Native PAGE vs SDS-PAGE for Protein Oligomerization Analysis: A Strategic Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on selecting and implementing electrophoresis techniques to accurately evaluate protein oligomerization states.

Native PAGE vs SDS-PAGE for Protein Oligomerization Analysis: A Strategic Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on selecting and implementing electrophoresis techniques to accurately evaluate protein oligomerization states. It covers the foundational principles distinguishing denaturing SDS-PAGE from native PAGE techniques, detailed methodologies including Blue Native (BN)-PAGE and Clear Native (CN)-PAGE variants, troubleshooting for common artifacts, and validation strategies using orthogonal biophysical methods. By synthesizing current research and practical applications, this resource enables informed methodological choices for studying protein complexes, interactions, and stability in biomedical research.

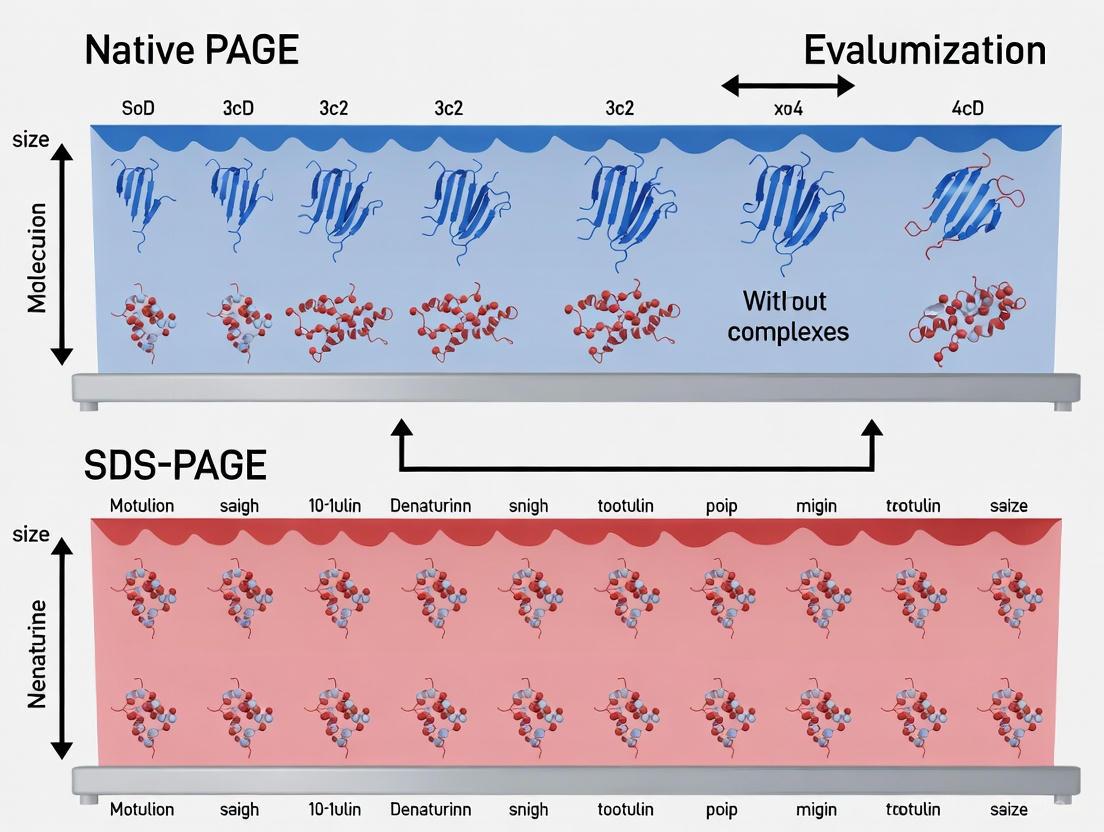

Core Principles: How Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE Reveal Different Aspects of Protein Structure

For researchers investigating protein oligomerization, selecting the appropriate electrophoretic technique is a critical strategic decision. The choice fundamentally hinges on the separation mechanism: whether to denature proteins for separation purely by molecular weight or to preserve their native state to separate by a combination of intrinsic charge, size, and shape. SDS-PAGE (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis) and Native-PAGE represent these two divergent philosophies. This guide provides an objective comparison of their performance in studying oligomeric states, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to inform method selection in drug development and basic research.

Core Principles and a Direct Comparison

The underlying mechanism of each technique dictates the type of information it can reveal about a protein complex.

SDS-PAGE: Separation by Molecular Weight Alone. This is a denaturing technique. The anionic detergent SDS unfolds proteins, breaking non-covalent interactions and, when combined with a reducing agent, cleaves disulfide bonds [1] [2]. SDS binds uniformly to the polypeptide backbone, imparting a high negative charge that masks the protein's intrinsic charge [3]. Consequently, all proteins adopt a similar shape and charge-to-mass ratio, migrating through the polyacrylamide gel matrix based almost exclusively on the molecular weight of their polypeptide subunits [3] [2]. It is ideal for determining subunit composition but destroys oligomeric structures.

Native-PAGE: Separation by Native Charge and Size. This is a non-denaturing technique. Proteins are separated in their folded, functional state without the use of denaturants [4] [3]. Their migration is driven by the protein's intrinsic net charge at the gel's pH and is sieved by the gel matrix according to the protein's size and three-dimensional shape [3]. This preserves protein-protein interactions, multi-subunit complexes, enzymatic activity, and non-covalently bound cofactors, making it the preferred method for analyzing native oligomeric states [4] [3].

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE

| Feature | SDS-PAGE | Native-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Molecular weight of polypeptide subunits [3] [2] | Native charge, size, and shape of the protein complex [3] |

| Protein State | Denatured and linearized [1] | Native, folded structure retained [4] |

| Oligomeric State | Disrupted; reveals subunits | Preserved; reveals functional oligomers |

| Biological Activity | Lost during separation [5] [6] | Often retained post-separation [3] |

| Information on Protein Complexes | Subunit composition and molecular weight | Stoichiometry, protein-protein interactions, quaternary structure [4] |

| Key Reagent | SDS (denaturant) & DTT (reductant) [2] | No SDS; may use Coomassie G-250 (in BN-PAGE) [7] |

Experimental Data and Performance in Oligomerization Studies

The practical application of these techniques reveals their distinct strengths and limitations, as demonstrated in studies focused on specific protein systems.

Case Study: Resolving HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase Oligomers with BN-AGE

A critical study on HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase (HIV-1 RT) highlights a key limitation of standard Native-PAGE methods. While Blue Native-PAGE (BN-PAGE) could separate the p66 homodimer from its monomer, it produced a severe "ladder of bands" artifact for the p51 homodimer under conditions where analytical ultracentrifugation confirmed only monomers were present [7]. This artifact persisted despite troubleshooting efforts, including omitting Coomassie dye, adding detergents, lowering voltage, and altering pH or gel composition.

The researchers developed a modified Blue Native Agarose Gel Electrophoresis (BN-AGE) protocol at pH 8.5 to resolve the issue. This method successfully separated p51 monomers and homodimers as discrete bands, and was used to characterize dimerization-deficient mutants (W401A, L234A) and the effect of the drug Efavirenz, which enhances dimerization [7]. This case underscores that the gel matrix itself (polyacrylamide vs. agarose) can be a source of artifact and requires due diligence.

Table 2: Troubleshooting p51 Artifacts in Native Gels [7]

| Condition Tested | Impact on p51 Multiple Band Artifact |

|---|---|

| BN-PAGE (Standard Protocol) | Severe laddering of monomeric p51 |

| Omission of Coomassie G-250 | Protein did not enter the gel |

| Addition of Detergents (e.g., DDM) | Did not resolve laddering |

| Reduced Voltage / Low Temperature | Did not resolve laddering |

| Increased pH (up to 8.5) in PAGE | Did not resolve laddering |

| BN-AGE at pH 8.5 (Modified Protocol) | Resolved p51 as a single, clean band |

Quantitative Functional Comparison: NSDS-PAGE as an Intermediate Method

A modified technique termed Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE) illustrates the spectrum between fully denaturing and fully native conditions. This method removes SDS and EDTA from the sample buffer, omits the heating step, and uses a greatly reduced SDS concentration (0.0375%) in the running buffer [5] [6].

The performance of this hybrid method was quantitatively compared to SDS-PAGE and BN-PAGE:

- Metal Retention: Retention of bound Zn²⁺ in proteomic samples increased from 26% in SDS-PAGE to 98% in NSDS-PAGE [5] [6].

- Enzyme Activity: Seven out of nine model enzymes, including four Zn²⁺ proteins, retained activity after NSDS-PAGE separation. All nine were active after BN-PAGE, while all were denatured and inactive after standard SDS-PAGE [5] [6].

- Resolution: NSDS-PAGE provided a high-resolution separation of the proteome comparable to standard SDS-PAGE, superior to the lower resolution typically achieved by BN-PAGE [5].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Below are the core methodologies for key techniques discussed, allowing for experimental replication.

Protocol: Blue Native Agarose Gel Electrophoresis (BN-AGE)

This protocol is adapted from the study on HIV-1 RT oligomer separation [7].

- Gel Preparation: Prepare a 3% (w/v) horizontal gel using SeaKem Gold agarose in Native Agarose Gel Buffer (NAGB: 25 mM Tris, 19.2 mM glycine, pH 8.5).

- Sample Preparation: Mix 10 µL of protein sample with 2.5 µL of sample buffer (NAGB containing 30% glycerol) and 0.3 µL of 5% Coomassie Blue G-250.

- Electrophoresis: Submerge the gel in the apparatus containing NAGB (pH 8.5). Perform electrophoresis at room temperature at 40 V for 4.5 hours.

- Detection: Stain and destain the gel using standard protein staining solutions (e.g., Coomassie-based stains).

Protocol: Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE)

This protocol is adapted from the method developed for high-resolution separation with native property retention [5].

- Sample Buffer (4X): 100 mM Tris HCl, 150 mM Tris base, 10% glycerol, 0.0185% Coomassie G-250, 0.00625% Phenol Red, pH 8.5. Note: Contains no SDS or EDTA, and the sample is not heated [5].

- Running Buffer: 50 mM MOPS, 50 mM Tris Base, 0.0375% SDS, pH 7.7. Note: The SDS concentration is significantly lower than in standard SDS-PAGE running buffers (typically 0.1%) [5].

- Gel: Standard precast or hand-cast polyacrylamide gels can be used (e.g., Invitrogen NuPAGE Novex 12% Bis-Tris gels) [5].

- Electrophoresis: Run at a constant voltage (e.g., 200V) at room temperature.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Successful electrophoresis relies on specific reagents. The table below details essential solutions for the protocols discussed.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Electrophoresis

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Description | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Ionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge [1] [2]. | Core component of SDS-PAGE sample and running buffers. |

| Coomassie Blue G-250 | Anionic dye used in BN-PAGE to impart negative charge to native proteins [7]. | Added to sample prior to BN-PAGE or BN-AGE to facilitate migration. |

| DTT or β-Mercaptoethanol | Reducing agents that break disulfide bonds between cysteine residues [1]. | Added to SDS-PAGE sample buffer for complete denaturation. |

| NativePAGE Novex Bis-Tris Gels | Precast polyacrylamide gels optimized for BN-PAGE separation. | Used for standard BN-PAGE according to manufacturer's protocol [7] [5]. |

| SeaKem Gold Agarose | High-strength, high-resolution agarose for gel electrophoresis. | Used as an alternative gel matrix for BN-AGE to avoid polyacrylamide artifacts [7]. |

| Tris-Glycine Buffer Systems | Common discontinuous buffer system for protein electrophoresis. | Used in both SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE at varying pH levels [7] [3]. |

Complementary and Advanced Methodologies

While electrophoresis is powerful, alternative and complementary techniques can validate and provide deeper insights.

Dual-Color Colocalization SMLM (DCC-SMLM): This advanced microscopy technique determines oligomeric states in situ without extracting proteins from their native membrane environment, thus avoiding potential disruption of weak interactions [8] [9]. It uses two spectrally distinct fluorescent proteins to tag subunits and counts colocalization events to determine the average oligomeric state, even with low fluorescent protein detection efficiency [9]. It has been used to resolve controversies, such as confirming the dimeric state of SLC26 transporters [8] [9].

Analytical Ultracentrifugation (AUC): Mentioned in the HIV-1 RT study, AUC is a gold-standard solution-based method for determining molecular mass and oligomeric states in a native solution, providing a critical benchmark for validating gel-based methods [7].

The choice between SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE for studying protein oligomerization is not a matter of which technique is superior, but which is appropriate for the specific research question. SDS-PAGE is the unrivaled method for determining the molecular weight and purity of denatured subunits. In contrast, Native-PAGE (and its variants like BN-PAGE and BN-AGE) is essential for probing functional, native oligomeric complexes. As demonstrated by the development of NSDS-PAGE and BN-AGE, researchers can and should modify standard protocols to overcome challenges, while techniques like DCC-SMLM offer a powerful way to validate findings in a near-native cellular context. A rigorous approach often requires the complementary use of multiple methods to build a definitive model of a protein's quaternary structure.

In the study of proteins, particularly for determining oligomerization states and complex structures, the choice of electrophoretic method dictates the informational outcome. Native PAGE (Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis) and SDS-PAGE (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate–Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis) represent two fundamentally different approaches: one preserves the native architecture of proteins, while the other systematically dismantles it [4] [10]. This guide provides a objective comparison of these techniques, focusing on their impact on protein function and quaternary structure within the context of oligomerization state research.

The core distinction lies in the treatment of the protein sample. Native-PAGE separates proteins in their folded, active state, allowing for the analysis of functional complexes and oligomers. In contrast, SDS-PAGE relies on a powerful denaturing detergent to unfold proteins and coat them with a uniform negative charge, separating polypeptides primarily by their molecular mass while destroying higher-order structure and function [11] [10]. The following sections will detail the principles, experimental protocols, and resulting data outputs of each method, providing a framework for selecting the appropriate technique for specific research goals in drug development and protein science.

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Native-PAGE: Preserving Native Structure

- Separation Basis: Native-PAGE separates proteins based on a combination of their inherent charge, size, and three-dimensional shape as they migrate through the polyacrylamide gel matrix [11] [10]. The gel acts as a sieve, where smaller and more negatively charged proteins migrate faster.

- Structural Integrity: Crucially, no denaturing agents are used. This preserves the protein's secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures [10]. Consequently, subunit interactions within a multimeric protein are retained, and many proteins maintain their enzymatic activity following separation [11].

- Charge Considerations: Because proteins retain their native charge, they can migrate toward either the anode or cathode depending on their net charge at the running buffer's pH. This makes molecular weight determination less straightforward than in denaturing methods [10].

SDS-PAGE: Denaturation for Size-Based Separation

- Separation Basis: SDS-PAGE separates proteins primarily, and almost exclusively, by their polypeptide molecular weight [12]. This is achieved by dismantling the native structure.

- Role of SDS: The anionic detergent SDS denatures proteins by binding to the polypeptide backbone, disrupting hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions. This unfolds the protein into a linear chain [13] [14]. SDS binds in a constant weight ratio (about 1.4 g SDS per 1 g of protein), conferring a uniform negative charge that overwhelms the protein's intrinsic charge [15] [11].

- Role of Reducing Agents: Agents like Dithiothreitol (DTT) or β-mercaptoethanol are added to break disulfide bonds, which are covalent bonds not disrupted by SDS alone [13] [15]. This ensures complete dissociation of protein subunits not covalently linked.

- The Result: All proteins become linear, negatively charged rods with very similar charge-to-mass ratios. When pulled through the gel by an electric field, their migration rate depends almost entirely on their size, enabling accurate molecular weight estimation [11] [12].

Table 1: Core Principles and Separation Mechanisms

| Feature | Native-PAGE | SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Separation Basis | Net charge, size, and shape | Molecular mass (polypeptide length) |

| Protein State | Native, folded | Denatured, linearized |

| Quaternary Structure | Preserved | Disrupted (except covalent cross-links) |

| Functional Activity | Often retained | Destroyed |

| Key Reagents | Non-denaturing buffer | SDS, Reducing agents (DTT) |

| Molecular Weight Determination | Not reliable due to charge/shape influence | Highly reliable |

Experimental Protocols and Key Reagents

The experimental workflows for Native-PAGE and SDS-PAGE are designed to either maintain or dismantle protein structure, a critical difference reflected in every step of sample preparation and electrophoresis.

Sample Preparation: A Critical Divergence

Native-PAGE Protocol:

- Sample Buffer: A non-denaturing buffer is used, typically containing Tris, glycerol for density, and a tracking dye like Bromophenol Blue. Crucially, it lacks SDS, reducing agents, and EDTA (which can chelate metal cofactors) [5] [16].

- No Heating: The sample is mixed with the buffer but not heated, as heat would denature proteins and defeat the purpose of the technique [16].

- Cell Lysis: Gentle lysis methods like ultrasonication are employed, followed by centrifugation to collect the supernatant [16].

SDS-PAGE Protocol:

- Sample Buffer (Laemmli Buffer): This contains SDS to denature and impart charge, a reducing agent (DTT or β-mercaptoethanol) to break disulfide bonds, glycerol, and a tracking dye [13] [14].

- Heating Step: The protein-sample buffer mixture is heated to 95–100°C for 5-10 minutes to ensure complete denaturation and disruption of all non-covalent interactions [15].

- Goal: The outcome is a solution of fully denatured, reduced, and negatively charged polypeptides.

Gel Composition and Electrophoresis Conditions

Native-PAGE Conditions:

- Gel & Buffer: The polyacrylamide gel and electrophoresis buffer are formulated without SDS or other denaturants [16].

- pH Consideration: The pH of the buffer system must be chosen based on the protein's isoelectric point (pI). For acidic proteins, a basic pH (e.g., 8.8) is used to ensure a net negative charge and migration toward the anode. For basic proteins, an acidic buffer and reversed electrode polarity may be necessary [16].

- Temperature Control: Electrophoresis is often performed at 4°C or with cooling to prevent heat-induced denaturation during the run [16].

SDS-PAGE Conditions:

- Gel & Buffer: Both the gel and the running buffer contain SDS to maintain protein denaturation [15] [14].

- Discontinuous System: Standard SDS-PAGE uses a stacking gel (lower pH, low % acrylamide) to concentrate all protein samples into a sharp band before they enter the resolving gel (higher pH, higher % acrylamide) where separation by size occurs [14].

- Glycine's Role: In the running buffer, glycine's charge state changes with the gel's pH, creating a voltage gradient that stacks proteins sharply at the interface between the two gels [14].

The following workflow summarizes the key decision points and procedural steps for both methods:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful electrophoresis requires specific reagents tailored to each method's goals.

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Native- and SDS-PAGE

| Reagent | Function in Native-PAGE | Function in SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Tris-Glycine Buffer | Running buffer at appropriate pH to maintain protein charge and activity [16]. | Running buffer; glycine's shifting charge enables stacking for sharp bands [14]. |

| Non-Denaturing Load Buffer | Provides density for well-loading and a visible dye; lacks SDS/DTT to preserve structure [16]. | Not applicable. |

| Laemmli Sample Buffer | Not applicable. | Denatures proteins (SDS), reduces disulfide bonds (DTT), adds density (glycerol) [14]. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Omitted to prevent denaturation. | Primary denaturant; unfolds proteins and confers uniform negative charge [13] [12]. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Omitted to prevent reduction of disulfide bonds. | Reducing agent; breaks disulfide bonds to fully dissociate subunits [13] [15]. |

| Acrylamide/Bis Solution | Forms the porous gel matrix for size-based separation in a native state. | Forms the porous gel matrix for size-based separation of denatured polypeptides. |

| Coomassie/Silver Stain | Detects separated protein bands after electrophoresis; compatible with native proteins [16]. | Detects separated polypeptide bands after electrophoresis. |

Data Output and Experimental Evidence

The functional and structural impacts of choosing Native-PAGE over SDS-PAGE are demonstrated by specific experimental data, particularly regarding metal cofactor retention and enzymatic activity.

Quantitative Comparison: Metal Retention and Enzyme Activity

A modified electrophoretic method known as NSDS-PAGE (Native SDS-PAGE), which uses minimal SDS and no EDTA or heating, provides a clear point of comparison. This method aims to balance the high resolution of SDS-PAGE with the functional preservation of Native-PAGE [5].

Table 3: Quantitative Data on Metal Retention and Enzyme Activity Post-Electrophoresis

| Analysis Metric | BN-PAGE (Fully Native) | NSDS-PAGE (Minimal Denaturation) | SDS-PAGE (Fully Denaturing) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zn²⁺ Retention in Proteomic Samples | Not Explicitly Reported | 98% [5] | 26% [5] |

| Activity of Model Zn²⁺ Enzymes | All nine enzymes active [5] | Seven of nine enzymes active [5] | All nine enzymes denatured/inactive [5] |

| Resolution Quality | Lower resolution, broader bands [5] | High resolution, comparable to SDS-PAGE [5] | High resolution, sharp bands [5] |

Key Interpretation: The data shows that standard SDS-PAGE is highly destructive to metal-protein interactions and enzymatic function, while fully native methods (BN-PAGE) preserve them completely. The hybrid NSDS-PAGE method demonstrates that high resolution can be achieved with minimal functional compromise, though not all activity is retained [5]. For research focused on metalloproteins or functional complexes, this trade-off is a critical consideration.

Analysis of Oligomerization State

The preservation of quaternary structure in Native-PAGE allows researchers to directly analyze the native oligomeric state of a protein.

- Native-PAGE Analysis: A single band on a Native-PAGE gel typically represents a protein in its intact oligomeric form (e.g., a dimer, tetramer). Its migration distance is a function of that entire complex's mass, charge, and shape [10]. This is invaluable for studying protein-protein interactions and complex stoichiometry.

- SDS-PAGE Analysis: SDS-PAGE dissociates non-covalent complexes. A multimeric protein will typically yield bands corresponding to the molecular weights of its individual subunits. If a complex is stabilized by disulfide bonds and a non-reducing buffer is used, the band may represent the intact, cross-linked complex, but in a denatured state [15] [10].

Application Scenarios and Selection Guide

The choice between Native-PAGE and SDS-PAGE is not a matter of which is better, but which is appropriate for the specific research question.

Choose Native-PAGE when your goal is to:

- Determine a protein's native oligomeric state or quaternary structure [10].

- Study protein-protein interactions within a complex [4].

- Isolate and subsequently test for enzymatic activity directly from the gel [11] [10].

- Analyze proteins with essential metal ion cofactors that would be stripped away by denaturation [5].

Choose SDS-PAGE when your goal is to:

- Determine the molecular weight of polypeptide subunits with high accuracy [11] [10].

- Assess the purity and integrity of a protein sample [10].

- Analyze the subunit composition of a complex [11].

- Prepare samples for western blotting or mass spectrometry analysis, where denaturation is required or beneficial [4].

In conclusion, the central thesis in evaluating protein oligomerization state is that Native-PAGE and SDS-PAGE are complementary tools. Native-PAGE provides a snapshot of the protein in its functional, assembled state, while SDS-PAGE provides a parts list of its constituent polypeptides. The decision on which method to use must be driven by the specific biological question, whether it pertains to the function of the whole machine or the identity of its components.

In the study of protein oligomerization, selecting the appropriate electrophoretic technique is paramount. The oligomerization state of a protein—whether it exists as a monomer, dimer, or larger complex—directly influences its function and regulatory mechanisms. Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE are foundational methods in this analysis, but they provide starkly different information based on their fundamental technical principles. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of the buffer composition, sample preparation, and running conditions of these two techniques, framing them within the context of protein oligomerization research for scientists and drug development professionals.

Technical Comparison at a Glance

The following table summarizes the core procedural differences between Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE, which dictate their applicability in studying oligomeric proteins [17] [3].

| Technical Criterion | Native PAGE | SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Gel Nature | Non-denaturing | Denaturing |

| Separation Principle | Size, charge, and 3D shape [17] [18] | Molecular weight (size only) [18] [19] [3] |

| Sample Buffer Additives | Non-denaturing buffer, often Coomassie dye (BN-PAGE) [5] | SDS (anionic detergent) and reducing agents (e.g., DTT, β-mercaptoethanol) [17] [15] |

| Sample Heating | Not heated [17] | Heated (typically 70–100°C) [3] [15] |

| Protein State Post-Prep | Native, folded, functional [17] [4] | Denatured, linearized, non-functional [3] [20] |

| Running Conditions | Run at 4°C [17] | Run at room temperature [17] |

| Impact on Oligomers | Preserves multimeric quaternary structure [3] [21] | Disrupts non-covalent quaternary structures [3] [15] |

Detailed Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation Protocols

The sample preparation phase is where the most critical differences lie, as it determines whether native structures are preserved or denatured.

Native PAGE Protocol (for Oligomer Preservation):

- Buffer Formulation: Prepare a non-denaturing sample buffer. A common formulation is 50 mM BisTris, 50 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 0.001% Ponceau S, pH 7.2 [5]. For Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE), Coomassie G-250 dye is added to the sample buffer [5].

- Sample Mixing: Combine the protein sample with the 4X non-denaturing sample buffer. A typical ratio is 7.5 µL sample to 2.5 µL 4X buffer [5].

- Critical Step - No Heating: The sample mixture is loaded directly onto the gel without heating [17]. This avoids thermal denaturation that would disrupt weak, non-covalent interactions holding protein complexes together.

SDS-PAGE Protocol (for Subunit Analysis):

- Buffer Formulation: Prepare a denaturing sample buffer. The Laemmli buffer system is standard, containing SDS and a reducing agent [15].

- Reduction and Denaturation: Combine the protein sample with the SDS-containing buffer and a reducing agent like dithiothreitol (DTT) or β-mercaptoethanol. These agents break disulfide bonds that stabilize some protein complexes [20] [15].

- Critical Step - Heating: Heat the sample at 95°C for 5 minutes (or 70°C for 10 minutes) [15]. This heat treatment fully denatures the proteins, allowing SDS to bind uniformly and linearize the polypeptides, effectively dismantling oligomeric complexes into their constituent subunits [3].

Buffer and Gel Composition

The composition of the gels and running buffers is engineered to support the goal of each technique.

Native PAGE Systems:

- Gel Buffer: Lacks SDS and denaturing agents. Common systems use BisTris-based buffers at neutral pH [5].

- Running Buffer: A discontinuous system is often used. For BN-PAGE, the cathode and anode buffers are different; the cathode buffer may contain Coomassie dye (e.g., 0.02% Coomassie G-250), which assists in protein charge-shifting and complex stabilization during the run [5]. The entire process is typically performed at 4°C to maintain protein stability and prevent denaturation [17].

SDS-PAGE Systems:

- Gel Buffer: Contains SDS (e.g., 0.1-0.2%) in both stacking and resolving gels [15]. The stacking gel has a lower acrylamide concentration (~4%) and pH (~6.8), while the resolving gel has a higher concentration (e.g., 10-12%) and pH (~8.8) for optimal separation [22] [15].

- Running Buffer: Contains SDS (e.g., 0.1% in traditional systems) and a conducting electrolyte like Tris-glycine [15]. The SDS ensures a constant charge-to-mass ratio for all proteins during electrophoresis.

Workflow Diagram: Native PAGE vs. SDS-PAGE

The diagram below illustrates the key procedural differences and their impact on protein oligomers.

Supporting Experimental Data and Advanced Techniques

Quantitative Data on Native Function Preservation

Research into modified SDS-PAGE conditions provides quantitative evidence for the importance of gentle protocols. A study comparing standard SDS-PAGE to Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE)—which uses minimal SDS and no heating or EDTA—yielded compelling data on function preservation [5].

| Experimental Condition | Zinc Retention in Zn-Proteome | Enzymatic Activity Retention\n(Model Enzymes) |

|---|---|---|

| Standard SDS-PAGE | 26% | 0 out of 9 active (All denatured) |

| Native (N)SDS-PAGE | 98% | 7 out of 9 active |

| Blue Native (BN)-PAGE | Not Reported | 9 out of 9 active |

This data underscores that omitting denaturing steps allows most proteins to retain their metal cofactors and enzymatic function, which is crucial for analyzing metalloenzymes and other functional complexes [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents used in these electrophoretic techniques and their specific roles in protein analysis.

| Reagent Solution | Function in Protocol | Impact on Protein Oligomerization |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Denatures proteins; confers uniform negative charge [3] [20]. | Disrupts non-covalent oligomers by unfolding subunits. Masks intrinsic charge. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) / β-Mercaptoethanol | Reducing agents that break disulfide bonds [17] [15]. | Disrupts oligomers held together by covalent disulfide linkages. |

| Coomassie G-250 (in BN-PAGE) | Imparts negative charge without full denaturation; stabilizes complexes [5]. | Preserves oligomeric structure during separation for native mass analysis. |

| TEMED / Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | Catalyzes acrylamide polymerization to form the gel matrix [3] [22]. | No direct impact on oligomers. Creates the sieving medium for separation. |

| Tris-Based Buffers | Maintains stable pH during electrophoresis to ensure consistent protein charge [15]. | Critical in native PAGE to maintain protein stability and native charge. |

Strategic Application in Oligomerization Research

The choice between Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE is not a matter of which is better, but of which is appropriate for the specific research question.

Use Native PAGE (or BN-PAGE) to:

- Determine the native molecular weight and oligomeric state (e.g., dimer, tetramer) of a protein complex [3] [4].

- Study protein-protein interactions and isolate active complexes for downstream functional assays (e.g., enzyme activity tests) [17] [5].

- Investigate proteins with non-covalently bound cofactors, such as metal ions, that are essential for function [5].

Use SDS-PAGE to:

- Determine the molecular weight of the individual polypeptide subunits that make up an oligomeric complex [3] [20].

- Analyze protein purity and subunit composition, confirming the number and size of distinct chains in a complex [4].

- Probe for the presence of disulfide bonds by comparing reducing and non-reducing conditions [20].

For the most comprehensive analysis, researchers often employ a two-dimensional approach: separating proteins by their native state in the first dimension (using BN-PAGE) followed by a second dimension under denaturing conditions (SDS-PAGE). This powerful combination can resolve the subunit composition of each individual complex from a mixture, providing a complete picture of the oligomeric proteome [5].

Protein oligomerization, the process by which multiple protein subunits assemble into a defined quaternary structure, represents a fundamental mechanism regulating biological function across diverse organisms. These homo-oligomers (comprising identical subunits) and hetero-oligomers (comprising different subunits) exhibit properties that often transcend the simple sum of their parts, enabling complex allosteric regulation, enhanced stability, and the formation of novel functional sites [23]. The symmetry and stoichiometry of these assemblies—ranging from cyclic (Cn) and dihedral (Dn) symmetries to complex helical and icosahedral arrangements—are crucial determinants of their physiological roles [23]. For instance, many enzymes become catalytically active only upon forming specific oligomeric states, while membrane transporters and receptors frequently rely on quaternary structures for proper regulation and function [9]. Conversely, aberrant oligomerization underpins numerous pathological conditions, including amyloid formation in neurodegenerative diseases and loss-of-function mutations that disrupt essential protein complexes. Consequently, accurately determining oligomeric states is paramount for understanding both normal physiology and disease mechanisms, driving the development of increasingly sophisticated analytical techniques.

Comparative Analysis of Electrophoretic Methods for Oligomerization State Determination

The accurate determination of a protein's oligomeric state is a fundamental challenge in structural biology. Among the most widely used techniques are Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (Native-PAGE) and Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), which provide complementary information through different mechanisms of separation. The following section provides a detailed comparison of these core methodologies.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Native-PAGE and SDS-PAGE

| Feature | Native-PAGE | SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Protein State | Native, folded conformation preserved [4] | Denatured, unfolded linear chains [15] [4] |

| Separation Basis | Combined effect of intrinsic charge, size, and shape [4] | Molecular weight of polypeptide chains [15] [4] |

| Quaternary Structure | Preserves oligomeric complexes and quaternary structure [24] [4] | Disrupts non-covalent quaternary structure [15] |

| Biological Activity | Often retained after separation [4] [5] | Destroyed due to denaturation [4] [5] |

| Disulfide Bonds | Remain intact unless reducing agents are added | Remain intact in non-reducing conditions [24] |

| Key Applications | Studying native complexes, protein-protein interactions, enzymatic activity assays [4] | Determining subunit molecular weight, protein purity, post-translational modifications [4] |

Experimental Data and Interpretation

The power of combining these techniques is illustrated by a classic experimental observation: a protein that migrates as a 60 kDa band on non-reducing SDS-PAGE but as a 120 kDa band on Native-PAGE provides a clear inference. This result strongly indicates that the native protein is a dimer of 60 kDa subunits [24]. Critically, the use of non-reducing conditions confirms that the subunits are not linked by disulfide bonds, as these covalent bonds would remain intact and the SDS-PAGE would still show the 120 kDa complex [24] [15]. The dissociation into monomers on SDS-PAGE demonstrates that the dimer is stabilized by non-covalent interactions (e.g., hydrophobic, electrostatic), which are disrupted by the denaturing action of SDS [24] [4].

Methodological Limitations and Advanced Variants

Both techniques have limitations. SDS-PAGE intentionally destroys native structure and function, making it unsuitable for functional studies [5]. While Native-PAGE preserves function, its resolution can be lower, and migration is influenced by factors beyond size, complicating molecular weight determination [4] [5]. To address the need for high resolution under semi-native conditions, Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE) has been developed. This modified technique uses minimal SDS and omits heating and chelating agents like EDTA, which allows for excellent protein separation while retaining enzymatic activity and bound metal cofactors in many proteins [5]. For example, Zn²⁺ retention in proteomic samples increased from 26% in standard SDS-PAGE to 98% in NSDS-PAGE, and most tested enzymes remained active after separation [5].

Experimental Data from Comparative Studies

To effectively illustrate the practical outcomes of these methods, the table below summarizes key experimental findings that highlight the resolving power and specific applications of different electrophoretic techniques.

Table 2: Experimental Data from Electrophoretic Analysis of Protein Oligomerization

| Protein / System | Technique | Key Finding | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pyruvate Dehydrogenase E2 (PDH E2) Complex | Negative Staining EM with Multiple Stains [25] | Multi-stain approach improved resolution to 21.7 Å, revealing icosahedral symmetry and detailed domain organization. | Enhanced visualization of large complex architecture, bridging initial characterization and high-resolution studies. |

| Generic Protein Complex | Native-PAGE vs. Non-reducing SDS-PAGE [24] | Native-PAGE: 120 kDa; SDS-PAGE: 60 kDa. | Identified a non-covalent homodimer, crucial for understanding functional quaternary structure. |

| Zinc Metalloproteins (e.g., Alcohol Dehydrogenase) | Standard SDS-PAGE vs. NSDS-PAGE [5] | Zn²⁺ retention: 26% (SDS-PAGE) vs. 98% (NSDS-PAGE); enzymatic activity preserved in NSDS-PAGE. | Enabled high-resolution separation of native metalloproteins, vital for studying metal-coupled function. |

| Plasma Membrane Transporters (SLC family) | DCC-SMLM (Microscopy) [9] | Resolved controversy, confirming dimeric state for SLC26A3 and prestin in situ. | Validated oligomeric state in native membrane environment without disruptive isolation. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Standard SDS-PAGE Protocol

The standard denaturing SDS-PAGE protocol is a workhorse for determining subunit molecular weight [15].

- Sample Preparation: Mix protein sample with an SDS-containing loading buffer (e.g., LDS buffer). A reducing agent like DTT or β-mercaptoethanol is often included to break disulfide bonds. Heat the sample at 70°C for 10 minutes or 95°C for 5 minutes to denature the proteins [15] [5].

- Gel Setup: Use a discontinuous gel system, typically with a stacking gel (pH ~6.8) and a separating gel (pH ~8.8) of appropriate acrylamide concentration (e.g., 4-20%) to create a pore size gradient for optimal separation [15].

- Electrophoresis: Load samples and a molecular weight marker onto the gel. Run in an SDS-containing running buffer (e.g., MOPS or Tris-Glycine-SDS) at constant voltage (e.g., 100-200 V) until the dye front migrates to the bottom of the gel [15] [5].

Native (Blue) PAGE Protocol

This protocol preserves protein complexes in their native state [5] [9].

- Sample Preparation: Mix protein sample with a non-denaturing, mild sample buffer. Crucially, no SDS or reducing agents are added. Glycerol is often included to facilitate gel loading, and a blue dye like Coomassie G-250 may be present to provide charge and visual tracking [5].

- Gel Setup: Use pre-cast NativePAGE gels or cast gels with a single, neutral pH buffer system (e.g., Bis-Tris, pH 7.2) to maintain native protein charge [5].

- Electrophoresis: Load samples and native molecular weight standards. Run using anode and cathode buffers of different compositions, often under dark conditions at 4°C to maintain protein stability, at constant voltage (e.g., 150 V) [5].

Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE) Protocol

This hybrid protocol balances resolution and native state preservation [5].

- Sample Preparation: Mix protein sample with a modified sample buffer that contains no SDS, EDTA, or reducing agents, and omit the heating step [5].

- Gel Setup: Use standard Bis-Tris gels. Pre-run the gel in water to remove storage buffers and unpolymerized acrylamide [5].

- Electrophoresis: Run the gel in a modified running buffer containing a very low concentration of SDS (e.g., 0.0375%) and no EDTA, at constant voltage (e.g., 200 V) [5].

The workflow below illustrates the decision-making process for selecting the appropriate electrophoretic method based on research goals.

Advanced and Emerging Techniques in Oligomerization Analysis

While electrophoretic methods are foundational, technological advances have provided powerful new tools for analyzing oligomeric states, particularly in complex cellular environments.

Single Molecule Localization Microscopy (SMLM)

Traditional biochemical methods require protein extraction, which can disrupt weak but physiologically relevant interactions [9]. Dual-Color Colocalization SMLM (DCC-SMLM) overcomes this by enabling in situ quantification of oligomeric states in plasma membranes. This super-resolution technique labels each subunit of a protein with two spectrally distinct fluorescent proteins—a "marker" (M) and an "indicator" (F). By statistically analyzing the co-localization of signals from both fluorophores, the average oligomeric state of the protein can be determined with high accuracy, even with low fluorescent protein detection efficiency and in the presence of background noise [9]. This method has been used to resolve controversies, such as confirming the dimeric state of SLC26 anion transporters within their native membrane environment [9].

Computational Prediction with Machine Learning

The rise of accurate protein structure prediction has enabled the development of computational tools for oligomer symmetry prediction. Seq2Symm is a machine learning model that leverages the ESM2 protein language model to predict the symmetry of homo-oligomers (e.g., cyclic C2, dihedral D3, helical) from a single protein sequence alone [23]. This approach is highly scalable, capable of predicting oligomeric states for approximately 80,000 proteins per hour, and significantly outperforms older template-based methods [23]. Such tools allow researchers to prioritize experimental characterization and generate hypotheses for proteins lacking experimental structures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful determination of protein oligomerization requires a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions and their specific functions in different electrophoretic protocols.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Oligomerization Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Anionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge. Binds ~1.4g per gram of protein [15]. | Standard SDS-PAGE: Essential. NSDS-PAGE: Greatly reduced (0.0375%) or omitted. Native-PAGE: Not used [4] [5]. |

| Polyacrylamide Gel Matrix | Porous network that sieves proteins during electrophoresis. | Pore size (determined by %T) dictates separation range. Gradient gels (e.g., 4-12%) offer wider size range resolution [15]. |

| β-Mercaptoethanol / DTT | Reducing agents that break disulfide bonds between cysteine residues. | Used in reducing SDS-PAGE to fully dissociate covalent complexes. Omitted in non-reducing SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE [24] [15]. |

| Coomassie G-250 | Blue dye used in sample and cathode buffers for Native/BN-PAGE. | Imparts a slight negative charge to proteins, aids in protein migration and visualization during the run [5]. |

| Uranyl Acetate (UA) | Heavy metal salt used for negative staining in Electron Microscopy (EM). | Provides high contrast; binds negatively charged protein regions. One of several stains used in multi-stain EM approaches [25]. |

| Photoactivatable Fluorescent Proteins (e.g., PA-GFP, mEos) | Genetically encoded tags for SMLM. Can be activated or converted with specific light wavelengths. | Essential for DCC-SMLM; allows precise localization of single molecules beyond the diffraction limit [9]. |

The precise determination of protein oligomerization states remains a cornerstone of structural and functional biology, with direct implications for understanding enzyme mechanisms, cellular signaling, and disease pathology. While classical electrophoretic techniques like Native-PAGE and SDS-PAGE provide a foundational and accessible approach, their limitations have spurred the development of advanced hybrid methods like NSDS-PAGE and sophisticated in-situ technologies like DCC-SMLM. The choice of method is critical, as it must align with the specific research question—whether it involves determining subunit stoichiometry, probing functional complexes, or visualizing oligomers in their native membrane environment. The ongoing integration of these experimental findings with powerful computational predictions, such as those generated by Seq2Symm, is creating a more comprehensive and dynamic atlas of protein oligomerization across biology. This multi-faceted toolkit empowers researchers to not only elucidate the fundamental principles of protein assembly but also to identify novel therapeutic targets for diseases driven by aberrant oligomerization.

For researchers investigating protein complexes, oligomerization state is a critical parameter influencing biological function, yet accurately determining this state requires careful methodological selection. When framing experiments within the context of protein oligomerization, the choice between Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE represents a fundamental crossroads, with each technique providing a distinct and often irreconcilable view of your protein's quaternary structure. Native PAGE preserves the delicate, non-covalent interactions that maintain multi-subunit complexes, allowing for analysis of proteins in their functional, native state [4]. In contrast, SDS-PAGE employs a strong ionic detergent to dismantle these complexes, providing information strictly on the molecular weights of denatured polypeptide subunits [4]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these techniques, supported by experimental data, to empower researchers in making informed decisions for their specific experimental objectives.

Core Principle and Impact on Oligomerization State

The most significant distinction between these methods lies in their treatment of the protein's structure, which directly dictates the information you can obtain about oligomerization.

Native PAGE: Preserves Oligomeric Structure This technique separates proteins under non-denaturing conditions. The gel matrix and running buffers lack disruptive detergents, allowing proteins to retain their secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures [4]. Separation is based on a combination of the protein's intrinsic charge, size, and shape [3]. Consequently, a protein complex will migrate as an intact entity. If a protein exists as a tetramer in its native state, it will appear on the Native PAGE gel at a molecular weight corresponding to that tetramer, providing direct evidence of its oligomeric state [4].

SDS-PAGE: Disrupts Oligomeric Structure SDS-PAGE is a denaturing technique. Proteins are heated in a sample buffer containing sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and a reducing agent [26]. SDS binds uniformly to the polypeptide backbone, masking the protein's intrinsic charge and unfolding it into a linear rod [4]. Crucially, this process dissociates non-covalent protein-protein interactions and reduces disulfide bonds, effectively dismantling protein oligomers into their constituent monomers [4]. Separation, therefore, occurs primarily by the mass of the individual polypeptide chains, not the intact complex [3].

The following workflow illustrates the procedural and outcome differences between these two methods:

Capabilities and Limitations: A Direct Comparison

The core differences in principle translate directly into distinct capabilities and limitations for protein characterization, particularly concerning oligomerization.

Table 1: Capabilities and Limitations of Native PAGE vs. SDS-PAGE in Protein Analysis

| Analysis Parameter | Native PAGE | SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Oligomerization State | Preserved and directly analyzable [4] | Disrupted; provides subunit composition only [4] |

| Biological Activity | Retained (enzymatic assays possible post-electrophoresis) [5] | Destroyed by denaturation [4] |

| Molecular Weight Determination | Approximate; based on native size/charge ratio [4] | Accurate for polypeptide chains using standards [3] |

| Protein Complex & Interaction Studies | Ideal for analyzing intact complexes [4] | Unsuitable for native interactions [4] |

| Key Limitation | Lower resolution for complex mixtures; native charge can complicate analysis [4] | Cannot distinguish between different oligomeric states of the same protein [4] |

Experimental Data and Protocol Comparison

To move from theoretical comparison to practical application, the following experimental data and detailed protocols are provided.

Quantitative Comparison: Retention of Native Properties

A critical study directly compared standard SDS-PAGE, Blue-Native (BN)-PAGE, and a modified "Native SDS-PAGE" (NSDS-PAGE) method for its ability to retain zinc ions and enzymatic activity in various proteins. The data clearly demonstrates the functional consequences of the methodological choice.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Functional Property Retention Across PAGE Methods [5]

| Protein / Sample | SDS-PAGE | BN-PAGE | NSDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retention of Zn²⁺ in Proteome | 26% | Not Reported | 98% |

| Active Enzymes (from 9 tested) | 0 | 9 | 7 |

| Yeast Alcohol Dehydrogenase (Zn-ADH) | Inactive | Active | Active |

| Carbonic Anhydrase (Zn-CA) | Inactive | Active | Active |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The following protocols are adapted from established methods and are critical for ensuring the validity of the results, particularly for Native PAGE [5].

Protocol for Native PAGE (Based on BN-PAGE)

- Sample Preparation: Mix 7.5 μL of protein sample with 2.5 μL of 4X BN-PAGE sample buffer (e.g., 50 mM BisTris, 50 mM NaCl, 10% Glycerol, 0.001% Ponceau S, pH 7.2). Do not heat.

- Gel Preparation: Use a pre-cast Native-PAGE Novex 4-16% Bis-Tris gradient gel or equivalent.

- Running Buffer: Prepare anode (50 mM BisTris, 50 mM Tricine, pH 6.8) and cathode (50 mM BisTris, 50 mM Tricine, 0.02% Coomassie G-250, pH 6.8) buffers separately.

- Electrophoresis: Load samples and run at a constant voltage of 150V at 4°C for approximately 90 minutes, or until the dye front migrates to the bottom of the gel [5].

Protocol for SDS-PAGE (Standard Denaturing)

- Sample Preparation: Mix 7.5 μL of protein sample with 2.5 μL of 4X LDS sample loading buffer (containing SDS and reducing agents). Heat the sample at 70°C for 10 minutes to ensure complete denaturation.

- Gel Preparation: Use a pre-cast gel, such as a Novex 12% Bis-Tris gel.

- Running Buffer: Use 1X MOPS SDS running buffer (e.g., 50 mM MOPS, 50 mM Tris Base, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.7).

- Electrophoresis: Load samples alongside molecular weight markers. Run at a constant voltage of 200V at room temperature for about 45 minutes, or until the dye front exits the gel [5].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions for executing these electrophoretic analyses.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for PAGE

| Item | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-Acrylamide | Forms the cross-linked porous gel matrix; concentration determines pore size and resolution range [3]. | A 29:1 or 37.5:1 ratio of acrylamide to bis-acrylamide is common. Stock solutions are light-sensitive and can hydrolyze over time [27]. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Ionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge [4]. | Use high-purity, electrophoresis-grade SDS. The critical factor for binding is the SDS monomer concentration, which requires low ionic strength in the sample buffer [27]. |

| TEMED & APS | Catalytic system for gel polymerization. TEMED catalyzes APS to produce free radicals that initiate polymerization [3]. | TEMED is volatile and corrosive. APS solution should be freshly prepared or aliquoted and frozen, as it decomposes over time [27]. |

| Reducing Agents (DTT, β-ME) | Cleave disulfide bonds to fully unfold polypeptides and disrupt oligomers stabilized by covalent links [26]. | Essential for reducing SDS-PAGE. Omitted from native PAGE protocols to preserve structure. |

| Coomassie G-250 | A key component in BN-PAGE running buffer; binds proteins, imparting a negative charge for electrophoresis without full denaturation [5]. | Distinct from the Coomassie used for staining (R-250). |

| Tris-based Buffers | Provide the conductive medium and maintain stable pH during electrophoresis [27]. | Different buffer systems (e.g., Tris-Glycine, Bis-Tris, Tris-Acetate) are optimized for different protein size ranges and gel stability [27]. |

Decision Workflow for Method Selection

Selecting the appropriate method depends squarely on the primary research question. The following decision pathway can guide researchers to the correct technique:

In the critical task of evaluating protein oligomerization state, Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE are not interchangeable but rather complementary tools that answer fundamentally different questions. Native PAGE provides a snapshot of the protein in its functional, assembled state, directly revealing oligomeric composition and preserving activity. SDS-PAGE provides a parts list, accurately defining the identity and molecular weight of the individual subunits that comprise the oligomer. The most powerful strategies often employ these techniques in tandem—for example, using Native PAGE in a first dimension to separate complexes, followed by SDS-PAGE in a second dimension to identify the subunits within each complex [28]. By understanding the distinct information each method provides and applying the appropriate experimental design, researchers can confidently interpret their results and advance our understanding of protein structure and function.

Practical Protocols: Implementing BN-PAGE, CN-PAGE, and SDS-PAGE for Oligomer Analysis

The analysis of protein oligomerization states and complex interactions is a cornerstone of modern molecular biology. While denaturing electrophoresis techniques like SDS-PAGE provide information on subunit composition, they fundamentally disrupt the native structures and interactions that define protein function in vivo. Within this context, Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) has emerged as a powerful technique for the separation and analysis of native protein complexes and supercomplexes under non-denaturing conditions. Originally developed by Schägger and von Jagow in 1991, this method enables researchers to characterize the size, abundance, stoichiometry, and functional state of multi-subunit complexes, particularly within the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) system [29] [30]. This guide provides a detailed comparison of BN-PAGE against alternative methodologies, supported by experimental data and protocols, for researchers evaluating techniques for protein oligomerization state analysis.

Principles and Comparative Advantages of BN-PAGE

BN-PAGE operates on the principle of using the anionic dye Coomassie Blue G-250 to impart a negative charge to protein surfaces. Unlike SDS-PAGE, which uses the ionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate to denature proteins and confer a uniform charge-to-mass ratio, BN-PAGE employs mild, non-ionic detergents for solubilization. The binding of Coomassie dye provides the charge shift necessary for electrophoretic migration while preserving native protein-protein interactions [31] [32]. This allows for the separation of protein complexes based on their molecular mass and native structure.

The table below summarizes the core differences between BN-PAGE and other predominant electrophoresis techniques.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of BN-PAGE Versus Alternative Electrophoresis Methods

| Feature | BN-PAGE | SDS-PAGE (Denaturing) | CN-PAGE (Clear Native) | NSDS-PAGE (Native SDS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core Mechanism | Coomassie dye charge shift [31] | SDS denaturation & charge masking [5] | Mixed detergent charge shift [30] | Greatly reduced SDS, no heating [5] |

| Protein State | Native complexes & supercomplexes [30] | Denatured subunits [5] | Native complexes [30] | Partially native, metal cofactors retained [5] |

| Key Detergent | Dodecyl maltoside / Digitonin [29] [30] | SDS (strong ionic) | Dodecyl maltoside / Digitonin [30] | Low SDS (0.0375%) [5] |

| Resolution Range | 100 kDa - 10 MDa [31] | 5 - 250 kDa | Similar to BN-PAGE [30] | Similar to SDS-PAGE (high) [5] |

| Functional Analysis | Yes (in-gel activity) [33] | No | Yes (improved activity staining) [30] | Yes (limited enzymatic activity) [5] |

The Critical Role of the Coomassie Dye

The Coomassie Blue G-250 dye is not merely a tracking agent but is fundamental to the BN-PAGE technique, serving multiple essential functions [32]:

- Inducing Negative Charge: The dye binds uniformly to the hydrophobic surfaces of proteins, providing the negative charge required for electrophoretic migration toward the anode at the neutral pH (7.0) used in BN-PAGE [30] [31].

- Maintaining Solubility: The bound dye coat prevents the aggregation of hydrophobic membrane proteins during electrophoresis, keeping them soluble even in the absence of detergent in the running gel [30].

- Visualization: The dye allows for the direct visualization of protein complexes as blue bands during and after separation [29].

A key limitation, however, is that the dye can sometimes disrupt weaker protein-protein interactions. In such cases, Clear Native PAGE (CN-PAGE), which replaces Coomassie with mixtures of anionic and neutral detergents in the cathode buffer, is the recommended alternative [30] [31]. CN-PAGE avoids potential dye-induced disruption and eliminates interference from residual dye in downstream in-gel activity assays [30].

Resolving Supercomplexes: BN-PAGE vs. CN-PAGE

The choice between BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE is critical when studying fragile supercomplexes, such as the respiratory chain respirasomes. The decisive factor is the detergent used for membrane protein solubilization prior to electrophoresis [30] [32].

Table 2: Detergent Selection Dictates Resolved Complexes

| Detergent | Solubilization Stringency | Typical Resolved Structures | Recommended Technique | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) | Medium [32] | Individual OXPHOS complexes (I-V) [30] | BN-PAGE | Analysis of individual complex assembly and stability [29] |

| Digitonin | Mild [30] [32] | Supercomplexes (e.g., I+III₂+IV, I+III₂) [30] | CN-PAGE or BN-PAGE | Analysis of native supercomplex interactions and composition [30] |

| Triton X-100 | Medium-High [32] | Individual OXPHOS complexes [32] | BN-PAGE | General purpose complex analysis |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the parallel paths of BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE for resolving individual complexes and supercomplexes.

Experimental Protocol and Data Output

A typical BN-PAGE workflow involves sample preparation, gel electrophoresis, and downstream analysis. The following protocol is adapted from validated sources [29] [30].

Stage 1: Sample Preparation

- Isolate mitochondria from cells or tissue. The use of whole tissue extracts is possible but may yield weaker signals [29].

- Solubilize 0.4 mg of mitochondrial pellet in 40 µL of buffer A (0.75 M 6-aminocaproic acid, 50 mM Bis-Tris/HCl, pH 7.0) containing protease inhibitors (e.g., 1 mM PMSF) [29].

- Add 7.5 µL of 10% n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (or digitonin for supercomplexes). Mix and incubate on ice for 30 minutes [29].

- Centrifuge at 72,000 x g for 30 minutes to remove insoluble material. Collect the supernatant [29].

- Add 2.5 µL of 5% Coomassie blue G (for BN-PAGE) to the supernatant prior to loading [29].

Stage 2: Native Gel Electrophoresis

- Use a linear acrylamide gradient gel (e.g., 4-16% or 3-12%) for optimal separation across a wide molecular weight range [29] [30].

- Prepare anode and cathode buffers as specified. The cathode buffer for BN-PAGE contains 0.02% Coomassie blue G [29].

- Load samples and run electrophoresis at 150 V for approximately 2 hours or until the dye front approaches the bottom of the gel [29].

Stage 3: Downstream Analysis

The first-dimension BN-PAGE gel can be used for several analytical techniques:

- In-Gel Activity Staining: To visualize functional complexes. Complexes I, II, IV, and V can be assessed, though Complex IV staining is comparatively insensitive and Complex III lacks a reliable activity stain [30] [33].

- Western Blotting: For immunodetection of specific complexes. PVDF membranes are recommended over nitrocellulose [29].

- Two-Dimensional Electrophoresis (2D-BN/SDS-PAGE): The BN-PAGE lane is excised, soaked in SDS buffer, and placed on a second SDS-PAGE gel to separate the individual subunits of each complex, providing a powerful tool for composition analysis [29] [30].

Table 3: In-Gel Activity Staining Results for OXPHOS Complexes (Adapted from Van Coster et al., 2001 [33])

| OXPHOS Complex | In-Gel Activity Stain Result | Notes on Clinical Application |

|---|---|---|

| Complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) | Strong, detectable band | Successfully identified severe and partial deficiencies in patient samples. |

| Complex II (Succinate dehydrogenase) | Strong, detectable band | Useful for diagnosing isolated complex II defects. |

| Complex III (bc₁ complex) | No reliable stain available | Diagnosis relies on immunoblotting or spectrophotometric assays. |

| Complex IV (Cytochrome c oxidase) | Detectable, but less sensitive | Bands are fainter; useful for severe deficiency diagnosis. |

| Complex V (ATP synthase) | Strong, detectable band | An enhanced staining step can markedly improve sensitivity [30]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of BN-PAGE relies on a specific set of reagents and equipment.

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Equipment for BN-PAGE

| Item | Function / Role | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Coomassie Blue G-250 | Imparts negative charge, prevents aggregation [30] | Distinct from G-250; Serva Blue G is a common source. |

| n-Dodecyl-β-D-Maltoside (DDM) | Mild detergent for solubilizing individual complexes [29] | Maintains complex integrity while dissolving membranes. |

| Digitonin | Very mild detergent for preserving supercomplexes [30] | Used at optimized detergent-to-protein ratio. |

| 6-Aminocaproic Acid | Zwitterionic salt; supports solubilization [30] | Provides a low-ionic strength environment, does not interfere with electrophoresis. |

| Bis-Tris | Buffering agent in gels and buffers (pH 7.0) [29] | Standard buffer for maintaining neutral pH. |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevents protein degradation during preparation [29] | PMSF, leupeptin, and pepstatin are commonly used. |

| Gradient Gel Former | For casting linear acrylamide gradient gels [30] | Essential for achieving high-resolution separation. |

| Precast Gels | Convenient, commercial alternative | Thermo Fisher Scientific's NativePAGE Bis-Tris gel system [30]. |

BN-PAGE remains an indispensable and cost-effective technique for the functional analysis of native protein complexes, particularly within the mitochondrial OXPHOS system. Its unique strength lies in its ability to resolve intact complexes and supercomplexes, providing insights that are completely lost in denaturing analyses. The choice between BN-PAGE and its close relative, CN-PAGE, depends heavily on the biological question and the stability of the interactions being studied. For robust individual complexes, BN-PAGE is highly effective, whereas for delicate supercomplexes and sensitive in-gel activity assays, CN-PAGE is often the superior choice. When integrated with downstream applications like 2D-SDS-PAGE and western blotting, BN-PAGE provides a comprehensive platform for diagnosing metabolic diseases, studying assembly pathways, and advancing our understanding of cellular energy transduction mechanisms.

In the field of protein biochemistry, accurately determining the oligomerization state of proteins is crucial for understanding their biological function and regulatory mechanisms. Within this context, native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Native PAGE) has emerged as an indispensable technique for analyzing proteins in their non-denatured state, preserving their higher-order structures and enzymatic activities. This guide focuses specifically on Clear Native PAGE (CN-PAGE), a specialized variant that offers distinct advantages for functional proteomics analyses. Unlike denaturing techniques such as SDS-PAGE, which dismantles protein complexes into individual subunits, CN-PAGE maintains the native conformation of protein complexes, allowing researchers to study their oligomeric states, protein-protein interactions, and catalytic capabilities directly within the gel matrix. This capability is particularly valuable for drug development professionals investigating the molecular mechanisms of diseases involving multimeric protein assemblies, such as metabolic disorders and mitochondrial pathologies.

The fundamental difference between Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE lies in their treatment of protein structure. While SDS-PAGE employs sodium dodecyl sulfate to denature proteins into uniformly charged linear polypeptides for separation primarily by molecular weight, Native PAGE preserves the intricate quaternary structures that define a protein's biological activity [4]. CN-PAGE represents a refinement of this principle, designed to overcome specific limitations of other native electrophoresis methods while expanding applications for in-gel enzymatic characterization. This technique has proven particularly valuable for studying membrane protein complexes, respiratory chain assemblies, and other multimeric structures where maintaining structural integrity is paramount for functional analysis.

Technical Variations of Clear Native PAGE

Clear Native PAGE has evolved significantly since its initial development, with several methodological variations emerging to address specific research needs. The standard CN-PAGE technique separates acidic water-soluble and membrane proteins (pI < 7) in an acrylamide gradient gel based on their intrinsic charge and size [34]. However, this original method presented challenges for estimating native masses and oligomerization states because migration distance depends on both the protein's intrinsic charge and the gel's pore size, complicating molecular weight determinations compared to techniques with uniform charge-shifting properties.

High-Resolution Clear Native PAGE (hrCN-PAGE)

To address the resolution limitations of conventional CN-PAGE, researchers developed high-resolution Clear Native PAGE (hrCN-PAGE), which substitutes the Coomassie dye used in BN-PAGE with non-colored mixtures of anionic and neutral detergents in the cathode buffer [35]. These mixed micelles impose a charge shift on membrane proteins to enhance their anodic migration while simultaneously improving membrane protein solubility during electrophoresis. The result is a resolution comparable to BN-PAGE but without the interfering Coomassie dye, making it particularly suitable for in-gel fluorescence detection and catalytic activity assays [35]. The detergent mixtures prevent the enhanced protein aggregation and band broadening that often plagued earlier CN-PAGE implementations, establishing hrCN-PAGE as a superior technique for functional proteomics analyses.

Pseudo Clear Native PAGE (pCN-PAGE)

Another significant innovation is pseudo Clear Native PAGE (pCN-PAGE), a modified approach developed specifically for quantifying the number of monomers present in oligomeric proteins [36]. This method has been successfully applied to characterize the previously established pentameric state of the intracellular domain of serotonin type 3A (5-HT3A) receptors, demonstrating its accuracy when combined with orthogonal techniques like size exclusion chromatography with multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS) [36]. The pCN-PAGE method provides researchers with a reliable, low-cost, and simple approach to assess the oligomeric state of protein complexes without requiring specialized equipment, making it accessible for routine laboratory use.

Table: Comparison of Clear Native PAGE Variations

| Method | Key Features | Optimal Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard CN-PAGE | Uses no Coomassie dye; separation based on intrinsic protein charge and size [34] | Retaining labile supramolecular assemblies; basic analyses of acidic proteins (pI < 7) | Lower resolution than BN-PAGE; challenging molecular weight estimation [34] |

| High-Resolution CN-PAGE | Non-colored anionic/neutral detergent mixtures in cathode buffer; enhanced protein solubility [35] | In-gel fluorescence detection; catalytic activity assays; high-resolution separation of membrane complexes | Requires optimization of detergent mixtures; may not retain all supercomplexes |

| Pseudo CN-PAGE | Modified approach for accurate oligomeric state determination [36] | Quantifying monomers in oligomeric proteins; combination with SEC-MALS | Limited track record for extremely large complexes; newer method with evolving protocols |

Comparative Analysis: CN-PAGE vs. BN-PAGE and SDS-PAGE

Understanding the relative strengths and limitations of CN-PAGE requires direct comparison with related electrophoretic techniques. The table below provides a comprehensive comparison of the three primary methods for protein separation, highlighting their distinct characteristics and optimal applications.

Table: Technical Comparison of Electrophoresis Methods for Protein Analysis

| Parameter | CN-PAGE | BN-PAGE | SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein State | Native, folded | Native, folded | Denatured, linearized |

| Separation Basis | Intrinsic charge, size, shape [34] | Size (with charge shift from Coomassie dye) [34] [30] | Molecular weight (subunit size) [4] |

| Coomassie Dye | Absent | Present in sample and cathode buffer [30] | May be used for staining after separation |

| Resolution | Moderate (standard) to High (hrCN) [35] | High [34] | High for subunit analysis |

| Molecular Weight Estimation | Challenging (depends on intrinsic charge) [34] | Reliable (consistent charge shift) [34] | Highly reliable |

| In-Gel Activity Assays | Excellent (no dye interference) [35] [37] | Poor (Coomassie dye interferes) [35] | Not possible (proteins denatured) |

| In-Gel Fluorescence | Excellent [35] | Poor [35] | Possible after separation |

| Supercomplex Preservation | Excellent (especially with digitonin) [34] | Good (with digitonin) [30] | Not applicable |

| Typical Applications | Catalytic activity measurements, FRET analyses, labile assemblies [34] [35] | Standard analysis of OXPHOS complexes, assembly studies [30] | Molecular weight determination, purity checks, subunit composition [4] |

Key Functional Distinctions

The comparative data reveals several critical functional distinctions between these techniques. The absence of Coomassie dye in CN-PAGE represents its most significant advantage for functional studies, as the dye used in BN-PAGE interferes with fluorescence detection and catalytic activity measurements [35]. This makes CN-PAGE particularly valuable for in-gel enzyme activity staining and FRET analyses where dye-free conditions are essential. Additionally, CN-PAGE is notably milder than BN-PAGE, especially when combined with the mild detergent digitonin, enabling the retention of labile supramolecular assemblies that dissociate under BN-PAGE conditions [34]. This property has led to the discovery of enzymatically active oligomeric states of mitochondrial ATP synthase that were previously undetectable using BN-PAGE [34].

For oligomerization state analysis, CN-PAGE provides distinct advantages over SDS-PAGE, which completely dissociates protein complexes into subunits. While SDS-PAGE offers excellent resolution for determining subunit composition and molecular weights, it destroys the very quaternary structures that researchers need to study when investigating protein oligomerization [4]. CN-PAGE preserves these structures, allowing direct visualization of different oligomeric states and their associated activities, as demonstrated in studies of medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) tetramers [37].

Advantages of CN-PAGE for In-Gel Activity Assays

The unique properties of Clear Native PAGE make it particularly suited for in-gel activity assays, providing researchers with the ability to directly correlate enzymatic function with specific protein complexes separated electrophoretically.

Uncompromised Catalytic Activity Measurements

The fundamental advantage of CN-PAGE for activity assays stems from the absence of Coomassie blue G-250 dye, which is known to interfere with enzymatic function. While BN-PAGE uses this dye to impose a charge shift on proteins and prevent aggregation, the bound dye molecules can inhibit or alter catalytic activity [35]. CN-PAGE eliminates this limitation, enabling accurate determination of enzymatic activities directly within the gel matrix. This superiority has been demonstrated for mitochondrial complexes I-V, including the first in-gel histochemical staining protocol for respiratory complex III [35]. The preserved enzymatic activity after CN-PAGE separation allows researchers to obtain functional information that would be inaccessible using BN-PAGE.

Enhanced Detection Sensitivity and Linearity

CN-PAGE-based activity assays demonstrate excellent sensitivity and linear correlation with protein amount, as evidenced by studies on medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD). Research has shown that in-gel activity staining after high-resolution CN-PAGE can detect activity with less than 1 µg of protein and exhibits linear correlation between protein amount, FAD content, and enzymatic activity [37]. This sensitivity enables researchers not only to detect presence or absence of activity but to perform quantitative assessments of how pathogenic variants affect enzyme function and oligomerization state, providing crucial insights for understanding molecular mechanisms of diseases.

Structural-Functional Correlations

Perhaps the most significant advantage of CN-PAGE for activity assays is the ability to directly correlate specific protein complexes with their enzymatic function. This capability was elegantly demonstrated in studies of MCAD variants, where the technique revealed that while the main band of MCAD tetramers remained active in various mutants, the fragmented lower molecular mass species observed in variants K329E and R206C were inactive [37]. This structural-functional correlation provides profound insights into how pathogenic mutations affect protein quaternary structure and function—information that would be lost in standard solution-based assays that only measure total enzymatic activity without distinguishing between different oligomeric forms.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard CN-PAGE Protocol for In-Gel Activity Assays

The following protocol outlines the key steps for implementing CN-PAGE to analyze protein complexes and their in-gel activities:

Sample Preparation: Solubilize membrane proteins using mild non-ionic detergents like digitonin or n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside. Digitonin is preferred for preserving supramolecular structures, while n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside is suitable for individual complexes [34] [30]. Include protease inhibitors and the zwitterionic salt 6-aminocaproic acid in the extraction buffer to support protein stability without affecting electrophoresis [30].

Gel Preparation: Prepare linear gradient polyacrylamide gels (typically 4-16% or 3-12%) using a gradient maker. The gradient gel system improves resolution across a broad molecular weight range. Bis-Tris-based buffer systems at pH 7.0 are commonly used [30]. Alternatively, commercial precast native gels can be used for convenience.

Electrophoresis Conditions:

- For standard CN-PAGE: Use cathode buffer without Coomassie dye [34].

- For high-resolution CN-PAGE: Use cathode buffer containing non-colored mixtures of anionic and neutral detergents instead of Coomassie dye [35].

- Conduct electrophoresis at 4°C to maintain protein stability, typically starting at 100V and increasing to 200V as the samples enter the separating gel.

- Use appropriate marker proteins for native molecular weight estimation.

In-Gel Activity Staining: After electrophoresis, incubate the gel in specific reaction mixtures containing substrates and colorimetric detection reagents. For example, for MCAD activity detection, incubate gels in solution containing octanoyl-CoA as substrate and nitro blue tetrazolium chloride (NBT) as electron acceptor, which forms an insoluble purple diformazan precipitate upon reduction [37].

MCAD In-Gel Activity Assay Protocol

A specific application of CN-PAGE for analyzing medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) activity demonstrates the power of this technique:

Protein Separation: Separate recombinant MCAD or mitochondrial extracts using high-resolution CN-PAGE (4-16% gradient gels) [37].

Activity Staining Solution: Prepare a reaction mixture containing:

- 100-200 µM octanoyl-CoA (physiological MCAD substrate)

- 0.2-0.5 mg/mL nitro blue tetrazolium chloride (NBT)

- 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.0

- Optional: 100 µM phenazine methosulfate as electron carrier

Incubation and Detection: