NDR1 Nuclear vs. NDR2 Cytoplasmic Localization: Mechanisms, Functional Divergence in Signaling and Disease, and Research Applications

The homologous serine/threonine kinases NDR1 and NDR2, despite their high sequence similarity, exhibit a fundamental divergence in subcellular localization that dictates their non-overlapping functions in health and disease.

NDR1 Nuclear vs. NDR2 Cytoplasmic Localization: Mechanisms, Functional Divergence in Signaling and Disease, and Research Applications

Abstract

The homologous serine/threonine kinases NDR1 and NDR2, despite their high sequence similarity, exhibit a fundamental divergence in subcellular localization that dictates their non-overlapping functions in health and disease. NDR1 is predominantly nuclear, while NDR2 is primarily cytoplasmic and membrane-associated. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the molecular mechanisms behind this differential localization and its profound functional consequences. We detail how this partitioning regulates distinct cellular processes—from innate immunity and antiviral response to synaptic plasticity, microglial activation, and cell cycle control. The content further covers advanced methodological approaches for studying these kinases, common troubleshooting pitfalls, and a direct comparative analysis of their roles in specific pathways like the Hippo signaling network. Understanding this NDR1/2 functional dichotomy is critical for developing targeted therapeutic strategies for cancer, inflammatory diseases, diabetic retinopathy, and neurodegenerative disorders.

Unraveling the NDR1/2 Dichotomy: Molecular Determinants of Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Partitioning

Nuclear Dbf2-related (NDR) kinases NDR1 (STK38) and NDR2 (STK38L) represent a conserved subclass of the AGC (protein kinase A/G/C) family of serine/threonine kinases, sharing approximately 87% amino acid sequence identity [1] [2]. These kinases are evolutionarily conserved from yeast to humans and belong to the NDR/LATS subfamily, which forms a crucial component of the Hippo signaling pathway [3]. While they perform overlapping functions in various cellular processes including cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and centrosome duplication, emerging evidence reveals critical functional specializations rooted in their distinct subcellular localization patterns [4] [5]. This comparative analysis delineates the core identity of NDR1 and NDR2 by examining their distribution, activation mechanisms, and specialized biological functions, providing researchers with structured experimental data and methodological guidance for investigating these kinases in physiological and pathological contexts.

Structural Similarities and Localization Differences

Despite their high degree of sequence similarity, NDR1 and NDR2 exhibit markedly different subcellular distributions that underpin their functional specialization. NDR1 is characterized primarily by its nuclear localization, while NDR2 displays a punctate cytoplasmic distribution [1] [6]. This fundamental difference in localization patterns was consistently observed across multiple cell types and experimental systems, suggesting distinct functional roles for these highly homologous kinases.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of NDR1 and NDR2

| Feature | NDR1 (STK38) | NDR2 (STK38L) |

|---|---|---|

| Amino Acid Identity | ~87% shared identity | ~87% shared identity |

| Subcellular Localization | Predominantly nuclear [3] [1] | Punctate cytoplasmic distribution [4] [1] |

| Tissue Expression | Widely expressed [1] | Highest expression in thymus; widely expressed [1] |

| Peroxisomal Targeting | Lacks functional PTS1; diffuse distribution [4] | Contains C-terminal GKL motif; peroxisomal localization [4] [7] |

| PTS1 Receptor (Pex5p) Binding | No binding detected [4] | Direct binding demonstrated [4] |

The mechanistic basis for this differential localization was elucidated through research revealing that NDR2 contains a C-terminal peroxisome-targeting signal type 1 (PTS1)-like sequence, Gly-Lys-Leu (GKL), which is absent in NDR1 (which terminates in Ala-Lys) [4]. This GKL motif enables NDR2 to bind to the PTS1 receptor Pex5p, facilitating its recruitment to peroxisomes [4] [7]. Mutational studies confirmed this mechanism, as deletion of the C-terminal leucine in NDR2 (NDR2-ΔL) resulted in loss of punctate localization and diffuse cellular distribution similar to NDR1 [4].

Experimental Protocols for Studying Localization and Function

Subcellular Localization Assessment

Protocol 1: Immunofluorescence Microscopy for NDR1/NDR2 Localization

- Cell Culture: Plate human telomerase-immortalized retinal pigment epithelial (RPE1) or HeLa cells on glass coverslips in appropriate growth medium [4].

- Transfection: Transfect cells with plasmids encoding YFP- or GFP-tagged NDR1, NDR2, or NDR2-ΔL using Lipofectamine 2000 or similar transfection reagents [4].

- Fixation and Staining: At 24-48 hours post-transfection, fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100, and incubate with primary antibodies against organelle markers (e.g., catalase for peroxisomes, EEA1 for early endosomes, GM130 for Golgi) [4].

- Imaging and Analysis: Capture images using confocal microscopy and analyze co-localization using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ with JaCoP plugin) [4]. NDR2 should show significant co-localization with peroxisomal markers but not with markers of other organelles.

Protocol 2: Subcellular Fractionation and Immunoblotting

- Cell Lysis: Harvest NDR2-expressing HeLa cells and homogenize in isotonic buffer [4].

- Fractionation: Centrifuge post-nuclear supernatant at high speed to separate organellar (pellet) and cytosolic (supernatant) fractions [4].

- Density Gradient Centrifugation: Further separate the post-nuclear supernatant using iodixanol density gradient ultracentrifugation [4].

- Analysis: Collect fractions and analyze by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting for NDR2 and organelle markers (e.g., Pex14p for peroxisomes) [4]. NDR2 should co-sediment with peroxisomal markers in specific density fractions.

Functional Interaction Studies

Protocol 3: Co-immunoprecipitation for NDR-MOB Interactions

- Cell Preparation: Culture Jurkat T-cells or HeLa cells and transfect with epitope-tagged NDR1, NDR2, and MOB constructs [1] [6].

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells in non-denaturing lysis buffer (e.g., 1% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris pH 8.0) with protease and phosphatase inhibitors [6].

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate lysates with anti-epitope tag antibodies (e.g., anti-HA, anti-myc) followed by protein A/G beads [6].

- Analysis: Wash beads, elute bound proteins, and analyze by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting for NDR and MOB proteins [6]. This protocol confirms physical interaction between NDR kinases and their regulatory MOB proteins.

Protocol 4: Kinase Activation Assay

- Reconstitution System: Express membrane-targeted versions of NDR and MOB proteins in COS-7, U2-OS, or HEK 293 cells [8].

- Stimulation: Treat cells with okadaic acid (1 μM, 60 minutes) to inhibit protein phosphatase 2A and enhance NDR phosphorylation [8].

- Phosphorylation Detection: Use phospho-specific antibodies against Ser281/Ser282 and Thr444/Thr442 of NDR1/NDR2 to assess activation status [8].

- Kinase Activity Measurement: Immunoprecipitate NDR kinases and perform in vitro kinase assays using specific substrate peptides [2] [9].

Activation Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

NDR kinases require phosphorylation for full activation and are regulated by a conserved mechanism involving MOB proteins and upstream kinases. Both NDR1 and NDR2 undergo phosphorylation at two critical sites: a conserved threonine residue in the activation loop (Thr444 in NDR1, Thr442 in NDR2) and a serine residue for autophosphorylation (Ser281 in NDR1, Ser282 in NDR2) [8]. The association with MOB proteins (hMOB1A, hMOB1B, and hMOB2) dramatically stimulates NDR1 and NDR2 catalytic activity [1] [6].

Table 2: Activation Mechanisms and Regulatory Components

| Activation Parameter | NDR1 | NDR2 |

|---|---|---|

| Critical Phosphorylation Sites | Ser281, Thr444 [8] | Ser282, Thr442 [8] |

| Upstream Activators | MST kinases, MOB proteins [2] [9] | MST kinases, MOB proteins [2] |

| Subcellular Site of Activation | Nucleus, cytoplasm [8] | Primarily at plasma membrane [8] |

| Activation by Membrane Targeting | Constitutively active when membrane-targeted [8] | Constitutively active when membrane-targeted [8] |

| MOB Protein Binding | Binds hMOB1, hMOB2; dramatically stimulates activity [1] [9] [6] | Binds hMOB1, hMOB2; dramatically stimulates activity [1] [6] |

Research has demonstrated that membrane targeting of either NDR kinase results in constitutive activation due to phosphorylation at both regulatory sites, and this activation is further enhanced by co-expression of MOB proteins [8]. The activation of NDR kinases by membrane-bound MOBs occurs rapidly within minutes after MOB translocation to membranous structures [8].

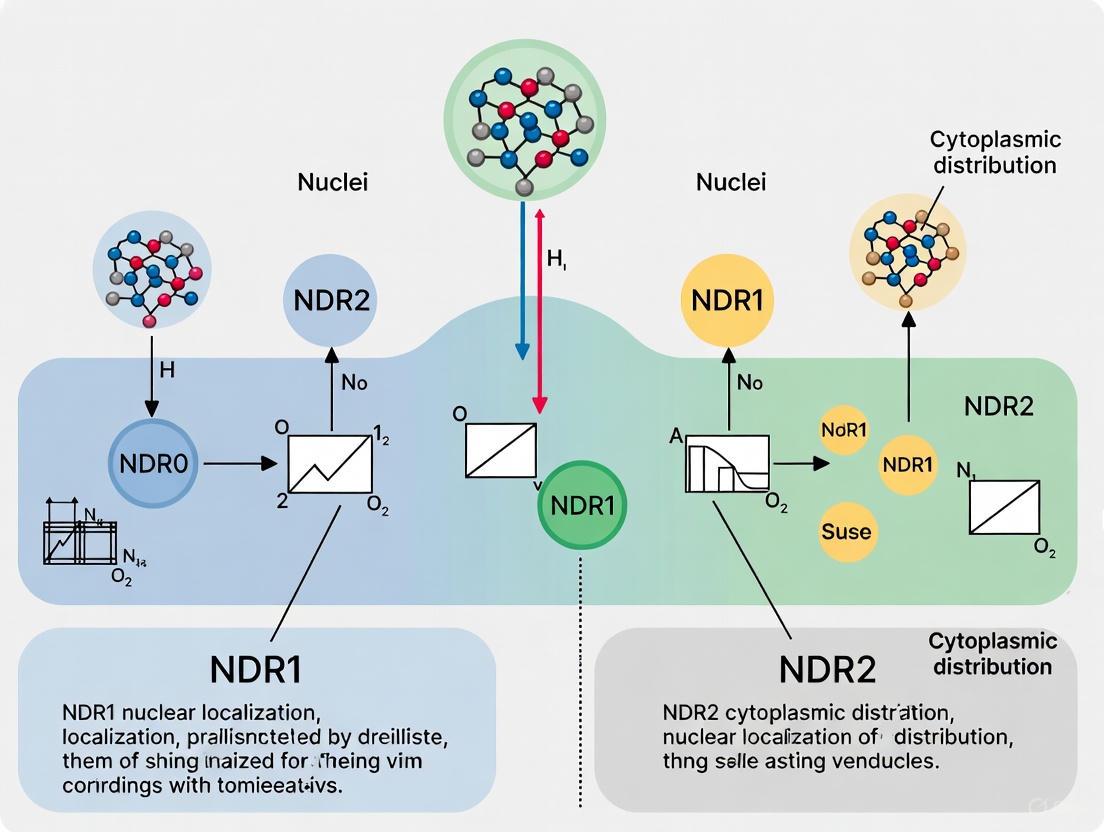

Diagram 1: NDR Kinase Activation Pathway. NDR1/2 are activated through phosphorylation by upstream kinases (MST) and binding to MOB cofactors, which releases autoinhibition. Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) negatively regulates this pathway. Activated NDR1/2 phosphorylate downstream substrates to control diverse cellular functions.

Functional Specialization in Physiological Processes

The distinct subcellular localization of NDR1 and NDR2 translates to specialized physiological functions, despite their biochemical similarity.

NDR2 in Ciliogenesis and Peroxisomal Function

NDR2 plays a critical role in primary cilium formation, a function not shared with NDR1 [4] [7]. This specialized function depends on NDR2's peroxisomal localization mediated by its C-terminal GKL motif [4]. In ciliogenesis, NDR2 phosphorylates Rabin8, a GDP/GTP exchange factor for Rab8 GTPase, promoting local activation of Rab8 in the vicinity of the centrosome, which is essential for ciliary vesicle formation and axoneme growth [4] [2]. Functional studies demonstrated that expression of wild-type NDR2, but not the peroxisome-non-targeting mutant NDR2(ΔL), rescues the suppressive effect of NDR2 knockdown on ciliogenesis [4]. Furthermore, knockdown of peroxisome biogenesis factors (PEX1 or PEX3) partially suppresses ciliogenesis, confirming the importance of peroxisomal localization for NDR2's function in this process [4].

Differential Roles in Innate Immunity and Inflammation

NDR1 and NDR2 play distinct but complementary roles in regulating immune responses:

NDR1 functions as a negative regulator of TLR9-mediated immune response in macrophages by promoting ubiquitination and degradation of MEKK2, thereby inhibiting CpG-DNA-induced ERK1/2 activation and subsequent production of TNF-α and IL-6 [3]. NDR1 also acts as a transcriptional regulator of miR146a, dampening its transcription to promote STAT1 translation and enhance antiviral immune response [3].

NDR2 promotes RIG-I-mediated antiviral response by directly associating with RIG-I and TRIM25, facilitating complex formation and enhancing K63-linked polyubiquitination of RIG-I [3].

This functional specialization in immune regulation demonstrates how the differential localization of NDR1 and NDR2 enables them to participate in distinct signaling pathways, with NDR1 primarily modulating inflammatory cytokine production and NDR2 enhancing antiviral responses.

Neuronal Development and Function

Both NDR1 and NDR2 are expressed in the brain and contribute to neuronal development, but they may have distinct functions in this context [2] [5]. Research using chemical genetics identified AAK1 and Rabin8 as NDR1/2 substrates in the brain [2]. NDR1/2 kinases limit dendrite branching and length in cultured hippocampal neurons and in vivo, and are required for dendritic spine development and excitatory synaptic function [2]. Loss of NDR1/2 function leads to more immature spines and reduced frequency of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents [2].

Table 3: Functional Specialization of NDR1 and NDR2 in Physiological Processes

| Biological Process | NDR1 Function | NDR2 Function |

|---|---|---|

| Ciliogenesis | No apparent role [4] | Critical role; phosphorylates Rabin8 to promote ciliary vesicle formation [4] |

| Centrosome Duplication | Involved [3] | Involved [3] |

| TLR9 Signaling | Negative regulator; targets MEKK2 for degradation [3] | Similar negative regulation based on siRNA studies [3] |

| Antiviral Immunity | Positive regulator; enhances STAT1 translation [3] | Positive regulator; enhances RIG-I ubiquitination [3] |

| Neuronal Development | Limits dendrite branching and length [2] | Limits dendrite branching and length [2] |

| Synaptic Function | Required for spine development [2] | Required for spine development [2] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for NDR1/2 Investigations

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | COS-7, U2-OS, HEK 293, HeLa, RPE1, Jurkat T-cells [8] [4] [1] | Model systems for localization, interaction, and functional studies |

| Expression Constructs | Epitope-tagged NDR1/2 (HA, myc, YFP, GFP), membrane-targeted versions, nucleus-targeted versions [8] [4] | Investigating localization, activation mechanisms, and functional consequences |

| Antibodies | Anti-NDR CT, Anti-NDR NT, phospho-specific antibodies (Ser281, Thr444) [8] | Detection, quantification, and localization of NDR kinases and activation status |

| Activation Reagents | Okadaic acid (PP2A inhibitor), 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA) [8] | Experimental activation of NDR kinase pathways |

| Mutant Constructs | Kinase-dead (K118A, S281A/T444A), constitutively active, peroxisome-targeting deficient (NDR2-ΔL) [4] [2] | Functional dissection through gain-of-function and loss-of-function approaches |

| Interaction Partners | MOB1/2 expression constructs, Pex5p constructs [4] [1] | Studying regulatory mechanisms and pathway interactions |

Pathological Implications and Research Directions

Dysregulation of NDR kinases has been implicated in various disease processes. NDR1 demonstrates tumor suppressor properties, with NDR1 knockout mice showing increased susceptibility to T-cell lymphoma [4] [5]. In contrast, NDR2 appears to function as an oncogene in certain cancers, particularly lung cancer, where it regulates processes including proliferation, apoptosis, migration, and invasion [10]. In the nervous system, NDR2 has been identified as the causal gene for canine early retinal degeneration, corresponding to the human ciliopathy Leber congenital amaurosis [4], highlighting its critical role in sensory neuronal maintenance.

The distinct subcellular localization patterns of NDR1 and NDR2—with NDR1 predominantly nuclear and NDR2 associated with peroxisomes—represent a fundamental aspect of their functional specialization. This differential targeting enables these highly similar kinases to participate in non-overlapping cellular processes while maintaining shared functions in other contexts. Future research should focus on further elucidating the complete interactomes of both kinases, developing more specific inhibitors, and exploring the therapeutic potential of targeting their distinct localization mechanisms in disease contexts, particularly cancer and neurological disorders.

Diagram 2: Functional Specialization and Pathological Implications. The distinct subcellular localization of NDR1 (nuclear) and NDR2 (peroxisomal) underlies their specialized cellular functions and associated disease implications when dysregulated.

The Nuclear Dbf2-Related (NDR) kinases NDR1 (STK38) and NDR2 (STK38L) are serine/threonine kinases belonging to the NDR/LATS subclass of AGC kinases, with crucial yet distinct roles in cellular processes including cell proliferation, apoptosis, morphogenesis, and immune regulation [4] [11]. Despite sharing 87% amino acid sequence identity and similar substrate specificities, these homologous kinases exhibit strikingly different subcellular localizations that dictate their non-overlapping functions in health and disease [4] [8].

NDR1 predominantly localizes to the nucleus, while NDR2 displays cytoplasmic distribution with specific organelle association [4] [8] [11]. This fundamental difference represents a fascinating molecular paradox: how do two highly similar proteins achieve such distinct localization patterns? The answer lies in divergent structural motifs—NDR1's functional Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS) versus NDR2's cytoplasmic anchors—that direct them to separate cellular compartments, thereby enabling specialized functional roles in cellular signaling networks.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of NDR1 and NDR2 Kinases

| Characteristic | NDR1 (STK38) | NDR2 (STK38L) |

|---|---|---|

| Amino Acid Sequence Similarity | 87% identity with NDR2 | 87% identity with NDR1 |

| Primary Subcellular Localization | Nuclear | Cytoplasmic (peroxisomal) |

| Key Localization Motif | Functional NLS (residues 265-276) | C-terminal GKL peroxisomal targeting signal |

| Conservation | Conserved from yeast to humans | Conserved from yeast to humans |

| Kinase Class | NDR/LATS subclass of AGC kinases | NDR/LATS subclass of AGC kinases |

Molecular Determinants of Differential Localization

NDR1's Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS)

NDR1 contains a canonical nuclear localization signal (NLS) at residues 265-276, which facilitates its active import into the nuclear compartment [8]. Intriguingly, this NLS sequence is largely conserved in NDR2, with only a single conservative amino acid change, yet fails to function effectively in nuclear import [8]. This suggests that the NDR2 sequence contains structural features or post-translational modifications that override the potential NLS function.

Experimental evidence demonstrates that when NDR1 is artificially targeted to the plasma membrane using the myristoylation/palmitylation motif of the Lck tyrosine kinase, it becomes constitutively active due to phosphorylation on Ser281 and Thr444 [8]. This membrane-targeted activation provides important insights into how subcellular localization directly regulates NDR1 kinase activity.

NDR2's Cytoplasmic Anchoring Mechanisms

NDR2 exhibits punctate cytoplasmic localization rather than the diffuse distribution observed with NDR1 [4]. Through systematic colocalization studies with organelle markers, researchers have demonstrated that NDR2 specifically localizes to peroxisomes—single-membrane organelles involved in metabolic pathways including β-oxidation of fatty acids and detoxification of reactive oxygen species [4].

The molecular basis for this peroxisomal targeting lies in a C-terminal tripeptide sequence Gly-Lys-Leu (GKL) that functions as a peroxisome-targeting signal type 1 (PTS1) [4]. This critical discovery explains NDR2's cytoplasmic retention despite its sequence similarity to NDR1. Several lines of experimental evidence confirm this mechanism:

- PTS1 Receptor Binding: NDR2, but not NDR1, binds to the PTS1 receptor Pex5p, which mediates import of proteins into peroxisomes [4]

- Mutational Analysis: An NDR2 mutant lacking the C-terminal leucine (NDR2(ΔL)) exhibits diffuse cellular distribution instead of punctate peroxisomal localization [4]

- Functional Rescue: Wild-type NDR2, but not the peroxisome-non-targeting NDR2(ΔL) mutant, rescues the suppressive effect of NDR2 knockdown on ciliogenesis [4]

Table 2: Molecular Mechanisms Governing NDR1 and NDR2 Localization

| Localization Mechanism | NDR1 | NDR2 |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Targeting Signal | NLS (residues 265-276) | C-terminal GKL motif |

| Signal Type | Nuclear Localization Signal | Peroxisomal Targeting Signal 1 (PTS1) |

| Receptor/Binding Partner | Importin family | Pex5p (PTS1 receptor) |

| Localization Disruption | Mutation of NLS residues | Deletion of C-terminal leucine (ΔL mutant) |

| Secondary Localization | Cytoplasmic (upon activation) | Cell periphery and tips of microglial processes |

Diagram 1: Molecular determinants of NDR1 nuclear versus NDR2 cytoplasmic localization. NDR1 contains a functional NLS that directs nuclear import, while NDR2 possesses a C-terminal GKL motif that binds Pex5p for peroxisomal targeting.

Functional Consequences of Distinct Localization Patterns

NDR1's Nuclear Functions

NDR1's nuclear localization enables specific regulatory roles in gene expression and cell cycle control. As a nuclear kinase, NDR1 participates in phosphorylation and negative regulation of the transcriptional co-activator YAP1, thereby exerting tumor-suppressive functions [4]. Additionally, NDR1 plays a specialized role in regulating inflammatory responses through its nuclear actions, particularly in negatively regulating Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9)-mediated immune responses in macrophages [11].

NDR1 deficiency leads to increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6, indicating its critical role in preventing excessive inflammation induced by TLR signaling [11]. This nuclear-specific function highlights how NDR1's localization dictates its physiological role in immune regulation.

NDR2's Cytoplasmic Functions

NDR2's cytoplasmic and peroxisomal localization enables distinct functions in cellular morphogenesis and metabolic adaptation. A primary function of NDR2 is regulating primary cilium formation through phosphorylation of Rabin8, which promotes local activation of Rab8 GTPase in the vicinity of the centrosome [4]. This ciliogenesis function is specifically dependent on NDR2's peroxisomal localization, as demonstrated by the inability of peroxisome-non-targeting NDR2 mutants to rescue ciliogenesis defects [4].

In microglial cells, NDR2 plays a critical role in metabolic adaptation under high-glucose conditions, with NDR2 downregulation impairing mitochondrial respiration and reducing metabolic flexibility [12]. NDR2 also regulates cytoskeleton-dependent processes including phagocytosis and migration in microglial cells, consistent with its localization at the cell periphery and tips of cellular processes [12].

In disease contexts, NDR2's cytoplasmic functions become particularly significant. In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), hypoxia-induced activation of NDR2 promotes brain metastasis by exacerbating HIF-1A, YAP, and C-Jun-dependent amoeboid migration [13]. NDR2 is more highly expressed in metastatic NSCLC than in localized NSCLC, and NDR2 silencing prevents xenograft formation and growth in lung cancer-derived brain metastasis models [13].

Table 3: Functional Specialization of NDR1 and NDR2 Based on Localization

| Functional Domain | NDR1 Nuclear Functions | NDR2 Cytoplasmic Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Morphogenesis | Limited role | Central role in ciliogenesis via Rabin8 phosphorylation |

| Metabolic Regulation | Indirect through transcriptional control | Direct regulation of mitochondrial respiration and metabolic flexibility |

| Disease Processes | Tumor suppressor in colorectal cancer | Promotes metastasis in lung cancer |

| Immune Function | Negative regulation of TLR9 signaling | Regulation of microglial activation in diabetic retinopathy |

| Inflammatory Response | Competitively binds TRAF3 to promote IL-17 signaling | Facilitates breakdown of signaling molecules to inhibit IL-17 signaling |

Experimental Analysis of Localization Mechanisms

Key Methodologies for Localization Studies

Several experimental approaches have been crucial for deciphering the distinct localization patterns of NDR1 and NDR2:

Immunofluorescence and Confocal Microscopy: Researchers used immunocytochemistry with antibodies targeting specific regions of NDR kinases (N-terminus for NDR1/2 and C-terminus for NDR2) to demonstrate localization in human iPSC-derived microglial cultures, BV-2 immortalized microglial cells, and mouse primary retinal microglial cultures [12]. Colocalization studies with organelle-specific markers (catalase for peroxisomes, IBA1 for microglial processes) provided definitive evidence of subcellular distribution [12] [4].

Subcellular Fractionation and Biochemical Analysis: Biochemical fractionation of cellular components followed by Western blot analysis confirmed NDR2's association with peroxisomal fractions [4]. When post-nuclear supernatant fractions from YFP-NDR2-expressing HeLa cells were separated by iodixanol density gradient ultracentrifugation, NDR2 co-sedimented with the peroxisomal protein Pex14p [4].

Live-Cell Imaging and Mutational Analysis: The functional significance of localization motifs was tested through mutagenesis studies. Deletion of the C-terminal leucine in NDR2 (NDR2(ΔL)) resulted in diffuse cytoplasmic distribution instead of punctate peroxisomal localization [4]. Similarly, artificial targeting experiments using myristoylation/palmitylation motifs or nuclear localization signals demonstrated how localization affects kinase activity [8].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for determining NDR1 and NDR2 subcellular localization. Critical methodologies include tagged protein expression, cellular fractionation, immunofluorescence microscopy, and functional validation through mutational analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Studying NDR1/NDR2 Localization and Function

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | NDR1/2 antibody (E-2) #sc-271703; NDR2 antibody #STJ94368; IBA1 antibody | Detection and visualization of endogenous proteins and specific cellular markers |

| Cell Lines | BV-2 microglial cells; Human iPSC-derived microglia; HEK293; COS-7; HeLa | Model systems for localization studies and functional assays |

| Expression Constructs | YFP-NDR2; HA-NDR1; NDR2(ΔL) mutant; Membrane-targeted NDR | Manipulation of protein expression and localization for functional studies |

| Biochemical Assays | Subcellular fractionation kits; Co-immunoprecipitation reagents; Western blot systems | Analysis of protein localization, interactions, and activation status |

| Localization Markers | Catalase (peroxisomes); CFP-SKL (peroxisomes); Lamin A/C (nucleus); α-tubulin (cytoskeleton) | Reference standards for determining subcellular compartments |

Pathophysiological Implications and Therapeutic Perspectives

The distinct subcellular localization of NDR1 and NDR2 has significant implications for human disease and potential therapeutic interventions. In cancer biology, NDR1 often functions as a tumor suppressor, while NDR2 frequently exhibits oncogenic properties, particularly in lung cancer progression and metastasis [10] [13]. The hypoxia-induced activation of NDR2 in NSCLC and its role in promoting brain metastases highlights the clinical relevance of understanding these localization-specific functions [13].

In neurological contexts, NDR2 regulates microglial metabolic adaptation under high-glucose conditions relevant to diabetic retinopathy [12]. NDR2 downregulation impairs mitochondrial respiration, reduces phagocytic capacity, and elevates pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF, IL-17, IL-12p70), identifying NDR2 as a potential therapeutic target for neuroinflammatory processes [12].

The opposing roles of NDR1 and NDR2 in inflammatory signaling further demonstrate the functional significance of their distinct localizations. NDR1 promotes IL-17 signaling by competitively binding TRAF3, while NDR2 inhibits IL-17 signaling by facilitating the breakdown of signaling molecules [11]. This opposition suggests potential for targeted therapeutic interventions in autoimmune diseases by specifically modulating one kinase without affecting the other.

Future research directions should focus on developing small molecules that can specifically target one NDR kinase without affecting the other, potentially by exploiting their distinct subcellular localizations. Additionally, understanding the precise mechanisms that regulate the trafficking of each kinase between cellular compartments may reveal new opportunities for therapeutic intervention in cancer, inflammatory diseases, and metabolic disorders.

The differential subcellular localization of NDR1 and NDR2 represents a compelling example of how highly similar proteins evolve distinct functions through the acquisition of specific localization signals. NDR1's nuclear localization enables roles in transcriptional regulation and specific immune signaling pathways, while NDR2's cytoplasmic and peroxisomal targeting facilitates functions in ciliogenesis, metabolic adaptation, and cell migration. Understanding this "localization code" provides crucial insights for developing targeted therapeutic strategies that can selectively modulate the specific functions of each kinase in disease contexts. The continuing elucidation of NDR1 and NDR2 signaling networks will undoubtedly yield new opportunities for therapeutic intervention across a spectrum of human diseases.

The NDR (Nuclear Dbf2-related) kinase family, comprising NDR1 and NDR2, represents a crucial subclass of serine/threonine kinases within the conserved Hippo signaling pathway. These kinases, sharing approximately 87% amino acid sequence identity, play pivotal roles in regulating diverse cellular processes including cell proliferation, apoptosis, morphogenesis, and centrosome duplication [4] [14] [6]. Despite their high structural similarity, NDR1 and NDR2 exhibit distinct subcellular localization patterns and non-overlapping functions in specific biological contexts. NDR1 primarily localizes to the nucleus, while NDR2 displays a punctate cytoplasmic distribution [4] [6]. This functional divergence is particularly evident in primary cilium formation, where NDR2, but not NDR1, plays an essential role [4]. Understanding the structural determinants governing these differences requires a detailed comparative analysis of their N-terminal regulatory and C-terminal hydrophobic motifs, which serve as critical regulatory elements controlling kinase activity, subcellular targeting, and functional specificity.

Structural Organization of NDR Kinases

NDR kinases share a conserved domain architecture characteristic of the AGC group of serine/threonine kinases. Both isoforms contain a central kinase catalytic domain flanked by an N-terminal regulatory domain (NTR) and a C-terminal extension featuring a hydrophobic motif [14] [6]. The N-terminal regulatory region encompasses approximately 80 amino acids and includes five β-strands and one α-helix, forming a structurally conserved module that participates in autoinhibition and regulatory interactions [15] [16]. The C-terminal hydrophobic motif represents a crucial regulatory element that undergoes phosphorylation to modulate kinase activity [17].

Despite their high sequence conservation, key structural differences in both N-terminal and C-terminal regions dictate their distinct cellular functions and localization patterns. These variations affect interaction interfaces, phosphorylation susceptibilities, and subcellular targeting signals, ultimately contributing to the functional specialization of NDR1 and NDR2 in specific signaling contexts and physiological processes.

Table 1: Domain Architecture of NDR1 and NDR2 Kinases

| Domain/Region | NDR1 Features | NDR2 Features | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| N-terminal Regulatory Domain | Contains nuclear localization signals | Lacks strong nuclear localization signals | Dictates differential subcellular localization |

| Kinase Domain | Contains atypically long activation segment (∼30 aa) | Similar activation segment structure | Autoinhibition in NDR1; regulated by phosphorylation |

| C-terminal Hydrophobic Motif | Thr444 phosphorylation site | Thr442 phosphorylation site | Activation by upstream kinases (MST3) |

| C-terminal Tail | Ends with Ala-Lys | Ends with Gly-Lys-Leu (GKL) peroxisomal targeting signal | NDR2 localizes to peroxisomes; NDR1 does not |

Comparative Analysis of N-terminal Regulatory Motifs

The N-terminal regulatory domains of NDR kinases play critical roles in autoinhibition, protein-protein interactions, and subcellular targeting. Structural studies have revealed that the NDR1 kinase domain adopts an autoinhibited conformation stabilized by an atypically long activation segment that blocks substrate binding and stabilizes a non-productive position of helix αC [16]. This 30-amino acid insertion between kinase subdomains VII and VIII represents a key structural feature that maintains NDR1 in a basally inactive state, requiring conformational changes for full activation.

Structural determination of the human NDR1 kinase domain at 2.2 Å resolution has provided detailed insights into its autoinhibition mechanism. The extended activation segment forms extensive contacts with both the N-lobe and C-lobe of the kinase domain, preventing productive substrate binding and orienting helix αC in an inactive configuration [16]. Mutational analysis within this activation segment dramatically enhances NDR1 catalytic activity, confirming its autoinhibitory function. Specifically, residues within the β4-β5 turn and adjacent regions contribute to stabilization of the inactive state, with mutation of these elements resulting in constitutive kinase activation.

The N-terminal regions of NDR kinases also serve as critical interfaces for regulatory protein interactions. Both NDR1 and NDR2 bind to MOB proteins (MOB1A/B and MOB2), which dramatically stimulate their catalytic activities [6]. This interaction is mechanistically distinct from activation segment-mediated regulation, as MOB1 binding further potentiates the activity of NDR1 mutants with truncated autoinhibitory segments [16]. The N-terminal domain also facilitates interactions with upstream Hippo pathway components including MST1/2 kinases and the Furry (FRY) scaffold protein, creating a complex regulatory network that controls NDR kinase activity in response to diverse cellular signals.

Table 2: Key Functional Motifs in N-terminal Regulatory Domains

| Structural Element | NDR1 Characteristics | NDR2 Characteristics | Regulatory Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activation Segment | 30-amino acid insertion; autoinhibitory | Similar insertion; regulatory | Controls basal kinase activity; phosphoregulation |

| MOB Protein Binding Interface | High-affinity for MOB1A/B and MOB2 | High-affinity for MOB1A/B and MOB2 | Dramatic kinase activation upon binding |

| Furry Scaffold Binding Site | Direct interaction demonstrated | Presumed similar interaction | Facilitates upstream kinase recognition |

| N-lobe Regulatory Surfaces | Unique residue composition | Distinct residue patterns | Differential regulation by upstream inputs |

Comparative Analysis of C-terminal Hydrophobic Motifs

The C-terminal hydrophobic motifs of NDR kinases represent critical regulatory elements that undergo phosphorylation to control kinase activation. Both NDR1 and NDR2 contain conserved hydrophobic phosphorylation sites (Thr444 in NDR1 and Thr442 in NDR2) that are targeted by upstream Ste20-like kinases, particularly MST3 [17]. Phosphorylation of these residues results in a 10-fold stimulation of NDR kinase activity, with further enhancement mediated by MOB1A binding, leading to fully active kinases [17].

The mechanism of hydrophobic motif phosphorylation involves a multi-step activation process. For NDR2, MST3 selectively phosphorylates Thr442 in vitro, initiating a conformational change that facilitates subsequent autophosphorylation of the activation loop site Ser282 [17]. This ordered phosphorylation mechanism ensures precise control of NDR kinase activity in response to specific cellular signals. In vivo studies using kinase-dead MST3 mutants (MST3KR) demonstrate potent inhibition of Thr442 phosphorylation after okadaic acid stimulation, confirming MST3 as a bona fide upstream kinase for NDR2 hydrophobic motif phosphorylation [17].

Beyond their regulatory functions, the C-terminal regions of NDR kinases confer distinct subcellular localization properties. Notably, NDR2 contains a C-terminal peroxisome-targeting signal type 1 (PTS1)-like sequence (Gly-Lys-Leu), while NDR1 terminates with Ala-Lys [4]. This structural difference enables NDR2 to localize to peroxisomes through direct interaction with the PTS1 receptor Pex5p, while NDR1 lacks this targeting capability. Mutational studies confirm the functional importance of this motif, as deletion of the C-terminal Leu in NDR2 (NDR2(ΔL)) results in diffuse cytoplasmic distribution and impaired function in ciliogenesis [4].

Figure 1: NDR2 Activation and Peroxisomal Targeting Pathway. This diagram illustrates the multi-step activation process of NDR2 kinase through MST3-mediated phosphorylation and subsequent peroxisomal localization via Pex5p recognition of the C-terminal GKL motif.

Experimental Approaches for Structural-Functional Analysis

Subcellular Localization Studies

The distinct subcellular localization patterns of NDR1 and NDR2 have been characterized using fluorescence microscopy and subcellular fractionation techniques. Experimental protocols typically involve transfection of mammalian cells (such as RPE1 or HeLa cells) with plasmids encoding YFP- or CFP-tagged NDR constructs, followed by immunostaining with organelle-specific marker proteins [4]. For NDR2 peroxisomal localization, co-localization studies with established peroxisomal markers (catalase, CFP-SKL) provide definitive evidence. Quantitative analysis of fluorescence overlap using Pearson's correlation coefficient validates the specificity of observed localization patterns.

Subcellular fractionation protocols involve preparation of post-nuclear supernatant (PNS) fractions from transfected cells, followed by separation into organellar and cytosolic fractions through differential centrifugation [4]. Further purification using iodixanol density gradient ultracentrifugation enables precise determination of protein distribution across cellular compartments. Western blot analysis of fractionated samples using antibodies against NDR kinases and organelle-specific markers (e.g., Pex14p for peroxisomes) provides biochemical confirmation of microscopic observations.

Functional Mutagenesis and Chimera Studies

Structure-function relationships in NDR kinases have been elucidated through systematic mutagenesis and domain-swapping approaches. Site-directed mutagenesis of critical regulatory residues (e.g., Thr444/Thr442 in hydrophobic motifs, Ser281/Ser282 in activation loops) followed by in vitro kinase assays quantifies the contribution of specific residues to catalytic activity [17]. Experimental protocols typically involve expression of mutant kinases in mammalian cells (HEK293F, COS-7) or bacterial systems, immunopurification using epitope tags (HA, myc), and kinase activity measurements using specific substrates (e.g., histone H1) in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP.

Chimeric kinase constructs, generated by swapping specific domains or motifs between NDR1 and NDR2, enable precise mapping of functional determinants [15]. For example, grafting the β4-β5 turn region from Src to Csk has demonstrated the functional importance of this motif in kinase regulation [15]. Similarly, C-terminal truncation and point mutation experiments (e.g., NDR2(ΔL)) establish the role of specific sequences in subcellular targeting and functional specialization [4].

Interaction Studies and Phosphorylation Mapping

Protein-protein interactions involving NDR kinases have been characterized using co-immunoprecipitation and yeast two-hybrid approaches. Standard protocols involve co-transfection of epitope-tagged NDR and candidate binding partners (MOB proteins, Pex5p, RIG-I), followed by immunoprecipitation with tag-specific antibodies and Western blot analysis to detect associated proteins [4] [17] [6].

Phosphorylation status of specific regulatory sites has been monitored using phospho-specific antibodies (e.g., anti-P-Ser282, anti-P-Thr442) in combination with pharmacological inhibitors and RNA interference targeting upstream kinases [17]. For in vitro phosphorylation assays, recombinant kinases (MST3, NDR) are incubated with ATP, and phosphorylation reactions are analyzed by Western blotting or mass spectrometry to identify modification sites and quantify kinetics.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for NDR Kinase Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Experimental Applications | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Constructs | pCMV5-HA-NDR1/2, pEGFP-NDR1/2, NDR2(ΔL) mutant | Localization, functional assays | Protein expression and mutagenesis studies |

| Antibodies | Anti-P-Ser282, Anti-P-Thr442, Anti-HA (12CA5), Anti-myc (9E10) | Western blot, immunoprecipitation | Detection of phosphorylation, protein expression |

| Cell Lines | HEK293F, COS-7, RPE1, HeLa | Kinase assays, localization studies | Cellular context for functional experiments |

| Biochemical Reagents | Okadaic acid, Microcystin, λ-phosphatase | Phosphatase inhibition/activation | Manipulating phosphorylation status |

| Interaction Partners | Recombinant MOB1A, MST3, Pex5p | In vitro binding and kinase assays | Studying regulatory mechanisms |

Functional Implications of Structural Differences

The structural variations in N-terminal and C-terminal motifs of NDR kinases have profound functional implications for their cellular roles. The peroxisomal localization of NDR2, mediated by its C-terminal GKL motif, directly links this kinase to primary cilium formation [4]. Functional studies demonstrate that wild-type NDR2, but not the peroxisome-targeting defective mutant NDR2(ΔL), rescues ciliogenesis defects in NDR2-knockdown cells. Furthermore, knockdown of peroxisome biogenesis factors (PEX1, PEX3) partially suppresses ciliogenesis, establishing a novel connection between peroxisomal signaling and cilium formation mediated by NDR2's unique C-terminal targeting motif [4].

The differential subcellular localization of NDR1 (nuclear) and NDR2 (cytoplasmic/peroxisomal) enables these kinases to participate in distinct signaling networks. NDR1 functions as a transcriptional regulator through binding to the intergenic region of miR146a, thereby modulating STAT1 translation and antiviral immune responses [14]. In contrast, NDR2 directly associates with cytoplasmic signaling complexes, such as the RIG-I/TRIM25 complex, enhancing K63-linked polyubiquitination of RIG-I and promoting antiviral type I interferon production [14]. These compartment-specific functions highlight how structural variations in regulatory motifs dictate functional specialization within the NDR kinase family.

Beyond their roles in innate immunity and ciliogenesis, the structural features of NDR kinases also influence their participation in cell cycle control, apoptosis, and Hippo pathway signaling. The autoinhibitory N-terminal extension in NDR1 provides an additional layer of regulation that may fine-tune its nuclear functions, while NDR2's peroxisomal targeting enables coordination between metabolic signaling and morphological changes. These functional specializations, rooted in structural differences, allow NDR1 and NDR2 to regulate diverse physiological processes while maintaining core kinase functions.

The comparative analysis of N-terminal regulatory and C-terminal hydrophobic motifs in NDR1 and NDR2 reveals how subtle structural variations generate functional diversity within a highly conserved kinase family. The extended N-terminal activation segment in NDR1 imposes autoinhibition that must be relieved through phosphorylation and MOB protein binding, while the C-terminal peroxisomal targeting motif in NDR2 directs this kinase to specific subcellular compartments where it regulates ciliogenesis. These structural differences, combined with variations in upstream activation mechanisms and binding partner interactions, enable NDR1 and NDR2 to perform non-redundant functions despite their high sequence similarity.

Understanding these structure-function relationships provides important insights for therapeutic targeting of NDR kinases in human diseases. The distinct subcellular localization patterns and activation mechanisms offer opportunities for isoform-specific modulation, potentially enabling selective intervention in pathological processes involving NDR signaling. Future structural studies, particularly focusing on full-length kinases in complex with their regulatory partners, will further elucidate the dynamic mechanisms governing NDR kinase function and regulation.

The nuclear Dbf2-related (NDR) kinases NDR1 (STK38) and NDR2 (STK38L) represent a crucial subfamily of AGC serine/threonine kinases that are highly conserved from yeast to humans [3]. These kinases function as key signaling nodes, integrating multiple regulatory inputs to control fundamental cellular processes including morphological changes, centrosome duplication, cell proliferation, apoptosis, and immune responses [3]. A defining characteristic of NDR kinase regulation involves a sophisticated mechanism dependent on phosphorylation at critical residues and interactions with MOB (Mps one binder) proteins. While NDR1 and NDR2 share approximately 87% sequence identity, they exhibit distinct subcellular localization patterns—NDR1 is primarily nuclear, whereas NDR2 is predominantly cytoplasmic [1]. This differential localization suggests non-redundant functions and potentially distinct activation mechanisms, forming a critical focus of ongoing research in the field. Understanding the precise molecular details of NDR kinase activation is essential not only for fundamental cell biology but also for therapeutic applications, given the roles of these kinases in cancer, neurodevelopment, and immune regulation [3] [2].

Molecular Machinery of NDR Kinase Activation

The Phosphorylation Code: Ser281 and Thr444

The activation mechanism of NDR1 hinges on phosphorylation at two conserved regulatory sites—Ser281 within the activation loop (T-loop) and Thr444 within the C-terminal hydrophobic motif (HM) [18] [19]. These phosphorylation events are essential for achieving full kinase activity and represent a convergence point for multiple upstream signals.

Ser281 undergoes autophosphorylation in a Ca²⁺-dependent manner and serves as a key indicator of kinase activation [18]. Experimental evidence demonstrates that chelating intracellular Ca²⁺ with BAPTA-AM suppresses both Ser281 phosphorylation and NDR1 activity, while treatments that increase cytoplasmic Ca²⁺ concentrations enhance this autophosphorylation [18].

Thr444 is predominantly phosphorylated by an upstream kinase rather than through autophosphorylation [18]. Multiple kinases have been implicated in this regulatory step, including members of the MST kinase family (MST1-3) and PLK1, which phosphorylates NDR1 at mitotic entry to suppress its activity [20] [2]. Phosphorylation at both residues is indispensable for full NDR1 activation, as mutation of either site to alanine dramatically reduces kinase activity [18] [2].

Table 1: Critical Phosphorylation Sites in NDR1 Kinase

| Residue | Location | Phosphorylation Mechanism | Functional Consequence | Regulating Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ser281 | Activation loop (T-loop) | Autophosphorylation | Induces kinase activation; essential for catalytic activity | Ca²⁺, S100B binding, MOB proteins |

| Thr444 | Hydrophobic motif (HM) | Trans-phosphorylation by upstream kinases | Enables full kinase activation; regulates substrate binding | MST1/2, PLK1, MOB proteins |

| Thr74 | N-terminal region | Autophosphorylation | Facilitates S100B binding; minor regulatory role | Ca²⁺ signaling |

MOB Proteins: Master Regulators of NDR Activity

MOB proteins function as critical cofactors that dictate NDR kinase activity through competitive binding and subcellular localization. The human genome encodes multiple MOB proteins, with MOB1 and MOB2 serving as the primary regulators of NDR kinases [1] [21].

MOB1 (including MOB1A and MOB1B isoforms) functions as a potent activator of NDR1/2. MOB1 binding to the N-terminal regulatory domain of NDR kinases stimulates kinase activity through multiple mechanisms: promoting autophosphorylation at Ser281, facilitating Thr444 phosphorylation by upstream kinases, and releasing autoinhibitory constraints within the catalytic domain [9] [19]. The association between MOB1 and NDR1 is particularly crucial for centrosome duplication, where it enables the formation of an MST1-MOB1-NDR1 signaling cascade [19].

MOB2 exhibits a more complex regulatory relationship with NDR kinases. While it binds to the same N-terminal domain as MOB1, it functions as a competitive inhibitor by preventing MOB1 binding and subsequent activation [21]. However, some contextual functions of MOB2 have been observed, particularly in neuronal development where it may contribute to NDR activation [2]. In hepatocellular carcinoma cells, MOB2 knockout promotes cell migration and invasion, while its overexpression has the opposite effect, suggesting tumor suppressor capabilities mediated through regulation of the Hippo pathway [21].

Table 2: MOB Protein Functions in NDR Kinase Regulation

| MOB Protein | Binding Partner | Effect on NDR Activity | Cellular Functions | Mechanistic Insights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOB1A/B | NDR1/2, LATS1/2 | Strong activation | Centrosome duplication, mitotic progression, Hippo signaling | Releases autoinhibition, promotes Ser281 and Thr444 phosphorylation |

| MOB2 | NDR1/2 only | Competitive inhibition | Cell migration, cell cycle progression, DNA damage response | Prevents MOB1 binding; may fine-tune NDR activity in specific contexts |

Integrated Activation Mechanism

The current model of NDR1 activation involves an intricate sequence of molecular events: (1) initial binding of MOB1 to the N-terminal regulatory domain, which induces a conformational change that releases autoinhibition; (2) subsequent phosphorylation of Thr444 by upstream kinases such as MST1; and (3) autophosphorylation at Ser281, resulting in full kinase activation [19]. This multi-step mechanism ensures precise temporal and spatial control of NDR1 signaling, allowing integration of diverse cellular inputs.

Experimental Approaches and Key Methodologies

Assessing NDR Kinase Activity: Phosphospecific Antibodies and Kinase Assays

Research into NDR activation mechanisms relies heavily on well-established experimental protocols that enable precise monitoring of phosphorylation events and kinase activity.

Phosphospecific Antibody Detection: A fundamental methodology involves using phosphospecific antibodies that recognize NDR1 only when phosphorylated at specific residues. Antibodies targeting pSer281 and pThr444 have been extensively validated and provide a direct readout of activation status [8] [18] [20]. These tools have revealed that NDR1 phosphorylation at Thr444 is significantly reduced during mitosis, correlating with suppressed kinase activity [20]. Western blotting with these antibodies typically involves resolving proteins by SDS-PAGE (8-12% gels), transfer to PVDF membranes, blocking with 5% skim milk, and incubation with primary antibodies overnight followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and ECL detection [8].

In Vitro Kinase Assays: Direct measurement of NDR1 activity utilizes immunoprecipitated NDR1 incubated with [γ-³²P]-ATP and specific substrate peptides (e.g., KKRNRRLSVA) [19]. The transfer of radioactive phosphate to the substrate quantifies catalytic activity. This approach demonstrated that NDR1 isolated from interphase cells exhibits approximately 10-fold higher activity than NDR1 from mitotic cells [20]. Kinase assays using purified components have also established that MOB1 binding can dramatically stimulate NDR1 activity (up to 10-fold) in combination with phosphorylation events [1] [9].

Mutational Analysis: Dissecting Regulatory Mechanisms

Structure-function studies employing site-directed mutagenesis have been instrumental in deciphering NDR1 regulation:

- Kinase-dead mutants (K118A, S281A, T444A) abolish catalytic activity and function as dominant-negative variants [2] [19]

- Constitutively active mutants include the NDR1-PIF variant (containing the PRK2 hydrophobic motif) and NDR1EAIS with mutations in the autoinhibitory sequence [20] [19]

- Phospho-mimetic mutants (T444D/E) surprisingly do not recapitulate Thr444 phosphorylation, indicating that negative charge alone is insufficient to activate NDR1 [19]

- MOB-binding mutants with impaired MOB1 interaction help delineate MOB-dependent and MOB-independent functions [19]

Expression of these mutants in cellular models (e.g., Cos-7, U2-OS, HeLa cells) followed by phenotypic analysis has revealed that persistent NDR1 activation perturbs proper spindle orientation in mitosis, while kinase-dead NDR1 increases dendrite length and branching in neurons [20] [2].

Subcellular Localization and Imaging Studies

The distinct localization patterns of NDR1 (nuclear) and NDR2 (cytoplasmic) despite high sequence similarity represent a key area of investigation [1]. Experimental approaches include:

- Immunofluorescence microscopy using specific antibodies against endogenous NDR1/2 or epitope-tagged constructs [8] [20]

- Live-cell imaging with GFP-tagged NDR kinases to monitor dynamic localization during cell division [20]

- Inducible translocation systems where membrane-targeted MOB proteins rapidly recruit NDR to membranes, resulting in phosphorylation and activation within minutes [8]

These techniques have demonstrated that membrane targeting of NDR alone is sufficient to generate a constitutively active kinase due to spontaneous phosphorylation at both Ser281 and Thr444 [8].

Visualization of NDR1 Activation Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the integrated activation mechanism of NDR1 kinase, highlighting the key regulatory steps and molecular interactions:

Diagram Title: Integrated Activation Pathway of NDR1 Kinase

Key Regulatory Complexities

The activation pathway demonstrates several sophisticated regulatory features:

- Dual phosphorylation requirement: Both Ser281 and Thr444 phosphorylation must occur for full activation

- MOB competition: MOB1 and MOB2 compete for the same binding site, creating a toggle switch for activation

- Contextual upstream regulation: Different upstream kinases (MST1 vs PLK1) phosphorylate Thr444 depending on cellular context

- Calcium sensitivity: Ca²⁺ signaling through S100B directly influences autophosphorylation capability

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Studying NDR Kinase Activation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphospecific Antibodies | Anti-pSer281-NDR1, Anti-pThr444-NDR1 | Monitoring activation status; Western blot, immunofluorescence | Validate kinase activation; assess regulation in different cellular states |

| Activation State Mutants | NDR1-K118A (kinase dead), NDR1-AA (S281A/T444A), NDR1-PIF (constitutively active) | Functional studies; pathway dissection | Determine necessity and sufficiency of NDR1 in cellular processes |

| MOB Expression Constructs | MOB1A/B (activator), MOB2 (inhibitor), membrane-targeted MOB variants | Mechanistic studies; pathway manipulation | Define MOB-specific functions; manipulate subcellular localization |

| Chemical Inhibitors/Activators | Okadaic acid (PP2A inhibitor), Thapsigargin (Ca²⁺ mobilizer), BAPTA-AM (Ca²⁺ chelator) | Probing regulatory mechanisms | Dissect phosphorylation dynamics; calcium dependence |

| Substrate Detection Systems | NDR substrate peptide (KKRNRRLSVA), AAK1, Rabin8 substrates | Kinase activity assays; substrate identification | Quantify enzymatic activity; identify downstream targets |

| Localization Tools | Centrosome-targeted NDR (AKAP-NDR1), NLS/NES tags, GFP-tagged NDR1/2 | Subcellular targeting studies | Investigate compartment-specific functions; live imaging |

Functional Consequences and Research Applications

The regulated activation of NDR kinases through MOB proteins and phosphorylation has profound implications for diverse biological processes:

Cell Division and Centrosome Duplication: Proper NDR1 activity control is essential for accurate mitotic progression. During mitosis, PLK1 phosphorylates NDR1 at three threonine residues (T7, T183, T407), which suppresses NDR1 activity by interfering with MOB1 binding [20]. Constitutively active NDR1 (NDR1EAIS) causes aberrant spindle rotation and orientation defects, highlighting the importance of temporal regulation [20].

Neuronal Development: NDR1/2 kinases limit dendrite length and proximal branching in mammalian pyramidal neurons [2]. Kinase-dead NDR1/2 mutants increase dendrite complexity, while constitutively active forms have the opposite effect. NDR1/2 also promotes dendritic spine maturation and excitatory synaptic function, with identified substrates including AAK1 (regulating dendrite growth) and Rabin8 (controlling spine development) [2].

Infection and Immunity: NDR1 plays complex roles in immune regulation, acting as a negative regulator of TLR9-mediated inflammation by promoting degradation of MEKK2, while positively regulating RIG-I-mediated antiviral response through enhancement of RIG-I/TRIM25 complex formation [3].

The experimental frameworks and reagents described in this guide provide researchers with comprehensive tools to further investigate the context-dependent functions of NDR kinases and their potential as therapeutic targets in cancer, neurological disorders, and inflammatory diseases.

The NDR (Nuclear Dbf2-related) kinase family represents a highly conserved subgroup of serine/threonine AGC kinases that function as crucial regulators of cell proliferation, apoptosis, morphogenesis, and cell polarity. These kinases are remarkably conserved throughout the eukaryotic domain, with orthologs identified from yeast to humans [22] [4] [23]. The founding member of this family, Dbf2, was first characterized in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, where it regulates mitotic exit and morphogenesis [6] [8]. In mammals, this family expanded to include four members: NDR1 (STK38), NDR2 (STK38L), LATS1, and LATS2, which form the core of the NDR/LATS kinase subfamily [24] [23]. The evolutionary conservation of these kinases extends beyond sequence homology to encompass their regulatory mechanisms and fundamental biological functions, making them a subject of intense research interest particularly in the context of differential subcellular localization and function between NDR1 (nuclear) and NDR2 (cytoplasmic).

Evolutionary Conservation Across Species

The NDR kinase family exhibits remarkable evolutionary conservation from lower eukaryotes to complex multicellular organisms. This conservation is evident not only in the amino acid sequences but also in their structural domains and activation mechanisms.

Table 1: NDR Kinase Orthologs Across Species

| Organism | NDR1/2 Ortholog | LATS1/2 Ortholog | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae (Budding yeast) | Cbk1p, Dbf2, Dbf20 | - | Mitotic exit, cell morphogenesis, cell integrity [23] |

| S. pombe (Fission yeast) | orb6, sid2 | - | Cell polarity, cytokinesis [23] |

| C. elegans (Nematode) | SAX-1 | WARTS/wts-1 | Neurite outgrowth, epidermal morphogenesis [4] [23] |

| D. melanogaster (Fruit fly) | Tricornered (Trc) | Warts (Wts) | Dendritic tiling, epidermal morphogenesis [4] [23] |

| H. sapiens (Human) | NDR1 (STK38), NDR2 (STK38L) | LATS1, LATS2 | Centrosome duplication, ciliogenesis, apoptosis, Hippo signaling [4] [24] [23] |

The sequence identity between human NDR1 and NDR2 is approximately 87%, highlighting their close relationship [4] [24]. Despite this high similarity, they exhibit distinct subcellular localizations—NDR1 is predominantly nuclear while NDR2 displays cytoplasmic distribution [4] [6]. This differential localization represents a key functional divergence that underscores their non-redundant biological roles.

Structural Conservation and Activation Mechanisms

NDR kinases share a conserved domain architecture consisting of an N-terminal regulatory domain (NTR) and a C-terminal kinase domain. A distinctive feature of all NDR kinases is an insert between catalytic subdomains VII and VIII characterized by high basic amino acid content [22]. Structural studies have revealed that this insert possesses autoinhibitory function, and binding of MOB proteins to the N-terminal domain induces conformational changes that release this autoinhibition [22].

The activation mechanism of NDR kinases is highly conserved and requires multiple phosphorylation events and regulatory interactions:

Phosphorylation Events

- Activation loop phosphorylation: Thr444 in NDR1 (Thr442 in NDR2) is phosphorylated by an upstream kinase [8]

- N-terminal phosphorylation: Ser281 in NDR1 (Ser282 in NDR2) involves autophosphorylation [8]

- Both phosphorylation events are essential for full kinase activation [8]

MOB Protein Interaction

MOB (Mps one binder) proteins serve as critical coactivators of NDR kinases. The interaction between NDR and MOB proteins is evolutionarily conserved from yeast to humans [22] [6]. Human MOB1 (hMOB1) directly binds to the N-terminal regulatory domain of NDR kinases, dramatically stimulating their catalytic activity [22] [6]. This interaction is so critical that membrane-targeted hMOBs can robustly promote NDR activation at the plasma membrane, demonstrating the functional significance of this conserved mechanism [8].

Diagram Title: Conserved NDR Kinase Activation Mechanism

Functional Divergence: NDR1 Nuclear Localization vs. NDR2 Cytoplasmic Distribution

Despite their high sequence similarity, NDR1 and NDR2 have evolved distinct subcellular localizations and functions, a key aspect of their functional divergence in mammalian systems.

NDR1 Nuclear Functions

NDR1 is predominantly localized in the nucleus and participates in critical nuclear processes:

- Cell cycle regulation: Controls centrosome duplication and mitotic chromosome alignment [4] [24]

- Transcriptional regulation: Phosphorylates and regulates transcriptional co-activators including YAP/TAZ in the Hippo pathway [4] [24] [23]

- Tumor suppression: Acts as a tumor suppressor in various cancers including prostate cancer and T-cell lymphoma [24] [25]

- Apoptosis regulation: Promotes apoptosis through phosphorylation of pro-apoptotic substrates [24] [25]

NDR2 Cytoplasmic Functions

NDR2 exhibits punctate cytoplasmic distribution and participates in distinct cellular processes:

- Ciliogenesis: Regulates primary cilium formation through phosphorylation of Rabin8, promoting local activation of Rab8 [4]

- Peroxisomal targeting: Localizes to peroxisomes using a C-terminal Gly-Lys-Leu (GKL) sequence that functions as a peroxisomal targeting signal (PTS1) [4]

- Vesicular trafficking: Controls trafficking of vesicles through regulation of Rab GTPase activity [4] [10]

- Metabolic adaptation: Regulates microglial metabolic adaptation under high-glucose conditions [12]

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of NDR1 and NDR2 Properties

| Property | NDR1 | NDR2 |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Identity | Reference | 87% identical to NDR1 [4] [24] |

| Subcellular Localization | Diffuse nuclear and cytoplasmic [4] [6] | Punctate cytoplasmic; peroxisomal [4] |

| Tissue Distribution | Widely expressed [6] | Highest expression in thymus [6] |

| C-terminal Targeting Signal | Ala-Lys [4] | Gly-Lys-Leu (PTS1-like) [4] |

| Role in Ciliogenesis | Not essential [4] | Critical regulator [4] |

| Cancer Association | Tumor suppressor in prostate cancer, lymphoma [24] [25] | Oncogenic in lung cancer [10] |

| Immune Function | Regulates inflammation and immunity [25] | Modulates microglial inflammatory response [12] |

The mechanistic basis for their differential localization was elucidated by Hori et al. (2017), who discovered that NDR2 contains a C-terminal Gly-Lys-Leu (GKL) sequence that functions as a peroxisomal targeting signal (PTS1), while NDR1 terminates in Ala-Lys and does not localize to peroxisomes [4]. This critical difference explains the distinct subcellular distributions and functional specializations of these kinases.

Experimental Approaches and Key Methodologies

Research on NDR kinases employs sophisticated experimental approaches to elucidate their conservation, activation mechanisms, and functional differences.

Key Experimental Protocols

Subcellular Localization Studies

Protocol:

- Transfect cells with plasmids encoding N-terminally tagged YFP-NDR2 or YFP-NDR1 [4]

- Immunostain with antibodies against organelle markers (catalase for peroxisomes, EEA1 for early endosomes, GM130 for Golgi) [4]

- Analyze co-localization using fluorescence microscopy [4]

- Perform subcellular fractionation by iodixanol density gradient ultracentrifugation [4]

- Confirm peroxisomal localization through Pex5p binding assays [4]

Key Finding: NDR2, but not NDR1, co-localizes with peroxisomal markers and binds to the PTS1 receptor Pex5p [4].

Kinase Activation Assays

Protocol:

- Express and purify GST-fused NDR1 from E. coli BL21 using glutathione-agarose affinity chromatography [25]

- Incubate purified NDR1 with substrate peptide (KKRNRRLSVA), ATP, and reaction buffer [25]

- Treat with potential activators (e.g., MOB proteins or small-molecule agonists) [22] [25]

- Measure kinase activity using luminescent kinase assay kits [25]

- Assess phosphorylation status using phospho-specific antibodies [8]

Key Finding: MOB binding dramatically stimulates NDR kinase activity, and membrane targeting results in constitutive NDR activation [22] [8].

Functional Rescue Experiments

Protocol:

- Knock down endogenous NDR2 using siRNA or CRISPR-Cas9 [4] [12]

- Transfect with wild-type NDR2 or mutant NDR2(ΔL) lacking the C-terminal leucine [4]

- Assess functional recovery in ciliogenesis assays [4]

- Evaluate peroxisomal localization by immunofluorescence [4]

Key Finding: Wild-type NDR2, but not NDR2(ΔL), rescues ciliogenesis defects caused by NDR2 knockdown, establishing the functional significance of peroxisomal localization [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for NDR Kinase Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|

| hMOB1A/B protein | NDR kinase co-activator for in vitro activation assays [22] | Recombinantly expressed [22] [8] |

| Phospho-specific antibodies | Detection of activated NDR (pThr444/442, pSer281/282) [8] | Custom-produced against phosphopeptides [8] |

| PTS1 receptor (Pex5p) | Investigation of NDR2 peroxisomal targeting mechanism [4] | Co-immunoprecipitation assays [4] |

| Okadaic acid (OA) | PP2A inhibitor used to activate NDR kinases by preventing dephosphorylation [8] | Commercial sources (Alexis Corp.) [8] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 plasmids | Generation of NDR knockout cell lines for functional studies [12] | sgRNA against exon 7 of Ndr2 gene [12] |

| Small-molecule agonists | Pharmacological activation of NDR kinases for therapeutic research [25] | aNDR1 compound [25] |

Therapeutic Implications and Research Applications

The evolutionary conservation of NDR kinases extends to their relevance in human disease pathways, making them attractive therapeutic targets:

Cancer Therapeutics: NDR1 functions as a tumor suppressor in prostate cancer, with decreased expression correlating with poorer prognosis [24] [25]. Small-molecule NDR1 agonists like aNDR1 show promising antitumor activity both in vitro and in vivo [25].

Ciliopathies: NDR2's essential role in ciliogenesis implicates it in ciliopathies such as Leber congenital amaurosis, a form of early retinal degeneration [4].

Metabolic and Inflammatory Disorders: NDR2 regulates microglial metabolic adaptation under high-glucose conditions, suggesting potential applications in diabetic retinopathy [12].

Aging and Neurodegeneration: NDR kinases have been linked to various aging hallmarks including cellular senescence, chronic inflammation, and autophagy, positioning them as potential regulators of aging processes [23].

The evolutionary journey from yeast Dbf2 to mammalian NDR kinases represents a compelling narrative of conservation and divergence. While the core structure and activation mechanisms have been remarkably preserved across eukaryotic evolution, the mammalian NDR kinases have diversified into specialized functions exemplified by the distinct nuclear and cytoplasmic roles of NDR1 and NDR2. The differential subcellular localization of these kinases—governed by discrete targeting signals—underpins their functional specialization in regulating diverse cellular processes from centrosome function to ciliogenesis. Continued research on these evolutionarily conserved kinases promises not only to advance our fundamental understanding of cellular regulation but also to unlock novel therapeutic approaches for cancer, ciliopathies, metabolic disorders, and age-related diseases.

Advanced Techniques for Isolating and Probing NDR1- and NDR2-Specific Functions

The highly homologous kinases NDR1 and NDR2, despite significant sequence similarity, exhibit distinct subcellular localizations and biological functions that necessitate rigorous detection strategies. NDR1 contains a functional nuclear localization signal (NLS) and is found predominantly in the nucleus, while NDR2 is primarily cytoplasmic, a differential distribution that underpins their non-redundant roles in cellular processes [8]. This subcellular partitioning is functionally significant, with NDR1 implicated in cell cycle regulation at the G1/S transition and NDR2 playing crucial roles in antiviral immune responses, vesicular trafficking, and autophagy [26] [27] [10]. Accurate differentiation between these kinases through validated antibodies and carefully designed localization reporters is therefore paramount for advancing our understanding of their distinct functions in both physiological and pathological contexts, including cancer and neurodegenerative diseases [10] [28].

The challenge of specific detection is compounded by the high amino acid identity (>80%) between NDR1 and NDR2, which can lead to antibody cross-reactivity and misinterpretation of experimental results [10]. Furthermore, the expanding roles of NDR kinases in fundamental cellular processes and disease pathways underscores the critical need for reliable detection methodologies. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of current strategies for the specific detection of NDR1 and NDR2, offering experimental protocols and analytical frameworks to empower researchers in generating reproducible and biologically relevant data.

Antibody Validation Strategies for Differentiating NDR1 and NDR2

The Five Pillars of Antibody Validation

Antibody validation is essential for ensuring specific, selective, and reproducible results in NDR kinase research. The following validation pillars provide a comprehensive framework for confirming antibody specificity in different experimental contexts [29]:

Genetic Knockout/Knockdown: This method involves using cells or organisms in which the gene encoding the target protein (NDR1 or NDR2) has been completely or partially inactivated. The specificity of an antibody is confirmed by a significant reduction or absence of signal in the knockout/knockdown samples compared to controls. For NDR kinases, this approach is particularly valuable due to their high similarity, requiring demonstration that an anti-NDR1 antibody does not recognize NDR2 in NDR1-knockout cells, and vice versa [29].

Orthogonal Validation: This strategy employs a non-antibody-based method to measure the same target protein. For NDR localization studies, this could involve comparing immunofluorescence results with genetically encoded fluorescent protein tags or mRNA detection techniques. Consistent results between the antibody-based method and the orthogonal approach provide strong validation evidence [29].

Use of Comparable Antibodies: Multiple antibodies raised against different epitopes of the same target protein should yield similar staining patterns. For NDR1 and NDR2, this would involve using antibodies targeting different regions of each kinase and confirming consistent subcellular localization patterns—nuclear for NDR1 and cytoplasmic for NDR2 [29] [8].

Immunoprecipitation Mass Spectrometry (IP/MS): An antibody is used to immunoprecipitate the target protein from a complex mixture, followed by identification of the pulled-down proteins via mass spectrometry. This method provides direct evidence for antibody specificity and can reveal potential off-target interactions, crucial for distinguishing between highly similar proteins like NDR1 and NDR2 [29].

Recombinant Protein Expression: Expressing the recombinant NDR1 or NDR2 protein in a heterologous system provides a positive control for antibody validation. The presence of a single band at the expected molecular weight in Western blot analysis confirms the antibody's specificity for its intended target [29].

Common Pitfalls in Antibody-Based Detection

Approximately 70% of researchers have struggled to reproduce experiments conducted by other scientists, often due to issues with antibodies [29]. Several critical pitfalls must be addressed when working with antibodies for NDR detection:

Nonspecific Antibodies: Antibodies may recognize unrelated epitopes or proteins with similar structures. This is particularly problematic for NDR1 and NDR2 due to their high sequence conservation. A study demonstrated that 35% of monoclonal antibody preparations analyzed had staining patterns unrelated to their intended antigenic specificity [30].

Non-reproducible Antibodies: Significant lot-to-lot variations can occur with commercial antibodies. One study highlighted two different lots of the same monoclonal antibody that showed completely different staining patterns—one nuclear and one membranous/cytoplasmic—with very poor correlation (R² = 0.038) [30].

Epitope Accessibility: The recognition of an antibody can be affected by protein conformation, post-translational modifications, and fixation methods. Epitopes accessible in denatured proteins for Western blot may be inaccessible in native proteins for immunohistochemistry, and vice versa [30].

Cellular Compartment Mislocalization: Staining patterns that contradict established biological knowledge indicate potential nonspecificity. For instance, cytoplasmic staining for a known nuclear transcription factor, or vice versa, should raise concerns about antibody validity [30].

Table 1: Troubleshooting Antibody Specificity for NDR Kinases

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unexpected bands in Western blot | Cross-reactivity with other proteins or modified forms | Validate by knockout/knockdown; optimize blocking conditions |

| Aberrant subcellular localization | Recognition of unrelated epitopes; fixation artifacts | Compare with orthogonal methods; optimize fixation protocol |

| High background noise | Non-specific antibody binding | Titrate antibody concentration; improve antigen retrieval |

| Inconsistent staining between lots | Variations in antibody production | Request validation data from vendor; test new lots extensively |

| Discrepancy between techniques | Differential epitope accessibility | Use multiple validation pillars; confirm antibody suitability for specific applications |

Experimental Protocol: Knockout Validation for NDR Antibodies

This protocol provides a robust method for validating NDR antibody specificity using genetic knockout cells:

Cell Culture: Maintain wild-type (WT) and NDR1 or NDR2 knockout (KO) cell lines (e.g., HEK293, HeLa, or U2OS) in appropriate medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator [26] [8].

Sample Preparation:

- For Western blotting: Lyse cells in RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Quantify protein concentration and resolve 20-30 μg by SDS-PAGE [8] [30].

- For immunofluorescence: Culture cells on glass coverslips, fix with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes, and permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes [8].

Immunodetection:

- For Western blotting: Transfer proteins to PVDF membranes, block with 5% non-fat milk in TBST, and incubate with primary antibodies against NDR1 or NDR2 (1:1000 dilution) overnight at 4°C. After washing, incubate with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5000) for 1 hour at room temperature and detect using ECL reagent [8].

- For immunofluorescence: After blocking with 3% BSA in PBS, incubate cells with primary antibodies (1:500 dilution) for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing, incubate with fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies (1:1000) for 45 minutes, counterstain with DAPI, and mount [8].

Validation Criteria: The antibody is considered specific if:

- A band at the expected molecular weight (approximately 54-60 kDa) is present in WT but absent or dramatically reduced in KO lysates.

- The subcellular localization pattern (nuclear for NDR1, cytoplasmic for NDR2) is observed in WT but not KO cells.

- No cross-reactivity with the other NDR kinase is detected [8].

Reporter Design Strategies for Studying NDR Localization and Function

Fluorescent Protein Reporters for Live-Cell Imaging