Mastering Primer Annealing: Principles, Optimization, and Validation for Robust PCR

This article provides a comprehensive guide to primer annealing, a critical determinant of PCR success.

Mastering Primer Annealing: Principles, Optimization, and Validation for Robust PCR

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to primer annealing, a critical determinant of PCR success. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles of duplex stability and Tm calculation, presents methodological advances including universal annealing buffers and high-fidelity enzymes, and offers systematic troubleshooting protocols for common challenges like non-specific amplification. Furthermore, it covers modern validation techniques, from computational prediction of amplification efficiency using machine learning to the comparative analysis of digital PCR platforms, equipping readers with the knowledge to design, optimize, and validate highly specific and efficient PCR assays for demanding biomedical applications.

The Fundamentals of Primer-Template Duplex Stability

In molecular biology, the melting temperature (Tm) is a fundamental thermodynamic property defined as the temperature at which half of the DNA duplex molecules dissociate and become single-stranded [1] [2]. This parameter serves as a critical predictor of oligonucleotide hybridization efficiency and stability, forming the scientific foundation for setting the annealing temperature in polymerase chain reaction (PCR) protocols. The precise determination of Tm is therefore not merely a theoretical exercise but a practical necessity for experimental success, influencing the specificity, yield, and accuracy of numerous molecular techniques including PCR, qPCR, cloning, and next-generation sequencing [2].

Within the broader context of primer annealing principles and stability research, Tm represents a key stability attribute of the DNA duplex. Its value directly impacts the design of stable and specific primer-template interactions, a concern that parallels stability testing in pharmaceutical development where the stability of drug substances and products is a critical quality attribute [3]. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering Tm calculations and applications is essential for developing robust, reproducible genetic assays and biopharmaceutical products.

Fundamental Principles of Tm

The stability of a primer-template DNA duplex, quantified by its Tm, is governed by the sum of energetic forces that hold the two strands together. When a DNA duplex is heated, it undergoes a sharp transition from a double-stranded helix to single-stranded random coils; the midpoint of this transition is the Tm [4]. At this temperature, the double-stranded and single-stranded states exist in equilibrium.

The stability of the duplex—and thus the Tm—is primarily influenced by two factors: * duplex length* and nucleobase composition. Longer duplexes have more stabilizing base-pair interactions, resulting in a higher Tm [1]. Furthermore, duplexes with a higher guanine-cytosine (GC) content are more stable than those with a higher adenine-thymine (AT) content due to the three hydrogen bonds that stabilize a GC base pair compared to the two that stabilize an AT base pair [1] [5]. This relationship between sequence composition and stability is the basis for the simplest Tm calculation formulas.

However, the actual Tm is not an intrinsic property of the DNA sequence alone. It is profoundly influenced by the physical and chemical environment, including the concentrations of monovalent cations (e.g., Na+, K+) and divalent cations (e.g., Mg2+), as well as the presence of cosolvents like formamide or DMSO [1] [2]. Divalent cations like Mg2+ have a particularly strong effect, and changes in their concentration in the millimolar range can significantly impact Tm [2]. The oligonucleotide concentration itself also affects Tm; when two or more strands interact, the strand in excess primarily determines the Tm, which can vary by as much as ±10°C due to concentration effects alone [2].

Methods for Calculating Tm

Calculation Formulas and Methods

Several methods exist for calculating Tm, ranging from simple empirical formulas to complex thermodynamic models. The choice of method depends on the required accuracy and the specific application.

Table 1: Common Methods for Calculating Primer Melting Temperature (Tm)

| Method | Formula/Approach | Key Considerations | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Rule-of-Thumb | ( Tm = 4(G + C) + 2(A + T) ) °C [1] | Highly simplistic; does not account for salt, concentration, or sequence context. | Quick, initial estimate. |

| Nearest-Neighbor Thermodynamics | Computes (\Delta G) & (\Delta H) using nearest-neighbor parameters [6] [7] | Highly accurate; accounts for sequence context, salt corrections, and probe concentration. | Gold standard for primer and probe design in PCR/qPCR. |

| Salt Correction Models | Incorporates monovalent & divalent cation concentrations into (\Delta G) calculations [2] | Essential for accurate Tm; free Mg2+ concentration is critical. | Critical for reactions with specific buffer conditions. |

The simplistic formula ( Tm = 4(G + C) + 2(A + T) ) provides a general estimate, suggesting that primers with melting temperatures between 52-58°C generally produce good results [1]. However, this method is outdated and fails to consider critical experimental variables. As noted by Dr. Richard Owczarzy, "Tm is not a constant value, but is dependent on the conditions of the experiment. Additional factors must be considered, such as oligo concentration and the environment" [2].

For modern molecular biology applications, nearest-neighbor thermodynamic models are the preferred method. These models provide a more accurate prediction by considering the sequence context—the stability of each dinucleotide step in the duplex—and integrating detailed salt correction formulas for both monovalent and divalent cations [6] [7] [2]. This approach forms the basis for sophisticated online algorithms and software tools used by researchers today.

Advanced Considerations in Tm Calculation

Advanced Tm calculations must account for several complicating factors to ensure experimental success:

- Mismatches and SNPs: Single base mismatches between hybridizing oligos can reduce Tm by 1°C to 18°C, depending on the identity of the mismatch, its position in the sequence, and the surrounding sequence context [2]. This is critical for designing assays to detect single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs).

- Strand Choice: For PCR/qPCR, the probe can be designed to bind to either the sense or antisense strand. The type of mismatch formed can differ depending on this choice, affecting Tm and discrimination efficiency [2].

- Cation Binding: It is important to note that Mg2+ binds to dNTPs, primers, and template DNA. Therefore, the free concentration of Mg2+ in solution, not the total concentration, is the relevant value for accurate Tm prediction [2].

Tm in PCR Primer Design and Annealing Optimization

The Relationship Between Tm and Annealing Temperature (Ta)

In PCR, the melting temperature of the primers directly determines the annealing temperature (Ta), a critical cycling parameter. The optimal annealing temperature is typically set 5°C below the calculated Tm of the primers [8]. If the Ta is set too low, the primers may tolerate internal single-base mismatches or partial annealing, leading to non-specific amplification and reduced yield of the desired product. Conversely, if the Ta is set too high, primer binding efficiency is drastically reduced, which can also cause PCR failure [9] [8].

For a successful amplification, the forward and reverse primers in a pair should have Tms that are closely matched, ideally within a 2°C range, to allow both primers to bind to their target sequences with similar efficiency at a single annealing temperature [5] [8]. The recommended melting temperature for PCR primers generally falls between 55°C and 70°C [9], with an optimal range of 60–64°C [8].

Experimental Optimization and Universal Annealing

Despite sophisticated calculations, the optimal annealing temperature for a primer set often requires empirical determination. A standard optimization practice involves using a gradient thermal cycler to test a range of annealing temperatures, typically from 5–10°C below the calculated Tm up to the Tm itself [9] [6]. The optimal temperature is identified as the one that produces the highest yield of the specific amplicon with minimal background [9].

To streamline workflow and simplify multiplexing, recent innovations include the development of novel DNA polymerases with specialized reaction buffers. These buffers contain isostabilizing components that increase the stability of primer-template duplexes, enabling the use of a universal annealing temperature of 60°C for primers with a wide range of calculated Tms [9]. This innovation allows for the co-cycling of different PCR targets with varying amplicon lengths using the same simplified protocol, saving significant time and optimization effort [9].

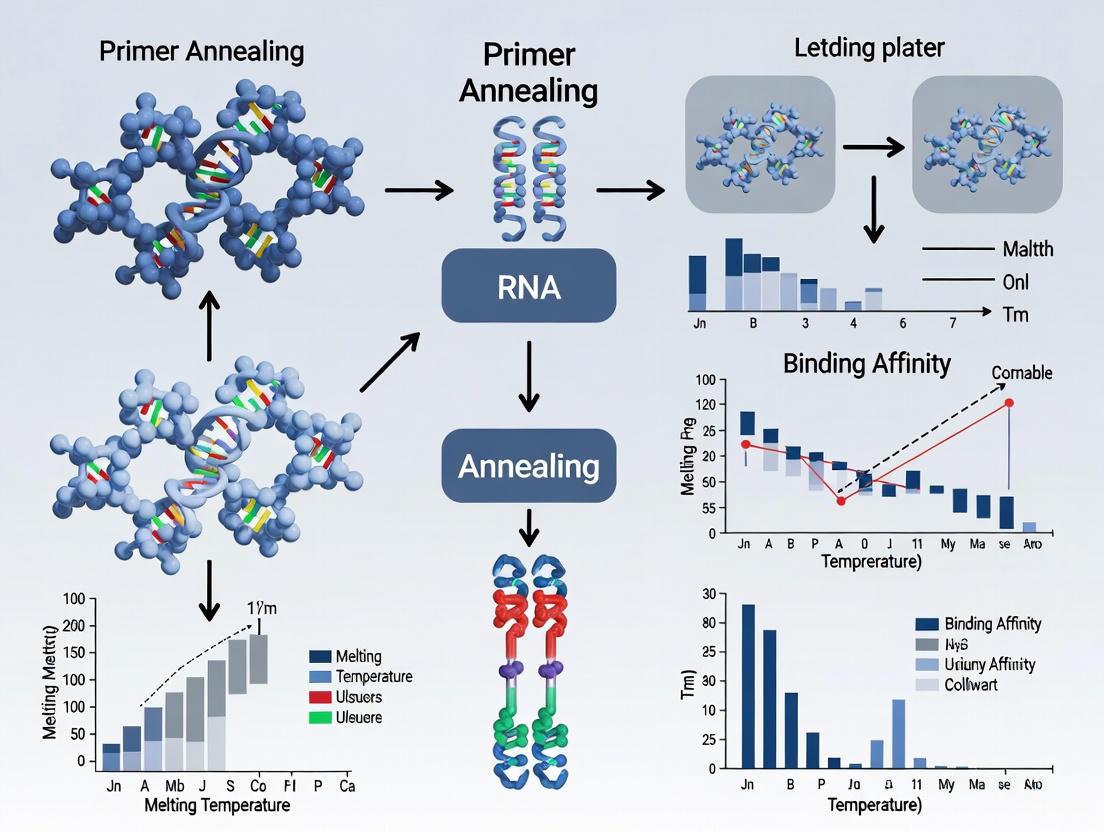

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key decision points for optimizing annealing temperature based on Tm, incorporating both traditional and modern approaches:

Essential Protocols and the Scientist's Toolkit

Protocol: Calculating Tm and Optimizing Annealing Temperature

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for determining the melting temperature of primers and empirically establishing the optimal annealing conditions for a PCR assay.

Materials and Reagents:

- Purified oligonucleotide primers (forward and reverse)

- DNA template

- DNA polymerase with appropriate buffer (often supplied with Mg2+)

- Deoxynucleotides (dNTPs)

- Sterile, nuclease-free water

- Thermal cycler with gradient functionality

Procedure:

- Primer Design and Tm Calculation: Design primers according to best practices: length of 18-30 bases, GC content of 40-60%, and avoidance of self-complementarity or long di-nucleotide repeats [5]. Use a sophisticated online Tm calculator (e.g., IDT OligoAnalyzer, Thermo Fisher Tm Calculator) to determine the Tm for each primer. Input the actual primer sequences, the final primer concentration, and the specific reaction conditions, including K+ and Mg2+ concentrations [6] [8]. A typical reaction condition is 50 mM K+, 3 mM Mg2+, and 0.8 mM dNTPs, though conditions may vary [8].

- Initial Annealing Temperature Setting: Calculate the initial annealing temperature (Ta) as 5°C below the average Tm of the primer pair [8].

- Gradient PCR Setup: Prepare a master mix containing all PCR components: 1X PCR buffer, 200 μM dNTPs, 1.5 mM Mg2+ (if not already in the buffer), 20-50 pmol of each primer, 10^4-10^7 molecules of DNA template, and 0.5-2.5 units of DNA polymerase per 50 μl reaction [5]. Aliquot the master mix into PCR tubes. Set up the thermal cycler with a gradient across the block such that the annealing temperature varies in 2°C increments, spanning from about 5-10°C below the calculated Tm up to the Tm itself [9] [6].

- Analysis and Optimal Ta Determination: Run the PCR and analyze the products using agarose gel electrophoresis. The optimal annealing temperature is the highest temperature within the gradient that yields a strong, specific amplicon with no or minimal non-specific products [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for PCR and Tm-Based Assay Development

| Reagent / Material | Function | Considerations for Tm & Assay Stability |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Polymerase & Buffer | Enzymatic amplification of DNA. | Buffer composition (e.g., Mg2+, K+, isostabilizers) is the primary factor affecting actual Tm in the reaction [9] [2]. |

| MgCl₂ Solution | Cofactor for DNA polymerase; stabilizes DNA duplex. | Concentration of free Mg2+ is critical; it strongly influences Tm and must be accounted for in calculations [5] [2]. |

| dNTP Mix | Building blocks for new DNA strands. | Bind Mg2+, reducing free [Mg2+] and thereby affecting Tm; use consistent concentrations [2]. |

| Primers | Sequence-specific binding to template. | Tm, GC content, and absence of secondary structures are key design parameters [5] [8]. |

| Additives (DMSO, Betaine) | Reduces secondary structure; equalizes Tm. | Can lower the effective Tm of the reaction; used for GC-rich templates [5]. |

| Gradient Thermal Cycler | Allows testing of a temperature range in one run. | Essential for empirical determination of optimal Ta based on calculated Tm [9]. |

| Online Tm Calculators | Predicts Tm based on sequence and conditions. | Use tools that employ nearest-neighbor models and allow input of exact salt concentrations [6] [8]. |

The melting temperature (Tm) is far more than a theoretical concept; it is a practical, indispensable cornerstone of successful primer annealing and PCR assay design. A deep understanding of its determinants—DNA sequence, oligonucleotide concentration, and buffer environment—is crucial for life scientists and drug development professionals. While foundational principles, such as the influence of GC content and length, provide a starting point, modern experimental biology demands the use of sophisticated, thermodynamics-based calculations that account for the full complexity of the reaction milieu.

The interplay between Tm and annealing temperature is a critical balance that dictates the specificity and yield of amplification. By leveraging the available tools and reagents, from advanced online calculators and specialized polymerases to empirical gradient optimization, researchers can transform the reliable calculation of Tm into robust, reproducible experimental outcomes. This rigorous approach to foundational molecular principles ensures the integrity and stability of research, from basic science to the development of novel therapeutics.

In molecular biology and drug development, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) serves as a fundamental technology for genetic analysis, diagnostics, and therapeutic discovery. The efficacy of any PCR-based experiment is critically dependent on the initial design of oligonucleotide primers, which guide the enzymatic amplification of specific DNA sequences. Within the broader context of primer annealing principles and stability research, three parameters emerge as paramount: primer length, GC content, and binding specificity. These interrelated factors collectively govern the thermodynamic stability of the primer-template duplex, the efficiency of polymerase initiation, and the fidelity of the amplification process. Proper optimization of these parameters ensures robust amplification yield, minimizes off-target products, and enhances the reproducibility of experimental results—essential qualities for high-stakes research and development environments. This technical guide examines the underlying principles and practical methodologies for optimizing these critical design parameters, providing researchers with a framework for developing robust PCR assays suitable for advanced applications in scientific research and pharmaceutical development.

Core Parameter I: Primer Length

Optimal Range and Thermodynamic Principles

Primer length directly influences both specificity and annealing efficiency. Short primers (below 18 bases) may demonstrate insufficient specificity by binding to multiple non-target sites, while excessively long primers (above 30 bases) can reduce hybridization kinetics and increase the likelihood of secondary structure formation. The consensus across major biochemical suppliers and research institutions identifies an optimal range of 18 to 30 nucleotides [10] [11] [12]. This length provides a sequence complex enough to be unique within a typical genome while maintaining practical hybridization kinetics. Research into annealing stability indicates that primers within this length range facilitate optimal binding energy for stable duplex formation without compromising the reaction cycle time. For specialized applications like bisulfite PCR, which deals with converted DNA of reduced sequence complexity, longer primers of 26–30 bases are recommended to achieve the necessary specificity and adequate melting temperature [10].

Relationship Between Length and Melting Temperature

Primer length is a primary determinant of melting temperature (Tm), the temperature at which 50% of the DNA duplex dissociates into single strands. Longer primers have higher Tm values due to increased hydrogen bonding and base-stacking interactions. The most straightforward formula for a preliminary Tm calculation is the Wallace Rule: Tm = 4(G + C) + 2(A + T) [13]. This rule underscores the direct correlation between length and Tm, as a longer primer will contain more bases. For more accurate predictions, especially for longer primers, the Salt-Adjusted Equation is preferred: Tm = 81.5 + 16.6(log[Na+]) + 0.41(%GC) – 675/primer length [13]. This formula accounts for experimental conditions and provides a critical bridge between in-silico design and wet-bench application, ensuring that the designed primers will function as expected under specific reaction buffer conditions.

Table 1: Primer Length Guidelines Across PCR Applications

| Application | Recommended Length (nt) | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Standard PCR/qPCR | 18 - 30 [10] [12] | Balances specificity with efficient hybridization. |

| Bisulfite PCR | 26 - 30 [10] | Compensates for reduced sequence complexity after bisulfite conversion. |

| TaqMan Probes | 20 - 25 [10] | Ensures probe remains bound during primer elongation. |

Core Parameter II: GC Content

The Role of GC Content in Primer Stability

GC content refers to the percentage of guanine (G) and cytosine (C) bases within a primer sequence. This parameter critically impacts primer stability because G and C bases form three hydrogen bonds, creating a stronger and more thermally stable duplex than A-T base pairs, which form only two bonds [13]. The recommended GC content for primers is a balanced range of 40–60%, with an ideal target of approximately 50% [10] [8] [12]. This range provides enough sequence complexity for unique targeting without introducing excessive stability that could promote non-specific binding. Primers with a GC content below 40% may be too unstable for efficient annealing, while those above 60% are prone to forming stable secondary structures or binding non-specifically to GC-rich regions elsewhere in the genome.

The GC Clamp and Sequence Distribution

Beyond the overall percentage, the sequence distribution of G and C bases is crucial. A "GC clamp" refers to the presence of one or more G or C bases at the 3' end of the primer [11]. This feature strengthens the initial binding of the primer's terminus, which is essential for the DNA polymerase to begin extension, thereby increasing amplification efficiency. However, stretches of more than three consecutive G or C bases should be avoided, as they can cause mispriming by forming unusually stable interactions with non-complementary sequences [10] [12]. Similarly, dinucleotide repeats (e.g., ATATAT) can lead to misalignment during annealing. Therefore, the goal is a uniform distribution of nucleotides that avoids homopolymeric runs and repetitive sequences.

Table 2: GC Content Specifications and Impacts

| Parameter | Ideal Value | Consequence of Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Overall GC Content | 40% - 60% [10] [8] [12] | Low (<40%): Low Tm, unstable annealing.High (>60%): High Tm, non-specific binding. |

| GC Clamp | A G or C at the 3' end [11] | Promotes specific initiation of polymerization. |

| Consecutive Bases | Avoid >3 consecutive G or C [10] [12] | Increases potential for non-specific, stable binding. |

Core Parameter III: Specificity

Ensuring On-Target Binding

Primer specificity is the guarantee that amplification occurs only at the intended target sequence. This is primarily achieved through computational verification. The NCBI Primer BLAST tool is the gold standard for this purpose, allowing researchers to check the specificity of their primer pairs against entire genomic databases to ensure they are unique to the desired target [14] [15]. Furthermore, primers must be screened for complementarity within and between themselves to avoid the formation of secondary structures. Key interactions to avoid include:

- Hairpins: Intramolecular folding where a primer anneals to itself, sequestering its sequence from the template [8] [13].

- Self-Dimers: A single primer molecule annealing to another copy of itself.

- Cross-Dimers (Hetero-dimers): The forward primer annealing to the reverse primer, forming a non-productive duplex [10] [11].

The stability of these unwanted structures is measured by Gibbs free energy (ΔG). Designs with a ΔG value more positive than -9.0 kcal/mol are generally considered acceptable, as weaker structures are less likely to form under standard cycling conditions [8].

Experimental Validation and Optimization

Even with impeccable in-silico design, empirical validation is crucial. A primary method for optimizing specificity is gradient PCR, which tests a range of annealing temperatures (Ta) to find the optimal stringency [16]. The annealing temperature is typically set at 3–5°C below the Tm of the primers [10] [8]. If the Ta is too low, primers will tolerate mismatches and bind to off-target sequences; if it is too high, specific amplification may fail. The use of hot-start polymerases is another critical experimental strategy for enhancing specificity. These enzymes remain inactive until a high-temperature activation step, preventing non-specific priming and primer-dimer formation that can occur during reaction setup at lower temperatures [10] [16].

Integrated Workflow and Experimental Protocol

Primer Design and Specificity Checking Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the critical steps for designing and validating primers, integrating the parameters of length, GC content, and specificity into a cohesive workflow.

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Validation

After in-silico design, the following wet-bench protocol is recommended for validating primer performance and optimizing reaction conditions.

Gradient PCR Setup:

- Prepare a master mix containing buffer, dNTPs (typically 0.2 mM each), MgCl2 (1.5–2.5 mM, requires titration), DNA polymerase (1–2 units), and template DNA (5–50 ng gDNA) [16] [12].

- Aliquot the master mix and add the forward and reverse primers to a final concentration of 0.1–1.0 μM each [12].

- Perform a thermal cycler run with a gradient across the block that covers a temperature range from 5°C below to 5°C above the calculated average Tm of the primer pair.

Product Analysis:

- Analyze the PCR products using agarose gel electrophoresis.

- The optimal annealing condition will produce a single, sharp band of the expected size. Multiple bands indicate non-specific amplification, often remedied by increasing the Ta. A lack of product suggests the Ta is too high or the primers are inefficient.

- For absolute confirmation, the band of correct size should be purified and subjected to Sanger sequencing.

Troubleshooting with Additives:

- For difficult templates, such as those with high GC content (>65%), additives like DMSO (2–10%) or Betaine (1–2 M) can be included in the reaction. These compounds help disrupt stable secondary structures in the template DNA that can impede polymerase progress [16].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PCR Primer Design and Validation

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Reduces non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation by requiring heat activation. | ZymoTaq DNA Polymerase [10]; various high-fidelity enzymes [16]. |

| Primer Design Software | Automates primer design based on customizable parameters (length, Tm, GC%). | IDT PrimerQuest [8], NCBI Primer-BLAST [14] [15]. |

| Oligo Analysis Tool | Analyzes Tm, secondary structures (hairpins, dimers), and performs BLAST checks. | IDT OligoAnalyzer [8]. |

| DNA Clean-up Kits | Purifies PCR products from primers, enzymes, and salts for downstream applications. | Zymo Research DNA Clean & Concentrator Kits [10]. |

| Buffer Additives | Improves amplification of problematic templates (e.g., GC-rich sequences). | DMSO, Betaine [16]. |

The rigorous design of PCR primers is a critical determinant of experimental success in research and drug development. By systematically applying the principles outlined for primer length, GC content, and specificity, scientists can create robust and reliable assays. Adherence to the recommended parameters—18–30 nucleotides in length, 40–60% GC content with a stabilized 3' end, and thorough in-silico and empirical specificity checks—forms the foundation of this process. The integrated use of sophisticated bioinformatics tools like Primer-BLAST, coupled with empirical validation through gradient PCR, provides a comprehensive strategy for transforming theoretical primer designs into highly specific and efficient reagents. Mastering these critical parameters ensures that PCR remains a powerful, precise, and reproducible tool at the forefront of molecular science.

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is most famously known for its canonical B-helix form, but it is not always present in this structure; it can form various alternative secondary structures, including Z-DNA, cruciforms, triplexes, quadruplexes, slipped-strand DNA, and hairpins [17]. These structured forms of DNA with intrastrand pairing are generated in several cellular processes and are involved in diverse biological functions, from replication and transcription regulation to site-specific recombination [17]. In the specific context of molecular amplification technologies, particularly the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), the propensity of single-stranded DNA to form these secondary structures presents a significant challenge to experimental success.

Hairpin structures are formed by sequences with inverted repeats (IRs) or palindromes and can arise through two primary mechanisms: on single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) produced during processes like replication or, relevantly, during the thermal denaturation steps of PCR, or as cruciforms extruded from double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) under negative supercoiling stress [17]. The stability of these nucleic acid hairpins is highly dependent on the ionic environment, as the polyanionic nature of the DNA backbone means metal ions like Na+ and Mg2+ play a crucial role in neutralizing charge and stabilizing the folded structure [18]. During PCR, primers must bind to their complementary sequences on a single-stranded DNA template. If these primers or the template itself form stable secondary structures, such as hairpins, they can physically block the primer from annealing, significantly reducing the yield of the desired PCR product [19].

Similarly, primer-dimers are another common artifact that plagues PCR efficiency. These spurious products form when two primers anneal to each other, typically via their 3' ends, rather than to the template DNA. The DNA polymerase can then extend these primers, creating short, double-stranded fragments that compete with the target amplicon for reagents [11] [20] [21]. Both hairpins and primer-dimers thus represent a significant failure of the core primer annealing principle, which depends on the predictable and specific binding of primers to a single target site. Understanding the formation, stability, and impact of these structures is therefore fundamental to research in primer stability and the development of robust molecular assays in drug development and diagnostic applications.

Molecular Mechanisms and Energetics of Structure Formation

Hairpin Formation and Stability

DNA hairpins, also known as stem-loop structures, are formed when a single-stranded DNA molecule folds back on itself, creating a double-stranded stem and a single-stranded loop. This folding is driven by intrastrand base pairing between inverted repeat sequences [17]. The formation and stability of these structures are governed by complex thermodynamic principles and are highly sensitive to experimental conditions.

The stability of a hairpin is quantitatively described by its free energy change (ΔG), where a more negative ΔG indicates a more stable structure. This stability is a function of several factors:

- Loop Length and Composition: The length of the single-stranded loop and the distance between the ends of the stem significantly influence the free energy. Shorter loops generally confer greater stability, but there is a thermodynamic penalty for extremely short loops due to conformational strain [18].

- Stem Stability: The length and GC content of the stem directly contribute to stability. GC base pairs, with three hydrogen bonds, confer more stability than AT base pairs, which have only two. Therefore, a hairpin with a GC-rich stem will be more stable than one with an AT-rich stem [11] [20].

- Ionic Environment: The electrostatic repulsion between negatively charged phosphate groups in the DNA backbone must be neutralized for the helix to form. Divalent cations like Mg2+ are particularly effective at stabilizing folded structures due to their high charge density and ability to be tightly bound in the electrostatic field of the DNA, potentially including correlation effects that are not accounted for in simpler mean-field theories [18].

Table 1: Key Factors Influencing Nucleic Acid Hairpin Stability

| Factor | Impact on Stability | Experimental Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Stem GC Content | Higher GC content increases stability due to stronger base pairing. | Avoid long runs of G or C bases, especially at the 3' end of primers [11] [20]. |

| Loop Length | Shorter loops (e.g., 3-5 nucleotides) are generally more stable. | Design primers without significant self-complementarity that can form short loops [21]. |

| Ion Concentration | Higher concentrations of monovalent (Na+) and especially divalent (Mg2+) cations stabilize folding. | PCR buffer composition (MgCl2 concentration) can inadvertently stabilize unwanted template secondary structures [18]. |

| Temperature | Stability decreases as temperature increases towards the melting temperature (Tm). | Annealing temperature must be high enough to melt primer and template secondary structures [19]. |

The kinetics of hairpin formation are also critical. While cruciform extrusion from dsDNA in vivo was once thought to be slow, techniques have since confirmed their existence and biological roles [17]. In the context of PCR, the rapid thermal cycling means that structures must form and melt on a short timescale. If a secondary structure is stable at or above the annealing temperature, it will prevent primer binding and abort the amplification [19].

Primer-Dimer Formation

Primer-dimer formation is a consequence of intermolecular interactions between primers, as opposed to the intramolecular folding seen in hairpins. The mechanism typically involves:

- Intermolecular Complementarity: The 3' ends of two primers (either two identical copies or the forward and reverse primers) have some degree of complementary sequence.

- Transient Annealing: At the annealing temperature, these primers can weakly bind to each other.

- Polymerase Extension: The DNA polymerase recognizes the 3' end of each primer as a valid starting point and extends it, synthesizing a short, double-stranded product that is a concatemer of the two primer sequences [11] [21].

The primary driver of primer-dimer artifacts is sequence complementarity, particularly at the 3' ends of the primers. Just a few complementary bases at the 3' end can provide a stable enough platform for the polymerase to initiate synthesis. Furthermore, low annealing temperatures and high primer concentrations can exacerbate this problem by increasing the probability of these off-target interactions [20]. The resulting primer-dimers consume precious reagents—primers, nucleotides, and polymerase—thereby reducing the efficiency of the desired amplification reaction and leading to false negatives or inaccurate quantification in quantitative PCR (qPCR) [22].

Experimental Detection and Analysis Methodologies

In Silico Prediction and Analysis

Before moving to the bench, comprehensive in silico analysis is a critical first step in predicting and preventing issues related to secondary structures.

Protocol: Computational Workflow for Secondary Structure Assessment

- Sequence Input: Obtain the nucleotide sequences for both the template and the candidate primers in FASTA format.

- Hairpin Prediction: Use secondary structure prediction software, such as the mfold server, to model the folding of each primer individually [19]. The analysis should be run at the intended annealing temperature and with salt concentrations matching the PCR buffer. Key parameters to examine are the predicted ΔG (where more negative values indicate stable structures) and the presence of hairpins with a ΔG of less than -9 kcal/mol, which are likely to be stable and problematic.

- Dimer Analysis: Utilize tools like OligoAnalyzer or similar software to screen for self-dimers (between two copies of the same primer) and cross-dimers (between the forward and reverse primer) [21]. The analysis should focus on the stability (ΔG) of any predicted dimer complexes, with particular attention to complementarity at the 3' ends.

- Specificity Check: Finally, use a tool like NCBI Primer-BLAST to check the specificity of the primer pair against the appropriate genome database to ensure they only bind to the intended target, minimizing the risk of off-target amplification that can complicate analysis [21].

Empirical Validation Techniques

Theoretical predictions must be confirmed experimentally, as the biological reality of the assay is more complex than any software simulation [20].

Protocol: Gel Electrophoresis for Artifact Detection

- Purpose: To separate and visualize PCR products and identify the presence of primer-dimer artifacts or non-specific amplification.

- Method:

- Prepare a standard agarose gel (concentration appropriate for the expected amplicon size, typically 2-3% for detecting small primer-dimers).

- Mix the PCR product with a DNA loading dye and load it into the gel wells. Include a DNA ladder for size determination.

- Run the gel at a constant voltage (e.g., 100V) until the dye front has migrated sufficiently.

- Stain the gel with an intercalating dye like ethidium bromide or a safer alternative and visualize under UV light [23].

- Interpretation: The desired amplicon should appear as a single, sharp band at the expected size. Primer-dimers typically appear as a diffuse, low molecular weight band, often around 50-100 bp or lower, sometimes smearing from the well [23].

Protocol: Melt Curve Analysis in qPCR

- Purpose: To assess the homogeneity of the PCR product and detect the presence of primer-dimers in real-time PCR assays without the need for gel electrophoresis.

- Method:

- Perform a qPCR run using a dsDNA-binding dye like SYBR Green I.

- After the final amplification cycle, the thermal cycler is programmed to gradually increase the temperature from a low (e.g., 60°C) to a high (e.g., 95°C) value while continuously monitoring the fluorescence.

- As the temperature rises, double-stranded DNA products melt into single strands, causing a drop in fluorescence. The negative derivative of fluorescence over temperature (-dF/dT) is plotted against temperature to generate a melt curve [22].

- Interpretation: A single, sharp peak indicates a homogeneous, specific PCR product. The presence of primer-dimers is revealed by an additional, lower-temperature peak, as these smaller fragments denature at a lower temperature than the larger target amplicon [22].

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Detecting Secondary Structure Artifacts

| Method | Principle | Application | Key Indicators of Problems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agarose Gel Electrophoresis | Separates DNA fragments by size in an electric field. | End-point analysis of PCR products. | A diffuse band ~50-100 bp (primer-dimer); multiple bands (non-specific amplification) [23]. |

| qPCR Melt Curve Analysis | Monographs fluorescence as dsDNA products are denatured by heat. | In-tube assessment of amplicon homogeneity post-qPCR. | Multiple peaks indicate different DNA species; a low-Tm peak suggests primer-dimer [22]. |

| qPCR Amplification Plot Analysis | Tracks fluorescence increase during cycling. | Real-time monitoring of amplification efficiency. | High Cq values, low amplification efficiency, or nonlinear standard curves can indicate inhibition from structures [22]. |

| Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) | Measures migration shift of DNA in a gel due to folding. | In vitro confirmation of template or primer secondary structure. | Reduced electrophoretic mobility suggests formation of a folded/hairpin structure [24]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and computational tools essential for researching and mitigating secondary structure issues.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Secondary Structure Research

| Item | Function/Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Bst DNA Polymerase | A recombinant DNA polymerase with strong strand displacement activity. | Used in isothermal amplification methods (e.g., LAMP, HAIR) to unwind stable template secondary structures without the need for thermal denaturation [25]. |

| Nt.BstNBI Nickase | An endonuclease that cleaves (nicks) one specific DNA strand. | A key enzyme in the Hairpin-Assisted Isothermal Reaction (HAIR) and NEAR; nicking creates new 3' ends for primer-free amplification and avoids full strand separation [25]. |

| SYBR Green I Dye | A fluorescent dye that intercalates into double-stranded DNA. | Used in qPCR with melt curve analysis to detect multiple amplicon species (e.g., specific product vs. primer-dimer) based on their melting temperatures [22]. |

| DMSO (Dimethyl Sulfoxide) | A chemical additive that reduces the stability of DNA secondary structures. | Added to PCR mixes to improve amplification efficiency through GC-rich regions or templates prone to forming hairpins by lowering the Tm of secondary structures [21]. |

| mfold Server | A web server for predicting the secondary structure of nucleic acids. | Used during primer design to simulate potential hairpin formation in primers and template under user-defined temperature and salt conditions [19]. |

| OligoAnalyzer Tool | A web-based tool for analyzing oligonucleotide properties. | Used to calculate Tm, check for self- and hetero-dimer formation, and predict hairpin stability based on ΔG values [21]. |

Advanced Applications and Isothermal Amplification

While often viewed as a nuisance in conventional PCR, the propensity of DNA to form secondary structures has been ingeniously harnessed in some advanced molecular methods, particularly isothermal amplification techniques. These methods operate at a constant temperature and often rely on structured DNA for their functionality.

The Hairpin-Assisted Isothermal Reaction (HAIR) is a prime example of this principle. This novel method of isothermal amplification is based on the formation of hairpins at the ends of DNA fragments containing palindromic sequences. The key steps in HAIR are the formation of a self-complementary hairpin and DNA breakage introduced by a nickase. The end hairpins facilitate primer-free amplification, and the amplicon strand cleavage by the nickase produces additional 3' ends that serve as new initiation points for DNA synthesis. This clever design allows the amount of DNA to increase exponentially at a constant temperature. Reported advantages of HAIR include an amplification rate more than five times that of the popular Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) method and a total DNA product yield more than double that of LAMP [25].

This paradigm shift from "problem" to "tool" highlights a fundamental principle in molecular biology: structural "complications" can be transformed into functional components with clever experimental design. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these mechanisms opens doors to developing novel diagnostics and research tools that are faster, simpler, and potentially more tolerant of inhibitors than traditional PCR [25]. The conceptual framework of leveraging, rather than fighting, DNA's structural properties promises to expand the toolbox available for genetic analysis.

Thermodynamic Rules for Stable 3' Ends and GC Clamps

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) stands as one of the most significant methodological advancements in modern molecular biology, enabling exponential amplification of specific DNA sequences from minimal starting material [26]. The success of this technique hinges critically on the precise binding of oligonucleotide primers to their complementary template sequences during the annealing phase. Within this process, the thermodynamic properties governing the 3' terminus of primers emerge as a fundamental determinant of amplification efficiency, specificity, and yield. This technical guide examines the thermodynamic principles underlying stable 3' ends and GC clamps, framing these concepts within a broader thesis on primer annealing principles and stability research essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The 3' end of a primer possesses distinct functional significance in PCR mechanics. Thermostable DNA polymerase initiates nucleotide incorporation exclusively from the 3' hydroxyl group, making complete annealing of the primer's 3' terminus to the template absolutely indispensable for successful amplification [27]. Incomplete binding at this critical juncture results in inefficient PCR or complete amplification failure, while excessively stable annealing may permit amplification from non-target sites, generating spurious products. Consequently, the thermodynamic stabilization of the primer's 3' end must be carefully balanced to promote specific binding without compromising reaction fidelity.

Thermodynamic Principles of Primer-Template Interactions

Gibbs Free Energy and 3' End Stability

The spontaneity and stability of primer-template binding is governed quantitatively by Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG), which represents the amount of energy required to break secondary structures or the amount of work that can be extracted from a process operating at constant pressure [28] [26]. The stability of the primer's 3' end is specifically defined as the maximum ΔG value of the five nucleotides at the 3' terminus [28] [26]. This parameter profoundly impacts false priming efficiency, as primers with unstable 3' ends (less negative ΔG values) function more effectively because incomplete bonding to non-target sites remains too unstable to permit polymerase extension [28].

The calculation of ΔG follows the nearest-neighbor method established by Breslauer et al., employing the fundamental thermodynamic relationship:

ΔG = ΔH - TΔS

Where ΔH represents the enthalpy change (in kcal/mol) for helix formation, T is the temperature (in Kelvin), and ΔS signifies the entropy change (in kcal/°K/mol) [28]. For primer design, the thermodynamic stability is typically calculated for the terminal five bases at the 3' end. The dimer and hairpin stability are also quantified using ΔG, with more negative values indicating stronger, more stable structures that are generally undesirable [29] [26].

Molecular Determinants of Binding Stability

The differential bonding strength between nucleotide bases constitutes the atomic foundation for primer-template stability. Guanine (G) and cytosine (C) form three hydrogen bonds when base-paired, whereas adenine (A) and thymine (T) form only two hydrogen bonds [13]. This disparity translates directly into thermodynamic stability, as GC-rich sequences demonstrate higher melting temperatures due to the increased energy requirement for duplex dissociation [13]. This fundamental principle informs the strategic placement of G and C bases within the 3' region to modulate primer binding characteristics.

The nearest-neighbor thermodynamic model provides the most accurate calculation of duplex stability by considering the sequential dependence of base-pair interactions [28] [26]. Rather than treating each base pair independently, this method accounts for the stacking interactions between adjacent nucleotide pairs, yielding superior predictions of melting behavior compared to simplified methods based solely on overall GC content [26].

Quantitative Design Parameters for Optimal 3' End Stability

Comprehensive Primer Design Specifications

Table 1: Optimal thermodynamic and sequence parameters for PCR primer design

| Parameter | Optimal Value | Functional Significance | Calculation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primer Length | 18-25 nucleotides [29] [30] [26] | Balances specificity with efficient hybridization | Determined by sequence selection |

| GC Content | 40-60% [16] [29] [13] | Provides balance between binding stability and secondary structure avoidance | (Number of G's + C's)/Total bases × 100 |

| GC Clamp | 2-3 G/C bases in last 5 positions at 3' end [29] [13] [26] | Promotes specific binding through stronger hydrogen bonding | Visual sequence inspection |

| Maximum 3' GC | ≤3 G/C in last 5 bases [31] [26] | Prevents excessive stability leading to non-specific binding | Count of G/C in terminal 5 bases |

| Melting Temperature (Tₘ) | 55-65°C [16] [30] [26] | Indicates duplex stability; determines annealing temperature | Tₘ = ΔH/(ΔS + R ln(C/4)) + 16.6 log([K+]/(1+0.7[K+])) - 273.15 [28] |

| 3' End Stability (ΔG) | Less negative values preferred [28] [26] | Reduces false priming by decreasing stability at non-target sites | ΔG = ΔH - TΔS for terminal 5 bases [28] |

| Annealing Temperature (Tₐ) | 5-10°C below Tₘ [29] or Tₐ = 0.3×Tₘ(primer) + 0.7×Tₘ(product) - 14.9 [26] | Optimizes specificity of primer-template binding | Calculated from Tₘ of primer and product |

Empirical Validation from Successful PCR Experiments

Analysis of 2,137 primer sequences from successful PCR experiments documented in the VirOligo database provides empirical validation for these thermodynamic principles [27]. The frequency distribution of 3' end triplets reveals clear preferences in experimentally verified functional primers, with the most successful triplets including AGG (3.27%), TGG (2.95%), CTG (2.76%), TCC (2.76%), and ACC (2.76%) [27]. Conversely, the least successful triplets were TTA (0.42%), TAA (0.61%), and CGA (0.66%) [27]. This dataset demonstrates that while all 64 possible triplet combinations can support amplification under specific conditions, clear thermodynamic preferences emerge in practice.

Notably, the most successful triplets typically contain 2-3 G/C residues, consistent with the GC clamp principle, while maintaining sequence diversity that potentially minimizes secondary structure formation. This empirical evidence underscores the importance of balanced stability rather than maximal stability at the 3' end.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Computational Assessment of Primer Thermodynamics

Table 2: Essential research reagents for thermodynamic analysis of primers

| Reagent/Software | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Design Software (Primer3, Primer Premier) | Calculates Tₘ, ΔG, and detects secondary structures [27] [26] | In silico primer optimization and validation |

| BLAST Analysis | Tests primer specificity against genetic databases [29] [26] | Verification of target-specific binding |

| NEBuilder Tool | Assembles primer sequences with template for visualization | Virtual PCR simulation |

| DMSO (2-10%) | Reduces secondary structure in GC-rich templates [16] | PCR additive for challenging templates |

| Betaine (1-2 M) | Homogenizes template stability in GC-rich regions [16] | Additive for long-range or GC-rich PCR |

| Mg²⁺ (1.5-2.0 mM) | Essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity [16] | PCR buffer component requiring optimization |

Protocol 1: In Silico Thermodynamic Analysis

- Sequence Input: Enter template DNA sequence in FASTA format into primer design software (e.g., Primer3, Primer Premier) [26].

- Parameter Setting: Configure software to apply standard thermodynamic parameters: primer length (18-25 bp), Tₘ (55-65°C), GC content (40-60%) [29] [26].

- GC Clamp Specification: Activate GC clamp function requiring 2-3 G/C bases in the last 5 positions at the 3' end [26].

- Stability Calculation: Software automatically computes ΔG values for 3' end stability, hairpins, and self-dimers using nearest-neighbor thermodynamics [28].

- Specificity Verification: Perform BLAST analysis to confirm primer binding uniqueness within the target genome [29] [26].

- Secondary Structure Assessment: Evaluate predicted hairpin formations (ΔG > -2 kcal/mol for 3' end; ΔG > -3 kcal/mol for internal) and self-dimers (ΔG > -5 kcal/mol) [26].

Protocol 2: Empirical Validation Through Gradient PCR

- Reaction Preparation: Prepare PCR master mix containing template DNA (100,000 copies), 0.5 μM of each primer, 1× reaction buffer, 1.5-2.0 mM Mg²⁺, 200 μM dNTPs, and 0.5 units DNA polymerase [32].

- Thermal Gradient Setup: Program thermocycler with annealing temperature gradient spanning 5-10°C below the calculated Tₘ of the primers [16] [29].

- Amplification Parameters: Execute 33 cycles of denaturation (95°C for 30s), gradient annealing (45-65°C for 30s), and extension (72°C for 30s) [32].

- Product Analysis: Separate PCR products via agarose gel electrophoresis (1.5% agarose, 100V, 40 minutes) and visualize with ethidium bromide staining [32].

- Optimal Temperature Determination: Identify the highest annealing temperature that produces a single, specific amplicon of expected size [16].

Workflow for Primer Design and Validation

Diagram 1: Primer design and validation workflow

Advanced Applications and Recent Methodologies

Machine Learning Approaches to PCR Prediction

Recent advancements have introduced machine learning methodologies for predicting PCR success based on primer and template sequences. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) trained on experimental PCR results can process pseudo-sentences generated from primer-template relationships, achieving approximately 70% accuracy in predicting amplification outcomes [32]. This approach comprehensively evaluates multiple factors simultaneously, including dimer formation, hairpin structures, and partial complementarities that traditional thermodynamic analysis might overlook.

Specialized PCR Applications

The thermodynamic principles governing 3' end stability find particular importance in specialized PCR applications including quantitative PCR (qPCR), multiplex PCR, and high-fidelity amplification. For qPCR, optimal amplicon lengths are typically shorter (approximately 100 bp), requiring precise 3' end stability to ensure efficient amplification [26]. High-fidelity PCR utilizing polymerases with proofreading capability (e.g., Pfu, KOD) demands especially stable 3' end binding to compensate for potentially slower enzymatic kinetics [16].

The thermodynamic rules governing stable 3' ends and GC clamps represent a critical component of primer annealing principles within PCR-based research and diagnostics. The strategic implementation of GC clamps—typically 2-3 G/C bases within the terminal five positions at the 3' end—promotes specific initiation of polymerase extension while maintaining sufficient specificity to minimize off-target amplification. The empirical success of primers with 3' end triplets such as AGG, TGG, and CTG underscores the practical validation of these thermodynamic principles [27].

As molecular techniques continue to evolve, particularly in diagnostic and therapeutic applications requiring absolute specificity, the precise thermodynamic optimization of primer-template interactions remains fundamental. The integration of classical thermodynamic calculations with emerging computational approaches, including machine learning, promises enhanced predictive capabilities for PCR success across diverse experimental contexts. For researchers in drug development and diagnostic applications, where reproducibility and specificity are paramount, adherence to these well-established thermodynamic rules provides a foundation for robust, reliable experimental outcomes.

The Direct Relationship Between Tm and Optimal Annealing Temperature (Ta)

In polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology, the melting temperature (Tm) and annealing temperature (Ta) share a fundamental relationship that directly determines the success of DNA amplification. The Tm is defined as the temperature at which 50% of the primer-DNA duplex dissociates into single strands and 50% remains bound, representing a critical equilibrium point [33]. The annealing temperature (Ta) is the actual temperature utilized during the PCR cycling process to facilitate primer binding to the complementary template sequence [33]. This relationship is not merely sequential but quantitative, with Ta typically being set 5°C below the calculated Tm of the primer to optimize the specificity and efficiency of the amplification process [34].

Understanding the precise interplay between Tm and Ta is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who rely on PCR for applications ranging from gene expression analysis to diagnostic test development. The stability of the primer-template duplex, which is governed by the Tm, directly influences the stringency of the annealing step, which in turn controls the specificity of the amplification reaction [35]. When the Ta is too low, primers may bind to non-complementary sequences, leading to nonspecific amplification and reduced yield of the desired product. Conversely, when the Ta is too high, primer binding may be insufficient, resulting in poor reaction efficiency or complete PCR failure [33] [36]. This technical guide explores the theoretical foundations, practical calculations, and experimental optimizations that define the direct relationship between Tm and Ta, providing a comprehensive resource for mastering primer annealing principles.

Theoretical Foundations of Tm and Its Calculation

The melting temperature of a primer is not a fixed value but is influenced by multiple factors that collectively determine the stability of the primer-template duplex. The theoretical foundation of Tm calculation revolves primarily on the sequence length and nucleotide composition of the oligonucleotide. Longer primers with higher guanine-cytosine (GC) content generally exhibit elevated Tm values due to the three hydrogen bonds in G-C base pairs compared to the two hydrogen bonds in A-T base pairs [11]. This fundamental relationship explains why GC-rich sequences demonstrate greater thermal stability and consequently higher melting temperatures.

Beyond sequence composition, Tm values are significantly affected by the chemical environment of the PCR reaction. The presence and concentration of monovalent cations (such as K+ and Na+) and divalent cations (particularly Mg2+) directly influence duplex stability by neutralizing the negative charges on the phosphate backbone of DNA, thereby reducing electrostatic repulsion between the primer and template strands [33] [35]. The concentration of primers themselves also affects Tm calculations, as the primers are present in molar excess relative to the template [33]. Additionally, reaction components like dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) can markedly decrease the Tm by disrupting DNA base pairing, with 10% DMSO concentration reportedly reducing Tm by approximately 5.5–6.0°C [37].

Several calculation methods have been developed to predict Tm based on these variables, with the modified Breslauer's method being implemented in many commercial Tm calculators [37]. These calculators incorporate algorithm-specific adjustments to account for buffer composition and other reaction conditions that affect duplex stability. It is important to note that different DNA polymerases may recommend specific calculation methods optimized for their respective buffer systems, highlighting the context-dependent nature of Tm determination in experimental planning.

Quantitative Relationship Between Tm and Ta

The relationship between Tm and optimal annealing temperature follows established mathematical formulas that enable researchers to systematically determine the appropriate Ta for their specific primer sequences. The most fundamental approach sets the annealing temperature at 5°C below the Tm of the primer with the lower melting temperature in the pair [34] [36]. This adjustment ensures sufficient binding stability while maintaining specificity, as it requires exact complementarity for successful primer elongation.

A more sophisticated calculation incorporates the Tm of the PCR product itself, providing enhanced precision for challenging amplifications. The optimal Ta formula is expressed as:

Ta Opt = 0.3 × (Tm of primer) + 0.7 × (Tm of product) – 14.9 [34] [38]

In this equation, the "Tm of primer" refers specifically to the melting temperature of the less stable primer-template pair, while the "Tm of product" represents the melting temperature of the PCR product. This calculation assigns greater weight to the product Tm (70%) than to the primer Tm (30%), reflecting the significant influence of amplicon characteristics on annealing efficiency. Some variations of this formula may use different constant values, such as -25 instead of -14.9, depending on the specific polymerase system and buffer conditions [36].

Table 1: Comparison of Ta Calculation Methods

| Method | Formula | Application Context | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Rule | Ta = Tm - 5°C | General PCR, primer pairs with similar Tms | Quick calculation, works well for simple amplifications [34] |

| Advanced Formula | Ta Opt = 0.3 × Tm primer + 0.7 × Tm product - 14.9 | Complex templates, difficult amplifications | Accounts for product characteristics, requires product Tm calculation [34] [38] |

| Polymerase-Specific | Varies by enzyme and buffer system | Specific polymerase systems (e.g., Phusion, Q5) | Incorporates proprietary buffer effects, follow manufacturer guidelines [37] [33] |

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for determining optimal annealing temperature based on Tm calculations and the consequences of suboptimal temperature selection:

Figure 1: Decision workflow for determining optimal annealing temperature based on Tm calculations

For primers of different lengths, specific adjustments are recommended. When using primers ≤20 nucleotides, the lower Tm value provided by the calculator should be used directly for annealing. For primers >20 nucleotides, an annealing temperature 3°C higher than the lower Tm is recommended [37]. This adjustment accounts for the increased stability of longer primers while maintaining appropriate stringency. These quantitative relationships provide a systematic framework for researchers to establish effective starting conditions for PCR amplification before empirical optimization.

Experimental Determination and Optimization

While theoretical calculations provide essential starting points, empirical determination of the optimal annealing temperature remains critical for PCR success, particularly for novel primer systems or challenging templates. The most reliable method for Ta optimization involves running a gradient PCR, where the annealing temperature is systematically varied across a range of temperatures during a single experiment [9] [33]. This approach efficiently identifies the temperature that provides the highest yield of the specific product while minimizing amplification artifacts.

A standard optimization protocol begins with calculating the theoretical Tm for both forward and reverse primers using an appropriate calculator. The thermal cycler is then programmed with an annealing temperature gradient that typically spans from 5°C below the calculated Tm to 5°C above it, creating a range of annealing conditions in a single run [37]. After amplification, the products are analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis, with the optimal Ta identified as the highest temperature that produces a strong, specific band of the expected size without nonspecific products or primer-dimers [9].

Table 2: Troubleshooting PCR Amplification Based on Annealing Temperature Effects

| Observed Result | Potential Cause | Solution | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple bands or smearing | Ta too low, causing nonspecific binding | Increase Ta in 2°C increments | Elimination of nonspecific products [33] [35] |

| Weak or no product band | Ta too high, preventing primer binding | Decrease Ta in 2°C increments | Improved product yield [33] [36] |

| Primer-dimer formation | Ta too low, enabling primer self-annealing | Increase Ta or redesign primers | Reduction of primer-dimer artifacts [33] [11] |

| Inconsistent results between primer pairs | Significant Tm mismatch between forward and reverse primers | Use universal annealing buffer or redesign primers | Balanced amplification with both primers [9] |

When standard optimization fails, researchers should consider the impact of reaction components on effective Ta. The presence of additives like DMSO, glycerol, or formamide typically requires a proportional reduction in annealing temperature, as these compounds decrease the actual Tm of primer-template duplexes [37] [35]. Similarly, variations in magnesium concentration directly affect reaction stringency, with higher Mg2+ concentrations stabilizing primer binding and effectively lowering the Ta requirement. Through systematic experimentation and component adjustment, researchers can establish robust PCR conditions that maximize amplification efficiency and specificity.

Advanced Concepts: Universal Annealing and Buffer Innovations

Recent advancements in PCR technology have introduced innovative approaches that mitigate the challenges associated with Tm-Ta optimization. Universal annealing buffers represent a significant development, incorporating specialized components that maintain primer binding specificity across a range of temperatures [9]. These buffers typically contain isostabilizing agents that modulate the thermal stability of primer-template duplexes, enabling specific binding even when primer melting temperatures differ substantially from the reaction temperature [9].

The primary advantage of universal annealing systems is the ability to use a standardized annealing temperature of 60°C for most PCR applications, regardless of the specific Tm of the primer pair [9]. This innovation significantly streamlines experimental workflow, particularly in diagnostic and drug development settings where multiple targets are routinely amplified. The technology also facilitates co-cycling of different PCR assays, allowing simultaneous amplification of targets with varying lengths and primer characteristics using a unified thermal cycling protocol [9]. By selecting the extension time based on the longest amplicon, researchers can amplify multiple targets in a single run without compromising specificity or yield.

The mechanism underlying universal annealing buffers involves stabilization of the primer-template duplex during the critical annealing step, effectively creating a more permissive environment for specific hybridization despite potential Tm mismatches [9]. This stabilization enables successful PCR amplification with primer pairs that would normally require extensive optimization under conventional buffer conditions. For research facilities handling high-throughput applications or screening multiple genetic targets, adoption of polymerase systems with universal annealing capability can dramatically reduce optimization time and improve reproducibility across experiments.

Successful implementation of Tm-Ta relationship principles requires access to specialized reagents and computational tools. The following table outlines essential resources for optimizing primer annealing conditions:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Annealing Temperature Optimization

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Tm Calculator (e.g., Thermo Fisher, NEB, IDT) | Computes primer melting temperature considering buffer composition | Use calculator specific to your polymerase system for most accurate results [37] [33] |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerases (e.g., Phusion, Q5) | DNA amplification with proofreading activity | Follow manufacturer-specific Tm calculation methods [37] [33] |

| Platinum DNA Polymerases with Universal Annealing Buffer | Enables fixed 60°C annealing temperature | Ideal for high-throughput applications, eliminates individual primer optimization [9] |

| Gradient Thermal Cycler | Empirically tests multiple annealing temperatures simultaneously | Essential for optimization of novel primer systems [37] [9] |

| Magnesium Chloride Solutions | Titrates Mg2+ concentration to optimize reaction stringency | Higher concentrations stabilize primer binding; requires Ta adjustment [33] [35] |

| PCR Additives (DMSO, BSA, glycerol) | Modifies template accessibility and duplex stability | Generally require lower Ta; 10% DMSO decreases Tm by ~5.5-6.0°C [37] [35] |

| Buffer Optimization Kits | Systematically tests different cation combinations | Identifies ideal buffer for specific primer-template systems [35] |

Modern online tools such as IDT's OligoAnalyzer and PrimerQuest provide researchers with comprehensive platforms for calculating Tm and designing optimal primer pairs [38]. These tools incorporate the latest thermodynamic parameters and allow customization of reaction conditions to match specific experimental setups. When designing primers, researchers should aim for sequences with balanced length (18-30 bases) and GC content (40-60%), with the 3' terminus ending in G or C to promote binding (GC clamp) [11]. Additionally, primers should be checked for secondary structures, self-complementarity, and repetitive elements that might compromise amplification efficiency. By leveraging these specialized tools and following established design principles, researchers can establish robust PCR conditions that reliably produce specific, high-yield amplification.

Advanced Methodologies and Practical Application in Complex Assays

In the realm of molecular biology, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) serves as a foundational technique for DNA amplification, with applications spanning from basic research to clinical diagnostics and drug development. The core of every PCR experiment lies in the DNA polymerase enzyme, which catalyzes the replication of target DNA sequences. The choice between standard and high-fidelity DNA polymerases represents a critical decision point that directly impacts experimental outcomes, balancing the competing demands of amplification accuracy, speed, and yield. Within the context of primer annealing principles and stability research, this selection becomes even more significant, as polymerase fidelity directly influences the reliability of results in studies investigating primer-template interactions, hybridization kinetics, and nucleic acid stability.

DNA polymerase fidelity refers to the accuracy with which a DNA polymerase copies a template sequence, measured by its error rate—the frequency at which it incorporates incorrect nucleotides during amplification [39]. Standard polymerases like Taq DNA polymerase have error rates typically ranging from (1 \times 10^{-4}) to (2 \times 10^{-5}) errors per base pair, meaning one error per 5,000-10,000 nucleotides synthesized [39] [40]. In contrast, high-fidelity polymerases such as Q5, Phusion, and Pfu exhibit significantly lower error rates, ranging from (5.3 \times 10^{-7}) to (5 \times 10^{-6}) errors per base pair, translating to approximately one error per 200,000 to 2,000,000 bases incorporated [39] [40]. This substantial difference in accuracy has profound implications for downstream applications, particularly those requiring precise DNA sequences such as cloning, genetic variant analysis, next-generation sequencing, and gene synthesis.

Mechanisms of Polymerase Fidelity: Structural and Functional Basis

The divergent fidelity profiles between standard and high-fidelity DNA polymerases stem from fundamental differences in their structural composition and biochemical mechanisms. Understanding these underlying principles provides crucial insights for selecting appropriate enzymes for specific experimental needs, particularly in studies focused on primer-template stability and hybridization dynamics.

Geometric Selection and Kinetic Proofreading

All DNA polymerases employ a fundamental mechanism known as geometric selection to ensure replication accuracy. The polymerase active site is structurally constrained to accommodate only correctly paired nucleotides that form proper Watson-Crick base pairs with the template strand. When a correct nucleotide is incorporated, the active site achieves optimal architecture for catalysis, facilitating efficient phosphodiester bond formation. However, when an incorrect nucleotide binds, the resulting suboptimal geometry slows the incorporation rate significantly. This delayed incorporation increases the opportunity for the incorrect nucleotide to dissociate from the ternary complex before being covalently added to the growing chain, allowing the correct nucleotide to bind instead [39]. This kinetic proofreading mechanism provides the first layer of fidelity control and is present in both standard and high-fidelity enzymes, though its efficiency varies among different polymerase families.

The 3'→5' Exonuclease Proofreading Domain

The most significant structural difference between standard and high-fidelity polymerases lies in the presence of a 3'→5' exonuclease domain in proofreading enzymes. High-fidelity polymerases such as Q5, Phusion, Pfu, and Pwo possess this dedicated domain that confers exceptional accuracy through exonucleolytic proofreading. When an incorrect nucleotide is incorporated, the resulting structural perturbation in the DNA duplex is detected by the polymerase, which then translocates the 3' end of the growing DNA chain into the exonuclease domain. Here, the mispaired nucleotide is excised before the chain is returned to the polymerase active site for incorporation of the correct nucleotide [39].

The impact of this proofreading activity on fidelity is substantial. Comparative studies between proofreading-deficient and proofreading-proficient versions of the same polymerase demonstrate that the presence of the 3'→5' exonuclease domain can improve fidelity by up to 125-fold. For instance, Deep Vent (exo-) polymerase exhibits an error rate of (5.0 \times 10^{-4}) errors per base per doubling, while the exonuclease-proficient Deep Vent polymerase shows a dramatically lower error rate of (4.0 \times 10^{-6}) [39]. This proofreading mechanism represents the most effective natural strategy for maximizing replication accuracy and is a defining characteristic of high-fidelity enzymes used in applications requiring minimal mutation rates.

Quantitative Fidelity Comparison: Error Rates and Measurement Methods

Accurate assessment of polymerase fidelity requires sophisticated methodological approaches that can detect and quantify rare replication errors. Different measurement techniques have been developed, each with specific sensitivities, limitations, and applications in fidelity characterization.

Fidelity Measurement Methodologies

Early fidelity assays relied on phenotypic screening systems, such as the lacZα complementation assay in M13 bacteriophage, where errors during amplification of the lacZ gene resulted in color changes in bacterial colonies [39]. While high-throughput, these methods were limited to detecting only specific types of mutations that affected the reporter gene's function. The development of Sanger sequencing of cloned PCR products offered more comprehensive error detection by enabling identification of all mutation types across the sequenced region [39] [40]. However, the relatively high cost and low throughput of traditional sequencing limited its statistical power for quantifying very high-fidelity enzymes.

The advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms revolutionized fidelity assessment by providing massive sequencing depth, enabling detection of rare errors with statistical significance [39]. More recently, single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing technologies have further advanced fidelity measurement by directly sequencing PCR products without molecular indexing or intermediary amplification steps, thereby providing unprecedented accuracy in error rate quantification with background error rates as low as (9.6 \times 10^{-8}) errors per base [39]. This exceptional sensitivity makes SMRT sequencing particularly suitable for characterizing ultra-high-fidelity polymerases whose error rates approach the detection limits of other methods.

Comparative Error Rates Across Polymerases

Table 1: Polymerase Fidelity Comparison by SMRT Sequencing

| DNA Polymerase | Substitution Rate (errors/base/doubling) | Accuracy (bases/error) | Fidelity Relative to Taq |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taq | (1.5 \times 10^{-4}) | 6,456 | 1X |

| Deep Vent (exo-) | (5.0 \times 10^{-4}) | 2,020 | 0.3X |

| KOD | (1.2 \times 10^{-5}) | 82,303 | 12X |

| PrimeSTAR GXL | (8.4 \times 10^{-6}) | 118,467 | 18X |

| Pfu | (5.1 \times 10^{-6}) | 195,275 | 30X |

| Phusion | (3.9 \times 10^{-6}) | 255,118 | 39X |

| Deep Vent | (4.0 \times 10^{-6}) | 251,129 | 44X |

| Q5 | (5.3 \times 10^{-7}) | 1,870,763 | 280X |

Data adapted from NeB fidelity analysis using PacBio SMRT sequencing [39]

Table 2: Polymerase Fidelity by Sanger Sequencing

| DNA Polymerase | Substitution Rate | Accuracy | Fidelity Relative to Taq |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taq | ~(3 \times 10^{-4}) | 3,300 | 1X |

| Q5 | ~(1 \times 10^{-6}) | 1,000,000 | ~300X |

Data adapted from NeB study using Sanger sequencing [39]

The quantitative comparison reveals striking differences between polymerase fidelities. Standard non-proofreading enzymes like Taq polymerase demonstrate moderate fidelity, while exonuclease-deficient variants exhibit even lower accuracy. Among high-fidelity enzymes, there is considerable variation, with Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase demonstrating exceptional accuracy—approximately 280-fold higher than Taq polymerase under the conditions tested [39]. Independent studies using direct sequencing of cloned PCR products have confirmed these trends, reporting error rates for Pfu, Phusion, and Pwo polymerases that are more than 10-fold lower than Taq polymerase [40].

Practical Considerations: Balancing Speed, Accuracy, and Experimental Requirements

The selection between standard and high-fidelity polymerases involves careful consideration of multiple practical factors beyond mere fidelity metrics. Understanding the performance characteristics of different enzyme types enables researchers to make informed choices aligned with their specific experimental goals and constraints.

Amplification Speed and Processivity

Standard polymerases like Taq are generally characterized by high processivity and fast catalytic rates, enabling rapid amplification—particularly for shorter templates. Early PCR protocols with Taq polymerase employed extension times of 1-2 minutes per kilobase [41]. However, modern high-fidelity polymerases have significantly closed this speed gap through enzyme engineering and optimized reaction formulations. Many contemporary high-fidelity enzymes now feature high processivity, enabling substantially faster extension rates. For instance, SpeedSTAR HS DNA Polymerase and SapphireAmp Fast PCR Master Mix allow extension times as short as 10 seconds per kilobase, while PrimeSTAR Max and GXL DNA Polymerases achieve rates of 5-20 seconds per kilobase [42]. This enhanced speed eliminates the traditional trade-off between accuracy and amplification velocity, making high-fidelity enzymes suitable for rapid PCR protocols.

The development of fast PCR protocols has been facilitated by several modifications to traditional cycling parameters: reducing denaturation times while increasing denaturation temperatures, shortening extension times, and employing two-step PCR protocols that combine annealing and extension steps [41] [43]. These approaches are particularly effective with highly processive DNA polymerases that can incorporate nucleotides rapidly during each binding event. When using slower polymerases, fast cycling conditions may only be feasible for short targets (<500 bp) that require minimal extension times [43].

Template-Specific Considerations

The nature of the DNA template significantly influences polymerase selection and performance. GC-rich templates (>65% GC content) present particular challenges due to their strong hydrogen bonding and tendency to form stable secondary structures that can impede polymerase progression [42] [43]. For such difficult templates, high-fidelity polymerases with strong strand displacement activity and high processivity are often advantageous. Additionally, specialized reaction conditions including higher denaturation temperatures (98°C instead of 95°C), shorter annealing times, co-solvents like DMSO (typically 2.5-5%), and specialized buffers with isostabilizing components can dramatically improve amplification efficiency [42] [43].