Native vs. Denaturing Gels: The Definitive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This comprehensive guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a strategic framework for selecting between native and denaturing gel electrophoresis methods.

Native vs. Denaturing Gels: The Definitive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This comprehensive guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a strategic framework for selecting between native and denaturing gel electrophoresis methods. Covering foundational principles, methodological protocols, and troubleshooting strategies, the article details how to preserve protein complexes and activity with native gels or separate by molecular weight using denaturing SDS-PAGE. It includes comparative validation approaches and optimization techniques for diverse applications from enzyme isolation to western blotting and protein sequencing, enabling informed experimental design in biomedical research.

Understanding the Core Principles: How Native and Denaturing Gels Work

Native gel electrophoresis represents a critical methodology in biochemical analysis that enables the separation of biomolecules in their folded, functional states. Unlike denaturing techniques that dismantle higher-order structures, native gels preserve the intricate quaternary structures, enzymatic activities, and binding capabilities of proteins and nucleic acids. This technical guide examines the fundamental principles, methodological considerations, and practical applications of native gel electrophoresis within the broader context of choosing between denaturing and non-denaturing approaches. By providing detailed protocols, quantitative comparisons, and advanced applications, this review serves as an essential resource for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to maintain biomolecular integrity throughout analytical procedures.

Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) operates on the fundamental principle of separating biomolecules according to their intrinsic charge, size, and three-dimensional shape under non-denaturing conditions. The technique employs mild buffer systems that preserve the native conformation of proteins and nucleic acids, maintaining their biological activity and subunit interactions [1]. This stands in direct contrast to denaturing methods such as SDS-PAGE, which uses sodium dodecyl sulfate to unfold proteins into linear chains, and urea-based gels that disrupt hydrogen bonding in nucleic acids [2]. The preservation of structure in native gels introduces additional separation parameters including molecular compactness, oligomeric state, and surface charge distribution, making it possible to study functional biomolecular complexes that would be disrupted in denaturing systems.

The strategic value of native gels lies in their ability to provide information about biological systems that is irrecoverable from denaturing analyses. While denaturing gels excel at determining molecular weights and establishing sample purity, native gels reveal hierarchical states, binding interactions, and enzymatic capabilities [2]. For drug development professionals, this capability is particularly valuable when characterizing therapeutic proteins, protein complexes, and protein-drug interactions where maintenance of tertiary and quaternary structure is essential for biological function. The choice between these complementary techniques must therefore be guided by the specific biological questions being addressed rather than procedural convenience alone.

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Theoretical Basis of Separation

In native PAGE, the electrophoretic mobility of a biomolecule is determined by a complex interplay of its net charge, hydrodynamic size, and molecular shape. Unlike denaturing systems where the charge-to-mass ratio is uniformized by denaturants, native systems maintain the intrinsic charge characteristics of each molecule [1]. Electrophoretic migration occurs because most proteins carry a net negative charge in alkaline running buffers, causing them to migrate toward the anode. The frictional force of the gel matrix creates a sieving effect that regulates molecular movement according to size and three-dimensional configuration [1]. This dual dependence on charge and size parameters means that a small protein with low charge density might migrate similarly to a larger protein with high charge density, necessitating careful interpretation of results.

The preservation of native structure enables the study of biologically critical assemblies that would be disrupted under denaturing conditions. Multimeric proteins maintain their subunit interactions, membrane proteins retain their lipid associations, and nucleic acid secondary structures remain intact [2] [1]. This structural preservation comes with increased complexity in result interpretation, as migration distance cannot be directly correlated to molecular weight through simple calibration curves as in denaturing systems. Instead, researchers must account for charge variations across different biomolecules and recognize that conformational changes induced by ligand binding or post-translational modifications will alter electrophoretic mobility independently of mass changes.

Comparative Analysis: Native vs. Denaturing Gels

The strategic selection between native and denaturing electrophoretic methods depends fundamentally on the analytical objectives. Each approach offers distinct advantages and limitations that must be weighed according to experimental goals.

Table 1: Comparative Applications of Native Versus Denaturing Gels

| Application Scenario | Native Gel | Denaturing Gel |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Investigation | Preserves secondary/tertiary/quaternary structure | Disrupts non-covalent interactions; analyzes primary structure |

| Functional Analysis | Maintains enzymatic activity; studies protein function | Not applicable (proteins denatured) |

| Binding Studies | Identifies protein-protein/ligand interactions | Disrupts non-covalent binding interactions |

| Complex Assembly | Resolves multimers and quaternary structures | Separates individual subunits |

| Purity Assessment | Limited by structural heterogeneity | Excellent for establishing sample purity |

| Molecular Weight Determination | Indirect (influenced by charge/shape) | Direct determination possible |

| Downstream Applications | Activity assays; structural biology | Sequencing; Western blotting |

The decision framework for method selection extends beyond these application-based considerations to include practical experimental factors. Native gels are generally simpler and cheaper to run, making them preferable for initial characterization when structural preservation is paramount [2]. Denaturing gels provide more straightforward interpretation for molecular weight determination and are essential techniques when establishing sample purity or preparing for protein sequencing [2]. For many research workflows, a complementary approach utilizing both methods provides the most comprehensive biomolecular characterization.

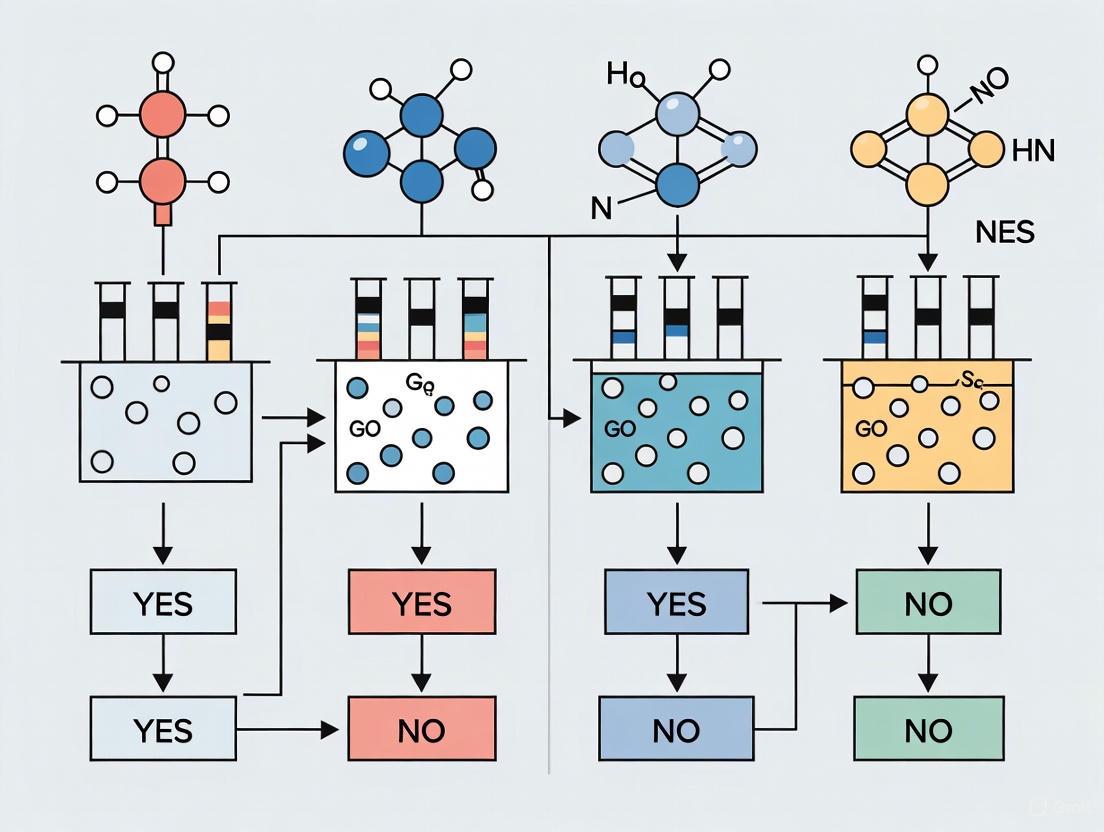

Diagram 1: Decision framework for gel type selection

Technical Methodologies and Experimental Design

Native Gel Chemistry Systems

Three primary gel chemistry systems have been developed for native PAGE, each optimized for specific protein characteristics and analytical requirements. The operating pH range represents a critical differentiating factor, as it determines the net charge of proteins during separation and must be compatible with protein stability.

Table 2: Native PAGE Gel Chemistry Systems and Specifications

| Parameter | Tris-Glycine System | Tris-Acetate System | NativePAGE Bis-Tris System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating pH Range | 8.3–9.5 | 7.2–8.5 | ~7.5 |

| Molecular Weight Range | 20–500 kDa | >150 kDa | Broad range with charge shifting |

| Key Features | Traditional Laemmli system | Enhanced resolution for larger proteins | Charge shifting with Coomassie G-250; detergent compatible |

| Optimal Applications | Maintaining native charge; smaller proteins | Maintaining native charge; larger proteins | Membrane proteins; hydrophobic proteins; molecular weight-based separation regardless of pI |

| Recommended Buffer | Tris-Glycine Native Running Buffer | Tris-Glycine Native Running Buffer | NativePAGE Running Buffer with Cathode Buffer Additive |

| Unique Characteristics | - | - | Converts basic proteins to net negative charge via Coomassie G-250 binding |

The Tris-Glycine system operates at a higher alkaline pH (8.3–9.5), making it suitable for proteins that maintain stability and negative charge in this environment [1]. The Tris-Acetate system functions at a more neutral pH range (7.2–8.5), providing better resolution for larger molecular weight proteins [1]. Most innovatively, the NativePAGE Bis-Tris system incorporates Coomassie G-250 dye in the cathode buffer, which binds nonspecifically to hydrophobic protein regions and confers a negative charge regardless of intrinsic protein pI [1]. This charge-shifting approach enables the separation of basic proteins that would otherwise migrate toward the cathode or remain stationary in conventional native systems.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The following protocol outlines the standard procedure for native PAGE using the Tris-Glycine system, with modifications noted for alternative chemistries:

Gel Preparation:

- Gel Concentration Selection: Choose appropriate acrylamide concentration based on target protein size. For Tris-Glycine systems, available percentages include 6%, 8%, 10%, 12%, 14%, 16%, and gradient gels (4-12%, 4-20%, 8-16%, 10-20%) [1].

- Gel Casting: Combine acrylamide/bis-acrylamide mixture at 37:1 ratio with Tris-Glycine buffer (25 mM Tris, 200 mM glycine, pH 8.3-9.5). Initiate polymerization with 0.1% (w/v) ammonium persulfate and 0.4 μl/ml TEMED [3].

- Gel Storage: Prepared gels can be stored at 2-8°C for up to 12 months when properly sealed to prevent dehydration [1].

Sample Preparation:

- Buffer Conditions: Dilute protein samples in Tris-Glycine Native Sample Buffer. Maintain physiological salt concentrations (<150 mM) to minimize disturbances during electrophoresis.

- Detergent Considerations: For membrane proteins, include non-ionic detergents (e.g., digitonin, dodecyl maltoside) at concentrations above their critical micelle concentrations to maintain solubility without denaturing proteins.

- Loading Requirements: For mini-gels (8 cm × 8 cm), load up to 60 μL per well using gel-loading tips to ensure proper deposition in well bottoms [1].

Electrophoretic Run:

- Buffer Assembly: Fill electrophoresis chamber with Tris-Glycine Native Running Buffer. For NativePAGE Bis-Tris systems, add Cathode Buffer Additive containing Coomassie G-250 to the cathode chamber [1].

- Run Conditions: Apply constant voltage of 5-15 V/cm. Lower voltages (5 V/cm) minimize Joule heating and improve band resolution, while higher voltages reduce run time [3].

- Temperature Control: Maintain temperature at 4-10°C throughout the run using a circulating cooler or by performing electrophoresis in a cold room to preserve protein stability.

Post-Electrophoresis Analysis:

- Protein Detection: Visualize proteins using Coomassie Brilliant Blue, silver stain, or specific activity stains for enzymes. For NativePAGE Bis-Tris systems, the Coomassie G-250 provides initial visualization during separation.

- Western Blotting: Transfer proteins to PVDF membranes using Tris-Glycine Transfer Buffer. Note that nitrocellulose is incompatible with NativePAGE Bis-Tris systems due to tight binding of Coomassie G-250 dye [1].

- Activity Assays: For functional studies, incubate gels in appropriate substrate solutions to detect enzymatic activity directly within the gel matrix.

Advanced Applications and Innovations

Single-Molecule Studies in Native Gels

The integration of native gel electrophoresis with single-molecule fluorescence spectroscopy has created powerful methodologies for studying biomolecular dynamics and interactions. The gel matrix serves dual purposes: purifying biomolecular complexes of interest from free components and aggregates, while simultaneously slowing translational diffusion to enable extended observation of conformational dynamics [3]. This approach, exemplified by in-gel alternating-laser excitation (ALEX) spectroscopy, allows researchers to monitor real-time FRET fluctuations within DNA hairpins and protein-nucleic acid complexes under native conditions [3].

The methodological implementation involves embedding pre-formed biomolecular complexes within non-denaturing polyacrylamide gels (typically 6% acrylamide) and performing single-molecule observations using confocal microscopy or total internal reflection fluorescence [3]. The gel matrix creates a biologically friendly environment that avoids surface immobilization artifacts while providing sufficient molecular immobilization to resolve millisecond-timescale conformational transitions [3]. This technique has been successfully applied to study RNA polymerase open complexes, DNA structural transitions, and protein folding pathways, demonstrating broad utility for investigating dynamic biomolecular processes under near-physiological conditions.

Advanced Detection Methodologies

Recent innovations in detection technologies have significantly enhanced the sensitivity and specificity of native gel analyses. The development of in-gel fluorescence detection using Connectase-mediated fluorophore labeling represents a particularly advanced methodology that surpasses traditional Western blotting in sensitivity and quantitative accuracy [4]. This approach utilizes a highly specific protein ligase from methanogenic archaea that recognizes a defined 12-amino acid sequence (CnTag) and transfers a fluorophore to tagged proteins within the gel matrix [4].

The standard protocol involves:

- Conjugate Formation: Incubate equimolar concentrations (5 μM) of Connectase and fluorescent peptide substrate for 1 minute to form the fluorophore-Connectase conjugate (N-Cnt) [4].

- Labeling Reaction: Mix 6.67 nM of the N-Cnt reagent with the protein sample and incubate for ≥5 minutes for qualitative analysis or 30 minutes for quantitative studies [4].

- Separation and Detection: Separate samples on native polyacrylamide gels and analyze using a fluorescence imager or scanner [4].

This method demonstrates remarkable sensitivity, detecting approximately 0.1 fmol (3 pg of a 30 kDa protein) of target protein—approximately three orders of magnitude more sensitive than conventional Western blotting [4]. Additionally, it provides superior quantitative accuracy with a linear signal-to-substrate relationship and minimal background interference, making it particularly valuable for precise quantification of recombinant proteins in complex mixtures.

Diagram 2: Advanced in-gel fluorescence detection workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of native gel electrophoresis requires specific reagent systems optimized for maintaining biomolecular structure and function throughout the separation process.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Native Gel Electrophoresis

| Reagent | Composition/Type | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| NativePAGE Bis-Tris Gels | 3-12% or 4-16% polyacrylamide with Bis-Tris buffer | High-resolution separation of native proteins | Provides near-neutral pH (7.5); compatible with Coomassie G-250 charge shifting |

| Tris-Glycine Native Running Buffer | 25 mM Tris, 200 mM glycine, pH 8.3-9.5 | Creates alkaline electrophoresis environment | Suitable for proteins stable at high pH; traditional Laemmli system |

| Coomassie G-250 Dye | Triphenylmethane compound | Binds hydrophobic protein regions; confers negative charge | Enables separation of basic proteins; included in cathode buffer |

| NativePAGE Sample Buffer | Non-denaturing buffer with G-250 additive | Maintains native protein structure during preparation | Contains non-ionic detergents for membrane proteins |

| PVDF Membrane | Polyvinylidene fluoride | Western blot transfer surface | Required for NativePAGE systems; nitrocellulose incompatible |

| Connectase Enzyme | Archaeal protein ligase | Mediates specific fluorophore transfer to CnTagged proteins | Enables ultra-sensitive in-gel fluorescence detection |

Native gel electrophoresis remains an indispensable tool in the biomolecular analysis toolkit, providing unique capabilities for studying proteins and nucleic acids in their functional states. The technique's ability to preserve higher-order structures, maintain biological activity, and resolve complex assemblies makes it particularly valuable for characterizing therapeutic proteins, investigating protein-protein interactions, and analyzing macromolecular complexes in drug development pipelines. While method selection must be guided by specific research objectives, with denaturing methods preferred for molecular weight determination and purity assessment, native methods offer irreplaceable insights into biomolecular function that cannot be obtained through denaturing approaches.

Recent methodological advancements, including single-molecule spectroscopy in gel matrices and Connectase-mediated fluorescence detection, have significantly expanded the analytical power of native electrophoresis. These innovations offer enhanced sensitivity, quantitative accuracy, and dynamic information that complement traditional native gel applications. As biomolecular therapeutics continue to increase in complexity and structural sensitivity, the preservation of native structure during analytical characterization becomes increasingly critical, ensuring native gel electrophoresis will remain an essential methodology for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to understand biomolecular function in addition to composition.

Gel electrophoresis stands as a cornerstone technique in molecular biology and biochemistry for separating biomolecules based on their physical properties. Within this methodology, denaturing gels represent a specialized approach that fundamentally alters the native structure of proteins and nucleic acids to create linear chains that separate strictly by molecular weight. This technical guide explores the core principles, mechanisms, and applications of denaturing gel electrophoresis, positioning it within the critical context of choosing appropriate separation techniques for research and drug development. By systematically comparing denaturing versus native conditions and providing detailed experimental protocols, this whitepaper serves as an essential resource for scientists requiring precise biomolecular separation and analysis.

Gel electrophoresis operates on the fundamental principle that charged molecules migrate through a porous gel matrix under the influence of an electric field. The rate of migration depends on several factors including the molecule's charge, size, and shape, as well as the resistance of the medium [5]. In protein electrophoresis, molecules exhibit varying charges depending on pH conditions, migrating toward oppositely charged electrodes except at their isoelectric point (pI) where their net charge is zero [5]. The gel matrix, typically composed of agarose or polyacrylamide, creates a molecular sieve that retards larger molecules while allowing smaller ones to migrate more rapidly.

The evolution of polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) revolutionized biomolecular separation by providing a chemically inert and stable matrix with tunable pore sizes [5]. The gel forms through chemical copolymerization of acrylamide monomers with an N-N'-methylene bisacrylamide cross-linker, with the pore size determined by the relative concentrations of acrylamide (%T) and bisacrylamide crosslinker (%C) [5]. This customizable matrix enables researchers to optimize separation conditions for specific molecular weight ranges, making PAGE an indispensable tool in modern biological research.

Core Principles of Denaturing Gels

Fundamental Mechanism

Denaturing gels operate on the principle of completely disrupting the native secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures of biomolecules, transforming them into linear chains whose migration depends primarily on molecular weight rather than complex structural features. For proteins, this structural unfolding is typically achieved using sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), an anionic detergent that binds to hydrophobic regions of proteins at a relatively constant ratio of approximately 1.4g SDS per 1g of protein [5]. This SDS coating confers a uniform negative charge density along the protein backbone, effectively masking the protein's intrinsic charge and creating a migration rate dependent almost exclusively on molecular size [2] [6].

For nucleic acids, denaturation is commonly accomplished using urea, which disrupts hydrogen bonding between base pairs, or alternative denaturants such as DMSO and glyoxal for RNA [2]. These agents unfold secondary structures like hairpins and stem-loops, ensuring that nucleic acids migrate as single-stranded molecules whose mobility correlates directly with chain length rather than structural complexity [2]. The result in both cases is a separation based primarily on molecular mass, with smaller molecules migrating faster through the gel matrix than larger ones [2] [6].

Comparison with Native Gel Electrophoresis

The critical distinction between denaturing and native (non-denaturing) gel electrophoresis lies in their treatment of biomolecular structure and the consequent separation parameters, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Differences Between Denaturing and Native Gel Electrophoresis

| Parameter | Denaturing Gels | Native Gels |

|---|---|---|

| Biomolecule Structure | Unfolded into linear chains; secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures disrupted [2] [6] | Native structure preserved; all levels of structure maintained [2] [6] |

| Separation Basis | Primarily molecular mass (length for nucleic acids) [2] [6] | Molecular mass, intrinsic charge, overall bulk, and cross-sectional area [2] [6] |

| Common Denaturants | SDS (proteins), urea, DMSO, glyoxal (nucleic acids) [2] | No denaturants used |

| Typical Applications | Western blotting, protein sequencing, purity assessment, molecular weight determination [2] | Enzyme activity assays, binding studies, quaternary structure analysis, complex isolation [2] |

| Information Obtained | Primary structure analysis, molecular weight estimation [6] | Analysis of all four levels of biomolecular structure [6] |

This fundamental difference in separation principle means that denaturing gels provide information primarily about the primary structure and molecular weight, while native gels allow researchers to probe complex structural features and functional states of biomolecules [6].

Experimental Methodology for Denaturing Gel Electrophoresis

SDS-PAGE Protocol for Proteins

The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for SDS-PAGE analysis of proteins, adapted from established laboratory practices [7].

Sample Preparation

Protein samples must be properly prepared to ensure complete denaturation and accurate separation:

Denaturation Buffer: Combine the protein sample with Tris-Glycine SDS Sample Buffer (2X) to achieve a final 1X concentration [7]. For reduced samples, add reducing agent (DTT or β-mercaptoethanol) to a final concentration of 1X immediately prior to electrophoresis to disrupt disulfide bonds [7] [5].

Heat Denaturation: Heat samples at 85°C for 2-5 minutes to complete the denaturation process [7]. Avoid heating at 100°C as this can promote proteolysis [7].

Loading Preparation: Adjust final volume with deionized water to achieve desired concentration. Typical loading volumes range from 10-20μL per well [7].

Note: For non-denaturing electrophoresis, use Tris-Glycine Native Sample Buffer instead and do not heat the samples [7].

Gel Preparation and Electrophoresis

Pre-cast gels offer convenience and consistency, while hand-cast gels provide customization options:

Gel Selection: Choose appropriate polyacrylamide percentage based on target protein size range. Lower percentages (8-10%) better resolve higher molecular weight proteins, while higher percentages (12-15%) optimize separation of smaller proteins.

Assembly: Remove gel cassette from packaging, rinse with deionized water, and remove tape from the bottom. Gently pull the comb from the cassette in one smooth motion and rinse wells with running buffer [7].

Buffer System: Prepare 1X Tris-Glycine SDS Running Buffer from 10X stock according to manufacturer recommendations [7]. The discontinuous buffer system utilizes Tris-glycine at pH 8.3 with SDS for optimal separation [7].

Loading and Separation: Load prepared samples and molecular weight markers into wells. Run gels at constant voltage (typically 125V for mini-gels) until the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel [7].

The workflow for denaturing gel electrophoresis can be visualized as follows:

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful denaturing gel electrophoresis requires specific reagents, each serving distinct functions in the separation process as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Denaturing Gel Electrophoresis

| Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Anionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge [5] | Critical for protein unfolding; typically used at 1-2% concentration |

| Urea | Denaturant that disrupts hydrogen bonding in nucleic acids [2] [6] | Used at high concentrations (6-8M) for complete denaturation of DNA/RNA |

| DTT or β-mercaptoethanol | Reducing agents that break disulfide bonds in proteins [7] [5] | Essential for analyzing reduced proteins; prevents reformation of disulfide bridges |

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms cross-linked polymer matrix for molecular sieving [5] | Concentration ratio determines gel pore size and separation range |

| Tris-Glycine Buffer | Discontinuous buffer system for optimal protein separation [7] | Creates stacking effect for sharp band formation; pH ~8.3-8.8 |

| APS and TEMED | Catalyst system for polyacrylamide polymerization [5] | Initiates and accelerates gel formation; TEMED is toxic - handle with care |

Applications in Research and Drug Development

Analytical Applications

Denaturing gels serve as fundamental tools across diverse research applications:

Molecular Weight Determination: By comparing migration distances against standard markers of known molecular weight, researchers can accurately estimate the size of unknown proteins or nucleic acids [2]. The logarithmic relationship between molecular weight and migration distance enables precise sizing across broad molecular weight ranges.

Purity Assessment and Quality Control: Denaturing gels provide critical quality control for samples prepared for downstream applications like next-generation sequencing (NGS), where DNA fragment size distribution directly impacts sequencing success [8]. Broad or unexpected bands indicate sample contamination or degradation.

Western Blotting: As a prerequisite for immunoblotting, SDS-PAGE separates complex protein mixtures before transfer to membranes for specific antibody detection [2]. This application is fundamental to protein expression analysis in both basic research and biopharmaceutical development.

Protein Sequencing Preparation: Isolated protein bands from denaturing gels can be excised for subsequent proteolytic digestion and mass spectrometric analysis, enabling protein identification and characterization [2].

Specialized Research Applications

Beyond routine analysis, denaturing gels enable sophisticated experimental approaches:

Quantitative Interaction Analysis: Modified electrophoresis approaches using programmable DNA nanoswitches enable quantitative kinetic and thermodynamic characterization of molecular interactions, including complex multi-component systems [9]. This innovative application extends traditional gel electrophoresis from analytical separation to precise biomolecular interaction analysis.

Fragment Size Selection for NGS: Denaturing gels facilitate precise size selection of DNA fragments for NGS library preparation, a critical step in optimizing sequencing coverage and reducing bias [8]. Specialized software tools have been developed to analyze quasi-continuous fragment-size distributions from gel images, providing cost-effective quality control [8].

The relationship between gel type and application can be visualized as follows:

Decision Framework: Denaturing vs. Native Gels

Selection Criteria

Choosing between denaturing and native gel electrophoresis requires careful consideration of experimental objectives and biomolecule properties:

Structural Integrity Requirements: Native gels are imperative when preserving biological activity is essential, such as for enzyme function assays or studying protein-protein interactions [2]. Conversely, denaturing gels are appropriate when molecular weight determination or primary structure analysis is the primary goal.

Complexity of the System: For heterogeneous samples with multiple interacting components, native gels can resolve complex quaternary structures and binding states that would be disrupted under denaturing conditions [2] [6]. Denaturing gels simplify complex mixtures into constituent polypeptides or nucleic acid strands.

Downstream Applications: Consider subsequent analytical steps—native gels allow for functional analysis after separation, while denaturing gels are compatible with techniques like Western blotting and protein sequencing that require denatured samples [2].

Practical Considerations

Beyond theoretical considerations, practical factors influence gel selection:

Simplicity and Cost: Native gels are generally simpler and cheaper to run since they require fewer additives and specialized reagents [2]. This makes them attractive for initial characterization studies or high-throughput screening applications.

Resolution Requirements: Denaturing gels typically provide superior resolution for complex protein mixtures due to the uniform charge-to-mass ratio and elimination of structural heterogeneity [5]. The stacking effect in discontinuous buffer systems further enhances resolution by concentrating samples into sharp bands before entry into the separating gel [5].

Compatibility with Molecular Standards: Denaturing gels enable accurate molecular weight determination using standardized protein or nucleic acid ladders, while migration in native gels depends on multiple factors beyond size alone [2] [6].

Denaturing gel electrophoresis represents a powerful and versatile methodology for biomolecular separation that has maintained its fundamental importance amid rapidly evolving technological landscapes. By systematically unfolding complex tertiary structures into linear chains, denaturing gels reduce separation parameters primarily to molecular weight, enabling precise sizing, purity assessment, and preparation for downstream analytical techniques. The strategic decision between denaturing and native approaches depends critically on experimental objectives, with denaturing conditions optimal for molecular weight determination, Western blotting, and sequencing applications, while native conditions preserve structural integrity and biological function.

As research advances toward increasingly complex biomolecular systems, both denaturing and native gel electrophoresis continue to evolve, finding new applications in quantitative interaction analysis, nanotechnology, and quality control for next-generation sequencing. The enduring utility of these complementary techniques underscores their foundational role in the molecular life sciences and drug development pipelines, providing accessible, cost-effective, and information-rich separation platforms for researchers worldwide.

This technical guide explores the fundamental separation mechanisms in gel electrophoresis, focusing on the distinct principles of non-denaturing (native) and denaturing gel systems. For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice between these systems is critical, as it determines whether biomolecules are separated based on their native conformation (mass, charge, and shape) or their linear length (mass alone). This document provides a comparative analysis of these mechanisms, supported by structured data tables, experimental protocols, and visual workflows to inform experimental design in biomedical research.

Gel electrophoresis is a foundational technique in molecular biology and biochemistry for separating macromolecules such as proteins, DNA, and RNA. The core principle involves applying an electric field to move charged molecules through a porous gel matrix [10] [11]. The gel acts as a sieve, retarding the movement of molecules based on their physical properties [11]. The specific conditions under which electrophoresis is performed—particularly whether the gel environment is native or denaturing—dictate which physical properties of the molecule govern its mobility, thereby defining the analytical outcome [6] [2].

In a non-denaturing (native) gel, the separation mechanism is threefold, incorporating the mass, intrinsic charge, and shape of the biomolecule [6] [12]. This approach preserves the molecule's secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures, allowing for the analysis of functional, folded states [6]. Conversely, in a denaturing gel, the separation mechanism is simplified to mass (or length) alone [2]. Denaturing conditions disrupt all higher-order structure, unfolding the molecule into a linear chain and standardizing its charge-to-mass ratio [6] [12]. This guide delves into the technical nuances of these two separation modes, providing a framework for researchers to make an informed choice based on their analytical goals.

Non-Denaturing Gels: Separation by Mass, Charge, and Shape

Core Separation Mechanism

Non-denaturing, or native, gel electrophoresis operates under conditions that meticulously preserve the natural structure of the biomolecule throughout the separation process. The gel matrix and running buffer lack chemical denaturants, allowing proteins to maintain their folded conformation and nucleic acids to retain their secondary structure, such as hairpins or double-stranded forms [2] [13]. Consequently, a molecule's electrophoretic mobility depends on a combination of its size (mass), its intrinsic net charge at the buffer pH, and its three-dimensional shape and cross-sectional area [6]. The net charge dictates the strength of the electrostatic pull from the electric field, while the mass and shape together determine the frictional drag experienced as the molecule navigates the gel's pores [12]. A smaller, more highly charged, and more compact molecule will migrate faster than a larger, less charged, or more extended one.

Key Applications in Research

The primary advantage of native gels is their ability to provide information about a biomolecule's state in its native environment. Key applications include:

- Analysis of Quaternary Structure and Complexes: Native PAGE is indispensable for studying protein-protein interactions and determining the stoichiometry of multi-subunit complexes [12]. Subunit interactions are retained, allowing researchers to analyze the native aggregation state [12].

- Functional Enzyme Isolation: Since the technique preserves the folded structure, many enzymes remain catalytically active after separation. This enables functional assays, zymography, and the isolation of active enzymes and isozymes [12].

- Study of DNA/RNA Secondary Structure: For nucleic acids, native gels can distinguish between linear, circular, and supercoiled conformations of the same molecule, as each has a different shape and thus migrates at a different rate [2].

- Protein-Ligand and Protein-Nucleic Acid Binding Studies: The mobility shift observed when a ligand binds to a protein or protein to DNA can be used to analyze binding interactions without disrupting the complex.

Denaturing Gels: Separation by Mass Alone

Core Separation Mechanism

Denaturing gel electrophoresis is designed to dismantle the native structure of biomolecules, simplifying the separation to a single parameter: mass or linear length. For proteins, this is most commonly achieved through Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) [12]. The sample is heated in a buffer containing SDS (an anionic detergent) and a reducing agent (like DTT or β-mercaptoethanol) [12]. SDS binds uniformly to the protein backbone, conferring a constant negative charge that masks the protein's intrinsic charge [12]. Meanwhile, the reducing agent breaks disulfide bonds, dismantling tertiary and quaternary structures [12]. The result is a solution of polypeptide chains that are linear, rod-like, and possess a uniform charge-to-mass ratio [12]. Under these conditions, electrophoretic mobility is determined solely by molecular weight, with smaller polypeptides migrating faster than larger ones [12].

For nucleic acids, denaturation is typically accomplished using urea [6] [2] or a combination of DMSO and glyoxal [2]. These agents break the hydrogen bonds that form secondary structures, forcing DNA or RNA into single-stranded, random coil conformations. Like SDS-treated proteins, these denatured nucleic acids have a charge-to-mass ratio determined solely by their sugar-phosphate backbone, allowing separation based strictly on the number of nucleotides (length) [6] [13].

Key Applications in Research

The power of denaturing gels lies in their simplicity and precision for specific analytical tasks:

- Molecular Weight Determination: SDS-PAGE is the standard method for estimating the molecular weight of unknown proteins by comparing their migration to a ladder of proteins with known masses [12].

- Assessing Purity and Integrity: Denaturing gels are ideal for establishing the purity of a protein sample or checking the integrity of nucleic acid extracts (e.g., RNA integrity), as they separate molecules based solely on size and can reveal contaminants or degradation products [2] [12].

- Preparative Steps for Downstream Analysis: Techniques like Western blotting, protein sequencing, and mass spectrometry often require proteins to be denatured, making SDS-PAGE an essential first step [2] [12].

- High-Resolution Nucleic Acid Separation: Denaturing polyacrylamide gels can achieve single-base-pair resolution, making them crucial for sequencing and analyzing small nucleic acid fragments [14].

Comparative Analysis and Selection Guidelines

Direct Mechanism Comparison

The table below provides a direct comparison of the separation characteristics of native and denaturing gel systems.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Native vs. Denaturing Gel Separation Mechanisms

| Feature | Non-Denaturing (Native) Gels | Denaturing Gels |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Mass, intrinsic charge, and shape/cross-sectional area [6] | Molecular mass (or length) alone [6] [2] |

| Structural Analysis | Primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structure [6] | Primary structure only [6] |

| Biomolecule State | Folded, in native conformation [2] [12] | Unfolded, linearized chains [6] [2] |

| Charge Profile | Native charge at buffer pH [12] | Masked by SDS (proteins) or uniform backbone (nucleic acids) [12] |

| Key Reagents | Non-denaturing, non-reducing buffers [12] | SDS, urea, DTT, β-mercaptoethanol [6] [12] |

| Functional Activity | Often preserved post-separation [12] | Destroyed [12] |

Gel Selection Guidelines for Experimental Goals

Choosing the correct gel type is paramount to experimental success. The following decision workflow and table outline the optimal choice based on common research objectives.

Figure 1: A decision workflow to guide researchers in selecting between native and denaturing gel systems based on their primary experimental objective.

Table 2: Experimental Goals and Recommended Gel Types

| Experimental Goal | Recommended Gel Type | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Determine protein aggregation state or quaternary structure [12] | Native | Preserves subunit interactions and complex size/shape. |

| Isolate an enzyme for functional activity assays [12] | Native | Maintains folded, active conformation. |

| Study protein-DNA/RNA binding interactions [2] | Native | Binding events alter the mass/charge/shape complex, shifting mobility. |

| Estimate protein molecular weight [12] | Denaturing (SDS-PAGE) | Mobility depends solely on polypeptide chain length. |

| Establish protein sample purity or nucleic acid integrity [2] [12] | Denaturing | Separates contaminants and degradation products by size. |

| Prepare samples for Western blotting or protein sequencing [12] | Denaturing | Downstream techniques often require denatured, linearized proteins. |

| Separate nucleic acids with single-base resolution [14] | Denaturing | Eliminates conformational heterogeneity, separating by length only. |

Practical Implementation: Gel Types and Specifications

Polyacrylamide Gel Formulations

Polyacrylamide gels, formed from the chemical polymerization of acrylamide and bis-acrylamide, offer highly tunable pore sizes and superior resolution [14]. The gel percentage (%T) must be matched to the size of the target analyte.

Table 3: Recommended Polyacrylamide Gel Percentages for Optimal Separation

| Gel Type | % Acrylamide | Optimal Separation Range | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Denaturing | 3.5% | 100 - 1,000 bp [14] | Large dsDNA fragments |

| 5.0% | 80 - 500 bp [14] | Medium dsDNA fragments | |

| 8.0% | 60 - 400 bp [14] | Small dsDNA fragments | |

| 12.0% | 50 - 200 bp [14] | Very small dsDNA fragments | |

| Denaturing | 5.0% | 70 - 400 bases [14] | Medium ssDNA/RNA |

| 8.0% | 30 - 200 bases [14] | Small ssDNA/RNA | |

| 12.0% | 20 - 100 bases [14] | Oligonucleotides | |

| 15.0% | 10 - 50 bases [14] | Short oligonucleotides |

Safety Note: Unpolymerized acrylamide is a potent neurotoxin. Handling of powdered acrylamide requires appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) including gloves and a mask. Using pre-made acrylamide solutions or pre-cast gels is highly recommended to minimize exposure risk [13].

Agarose Gel Formulations

Agarose, a polysaccharide derived from seaweed, forms gels via thermal setting and is generally non-toxic and easy to handle [14] [11]. It is ideal for separating larger nucleic acids.

Table 4: Recommended Agarose Gel Percentages for DNA Separation

| % Agarose | Optimal Separation Range (bp) |

|---|---|

| 0.5% | 2,000 - 50,000 [14] |

| 0.7% | 800 - 12,000 [14] |

| 1.0% | 500 - 10,000 [14] |

| 1.2% | 400 - 7,000 [14] |

| 1.5% | 200 - 3,000 [14] |

| 2.0% | 100 - 2,000 [14] |

| 3.0% | 25 - 1,000 [14] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful gel electrophoresis relies on a suite of specific reagents, each serving a critical function in the preparation, separation, and visualization of samples.

Table 5: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Gel Electrophoresis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms the cross-linked polymer matrix for PAGE [14]. | Neurotoxic in monomeric form; use pre-made solutions for safety [13]. |

| Agarose | Forms the thermo-reversible hydrogel matrix for agarose gels [14]. | Low melting point (LMP) agarose allows gentle extraction of intact nucleic acids [14]. |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | Initiator for acrylamide polymerization [14]. | Use fresh aliquots stored at -20°C for efficient and complete polymerization [13]. |

| TEMED | Catalyst for acrylamide polymerization [14]. | Works with APS to accelerate the radical polymerization reaction. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Anionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge [12]. | Critical for SDS-PAGE; disrupts hydrophobic interactions and masks native charge. |

| Urea | Denaturing agent that disrupts hydrogen bonds in nucleic acids and proteins [6] [2]. | Used in denaturing PAGE to keep nucleic acids single-stranded. |

| DTT/β-Mercaptoethanol | Reducing agents that break disulfide bonds in proteins [12]. | Essential for complete denaturation and linearization of proteins in SDS-PAGE. |

| TAE/TBE Buffer | Running buffer that carries current and maintains stable pH [13]. | TBE provides sharper bands for small DNA fragments; TAE is better for DNA recovery from gels [13]. |

| Ethidium Bromide/SYBR Safe | Fluorescent dyes that intercalate between DNA bases for visualization [13]. | Ethidium bromide is mutagenic; safer alternatives like SYBR Safe are recommended [13]. |

| Tracking Dye | Contains colored markers (e.g., bromophenol blue) to monitor run progress [13]. | Migrates at a known rate, providing an estimate of when to stop the run. |

The strategic decision to use a native or denaturing gel system is foundational to the successful separation and analysis of biomolecules. Native gels, which separate based on mass, charge, and shape, are the unequivocal choice for experiments focused on the functional, folded state of a molecule, including its enzymatic activity, quaternary structure, and interaction with other molecules. In contrast, denaturing gels, which separate based on mass alone, provide a simplified and highly effective means to determine molecular weight, assess purity, and prepare samples for downstream analytical techniques. By understanding these core separation mechanisms and applying the guidelines and data provided in this document, researchers can rationally select the optimal electrophoretic method to advance their scientific inquiries and drug development processes.

In the field of biomolecular research, gel electrophoresis stands as a fundamental technique for separating and analyzing proteins and nucleic acids. The critical choice between denaturing and non-denaturing (native) gel systems fundamentally shapes experimental outcomes and data interpretation. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the three primary chemical agents—sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), reducing agents, and urea—that enable denaturing electrophoresis. Within the context of a broader research framework on choosing appropriate gel systems, understanding the specific mechanisms and applications of these chemicals is paramount for designing rigorous experiments, particularly in drug development where characterizing therapeutic molecules like proteins and oligonucleotides requires precise conditions [15]. This whitepaper delineates their distinct molecular mechanisms, experimental protocols, and appropriate applications to equip researchers with the knowledge necessary to select optimal conditions for their specific experimental goals, whether for protein analysis, nucleic acid separation, or quality control of biopharmaceuticals.

Fundamental Concepts: Denaturing vs. Non-Denaturing Gels

The core distinction in gel electrophoresis lies in whether the native structure of the biomolecule is preserved during analysis. Denaturing gels are run under conditions that disrupt the natural secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures of proteins or the secondary structure of nucleic acids. These conditions unfold the molecules into linear chains, meaning their migration through the gel matrix depends primarily on their molecular mass and, with modifications like SDS-coating, can be made dependent on molecular mass alone [2] [6]. In contrast, non-denaturing gels (native gels) maintain the molecule's structure as it exists in its native state. Separation in native gels depends not only on molecular mass and intrinsic charge but also on the overall bulk, shape, and cross-sectional area of the macromolecule [2] [6]. This allows for the analysis of all four levels of biomolecular structure and is crucial for studying functional complexes, enzymatic activity, and binding interactions [6].

The decision to use one system over the other is driven by the experimental objective. Table 1 outlines the primary applications for each gel type.

Table 1: Guidelines for Selecting Gel Conditions Based on Experimental Goals

| Application | Recommended Gel Type |

|---|---|

| Isolating Enzymes or Studying Binding in Proteins [2] | Non-Denaturing Gel |

| Determining Protein Hierarchical State (e.g., circular vs. linear DNA) [2] | Non-Denaturing Gel |

| Teasing Apart Macromolecular Complexes with Quaternary Structure [2] | Non-Denaturing Gel |

| Western Blotting [2] | Denaturing Gel |

| Establishing Sample Purity Based on Molecular Weight [2] | Denaturing Gel |

| Protein Sequencing [2] | Denaturing Gel |

| Separating Molecules Based Solely on Mass [2] | Denaturing Gel |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the critical decision points when choosing between denaturing and non-denaturing gel systems for an experiment.

Detailed Analysis of Denaturing Agents

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS)

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) is an ionic detergent and is the cornerstone of SDS-PAGE, the most common method for denaturing protein electrophoresis. Its mechanism of action is two-fold. First, SDS binds to the hydrophobic regions of proteins, effectively masking their intrinsic charge. SDS molecules bind to proteins in a constant mass ratio of approximately 1.4 μg SDS per 1.0 μg protein, conferring a uniform negative charge per unit mass [16]. Second, it disrupts nearly all non-covalent interactions—specifically hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions—causing the protein to unfold into a linear chain [17]. It is critical to note that SDS does not break covalent disulfide bonds [17]. The result is that proteins separated on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel migrate based almost exclusively on their molecular weight, allowing for accurate size determination [2].

Reducing Agents

Reducing agents are specifically designed to break disulfide bonds (-S-S-), which are covalent bonds that stabilize the three-dimensional structure of many proteins [17] [18]. The reduction of these bonds is often necessary to fully unfold proteins that contain them. Commonly used reducing agents include:

- Dithiothreitol (DTT) and β-mercaptoethanol (BME): These thiol-based reducing agents work by undergoing thiol-disulfide exchange reactions, reducing protein disulfide bonds to free thiol groups [18].

- Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP): A potent, odor-free, and more stable alternative to DTT and BME. A key advantage of TCEP is that it is thiol-free, which prevents its reoxidation and makes it suitable for reactions where thiols might interfere [18].

In a typical denaturing SDS-PAGE protocol, SDS and a reducing agent like DTT are used in concert. The SDS denatures the non-covalent structure, while the reducing agent cleaves the disulfide bonds, resulting in a fully unfolded, linear polypeptide chain.

Urea

Urea is a potent protein denaturant that operates through a different mechanism. It acts primarily by disrupting hydrogen bonds and, to a lesser extent, hydrophobic interactions [17]. Urea is a polar molecule that integrates into the water structure and forms hydrogen bonds with the peptide backbone and polar side chains, effectively competing with the intramolecular hydrogen bonds that stabilize the protein's native structure [17]. This leads to the unfolding of the protein molecule. Urea is commonly used at high concentrations (e.g., 6-8 M) in gel electrophoresis to denature proteins, and it is also frequently employed for nucleic acid denaturation [2] [16]. A critical consideration when using urea is the potential for carbamylation, where isocyanic acid (a decomposition product in equilibrium with urea solutions) can modify lysine residues and protein N-termini. This can be mitigated by using fresh urea solutions, adding scavengers, or using urea for the shortest time possible [16].

Table 2 provides a comparative summary of the mechanisms, strengths, and limitations of these key denaturing agents.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Key Denaturing Agents

| Agent | Primary Mechanism of Action | Key Interactions Disrupted | Advantages | Limitations & Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDS | Binds protein backbone; confers negative charge. | Hydrophobic interactions, Hydrogen bonds [17]. | Uniform charge-to-mass ratio; ideal for molecular weight determination [2]. | Does not break disulfide bonds [17]; can interfere with enzyme function. |

| Reducing Agents (DTT, TCEP) | Thiol-disulfide exchange (DTT) or direct reduction (TCEP). | Covalent Disulfide bonds [18]. | TCEP is odor-free, more stable, and thiol-free [18]. | DTT/BME can oxidize over time; necessary for complete unfolding of disulfide-linked proteins. |

| Urea | Forms H-bonds with protein backbone; disrupts water structure. | Hydrogen bonds, Hydrophobic interactions [17]. | Effective for proteins and nucleic acids; useful for solubilizing hydrophobic proteins [16]. | Forms cyanate ions that can cause protein carbamylation; solution stability is time-sensitive [16]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard SDS-PAGE Protocol for Denaturing Protein Electrophoresis

The following protocol is adapted for pre-cast Tris-Glycine gels using a standard mini-gel system [7].

- Gel Preparation: Remove a pre-cast Tris-Glycine gel from refrigeration and bring to room temperature. Rinse the gel cassette with deionized water, peel the tape from the bottom, and gently remove the comb in one smooth motion. Rinse the sample wells with 1X SDS Running Buffer [7].

- Sample Preparation:

- Mix the protein sample with an equal volume of 2X Tris-Glycine SDS Sample Buffer to achieve a 1X final concentration.

- For reduced samples, add a reducing agent (e.g., DTT or TCEP) to a final concentration of 1X immediately before heating [7].

- Heat the samples at 85°C for 2 minutes to denature the proteins. Do not heat samples for native electrophoresis. Centrifuge briefly to bring down condensation [7].

- Electrophoresis Setup: Place the gel cassette in the electrophoresis chamber. Fill the inner (upper) and outer (lower) chambers with 1X Tris-Glycine SDS Running Buffer. Load the prepared samples and an appropriate protein molecular weight marker into the wells [7].

- Electrophoretic Run: Run the gel at a constant voltage of 125 V for approximately 90 minutes, or until the bromophenol blue tracking dye front reaches the bottom of the gel. The current should start at 30-40 mA per gel and end at 8-12 mA [7].

- Post-Run Analysis: After electrophoresis, carefully open the cassette using a gel knife. The gel can then be processed for staining (e.g., Coomassie Blue or silver stain) or transferred to a membrane for western blotting [7].

Critical Considerations for Sample Integrity

Sample preparation is a critical step where artifacts can be introduced. Key pitfalls and their solutions include:

- Protease Activity: Proteases in the sample can remain active in SDS sample buffer at room temperature. To prevent protein degradation, heat samples immediately after adding them to the sample buffer. A control experiment can involve comparing a sample heated immediately versus one left at room temperature for 2-4 hours before heating [16].

- Asp-Pro Bond Cleavage: Heating proteins at 100°C for extended periods can cleave acid-labile Asp-Pro bonds. Heating at 75°C for 5 minutes is often sufficient for denaturation while avoiding this specific cleavage [16].

- Keratin Contamination: Contamination from skin and hair (keratin) is a common artifact, visible in sensitive stains. Always wear gloves, and use aliquoted, stored sample buffer to minimize contamination. Running a sample buffer-only control can help identify this issue [16].

- Insufficient SDS Ratio: An inadequate sample buffer-to-protein ratio can lead to incomplete denaturation and skewed results. A ratio of 3:1 (SDS to protein) is recommended to ensure an excess of SDS [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Denaturing Electrophoresis

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Denaturing Gel Electrophoresis

| Reagent | Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Ionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge. | Essential for SDS-PAGE; disrupts hydrophobic interactions and H-bonds [17]. |

| TCEP (Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine) | Reduces disulfide bonds. | Thiol-free, odor-free, and more stable than DTT; ideal for stable reduction [18]. |

| DTT (Dithiothreitol) | Reduces disulfide bonds. | Common thiol-based reducing agent; requires fresh preparation or aliquoting [18]. |

| Urea | Denatures proteins and nucleic acids by disrupting hydrogen bonds. | Used at high concentrations (e.g., 8 M); effective for solubilizing hydrophobic proteins [16] [18]. |

| Tris-Glycine SDS Sample Buffer | Ready-to-use buffer for denaturing protein samples. | Contains SDS, buffer, and tracking dye; simplifies sample preparation [7]. |

| Acrylamide/Bis-Acrylamide | Forms the cross-linked matrix of polyacrylamide gels. | Pore size is determined by the total concentration (%T); a neurotoxin in its monomeric form [14]. |

| Agarose | Polysaccharide polymer used for nucleic acid gel matrices. | Separates larger DNA/RNA fragments (0.1-25 kb); pore size controlled by gel percentage [14]. |

The strategic selection of denaturing agents—SDS, reducing agents, and urea—is a foundational decision that directly determines the success of gel electrophoresis experiments. SDS provides uniform charge and disrupts non-covalent interactions, reducing agents specifically target stable disulfide bridges, and urea effectively dismantles hydrogen bonding networks. Their combined and individual use allows researchers to tailor the level of denaturation to their specific needs, from determining simple molecular weight to analyzing complex structural forms. By understanding their distinct mechanisms, adhering to robust protocols that guard against common artifacts, and selecting the appropriate reagents from the available toolkit, scientists and drug development professionals can generate reliable, reproducible, and interpretable data, thereby advancing research and therapeutic development.

Practical Applications: Choosing the Right Gel for Your Experimental Goals

Native gel electrophoresis serves as a critical tool for researchers studying proteins in their biologically active states. Unlike denaturing techniques that dismantle protein structure, native methods preserve macromolecular complexes, enzymatic activity, and higher-order assemblies, providing unique insights into protein function that would otherwise be lost. This technical guide examines the core applications, methodological considerations, and practical protocols for implementing native gel electrophoresis in research and drug development. Within the broader context of choosing between denaturing and non-denaturing gel systems, we demonstrate how native gels enable the characterization of enzymatically active complexes, analysis of protein-protein interactions, and identification of aggregation states relevant to disease pathology and therapeutic development.

Native gel electrophoresis represents a family of techniques that separate proteins based on their intrinsic charge, size, and shape under non-denaturing conditions, preserving their tertiary and quaternary structures [19]. The fundamental principle distinguishing native from denaturing electrophoresis lies in the absence of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and reducing agents that would otherwise dismantle non-covalent interactions and disulfide bonds [19]. This preservation is crucial for investigating biologically relevant protein states, as most proteins function as part of larger complexes rather than as isolated polypeptides [20].

The separation mechanism in native gels depends on both the protein's net charge at the running pH and its ability to migrate through the gel matrix via molecular sieving [19]. Unlike SDS-PAGE, where migration correlates primarily with polypeptide molecular weight, native separation reflects the combined effects of charge, size, and shape of the intact macromolecular assembly [19]. This complexity enables researchers to probe protein function, interaction networks, and assembly pathways that remain inaccessible to denaturing methods.

Core Applications of Native Gels

Analysis of Enzyme Complexes and Activity

Native gel electrophoresis uniquely enables the study of enzymatically active complexes directly within the gel matrix. This application is particularly valuable for investigating mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) complexes, which consist of five multimeric enzyme complexes embedded in mitochondrial cristae membranes [21] [22]. Blue-native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) and clear-native PAGE (CN-PAGE) have become indispensable techniques for resolving these hydrophobic enzyme systems while maintaining their catalytic function [21] [23] [22].

After electrophoretic separation, specific in-gel activity staining protocols allow direct visualization of functional complexes. For example, Complex I (NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase) activity can be detected using NADH and nitroblue tetrazolium, while Complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase) activity is visualized via cytochrome c oxidation coupled to diaminobenzidine staining [21] [22]. A key advantage of CN-PAGE over BN-PAGE for these applications is the absence of residual Coomassie blue dye, which can interfere with activity staining results [21] [22]. These approaches have proven instrumental for identifying pathological mechanisms in patients with monogenetic OXPHOS disorders and for studying assembly pathways of respiratory chain complexes [22].

Table 1: Enzyme Complexes Amenable to Native Gel Analysis

| Enzyme Complex | Detection Method | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) | NADH/NBT reduction assay | Assembly analysis, mitochondrial disorders | Requires specific staining conditions |

| Complex II (Succinate dehydrogenase) | Succinate/PMS/NBT assay | Metabolic capacity assessment | May detect partial assemblies |

| Complex IV (Cytochrome c oxidase) | Cytochrome c/DAB oxidation | Respiratory chain function | Comparative insensitivity in-gel [22] |

| Complex V (ATP synthase) | ATP-dependent lead phosphate precipitation | Energy transduction studies | Enhancement step improves sensitivity [22] |

| Halide Methyltransferase | Alkyltransferase activity assay | Enzyme engineering, substrate preference | Requires specific substrates [24] |

| Phytase | Phosphate release assays | pH activity profiling, engineering | Neutral pH activity detection [24] |

Characterization of Protein Complexes and Supercomplexes

Beyond individual enzymes, native gels excel at resolving higher-order assemblies including respiratory supercomplexes (respirasomes) consisting of Complexes I, III, and IV [21] [22]. The choice of detergent during sample preparation determines whether individual complexes or supercomplexes are preserved. While n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (DDM) solubilizes membranes while maintaining individual OXPHOS complexes, the milder detergent digitonin preserves supercomplex interactions [21] [22]. This capability has revolutionized our understanding of mitochondrial organization, revealing how respiratory complexes form functional units within cristae membranes rather than existing as isolated entities.

The two-dimensional BN/SDS-PAGE technique further extends these analyses by combining native separation in the first dimension with denaturing separation in the second dimension [21] [22] [20]. This approach reveals the subunit composition of each complex, identifies assembly intermediates, and detects pathological alterations in protein complex biosynthesis. Such detailed characterization is invaluable for drug development targeting multi-protein complexes, as it enables researchers to monitor how therapeutic interventions affect complex assembly, stability, and composition.

Investigation of Protein Aggregation States

Native gels provide critical insights into protein aggregation phenomena relevant to numerous diseases. Unlike denaturing gels that would dissociate non-covalent aggregates, native systems preserve these higher-order assemblies, allowing researchers to distinguish oligomers, aggregates, and functional complexes [25]. For example, native Tris-glycine polyacrylamide gels with 4.5% stacking and 7.5% separation gels have been used to detect BiP oligomers in mammalian cell lysates, revealing chaperone assembly states critical for protein folding homeostasis [25].

These applications extend to neurodegenerative diseases characterized by protein aggregation, where native gels can help identify early oligomeric species potentially more toxic than larger fibrillar aggregates. The technique also supports biopharmaceutical development by characterizing therapeutic protein products, detecting unwanted aggregates that could affect efficacy or immunogenicity, and ensuring product quality throughout development and manufacturing.

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Design

Native Gel Systems: BN-PAGE, CN-PAGE, and Native-PAGE

Several specialized native gel systems have been developed to address different research questions:

Blue-Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) utilizes the anionic dye Coomassie blue G-250, which binds to hydrophobic protein surfaces and imposes a negative charge shift [21] [22] [20]. This charge shift forces even basic proteins to migrate toward the anode at pH 7.0 while preventing aggregation of hydrophobic proteins during electrophoresis [21] [22]. First described by Schägger and Von Jagow in 1991, BN-PAGE has become the gold standard for analyzing mitochondrial membrane protein complexes [21] [22] [20]. The protocol typically involves solubilizing membrane proteins with mild nonionic detergents like n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside in the presence of 6-aminocaproic acid, which provides a zero net charge at pH 7.0 and supports extraction without affecting electrophoresis [21] [22].

Clear-Native PAGE (CN-PAGE) replaces Coomassie blue with mixtures of anionic and neutral detergents in the cathode buffer to induce the necessary charge shift [21] [22]. These mixed micelles enhance protein solubility and electrophoretic migration similar to Coomassie blue, but avoid blue dye interference during downstream in-gel enzyme activity staining [21] [22]. CN-PAGE typically offers higher resolution than BN-PAGE but may not be suitable for all protein complexes.

Standard Native-PAGE systems, such as Tris-glycine native gels, maintain proteins in their native state without additional charge-shifting agents [25]. These systems are simpler to implement but may have limitations with very hydrophobic or basic proteins. The separation depends on the intrinsic charge of the proteins at the running pH, which must be carefully considered during experimental design.

Table 2: Comparison of Native Gel Electrophoresis Techniques

| Parameter | BN-PAGE | CN-PAGE | Standard Native-PAGE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charge modifier | Coomassie blue G-250 | Mixed detergent micelles | None |

| Resolution | High | Higher | Moderate |

| Compatibility with activity staining | Limited due to dye interference | High | High |

| Best for | Membrane protein complexes, initial characterization | High-resolution separation, activity assays | Soluble complexes, simple applications |

| Typical gel composition | 3-12% or 4-16% linear gradient | 3-12% or 4-16% linear gradient | Variable (e.g., 7.5% separation gel) |

| Sample buffers | 50 mM Bis-Tris, 0.75 M 6-aminocaproic acid, pH 7.0 [20] | Detergent-based cathode buffers | Tris-glycine, pH ~8.8 [25] |

Gel Matrix Selection: Polyacrylamide vs. Polysaccharide

The choice of gel matrix significantly impacts separation performance and application suitability:

Polyacrylamide gels offer smaller pore sizes (e.g., 70-130 nm for 3.5-10.5% gels) and are ideal for separating most protein complexes [19]. The cross-linked structure formed by polyacrylamide chains and bis-acrylamide creates a molecular sieving environment that separates complexes based on size and shape [19]. Linear gradient gels (e.g., 3-12% or 4-16%) provide superior resolution across a broad molecular weight range compared to single-percentage gels [21] [23].

Agarose gels, composed of polysaccharide chains that form α-helical bundles creating a network structure, have larger pore sizes (0.05-0.1 μm) [19]. These are particularly suitable for very large complexes, aggregates, or nucleic acid-protein interactions. Agarose offers advantages for native separation of large macromolecular assemblies that would be excluded from polyacrylamide matrices.

Critical Experimental Parameters

Successful native gel electrophoresis requires careful optimization of several parameters:

Detergent selection dictates which complexes remain intact. Mild nonionic detergents like digitonin preserve weak interactions and supercomplexes, while slightly harsher detergents like DDM maintain individual complexes but may disrupt superassemblies [21] [22].

Buffer composition must maintain appropriate pH and ionic strength to preserve native structures while supporting electrophoretic separation. Bis-Tris-based buffers at pH 7.0 are commonly used in BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE, while Tris-glycine at higher pH (~8.8) works for standard native-PAGE [20] [25]. The zwitterionic salt 6-aminocaproic acid is often included to support solubilization without interfering with electrophoresis [21] [22].

Sample preparation techniques vary by starting material. For mitochondrial studies, isolated mitochondria are typically solubilized in 0.75 M 6-aminocaproic acid, 50 mM Bis-Tris (pH 7.0) with added detergent (1-2% DDM for individual complexes or 2-4% digitonin for supercomplexes) [20]. After 30-minute incubation on ice, insoluble material is removed by centrifugation at 72,000 × g before adding Coomassie blue dye (for BN-PAGE) or loading directly (for CN-PAGE).

Experimental Workflows and Visualization

Standard BN-PAGE Protocol

The following workflow outlines a typical BN-PAGE procedure for analyzing mitochondrial complexes:

Downstream Applications and Two-Dimensional Analysis

Following native separation, multiple downstream applications enable comprehensive characterization:

In-gel activity staining utilizes specific substrates and colorimetric reactions to detect functional complexes directly within the gel matrix. For example, Complex V activity can be enhanced through a simple modification that markedly improves sensitivity [22].

Western blot analysis after native transfer to PVDF membranes enables specific detection of complex components using antibodies. Fully submerged electroblotting systems at 150 mA for 1.5 hours using Tris-glycine transfer buffer with 10% methanol are recommended [20].

Two-dimensional BN/SDS-PAGE provides the most comprehensive analysis by combining native separation in the first dimension with denaturing separation in the second dimension. After BN-PAGE, individual lanes are excised, soaked in SDS denaturing buffer, and placed on top of SDS-PAGE gels for orthogonal separation [20]. This reveals subunit composition, identifies assembly intermediates, and detects pathological alterations in complex biosynthesis.

Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Native Gel Electrophoresis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) | Mild nonionic detergent for solubilizing membrane complexes | 10% solution in water [20] |

| Digitonin | Very mild detergent for preserving supercomplexes | 5% (w/v) solution [23] |

| 6-Aminocaproic acid | Zwitterionic salt supporting solubilization | 0.75 M in 50 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0 [20] |

| Coomassie blue G-250 | Charge-shift dye for BN-PAGE | 5% solution in 0.5 M aminocaproic acid [20] |

| Bis-Tris | Buffer component for native conditions | 50 mM anode buffer, 15 mM cathode buffer [20] |

| Protease inhibitors | Prevent protein degradation during processing | 1 mM PMSF, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, 1 μg/mL pepstatin [20] |

| Linear gradient gels | Separation matrix for broad size range | 3-12% or 4-16% acrylamide [21] [23] |

| PVDF membrane | Transfer matrix for western blotting | 0.2 μm pore size [20] |

Native gel electrophoresis provides an indispensable toolkit for researchers investigating protein function in biologically relevant contexts. By preserving enzymatic activity, maintaining protein-protein interactions, and revealing aggregation states, these techniques offer insights fundamentally inaccessible to denaturing methods. Within the broader decision framework for choosing electrophoretic methods, native gels occupy the essential niche of functional proteomics—answering questions not just about what proteins are present, but how they assemble, interact, and function within the cell.

The continuing development of more sensitive detection methods, improved separation matrices, and enhanced compatibility with downstream analytical techniques ensures that native gel electrophoresis will remain a cornerstone technique for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to understand and manipulate complex biological systems at the molecular level.

In molecular biology and biochemistry, the choice between denaturing and non-denaturing (native) gel electrophoresis is fundamental and directly dictates the type of information an experiment can yield. Denaturing gel electrophoresis is a technique designed to disrupt the native structure of biomolecules—such as proteins and nucleic acids—unfolding them into linear chains. This process ensures that separation occurs primarily based on molecular weight, as the intrinsic charge and complex three-dimensional shape of the molecule are eliminated as factors [2] [6]. This stands in stark contrast to native gel electrophoresis, where the biomolecule's structure, charge, and cross-sectional area all influence its migration, providing information on the molecule's natural, folded state [2] [6].

The core thesis of this guide is that denaturing gels are the indispensable tool for experiments where the analytical goal requires the disruption of higher-order structure to assess linear length, molecular weight, or the composition of a complex protein mixture. The three primary applications that fulfill this criterion are accurate molecular weight determination, western blotting, and the assessment of protein sample purity. This technical guide will delve into the specific protocols and rationale for employing denaturing gels in these key research contexts, providing a clear framework for scientists and drug development professionals to inform their experimental design.

Key Applications and Experimental Protocols

Molecular Weight Determination

Principle and Rationale: For accurate molecular weight determination, denaturing gel electrophoresis is the method of choice. The foundation of this application is the complete denaturation of the protein sample, typically using Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS), in a technique known as SDS-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). SDS is an anionic detergent that binds to hydrophobic regions of proteins, coating them in a uniform negative charge. This action overwhelms the protein's intrinsic charge and, with the aid of heat and a reducing agent like Dithiothreitol (DTT) or 2-mercaptoethanol to break disulfide bonds, forces the protein to unfold into a linear polypeptide chain [26] [27]. Consequently, the charge-to-mass ratio becomes nearly identical for all proteins, and their migration through the polyacrylamide gel matrix depends almost exclusively on their molecular weight [2] [6]. Smaller proteins migrate faster and farther than larger ones, allowing for size-based separation [27].

Detailed Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Protein samples are mixed with an SDS-containing loading buffer that includes a reducing agent (DTT or 2-mercaptoethanol) and glycerol for density. The mixture is then heated at 95-100°C for 5-10 minutes to ensure complete denaturation [26] [27].

- Gel Selection and Loading: A polyacrylamide gel is used, consisting of a stacking gel (pH ~6.8, lower acrylamide concentration) and a separating/resolving gel (pH ~8.8, higher acrylamide concentration). The percentage of acrylamide in the separating gel should be chosen based on the target protein's size (e.g., 8% for large proteins >150 kDa, 10-15% for proteins 10-150 kDa, and up to 20% for very small proteins) [27]. A molecular weight ladder (protein standard) containing proteins of known sizes must be loaded alongside the samples [27].

- Electrophoresis: The gel is immersed in a running buffer and an electric current is applied. The stacking gel allows the proteins to concentrate into sharp bands before entering the separating gel, where they are resolved by size. The gel is run until the dye front (bromophenol blue) approaches the bottom [26] [27].

- Visualization and Analysis: After electrophoresis, the gel is stained with a protein-specific stain (e.g., Coomassie Brilliant Blue, silver stain, or "fast stain" alternatives) to reveal the protein bands [28]. The distance migrated by the protein of interest is compared to the logarithmic plot of the molecular weight standard's migration to determine its apparent molecular weight.

Figure 1: SDS-PAGE workflow for determining protein molecular weight.

Western Blotting