MOB2 as a Key Inhibitory Regulator of NDR1/2 Kinase Activity: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the molecular mechanism by which the Mps one binder 2 (MOB2) protein inhibits the NDR1/2 (STK38/STK38L) kinases.

MOB2 as a Key Inhibitory Regulator of NDR1/2 Kinase Activity: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the molecular mechanism by which the Mps one binder 2 (MOB2) protein inhibits the NDR1/2 (STK38/STK38L) kinases. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we synthesize foundational biochemical studies, competitive binding models, and functional consequences of the MOB2-NDR interaction. The content explores methodological approaches for studying this interaction, addresses controversies in the field, compares MOB2's function with other MOB family members, and validates its biological significance in processes like the DNA damage response and cell cycle regulation. This review aims to clarify MOB2's unique role as an NDR1/2 inhibitor and discusses its potential as a therapeutic target.

The MOB2-NDR Axis: Unraveling the Core Inhibitory Mechanism

The NDR Kinase Family: Core Regulators of Cell Physiology

The Nuclear Dbf2-related (NDR) kinases are a subgroup of evolutionarily conserved AGC serine-threonine protein kinases that function as essential regulators of growth, morphogenesis, and cellular homeostasis [1]. In mammals, this family includes four members: NDR1 (STK38), NDR2 (STK38L), LATS1, and LATS2 [2] [1]. These kinases serve as core components of the Hippo signaling pathway, an ancient signaling system that controls cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis across diverse eukaryotic species [1].

NDR1 and NDR2 share approximately 87% sequence identity but exhibit distinct subcellular localization and may serve non-redundant functions [3]. While NDR1 is widely expressed and predominantly localizes to the nucleus, NDR2 is excluded from the nucleus and displays a punctate cytoplasmic distribution [3] [4]. This differential localization suggests specialized biological roles for each kinase, with NDR2 being highly expressed in tissues such as the thymus [3].

Table 1: Mammalian NDR/LATS Kinases and Their Characteristics

| Kinase | Other Names | Subcellular Localization | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| NDR1 | STK38 | Predominantly nuclear [3] | Cell cycle progression, centrosome duplication [5] |

| NDR2 | STK38L | Cytoplasmic, excluded from nucleus [3] | Vesicle trafficking, autophagy, ciliogenesis [6] |

| LATS1 | Large tumor suppressor 1 | Cytoplasmic, cortical localization [7] | Phosphorylation of YAP/TAZ, tumor suppression [7] |

| LATS2 | Large tumor suppressor 2 | Cytoplasmic, cortical localization [7] | Phosphorylation of YAP/TAZ, tumor suppression [7] |

NDR kinases regulate diverse cellular processes including cell cycle progression, DNA damage response, apoptosis, transcription, and cell migration [5] [6] [1]. Their dysfunction has been implicated in various pathological conditions, particularly cancer, where NDR2 in particular often exhibits oncogenic properties [6]. The activity of NDR kinases is tightly controlled through phosphorylation and interaction with binding partners, most notably the MOB family cofactors [3] [4].

MOB Protein Cofactors: Key Regulatory Partners

MOB (Mps one binder) proteins represent a family of highly conserved eukaryotic signal transducers that function as essential coactivators for NDR/LATS kinases [3] [5]. The human genome encodes at least six different MOB genes: MOB1A, MOB1B, MOB2, MOB3A, MOB3B, and MOB3C [5] [8]. These proteins share a conserved structure but exhibit distinct binding specificities and functional outcomes.

Table 2: MOB Family Cofactors and Their Kinase Interactions

| MOB Protein | Primary Kinase Partners | Effect on Kinase Activity | Cellular Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOB1A/B | NDR1/2, LATS1/2 [5] [8] | Strong activation [3] [9] | Hippo signaling, mitotic exit, cytokinesis [5] |

| MOB2 | NDR1/2 (specific) [5] [8] | Context-dependent; can inhibit NDR [5] [8] | Cell cycle regulation, DNA damage response, cell motility [5] [8] |

| MOB3A/B/C | MST1 (aka STK4) [5] | Not applicable to NDR/LATS | Apoptosis regulation [5] |

The interaction between MOB proteins and their kinase partners is highly specific and occurs through the N-terminal regulatory (NTR) region of the kinases [10]. Structural studies have revealed that MOB binding organizes this NTR region into a V-shaped helical hairpin that mediates interaction with the C-terminal hydrophobic motif (HM) of the kinase, facilitating proper activation [10]. This kinase-coactivator interface represents a unique regulatory mechanism for the NDR/LATS kinase family.

MOB2 as a Critical Regulator of NDR1/2 Kinase Activity

MOB2 exhibits distinctive regulatory properties compared to other MOB family members. While MOB1 strongly activates NDR kinases, MOB2 has been reported to exert inhibitory effects through multiple molecular mechanisms, making it a focal point for understanding the nuanced regulation of NDR signaling.

Competitive Binding with MOB1

A primary mechanism of MOB2-mediated inhibition involves competitive binding with the activating cofactor MOB1. Both MOB1 and MOB2 interact with the same N-terminal regulatory domain of NDR1/2, creating a competitive dynamic where MOB2 binding can displace MOB1 and prevent kinase activation [8]. This competition establishes a regulatory switch where the relative abundance and activation state of MOB1 versus MOB2 determines NDR kinase activity [5].

Research has demonstrated that the MOB1/NDR complex is associated with increased NDR kinase activity, while the MOB2/NDR complex correlates with diminished NDR activity [5]. This competitive mechanism allows cells to fine-tune NDR signaling in response to various cellular cues and conditions.

Structural Basis of MOB2-NDR Interaction

The structural basis for the specific interaction between MOB2 and NDR kinases has been elucidated through crystallographic studies. The NDR N-terminal regulatory region forms a bihelical conformation that specifically associates with MOB2 [10]. This interface serves as a structural platform that mediates kinase-cofactor binding and contributes to the inhibitory function of MOB2.

Structural analyses comparing Cbk1NTR-Mob2 (NDR-MOB2) and Dbf2NTR-Mob1 (LATS-MOB1) complexes have identified discrete molecular determinants that enforce binding specificity between different MOB and kinase subfamilies [10]. These specificity determinants explain why MOB2 interacts exclusively with NDR kinases and not with LATS kinases [8], and why alterations in these specific residues can permit non-cognate complex formation [10].

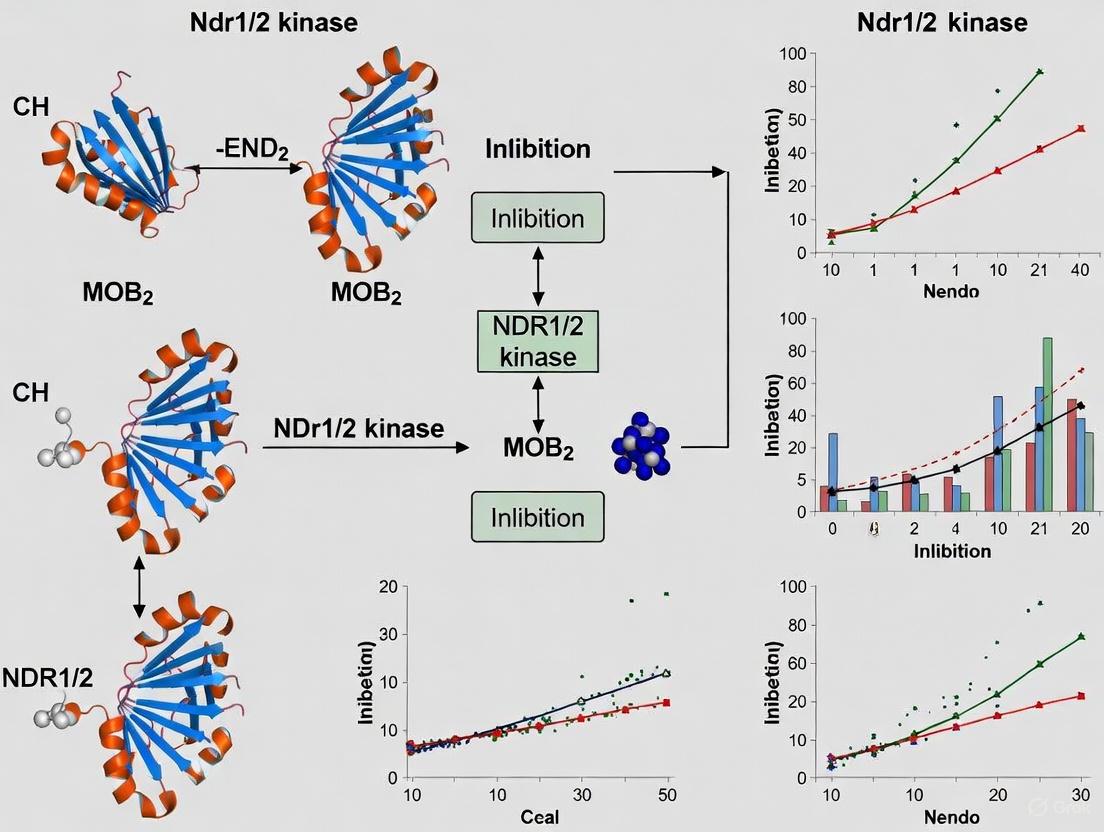

Diagram 1: MOB2 competes with MOB1 for NDR binding. MOB1 binding strongly activates NDR kinases, while MOB2 binding is associated with diminished NDR activity, creating a competitive regulatory switch.

Functional Consequences of MOB2-Mediated Regulation

The inhibitory function of MOB2 has significant implications for cellular physiology, particularly in processes such as cell motility, cell cycle progression, and DNA damage response. In hepatocellular carcinoma SMMC-7721 cells, MOB2 knockout promoted migration and invasion, while MOB2 overexpression inhibited these processes [8]. This effect was linked to MOB2's ability to regulate the Hippo pathway through alternative interactions with NDR1/2 and LATS1, leading to increased phosphorylation of LATS1 and subsequent inactivation of YAP [8].

Furthermore, MOB2 plays a role in DNA damage response and cell cycle checkpoints. MOB2 depletion causes accumulation of DNA damage and activation of p53/p21-dependent G1/S cell cycle checkpoints [5]. Interestingly, this function may operate independently of NDR1/2 kinase signaling, as knockdown of NDR1 or NDR2 does not recapitulate the cell cycle arrest phenotype observed in MOB2-depleted cells [5]. MOB2 also interacts with RAD50, a component of the MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 (MRN) DNA damage sensor complex, suggesting additional mechanisms beyond NDR regulation [5].

Experimental Approaches for Studying MOB2-NDR Interactions

Investigating the functional relationship between MOB2 and NDR kinases requires a multidisciplinary approach combining biochemical, cellular, and structural techniques. Below are key methodological frameworks used in this field.

Biochemical and Cellular Assays

Co-immunoprecipitation experiments have been fundamental for identifying and validating MOB2-NDR interactions. Epitope-tagged kinases immunoprecipitated from Jurkat T-cells revealed associations with MOB proteins, confirming their physical interaction in cellular contexts [3]. These approaches can be complemented by kinase activity assays to quantify the functional consequences of MOB2 binding, demonstrating that MOB2 association dramatically stimulates NDR1 and NDR2 catalytic activity despite its overall inhibitory role in cellular contexts [3].

Colocalization studies using fluorescence microscopy in HeLa cells have shown that NDR1 and NDR2 partially colocalize with human MOB2, providing spatial context for their functional interactions [3]. Additionally, membrane targeting experiments have revealed that NDR activation by MOB proteins occurs specifically at the plasma membrane, with phosphorylation and activation occurring within minutes after MOB association with membranous structures [4].

Genetic Manipulation Strategies

Genetic approaches have been instrumental in elucidating MOB2 functions. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of MOB2 in SMMC-7721 hepatocellular carcinoma cells, using sgRNA targeting the sequence 5'-AGAAGCCCGCTGCGGAGGAG-3', has demonstrated its role in inhibiting cell migration and invasion [8]. Conversely, lentiviral overexpression of MOB2 in the same cell system produced opposite effects, confirming its inhibitory function [8].

RNA interference techniques have also been employed to investigate MOB2 functions. MOB2 knockdown studies revealed its necessity for preventing accumulation of endogenous DNA damage and for proper activation of cell cycle checkpoints in response to DNA damaging agents such as ionizing radiation and doxorubicin [5].

Structural Biology Techniques

X-ray crystallography has provided high-resolution insights into the MOB2-NDR interaction. The structure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cbk1NTR-Mob2 complex was determined to 2.8 Å resolution, revealing the molecular details of this specific interaction [10]. Similarly, the structure of the Dbf2NTR-Mob1 complex provided a comparative framework for understanding binding specificity between different MOB-kinase pairs [10].

These structural studies have identified key interfacial residues that determine binding specificity and have illuminated how MOB binding organizes the NDR N-terminal regulatory region to interact with the kinase domain, facilitating activation through a unique mechanism [10] [7].

Diagram 2: Experimental approaches for studying MOB2-NDR interactions. A combination of biochemical, genetic, and structural methods is essential for comprehensively understanding the regulatory relationship between MOB2 and NDR kinases.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating MOB2-NDR Kinase Interactions

| Reagent / Method | Key Function / Target | Experimental Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| hMOB1A/B cDNA | NDR1/2 kinase activator | Positive control for kinase activation assays [4] | Stimulates NDR kinase activity in vitro and in vivo [4] |

| hMOB2 cDNA | NDR1/2 kinase interactor | Competitive binding and inhibitory function studies [3] [4] | Associates with NDR1/2 and modulates activity [3] |

| Phospho-specific antibodies | Ser281/Thr444 (NDR1) Ser282/Thr442 (NDR2) | Monitor activation loop phosphorylation [4] | Detect NDR phosphorylation and activation status [4] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 sgRNA | MOB2 gene knockout | Loss-of-function studies [8] | Target sequence: 5'-AGAAGCCCGCTGCGGAGGAG-3' [8] |

| Lentiviral expression vectors | MOB2 overexpression | Gain-of-function studies [8] | Enables stable MOB2 expression in cell lines [8] |

| Okadaic acid (OA) | PP2A phosphatase inhibitor | Indirect NDR kinase activation [4] | Demonstrates NDR phosphorylation requirement [4] |

| Membrane-targeting constructs | Recruit proteins to plasma membrane | Study localization-dependent activation [4] | mp-HA or mp-myc tagged constructs [4] |

The regulation of NDR kinases by MOB protein cofactors represents a sophisticated control mechanism for fundamental cellular processes. MOB2 emerges as a critical inhibitory regulator that fine-tunes NDR activity through competitive binding with the activating cofactor MOB1, with additional MOB2-specific functions that may operate independently of NDR kinases.

Future research should focus on elucidating the precise structural determinants of MOB2's inhibitory function and the contextual cellular signals that modulate the MOB1-MOB2 competitive balance. The development of specific inhibitors or stabilizers of these interactions could have significant therapeutic potential, particularly in cancer contexts where NDR2 often functions as an oncogene [6]. Furthermore, understanding the NDR2-specific interactome in different pathological conditions may reveal novel targets for anticancer therapies [6].

The complex relationship between MOB2 and NDR kinases exemplifies how sophisticated regulatory mechanisms enable precise control of fundamental cellular signaling pathways, with important implications for both basic biology and therapeutic development.

The Mps one binder (MOB) proteins are highly conserved eukaryotic signal transducers that primarily function as regulatory subunits for serine/threonine kinases of the NDR/LATS family [5] [8]. In mammals, at least six different MOB genes (MOB1A, MOB1B, MOB2, MOB3A, MOB3B, and MOB3C) have been identified, with MOB1 and MOB2 being the best-characterized members [8]. While MOB1A/B directly interact with both NDR1/2 and LATS1/2 kinases to enhance their activity through the Hippo signaling pathway, MOB2 exhibits distinct binding specificity [8]. Extensive biochemical evidence confirms that MOB2 interacts specifically with NDR1/2 kinases but shows no detectable binding to LATS1/2 kinases in mammalian cells [5] [8]. This specific binding interface between MOB2 and NDR1/2, and its functional consequences, forms a critical regulatory node in cellular signaling networks with implications for cell cycle control, DNA damage response, and neuronal development.

Molecular Basis of MOB2-NDR1/2 Specificity

Structural Determinants of Selective Binding

The specific interaction between MOB2 and NDR1/2 kinases is mediated through structural elements that are conserved across species. Both MOB1 and MOB2 bind to the positively charged N-terminal regulatory domain (NTR) of NDR1/2 via a negatively charged region on their protein surfaces [11]. However, key structural differences prevent MOB2 from productively engaging with LATS kinases. Biochemical experiments have demonstrated that MOB2 competes with MOB1 for binding to the same N-terminal regulatory domain on NDR1/2 [8]. This competitive binding has significant functional implications, as MOB1 binding to NDR1/2 promotes kinase activity, while MOB2 interaction interferes with NDR1/2 activation [8] [11].

Table 1: Key Structural Domains Involved in MOB2-NDR1/2 Interaction

| Protein | Domain | Function | Binding Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| NDR1/2 | N-terminal regulatory domain (NTR) | MOB protein binding | Binds both MOB1 and MOB2 |

| MOB1 | Negatively charged surface region | NDR/LATS kinase activation | Binds NDR1/2 and LATS1/2 |

| MOB2 | Negatively charged surface region | NDR kinase regulation | Binds only NDR1/2 |

| LATS1/2 | N-terminal regulatory domain | MOB protein binding | Binds MOB1 but not MOB2 |

Experimental Validation of Binding Specificity

The specific MOB2-NDR1/2 interaction has been consistently demonstrated across multiple experimental systems and techniques. In mammalian cells, co-immunoprecipitation assays have confirmed that MOB2 forms stable complexes with NDR1 and NDR2 but fails to co-precipitate with LATS1 or LATS2 [8]. This binding specificity is evolutionarily conserved, as demonstrated by studies in Drosophila where MOB2 (dMOB2) genetically interacts with the NDR kinase Tricornered but not with the LATS homolog Warts [5]. The molecular basis for this specificity stems from complementary electrostatic surfaces and specific residue interactions that allow MOB2 to engage with NDR1/2 while being sterically or electrostatically incompatible with LATS kinases.

Experimental Evidence and Methodologies

Key Biochemical Assays for Demonstrating Specific Interaction

Researchers have employed multiple biochemical approaches to characterize the MOB2-NDR1/2 interaction. The following experimental protocols represent methodologies commonly used in this field:

Co-immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting:

- Cell Transfection: Transfect mammalian cells (e.g., HEK293T, SMMC-7721) with expression vectors encoding tagged MOB2 and either NDR1/2 or LATS1/2.

- Cell Lysis: Harvest cells 24-48 hours post-transfection and lyse using RIPA buffer (25mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate cell lysates with antibody against the tag on MOB2 (or kinase) for 2-4 hours at 4°C, then add Protein A/G agarose beads for an additional 1-2 hours.

- Washing and Elution: Wash beads 3-5 times with lysis buffer, elute proteins with 2X Laemmli buffer by heating at 95°C for 5 minutes.

- Detection: Separate proteins by SDS-PAGE, transfer to PVDF membrane, and probe with antibodies against NDR1/2 or LATS1/2 to detect specific interactions [8].

Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening:

- Strain Transformation: Co-transform yeast strain (e.g., AH109) with bait (NDR1/2 or LATS1/2 kinase domains) and prey (MOB2) plasmids.

- Selection Culture: Plate transformations on minimal medium lacking leucine and tryptophan to select for double transformants.

- Interaction Assay: Transfer colonies to medium lacking leucine, tryptophan, and histidine to test for protein-protein interaction, with increasing concentrations of 3-AT (0-50mM) to reduce false positives.

- β-galactosidase Assay: Perform quantitative assessment of interaction strength using ONPG substrate and measuring absorbance at 420nm [5].

In Vitro Binding Assay:

- Protein Purification: Express and purify recombinant GST-tagged MOB2 and His-tagged NDR1/2 or LATS1/2 kinase domains from E. coli or insect cells.

- Binding Reaction: Incubate GST-MOB2 immobilized on glutathione-sepharose beads with purified kinase domains in binding buffer (20mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150mM NaCl, 1mM DTT, 0.1% Triton X-100) for 1 hour at 4°C.

- Wash and Elution: Wash beads 3-4 times with binding buffer, elute bound proteins with reduced glutathione (10-20mM) or directly with SDS-PAGE sample buffer.

- Analysis: Analyze eluates by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining or Western blotting with anti-His antibody to detect specific binding [8].

Quantitative Binding Data

Table 2: Experimental Evidence for MOB2 Binding Specificity

| Experimental Method | MOB2-NDR1/2 Interaction | MOB2-LATS1/2 Interaction | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-immunoprecipitation | Strong positive | Not detected | [8] |

| Yeast two-hybrid | Positive interaction | No interaction | [5] |

| In vitro binding assay | Direct binding confirmed | No binding observed | [8] |

| Competitive binding | Competes with MOB1 for NDR1/2 binding | No competition with MOB1 for LATS1/2 | [8] [11] |

Functional Consequences: MOB2-Mediated Inhibition of NDR1/2

Mechanism of Kinase Inhibition

The specific binding of MOB2 to NDR1/2 kinases has significant functional consequences, primarily through the inhibition of NDR1/2 kinase activity. Biochemical studies have revealed that while MOB1 binding to NDR1/2 promotes kinase activation, MOB2 interaction is associated with diminished NDR activity [5] [8]. This inhibitory effect occurs through multiple mechanisms:

Competitive Binding Mechanism: MOB2 and MOB1 compete for binding to the same N-terminal regulatory domain on NDR1/2 [8] [11]. Since MOB1 functions as a co-activator that enhances NDR1/2 kinase activity, displacement of MOB1 by MOB2 results in reduced phosphorylation of NDR1/2 substrates. This competition creates a regulatory balance where the relative abundance and activation state of MOB1 versus MOB2 determines the net output of NDR1/2 signaling.

Allosteric Inhibition: Structural studies suggest that MOB2 binding may induce conformational changes in NDR1/2 that stabilize an auto-inhibitory state. Research on the related NDR kinase Cbk1 in yeast has revealed that Mob2 binding communicates with the kinase domain through the C-terminal hydrophobic motif, potentially influencing activation segment conformation [12]. Although the precise structural mechanism for MOB2-mediated inhibition of mammalian NDR1/2 requires further elucidation, the conservation of this regulatory mechanism across species supports its fundamental importance.

Biological Context of MOB2-NDR1/2 Regulation

The MOB2-NDR1/2 regulatory axis functions in specific cellular contexts to fine-tune kinase activity. In human hepatocellular carcinoma cells (SMMC-7721), MOB2 knockout promotes cell migration and invasion while decreasing phosphorylation of the Hippo pathway effector YAP, suggesting that MOB2-mediated inhibition of NDR1/2 influences cell motility through Hippo signaling modulation [8]. Additionally, MOB2 has been implicated in DNA damage response pathways, where it interacts with RAD50 independently of NDR1/2, suggesting context-specific functions beyond kinase regulation [5].

Figure 1: MOB2 specifically binds and inhibits NDR1/2 but not LATS kinases, influencing downstream cellular processes like cell motility.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying MOB2-NDR1/2 Interactions

| Reagent/Tool | Specific Example | Application | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | LV-MOB2 lentivirus; lentiCRISPRv2-sgMOB2 | Gain/loss-of-function studies | Modulates MOB2 expression in cells [8] |

| Cell Lines | SMMC-7721; HEK293T; HBEC-3 | Cellular assays | Models for studying MOB2-NDR signaling [8] [6] |

| Antibodies | Anti-NDR1/2; Anti-MOB2; Anti-LATS1/2 | Immunodetection | Detects protein expression and interactions [8] [11] |

| Kinase Assay Kits | Radioactive or luminescent kinase assays | In vitro activity measurement | Quantifies NDR1/2 kinase activity [11] [13] |

Substantial biochemical evidence confirms that MOB2 binds specifically to NDR1/2 kinases but not to LATS1/2 kinases, and this specific interaction functionally inhibits NDR1/2 kinase activity primarily through competition with the activator protein MOB1. This regulatory mechanism represents a sophisticated fine-tuning system within the broader Hippo signaling network, with implications for diverse physiological processes including cell cycle progression, DNA damage response, and cell motility. The consistent demonstration of this specific interaction across multiple experimental systems and species underscores its fundamental importance in cellular signaling homeostasis. Future research should focus on elucidating the precise structural basis for MOB2's binding specificity and developing targeted interventions that can modulate this interaction for therapeutic benefit in cancer and other diseases.

The NDR1/2 (STK38/STK38L) kinases are core components of the conserved Hippo tumor suppressor pathway, playing critical roles in processes such as cell cycle progression, centrosome duplication, and the DNA damage response [12] [5]. Their activity is tightly regulated through interactions with Mps one binder (MOB) coactivator proteins. MOB1 binding to the N-terminal regulatory domain (NTR) of NDR1/2 promotes kinase activation and downstream signaling [14] [15]. In contrast, MOB2 competes with MOB1 for the same binding site on NDR1/2, thereby inhibiting kinase activity and modulating pathway output [5] [8]. This competitive binding represents a crucial regulatory mechanism for fine-tuning cellular signaling. This whitepaper delineates the structural basis, molecular mechanisms, and functional consequences of the MOB2-MOB1 competition, providing a framework for understanding its implications in cell biology and therapeutic development.

Structural Basis of MOB1-NDR Activation

Architecture of the Active Complex

Activation of NDR1/2 kinases requires binding of the coactivator MOB1 to the N-terminal regulatory domain (NTR). Structural analyses reveal that the NTR of NDR kinases forms a V-shaped structure composed of two antiparallel α-helices that dock onto a specific electropositive surface of MOB1 [15].

Table 1: Key Interacting Residues in the MOB1-NDR2 Complex

| NDR2 Residue | MOB1 Residue | Interaction Type |

|---|---|---|

| Lys25 | Leu36, Gly39 | Van der Waals |

| Tyr32 | Gln67, Met70 | Hydrogen bonding |

| Arg42 | Glu51, Glu55 | Electrostatic |

| Arg79 | Phe132, Pro133 | Hydrogen bonding |

| Arg82 | Val138, Lys135 | Electrostatic |

This interaction is characterized by extensive hydrogen bonds and van der Waals interactions that stabilize the complex. The binding of MOB1 induces conformational changes that promote NDR kinase activation through mechanisms that may involve allosteric regulation and stabilization of the kinase domain [7] [15].

Structural Determinants of MOB Specificity

While MOB1 and MOB2 share structural similarities, key residue differences dictate their opposing functional outcomes. A crucial distinction is Asp63 in MOB1, which forms a specific bond with His646 in LATS1 (a related kinase), and contributes to differential binding affinity across kinase family members [15]. This residue, along with other conserved positions within the MOB protein family, creates distinct interaction surfaces that govern binding specificity to NDR/LATS kinases.

Figure 1: MOB1-mediated activation of NDR kinase. MOB1 binding to the N-terminal domain induces conformational changes that promote kinase activation.

Molecular Mechanism of MOB2 Antagonism

Competitive Binding at the NTR Interface

MOB2 antagonizes NDR kinase activation through direct competition with MOB1 for the same binding site on the NDR N-terminal regulatory domain. Biochemical studies demonstrate that MOB2 forms a complex with NDR1/2 that is associated with diminished kinase activity, in contrast to the activating function of MOB1 [5]. This competition arises from the structural similarity between MOB1 and MOB2, which enables both proteins to interact with the NTR of NDR kinases but with different functional outcomes.

The binding affinity and stoichiometry of these interactions have been quantified through biochemical assays, revealing the quantitative dynamics of this competitive system:

Table 2: Functional Consequences of MOB Protein Binding to NDR Kinases

| Parameter | MOB1-NDR Complex | MOB2-NDR Complex |

|---|---|---|

| Kinase Activity | Increased | Decreased |

| Cellular Process | Cell cycle progression, Centrosome duplication | G1/S cell cycle arrest, DNA damage response |

| Downstream Signaling | YAP phosphorylation, Hippo pathway activation | Altered YAP localization, Reduced Hippo output |

| Competitive Dynamics | Activation impaired by MOB2 co-expression | Inhibition reversed by MOB1 overexpression |

Structural Basis of Uncompetitive Behavior

While MOB2 binds to the same NTR site as MOB1, subtle differences in the binding interface prevent the conformational changes required for kinase activation. Structural comparisons suggest that MOB2 may stabilize an auto-inhibitory conformation of NDR1/2, particularly through interactions that maintain the atypically long activation segment in its inhibitory state [12] [16]. This activation segment, when in its auto-inhibitory position, blocks substrate binding and stabilizes a non-productive position of helix αC in the kinase domain [12]. The MOB2-NDR complex may therefore represent a structurally distinct entity that not only lacks activation capacity but actively enforces an inactive kinase state.

Experimental Validation & Functional Evidence

Biochemical and Cellular Assays

The competitive binding model is supported by multiple lines of experimental evidence:

Co-immunoprecipitation Studies: Pull-down assays using purified NDR1/2 N-terminal domains demonstrate that MOB1 and MOB2 binding is mutually exclusive. When MOB2 is pre-bound to NDR, subsequent MOB1 binding is significantly reduced, and vice versa [5] [8].

Kinase Activity Measurements: In vitro kinase assays using purified components show that MOB2 binding correlates with reduced phosphorylation of NDR1/2 substrates. The presence of MOB2 can counteract MOB1-mediated activation in a dose-dependent manner [5].

Cellular Phenotypes: Knockdown of MOB2 in human cell lines leads to increased NDR kinase activity and promotes cell migration and invasion, particularly in hepatocellular carcinoma models [8]. Conversely, MOB2 overexpression suppresses these phenotypes, consistent with its role as a negative regulator of NDR signaling.

Protocol: Co-Immunoprecipitation to Assess Competitive Binding

Purpose: To demonstrate competitive binding between MOB1 and MOB2 to NDR1/2 kinases.

Procedure:

- Transfection: Co-transfect HEK293T cells with constructs expressing tagged NDR1 (or NDR2) along with varying ratios of MOB1 and MOB2 expression vectors.

- Lysis: Harvest cells 48 hours post-transfection and lyse in NP-40 buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 10% glycerol) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate lysates with anti-NDR antibody overnight at 4°C, then add Protein A/G beads for 2 hours.

- Washing: Pellet beads and wash 3 times with lysis buffer.

- Elution & Analysis: Elute proteins with 2× Laemmli buffer, separate by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblot for MOB1, MOB2, and NDR.

Interpretation: As MOB2 expression increases while MOB1 remains constant, the amount of MOB1 co-precipitating with NDR should decrease, demonstrating competition [5] [8].

Figure 2: MOB2 competitively inhibits MOB1-NDR activation. MOB2 binding to the NDR N-terminal domain prevents MOB1 binding and kinase activation.

Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying MOB-NDR Interactions

| Reagent / Method | Specific Example | Application & Function |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Constructs | NDR1 (12-418), MOB1A (2-216), MOB2 full-length | Recombinant protein expression; interaction studies [14] |

| Kinase Activity Assays | In vitro kinase assay with NDR substrates | Quantify enzymatic activity of NDR under different MOB conditions [12] |

| Structural Methods | X-ray crystallography (MOB1/NDR2 complex) | Determine atomic-level interaction interfaces [15] |

| Cell-Based Assays | Wound healing, Transwell invasion | Assess functional consequences of MOB competition [8] |

| Gene Manipulation | CRISPR/Cas9 KO, shRNA knockdown | Modulate MOB1/MOB2 expression in cellular models [8] |

| Interaction Mapping | Yeast two-hybrid, Co-IP variants | Identify novel binding partners and competitive interactions [5] |

The competitive binding model between MOB2 and MOB1 for NDR1/2 kinases represents a sophisticated regulatory mechanism for controlling Hippo pathway signaling output. The structural homology yet functional antagonism between MOB1 and MOB2 illustrates how subtle differences in protein-protein interaction interfaces can determine signaling outcomes. Understanding this competitive balance has significant implications for therapeutic development, particularly in cancer contexts where modulating Hippo pathway activity could alter tumor growth and metastasis. Future research should focus on quantifying the dynamics of this competition in different cellular compartments and under various physiological conditions to fully elucidate its role in health and disease.

The interaction between MOB2 and the NDR1/2 kinases represents a critical regulatory node in cellular signaling, influencing pathways that control the cell cycle, DNA damage response, and Hippo signaling. This whitepaper synthesizes current structural and mechanistic insights into the molecular domains governing this interaction, with a specific focus on the inhibitory mechanism exerted by MOB2 on NDR1/2 kinase activity. We examine the competitive binding mechanism, the auto-inhibitory conformation of NDR1, and the functional consequences of this interaction on downstream cellular processes. Furthermore, we provide detailed experimental methodologies for studying this interaction and a curated toolkit of research reagents to facilitate further investigation. This comprehensive analysis aims to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in their pursuit of targeting this regulatory axis for therapeutic intervention.

The NDR (Nuclear Dbf2-related) kinase family, comprising NDR1 (STK38) and NDR2 (STK38L), serves as a crucial regulator of diverse cellular processes including cell cycle progression, DNA damage response, apoptosis, and stem cell differentiation [5] [1]. These serine-threonine kinases, belonging to the AGC kinase family, are themselves tightly regulated by interacting proteins, most notably the Mps one binder (MOB) family proteins. Among these, MOB2 has emerged as a key regulatory partner that specifically interacts with NDR1/2 but not with the related LATS1/2 kinases [5] [17]. The MOB2-NDR1/2 interaction represents a fascinating biological switch; while MOB1 binding activates NDR kinases, MOB2 competitively binds to the same regulatory domain but is associated with diminished NDR activity [5] [12]. This competitive inhibition positions MOB2 as a critical modulator of NDR-mediated signaling pathways, with implications for understanding cellular homeostasis and disease pathogenesis, particularly in cancer and neurological disorders. This review delves into the structural basis of this interaction and its functional consequences.

Structural Domains and Binding Interfaces

Domain Architecture of NDR1/2 Kinases

NDR1 and NDR2 share approximately 87% sequence identity but exhibit distinct subcellular localization—NDR1 is primarily nuclear while NDR2 displays a punctate cytoplasmic distribution [3]. Despite this differential localization, both kinases share a conserved domain architecture essential for their regulation and function [12]:

- N-terminal Regulatory Domain (MBD): This domain serves as the primary docking site for MOB proteins. It consists of an α-helix (αMOB) followed by an extended strand element (N-linker) that together create the binding interface for MOB proteins [12].

- Central Kinase Domain: This catalytic domain features an atypically long activation segment (63 residues in NDR1/2) that plays a critical auto-inhibitory role in kinase regulation [12].

- C-terminal Hydrophobic Motif (HM): This motif is nestled in a cleft between the MBD and the N-lobe of the kinase domain, and its phosphorylation by upstream kinases (MST1/2/3) contributes to NDR activation [12].

Table 1: Key Structural Domains of NDR1/2 Kinases

| Domain | Location | Structural Features | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| N-terminal MOB-binding Domain (MBD) | N-terminal | α-helix (αMOB) + extended strand (N-linker) | Primary docking site for MOB1/MOB2 proteins |

| Kinase Domain | Central | Atypically long activation segment (63 residues) | Catalytic activity; auto-inhibition via activation segment |

| Hydrophobic Motif (HM) | C-terminal | Phosphorylatable motif | Activation via phosphorylation by MST1/2/3 kinases |

MOB2 Structural Characteristics

MOB2 belongs to a highly conserved family of eukaryotic signal transducers that function through regulatory interactions with serine/threonine kinases of the NDR/LATS family [5]. While the exact three-dimensional structure of human MOB2 remains to be fully elucidated, insights from orthologous structures (e.g., yeast Cbk1-Mob2 complex) reveal that MOB proteins typically adopt a conserved globular fold that engages with the MBD of their kinase partners [12]. The structural basis for MOB2's specificity for NDR1/2 over LATS kinases likely resides in key surface residues that complement the binding interface of the NDR MBD.

The MOB2-NDR Binding Interface

Biochemical experiments have demonstrated that MOB2 interacts specifically with the N-terminal regulatory domain of NDR1/2 [3] [12]. This interaction is mutually exclusive with MOB1 binding, indicating overlapping binding sites [17] [8]. The binding interface has been mapped to the same N-terminal regulatory domain where MOB1 binds, with both MOB proteins competing for interaction with this region [6]. Structural studies of the related yeast Cbk1-Mob2 complex reveal that the MOB protein binds to the MBD through extensive surface contacts, with the HM of the kinase nestled in a cleft between the MBD and the N-lobe of the kinase domain, suggesting an indirect mechanism of communication between MOB binding and kinase catalytic activity [12].

Mechanism of Kinase Inhibition by MOB2

Competitive Displacement of MOB1

The primary mechanism through which MOB2 inhibits NDR1/2 kinase activity is by competitively displacing the activating partner MOB1. MOB2 and MOB1 compete for binding to the same N-terminal regulatory domain of NDR1/2 [17] [8]. While the MOB1/NDR complex corresponds to increased NDR kinase activity, the MOB2/NDR complex is associated with diminished NDR activity [5] [12]. This competition creates a dynamic regulatory switch where the relative abundance and activation state of MOB1 versus MOB2 can determine the signaling output through NDR1/2 kinases.

Stabilization of Auto-inhibitory Conformation

Recent structural insights into NDR1 regulation reveal an additional layer of inhibition potentially influenced by MOB2 binding. The crystal structure of the human NDR1 kinase domain in its non-phosphorylated state reveals a fully resolved, atypically long activation segment that blocks substrate binding and stabilizes a non-productive position of helix αC [12]. This activation segment acts as an auto-inhibitory module, and mutations within this region dramatically enhance in vitro kinase activity [12]. While MOB1 binding and the auto-inhibitory activation segment appear to act through independent mechanisms [12], the precise effect of MOB2 binding on this auto-inhibitory conformation warrants further investigation. It is plausible that MOB2 binding may stabilize or reinforce this auto-inhibitory state, thereby contributing to kinase suppression.

Impact on Downstream Signaling

The inhibition of NDR1/2 kinase activity by MOB2 has significant consequences for downstream signaling pathways. Research indicates that MOB2 regulates the alternative interaction of MOB1 with NDR1/2 and LATS1, resulting in increased phosphorylation of LATS1 and MOB1, thereby leading to the inactivation of YAP and consequent inhibition of cell motility [17] [8]. This demonstrates how MOB2-mediated inhibition of NDR1/2 can redirect signaling flux through the Hippo pathway, ultimately influencing transcriptional programs controlled by YAP/TAZ.

Figure 1: MOB2 Inhibition Mechanism on NDR1/2 Signaling. MOB2 competes with MOB1 for binding to the N-terminal regulatory (NTR) domain of NDR1/2 kinases, preventing MOB1-mediated activation. This inhibition redirects signaling to promote LATS1 activation and subsequent YAP phosphorylation, leading to transcriptional changes that inhibit cell motility.

Functional Consequences of MOB2-NDR1/2 Interaction

Cell Cycle and DNA Damage Response

MOB2 plays a significant role in cell cycle progression and the DNA damage response (DDR), potentially through its interaction with NDR1/2. MOB2 knockdown triggers a p53/p21-dependent G1/S cell cycle arrest in untransformed human cells [5]. This effect appears to be independent of NDR1/2 signaling, as knockdown of NDR1 or NDR2 does not recapitulate the same cell cycle arrest phenotype [5]. Additionally, MOB2 has been implicated in DDR through its interaction with RAD50, a component of the MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 (MRN) DNA damage sensor complex [5] [18]. MOB2 supports the recruitment of MRN and activated ATM to DNA-damaged chromatin, suggesting a role in DDR that may be both dependent and independent of its interaction with NDR kinases [5].

Cell Motility and Cancer Progression

The MOB2-NDR1/2 interaction significantly influences cell motility and invasion, with important implications for cancer progression. In hepatocellular carcinoma cells, MOB2 knockout promotes migration and invasion, induces phosphorylation of NDR1/2, and decreases phosphorylation of YAP [17] [8]. Conversely, MOB2 overexpression produces the opposite effects, indicating that MOB2 serves a positive role in LATS/YAP activation through the Hippo signaling pathway [8]. Similarly, in glioblastoma (GBM), MOB2 functions as a tumor suppressor by negatively regulating the FAK/Akt pathway [18]. MOB2 expression is significantly downregulated in GBM patient specimens, and its overexpression suppresses malignant phenotypes including migration, invasion, and clonogenic growth [18].

Table 2: Functional Consequences of MOB2-NDR1/2 Interaction in Different Cellular Contexts

| Cellular Process | Effect of MOB2 | NDR1/2-Dependent | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Cycle Progression | Knockdown causes G1/S arrest | Partially Independent | Triggers p53/p21-dependent checkpoint; NDR1/2 knockdown does not replicate effect [5] |

| DNA Damage Response | Promotes DDR | Partially Independent | Interacts with RAD50; supports MRN complex recruitment to damage sites [5] |

| Cell Motility (HCC) | Inhibits migration/invasion | Dependent | Regulates MOB1 alternative interaction with LATS1; inactivates YAP [17] [8] |

| Tumor Suppression (GBM) | Suppresses malignancy | Partially Independent | Downregulated in GBM; negatively regulates FAK/Akt pathway [18] |

Experimental Approaches for Structural and Functional Analysis

Mapping Protein-Protein Interactions

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) Assays:

- Protocol: Express epitope-tagged NDR1 or NDR2 kinases in Jurkat T-cells or HeLa cells. Immunoprecipitate using tag-specific antibodies and analyze co-precipitating proteins by western blotting or mass spectrometry [3]. For endogenous interactions, use specific antibodies against native NDR1/2 and MOB2 proteins.

- Applications: Confirmation of direct binding between MOB2 and NDR1/2; competition studies with MOB1 [3] [12].

Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening:

- Protocol: Clone MOB2 as bait and screen against a human cDNA library. Validate positive clones through retransformation and domain mapping [5].

- Applications: Identification of novel binding partners (e.g., RAD50) [5]; mapping of interaction domains through truncation mutants.

Structural Characterization

X-ray Crystallography:

- Protocol: Express and purify human NDR1 kinase domain (residues 82-418) from E. coli. Perform limited proteolysis to identify stable fragments. Crystallize using vapor diffusion methods and solve structure by molecular replacement [12].

- Applications: Determination of atomic-level structure of NDR1 kinase domain; visualization of auto-inhibitory activation segment [12].

Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange (HDX) Analysis:

- Protocol: Incubate NDR1 with and without MOB2 in deuterated buffer for various time points. Quench reactions, digest with pepsin, and analyze by mass spectrometry to monitor conformational changes [12].

- Applications: Mapping of protein dynamics and conformational changes induced by MOB2 binding [12].

Functional Validation

Kinase Activity Assays:

- Protocol: Purify NDR1/2 kinases and MOB2 proteins. Perform in vitro kinase reactions with [γ-32P]ATP and appropriate substrates. Measure phosphate incorporation by scintillation counting or western blotting with phospho-specific antibodies [3] [12].

- Applications: Quantitative assessment of MOB2's effect on NDR1/2 kinase activity; comparison with MOB1-mediated activation [3].

CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Gene Editing:

- Protocol: Design sgRNA targeting MOB2 (e.g., 5'-AGAAGCCCGCTGCGGAGGAG-3'). Clone into lentiCRISPRv2 vector and transduce into target cells (e.g., SMMC-7721 hepatocellular carcinoma cells). Select with puromycin and validate knockout by western blotting [17] [8].

- Applications: Generation of MOB2-deficient cell lines for functional studies of migration, invasion, and signaling pathway analysis [17] [8].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Characterizing MOB2-NDR1/2 Interaction. A comprehensive approach combining protein interaction mapping, structural characterization, in vitro functional validation, and cellular phenotypic analysis provides a complete understanding of the MOB2-NDR1/2 regulatory axis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating MOB2-NDR1/2 Interaction

| Reagent/Tool | Specifications | Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| lentiCRISPRv2 Vector | Addgene #52961; puromycin resistance | MOB2 knockout | CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing [17] |

| NDR1 Kinase Domain Fragment | residues 82-418 | Structural studies | Crystallization and structure determination [12] |

| MOB2 Binding Mutant | MOB2-H157A | Functional rescue experiments | Defective in NDR1/2 binding; determines specificity [18] |

| Hyperactive NDR1 Mutant | NDR1-PIF | Functional studies | Bypasses regulatory mechanisms to assess downstream effects [5] |

| Lentiviral MOB2 Overexpression | LV-MOB2 | Gain-of-function studies | Stable MOB2 expression in various cell lines [17] [18] |

| Phospho-specific Antibodies | anti-pYAP; anti-pNDR1/2 | Signaling pathway analysis | Detection of pathway activity through phosphorylation status [17] [8] |

The structural insights into the molecular domains governing MOB2-NDR1/2 interaction reveal a sophisticated regulatory mechanism centered on competitive binding and potential stabilization of auto-inhibitory states. The MOB2-NDR1/2 axis represents a critical signaling node integrating multiple cellular processes, from cell cycle control and DNA damage response to cell motility and cancer progression. The dual nature of MOB2's functions—both dependent and independent of NDR1/2 inhibition—highlights the complexity of this regulatory system and suggests cell context-dependent variations.

Future research should focus on obtaining high-resolution structures of the full-length MOB2-NDR1/2 complex to precisely elucidate the molecular determinants of binding specificity and inhibition. Additionally, the development of small molecule modulators targeting this interaction would provide valuable chemical tools for dissecting its biological functions and potential therapeutic applications. Given MOB2's role as a tumor suppressor in multiple cancer contexts, strategies to enhance its expression or mimic its inhibitory function on pro-oncogenic signaling pathways represent promising avenues for therapeutic intervention. The integration of structural biology, chemical biology, and disease models will be essential to fully exploit the therapeutic potential of the MOB2-NDR1/2 regulatory axis.

The Mps one binder (MOB) family of proteins represents a class of crucial kinase regulators conserved across eukaryotes. While MOB1 is well-established as a co-activator of Nuclear Dbf2-related (NDR1/2) kinases, its paralog, MOB2, has emerged as a critical inhibitory regulator of the same kinases. This whitepaper synthesizes current research to elaborate on the precise molecular mechanism by which MOB2 inhibits NDR1/2 kinase activity and delineates the direct cellular consequences of this regulation. Framed within a broader thesis on NDR kinase regulation, we explore how the MOB2-NDR axis influences fundamental processes including cell motility, cell cycle progression, and the DNA damage response, with significant implications for diseases such as cancer.

The NDR kinase family (including NDR1/STK38 and NDR2/STK38L in mammals) constitutes a subgroup of AGC serine-threonine kinases with essential roles in governing cell cycle progression, morphological changes, mitotic exit, apoptosis, and DNA damage signaling [19]. The activity of NDR kinases is stringently controlled through a multi-step process requiring phosphorylation at two conserved sites: i) autophosphorylation of a serine residue in the activation loop (Ser281 in NDR1, Ser282 in NDR2), and ii) phosphorylation of a threonine residue in the hydrophobic motif (Thr444 in NDR1, Thr442 in NDR2) by an upstream kinase, such as the Ste20-like kinase MST3 [20]. A third critical step is the binding of regulatory proteins from the MOB family [20] [3].

MOB proteins function as central signal transducers but do not possess catalytic activity themselves. The human genome encodes six MOB genes (MOB1A, MOB1B, MOB2, MOB3A, MOB3B, MOB3C), with MOB1 and MOB2 being the primary regulators of NDR/LATS kinases [5]. MOB1 binding to the N-terminal regulatory domain of NDR1/2 dramatically stimulates kinase activity, forming an active complex crucial for various cellular functions [3]. In stark contrast, MOB2, while binding to the same regulatory domain on NDR1/2, acts as a potent negative regulator, thereby establishing a competitive regulatory paradigm for NDR kinase activity [21] [5].

The Molecular Mechanism of MOB2-Mediated Inhibition

Competitive Binding with MOB1

The primary mechanism of MOB2-mediated inhibition is its direct competition with the activator protein MOB1 for binding to the same N-terminal regulatory domain of NDR1/2 kinases [21] [22] [23]. Biochemical studies have demonstrated that MOB2 competes with MOB1 for interaction with NDR1/2. The formation of a MOB1/NDR complex is associated with increased NDR kinase activity, whereas the formation of a MOB2/NDR complex is associated with diminished NDR activity [5]. This competition creates a molecular switch that finely tunes the output of NDR kinase signaling pathways.

Suppression of Kinase Activation

The formation of the MOB2-NDR complex directly suppresses the catalytic activity of NDR kinases. In vitro and in vivo experiments have consistently shown that the association of MOB2 with NDR1/2 prevents their full activation. This inhibitory relationship was quantified in a study showing that knockout of MOB2 in SMMC-7721 hepatocellular carcinoma cells promoted the phosphorylation (and thus activation) of NDR1/2, whereas overexpression of MOB2 resulted in the opposite effect [21] [22]. By displacing MOB1 and preventing the formation of the active kinase complex, MOB2 effectively functions as a natural antagonist of NDR1/2 signaling.

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of MOB2 Manipulation on NDR Kinase Activity and Downstream Pathways in SMMC-7721 Cells

| Experimental Manipulation | NDR1/2 Phosphorylation | YAP Phosphorylation | Cell Migration/Invasion |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOB2 Knockout (CRISPR/Cas9) | Increased | Decreased | Promoted |

| MOB2 Overexpression | Decreased | Increased | Inhibited |

Cellular Consequences of MOB2-Mediated NDR Inhibition

The inhibition of NDR kinases by MOB2 has profound and diverse effects on cellular behavior, impacting processes central to tissue homeostasis and disease pathogenesis.

Inhibition of Cell Motility and the Hippo Pathway

One of the most characterized consequences is the regulation of the Hippo tumor suppressor pathway and its effect on cell motility. Research in SMMC-7721 hepatocellular carcinoma cells revealed a surprising finding: while MOB2 directly inhibits NDR, its overall effect on the broader Hippo pathway is stimulatory [21] [22]. Mechanistically, by sequestering NDR1/2, MOB2 regulates the alternative interaction of MOB1 with NDR1/2 and LATS1. This re-routing of MOB1 to LATS1 results in increased phosphorylation of both LATS1 and MOB1, thereby activating the LATS kinase. Active LATS, in turn, phosphorylates and inactivates the transcriptional co-activator YAP (Yes-associated protein), leading to the inhibition of genes that promote cell migration and invasion [21] [22]. Consequently, MOB2 overexpression inhibits, while its knockout promotes, the motility and invasive capacity of cancer cells.

Figure 1: MOB2 Regulates Cell Motility via the Hippo Pathway. High MOB2 levels inhibit NDR, freeing MOB1 to activate LATS1, which phosphorylates and inactivates YAP, ultimately inhibiting cell motility. Conversely, low MOB2 allows MOB1-NDR complex formation, reducing LATS1 activity and leading to YAP-mediated gene expression that promotes motility.

Regulation of Cell Cycle and DNA Damage Response

Beyond the Hippo pathway, MOB2 plays a critical role in maintaining genome stability. Depletion of endogenous MOB2 in untransformed human cells triggers a p53/p21-dependent G1/S cell cycle arrest [5] [23]. This arrest is a consequence of the accumulation of endogenous DNA damage and the subsequent activation of the DNA damage response (DDR) kinases ATM and CHK2. MOB2 is required for efficient cell survival and proper G1/S checkpoint activation following exposure to DNA-damaging agents like ionizing radiation or doxorubicin [5]. Mechanistically, MOB2 has been shown to interact with RAD50, a core component of the MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 (MRN) complex, which is the primary sensor for DNA double-strand breaks. This interaction suggests that MOB2 supports the recruitment of the MRN complex and activated ATM to sites of DNA damage, thereby facilitating efficient DDR signaling [5]. Intriguingly, this function of MOB2 in the DDR appears to be independent of its regulation of NDR1/2 kinases, as knockdown of NDR1 or NDR2 does not recapitulate the DNA damage phenotypes observed upon MOB2 loss [5] [23].

Experimental Protocols for Studying MOB2-NDR Interactions

To investigate the functional relationship between MOB2 and NDR kinases, researchers employ a suite of molecular and cellular biology techniques. Below are detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in this field.

CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Gene Knockout

This protocol was used to generate MOB2-knockout SMMC-7721 cells to study loss-of-function phenotypes [22].

- sgRNA Design: Design a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting an early exon of the human MOB2 gene using an online tool (e.g., CRISPR Design Tool, http://crispr.mit.edu/). The cited study used sequence: 5'-AGAAGCCCGCTGCGGAGGAG-3'.

- Vector Construction: Digest the lentiCRISPRv2 vector (or similar) with BsmBI. Anneal the oligonucleotide pairs encoding the sgRNA and ligate them into the digested vector.

- Lentivirus Production: Co-transfect the constructed vector with lentiviral packaging plasmids (pSPAX2 and pCMV-VSV-G) into 293T cells using a transfection reagent like EndoFectin Lenti.

- Viral Harvest and Infection: Collect the viral supernatant 48 hours post-transfection. Infect the target SMMC-7721 cells in the presence of polybrene (5 µg/ml).

- Selection and Clonal Isolation: Select transduced cells with puromycin (e.g., 1.0 µg/ml) for 1-2 weeks. Isolate single clones and validate MOB2 knockout via western blotting.

Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and Kinase Activity Assays

This method is essential for confirming direct protein-protein interactions and assessing functional consequences [20] [3].

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells (e.g., HEK293F, Jurkat T-cells) in a non-denaturing IP buffer (e.g., 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 10% glycerol, supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors).

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate the cell lysate with an antibody specific to your protein of interest (e.g., anti-NDR1) or an epitope tag (e.g., anti-HA for HA-tagged NDR2). Capture the antibody-protein complex using Protein A/G beads.

- Washing and Elution: Wash the beads extensively with IP buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins. Elute the bound proteins by boiling in SDS-PAGE sample buffer.

- Western Blot Analysis: Resolve the eluted proteins by SDS-PAGE, transfer to a membrane, and probe with antibodies against the interacting partner (e.g., anti-MOB2) to confirm interaction.

- Kinase Assay: For activity, perform an in vitro kinase assay using immunoprecipitated NDR kinase. Incubate the beads with a reaction mix containing ATP, Mg²⁺, and a substrate (e.g., myelin basic protein or a specific peptide). Quantify kinase activity by measuring radioactive phosphate incorporation (using [γ-³²P]ATP) or via phospho-specific antibodies.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for MOB2-NDR Research. A typical research pipeline begins with genetic manipulation of MOB2, followed by phenotypic and mechanistic analyses to dissect its role in NDR kinase regulation and cellular functions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Investigating MOB2 and NDR Kinase Biology

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Lentiviral Vectors (e.g., lentiCRISPRv2) | For stable gene knockout (CRISPR/Cas9) or overexpression in diverse cell lines. | lentiCRISPRv2 for KO; pLent-U6-GFP-Puro for shRNA (e.g., shYAP) [22]. |

| Specific Antibodies | Detection and quantification of proteins and their post-translational modifications. | Anti-MOB2, anti-NDR1/2, anti-phospho-NDR (Ser281/Thr444), anti-phospho-YAP, anti-RAD50 [21] [5] [20]. |

| DNA Damage Inducers | To study the role of MOB2 in the DNA Damage Response (DDR). | Ionizing Radiation (IR), Doxorubicin (Topoisomerase II poison) [5]. |

| Cell Lines | Model systems for in vitro functional studies. | SMMC-7721 (Hepatocellular Carcinoma), HEK293T (Virus Production, Transfection), HeLa (Localization) [21] [22]. |

| Transwell / Boyden Chambers | Quantitative assessment of cell migration and invasion capabilities. | 6.5 mm diameter, 8.0 µm pore size; pre-coat with Matrigel for invasion assays [22]. |

The body of evidence unequivocally establishes MOB2 as a critical inhibitory regulator of NDR1/2 kinases, operating primarily through a competitive binding mechanism with its activator counterpart, MOB1. The cellular consequences of this interaction are multifaceted, directly impacting cell fate decisions through the regulation of the Hippo-YAP pathway, cell cycle checkpoints, and genome integrity maintenance via the DNA damage response. The finding that MOB2's function in DDR is potentially independent of NDR inhibition adds a layer of complexity to its role, suggesting the existence of additional, yet-to-be-discovered binding partners and functions.

From a therapeutic perspective, the MOB2-NDR axis presents an attractive target for drug development, particularly in cancers where YAP activation or defective DDR contributes to pathogenesis. Future research should focus on elucidating the structural basis of MOB2-NDR versus MOB1-NDR complex formation, which could enable the rational design of small molecules that modulate these interactions. Furthermore, comprehensive in vivo studies are needed to validate these mechanisms in physiological and disease contexts, ultimately translating our molecular understanding into novel therapeutic strategies for cancer and other proliferation-related diseases.

Techniques for Probing the MOB2-NDR Functional Relationship

The Mps one binder 2 (MOB2) protein is a highly conserved signal transducer that plays a critical role in cellular homeostasis by specifically interacting with NDR1/2 kinases (also known as STK38/STK38L). MOB2 functions as an important regulatory component that competes with MOB1 for binding to the same N-terminal regulatory domain of NDR1/2 kinases [5] [17]. This competitive interaction has significant functional consequences, as MOB1 binding promotes NDR kinase activity, while MOB2 binding is associated with diminished NDR activity [5]. The MOB2-NDR1/2 axis has been implicated in diverse biological processes including cell cycle progression, DNA damage response, and cell motility, making it a compelling subject for biochemical investigation [5] [18]. This technical guide provides detailed methodologies for studying the MOB2-NDR1/2 interaction and its functional consequences using co-immunoprecipitation and kinase activity assays.

Table 1: Key Functional Relationships Between MOB2 and NDR1/2 Kinases

| Experimental Manipulation | Effect on NDR1/2 Phosphorylation | Functional Outcome | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOB2 Knockout (CRISPR/Cas9) | Increased phosphorylation | Enhanced cell migration and invasion | Hepatocellular carcinoma cells [17] |

| MOB2 Overexpression | Decreased phosphorylation | Suppressed cell motility | Glioblastoma and HCC cells [17] [18] |

| MOB2 Knockdown | Not directly measured | G1/S cell cycle arrest via p53/p21 | Untransformed human cells [5] |

| MOB2 Binding to NDR1/2 | Blocks activation | Competition with activating MOB1 | In vitro binding assays [5] |

Molecular Mechanism of MOB2-Mediated NDR1/2 Inhibition

MOB2 regulates NDR1/2 kinase activity through a multifaceted molecular mechanism. Biochemically, MOB2 binds specifically to NDR1/2 kinases but not to the related LATS1/2 kinases in mammalian cells [17]. Structural analyses indicate that MOB2 and MOB1 compete for binding to the same N-terminal regulatory domain of NDR1/2 [8]. When MOB1 binds to NDR1/2, it promotes kinase activation, whereas MOB2 binding interferes with this activation [17] [8]. This competition creates a regulatory switch that controls NDR1/2 output in response to cellular signals.

Beyond direct competition, MOB2 influences the broader signaling network by regulating the alternative interaction of MOB1 with NDR1/2 and LATS1 [17]. This regulation results in increased phosphorylation of LATS1 and MOB1, leading to subsequent inactivation of YAP (Yes-associated protein) and ultimately inhibition of cell motility [17]. The interaction between MOB2 and NDR1/2 represents a critical signaling node that integrates multiple cellular pathways to control fundamental processes including cell proliferation, survival, and migration.

Diagram 1: MOB2 competitive inhibition mechanism. MOB2 (yellow) competes with the activating MOB1 (green) for binding to NDR1/2 (blue), resulting in kinase inactivation and downstream effects on YAP-mediated cell migration.

Co-immunoprecipitation Assay for MOB2-NDR1/2 Interaction

Protocol for MOB2-NDR1/2 Co-Immunoprecipitation

Step 1: Cell Lysis Gently lyse cells using a non-detergent or low-detergent lysis buffer to preserve protein-protein interactions while making target proteins accessible to antibodies [24]. A recommended buffer composition includes:

- 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4)

- 10 mM KCl

- 0.05% Nonidet P-40 (v/v)

- Protease and phosphatase inhibitors (added fresh) [25]

For less soluble protein complexes, non-ionic detergents such as NP-40 or Triton X-100 may be necessary, though conditions should be optimized empirically [24]. Use at least 1 mg of total protein as starting material, adjusting based on protein abundance and interaction strength.

Step 2: Antibody Selection and Incubation Select antibodies specific to your protein-of-interest (MOB2 or NDR1/2). Key considerations include:

- Prefer polyclonal antibodies over monoclonal when possible, as they recognize multiple epitopes

- Ensure antibodies recognize the native protein conformation, not just denatured forms

- Choose antibodies targeting epitopes not masked by protein-protein interactions [24]

- Incubate lysate with antibody under gentle agitation for optimal interaction

Step 3: Bead Preparation and Incubation Select appropriate beads based on antibody species and type:

- Protein A/G beads for general antibody capture

- Magnetic beads (1-4 µM) for gentle handling and minimal sample loss

- Agarose beads (50-150 µM) for superior yield due to larger surface area [24] Incubate bead-antibody-protein complexes with gentle agitation for 30 minutes to overnight, depending on interaction strength.

Step 4: Complex Collection and Washing Collect antibody-protein complexes using either magnets (for magnetic beads) or centrifugation (for agarose beads) [24]. Wash complexes 3-5 times with cold lysis buffer or PBS to remove non-specifically bound cellular components while maintaining specific interactions.

Step 5: Protein Elution and Detection Elute proteins using:

- SDS-PAGE loading buffer for subsequent western blot analysis

- 0.1M glycine (pH 2.5-3) for non-denaturing conditions when maintaining protein activity is essential [24] Detect interaction partners via western blotting, mass spectrometry, or enzymatic assays.

Critical Controls and Optimization

Include these essential controls to validate Co-IP specificity:

- IgG control: Use non-specific antibody from the same species

- Bead-only control: Assess non-specific binding to beads

- Input sample: Verify presence of target proteins in lysate

- Knockdown/knockout validation: Use MOB2-deficient cells to confirm interaction specificity [18]

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for MOB2-NDR1/2 Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | SMMC-7721 (HCC), LN-229 (GBM), HEK293 | Provide cellular context for experiments | Select based on endogenous MOB2/NDR expression levels [17] [18] |

| Lysis Buffers | HEPES-based with NP-40 | Extract proteins while preserving interactions | Optimize detergent concentration for solubility vs. interaction preservation [25] |

| Antibodies | Anti-MOB2, Anti-NDR1/2, Anti-p-NDR1/2 | Detect and capture proteins of interest | Validate for Co-IP applications; prefer polyclonal for multiple epitopes [24] |

| Bead Systems | Protein A/G agarose, Magnetic beads | Immobilize antibodies for pulldown | Magnetic beads allow gentler handling; agarose provides higher capacity [24] |

| Protease Inhibitors | Commercial cocktails (e.g., Sigma P8340) | Prevent protein degradation during processing | Essential for maintaining complex integrity [25] |

Diagram 2: Co-immunoprecipitation workflow. Key optimization points (yellow) highlight critical steps where protocol adjustments significantly impact interaction preservation and specificity.

In Vitro Kinase Activity Measurements

Assessing NDR1/2 Kinase Activity in MOB2 Experiments

Measuring NDR1/2 kinase activity is essential for quantifying the functional consequences of MOB2 binding. The phosphorylation status of NDR1/2 serves as a direct indicator of kinase activation and can be monitored through various techniques.

Phospho-Specific Antibody Detection Utilize phospho-specific antibodies that recognize the activated (phosphorylated) forms of NDR1/2. Western blot analysis of immunoprecipitated NDR1/2 or whole cell lysates can reveal changes in phosphorylation status following MOB2 manipulation [17]. This approach provides semi-quantitative data on kinase activation states under different experimental conditions.

In Vitro Kinase Assays Direct measurement of NDR1/2 kinase activity can be performed using in vitro kinase assays with recombinant proteins:

- Immunoprecipitate NDR1/2 from cell lysates

- Incubate with ATP and appropriate substrates

- Measure substrate phosphorylation via radiometric or fluorescence-based methods

Functional Correlates of Kinase Activity Since NDR1/2 kinases regulate downstream effectors including p21 stability and YAP phosphorylation [26] [17], monitoring these downstream targets provides indirect assessment of NDR1/2 activity in MOB2 experiments.

Protocol for NDR1/2 Kinase Activity Measurement

Step 1: Sample Preparation

- Prepare lysates from MOB2-manipulated cells (overexpression, knockdown, or knockout)

- Use optimized lysis buffer (as in Co-IP protocol) to preserve protein complexes and phosphorylation states

- Consider including phosphatase inhibitors during lysis to maintain phosphorylation status

Step 2: NDR1/2 Immunoprecipitation

- Incubate lysates with NDR1/2-specific antibodies conjugated to beads

- Include control IgG to assess non-specific binding

- Wash beads with kinase-compatible buffer to remove contaminants

Step 3: Kinase Reaction

- Resuspend beads in kinase reaction buffer containing:

- 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4)

- 10 mM MgCl₂

- 1 mM DTT

- 100 μM ATP

- Appropriate substrate (e.g., myelin basic protein or specific NDR substrates)

- Incubate at 30°C for 30 minutes

- Terminate reaction with SDS-PAGE loading buffer

Step 4: Phosphorylation Detection

- Analyze substrate phosphorylation via:

- Western blot with phospho-specific antibodies

- Radiometric detection when using [γ-³²P]ATP

- Fluorescence-based methods for quantitative assessment

Table 3: Quantitative Effects of MOB2 Manipulation on Signaling Pathways

| Experimental Condition | NDR1/2 Phosphorylation | YAP Phosphorylation | Downstream Phenotype | Reference Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOB2 Knockout | Increased ~2-3 fold | Decreased ~40-60% | Enhanced migration and invasion | Hepatocellular carcinoma [17] |

| MOB2 Overexpression | Decreased ~50-70% | Increased ~2 fold | Suppressed tumor growth | Glioblastoma xenograft [18] |

| MOB2 Knockdown | Not directly measured | Not reported | G1/S cell cycle arrest | Untransformed human cells [5] |

| MOB2 Depletion + RAD50 disruption | Not measured | Not reported | Defective DNA damage response | Human cell lines [5] |

Integrated Workflow for Comprehensive MOB2-NDR1/2 Analysis

A comprehensive analysis of MOB2-NDR1/2 interactions requires integrating multiple methodological approaches to establish both physical interaction and functional consequences.

Parallel Validation Strategy Implement Co-IP and kinase assays in parallel using the same cellular models to correlate MOB2-NDR1/2 binding with functional outcomes. For example, demonstrate that MOB2 overexpression increases physical association with NDR1/2 while decreasing kinase activity toward substrates.

Reciprocal Co-Immunoprecipitation Perform reciprocal Co-IP experiments using both MOB2 and NDR1/2 as bait proteins to validate the interaction. This approach controls for potential artifacts associated with antibody specificity or epitope masking.

Structure-Function Analysis Utilize MOB2 mutants (e.g., MOB2-H157A, which is defective in NDR1/2 binding) to demonstrate the specificity of observed effects [18]. These mutants serve as critical controls to distinguish NDR-dependent versus NDR-independent functions of MOB2.

Diagram 3: Integrated experimental workflow. A comprehensive approach combining genetic manipulation, interaction studies, functional assays, and data integration provides robust evidence for MOB2-NDR1/2 regulatory relationships.

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

Common Co-IP Challenges

- Non-specific binding: Increase wash stringency, optimize antibody concentration, include appropriate controls

- Weak or transient interactions: Consider crosslinking or proximity labeling techniques as alternatives [27]

- Protein complex disruption: Use gentler lysis conditions, avoid excessive mechanical force

Kinase Assay Optimization

- Low signal: Ensure adequate protein input, optimize reaction time and temperature

- High background: Include no-substrate and no-enzyme controls, improve wash stringency

- Variable results: Standardize cell culture conditions, lysis procedures, and reaction timing

Validation Strategies

- Rescue experiments: Express wild-type MOB2 in knockout cells to confirm phenotype reversal

- Multiple cell models: Validate findings across different cellular contexts

- Orthogonal methods: Confirm key findings using alternative approaches (e.g., proximity ligation, FRET)

The methodologies outlined in this guide provide a robust framework for investigating the functional relationship between MOB2 and NDR1/2 kinases. Proper implementation of these Co-IP and kinase activity assays will advance our understanding of how MOB2 serves as a critical regulator of NDR1/2 signaling in both physiological and pathological contexts.

Mps one binder 2 (MOB2) is a highly conserved signal transducer that plays crucial roles in essential cellular processes, including cell cycle progression, DNA damage response (DDR), and cell motility [5]. Biochemically, MOB2 interacts specifically with the NDR1/2 (STK38/STK38L) serine-threonine kinases, which are members of the Nuclear Dbf2-related (NDR/LATS) kinase family [5] [3]. The MOB2-NDR1/2 interaction represents a key regulatory node in cellular signaling networks, particularly within the broader context of Hippo signaling [17] [28]. MOB2 exhibits a unique functional relationship with NDR1/2 kinases—while MOB1 binding activates NDR1/2 kinase activity, MOB2 competes with MOB1 for binding to the same N-terminal regulatory domain of NDR1/2, thereby functioning as an inhibitor of NDR kinase activity [17] [8]. This competitive binding mechanism positions MOB2 as a critical negative regulator of NDR1/2 signaling, with important implications for understanding its roles in tumor biology and cellular homeostasis.

Molecular Mechanism of MOB2-Mediated NDR1/2 Inhibition

Competitive Binding Mechanism

The inhibitory function of MOB2 on NDR1/2 kinases operates through a sophisticated competitive binding mechanism. Structural and biochemical analyses have revealed that both MOB1 and MOB2 share the same binding interface on the N-terminal regulatory domain of NDR1/2 kinases [17] [3]. However, the functional outcomes of these interactions are diametrically opposed. MOB1 binding to NDR1/2 promotes kinase activation and is associated with increased NDR catalytic activity [3]. In contrast, MOB2 binding to the same site fails to activate the kinases and instead prevents MOB1 from accessing its binding site, thereby effectively suppressing NDR1/2 kinase activity [5] [17]. This competition creates a dynamic regulatory switch where the relative abundance and binding affinity of MOB1 versus MOB2 determines the activation status of NDR1/2 signaling pathways.

Structural Basis for Functional Differences

Although MOB1 and MOB2 compete for the same binding domain on NDR1/2 kinases, the structural basis for their opposing functional effects lies in their differing abilities to induce conformational changes required for kinase activation. The MOB1-NDR complex formation induces specific structural rearrangements that facilitate kinase autophosphorylation and full activation [3]. In contrast, the MOB2-NDR complex lacks these activating conformational changes, resulting in a kinase-inactive state [5]. This molecular understanding provides the foundation for employing genetic manipulation approaches to dissect the functional consequences of perturbing the MOB2-NDR1/2 axis in various biological contexts.

Knockdown Approaches for MOB2 Functional Analysis

RNA Interference (RNAi) Methodology

RNAi-mediated knockdown represents a powerful approach for investigating MOB2 function in cellular models. The standard protocol involves using small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) or short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) specifically targeting MOB2 transcripts:

Transfection Protocol:

- Seed cells (e.g., RPE1-hTert, BJ-hTert fibroblasts) at consistent confluence in appropriate growth media [29]

- Transfect with MOB2-specific siRNAs using Lipofectamine RNAiMax or similar transfection reagents [29]

- Use siRNA concentrations of 20-50 nM for optimal knockdown efficiency

- Include appropriate negative control siRNAs (non-targeting sequences)

- Harvest cells 48-96 hours post-transfection for functional analyses

Validation of Knockdown Efficiency:

- Assess MOB2 mRNA levels using RT-qPCR with primers specific for MOB2 transcripts

- Evaluate protein depletion via western blotting with anti-MOB2 antibodies

- Confirm functional consequences through monitoring NDR1/2 phosphorylation status

Phenotypic Outcomes of MOB2 Knockdown

MOB2 knockdown consistently produces several hallmark phenotypic outcomes across multiple cell types. The most pronounced effect is the accumulation of endogenous DNA damage, which subsequently triggers a p53/p21-dependent G1/S cell cycle arrest [5] [29]. This phenotype manifests as significantly reduced cell proliferation and impaired colony formation capacity. Additionally, MOB2-depleted cells exhibit heightened sensitivity to exogenous DNA damaging agents such as ionizing radiation and doxorubicin, demonstrating compromised DNA damage response signaling [29]. Mechanistically, these phenotypes are linked to impaired recruitment of the MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 (MRN) complex and activated ATM to DNA damage sites, revealing MOB2's crucial role in facilitating early DNA damage sensing and repair machinery [29].

Table 1: Phenotypic Consequences of MOB2 Knockdown in Human Cells

| Phenotypic Readout | Experimental Assessment | Key Observations | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Cycle Progression | Flow cytometry, p21/p53 activation | G1/S arrest, p53/p21 activation | Prevents proliferation with accumulated DNA damage |

| DNA Damage Response | Immunofluorescence for γH2AX, ATM phosphorylation; comet assay | Increased endogenous DNA damage; impaired IR-induced ATM activation | Compromised genome maintenance |

| Cell Survival | Clonogenic assays, apoptosis markers | Reduced survival after DNA damage | Increased sensitivity to genotoxic stress |