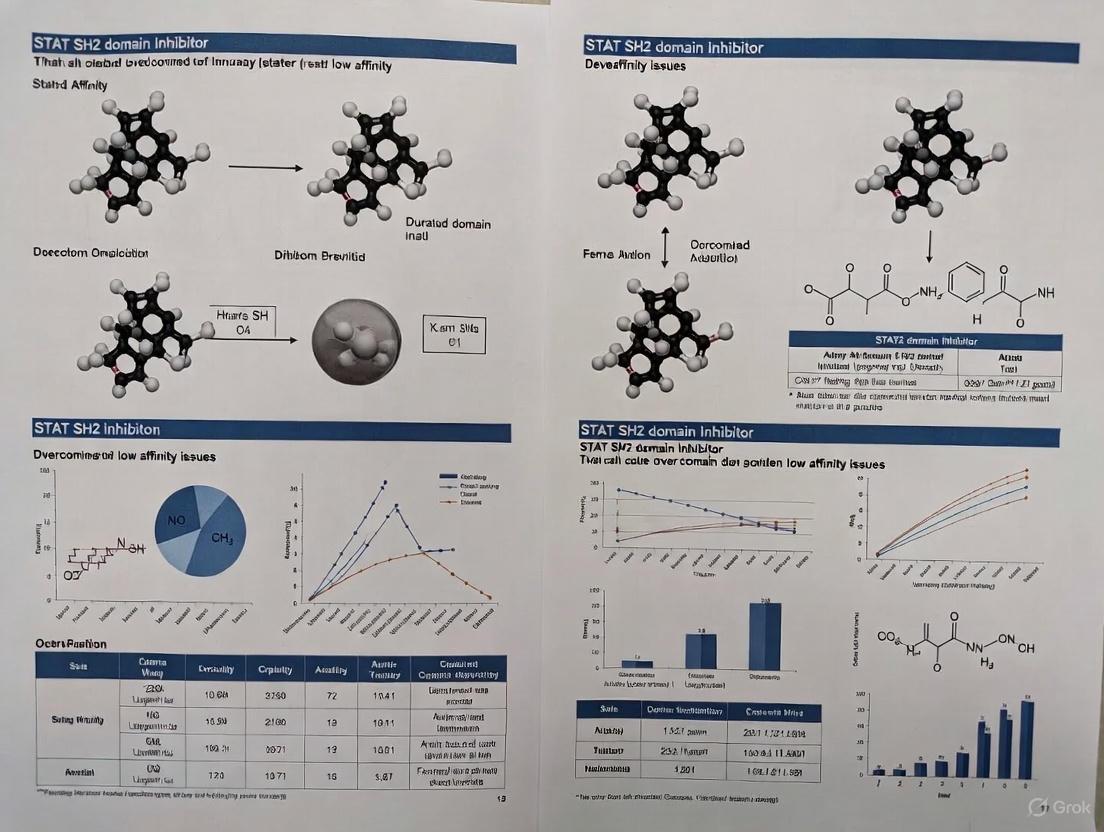

Overcoming Low Affinity in STAT SH2 Domain Inhibitor Development: Strategies for Selective and Potent Therapeutics

The development of high-affinity inhibitors targeting the STAT-SH2 domain represents a formidable challenge in drug discovery, primarily due to the conserved nature of the phosphotyrosine-binding pocket and the poor pharmacokinetic...

Overcoming Low Affinity in STAT SH2 Domain Inhibitor Development: Strategies for Selective and Potent Therapeutics

Abstract

The development of high-affinity inhibitors targeting the STAT-SH2 domain represents a formidable challenge in drug discovery, primarily due to the conserved nature of the phosphotyrosine-binding pocket and the poor pharmacokinetic properties of early compounds. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the structural basis of STAT-SH2 domains, innovative design strategies from small molecules to peptidomimetics and PROTACs, optimization techniques to enhance binding and cellular delivery, and rigorous validation methods to ensure specificity and efficacy. By synthesizing recent advances, this review aims to guide the creation of next-generation STAT inhibitors with the potential to treat cancers and other diseases driven by aberrant STAT signaling.

The STAT-SH2 Domain: Understanding the Structural Hurdles to High-Affinity Binding

The Canonical and Non-Canonical Roles of SH2 Domains in Cellular Signaling

Core Concepts: SH2 Domain Structure and Function

What is the primary function of an SH2 domain?

SH2 (Src Homology 2) domains are protein modules, approximately 100 amino acids in length, that function as key regulators of intracellular signal transduction. Their canonical role is to specifically bind to peptides containing phosphotyrosine (pY) residues. This binding recruits SH2-containing proteins to specific sites on activated receptors or scaffold proteins, facilitating the formation of larger signaling complexes and transmitting signals downstream from protein tyrosine kinases [1] [2] [3]. A universally conserved arginine residue within the SH2 domain is critical for forming a salt bridge with the phosphate group on the tyrosine [2] [3].

How do SH2 domains achieve ligand specificity beyond the phosphotyrosine?

While the pY residue is essential, affinity and specificity are largely determined by interactions between the SH2 domain and the three to six amino acid residues flanking the C-terminal side of the pY. Different SH2 domains have distinct preferences for specific amino acids at these positions (e.g., pY+1, pY+2, pY+3), creating a recognition code that allows them to discriminate between different pY-containing motifs [4] [2]. Selectivity is further refined by the recognition of non-permissive residues—amino acids that cause steric clash or charge repulsion, thereby inhibiting binding to a particular SH2 domain [4].

What are the non-canonical functions of SH2 domains?

Emerging research reveals that SH2 domains have functions beyond simple pY-peptide recognition:

- Lipid Binding: Nearly 75% of SH2 domains can interact with membrane lipids, particularly phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) and phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3). This interaction helps recruit SH2-containing proteins to the plasma membrane and can modulate their activity [2].

- Promoting Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation (LLPS): Multivalent interactions mediated by SH2 domains (and other modules like SH3 domains) can drive the formation of biomolecular condensates. For example, interactions among GRB2, Gads, and the LAT receptor contribute to LLPS, which enhances T-cell receptor signaling efficiency [2].

The diagram below illustrates the core structure of an SH2 domain and its key interactions.

Troubleshooting SH2 Domain Research

FAQ: Why is achieving high affinity and selectivity for STAT SH2 domains particularly challenging?

Developing potent inhibitors for STAT SH2 domains is difficult due to several inherent factors:

- Moderate Intrinsic Affinity: SH2 domain-pY peptide interactions typically have moderate binding affinities, with Kd values in the 0.1–10 µM range. This low inherent affinity makes it challenging to design small molecules that can effectively compete with the native ligand [2].

- High Charge of pY Pocket: The pY-binding pocket is highly positively charged to accommodate the negatively charged phosphate. Designing drug-like molecules that mimic the phosphate group yet retain good cellular permeability and pharmacokinetic properties is a major hurdle [5] [6].

- Specificity Challenges: The human genome encodes about 110 SH2 domain-containing proteins. Achieving selectivity for a single SH2 domain (like those in STATs) over others is crucial to avoid off-target effects and toxicities [2] [7].

FAQ: How can I profile the binding specificity of my SH2 domain of interest?

The table below summarizes modern quantitative methods used to profile SH2 domain specificity.

Table 1: Experimental Methods for Profiling SH2 Domain Specificity

| Method | Key Feature | Typical Library Size | Primary Output | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Peptide Display + NGS | Combines display of random peptide libraries with next-generation sequencing | 10^6–10^7 sequences | Quantitative binding free energy (∆∆G) across sequence space | [8] |

| SPOT Peptide Array | Semiquantitative; peptides synthesized on cellulose membrane | 192 (focused) to 6200+ peptides | Binding specificity profiles for physiological peptide sets | [4] [7] |

| Inhibitor Affinity Purification (IAP) | Uses immobilized, broad-specificity probes to capture SH2 proteins from lysates | N/A (captures native proteins) | Identification of SH2 proteins bound by a probe from complex mixtures | [7] |

FAQ: Our SH2 domain inhibitor shows good biochemical potency but poor cellular activity. What could be the cause?

This common issue often stems from poor cellular permeability or rapid dephosphorylation of phosphotyrosine-mimicking groups. Consider these solutions:

- Use Prodrug Strategies: As demonstrated by Recludix Pharma for their BTK SH2 inhibitor, a prodrug approach can dramatically enhance intracellular exposure of the active compound, leading to durable target engagement in cells [9] [10].

- Explore Stable pTyr Mimetics: Incorporate non-hydrolysable, cell-permeable phosphotyrosine mimetics. However, note that mimetics like Phosphonodifluoromethyl phenylalanine (F2Pmp) do not universally bind all SH2 domains and require empirical testing. Alternatives like l-O-malonyltyrosine (l-OMT) have shown success for specific targets like the SHP2 C-SH2 domain [6].

The following workflow outlines a coordinated strategy for developing and testing SH2 domain inhibitors.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SH2 Domain Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Key Consideration | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| SH2 GST-Fusion Proteins | Recombinant protein for in vitro binding assays (FP, SPR). | Ensure proper folding and phosphorylation-state independence. | Commercial vendors (e.g., ATCC clones); pGEX vectors [4]. |

| Random Peptide Phage/Bacterial Libraries | High-throughput profiling of SH2 domain binding specificity. | Library complexity (10^6-10^7) is key for coverage. | Custom synthesized; available from academic core facilities [8]. |

| pY-Peptide SPOT Membranes | Semiquantitative analysis of binding to defined or degenerate peptides. | Ideal for focused validation of physiological ligands. | Custom synthesized via Intavis MultiPep [4] [7]. |

| Dipeptide-Derived IAP Probe | Broad-spectrum enrichment of SH2 proteins from cell lysates. | Useful for target engagement studies and interactome analysis. | Synthesized via solid-phase peptide synthesis [7]. |

| Non-hydrolysable pTyr Mimetics (e.g., l-OMT, F2Pmp) | Enhance stability and cellular activity of peptide-based inhibitors. | Mimetic suitability is SH2-domain dependent; test empirically. | Custom chemical synthesis [6]. |

| DNA-Encoded Libraries (DELs) | Screen vast chemical space for small-molecule SH2 binders. | Integrated with structural biology for rational design. | Core platform of companies like Recludix Pharma [9] [10]. |

Advanced Applications & Emerging Frontiers

FAQ: Are there any successful examples of therapeutic SH2 domain inhibitors?

Yes, targeting SH2 domains has moved from a theoretical possibility to a clinical reality. A prominent example is the development of BTK SH2 domain inhibitors by Recludix Pharma. This approach offers significant advantages over traditional kinase domain inhibitors:

- Exceptional Selectivity: Their BTK SH2 inhibitor (BTK SH2i) showed >8000-fold selectivity over off-target SH2 domains and, unlike kinase inhibitors, did not inhibit TEC kinase, potentially avoiding platelet dysfunction side effects [9] [10].

- Durable Pathway Inhibition: The inhibitor demonstrated sustained intracellular concentrations and dose-dependent, prolonged BTK target engagement in preclinical models [10].

- In Vivo Efficacy: In a mouse model of chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU), a single dose of the BTK SH2i led to a significant reduction in skin inflammation, outperforming traditional kinase inhibitors like ibrutinib [9].

FAQ: How can computational methods accelerate SH2 inhibitor development?

Computational strategies are now indispensable. The ProBound algorithm is a key tool that uses next-generation sequencing data from multi-round affinity selection experiments to build quantitative sequence-to-affinity models. Unlike simple classification models, ProBound predicts binding free energy (∆∆G) across the entire theoretical ligand sequence space, enabling more rational inhibitor design [8].

FAQ: What is the role of contextual sequence in SH2 domain binding?

Early models assumed each position in a peptide ligand contributed independently to binding. It is now clear that context matters. The effect of a residue at one position can depend on the identity of residues at neighboring positions. SH2 domains integrate both permissive residues (enhance binding) and non-permissive residues (oppose binding, e.g., via steric clash) in a context-dependent manner to achieve sophisticated ligand discrimination [4]. This complexity must be considered when designing competitive inhibitors.

The Core Mechanism: How do reciprocal pTyr-SH2 interactions drive STAT dimerization?

In the canonical JAK-STAT signaling pathway, STAT dimerization is directly mediated by a specific and reciprocal interaction between a phosphorylated tyrosine residue on one STAT monomer and the Src homology 2 (SH2) domain on another STAT monomer [11]. This mechanism is fundamental to the activation of STAT transcription factors.

The process can be broken down into three key stages:

- Tyrosine Phosphorylation: In response to extracellular signals like cytokines, STAT proteins are phosphorylated on a conserved tyrosine residue. For STAT1 and STAT3, this critical residue is Tyr701 and Tyr705, respectively [12] [11].

- Reciprocal SH2-pTyr Binding: The phosphorylated tyrosine (pTyr) of one STAT monomer is recognized and bound by the SH2 domain of a second STAT monomer, and vice versa. This creates a reciprocal "phosphotyrosine-SH2 domain" interface that stabilizes the dimer [13] [11].

- Dimer Stabilization and Nuclear Translocation: This reciprocal interaction facilitates the formation of a stable, parallel STAT dimer that can then translocate into the nucleus to bind DNA and regulate transcription [13].

The crystal structure of a tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT-1 homodimer bound to DNA revealed that the dimer forms a contiguous C-shaped clamp around the DNA, which is "stabilized by reciprocal and highly specific interactions between the SH2 domain of one monomer and the C-terminal segment, phosphorylated on tyrosine, of the other" [13]. Furthermore, the phosphotyrosine-binding site of each SH2 domain is structurally coupled to its DNA-binding domain, suggesting this interaction also helps stabilize the elements that contact DNA [13].

Table 1: Key Components of the STAT Dimerization Mechanism

| Component | Function in Dimerization | Structural Features |

|---|---|---|

| SH2 Domain | Binds specifically to phosphotyrosine (pTyr) residues on a partner STAT monomer [14] [11]. | Contains a highly conserved Arg residue (within the FLVR motif) that binds the phosphate group of pTyr [14]. |

| Phosphotyrosine (pTyr) | Serves as the docking site for the SH2 domain of a partner STAT monomer [14] [11]. | A tyrosine residue phosphorylated by kinases like JAKs; the surrounding amino acid sequence can influence specificity [14]. |

| N-terminal Domain (NTD) | Facilitates weak dimerization between unphosphorylated STATs and may contribute to tetramer formation on DNA [11]. | Comprises multiple alpha-helices forming a hook-like structure [11]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for STAT Dimerization Research

How can I detect and quantify dynamic STAT dimerization in living cells?

Detecting transient and reversible STAT dimerization in live cells has been a technical challenge. Traditional methods like co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) lack the temporal resolution to capture dynamics, and techniques like FRET/BRET can be time-consuming to optimize [12]. A modern solution is the homoFluoppi system, a method based on phase separation that allows for reversible and quantitative detection of homodimerization in living cells [12].

Protocol: Using the homoFluoppi System for STAT3 [12]

- Construct Design: Fuse the gene encoding your STAT protein (e.g., STAT3) to a single construct containing both the PB1 and mAG1 (monomeric Azami Green) tags. The optimal configuration for STAT3 was found to be PB1-mAG1-STAT3 at the N-terminus.

- Cell Transfection: Transfect the PB1-mAG1-STAT3 construct into an appropriate cell line (e.g., HEK293 for low endogenous STAT3).

- Stimulation & Puncta Formation: Stimulate the cells with a relevant cytokine (e.g., Oncostatin M (OSM), IL-6). Upon STAT3 phosphorylation and dimerization, the PB1 and mAG1 tags interact, forming condensed droplets visible as fluorescent puncta within the cell.

- Image Acquisition & Quantification: Use automated microscopy (e.g., ArrayScan microscope) to capture images. Quantify the "punctate signal" (fluorescent punctate intensity per cell) using image analysis software.

- Validation: Always confirm that puncta formation depends on the conserved tyrosine (Y705 for STAT3) and an intact SH2 domain by running appropriate mutant controls.

Table 2: Comparison of STAT Dimerization Detection Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| homoFluoppi [12] | Phase-separated puncta formation via PB1-mAG1 interaction. | Reversible, quantitative, suitable for live-cell HTS. | Tagging may interfere with function; requires optimization of tag position. |

| Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) | Physical pull-down of interacting proteins. | Well-established; detects endogenous proteins. | End-point assay; cannot capture dynamics; may miss weak/transient interactions. |

| FRET/BRET [12] | Energy transfer between two fluorophores/luciferases on interacting proteins. | Can detect real-time interactions in live cells. | Technically challenging; requires extensive optimization of linkers and expression levels. |

| Biomolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC) [12] | Formation of a fluorescent complex from two non-fluorescent fragments. | High signal-to-noise ratio. | Irreversible complex formation; not suitable for studying dimer dynamics. |

What are the critical controls for validating specific STAT dimerization?

To ensure that the dimerization you observe is specific and dependent on the canonical pTyr-SH2 mechanism, the following controls are essential [12]:

- SH2 Domain Mutant: Create a point mutation in the critical arginine residue of the SH2 domain's FLVR motif (e.g., R→A). This disrupts pTyr binding and should abolish stimulus-induced dimerization [14] [12].

- Phosphorylation Site Mutant: Mutate the conserved tyrosine phosphorylation site (e.g., Y705F in STAT3). This prevents phosphorylation and thus blocks the reciprocal SH2-pTyr interaction, serving as a negative control for dimerization [12].

- Stimulus Time Course: Perform a time-course experiment after cytokine stimulation. Dimerization should increase post-stimulation and decrease upon stimulus washout, demonstrating reversibility [12].

- Unstimulated Control: Always include an unstimulated cell sample to establish the baseline dimerization level.

Why might my dimerization assay fail, and how can I optimize it?

Common pitfalls and their solutions are listed below.

Table 3: Troubleshooting STAT Dimerization Experiments

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No dimerization detected after stimulation. | Non-functional SH2 domain; unsuccessful tyrosine phosphorylation; incorrect tag orientation. | Verify SH2 domain integrity and tyrosine mutation via sequencing. Use phospho-specific antibodies to confirm phosphorylation. Test different tag positions (N- vs C-terminal) [12]. |

| High background dimerization in unstimulated cells. | Overexpression can cause artifactual dimerization; some disease-associated STAT mutants are constitutively active [12]. | Titrate DNA to use the lowest effective expression level. Include known constitutive dimerizing mutants (e.g., some STAT3 IHCA mutants) as positive controls and compare background levels [12]. |

| Irreversible dimerization. | Methodological artifact (e.g., as seen in BiFC assays) [12]. | Switch to a reversible detection method like homoFluoppi or FRET/BRET. Ensure that washout of the stimulating cytokine leads to a decrease in the dimerization signal [12]. |

| Cellular toxicity or aberrant localization. | Protein overexpression; tags interfering with normal STAT function or localization. | Check cell viability and protein localization (e.g., constitutive nuclear localization). Use a different tagging strategy or validate findings with an untagged protein via alternative methods like Co-IP. |

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key reagents and their applications for studying STAT dimerization, as derived from the cited experimental approaches.

Table 4: Essential Reagents for STAT Dimerization Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Specific Example / Sequence | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| homoFluoppi Vector | PB1-mAG1-STAT3 (N-terminal tag) [12] | Live-cell, quantitative, and reversible detection of STAT3 homodimerization. |

| SH2 Domain Inhibitor | 3,4-methylenedioxy-β-nitrostyrene (MNS) [12] | Tool compound to inhibit STAT3 dimerization in screening or validation assays. |

| Broad-Spectrum SH2 Probe | pY-containing dipeptide probe (e.g., pY-E) [15] | Affinity purification resin to enrich multiple SH2 domain-containing proteins from lysates. |

| Cytokine for Activation | Oncostatin M (OSM), Interleukin-6 (IL-6) [12] | Extracellular stimulus to activate the JAK-STAT pathway and induce STAT phosphorylation and dimerization. |

| STAT Mutant Constructs | STAT3-Y705F, STAT3-SH2 mutant (e.g., R609A) [12] | Critical negative controls to confirm the specificity of dimerization via the pTyr-SH2 mechanism. |

The Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STAT) family of proteins represents a critical node in cellular signaling, regulating essential processes like proliferation, survival, and immune responses. A primary obstacle in developing targeted therapies is the exceptional degree of structural conservation, particularly within the Src Homology 2 (SH2) domains that are crucial for STAT activation and function. This conservation makes the design of inhibitors that can distinguish between different STAT family members extraordinarily challenging.

The SH2 domain facilitates phosphotyrosine-dependent protein-protein interactions, which for STAT proteins, is essential for their activation and subsequent dimerization. When a STAT becomes phosphorylated, its SH2 domain interacts with the phosphotyrosine motif of another STAT protein, forming a functional dimer that translocates to the nucleus to regulate gene expression. However, because this mechanism is conserved across STAT family members, targeting one STAT protein without affecting others has proven difficult. Researchers face the fundamental challenge of achieving meaningful therapeutic selectivity while navigating this high degree of structural similarity, where even minor off-target effects can lead to unacceptable toxicity or diminished therapeutic efficacy.

FAQ: Understanding STAT Selectivity Challenges

Why is achieving selectivity among STAT family members so difficult?

Achieving selectivity is primarily hampered by the high sequence and structural conservation among STAT family members. The SH2 domains, which are attractive targets for inhibition because of their critical role in STAT activation, share significant structural similarity across different STAT proteins. This conservation means that an inhibitor designed to bind one STAT's SH2 domain often exhibits cross-reactivity with other STATs, limiting therapeutic utility. Furthermore, the phosphotyrosine-binding pocket itself is highly conserved, making it challenging to design small molecules or peptides that can discriminate between family members based on subtle structural differences [16] [17].

What are the functional consequences of non-selective STAT inhibition?

Non-selective STAT inhibition can lead to significant adverse effects due to the diverse physiological roles of different STAT family members. For example, STAT1 is crucial for antiviral responses and immune surveillance, while STAT3 is often implicated in cancer cell survival and proliferation. Simultaneously inhibiting both could simultaneously compromise antitumor immunity while targeting cancer cells. Additionally, different STATs can have opposing functions in some contexts; STAT1 often promotes inflammatory responses while STAT3 can have anti-inflammatory effects. Non-selective inhibition could therefore disrupt delicate immunological balances essential for maintaining health [18].

Beyond the SH2 domain, what other targeting strategies exist?

Innovative approaches are emerging that target less conserved STAT domains to achieve better selectivity. These include:

- Coiled-coil domain targeting: This domain is less conserved than the SH2 domain and plays roles in nuclear translocation and protein-protein interactions.

- N-terminal domain targeting: Involved in STAT dimerization and DNA binding, this domain offers alternative targeting opportunities.

- DNA-binding domain interference: Directly blocking STAT interaction with DNA response elements.

- Allosteric inhibition: Targeting unique regulatory sites outside the primary functional domains.

Monobodies (synthetic binding proteins) have successfully been developed to target the coiled-coil and N-terminal domains of STAT3, demonstrating nanomolar affinity and exceptional selectivity over other STAT family members, including the closely related STAT5 [17].

Troubleshooting Guide: Experimental Challenges in STAT Inhibitor Development

Problem: Lead compounds show promising in vitro binding but fail in cellular assays

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cellular penetration issues: Phosphotyrosine mimetics often contain multiple negative charges that impede cytosolic delivery.

- Solution: Incorporate cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) such as CPP12, which has demonstrated 30-60-fold improved delivery compared to traditional options like Tat peptide [19].

Rapid degradation in biological systems: Phosphopeptides are susceptible to hydrolysis by phosphatases.

Insufficient binding affinity: Micromolar affinities are often inadequate for functional inhibition in cells.

- Solution: Explore monobody technology – synthetic binding proteins that can achieve nanomolar affinity with exceptional selectivity, as demonstrated with STAT3 inhibitors [17].

Problem: Difficulty in assessing STAT inhibitor selectivity profiles

Recommended Solutions:

Implement comprehensive interactome analysis: When monobodies targeting STAT3 were expressed intracellularly and subjected to tandem affinity purification-mass spectrometry (TAP-MS), they showed no significant binding to other STATs or off-target proteins, confirming exquisite specificity [17].

Utilize competitive binding assays: Fluorescence polarization (FP) assays can quantitatively measure a compound's ability to compete with native phosphopeptides for STAT binding, providing quantitative affinity data [19].

Employ targeted degradation systems: Fusing selective binders to E3 ubiquitin ligase components (e.g., VHL) can demonstrate functional engagement through induced degradation of specific STAT proteins without affecting other family members [17].

Problem: Discrepancy between biochemical and cellular activity measurements

Troubleshooting Approach:

Systematically evaluate these three critical parameters that determine functional efficacy:

Table: Key Parameters for Functional STAT Inhibitor Development

| Parameter | Assessment Method | Target Benchmark | Strategic Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binding Affinity | Fluorescence polarization (FP); Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) | Low nanomolar (e.g., 7.6 nM for monobodies) [17] | Optimize chemical scaffold; Use non-hydrolyzable pTyr isosteres |

| Proteolytic Stability | Serum stability assays; Cell lysate stability tests | >24 hours in biological media | Incorporate stabilized peptide backbones; Macrocyclization |

| Cytosolic Delivery | Chloroalkane penetration assay; Cellular fractionation | High efficiency (e.g., CPP12 provides 6-fold improvement) [19] | Conjugate to advanced CPPs; Utilize nanoparticle formulations |

Research indicates that successful inhibition requires a delicate balance between these factors. For instance, a compound might exhibit excellent binding affinity but fail functionally due to poor cellular penetration or rapid degradation [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for STAT-Selective Inhibition Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-hydrolyzable pTyr Isosteres | F₂Pmp (difluorophosphonomethyl phenylalanine) | Replaces phosphotyrosine in peptide inhibitors | Phosphatase-resistant; Maintains negative charge for SH2 binding [19] |

| Cell-Penetrating Peptides | CPP12 (cyclo(FφR₄) improved version) | Enhances cytosolic delivery of impermeable inhibitors | 6-fold improvement over cyclo(FφR₄); 30-60x better than Tat [19] |

| Monobody Scaffolds | FN3 domain-based binders | Target-specific protein inhibition without enzymatic activity | High affinity (nM range); Exceptional selectivity; Can target multiple domains [17] |

| Targeted Degradation Systems | VHL fusion constructs | Induces degradation of specific target proteins | Demonstrates target engagement; Validates functional inhibition [17] |

| Affinity Measurement Tools | Fluorescence polarization (FP) | Quantifies binding affinity and competitive inhibition | Sensitive; Suitable for high-throughput screening [19] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol: Assessing STAT-Inhibitor Binding Affinity Using Fluorescence Polarization

Purpose: To quantitatively measure the binding affinity between STAT proteins and potential inhibitors.

Materials:

- Recombinant STAT protein (e.g., STAT3-SH2 domain)

- Fluorescein-labeled phosphopeptide (e.g., Flu-G(pTyr)LPQTV-NH₂)

- Test compounds for screening

- Black 384-well plates

- Fluorescence polarization plate reader

Procedure:

- Prepare a fixed concentration of fluorescein-labeled phosphopeptide (typically 1-10 nM) in binding buffer.

- Titrate increasing concentrations of STAT protein (e.g., 0.1 nM to 10 µM) to establish a binding curve.

- For competition assays, pre-incubate STAT with test compounds before adding labeled peptide.

- Incubate mixtures for 30-60 minutes at room temperature protected from light.

- Measure fluorescence polarization values (excitation: 485 nm, emission: 535 nm).

- Calculate Kd values using non-linear regression analysis of binding curves.

- For competitors, determine IC50 values from dose-response curves.

Troubleshooting Tip: If binding curves show poor signal-to-noise ratio, optimize peptide concentration or consider using longer incubation times to reach equilibrium [19].

Protocol: Evaluating Cellular Engagement Using Targeted Protein Degradation

Purpose: To confirm functional engagement of STAT inhibitors in a cellular context.

Materials:

- Plasmid encoding monobody-VHL fusion construct

- Appropriate cell line with endogenous STAT expression

- Proteasome inhibitor (e.g., MG132)

- Western blot equipment

- STAT3-specific antibody

Procedure:

- Transfect cells with monobody-VHL fusion construct or control empty vector.

- Incubate for 24-48 hours to allow protein expression and degradation.

- For proteasome inhibition control, treat parallel samples with 10 µM MG132 for 6 hours before harvesting.

- Lyse cells and quantify protein concentration.

- Perform Western blot analysis using STAT3-specific antibodies.

- Probe for housekeeping proteins (e.g., GAPDH) as loading controls.

- Quantify band intensity to measure STAT3 degradation efficiency.

Expected Outcome: Selective STAT3 degradation should be observed in cells expressing specific monobody-VHL fusions but not controls, and this degradation should be blocked by proteasome inhibition [17].

Visualizing STAT Activation and Inhibition Strategies

The diagram illustrates the JAK-STAT signaling pathway from cytokine stimulation to gene transcription, highlighting multiple points where inhibitors can intervene. The SH2 domain-mediated dimerization represents the primary challenge due to high structural conservation across STAT family members. Alternative targeting strategies focusing on the N-terminal domain (NTD) or coiled-coil (CC) domains offer promising avenues for achieving better selectivity, as these domains exhibit lower conservation while still playing critical roles in STAT function [17].

Quantitative Data Comparison of STAT Targeting Approaches

Table: Comparative Analysis of STAT-Targeting Therapeutic Strategies

| Strategy | Molecular Target | Reported Affinity/IC₅₀ | Selectivity Profile | Cellular Efficacy | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphopeptide + CPP | SH2 Domain | ~7 µM (CPP12-F₂Pmp) [19] | Limited (SH2 conservation) | Poor despite good delivery | Low affinity; Limited selectivity |

| Small Molecule (TTI-101) | Canonical STAT3 signaling | In clinical trials [20] | Selective for canonical STAT3 | Reduces tumor burden in vivo [20] | Specific molecular target not fully characterized |

| Monobodies (MS3-6) | Coiled-coil domain | 7.6 nM (ITC) [17] | Excellent (no STAT5 binding) | Strong inhibition of transcriptional activity | Delivery method for therapeutic application |

| Monobodies (MS3-N3) | N-terminal domain | 40 nM (yeast display) [17] | Highly STAT3-selective | Effective targeted degradation | Requires intracellular expression |

The development of STAT-selective inhibitors remains a formidable challenge primarily due to the structural conservation of SH2 domains across family members. However, emerging strategies that target alternative domains, such as the coiled-coil and N-terminal domains, show remarkable promise in achieving the selectivity required for therapeutic applications. Technologies like monobodies demonstrate that high affinity and exceptional specificity are attainable, providing new tools for both basic research and therapeutic development.

Future directions will likely focus on improving delivery mechanisms for these selective inhibitors, combining STAT inhibition with complementary therapeutic approaches, and further exploiting structural nuances between STAT family members. As our understanding of STAT biology deepens and targeting technologies advance, the goal of achieving clinically viable STAT-selective inhibition appears increasingly attainable.

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for STAT-SH2 Domain Research

FAQ 1: Why do my STAT-SH2 directed phosphopeptide inhibitors show weak cellular activity despite high in vitro affinity?

Problem: A common issue is the sole focus on the pY+pY+3 binding pockets, neglecting critical membrane interactions. The SH2 domain does not function in isolation.

Solution:

- Investigate Lipid Binding Properties: Recognize that approximately 90% of human SH2 domains, including STAT6-SH2, bind plasma membrane lipids with high affinity (e.g., STAT6-SH2 has a Kd of ~20 nM for PM-mimetic vesicles) [21]. Design inhibitors that account for or mimic this membrane-targeting function.

- Utilize Prodrug Strategies: Incorporate phosphatase-stable, cell-permeable prodrug moieties like pivaloyloxymethyl (POM) groups to mask negative charges, improving cellular uptake. This strategy has successfully inhibited STAT6 phosphorylation at concentrations as low as 100 nM in human airway cells [22].

FAQ 2: How can I detect and characterize non-canonical SH2 domain functions like lipid binding and phase separation in my experiments?

Problem: Standard pull-down assays using only pY-peptides may miss significant lipid-mediated interactions or higher-order condensate formation.

Solution:

- Employ Comprehensive Binding Assays:

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): Use PM-mimetic lipid vesicles to quantitatively measure SH2 domain lipid-binding affinity and specificity [21].

- Inhibitor Affinity Purification (IAP): Use broad-spectrum dipeptide-derived probes (e.g., pY-E) immobilized on sepharose beads to enrich multiple SH2 proteins from mixed cell lysates, capturing interactions beyond strict pY-sequence specificity [7].

- Monitor for Phase Separation:

- Live-Cell Fluorescence Microscopy: Express fluorescently tagged SH2 domain-containing proteins (e.g., SHP2-mEGFP). Disease-associated mutants (both gain-of-function and loss-of-function) often form discrete, liquid-like puncta not seen with wild-type proteins [23].

- FRAP (Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching): Test the liquid-like properties of observed puncta. True condensates typically show rapid fluorescence recovery, indicating dynamic component exchange [23].

FAQ 3: Why do both activating and inactivating disease mutations in the same SH2-containing protein (like SHP2) lead to similar pathogenic outcomes?

Problem: This apparent paradox, where both gain-of-function (GOF) and loss-of-function (LOF) mutations cause overlapping disease phenotypes, challenges conventional structure-function understanding.

Solution:

- Investigate Phase Separation as a Convergent Mechanism: Evidence indicates that diverse SHP2 mutants (both NS/JMML GOF and NS-ML LOF) share an acquired capability to undergo liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS), which wild-type SHP2 does not [23]. This LLPS can:

- Recruit and Activate Wild-Type Proteins: Mutant SHP2 can recruit WT SHP2 into condensates, promoting RAS-MAPK signaling irrespective of the mutant's intrinsic catalytic activity [23].

- Create a Gain-of-Function Phenotype: LLPS itself acts as a gain-of-function mechanism, potentially explaining how LOF mutants can drive disease [23].

- Consider Allosteric Inhibitors: Small-molecule allosteric inhibitors (e.g., SHP099) can attenuate mutant LLPS, providing a potential therapeutic strategy and a tool to validate the role of phase separation in your experimental system [23].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Screening for STAT SH2 Domain Inhibitors

Method: Thermofluor-Based Thermal Denaturation Assay [24]

- Protein Preparation: Recombinantly express and purify untagged STAT1, STAT3, or STAT5 proteins in E. coli.

- Assay Setup: In a multi-well plate, mix the STAT protein with a fluorescently labelled phosphopeptide that binds its SH2 domain.

- Thermal Denaturation: Use a real-time PCR instrument to gradually increase the temperature while monitoring fluorescence.

- Data Analysis:

- Control (Protein + Labelled Peptide): Generates a characteristic melt curve profile.

- Test (Protein + Labelled Peptide + Inhibitor Candidate): A compound that displaces the labelled peptide will cause a quantifiable shift in the melt profile, calculated as a change in the area under the curve (AUC).

- Advantage: This method provides a high-throughput, complementary strategy to traditional fluorescence polarization for identifying and characterizing STAT SH2 inhibitors.

Protocol 2: Probing Broad-Spectrum SH2 Domain Interactions

Method: Inhibitor Affinity Purification (IAP) with a Dipeptide Probe [7]

- Probe Design and Synthesis: Synthesize a cell-permeable, dipeptide-derived probe featuring a non-hydrolysable phosphotyrosine mimic (e.g., F2Pmp) and a glutamic acid at the pY+1 position (sequence: Ac-pY-E-NH2), with a pentyl linker for attachment.

- Immobilization: Covalently link the probe to sepharose beads.

- Pull-Down: Incubate the probe-bound beads with a mix of cell lysates (e.g., from Colo205, K562, Ovcar8, SKNBE2 lines) to enrich SH2 domain-containing proteins.

- Wash and Elution: Wash with buffer containing 10% glycerol to reduce non-specific binding. Elute bound proteins.

- Analysis: Digest eluted proteins with trypsin and identify them via Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). This protocol has successfully enriched 22 different SH2 proteins from a complex lysate [7].

Table 1: Lipid Binding Affinities of Selected SH2 Domains [21]

| SH2 Domain | Kd for PM-Mimetic Vesicles (nM) | Phosphoinositide Selectivity |

|---|---|---|

| STAT6-SH2 | 20 ± 10 | Not Specified |

| GRB7-SH2 | 70 ± 12 | Low selectivity |

| ZAP70-cSH2 | 340 ± 35 | PIP3 > PI(4,5)P2 > others |

| PI3K p85α-nSH2 | 440 ± 80 | PIP3 > PI(4,5)P2 >> others |

| SRC-SH2 | 450 ± 60 | Not Specified |

| GRB2-SH2 | 520 ± 15 | Not Specified |

Table 2: Functional Lipid Associations of SH2 Domain-Containing Proteins [2]

| Protein Name | Function of Lipid Association | Lipid Moisty |

|---|---|---|

| SYK | PIP3-dependent membrane binding required for non-catalytic activation of STAT3/5. | PIP3 |

| ZAP70 | Essential for facilitating and sustaining interactions with TCR-ζ chain. | PIP3 |

| LCK | Modulates interaction with binding partners in the TCR signaling complex. | PIP2, PIP3 |

| VAV2 | Modulates interaction with membrane receptors (e.g., EphA2). | PIP2, PIP3 |

| C1-Ten/Tensin2 | Regulation of Abl activity and IRS-1 phosphorylation in insulin signaling. | PIP3 |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating Non-Canonical SH2 Functions

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| PM-Mimetic Lipid Vesicles | Quantitative lipid-binding analysis via SPR. | Recapitulates cytofacial leaflet of plasma membrane [21]. |

| Broad-Spectrum Dipeptide Probe (Ac-pY-E-NH2) | Inhibitor Affinity Purification (IAP) of diverse SH2 proteins. | Targets conserved pY-core motif; enriches multiple SH2 domains simultaneously [7]. |

| Phosphatase-Stable Prodrugs (e.g., Bis-POM) | Cellular delivery of phosphonate-based SH2 inhibitors. | POM groups mask charge, are cleaved by intracellular esterases [22]. |

| Fluorescent Protein Tags (mEGFP, mScarlet) | Live-cell imaging of protein localization and phase separation. | Enables visualization of mutant-induced puncta formation via microscopy [23]. |

| Allosteric SHP2 Inhibitor (SHP099) | Tool compound for modulating LLPS. | Attenuates phase separation of disease-associated SHP2 mutants [23]. |

Signaling and Experimental Pathway Visualizations

Dual Mechanisms Governing STAT-SH2 Function

Workflow for Broad-Spectrum SH2 Protein Enrichment

Analyzing the pY+0, pY+1, and pY-X Sub-pockets for Druggable Opportunities

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the key binding determinants within the STAT3 SH2 domain's pY+0 sub-pocket, and why is it challenging to target with small molecules?

The pY+0 sub-pocket is the primary site for phosphotyrosine (pY) binding and is highly conserved across SH2 domains. Its key feature is a deep pocket within the βB strand that contains an invariant arginine residue (e.g., R609 in STAT3). This arginine forms a critical salt bridge with the phosphate moiety of the pY residue [25] [26]. The challenge in targeting this pocket with small, drug-like molecules stems from the strong polar and charged nature of this interaction, which often necessitates compounds with negatively charged groups that can impair cell permeability [26] [27].

FAQ 2: During affinity maturation, our antibody inhibitors are losing thermodynamic stability. What strategies can we use to co-optimize for both affinity and stability?

This is a common trade-off in protein optimization. Affinity-enhancing mutations often carry a high risk of destabilizing the protein's structure [28]. To overcome this, you can implement a dual-selection strategy during directed evolution. Instead of selecting only for antigen binding, simultaneously select for structural stability. For instance, using a conformational probe like Protein A (for VH3 domain antibodies) during yeast surface display provides a readout of correct folding and stability. This allows for the direct selection of variants where compensatory, stabilizing mutations (e.g., in framework regions) counteract the destabilizing effects of affinity-enhancing CDR mutations [28].

FAQ 3: Our small-molecule inhibitors show weak binding affinity despite good in-silico docking scores. Could the flexibility of the SH2 domain be a factor, and how can we address this?

Yes, the conformational flexibility of the SH2 domain is a significant factor. Traditional docking uses a single, static protein structure from a crystal lattice, which may not represent the dynamic state in solution [26]. To address this, employ Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations to observe the flexible nature of the domain. You can then use an averaged structure from the MD trajectory or an "induced-active site" model for structure-based virtual screening. This method accounts for protein flexibility and can identify compounds that bind with higher affinity to the physiologically relevant conformations of the SH2 domain [26].

FAQ 4: How can we effectively characterize and compare the druggability of novel sub-pockets outside the canonical pY binding site?

Advanced computational methods now allow for the systematic characterization of binding pockets. The PocketVec approach is particularly useful. It generates a descriptor for any pocket by performing inverse virtual screening against a predefined set of lead-like molecules. The resulting docking scores are converted into a ranking vector, which serves as a quantitative descriptor [29]. You can then compare the similarity of different pockets across the proteome by measuring the distance between their PocketVec descriptors, identifying potentially druggable sub-pockets that might be missed by sequence- or structure-alignment methods [29].

FAQ 5: What are the critical residues and structural considerations for engaging the pY+3 sub-pocket to achieve specificity for STAT3?

The pY+3 sub-pocket is a major determinant of specificity for STAT3. The key interaction is a hydrogen bond between the side chain amide of a glutamine (Gln) in the peptide ligand (e.g., from the gp130 receptor sequence pY905LPQTV) and the protein [27]. This site has a strict requirement for glutamine; substitutions with alanine, glutamic acid, or asparagine significantly reduce binding affinity [27]. When designing inhibitors, ensure your compound can act as a hydrogen bond donor at this position. The proline at pY+2 also contributes significantly to binding, and the Leu-Pro peptide bond is predominantly in the trans conformation when bound [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Binding Affinity of Peptidomimetic Inhibitors Your phosphopeptide-based inhibitor has high affinity but suffers from poor cellular permeability and stability.

| Possible Cause | Solution | Experimental Protocol to Validate |

|---|---|---|

| Negative charge on phosphate prevents passive diffusion across cell membranes [27]. | Replace the phosphate with phosphatase-stable, negatively charged bioisosteres (e.g., phosphonate, malonate, phosphonodifluoromethyl) or use bioreversible protecting groups (e.g., pivaloyloxymethyl (POM)) to mask the charge [27]. | 1. Synthesize prodrug analogs with proposed bioisosteres or protecting groups. 2. Test stability in human plasma and against purified phosphatases. 3. Measure cellular uptake using LC-MS/MS and assess target engagement (e.g., reduction in STAT3 Tyr705 phosphorylation via Western blot). |

| Proteolytic cleavage leads to short plasma half-life [26] [27]. | Incorporate D-amino acids or pseudoproline residues (e.g., 2,2-dimethyl-1,3-oxazole-4-carboxylate) to enhance metabolic stability. Note: For STAT3, ensure pseudoproline does not force a cis conformation if the bound state requires trans [27]. | 1. Incubate compounds in mouse or human liver microsomes. 2. Analyze by LC-MS to determine half-life and identify metabolic hot spots. 3. Perform pharmacokinetic studies in rodents to measure in vivo plasma half-life. |

Problem: Lack of Specificity and Off-Target Effects Your inhibitor against the STAT3 SH2 domain is showing activity against other SH2 domain-containing proteins.

| Possible Cause | Solution | Experimental Protocol to Validate |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient engagement of specificity-determining sub-pockets like pY+3 and pY+4 [25] [27]. | Focus optimization on residues C-terminal to pY. Use alanine scanning of your lead peptide to identify critical residues. Optimize interactions at pY+3 (Gln surrogate) and pY+4 (e.g., with a C-terminal benzylamide) to enhance STAT3 selectivity [27]. | 1. Perform a competitive fluorescence polarization (FP) assay with your inhibitor against a panel of purified SH2 domains (e.g., STAT1, STAT3, SRC). 2. Determine IC50 values for each domain to build a selectivity profile. |

| Compound is too promiscuous due to undesirable physicochemical properties. | Avoid highly hydrophobic or positively charged (arginine) groups in the inhibitor's pharmacophore. Studies show that tyrosine and serine are optimal CDR residues for maximizing specificity in protein-binding agents [28]. | 1. Run a surface plasmon resonance (SPR) screen against a diverse protein panel to assess non-specific binding. 2. Profile compound in cell-based panels measuring activity of multiple signaling pathways (e.g., phospho-RTK arrays). |

Quantitative Data on SH2 Domain Ligand Binding

Table 1: Structure-Affinity Relationship (SAR) of a STAT3-Targeting Phosphopeptide (Based on Peptide 3.1: Ac-pTyr-Leu-Pro-Thr-NH₂) [27]

| Position | Wild-Type Residue | Key Modifications & Effect on Affinity | Structural Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| pY-1 (N-term to pY) | Acetyl Group | Appending hydrophobic groups increased affinity. | Suggests a hydrophobic patch on the protein surface adjacent to the pY-binding pocket. |

| pY+1 | Leucine | Substitution with aliphatic residues (e.g., norleucine, cyclohexylalanine) provided higher affinity than aromatic Phe. N-methylation abrogated binding. | Methylation disrupts a critical hydrogen bond between the NH of Leu and the C=O of Ser636 in STAT3. |

| pY+2 | Proline | Substitution with cis-3,4-methanoproline (mPro) provided a two-fold increase in affinity. Pseudoproline derivatives forcing a cis conformation decreased affinity 3-5 fold. | The Leu-Pro peptide bond is in the trans conformation when bound to the STAT3 SH2 domain. |

| pY+3 | Glutamine | Methylation of the side chain amide nitrogen was not tolerated. Isosteric replacement with methionine sulfoxide caused a >10-fold loss. | The side chain amide must function as a hydrogen bond donor. |

| pY+4 | Threonine | Replacement with a simple benzylamide was an effective substitution. | The C-terminal region can accommodate diverse hydrophobic groups. |

Table 2: Summary of Druggable Sub-pockets in the STAT3 SH2 Domain

| Sub-pocket | Key Functional Residues | Nature of Interaction | Druggability Challenges | Opportunities for Inhibitor Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pY+0 | Invariant Arg (e.g., R609) | Salt bridge with phosphate moiety; high conservation [25] [26]. | Requires charged groups, impairing permeability [26] [27]. | Develop prodrug strategies; explore partial charge neutralization with halogens [27]. |

| pY+1 | Hydrophobic pocket | Binds aliphatic side chains (Leu, Nle, Cha) [27]. | Specific hydrogen bonding (e.g., Leu NH) must be maintained. | Optimize with non-natural aliphatic hydrophobic residues; avoid N-methylation. |

| pY+3 | Gln-binding site | Critical hydrogen bond donation from the Gln side chain amide [27]. | Strict requirement for H-bond donor capability. | Design constrained Gln mimetics that lock the donor conformation; a major specificity hotspot. |

| pY+4 / C-term | Hydrophobic region | Accommodates diverse groups like benzylamide [27]. | Relative solvent exposure. | Ideal for adding permeability-enhancing (logP) or prodrug groups without sacrificing affinity. |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathway

Workflow for STAT3 SH2 Inhibitor Discovery

STAT3 Activation Pathway and Inhibitor Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for SH2 Domain Inhibitor Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Features / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescein-Labeled Peptide (e.g., FAM-Peptide 1.6) | Core tracer for Fluorescence Polarization (FP) Assays to quantify inhibitor binding affinity to full-length STAT3 or its SH2 domain [27]. | Allows for high-throughput competition binding studies. Example: FAM-Ala-pTyr-Leu-Pro-Thr-Val-NH₂ [27]. |

| Full-Length STAT3 Protein | Preferable binding partner for FP assays to avoid potential conformational artifacts associated with isolated SH2 domains at non-physiological pH [27]. | Maintains native protein conformation and binding characteristics at physiological pH. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Software | To simulate the dynamic flexibility of the SH2 domain and generate more druggable "induced-active site" models for screening [26]. | Software like GROMACS or AMBER can be used to run simulations of the STAT3 SH2 domain in complex with a reference ligand (e.g., CJ-887) [26]. |

| Lead-Like Molecule Library (200-450 g/mol) | A predefined set of compounds for inverse virtual screening using tools like PocketVec to characterize and compare druggable pockets [29]. | Used with docking programs (e.g., SMINA, rDock) to generate a fingerprint of a binding site's druggability [29]. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | To experimentally validate the role of specific sub-pocket residues (e.g., R609 in pY+0, S613) identified in structural models [25] [26]. | Critical for confirming the functional importance of residues through point mutations and subsequent binding assays. |

Innovative Design Strategies to Bypass Affinity and Delivery Barriers

Frequently Asked Questions: Troubleshooting STAT3 SH2 Domain Inhibitor Development

FAQ 1: Why does my high-affinity STAT3 SH2 domain inhibitor show significant off-target effects against other SH2-containing proteins? The SH2 domains across different proteins share a highly conserved phosphotyrosine (pY)-binding pocket [25]. An inhibitor with a high affinity for STAT3's SH2 domain might also bind tightly to similar pockets in SH2 domains of proteins like SRC or PI3K. To improve selectivity, focus on interactions with the less conserved regions that bind to the residues C-terminal to the phosphotyrosine in the peptide ligand [25]. Employ biased molecular dynamics simulations to generate ensembles of protein conformations; selectivity can be predicted by determining whether a given inhibitor's structure is complementary to the unique surface pockets sampled by STAT3 but not by off-target SH2 domains [30].

FAQ 2: Our virtual screening identified a compound with excellent predicted affinity for the STAT3 SH2 domain, but it shows no activity in cellular assays. What could be the reason? This is a common issue often related to cell permeability and stability. The compound might be too polar to cross the cell membrane, or it could be metabolically degraded before reaching its target. Furthermore, the intracellular environment is highly reducing, which can destabilize compounds that rely on disulfide bonds. Re-evaluate the physicochemical properties of your compound (e.g., molecular weight, logP) and consider prodrug strategies or structural modifications to improve metabolic stability without compromising binding affinity [31].

FAQ 3: How can we overcome the challenge of low binding affinity in initial hit compounds from a screen? Initial hits often have low affinity. Use a fragment-based drug design approach to build upon these hits [31]. This involves optimizing the core structure of the hit compound by systematically modifying functional groups to enhance interactions with the target. As demonstrated with the STAT3 inhibitor 6f, optimization of substituents on the phenyl ring and pyrazole scaffold can lead to derivatives like WR-S-462 with significantly improved binding affinity (Kd = 58 nM) [31].

FAQ 4: What experimental and computational methods are best for validating the binding mode and selectivity of a new inhibitor? An integrated approach is most effective:

- Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA): Directly confirms target engagement within a cellular environment.

- Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) or Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): Provides quantitative data on binding affinity (Kd) and kinetics [31].

- Molecular Docking and Dynamics Simulation: Predicts the binding pose and stability of the inhibitor-target complex. A framework that considers binding site selectivity can help identify if the molecule preferentially binds to the desired site over other sites on the same protein [32].

- Selectivity Profiling: Test the compound against a panel of related SH2 domain-containing proteins to experimentally define its selectivity profile [25] [30].

Experimental Protocols for Key Experiments

Protocol 1: Determining Inhibitor Binding Affinity (Kd) via Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

- Immobilization: Covalently immobilize the purified STAT3 SH2 domain protein onto a CMS sensor chip using standard amine-coupling chemistry.

- Liquid Handling: Prepare a series of dilutions of the inhibitor in a suitable running buffer (e.g., HBS-EP).

- Binding Analysis: Inject the inhibitor solutions over the chip surface at a constant flow rate (e.g., 30 µL/min). The instrument will record the association phase.

- Dissociation Analysis: Switch back to running buffer to initiate the dissociation phase.

- Regeneration: Regenerate the chip surface with a short pulse of glycine-HCl (pH 2.0) to remove all bound analyte.

- Data Processing: Subtract the signal from a reference flow cell. Fit the resulting sensograms to a 1:1 binding model using the SPR evaluation software to calculate the association rate (ka), dissociation rate (kd), and equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd = kd/ka) [31].

Protocol 2: Assessing Anti-Proliferative Activity in TNBC Cell Lines

- Cell Seeding: Seed triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells (e.g., MDA-MB-231) in a 96-well plate at a density of 2,000-5,000 cells per well and allow them to adhere overnight.

- Compound Treatment: Treat the cells with a range of concentrations of the STAT3 inhibitor (e.g., WR-S-462) or a vehicle control (DMSO). Include a minimum of five different concentrations to generate a dose-response curve.

- Incubation: Incubate the cells for 72-96 hours at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

- Viability Assay: Add a cell viability reagent like MTT or CCK-8 to each well and incubate for 1-4 hours.

- Measurement: Measure the absorbance of the formazan product at 450 nm using a microplate reader.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of cell viability relative to the control and determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) using non-linear regression analysis [31].

The following table summarizes key quantitative data for the STAT3 inhibitor WR-S-462 and related compounds, illustrating the progression from hit to optimized inhibitor.

| Inhibitor / Parameter | Binding Affinity (Kd) | Cellular IC₅₀ (Proliferation) | Key Finding | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Hit (6f) | Not specified | Active in osteosarcoma | Identified via phenotypic screening; basis for optimization. | [31] |

| Optimized Inhibitor (WR-S-462) | 58 nM | Significant dose-dependent inhibition of TNBC growth and metastasis | High-affinity binding to STAT3 SH2 domain; robust in vivo efficacy. | [31] |

| SD-36 (PROTAC) | N/A (Degrader) | Tumor regression in xenograft models | Demonstrates efficacy of STAT3 degradation as an alternative strategy. | [31] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Purified STAT3 SH2 Domain Protein | Essential for in vitro binding assays (SPR, ITC) and crystallography to determine the inhibitor's binding mode and affinity. |

| TNBC Cell Lines (e.g., MDA-MB-231) | Model systems for evaluating the cellular efficacy, anti-proliferative, and anti-metastatic effects of STAT3 inhibitors. |

| Phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705) Antibody | A critical tool for Western Blot analysis to confirm that the inhibitor effectively blocks STAT3 phosphorylation and activation. |

| Molecular Dynamics Simulation Software (e.g., Rosetta) | Used to generate conformational ensembles of the target protein, aiding in understanding and predicting inhibitor selectivity [30]. |

| Virtual Screening Libraries (e.g., ZINC20) | Ultra-large chemical databases (billions of compounds) for the in silico discovery of novel inhibitor scaffolds [33]. |

Visualizing Key Concepts and Workflows

The diagrams below illustrate the STAT3 signaling pathway and a systematic workflow for addressing the affinity-selectivity trade-off in inhibitor development.

STAT3 Activation and Inhibition Pathway

Inhibitor Optimization Workflow

What is the core problem in developing STAT SH2 domain inhibitors? The primary challenge is achieving high affinity and selectivity. SH2 domains are protein interaction modules that recognize phosphorylated tyrosine (pY) residues. However, the binding pockets of different STAT SH2 domains are highly conserved, making it difficult to develop inhibitors that distinguish between related STAT proteins (e.g., STAT3 vs. STAT4). Furthermore, obtaining drug-like molecules that can block these protein-protein interactions without the pharmacokinetic drawbacks of natural peptides is a significant hurdle.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Affinity and Selectivity Issues

FAQ: My peptidomimetic compound shows poor selectivity for STAT3 over STAT1. What could be the cause? This is a common problem due to the high sequence similarity (76-82%) in the SH2 domains of different STAT family members. The solution often lies in optimizing interactions with less conserved regions of the binding pocket. Recent research on STAT4 inhibitors demonstrates that para-biaryl phosphates can achieve surprising selectivity despite shared core binding motifs. For instance, compound 6m showed 14-fold selectivity for STAT4 over STAT3, achieved by extending the inhibitor structure to interact with adjacent hydrophobic pockets that differ between STAT proteins [34].

FAQ: How can I accurately determine the binding affinity of my SH2 domain inhibitors? Fluorescence polarization (FP) assays are widely used for determining inhibition constants (Kᵢ). The experimental protocol involves:

- Prepare a fluorescently labeled peptide corresponding to the optimal binding motif for your target SH2 domain (e.g., Ac-GpYLPQNID for STAT4).

- Incubate the tracer peptide with the SH2 domain protein in the presence of varying concentrations of your inhibitor compound.

- Measure polarization values across a concentration range of the test compound.

- Calculate Kᵢ values from the competition curve. Recent studies have validated this approach, with optimal peptides showing Kᵢ values of approximately 0.22 µM for STAT4 [34].

FAQ: My peptidomimetic has good in vitro affinity but shows cellular instability. What strategies can help? Phosphate groups in peptidomimetics are often susceptible to cellular phosphatases. Consider these approaches:

- Develop prodrug strategies: As demonstrated with Pomstafori-1, cell-permeable prodrugs can be designed to protect phosphate groups until cellular entry is achieved [34].

- Explore phosphonate replacements: Phosphonates can mimic phosphates while offering better stability against phosphatases, as shown in the STAT4 inhibitor Stafori-1 [34].

- Implement backbone modification: Shifting side chains from the α-carbon to the amide nitrogen (peptoid approach) can dramatically improve metabolic stability while retaining binding capacity [35].

Experimental Design and Validation

FAQ: What methods can validate that my compound directly targets the SH2 domain? Several complementary approaches provide validation:

- Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC): Directly measures binding affinity and thermodynamics. Recent studies used ITC to confirm STAT4 binding (Kᵢ = 1.3 ± 0.3 µM) and validate key residues (Lys580, Arg598) through point mutation analysis [34].

- Thermal shift assays: Compounds that selectively stabilize their target protein against thermal denaturation indicate direct binding. Stafori-1 protected STAT4 but not STAT3 in cell lysates [34].

- Cellular phosphorylation assays: Monitor inhibition of STAT phosphorylation in cells. Pomstafori-1 selectively inhibited STAT4 phosphorylation at low micromolar concentrations [34].

FAQ: How can I profile SH2 domain binding specificity across a wide sequence space? Bacterial peptide display combined with next-generation sequencing (NGS) provides a powerful approach:

- Create a random phosphopeptide library with high diversity (10⁶-10⁷ sequences).

- Perform multi-round affinity selection using your SH2 domain of interest.

- Sequence enriched pools using NGS after each selection round.

- Analyze with computational tools like ProBound to build quantitative sequence-to-affinity models that cover the full theoretical ligand space [8]. This method has successfully generated accurate binding free energy predictions for SH2 domains and can identify novel phosphosite targets [8].

Quantitative Data on STAT SH2 Domain Inhibitors

Table 1: Potency and Selectivity Profiles of Recent STAT SH2 Domain Inhibitors

| Compound | Target | Kᵢ (µM) | Selectivity Profile | Key Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6m | STAT4 | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 14-fold over STAT3; 10-70-fold over other STATs [34] | p-biaryl phosphate with 2-naphthyl and ortho-fluorine substituents |

| 1 | STAT4 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 7-8-fold over STAT1, STAT3, STAT6 [34] | Basic p-biphenyl phosphate scaffold |

| 6g | STAT4 | 0.44 ± 0.09 | Improved over lead compound 1 [34] | 2-naphthyl replacement of upper phenyl ring |

| 6h | STAT4 | 0.56 ± 0.08 | Improved selectivity over STAT1/3/6 [34] | Fluorine substituent at 2-position of lower ring |

| Optimal peptide | STAT4 | 0.22 ± 0.02 | Binds STAT3 with Kᵢ = 0.24 µM [34] | Ac-GpYLPQNID sequence |

Table 2: Comparison of Peptidomimetic Approaches for SH2 Domain Targeting

| Approach | Examples | Affinity Range | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class B Peptidomimetics | Peptoid-peptide hybrids [35] | IC₅₀ 5-8× higher than native peptide [35] | Improved metabolic stability, side chain positioning | Binding sensitive to shifting position |

| Small Molecule Scaffolds | p-biaryl phosphates [34] | Kᵢ = 0.35-22 µM [34] | High selectivity, drug-like properties | Susceptible to phosphatases |

| Stapled Peptides | Hydrocarbon-stapled BH3 helix [36] | Activates apoptosis at cellular concentrations [36] | Enhanced helical structure, cell permeability | Complex synthesis |

| Prodrug Strategies | Pomstafori-1 [34] | Cellular activity at low µM [34] | Improved cell permeability, phosphate protection | Requires metabolic activation |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for SH2 Domain Inhibitor Development

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial peptide display libraries | Generation of highly diverse (10⁶-10⁷) peptide sequences for profiling [8] | SH2 domain specificity profiling, epitope mapping |

| Fluorescence polarization assay kits | Quantitative binding affinity measurements [34] | Kᵢ determination for inhibitor compounds |

| Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) | Direct measurement of binding thermodynamics [34] | Validation of direct target engagement |

| Phospho-specific STAT antibodies | Detection of phosphorylated STAT proteins in cellular assays [34] | Cellular target engagement validation |

| SH2 domain point mutants | Validation of binding site interactions [34] | Mechanistic studies (e.g., Lys580Ala, Arg598Ala) |

| Custom peptoid synthesis building blocks | Creation of peptoid-peptide hybrid libraries [35] | Metabolic stability optimization while retaining binding |

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow

SH2 Domain Inhibitor Development Workflow

JAK-STAT Signaling and Inhibitor Mechanism

Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (STAT3) is a transcription factor widely recognized as an attractive cancer therapeutic target due to its significant role in tumor initiation and progression [37]. However, STAT3 has been historically considered "undruggable" due to the challenging nature of identifying active sites or allosteric regulatory pockets amenable to small-molecule inhibition [37]. Conventional occupancy-driven pharmacology, which relies on inhibitors binding to active sites, has fundamental limitations for proteins like STAT3 that lack well-defined binding pockets [38].

PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras (PROTACs) represent a paradigm shift from inhibition to degradation, offering a catalytic, event-driven strategy that circumvents the affinity limitations of traditional SH2 domain inhibitors [38]. This technical resource center provides experimental guidance for researchers developing STAT3-targeted PROTACs, with particular emphasis on overcoming affinity challenges in SH2 domain-targeted drug development.

PROTAC Mechanism: FAQ

What is a PROTAC and how does it differ from traditional inhibitors?

PROTAC (PROteolysis TArgeting Chimera) molecules are heterobifunctional structures consisting of three key components: a target protein-binding ligand ("warhead"), an E3 ubiquitin ligase-recruiting ligand ("anchor"), and a connecting linker [38] [39]. Unlike traditional small-molecule inhibitors that merely block protein function through occupancy-driven pharmacology, PROTACs catalytically induce the degradation of the target protein via the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) [40].

How does the catalytic mechanism of PROTACs overcome affinity limitations?

The PROTAC mechanism is event-driven rather than occupancy-driven [38]. A single PROTAC molecule can facilitate the degradation of multiple copies of the target protein through a cyclic process:

- Ternary Complex Formation: The PROTAC simultaneously binds both the target protein (STAT3) and an E3 ubiquitin ligase

- Ubiquitination: The recruited E3 ligase mediates the transfer of ubiquitin chains to STAT3

- Degradation: The ubiquitinated STAT3 is recognized and degraded by the 26S proteasome

- PROTAC Recycling: The PROTAC is released unchanged and can initiate another cycle [38]

This catalytic mechanism means PROTACs can achieve efficient degradation even with lower binding affinity warheads, as the warhead doesn't need to compete with natural ligands at active sites [40].

Why are PROTACs particularly advantageous for targeting STAT3?

STAT3 has been difficult to target with conventional inhibitors due to its challenging protein structure and the lack of well-defined binding pockets [37]. PROTACs offer several distinct advantages for STAT3 targeting:

- Allosteric Targeting: PROTACs can bind to allosteric sites on STAT3, eliminating competition with natural substrates [40]

- Overcoming Resistance: Complete degradation removes the entire protein rather than just inhibiting function, potentially overcoming mutation-based resistance mechanisms [40]

- SH2 Domain Challenges: Traditional SH2 domain inhibitors face affinity limitations that PROTACs can overcome through their catalytic mechanism [37]

STAT3-Targeted PROTAC Design: Technical Guide

Warhead Selection Strategies

The warhead (target-binding ligand) is critical for STAT3 PROTAC efficacy. Research has validated multiple approaches:

Small Molecule Warheads:

- BP-1-102: A well-established STAT3 inhibitor that binds to the SH2 domain, used in the development of S3D5 PROTAC with DC₅₀ = 110 nM in HepG2 cells [41]

- SI-109: Peptidomimetic compound with high binding affinity for STAT3, utilized in SD-36 PROTAC which induces degradation at low nanomolar concentrations [41]

- S31-201: Basis for SDL-1 PROTAC showing anti-gastric cancer activity [41]

DNA Decoy Warheads:

- STAT3-D: A novel approach using DNA decoys that target STAT3's DNA binding domain (DBD), fused to E3 ligase ligands via click chemistry [37]

- Advantage: DNA decoys improve selectivity by leveraging STAT3's natural DNA-binding specificity [37]

E3 Ligase Selection and Optimization

The E3 ligase ligand determines degradation efficiency and tissue specificity. The most commonly utilized E3 ligases for STAT3 PROTACs include:

Cereblon (CRBN) Ligands:

- Pomalidomide-based recruiters used in S3D5 STAT3 PROTAC [41]

- Advantages: Good cell permeability, well-characterized binding

Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) Ligands:

- Used in D-PROTAC systems for STAT3 degradation [37]

- VHL Ligand-Linker Conjugates 8 utilized in DNA decoy-based approaches [37]

Emerging Strategies:

- Context-Specific E3 Ligases: Selecting E3s based on tissue expression (e.g., DCAF16 for CNS targets, RNF114 for epithelial cancers) [42]

- Ligase-Switchable Designs: Controlling degradation in precise biological contexts [42]

Linker Design and Optimization

Linker composition critically influences PROTAC efficacy by determining optimal spatial orientation for ternary complex formation:

Linker Length Optimization: D-PROTAC systems systematically evaluated linkers of 7, 11, 15, 19, 23, and 27 bases to determine optimal degradation efficiency [37].

Linker Composition: PEG-based linkers of varying lengths were used in S3D5 development to connect BP-1-102 derivatives to pomalidomide [41].

Experimental Protocols for STAT3 PROTAC Development

Protocol 1: D-PROTAC Synthesis and Purification

Materials:

- DNA Oligonucleotides (Sangon Biotech)

- VHL Ligand-Linker Conjugates 8 (TargetMol Chemicals, T17909)

- Ultrafiltration centrifuge tube (3K MWCO)

- PBS Buffer, Ultrapure Water

Synthesis Procedure:

- Oligonucleotide Preparation: Dilute DNA decoys with different linker lengths (7, 11, 15, 19, 23, 27 bases) to 10 μM in PBS

- Denaturation/Renaturation: Denature at 95°C for 5 minutes, then rapidly cool on ice and stand at room temperature for 1 hour

- Conjugation: Mix DNA:VHL Ligand-Linker Conjugates in 1:100 ratio, incubate at 37°C with shaking for 12 hours

- Purification: Use ultrafiltration centrifuge tubes (3K MWCO), centrifuge at 7500 rpm for 25 minutes

- Wash: Add 400 μL ultrapure water, repeat centrifugation twice

- Storage: Store prepared D-PROTACs at -20°C protected from light [37]

Characterization Methods:

- Mass Spectrometry: Confirm molecular weight and conjugation efficiency

- Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE): 12% polyacrylamide gel, 100V in 1×TBE buffer for 60 minutes, visualize with Gel-Red staining [37]

Protocol 2: STAT3 Degradation Validation Assay

Materials:

- Cell lines: HepG2 (hepatocellular carcinoma), HeLa, MCF-7, Jurkat (various cancers)

- Proteasome Inhibitor: MG132 (TargetMol Chemicals, T2154)

- Ubiquitination Inhibitor: MLN4924

- CRBN Competitor: Pomalidomide

- STAT3 Inhibitor: BP-1-102

- Antibodies: STAT3 (Cell Signaling Technology, 4904), p-STAT3 (Y705) (Cell Signaling Technology, 9145), STAT1, STAT2, STAT4, STAT5, STAT6 (Abcam)

- Cell Viability Assay: CCK-8 (MedChemExpress, HY-K0301) [37] [41]

Degradation Kinetics Protocol:

- Cell Treatment: Seed HepG2 cells in 6-well plates (2×10⁵ cells/well), incubate overnight

- PROTAC Exposure: Treat with S3D5 PROTAC (0-1000 nM) for 48 hours for dose-response, or fixed concentration for time course (0-48 hours)

- Western Blot Analysis: Lyse cells, separate proteins by SDS-PAGE, transfer to membrane, incubate with STAT3 antibody (1:2000), detect with chemiluminescence

- DC₅₀ Calculation: Quantify band intensity, plot dose-response curve, calculate half-maximal degradation concentration [41]

Mechanism Validation:

- Ternary Complex Competition: Pre-treat with BP-1-102 (STAT3 competitor) or pomalidomide (CRBN competitor) before S3D5 addition

- Proteasome Inhibition: Pre-treat with MG132 (10 μM, 4 hours) to block proteasomal degradation

- Ubiquitination Inhibition: Pre-treat with MLN4924 to inhibit ubiquitin activation [41]

Protocol 3: Functional Validation of STAT3 Degradation

Antiproliferative Activity:

- CCK-8 Assay: Seed HepG2 cells in 96-well plates (5×10³ cells/well), treat with S3D5 (0-20 μM) for 48-72 hours, add CCK-8 reagent, measure absorbance at 450nm [41]

Apoptosis and Cell Cycle Analysis:

- Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Assay: Use commercial kit (Beyotime, C1062L), analyze by flow cytometry

- Cell Cycle Analysis: Use cell cycle staining kit (Beyotime, C1052), analyze DNA content by flow cytometry [37]

Downstream Signaling Assessment:

- Western Blot for STAT3 Targets: Analyze BCL-2, c-Myc, VEGF, cyclin D1 expression changes post-degradation [37] [41]

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Inefficient STAT3 Degradation

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Insufficient Ternary Complex Formation: Optimize linker length (test 7-27 atom/moiety linkers), confirm warhead binding affinity via SPR (KD = 4.35 μM for S3D5) [41]

- Suboptimal E3 Ligase Selection: Screen multiple E3 ligase recruits (CRBN, VHL, others), consider tissue-specific E3 expression [42]

- Hook Effect: Test multiple PROTAC concentrations (0.1-10 μM), as high concentrations can cause binary complex formation and reduce degradation efficiency [42]

Problem: Lack of Specificity - Off-target Degradation

Validation Approaches:

- STAT Family Selectivity: Check STAT1, STAT2, STAT4, STAT5, STAT6 levels alongside STAT3 - S3D5 showed no significant effect on other STAT proteins [41]

- Proteome-Wide Screening: Use TMT-based mass spectrometry to identify off-target degradation [42]

- DNA Decoy Strategy: Implement STAT3-D decoy to enhance specificity through DNA binding domain recognition [37]

Problem: Poor Cellular Permeability

Optimization Strategies:

- Warhead Modification: Use cell-permeable warheads like BP-1-102 derivatives

- Linker Optimization: Adjust linker hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity balance

- Delivery Systems: Consider nanoparticle encapsulation or transient permeabilization for initial validation

Quantitative Comparison of STAT3 PROTACs

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Representative STAT3 PROTACs

| PROTAC | Warhead | E3 Ligase | DC₅₀ | Cellular Models | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S3D5 | BP-1-102 derivative | CRBN (Pomalidomide) | 110 nM | HepG2 cells | Selective STAT3 degradation, activates p53 pathway [41] |

| SD-36 | SI-109 | CRBN | Low nM | Leukemia, lymphoma cells | Complete degradation in xenograft models [41] |

| SDL-1 | S31-201 | CRBN | Not specified | Gastric cancer cells | Anti-gastric cancer proliferation activity [41] |

| TSM-1 | Triterpenoid toosendanin | CRBN (Lenalidomide) | Not specified | Neck squamous cell carcinoma, colorectal cancer | Potent antitumor effects in STAT3-dependent cancers [41] |

| D-PROTAC | STAT3-D DNA decoy | VHL | Not specified | Various cancer cell types | Novel decoy approach, targets DNA binding domain [37] |

Table 2: Experimental Reagents for STAT3 PROTAC Development

| Reagent | Supplier/Catalog | Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| VHL Ligand-Linker Conjugates 8 | TargetMol (T17909) | D-PROTAC synthesis | Critical for VHL-based degradation systems [37] |

| MG132 | TargetMol (T2154) | Proteasome inhibition | Mechanism validation (10 μM, 4h pre-treatment) [37] [41] |

| MLN4924 | Not specified | Ubiquitination inhibition | Confirms ubiquitin-dependent mechanism [41] |

| CCK-8 Assay Kit | MedChemExpress (HY-K0301) | Cell viability | Measure anti-proliferative effects [41] |

| Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Kit | Beyotime (C1062L) | Apoptosis detection | Validate functional consequences of degradation [37] |