Mastering Method Linearity and Dynamic Range: A 2025 Guide for Robust Analytical Validation

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on validating the linearity and dynamic range of analytical methods.

Mastering Method Linearity and Dynamic Range: A 2025 Guide for Robust Analytical Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on validating the linearity and dynamic range of analytical methods. It covers foundational principles from ICH Q2(R2) and regulatory standards, details step-by-step methodologies for standard preparation and data analysis, and offers advanced troubleshooting strategies for complex modalities. By integrating modern approaches like lifecycle management and Quality-by-Design (QbD), the content delivers actionable insights for achieving regulatory compliance, ensuring data integrity, and enhancing method reliability in pharmaceutical development and biomedical research.

Understanding Linearity and Dynamic Range: Core Principles and Regulatory Importance

Defining Linearity and Dynamic Range in Analytical Procedures

In the pharmaceutical industry, demonstrating the suitability of analytical methods is a fundamental requirement for drug development and quality control. Among the key performance characteristics assessed during method validation are linearity and dynamic range. These parameters ensure that an analytical procedure can produce results that are directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte within a specified range, providing confidence in the accuracy and reliability of the generated data. This guide objectively compares established and emerging strategies for defining and extending these critical parameters, providing experimental protocols and data for researchers and drug development professionals.

Understanding the distinction between linearity and dynamic range is crucial for proper method validation.

- Linearity refers to the ability of an analytical procedure to obtain test results that are directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte in a sample within a given range [1]. It is a measure of the proportionality between the signal response and the analyte concentration.

- Dynamic Range is the interval between the upper and lower concentrations of an analyte for which the analytical procedure has a suitable level of precision, accuracy, and linearity [1] [2]. The lower end is often constrained by signal-to-noise ratio, while the upper end can be limited by detector saturation or non-linear behavior such as "concentration quenching" [2].

The following table summarizes the key relationships and distinctions:

Table 1: Comparison of Analytical Range Concepts

| Concept | Definition | Primary Focus | Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linearity | The ability to produce results directly proportional to analyte concentration [1]. | Proportionality of response. | A subset of the dynamic range where the response is linear. |

| Dynamic Range | The full concentration range producing a measurable response [3]. | Breadth of detectable concentrations. | Encompasses the linear range but may include non-linear portions. |

| Quantitative Range | The range where accurate and precise quantitative results are produced [1]. | Reliability of numerical results. | A subset of the linear range with demonstrated accuracy and precision. |

Established vs. Advanced Strategies for Extending Dynamic Range

A common challenge in bioanalysis is that sample concentrations can fall outside the validated linear dynamic range, necessitating sample dilution and re-analysis. The following section compares traditional and novel strategies to overcome this limitation.

Strategy 1: Multiple Product Ions in LC-MS/MS

- Principle: This strategy uses a primary, highly sensitive product ion for quantification at low concentrations and a secondary, less sensitive product ion for high concentrations [4].

- Experimental Protocol: A rat plasma assay for a proprietary drug was validated using two calibration curves. The primary ion established a high-sensitivity range (0.400 to 100 ng/mL), while the secondary ion established a low-sensitivity range (90.0 to 4000 ng/mL). Quality control samples at low, mid, and high levels within each range demonstrated precision and accuracy within 20% [4].

- Outcome: The linear dynamic range was successfully expanded from 2 to 4 orders of magnitude, allowing for accurate quantification of a wider range of sample concentrations without re-analysis [4].

Strategy 2: Natural Isotopologues in HRMS

- Principle: This approach leverages the different natural abundances of analyte isotopologues. The most abundant isotopologue (Type A ion) is used for low-concentration quantitation, while less abundant isotopologues (Type B and C ions) are used for high-concentration quantitation, thereby avoiding ion detector saturation [5].

- Experimental Protocol: Standard mixtures of compounds like diazinon and imazapyr were analyzed using LC-HRMS. During data processing, different isotopologue ions (A, B, and C) were selected for quantification based on their relative abundances and the concentration of the analyte.

- Outcome: The upper limit of the linear dynamic range (ULDR) was extended by 25 to 50 times for the tested compounds. This method is particularly efficient on Time-of-Flight (TOF) instruments, as data for all ions is acquired simultaneously without sacrificing sensitivity [5].

Comparative Performance Data

The table below summarizes experimental data from the application of these strategies.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Range Extension Strategies

| Strategy | Technique | Reported Linear Dynamic Range | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Product Ions [4] | HPLC-MS/MS (Unit Mass Resolution) | Expanded from 2 to 4 orders of magnitude | Well-established, can be implemented on standard triple-quadrupole MS | Requires method development for multiple transitions |

| Natural Isotopologues [5] | LC-HRMS (Time-of-Flight) | ULDR extended by 25-50x | Leverages full-scan HRMS data; no pre-definition of ions needed | Ultimate ULDR may be limited by ionization source saturation |

| Sample Dilution [5] [3] | Universal | Dependent on original method range | Simple in concept | Increases analysis time, cost, and potential for error |

| Reduced ESI Flow Rate [3] | LC-ESI-MS | Varies by compound | Reduces charge competition in ESI source | Requires instrumental optimization, may not be sufficient alone |

Experimental Protocols for Determining Linearity and Range

For a method to be considered validated, its linearity and range must be demonstrated through a formal experimental procedure.

Standard Protocol for Linearity and Range Assessment

The following workflow outlines the standard process for estimating the linear range of an LC-MS method, which can be adapted to other techniques [3].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Experimental Design:

- Prepare a set of standard solutions with known concentrations of the analyte to cover the expected working range. According to ICH guidelines, this typically should be from 0% to 150% or 50% to 150% of the target concentration, with at least 5 concentration levels [6] [3].

- For an assay of a drug product, the reportable range is typically from 80% to 120% of the declared content or specification [6].

- Analyze multiple replicates (e.g., 3) at each concentration level to assess precision [1].

- Randomize the order of analysis to minimize systematic bias [1].

Data Analysis:

- Perform a linear regression analysis on the data, plotting the instrument response against the analyte concentration [1].

- The mathematical expression is: ( y = mx + b ), where ( y ) is the response, ( x ) is the concentration, ( m ) is the slope, and ( b ) is the intercept [1].

- Evaluate the correlation coefficient (r), slope, and y-intercept of the regression line.

- Statistically assess the residual plots and lack-of-fit to confirm linearity [1].

Method Validation:

- Demonstrate that the method has acceptable accuracy (closeness to true value) and precision (repeatability) across the entire claimed range [1] [6].

- The range is confirmed as the interval between the upper and lower levels of analyte that have been demonstrated to be determined with suitable precision, accuracy, and linearity [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key solutions and materials required for conducting these experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Linearity and Range Studies

| Item | Function / Explanation | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Reference Standards | High-purity characterized material of the analyte; essential for preparing calibration solutions with known concentration. | Used to create the primary calibration curve in all quantitative assays [6]. |

| Stable-Labeled Internal Standard (e.g., ILIS) | Isotopically labeled version of the analyte; corrects for variability in sample preparation and ionization efficiency in LC-MS. | Expands the linear range by compensating for signal suppression/enhancement [3]. |

| Matrix Samples (Blank & Spiked) | Real sample material without analyte (blank) and with added analyte (spiked); used to assess specificity, accuracy, and matrix effects. | Critical for validating methods in bioanalysis (e.g., plasma, urine) [4] [6]. |

| Forced Degradation Samples | Samples of the analyte subjected to stress conditions (heat, light, acid, base, oxidation); demonstrate specificity and stability-indicating properties. | Used to prove the method can accurately measure the analyte in the presence of its degradation products [6]. |

Defining linearity and dynamic range is a cornerstone of analytical method validation in drug development. While established protocols for assessing these parameters are well-defined, innovative strategies such as monitoring multiple product ions in MS/MS or leveraging natural isotopologues in HRMS provide powerful means to extend the usable dynamic range. The choice of strategy depends on the available instrumentation and the specific analytical challenge. By implementing robust experimental designs and leveraging these advanced techniques, scientists can develop more resilient and efficient analytical methods, ultimately saving time and resources while generating highly reliable data.

The Critical Role in Method Validation and Data Reliability

Method validation is a critical process in instrumental analysis that ensures the reliability and accuracy of analytical results. It involves verifying that an analytical method is suitable for its intended purpose and produces consistent results, which is crucial in various industries such as pharmaceuticals, food, and environmental monitoring [7]. The process provides documented evidence that a specific method consistently meets the pre-defined criteria for its intended use, forming the foundation for credible scientific findings and regulatory compliance [8].

Regulatory agencies including the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) have established rigorous guidelines for method validation. The FDA states that "the validation of analytical procedures is a critical component of the overall validation program," while the ICH Q2(R1) and the newly adopted ICH Q2(R2) guidelines provide detailed requirements for validating analytical procedures, including parameters to be evaluated and specific acceptance criteria [7] [8]. These guidelines ensure that methods used in critical decision-making processes, particularly in drug development and manufacturing, demonstrate proven reliability.

The method validation process follows a systematic approach with several key steps. It begins with defining the purpose and scope of the method, followed by identifying the specific parameters to be evaluated. Researchers then design and execute an experimental plan, finally evaluating the results to determine whether the method meets all validation criteria [7]. This structured approach ensures that all aspects of method performance are thoroughly assessed before implementation in regulated environments.

Table: Key Regulatory Guidelines for Method Validation

| Regulatory Body | Guideline | Key Focus Areas |

|---|---|---|

| International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) | ICH Q2(R1) & Q2(R2) | Validation of analytical procedures: text and methodology |

| US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) | FDA Guidance on Analytical Procedures | Analytical procedure development and validation requirements |

Performance Characteristics in Method Validation

According to ICH guidelines, method validation requires assessing multiple performance characteristics that collectively demonstrate a method's reliability. These characteristics include specificity/selectivity, linearity, range, accuracy, precision, detection limit, quantitation limit, and robustness [8]. Each parameter addresses a different aspect of method performance, and together they provide comprehensive evidence that the method is fit for its intended purpose.

Linearity represents the ability of an assay to demonstrate a direct and proportionate response to variations in analyte concentration within the working range [8]. To confirm linearity, results are evaluated using statistical methods such as calculating a regression line by the method of least squares, with a minimum of five concentration points appropriately distributed across the entire range. The acceptance criteria for linear regression in most test methods typically require R² > 0.95, though methods can show non-linear responses and still be validated using different assessment approaches like coefficient of determination [8].

The range of an analytical method is the interval between the upper and lower concentration of analyte that has been demonstrated to be determined with suitable levels of precision, accuracy, and linearity [8]. The specific range depends on the intended application, with different acceptable ranges established for various testing methodologies. For drug substance and drug product assays, the range is typically 80-120% of the test concentration, while for content uniformity assays, it extends from 70-130% of test concentration [8].

Accuracy and precision are complementary parameters that assess different aspects of method reliability. Accuracy refers to the closeness of agreement between the test result and the true value, usually reported as percentage recovery of the known amount [8]. Precision represents the closeness of agreement between a series of measurements obtained from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample under prescribed conditions, and may be considered at three levels: repeatability, intermediate precision, and reproducibility [8].

Table: Acceptance Criteria for Key Validation Parameters

| Parameter | Acceptance Criteria | Experimental Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity/Selectivity | No interference from blank samples or potential interferents | Analysis of blank samples, samples spiked with analyte, and samples spiked with potential interferents |

| Linearity | Correlation coefficient > 0.99, linearity over specified range | Analysis of series of standards with known concentrations (minimum 5 points) |

| Accuracy | Recovery within 100 ± 2% | Analysis of samples with known concentrations, comparison with reference method |

| Precision | RSD < 2% | Repeat analysis of samples, analysis of samples at different concentrations |

Detection Limit (DL) and Quantitation Limit (QL) represent the lower range limits of an analytical method. DL is described as the lowest amount of analyte in a sample that can be detected but not necessarily quantified, while QL is the lowest amount that can be quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision [8]. These parameters can be estimated using different approaches, including signal-to-noise ratio (typically 3:1 for DL and 10:1 for QL) or based on the standard deviation of a linear response and slope [8].

Experimental Design and Protocols

Linearity and Range Assessment

The experimental protocol for demonstrating linearity requires preparing a minimum of five standard solutions at concentrations appropriately distributed across the claimed range [8]. For drug substance and drug product assays, this typically covers 80-120% of the test concentration, while for content uniformity, the range extends from 70-130% [8]. Each concentration should be analyzed in replicate, with the complete analytical procedure followed for every sample to account for method variability.

The linear relationship between analyte concentration and instrument response is evaluated using statistical methods, primarily calculating the regression line by the method of least squares [8]. The correlation coefficient (R²) should exceed 0.95 for acceptance in most test methods, though more complex methods may require additional concentration points to adequately demonstrate linearity [8]. For methods where assay and purity tests are performed together as one test using only a standard at 100% concentration, linearity should be covered from the reporting threshold of impurities to 120% of labelled content for the assay [8].

Accuracy and Precision Evaluation

Accuracy should be verified over the reportable range by comparing measured findings to their predicted values, typically demonstrated under regular testing conditions using a true sample matrix [8]. For drug substances, accuracy is usually demonstrated using an analyte of known purity, while for drug products, a known quantity of the analyte is introduced to a synthetic matrix containing all components except the analyte of interest [8]. Accuracy should be assessed using at least three concentration points covering the reportable range with three replicates for each point [8].

Precision should be evaluated at multiple levels. Repeatability is assessed under the same operating conditions over a short interval of time, requiring a minimum of nine determinations (three concentrations × three replicates) covering the reportable range or a minimum of six determinations at 100% of the test concentration [8]. Intermediate precision evaluates variations within the laboratory, including tests performed on different days, by different analysts, and on different equipment [8]. Reproducibility demonstrates precision between different laboratories, which is particularly important for standardization of analytical procedures included in pharmacopoeias [8].

Comparative Analysis: Batch vs. Real-Time Data Validation

The choice between batch and real-time data validation approaches represents a critical decision point in method validation strategies, with each method offering distinct advantages for different applications. Batch data validation processes large data volumes in scheduled batches, often during off-peak hours, making it efficient for handling massive datasets in a cost-effective manner [9]. In contrast, real-time data validation checks data instantly as it enters the system, ensuring immediate error detection and correction, which is ideal for applications requiring rapid data processing like fraud detection, customer data validation, and shipping charge calculations [9].

The speed and latency characteristics differ significantly between these approaches. Batch validation features slower processing speed as data is collected over time and processed in batches, leading to delays between receiving and validating data, with latency ranging from minutes to hours or even days depending on the batch schedule [9]. Real-time validation provides faster processing speed with data validated immediately as it enters the system, ensuring errors are detected and corrected instantly without delays [9].

Infrastructure requirements also vary substantially. Batch processing utilizes idle system resources during off-peak hours, reducing the need for specialized hardware, and is simpler to design and implement due to its scheduled nature [9]. Real-time validation requires powerful computing resources and sophisticated architecture to process data instantly, necessitating high-end servers to ensure swift processing and immediate feedback, resulting in higher infrastructure costs [9].

Table: Batch vs. Real-Time Data Validation Comparison

| Characteristic | Batch Data Validation | Real-Time Data Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Data Processing | Processes data in groups or batches at scheduled intervals | Validates data instantly as it enters the system |

| Speed & Latency | Higher latency (minutes to days); delayed processing | Lower latency; immediate processing with instant error detection |

| Data Volume | Suitable for large datasets | Suitable for smaller, continuous data streams |

| Infrastructure Needs | Lower resource needs; cost-effective; uses idle resources | High-performance resources required; more complex and costly |

| Error Handling | Detects and corrects errors in batches; detailed error reports | Prevents errors from entering system; automatic recovery mechanisms |

| Use Cases | Periodic reporting, end-of-day processing, data warehousing | Fraud detection, real-time monitoring, immediate validation needs |

Error handling mechanisms differ fundamentally between these approaches. Batch validation detects and corrects errors in batches at scheduled intervals, allowing failed batches to be retried, with developers receiving detailed reports to pinpoint and resolve issues [9]. Real-time validation detects errors immediately as data enters the system, employing automatic correction mechanisms and built-in redundancy to maintain data integrity [9].

Data quality implications also vary between these methods. Batch validation enables thorough data cleaning and transformations in bulk, allowing comprehensive error detection and correction that improves overall data reliability, with processing schedulable during off-peak hours [9]. Real-time validation ensures data consistency and quality as it enters the system, preventing errors from propagating throughout the database and enabling accurate business decisions based on reliable, up-to-date information [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful method validation requires specific reagents and materials that ensure accuracy, precision, and reliability throughout the analytical process. The selection of appropriate research reagent solutions is fundamental to obtaining valid and reproducible results that meet regulatory standards.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Method Validation

| Research Reagent | Function in Validation | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Certified materials with known purity and concentration used to establish analytical response | Critical for accuracy demonstrations; should be traceable to certified reference materials |

| Isotopically Labeled Internal Standards (ILIS) | Improves method reliability by accounting for matrix effects and ionization efficiency | Particularly valuable in LC-MS to widen linear range via signal-concentration dependence [3] |

| Sample Matrix Blanks | Authentic matrix without analyte to assess specificity and selectivity | Essential for demonstrating no interference from matrix components |

| Spiked Samples | Samples with known quantities of analyte added to assess accuracy and recovery | Prepared at multiple concentration levels across the validation range |

| System Suitability Solutions | Reference materials used to verify chromatographic system performance | Ensures the analytical system is operating within specified parameters before validation experiments |

The selection of appropriate reference materials represents a critical foundation for method validation. These certified materials with known purity and concentration are used to establish analytical response and are essential for accuracy demonstrations [8]. Reference standards should be traceable to certified reference materials whenever possible, and their proper characterization and documentation is essential for regulatory compliance.

Isotopically labeled internal standards (ILIS) play a particularly important role in chromatographic method validation, especially in LC-MS applications. While the signal-concentration dependence of the compound and an ILIS may not be linear, the ratio of the signals may be linearly dependent on the analyte concentration, effectively widening the method's linear dynamic range [3]. This approach helps mitigate matrix effects and variations in ionization efficiency, significantly improving method reliability for quantitative applications.

Sample preparation reagents including matrix blanks and spiked samples are essential for demonstrating method specificity and accuracy. Matrix blanks (authentic matrix without analyte) assess potential interference from sample components, while spiked samples with known quantities of analyte at multiple concentration levels across the validation range enable accuracy and recovery assessments [8]. Proper preparation of these solutions requires careful attention to maintaining the integrity of the sample matrix while ensuring accurate fortification with target analytes.

System suitability solutions represent another critical component of the validation toolkit. These reference materials verify chromatographic system performance before validation experiments, ensuring the analytical system is operating within specified parameters [8]. The use of system suitability tests provides assurance that the complete analytical system—including instruments, reagents, columns, and analysts—is capable of producing reliable results on the day of validation experiments.

Method validation serves as the cornerstone of reliable analytical data in pharmaceutical development and other regulated industries. The comprehensive assessment of performance characteristics including linearity, range, accuracy, and precision provides documented evidence that analytical methods are fit for their intended purpose [8]. As regulatory requirements continue to evolve with guidelines such as ICH Q2(R2), the approach to method validation must remain rigorous and scientifically sound, ensuring that data generated supports critical decisions in drug development and manufacturing.

The choice between batch and real-time data validation strategies depends on specific application requirements, with each approach offering distinct advantages [9]. Batch validation provides a cost-effective solution for processing large datasets where immediate results aren't required, while real-time validation is essential for applications demanding instant error detection and correction. In many cases, a hybrid approach leveraging both methods may provide the most effective solution, balancing comprehensive data quality assessment with the need for immediate feedback in critical processes.

Ultimately, robust method validation practices combined with appropriate data validation strategies create a foundation of data reliability that supports product quality, patient safety, and regulatory compliance. By implementing thorough validation protocols and maintaining them throughout the method lifecycle, organizations can ensure the continued reliability of their analytical data and the decisions based upon it.

The validation of analytical methods is a fundamental requirement in the pharmaceutical industry, serving as the cornerstone for ensuring the safety, efficacy, and quality of drug substances and products. This process provides verifiable evidence that an analytical procedure is suitable for its intended purpose, consistently producing reliable results that accurately reflect the quality attributes being measured [10]. Regulatory authorities worldwide, including the FDA and EMA, require rigorous method validation to guarantee that pharmaceuticals released to the market meet stringent quality standards, thereby protecting public health [10] [11].

The landscape of analytical method validation has recently evolved significantly with the introduction of updated and new guidelines. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) has finalized Q2(R2) on "Validation of Analytical Procedures" and Q14 on "Analytical Procedure Development," which provide a modernized framework for analytical procedures throughout their lifecycle [12] [13]. These guidelines, along with existing FDA requirements and EMA expectations, create a comprehensive regulatory framework that pharmaceutical scientists must navigate to ensure compliance during drug development and commercialization.

This guide objectively compares the expectations for one critical validation parameter—method linearity and dynamic range—across these key regulatory guidelines, providing researchers with clear comparisons, experimental protocols, and practical implementation strategies to facilitate successful method validation and regulatory submissions.

Comparative Analysis of Regulatory Guidelines

ICH Q2(R2): Validation of Analytical Procedures

ICH Q2(R2) represents the updated international standard for validating analytical procedures used in the testing of pharmaceutical drug substances and products. The guideline applies to both chemical and biological/biotechnological products and is directed at the most common purposes of analytical procedures, including assay/potency, purity testing, impurity determination, and identity testing [13]. The revised guideline expands on the original ICH Q2(R1) to address emerging analytical technologies and provide more detailed guidance on validation methodology.

Regarding linearity and range, Q2(R2) maintains that linearity should be demonstrated across the specified range of the analytical procedure using a minimum number of concentration levels, typically at least five [14]. The guideline emphasizes that the correlation coefficient, y-intercept, and slope of the regression line should be reported alongside a visual evaluation of the regression plot [14]. The range is established as the interval between the upper and lower concentration of analyte for which the method has demonstrated suitable levels of precision, accuracy, and linearity [15].

ICH Q14: Analytical Procedure Development

ICH Q14, released concurrently with Q2(R2), introduces a structured framework for analytical procedure development and promotes a lifecycle approach to analytical procedures [12]. The guideline establishes the concept of an Analytical Target Profile (ATP), which defines the required quality of the analytical measurement before method development begins [12]. This proactive approach ensures that method validation parameters, including linearity, are appropriately considered during the development phase rather than as an afterthought.

The guideline introduces both minimal and enhanced approaches to analytical development, allowing flexibility based on the complexity of the method and its criticality to product quality assessment [12]. For linearity assessment, Q14 emphasizes establishing a science-based understanding of how method variables impact the linear response, moving beyond mere statistical compliance to genuine methodological understanding. The enhanced approach encourages more extensive experimentation to define the method's operable ranges and robustness as part of the control strategy.

FDA Guidelines on Analytical Method Validation

The FDA's approach to analytical method validation is detailed in its "Guidance for Industry: Analytical Procedures and Methods Validation for Drugs and Biologics," which aligns with but sometimes extends beyond ICH recommendations [10]. The FDA emphasizes that validation must be conducted under actual conditions of use—specifically for the sample to be tested and by the laboratory performing the testing [15]. This practical focus ensures that linearity is demonstrated in the relevant matrix and reflects real-world analytical conditions.

The FDA requires that accuracy, precision, and linearity must be established across the entire reportable range of the method [11]. For linearity verification, the FDA expects laboratories to test samples with different analyte concentrations covering the entire reportable range, with results plotted on a graph to visually confirm the linear relationship [11]. The agency places particular emphasis on comprehensive documentation with a complete audit trail, including any data points excluded from regression analysis with appropriate scientific justification [14].

EMA Expectations for Method Validation

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) adopts the ICH Q2(R2) guideline as its scientific standard for analytical procedure validation [13]. As an ICH member regulatory authority, the EMA incorporates ICH guidelines into its regulatory framework, ensuring harmonization with other major regions. The EMA emphasizes that analytical procedures should be appropriately validated and the documentation submitted in Marketing Authorization Applications must contain sufficient information to evaluate the validity of the analytical method.

The EMA pays particular attention to the justification of the range in relation to the intended use of the method, especially for impurity testing where the range should extend to the reporting threshold or lower [13]. Like the FDA, the EMA expects that linearity is demonstrated using samples prepared in the same matrix as the actual samples and that the statistical parameters used to evaluate linearity are clearly reported and justified.

Comparative Tables of Regulatory Expectations

Linearity and Range Requirements Across Guidelines

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Linearity and Range Requirements

| Parameter | ICH Q2(R2) | FDA | EMA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum Concentration Levels | At least 5 [14] | Not explicitly specified, but follows ICH principles [10] | Not explicitly specified, but follows ICH principles [13] |

| Recommended Range | Typically 50-150% of target concentration [14] | Similar to ICH; entire reportable range must be covered [11] | Similar to ICH; appropriate to intended application [13] |

| Statistical Parameters | Correlation coefficient, y-intercept, slope, residual plot [14] | Correlation coefficient, visual evaluation of plot [11] | Correlation coefficient, residual analysis [13] |

| Acceptance Criteria (r²) | >0.995 typically expected [14] | Similar to ICH; must be justified for intended use [10] | Similar to ICH; must be justified for intended use [13] |

| Documentation | Complete validation report [12] | Complete with audit trail; justified exclusions [14] | Sufficient for regulatory evaluation [13] |

Analytical Procedure Lifecycle Management Across Guidelines

Table 2: Analytical Procedure Lifecycle Management Comparison

| Aspect | ICH Q2(R2)/Q14 | FDA | EMA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Development Approach | Minimal and Enhanced approaches [12] | Science-based; fit for intended use [10] | Science-based; risk-informed [13] |

| Lifecycle Management | Integrated with ICH Q12 [12] | Post-approval changes per SUPAC [10] | Post-authorization changes per variations regulations [13] |

| Control Strategy | Based on enhanced understanding [12] | Based on validation data and ongoing verification [15] | Based on validation data and risk assessment [13] |

| Established Conditions | Defined for analytical procedures [12] | Defined in application [10] | Defined in application [13] |

| Knowledge Management | Systematic recording of development knowledge [12] | Expected but not explicitly structured [10] | Expected but not explicitly structured [13] |

Experimental Protocols for Linearity and Range Validation

Standard Preparation and Analysis

The foundation of reliable linearity assessment lies in meticulous standard preparation. Prepare a minimum of five concentration levels spanning 50-150% of the target analyte range [14]. For example, if the target concentration is 100 μg/mL, prepare standards at 50, 75, 100, 125, and 150 μg/mL. To ensure accuracy, use certified reference materials and calibrated pipettes, weighing all components on an analytical balance [14]. Prepare standards independently rather than through serial dilution to avoid propagating errors.

Analyze each standard in triplicate in random order to eliminate systematic bias [14]. The analysis should be performed over multiple days by different analysts to incorporate realistic variability into the assessment. For methods susceptible to matrix effects, prepare standards in blank matrix rather than pure solvent to account for potential interferences that may affect linear response [14]. For liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS) methods, which typically have a narrower linear range, consider using isotopically labeled internal standards to widen the linear dynamic range [3].

Statistical Evaluation and Acceptance Criteria

For statistical evaluation, begin by plotting analyte response against concentration and performing regression analysis. Calculate the correlation coefficient (r), with r² typically expected to exceed 0.995 for acceptance [14]. However, don't rely solely on r² values, as they can be misleading—high r² values may mask subtle non-linear patterns [14].

Critically examine the residual plot for random distribution around zero, which indicates true linearity [14]. Non-random patterns in residuals suggest potential non-linearity that requires investigation. For some methods, ordinary least squares regression may be insufficient; consider weighted regression when heteroscedasticity is present (variance changes with concentration) [14]. The y-intercept should not be significantly different from zero, typically validated through a confidence interval test.

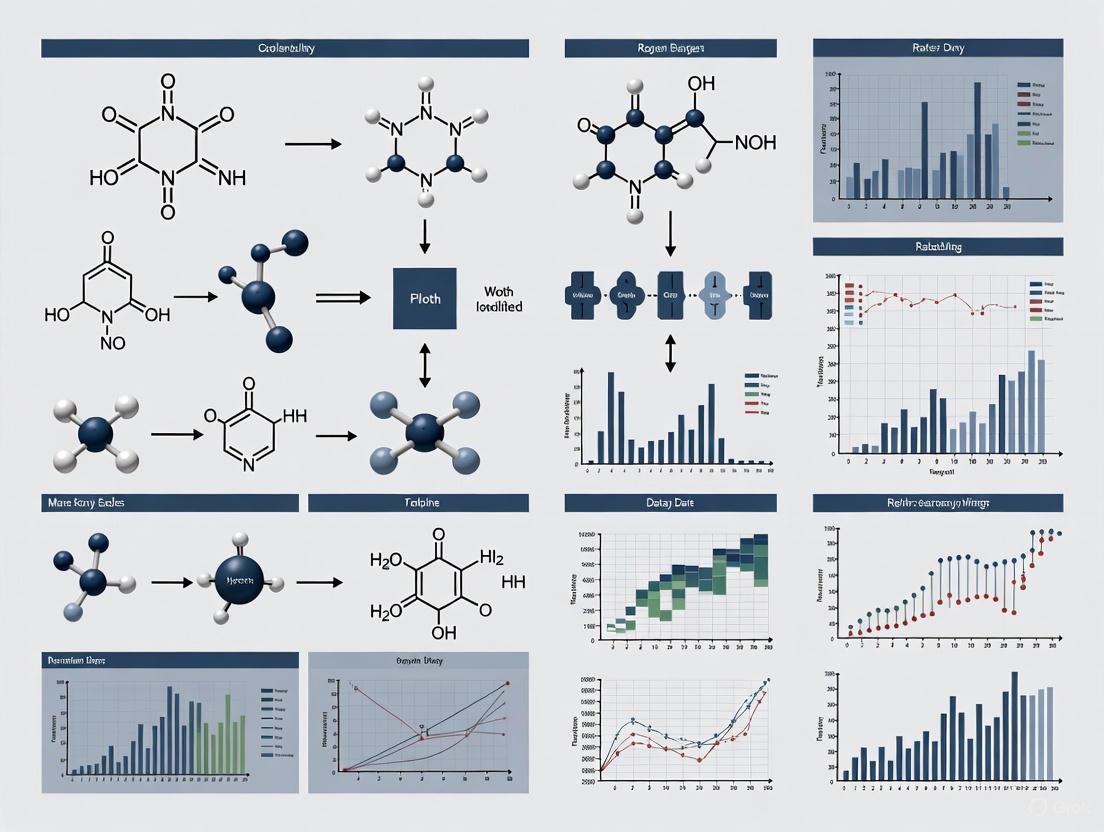

The following workflow outlines the comprehensive linearity validation process:

Linearity Validation Workflow

Troubleshooting Common Linearity Issues

When linearity issues emerge, systematic troubleshooting is essential. If detector saturation is suspected at higher concentrations, consider sample dilution or reduced injection volume [14]. For non-linear responses at lower concentrations, evaluate whether the analyte is adhering to container surfaces or if the detection limit is being approached. For LC-MS methods, a narrowed linear range may be addressed by decreasing flow rates in the ESI source to reduce charge competition [3].

When matrix effects cause non-linearity, employ alternative sample preparation techniques such as solid-phase extraction or protein precipitation to remove interfering components [14]. If these approaches fail, consider using the standard addition method for particularly complex matrices where finding a suitable blank matrix is challenging [14]. Document all troubleshooting activities thoroughly, including the rationale for any methodological adjustments, to demonstrate a science-based approach to method optimization.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Linearity Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards | Primary standard for accurate quantification | Certified purity and stability; proper storage conditions [14] |

| Isotopically Labeled Internal Standards | Normalize instrument response variability | Especially critical for LC-MS methods to widen linear range [3] |

| Blank Matrix | Prepare matrix-matched calibration standards | Should be free of analyte and representative of sample matrix [14] |

| High-Purity Solvents | Sample preparation and mobile phase components | LC-MS grade for sensitive techniques; minimal interference [14] |

| Quality Control Materials | Verify method performance during validation | Should span low, medium, and high concentrations of range [11] |

The regulatory landscape for analytical method validation continues to evolve, with ICH Q2(R2) and Q14 representing the most current scientific consensus on analytical procedure development and validation. While regional implementations may differ in emphasis, the core principles of demonstrating method linearity across a specified range remain consistent across ICH, FDA, and EMA expectations. Successful validation requires not only statistical compliance but also scientific understanding of the method's performance characteristics and limitations.

The enhanced approach introduced in ICH Q14, with its emphasis on analytical procedure lifecycle management and science-based development, represents the future direction of analytical validation. By adopting these principles proactively and maintaining comprehensive documentation, pharmaceutical scientists can ensure robust method validation that meets current regulatory expectations while positioning their organizations for efficient adoption of emerging regulatory standards.

The Impact on Product Quality and Patient Safety

In the pharmaceutical industry, the quality of a drug product and the safety of the patient are intrinsically linked to the reliability of the analytical methods used to ensure product purity, identity, strength, and composition. The validation of an analytical method's linearity and dynamic range is a critical scientific foundation that underpins this reliability. A method with poorly characterized linearity can produce inaccurate concentration readings, leading to the release of a subpotent, superpotent, or adulterated drug product. This article objectively compares the performance of different analytical approaches and techniques in establishing a robust linear dynamic range, framing the discussion within the broader thesis that rigorous method validation is a non-negotiable prerequisite for patient safety and product quality.

Linearity and Dynamic Range: Foundational Concepts

Definitions and Regulatory Significance

Linearity is the ability of an analytical method to produce test results that are directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte in a sample within a given range [8]. It demonstrates that the method's response—whether from an HPLC detector, a mass spectrometer, or another instrument—consistently changes in a predictable and consistent manner as the analyte concentration changes.

The dynamic range (or linear dynamic range) is the specific span of concentrations across which this proportional relationship holds true [3] [2]. It is bounded at the lower end by the limit of quantitation (LOQ) and at the upper end by the point where the signal response plateaus or becomes non-linear. The working range or reportable range is the interval over which the method provides results with an acceptable level of accuracy, precision, and uncertainty, and it must fall entirely within the demonstrated linear dynamic range [3] [16].

From a regulatory perspective, guidelines like ICH Q2(R1) mandate the demonstration of linearity as a core validation parameter [8]. The range is subsequently established as the interval over which the method has been proven to deliver suitable linearity, accuracy, and precision [17]. For a drug assay, a typical acceptable range is 80% to 120% of the test concentration, ensuring the method is accurate not just at 100%, but across reasonable variations in product potency [8].

The Direct Link to Product Quality and Patient Safety

The failure to adequately establish and verify linearity and range has a direct and severe impact on product quality and patient safety.

- Inaccurate Potency Assessment: A non-linear response outside the validated range can lead to systematic overestimation or underestimation of the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API). Releasing a superpotent drug risks patient toxicity, while a subpotent drug fails to provide the intended therapeutic effect.

- Undetected Impurities: In impurity testing, the linear range must extend from the reporting threshold to at least 120% of the specification limit [8]. An improperly defined lower range can lead to an inability to accurately quantify low-level impurities that may be toxic or have unexpected pharmacological effects, allowing harmful degraded products or process-related impurities to go unreported [8].

- Erosion of Quality Control: The entire quality control system is built on trustworthy data. A method with an ill-defined linear range produces unreliable data, undermining the foundation of batch release decisions and stability studies, ultimately jeopardizing the entire product lifecycle.

Comparative Analysis of Analytical Techniques

The ability to achieve a wide and reliable linear dynamic range varies significantly across analytical techniques and is influenced by the detection principle and sample composition.

Comparison of Detection Principles and Their Linearity Performance

Table 1: Comparison of Linearity and Range Performance Across Analytical Techniques

| Analytical Technique | Typical Challenges to Linearity | Typical Strategies to Widen Range | Impact on Data Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC-UV/Vis | Saturation of absorbance at high concentrations (deviation from Beer-Lambert law). | Sample dilution; reduction in optical path length. | Generally wide linear range; high reliability for potency assays when within validated range. |

| LC-MS (Electrospray Ionization) | Charge competition in the ion source at high concentrations, leading to signal suppression and non-linearity [3]. | Use of isotopically labeled internal standards (ILIS); lowering flow rate (e.g., nano-ESI); sample dilution [3] [18]. | Narrower linear range compared to UV; requires careful mitigation. ILIS is highly effective for maintaining accuracy. |

| Fluorescence Spectroscopy | Concentration quenching at high concentrations, where fluorescence intensity decreases instead of increasing [2]. | Sample dilution; adjustment of optical path length. | Linear range can be very narrow; necessitates verification for each sample type to prevent severe underestimation. |

| Time-over-Threshold (ToT) Readouts | Saturation of time measurement due to exponential signal decay, degrading linearity and dynamic range [19]. | Signal shaping circuits to linearize the trailing edge of the pulse [19]. | Improved linearity and range in particle detector readouts, leading to better energy resolution. |

Experimental Data and Protocol Comparison

To illustrate the practical differences in establishing linearity, consider the following experimental protocols for two common techniques:

Protocol A: Linearity Validation for an HPLC-UV Assay of a Drug Substance

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a minimum of 5 standard solutions at concentrations of 50%, 80%, 100%, 120%, and 150% of the target test concentration (e.g., 1.0 mg/mL) [14] [17]. Use an independent dilution scheme or weigh standards separately to avoid error propagation.

- Analysis: Inject each solution in a randomized sequence to prevent systematic bias from instrument drift. Replicate injections (e.g., n=3) are recommended [18] [14].

- Data Analysis: Plot peak area (y-axis) against concentration (x-axis). Perform ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. Calculate the correlation coefficient (R²), slope, and y-intercept.

- Evaluation: The R² value should typically be ≥ 0.995 or 0.997 [17]. The y-intercept should be statistically insignificant from zero. Visually inspect the residual plot (difference between experimental and calculated responses) for random scatter around zero, which confirms a good fit [18] [14].

Protocol B: Linearity Validation for an LC-MS Bioanalytical Method

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a minimum of 6 non-zero calibration standards covering the entire expected range, plus a blank sample [18]. To account for matrix effects, prepare standards in the blank biological matrix (e.g., plasma) rather than pure solvent, using a matrix-matched calibration curve [3] [18].

- Internal Standard: Add an isotopically labeled internal standard (ILIS) to all calibration standards and samples. The ILIS corrects for variability in sample preparation and ionization efficiency [3].

- Analysis: Analyze samples in random order. The ratio of the analyte peak area to the ILIS peak area is used for the calibration curve.

- Data Analysis & Evaluation: Plot the analyte/ILIS response ratio against concentration. Due to potential heteroscedasticity (variance that increases with concentration), weighted least squares (WLS) regression (e.g., 1/x² weighting) is often more appropriate than OLS [14]. The same statistical and visual checks (R², residuals) are applied.

The workflow for establishing and evaluating linearity, applicable to both protocols with technique-specific adjustments, is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The integrity of a linearity study is contingent on the quality and appropriateness of the materials used. The following table details key research reagent solutions and their critical functions.

Table 2: Essential Materials for Linearity and Range Validation

| Item / Reagent Solution | Function in Validation | Critical Quality Attribute |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standard | Serves as the benchmark for accuracy; used to prepare calibration standards of known purity and concentration. | High purity (>95%), well-characterized structure, and certified concentration or potency. |

| Blank Matrix | Used to prepare matrix-matched calibration standards for bioanalytical or complex sample analysis to account for matrix effects. | Should be free of the target analyte and as similar as possible to the sample matrix (e.g., human plasma, tissue homogenate). |

| Isotopically Labeled Internal Standard (ILIS) | Added to all samples and standards to correct for losses during sample preparation and variability in instrument response (especially in LC-MS). | Should be structurally identical to the analyte but with stable isotopic labels (e.g., ²H, ¹³C); high isotopic purity. |

| High-Purity Solvents & Reagents | Used for dissolution, dilution, and mobile phase preparation to prevent interference or baseline noise. | HPLC/MS grade; low UV cutoff; free of particulates and contaminants. |

| System Suitability Standards | Used to verify the performance of the chromatographic system (e.g., retention time, peak shape, resolution) before and during the validation run. | Stable and capable of producing a characteristic chromatogram that meets predefined criteria. |

The rigorous validation of an analytical method's linearity and dynamic range is far more than a regulatory formality; it is a fundamental component of a robust product quality system and a direct contributor to patient safety. As demonstrated, the performance of different analytical techniques varies significantly, with LC-MS requiring more sophisticated strategies like ILIS and matrix-matched calibration to overcome inherent challenges like ionization suppression. In contrast, techniques like HPLC-UV, while generally more robust, still demand meticulous experimental design and statistical evaluation. The consistent theme is that a one-size-fits-all approach is inadequate. A deep understanding of the technique's limitations, a well-designed experimental protocol, and a critical interpretation of the resulting data are paramount. By investing in a thorough understanding and validation of the linear dynamic range, the pharmaceutical industry strengthens its first line of defense, ensuring that every released product is safe, efficacious, and of the highest quality.

In the field of analytical science and drug development, the validation of method linearity and dynamic range is a fundamental requirement for ensuring reliable quantification. This process relies heavily on three core statistical concepts: the correlation coefficient (r), its squared value R-squared (r²), and the components of the linear regression equation—slope and y-intercept. These statistical parameters form the backbone of calibration model assessment, allowing researchers to determine whether an analytical method produces results that are directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte [14].

For researchers and scientists developing analytical methods, understanding the distinction and interplay between these measures is critical. While often discussed together, they provide different insights into the relationship between variables. The correlation coefficient (r) quantifies the strength and direction of a linear relationship, R-squared (r²) indicates the proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by the independent variable, while the slope and y-intercept define the functional relationship used for prediction [20] [21]. Within the framework of guidelines from regulatory bodies such as ICH, FDA, and EMA, proper interpretation of these statistics is essential for demonstrating method suitability across the intended working range [14].

Defining the Core Concepts

Correlation Coefficient (r)

The correlation coefficient, often denoted as r or Pearson's correlation coefficient, is a statistical measure that quantifies the strength and direction of a linear relationship between two continuous variables [21].

- Definition and Interpretation: The value of

rranges from -1 to +1. A positive value indicates a positive relationship (as one variable increases, the other tends to increase), while a negative value indicates an inverse relationship (as one variable increases, the other tends to decrease) [20] [21]. A value of zero suggests no linear relationship [21]. - Calculation: The formula for Pearson's correlation coefficient is:

\begin{array}{l}\large r = \frac{n\Sigma(xy)-\Sigma x \Sigma y}{\sqrt{[n\Sigma x^2 - (\Sigma x)^2][n\Sigma y^2 - (\Sigma y)^2]}}\end{array}

Where

nis the number of observations,xis the independent variable, andyis the dependent variable [22].

R-Squared (r²) - The Coefficient of Determination

R-squared, also known as the coefficient of determination, is a primary metric for evaluating regression models [20] [22].

- Definition and Interpretation: R-squared represents the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variable(s) [20] [22]. Its value ranges from 0 to 1 (or 0% to 100%). For example, an R-squared value of 0.80 means that 80% of the variation in the dependent variable (e.g., instrument response) can be explained by the independent variable (e.g., analyte concentration) [20].

- Calculation: In simple linear regression, R-squared is simply the square of the correlation coefficient: ( R^2 = r^2 ) [20] [22]. It can also be calculated using the formula involving sums of squares:

( R^2 = 1 – \frac{RSS}{TSS} )

where

RSSis the residual sum of squares andTSSis the total sum of squares [22].

Slope and Y-Intercept

In a linear regression model, the relationship between two variables is defined by the equation of a straight line: ( y = b0 + b1x ) [23] [24].

- Slope (b₁): The slope represents the average rate of change in the dependent variable (

y) for a one-unit change in the independent variable (x) [24]. In a calibration curve, it indicates the sensitivity of the analytical method; a steeper slope means a greater change in instrument response per unit change in concentration [24]. - Y-Intercept (b₀): The y-intercept is the value of

ywhenxequals zero [23] [24]. In analytical chemistry, it often represents the background signal or the theoretical instrument response for a blank sample [14].

Comparative Analysis of r², r, Slope, and Intercept

While these statistical measures are derived from the same dataset and model, they serve distinct purposes and convey different information. The following table summarizes their key differences and roles in regression analysis.

Table 1: Comparative overview of correlation and regression statistics

| Aspect | Correlation Coefficient (r) | R-squared (r²) | Slope (b₁) | Y-Intercept (b₀) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Strength and direction of a linear relationship [20] | Proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by the model [20] [22] | Rate of change of y with respect to x [24] | Expected value of y when x is zero [23] |

| Value Range | -1 to +1 [20] [21] | 0 to 1 (or 0% to 100%) [20] | -∞ to +∞ | -∞ to +∞ |

| Indicates Direction | Yes (positive/negative) [20] | No (always positive) [20] | Yes (positive/negative change) | No |

| Primary Role | Measure of linear association [21] | Measure of model fit and explanatory power [20] | Quantifies sensitivity in the relationship [24] | Provides baseline or constant offset [24] |

| Unit | Unitless | Unitless | y-unit / x-unit | y-unit |

| Impact on Prediction | Does not directly enable prediction | Assesses prediction quality | Directly used in prediction equation | Directly used in prediction equation |

Interrelationships and Distinctions

The relationship between these concepts can be visualized as a process where each statistic informs a different aspect of the model's performance and utility. The following diagram illustrates how these core concepts interrelate within the framework of a linear regression model.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Linearity

Establishing the linearity of an analytical method is a systematic process that requires careful experimental design and execution. The following workflow outlines the key stages in a typical linearity assessment study, which is fundamental to method validation.

Detailed Methodological Framework

The experimental assessment of linearity follows a structured protocol to ensure reliable and defensible results.

Step 1: Define Concentration Range and Levels The linear range should cover 50-150% of the expected analyte concentration or the intended working range [14]. A minimum of five to six concentration levels are recommended to adequately characterize the linear response [14]. The calibration range must bracket all expected sample values.

Step 2: Prepare Calibration Standards Prepare standard solutions at each concentration level in triplicate to account for variability [14]. Use calibrated pipettes and analytical balances for accurate dilution and preparation. For bioanalytical methods, prepare standards in blank matrix rather than pure solvent to account for matrix effects [14].

Step 3: Analyze Samples Analyze the calibration standards in random order rather than sequential concentration to prevent systematic bias [14]. The instrument response (e.g., peak area, absorbance) is recorded for each standard.

Step 4: Perform Regression Analysis Plot instrument response against concentration and calculate the regression line ( y = b0 + b1x ), where

yis the response andxis the concentration [23]. Calculate the correlation coefficient (r) and R-squared (r²) value [22]. For most analytical methods, regulatory guidelines typically require ( r^2 > 0.995 ) [14]. Some methods may require weighted regression if heteroscedasticity is present (variance changes with concentration) [14].Step 5: Evaluate Residual Plots Plot the residuals (difference between observed and predicted values) against concentration [14]. A random scatter of residuals around zero indicates good linearity. Patterns in the residual plot (e.g., U-shaped curve) suggest potential non-linearity that a high r² value alone might mask [14].

Step 6: Document Validation Thoroughly document all procedures, raw data, statistical analyses, and any deviations with justifications to meet regulatory requirements from ICH, FDA, and EMA [14].

Essential Reagents and Materials for Linearity Studies

The following table lists key research reagent solutions and materials essential for conducting robust linearity assessments in analytical method development.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for linearity validation

| Item | Function in Linearity Assessment |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Provides analyte of known purity and concentration for accurate standard preparation [14]. |

| Blank Matrix | Used for preparing calibration standards in bioanalytical methods to account for matrix effects [14]. |

| Internal Standards (e.g., Isotopically Labeled) | Corrects for variability in sample preparation and analysis, helping to maintain linearity across the range [3]. |

| Mobile Phase Solvents | High-purity solvents are essential for chromatography-based methods to maintain stable baseline and response. |

| Calibrated Pipettes & Analytical Balances | Ensures accurate and precise preparation of standard solutions at different concentration levels [14]. |

Data Interpretation in Regulatory Context

Acceptance Criteria and Regulatory Standards

In analytical method validation for pharmaceutical and clinical applications, specific acceptance criteria apply to linearity parameters:

- R-squared (r²): Typically required to be >0.995 for chromatographic methods, demonstrating sufficient explanatory power in the calibration model [14].

- Correlation Coefficient (r): While not always explicitly stated, an r value of >0.9975 corresponds to the common r² threshold of 0.995 [20] [14].

- Visual Inspection of Residuals: Regulatory authorities emphasize that statistical parameters alone are insufficient; residual plots must show random scatter around zero without systematic patterns [14].

Troubleshooting Common Linearity Issues

Several factors can compromise linearity in analytical methods, requiring systematic troubleshooting:

- Matrix Effects: Can cause non-linearity, particularly at concentration extremes. Solution: Use matrix-matched calibration standards or standard addition methods [14].

- Detector Saturation: Occurs at high concentrations, flattening the response. Solution: Dilute samples or use a less sensitive detection technique [3].

- Insufficient Dynamic Range: The instrument may not respond linearly across the entire concentration range of interest. Solution: Use multiple product ions or detection channels to expand the working range [4].

- Inappropriate Regression Model: Simple linear regression may not fit data with non-constant variance. Solution: Apply weighted regression or polynomial fitting when justified [14].

The statistical concepts of correlation coefficient (r), R-squared (r²), slope, and y-intercept form an interconnected framework for evaluating method linearity in analytical science. While r and r² help assess the strength and explanatory power of the relationship, the slope and y-intercept define the functional relationship used for quantitative prediction. In regulatory environments, these statistics must be interpreted collectively rather than in isolation, with visual tools like residual plots providing critical context beyond numerical values alone. A comprehensive understanding of these foundational concepts enables researchers and drug development professionals to develop robust, reliable analytical methods that meet rigorous validation standards.

A Step-by-Step Protocol: From Standard Preparation to Data Evaluation

In the realm of analytical method validation, the selection of an appropriate concentration range and levels is a foundational step that directly determines the method's reliability and regulatory acceptance. The 50-150% range of the target analyte concentration has emerged as a standard framework for demonstrating method linearity, accuracy, and precision in pharmaceutical analysis [3] [14]. This range provides a safety margin that ensures reliable quantification not only at the exact target concentration but also at the expected extremes during routine analysis. Proper experimental design for this validation parameter requires careful consideration of concentration spacing, matrix effects, and statistical evaluation to generate scientifically sound and defensible data. This guide objectively compares the performance of different experimental approaches against established regulatory standards, providing researchers with a clear pathway for designing robust linearity experiments.

Core Principles of Concentration Range Selection

The linear range of an analytical method is defined as the interval between the upper and lower concentration levels where the analytical response is directly proportional to analyte concentration [3]. When designing experiments to establish this range, several critical principles must be considered:

Bracketing Strategy: The selected range must extend beyond the expected sample concentrations encountered during routine analysis. The 50-150% bracket effectively covers potential variations in drug product potency, sample preparation errors, and other analytical variables that could push concentrations beyond the nominal 100% target [14].

Dynamic Range Considerations: It is crucial to distinguish between the dynamic range (where response changes with concentration but may be non-linear) and the linear dynamic range (where responses are directly proportional). A method's working range constitutes the interval where results demonstrate acceptable uncertainty and may extend beyond the strictly linear region [3].

Matrix Compatibility: For methods analyzing complex samples, the linearity experiment must account for potential matrix effects. Calibration standards should be prepared in blank matrix rather than pure solvent to accurately reflect the analytical environment of real samples [14] [25].

Experimental Design Comparison: Approaches to Linearity Validation

Different methodological approaches yield varying levels of reliability, efficiency, and regulatory compliance. The following comparison evaluates three common experimental designs for establishing the 50-150% concentration range:

Table 1: Comparison of Experimental Approaches for Linearity Validation

| Experimental Approach | Key Features | Performance Metrics | Regulatory Alignment | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional ICH-Compliant Design [26] [14] [25] | - Minimum 5 concentration levels (50%, 80%, 100%, 120%, 150%)- Triplicate injections at each level- Ordinary Least Squares regression- Residual plot analysis | - R² > 0.995- Residuals within ±2%- Accuracy 100±5% across range | Aligns with ICH Q2(R1/R2), FDA, and EMA requirements; Well-established precedent | May miss non-linearity between tested points; Requires manual inspection for patterns |

| Enhanced Spacing Design [14] | - 6-8 concentration levels with tighter spacing at extremes- Weighted regression (1/x or 1/x²) for heteroscedasticity- Independent standard preparation | - Improved detection of curve inflection points- Better variance characterization across range | Exceeds minimum regulatory requirements; Provides enhanced data integrity | Increased reagent consumption and analysis time; More complex statistical analysis |

| Matrix-Matched Design [14] [25] | - Standards prepared in blank matrix- Standard addition for complex matrices- Evaluation of matrix suppression/enhancement | - Identifies matrix effects early- More accurate prediction of real-sample performance | Addresses specific FDA/EMA guidance on bioanalytical method validation; Higher real-world relevance | Requires access to appropriate blank matrix; More complex sample preparation |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: ICH-Compliant Linearity Validation

Based on the comparative analysis, the Traditional ICH-Compliant Design represents the most universally applicable methodology. The following detailed protocol ensures robust linearity demonstration across the 50-150% concentration range:

Standard Solution Preparation

Prepare a stock solution of the reference standard at approximately the target concentration (100%). From this stock, prepare a series of standard solutions at five concentration levels: 50%, 80%, 100%, 120%, and 150% of the target concentration. For enhanced reliability, prepare these solutions independently rather than through serial dilution to avoid propagating preparation errors [14]. For methods analyzing complex matrices such as biological samples, prepare these standards in blank matrix to account for potential matrix effects [25].

Chromatographic Analysis and Data Collection

Analyze each concentration level in triplicate using the developed chromatographic conditions. Randomize the injection order rather than analyzing in ascending or descending concentration to prevent systematic bias from instrumental drift [14]. Record the peak area responses for each injection. The fluticasone propionate validation study exemplifies this approach, analyzing multiple concentrations across the 50-150% range with triplicate measurements to establish linearity [25].

Table 2: Exemplary Linearity Data Structure (Fluticasone Propionate Validation)

| Concentration Level | Concentration (mg/mL) | Peak Area (mAU) | Response Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50%_1 | 0.0303 | 690.49 | 22826.24 |

| 80%_1 | 0.0484 | 1085.78 | 22433.37 |

| 100%_1 | 0.0605 | 1323.72 | 21879.67 |

| 120%_1 | 0.0726 | 1624.14 | 22371.11 |

| 150%_1 | 0.0908 | 2077.45 | 22891.96 |

Statistical Evaluation and Acceptance Criteria

Calculate the correlation coefficient (r), coefficient of determination (r²), slope, and y-intercept of the regression line. The method should demonstrate r² > 0.995 for acceptance [14]. However, do not rely solely on r² values, as they can mask non-linear patterns. Visually inspect the residual plot, which should show random scatter around zero without discernible patterns [14]. Calculate the percentage deviation of the back-calculated concentrations from the nominal values; these should typically fall within ±5% for the 50-150% range [25].

Advanced Techniques for Challenging Analyses

In cases where traditional approaches face limitations, advanced methodologies can provide effective solutions:

Weighted Regression: When data exhibits heteroscedasticity (variance increasing with concentration), employ weighted least squares regression (typically 1/x or 1/x²) instead of ordinary least squares to ensure proper fit across the entire range [14].

Peak Deconvolution: For partially co-eluting peaks where baseline separation is challenging, advanced processing techniques like Intelligent Peak Deconvolution Analysis (i-PDeA) can mathematically resolve overlapping signals, enabling accurate quantification without complete chromatographic separation [27].

Extended Range Strategies: For compounds with narrow linear dynamic ranges, several approaches can extend the usable range: using isotopically labeled internal standards, employing sample dilution for concentrated samples, or for LC-ESI-MS systems, reducing flow rates to decrease charge competition in the ionization source [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Linearity Experiments

| Item | Function in Linearity Validation | Critical Quality Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standard [14] [25] | Primary material for preparing calibration standards; establishes measurement traceability | High purity (>95%), certified concentration, appropriate stability |

| Appropriate Solvent/Blank Matrix [14] [25] | Medium for standard preparation; should match sample matrix for bioanalytical methods | Compatibility with analyte, free of interferences, consistent composition |

| Chromatographic Mobile Phase [25] | Liquid phase for chromatographic separation; isocratic or gradient elution | HPLC-grade solvents, appropriate pH and buffer strength, degassed |

| Internal Standard (where applicable) [3] | Correction for procedural variations; especially valuable in mass spectrometry | Isotopically labeled analog of analyte; similar retention time and ionization |

| System Suitability Standards [26] | Verification of proper chromatographic system function prior to linearity testing | Reproducible retention time, peak shape, and response |

Regulatory Framework and Documentation Requirements

Regulatory compliance requires thorough documentation of linearity experiments. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines Q2(R1) and the forthcoming Q2(R2) establish the benchmark for validation parameters, including linearity and range [28]. Documentation must include:

- Raw data for all concentration levels with replicate injections [14]

- Statistical analysis including correlation coefficient, y-intercept, slope, and residual values [26] [14]

- Visual representations of the calibration curve and residual plots [14]

- Justification for any excluded data points with scientific rationale [14]

- Comparison of results against predefined acceptance criteria [14] [25]

Adherence to the ALCOA+ principles (Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, Accurate) for data integrity is essential for regulatory acceptance [28].

Proper experimental design for concentration range and level selection (50-150%) forms the cornerstone of defensible analytical method validation. The Traditional ICH-Compliant Design, with five concentration levels analyzed in triplicate, provides a robust framework for most applications, while enhanced spacing and matrix-matched approaches address specific analytical challenges. By implementing the detailed protocols, statistical evaluations, and documentation practices outlined in this guide, researchers can generate reliable data that demonstrates method suitability and complies with global regulatory standards. As analytical technologies evolve, incorporating advanced data processing techniques and risk-based approaches will further strengthen linearity validation practices in pharmaceutical development.

In analytical chemistry, the linearity of a method is its ability to produce test results that are directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte in the sample within a given range [29]. This parameter is fundamental to method validation as it ensures the reliability of quantitative analyses across the intended working range. The preparation of linearity standards—solutions of known concentration used to establish this relationship—is a critical step that directly impacts the accuracy and credibility of analytical results. The dynamic range, on the other hand, refers to the concentration interval over which the instrument response changes, though this relationship may not necessarily be linear throughout [3].

The process of preparing these standards involves careful selection of materials, matrices, and dilution schemes, each choice introducing potential sources of error or bias. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the nuances of standard preparation is essential for developing robust analytical methods that meet regulatory requirements from bodies such as the ICH, FDA, and EMA [14]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of different approaches to preparing linearity standards, supported by experimental data and protocols, to inform best practices in analytical method development and validation.

Essential Materials and Reagents

The foundation of reliable linearity assessment begins with high-quality materials and reagents. Consistent results depend on the purity, stability, and appropriate handling of all components used in standard preparation.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Materials for Preparing Linearity Standards

| Material/Reagent | Function and Importance | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Reference Standard | The authentic, highly pure analyte used to prepare stock solutions. | Purity should be certified and traceable; stability under storage conditions must be established [14]. |

| Appropriate Solvent | Liquid medium for dissolving the analyte and preparing initial stock solutions. | Must completely dissolve the analyte without degrading it; should be compatible with the analytical technique (e.g., HPLC mobile phase) [17]. |

| Blank Matrix | The analyte-free biological or sample material used for preparing standards in matrix-based calibration. | Must be verified as analyte-free; should match the composition of the actual test samples as closely as possible to account for matrix effects [14] [30]. |

| Volumetric Glassware | Pipettes, flasks, and cylinders used for precise volume measurements. | Requires regular calibration; choice between glass and plastic can affect accuracy; proper technique is critical to minimize errors [31] [14]. |

| Analytical Balance | Instrument for accurate weighing of the reference standard. | Should have appropriate sensitivity; must be calibrated regularly to ensure measurement traceability [14]. |

Preparation Matrices and Their Impact

The matrix in which linearity standards are prepared can significantly influence analytical results due to matrix effects, where components of the sample interfere with the accurate detection of the analyte [30]. Selecting the appropriate matrix is therefore crucial for validating a method that will produce reliable results for real-world samples.

Types of Preparation Matrices

Pure Solvent: Standards are prepared in a simple solvent or mobile phase. This approach is straightforward and minimizes potential interference during the initial establishment of a method's linear dynamic range. However, it fails to account for the matrix effects that will be encountered when analyzing complex samples, such as biological fluids, potentially leading to inaccuracies [30].