Optimizing Protein Recovery from Native PAGE: A Guide to Maximizing Yield and Downstream Applications

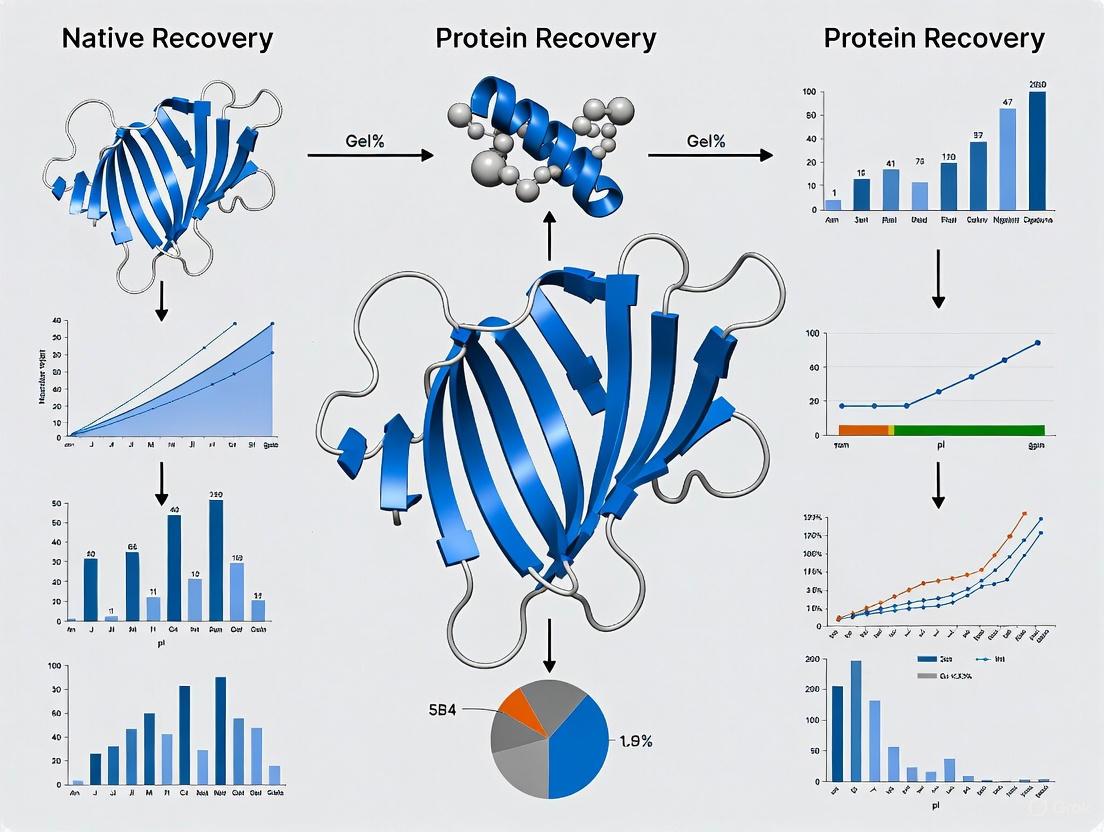

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing protein recovery from native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE).

Optimizing Protein Recovery from Native PAGE: A Guide to Maximizing Yield and Downstream Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing protein recovery from native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). It covers the fundamental principles of preserving native protein complexes during electrophoresis, details advanced methodological approaches for efficient extraction, and offers robust troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls. Furthermore, it outlines validation techniques to ensure the integrity of recovered proteins for sensitive downstream applications, including native mass spectrometry and functional enzymatic assays. The protocols and recommendations are designed to help scientists maximize protein yield and maintain biological activity, thereby enhancing the reliability of structural and functional studies.

Understanding Native PAGE and Its Critical Role in Protein Complex Analysis

Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Native PAGE) is a fundamental technique in biochemical research that enables the separation of proteins under non-denaturing conditions. Unlike its denaturing counterpart, SDS-PAGE, Native PAGE preserves protein complexes in their native state, maintaining their quaternary structure, biological activity, and protein-protein interactions. This technical support center provides comprehensive guidance for researchers working with Native PAGE methodologies, with particular emphasis on optimizing protein recovery for downstream applications. The following sections address common experimental challenges and provide detailed protocols to ensure successful implementation of these powerful techniques.

Core Principles and FAQs

What is the fundamental difference between Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE? Native PAGE separates proteins based on their intrinsic charge, size, and shape while maintaining the protein's native conformation and biological activity. In contrast, SDS-PAGE denatures proteins with sodium dodecyl sulfate, disrupting non-covalent interactions and masking the protein's intrinsic charge, resulting in separation primarily by molecular weight [1].

Why is Native PAGE particularly valuable for studying mitochondrial complexes? Native PAGE, especially Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE), is ideal for studying mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) complexes because it preserves the integrity of these multi-subunit membrane protein assemblies. This allows researchers to analyze intact complexes, their assembly pathways, and even higher-order supercomplexes known as respirasomes [2] [3].

What are the main variants of Native PAGE? The two primary variants are Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE), which uses Coomassie Blue G-250 to impart charge to proteins, and Clear Native PAGE (CN-PAGE), which uses mixtures of anionic and neutral detergents instead of the blue dye. CN-PAGE is particularly advantageous for downstream in-gel enzyme activity staining due to the absence of dye interference [2] [3].

How can I optimize my sample preparation for Native PAGE? For BN-PAGE, it is recommended to isolate mitochondria from cells before analysis. A standard protocol involves resuspending 0.4 mg of sedimented mitochondria in 40 μL of 0.75 M aminocaproic acid, 50 mM Bis-Tris (pH 7.0), followed by addition of 7.5 μL of 10% n-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside for solubilization. After incubation on ice and centrifugation, the supernatant is mixed with Coomassie Blue G dye prior to loading [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Native PAGE Issues

The table below summarizes frequent problems encountered during Native PAGE experiments, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

| Problem Observed | Potential Causes | Troubleshooting Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Smeared bands | Voltage too high, sample degradation, improper buffer preparation | Run gel at lower voltage (10-15 V/cm); ensure proper sample preparation and buffer formulation [4]. |

| Poor band resolution | Insufficient run time, incorrect gel concentration, improper buffer ions | Run gel until dye front reaches bottom; optimize acrylamide percentage; ensure proper running buffer ion concentration [4]. |

| "Smiling" bands (curved bands) | Excessive heat generation during electrophoresis | Run gel in cold room or with ice packs; use lower voltage for longer duration [4]. |

| Distorted bands in peripheral lanes | Edge effect from empty wells | Load all wells with samples, ladder, or control proteins; avoid leaving wells empty [4]. |

| Protein samples migrating out of wells before run | Delay between loading and starting electrophoresis | Minimize time between sample loading and applying current; start electrophoresis immediately after loading [4]. |

| Faint or no bands | Low protein quantity, sample degradation, over-run gel | Load minimum 0.1–0.2 μg protein per mm well width; prevent nuclease/protease contamination; monitor run time to prevent samples running off gel [5]. |

| Unusually fast migration | Running buffer too diluted, very high voltage | Prepare running buffer with proper salt concentration; run gel at standard voltage (~150V for BN-PAGE) [4] [1]. |

Essential Protocols for Native PAGE

Sample Preparation for BN-PAGE

- Mitochondrial Isolation: Isolate mitochondria from cells or tissues using standard differential centrifugation methods.

- Solubilization: Resuspend 0.4 mg of mitochondrial pellet in 40 μL of buffer containing 0.75 M 6-aminocaproic acid and 50 mM Bis-Tris (pH 7.0). Add 7.5 μL of 10% n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (lauryl maltoside) [1].

- Incubation: Mix and incubate on ice for 30 minutes to allow complete solubilization of membrane protein complexes.

- Clarification: Centrifuge at high speed (72,000 x g recommended, but 16,000 x g may suffice) for 30 minutes to remove insoluble material [1].

- Dye Addition: Collect supernatant and add Coomassie Blue G dye (2.5 μL of 5% solution) to the solubilized protein extract [1].

Gel Casting and Electrophoresis

- Gel Preparation: While single-concentration gels can be used, linear gradient gels (e.g., 6-13% acrylamide) provide superior resolution for complexes of varying sizes [1]. Use a gradient maker for pouring gradient gels.

- Recipe Example: For a 6-13% gradient gel, prepare 38 mL of 6% acrylamide solution (7.6 mL 30% acrylamide, 19 mL 1 M aminocaproic acid, 1.9 mL 1 M Bis-Tris, 200 μL 10% APS, 20 μL TEMED) and 32 mL of 13% acrylamide solution (14 mL 30% acrylamide, 16 mL 1 M aminocaproic acid, 1.6 mL 1 M Bis-Tris, 200 μL 10% APS, 20 μL TEMED) [1].

- Electrophoresis Conditions: Load 5-20 μL of prepared samples into wells. Run the gel at constant voltage (approximately 150V for BN-PAGE) for about 2 hours or until the dye front approaches the bottom of the gel [1].

- Buffer Systems: Use appropriate anode and cathode buffers as specified in BN-PAGE protocols [1].

Two-Dimensional BN/SDS-PAGE

- First Dimension: Complete BN-PAGE as described above.

- Gel Lane Excision: Carefully cut out individual lanes from the first-dimension native gel.

- Denaturation: Soak the gel strip in SDS-PAGE denaturing buffer (containing SDS and dithiothreitol) to denature the protein complexes.

- Second Dimension: Place the gel strip horizontally on top of an SDS-PAGE gel (e.g., 10-20% acrylamide gradient) and run the second dimension to separate the individual subunits of each complex [1].

Experimental Workflow and Troubleshooting Logic

Native PAGE Workflow and Troubleshooting

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below outlines essential reagents and materials required for successful Native PAGE experiments, based on established protocols.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Native PAGE | Specific Examples and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Mild Detergents | Solubilize membrane proteins while preserving native complexes | n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) for individual complexes; Digitonin for respiratory supercomplexes [2] [1]. |

| Charge-Shift Reagents | Impart negative charge to proteins for electrophoretic migration | Coomassie Blue G-250 (BN-PAGE); Mixed anionic/neutral detergents (CN-PAGE) [2] [3]. |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevent protein degradation during sample preparation | PMSF, leupeptin, pepstatin A added to extraction buffers [1]. |

| Aminocaproic Acid | Zwitterionic salt that supports protein extraction and stability | 6-Aminocaproic acid (0.75 M) in extraction buffers helps maintain protein integrity [1]. |

| Gel Components | Matrix for electrophoretic separation | Acrylamide/bis-acrylamide (37.5:1), Bis-Tris buffers (pH 7.0), APS, TEMED [1]. |

| Specialized Equipment | For optimal gel casting and separation | Gradient mixer, peristaltic pump, vertical electrophoresis systems (e.g., BioRad Mini-PROTEAN) [6] [1]. |

Advanced Applications and Considerations

Native PAGE techniques, particularly BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE, enable sophisticated analyses of protein complexes beyond simple separation. These include in-gel activity staining to assess the enzymatic function of resolved complexes, which is invaluable for studying mitochondrial disorders and metabolic diseases [2] [3]. When optimizing protein recovery from native gels for downstream applications, consider the trade-offs between BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE: while BN-PAGE typically provides superior resolution, CN-PAGE eliminates potential interference from Coomassie dye in functional assays [2] [3]. For immunodetection, PVDF membranes are recommended over nitrocellulose for better protein retention during western blotting after Native PAGE [1].

Electrophoresis is a fundamental technique in biochemical research for separating macromolecules based on their size, charge, or conformation. Within protein analysis, native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) methods preserve protein complexes in their functional states, providing critical insights that denaturing methods cannot offer. This technical support center focuses on two powerful native electrophoresis techniques—Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) and Colorless Native PAGE (CN-PAGE)—and contrasts them with high-resolution agarose gels, which are primarily used for nucleic acid separation but provide useful comparisons for understanding electrophoretic principles.

BN-PAGE is characterized by its use of the anionic dye Coomassie Blue G-250, which binds to protein complexes and confers negative charge without causing significant denaturation [7]. This technique is particularly valuable for studying membrane protein complexes, mitochondrial respiratory chains, and protein-protein interactions. CN-PAGE represents a milder alternative that relies on the intrinsic charge of proteins for separation, making it suitable for delicate protein complexes that might be disrupted by dye binding [8]. High-resolution agarose gels, while predominantly applied to nucleic acid separation, offer a contrasting methodology with different matrix properties and separation mechanisms [9] [10].

Understanding the capabilities, limitations, and optimal applications of each modality is essential for researchers investigating protein complexes, particularly when planning downstream applications such as protein recovery, activity assays, or structural studies. This guide provides comprehensive troubleshooting and methodological support to optimize experimental outcomes across these electrophoretic techniques.

Technical Comparison of Methodologies

The selection of an appropriate electrophoresis modality depends on research goals, sample characteristics, and intended downstream applications. Below is a systematic comparison of BN-PAGE, CN-PAGE, and high-resolution agarose gels to guide researchers in making informed methodological choices.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Electrophoresis Modalities

| Characteristic | BN-PAGE | CN-PAGE | High-Resolution Agarose Gels |

|---|---|---|---|

| Separation Principle | Size in native state with charge shift from Coomassie dye [7] | Intrinsic charge and size in native state [8] | Molecular size through matrix sieving [9] |

| Optimal Application Range | 100 kDa - 10 MDa (protein complexes) [7] | 50 kDa - 5 MDa (protein complexes) [8] | 100 bp - 25 kbp (nucleic acids) [9] |

| Typical Gel Composition | 3-16% gradient polyacrylamide [7] | 3-16% gradient polyacrylamide [8] | 0.7-2% agarose [9] |

| Detergent Requirement | Mild non-ionic detergents (e.g., digitonin, dodecylmaltoside) [7] | Mild non-ionic detergents [8] | Not required (for DNA) |

| Visualization Method | Coomassie staining, in-gel activity assays, western blotting [7] | Coomassie/silver staining, in-gel activity, western blotting [8] | Ethidium bromide, SYBR Safe, SYBR Gold [9] |

| Protein Complex Stability | High (maintains most interactions) [7] | Very high (preserves supramolecular assemblies) [8] | Not applicable (primarily for nucleic acids) |

| Downstream Compatibility | MS analysis, 2D electrophoresis, in-gel activity assays [7] | FRET analyses, activity assays, MS [8] | Cloning, sequencing, purification [9] |

Table 2: Advantages and Limitations Comparison

| Aspect | BN-PAGE | CN-PAGE | High-Resolution Agarose Gels |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Advantages | High resolution for membrane proteins; Enables in-gel activity assays; Well-established for supercomplex analysis [7] [11] | Preserves fragile supramolecular assemblies; No dye interference; Compatible with fluorescence techniques [8] | Easy to prepare and handle; Non-toxic casting; Suitable for large DNA fragments; High DNA recovery [9] [10] |

| Major Limitations | Coomassie dye may cause dissociation; Potential quenching in detection; Requires optimization of detergent conditions [7] [8] | Lower resolution for some complexes; Relies on intrinsic protein charge; Limited for very acidic proteins [8] | Limited protein separation capability; Lower resolution than PAGE for small fragments; Potential electroendosmosis [10] |

| Technical Challenges | Detergent optimization; Current fluctuations; Streaking issues; Dye aggregation [7] [12] | Buffer composition; Maintaining complex stability; Limited staining options [8] | Gel concentration optimization; Voltage effects; Buffer exhaustion; "Smiling" effect [9] |

Decision Framework for Modality Selection

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting the appropriate electrophoresis modality based on research objectives and sample characteristics:

Troubleshooting Guides

BN-PAGE Troubleshooting

BN-PAGE presents unique technical challenges that can impact protein separation and complex integrity. The following table addresses common issues and their solutions:

Table 3: BN-PAGE Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gel stops running or voltage increases dramatically | Cathode buffer dye aggregation; Insufficient buffering capacity; Incorrect buffer formulation [12] | Replace cathode buffer with fresh preparation; Ensure proper pH (7.0 for imidazole systems); Verify Coomassie G250 concentration (0.02%) [13] [12] | Prepare cathode buffer fresh; Do not store Coomassie-containing buffers at 4°C; Use high-quality power supply (500V+ capacity) [12] |

| Excessive streaking or smearing | RNA contamination; Protein aggregation; Insufficient detergent; Sample overloading [12] | Treat with RNase if RNA presence confirmed; Optimize detergent type and concentration; Centrifuge samples at 15,000 ×g before loading [12] [14] | Include mild detergents (1% digitonin); Use nuclease treatment; Optimize detergent-to-protein ratio [7] [14] |

| Poor complex resolution or band distortion | Improper gradient gel formation; Incorrect running conditions; Incompatible detergent [12] [14] | Verify gradient mixer function; Run at constant voltage (100V) in cold room; Test alternative detergents (dodecylmaltoside, digitonin) [13] [12] | Use validated gradient protocols; Maintain temperature at 4°C throughout; Optimize detergent for specific complexes [7] [11] |

| Loss of enzyme activity after separation | Coomassie dye interference; Complex dissociation during run; Overheating during electrophoresis [7] [8] | Reduce Coomassie concentration; Switch to CN-PAGE; Ensure adequate cooling during run [8] [14] | Optimize dye-to-protein ratio; Use milder detergents; Maintain temperature at 4°C [7] |

| Inconsistent migration between runs | Buffer exhaustion; Variation in gel porosity; Dye lot variability | Prepare fresh buffers for each run; Standardize gradient gel preparation; Use same Coomassie G250 source [13] | Prepare larger buffer batches; Document gel casting parameters; Standardize reagent sources [13] |

CN-PAGE Troubleshooting

CN-PAGE eliminates potential dye-related issues but introduces other technical considerations:

Table 4: CN-PAGE Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor band resolution | Insufficient intrinsic charge; Inappropriate pH; Complex dissociation [8] | Optimize buffer pH to enhance protein charge; Use higher polyacrylamide concentrations; Add compatible salts [8] | Pre-test protein migration at different pH values; Use mild detergents that maintain complex stability [8] |

| Limited protein detection sensitivity | Absence of charge-providing dye; Low abundance complexes; Incompatible staining [8] | Use highly sensitive staining (silver stain); Employ fluorescent labeling before electrophoresis; Transfer to membrane for immunodetection [8] | Consider pre-fractionation to concentrate samples; Use extended staining protocols [14] |

| Vertical streaking | Salt concentration too high; Protein precipitation; Particulate matter [14] | Desalt samples before loading; Centrifuge at high speed before loading; Filter samples through 0.22μm filter [14] | Dialyze samples into low-salt buffers (≤50 mM NaCl); Clarify all samples by centrifugation [13] |

High-Resolution Agarose Gel Troubleshooting

While primarily used for nucleic acids, understanding agarose gel issues provides valuable electrophoretic principles:

Table 5: High-Resolution Agarose Gel Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| "Smiling" effect (bands curve upward) | Uneven heating across gel; Excessive voltage; Loose contacts in tank [9] | Reduce voltage (80-150V); Ensure buffer covers gel evenly; Check electrode connections [9] | Use consistent voltage; Submerge gel with 3-5mm buffer above surface; Verify apparatus integrity [9] |

| Poor band separation | Incorrect agarose concentration; Incorrect buffer choice; Migration distance too short [9] | Adjust agarose % (0.7% for large fragments, 2% for small); Choose TBE for small fragments, TAE for large; Extend run time [9] | Match agarose percentage to fragment size; Use TBE for better small fragment resolution [9] |

| Faint or no bands | Insufficient DNA loading; Ethidium bromide degradation; Photography issues [9] | Load at least 20ng DNA per band with EtBr; Use fresh staining solution; Verify imaging system [9] | Use appropriate DNA markers; Prepare fresh running buffers; Verify stain activity [9] |

| Band distortion or melting | Insufficient buffer covering; Excessive voltage; Buffer exhaustion [9] | Ensure gel fully submerged; Reduce voltage; Use fresh buffer for each run [9] | Maintain 3-5mm buffer above gel; Monitor buffer ion depletion; Do not reuse buffers [9] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I choose BN-PAGE over CN-PAGE for my protein complex analysis?

BN-PAGE is generally preferred when studying membrane protein complexes, particularly mitochondrial respiratory chains, and when maximum resolution is required for complexes larger than 500 kDa [7] [11]. The Coomassie dye provides uniform charge shifting, enabling separation primarily by size. CN-PAGE is superior when studying supramolecular assemblies that might be disrupted by Coomassie binding, or when planning downstream applications sensitive to dye interference, such as FRET analyses or fluorescence measurements [8]. For unknown complexes, empirical testing of both methods is recommended.

Q2: What detergents work best for BN-PAGE, and how do I select the appropriate one?

The most common detergents for BN-PAGE include dodecylmaltoside (DDM), Triton X-100, and digitonin [7] [14]. DDM and Triton X-100 typically solubilize individual complexes well, while digitonin is superior for preserving labile supercomplexes, particularly in mitochondrial studies [11] [14]. Selection should be based on your specific complexes: DDM for general membrane protein work, digitonin for respiratory supercomplexes, and Triton X-100 as a cost-effective alternative for robust complexes. Always optimize detergent-to-protein ratios for specific applications.

Q3: How can I improve the resolution of my BN-PAGE separation?

Several strategies can enhance BN-PAGE resolution: (1) Optimize the acrylamide gradient (typically 3-13% or 4-16%) to match your complex sizes [7]; (2) Ensure proper buffer preparation with fresh Coomassie G250 in cathode buffer [13] [12]; (3) Maintain temperature at 4°C throughout electrophoresis to prevent overheating [13]; (4) Include 50-500mM aminocaproic acid in samples to improve solubility [13]; (5) Reduce sample salt concentration to below 50mM NaCl [13]; (6) Avoid overloading by optimizing protein concentration.

Q4: My protein complexes dissociate during BN-PAGE. What alternatives do I have?

If complexes dissociate during BN-PAGE, consider these approaches: (1) Switch to CN-PAGE, which eliminates potential dye-induced dissociation [8]; (2) Reduce Coomassie dye concentration or add it only to the cathode buffer rather than the sample [14]; (3) Test milder detergents such as digitonin instead of dodecylmaltoside [14]; (4) Include stabilizing additives like glycerol (5-10%) or mild salts in the sample buffer [13]; (5) Reduce electrophoresis time and maintain lower voltage throughout the run.

Q5: How can I detect and quantify proteins after CN-PAGE since Coomassie staining is less sensitive?

While CN-PAGE typically has lower detection sensitivity than BN-PAGE, several enhanced detection methods are available: (1) High-sensitivity silver staining [13]; (2) Fluorescent staining with dyes like Sypro Ruby [8]; (3) Western blotting with specific antibodies after electrotransfer [13] [8]; (4) In-gel activity assays for enzymatic complexes [11]; (5) Pre-labeling samples with fluorescent tags before electrophoresis [15]. For quantification, fluorescent methods generally offer better linear dynamic range than conventional staining.

Q6: What are the most common mistakes in sample preparation that affect native PAGE results?

Common sample preparation errors include: (1) Using high salt concentrations (>50mM NaCl) that interfere with electrophoresis [13]; (2) Employing inappropriate or excessive detergents that disrupt complexes [14]; (3) Subjecting samples to freeze-thaw cycles that promote aggregation; (4) Failure to remove insoluble material by centrifugation [13]; (5) Using incorrect pH in sample buffers (optimal is pH 7.0-7.5) [13]; (6) Overloading wells, leading to poor resolution; (7) Adding Coomassie dye to samples too early, potentially causing dissociation [14].

Experimental Protocols

Standard BN-PAGE Protocol for Protein Complexes

The following workflow illustrates the key steps in BN-PAGE analysis of protein complexes:

Reagents and Solutions:

- Imidazole/HCl buffer (1M, pH 7.0): Store at 4°C [13]

- Detergent solution (10% digitonin or dodecylmaltoside): Aliquot and store at -80°C [13]

- Coomassie G250 solution (5%): In 500mM 6-aminohexanoic acid; store at room temperature [13]

- Acrylamide-bisacrylamide mix (49.5% T, 3% C): Store at 4°C [13]

- Gel buffer (3X): 75mM imidazole/HCl, pH 7.0, 1.5M 6-aminohexanoic acid; store at 4°C [13]

- Cathode buffer: 50mM tricine, 7.5mM imidazole, 0.02% Coomassie G250; prepare fresh [13]

- Anode buffer: 25mM imidazole, pH 7.0; prepare fresh [13]

Detailed Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize tissue or cells in isolation buffer (250mM sucrose, 20mM HEPES, 1mM EGTA, pH 7.4) with protease inhibitors [11]. Centrifuge at 600 ×g for 10min at 4°C to remove debris and nuclei.

- Membrane Solubilization: Add appropriate detergent (typically 1-2g detergent/g protein) to the supernatant [14]. Incubate on ice for 10-30min with gentle mixing. Centrifuge at 15,000 ×g for 15min at 4°C to remove insoluble material.

- Sample Buffer Preparation: Mix solubilized supernatant with loading buffer (100mM Bis-Tris, 500mM 6-aminohexanoic acid, 30% glycerol, 5% Coomassie G250) [12]. For sensitive complexes, add Coomassie only to cathode buffer.

- Gradient Gel Preparation: Using a gradient mixer, prepare separating gel with acrylamide gradient from 3% to 13% in gel buffer [13]. Layer with water and polymerize for 1hr. Add 4% stacking gel with comb and polymerize for 30min.

- Electrophoresis: Assemble gel in electrophoresis apparatus with anode and cathode buffers. Load samples and run at constant voltage (100V) for 30-60min until samples enter separating gel, then increase to 15mA constant current at 4°C until dye front reaches bottom [13].

- Detection: Process gel for Coomassie staining, activity assays, or transfer for western blotting. For mass spectrometry, excise bands and process for protein identification.

CN-PAGE Protocol for Sensitive Complexes

Modified Steps from BN-PAGE:

- Sample Preparation: Follow same procedure as BN-PAGE but omit Coomassie dye from sample buffer [8].

- Electrophoresis Buffers: Use same anode buffer but prepare cathode buffer without Coomassie dye [8].

- Running Conditions: Electrophoresis conditions similar to BN-PAGE but may require slightly higher voltage or longer run times due to reduced charge on proteins.

- Detection: Enhanced staining methods typically required due to lower sensitivity [8].

High-Resolution Agarose Gel Protocol for Nucleic Acids

Procedure:

- Gel Preparation: Mix agarose with appropriate buffer (TAE or TBE) to desired concentration (0.7-2%) [9]. Microwave until completely dissolved, cool to 50°C, pour into casting tray with comb, and allow to solidify.

- Sample Preparation: Mix DNA samples with loading buffer (e.g., 6X Orange G) containing glycerol and tracking dyes [9].

- Electrophoresis: Submerge gel in running buffer, load samples, and run at 80-150V until adequate separation achieved [9].

- Visualization: Stain with ethidium bromide, SYBR Safe, or SYBR Gold and image under UV light [9].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 6: Essential Reagents for Native PAGE Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detergents | Dodecylmaltoside, Digitonin, Triton X-100 [14] | Solubilize membrane proteins while preserving native interactions | Digitonin preserves supercomplexes; DDM for general use; Triton X-100 as cost-effective alternative [14] |

| Charge Shift Agents | Coomassie Blue G-250 [7] | Provide uniform negative charge to protein complexes | Use at 0.02% in cathode buffer; 0.5-1% in sample buffer; may cause complex dissociation in sensitive samples [7] |

| Stabilizing Compounds | 6-Aminohexanoic acid, Glycerol, EDTA [13] | Enhance complex stability; improve solubility; inhibit proteases | 6-Aminohexanoic acid (50-500mM) improves membrane protein solubility; Glycerol (5-10%) stabilizes complexes [13] |

| Gel Matrix Components | Acrylamide-bisacrylamide (49.5% T, 3% C) [13] | Form porous gel matrix for size-based separation | Gradient gels (3-13%) provide optimal resolution for diverse complex sizes [7] |

| Buffer Systems | Imidazole/HCl, Bis-Tris, Tricine [13] [12] | Maintain pH and conductivity during electrophoresis | Imidazole systems avoid interference with protein assays; pH 7.0 critical for optimal separation [13] [12] |

| Visualization Reagents | Coomassie R-250, Silver stain, SYPRO Ruby [8] | Detect proteins after separation | Silver staining offers highest sensitivity; fluorescent stains provide better quantification [8] |

Advanced Applications and Emerging Techniques

Supercomplex Analysis Using BN-PAGE

BN-PAGE has become indispensable for studying mitochondrial supercomplexes—higher-order assemblies of respiratory chain complexes [11]. These assemblies, including respirasomes (CI+CIII₂+CIV), play crucial roles in efficient cellular energy production [11]. The technique has revealed tissue-specific and strain-specific differences in supercomplex formation, with important implications for understanding mitochondrial disorders [11].

Fluorescent Protein Detection in Gels

Recent advances demonstrate that fluorescent proteins (FPs) can be detected directly in SDS-PAGE gels through their intrinsic fluorescence, bypassing the need for antibody-based detection [15]. This approach, termed in-gel fluorescence (IGF), provides superior sensitivity, reduced background, and broader dynamic range compared to traditional western blotting [15]. While this technique currently applies primarily to denaturing conditions, adaptations for native systems are emerging.

Two-Dimensional Electrophoresis Approaches

Both BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE serve as excellent first-dimension separations for two-dimensional electrophoresis, with second-dimension SDS-PAGE providing information on subunit composition [7] [14]. This approach powerfully combines native complex separation with denaturing subunit analysis, offering comprehensive characterization of complex stoichiometry and composition.

Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Native PAGE) is a fundamental technique that separates proteins based on their charge, size, and shape in their native, non-denatured state [16]. Unlike its denaturing counterpart (SDS-PAGE), native PAGE preserves protein complexes, higher-order structures, and biological activity, making it invaluable for studying functional proteomics, protein-protein interactions, and enzyme activity [16]. However, the very conditions that preserve native structure also create unique challenges for efficiently recovering proteins from the gel matrix for subsequent analysis. This technical resource center provides targeted troubleshooting and methodologies to optimize this critical link between separation and analysis, enabling researchers to maximize the value of their native PAGE experiments.

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Issues in Native PAGE and Protein Recovery

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Native PAGE and Recovery Problems

| Problem | Possible Causes | Troubleshooting Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Smeared bands [17] | Voltage too high; Buffer overheating [17] | Run gel at lower voltage for longer time; Use cold room or ice packs in apparatus [17]. |

| Poor band resolution [17] | Gel run time too short; Improper buffer pH/ions [17] | Run gel until dye front nears bottom; Remake running buffer to ensure correct ion concentration and pH [17]. |

| Low protein recovery from gel | Excessive fixation; Inefficient extraction method; Protein aggregation | Use mild, reversible stains; Optimize extraction solution; Keep apparatus cool to prevent denaturation/aggregation [16]. |

| Loss of protein activity post-recovery | Harsh extraction conditions; Proteolysis; pH extremes during electrophoresis | Use gentle, MS-compatible buffers; Include protease inhibitors; Avoid pH extremes during electrophoresis [16]. |

| 'Smiling' bands (curved edges) [17] | Excessive heat generation during run [17] | Reduce voltage; Use a cooling system during electrophoresis [17]. |

FAQs on Native PAGE and Downstream Recovery

1. How does native PAGE differ from SDS-PAGE, and why does it matter for recovery? In SDS-PAGE, the detergent SDS denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge, so separation is based primarily on molecular mass. In native PAGE, no denaturants are used. Proteins are separated based on their intrinsic charge, size, and three-dimensional shape [16]. This means subunit interactions in multimeric proteins are retained [16]. For recovery, the absence of SDS means proteins are less hydrophobic and may not be uniformly charged, which can affect their elution behavior from the gel matrix. The goal is to extract the protein without disrupting its native conformation or complex integrity.

2. What is the most efficient method to recover intact proteins from a native gel? While traditional methods like passive extraction and electroelution can be used [18], the PEPPI-MS (Passively Eluting Proteins from Polyacrylamide gels as Intact species for MS) workflow represents a significant advance. This method uses an optimized Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) staining step followed by passive extraction in a specialized buffer (e.g., 0.1% SDS/100 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8, or native running buffer with 0.1% octylglucoside) [19]. The process involves macerating the gel piece and shaking it vigorously in the extraction solution for about 10 minutes, enabling efficient recovery of a wide range of proteins [19] [18].

3. Can I use the same recovery protocol for both stained and unstained gels? No. The staining process, particularly with traditional formulations of Coomassie Brilliant Blue, can strongly immobilize proteins within the gel matrix [19]. Conventional CBB, dissolved in an acidic solution with organic solvents, enhances protein fixation, which dramatically impairs recovery [19]. If high recovery yield is critical, use aqueous, MS-compatible CBB stains or minimize staining before recovery [19].

4. My recovered protein is inactive. What could have gone wrong? Native PAGE and subsequent handling must maintain conditions that preserve protein structure. To avoid activity loss:

- Keep it cool: Run the electrophoresis apparatus in a cold room or with a cooling unit to minimize heat-induced denaturation [16].

- Avoid pH extremes: Use the correct running buffer and avoid solutions that could drive the protein to its isoelectric point (pI), where it may precipitate [16].

- Use gentle elution: Harsh organic solvents or high concentrations of strong detergents in the extraction buffer can disrupt a protein's native structure.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Detailed Protocol: PEPPI-MS for Intact Protein Recovery

This protocol is adapted from methods developed for top-down proteomics and allows for efficient recovery of intact proteins from polyacrylamide gels for downstream analysis such as mass spectrometry or activity assays [19].

1. Gel Electrophoresis and Staining

- Perform native PAGE according to your standard protocol.

- After electrophoresis, stain the gel using an aqueous formulation of Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB). Avoid traditional CBB formulations containing methanol and acetic acid, as they cause excessive protein fixation and impair recovery [19].

- Destain the gel with water or a mild aqueous solution.

2. Gel Excision and Homogenization

- Excise the protein band of interest from the wet gel with a clean razor blade.

- Transfer the gel slice to a disposable homogenizer tube (e.g., BioMasher II).

- Grind the gel segment uniformly for about 30 seconds using a plastic pestle to increase the surface area for extraction [19].

3. Passive Protein Extraction

- Add 300-500 μL of protein extraction solution to the homogenizer tube. The choice of buffer depends on your downstream application:

- Shake the mixture vigorously (e.g., 1500 rpm) at room temperature for 10 minutes [19].

4. Sample Filtration and Concentration

- Filter the extract through a 0.45-μm cellulose acetate membrane in a spin filter tube to remove gel debris [19].

- Concentrate the protein filtrate using an appropriate centrifugal ultrafiltration device (e.g., a 3-kDa molecular weight cut-off filter) [19].

- The recovered protein is now ready for downstream analysis.

Workflow for Native PAGE and Protein Recovery

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Native PAGE and Recovery

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide [16] | Forms the cross-linked porous gel matrix for size-based separation. | Pore size is inversely related to % concentration; adjust for target protein size [16]. |

| Native Running Buffer | Conducts current and maintains pH during electrophoresis. | Must be non-denaturing (no SDS); common buffers are Tris-Glycine or Tris-Borate [16]. |

| Aqueous CBB Stain [19] | Visualizes protein bands without strong fixation. | Critical for high recovery yields; avoids methanol/acetic acid of traditional stains [19]. |

| Extraction Buffer [19] | Liberates proteins from the gel matrix. | For MS: 0.1% SDS/100 mM AmBic. For native state: native buffer with 0.1% octylglucoside [19]. |

| Disposable Homogenizer [19] | Macerates gel to increase surface area for extraction. | Essential for efficient passive extraction (e.g., PEPPI-MS) [19]. |

| Spin-X Centrifuge Tube Filter [19] | Filters extracted solution to remove gel debris. | Uses a 0.45-μm cellulose acetate membrane [19]. |

| Centrifugal Ultrafiltration Device [19] | Concentrates the recovered protein sample. | Choose molecular weight cut-off (e.g., 3-kDa) appropriate for your target protein [19]. |

For researchers focused on optimizing protein recovery from native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (native PAGE), success begins long before the elution step. Native PAGE separates proteins based on their charge, size, and shape, preserving their native conformation and biological activity [16]. This technique is invaluable for studying multimeric proteins, enzymatic activity, and protein-protein interactions. However, the recovery of functional, non-denatured proteins is highly sensitive to experimental conditions from sample preparation through the final elution. This guide addresses common challenges and provides proven methodologies to ensure optimal native state preservation, enabling successful downstream applications in drug development and proteomic research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

1. Why are my protein bands poorly resolved or smeared on my native gel?

Poor resolution in native PAGE can result from several factors related to sample composition and gel conditions:

- Sample Contamination with Nucleic Acids: The presence of high molecular weight DNA in your sample can create a viscous solution and cause smearing or V-shaped band artifacts [20]. This can be remedied by shearing the DNA through additional sonication post-solubilization or by removing the DNA using an ultracentrifuge [20].

- Protein Aggregation or Multiple Folding States: Your protein may exist in different conformational states or form aggregates. As noted in one researcher's experience, a single monomeric protein can sometimes appear as two distinct bands on a native gel, potentially due to different folding states or post-translational modifications like glycosylation [21]. Ensuring fresh, properly stored samples and optimizing buffer conditions can mitigate this.

- Incorrect Gel Pore Size: The concentration of your resolving gel must be appropriate for the size of your target protein. A 6% gel is often suitable for large complexes, but the percentage may need optimization [22].

- Edge Effect: Distorted bands in the peripheral lanes can occur if the outer wells are left empty. To ensure uniform electric field distribution, load all wells with either experimental samples, protein ladders, or a standard protein solution [23].

2. My current drops significantly or the power supply shuts off during the run. What is happening?

It is common for the current to drop below 1 mA during NativePAGE electrophoresis. Most power supplies register this as a "No Load" error and automatically shut off. This can typically be bypassed on your power supply by disabling or turning off the "Load Check" feature [20].

3. My protein sample migrated out of the wells before I started the run. How can I prevent this?

This occurs due to diffusion when there is a significant time lag between loading the samples and applying the electric current. The electric current is necessary for concordant migration of the proteins from the wells [23]. To prevent this, minimize the time between loading your first sample and starting the electrophoresis run. If you have a large number of samples, try to load faster or run fewer samples at once [23].

4. I see a "smiling" or curved shape in my protein bands. What causes this?

"Smiling" bands are typically caused by excessive heat generation during electrophoresis. The heat causes the gel to expand, leading to uneven migration of proteins across the lane [23]. To minimize heat production, you can:

- Run the gel in a cold room.

- Place ice packs in the gel-running apparatus.

- Run the gel at a lower voltage for a longer duration [23].

5. How can I improve the recovery of native, active proteins from gel slices?

A high-yield method for recovering native proteins from preparative gel slices is reverse polarity elution. This technique has been shown to recover various proteins, from 9,000 to 186,000 daltons, in biologically active form at yields up to 90% without requiring specialized apparatus beyond a standard slab gel system [24]. The key is to maintain non-denaturing conditions throughout the process to preserve quaternary structure and function [16].

Optimized Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Sample Preparation for Native PAGE

Proper sample preparation is the most critical step for preserving native state proteins.

- Buffer Composition: Avoid denaturing agents like SDS or high concentrations of urea. Use non-denaturing buffers such as 50 mM Tris-HCl or PBS. The ionic strength should be low to facilitate entry into the gel [22] [21].

- Insoluble Material: Remove insoluble material by centrifuging the sample at 17,000 x g for 2 minutes after mixing with the native sample buffer. Load only the supernatant to prevent streaking in the gel [25].

- Protein Concentration: Determine protein concentration accurately using a standard assay. For native PAGE, load 0.5–4.0 µg of a purified protein or 40–60 µg for a crude sample if using Coomassie Blue stain. Overloading will cause distorted, poorly resolved bands [25].

- Immediate Processing: Load samples and start electrophoresis immediately to prevent proteins from diffusing out of the wells or undergoing degradation [23].

- Additives (if needed): For proteins with free cysteines, consider adding low concentrations of a reducing agent like β-mercaptoethanol to the sample buffer to prevent inter-subunit disulfide bonding that can cause smearing [22].

Protocol 2: Preparative Native PAGE for Protein Purification

This protocol is adapted from methods used for purifying proteins like GFP directly from intact E. coli cells [26].

- Goal: To separate and purify a native protein on a preparative scale for downstream functional studies.

- Gel System: A discontinuous native gel system is used. A typical setup might include a 4% stacking gel (pH 6.8) and a 6-8% resolving gel (pH 8.8) [22] [26].

- Sample Load: The volume and concentration of the feedstock are critical. For a gel column with a 1.7 cm internal diameter, an optimal loading volume is 100 µL, yielding high purity (87%) and recovery (86%). Higher loads can decrease resolution and yield [26].

- Running Conditions: Use Tris-Glycine running buffer (pH ~8.3). Run the gel at a constant current (e.g., 23-30 mA) at 4°C to minimize heat-induced denaturation [22].

- Recovery: After electrophoresis, locate the protein band (visually if colored, or by brief staining). Excise the gel slice and recover the native protein using a method such as reverse polarity elution [24].

The following workflow summarizes the key stages of this optimized process:

Quantitative Data for Experimental Optimization

The following table summarizes key findings from a scale-up study on the purification of Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) using preparative native PAGE, highlighting the impact of critical parameters on yield and purity [26].

Table 1: Effects of Operational Parameters on GFP Purity and Yield in Preparative Native PAGE

| Parameter | Condition Tested | Effect on Purity | Effect on Yield | Optimal Condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Load Volume | 50 - 150 µL | Constant (~0.85) | Decreased with higher volume | 100 µL |

| >150 µL | Decreased | Decreased | ||

| Resolving Gel Height | 2 - 4 cm | No significant effect | Decreased with greater height | 2 cm |

| Resolving Gel Concentration | 6 - 10% | No significant effect | Decreased with higher % | 6% |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for Native PAGE and Protein Recovery

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Key Consideration for Native State |

|---|---|---|

| Tris-Glycine Buffer | Standard running buffer for native PAGE; conducts current and maintains pH [16]. | Avoid SDS and other denaturing detergents to preserve protein structure. |

| Native Sample Buffer | Loads sample into wells; typically contains glycerol and a tracking dye [16]. | Lacks SDS and reducing agents. May contain a mild non-ionic detergent. |

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms the cross-linked gel matrix that acts as a molecular sieve [16]. | Pore size (determined by %) must be optimized for target protein size [26]. |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) & TEMED | Catalyzes the polymerization of acrylamide to form the gel [16]. | Ensure complete polymerization before use to avoid introducing free radicals that could damage proteins. |

| SimplyBlue SafeStain | A Coomassie-based dye for visualizing proteins after electrophoresis [27]. | Compatible with downstream protein recovery; does not permanently denature all proteins. |

| Ultrapure Water | Used for preparing all solutions and washing steps [27]. | Essential for preventing keratin and other contaminants that interfere with staining and analysis. |

The relationships between critical parameters and their collective impact on the success of native protein recovery are summarized below. This diagram illustrates how optimizing these factors leads to the desired experimental outcome.

Advanced Techniques for Efficient Protein Elution and Post-Electrophoresis Handling

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

What are the primary methods for eluting proteins from native PAGE gels, and how do I choose?

The three main strategic approaches for protein recovery from native polyacrylamide gels are the crush-and-soak method (a diffusion-based technique), electroelution, and more advanced integrated systems like micropreparative PAGE (MP-PAGE). Your choice depends on your required yield, purity, and the sensitivity of your target protein.

- Crush-and-Soak (Diffusion): This is a classic, equipment-free method where the gel slice containing your protein is physically crushed and soaked in an elution buffer. The protein diffuses out into the buffer over time. It is simple and accessible but is time-consuming, often requiring overnight incubation, and typically yields only 30-50% of your protein, making it less suitable for dilute or precious samples [28].

- Electroelution: This method uses an electric current to actively drive the protein out of the gel slice into a small volume of buffer. It generally offers higher yields and is faster than crush-and-soak. However, it often requires specialized equipment and can generate heat, which may denature sensitive proteins.

- Micropreparative PAGE (MP-PAGE): A modern one-step purification setup uses a trilayered gel system in a standard vertical electrophoresis tank. The protein is electrophoresed out of the separating gel and is collected directly from a viscous glycerol layer. This method has demonstrated superior performance, with recovery yields for DNA of up to 90%, significantly higher than the 58% yield from the crush-and-soak method [29]. It is particularly effective for purifying dilute bioconjugates that are challenging with other techniques.

My protein recovery yield from the crush-and-soak method is low. How can I improve it?

Low yield is a common limitation of the crush-and-soak technique. You can optimize the following parameters to improve recovery:

- Increase Surface Area: Ensure the gel slice is thoroughly crushed into very small pieces using a Teflon pestle. Freezing the gel slab before crushing can make this process easier and more effective [28].

- Optimize Soaking Time: The diffusion process is slow. Extending the incubation time on a gentle rotator to up to 48 hours can significantly improve recovery, especially for larger proteins or nucleic acid fragments over 500 bp [28].

- Buffer Volume and Composition: Use approximately 3 volumes of "crush and soak" buffer relative to the gel volume. A standard buffer consists of 300 mM Sodium Acetate, 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), and sometimes 0.1% SDS [28]. Ensure the buffer is fresh and correctly formulated.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Low Yields in Crush-and-Soak Elution

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low recovery for all proteins | Insufficient crushing | Freeze gel before crushing; use a pestle to create a fine slurry [28]. |

| Low recovery for large proteins | Short incubation time; slow diffusion | Extend soaking time to 36-48 hours [28]. |

| Low recovery and poor protein activity | Incorrect buffer | Prepare fresh buffer with correct pH and salt concentration (e.g., 300 mM Sodium Acetate) [28]. |

I am using an electroelution system, but my protein is denaturing. What could be wrong?

Protein denaturation during electroelution is often linked to heat generation or problematic buffer conditions.

- Excessive Heat Generation: The electric current passing through the elution chamber can generate significant heat. To mitigate this, run the elution in a cold room or use an apparatus with a cooling system. You can also reduce the voltage, opting for a longer run time at a lower power setting to minimize heat buildup [30].

- Incorrect Buffer Conditions: The concentration and composition of the elution buffer are critical. Overly concentrated or incorrect buffers can generate excess heat and damage proteins [31]. Always use the recommended buffer for your specific protein and system. Verify the buffer recipe and remake it if necessary [31].

My protein samples are running off the gel before I start the elution process. What should I do?

This issue occurs due to diffusion when there is a delay between sample separation and the start of the elution step.

- Minimize Time Lag: The electric current ensures unified migration. If there is a lag between electrophoresis and elution, proteins can diffuse haphazardly out of their bands. To prevent this, you should begin the elution process (whether crush-and-soak or setting up an electroelution device) immediately after the gel run is complete [30]. Load and process your samples promptly to avoid diffusion.

How can I prevent protein aggregation or re-oxidation during elution from a native gel?

Maintaining protein native state is crucial for downstream activity assays.

- Use Fresh Reducing Agents: For proteins prone to re-oxidation, especially in systems like Tricine gels, adding fresh reducing agents to your running or elution buffer may be necessary. In some cases, alkylating the sample post-elution (e.g., with iodoacetic acid after reduction with DTT) can prevent re-oxidation [32].

- Avoid Denaturing Conditions: The "crush-and-soak" method has an advantage over some commercial kits that use denaturing agents like guanidinium thiocyanate, which can denature shorter DNA fragments and potentially affect proteins. The traditional crush-and-soak buffer is generally non-denaturing, helping to preserve protein structure and activity [28].

Experimental Protocol: Comparative Analysis of Elution Methods

Objective

To directly compare the recovery yield and purity of a model protein (Enhanced Yellow Fluorescent Protein, EYFP) eluted from a native PAGE gel using the traditional crush-and-soak method versus the MP-PAGE technique.

Materials

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Elution Buffer (Crush-and-Soak): 300 mM Sodium Acetate, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0 [28].

- MP-PAGE Collection Layer: High-purity glycerol.

- Native PAGE Running Buffer: Commercially available NativePAGE buffer or laboratory-prepared bis-tris buffer at pH 7.0 [33].

- Solubilization Buffer: 1X solution of n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside in 750 mM 6-aminocaproic acid for membrane protein extraction [33].

- Staining Solution: Coomassie Brilliant Blue or compatible fluorescent imager for EYFP detection.

Methodology

A. Sample Preparation

- Purify EYFP from a crude E. coli extract. Use a simplified solubilization procedure with n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside to extract proteins without dissociating complexes [33].

- Concentrate the protein sample and resuspend in a native sample buffer.

B. Native Gel Electrophoresis

- Load the EYFP sample onto a 4-16% high-resolution clear native polyacrylamide gel (hrCN-PAGE) [34] [33].

- Run the gel at a constant voltage (e.g., 100-150V) at 4°C to minimize heat-induced damage. Stop the run when the dye front is about 0.5 cm from the bottom of the gel.

C. Gel Elution

- Crush-and-Soak Method:

- Excise the EYFP band from the gel using a clean razor blade.

- Freeze the gel slice at -20°C for 15 minutes, then crush it thoroughly in a microcentrifuge tube using a Teflon pestle.

- Add 3 volumes of elution buffer and incubate on a rotator for 36 hours at 4°C.

- Centrifuge the mixture to pellet the gel debris and collect the supernatant containing the eluted protein.

- Precipitate the protein using ethanol precipitation [28].

- MP-PAGE Method:

- Follow a published MP-PAGE protocol to set up a trilayered gel (stacking gel, resolving gel, glycerol collection layer) in a standard vertical electrophoresis apparatus [29].

- Load the EYFP sample and run the gel until the protein band migrates out of the resolving gel and into the glycerol layer.

- Carefully collect the solution from the glycerol layer, which now contains the purified EYFP.

Data Analysis

- Yield Calculation: Quantify the protein concentration in the eluates from both methods using an assay like BCA. Calculate the percentage recovery based on the initial loaded amount.

- Purity Analysis: Analyze the eluates using analytical SDS-PAGE and spectrophotometry. Calculate purity by comparing the specific absorption of native EYFP at 514 nm with the total protein absorption at 280 nm [29].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Elution Method Performance

| Method | Typical Recovery Yield | Purity | Time Required | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crush-and-Soak | ~30-50% for DNA; often lower for proteins [28] | Moderate (prone to contamination) | 36-48 hours [28] | Simple; no special equipment [28] |

| MP-PAGE | Up to 90% for DNA; ~90% purity for EYFP [29] | High (comparable to IMAC+SEC) [29] | < 4 hours (gel run time) | High yield and purity in one step [29] |

Diagram 1: Decision workflow for selecting a gel elution method.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Why are my protein bands smeared after buffer exchange and native PAGE analysis?

Smeared bands can result from several factors related to sample preparation and gel running conditions.

- Voltage Too High: Running the gel at excessive voltage can cause smearing and overheating. For better resolution, run the gel at 10-15 volts/cm and consider using a lower voltage for a longer duration [35].

- Incomplete Buffer Exchange: Contaminants like salts or detergents from the original buffer can interfere with migration. Ensure thorough buffer exchange using an appropriate method and confirm the compatibility of your final buffer with native PAGE [36] [37].

- Protein Degradation or Aggregation: Proteolysis or protein aggregation can cause smearing. Keep samples on ice, use protease inhibitors, and consider the protein's stability in the new buffer. If disulfide bridging is suspected, add a reducing agent like β-mercaptoethanol to the loading buffer [22].

How do I remove detergents without losing my protein during buffer exchange?

Detergent removal is critical, as they can interfere with downstream applications. The key is selecting the right molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) for your concentrator.

- For proteins > 60 kDa: Use a 30 kDa MWCO concentrator. This allows detergents (e.g., a 12.5 kDa nonionic detergent) to pass through while retaining your protein [38].

- For proteins < 60 kDa: Use a smaller MWCO filter but substitute the buffers with a detergent-free version. If you have used buffers containing detergent, dilute the protein in a detergent-free buffer and reconcentrate to reduce detergent content effectively [38].

Be aware that detergent removal can sometimes affect protein solubility or conformation [38].

My protein recovery yield is low after concentration. What can I do?

Low recovery is often due to non-specific binding to the concentrator membrane or protein precipitation.

- Membrane Compatibility: Use low-protein-binding membranes made from materials like regenerated cellulose (e.g., Amicon devices) to achieve recovery rates of 90% or higher [39].

- Check Buffer Composition: Some buffer components can promote aggregation or precipitation during concentration. If possible, exchange into a compatible, stabilizing buffer before concentration.

- Optimize Concentration Factor: Over-concentration can lead to precipitation. Concentrate to a moderate level and avoid reducing the sample volume to an excessively small quantity.

The current drops or the gel runs abnormally slowly during native PAGE. What is wrong?

This is a common issue in native PAGE, often related to the running buffer or sample composition.

- "No Load" Error: In native PAGE systems, it is common for the current to drop very low (below 1 mA). Many power supplies interpret this as a fault and shut down. To resolve this, disable the "Load Check" feature on your power supply, if available [32].

- Incorrect Running Buffer: Using the wrong running buffer system (e.g., Tris-Glycine buffer on a Tricine gel) will lead to longer run times and poor resolution. Always use the running buffer specified for your gel type [32].

- DNA Contamination: The presence of DNA in the sample can create a viscous solution that migrates poorly and can cause V-shaped bands. Shearing the DNA by brief sonication or removing it via ultracentrifugation can eliminate this artifact [32].

Buffer Exchange Method Comparison

The following table summarizes the primary techniques for buffer exchange, helping you select the most suitable one for your experimental needs.

| Method | Principle | Best For | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Protein Recovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dialysis [36] [40] | Passive diffusion through a semi-permeable membrane. | Large sample volumes; proteins sensitive to pressure or shear forces. | Gentle on proteins; suitable for large volumes. | Time-consuming (hours to days); not ideal for rapid exchange. | High (with proper membrane selection) |

| Desalting / Gel Filtration [36] [40] | Size exclusion chromatography to separate proteins from small molecules. | Rapid desalting or buffer exchange for small to moderate volumes. | Fast and efficient; high-throughput potential. | Limited sample volume per column; potential for sample dilution. | Variable, potential loss from column binding |

| Diafiltration (Ultrafiltration) [39] [40] | Uses pressure or centrifugation to force buffer through an MWCO membrane. | Rapid buffer exchange and concentration of samples of various sizes. | Faster than dialysis; scalable; simultaneous concentration and exchange. | Requires specialized equipment; risk of protein denaturation if not controlled. | High (e.g., ~90% with Amicon devices) [39] |

| Precipitation [40] | Using agents (e.g., acetone, TCA) to precipitate protein, followed by resuspension in new buffer. | Removing interfering substances or concentrating proteins from large, dilute volumes. | Simple and cost-effective; good for large-scale applications. | Can cause protein denaturation or loss of activity; requires optimization. | Variable |

Experimental Protocol: Standard Buffer Exchange via Centrifugal Ultrafiltration

This protocol is adapted for processing a protein sample recovered from a native PAGE gel band.

Objective: To exchange the protein into a compatible storage or assay buffer and concentrate it for downstream applications.

Materials Needed:

- Centrifugal concentrator (e.g., Amicon Ultra) with appropriate MWCO [39]

- Microcentrifuge

- Exchange buffer (e.g., desired final buffer, such as Tris-Cl, pH 7-8)

- Protein sample in elution buffer

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- MWCO Selection: Choose a centrifugal concentrator with a nominal MWCO that is 2-3 times smaller than the molecular weight of your target protein to ensure efficient retention [38].

- Membrane Preparation (Optional): Pre-rinse the device with the exchange buffer by adding a small volume, spinning briefly, and discarding the flow-through. This conditions the membrane and removes storage solution.

- Sample Loading: Load your protein sample (up to the maximum volume of the device) into the concentrator's sample reservoir.

- Centrifugation: Place the device in a microcentrifuge, ensuring proper orientation. Centrifuge at the recommended speed and time (typically 10-20 minutes at 14,000 x g). Centrifuge until the sample volume is significantly reduced but not dry.

- Buffer Exchange: a. Dilution and Re-concentration: Add the exchange buffer to the concentrated sample in the reservoir, bringing the volume back up to the original load volume. Gently mix by pipetting. Centrifuge again to the desired volume. Repeat this process 2-3 times for effective buffer exchange [38] [40]. b. Continuous Diafiltration: For a more efficient exchange, after an initial concentration step, continuously add exchange buffer to the sample reservoir at a rate equal to the formation of filtrate. This method is more advanced but highly effective [39].

- Sample Recovery: After the final concentration spin, recover the concentrated protein by inverting the device into a fresh collection tube and centrifuging for 1-2 minutes at a low speed (1,000 x g).

Workflow Diagram: From Gel to Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for recovering and preparing proteins from native PAGE gels for downstream applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Centrifugal Concentrators (e.g., Amicon Ultra) [39] | Simultaneous buffer exchange and protein concentration via ultrafiltration. | Select MWCO 2-3x smaller than protein size. Low-binding membranes maximize recovery. |

| Spin Desalting Columns (e.g., Zeba) [36] | Rapid desalting and buffer exchange via size exclusion chromatography. | Ideal for small volumes (μL to mL). Fast (minutes). Pre-equilibrated for convenience. |

| Dialysis Cassettes & Devices (e.g., D-Tube Dialyzers, Slide-A-Lyzer) [36] [39] | Gentle removal of salts and small contaminants through passive diffusion. | Best for stable proteins. Requires long incubation. Choose MWCO based on protein size. |

| Chemical Cleavage Agents (e.g., Iodoacetic acid) [32] | Alkylates reduced cysteine residues to prevent protein re-oxidation and aggregation. | Useful for proteins prone to oxidation in certain buffer systems (e.g., Tricine). |

| Thioglycolic Acid [32] | Added to running buffer to inhibit sample re-oxidation during electrophoresis. | Handle with care as it is toxic and expensive. Must be fresh to be effective. |

Troubleshooting Guide

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when recovering proteins from Native-PAGE gels for downstream functional analyses.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Protein Recovery and Downstream Analysis

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Signal in Western Blot | Inefficient transfer of high molecular weight (MW) complexes from gel to membrane [41]. | • Add 0.01–0.05% SDS to transfer buffer to help move large complexes from the gel [41].• For low MW targets, add 20% methanol to transfer buffer and reduce transfer time to prevent "blow-through" [41]. |

| Low antibody affinity for native protein conformation [42]. | • Increase primary antibody concentration [41] [42].• Verify antibody is validated for detecting native proteins; a positive control is essential [42]. | |

| Poor Protein Elution from Gel | Protein aggregation or trapping within the gel matrix. | • Section the gel band into 1-2 mm slices before elution to increase surface area [43].• Use electroelution or crush the gel slice, then vortex and sonicate in a suitable buffer [43]. |

| Loss of Protein Activity | Denaturation during electrophoresis or elution. | • Avoid SDS and heating samples [44] [45].• Maintain cold temperatures during electrophoresis; run the gel on ice and use buffers without denaturants [44] [45].• For functional recovery, use Native-PAGE instead of SDS-PAGE [43] [45]. |

| Diffuse or Smeared Bands | Protein degradation or sample overloading [41]. | • Include protease and phosphatase inhibitors in all buffers [46] [42].• Shear genomic DNA in cell lysates to reduce viscosity [41].• Reduce the amount of protein loaded per lane [41]. |

| High Background in Western Blot | Non-specific antibody binding or insufficient blocking [41]. | • Decrease concentration of primary and/or secondary antibody [41].• Optimize blocking buffer; for phosphoproteins, use BSA in Tris-buffered saline instead of milk [41].• Add 0.05% Tween 20 to wash and antibody dilution buffers [41]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Can I use a protein recovered from a Native-PAGE gel for Mass Spectrometry (Native MS)?

Yes. Proteins recovered from Native-PAGE are ideal for Native MS because the technique preserves proteins in their native, folded state, maintaining non-covalent interactions with cofactors and between subunits. The key is to use compatible, non-ionic buffers during electrophoresis and elution to avoid adducts that interfere with MS analysis. The eluted protein can often be analyzed directly after buffer exchange.

2. Why is my in-gel activity assay showing no signal, even though my Western blot confirms the protein is present?

A positive Western blot confirms the protein's presence but not its functionality. Loss of activity can occur due to:

- Denaturing Conditions: Even mild denaturants or heat during sample preparation can destroy active sites [45].

- Incorrect Buffer: The assay buffer must contain essential cofactors (e.g., metal ions like Zn²⁺) for the enzyme's activity, which are preserved in Native-PAGE [45].

- Insufficient Protein: The protein amount needed for detection by an activity assay may be higher than for Western blot. Ensure you load an adequate amount of protein [46].

3. What is the most reliable method to elute a protein from a Native-PAGE gel while preserving its function?

Electrophoretic elution is highly effective. It uses an electric field to drive the protein out of the gel slice into a small volume of a compatible buffer, minimizing dilution and handling time. As an alternative, the passive "crush and soak" method—where the gel slice is fragmented and incubated in elution buffer—can also be used, often assisted by vortexing and sonication [43].

4. How can I improve the resolution of my Native-PAGE to get sharper bands for excision?

- Gel Percentage: Optimize the acrylamide concentration of your separating gel. Use lower percentages (e.g., 6-8%) for high molecular weight complexes and higher percentages (10-12%) for smaller proteins [44].

- Sample Preparation: Avoid high salt concentrations (>100 mM) in your sample, as they can cause band spreading and distortion [41]. Dialyze or desalt your sample if necessary.

- Running Conditions: Run the gel at a low voltage and on ice to prevent heat-induced denaturation and band smearing [44].

Experimental Workflow and Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the optimized pathway for recovering functional protein from a Native-PAGE gel and the compatible downstream analyses.

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential reagents and their critical functions for successful Native-PAGE and downstream applications.

Table 2: Key Reagents for Native-PAGE and Downstream Analysis

| Reagent | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Non-denaturing Lysis Buffer (e.g., TSDG or OK Buffer [46]) | Extracts proteins while preserving protein complexes, enzymatic activity, and bound cofactors (e.g., metal ions). | Must contain protease inhibitors. Avoid ionic detergents like SDS. Aliquot and limit freeze-thaw cycles to maintain integrity of components like DTT and ATP [46]. |

| Native Sample Buffer | Prepares the sample for loading without denaturation. Typically contains Tris, glycerol, and a tracking dye. | Critical: Does not contain SDS, mercaptoethanol, or other reducing/denaturing agents. Do not heat the sample before loading [44]. |

| Tris-Glycine Running Buffer | Provides the ion front and pH environment for electrophoresis. | Standard buffer is 25 mM Tris / 192 mM Glycine, pH ~8.3 [44]. Do not adjust the pH. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Prevents proteolytic degradation of your target protein during and after extraction. | Essential for maintaining sample integrity. Use a fresh cocktail in the lysis buffer [42] [47]. |

| Specialized Substrates (e.g., Suc-LLVY-AMC [46]) | Used for in-gel fluorescent or colorimetric activity assays to detect specific enzymatic function. | The substrate must be compatible with the enzyme's activity and able to penetrate the gel matrix after electrophoresis. |

Specialized Protocols for Membrane Protein Complexes Using SMA-PAGE Technology

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for successful SMA-PAGE experiments, including their specific functions.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Key Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| SMA Copolymers | Amphiphilic polymers that solubilize membrane proteins within native lipid discs (SMALPs) [48] [49]. | Varying S:MA ratios (e.g., 1.4:1 to 3:1) and molecular weights (e.g., 5-10 kDa); choice affects extraction efficiency [49]. |

| Alternative Polymers (e.g., DIBMA) | Gentler, poly(diisobutylene-alt-maleic acid) polymers for extracting more fragile protein complexes [49]. | Different backbone chemistry; often used in screening kits to find optimal polymer for a specific target [49]. |

| Native Gel Electrophoresis System | Separates SMALP-encapsulated protein complexes by size/charge without denaturation [48] [50]. | Requires non-denaturing conditions (e.g., no SDS) to preserve native protein complexes and lipid environment [48]. |

| Mass Spectrometry | Identifies and characterizes proteins and bound lipids within the SMALP nanodisc [48] [50]. | Probes the specific lipid environment surrounding the protein complex after separation [48]. |

| Electron Microscopy (EM) | Visualizes intact membrane protein-SMALPs extracted from gel bands for structural analysis [48] [51]. | Enables direct visualization of the protein complex and its architecture after purification [48]. |

Experimental Workflow: From Membrane to Analysis

The following diagram outlines the core workflow for isolating and analyzing membrane protein complexes using SMA-PAGE technology.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Poor Protein Extraction or Solubilization

Q: I am getting low yields of my target membrane protein after SMA extraction. What could be the cause?

- A: Low yields can often be attributed to using a suboptimal SMA polymer. SMA polymers come in different styrene-to-maleic acid (S:MA) ratios and molecular weights, which can significantly impact extraction efficiency for different membrane proteins [49]. It is recommended to screen multiple polymers (e.g., SMALP 140 with a 1.4:1 ratio vs. SMALP 300 with a 3:1 ratio) to identify the best one for your specific target [49]. Furthermore, ensure that the pH and buffer composition are suitable for the polymer you are using, as SMA function is pH-dependent [51] [50].

Q: My protein complex appears to be disrupted during extraction.

- A: Traditional detergents are known to denature proteins or dissociate complexes. While SMA polymers are gentler, some delicate complexes may still be sensitive. Consider switching to an even milder polymer like DIBMA (diisobutylene-maleic acid copolymer), which has a different backbone structure and is reported to be less disruptive to some protein complexes and their lipid environments [49] [51].

Issues with SMA-PAGE Electrophoresis and Analysis

Q: I see smearing or poor resolution of bands on my native gel.

- A: Smearing can indicate instability of the protein complex or suboptimal gel conditions. Ensure that all steps of the native gel electrophoresis are performed under non-denaturing conditions (e.g., no SDS, correct pH, and temperature) [48] [50]. The method is designed to separate complexes based on their native charge and size, so maintaining native state buffers is critical [52].

Q: How can I confirm the identity and oligomeric state of the protein in a specific gel band?

- A: The SMA-PAGE method is highly complementary to several techniques. You can:

- Extract the SMALP-containing band from the gel [48].

- Use immunoblotting with target-specific antibodies on a parallel gel to confirm identity [48] [53].

- For oligomeric state, the migration distance on the native gel provides an excellent measure of the protein's quaternary structure, which can be compared to standards [48]. Furthermore, the extracted SMALPs can be directly visualized for size and shape using electron microscopy [48] [51].

- A: The SMA-PAGE method is highly complementary to several techniques. You can:

Optimizing for Downstream Structural Biology

- Q: Can SMALP-extracted proteins be used directly for high-resolution structural studies?

- A: Yes. The Native Cell Membrane Nanoparticle (NCMN) system, an evolution of the SMALP method, has been successfully used to solve high-resolution structures via cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) [51]. The key is using a well-optimized protocol, including a single-step affinity purification, which has yielded structures at resolutions as high as 3.0 Å [51]. This demonstrates the power of the system for providing structurally intact samples.

Solving Common Recovery Challenges and Maximizing Protein Yield

Addressing Poor Elution Efficiency and Low Protein Yield

FAQ: Why is my protein yield low after elution from a native PAGE gel?

Several factors can contribute to low protein yield during elution from native PAGE gels. The table below summarizes common causes and their solutions.

| Cause of Low Yield | Underlying Reason | Troubleshooting Action |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Aggregation | Proteins aggregate in the gel matrix, preventing diffusion into the elution buffer [54]. | Add mild non-ionic detergents (e.g., Triton X-100) or 6–8 M urea to the elution buffer to improve solubility [25]. |

| Inefficient Elution Method | Passive diffusion is too slow, leading to protein degradation or low recovery [16]. | Use electro-elution for more efficient and rapid protein recovery from gel slices [16]. |

| Improper Gel Staining | Some staining methods (e.g., certain silver stains) chemically crosslink and immobilize proteins within the gel [55]. | Use MS-compatible stains like Coomassie, zinc, or SYPRO Ruby, which do not permanently modify proteins [55]. |

| Incorrect Buffer Conditions | The pH or ionic strength of the elution buffer is unsuitable for the target protein's stability and solubility [16]. | Optimize elution buffer pH and composition; include stabilizing agents like glycerol or salts specific to your protein [16]. |

FAQ: How does the choice of gel stain impact my protein recovery?

The staining method you choose directly impacts whether your protein can be eluted from the gel, as some stains permanently modify proteins. The following table compares common stains and their compatibility with protein recovery.

| Staining Method | Sensitivity (Approx.) | Compatibility with Protein Elution & Downstream Analysis | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coomassie Staining | 5-25 ng [55] | High. Does not permanently chemically modify proteins; fully reversible for recovery and MS analysis [55]. | The simplest and most recommended method when planning to elute functional protein [55]. |

| Zinc Staining | 0.25-0.5 ng [55] | High. Stains the gel background, leaving proteins unmodified. The stain is easily reversed [55]. | Ideal for quick visualization before elution, as it does not stain the protein itself [55]. |

| Fluorescent Staining (e.g., SYPRO Ruby) | 0.25-0.5 ng [55] | High. Most involve dye-binding without chemical reaction, making them compatible with MS and western blotting [55]. | Requires a fluorescence imager for visualization before excision [55]. |