Nanotechnology in Targeted Drug Delivery: Current Platforms, Clinical Translation, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the application of nanotechnology in targeted drug delivery systems for a professional audience of researchers and drug development scientists.

Nanotechnology in Targeted Drug Delivery: Current Platforms, Clinical Translation, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the application of nanotechnology in targeted drug delivery systems for a professional audience of researchers and drug development scientists. It explores the foundational principles of nanocarrier design, including key platforms like lipid nanoparticles, polymeric systems, and inorganic nanoparticles. The scope covers methodological advances in active and passive targeting, tackles critical challenges in manufacturing and translational science, and evaluates the current clinical and regulatory landscape. By synthesizing recent data and future trends, this review serves as a strategic resource for navigating the development of next-generation nanomedicines.

The Foundations of Nanomedicine: Principles and Nanoparticle Platforms

Core Defining Parameters of Nanoscale Drug Delivery Systems

Nanoscale Drug Delivery Systems (NDDS) are engineered materials with at least one dimension between 1 to 100 nanometers, though for biomedical applications, the effective size range often extends to several hundred nanometers. [1] Working at this scale unlocks unique physicochemical properties that are critical for overcoming the limitations of conventional drug delivery.

The table below summarizes the fundamental nanoscale parameters that define a NDDS and their primary roles in drug delivery.

Table 1: Core Defining Parameters of Nanoscale Drug Delivery Systems

| Parameter | Definition & Typical Range | Role in Drug Delivery |

|---|---|---|

| Size | 1–100 nm in at least one dimension; effective intravenous range is up to 5 μm to avoid capillary embolism. Optimal EPR effect is seen with particles of 50–200 nm. [2] [1] | Governs biodistribution, circulation time, cellular uptake, and tumor penetration via the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect. [2] |

| Surface Charge | Measured as Zeta potential; can be cationic (positive), anionic (negative), or neutral. | Influences colloidal stability, interaction with cell membranes (cellular uptake), and protein corona formation. [3] |

| Surface Chemistry | The chemical composition and functional groups present on the nanoparticle surface. | Determines biocompatibility, stealth properties (e.g., via PEGylation), and provides attachment points for active targeting ligands. [4] [5] |

| Shape & Morphology | Includes spherical micelles, cylindrical structures, vesicles (polymersomes/liposomes), and other defined geometries. [4] | Affects flow dynamics, margination toward vessel walls, and internalization efficiency by target cells. [4] |

| Drug Release Profile | The kinetics of API release from the nanocarrier (e.g., burst, sustained, or stimuli-responsive). | Critical for achieving therapeutic drug levels at the target site while minimizing systemic exposure and toxicity. [4] [6] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Characterization assays

Protocol: Determining Nanoparticle Size, Size Distribution, and Surface Charge

This protocol outlines the use of Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) and Electrophoretic Light Scattering (ELS) to characterize the hydrodynamic diameter, polydispersity (PDI), and zeta potential of NDDS. [4]

- Principle: DLS measures Brownian motion to calculate particle size, while ELS measures particle mobility under an electric field to determine surface charge.

- Materials:

- Nanoparticle suspension

- Disposable folded capillary zeta cells

- Cuvettes for size measurement

- Appropriate dispersion medium (e.g., purified water, phosphate-buffered saline)

- DLS/ELS instrument (e.g., Zetasizer)

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dilute the nanoparticle suspension with a clear, particle-free dispersion medium to an optimal concentration that avoids signal saturation (multiple scattering) or weak signal. Filter the sample through a 0.45 μm or 0.2 μm syringe filter if necessary to remove dust.

- Equipment Setup: Turn on the instrument and laser, allowing for sufficient warm-up time. Set the measurement temperature to 25°C.

- Size Measurement (DLS):

- Transfer the diluted sample into a disposable sizing cuvette.

- Place the cuvette in the instrument.

- Set the number of runs and measurement duration per run (typically 10-15 runs).

- Initiate measurement. The software will report the Z-average diameter (hydrodynamic size) and the Polydispersity Index (PDI).

- Zeta Potential Measurement (ELS):

- Carefully load the sample into a disposable zeta potential cell using a syringe, avoiding air bubbles.

- Insert the cell into the instrument.

- Set the field voltage and select the appropriate model for Henry's function calculation.

- Perform at least 3-12 measurements per sample and calculate the mean zeta potential and standard deviation.

- Data Interpretation:

- Z-Average: Represents the intensity-weighted mean hydrodynamic size.

- PDI: Values below 0.1 indicate a highly monodisperse sample; values above 0.3 suggest a broad size distribution.

- Zeta Potential: Values greater than +30 mV or less than -30 mV typically indicate good physical stability due to strong electrostatic repulsion.

Protocol: Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Analysis of Polymeric Nanoparticles

NMR spectroscopy is a powerful technique for confirming polymer structure, monitoring polymerization conversion, and verifying drug conjugation. [4]

- Principle: NMR detects the magnetic properties of atomic nuclei (e.g., ^1H, ^13C) to provide information on molecular structure, dynamics, and environment.

- Materials:

- Lyophilized or concentrated nanoparticle sample

- Deuterated solvent (e.g., CDCl₃, D₂O)

- NMR tubes

- High-resolution NMR spectrometer

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve 2-10 mg of the nanoparticle or polymer sample in 0.6-0.7 mL of an appropriate deuterated solvent. Transfer the solution to a clean, dry NMR tube.

- Data Acquisition:

- Insert the sample tube into the magnet.

- For ^1H NMR, standard parameters are used (e.g., 90° pulse, 10-15 sec relaxation delay, 16-64 scans).

- Acquire the spectrum. For more detailed structural analysis, 2D NMR techniques like COSY, HSQC, or HMBC can be employed. [4]

- Diffusion-Ordered NMR Spectroscopy (DOSY) can be used to estimate molecular weights. [4]

- Data Analysis:

- Reference the spectrum to the residual proton signal of the deuterated solvent.

- Identify peaks corresponding to the polymer backbone, functional groups, and conjugated drugs or dyes.

- Calculate monomer conversion by comparing the integral of vinyl proton signals from the monomer to the integral of polymer chain signals.

- Quantify drug loading efficiency by comparing the integrals of characteristic drug peaks to polymer backbone peaks.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for the comprehensive characterization of a NDDS, integrating the protocols described above.

Protocol: Analysis of Protein Corona Formation

Understanding the nano-bio interface is critical, as nanoparticles in biological fluids rapidly adsorb proteins, forming a "corona" that defines their biological identity. [3]

- Principle: Incubate nanoparticles with relevant biological fluid (e.g., human plasma), isolate the nanoparticle-protein corona complex, and identify the adsorbed proteins.

- Materials:

- Nanoparticle suspension

- Human plasma or serum (preferably from relevant disease demographics)

- Ultracentrifuge and rotors

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

- SDS-PAGE gel or Mass Spectrometry equipment

- Procedure:

- Corona Formation: Incubate a known concentration of nanoparticles with 1 mL of human plasma (e.g., 1:1 v/v ratio) for a predetermined time (e.g., 0.5 to 60 minutes) at 37°C with gentle agitation.

- Isolation of Hard Corona: Centrifuge the mixture at high speed (e.g., 100,000 × g for 1 hour) to pellet the nanoparticle-corona complex.

- Washing: Carefully remove the supernatant and gently wash the pellet with cold PBS to remove loosely associated proteins (soft corona). Repeat centrifugation.

- Protein Elution and Analysis:

- Re-suspend the final pellet in SDS-PAGE loading buffer to elute proteins.

- Heat the sample and load onto an SDS-PAGE gel for protein separation and Coomassie/silver staining.

- For precise identification, use liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to characterize the protein composition of the corona.

- Data Interpretation: Analyze the MS data to identify the most abundant proteins in the corona (e.g., albumin, immunoglobulins, apolipoproteins). Correlate the corona composition with changes in nanoparticle physicochemical properties and its impact on cellular uptake and drug release kinetics. [3]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful development and characterization of NDDS rely on a suite of specialized materials and reagents.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NDDS Development

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| PLGA (Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)) | A biodegradable and FDA-approved polymer used to form nanoparticles for controlled drug release. [7] |

| DSPC (1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) | A phospholipid used as a primary component in liposomes and lipid nanoparticles, forming the core bilayer structure. |

| PEG-lipid (e.g., DMG-PEG2000) | Used for surface PEGylation ("stealth" coating) to reduce protein adsorption, prolong circulation time, and improve stability. [7] [5] |

| Ionizable Cationic Lipids (e.g., DLin-MC3-DMA) | Critical for mRNA encapsulation in LNPs; ionizable at low pH to facilitate endosomal escape. [7] |

| Targeting Ligands (e.g., Antibodies, Peptides) | Conjugated to the nanoparticle surface for active targeting of specific cell surface receptors (e.g., PD-L1 antibodies for cancer). [5] |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., CDCl₃, D₂O) | Essential for NMR spectroscopy to analyze polymer structure, drug conjugation, and nanoparticle "livingness." [4] |

| Human Plasma (from various demographics) | Used for in vitro protein corona studies to better simulate the complex biological environment encountered in vivo. [3] |

Critical Considerations for Clinical Translation

The journey from a well-characterized NDDS in the lab to a clinically viable product involves navigating several critical hurdles.

- Manufacturing and Scalability: Transitioning from lab-scale synthesis (e.g., nanoprecipitation) to Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) compliant, large-scale production is a major challenge. Advanced manufacturing technologies like microfluidics and 3D printing are being explored for better control and reproducibility. [2] Maintaining batch-to-batch consistency in Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) like size, PDI, and drug loading is paramount. [7] [2]

- Biological Hurdles: The Protein Corona significantly alters the nanoparticle's synthetic identity, impacting its targeting capability, immune response, biodistribution, and cargo release profile. [3] A major challenge is evading hepatic uptake to improve extrahepatic targeting. Strategies include modulating size, surface charge, and employing sophisticated surface coatings to avoid rapid clearance by the reticuloendothelial system (RES). [8]

- Regulatory Pathways: The complexity of NDDS presents challenges for regulatory bodies. Demonstrating a robust safety profile, including long-term biodistribution, biodegradation, and nanotoxicology data, is essential for approval. [7] [1] Implementing a Quality-by-Design (QbD) framework and Process Analytical Technology (PAT) for real-time monitoring is increasingly important for regulatory compliance. [1]

Concluding Synthesis

Defining a NDDS requires a multi-faceted approach that integrates precise control over its size, surface properties, and morphology with a deep understanding of its dynamic biological interactions, particularly the protein corona. Rigorous characterization using the outlined protocols is non-negotiable for establishing structure-property-performance relationships. While challenges in manufacturing, scalability, and safety remain significant, the continued evolution of nanoscale fabrication and characterization technologies holds immense promise for bridging the translational gap and realizing the full potential of targeted nanomedicines.

Within the broader scope of applying nanotechnology in targeted drug delivery systems research, three nanoparticle platforms have emerged as foundational: liposomes, lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), and polymeric nanoparticles. These systems offer distinct advantages for encapsulating and delivering therapeutic agents, improving their bioavailability, and enabling targeted delivery to specific tissues while minimizing off-target effects [9] [10] [11]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for these core platforms, focusing on their design, characterization, and implementation in pharmaceutical research and development. The content is structured to provide researchers with practical methodologies and comparative data to inform platform selection for specific therapeutic applications.

Liposomes

Application Notes

Liposomes are spherical nanocarriers composed of one or more concentric lipid bilayers enclosing an aqueous core. Their biomimetic architecture, which is structurally similar to cellular membranes, grants them high biocompatibility and the ability to encapsulate both hydrophilic (in the aqueous core) and hydrophobic (within the lipid bilayer) active ingredients [9] [12]. A key clinical feature is their ability to accumulate in malignant or inflamed tissues via the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect, which takes advantage of the leaky vasculature and poor lymphatic drainage typical of these pathological sites [9]. Advances in liposomal engineering, such as PEGylation (the attachment of polyethylene glycol chains), have significantly enhanced their pharmacokinetic profiles by reducing recognition and clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system, thereby prolonging systemic circulation [9].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Liposome Structural Types

| Liposome Structure | Number of Bilayers | Typical Size Range | Key Features and Preferred Drug Encapsulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unilamellar Vesicles | Single | 50 – 250 nm | Prominent aqueous core; well-suited for hydrophilic drugs [9]. |

| Multilamellar Vesicles | Multiple, concentric | 1 – 5 μm | High lipid content; effective for entrapping lipophilic drugs [9]. |

| Oligolamellar Vesicles | A few | Varies | Intermediate structure [9]. |

Protocol: Preparation of Galloylated Liposomes for Targeted Drug Delivery

This protocol details the synthesis of galloylated liposomes (GA-lipo), a platform enabling stable, non-covalent adsorption of targeting ligands (e.g., antibodies) while preserving their functionality and overcoming the protein corona challenge [13].

1. Synthesis of Gallic Acid-Modified Lipid (GA-Chol):

- React gallic acid with cholesterol derivatives (e.g., using P0 linker) via a carbodiimide-mediated coupling reaction in anhydrous dimethylformamide (DMF) under an inert atmosphere for 24 hours [13].

- Purify the resulting GA-P0-Chol product using silica gel column chromatography and confirm structure via NMR and mass spectrometry [13].

2. Formation of GA-lipo by Thin-Film Hydration and Extrusion:

- Prepare a lipid mixture in chloroform with a molar composition of HSPC:Cholesterol:GA-P0-Chol = 60:30:10 [13].

- Form a thin lipid film by rotary evaporation under reduced pressure at 40°C.

- Hydrate the film with an appropriate aqueous buffer (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4) to form multilamellar vesicles.

- Size the liposomes by sequentially extruding the suspension through polycarbonate membranes (e.g., 400 nm, 200 nm, and finally 100 nm) at a temperature above the lipid phase transition temperature.

3. Remote Loading of Drug (e.g., Doxorubicin derivative, DXdd):

- Establish a transmembrane gradient (e.g., ammonium sulfate) to drive the active loading of weakly basic drugs into the liposomal aqueous core [13].

- Incubate the drug with the pre-formed, extruded GA-lipo for a specified duration and temperature to achieve high encapsulation efficiency (protocol achieved ~95%) [13].

4. Functionalization with Targeting Ligand (e.g., Trastuzumab):

- Incubate the drug-loaded GA-lipo with the purified antibody (e.g., Trastuzumab) at a molar ratio of approximately 0.025% (protein:lipids) [13].

- Allow adsorption to proceed at 25°C for 1 hour with gentle agitation. The galloyl moieties on the liposome surface will stably adsorb the protein [13].

- Purify the resulting immunoliposomes (Trastuzumab@GA-lipo) from unbound antibody using size exclusion chromatography [13].

Diagram 1: Workflow for preparing targeted galloylated liposomes.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Liposome Formulation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Hydrogenated Soy Phosphatidylcholine (HSPC) | A high-transition-temperature phospholipid providing structural integrity to the liposomal bilayer [13]. |

| Cholesterol | Incorporated into the lipid bilayer to enhance membrane stability and reduce fluidity, decreasing drug leakage [9] [13]. |

| GA-P0-Chol (Gallic Acid-modified Cholesterol) | Enables stable, non-covalent adsorption of protein-based targeting ligands (e.g., antibodies) onto the liposome surface [13]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG)-Lipid Conjugate | Used to create "stealth" liposomes by forming a hydrophilic corona that reduces opsonization and extends circulation half-life [9]. |

| Ammonium Sulfate Buffer | Used to create a transmembrane pH gradient for the active remote loading of weakly basic drugs into the liposomal core [13]. |

Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs)

Application Notes

LNPs represent a significant breakthrough in the delivery of nucleic acids (RNA, DNA), enabling gene therapy, vaccine delivery, and personalized medicine [10] [14]. Their effectiveness is highly dependent on optimization for specific routes of administration, which significantly influences organ distribution, expression kinetics, and therapeutic outcomes [10]. Recent advances include tailoring PEGylated lipids to impact mRNA delivery efficiency and stability, incorporating anti-inflammatory lipids to mitigate immune responses, and engineering LNPs capable of traversing the blood-brain barrier for neurological applications [14] [15].

Protocol: Formulation of Brain-Targeting mRNA LNPs

This protocol outlines the engineering and preparation of LNPs for intravenous delivery of mRNA across the blood-brain barrier [14].

1. LNP Lipid Composition Preparation:

- Prepare an ethanol phase containing a ionizable cationic lipid, phospholipid, cholesterol, and a PEGylated lipid at a defined molar ratio. The specific ionizable lipid and PEG-lipid structure are critical for brain targeting and must be optimized [14].

- Prepare an aqueous phase containing the mRNA of interest in a citrate buffer (pH 4.0).

2. Microfluidic Mixing for Nanoparticle Formation:

- Use a microfluidic device (e.g., a staggered herringbone mixer or a comparable chip-based system) to facilitate rapid mixing.

- Set the flow rate ratio (aqueous:ethanol) typically between 3:1 and 5:1 to ensure efficient nanoprecipitation and high mRNA encapsulation efficiency.

- Maintain total flow rates that induce sufficient turbulent mixing to form particles with a size of 60-150 nm, which is suitable for the intended application.

3. Buffer Exchange and Dialysis:

- Collect the LNP formulation and immediately dilute it in a large volume of PBS (pH 7.4) to dilute the ethanol and prevent destabilization.

- Dialyze the resulting suspension against a large volume of PBS (pH 7.4) for 18-24 hours at 4°C to remove residual ethanol and establish a neutral pH.

4. Characterization and Validation:

- Particle Size and PDI: Measure by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS). Target a polydispersity index (PDI) < 0.2.

- Encapsulation Efficiency: Quantify using a Ribogreen assay. Compare fluorescence with and without a detergent to distinguish encapsulated from free mRNA.

- In Vivo Validation: Administer LNPs intravenously to mice and assess functional protein expression in brain tissues (neurons and glial cells) via immunohistochemistry or Western blot [14].

Diagram 2: LNP formulation via microfluidic mixing.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Key Reagents for LNP Formulation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Ionizable Cationic Lipid | Critical for mRNA encapsulation and endosomal escape; its pKa determines efficiency and tolerability [14] [15]. |

| PEGylated Lipid | Modulates LNP size, surface properties, and pharmacokinetics; reduces particle aggregation and improves stability [14]. |

| Nitro-oleic acid (NOA) | An anti-inflammatory lipid that can be incorporated to inhibit the cGAS-STING pathway, reducing inflammation from plasmid DNA delivery [14] [15]. |

| DSPC (Phospholipid) | A structural lipid that contributes to the formation and stability of the LNP bilayer [14]. |

| Microfluidic Mixer | Essential equipment for the reproducible and scalable production of LNPs with narrow size distribution [15]. |

Polymeric Nanoparticles

Application Notes

Polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) offer superior stability and versatility for the controlled delivery of a wide range of therapeutics, including biologics [11] [16] [17]. Their nanoscale dimensions facilitate targeted cellular uptake and navigation of biological barriers. A key advantage is the ability to engineer "smart" polymers that respond to specific physiological stimuli (e.g., pH, temperature, enzymes), enabling precise drug release at the target site [17]. Surface modification techniques, such as PEGylation and the incorporation of active targeting ligands (antibodies, peptides), further enhance targeting efficiency and penetration into target tissues [17].

Protocol: Preparation of Stimuli-Responsive Polymeric Nanoparticles

This protocol describes the formulation of PNPs using the nano-precipitation method, with a focus on creating particles capable of releasing their payload in response to the acidic tumor microenvironment [17].

1. Polymer and Drug Solution Preparation:

- Select a biodegradable, pH-sensitive polymer (e.g., poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) with acid-labile side chains or a poly(β-amino ester)).

- Dissolve the polymer and a hydrophobic model drug (e.g., Docetaxel) in a water-miscible organic solvent such as acetone or acetonitrile.

2. Nano-precipitation and Self-Assembly:

- Add the organic solution drop-wise into a stirred aqueous phase (e.g., deionized water or a surfactant solution like polysorbate 80) under constant magnetic stirring.

- The rapid diffusion of the organic solvent into the water phase causes the polymer to precipitate, entrapping the drug and forming nanoparticles.

- Continue stirring for 3-4 hours to allow for complete solvent evaporation.

3. Surface Functionalization for Active Targeting:

- For active targeting, conjugate a targeting ligand (e.g., a folate moiety or an RGD peptide) to the surface of the pre-formed nanoparticles.

- This can be achieved via carbodiimide chemistry, where surface carboxyl groups on the PNPs are activated with EDC/NHS before reacting with primary amine groups on the ligand.

4. Purification and Characterization:

- Purify the PNPs by ultracentrifugation (e.g., at 40,000 rpm for 30 minutes) and resuspend the pellet in PBS.

- Particle Size and Zeta Potential: Characterize using DLS and laser Doppler anemometry.

- Drug Loading and Encapsulation Efficiency: Determine by HPLC after dissolving a known amount of PNPs in organic solvent.

- In Vitro Release Kinetics: Perform a dialysis-based release study in buffers at pH 7.4 and 5.5 to validate the pH-responsive release profile.

Diagram 3: Workflow for preparing stimuli-responsive polymeric nanoparticles.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Key Reagents for PNP Formulation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| PLGA (Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)) | A biodegradable and FDA-approved copolymer widely used for sustained and controlled drug release [17]. |

| EDC and NHS | Crosslinking agents used in carbodiimide chemistry to activate carboxyl groups for covalent conjugation of targeting ligands to the nanoparticle surface [17]. |

| Folate or RGD Peptide | Targeting ligands that can be conjugated to PNPs to promote active targeting to folate receptor-overexpressing cancers or integrins in the tumor vasculature, respectively [17]. |

| Polysorbate 80 | A surfactant used in the nano-precipitation process to stabilize the formed nanoparticles and prevent aggregation [17]. |

Comparative Analysis

Table 2: Comparative Overview of Core Nanoparticle Platforms for Drug Delivery

| Parameter | Liposomes | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Polymeric Nanoparticles (PNPs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Composition | Phospholipids, Cholesterol [9] | Ionizable Lipids, Phospholipid, Cholesterol, PEG-lipid [14] | Biodegradable Polymers (e.g., PLGA, Chitosan) [17] |

| Typical Load Cargo | Hydrophilic & Hydrophobic small molecules [9] | Nucleic Acids (mRNA, pDNA, CRISPR) [10] [14] | Small molecules, Proteins, Peptides, Biologics [16] [17] |

| Key Advantage | High biocompatibility, Established clinical use [9] [12] | High efficiency for nucleic acid delivery, Rapidly advancing platform [10] [14] | Superior stability, Controlled & stimuli-responsive release [11] [17] |

| Common Preparation Method | Thin-Film Hydration & Extrusion [12] [13] | Microfluidic Mixing [15] | Nano-precipitation, Emulsion-Solvent Evaporation [17] |

| Targeting Strategy | Passive (EPR), Ligand adsorption/conjugation [9] [13] | Tissue-specific lipid selection, Ligand functionalization [14] [15] | Surface PEGylation, Stimuli-responsive polymers, Ligand conjugation [17] |

Application Notes

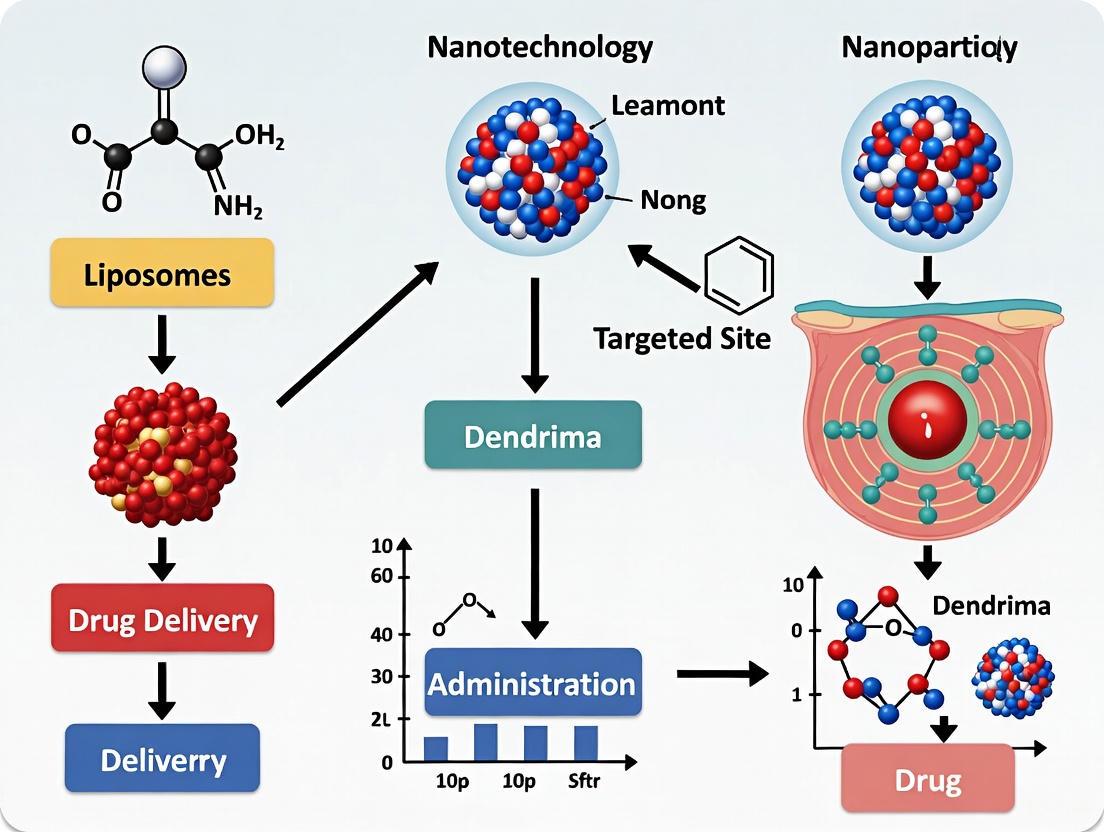

The application of nanotechnology in targeted drug delivery is revolutionizing the treatment of complex diseases by enhancing drug solubility, enabling targeted delivery, and improving therapeutic efficacy. Dendrimers, metallic nanoparticles, and drug nanocrystals represent three prominent classes of nanocarriers with distinct advantages for pharmaceutical development.

Dendrimers in Targeted Drug Delivery

Dendrimers are highly branched, monodisperse, tree-like polymeric molecules with three main architectural components: a central core, branching units, and functional surface end groups. Their nanoscopic size (typically 1-15 nm), nearly spherical shape, and highly tunable surface chemistry make them exceptional candidates for drug delivery [18] [19] [20].

Table 1: Key Characteristics and Biomedical Applications of Dendrimers

| Characteristic | Description | Application Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Structure | Three-dimensional, globular, with internal cavities [18] | Allows for encapsulation of hydrophobic drugs and genes [19] |

| Surface Functionalization | High density of tunable terminal groups [20] | Enables conjugation of drugs, targeting ligands (e.g., folates, peptides), and PEG for stealth properties [19] [21] |

| Monodispersity | Uniform size and molecular weight within each generation [19] | Provides predictable pharmacokinetics and reproducible behavior [19] |

| Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) | Nanoscale size and long circulation [19] | Facilitates passive targeting and accumulation in tumor tissues [18] [21] |

| Cationic Surface | Positive charge on amine-terminated dendrimers (e.g., PAMAM) [19] | Allows for complexation with nucleic acids (DNA, siRNA) for gene delivery [19] [21] |

Dendrimers have shown significant promise in oncology. They can deliver chemotherapeutic agents like doxorubicin, methotrexate, and paclitaxel, enhancing water solubility and enabling controlled, stimuli-responsive release in the tumor microenvironment via pH-sensitive or redox-sensitive linkers [18] [19]. In neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, dendrimers can cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB), delivering therapeutic agents to target amyloid-beta plaques and neurofibrillary tangles [22] [23]. Furthermore, their application as antimicrobial and antiviral agents is being explored, with studies demonstrating efficacy against respiratory viruses, HIV, and herpes simplex virus, and more recently, in strategies against COVID-19 [18].

Metallic Nanoparticles as Nanocarriers

Metallic nanoparticles (MNPs), including those made from gold, silver, platinum, and zinc oxide, offer unique mechanical, electromagnetic, and optical properties for drug delivery [24] [25]. Their primary advantages include increased stability and half-life of drug carriers in circulation, required biodistribution, and passive or active targeting to specific sites [25].

Table 2: Applications of Selected Metallic Nanoparticles (MNPs)

| Metal Nanoparticle | Key Properties | Exemplary Drug Delivery Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Gold (Au) | Biocompatibility, tunable surface plasmon resonance, easy functionalization [25] | Photothermal therapy, targeted delivery of anticancer drugs [25] |

| Silver (Ag) | Intrinsic antimicrobial activity [25] | Delivery of antibiotics to treat bone infections; combating multidrug-resistant bacteria [25] |

| Zinc Oxide (ZnO) | Semiconductor properties, ROS generation [25] | Cancer therapy, drug delivery systems [25] |

A significant trend in MNP synthesis is the move toward green synthesis methods, which use biological organisms (e.g., plant extracts, microbes) as reducing and stabilizing agents. This approach provides economic and environmental benefits compared to traditional chemical and physical methods [24] [25].

Drug Nanocrystals for Bioavailability Enhancement

Drug nanocrystals are pure crystalline drug particles with a size in the nanometer range. They represent a versatile platform to overcome the primary challenge of poor water solubility for many new chemical entities [26].

Table 3: Advantages and Applications of Drug Nanocrystals

| Advantage | Mechanism | Therapeutic Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Enhanced Dissolution Rate | Increased surface area-to-volume ratio [26] | Improved saturation solubility and faster dissolution velocity [26] |

| Improved Bioavailability | Higher dissolution leads to greater absorption [26] | Increased drug concentration in systemic circulation; improved treatment effectiveness [26] |

| Versatile Delivery Platforms | Can be administered via oral, pulmonary, or injectable routes [26] | Broad application across disease areas [26] |

| Surface Functionalization | Coating with ligands for active targeting [26] | Enables targeted delivery, particularly in cancer therapy [26] |

Surface engineering of drug nanocrystals is critical for stabilizing the particles and functionalizing them with targeting ligands, transforming them from simple solubility enhancers into sophisticated targeted delivery systems [26].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Synthesis and Drug Loading of PAMAM Dendrimers

This protocol describes the divergent synthesis of a Generation 4 (G4) PAMAM dendrimer and its subsequent loading with an anticancer drug (e.g., Doxorubicin) via a pH-sensitive hydrazone bond [19] [20] [21].

Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent/Material | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Ethylenediamine (EDA) Core | Serves as the central initiator core for PAMAM dendrimer growth [20] |

| Methyl Acrylate | Reacts with amine groups via Michael addition to create ester-terminated intermediates [19] [21] |

| Ethylenediamine (EDA) (excess) | Used in the amidation step to convert ester terminals to amine terminals, creating a new generation [19] [21] |

| Methanol | Acts as a solvent for the synthesis reactions [19] |

| Doxorubicin HCl | Model chemotherapeutic drug to be conjugated to the dendrimer [18] [21] |

| Hydrazine Hydrate | Provides the hydrazone linker, which is stable at physiological pH (7.4) but cleaves in the acidic tumor microenvironment (pH ~5-6) [19] |

Procedure:

- Divergent Synthesis of G4 PAMAM Dendrimer:

- Michael Addition (Generation 0.5): Add a large excess of methyl acrylate to the ethylenediamine core in methanol. React under inert atmosphere (N₂) with stirring for 24-48 hours at room temperature. Remove excess methyl acrylate and solvent via vacuum distillation to obtain a half-generation (G0.5) ester-terminated dendrimer [19] [21].

- Amidation (Generation 1.0): Dissolve the G0.5 product in a large excess of ethylenediamine in methanol. React with stirring for 24-48 hours at room temperature. Remove excess EDA and solvent via vacuum distillation to obtain a full-generation (G1.0) amine-terminated dendrimer [19] [21].

- Repetition: Repeat steps a and b three more times to sequentially build Generations 2.0, 3.0, and the target 4.0 (G4) PAMAM dendrimer.

- Purification: Purify the final G4 dendrimer product using dialysis or ultrafiltration. Confirm structure and monodispersity using techniques such as NMR spectroscopy and gel permeation chromatography (GPC) [19].

- Drug Conjugation via pH-Sensitive Linker:

- Activation: React the G4 PAMAM dendrimer with hydrazine hydrate to create hydrazide-terminated groups on the dendrimer surface.

- Conjugation: React the hydrazide-activated dendrimer with doxorubicin in an organic solvent (e.g., DMSO) under inert conditions. The carbonyl group of doxorubicin reacts with the hydrazide to form a pH-sensitive hydrazone bond.

- Purification and Characterization: Purify the final dendrimer-doxorubicin conjugate (Den-Dox) using dialysis. Characterize the conjugate using UV-Vis spectroscopy to determine the drug loading efficiency and dynamic light scattering (DLS) to measure the hydrodynamic size and zeta potential [19] [21].

Protocol: Preparation of Targeted Drug Nanocrystals

This protocol outlines the preparation of drug nanocrystals of a poorly water-soluble drug (e.g., Rapamycin) using anti-solvent precipitation, followed by surface stabilization and functionalization with a targeting ligand (e.g., Folic Acid) for cancer therapy [26].

Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent/Material | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Rapamycin | A model poorly water-soluble drug (BCS Class II) with immunosuppressant and anticancer properties. |

| Acetone | A water-miscible organic solvent (good solvent) to dissolve the drug. |

| Poloxamer 407 (Pluronic F127) | A polymeric stabilizer that adsorbs to the nanocrystal surface to prevent aggregation via steric hindrance [26]. |

| DSPE-PEG(2000)-Folate | A phospholipid-PEG conjugate terminated with folic acid. Serves as a co-stabilizer and targeting ligand for cancer cells overexpressing folate receptors [26]. |

| Deionized Water | Acts as the anti-solvent in which the drug has very low solubility. |

Procedure:

- Anti-Solvent Precipitation:

- Drug Solution: Dissolve rapamycin and DSPE-PEG(2000)-Folate in acetone to create an organic phase.

- Aqueous Stabilizer Solution: Dissolve Poloxamer 407 in deionized water to create the aqueous phase.

- Precipitation: Under high-speed homogenization or sonication, rapidly inject the organic drug solution into the aqueous stabilizer solution. The rapid mixing causes immediate supersaturation and precipitation of the drug into nanocrystals. The stabilizers (Poloxamer and DSPE-PEG-Folate) instantly adsorb onto the newly formed crystal surfaces.

- Stabilization and Functionalization:

- The nanocrystal suspension is continuously stirred for several hours to allow for complete stabilizer adsorption and evaporation of the organic solvent.

- The simultaneous presence of DSPE-PEG-Folate during precipitation leads to its incorporation into the stabilizer shell, functionally targeting the nanocrystals.

- Purification and Analysis:

- Purify the nanocrystal suspension by centrifugation or ultrafiltration to remove any non-incorporated drug and free stabilizers.

- Characterize the final product using Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) for particle size and polydispersity index (PDI), and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) for morphological analysis. Confirm surface functionalization via X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) or a similar surface analysis technique [26].

Visualizations

Dendrimer Drug Delivery and Release Pathway

Nanocrystal Preparation Workflow

The Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect is a universal pathophysiological phenomenon observed in solid tumors, serving as a fundamental principle for the passive targeting of macromolecular drugs and nanomedicines [27]. First described by Hiroshi Maeda and colleagues in 1986, the EPR effect leverages the unique anatomical and physiological abnormalities of tumor vasculature to achieve selective accumulation of therapeutic agents in tumor tissue [27] [28]. This targeting mechanism has become a cornerstone concept in oncology nanomedicine, enabling the design of drug delivery systems that theoretically increase therapeutic efficacy while reducing systemic toxicity.

The EPR effect arises from two key pathological features of solid tumors. First, tumor blood vessels exhibit enhanced permeability due to poorly aligned endothelial cells with wide fenestrations, deficient basement membranes, and reduced pericyte coverage [27] [29]. These structural abnormalities create gaps ranging from 100 to 780 nm in diameter, allowing macromolecules and nanoparticles to extravasate from the bloodstream into tumor tissue [30]. Second, tumors display impaired lymphatic drainage, which limits the clearance of these extravasated molecules, leading to their prolonged retention in the tumor interstitium [27] [28]. This combination of leaky vasculature and poor drainage enables the passive accumulation of nanomedicines in solid tumors.

Table 1: Pathophysiological Characteristics Underpinning the EPR Effect

| Characteristic | Description | Impact on EPR Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Abnormal Tumor Vasculature | Dilated, tortuous vessels with defective endothelial cells, wide fenestrations, and deficient smooth muscle layers [27] [29] | Enables extravasation of macromolecules and nanoparticles into tumor tissue |

| Vascular Hyperpermeability | Gaps between endothelial cells (100-780 nm) and transcellular pathways via vesiculo-vacuolar organelles (VVOs) [27] [30] | Facilitates passive accumulation of nanomedicines in tumor interstitium |

| Lack of Lymphatic Drainage | Impaired or absent lymphatic systems in solid tumor tissue [27] [28] | Prolongs retention of extravasated macromolecules and nanoparticles |

| Inflammatory Mediators | Elevated expression of bradykinin, nitric oxide, prostaglandins, VEGF, and other permeability factors [27] [30] | Sustains and enhances vascular permeability in tumor tissue |

The EPR effect is further sustained by various inflammatory factors and mediators present in the tumor microenvironment, including prostaglandins, bradykinin, nitric oxide, peroxynitrite, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [27] [30]. These factors coordinate to maintain the hyperpermeability of tumor vessels, thereby enhancing the EPR effect. The phenomenon has been consistently observed in rodent models, rabbits, canines, and human patients, although with significant heterogeneity in its intensity and effectiveness [27].

Quantitative Analysis of EPR Efficacy

Understanding the quantitative aspects of the EPR effect is crucial for evaluating its therapeutic potential and limitations. While the EPR effect does enhance tumor accumulation of nanomedicines compared to normal tissues, the actual delivery efficiency is often modest. Studies indicate that the EPR effect typically provides less than a 2-fold increase in nano-drug delivery to tumors compared with critical normal organs [29]. This modest enhancement frequently results in drug concentrations that are insufficient for curing most cancers, highlighting a significant challenge in clinical translation.

The percentage of the total administered nanoparticle dose that successfully reaches solid tumors is remarkably low, with a median of only 0.7% accumulating in the target tissue [28]. This low accumulation efficiency is attributed to multiple biological barriers, including rapid clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system, elevated interstitial fluid pressure in tumors, and heterogeneous tumor blood flow [29]. Despite these limitations, the EPR effect remains clinically relevant as it still enables significantly higher tumor concentrations compared to conventional chemotherapeutic agents, often with reduced side effects due to lower accumulation in healthy tissues.

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters of Nanoparticle Delivery via EPR Effect

| Parameter | Typical Value/Range | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor Accumulation Efficiency | Median of 0.7% of injected dose [28] | Low delivery efficiency necessitates high initial dosing or complementary strategies |

| Enhanced Delivery Ratio | Less than 2-fold increase compared to normal organs [29] | Modest targeting effect may be insufficient for curative monotherapies |

| Optimal Size Threshold | >40 kDa molecular weight [27] | Guides design of macromolecular drugs and nanocarriers for EPR-based targeting |

| Vascular Pore Size | 100-780 nm in tumor vasculature [30] | Informs nanoparticle size optimization for extravasation |

| Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin Tumor Concentration | 10-15 fold higher in tumor vs. normal tissues [27] | Demonstrates clinical proof-of-concept for EPR-mediated targeting |

The size and physicochemical properties of nanomedicines significantly influence their EPR-mediated tumor accumulation. The molecular size threshold for effective EPR-mediated accumulation is approximately 40 kDa, with larger macromolecules and nanoparticles exhibiting more pronounced tumor retention [27]. Nanoparticle characteristics such as size, surface charge, and spatial configuration are crucial determinants of their circulation half-life, extravasation potential, and tumor retention [27]. For instance, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin achieves about a 10-15 fold higher concentration in tumor tissues compared with surrounding normal tissues, demonstrating the clinical viability of the EPR effect despite its limitations [27].

Experimental Protocols for EPR Evaluation

MRI-Based Quantification of EPR Effect

Objective: To non-invasively quantify the EPR effect in tumor models using dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI) with a nano-sized contrast agent [31].

Materials:

- GadoSpin P: A 200 kDa biodegradable polymeric gadolinium-based MRI contrast agent (25 mM concentration after reconstitution) [31]

- Animal Models: Mice with subcutaneously implanted xenograft tumors (e.g., SKOV-3, OVCAR-8, or OVASC-1 ovarian cancer cell lines) [31]

- MRI System: 1.0-tesla ASPECT M2 MRI System with a 35 mm Tx/Rx mouse solenoid whole-body coil [31]

- Anesthesia Equipment: Isoflurane/oxygen delivery system for animal anesthesia [31]

Procedure:

- Animal Preparation: Anesthetize tumor-bearing mice using 4-5% isoflurane/oxygen mixture, maintained with 1-2% isoflurane during scanning [31].

- Pre-contrast Imaging: Position tumor within MRI system using Scout mode scan. Acquire T2-weighted fast spin echo (FSE) sequence for anatomical reference with the following parameters: coronal direction, field of view (FOV) 100 mm × 100 mm, 20 slices, slice thickness 1 mm, flip angle 90 degrees, sampling 256 [31].

- Contrast Administration: Inject 100 μL of reconstituted GadoSpin P solution retro-orbitally at a dosage of 25 μL per gram of mouse body weight [31].

- DCE-MRI Acquisition: Perform dynamic T1-weighted MRI scans pre- and post-contrast injection using a quantitative varied flip-angle (VFA) approach to measure contrast agent concentration kinetics [31].

- Data Analysis: Apply Tofts pharmacokinetic modeling to calculate:

- Parametric Mapping: Generate maps of gadolinium concentration in tumor tissue to visualize spatial heterogeneity of EPR effect [31].

Data Interpretation: Higher Ktrans and Ve values indicate stronger EPR effect. Significant differences in these parameters have been observed among different tumor models, with tumor growth influencing both permeability and retention [31].

Evaluation of Nanoparticle Extravasation and Retention

Objective: To assess the extravasation and retention kinetics of nanoparticles in tumor tissue using intravital microscopy [32].

Materials:

- Fluorescently Labeled Nanoparticles: Various formulations (liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, etc.) with appropriate fluorophores [32]

- Animal Models: Mice with window chamber tumors or other models suitable for intravital imaging [32]

- Intravital Microscopy System: High-resolution fluorescence microscope with capabilities for in vivo time-lapse imaging [32]

- Image Analysis Software: For quantifying fluorescence intensity and spatial distribution over time [32]

Procedure:

- Nanoparticle Administration: Intravenously inject fluorescent nanoparticles into tumor-bearing animals at therapeutically relevant doses [32].

- Real-time Imaging: Perform time-lapse intravital microscopy at multiple time points post-injection (e.g., 1, 4, 24, 48 hours) to track nanoparticle distribution [32].

- Multi-scale Analysis: Quantify nanoparticles at different biological scales:

- Barrier Assessment: Evaluate alternative pathways beyond passive extravasation, including:

- Kinetic Modeling: Calculate accumulation rates and retention half-lives of nanoparticles in different tumor compartments [32].

Data Interpretation: This protocol enables the differentiation between vascular permeability and cellular uptake, providing insights into both EPR effect and active transport mechanisms that contribute to tumor accumulation of nanomedicines [32].

Figure 1: Nanoparticle Journey via EPR Effect. This workflow illustrates the pathway of nano-sized drugs from administration to tumor accumulation and clearance, highlighting key biological processes that enable passive targeting.

Strategies to Enhance EPR-Based Drug Delivery

Nanocarrier Design Optimization

The design of nanocarriers significantly influences their ability to leverage the EPR effect for tumor targeting. Key parameters include:

Size Optimization: Studies using serial molecular sizes of HPMA copolymers in solid tumor animal models have identified optimal size ranges for tumor accumulation [27]. Nanoparticles between 10-100 nm typically exhibit the most favorable balance between circulation time and extravasation potential, with smaller particles (<20 nm) showing improved penetration but potentially faster clearance [27] [29].

Surface Modification: Polyethylene glycol (PEG) conjugation (PEGylation) prolongs circulation time by reducing opsonization and recognition by the mononuclear phagocyte system [33] [30]. However, excessive PEGylation can compromise cytotoxicity, as demonstrated by pegylated liposomal doxorubicin which showed significantly reduced cytotoxicity compared to free drug (25% vs. 75% at 72 hours) [27].

Material Composition: Different nanocarrier materials offer distinct advantages:

- Lipid nanoparticles (liposomes, SLNs, NLCs) enhance drug bioavailability and can bypass multidrug resistance mechanisms [30] [6]

- Polymeric nanoparticles (PEG, PLGA, PAMAM) enable controlled drug release and high drug loading capacity [30]

- Inorganic nanoparticles (gold, silver, iron oxide) provide additional functionalities for imaging and therapy [30]

- Hybrid nanoparticles combine multiple materials to create theranostic systems with both diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities [30]

Table 3: Nanocarrier Types and Their Applications in EPR-Based Drug Delivery

| Nanocarrier Type | Key Characteristics | Applications in Cancer Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Liposomes | Phospholipid bilayers encapsulating hydrophilic drugs, modifiable size and surface | Doxil/Caelyx (pegylated liposomal doxorubicin) for various cancers [27] [6] |

| Polymeric Nanoparticles | Biodegradable polymers (PLGA, chitosan) enabling sustained release | Paclitaxel-loaded nanoparticles for localized, prolonged action [30] |

| Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs) | Lipid matrix solid at room temperature, improved stability | Co-delivery of doxorubicin and curcumin to enhance cytotoxicity [30] |

| Dendrimers | Highly branched, monodisperse structures with multiple surface groups | PAMAM dendrimers for optimized targeted therapy with high drug loading [30] |

| Inorganic Nanoparticles | Unique optical, magnetic, electronic properties | Gold nanoparticles for thermal ablation; iron oxide for MRI and therapy [30] |

| Hybrid Nanoparticles | Combination of organic/inorganic materials for multifunctionality | AGuIX nanoparticles for radiotherapy enhancement and imaging [30] |

EPR Enhancement Through Tumor Microenvironment Modulation

Several strategies have been developed to enhance the EPR effect by modifying the tumor microenvironment:

Vascular Normalization: Anti-VEGF therapies can temporarily "normalize" the abnormal tumor vasculature, reducing hyperpermeability and improving perfusion [27]. This approach increases the uptake of small particles (<20 nm) but may hinder the extravasation of larger particles (>125 nm) [27]. The timing of nanomedicine administration relative to vascular normalization is critical for optimal delivery [27].

Physical Priming Methods:

- Hyperthermia: Mild heating of tumors increases blood flow and vascular permeability, enhancing nanoparticle extravasation [27] [34]

- Sonoporation: Ultrasound, particularly in combination with microbubbles, mechanically untightens vessel walls and the extracellular matrix [34]

- Radiation therapy: Can modify tumor vasculature and increase permeability to nanomedicines [34]

Pharmacological Approaches:

- Angiogenic factors to increase vascular maturity [34]

- Erythropoietin to improve tumor perfusion [34]

- Corticosteroids to remodel vessels and extracellular matrix [34]

- Enzymes such as collagenase or hyaluronidase to degrade dense extracellular matrix and reduce interstitial fluid pressure [30]

Figure 2: Multimodal Strategies to Overcome EPR Limitations. This diagram outlines the four primary approaches to enhance drug delivery efficacy by addressing the inherent limitations of the EPR effect through complementary strategies.

Patient Stratification and Companion Diagnostics

The significant heterogeneity in EPR effect among different tumors and patients necessitates advanced stratification approaches:

Imaging Biomarkers: Quantitative MRI-based approaches, as described in Protocol 3.1, can assess EPR efficacy in individual patients before treatment [31]. Tumors showing sufficient EPR levels can be selected for nanomedicine therapies, while those with poor EPR can be directed to alternative treatments [31] [34].

Histological and Omics Biomarkers: Analysis of tumor specimens for vascular density, pericyte coverage, extracellular matrix composition, and expression of permeability factors can predict EPR efficacy [34].

Companion Diagnostics and Theranostics: The development of nanomedicines with built-in imaging capabilities allows simultaneous diagnosis and treatment, enabling real-time monitoring of drug delivery and accumulation [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for EPR Effect Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Nanoparticle Contrast Agents | Enable visualization and quantification of EPR effect using medical imaging | GadoSpin P (200 kDa biodegradable polymeric gadolinium for MRI) [31] |

| Fluorescent Nanoparticles | Permit tracking of nanoparticle distribution using intravital microscopy | Liposomes, polymeric NPs with Cy5.5, DiD, or other fluorophores [32] |

| Tumor Model Systems | Provide biologically relevant platforms for EPR evaluation | Xenograft models (SKOV-3, OVCAR-8, OVASC-1 cell lines) [31] |

| Vascular Permeability Modulators | Experimental manipulation of EPR effect | VEGF inhibitors, bradykinin agonists, nitric oxide donors [27] [34] |

| Lymphatic Function Assays | Assessment of lymphatic drainage impairment in tumors | Fluorescent dextran drainage assays, lymphatic marker staining [27] [30] |

| Image Analysis Software | Quantification of nanoparticle accumulation and distribution | Tofts pharmacokinetic modeling for DCE-MRI data [31] |

The EPR effect remains a fundamental principle in cancer nanomedicine, providing a rational basis for the passive targeting of solid tumors. While clinical translation has been challenged by the effect's heterogeneity and modest delivery efficiency, recent advances in nanocarrier design, tumor microenvironment modulation, and patient stratification offer promising pathways to enhance therapeutic outcomes. The experimental protocols and reagents outlined in this application note provide researchers with robust methodologies to evaluate and optimize EPR-based drug delivery systems. As the field progresses toward personalized nanomedicine, the integration of quantitative EPR assessment with multifunctional nanocarriers and complementary delivery strategies will be essential to fully realize the potential of this cornerstone targeting mechanism in oncology.

In the pursuit of advanced targeted drug delivery systems, nanotechnology provides powerful solutions to three fundamental pharmaceutical challenges: poor solubility, low bioavailability, and short circulation half-life of active therapeutic compounds [35] [36]. By engineering materials at the nanoscale (typically 1-100 nm), researchers can create carriers that fundamentally reshape drug pharmacokinetics and biodistribution [1] [33]. These nanocarriers protect therapeutic agents from degradation, enhance their aqueous solubility, and facilitate targeted delivery to specific tissues while minimizing off-target effects [35] [37]. This document outlines the key advantages, quantitative benchmarks, and experimental protocols for leveraging nanotechnology in pharmaceutical development, providing researchers with practical methodologies for evaluating and optimizing nanocarrier systems.

Quantitative Advantages of Nanocarrier Systems

Nanocarriers significantly enhance drug performance by improving solubility, bioavailability, and circulation time. The tables below summarize key quantitative improvements achieved with various nanocarrier platforms.

Table 1: Solubility and Bioavailability Enhancement of Nano-Formulated Drugs

| Drug/Nanocarrier System | Solubility Enhancement | Bioavailability/ Efficacy Improvement | Reference Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paclitaxel in Ionic Co-aggregates (ICAs) | 10-fold solubility increase | Data Not Specified | Intravenous delivery of poorly soluble drug [35] |

| Ivermectin in Mesoporous Silica/Poly(ε-caprolactone) | Significant dissolution rate improvement | ~90% increased drug release (72h) vs. 40% for crystalline drug | Treatment of parasitic infections [35] |

| Polymeric Nanoparticles (General) | Data Not Specified | ~50% increase vs. conventional formulations | Colorectal cancer therapy [37] |

| Mitoxantrone in Carbon Quantum Dots (CQDs) | Data Not Specified | 97% drug loading efficiency; maximal cancer cell growth inhibition | Cancer therapy [35] |

Table 2: Circulation Half-Life Optimization for Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs)

| AuNP Size | PEG Molecular Weight | Impact on Blood Circulation Half-Life |

|---|---|---|

| < 40 nm | ≥ 5 kDa | Optimal, synergistic effect for significantly prolonged circulation [38] |

| > 40 nm | ≥ 5 kDa | Moderate half-life extension [38] |

| Any size | ≤ 2 kDa | Minimal impact on prolonging circulation, irrespective of GNP size [38] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Evaluations

Protocol: Assessing Drug Solubility and Release Kinetics

This protocol evaluates the efficiency of nanocarriers in improving the solubility and release profile of poorly soluble drugs, using ivermectin as a model compound [35].

1. Key Research Reagent Solutions

- Mesoporous Silica Nanomaterials: Serve as a porous carrier for drug loading via adsorption.

- Poly(ε-caprolactone) Nanocapsules: Biodegradable polymeric shells for drug encapsulation.

- Dialysis Membranes (MWCO appropriate for drug): Allow separation of released drug from nanocarriers.

- Aqueous Buffer (e.g., PBS, pH 7.4): Simulates physiological conditions for release study.

2. Methodology 1. Nanocarrier Preparation and Drug Loading: Synthesize mesoporous silica nanomaterials and poly(ε-caprolactone) nanocapsules using established methods (e.g., sol-gel for silica, nano-precipitation for polymers). Load ivermectin into the nanocarriers. 2. Solubility Measurement: Dispense crystalline ivermectin and each nano-encapsulated ivermectin formulation into separate vessels containing the aqueous buffer. Agitate for a predetermined time. 3. Centrifugation/Filtration: Separate undissolved drug from the solution by centrifugation or filtration using a 0.1 µm filter. 4. Quantification: Analyze the concentration of dissolved ivermectin in the supernatant/filtrate using a validated analytical method such as High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC). 5. In Vitro Release Study: Place a known quantity of each drug formulation (crystalline, silica-loaded, nanocapsule-loaded) into a dialysis bag. Immerse the bag in a large volume of release buffer (sink condition). 6. Sampling: At fixed time intervals (e.g., 1, 2, 4, 8, 24, 48, 72 hours), withdraw aliquots from the external buffer. 7. Analysis: Quantify the amount of drug released in each sample using HPLC. Replenish the release medium to maintain sink conditions.

3. Data Analysis

- Plot cumulative drug release (%) versus time to generate release profiles.

- Calculate the enhancement factor by comparing the release percentage of nano-formulations versus the crystalline drug at specific time points (e.g., 72 hours).

Protocol: Optimizing Circulation Time via PEGylation

This protocol outlines a method to evaluate how nanoparticle size and polyethylene glycol (PEG) coating molecular weight synergistically impact blood circulation half-life, based on a meta-analysis of gold nanoparticle (GNP) studies [38].

1. Key Research Reagent Solutions

- Gold Nanoparticles (GNPs): Synthesized in a range of sizes (e.g., 2-100 nm) as a model platform.

- Methoxy-PEG-Thiol (mPEG-SH): Thiol-terminated PEG polymers of varying molecular weights (e.g., 0.2, 2, 5, 10, 20 kDa) for covalent surface coating.

- Animal Model (e.g., Mice): For in vivo pharmacokinetic studies.

2. Methodology 1. GNP Synthesis and Characterization: Synthesize GNPs of precise, monodisperse sizes (e.g., 20 nm, 40 nm, 60 nm, 80 nm) using methods like the Turkevich or Brust-Schiffrin synthesis. Characterize the size, shape, and surface charge (zeta potential) of the bare particles. 2. PEG Functionalization: Incubate each GNP size variant with a series of mPEG-SH ligands of different molecular weights. Purify the PEGylated GNPs to remove unbound PEG. 3. Characterization of Coated Particles: Re-measure the hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential of the PEGylated GNPs to confirm successful coating. Use techniques like FTIR or NMR to verify PEG attachment. 4. In Vivo Pharmacokinetic Study: Administer the library of PEGylated GNPs intravenously to animal cohorts. Collect blood samples at multiple time points post-injection. 5. Sample Analysis: Quantify GNP concentration in blood samples using an appropriate technique, such as Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS). 6. Pharmacokinetic Modeling: Plot blood concentration versus time for each formulation. Calculate the circulation half-life (t₁/₂) using non-compartmental analysis.

3. Data Analysis

- Use a statistical model (e.g., Generalized Additive Model) to analyze the interaction between GNP size and PEG MW on half-life.

- Identify the optimal parameter combination (e.g., sub-40 nm GNPs with ≥5 kDa PEG) for maximal circulation time.

Visualizing the Nanocarrier Journey and Design Logic

The following diagrams illustrate the in vivo journey of a long-circulating nanocarrier and the decision-making workflow for its design.

Diagram 1: In Vivo Journey of a Long-Circulating Nanocarrier. PEGylation shields the carrier from immune recognition, enabling prolonged circulation and accumulation at the target site via the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect or active targeting, followed by cellular uptake and drug release [38] [39].

Diagram 2: Nanocarrier Design and Evaluation Workflow. A strategic workflow for selecting nanocarrier engineering strategies based on specific therapeutic challenges, leading to synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation [1] [35] [38].

The strategic application of nanotechnology in drug formulation directly addresses the critical pharmaceutical challenges of solubility, bioavailability, and circulation time. The data and protocols provided herein demonstrate that through rational design—such as selecting appropriate nanocarrier platforms, optimizing particle size, and implementing effective surface engineering like PEGylation—researchers can significantly enhance the therapeutic potential of drug candidates. As the field advances, the integration of these foundational principles with emerging technologies like AI-driven design and biomimetic coatings will further accelerate the development of sophisticated, targeted drug delivery systems, ultimately improving clinical outcomes across a spectrum of diseases.

Engineering Precision: Methodologies for Targeted Delivery and Controlled Release

Targeted drug delivery represents a cornerstone of modern nanomedicine, aiming to maximize therapeutic efficacy while minimizing off-target effects. The two principal strategies for achieving this specificity are passive and active targeting. Passive targeting relies on the inherent physicochemical properties of nanocarriers and the pathological characteristics of tissues, such as the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect in tumors. In contrast, active targeting involves the functionalization of nanocarriers with biological ligands designed to bind specifically to receptors overexpressed on target cells [40] [41]. This document, framed within a broader thesis on applying nanotechnology in targeted drug delivery systems research, provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for leveraging these strategies. It is intended to serve as a practical guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working to design and evaluate novel targeted nanotherapeutics.

Core Principles and Key Differences

Understanding the distinct mechanisms of passive and active targeting is fundamental to designing an effective drug delivery system. The following table summarizes their core characteristics.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Passive and Active Targeting Strategies

| Feature | Passive Targeting | Active Targeting |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Mechanism | Exploits the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect of pathological sites like tumors [40]. | Utilizes ligand-receptor interactions for specific cellular binding and internalization [41] [42]. |

| Basis of Specificity | Physiological/pathological features of the tissue (e.g., leaky vasculature, poor lymphatic drainage) [40]. | Molecular recognition between surface ligands and overexpressed cell receptors [43] [42]. |

| Role of Nanocarrier Design | Optimizing size (typically 20-200 nm), surface charge, and composition for long circulation and EPR-based accumulation [44]. | Decorating the nanocarrier surface with targeting ligands (antibodies, peptides, etc.) without compromising stability [41] [42]. |

| Primary Interaction | Non-specific accumulation in tissues with permeable vasculature. | Specific binding to target cells, often leading to receptor-mediated endocytosis [41]. |

| Main Challenge | High heterogeneity of the EPR effect between tumor types and patients [40]. | Potential for immune recognition and off-target ligand interactions, complicating in vivo efficacy [45]. |

The following diagram illustrates the sequential relationship and key mechanisms of these two targeting strategies within a tumor microenvironment.

Application Notes: Ligand Selection and Nanocarrier Design

The choice of ligand is critical for the success of an active targeting strategy. Ligands are selected based on their affinity for receptors that are highly and preferentially expressed on the target cell population.

Table 2: Common Ligands and Their Target Receptors in Oncology

| Ligand Class | Specific Example | Target Receptor | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peptides | Linear or Cyclic RGD (Arg-Gly-Asp) [45] [42] | αvβ3 Integrin | Overexpressed on tumor endothelial and cancer cells; promotes angiogenesis [45]. |

| Antibodies | Bevacizumab (BVZ) fragment [41] [43] | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) | Targets tumor vasculature; full antibodies can be immunogenic, fragments are often preferred [43]. |

| Small Molecules | Folic Acid (Folates) [41] [42] | Folate Receptor | Highly overexpressed in many cancers (e.g., ovarian); enables efficient internalization [41]. |

| Polysaccharides | Hyaluronic Acid (HA) [41] [42] | CD44 Receptor | Binds to CD44, overexpressed in cancer stem cells and many metastatic tumors [41]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details essential materials and reagents required for the formulation and evaluation of ligand-decorated nanocarriers.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Targeted Nanocarrier Development

| Item | Function/Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lipids | Form the core matrix of lipid nanocarriers [41] [42]. | Solid Lipids (e.g., Glyceryl dibehenate/Compritol); Liquid Lipids (e.g., Oleic acid, Caprylic/Capric Triglycerides) [41]. |

| Surfactants | Stabilize the nanoparticle dispersion in aqueous media [41]. | Poloxamer 407, Polysorbate 80, Soy phosphatidylcholine (SPC) [41]. |

| Targeting Ligands | Confer specificity to the target cell population. | RGD Peptides [45], Folate [41], Hyaluronic Acid [41], Antibodies (e.g., anti-EGFR) [43]. |

| PEG-Lipid Conjugates | Impart "stealth" properties by reducing opsonization and MPS clearance [45] [44]. | DSPE-PEG(2000)-COOH, DSG-PEG-NHS; also used for ligand conjugation. |

| Characterization Instruments | Determine physicochemical properties of nanocarriers. | Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS), Zeta Potential Analyzer, Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) [45]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Preparation of Ligand-Decorated Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLCs)

This protocol describes the formulation of NLCs, a second-generation lipid-based platform known for high drug loading and stability, followed by post-insertion ligand functionalization [41] [42].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Procedure:

NLC Core Formulation:

- Weigh a mixture of solid lipid (e.g., Compritol 888 ATO) and liquid lipid (e.g., Oleic acid) at a ratio between 70:30 and 99.9:0.1 [41].

- Heat the lipid blend to approximately 5-10°C above the solid lipid's melting point until a clear, homogeneous melt is obtained.

- Separately, heat an aqueous surfactant solution (e.g., 0.5-5% w/v Poloxamer 188) to the same temperature.

- Add the hot aqueous phase to the hot lipid melt under high-speed homogenization (e.g., 10,000-15,000 rpm for 5-10 minutes) to form a coarse pre-emulsion.

- Process the pre-emulsion using a high-pressure homogenizer (HPH) for 3-5 cycles at 500-1500 bar to form fine, uniform NLCs [41].

- Allow the resulting NLC dispersion to cool to room temperature under mild stirring.

Purification and Characterization of "Blank" NLCs:

- Purify the cooled NLC dispersion using dialysis or ultrafiltration to remove free surfactants and any unencapsulated drug.

- Characterize the purified NLCs for:

- Size, Polydispersity Index (PDI), and Zeta Potential: Using Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS). Target size: 20-200 nm; PDI < 0.3 indicates a monodisperse population [44].

- Entrapment Efficiency (EE%): Determine by quantifying the unentrapped drug in the supernatant after ultracentrifugation or filtration. Calculate EE% = (Total drug added - Free drug) / Total drug added × 100% [41].

Ligand Conjugation via Post-Insertion:

- Ligand-PEG-Lipid Preparation: Conjugate the selected ligand (e.g., cRGD peptide) to the terminal group of a functionalized PEG-lipid (e.g., DSPE-PEG(2000)-NHS) via covalent coupling in an appropriate buffer.

- Incubation: Incubate the pre-formed, purified NLCs with the ligand-PEG-lipid conjugate (at a predetermined molar ratio) for 1-2 hours at room temperature or 4°C with gentle agitation. This allows the lipid anchor (DSPE) to insert into the NLC's lipid membrane [42].

- Final Purification: Purify the ligand-decorated NLCs using size exclusion chromatography (e.g., Sephadex G-25 column) or dialysis to remove any uninserted ligand-PEG-lipid conjugates.

Protocol 2: In Vitro Evaluation of Targeting Efficacy

This protocol outlines methods to validate the specificity and enhanced cellular uptake of ligand-functionalized nanocarriers using cell culture models.

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Procedure:

Cell Culture:

- Maintain at least two cell lines: a target cell line that overexpresses the receptor of interest (e.g., KPCY murine pancreatic cancer cells for αvβ3 integrin [45]) and a control cell line with low receptor expression.

- Culture cells in appropriate media and passage them at 70-80% confluence.

Cellular Uptake Study (Quantitative):

- Seed cells in 12-well or 24-well plates at a density of 1-2 x 10^5 cells/well and allow them to adhere for 24 hours.

- Treat cells with equivalent doses (e.g., 50-100 µg/mL nanoparticle content) of non-targeted (PEGylated) and ligand-targeted nanocarriers. For gold nanoparticles (GNPs), a concentration of 7.5 µg/mL has been used [45].

- Incubate for predetermined time points (e.g., 1 h, 4 h, 8 h).

- After incubation, wash the cells thoroughly with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove non-internalized nanoparticles.

- Lyse the cells using a suitable lysis buffer (e.g., RIPA buffer).

- Quantification: Analyze the cell lysates for nanoparticle content.

- For metal-core NPs (e.g., Gold NPs): Use Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) to quantify the metal content, which corresponds to the amount of internalized NPs [45].

- For fluorescently-labeled NPs: Use fluorescence spectrometry or flow cytometry.

Cellular Uptake Study (Qualitative - Confocal Microscopy):

- Seed cells on glass-bottom confocal dishes.

- Treat with fluorescently-labeled non-targeted and targeted nanoparticles.

- After incubation, wash with PBS, fix the cells with 4% paraformaldehyde, and stain cell membranes and nuclei with appropriate dyes (e.g., Wheat Germ Agglutinin-Alexa Fluor 488, DAPI).

- Image using a confocal laser scanning microscope to visualize the intracellular localization of the nanoparticles [45].

Cytotoxicity Assessment (MTT Assay):

- Seed cells in 96-well plates.

- Treat with a concentration range of free drug, non-targeted, and targeted nanocarriers.

- After 24-72 hours, add MTT reagent (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) to each well and incubate for 2-4 hours.

- Solubilize the formed formazan crystals with DMSO and measure the absorbance at 570 nm.

- Calculate cell viability relative to untreated control wells. Targeted formulations should demonstrate lower IC50 values in receptor-positive cells compared to non-targeted ones.

Protocol 3: In Vivo Biodistribution and Tumor Targeting

Evaluating performance in an immunocompetent animal model is crucial, as it accounts for immune system interactions that can significantly impact nanoparticle fate [45].

Detailed Procedure:

Animal Model:

- Use an immunocompetent, syngeneic mouse model bearing relevant tumors (e.g., KPCY pancreatic tumor model in C57BL/6 mice) [45]. This provides a more physiologically relevant assessment of the tumor microenvironment and immune interactions than immunodeficient models.

Biodistribution Study:

- Randomize tumor-bearing mice into treatment groups (e.g., non-targeted NPs vs. ligand-targeted NPs).

- Administer a single dose of nanoparticles via intravenous injection (e.g., via the tail vein).

- At predetermined time points post-injection (e.g., 24 h, 48 h), euthanize the animals and collect tissues of interest: tumor, liver, spleen, kidneys, lungs, and blood.

- Homogenize the tissues and digest the samples.

- Quantification: Use ICP-MS (for metal-core NPs) or fluorescence imaging (for fluorescent NPs) to quantify the amount of nanoparticle accumulation in each tissue. Calculate the percentage of injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g) [45].

- Key Analysis: Compare the tumor-to-liver and tumor-to-spleen ratios between non-targeted and targeted groups. An effective targeting strategy should show a statistically significant increase in tumor accumulation and/or a decrease in off-target accumulation in clearance organs.

Critical Considerations and Data Interpretation

When interpreting data from these experiments, researchers must be aware of key challenges. The heterogeneity of the EPR effect between different tumor models and human patients is a major limitation for passive targeting [40]. For active targeting, a critical finding from recent research is that enhanced cellular uptake in vitro does not always translate to improved tumor accumulation in vivo. For instance, RGD-functionalized gold nanoparticles showed significantly higher uptake in cancer cells in vitro but reduced tumor accumulation in vivo due to enhanced clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) [45]. This underscores the necessity of using immunocompetent models for preclinical validation. Furthermore, the density of ligands on the nanoparticle surface must be optimized, as high densities can paradoxically lead to increased immune recognition and rapid clearance [45] [44].

Application Notes

Stimuli-responsive nanosystems represent a paradigm shift in targeted drug delivery, moving from passive carriers to intelligent vehicles that release their payload in response to specific pathological cues. By exploiting the distinct biochemical environments of diseased tissues, these systems significantly enhance therapeutic efficacy while minimizing off-target effects [46] [47]. The following application notes detail the mechanisms and uses of three primary triggers: pH, redox potential, and enzymes.

pH-Responsive Nanosystems

Mechanism and Applications: pH-responsive nanoparticles are designed to exploit the pH gradients that exist at the organ, tissue, and subcellular levels [46]. These systems undergo physicochemical changes—such as swelling, dissociation, or surface charge switching—upon exposure to specific pH thresholds, facilitating targeted drug release [46] [47].

A key application is in oral drug delivery, where systems must survive the acidic stomach (pH 1-3) and release drugs in the more neutral intestines (pH ~7.4). Nanoparticles formulated with acrylic-based polymers like poly(methacrylic acid) (PMAA) remain stable and release minimal drug (e.g., ~10% insulin) in gastric acid. Upon intestinal entry, the carboxyl groups ionize, causing the polymer to swell and release the drug cargo (e.g., ~90% insulin release at pH 7.4) [46]. Commercial formulations like Eudragit L100-55 (dissolves at pH >5.5) and Eudragit S100 (dissolves at pH >7.0) allow for targeted release in specific intestinal regions [46].

In oncology, pH-sensitivity targets the acidic tumor microenvironment (pH 6.5-7.8) and even more acidic endosomal/lysosomal compartments (pH <5.0) [46] [48]. For instance, NPs cross-linked with pH-labile protecting groups (e.g., 2,4,6-trimethoxybenzaldehyde) are stable at neutral pH but swell and release nearly all of their paclitaxel payload within 24 hours at pH 5.0 [46]. Similarly, polymers like PEG-poly(β-amino ester) with a pKb of ~6.5 undergo amine protonation and a sharp micellization-demicellization transition in the mildly acidic tumor environment, triggering drug release [46].

Key Polymers and Their Properties: Numerous synthetic and natural polymers exhibit pH-dependent behavior. The table below summarizes polymers commonly used in pH-responsive drug delivery, along with their specific triggers and applications.

Table 1: Key Polymers for pH-Responsive Drug Delivery

| Polymer/Chemical Group | pH Trigger Mechanism | Application Context | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|