Overcoming PCR Hurdles: A Comprehensive Guide to Tackling Hairpin Structures and GC-Rich Templates

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and drug development professionals facing PCR failure due to challenging secondary structures.

Overcoming PCR Hurdles: A Comprehensive Guide to Tackling Hairpin Structures and GC-Rich Templates

Abstract

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and drug development professionals facing PCR failure due to challenging secondary structures. It covers the fundamental principles of how DNA hairpins and GC-rich regions impede polymerase progression, outlines specialized laboratory protocols and reagent choices for robust amplification, presents a step-by-step troubleshooting framework, and discusses validation techniques to confirm reaction success. By integrating foundational knowledge with practical application, this resource aims to equip scientists with the strategies needed to reliably amplify even the most recalcitrant DNA targets, thereby accelerating biomedical research and diagnostic assay development.

Understanding the Enemy: The Science Behind Hairpin Structures and GC-Rich Barriers in PCR

What is a 'GC-Rich' Sequence?

In molecular biology, a DNA sequence is generally considered 'GC-rich' when 60% or more of its nucleotide bases are guanine (G) or cytosine (C) [1]. This simple quantitative definition, however, belies a significant biochemical challenge. While only about 3% of the human genome is composed of such GC-rich regions, they are critically important as they are often found in the promoters of genes, including housekeeping and tumor suppressor genes [1].

The core of the challenge lies in the molecular stability of the GC base pair. A G-C pair is stabilized by three hydrogen bonds, whereas an A-T pair has only two [1] [2]. This extra hydrogen bond makes GC-rich DNA sequences inherently more thermostable, meaning they require more energy (in the form of higher temperature) to separate (denature) than AT-rich regions [1]. It is a common misconception that hydrogen bonding is the primary stabilizer; in fact, base stacking interactions play a major role in the overall stability of the DNA double helix [3].

Why Do Secondary Structures Form?

The combination of high thermostability and single-stranded DNA dynamics during the PCR process creates a perfect environment for problematic secondary structures.

During a PCR cycle, the template DNA is denatured into single strands at a high temperature (e.g., 95°C). The reaction temperature is then quickly lowered for primer annealing. This rapid cooldown favors the formation of intramolecular secondary structures within the single-stranded DNA template before the primers have a chance to bind intermolecularly [4]. The strong bonding of G and C bases means that GC-rich stretches can easily fold back on themselves to form highly stable secondary structures.

The most common and troublesome secondary structures include [1] [3] [2]:

- Hairpin Loops: Also known as stem-loop structures, these form when complementary regions within the same single strand of DNA base-pair with each other.

- Primer-Dimers: These can form when primers anneal to each other due to complementary sequences, instead of to the template DNA.

The table below summarizes how these properties directly lead to experimental failure.

Table 1: Core Characteristics and Consequences of GC-Rich DNA

| Feature | Molecular Basis | Direct Consequence in PCR |

|---|---|---|

| High Thermal Stability | Three hydrogen bonds per G-C base pair (vs. two for A-T); significant base stacking interactions [1] [3]. | Requires higher denaturation temperatures; resists strand separation, preventing primer access [1]. |

| Secondary Structure Formation (e.g., Hairpins) | Stable, intramolecular folding of single-stranded DNA, driven by GC complementarity [3] [4]. | Physically blocks polymerase progression, leading to truncated products and failed amplification [1] [4]. |

| High Melting Temperature (Tm) | The temperature required to denature 50% of the DNA duplex is directly correlated with its GC content [2]. | Makes standard PCR annealing/denaturation temperatures ineffective, requiring specialized cycling conditions [3]. |

The Molecular Mechanism of PCR Failure

Recent research provides a deeper mechanistic insight into how these stable secondary structures cause PCR failure. The process can be visualized as follows:

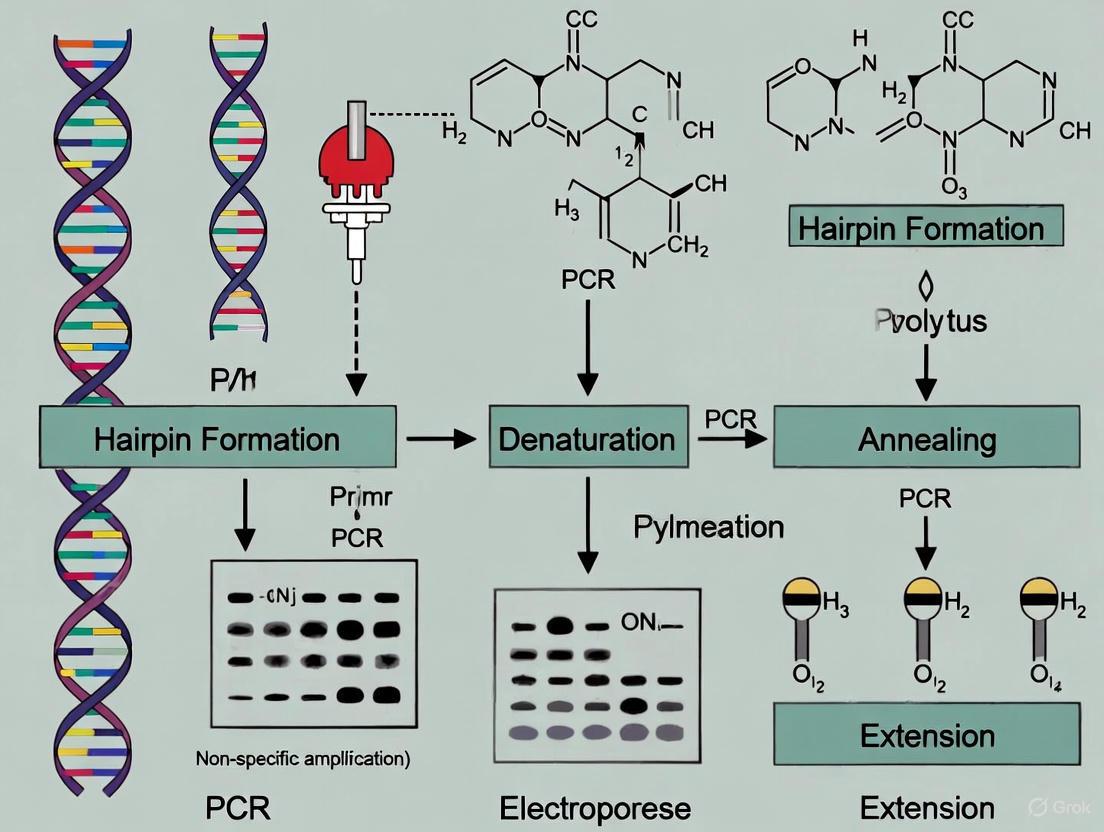

Diagram Title: Mechanism of PCR Failure via Stem-Loop Structures

The diagram shows the cascade of events leading to failure. A critical step involves the endonuclease activity of Taq DNA polymerase. When the polymerase encounters a stable stem-loop structure it cannot unwind, its inherent 5'→3' exonuclease activity can actually cleave the template strand itself. This digestion unwinds the structure, allowing replication to continue—but now from a truncated template, resulting in shorter, incorrect products [4]. This explains the smeared or multiple bands often seen on gels when amplifying difficult templates.

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

This section addresses specific, common problems researchers encounter when working with GC-rich DNA and provides targeted solutions.

Why is my PCR result a blank gel or a DNA smear?

A blank gel (no product) or a DNA smear typically indicates that the polymerase is unable to efficiently amplify the target due to the challenges outlined above. The polymerase may be stalling at secondary structures or failing to denature the template sufficiently [1].

Solutions:

- Use a Specialized Polymerase: Switch to a polymerase specifically engineered for GC-rich or difficult templates, such as Q5 High-Fidelity or OneTaq DNA Polymerase [1] [5]. These often come with specialized buffers and GC Enhancers.

- Employ PCR Additives: Additives can be highly effective. Betaine can help by destabilizing secondary structures. DMSO can also reduce secondary structure formation. BSA can help by binding contaminants that may inhibit the reaction [1] [6] [3].

- Optimize Mg2+ Concentration: Magnesium is a critical cofactor for polymerase activity. Test a gradient of MgCl2 (e.g., from 1.0 mM to 4.0 mM in 0.5 mM increments) to find the optimal concentration for your specific amplicon [1].

How can I prevent non-specific bands and primer-dimer formation?

Non-specific bands and primer-dimer are signs of low reaction specificity, often caused by primers binding to off-target sites or to each other [7] [6].

Solutions:

- Increase Annealing Temperature (Ta): A higher Ta promotes more specific primer binding. Use a temperature gradient to find the highest possible Ta that still yields your product. Touchdown PCR can also be effective [1] [8] [5].

- Use a Hot-Start Polymerase: These enzymes are inactive until a high-temperature activation step, preventing non-specific priming and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup [6] [5].

- Optimize Primer Design: Ensure primers have a GC content between 40-60%, avoid long stretches of Gs or Cs (especially at the 3' end), and have minimal self-complementarity or cross-complementarity [8] [2].

My polymerase seems to be stalling and producing truncated products. What can I do?

This is a classic symptom of the polymerase being blocked by stable secondary structures like hairpins [4].

Solutions:

- Increase Denaturation Temperature: For the first few cycles, using a denaturation temperature of 95-98°C can help melt stubborn structures. Be cautious, as very high temperatures can degrade the polymerase over many cycles [3].

- Use a Polymerase Mix with Proofreading Activity: Proofreading polymerases (those with 3'→5' exonuclease activity) are often more processive and can handle complex templates better. A blend containing a small amount of a proofreading enzyme can significantly improve the amplification of long or difficult products [9].

- Incorporate dGTP Analogs: Adding 7-deaza-2'-deoxyguanosine, a dGTP analog, to the PCR mixture can improve yield. This analog base-pairs with cytosine but disrupts Hoogsteen bonding, which is involved in higher-order structures, making the DNA easier to denature [1] [3].

Experimental Protocols for GC-Rich PCR

Protocol 1: Standard Optimization with Additives

This protocol provides a baseline for amplifying a GC-rich target using a standard Taq polymerase and common additives.

Materials:

- DNA template

- Forward and Reverse primers (designed with GC-content between 40-60%)

- Standard Taq DNA Polymerase and corresponding buffer

- MgCl2 solution

- dNTP mix

- PCR-grade water

- Additives: DMSO, Betaine, BSA

Method:

- Prepare a master mix on ice according to the table below. Set up multiple tubes to test different conditions.

- Run the PCR with the following cycling conditions, optimizing the annealing temperature (Ta) as a gradient:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2 minutes

- 35 Cycles:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds

- Annealing: Ta Gradient from 55°C to 68°C for 30 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per kb

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5 minutes

- Hold: 4°C

Table 2: Master Mix Setup for Additive Testing

| Component | Control | Test 1 (DMSO) | Test 2 (Betaine) | Test 3 (Combination) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10X PCR Buffer | 5 µL | 5 µL | 5 µL | 5 µL |

| 25 mM MgCl2 | 3 µL | 3 µL | 3 µL | 3 µL |

| 10 mM dNTPs | 1 µL | 1 µL | 1 µL | 1 µL |

| Forward Primer (10 µM) | 1.25 µL | 1.25 µL | 1.25 µL | 1.25 µL |

| Reverse Primer (10 µM) | 1.25 µL | 1.25 µL | 1.25 µL | 1.25 µL |

| Taq Polymerase | 0.25 µL | 0.25 µL | 0.25 µL | 0.25 µL |

| Template DNA | Variable | Variable | Variable | Variable |

| DMSO | - | 2.5 µL (5%) | - | 1.25 µL (2.5%) |

| 5M Betaine | - | - | 10 µL (1M) | 10 µL (1M) |

| PCR-Grade Water | to 50 µL | to 50 µL | to 50 µL | to 50 µL |

Protocol 2: Using Specialized Polymerase Systems

For the most challenging targets, using a dedicated system is often the most efficient path to success.

Materials:

- DNA template

- Forward and Reverse primers

- Specialized polymerase (e.g., NEB Q5 or OneTaq)

- Companion GC Enhancer or High GC Buffer

Method:

- Follow the manufacturer's instructions precisely. For example, with NEB's Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase:

- Use the provided 5X Q5 Reaction Buffer.

- Add the optional 5X Q5 High GC Enhancer to the reaction mixture for targets with >70% GC content [1].

- Cycling conditions may need to be adjusted according to the manufacturer's recommendations, which often include a higher denaturation temperature.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for GC-Rich PCR

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application | Example Product |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerases | Engineered for high processivity and fidelity on complex templates; often have proofreading activity. | Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB #M0491) [1] |

| Specialized Master Mixes | Pre-mixed optimized buffers and enzymes for specific challenges like GC-rich amplification. | OneTaq Hot Start 2X Master Mix with GC Buffer (NEB) [1] |

| GC Enhancer Buffers | Proprietary buffer formulations containing additives that help destabilize secondary structures and increase primer stringency. | OneTaq GC Buffer, Q5 High GC Enhancer [1] |

| PCR Additives | Chemical modifiers that help denature stable DNA structures or reduce non-specific binding. | DMSO, Betaine, Glycerol, Formamide [1] [6] |

| Hot-Start Polymerases | Polymerases inactive at room temperature, preventing non-specific priming and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup. | OneTaq Hot Start DNA Polymerase [5] |

| dGTP Analogs | Nucleotide analogs that replace dGTP to disrupt stable secondary structures during amplification. | 7-deaza-2'-deoxyguanosine [1] [3] |

FAQs: Hydrogen Bonding and Thermostability

Q1: What is the fundamental reason G-C base pairs are more stable than A-T pairs? The higher thermostability of G-C base pairs compared to A-T pairs is fundamentally due to a difference in hydrogen bonding. A G-C pair forms three hydrogen bonds, while an A-T pair forms only two. The additional hydrogen bond in the G-C pair requires more energy (heat) to break, resulting in a higher melting temperature (Tm) for DNA regions rich in G-C content [10] [11].

Q2: How does this hydrogen bond disparity directly impact my PCR experiments? GC-rich DNA templates require higher denaturation temperatures because the three hydrogen bonds in each G-C pair make the double helix more stable and resistant to melting. If the denaturation temperature is too low, the DNA may not fully separate, leading to PCR failure due to polymerase stalling, low yield, or complete amplification failure [11].

Q3: Beyond hydrogen bonds, what other factors make GC-rich sequences problematic in PCR? GC-rich sequences are prone to forming stable secondary structures, such as hairpin loops. These structures form when a single-stranded DNA segment folds back and base-pairs with itself, which can block primer binding or polymerase progression. The same strong hydrogen bonding that stabilizes the double helix also stabilizes these intramolecular structures, compounding the challenge [12] [11].

Q4: What is a DNA hairpin, and how does it interfere with amplification? A DNA hairpin is a secondary structure where a single strand folds back on itself, creating a stem (double-stranded region) and a loop (unpaired region). During PCR, if a hairpin forms within the template or a primer, it can:

- Physically block the DNA polymerase, causing it to stall and produce truncated products [11].

- Prevent primers from annealing to their target sequence, leading to reduced sensitivity or false negatives [12].

Troubleshooting Guide: PCR Amplification of GC-Rich Regions and Hairpin-Prone Templates

Problem: PCR failure (no product or faint smears) with a suspected GC-rich template.

Step 1: Polymerase and Buffer Selection

- Action: Switch to a polymerase specifically engineered for high GC content and use its accompanying specialized buffer.

- Rationale: Standard polymerases like Taq may stall at the stable secondary structures formed by GC-rich templates. High-fidelity polymerases such as Q5 or kits like OneTaq are often optimized for these challenging templates. Many are supplied with a GC Enhancer that contains additives to help disrupt secondary structures [11].

- Protocol:

- Set up a parallel reaction using a polymerase known for amplifying GC-rich targets.

- If provided, add the manufacturer's GC Enhancer at the recommended starting concentration (e.g., 5-10%).

- Compare the results with your standard protocol on an agarose gel.

Step 2: Optimize Thermal Cycling Conditions

- Action: Increase the denaturation temperature and/or use additives.

- Rationale: A higher denaturation temperature provides more energy to break the three hydrogen bonds of G-C pairs and melt hairpin structures.

- Protocol:

- Denaturation: Increase the temperature from the standard 94-95°C to 98°C.

- Annealing: Perform a temperature gradient PCR (e.g., from 60°C to 72°C) to determine the most specific annealing temperature for your primer-template combination. A higher Ta can increase specificity [11].

- Additives: Test the effect of additives like DMSO, betaine, or formamide, which can help denature secondary structures by interfering with hydrogen bonding. Note: It is often more efficient to use a pre-optimized GC Enhancer solution than to test individual additives manually [11].

Step 3: Magnesium Concentration Titration

- Action: Test a range of MgCl₂ concentrations.

- Rationale: Mg²⁺ is a crucial cofactor for polymerase activity and affects primer annealing stringency. The optimal concentration for GC-rich templates may differ from the standard 1.5-2.0 mM [11].

- Protocol:

- Prepare a master mix without MgCl₂.

- Aliquot the master mix and supplement with MgCl₂ to final concentrations of 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0, and 3.5 mM.

- Run the PCR and analyze the products by gel electrophoresis to identify the concentration that gives the strongest specific band.

Problem: Suspected hairpin formation in template or primers.

Step 1: In Silico Analysis

- Action: Use primer design software to check for secondary structures.

- Rationale: Software tools can predict the formation of hairpins in your primers and the stability of secondary structures in the template at the annealing temperature, allowing you to select optimal primer binding sites [12].

- Protocol:

- Use tools like NCBI Primer-BLAST or Primer3 to analyze your primer sequences for self-complementarity and hairpin formation.

- Avoid primers with strong secondary structures, particularly at their 3' ends.

Step 2: Primer Re-design

- Action: Design new primers that anneal to a less structured region.

- Rationale: If the template itself has a persistent hairpin in the amplification region, moving the primer binding site to a more accessible area is the most effective solution [12].

- Protocol:

- Refer to the results of your in silico analysis.

- Design new primers where the binding site has a lower predicted propensity for secondary structure.

Step 3: Utilize a Touchdown PCR Protocol

- Action: Implement a PCR program where the annealing temperature starts high and gradually decreases in later cycles.

- Rationale: A high initial annealing temperature promotes highly specific primer binding and can prevent amplification from primers that are bound non-specifically to secondary structures. As the temperature lowers in subsequent cycles, the specific product is already amplified and can be efficiently replicated [13].

The following tables consolidate key experimental data relevant to the thermodynamics of DNA structures and PCR optimization.

Table 1: Thermodynamic Parameters of DNA Hairpins with Varying Loop Sizes This data demonstrates how the size of the hairpin loop influences its stability, with larger loops generally decreasing the melting temperature (Tm) [14].

| Hairpin Sequence | Loop Size (dT residues) | Melting Temperature (Tm, °C) | Transition Enthalpy (ΔH, kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| d(GCGCT₃GCGC) | 3 | 79.1 | ~38.5 |

| d(GCGCT₅GCGC) | 5 | Not Specified | ~38.5 |

| d(GCGCT₇GCGC) | 7 | 57.5 | ~38.5 |

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Troubleshooting GC-Rich PCR This table lists common reagents used to overcome challenges in amplifying difficult templates [11].

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Rationale | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| High-GC Polymerase Mix | Polymerase and buffer optimized for denaturing stable structures. | First-choice solution for amplicons with >60% GC content. |

| GC Enhancer | Proprietary mix of additives (e.g., betaine) to disrupt secondary structures. | Added to the reaction mix to improve yield from structured templates. |

| DMSO | Additive that reduces DNA secondary structure formation. | Typically used at 1-10% final concentration. |

| 7-deaza-dGTP | dGTP analog that reduces hydrogen bonding, incorporated into the product. | Can improve yield but may complicate downstream analysis. |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Hairpin Formation and Stability

This protocol outlines a method to study DNA hairpin stability using ultraviolet (UV) melting curve analysis, a technique that provides the thermodynamic parameters shown in Table 1 [14].

Objective: To determine the melting temperature (Tm) and thermodynamic profile of a synthesized DNA hairpin.

Materials:

- Synthesized and purified DNA oligonucleotide (e.g., d(GCGCT₅GCGC)).

- UV-vis spectrophotometer with a temperature-controlled cuvette holder.

- Appropriate buffer (e.g., 1X PBS or 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5).

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve the DNA oligonucleotide in buffer to a final concentration of 1-5 µM. Ensure a homogeneous solution.

- Denaturation and Renaturation: Heat the sample to 95°C for 5 minutes, then slowly cool it to room temperature over 1-2 hours to allow proper hairpin formation.

- UV Melting Experiment:

- Load the sample into a quartz cuvette and place it in the spectrophotometer.

- Set the spectrophotometer to monitor absorbance at 260 nm.

- Program the instrument to heat the sample from 20°C to 95°C at a slow, constant rate (e.g., 0.5-1.0°C per minute).

- Record the absorbance at 260 nm at regular temperature intervals.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the absorbance at 260 nm versus temperature to generate a melting curve.

- The Tm is defined as the temperature at the midpoint of the absorbance transition (where 50% of the hairpins are unfolded).

- The transition enthalpy (ΔH) can be calculated from the shape and steepness of the melting curve.

Conceptual Diagrams

Diagram 1: Hydrogen Bonding and DNA Thermostability. This diagram illustrates the fundamental structural difference between a G-C base pair, stabilized by three hydrogen bonds, and an A-T base pair, stabilized by two. The additional hydrogen bond in the G-C pair directly contributes to the higher energy requirement for melting, leading to greater thermostability in GC-rich DNA regions [10] [11].

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting Workflow for GC-Rich/Hairpin PCR. This flowchart provides a logical sequence of experimental steps to diagnose and resolve common PCR issues arising from GC-rich templates and hairpin structures. The process begins with in silico analysis and proceeds through wet-lab optimizations of reagents and thermal cycling parameters [12] [11].

What are DNA hairpins and why do they disrupt PCR? DNA hairpins are secondary structures that form when a single-stranded DNA molecule folds back on itself, creating a stem-loop structure. These formations are particularly prevalent in GC-rich sequences, where the strong triple hydrogen bonding between guanine (G) and cytosine (C) nucleotides creates stable structures that can resist denaturation even at high temperatures [15]. During polymerase chain reaction (PCR), these structures present a significant physical barrier to DNA polymerase progression, leading to abrupt stops in amplification, failed reactions, and uninterpretable sequencing results [15] [16].

The challenge is particularly pronounced in specific genomic contexts. Research on the murine Foxd3 locus revealed a 370-nucleotide segment that consistently resisted polymerase read-through during both PCR and sequencing reactions. This region, characterized by 61% GC content, was predicted to form a tight cluster of hairpin structures that defined precise boundaries beyond which polymerases could not extend [15]. Understanding this mechanism is crucial for researchers working with difficult templates, particularly in applications requiring high fidelity such as diagnostic assay development, cloning, and mutational analysis.

The Molecular Mechanism of Polymerase Blockage

How Hairpins Form Physical Barriers

DNA hairpins create impediments to PCR amplification through several interconnected mechanisms:

- Steric Hindrance: The three-dimensional structure of the hairpin physically blocks the polymerase enzyme's progression along the template strand. The enzyme's catalytic site cannot properly engage with bases involved in secondary structures.

- Thermodynamic Stability: GC-rich hairpins exhibit exceptional thermal stability due to their increased number of hydrogen bonds. While typical PCR denaturation temperatures (94-95°C) separate standard double-stranded DNA, stable hairpins can persist at these temperatures, maintaining their structure throughout thermal cycling [17].

- Polymerase Processivity Limitations: Most DNA polymerases have limited strand-displacement activity. When they encounter a stable secondary structure, they cannot unwind it efficiently and may dissociate from the template, terminating amplification [18].

Experimental Evidence from the Foxd3 Locus

A case study examining the Foxd3 locus provides compelling evidence for these mechanisms. Researchers discovered that:

- Sequencing reads consistently terminated at precise positions 442 nt and 811 nt upstream of the Foxd3 ATG start codon, defining a 370-nt resistant region [15]

- PCR amplification across this region failed universally, even with polymerases and conditions tailored for GC-rich templates [15]

- The resistant region exhibited 61% GC content and was predicted by RNAfold software to form a tight cluster of hairpins at 72°C (standard polymerase extension temperature) [15]

- The boundaries of the polymerase-resistant segment corresponded precisely to nucleotides located within long, stable hairpins with the highest base-pairing probability [15]

Table 1: Characteristics of the Polymerase-Resistant Region in Foxd3 Locus

| Parameter | Resistant Region (β) | Upstream Flank (α) | Downstream Flank (γ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GC Content | 61% | 39% | 71% |

| Polymerase Read-through | No | Yes | Yes |

| Predicted Secondary Structure | Tight hairpin cluster | Minimal structure | Hairpins without strong stability |

| Conservation Across Vertebrates | High | Low | Moderate (mammals only) |

Visualizing the Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates how hairpin structures block polymerase progression during PCR amplification:

Troubleshooting Guide: PCR Failure Due to Hairpin Structures

FAQ: Common Researcher Questions

Q1: How can I determine if my PCR failure is due to hairpin structures rather than other issues? A: Several indicators suggest hairpin-related failure:

- Abrupt sequencing stops at consistent positions despite good signal quality up to that point [16]

- PCR failure specifically in GC-rich regions while other regions amplify successfully

- Inability to amplify even with optimized primer design and standard troubleshooting

- Experimental confirmation through restriction enzyme excision of the problematic region followed by successful amplification of flanking regions [15]

Q2: What specific sequence features should alert me to potential hairpin problems? A: Be vigilant for:

- GC content exceeding 60% [15]

- Long mononucleotide runs (e.g., GGGGG or CCCCC) [19] [20]

- Inverted repeats that can form stable stem-loop structures

- Sequences with dyad symmetry that enable folding back on themselves

Q3: Are there polymerases specifically designed to handle hairpin structures? A: While no polymerase completely eliminates the problem, those with high processivity show better performance on difficult templates [17]. These enzymes maintain stronger attachment to the template and have better strand-displacement activity. Additionally, specialized enzyme blends containing structure-disrupting components may improve results.

Comprehensive Troubleshooting Strategies

Table 2: Troubleshooting Approaches for Hairpin-Related PCR Failure

| Approach | Specific Protocol/Reagent | Mechanism of Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCR Additives | DMSO (1-10%) [19], Formamide (1.25-10%) [19], Betaine (0.5-2.5 M) [19] | Destabilizes secondary structures by interfering with hydrogen bonding | Reduced hairpin stability, improved amplification |

| Modified Nucleotides | 7-deaza-dGTP, dITP [16] | Reduces hydrogen bonding capacity of GC base pairs | Decreased melting temperature of hairpins |

| Specialized Polymerases | High-processivity enzymes [17], Polymerases with strong strand-displacement activity | Enhanced ability to unwind secondary structures | Better read-through of structured regions |

| Thermal Cycling Modifications | Increased denaturation temperature (up to 98°C) and time [17] | More complete separation of DNA strands | Reduced hairpin formation in single-stranded templates |

| Template Modification | Restriction enzyme digestion to remove problematic region [15] | Physical elimination of hairpin-forming sequence | Enables amplification of flanking regions |

| Primer Placement | One primer annealing within resistant region [15] | Polymerase only needs to traverse one hairpin boundary | Successful amplification across previously blocked regions |

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Amplification Across Hairpin-Forming Regions

This protocol adapts methods from successful amplification of the Foxd3 hairpin region [15]:

Design one primer to anneal within the resistant region and one outside it. This strategy requires prior knowledge of the region's sequence, which can be obtained by sequencing outward from within the region using internal primers [15].

Prepare PCR reaction with enhanced conditions:

Apply modified thermal cycling parameters:

- Extended denaturation: 98°C for 1-2 minutes

- Touchdown annealing: Start 10°C above calculated Tm and decrease 1°C per cycle for 10 cycles

- Extended extension: 2-3 minutes per kilobase at 68-72°C

- Increased cycle number: 35-40 cycles

Amplify the region in segments using multiple primer sets that generate overlapping amplicons, then assemble the complete sequence computationally or through subsequent cloning.

Protocol: Sequencing Through Hairpin Barriers

For sequencing through problematic hairpin regions [16]:

Modify sequencing reaction composition:

- Use a 1:4 ratio mix of BigDye to dGTP Sequencing premix

- Alternatively, add approximately 40µM dGTP nucleotide to standard BigDye mix

- Consider using 7-deaza-GTP or dITP in PCR amplification prior to sequencing

Adjust sequencing reaction conditions:

- Increase reaction volume to 20µl

- Extend initial denaturation to 3 minutes at 96°C

- Implement slower ramp times between temperatures

- Use longer extension times (60-90 seconds per cycle)

Employ the Sequence-By-Mutagenesis (SAM) approach to eliminate long mononucleotide runs through silent mutations while maintaining amino acid sequence.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Hairpin-Related PCR Challenges

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes | Commercial Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Betaine | PCR additive that equalizes DNA melting temperatures | Particularly effective for GC-rich templates; use at 0.5-2.5 M final concentration | Sigma-Aldrich B2629, Thermo Fisher Scientific B0300 |

| DMSO | Secondary structure destabilizer | Typically used at 1-10%; higher concentrations may inhibit polymerase | Various molecular biology grade suppliers |

| 7-deaza-dGTP | Modified nucleotide reducing hydrogen bonding | Partial replacement for dGTP (3:1 ratio dGTP:7-deaza-dGTP) | Roche Diagnostics 988 539, Sigma-Aldirect C2899 |

| High-Processivity DNA Polymerases | Enzymes with enhanced strand displacement | Superior performance on structured templates | Platinum SuperFi II, Q5 High-Fidelity, Phusion Plus |

| GC Enhancer Solutions | Proprietary mixtures for difficult templates | Optimized for specific polymerase systems | Invitrogen GC Enhancer, Q5 GC Enhancer |

| dITP Sequencing Mix | Modified nucleotides for sequencing | Helps resolve compression and stops in G-rich regions | BigDye dGTP Sequencing Mix |

Hairpin structures represent a significant challenge in molecular biology applications, particularly for researchers working with GC-rich genomic regions. The mechanisms by which these structures block polymerase progression - through steric hindrance, thermodynamic stability, and limitations in polymerase processivity - can be mitigated through strategic experimental design and specialized reagents.

Successful navigation of these challenges requires a multifaceted approach combining informed primer design, specialized reaction conditions, and appropriate enzyme selection. The protocols and troubleshooting guides presented here provide a foundation for overcoming these obstacles, enabling reliable amplification and sequencing of even the most challenging templates.

As molecular techniques continue to advance, particularly in the realms of genome editing and synthetic biology, understanding and addressing the limitations imposed by DNA secondary structure will remain essential for research progress and technical innovation.

FAQ: Understanding the Core Issue

What is the Foxd3 locus polymerase-resistant region? Researchers discovered a specific 370-nucleotide segment within the murine Foxd3 locus that consistently resisted polymerase read-through during sequencing and PCR amplification, hindering the creation of vectors for genetic engineering [21].

What causes this PCR failure? The resistant segment correlates with a predicted DNA hairpin cluster just upstream of the Foxd3 gene's 5' untranslated region. These stable secondary structures form physical barriers that impede the polymerase enzyme during replication [21].

Is this region biologically significant? Yes, this hairpin-forming region is highly conserved across vertebrate species, suggesting it may have an important, though not yet fully understood, functional role in gene regulation beyond causing technical challenges [21].

Are such PCR failures common? Yes, target secondary structure is a widely recognized cause of false negatives and uneven amplification in PCR. When a DNA template is folded, primers cannot bind effectively, and the polymerase has difficulty traversing the region [12].

Troubleshooting Guide: Overcoming PCR Barriers

Problem: PCR Failure or Weak Amplification Due to Suspected Secondary Structures

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No product or very low yield on gel [7] | Stable hairpins in template blocking polymerase [12] [21] | Use PCR enhancers/additives (see Table below). |

| Amplification fails only in specific regions [22] | Localized, high-stability secondary structures [21] | Redesign primers to flank the structured region [22]. |

| Inconsistent results between primer sets [22] | Hairpin formation within the amplicon itself [22] | Switch to a polymerase mixture optimized for complex templates. |

| Allele Dropout (false homozygosity) [22] | Non-primer-site SNV promoting strong amplicon hairpin [22] | Check for SNVs in the amplicon and redesign primers. |

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Step 1: Diagnosis and Confirmation

- Verify Amplification Failure: Use a standard PCR protocol and Taq polymerase. Include a positive control to confirm the reaction itself is not the issue [19].

- In Silico Analysis: Use software like mfold to predict secondary structures within your target DNA sequence. Input the 370-nt Foxd3 sequence to confirm the predicted hairpin cluster [22].

- Test with Alternate Primers: Design a new primer set (E12B in the allele dropout case) that produces a larger amplicon. Successful amplification with the new primers confirms that the original failure was due to local sequence context and not a global issue with the template [22].

Step 2: Implementing Solutions (Methodologies)

- PCR with Additives:

- Prepare a master mix for multiple reactions to minimize pipetting error [19].

- Add potential enhancers to the reaction. A recommended starting formulation is:

- Use a touchdown PCR protocol: Start with an annealing temperature 5-10°C above the calculated Tm and decrease by 0.5°C per cycle for the first 10-20 cycles, then continue at a lower annealing temperature for the remaining cycles [24].

- Primer Redesign:

- Check for SNVs: Always consult updated SNV databases (like dbSNP) for variations in both the primer-binding sites and the entire amplicon region [22].

- Avoid structured regions: Use primer design tools (e.g., NCBI Primer-Blast, Primer3) to create primers that flank, rather than encompass, predicted hairpin clusters [19] [21].

- Validate new primers: Check new primers for self-complementarity and dimer formation before ordering [19].

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Betaine | Reduces secondary structure formation by equalizing the stability of GC and AT base pairs, helping polymerases traverse GC-rich and structured regions [19] [23]. |

| DMSO | A destabilizing agent that helps unwind DNA secondary structures by interfering with base pairing, facilitating primer annealing and polymerase progression [19]. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Binds to inhibitors that may be present in the reaction and can stabilize polymerase enzymes, improving overall reaction robustness [19] [23]. |

| High-Fidelity/Proofreading Polymerases | Enzymes like Q5 possess high processivity, enabling them to better unwind and copy through challenging secondary structures where Taq may fail [25]. |

| Touchdown PCR Protocol | A technique that starts with high-stringency annealing to promote specific primer binding first, increasing the chance of initial amplification before lower-stringency cycles [24]. |

| In Silico Prediction Tools (mfold) | Web servers that predict the secondary structure and folding stability (ΔG) of DNA or RNA sequences, allowing for pre-experimental identification of problem areas [22]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for diagnosing and resolving PCR failure caused by secondary structures, based on the Foxd3 case study.

Quantitative Data from Related Case Studies

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from the Foxd3 case and a related allele dropout study, highlighting the impact of secondary structures.

| Case | Affected Region / Variant | Observed Effect | Energetic Stability (ΔG) | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foxd3 Locus [21] | 370 nt upstream of Foxd3 | Barrier to PCR, sequencing, and BAC recombineering | Not specified | Primer redesign to avoid the structured region |

| FAH Gene Allele Dropout [22] | SNV (rs2043691, c.961-35C) in amplicon | False homozygosity due to failed amplification of one allele | -18.25 kcal/mol (C allele) vs.-17.43 kcal/mol (A allele) | New primer set (E12B) producing a larger amplicon |

Key Takeaways for Researchers

- Pre-Emptive Analysis is Crucial: Before experimental work, use tools like mfold to scan your target sequence for potential hairpins, especially in conserved genomic regions [22].

- Think Beyond Primer Binding: The Foxd3 and FAH cases demonstrate that the problem can lie within the amplicon itself, not just at the primer binding sites. A non-primer-site SNV can be enough to create a PCR-resistant structure [21] [22].

- Systematic Troubleshooting Works: A methodical approach combining in silico prediction, primer redesign, and wet-lab optimization with enhancers can overcome even well-defined polymerase-resistant barriers [12] [22].

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the most common symptoms of secondary structure issues in Sanger sequencing?

The most common symptoms in the sequencing chromatogram include:

- Sequence suddenly coming to a hard stop after a region of good quality data.

- Poor data quality following a stretch of mononucleotides (a run of a single base), where the trace becomes mixed and unreadable.

- A gradual die-out of the sequence read, where the signal intensity drops dramatically downstream [26].

Q2: Beyond sequencing, how can secondary structures negatively impact PCR?

Secondary structures in the DNA template, such as hairpin loops, can inhibit primer binding. This is a major cause of false negatives and low sensitivity in assays because the polymerase cannot efficiently bind and extend. This problem is exacerbated in multiplex PCR, where uneven amplification of different amplicons can occur [12].

Q3: My sequencing fails repeatedly. What are the primary culprits I should check?

The number one reason for failed sequencing reactions or poor-quality data is suboptimal template concentration and quality [26]. You should verify that:

- The template DNA is free of contaminants like salts, proteins, or ethanol.

- The concentration is within the recommended range (typically 100-200 ng/µL for plasmid DNA).

- The primer is well-designed and not degraded.

Q4: What is a key advantage of using BAC transgenesis over conventional methods?

BAC transgenesis allows for the incorporation of very large DNA segments, often encompassing an entire gene along with its native regulatory elements and tissue-specific enhancers. This enables more physiologically relevant gene expression patterns in model organisms, which is crucial for accurate functional studies and disease modeling [27].

Q5: How does gap-repair recombineering simplify the manipulation of large plasmids?

This method uses λ Red phage-mediated homologous recombination in E. coli to repair a "gap" introduced into a parent plasmid. It is highly efficient for retrieving large DNA fragments from BACs or for introducing specific mutations into large, high-copy-number plasmids, overcoming the inefficiencies of traditional ligation-based cloning, especially for large fragments [28].

Troubleshooting Guide

Here is a structured guide to diagnosing and resolving common issues related to secondary structures and complex cloning.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Sequencing and Cloning Failures

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Failed sequencing reaction (messy trace, no peaks) [26] | Low template concentration or poor quality DNA. | Check concentration via Nanodrop; ensure 260/280 ratio ≥1.8; clean up DNA to remove contaminants. |

| Sequence hard stop or severe degradation after a specific point [26] | Secondary structure (hairpins) in the template DNA blocking polymerase. | Use an "difficult template" sequencing chemistry/kit; design a new primer to sequence through the hairpin or from the reverse direction. |

| Poor sequence quality after mononucleotide repeats [26] | Polymerase slippage on homopolymer stretches. | Design a sequencing primer that starts just after the repeat region. |

| Few or no transformants after BAC/recombineering [29] [30] | Toxic DNA insert; inefficient recombination; suboptimal transformation efficiency. | Use a low-copy-number plasmid and grow cells at a lower temperature (e.g., 30°C); ensure high-quality competent cells and correct electroporation parameters [30] [28]. |

| Transformants with incorrect or truncated inserts [29] | Unstable DNA sequences with direct/inverted repeats. | Use specialized bacterial strains (e.g., Stbl2/Stbl4); pick colonies from fresh plates; avoid over-growing bacterial cultures. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting PCR for Problematic Templates

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low or no PCR product [7] [19] | High GC content or secondary structure preventing primer binding. | Use PCR additives/enhancers like DMSO (1-10%), formamide (1.25-10%), or Betaine (0.5-2.5 M). Optimize annealing temperature. |

| Multiple/non-specific PCR products [7] | Non-specific primer annealing due to secondary structures. | Incrementally increase the annealing temperature; optimize primer design to avoid self-complementarity; check primer concentration. |

| False negatives in multiplex PCR [12] | Primer-dimer formation or primer-amplicon interactions depleting reagents. | Redesign primers using software that accounts for complex interactions; use a temperature gradient to find optimal annealing conditions. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Gap-Repair Recombineering for BAC Retrieval and Plasmid Manipulation

This protocol allows for the efficient retrieval of large DNA fragments from a BAC clone into a high-copy-number plasmid, enabling easier manipulation [28].

1. Design and Clone Homology Arms:

- Design two short (300–600 bp) homology arms (HA) corresponding to the start and end of the genomic sequence you wish to retrieve from the BAC.

- Clone these HAs into your retrieval vector (e.g., a pUC19-based vector). When fused, these arms should form a blunt-cutting restriction site (e.g., EcoRV) for subsequent linearization.

2. Prepare Electrocompetent Cells Expressing λ Red Proteins:

- Transform the pSC101-BAD-gbaA plasmid (which carries the λ Red genes exo, bet, gam under an L-arabinose inducible promoter) into your preferred E. coli strain (e.g., DH5α).

- Grow a culture of these cells to an OD600 of ~0.4-0.6 and induce λ Red expression with 10% L-arabinose for 1 hour.

- Make the cells electrocompetent by washing them repeatedly with ice-cold 10% glycerol [28].

3. Perform Gap-Repair Recombineering:

- Linearize the retrieval vector using the blunt-cutting restriction enzyme at the site joining the two HAs.

- Electroporation: Mix ~100 ng of the linearized vector with 1 µL of purified BAC DNA. Electroporate this mixture into 50 µL of the prepared electrocompetent cells.

- Recovery and Plating: Immediately add SOC media to the cells, recover for 1 hour at 37°C, and then plate on LB agar with the appropriate antibiotic to select for the retrieval vector.

4. Screen and Validate:

- Screen resulting colonies by colony PCR or restriction digest (using a rapid boiling miniprep method) to identify correct clones.

- Validate the final plasmid by full-length sequencing.

Protocol 2: Overcoming Secondary Structures in Sanger Sequencing

This protocol outlines steps to obtain high-quality sequence data from DNA templates prone to forming secondary structures [26].

1. Verify Template Quality and Quantity:

- Precisely quantify your DNA using a fluorescence-based method. For plasmid DNA, aim for a concentration of 100-200 ng/µL in a volume of 5-10 µL. Using too much DNA is a common cause of early sequence termination.

2. Utilize Specialized Sequencing Chemistry:

- If standard sequencing fails with symptoms of a hard stop, request a "difficult template" sequencing service from your core facility. These kits use different dye-terminator chemistries that can help the polymerase navigate through secondary structures.

3. Re-sequence with Strategically Designed Primers:

- Sequence from the reverse direction: Design a primer binding downstream of the problematic region and sequence back through it.

- Prime within the structure: If possible, design a new primer that binds immediately after the predicted secondary structure to obtain the subsequent sequence.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| DMSO (Dimethyl sulfoxide) | A PCR additive that disrupts base pairing, helping to denature DNA templates with high GC content or strong secondary structures [19]. |

| Betaine | A chemical additive used in PCR to equalize the stability of AT and GC base pairs, promoting uniform amplification and aiding in the amplification of structured regions [19]. |

| pSC101-BAD-gbaA Plasmid | A low-copy-number plasmid that provides inducible expression of the λ Red recombineering proteins (Exo, Beta, Gam), essential for gap-repair recombineering in standard lab E. coli strains [28]. |

| NEB 5-alpha Competent E. coli | A general-purpose, recA- endA- E. coli strain suitable for high-efficiency transformation and stable propagation of most plasmid DNA, including those generated by recombineering [28]. |

| Stbl2/Stbl4 Competent E. coli | Specialized bacterial strains designed for the stable propagation of unstable DNA sequences, such as those containing direct repeats or retroviral sequences, which can be a problem in BAC manipulation [29]. |

| Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | A high-fidelity PCR enzyme used to generate amplicons with extremely low error rates, which is critical when creating fragments for cloning or recombineering where mutations are undesirable [28]. |

Visualizing Workflows and Problems

Secondary Structure Impact on Sequencing

Gap-Repair Recombineering Workflow

Strategic Reagent Selection and Specialized Protocols for Successful Amplification

Why GC-Rich and Structured Templates Challenge Conventional PCR

GC-rich DNA sequences (typically defined as ≥60% GC content) present three major hurdles for polymerase chain reaction (PCR). First, the triple hydrogen bonds of G-C base pairs confer higher thermal stability, requiring higher denaturation temperatures to separate strands [31] [3]. Second, these sequences readily form stable intra-strand secondary structures, such as hairpin loops, which can cause DNA polymerases to stall during extension, leading to truncated products or complete amplification failure [12] [31]. Finally, the primers themselves can form secondary structures or primer-dimers, further depleting reaction components and reducing yield [19] [12]. Overcoming these challenges often requires specialized polymerases, tailored reaction buffers, and optimized thermal cycling protocols.

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: My PCR for a GC-rich target shows no product or a very faint band on the gel. What should I do?

A failed or low-yield PCR with a GC-rich template is often due to inefficient denaturation or polymerase stalling at secondary structures.

Step 1: Verify Template Quality and Quantity Confirm your template DNA is of high quality and sufficient concentration. Use spectrophotometry/fluorometry and check integrity via gel electrophoresis. For genomic DNA, use 1 ng–1 µg; for plasmid DNA, use 1 pg–10 ng [32].

Step 2: Optimize Your Polymerase and Buffer System Switch to a polymerase specifically engineered for difficult templates. These often come with specialized buffers or enhancers.

Step 3: Adjust Thermal Cycling Conditions

- Increase Denaturation Temperature/Time: Use an initial denaturation at 94°C for 2–4 minutes, and consider a denaturation step up to 98°C for the first 3-5 cycles to help melt stubborn secondary structures [32] [3]. Avoid prolonged high temperatures with less stable polymerases.

- Use a Temperature Gradient: Empirically determine the optimal annealing temperature using a thermal gradient, testing a range above and below the calculated Tm [17].

Step 4: Incorporate PCR Additives Additives can help denature stable structures. Test them systematically, as their effects are target-specific [19] [31] [3].

- DMSO: Use at a final concentration of 1–10%.

- Betaine: Use at a final concentration of 0.5 M to 2.5 M.

- Formamide: Use at 1.25–10%.

- Note: Some additives can inhibit polymerase activity, so may require a slight increase in enzyme concentration [17].

FAQ 2: My gel shows multiple non-specific bands or a smear with my GC-rich target. How can I improve specificity?

Non-specific amplification and smearing occur when primers bind to incorrect sites, often due to low reaction stringency.

Step 1: Increase Annealing Stringency The most common fix is to increase the annealing temperature in increments of 1–2°C. Use a gradient cycler to find the highest temperature that still provides robust yield of your specific product [17]. The optimal temperature is typically 3–5°C below the primer Tm [32].

Step 2: Use a Hot-Start Polymerase Hot-start enzymes remain inactive until a high-temperature activation step, preventing primer-dimer formation and non-specific priming during reaction setup [17]. OneTaq Hot Start DNA Polymerase is an example that reduces these artifacts [32].

Step 3: Optimize Mg²⁺ Concentration Excess Mg²⁺ can reduce specificity. Titrate MgCl₂ or MgSO₄ in 0.2 mM increments from 1.0 mM up to 4.0 mM to find the lowest concentration that supports specific amplification [32] [17]. Remember, dNTPs chelate Mg²⁺, so ensure a sufficient surplus.

Step 4: Check Primer Design Re-evaluate your primers. Ensure they are specific, have minimal self-complementarity (to avoid hairpins), and minimal 3'-end complementarity (to avoid primer-dimers) [19]. Use tools like NCBI Primer-BLAST to check for specificity.

FAQ 3: What is the step-by-step protocol for setting up an optimized PCR for a difficult, GC-rich template?

This protocol uses a specialized polymerase system for robust amplification.

Materials:

- OneTaq Hot Start DNA Polymerase (NEB #M0481) or Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB #M0493)

- Corresponding 5X Reaction Buffer (Standard and GC Buffer for OneTaq)

- Corresponding High GC Enhancer

- 10 mM dNTPs

- Template DNA and primer pair

- Nuclease-free water

Method:

- Thaw and Prepare Reagents: Thaw all reagents on ice and mix gently before use.

- Assemble Reaction: Set up a 50 µL reaction on ice as follows [19] [32] [31]:

| Component | Final Concentration/Amount | Volume for 50 µL Reaction (OneTaq) |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclease-free Water | Q.S. to 50 µL | 28.5 µL |

| 5X OneTaq GC Buffer | 1X | 10 µL |

| OneTaq High GC Enhancer | 10% (v/v) | 5 µL |

| 10 mM dNTPs | 200 µM | 1 µL |

| Forward Primer (20 µM) | 0.2 µM | 0.5 µL |

| Reverse Primer (20 µM) | 0.2 µM | 0.5 µL |

| Template DNA | 1 ng–1 µg (genomic) | Variable (e.g., 2 µL) |

| OneTaq Hot Start DNA Polymerase | 1.25 units | 0.5 µL |

| Total Volume | 50 µL |

Thermal Cycling: Use the following conditions in a thermal cycler:

Analysis: Analyze 5–10 µL of the PCR product by agarose gel electrophoresis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential reagents for amplifying GC-rich and structured templates.

| Reagent | Function & Mechanism | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Polymerase Blends | Engineered for high processivity and affinity to unwind and copy through stubborn secondary structures. | OneTaq (blend of Taq and Deep Vent) for robust routine/difficult PCR; Q5 for high-fidelity amplification of long or GC-rich targets [32] [31]. |

| GC-Specific Reaction Buffers | Formulated with undisclosed additives that help destabilize G-C bonds and inhibit secondary structure formation. | OneTaq GC Reaction Buffer for targets >50% GC content [32]. |

| High GC Enhancer | A proprietary cocktail of co-solvents (e.g., betaine) that equalizes DNA melting temperatures, reducing secondary structure stability. | Add 10–20% (v/v) to OneTaq or Q5 reactions for targets >65% GC [32] [31]. |

| Mg²⁺ Solution (MgCl₂/MgSO₄) | Essential polymerase cofactor. Concentration directly affects enzyme activity, fidelity, and primer-template stability. | Optimize between 1.0–4.0 mM in 0.2–0.5 mM increments to balance yield and specificity [32] [17]. |

| Chemical Additives (DMSO, Betaine) | Act as DNA denaturants by directly interfering with hydrogen bonding and base stacking, helping to keep templates single-stranded. | Test DMSO at 1–10% or Betaine at 0.5–2.5 M for particularly stubborn hairpins [19] [31] [3]. |

| Hot-Start Polymerases | Remain inactive until a high-temperature activation step, preventing non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation during setup. | Critical for improving specificity in complex multiplex assays or with sensitive templates [32] [17]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Standardized Optimization Workflow

The following diagram outlines a logical, step-by-step strategy for troubleshooting failed PCRs due to hairpin structures and GC-richness.

Quantitative Data for Informed Decision-Making

Table 2: Polymerase and buffer selection guide based on amplicon GC content. Data synthesized from manufacturer guidelines [32] [31].

| Amplicon GC Content | Recommended Default Buffer | Optimization Notes & Reagent Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| <50% | OneTaq Standard Reaction Buffer | Standard protocols usually sufficient. Adjust annealing temperature or primer concentration if needed. |

| 50–65% | OneTaq Standard Reaction Buffer | OneTaq GC Reaction Buffer can be used to enhance performance of difficult amplicons. |

| >65% | OneTaq GC Reaction Buffer | Supplement with 10–20% OneTaq High GC Enhancer for robust amplification. For Q5 polymerase, use the supplied Q5 High GC Enhancer. |

Table 3: Optimization of critical cycling parameters for GC-rich targets [32] [31] [3].

| Parameter | Typical Standard Condition | Recommended GC-Rich Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Denaturation | 94°C for 30 sec | 94°C for 2–4 min; or 98°C for 30 sec (first 3-5 cycles) |

| Denaturation (Cycling) | 94°C for 15–30 sec | 98°C for 5–10 sec (if enzyme permits) |

| Annealing Temperature (Tₐ) | 5°C below primer Tₘ | Use a gradient to test Tₐ from 45–68°C; often higher than standard. |

| Extension Time | 1 min/kb | 1–2 min/kb; may require increase due to polymerase stalling. |

| Number of Cycles | 25–30 | Increase to 35–40 cycles if input copy number is low. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the primary challenges when amplifying GC-rich DNA templates? GC-rich DNA sequences (typically defined as ≥60% GC content) present two major challenges. First, the triple hydrogen bonds of G-C base pairs make these regions more thermally stable and resistant to denaturation than A-T rich areas. Second, this stability promotes the formation of rigid secondary structures, such as hairpin loops, which can block the progression of the DNA polymerase, leading to incomplete or failed amplification [33] [3] [34].

How do commercial enhancer buffers work to overcome these challenges? Commercial enhancer buffers are proprietary mixtures of chemical additives designed to disrupt the secondary structures that inhibit PCR. They generally function through two main mechanisms:

- Destabilizing Secondary Structures: Additives like DMSO, glycerol, and betaine reduce the melting temperature of DNA, helping to unwind stable hairpins and other structures, which makes the template more accessible to the polymerase [33] [3].

- Increasing Primer Stringency: Additives such as formamide and tetramethyl ammonium chloride promote more specific binding between the primer and the template, thereby reducing non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation [33] [34].

I am using a specialized polymerase but my amplification is still weak. What else can I do? Combining a specialized polymerase with its matched GC enhancer is a powerful first step. Further optimization often involves fine-tuning the Mg²⁺ concentration and annealing temperature. A Mg²⁺ concentration gradient from 1.0 mM to 4.0 mM (in 0.5 mM increments) can identify the optimal level for your specific reaction [33] [35] [34]. Similarly, performing a temperature gradient around your calculated annealing temperature can help find the ideal balance between specificity and yield [33] [34].

Are there any novel methods beyond traditional additives? Yes, recent research has introduced innovative approaches like "disruptor" oligonucleotides. These are specially designed oligonucleotides that bind to the template and actively unwind intramolecular secondary structures through a strand-displacement mechanism. They have proven effective for extremely challenging templates, such as the inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) of adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors, where traditional additives like DMSO and betaine fail [36].

Troubleshooting Guide for PCR Hindered by Secondary Structures

Problem: No Amplification Product (Blank Gel)

- Potential Cause: The polymerase is completely stalled by stable secondary structures, or the DNA fails to denature properly.

- Solutions:

- Switch Your Enzyme: Use a polymerase system specifically designed for GC-rich templates, such as OneTaq DNA Polymerase with GC Buffer or Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase [33] [34].

- Apply a GC Enhancer: Supplement your reaction with the commercial GC enhancer that matches your polymerase. These mixtures often contain a combination of structure-disrupting agents [33] [3].

- Increase Denaturation Temperature: Temporarily increase the denaturation temperature to 98°C for the first 3-5 cycles to help melt stubborn structures, then return to a standard temperature (e.g., 95°C) to preserve polymerase activity [3].

Problem: DNA Smear or Multiple Non-Specific Bands

- Potential Cause: Reduced primer annealing specificity, often due to suboptimal Mg²⁺ levels or annealing temperature.

- Solutions:

- Optimize Mg²⁺: Titrate MgCl₂ concentration between 1.0 and 4.0 mM. High Mg²⁺ can reduce specificity [33] [35].

- Increase Annealing Temperature: Raise the annealing temperature in 2°C increments to promote more specific primer binding. Use the NEB Tm Calculator for guidance [33] [34].

- Use High-Stringency Additives: Additives like formamide can be included to increase primer annealing stringency [33].

Problem: Faint or Weak Target Band

- Potential Cause: The polymerase is slowed by secondary structures but not completely blocked.

- Solutions:

- Use Additives: Incorporate DMSO (typically 1-10%), betaine (0.5 M to 2.5 M), or a commercial enhancer to destabilize hairpins [33] [3] [19].

- Increase Cycle Number: Slightly increase the number of PCR cycles (e.g., from 30 to 35) to accumulate more product [37].

- Try "Slow-down PCR": This method uses a dGTP analog (7-deaza-2′-deoxyguanosine) and slower ramp rates to help the polymerase navigate through difficult structures [3].

Quantitative Data on Common PCR Additives

The following table summarizes the concentrations and primary functions of commonly used additives in PCR enhancer buffers.

Table 1: Common Additives in PCR Enhancer Buffers and Their Functions

| Additive | Typical Final Concentration | Primary Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) | 1 - 10% [19] | Disrupts secondary DNA structures (e.g., hairpins) by reducing thermal stability [33] [3]. |

| Betaine | 0.5 M - 2.5 M [19] | Equalizes the contribution of GC and AT base pairs to DNA stability, aiding in the denaturation of GC-rich regions [33]. |

| Glycerol | - | Helps destabilize secondary structures, similar to DMSO [33]. |

| Formamide | 1.25 - 10% [19] | Increases primer annealing stringency, reducing non-specific binding and off-target amplification [33]. |

| 7-deaza-dGTP | (Partial or full dGTP substitution) | A dGTP analog that incorporates into DNA and reduces the strength of hydrogen bonding, making GC-rich regions easier to denature [33] [3]. |

Experimental Protocol: Testing a Commercial GC Enhancer Buffer

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for testing the efficacy of a commercial GC enhancer on a difficult template.

1. Objective: To determine the optimal concentration of a GC enhancer for the robust amplification of a specific GC-rich DNA target.

2. Materials:

- DNA template (GC-rich target, e.g., >70% GC)

- Forward and Reverse primers (designed with optimal GC content and Tm)

- High-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase)

- 5X Q5 Reaction Buffer

- Companion GC Enhancer

- dNTP mix (10 mM)

- Nuclease-free water

- Thermal cycler

3. Procedure:

- Prepare Reaction Master Mix: On ice, prepare a master mix for 6 reactions as specified below. The GC enhancer volume is varied to create a concentration gradient.

Table 2: PCR Reaction Setup for GC Enhancer Titration

| Component | Positive Control | Test Reaction 1 | Test Reaction 2 | Test Reaction 3 | Negative Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5X Q5 Reaction Buffer | 10 µL | 10 µL | 10 µL | 10 µL | 10 µL |

| 10 mM dNTPs | 1 µL | 1 µL | 1 µL | 1 µL | 1 µL |

| 10 µM Forward Primer | 2.5 µL | 2.5 µL | 2.5 µL | 2.5 µL | 2.5 µL |

| 10 µM Reverse Primer | 2.5 µL | 2.5 µL | 2.5 µL | 2.5 µL | 2.5 µL |

| Template DNA | 1 µL (~10-100 ng) | 1 µL | 1 µL | 1 µL | - |

| GC Enhancer | - | 5 µL | 10 µL | 15 µL | 10 µL |

| Nuclease-free Water | 32 µL | 27 µL | 22 µL | 17 µL | 33 µL |

| Q5 Hot Start Polymerase | 0.5 µL | 0.5 µL | 0.5 µL | 0.5 µL | 0.5 µL |

| Total Volume | 50 µL | 50 µL | 50 µL | 50 µL | 50 µL |

Thermal Cycling:

- 98°C for 2 minutes (Initial Denaturation)

- 35 cycles of:

- 98°C for 15-30 seconds (Denaturation)

- Tm + 3°C* for 15-30 seconds (Annealing)

- 72°C for 30-60 seconds/kb (Extension)

- 72°C for 5 minutes (Final Extension)

- 4°C hold

*Note: A higher annealing temperature is often used with GC enhancers to maximize specificity [33].

Analysis:

- Run the PCR products on an agarose gel.

- Compare the yield and specificity of the target band across the different enhancer concentrations.

- The optimal concentration is the one that produces a strong, specific band with the least background smear.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Commercial Reagents for Amplifying Challenging Templates

| Reagent / Kit Name | Supplier | Key Feature & Application |

|---|---|---|

| OneTaq DNA Polymerase with GC Buffer | New England Biolabs | Includes a specialized GC Buffer and optional GC Enhancer for routine amplification of difficult amplicons up to 80% GC content [33] [34]. |

| Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | New England Biolabs | A high-fidelity enzyme ideal for long or difficult amplicons. Its GC Enhancer allows robust amplification of templates with very high GC content [33]. |

| AccuPrime GC-Rich DNA Polymerase | ThermoFisher | Sourced from Pyrococcus furiosus, this enzyme is highly processive and thermostable, remaining active after 4 hours at 95°C, making it suitable for high denaturation temperatures [3]. |

| Hieff Ultra-Rapid II HotStart PCR Master Mix | Yeasen Bio | A master mix designed for fast and efficient amplification of complex templates, including high GC content and long fragments [37]. |

| Disruptor Oligonucleotides | (Research Reagent) | A novel class of oligonucleotides that actively unwind ultra-stable secondary structures (e.g., AAV ITRs) via strand displacement, outperforming traditional additives [36]. |

Mechanism of PCR Enhancer Action

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of how different enhancer solutions mitigate PCR failure caused by template secondary structures.

This guide addresses a common and persistent challenge in molecular biology research: the failure of Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) due to the formation of stable secondary structures, notably hairpins, within the DNA template. These structures are particularly prevalent in GC-rich sequences (where guanine (G) and cytosine (C) content is 60% or higher), as G-C base pairs form three hydrogen bonds, making them more thermostable than A-T pairs [34] [38]. When a DNA strand folds back on itself, it creates a hairpin that can physically block the progression of the DNA polymerase, leading to failed experiments, blank gels, or uninterpretable smears [34] [39]. This technical brief provides a targeted, troubleshooting-focused resource to help researchers overcome these obstacles by strategically employing chemical additives.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why are GC-rich regions particularly prone to causing PCR failure? GC-rich templates are challenging for two primary reasons. First, the triple hydrogen bonds between G and C bases require more energy to denature, meaning standard denaturation temperatures and times may be insufficient to fully separate the DNA strands [34] [38]. Second, these regions are highly "bendable," readily forming stable secondary structures like hairpins and stem-loops during the annealing and extension steps of PCR, which can halt polymerase progression [34] [38].

Q2: I see a blank gel or a DNA smear after my PCR. Could hairpins be the cause? Yes. A blank gel often indicates a complete failure of amplification, which can occur if the polymerase is consistently blocked by a structure like a hairpin, preventing any product synthesis [34]. A DNA smear can result from the polymerase stuttering or falling off at the hairpin, generating a heterogeneous mixture of incomplete, shorter molecules [34] [19].

Q3: Besides additives, what other strategies can I use to amplify difficult templates? A multi-pronged approach is often most effective:

- Polymerase Choice: Use polymerases specifically engineered for difficult templates, such as Q5 High-Fidelity or OneTaq DNA Polymerase, which are often supplied with proprietary GC Enhancers [34] [38].

- Thermal Cycling Adjustments: Increase the denaturation temperature or use a longer denaturation time to help melt secondary structures [17] [40].

- Primer Design: Redesign primers to anneal outside the problematic region if possible, or ensure they have optimal melting temperatures and lack self-complementarity [2] [19].

- Magnesium Concentration: Optimize Mg²⁺ concentration, as it is a critical cofactor for polymerase activity and can influence reaction specificity and yield [34] [40].

Troubleshooting Guide: Solving Hairpin-Related PCR Failure

| Problem Observed | Possible Cause | Recommended Actions |

|---|---|---|

| No Product (Blank Gel) | Hairpins completely blocking polymerase; insufficient denaturation. | 1. Add Betaine (1-1.5M) or DMSO (1-10%) to destabilize secondary structures [41] [40] [19]. 2. Increase denaturation temperature or time [17]. 3. Use a polymerase with high processivity and a proprietary GC enhancer [34]. |

| Smear of DNA or Multiple Bands | Polymerase stuttering at hairpins; non-specific priming. | 1. Add Formamide (1.25-10%) or DMSO (3-5%) to increase primer stringency and reduce secondary structures [34] [41] [19]. 2. Optimize Mg²⁺ concentration (test 1.0-4.0 mM in 0.5 mM increments) [34] [40]. 3. Increase the annealing temperature [34] [17]. |

| Sequence "Hard Stops" in Sanger Sequencing | Sequencing polymerase blocked by secondary structures. | 1. Use DMSO (5-10%) or Betaine (1-1.5M) in the sequencing reaction [39]. 2. Switch to a sequencing kit that uses dGTP instead of dITP [39]. 3. Substitute 7-deaza-dGTP for dGTP in the PCR amplification prior to sequencing; this analog disrupts Hoogsteen base pairing in hairpins [39]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents used to troubleshoot and resolve PCR issues related to hairpins and difficult templates.

Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent | Function & Mechanism | Common Working Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Betaine (Trimethylglycine) | A destabilizer of secondary structures. It acts as a kosmotrope, equalizing the stability of G-C and A-T base pairs by hydrating DNA non-specifically. This reduces the melting temperature (Tm) of GC-rich regions, facilitating denaturation and preventing hairpin formation [41] [40]. | 0.5 M to 2.5 M [19]; commonly 1.5 M is used [40]. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | A cosolvent and denaturant. It disrupts base pairing by reducing the DNA's thermal stability, which helps to denature GC-rich templates and secondary structures, allowing the polymerase to proceed [34] [41] [19]. | 1% to 10% (v/v) [17] [40] [19]; 5% is a typical starting point. |

| Formamide | A denaturant and stringency enhancer. It strongly destabilizes hydrogen bonding in DNA, effectively lowering the Tm and helping to keep templates single-stranded. It also increases the specificity of primer annealing [34] [41]. | 1.25% to 10% (v/v) [19]. |

| Glycerol | A stabilizer and secondary structure reducer. It reduces the formation of secondary structures that can inhibit the polymerase, and can also help stabilize the enzyme at higher temperatures [34] [40]. | 1-10% (v/v) [41] [40]; often used at 5-10%. |

| 7-deaza-2'-deoxyguanosine (7-deaza-dGTP) | A nucleotide analog. It lacks a nitrogen atom at the 7-position of the purine ring, which prevents Hoogsteen base pairing critical for guanine quartet formation and hairpin stabilization. This allows the polymerase to read through otherwise impassable structures [39]. | Used as a partial or complete substitute for dGTP in the dNTP mix (e.g., in a 1:3 ratio with dGTP) [39]. |

| GC Enhancer (Proprietary) | Multi-component solutions. Commercial enhancers (e.g., from NEB) often contain a optimized mixture of additives, which may include betaine, DMSO, and other compounds, to provide a synergistic effect against difficult templates [34] [38]. | As per manufacturer's instructions (e.g., 10-20% v/v) [34]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Systematic Optimization of PCR Additives for Hairpin Resolution

This protocol provides a methodology for testing different additives and their concentrations to overcome hairpin-related PCR failure.

1. Principle: Different additives combat secondary structures through distinct mechanisms. By testing them in a systematic grid, the optimal reagent and concentration for a specific problematic amplicon can be identified empirically.

2. Reagents:

- Standard PCR components: polymerase, buffer, dNTPs, primers, template DNA.

- Additive stock solutions:

- 5M Betaine

- Molecular biology grade DMSO (100%)

- Formamide (100%)

- 100% Glycerol

- Proprietary GC Enhancer (if available)

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Master Mix Preparation. Prepare a master mix containing all standard PCR components except the additive, calculating for

n+1reactions (wherenis the number of additive conditions plus a negative control). - Step 2: Additive Aliquot Preparation. Aliquot the master mix into separate PCR tubes.

- Step 3: Additive Addition. Add each additive to the tubes according to the testing grid below. Ensure the final reaction volume is adjusted with sterile water.

- Step 4: Thermal Cycling. Run the PCR using your standard protocol, or one with a slightly elevated denaturation temperature (e.g., 98°C).

- Step 5: Analysis. Analyze the results by agarose gel electrophoresis. The condition that yields a single, bright band of the expected size should be selected for further validation.

4. Data Presentation: Additive Testing Grid The following table outlines a suggested experimental setup for testing multiple additives. The "Final Concentration" column indicates the target concentration in the total PCR reaction volume.

| Tube | Additive | Volume of Stock to Add (per 50µL rxn) | Final Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | None (Negative Control) | - | - |

| 2 | Betaine | 15 µL of 5M stock | 1.5 M |

| 3 | DMSO | 2.5 µL of 100% stock | 5% |

| 4 | Formamide | 2.5 µL of 100% stock | 5% |

| 5 | Glycerol | 5 µL of 100% stock | 10% |

| 6 | GC Enhancer | 5 µL (per mfr. instructions) | 10% |

Protocol 2: HairpinSeq Sequencing for Difficult Templates

For templates where hairpins cause "hard stops" in Sanger sequencing, this specialized protocol is recommended [39].

1. Principle: This method combines chemical destabilization of secondary structures with the use of a nucleotide analog (7-deaza-dGTP) that is incorporated during the prior PCR amplification, fundamentally altering the DNA's ability to form stable hairpins for the subsequent sequencing reaction.

2. Workflow Diagram: The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of the HairpinSeq protocol.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: PCR with 7-deaza-dGTP. Amplify your target region using a standard PCR protocol, but substitute the dGTP in the dNTP mix with 7-deaza-dGTP. A common starting point is a 1:3 ratio of 7-deaza-dGTP to dGTP, or a complete substitution as recommended by the supplier [39]. Using a hot-start polymerase is advised.

- Step 2: Purification. Purify the PCR product using a standard PCR cleanup kit to remove excess nucleotides, enzymes, and salts.

- Step 3: Sequencing Reaction with Additives. Set up the sequencing reaction using the purified product. Include an additive such as 5% DMSO or 1M Betaine in the reaction mix [39].

- Step 4: Kit Selection. Preferably, use a sequencing kit that utilizes dGTP rather than dITP, as dGTP can be more effective for reading through difficult structures, despite a higher risk of compression artifacts [39].

- Step 5: Thermal Cycling. Use a modified sequencing cycle that includes a higher denaturation temperature (e.g., 96°C) and may incorporate a pre-incubation heat denaturation step.

The following diagram provides a logical flowchart for diagnosing and resolving PCR failures suspected to be caused by hairpin structures, integrating the information from this guide.

FAQs: Understanding Hairpin-PCR

What is Hairpin-PCR and what is its primary advantage? Hairpin-PCR is a specialized molecular technique designed to completely separate genuine mutations in a DNA sequence from errors (misincorporations) introduced by the DNA polymerase during amplification [42]. Its primary advantage is the radical elimination of PCR errors, which can improve the sensitivity of mutation detection methods by one to two orders of magnitude [42]. This is crucial for applications like early cancer diagnosis, identification of drug-resistance mutations, and studying spontaneous mutagenesis, where even rare variants must be reliably detected.

How does Hairpin-PCR technically distinguish between real mutations and polymerase errors? The method works by first converting the target DNA sequence into a hairpin structure through the ligation of oligonucleotide "caps" to the DNA ends [42]. This hairpin is then amplified. When the polymerase copies both DNA strands in a single pass within this structure, any misincorporation it makes creates a mismatch in the resulting double-stranded hairpin. In contrast, genuine pre-existing mutations remain fully matched. These mismatches (heteroduplexes) can then be separated from the error-free homoduplex hairpins using techniques like dHPLC [42].

In what research contexts is Hairpin-PCR particularly valuable? This technique is particularly valuable in two main contexts: