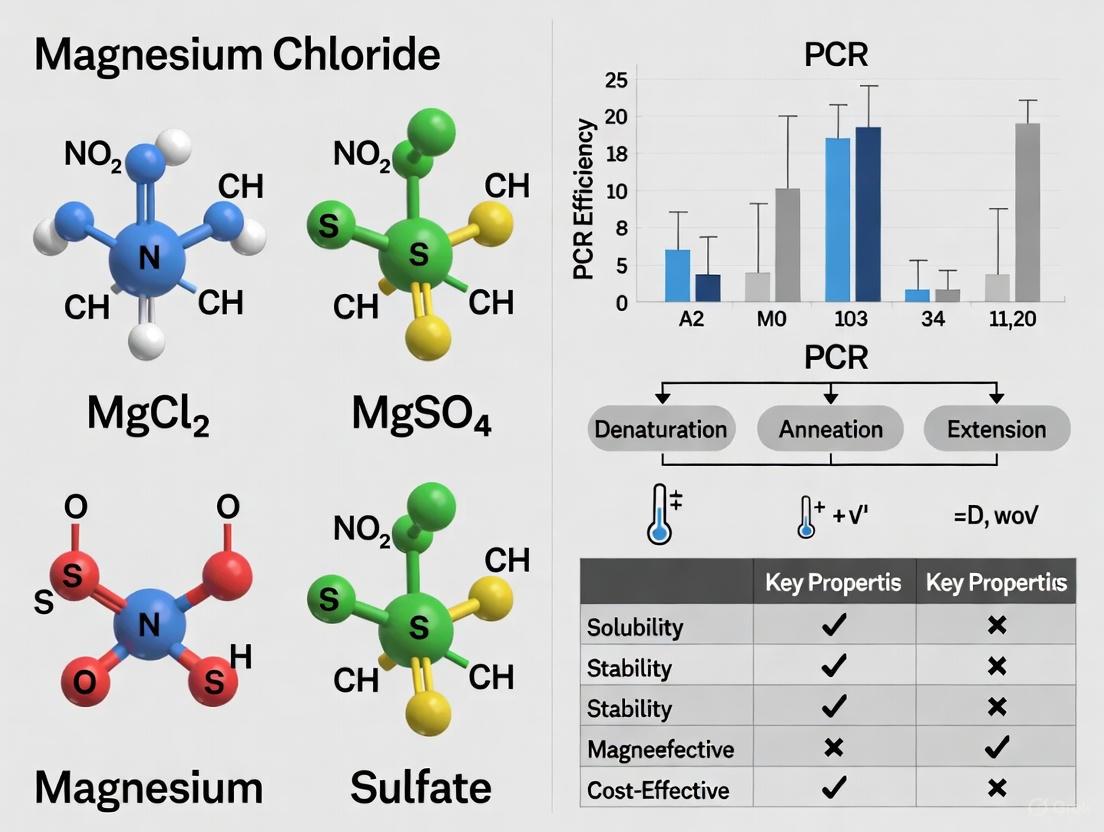

Magnesium Chloride vs. Magnesium Sulfate: A Definitive Guide to Optimizing PCR Efficiency

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of magnesium chloride (MgCl2) and magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) as cofactors for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) efficiency.

Magnesium Chloride vs. Magnesium Sulfate: A Definitive Guide to Optimizing PCR Efficiency

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of magnesium chloride (MgCl2) and magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) as cofactors for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) efficiency. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational biochemical roles of magnesium ions, delivers practical methodological guidance for reagent use, addresses common troubleshooting scenarios for inhibition and optimization, and validates findings through comparative analysis of specificity, yield, and application-specific performance. The synthesis of current evidence aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to make informed decisions that enhance PCR robustness, reproducibility, and success across diverse experimental setups.

The Fundamental Role of Magnesium: How Mg²⁺ Ions Power Your PCR

In the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), magnesium acts as an indispensable cofactor, forming a literal bridge between the enzyme—DNA polymerase—and its substrates, the deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs). The divalent magnesium ion (Mg²⁺) is fundamental to the catalytic machinery of DNA polymerization, influencing nearly every aspect of PCR efficiency and specificity. While magnesium chloride (MgCl₂) is the conventional source of this cofactor in most PCR protocols, magnesium sulfate (MgSO₄) serves as a vital alternative, particularly in specialized systems. The choice between these salts is not merely a matter of convenience; it directly impacts DNA polymerase activity, fidelity, and the overall success of amplification [1] [2] [3].

This guide provides an objective comparison of MgCl₂ and MgSO₄ for PCR efficiency, drawing on current research and experimental data. We summarize quantitative findings in structured tables, detail key methodologies, and outline the essential reagents that constitute the researcher's toolkit for optimizing magnesium-dependent PCR.

Comparative Performance Data: MgCl₂ vs. MgSO₄

Quantitative Comparison of Magnesium Salts

The table below summarizes the core characteristics and performance metrics of MgCl₂ and MgSO₄ in PCR based on current research and standard protocols.

| Parameter | Magnesium Chloride (MgCl₂) | Magnesium Sulfate (MgSO₄) |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Concentration Range | 1.0 to 5.0 mM, with 1.5 to 2.0 mM being most common [3] | Often used at comparable molar concentrations, but system-dependent |

| Primary Function | Essential cofactor for thermostable DNA polymerases (e.g., Taq) [1] | Essential cofactor for certain thermostable polymerases |

| Mechanism of Action | Stabilizes enzyme-substrate complex; neutralizes negative charge on DNA backbone; facilitates phosphodiester bond formation [1] | Functions as a cofactor for polymerases such as those from Thermus thermophilus |

| Impact on Specificity | Critical; insufficient Mg²⁺ reduces yield; excess Mg²⁺ promotes non-specific binding and primer-dimer formation [3] | Similar principle applies; optimal concentration is key for specificity |

| Theoretical Optimization | Predictive models using Taylor series expansion can achieve R² = 0.9942 for optimal [MgCl₂] prediction [4] | Information missing from search results; specific predictive models not detailed |

| Notable Features | - The most widely used magnesium source in PCR- [Mg²⁺] is a key variable in optimization experiments [2] | - Required for the activity of some specialized DNA polymerases- May be included in proprietary enhanced buffer systems |

Experimental Data on Optimization and Performance

Advanced modeling underscores the need for precise magnesium optimization. One study developed a predictive framework for MgCl₂ concentration using a multivariate Taylor series expansion integrated with thermodynamic principles. This model demonstrated excellent predictive capability (R² = 0.9942) for optimal MgCl₂ concentration, highlighting the profound influence of factors like melting temperature (Tm), GC content, and amplicon length. The research further identified the interaction between dNTP and primer concentrations as the most critical variable, with 28.5% relative importance for determining the optimal [MgCl₂] [4].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Standard PCR Setup with Magnesium Optimization

The following methodology outlines a standard protocol for setting up a PCR reaction, with an emphasis on the role and optimization of magnesium [2].

Materials and Reagents:

- Template DNA: 1–1000 ng (e.g., genomic DNA, cDNA, or plasmid DNA).

- Primers: 20–50 pmol of each forward and reverse primer. Primers should be 15–30 nucleotides long, with a Tm of 55–70°C and GC content of 40–60% [1].

- DNA Polymerase: 0.5–2.5 units per 50 µL reaction (e.g., Taq DNA polymerase).

- 10X Reaction Buffer: Usually supplied with the enzyme. May or may not contain MgCl₂.

- dNTP Mix: 200 µM of each dNTP (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP).

- Magnesium Stock Solution: 25 mM MgCl₂ (or MgSO₄, if required).

- Nuclease-Free Water: To adjust the final volume.

Procedure:

- Prepare Reaction Mixture: In a sterile, thin-walled 0.2 mL PCR tube, assemble the following components on ice in the order listed to a final volume of 50 µL:

- Nuclease-free water (QS to 50 µL)

- 10X PCR buffer (5 µL)

- dNTP mix (1 µL of a 10 mM stock)

- Magnesium stock solution (Volume varies; start with 1.5–3 µL of 25 mM stock for 0.75–1.5 mM final concentration)

- Forward primer (1 µL of a 20 µM stock)

- Reverse primer (1 µL of a 20 µM stock)

- Template DNA (variable volume)

- DNA polymerase (0.5–1 µL)

- Mix and Centrifuge: Gently mix the reaction by pipetting up and down. Briefly centrifuge to collect all liquid at the bottom of the tube.

- Thermal Cycling: Place the tube in a thermal cycler and run a program appropriate for the template, primers, and polymerase. A basic program is:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2–5 minutes.

- Amplification (25–35 cycles):

- Denature: 95°C for 30 seconds.

- Anneal: 50–65°C (Tm-dependent) for 30 seconds.

- Extend: 72°C for 1 minute per kb of amplicon.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5–10 minutes.

- Hold: 4°C.

- Analysis: Analyze PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Protocol for Magnesium Titration

To empirically determine the optimal magnesium concentration for a specific PCR assay, a titration experiment is essential [2] [3].

- Prepare a Master Mix: Create a master mix containing all reaction components except the magnesium stock and template DNA. Aliquot this mix equally into multiple PCR tubes.

- Vary Magnesium Concentration: Add a range of volumes of the magnesium stock solution (e.g., 0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0 µL of a 25 mM stock) to the individual tubes. This will create a concentration gradient (e.g., 0 to 5.0 mM final concentration).

- Add Template and Run PCR: Add template DNA to each tube and run the PCR under the chosen cycling conditions.

- Evaluate Results: Analyze the results by gel electrophoresis. The optimal [Mg²⁺] is the lowest concentration that produces a strong, specific amplicon band with minimal to no non-specific background.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Magnesium's Role in DNA Polymerization

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental biochemical role of Mg²⁺ as a cofactor in the DNA polymerization catalyzed by DNA polymerase.

PCR Optimization Workflow

This workflow outlines the logical process for optimizing magnesium concentration in a PCR experiment, integrating both theoretical prediction and empirical validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists key reagents and materials required for conducting and optimizing PCR with magnesium cofactors.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Polymerase | Enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands. | Taq polymerase is common; proofreading enzymes may require MgSO₄. Thermostability is critical [1]. |

| Magnesium Salts (MgCl₂/MgSO₄) | Essential cofactor. | Concentration must be optimized for each primer-template system. MgCl₂ is the standard for most applications [2] [3]. |

| dNTP Mix | Building blocks (A, C, G, T) for new DNA synthesis. | Used at 200 µM of each dNTP. Higher concentrations may require more Mg²⁺ for chelation [1]. |

| Oligonucleotide Primers | Define the start and end of the target sequence. | Must be well-designed with appropriate Tm and minimal self-complementarity [2]. |

| Template DNA | The DNA to be amplified. | Quality and quantity are vital. Common templates: gDNA (5–50 ng), cDNA, plasmid DNA (0.1–1 ng) [1]. |

| PCR Buffer | Provides optimal chemical environment (pH, ionic strength). | Often supplied with the polymerase; may contain MgCl₂ [2]. |

| Thermal Cycler | Instrument that automates temperature cycles. | Precise temperature control is necessary for specificity and yield. |

The Fundamental Two-Metal-Ion Mechanism in DNA Polymerization

The catalysis of phosphodiester bond formation by DNA polymerase is universally governed by a two-metal-ion mechanism [5] [6]. This process facilitates the nucleophilic attack of the primer strand's 3'-OH group on the α-phosphorus of an incoming deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) [7]. Structural analyses reveal that the enzyme's active site employs two invariant aspartate residues to coordinate two magnesium ions (Mg²⁺), which are critical for both the catalysis and the correct geometric alignment of the substrates [5] [6].

The following diagram illustrates the core two-metal-ion mechanism and the key subsequent step of fingers domain closure.

The specific roles of these two metal ions are distinct and essential:

- Metal Ion A (Catalytic Metal): This ion activates the 3'-OH group of the primer terminus by facilitating its deprotonation, enhancing its nucleophilicity for the attack on the α-phosphate of the dNTP [6] [7]. It is coordinated by the 3'-OH, the α-phosphate, and one of the catalytic aspartates.

- Metal Ion B (Product Stabilization Metal): This ion coordinates with the β- and γ-phosphates of the incoming dNTP, stabilizing the negative charge that develops on the pyrophosphate leaving group during the reaction [5] [6]. It binds to the triphosphate moiety and the other catalytic aspartate.

Recent time-resolved crystallographic studies on human DNA polymerase η have provided unprecedented insight into this process, even suggesting the transient involvement of a third Mg²⁺ ion that may stabilize the intermediate state of the reaction [6]. The reaction proceeds through an SN2-type mechanism involving a pentacovalent phosphate intermediate transition state [6].

Magnesium Cofactor Optimization in PCR: A Quantitative Guide

In Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), Mg²⁺ is a critical cofactor, and its concentration must be carefully optimized. A 2025 meta-analysis of 61 studies provides robust, evidence-based guidelines, establishing that MgCl₂ concentration has a logarithmic relationship with DNA melting temperature (Tm) [8] [9]. The optimal concentration range for most reactions is between 1.5 mM and 3.0 mM [8]. Within this range, every 0.5 mM increase in MgCl₂ raises the DNA melting temperature by approximately 1.2 °C [8].

The table below summarizes the key quantitative relationships and recommendations for Mg²⁺ optimization in PCR.

Table 1: Quantitative Effects and Guidelines for Mg²⁺ Optimization in PCR

| Aspect | Optimal Range / Effect | Key Influencing Factors | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| General MgCl₂ Concentration [8] | 1.5 – 3.0 mM | Template complexity, dNTP concentration, primer design | Start at 1.5 mM and titrate in 0.5 mM increments. |

| Tm Increase per [MgCl₂] [8] | +1.2 °C per 0.5 mM | Found within 1.5-3.0 mM range | Critical for accurate annealing temperature calculation. |

| Template-Specific Needs [8] | gDNA requires higher [Mg²⁺] than plasmid DNA | Template complexity and GC-content | Use higher concentrations (e.g., 2.0-3.0 mM) for complex genomic DNA. |

| dNTP Interaction [1] | dNTPs bind Mg²⁺, reducing free [Mg²⁺] | Total dNTP concentration (typically 0.2-0.8 mM) | Ensure >0.01-0.015 mM free Mg²⁺; balance [Mg²⁺] with [dNTP]. |

| Inhibitor Tolerance [10] | Polymerase-dependent (e.g., KOD > Taq) | Metal contaminants (Zn²⁺, Fe²⁺, Cu²⁺, Ca²⁺) [11] | Select a robust polymerase or use chelators (e.g., EGTA for Ca²⁺) [11]. |

Magnesium Salt Selection: Chloride vs. Sulfate

The choice between magnesium chloride (MgCl₂) and magnesium sulfate (MgSO₄) is not arbitrary and can significantly impact PCR efficiency. This decision is often dictated by the specific DNA polymerase employed.

Table 2: Magnesium Salt Compatibility with Common DNA Polymerases

| DNA Polymerase | Origin / Family | Recommended Mg²⁺ Salt | Rationale & Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taq Polymerase | Thermus aquaticus / A | MgCl₂ | Standard for most common PCR applications; the classic enzyme for which MgCl₂ optimization was established. |

| Pfu Polymerase | Pyrococcus furiosus / B | MgSO₄ | Often preferred for proofreading enzymes from archaeal B-family; sulfate may provide a more stable ionic environment. |

| Pab-polD | Pyrococcus abyssi / D | MgCl₂ (in optimized buffer) | A proof-reading heterodimeric polymerase noted for high thermostability and resistance to PCR inhibitors [10]. |

The underlying reason for this specificity lies in the unique ionic requirements and structural adaptation of each polymerase. Archaeal B-family polymerases (e.g., Pfu) are often used with MgSO₄, whereas the more common Taq polymerase and the specialized D-family polymerase Pab-polD are typically used with MgCl₂ in their optimized buffers [10]. The sulfate ion may provide a different coordination chemistry or stability to the active site of certain archaeal enzymes. Using the incorrect salt can lead to suboptimal activity, as the ionic strength and specific anion can influence enzyme structure and the kinetics of the nucleotidyl transfer reaction.

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Mg²⁺ Function

Methodology for Kinetic Analysis of Active Site Aspartate Mutants

To dissect the precise role of Mg²⁺ ions and their coordination, researchers have employed stopped-flow fluorescence assays with mutant DNA polymerases.

- Protein Engineering: Mutations (e.g., D705A and D882A) are introduced into the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I, replacing the metal-coordinating aspartate residues with alanine [5].

- Fluorescent Reporter Assays:

- A 2-aminopurine (2-AP) probe incorporated into the DNA template reports on an early DNA rearrangement step (conformational transition step 2.1) [5].

- A FRET-based assay using a fluorophore (IAEDANS) site-specifically attached to the fingers subdomain (e.g., residue 744) reports on the fingers-closing transition (step 2.2) [5].

- Experimental Procedure: The mutant or wild-type polymerase is rapidly mixed with DNA and dNTP in a stopped-flow instrument. Fluorescence changes are monitored in real-time to track the kinetics of each conformational step [5].

- Key Finding: This approach revealed that the Asp882 carboxylate is essential for the fingers-closing step, while Asp705 is not required until after fingers-closing, likely to facilitate the entry of the second catalytic Mg²⁺ ion [5].

Protocol for Systematic PCR Mg²⁺ Optimization

The following workflow, derived from meta-analysis and modeling studies, provides a robust strategy for optimizing Mg²⁺ conditions for any novel PCR application [8] [4].

- Initial Setup: Prepare a master mix and aliquot it into several tubes. Set up a series of reactions with MgCl₂ concentrations spanning 1.0 mM to 4.0 mM, typically in 0.5 mM increments [1] [8].

- Thermocycling and Analysis: Run the PCR and analyze the products using agarose gel electrophoresis. Assess for the presence of a single, intense band of the expected size (specific product) versus smears or multiple bands (nonspecific amplification) [1].

- Fine-Tuning: Identify the concentration that yields the highest amount of specific product with the least background. Use this concentration for all subsequent experiments. If nonspecific amplification persists, consider lowering the Mg²⁺ concentration or the amount of DNA polymerase [1].

- Advanced Predictive Modeling: For high-throughput workflows, leverage modern predictive models that use parameters like primer Tm, GC content, amplicon length, and dNTP concentration to computationally predict a near-optimal MgCl₂ starting point, reducing experimental optimization time [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Mg²⁺-Dependent Polymerization Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Mg²⁺ in DNA Polymerization

| Reagent / Material | Critical Function | Experimental Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity MgCl₂ / MgSO₄ | Source of Mg²⁺ cofactor. | Salt type must match polymerase preference; concentration is critical and requires optimization [1] [8]. |

| dNTP Mix | Building blocks for DNA synthesis. | High purity is essential; total concentration chelates Mg²⁺, affecting free [Mg²⁺] available for the enzyme [1]. |

| Catalytic Aspartate Mutants | Mechanistic probes. | e.g., D705A/D882A Pol I(KF); reveal roles of metal ligands in specific reaction steps [5]. |

| Fluorescent Nucleotide Analogs | Conformational reporters. | e.g., 2-Aminopurine (2-AP); monitors local DNA structural changes during catalysis [5]. |

| Stopped-Flow Spectrofluorometer | Kinetics measurement. | Enables real-time observation of rapid pre-chemistry conformational changes (µs to s timescale) [5]. |

| EGTA | Specific calcium chelator. | Reverses Ca²⁺-induced PCR inhibition without strongly chelating Mg²⁺ [11]. |

| Thermostable DNA Polymerases | Catalytic engines for PCR. | Choice (e.g., Taq, Pfu, Pab-polD, KOD) dictates salt preference, fidelity, and inhibitor resistance [11] [10]. |

In the realm of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) optimization, magnesium ions (Mg²⁺) have long been recognized as an essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity. However, their critical role extends far beyond facilitating enzymatic polymerization. Mg²⁺ significantly influences the fundamental thermodynamics of nucleic acid interactions, particularly in stabilizing primer-template duplexes and modulating DNA melting temperature (Tm). This guide provides a detailed comparative analysis of the two most common magnesium sources in PCR—magnesium chloride (MgCl₂) and magnesium sulfate (MgSO₄)—evaluating their distinct effects on PCR efficiency, specificity, and robustness. Understanding these nuances is paramount for researchers aiming to develop highly specific and efficient amplification protocols, especially when working with challenging templates or complex reaction setups.

The selection between chloride and sulfate anions represents more than a trivial chemical distinction; it directly impacts ionic strength, DNA duplex stability, and enzyme performance. As PCR applications expand into more demanding areas such as diagnostics, forensics, and quantitative gene expression analysis, the empirical optimization of magnesium formulations becomes increasingly critical. This article examines the mechanistic basis for magnesium's effects on nucleic acid thermodynamics and presents experimental data to guide evidence-based selection of magnesium salts for specific research applications.

Mechanistic Insights: How Mg²⁺ Stabilizes Nucleic Acid Structures

Electrostatic Shielding and Duplex Stability

The negative charges on the phosphate backbones of DNA strands create substantial electrostatic repulsion that would prevent duplex formation under physiological conditions. Mg²�+, with its high charge density, acts as a powerful electrostatic shield that neutralizes these repulsive forces, thereby facilitating the annealing of primers to their complementary template sequences [1]. This shielding effect occurs through the formation of a diffuse ion atmosphere around the DNA helix, with Mg²⁺ being particularly effective due to its divalent nature.

The mechanism involves both nonspecific, delocalized binding along the DNA backbone and specific site-binding in major and minor grooves. This dual binding mode allows Mg²⁺ to stabilize not only standard double-stranded DNA but also various secondary structures that might form within primers or templates. The stabilization effect is quantitatively significant; research indicates that every 0.5 mM increase in MgCl₂ concentration within the optimal PCR range (1.5-3.0 mM) correlates with an approximately 1.2°C increase in DNA melting temperature [9].

Direct Impact on Melting Temperature (Tm)

The melting temperature of a primer-template duplex—the temperature at which half of the double-stranded molecules dissociate into single strands—is directly influenced by Mg²⁺ concentration. This relationship follows a logarithmic pattern, with diminishing returns at higher concentrations [9]. The magnitude of this effect varies based on the DNA sequence characteristics, with GC-rich templates typically exhibiting greater Tm shifts due to the more compact structure and higher charge density of GC base pairs compared to AT pairs.

Table 1: Quantitative Effect of MgCl₂ Concentration on DNA Melting Temperature

| MgCl₂ Concentration (mM) | Relative Increase in Tm (°C) | Impact on PCR Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | Baseline | Often insufficient for complex templates |

| 1.5 | +1.2 | Suitable for simple templates |

| 2.0 | +2.4 | Optimal for most standard PCR |

| 2.5 | +3.6 | Beneficial for GC-rich targets |

| 3.0 | +4.8 | May reduce specificity |

| 4.0+ | >5.0 | High risk of nonspecific amplification |

This Tm modulation has direct practical implications for PCR optimization. As Mg²⁺ concentration increases, the actual annealing temperature effectively decreases relative to the calculated Tm, potentially leading to nonspecific priming if not properly accounted for in thermal cycling parameters.

Comparative Analysis: Magnesium Chloride vs. Magnesium Sulfate

Biochemical Performance in PCR

The choice between MgCl₂ and MgSO₄ extends beyond mere anion differences, significantly impacting enzyme performance and reaction specificity. Experimental evidence indicates that MgSO₄ generally produces more robust and reproducible amplification products with certain high-fidelity DNA polymerases [12]. This enhanced performance is particularly notable with engineered enzymes such as Platinum Taq High Fidelity, where the sulfate anion creates a more favorable enzymatic environment.

The differential effects stem from distinct interactions with polymerase structures and DNA substrates. Sulfate ions appear to provide superior stabilization of the polymerase-DNA complex during the elongation phase, particularly for amplicons with secondary structures or high GC content. Additionally, MgSO₄ demonstrates better compatibility with specialized PCR additives such as GC enhancers and isostabilizing agents designed for challenging templates [12].

Table 2: Direct Comparison of Magnesium Chloride and Magnesium Sulfate in PCR

| Parameter | Magnesium Chloride (MgCl₂) | Magnesium Sulfate (MgSO₄) |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Concentration | 1.5-3.0 mM [9] | 3-6 mM [13] |

| Anion Effect | Chloride may increase ionic strength more significantly | Sulfate provides better enzyme stabilization |

| Polymerase Compatibility | Broad compatibility with standard Taq polymerases | Preferred for high-fidelity and engineered enzymes [12] |

| Template Specificity | Suitable for standard templates | Enhanced performance with complex, GC-rich targets [12] |

| Buffer System | Works with standard Tris-based buffers | Optimal with specialized formulations containing (NH₄)₂SO₄ [14] |

| Reproducibility | Standard for routine applications | Superior lot-to-lot consistency for regulated environments [12] |

Template-Dependent Optimization Strategies

The optimal magnesium concentration and salt selection vary significantly based on template characteristics. Complex templates such as genomic DNA typically require higher magnesium concentrations (2.5-4.5 mM) compared to simpler templates like plasmid DNA (1.5-2.5 mM) [9]. This requirement stems from the greater structural complexity and potential secondary structures in genomic DNA that must be stabilized during amplification.

GC-rich templates present particular challenges due to their higher intrinsic Tm and stronger secondary structure formation. For these difficult targets, MgSO₄ often outperforms MgCl₂, especially when used in conjunction with specialized polymerase systems and buffer additives. The enhanced performance manifests as higher yields, reduced nonspecific amplification, and better reproducibility across technical replicates [12].

For long-range PCR (amplicons >5 kb), magnesium concentration optimization becomes even more critical. The extended elongation times increase the opportunity for polymerase dissociation or mispriming, making magnesium-mediated stabilization of the enzyme-template complex particularly important. In these applications, a slight increase in magnesium concentration (typically 0.5-1.0 mM above standard conditions) coupled with MgSO₄ often yields superior results.

Experimental Approaches for Magnesium Optimization

Systematic Concentration Titration

A rigorous optimization protocol begins with a magnesium titration series across a physiologically relevant range. The following procedure ensures comprehensive assessment:

Master Mix Preparation: Prepare a master mix containing all PCR components except magnesium, then aliquot equal volumes into separate tubes.

Magnesium Dilution Series: Create a stock solution series of both MgCl₂ and MgSO₄ to cover concentrations from 0.5 mM to 5.0 mM in 0.5 mM increments.

Reaction Assembly: Add the appropriate magnesium stock to each aliquot to achieve the desired final concentration, maintaining constant volume with nuclease-free water.

Thermal Cycling: Perform amplification using touchdown or gradient protocols to account for Tm variations across concentrations.

Product Analysis: Resolve amplification products by agarose gel electrophoresis and quantify yield and specificity through densitometry or fluorescent DNA binding dyes.

This systematic approach directly reveals the concentration-dependent effects on amplification efficiency, specificity, and yield for each magnesium salt. Researchers should note that the optimal concentration may differ between MgCl₂ and MgSO₄ for the same primer-template system.

Quantitative Assessment Metrics

Evaluation of magnesium optimization experiments should incorporate multiple metrics:

- Amplification Efficiency: Calculated from real-time PCR curves or end-point yield measurements

- Specificity Index: Ratio of target band intensity to total DNA product

- Time to Threshold (Cq): For real-time applications, the cycle at which fluorescence crosses the detection threshold

- Inter-Replicate Variability: Coefficient of variation across technical replicates

These metrics collectively provide a comprehensive picture of how magnesium formulation affects overall PCR performance, enabling data-driven selection of optimal conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Magnesium Optimization

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Magnesium Optimization Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Magnesium Salts | MgCl₂, MgSO₄ | Primary optimization variables; provide Mg²⁺ cofactor |

| DNA Polymerases | Taq, Platinum Taq, High-fidelity enzymes | Catalyze DNA synthesis; different enzymes have distinct magnesium requirements |

| Buffer Systems | Tris-based, Bicine, proprietary formulations | Maintain pH and provide appropriate ionic environment |

| dNTPs | dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP | DNA synthesis substrates; compete with primers for Mg²⁺ binding |

| Enhancer Additives | GC Enhancer, KB Extender, TMAC | Improve amplification of challenging templates; interact with magnesium |

| Template DNA | Genomic DNA, plasmid, cDNA | Target for amplification; complexity influences magnesium requirements |

| Fluorescent Dyes | EvaGreen, SYBR Green | Enable real-time monitoring of amplification kinetics |

The strategic selection between magnesium chloride and magnesium sulfate, coupled with precise concentration optimization, represents a critical parameter in PCR protocol development that extends far beyond the canonical understanding of magnesium as merely a polymerase cofactor. The demonstrated ability of Mg²⁺ to stabilize primer-template duplexes and modulate melting temperature directly influences assay specificity, efficiency, and reproducibility. The experimental data and comparative analysis presented herein provide researchers with an evidence-based framework for magnesium optimization tailored to specific template characteristics and application requirements. For standard applications, MgCl₂ at 1.5-3.0 mM provides satisfactory results, while for complex templates, GC-rich targets, and high-fidelity applications, MgSO₄ at optimized concentrations often delivers superior performance. As PCR technologies continue to evolve toward more demanding applications, understanding these fundamental biochemical interactions will remain essential for developing robust, reliable amplification protocols in both research and diagnostic settings.

In molecular biology, particularly in optimizing critical techniques like the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), the role of cations such as magnesium (Mg²⁺) is well-documented. However, the influence of their accompanying anions—chloride (Cl⁻) and sulfate (SO₄²⁻)—is often overlooked. These anions are not mere spectators; their distinct chemical properties significantly modulate biochemical reactions, enzyme kinetics, and overall assay performance. The choice between magnesium chloride (MgCl₂) and magnesium sulfate (MgSO₄) as a source of the essential Mg²⁺ cofactor can be a determining factor for the success and efficiency of PCR protocols [15].

This guide provides an objective comparison of chloride and sulfate anions, framing their properties and effects within the context of PCR efficiency research. For scientists and drug development professionals, understanding this anionic influence is crucial for robust experimental design, troubleshooting, and reagent selection. We present quantitative data, detailed methodologies from key studies, and visual tools to elucidate the fundamental differences between these two anions and their practical implications in a laboratory setting.

The distinct behaviors of chloride and sulfate anions originate from their foundational physico-chemical characteristics. The table below summarizes and contrasts these key properties.

Table 1: Basic Chemical Properties of Chloride and Sulfate Anions

| Property | Chloride (Cl⁻) | Sulfate (SO₄²⁻) |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Formula | Cl⁻ | SO₄²⁻ |

| Ionic Charge | -1 | -2 |

| Ionic Radius | ~181 pm | ~258 pm (for tetrahedral) |

| Geometry | Spherical | Tetrahedral |

| Charge Density | Low | High |

| Base Strength | Very weak (conjugate base of strong HCl) | Weak (conjugate base of weak H₂SO₄, but HSO₄⁻ is strong) |

| Common Magnesium Salt | MgCl₂ | MgSO₄ |

| Solubility in Water | Highly soluble | Highly soluble |

| Protein Interaction | Can destabilize protein structures (chaotrope) | Can stabilize protein structures (compatible osmolyte) |

The most pronounced difference lies in their ionic charge and structure. The monovalent, spherical chloride ion presents a low charge density, while the divalent, tetrahedral sulfate ion carries a higher charge density distributed over a larger volume. This makes sulfate a more potent coordinator of metal ions in solution. In terms of acidity, chloride is the conjugate base of a strong acid (HCl) and is therefore negligible as a base in aqueous solutions. Sulfate, being the conjugate base of a weak acid (H₂SO₄, though HSO₄⁻ is strong), can accept protons and influence local pH to a greater extent. Their interactions with biomolecules also differ; chloride is often classified as a chaotrope, capable of disrupting the hydration shell around proteins and potentially destabilizing their structure, whereas sulfate can have a stabilizing effect on protein structure [15].

The PCR Context: Magnesium Cofactor and Anionic Effects

In PCR, magnesium ions (Mg²⁺) are an absolute requirement, serving as an essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity. The Mg²⁺ catalyzes the formation of the phosphodiester bond by facilitating the nucleophilic attack of the 3'-OH group of the primer on the phosphate group of the incoming dNTP [1]. It also stabilizes the double-stranded structure of DNA by neutralizing the negative charges on the phosphate backbone of the DNA template and primers [9] [1].

The choice of the anionic partner for magnesium is critical because the anion can influence the availability and activity of the Mg²⁺ cation. The divalent sulfate ion (SO₄²⁻) has a higher affinity for Mg²⁺ than the monovalent chloride ion (Cl⁻). This stronger ion pairing in MgSO₄ can potentially reduce the effective concentration of free Mg²⁺ available for the PCR enzyme, unless carefully calibrated. Furthermore, the anions can directly interact with the DNA polymerase enzyme itself, affecting its stability and catalytic efficiency. A review by Durlach et al. suggests that from a clinical and pharmacological perspective, MgCl₂ demonstrates "more interesting clinical and pharmacological effects and its lower tissue toxicity as compared to MgSO₄," hinting at fundamental differences in biochemical compatibility that could extend to enzymatic reactions [15].

Table 2: Comparative Effects of MgCl₂ and MgSO₄ in PCR

| Parameter | MgCl₂ | MgSO₄ | Experimental Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Use | Standard PCR | Often used with specific polymerases (e.g., some reverse transcriptases) | Reagent choice is polymerase-specific. |

| Mg²⁺ Availability | Weaker ion pairing; potentially higher free [Mg²⁺] | Stronger ion pairing; potentially lower free [Mg²⁺] | Optimal concentration ranges differ; requires separate optimization. |

| Enzyme Compatibility | Universal cofactor for DNA polymerases (Taq, Q5, KOD) | Required for some enzyme formulations | Check manufacturer's instructions. |

| Buffer System | Compatible with Tris-HCl, Bicine-based buffers | Compatible with Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE) gels, but PCR buffers may vary | Anion can influence buffer capacity and pH. |

| Reported Efficiency | Well-established; optimal range 1.5-3.0 mM [9] | Less commonly reported for standard PCR | MgCl₂ is the predominantly researched and used source. |

Experimental Data and Optimization Protocols

Quantitative Meta-Analysis of MgCl₂ Optimization

A comprehensive meta-analysis of 61 peer-reviewed studies provides quantitative insights into MgCl₂ optimization in PCR. The analysis established a clear logarithmic relationship between MgCl₂ concentration and DNA melting temperature (Tm). Within the optimal range of 1.5 to 3.0 mM, every 0.5 mM increase in MgCl₂ concentration was associated with a 1.2 °C increase in melting temperature [9]. This highlights the critical role of the chloride salt in stabilizing the DNA duplex. The study further found that template complexity dictates optimal concentration; genomic DNA requires higher MgCl₂ concentrations than simpler plasmid DNA templates [9].

Protocol for MgCl₂ Titration

To achieve optimal PCR results with MgCl₂, researchers should perform a titration experiment. The following protocol is adapted from standard optimization procedures:

- Prepare Master Mix: Create a master mix containing all PCR components except MgCl₂ and the template DNA. Use a DNA polymerase known for consistent performance, such as Taq, Q5, or KOD [11].

- Set Up Titration Series: Aliquot the master mix into a series of PCR tubes or a plate. Add MgCl₂ from a stock solution to achieve a final concentration gradient. A recommended range is 0.5 mM to 5.0 mM in 0.5 mM increments.

- Add Template and Run PCR: Add a fixed, optimized amount of template DNA (e.g., 5–50 ng of genomic DNA) to each reaction [1]. Perform amplification using the standard thermal cycling parameters for your primers and polymerase.

- Analyze Results: Analyze the PCR products using agarose gel electrophoresis. Identify the MgCl₂ concentration that yields the strongest specific amplification band with the least or no non-specific products [9] [1]. For qPCR, the concentration yielding the lowest Cq value and highest amplification efficiency should be selected [16].

Investigating Metal Ion Inhibition

Beyond optimization, the anionic environment is crucial when dealing with inhibitors. Metal ions like Zinc (Zn²⁺), Tin (Sn²⁺), Iron (Fe²⁺), and Copper (Cu²⁺) are potent PCR inhibitors, with IC₅₀ values significantly below 1 mM [11]. The anion can influence the solubility and behavior of these contaminants. Furthermore, calcium ions (Ca²⁺) can competitively inhibit Taq polymerase by displacing Mg²⁺ from its active site [11].

Protocol for Reversing Calcium Inhibition: A simple and effective method to counteract calcium-induced PCR inhibition is the use of the calcium-specific chelator EGTA (ethylene glycol-bis(2-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid). EGTA can be added directly to the PCR mix at a low concentration (e.g., 0.1-1.0 mM) to sequester Ca²⁺ ions without significantly chelating the essential Mg²⁺, thus restoring polymerase activity [11].

Visualization of PCR Workflow and Anionic Influence

The following diagram illustrates the key stages of a PCR protocol and the points where the choice of anion (Cl⁻ or SO₄²⁻) can influence the reaction's outcome.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the appropriate reagents is fundamental for controlled and reproducible PCR experiments. The following table details essential materials and their functions, with a focus on the components relevant to magnesium and anion selection.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PCR Optimization and Metal Ion Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Relevance to Anion/Mg²⁺ Studies |

|---|---|---|

| MgCl₂ Solution | Standard source of Mg²⁺ cofactor for most DNA polymerases. | The chloride anion is the benchmark for PCR optimization; requires concentration titration [9] [1]. |

| MgSO₄ Solution | Alternative Mg²⁺ source for specific enzyme systems. | Used to compare anionic effects on Mg²⁺ availability and polymerase activity [15]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerases (e.g., Q5, KOD) | Enzymes with proofreading activity for high-accuracy amplification. | KOD polymerase has demonstrated higher resistance to metal ion inhibition compared to Taq [11]. |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Standard, thermostable polymerase for routine PCR. | The model enzyme for establishing baseline MgCl₂ optimization protocols [1]. |

| dNTP Mix | Equimolar mix of the four deoxynucleoside triphosphates. | Mg²⁺ binds dNTPs; their concentration must be balanced with Mg²⁺ concentration [1]. |

| EGTA | Calcium-specific chelating agent. | Used to reverse PCR inhibition caused by calcium ions, clarifying the role of Mg²⁺ [11]. |

| SYBR Green I Dye | Fluorescent dye for qPCR and melt curve analysis. | Critical for assessing amplification efficiency and specificity in qPCR optimization [16]. |

The distinction between chloride and sulfate anions extends far beyond simple chemical formulae. Their differences in charge, structure, and base strength translate into tangible effects on the efficiency of critical molecular biology techniques like PCR. While MgCl₂ is the established and extensively optimized source of magnesium for the vast majority of PCR applications, understanding the properties of SO₄²⁻ is vital for troubleshooting and for specialized protocols where it is specified. The experimental data and protocols provided here underscore that precise optimization of the magnesium salt concentration—tailored to the specific anion, DNA template, and polymerase—is a non-negotiable step in the development of robust, reliable, and efficient PCR assays. For the research scientist, an appreciation of this anionic influence is a key component of rigorous experimental design.

In the orchestration of a Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), magnesium plays an indispensable role, not merely as a component but as the fundamental cofactor for DNA polymerase activity. The selection of the specific magnesium salt, however, is a critical and often overlooked variable that can dictate the success and efficiency of the amplification. Magnesium ions (Mg²⁺) are directly involved in the catalytic process of DNA synthesis, stabilizing the enzyme's structure and facilitating the formation of the phosphodiester bond between nucleotides [1]. While the necessity of Mg²⁺ is universally acknowledged, the choice between the two most common sources—magnesium chloride (MgCl₂) and magnesium sulfate (MgSO₄)—introduces a significant variable. This decision is profoundly influenced by the specific DNA polymerase employed in the reaction, making the salt choice a crucial initial step in experimental design rather than an afterthought. This guide provides an objective comparison of MgCl₂ and MgSO₄, equipping researchers with the data and protocols needed to make an informed choice for their PCR efficiency research.

Molecular Mechanisms: How Magnesium Influences PCR

To understand why the salt choice matters, one must first appreciate the multiple roles Mg²⁺ plays in the reaction dynamics. Its functions extend beyond being a simple enzyme cofactor.

Core Biochemical Functions

- Enzyme Cofactor: Mg²⁺ is an essential cofactor for DNA polymerases, enabling the incorporation of dNTPs during polymerization. The ions at the enzyme's active site catalyze the nucleophilic attack by the 3'-OH group of the primer on the phosphate group of the incoming dNTP [1].

- Nucleic Acid Stabilization: Mg²⁺ facilitates the formation of the primer-template complex by stabilizing the negative charges on the phosphate backbones of the nucleic acids. This neutralization reduces electrostatic repulsion, allowing for efficient hybridization [1].

- Thermodynamic Modulator: Mg²⁺ concentration directly affects the melting temperature (Tm) of DNA. A comprehensive meta-analysis established a logarithmic relationship between MgCl₂ concentration and Tm, demonstrating that within the 1.5–3.0 mM range, every 0.5 mM increase in MgCl₂ raises the melting temperature by approximately 1.2°C [8] [9]. This directly impacts the efficiency of DNA denaturation and primer annealing.

Mechanism of Magnesium-Dependent DNA Polymerization

The following diagram illustrates the critical role of the magnesium ion in the catalytic center of DNA polymerase.

Head-to-Head Comparison: MgCl₂ vs. MgSO₄

The anion (Cl⁻ or SO₄²⁻) can significantly influence reaction kinetics, polymerase stability, and overall performance. The optimal choice is often determined by the enzyme's biological origin.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Magnesium Chloride vs. Magnesium Sulfate in PCR

| Parameter | Magnesium Chloride (MgCl₂) | Magnesium Sulfate (MgSO₄) |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Application | The most common and versatile source of Mg²⁺ for a wide range of PCR applications [1] [17]. | Typically specified for use with certain proprietary or specialized enzyme systems [18]. |

| Typical Working Concentration | 1.5 to 3.0 mM (with optimization often required) [8] [19]. | Often used at similar molarities (e.g., 1-3 mM) but depends on the specific buffer system. |

| Compatible DNA Polymerases | Taq DNA polymerase and many other standard polymerases [1] [10]. | Some high-fidelity & proof-reading polymerases (e.g., from New England Biolabs [18]). |

| Impact on DNA Melting Temperature (Tₘ) | Strong logarithmic relationship; +1.2°C Tₘ per +0.5 mM within 1.5-3.0 mM range [8] [9]. | Expected to have a similar effect, though the relationship may be less characterized in literature. |

| Inhibition by Metal Contaminants | Susceptible to competitive inhibition by metal ions like Ca²⁺ [11]. | Similar susceptibility; chelators like EGTA can reverse Ca²⁺-induced inhibition [11]. |

| Primary Consideration | The default choice for most conventional PCR setups; requires empirical optimization. | Often used with specific engineered or archaeal polymerases where the sulfate buffer is optimal. |

Polymerase-Specific Salt Requirements

The fundamental distinction in salt choice is driven by the origin and properties of the DNA polymerase. Bacterial-derived DNA polymerases (e.g., the ubiquitous Taq polymerase from Thermus aquaticus) are typically optimized for use with MgCl₂ in KCl-based buffers [1] [10]. In contrast, many archaeal-derived polymerases, particularly high-fidelity and proof-reading enzymes (e.g., some from Pyrococcus species), demonstrate superior performance with MgSO₄ in (NH₄)₂SO₄-based buffers [10]. This preference is rooted in the native ionic environments of these organisms. Using the incorrect salt can lead to suboptimal enzyme activity, reduced processivity, and even complete reaction failure.

Experimental Data and Optimization Protocols

Quantitative Effects of MgCl₂ Concentration

A meta-analysis of 61 studies provides robust, quantitative data on how MgCl₂ concentration influences PCR outcomes [8] [9]. The relationship between Mg²⁺ and performance is not linear but follows distinct functional phases.

Table 2: Effect of MgCl₂ Concentration on PCR Performance Based on Meta-Analysis

| MgCl₂ Concentration | Impact on PCR Efficiency | Impact on Specificity | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 1.5 mM | Sharply declines due to insufficient dNTP incorporation and unstable primer-template complexes [1] [8]. | High, but yield is severely compromised. | Not recommended. |

| 1.5 – 3.0 mM (Optimal Range) | Maximized. The logarithmic relationship with Tₐ ensures high efficiency and yield [8] [9]. | High, provided other components (e.g., primer Tₐ) are correctly balanced. | Standard amplification of most templates. |

| > 3.0 mM | Declines as excessively high Tₐ can reduce efficiency; also increases error rate with non-proofreading enzymes [1]. | Decreases significantly, leading to mispriming and nonspecific amplification [1]. | May be required for challenging templates (e.g., high GC-content). |

Detailed Optimization Protocol

The following workflow outlines a standardized procedure for empirically determining the optimal magnesium concentration for any new PCR setup.

Methodology:

- Prepare a Master Mix: Create a master mix containing all standard PCR components: buffer, template DNA (e.g., 5–50 ng of genomic DNA), primers (0.1–1.0 μM each), dNTPs (0.2 mM each), and DNA polymerase (1–2 units), but omit magnesium [1] [19].

- Set Up a Magnesium Gradient: Aliquot the master mix into multiple PCR tubes. Add MgCl₂ or MgSO₄ to each tube to create a concentration gradient. A standard starting range is 0.5 mM to 5.0 mM, in increments of 0.5 mM [1] [19].

- Perform PCR Amplification: Run the reactions under standard thermocycling conditions recommended for your polymerase and primer set.

- Analyze Results: Separate the PCR products using agarose gel electrophoresis. Analyze for:

- Specificity: A single, sharp band of the expected size.

- Efficiency: The intensity of the target band indicates yield.

- Non-specific Products: Smearing or multiple bands indicate excessive magnesium.

- No Product: Insufficient magnesium or other optimization issues [19].

Addressing Metal Ion Inhibition

Metal ions common in forensic or clinical samples (e.g., Ca²⁺, Zn²⁺, Fe²⁺, Cu²⁺) can be potent PCR inhibitors by competitively binding to the polymerase's active site or causing DNA degradation [11]. A key experimental finding is that the calcium chelator ethylene glycol-bis(2-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA) can be used as a simple and non-destructive method to reverse calcium-induced PCR inhibition. EGTA has a higher affinity for Ca²⁺ than for Mg²⁺, allowing it to chelate the inhibitor without depleting the essential cofactor [11]. Furthermore, studies show that DNA polymerase enzymes differ in their susceptibility to metal inhibition; for instance, KOD polymerase was demonstrated to be more resistant to metal inhibition compared to Taq and Q5 polymerases [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Magnesium Salt and PCR Optimization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| 1M MgCl₂ Solution | A ready-to-use, sterile aqueous source of Mg²⁺ ions [17]. | Supplying the Mg²⁺ cofactor for standard PCR with Taq polymerase; creating optimization gradients. |

| 100 mM MgSO₄ Solution | A ready-to-use source of Mg²⁺ in sulfate form [18]. | Optimizing reactions for specific high-fidelity polymerases that require sulfate-based buffers. |

| dNTP Mix | An equimolar mixture of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP; the building blocks for new DNA strands [1]. | Standard PCR amplification. The concentration of dNTPs must be balanced with Mg²⁺, as Mg²⁺ binds to dNTPs. |

| Hot Start DNA Polymerase | A modified enzyme inactive at room temperature, preventing non-specific amplification during reaction setup [10]. | Improving specificity and yield, especially in complex multiplex PCR or with low-copy-number templates. |

| Proofreading DNA Polymerase | An enzyme with 3'→5' exonuclease activity (e.g., Pfu, Pab-polD) for high-fidelity amplification [10]. | PCR cloning, mutagenesis, and any application where sequence accuracy is critical. |

| EGTA | A selective calcium chelator used to counteract calcium-induced PCR inhibition [11]. | Reversing inhibition in samples contaminated with calcium, such as those derived from bone or soil. |

The choice between magnesium chloride and magnesium sulfate is a critical foundational decision in PCR setup, primarily dictated by the DNA polymerase formulation. Magnesium chloride (MgCl₂) serves as the versatile, general-purpose choice, compatible with a wide array of polymerases like Taq, but requires careful concentration optimization to balance specificity and efficiency. In contrast, magnesium sulfate (MgSO₄) is often specified for use with specialized, high-performance enzyme systems, particularly those derived from archaea, where the sulfate-based buffer environment is integral to their engineered performance.

For the researcher, the optimal path is to first adhere to the manufacturer's recommendation for the selected DNA polymerase. When empirical optimization is necessary, conducting a magnesium gradient experiment is an indispensable step. Furthermore, one must be cognizant of the broader ionic environment, including the presence of inhibitory metal ions and the concentration of dNTPs, which directly chelate Mg²⁺. By systematically approaching magnesium salt selection and optimization, scientists can significantly enhance the robustness, specificity, and success rate of their PCR assays, ensuring reliable data for drug development and broader research applications.

Protocol in Practice: Selecting and Using MgCl2 and MgSO4 in Your Experiments

In the realm of molecular biology, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) stands as a groundbreaking technique pivotal to genetic analysis and diagnostic testing. Achieving optimal PCR conditions remains a critical challenge, with magnesium ion concentration representing one of the most crucial parameters affecting reaction success [8]. Magnesium salts serve not merely as passive buffer components but as active cofactors essential for DNA polymerase activity and DNA strand separation dynamics [8] [1]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of the two primary magnesium sources—magnesium chloride (MgCl₂) and magnesium sulfate (MgSO₄)—evaluating their performance across various PCR applications to establish evidence-based selection criteria for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The divalent magnesium cation (Mg²⁺) functions at multiple levels in PCR biochemistry: it acts as an essential cofactor for DNA polymerase enzyme activity, stabilizes the double-stranded DNA structure through interactions with the phosphate backbone, and facilitates the formation of the primer-template complex [1] [20]. The precise coordination of Mg²⁺ ions at the enzyme's active site catalyzes phosphodiester bond formation between the 3′-OH of a primer and the phosphate group of an incoming dNTP, thereby driving the polymerase reaction forward [20]. Understanding the differential effects of MgCl₂ versus MgSO₄ in providing these essential ions forms the foundation for rational PCR optimization.

Magnesium Chloride: The Standard Benchmark

Concentration Ranges and Effects

Magnesium chloride (MgCl₂) represents the most widely utilized magnesium source in conventional PCR protocols. Extensive meta-analysis of peer-reviewed studies reveals a well-established optimal range between 1.5 mM and 4.5 mM for standard applications [21], with the most frequently employed concentration being approximately 2.0 mM [20]. This meta-analysis, encompassing 61 experimental investigations published between 1973 and 2024, demonstrated a significant logarithmic relationship between MgCl₂ concentration and DNA melting temperature, with every 0.5 mM increment within the 1.5–3.0 mM range consistently raising melting temperature by approximately 1.2°C [8] [9].

The quantitative effects of MgCl₂ concentration on PCR efficiency follow a triphasic pattern: below 1.5 mM, reactions typically fail due to insufficient DNA polymerase activity and impaired primer binding; between 1.5–4.5 mM, optimal amplification occurs with high specificity and yield; and beyond 4.5 mM, nonspecific amplification increases dramatically due to reduced primer binding stringency [8] [21] [20]. Template characteristics significantly influence these optimal ranges, with complex genomic DNA templates requiring higher MgCl₂ concentrations (2.5–4.5 mM) compared to simpler plasmid DNA templates (1.5–2.5 mM) [9] [1].

Table 1: MgCl₂ Concentration Effects on PCR Performance

| Concentration Range | PCR Efficiency | Specificity | Template Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 1.5 mM | Poor to no amplification | N/A | Not recommended |

| 1.5–2.5 mM | High | High | Plasmid DNA, cDNA, standard amplicons |

| 2.5–4.0 mM | High | Moderate to high | Genomic DNA, GC-rich templates |

| > 4.0 mM | Variable with high yield | Low (nonspecific bands) | Special applications only |

Mechanistic Basis of MgCl₂ Function

The mechanism of MgCl₂ action in PCR operates through two primary biochemical pathways: enzyme cofactor activity and nucleic acid stabilization. In its role as an enzyme cofactor, the Mg²⁺ ion binds to a dNTP at its alpha phosphate group, facilitating the removal of beta and gamma phosphates and enabling the resulting dNMP to form a phosphodiester bond with the 3′ hydroxyl group of the adjacent nucleotide [20]. This catalytic function occurs at the active site of DNA polymerase, where the metal ion precisely orients the reacting molecules for efficient catalysis.

Simultaneously, MgCl₂ influences primer-template interactions by binding to the negatively charged phosphate groups of DNA backbone, thereby reducing electrostatic repulsion between complementary strands and increasing the effective melting temperature (Tₘ) of the duplex [20]. This dual mechanism explains the concentration-dependent effects observed in experimental studies: insufficient Mg²⁺ compromises both enzymatic activity and primer annealing, while excessive Mg²⁺ promotes non-specific annealing by overly stabilizing transient primer-template interactions [8] [20].

Figure 1: Dual Mechanism of MgCl₂ in PCR: The diagram illustrates how MgCl₂ dissociates to provide Mg²⁺ ions that both activate DNA polymerase catalysis and stabilize the DNA duplex structure during PCR amplification.

Magnesium Sulfate: Specialized Applications

Concentration Ranges and Comparative Performance

Magnesium sulfate (MgSO₄) serves as a specialized alternative to MgCl₂, primarily employed with particular DNA polymerase systems. While comprehensive concentration range studies specific to MgSO₄ are less extensive in the literature, its applications center primarily on proof-reading polymerases from archaeal sources, such as Pfu and Pab polB [10]. The optimal concentration range for MgSO₄ typically falls between 1.5–3.0 mM for these specialized enzymes, with some protocols recommending slightly lower concentrations compared to standard MgCl₂ conditions [10].

The theoretical basis for MgSO₄ preference with certain polymerase systems relates to the differential effects of chloride versus sulfate anions on enzyme structure and function. Some archaeal DNA polymerases exhibit reduced activity in chloride-rich environments, making MgSO₄ the preferred cofactor source for these enzymes [10]. Additionally, the sulfate ion may contribute to enhanced thermal stability of certain hyperthermophilic enzymes, though this effect is polymerase-specific and requires empirical validation for each application.

Table 2: Magnesium Salt Comparison for PCR Applications

| Parameter | Magnesium Chloride (MgCl₂) | Magnesium Sulfate (MgSO₄) |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Concentration | 1.5–4.5 mM [21] | 1.5–3.0 mM (polymerase-dependent) |

| Primary Applications | Conventional PCR with Taq polymerase, routine amplification | Proof-reading archaeal polymerases (Pfu, Pab polB) |

| Theoretical Basis | Standard chloride buffer conditions | Reduced chloride sensitivity for certain enzymes |

| Template Specificity | Concentration-dependent: higher concentrations reduce specificity [20] | Polymerase-dependent rather than salt-dependent |

| Inhibition Profile | Lower tissue toxicity [22] | Higher reported toxicity in some systems [22] |

Experimental Evidence for Magnesium Salt Comparisons

Direct comparative studies between MgCl₂ and MgSO₄ in PCR applications remain limited in the scientific literature. However, a 2005 review examining their therapeutic applications concluded that MgCl₂ demonstrates "more interesting clinical and pharmacological effects and its lower tissue toxicity as compared to MgSO₄" [22]. While these findings originate from clinical rather than molecular contexts, they suggest potential biocompatibility advantages for MgCl₂ in diagnostic PCR applications.

In experimental protocols utilizing the proof-reading D-type DNA polymerase from Pyrococcus abyssi (Pab-polD), researchers employed MgSO₄ rather than MgCl₂ in the optimized reaction buffer for amplification of 3-kilobase fragments [10]. This enzyme demonstrated superior tolerance to PCR inhibitors compared to conventional Taq polymerase, suggesting that polymerase-specific magnesium salt optimization can enhance performance in challenging applications. The selection of MgSO₄ for this archaeal polymerase system underscores the importance of matching magnesium salt to polymerase characteristics rather than applying a universal standard.

Experimental Protocols and Optimization Strategies

Standardized Optimization Methodology

Determining the optimal magnesium concentration for specific PCR applications requires systematic empirical optimization. The following protocol, synthesized from multiple experimental approaches [8] [1] [20], provides a standardized methodology for magnesium titration:

Prepare a master mix containing all PCR components except magnesium salt and template DNA, maintaining uniform enzyme, primer, dNTP, and buffer concentrations across all reactions.

Create magnesium dilution series spanning 0.5 mM to 5.0 mM in 0.5 mM increments, using either MgCl₂ or MgSO₄ stock solutions appropriate for the DNA polymerase system.

Add template DNA to each reaction tube, ensuring identical template quantity and quality across the series.

Perform amplification using standardized cycling parameters appropriate for the primer-template system.

Analyze results via agarose gel electrophoresis or quantitative PCR to determine the magnesium concentration producing the highest target yield with minimal nonspecific amplification.

This methodological approach was employed in the comprehensive meta-analysis that identified the logarithmic relationship between MgCl₂ concentration and DNA melting temperature [8] [9]. For templates with high GC content (≥60%), the optimal magnesium concentration typically falls in the upper range of standard concentrations (3.0–4.0 mM for MgCl₂) to counteract the increased template stability [8].

Inhibition Resistance and Metal Interference

Magnesium concentration optimization becomes particularly critical when working with samples containing potential PCR inhibitors. Forensic studies demonstrate that metal ions such as zinc, tin, iron(II), and copper exhibit strong inhibitory properties with IC₅₀ values significantly below 1 mM [11]. These inhibitory metals commonly encountered in forensic samples interfere with DNA polymerase activity, potentially through competitive binding at enzyme active sites or disruption of nucleic acid structure.

In such challenging applications, researchers can employ several counterstrategies:

Magnesium concentration elevation: Increasing magnesium concentration (typically to 4.0–4.5 mM for MgCl₂) can overcome inhibition by providing excess cofactor ions that outcompete inhibitors for binding sites [11] [20].

Polymerase selection: Certain DNA polymerases demonstrate inherently greater resistance to metal inhibition. Comparative studies revealed KOD polymerase as the most resistant to metal inhibition when compared with Q5 and Taq polymerase [11].

Chelator incorporation: The calcium chelator ethylene glycol-bis(2-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA) provides an effective non-destructive method for reversing calcium-induced PCR inhibition [11].

Figure 2: Magnesium Optimization Workflow: A decision pathway for systematic optimization of magnesium salt type and concentration based on template characteristics, polymerase system, and potential inhibitor presence.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Magnesium Optimization Studies

| Reagent/Category | Standard Concentration | Function in PCR | Optimization Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| MgCl₂ stock solution | 25–100 mM (storage) 1.5–4.5 mM (final) | Primary magnesium source, DNA polymerase cofactor | Titrate in 0.5 mM increments; increase for GC-rich templates [8] [21] |

| MgSO₄ stock solution | 25–100 mM (storage) 1.5–3.0 mM (final) | Alternative for chloride-sensitive polymerases | Use with proof-reading archaeal enzymes [10] |

| DNA polymerase selection | 1–2 units/50 µL reaction | Catalyzes DNA synthesis | Vary enzyme amount with difficult templates; higher amounts may improve yields with inhibitors [1] |

| dNTP mix | 0.2 mM each dNTP (final) | DNA synthesis building blocks | Balance with Mg²⁺ concentration (Mg²⁺ binds dNTPs); reduce for improved fidelity [1] |

| Buffer system | 1× concentration | Maintains pH and ionic strength | Tris-HCl standard; may contain (NH₄)₂SO₄ for specificity [23] |

| Template DNA | 0.1–50 ng (variable by type) | Amplification target | Higher complexity templates (gDNA) require more DNA than simple templates (plasmid) [1] |

This systematic comparison establishes magnesium chloride as the predominant choice for standard PCR applications, with well-characterized concentration ranges between 1.5–4.5 mM and extensive experimental validation across diverse template types [8] [9] [21]. The quantitative relationship between MgCl₂ concentration and DNA melting temperature—approximately 1.2°C increase per 0.5 mM increment within the 1.5–3.0 mM range—provides researchers with a predictive framework for protocol optimization [8] [9]. Magnesium sulfate serves a more specialized role, primarily reserved for proof-reading polymerase systems that demonstrate enhanced performance with sulfate-based buffers [10].

The selection between these magnesium salts should be guided by polymerase specification rather than assumed equivalence. For the majority of conventional applications utilizing Taq polymerase or related variants, MgCl₂ remains the recommended choice due to its comprehensive optimization profile and lower observed toxicity [22]. Future research directions should include more direct comparative studies of MgCl₂ versus MgSO₄ across diverse polymerase systems, expanded investigation of magnesium salt effects on long-amplicon and difficult-template PCR, and standardized assessment of magnesium interactions with common PCR inhibitors. Through continued refinement of magnesium optimization protocols, researchers can enhance the efficiency, specificity, and reliability of one of molecular biology's most fundamental techniques.

The Critical Role of Magnesium in PCR

In the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), magnesium ion (Mg²⁺) is an essential cofactor without which DNA polymerases exhibit minimal to no activity [1] [20] [24]. Its role is dual in nature: it is fundamental for enzyme catalysis and it significantly influences the hybridization dynamics between the primer and the template [1] [8].

Biochemically, Mg²⁺ is directly involved in the catalytic mechanism of DNA synthesis. It facilitates the formation of the phosphodiester bond by enabling the nucleophilic attack of the 3'-hydroxyl group of the primer on the alpha-phosphate of the incoming dNTP [1] [20]. Furthermore, Mg²⁺ stabilizes the interaction between the primer and the single-stranded DNA template by neutralizing the negative charges on the phosphate backbones of both molecules. This reduces electrostatic repulsion, thereby promoting proper annealing and increasing the observed melting temperature (Tm) of the duplex [1] [8] [20].

The concentration of Mg²⁺ requires precise optimization because its effects are concentration-dependent. Insufficient Mg²⁺ leads to poor polymerase activity and weak or failed amplification, while excess Mg²⁺ can promote non-specific primer binding, resulting in spurious amplification products and reduced enzyme fidelity [24] [25]. A recent comprehensive meta-analysis established a clear logarithmic relationship between MgCl₂ concentration and DNA melting temperature, quantifying that every 0.5 mM increase within the 1.5–3.0 mM range consistently raises the Tm by approximately 1.2 °C [9] [8].

Template-Specific Magnesium Optimization

The optimal concentration of magnesium is not a universal value; it is profoundly affected by the composition and complexity of the DNA template used in the PCR [1] [9]. The following guidelines are synthesized from current research and manufacturer recommendations.

Quantitative Magnesium Guidelines by Template Type

Table 1: Recommended magnesium chloride (MgCl₂) concentrations and key considerations for different DNA templates.

| Template Type | Recommended MgCl₂ Range | Typical Starting Amount | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic DNA (gDNA) | 1.5 – 3.0 mM [9] | 5 – 50 ng in a 50 µL reaction [1] | Higher complexity often requires higher [Mg²⁺]; more prone to co-purified inhibitors [9] [11]. |

| Plasmid DNA | 1.0 – 2.5 mM | 0.1 – 1.0 ng in a 50 µL reaction [1] | Lower complexity requires less [Mg²⁺]; supercoiled structure can influence accessibility. |

| cDNA | 1.5 – 3.0 mM | Varies by target abundance | Optimization is critical; depends on reverse transcription efficiency and target gene abundance. |

| Re-amplified PCR Products | 1.5 – 3.0 mM | Diluted 1:10 – 1:100 [1] | Requires dilution or purification to remove carryover dNTPs and salts that chelate Mg²⁺ [1]. |

Detailed Rationale by Template Type

Genomic DNA (gDNA): Meta-analyses confirm that gDNA, due to its high complexity and size, generally requires magnesium concentrations at the higher end of the spectrum [9] [8]. This is partly because gDNA samples are more likely to contain PCR inhibitors that can chelate or otherwise make Mg²⁺ unavailable for the polymerase [11]. In such cases, a slight increase in MgCl₂ concentration may be necessary to compensate.

Plasmid DNA: The relatively low complexity of plasmid DNA means that a lower concentration of magnesium is typically sufficient for efficient amplification [1]. The recommended starting amount of plasmid template is substantially less than that of gDNA, which also influences the ionic requirements of the reaction.

cDNA: Synthesized from mRNA, cDNA's properties are highly variable. The optimal Mg²⁺ concentration is influenced by the reverse transcription process and the abundance of the target transcript. Therefore, cDNA often requires empirical optimization similar to gDNA.

Experimental Protocols for Magnesium Optimization

Standard MgCl₂ Titration Protocol

A standard approach to optimizing magnesium concentration involves setting up a series of reactions with a gradient of MgCl₂ [1] [24].

Materials:

- DNA Template (e.g., 20 ng gDNA, 1 ng plasmid, or 2 µL cDNA per reaction)

- Thermostable DNA Polymerase and its corresponding buffer (without Mg²⁺)

- 25 mM MgCl₂ Stock Solution

- Primers (0.1 – 1.0 µM final concentration each)

- dNTP Mix (0.2 mM each dNTP final concentration)

- Nuclease-free Water

Method:

- Prepare a master mix containing all reaction components except the MgCl₂ and DNA template.

- Aliquot the master mix into individual PCR tubes.

- Add a variable volume of the 25 mM MgCl₂ stock to each tube to create a concentration series (e.g., 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0, 3.5, 4.0 mM final concentration).

- Add the DNA template to each tube.

- Run the PCR using the appropriate cycling conditions for your target.

- Analyze the results using agarose gel electrophoresis. The optimal condition produces a strong, specific band with minimal to no non-specific products or primer-dimer [1].

Accounting for Chelators and dNTPs

The concentration of "free" Mg²⁺ available to the polymerase is critical. This can be calculated by considering ligands that chelate magnesium.

- dNTPs: dNTPs bind Mg²⁺ stoichiometrically. A general rule is that the final concentration of free Mg²⁺ should be 0.5 – 2.5 mM above the total dNTP concentration [1].

- EDTA: If your DNA template is in a TE buffer or prepared using methods containing EDTA (e.g., the HOTSHOT method [26]), this chelator will sequester Mg²⁺. The amount of MgCl₂ in the PCR master mix must be increased accordingly to overcome this [26] [24].

The workflow for a systematic optimization is summarized in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for PCR Optimization

Table 2: Key reagents and materials required for magnesium optimization experiments.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Optimization | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| MgCl₂ Stock Solution | Provides the magnesium cofactor; the variable being tested. | Use a high-purity, nuclease-free solution. Concentration typically 25 mM [24]. |

| DNA Polymerase with Separate Buffer | Enzyme for DNA synthesis; requires a buffer supplied without Mg²⁺. | Essential for titration. Enzymes like Takara Ex Taq are supplied with MgCl₂ separately [24]. |

| Ultra-Pure dNTPs | Building blocks for new DNA strands. | dNTPs chelate Mg²⁺; use consistent, balanced concentrations (typically 0.2 mM each) [1]. |

| Template DNA | The target DNA to be amplified. | Purity and concentration are critical. Use recommended starting amounts [1]. |

| Agarose Gel Electrophoresis System | Standard method for visualizing PCR success and specificity. | Allows assessment of amplicon yield and purity against Mg²⁺ concentration [1]. |

Magnesium Salt Selection: Chloride vs. Sulfate

The choice of magnesium salt can impact PCR efficiency. Magnesium chloride (MgCl₂) is the most widely used and referenced source of Mg²⁺ in PCR protocols [1] [9] [8]. Its effects on DNA polymerase activity, primer annealing, and DNA stability are well-characterized.

While less common, magnesium sulfate (MgSO₄) is used with certain specialized DNA polymerases. For instance, some high-fidelity polymerases derived from deep-sea vent archaea perform optimally with MgSO₄ in their proprietary buffers. The different anions (Cl⁻ vs. SO₄²⁻) can differentially affect enzyme activity and stability. However, for the vast majority of standard PCR applications, particularly with Taq polymerase and its common derivatives, MgCl₂ remains the definitive and recommended cofactor salt for reaction optimization, as evidenced by its use in foundational studies and commercial kits [1] [24].

In the realm of molecular biology, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) stands as a foundational technique, and its success hinges on the precise optimization of multiple reaction components. Among these, magnesium ions (Mg²⁺) serve as an indispensable cofactor for DNA polymerase activity [1]. Magnesium facilitates the formation of the complex between primers and DNA templates by stabilizing negative charges on their phosphate backbones and enables the incorporation of dNTPs during polymerization by catalyzing phosphodiester bond formation [1]. The selection of the appropriate magnesium salt—typically magnesium chloride (MgCl₂) or magnesium sulfate (MgSO₄)—is not merely a matter of convenience but a genuine question that significantly impacts PCR efficiency, specificity, and yield [27] [22]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two magnesium salts within PCR master mixes, offering experimental data and protocols to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in their reaction optimization strategies.

Biochemical Properties and General Compatibility

The choice between MgCl₂ and MgSO₄ extends beyond simply providing Mg²⁺ ions; the accompanying anion influences the reaction environment and enzyme compatibility. The table below summarizes the core properties and typical applications of each salt.

Table 1: Fundamental Properties and Application Profiles of Magnesium Salts in PCR

| Characteristic | Magnesium Chloride (MgCl₂) | Magnesium Sulfate (MgSO₄) |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Formula | MgCl₂ | MgSO₄ |

| Primary Role in PCR | Essential cofactor for DNA polymerase | Essential cofactor for DNA polymerase |

| Ion Provided | Mg²⁺ | Mg²⁺ |

| Standard Concentration Range | 1.5 to 4.5 mM [28] | Varies, typically used with specific enzyme systems |

| Most Compatible Polymerase Types | Standard Taq DNA polymerase and many related variants [1] | Proof-reading archaeal polymerases (e.g., KOD, Pfu) [29] [10] |

| Considerations | The most commonly used magnesium source in PCR | Required for optimal activity of certain high-fidelity polymerases |

MgCl₂ is the most ubiquitous magnesium source in PCR, forming the basis of most standard protocols [28]. Its concentration is a critical optimization parameter, with a typical working range of 1.5 to 4.5 mM [28]. Conversely, MgSO₄ is specifically recommended for use with certain high-fidelity or proof-reading DNA polymerases, many of which are derived from archaeal organisms [29] [10]. For instance, the KOD Hot Start DNA polymerase kit utilizes a master mix containing MgSO₄ [29]. The differential effect is attributed to the unique enzymatic requirements and buffer compositions that maximize the activity of these specialized polymerases.

Quantitative Comparison and Experimental Data

Concentration-Dependent Effects on PCR Efficiency

A comprehensive meta-analysis of 61 studies provides quantitative insights into the effects of MgCl₂ concentration on PCR thermodynamics. The analysis established a clear logarithmic relationship between MgCl₂ concentration and DNA melting temperature, which is fundamental to primer annealing and reaction efficiency [9].

Table 2: Quantitative Effects of MgCl₂ Concentration on PCR Parameters Based on Meta-Analysis

| MgCl₂ Concentration | Impact on Melting Temperature (Tm) | Effect on PCR Efficiency | Effect on Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 1.5 mM | Suboptimal Tm | Weak or failed amplification due to poor primer binding and low enzyme activity [28] | High specificity but potentially no product |

| 1.5 - 3.0 mM (Optimal) | Every 0.5 mM increase raises Tm by ~1.2°C [9] | High efficiency and yield | High specificity with minimal non-specific products |

| > 3.0 mM | Tm elevated beyond optimum | Sustained or slightly increased yield | Increased risk of non-specific binding and primer-dimer formation [28] |

The meta-analysis further revealed that template complexity influences optimal Mg²⁺ requirements. Genomic DNA, with its higher complexity, often requires higher magnesium concentrations compared to more straightforward templates like plasmid DNA [9]. This underscores the need for empirical optimization even when using a standard salt like MgCl₂.

Comparative Performance with Different DNA Polymerases