MOB1 vs MOB2: Decoding Binding Specificity and Functional Regulation of NDR Kinases in Hippo Signaling

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the distinct binding specificities of MOB1 and MOB2 coactivators for NDR/LATS kinases, crucial regulators in Hippo signaling pathways.

MOB1 vs MOB2: Decoding Binding Specificity and Functional Regulation of NDR Kinases in Hippo Signaling

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the distinct binding specificities of MOB1 and MOB2 coactivators for NDR/LATS kinases, crucial regulators in Hippo signaling pathways. We explore the structural basis for selective kinase-coactivator complex formation, examining how MOB1 activates LATS kinases while MOB2 exhibits a context-dependent regulatory relationship with NDR kinases. The content covers experimental methodologies for studying these interactions, addresses common research challenges, and validates functional consequences in physiological and disease contexts, particularly cancer. This synthesis aims to equip researchers and drug development professionals with mechanistic insights and practical frameworks for targeting these specific protein interactions in therapeutic development.

Structural Foundations and Evolutionary Conservation of MOB-NDR Kinase Interactions

The Hippo signaling pathway is an evolutionarily conserved system crucial for controlling cell proliferation, morphogenesis, and organ size in eukaryotes. At the heart of this pathway are the NDR/LATS kinases (Nuclear Dbf2-related / Large Tumor Suppressor kinases), which belong to the AGC family of serine-threonine protein kinases. These kinases form functional complexes with MOB coactivator proteins (Monopolar spindle one-binder), an association that is essential for kinase activity and pathway function [1] [2].

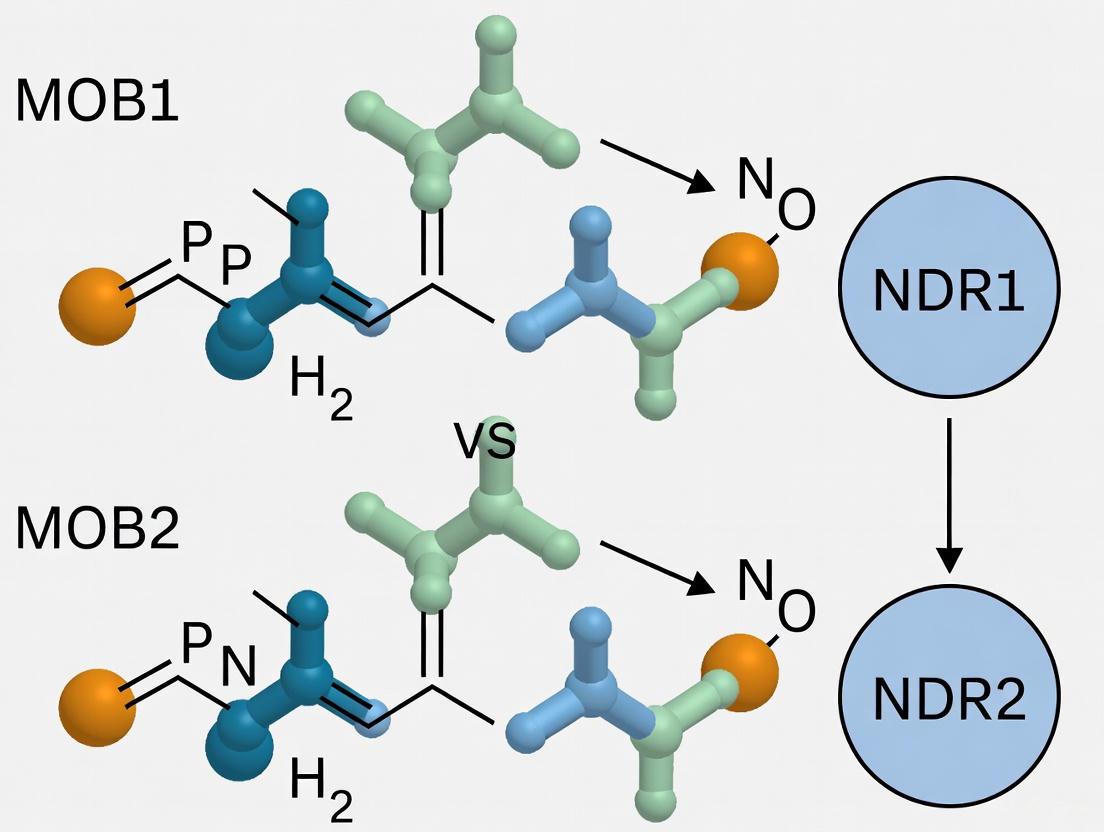

The NDR/LATS family is divided into two main subfamilies: the LATS kinases (including Dbf2 and Dbf20 in yeast, LATS1/2 in mammals) that primarily associate with MOB1 proteins, and the NDR kinases (including Cbk1 in yeast, NDR1/STK38 and NDR2/STK38L in mammals) that specifically bind MOB2 proteins [1] [3]. This specific kinase-cofactor pairing is maintained from yeast to humans despite significant sequence conservation among MOB proteins, indicating strong evolutionary pressure to preserve binding specificity [1] [4].

Table 1: Core NDR/LATS Kinases and Their MOB Cofactors Across Model Organisms

| Organism | NDR-subfamily Kinases | MOB Cofactor | LATS-subfamily Kinases | MOB Cofactor | Biological Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae (Budding Yeast) | Cbk1 | Mob2 | Dbf2, Dbf20 | Mob1 | RAM network: cell separation, morphogenesis; MEN: mitotic exit, cytokinesis [1] [2] |

| D. melanogaster (Fruit Fly) | – | dMob2 | Warts | dMob1 (Mats) | Hippo pathway: tissue growth, neuromuscular junction morphology [4] [5] |

| H. sapiens (Human) | NDR1/STK38, NDR2/STK38L | MOB2 | LATS1, LATS2 | MOB1A/B | Cell cycle progression, DNA damage response, neuronal development [3] [4] [6] |

Structural Basis of Kinase-Cofactor Interactions

The association between NDR/LATS kinases and MOB cofactors is mediated through a characteristic N-terminal regulatory (NTR) region in the kinases that binds to a specific surface on the MOB proteins. Structural analyses of complexes such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cbk1NTR–Mob2 and Dbf2NTR–Mob1 have revealed that the NTR forms a V-shaped helical hairpin that docks onto the MOB protein [1]. This NTR–Mob interface serves as a common structural platform that mediates kinase–cofactor binding across the entire NDR/LATS family.

The MOB cofactor plays a critical role in kinase activation by organizing the NTR to interact with the AGC kinase C-terminal hydrophobic motif (HM), which is involved in allosteric regulation. This Mob-organized NTR appears to mediate association of the HM with an allosteric site on the N-terminal kinase lobe, facilitating kinase activation [1]. This mechanism represents a distinctive kinase regulation mechanism unique to NDR/LATS kinases.

Molecular Determinants of MOB1 vs. MOB2 Specificity

The specific pairing of LATS kinases with MOB1 and NDR kinases with MOB2 is enforced by discrete structural elements rather than broadly distributed interface differences. Several key determinants have been identified:

- Short specificity motifs: A short motif in the Mob structure that differs between Mob1 and Mob2 strongly contributes to molecular recognition [1]

- Key residue interactions: Alteration of specific residues in the Cbk1 NTR allows association with the noncognate Mob cofactor, demonstrating that specificity is restricted to discrete sites [1]

- Competitive binding mechanisms: In mammalian cells, MOB2 competes with MOB1 for NDR binding, with MOB1/NDR complexes associated with increased NDR kinase activity while MOB2/NDR complexes show diminished activity [4]

Table 2: Structural and Functional Differences Between MOB1 and MOB2 Complexes

| Characteristic | MOB1 Complexes | MOB2 Complexes |

|---|---|---|

| Kinase Partners | LATS kinases (Dbf2/Dbf20 in yeast, LATS1/2 in mammals) [1] | NDR kinases (Cbk1 in yeast, NDR1/2 in mammals) [1] [3] |

| Cellular Functions | Mitotic exit, cytokinesis, Hippo pathway regulation, YAP/TAZ inhibition [2] | Cell morphogenesis, polarization, DNA damage response, neural development [4] [6] |

| Subcellular Localization | Cytoplasmic, spindle pole bodies, cell cortex [2] | Nuclear and cytoplasmic, punctate cytoplasmic distribution [3] |

| Activation Outcome | Enhanced kinase activity toward specific substrates (e.g., YAP/TAZ) [2] | Varied effects: can stimulate or diminish kinase activity depending on context [4] |

| Regulatory Role | Core pathway component [2] | Context-dependent modulator [4] |

Functional Consequences of Kinase-Cofactor Interactions

Activation Mechanisms and Downstream Signaling

The binding of MOB cofactors to NDR/LATS kinases dramatically influences kinase activity and substrate specificity. For mammalian NDR kinases, association with MOB2 strongly stimulates catalytic activity [3]. This activation depends on the phosphorylation status of key regulatory sites, including the hydrophobic motif (HM) and activation loop (AL). The MOB-organized NTR facilitates proper positioning of the phosphorylated HM, enabling optimal orientation of the kinase αC helix, a component critical for kinase activation [1].

The functional outcomes of NDR/LATS-MOB complexes differ significantly between the two subfamilies:

- MOB1-LATS complexes: Primarily regulate cell proliferation and organ size through phosphorylation of YAP/TAZ transcriptional coactivators, leading to their cytoplasmic sequestration and degradation [2]

- MOB2-NDR complexes: Govern diverse processes including cell morphogenesis, polarization, DNA damage response, and neuronal development through phosphorylation of distinct substrates [4] [6]

Biological Functions in Cellular Processes

MOB2-NDR kinase signaling plays critical roles in several fundamental cellular processes:

- Cell cycle and DNA damage response: Endogenous MOB2 is required to prevent accumulation of DNA damage and avoid undesired activation of cell cycle checkpoints. MOB2 depletion triggers p53/p21-dependent G1/S cell cycle arrest [4]

- Neural development: NDR kinases regulate vesicle trafficking, polarity, and morphogenesis in neuronal tissues. Deletion of Ndr kinases leads to concurrent apoptosis and proliferation of retinal neurons [6]

- Cell proliferation control: MOB2 competes with MOB1 for NDR binding, potentially creating a regulatory switch that modulates NDR kinase activity in response to cellular cues [4]

Experimental Approaches for Studying MOB-Kinase Interactions

Structural Biology Methodologies

Protein Expression and Purification

- Challenge: Recombinant expression of monomeric Mob2 in E. coli can be problematic due to stability issues

- Solution: Engineering of zinc-binding Mob2 (V148C Y153C) that recapitulates zinc-binding motifs found in metazoan Mob2 orthologs, enabling suitable E. coli expression for biochemistry [1]

- Protocol: Express NTR regions (e.g., Cbk1NTR residues 251-351) and Mob proteins in E. coli, purify using affinity chromatography, and form complexes for crystallography

Crystallographic Data Collection and Structure Determination

- Crystallization: Co-crystallize NTR-Mob complexes using vapor diffusion methods

- Data Collection: Collect X-ray diffraction data at synchrotron sources (e.g., wavelength ~0.978-1.000 Å)

- Structure Determination: Solve structures using molecular replacement with existing related structures as search models

- Refinement: Iterative model building and refinement to achieve final structures with R-work/R-free values typically around 0.23/0.30 [1]

Table 3: Crystallographic Data Collection and Refinement Statistics for Representative NTR-MOB Complexes

| Parameter | Dbf2NTR–Mob1 | Cbk1NTR–Mob2 | Cbk1–Mob2–pepSsd1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution (Å) | 46.9–3.5 (3.59–3.50) | 39.9–2.8 (2.87–2.80) | 44.60–3.15 (3.23–3.15) |

| Space Group | P61 2 2 | P41 2 12 | C1 2 1 |

| Cell Dimensions (Å) | a=108.28, b=108.28, c=134.76 | a=126.23, b=126.27, c=49.34 | a=138.43, b=79.99, c=117.59 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (100) | 99.8 (100) | 99.7 (99.7) |

| R-work/R-free | 0.2292/0.2631 | 0.2490/0.2838 | 0.2310/0.2983 |

| Ramachandran Favored (%) | 93.5 | 93 | 76 |

| PDB Reference | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

Interaction Mapping Techniques

Proximity-Dependent Biotin Identification (BioID)

- Principle: Fuse MOB proteins to a promiscuous biotin ligase (BirA*) that biotinylates proximal proteins within ~10 nm

- Cell Systems: Generate tetracycline-inducible HEK293 and HeLa Flp-In T-REx cells expressing BirA*-FLAG-MOB fusions

- Controls: Include BirA-FLAG and BirA-FLAG-EGFP as negative controls

- Validation: Confirm interactions by affinity purification-mass spectrometry and functional assays [7]

Binding Affinity and Specificity Assays

- Quantitative approaches: Fluorescence polarization (FP) to measure binding affinities of wild-type and mutant complexes

- Specificity mapping: Systematic mutagenesis of interface residues to identify determinants of MOB1 vs. MOB2 specificity [1]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Studying NDR/LATS-MOB Interactions

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Zinc-binding Mob2 mutant | Stabilizes Mob2 for structural studies | Mob2 V148C Y153C engineering recapitulates metazoan zinc-binding motif [1] |

| NTR construct plasmids | Expression of kinase regulatory regions | Cbk1NTR (251-351), Dbf2NTR for binding studies [1] |

| Tetracycline-inducible BioID cell lines | Proximity-dependent interaction mapping | HEK293 and HeLa Flp-In T-REx BirA*-FLAG-MOB cells [7] |

| Crystallization screens | Optimization of protein crystal growth | Commercial sparse matrix screens for various space groups [1] |

| Phospho-specific antibodies | Detection of HM and AL phosphorylation | Critical for monitoring kinase activation status [1] |

| Docking motif peptides | Substrate interaction studies | pepSsd1 for Cbk1 substrate docking characterization [1] |

| Kinase activity assays | Measuring NDR/LATS kinase activation | Radioactive or luminescent kinase assays with specific substrates [3] |

Future Perspectives and Research Directions

The study of NDR/LATS kinases and their MOB cofactors continues to evolve with several emerging research directions:

- MOB3 subfamily characterization: MOB3 proteins represent a poorly characterized branch that associates with the pro-apoptotic kinase MST1 rather than NDR/LATS kinases [4]. Recent BioID studies revealed an unexpected connection between MOB3C and the RNase P complex, suggesting potential roles in RNA biology [7]

- Therapeutic targeting: The distinct roles of NDR1 and NDR2 in processes like vesicle trafficking, autophagy, and immune response position them as potential therapeutic targets, particularly in cancer contexts [8] [6]

- Neurobiological functions: Emerging evidence indicates crucial roles for NDR kinases in neuronal development, homeostasis, and inflammation, suggesting potential therapeutic applications for neuronal diseases [6]

Understanding the precise molecular determinants governing MOB1 versus MOB2 binding specificity remains a crucial area of investigation, with implications for targeted therapeutic intervention in cancer and other diseases where Hippo signaling is disrupted.

The NDR/LATS family of kinases and their MOB coactivators constitute an evolutionarily conserved signaling module central to eukaryotic cell proliferation, morphogenesis, and survival. This whitepaper delineates the stringent binding specificity that defines the CBK1-Mob2 and DBF2-Mob1 paradigms, drawing on structural, biochemical, and functional evidence from yeast to human homologs. We examine the molecular determinants that enforce selective kinase-coactivator pairing, the downstream physiological consequences of these specific complexes, and their implications for therapeutic targeting. Within the broader context of MOB1 versus MOB2 binding specificity for NDR kinase research, this analysis underscores how conserved structural frameworks yield diverse, context-dependent biological outputs, from regulating mitotic exit to controlling organ size.

The NDR (Nuclear Dbf2-related) / LATS (Large Tumor Suppressor) family of AGC kinases represents a deeply conserved branch of eukaryotic signaling pathways [9]. These kinases, which include Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cbk1 and Dbf2, and their human counterparts NDR1/2 and LATS1/2, require binding to Mob (Mps one binder) coactivator proteins for their full activity and biological function [1] [3] [10]. A fundamental characteristic of this system is the high specificity of kinase-coactivator interactions: NDR-subfamily kinases (e.g., Cbk1) specifically associate with Mob2 proteins, while LATS-subfamily kinases (e.g., Dbf2) specifically associate with Mob1 proteins [1] [2]. This specificity is maintained despite significant sequence conservation within both the kinase and Mob protein families, suggesting strong evolutionary pressure to preserve discrete functional partnerships.

These specific kinase-Mob complexes form the core of ancient signaling networks, notably the Hippo pathway, which controls cell proliferation, morphogenesis, and apoptosis from yeast to humans [2] [9]. In budding yeast, the two primary networks are the Regulation of Ace2 and Morphogenesis (RAM) network, governed by Cbk1-Mob2, and the Mitotic Exit Network (MEN), governed by Dbf2/20-Mob1 [11] [2]. The functional segregation of these pathways underscores the critical importance of specific Mob pairing: despite simultaneous presence of all proteins in the cytosol, Cbk1–Mob1 or Dbf2–Mob2 complexes do not form, ensuring proper signaling fidelity [1].

Structural Basis of Kinase-MOB Specificity

Structural biology has been instrumental in elucidating the molecular basis for selective Mob recognition. The crystal structure of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cbk1 kinase bound to Mob2 provides a high-resolution model of an NDR kinase-Mob complex [1] [2]. The NDR/LATS kinases contain a distinctive N-terminal regulatory (NTR) region that directly binds the Mob coactivator. This NTR region forms a V-shaped helical hairpin that docks against a conserved surface on the Mob protein [1].

Table 1: Key Structural Features of Kinase-MOB Complexes

| Component | Structural Feature | Functional Role | Conservation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinase NTR | V-shaped helical hairpin | Mob coactivator binding | High from yeast to humans |

| Mob Protein | Conserved core fold | Kinase activation & localization | High from yeast to humans |

| Hydrophobic Motif (HM) | C-terminal motif | Allosteric kinase regulation | Conserved in AGC kinases |

| Specificity Motif | Variable loop in Mob | Determines Mob1 vs. Mob2 binding | Key residues differ between Mob1/2 |

The binding of Mob to the kinase NTR organizes this region, enabling it to interact with the kinase's C-terminal hydrophobic motif (HM), a critical element for allosteric kinase activation [1]. This Mob-organized NTR appears to mediate association of the HM with an allosteric site on the N-terminal kinase lobe, facilitating kinase activation. This mechanism represents a distinctive mode of kinase regulation unique to the NDR/LATS family.

Molecular Determinants of MOB1 vs. MOB2 Specificity

Specificity for cognate Mob binding is restricted by discrete molecular recognition sites rather than being broadly distributed across the interaction surface. Comparative structural analysis of Cbk1NTR–Mob2 and Dbf2NTR–Mob1 complexes reveals that a short, variable motif within the Mob structure, which differs between Mob1 and Mob2, strongly contributes to molecular recognition [1]. Alteration of specific residues in this motif in Cbk1's NTR allows association with the non-cognate Mob cofactor, confirming that these discrete sites act as specificity gates.

The improved structural model of the Cbk1-Mob2 interface highlights the role of Mob binding in positioning the phosphorylated threonine (Thr-743 in Cbk1) within the kinase's HM. Upon Mob binding, this phosphorylated residue becomes proximal to a conserved arginine in the NTR, driving optimal positioning of the kinase's αC helix, a component critical for kinase activation [1]. This precise geometric arrangement is only achievable with the cognate Mob partner, thereby coupling binding specificity to catalytic activation.

Diagram 1: Structural basis of kinase-MOB specificity. The NTR and MOB specificity motif enforce selective binding, leading to stable, active cognate complexes.

Functional Consequences of Specific Pairing

The CBK1-Mob2 Complex in the RAM Network

The Cbk1-Mob2 complex is the central effector of the RAM network in budding yeast. This pathway is essential for controlling cell separation and polarized morphogenesis [11] [12]. During hyphal development in Candida albicans, Cbk1 and Mob2 localize to the tips of growing hyphae and the region of the septum, where they regulate the maintenance of polarisome components [11]. A key mechanism involves CDK-dependent phosphorylation of Mob2, which is essential for normal hyphal development. Mutations in CDK consensus sites within Mob2 significantly impair hyphal development, causing short hyphae with enlarged tips and illicit activation of cell separation programs [11].

A critical function of the Cbk1-Mob2 complex is the direct phosphorylation and regulation of the Ace2 transcription factor. Cbk1 phosphorylates Ace2 at specific sites matching its unusual consensus motif (strong preference for histidine at position -5: H-X-[K/R]-[K/R]-X-[S/T]), which controls Ace2's asymmetric localization to the daughter cell nucleus and its transcriptional activity [12]. This phosphorylation blocks Ace2's interaction with nuclear export machinery, trapping it in the daughter nucleus where it drives expression of genes required for cell separation [12].

The DBF2-Mob1 Complex in the Mitotic Exit Network

The Dbf2-Mob1 complex functions as a central component of the MEN, which controls cytokinesis and the transition from M phase to G1 [1] [2]. This pathway ensures the coordinated completion of mitosis and cell division. The Dbf2-Mob1 complex is recruited to the spindle pole bodies by the scaffold protein Nud1, where it becomes activated and promotes the release of the Cdc14 phosphatase from the nucleolus, leading to the reversal of mitotic CDK phosphorylation and mitotic exit [2].

The specific pairing of Dbf2 with Mob1, rather than Mob2, is essential for directing this complex to its correct mitotic functions. While the structural basis of activation is similar to Cbk1-Mob2, the downstream substrates and cellular localization differ dramatically, driven by the distinct protein-protein interaction networks enabled by Mob1 versus Mob2.

Conservation in Metazoans: From Flies to Humans

The functional specificity of Mob pairing is conserved in metazoans. Human NDR1 and NDR2 kinases associate specifically with MOB2 proteins, while LATS1 and LATS2 associate with MOB1 proteins [13] [3]. Human MOB proteins dramatically stimulate the catalytic activity of their cognate NDR kinases [3] [10]. The activation mechanism involves recruitment to cellular membranes, where membrane-targeted MOBs robustly promote NDR phosphorylation and activation within minutes of association with membranous structures [13].

In humans, the LATS1/2-MOB1 complex phosphorylates the YAP/TAZ transcriptional coactivators, leading to their cytoplasmic retention and degradation, thereby suppressing cell proliferation—a function disrupted in many cancers [2] [9]. The NDR1/2-MOB2 complex, while less characterized, contributes to neuronal morphogenesis, cell cycle progression, and control of the G1/S restriction point [9].

Table 2: Functional Specialization of Kinase-MOB Complexes Across Species

| Complex | Yeast Pathway | Primary Yeast Functions | Mammalian Homologs | Mammalian Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBK1-Mob2 | RAM Network | Cell separation, polarized growth, Ace2 regulation | NDR1/2 - MOB2 | Neurite outgrowth, cell proliferation, Golgi organization |

| DBF2-Mob1 | MEN | Mitotic exit, cytokinesis, Cdc14 activation | LATS1/2 - MOB1 | Hippo signaling, YAP/TAZ phosphorylation, tumor suppression |

Experimental Analysis of Kinase-MOB Interactions

Key Methodologies and Reagents

Research into kinase-MOB specificity employs a multidisciplinary approach combining structural biology, biochemistry, and genetics. The following experimental protocols are central to this field.

Protocol 1: Structural Determination of Kinase-MOB Complexes

- Protein Expression and Purification: Express the kinase N-terminal regulatory region (NTR) and full-length Mob protein in E. coli. For unstable Mob proteins (e.g., wild-type Mob2), engineering a zinc-binding motif (e.g., Mob2 V148C Y153C) can improve stability and expression [1].

- Complex Formation: Mix purified kinase NTR and Mob proteins in equimolar ratios and purify the complex using size-exclusion chromatography.

- Crystallization: Screen for crystallization conditions using robotic systems. For Cbk1NTR–Mob2, crystals grew in condition containing 0.1 M sodium citrate tribasic dihydrate pH 5.5, 15% (v/v) 2-Propanol, 15% (w/v) PEG 4,000 [1].

- Data Collection and Structure Determination: Collect X-ray diffraction data (e.g., at 2.8 Å resolution for Cbk1NTR–Mob2). Solve the structure by molecular replacement using known Mob and kinase domain structures as search models. Refine the model iteratively [1] [2].

Protocol 2: Assessing MOB-Dependent Kinase Activation

- Kinase Assay Setup: Prepare reaction buffer containing 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM MgCl2.

- Mob Stimulation: Incubate NDR kinase with increasing concentrations of cognate or non-cognate Mob protein (e.g., 0-10 μM) for 15-30 minutes at 30°C.

- Phosphorylation Reaction: Initiate reaction by adding ATP mix (100 μM ATP containing [γ-32P]ATP). Use a suitable substrate such as the histone H1 or a specific peptide substrate (e.g., for Cbk1: a peptide derived from Ace2 containing the H-X-[K/R]-[K/R]-X-[S/T] motif) [12].

- Detection: Terminate reactions with SDS sample buffer, separate proteins by SDS-PAGE, and visualize phosphorylated substrates by autoradiography or phosphorimaging [3] [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Investigating Kinase-MOB Specificity

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Zinc-binding Mob2 Mutant | Stabilizes Mob2 for structural studies and biochemical assays | Mob2 V148C Y153C for E. coli expression [1] |

| λ-Phosphatase | Distinguishes phosphorylated protein isoforms; confirms phospho-mobility shifts on gels | Treatment of Mob2 extracts to confirm phosphorylation-dependent mobility shift [11] |

| Phospho-specific Antibodies | Detects activated, phosphorylated kinases; assesses kinase activation state | Antibodies against phosphorylated Ser281 and Thr444 of human NDR1 [13] |

| Membrane-Targeting Constructs | Investigates role of subcellular localization in kinase activation | Myristoylation/palmitylation motif fusions for membrane targeting of NDR/MOB [13] |

| Conditional Expression Systems | For inducible membrane translocation to study kinetics of activation | Chimeric hMOB with C1 domain for phorbol ester-induced membrane recruitment [13] |

| Peptide Scanning Arrays | Defines kinase phosphorylation consensus motifs | Used to determine Cbk1's unique basophilic motif with histidine at -5 [12] |

Visualization of Signaling Pathways and Molecular Interactions

Diagram 2: Specific kinase-MOB complexes in distinct signaling pathways. The CBK1-Mob2 and DBF2-Mob1 complexes function in separate pathways (RAM and MEN) with different inputs and biological outputs.

Discussion and Research Implications

The evolutionary conservation of specific CBK1-Mob2 and DBF2-Mob1 pairing from yeast to humans highlights the fundamental importance of this regulatory paradigm. The structural mechanisms enforcing this specificity are remarkably conserved, yet these core signaling modules have been adapted to control diverse biological processes across eukaryotes—from fungal cell polarity to mammalian organ size and neuronal development [2] [9].

From a therapeutic perspective, the NDR/LATS kinases and their Mob coactivators represent attractive targets, particularly in cancer where Hippo signaling is frequently disrupted. The discrete nature of the specificity determinants suggests it might be possible to develop small molecules that selectively disrupt specific kinase-Mob interactions or modulate the activity of particular complexes. Furthermore, the recent implication of NDR kinases in aging hallmarks—including cellular senescence, chronic inflammation, and loss of proteostasis—opens new avenues for research into therapeutic interventions for age-related diseases [9].

Future research directions should focus on: (1) elucidating the complete regulatory network of phosphorylation events controlling kinase-Mob complex assembly and activity; (2) developing selective chemical probes to manipulate specific kinase-Mob interactions in cellular and animal models; and (3) exploring the therapeutic potential of targeting these complexes in cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and other age-associated conditions. The deep evolutionary conservation of these pathways from yeast to humans provides a powerful foundation for using model organisms to unravel fundamental mechanisms with direct relevance to human health and disease.

The NDR (Nuclear Dbf2-related) kinase family and their MOB (Mps one binder) coactivators constitute an evolutionarily conserved signaling module central to eukaryotic biology, governing processes from cell proliferation and morphogenesis to neuronal development and tumor suppression [14] [15]. The functional core of this module is the specific complex formed between the N-terminal Regulatory (NTR) domain of an NDR/LATS kinase and its cognate MOB protein. For researchers and drug development professionals, a precise understanding of this interface is paramount, as it dictates signaling specificity and presents a potential target for therapeutic intervention. This whitepaper delineates the structural principles governing NDR-MOB complexes, with a specific focus on the mechanistic basis for selective binding of MOB1 versus MOB2 to their respective kinase partners, a critical determinant in the functional output of Hippo and Hippo-like signaling pathways.

The NDR-MOB complex is characterized by a conserved architecture where the MOB coactivator binds the NTR region of the kinase, facilitating its activation and defining its functional role within cellular signaling networks.

The Conserved NTR-MOB Interface

The NDR kinase NTR domain adopts a V-shaped helical hairpin conformation upon binding to its MOB coactivator [1]. This structural motif is a common platform, observed in complexes from yeast to humans, including S. cerevisiae Cbk1–Mob2, Dbf2–Mob1, and human Lats1–Mob1 and Ndr–Mob1 [1]. The MOB protein itself possesses a highly conserved globular fold, a four alpha-helix bundle, which presents distinct surfaces for interaction with the kinase NTR and other regulatory proteins [15].

The primary role of MOB binding is to organize the NTR domain, enabling it to interact with the C-terminal hydrophobic motif (HM) of the kinase [1]. The HM is a critical regulatory element in AGC kinases, and in NDR/LATS kinases, its phosphorylation by upstream Hippo or Hippo-like kinases is essential for activation. The MOB-organized NTR mediates the association of the phosphorylated HM with an allosteric site on the kinase's N-terminal lobe, thereby stabilizing the active conformation of the kinase [1].

Table 1: Key Structural Features of Characterized NDR-MOB Complexes

| Complex | Organism | PDB Code(s) | Resolution (Å) | Key Structural Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cbk1–Mob2 | S. cerevisiae | 4LQS, 4LQP, 4LQQ [2] | ~3.15 [1] | First full-length NDR/LATS-Mob structure; revealed novel coactivator-organized activation region and substrate docking mechanism [14]. |

| Cbk1NTR–Mob2 | S. cerevisiae | N/A | 2.8 [1] | Improved view of NTR-Mob2 interface; showed Mob2 organizes NTR to position the hydrophobic motif [1]. |

| Dbf2NTR–Mob1 | S. cerevisiae | N/A | 3.5 [1] | Provided a comparative structure to understand the basis of Mob binding specificity [1]. |

| Lats1NTR–hMob1 | H. sapiens | PDB 4RV9 [1] | N/A | Structural model of a human Hippo pathway core complex. |

Functional Consequences of MOB Binding

The formation of the NDR-MOB complex has several critical functional outcomes:

- Kinase Activation: MOB binding is essential for NDR/LATS kinase function. The association dramatically stimulates NDR1 and NDR2 catalytic activity [3].

- Allosteric Regulation: The complex creates a novel binding pocket that participates in the formation of the active state of the kinase after phosphorylation by upstream kinases [14].

- Substrate Docking: The structure of the Cbk1-Mob2 complex revealed a substrate docking mechanism previously unknown in AGC kinases, which provides robustness to the kinase's regulation of its in vivo substrates [14] [2].

Figure 1: MOB-Coordinated Kinase Activation Pathway. The MOB coactivator binds and organizes the NTR domain, which in turn mediates the positioning of the phosphorylated hydrophobic motif (HM) for allosteric kinase activation.

MOB1 vs. MOB2 Binding Specificity

A defining feature of NDR-MOB signaling is the high specificity of kinase-coactivator pairing. Generally, Lats kinases bind MOB1 proteins, while Ndr kinases bind MOB2 proteins, forming non-overlapping functional complexes in vivo [1] [16].

Structural Basis for Specificity

The specificity of MOB binding is not distributed across the entire interface but is restricted by discrete sites [1]. A short, variable motif within the MOB protein structure, which differs between MOB1 and MOB2, is a major determinant of this molecular recognition. Mutagenesis studies have shown that altering residues in the Cbk1 (Ndr) NTR allows association with the non-cognate MOB1 cofactor, confirming that specificity is governed by a limited set of interactions [1].

Functional Consequences of Specific Pairing

The specific MOB1-NDR and MOB2-NDR pairings lead to distinct functional outcomes:

- MOB1 Complexes: Typically activate kinases involved in mitotic exit and growth suppression, such as the Dbf2/20-Mob1 complex in the Mitotic Exit Network (MEN) and the LATS1/2-MOB1 complex in the metazoan Hippo pathway [14] [15].

- MOB2 Complexes: Typically activate kinases regulating cell polarity and morphogenesis, such as the Cbk1-Mob2 complex in the RAM network and the NDR1/2-MOB2 complex in animals [14].

In mammalian systems, the binding and functional outcomes can be more complex. hMOB2 binds to the N-terminal region of NDR1, but this binding differs significantly from hMOB1A. hMOB2 competes with hMOB1A for NDR binding and, unlike the activating hMOB1A, hMOB2 binding is associated with unphosphorylated NDR and functions as a negative regulator of NDR kinase activity [16]. RNAi depletion of hMOB2 results in increased NDR kinase activity, and its overexpression impairs NDR functions in apoptosis and centrosome duplication [16].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of MOB1 vs. MOB2 Binding and Function

| Feature | MOB1 | MOB2 |

|---|---|---|

| Cognate Kinases | LATS subfamily (e.g., LATS1/2, Dbf2/20) [1] [14] | NDR subfamily (e.g., NDR1/2, Cbk1, SAX-1) [1] [17] |

| Primary Signaling Role | Hippo Pathway / MEN; growth control, mitotic exit [14] [15] | Hippo-like Pathway / RAM; morphogenesis, polarity, dendrite pruning [14] [17] |

| Effect on Kinase Activity | Activator [3] [15] | Context-dependent: Activator in yeast [14]; Competitor/Inhibitor of NDR in humans [16] |

| Key Specificity Determinant | Discrete short motif in MOB structure [1] | Discrete short motif in MOB structure [1] |

Figure 2: MOB-Kinase Binding Specificity and Competition. MOB1 and MOB2 typically form specific cognate complexes with LATS and NDR kinases, respectively. In human cells, MOB2 can compete with MOB1 for binding to NDR kinases and act as an inhibitor.

Experimental Protocols for Studying NDR-MOB Interactions

A multidisciplinary approach is required to dissect the structural and functional details of the NDR-MOB complex. The following protocols are based on methodologies successfully employed in the cited literature.

Protein Expression and Complex Purification

Objective: To produce high-quality, recombinant NDR and MOB proteins for structural and biochemical studies.

Detailed Protocol:

- Construct Design: Clone the DNA sequences encoding the NTR domain of the NDR kinase (e.g., Cbk1 residues 251-351) and the full-length MOB protein (e.g., Mob2) into compatible E. coli expression vectors, such as pGEX-4T1 or pMal-2c for generating GST- or MBP- fusion proteins, respectively [1] [16].

- Protein Stabilization (for unstable MOBs): For MOB proteins that are unstable in monomeric form (e.g., S. cerevisiae Mob2), engineer a stabilizing disulfide bond by introducing cysteine residues (e.g., Mob2 V148C Y153C) to mimic a zinc-binding motif found in metazoan orthologs [1].

- Co-expression and Purification:

- Co-express the His-tagged kinase NTR and the MOB protein in E. coli [1].

- Lyse cells and purify the complex using immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) via the His-tag.

- Further purify the complex by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) to ensure homogeneity and remove aggregates. The complex typically elutes at a volume corresponding to a 1:1 heterodimer.

Crystallization and Structure Determination

Objective: To determine the high-resolution three-dimensional structure of the NDR-MOB complex.

Detailed Protocol:

- Crystallization: Use the vapor-diffusion method. Set up trials with the purified complex at concentrations of 10-20 mg/mL. Crystals of the Cbk1NTR–Mob2 complex were obtained in conditions such as 0.1M sodium citrate tribasic dihydrate pH 5.5, 15% v/v 1,4-Dioxane, 15% w/v PEG-20,000 [1].

- Data Collection and Processing: Flash-cool crystals in liquid nitrogen using a cryoprotectant. Collect X-ray diffraction data at a synchrotron beamline. Process the data (indexing, integration, and scaling) using software like XDS or HKL-2000 [1].

- Structure Solution: Solve the phase problem by molecular replacement (MR) using a known MOB structure (e.g., PDB 4JIZ) and an NTR model as search models. Iterative model building and refinement are performed using Coot and Phenix/Refmac [1] [14].

Table 3: Crystallographic Data Collection and Refinement Statistics (Example from [1])

| Parameter | Cbk1NTR–Mob2 | Dbf2NTR–Mob1 |

|---|---|---|

| Data Collection | ||

| Space Group | P41212 | P6122 |

| Resolution (Å) | 39.9 - 2.8 | 46.9 - 3.5 |

| Refinement | ||

| Rwork / Rfree | 0.2490 / 0.2838 | 0.2292 / 0.2631 |

| No. of Atoms | 2196 | 2024 |

| B-factors (Ų) | 92.7 | 88.3 |

| Ramachandran Plot | ||

| - Favored (%) | 93 | 93.5 |

| - Outliers (%) | 3 | 1.6 |

Functional Analysis of Binding Specificity and Kinase Activity

Objective: To validate the structural findings and quantify the functional impact of NDR-MOB interactions.

Detailed Protocol:

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Generate point mutations in the specificity-determining motifs of the NTR (e.g., Cbk1 NTR) or the MOB protein to test their effect on binding and specificity [1].

- Binding Affinity Measurements:

- Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP): Express wild-type and mutant proteins in mammalian cells (e.g., COS-7, HEK 293). Immunoprecipitate the kinase and probe for co-precipitating MOB protein by western blotting [16].

- Quantitative Binding Assays: Use techniques like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) to determine the binding affinity (KD) between purified wild-type and mutant NTR and MOB proteins.

- Kinase Activity Assays: Measure the activity of the full-length NDR kinase in the presence of its cognate or non-cognate MOB partner. Use in vitro kinase assays with a suitable substrate (e.g., myelin basic protein) and [γ-32P]ATP. Quantify phosphate incorporation to assess the stimulatory or inhibitory effect of MOB binding [16] [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Investigating NDR-MOB Complexes

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Stabilized MOB Variants | Enables structural studies of unstable MOB proteins. | S. cerevisiae Mob2 V148C Y153C (zinc-binding variant) [1]. |

| Kinase Activation Reporters | Measures NDR/LATS kinase activity in vitro and in cells. | Phospho-specific antibodies against NDR HM (e.g., pT444/T442); generic kinase substrates (e.g., Myelin Basic Protein) [16]. |

| Specificity Mutants | Probes the structural basis of selective MOB binding. | Mutations in the short specificity motif of the NTR (e.g., Cbk1 NTR mutants) or MOB protein [1]. |

| Tet-Inducible Expression Vectors | Allows controlled overexpression of MOB proteins in mammalian cells for functional studies. | pT-Rex-DEST30 vectors for inducible expression of hMOB2 [16]. |

| RNAi Knockdown Systems | Assesses the functional consequences of depleting specific MOBs. | pTER vectors expressing shRNA against hMOB2 to study its role as a negative regulator [16]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Software | Models the dynamics and conformational changes of the NDR-MOB complex. | Used to simulate HM engagement and allosteric activation [14]. |

Molecular Determinants of MOB1 Specificity for LATS Kinases

The Mps One Binder (MOB) family of adapter proteins represents crucial regulatory components in key signaling pathways, including the Hippo tumor suppressor network. While MOB proteins share structural homology, they exhibit distinct binding specificities for members of the NDR/LATS kinase family. This technical analysis examines the molecular determinants governing MOB1's specific recognition of LATS kinases over the closely related NDR kinases. Through structural, biochemical, and genetic perspectives, we delineate how specific residue interactions, phosphorylation events, and allosteric mechanisms confer binding specificity. Understanding these precise molecular interactions provides critical insights for targeted therapeutic interventions in cancers where Hippo pathway dysregulation plays a fundamental role.

MOB proteins constitute an evolutionarily conserved family of signal transducers that function as essential coactivators of AGC group kinases, particularly the NDR/LATS subfamily [13] [18]. In humans, six MOB proteins (MOB1A/B, MOB2, MOB3A/B/C, MOB4) have been identified, with MOB1A and MOB1B sharing 95% sequence identity and functioning redundantly in Hippo pathway signaling [18]. MOB1 has emerged as a pivotal integrator within the core kinase cassette of the Hippo pathway, binding both upstream MST1/2 kinases and downstream LATS1/2 kinases to facilitate signal transduction [19] [20].

The specificity of MOB proteins for their kinase partners represents a critical regulatory node in cellular signaling. While MOB1 interacts with both LATS and NDR kinases, MOB2 demonstrates exclusive binding to NDR kinases, creating distinct functional branches [4]. This specificity is not merely a binary interaction but governs fundamental biological processes including cell proliferation, apoptosis, organ size control, and tumor suppression [18] [21]. Disruption of specific MOB1-LATS interactions has been directly linked to tumorigenesis, highlighting the physiological importance of precise molecular recognition [18].

Table 1: MOB Family Binding Specificities for NDR/LATS Kinases

| MOB Protein | NDR1/2 Binding | LATS1/2 Binding | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOB1A/B | Yes | Yes | Hippo pathway core signaling, tumor suppression |

| MOB2 | Yes | No | Cell cycle regulation, DNA damage response |

| MOB3A/B/C | No | No | Binds MST1, apoptotic regulation? |

| MOB4 | Unknown | Unknown | Poorly characterized |

Structural Basis of MOB-Kinase Interactions

Structural analyses of MOB1 in complex with its kinase partners have revealed conserved yet distinct binding modes. The crystal structure of MOB1 adopts a globular shape consisting of nine α-helices (α1–α9) and two β-strands, forming a characteristic phosphopeptide-binding pocket and kinase interaction surface [18] [22]. Comparative analysis of MOB1 bound to LATS1 versus NDR2 reveals that both kinases bind MOB1 through a V-shaped structure composed of two antiparallel α-helices that engage with negatively charged electrostatic surfaces on MOB1 [18].

The determination of the MOB1/NDR2 complex structure at 2.1 Å resolution enabled direct comparison with existing MOB1/LATS1 structures, revealing both shared core interaction principles and critical differences that underlie specificity [18]. In both complexes, the N-terminal regulatory domains (NTR) of the kinases interact with overlapping but distinct surfaces on MOB1 through a combination of hydrogen bonds, van der Waals interactions, and electrostatic complementarity [18] [22].

The Critical Asp63 Determinant for LATS Specificity

Comparative structural analysis between MOB1/NDR2 and MOB1/LATS1 complexes revealed a key specificity determinant at position Asp63 of MOB1 [18] [22]. This residue forms a specific bond with His646 of LATS1, supported by a cluster of surrounding residues involving Phe642, Met643, Gln645, Val647, and Val650 [22]. In contrast, Phe31 of NDR2 does not interact with Asp63 of MOB1, explaining the lack of this specific stabilizing interaction in the MOB1/NDR complex [18].

Mutagenesis studies confirm the functional importance of this interaction, where MOB1-D63A mutation selectively disrupts LATS1 binding while preserving NDR2 interaction [18]. This single residue thereby serves as a molecular switch governing kinase partner specificity, with profound functional consequences for Hippo pathway signaling and tumor suppressor activity.

Table 2: Key Residues in MOB1-Kinase Interfaces

| Complex | MOB1 Residues | Kinase Residues | Interaction Type | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOB1/LATS1 | Asp63, Glu51, Glu55, Trp56, Val59 | His646, Phe642, Met643, Gln645, Val647 | Hydrogen bonding, van der Waals | LATS-specific binding, essential for tumor suppression |

| MOB1/NDR2 | Leu36, Gly39, Leu41, Ala44, Gln67 | Lys25, Leu28, Tyr32, Leu35, Ile36 | Hydrophobic interactions, van der Waals | Conserved NDR/LATS binding |

| MOB1/MST1/2 | K153, R154, R157 | Phospho-Thr/Ser motifs (e.g., pT353, pT367) | Phosphopeptide recognition | Upstream regulation, pathway activation |

Biochemical and Functional Validation

Quantitative Binding Analyses

Systematic biochemical analyses have quantified the binding affinities and specificities of MOB1 for its kinase partners. Fluorescence polarization binding experiments with purified components demonstrate that MOB1 binds LATS1 with approximately 5-10 fold higher affinity compared to NDR2, with dissociation constants in the low micromolar range [19] [20]. This enhanced affinity for LATS1 is largely abolished in MOB1-D63A mutants, confirming the structural observations at a quantitative level [18].

Phosphorylation events further modulate these interactions. MOB1 phosphorylation by MST1/2 increases its ability to activate LATS1/2 approximately 3-fold, creating a positive feedback loop that enhances pathway signaling [19] [20]. This phosphorylation-dependent enhancement is less pronounced for NDR kinase activation, suggesting additional layers of specificity regulation.

Functional Consequences in Cellular Contexts

Genetic studies utilizing MOB1 variants with selective loss-of-interaction have demonstrated the functional importance of specific MOB1-LATS binding. In human cancer cells, disruption of MOB1-LATS interaction (but not MOB1-NDR interaction) abrogates the tumor-suppressive properties of MOB1, including growth inhibition and YAP/TAZ phosphorylation [18].

Drosophila genetics corroborate these findings, demonstrating that the MOB1/Warts (LATS homolog) interaction is essential for development and tissue growth control, while stable MOB1/Hippo (MST homolog) binding is dispensable [18] [22]. This in vivo evidence establishes the MOB1-LATS interaction as the critical node for Hippo pathway tumor suppressor function.

Experimental Approaches for Characterizing MOB1 Specificity

Structural Biology Methodologies

Protein Expression and Purification: Recombinant MOB1 and kinase N-terminal domains (e.g., NDR2 25-88, LATS1 homologous region) are expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) as N-terminal dual 6xhistidine and glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins using modified pETM-30 vectors [19]. Proteins are purified using glutathione-Sepharose resin, followed by TEV protease cleavage to remove affinity tags, and final purification by size exclusion chromatography.

Crystallization and Structure Determination: Complexes of MOB1 with kinase peptides are formed by mixing at 1:1.5 mole ratio. Crystals are obtained by vapor diffusion using hanging drops with 1:1 mixtures of protein (7 mg/ml concentration) with precipitant solution (0.1 M MES pH 6.0, 0.2 M LiCl, 20% PEG 6000) [19]. X-ray diffraction data are collected at synchrotron sources (e.g., Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beamlines), and structures solved by molecular replacement.

Biochemical Interaction Assays

Fluorescence Polarization Binding Assays: FITC-labeled phosphopeptides corresponding to MOB1-binding motifs in MST1/2 (e.g., T353, T367 peptides) are used for quantitative binding measurements [19]. Serial dilutions of MOB1 proteins are incubated with fixed concentrations of labeled peptides, and polarization values measured to determine dissociation constants.

GST Pull-Down and Far-Western Analyses: For protein-protein interaction studies, GST-tagged MOB1 variants are immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose resin and incubated with potential binding partners [19] [18]. After washing, bound proteins are eluted and detected by immunoblotting. For Far-Western analysis, proteins are separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to membranes, and probed with purified MOB1 proteins followed by anti-MOB1 antibodies.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MOB1-LATS Specificity Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | pETM-30 (modified) | Recombinant protein expression | Dual 6xHis-GST tags, TEV cleavage site |

| MOB1 Variants | MOB1A wild-type, MOB1-D63A, MOB1 phosphomimetics | Structure-function studies | Selective binding defects, modified regulation |

| Kinase Constructs | NDR2 NTR (25-88), LATS1 NTR, full-length kinases | Interaction partners | Defined binding domains, functional assays |

| Phosphopeptides | MST1 pT353, MST1 pT367, optimized Nud1-like | Binding specificity studies | FITC-labeled for quantitative assays |

| Crystallization Reagents | MES pH 6.0, LiCl, PEG 6000, ethylene glycol | Structural biology | Crystal optimization, cryoprotection |

| Detection Tools | Anti-phospho-NDR/LATS antibodies, anti-MOB1 antibodies | Functional validation | Pathway activation status, complex formation |

Discussion: Implications for Therapeutic Targeting

The precise molecular determinants governing MOB1 specificity for LATS kinases represent attractive targets for therapeutic intervention in cancers characterized by Hippo pathway dysregulation. The identification of Asp63 as a key residue for LATS-specific binding suggests that small molecules mimicking or disrupting this interaction could selectively modulate Hippo signaling branch outcomes.

Furthermore, the phosphoregulation of MOB1 interactions offers additional opportunities for pharmacological manipulation. As MOB1 phosphorylation enhances LATS activation, strategies to promote this specific phosphorylation event could potentiate tumor suppressor activity in contexts where pathway activity is diminished [19] [20]. Conversely, in conditions of excessive pathway activation, targeted disruption of MOB1-LATS complex formation might provide therapeutic benefit.

The differential binding properties of MOB1 versus MOB2 also suggest that tissue-specific expression patterns of these adapters could create natural specificities that might be exploited for targeted therapies with reduced off-target effects [4]. As our structural understanding of these complexes advances, structure-based drug design approaches become increasingly feasible for developing next-generation cancer therapeutics targeting the Hippo pathway.

The molecular determinants of MOB1 specificity for LATS kinases encompass a sophisticated integration of structural complementarity, specific residue interactions, and regulatory phosphorylation events. The Asp63-His646 interaction emerges as a critical specificity switch that distinguishes LATS from NDR binding, with profound functional consequences for tumor suppression and tissue growth control. Continued structural and biochemical dissection of these interfaces, coupled with functional validation in physiological contexts, will further refine our understanding of this crucial signaling node and its therapeutic potential.

Key Structural Motifs Governing MOB2 Binding to NDR1/2

The Mps one binder (MOB) proteins are highly conserved eukaryotic signal transducers that function as crucial regulatory cofactors for the NDR/LATS family of serine/threonine kinases [4]. In humans, the MOB family consists of six members (MOB1A, MOB1B, MOB2, MOB3A, MOB3B, and MOB3C) that exhibit distinct binding specificities toward the NDR/LATS kinases [16]. MOB2 displays remarkable specificity for the NDR1 and NDR2 kinases (also known as STK38 and STK38L, respectively), in contrast to MOB1, which can bind to both NDR1/2 and LATS1/2 kinases [16] [23]. This review focuses on the key structural motifs governing MOB2 binding to NDR1/2, framed within the broader context of MOB1 versus MOB2 binding specificity. Understanding these molecular determinants is essential for elucidating how specific MOB-NDR complexes control diverse cellular processes, including cell cycle progression, the DNA damage response, and cell motility [4] [23]. The competitive relationship between MOB1 and MOB2 for NDR binding represents a critical regulatory mechanism for Hippo pathway signaling, with significant implications for both fundamental biology and therapeutic development [16].

Structural Organization of NDR Kinases and MOB Cofactors

Domain Architecture of NDR Kinases

NDR1 and NDR2 are serine-threonine kinases belonging to the AGC kinase family that share approximately 87% sequence identity [3] [8]. Despite their high similarity, they exhibit distinct subcellular localizations—NDR1 is primarily nuclear, while NDR2 displays a punctate cytoplasmic distribution—suggesting non-redundant cellular functions [3]. Beyond the conserved kinase domain characteristic of AGC kinases, NDR kinases possess two critical regulatory regions: an N-terminal regulatory (NTR) region and a C-terminal hydrophobic motif (HM) [1] [24]. The NTR forms a structural platform specifically dedicated to MOB protein binding, while the HM contains a threonine residue (T444 in NDR1) whose phosphorylation by upstream kinases is essential for NDR activation [1] [24].

Structural Features of MOB Proteins

MOB proteins adopt a conserved globular fold known as the Mob1/Phocein domain, which consists of a core β-sandwich structure formed by two β-sheets [1] [2]. Despite this common structural framework, MOB1 and MOB2 possess distinct surface properties that dictate their binding specificities for different NDR/LATS kinases. Structural analyses reveal that while MOB1 can bind both NDR and LATS kinases, MOB2 exhibits specific binding only to NDR1/2 kinases [16] [23]. This specificity is mediated by discrete molecular recognition motifs rather than broadly distributed interface properties [1].

Table 1: Key Structural Features of MOB Proteins and NDR Kinases

| Component | Key Structural Features | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|

| NDR Kinase NTR | V-shaped helical hairpin [1] | MOB protein binding platform |

| NDR Kinase HM | C-terminal extension with phosphorylatable threonine [24] | Kinase activation through allosteric regulation |

| MOB Protein Core | Conserved globular β-sandwich fold [2] | Scaffold for kinase interaction |

| MOB Specificity Determinants | Discrete surface motifs [1] | Dictate binding preference for NDR vs. LATS kinases |

Molecular Basis of MOB2-NDR1/2 Interactions

The NTR-MOB Interface: A Structural Platform for Kinase Regulation

The primary interaction between MOB2 and NDR1/2 occurs through the N-terminal regulatory (NTR) region of the kinases, which forms a V-shaped helical hairpin that docks against a complementary surface on MOB2 [1]. Structural studies of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cbk1 (NDR homolog)-Mob2 complex, which serves as a model for understanding human NDR-MOB interactions, reveal that the NTR-Mob interface provides a distinctive kinase regulation mechanism [1] [2]. In this complex, the MOB2 cofactor organizes the NDR NTR to interact with the AGC kinase C-terminal hydrophobic motif (HM), facilitating its positioning for allosteric regulation [1]. This MOB-organized NTR appears to mediate association of the HM with an allosteric site on the N-terminal kinase lobe, creating an integrated regulatory system unique to NDR/LATS kinases [1].

High-resolution crystal structures of the Cbk1NTR–Mob2 complex show that the NTR forms a bihelical conformation similar to those observed in LatsNTR– and NdrNTR–Mob1 structures, indicating evolutionary conservation of this structural platform [1]. The improved resolution of these recent structures (2.8 Å) compared to earlier models has highlighted the critical role of MOB binding in positioning the hydrophobic motif of the kinase, revealing how MOB-driven orientation promotes optimal positioning of the kinase's otherwise flexible αC helix, a component critical for kinase activation [1].

Key Residues and Motifs Governing Binding Specificity

The specificity of MOB2 for NDR1/2 kinases, as opposed to the broader binding capacity of MOB1, is mediated by discrete molecular recognition sites. Research indicates that alteration of specific residues in the Cbk1 NTR allows association with the noncognate Mob1 cofactor, demonstrating that cofactor specificity is restricted by discrete sites rather than being broadly distributed across the interaction surface [1]. These specificity determinants include a short motif in the Mob structure that differs between Mob1 and Mob2, strongly contributing to molecular recognition between the kinase and cofactor [1].

Biochemical studies demonstrate that MOB2 competes with MOB1 for binding to the same N-terminal region of NDR1, but with fundamentally different functional outcomes [16]. While MOB1 binding activates NDR kinases by stimulating autophosphorylation on the activation segment, MOB2 associates predominantly with unphosphorylated NDR and is associated with diminished NDR kinase activity [16]. This competitive relationship creates a regulatory switch where the relative abundance and activation state of MOB1 versus MOB2 can determine NDR kinase activity levels.

Table 2: Functional Consequences of MOB1 vs. MOB2 Binding to NDR1/2

| Parameter | MOB1-NDR Complex | MOB2-NDR Complex |

|---|---|---|

| NDR Kinase Activity | Increased [16] | Diminished [16] |

| NDR Phosphorylation State | Preferentially binds phosphorylated NDR [16] | Preferentially binds unphosphorylated NDR [16] |

| Competitive Binding | Displaced by MOB2 overexpression [16] | Competes with MOB1 for NDR binding [16] |

| Cellular Function | Promotes NDR-mediated signaling [4] | May buffer or modulate NDR signaling [4] |

MOB1 vs. MOB2: A Comparative Analysis of Binding Specificity

Structural Determinants of Differential Binding

While both MOB1 and MOB2 bind to the NTR region of NDR kinases, structural and biochemical evidence indicates their binding modes differ significantly [16]. The human MOB1-NDR2 complex structure (PDB: 5XQZ) reveals specific interactions mediated by key MOB1 residues that enable its differential binding to Hippo core kinases [25]. Comparative analyses suggest that MOB2 lacks certain structural features present in MOB1 that are necessary for stable interaction with LATS kinases, explaining its restriction to NDR kinases [16] [23].

The specificity of MOB-NDR/LATS interactions is evolutionarily conserved. In budding yeast, the NDR-subfamily kinase Cbk1 associates specifically with Mob2, while the LATS-related kinases Dbf2 and Dbf20 bind exclusively to Mob1 [1]. This specific pairing is maintained despite the simultaneous presence of all proteins in the cytosol, indicating a robust mechanism enforcing kinase-coactivator association specificity [1]. Studies of homologous Schizosaccharomyces pombe Sid2(Lats)-Mob1 and Orb6(Ndr)-Mob2 complexes further demonstrate highly specific NDR/LATS-Mob interactions, preserved across vast evolutionary distances [1].

Functional Consequences of Distinct MOB Binding

The differential binding of MOB1 and MOB2 to NDR kinases has significant functional implications. MOB1 binding activates NDR1/2 kinases by stimulating autophosphorylation on the activation segment and facilitates phosphorylation by upstream kinases such as MST1 [16] [20]. In contrast, MOB2 binding is associated with diminished NDR activity, and RNA interference-mediated depletion of MOB2 results in increased NDR kinase activity, indicating that MOB2 functions as a negative regulator of human NDR kinases [16].

This competitive regulation extends to biological functions. Overexpression of MOB2 interferes with NDR roles in death receptor signaling and centrosome duplication, consistent with its function as a competitive inhibitor of MOB1-NDR complex formation [16]. Furthermore, research suggests that MOB2 regulates the alternative interaction of MOB1 with NDR1/2 and LATS1, leading to increased phosphorylation of LATS1 and MOB1 and consequent inactivation of YAP, ultimately inhibiting hepatocellular carcinoma cell motility [23].

Experimental Approaches for Studying MOB2-NDR Interactions

Structural Biology Methodologies

Determining the molecular details of MOB2-NDR interactions has required sophisticated structural biology approaches. X-ray crystallography has been instrumental, with structures of complexes such as Cbk1NTR–Mob2 determined to 2.8 Å resolution [1]. These studies often require protein engineering to enhance stability; for instance, introducing a zinc-binding motif (Mob2 V148C Y153C) stabilizes Mob2 for suitable Escherichia coli expression [1].

Crystallographic data collection typically involves several steps as shown in the workflow below:

Diagram 1: Structural Biology Workflow for MOB-NDR Complex Analysis

Biochemical and Cellular Assays

Beyond structural approaches, researchers employ diverse biochemical and cellular assays to characterize MOB2-NDR interactions. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments demonstrate physical association between MOB2 and NDR kinases in cellular contexts [16] [3]. Kinase activity assays show that MOB2 association dramatically stimulates NDR1 and NDR2 catalytic activity, in contrast to its competitive regulatory role with MOB1 [3].

Functional studies often utilize RNA interference-mediated depletion of MOB2, which results in increased NDR kinase activity, supporting MOB2's role as a negative regulator [16]. Overexpression approaches further reveal that MOB2 impairs NDR1/2 activation in a binding-dependent manner and affects NDR functions in centrosome duplication and apoptotic signaling [16]. More recently, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of MOB2 has been employed to investigate its role in hepatocellular carcinoma cell migration and invasion, demonstrating that MOB2 knockout promotes these processes while decreasing phosphorylation of YAP [23].

Table 3: Key Experimental Reagents for Studying MOB2-NDR Interactions

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| pcDNA3 vectors with epitope tags | Mammalian expression of MOB/NDR proteins [16] | Immunoprecipitation, localization studies |

| pGEX-4T1/pMal-2c vectors | Bacterial expression for protein purification [16] | Structural studies, in vitro binding assays |

| pTER-shMOB2 vectors | RNAi-mediated MOB2 knockdown [16] | Functional analysis of MOB2 depletion |

| LentiCRISPRv2 vector | CRISPR/Cas9-mediated MOB2 knockout [23] | Generation of stable knockout cell lines |

| Tet-regulated expression vectors | Inducible MOB2 expression [16] | Controlled overexpression studies |

Implications for Cellular Signaling and Therapeutic Development

Roles in Cell Cycle Regulation and DNA Damage Response

The MOB2-NDR interaction plays significant roles in cell cycle progression and DNA damage response. MOB2 depletion triggers a p53/p21-dependent G1/S cell cycle arrest in untransformed human cells, suggesting its importance in cell cycle checkpoint control [4]. Furthermore, MOB2 is required to prevent the accumulation of endogenous DNA damage and prevent undesired activation of cell cycle checkpoints [4]. Intriguingly, these functions may operate independently of NDR1/2 kinase signaling, as NDR1 or NDR2 knockdown does not recapitulate the cell cycle arrest phenotype observed with MOB2 depletion [4].

MOB2 also functions as a novel DNA damage response (DDR) factor that plays roles in DDR signaling, cell survival, and cell cycle checkpoints upon exposure to DNA damage [4]. It is required to promote cell survival and G1/S cell cycle arrest upon exposure to DNA damaging agents such as ionizing radiation or doxorubicin [4]. MOB2 supports ionizing radiation-induced DDR signaling through the DDR kinase ATM and facilitates recruitment of the MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 (MRN) DNA damage sensor complex and activated ATM to DNA damaged chromatin [4].

Relevance to Cancer and Therapeutic Opportunities

The MOB2-NDR interaction has significant implications for cancer biology and therapeutic development. In hepatocellular carcinoma, MOB2 inhibits cell motility by regulating the alternative interaction of MOB1 with NDR1/2 and LATS1, resulting in increased phosphorylation of LATS1 and MOB1 and consequent inactivation of YAP [23]. This positions MOB2 as a potential tumor suppressor in specific contexts.

The diagram below illustrates how MOB2 integrates into Hippo signaling and impacts cancer-relevant processes:

Diagram 2: MOB2 Integration in Hippo Signaling and Cancer

Given NDR2's role as an oncogene in most cancers—particularly lung cancer, where it regulates processes including proliferation, apoptosis, migration, invasion, and vesicular trafficking—the MOB2-NDR interface represents a potential therapeutic target [8]. The specific structural motifs governing MOB2-NDR binding could be exploited for developing targeted protein-protein interaction inhibitors that modulate this signaling axis in cancer therapy.

The structural motifs governing MOB2 binding to NDR1/2 represent a sophisticated molecular recognition system that controls specific signaling outputs within the broader Hippo pathway framework. The NTR region of NDR kinases serves as a structural platform that binds MOB cofactors, with discrete molecular determinants dictating the specificity of MOB2 for NDR kinases versus the broader binding capacity of MOB1. This specific interaction, characterized by competitive binding with MOB1 and association with unphosphorylated NDR, positions MOB2 as a negative regulator of NDR kinase activity. The functional consequences of MOB2-NDR interactions extend to diverse cellular processes, including cell cycle regulation, DNA damage response, and control of cell motility in cancer contexts. Future research elucidating the full complement of regulatory inputs and outputs of the MOB2-NDR axis will undoubtedly yield valuable insights for therapeutic intervention in cancer and other diseases.

The hydrophobic motif (HM) represents a critical regulatory element in the C-terminal tail of AGC family protein kinases, serving as a central interface for controlling kinase activity, substrate recognition, and integration into cellular signaling networks. This conserved motif functions as a molecular switch that governs allosteric activation through phosphorylation-dependent mechanisms and protein-protein interactions. Within the NDR/LATS kinase subfamily, the HM serves as a pivotal regulatory hub that integrates signals from upstream kinases, coactivator proteins, and scaffolding elements to control diverse cellular processes including cell division, morphogenesis, and proliferation [26] [1].

The significance of HM regulation extends beyond fundamental biology to therapeutic applications, as evidenced by the critical role of HM phosphorylation in AKT activation, a prominent oncogenic signaling pathway [27]. This technical review examines the structural and mechanistic principles of HM function, with particular emphasis on the molecular determinants governing MOB coactivator binding specificity in NDR kinase regulation. Through integrated analysis of quantitative biochemical data, structural insights, and experimental methodologies, we provide a comprehensive framework for understanding HM-mediated kinase control and its implications for targeted therapeutic development.

Structural and Mechanistic Principles of Hydrophobic Motif Function

Consensus Features and Structural Location

The hydrophobic motif is characterized by a conserved sequence profile typically containing a phosphorylation site (most commonly a threonine residue) embedded within a hydrophobic context. In NDR kinases, this motif is located C-terminal to the kinase catalytic domain and adopts specific structural configurations that are stabilized by phosphorylation-dependent interactions. Structural analyses reveal that the phosphorylated HM engages in intramolecular interactions with the N-lobe of the kinase domain, particularly stabilizing the αC-helix in an active conformation [1] [24].

This HM-mediated stabilization is essential for proper alignment of catalytic residues and formation of the regulatory (R) and catalytic (C) spines that traverse the kinase core. The NDR/LATS kinase family exhibits a unique structural adaptation where the Mob coactivator organizes the N-terminal regulatory (NTR) region to mediate interaction between the phosphorylated HM and an allosteric site on the N-terminal kinase lobe [1]. This configuration creates a distinctive kinase-coactivator system that integrates HM phosphorylation with coactivator binding for full kinase activation.

Phosphorylation-Dependent Activation Mechanisms

HM phosphorylation triggers a conformational transition from an autoinhibited state to an active kinase configuration. In NDR1, structural studies have identified an atypically long activation segment that autoinhibits the kinase domain by blocking substrate binding and stabilizing the αC-helix in a non-productive position [24]. Phosphorylation of the HM residue (Thr444 in NDR1, Thr442 in NDR2) relieves this autoinhibition and enables the conformational rearrangements necessary for catalytic competence.

The activation mechanism involves a multi-step process wherein HM phosphorylation enhances the efficiency of activation loop phosphorylation and stabilizes the active conformation against phosphatases. This cooperative activation creates a switch-like response to upstream signals and ensures precise temporal control of kinase activity. In NDR kinases, this process is further refined through interaction with MOB coactivators, which potentiate kinase activity through mechanisms distinct from HM phosphorylation [24].

Table 1: Hydrophobic Motif Characteristics in Selected AGC Kinases

| Kinase | HM Sequence | Phosphorylation Site | Upstream Regulator | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NDR1 | FXXT444 | Thr444 | MST3 | 10-fold activation; enhanced MOB1A binding [26] |

| NDR2 | FXXT442 | Thr442 | MST3 | Conformational activation; cytoplasmic localization [28] |

| AKT1 | FPQFS473 | Ser473 | mTORC2 | Stabilizes Thr308 phosphorylation; maximal activity [27] |

| Cbk1 | FXXT743 | Thr743 | Unknown | Promotes HM positioning via Mob2-organized NTR [1] |

MOB Coactivator Binding Specificity in NDR Kinase Regulation

Structural Basis of MOB-NDR Interactions

The NDR/LATS kinases possess a distinctive N-terminal regulatory (NTR) region that forms a highly specific interface with Mob coactivator proteins. Structural analyses of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cbk1NTR–Mob2 and Dbf2NTR–Mob1 complexes reveal that the NTR forms a V-shaped helical hairpin that docks against the conserved surface of Mob coactivators [1]. This interface serves as a structural platform that mediates kinase-cofactor binding and enables allosteric regulation of the HM.

The specificity determinants that govern selective association of Ndr kinases with Mob2 (versus Lats kinases with Mob1) reside in discrete structural elements rather than being broadly distributed across the interaction surface. In Cbk1, alteration of specific residues in the NTR allows association with the non-cognate Mob1 cofactor, indicating that specificity is controlled by molecular complementarity at restricted sites [1]. This precise molecular recognition ensures proper pathway specificity despite the high conservation of both the Mob cofactors and kinase NTR regions across the NDR/LATS family.

Functional Integration of HM Phosphorylation and MOB Binding

The activation of NDR kinases requires the functional integration of HM phosphorylation with MOB coactivator binding. Research demonstrates that MST3-mediated phosphorylation of Thr442 in NDR2 results in approximately 10-fold stimulation of kinase activity, while subsequent MOB1A binding further increases activity, leading to a fully active kinase [26]. This cooperative activation creates a multi-step mechanism that enables signal integration and precise control of NDR kinase function.

Structural evidence indicates that MOB binding organizes the NTR to interact with the phosphorylated HM, thereby facilitating optimal positioning of the otherwise flexible αC-helix critical for kinase activation [1]. This mechanism explains the essential role of both HM phosphorylation and MOB coactivator binding for NDR kinase function, and illustrates how these two regulatory inputs are structurally coupled through the NTR-Mob interface.

Table 2: MOB Cofactor Specificity and Functional Roles in NDR/LATS Kinases

| Kinase | MOB Cofactor | Binding Specificity Determinants | Functional Consequences | Biological Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cbk1 (NDR) | Mob2 | Discrete sites in NTR; short motif in Mob structure | Organizes NTR for HM positioning; substrate docking [1] | RAM network; cell separation, morphogenesis [2] |

| Dbf2 (LATS) | Mob1 | Molecular complementarity at restricted interface | Kinase coactivation; spindle pole recruitment [1] | Mitotic Exit Network (MEN); cytokinesis [2] |

| SAX-1/NDR | MOB-2 | Conserved interface with helical hairpin NTR | Dendrite pruning; membrane dynamics regulation [17] | Neuronal remodeling; C. elegans [17] |

Experimental Analysis of Hydrophobic Motif Regulation

Methodologies for Assessing HM Phosphorylation

The investigation of HM phosphorylation employs multiple complementary approaches to establish regulatory mechanisms:

In Vitro Kinase Assays: Recombinant MST3 kinase selectively phosphorylates Thr442 of NDR2 in vitro, resulting in significant kinase activation. These assays typically use purified components under controlled conditions to establish direct phosphorylation relationships [26].

Phosphospecific Antibodies: Antibodies specifically recognizing phosphorylated HM residues (e.g., anti-P-Thr-442 for NDR2) enable quantitative assessment of HM phosphorylation status in both in vitro and cellular contexts [26] [28].

Kinase-Dead Mutants: MST3KR, a kinase-dead mutant of MST3, potently inhibits Thr442 phosphorylation following okadaic acid stimulation in vivo, establishing the functional requirement for MST3 catalytic activity [26].

Knockdown Approaches: Short hairpin RNA constructs targeting MST3 effectively abolish Thr442 hydrophobic motif phosphorylation in HEK293F cells, demonstrating necessity in a cellular context [26].

Structural Biology Techniques

High-resolution structural biology provides essential insights into HM regulatory mechanisms:

X-ray Crystallography: Crystal structures of NDR1 kinase domain (2.2 Å resolution) reveal the autoinhibitory function of an atypically long activation segment that blocks substrate binding and stabilizes the αC-helix in a non-productive position [24].

Complex Structure Determination: Structures of Cbk1NTR–Mob2 (2.8 Å resolution) and Dbf2NTR–Mob1 complexes elucidate the molecular basis of coactivator binding specificity and HM positioning [1].

Mutational Analysis: Structure-guided mutations within the activation segment of NDR1 dramatically enhance in vitro kinase activity, confirming autoinhibitory function [24].

Diagram 1: HM Phosphorylation Analysis Workflow. This experimental workflow outlines key methodological steps for assessing hydrophobic motif phosphorylation status, incorporating specific reagents and conditions from cited studies [26].

Research Reagent Solutions for HM Regulation Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating HM Regulation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Experimental Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphospecific Antibodies | Anti-P-Thr-442 (NDR2); Anti-P-Ser-282 (NDR2) | Detect HM and activation loop phosphorylation | Western blotting; monitoring cellular phosphorylation status [26] |

| Kinase Constructs | HA-NDR2; myc-MST3; HA-MST3KR (kinase-dead) | Functional analysis of kinase activity and regulation | Transfection studies; in vitro kinase assays [26] [29] |

| Mob Coactivators | myc-C1-MOB1A; pGEX-2T-MOB1A | Investigate coactivator-kinase functional interactions | Co-immunoprecipitation; kinase activation assays [26] |

| Expression Vectors | pCMV5-HA-NDR2; pTER-shMST3 (shRNA) | Modulate protein expression in cellular systems | Knockdown studies; heterologous protein expression [26] |

| Chemical Inhibitors/Activators | Okadaic acid (PP2A inhibitor); BAPTA-AM (Ca2+ chelator) | Perturb phosphorylation status or signaling context | Pathway manipulation; assessing phosphorylation dynamics [26] [30] |

Biological Context and Pathophysiological Relevance

NDR Kinases in Cellular Morphogenesis and Neuronal Regulation

The functional significance of HM-mediated NDR kinase regulation is exemplified in neuronal development and remodeling processes. In C. elegans, the NDR kinase homolog SAX-1 controls dendrite branch-specific elimination during stress-induced neuronal remodeling, functioning with its conserved interactors SAX-2/Furry and MOB-2 [17]. This system reveals unexpected specificity in pruning processes, with distinct genetic requirements for eliminating different dendritic branch orders.

The SAX-1/NDR pathway promotes endocytosis during neuronal remodeling through functional interactions with the guanine-nucleotide exchange factor RABI-1/Rabin8 and the small GTPase RAB-11.2, linking HM-mediated kinase regulation to membrane dynamics [17]. This illustrates how the fundamental regulatory mechanism of NDR kinases interfaces with specific cellular processes through specialized effector systems.

Hippo Pathway Integration and Therapeutic Implications

NDR/LATS kinases function as essential components of evolutionarily conserved Hippo signaling pathways that control cell proliferation and morphogenesis [1] [2]. In both mammalian cells and model organisms, these kinases form central regulatory nodes that integrate signals from upstream Ste20-family kinases (MST/hippo) and transmit them to diverse downstream effectors.