Native PAGE in Protein Interaction Studies: From Fundamental Principles to Cutting-Edge Applications in Biomedicine

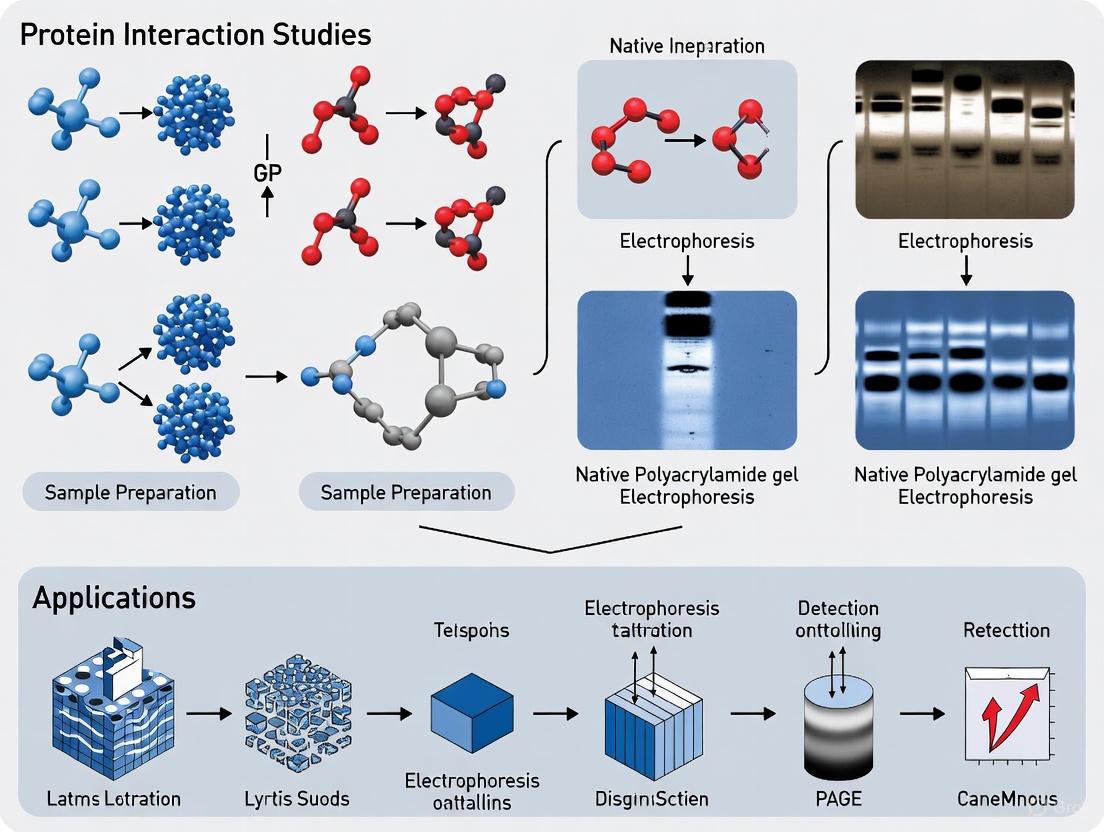

This comprehensive review explores the versatile applications of Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE) in studying protein-protein interactions, with particular emphasis on Blue-Native PAGE.

Native PAGE in Protein Interaction Studies: From Fundamental Principles to Cutting-Edge Applications in Biomedicine

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the versatile applications of Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE) in studying protein-protein interactions, with particular emphasis on Blue-Native PAGE. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the article covers fundamental principles, advanced methodological applications across various biological systems, troubleshooting strategies for complex samples, and integrative approaches combining Native PAGE with modern proteomic technologies. By preserving native protein structures and complexes, Native PAGE provides unique insights into interactome dynamics, oligomeric states, and protein complex assembly—critical information for understanding disease mechanisms and developing targeted therapeutics. The content synthesizes both established protocols and emerging innovations, offering a practical guide for implementing these techniques in basic research and translational medicine contexts.

Understanding Native PAGE: Fundamental Principles and Advantages for Protein Interaction Studies

Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (Native PAGE) is a fundamental technique in protein science that enables the separation of proteins under non-denaturing conditions. Unlike its counterpart, SDS-PAGE, which denatures proteins with sodium dodecyl sulfate, Native PAGE preserves protein structure, biological activity, and protein-protein interactions throughout the electrophoretic process. This preservation is paramount when studying functional protein complexes, enzyme activity, and protein interactions within the broader context of cellular processes. As research into protein interactomes—the comprehensive networks of protein interactions—advances with techniques like mass spectrometry and computational predictions [1] [2], Native PAGE remains a critical orthogonal method for validating interactions in a near-native state. This article details the core principles, protocols, and applications of Native PAGE, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a robust framework for its implementation.

Core Principles and Advantages

The fundamental principle of Native PAGE is the separation of proteins based on their intrinsic charge, size, and shape within a porous polyacrylamide gel matrix under the influence of an electric field. The integrity of the protein's secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures is maintained because no denaturing agents are used.

Key Differentiators from SDS-PAGE

The following table contrasts the core characteristics of Native PAGE with the denaturing SDS-PAGE method:

| Parameter | Native PAGE | SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Protein State | Native, folded; structure and activity preserved [3]. | Denatured, unfolded; structure and activity lost. |

| Separation Basis | Combined effect of intrinsic charge, size, and shape. | Primarily molecular weight (due to SDS coating). |

| Sample Buffer | Non-denaturing, may lack SDS and reducing agents. | Contains SDS and often DTT/β-mercaptoethanol. |

| Key Application | Studying oligomeric state, protein complexes, and functional activity. | Determining molecular weight and protein purity. |

| Protein Detection | Can use activity stains (zymography) for enzymes. | Typically uses general protein stains (e.g., Coomassie). |

Advantages in Protein Interaction Studies

The primary advantage of Native PAGE is its ability to preserve macromolecular complexes. This makes it indispensable for:

- Verifying Protein-Protein Interactions (PPIs): Native PAGE can resolve stable protein complexes from individual subunits, providing direct biochemical evidence for interactions suggested by high-throughput methods like affinity purification-mass spectrometry (AP-MS) [1] or yeast two-hybrid screens.

- Analyzing Oligomeric States: The technique can reveal whether a protein exists as a monomer, dimer, or higher-order oligomer under specific conditions, as the migration pattern depends on the complex's overall size and shape.

- Functional Assays: Since enzymatic activity is preserved, proteins can be detected post-electrophoresis using activity-specific stains, allowing researchers to link a specific band on a gel to a functional protein complex.

Experimental Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for running a Native PAGE experiment to analyze a protein complex.

Materials and Reagents

The table below lists the essential "Research Reagent Solutions" required for a successful Native PAGE experiment.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-Acrylamide Solution (e.g., 30-40%) | Forms the cross-linked polyacrylamide gel matrix that acts as a molecular sieve for protein separation [3]. |

| Non-Denaturing Lysis Buffer (e.g., NP-40 or Triton X-100) | Extracts proteins from cells or tissues while maintaining protein-protein interactions and native conformation [3]. |

| Native Sample Buffer | A non-reducing, SDS-free buffer that prepares the protein sample for loading without denaturation. Typically contains glycerol and a tracking dye. |

| Tris-Glycine-Native Running Buffer (e.g., 10X) | Provides the conductive medium and pH environment (typically ~pH 8.3-8.8) for electrophoresis without denaturing proteins [3]. |

| Protein Standard (Native Marker) | A mixture of colored native proteins of known molecular weight and charge used to monitor electrophoresis progress and for rough size estimation. |

| Coomassie Blue Stain / Reversible Stain (Ponceau S) | For general protein detection. Ponceau S offers a reversible, non-fixing stain for quick verification of transfer or protein bands [3]. |

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of a Native PAGE experiment, from sample preparation to analysis.

Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: Sample Preparation

- Lysis: Gently lyse cells or tissues using a non-denaturing lysis buffer (e.g., NP-40-based) to preserve protein complexes [3].

- Clarification: Centrifuge the lysate at high speed (e.g., 14,000 x g for 15 minutes) to remove insoluble debris. Transfer the supernatant (soluble protein fraction) to a new tube [3].

- Quantification: Measure protein concentration using an appropriate assay (e.g., Bradford or BCA). Note: The BCA assay is recommended for higher sensitivity, especially with low detergent concentrations [3].

- Preparation: Mix the recommended amount of protein (e.g., 10-50 μg) with native sample buffer. Crucially, do not boil the samples. Incubate on ice or at room temperature to maintain native structure.

Step 2: Gel Preparation

- Casting: Prepare a discontinuous gel system consisting of a resolving (separating) gel and a stacking gel. The table below provides a basic recipe for a 1-gel system.

- Polymerization: Add catalysts 10% APS and TEMED last, only when ready to pour the gel, as polymerization begins immediately [3].

| Component | Resolving Gel (10%) | Stacking Gel |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide (40%) | 1.25 mL | 0.25 mL |

| Separating Buffer (4X) | 1.25 mL | -- |

| Stacking Buffer (4X) | -- | 0.625 mL |

| Deionized Water | 2.5 mL | 1.625 mL |

| 10% APS | 50 μL | 25 μL |

| TEMED | 5 μL | 2.5 μL |

| Total Volume | 5 mL | 2.5 mL |

Step 3: Electrophoresis

- Loading: Carefully load equal amounts of protein across wells. Include a native molecular weight marker in one lane. Avoid touching the bottom of the wells with the pipette tip to prevent distorted bands [3].

- Running Conditions: Run the gel at a constant voltage (e.g., 100-150 V) in a tank filled with native running buffer. Maintain cool conditions by using an ice pack or running in a cold room to prevent overheating and protein denaturation [3].

Step 4: Post-Electrophoresis Analysis

- Direct Staining: For total protein visualization, stain the gel with Coomassie Blue or a reversible stain like Ponceau S.

- In-Gel Activity Assay (Zymography): For enzymes, incubate the gel in a specific substrate solution to detect a band of activity.

- Western Blotting: For specific identification, proteins can be transferred to a membrane (e.g., PVDF or nitrocellulose). Note: For a standard Western blot, Ponceau staining is not recommended if using fluorescent detection methods, as it can cause high background [3].

Data Interpretation and Applications

Troubleshooting Common Issues

| Issue | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Smearing | Protein aggregation or degradation; overloading. | Optimize lysis conditions; reduce loading amount; ensure samples are kept cold. |

| Poor Resolution | Incorrect gel percentage; incorrect pH of buffers. | Adjust acrylamide concentration for target protein size; verify buffer pH. |

| No or Faint Bands | Insufficient protein loaded; protein did not enter gel. | Increase loading amount; check sample buffer composition (ensure no precipitation). |

Application in Broader Research Context

Native PAGE serves as a critical validation tool within the modern interactome research pipeline. While cutting-edge computational models like PaRPI (for RNA-protein interactions) [4] and deep learning frameworks for PPI prediction [2] can process vast datasets, they require experimental validation. Similarly, high-throughput MS-based techniques like AP-MS and cross-linking MS (XL-MS) [1] [5] provide large-scale interaction maps but are conducted in non-native contexts. Native PAGE provides a direct, biochemical confirmation of predicted or identified interactions under conditions that maintain the native cellular environment of the complex, bridging the gap between in silico predictions and in vivo functionality. This is especially valuable in drug development, where understanding the functional oligomeric state of a target protein is crucial for therapeutic design.

Within the framework of a broader thesis on the applications of native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) in protein interaction studies, this document delineates the core mechanisms, advantages, and specific protocols for two pivotal techniques: Blue-Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) and Clear-Native PAGE (CN-PAGE). The study of protein-protein interactions (PPIs) is fundamental to proteomics, as most cellular processes are executed by dynamic networks of protein complexes rather than by individual proteins [6]. While classical methods like yeast two-hybrid and co-immunoprecipitation have contributed significantly to the field, proteomics-based methods such as native electrophoresis offer distinct advantages for analyzing intact complexes [6].

BN-PAGE, pioneered by Hermann Schägger in the 1990s, has become an indispensable tool for resolving native protein complexes, especially those involved in oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) [7] [8]. Its variant, CN-PAGE, was developed to circumvent certain limitations of the former. This application note provides a comparative analysis of these two techniques, summarizing their principles in an accessible format, detailing standardized protocols, and illustrating their application in the analysis of mitochondrial protein complexes, thereby providing a robust resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

Principles and Mechanisms

Fundamental Concepts of Native Electrophoresis

Both BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE are one-dimensional native electrophoresis techniques used for the separation of individual proteins, protein complexes, and supercomplexes under mild, non-denaturing conditions [9]. This allows for the identification of stable and labile protein-protein interactions, the determination of native masses and oligomeric states, and the subsequent analysis of enzymatic activities [9] [10]. The primary distinction between the two techniques lies in the method by which a negative charge is imposed upon the proteins to facilitate their migration toward the anode during electrophoresis.

The Mechanism of Blue-Native PAGE (BN-PAGE)

In BN-PAGE, the anionic dye Coomassie Blue G-250 is used to confer a uniform negative charge to the solubilized protein complexes. This dye binds non-stoichiometrically to the hydrophobic surfaces of proteins [11]. The binding imposes a charge shift on the proteins, which forces even basic proteins with hydrophobic domains to migrate towards the anode at a neutral pH of 7.0 [7] [8]. A key secondary function of the bound dye is that the induced negative surface charge helps to prevent the aggregation of hydrophobic membrane proteins, thereby keeping them soluble during electrophoresis in the absence of detergent [7]. The dye is present both in the sample buffer and the cathode buffer during the run, giving the gel its characteristic blue color [12].

The Mechanism of Clear-Native PAGE (CN-PAGE)

CN-PAGE, a related variant, omits the Coomassie dye from the sample and instead uses mixtures of anionic and neutral detergents in the cathode buffer to impose the necessary charge shift for electrophoretic migration [7] [8]. Similar to Coomassie Blue G-250, the mixed micelles formed by these detergents induce a negative charge on membrane proteins to enhance their solubility and migration [7]. As the name implies, the gels remain clear during and after the electrophoresis process.

Comparative Advantages and Limitations

The choice between BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE is application-dependent, as each technique offers distinct advantages and suffers from specific limitations. A summary of these characteristics is provided in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparative Advantages and Limitations of BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE

| Feature | Blue-Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) | Clear-Native PAGE (CN-PAGE) |

|---|---|---|

| Charging Agent | Coomassie Blue G-250 dye [7] [12] | Anionic/neutral detergent mixtures [7] |

| Typical Resolution | Higher resolution [13] | Lower resolution [13] |

| Mass Estimation | More reliable for native mass and oligomeric state [13] | Less reliable; depends on protein charge and gel pore size [13] |

| Mildness | Standard mildness | Milder; can retain labile supramolecular assemblies [13] |

| Dye Interference | Coomassie dye can interfere with downstream activity assays or FRET analyses [13] [7] | No dye interference; superior for in-gel activity staining and FRET [13] [7] |

| Key Application | Standard analysis of OXPHOS complexes and supercomplexes [7] [8] | Analysis of catalytically active complexes and labile assemblies [13] |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental procedural differences between the two methods, from sample preparation to separation.

Essential Reagents and Materials

The successful execution of BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE relies on a specific set of reagents. The following table details the key research reagent solutions and their functions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Native PAGE

| Reagent | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Coomassie Blue G-250 | Imposes negative charge on proteins in BN-PAGE; prevents aggregation [7] [12]. | Can interfere with downstream activity assays and FRET [13]. |

| Detergents (for Solubilization) | Solubilizes membrane protein complexes without disrupting protein-protein interactions [12] [11]. | Choice is critical: - n-Dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (DDM): Common for individual complexes [7] [8].- Digitonin: Milder; preserves supercomplexes [7] [12]. |

| 6-Aminocaproic Acid | Zwitterionic salt; supports solubilization and acts as a protease inhibitor without affecting electrophoresis at pH 7.0 [7] [8]. | Provides a zero net charge at neutral pH [7]. |

| Cathode Buffer Detergents (CN-PAGE) | Replaces Coomassie dye; anionic/neutral detergent mixtures induce charge shift and enable migration [7]. | Avoids dye-related interference in downstream applications [7]. |

| Acrylamide Gradient Gels | Separates protein complexes by size; typical gradients are 3-12% or 4-16% [7] [12]. | Maximizes resolution of complexes ranging from ~100 kDa to 10 MDa [14]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: BN-PAGE for OXPHOS Complexes

This protocol, adapted from Aref et al. (2025) and Schägger's foundational work, is optimized for the analysis of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complexes [7] [8] [10].

Sample Preparation (for mitochondrial membranes):

- Harvesting and Homogenization: Wash cell pellets (e.g., from two 10-cm plates of cultured fibroblasts) with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Pellet cells by centrifugation and store at -80°C if not used immediately [7].

- Solubilization: Resuspend the cell or mitochondrial pellet in solubilization buffer (e.g., 1M 6-aminocaproic acid, 50 mM Bis-Tris/HCl, pH 7.0). Add a mild, non-ionic detergent. For individual OXPHOS complexes, use n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (DDM) at a final concentration of 1-2% or a detergent-to-protein ratio of 2-4 g/g [7] [11]. For respiratory supercomplexes, use the milder detergent digitonin (typically 2-4 g digitonin per g protein) [7] [12].

- Incubation and Clarification: Incubate the sample on ice for 5-30 minutes. Subsequently, centrifuge at 20,000 × g for 15-30 minutes at 4°C to remove insoluble material [7] [8].

- Dye Addition: Prior to loading, add Coomassie Blue G-250 dye to the supernatant to a final concentration of 0.25-0.5% [7] [8].

Gel Electrophoresis:

- Gel Casting: Manually cast a native linear gradient polyacrylamide gel (e.g., 3-12% or 4-16%) using a gradient maker and peristaltic pump. The gel and cathode buffer should be based on Bis-Tris or imidazole, pH 7.0 [7] [8]. Precast gels are also commercially available.

- Loading and Running: Load the prepared samples onto the gel. Add Coomassie Blue G-250 (e.g., 0.02%) to the cathode buffer (colored blue). Run the electrophoresis at 4°C, starting with a low voltage (e.g., 50 V) until the sample has entered the gel, then increase to 100-150 V until the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel [7] [8].

Protocol 2: CN-PAGE for In-Gel Activity Assays

CN-PAGE is the method of choice when the goal is to detect catalytic activity directly within the gel, as it avoids interference from the Coomassie dye [13] [7].

Sample Preparation: The initial steps for solubilization are identical to the BN-PAGE protocol (steps 1-3 above). However, the critical difference is that Coomassie Blue G-250 is omitted from the sample [13] [7].

Gel Electrophoresis:

- The same gradient gels used for BN-PAGE can be employed.

- The key modification is in the cathode buffer. Instead of Coomassie dye, the cathode buffer contains a mixture of anionic and neutral detergents (e.g., 0.02% sodium deoxycholate and 0.02% dodecylmatloside) to provide the charge shift for migration [7].

- The electrophoresis run conditions are similar to BN-PAGE, but the gel remains clear throughout the process.

In-Gel Activity Staining: Following electrophoresis, the gel can be incubated in specific assay buffers to visualize enzymatic activity [7] [8]:

- Complex I (NADH dehydrogenase): Stained by NADH reduction of nitrotetrazolium blue.

- Complex II (Succinate dehydrogenase): Stained by phenazine methosulfate-mediated reduction of nitrotetrazolium blue in the presence of succinate.

- Complex IV (Cytochrome c oxidase): Stained by the oxidation of cytochrome c, detected as a loss of brown color.

- Complex V (ATP synthase): Stained by an ATP-hydrolysis-linked lead precipitation method, with sensitivity that can be markedly improved by an enhancement step [7].

The following diagram illustrates the critical decision points in selecting and executing the appropriate native PAGE protocol for a given research goal.

Applications in Protein Interaction Studies

The application of BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE extends far beyond simple protein separation, playing a transformative role in modern protein interaction research.

Analysis of Respiratory Chain Supercomplexes: The use of different detergents has fundamentally changed models of the respiratory chain. While DDM solubilization revealed individual OXPHOS complexes, supporting a "liquid state model," the use of the milder digitonin in BN/CN-PAGE allowed the identification of stable respirasomes (supercomplexes of I, III, and IV), supporting a "solid-state model" of organization within the mitochondrial membrane [7] [12]. CN-PAGE, being even milder, can retain labile supramolecular assemblies that might dissociate under standard BN-PAGE conditions [13].

Clinical Diagnostics and Disease Research: BN-PAGE is instrumental in diagnosing mitochondrial encephalomyopathies and other metabolic diseases caused by OXPHOS dysfunction [9] [8]. It allows researchers to investigate pathologic mechanisms, including assembly pathways of the complexes and the disruptive effects of mutations, in patient-derived samples like fibroblasts and muscle biopsies [7] [8].

Comprehensive Proteomic and Structural Studies: Two-dimensional electrophoresis, combining BN-PAGE in the first dimension with SDS-PAGE in the second, creates a powerful tool for resolving the constituent subunits of a complex [7] [10]. This 2D system, combined with western blot analysis or mass spectrometry, enables the detailed characterization of complex composition and the identification of novel protein-protein interactions within a proteome [7] [12] [15]. Furthermore, protein complexes isolated by BN-PAGE can be used for advanced structural studies, such as 2D crystallization and electron microscopy [10].

In the study of biomolecular interactions, the preservation of a protein's native structure is not merely an option but a fundamental requirement for obtaining biologically relevant data. Native conditions, which maintain the protein's tertiary and quaternary structure, along with its associated cofactors and binding partners, stand in stark contrast to denaturing methods that dismantle these intricate assemblies. Techniques like Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (Native PAGE) and Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) are cornerstone methodologies that leverage non-denaturing conditions to separate intact protein complexes based on their charge, size, and shape [16] [17]. This capability is indispensable for probing the functional interactome—the dynamic network of protein-protein, protein-DNA, and protein-ligand interactions that underpin all cellular processes. The choice between native and denaturing methods thus fundamentally shapes the biological questions a researcher can answer, directing the inquiry either towards the deconstructed properties of polypeptide chains or the functional dynamics of macromolecular machines.

Key Differences Between Native and Denaturing Methods

The distinction between native and denaturing methods extends beyond a simple checklist of buffer components; it represents a fundamental philosophical divide in experimental approach. Denaturing methods, such as SDS-PAGE, employ agents like Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) and urea to unfold proteins into random coils, effectively masking their intrinsic charge and rendering all proteins with a uniform negative charge-to-mass ratio. Separation occurs almost exclusively by molecular weight. In contrast, native methods use mild, non-ionic detergents and avoid heating or strong denaturants to preserve the protein's native conformation. This allows separation based on a combination of the protein's inherent charge, molecular size, and three-dimensional shape [18] [16].

Table 1: Core Differences Between Native and Denaturing Electrophoresis Methods.

| Feature | Native Conditions | Denaturing Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure | Native, folded; Quaternary structures preserved | Unfolded, random coil; Subunits dissociated |

| Key Reagents | Mild detergents (e.g., Lauryl Maltose Neopentyl Glycol), Coomassie G-250, Bis-Tris buffers | SDS, Urea, β-Mercaptoethanol, Dithiothreitol |

| Basis of Separation | Charge, size, and native shape | Primarily molecular mass |

| Information Obtained | Oligomeric state, protein-protein interactions, functional activity | Subunit molecular weight, purity, polypeptide composition |

| Typical Applications | Studying complexes, enzyme activity assays, interaction mapping | Estimating molecular weight, proteomics, Western blotting |

The implications of these differences are profound. For instance, a researcher studying the oligomeric state of a enzyme would find native PAGE indispensable, as it can resolve active tetramers from inactive monomers. In a denaturing gel, however, both forms would migrate identically as dissociated subunits. Similarly, techniques like Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) rely on native conditions to detect the formation of protein-DNA complexes, as the interaction would be obliterated by SDS [19]. The strategic choice of method is therefore the first and most critical step in designing an interaction study.

Experimental Protocols for Native Interaction Analysis

Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) for Complexome Profiling

BN-PAGE is a powerful protocol specifically designed for the analysis of mitochondrial complexes and other multisubunit enzymes [16]. The method utilizes Coomassie Blue G-250, which binds to proteins imparting a negative charge, allowing them to migrate in an electric field without disrupting non-covalent interactions.

Protocol Steps:

- Sample Preparation: Isolate mitochondria or membrane fractions. Solubilize 0.4 mg of sedimented mitochondria in 40 µL of Buffer A (0.75 M 6-aminocaproic acid, 50 mM Bis-Tris/HCl, pH 7.0) containing protease inhibitors (e.g., 1 mM PMSF). Add 7.5 µL of 10% n-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside and incubate on ice for 30 minutes. Centrifuge at 72,000 x g for 30 minutes and collect the supernatant [16].

- Dye Addition: Add 2.5 µL of a 5% Coomassie blue G solution to the supernatant [16].

- Gel Electrophoresis (First Dimension): Cast a native gradient gel (e.g., 6–13% acrylamide). Load 5–20 µL of the prepared sample and run the gel at 150 V for approximately 2 hours using anode (50 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0) and cathode (50 mM Tricine, 15 mM Bis-Tris, 0.02% Coomassie blue G, pH 7.0) buffers until the blue dye front has almost run off the gel [16].

- Second Dimension (Optional): For subunit analysis, excise a lane from the first-dimension gel, soak it in SDS-PAGE denaturing buffer, and place it on top of an SDS-PAGE gel (e.g., 10-20% acrylamide). This 2D separation resolves the individual subunits of each complex [16].

- Detection: Electroblot the proteins to a PVDF membrane using a fully submerged system (e.g., 150 mA for 1.5 h) and perform immunodetection with specific antibodies [16].

Native PAGE for GPCR-G Protein Coupling

This protocol exemplifies a specialized application of native PAGE for studying the interactions of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), a major class of drug targets, with their signaling partners [17].

Protocol Steps:

- Receptor Preparation: Transiently express an EGFP-tagged GPCR (e.g., the calcitonin receptor-like receptor) in HEK293S GnT1– cells. Prepare crude membranes from the cells.

- Solubilization and Complex Formation: Solubilize the membranes with a detergent such as Lauryl Maltose Neopentyl Glycol (LMNG) supplemented with Cholesteryl Hemisuccinate (CHS). Incubate the solubilized receptor with a surrogate "mini-G" protein and the desired agonist.

- High-Resolution Clear Native Electrophoresis (hrCNE): Load the samples onto a native polyacrylamide gel. The hrCNE conditions preserve the detergent-solubilized GPCR-mini-G complexes.

- Visualization and Quantification: Visualize the complexes directly in the gel using in-gel fluorescence imaging (detecting the EGFP tag). A mobility shift indicates successful complex formation. This assay can be used in a quantitative format to determine the apparent affinity of agonists for the receptor-G protein complex [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Native PAGE

Successful execution of native PAGE experiments relies on a carefully selected set of reagents, each serving a specific function to maintain complex integrity.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Native PAGE.

| Reagent | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Mild Detergents | Solubilize membrane proteins while preserving native interactions | n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside [16], Lauryl Maltose Neopentyl Glycol (LMNG) [17]; Critical for extracting complexes from membranes. |

| Charge-Confering Dye | Impart uniform negative charge for electrophoretic mobility | Coomassie Blue G-250; Used in BN-PAGE, binds hydrophobically without denaturing [16]. |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevent proteolytic degradation during sample preparation | PMSF, Leupeptin, Pepstatin A; Essential for preserving intact protein complexes [16] [17]. |

| Specialized Buffers | Maintain optimal pH and ionic strength | Bis-Tris/Tricine-based systems [16], 6-aminocaproic acid; Provide buffering capacity without interfering with separation. |

| "Mini-G" Proteins | Stabilize GPCRs in an active state for interaction studies | Engineered Gα subunits; Tool for studying GPCR-G protein coupling in detergent [17]. |

| Membrane Cholesterol Mimetic | Stabilizes native conformation of membrane proteins | Cholesteryl Hemisuccinate (CHS); Often added with detergent for solubilizing GPCRs and other membrane proteins [17]. |

Visualizing Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical flow of two key native PAGE protocols, highlighting their application for different biological questions.

Diagram 1: GPCR-mini-G Protein Coupling Assay.

Diagram 2: BN-PAGE for Protein Complexes.

Application Notes: From Detection to Discovery

The true power of native methods is realized in their diverse applications, which range from confirming simple interactions to mapping complex cellular networks.

- Detecting Unstable Complexes: A significant advantage of native EMSA is its ability to identify not only stable DNA-protein complexes but also unstable complexes that undergo dissociation during electrophoresis. The gel matrix provides a "caging" effect that can stabilize transient interactions, allowing their detection and subsequent identification [19].

- Mapping DNA-Protein Interactions on Long Fragments: A combination of native and denaturing PAGE can be used to localize protein binding regions within long fragments of genomic DNA (up to 10 kb). After an initial EMSA step under native conditions to select bound fragments, the shifted DNA is eluted and analyzed on a denaturing gel. This allows precise identification of protein-binding regions within the larger DNA sequence [19].

- Integration with Mass Spectrometry: The field of interactome studies has been revolutionized by the integration of native methods with mass spectrometry (MS). Native MS allows for the determination of the mass of intact biomolecular assemblies, providing precise information on stoichiometry, topology, and interaction dynamics without disrupting non-covalent bonds [20]. Furthermore, co-fractionation MS (CF-MS) involves separating native protein complexes via chromatography or electrophoresis followed by MS-based identification, enabling large-scale mapping of protein interaction networks [5].

- A Tool for Drug Development: The native PAGE assay for GPCR-mini-G protein coupling provides a relatively simple, cost-effective, and quantitative method to characterize agonist-dependent receptor coupling. This allows for the determination of apparent binding affinities and can serve as a measure of agonist efficacy, making it highly valuable for screening and characterizing potential therapeutics targeting GPCRs [17].

The methodological divide between native and denaturing conditions defines two parallel paths in biological research. While denaturing methods provide essential information on protein composition and primary structure, they inevitably erase the higher-order functional information encoded in a protein's quaternary structure and interaction network. Native methods, with their careful preservation of the protein's native state, unlock this dimension of biological understanding. From the detailed characterization of a single drug target like a GPCR to the large-scale mapping of mitochondrial complexomes and interactomes, techniques like Native PAGE and BN-PAGE provide the critical lens through which we can observe the dynamic macromolecular machines that perform the work of the cell. As mass spectrometry and other analytical technologies continue to advance in sensitivity and compatibility with native preparations, the application of native condition methodologies is poised to become even more central to our quest to understand and manipulate cellular function.

Historical Development and Evolution of Native Electrophoresis Techniques

Within the broader context of research on protein-protein interactions (PPIs), the ability to study proteins in their native, functionally active state is paramount. Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Native-PAGE) is a foundational technique that enables this by preserving protein complexes, quaternary structures, and biological activity during separation. Unlike denaturing methods such as SDS-PAGE, Native-PAGE does not use harsh detergents, allowing proteins to migrate based on a combination of their intrinsic charge, size, and shape [21] [22]. This Application Note details the historical evolution, current methodologies, and practical protocols for Native-PAGE, framing it as an essential tool in the modern protein interaction studies research toolkit.

Historical Development

The genesis of electrophoresis dates back to the early 19th century, with the first observation of the electrokinetic phenomenon by Russian professors Peter Ivanovich Strakhov and Ferdinand Frederic Reuß at Moscow University in 1807 [23]. However, the modern era of protein electrophoresis began with the pioneering work of Arne Tiselius, who developed the moving-boundary electrophoresis apparatus in the 1930s [23] [24]. His work, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1948, demonstrated that charged particles could be separated using an electrical field [23] [21].

A critical evolution occurred in the late 1940s and 1950s with the shift from Tiselius's free-flowing method to zone electrophoresis, which used solid supporting media like filter paper or gels to separate compounds into discrete bands [23]. The subsequent introduction of starch gel by Oliver Smithies in 1955, and later polyacrylamide gel, revolutionized the field by enabling high-resolution separation of complex protein mixtures [23]. Polyacrylamide gel, formed by polymerizing acrylamide and bis-acrylamide, was particularly transformative because its pore size could be precisely controlled, allowing for excellent resolution based on molecular sieving and minimal interaction with the matrix [21].

While early gel electrophoresis was inherently "native," the later development of SDS-PAGE provided a powerful tool for molecular weight determination under denaturing conditions, thereby highlighting the unique value of Native-PAGE for studying intact protein complexes [22]. The development of techniques like Blue Native (BN)-PAGE in the 1990s further cemented the role of native electrophoresis in biochemistry, allowing for the isolation of membrane protein complexes in enzymatically active form [24].

Table 1: Key Milestones in the Development of Native Electrophoresis

| Year | Development | Key Innovator(s) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1807 | First observation of electrokinetics | Strakhov & Reuß | Established the fundamental principle [23] |

| 1937 | Moving-boundary electrophoresis apparatus | Arne Tiselius | Enabled first electrophoretic analysis of colloidal mixtures; Nobel Prize-winning work [23] [24] |

| 1950s | Zone electrophoresis | Multiple | Use of supporting gels (paper, starch) to create discrete separation zones [23] |

| 1955 | Starch gel electrophoresis | Oliver Smithies | Allowed efficient separation of complex protein mixtures [23] |

| 1959 | Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) | Raymond & Weintraub | Introduced controllable polyacrylamide matrix for superior resolution [23] |

| 1991 | Blue Native (BN)-PAGE | Schägger & von Jagow | Enabled isolation of active membrane protein complexes [24] |

Principles and Applications in Protein Interaction Studies

The core principle of Native-PAGE is the migration of charged molecules through an inert gel matrix under the influence of an electric field. A critical distinction from SDS-PAGE is that the native protein's intrinsic net charge and three-dimensional conformation dictate its mobility [21]. Proteins with a greater negative charge migrate faster toward the anode, while larger, more complex structures experience more resistance moving through the gel pores.

This makes Native-PAGE exceptionally powerful for studying protein interactions because it can directly probe quaternary structure. A classic application is distinguishing between monomeric and multimeric states of a protein. For instance, a protein that runs as a 60 kDa band on a non-reducing SDS-PAGE but migrates at 120 kDa on Native-PAGE can be reasonably inferred to be a non-covalent dimer of 60 kDa subunits [22]. The SDS treatment disrupts the non-covalent bonds holding the dimer together, revealing the monomeric weight, while Native-PAGE preserves the intact dimer, whose migration reflects its larger native size [22].

Beyond analyzing static complexes, Native-PAGE is integrated into advanced, high-throughput workflows for monitoring dynamic changes in protein complexes. For example, the recently developed FLiP-MS (serial Ultrafiltration combined with Limited Proteolysis-coupled Mass Spectrometry) uses native size-separation fractions, analyzed via Native-PAGE and other techniques, to generate a library of peptide markers that report on changes in PPIs [25]. This library can then be used to profile protein complex dynamics proteome-wide in response to cellular perturbations, providing both global and molecular views of a system under study [25].

Table 2: Comparison of Electrophoresis Techniques for Protein Analysis

| Parameter | Native-PAGE | SDS-PAGE | Isoelectric Focusing (IEF) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle of Separation | Native charge, size, and shape | Molecular weight only | Isoelectric point (pI) |

| Protein State | Native, functional, complexes intact | Denatured, linearized | Denatured, focused by pI |

| Information Obtained | Oligomeric state, protein interactions | Subunit molecular weight | Protein charge identity |

| Common Applications | Studying quaternary structure, enzyme activity assays | Purity check, Western blotting | First dimension in 2D-PAGE |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Native-PAGE for Oligomeric State Analysis

This protocol is designed to determine the native molecular size and oligomeric state of a protein sample, as exemplified in [22].

Materials (The Scientist's Toolkit):

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide Solution (30-40%): Forms the cross-linked polyacrylamide gel matrix. The ratio and concentration determine the gel pore size [21].

- Non-Denaturing Buffer (e.g., Tris-Glycine, pH 8.3-8.8): Carries the current and maintains a pH that preserves protein native charge and structure. Avoids SDS or reducing agents [21].

- Ammonium Persulfate (APS) and TEMED: Catalysts for the polymerization of the polyacrylamide gel [21].

- Native Gel Staining Solution (e.g., Coomassie Brilliant Blue): For visualizing protein bands after electrophoresis.

- High-Molecular-Weight Native Protein Standards: A mix of colored proteins of known native molecular weights for calibration.

Methodology:

- Gel Casting: Prepare a resolving gel (e.g., 4-12% gradient gel) by mixing acrylamide/bis-acrylamide, non-denaturing Tris-HCl buffer (pH ~8.8), and water. Initiate polymerization by adding APS and TEMED. Pour the gel and overlay with isopropanol. Once set, prepare a stacking gel (lower percentage acrylamide in Tris-HCl, pH ~6.8) and insert a well comb.

- Sample Preparation: Mix the protein sample with a native loading dye (containing glycerol for density and a tracking dye, but no SDS or reducing agents). Do not boil the sample.

- Electrophoresis: Load the prepared samples and native molecular weight markers into the wells. Run the gel in a non-denaturing running buffer (e.g., Tris-Glycine, pH ~8.3) at a constant voltage (e.g., 100-150 V) at 4°C to minimize heat-induced denaturation or complex dissociation. Stop the run when the tracking dye front reaches the bottom of the gel.

- Visualization and Analysis: Carefully remove the gel from the plates and stain with Coomassie Blue or a compatible stain. Destain as needed. Compare the migration distance (Rf) of the protein of interest to the calibration curve generated from the native standards to estimate its apparent native molecular weight.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical process and key decision points in this protocol:

Protocol 2: Integration with Structural Proteomics (FLiP-MS Workflow)

This advanced protocol, adapted from [25], uses native electrophoresis as an analytical step within a comprehensive workflow for profiling protein complex dynamics.

Materials (The Scientist's Toolkit):

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Lysis Buffer (Native Conditions): Contains mild detergents and protease inhibitors to maintain protein interactions.

- RNase A: For destabilizing RNA-dependent protein complexes during fractionation.

- Serial Ultrafiltration Filters (e.g., 100, 50, 30, 10 kDa MWCO): For size-based fractionation of native protein complexes from cell lysate.

- Limited Proteolysis (LiP) Buffer and Protease (e.g., Proteinase K): For probing differential protease susceptibility of protein states.

Methodology:

- Native Lysate Preparation: Lyse cells under native conditions. Treat lysate with RNase to destabilize RNA-dependent complexes.

- Serial Ultrafiltration: Pass the lysate sequentially through ultrafiltration filters with decreasing molecular weight cut-offs (e.g., 100 kDa, 50 kDa, 30 kDa, 10 kDa). This generates fractions enriched in different assembly states of proteins, from large complexes to monomers.

- Fraction Analysis (via Native-PAGE): Analyze each fraction using Native-PAGE to confirm the size separation and enrichment of different molecular weight forms, as performed in [25].

- Limited Proteolysis-Mass Spectrometry (LiP-MS): Subject each fraction to limited proteolysis with a non-specific protease. The differential protease accessibility of a protein in its complex-bound versus monomeric state generates unique peptide patterns.

- Marker Library Creation and Application: Identify and compile the peptides that show differential protease susceptibility between fractions into a "PPI marker library." This library can then be used to interrogate LiP-MS data from perturbed cellular systems to pinpoint specific PPI changes on a global scale.

The FLiP-MS workflow for system-wide protein interaction profiling is illustrated below:

Advanced Data Interpretation

Interpreting Native-PAGE results requires careful consideration. A key application is deducing quaternary structure, as shown in the example where a protein migrates at 60 kDa on non-reducing SDS-PAGE but at 120 kDa on Native-PAGE, indicating a non-covalent dimer [22]. It is crucial to remember that migration is influenced by both size and charge. A protein with a high negative charge may migrate faster than a larger, more neutral protein. Therefore, using appropriate native molecular weight markers is essential for accurate size estimation.

Native-PAGE is also a vital quality control step in complex workflows. In the FLiP-MS protocol, Native-PAGE visually confirms the successful size-based fractionation of the proteome by serial ultrafiltration, validating that different fractions are uniquely enriched for proteins and assemblies of progressively decreasing molecular weight [25].

Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

Native electrophoresis has evolved dramatically from Tiselius's moving-boundary apparatus to a sophisticated family of techniques integral to modern structural and systems biology. Its unique power lies in its ability to probe the native state of proteins and their complexes, a capability that denaturing methods fundamentally lack. As demonstrated by its role in cutting-edge methodologies like FLiP-MS, Native-PAGE remains a critical tool for validating and analyzing protein interactions.

The future of Native-PAGE lies in its continued integration with other technologies, particularly mass spectrometry and computational modeling. The development of more sensitive in-gel detection methods and the standardization of protocols will further enhance its reproducibility and quantitative power. For researchers focused on protein-protein interactions, from initial characterization to system-wide dynamic studies, Native-PAGE is not a historical relic but an indispensable component of the contemporary analytical arsenal.

This application note details the unique molecular mechanism by which Coomassie Blue G-250 facilitates the electrophoretic separation of proteins by imparting a negative charge without disrupting their native, three-dimensional structure. Within the context of Blue Native-PAGE (BN-PAGE), this property is indispensable for studying protein-protein interactions, oligomeric states, and the assembly of macromolecular complexes. We provide a foundational protocol for BN-PAGE, a curated toolkit of essential reagents, and data demonstrating its application in evaluating protein complex monodispersity for crystallization trials.

In standard SDS-PAGE, the denaturing detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) unravels proteins and confers a uniform negative charge, enabling separation primarily by molecular weight. This process, however, destroys native structure and protein-protein interactions. Blue Native-PAGE (BN-PAGE) presents a powerful alternative by leveraging the specific properties of Coomassie Blue G-250 to analyze protein complexes in their native state [16] [12].

The technique, pioneered by Schägger and von Jagow, is particularly vital for investigating the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) system and other multisubunit assemblies [16] [7]. The core innovation lies in the dye's ability to provide the necessary charge for electrophoresis while preserving complex integrity, a feat that allows researchers to determine the size, abundance, and subunit composition of native complexes, and even detect assembly intermediates [16].

Molecular Mechanism: A Non-Denaturing Charge Shift

The unique functionality of Coomassie Blue G-250 stems from its chemical properties and its specific mode of interaction with proteins.

Chemical Properties and Ionic States

Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 is a triphenylmethane dye that exists in different ionic forms depending on the pH [26]:

- Below pH 0.3: It exists as a double cation (red).

- At pH 1.3: It is neutral (green).

- Above pH 1.3: It forms a monoanion (blue).

The BN-PAGE procedure is conducted at a near-neutral pH (∼7.0-7.5), ensuring the dye is in its blue anionic form [16] [27].

Mechanism of Protein Binding and Charge Conferral

The binding of Coomassie G-250 to proteins is a non-covalent, colloidal process that does not disrupt the protein's folded structure. The mechanism involves two primary interactions [26] [27]:

- Ionic Interactions: The dye's sulfonic acid groups interact with positively charged residues on the protein surface, primarily the primary amines of arginine, lysine, and histidine.

- Hydrophobic Interactions: The dye's aromatic structure engages in van der Waals forces with hydrophobic patches on the protein surface.

The binding is stoichiometric, meaning the amount of dye bound is proportional to the protein's surface area and, consequently, its mass [16]. This binding imparts a uniform negative charge density to the protein complex, allowing it to migrate toward the anode during electrophoresis. This mechanism overcomes two major hurdles of native electrophoresis [27]:

- It ensures that even basic proteins (with high pI), which would normally carry a positive net charge at neutral pH, gain a negative charge and migrate unidirectionally.

- It solubilizes membrane proteins and prevents aggregation by coating their exposed hydrophobic surfaces, converting them into charged, soluble entities.

Table 1: Comparison of Charge-Shift Mechanisms in SDS-PAGE vs. BN-PAGE.

| Feature | SDS-PAGE | BN-PAGE (with Coomassie G-250) |

|---|---|---|

| Charge Agent | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 |

| Protein State | Denatured; primary structure | Native; intact 2°, 3°, 4° structure |

| Binding | Strong, uniform denaturation | Mild, surface binding |

| Primary Interaction | Hydrophobic, with polypeptide backbone | Ionic (basic residues) & Hydrophobic |

| Charge Imparted | Strong negative charge | Proportional negative charge (to mass) |

| Separation Basis | Polypeptide chain length (mass) | Size, charge & shape of native complex |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental difference in how SDS and Coomassie Blue interact with proteins to facilitate electrophoresis.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for BN-PAGE

A successful BN-PAGE experiment requires specific reagents tailored to maintain protein complexes in their native state.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for a BN-PAGE Workflow.

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Mild Detergents | n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM), Digitonin, Triton X-100 [16] [12] | Solubilizes membrane proteins and lipid bilayers without disrupting protein-protein interactions. Digitonin is preferred for preserving supercomplexes [12]. |

| Charge-Shift Dye | Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 [16] [27] | Imparts negative charge for electrophoresis, prevents aggregation of hydrophobic proteins, and maintains solubility. |

| Solubilization Buffer | 0.75 M 6-Aminocaproic acid, 50 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0 [16] | Provides a low-ionic-strength, near-physiological pH environment to stabilize complexes during extraction. |

| Protease Inhibitors | PMSF, Leupeptin, Pepstatin [16] | Prevents proteolytic degradation of protein complexes during the isolation and solubilization process. |

| Gel System | Linear gradient gels (e.g., 4-16%, 3-12% acrylamide) [16] [27] | Resolves a wide range of protein complex sizes. A gradient is highly recommended over a single percentage gel. |

| Cathode Buffer | With 0.02% Coomassie G-250 (initial phase) [16] [28] | Provides a continuous supply of dye during electrophoresis to ensure consistent charge-shift. |

| Blotting Membrane | PVDF [16] [27] | Nitrocellulose is not recommended as it binds Coomassie dye too tightly, interfering with transfer and detection. |

Core BN-PAGE Protocol for Analysis of Mitochondrial Complexes

The following is an abridged protocol for analyzing mitochondrial protein complexes, adapted from Schägger and von Jagow [16].

Stage 1: Sample Preparation

- Solubilization: Resuspend 0.4 mg of sedimented mitochondria in 40 µL of Buffer A (0.75 M 6-aminocaproic acid, 50 mM Bis-Tris/HCl, pH 7.0) containing protease inhibitors (e.g., 1 mM PMSF).

- Detergent Extraction: Add 7.5 µL of 10% n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM). Mix and incubate for 30 minutes on ice.

- Clarification: Centrifuge at 72,000 x g for 30 minutes at 4°C to pellet insoluble material.

- Dye Addition: Collect the supernatant and add 2.5 µL of a 5% Coomassie Blue G-250 solution in 0.5 M aminocaproic acid.

Stage 2: Native Gel Electrophoresis (First Dimension)

- Gel Casting: Prepare a native linear gradient gel (e.g., 4-16% or 3-12% acrylamide) in a Bis-Tris/aminocaproic acid system. A stacking gel is used without a comb.

- Buffer Setup: Fill the anode chamber with anode buffer (50 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0). Add the cathode buffer with 0.02% Coomassie G-250 to the upper chamber.

- Loading and Run: Load 5–20 µL of prepared sample into the wells. Run the gel at a constant voltage (e.g., 100-150 V) at 4°C. To reduce dye interference in downstream steps, the cathode buffer can be replaced with a colorless cathode buffer once the sample has entered the stacking gel [28].

- Completion: Stop the run when the blue dye front has almost reached the bottom of the gel.

Stage 3: Downstream Applications

The first-dimension BN-PAGE gel can be used for several analyses:

- Immunodetection: Proteins can be transferred to a PVDF membrane for western blotting with specific antibodies [16].

- In-Gel Activity Staining: The separated OXPHOS complexes often remain enzymatically active and can be visualized by specific activity stains [7].

- Second Dimension (SDS-PAGE): For subunit analysis, excise a lane from the BN-PAGE gel, soak it in SDS-PAGE denaturing buffer, and place it horizontally on top of an SDS-PAGE gel. This resolves the individual subunits of each native complex [16].

Application in Protein Interaction Studies: Evaluating Complex Monodispersity for Crystallography

A critical application of BN-PAGE in drug development and structural biology is the evaluation of membrane protein sample quality for crystallization. There is a strong correlation between a protein's monodispersity (existing in a single, well-defined oligomeric state) and its propensity to form crystals [29].

Experimental Workflow and Data Interpretation

In this application, the purified membrane protein of interest is solubilized in different mild detergents and analyzed by BN-PAGE. The resulting gel profile serves as a direct indicator of the sample's aggregation state in solution [29].

Table 3: Interpreting BN-PAGE Results for Crystallization Screening.

| BN-PAGE Banding Pattern | Interpretation | Crystallization Propensity |

|---|---|---|

| Single, Sharp Band | Monodisperse sample; protein exists primarily as a single, homogeneous oligomer. | High |

| Multiple Discrete Bands | Polydisperse sample; presence of different oligomeric states or stable assembly intermediates. | Low to Moderate |

| Diffuse Smearing | Heterogeneous or aggregated sample; significant polydispersity and instability. | Very Low |

The following diagram outlines the logical workflow for using BN-PAGE in this capacity.

Key Experimental Findings

Research has demonstrated that BN-PAGE is more informative for assessing the aggregation states of membrane proteins than other techniques like dynamic light scattering (DLS) or size exclusion chromatography (SEC), which can be complicated by interference from detergent micelles [29]. A strong correlation exists between the monodispersity observed on BN-PAGE gels and the successful crystallization of various membrane proteins, and the oligomeric states resolved by BN-PAGE often correspond directly to those found in the final crystalline lattice [29].

The molecular basis of Coomassie Blue G-250's function—its ability to bind protein surfaces via non-denaturing ionic and hydrophobic interactions—makes it the cornerstone of the BN-PAGE technique. This unique charge-shift mechanism enables the high-resolution separation of intact protein complexes by their native size and shape. As a robust and informative tool, BN-PAGE is indispensable for modern research into protein-protein interactions, complexome profiling, and the preparation of high-quality samples for structural biology and drug discovery.

Practical Applications: Implementing Native PAGE for Protein Complex Analysis in Biomedical Research

The success of native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Native PAGE) in protein interaction studies fundamentally depends on the initial solubilization and stabilization of protein complexes. This step is particularly critical for membrane proteins, which require extraction from their native lipid environment into a stable, water-soluble form without disrupting their native structure or interactions [30] [11]. For soluble complexes, the challenge lies in maintaining non-covalent interactions during preparation. The selection of an appropriate solubilization strategy directly determines the accuracy and reliability of downstream Native PAGE analysis, influencing the biological relevance of the findings. This document outlines current, evidence-based protocols for solubilizing both membrane and soluble protein complexes, providing a standardized framework for researchers in structural biology and drug development.

Solubilization Techniques for Membrane Proteins

Membrane proteins pose a unique challenge due to their extensive hydrophobic surfaces that are normally embedded in the lipid bilayer. Effective solubilization involves disrupting the membrane while preserving the protein's functional conformation and its interactions with essential lipids and partner proteins [30] [31].

Conventional Detergent-Based Solubilization

Detergents are amphipathic molecules that solubilize membrane proteins by incorporating them into micellar structures, burying hydrophobic regions inside while exposing hydrophilic surfaces to the aqueous environment [31]. A general screening protocol is essential for identifying the optimal detergent for a specific membrane protein.

Table 1: Common Detergent Classes for Membrane Protein Solubilization [30] [11] [31]

| Detergent Class | Examples | CMC Range (%) | Key Characteristics | Considerations for Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-ionic | DDM, Triton X-100, Digitonin | 0.0087 (DDM) - 0.015 | Mild, generally preserve protein-protein interactions; low charge minimizes complex disruption. | Often the first choice for native complex isolation; Digitonin is noted for preserving labile complexes. |

| Zwitterionic | CHAPS, Fos-Choline-12 | 0.4 (CHAPS) - 0.3-0.6 (FC-12) | Charge neutrality helps maintain solubility without strong ionic interference. | Useful for proteins sensitive to non-ionic detergents; compatible with many functional assays. |

| Anionic | SDS, LDAO | 0.023 (SDS) - 0.1-0.2 | Powerful solubilization strength. | Typically too denaturing for native complex studies; can be considered for initial extraction before exchange. |

| Cationic | CTAB, DTAB | ~0.9 (CTAB) | Strong solubilizers. | Can denature proteins and are rarely used for native state preservation. |

Table 2: Preliminary Solubilization Screening Results for a Histidine-Tagged E. coli Membrane Protein (EM29) [31]

| Detergent Tested | Solubilization Yield (Qualitative) | Suitability Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| FOS-Choline-12 (FC12) | Weak Band | Less Suitable |

| n-Undecyl-β-D-Maltopyranoside (UDM) | Strong Band | Suitable |

| n-Dodecyl-β-D-Maltopyranoside (DDM) | Strong Band | Suitable |

| Octyl Glucoside (OG) | Strong Band | Suitable |

| Triton X-100 | Weak Band | Less Suitable |

| Lauryl Dimethylamine-N-Oxide (LDAO) | Weak Band | Less Suitable |

Protocol 1: General Detergent Screening for Membrane Proteins [31]

- Buffer Preparation: Prepare a standard buffer such as PBS (10 mM phosphate, 2.7 mM KCl, 137 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) or Tris buffer (20 mM, pH 7.4). Consider adding protease inhibitors and a reducing agent like DTT (0.5-1 mM) as needed.

- Solubilization Mixture: In a 1 mL total volume, combine the membrane preparation (typical protein concentration of 1-10 mg/mL) with the test detergent at a final concentration of 1-2% (w/v). A detergent-to-protein ratio (w/w) of 1:1 to 10:1 should be evaluated.

- Incubation: Incubate the mixture with gentle mixing (e.g., end-over-end rotation) for 1-2 hours at 4°C. The optimal temperature and duration may vary.

- Clarification: Centrifuge the solubilisate at 100,000 × g at 4°C for 45 minutes to pellet non-solubilized material and cellular debris.

- Analysis: Assay the supernatant (solubilized fraction) for the presence and activity of the target protein. Methods include:

- SDS-PAGE & Western Blot: For detection and preliminary yield assessment.

- Affinity Purification & Gel Filtration: Rapidly assesses yield and, under native conditions, homogeneity.

- Activity Assays: The most critical indicator of successful native structure preservation.

Advanced Detergent-Free Solubilization Strategies

Recent innovations aim to circumvent the potential destabilizing effects of detergents by using alternative amphipathic systems that maintain a more native-like lipid environment.

A. Styrene-Maleic Acid (SMA) Copolymer and Derivatives SMA and related copolymers like DIBMA can directly solubilize membrane proteins by incorporating a segment of the native lipid bilayer along with the protein, forming SMA Lipid Particles (SMALPs) [30]. This "detergent-free" technique stabilizes proteins in their native conformation and is particularly valuable for cryo-EM characterization [30].

B. Designer Solubilizing Proteins (WRAPs) This deep learning-based approach designs Water-soluble RFdiffused Amphipathic Proteins (WRAPs) that genetically fuse to the target membrane protein. The WRAP domain features a polar exterior for solubility and a non-polar interior complementary to the target's hydrophobic surface, effectively shielding it [32]. This method has successfully solubilized beta-barrel OMPs and multi-pass helical proteins like GlpG with enhanced stability and retained enzymatic function [32].

C. Engineered Membrane Scaffold Peptides (DeFrND) The DeFrND technology employs engineered Apolipoprotein-A1 mimetic peptides, potentiated with fatty acid modifications, to directly extract membrane proteins from native cell membranes into nanodiscs without prior detergent solubilization [33]. This method preserves functional integrity, as demonstrated by the coupled ATPase activity of the extracted MalFGK2 transporter, which is often lost in detergent [33].

Solubilization and Stabilization of Soluble Complexes

For soluble protein complexes, the goal of solubilization is not extraction from a membrane but the maintenance of non-covalent protein-protein interactions (PPIs) in solution during lysis and preparation.

Buffers and Additives for Complex Stability

The composition of the lysis and solubilization buffer is critical. Harsh ionic detergents like SDS must be avoided. Instead, buffers should contain:

- Mild Non-Ionic or Zwitterionic Detergents (e.g., Digitonin, DDM): Used at low concentrations (e.g., 0.1-0.5%) to solubilize membranes without disrupting protein complexes [11].

- Stabilizing Salts and Osmolytes: Salts like NaCl (e.g., 150 mM) and osmolytes like glycerol (5-10%) can help maintain the native state.

- Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitors: Essential to prevent proteolytic degradation and preserve post-translational modifications that often regulate PPIs.

Systematic Analysis of Complex Dynamics with FLiP-MS

The FLiP-MS (serial Ultrafiltration combined with Limited Proteolysis-coupled Mass Spectrometry) workflow represents a major advance for systematically probing protein complex dynamics [25]. It generates a library of peptide markers that report on changes in protease accessibility between complex-bound and monomeric forms of proteins, often mapping to protein-binding interfaces [25]. This library can then be used to interpret LiP-MS data from perturbed systems, specifically highlighting changes in PPIs with peptide-level resolution, providing a powerful tool for interactome-wide studies ahead of techniques like Native PAGE [25].

Integrated Workflow for Native PAGE Sample Preparation

The following diagram and workflow integrate the techniques described above into a coherent strategy for preparing samples for Native PAGE analysis.

Diagram 1: Integrated sample preparation workflow for Native PAGE, showing parallel paths for membrane protein solubilization and soluble complex stabilization.

Workflow Description:

- Sample Preparation: Begin with a cell lysate. For membrane proteins, a membrane fraction is often isolated.

- Solubilization Method Selection:

- For Membrane Proteins, choose between:

- Detergent-Based Path: Perform a general detergent screen (Protocol 1) and optimize conditions (e.g., pH, salt, incubation time).

- Detergent-Free Path: Evaluate advanced methods like SMA copolymers, computationally designed WRAPs, or DeFrND peptides for a more native environment.

- For Soluble Complexes, use mild non-ionic detergents and consider applying the FLiP-MS workflow to profile complex dynamics systematically.

- For Membrane Proteins, choose between:

- Clarification: Remove non-solubilized material and cellular debris via ultracentrifugation.

- Target Complex Analysis: The clarified supernatant, containing solubilized and stabilized proteins or complexes, is now ready for Native PAGE and subsequent analysis (e.g., in-gel activity assays, Western blotting, or complexomic profiling).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Solubilization and Stabilization Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|

| n-Dodecyl-β-D-Maltoside (DDM) | Non-ionic detergent for mild solubilization of membrane protein complexes. | First-choice detergent for initial screens; often preserves activity for Native PAGE [11] [31]. |

| Digitonin | Non-ionic, plant-derived detergent known for preserving native protein-protein interactions. | Ideal for solubilizing labile multi-subunit complexes for native analyses [11]. |

| Styrene-Maleic Acid (SMA) Copolymer | Amphipathic polymer for detergent-free extraction of membrane proteins with a native lipid annulus. | Formation of SMALPs for cryo-EM or functional studies where a native lipid environment is critical [30]. |

| Membrane Scaffold Peptides (DeFrND) | Engineered peptides for direct extraction of proteins into nanodiscs from native membranes. | Studying detergent-sensitive membrane proteins and complexes with preserved function and native lipids [33]. |

| WRAPs (Computationally Designed) | Genetically encoded solubilizing domains designed for specific membrane protein targets. | Creating hyperstable, soluble versions of specific membrane proteins for structural or therapeutic development [32]. |

| FLiP-MS Marker Library | A resource of peptide markers that report on changes in protein complex assembly state. | Systematically probing global interactome dynamics in response to cellular perturbations [25]. |

Within the context of a broader thesis on applications of native PAGE in protein interaction studies, the critical role of detergent selection cannot be overstated. The fundamental goal of native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) is to separate protein complexes by molecular weight while preserving their native structure and enzymatic activity [14]. For membrane proteins, which are embedded in lipid bilayers, achieving this requires the use of mild detergents to solubilize them without disrupting essential protein-protein interactions [34]. The choice of detergent directly influences which protein complexes remain intact, which dissociate into subcomplexes, and whether higher-order supercomplexes can be observed, thereby shaping the biological conclusions drawn from the experiment [34].

This application note focuses on three widely used detergents—dodecylmaltoside, digitonin, and Triton X-100—providing a structured guide for researchers to select the optimal detergent based on their experimental goals. Proper detergent selection is paramount for successful outcomes in techniques like Blue Native-PAGE (BN-PAGE) and Clear Native Electrophoresis (CNE), which are cornerstone methods for investigating respiratory chains, GPCR signaling, and other vital membrane protein complexes in drug development research [34] [35] [17].

Detergent Properties and Selection Criteria

Key Characteristics and Mechanisms of Action

Detergents used for native protein analysis are mild, non-ionic agents that function by disrupting lipid-lipid and lipid-protein interactions while ideally leaving protein-protein interactions undisturbed [34]. Their effectiveness hinges on the delicate balance between efficient solubilization of the membrane and preservation of the native protein complex.

- Dodecylmaltoside (DDM): A maltoside-based detergent with a relatively large polar headgroup, offering a good balance between efficient solubilization and gentle treatment of protein complexes. It is a well-defined, homogeneous synthetic detergent [34] [35].

- Digitonin: A natural plant-derived glycoside known for its exceptionally mild properties. It is a complex mixture purified from natural sources, which can lead to batch-to-batch variability [34]. Its mildness is key to preserving weak protein-protein interactions and supercomplexes.

- Triton X-100: A synthetic detergent with a smaller hydrophilic headgroup compared to DDM. It is considered slightly harsher but is effective for solubilizing a wide range of membrane proteins [34] [35].

The working principle of BN-PAGE relies on these detergents for solubilization, while the anionic dye Coomassie Blue G250 provides the negative charge required for electrophoretic migration. This combination avoids the denaturing conditions of SDS-PAGE, allowing complexes to remain intact and active [34] [14].

Comparative Analysis and Selection Guide

The table below summarizes the fundamental properties of these detergents to guide initial selection.

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Key Detergents for Native PAGE

| Property | Dodecylmaltoside (DDM) | Digitonin | Triton X-100 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Class | Non-ionic maltoside | Non-ionic glycoside | Non-ionic polyoxyethylene ether |

| Aggregation Number | ~78 [36] | ~60 [36] | ~100 [36] |

| Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) | ~0.17 mM [36] | ~0.2 mM [36] | ~0.3 mM [36] |

| Micelle Molecular Weight (kDa) | ~50 [36] | ~70 [36] | ~90 [36] |

| Key Characteristic | Well-defined, synthetic; general-purpose mild detergent | Very mild; preserves weak interactions and supercomplexes | Moderately harsh; cost-effective for robust complexes |

The choice of detergent profoundly impacts the experimental outcome, as different detergents can stabilize distinct organizational states of protein complexes. A classic example comes from mitochondrial research:

- When dodecylmaltoside or Triton X-100 is used, individual respiratory complexes (I, II, III, IV, and V) are typically observed. This supported the "liquid state model" where complexes diffuse freely in the membrane [34].

- When the milder digitonin is employed, defined associations of these complexes, known as supercomplexes or "respirasomes," are revealed. This discovery supported an alternative "solid state model" of the respiratory chain [34].

Therefore, digitonin is the detergent of choice for investigating higher-order assemblies, while DDM is excellent for analyzing individual, stable complexes.

Table 2: Functional Application Guide for Protein Complex Analysis

| Target Complex Type | Recommended Detergent | Typical Working Concentration | Expected Outcome & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Stable Complexes (e.g., Complex V) | Dodecylmaltoside (DDM) | 1.0 - 1.5% [34] | Yields well-resolved individual complexes; ideal for initial characterization and activity assays. |

| Labile Supercomplexes (e.g., Respirasomes) | Digitonin | 1.5 - 5.0 g/g protein [34] | Preserves weak interactions between complexes; essential for studying supercomplex formation and function. |

| Robust Monomeric Complexes | Triton X-100 | 0.1 - 0.5% [34] | Effective solubilization at low cost; may dissociate some weaker oligomeric states. |

| GPCR-G Protein Coupling | Lauryl Maltose Neopentyl Glycol (LMNG) / DDM | e.g., 0.01% LMNG [17] | Newer detergents like LMNG offer enhanced stability for dynamic complexes like GPCR-G protein assemblies. |

Experimental Protocols for Complex Analysis

Protocol 1: Analysis of Mitochondrial Respiratory Supercomplexes Using BN-PAGE

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used to demonstrate the differential effects of detergents on respiratory supercomplexes [34].

Research Reagent Solutions

- Solubilization Buffer: 50 mM NaCl, 50 mM Imidazole/HCl, 2 mM 6-aminohexanoic acid, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.0. Store at 4°C.

- Digitonin Stock: 5% (w/v) in solubilization buffer. Gently heat and vortex to dissolve. Store at -20°C.

- DDM Stock: 2% (w/v) dodecylmaltoside in water. Store at -20°C.

- Cathode Buffer: 50 mM Tricine, 15 mM Bis-Tris, 0.02% Coomassie G-250 (pH ~7.0 at 4°C). Prepare fresh.

- Anode Buffer: 50 mM Bis-Tris/HCl, pH 7.0.

- Gradient Gel: A pre-cast or hand-cast 4-16% polyacrylamide gradient gel is optimal for separating complexes ranging from 100 kDa to several MDa.

Procedure

- Isolate Mitochondria: Prepare mitochondrial fractions from plant or mammalian tissue using standard differential centrifugation.

- Protein Quantification: Determine the protein concentration of the mitochondrial suspension using a compatible assay (e.g., BCA assay).

- Solubilization:

- Clarification: Centrifuge the solubilized mixture at 100,000 x g for 30 minutes at 4°C to remove insoluble material.

- Load Sample: Carefully mix the supernatant with a 50% glycerol solution (to a final concentration of 5-10%) and load it onto the gradient gel.

- Electrophoresis: Run the gel with blue cathode buffer at 4°C. Start at 100 V for about 30 minutes, then continue at 15-20 mA until the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel.

- Analysis: Complexes can be visualized by Coomassie staining, immunoblotting, or subjected to in-gel activity assays [35].

Protocol 2: Assessing GPCR-Mini-G Protein Coupling via hrCNE

This protocol leverages high-resolution Clear Native Electrophoresis (hrCNE) to study detergent-stable GPCR complexes, a key application in drug development [17].

Research Reagent Solutions

- Membrane Preparation Buffer: 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl₂, 1 mM MgCl₂. Supplement with protease inhibitors before use.

- Solubilization Buffer: Membrane preparation buffer supplemented with 0.01% Lauryl Maltose Neopentyl Glycol (LMNG) and 0.001% Cholesteryl Hemisuccinate (CHS). Keep on ice.

- hrCNE Anode Buffer: 50 mM Tricine, 15 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0 (at 4°C).

- hrCNE Cathode Buffer: 50 mM Tricine, 15 mM Bis-Tris, 0.05% sodium deoxycholate, pH 7.0 (at 4°C). Note: The lack of Coomassie is key for hrCNE.

- 4x Native Sample Buffer: 200 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 40% glycerol, 4 mM MgCl₂, 4 mM TCEP. Store at -20°C.

- Purified Mini-G Protein: Express and purify mini-G protein(s) of interest (e.g., mini-Gs) as described in literature [17].

Procedure

- Prepare Membranes: Harvest HEK293S GnT1- cells expressing the EGFP-tagged GPCR of interest. Prepare crude membranes by Dounce homogenization and differential centrifugation [17].

- Solubilize Receptor: Resuspend membranes in solubilization buffer to a final protein concentration of 1-2 mg/mL. Incubate with gentle agitation for 2 hours at 4°C.

- Form Receptor-Mini-G Complex: Clarify the solubilized lysate by centrifugation (21,000 x g, 30 min, 4°C). Incubate the supernatant with a saturating concentration of purified mini-G protein and the desired agonist/antagonist for 1 hour on ice.

- Prepare for Electrophoresis: Mix the sample with ¼ volume of 4x Native Sample Buffer.

- Load and Run: Load the sample onto a 4-16% BN-PAGE gel (run under CNE conditions, i.e., without Coomassie in the cathode buffer). Run at 100 V for 1 hour, then increase to 200 V for another 2-3 hours at 4°C, protected from light.

- Visualize Complex: Directly image the gel using a fluorescence scanner (e.g., Typhoon Imager) with settings for EGFP detection (excitation: 488 nm, emission: 520 nm BP 40). The formation of a GPCR-mini-G complex will be indicated by a distinct, agonist-dependent mobility shift to a higher molecular weight [17].

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Detergent Selection and Experimental Workflow

Diagram 1: Detergent selection workflow for complex analysis.

BN-PAGE Process from Sample to Analysis

Diagram 2: BN-PAGE process from sample to analysis.

The strategic selection of dodecylmaltoside, digitonin, or Triton X-100 is a decisive factor in the successful analysis of protein complexes using native PAGE. Dodecylmaltoside serves as an excellent general-purpose detergent for stable individual complexes, while digitonin is indispensable for revealing the architecture of labile supercomplexes. Triton X-100 provides a cost-effective option for robust complexes where preservation of the finest interactions is less critical. As the field advances, novel detergents and detergent-free systems like native nanodiscs continue to expand the toolkit available to researchers [33] [37]. By following the guidelines, protocols, and visual workflows provided in this application note, scientists and drug development professionals can make informed decisions to optimally design experiments that accurately capture the native state of their protein complexes of interest.