activity) generally exhibit higher fidelity, with error rates for Pfu, Phusion, and Pwo polymerases being more than 10-fold lower than that of Taq polymerase [7]. This enhanced fidelity is partially attributable to more precise metal ion coordination at the active site, which improves the discrimination against incorrect nucleotides during the catalytic cycle.

Structural Determinants of Metal Ion Coordination

The precise coordination of Mg²⁺ ions is maintained by specific amino acid residues within the polymerase active site. In the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I, the carboxylate ligands Asp705 and Asp882 play critical but distinct roles in managing the two metal ions [5].

Mutational analyses reveal that Asp882 is essential for the fingers-closing step that converts the open ternary complex into the closed conformation, creating the active-site geometry required for catalysis. This side chain appears to serve as an anchor point to receive the dNTP-associated metal ion (Metal B) as the nucleotide is delivered into the active site [5].

In contrast, Asp705 is not required until after the fingers-closing step, where it likely facilitates the entry of the second catalytic Mg²⁺ (Metal A) into the active site. These findings suggest a sequential assembly of the active site where metal ion binding is coordinated with specific conformational changes [5].

The structural basis for metal ion specificity is further highlighted by polymerases from archaeal organisms like Pfu, which possess a uracil-binding pocket that prevents incorporation of dUTP unless specially modified [1]. This structural feature influences the enzyme's interaction with modified nucleotides in the presence of Mg²⁺.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Research Reagent Solutions for Magnesium Studies

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Magnesium in PCR Applications

| Reagent/Chemical | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MgCl₂ solutions | Source of divalent cations | Concentration must be optimized for each PCR system; avoid concentration gradients by complete thawing and mixing |

| Chelating Agents (EDTA) | Controls free Mg²⁺ availability | Useful for troubleshooting; present in some storage buffers but can inhibit PCR if carryover occurs |

| Proofreading Polymerases (Pfu, Pwo) | High-fidelity amplification | Feature distinct Mg²⁺ coordination properties; often require specific optimized buffers |

| Non-proofreading Polymerases (Taq) | Standard PCR applications | More error-prone; Mg²⁺ concentration critically affects error rate |

| dNTP mixtures | DNA synthesis substrates | Compete for Mg²⁺ binding; imbalanced ratios affect fidelity; typically used at 0.2 mM each |

| PCR Additives (DMSO, Betaine) | Modify nucleic acid stability | Can reduce secondary structures; may interact with Mg²⁺ availability indirectly |

Experimental Protocol: Standard Magnesium Titration

A robust methodology for optimizing Mg²⁺ concentration in a novel PCR system involves the following steps:

Prepare a Master Mix: Create a standard PCR master mix containing all components except the Mg²⁺ and template DNA. Include a negative control (no template) for each Mg²⁺ concentration to be tested.

Set Up Mg²⁺ Gradient: Aliquot the master mix into separate tubes and add MgCl₂ to create a concentration series, typically ranging from 1.0 mM to 4.0 mM in increments of 0.5 mM.

Amplify and Analyze: Run the PCR using cycling parameters appropriate for your primer-template system, then analyze the products by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Evaluate Results: Identify the Mg²⁺ concentration that yields the strongest specific amplification with minimal nonspecific products. Consider that some template-primer systems may show a narrow optimal range while others tolerate a broader concentration window.

For more challenging templates (e.g., GC-rich regions or complex secondary structures), additional optimization can be performed by combining Mg²⁺ titration with specific PCR enhancers like DMSO (2-10%), betaine (1-1.7 M), or formamide (1-5%) [2]. These additives can help overcome amplification barriers by modulating DNA melting behavior and polymerase processivity, often in Mg²⁺-dependent manners.

Advanced Applications and Research Implications

Specialized PCR Applications and Metal Ion Considerations

The role of Mg²⁺ extends beyond standard PCR into specialized applications, each with unique considerations:

Long-Range PCR: Amplification of targets >5 kb requires polymerases with high processivity and optimized buffer systems. These often include balanced Mg²⁺ concentrations and additives that stabilize the polymerase-DNA complex over extended elongation periods [1].

High-Fidelity Cloning: For cloning applications where sequence accuracy is paramount, proofreading polymerases with their distinct Mg²⁺ coordination are essential. The use of such enzymes with optimized Mg²⁺ concentrations can dramatically reduce the burden of sequencing multiple clones to find error-free constructs [7].

Rapid Diagnostic PCR: Novel systems like the AMDI Fast PCR Mini Respiratory Panel demonstrate that optimized reaction chemistry, including Mg²⁺ management, enables extremely fast (<10 minute) RT-PCR for point-of-care diagnostics while maintaining high sensitivity and specificity (97.2% overall agreement with comparator assays) [8].

Magnesium in Modified Nucleotide Incorporation

The essential nature of Mg²⁺ extends to specialized applications involving modified nucleotides. For instance, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT), a template-independent DNA polymerase, requires Mg²⁺ for its activity but shows complex interactions when polymerizing unnatural nucleotides [9].

Studies on hydroxypyridone-bearing artificial nucleotides reveal that Mg²⁺ concentration significantly affects TdT processivity. At high Mg²⁺ concentrations (10 mM), polymerization halts after several nucleotide incorporations, while lower concentrations (2.0 mM) enable further elongation. This appears to be due to Mg²⁺-induced folding of the product strands into secondary structures that prevent enzyme binding [9].

Similarly, strategies to prevent PCR carryover contamination involve substituting dTTP with deoxyuridine triphosphate (dUTP) coupled with uracil DNA glycosylase (UDG) pretreatment. This approach requires careful consideration, as proofreading archaeal polymerases like Pfu cannot incorporate dUTP efficiently due to their structural constraints, unless specially modified [1].

The experimental workflow below summarizes the key decision points in optimizing magnesium-dependent PCR systems:

Magnesium ions stand as indispensable cofactors in DNA polymerase function, operating through an evolutionarily conserved two-metal ion mechanism that ensures both catalytic efficiency and substrate specificity. The concentration of Mg²⁺ in PCR represents a critical parameter that directly influences multiple aspects of reaction performance, from product yield to amplification fidelity. The experimental data compiled in this review demonstrate that systematic optimization of Mg²⁺ concentration remains an essential step in developing robust PCR-based assays, particularly for applications requiring high sensitivity or accuracy.

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these mechanisms provides a foundation for troubleshooting challenging amplifications and designing novel PCR-based applications. As molecular techniques continue to evolve, the precise management of metal ion cofactors will undoubtedly remain central to achieving reproducible, reliable results in both basic research and applied diagnostic contexts.

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a foundational technique in molecular biology, but its success is critically dependent on the reaction environment provided by the PCR buffer. While magnesium chloride (MgCl₂) is widely recognized as an essential cofactor for DNA polymerase, commercial PCR buffers are complex formulations containing a precise mix of salts, additives, and stabilizers that collectively determine the efficiency, specificity, and yield of the amplification [1] [10]. The composition of these buffers is often proprietary, creating a "black box" for many researchers. This guide deconstructs these formulations, moving beyond the role of MgCl₂ to explore how other components and commercial solutions impact PCR performance. Framed within a broader thesis on PCR efficiency, this analysis provides researchers and drug development professionals with a data-driven comparison to inform their selection of commercial PCR buffers for diverse applications.

Core Components of PCR Buffers

A standard PCR buffer is more than just a pH-stabilizing agent; it is a carefully balanced cocktail designed to create optimal conditions for the DNA polymerase enzyme.

Essential Salts and Ions

- Magnesium Ions (Mg²⁺): Acting as a crucial cofactor for DNA polymerase, Mg²⁺ is directly involved in the catalytic reaction by facilitating the formation of phosphodiester bonds between nucleotides [11]. Its concentration is critical; too little leads to weak or failed amplification, while too much promotes non-specific binding and increases error rates [11] [10]. The optimal concentration typically ranges from 1.0 mM to 5.0 mM and must be determined empirically for each primer-template system [10].

- Potassium Ions (K⁺): Typically supplied as KCl, potassium ions help to neutralize the negative charge on the phosphate backbone of DNA. This reduces electrostatic repulsion between the primer and the template strand, facilitating proper annealing [12] [10]. For longer amplicons, a final concentration of 35-100 mM is often used, sometimes alongside additives like DMSO [10].

- Tris-HCl: This buffer maintains a stable pH, usually around 8.3, throughout the thermal cycling process, which is vital for consistent enzyme activity [10].

Common Additives and Enhancers

To overcome challenges like high GC content, secondary structures, or problematic templates, a range of enhancers can be included.

Table 1: Common PCR Additives and Their Functions

| Additive | Primary Function | Common Concentration | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO | Disrupts base pairing, reduces secondary structures, lowers Tm [12] [10]. | 1-10% (often <2%) | Can inhibit Taq polymerase at higher concentrations [10]. |

| Betaine | Reduces DNA Tm dependence on GC content, equalizes Tm [12]. | 0.5 - 2.5 M | Often used in tandem with DMSO for GC-rich templates [10]. |

| Formamide | Destabilizes DNA double helix, increases primer annealing stringency [12] [10]. | 1-10% (often <5%) | - |

| BSA | Binds to inhibitors present in sample preparations (e.g., from feces, water) [10]. | Up to 0.8 mg/ml | - |

| Non-ionic Detergents | Stabilizes DNA polymerase, neutralizes inhibitors like SDS [12] [10]. | 0.1 - 1% | Higher concentrations can be inhibitory [10]. |

| TMAC | Increases hybridization specificity, eliminates mismatches [10]. | 15 - 100 mM | Particularly useful with degenerate primers [10]. |

Comparative Analysis of Commercial Buffer Performance

Different commercial buffers are engineered with specific proportions of these components to enhance performance for particular applications.

Experimental Data from Platform Comparisons

A 2025 study in Scientific Reports directly compared the QX200 droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) system from Bio-Rad with the QIAcuity One nanoplate digital PCR (ndPCR) system from QIAGEN, using synthetic oligonucleotides and DNA from the ciliate Paramecium tetraurelia [13]. The study evaluated the Limit of Detection (LOD), Limit of Quantification (LOQ), precision, and accuracy of both platforms.

Table 2: Comparative Performance Metrics of Digital PCR Platforms [13]

| Parameter | QIAcuity One (ndPCR) | QX200 (ddPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | 0.39 copies/µL input | 0.17 copies/µL input |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | 1.35 copies/µL input | 4.26 copies/µL input |

| Dynamic Range Precision | CV 7-11% (concentrations ~31-534 copies/µL) | CV 6-13%; highest precision at ~270 copies/µL |

| Impact of Restriction Enzyme (EcoRI) | CV range: 0.6% - 27.7% | CV range: 2.5% - 62.1% |

| Impact of Restriction Enzyme (HaeIII) | CV range: 1.6% - 14.6% | CV < 5% for all cell numbers |

The study also highlighted the significant impact of restriction enzyme choice on precision. Using HaeIII instead of EcoRI dramatically increased precision for the QX200 system, bringing CVs below 5% for all tested cell numbers [13]. This underscores that buffer-enzyme compatibility is a critical factor in experimental design, as the formulation can affect enzyme efficiency and access to template DNA.

Market Landscape and Key Suppliers

The global PCR buffer market includes several major players who supply buffers tailored for various needs. Key suppliers include Thermo Fisher Scientific, QIAGEN, Promega, New England Biolabs (NEB), Takara Bio, and Bio-Rad [14]. The market is characterized by continuous innovation, with trends pointing toward the development of high-fidelity buffers for increased amplification accuracy and formulations designed for multiplex PCR and integration with automated systems [14].

Experimental Protocols for Buffer Evaluation

To objectively compare the performance of different commercial buffers, researchers can adopt the following methodologies.

Protocol 1: Determining LOD and LOQ

This protocol is adapted from studies comparing digital PCR platforms [13].

- Material Preparation: Prepare a serial dilution of a known standard (e.g., synthetic oligonucleotides or a plasmid with the target sequence) across a range that spans from below the expected detection limit to a concentration that saturates the system.

- PCR Setup: Amplify each dilution in replicate (n≥5) using the commercial buffers and systems under comparison. The reaction conditions (cycling parameters, primer, and enzyme concentrations) must be kept constant.

- Data Analysis:

- LOD: Determine the lowest concentration at which the target is detected in 95% of the replicates.

- LOQ: Determine the lowest concentration at which the quantification result has an acceptable level of precision (e.g., a CV < 20-25%). This can be established by plotting the CV against the concentration and identifying the point where precision becomes stable.

Protocol 2: Assessing Precision with Complex Templates

This protocol evaluates buffer performance with genetically complex or inhibitor-containing samples [13].

- Template Selection: Use genomic DNA extracted from an organism with a known range of gene copy numbers, such as ciliates, or DNA spiked with common PCR inhibitors (e.g., humic acids).

- Amplification: Run the PCR using a fixed amount of template DNA and the different buffer systems. Include variations, such as the addition of restriction enzymes, to test for compatibility.

- Quantification and Analysis: Use a highly precise method like dPCR to quantify the target. Calculate the Coefficient of Variation (CV) across technical replicates for each buffer-condition combination. A lower CV indicates higher precision and better buffer robustness.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PCR Optimization

| Reagent / Solution | Critical Function in PCR |

|---|---|

| MgCl₂ Solution | Serves as the essential source of Mg²⁺ ions, a DNA polymerase cofactor [15] [11]. |

| PCR Enhancer Cocktails | Proprietary or custom mixes (e.g., containing betaine, DMSO) designed to overcome amplification challenges like high GC content [12]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase Systems | Enzyme bundles include a proprietary optimized buffer that is validated for high accuracy and long-range PCR [12]. |

| dNTP Mix | Provides the equimolar building blocks (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) for new DNA strand synthesis; quality is critical [1] [10]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Serves as the reaction medium without introducing RNases, DNases, or ions that could inhibit or skew the reaction. |

The formulation of a commercial PCR buffer is a sophisticated balance of salts, additives, and stabilizers that extends far beyond the provision of MgCl₂. As comparative studies show, the choice of buffer system significantly impacts key performance metrics like sensitivity, precision, and robustness to experimental variables such as restriction enzymes [13]. Furthermore, the strategic use of enhancers like DMSO, betaine, and BSA is crucial for optimizing the amplification of difficult templates. For researchers, a deep understanding of these components empowers informed buffer selection. The most effective approach often involves empirical testing of different commercial buffers and additives alongside their specific primer-template system to achieve maximal PCR efficiency and data reliability.

In the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), the concentration of free magnesium ions (Mg²⁺) is a pivotal factor that directly determines the success of DNA amplification. Mg²⁺ is an essential cofactor for all thermostable DNA polymerases, and its availability governs enzyme activity, reaction fidelity, and product specificity [16] [17]. However, the total magnesium added to a reaction does not equate to the concentration available for the enzymatic reaction. The "Magnesium-Dependency Equation" describes the dynamic competition for this precious cation, primarily between the polymerase enzyme and common PCR components: deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and template DNA [18] [16] [19].

Understanding this equilibrium is not merely an academic exercise; it is a practical necessity for researchers aiming to develop robust and reproducible PCR protocols. This guide objectively compares how different commercial buffer systems and optimization strategies manage Mg²⁺ availability, providing a scientific framework for maximizing PCR efficiency across various applications.

The Biochemistry of Magnesium in PCR

Magnesium as an Essential Cofactor

Mg²⁺ plays a non-negotiable role in the catalytic mechanism of DNA polymerases. The enzyme employs a two-metal-ion mechanism for catalyzing the formation of phosphodiester bonds. One metal ion (Metal A) activates the 3'-OH group of the primer for nucleophilic attack, while the other (Metal B) facilitates the departure of the pyrophosphate group from the incoming dNTP [5]. When Mg²⁺ is sequestered by other components, the polymerase cannot function correctly, leading to reduced yield or complete amplification failure.

The Competition for Magnesium Ions

The following diagram illustrates the competitive landscape for free Mg²⁺ in a typical PCR reaction.

This competition means that the free Mg²⁺ concentration—the amount not bound to other reaction components—is the critical parameter for polymerase activity. As summarized by the National Institute of Justice, "Taq DNA polymerase requires free magnesium (0.5 to 2.5mM) additional to that bound by template DNA, primers, and dNTPs" [16].

Quantitative Analysis of Mg2+ Chelation

The Mg2+-dNTP Stoichiometry

dNTPs are the most significant chelators of Mg²⁺ in a standard PCR. The phosphate groups of dNTPs have a high affinity for Mg²⁺, forming Mg-dNTP complexes that serve as the actual substrates for DNA polymerases. The table below summarizes the quantitative impact of major reaction components on free Mg²⁺.

Table 1: Mg²⁺ Chelation by PCR Components

| Component | Mechanism of Interaction | Impact on Free Mg²⁺ | Consequence of Imbalance |

|---|---|---|---|

| dNTPs | Strong chelation via phosphate groups; ~1:1 Mg²⁺ to dNTP binding [18]. | 200 µM dNTPs can chelate ~200 µM Mg²⁺. | Low Mg²⁺: Reduced enzyme activity, poor yield [17] [20]. |

| Template DNA | Electrostatic binding to the negatively charged phosphate backbone [19]. | Higher DNA complexity/concentration increases Mg²⁺ binding. | Low Mg²⁺: Increased melting temp, reduced product specificity [16]. |

| EDTA | Potent chelation; common carryover contaminant from DNA extraction kits [17]. | Directly and irreversibly removes Mg²⁺ from the available pool. | Severe inhibition: Polymerase inactivity, PCR failure [17] [19]. |

The optimal free Mg²⁺ concentration for Taq DNA Polymerase typically falls between 1.5 and 2.0 mM [20]. A standard PCR with 200 µM of each dNTP requires a minimum of 0.8 mM Mg²⁺ just to saturate the nucleotides, not accounting for the needs of the polymerase, template, and primers. This explains why most commercial buffers supply Mg²⁺ at a final concentration of 1.5 to 2.5 mM.

The Inhibitory Role of Contaminating Metal Ions and EDTA

The Mg²⁺ balance can be disrupted not only by internal chelation but also by external contaminants. EDTA, a potent chelator used in DNA storage buffers, can be co-purified with template DNA. Even small amounts can sequester Mg²⁺ and abolish amplification [17]. Furthermore, other metal ions can act as potent PCR inhibitors. For instance, Ca²⁺ competes with Mg²⁺ for binding sites on the polymerase but does not support catalysis, effectively inhibiting the reaction [19]. A study on metal inhibition found that zinc, tin, iron(II), and copper had IC₅₀ values significantly below 1 mM, highlighting their extreme inhibitory potential [19].

Comparative Analysis of Commercial PCR Buffer Strategies

Different commercial polymerases and buffer systems employ distinct strategies to manage the Mg²⁺ equilibrium, which directly impacts their performance, fidelity, and resistance to inhibitors.

Table 2: Comparison of Commercial Polymerase and Buffer Systems

| Polymerase Type | Typical Mg²⁺ Optimum | Buffer Strategy for Mg²⁺ Management | Resistance to Metal Inhibition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Taq | 1.5 - 2.0 mM [20] | Provides a baseline MgCl₂ concentration; requires user optimization. | Lower resistance; highly susceptible to inhibition by metals like Cu²⁺ and Zn²⁺ [19]. |

| High-Fidelity (e.g., Q5) | Varies; often supplied with Mg²⁺ | Optimized proprietary buffer; may require Mg²⁺ supplementation. | More resistant than Taq, but less than KOD polymerase [19]. |

| KOD Polymerase | Varies; often supplied with Mg²⁺ | Proprietary buffer with enhanced stability. | Most resistant to metal inhibition compared to Taq and Q5 [19]. |

| Hot Start Formulations | 1.5 - 2.5 mM [18] | Mg²⁺ is often pre-included in the buffer; system is inactive until heated, preventing mis-priming at low Mg²⁺. | Varies by polymerase type, but improved specificity reduces false-positive results. |

The experimental data shows that KOD polymerase is the most robust option for challenging samples potentially contaminated with metal ions, while Hot Start systems provide superior specificity by controlling the timing of enzyme activation in relation to the reaction's thermal profile [18] [19].

Experimental Protocols for Mg2+ Optimization

Standard Mg2+ Titration Protocol

To empirically determine the optimal Mg²⁺ concentration for a specific PCR assay, a titration experiment is the gold standard.

Methodology:

- Prepare a Master Mix: Create a master mix containing 1X PCR buffer (without MgCl₂), 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 0.2-0.5 µM of each primer, 0.5-2 units of DNA polymerase, and template DNA.

- Set Up Titration Series: Aliquot the master mix into multiple tubes. Supplement each tube with MgCl₂ from a stock solution (e.g., 25 mM) to create a final concentration series. A recommended range is 0.5 mM to 4.0 mM in increments of 0.5 mM [17] [20].

- Perform PCR Amplification: Run the reactions under the standard thermal cycling conditions for the primer pair and template.

- Analyze Results: Analyze the PCR products using agarose gel electrophoresis. The optimal Mg²⁺ concentration is the one that produces a single, intense band of the expected size with minimal to no non-specific products or primer-dimers [17].

Protocol for Reversing Calcium-Induced Inhibition

For samples contaminated with Ca²⁺, such as those derived from bone, a simple chelation strategy can be employed.

Methodology:

- Add Chelator: Include the calcium-specific chelator ethylene glycol-bis(2-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA) in the PCR master mix. EGTA has a high affinity for Ca²⁺ over Mg²⁺, effectively scavenging the inhibitory calcium ions without significantly depleting the essential magnesium pool [19].

- Optimize Concentration: Titrate EGTA to find the minimal effective concentration, typically starting in the low millimolar range, as this is a non-destructive and easy method to reverse calcium-induced inhibition [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Managing Mg2+ Availability

| Reagent | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| MgCl₂ Stock Solution (25 mM) | Allows fine-tuning of Mg²⁺ concentration to balance yield and specificity. | Titrate in 0.5 mM increments from 0.5-4.0 mM [20]. |

| PCR Buffer (without Mg²⁺) | Provides pH stability and ionic strength while allowing full customization of Mg²⁺. | Essential for systematic optimization experiments. |

| dNTP Mix (100 mM) | Provides nucleotides for DNA synthesis. | A 200 µM final concentration of each dNTP is standard; higher concentrations chelate more Mg²⁺ [17]. |

| EGTA | Calcium-specific chelator to reverse Ca²⁺-induced inhibition. | Preferred over EDTA for this purpose due to its selectivity for Ca²⁺ over Mg²⁺ [19]. |

| Hot Start DNA Polymerase | Enzyme rendered inactive until initial denaturation step. | Prevents primer-dimer and non-specific amplification at low, pre-cycled free Mg²⁺ levels [18]. |

The "Magnesium-Dependency Equation" underscores that successful PCR is a function of available Mg²⁺, not just added Mg²⁺. The competition between polymerase, dNTPs, template DNA, and potential contaminants like EDTA and Ca²⁺ dictates the reaction's efficiency and specificity. Commercial polymerase systems address this challenge through proprietary buffers and specialized enzyme formulations, with KOD polymerase showing particular resilience to metal ion inhibition [19]. A thorough understanding of these interactions, combined with empirical optimization using the provided protocols, empowers researchers to systematically overcome amplification challenges and achieve reliable, high-quality results across diverse genetic applications.

In the realm of molecular biology, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) stands as a foundational technique for genetic analysis and diagnostic testing. A critical factor influencing PCR success is the precise optimization of reaction components, particularly magnesium chloride (MgCl2) concentration. Magnesium ions (Mg²⁺) function as an essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity and significantly influence the thermodynamics of DNA hybridization and denaturation. Understanding the quantitative relationship between MgCl2 concentration and DNA melting temperature (Tm) is therefore paramount for developing efficient and reliable PCR protocols. This guide examines the logarithmic influence of MgCl2 on DNA melting temperature, providing a objective comparison of how this relationship impacts PCR efficiency across different experimental conditions and template types.

The Role of Mg²⁺ in PCR Thermodynamics

Biochemical Mechanisms

Magnesium ions play multiple indispensable roles in the PCR process. Primarily, they act as a crucial cofactor required for DNA polymerase activity by facilitating the incorporation of dNTPs during polymerization. Mg²⁺ coordinates with both the dNTPs and the DNA template, stabilizing the transition state during phosphodiester bond formation [1] [18]. Additionally, Mg²⁺ influences DNA strand separation dynamics by stabilizing the double-helix structure through neutralization of negative charges on the phosphate backbones of DNA strands [21] [1]. This dual function means Mg²⁺ concentration directly affects the thermodynamics and kinetics of both DNA denaturation and primer annealing, making it one of the most crucial parameters for PCR optimization [21] [22].

Quantitative Analysis: The Logarithmic Relationship

Evidence from Meta-Analysis

A comprehensive meta-analysis of 61 peer-reviewed studies published between 1973 and 2024 revealed a strong logarithmic relationship between MgCl2 concentration and DNA melting temperature [21] [23]. The analysis identified an optimal MgCl2 concentration range of 1.5–3.0 mM for efficient PCR performance [21]. Within this range, every 0.5 mM increase in MgCl2 concentration was associated with an approximately 1.2°C increase in DNA melting temperature [21] [23]. This quantitative relationship provides researchers with a predictive framework for adjusting PCR conditions based on desired Tm modifications.

Table 1: Quantitative Relationship Between MgCl2 Concentration and DNA Melting Temperature

| MgCl2 Concentration (mM) | Effect on Melting Temperature | Impact on PCR Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| < 1.0 mM | Substantially lowered Tm | Insufficient enzyme activity; poor or no amplification [18] |

| 1.5 – 3.0 mM | Optimal Tm modulation | Balanced specificity and yield; efficient amplification [21] |

| > 4.0 mM | Excessively elevated Tm | Increased nonspecific amplification; primer-dimer formation [22] [18] |

| 0.5 mM increments | ~1.2°C increase in Tm | Predictable tunability of reaction stringency [21] |

Template-Dependent Variations

The meta-analysis further demonstrated that template complexity significantly influences optimal MgCl2 requirements [21]. Genomic DNA templates, with their higher structural complexity, generally require MgCl2 concentrations at the higher end of the optimal range (2.0–3.0 mM), while simpler templates such as plasmid DNA and cDNA perform well at the lower end (1.5–2.0 mM) [21] [1]. This template-specific response underscores the importance of customizing MgCl2 concentrations based on template characteristics rather than applying universal standards.

Experimental Protocols for Determination

High-Throughput Melting Measurement (Array Melt)

The Array Melt technique represents a cutting-edge methodology for quantifying DNA folding thermodynamics at scale [24]. This protocol enables simultaneous measurement of melting behavior for thousands of DNA sequences:

Library Design: Design a DNA library of hairpin sequences (41,171 variants in the original study) with diverse structural motifs including Watson-Crick pairs, mismatches, bulges, and hairpin loops of various lengths [24].

Flow Cell Preparation: Synthesize the oligo pool, amplify with sequencing adapter sequences, and load onto a repurposed Illumina MiSeq flow cell. Cluster amplification generates groups of approximately 1000 copies of each sequence [24].

Fluorescence Quenching System: Engineer a common region for annealing a 3'-fluorophore-labeled oligonucleotide (Cy3) to the 5'-end of the hairpin and a 5'-quencher-labeled oligonucleotide (Black Hole Quencher) to the 3'-end [24].

Temperature Ramping: Expose the flow cell to increasing temperatures (20°C to 60°C) while monitoring fluorescence. As hairpins unfold at their melting temperatures, the distance between fluorophore and quencher increases, resulting in brighter fluorescence signals [24].

Data Analysis: Fit normalized melt curves to a two-state model to determine ΔH and Tm, then calculate ΔG37 and ΔS from ΔH and Tm. Apply quality control criteria to exclude non-two-state variants [24].

Conventional UV Melting Methodology

For individual oligonucleotide duplex analysis, traditional optical melting studies provide reliable Tm determination:

Oligonucleotide Preparation: Synthesize and purify RNA or DNA oligonucleotides using standard procedures [25].

Buffer Conditions: Prepare solutions with varying MgCl2 concentrations (0.5, 1.5, 3.0, and 10.0 mM) in appropriate buffer (e.g., 2 mM Tris, pH 8.3) without monovalent cations to isolate Mg²⁺ effects [25].

Spectrophotometric Measurement: Use a spectrophotometer equipped with a high-performance temperature controller. Obtain absorbance versus temperature melting curves between 15°C and 95°C at appropriate wavelengths (280 nm for purely G-C duplexes, 260 nm for others) with a heating rate of 1°C/min [25].

Data Processing: Analyze absorbance versus temperature curves using appropriate software (e.g., MeltWin v3.5) to produce Tm−1 versus ln CT plots for thermodynamic parameter determination [25].

Comparative Analysis of Commercial PCR Buffers

Magnesium Optimization Strategies

Different commercial PCR buffers employ varying strategies for magnesium optimization. Some systems provide MgCl2 separately, allowing researchers full control over final concentration, while others incorporate optimized concentrations within ready-to-use buffer formulations [18]. The "Hot Start – With Buffer – With MgCl₂ – Without dNTP" configuration exemplifies a balanced approach, providing optimized magnesium while excluding dNTPs to prevent premature Mg²⁺ chelation before thermal activation [18].

Table 2: Magnesium Handling in Commercial PCR Systems

| Buffer Type | MgCl2 Provision | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complete Master Mix | Pre-optimized concentration in buffer | Convenience; reduced setup time | Limited optimization flexibility [1] |

| Separate MgCl2 Component | Supplied as separate solution | Full concentration control; precise titration | Requires additional optimization steps [26] |

| Hybrid Systems (With Buffer, With MgCl₂, Without dNTP) | Pre-added at optimized level, with supplementation option | Balance of convenience and flexibility; prevents pre-activation chelation | May still require fine-tuning for challenging templates [18] |

Buffer-Specific Performance Characteristics

Commercial PCR buffers vary in their composition of additional cations that influence magnesium effects. Buffers containing special cation combinations can maintain high primer annealing specificity over a broader range of annealing temperatures, potentially reducing the need for extensive magnesium optimization for each primer pair [22]. The presence of potassium ions (K⁺) at 35-100 mM or ammonium sulfate ((NH₄)₂SO₄) in some buffer systems can interact with magnesium's effects on DNA stability, creating buffer-specific thermodynamic environments [26].

Visualization of Mg²⁺ Effects on PCR Thermodynamics

Mg²⁺ Mechanisms in PCR - This diagram illustrates the multifaceted role of magnesium ions in PCR thermodynamics, showing how MgCl2 concentration logarithmically influences DNA melting temperature while also affecting enzyme activity and primer binding.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Mg:Tm Relationship Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Function | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| MgCl2 Solutions | DNA polymerase cofactor; stabilizes nucleic acid interactions | Concentration critically affects Tm; chelates dNTPs; optimal range 1.5-3.0 mM [21] [1] |

| Thermostable DNA Polymerase | Catalyzes DNA synthesis; requires Mg²⁺ for activity | Different polymerases may have varying Mg²⁺ optima; typically 1-2.5 units per 50 µL reaction [1] [26] |

| dNTP Mix | Building blocks for DNA synthesis | Compete for free Mg²⁺; standard final concentration 200 µM of each dNTP; imbalance affects free Mg²⁺ availability [1] [18] |

| Fluorophore-Quencher Pairs | Detection of hybridization state in melt experiments | Cy3-BHQ pair used in Array Melt; distance-dependent fluorescence indicates unfolded state [24] |

| Buffer Additives | Modifiers of nucleic acid stability | DMSO, BSA, glycerol, betaine can affect Mg²⁺ availability and Tm relationships [22] [26] |

Implications for PCR Optimization

Practical Guidelines

The logarithmic relationship between MgCl2 and Tm provides a mathematical foundation for systematic PCR optimization rather than relying on empirical approaches. Researchers can apply the 1.2°C per 0.5 mM adjustment factor as a starting point for fine-tuning annealing temperatures when modifying MgCl2 concentrations [21]. For templates with high GC content or complex secondary structures, incremental increases in MgCl2 within the optimal range can help raise Tm sufficiently to overcome amplification barriers without resorting to extreme conditions that promote nonspecific binding [21] [22].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Understanding the MgCl2-Tm relationship aids in diagnosing PCR problems. Excessive nonspecific amplification often results from MgCl2 concentrations >3.0 mM, which stabilizes non-complementary primer-template interactions [22] [18]. Conversely, weak or absent amplification with clean backgrounds typically indicates insufficient MgCl2 (<1.5 mM) for adequate polymerase activity or primer binding [18]. The competing binding of Mg²⁺ to dNTPs must also be considered, particularly when using high dNTP concentrations (>0.4 mM total), which can effectively reduce free Mg²⁺ availability below optimal levels [1] [18].

The quantitative relationship between MgCl2 concentration and DNA melting temperature follows a predictable logarithmic pattern, with each 0.5 mM increment within the 1.5-3.0 mM optimal range increasing Tm by approximately 1.2°C. This fundamental thermodynamic principle provides researchers with an evidence-based framework for PCR optimization that transcends specific commercial buffer systems. By understanding and applying this relationship, scientists can strategically manipulate reaction conditions to enhance specificity, efficiency, and reliability across diverse PCR applications, from routine genotyping to challenging diagnostic assays. The continued refinement of magnesium correction factors and predictive models promises to further advance the design of precision PCR protocols tailored to specific template characteristics and experimental requirements.

In polymerase chain reaction (PCR), success is fundamentally determined by the precise matching of buffer composition to the intrinsic properties of the DNA template. While enzyme selection and cycling conditions receive significant attention, the base buffer—particularly its magnesium concentration, pH, and stabilizing additives—serves as the foundational element that either unlocks robust amplification or leads to reaction failure. This guide systematically examines how three critical template characteristics—GC content, amplicon size, and template complexity—dictate specific requirements for PCR base buffer formulation. The optimization strategies presented herein are contextualized within broader research on PCR efficiency, providing scientists with evidence-based protocols for matching commercial buffer systems to template challenges.

Experimental data consistently demonstrates that non-homogeneous amplification in multi-template PCR often stems from sequence-specific efficiency variations independent of traditional optimization parameters [27]. By adopting a template-driven approach to buffer selection, researchers can mitigate these biases, enhance reproducibility, and achieve more accurate quantitative results across diverse applications from gene expression analysis to diagnostic assay development.

Template Characteristics and Their Buffer Implications

GC Content

GC-rich templates ( >65% GC content) present formidable challenges due to their high thermodynamic stability, which impedes complete denaturation and promotes secondary structure formation. These templates routinely require specialized buffer formulations to achieve efficient amplification [28].

- Denaturation Efficiency: Standard denaturation at 94–98°C may be insufficient for GC-rich templates. Prolonged initial denaturation (up to 3-5 minutes) or higher denaturation temperatures (98°C) are often necessary for complex genomic DNA [28]. In one study, increasing the initial denaturation time from 0 to 5 minutes dramatically improved the yield of a 0.7 kb GC-rich fragment from human genomic DNA [28].

- Buffer Additives: The presence of co-solvents such as DMSO (1-10%), formamide (1.25-10%), betaine (0.5 M to 2.5 M), or glycerol can significantly enhance amplification of GC-rich templates by destabilizing DNA secondary structures and lowering the melting temperature of primer-template complexes [28] [26]. These additives help overcome the need for excessively long denaturation times or higher temperatures that might compromise polymerase activity.

AT-rich templates, conversely, face different challenges including lower melting temperatures and potential for non-specific primer binding. While less frequently problematic, they may benefit from:

- Higher Annealing Temperatures: Implemented through buffer systems with isostabilizing properties that allow for increased stringency without compromising primer binding efficiency [28].

- Optimized Magnesium Concentrations: Slightly reduced Mg²⁺ concentrations (1.5-2.0 mM) can help increase specificity for AT-rich sequences by stabilizing primer-template interactions without promoting mispriming [29].

Amplicon Size

The length of the target amplicon directly influences buffer requirements, particularly regarding polymerase processivity, extension times, and dNTP availability.

Short Amplicons (< 1 kb):

- Standard Buffer Systems: Conventional Taq polymerase buffers typically suffice.

- Brief Extension Times: 15-60 seconds per kb depending on polymerase speed [28] [29].

- Potential for Primer-Dimer Formation: Hot-start enzyme formulations incorporated into specialized buffers can prevent spurious amplification during reaction setup [30].

Long Amplicons (> 5 kb, up to 20+ kb):

- Polymerase Blends: Require specialized buffers optimized for enzyme mixtures containing both non-proofreading (e.g., Taq) and proofreading (e.g., Pfu) polymerases to correct misincorporations that would otherwise terminate elongation [30].

- Extended Extension Times: 1-2 minutes per kb for standard polymerases, with potential for further extension for very long targets [28] [29].

- Stabilizing Additives: Enhancements such as BSA (10-100 μg/ml) may help maintain polymerase activity during prolonged extension cycles [26].

- Modified Buffer pH and Salt Composition: Optimized to support polymerase processivity over extended templates.

Template Complexity

The structural nature and abundance of the template DNA significantly influence input requirements and buffer composition.

Plasmid and Viral DNA (Low Complexity):

Genomic DNA (High Complexity):

- Higher Input Requirements: 10-100 ng per 50 μL reaction for mammalian genomic DNA [1] [29].

- Enhanced Denaturation Conditions: Often benefits from prolonged initial denaturation to separate intertwined strands [28].

- Inhibitor-Resistant Formulations: May require buffers containing BSA or other compounds to counteract inhibitors commonly present in DNA extracts.

cDNA (Reverse Transcription Products):

- Compatibility with RT Components: Buffers must accommodate potential carryover of reverse transcription reagents.

- Mg²⁺ Optimization: Critical as Mg²⁺ requirements may differ from standard DNA amplification.

Comparative Data Analysis

Table 1: Template-Specific Buffer and Cycling Parameter Recommendations

| Template Characteristic | Recommended Mg²⁺ Concentration | Key Buffer Additives | Critical Cycling Modifications | Optimal DNA Input |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GC-rich (>65%) | 1.5-2.5 mM (may require titration) | DMSO (1-10%), Betaine (0.5-2.5 M), Formamide (1.25-10%) [28] [26] | Longer initial denaturation (1-3 min at 98°C); higher denaturation temp during cycling [28] | 1-100 ng (gDNA) [1] |

| AT-rich (<40%) | 1.5-2.0 mM | Possibly lower additive concentrations | Higher annealing temperature; two-step PCR [31] | 1-100 ng (gDNA) [1] |

| Long Amplicon (>5 kb) | 2.0-4.0 mM (polymerase-dependent) | BSA (10-100 μg/ml), Glycerol [26] [30] | Extended extension time (1-2 min/kb); polymerase blends recommended [28] [30] | 10-100 ng (gDNA) [29] |

| Short Amplicon (<1 kb) | 1.5-2.0 mM | Typically none required | Standard extension times (15-60 sec total) [29] | 0.1-50 ng [1] [31] |

| Complex Genomic DNA | 1.5-2.5 mM | BSA (10-100 μg/ml) for inhibitor resistance [26] | Longer initial denaturation (1-3 min) [28] | 10-100 ng [1] [29] |

| Plasmid/Viral DNA | 1.5-2.0 mM | Typically none required | Standard parameters usually sufficient | 0.1-1 ng [1] [29] |

Table 2: Commercial DNA Polymerases and Their Buffer Systems

| DNA Polymerase | Proofreading Activity | Recommended Buffer Formulations | Optimal Template Types | Extension Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taq | No | Standard Mg²⁺-containing buffer, often with (NH₄)₂SO₄ [28] | Routine amplification of targets <5 kb; cloning (adds 3´ dA overhangs) [28] [30] | ~60 bases/sec at 70°C [1] |

| Q5 / Phusion | Yes | High-fidelity buffers with Mg²⁺ added separately; requires 0.5-1.0 mM Mg²⁺ above dNTP concentration [29] | High-fidelity applications, long amplicons, GC-rich targets [29] | 15-30 sec/kb [29] |

| Pfu | Yes | Blended systems for long-range PCR; may require 2 min/kb extension [28] [30] | Applications requiring high fidelity; often used in blends with Taq [30] | ~2 min/kb (slower enzyme) [28] |

| OneTaq / LongAmp | Yes (OneTaq) | Specialized long-range buffers with higher Mg²⁺ (2.0 mM for LongAmp) [29] | Long amplicons (>10 kb); complex genomic templates [29] | 1 min/kb (OneTaq); 50 sec/kb (LongAmp) [29] |

| Vent / Deep Vent | Yes | Buffers often requiring Mg²⁺ titration in 2 mM increments up to 8 mM [29] | High-temperature applications; difficult templates [29] | 1 min/kb [29] |

Experimental Protocols for Buffer Optimization

Magnesium Titration Protocol

Purpose: To empirically determine the optimal Mg²⁺ concentration for a specific template-primer combination, as Mg²⁺ serves as an essential cofactor for polymerase activity and influences primer annealing stringency [1] [26].

Materials:

- PCR-grade water

- 10X PCR buffer (without Mg²⁺)

- MgCl₂ solution (25 mM)

- dNTP mix (10 mM each)

- Forward and reverse primers (20 μM each)

- DNA template (10-100 ng/μL)

- Thermostable DNA polymerase

- Thin-walled PCR tubes

Method:

- Prepare a master mix containing all reaction components except MgCl₂ and DNA template. Calculate for n+1 reactions to account for pipetting error.

- Aliquot the master mix into 8 PCR tubes.

- Add MgCl₂ to achieve a concentration gradient from 0.5 mM to 5.0 mM in 0.5-1.0 mM increments (e.g., 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0 mM).

- Add DNA template to each tube, mix gently, and briefly centrifuge.

- Run the following thermocycling program:

- Initial denaturation: 94-98°C for 2 minutes

- 25-35 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 94-98°C for 15-30 seconds

- Annealing: Primer-specific temperature for 15-30 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per kb

- Final extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes

- Analyze PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Interpretation: Identify the Mg²⁺ concentration that yields the strongest specific band with minimal nonspecific products. Higher Mg²⁺ concentrations generally decrease specificity but may be necessary for difficult templates [29].

Additive Screening Protocol for GC-Rich Templates

Purpose: To identify which enhancing additives improve yield and specificity for challenging GC-rich templates by disrupting stable secondary structures [28] [26].

Materials:

- Standard PCR reagents (as above)

- Additive stock solutions:

- DMSO (100%)

- Betaine (5 M)

- Formamide (100%)

- Glycerol (100%)

- BSA (10 mg/mL)

Method:

- Prepare a master mix with optimized Mg²⁺ concentration and all essential components.

- Aliquot the master mix into 6 tubes.

- Add additives to achieve the following final concentrations:

- Tube 1: Control (no additive)

- Tube 2: DMSO (5%)

- Tube 3: Betaine (1 M)

- Tube 4: Formamide (5%)

- Tube 5: Glycerol (5%)

- Tube 6: BSA (0.1 μg/μL)

- Add template DNA and run the thermocycling program with potentially longer denaturation steps (98°C for 15-30 seconds).

- Analyze by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Interpretation: Compare band intensity and specificity against the no-additive control. Note that some additives (particularly DMSO) lower the effective annealing temperature, which may require compensatory adjustments [28].

Protocol for Long Amplicon Amplification

Purpose: To amplify targets >5 kb using polymerase blends and optimized buffer conditions that support processivity and correct misincorporations [30].

Materials:

- High-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., Q5, Phusion) or polymerase blend (e.g., Taq+Pfu)

- Appropriate buffer system (often supplied with enzyme blend)

- High-quality dNTPs (200-300 μM each)

- Longer primers (25-30 nucleotides) with higher Tm (>68°C) [31]

Method:

- Set up reactions on ice with increased DNA template (50-100 ng genomic DNA).

- Use a polymerase blend according to manufacturer's recommendations or mix Taq and proofreading enzymes at approximately 100:1 unit ratio.

- Implement a "touchdown" or "hot-start" protocol to enhance specificity.

- Run with extended cycling parameters:

- Initial denaturation: 94-98°C for 2-3 minutes

- 25-35 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 94-98°C for 15-30 seconds

- Annealing: 55-65°C for 20-30 seconds

- Extension: 68-72°C for 2-4 minutes per kb (depending on polymerase)

- Final extension: 68-72°C for 10-15 minutes to ensure complete product extension.

Interpretation: Success is indicated by a single discrete band of expected size. Smearing or multiple bands may require further optimization of Mg²⁺, template quality, or cycling conditions.

Template-Buffer Interaction Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for matching buffer composition to template characteristics.

Template-Buffer Matching Workflow: This diagram outlines the systematic approach to selecting base buffer components based on template characteristics. Researchers should begin by analyzing GC content, amplicon size, and template complexity, then follow the appropriate pathways to determine initial buffer strategies before proceeding to final optimization.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Template-Specific PCR Optimization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Template Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Magnesium Salts | MgCl₂, MgSO₄ | DNA polymerase cofactor; stabilizes primer-template binding [1] [26] | All PCR applications; concentration must be optimized for each template |

| Polymerase Enhancers | DMSO, Betaine, Formamide, Glycerol [28] [26] | Destabilize DNA secondary structures; lower melting temperature | GC-rich templates, long amplicons, sequences with stable secondary structure |

| Stabilizing Proteins | BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Binds inhibitors; stabilizes polymerase during extended cycling [26] | Complex genomic DNA, environmental samples, long amplicons |

| Hot-Start Enzymes | Antibody-mediated, Aptamer-based, Chemical modification [30] | Prevents nonspecific amplification during reaction setup; increases specificity | All applications, particularly those with low template concentration or multiplexing |

| Proofreading Enzymes | Pfu, Q5, Phusion, Vent [29] [30] | 3'→5' exonuclease activity corrects misincorporated nucleotides; increases fidelity | Cloning, sequencing, long amplicon amplification, any application requiring high accuracy |

| dNTP Formulations | dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP (balanced) [1] [29] | Building blocks for DNA synthesis; balanced concentrations critical for fidelity | All PCR applications; concentration affects yield and error rate |

| Specialized Primers | Longer primers (25-40 nt), modified bases (phosphorothioate) [31] [29] | Enhanced specificity and binding efficiency; resistance to proofreading activity | Long amplicons, GC-rich targets, applications requiring high specificity |

Template-driven buffer formulation represents a paradigm shift in PCR optimization, moving beyond one-size-fits-all approaches to precision amplification. As demonstrated through the comparative data and experimental protocols presented, the systematic matching of buffer components to template characteristics—GC content, amplicon size, and complexity—significantly enhances amplification efficiency, specificity, and reproducibility. The growing understanding of sequence-specific amplification biases, as revealed through deep learning approaches [27], further underscores the need for tailored reaction conditions.

The implementation of these template-driven foundations enables researchers to preemptively address amplification challenges rather than reactively troubleshooting failed reactions. This approach is particularly valuable in quantitative applications where amplification efficiency directly impacts result accuracy [32], and in next-generation sequencing library preparation where uniform amplification across templates is essential. As PCR continues to evolve as a foundational technology across life sciences, diagnostics, and synthetic biology, the principles of template-buffer compatibility will remain essential for achieving robust, reliable results across the expanding spectrum of molecular applications.

Applied Strategies for Template-Specific Buffer and Magnesium Optimization

In polymerase chain reaction (PCR), success hinges on the precise partnership between the DNA polymerase enzyme and the chemical environment provided by its buffer system. While standard polymerases like Taq are sufficient for routine amplification, advanced applications in cloning, sequencing, and diagnostics demand specialist polymerases with superior fidelity and processivity. These high-performance enzymes, in turn, require meticulously optimized buffer systems to function at their peak. This guide objectively compares the performance of standard and specialist polymerases, detailing how matching them with their intended buffer systems impacts critical outcomes such as yield, accuracy, and robustness, providing researchers with a framework for informed reagent selection.

Polymerase Fidelity and Key Characteristics

Fidelity refers to a DNA polymerase's accuracy in incorporating nucleotides during DNA synthesis. Specialist high-fidelity polymerases significantly reduce error rates, which is critical for applications like cloning and sequencing where sequence integrity is paramount.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Standard and Specialist DNA Polymerases

| Feature | Standard Polymerase (e.g., Taq) | Specialist High-Fidelity Polymerase (e.g., Platinum SuperFi II) |

|---|---|---|

| Proofreading Activity | No | Yes (3'→5' exonuclease activity) |

| Relative Fidelity | 1x (Baseline) | >300x Taq [33] |

| Processivity | Moderate | High (often engineered) |

| Common Applications | Routine PCR, genotyping | Cloning, sequencing, mutagenesis |

| Typical Error Rate | ~1 x 10⁻⁵ | ~3.3 x 10⁻⁸ (extrapolated from [33]) |

| Optimal Mg²⁺ Concentration | 1.5-2.0 mM | Varies; requires optimization |

The exceptional accuracy of specialist enzymes like Platinum SuperFi II DNA Polymerase, quantified at >300 times the fidelity of Taq DNA polymerase, is achieved through proofreading activity [33]. This 3'→5' exonuclease capability allows the enzyme to detect and correct misincorporated nucleotides, ensuring a highly accurate final amplicon.

The Role of the Buffer System

The PCR buffer is far more than a mere pH-stabilizing agent; it is a critical determinant of reaction efficiency and specificity. Its components create the optimal chemical environment for the polymerase to function.

Magnesium Ions: The Essential Cofactor

Magnesium chloride (MgCl₂) is arguably the most important component of any PCR buffer. It acts as an essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity and influences DNA strand separation dynamics [21]. A meta-analysis of optimization studies identified an optimal MgCl₂ concentration range of 1.5–3.0 mM for efficient PCR performance [21]. This study quantitatively demonstrated that every 0.5 mM increase in MgCl₂ within this range raises DNA melting temperature by approximately 1.2°C, directly impacting annealing efficiency and template specificity [21]. Furthermore, template complexity influences required MgCl₂ concentration, with genomic DNA templates often requiring higher concentrations than simpler templates [21].

Monovalent Ions and pH Stabilizers

- Potassium Ions (K⁺): Typically used at concentrations of 50-100 mM, K⁺ contributes to the stability and activity of the polymerase enzyme and helps promote primer annealing [34].

- Tris-HCl Buffer: Usually present at concentrations from 10-100 mM, this buffer maintains the reaction pH within the optimal range (typically pH 8.0-8.5) for polymerase function, which is crucial throughout the thermal cycling process [34].

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Direct Enzyme Fidelity Comparison

Next-generation sequencing methods have enabled the precise quantification of polymerase fidelity. In one comparative study, a 3.9 kb sequence was amplified with various enzymes, and the resulting amplicons were analyzed for errors.

Table 2: Experimental Fidelity Comparison of Commercial Polymerases

| DNA Polymerase | Relative Fidelity (vs. Taq) | Key Feature | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taq DNA Polymerase | 1x (Baseline) | Standard for routine PCR | [33] |

| KOD DNA Polymerase | High (specific data not shown) | Notably resistant to metal inhibition | [19] |

| Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity | High (specific data not shown) | Common high-fidelity enzyme | [33] |

| Platinum SuperFi II | >300x | Engineered for ultra-high accuracy | [33] |

Tolerance to Common PCR Inhibitors

The performance of specialist polymerases in suboptimal conditions is a key differentiator. Experimental data demonstrates that engineered enzymes like Platinum SuperFi II DNA Polymerase show high tolerance to common PCR inhibitors such as humic acid (4 µg/mL), hemin (20 µM), and bile salt (1 mg/mL), whereas other high-fidelity polymerases like Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity and KOD Hot Start show significantly reduced or completely absent amplification under the same inhibitory conditions [33].

Protocol: Evaluating Metal Ion Inhibition on Polymerase Efficiency

Objective: To assess the susceptibility of different DNA polymerases to inhibition by metal ions commonly encountered in forensic or environmental samples [19].

Materials:

- Tested Polymerases: KOD polymerase (from KOD Hot Start DNA Polymerase kit), Taq polymerase (from MyTaq Red Mix), Q5 DNA polymerase (from Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase kit) [19].

- Metal Stock Solutions (40 mM): Prepare in water using salts of copper(II) sulfate, iron(II) sulfate, aluminium sulfate, nickel(II) sulfate, iron(III) chloride, lead(II) nitrate, tin(II) chloride, zinc chloride, and calcium chloride [19].

- Template DNA: 1 ng of control human genomic DNA.

- Primers: GAPDH primers (sense: 5'-AAAGGGCCCTGACAACTCTTT-3', antisense: 5'-TCAGTCTGAGGAGAACATACCA-3') for a 400 bp product [19].

- PCR Instrument: Veriti 96-Well Thermal Cycler or equivalent.

Method:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare PCR master mixes according to each manufacturer's recommended protocol. Adjust primer concentrations as per recommendations (e.g., 0.3 µM for KOD, 0.5 µM for Q5) [19].

- Metal Ion Addition: Spike reaction mixtures with metal ion solutions to achieve a final concentration series (e.g., 0 µM, 10 µM, 100 µM, 500 µM, 1 mM).

- Thermal Cycling:

- For Q5 polymerase: Initial denaturation at 98°C for 30s; 30 cycles of: 98°C for 10s, 63°C for 30s, 72°C for 30s; final extension at 72°C for 30s.

- For KOD polymerase: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 2min; 30 cycles of: 95°C for 20s, 63°C for 30s, 72°C for 30s.

- For Taq polymerase: Use manufacturer's recommended cycling conditions.

- Analysis: Analyze PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis (1% gel, 120V for 35-40 min). The detection limit for the system described is 250 pg of DNA per band [19].

Key Findings: Of the nine metals tested in the original study, zinc, tin, iron(II), and copper demonstrated the strongest inhibitory properties. Furthermore, KOD polymerase was found to be the most resistant to metal inhibition when compared with Q5 and Taq polymerase [19].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Polymerase and Buffer Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| KOD DNA Polymerase | High-fidelity, thermostable enzyme; shows high resistance to metal ion inhibition. | Used in metal inhibition studies [19]. |

| Platinum SuperFi II DNA Polymerase | Engineered high-fidelity polymerase for applications requiring utmost accuracy. | Used in fidelity and inhibitor tolerance comparisons [33]. |

| Magnesium Chloride (MgCl₂) | Essential cofactor for DNA polymerases; concentration must be optimized for each enzyme and template. | Studied in meta-analysis on PCR optimization [21]. |

| dNTPs | Nucleotide building blocks for DNA synthesis. | Component of all PCR master mixes. |

| SYBR Green I / TaqMan Probes | Fluorescent dyes/probes for real-time PCR and digital PCR quantification. | Used in dPCR platform comparisons and real-time assays [13] [35]. |

| Ethylene Glycol-bis(2-aminoethylether)-N,N,N',N'-tetraacetic acid (EGTA) | Calcium chelator; can reverse calcium-induced PCR inhibition. | Used as a non-destructive method to counteract inhibition [19]. |

| Restriction Enzymes (e.g., HaeIII, EcoRI) | Used in digital PCR to digest DNA and improve access to target sequences, enhancing precision. | HaeIII showed higher precision vs. EcoRI in dPCR copy number analysis [13]. |

A Workflow for Polymerase and Buffer Selection

The following diagram illustrates a systematic approach for selecting the appropriate polymerase and buffer system based on application requirements, incorporating key decision points revealed by experimental data.

Emerging Trends and Advanced Applications

The field of PCR enzymology continues to evolve, driven by demands for greater simplicity, multiplexing, and precision.

Next-Generation Digital PCR (dPCR): dPCR platforms, such as the QX200 droplet-based system (Bio-Rad) and the QIAcuity One nanoplate-based system (QIAGEN), enable absolute quantification of nucleic acids. Studies show that platform choice and reaction setup, including the selection of restriction enzymes (e.g., HaeIII vs. EcoRI), can impact the precision of gene copy number measurements, especially in organisms with complex genomes [13].

Engineered Multi-Functional Enzymes: Recent research has led to the development of novel Taq polymerase variants capable of catalyzing both reverse transcription (RT) and DNA amplification in a single tube without needing viral reverse transcriptases [35]. These engineered enzymes, derived from combinations of fidelity- and RT-boosting mutations, are suitable for probe-based RNA detection and multiplex detection of various RNA targets, representing a significant simplification of molecular diagnostic workflows [35].

Matching a DNA polymerase with its optimal buffer system is a critical step in experimental design that directly dictates the success and reliability of PCR. While standard polymerases are cost-effective for simple applications, specialist enzymes offer demonstrably superior fidelity, inhibitor tolerance, and versatility for demanding workflows. As polymerase engineering becomes more sophisticated, the trend is moving towards integrated systems where the enzyme and its buffer are co-optimized to provide robust, reproducible performance, empowering researchers to push the boundaries of molecular biology and diagnostic science.

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) serves as a foundational technique in molecular biology, yet achieving optimal amplification from genomic DNA (gDNA) templates presents significant challenges due to their inherent complexity and the frequent presence of inhibitors. The success of PCR is critically dependent on a carefully balanced reaction milieu, where components such as magnesium ions, buffer composition, and DNA polymerase interact in complex ways. gDNA templates are particularly demanding due to their size, structural complexity, and high likelihood of containing sequence regions that impede efficient amplification, such as those with extreme GC content or secondary structures [12]. Furthermore, contaminants co-purified with gDNA from biological samples can inhibit polymerase activity, leading to reduced sensitivity, specificity, and yield.

This guide objectively compares the performance of different optimization strategies and commercial reagents, framing the analysis within broader research on PCR efficiency with commercial buffers and magnesium. The optimization workflow outlined herein is designed to systematically address the multifaceted challenges associated with gDNA amplification, providing researchers with a structured approach to enhance assay robustness, reproducibility, and accuracy in applications ranging from basic biomedical research to clinical diagnostics and drug development.

Core Principles of a Systematic Optimization Workflow

A structured, sequential approach to PCR optimization prevents the common pitfall of simultaneously adjusting multiple variables, which often leads to ambiguous results and prolonged development time. The most effective workflow progresses from addressing the most influential factors to more refined adjustments, ensuring that each step builds upon a stabilized foundation.

The following diagram illustrates the recommended sequential optimization workflow for genomic DNA PCR assays:

Sequential PCR Optimization Workflow

This systematic progression ensures that fundamental parameters are stabilized before addressing more specialized enhancements. The process begins with verifying template integrity and quantity, as poor-quality gDNA represents one of the most common sources of PCR failure [36]. Subsequent stages focus on reaction chemistry and cycling conditions, with magnesium optimization representing a particularly critical juncture due to its central role as a polymerase cofactor and its influence on DNA duplex stability.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Optimization

Protocol 1: Magnesium Titration for gDNA Templates

Principle: Magnesium chloride (MgCl₂) concentration directly affects DNA polymerase activity, reaction specificity, and primer-template binding efficiency. Its optimal concentration varies significantly with template complexity, making empirical titration essential for gDNA applications [21] [37].

Reagents:

- 10X Commercial PCR Buffer (without MgCl₂)

- 50 mM MgCl₂ stock solution

- Template gDNA (50 ng/μL)

- Forward and reverse primers (10 μM each)

- dNTP mix (10 mM total)

- DNA polymerase (1-2 U/μL)

- Nuclease-free water

Procedure:

- Prepare a master mix containing 1X PCR buffer, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 0.5 μM of each primer, 1.0 U DNA polymerase, and 50 ng gDNA template.

- Aliquot the master mix into 8 PCR tubes.

- Add MgCl₂ from the stock solution to achieve final concentrations of: 1.0 mM, 1.5 mM, 2.0 mM, 2.5 mM, 3.0 mM, 3.5 mM, 4.0 mM, and 5.0 mM.

- Perform amplification using the following cycling parameters:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 2 minutes

- 35 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds

- Annealing: Primer-specific Tm for 30 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per kb

- Final extension: 72°C for 5 minutes

- Analyze results by agarose gel electrophoresis to identify the MgCl₂ concentration yielding the strongest specific band with minimal nonspecific amplification.

Data Interpretation: Meta-analyses indicate that most gDNA applications achieve optimal efficiency with MgCl₂ concentrations between 1.5 mM and 3.0 mM, with each 0.5 mM increase raising DNA melting temperature by approximately 1.2°C [21] [23]. Genomic DNA templates typically require higher concentrations than simpler templates like plasmids due to their complexity [21].

Protocol 2: PCR Enhancer Screening for Inhibitor-Rich gDNA