Navigating Selectivity: A Comprehensive Guide to Cross-Reactivity Profiling of STAT SH2 Domain Inhibitors

The development of selective inhibitors for STAT (Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription) SH2 domains represents a promising therapeutic strategy for cancers and inflammatory diseases.

Navigating Selectivity: A Comprehensive Guide to Cross-Reactivity Profiling of STAT SH2 Domain Inhibitors

Abstract

The development of selective inhibitors for STAT (Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription) SH2 domains represents a promising therapeutic strategy for cancers and inflammatory diseases. However, the high structural conservation across the human SH2 domain family, which includes over 120 domains, poses a significant challenge, making cross-reactivity a critical parameter in drug discovery. This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of STAT SH2 domain structure and function, advanced methodological approaches for profiling selectivity, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing inhibitor specificity, and frameworks for the validation and comparative analysis of lead compounds. By synthesizing current research and emerging technologies, this review aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to design more effective and selective therapeutic agents.

The Structural and Functional Landscape of STAT SH2 Domains

The αβββα motif represents a canonical architectural foundation for protein domains that mediate critical protein-protein and protein-nucleic acid interactions in cellular signaling. This conserved structural fold consists of a central anti-parallel β-sheet composed of three strands, flanked on either side by two α-helices, creating a stable scaffold for molecular recognition [1] [2]. Despite sharing this common structural blueprint, nature has evolved this versatile fold to serve distinct functions across different protein families.

Two prominent domain families utilizing this motif play essential roles in cellular information processing: SH2 (Src Homology 2) domains that recognize phosphotyrosine sites in signaling proteins, and dsRBDs (double-stranded RNA binding domains) that interact with double-stranded RNA molecules [1] [2] [3]. The structural adaptability of the αβββα fold allows it to accommodate different binding surfaces and recognition mechanisms, making it a fundamental component in signal transduction pathways from metazoans to humans. This review examines the architectural principles of this motif, with particular emphasis on its role in phosphotyrosine recognition by STAT SH2 domains and the implications for targeted therapeutic development.

Structural Comparison of αβββα Domains

Architectural Principles and Functional Diversification

Despite their shared structural foundation, SH2 and dsRBDs have evolved distinct functional specializations through variations in their surface chemistry and binding interfaces. The table below summarizes the key comparative features of these domains:

Table 1: Structural and Functional Comparison of αβββα Domains

| Feature | SH2 Domains | dsRBDs |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Phosphotyrosine recognition | Double-stranded RNA binding |

| Central β-sheet | 3 anti-parallel strands (βB-βD) | 3 anti-parallel strands |

| Flanking α-helices | αA and αB | Two α-helices |

| Key Binding Pockets | pY (phosphate-binding) and pY+3 (specificity) pockets | RNA-binding surface across α-helices and β1-β2 loop |

| Binding Mechanism | Sequence-specific phosphopeptide recognition | Primarily shape-dependent RNA recognition with some sequence specificity in minor groove |

| Conserved Motifs | FLVRES motif with critical arginine residue | Conserved C-terminal region |

| Structural Variations | STAT-type vs. Src-type differences in C-terminal region | Variations in α-helix 1 mediating specific recognition |

The SH2 domain utilizes two primary binding pockets: the pY pocket formed by the αA helix, BC loop, and one face of the central β-sheet that engages the phosphotyrosine moiety, and the pY+3 pocket created by the opposite face of the β-sheet along with residues from the αB helix and CD/BC* loops that provide binding specificity [1]. The dsRBD typically interacts with approximately 15 base pairs of RNA through a binding surface that spans both α-helices and the β1-β2 loop, contacting two consecutive minor grooves separated by a major groove [2] [3].

STAT-Type SH2 Domains: Specialized Architecture for Transcription Factor Signaling

STAT-type SH2 domains represent a specialized subclass that diverges from canonical Src-type SH2 domains in their C-terminal architecture. While Src-type SH2 domains feature a β-sheet at the C-terminus, STAT-type SH2 domains incorporate an α-helix (αB') in this region, creating what is known as the evolutionary active region (EAR) [1]. This structural variation enables STAT proteins to form reciprocal dimers through phosphotyrosine-SH2 domain interactions between two STAT monomers, which is essential for their function as transcription factors [1] [4].

Table 2: Key Structural Features of STAT-type SH2 Domains

| Structural Element | Composition | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|

| pY Pocket | αA helix, BC loop, β-sheet face | Binds phosphotyrosine moiety |

| pY+3 Pocket | Opposite β-sheet face, αB helix, CD/BC* loops | Determines sequence specificity |

| Hydrophobic System | Cluster of non-polar residues | Stabilizes β-sheet and domain integrity |

| EAR (Evolutionary Active Region) | αB' helix | STAT-specific feature involved in dimerization |

| BC* Loop | Connection between αB and αC helices | Participates in SH2-mediated dimerization |

The structural flexibility of STAT SH2 domains presents both challenges and opportunities for drug discovery. Molecular dynamics simulations reveal that these domains exhibit considerable flexibility even on sub-microsecond timescales, with the accessible volume of the pY pocket varying dramatically [1]. This inherent flexibility must be accounted for in rational drug design approaches targeting these domains.

STAT SH2 Domains in Cellular Signaling and Disease

Mechanistic Role in JAK-STAT Signaling Pathway

STAT SH2 domains mediate crucial interactions in the JAK-STAT signaling cascade. The following diagram illustrates the activation pathway and key molecular interactions:

STAT SH2 Domain Signaling Pathway

The activation mechanism begins when cytokines or growth factors bind to their cognate receptors, stimulating JAK kinases to phosphorylate tyrosine residues on receptor intracellular domains [4]. STAT monomers are then recruited to these phosphotyrosine sites via their SH2 domains. Following recruitment, STATs become phosphorylated on a conserved tyrosine residue, enabling reciprocal SH2 domain-phosphotyrosine interactions that stabilize active parallel dimers [5] [4]. These dimers translocate to the nucleus where they bind specific DNA response elements and regulate target gene expression.

Dysregulation in Human Disease

Mutations in STAT SH2 domains are particularly consequential given their critical role in activation and dimerization. Sequencing analyses of patient samples have identified the SH2 domain as a hotspot in the mutational landscape of STAT proteins [1]. The following table catalogues disease-associated mutations in STAT3 and STAT5 SH2 domains:

Table 3: Disease-Associated Mutations in STAT3 and STAT5 SH2 Domains

| Mutation | Location | Pathology | Type | Functional Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAT3 K591E/M | αA2 helix, pY pocket | AD-HIES | Germline | Loss-of-function |

| STAT3 S611N | βB7 strand, pY pocket | AD-HIES | Germline | Loss-of-function |

| STAT3 S614R | BC loop, pY pocket | T-LGLL, NK-LGLL, ALK-ALCL | Somatic | Gain-of-function |

| STAT3 E616K | BC loop, pY pocket | NKTL | Somatic | Gain-of-function |

| STAT5 Mutations | Various SH2 locations | Leukemias, Immunodeficiencies | Both | Either loss or gain-of-function |

The genetic volatility of specific regions in the SH2 domain can result in either activating or deactivating mutations at the same site, underscoring the delicate evolutionary balance of wild-type STAT structural motifs in maintaining precise levels of cellular activity [1]. For instance, STAT3 S614R is a recurrent somatic gain-of-function mutation found in T-cell large granular lymphocytic leukemia (T-LGLL), while other mutations at the same position (S614G) cause loss-of-function in autosomal-dominant hyper IgE syndrome (AD-HIES) [1].

Experimental Approaches for STAT SH2 Domain Investigation

Methodologies for Inhibitor Development and Validation

The development of STAT SH2 domain inhibitors has employed diverse experimental strategies, ranging from peptide mimetics to small molecule compounds. The following workflow outlines key experimental approaches:

STAT SH2 Inhibitor Development Workflow

Fluorescence Polarization (FP) Assays provide quantitative measurements of inhibitor binding affinity. For example, in the development of STAT6 inhibitors, FP assays demonstrated IC50 values ranging from 50 nM to 2.33 μM for various compounds, with PM-71I-B showing particularly high affinity (IC50 = 50 nM) [6]. These assays typically utilize fluorescently-labeled phosphopeptides that compete with test compounds for binding to recombinant SH2 domains.

Cellular Activity Screening evaluates membrane permeability and target engagement in live cells. For instance, STAT inhibitors are typically converted to phosphatase-stable prodrugs through addition of protecting groups (e.g., POM groups) to mask phosphate moieties and enhance cellular uptake [6]. Cellular potency is determined by monitoring inhibition of STAT phosphorylation (e.g., pY694 for STAT5A) via Western blotting or similar techniques, with EC50 values for lead compounds typically ranging from 100-500 nM [6].

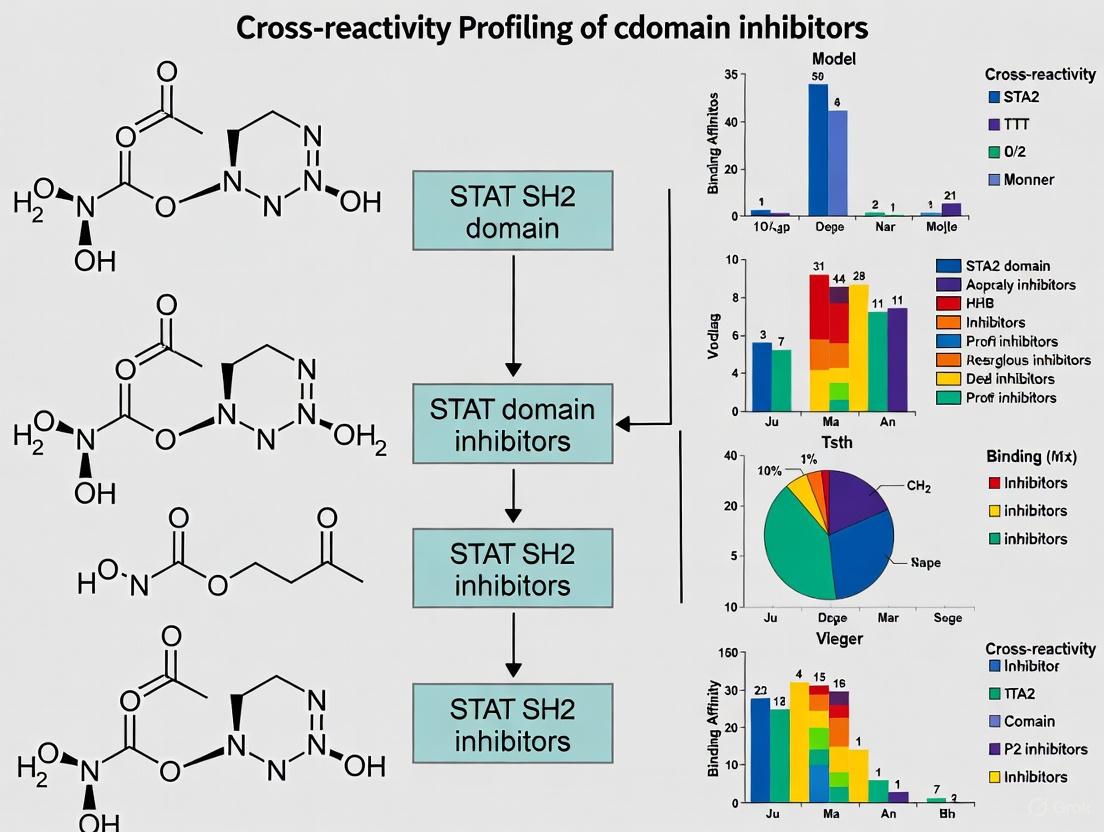

Cross-reactivity Profiling ensures selective targeting of specific STAT family members. This involves screening compounds against multiple SH2 domain-containing proteins, including STAT1, STAT3, STAT5, and non-STAT SH2 domains such as those in p85 (PI3K) and Src [6]. For example, PM-86I exhibited high specificity for STAT6 with minimal cross-reactivity to other STAT family members, while PM-43I showed significant cross-reactivity with STAT5 [6].

Advanced Biosensor Technologies for Real-Time Monitoring

Recent advances in biosensor technology have enabled real-time monitoring of STAT activation in live cells. STATeLights represent a class of genetically encoded biosensors that utilize FRET (Förster Resonance Energy Transfer) to detect STAT conformational changes [4]. These biosensors typically employ mNeonGreen (mNG) and mScarlet-I (mSC-I) as FRET pairs, fused to truncated STAT5A constructs at positions that maximize FRET efficiency changes upon activation-induced conformational switching from antiparallel to parallel dimers [4].

The optimal biosensor configuration identified through empirical testing involves C-terminal fusion of fluorophores directly to the SH2 domain, which yielded FRET efficiency up to 12% upon IL-2 stimulation [4]. These biosensors enable direct continuous detection of STAT5 activation with high spatiotemporal resolution, facilitating compound screening and evaluation of disease-associated STAT5 mutants without requiring cell fixation or permeabilization.

Research Reagent Solutions for SH2 Domain Studies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for STAT SH2 Domain Investigations

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant SH2 Domains | His-tagged Stat3 SH2 domain [5] | In vitro binding assays, biophysical studies | Enables FP assays, crystallography, binding affinity measurements |

| Cell-Based Reporter Systems | HEK-Blue IL-2 cells [4] | Cellular signaling assessment | Functional IL-2R-JAK1/3-STAT5 pathway for compound screening |

| Biosensors | STATeLight5A [4] | Real-time STAT activation monitoring | FLIM-FRET detection of conformational changes in live cells |

| Peptide Inhibitors | SPI peptide (FISKERERAILSTKPPGTFLLRFSESSK) [5] | Proof-of-concept inhibition studies | Stat3 SH2 domain mimetic, cell-permeable, inhibits Stat3 phosphorylation |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | PM-43I, PM-63I, PM-86I [6] | Specific STAT pathway inhibition | Peptidomimetic compounds targeting SH2 domains with varying specificity |

| Molecular Modeling Tools | Molecular docking (Smina/Autodock Vina) [7] | In silico inhibitor screening | Structure-based drug discovery for SH2 domain targets |

| Dynamic Simulation Software | Gromacs MD simulations [7] | Protein-ligand interaction analysis | Molecular dynamics and MM/PBSA binding free energy calculations |

Comparative Analysis of STAT SH2-Targeted Therapeutic Approaches

Targeting Strategies and Clinical Implications

Various approaches have been developed to target STAT SH2 domains therapeutically, each with distinct mechanisms and limitations. The primary strategies include phosphopeptide competitors that mimic native phosphotyrosine motifs, SH2 domain mimetics that imitate the receptor interface, and small molecule inhibitors that target specific pockets within the SH2 domain [5] [6].

The SPI peptide exemplifies the SH2 domain mimetic approach. This 28-mer peptide derived from the Stat3 SH2 domain (sequence: FISKERERAILSTKPPGTFLLRFSESSK) replicates Stat3 biochemical properties, binding to cognate phosphotyrosine peptide motifs with similar affinity as the native SH2 domain [5]. SPI is cell membrane-permeable, localizes to the cytoplasm and nucleus in malignant cells, and specifically blocks constitutive Stat3 phosphorylation, DNA binding activity, and transcriptional function at concentrations of 50-60 μM [5].

Small molecule peptidomimetics represent a more drug-like approach. PM-43I, developed as a STAT6 inhibitor, demonstrates potent inhibition of STAT6-dependent allergic airway disease in mice with a remarkably low ED50 of 0.25 μg/kg [6]. However, this compound shows significant cross-reactivity with STAT5, highlighting the challenge of achieving selectivity among structurally similar SH2 domains [6]. In contrast, PM-86I exhibits higher specificity for STAT6 with minimal cross-reactivity to other STAT family members at concentrations up to 5 μM [6].

Experimental Data on Inhibitor Efficacy and Specificity

Table 5: Quantitative Profiling of STAT SH2 Domain Inhibitors

| Compound | Target | Binding Affinity (IC50) | Cellular Potency (EC50) | Cross-Reactivity | Therapeutic Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPI Peptide | Stat3 SH2 | Similar to native Stat3 SH2 [5] | 50-60 μM (phosphorylation inhibition) [5] | Selective for Stat3 over Stat1, Stat5, Erk1/2 [5] | Breast, pancreatic, prostate, NSCLC cancer models [5] |

| PM-43I | STAT6 SH2 | ~230-260 nM [6] | 1-2 μM (pSTAT6 inhibition) [6] | Significant STAT5 cross-reactivity [6] | Murine allergic airway disease (ED50 = 0.25 μg/kg) [6] |

| PM-86I | STAT6 SH2 | Not specified | >90% inhibition at 5 μM [6] | Minimal cross-reactivity [6] | Potential for allergic airway disease [6] |

| CID 60838 (Irinotecan) | N-SH2 of SHP2 | Docking score: -10.2 kcal/mol [7] | Not tested | Not assessed | Computational identification for SHP2-related pathologies [7] |

The development of SH2 domain inhibitors faces several challenges, including achieving sufficient selectivity among closely related SH2 domains, ensuring optimal cellular permeability, and avoiding disruption of essential physiological signaling pathways. Moderate affinity (typical KD values between 0.1-10 μM) is considered crucial for allowing transient association and dissociation events in cell signaling, as artificially increased affinity can cause detrimental cellular consequences [8].

The canonical αβββα motif represents a remarkable example of structural conservation with functional diversification in eukaryotic signaling domains. STAT SH2 domains have emerged as compelling therapeutic targets due to their central role in mediating phosphorylation-dependent protein-protein interactions in oncogenic and inflammatory signaling pathways. The development of selective STAT SH2 domain inhibitors requires sophisticated approaches that account for structural flexibility, binding kinetics, and cellular permeability.

Recent advances in biosensor technology, such as STATeLights, combined with traditional biochemical and cellular assays, provide powerful tools for interrogating STAT activation and evaluating potential therapeutic compounds. As our understanding of the structural nuances of STAT-type SH2 domains continues to evolve, so too will opportunities for developing targeted interventions for cancers, autoimmune disorders, and other diseases driven by aberrant STAT signaling. The strategic targeting of these domains holds significant promise for next-generation therapeutics that modulate transcriptional responses at the most proximal step of the signaling cascade.

Src Homology 2 (SH2) domains are approximately 100-amino-acid modular protein domains that specifically recognize and bind phosphorylated tyrosine (pTyr) motifs, forming a crucial part of the protein-protein interaction network in metazoan signaling pathways [9] [10] [11]. These domains arose within multicellular life approximately 600 million years ago and are therefore heavily tied to complex signal transduction mechanisms [9] [12]. The human proteome contains roughly 110-121 SH2 domains distributed across functionally diverse proteins, including enzymes, adaptor proteins, docking proteins, and transcription factors [11] [13]. In signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) proteins, SH2 domain interactions are critically important for molecular activation, nuclear accumulation of phosphorylated STAT dimers, and subsequent driving of target gene transcription [9] [12]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of STAT-type SH2 domains against other SH2 domain types, with particular focus on their unique structural features, dimerization mechanisms, and implications for targeted therapeutic development.

Structural Classification: STAT-type vs. Src-type SH2 Domains

Fundamental Structural Organization of SH2 Domains

All SH2 domains share a conserved structural core consisting of a three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet (βB-βD) flanked by two α-helices (αA and αB) in an αβββα motif [9] [11] [13]. This core structure creates two functionally distinct binding pockets: the phosphotyrosine (pY) pocket formed by the αA helix, BC loop, and one face of the central β-sheet; and the pY+3 specificity pocket created by the opposite face of the β-sheet along with residues from the αB helix and CD and BC* loops [9]. Despite this common scaffold, SH2 domains exhibit significant structural and functional diversity, leading to their classification into two major subgroups: STAT-type and Src-type SH2 domains [11] [13].

Table 1: Comparative Structural Features of STAT-type vs. Src-type SH2 Domains

| Structural Feature | STAT-type SH2 Domains | Src-type SH2 Domains |

|---|---|---|

| C-terminal Structure | Additional α-helix (αB') | β-sheet (βE and βF strands) |

| Conserved Motifs | Lacks βE and βF strands | Contains βE and βF strands |

| αB Helix Configuration | Split into two helices | Single continuous helix |

| Ancestral Function | Transcriptional regulation | Cytoplasmic signaling |

| Representative Proteins | STAT1, STAT3, STAT5 | Src, Fps, Abl, Grb2 |

Unique Characteristics of STAT-type SH2 Domains

STAT-type SH2 domains possess several distinctive structural characteristics that differentiate them from Src-type domains. The most notable difference lies in their C-terminal architecture, where STAT-type domains feature an additional α-helix (αB') instead of the β-sheet (βE and βF strands) found in Src-type domains [9] [11]. This C-terminal region, known as the evolutionary active region (EAR), contains important structural elements that participate in SH2-mediated STAT dimerization through cross-domain interactions [9]. Additionally, the αB helix in STAT-type SH2 domains is split into two separate helices, a configuration believed to be an evolutionary adaptation that facilitates the dimerization process critical for STAT-mediated transcriptional regulation [13]. This structural disparity likely reflects the ancestral function of SH2 domain-containing proteins that predate animal multicellularity, as organisms like Dictyostelium employ SH2 domain/phosphotyrosine signaling for transcriptional regulation [13].

STAT SH2 Domain Dimerization: Mechanisms and Functional Consequences

Conventional Dimerization Mechanism

The canonical STAT activation pathway involves cytokine or growth-factor interactions with extracellular receptors, which stimulates SH2 domain-mediated recruitment of tyrosine kinases and STAT isoforms to receptor cytoplasmic domains [9] [12]. Following phosphorylation, STAT proteins dimerize through reciprocal SH2-phosphotyrosine interactions, forming parallel architectures that facilitate nuclear translocation and DNA binding [9]. In this conventional dimerization mode, the phospho-Tyr (pY) of one STAT monomer interacts with conserved amino acids in the pY pocket of the partnering monomer's SH2 domain, while C-terminal residues extend across the SH2 domain into the pY+3 specificity pocket [9]. These interactions are critical for maintaining proper binding to facilitate stable protein dimerization, and specific mutations in these regions can profoundly alter normal STAT function [9].

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental signaling pathway mediated by STAT SH2 domain dimerization:

Domain-Swapping as an Alternative Dimerization Mechanism

Beyond conventional reciprocal SH2-pTyr interactions, certain SH2 domains can mediate dimerization through domain-swapping mechanisms. Although not yet confirmed in full-length STAT proteins, this mechanism has been extensively characterized in other SH2 domain-containing proteins such as GRB2 [14]. In SH2 domain-swapping, protein segments exchange between domains of adjacent monomers, creating stable dimeric architectures with potentially altered functional properties [14]. For GRB2, SH2 domain-swapping involves the extension of a C-terminal α-helix and part of the preceding hinge loop (Trp121-Val123) toward an adjacent SH2 protomer, effectively exchanging α-helices between monomers [14]. This domain-swapped configuration can significantly impact SH2 binding affinity for phosphopeptides, with reported increases or decreases depending on the specific ligand [14]. The functional significance of domain-swapping in GRB2 is highlighted by experiments showing that mutations at the hinge loop (Val122 and Val123) that disrupt SH2 domain-swapping impair T-cell signaling and IL-2 production, mirroring defects observed in GRB2-deficient cells [14].

Disease-Associated Mutations in STAT3 and STAT5 SH2 Domains

Mutation Spectrum and Functional Impact

Sequencing analyses of patient samples have identified the SH2 domain as a hotspot in the mutational landscape of STAT proteins, particularly STAT3 and STAT5 [9] [12]. These mutations can have either loss-of-function (LOF) or gain-of-function (GOF) effects, sometimes with mutations at identical sites producing opposite physiological consequences, underscoring the delicate evolutionary balance of wild-type STAT structural motifs in maintaining precise levels of cellular activity [9]. The table below summarizes key disease-associated mutations in STAT3 and STAT5B SH2 domains and their clinical correlates:

Table 2: Disease-Associated Mutations in STAT3 and STAT5B SH2 Domains

| Mutation | Location | Pathology | Mutation Type | Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAT3 K591E/M | αA2 helix, pY pocket | AD-HIES | Germline | Loss-of-function |

| STAT3 S611N | βB7 strand, pY pocket | AD-HIES | Germline | Loss-of-function |

| STAT3 S614R | BC loop, pY pocket | T-LGLL, NK-LGLL, ALK-ALCL | Somatic | Gain-of-function |

| STAT3 E616K | BC loop, pY pocket | NKTL | Somatic | Gain-of-function |

| STAT5B N642H | SH2 domain | Growth hormone insensitivity, Immunodeficiency | Germline | Loss-of-function |

Pathophysiological Mechanisms of SH2 Domain Mutations

Loss-of-function mutations in STAT3 typically manifest as autosomal-dominant hyper IgE syndrome (AD-HIES), resulting from reduced STAT3-mediated Th17 T-cell response [9] [12]. Classical STAT3 function is implicated in Th17 T-cell lineage commitment through upregulation of RORγt, which promotes release of IL-17 and IL-22 and stimulates transcription of genes associated with Th17 development [9]. STAT3 LOF strongly diminishes Th17 T-cell expansion, thereby reducing immunologic response and leading to recurrent staphylococcal infections with exceedingly high IgE levels [9]. In contrast, gain-of-function mutations in STAT3 present with autoimmune responses likely due to Th17 clonal expansion, which also suppresses regulatory T-cell (Treg) formation [12]. Interestingly, STAT3 GOF mutations show clinical parallels with STAT5 LOF mutations, partially due to compensatory upregulation of SOCS3 (suppressor of cytokine signaling-3) that strongly inhibits hyperactivated STAT3 but also dampens STAT5 and STAT1 activity [12].

Experimental Approaches for Studying STAT SH2 Domain Function

Methodologies for Structural and Functional Characterization

Comprehensive understanding of STAT SH2 domain structure and function relies on multiple complementary experimental approaches. Structural biology techniques including X-ray crystallography (XRC), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) have been instrumental in elucidating SH2 domain architecture and conformational dynamics [14] [11]. For example, SAXS analyses combined with size-exclusion chromatography and multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS) have enabled characterization of novel oligomeric conformations in GRB2, revealing previously unrecognized SH2 domain-swapped dimers in full-length proteins [14]. Biochemical assays measuring dissociation constants (Kd) for phosphopeptide interactions provide quantitative data on binding affinity and specificity, with typical SH2 domain Kd values ranging from 0.2 to 5 μM for preferred peptide motifs [10] [11]. Cellular functional assays, including measurement of downstream signaling events (e.g., pERK signaling), CD69 expression in B cells, and cytokine production (e.g., IL-2 release in T cells), validate the physiological relevance of structural findings [15] [14].

The following workflow illustrates a comprehensive experimental approach for characterizing STAT SH2 domain function:

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for STAT SH2 Domain Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Biology Kits | Crystallization screens, NMR isotope-labeled compounds | Determine high-resolution structures of SH2 domains and complexes |

| Binding Assay Platforms | Surface plasmon resonance (SPR), Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) | Quantify protein-protein and protein-ligand interaction affinities |

| Cellular Reporter Systems | Luciferase-based STAT activity reporters, CD69 expression assays | Monitor functional STAT signaling output in live cells |

| SH2 Domain Inhibitors | STAT3 SH2 domain-targeted compounds, BTK SH2 inhibitors | Probe functional roles and therapeutic targeting of specific SH2 domains |

| Mutant Constructs | Disease-associated mutants (e.g., STAT3 S614R), Domain-swapping variants | Establish causality between structural changes and functional outcomes |

Emerging Therapeutic Targeting Strategies

SH2 Domain Inhibition as a Therapeutic Approach

The critical role of SH2 domains in mediating protein-protein interactions in disease-relevant signaling pathways has made them attractive targets for therapeutic intervention [9] [11]. This is particularly true for STAT proteins, where the relatively shallow binding surfaces elsewhere on the protein have focused therapeutic interest on the STAT SH2 domain for small molecule inhibitor development [9] [12]. However, developing effective SH2 domain inhibitors has proven challenging due to the dynamic nature of these domains and the conserved, charged character of pTyr-binding pockets [9]. Recent advances include the development of BTK SH2 domain inhibitors that demonstrate enhanced selectivity and durability over traditional kinase domain inhibitors, minimizing off-target effects like TEC kinase inhibition associated with conventional BTK inhibitors [15]. Preclinical studies show that BTK SH2 inhibitors achieve potent inhibition of BTK signaling and reduce skin inflammation in chronic spontaneous urticaria models while avoiding platelet dysfunction side effects [15].

Innovative Targeting Strategies

Emerging strategies for targeting SH2 domains include exploring allosteric binding sites outside the conserved pTyr-binding pocket, developing compounds that disrupt domain-swapped dimer interfaces, and designing molecules that target lipid-binding regions adjacent to SH2 domains [16] [11]. Research has revealed that nearly 75% of SH2 domains interact with lipid molecules in the membrane, particularly phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) and phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3), with cationic regions near the pY-binding pocket serving as lipid-binding sites [11] [13]. Targeting these lipid-protein interactions represents a promising avenue for developing highly selective inhibitors, as demonstrated by successful development of nonlipidic inhibitors of Syk kinase that potently inhibit lipid-protein interactions [11] [13]. Additionally, the role of SH2 domain-containing proteins in liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) presents novel targeting opportunities, as multivalent SH2 domain interactions drive formation of intracellular signaling condensates in pathways such as LAT-GRB2-SOS1 in T-cell activation [11] [13].

STAT-type SH2 domains represent a distinct subclass of SH2 domains with unique structural features—particularly their C-terminal α-helical architecture—that enable their critical role in STAT dimerization and transcriptional activation. The structural and functional characterization of these domains has been significantly advanced through integrated methodological approaches combining structural biology, biophysical analyses, and cellular assays. Disease-associated mutations in STAT3 and STAT5 SH2 domains highlight the delicate balance maintained by wild-type structures and demonstrate how subtle structural alterations can produce either loss or gain of function with profound physiological consequences. Emerging therapeutic strategies that target SH2 domains through innovative approaches, including allosteric inhibition and disruption of domain-swapped interfaces, offer promising avenues for developing highly selective inhibitors with improved safety profiles. Continued research into the structural dynamics and non-canonical functions of STAT-type SH2 domains will undoubtedly yield new insights into their biological roles and therapeutic potential.

The Src Homology 2 (SH2) domain is a critical protein interaction module that specifically recognizes phosphotyrosine (pY) motifs, serving as a central conductor in orchestrating cellular signaling pathways [13]. In multidomain signaling proteins, SH2 domains regulate catalytic activity, facilitate subcellular localization, and mediate the formation of complex signaling networks. The structural and functional integrity of these domains is therefore paramount, and their disruption through mutation is a major mechanism of human disease. This review analyzes disease-associated mutations in STAT and tyrosine kinase SH2 domains within the broader context of developing selective STAT SH2 domain inhibitors. We examine how mutations create "hotspots of volatility" that alter protein function, provide a comparative analysis of experimental platforms for characterizing these variants, and discuss emerging therapeutic strategies that target these volatile regions.

SH2 Domain Structure and Functional Roles

Canonical Structure and Phosphopeptide Recognition

SH2 domains maintain a highly conserved structural fold despite sequence diversity, consisting of a central antiparallel β-sheet flanked by two α-helices in an αβββα configuration [1] [13]. This architecture forms two primary binding pockets: a phosphorylated tyrosine (pY) binding pocket and a specificity (pY+3) pocket that recognizes residues C-terminal to the phosphotyrosine [1]. The pY pocket contains a nearly invariant arginine residue (βB5) that forms a critical salt bridge with the phosphate moiety of phosphotyrosine [13]. This combination of conserved structural elements with variable specificity determinants enables SH2 domains to recognize distinct phosphopeptide motifs with moderate affinity (Kd 0.1–10 μM), balancing specificity with the reversibility required for dynamic signaling [13].

Table 1: Key Structural Features of SH2 Domains

| Structural Element | Functional Role | Conservation Level | Ligand Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central β-sheet (βB-βD) | Partitions domain into pY and pY+3 pockets | High | Forms backbone of binding interface |

| αA helix | Forms one wall of pY pocket | Moderate | Contributes to pY binding |

| αB helix | Contributes to pY+3 pocket | Variable | Determines specificity |

| BC loop | Connects βB-βC strands | Variable | Influences pY pocket accessibility |

| FLVR motif | pY recognition | Very High | Arg residue directly binds phosphate |

Classification and Specialization

SH2 domains are broadly classified into STAT-type and Src-type based on structural variations at their C-termini [1] [13]. STAT-type SH2 domains lack the βE and βF strands found in Src-type domains and feature a split αB helix, adaptations that facilitate the dimerization required for STAT transcriptional function [13]. This structural specialization reflects the ancestral role of SH2 domains in metazoan signaling, with STAT-type domains being particularly specialized for nuclear signaling and gene regulation. Beyond canonical phosphopeptide binding, approximately 75% of SH2 domains interact with membrane lipids such as PIP2 and PIP3, with cationic regions near the pY pocket mediating these interactions and facilitating membrane recruitment [13].

Disease-Associated Mutations in SH2 Domains

STAT SH2 Domain Mutations in Disease

The STAT SH2 domain is a recognized hotspot in the mutational landscape, with patient sequencing revealing numerous point mutations that profoundly alter STAT function [1]. These mutations can be either activating or inactivating, sometimes occurring at identical positions, highlighting the delicate evolutionary balance maintained in wild-type STAT structural motifs [1].

Table 2: Disease-Associated Mutations in STAT3 and STAT5 SH2 Domains

| Mutation | Location | Domain Position | Associated Pathology | Functional Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAT3 S614R | BC loop | pY pocket | T-LGLL, NK-LGLL, ALK-ALCL | Activating [1] |

| STAT3 K591E/M | αA helix | pY pocket | AD-HIES | Inactivating [1] |

| STAT3 S611N | βB strand | pY pocket | AD-HIES | Inactivating [1] |

| STAT3 E616K | BC loop | pY pocket | NKTL | Activating [1] |

| STAT5B N642H | SH2 domain | Not specified | Leukemias, Lymphomas | Activating [1] |

In STAT3, germline heterozygous loss-of-function mutations cause autosomal-dominant Hyper IgE Syndrome (AD-HIES), characterized by recurrent Staphylococcal infections, eczema, and eosinophilia due to impaired Th17 T-cell differentiation [1]. These mutations (e.g., K591E/M, S611N, S614R) typically cluster in the pY binding pocket, disrupting phosphopeptide recognition and STAT activation. Conversely, somatic gain-of-function mutations (e.g., S614R, E616K) drive oncogenesis in T-cell leukemias and lymphomas by enhancing STAT dimerization and nuclear translocation, leading to constitutive transcription of pro-survival genes like BCL-XL and MCL-1 [1].

SHP2 SH2 Domain Mutations and Allosteric Regulation

SHP2 phosphatase exemplifies the regulatory importance of SH2 domains in multi-domain proteins. Its N-SH2 domain allosterically inhibits the PTP domain in the basal state, with phosphoprotein binding to the SH2 domains relieving this autoinhibition [17] [18]. Mutations at the N-SH2/PTP interface (e.g., E76K) disrupt autoinhibition, leading to constitutive SHP2 activation associated with Noonan syndrome and juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia [17] [18]. Deep mutational scanning of SHP2 has revealed that disease-associated mutations cluster not only at the canonical N-SH2/PTP interface but also in the core of the N-SH2 domain and at the C-SH2/PTP interface, suggesting alternative mechanisms of dysregulation [18].

Structural Consequences of SH2 Domain Mutations

Mutations can affect SH2 domain function through multiple structural mechanisms. Some mutations directly disrupt conserved binding motifs, such as the invariant arginine in the FLVR motif, abolishing phosphopeptide recognition [13]. Others induce allosteric changes that alter domain dynamics or affect inter-domain interactions critical for autoinhibition, as seen in nonreceptor tyrosine kinases where the SH2 domain stabilizes the active kinase conformation through interactions with the regulatory αC helix [19]. The particularly flexible nature of STAT SH2 domains, with pY pocket accessibility varying dramatically even on sub-microsecond timescales, makes them especially vulnerable to mutational perturbation [1].

Experimental Platforms for Profiling SH2 Domain Mutations

Deep Mutational Scanning of Multi-Domain Proteins

Recent advances in deep mutational scanning enable comprehensive characterization of SH2 domain mutations. A 2025 study established a yeast growth rescue assay for profiling SHP2 mutations, where yeast proliferation arrested by tyrosine kinase expression is rescued by functional SHP2 variants [18]. This platform tested over 11,000 SHP2 mutants, revealing that pathogenic mutations generally skew toward gain-of-function, though with significant heterogeneity across cancer types [18]. The experimental workflow involves:

- Library Construction: SHP2 divided into 15 sub-libraries (tiles) using mutagenesis by integrated tiles (MITE) method [18]

- Selection System: Co-expression of SHP2 variants with active Src kinase (v-SrcFL or c-SrcKD) in yeast [18]

- Growth Selection: 24-hour outgrowth under kinase induction pressure [18]

- Deep Sequencing: Variant frequency quantification before and after selection to calculate enrichment scores [18]

- Validation: Correlation of enrichment scores with catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) measurements [18]

This approach successfully identified known activating mutations at the N-SH2/PTP interface (e.g., E76, D61) and inactivating mutations at catalytic residues (C459), while also revealing novel mutational hotspots in the N-SH2 domain core and C-SH2/PTP interface [18].

Structural and Biophysical Approaches

Structural biology provides essential insights into mutation effects. X-ray crystallography of STAT-type SH2 domains reveals unique features compared to Src-type domains, including the distinctive α-helical C-terminus and specialized dimerization interfaces [1]. Protein visualization tools like 3matrix and 3motif map sequence conservation information onto three-dimensional structures, helping researchers understand the structural context of conserved residues and target them for mutagenesis or drug design [20]. Biolayer interferometry enables quantitative assessment of mutation effects on binding affinity and kinetics, with dissociation rate constants (kd) being particularly important determinants of affinity in SH2 domain interactions [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for SH2 Domain Investigation

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Function and Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monobodies (Mb11, Mb13) | Protein Biologics | Selective inhibition of SHP2 PTP domain; tool for probing allostery [17] | Crystal structure determination of PTP-monobody complex [17] |

| DNA-encoded Libraries (DELs) | Chemical Biology | SH2-targeted compound discovery through high-throughput screening [15] | Identification of BTK SH2 inhibitors with 0.055 nM Kd [15] |

| 3matrix/3motif | Bioinformatics | 3D visualization of sequence motifs in structural context [20] | Mapping conserved residues in SH2 domains for mutagenesis [20] |

| GoFold | Bioinformatics | Educational visualization of contact map overlap for protein folding [21] | Template selection and contact map analysis for beginners [21] |

| Cryptotanshinone | Small Molecule Inhibitor | Active site binder used to validate SH2 domain inhibitor binding [17] | Competition assays with monobody binding [17] |

Emerging Therapeutic Strategies Targeting SH2 Domains

STAT SH2 Domain-Targeted Therapies

The STAT SH2 domain represents an attractive therapeutic target due to its central role in STAT activation through phosphotyrosine-mediated dimerization [1]. Despite considerable interest, developing small-molecule inhibitors has proven challenging due to the relatively shallow binding surfaces and high flexibility of STAT SH2 domains [1]. Current strategies focus on stabilizing inactive states or developing protein-protein interaction inhibitors that disrupt the critical dimerization interface. The prevalence of mutations in the SH2 domain hotspot further underscores its therapeutic importance while presenting challenges for targeted therapy development against both wild-type and mutant forms [1].

BTK SH2 Domain Inhibition: A Case Study in Selectivity

Recludix Pharma's development of BTK SH2 domain inhibitors exemplifies innovative targeting strategies addressing limitations of conventional kinase inhibitors [15]. Unlike traditional BTK inhibitors that target the conserved kinase domain and cause off-target effects like TEC kinase inhibition, SH2 domain targeting achieves exceptional selectivity (>8000-fold over off-target SH2 domains) and sustained pathway inhibition [15]. The compound demonstrated potent biochemical binding (Kd = 0.055 nM), minimal cytotoxicity, and efficacy in a chronic spontaneous urticaria model with reduced skin inflammation and inflammatory cell infiltration [15]. This approach highlights how SH2 domain targeting can overcome durability and selectivity limitations of kinase-focused strategies.

Allosteric Modulation and Conformational Control

Understanding SH2 domain mutations provides insights for allosteric drug development. For SHP2, mutations that stabilize the open, active conformation (e.g., E76K) inform the design of allosteric inhibitors that stabilize the closed, autoinhibited state [17] [18]. Monobodies that inhibit the SHP2 PTP domain have been used to develop simple, nonenzymatic assays for monitoring the allosteric regulation of SHP2, enabling characterization of conformational equilibrium and mutant effects [17]. These tools facilitate drug discovery by allowing rapid assessment of how mutations and ligands affect the open-closed equilibrium central to SHP2 regulation.

Disease-associated mutations in SH2 domains create genuine "hotspots of volatility" that profoundly alter cellular signaling in pathologies ranging from immunodeficiencies to cancer. The integrated application of deep mutational scanning, structural biology, and selective inhibitor development has dramatically advanced our understanding of how mutations disrupt SH2 domain function through diverse mechanisms—direct phosphopeptide binding disruption, allosteric regulation alteration, or inter-domain communication interference. As therapeutic targeting of SH2 domains progresses, exemplified by the selective BTK SH2 inhibitors, understanding these mutational hotspots will be crucial for developing effective treatments that can overcome the challenges of selectivity and resistance. The continued integration of comprehensive mutation profiling with mechanistic structural studies will illuminate new aspects of SH2 domain function and identify novel therapeutic opportunities for targeting these critical signaling modules in human disease.

Src Homology 2 (SH2) domains are modular protein domains that arose within metazoan signaling pathways approximately 600 million years ago, making them heavily tied to complex signal transduction [1]. These approximately 100-amino acid domains specifically recognize phosphotyrosine (pY) containing motifs, thereby mediating precise spatial and temporal regulation of cellular processes by facilitating protein-protein interactions in response to tyrosine phosphorylation [22]. In the human genome, approximately 120 different SH2 domains are distributed among more than a hundred different proteins, highlighting their fundamental importance in cell physiology [22]. The invariant structural fold of SH2 domains—comprising a central three-stranded antiparallel β sheet flanked by two α helices—presents a significant challenge for drug development: how can a highly conserved structural scaffold achieve the binding specificity necessary for selective therapeutic intervention without unintended cross-reactivity? [22] [1]

This challenge is particularly acute in the development of inhibitors targeting STAT (Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription) SH2 domains. STAT proteins are crucial therapeutic targets for cancer and other diseases, with their conventional activation being dependent on SH2 domain-mediated recruitment and dimerization [1] [23]. The structural conservation of the phosphotyrosine (pY) and specificity (pY+3) binding pockets across different SH2 domains creates a substantial risk of cross-reactivity when designing small-molecule inhibitors. This review comprehensively examines the structural basis of this conservation, analyzes experimental evidence of cross-reactivity in current inhibitors, and provides methodological guidance for characterizing binding specificity in STAT SH2 domain drug discovery campaigns.

Structural Foundations of SH2 Domain Conservation and Specificity

The Canonical SH2 Domain Architecture

All SH2 domains share a conserved structural motif known as the αβββα motif, consisting of a central anti-parallel β-sheet (with strands conventionally labeled βB-βD) interposed between two α-helices (αA and αB) [1]. This core structure partitions the SH2 domain into two primary binding subpockets that determine its interaction specificity:

- The pY Pocket (Phosphate-Binding Pocket): This pocket is formed by the αA helix, the BC loop (region connecting βB-βC strands), and one face of the central β-sheet. It specializes in recognizing the phosphotyrosine residue itself through conserved electrostatic interactions [1].

- The pY+3 Pocket (Specificity Pocket): This pocket is created by the opposite face of the β-sheet along with residues from the αB helix and CD and BC* loops. It accommodates peptide residues C-terminal to the pY, particularly the residue at the pY+3 position, which provides key determinants of binding specificity [22] [1].

Table 1: Key Conserved Structural Elements in SH2 Domain Binding Pockets

| Structural Element | Location | Conserved Feature | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| ArgβB5 | βB strand | Universally conserved arginine | Forms bidentate salt bridge with phosphate group of pY |

| pY Pocket | αA helix, BC loop, β-sheet | Positively charged residues | Electrostatic stabilization of phosphotyrosine |

| pY+3 Pocket | αB helix, CD loop, β-sheet | Hydrophobic character | Determines specificity by accommodating pY+3 residue |

| βD5 residue | βD strand | Variable amino acid | Critical determinant of phosphopeptide specificity |

| Central β-sheet | Core domain | Anti-parallel configuration | Positions both binding pockets relative to each other |

STAT-Type Versus Src-Type SH2 Domains

Despite their common fold, SH2 domains are broadly classified into either STAT- or Src-type based on distinct structural features at the C-terminus [1]. STAT-type SH2 domains contain an additional α-helix (αB') in what is known as the evolutionary active region (EAR), whereas Src-type SH2 domains harbor a β-sheet (βE and βF) in this region [1]. This distinction is particularly relevant for drug discovery, as the unique features of STAT-type SH2 domains may offer opportunities for developing more selective inhibitors.

The conserved binding mode across all SH2 domains involves the phosphopeptide adopting an extended conformation perpendicular to the central β-sheet, with the pY residue hosted in the pY pocket and held in place by critical electrostatic interactions [22]. A universally conserved arginine (ArgβB5), whose side chain is buried from solvent in both free and bound forms, contributes a bidentate salt bridge to two oxygen atoms of the phosphate group [22]. Mutation of this residue abrogates pY binding both in vitro and in vivo, underscoring its fundamental importance [22].

Diagram 1: Structural organization of SH2 domains showing the conserved core fold and the two primary binding pockets that engage phosphopeptide ligands. The pY pocket provides general phosphotyrosine recognition, while the pY+3 pocket confers binding specificity.

Molecular Determinants of Specificity and Cross-Reactivity

The specificity paradox of SH2 domains lies in how a structurally conserved fold can achieve diverse binding specificities. While early models suggested that specificity was determined primarily by interactions with peptide residues at pY+1, pY+2, and pY+3 positions, this view has proven overly simplistic [22]. Research now indicates that selective phosphopeptide recognition is governed by both structure and dynamics of the SH2 domain, as well as binding kinetics [22].

The βD5 residue has been empirically demonstrated to be a critical determinant in distinguishing SH2 domain specificity groups [24]. Remarkably, replacing aliphatic residues at the βD5 positions of Group III SH2 domains (phosphoinositide 3-kinase N-terminal SH2 domain and phospholipase C-γ C-terminal SH2 domain) with tyrosine (as found in Group I SH2 domains) results in a complete switch in phosphopeptide selectivity to match Group I specificities [24]. This finding establishes the importance of the βD5 residue as a key specificity switch and highlights the structural plasticity that enables functional diversity within the conserved SH2 fold.

Experimental Evidence of Cross-Reactivity in SH2 Domain Inhibitors

Case Study: STAT5/6 Inhibitor Profiling

The challenge of cross-reactivity is well-illustrated by development efforts for STAT5/6 SH2 domain inhibitors. In one comprehensive study, multiple peptidomimetic compounds were developed to block the docking site of STAT6 to IL-4Rα and phosphorylation of Tyr641 [6]. When researchers evaluated six lead compounds for cross-reactivity against additional SH2 domain-containing proteins, they observed considerable variability:

Table 2: Cross-Reactivity Profile of STAT6 SH2 Domain Inhibitors [6]

| Compound | STAT6 Inhibition | Cross-Reactive Targets | Specificity Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| PM-43I | Complete at 1-2 μM | STAT5 (significant), STAT3 (slight) | Moderate cross-reactivity |

| PM-63I | >90% at 5 μM | STAT5 (significant) | Moderate cross-reactivity |

| PM-74I | >90% at 5 μM | STAT1, STAT3, STAT5, AKT | Broad cross-reactivity |

| PM-80I | >90% at 5 μM | STAT5 (below 5 μM) | Selective STAT5/6 cross-reactivity |

| PM-81I | >90% at 5 μM | None detected | Highly specific |

| PM-86I | >90% at 5 μM | None detected | Highly specific |

This profiling revealed that PM-43I, despite its potency against STAT6, showed significant cross-reactivity with STAT5 and slight inhibition of STAT3, while PM-74I displayed broad cross-reactivity with STAT1, STAT3, STAT5, and AKT (via the SH2 domain-containing p85 subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase) [6]. In contrast, PM-86I showed the highest specificity for STAT6 with no cross-reactivity to any of the additional targets at the highest dose tested [6]. These findings underscore how compounds targeting the conserved pY and pY+3 pockets can exhibit varying degrees of cross-reactivity, necessitating comprehensive profiling during inhibitor development.

Structural Implications of Disease-Associated Mutations

Analysis of disease-associated mutations in STAT3 and STAT5B SH2 domains provides natural experiments illustrating the functional importance of specific residues in the pY and pY+3 pockets. Sequencing of patient samples has identified the SH2 domain as a hotspot in the mutational landscape of STAT proteins [1]. For example, the N642H mutation in STAT5B—associated with aggressive and drug-resistant forms of leukemia—directly affects the hydrogen bonding network within the pY-binding pocket, enhancing pY-binding interaction and stabilizing the active, parallel dimer state [23]. Molecular dynamics simulations indicate that this mutation restricts conformational flexibility, with apo STAT5BN642H accessing distinct conformational states that resemble the parallel dimer conformation [23].

Similarly, multiple mutations in STAT3 associated with autosomal-dominant Hyper IgE syndrome (AD-HIES) cluster in critical regions of the SH2 domain, including residues K591 and S611 in the pY pocket, which are part of conserved "Sheinerman" and "Signature" motifs [1]. The genetic volatility of specific regions in the SH2 domain can result in either activating or deactivating mutations at the same site, underscoring the delicate evolutionary balance of wild-type STAT structural motifs in maintaining precise levels of cellular activity [1].

Diagram 2: Cross-reactivity pathways in SH2 domain-targeted therapeutics. Inhibitors designed against conserved pY and pY+3 pockets may bind unintended SH2 domains, leading to potential adverse effects through disruption of multiple signaling pathways.

Methodological Framework for Assessing Binding Specificity

Experimental Protocols for Cross-Reactivity Screening

Comprehensive specificity profiling requires a multi-tiered experimental approach. The following methodology adapted from published studies provides a robust framework for evaluating SH2 domain inhibitor cross-reactivity [6]:

Primary Screening Protocol:

- Cellular Activity Assay: Titrate inhibitors in relevant cell lines (e.g., Beas-2B bronchial epithelial cells) and stimulate with appropriate cytokines (e.g., IL-4 for STAT6 activation). Measure inhibition of target phosphorylation (pSTAT6) via Western blot to determine EC₅₀ values.

- Specificity Panel: Evaluate compounds against a panel of SH2 domain-containing proteins in appropriate cell models (e.g., MDA-MB-468 breast cancer cells):

- Stimulate with EGF for STAT3, STAT5, AKT (via p85 SH2 domains), and FAK activation (via SH2-containing Src kinase activity)

- Stimulate with IFN-γ for STAT1 activation

- Assess inhibition of phosphorylation for each target at multiple compound concentrations (e.g., 0.5, 1, 5 μM)

- Affinity Measurements: Determine IC₅₀ values using fluorescence polarization assays with purified SH2 domains and fluorescently-labeled phosphopeptides.

Secondary Validation Protocols:

- Kinase Profiling: Screen against panels of recombinant tyrosine kinases to exclude off-target kinase inhibition.

- Cellular Pathway Analysis: Evaluate effects on downstream signaling pathways (e.g., MAPK, PI3K/AKT) to identify unintended pathway modulation.

- Structural Studies: Employ X-ray crystallography or NMR to characterize binding modes and identify molecular determinants of specificity.

Computational Approaches for Specificity Prediction

Computational methods provide valuable tools for predicting potential cross-reactivity early in the drug discovery process:

Structure-Based Analysis:

- Molecular Dynamics Simulations: As demonstrated in studies of STAT5B N642H mutation, MD simulations can reveal how mutations or inhibitors affect flexibility and hydrogen bonding networks within the pY pocket [23]. Cumulative sampling times of nearly 100 μs can provide insights into conformational states and dynamics relevant to specificity.

- Binding Site Detection: Tools like pyCAST employ the CAST methodology to detect cavities on protein surfaces, aiding in the comparison of pY and pY+3 pockets across different SH2 domains [25].

- Ligand Binding Site Prediction: Recent benchmarks have evaluated methods like VN-EGNN, IF-SitePred, GrASP, PUResNet, and DeepPocket, with re-scoring of fpocket predictions by PRANK and DeepPocket displaying the highest recall (60%) [26].

Theoretical Modeling of Multivalent Interactions: For tandem SH2 domain-containing proteins, ordinary differential equation (ODE) models can simulate surface plasmon resonance experiments between multivalent receptor-ligand pairs, tracking all possible binding configurations over time [27]. These models incorporate parameters including monovalent kₒₙ and kₒff rate constants, species concentrations, and linker properties (sequence length and persistence length) to calculate "effective concentration" and predict avidity effects [27].

Research Reagent Solutions for SH2 Domain Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for SH2 Domain Binding and Specificity Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphopeptide Libraries | Chemical Probes | PM-301, PM-43I, PM-63I | Affinity measurements, specificity profiling |

| Fluorescence Polarization Kits | Assay Systems | Commercial FP kits | High-throughput affinity screening |

| SH2 Domain Expression Constructs | Protein Tools | STAT1, STAT3, STAT5, STAT6 SH2 domains | Structural studies, binding assays |

| Phosphospecific Antibodies | Detection Reagents | pSTAT1, pSTAT3, pSTAT5, pSTAT6 antibodies | Cellular activity validation |

| Cell-Based Reporter Assays | Functional Systems | STAT-responsive luciferase reporters | Functional activity in cellular context |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Computational Tools | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD | Simulation of SH2 domain dynamics |

| Binding Site Prediction | Bioinformatics | pyCAST, P2Rank, fpocket | Identification of potential binding pockets |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance | Biophysical Instruments | Biacore systems | Kinetic parameter determination |

The structural conservation of the pY and pY+3 pockets across SH2 domains presents a formidable challenge for developing specific inhibitors, particularly for STAT SH2 domains implicated in human disease. The experimental evidence clearly demonstrates that compounds targeting these conserved regions frequently exhibit cross-reactivity with unintended SH2 domain targets, potentially leading to off-target effects and toxicity. However, methodological advances in specificity screening, computational modeling, and structure-based design provide pathways to overcome these challenges.

Successful navigation of the cross-reactivity landscape requires an integrated approach that combines comprehensive experimental profiling with computational predictions informed by structural biology. The delicate balance between achieving sufficient potency while maintaining specificity underscores the need for continued refinement of screening methodologies and deeper investigation into the dynamic properties of SH2 domains that contribute to binding specificity. As our understanding of these fundamental determinants improves, so too will our ability to design selective therapeutics that target the conserved yet functionally diverse SH2 domain family.

For decades, the paradigm of Src homology 2 (SH2) domain function centered exclusively on phosphotyrosine (pY) recognition, governing specific protein-protein interactions in cellular signaling networks. However, emerging research has revealed two crucial mechanisms that profoundly expand SH2 domain functionality and specificity: membrane lipid binding and liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS). These discoveries fundamentally reshape our understanding of how SH2 domain-containing proteins achieve precise spatiotemporal control in signaling pathways, particularly for STAT transcription factors and other signaling molecules. This guide compares these non-canonical mechanisms against traditional pY-peptide binding, providing experimental data and methodologies essential for cross-reactivity profiling in STAT SH2 inhibitor development.

Lipid Binding as a Specificity Determinant

Genomic Evidence for Prevalent Lipid Binding

Systematic genomic screening has demonstrated that lipid binding is a widespread property of SH2 domains, not merely a specialized function of a few family members. Quantitative surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis of 76 human SH2 domains revealed that approximately 90% bind plasma membrane lipids, with 74% exhibiting submicromolar affinity for plasma membrane-mimetic vesicles [28]. This lipid binding activity occurs through surface cationic patches distinct from pY-binding pockets, enabling simultaneous, independent interaction with both membrane lipids and pY-motifs [28] [11].

Table 1: Lipid Binding Affinities and Specificities of Selected SH2 Domains

| SH2 Domain | Kd for PM (nM) | Lipid Binding Residues | Phosphoinositide Selectivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| STAT6-SH2 | 20 ± 10 | Not specified | Not specified |

| GRB7-SH2 | 70 ± 12 | Not specified | Low selectivity |

| YES1-SH2 | 110 ± 12 | R215, K216 | PI45P2 > PIP3 > others |

| BLNK-SH2 | 120 ± 19 | Not specified | PIP3 > PI45P2 ≫ others |

| ZAP70-cSH2 | 340 ± 35 | K176, K186, K206, K251 | PIP3 > PI45P2 > others |

| BTK-SH2 | 640 ± 55 | K311, K314 | Low selectivity |

Structural Basis of Lipid Recognition

SH2 domains employ distinct structural motifs for lipid interaction, primarily utilizing cationic patches near the pY-binding pocket that are typically flanked by aromatic or hydrophobic amino acid side chains [11]. These patches form either grooves for specific lipid headgroup recognition or flat surfaces for non-specific membrane binding [28]. The lipid binding sites are functionally important, as many disease-causing mutations map to these regions [11].

The structural implications are particularly significant for STAT-type SH2 domains, which differ from Src-type domains by containing a C-terminal α-helix rather than β-sheets [1]. This unique architecture may influence both lipid binding capabilities and dimerization properties critical for STAT transcriptional function.

Diagram Title: SH2 Domain Lipid Binding Mechanism

Functional Consequences of Lipid Interaction

Lipid binding profoundly influences SH2 domain function through multiple mechanisms:

- Membrane Recruitment: SH2 domains from proteins including SYK, ZAP70, and LCK require phosphoinositide binding for proper membrane localization and interaction with signaling complexes [11].

- Allosteric Regulation: Lipid binding can modulate SH2 domain structure to either promote or inhibit pY-peptide binding, adding a regulatory layer to SH2 domain function [28].

- Spatiotemporal Control: As demonstrated with ZAP70, multiple lipids bind its C-terminal SH2 domain in a spatiotemporally specific manner, exerting exquisite control over protein interactions and signaling activities in T cells [28].

Phase Separation in SH2 Domain Function

LLPS as an Organizing Principle

Liquid-liquid phase separation has emerged as a fundamental mechanism organizing SH2 domain-containing proteins into biomolecular condensates that enhance signaling specificity and efficiency. These multivalent interactions, often involving SH2 and SH3 domain networks, drive condensate formation [11]. Post-translational modifications, particularly phosphorylation, critically modulate the assembly and disassembly of these condensates [11].

Table 2: SH2 Domain-Containing Proteins in Signaling Condensates

| Condensate Complex | SH2-Containing Proteins | Biological Role |

|---|---|---|

| FGFR2:SHP2:PLCγ1 | SHP2, PLCγ1 | Enhanced RTK signaling activity |

| LAT-GRB2-SOS1 | ZAP70, LCK, GRB2, PLCγ1 | T-cell activation and phosphorylation |

| N-WASP–NCK | NCK | T-cell signaling amplification |

| SLP65, CIN85 | SLP65 | B-cell signaling regulation |

Experimental Evidence for SH2-Mediated Phase Separation

Studies have demonstrated that interactions among GRB2, Gads, and the LAT receptor contribute to LLPS formation, enhancing T-cell receptor signaling [11]. In podocyte kidney cells, LLPS increases the ability of adapter NCK to promote N-WASP–Arp2/3–mediated actin polymerization by extending the membrane dwell time of N-WASP and Arp2/3 complexes [11].

Visualization of these processes employs sophisticated imaging approaches, including:

- Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) to assess dynamics and liquid properties [29]

- Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) imaging to track droplet formation [29]

- Spectral and lifetime phasor analysis to characterize protein microenvironments in different phases [29]

Diagram Title: SH2 Domain Phase Separation Mechanism

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Quantitative Lipid Binding Assays

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Methodology [28]:

- Membrane mimics: Prepare plasma membrane-mimetic vesicles containing phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) or phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3)

- Protein preparation: Express SH2 domains as EGFP-fusion proteins to improve stability and expression yield

- Binding measurements: Measure real-time association and dissociation kinetics at 25°C

- Data analysis: Determine equilibrium dissociation constants (Kd) using steady-state affinity models

Supporting techniques:

- Lipid co-sedimentation assays: Validate lipid interactions qualitatively

- Confocal microscopy: Visualize membrane localization in cellular contexts

Phase Separation Visualization Protocols

In Vitro Reconstitution [29]:

- Sample preparation: Express and purify target SH2 domain-containing proteins

- Induction of phase separation: Incubate samples with changing salt concentrations, RNA, pH, or temperature

- Imaging: Employ bright-field DIC and fluorescence microscopy to track droplet dynamics

- Reversibility testing: Remove driving forces to confirm LLPS suppression

Cellular LLPS Analysis [29]:

- FRAP protocol: Photobleach specific condensate regions and monitor fluorescence recovery over time

- Quantitative analysis: Calculate recovery half-times and mobile fractions to assess material properties

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Studying Non-canonical SH2 Domain Functions

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid Vesicles | PM-mimetic vesicles, PIP2/PIP3-containing liposomes | Lipid binding affinity measurements |

| Imaging Reagents | Laurdan dye, Carboxyfluorescein | Membrane order and permeability assessment |

| Phase Separation Inducers | PEG, specific salt conditions | LLPS induction in reconstituted systems |

| SH2 Domain Constructs | EGFP-fusion proteins, STAT-type vs Src-type variants | Comparative functional studies |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | PM-43I, other peptidomimetics | Functional perturbation studies |

Implications for STAT SH2 Inhibitor Development

Overcoming Traditional Limitations

Traditional SH2 domain inhibitor design has focused exclusively on blocking pY-peptide binding pockets, facing challenges due to:

- High conservation across SH2 domains leading to cross-reactivity

- Moderate binding affinities (Kd 0.1–10 μM) limiting therapeutic efficacy [11]

- Dynamic protein flexibility complicating structure-based drug design [1]

Emerging strategies now target lipid-binding interfaces or phase separation properties to achieve greater specificity:

- Nonlipidic small molecules that target lipid-protein interaction interfaces, as demonstrated with Syk kinase inhibitors [11]

- Peptidomimetic compounds like PM-43I that block STAT6 docking to IL-4Rα and phosphorylation of Tyr641 [30]

- Modulators of condensate formation that disrupt multivalent interactions without completely abrogating signaling

Cross-Reactivity Profiling Considerations

When profiling STAT SH2 inhibitor specificity, assessment must expand beyond traditional pY-peptide competition to include:

- Lipid binding interference using SPR with lipid membranes

- Phase separation disruption through in vitro condensation assays

- Cellular localization changes via imaging of membrane recruitment

- Signal duration alterations in pathway-specific reporter assays

The distinct structural features of STAT-type SH2 domains—particularly their unique C-terminal α-helix and differences in CD-loop length compared to Src-type domains—offer promising targets for developing STAT-specific inhibitors [1] [11].

The paradigm of SH2 domain function has expanded significantly beyond pY-recognition to encompass lipid binding and phase separation as critical specificity determinants. These mechanisms work in concert to provide the spatiotemporal precision necessary for high-fidelity signaling in complex cellular environments. For STAT SH2 inhibitor development, targeting these non-canonical functions offers promising avenues for achieving greater specificity and reduced cross-reactivity. Comprehensive profiling must now integrate assessment of lipid membrane interactions and phase separation properties alongside traditional pY-peptide binding metrics to fully characterize inhibitor specificity and potential therapeutic utility.

Advanced Technologies for Profiling Inhibitor Selectivity

The Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STAT) family proteins, particularly STAT3 and STAT5b, are compelling therapeutic targets in oncology and inflammatory diseases. Their activity depends on Src homology 2 (SH2) domain-mediated binding to phosphorylated tyrosine sequences, making this interaction a focal point for inhibitor development [31]. However, a significant challenge in this field is the high degree of structural conservation among SH2 domains across different STAT proteins, which can lead to cross-reactivity and reduced therapeutic specificity. This review objectively compares current multiplexed assay platforms designed to simultaneously profile compound activity against both STAT3 and STAT5b, providing researchers with experimental data and methodologies to guide technology selection for cross-reactivity profiling.

Comparative Analysis of Multiplexed Assay Platforms

Multiplexed assays represent a technological evolution in high-throughput screening (HTS) by enabling multiple targets or readouts to be monitored in the same experiment. For STAT profiling, this primarily involves two methodological approaches: bead-based luminescent proximity assays and flow cytometry-based fluorescent cell barcoding.

Table 1: Platform Comparison for STAT3/STAT5b Multiplexed Assays

| Platform Feature | Amplified Luminescent Proximity Assay (Alpha) | Fluorescent Cell Barcoding (FCB) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Luminescent signal upon bead proximity | Antibody-based staining of barcoded cell populations |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Simultaneous STAT3 & STAT5b SH2 binding [31] | High-dimensional phospho-protein & surface marker analysis [32] |

| Key Readouts | SH2 domain-phosphopeptide binding inhibition | Intracellular pSTAT signaling; immunophenotyping |

| Reported Z' Factor | >0.6 for both STAT3 & STAT5b [31] | High intra- and inter-assay reproducibility [32] |

| Therapeutic Context | Ideal for SH2 domain antagonist screening [31] | Suitable for clinical trial signaling profiling [32] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: AlphaLISA/Screen-Based Multiplexed SH2 Binding Assay

This protocol, adapted from Takakuma et al., details a robust method for identifying SH2 domain antagonists [31].

- Recombinant Protein Preparation: Generate N- and C-terminal deletion mutants of human STAT3 and STAT5b to isolate their SH2 domains. Purify the proteins and label with biotin for detection.

- Peptide Ligand Design: Utilize phosphotyrosine peptides derived from physiological receptors: for STAT3, use the gp130-derived sequence GpYLPQTV; for STAT5b, use the EpoR-derived sequence GpYLVLDKW. Label these peptides with DIG (for STAT3 detection) and FITC (for STAT5b detection), respectively [31].

- Multiplexed Assay Setup: In a single well, combine the following components:

- Biotinylated STAT3-SH2 and STAT5b-SH2 proteins

- DIG-labeled STAT3 peptide and FITC-labeled STAT5b peptide

- Streptavidin-coated donor beads

- Anti-DIG AlphaLISA acceptor beads (for STAT3 signal)

- Anti-FITC AlphaScreen acceptor beads (for STAT5b signal)

- Binding Reaction and Detection: The reaction is optimized for spacer length, reaction time, and salt concentration (e.g., sodium chloride). Signal is generated only when the SH2 domain binds its cognate peptide, bringing the acceptor and donor beads into proximity. The two acceptor bead types emit distinct, simultaneously measurable signals, allowing for the parallel monitoring of both STAT3 and STAT5b binding events [31].

- HTS and Hit Identification: Screen chemical libraries against this multiplexed system. Validate hits in secondary assays, such as monitoring nuclear translocation of STAT3 in cell lines like HeLa to confirm functional biological activity [31].

Protocol 2: Fluorescent Cell Barcoding for pSTAT Signaling

This protocol, based on the work in ScienceDirect, enables high-throughput analysis of phospho-signaling in complex cell populations [32].

- Cell Preparation and Barcoding: Isolate human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs). Barcode up to nine samples by staining with unique combinations of two fluorescent dyes, DyLight 350 and Pacific Orange, at varying concentrations (e.g., 0, 15, 30, and 250 μg/mL).

- Stimulation and Fixation: Pool the barcoded cells and stimulate them with cytokines or growth factors known to activate STAT3 and STAT5b pathways. After stimulation, fix the cells immediately to preserve phosphorylation states.

- Surface and Intracellular Staining: Stain the pooled, fixed cell sample with conjugated antibodies against surface markers (e.g., CD3, CD4, CD8, CD20, CD14) to define cell populations. Subsequently, permeabilize the cells and stain intracellularly with antibodies specific for phosphorylated STAT proteins (e.g., pY705-STAT3).

- Flow Cytometry and Computational Analysis: Acquire data on a flow cytometer capable of detecting the barcoding dyes and antibody fluorochromes. Deconvolute the single, pooled data file into individual samples based on their unique barcode. Analyze pSTAT levels within specific immune cell subsets (T cells, B cells, monocytes) using either conventional manual gating strategies or semi-automated computational workflows built with R software to minimize inter-operator variability [32].

Diagram 1: Multiplexed Assay Workflows

Supporting Data and Validation Studies

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Multiplexed assays must meet stringent quality control standards to be deployable in HTS campaigns. The Alpha-based multiplexed STAT3/STAT5b assay demonstrated excellent statistical reliability, with Z' factors consistently greater than 0.6 for both targets, indicating a robust assay suitable for high-throughput screening [31]. The FCB protocol also demonstrated high reproducibility across operators, particularly when an internal bridge control was included across experimental runs to minimize technical variability [32].

Case Study: Identification of a Selective STAT3 Inhibitor

The practical utility of the Alpha multiplexed assay was demonstrated in a HTS campaign of chemical libraries. The screen identified a 2-chloro-1,4-naphthalenedione derivative (Compound 1) that preferentially inhibited STAT3-SH2 binding over STAT5b in the in vitro assay [31]. This selectivity was functionally validated in cell-based studies, where the compound effectively inhibited the nuclear translocation of STAT3 in HeLa cells. Furthermore, initial structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies conducted using the same multiplexed platform revealed that the 3-substituent on the compound scaffold had a significant effect on both potency and STAT3/STAT5b selectivity [31].

Table 2: Experimental Data from Multiplexed Profiling Applications

| Study / Platform | Key Experimental Finding | Impact on Inhibitor Development |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaPlex Screen [31] | Identification of a 2-chloro-1,4-naphthalenedione derivative with preferential STAT3 inhibition. | Enabled rapid SAR to explore 3-substituent effects on potency and selectivity. |

| Genetic Analysis [33] | STAT5B-N642H mutation in lymphoma increases phosphotyrosine-binding affinity. | Provides a rationale for developing mutant-specific inhibitors and validates SH2 domain targeting. |

| FCB Signaling Profiling [32] | Enables quantification of pSTAT in specific immune cell subsets from barcoded PBMCs. | Allows for ex vivo assessment of inhibitor specificity and potential immune-related toxicities. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of these multiplexed assays requires specific, high-quality reagents.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for STAT Multiplexed Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function in Assay | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant STAT-SH2 Proteins | The primary target for binding assays; requires high purity. | Use N- and C-terminal deletion mutants to isolate the SH2 domain [31]. |

| Phosphotyrosine Peptides | Serve as the binding partner for the SH2 domain. | Use high-affinity sequences: GpYLPQTV for STAT3, GpYLVLDKW for STAT5b [31]. |