Native PAGE vs. SDS-PAGE: The Ultimate Guide for Protein Analysis in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive decision-making framework for researchers and drug development professionals selecting between Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE.

Native PAGE vs. SDS-PAGE: The Ultimate Guide for Protein Analysis in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive decision-making framework for researchers and drug development professionals selecting between Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE. It covers the foundational principles of each technique, their specific methodological applications in studying protein complexes and molecular weight, practical troubleshooting advice, and validation strategies for interpreting results. The guide synthesizes current protocols to empower scientists in choosing the optimal electrophoresis method for their specific research objectives in structural biology, proteomics, and therapeutic development.

Core Principles: How Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE Work at the Molecular Level

Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE) is a foundational technique in biochemistry and molecular biology laboratories for separating protein molecules based on their physical characteristics [1]. The principle of electrophoresis involves transporting charged protein molecules through a porous gel matrix under the influence of an electrical field, where their mobility depends on factors including field strength, the molecule's net charge, size, shape, and the properties of the matrix itself [2]. The polyacrylamide gel, created through the copolymerization of acrylamide and a cross-linker (N,N'-methylenebisacrylamide), acts as a molecular sieve with a tunable pore size that determines the range of protein sizes that can be effectively resolved [3] [2].

Two principal variants of this technique—SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE—have become indispensable tools for protein analysis, each providing distinct insights based on their separation mechanisms [4] [1]. SDS-PAGE, or sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, separates proteins that have been denatured into their constituent polypeptides, primarily by molecular mass [5]. In contrast, Native PAGE (non-denaturing PAGE) separates proteins in their folded, native state, with migration influenced by the protein's intrinsic charge, size, and three-dimensional shape [4] [2]. The choice between these methods is critical and depends entirely on the specific research objectives, whether determining molecular weight, studying protein function, investigating protein complexes, or analyzing subunit composition [1].

Fundamental Principles and Separation Mechanisms

SDS-PAGE: Separation by Molecular Weight Alone

SDS-PAGE is designed to separate proteins based almost exclusively on their molecular weight [5] [2]. This is achieved through the use of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), a strong anionic detergent that binds uniformly to the protein's polypeptide backbone in a constant weight ratio of approximately 1.4 grams of SDS per 1 gram of protein [6] [2]. This extensive binding accomplishes two critical functions: first, it denatures the protein, disrupting its secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures by breaking hydrogen bonds and unfolding the polypeptide into a linear chain; second, it confers a uniform negative charge density along the length of the denatured protein, effectively masking the protein's intrinsic charge [4] [1] [2].

When an electric field is applied, the resulting SDS-polypeptide complexes migrate through the polyacrylamide gel toward the anode, with separation governed primarily by the sieving effect of the gel matrix [2]. Smaller polypeptides navigate the porous network more easily and migrate faster, while larger polypeptides are retarded [4]. Consequently, the migration distance is inversely proportional to the logarithm of the molecular mass, allowing for accurate molecular weight estimation when compared with standard protein markers [5]. The sample is typically heated to 95°C in the presence of SDS and a reducing agent like β-mercaptoethanol or dithiothreitol (DTT) to ensure complete denaturation and the cleavage of disulfide bonds [4] [5].

Native PAGE: Separation by Size, Charge, and Shape

In stark contrast, Native PAGE separates proteins based on their native charge, size, and three-dimensional shape, as it is performed under non-denaturing conditions without SDS [4] [2]. In this technique, proteins remain in their folded, functional conformation, and their migration through the gel depends on the protein's intrinsic charge at the running buffer's pH and the frictional force it experiences, which is dictated by its size and shape [1] [2].

A protein's net charge in Native PAGE is determined by the pH of the electrophoresis buffer relative to the protein's isoelectric point (pI) [3]. Proteins carry a net negative charge in alkaline running buffers and migrate toward the anode [2]. The higher the negative charge density (more charge per unit mass), the faster the migration. Simultaneously, the gel matrix creates a frictional force, with larger and more asymmetrically shaped proteins experiencing greater resistance [2]. Because subunit interactions within a multimeric protein are generally retained, Native PAGE can provide valuable information about a protein's quaternary structure [2]. This preservation of native structure allows many proteins to retain their enzymatic activity and biological function following separation [4] [2].

Comparative Analysis: SDS-PAGE vs. Native PAGE

The choice between SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE represents a fundamental strategic decision in experimental design, as the techniques differ significantly in their procedures, outcomes, and applications. The table below summarizes the core operational and practical differences between these two methods.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE

| Criteria | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Molecular weight only [4] [2] | Size, overall charge, and shape [4] [2] |

| Protein State | Denatured/unfolded [4] [1] | Native/folded conformation [4] [1] |

| Detergent (SDS) | Present (0.1-0.2%) [6] [5] | Absent [4] |

| Sample Preparation | Heated (95°C for 5 min) with reducing agents [4] [5] | Not heated; no denaturing/reducing agents [4] |

| Protein Function | Lost post-separation [4] | Retained post-separation [4] [2] |

| Net Charge on Proteins | Uniformly negative (from SDS) [5] [2] | Intrinsic charge (positive or negative) [4] |

| Typical Run Temperature | Room temperature [4] | 4°C [4] |

| Protein Recovery | Cannot be recovered functionally [4] | Can be recovered in functional form [4] [2] |

| Primary Applications | Molecular weight determination, purity check, protein expression analysis [4] [1] | Study of protein structure, subunit composition, oligomerization, and functional activity [4] [1] |

Advanced Technical Considerations and Methodologies

Experimental Protocols for Standard Techniques

SDS-PAGE Protocol:

- Gel Preparation: Polyacrylamide gels are typically cast as a discontinuous system with a stacking gel (pH ~6.8, 4-6% acrylamide) layered on top of a resolving gel (pH ~8.8, 8-20% acrylamide). The stacking gel concentrates the protein samples into sharp bands before they enter the resolving gel, enhancing resolution [5] [2]. Polymerization is initiated by ammonium persulfate (APS) and catalyzed by TEMED [5].

- Sample Preparation: Protein samples are mixed with a sample buffer containing SDS, a reducing agent (e.g., DTT or β-mercaptoethanol), glycerol, and a tracking dye (e.g., bromophenol blue) [5]. The mixture is heated at 95°C for 5 minutes or 70°C for 10 minutes to ensure complete denaturation [4] [5].

- Electrophoresis: Samples are loaded into wells, and electrophoresis is performed at a constant voltage (typically 100-200 V) using a running buffer containing Tris, glycine, and SDS (e.g., 0.1% SDS) [5] [7]. The run is stopped once the tracking dye front reaches the bottom of the gel [5].

Native PAGE Protocol:

- Gel Preparation: Polyacrylamide gels are cast without SDS or other denaturing agents [4]. Both the gel and the running buffer lack SDS and typically have a near-neutral pH to help maintain protein stability and native conformation [4] [2].

- Sample Preparation: Protein samples are mixed with a non-denaturing sample buffer containing glycerol and a tracking dye but no SDS, reducing agents, or heat application [4].

- Electrophoresis: The electrophoresis apparatus is often kept cool (e.g., at 4°C) throughout the run to minimize protein denaturation and proteolysis [4]. The running buffer is also devoid of denaturing agents [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for PAGE Experiments

| Reagent | Function | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Anionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge [6] [2] | SDS-PAGE sample and running buffers [5] |

| DTT or β-Mercaptoethanol | Reducing agents that cleave disulfide bonds [5] | Added to SDS-PAGE sample buffer before heating [5] |

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Monomer and cross-linker that form the porous gel matrix [3] [2] | Gel formulation at specific percentages (e.g., 8%, 12%) to control pore size [2] |

| APS and TEMED | Polymerization initiator and catalyst for gel formation [5] [2] | Added last to initiate gel polymerization [5] |

| Tris-based Buffers | Provide the required pH and ionic environment for electrophoresis [5] | Running buffer (Tris-Glycine) and gel buffers [5] |

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue | Reversible protein stain for visualization; also enhances protein extraction in PEPPI-MS [8] | Staining proteins after electrophoresis; passive extraction from gels [8] |

Hybrid and Advanced Techniques: Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE)

Recent methodological advances have led to the development of hybrid techniques like Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE), which aims to balance the high resolution of traditional SDS-PAGE with the preservation of native protein features [7]. This modified procedure involves removing SDS and EDTA from the sample buffer, omitting the heating step, and significantly reducing the SDS concentration in the running buffer (e.g., from 0.1% to 0.0375%) [7]. Research has demonstrated that these conditions allow for the retention of Zn²⁺ bound in proteomic samples to increase from 26% to 98% compared to standard SDS-PAGE, with seven out of nine model enzymes retaining their activity post-electrophoresis [7]. This approach is particularly valuable in metalloprotein research, where preserving metal cofactors is essential for functional studies [7].

Applications and Research Implications

Strategic Selection for Research Objectives

The decision to use SDS-PAGE or Native PAGE must be guided by the specific research questions and desired outcomes. SDS-PAGE is the unequivocal method of choice for determining polypeptide molecular weight, assessing sample purity, verifying protein expression levels, and preparing for western blotting or mass spectrometry analysis where denatured proteins are suitable [4] [1]. Its strength lies in its simplicity, reproducibility, and high resolution based primarily on a single attribute—molecular mass.

Conversely, Native PAGE is indispensable for investigations requiring the preservation of protein function and native structure. This includes studying oligomerization states, protein-protein interactions, enzymatic activity, and the composition of multi-subunit complexes [1] [2]. A classic example of their complementary use is the analysis of a protein that migrates as a 60 kDa band under non-reducing SDS-PAGE but as a 120 kDa band under Native PAGE. This pattern strongly suggests that the native protein exists as a dimer of 60 kDa subunits held together by non-covalent interactions (not disulfide bonds), which are disrupted by SDS treatment but maintained under native conditions [9].

Case Study: Integrating PAGE with Structural Mass Spectrometry

The integration of PAGE with advanced mass spectrometry (MS) techniques highlights its ongoing evolution and critical role in modern proteomics. While SDS-PAGE has long been used in bottom-up proteomics (GeLC-MS), recent breakthroughs in protein recovery from gels, such as the PEPPI-MS (Passively Eluting Proteins from Polyacrylamide Gels as Intact species for MS) method, have enabled its application in top-down proteomics [8]. This method uses Coomassie Brilliant Blue as an extraction enhancer, allowing efficient recovery of intact proteins from gel pieces with a mean recovery rate of 68% for proteins below 100 kDa [8]. This facilitates in-depth structural proteomics by integrating gel-based fractionation with high-sensitivity MS, enabling researchers to obtain comprehensive structural information on complex proteome samples while overcoming the traditional limitations of detecting low-abundance components [8].

SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE represent two powerful, yet fundamentally different, approaches to protein separation, each with distinct advantages and limitations. SDS-PAGE provides high-resolution separation based primarily on molecular weight by denaturing proteins and masking their intrinsic charges, making it ideal for analytical applications like molecular weight determination and purity assessment. In contrast, Native PAGE separates proteins under non-denaturing conditions based on their combined size, charge, and shape, preserving native conformation, biological activity, and protein complexes for functional studies.

The strategic choice between these techniques should be guided by the overarching research goals within a drug development or basic research context. For researchers focused on protein identity, quantity, and subunit composition, SDS-PAGE remains the gold standard. For those investigating protein function, interactions, and higher-order structure, Native PAGE is the appropriate choice. The emergence of hybrid techniques like Native SDS-PAGE and improved integration with structural mass spectrometry further expands the utility of electrophoretic methods, ensuring their continued relevance in the evolving landscape of protein science and biopharmaceutical research.

In protein analysis, the choice between denaturing and non-denaturing electrophoretic techniques is fundamental to research outcomes. Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Native PAGE serve distinct purposes, primarily governed by the presence or absence of the denaturing detergent SDS. This detergent fundamentally alters protein structure, masking intrinsic properties to enable separation by molecular weight alone. In contrast, native conditions preserve protein structure, functionality, and complex interactions, allowing separation based on a combination of size, charge, and shape. Understanding the precise role of detergents is critical for researchers and drug development professionals to select the appropriate method for characterizing protein identity, purity, structure, or function. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these mechanisms and their practical implications for experimental design.

Fundamental Mechanisms of SDS Denaturation

The denaturing power of SDS arises from its specific chemical properties and its mode of interaction with proteins. SDS is an anionic detergent composed of a 12-carbon aliphatic tail and a sulfate head group [6]. Its action is concentration-dependent and leads to the complete disruption of the native protein structure.

Molecular and Micellar Interactions

SDS interacts with proteins through two primary modes:

- Stoichiometric Binding (Below Critical Micelle Concentration - CMC): At low concentrations (e.g., 0.1% or below CMC), SDS binds to proteins in a specific molar ratio, which can sometimes lead to partial denaturation or the formation of defined SDS-protein complexes that may retain elements of native structure in certain contexts [6].

- Micellar Binding (Above CMC): At concentrations well above the CMC (e.g., 1-2%), SDS binds extensively and cooperatively to the protein backbone. A consistent ratio of 1.4 g of SDS per 1 g of polypeptide is typical, which effectively coats the protein [2] [10]. This extensive binding is the basis for the uniform charge distribution required for SDS-PAGE.

Structural Consequences of SDS Binding

The binding of SDS at high concentrations leads to several key structural alterations:

- Disruption of Non-Covalent Bonds: The aliphatic tail of SDS interacts with hydrophobic regions of the protein, while the ionic head group interacts with water. This disrupts hydrophobic interactions within the protein core and other non-covalent bonds, leading to the loss of tertiary and quaternary structure [6] [10].

- Unfolding and Linearization: The repulsion between the negatively charged SDS molecules bound along the polypeptide chain forces the protein to unfold into a rod-like shape [2] [1]. The addition of reducing agents (e.g., DTT, β-mercaptoethanol) cleaves disulfide bonds, ensuring complete dissociation into individual subunits and linearization [11] [10].

The following diagram illustrates the transformative effect of SDS on protein structure.

SDS-Mediated Protein Denaturation

This transformation is the cornerstone of SDS-PAGE, as it creates a population of proteins that are uniformly charged and share a similar shape, thereby making molecular weight the sole determinant of electrophoretic mobility.

Principles of Native Conditions for Structure Preservation

Native PAGE (Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis) operates on the principle of preserving the protein's higher-order structure throughout the separation process. The absence of denaturing agents like SDS is the defining feature of this technique.

Key Characteristics of Native State Electrophoresis

- Intact Structure: Proteins remain in their folded, native conformation, retaining their secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures [1] [4]. Multimeric proteins maintain their subunit interactions [2].

- Functional Activity: Because the native structure is preserved, proteins frequently retain their biological activity after separation. This allows for subsequent functional assays, such as enzyme activity tests, directly from the gel [2] [7].

- Separation Based on Multiple Properties: Migration depends on the protein's intrinsic charge, size, and shape [1] [4]. The net charge at the running buffer pH determines the direction and rate of migration, while the gel matrix sieves proteins based on their hydrodynamic volume and three-dimensional structure.

The Role of Buffer and Environment

The buffer system in native PAGE is designed to maintain a non-denaturing environment:

- No Denaturants: Buffers lack SDS, urea, or guanidine hydrochloride [11] [4].

- Controlled Temperature: Electrophoresis is often performed at 4°C to stabilize proteins and prevent denaturation during the run [4].

- pH Considerations: The running buffer pH is carefully selected to maintain protein stability and exploit the protein's natural isoelectric point (pI) for separation [2].

Comparative Analysis: SDS-PAGE vs. Native PAGE

The choice between these two techniques has profound implications for the type of information obtained. The following table provides a direct comparison of their core characteristics.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of SDS-PAGE vs. Native PAGE

| Feature | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Gel Type | Denaturing [4] | Non-denaturing [4] |

| Presence of SDS | Present (0.1% - 1%) [6] [11] | Absent [11] [4] |

| Sample Preparation | Heated with SDS and reducing agent [11] [4] | Not heated; no denaturants [11] [4] |

| Protein State | Denatured and linearized [1] [10] | Native, folded conformation [1] [4] |

| Separation Basis | Molecular weight of polypeptides [2] [10] | Size, intrinsic charge, and shape [2] [1] |

| Protein Function Post-Separation | Lost [1] [4] | Often retained [2] [1] |

| Protein Recovery | Typically non-functional [4] | Functional proteins can be recovered [2] [4] |

Experimental Workflows

The procedural differences between the two methods are critical for experimental success. The workflows below outline the key steps for each technique.

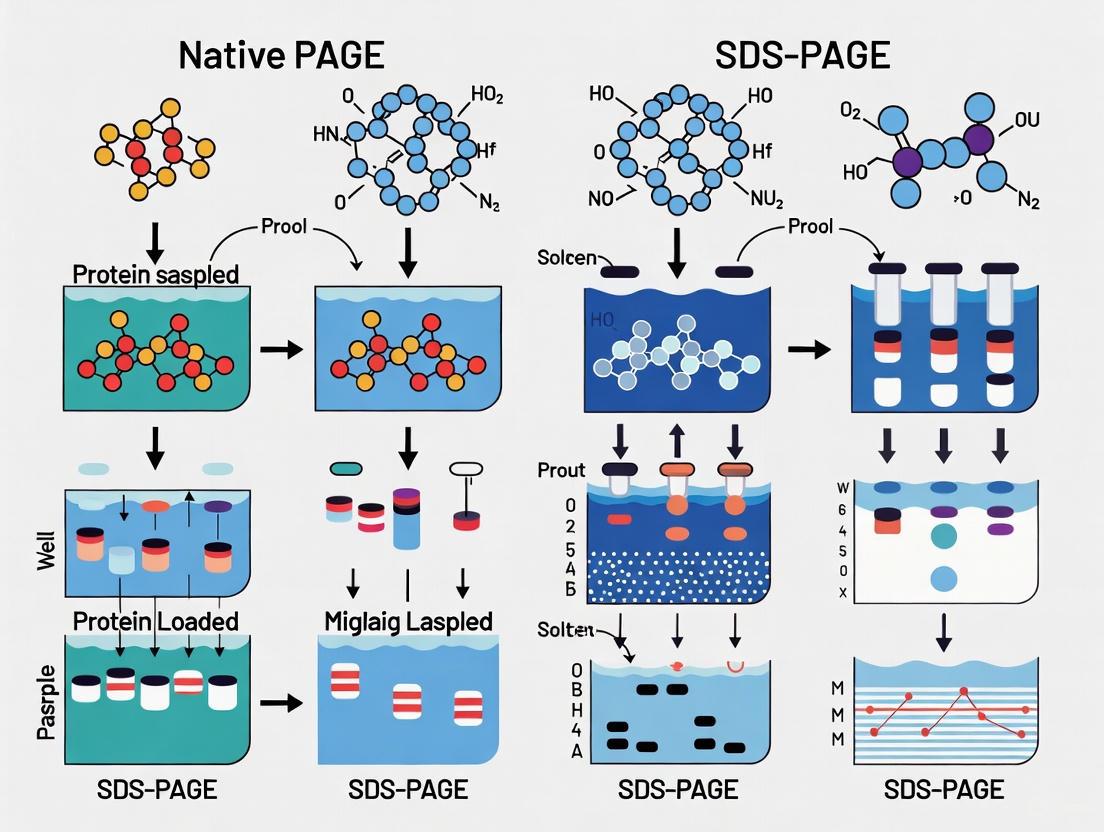

SDS-PAGE vs. Native PAGE Experimental Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs the essential reagents required for each method, highlighting their specific functions in either denaturing or preserving protein structure.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE

| Reagent | Function | Use in SDS-PAGE | Use in Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins; confers uniform negative charge [2] [10] | Core component of sample and running buffers [11] | Absent [11] |

| Reducing Agent (DTT, BME) | Breaks disulfide bonds; linearizes subunits [11] [10] | Added to sample buffer [11] | Absent [11] [4] |

| Polyacrylamide Gel | Molecular sieve; separates based on size [2] | Used (e.g., 12% Bis-Tris) [7] | Used (e.g., 4-16% gradient) [7] |

| Tris-Glycine Buffer | Common electrophoretic buffer system [11] | Used in SDS-running buffer (pH ~8.3) [11] | Used in native running buffer [11] |

| Coomassie Dye | Stains proteins for visualization [7] | Used post-electrophoresis | Used post-electrophoresis or in BN-PAGE [7] |

| Heat Block | Aids denaturation | Used (85-100°C) [11] | Not used [11] |

Advanced Concepts and Methodological Innovations

Hybrid Approaches: Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE)

An advanced technique known as Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE) demonstrates that the effects of SDS are not purely binary. This method uses drastically reduced SDS concentrations in the running buffer (e.g., 0.0375% instead of the standard 0.1%) and omits SDS and heating from the sample preparation [7]. Under these conditions, the resolution of complex protein mixtures remains high, but a significant proportion of proteins can retain their bound metal ions and enzymatic activity. In one study, Zn²⁺ retention increased from 26% in standard SDS-PAGE to 98% in NSDS-PAGE, and seven out of nine model enzymes remained active post-electrophoresis [7]. This highlights that SDS denaturation is a matter of degree, and careful optimization can yield a hybrid approach with unique benefits.

Emerging Alternatives: Denaturing Mass Photometry

While gel electrophoresis remains a cornerstone, new technologies are emerging. Denaturing Mass Photometry (dMP) is a recent innovation that allows for the analysis of protein mixtures under denaturing conditions without a gel matrix [12]. This single-molecule technique uses denaturants like urea or guanidine HCl to unfold proteins and provides accurate mass identification and quantification of coexisting species across a broad mass range (30 kDa–5 MDa) in minutes, using significantly less sample material than SDS-PAGE [12]. It is particularly useful for optimizing cross-linking reactions, overcoming limitations of SDS-PAGE such as poor resolution of very high molecular weight complexes and low throughput.

Decision Framework: Selecting the Appropriate Method

The following decision matrix provides a clear guideline for researchers to select the most appropriate electrophoretic method based on their experimental goals.

Table 3: Method Selection Guide Based on Research Objective

| Research Objective | Recommended Method | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Determine polypeptide molecular weight | SDS-PAGE [2] [10] | Masks charge/shape, separation by mass alone. |

| Assess sample purity & homogeneity | SDS-PAGE [10] | High resolution reveals contaminating bands. |

| Study subunit composition | SDS-PAGE (with reducing agent) [10] | Dissociates multimeric proteins into subunits. |

| Analyze protein function / enzyme activity | Native PAGE [2] [1] | Preserves native conformation and activity. |

| Investigate protein-protein interactions / oligomeric state | Native PAGE [2] [1] | Maintains quaternary structure of complexes. |

| Purify functional proteins from a mixture | Native PAGE [4] | Proteins can be recovered in their active state. |

| Analyze post-translational modifications affecting charge | Native PAGE [10] | Separation is sensitive to intrinsic charge. |

The role of detergents, specifically SDS, in protein analysis is definitive. SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE are not interchangeable but are complementary tools in the researcher's arsenal. SDS-PAGE provides a simplified, mass-based view of a protein mixture, ideal for analytical characterization, while Native PAGE offers a functional, structural view crucial for understanding protein activity and complex interactions. The emergence of hybrid techniques like NSDS-PAGE and advanced methods like denaturing Mass Photometry further expands the analytical toolbox. By understanding the fundamental mechanisms of how detergents denature versus how native conditions preserve structure, scientists and drug developers can make informed decisions, selecting the optimal method to answer specific biological questions and drive innovation.

In the realm of drug development and proteomics research, the structural state of a protein—whether in its native, active conformation or in a denatured, non-functional form—profoundly influences experimental outcomes and therapeutic efficacy. Protein function is intrinsically linked to its three-dimensional structure, which is maintained by weak non-covalent interactions including hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and van der Waals forces, as well as disulfide bridges [13]. Denaturation describes the process where these structural elements are disrupted, resulting in the loss of the protein's biologically active conformation without breaking the covalent peptide bonds of its primary structure [13] [14]. This loss of structure invariably leads to loss of function, as exemplified by enzymes that can no longer bind substrates or metal cofactors when denatured [13].

The choice between analyzing proteins in their native or denatured states is not merely technical but strategic, forming the core thesis of this whitepaper. Native-PAGE and SDS-PAGE represent two foundational electrophoretic techniques that enable researchers to interrogate these distinct protein states, each providing complementary insights critical for biopharmaceutical advancement. This guide provides a detailed technical framework for understanding these protein states and selecting the appropriate analytical method based on specific research objectives in drug development.

Fundamental Principles: Protein Denaturation Versus Native Structure

The Hierarchy of Protein Structure and Denaturation

Proteins organize into four hierarchical structural levels, each vulnerable to different denaturing conditions [13]:

- Primary Structure: The linear sequence of amino acids connected by covalent peptide bonds. This structure remains intact during denaturation.

- Secondary Structure: Local folded structures, primarily alpha-helices and beta-pleated sheets, stabilized by hydrogen bonds. Denaturation disrupts these patterns, converting the protein to a random coil configuration.

- Tertiary Structure: The overall three-dimensional shape of a single polypeptide chain, stabilized by hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, salt bridges, and disulfide bonds. Denaturation disrupts these stabilizing forces.

- Quaternary Structure: The arrangement of multiple polypeptide chains (subunits) into a multi-subunit complex. Denaturation dissociates these subunits.

Mechanisms and Agents of Protein Denaturation

Common laboratory denaturation methods and their molecular effects are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Common Protein Denaturation Methods and Their Effects

| Denaturing Agent | Molecular Effect | Practical Example |

|---|---|---|

| Heat ( > 50°C) | Increases kinetic energy, disrupting hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions [14]. | Boiled egg white turning opaque and solid [13]. |

| Extreme pH (Acids/Bases) | Alters charges on amino acid side chains, disrupting salt bridges and hydrogen bonding [13] [14]. | Ceviche preparation where acid in citrus marinade "cooks" raw fish [13] [15]. |

| Detergents (e.g., SDS) | Binds to hydrophobic regions, unfolds proteins, and masks intrinsic charge [4] [2]. | Sample preparation for SDS-PAGE. |

| Reducing Agents (e.g., DTT, BME) | Breaks disulfide bonds between cysteine residues [14]. | Breaking disulfide bonds during hair perming [14]. |

| Heavy Metal Ions (e.g., Ag⁺, Pb²⁺) | Form strong bonds with carboxylate groups or thiols, disrupting ionic bonds and disulfide linkages [14]. | Enzyme inhibition and toxicity. |

| Organic Solvents & Radiation | Disrupts hydrogen bonding and provides energy to break weak interactions [13] [14]. | Precipitation of proteins with alcohol. |

The following diagram illustrates the process of protein denaturation and its consequences.

Analytical Techniques: Native PAGE versus SDS-PAGE

Technical Foundations and Separation Mechanisms

Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE) separates proteins as they migrate through a cross-linked polymer matrix under an electric field. The fundamental difference between Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE lies in their treatment of protein structure [4] [2].

SDS-PAGE employs the anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and often a reducing agent. SDS denatures proteins by wrapping around the polypeptide backbone, masking the protein's intrinsic charge, and imparting a uniform negative charge proportional to its mass [2]. Heating the sample (70-100°C) in the presence of SDS and a thiol reagent fully dissociates subunits by reducing disulfide bonds [2]. Consequently, separation occurs almost exclusively by molecular weight, as all proteins become linear, negatively charged chains [4] [2].

Native PAGE uses non-denaturing conditions without SDS or reducing agents. Proteins retain their higher-order structure (secondary, tertiary, quaternary), and separation depends on the protein's intrinsic charge, size, and three-dimensional shape [2] [1]. The net charge depends on the pH of the running buffer and the protein's isoelectric point (pI) [2].

Comparative Analysis: A Decision Framework for Researchers

The choice between these techniques hinges on the research question. The table below provides a comprehensive comparison to guide experimental design.

Table 2: Comprehensive Comparison of SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE

| Analysis Criteria | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Molecular weight [4] [2] | Size, intrinsic charge, and 3D shape [4] [2] |

| Gel Condition | Denaturing [4] | Non-denaturing [4] |

| Sample Preparation | Heated with SDS and reducing agent (e.g., DTT, BME) [4] | Not heated; no denaturing/reducing agents [4] |

| Protein State | Denatured, unfolded, non-functional [4] [1] | Native, folded, often functional [4] [1] |

| Protein Recovery/Function | Cannot be recovered; function destroyed [4] | Can be recovered; function often retained [4] [2] |

| Information Provided | Polypeptide molecular weight, subunit composition, purity [4] [16] | Oligomeric state, protein-protein interactions, native charge [4] [1] |

| Typical Applications | - Molecular weight estimation [4]- Checking purity/expression [4] [16]- Western blotting [2] | - Studying native complexes & oligomerization [4] [1]- Enzyme activity assays [4] [2]- Purification of active proteins [4] |

| Key Limitations | Destroys native structure and function [1] | Complex migration; not for precise MW determination [16] |

The following workflow diagram aids in selecting the appropriate electrophoretic method based on research goals.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard SDS-PAGE Protocol

This protocol is adapted from common commercial systems (e.g., Invitrogen NuPAGE) and is suitable for most denaturing analyses [2] [7].

Sample Preparation:

- Sample Buffer: Mix protein sample with a loading buffer containing SDS (e.g., LDS), a reducing agent (e.g., DTT or β-mercaptoethanol), and glycerol [7].

- Denaturation: Heat the mixture at 70-100°C for 10 minutes to ensure complete denaturation and reduction of disulfide bonds [2] [7].

- Molecular Weight Markers: Load a protein ladder (mass markers) in one well for molecular weight calibration [2].

Gel Composition and Electrophoresis:

- Gel Matrix: Use a polyacrylamide gel, typically between 8% and 15% acrylamide. Lower percentages resolve larger proteins; higher percentages resolve smaller proteins. Gradient gels (e.g., 4-20%) provide a broad separation range [2].

- Running Buffer: Use a Tris-based buffer (e.g., MOPS or MES) containing 0.1% SDS to maintain denaturing conditions during the run [7].

- Electrophoresis: Load samples and run at constant voltage (e.g., 150-200 V) for approximately 45 minutes at room temperature until the dye front reaches the bottom [7].

Standard Native PAGE Protocol

This protocol maintains proteins in their native state throughout the process [4] [7].

Sample Preparation:

- Sample Buffer: Mix protein sample with a non-denaturing loading buffer containing glycerol and a tracking dye (e.g., Phenol Red). No SDS, no reducing agents, and no heating are used [7].

- Native Markers: Use protein standards compatible with native electrophoresis for size estimation [7].

Gel Composition and Electrophoresis:

- Gel Matrix: Use a polyacrylamide gel without SDS. The pH of the gel and running buffer is critical as it determines the protein's net charge [2].

- Running Buffer: Use a Tris-based buffer without SDS or other denaturants. Some protocols, like Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE), use Coomassie dye in the cathode buffer to impart charge for separation [7].

- Electrophoresis: Run at constant voltage (e.g., 150 V) for a longer duration (e.g., 90 minutes), often at 4°C to minimize denaturation and proteolysis [4] [2].

Advanced Hybrid Protocol: Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE)

Recent research has developed a hybrid technique, Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE), to balance the high resolution of SDS-PAGE with the need to retain native protein functions like metal binding and enzymatic activity [7].

Key Modifications from Standard SDS-PAGE [7]:

- Sample Buffer: Removes SDS and EDTA. Sample is not heated.

- Running Buffer: Reduces SDS concentration from 0.1% to 0.0375% and removes EDTA.

- Outcome: This method was shown to increase Zn²⁺ retention in proteomic samples from 26% to 98% and preserve the activity of 7 out of 9 model enzymes, while still providing high-resolution separation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful protein state analysis requires specific reagents, each with a defined role in preparing and separating samples.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Protein Electrophoresis

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Purpose | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge [2]. | Core of SDS-PAGE; omitted in Native PAGE [4]. |

| Reducing Agents (DTT, BME) | Cleaves disulfide bonds to fully dissociate subunits [4] [2]. | Used in SDS-PAGE; omitted to preserve structure in Native PAGE [4]. |

| Polyacrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms the cross-linked gel matrix that acts as a molecular sieve [2]. | Pore size is determined by the concentration and bis-acrylamide ratio [2]. |

| APS & TEMED | Catalyzer (APS) and catalyst (TEMED) for polyacrylamide gel polymerization [2]. | Required to initiate and accelerate the gel casting process. |

| Tris-based Buffers | Provides the conductive ionic medium and maintains stable pH during run [2]. | pH is critical, especially in Native PAGE, as it determines protein charge [2]. |

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue | Dye used for staining proteins post-electrophoresis [7]. | In BN-PAGE, it is also added to the running buffer to charge proteins [7]. |

| Molecular Weight Markers | Pre-stained or unstained protein ladders for calibrating gel migration [2]. | Must be compatible with the method (denaturing vs. non-denaturing) [7]. |

Data Interpretation: A Case Study in Protein Quaternary Structure

Interpreting electrophoretic results requires understanding the principles behind each technique. A classic example involves determining a protein's oligomeric state.

Scenario: A protein isolated from a natural source is analyzed on two different gels [9]:

- On non-reducing SDS-PAGE, it migrates as a single band corresponding to 60 kDa.

- On Native PAGE, it migrates as a single band corresponding to 120 kDa.

Inference and Rationale:

- The SDS-PAGE result shows that the protein's basic polypeptide chain has a mass of 60 kDa. The "non-reducing" condition means disulfide bonds between chains remain intact. The fact that it runs at 60 kDa indicates no disulfide-linked partners are present [9].

- The Native PAGE result shows that in its native, folded state, the protein exists as a dimer with a total mass of 120 kDa. The two 60 kDa subunits are held together by non-covalent interactions (e.g., hydrophobic, electrostatic), which are disrupted by SDS in the first gel but maintained in the second [9].

Conclusion: The protein is a dimer of 60 kDa subunits that are not linked by disulfide bonds. This case highlights how combining both techniques provides powerful insights into protein quaternary structure that neither method could deliver alone [9].

Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE) encompasses a family of techniques that are fundamental to protein analysis in biochemistry and molecular biology. While methods like SDS-PAGE and native PAGE serve distinct purposes and yield different information, they share a common technological foundation. Understanding these core similarities is essential for researchers to select the appropriate technique for their specific application, whether it involves determining molecular weight, studying protein-protein interactions, or analyzing enzymatic activity. This guide examines the fundamental principles, materials, and setups that unite these seemingly different methodologies, providing a framework for making informed decisions in experimental design.

Core Principles and Shared Mechanisms

At its essence, all forms of PAGE operate on the same basic principle: the movement of charged molecules through an inert gel matrix under the influence of an electric field [2]. The polyacrylamide gel acts as a molecular sieve, separating proteins based on their differential migration rates.

The Electrophoretic Process

In both SDS-PAGE and native PAGE, proteins are loaded into wells at the cathodic end of a polyacrylamide gel. When voltage is applied, the negatively charged proteins migrate toward the positively charged anode [4]. The gel matrix creates a sieving effect that regulates this movement; smaller proteins or complexes encounter less resistance and migrate faster, while larger ones move more slowly [2]. This shared mechanism means that in both techniques, proteins are separated from each other as they travel through the gel, forming discrete bands that can be visualized and analyzed post-separation.

The Polyacrylamide Gel Matrix

A key similarity between all PAGE techniques is the use of polyacrylamide as the gel matrix of choice for protein separation [2] [4]. These gels are formed through a chemical polymerization reaction where acrylamide monomers are cross-linked by bisacrylamide (N,N'-methylenebisacrylamide) to form a three-dimensional network [2] [17]. The polymerization is typically initiated by ammonium persulfate (APS) and catalyzed by TEMED (N,N,N',N'-Tetramethylethylenediamine) [2]. The pore size of this network, which determines its sieving properties, is controlled by varying the concentrations of acrylamide and bisacrylamide [2]. Lower percentage gels (e.g., 8%) have larger pores and are better for separating high molecular weight proteins, while higher percentage gels (e.g., 15%) have smaller pores and resolve smaller proteins more effectively [2].

Comparative Analysis: SDS-PAGE vs. Native PAGE

While sharing fundamental similarities in their setup and basic principles, SDS-PAGE and native PAGE differ significantly in their sample preparation, separation criteria, and applications. The table below summarizes these key differences, which are crucial for selecting the appropriate method for a given research question.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE

| Parameter | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Gel Type | Denaturing [4] | Non-denaturing [4] |

| SDS Presence | Present [2] [4] | Absent [4] |

| Sample Preparation | Heated with SDS and reducing agents [2] [4] | Not heated; no denaturants [4] |

| Protein State | Denatured into linear polypeptides [2] [1] | Native, folded conformation [1] [4] |

| Separation Basis | Primarily by molecular mass [2] [1] | By size, charge, and shape [1] [4] |

| Protein Charge | Uniformly negative (from SDS) [2] [18] | Native charge (positive or negative) [4] |

| Protein Function Post-Separation | Lost [1] [4] | Often retained [1] [4] |

| Protein Recovery | Typically not functional [4] | Possible in functional form [4] |

| Primary Applications | Molecular weight determination, purity checks, protein expression analysis [4] [9] | Studying protein complexes, oligomeric state, enzymatic activity [1] [4] |

Key Differentiating Factors

Role of SDS: Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) is the critical component that defines SDS-PAGE. This anionic detergent denatures proteins by binding to the polypeptide backbone in a constant weight ratio (approximately 1.4 g SDS per 1 g of protein) and confers a uniform negative charge that overwhelms the protein's intrinsic charge [2]. This results in separation based almost exclusively on molecular mass [2] [1]. In contrast, native PAGE intentionally avoids denaturants to preserve the protein's native structure, charge, and function [1].

Information Output: The choice between these techniques directly determines the type of biological information obtained. For example, a protein that migrates as a 60 kDa band on non-reducing SDS-PAGE but as a 120 kDa band on native PAGE strongly suggests the protein exists as a non-covalently linked dimer (two 60 kDa subunits) in its native state [9]. SDS-PAGE would only show the monomeric subunits, while native PAGE reveals the functional oligomeric structure.

Common Methodological Framework

The fundamental similarities between SDS-PAGE and native PAGE are most evident in their core experimental workflows and setup requirements. The diagram below illustrates the shared procedural framework and key divergence points.

Shared Instrumentation and Basic Setup

The basic electrophoresis apparatus is remarkably consistent between techniques. Both typically use a vertical gel setup where the gel is cast between two glass plates and placed in an electrophoresis tank containing running buffer [2]. The system includes a cathode (-) and anode (+) to create the electric field that drives protein migration [4] [19]. A power supply provides the necessary voltage or current to facilitate separation over a typical timeframe of 20 minutes to several hours, depending on gel size and voltage [2].

Standardized Detection and Visualization Methods

Following electrophoresis, proteins in both SDS-PAGE and native PAGE gels are typically visualized using similar staining techniques. Common protein stains include Coomassie Blue, silver stain, and fluorescent dyes [2] [4]. For both techniques, the resulting band patterns can be analyzed to determine relative mobility, with SDS-PAGE bands providing molecular weight estimates when compared to standards, and native PAGE bands indicating differences in charge, size, and oligomeric state.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of either PAGE technique requires a core set of laboratory reagents and materials. The table below details these essential components and their functions in the electrophoretic process.

Table 2: Essential reagents and materials for PAGE experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide-Bis Solution | Forms the polyacrylamide gel matrix when polymerized [2] [17] | Acrylamide is a neurotoxin; handle with gloves [17] |

| APS (Ammonium Persulfate) | Initiates the polymerization reaction [2] | Fresh solutions are recommended for consistent results |

| TEMED | Catalyzes the free-radical polymerization of acrylamide [2] [17] | Amount affects polymerization speed |

| Tris Buffers | Maintains stable pH during gel formation and electrophoresis [2] | Different pH for stacking (e.g., 6.8) and resolving (e.g., 8.8) gels [2] |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge (SDS-PAGE only) [2] [18] | Typically used at 0.1% in gels and running buffers [2] |

| Reducing Agents (DTT, BME) | Breaks disulfide bonds for complete denaturation (SDS-PAGE only) [4] | Essential for accurate molecular weight determination |

| Tracking Dye | Visualizes migration progress during electrophoresis [2] | Contains glycerol to increase sample density for well loading [20] |

| Protein Molecular Weight Markers | Reference standards for estimating protein size [2] | Pre-stained markers allow visual tracking during runs |

Strategic Selection Guide: When to Use Each Technique

The decision to use SDS-PAGE or native PAGE should be driven by the specific research question. The following diagram provides a logical framework for this decision-making process, highlighting how the fundamental similarities in setup enable complementary information to be gathered.

Applications in Drug Development and Biotechnology

In pharmaceutical research, the complementary use of both techniques provides comprehensive characterization of therapeutic proteins. SDS-PAGE is indispensable for quality control to verify molecular weight, monitor degradation, and ensure batch-to-batch consistency of protein drugs [1]. Native PAGE, meanwhile, is crucial for studying protein-drug interactions, confirming the integrity of multi-subunit complexes, and ensuring that purified proteins retain their biological activity throughout the development process [1] [4].

Advanced Technical Considerations

Gel Percentage Selection Guide

The appropriate polyacrylamide percentage is critical for optimal resolution in both SDS-PAGE and native PAGE. The table below provides guidance on gel percentages for separating proteins of different molecular weights.

Table 3: Recommended gel percentages for protein separation

| Gel Percentage | Optimal Separation Range (SDS-PAGE) | Optimal Separation Range (Native PAGE) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6-8% | 50-150 kDa | High molecular weight complexes | Better for large proteins/complexes [2] |

| 10% | 30-100 kDa | Medium to large proteins | Standard workhorse gel for most applications |

| 12% | 20-80 kDa | Medium-sized proteins | Common for many cellular proteins |

| 15% | 10-50 kDa | Small proteins | Better for small polypeptides [2] |

| 4-20% Gradient | 10-300 kDa | Broad range of sizes | Single gel for analyzing diverse samples [2] |

Buffer Systems and Electrophoresis Conditions

Both techniques employ similar buffer systems, typically based on Tris-glycine, though the specific composition may vary. SDS-PAGE running buffer contains SDS (0.1%) to maintain protein denaturation during electrophoresis [2]. Native PAGE uses the same basic buffer without SDS or reducing agents. While SDS-PAGE is typically run at room temperature, native PAGE is often performed at 4°C to minimize denaturation and proteolysis during the run [4]. Running voltages are similar for both techniques, with standard mini-gel systems typically running at 100-200 V for 30-60 minutes [2].

SDS-PAGE and native PAGE, while serving distinct analytical purposes, are built upon a shared foundation of electrophoretic principles, polyacrylamide gel matrices, and basic instrumentation. This common framework allows researchers to leverage both techniques within a unified laboratory setup, selecting the appropriate method based on whether they need structural information about protein subunits (SDS-PAGE) or functional information about native complexes (native PAGE). Understanding these fundamental similarities enables more strategic experimental design and more insightful interpretation of results across diverse research applications in biochemistry, molecular biology, and drug development.

Strategic Application: Choosing the Right Technique for Your Research Goal

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) is a cornerstone technique in biochemistry and molecular biology labs worldwide. Its development in the 1970s by Ulrich Laemmli, building on earlier work by Davis and Ornstein, provided a revolutionary method for separating proteins based primarily on their molecular weight [21]. Understanding when to employ SDS-PAGE, as opposed to native PAGE, is a critical decision point in experimental design. This technical guide details the core applications of SDS-PAGE—determining molecular weight, assessing purity, and analyzing subunit composition—within the broader context of choosing the appropriate electrophoretic method for research and drug development.

The Fundamental Principle of SDS-PAGE

The power of SDS-PAGE lies in its ability to simplify protein separation to a single parameter: molecular weight. This is achieved through the action of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), an anionic detergent that plays two crucial roles:

- Protein Denaturation: SDS binds extensively to hydrophobic regions of proteins, disrupting hydrogen bonds and van der Waals forces. This unfolds the protein, masking its intrinsic three-dimensional structure and shape [4] [21].

- Uniform Negative Charge: SDS coats the denatured polypeptide chains in a uniform layer of negative charge. This gives all proteins a similar charge-to-mass ratio, ensuring that during electrophoresis, migration through the polyacrylamide gel matrix is determined solely by polypeptide size, not by the protein's original charge [2] [22].

The polyacrylamide gel acts as a molecular sieve; smaller proteins migrate faster and farther than larger ones [23]. This process is typically performed under reducing conditions, where agents like Dithiothreitol (DTT) or β-mercaptoethanol break disulfide bonds, ensuring complete dissociation of protein subunits [4] [24].

SDS-PAGE vs. Native PAGE: The Critical Choice

The decision to use SDS-PAGE or native PAGE hinges on the research question. The table below summarizes the key differences to guide method selection.

Table 1: Key Differences Between SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE

| Criteria | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Molecular weight (mass) of polypeptides [4] [1] | Native size, overall charge, and 3D shape of the protein [4] [1] |

| Protein State | Denatured and linearized [2] | Native, folded conformation [4] |

| Detergent | SDS present [4] | SDS absent [4] |

| Sample Preparation | Heated with SDS and often a reducing agent [4] | Not heated; no denaturing agents [4] |

| Protein Function | Destroyed; proteins lose activity [4] | Preserved; proteins retain activity [4] [2] |

| Primary Applications | Molecular weight determination, purity check, subunit analysis [4] [21] | Studying native structure, protein-protein interactions, enzymatic activity [4] [1] |

Core Application 1: Determining Molecular Weight

Experimental Protocol

Determining the molecular weight of an unknown protein is one of the most frequent applications of SDS-PAGE.

- Sample Preparation: The protein sample is mixed with an SDS-containing loading buffer. A reducing agent like DTT or 2-mercaptoethanol is added to break disulfide bonds. The mixture is then heated at 70–100°C for 5-10 minutes to ensure complete denaturation [2] [21].

- Gel Selection and Loading: A polyacrylamide gel of appropriate percentage is chosen (see Table 2). A molecular weight marker (protein ladder) containing proteins of known sizes is loaded into one lane, and the unknown sample(s) into adjacent lanes [2] [23].

- Electrophoresis: The gel is run at constant voltage (e.g., 100-150V) until the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel [21].

- Analysis: After staining, the distance migrated by each band of the marker and the unknown protein is measured. A standard curve is plotted (logarithm of molecular weight vs. migration distance), and the molecular weight of the unknown protein is interpolated from this curve [2] [21].

Table 2: Guide to Gel Percentage Selection for Optimal Separation

| Acrylamide Percentage | Optimal Separation Range (kDa) |

|---|---|

| 15% | 10 – 50 kDa [23] |

| 12% | 15 – 100 kDa [21] |

| 10% | 40 – 100 kDa [23] |

| 8% | 25 – 200 kDa [21] |

Diagram 1: Molecular Weight Determination Workflow

Core Application 2: Assessing Protein Purity

SDS-PAGE provides a rapid and effective method to assess the homogeneity of a protein sample during purification (e.g., after column chromatography) or to check the quality of recombinant protein expression.

Experimental Protocol

- Sample Preparation: The purified protein sample and a control (e.g., crude lysate) are prepared under standard reducing and denaturing conditions [21].

- Gel Loading and Electrophoresis: Equal amounts of total protein are loaded onto the gel to allow for direct comparison. Electrophoresis is performed as described previously.

- Visualization and Interpretation: Following staining (e.g., with Coomassie Brilliant Blue or silver stain), the gel is analyzed. A pure protein preparation will typically show a single, dominant band at the expected molecular weight. The presence of multiple, unexpected bands indicates contamination, proteolytic degradation, or the presence of protein aggregates [23] [21].

Troubleshooting Purity Analysis:

- Multiple Bands/Smearing: Can result from incomplete denaturation, protein degradation, or protease activity. Solutions include adding fresh reducing agent, boiling samples thoroughly, and using protease inhibitors during sample preparation [23].

- Weak/Faint Bands: Often a sign of low protein concentration. Quantifying protein concentration before loading using assays like Bradford, BCA, or Lowry is essential [23].

Core Application 3: Analyzing Subunit Composition

SDS-PAGE is indispensable for characterizing the quarternary structure of multi-subunit proteins. By comparing samples run under reducing and non-reducing conditions, researchers can deduce the number and size of subunits and the nature of their associations.

Experimental Protocol

- Parallel Sample Preparation: The same protein sample is split into two aliquots.

- Reducing Condition: Prepared with SDS and a reducing agent (DTT or 2-ME).

- Non-reducing Condition: Prepared with SDS but without any reducing agent.

- Gel Electrophoresis: Both samples are run on the same gel.

- Interpretation of Results:

- If a protein runs at the same molecular weight under both conditions, it is likely a single polypeptide chain.

- If a protein runs at a higher molecular weight under non-reducing conditions but shifts to a lower molecular weight under reducing conditions, it indicates a multimeric structure held together by disulfide bonds [24] [9].

Table 3: Interpreting Subunit Composition from SDS-PAGE

| Observation | Interpretation | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Single band, same MW in both conditions | Monomeric protein with no inter-chain disulfide bonds. | A 50 kDa protein runs at 50 kDa in both gels. |

| Higher MW band (non-reducing) shifts to lower MW band (reducing) | Multimeric protein with subunits linked by disulfide bonds. | A 120 kDa band under non-reducing conditions splits into 60 kDa subunits under reducing conditions [9]. |

| Higher MW band (non-reducing) that dissociates without reducing agent | Multimeric protein with subunits held by non-covalent interactions (disrupted by SDS alone). | A 120 kDa band under native PAGE runs as 60 kDa under non-reducing SDS-PAGE, indicating a non-covalent dimer [9]. |

Diagram 2: Subunit Composition Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for SDS-PAGE

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for SDS-PAGE Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function and Importance |

|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Anionic detergent responsible for denaturing proteins and imparting uniform negative charge [21]. |

| Reducing Agents (DTT, BME) | Cleave disulfide bonds to ensure complete protein unfolding and subunit dissociation [4] [24]. |

| Polyacrylamide Gel | Cross-linked polymer matrix that acts as a molecular sieve to separate proteins by size [2]. |

| Molecular Weight Markers | Pre-stained or unstained proteins of known sizes used to calibrate the gel and estimate unknown protein weights [2] [23]. |

| Tris-Glycine Buffer | Standard discontinuous buffer system that stacks proteins into sharp bands before separation in the resolving gel [23]. |

| Coomassie/Silver Stain | Dyes used to visualize separated protein bands in the gel after electrophoresis [21]. |

SDS-PAGE remains an indispensable, robust, and accessible technique for any researcher working with proteins. Its primary strength lies in its ability to simplify complex protein mixtures into components separated by polypeptide chain length, enabling precise molecular weight determination, critical assessment of sample purity, and detailed analysis of subunit architecture. The choice to use SDS-PAGE is clear when the experimental goal requires information on these fundamental protein properties, particularly when the preservation of native structure or function is not necessary. In these scenarios, especially within drug development for characterizing biologics, assessing purity, and validating expression, SDS-PAGE provides irreplaceable data that forms the foundation for further advanced analytical and functional studies.

In protein analysis, the choice between Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (Native PAGE) and Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-PAGE (SDS-PAGE) represents a fundamental methodological crossroads that directly dictates the biological insights a researcher can obtain. While SDS-PAGE denatures proteins into uniform linear chains for separation primarily by molecular weight, Native PAGE preserves proteins in their folded, functional states, enabling the study of higher-order structure, complexes, and function within a gel electrophoresis platform [4] [1] [2]. This technical guide frames this critical distinction within the broader thesis that Native PAGE is the technique of choice when the experimental goal requires maintaining the native conformation, oligomeric state, or biological activity of proteins, whereas SDS-PAGE is optimal for determining subunit molecular weight, purity, and primary structure. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this distinction is paramount for designing experiments that accurately probe protein function in areas ranging from enzyme characterization to target identification for therapeutic development.

Core Principles: How Native PAGE Preserves Native Protein Architecture

The fundamental operating principle of Native PAGE is its non-denaturing environment. Unlike SDS-PAGE, which employs the anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) to denature proteins and mask their intrinsic charge, Native PAGE uses no denaturing agents [4] [2]. Consequently, separation depends on a combination of the protein's intrinsic net charge, size, and three-dimensional shape as it migrates through the polyacrylamide gel matrix [2]. The higher the negative charge density and the smaller the size, the faster a protein will migrate toward the anode.

This preservation of native structure has two critical implications. First, subunit interactions within a multimeric protein are generally retained, providing information about the protein's quaternary structure [2]. Second, many proteins retain their enzymatic activity and ligand-binding capabilities following separation, allowing for direct functional assays in-gel [4] [25]. This combination of separation and preserved functionality makes Native PAGE a powerful and unique tool in the protein scientist's arsenal.

Table 1: Fundamental differences between Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE

| Criterion | Native PAGE | SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Size, intrinsic charge, and 3D shape [4] [2] | Primarily molecular weight of polypeptides [4] [2] |

| Gel Condition | Non-denaturing [4] | Denaturing [4] |

| SDS Presence | Absent [4] | Present [4] |

| Sample Preparation | Not heated [4] | Heated (70-100°C) with SDS and reducing agent [4] |

| Protein State | Native, folded conformation [4] | Denatured, linearized subunits [4] |

| Protein Function | Retained post-separation [4] [1] | Lost post-separation [4] [1] |

| Protein Recovery | Recoverable in functional form [4] | Cannot be recovered functionally [4] |

| Primary Applications | Studying structure, oligomerization, function, and protein complexes [4] | Determining molecular weight, purity, and protein expression [4] |

Key Applications of Native PAGE in Research and Drug Development

Studying Oligomeric State and Protein-Protein Interactions

A premier application of Native PAGE is the analysis of protein quaternary structure. The technique can resolve different oligomeric states (e.g., monomers, dimers, tetramers) of a protein based on their distinct mass-to-charge ratios and sizes [4] [1]. This is crucial for understanding the functional unit of many proteins, as exemplified by medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD), which functions as an active homotetramer [25]. Research on MCAD deficiency (MCADD) has leveraged high-resolution clear native PAGE (hrCN-PAGE) to show how pathogenic variants destabilize the tetramer, leading to fragmentation into lower molecular mass forms or aggregation [25]. Such insights into oligomeric integrity are vital for elucidating the molecular basis of diseases and for developing strategies to stabilize functional complexes.

In-Gel Activity Assays for Functional Analysis

Perhaps the most powerful feature of Native PAGE is the ability to conduct enzymatic activity assays directly after electrophoretic separation. This application was prominently featured in a 2025 Scientific Reports study, which adapted a colorimetric in-gel assay for MCAD [25]. The protocol involves separating proteins by hrCN-PAGE, then incubating the gel in a solution containing the substrate (octanoyl-CoA) and a tetrazolium salt (nitro blue tetrazolium chloride, NBT). Active enzyme oxidizes its substrate, reducing NBT to an insoluble, purple-colored diformazan precipitate, revealing the position of active enzyme bands [25]. This method allowed researchers to quantitatively distinguish the activity of functional tetramers from other protein forms, providing novel insights into how pathogenic variants affect MCAD structure and function [25]. Similar in-gel activity assays have been established for various mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complexes [26].

Analysis of Membrane Protein Complexes and Supercomplexes

Native PAGE, particularly Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE), has become indispensable for studying membrane protein complexes, which are often targets for therapeutics [26] [27]. BN-PAGE uses Coomassie dye to impart a negative charge to membrane proteins solubilized in mild detergents, allowing separation by molecular weight under native conditions [26] [27]. This enables the analysis of individual complexes and even larger supercomplexes, such as those in the mitochondrial respiratory chain [26]. Clear Native PAGE (CN-PAGE) offers a milder alternative that is superior for retaining labile supramolecular assemblies and for performing subsequent catalytic activity measurements, as the Coomassie dye can interfere with such assays [27]. These techniques provide critical information on complex assembly pathways and composition, which is often disrupted in genetic diseases [26].

Diagram 1: Decision pathway for selecting the appropriate electrophoresis method. BN-PAGE is ideal for membrane complexes, while CN-PAGE is preferred for subsequent activity assays.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: High-Resolution In-Gel Activity Assay

The following protocol, adapted from a 2025 study on MCAD deficiency, details the steps for performing a high-resolution clear native PAGE (hrCN-PAGE) coupled with an in-gel activity assay [25]. This methodology allows for the simultaneous assessment of protein oligomeric state and enzymatic function.

Gel Casting and Electrophoresis

Materials:

- Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide Stock Solution (40%): Forms the cross-linked polymer matrix for separation.

- TEMED (N,N,N',N'-Tetramethylethylenediamine): Catalyzes the polymerization reaction.

- Ammonium Persulfate (APS): Initiates the free-radical polymerization of acrylamide.

- Gradient Gel Former: For casting gels with an acrylamide gradient (e.g., 4-16%) to resolve a broad range of protein sizes.

- Cathode and Anode Buffers: Specific buffers for native electrophoresis, typically without SDS [25].

Method:

- Prepare the Gradient Gel: Using a gradient maker, prepare a 4-16% polyacrylamide gradient gel. The lower-percentage region resolves larger complexes, while the higher-percentage region resolves smaller complexes. Add TEMED and APS to the acrylamide solutions to initiate polymerization and promptly pour the gel.

- Prepare Protein Samples: Mix the protein sample (either recombinant protein or a mitochondrial-enriched fraction) with a native loading buffer that lacks denaturants or reducing agents. Do not heat the samples [4].

- Run Electrophoresis: Load the samples into the wells. Run the gel in a cold room (4°C) to minimize denaturation and proteolysis during separation [4]. Apply a constant current until the dye front migrates to the bottom of the gel.

In-Gel Activity Staining for MCAD

Materials:

- Octanoyl-CoA: The physiological MCAD substrate, which acts as a reductant in the assay [25].

- Nitro Blue Tetrazolium Chloride (NBT): An oxidizing agent that, upon reduction, forms an insoluble purple diformazan precipitate [25].

- Phenazine Methosulfate (PMS): An electron coupler that facilitates electron transfer from the reduced enzyme to NBT (optional, depending on the specific assay setup).

Method:

- Incubate the Gel: Following electrophoresis, carefully transfer the gel to a staining tray. Incubate the gel in a reaction solution containing 100-200 µM octanoyl-CoA and 0.5-1.0 mg/mL NBT in an appropriate buffer (e.g., Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) [25].

- Develop the Reaction: Protect the gel from light and incubate at room temperature with gentle agitation. Purple bands indicating enzymatic activity typically become visible within 10-15 minutes [25].

- Terminate and Analyze: Once bands are sufficiently developed, rinse the gel with distilled water to stop the reaction. The gel can be imaged using a standard densitometer for quantification. The linear correlation between protein amount, FAD content, and in-gel activity can be established, allowing for quantitative comparisons [25].

Diagram 2: Workflow for a native PAGE in-gel activity assay, demonstrating how functional separation is achieved.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential reagents for Native PAGE and in-gel activity assays

| Reagent | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms the porous gel matrix for sieving proteins. | The ratio and concentration determine pore size; gradients (e.g., 4-16%) broaden separation range [25] [2]. |

| Digitonin | A mild detergent for solubilizing membrane proteins without disrupting labile complexes. | Preferred over harsher detergents for CN-PAGE to preserve supercomplexes [27]. |

| Coomassie G-250 | Imparts negative charge to proteins in BN-PAGE; also used for staining. | In BN-PAGE, it is included in the cathode buffer; it can interfere with some downstream activity assays [26] [27]. |

| Octanoyl-CoA | Physiological substrate for MCAD in the featured activity assay. | Serves as the reductant in the coupled reaction; other substrates are used for different enzymes [25]. |

| Nitro Blue Tetrazolium (NBT) | A tetrazolium salt that acts as an electron acceptor. | Upon reduction by the enzymatic reaction, it forms an insoluble purple formazan precipitate for colorimetric detection [25]. |

| TEMED/APS | Catalyst (TEMED) and initiator (APS) for acrylamide polymerization. | The polymerization rate is temperature-dependent; the gel mixture must be poured quickly after their addition [2]. |

Native PAGE stands as an essential technique for researchers whose investigations extend beyond primary protein structure to the dynamic world of tertiary and quaternary structure, functional oligomerization, and native complex formation. Its unique ability to separate proteins under non-denaturing conditions and preserve biological activity for in-gel analysis provides a window into protein function that is simply not accessible through denaturing methods like SDS-PAGE. As the field of drug development increasingly focuses on complex targets, including membrane receptors and multi-subunit enzymes, the application of Native PAGE and its variants will remain critical for validating target engagement, understanding pathogenic mechanisms, and ultimately guiding the development of effective therapeutics.

The structural and functional analysis of membrane proteins presents significant challenges due to their hydrophobic nature and existence within lipid bilayers. Unlike their soluble counterparts, membrane proteins require specialized techniques that can preserve their native lipid environment and maintain their intricate quaternary structures. Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Native-PAGE) has emerged as an indispensable tool for this purpose, allowing researchers to study membrane protein complexes under non-denaturing conditions. Among the various Native-PAGE techniques, Blue Native (BN-PAGE) and Clear Native (CN-PAGE) have proven particularly valuable for membrane protein research, each offering distinct advantages depending on the specific research objectives.

The fundamental distinction between native and denaturing electrophoresis approaches lies in their treatment of protein structure. While SDS-PAGE completely denatures proteins into linear polypeptide chains, Native-PAGE maintains proteins in their folded, functional states [28] [1]. This preservation of native structure is crucial when studying membrane protein complexes, as their biological activity often depends on specific three-dimensional arrangements and protein-protein interactions that would be disrupted by denaturing conditions. The choice between these techniques therefore represents a strategic decision that should align with the ultimate research goals—whether determining molecular weight and purity (SDS-PAGE) or investigating native structure and function (Native-PAGE).

Fundamental Principles: Native PAGE vs. SDS-PAGE

Core Mechanistic Differences

The separation mechanisms of Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE differ fundamentally in their treatment of protein structure and charge characteristics. In SDS-PAGE, the powerful anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) binds to proteins at a relatively constant ratio of approximately 1.4g SDS per 1g protein, effectively masking the protein's intrinsic charge and conferring a uniform negative charge density [28]. This charge masking, combined with the denaturing action of SDS that linearizes proteins into random coils, means that separation occurs primarily according to molecular weight as proteins migrate through the polyacrylamide gel matrix [1]. The addition of reducing agents like dithiothreitol (DTT) further disrupts protein structure by breaking disulfide bonds, ensuring complete unfolding [29].

In contrast, Native PAGE is performed without denaturing agents, preserving proteins in their biologically active states [29] [28]. This maintenance of native structure means that protein separation depends on multiple intrinsic properties simultaneously—including molecular size, three-dimensional shape, and inherent electrical charge [29] [1]. The resulting migration pattern reflects a combination of these factors rather than solely molecular weight, making Native PAGE particularly suitable for studying functional protein complexes but less ideal for precise molecular weight determination.

Strategic Application Decisions

The choice between these techniques should be guided by specific research objectives, as each approach offers complementary strengths. SDS-PAGE excels in applications requiring molecular weight determination, assessment of protein purity, analysis of subunit composition, or when performing western blotting with antibodies that recognize linear epitopes [28]. The denaturing conditions effectively disrupt non-covalent interactions, preventing protein aggregation and ensuring consistent, predictable migration based primarily on polypeptide chain length [28].

Native PAGE is indispensable when maintaining protein function is paramount, such as when studying enzymatic activity, protein-protein interactions, oligomerization states, or protein-ligand binding [29] [28] [1]. Because proteins remain folded with their binding interfaces intact, complexes can be analyzed in their functional assemblies. This preservation of native structure comes at the cost of resolution, as the multiple factors influencing migration can complicate interpretation compared to the straightforward size-based separation of SDS-PAGE.

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE

| Parameter | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Protein State | Denatured and linearized | Native, folded structure |

| Charge During Separation | Uniform negative charge from SDS | Intrinsic charge of the protein |

| Separation Basis | Primarily molecular weight | Size, charge, and 3D shape |

| Protein Activity | Lost during denaturation | Preserved |

| Protein Complexes | Disrupted into subunits | Maintained intact |

| Typical Applications | Molecular weight determination, purity assessment, western blotting | Enzyme activity assays, protein-protein interaction studies, complex analysis |

Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) for Membrane Protein Complexes

Historical Development and Fundamental Principles

Blue Native PAGE stands as one of the earliest and most widely utilized native electrophoresis techniques, particularly renowned for its application in membrane protein research. The method was initially developed by Schägger and colleagues specifically to separate protein complexes from bovine heart mitochondria, establishing its utility for studying intricate membrane-bound systems [30]. The technique derives its name from the characteristic blue coloration imparted by the anionic dye Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250, which serves both functional and visual roles in the separation process.

The fundamental innovation of BN-PAGE lies in its use of Coomassie dye as a charge-conferring agent rather than merely a staining compound. Unlike SDS, which denatures proteins, Coomassie dye binds to the surface of membrane proteins without disrupting their tertiary or quaternary structures [31] [30]. This binding accomplishes two critical functions: it provides a uniform negative charge that facilitates electrophoretic migration toward the anode, and it enhances the solubility of hydrophobic membrane proteins by converting them from hydrophobic to hydrophilic states [31]. This solubilization is particularly crucial for membrane proteins, which tend to aggregate in aqueous environments due to their exposed hydrophobic surfaces.

Separation Mechanism and Technical Considerations

The separation mechanism in BN-PAGE represents a sophisticated interplay between charge-based migration and size-based sieving. While the Coomassie dye confers negative charge to drive proteins through the electric field, the ultimate resolution depends on the pore size of the polyacrylamide gradient gel [31]. As protein complexes migrate through the gradually decreasing pore sizes, they eventually reach positions where the gel matrix physically restricts further movement—effectively sorting complexes according to their hydrodynamic sizes [31]. This dual mechanism enables BN-PAGE to separate an impressive size range of complexes, from approximately 100 kDa to 10 MDa, making it suitable for everything from simple dimers to massive multiprotein assemblies [31] [30].

Despite its considerable utility, BN-PAGE does present certain limitations that researchers must consider. The Coomassie dye can potentially act as a detergent under some conditions, leading to the partial disassembly of particularly labile complexes [31] [30]. Additionally, the dye can quench certain fluorescence detection methods and interfere with the activity of some enzymes, complicating downstream functional analyses [31] [30]. These limitations necessitate careful experimental design and appropriate controls when applying BN-PAGE to novel membrane protein systems.

Figure 1: BN-PAGE Experimental Workflow. The diagram illustrates the key steps in Blue Native PAGE, from sample preparation with Coomassie dye to final analysis of separated membrane protein complexes.

Clear Native PAGE (CN-PAGE): A Gentler Alternative

Principle and Advantages for Delicate Complexes