NDR1/2 Kinases in Centrosome Duplication: Regulatory Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications

This article provides a comprehensive review of the established and emerging roles of NDR1/2 kinases in the critical process of centrosome duplication.

NDR1/2 Kinases in Centrosome Duplication: Regulatory Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review of the established and emerging roles of NDR1/2 kinases in the critical process of centrosome duplication. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational knowledge on NDR kinase biology, explores the methodological landscape for studying their function, and discusses troubleshooting for experimental challenges. Furthermore, it validates these findings by situating NDR1/2 within broader signaling networks, including the Hippo pathway, and evaluates their potential as therapeutic targets in cancer, given the direct link between centrosome amplification and genomic instability.

Understanding NDR1/2 Kinases: Core Biology and the Centrosome Connection

The Nuclear Dbf2-related (NDR) kinase family constitutes a structurally and functionally conserved subgroup of the AGC serine/threonine protein kinases, which also includes well-known kinases such as PKA, PKG, and PKC [1] [2]. NDR kinases are evolutionarily conserved from yeast to humans and have been independently implicated in regulating diverse cellular processes including cell cycle progression, transcription, intercellular communication, apoptosis, and stem cell differentiation [1]. In mammals, the NDR kinase subfamily consists of four members: NDR1 (STK38), NDR2 (STK38L), LATS1, and LATS2 [1] [3]. These kinases share characteristic structural features that define their regulatory mechanisms, including an N-terminal regulatory (NTR) domain that binds co-activator proteins and a kinase domain insert that functions as an auto-inhibitory sequence (AIS) [2]. The NDR kinases form the core of the Hippo signaling pathway alongside their upstream activators, the mammalian sterile 20-like kinases (MST1/2), playing essential roles in controlling organ size, cell proliferation, and cell death across species and tissues [1].

Structural Characteristics and Classification

Defining Structural Motifs

NDR kinases possess several defining structural characteristics that facilitate their classification within the AGC kinase group and distinguish them from other kinase families. Like all AGC kinases, NDR kinases require phosphorylation of conserved serine and threonine residues for full activation [2]. However, they also contain two unique primary sequence elements: the N-terminal regulatory (NTR) domain and a distinctive insert between kinase subdomains VII and VIII that serves as an auto-inhibitory sequence [2]. The NTR domain specifically binds MOB (Mps-one binder) co-activator proteins, which releases NDR kinases from autoinhibition and enables autophosphorylation [2]. This activation mechanism is conserved across the NDR kinase family from yeast to mammals and represents a key regulatory checkpoint controlling NDR kinase activity in response to various cellular signals.

Activation Mechanism and Regulation

The activation mechanism of NDR kinases involves a multi-step process requiring coordinated phosphorylation and protein-protein interactions. Structural studies have revealed that the auto-inhibitory sequence within the kinase domain maintains NDR kinases in an inactive state under basal conditions [2]. Activation initiates when MOB proteins bind to the NTR domain, inducing a conformational change that relieves autoinhibition [2]. Subsequently, upstream kinases, particularly the MST kinases (MST1, MST2, and MST3), phosphorylate conserved residues in the hydrophobic motif of NDR kinases, leading to full catalytic activation [4]. This precise regulatory mechanism allows NDR kinases to integrate signals from various pathways and respond appropriately to cellular cues, positioning them as crucial signaling nodes in multiple biological processes.

Evolutionary Conservation Across Species

NDR Kinase Orthologs

The NDR kinase family demonstrates remarkable evolutionary conservation across diverse species, with orthologs identified in organisms ranging from yeast to mammals. The table below summarizes the key NDR kinase orthologs and their taxonomic distribution:

Table 1: Evolutionary Conservation of NDR Kinase Family Members

| Protein | Gene | Taxonomy | Cellular Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| NDR1/NDR2, LATS1/LATS2 | STK38/STK38L, LATS1/LATS2 | Mammals | Centrosome duplication, cell cycle regulation, Hippo signaling |

| Tricornered (Trc), Warts (Wts) | trc, wts | Drosophila melanogaster | Cell morphogenesis, proliferation, apoptosis |

| SAX-1, WARTS | sax-1, wts-1 | Caenorhabditis elegans | Cell division, morphogenesis |

| CBK1, DBF20, DBF2 | CBK1, DBF20, DBF2 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Mitotic exit, polarized growth |

| orb6, sid2 | orb6, sid2 | Schizosaccharomyces pombe | Cell polarity, cytokinesis |

| COT1 | cot-1 | Neurospora crassa | Hyphal growth, morphogenesis |

| Ukc1 | ukc1 | Ustilago maydis | Fungal development |

Functional Conservation and Divergence

Despite structural similarities, NDR kinases have evolved distinct yet partially overlapping functions across species. In yeast, two distinct NDR signaling pathways exist: the Mitotic Exit Network (MEN) and the Regulation of Ace2 and polarized Morphogenesis (RAM) network [5]. The MEN pathway, represented by kinases such as Dbf2p in S. cerevisiae and Sid2p in S. pombe, regulates mitotic exit and cytokinesis [5]. In contrast, the RAM pathway, including Cbk1p in S. cerevisiae and Orb6p in S. pombe, controls polarized cell growth, morphogenesis, and vesicle trafficking [5]. In mammals, this functional divergence is reflected in the division between LATS1/2 kinases (core components of the canonical Hippo pathway, orthologous to yeast MEN) and NDR1/2 kinases (components of a non-canonical Hippo pathway, orthologous to yeast RAM) [5]. This evolutionary conservation highlights the fundamental importance of NDR kinases in essential cellular processes throughout eukaryotic evolution.

NDR Kinases in Centrosome Duplication

Centrosomal Localization and Function

A key functional role of mammalian NDR kinases, particularly relevant to the context of this thesis, is their regulation of centrosome duplication. Research has demonstrated that a subpopulation of endogenous NDR kinase localizes to centrosomes in a cell-cycle-dependent manner [6]. This centrosomal association is functionally significant, as experimental evidence has established that NDR kinases directly contribute to the control of centrosome duplication. Overexpression of wild-type NDR kinase induces centrosome overduplication in a kinase-activity-dependent manner, while expression of kinase-dead NDR mutants or depletion of NDR via RNA interference negatively impacts centrosome duplication [6]. Importantly, targeting NDR specifically to the centrosome is sufficient to generate supernumerary centrosomes, indicating that the centrosomal pool of NDR regulates this process [6].

Molecular Mechanisms and CDK2 Integration

The molecular mechanism through which NDR kinases regulate centrosome duplication involves integration with core cell cycle machinery. Studies have revealed that NDR-driven centrosome duplication requires Cdk2 activity, and conversely, Cdk2-induced centrosome amplification is impaired upon reduction of NDR activity [6]. This functional interdependence suggests that NDR kinases and Cdk2 operate in a coordinated pathway to ensure proper centrosome duplication. The discovery that NDR kinases are upregulated in certain cancer types, combined with the established link between centrosome overduplication and cellular transformation, provides a potential molecular connection between NDR kinase dysregulation and cancer development [6]. This centrosome duplication function represents one of the first clearly defined biological roles for mammalian NDR1/2 kinases and continues to be an active area of investigation.

Table 2: Experimental Evidence for NDR Kinase Role in Centrosome Duplication

| Experimental Approach | Key Finding | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Endogenous localization | NDR localizes to centrosomes in cell-cycle-dependent manner | Establishes spatial regulation of NDR function |

| Overexpression studies | Wild-type NDR causes centrosome overduplication | Demonstrates sufficiency for centrosome amplification |

| Kinase-dead mutants | Dominant-negative NDR inhibits centrosome duplication | Confirms kinase activity requirement |

| RNA interference | NDR depletion blocks centrosome duplication | Establishes necessity for normal duplication |

| Centrosome-targeting | Centrosomal NDR sufficient for overduplication | Localized activity drives centrosome function |

| Cdk2 inhibition | Blocks NDR-driven centrosome overduplication | Places NDR upstream of cell cycle machinery |

Research Reagent Solutions for Centrosome Duplication Studies

The investigation of NDR kinase function in centrosome duplication relies on specific research reagents and methodologies. The following table outlines key experimental tools and their applications in this research domain:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying NDR Kinases in Centrosome Duplication

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Experimental Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression constructs | Wild-type NDR1/2, kinase-dead NDR (K118R), centrosome-targeted NDR | Functional manipulation of NDR activity | Determine sufficiency/necessity of NDR in centrosome duplication |

| RNA interference tools | siRNA/shRNA against NDR1/2, inducible shRNA systems | Depletion of endogenous NDR | Assess consequences of NDR loss-of-function |

| Cell line models | HeLa, U2OS with tetracycline-inducible shRNA, NDR rescue constructs | Controlled modulation of NDR expression | Enable reversible knockdown and complementation studies |

| Pharmacological inhibitors | Cdk2 inhibitors, Okadaic acid, MG132 | Pathway manipulation and protein stabilization | Dissect NDR relationship to cell cycle and degradation pathways |

| Detection antibodies | Anti-NDR1/2, anti-T444-P, anti-centrosomal markers | Localization and activity assessment | Visualize centrosome association and activation state |

| Cell cycle synchronization | Nocodazole, thymidine | Cell cycle phase enrichment | Study cell-cycle-dependent NDR regulation |

Methodologies for Investigating NDR Kinase Function

Centrosome Duplication Assay Protocol

A critical experimental approach for studying NDR kinase function in centrosome duplication involves the following methodology:

Cell Synchronization and Transfection: Synchronize cells in G1/S phase using thymidine block or similar methods. Transfect with NDR expression constructs (wild-type, kinase-dead, or centrosome-targeted variants) using appropriate transfection reagents (e.g., Fugene 6, Lipofectamine 2000) [4].

Centrosome Visualization and Quantification: After 48-72 hours, fix cells and stain with antibodies against centrosomal markers (e.g., γ-tubulin, pericentrin) and DNA dyes (e.g., DAPI) [6]. Score centrosome numbers in multiple cells (typically >100) across multiple experiments.

Functional Validation: For RNAi approaches, transfert cells with NDR-specific siRNA or establish stable cell lines with inducible shRNA systems. Validate knockdown efficiency by immunoblotting and assess centrosome numbers following NDR depletion [6] [4].

Cell Cycle Integration: Assess requirement for Cdk2 activity using pharmacological inhibitors (e.g., roscovitine) or dominant-negative Cdk2 constructs in conjunction with NDR manipulation [6].

This methodology has been instrumental in establishing the essential role of NDR kinases in centrosome duplication and continues to be refined for more precise investigation of this process.

NDR Kinase Activation and Signaling Analysis

To complement centrosome duplication assays, researchers have developed specific protocols for analyzing NDR kinase activation and downstream signaling:

Kinase Activity Assessment: Monitor NDR activation status using phospho-specific antibodies against the hydrophobic motif phosphorylation site (Thr444 in NDR1, Thr442 in NDR2) [4]. Combine with immunoprecipitation of NDR kinases for in vitro kinase assays using specific substrates.

Upstream Activator Identification: Identify relevant upstream MST kinases (MST1, MST2, or MST3) using specific siRNA-mediated knockdown followed by assessment of NDR phosphorylation and centrosome phenotype [4].

Downstream Substrate Characterization: Identify and validate physiological NDR substrates through phosphoproteomic approaches, in vitro phosphorylation assays, and phospho-specific antibody development, as demonstrated for the cyclin-Cdk inhibitor p21 [4].

These methodologies provide a comprehensive toolkit for dissecting NDR kinase function in centrosome duplication and related cellular processes, enabling researchers to establish precise mechanistic relationships within this important signaling pathway.

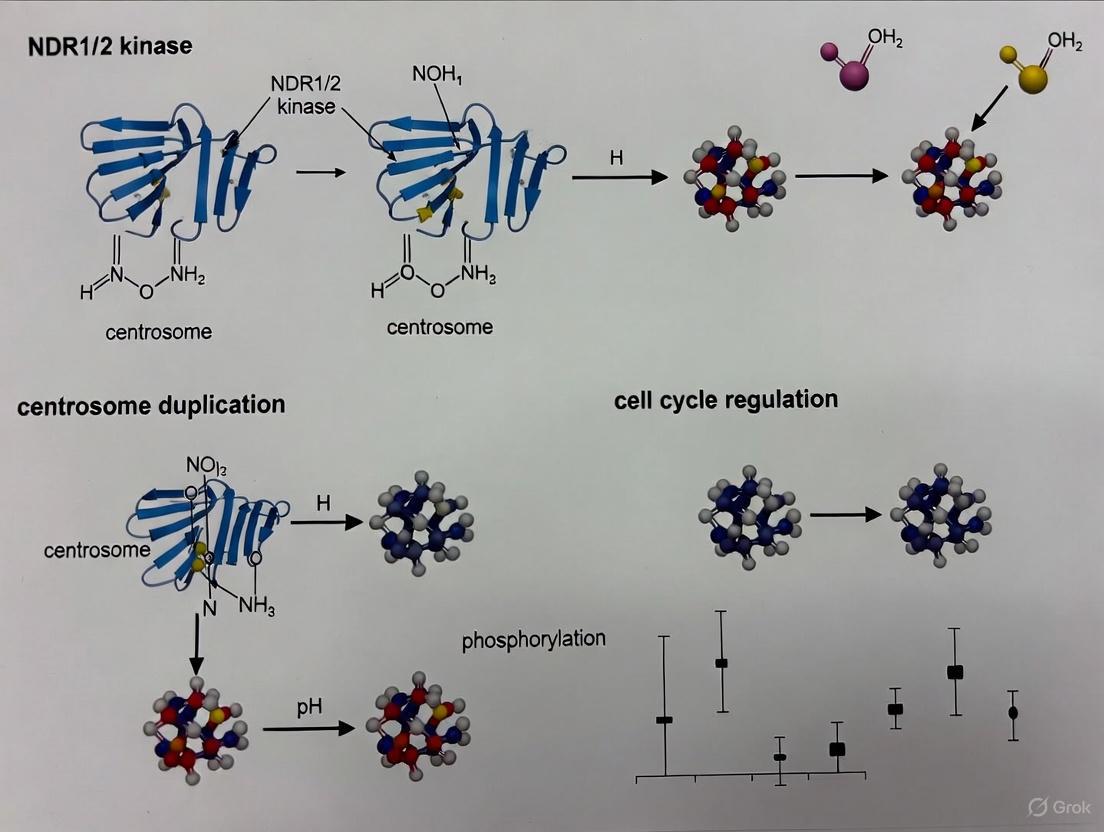

Visualizing NDR Kinase Signaling Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the classification, evolutionary relationships, and functional roles of NDR kinases in centrosome duplication, created using DOT language with specified color palette.

Diagram 1: NDR Kinase Evolutionary Relationships

Diagram 2: NDR Kinase Function in Centrosome Duplication

Nuclear Dbf2-related (NDR) kinases 1 and 2 are serine/threonine kinases belonging to the AGC kinase family that function as critical regulators of centrosome duplication, cell cycle progression, and cellular homeostasis. Their activity is tightly controlled through a sophisticated regulatory mechanism involving phosphorylation at specific residues and interaction with MOB (Mps one binder) co-activators. This technical review comprehensively examines the molecular machinery governing NDR1/2 activation, with particular emphasis on its implications for centrosome duplication research. We detail the specific phosphorylation events required for kinase activation, the structural and functional roles of MOB proteins in regulating NDR1/2, and provide experimentally validated methodologies for investigating this signaling axis. The content is structured to serve as a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals investigating Hippo signaling and cell cycle regulation.

The NDR kinase family represents a highly conserved subgroup of AGC kinases with essential functions in cell proliferation, apoptosis, centrosome biology, and morphological control. In mammals, this family includes four members: NDR1 (STK38), NDR2 (STK38L), LATS1, and LATS2 [7] [8]. These kinases share a conserved structure featuring an N-terminal regulatory domain (NTR), a central catalytic domain, and a C-terminal hydrophobic motif (HM) [9]. While initially identified as nuclear kinases, subsequent research has revealed that both active and inactive NDR isoforms display predominantly cytoplasmic localization with specific recruitment to membranous structures upon activation [10].

Within the context of centrosome duplication research, NDR1/2 kinases have emerged as critical regulators of the centrosome cycle. Proper centrosome duplication is fundamental for genomic stability, and errors in this process can lead to mitotic defects and carcinogenesis [7] [4]. NDR kinases localize to centrosomes in a cell cycle-dependent manner and their activity is required for normal centrosome duplication during S-phase [7]. Furthermore, aberrant NDR signaling has been implicated in centrosome overduplication phenotypes, establishing these kinases as essential guardians of centrosome number regulation [11].

Molecular Mechanisms of NDR1/2 Activation

Phosphorylation-Based Activation Mechanism

NDR kinase activity is principally regulated through phosphorylation at two conserved residues: a threonine residue in the activation segment (T-loop) and a threonine residue in the hydrophobic motif at the C-terminus.

Table 1: Key Phosphorylation Sites Regulating NDR1/2 Kinase Activity

| Kinase | T-loop Site | Hydrophobic Motif Site | Upstream Kinase | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NDR1 | Ser281 | Thr444 | MST1/2/3 | Full kinase activation [10] [8] |

| NDR2 | Ser282 | Thr442 | MST1/2/3 | Full kinase activation [10] [8] |

Phosphorylation of these two sites occurs through distinct mechanisms. Hydrophobic motif phosphorylation (Thr444 in NDR1, Thr442 in NDR2) is mediated by upstream kinases from the mammalian STE20-like family (MST1/2/3) [8]. In contrast, phosphorylation of the activation segment (Ser281 in NDR1, Ser282 in NDR2) occurs primarily through autophosphorylation, though this process is dramatically enhanced by MOB protein binding [10] [11]. Importantly, these phosphorylation events are counteracted by protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), demonstrating that the phosphorylation status of NDR kinases represents a dynamic balance between kinase and phosphatase activities [10] [8].

Experimental evidence indicates that membrane recruitment of NDR kinases represents a potent activation mechanism. Artificial targeting of NDR to membranes results in constitutive kinase activation through phosphorylation at both regulatory sites, establishing subcellular localization as a critical regulatory layer in NDR signaling [10].

MOB Co-activators in NDR Regulation

MOB proteins function as essential co-activators of NDR kinases, with the human genome encoding six distinct MOB family members (MOB1A, MOB1B, MOB2, MOB3A, MOB3B, and MOB3C) [11]. These proteins exhibit distinct binding specificities and functional consequences for NDR kinase regulation.

Table 2: MOB Protein Interactions with NDR1/2 Kinases

| MOB Protein | Binding to NDR1/2 | Effect on Kinase Activity | Cellular Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOB1A/B | Yes | Activation | Promotes apoptosis, centrosome duplication [11] |

| MOB2 | Yes | Inhibition | Competes with MOB1A/B, negative regulation [11] |

| MOB3A/B/C | No | No effect | Unknown in NDR context [11] |

MOB1A and MOB1B bind directly to the N-terminal regulatory domain of NDR kinases through a conserved interaction interface. This binding stimulates NDR autophosphorylation on the activation segment (Ser281/282) and facilitates phosphorylation of the hydrophobic motif (Thr444/442) by MST kinases [10] [11]. Structural studies indicate that MOB1 proteins function as scaffolds that stabilize NDR kinases in an active conformation.

In contrast, MOB2 employs a different binding mode despite interacting with the same general region of NDR kinases. MOB2 preferentially binds to unphosphorylated NDR and competes with MOB1A/B for NDR binding. Consequently, MOB2 overexpression inhibits NDR activation, while RNAi-mediated depletion of MOB2 enhances NDR kinase activity, establishing MOB2 as a physiological negative regulator of NDR signaling [11].

Strikingly, membrane targeting of MOB1 proteins alone is sufficient to robustly activate NDR kinases, indicating that MOB proteins not only directly stimulate NDR kinase activity but also regulate their subcellular localization [10]. This membrane recruitment mechanism appears to be physiologically relevant, as evidenced by experiments using a chemically inducible membrane-targeted MOB1 construct that triggers rapid NDR phosphorylation and activation within minutes of membrane association [10].

Experimental Analysis of NDR Activation

Methodologies for Monitoring NDR Activation

Kinase Activity Assays: Immunocomplex kinase assays represent the gold standard for directly measuring NDR kinase activity. In this protocol, NDR kinases are immunoprecipitated from cell lysates using specific antibodies (e.g., anti-NDR1/2 CT) and incubated with recombinant substrates (such as the C-terminal fragment of p21) in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP [4]. Reactions are terminated by adding SDS sample buffer, and phosphorylation is visualized by autoradiography after SDS-PAGE separation. As an alternative approach, commercial kinase activity assays using specific peptide substrates can be employed for quantitative measurements.

Phospho-Specific Antibody Detection: Phosphorylation-specific antibodies enable direct assessment of NDR activation status. Antibodies recognizing phosphorylated Thr444/442 (hydrophobic motif) and Ser281/282 (activation segment) have been developed and validated [10] [4]. For Western blot analysis, cells are lysed in RIPA buffer supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitors. Proteins are separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, and probed with phospho-specific antibodies. To confirm specificity, identical samples should be probed in the presence of competing phospho- and dephospho-peptides [10].

Subcellular Localization Studies: Inducible membrane translocation assays provide robust experimental systems for investigating NDR activation. A chemically inducible membrane-targeted hMOB1 construct can be generated by fusing hMOB1A with the C1 domain of PKCα (amino acids 26-162), which binds phorbol esters such as 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA) [10]. Transfected cells are serum-starved overnight before stimulation with 100 ng/ml TPA. Membrane translocation and NDR activation can be monitored by live-cell imaging and Western blotting with phospho-specific antibodies at various time points after stimulation.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for NDR1/2 Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Application & Function |

|---|---|---|

| Activation Chemicals | Okadaic acid (1 μM), 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA, 100 ng/ml) | PP2A inhibition, membrane translocation [10] [4] |

| Expression Plasmids | pcDNA3-HA-NDR1/2, mp-HA-NDR1/2 (membrane-targeted), NLS-HA-NDR1/2 (nuclear) | Subcellular targeting studies [10] |

| Antibodies | Anti-T444-P, Anti-S281-P, Anti-NDR CT, Anti-HA (12CA5, Y-11) | Activation status detection, immunoprecipitation [10] [4] |

| Cell Lines | COS-7, HEK 293, U2-OS, HeLa | Model systems for NDR functional studies [10] [4] [11] |

| Kinase Tools | MST1/2/3 expression constructs, MOB1A/B and MOB2 plasmids | Upstream pathway modulation [8] [11] |

Signaling Pathway Visualization

Figure 1: NDR1/2 Activation Pathway and Connection to Centrosome Function. The diagram illustrates the phosphorylation cascade regulating NDR kinase activity, highlighting the opposing effects of MOB co-activators and the connection to centrosome biology through relevant substrates.

Connection to Centrosome Duplication Research

Within the context of centrosome duplication, NDR kinases function as critical regulators that ensure proper centrosome copy number through multiple mechanisms. First, NDR kinases control G1/S cell cycle progression via an MST3-NDR-p21 axis, directly phosphorylating the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 on Ser146 [4]. This phosphorylation event stabilizes p21 by preventing its proteasomal degradation, thereby influencing cyclin-CDK activity and cell cycle progression—a prerequisite for proper centrosome duplication.

Second, NDR kinases localize to centrosomes in a cell cycle-dependent manner and their activity is required for normal centrosome duplication during S-phase [7]. Experimental evidence demonstrates that interference with NDR function leads to centrosome overduplication phenotypes, particularly evident in cells arrested in S-phase with aphidicolin [11]. This centrosome amplification phenotype establishes NDR kinases as essential guardians of centrosome number regulation.

The functional outcome of NDR signaling in centrosome biology is regulated by the balance between activating (MOB1) and inhibitory (MOB2) co-factors. In experimental settings, overexpression of MOB2 disrupts normal NDR function in centrosome duplication, leading to overduplication phenotypes [11]. Conversely, RNA interference-mediated depletion of MOB2 enhances NDR activity and is predicted to restrict centrosome duplication, though comprehensive studies directly linking MOB2 modulation to centrosome phenotypes remain an area of active investigation.

Technical Protocols for Centrosome Studies

Centrosome Overduplication Assay

To evaluate NDR function in centrosome duplication, researchers can employ a well-established centrosome overduplication assay [11]. The experimental workflow proceeds as follows:

Cell Synchronization: Plate U2-OS or HeLa cells at consistent confluence (3 × 10^5 cells/6-cm dish) and transfect with appropriate NDR or MOB expression constructs using Fugene 6 or Lipofectamine 2000 according to manufacturer specifications.

S-phase Arrest: At 24 hours post-transfection, arrest cells in S-phase by treating with 5 μg/mL aphidicolin for 48 hours. This extended S-phase arrest induces centrosome overduplication in cells with compromised NDR function.

Immunofluorescence Staining: Fix cells with methanol at -20°C for 10 minutes, permeabilize with 0.5% Triton X-100, and block with 3% BSA in PBS. Stain centrosomes with mouse anti-γ-tubulin antibody (1:1000) and appropriate secondary antibodies (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse, 1:2000). Counterstain DNA with DAPI (0.5 μg/mL) to visualize nuclei.

Quantification: Score centrosome numbers in at least 100 cells per condition using fluorescence microscopy. Cells with more than two γ-tubulin-positive foci are considered to contain supernumerary centrosomes. Statistical analysis can be performed using chi-square tests comparing experimental conditions to appropriate controls.

This assay provides a robust readout of NDR kinase function in centrosome number control, with particular utility for evaluating the functional consequences of MOB protein manipulation or NDR phosphorylation site mutations.

Subcellular Fractionation and Localization Analysis

To investigate the dynamic redistribution of NDR kinases during activation, subcellular fractionation protocols can be employed:

Membrane Translocation Assay: Transfect COS-7 cells with membrane-targeted NDR or MOB constructs (created by fusing the myristoylation/palmitylation motif of Lck tyrosine kinase - MGCVCSSN - to NDR or MOB cDNAs) [10]. Include controls with non-targeted versions.

Cellular Fractionation: Harvest cells 24-48 hours post-transfection and resuspend in hypotonic lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, protease and phosphatase inhibitors). Dounce homogenize and centrifuge at 1000 × g to remove nuclei. Collect the supernatant and centrifuge at 100,000 × g for 1 hour to separate membrane (pellet) and cytosolic (supernatant) fractions.

Analysis: Solubilize membrane fractions in RIPA buffer and analyze equal protein amounts from each fraction by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. Probe with anti-NDR and anti-HA antibodies to detect transfected constructs. Use markers such as Na+/K+ ATPase (membrane) and GAPDH (cytosol) to validate fractionation efficiency.

This protocol enables quantitative assessment of NDR redistribution following experimental manipulations and provides insight into the spatial regulation of NDR kinase activity.

The molecular regulation of NDR1/2 kinases through phosphorylation and MOB co-activators represents a sophisticated control mechanism that integrates multiple cellular signals to coordinate fundamental processes including centrosome duplication. The experimental methodologies outlined in this review provide robust tools for investigating this regulation in diverse cellular contexts. As research in this field advances, a more comprehensive understanding of NDR signaling may yield novel therapeutic approaches for cancers characterized by centrosome amplification and genomic instability.

The precise subcellular localization of protein kinases is a critical determinant of their specific biological functions. For the Nuclear Dbf2-related (NDR) kinases NDR1 and NDR2, a distinct pool localized at the centrosome is essential for regulating a fundamental cellular process: centrosome duplication [12] [2]. This centrosome-associated function positions NDR kinases as crucial players in maintaining genomic integrity, and their dysregulation presents a potential molecular link to cancer [12]. This whitepaper delves into the mechanisms defining the centrosome-associated pool of NDR kinase, its functional role in the centrosome cycle, and the experimental methodologies that underpin this key finding within the broader context of NDR1/2 kinase research.

The Centrosomal Localization of NDR Kinases

The centrosome serves as the primary microtubule-organizing center in animal cells and must duplicate precisely once per cell cycle to ensure mitotic fidelity. A key breakthrough was the discovery that a subpopulation of endogenous NDR1/2 kinases localizes to centrosomes in a cell-cycle-dependent manner [12] [2].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Centrosome-Associated NDR Kinase

| Feature | Description | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Localization Pattern | A distinct subpopulation at the centrosome. | Immunofluorescence staining [12]. |

| Cell Cycle Dependence | Localization varies across the cell cycle. | Cell cycle synchronization experiments [12]. |

| Functional Pool | The centrosomal pool is sufficient to influence duplication. | Forced centrosomal targeting (e.g., via PCM1) [12]. |

| Dependency | Centrosome overduplication requires NDR kinase activity. | Kinase-dead (KD) mutant acts as a dominant-negative [12]. |

The centrosomal localization of NDR kinases is not static but is regulated during cell division. This dynamic association ensures that NDR kinase activity is spatially and temporally coordinated to control the centrosome duplication cycle accurately [12].

Functional Role in Centrosome Duplication

The functional significance of the centrosomal NDR pool was elucidated through a series of gain-of-function and loss-of-function experiments. These studies established a direct role for NDR kinases in controlling the initiation of centrosome duplication.

Table 2: Functional Evidence for NDR in Centrosome Duplication

| Experimental Approach | Observed Phenotype | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| NDR Overexpression | Centrosome overduplication (>2 centrosomes per cell) [12]. | Excess NDR activity drives multiple rounds of duplication. |

| siRNA Knockdown | Inhibition of centrosome duplication (<2 centrosomes per cell) [12]. | NDR activity is necessary for the duplication process. |

| Kinase-Dead (KD) Mutant | Negatively affects centrosome duplication [12]. | NDR's catalytic function is required for its role in duplication. |

| Cdk2 Requirement | NDR-driven overduplication requires Cdk2 activity [12]. | NDR functions in a pathway that integrates with the core cell cycle machinery. |

Mechanistically, NDR-driven centrosome duplication is integrated with the core cell cycle engine. The process requires the activity of Cdk2, a central regulator of S-phase entry, and conversely, Cdk2-induced centrosome amplification is impaired when NDR activity is reduced [12]. This places the centrosomal pool of NDR kinase as a key node linking cell cycle progression to the duplication of the centrosome.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The seminal findings on centrosomal NDR were established using a suite of standard cell biological and molecular techniques. Below is a detailed methodology for the key experiments.

Protocol 1: Assessing Centrosome Association via Immunofluorescence

This protocol is used to visualize the subcellular localization of endogenous or exogenously expressed NDR kinase.

- Cell Culture and Seeding: Grow appropriate cells (e.g., U2OS, HeLa) on sterile glass coverslips in a culture dish until they are 50-70% confluent.

- Cell Fixation: Aspirate the culture medium and fix cells with pre-warmed 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 minutes at room temperature.

- Permeabilization and Blocking: Permeabilize cells with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes, then block with a solution of 5% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) in PBS for 1 hour to reduce non-specific antibody binding.

- Antibody Staining: Incubate cells with primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. Key antibodies include:

- Anti-NDR1/2: To detect the kinase.

- Anti-γ-tubulin or Anti-pericentrin: Well-established centrosomal markers.

- After PBS washes, incubate with appropriate fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488, 555) for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Microscopy and Analysis: Mount coverslips and image using a confocal or high-resolution fluorescence microscope. Co-localization of NDR and γ-tubulin signals confirms centrosome association [12].

Protocol 2: Functional Analysis via RNA Interference (RNAi)

This protocol is used to deplete endogenous NDR and assess the functional consequence on centrosome number.

- siRNA Design and Transfection: Design or purchase validated siRNA oligonucleotides targeting the mRNA sequences of NDR1 and/or NDR2. A non-targeting (scrambled) siRNA should be used as a negative control.

- Cell Transfection: Transfect cells with siRNAs using a standard transfection reagent (e.g., Lipofectamine RNAiMAX) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

- Incubation and Fixation: Allow 48-72 hours for effective protein knockdown. Subsequently, fix the cells and process for immunofluorescence as described in Protocol 1.

- Phenotypic Scoring: Count the number of centrosomes (γ-tubulin foci) per cell in both control and NDR-depleted populations. A significant increase in cells with fewer than two centrosomes indicates a failure in duplication [12].

Protocol 3: Centrosome Overduplication Assay

This protocol tests the sufficiency of NDR activity to drive centrosome overduplication.

- Construct Generation: Clone cDNA for wild-type (WT) and kinase-dead (KD) NDR1/2 into mammalian expression vectors.

- Cell Transfection: Transfect cells with the constructed plasmids.

- Cell Cycle Arrest: To uncouple centrosome duplication from DNA replication and mitosis, arrest cells at the G1/S boundary using a double thymidine block or treatment with hydroxyurea.

- Analysis: After release from the block for a time sufficient for centrosome duplication (e.g., 24 hours), process cells for immunofluorescence. An increased percentage of cells with more than two centrosomes upon WT-NDR overexpression, but not with KD-NDR, confirms its role in driving the process [12].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Relationships

The centrosomal function of NDR kinases is part of a broader regulatory network that controls organ size and cell proliferation, known as the Hippo pathway, and intersects with core cell cycle regulators.

Diagram 1: NDR regulation and centrosome function. NDR kinases are activated by Hippo pathway kinases (MST1/2, MST3) and the co-activator MOB1. A cell-cycle-regulated pool localizes to the centrosome, where it functions alongside Cdk2 to promote centriole duplication.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for studying NDR. A logical flow for investigating NDR kinase function at the centrosome, encompassing loss-of-function, gain-of-function, and localization studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Progress in defining the centrosomal role of NDR kinase has relied on a specific set of molecular and chemical tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Centrosomal NDR

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Purpose | Key Application in NDR Research |

|---|---|---|

| siRNA / shRNA | Targeted degradation of specific mRNA transcripts. | To knock down endogenous NDR1/2 and observe centrosome duplication defects [12]. |

| Kinase-Dead (KD) Mutant | A catalytically inactive version that acts as a dominant-negative. | To compete with and inhibit the function of endogenous NDR kinase [12] [13]. |

| Constitutively Active (CA) Mutant | A mutant with enhanced or unregulated kinase activity. | To drive centrosome overduplication and study hyperactive phenotypes [12]. |

| Centrosomal Marker Antibodies | Proteins that reliably label the centrosome (e.g., γ-tubulin, pericentrin). | To identify centrosomes and quantify their number in immunofluorescence assays [12]. |

| Cell Cycle Inhibitors | Chemical agents that synchronize the cell cycle (e.g., thymidine, hydroxyurea). | To arrest cells at G1/S and specifically study centrosome duplication independent of mitosis [12]. |

| Okadaic Acid (OA) | A potent inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A). | Used to experimentally activate NDR kinases by preventing their dephosphorylation [2] [8]. |

The definition of a centrosome-associated pool of NDR kinase has provided a molecular framework for understanding the regulated process of centrosome duplication. The experimental evidence firmly establishes that the spatial control of NDR kinase activity at this organelle is indispensable for genomic stability. Given that centrosome overduplication is a hallmark of many cancers, the findings reviewed here underscore the potential of the NDR-centrosome axis as a target for therapeutic intervention in oncology drug development. Future research aimed at identifying the specific centrosomal substrates of NDR kinases will be crucial for completing this mechanistic picture.

The NDR (nuclear Dbf2-related) kinase family, a subgroup of the AGC family of serine/threonine kinases, is highly conserved from yeast to humans. Mammalian cells express two primary NDR kinases, NDR1 and NDR2 (also known as STK38 and STK38L, respectively), which have emerged as critical regulators of essential cellular processes such as mitotic exit, cell polarity, apoptosis, and cell cycle progression [2] [14]. A pivotal breakthrough in understanding their function was the discovery of their specific, kinase-activity-dependent role in controlling centrosome duplication, a process critical for genomic stability [6]. This whitepaper consolidates the key experimental evidence establishing the fundamental role of NDR kinases in centrosome duplication, providing a resource for researchers and drug development professionals working in cancer biology and cell cycle regulation.

Key Experimental Evidence Linking NDR to Centrosome Duplication

The foundational evidence for NDR's role in centrosome duplication comes from a combination of cell biological, biochemical, and genetic experiments. The table below summarizes the core findings from these key studies.

Table 1: Summary of Key Experimental Evidence for NDR in Centrosome Duplication

| Experimental Approach | Key Finding | Biological Implication | Primary Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subcellular Localization | A subpopulation of endogenous NDR1/2 localizes to centrosomes in a cell-cycle-dependent manner. | NDR kinases are positioned at the correct location and time to directly regulate centrosome function. | [6] |

| Kinase Overexpression | Overexpression of wild-type NDR, but not kinase-dead NDR, induces centrosome overduplication. | NDR kinase activity is both necessary and sufficient to drive the centrosome duplication cycle. | [6] |

| Loss-of-Function (siRNA) | siRNA-mediated depletion of NDR1/2 negatively affects centrosome duplication. | Endogenous NDR activity is required for the normal process of centrosome duplication. | [6] |

| Specific Centrosomal Targeting | Artificial targeting of NDR specifically to the centrosome is sufficient to generate supernumerary centrosomes. | The centrosomal pool of NDR is functionally critical for its role in duplication. | [6] |

| Regulatory Competition | RNAi depletion of the negative regulator hMOB2 results in increased NDR kinase activity and centrosome overduplication. | The NDR-MOB2 interaction is a key regulatory node controlling centrosome number. | [11] |

| Interaction with Cell Cycle Machinery | NDR-driven centrosome duplication requires Cdk2 activity, and Cdk2-induced amplification is impaired upon NDR reduction. | NDR functions in an integrated pathway with core cell cycle regulators to control centrosome copying. | [6] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

To enable replication and further investigation, this section details the methodologies underpinning the critical experiments cited in this review.

Centrosome Localization Assay

This protocol is used to confirm the cell-cycle-dependent recruitment of NDR kinases to centrosomes [6].

- Cell Culture and Synchronization: Human U2-OS or HeLa cells are cultured in standard Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Cells are synchronized at the G1/S boundary using a double thymidine block or arrested in mitosis using nocodazole.

- Immunofluorescence and Microscopy: Cells are plated on coverslips, fixed, and permeabilized. Centrosomes are stained using antibodies against γ-tubulin or pericentrin. Endogenous NDR is detected using specific anti-NDR1/2 antibodies, followed by appropriate fluorescent secondary antibodies (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488 and 594).

- Image Analysis: Colocalization of NDR and γ-tubulin signals is quantified using confocal microscopy and image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ). The intensity of NDR at centrosomes across different cell cycle stages is measured to establish dependency.

Functional Centrosome Overduplication Assay

This assay assesses the functional consequence of perturbing NDR kinase activity on centrosome numbers [6].

- Experimental Perturbation:

- Gain-of-Function: Cells are transfected with plasmids encoding wild-type NDR, a constitutively active NDR mutant, or a kinase-dead (KD) NDR mutant (e.g., K118A for NDR1) as a negative control. A myristoylation/palmitylation motif (e.g., from Lck tyrosine kinase, MGCVCSSN) can be fused to NDR to force its recruitment to membranes or specific organelles.

- Loss-of-Function: Cells are transfected with small interfering RNA (siRNA) or short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting NDR1/2 mRNA. A non-targeting shRNA (e.g., targeting luciferase, shLuc) is used as a control [11] [4].

- Centrosome Quantification: 48-72 hours post-transfection, cells are stained for γ-tubulin and DNA. The number of centrosomes (γ-tubulin foci) in S-phase arrested cells (identified by EdU incorporation or DNA content analysis) is counted. Cells with more than two centrosomes are scored as having overduplicated.

NDR Kinase Activity and Regulatory Protein Interaction Assay

This biochemical protocol is used to measure NDR kinase activity and its modulation by binding partners like MOB proteins [11].

- Kinase Assay: Immunoprecipitated NDR (wild-type or mutant) from cell lysates is incubated in a kinase reaction buffer with a substrate (e.g., myelin basic protein or a purified protein fragment) and [γ-³²P]ATP. The reaction is stopped, and proteins are separated by SDS-PAGE. Kinase activity is quantified by autoradiography to detect radiolabeled phosphate incorporated into the substrate.

- Competition Binding Assay: COS-7 or HEK 293 cells are transfected with plasmids encoding NDR1 and increasing amounts of hMOB1A and hMOB2 [11]. Cell lysates are subjected to co-immunoprecipitation using an anti-NDR1 antibody. The precipitates are immunoblotted for hMOB1A and hMOB2 to assess competitive binding.

Mechanistic Insights and Integrated Signaling

The experimental data support a model where centrosome-associated NDR kinase acts as a key node in a regulated signaling network. The following diagram illustrates this integrated mechanism and the experimental workflow used to decipher it.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

To facilitate further research, the table below catalogs key reagents and their applications for studying NDR kinase function in centrosome biology.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Investigating NDR and Centrosome Duplication

| Reagent / Tool | Function and Application | Example Use Case | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinase-Dead NDR Mutant (e.g., K118A/R) | Acts as a dominant-negative inhibitor; used to assess requirement for NDR catalytic activity in functional assays. | Blocking endogenous NDR function in centrosome duplication assays. | [6] [4] |

| Constitutively Active NDR Mutants | Mimics active NDR; used to probe sufficiency of NDR activation. Includes mutations in the auto-inhibitory segment or hydrophobic motif. | Inducing centrosome overduplication. | [15] [14] |

| siRNA / shRNA vs NDR1/2 | RNAi-mediated knockdown to deplete endogenous NDR protein; used for loss-of-function studies. | Validating the necessity of NDR for accurate centrosome copy number. | [11] [6] [4] |

| Anti-NDR1/2 Antibodies | Detect endogenous protein expression, localization (via immunofluorescence), and phosphorylation status (via Western blot). | Visualizing cell-cycle-dependent centrosome localization. | [6] [4] |

| Anti-γ-Tubulin / Pericentrin Antibodies | Mark centrosomes for quantification and colocalization studies in immunofluorescence assays. | Counting centrosomes in overduplication assays. | [6] |

| Recombinant MOB1 & MOB2 Proteins | Used in binding and kinase assays to dissect the distinct roles of these regulators. MOB2 acts as a competitive inhibitor of MOB1. | Demonstrating competitive binding and its effect on NDR kinase activity. | [11] |

| Centrosome-Targeting NDR Constructs | Artificially recruits NDR specifically to centrosomes; tests the sufficiency of the centrosomal NDR pool. | Confirming that centrosomal NDR drives duplication. | [6] |

The body of evidence firmly establishes NDR1/2 kinases as essential, kinase-activity-dependent regulators of centrosome duplication. Their function is spatially controlled through centrosomal localization and tightly regulated by a network of upstream inputs, including MOB proteins and Cdk2. Given that centrosome overduplication can lead to aneuploidy and genomic instability—hallmarks of cancer [6]—understanding the NDR-centric pathway provides valuable insights for cancer research. Future work aimed at identifying specific NDR substrates at the centrosome and developing small-molecule inhibitors of NDR kinase activity could open new avenues for therapeutic intervention in cancers driven by centrosome amplification.

Linking Centrosome Overduplication to Cellular Transformation and Cancer

Centrosome overduplication, a hallmark of human cancers, represents a critical pathway to chromosomal instability and cellular transformation. This whitepaper examines the molecular mechanisms through which aberrant centrosome duplication drives tumorigenesis, with particular emphasis on the under-investigated role of NDR1/2 kinases. We synthesize current understanding of centrosome amplification mechanisms, their functional consequences in cancer progression, and emerging therapeutic strategies targeting cells with supernumerary centrosomes. Within this framework, we highlight the compelling but underexplored connection between NDR kinase signaling and centrosome duplication, proposing a new dimension to the regulatory circuitry controlling centriole copy number. This technical guide provides detailed experimental methodologies and curated research resources to facilitate investigation into this promising area of cancer biology.

The centrosome, the primary microtubule-organizing center in animal cells, ensures genomic stability by coordinating bipolar spindle formation and faithful chromosome segregation during mitosis. Like DNA replication, centrosome duplication occurs once per cell cycle through a tightly regulated process that produces exactly two centrosomes prior to mitosis. Centrosome amplification (CA), defined by the presence of more than two centrosomes in a cell, is a well-established hallmark of diverse human cancers that promotes chromosomal instability (CIN), aneuploidy, and tumor progression [16] [17].

The link between centrosome abnormalities and cancer was first proposed over a century ago by Theodor Boveri, who observed that dispermic eggs containing multiple centrosomes underwent multipolar mitoses, producing highly aneuploid progeny with disparate developmental characteristics [16]. This foundational observation established the conceptual framework for understanding how extra centrosomes could drive malignant transformation. Contemporary research has validated Boveri's hypothesis, demonstrating that centrosome abnormalities are prevalent across solid tumors and hematological malignancies, including breast, prostate, colon, ovarian, and pancreatic cancers, as well as multiple myeloma and lymphomas [16] [17].

The NDR Kinase Context

The NDR (Nuclear Dbf2-related) kinase family, comprising NDR1 and NDR2 in mammals, represents a crucial but underexplored regulatory axis in centrosome biology. These highly conserved AGC-family serine/threonine kinases have been implicated in diverse cellular processes including proliferation, differentiation, and mitochondrial health [2] [3]. Seminal work identified that the centrosomal subpopulation of human NDR1/2 kinases is required for proper centrosome duplication, with NDR-driven centrosome overduplication potentially contributing to cellular transformation [2]. Despite this compelling association, the molecular mechanisms through which NDR kinases regulate centriole duplication and how their dysregulation might initiate centrosome amplification remain incompletely characterized, presenting a significant knowledge gap in cancer biology.

Molecular Mechanisms of Centrosome Overduplication

Centrosome overduplication occurs when cells accumulate extra centrioles through various mechanisms, with deregulation of the core duplication cycle representing a principal pathway. Understanding these molecular mechanisms is essential for developing targeted therapeutic interventions.

Core Regulatory Machinery of Centriole Duplication

The centrosome duplication cycle is controlled by an evolutionarily conserved core of regulatory proteins that ensure precise once-per-cycle duplication [16] [17]:

Table 1: Core Regulators of Centrosome Duplication

| Regulator | Function | Consequences of Dysregulation |

|---|---|---|

| Plk4 | Master regulator of centriole duplication; serine/threonine kinase that initiates procentriole formation | Overexpression → multiple centrioles; Depletion → reduced centriole numbers [16] |

| SAS-6 | Essential for cartwheel structure establishing 9-fold symmetry of centrioles | Level control critical for proper number; regulated by proteolysis [16] |

| CPAP/SAS-4 | Controls centriole elongation and stabilization | Overexpression increases centriole length and promotes fragmentation [16] |

| CP110/Cep97 | Capping proteins that control centriole length | Dysregulation associated with structural abnormalities [16] |

Plk4 stands as the principal regulator of centriole duplication, with its protein levels tightly controlled through SCFβTrCP/ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis [16]. Elevated Plk4 activity leads to centriole overduplication, while Plk4 depletion reduces centriole numbers [16]. The tumor suppressor p53 indirectly regulates Plk4 by recruiting HDAC repressors to the Plk4 promoter, providing a mechanistic link between p53 loss and centrosome amplification in some cellular contexts [17].

Mechanisms Generating Centrosome Amplification

Multiple pathways can generate supernumerary centrosomes in cancer cells:

- Centriole overduplication: The predominant mechanism in many cancers, characterized by repeated initiation of procentriole formation within a single cell cycle [17]

- Cytokinesis failure: Produces tetraploid cells with doubled centrosome content

- Cell-cell fusion: Generates hybrid cells with combined centrosome complements

- Mitotic slippage: Cells exit mitosis without division, retaining duplicated centrosomes

- De novo centriole assembly: Ectopic formation of centrioles without template

Recent clinical evidence from melanoma specimens indicates that centriole overduplication, rather than cytokinesis failure or cell fusion, represents the primary contributor to centrosome amplification in human tumors [17].

The NDR Kinase Connection

NDR1/2 kinases have been demonstrated to localize to centrosomes and regulate proper centrosome duplication, though their precise molecular functions and substrates in this process remain active areas of investigation [2]. The high degree of homology between NDR1 and NDR2 (87% amino acid identity) suggests functional redundancy, as dual knockout of both kinases is embryonically lethal while individual knockouts are viable [18]. This compensation extends to neuronal development, where only dual deletion of Ndr1/2 in excitatory neurons causes neurodegeneration, while individual knockouts display normal brain development [18].

The molecular activation mechanism of NDR kinases involves binding of MOB (Mps-one binder) co-activator proteins to the N-terminal regulatory domain, which releases the kinases from autoinhibition [2]. Despite advances in understanding their activation, most biological substrates of NDR kinases remain unidentified, presenting a significant opportunity for future research into their centrosomal functions.

Functional Consequences of Centrosome Amplification

Chromosomal Instability and Aneuploidy

Centrosome amplification promotes CIN through several interconnected mechanisms:

- Multipolar spindle formation: Extra centrosomes can organize multipolar spindles during mitosis, resulting in unequal chromosome distribution to daughter cells

- Merotelic attachments: Supernumerary centrosomes increase incidence of improper kinetochore-microtubule attachments where a single kinetochore connects to microtubules from different spindle poles

- Centrosome clustering: Cancer cells develop mechanisms to cluster extra centrosomes into two functional poles, enabling bipolar division but with increased chromosome mis-segregation

The relationship between CA and CIN is well-established in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma (HGSOC), where recent multi-regional analysis of 287 clinical tissues revealed that CA through centriole overduplication is highly recurrent and strongly associated with CIN and genome subclonality [19].

Cancer Cell Survival Mechanisms

To circumvent the potentially lethal consequences of multipolar division, cancer cells employ adaptive strategies:

- Centrosome clustering: Extra centrosomes are clustered into two poles to form pseudobipolar spindles, enabled by proteins including LIMK2, MST4, and NPM1 [20]

- Cell cycle arrest activation: Transient delays to resolve spindle abnormalities

- Selective inheritance: Asymmetric partitioning of damaged components during division

Recent research has identified the LIMK2/MST4/NPM1 pathway as a critical regulator of centrosome clustering. LIMK2 phosphorylates MST4 at threonine 178, activating its kinase function toward NPM1 at threonine 95—a modification essential for centrosome clustering and tumor cell proliferation [20].

Clinical Correlations and Prognostic Significance

Centrosome abnormalities demonstrate significant clinical relevance:

Table 2: Clinical Correlations of Centrosome Amplification in Human Cancers

| Cancer Type | Prevalence of CA | Clinical Correlations |

|---|---|---|

| Invasive Breast Cancer | ~80% of cases [17] | Associated with high grade and metastasis [16] |

| B-acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia | 72% of patients [17] | Correlated with disease progression |

| High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer | 63.5% of cases (n=287) [19] | Associated with CIN but not prognostic for survival [19] |

| Urothelial Cancers | Frequent [16] | Strong predictor of tumor recurrence |

| Head and Neck Tumors | Common [16] | Correlated with lymph node and distant metastasis |

Notably, in HGSOC, CA does not appear to be an independent prognostic marker for overall survival, despite its high prevalence and association with CIN [19]. This highlights the complex relationship between centrosome abnormalities and clinical outcomes, which may be cancer-type specific and influenced by complementary genetic alterations.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Detection and Quantification of Centrosome Amplification

High-Throughput Microscopy-Based Assay for Clinical Tissues Recent advances enable robust quantification of CA in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues [19]:

- Sample Preparation: Section FFPE tissues at 25μm thickness; include normal fallopian tube (negative control) and liver tissues (positive control for CA)

- Immunofluorescence Staining: Label with centrosome markers (γ-tubulin, pericentrin, centrin) and nuclear stain

- Automated Imaging: Acquire images using confocal high-throughput systems (e.g., Operetta CLS) with 50+ non-overlapping random fields per sample

- Image Analysis:

- Identify centrosomes as distinct foci adjacent to nuclei

- Calculate CA score as ratio of centrosome count to nucleus count

- Normalize to median CA score of normal control tissues within cohort

- Statistical Analysis: Account for intratumoral heterogeneity using hierarchical linear mixed models

Electron Microscopy for Ultrastructural Analysis For detailed assessment of centriole structure [21]:

- Fix cells in glutaraldehyde followed by osmium tetroxide

- Embed in resin and prepare 85nm serial sections

- Image with transmission electron microscope

- Measure centriole dimensions and identify structural abnormalities

Functional Validation of Centrosome Duplication Mechanisms

Cell Cycle Arrest Models To determine permissive phases for centrosome duplication [21]:

- G1 Arrest: Release serum-starved G0 cells into 600μM mimosine

- S-phase Arrest: Treat with 10μg/mL aphidicolin or 2mM hydroxyurea

- G2 Arrest: Use topoisomerase inhibitors

- Assess centrosome duplication status via immunofluorescence at intervals

Kinase Functional Studies For investigating NDR kinase roles in centrosome duplication [2] [18]:

- Genetic Manipulation:

- Generate knockout cells using CRISPR/Cas9

- Express wild-type and kinase-dead variants

- Create point mutations in regulatory domains

- Interaction Mapping:

- Perform proximity-dependent biotin identification (BioID)

- Conduct co-immunoprecipitation assays

- Kinase Activity Assessment:

- In vitro kinase assays with purified components

- Phosphospecific antibody development for substrates

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Centrosome Duplication Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Line Models | CHO-K1, CHEF IIC9, KYSE series (esophageal), DT40 (vertebrate) [21] [20] | Centrosome duplication studies in different genetic backgrounds |

| Centrosome Markers | γ-tubulin, pericentrin, centrin-2, CEP170 [16] [17] | Identification and quantification of centrosomes |

| Cell Cycle Inhibitors | Mimosine (G1 arrest), aphidicolin (S-phase arrest), hydroxyurea (S-phase arrest) [21] | Cell cycle synchronization to study stage-specific duplication |

| Kinase Inhibitors | CRT0105950 (LIMK2 inhibitor) [20] | Functional studies of kinase pathways in centrosome clustering |

| Expression Constructs | GFP-centrin 2 (pJLS 148), Plk4 WT and mutants, NDR1/2 variants [16] [21] | Molecular manipulation of centrosome components |

| Animal Models | Ndr1/2 conditional KO mice, 4NQO-induced esophageal tumor model [18] [20] | In vivo validation of centrosome duplication mechanisms |

Signaling Pathways in Centrosome Duplication and Clustering

Core Centrosome Duplication Pathway

Centrosome Clustering Pathway in Cancer Cells

Therapeutic Targeting of Centrosome Amplification

The unique dependency of cancer cells on centrosome clustering mechanisms presents a promising therapeutic avenue. Several targeting strategies are under investigation:

Direct Centrosome Duplication Inhibition

- Plk4 inhibitors: Target the master regulator of centriole formation

- SAS-6 interference: Disrupt cartwheel assembly and procentriole formation

- CPAP modulation: Regulate centriole elongation and stabilization

Centrosome Declustering Approaches

- LIMK2 inhibition: CRT0105950 demonstrates preclinical efficacy in suppressing centrosome clustering and tumor growth [20]

- MST4 targeting: Disrupts downstream phosphorylation of NPM1

- NPM1 function blockade: Prevents centrosome clustering, inducing multipolar mitosis

Synthetic Lethal Strategies

Therapeutic approaches that exploit the vulnerability of CA-positive cells to additional perturbations:

- Combination with paclitaxel: CA-high ovarian cancer cells show increased resistance to paclitaxel, suggesting the need for alternative targeting strategies [19]

- DNA damage response inhibitors: Enhanced efficacy in cells with centrosome amplification and CIN

- Immune activation: cGAS-STING pathway activation by micronuclei resulting from chromosome missegregation

Centrosome overduplication represents a critical oncogenic mechanism that drives chromosomal instability and cellular transformation across diverse cancer types. While significant progress has been made in understanding the core regulatory machinery, particularly the Plk4-centered duplication pathway, important questions remain regarding the contextual factors that determine whether extra centrosomes promote tumor initiation versus progression.

The role of NDR1/2 kinases in centrosome duplication presents a particularly promising area for future investigation. These conserved regulators appear to integrate multiple signaling pathways at the centrosome, yet their precise molecular functions, critical substrates, and therapeutic potential remain underexplored. The development of selective NDR kinase inhibitors and comprehensive substrate identification efforts will be essential to elucidate their full contribution to centrosome biology and cancer pathogenesis.

Future research directions should prioritize:

- Defining the molecular mechanisms connecting NDR kinase activity to centriole assembly

- Establishing the clinical utility of CA as a biomarker for therapy selection

- Developing targeted therapies that exploit the unique vulnerabilities of CA-positive cells

- Understanding the relationship between centrosome abnormalities and tumor immunity

- Elucidating how cellular context influences the consequences of centrosome amplification

As these investigative pathways mature, targeting centrosome amplification represents an increasingly promising strategy for selective eradication of cancer cells while sparing normal tissues, potentially offering new hope for patients with chromosomally unstable cancers.

Investigating NDR1/2 Function: From Core Assays to Disease Modeling

The centrosome is a non-membranous organelle that serves as the primary microtubule-organizing center (MTOC) in animal cells, playing a critical role in cellular processes including cell polarity, motility, adhesion, and mitotic spindle assembly [22] [23]. Each centrosome consists of a pair of centrioles—microtubule-based cylindrical structures—surrounded by a protein matrix known as the pericentriolar material (PCM) [22] [23]. The numerical and structural integrity of centrosomes is tightly regulated, with duplication occurring precisely once per cell cycle, coupled with DNA replication during the S phase [22] [24]. Deregulation of centrosome duplication leads to centrosome amplification (≥3 centrosomes per cell), a hallmark of human tumors that promotes chromosome mis-segregation, aneuploidy, and genomic instability [23] [24] [19]. This technical guide details standard assays for imaging and quantifying centrosome duplication, with specific emphasis on their application in research investigating the role of NDR1/2 kinases in centrosome biology.

The Centrosome Duplication Cycle and Key Regulatory Proteins

The Centriole Duplication Cycle

The centrosome duplication cycle is a tightly coordinated process that ensures each daughter cell inherits exactly two centrosomes:

- G1 Phase: Cells begin the cycle with two centrosomes, each containing one mother and one engaged daughter centriole.

- S Phase: Each mother centriole nucleates the formation of a single new (daughter) procentriole, forming a conserved architectural unit [24].

- Late Mitosis: The engagement between mother and daughter centrioles is dissolved in a process known as centriole disengagement, which licenses centrosome duplication for the next cycle [24].

- Subsequent Interphase: Disengaged daughter centrioles undergo maturation into new centrosomes through PCM acquisition in a process called centriole-to-centrosome conversion [24].

NDR1/2 Kinases as Regulators of Centrosome Duplication

The NDR (nuclear Dbf2-related) family kinases, NDR1 and NDR2, are crucial regulators of centrosome duplication. These kinases belong to the AGC family of serine/threonine kinases and require phosphorylation of conserved residues and binding to co-activator MOB proteins for full activation [25]. Research has demonstrated that the centrosomal subpopulation of human NDR1/2 is required for proper centrosome duplication [25]. Dysregulation of these kinases can lead to centrosome overduplication, potentially contributing to cellular transformation [25].

Standardized Assays for Centrosome Analysis

The Centriole Stability Assay in Drosophila Cells

The Centriole Stability Assay utilizes Drosophila melanogaster cultured cells (DMEL-2) to decouple centrosome biogenesis from maintenance, allowing specific investigation of factors affecting centrosome integrity [22].

Key Features and Rationale

- Resistance to Reduplication: Unlike some human cell lines, Drosophila cells are resistant to centriole reduplication during S phase arrest, enabling study of centrosome maintenance without confounding effects from ongoing biogenesis [22].

- Experimental Uncoupling: By arresting cells in S phase, the number of centrioles is stabilized, allowing researchers to isolate the effects of experimental manipulations on centrosome stability rather than duplication [22].

- Simultaneous Manipulation Capability: The system permits simultaneous depletion of multiple proteins using long double-stranded RNAs (dsRNA) [22].

Detailed Protocol

Cell Culture and Reagents:

- Culture Schneider's Drosophila melanogaster cell line 2 (DMEL-2, ATCC CRL-1963) in Express 5 SFM medium supplemented with L-glutamine or penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine [22].

- Prepare S phase arrest reagents: Aphidicolin (APH) and Hydroxyurea (HU) [22].

Experimental Workflow:

- Cell Seeding: Plate DMEL-2 cells on round coverslips in 24-well tissue culture plates.

- S Phase Arrest: Treat cells with APH and HU to stall DNA replication and prevent centriole reduplication.

- Protein Depletion: Transfert cells with dsRNA targeting proteins of interest (e.g., NDR kinases) using Effectene Transfection Reagent.

- Fixation: After appropriate incubation, fix cells using freshly prepared paraformaldehyde fixative solution (4% PFA in PIPES/HEPES buffer with EGTA and MgSO₄).

- Immunostaining: Process cells for immunofluorescence using antibodies against centrosomal markers.

High-Throughput Microscopy-Based Assay for Clinical Samples

For analyzing centrosome amplification in clinical specimens, a high-throughput immunofluorescence microscopy approach has been developed that can be adapted for basic research applications [19].

Protocol for Tissue Samples and Cultured Cells

Sample Preparation:

- For tissues: Use formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections (e.g., 25 μm thickness) mounted on slides.

- For cells: Culture on coverslips or in chamber slides, followed by fixation.

Immunofluorescence Staining:

- Antigen Retrieval: For FFPE sections, perform antigen retrieval using standard methods.

- Blocking: Incubate samples with blocking buffer (e.g., PBSTB: PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 1% BSA).

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Use centrosome markers such as anti-γ-tubulin, anti-pericentrin, or anti-CEP192 antibodies.

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: Use fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies.

- Counterstaining: Include DAPI for nuclear visualization.

Image Acquisition and Analysis:

- Acquire images using high-throughput confocal systems (e.g., Operetta CLS or similar).

- Acquire z-stacks through the entire volume of cells or tissue sections to ensure all centrosomes are captured.

- For quantitative analysis, count centrosome numbers per cell and measure PCM area (width × length from 2D maximum intensity projections) [19].

Quantitative Frameworks for Centrosome Amplification

Centrosome Amplification Scoring

Centrosome amplification (CA) is typically defined as the presence of >2 centrosomes in non-dividing cells or cells in G1 phase [19]. Standardized scoring approaches include:

- CA Threshold Method: Establish a threshold based on control samples (e.g., 95% confidence interval of normal tissues). In HGSOC studies, a CA threshold of 1.83 (relative to normal fallopian tube tissues) effectively distinguished tumor samples [19].

- Heterogeneity Index: Calculate intra-tumoral heterogeneity by estimating the standard deviation of log-transformed CA scores across multiple imaging fields [19].

Statistical Modeling for Population-Level Analysis

For comprehensive studies, employ hierarchical linear mixed models that account for:

- Intra-tissue dependence of mean and variance CA scores

- Inter- and intra-tumoral heterogeneity

- Batch effects between different experimental cohorts [19]

Table 1: Key Centrosomal Markers for Imaging and Quantification

| Marker | Localization | Function | Application in Assays |

|---|---|---|---|

| CEP192 | PCM | Scaffold protein required for PCM recruitment and mitotic spindle formation | General centrosome visualization and counting [24] |

| γ-tubulin | PCM | Core component of the γ-tubulin ring complex (γ-TuRC) essential for microtubule nucleation | Standard marker for centrosome identification and PCM area measurement [19] |

| Pericentrin | PCM | Scaffold protein that organizes PCM components | Structural marker; overexpression linked to CA in breast and bladder cancers [23] |

| Centrin | Centrioles | EF-hand calcium-binding protein associated with centrioles | Specific marker for centriole identification and counting |

Table 2: Experimental Approaches for Centrosome Duplication Analysis

| Method | Key Readouts | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Centriole Stability Assay [22] | Centriole number maintenance under S-phase arrest | Uncovers biogenesis from maintenance; resistant to reduplication | Limited to Drosophila cell lines; may not fully translate to human systems |

| High-Throughput Microscopy [19] | CA scores, PCM size, intra-tumoral heterogeneity | Applicable to clinical samples; quantitative and scalable | Requires specialized equipment; complex data analysis |

| Functional Perturbation + Centrosome Counting | Centrosome number after gene manipulation (e.g., NDR1/2 knockdown) | Direct assessment of gene function; can be performed in various cell types | May not distinguish direct vs. indirect effects |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Centrosome Duplication Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Assays |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | Drosophila DMEL-2 (CRL-1963), Human hTERT-immortalized fibroblasts | Model organisms for centrosome stability and duplication studies [22] [24] |

| S Phase Arrest Agents | Aphidicolin (APH), Hydroxyurea (HU) | Synchronize cells in S phase to prevent centriole reduplication [22] |

| Fixation Reagents | Paraformaldehyde fixative (4% in PIPES/HEPES buffer with EGTA, MgSO₄) | Preserve cellular architecture and antigen integrity for imaging [22] |

| Centrosome Markers | Antibodies against CEP192, γ-tubulin, pericentrin, centrin | Visualize and quantify centrosomes and centrioles [24] [19] |

| Gene Manipulation Tools | dsRNA (Drosophila), siRNA (mammalian), Expression vectors | Deplete or overexpress target proteins (e.g., NDR kinases) [22] [25] |

| Imaging Systems | Confocal microscopy (e.g., Operetta CLS) | High-resolution, high-throughput centrosome visualization and quantification [19] |

Application in Disease Contexts and Therapeutic Development

Centrosome amplification is prevalent in diverse cancers, with 63.5% of high-grade serous ovarian carcinomas (HGSOC) showing significant CA [19]. Beyond its role in tumorigenesis, CA has emerged as a key determinant of therapeutic response. Studies demonstrate that high CA is associated with multi-treatment resistance, particularly to paclitaxel, a standard microtubule-targeting agent in HGSOC treatment [19]. Several centrosome-related proteins, including NEK2, KIFC1, and PLK4, have been implicated in drug resistance mechanisms, suggesting that targeting centrosome duplication pathways may overcome treatment limitations [23].

The NDR1/2 kinases represent promising targets given their direct role in regulating centrosome duplication. As AGC family kinases, they belong to a class of proteins with established druggability [25]. Small molecule inhibitors of centrosome-associated kinases like PLK4 are already in development, suggesting similar approaches could be applied to NDR1/2 [25]. Furthermore, the association between centrosome amplification and taxane resistance highlights the potential of CA as a predictive biomarker for treatment selection [19].

Standardized imaging and quantification techniques for centrosome duplication, including the Centriole Stability Assay and high-throughput microscopy approaches, provide robust methods for investigating centrosome biology in health and disease. These assays enable researchers to dissect the functional contributions of specific regulators, including NDR1/2 kinases, to centrosome duplication and maintenance. With strong links between centrosome amplification, chromosomal instability, and therapeutic resistance, these technical approaches will continue to drive both basic scientific discovery and translational applications in cancer biology and drug development.

The Nuclear Dbf2-related (NDR) kinases, NDR1 (STK38) and NDR2 (STK38L), are serine/threonine kinases belonging to the AGC kinase family and are highly conserved from yeast to humans. These kinases have emerged as crucial regulators of diverse cellular processes including cell cycle progression, centrosome duplication, apoptosis, and neuronal development [25] [26]. Within the context of centrosome duplication, NDR kinases play an indispensable role in maintaining genomic stability. Research has demonstrated that a subpopulation of endogenous NDR kinase localizes to centrosomes in a cell-cycle-dependent manner, directly regulating the proper duplication of these critical microtubule-organizing centers [12] [6]. Aberrant centrosome duplication leads to supernumerary centrosomes, which can promote aneuploidy and genomic instability—hallmarks of many cancers [6] [25]. This technical guide comprehensively details the experimental approaches for modulating NDR kinase activity to investigate its function in centrosome duplication, providing researchers with robust methodologies for probing this critical biological pathway.

NDR Kinase Signaling Pathways in Centrosome Duplication

The diagram below illustrates the core signaling pathways regulating NDR kinase activity and its central role in centrosome duplication.

Figure 1: NDR kinase signaling pathway in centrosome duplication. The pathway illustrates upstream activation by MST3 and MOB1, cell cycle regulation through CDK2, and downstream effects on centrosome duplication. Experimental modulation approaches (overexpression, kinase-dead mutants, and siRNA) are shown with their points of intervention. Created with DOT language.

Experimental Approaches for Modulating NDR Kinase Activity

Overexpression of Wild-Type NDR Kinases

Objective: To investigate the effects of increased NDR kinase activity on centrosome duplication and potentially induce centrosome overduplication.

Methodology:

- Plasmid Constructs: Utilize mammalian expression vectors (e.g., pcDNA3, pCMV) containing full-length cDNA for human NDR1 or NDR2 [13] [4].

- Cell Transfection: Employ transfection reagents such as Fugene 6, Lipofectamine 2000, or jetPEI according to manufacturer protocols [4].

- Validation: Confirm overexpression via Western blot using anti-NDR1/2 antibodies and assess kinase activity through in vitro kinase assays with specific NDR substrate peptides [13].

Key Findings: Overexpression of wild-type NDR kinases in mammalian cells results in centrosome overduplication in a kinase-activity-dependent manner. This effect requires Cdk2 activity, indicating functional interaction between NDR and cell cycle regulators [12] [6].

Kinase-Dead Dominant Negative Mutants

Objective: To inhibit endogenous NDR kinase activity and assess the necessity of NDR catalytic function in centrosome duplication.

Methodology:

- Mutant Construction: Generate kinase-dead mutants through site-directed mutagenesis of critical residues:

- Expression and Analysis: Transfert mutant constructs and assess effects on centrosome number using centrosomal markers (e.g., γ-tubulin, centrin) [12].

Key Findings: Expression of kinase-dead NDR mutants negatively affects centrosome duplication, demonstrating the requirement for NDR kinase activity in this process [12] [6].

siRNA/RNAi Knockdown Approaches

Objective: To deplete endogenous NDR kinases and evaluate consequences for centrosome duplication.

Methodology: