Native-PAGE vs. Denaturing PAGE: A Comprehensive Guide for Life Science Researchers

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical differences between native (non-denaturing) and denaturing (SDS-PAGE) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Native-PAGE vs. Denaturing PAGE: A Comprehensive Guide for Life Science Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical differences between native (non-denaturing) and denaturing (SDS-PAGE) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. It covers foundational principles, methodological protocols, and application-specific guidelines to inform experimental design. The content addresses troubleshooting common issues, explores advanced hybrid techniques like NSDS-PAGE, and validates method selection through comparative analysis of protein complexes, enzymatic activity, and molecular weight determination. This resource enables scientists to optimize their electrophoretic approaches for structural biology, proteomics, and therapeutic development.

Core Principles: How Native and Denaturing Gels Work at the Molecular Level

Defining the Fundamental Separation Mechanisms

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the core separation mechanisms underlying denaturing and non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Within the broader context of protein research methodology, these techniques represent fundamentally divergent approaches to biomolecular separation. Denaturing PAGE disrupts native protein structure to separate polypeptides based primarily on molecular mass, while non-denaturing PAGE preserves higher-order structure and biological function, enabling separation based on charge, size, and shape. This whitepaper details the theoretical principles, methodological protocols, and practical applications of both techniques to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting appropriate electrophoretic methods for specific research objectives.

Protein electrophoresis is a standard laboratory technique by which charged protein molecules are transported through a solvent by an electrical field [1]. The mobility of a molecule through an electric field depends on several factors: field strength, net charge on the molecule, size and shape of the molecule, ionic strength, and properties of the matrix through which the molecule migrates [1]. Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) represents one of the most powerful analytical tools for protein separation, with denaturing and non-denaturing configurations serving distinct purposes in biochemical analysis [2] [3].

The fundamental divergence between these approaches lies in their treatment of protein structure. Denaturing PAGE methods deliberately disrupt non-covalent interactions and secondary structure, while non-denaturing PAGE maintains the native conformation and biological activity of proteins [4] [5]. This core distinction dictates their separation mechanisms, applications, and limitations within research environments.

Theoretical Foundations of Separation Mechanisms

Denaturing PAGE Separation Mechanism

In denaturing PAGE (typically SDS-PAGE), the separation mechanism relies on the uniform denaturation of proteins to create linear polypeptides that migrate based primarily on molecular weight [2] [1]. The anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) plays a critical role in this process by binding to proteins in a constant weight ratio (approximately 1.4 g SDS per 1 g of polypeptide) [1]. This SDS coating confers a uniform negative charge density that masks the proteins' intrinsic charge [3]. Simultaneously, reducing agents such as dithiothreitol (DTT) or β-mercaptoethanol break disulfide bonds, while heat treatment further disrupts secondary and tertiary structure [6].

The result is a population of SDS-polypeptide complexes that assume essentially identical rod-like shapes with equivalent charge-to-mass ratios [1]. Consequently, separation occurs principally according to polypeptide size as molecules navigate the porous polyacrylamide matrix [2]. Smaller proteins migrate more rapidly through the gel, while larger proteins experience greater frictional resistance and migrate more slowly [2]. This relationship enables accurate molecular weight determination when samples are compared to appropriate protein standards [1].

Non-Denaturing PAGE Separation Mechanism

Non-denaturing PAGE (native PAGE) employs a fundamentally different separation mechanism that preserves protein structure and function. Without denaturants, proteins maintain their native conformation, including secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures [5]. Separation depends on three interdependent factors: intrinsic charge, size, and shape [4] [1].

In native PAGE, proteins carry their inherent net charge at the running buffer pH, which determines their electrophoretic mobility direction and velocity [1]. Most proteins possess a net negative charge in basic pH buffers and migrate toward the anode [2]. However, the gel matrix simultaneously exerts a sieving effect based on protein size and three-dimensional structure [1]. Smaller, more compact proteins navigate the porous network more readily than larger proteins or complex assemblies [4]. Additionally, protein shape influences mobility, as globular proteins typically migrate differently than fibrous proteins of equivalent mass [1]. The combined effect results in separation according to both charge-to-mass ratio and molecular geometry [3].

Comparative Analysis of Separation Characteristics

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Denaturing and Non-Denaturing PAGE

| Parameter | Denaturing PAGE | Non-Denaturing PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Protein State | Denatured to linear chains [5] | Native conformation preserved [5] |

| Separation Basis | Molecular mass primarily [1] | Charge, size, and shape [1] |

| Detergent Use | SDS present [6] | No SDS [6] |

| Sample Treatment | Heating with reducing agents [6] | No heating; non-denaturing buffers [7] |

| Structural Level Analyzed | Primary structure only [5] | All four structural levels [5] |

| Biological Activity | Destroyed [3] | Often preserved [3] |

| Molecular Weight Determination | Accurate [2] | Not reliable [2] |

| Protein Complex Analysis | Subunits separated [6] | Complexes maintained [6] |

Table 2: Applications and Limitations of Electrophoresis Methods

| Aspect | Denaturing PAGE | Non-Denaturing PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Applications | Molecular weight estimation [2], purity assessment [2], western blotting [4], protein sequencing preparation [4] | Enzyme isolation [4] [6], protein complex analysis [6], quaternary structure study [2], aggregation state determination [2] |

| Key Advantages | High resolution [2], simple interpretation [2], broad applicability [1], accurate mass determination [1] | Functional activity preservation [3], protein-protein interaction studies [3], metal cofactor retention [8] |

| Major Limitations | Loss of native structure [8], destruction of function [3], inability to study complexes [3] | Lower resolution for complex mixtures [8], unpredictable migration [2], potential protein aggregation [1] |

Experimental Methodologies

Denaturing SDS-PAGE Protocol

The following protocol describes a standard SDS-PAGE procedure based on the Laemmli discontinuous buffer system for optimal protein separation [7].

Sample Preparation:

- Combine protein sample with 2X Tris-Glycine SDS Sample Buffer to achieve final 1X concentration [7].

- Add reducing agent (DTT or β-mercaptoethanol) to final concentration of 50 mM for reduced conditions [7].

- Heat samples at 85°C for 2-5 minutes to ensure complete denaturation [7].

- Centrifuge briefly to collect condensed sample before loading [7].

Gel Electrophoresis:

- Prepare precast Tris-Glycine polyacrylamide gel (appropriate percentage based on target protein size) [7].

- Rinse wells with 1X SDS Running Buffer to remove residual acrylamide and storage buffer [7].

- Load prepared samples and molecular weight markers into wells [7].

- Assemble electrophoresis apparatus with inner (upper) and outer (lower) buffer chambers filled with appropriate running buffer [7].

- Run gels at constant voltage (125 V for mini-gels) until dye front reaches bottom of gel (approximately 90 minutes) [7].

Buffers and Reagents:

- SDS Sample Buffer (2X): 125 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, 0.02% bromophenol blue [7].

- SDS Running Buffer (10X): 250 mM Tris, 1.92 M glycine, 1% SDS (pH 8.3) [7].

- Reducing Agent: 500 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) in stable liquid form [7].

Non-Denaturing PAGE Protocol

This protocol outlines native PAGE methodology for separating proteins while maintaining biological activity and complex structure.

Sample Preparation:

- Mix protein sample with 2X Tris-Glycine Native Sample Buffer to achieve final 1X concentration [7].

- Do not heat samples or include reducing agents [7] [6].

- Keep samples on ice to prevent degradation or denaturation before loading [1].

Gel Electrophoresis:

- Select appropriate percentage polyacrylamide gel based on protein size and complexity [1].

- Rinse wells with 1X Native Running Buffer [7].

- Load prepared samples carefully to avoid well overflow [7].

- Fill buffer chambers with Native Running Buffer (without SDS) [7].

- Run gels at constant voltage (125 V for mini-gels) for 1-12 hours depending on protein size and gel percentage [7].

- Maintain cool temperature during electrophoresis to prevent denaturation [1].

Buffers and Reagents:

- Native Sample Buffer (2X): 125 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 20% glycerol, 0.02% bromophenol blue (no SDS) [7].

- Native Running Buffer (10X): 250 mM Tris, 1.92 M glycine (no SDS) (pH 8.3) [7].

Advanced Methodology: Native SDS-PAGE

Recent methodological developments have yielded hybrid approaches such as Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE), which modifies traditional SDS-PAGE conditions to retain certain functional properties while maintaining high resolution [8]. This technique eliminates EDTA from buffers, reduces SDS concentration in the running buffer to 0.0375%, and omits the heating step during sample preparation [8]. Research demonstrates that NSDS-PAGE preserves bound metal ions in metalloproteins and maintains enzymatic activity in seven of nine model enzymes tested, while achieving resolution comparable to standard SDS-PAGE [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PAGE Experiments

| Reagent | Function | Denaturing PAGE | Non-Denaturing PAGE |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins; confers uniform negative charge [1] | Required [6] | Omitted [6] |

| DTT or β-mercaptoethanol | Reduces disulfide bonds [6] | Required [6] | Omitted [6] |

| Polyacrylamide | Forms porous gel matrix for molecular sieving [1] | Required | Required |

| Tris-Glycine Buffer | Maintains pH and conducts current [7] | With SDS [7] | Without SDS [7] |

| Glycerol | Increases sample density for well loading [7] | Included | Included |

| Tracking Dye | Visualizes migration progress [7] | Bromophenol blue | Bromophenol blue |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) & TEMED | Catalyzes acrylamide polymerization [1] | Required | Required |

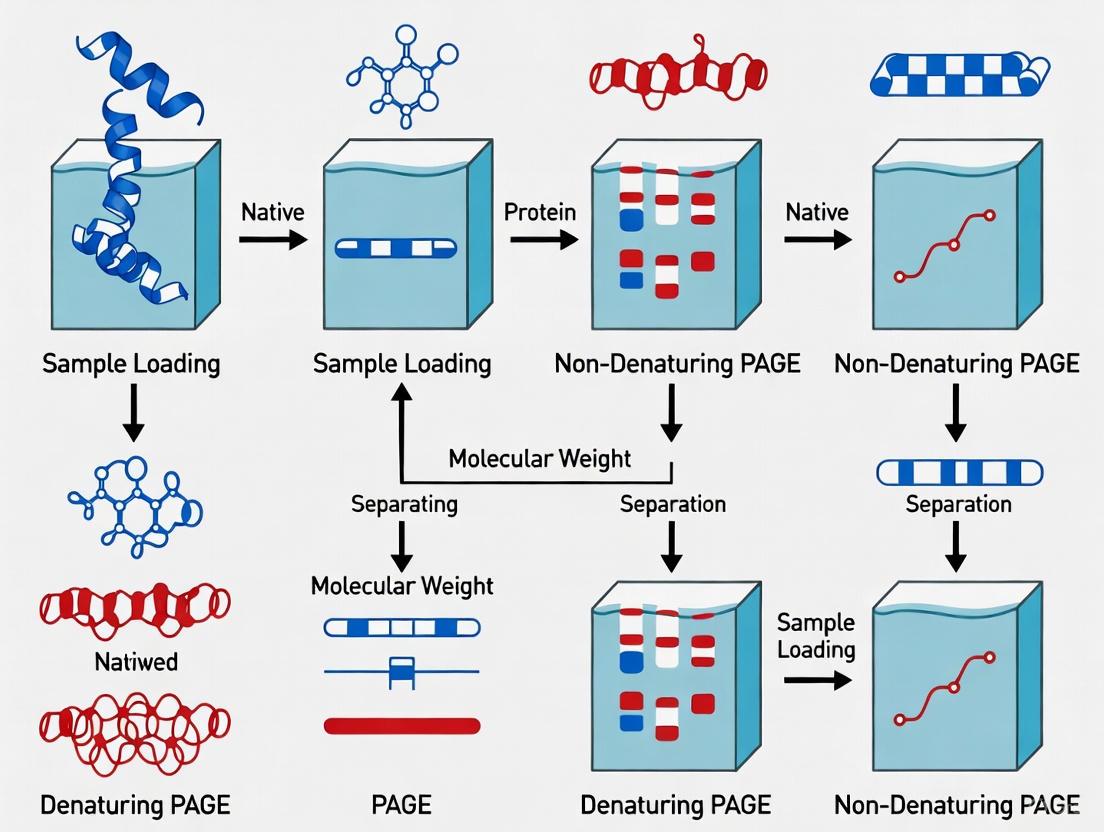

Workflow Visualization

Denaturing and non-denaturing PAGE represent complementary approaches with fundamentally distinct separation mechanisms tailored to specific research objectives. Denaturing PAGE provides high-resolution separation based primarily on molecular mass, making it ideal for molecular weight determination, purity assessment, and western blotting. Conversely, non-denaturing PAGE preserves native protein structure and function, enabling studies of protein complexes, enzymatic activity, and quaternary structure. The selection between these techniques should be guided by experimental goals, with denaturing methods preferred for structural analysis and non-denaturing methods chosen for functional studies. Advanced hybrid approaches such as NSDS-PAGE offer promising alternatives that balance resolution with preservation of certain functional properties, particularly valuable in metalloprotein research and drug development applications.

In the analysis of biomolecules via polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), the fundamental distinction between denaturing and non-denaturing (native) systems lies in the preservation of molecular structure. Non-denaturing PAGE maintains proteins and nucleic acids in their native, folded conformations, enabling the study of functional complexes, quaternary structures, and enzymatic activity [4] [2]. In contrast, denaturing PAGE deliberately disrupts the higher-order structure of these molecules to separate them based primarily on molecular weight [4]. This structural disruption is achieved through specific chemical conditions employing agents such as sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), reducing agents, and urea. These chemicals systematically target the non-covalent interactions and covalent disulfide bonds that maintain molecular structure, thereby unfolding the biomolecules into linear chains. The intentional application of these denaturants represents a cornerstone technique in molecular biology and biochemistry, providing researchers with tools to dissect complex biological systems. This technical guide explores the mechanisms, applications, and protocols associated with these critical chemical agents, framing them within the broader methodological context of PAGE-based research.

Core Chemical Mechanisms in Denaturing PAGE

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS)

Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) is an anionic detergent that plays a pivotal role in protein denaturation for SDS-PAGE. Its mechanism involves two primary actions. First, SDS binds quantitatively to proteins, with approximately one SDS molecule binding per two amino acid residues [2]. This extensive binding confers a uniform negative charge to all proteins in the sample, effectively masking their intrinsic charge and creating a consistent charge-to-mass ratio [2]. Second, SDS disrupts hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds that stabilize protein tertiary and quaternary structures [9]. This disruption occurs as the hydrophobic tail of SDS interacts with hydrophobic regions of the protein, while the ionic head group interacts with the aqueous environment. The combined effect of charge masking and structural disruption transforms complex globular proteins into linear, rod-like polypeptides [2]. Consequently, separation during electrophoresis becomes dependent almost exclusively on molecular weight rather than native charge or shape, enabling accurate molecular weight determination [2].

Reducing Agents

Reducing agents specifically target disulfide bonds, the covalent linkages between cysteine residues that stabilize tertiary and quaternary protein structures. Common reducing agents include dithiothreitol (DTT), β-mercaptoethanol (BME), and tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) [10]. These compounds work through thiol-disulfide exchange reactions, where the thiol groups (-SH) of the reducing agent nucleophilically attack the disulfide bonds (-S-S-) in proteins, reducing them to free thiol groups [10]. DTT and BME operate through this mechanism, requiring careful handling due to their susceptibility to oxidation. In contrast, TCEP represents an advance in reducing agent technology as it reduces disulfide bonds through a non-thiol-based, phosphine-mediated mechanism, making it more stable in aqueous solutions and effective over a wider pH range [10]. The application of reducing agents is particularly crucial for analyzing multimetric proteins or proteins with extensive disulfide bonding, as it ensures complete unfolding into monomeric polypeptide chains prior to separation [2].

Urea

Urea serves as a potent denaturant primarily used in nucleic acid electrophoresis and specialized protein applications. It functions at high concentrations (typically 6-8 M) as a chaotropic agent that disrupts hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions [9] [11]. Urea molecules form hydrogen bonds with the peptide backbone and polar side chains more effectively than water, thereby competing with the intramolecular hydrogen bonds that stabilize secondary structures like α-helices and β-sheets [9]. For RNA analysis, urea is particularly valuable because it eliminates secondary structures formed by intramolecular base pairing, ensuring that migration through the polyacrylamide gel depends solely on nucleotide chain length rather than structural conformation [11] [12]. The effectiveness of urea is temperature-dependent, with optimal denaturation occurring when gels are run at 45-55°C [11]. This temperature range maintains urea in solution while facilitating the complete unfolding of biomolecules.

Table 1: Key Denaturing Agents and Their Properties

| Denaturing Agent | Primary Mechanism of Action | Common Concentrations | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Binds proteins, conferring negative charge; disrupts hydrophobic interactions | 0.1-2% in buffers; 1% in sample buffer | SDS-PAGE for protein separation and molecular weight determination [2] |

| Urea | Disrupts hydrogen bonds; chaotropic effect | 6-8 M in gel and buffers | Denaturing DNA/RNA PAGE; protein unfolding studies [11] [12] |

| DTT (Dithiothreitol) | Reduces disulfide bonds via thiol-disulfide exchange | 1-100 mM (typically 10-20 mM in sample buffer) | Reducing SDS-PAGE; protein denaturation [7] [10] |

| TCEP (Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine) | Reduces disulfide bonds via phosphine mechanism | 1-50 mM (typically 5-10 mM in sample buffer) | Stable reduction for SDS-PAGE; wide pH range applications [10] |

Molecular Interactions Targeted by Denaturing Agents

The denaturing agents used in PAGE methodologies systematically disrupt specific molecular interactions that maintain biomolecular structure. Disulfide bonds, with the highest bond strength among protein interactions at approximately -230 kJ/mol, are specifically targeted by reducing agents such as DTT and TCEP [9]. These covalent linkages are cleaved through reduction-oxidation (redox) reactions. Electrostatic interactions, possessing a bond strength of about -21 kJ/mol, are disrupted by SDS, which masks intrinsic charges and imposes a uniform negative charge density [9]. Hydrogen bonds, with bond strengths of approximately -15 kJ/mol, are effectively broken by both urea and SDS [9]. Although individually weak, hydrophobic interactions are collectively significant for protein folding and are primarily disrupted by SDS through its amphiphilic properties [9]. The coordinated application of these agents enables researchers to selectively dismantle the structural integrity of biomolecules in a controlled manner, facilitating analysis based primarily on molecular dimensions rather than structural complexity.

Comparative Analysis: Denaturing vs. Non-Denaturing PAGE

Fundamental Methodological Differences

The distinction between denaturing and non-denaturing PAGE systems extends beyond the simple presence or absence of denaturing agents to encompass fundamental differences in methodology, information output, and application. Non-denaturing PAGE, performed without SDS, urea, or reducing agents, preserves the native structure and biological activity of macromolecules [4] [2]. In this system, separation depends on a combination of intrinsic charge, molecular size, and three-dimensional shape, making it ideal for studying functional biomolecular complexes [5]. In contrast, denaturing PAGE employs chemical agents to unfold biomolecules into linear chains, with separation based primarily on molecular weight due to the charge-homogenizing effect of SDS or the structure-disrupting properties of urea [4] [5]. This fundamental difference in separation principles dictates their respective applications in research, with native PAGE illuminating functional complexes and denaturing PAGE providing precise molecular weight and purity information.

Table 2: Applications of Denaturing vs. Non-Denaturing PAGE

| Application | Denaturing PAGE | Non-Denaturing PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight Determination | Yes - accurate determination due to linearized structures [2] | No - migration depends on multiple factors beyond size [2] |

| Structure Analysis | Primary structure only [5] | All four levels of structure (primary, secondary, tertiary, quaternary) [5] |

| Enzyme Activity Studies | Not possible (proteins denatured) | Possible - activity often preserved after electrophoresis [2] |

| Protein Complex Analysis | Separates complexes into individual subunits [2] | Preserves and separates intact complexes [4] |

| Binding Studies | Not suitable | Suitable for protein-protein or protein-ligand interactions [4] |

| Purity Assessment | Excellent for establishing sample purity [2] | Limited due to complex migration patterns |

Chemical Conditions and Buffer Composition

The chemical conditions for denaturing and non-denaturing PAGE differ significantly in their composition, particularly regarding detergents, reducing agents, and chaotropes. Denaturing systems for proteins typically include SDS (0.1-1%) in both sample buffers and running buffers, often combined with reducing agents like DTT (10-100 mM) or β-mercaptoethanol (0.1-1%) [7]. Sample preparation for denaturing PAGE involves heating (85-100°C for 2-5 minutes) to ensure complete denaturation [7]. For nucleic acids, denaturing conditions employ 6-8 M urea in the gel matrix and running buffers, with formamide often included in loading buffers [11]. Non-denaturing systems deliberately exclude these denaturing agents, instead using mild buffers at neutral or slightly basic pH to maintain protein structure and activity [7]. Non-denaturing sample preparation occurs without heating to preserve native conformations [7]. The running buffers for native PAGE typically lack SDS, though they maintain similar ion systems (e.g., Tris-Glycine) to facilitate proper electrophoresis [7].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

SDS-PAGE for Protein Separation

The SDS-PAGE protocol represents a standardized method for protein separation based on molecular weight. Begin with sample preparation by mixing protein samples with 2X SDS sample buffer (125 mM Tris-Cl, pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, 0.004% bromophenol blue) containing 100 mM DTT or 5% β-mercaptoethanol for reducing conditions [7]. Heat samples at 85°C for 2-5 minutes to ensure complete denaturation [7]. For non-reducing SDS-PAGE, omit the reducing agent but maintain SDS and heating. Assemble the gel apparatus according to manufacturer instructions, using pre-cast or freshly poured polyacrylamide gels with appropriate percentages for the target protein size range [7]. Fill the upper and lower buffer chambers with 1X Tris-Glycine-SDS running buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.3) [7]. Load prepared samples and molecular weight markers into wells. Run electrophoresis at constant voltage (100-150 V) until the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel [7]. Following electrophoresis, process gels for staining, western blotting, or further analysis as required by the experimental design.

Urea-PAGE for RNA Analysis

Urea-PAGE provides high-resolution separation of RNA molecules by eliminating secondary structure. Begin by preparing the gel solution according to Table 1, using ultrapure urea and appropriate acrylamide concentration based on the target RNA size range [11]. For a standard 15% gel, mix 24 g urea, 18.75 mL of 40% acrylamide solution (29:1), 5 mL of 10X TBE buffer (890 mM Tris, 890 mM boric acid, 20 mM EDTA), and deionized water to 50 mL total volume [11]. Heat the solution briefly to dissolve urea completely, then add 166 μL of 10% ammonium persulfate and 20 μL TEMED to initiate polymerization [11]. Pour the gel immediately between assembled glass plates, insert an appropriate comb, and allow 30-60 minutes for complete polymerization [11]. Assemble the gel apparatus, add 1X TBE running buffer to both chambers, and pre-run the gel for 30 minutes at 15-25 W to reach the optimal temperature of 45-55°C [11]. For sample preparation, mix RNA samples with 2X loading buffer (90% formamide, 0.5% EDTA, 0.1% xylene cyanol, 0.1% bromophenol blue), heat at 70-90°C for 2-3 minutes to denature secondary structures, then immediately place on ice [11]. Load denatured samples and run electrophoresis at constant power maintaining 45-55°C gel temperature until adequate separation is achieved [11]. Post-electrophoresis, stain with appropriate dyes (e.g., ethidium bromide, SYBR Gold) or process for transfer to membranes.

Diagram 1: Urea-PAGE workflow for RNA analysis

Native PAGE for Protein Complexes

Non-denaturing PAGE preserves protein structure and function during electrophoresis. Begin with sample preparation using native sample buffer (typically containing Tris, glycerol, and tracking dyes but no SDS or reducing agents) [7]. Crucially, do not heat samples before loading [7]. Prepare native running buffer (e.g., Tris-Glycine without SDS, pH ~8.3) [7]. Cast polyacrylamide gels without SDS or other denaturants, using the same percentage considerations as denaturing gels but noting that migration will depend on both size and native charge [7]. Load samples and run electrophoresis at constant voltage (typically 125 V) with lower current compared to SDS-PAGE due to the absence of SDS [7]. Running times may be longer than SDS-PAGE as proteins migrate more slowly in their native conformation [7]. Following electrophoresis, process gels for activity staining, western blotting under native conditions, or other detection methods compatible with preserved protein function.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of denaturing and non-denaturing PAGE requires specific reagents carefully selected for their properties and applications. The following table summarizes essential components for PAGE experiments, their functions, and considerations for use.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Denaturing and Non-Denaturing PAGE

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Mechanism | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detergents | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Disrupts hydrophobic interactions; confers uniform charge | Core component of SDS-PAGE; use at 0.1-1% concentration [2] |

| Chaotropic Agents | Urea, Guanidine HCl | Disrupts hydrogen bonding; unfolds macromolecules | Use 6-8 M for RNA/DNA denaturation; handle at controlled temperatures [11] [10] |

| Reducing Agents | DTT, β-mercaptoethanol, TCEP | Reduces disulfide bonds; linearizes proteins | DTT/BME require fresh preparation; TCEP more stable [10] |

| Gel Matrix Components | Acrylamide/bis-acrylamide, TEMED, APS | Forms cross-linked polymer network for separation | Adjust percentage based on target size range; TEMED catalyzes polymerization |

| Buffer Systems | Tris-Glycine, TBE, TAE | Provides conducting medium; maintains pH | Tris-glycine for proteins; TBE for nucleic acids; concentration affects resolution |

| Tracking Dyes | Bromophenol blue, Xylene cyanol | Visualize migration front; monitor run progress | Different migration rates based on matrix; may interfere with fluorescence |

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Common Challenges in Denaturing PAGE

Several technical challenges may arise when performing denaturing PAGE, often manifesting as poor resolution, aberrant migration, or artifacts. In SDS-PAGE, incomplete denaturation frequently results from insufficient heating or inadequate SDS concentration, leading to curved bands or multiple bands for a single protein [7]. This can be addressed by ensuring sample heating at 85°C for 2-5 minutes in the presence of at least 1% SDS [7]. Oxidation of reducing agents, particularly DTT and β-mercaptoethanol, causes reappearance of disulfide bonds and improper unfolding, which can be prevented by preparing fresh reducing agent solutions for each use or switching to more stable alternatives like TCEP [10]. In urea-PAGE for RNA analysis, incomplete denaturation often stems from incorrect urea concentration (deviations from 6-8 M) or suboptimal temperature during electrophoresis [11] [12]. Maintaining gel temperature at 45-55°C throughout the run is critical for consistent results [11]. RNase contamination represents another common issue in RNA work, requiring strict RNase-free conditions including use of certified reagents, DEPC-treated water, and dedicated equipment [12].

Optimization Strategies

Systematic optimization of denaturing PAGE methods enhances resolution and reproducibility. For protein separation via SDS-PAGE, acrylamide concentration should be matched to protein size range, with lower percentages (8-12%) optimal for high molecular weight proteins and higher percentages (12-20%) better for smaller proteins [2]. Gel thickness affects resolution, with thinner gels (0.75-1.0 mm) typically providing sharper bands than thicker gels (1.5 mm) [11]. For urea-PAGE of nucleic acids, sample loading volume significantly impacts band sharpness, with ideal volumes between 1-5 μL providing optimal resolution [11]. Including 10% glycerol in loading buffers can improve sample settling in wells without affecting denaturation [11]. "Gel smiling" (uneven migration across the gel) results from uneven heat distribution and can be mitigated by using proper electrophoresis apparatus with temperature regulation or attaching metal plates to distribute heat evenly [11]. Voltage optimization is also crucial, with lower voltages at the beginning of runs sometimes improving band sharpness by allowing smooth entry of samples into the gel matrix [11].

Diagram 2: Common PAGE issues and solutions

The strategic application of specific chemical conditions—employing SDS, reducing agents, and urea—enables researchers to manipulate biomolecular structure during polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis to address distinct research questions. Denaturing conditions that disrupt native structure facilitate molecular weight determination, purity assessment, and analysis of individual macromolecular components. In contrast, non-denaturing conditions that preserve native conformation enable the study of functional complexes, enzymatic activity, and higher-order structures. The informed selection between these approaches, along with careful optimization of chemical conditions, represents a fundamental methodological decision in biomolecular research. As electrophoretic techniques continue to evolve, particularly in drug development and structural biology, the precise control over denaturing conditions remains essential for generating reproducible, interpretable data across diverse applications. Understanding these chemical principles provides researchers with a powerful framework for experimental design and data interpretation in the broader context of biomolecular analysis.

In polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), the separation of proteins is governed by the complex interplay of their fundamental physical properties: size, charge, and shape. The extent to which each property influences migration fundamentally depends on whether the experiment is conducted under denaturing or non-denaturing (native) conditions [4] [1]. In denaturing PAGE, the inherent charge and shape of proteins are masked, making molecular mass the primary determinant of mobility. In contrast, native PAGE leverages the protein's intrinsic charge, its three-dimensional structure, and its mass, allowing for the separation of functional complexes [1] [13]. This technical guide explores how these properties govern electrophoretic migration, framed within the core distinction between denaturing and non-denaturing PAGE methodologies, which is pivotal for researchers and drug development professionals to select the appropriate technique for their analytical goals.

Core Principles of Electrophoretic Migration

Fundamental Factors Influencing Mobility

The electrophoretic mobility of a molecule in a gel matrix is a function of the force exerted by the electric field and the retarding frictional forces encountered during migration. The general factors affecting this mobility include [14] [15]:

- Net Charge: The overall charge of the molecule at the buffer's pH determines the direction and magnitude of the force from the electric field. Mobility is directly proportional to the net charge [15].

- Size and Mass: Larger molecules experience greater frictional drag within the gel matrix, leading to slower migration. Mobility is inversely proportional to size [15].

- Molecular Shape: The three-dimensional conformation affects the frictional coefficient. Compact, globular proteins migrate faster than elongated, fibrous proteins of similar molecular weight [15].

- Gel Matrix Pore Size: The concentration of polyacrylamide determines the pore size, which acts as a molecular sieve. Higher percentage gels have smaller pores, providing better resolution for smaller proteins [1] [13].

- Buffer Conditions: The pH of the buffer determines the ionization state of the protein, thus its net charge. The ionic strength affects the conductivity of the medium and the sharpness of the separated bands [14] [15].

- Field Strength: A higher voltage increases the rate of migration but can also generate heat, leading to diffusion of bands and potential protein denaturation in native gels [15].

The Gel Matrix as a Molecular Sieve

Polyacrylamide gels are created through the polymerization of acrylamide monomers cross-linked by bisacrylamide [1] [13]. The resulting meshwork provides a porous medium through which molecules travel. The pore size is controlled by the total concentration of acrylamide (%T) and the degree of cross-linking (%C) [13]. This matrix is critical for separating molecules based on size, as smaller molecules can navigate the pores more easily than larger ones [14] [1].

Denaturing vs. Native PAGE: A Mechanistic Comparison

The decision to use denaturing or native PAGE dictates which molecular properties govern the separation. The table below summarizes the core differences between these two fundamental approaches.

Table 1: Core Differences Between Denaturing and Native PAGE

| Parameter | Denaturing PAGE (e.g., SDS-PAGE) | Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Separation Basis | Molecular mass (kDa) [1] [13] | Combined effect of net charge, size, and native shape [1] [13] |

| Protein Structure | Disrupted; proteins are linearized [4] [13] | Preserved in its native, folded state [4] [5] |

| Key Reagents | SDS (sodium dodecyl sulfate), reducing agents (e.g., β-mercaptoethanol) [1] [13] | No denaturing agents; may use milder detergents for membrane proteins [1] |

| Sample Preparation | Heating (∼100°C) in sample buffer containing SDS and reductant [13] | No heating; mixed with non-denaturing loading dye [13] |

| Charge Manipulation | SDS confers a uniform negative charge, masking intrinsic charge [1] | Relies on the protein's intrinsic charge at the running buffer's pH [1] |

| Information Obtained | Polypeptide chain molecular mass, sample purity [4] [1] | Oligomeric state (quaternary structure), protein-protein interactions, enzymatic activity [4] [1] |

Denaturing PAGE: Separation by Mass

In denaturing PAGE, most commonly performed as SDS-PAGE, the goal is to separate proteins based almost exclusively on the mass of their polypeptide chains [1] [13].

- Role of SDS: The anionic detergent SDS binds to the hydrophobic regions of proteins in a constant weight ratio (approximately 1.4 g SDS per 1 g of protein) [1]. This extensive coating confers a uniform negative charge per unit mass, effectively masking the protein's intrinsic charge [1] [13].

- Role of Reducing Agents: Agents like β-mercaptoethanol or dithiothreitol (DTT) break disulfide bonds that hold protein subunits together, ensuring complete denaturation into individual polypeptide chains [13].

- Effect on Molecular Properties: The combination of SDS, heat, and reductant linearizes the proteins, destroying their secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures [4] [5]. This process eliminates the influence of both native charge and shape on migration. Consequently, the SDS-polypeptide complexes migrate through the gel as linear chains with identical charge densities, and their mobility depends solely on their molecular mass through the sieving effect of the gel [1].

Native PAGE: Separation by Charge, Size, and Shape

Native PAGE is performed without denaturants to preserve the protein's biological activity and higher-order structure [1] [13].

- Preservation of Properties: Under these conditions, a protein's intrinsic net charge (dictated by its amino acid composition and the buffer pH), its native size (including its oligomeric state), and its three-dimensional shape all contribute to its electrophoretic mobility [1] [13].

- Complex Migration: A highly charged protein will migrate faster than a less charged one of the same mass. Similarly, a compact, globular protein will migrate faster than an elongated, fibrous protein of the same mass and charge due to differences in frictional drag [15]. This allows native PAGE to separate proteins based on their functional states and complexes [4].

The following diagram illustrates the distinct migration mechanisms in these two techniques.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard SDS-PAGE (Denaturing) Protocol

This protocol is adapted from common laboratory practices as detailed across multiple sources [1] [13].

1. Gel Preparation:

- Resolving Gel: First, a resolving gel with an appropriate acrylamide percentage (typically 8-15%) is cast at pH ~8.8. The percentage is chosen based on the target protein's size [1] [13].

- Stacking Gel: After polymerization, a stacking gel with a lower percentage of acrylamide (∼4%) and a lower pH (~6.8) is cast on top. The discontinuity in pH and gel pore size helps concentrate all protein samples into a sharp band before they enter the resolving gel, greatly improving resolution [1] [13].

2. Sample Preparation:

- Protein samples are mixed with an SDS-PAGE loading buffer containing SDS (for denaturation and charge), a reducing agent (e.g., β-mercaptoethanol to break disulfide bonds), glycerol (to weigh down the sample), and a tracking dye (e.g., bromophenol blue) [13].

- The mixture is heated at 95-100°C for 3-5 minutes to fully denature the proteins [13].

3. Electrophoresis:

- The prepared samples and a molecular weight marker (protein ladder) are loaded into the wells.

- The gel is run in an electrophoresis tank filled with a running buffer (e.g., Tris-Glycine-SDS) at a constant voltage until the tracking dye front reaches the bottom of the gel [13].

Standard Native PAGE Protocol

The setup for native PAGE is similar but omits denaturing agents [1] [13].

1. Gel Preparation:

- The gel is cast without SDS. The choice of acrylamide percentage and buffer system (e.g., Tris-Glycine, Tris-Borate) is critical and must be optimized to maintain protein stability and activity [13].

2. Sample Preparation:

- Samples are mixed with a non-denaturing loading buffer that lacks SDS and reductants. The buffer typically contains glycerol and a tracking dye, but the sample is not heated [13].

3. Electrophoresis:

- The gel is run in a running buffer without SDS. It is often advisable to run native PAGE at lower voltages or with cooling to prevent heat-induced denaturation during the run [1] [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PAGE

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms the cross-linked polymer matrix (gel) that acts as a molecular sieve. | Total concentration (%T) dictates pore size and resolution range [1] [13]. |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) & TEMED | APS (initiator) and TEMED (catalyst) are required to polymerize the acrylamide solution into a gel. | Freshly prepared APS solutions are critical for efficient polymerization [1] [13]. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Ionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge. | Essential for SDS-PAGE; must be omitted for native PAGE [1] [13]. |

| β-Mercaptoethanol or DTT | Reducing agents that cleave disulfide bonds between cysteine residues. | Ensures complete denaturation into monomeric subunits in SDS-PAGE [13]. |

| Tris-based Buffers | Provide the necessary ions to conduct current and maintain a stable pH during electrophoresis. | A discontinuous system (different pH in stacking vs. resolving gel) is key for sharp bands in SDS-PAGE [1] [13]. |

| Molecular Weight Markers | A set of pre-stained or unstained proteins of known sizes run alongside samples to estimate molecular mass. | Critical for calibrating and interpreting SDS-PAGE results [1]. |

| Coomassie Blue/Silver Stain | Dyes used to visualize separated protein bands on the gel post-electrophoresis. | Coomassie is common for general use; silver stain offers higher sensitivity [15]. |

Advanced Techniques and Applications

Two-Dimensional (2D) PAGE

2D-PAGE combines two orthogonal separation techniques to achieve extremely high resolution. In the first dimension, proteins are separated by their native isoelectric point (pI) using isoelectric focusing (IEF). In the second dimension, the same proteins are separated by their molecular mass using SDS-PAGE [1] [15]. This method allows for the resolution of thousands of proteins from a single sample and is a powerful tool in proteomics for analyzing complex protein mixtures, post-translational modifications, and changes in protein expression [1].

Capillary Electrophoresis (CE)

Capillary electrophoresis is a modern evolution of traditional gel electrophoresis. It uses narrow-bore capillaries filled with a polymer matrix or buffer. The high surface-area-to-volume ratio allows for efficient heat dissipation, enabling the use of very high voltages for fast separations with exceptional resolution [14] [15]. CE can be coupled with sophisticated detectors like mass spectrometers, enhancing its analytical capabilities for both proteins and nucleic acids [14].

The migration of proteins in polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis is a physical process dictated by the triumvirate of molecular properties: size, charge, and shape. The fundamental choice between denaturing and native PAGE determines which of these properties becomes the dominant factor for separation. SDS-PAGE, by homogenizing charge and destroying native structure, simplifies analysis to molecular mass, making it an indispensable tool for estimating purity and polypeptide size. In contrast, native PAGE embraces the complexity of proteins in their functional state, allowing researchers to probe quaternary structure, interactions, and activity. A deep understanding of how these properties affect migration under different conditions is essential for designing robust experiments, accurately interpreting electrophoretic data, and selecting the optimal strategy to answer specific biological questions in basic research and drug development.

Preservation vs. Disruption of Protein Structure and Function

The fundamental principle underlying many analytical techniques in biochemistry and molecular biology is the deliberate choice between preserving or disrupting the native structure of proteins. This distinction is particularly pronounced in polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), where researchers must select between native (non-denaturing) and denaturing conditions based on their experimental objectives. The strategic decision to preserve or disrupt protein structure directly impacts the type of information obtained, ranging from molecular weight determination to functional activity assessment and complex formation [4] [2].

Within the context of a broader thesis on denaturing versus non-denaturing PAGE research, this technical guide explores the fundamental principles, methodological considerations, and practical applications of both approaches. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding these distinctions is crucial for designing appropriate experiments, particularly when studying protein complexes that serve as important drug targets or when analyzing conformational changes implicated in neurodegenerative diseases [16].

Fundamental Principles of Protein Electrophoresis

Molecular Basis of Separation

Gel electrophoresis separates proteins through a matrix under the influence of an electric field. The migration behavior of proteins depends on their physical properties, which are manipulated differently in native versus denaturing conditions.

In native PAGE, proteins maintain their higher-order structure (secondary, tertiary, and quaternary), allowing separation based on a combination of size, shape, and intrinsic charge [4] [5]. The gel matrix serves as a molecular sieve through which compact, highly charged proteins migrate faster than larger or less charged counterparts. This method preserves protein function and activity, enabling subsequent enzymatic assays or analysis of protein complexes [2].

In denaturing SDS-PAGE, the anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) binds to hydrophobic regions of proteins at a relatively constant ratio (approximately 1.4g SDS per 1g protein), conferring a uniform negative charge that masks the protein's intrinsic charge [2]. Reducing agents like dithiothreitol (DTT) or β-mercaptoethanol break disulfide bonds, destroying tertiary and quaternary structures [2]. This linearizes proteins into rod-like chains, creating a near-uniform charge-to-mass ratio across different proteins [2]. Consequently, separation occurs primarily by molecular weight, with smaller polypeptides migrating faster through the gel matrix [2].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Native Versus Denaturing PAGE

| Parameter | Native (Non-Denaturing) PAGE | Denaturing (SDS) PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure | Maintains native conformation; preserves secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structure | Disrupts higher-order structure; proteins unfolded into linear chains |

| Separation Basis | Size, shape, and intrinsic charge | Primarily molecular mass |

| Sample Preparation | Non-denaturing, non-reducing buffers; no SDS | Heated with SDS and reducing agents (DTT) |

| Charge-to-Mass Ratio | Variable | Uniform (due to SDS binding) |

| Molecular Weight Determination | Not accurate due to structural and charge variables | Accurate for polypeptide chain size |

| Functional Preservation | Enzymatic activity often preserved | Activity destroyed |

| Applications | Studying protein complexes, isolation of enzymes, analysis of quaternary structure | Molecular weight estimation, purity assessment, Western blotting, protein sequencing preparation |

Quantitative Analysis in Protein Research

Beyond simple separation, both native and denaturing electrophoresis can be incorporated into quantitative proteomic approaches. Quantitative protein profiling is essential for understanding cellular processes, with methods ranging from label-free techniques to those using isotopic labelling with amino acids (SILAC), isobaric tags (iTRAQ), or isotope-coded affinity tag reagents [17] [18]. These techniques enable researchers to quantify changes in protein abundance across different biological states, providing crucial information for systems biology and drug development [17].

Methodological Approaches

Native (Non-Denaturing) PAGE Protocols

Basic Native PAGE for Protein Complex Analysis

Objective: To separate and analyze functionally active protein complexes while preserving their native state.

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare protein samples in non-denaturing, SDS-free buffer (e.g., Tris-glycine or Tris-borate at neutral to slightly basic pH)

- Avoid heating or using reducing agents

- Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove insoluble material

- Maintain samples at 4°C throughout preparation to preserve stability

Gel Preparation:

- Prepare resolving gel (typically 6-12% acrylamide depending on protein size)

- Composition: Acrylamide/bis-acrylamide (29:1), 0.375 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 0.1% ammonium persulfate (APS), and 0.1% TEMED

- Stacking gel: 4% acrylamide, 0.125 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 0.1% APS, and 0.1% TEMED

- Pour gel and allow to polymerize for 30-60 minutes

Electrophoresis Conditions:

- Running buffer: 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine (pH 8.3)

- Load 10-50 μg protein per lane alongside native molecular weight standards

- Run at constant voltage (100-150V) for 1.5-2 hours at 4°C to prevent heat denaturation

- Monitor migration of pre-stained standards or tracking dye

Post-Electrophoresis Analysis:

- Proteins can be visualized with Coomassie Brilliant Blue, silver stain, or specific activity stains

- For functional assays, proteins can be electroeluted or transferred to suitable membranes under native conditions

- Alternatively, gel slices can be excised and used directly in activity assays

Advanced Native Techniques for Structural Biology

Recent advances in native separation techniques include capillary electrophoresis-mass spectrometry (CE-MS), which enables structural analysis of large protein complexes under near-physiological conditions [16]. This method:

- Uses minimal sample amounts (10,000-fold lower than conventional techniques)

- Provides results in less than 30 minutes

- Maintains proteins at near-physiological conditions in solution

- Allows real-time monitoring of conformational changes and dynamic interactions [16]

Denaturing (SDS-PAGE) Protocols

Standard SDS-PAGE for Molecular Weight Determination

Objective: To separate protein subunits by molecular weight after disruption of higher-order structures.

Sample Preparation:

- Dilute protein samples in 2× Laemmli buffer: 125 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, 0.02% bromophenol blue

- Add 100 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) or 5% β-mercaptoethanol as reducing agent

- Heat at 95-100°C for 5-10 minutes to ensure complete denaturation

- Centrifuge briefly to collect condensed sample

Gel Preparation:

- Discontinuous system with stacking (4-5%) and resolving (8-20%) gels

- Resolving gel: Acrylamide/bis-acrylamide (29:1 or 37.5:1), 0.375 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 0.1% SDS, 0.1% APS, and 0.1% TEMED

- Stacking gel: 4-5% acrylamide, 0.125 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 0.1% SDS, 0.1% APS, and 0.1% TEMED

- Allow complete polymerization (30-60 minutes)

Electrophoresis Conditions:

- Running buffer: 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS (pH 8.3)

- Load 10-100 μg protein per lane alongside pre-stained molecular weight markers

- Run at constant voltage (100-200V) until dye front reaches bottom

- Maintain cooling for consistent band patterns

Post-Electrophoresis Analysis:

- Fix proteins in gel with 40% ethanol/10% acetic acid

- Visualize with Coomassie Blue, silver stain, or fluorescent dyes

- For Western blotting, transfer to PVDF or nitrocellulose membranes

- For protein sequencing, electroblot to appropriate membranes

Variations and Specialized Denaturing Protocols

Urea-PAGE for Nucleic Acid-Protein Complexes:

- Uses 6-8 M urea to denature nucleic acids while maintaining protein denaturation

- Particularly useful for analyzing RNA-protein interactions [4]

Gradient Gels for Enhanced Resolution:

- Linear or nonlinear acrylamide gradients (e.g., 4-20%) improve resolution across broad molecular weight ranges

- Allow better separation of large and small proteins on the same gel

Two-Dimensional Electrophoresis:

- Combines isoelectric focusing (first dimension) with SDS-PAGE (second dimension)

- Enables high-resolution separation of complex protein mixtures [18]

Comparative Analysis and Applications

Strategic Selection Guide

The decision to use native versus denaturing PAGE depends fundamentally on the research question and desired outcomes. The table below summarizes key application scenarios for each method.

Table 2: Application Guide for Native Versus Denaturing PAGE

| Research Objective | Recommended Method | Rationale | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight Determination | Denaturing SDS-PAGE | Eliminates structural and charge variables; separation by polypeptide chain size only | Use appropriate molecular weight markers; linear range of gel should match protein size |

| Enzyme Activity Analysis | Native PAGE | Preserves tertiary structure and active site conformation | Maintain cool temperatures; use specific activity stains; avoid fixatives that denature proteins |

| Protein Complex/ Oligomeric State Study | Native PAGE | Maintains quaternary structure and subunit interactions | Vary gel concentration to assess size and shape; cross-linking may stabilize weak complexes |

| Western Blotting | Denaturing SDS-PAGE | Improves antibody accessibility to linear epitopes; standard transfer protocols | Reduction required for disulfide-linked proteins; confirm antibody recognizes denatured epitopes |

| Sample Purity Assessment | Denaturing SDS-PAGE | Reveals individual polypeptide chains; detects proteolytic fragments | Multiple staining methods available; Coomassie for major bands, silver for trace contaminants |

| Protein-Protein Interactions | Native PAGE | Preserves binding interfaces and complex formation | Vary running conditions to detect weak interactions; combine with cross-linking for stability |

| Protein Sequencing | Denaturing SDS-PAGE | Isolates individual polypeptide chains for sequencing | Electroblot to suitable membranes; minimal staining to avoid N-terminal blockage |

| Isoenzyme Separation | Native PAGE | Separates isoforms with subtle structural differences | Optimize pH and buffer systems; activity staining often required for specific detection |

| Binding Studies | Native PAGE | Maintains binding pockets and ligand interactions | May incorporate ligands in gel or buffer; mobility shifts indicate binding |

Quantitative Data from Method Applications

The effects of various processing methods on protein properties provide valuable quantitative insights for researchers selecting appropriate electrophoretic techniques.

Table 3: Quantitative Effects of Processing Methods on Protein Properties

| Processing Method | Affected Protein Properties | Quantitative Changes | Functional Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ohmic Heating | Structure, solubility, emulsifying and foaming properties | Increased particle size and turbidity; enhanced water and oil holding capacity [19] | Improved bioactivity in sheep milk via proteolysis; increased bioactive peptides [19] |

| High-Pressure Processing (HPP) | Particle size, secondary structure, coagulation properties | Significant modification of structural parameters [19] | Alters functional properties for specific food applications |

| Pulsed Electric Fields (PEF) | Solubility, structure | Enhanced protein solubility; structural modifications [19] | Improves technological applications in food systems |

| Enzymatic Hydrolysis | Texture, proteolytic activity, degree of hydrolysis, solubility | Breakdown of proteins into smaller peptides [19] | Improved digestibility and absorption of amino acids [19] |

| Novel CE-MS Method | Structural analysis, conformational changes | 10,000-fold lower sample requirement; analysis in <30 minutes [16] | Enables study of protein complexes in near-native state; potential for drug development |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of native and denaturing electrophoresis requires specific reagents optimized for each method. The table below details essential solutions and their functions.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Electrophoresis

| Reagent Solution | Composition | Function | Method Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laemmli Sample Buffer | 125 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, 0.02% bromophenol blue, with reducing agent | Denatures proteins, provides uniform charge, adds density for loading, provides visible migration marker | Denaturing SDS-PAGE |

| Tris-Glycine Running Buffer | 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine (pH 8.3) with or without 0.1% SDS | Maintains pH during electrophoresis, provides conducting medium | Both native and denaturing PAGE (with/without SDS) |

| Non-Denaturing Sample Buffer | Tris-HCl or Tris-borate (pH 7-8), glycerol, tracking dye | Maintains native state, provides density for loading, visible migration marker | Native PAGE |

| Acrylamide/Bis Solution | 29:1 or 37.5:1 acrylamide:bis-acrylamide in water | Forms cross-linked polymer network for size-based separation | Both methods (gel matrix) |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | 10% solution in water | Free radical source for acrylamide polymerization | Both methods (gel formation) |

| TEMED | N,N,N',N'-Tetramethylethylenediamine | Catalyzes acrylamide polymerization by generating free radicals | Both methods (gel formation) |

| Coomassie Staining Solution | 0.1% Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250, 40% methanol, 10% acetic acid | Visualizes protein bands by binding to amino acids | Both methods (post-electrophoresis) |

| Destaining Solution | 40% methanol, 10% acetic acid | Removes background stain while retaining protein-bound dye | Both methods (post-electrophoresis) |

| Transfer Buffer | 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 20% methanol | Facilitates protein transfer from gel to membrane for Western blotting | Primarily denaturing PAGE |

| Sodium Cholate Solution | 10% (w/v) sodium cholate in Tris-EDTA buffer | Non-denaturing detergent for tissue clearing; preserves native protein state [20] | Specialized native applications |

Emerging Technologies and Future Perspectives

Innovations in Native State Analysis

The field of protein analysis continues to evolve with emerging technologies that enhance our ability to study proteins in their native states. Capillary electrophoresis-mass spectrometry (CE-MS) represents a significant advancement, enabling researchers to:

- Analyze protein complexes under near-physiological conditions [16]

- Detect conformational changes in real-time [16]

- Study interactions with small molecules, nucleotides, and metal ions [16]

- Identify point mutations within large protein complexes [16]

This method substantially minimizes sample consumption and simplifies analytical workflows while maintaining proteins at near-physiological conditions, making it particularly valuable for drug development where understanding protein-ligand interactions is crucial [16].

Novel Applications in Tissue Clearing

Innovative approaches to protein preservation are emerging in fields beyond traditional electrophoresis. The development of OptiMuS-prime, a passive tissue clearing method using sodium cholate and urea, offers enhanced protein preservation compared to traditional SDS-based methods [20]. This technique:

- Replaces SDS with sodium cholate, a non-denaturing detergent with smaller micelles [20]

- Better preserves proteins in their native state while enabling tissue transparency [20]

- Combines urea to disrupt hydrogen bonds and induce hyperhydration for enhanced probe penetration [20]

- Allows 3D imaging of immunolabeled structures while maintaining protein integrity [20]

Such advancements highlight the continuing importance of the fundamental choice between preservation and disruption of protein structure across multiple scientific disciplines.

The deliberate choice between preserving or disrupting protein structure represents a fundamental strategic decision in biochemical research. Native and denaturing electrophoresis methods provide complementary information that, when selected appropriately, enables comprehensive protein characterization. Native PAGE excels at maintaining functional activity and studying protein complexes, while denaturing SDS-PAGE provides precise molecular weight determination and purity assessment.

For researchers engaged in drug development, where protein complexes serve as critical therapeutic targets, or for those studying conformational diseases, the ability to analyze proteins under near-native conditions becomes particularly valuable. Emerging technologies that enhance our capability to study proteins with minimal structural disruption while providing high sensitivity and rapid analysis will continue to advance our understanding of protein function and facilitate therapeutic development.

The continuing evolution of both preservation and disruption techniques ensures that researchers will have increasingly sophisticated tools to address the complex questions in protein science, each method providing unique insights based on the fundamental principles outlined in this technical guide.

Understanding the Impact on Quaternary Structures and Complexes

Core Principles of PAGE: Denaturing vs. Non-Denaturing Environments

In protein research, the choice of electrophoretic method is critical, as it directly dictates the level of structural information that can be obtained. Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE) separates biological molecules based on their physical properties as they migrate through a gel matrix under an electrical field. [1] The fundamental division in these techniques lies in the use of denaturing or non-denaturing conditions, which have a profound and direct impact on the preservation of a protein's quaternary structure and native complexes. [4] [2]

In a denaturing environment, such as SDS-PAGE, proteins are unfolded into linear chains. [5] This is achieved using anionic detergents like sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and reducing agents like beta-mercaptoethanol or dithiothreitol (DTT). SDS denatures the protein and coats the polypeptide backbone with a uniform negative charge, while the reducing agent breaks disulfide bonds. [2] [1] [21] This process destroys the protein's secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures, meaning multi-subunit complexes are dissociated into their individual components. Consequently, separation occurs based almost solely on molecular mass, as all proteins have a similar charge-to-mass ratio. [21] [22]

In contrast, a non-denaturing or native environment deliberately avoids these disruptive agents. [2] Without SDS or reducing agents, the protein's native conformation—including its secondary, tertiary, and critically, its quaternary structure—is preserved throughout the electrophoresis. [5] This means that protein complexes remain intact. Separation in native PAGE depends on a combination of the protein's intrinsic charge, size, and three-dimensional shape, allowing for the analysis of functional, folded proteins and their interactions. [1]

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Denaturing and Non-Denaturing PAGE

| Characteristic | Denaturing (SDS-)PAGE | Non-Denaturing (Native) PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Gel Conditions | Denatured (contains SDS & reducing agents) [23] | Non-denatured (no SDS or reducing agents) [23] |

| Protein State | Unfolded, linear chains [5] | Folded, native conformation [2] |

| Impact on Quaternary Structure | Destroyed; complexes dissociated [2] | Preserved; complexes remain intact [2] [1] |

| Basis of Separation | Molecular mass only [21] [22] | Size, shape, and intrinsic net charge [2] [23] |

| Protein Recovery & Function | Proteins are denatured and functional activity is typically lost [23] | Proteins can often be recovered with functional/ enzymatic activity retained [2] [1] |

Experimental Methodologies: A Detailed Guide

The practical application of these techniques involves specific protocols tailored to their respective goals. Below are detailed methodologies for standard SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE, highlighting the key differences in sample preparation and running conditions.

Denaturing SDS-PAGE Protocol

This protocol is designed for complete protein denaturation and separation by mass. [1]

Sample Preparation:

- Denaturation: Mix the protein sample with an SDS-based sample loading buffer (e.g., LDS or Laemmli buffer). A common 4X buffer may contain 106 mM Tris HCl, 141 mM Tris Base, 2% LDS (lithium dodecyl sulfate), and 10% glycerol at pH 8.5. [8]

- Reduction: Include a reducing agent, such as 50-100 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) or 5% beta-mercaptoethanol, in the sample buffer to break disulfide bonds. [2]

- Heating: Heat the sample at 70-100°C for 10 minutes to ensure complete denaturation. [1] [8]

Gel Composition and Electrophoresis:

- Gel Casting: Use a polyacrylamide gel (e.g., 12% Bis-Tris) cast in a buffer containing 0.1% SDS. [8] The percentage of acrylamide should be chosen based on the target protein size (low percentage for large proteins, high percentage for small proteins). [1]

- Running Buffer: The running buffer typically contains 50 mM MOPS, 50 mM Tris Base, 0.1% SDS, and 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.7. [8] The SDS in the running buffer maintains the denatured state of the proteins during the run.

- Electrophoresis: Load the denatured samples and run at a constant voltage (e.g., 200V for 45-60 minutes) until the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel. [8]

Non-Denaturing PAGE Protocol

This protocol is designed to maintain proteins in their native, functional state. [1]

Sample Preparation:

- Native Conditions: Mix the protein sample with a non-denaturing sample buffer. This buffer is typically SDS-free and non-reducing. A example formulation is 50 mM BisTris, 50 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 0.001% Ponceau S, pH 7.2. [8] The sample is not heated. [1] [8]

Gel Composition and Electrophoresis:

- Gel Casting: Use a polyacrylamide gel cast in a buffer without SDS or other denaturants. [2]

- Running Buffer: The running buffer is also free of denaturing agents. A common system uses a cathode buffer (50 mM BisTris, 50 mM Tricine, 0.02% Coomassie G-250, pH 6.8) and an anode buffer (50 mM BisTris, 50 mM Tricine, pH 6.8). [8]

- Electrophoresis: Load the native samples and run at a constant voltage (e.g., 150V for 90-95 minutes). It is crucial to keep the apparatus cool to minimize denaturation during the run. [1] [8]

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key decision points and procedural steps in selecting and executing the appropriate PAGE method.

Advanced Techniques and Hybrid Approaches

The binary choice between fully native and fully denaturing conditions has been expanded by advanced and hybrid methodologies that offer nuanced insights into protein complexes.

Two-Dimensional (2D) PAGE

This high-resolution technique combines two separate electrophoresis principles to resolve complex protein mixtures. In the first dimension, proteins are separated by their native isoelectric point (pI) using isoelectric focusing (IEF). In the second dimension, the same proteins are separated by their molecular mass using standard SDS-PAGE. [1] This allows for the separation of thousands of proteins on a single gel, making it a powerful tool in proteomic research. [1]

Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE)

A hybrid approach has been developed to bridge the gap between the high resolution of SDS-PAGE and the functional preservation of native PAGE. In this method, the standard SDS-PAGE protocol is modified by removing SDS and EDTA from the sample buffer and omitting the heating step. The SDS in the running buffer is also significantly reduced (e.g., from 0.1% to 0.0375%). [8] This results in a technique that achieves excellent protein resolution while allowing many proteins to retain their enzymatic activity and bound metal cofactors. In one study, this method retained Zn²⁺ in proteomic samples much more effectively than standard SDS-PAGE. [8]

Combination EMSA and Denaturing PAGE

For studying protein-DNA interactions, a combined method uses a native gel for an Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) to isolate DNA-protein complexes, followed by a denaturing gel to identify the bound DNA fragments. After isolating shifted complexes from the native gel, the fragments are eluted and heated in formamide to denature them. They are then run on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel (e.g., 6% gel with 7 M urea) alongside reference markers to identify the specific DNA sequences involved in the binding. [24]

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for PAGE-Based Research

| Research Reagent | Function in Electrophoresis |

|---|---|

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Anionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge, enabling separation by mass. [2] [1] |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) / Beta-mercaptoethanol | Reducing agents that break disulfide bonds within and between polypeptide chains. [2] |

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Monomer and crosslinker that polymerize to form the porous gel matrix, which acts as a molecular sieve. [1] |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) & TEMED | Catalysts that initiate and accelerate the free-radical polymerization of acrylamide gels. [1] |

| Coomassie Blue G-250 | A dye used in native buffer systems (like BN-PAGE) to confer a negative charge on proteins and visualize migration. [8] |

| Poly (dI-dC) | A non-specific competitor DNA used in EMSA experiments to reduce background protein binding to the labeled probe. [24] |

The impact of electrophoretic conditions on quaternary structures is definitive and fundamental. Denaturing PAGE is an indispensable tool for analyzing the primary building blocks of proteins—their polypeptide subunits—by mass. In contrast, non-denaturing PAGE provides a window into the functional, higher-order architecture of proteins, allowing researchers to study complexes intact. The choice between them is not a matter of superiority but of strategic alignment with the research question, whether it is determining molecular weight or probing the intricate interactions that define a protein's biological activity. Advanced techniques like 2D-PAGE and NSDS-PAGE further empower researchers to dissect complex proteomes with increasing precision and functional insight.

Protocols and Applications: Choosing the Right Method for Your Research Goal

In the realm of protein analysis, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) stands as a fundamental technique for separating and characterizing proteins based on their physical properties. The dichotomy between denaturing and non-denaturing PAGE represents a fundamental methodological divide, each approach preserving or disrupting different aspects of protein structure to serve distinct analytical purposes. Denaturing PAGE, most commonly implemented as SDS-PAGE (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-PAGE), deliberately dismantles the higher-order structure of proteins to separate them based primarily on molecular weight [1] [2]. In contrast, native PAGE (non-denaturing PAGE) maintains proteins in their natural, folded conformation, enabling separation based on a combination of size, charge, and shape [4] [25]. The critical distinction between these techniques is established at the very beginning of the experimental process: sample preparation. Specifically, the composition of loading buffers and the application of heat during sample preparation determine whether proteins will be denatured into uniform linear chains or preserved in their native functional states, thereby dictating the type of information that can be extracted from the electrophoretic analysis [2] [13]. This technical guide examines the crucial differences in buffer composition and heating protocols that define these two electrophoretic approaches, providing researchers with the foundational knowledge needed to select and optimize preparation methods for their specific experimental objectives.

Core Principles: Denaturing Versus Non-Denaturing Electrophoresis

Denaturing PAGE (SDS-PAGE)

The primary objective of denaturing PAGE is to eliminate the influence of protein tertiary and quaternary structure, as well as inherent charge differences, thereby enabling separation based almost exclusively on molecular weight [1] [26]. This is achieved through a sample preparation regime that employs powerful denaturing and reducing agents. Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), an anionic detergent, plays the central role by binding to hydrophobic regions of proteins at a relatively constant ratio of approximately 1.4 g SDS per 1 g of polypeptide [1]. This SDS coating confers a uniform negative charge to all proteins, effectively masking their intrinsic charge properties [2]. The process is typically augmented by heating samples to 70-100°C for several minutes, which further disrupts hydrogen bonds that stabilize secondary and tertiary structures [1] [13].

A critical component of denaturing sample buffers is the inclusion of reducing agents such as dithiothreitol (DTT) or β-mercaptoethanol, which cleave disulfide bonds that covalently stabilize tertiary and quaternary structures [25] [13]. The combined action of SDS, heat, and reducing agents transforms complex three-dimensional protein structures into linear, rod-like polypeptides with equivalent charge-to-mass ratios [2]. Consequently, during electrophoresis, these denatured proteins migrate through the polyacrylamide gel matrix at rates inversely proportional to the logarithm of their molecular weights, with smaller polypeptides moving faster than larger ones [1] [25]. This predictable relationship enables accurate molecular weight estimation when samples are run alongside standardized protein markers.

Non-Denaturing PAGE (Native PAGE)

In direct contrast to the denaturing approach, non-denaturing PAGE aims to preserve the native conformation, biological activity, and multimetric state of proteins throughout the separation process [2] [25]. Sample preparation for native PAGE deliberately omits SDS and reducing agents, and avoids heating, thereby maintaining the intricate structural features that define protein function [5] [13]. Without SDS to impart uniform charge, proteins in native PAGE migrate based on their intrinsic charge, size, and three-dimensional shape [1]. The net charge of a protein in native PAGE depends on the pH of the running buffer relative to the protein's isoelectric point (pI), with proteins carrying a net negative charge in alkaline running buffers migrating toward the anode [1].

The preservation of native structure means that multimeric proteins maintain their subunit interactions, allowing researchers to study quaternary structure and protein complexes [2]. Additionally, many proteins retain enzymatic activity following native PAGE separation, enabling functional assays directly from gel slices [1] [25]. This preservation of structure and function comes at the cost of resolution and straightforward molecular weight determination, as migration depends on multiple factors beyond mass alone [26] [8]. The frictional force experienced by proteins during electrophoresis through the gel matrix is influenced by both size and shape, resulting in complex migration patterns that reflect the overall bulk or cross-sectional area of the native macromolecule rather than simply the mass of its polypeptide chains [4] [5].

Critical Differences in Sample Preparation

Buffer Composition

The composition of sample buffers represents the most fundamental distinction between denaturing and non-denaturing PAGE methodologies. These buffers contain specific reagents that determine whether proteins will maintain their native structure or be unfolded into linear polypeptides.

Table 1: Key Components of Denaturing vs. Non-Denaturing Sample Buffers

| Component | Denaturing (SDS-PAGE) Buffer | Non-Denaturing (Native) Buffer | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detergent | SDS (0.5-2%) [1] [13] | Absent [25] | Denatures proteins; confers uniform negative charge |

| Reducing Agent | DTT or β-mercaptoethanol (50-100 mM) [25] [13] | Absent [25] | Cleaves disulfide bonds |

| Heating Step | 70-100°C for 3-10 minutes [1] [13] | Omitted [25] | Disrupts hydrogen bonds; completes denaturation |

| Buffer Base | Tris-HCl (pH 6.8) [13] | Tris-based (varies) [13] | Maintains pH environment |

| Glycerol | 5-10% [8] | 5-10% [8] | Increases density for well loading |

| Tracking Dye | Bromophenol blue [13] | Bromophenol blue or similar [8] | Visualizes migration front |

In denaturing buffers, SDS serves as the primary denaturant by binding to polypeptide chains in a constant weight ratio, effectively overwhelming the protein's intrinsic charge with negative sulfate groups [1]. The reducing agents work synergistically with SDS by breaking covalent disulfide linkages that might otherwise maintain elements of tertiary structure [13]. This combination ensures complete unfolding of proteins into linear chains that can be separated strictly by molecular weight.

Non-denaturing buffers lack these disruptive components, instead focusing on maintaining physiological conditions that preserve protein structure [25]. The buffer typically includes glycerol to add density for sample loading and a tracking dye to monitor electrophoretic progress, but deliberately excludes detergents and reducing compounds [8]. Some specialized native buffers may include cofactors, substrates, or allosteric effectors specifically designed to stabilize certain protein conformations during separation.

Heating Protocols