Native PAGE for Protein Complexes: A Comprehensive Guide from Principles to Advanced Applications

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete guide to separating and analyzing native protein complexes using Blue Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) and related techniques.

Native PAGE for Protein Complexes: A Comprehensive Guide from Principles to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete guide to separating and analyzing native protein complexes using Blue Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) and related techniques. It covers foundational principles, detailed step-by-step protocols, advanced troubleshooting for common artifacts, and validation methods essential for studying mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complexes, interactomes, and other multisubunit assemblies. The content synthesizes current methodologies with practical optimization strategies to ensure reproducible, high-quality results in proteomics and biomedical research.

Understanding Native PAGE: Preserving Protein Complexes in Their Functional State

In the field of protein analysis, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) serves as a fundamental tool for separating and characterizing proteins. However, the choice between native PAGE and denaturing SDS-PAGE represents a critical methodological branch point, each leading to dramatically different information about the protein sample. These techniques diverge most significantly in their treatment of the protein's native structure. While SDS-PAGE unravels and denatures proteins to determine molecular weight, native PAGE preserves the protein's three-dimensional structure, enabling the study of functional complexes and biological activity [1] [2].

This distinction makes these techniques complementary rather than interchangeable. SDS-PAGE has become the workhorse for routine protein analysis due to its simplicity and consistency, whereas native PAGE provides a specialized approach for functional studies where maintaining native conformation is paramount [3]. Understanding their fundamental differences allows researchers to select the optimal tool for specific research questions in biochemistry, structural biology, and drug development.

Fundamental Principles and Separation Mechanisms

SDS-PAGE: Separation by Molecular Weight Alone

Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) operates on the principle of complete protein denaturation and uniform charge masking to achieve separation based almost exclusively on molecular weight. The key agent in this process is the anionic detergent SDS, which binds extensively to hydrophobic regions of proteins in a constant weight ratio (approximately 1.4 g SDS per 1 g of protein) [2]. This binding process unfolds the proteins into linear chains and confers a uniform negative charge density, effectively masking the proteins' intrinsic electrical charges [1] [3].

Sample preparation for SDS-PAGE typically involves heating at 95-100°C for 5-10 minutes in the presence of SDS and reducing agents like dithiothreitol (DTT) or β-mercaptoethanol (BME) to break disulfide bonds [1] [4]. When an electric field is applied, the resulting SDS-polypeptide complexes migrate through the polyacrylamide gel matrix toward the positive electrode, with smaller polypeptides moving faster due to less resistance from the gel pores [2]. This molecular sieving effect results in a separation where migration distance correlates precisely with logarithm of molecular weight, enabling accurate molecular weight determination when compared with standard protein markers [3].

Native PAGE: Separation by Charge, Size, and Shape

In stark contrast, native PAGE (including variants like Blue Native [BN]-PAGE and Clear Native [CN]-PAGE) separates proteins based on their inherent charge, size, and three-dimensional shape under conditions that preserve their native conformation and biological activity [1] [2]. Without denaturing agents, proteins maintain their complex quaternary structures, subunit interactions, and associated cofactors [3].

In this technique, proteins are prepared in non-denaturing buffers without SDS or reducing agents, and samples are not heated before loading [1]. During electrophoresis, proteins migrate according to their intrinsic charge density (net charge per mass) at the buffer pH, while the gel matrix provides a sieving effect based on the protein's hydrodynamic volume and shape [2]. Basic proteins may be separated using cathode buffer systems that maintain a slightly basic pH, facilitating their migration toward the negative electrode [5].

For membrane proteins, specialized native techniques like BN-PAGE use Coomassie Blue G-250 or mild detergents to impose a charge shift that facilitates migration while maintaining complex integrity [5] [6]. This preservation of native structure allows for subsequent functional assays, as separated proteins often retain enzymatic activity and can be recovered in their functional form [1] [2].

Table 1: Core Fundamental Differences Between SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE

| Parameter | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Molecular weight only | Size, charge, and 3D shape |

| Protein State | Denatured and linearized | Native, folded conformation |

| Detergent Usage | SDS present (denaturing) | No SDS (mild, non-ionic detergents may be used) |

| Sample Preparation | Heating with SDS and reducing agents | No heating, no denaturants |

| Protein Function Post-Separation | Lost | Preserved |

| Protein Recovery | Not feasible in functional form | Possible with retained activity |

| Typical Running Temperature | Room temperature | 4°C to maintain stability |

| Information Obtained | Polypeptide size, purity, abundance | Oligomeric state, protein-protein interactions, activity |

Comparative Analysis: Applications and Limitations

Application Scope for SDS-PAGE Versus Native PAGE

The applications of SDS-PAGE and native PAGE diverge according to the research objectives, with SDS-PAGE excelling in analytical tasks requiring molecular weight determination, while native PAGE provides unique capabilities for functional studies.

SDS-PAGE Applications:

- Molecular weight determination of polypeptide chains under denaturing conditions [1] [2]

- Assessment of protein purity and homogeneity in samples [7]

- Analysis of protein expression levels in cellular systems [1]

- Western blotting preparation, where denatured proteins are transferred to membranes for antibody detection [7]

- Protein quantification through band intensity analysis [2]

Native PAGE Applications:

- Study of protein-protein interactions and oligomeric states in multiprotein complexes [3] [7]

- Analysis of enzymatic activity through in-gel functional assays post-separation [5]

- Investigation of protein complexes such as mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) supercomplexes [5] [8]

- Purification of functional proteins for downstream applications [1]

- Characterization of binding properties and conformational changes [3]

Technical Considerations and Limitations

Each method presents distinct limitations that must be considered during experimental design. SDS-PAGE's primary limitation is the complete loss of structural and functional information due to denaturation [1] [3]. While it provides excellent resolution based on size, it cannot reveal native oligomeric states or interactions between subunits in multimeric proteins [2]. The uniform charge masking also means that post-translational modifications affecting charge may not be detectable [3].

Native PAGE, while powerful for functional studies, presents challenges in interpretation and reproducibility. Without charge masking, migration depends on multiple factors including intrinsic charge, size, and shape, making molecular weight estimation unreliable [2]. The technique may also struggle with protein solubility and aggregation in the absence of denaturants, particularly for hydrophobic membrane proteins [6]. Additionally, maintaining native conditions throughout the process requires careful temperature control (often at 4°C) and pH management to prevent denaturation or proteolysis [1] [2].

Table 2: Application-Based Selection Guide

| Research Goal | Recommended Technique | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Determine subunit molecular weight | SDS-PAGE | Provides accurate size estimation under denaturing conditions |

| Study protein oligomerization | Native PAGE | Preserves quaternary structure and interactions |

| Detect specific epitopes via western blot | SDS-PAGE | Denaturation exposes linear epitopes for antibody binding |

| Perform in-gel activity assays | Native PAGE | Maintains protein function and enzymatic capability |

| Analyze complex protein mixtures | SDS-PAGE | Offers superior resolution for complex samples |

| Investigate membrane protein complexes | BN-PAGE/CN-PAGE | Specialized variants preserve membrane complex integrity |

| Purify functional proteins | Native PAGE | Enables recovery of active proteins post-separation |

Practical Implementation: Protocols and Reagents

Standard SDS-PAGE Protocol

Materials Required:

- Acrylamide/bis-acrylamide solution (typically 30-40%)

- Tris buffer (pH 8.8 for resolving gel, pH 6.8 for stacking gel)

- SDS (sodium dodecyl sulfate)

- TEMED (N,N,N',N'-tetramethylethylenediamine)

- APS (ammonium persulfate)

- Running buffer (Tris-Glycine with SDS)

- Protein sample

- Loading buffer with SDS and reducing agent

- Electrophoresis apparatus and power supply [4]

Procedure:

- Prepare the separating gel by mixing appropriate volumes of acrylamide/bis-acrylamide, Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), SDS, TEMED, and APS. Pour between glass plates and overlay with water or isopropanol to ensure even polymerization. Allow to polymerize for approximately 30 minutes [4] [2].

Prepare the stacking gel using lower acrylamide concentration (typically 4-5%) and Tris-HCl (pH 6.8). After removing the overlay from the polymerized separating gel, pour the stacking gel and immediately insert a comb to form wells. Allow to polymerize for 30 minutes [4] [2].

Prepare protein samples by mixing with loading buffer containing SDS and reducing agent (e.g., DTT or BME). Heat denature samples at 95-100°C for 5-10 minutes to ensure complete denaturation [4].

Assemble the electrophoresis apparatus and fill with running buffer. Remove the comb and load samples into wells using a micropipette. Include molecular weight markers in one lane [4].

Run the gel at constant voltage (typically 100-150V for mini-gels) until the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel. Running time varies with gel percentage and size [4].

Visualize proteins by staining with Coomassie Blue, silver stain, or other suitable detection methods. For western blotting, transfer proteins to a membrane instead of staining [4] [2].

Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) Protocol for Membrane Complexes

Materials Required:

- Acrylamide/bis-acrylamide for gradient gels

- Bis-Tris or imidazole-based buffers (pH 7.0)

- Mild detergents (n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside, digitonin)

- Coomassie Blue G-250 dye

- 6-aminocaproic acid

- Gradient gel casting system

- Cathode and anode buffers specific for BN-PAGE [5] [8]

Procedure:

- Prepare mitochondrial or membrane fractions from tissues or cells using appropriate homogenization and differential centrifugation methods [5].

Solubilize membrane proteins using mild non-ionic detergents like n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (typically 1-2%) or digitonin for supercomplex preservation. Maintain a detergent-to-protein ratio between 1:1 to 10:1, optimizing for specific complexes [5] [6] [8].

Prepare gradient gels (typically 3-12% or 4-16% acrylamide) using a gradient maker. Linear gradients provide optimal resolution for high molecular weight complexes. Allow gels to polymerize completely [5].

Prepare samples by adding Coomassie Blue G-250 dye (0.5-1% final concentration) to the solubilized protein complexes. The dye imposes a charge shift and enhances solubility [5] [8].

Load samples and run electrophoresis at 4°C to maintain complex stability. Begin at low voltage (e.g., 50V) and increase gradually (up to 200V) as the dye front enters the separating gel [5].

For downstream applications:

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE

| Reagent | Function | Specific Examples/Types |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms porous gel matrix for separation | Standard 29:1 or 37.5:1 acrylamide:bis ratio [4] [2] |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins and confers uniform charge | Used in SDS-PAGE at 0.1-0.2% in gels and buffers [1] [2] |

| TEMED/APS | Catalyzes acrylamide polymerization | TEMED with ammonium persulfate as initiator [4] [2] |

| Mild Detergents | Solubilizes native complexes without denaturation | n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside, digitonin, Triton X-100 [5] [6] |

| Coomassie Dyes | Impose charge shift in BN-PAGE; protein staining | Coomassie Blue G-250 for BN-PAGE; G-250/R-250 for staining [5] |

| Charge Shift Agents | Facilitate migration in CN-PAGE | Mixed micelles of anionic and neutral detergents [5] |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevent protein degradation during native procedures | Cocktails included in extraction buffers [5] |

Experimental Design and Workflow Strategies

This decision pathway provides researchers with a systematic approach to selecting the appropriate electrophoretic method based on their specific research objectives. The workflow emphasizes how fundamental questions about protein characterization needs should guide methodological choices.

Advanced Applications and Future Perspectives

Specialized Native PAGE Variants

The basic native PAGE technique has evolved into specialized variants that address specific research challenges. Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) has become indispensable for studying mitochondrial complexes and respiratory supercomplexes [5] [8]. The method uses Coomassie Blue G-250 to impose a negative charge on membrane proteins solubilized with mild detergents like n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside, enabling the resolution of intact complexes with molecular weights up to several megadaltons [5] [6]. Recent protocol refinements have shortened sample extraction procedures and enhanced in-gel activity detection sensitivity, particularly for Complex V (ATP synthase) [5].

Clear Native PAGE (CN-PAGE) represents a further refinement where mixed micelles of anionic and neutral detergents replace Coomassie dye in the cathode buffer [5]. This approach eliminates potential dye interference with in-gel enzyme activity assays and provides superior resolution for certain applications [5] [8]. The choice between BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE depends on the specific complexes being studied and the intended downstream applications, with BN-PAGE generally providing better resolution for high molecular weight complexes, while CN-PAGE offers advantages for functional assays [5].

Integration with Downstream Analytical Techniques

Both native PAGE and SDS-PAGE serve as foundational separation methods that integrate with various downstream analysis platforms:

Two-Dimensional Electrophoresis combining BN-PAGE with SDS-PAGE provides a powerful comprehensive analysis tool. In this approach, protein complexes are first separated by BN-PAGE, then individual lanes are excised and applied to SDS-PAGE gels to resolve complex subunits in the second dimension [5]. This technique has proven invaluable for analyzing assembly intermediates of mitochondrial complexes and identifying defective assembly pathways in genetic disorders [5].

Mass Spectrometry Integration has expanded the applications of both techniques. Proteins separated by SDS-PAGE can be excised, digested, and identified by LC-MS/MS, while native PAGE enables the characterization of intact complexes by native mass spectrometry [9] [10]. Recent advances in supercharger-assisted native top-down mass spectrometry now allow analysis of membrane protein complexes directly from native membranes, providing new insights into oligomeric states, proteoforms, and endogenous ligand binding [9] [10].

Functional Assays following native PAGE separation include in-gel enzyme activity staining for respiratory complexes, which maintains clinical relevance for diagnosing mitochondrial disorders [5]. The preservation of biological activity after separation enables zymogram techniques for detecting various enzymatic activities directly in the gel matrix.

Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE represent complementary approaches in the protein researcher's toolkit, each with distinct advantages and applications. SDS-PAGE provides unparalleled resolution for molecular weight determination and analytical simplicity, while native PAGE offers unique capabilities for studying protein function, interactions, and native structure. The continued development of specialized variants like BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE, coupled with integration with advanced downstream analysis techniques, ensures that both methods will remain essential for protein characterization in basic research and drug development.

Blue Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) is an indispensable technique for analyzing native protein complexes, particularly those from mitochondrial and membrane preparations. The central component enabling this method is Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250, which serves a dual function: it imparts a uniform negative charge to native protein complexes, facilitating their electrophoretic migration, and enhances the solubility of hydrophobic membrane proteins, preventing aggregation under native conditions. This application note details the underlying mechanisms of Coomassie dye, provides a validated step-by-step protocol for the separation of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) complexes, and discusses advanced applications and troubleshooting, serving as a comprehensive resource for researchers in proteomics and drug development.

In the analysis of protein complexes, maintaining native structure is paramount for understanding true physiological interactions, stoichiometry, and function. BN-PAGE, first described by Schägger and von Jagow in 1991, fulfills this need by enabling the separation of intact protein complexes under non-denaturing conditions [11] [5]. Unlike SDS-PAGE, which uses the denaturing detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate to impart charge and unfold proteins, BN-PAGE relies on the mild, non-ionic detergent n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside for initial solubilization and, crucially, the dye Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 for charge conferral and solubility enhancement [11] [12] [13].

The core challenge BN-PAGE overcomes is the inherent insolubility of membrane proteins and their complexes in aqueous environments once detached from their lipid bilayers. Coomassie G-250 addresses this by binding to protein surfaces via hydrophobic interactions and heteropolar bonding to basic amino acids, effectively masking their hydrophobic character and conferring a strong negative charge [14] [15]. This allows complexes to remain soluble and migrate through the polyacrylamide gel based on their size and shape, without the need for denaturing agents. The technique has become the gold standard for investigating mitochondrial respiratory chains, revealing the existence and composition of supercomplexes (respirasomes), and diagnosing mitochondrial disorders [13] [5].

Table: Key Properties of Coomassie Brilliant Blue Dyes in Protein Analysis

| Property | Coomassie Blue R-250 | Coomassie Blue G-250 |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use | Protein staining in SDS-PAGE & IEF gels | BN-PAGE & Bradford protein assay |

| Color Characteristic | Reddish-blue | Greenish-blue |

| Charge Imparting in BN-PAGE | Not typically used | Yes, essential function |

| Typical Form | Solution in methanol/acetic acid | Colloidal suspension |

| Binding Mechanism | Hydrophobic & ionic interactions | Hydrophobic & ionic interactions |

Core Mechanism: How Coomassie Dye Imparts Charge and Solubility

The functionality of Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 in BN-PAGE is rooted in its unique chemical behavior and interaction with proteins.

Chemical Properties and Charge States

Coomassie Brilliant Blue is a triphenylmethane dye whose ionic state and color are highly dependent on pH [14] [15]. For Coomassie G-250:

- At pH < 0.3, it exists as a double cation and is red.

- At pH ~1.3, it is neutral and green.

- At pH > 1.3, it forms an anion and is blue [15].

In the neutral pH conditions (pH 7.0) used in BN-PAGE, the dye molecule is a negatively charged anion with an overall charge of -1, which allows it to bind to proteins and impart the negative charge necessary for anodal migration [14].

Mechanism of Action in BN-PAGE

The dye performs two critical, simultaneous functions:

- Imparting Negative Charge: The binding of numerous Coomassie G-250 anions to a protein complex confers a large negative charge shift. This charge is roughly proportional to the surface area of the complex, ensuring that even basic proteins migrate toward the anode. This replaces the function of SDS in denaturing electrophoresis [13] [5].

- Enhancing Solubility: The dye binds to hydrophobic patches on protein surfaces. This binding converts the surface character of membrane proteins from hydrophobic to more hydrophilic, dramatically increasing their solubility in the aqueous electrophoresis buffer and preventing aggregation. This eliminates the need for detergents in the running gel itself, minimizing the risk of denaturation [12] [13] [5].

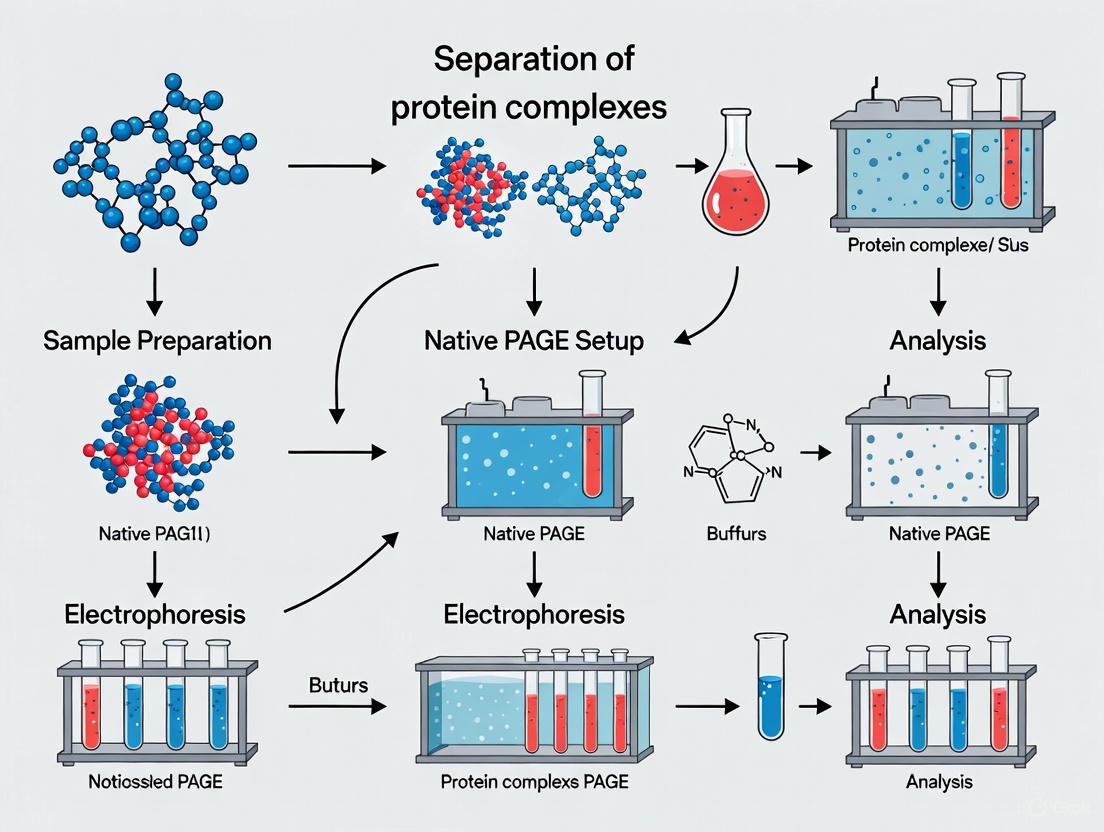

The diagram below illustrates this core mechanism and the subsequent electrophoresis process.

Experimental Protocol: BN-PAGE for OXPHOS Complexes

The following is a consolidated and validated protocol for analyzing mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) complexes, adapted from key sources [11] [13] [5].

Sample Preparation: Mitochondrial Solubilization

- Mitochondria Isolation: Isolate mitochondria from target tissue (e.g., mouse liver) or cells. Resuspend the mitochondrial pellet (0.5 - 2 mg total protein) in 50-100 µL of Buffer A (0.75 M 6-aminocaproic acid, 50 mM Bis-Tris/HCl, pH 7.0) containing protease inhibitors (e.g., 1 mM PMSF) [11].

- Solubilization: Add a 10% solution of the mild, non-ionic detergent n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) to achieve a detergent-to-protein ratio of 2-4 g/g. Gently mix and incubate on ice for 30 minutes [11] [5].

- Clarification: Centrifuge the solubilized mixture at 72,000 x g for 30 minutes at 4°C to remove insoluble material.

- Dye Addition: Collect the supernatant and add Coomassie Blue G-250 (from a 5% stock solution in 0.5 M aminocaproic acid) to a final concentration of approximately 0.5% (v/v) [11].

Native Gel Electrophoresis (First Dimension)

- Gel Casting: Pour a native polyacrylamide gradient gel (e.g., 3-12% or 4-16%) using a gradient former. The gel matrix should contain 0.5 M 6-aminocaproic acid and 50 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0. A stacking gel (without gradient) is often used on top [11] [5].

- Electrophoresis Setup: Use specific anode and cathode buffers.

- Running Conditions: Load the prepared samples (5-20 µL) into the wells. Run the gel at 4°C to maintain complex integrity. Start with a constant voltage of 100 V until the sample has entered the stacking gel, then continue at 150 V for 2-3 hours until the dye front has almost migrated off the gel [11].

Downstream Applications

- In-Gel Activity Staining: The separated OXPHOS complexes remain enzymatically active. Specific assays can be performed to visualize the activity of Complexes I, II, IV, and V directly in the gel [13] [5] [16].

- Second Dimension SDS-PAGE: For subunit analysis, excise a lane from the BN-PAGE gel, soak it in SDS-PAGE denaturing buffer, and place it horizontally on top of an SDS-polyacrylamide gel. This resolves the individual subunits of each native complex [11].

- Western Blotting: Proteins can be transferred to a PVDF membrane for immunodetection with specific antibodies. A fully submerged electroblotting system at 150 mA for 1.5 hours is recommended [11].

Table: Key Buffer Formulations for BN-PAGE

| Buffer | Composition | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Solubilization Buffer | 0.75 M 6-aminocaproic acid, 50 mM Bis-Tris/HCl, pH 7.0 | Stabilizes proteins during solubilization, provides ionic strength |

| Cathode Buffer (Blue) | 50 mM Tricine, 15 mM Bis-Tris, 0.02% Coomassie G-250, pH 7.0 | Provides charge for electrophoresis & replenishes dye |

| Cathode Buffer (Clear) | 50 mM Tricine, 15 mM Bis-Tris, 0.05% Sodium Deoxycholate, 0.02% DDM, pH 7.0 | Used in CN-PAGE for better in-gel activity visualization |

| Anode Buffer | 50 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0 | Completes the electrical circuit |

| SDS Denaturing Buffer | 2% SDS, 10% Glycerol, 50 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 50 mM DTT, 0.002% Bromophenol Blue | Denatures complexes for 2nd dimension SDS-PAGE |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for BN-PAGE

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for BN-PAGE

| Reagent | Function/Explanation | Example Product/Composition |

|---|---|---|

| Coomassie G-250 | Imparts charge & solubility; core of BN-PAGE | 5% solution in 0.5 M aminocaproic acid [11] |

| n-Dodecyl-β-D-Maltoside (DDM) | Mild detergent for solubilizing individual complexes | 10% solution in water [11] |

| Digitonin | Very mild detergent for preserving supercomplexes | 2-4% solution from plant source [12] [13] |

| 6-Aminocaproic Acid | Zwitterionic salt; aids solubilization & prevents aggregation | 0.75 M in solubilization buffer [11] [5] |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevents protein degradation during isolation | PMSF, Leupeptin, Pepstatin [11] |

| Linear Gradient Gels | Separates a wide range of complex sizes | 3-12% or 4-16% acrylamide gradient [11] [5] |

Advanced Applications and Beneficial Effects

The utility of BN-PAGE and Coomassie staining extends beyond basic separation.

- Supercomplex Analysis: Using digitonin for solubilization, BN-PAGE has been instrumental in demonstrating the "solid-state" model of the respiratory chain, where Complexes I, III, and IV associate into stable supercomplexes (e.g., I+III₂+IV) with proposed functional advantages in electron channeling and complex stability [12] [13].

- In-Gel Enzymology: The compatibility of BN-PAGE with in-gel activity assays allows direct functional assignment. This has been successfully applied not only to OXPHOS complexes but also to other multimeric enzymes like medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD), enabling the differentiation of active tetramers from inactive aggregates caused by pathogenic variants [16].

- Enhanced Proteomic Analysis: Contrary to the assumption that skipping staining saves time, Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 staining has been shown to significantly improve subsequent LC-MS/MS analysis. It enhances protein retention in the gel matrix, leading to the detection of ~40% more proteins in native PAGE and ~18% more in SDS-PAGE, with particular benefit for lower molecular weight proteins [17] [18].

Troubleshooting and Best Practices

- Weak or No Bands: Can result from insufficient protein loading, over- or under-solubilization, or loss of complexes during preparation. Optimize detergent-to-protein ratio and ensure mitochondrial integrity [11] [5].

- High Background: Caused by incomplete destaining (if using post-electrophoresis staining) or interference from contaminants. Increase washing steps or use high-purity reagents [15].

- Smearing: Often due to protein aggregation from incomplete solubilization or insufficient Coomassie dye. Ensure fresh dye is used in both sample and cathode buffer [12].

- Diffuse Bands in 2D-Gels: Can occur if the first-dimension BN-PAGE strip is not properly equilibrated with SDS denaturing buffer before the second dimension [11].

The workflow below summarizes the key decision points and steps in a comprehensive BN-PAGE experiment.

The oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) system, which plays a pivotal role in cellular energy conversion, is composed of five multi-subunit protein complexes embedded in the mitochondrial inner membrane [5]. Understanding the structure, function, and assembly of these complexes is crucial in fundamental research and for investigating severe metabolic diseases. Blue Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (BN-PAGE), first developed by Hermann Schägger in the 1990s, has become an indispensable technique for resolving these hydrophobic enzyme systems in their native state [5] [11]. This Application Note details the key applications of BN-PAGE and the related Clear Native PAGE (CN-PAGE) for analyzing the size, relative abundance, and composition of mitochondrial complexes, providing researchers with robust protocols for comprehensive complexome analysis.

Table: Key Characteristics of BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE

| Feature | BN-PAGE | CN-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Dye/Detergent System | Coomassie Blue G-250 | Mixed anionic and neutral detergents |

| Charge Shift Mechanism | Anionic dye binds hydrophobic protein surfaces | Mixed micelles induce charge shift |

| Resolution of Individual Complexes | Excellent | Excellent |

| Resolution of Supercomplexes | Good (with digitonin) | Good (with digitonin) |

| Interference with Downstream Applications | Possible due to residual Coomassie dye | Minimal |

| Ideal for In-Gel Activity Staining | Moderate | Superior |

Key Applications and Experimental Workflow

Analysis of Individual OXPHOS Complexes and Supercomplexes

BN-PAGE enables the resolution of all five individual OXPHOS complexes when membranes are solubilized with the mild detergent n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside [5] [11]. When the even milder detergent digitonin is used, the technique preserves and reveals the higher-order organization of the respiratory chain: respirasomes (supercomplexes containing Complexes I, III, and IV) remain intact, allowing for the study of their stoichiometry and interactions [5] [19]. This is vital for understanding the functional plasticity of the respiratory chain. The protocol can be applied to various sample types, including cultured human fibroblasts, tissue biopsies (e.g., skeletal muscle), and model organisms like yeast and zebrafish [5].

Investigation of Assembly Pathways and Defects

BN-PAGE is a powerful tool for delineating the assembly pathways of multi-subunit complexes. It can resolve and identify transient assembly intermediates, providing insights into the stepwise incorporation of subunits and the role of specific assembly factors [5] [11]. This application is particularly valuable in diagnosing mitochondrial disorders, as it allows researchers to pinpoint the pathologic consequences of genetic mutations that disrupt the normal assembly process of OXPHOS complexes, often revealing a characteristic accumulation of specific assembly intermediates [5].

In-Gel Functional Enzymatic Assays

A significant advantage of native PAGE techniques is that the separated protein complexes retain their catalytic activity. This enables direct functional analysis through in-gel activity staining [5] [20]. Established histochemical methods can be used to detect the activities of Complex I, II, IV, and V on the same gel or separate gels. Recent protocol enhancements include a simple step that markedly improves the sensitivity of in-gel Complex V (ATP synthase) activity staining [5]. A limitation to note is the comparative insensitivity for Complex IV and the current lack of an in-gel activity stain for Complex III [5].

Proteomic Characterization and Complexome Profiling

When combined with mass spectrometry, BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE transition from a biochemical tool to a powerful proteomic platform for complexome profiling [21] [22]. After separation, gel lanes are sliced into numerous fractions, and the proteins in each fraction are identified and quantified by MS. This generates an abundance profile for each protein across the molecular weight range, serving as a fingerprint that reveals its distribution across different assemblies, complexes, and supercomplexes [21] [22]. A notable example is the MitCOM project, which used high-resolution complexome profiling to map over 5,200 protein peaks from more than 90% of the yeast mitochondrial proteome, uncovering a remarkable complexity of protein assemblies and novel quality-control pathways [22].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for mitochondrial complex analysis using native PAGE and downstream applications.

Detailed Protocols

Protocol 1: Sample Preparation and BN-PAGE for OXPHOS Complexes

This protocol is adapted for small patient samples (e.g., cultured fibroblasts, muscle biopsies) and uses a shortened extraction procedure for robustness [5] [23].

Materials and Reagents

- Buffer A: 0.75 M 6-aminocaproic acid, 50 mM Bis-Tris/HCl, pH 7.0 [11] [23]

- Protease Inhibitors: e.g., 1 mM PMSF, 1 µg/mL leupeptin, 1 µg/mL pepstatin [11]

- Detergent: 10% n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) for individual complexes; 5% digitonin for supercomplexes [5] [23]

- Coomassie Dye: 5% Coomassie Blue G-250 in 0.5 M aminocaproic acid [11]

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Mitochondrial Isolation: Isolate mitochondria from cells or tissue using standard differential centrifugation. Using isolated mitochondria, rather than whole-cell extracts, is strongly recommended for a stronger signal and cleaner results [11].

- Solubilization: Resuspend a mitochondrial pellet (0.4 mg protein) in 40 µL of ice-cold Buffer A containing protease inhibitors. Add 7.5 µL of 10% DDM (for a final concentration of ~1.5%), mix, and incubate on ice for 30 minutes [11] [23].

- Clarification: Centrifuge the solubilized mixture at 72,000 x g for 30 minutes at 4°C to remove insoluble material. A bench-top microcentrifuge at maximum speed (≈16,000 x g) can be used, though it is not ideal [11].

- Sample Preparation: Collect the supernatant and add 2.5 µL of 5% Coomassie Blue G-250 solution [11].

- Gel Electrophoresis: Load 5-20 µL of the prepared sample onto a hand-cast linear gradient gel (e.g., 6-13% acrylamide). A stacking gel (e.g., 4%) is used on top of the resolving gel. Run the gel using anode (50 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0) and cathode (50 mM Tricine, 15 mM Bis-Tris, 0.02% Coomassie Blue G-250, pH 7.0) buffers. Start electrophoresis at 150 V for approximately 2 hours, or until the blue dye front has nearly run off the gel [11] [23].

Protocol 2: In-Gel Activity Staining for OXPHOS Complexes

After BN-PAGE, the following activity stains can be performed on gel strips at room temperature. Reactions are stopped by fixing gels in 50% methanol / 10% acetic acid [20].

Table: In-Gel Activity Staining Recipes for OXPHOS Complexes

| Complex | Staining Solution Composition | Incubation Time | Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complex I | 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 0.2 mg/mL NBT, 0.1 mg/mL NADH [20] | 30-60 min | NADH oxidation reduces NBT to purple formazan |

| Complex II | 5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 0.5 M sodium succinate, 215 µM PMS, 1 mg/mL NBT [20] | 30-60 min | Succinate oxidation reduces NBT via PMS |

| Complex IV | 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.2), 1 mg/mL DAB, 0.1 mg/mL cytochrome c [20] | 1-2 hours | Cytochrome c oxidation by DAB |

| Complex V | 35 mM Tris, 270 mM glycine (pH 8.3), 14 mM MgCl₂, 0.2% Pb(NO₃)₂, 8 mM ATP [20] | 1-2 hours | Lead phosphate precipitate from released Pi |

Protocol 3: Two-Dimensional BN/SDS-PAGE for Subunit Resolution

This protocol is used to resolve the individual subunits that constitute each native complex separated in the first dimension [5] [11].

- First Dimension: Perform BN-PAGE as described in Protocol 1.

- Gel Strip Equilibration: Excise the entire BN-PAGE lane and soak it in SDS denaturing buffer (2% SDS, 50 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 10% glycerol, 50 mM DTT, 0.002% Bromophenol Blue) for 30-60 minutes with gentle agitation [11].

- Second Dimension: Place the equilibrated gel strip horizontally on top of a standard SDS-PAGE gel (e.g., 10-20% gradient). Seal it in place with agarose.

- Electrophoresis and Analysis: Run the second-dimension SDS-PAGE according to standard procedures. The resulting 2D gel can be used for western blotting with specific antibodies or stained for total protein (e.g., with Coomassie or silver stain) to create a map of the subunits for each OXPHOS complex [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Native PAGE

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application | Example Supplier / Reference |

|---|---|---|

| n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) | Mild detergent for solubilizing individual OXPHOS complexes | Thermo Fisher Scientific [23] |

| Digitonin (5% solution) | Mild detergent for preserving supercomplexes | Thermo Fisher Scientific [23] |

| Serva Blue G / Coomassie G-250 | Charge-shift dye for BN-PAGE | Serva, Sigma-Aldrich [11] [23] |

| 6-Aminocaproic Acid | Zwitterionic salt to support solubilization and improve resolution | Sigma-Aldrich/Merck [23] |

| NativePAGE Bis-Tris Gel System | Precast gels and buffers for BN-PAGE | Thermo Fisher Scientific [5] |

| Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit | For accurate protein quantification before loading | Thermo Fisher Scientific [23] |

| Primary Antibodies (Anti-OXPHOS) | For western blot detection of specific complexes | Various commercial suppliers [23] |

Technology Comparison and Strategic Implementation

Figure 2: A decision tree for selecting the appropriate native PAGE method based on research goals.

The choice between BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE depends on the specific research objectives. BN-PAGE is the established, robust workhorse technique, providing excellent resolution of complexes and supercomplexes. Its main drawback is potential interference from Coomassie dye in downstream in-gel activity assays. CN-PAGE, which replaces the blue dye with mixtures of anionic and neutral detergents in the cathode buffer, eliminates this interference and is therefore superior for sensitive in-gel activity measurements [5] [21]. For the most comprehensive, system-wide studies, the BN-PAGE methodology can be scaled up to a high-resolution complexome profiling pipeline. As demonstrated in the MitCOM project, this involves coupling BN-PAGE with cryo-slicing of gel lanes into hundreds of fine fractions followed by quantitative mass spectrometry, enabling the unbiased identification and quantification of thousands of protein assemblies [22].

Troubleshooting and Best Practices

- Gel Casting: For optimal separation, manually cast linear gradient gels (e.g., 6-13% acrylamide) are highly recommended over single-concentration gels [11] [23]. This provides a superior separation range for high-molecular-weight complexes.

- Sample Quality: Always use freshly prepared or properly stored mitochondrial isolates. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles of samples. Include protease inhibitors in all buffers during mitochondrial preparation and solubilization to prevent degradation [11].

- Detergent Optimization: The detergent-to-protein ratio is critical. For initial experiments, a ratio of 2-4 g DDM per g protein is a good starting point. For supercomplex preservation with digitonin, optimization of the digitonin-to-protein ratio is essential [5].

- Activity Stain Sensitivity: If in-gel activity stains for Complex IV are weak, consider using the CN-PAGE method instead of BN-PAGE to avoid Coomassie dye interference. For Complex V, the reported enhancement step (adding lead nitrate and ATP) significantly improves sensitivity [5] [20].

- Controls: Always include a control sample (e.g., from a wild-type cell line or tissue) on the same gel for comparison when analyzing patient samples or experimental models. The use of mtDNA-depleted (ρ0) cell lines can serve as excellent negative controls for complexes containing mtDNA-encoded subunits [5].

Advantages for Studying Assembly Intermediates and Multisubunit Enzymes

Blue Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) and related native gel techniques provide powerful tools for investigating the assembly and function of multisubunit protein complexes. These methods enable the separation of intact protein complexes under non-denaturing conditions, preserving enzymatic activity and protein-protein interactions. This application note details how native PAGE methodologies facilitate the study of assembly intermediates and the functional characterization of complex enzymes, with direct applications in basic research and drug development.

Most cellular processes are executed not by individual proteins but by complex macromolecular assemblies. Understanding the formation, structure, and function of these complexes is essential for elucidating fundamental biological mechanisms and developing targeted therapeutics. Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) encompasses several techniques designed to separate protein complexes while maintaining their native conformation and activity [24]. Unlike denaturing SDS-PAGE, which dissociates complexes into individual subunits, native PAGE preserves higher-order structures, making it indispensable for studying assembly intermediates and multisubunit enzymes [25] [12].

The unique capability to analyze enzymatically active complexes directly from cellular extracts provides researchers with a snapshot of the native cellular state, enabling investigations into how protein complex assembly, disassembly, and dysfunction contribute to both normal physiology and disease pathogenesis [26] [27].

Key Advantages of Native PAGE for Complex Analysis

Native PAGE methodologies offer several distinct advantages for the analysis of protein complexes, particularly when studying assembly pathways and enzyme function.

Table 1: Key Advantages of Native PAGE in Protein Complex Studies

| Advantage | Description | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Preservation of Native State | Maintains non-covalent protein-protein interactions and complex integrity [12] [11]. | Analysis of endogenous complexes without reconstruction artifacts. |

| Enzymatic Activity Retention | Enzymes remain functional after separation, enabling in-gel activity assays [26] [27]. | Functional characterization and detection of catalytically active complexes. |

| Detection of Assembly Intermediates | High resolution separates low-abundance intermediates from mature complexes [25] [28]. | Elucidation of assembly pathways and identification of assembly bottlenecks. |

| Analysis of Oligomeric States | Resolves different oligomeric forms based on size and charge [29]. | Determination of quaternary structure and stoichiometry. |

| Compatibility with Downstream Analyses | Gel lanes can be excised for second-dimension denaturing electrophoresis or mass spectrometry [25] [11]. | Identification of complex subunit composition (proteomics). |

A unique strength of BN-PAGE is its capacity to resolve early aggregation intermediates and misfolded species that are challenging to detect by other methods [28]. This sensitivity makes it invaluable for studying protein aggregation diseases and optimizing recombinant protein expression. Furthermore, the technique allows direct correlation of oligomeric state with biological function, as demonstrated in studies of the antiviral GTPase MxA, where dimeric forms were shown to be active against influenza virus [29].

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for key applications of native PAGE in studying protein complexes.

Protocol 1: BN-PAGE for Mitochondrial Complex Analysis

This protocol, adapted from established methods [11], is optimized for analyzing mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complexes, which are frequently studied as model multisubunit enzymes.

Sample Preparation from Isolated Mitochondria

- Resuspend 0.4 mg of sedimented mitochondria in 40 µL of Buffer A (0.75 M 6-aminocaproic acid, 50 mM Bis-Tris/HCl, pH 7.0) containing protease inhibitors (e.g., 1 mM PMSF, 1 µg/mL leupeptin, 1 µg/mL pepstatin) [11].

- Solubilize by adding 7.5 µL of 10% n-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (DDM). Mix and incubate for 30 minutes on ice.

- Clarify the lysate by centrifugation at 72,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C. Collect the supernatant.

- Add Coomassie Dye by mixing the supernatant with 2.5 µL of a 5% Coomassie blue G solution in 0.5 M aminocaproic acid [11].

Gel Electrophoresis and Visualization

- Gel Casting: Prepare a linear gradient native gel (e.g., 6-13% acrylamide). A recommended recipe for a 13% gel solution (32 mL total) is: 14 mL 30% acrylamide/Bis solution, 16 mL 1 M aminocaproic acid (pH 7.0), 1.6 mL 1 M Bis-Tris (pH 7.0), 0.2 mL ddH₂O, 200 µL 10% ammonium persulfate (APS), and 20 µL TEMED [11].

- Sample Loading: Load 5-20 µL of prepared sample per well.

- Electrophoresis: Run the gel at 150 V for approximately 2 hours using anode (50 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0) and cathode (50 mM Tricine, 15 mM Bis-Tris, 0.02% Coomassie blue G, pH 7.0) buffers until the dye front approaches the bottom of the gel [11].

- In-Gel Activity Assay: For continuous monitoring of enzymatic activity, incubate the gel in an appropriate assay buffer within a custom chamber that allows media recirculation and filtering. Collect time-lapse images to obtain kinetic traces of the reaction [26].

Protocol 2: Non-Denaturing PAGE for Oligomeric State Analysis

This protocol is designed to assess the oligomeric state of proteins, such as the human MxA protein, directly from cell lysates [29].

Cell Lysis under Non-Denaturing Conditions

- Harvest and Wash approximately 1.0 × 10⁶ cells using ice-cold PBS.

- Lyse Cells by resuspending the pellet in 200 µL of ice-cold lysis buffer (e.g., 40 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 1% Digitonin, 2 mM MgCl₂, 10% Glycerol, pH 7.4) containing 5 mM iodoacetamide to protect free thiol groups and prevent artificial disulfide bond formation [29].

- Incubate the lysate for 30 minutes on ice, protected from light.

- Clarify by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C.

- Dialyze the cleared supernatant against ice-cold dialysis buffer (e.g., 40 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl₂, 10% Glycerol, pH 7.4) for at least 4 hours or overnight at 4°C to remove detergents and salts that may interfere with electrophoresis [29].

Non-Denaturing Electrophoresis

- Pre-run a pre-cast 4-15% gradient gel with pre-chilled running buffer (e.g., 25 mM Tris, 192 mM Glycine, pH 8.3) at 25 mA per gel for 15 minutes at 4°C.

- Load Sample mixed with 4x non-denaturing sample buffer (e.g., 40% Glycerol, 100 mM Tris, 0.5% Bromophenol Blue, pH 6.8).

- Run Gel at 25 mA per gel in the cold room until the dye front migrates to the bottom.

- Transfer and Detect proteins using a fully submerged wet transfer system onto a PVDF membrane. Perform immunodetection with target-specific antibodies [29].

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful native PAGE experiments depend on the careful selection and optimization of key reagents.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Native PAGE Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Selection Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Detergents | n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM), Digitonin, Triton X-100 [12] [29] | Solubilize membrane proteins and stabilize complexes. Digitonin can preserve weak supercomplex interactions [12]. |

| Charge Conferral | Coomassie Blue G250 [12] [11] | Binds hydrophobic protein surfaces, imparting negative charge for electrophoresis without denaturation. |

| Protease Inhibitors | PMSF, Leupeptin, Pepstatin [11] | Prevent proteolytic degradation during sample preparation, preserving complex integrity. |

| Thiol Protection | Iodoacetamide [29] | Alkylates free cysteine residues to prevent artificial interchain disulfide bonding and aggregation. |

| Buffers | 6-Aminocaproic Acid, Bis-Tris, Tricine [11] | Maintain neutral pH and provide appropriate ionic conditions for complex stability and separation. |

The choice of detergent is particularly critical. While dodecylmaltoside is effective for solubilizing individual respiratory complexes, the use of digitonin has been instrumental in revealing the existence of respiratory supercomplexes (respirasomes), fundamentally changing models of electron transport chain organization [12].

Data Presentation and Analysis

Native PAGE generates rich, quantitative data on protein complex size, abundance, composition, and activity.

Table 3: Quantitative Data from Representative Native PAGE Studies

| Protein Complex / Process | Technique | Key Quantitative Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Proteasome Assembly | 2D Native-SDS-PAGE [25] | Identification and characterization of low-abundance assembly intermediates among 66 subunits. |

| Mitochondrial Complex IV | In-Gel Kinetics [26] | Activity kinetics showed a short initial linear phase for catalytic rate calculation. |

| Mitochondrial Complex V | In-Gel Kinetics [26] | ATPase activity revealed a significant lag phase followed by two distinct linear phases. |

| MxA Antiviral GTPase | Non-denaturing PAGE [29] | Correlation of dimeric oligomeric state with antiviral activity against influenza virus. |

| Respiratory Chain | BN-PAGE with different detergents [12] | DDM/Triton X-100: separated individual complexes. Digitonin: revealed higher-order supercomplexes. |

Native PAGE technologies provide an indispensable toolkit for dissecting the assembly, architecture, and function of multisubunit protein complexes. The ability to separate intact complexes under native conditions, coupled with versatile downstream analytical applications, makes these methods particularly powerful for functional proteomics. As research increasingly focuses on complex molecular machines in health and disease, BN-PAGE and related techniques will continue to be vital for uncovering the mechanisms of complex assembly and for evaluating how perturbations in these processes contribute to human disease, thereby informing targeted therapeutic development.

BN-PAGE in Practice: Step-by-Step Protocols from Sample Prep to Immunodetection

The study of native mitochondrial protein complexes, particularly those involved in oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), provides crucial insights into cellular energy metabolism, the pathogenesis of metabolic diseases, and the identification of novel therapeutic targets [8]. Blue Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) has emerged as a foundational technique for resolving intact, enzymatically active protein complexes, enabling the analysis of their assembly, stoichiometry, and interactions within supercomplexes [30] [11]. The success of BN-PAGE and related techniques is critically dependent on the initial steps of mitochondrial isolation and solubilization. Inadequate sample preparation can lead to protein degradation, loss of enzymatic activity, or dissociation of labile protein complexes, thereby compromising all downstream analyses [30]. This application note details a validated and robust protocol for the isolation of functional mitochondria and their subsequent solubilization using the nonionic detergent n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM), framing these steps within the context of a broader native PAGE research workflow for the analysis of mitochondrial complexome.

The Role of Sample Preparation in Native PAGE

In native electrophoresis, the goal is to preserve the non-covalent interactions that hold protein complexes together. This stands in stark contrast to denaturing techniques like SDS-PAGE, which deliberately dismantle these structures. The physiological protein-protein interactions within the OXPHOS system are maintained during BN-PAGE, allowing for the separation of individual complexes (I-V) and their higher-order assemblies, known as respirasomes [30] [8]. The binding of Coomassie blue G-250 to solubilized proteins imposes a negative charge shift that facilitates migration toward the anode while simultaneously enhancing protein solubility and preventing aggregation, effectively converting membrane proteins into water-soluble forms [30]. However, this process can only be successful if the native complexes are first gently and efficiently extracted from the mitochondrial membrane, a feat achieved through the critical use of detergents like DDM.

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues the essential reagents required for mitochondrial isolation and solubilization.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for Mitochondrial Preparation and Solubilization

| Reagent | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) | Mild, nonionic detergent for solubilizing mitochondrial membranes while preserving protein-protein interactions and complex integrity [11] [8]. |

| 6-Aminocaproic Acid (ACA) | Zwitterionic salt used in solubilization and gel buffers; improves protein solubilization and acts as a protease inhibitor [11] [20] [31]. |

| Bis-Tris | Buffering agent used to maintain a stable pH of 7.0 throughout the solubilization and electrophoresis process, critical for native conditions [11] [20]. |

| Coomassie Blue G-250 | Anionic dye that binds to protein surfaces, imparting a uniform negative charge for electrophoretic migration and preventing protein aggregation [30] [11]. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (e.g., PMSF, Leupeptin, Pepstatin) | Essential for preventing proteolytic degradation of mitochondrial proteins during the isolation and solubilization procedures [11] [20]. |

| Digitonin | Mild, nonionic detergent alternative to DDM; used specifically when the goal is to preserve respiratory supercomplexes for analysis [30] [8]. |

Detailed Methodologies

Mitochondrial Isolation from Rat Tissues

This protocol, adapted from established methods, is designed for tissues such as heart and brain [32] [20] [31].

- Homogenization: Fresh or frozen tissue (e.g., heart, brain) is homogenized (1 g tissue per 10 ml isolation buffer) in a cold, isotonic buffer containing 70 mM sucrose, 230 mM mannitol, 15 mM MOPS (pH 7.2), and 1 mM potassium EDTA [31]. The inclusion of protease inhibitors (e.g., 1 mM PMSF) at this stage is critical.

- Differential Centrifugation:

- Centrifuge the homogenate at 800 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to remove nuclei and unbroken cells.

- Transfer the supernatant to a new tube and centrifuge at 8,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to pellet the mitochondrial fraction.

- Washing: Gently resuspend the mitochondrial pellet in fresh isolation buffer and repeat the 8,000 × g centrifugation step. This wash removes contaminating cytosolic proteins.

- Storage: The final mitochondrial pellet can be used immediately or flash-frozen and stored at -80°C until use. Protein concentration should be determined using an assay compatible with detergents, such as the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay [20].

Solubilization of Mitochondrial Membranes with n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM)

The following procedure, consolidated from multiple sources, is optimized for a starting amount of 0.4 - 1.0 mg of mitochondrial protein [32] [11] [8].

- Resuspension: Resuspend the mitochondrial pellet in a solubilization buffer containing 750 mM 6-aminocaproic acid and 50 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0 [11] [20]. The final protein concentration should be approximately 1 mg/mL [20].

- Detergent Addition: Add 10% (w/v) DDM solution to achieve a final detergent-to-protein ratio of 2.25:1 to 4.5:1 (w/w) [32] [11]. For example, for 0.4 mg of mitochondria in 40 µL, add 7.5 µL of 10% DDM [11].

- Incubation: Mix thoroughly and incubate the suspension on ice for 30 - 60 minutes with occasional gentle vortexing [32] [31]. This allows for efficient membrane solubilization.

- Clarification: Centrifuge the solubilized mixture at high speed (20,000 × g to 72,000 × g) for 30 minutes at 4°C to remove insoluble material [32] [11].

- Sample Preparation for BN-PAGE: Collect the supernatant (the solubilized protein extract) and add Coomassie blue G-250 from a 5% solution to a final concentration of ~0.3% [11] [20]. The sample is now ready for loading onto a native gel.

Critical Parameters and Quantitative Data

The efficiency of solubilization is highly dependent on several key variables. The tables below summarize optimized conditions and their impacts.

Table 2: Optimized Solubilization Conditions for BN-PAGE

| Parameter | Optimal Condition | Effect of Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Detergent/Protein Ratio | 2.25:1 - 4.5:1 (w/w) DDM [32] [11] | Lower: Incomplete solubilization. Higher: Disruption of supercomplexes. |

| Solubilization Buffer pH | 7.0 (Bis-Tris/Imidazole buffer) [11] [20] | Drift from neutrality can denature proteins and disrupt native interactions. |

| Solubilization Time | 30 - 60 minutes on ice [32] [31] | Shorter: Incomplete. Longer: Risk of proteolysis or complex dissociation. |

| ACA Concentration | 750 mM (solubilization), 500 mM (gel) [11] [20] | Lower concentration reduces solubilization efficiency and protease inhibition. |

Table 3: Detergent Selection for Specific Analytical Goals

| Detergent | Typical Use Concentration | Application and Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) | 1-2% (w/v); DDM/Protein ~2.25:1 - 4.5:1 [32] [11] | Standard for individual complexes. Effectively solubilizes membranes while preserving the integrity of individual OXPHOS complexes (I-V) [8]. |

| Digitonin | 2-8 g/g protein [30] | Preservation of supercomplexes. A gentler detergent used to maintain the structural integrity of respirasomes (e.g., CI/CIII₂/CIV) for their analysis [30] [8]. |

Integrated Workflow for Native PAGE Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow from tissue to analysis, highlighting the central role of sample preparation.

Diagram 1: From Tissue to BN-PAGE Analysis

Troubleshooting Common Issues

- Poor Resolution or Smearing in BN-PAGE Gel: This is often due to incomplete solubilization or protein aggregation. Remedy: Ensure fresh DDM is used and verify the detergent-to-protein ratio. Increase the concentration of 6-aminocaproic acid in the solubilization buffer [30] [20].

- Loss of Enzyme Activity: Repeated freeze-thaw cycles of mitochondria or extended solubilization times can degrade complexes. Remedy: Use freshly isolated mitochondria whenever possible and strictly adhere to the recommended incubation times on ice [8].

- Incomplete Transfer to Second Dimension SDS-PAGE: The high molecular weight of native complexes can impede electroelution. Remedy: For subsequent 2D-SDS-PAGE, ensure the BN-PAGE gel strip is adequately equilibrated in SDS-containing buffer (e.g., with 2% SDS and 5% 2-mercaptoethanol) for at least 20 minutes before the second run [20] [31].

The meticulous preparation of mitochondrial samples through optimized isolation and DDM-based solubilization is the cornerstone of reliable and interpretable native PAGE analysis. The protocols detailed herein, emphasizing critical parameters such as detergent selection, concentration, and buffer composition, provide a robust framework for researchers to study the intricate world of mitochondrial protein complexes. By mastering these foundational techniques, scientists can effectively probe the assembly, function, and pathology of the OXPHOS system, thereby accelerating discovery in basic biochemistry and applied drug development.

Within the framework of native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) research for separating protein complexes, the choice between linear gradient and single concentration gels is a critical methodological decision. Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) and related techniques separate native proteins and protein complexes in the mass range of 10 kDa to 10 MDa under non-denaturing conditions, preserving their oligomeric states and biological activities [33]. This application note provides a detailed comparison of linear gradient versus single concentration gels, supported by structured protocols and data to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the optimal system for their experimental needs.

Principles and Comparative Advantages

Fundamental Separation Mechanisms

In native PAGE, the polyacrylamide matrix acts as a molecular sieve. Single concentration gels feature a uniform pore size throughout, which is optimal for resolving a narrow range of protein sizes [34]. In contrast, linear gradient gels are formulated with a continuously changing polyacrylamide concentration, typically from a low percentage to a high percentage, creating a pore size gradient that narrows as proteins migrate through the gel [33] [34].

The key distinction lies in the separation dynamics. In gradient gels, the leading edge of a protein band encounters smaller pore sizes and slows down before the trailing edge, causing the band to stack into a sharper, more focused zone [34]. This phenomenon, often described as a "traffic jam" effect, significantly improves band sharpness and resolution compared to single percentage gels.

Direct Comparison of Gel Properties

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Single Concentration vs. Linear Gradient Gels

| Property | Single Concentration Gels | Linear Gradient Gels |

|---|---|---|

| Resolving Range | Limited to a narrow size range [34] | Broad; capable of resolving proteins from 4 kDa to >200 kDa on a single gel [34] |

| Band Sharpness | Standard; bands can diffuse over longer migration distances [34] | Enhanced; the "stacking" effect produces sharper, more discrete bands [34] |

| Separation of Similar Sizes | Limited ability to resolve proteins of similar molecular weights [34] | Superior; can better separate similarly-sized proteins, especially with longer run times [34] |

| Experimental Flexibility | Ideal for routine analysis of known complexes | Essential for discovery work and when sample quantity is limited [34] |

| Ease of Preparation | Simpler to cast | Requires gradient mixers or specialized techniques [33] [34] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Casting Linear Gradient Gels

Key Reagents:

- Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide stock solutions (e.g., 30% Acrylamide/Bis Solution 37.5:1) [11]

- 4x or 3x Gel Buffer (e.g., 1.5 M aminocaproic acid, 150 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0) [11] [35]

- Ammonium Persulfate (APS) and TEMED

- Glycerol (for density)

Methodology:

- Gel Casting Setup: Assemble gel cassettes in a casting chamber. Use a gradient mixer connected via tubing to the casting chamber, preferably using a peristaltic pump for even flow [33].

- Solution Preparation: Prepare low-percentage and high-percentage acrylamide solutions on ice. A typical gradient for resolving a broad mass range is 3.5% to 12% or 4% to 16% acrylamide [33] [5]. To the high-percentage solution, add glycerol to increase density and ensure a stable gradient during pouring. For a 6-13% gradient gel for BN-PAGE [11]:

- Light Solution (6%): Mix 7.6 mL of 30% acrylamide/bis, 9 mL ddH₂O, 19 mL of 1 M aminocaproic acid (pH 7.0), and 1.9 mL of 1 M Bis-Tris (pH 7.0).

- Dense Solution (13%): Mix 14 mL of 30% acrylamide/bis, 0.2 mL ddH₂O, 16 mL of 1 M aminocaproic acid (pH 7.0), and 1.6 mL of 1 M Bis-Tris (pH 7.0).

- Initiate Polymerization: Add APS and TEMED to both solutions immediately before pouring. Transfer the light solution to the exit arm of the gradient mixer and the dense solution to the other arm [33].

- Pour the Gradient: Open the connection between the mixer chambers and start the pump or gravity flow. The dense solution will flow first, followed by a linear gradient of decreasing density. Ensure a smooth flow to prevent gradient disruption [33].

- Add Stacking Gel: After polymerization, pour off the isopropanol overlay and add a native stacking gel (e.g., 3-4% acrylamide) [11].

Protocol for Single Concentration Gels

Methodology:

- Solution Preparation: Mix all components for a single acrylamide percentage. For a standard 10% BN-PAGE gel, combine acrylamide/bis, gel buffer, and water in the appropriate ratios [11].

- Polymerization: Add APS and TEMED, mix thoroughly, and pipette the solution into the gel cassette. Overlay with isopropanol or water to ensure a flat gel surface.

- Stacking Gel: Once polymerized, replace the overlay with a stacking gel solution and insert the comb.

Sample Preparation and Electrophoresis for BN-PAGE

Key Reagents:

- Detergents: Dodecylmaltoside, Triton X-100, or Digitonin [33]

- Coomassie Blue G-250 dye [11]

- 6-Aminocaproic Acid [11]

Sample Preparation:

- Solubilization: Suspend sedimented mitochondria (e.g., 0.4 mg) in 40 µL of aminocaproic acid/Bis-Tris buffer [11]. Add detergent (e.g., 7.5 µL of 10% n-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside) and incubate on ice for 30 minutes [11].

- Clarification: Centrifuge at high speed (e.g., 20,000-100,000 × g) for 10-30 minutes to remove insoluble material [33] [11].

- Dye Addition: Collect the supernatant and add Coomassie Blue G-250 dye (e.g., 2.5 µL of a 5% suspension) to achieve a 1:8 dye/detergent ratio [33] [11].

Electrophoresis:

- Anode Buffer: 50 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0 [11].

- Cathode Buffer: 50 mM Tricine, 15 mM Bis-Tris, 0.02% Coomassie Blue G-250, pH 7.0 [11].

- Load samples and run at constant voltage (e.g., 150 V) until the dye front approaches the bottom of the gel [11].

Application Guidelines and Data Interpretation

Selecting the Appropriate Gel Type and Gradient

The choice of gel system should be guided by the experimental objective. Single concentration gels are sufficient for analyzing proteins of known size or for routine checks of specific complexes. Linear gradient gels are preferable for discovery-driven proteomics, analyzing samples with a wide mass distribution, or when sample is limited [34].

Table 2: Guideline for Selecting a Native Gel Gradient Based on Protein Size

| Target Protein Size Range | Recommended Gradient | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| 4 - 250 kDa | 4% / 20% | Discovery work analyzing a very broad mass range [34] |

| 10 - 100 kDa | 8% / 15% | Targeted analysis of a wide range of sizes on a single gel [34] |

| 15 - 100 kDa | 10% (Single %) | Analysis of a specific, known complex within this range [34] |

| 50 - 75 kDa | 10% / 12.5% | High-resolution separation of similarly sized proteins [34] |

Mass Estimation and Marker Selection

Accurate mass estimation requires appropriate calibration. A significant pitfall is using soluble protein markers to estimate the mass of membrane proteins. The binding of Coomassie dye, lipids, and detergent can alter the migration of membrane proteins, leading to considerable errors [33]. For reliable mass estimation of membrane proteins, it is recommended to use membrane protein markers derived from tissues rich in mitochondrial complexes, such as bovine, chicken, rat, or mouse heart [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Native PAGE

| Reagent | Function/Description | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| Detergents | Solubilize membrane proteins while preserving native interactions. | Dodecylmaltoside: Solubilizes individual complexes. Digitonin: A milder detergent that preserves supercomplexes [33] [35]. |

| Coomassie Blue G-250 | Anionic dye that binds hydrophobic protein surfaces, imparting negative charge and preventing aggregation [33] [5]. | Added to sample and cathode buffer in BN-PAGE to facilitate migration toward the anode [11]. |

| 6-Aminocaproic Acid (ACA) | Zwitterionic salt; used in homogenization and gel buffers to improve protein solubility without disrupting native structure [33] [11]. | A key component of the extraction and gel buffers to support protein stability [11]. |

| Bis-Tris | A buffering agent used to maintain stable pH (~7.0) during native electrophoresis, which is crucial for preserving protein complexes [11] [35]. | Used in gel polymerization, running buffers, and sample preparation buffers [11]. |

| Heart Homogenate (Bovine/Chicken) | A convenient and reliable source of high molecular weight membrane protein standards for mass calibration [33]. | Solubilized with detergent and run alongside unknown samples for accurate mass estimation [33]. |

The decision between linear gradient and single concentration gels for native PAGE is fundamental to the success of protein complex separation. Linear gradient gels offer superior resolution across a wide mass range and are indispensable for exploratory research and the analysis of complex samples. Single percentage gels provide a straightforward and effective solution for more targeted applications. By adhering to the detailed protocols and guidelines outlined herein, researchers can confidently select and implement the appropriate gel system to advance their investigations into the structure and function of native protein complexes.

First-dimension electrophoresis is a critical separation step in techniques such as Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) and other native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis methods, enabling the analysis of protein complexes in their native, functionally active state. This initial separation dimension preserves protein-protein interactions, allowing researchers to investigate the composition and stoichiometry of multiprotein assemblies. The technique is indispensable for functional proteomics, providing a foundation for understanding protein complex dynamics in various biological contexts, from mitochondrial respiratory chains to G protein-coupled receptor signaling pathways [6] [36]. The success of first-dimension separation hinges on appropriate buffer systems, detergent selection, and running conditions, which collectively maintain protein complexes in their native conformation while ensuring effective electrophoretic separation.

Critical Buffer Components and Chemical Environment

The buffer system forms the foundation of successful first-dimension native electrophoresis, maintaining protein stability and ensuring consistent migration patterns.

Table 1: Core Components of First-Dimension Electrophoresis Buffer Systems

| Component | Representative Concentrations | Primary Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buffering Agent | 50-200 mM Bis-Tris [37] | Maintains stable pH (~7.0) during separation | Imidazole can be alternative to avoid interference with downstream assays [38] |

| Aminocaproic Acid | 0.5-2 mM [35] [38] | Replaces NaCl to reduce aggregation; improves membrane protein solubility | Enhances resolution of hydrophobic membrane proteins [35] |

| Detergent | 0.5-2% concentration [6] | Solubilizes membrane proteins while preserving native interactions | Critical detergent-to-protein ratio (typically 1:1 to 10:1) [6] |

| Coomassie Dye G-250 | 0.002-0.02% in cathode buffer [37] [38] | Imparts negative charge to protein complexes | Enables migration toward anode; can be removed during run to improve downstream blotting [38] |

The fundamental principle of first-dimension native electrophoresis involves applying an electric field to protein complexes suspended in a gel matrix, causing charged complexes to migrate according to their size and charge [39]. The buffer pH is critical, as it must be maintained below the isoelectric points of most proteins to ensure net negative charge and proper anodal migration. Bis-Tris-based buffers at pH 7.0 are commonly employed, as this mildly acidic environment supports protein stability while facilitating Coomassie dye binding [40] [37]. The inclusion of 6-aminocaproic acid in place of salts helps prevent protein aggregation without introducing disruptive ionic strength, particularly crucial for membrane protein complexes [35].

Detergent Selection for Membrane Protein Complex Solubilization

Detergent choice represents perhaps the most critical parameter for successful native electrophoresis of membrane protein complexes, as it directly determines the integrity of solubilized complexes.

Table 2: Common Detergents for Native Electrophoresis Applications

| Detergent | Typical Concentration | Applications and Properties | Strength & Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digitonin | 2-4% [37] [35] | Preserves weak protein-protein interactions; ideal for labile supercomplexes [35] | Very mild; maintains supercomplex stability but has selective solubilization [35] |

| n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) | 1-2% [6] [35] | General-purpose non-ionic detergent; balances solubilization & stability [6] | Intermediate strength; suitable for many holo-complexes [6] |

| Triton X-100 | 1-2% [6] | Effective solubilization with moderate protein preservation [6] | Stronger than digitonin/DDM; may disrupt some weaker interactions [6] |

| Lauryl Maltose Neopentyl Glycol (LMNG) | Concentration varies [36] | Advanced detergent for challenging membrane proteins like GPCRs [36] | High stability; often used with CHS for enhanced complex preservation [36] |

Non-ionic detergents are preferred for native electrophoresis as they effectively solubilize membrane proteins while preserving protein-protein interactions [6]. The "mildness" of a detergent—its ability to solubilize membranes without disrupting protein complexes—is influenced by the size relationship between its hydrophilic head group and hydrophobic alkyl chain [6]. In practice, digitonin is exceptional for preserving weak interactions in supercomplexes and megacomplexes, as demonstrated in studies of thylakoid membrane proteins where it maintains associations between photosystem II, photosystem I, and light-harvesting complexes [35]. For more robust solubilization while still maintaining native complexes, n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside and Triton X-100 offer effective alternatives [6].

Optimal Electrophoresis Running Conditions

Establishing proper running conditions is essential for maintaining complex stability and achieving high-resolution separation.

Maintaining low temperature (4°C) throughout electrophoresis is crucial for preserving labile protein complexes [38]. The protocol typically employs a two-stage running approach: initial migration at constant voltage (100-150V) with Coomassie-containing cathode buffer until the dye front enters the resolving gel, followed by replacement with colorless cathode buffer and continuation at constant current (12-15mA) [38]. This approach provides the necessary charge shift for protein migration while minimizing dye interference with downstream applications like immunoblotting. For the Invitrogen NativePAGE system, specific buffers are optimized for their corresponding precast gels and should not be interchanged with Tris-Glycine or Tris-Acetate systems [40].

Integrated Protocol for First-Dimension BN-PAGE Electrophoresis

Sample Preparation

- Homogenize tissue or cells in ice-cold BN-PAGE sample buffer (e.g., 50 mM Bis-Tris, 50 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, pH 7.2) with protease inhibitors [37].

- For membrane proteins, add appropriate detergent (e.g., 2% digitonin) and incubate on ice for 30 minutes [37] [35].

- Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C to pellet insoluble material [37].

- Determine supernatant protein concentration using BCA or similar assay [37].

- Add Coomassie Blue G-250 to sample (final 0.25%) to impart negative charge [37].

Gel Preparation and Electrophoresis

- Use NativePAGE Bis-Tris precast gels or prepare discontinuous gradient gels (e.g., 3.5-12.5% acrylamide) [40] [35].

- Prepare anode buffer (50 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0) and cathode buffers (50 mM Bis-Tris, 15 mM Tricine, pH 7.0, with and without 0.02% Coomassie G-250) [37] [38].

- Chill all buffers to 4°C before use.

- Load samples (typically 20-50 μg protein) and molecular weight standards in designated wells [37].

- Run with blue cathode buffer at constant 100-150V until samples enter resolving gel [38].

- Replace cathode buffer with colorless buffer and continue at 12-15mA constant current [38].

- Maintain apparatus at 4°C throughout electrophoresis [38].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for First-Dimension Native Electrophoresis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Detergents | Digitonin, n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside, Lauryl Maltose Neopentyl Glycol (LMNG) [6] [36] [35] | Solubilize membrane proteins while preserving native interactions; choice depends on complex stability |

| Coomassie Dye | Coomassie Blue G-250 [37] [35] | Imparts negative charge to protein complexes enabling migration in electric field; critical for BN-PAGE |

| Protease Inhibitors | Pefabloc SC, complete protease inhibitor cocktails [37] [35] | Prevent protein degradation during sample preparation and electrophoresis |

| Native Protein Standards | NativeMark Unstained Protein Standard [40] | Provides molecular weight estimates for native protein complexes |

| Specialized Buffer Components | 6-Aminocaproic acid, Bis-Tris, Tricine [37] [35] | Maintain optimal pH and ionic conditions while preventing protein aggregation |

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations