Native-PAGE: A Comprehensive Guide to Analyzing Proteins in Their Natural State

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (Native-PAGE), a pivotal technique for analyzing proteins and protein complexes in their biologically active, non-denatured states.

Native-PAGE: A Comprehensive Guide to Analyzing Proteins in Their Natural State

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (Native-PAGE), a pivotal technique for analyzing proteins and protein complexes in their biologically active, non-denatured states. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content spans from foundational principles and practical methodologies to advanced troubleshooting and validation strategies. It explores the critical role of Native-PAGE in functional proteomics, covering the analysis of oligomeric states, protein-protein interactions, and enzymatic activity. The article also highlights the synergy between Native-PAGE and cutting-edge techniques like native mass spectrometry, positioning it as an indispensable tool for advancing integrative structural biology, disease modeling, and therapeutic development.

Understanding Native-PAGE: Principles and Advantages for Functional Protein Analysis

Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (Native-PAGE) is a fundamental technique in protein science used to separate proteins in their native, folded state. Unlike denaturing methods such as SDS-PAGE, Native-PAGE preserves protein complexes, multi-subunit structures, and biological activity, enabling researchers to analyze proteins as they exist in their natural cellular environment [1]. This technique, pioneered by Ornstein and Davis, separates proteins based on the combined effects of their intrinsic charge, molecular size, and three-dimensional conformation [1] [2]. For researchers and drug development professionals, maintaining native protein structure is crucial for studying functional interactions, enzymatic activity, protein-protein interactions, and complex assembly—all essential aspects of structural biology and therapeutic development.

The core principle of Native-PAGE hinges on the fact that under non-denaturing conditions, a protein's migration through a polyacrylamide gel matrix depends on its net negative charge (driving force), molecular size and shape (frictional forces), and the pore size of the gel (sieving effect) [1]. This multi-parameter separation provides a powerful tool for analyzing protein samples in their natural state, making it indispensable for native state research where preserving biological function is paramount.

Core Principles of Separation

The separation mechanism in Native-PAGE operates through a sophisticated interplay of three fundamental protein properties: net charge, size, and conformation. Understanding how these factors collectively influence electrophoretic mobility is key to effectively applying this technique.

The Tripartite Separation Mechanism

Influence of Net Charge: In the absence of denaturing agents like SDS, proteins retain their inherent charge determined by their amino acid composition and post-translational modifications. When an electric field is applied, the net negative charge of the protein at the buffer system's pH creates the electromotive force propelling the protein toward the positive electrode (anode) [1]. Proteins with higher net negative charge experience greater electrophoretic pull and migrate faster through the gel matrix, all other factors being equal.

Influence of Size and Shape: While charge provides the driving force, protein migration is resisted by frictional drag determined by the protein's effective hydrodynamic volume. Larger proteins experience greater resistance than smaller ones. Critically, a protein's three-dimensional shape significantly affects this frictional drag—compact globular proteins migrate faster than elongated fibrous proteins of identical molecular weight [1]. This shape-dependent migration is a distinctive feature separating Native-PAGE from purely size-based techniques like SDS-PAGE.

Gel Matrix as a Molecular Sieve: The polyacrylamide gel creates a porous network through which proteins must travel. The gel pore size, determined by the acrylamide concentration, selectively retards proteins based on their hydrodynamic radius [2]. Higher percentage gels with smaller pores provide better resolution for lower molecular weight proteins, while lower percentage gels with larger pores are more suitable for high molecular weight complexes.

The following diagram illustrates how these three factors collectively determine a protein's final position in a Native-PAGE gel:

Comparative Analysis: Native-PAGE vs. SDS-PAGE

Understanding the distinctive features of Native-PAGE becomes clearer when contrasted with its denaturing counterpart, SDS-PAGE. The following table summarizes the key operational and outcome differences between these two fundamental electrophoretic techniques:

| Criteria | Native-PAGE | SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Size, charge, and shape [1] | Molecular weight only [1] |

| Gel Conditions | Non-denaturing [1] | Denaturing [1] |

| SDS Presence | Absent [1] | Present [1] |

| Reducing Agents | Not used [1] | DTT or BME used [1] |

| Sample Preparation | Not heated [1] | Heated [1] |

| Protein State | Native, folded conformation [1] | Denatured, linearized [1] |

| Protein Function | Retained [1] | Lost [1] |

| Protein Recovery | Possible post-separation [1] | Not possible [1] |

| Temperature | Typically run at 4°C [1] | Typically run at room temperature [1] |

| Primary Applications | Study structure, composition, and function; protein purification [1] | Determine molecular weight; check protein expression [1] |

Table 1: Key differences between Native-PAGE and SDS-PAGE separation techniques [1].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

This section provides a comprehensive, step-by-step protocol for performing Native-PAGE, optimized for preserving protein structure and function throughout the process.

Materials and Reagent Solutions

The success of Native-PAGE depends on using appropriate, high-quality reagents that maintain non-denaturing conditions.

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples & Concentrations | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Gel Matrix Components | Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide (e.g., 29:1, 37.5:1 ratios) | Forms the porous polyacrylamide network for molecular sieving [2]. |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | Free radical initiator for gel polymerization [2]. | |

| TEMED (Tetramethylethylenediamine) | Catalyst that accelerates acrylamide polymerization [2]. | |

| Buffer Systems | Tris-HCl (pH ~8.8 for separating gel) | Maintains pH during electrophoresis; no SDS [1] [2]. |

| Tris-Glycine (or Tris-Borate) as running buffer | Provides conducting ions and maintains stable pH during run [2]. | |

| Sample Preparation | Non-denaturing sample buffer (e.g., with glycerol, tracking dye) | Provides density for well loading; contains no SDS or reducing agents [1]. |

| Native Protein Ladder/Marker | Mixture of colored native proteins with known molecular weights and charges. | |

| Visualization | Coomassie Brilliant Blue, Silver Stain | General protein stains for detection post-electrophoresis [2]. |

| Activity stains (zymography) | Detects specific enzymatic activity in situ (e.g., for native enzymes). |

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for Native-PAGE experiments.

Step-by-Step Methodological Workflow

The following detailed workflow ensures reproducible results while maintaining proteins in their native state:

Gel Preparation (Non-Denaturing)

- Separating Gel: Prepare the separating gel solution by mixing appropriate volumes of acrylamide/bis-acrylamide stock (concentration chosen based on target protein size), non-denaturing Tris-HCl buffer (e.g., 1.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.8), and deionized water. Avoid SDS and heating. Add catalysts TEMED and APS last, mix thoroughly, and pipette into the gel cassette. Carefully layer a thin level of water-saturated butanol or isopropanol on top to create a flat interface and exclude oxygen. Allow complete polymerization (typically 20-30 minutes) [2].

- Stacking Gel: Once the separating gel has polymerized, pour off the butanol layer and rinse with water. Prepare the stacking gel solution with a lower acrylamide concentration (e.g., 4-5%) and a different pH Tris buffer (e.g., 0.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8). Add APS and TEMED, pour over the separating gel, and immediately insert a clean comb. Allow to polymerize fully (15-20 minutes) [2].

Sample Preparation (Critical Step)

- Buffer Compatibility: Dialyze or dilute protein samples into a non-denaturing, low-ionic-strength buffer compatible with the electrophoresis buffer (e.g., same Tris-Glycine system) to prevent precipitation and band distortion during the run.

- Mixing: Gently mix the prepared protein sample with an equal volume of 2X native sample buffer (containing glycerol, tracking dye like Bromophenol Blue, and no SDS/reducing agents). Do not boil the sample. Keep samples on ice until loading [1].

Electrophoresis Setup and Execution

- Assembly: Place the polymerized gel into the electrophoresis chamber. Fill the inner (upper) and outer (lower) chambers with the chosen non-denaturing running buffer (e.g., Tris-Glycine). Ensure no leaks and that wells are fully submerged.

- Loading: Carefully remove the comb. Using a microsyringe, load equal volumes (10-20 µL) of prepared protein samples and native molecular weight markers into individual wells.

- Running Conditions: Connect the power supply, ensuring correct polarity (proteins migrate toward the anode/+). Run the gel at constant voltage or current. Crucially, perform the run in a cold room (4°C) or using a cooling apparatus to maintain low temperature and prevent protein denaturation from Joule heating [1]. Continue electrophoresis until the tracking dye front reaches the bottom of the gel.

Post-Electrophoresis Processing

- Protein Visualization: After the run, carefully disassemble the cassette and remove the gel. Stain the gel using a standard Coomassie Brilliant Blue protocol or a more sensitive silver stain to visualize protein bands [2]. For functional analysis, alternative detection methods like activity staining (zymography) or Western blotting (with mild transfer conditions) can be employed.

- Protein Recovery (Elution): If functional protein recovery is required, corresponding unstained gel bands can be excised, and native protein can be passively eliated or electroeluted into an appropriate buffer for downstream applications [1].

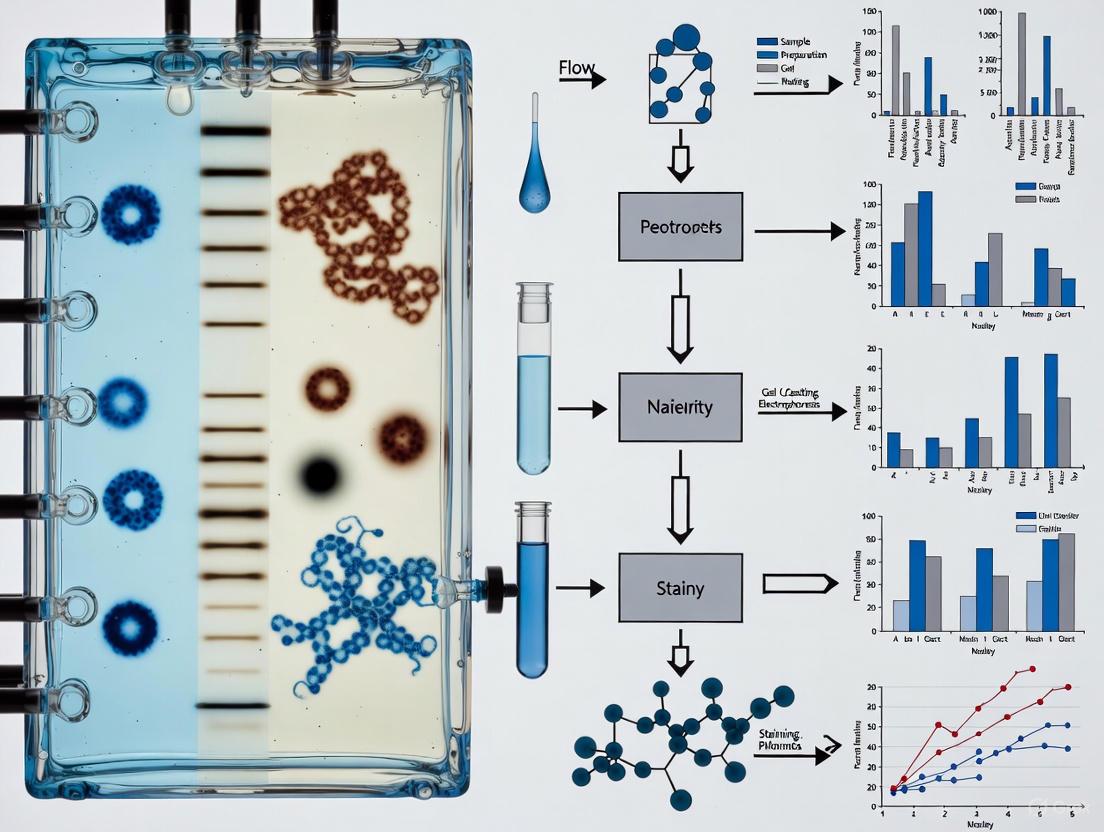

The complete experimental workflow, from gel casting to analysis, is visualized below:

Advanced Techniques and Applications in Native State Research

Building upon standard Native-PAGE, several advanced variants have been developed to address specific research questions in protein science and drug development.

Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) and Clear Native PAGE (CN-PAGE)

Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE): This powerful variant utilizes Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250, which binds non-covalently to proteins, imparting a uniform negative charge. This allows separation based primarily on size while maintaining proteins in their native state. BN-PAGE is particularly invaluable for resolving native membrane protein complexes and determining the oligomeric states and molecular masses of intricate multi-subunit assemblies [1].

Clear Native PAGE (CN-PAGE): In this technique, proteins are separated based on their intrinsic charge and size in a gradient gel without using Coomassie dye. CN-PAGE is suitable for analyzing labile protein complexes that might be disrupted by the dye binding in BN-PAGE, providing a milder alternative for studying delicate supra-molecular structures [1].

Key Research Applications in Drug Development and Structural Biology

Native-PAGE serves as a critical tool for addressing fundamental and applied research questions:

- Protein Complex and Oligomeric State Analysis: Determining the subunit composition, stoichiometry, and quaternary structure of protein complexes is essential for understanding biological function and for the development of biologics [1]. Shifts in band mobility can indicate assembly or disassembly.

- Protein-Protein Interaction Studies: Native-PAGE can monitor the formation of hetero-protein complexes, as the formation of a larger complex results in a distinct, slower-migrating band compared to the individual components. This is useful for studying receptor-ligand interactions or mapping interaction domains.

- Enzymatic Activity and Functional Characterization: Since biological activity is preserved, specific in-gel activity stains (zymography) can be used to detect enzymes like proteases, nucleases, or dehydrogenases directly after electrophoresis. This allows for the correlation of specific bands with function [1].

- Therapeutic Protein and Antibody Characterization: Native-PAGE is used in the quality control of biopharmaceuticals like monoclonal antibodies and recombinant proteins to assess aggregation, fragmentation, and overall charge heterogeneity under non-denaturing conditions, which can impact efficacy and stability.

- Protein Purification Monitoring: As a rapid analytical method, Native-PAGE is routinely used to assess the purity and native integrity of proteins during various stages of purification, ensuring that the final product is both pure and functionally competent [1].

Native-PAGE remains an indispensable technique in the molecular biologist's toolkit, offering a unique capability to analyze proteins in their functional, folded state. Its core principle of multi-parameter separation—based on intrinsic charge, size, and conformation—provides information that is complementary and often critical beyond what can be learned from denaturing methods. For researchers focused on native state research, particularly in structural biology, complex analysis, and drug development, mastering Native-PAGE and its advanced variants like BN-PAGE is fundamental. The protocols and principles outlined herein provide a foundation for the rigorous application of this technique, enabling the study of protein function, interaction, and architecture in a native context, thereby driving discovery and innovation in protein science.

In the study of proteins, maintaining the intricate architecture and functional state of these biomolecules is paramount for understanding their true physiological roles. While denaturing gel electrophoresis techniques like SDS-PAGE provide information on subunit molecular weight, they dismantle the very structures researchers seek to understand. Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Native PAGE) emerges as a critical analytical tool that enables the separation of protein mixtures under non-denaturing conditions, thereby preserving their native conformation, physiological protein-protein interactions, and biological activity [3]. This capability makes Native PAGE indispensable for researchers and drug development professionals requiring accurate analysis of protein complexes, oligomeric states, and functional characteristics in areas ranging from mitochondrial research to therapeutic antibody development.

Principles of Native PAGE Technology

Fundamental Separation Mechanism

Unlike denaturing electrophoresis methods that rely solely on molecular mass, Native PAGE separates proteins based on a combination of their intrinsic charge, size, and three-dimensional shape [4]. In this technique, proteins migrate through a polyacrylamide matrix under an applied electric field, with their movement governed by their net negative charge in alkaline running buffers and the frictional forces imposed by the gel matrix [4]. The higher the negative charge density (more charges per molecule mass), the faster a protein migrates, while larger proteins and complexes experience greater frictional resistance [4]. This dual mechanism allows for the separation of proteins in their native state, maintaining their quaternary structure and enzymatic activity [4].

Key Variants and Their Applications

Several variants of Native PAGE have been developed to address specific research needs, with Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) and Clear Native PAGE (CN-PAGE) being the most prominent [3] [5].

Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) utilizes the anionic dye Coomassie Blue G-250, which binds nonspecifically to hydrophobic regions on protein surfaces [6] [4]. This binding induces a charge shift that ensures all proteins, including those with basic isoelectric points (pI) and membrane proteins, migrate toward the anode [5] [4]. The dye also helps prevent aggregation of membrane proteins and those with significant surface-exposed hydrophobic areas by converting these sites to negatively charged sites [4]. BN-PAGE represents the most robust variant and is particularly valuable for analyzing membrane protein complexes and determining native protein masses and oligomeric states [6] [5].

Clear Native PAGE (CN-PAGE) is performed without Coomassie dye, with proteins migrating according to their intrinsic charge-to-mass ratio [3] [5]. This method is considered to show the "true" mobility of enzymes and protein complexes but has limitations for basic proteins, which may be lost due to cathodal migration [5]. A modified version, high-resolution clear native electrophoresis (hrCNE), uses mixed anionic micelles in the cathode buffer to facilitate separation of membrane proteins while maintaining the absence of dye [5].

Table: Comparison of Native PAGE Variants

| Method | Charge Modifier | Separation Basis | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BN-PAGE | Coomassie Blue G-250 | Size, shape, and charge after dye binding | Resolves basic proteins and membrane complexes; prevents aggregation | Dye may interfere with some downstream applications |

| CN-PAGE | None | Intrinsic charge-to-mass ratio and size | Shows "true" protein mobility; suitable for fluorescently labeled proteins | Limited to acidic proteins; basic proteins may be lost |

| hrCNE | Mixed anionic micelles | Size and charge with minimal perturbation | Good for in-gel activity assays and fluorescent proteins | Less robust than BN-PAGE for some membrane proteins |

Practical Implementation: System Selection and Setup

Choosing the Appropriate Gel Chemistry

Selecting the correct gel system is crucial for successful native electrophoresis experiments. Commercial systems offer different operating parameters optimized for various protein types and research goals [4].

Table: Native PAGE Gel Chemistry Systems

| Gel System | Operating pH Range | Optimal Protein Size Range | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tris-Glycine | 8.3-9.5 | 20-500 kDa | Maintaining native net charge; studying smaller proteins |

| Tris-Acetate | 7.2-8.5 | >150 kDa | Larger molecular weight proteins; maintaining native charge |

| Bis-Tris (with G-250) | ~7.5 | 10 kDa - 10 MDa | Membrane proteins; hydrophobic proteins; molecular weight estimation |

The Tris-Glycine system operates at a higher pH (8.3-9.5), making it suitable for proteins that maintain stability under alkaline conditions [4]. The Tris-Acetate system provides better resolution for larger proteins (>150 kDa) at a slightly lower pH range (7.2-8.5) [4]. For the most challenging applications involving membrane proteins or when seeking to separate proteins by molecular weight regardless of isoelectric point, the NativePAGE Bis-Tris system with Coomassie G-250 dye offers optimal performance at near-neutral pH [4].

Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful Native PAGE requires specific reagents and materials tailored to preserve native protein structures:

- Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide Solutions: Form the porous gel matrix; different concentrations (typically 4-16% gradient or 6-15% single percentage) provide optimal separation ranges for various protein sizes [7] [4].

- Polymerization Initiators: Ammonium persulfate (APS) and TEMED catalyze the free-radical polymerization of acrylamide [3].

- Native Sample Buffer: Non-denaturing buffer containing glycerol for density and tracking dye (e.g., bromophenol blue) without SDS or reducing agents [7].

- Running Buffers: Tris-glycine (pH ~8.3) for traditional systems; Bis-Tris with Coomassie G-250 additive for BN-PAGE systems [7] [4].

- Detergents: Mild non-ionic detergents like digitonin, dodecylmaltoside (DDM), or Triton X-100 for solubilizing membrane proteins while preserving complexes [5] [8].

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Native PAGE

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Gel Matrix Components | Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide (30%/0.8%) | Forms porous separation matrix with controlled pore sizes |

| Polymerization Catalysts | APS, TEMED | Initiates and catalyzes acrylamide polymerization |

| Buffer Systems | Tris-glycine, Bis-Tris, Imidazole/HCl | Maintains pH stability during electrophoresis |

| Charge Modifiers | Coomassie Blue G-250 | Imparts negative charge to proteins for consistent migration |

| Solubilization Agents | Digitonin, Dodecylmaltoside, Triton X-100 | Solubilizes membrane proteins while preserving complexes |

| Stabilizing Additives | Glycerol, 6-Aminocaproic acid, EDTA | Enhances sample density and inhibits proteolysis |

Advanced Applications and Protocols

Analysis of Membrane Protein Complexes

Blue Native PAGE has revolutionized the study of membrane protein complexes, particularly in mitochondrial and photosynthetic systems. The technique enables one-step isolation of protein complexes from biological membranes and total cell homogenates while maintaining enzymatic activity [6]. For mitochondrial complexes, solubilization of heart tissue (bovine, chicken, rat, or mouse) with appropriate detergents provides ideal high molecular weight markers for mass calibration [5]. The protocol involves:

- Homogenization: Carefully mince and homogenize heart tissue (e.g., 1 g tissue in 9 ml homogenization buffer) using a motor-driven Potter-Elvehjem homogenizer [5].

- Solubilization: Suspend pelleted homogenate in low salt buffer and solubilize with dodecylmaltoside (10%), Triton X-100 (10%), or digitonin (20%) [5].

- Sample Preparation: Add Coomassie dye to achieve a 1:8 Coomassie dye/detergent ratio for BN-PAGE [5].

- Electrophoresis: Perform using 3.5-12% or 3.5-16% linear acrylamide gradient gels [5].

This approach has been instrumental in identifying respiratory chain supercomplexes and determining the oligomeric states of ATP synthase, advancing our understanding of oxidative phosphorylation [6].

Multi-Dimensional Separation Techniques

For comprehensive analysis of complex protein assemblies, two-dimensional (2D) native electrophoresis provides superior resolution. The protocol for separation of thylakoid membrane complexes exemplifies this powerful approach [8]:

- First Dimension: Separate digitonin-solubilized protein supercomplexes using BN-PAGE [8].

- Gel Lane Excison: Carefully excise the lane containing separated complexes.

- Second Dimension Solubilization: Treat the gel lane with stronger detergent (β-D-maltoside) to dissociate supercomplexes into subcomplexes [8].

- Second Dimension Electrophoresis: Perform orthogonal BN-PAGE to separate the subcomplexes [8].

This 2D BN/BN-PAGE approach reveals the hierarchical composition of labile protein supercomplexes and their subunit arrangements, providing insights into the modular organization of photosynthetic machinery [8]. For even more detailed analysis, a three-dimensional approach incorporating isoelectric focusing or Tricine-SDS-PAGE can further separate individual subunits [6].

Activity Staining and Functional Assays

A significant advantage of Native PAGE is the retention of enzymatic activity post-separation, enabling direct functional analysis within the gel matrix. After electrophoresis, gels can be incubated with specific substrates to detect active enzymes [3]. For example, hydrogen peroxide and diaminobenzidine can detect peroxidases, while esterase activity can be visualized with α-naphthyl acetate and Fast Blue RR salt [3]. This approach allows researchers to directly correlate protein bands with biological function, confirming the preservation of native structure throughout the separation process.

Emerging Innovations: Native SDS-PAGE

Recent methodological advances have led to the development of Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE), which bridges the gap between high-resolution separation and native state preservation. This technique modifies standard SDS-PAGE conditions by eliminating SDS and EDTA from the sample buffer, omitting the heating step, and reducing SDS concentration in the running buffer from 0.1% to 0.0375% [9]. Remarkably, these modifications result in retention of 98% of bound Zn²⁺ in proteomic samples compared to only 26% with standard SDS-PAGE [9]. Furthermore, seven of nine model enzymes, including four Zn²⁺ proteins, retained activity after NSDS-PAGE separation [9]. This innovation provides researchers with a valuable tool for high-resolution separation of metalloproteins and other metal-binding proteins while maintaining their functional state.

Native PAGE technologies provide an indispensable platform for analyzing proteins in their natural state, offering critical advantages for understanding protein complex organization, oligomeric states, and structure-function relationships. From fundamental research on mitochondrial respiratory chains and photosynthetic complexes to drug development requiring accurate characterization of therapeutic proteins, these methods enable researchers to preserve the intricate structural and functional attributes that define protein activity in physiological contexts. As innovations like NSDS-PAGE and improved solubilization strategies continue to emerge, the capabilities for native protein analysis will further expand, driving discoveries in both basic science and applied biotechnology.

Electrophoresis is a foundational laboratory technique in which charged protein molecules are transported through a solvent by an electrical field, serving as a simple, rapid, and sensitive analytical tool for separating proteins and nucleic acids [10]. The mobility of a molecule through an electric field depends on factors including field strength, net charge, molecular size and shape, ionic strength, and the properties of the matrix through which the molecule migrates [10]. This application note details three core electrophoretic methods—Native-PAGE, Denaturing SDS-PAGE, and Isoelectric Focusing—framed within the context of a broader thesis on utilizing native electrophoresis for analyzing proteins in their natural state. These techniques provide complementary information for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to understand protein structure, function, and interaction.

Fundamental Principles and Comparative Analysis

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

SDS-PAGE separates proteins primarily by molecular mass under denaturing conditions [10]. The ionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) denatures proteins by wrapping around the polypeptide backbone, and when combined with heating and reducing agents like dithiothreitol (DTT), it cleaves disulfide bonds to fully dissociate proteins into their subunits [10] [11]. Under these conditions, most polypeptides bind SDS in a constant weight ratio (approximately 1.4 g SDS per 1 g of polypeptide), rendering the intrinsic charges of the polypeptide insignificant compared to the negative charges provided by the bound detergent [10]. The resulting SDS-polypeptide complexes have essentially identical negative charge and similar shapes, allowing them to migrate through the gel strictly according to polypeptide size with minimal effect from compositional differences [10] [11]. The simplicity, speed, and minimal protein requirements of this method have made SDS-PAGE the most widely used technique for molecular mass determination [10].

Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (Native-PAGE)

Native-PAGE separates protein mixtures under non-denaturing conditions, preserving their natural conformation, charge, and biological activity [3]. In this method, proteins are separated according to their intrinsic net charge, size, and three-dimensional shape [10] [3]. Electrophoretic migration occurs because most proteins carry a net negative charge in alkaline running buffers, with migration rate proportional to their charge density [10]. The frictional force of the gel matrix simultaneously creates a sieving effect that regulates protein movement according to size and shape [10] [12]. Because no denaturants are used, subunit interactions within multimeric proteins are generally retained, allowing researchers to gain information about quaternary structure and enzymatic activity [10] [3]. This preservation of native properties makes Native-PAGE particularly valuable for studying protein complexes, oligomeric states, and functional forms [3].

Isoelectric Focusing (IEF)

Isoelectric Focusing separates proteins based on their isoelectric point (pI), the specific pH at which a protein carries no net electrical charge [11]. This technique utilizes a gel containing a stabilized pH gradient through which an electric current passes [11]. When a protein is placed in this gradient, it initially moves toward the electrode with opposite charge [10]. As it migrates, the surrounding pH changes, altering the protein's charge until it reaches the pH position where its net charge becomes zero—its isoelectric point [11]. At this position, the protein stops migrating and focuses into a sharp band [11]. Immobilized pH gradients (IPGs) are typically used for IEF because they provide fixed pH gradients that remain stable even at high voltages for extended periods [11]. IEF commonly serves as the first dimension in two-dimensional electrophoresis, where proteins are first separated by pI and then by mass using SDS-PAGE in the second dimension [10].

Technical Comparison of Methodologies

Table 1: Comparative analysis of key electrophoretic techniques

| Parameter | SDS-PAGE | Native-PAGE | Isoelectric Focusing (IEF) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Molecular mass | Size, charge, and shape | Isoelectric point (pI) |

| Gel Condition | Denaturing | Non-denaturing | Denaturing or native |

| Sample Preparation | Heating with SDS and reducing agents | No heating, no denaturants | Solubilized in appropriate buffer |

| Protein Charge | Uniformly negative by SDS binding | Native charge (positive or negative) | Becomes neutral at pI |

| Protein State | Denatured and linearized | Native, folded conformation | Depends on conditions |

| Functional Retention | Function destroyed | Function retained | May be retained in native IEF |

| Typical Applications | Molecular weight determination, purity assessment | Protein complexes, enzymatic activity, oligomeric states | pI determination, 1st dimension in 2D-PAGE |

| Buffer System | Discontinuous with SDS | Discontinuous without SDS | pH gradient with ampholytes |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

SDS-PAGE Protocol

Gel Preparation: Traditional discontinuous SDS-PAGE gels consist of a stacking gel and a resolving gel. A representative recipe for a 10% Tris-glycine mini gel for SDS-PAGE includes 7.5 mL 40% acrylamide solution, 3.9 mL 1% bisacrylamide solution, 7.5 mL 1.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.7), water to 30 mL total volume, 0.3 mL 10% APS, 0.3 mL 10% SDS, and 0.03 mL TEMED [10]. The ratio of bisacrylamide to acrylamide and total concentration of both components determines the pore size and rigidity of the final gel matrix, which affects the range of protein sizes that can be resolved [10].

Sample Preparation: Protein samples (5-25 μg) are mixed with loading buffer containing SDS and reducing agent (e.g., DTT or β-mercaptoethanol), then heated at 70-100°C for 10 minutes to denature proteins [10] [9]. The denatured samples are loaded into wells at the top of the gel alongside molecular weight markers.

Electrophoresis Conditions: Prepared gel cassettes are mounted vertically into an apparatus with top and bottom edges in contact with buffer chambers containing cathode and anode, respectively [10]. Electrophoresis is typically performed at room temperature for 20-45 minutes using a constant voltage (e.g., 200V) in running buffer containing SDS until the dye front reaches the gel bottom [10] [9].

Native-PAGE Protocol

Gel Preparation: Native gels are prepared similarly to SDS-PAGE gels but without SDS or other denaturants. The acrylamide percentage is selected based on the target protein size—lower percentages (5-7%) for high molecular weight complexes and higher percentages (10-15%) for smaller proteins [3]. Gradient gels (e.g., 4-20%) can be cast for separating complex mixtures with broad molecular weight ranges [3].

Sample Preparation: Protein samples are prepared in non-denaturing buffer that preserves physiological pH and ionic strength, with no SDS, urea, or reducing agents [3]. Samples are clarified by centrifugation to remove particulate matter, and protein concentration is adjusted to approximately 0.1-2 μg/μL depending on the detection method [3]. A non-denaturing loading dye containing tracking dye (like bromophenol blue) and glycerol is added to provide density [3].

Electrophoresis Conditions: The gel is run at a constant voltage or current (typically 50-150V depending on gel size) with temperature control (often at 4°C) to prevent overheating and denaturation [3] [1]. The run is stopped when satisfactory separation is achieved, typically when the tracking dye reaches the gel bottom [3].

Specialized Native-PAGE Variants

Blue Native-PAGE (BN-PAGE): This technique uses Coomassie Blue G-250 dye, which binds to protein surfaces and creates a charge shift, enabling the separation of large protein complexes (100 kDa to 10 MDa) in their native conformation [13]. BN-PAGE is particularly useful for characterizing respiratory supercomplexes, assessing stoichiometric amounts of native complexes, and identifying protein-protein interactions [13]. Mild detergents such as digitonin or dodecylmaltoside are typically used to maintain complexes [13].

Clear Native-PAGE (CN-PAGE): This method is performed without Coomassie dye, with proteins migrating according to their intrinsic charge-to-mass ratio [14]. CN-PAGE offers advantages when Coomassie dye interferes with downstream techniques like catalytic activity determination [14]. It is milder than BN-PAGE and can retain labile supramolecular assemblies of membrane protein complexes that dissociate under BN-PAGE conditions [14].

High-Resolution Clear Native PAGE (hrCN-PAGE): A modified CN approach using optimized buffers and gradient gels to achieve better separation of membrane complexes, often with increased ampholyte content for more distinct bands [3].

Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE): A hybrid approach that reduces SDS concentration in running buffer from 0.1% to 0.0375% and eliminates EDTA and heating steps [9]. This method retains Zn²⁺ bound in proteomic samples (increasing from 26% to 98% compared to standard SDS-PAGE) and preserves enzymatic activity in most model enzymes while maintaining high resolution [9].

Isoelectric Focusing Protocol

Sample Preparation: Protein samples are solubilized in appropriate rehydration/sample buffer compatible with IEF [11]. For optimal results, samples should be clarified to remove particulate matter that might disrupt the pH gradient.

IEF Procedure: IPG strips loaded with protein are rehydrated in rehydration/sample buffer, either actively (with application of low voltage) or passively [11]. Active rehydration is particularly beneficial for loading larger proteins [11]. IEF is then performed at high voltages for extended periods until proteins have migrated to their isoelectric points. After electrophoresis, focused strips can be frozen for storage or immediately used for second-dimension analysis [11].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Essential reagents and materials for electrophoretic separations

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms cross-linked polymer network for sieving matrix | Ratio determines pore size; typically 29:1 or 37:1 acrylamide:bis |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | Initiates polymerization as free radical source | Fresh preparation recommended for optimal polymerization |

| TEMED | Catalyzes polymerization by promoting free radical production | Amount affects polymerization rate; excess can cause brittle gels |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge | Critical for mass-based separation in SDS-PAGE; omitted in Native-PAGE |

| Tris-based Buffers | Maintain pH during electrophoresis | Different pH for stacking (∼6.8) and resolving (∼8.8) gels in discontinuous systems |

| Coomassie G-250 Dye | Imparts charge shift in BN-PAGE; staining | Binds non-covalently to proteins without significant denaturation |

| Reducing Agents (DTT, β-ME) | Breaks disulfide bonds | Essential for complete denaturation in SDS-PAGE; omitted in Native-PAGE |

| Molecular Weight Markers | Reference for size estimation | Pre-stained or unstained options available for different applications |

| IPG Strips | Establish immobilized pH gradients for IEF | Available in various pH ranges and lengths to suit different applications |

| Mild Detergents (Digitonin, DDM) | Solubilize membrane proteins while preserving complexes | Critical for Native-PAGE of membrane protein complexes |

Workflow Integration and Application Scenarios

The selection and integration of appropriate electrophoretic techniques depends on specific research goals. For routine molecular weight determination and purity assessment, SDS-PAGE remains the standard approach [10] [1]. When studying native protein structure, complexes, or function, Native-PAGE variants are essential [3]. For comprehensive proteomic analysis, 2D-PAGE combining IEF and SDS-PAGE provides the highest resolution [10] [15].

Diagram 1: Decision workflow for selecting electrophoretic techniques based on research goals

Concluding Perspectives

Native-PAGE, SDS-PAGE, and IEF represent complementary approaches for protein separation, each with distinct advantages and applications. SDS-PAGE provides excellent resolution for molecular weight determination but destroys native protein structure and function [10] [1]. Native-PAGE preserves native properties, enabling functional studies and analysis of protein complexes, though with potentially more complex interpretation due to multiple factors influencing migration [3] [12]. IEF offers unique separation based on isoelectric point, making it invaluable for proteomic applications, particularly as the first dimension in 2D-PAGE [10] [11]. Recent methodological advances, including Native SDS-PAGE, bridge the gap between these approaches by offering high resolution with retention of some native properties [9]. For researchers focused on analyzing proteins in their natural state, Native-PAGE and its variants provide indispensable tools for elucidating protein structure, function, and interactions in drug development and basic research.

For researchers dedicated to the study of proteins in their natural, functional state, selecting the appropriate analytical separation method is paramount. While denaturing sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) is a ubiquitous workhorse for determining molecular weight, it deliberately destroys native structure, stripping proteins of essential cofactors and obliterating enzymatic activity [9]. In contrast, Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (Native-PAGE) is a powerful technique designed to separate protein mixtures based on their intrinsic charge, size, and shape under non-denaturing conditions, thereby preserving their native conformation and biological function [16]. This application note delineates the ideal research scenarios for employing Native-PAGE, providing a direct comparison with alternative methods, a detailed experimental protocol, and a curated list of essential reagents to empower researchers and drug development professionals in their investigative pursuits.

Core Principles and Key Advantages of Native-PAGE

Native-PAGE operates on the principle of separating proteins based on their charge-to-mass ratio and overall three-dimensional structure as they migrate through a porous polyacrylamide gel matrix [7] [16]. Unlike SDS-PAGE, which imparts a uniform negative charge using detergent, Native-PAGE relies on the protein's own charge, which is dependent on its amino acid composition and the pH of the running buffer. This fundamental difference is the source of its major advantage: the preservation of native properties.

Research has demonstrated that modified Native-PAGE conditions, sometimes referred to as NSDS-PAGE, can achieve high-resolution separation while retaining up to 98% of bound metal ions in metalloproteins, a stark contrast to the 26% retention observed in standard SDS-PAGE [9]. Furthermore, enzymatic activity assays confirm that most model enzymes remain functional after separation by Native-PAGE, enabling direct downstream analysis of protein function [9].

Ideal Research Applications for Native-PAGE

The unique strengths of Native-PAGE make it the method of choice for several critical research areas, particularly within the context of natural state protein analysis.

Analysis of Protein Oligomerization and Complex Assembly

Native-PAGE is exceptionally well-suited for investigating multi-protein complexes. It can resolve different oligomeric states (e.g., monomers, dimers, trimers) based on their size and shape, allowing researchers to study subunit interactions and stoichiometry without the disruptive force of denaturing agents.

Functional Enzymology and Activity Screening

When the research goal is to correlate a protein band with a specific enzymatic activity, Native-PAGE is indispensable. Following electrophoresis, gels can be incubated with specific substrates to detect enzyme activity directly within the gel matrix, enabling the identification of active isoforms or the assessment of enzyme purity.

Metalloprotein and Cofactor Characterization

For proteins that require bound metal ions or non-covalently attached cofactors for their function, Native-PAGE is the preferred method. It maintains these essential partnerships, allowing for the study of metalloprotein complexes and the identification of metal-binding proteins in proteomic samples using techniques like laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry [9].

Protein-Protein and Protein-Nucleic Acid Interactions

The technique is widely used in mobility shift assays to study binding events. Protein-protein interactions can be visualized as discrete bands with altered mobility, while protein-nucleic acid interactions (such as transcription factor-DNA binding) are routinely probed using this method [17].

Conformational Studies and Folding Analysis

Native-PAGE can reveal different conformational states of a protein or nucleic acid. As the electrophoretic mobility is sensitive to the compactness of the molecule, folded, unfolded, and misfolded conformers can often be separated and quantified, providing insights into folding pathways and stability [17].

Comparative Analysis of Electrophoretic Methods

The choice between different PAGE methods should be guided by the specific research question. The table below provides a clear, side-by-side comparison of three common techniques to aid in this decision-making process.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of PAGE Methodologies for Protein Analysis

| Feature | SDS-PAGE | BN-PAGE | Native-PAGE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Separation Principle | Molecular mass | Size & Shape | Charge-to-mass ratio & Shape [16] |

| Protein State | Denatured & unfolded | Native (as complexes) | Native (folded) |

| Key Reagents | SDS, Reducing agents | Coomassie G-250 | Non-denaturing detergents (optional) |

| Retention of Activity | Destroyed [9] | Preserved [9] | Preserved [9] |

| Metal Ion Retention | Low (e.g., ~26% Zn²⁺) [9] | High | High (e.g., ~98% Zn²⁺) [9] |

| Resolution | High | Moderate [9] | High [9] |

| Ideal for | Molecular weight determination, purity checks | Analysis of large membrane protein complexes | Studying oligomeric state, enzyme activity, native charge |

To visually guide the selection process, the following decision flowchart outlines the key questions to ask when choosing an electrophoresis method.

Detailed Native-PAGE Experimental Protocol

The following section provides a step-by-step protocol for setting up and running a standard Native-PAGE experiment, from gel preparation to post-electrophoresis analysis.

Gel Preparation

Native-PAGE utilizes a discontinuous buffer system with stacking and separating gels. The separating gel concentration should be chosen based on the expected size of the target proteins; lower percentages (e.g., 8%) are better for larger proteins, while higher percentages (e.g., 12%) provide superior resolution for smaller proteins [7].

Table 2: Recipes for Native-PAGE Gels

| Component | Stacking Gel (5 mL) | Separating Gel (10 mL at 8%) |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide (30%/0.8% w/v) | 0.67 mL | 2.6 mL |

| 0.375 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.8 | 4.275 mL | 7.29 mL |

| 10% (w/v) Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | 50 µL | 100 µL |

| TEMED | 5 µL | 10 µL |

Procedure:

- Combine all components for the separating gel, adding APS and TEMED last. Swirl gently to mix and pipette the solution into the gap between glass plates. Overlay with water or isopropanol to ensure a flat surface and allow 20-30 minutes for complete polymerization [7].

- Once set, pour off the overlay and prepare the stacking gel solution similarly.

- Pipette the stacking gel solution on top of the polymerized separating gel, insert a comb, and allow another 20-30 minutes to polymerize [7].

Sample Preparation

Critical Note: Do not heat the samples [7]. Heating will denature proteins and defeat the purpose of native electrophoresis.

- Prepare a 2X non-reducing, non-denaturing sample buffer [7]:

- 62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8

- 25% Glycerol

- 1% Bromophenol Blue (tracking dye)

- Mix the protein sample with an equal volume of the 2X sample buffer.

Electrophoresis Conditions

- Use a running buffer of 25 mM Tris and 192 mM glycine (pH ~8.3). Do not adjust the pH of this buffer [7].

- Carefully load the prepared samples into the wells of the gel.

- Run the electrophoresis at a constant voltage. It is advisable to place the gel apparatus on ice or use a cooling unit to prevent heat-induced denaturation during the run [7].

- Continue electrophoresis until the bromophenol blue tracking dye has migrated to the bottom of the gel.

Post-Electrophoresis Analysis

Once separated, proteins can be visualized using standard Coomassie-blue or silver staining protocols. For functional analysis, such as enzyme activity assays, the gel should be incubated with an appropriate substrate solution instead of being fixed and stained [9]. For subsequent analysis like Western blotting, standard immuno-blotting procedures can be followed [7].

The entire experimental workflow, from sample preparation to analysis, is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A successful Native-PAGE experiment relies on high-quality, specific reagents. The following table details the key materials and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Native-PAGE Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide (30%/0.8%) | Forms the porous gel matrix that separates proteins based on size and shape. |

| Tris-HCl Buffer (pH 8.8 & 6.8) | Provides the appropriate pH environment for gel polymerization and electrophoresis. The discontinuous pH is key to sample stacking. |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) & TEMED | Catalyzes the free-radical polymerization of acrylamide to form the polyacrylamide gel. |

| Tris-Glycine Running Buffer | The standard running buffer for native electrophoresis, providing the ions necessary for conduction and the pH for separation. |

| Glycerol | Added to the sample buffer to increase density, allowing the sample to sink neatly into the well. |

| Bromophenol Blue | A tracking dye that migrates ahead of the smallest proteins, providing a visual indicator of the electrophoresis progress. |

| Coomassie Blue R-250 / G-250 | Stains proteins post-electrophoresis for visualization. Can also be used in the cathode buffer for Blue-Native PAGE. |

Native-PAGE is an indispensable tool in the structural and functional proteomics arsenal, uniquely capable of providing high-resolution separation of proteins while preserving their delicate native architectures and biological activities. Its ideal applications are clearly defined: the study of oligomeric complexes, functional enzymology, metalloprotein characterization, and biomolecular interactions. By integrating this technique into a research framework focused on natural state analysis—supported by the detailed protocols and reagents outlined in this document—scientists and drug developers can unlock deeper insights into protein function, mechanism, and regulation, thereby accelerating the pace of discovery and therapeutic innovation.

Practical Protocols and Translational Applications in Disease and Drug Research

Within the context of advanced protein research, Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (Native-PAGE) is an indispensable technique for analyzing proteins in their natural, folded state. Unlike denaturing methods such as SDS-PAGE, Native-PAGE preserves protein complexes, multi-subunit structures, and biological activity by omitting harsh denaturants and reducing agents [18]. This allows researchers to study critical aspects of protein function, including enzyme activity, protein-protein interactions, and conformational changes, which are essential in fields ranging from structural biology to drug development [17] [19]. The separation mechanism relies on both the intrinsic charge of the protein and its molecular shape and size, allowing for the resolution of complex mixtures under conditions that mimic the native physiological environment [20].

A fundamental consideration in Native-PAGE is the isoelectric point (pI) of the target protein. The optimal conditions for resolving a protein depend on whether it is acidic or basic, influencing the choice of buffer pH and the configuration of the electrical field during electrophoresis [20] [21]. This protocol provides detailed methodologies for the analysis of both acidic and basic proteins, ensuring researchers can effectively apply Native-PAGE to a broad spectrum of experimental questions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and materials required for successful Native-PAGE experimentation.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Native-PAGE

| Reagent/Material | Function and Key Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms the porous polyacrylamide gel matrix that separates proteins based on size and charge [20]. |

| Tris-HCl Buffers | Provides the appropriate pH environment for separation (e.g., pH 8.8 for separating gel, pH 6.8 for stacking gel) [7] [20]. |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) & TEMED | Catalyzes the polymerization reaction of acrylamide and bis-acrylamide to form the gel [7] [20]. |

| Glycine | A component of the running buffer, it forms moving ion fronts for effective stacking and separation of proteins [7]. |

| Glycerol | Adds density to the sample loading buffer, allowing samples to sink neatly into the gel wells [7] [22]. |

| Bromophenol Blue | A tracking dye that migrates ahead of the proteins, allowing visualization of the electrophoresis progress [7] [22]. |

Experimental Workflow and Methodologies

The following diagram outlines the core decision-making and experimental workflow for a Native-PAGE experiment, from initial sample preparation to data analysis.

Sample Preparation Protocol

The goal of sample preparation is to maintain the protein's native conformation.

- Sample Buffer Preparation: Prepare a non-reducing, non-denaturing 2X sample loading buffer. A standard formulation is:

- Sample Mixing: Combine your protein sample with an equal volume of the 2X loading buffer. A typical ratio is 3:1 (sample : 4X buffer) [21]. Mix gently by pipetting.

- Critical Note: Do not heat the samples [7] [22]. Heating denatures proteins and is counterproductive to native electrophoresis.

- Clarification: Centrifuge the sample mixture at high speed (e.g., 17,000 x g for 5 minutes) to pellet any solid debris or insoluble aggregates [21]. Load the supernatant into the gel well.

Gel Casting Protocol

This protocol describes a discontinuous gel system, which provides superior resolution. The tables below provide recipes for both acidic and basic protein systems.

Table 2: Separating Gel Recipes for Different Acrylamide Concentrations (for Acidic Proteins, pH 8.8) [7]

| Reagent | 6% Gel | 8% Gel | 10% Gel | 12% Gel | 15% Gel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis (30%/0.8% w/v) | 2.00 mL | 2.60 mL | 3.40 mL | 4.00 mL | 5.00 mL |

| 0.375 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.8 | 7.89 mL | 7.29 mL | 6.49 mL | 5.89 mL | 4.89 mL |

| Deionized Water | - | - | - | - | - |

| 10% APS (Fresh) | 100 µL | 100 µL | 100 µL | 100 µL | 100 µL |

| TEMED | 10 µL | 10 µL | 10 µL | 10 µL | 10 µL |

| Total Volume | ~10 mL | ~10 mL | ~10 mL | ~10 mL | ~10 mL |

Table 3: Stacking and Separating Gel Compositions for a Basic Gel System (e.g., for a basic protein) [20]

| Reagent | Stacking Gel (4%) | Separating Gel (17%) |

|---|---|---|

| 40% Acr-Bis (Acr:Bis = 19:1) | 0.50 mL | 4.25 mL |

| 4x Separating Gel Buffer (1.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.8) | - | 2.50 mL |

| 4x Stacking Gel Buffer (0.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8) | 1.25 mL | - |

| Deionized Water | 3.20 mL | 3.20 mL |

| 10% APS | 35 µL | 35 µL |

| TEMED | 15 µL | 15 µL |

| Total Volume | ~5 mL | ~10 mL |

Gel Casting Procedure:

- Assemble Gel Cassette: Clean and dry the glass plates before assembling them into the casting cassette according to the manufacturer's instructions [21].

- Prepare Separating Gel: In a small beaker or tube, mix all components for the separating gel except APS and TEMED. Choose the acrylamide percentage based on the expected size of your target protein (higher % for smaller proteins) [7].

- Catalyze Polymerization: Add the 10% APS and TEMED to the solution. Swirl gently to mix. Polymerization begins immediately [21].

- Pour the Gel: Quickly pipet the separating gel solution into the gap between the glass plates, filling to about ¾ of the total height.

- Add Sealing Layer: Carefully overlay the gel solution with 1 mL of isopropanol or water to create a flat, even interface [7] [20]. Allow the gel to polymerize completely for 20-30 minutes.

- Prepare and Pour Stacking Gel: After polymerization, pour off the sealing layer and rinse with deionized water. Prepare the stacking gel solution (typically 4%) as described in the tables above, adding APS and TEMED last. Pour the stacking gel on top of the separating gel and immediately insert a clean comb. Allow to polymerize for 20-30 minutes.

Electrophoresis Protocol

The running conditions differ significantly based on the protein's pI.

- Buffer and Setup: Dilute the 10X running buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, pH ~8.3) to 1X with deionized water [7] [21]. Fill the inner and outer chambers of the electrophoresis tank. Check for leaks.

- Load Samples: Carefully load the prepared protein samples (10-20 µL, containing 1-5 µg protein for Coomassie staining) into the wells [21].

- Run Electrophoresis:

- For Acidic Proteins: The negatively charged proteins will migrate towards the positive anode (bottom of the gel). Connect the electrodes in the standard configuration (anode at bottom).

- For Basic Proteins: The positively charged proteins will migrate towards the negative cathode. You must reverse the anode and cathode so the proteins run down the gel towards the top of the tank [7] [20].

- Running Conditions: Apply a constant voltage.

- Begin at a low voltage (50-100 V) until the samples have entered the stacking gel [21] [22].

- Then, increase the voltage to 120-150 V for the remainder of the run [21] [22].

- To prevent heat-induced denaturation, it is advisable to run the gel in a cold room or place the entire apparatus on ice, especially for longer runs [7] [20].

- Completion: Stop electrophoresis when the bromophenol blue dye front has reached the bottom of the gel.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Following electrophoresis, the gel can be stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue or other compatible stains to visualize protein bands [7] [22]. For functional studies, activity assays or immunoblotting (Western blot) can be performed [7].

When interpreting results, remember that migration distance is a function of the protein's net charge, size (hydrodynamic radius), and shape [17] [20]. A shift in mobility between samples can indicate a conformational change, ligand binding, or the formation of a protein complex. The ability to distinguish between different oligomeric states is a key strength of Native-PAGE, as larger complexes will migrate more slowly through the gel matrix [7] [17]. For quantitative studies, the fraction of a population in a particular conformational state can be determined by quantifying the amount of material in each distinct band [17].

The analysis of proteins in their natural, folded state is paramount for understanding the intricate machinery of cellular processes. Many critical biological functions, from oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria to light-harvesting in chloroplasts, are carried out not by individual proteins but by sophisticated multi-protein complexes. Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Native-PAGE) has emerged as an indispensable technique for resolving these fragile macromolecular assemblies in their active, oligomeric states, preserving both their structural integrity and functional capabilities [16]. Unlike denaturing SDS-PAGE, which dissociates complexes into individual polypeptides, Native-PAGE maintains the native charge, conformation, and protein-protein interactions through the use of non-reducing, non-denaturing conditions [7] [16].

The application of Native-PAGE has been particularly transformative in membrane protein biology, where it has enabled researchers to address fundamental questions about the structural organization of respiratory chains in mitochondria and photosynthetic systems in plants. The development of Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) by Schägger and von Jagow represented a pivotal advancement, allowing for the one-step isolation of protein complexes from biological membranes and total cell homogenates [6]. This technique employs the anionic dye Coomassie Blue G-250, which binds to hydrophobic protein domains, providing negative charge for electrophoretic migration while preventing aggregation through charge repulsion [8]. The subsequent introduction of two-dimensional and three-dimensional Native-PAGE systems has further empowered researchers to delineate the subunit composition of these complexes with remarkable precision [6].

Fundamental Principles and Methodologies

Core Principles of Native Electrophoresis

Native PAGE operates on the fundamental principle of separating proteins based on their intrinsic charge, size, and shape under conditions that preserve their native conformation. The technique utilizes the same discontinuous chloride and glycine ion fronts as SDS-PAGE to form moving boundaries that stack and then separate protein complexes according to their charge-to-mass ratio [7]. During electrophoresis, most proteins, which possess isoelectric points (pI) typically ranging from 3 to 8, migrate toward the anode. For exceptional cases where proteins have strongly basic pI values exceeding 8-9, the electrode polarity must be reversed to ensure proper migration [7].

A critical distinction between Native PAGE and BN-PAGE lies in their detergent requirements. While clear Native PAGE can separate hydrophilic proteins without detergents, BN-PAGE specifically requires mild non-ionic detergents for membrane protein solubilization. The choice of detergent is crucial: digitonin effectively preserves weak protein-protein interactions, making it ideal for supercomplex analysis, whereas stronger detergents like β-DM (n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside) can dissociate larger assemblies into smaller subcomplexes [8]. This differential solubilization property is strategically exploited in multidimensional electrophoretic approaches to analyze the hierarchical organization of protein complexes.

Essential Reagent Solutions for Native-PAGE

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Native-PAGE

| Reagent | Composition/Properties | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Digitonin | Mild, non-ionic detergent with bulky structure | Solubilizes membrane proteins while preserving weak interactions between complexes; maintains supercomplex integrity [23] [8] |

| β-DM (n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside) | Stronger non-ionic detergent | Disrupts protein-protein interactions; dissociates supercomplexes into subcomplexes for 2D analysis [8] |

| Coomassie Blue G-250 | Anionic dye | Binds hydrophobic protein domains; provides negative charge for electrophoretic migration; prevents aggregation [8] |

| Aminocaproic Acid (ACA) | Low ionic strength salt | Enhances detergent access to membrane domains; improves solubilization efficiency [8] |

| Bis-Tris Buffer System | pH range ~6.0-7.0 | Maintains neutral pH throughout electrophoresis; minimizes protein denaturation and complex dissociation [8] |

Standard BN-PAGE Protocol

The following protocol outlines the core methodology for Blue Native PAGE, adaptable for various biological sources including mitochondrial and thylakoid membranes:

Sample Preparation: Isolate membranes (mitochondrial, thylakoid, or cellular) in the presence of protease inhibitors (e.g., Pefabloc) and phosphatase inhibitors (e.g., NaF) when studying phosphorylation-dependent interactions [8]. Solubilize membrane proteins using 1-4% digitonin in ACA buffer (6-aminocaproic acid, Bis-Tris, EDTA, pH 7.0) at a detergent-to-protein ratio of 2-4 g/g [6] [8]. Following centrifugation (20,000 × g, 30 min, 4°C), supplement the supernatant with Coomassie Blue G-250 dye (0.5-1.0% final concentration) in glycerol [8].

Gel Casting and Electrophoresis: Prepare a discontinuous gradient gel (e.g., 3.5-12.5% acrylamide) using acrylamide bis-acrylamide solutions (48%:1.5% for separating gel). Cast the gel with 1-2% acrylamide stacking gel. Use anode buffer (50 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0) and cathode buffer (50 mM Tricine, 15 mM Bis-Tris, 0.02% Coomassie Blue G-250, pH 7.0) for electrophoresis [6] [8]. Run the gel at constant voltage (50-100 V) with cooling (4°C) until the dye front migrates to the bottom.

Post-Electrophoresis Analysis: Following separation, protein complexes can be visualized by Coomassie staining, subjected to in-gel activity assays, or processed for downstream applications including electroelution for functional studies, native electroblotting for immunodetection, or second-dimension electrophoresis for subunit analysis [6].

Application to Respiratory Chain Supercomplexes

Architectural Organization of Mitochondrial Respirasomes

The mitochondrial respiratory chain represents one of the most significant applications of BN-PAGE in elucidating macromolecular organization. BN-PAGE analyses have revealed that the individual complexes of the respiratory chain (CI: NADH dehydrogenase, CII: succinate dehydrogenase, CIII: cytochrome bc1 complex, CIV: cytochrome c oxidase) do not exist in isolation but form supramolecular assemblies known as supercomplexes or "respirasomes" [23] [24]. The most prominent of these is the respirasome, containing complexes I, III, and IV, along with the mobile electron carriers ubiquinone and cytochrome c [24].

Structural insights gained through BN-PAGE combined with cryo-electron microscopy have delineated the precise architecture of these supercomplexes. In the mammalian respirasome, the membrane arm of complex I curves around the complex III dimer, with complex IV positioned between complexes I and III at the "toe" of complex I [24]. This specific arrangement is evolutionarily conserved, with similar organizational patterns observed in mammals, yeast, and plants [24]. The table below summarizes the major respiratory supercomplexes identified through BN-PAGE analysis:

Table 2: Respiratory Chain Supercomplexes Resolved by BN-PAGE

| Supercomplex Composition | Stoichiometry | Functional Significance | Biological Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respirasome | CI₁CIII₂CIV₁-₂ | Simplest entity capable of independent respiration; contains all complexes for NADH oxidation and oxygen reduction [24] | Mammalian heart, liver, muscle tissues [23] |

| CI-CIII Supercomplex | CI₁CIII₂ | Electron transfer from NADH to cytochrome c; proposed to stabilize complex I [23] | Yeast mitochondria, plants [23] |

| CIII-CIV Supercomplex | CIII₂CIV₁-₂ | Electron transfer from ubiquinol to oxygen | Saccharomyces cerevisiae, some mammalian tissues [23] |

| ATP Synthase Dimer | (CV)₂ | Induction of inner membrane curvature; crucial for mitochondrial cristae morphology [6] | Mammalian and yeast mitochondria [6] |

Functional Significance and Current Debates

The functional advantages conferred by respiratory supercomplex organization remain an area of intense investigation and debate. Three primary models have emerged to explain their physiological relevance:

The "plasticity" model proposes a dynamic equilibrium between individual complexes and supercomplexes, allowing the respiratory chain to adapt its structural organization to optimize electron flux under different metabolic conditions [23]. This model suggests that supercomplexes may create partitioned pools of ubiquinone and cytochrome c, potentially channeling substrates between sequentially interacting complexes [23].

However, rigorous biophysical experiments have challenged the substrate channeling hypothesis. Spectroscopic measurements and kinetic analyses indicate that cytochrome c does not encounter major diffusion barriers between complexes [24]. Furthermore, incorporation of alternative quinol oxidases into mitochondrial membranes demonstrates that ubiquinol can exchange freely between respirasomes and external enzymes, arguing against strict substrate channeling [24].

An alternative perspective suggests that supercomplexes represent a physical adaptation to the densely packed protein environment of the mitochondrial inner membrane. By serving as "fenders" that prevent unfavorable interactions, supercomplexes may enable higher packing densities while minimizing aggregation [24]. This model is supported by the observation that many intercomplex interactions are mediated by supernumerary subunits that have accumulated through evolution, potentially to protect catalytic cores from restrictive interactions [24].

Figure 1: Relationship between mitochondrial respiratory chain organization and functional implications as revealed by BN-PAGE

Advanced Technical Approaches

Multidimensional Electrophoretic Separations

Two-dimensional (2D) BN-PAGE has dramatically enhanced the resolution of complex protein assemblies by coupling size-based native separation in the first dimension with additional separation parameters in the second dimension. The most powerful implementations include:

BN-PAGE/Tricine-SDS-PAGE: Following BN-PAGE separation, individual lanes are excised and incubated in SDS-containing buffer to denature complexes into constituent polypeptides. The lane is then applied to a tricine-SDS-PAGE gel, which separates subunits by molecular weight with superior resolution for low-mass proteins [6]. This approach allows researchers to determine the subunit composition of each complex resolved in the first dimension.

BN-PAGE/BN-PAGE: This technique employs differential detergent strength between dimensions to dissect hierarchical relationships within supercomplexes. After initial separation using digitonin, which preserves supercomplex integrity, gel lanes are treated with β-DM, which disrupts weaker protein-protein interactions [8]. The second dimension BN-PAGE then resolves the dissociated subcomplexes, revealing structural dependencies and interaction stability.

3D BN-PAGE/IEF/SDS-PAGE: For ultimate resolution, a three-dimensional approach can be implemented where BN-PAGE-separated complexes are subjected to isoelectric focusing (IEF) in the second dimension, followed by tricine-SDS-PAGE in the third dimension [6]. This comprehensive separation resolves individual subunits by both isoelectric point and molecular weight, providing exhaustive characterization of complex composition.

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for multidimensional native electrophoresis analysis of macromolecular complexes

Specialized Applications in Photosynthetic Systems

The principles of BN-PAGE have been successfully adapted to study the macromolecular organization of photosynthetic machinery in thylakoid membranes. The protocol involves solubilizing Arabidopsis thaliana thylakoids with digitonin in the presence of aminocaproic acid, which provides access to the appressed grana regions and allows analysis of the overall organization of labile protein complexes [8].

This approach has revealed that photosystem II (PSII) core dimers assemble with light-harvesting complexes (LHCII) to form C₂S₂M₂ supercomplexes, while photosystem I (PSI) associates with loosely bound LHCII to create PSI-LHCII supercomplexes [8]. Most remarkably, BN-PAGE has enabled the identification of megacomplexes containing both PSII and PSI connected by L-LHCII, challenging the traditional view of strictly segregated photosystems [8]. The ability to resolve these fragile superstructures underscores the power of Native-PAGE in probing native macromolecular organization.

Native-PAGE, particularly in its Blue Native implementation, has revolutionized our ability to resolve macromolecular complexes from oligomers to respiratory chain supercomplexes. By preserving native protein-protein interactions during separation, this technique has provided unequivocal evidence for the structural organization of respiratory chains into respirasomes and photosynthetic systems into megacomplexes. The ongoing refinement of multidimensional approaches continues to enhance resolution, while integration with complementary techniques such as cryo-EM, mass spectrometry, and functional assays promises a more comprehensive understanding of complex biology. As methodological advancements address current limitations in sensitivity and quantification, Native-PAGE will undoubtedly remain a cornerstone technique for elucidating the structural and functional organization of cellular machinery in its native state.

Within the context of native-state protein research, the separation of proteins via Blue Native-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) is only the first step. The true analytical power is unlocked through downstream functional analysis techniques that probe the activity, composition, and identity of the separated protein complexes. Two principal methods for this downstream analysis are in-gel enzyme activity staining and western blotting. In-gel activity staining directly visualizes the catalytic function of enzymes within the gel matrix, confirming the integrity of the native complexes. Western blotting, following a native gel, allows for the specific immunodetection of individual protein subunits within these complexes. This application note provides detailed protocols and data for implementing these critical downstream analyses, enabling researchers to fully characterize proteins in their natural state.

Detection Method Comparison and Selection

The choice of downstream analysis method depends on the experimental objectives, the protein complexes of interest, and the required sensitivity. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of major detection techniques compatible with native separations.

Table 1: Comparison of Downstream Detection Methods for Native Gels

| Method | Typical Sensitivity | Typical Protocol Time | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-Gel Enzyme Activity Staining | Varies by enzyme [25] | 30 min - 4 hours [25] | Confirming native function and integrity of enzymatic complexes (e.g., OXPHOS complexes) [25]. | Directly confirms functional integrity; no specific reagents required beyond substrates. | Requires optimized substrate penetration; not all enzymes are amenable; may have insensitivity (e.g., Complex III) [25]. |

| Western Blotting (after BN-PAGE) | ~1-10 ng (antibody-dependent) | 3-4 hours (post-electrophoresis) | Identifying specific protein subunits within a native complex; assessing complex composition [26] [19]. | High specificity for target proteins; widely accessible. | Requires specific, high-quality antibodies; potential for epitope masking in native state [26]. |

| Zinc Staining | 0.25 - 0.5 ng [27] | ~15 min [27] | Rapid, reversible total protein stain; ideal for protein recovery for MS or western blotting [27]. | Fast; no chemical protein modification; fully compatible with downstream MS. | Does not provide functional or identity information. |

| Coomassie Staining | 5 - 25 ng [27] | 10 - 135 min [27] | General total protein detection; compatible with mass spectrometry [27]. | Simple, robust protocols; reversible staining. | Lower sensitivity compared to other methods. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

In-Gel Enzyme Activity Staining for OXPHOS Complexes

This protocol is adapted from validated methods for analyzing mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complexes, which are frequently studied using BN-PAGE [25]. The following diagram outlines the core workflow.

Workflow Overview: In-Gel Enzyme Activity Staining

Materials

- BN-PAGE or CN-PAGE Gel: Containing separated mitochondrial protein complexes [25]. CN-PAGE is preferred to avoid interference from Coomassie dye [25].

- Reaction Buffers: Specific to each OXPHOS complex (details below).

- Substrates: e.g., Nitrotetrazolium Blue (NBT), NADH, Succinate, 3,3'-Diaminobenzidine (DAB), ATP, Lead Nitrate [25].

- Equipment: Orbital shaker, imaging system.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Post-Electrophoresis Gel Handling: Following BN-PAGE or CN-PAGE, carefully remove the gel from the electrophoresis apparatus.

- Equilibration: Rinse the gel gently with deionized water to remove residual electrophoresis buffers.

- Complex-Specific Staining Incubation: Submerge the gel in the appropriate pre-warmed reaction buffer for the target complex. Use approximately 10-20 mL of solution for a mini-gel.

- Complex I (NADH Dehydrogenase):

- Reaction Buffer: 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 0.1 mg/mL NADH, 0.25 mg/mL NBT.

- Incubation: Protect from light and incubate with gentle shaking until purple formazan bands develop [25].

- Complex II (Succinate Dehydrogenase):

- Reaction Buffer: 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 0.1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Sodium Succinate, 0.25 mg/mL NBT.

- Incubation: Incubate with gentle shaking in the dark until purple bands appear [25].

- Complex IV (Cytochrome c Oxidase):

- Reaction Buffer: 50 mM Phosphate Buffer (pH 7.4), 1 mg/mL DAB, 1 mg/mL Cytochrome c, 0.2% Sucrose.

- Incubation: Incubate with gentle shaking in the dark. Brown-colored bands indicate activity [25].

- Complex V (ATP Synthase):

- Reaction Buffer: 50 mM Glycine (pH 8.4), 5 mM MgCl₂, 5 mM ATP, 2 mM Lead Nitrate.

- Incubation: Incubate for 30-60 minutes with shaking. A white precipitate of lead phosphate forms at the site of activity.

- Enhancement (Critical for Sensitivity): To markedly improve sensitivity, replace the reaction buffer with a 1-2% (w/v) ammonium sulfide solution. Incubate for 1-2 minutes with shaking. The lead phosphate is converted to a brown-black lead sulfide precipitate. Stop the reaction by extensively washing the gel with distilled water [25].

- Complex I (NADH Dehydrogenase):

- Termination and Documentation: Once bands of sufficient intensity have developed, stop the reaction by washing the gel with distilled water. Capture an image of the gel using a standard documentation system.

Western Blotting After BN-PAGE

Western blotting following native electrophoresis allows for the specific identification of proteins within a complex. The process requires careful handling to preserve the separation achieved in the first dimension.

Workflow Overview: Western Blotting After Native PAGE

Materials

- PVDF Membrane: Do NOT use nitrocellulose for BN-PAGE blots, as it is less robust [26] [19].

- Transfer Buffer: Tris/Glycine buffer with 10% methanol is recommended [19]. For high molecular weight complexes, reducing methanol to 5-10% can improve transfer [28].

- Blocking Buffer: Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 5% non-fat milk powder [19]. For phosphoproteins, use Tris-buffered saline (TBS) with BSA instead [29].

- Primary and Secondary Antibodies: Validated for the target antigen.

- Wash Buffer: PBS or TBS with 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST/TBST) [19].

Step-by-Step Procedure for 1D Western Blot

- Electroblotting: