Optimizing SH2 Domain Structural Models for Enhanced Virtual Screening in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing SH2 domain structural models to improve the success rate of virtual screening.

Optimizing SH2 Domain Structural Models for Enhanced Virtual Screening in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing SH2 domain structural models to improve the success rate of virtual screening. It covers the foundational role of SH2 domains in cellular signaling and disease, explores advanced computational methodologies including molecular dynamics and AI-based structure prediction, addresses common challenges in accounting for domain flexibility and solvation effects, and outlines robust validation strategies using binding free energy calculations and experimental assays. By synthesizing recent methodological advances, this resource aims to bridge the gap between static structural data and the dynamic reality of SH2 domain-ligand interactions, facilitating the identification of novel therapeutic agents.

The Critical Role of SH2 Domains in Signaling and Disease: Structural Foundations for Drug Discovery

TROUBLESHOOTING GUIDE & FAQs

FAQ: What are the core structural components of an SH2 domain and how do they define binding pockets? SH2 domains are ~100-amino acid protein modules that adopt a conserved fold characterized by a central anti-parallel β-sheet flanked by two α-helices, commonly described as an αβββα motif [1] [2] [3]. This conserved architecture forms three key specificity pockets that engage phosphotyrosine (pY) residues and the surrounding amino acids:

- pY+0 Pocket: A highly conserved, deep, positively charged pocket that binds the phosphorylated tyrosine residue. A key invariant arginine residue (Arg βB5) forms hydrogen bonds with the phosphate group [4] [3].

- pY+1 Pocket: This pocket interacts with the amino acid immediately C-terminal to the phosphotyrosine. Its properties can influence the local conformation of the bound peptide [5].

- pY+X Pocket: A variable pocket that dictates the primary sequence specificity of different SH2 domains. It typically binds a hydrophobic residue at the P+3 or P+4 position, but its exact location and specificity are determined by the surrounding loops [3].

FAQ: Why does my virtual screening campaign fail to distinguish between different SH2 domains, despite targeting their specificity pockets? A common failure point is an overemphasis on the pY+0 and pY+X pockets while neglecting the critical role of surface loops. The EF and BG loops, which connect the secondary structure elements, act as gatekeepers for the pY+X pocket [6] [3]. They can physically block access to sub-pockets or alter their shape. In some SH2 domains, a bulky residue in the EF loop can plug the P+3 pocket, forcing the peptide to adopt a different binding mode and shifting specificity to the P+2 position, as seen in Grb2 [3]. Always verify the conformation and residue composition of these loops in your structural model.

FAQ: How can I validate the binding specificity of a compound identified as a potential SH2 domain inhibitor? Beyond standard binding affinity assays, you should perform competitive binding studies. A true pY-competitive inhibitor will be displaced by high-affinity phosphopeptides that bind the same SH2 domain [7] [8]. For example, in the STAT3 SH2 domain, a confirmed inhibitor was shown to compete with pTyr peptides for binding, demonstrating it acts as a pY bioisostere [8]. Furthermore, use isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to obtain thermodynamic parameters; unexpected entropy/enthalpy compensation can indicate non-specific binding or incorrect binding mode prediction [5].

FAQ: What are the best experimental methods to define the intrinsic specificity of an SH2 domain? Combinatorial peptide library screening is the gold standard for empirically determining SH2 domain specificity. The "one-bead-one-compound" (OBOC) method is particularly powerful [4]. In this protocol:

- Library Synthesis: A pY peptide library is synthesized on solid-phase beads using the split-and-pool method, ensuring each bead displays a unique peptide sequence.

- Screening: The library is screened against the purified SH2 domain of interest. Beads with tight-binding sequences are selected.

- Sequencing: Positive beads are individually sequenced using high-throughput techniques like partial Edman degradation and mass spectrometry (PED/MS) [4]. This method directly identifies the preferred amino acids at positions flanking the phosphotyrosine.

QUANTITATIVE BINDING SPECIFICITY DATA

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Specificity Motifs for Select SH2 Domains. Data sourced from high-throughput peptide library screens [3].

| SH2 Domain | Specificity Group | Recognized Motif | Key Specificity Residue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Src, Fyn, Lck | IA | pY--ψ | Hydrophobic (ψ) at P+3 |

| Grb2 | IC | pY--N--_ | Asparagine (N) at P+2 |

| BRDG1/STAP-1 | IIC | pY---_-ψ | Hydrophobic (ψ) at P+4 |

| STAT3 | III | pY---Q | Glutamine (Q) at P+3 |

Table 2: Thermodynamic Parameters for Grb2 SH2 Domain Binding to Peptides with Varying pY+1 Residues. Data obtained by Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) [5].

| Ligand (pY+1 Ring Size) | Kₐ (×10⁵ M⁻¹) | ΔG° (kcal•mol⁻¹) | ΔH° (kcal•mol⁻¹) | -TΔS° (kcal•mol⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-membered | 1.6 ± 0.1 | -7.1 ± 0.1 | -3.3 ± 0.3 | -3.8 ± 0.1 |

| 4-membered | 4.3 ± 0.4 | -7.7 ± 0.1 | -5.4 ± 0.3 | -2.3 ± 0.2 |

| 5-membered | 16.1 ± 1.1 | -8.5 ± 0.1 | -6.3 ± 0.4 | -2.2 ± 0.2 |

| 6-membered | 69.6 ± 12.0 | -9.3 ± 0.1 | -8.5 ± 0.4 | -0.8 ± 0.4 |

| 7-membered | 37.0 ± 3.3 | -8.9 ± 0.1 | -6.8 ± 0.3 | -2.1 ± 0.2 |

THE SCIENTIST'S TOOLKIT: RESEARCH REAGENT SOLUTIONS

Table 3: Essential Reagents for SH2 Domain Specificity and Inhibition Studies

| Reagent / Method | Function in SH2 Research | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| One-Bead-One-Compound (OBOC) pY Library | Defines intrinsic sequence specificity of an SH2 domain by screening millions of peptide sequences [4]. | Empirical determination of binding motifs. |

| Monobodies (Synthetic Binding Proteins) | High-affinity, highly selective protein-based inhibitors that can target specific SH2 domains, even within subfamilies [7]. | Potent and selective disruption of SH2-mediated interactions in cells. |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Provides a full thermodynamic profile (Kₐ, ΔG, ΔH, ΔS) of SH2-phosphopeptide interactions [5]. | Mechanistic studies of binding, validating interactions with small molecules. |

| Virtual Screening with Consensus Docking | Identifies potential small-molecule inhibitors by computationally screening compound libraries against SH2 domain structures [1] [8] [9]. | Hit identification for difficult-to-target SH2 domains like STAT3 or PTK6. |

SH2 DOMAIN POCKET ARCHITECTURE

EXPERIMENTAL WORKFLOW: DETERMINING SH2 SPECIFICITY

FAQ: Addressing Common Research Challenges

FAQ 1: Why does my virtual screening against the STAT3 SH2 domain yield an unacceptably high false-positive rate?

This is a common challenge, often stemming from the shallow, solvent-exposed nature of the protein-protein interaction (PPI) interface typical of many SH2 domains. To improve results:

- Employ Iterative AI Workflows: Replace brute-force docking with AI-enhanced workflows like Deep Docking. This method uses a deep learning model trained on a subset of docked compounds to prioritize molecules from ultra-large libraries that are most likely to be true hits, significantly improving hit rates [10].

- Incorporate Specificity Pockets: Ensure your docking model accurately accounts for residues in the pY+3 pocket (e.g., V637, Y657, Q644, E638), which are critical for binding specificity. Mutations or incorrect conformational sampling in this hydrophobic pocket can drastically reduce prediction accuracy [11].

- Benchmark Your Docking Protocol: Before screening, perform a retrospective virtual screen with a known set of active and decoy molecules to calculate performance metrics like the Area Under the Curve (AUC) and Enrichment Factor (EF). This validates that your chosen protein structure and docking parameters are appropriate for the target [10].

FAQ 2: What are the primary strategies for targeting SH2 domains with small molecules?

The main strategies involve targeting two key areas, with a third emerging avenue:

- Direct, Competitive Inhibition: Develop molecules that directly compete with phosphotyrosine (pY) peptides for binding to the conserved pY pocket. A universally conserved arginine residue (ArgβB5) in this pocket is critical for binding the phosphate group and is a key anchor for inhibitors [12] [13].

- Allosteric Inhibition: Target regulatory sites outside the pY pocket to modulate SH2 domain function indirectly. For STAT3, the Coiled-Coil Domain (CCD) is a validated allosteric site. Effectors like small molecule K116 or polypeptide MS3-6 bind to the CCD and induce conformational changes that propagate to the SH2 domain, diminishing its phosphopeptide binding affinity [11].

- Targeting Lipid Interactions: Many SH2 domains (e.g., in SYK, ZAP70, LCK) possess cationic lipid-binding sites near the pY-pocket. Targeting these sites with nonlipidic small molecules is a promising strategy to disrupt membrane recruitment and activation, potentially offering high specificity [13].

FAQ 3: How can I improve the affinity and specificity of my SH2 domain inhibitors?

Beyond the pY-binding pocket, engage the specificity-determining regions.

- Engage the pY+1, pY+2, and pY+3 Pockets: The C-terminal residues of the phosphopeptide (positions +1, +2, +3 relative to pY) bind into a largely hydrophobic pocket on the SH2 domain. Designing inhibitors that make specific interactions with the EF loop and BG loop, which form this pocket, can dramatically enhance both affinity and selectivity [12] [13].

- Consider Non-Equilibrium Kinetics: High-affinity interactions are not always better. In vivo, signaling requires rapid on/off rates for quick cellular responses. Optimize for a balance of moderate affinity (Kd 0.1–10 µM) and favorable binding kinetics to achieve functional efficacy without compromising specificity [12].

FAQ 4: My SH2 domain target is involved in liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS). How does this impact my experimental approach?

LLPS introduces a layer of complexity that can be leveraged for discovery.

- Recognize Multivalent Interactions: SH2 domain-mediated interactions are often multivalent, a key driver of LLPS and biomolecular condensate formation. For example, interactions among GRB2, Gads, and the LAT receptor contribute to LLPS that enhances T-cell receptor signaling [13].

- Adjust Screening Assays: If your target forms condensates, biochemical affinity measurements (e.g., Kd) from isolated systems may not fully capture its functional behavior in a phase-separated state. Consider developing or incorporating cellular assays that report on condensate formation or disruption [13].

Troubleshooting Guides for Critical Experiments

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Low Hit Rates in uHTVS

Problem: An ultra-high-throughput virtual screen (uHTVS) of a billion-compound library failed to yield validated hits in biochemical assays.

| Step | Checkpoint | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Pre-Screening | Underlying Docking Model | Retrospectively validate the docking pose and score prediction using known active compounds. The performance of AI pre-screens (e.g., Deep Docking) is highly dependent on the underlying docking model [10]. |

| 2. Library Curation | Chemical Library Choice | Use a synthetically accessible library like the Enamine REAL database. Filter for drug-like properties (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five) and pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) [10] [14]. |

| 3. AI Workflow | Deep Docking Parameters | Ensure the initial training set for the deep learning model is sufficiently large and diverse. For a library of millions, docking 1-5% of compounds to train the model can be effective [10]. |

| 4. Post-Screening | Hit Validation | Confirm hits using orthogonal assays. A high hit rate (e.g., 42.9-50.0% as achieved in some STAT3/STAT5b screens) validates the workflow; a low rate suggests a problem upstream [10]. |

Guide 2: Troubleshooting SH2 Domain Binding Assays

Problem: A fluorescence polarization (FP) or surface plasmon resonance (SPR) assay shows weak or no binding between the purified SH2 domain and a known peptide ligand.

| Observation | Potential Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| No binding signal | Protein misfolding or instability | Check protein purity and stability. Ensure the conserved ArgβB5 in the pY-binding pocket is intact, as its mutation abrogates pY binding [12] [15]. |

| Weak affinity (Kd >10 µM) | Incorrect peptide sequence or low phosphorylation | Verify peptide purity and phosphorylation status (e.g., via mass spectrometry). The pY residue is absolutely essential [12]. |

| High non-specific binding | Issues with assay buffer conditions | Optimize buffer salt concentration and add a non-ionic detergent (e.g., 0.01% Tween-20) to reduce non-specific interactions. |

| Inconsistent data | Protein degradation or dephosphorylation | Include phosphatase and protease inhibitors in all buffers and use fresh protein aliquots for each experiment. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Deep Docking for uHTVS of SH2 Domains

This protocol outlines an economic AI-based workflow for screening large compound libraries, adapted from successful screens against STAT3 and STAT5b [10].

1. Library Preparation:

- Obtain a synthetically accessible compound library (e.g., Enamine REAL, Mcule-in-stock).

- Apply pre-processing filters: Lipinski's Rule of Five, Veber criteria, and PAINS removal using a tool like KNIME with RDKit nodes [10].

2. Benchmark Docking:

- Select a representative protein structure for the SH2 domain (e.g., STAT3-SH2).

- Conduct a retrospective virtual screen with a data set of known actives and decoys from a database like DUD-E.

- Calculate the AUC and EF to confirm the docking setup can enrich known actives.

3. Deep Docking Execution:

- Iteration 1: Dock a randomly selected subset of the large library (e.g., 1-2% of compounds, or ~100,000 molecules) to generate initial training data.

- Iteration 2: Train a deep neural network (DNN) to predict docking scores based on the chemical structures from the first iteration.

- Iteration 3: Use the trained DNN to predict scores for all remaining compounds in the library. Select the top-ranked compounds (e.g., top 1%) for the next round of docking.

- Iteration 4-n: Retrain the DNN with new docking results and iterate until a predefined number of compounds (e.g., 100,000-200,000) have been physically docked.

- Output: The final list of top-ranked compounds from the last docking iteration constitutes the virtual hits for experimental testing.

Protocol 2: Validating Allosteric Regulation of STAT3 SH2 via CCD

This protocol uses mutagenesis and binding assays to study the allosteric link between the Coiled-Coil Domain (CCD) and the SH2 domain [16] [11].

1. Mutagenesis:

- Design a point mutation in the CCD, such as D170A, which is known to diminish SH2 domain function allosterically [16] [11].

- Generate the mutant STAT3 construct using a site-directed mutagenesis kit in a FLAG-tagged expression vector.

2. Transfection and Cell Lysis:

- Transfect COS-1 or HepG2 cells with plasmids encoding wild-type (WT) and D170A STAT3 using a transfection reagent like Lipofectamine or FuGENE 6.

- After 24-48 hours, lyse cells in RIPA buffer supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitors.

3. Binding Assay:

- Incubate cell lysates containing WT or mutant STAT3 with biotinylated phosphopeptides derived from a natural binding partner (e.g., gp130 receptor peptide pY2 or pY3).

- Use streptavidin-conjugated beads to pull down the peptide-protein complexes.

- Wash the beads extensively with lysis buffer to remove non-specific interactions.

4. Analysis:

- Elute the bound proteins and analyze them by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

- Probe the blot with an anti-FLAG antibody to detect STAT3 pulled down by the phosphopeptide.

- Expected Outcome: The D170A mutant will show significantly reduced binding to the phosphopeptide compared to the WT STAT3, demonstrating the allosteric role of the CCD in regulating SH2 domain affinity [16].

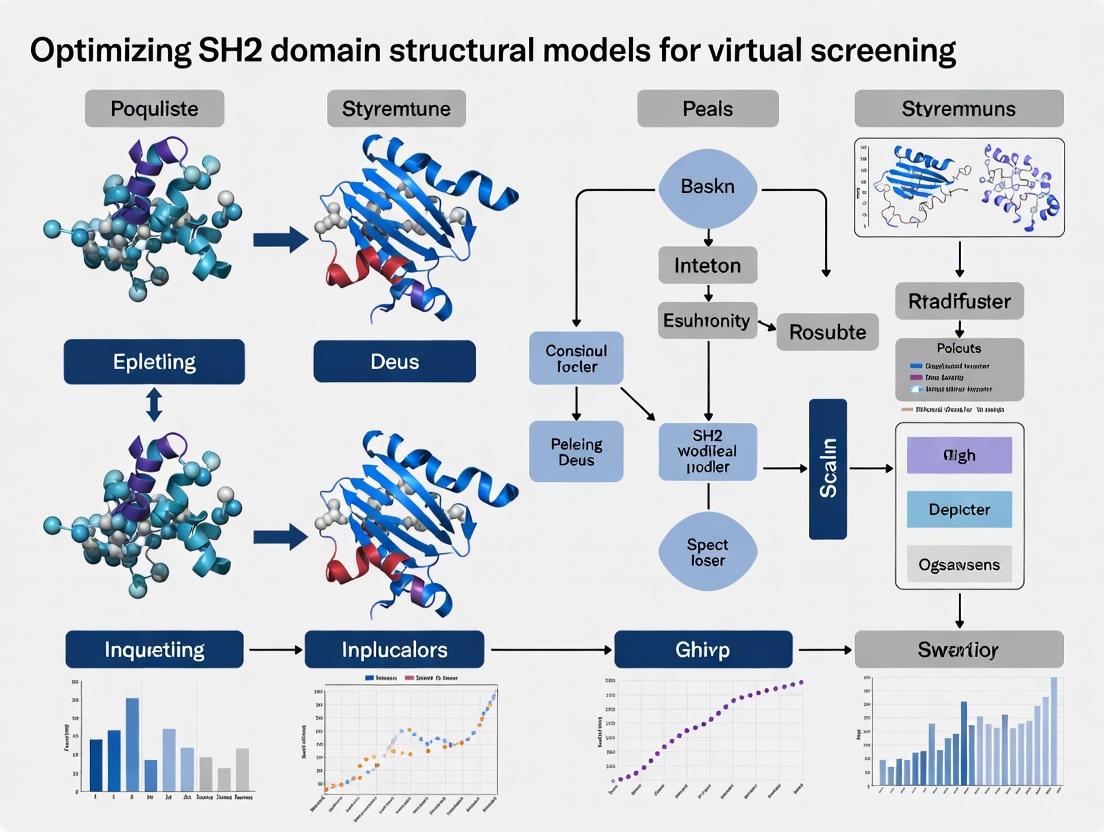

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: SH2 Domain-Mediated JAK-STAT3 Signaling Pathway

Diagram Title: SH2 Domain Role in JAK-STAT3 Activation

Diagram 2: Deep Docking uHTVS Workflow

Diagram Title: AI-Powered Deep Docking Screening

Diagram 3: Allosteric Inhibition of STAT3 via CCD

Diagram Title: STAT3 Allosteric Inhibition Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for SH2 Domain-Targeted Research

| Research Reagent | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| SH2 Domain Focused Library (e.g., Life Chemicals) | A pre-selected collection of ~2,200 drug-like compounds with predicted affinity for SH2 domains. Used for initial hit identification in HTS [14]. | Designed using pharmacophore models based on X-ray structures of SH2-inhibitor complexes. PAINS and reactive compounds are filtered out. |

| Synthetically Accessible Libraries (e.g., Enamine REAL, Mcule-in-stock) | Ultra-large chemical libraries (millions to billions of compounds) for uHTVS. Crucial for exploring vast chemical space to find novel inhibitors [10]. | Compounds are "make-on-demand" and pre-filtered for drug-like properties (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five). |

| Phosphotyrosine-Containing Peptides | Essential tools for binding assays (FP, SPR, Pull-down) to validate SH2 domain function and probe binding specificity [16] [15]. | Must be high-purity and verify phosphorylation status. Residues at pY+1, pY+2, pY+3 determine binding specificity. |

| Anti-Phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705) Antibody | A critical reagent for Western Blot and immunofluorescence to detect activated, phosphorylated STAT3 in cellular assays [16]. | Confirms downstream functional effect of SH2 domain inhibition in cell-based models. |

| Allosteric CCD Effectors (e.g., K116) | Small-molecule inhibitors that bind the STAT3 Coiled-Coil Domain, providing an alternative to direct SH2 domain targeting [11]. | Useful for studying allosteric regulation and as a tool compound to validate this therapeutic strategy. |

FAQs: SH2 Domain Biology and Experimental Design

Q1: What are the primary functions of SH2 domains in cellular signaling? SH2 (Src Homology 2) domains are protein modules that specifically recognize and bind to sequences containing phosphorylated tyrosine (pY). They are fundamental "readers" in tyrosine phosphorylation signaling, a key post-translational modification regulating cell proliferation, differentiation, and immune responses. Their primary role is to induce proximity between proteins, such as bringing tyrosine kinases to their substrates or recruiting effector proteins to activated receptors [17] [13].

Q2: Besides peptide binding, what other molecular interactions are SH2 domains involved in? Emerging research shows that many SH2 domains participate in non-canonical interactions:

- Lipid Binding: Nearly 75% of SH2 domains can interact with membrane lipids, particularly phosphoinositides like PIP₂ and PIP₃. This interaction is crucial for membrane recruitment and can modulate the domain's activity or its interaction with other proteins [13].

- Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation (LLPS): Multivalent interactions mediated by SH2 domains can drive the formation of biomolecular condensates. For example, interactions between GRB2 (SH2/SH3 adapter) and the LAT receptor contribute to condensate formation that enhances T-cell receptor signaling [13].

Q3: What determines the specificity of different SH2 domains for their target peptides? While all SH2 domains share a conserved fold that binds pY, their specificity for residues C-terminal to the pY is largely governed by variable surface loops. These loops control access to key binding pockets (e.g., for P+2, P+3, or P+4 residues). By "plugging" or "opening" these pockets, the loops define which peptide sequences an SH2 domain can recognize [3].

Q4: Why is understanding non-canonical SH2 interactions important for drug discovery? Dysregulation of SH2-mediated interactions is linked to many diseases, including cancer. Targeting lipid-binding sites or disrupting pathogenic condensates offers alternative therapeutic strategies, especially when the canonical pY-binding pocket is considered "undruggable." Developing non-lipidic inhibitors for the lipid-binding site of Syk kinase is one promising example [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Specificity or Affinity in SH2-Peptide Binding Assays

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inadequate consideration of SH2 loop structure.

- Solution: Before experimental design, consult structural data if available. The EF and BG loops are critical for defining binding pocket accessibility. If your peptide ligand contains a P+4 hydrophobic residue, ensure the target SH2 domain (e.g., from BRDG1, BKS, or Cbl) has an open P+4 pocket and is not one where this pocket is blocked by a loop residue [3].

- Cause: Impact of non-peptide binding interactions.

- Solution: Consider the experimental context. If using liposomes or cellular membranes, remember that lipid interactions (e.g., with PIP₂) can compete with or modulate peptide binding. Include controls that account for potential membrane-mediated effects [13].

Issue 2: Unexpected Aggregation or Condensate Formation In Vitro

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Multivalent interactions promoting LLPS.

- Solution: If your experiment involves proteins with multiple SH2 and SH3 domains (e.g., GRB2, NCK) and their binding partners, the observed aggregation may be functional LLPS. Characterize it by testing for reversibility, concentration-dependence, and sensitivity to 1,6-hexanediol. This may not be a problem but a key finding [13].

- Cause: Non-specific aggregation due to lipid composition.

Issue 3: Difficulty in Achieving Selective Inhibition of SH2 Domain Function

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: High conservation of the canonical pY-binding pocket.

- Cause: Compound interference from lipid membranes.

- Solution: When screening for inhibitors in cellular assays, consider that some compounds might localize to membranes and indirectly affect SH2 domain function by altering lipid availability, rather than by direct binding to the domain. Use counter-screens to distinguish direct binders from membrane-active compounds [13].

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: SH2 Domain-Containing Proteins with Lipid-Binding Activity

This table summarizes key proteins where SH2 domain-lipid interaction has a demonstrated functional role [13].

| Protein Name | Function of Lipid Association | Lipid Moiety |

|---|---|---|

| SYK | PIP₃-dependent membrane binding required for non-catalytic activation of STAT3/5. | PIP₃ |

| ZAP70 | Essential for facilitating and sustaining interactions with TCR-ζ chain. | PIP₃ |

| LCK | Modulates interaction with binding partners in the TCR signaling complex. | PIP₂, PIP₃ |

| ABL | Mediates membrane recruitment and modulates Abl kinase activity. | PIP₂ |

| VAV2 | Modulates interaction with membrane receptors like EphA2. | PIP₂, PIP₃ |

| C1-Ten/Tensin2 | Regulates Abl activity and IRS-1 phosphorylation in insulin signaling. | PIP₃ |

Table 2: Classification of Human SH2 Domain Specificity

This table categorizes SH2 domains based on their preferred peptide recognition motifs, highlighting the role of the βD5 residue and key binding pockets [3].

| Specificity Group | Example SH2 Domains | βD5 Residue | OPAL Motif | Key Specificity Residue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group IA/IB | SRC, FYN, ABL1 | Y/F | pY[-][-]ψ / pYxxψ | P+3 (Hydrophobic) |

| Group IC | GRB2, GRB7, CSK | Y/F | pYxN | P+2 (Asparagine) |

| Group IIA/IIB | VAV, PI3K-p85α, SHP-2 | I/C/L/V/A/T | pYψxψ / pY[E/D/x]xψ | P+3 (Hydrophobic) |

| Group IIC | BRDG1, BKS, CBL | Y/T | pYxxxψ | P+4 (Hydrophobic) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing SH2 Domain Lipid Binding Using Liposome Co-sedimentation

Application: Determine if a purified SH2 domain binds directly to specific lipids (e.g., PIP₂ or PIP₃). Methodology:

- Liposome Preparation: Prepare liposomes of defined composition. Include a test group containing the lipid of interest (e.g., 5% PIP₃ in a PC background) and a control group without it.

- Incubation: Mix the purified SH2 domain protein with the liposomes in a suitable buffer.

- Ultracentrifugation: Sediment the liposomes via high-speed centrifugation. Protein bound to liposomes will co-sediment into the pellet.

- Analysis: Separate the supernatant (unbound protein) from the pellet (liposome-bound protein). Analyze both fractions by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting or quantitative staining to determine the fraction of protein bound [13].

Protocol 2: Characterizing SH2-Mediated Condensate Formation

Application: Investigate the role of an SH2 domain-containing protein in liquid-liquid phase separation. Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Use purified proteins, including the SH2 protein and its binding partner(s) which should contain multiple pY sites or other complementary domains.

- Induction of Phase Separation: Mix the proteins in a physiologically relevant buffer. Phase separation is often concentration-dependent and may require crowding agents (e.g., PEG).

- Imaging and Analysis:

- Use differential interference contrast (DIC) or fluorescence microscopy (if proteins are labeled) to visualize droplet formation.

- Test for liquid-like properties by demonstrating fusion of droplets over time.

- Verify the role of SH2-pY interactions by adding a competitive inhibitor (e.g., a high-affinity pY peptide) which should dissolve the condensates.

- Confirm specificity by using mutant proteins that lack functional SH2 domains [13].

Signaling Pathway and Mechanism Diagrams

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for SH2 Domain Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphopeptide Libraries | Profiling SH2 domain specificity using techniques like Oriented Peptide Array Library (OPAL). | Determine the consensus binding motif for a novel or poorly characterized SH2 domain [3]. |

| Defined Liposomes | Model membranes for studying lipid-protein interactions. | Investigate the binding of an SH2 domain to specific phosphoinositides like PIP₂ or PIP₃ [13]. |

| 1,6-Hexanediol | A chemical that disrupts weak hydrophobic interactions, commonly used to probe LLPS. | Test if observed subcellular puncta formed by an SH2-containing protein are liquid-like condensates [13]. |

| Rule-Based Modeling Software (e.g., BioNetGen, VCell) | Computational modeling to manage combinatorial complexity in signaling networks. | Build a predictive model of a signaling pathway where an SH2-containing protein (e.g., Grb2) interacts with multiple partners [20] [21]. |

FAQs: Core Concepts and Definitions

What is the FLVRES sequence, and what is its primary function?

The FLVRES sequence is a highly conserved amino acid motif found within the phosphotyrosine (pTyr)-binding pocket of the SH2 domain [22]. Its primary function is to facilitate specific recognition and binding to phosphorylated tyrosine residues. The central arginine residue (designated as βB5) within this motif is particularly critical, as it interacts directly with the phosphate group of the phosphotyrosine [22] [23]. This interaction contributes a significant portion of the binding free energy, and mutation of this arginine can cause up to a 1,000-fold reduction in binding affinity [22].

Are there variations in the FLVRES motif across different SH2 domains?

While the FLVR motif is exceptionally well-conserved, variations do exist. Research indicates that out of over 120 human SH2 domains, all but three contain the conserved FLVR arginine [22]. Furthermore, studies on the v-Src SH2 domain have shown that while the canonical arginine (R175) is essential, certain mutations (e.g., R175H or R175K) can reduce but not eliminate phosphotyrosine binding, and may still support biological function, such as cellular transformation [23].

How does the binding specificity of tandem SH2 domains differ from single domains?

Tandem SH2 domains, found in proteins like ZAP-70 and phospholipase C-γ1, achieve a dramatically higher level of specificity compared to single SH2 domains. They simultaneously engage bisphosphorylated tyrosine-based activation motifs (TAMs) on receptors [24]. This dual interaction results in affinities in the 0.5–3.0 nM range for the correct biological partner, with discrimination against alternative TAMs being 1,000 to over 10,000-fold greater than that typically observed (20–50-fold) for individual SH2 domains [24].

Troubleshooting Guide: Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Issue: Poor or Unexpected Binding Affinity

Potential Cause 1: Mutation or Dysfunction of the FLVR Arginine The conserved arginine in the FLVR motif is responsible for a large part of the binding energy.

- Solution: Verify the integrity of the FLVRES sequence in your SH2 domain construct.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Sequence Analysis: Confirm the protein sequence via DNA sequencing.

- Functional Assay: Perform a fluorescence polarization or surface plasmon resonance (SPR) binding assay using a known phosphotyrosine peptide. A significant drop in affinity suggests a problem with the binding pocket.

- Positive Control: Use a wild-type SH2 domain protein in parallel to benchmark performance.

Potential Cause 2: Incorrect Recognition of Specificity Determinants SH2 domain binding depends on the phosphotyrosine and residues C-terminal to it, particularly the amino acid at the +3 position.

- Solution: Ensure you are using the correct phosphopeptide ligand for your specific SH2 domain.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Ligand Verification: Consult literature for the established binding preference of your SH2 domain (e.g., using sources like the SMALI database).

- Peptide Design: Synthesize phosphopeptides with the correct +3 residue and other known specificity determinants.

- Competition Assay: Validate binding specificity by showing that an unphosphorylated peptide or a peptide with a scrambled sequence does not compete for binding.

Issue: Protein Instability or Insolubility

Potential Cause: Disruption of the SH2 Domain Fold Some mutations, particularly those introducing charged residues in the core of the domain, can destabilize the native structure.

- Solution: Engineer mutations that maintain structural stability.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Structural Modeling: Use available crystal structures (e.g., from the Protein Data Bank) to model your mutation and assess its potential impact on the hydrophobic core or key hydrogen bonds.

- Stability Assessment: Utilize circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy to monitor the thermal denaturation of your SH2 domain. A lower melting temperature ((T_m)) indicates reduced stability.

- Alternative Mutagenesis: As evidenced by studies on v-Src, consider conservative mutations (e.g., R175K) that may preserve structure and partial function better than radical ones (e.g., R175E), which can lead to insolubility [23].

Table 1: Impact of FLVR Arginine Mutations on SH2 Domain Function

| SH2 Domain | Mutation | Observed Impact on pTyr Binding | Impact on Biological Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| v-Src | R175H | Reduced, but not eliminated | Compatible with wild-type transformation [23] |

| v-Src | R175K | Reduced, but not eliminated | Compatible with wild-type transformation [23] |

| v-Src | R175E | Disrupted SH2 structure; domain insoluble | Fusiform transformation; failed to transform Rat-2 cells [23] |

| Canonical SH2 Domains | R→A (βB5) | ~1,000-fold reduction in affinity | Not directly measured; predicted severe disruption [22] |

Table 2: Binding Affinity Comparison: Single vs. Tandem SH2 Domains

| SH2 Domain Configuration | Typical Affinity for Correct Ligand | Specificity (Fold over non-cognate ligand) |

|---|---|---|

| Single SH2 Domain | Variable (µM - nM range) | 20 - 50 fold [24] |

| Tandem SH2 Domains | 0.5 - 3.0 nM [24] | 1,000 - >10,000 fold [24] |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 1: Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) for Binding Affinity Measurement

Purpose: To directly measure the thermodynamic parameters (K(_d), ΔH, ΔS, stoichiometry) of the interaction between an SH2 domain and a phosphopeptide.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dialyze both the purified SH2 domain protein and the phosphopeptide into the same buffer (e.g., 20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4).

- Instrument Setup: Load the SH2 domain into the sample cell and the phosphopeptide into the syringe. Set the reference cell with dialysate.

- Titration: Program the instrument to perform a series of injections of the peptide into the protein solution while maintaining a constant temperature.

- Data Analysis: Integrate the heat pulses from each injection and fit the data to a suitable binding model (e.g., one-set-of-sites) to extract the binding parameters.

Protocol 2: Molecular Docking for Virtual Screening

Purpose: To computationally identify and prioritize small molecules that may inhibit the SH2 domain-phosphopeptide interaction.

Procedure:

- Structure Preparation: Obtain a 3D structure of the target SH2 domain from the PDB. Remove water molecules and add hydrogens. Define the binding pocket, often centered on the FLVR arginine.

- Ligand Library Preparation: Prepare a library of small molecule compounds in a suitable format (e.g., SDF, MOL2). Generate plausible 3D conformations.

- Docking Run: Use docking software (e.g., AutoDock Vina, Glide) to predict the binding pose and score of each compound in the library against the SH2 domain.

- Post-Processing: Analyze the top-ranking compounds visually to check for sensible interactions with the FLVR arginine and other key residues in the binding pocket.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for SH2 Domain Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SH2 Domain Constructs | Recombinant protein for biophysical and binding assays. | Available from cDNA libraries; often cloned with tags (GST, His) for purification. |

| Phosphotyrosine Peptides | Ligands for binding and specificity assays. | Synthesized to match known SH2 domain consensus sequences; contain phosphotyrosine. |

| Anti-pTyr Antibodies | Detection of tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins in pull-down/cell-based assays. | e.g., 4G10; crucial for validating SH2 domain interactions in a cellular context. |

| Virtual Screening Libraries | Source of compounds for inhibitor discovery. | e.g., Enamine REAL, Mcule-in-stock; can be filtered for SH2 domain-targeted compounds [10]. |

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow

Diagram 1: SH2 Domain Experimental Workflow

Diagram 2: High-Specificity Signaling via Tandem SH2 Domains

Advanced Computational Workflows: From Static Docking to Dynamic Screening Strategies

High-Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS) Pipelines for SH2-Targeted Libraries

FAQs: High-Throughput Virtual Screening for SH2 Domains

Q1: What makes SH2 domains particularly challenging targets for virtual screening?

SH2 domains are challenging due to their role in mediating protein-protein interactions (PPIs). Their binding surfaces are typically large, shallow, and solvent-exposed, lacking the deep, well-defined pockets characteristic of traditional drug targets like enzymes. This makes identifying high-affinity small molecules difficult [10]. Furthermore, achieving selectivity is a major hurdle because the human proteome contains approximately 110 different SH2 domains, all of which share a highly conserved structural fold centered on an arginine residue (in the FLVR motif) that binds the phosphotyrosine (pY) moiety [13].

Q2: My virtual screen yielded a large number of hits with promising docking scores, but experimental validation failed. What could be the reason?

This is a common issue often stemming from limitations in the docking scoring functions. Docking scores are approximations and may not accurately reflect true binding affinities, especially for the flat PPI interfaces of SH2 domains. To improve the reliability of your hit list, consider these strategies:

- Implement Rescoring Protocols: Use more computationally intensive but accurate methods like Molecular Mechanics with Generalized Born Surface Area (MM-GBSA) to rescore top-ranked docking hits. This provides a better estimation of binding free energy [1] [25].

- Incorporate Flexibility: Standard docking often uses a rigid protein structure. Using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to account for protein flexibility can help identify more physiologically relevant poses [1].

- Refine Your Initial Model: Ensure your starting SH2 domain structural model is of high quality. The performance of the entire screening pipeline is highly dependent on the underlying docking model's reliability [10].

Q3: What are the key structural features of an SH2 domain that I should focus on for screening and analysis?

The SH2 domain has a conserved "sandwich" structure (αA-βB-βC-βD-αB) with key specificity determinants. The binding pocket for phosphopeptides is divided into three main sub-pockets [1] [13]:

- pY+0 Pocket: Binds the phosphotyrosine (pY705 in STAT3) and contains a highly conserved arginine residue that forms a critical salt bridge with the phosphate group.

- pY+1 Pocket: Binds the residue immediately C-terminal to the phosphotyrosine (e.g., L706 in STAT3) and is a primary determinant of binding specificity.

- pY+X Pocket: A hydrophobic pocket that binds to more distal residues, providing additional specificity. Focusing on ligands that can effectively engage these sub-pockets, particularly the pY+0 and pY+1, will increase the chance of success.

Q4: Are AI-based methods like Deep Docking feasible for screening billion-compound libraries against SH2 domains?

Yes, AI-based ultrahigh-throughput virtual screening (uHTVS) has become a viable strategy. For example, the Deep Docking workflow can screen libraries of over 5 billion compounds by using a deep learning model to iteratively exclude molecules unlikely to be high-ranking, drastically reducing the number of compounds that require physics-based docking. This approach has successfully identified inhibitors for the STAT3 and STAT5b SH2 domains with exceptionally high hit rates (up to 50.0% for STAT3) [10]. However, its performance is contingent on the quality of the initial docking data used to train the AI model.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Enrichment in Retrospective Screening

Problem: During validation, your screening protocol fails to successfully enrich known active compounds from a set of decoys.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal protein structure | Check the resolution of the crystal structure (e.g., prefer 6NJS at 2.70 Å over 6NUQ at 3.15 Å for STAT3). Ensure there are no critical mutations in the binding site [1]. | Select a high-resolution structure without mutations in the SH2 domain. Use a structure co-crystallized with a high-affinity ligand if available. |

| Incorrect binding site definition | Redock the native co-crystallized ligand and calculate the Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD). An RMSD > 2.0 Å indicates poor reproducibility. | Carefully define the grid box centered on the known pharmacophore, ensuring it is large enough to allow ligand movement. The use of a receptor grid generation tool is recommended [1]. |

| Inadequate scoring function | Review the Area Under the Curve (AUC) and Enrichment Factors (EF) at 1% from your validation. Low values indicate poor scoring discrimination. | Switch to a more rigorous docking precision (e.g., from Standard Precision to Extra Precision) or implement a MM-GBSA rescoring step for the top hits [1] [25]. |

Issue 2: Computationally Identified Binders Show No Activity in Cellular Assays

Problem: Hits from your virtual screen confirm binding in vitro but are ineffective in cell-based models.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor cellular permeability | Analyze the physicochemical properties of the hit compounds (e.g., molecular weight, logP). Use tools like QikProp to predict ADME properties [1]. | Optimize the structure to reduce molecular weight and polar surface area. Consider prodrug strategies for phosphate-containing compounds. |

| Lack of target engagement in cells | Employ cellular techniques like Fluorescence Polarization (FP) or Microscale Thermophoresis (MST) to directly measure binding in a cellular lysate or live-cell context [26]. | Use cell-permeable versions of assays or switch to a phenotypic screening approach to first identify compounds with cellular activity. |

| Off-target effects or toxicity | Screen the hits against a panel of related SH2 domains to assess selectivity. Check for known toxicophores or pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) [10]. | Perform counter-screening and early ADMET profiling. Structurally optimize hits to improve selectivity for the target SH2 domain. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Cited Experiments

Protocol 1: Deep Docking for uHTVS against SH2 Domains

This protocol summarizes the AI-powered workflow for screening ultra-large libraries, as applied to the STAT3 SH2 domain [10].

1. Library Preparation:

- Obtain a synthetically accessible compound library, such as the Enamine REAL library (5.51 billion compounds) or the smaller Mcule-in-stock library (5.59 million compounds).

- Apply initial filtering to remove compounds with undesirable properties, such as Pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS).

2. Benchmark Docking and AI Training:

- Randomly select a subset of the library (e.g., 1-2%) and perform brute-force docking against the prepared SH2 domain structure.

- Use the docking scores from this subset to train a deep neural network (Deep Docking model). The model learns to predict docking scores based on chemical structure.

3. Iterative Screening:

- The trained AI model predicts scores for the entire library and excludes the worst-scoring compounds.

- A new, smaller subset of the remaining, high-predicted-score compounds is selected for actual docking.

- The new docking results are used to retrain and refine the AI model.

- This process repeats iteratively until a manageable number of top-ranking compounds (e.g., 100,000) have been physically docked, effectively screening billions of compounds at a fraction of the computational cost.

4. Hit Selection and Validation:

- Select the top-ranked compounds from the final docking for in vitro experimental validation.

Protocol 2: Multi-Stage Virtual Screening of Natural Product Libraries

This detailed protocol is adapted from a study screening natural compounds against the STAT3 SH2 domain [1].

1. Protein and Ligand Preparation:

- Protein Preparation: Retrieve the SH2 domain crystal structure (e.g., PDB: 6NJS). Use a protein preparation wizard to add hydrogens, fill in missing side chains, and minimize the structure using a force field like OPLS3e.

- Ligand Library Preparation: Download a library of natural compounds (e.g., ~182,455 compounds from ZINC15). Prepare the ligands using a tool like LigPrep to generate 3D structures, correct chirality, and set appropriate ionization states at pH 7.4 ± 0.5.

2. Grid Generation and Docking:

- Receptor Grid Generation: Generate a grid box for docking centered on the co-crystallized ligand's location in the SH2 domain pY pocket. The grid should be large enough to accommodate ligand movement (e.g., 20 Å cube).

- Hierarchical Docking:

- Step 1 - HTVS: Dock the entire prepared library using a High-Throughput Virtual Screening mode.

- Step 2 - SP: Take the top-scoring compounds from HTVS (e.g., ~30% of the library) and dock them using Standard Precision mode.

- Step 3 - XP: Take the top-scoring compounds from SP (e.g., with a score cut-off of -6.5 kcal/mol) and dock them using Extra Precision mode for the most accurate pose prediction and scoring.

3. Post-Docking Analysis:

- MM-GBSA Calculation: Subject the top-ranked protein-ligand complexes from XP docking to MM-GBSA analysis to calculate the binding free energy (ΔG Binding). This uses the OPLS3e force field and a VSGB solvation model.

- ADME Prediction: Use a tool like QikProp to analyze the pharmacokinetic properties of the potential hit compounds.

4. Advanced Simulation (For Finalist Hits):

- Perform molecular dynamics (MD) simulations (e.g., 100 ns) on the top 2-3 complexes to evaluate stability and binding interactions over time.

- Complementary analyses like WaterMap can be used to gain insights into the role of water molecules in the binding site.

Visualized Workflows and Signaling Pathways

SH2 Domain-Mediated STAT3 Signaling and Dimerization

Hierarchical Virtual Screening Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and resources used in advanced virtual screening campaigns against SH2 domains.

| Resource Name | Function / Application in SH2 Screening | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Enamine REAL Library [10] | Ultra-large library for uHTVS; contains billions of synthetically accessible compounds. | Ideal for AI-driven workflows like Deep Docking; ensures identified hits can be synthesized. |

| ZINC15 Database [1] | Public database of commercially available compounds, including natural products. | Contains a curated subset of natural products; useful for knowledge-based screening approaches. |

| OTAVAchemicals SH2 Targeted Library [10] | Focused library of drug-like compounds designed with pharmacophores for SH2 domains. | A knowledge-based approach to screening; smaller size allows for brute-force docking. |

| PDB Structures 6NJS & 6NUQ [1] | High-resolution crystal structures of the STAT3 SH2 domain, often used for docking. | 6NJS is preferred due to its higher resolution (2.70 Å) and lack of mutations in the SH2 domain. |

| Schrödinger Suite (Maestro) [1] | Integrated software for structure preparation (Protein Prep Wizard), docking (GLIDE), and simulation (Desmond). | Provides a complete workflow from preparation to MD simulation and free energy calculations (MM-GBSA). |

| Web-Accessible Servers (e.g., pepATTRACT) [27] | In silico tools for blind docking of peptide sequences to a target protein. | Useful for identifying peptide-based inhibitors that target the extensive PPI interface of SH2 domains. |

Harnessing Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations to Model Domain Flexibility and Create 'Induced-Active Site' Models

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My virtual screening results are poor when I use a single, rigid SH2 domain structure. My target is known to have significant flexibility. What strategies can I use? The poor results are likely because a rigid receptor cannot model the ligand-induced structural changes (induced fit) crucial for binding. You should employ strategies that account for this flexibility.

- Solution: Leverage multiple receptor structures if available. Using all available receptor/ligand co-crystals as templates for docking ("close" methods) has been shown to yield the most accurate pose predictions for flexible targets like HSP90. If multiple structures are not available, use a single holo-receptor structure and employ a "min-cross" method, where compounds are aligned to similar known ligands and minimized against the receptor [28].

- Protocol: The "Align-Close" Method

- Conformer Generation: Generate multiple conformers for each compound in your test set using a tool like Omega2 [28].

- Identify Closest Ligand: Using chemical similarity (e.g., with Babel FP3 fingerprint), identify the most similar compound among your known bound ligands [28].

- Structural Alignment: Align the generated conformers to the structure of the identified "closest" compound [28].

- Minimization: Minimize the aligned conformers into the receptor structure that was co-crystallized with the "closest" ligand using a docking tool like Smina [28].

- Scoring: Use the best predicted score (e.g., Vina score) to predict affinity [28].

Q2: How can I determine if my MD simulation has sampled enough conformational space to create a representative structural ensemble? Adequate sampling is critical for generating meaningful 'induced-active site' models. You can validate this using quantitative metrics.

- Solution: Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on your combined MD trajectories. Project all trajectories onto the first two principal components and check if independent simulations (e.g., starting from different conformations) sample a broad and overlapping region of this essential subspace. Multiple short simulations from different starting points often sample a broader region than a single long simulation [29]. Additionally, use the Ensemble Optimization Method (EOM) to select a sub-ensemble from your MD pool and check if it reproduces experimental data, such as Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS) profiles [29].

- Protocol: PCA and Ensemble Validation

- Feature Extraction: From your MD trajectory frames, calculate a feature matrix, such as all Cα-Cα distances within the protein [30].

- Dimensionality Reduction: Perform PCA on this feature matrix to reduce the data to its most significant components (e.g., the first 3 principal components that explain 80% of variance) [30].

- Clustering Analysis: Use clustering methods (e.g., Gaussian Mixture Models) on the reduced data to identify the major conformational states sampled [30].

- Experimental Validation: Use EOM or a similar method to select a weighted ensemble of structures from your MD-derived pool that best fits an experimental SAXS profile. A good fit (low χ value) indicates your simulation has sampled biologically relevant states [29].

Q3: I am studying a multi-domain protein with an SH2 domain. How can I use MD simulations and experimental data to determine its dynamic structural ensemble? Combining MD with low-resolution experimental data is a powerful approach for studying flexible multi-domain proteins.

- Solution: Integrate MD simulations with SAXS data. Generate a large pool of conformations via MD simulations, then use an algorithm to select a minimal ensemble that best fits the experimental SAXS curve [29].

- Protocol: SAXS-Restrained Ensemble Generation

- MD Sampling: Run multiple MD simulations (e.g., several µs in total), starting from different conformations if available, to explore the domain orientations [29].

- Create a Structural Pool: Combine frames from all trajectories to create a diverse pool of possible conformations [29].

- Ensemble Selection: Use the Ensemble Optimization Method (EOM) to select a group of structures from the pool whose averaged theoretical SAXS profile minimizes the discrepancy (χ) with the experimental SAXS data [29].

- Analysis: Analyze the selected ensemble for properties like the distribution of radii of gyration (Rg) and dominant domain orientations [29].

Q4: How can I quantitatively predict the impact of a phosphopeptide sequence variation on SH2 domain binding affinity? Beyond qualitative motifs, you can build quantitative sequence-to-affinity models.

- Solution: Use high-throughput experimental binding data from peptide display libraries coupled with next-generation sequencing (NGS) to train a biophysical model. The ProBound method, for example, can perform free-energy regression on such data to learn an additive model that predicts the binding free energy (∆∆G) for any peptide sequence within the theoretical space [31].

- Protocol: Building a Sequence-to-Affinity Model

- Library Selection: Use bacterial display of a highly degenerate random phosphopeptide library [31].

- Affinity Selection: Perform multi-round affinity selection against the SH2 domain of interest [31].

- Sequencing: Subject the input and selected pools to NGS [31].

- Model Training: Use the ProBound framework to analyze the NGS data and train a model that predicts relative binding affinity (∆∆G) across the full sequence space [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inadequate Conformational Sampling in MD Simulations

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High RMSD in domain orientations that does not plateau [29]. | Simulation time is too short to overcome energy barriers. | Perform multiple independent simulations starting from different initial conformations (e.g., "open" and "closed" states) [29] [30]. |

| PCA shows that trajectories from different starting points occupy non-overlapping regions [29]. | Insufficient sampling of transitions between states. | Combine many shorter simulations from diverse starting points rather than relying on a single long trajectory [29]. |

| The simulated ensemble fails to fit experimental SAXS or NMR data [29]. | The simulation is trapped in a non-native conformational basin. | Use enhanced sampling techniques or explicitly bias the simulation using experimental restraints. |

Problem 2: Poor Pose Prediction in Virtual Screening of Flexible SH2 Domains

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Docked ligand poses have high Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) from crystallographic poses [28]. | Using a single, rigid receptor structure that cannot accommodate induced-fit changes [28]. | Use a "close" method: dock into the receptor structure that co-crystallized with the most chemically similar ligand you know of [28]. |

| Inability to rank-order compounds by binding affinity correctly [28]. | Scoring function cannot account for the energetic cost of receptor flexibility and conformational selection. | For affinity ranking, test a "cross" method: dock all compounds to a single, carefully selected holo-receptor structure. The optimal structure can be chosen based on its performance on a training set with known affinities [28]. |

| General poor performance in virtual screening benchmarks. | Use of a default docking protocol not optimized for flexible targets. | Employ a docking method that incorporates explicit receptor flexibility, such as RosettaVS, which allows for side-chain and limited backbone movement during docking [32]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Tools

Table: Key Resources for Modeling SH2 Domain Flexibility

| Item | Function/Description | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Smina [28] | A version of AutoDock Vina optimized for high-throughput scoring and minimization. | Fast minimization of aligned ligand conformers into a fixed receptor during virtual screening workflows [28]. |

| RosettaVS [32] | A physics-based virtual screening protocol within the Rosetta framework that allows for receptor flexibility. | Accurate pose prediction and affinity ranking for targets requiring induced-fit modeling [32]. |

| FoldX [33] | An empirical force field for quick in silico mutagenesis and energy calculations. | Predicting the change in binding free energy (∆∆G) upon mutation in SH2-phosphopeptide complexes [33]. |

| ProBound [31] | A statistical learning method for building quantitative sequence-to-affinity models from NGS data. | Predicting the binding free energy of any phosphopeptide sequence for a profiled SH2 domain [31]. |

| Ensemble Optimization Method (EOM) [29] | An algorithm for selecting a structural ensemble from a large pool that best fits a SAXS profile. | Determining representative conformational ensembles of flexible multi-domain proteins from MD trajectories and SAXS data [29]. |

| Random Phosphopeptide Library [31] | A genetically encoded library of random peptides for bacterial display, which can be enzymatically phosphorylated. | Experimentally profiling the binding specificity and affinity of SH2 domains on a large scale [31]. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Diagram 1: MD-Driven Induced-Active Site Modeling Workflow

Diagram 2: SH2 Domain Allostery and Activation Signaling

Integrating Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) and MM-GBSA for Accurate Binding Affinity Prediction

Quantitative Method Comparison

The table below summarizes the performance and resource requirements of FEP and MM-GBSA based on benchmarking studies.

| Method | Ranking Correlation (rₛ) | Computational Cost | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) | 0.854 (PLK1 study) [35] | Very High (~60 ns/perturbation in PLK1 study) [35] | Lead optimization for congeneric series; ultimate accuracy [35] [36] |

| MM-GBSA | 0.767 (PLK1 study) [35] | Lower (~1/8th the time of FEP in PLK1 study) [35] | Post-docking refinement; screening large virtual libraries [35] [1] |

| QM/MM-GBSA | Can improve upon standard MM-GBSA [35] | Moderate (higher than MM-GBSA) [35] | Systems where ligand electronic effects are critical [35] |

| Docking Scores | Variable (R² ≥ 0.5 in one of three KLK6 datasets) [36] | Very Low | Initial high-throughput virtual screening [35] [1] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I use FEP over MM-GBSA in my SH2 domain project? Use FEP during the lead optimization stage when you have a congeneric series of compounds and need the highest possible accuracy for predicting relative binding affinities. For earlier stages, such as post-docking refinement of a large virtual screen against the STAT3 SH2 domain, MM-GBSA provides a good balance of accuracy and speed [35] [1] [36].

Q2: My MM-GBSA results are inconsistent. What are the key parameters to optimize? The performance of MM-GBSA is highly sensitive to several factors. Key parameters to optimize include [35]:

- Sampling Method: Single long molecular dynamics (SLMD) may outperform multiple short trajectories (MSMD) for some systems [35].

- Implicit Solvent Model: The

igbparameter in AMBER (e.g.,igb5). - Ligand Treatment: Using QM-treated ligands (QM/MM-GBSA) can significantly improve ranking performance [35].

- Simulation Length: Ensure the simulation is long enough for convergence.

Q3: Can FEP and MM-GBSA be used to study the effect of mutations on binding affinity? Yes, both methods are excellent for this. A study on the guanine riboswitch successfully integrated FEP, MM-GBSA, and MD simulations to probe the effect of mutations on ligand binding, showing that both methods can achieve an excellent correlation in predicting the associated changes in binding free energy [37].

Q4: What are the minimum simulation times required for reliable MM-GBSA? While there is no universal rule, one study on PLK1 found that a protocol using "single long molecular dynamics" outperformed "multiple short molecular dynamics" for MM-GBSA [35]. The total simulation time required will depend on the specific system, and convergence should always be checked.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Correlation Between Predicted and Experimental Binding Affinities

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inadequate Sampling.

- Cause: Incorrect Protonation States or Tautomers.

- Solution: Carefully check the protonation states of key residues in the SH2 domain's binding pocket (e.g., Arg609, Glu594) and the ligand at the relevant pH (e.g., 7.4) using tools like the Protein Preparation Wizard in Maestro [1].

- Cause: Sub-Force Field for the Ligand.

Issue 2: FEP Calculations Fail or Produce High-Energy Errors

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Overlapping Atomistic Topologies.

- Solution: Carefully design the transformation map (morphs) to avoid large, non-physical perturbations. Ensure a reasonable structural and electrostatic difference between the perturbed ligands.

- Cause: Inefficient Sampling at a Specific Lambda Window.

- Solution: Increase the simulation time for the problematic window or use enhanced sampling techniques like Hamiltonian Replica Exchange (HREX) or the REST2 (Replica Exchange with Solute Tempering) method [35].

Issue 3: MM-GBSA Values are Unphysically High or Low

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Unstable Molecular Dynamics Trajectory.

- Solution: Re-examine the equilibration protocol. Ensure the system is properly minimized and gently heated before the production run. Check for stable temperature and pressure during the simulation [37].

- Cause: Poor Selection of the Internal Dielectric Constant.

- Solution: The internal dielectric constant (

intdiel) is a critical parameter. While a value of 1 is common, for protein interiors, a value between 2 and 4 is sometimes used. Systematically test different values to see which best correlates with experimental data.

- Solution: The internal dielectric constant (

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: MM-GBSA Workflow for SH2 Domain Inhibitors

This protocol is adapted from studies on the STAT3 SH2 domain and other kinase targets [35] [1].

System Preparation:

- Protein: Obtain the SH2 domain structure (e.g., PDB ID: 6NJS). Prepare it using a tool like the Protein Preparation Wizard (Schrödinger), which adds hydrogens, fills missing side chains, and minimizes the structure using a force field like OPLS3e [1].

- Ligand: Prepare the 3D structures of small molecules, generating possible states at pH 7.4 ± 0.5 using a tool like LigPrep (Schrödinger) [1].

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation:

- Solvation: Solvate the protein-ligand complex in an orthorhombic water box (e.g., TIP3P model) with a buffer distance of at least 10 Å.

- Neutralization: Add counterions (e.g., Na⁺/Cl⁻) to neutralize the system.

- Equilibration: Minimize the energy, then heat the system to 300 K under constant volume (NVT), followed by equilibration at constant pressure (NPT).

- Production Run: Run an unrestrained MD simulation for a sufficient duration (e.g., 100 ns or more). Use a 2 fs time step and apply constraints to bonds involving hydrogen atoms. Use the PME method for long-range electrostatics [37].

MM-GBSA Calculation:

- Trajectory Snapshot Extraction: Extract snapshots from the stable portion of the MD trajectory at regular intervals (e.g., every 100 ps).

- Free Energy Calculation: Use a tool like the

MMPBSA.pyscript from AMBER or the Prime MM-GBSA module (Schrödinger) to calculate the binding free energy for each snapshot with the following equation [1]:ΔG_bind = G_complex - (G_receptor + G_ligand)WhereGis estimated asG = E_MM + G_sol - TS, withE_MMbeing the molecular mechanics gas-phase energy,G_solthe solvation free energy, andTSthe entropy term. - Averaging: Average the ΔG_bind values from all snapshots to obtain the final predicted binding free energy.

Protocol 2: FEP Setup and Execution for a Congeneric Series

This protocol is based on FEP applications in PLK1 and KLK6 inhibitor studies [35] [36].

Ligand Preparation and Perturbation Map:

- Design a perturbation map that connects all ligands in the congeneric series through a set of alchemical transformations. The map should be a cycle or hub-and-spoke model to maximize efficiency and allow for consistency checks.

Initial Structure Generation:

- For each ligand, generate a high-quality binding pose, typically through molecular docking followed by MD equilibration. Consistent binding modes are critical.

FEP Simulation Parameters:

- Lambda Windows: Use 12-16 lambda windows for each transformation to smoothly couple/decouple the ligands.

- Simulation Length: Run each lambda window for at least 5 ns, leading to a total of 60+ ns per perturbation [35].

- Enhanced Sampling: Employ an enhanced sampling method such as REST2 to improve sampling efficiency [35].

Analysis and Validation:

- Calculate the relative free energy change (ΔΔG) for each transformation.

- Check for hysteresis between forward and backward perturbations.

- Validate the predictions against a set of known experimental activities to ensure correlation.

Signaling Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

SH2 Domain STAT3 Activation Pathway

FEP/MM-GBSA Integration Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

| Category | Item / Software | Function / Description | Example Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics | AMBER (ff14SB, ff19SB), GROMACS, Desmond | Engine for running MD and FEP simulations to sample conformations. | Simulating the binding of a candidate drug to the STAT3 SH2 domain [1] [37] [36]. |

| Free Energy Calculations | FEP+ (Schrödinger), AMBER FEP, GROMACS | Calculates relative binding free energies (ΔΔG) with high accuracy. | Predicting the affinity of a new analog in a congeneric series of PLK1 inhibitors [35] [36]. |

| End-State Methods | MMPBSA.py (AMBER), Prime MM-GBSA (Schrödinger) | Calculates absolute binding free energies (ΔG) from MD snapshots. | Ranking a library of natural compounds docked against the STAT3 SH2 domain [1]. |

| Force Fields | OPLS3e, OPLS4, ff19SB, GAFF2 | Defines potential energy functions for proteins, nucleic acids, and ligands. | Parameterizing a novel small molecule inhibitor for simulation [1] [37]. |

| Solvent Models | TIP3P, SPC, GBSA (igb=5, igb=8), PBSA | Explicit water model or implicit solvent for solvation free energy calculation. | Solvating the SH2 domain system and calculating the polar solvation contribution in MM-GBSA [35] [37]. |

| Quantum Mechanics | Gaussian, QM/MM-GBSA | Provides accurate electronic structure calculations for ligands or specific residues. | Improving the treatment of metal ions or charged ligands in the binding pocket [35]. |

Leveraging AI-Based Structure Prediction with AlphaFold for Mutant and Unresolved Structures

Troubleshooting Guide: Core Issues and Solutions

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when using AlphaFold for modeling SH2 domains and similar structures for virtual screening.

Problem 1: Low Confidence Predictions in Flexible Regions

Symptoms: Your model shows regions with low pLDDT scores (typically <70), appearing as unstructured loops or filaments. This is common in linkers, disordered regions, and loops [38] [39].

Solutions:

- Cross-reference with experimental data: Integrate sparse NMR data or SAXS profiles to constrain flexible regions [38] [40].

- Use confidence metrics strategically: Focus drug design efforts on high-confidence regions (pLDDT > 70) and avoid building hypotheses around low-confidence areas [39].

- Generate multiple models: Run predictions with different MSA depths or recycling counts to sample conformational variability [40].

Problem 2: Inaccurate Domain Placement in Multi-Domain Proteins

Symptoms: The relative orientation of protein domains appears incorrect compared to known biological complexes or creates steric clashes [39].

Solutions:

- Check Predicted Aligned Error (PAE): Always consult the PAE plot alongside pLDDT. High inter-domain PAE values (>5 Å) indicate low confidence in relative domain placement [38] [39].

- Model domains individually: For virtual screening against specific domains, consider isolating high-confidence domains and modeling them separately.

- Use template-based refinement: If experimental structures of homologous complexes exist, use them as templates in AlphaFold3 or for subsequent refinement [41] [40].

Problem 3: Modeling Mutations and Their Structural Impact

Symptoms: You need to understand how a point mutation affects SH2 domain structure, but direct mutation prediction is challenging.

Solutions:

- Leverage generic numbering systems: Use SH2 domain-specific resources like SH2db that employ generic numbering to compare equivalent positions across different SH2 domains [42].

- Structural superposition: Superimpose your mutant model on wild-type structures using conserved core elements (e.g., β-strands bB, bC, bD for SH2 domains) to highlight structural deviations [42].

- Context-aware analysis: Consider if the mutation occurs in conserved structural elements (e.g., FLVR binding pocket) versus variable regions [42].

Problem 4: Handling Large Proteins and Length Limitations

Symptoms: Your target protein exceeds 2,700 residues, and no full-length model is available in the AlphaFold database [39].

Solutions:

- Use overlapping fragments: Download and analyze overlapping fragments available for large proteins in the AlphaFold database [39].

- Domain-based modeling: Identify and model individual domains separately, then assemble using experimental constraints.

- Check alternative resources: Some servers and implementations may handle longer sequences than the public database.

Problem 5: Integrating AI Predictions with Experimental Data

Symptoms: Your AlphaFold model conflicts with experimental data, or you need to validate predictions for drug discovery applications.

Solutions:

- Derive distance restraints: Convert high-confidence regions of AlphaFold predictions into distance restraints for NMR structure determination [40].

- Use competitive docking: Implement pairwise competitive docking strategies that directly compare compound binding to rank drug candidates [43].

- Multi-method validation: Cross-validate predictions with complementary methods like cryo-EM, X-ray crystallography, or biochemical data [38].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General AlphaFold Application

Q: What coverage can I expect for the human proteome, specifically for SH2 domains? A: The AlphaFold database covers 98.5% of the human proteome at the protein level, but only 58% of residues are modeled with high confidence (pLDDT > 70) [39]. SH2 domains, being well-structured, typically fall in the high-confidence category, but inter-domain linkers and flexible loops may have lower confidence.

Q: How reliable are AlphaFold models for virtual screening? A: High-confidence regions (pLDDT > 70) can be reliable for binding site identification, but always verify with these steps:

- Check for conservation of known functional residues

- Compare with any available experimental structures

- Assess pocket physicochemical properties for plausibility [39] [32]

Q: Can AlphaFold predict structures with bound ligands or post-translational modifications? A: AlphaFold3 can model some protein-ligand complexes and modifications, but performance varies. The model may generate apo structures even when trained on holo structures [38] [41]. For critical drug discovery applications, experimental validation or MD simulations are recommended.

Technical Implementation

Q: What are the computational requirements for running AlphaFold locally? A: Local installation requires significant resources: up to 3 TB disk space and modern NVIDIA GPUs with substantial memory. Cloud-based options like ColabFold or the AlphaFold Server reduce these barriers [38] [40].

Q: How do I choose between AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold3? A: Consider your specific needs:

Table: AlphaFold2 vs. AlphaFold3 Comparison

| Feature | AlphaFold2 | AlphaFold3 |

|---|---|---|

| Input Types | Proteins only | Proteins, DNA, RNA, ligands, ions |

| License | Apache 2.0 (commercial use allowed) | CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 (non-commercial only) |

| Availability | Full open source | Restricted model parameters |

| Best For | Academic/commercial protein prediction | Academic non-commercial complexes |

Q: What do the confidence scores (pLDDT and PAE) actually mean? A:

- pLDDT (0-100): Per-residue confidence estimate. >90: very high, 70-90: confident, 50-70: low, <50: very low (often disordered) [38].

- PAE (Å): Estimates positional error between residues. Lower values indicate more confident relative placement [38].

SH2 Domain-Specific Questions

Q: How can I quickly compare structures across different SH2 domains? A: Use SH2db, which provides:

- Pre-aligned structural files ready for PyMOL

- Generic numbering system for equivalent positions

- Phylogenetic and sequence analysis tools [42]

Q: What are the most reliable structural elements in SH2 domains for superposition? A: The core β-strands (bB, bC, bD) provide the most reliable framework for structural comparison, as other segments are more flexible [42].

Q: How can I assess the functional impact of SH2 domain mutations using AlphaFold? A:

- Identify the mutation's position in the generic numbering system

- Check if it occurs in conserved binding or structural motifs

- Compare with known functional mutations in the SH2db

- Assess structural perturbations in the binding interface [42]

AlphaFold Confidence Score Interpretation

Table: Guide to Interpreting AlphaFold Confidence Metrics

| pLDDT Range | Confidence Level | Interpretation | Recommended Use in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| 90-100 | Very high | High accuracy backbone and side chains | Suitable for binding site identification and docking |

| 70-90 | Confident | Generally reliable backbone | Useful for binding pocket analysis |

| 50-70 | Low | Caution advised, potentially flexible | Use with experimental validation |

| 0-50 | Very low | Likely disordered | Avoid for structure-based design |

Experimental Protocol: Deriving Distance Restraints from AlphaFold for NMR Structure Determination

This protocol enables integration of AlphaFold predictions with experimental NMR data, particularly valuable for validating SH2 domain models [40].

Step-by-Step Methodology

Generate and Evaluate AlphaFold Predictions

- Input target sequence in FASTA format to AlphaFold2 or AlphaFold3

- Assess model quality using pLDDT and PAE metrics

- Select models with high confidence (pLDDT > 70) in regions of interest

Install Required Software and Plugins

- Install PyMOL (v3.0+) or ChimeraX (v1.9.1+)

- Download and install the 'atom_distances' plugin for your visualization software

- Ensure Python 3 compatibility

Visualize and Generate Distance Restraints

- Load high-confidence AlphaFold structure (.pdb or .cif format)

- Run the atom_distances plugin to identify reliable atom-atom distances

- Focus on Cα-Cα distances for backbone validation

- Generate distance restraint files compatible with NMR structure calculation software (CYANA/CNS/XPLOR)

Integrate with Experimental NMR Data

- Use AlphaFold-derived restraints to guide NOE assignment

- Combine with experimentally collected NOEs, chemical shifts, and torsion angles

- Calculate structural ensembles using hybrid experimental-computational restraints

Workflow Visualization

Table: Key Resources for AlphaFold-Based Structural Biology

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Database | Pre-computed structures for common proteins | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/ |

| ColabFold | Cloud Tool | Simplified AlphaFold2 with adjustable parameters | https://colabfold.mmseqs.com |

| AlphaFold Server | Cloud Tool | AlphaFold3 for multi-molecule complexes | https://alphafoldserver.com |

| SH2db | Specialized Database | Curated SH2 domain structures and alignments | http://sh2db.ttk.hu |

| PyMOL with AF Plugins | Visualization | Molecular viewing with AlphaFold-specific tools | https://pymol.org/ |

| ChimeraX | Visualization | Alternative with AlphaFold integration | https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimerax/ |

| RosettaVS | Docking Platform | Structure-based virtual screening | Open-source platform |

| NMRBox | Virtual Environment | Pre-configured AlphaFold2 installation | https://nmrbox.org |

Pharmacophore Modeling and Focused Library Design for SH2 Domains

Core Concepts and Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary functional role of an SH2 domain, and why is it a valuable drug target? SH2 (Src Homology 2) domains are protein modules approximately 100 amino acids long that specifically recognize and bind to tyrosine-phosphorylated peptide sequences on target proteins [44] [13]. They are critical mediators of intracellular protein-protein interactions, facilitating the assembly of signaling complexes in pathways that regulate cell growth, differentiation, migration, and apoptosis [44] [13]. Because aberrant SH2 domain activity is linked to cancers, autoimmune disorders, and inflammatory conditions, targeting them presents a strategic opportunity for therapeutic intervention to restore normal signaling dynamics [44] [13].

FAQ 2: What is the fundamental structural basis for phosphopeptide recognition by SH2 domains? All SH2 domains share a conserved fold: a central anti-parallel beta sheet flanked on either side by two alpha helices [45] [13]. This structure creates two key binding pockets [45]: