Identifying MOB2 Binding Partners: A Comprehensive Guide to Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening

This article provides a detailed methodological and conceptual framework for using yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) screening to identify and characterize binding partners of the MOB2 protein, a key adaptor in Hippo...

Identifying MOB2 Binding Partners: A Comprehensive Guide to Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening

Abstract

This article provides a detailed methodological and conceptual framework for using yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) screening to identify and characterize binding partners of the MOB2 protein, a key adaptor in Hippo and Hippo-like signaling pathways. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, the content covers foundational MOB2 biology, state-of-the-art Y2H protocols—including high-throughput batch screening and optimized bait/prey vector design—and rigorous validation strategies using orthogonal assays like proximity labeling and split-protein systems. It further addresses critical troubleshooting for false positives/negatives and explores the translational potential of discovered interactions in diseases such as cancer, offering a complete roadmap from initial screen to functional insight.

MOB2 in Cell Signaling: Unraveling Its Biological Context and Interaction Potential

The Mps one binder (MOB) family constitutes a group of highly conserved eukaryotic kinase adaptor proteins, first identified in a yeast two-hybrid screen for interactors of Mps1p kinase [1]. MOB proteins are universally distributed, found in at least 41 out of 43 sequenced eukaryotic genomes, underscoring their fundamental biological importance [2]. These proteins are characterized as non-catalytic signal transducers that physically associate with and regulate serine/threonine kinases, thereby controlling essential cellular processes from yeast to humans [3] [4].

Historically, research in budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and fission yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe) revealed that MOB proteins are crucial regulators of mitotic exit and cell morphogenesis [2] [1]. In multicellular organisms, MOBs have expanded in number and function, playing central roles in tissue homeostasis, morphogenesis, and tumor suppression [3]. The MOB family has undergone functional diversification through gene expansion, with fungi typically possessing two MOB genes, while mammals express up to six distinct MOB proteins [2] [1].

Classification and Structural Characteristics

MOB Family Classes

MOB proteins are phylogenetically classified into four distinct classes in animals, with some species containing sub-isotypes within these classes [3] [5]. The table below summarizes the classification and key characteristics of human MOB proteins.

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Human MOB Proteins

| Class | Protein Names | Key Interacting Kinases | Reported Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | MOB1A, MOB1B | LATS1/2, NDR1/2 | Core component of Hippo signaling, tumor suppression, mitotic exit [3] [4] [1] |

| Class II | MOB2 | NDR1/2 | Cell morphogenesis, DNA damage response, competes with MOB1 for NDR binding [6] [7] |

| Class III | MOB3A, MOB3B, MOB3C | MST1 | Apoptosis regulation; MOB3A (Phocein) associates with STRIPAK [1] [7] |

| Class IV | MOB4/Phocein | MST3/4, STRIPAK complex | Component of STRIPAK complex, antagonizes Hippo signaling [3] [4] |

Conserved Structural Fold

MOB proteins are generally single-domain proteins, averaging 210-240 amino acids in length [5]. Despite sequence divergence between classes, they share a conserved tertiary structure known as the Mob family fold. As revealed by the crystal structure of human MOB1A, the core of this fold consists of a four-helix bundle stabilized by a zinc atom [8]. This structure creates conserved surfaces for protein-protein interactions, particularly with partner kinases [4] [8].

The N-terminal helix of the bundle is solvent-exposed and forms an evolutionarily conserved surface with a strong negative electrostatic potential [8]. Conditional mutant alleles of S. cerevisiae MOB1 target this surface, reducing its net negative charge and impairing function. This suggests that MOB proteins may regulate their target kinases through electrostatic interactions mediated by these conserved charged surfaces [8].

Conserved Biological Functions Across Eukaryotes

Regulation of Cell Division and Mitotic Exit

The founding function of MOB proteins lies in regulating cell cycle progression, particularly mitotic exit and cytokinesis [2] [1]. In both S. cerevisiae and S. pombe, Mob1p associates with the Dbf2p/Sid2p kinases and is essential for the Mitotic Exit Network (MEN) and Septation Initiation Network (SIN), respectively [2] [1]. These pathways ensure the correct transition from mitosis to cytokinesis and the proper initiation of septum formation [3]. Depletion of Mob1 in either yeast leads to failure in cytokinesis, resulting in multinucleated cells and ploidy defects [2].

Control of Cell Morphogenesis and Polarity

MOB proteins simultaneously coordinate cell cycle progression with cell polarity and morphogenesis [2]. In yeast, Mob2p forms a complex with the Cbk1p/Orb6p kinases, regulating polarized growth and cellular morphology throughout the cell cycle [1]. This function is conserved in higher eukaryotes, where MOB proteins contribute to processes requiring precise morphological control, including neurite outgrowth, photoreceptor morphology, and neuromuscular junction development [7].

Roles in Multicellular Organisms: Hippo Signaling and Beyond

In metazoans, MOB proteins have been integrated into more complex signaling pathways, most notably the Hippo tumor suppressor pathway [3] [4]. The canonical Hippo pathway comprises a core kinase cascade where MOB1 functions as a crucial adaptor. When activated, Hippo/MST kinases phosphorylate and activate MOB1 in complex with Warts/LATS kinases, which in turn phosphorylate the YAP/TAZ transcriptional co-activators, preventing their nuclear translocation and inhibiting proliferation-associated gene expression [3].

Beyond Hippo signaling, MOB proteins participate in alternative regulatory networks. MOB4/Phocein is a component of the STRIPAK complex (Striatin-Interacting Phosphatase and Kinase), which includes protein phosphatase PP2A and regulates processes including vesicular trafficking, microtubule dynamics, and morphogenesis [3] [4]. Interestingly, the STRIPAK complex can antagonize Hippo signaling, creating a balance of regulatory inputs [4].

Genome Stability and DNA Damage Response

Recent research has uncovered a role for MOB2 in the DNA damage response (DDR) [6] [7]. MOB2 promotes DDR signaling, cell survival, and cell cycle arrest following exogenously induced DNA damage [6]. Under normal growth conditions, MOB2 prevents the accumulation of endogenous DNA damage and subsequent p53/p21-dependent G1/S cell cycle arrest [6]. Mechanistically, MOB2 interacts with RAD50, facilitating recruitment of the MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 (MRN) DNA damage sensor complex and activated ATM to damaged chromatin [6]. This function appears to be independent of NDR kinase signaling, expanding the functional repertoire of MOB proteins beyond kinase regulation [7].

Experimental Protocols for MOB2 Binding Partner Research

Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening for MOB2 Interactors

The Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) system is a powerful method for identifying novel protein-protein interactions. Below is a detailed protocol for screening a cDNA library to identify MOB2 binding partners, adapted from methodologies used in recent studies [6] [9].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Yeast Strains | Y2HGold, Y190 | Reporter strains with complementary auxotrophic and chromogenic markers [9] |

| Vectors | pGBKT7 (bait), pGADT7 (prey) | GAL4-based vectors for expressing DNA-Binding Domain and Activation Domain fusions [9] |

| cDNA Libraries | Normalized universal human tissue cDNA library | Source of "prey" genes for identifying novel binding partners [6] |

| Selection Media | SD/-Trp, SD/-Leu, SD/-Trp/-Leu/-His + 3-AT | Selective media for screening interacting protein pairs [9] |

Bait Vector Construction and Validation

- Amplify the coding sequence of MOB2 using gene-specific primers with appropriate restriction sites.

- Clone MOB2 into the pGBKT7 bait vector downstream of the DNA-Binding Domain using standard molecular biology techniques. Verify the construct by sequencing.

- Transform the pGBKT7-MOB2 bait construct into the Y2HGold yeast strain and plate on SD/-Trp medium to select for transformants.

- Test for autoactivation by streaking positive colonies on high-stringency media (SD/-Trp/-His/-Ade with X-α-Gal). A bait with no autoactivation will not turn blue or grow on this medium, confirming suitability for library screening [9].

Library Screening and Validation

- Transform the cDNA library cloned into the pGADT7 prey vector into Y2HGold yeast already containing the pGBKT7-MOB2 bait.

- Plate transformation mixtures on high-stringency selection media (SD/-Trp/-Leu/-His/-Ade with X-α-Gal) to select for interacting clones. Incubate at 30°C for 3-7 days.

- Isolate positive colonies and sequence the prey plasmids to identify potential interacting partners.

- Confirm interactions by co-transforming the isolated prey plasmids with the original pGBKT7-MOB2 bait and empty pGBKT7 control into fresh yeast cells. Repeat plating on selective media to verify specific interaction with MOB2 [9].

Functional Validation of MOB2 in DNA Damage Response

Based on findings that MOB2 plays a role in DDR, the following protocol can be used to validate its functional significance [6].

MOB2 Knockdown and DNA Damage Assessment

- Transfert cells with MOB2-specific siRNAs or non-targeting control siRNAs using appropriate transfection reagents.

- 48-72 hours post-transfection, treat cells with DNA damaging agents such as doxorubicin (topoisomerase II poison) or expose to ionizing radiation.

- Assess DNA damage by immunofluorescence staining for γH2AX foci or perform comet assays to detect DNA strand breaks.

- Analyze cell cycle profiles by flow cytometry to detect G1/S arrest. Monitor activation of the p53/p21 pathway by immunoblotting.

- Evaluate cell survival using clonogenic assays following DNA damage induction.

Interaction with MRN Complex

- Co-immunoprecipitation: Immunoprecipitate endogenous MOB2 from cell lysates and probe for co-precipitating RAD50 to confirm physical interaction.

- Chromatin fractionation: Isolate chromatin fractions from cells with and without DNA damage treatment. Monitor recruitment of MOB2, RAD50, and activated ATM to chromatin.

- Functional rescue: Express siRNA-resistant wild-type MOB2 in MOB2-depleted cells to confirm rescue of DDR defects.

Visualization of MOB Protein Functions and Signaling Pathways

MOB Protein Functions in Signaling Pathways

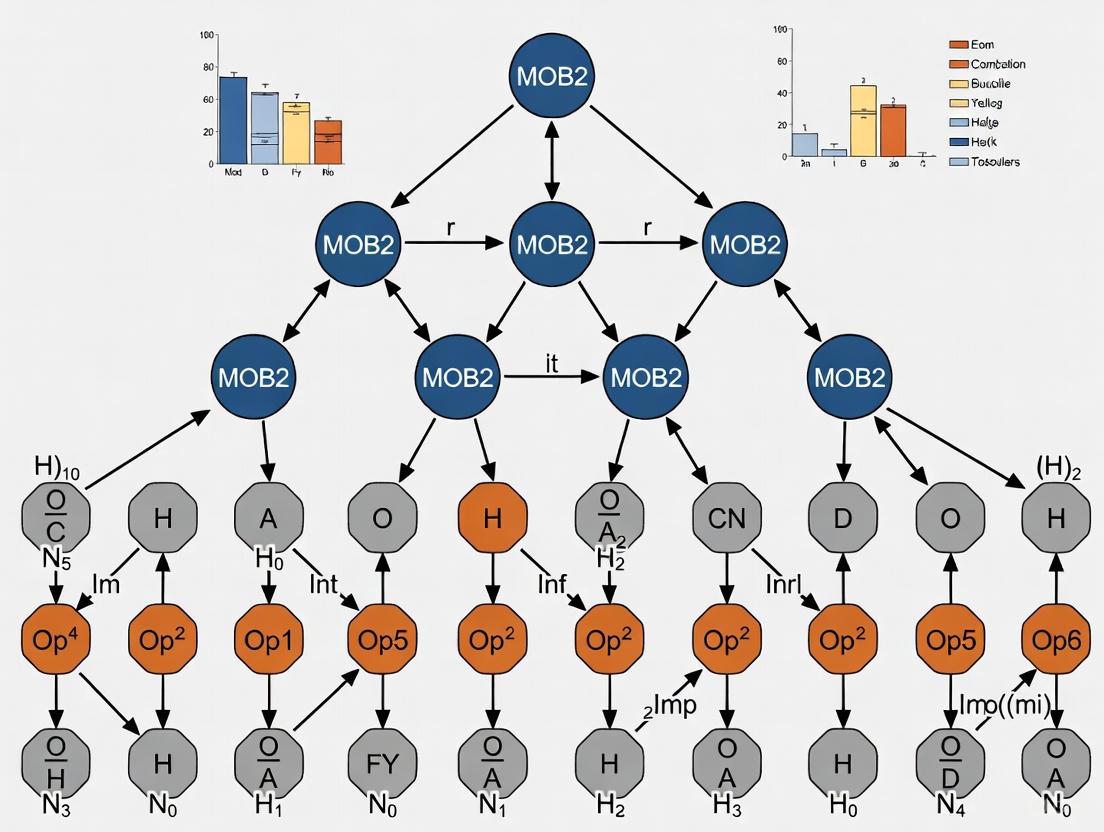

Diagram 1: MOB Protein Functions in Key Signaling Pathways. This diagram illustrates the roles of different MOB proteins in Hippo signaling (MOB1), STRIPAK complex (MOB4), and DNA Damage Response (MOB2). MOB proteins serve as adaptors that either activate or inhibit these crucial cellular pathways [3] [6] [4].

Experimental Workflow for Y2H Screening of MOB2 Partners

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening of MOB2 Partners. This workflow outlines the key steps in identifying novel MOB2 binding partners, from bait construction to final validation of protein-protein interactions [6] [9].

The MOB protein family represents a conserved group of kinase adaptors that have evolved from regulating fundamental cell cycle processes in yeast to controlling complex signaling networks in multicellular organisms. Their classification into four structural classes reflects functional diversification, with different MOB isoforms participating in distinct yet interconnected cellular pathways including Hippo signaling, STRIPAK complex regulation, and DNA damage response. The experimental protocols outlined here, particularly yeast two-hybrid screening followed by functional validation, provide robust methodologies for expanding our understanding of MOB2 interactions and functions. Continued research on MOB proteins promises to yield important insights into cell cycle regulation, tissue homeostasis, and cancer biology, with potential applications in therapeutic development.

MOB2's Role in Hippo and Hippo-Like Intracellular Signaling Pathways

MOB2 is a member of the highly conserved monopolar spindle-one-binder (MOB) family of proteins, which function as critical regulatory adaptors in key cellular signaling pathways [10]. Unlike their catalytic counterparts, MOB proteins act as globular scaffold proteins without enzymatic activity, serving as signal transducers in essential intracellular pathways [10]. MOB2 belongs to Class II of the four MOB protein classes identified in animals and has been implicated in diverse cellular processes including cell survival, cell cycle progression, responses to DNA damage, and cell motility [11] [5].

The Hippo signaling pathway represents a crucial evolutionarily conserved mechanism that restricts tissue growth and regulates organ size [5]. MOB2 functions within this network primarily through its interactions with Nuclear Dbf2-related (NDR) kinases, positioning it as a significant regulator of both Hippo and Hippo-like signaling pathways that coordinate cellular morphogenesis and proliferation [5]. This application note details the molecular functions of MOB2 and provides standardized protocols for investigating MOB2-binding partners, with particular emphasis on yeast two-hybrid screening methodologies.

Molecular Functions and Binding Characteristics of MOB2

MOB2 as a Regulator of NDR Kinases

MOB2 exerts its primary cellular functions through direct interaction with NDR1/2 kinases (also known as STK38 and STK38L in mammals) [11] [5]. This interaction places MOB2 within a Hippo-like signaling pathway that runs parallel to the canonical Hippo pathway and is dedicated to regulating cell morphology and polarity [5]. Structural analyses reveal that MOB proteins share a conserved globular Mob/Phocein domain that forms the NDR kinase binding surface, with MOB2 specifically competing with MOB1 for binding to the same N-terminal regulatory domain of NDR1/2 [11] [5].

The functional outcome of MOB2 binding to NDR kinases appears context-dependent. Multiple studies indicate that MOB2 functions as an inhibitor of NDR kinase activity by competing with the activating MOB1 protein [11]. This competitive inhibition model positions MOB2 as a negative regulator of NDR1/2, in contrast to MOB1 which serves as a co-activator of both NDR and LATS kinases in the canonical Hippo pathway [5]. The balance between MOB1 and MOB2 binding thus determines the activity state of NDR kinases and consequently modulates downstream signaling outputs.

Table 1: MOB2 Protein Interactions and Functional Consequences

| Interaction Partner | Interaction Type | Functional Consequence | Biological Process |

|---|---|---|---|

| NDR1/STK38 | Direct binding | Inhibition of NDR1 kinase activity | Cell morphogenesis, neuronal development |

| NDR2/STK38L | Direct binding | Inhibition of NDR2 kinase activity | Cell polarity, migration |

| MOB1 | Competition | Modulation of NDR kinase activation | Hippo pathway regulation |

| LATS1/2 | No binding reported | Indirect regulation via YAP | Cell proliferation, migration |

MOB2 in Cellular Processes and Disease Contexts

Research across multiple model systems has established MOB2's involvement in fundamental cellular processes, particularly in neuronal development and cancer biology. In neuronal systems, MOB2 insufficiency disrupts neuronal migration during cortical development, leading to periventricular nodular heterotopia where neurons fail to reach their appropriate positions in the cerebral cortex [12]. This function appears conserved in C. elegans, where the MOB-2 homolog functions with the NDR kinase SAX-1 to promote dendrite pruning during neuronal remodeling [13].

In cancer contexts, MOB2 demonstrates tumor-suppressive properties in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), where its overexpression inhibits cell migration and invasion [11]. Mechanistically, MOB2 regulates the alternative interaction of MOB1 with NDR1/2 and LATS1, resulting in increased phosphorylation of LATS1 and MOB1. This leads to subsequent inactivation of YAP (Yes-associated protein) and consequently inhibition of cell motility [11]. The regulation of YAP activity connects MOB2 to the core Hippo signaling pathway despite its primary association with the NDR kinase branch.

Table 2: MOB2-Associated Phenotypes Across Model Systems

| Model System | Experimental Manipulation | Observed Phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human HCC cells (SMMC-7721) | MOB2 knockout | Promoted migration and invasion, decreased YAP phosphorylation | [11] |

| Human HCC cells (SMMC-7721) | MOB2 overexpression | Inhibited migration and invasion, increased YAP phosphorylation | [11] |

| Developing mouse cortex | Mob2 knockdown | Disrupted neuronal migration, periventricular heterotopia | [12] |

| C. elegans (IL2 neurons) | MOB-2 loss of function | Defective dendrite branch elimination | [13] |

Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening for MOB2 Binding Partners

Principles of Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening

The yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) system is a powerful molecular biology technique used to discover protein-protein interactions (PPIs) by testing for physical binding between two proteins [14]. The foundational principle relies on the modular nature of transcription factors, typically the Gal4 protein from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which can be separated into two functional domains: the DNA-binding domain (DBD) and the activation domain (AD) [15] [14]. When these domains are brought into proximity through interaction between proteins fused to each domain, they reconstitute a functional transcription factor that drives expression of reporter genes [14].

For investigating MOB2 interactions, Y2H screening offers distinct advantages, including sensitivity to weak or transient interactions, applicability to high-throughput formats, and the ability to screen cDNA libraries against a MOB2 bait protein [15] [14]. The methodology has been successfully employed to characterize interactions within signaling pathways, including those involving MOB family proteins and their kinase partners [10] [5].

Protocol: Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening to Identify MOB2-Binding Partners

Reagents and Equipment

- Yeast Strains: AH109 or other appropriate Y2H reporter strains with auxotrophic markers (HIS3, ADE2) under GAL promoter control [15]

- Plasmids: pGBKT7 (bait vector) and pGADT7 (prey vector) or equivalent Y2H vectors [15]

- Media: Synthetic Dropout (SD) medium lacking appropriate amino acids for selection (-Trp, -Leu, -His, -Ade) [15]

- Small Molecules: 3-Amino-1,2,4-triazole (3-AT) for increasing stringency in HIS3 selection [14]

- MOB2 Constructs: Human MOB2 cDNA (UniProtKB: Q70IA6) for bait construction [10]

Step-by-Step Procedure

Bait and Prey Construction (4-5 days)

- Amplify MOB2 coding sequence using PCR with appropriate restriction sites.

- Digest both MOB2 PCR product and pGBKT7 bait vector with restriction enzymes.

- Ligate MOB2 into the multiple cloning site of pGBKT7 to create a Gal4 DBD-MOB2 fusion.

- Transform ligation product into E. coli, select on kanamycin plates, and verify constructs by sequencing.

- For prey construction, prepare a cDNA library from tissues or cell lines of interest (e.g., neural tissues) cloned into pGADT7 vector.

Yeast Transformation and Mating (3-4 days)

- Transform the Gal4 DBD-MOB2 bait construct into AH109 yeast strain using lithium acetate method.

- Select transformed yeast on SD medium lacking tryptophan (-Trp) to maintain bait plasmid.

- Transform prey library into Y187 yeast strain and select on SD medium lacking leucine (-Leu).

- Mate bait and prey strains by combining equal volumes of each culture in rich medium (YPDA) overnight at 30°C.

Selection and Interaction Screening (5-7 days)

- Plate mated yeast cultures on high-stringency selection media (SD/-Trp/-Leu/-His/-Ade).

- Include controls: empty bait vector with prey library (negative control), known interactors (positive control).

- Incubate plates at 30°C for 3-5 days until colonies appear.

- For quantitative assessment, perform β-galactosidase filter assays to confirm interactions.

Interaction Confirmation and Analysis (7-10 days)

- Isolate prey plasmids from positive yeast colonies by plasmid rescue.

- Sequence isolated prey plasmids to identify interacting proteins.

- Retransform purified prey plasmids with MOB2 bait to confirm interaction specificity.

- Validate biologically relevant interactions using complementary methods (co-immunoprecipitation, biophysical assays).

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for yeast two-hybrid screening to identify MOB2-binding partners

Technical Considerations and Optimization

Successful implementation of Y2H screening for MOB2 interactions requires attention to several technical aspects. First, verification of bait autoactivation is essential—the Gal4 DBD-MOB2 fusion should not autonomously activate reporter genes in the absence of a prey protein [15]. Second, yeast permeability to potential small molecules can be enhanced using engineered strains; the ABC9Δ yeast strain with deleted ABC transporter genes improves detection of protein-protein interaction inhibitors by preventing efflux of small molecules [15]. Third, selection stringency should be optimized using 3-AT titration for the HIS3 reporter to reduce false positives [14].

For MOB2 specifically, researchers should consider potential competition with MOB1 when screening for NDR kinase interactions. Including controls with MOB1 can help distinguish MOB2-specific interactors. Additionally, given MOB2's role in neuronal development, cDNA libraries from neural tissues may yield particularly relevant binding partners [12].

Complementary Methods for MOB2 Interaction Studies

Proximity-Dependent Biotin Identification (BioID)

BioID represents a powerful complementary approach to Y2H for mapping MOB2 protein interactions in live cells [16]. This method utilizes a promiscuous biotin ligase (BirA*) fused to MOB2, which biotinylates proximate proteins in living cells. These biotinylated proteins can then be captured and identified using streptavidin affinity purification followed by mass spectrometry [16].

Protocol Overview:

- Fuse MOB2 to BirA* R118G mutant using appropriate mammalian expression vector.

- Transfect fusion construct into HeLa or HEK293 cells and culture with biotin supplementation.

- Harvest cells after 24 hours and lyse under denaturing conditions.

- Capture biotinylated proteins using streptavidin beads.

- Identify interacting proteins using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

Recent BioID studies have revealed novel aspects of MOB protein interactions, including a unique association between MOB3C and the RNase P complex, highlighting the potential of this method for uncovering unexpected functional relationships [16].

Fluorescent Two-Hybrid (F2H) Assay

The fluorescent two-hybrid assay provides a visually tractable method for confirming MOB2 interactions in mammalian cells [17]. This approach detects co-localization of fluorescently tagged proteins at defined subcellular locations, offering real-time visualization of protein-protein interaction dynamics.

Key Steps:

- Fuse MOB2 to a fluorescent protein (e.g., GFP) and potential partners to a complementary fluorescent tag (e.g., RFP).

- Co-transfect constructs into mammalian cells and culture for 24-48 hours.

- Image live cells using fluorescence microscopy and quantify co-localization.

- Assess interaction disruption using specific inhibitors or competing peptides.

Research Reagent Solutions for MOB2 Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MOB2 Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Plasmids | pGBKT7-MOB2, pGADT7-NDR1 | Y2H bait and prey constructs | [15] [14] |

| Antibodies | Anti-MOB2, Anti-NDR1, Anti-pYAP | Protein detection and validation | [11] [12] |

| Cell Lines | HEK293, HeLa, SMMC-7721 | Functional assays and interaction studies | [11] [16] |

| Yeast Strains | AH109, Y187, ABC9Δ | Y2H screening with enhanced permeability | [15] |

| Critical Chemicals | 3-AT, Nutlin-3, Doxycycline | Selection modulation, pathway inhibition | [15] [14] |

MOB2 in Hippo Signaling Pathway Context

MOB2's positioning within the broader Hippo signaling network reveals its unique regulatory functions. While the canonical Hippo pathway centers on MST1/2 kinases activating LATS1/2 kinases with MOB1 co-activation, leading to YAP/TAZ phosphorylation and inhibition, MOB2 operates primarily through the parallel NDR kinase pathway [5]. This Hippo-like pathway regulates cellular morphogenesis rather than proliferation and is conserved from yeast to mammals.

Figure 2: MOB2 in Hippo and Hippo-like signaling pathways. MOB2 primarily regulates the NDR kinase branch, with competitive binding with MOB1 determining signaling output.

The interplay between MOB2 and MOB1 creates a regulatory node that integrates signals from both Hippo pathway branches. MOB2's competitive relationship with MOB1 for NDR kinase binding suggests a mechanism for fine-tuning cellular responses to morphogenetic and proliferative cues [5]. This balanced regulation has implications for developmental processes and disease states, particularly in neurological disorders and cancer where proper cellular positioning and growth control are essential [11] [12].

MOB2 represents a significant regulatory component within Hippo and Hippo-like intracellular signaling pathways, primarily through its interactions with NDR kinases. The yeast two-hybrid system provides a powerful methodological approach for identifying novel MOB2-binding partners, with optimized protocols enabling comprehensive mapping of its interaction network. Combined with complementary techniques such as BioID and fluorescent two-hybrid assays, researchers can obtain a detailed understanding of MOB2's molecular functions and regulatory mechanisms. These insights contribute to elucidating MOB2's roles in development and disease, potentially revealing new therapeutic targets for conditions involving disrupted cellular growth and migration.

MOB kinase activator 2 (MOB2) is a member of the highly conserved Mps one binder (Mob) family of adaptor proteins, which function as essential regulatory partners in intracellular signaling pathways [4]. MOB2 plays a critical role in regulating the Nuclear Dbf2-Related (NDR) family of serine-threonine kinases, which are central components of the Hippo and Hippo-like signaling pathways that control fundamental processes including cell cycle progression, cell shape, tissue growth, and morphogenesis [4] [18]. As a non-catalytic scaffold protein, MOB2 functions as an allosteric activator and adaptor that contributes to the assembly of multiprotein NDR kinase activation complexes, thereby modulating key cellular functions from yeast to humans [4].

The study of MOB2-protein interactions is crucial for understanding its role in cellular homeostasis and disease. MOB2 dysfunction has been implicated in various pathological conditions, highlighting its importance as a research target [4]. The yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) system has emerged as a powerful genetic tool for identifying and characterizing MOB2 binding partners, providing invaluable insights into its molecular functions [19] [20]. This Application Note details experimental frameworks and protocols for investigating MOB2 interactors using Y2H-based approaches, with emphasis on technical considerations for researchers studying NDR kinase signaling networks.

MOB2 Characterization and Classification

Structural and Functional Properties

MOB proteins adopt a conserved globular fold with a core consisting of a four alpha-helix bundle, known as the "Mob family fold" [4]. This structure provides distinct surfaces for binding to NDR kinases or upstream regulatory kinases. Animal Mob proteins have expanded into four classes (I-IV) through evolutionary diversification, with MOB2 belonging to Class II of this family [4]. Unlike Class I Mobs (MOB1A/B) that are established core components of Hippo signaling, Class II Mobs like MOB2 exhibit more specialized functions and regulatory properties within Hippo-like signaling pathways [4].

MOB2 is expressed ubiquitously across human tissues with low tissue specificity, showing detectable expression in all tissues examined according to the Human Protein Atlas [21]. It clusters with non-specific signal transduction proteins and is classified as intracellular in its subcellular localization [21]. The widespread expression pattern suggests MOB2 participates in fundamental cellular processes across multiple tissue types.

MOB2 in NDR Kinase Signaling Pathways

MOB2 functions as a key regulatory partner for Tricornered-like NDR kinases (STK38/STK38L in mammals) in the Hippo-like signaling pathway, which operates parallel to the canonical Hippo pathway and primarily regulates cell and tissue morphogenesis rather than growth control [4]. The effect of MOB2 binding to Tricornered-like kinases appears complex, with studies reporting both activating and inhibitory roles depending on cellular context [4]. MOB2 can compete with Class I Mob proteins for binding to Tricornered-like kinases, suggesting a potential mechanism for fine-tuning NDR kinase activity through relative Mob availability [4].

Table 1: Mob Family Protein Classification and Characteristics

| Mob Class | Representative Members | Primary Kinase Partners | Cellular Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | MOB1A, MOB1B | Warts/LATS kinases [4] | Hippo signaling, growth control, cell division [4] |

| Class II | MOB2 | Tricornered/STK38/STK38L kinases [4] | Hippo-like signaling, cell morphogenesis, neuronal development [13] [4] |

| Class III | MOB3 | Not well characterized [4] | Unknown, potentially specialized functions [4] |

| Class IV | MOB4/Phocein | STRIPAK complex [4] | PP2A phosphatase regulation, Hippo pathway antagonism [4] |

Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening for MOB2 Interactors

Fundamental Principles of Y2H Screening

The yeast two-hybrid system is a powerful molecular biology technique for detecting protein-protein interactions (PPIs) in vivo [19] [14]. Pioneered by Stanley Fields and Ok-Kyu Song in 1989, the method is based on the modular nature of transcription factors, typically using the Gal4 protein from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which can be split into two separate fragments: the DNA-binding domain (BD) and activation domain (AD) [19] [14]. The core principle involves fusing a "bait" protein (e.g., MOB2) to the BD and "prey" proteins to the AD. If the bait and prey proteins interact, they reconstruct a functional transcription factor that drives expression of reporter genes, enabling yeast survival on selective media or producing a detectable color reaction [19] [14].

The Y2H system offers several advantages for studying MOB2 interactions: it occurs in vivo within a eukaryotic cellular environment, can detect weak or transient interactions through reporter gene amplification, and can be adapted for high-throughput screening of complex libraries [19]. Recent advancements have addressed previous limitations, such as yeast cell permeability to small molecules, through engineered strains like ABC9Δ that lack nine ABC transporter genes, enabling more effective screening of interaction inhibitors [15].

Y2H Screening Methodologies for MOB2 Research

Library Screening Approach

The library screening approach identifies novel MOB2 binding partners from pooled cDNA libraries [20]. This method is particularly valuable when prior knowledge of potential interactors is limited. The general workflow involves:

Library Construction: Create a cDNA library from relevant tissues or cell lines, cloning cDNA fragments into a prey vector containing the Gal4 AD [14] [20]. For MOB2 studies, libraries from neuronal tissues or developing organisms may be particularly relevant given MOB2's role in neuronal remodeling [13].

Bait Vector Construction: Clone MOB2 into a bait vector containing the Gal4 BD [14].

Transformation: Co-transform the bait and prey vectors into appropriate yeast reporter strains (e.g., AH109, Y187) [14] [15].

Selection: Plate transformed yeast on selective media lacking specific nutrients (e.g., histidine, adenine) to identify colonies where interaction-activated reporter genes enable growth [14] [15].

Interaction Validation: Sequence positive clones and validate interactions through secondary assays [14].

This approach can identify unknown binding partners but typically requires sequencing of positive clones and may yield higher false-positive rates compared to matrix approaches [20].

Matrix/Array Screening Approach

The matrix approach systematically tests interactions between MOB2 and a defined set of potential protein partners arrayed in multiwell plates [20]. This method is ideal for:

- Testing MOB2 against known NDR kinase family members and related signaling proteins

- Validating interactions suggested by proteomic studies

- Systematic mapping of MOB2 interactions within specific signaling pathways

The matrix approach offers higher reproducibility and lower false-positive rates than library screening, as the identity and position of each prey protein are predetermined [20]. However, it is restricted to the specific ORFs included in the array and may miss novel interactors not represented in the predefined set [20].

Advanced Y2H Techniques for MOB2 Interaction Mapping

Next-Generation Sequencing Enhanced Y2H

Recent innovations have integrated next-generation sequencing (NGS) with Y2H screening to create quantitative, high-resolution interaction mapping techniques. QIS-Seq (Quantitative Interactor Screening with Sequencing) provides quantitative measurements of enrichment for each interactor relative to its frequency in the library, enabling statistical evaluation of interaction strength and specificity [22]. This approach is particularly valuable for distinguishing specific MOB2 interactions from non-specific "sticky" partners.

DoMY-Seq (Protein Domain mapping using Yeast 2 Hybrid-Next Generation Sequencing) offers high-resolution mapping of interaction interfaces by creating a library of fragments derived from an ORF of interest and enriching for interacting fragments using Y2H selection [23]. For MOB2 research, this technique can precisely identify which protein domains mediate interactions with NDR kinases and other binding partners, providing mechanistic insights into MOB2 function.

Specialized Y2H Systems for Membrane-Associated Complexes

As some MOB2 interactions may occur in specific cellular compartments, specialized Y2H variants have been developed. The split-ubiquitin yeast two-hybrid system is designed for membrane-associated bait proteins and may be appropriate for studying MOB2 interactions that occur at cellular membranes [22]. This technique has been successfully used to identify interactors of membrane-associated proteins in Arabidopsis, demonstrating its utility for compartment-specific interaction mapping [22].

Experimental Protocol: Y2H Screening for MOB2 Binding Partners

Phase 1: Bait Vector Construction and Validation

Step 1: Primer Design and Amplification

- Design gene-specific primers with appropriate restriction sites for MOB2 amplification

- Include sequences for in-frame fusion with Gal4 DNA-binding domain

- Amplify MOB2 coding sequence via PCR using high-fidelity DNA polymerase

Step 2: Vector Ligation and Transformation

- Digest both PCR product and bait vector (e.g., pGBKT7) with restriction enzymes

- Purify digested fragments and ligate using T4 DNA ligase

- Transform ligation product into competent E. coli cells and plate on selective media

- Isolate plasmid DNA from resulting colonies and verify insertion by sequencing

Step 3: Bait Functionality and Autoactivation Testing

- Transform validated MOB2 bait vector into yeast reporter strain (e.g., AH109)

- Plate on selective media lacking tryptophan (-Trp) to select for bait-containing cells

- Test for autoactivation by plating on media lacking histidine (-His) and adenine (-Ade)

- If autoactivation occurs, consider using lower-stringency selection or truncated bait

Phase 2: Library Screening and Interaction Detection

Step 4: Library Transformation and Mating

- For library screening, transform prey library into mating-compatible yeast strain (e.g., Y187)

- Mate bait-containing yeast with prey library-containing yeast by combining cultures

- Alternatively, co-transform bait and prey libraries directly into same yeast strain

Step 5: Selection of Interactors

- Plate mated yeast on high-stringency selective media (-Trp, -Leu, -His, -Ade)

- Include appropriate controls: empty bait vector, known non-interacting proteins

- Incubate plates at 30°C for 3-7 days until colonies appear

- Pick positive colonies and restreak on fresh selective media to confirm phenotype

Step 6: Interaction Validation and Identification

- Isolate prey plasmids from positive yeast colonies

- Transform isolated plasmids into E. coli for amplification

- Sequence prey inserts using vector-specific primers

- Identify interacting proteins through database searches (BLAST)

- Confirm interactions through secondary assays (co-IP, BiFC)

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Issues in MOB2 Y2H Screening

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Bait autoactivation | MOB2 has intrinsic transcriptional activity | Use truncated MOB2 constructs; lower-stringency selection; different bait vector [15] |

| No interactions detected | Poor expression; improper localization; weak interactions | Verify bait expression (Western); try different screening conditions; use sensitive reporter genes [20] |

| High background | Non-specific interactions; insufficient selection | Optimize 3-AT concentration; include more stringent selection; use dual reporter systems [14] |

| Inconsistent results | Experimental variability; plasmid loss | Standardize protocols; include controls; ensure selective pressure maintenance [20] |

MOB2-NDR Kinase Signaling Pathway

The diagram below illustrates the core signaling pathway involving MOB2 and its NDR kinase partners, highlighting key molecular relationships and regulatory mechanisms.

MOB2 Signaling and Regulatory Network

Research Reagent Solutions for MOB2-NDR Kinase Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MOB2 Interaction Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Applications and Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Yeast Two-Hybrid Systems | Gal4-based (pGBKT7/pGADT7); Split-ubiquitin system | Detect protein-protein interactions; study membrane-associated complexes [14] [22] |

| Yeast Strains | AH109, Y187, ABC9Δ (engineered for permeability) | Reporter strains for interaction detection; enhanced compound permeability for inhibitor studies [15] |

| MOB2 Constructs | Full-length MOB2; Domain-specific variants; Tagged versions (HA, FLAG, GFP) | Bait protein for interaction screens; functional domain mapping; localization studies [4] |

| NDR Kinase Constructs | SAX-1 (C. elegans); Tricornered (Drosophila); STK38/STK38L (mammalian) | Known MOB2 binding partners for validation; pathway mapping [13] [4] [18] |

| Selection Agents | 3-Amino-1,2,4-triazole (3-AT); Aureobasidin A | Control background; increase stringency; additional selection pressure [14] |

| Interaction Inhibitors | Kinase inhibitors; Small molecule libraries | Characterize MOB2-kinase interactions; identify potential therapeutic compounds [15] |

Key Findings from MOB2 Interaction Studies

MOB2 in Neuronal Remodeling

Recent research using C. elegans has revealed MOB2's essential role in neuronal remodeling through its interaction with the NDR kinase SAX-1. In this model, MOB2 (encoded by sax-2) forms a complex with SAX-1 and MOB-2 to promote dendrite pruning during stress-induced developmental transitions [13]. This complex demonstrates branch-specific elimination of dendritic arbors, with SAX-1/MOB2 required for removing secondary and tertiary branches but not quaternary branches, revealing unexpected specificity in the pruning process [13]. The interaction between MOB2 and SAX-1 regulates membrane dynamics through endocytosis during neuronal remodeling, highlighting the functional significance of this partnership in cellular morphogenesis [13].

MOB2 in Hippo-like Signaling Pathways

MOB2 functions as a key regulatory partner for Tricornered-like NDR kinases (STK38/STK38L in mammals) in the Hippo-like signaling pathway, which operates parallel to the canonical Hippo pathway and primarily regulates cell and tissue morphogenesis rather than growth control [4]. The effect of MOB2 binding to Tricornered-like kinases appears complex, with studies reporting both activating and inhibitory roles depending on cellular context [4]. MOB2 can compete with Class I Mob proteins for binding to Tricornered-like kinases, suggesting a potential mechanism for fine-tuning NDR kinase activity through relative Mob availability [4].

Table 4: Quantitative Data from MOB2 Functional Studies

| Experimental System | Observed Phenotype | Genetic Requirements | Biological Process |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. elegans IL2 dendrite remodeling [13] | Defective secondary/tertiary branch elimination | SAX-1/NDR, SAX-2/MOB2, MOB-2 | Stress-induced dendrite pruning |

| C. elegans neuronal development [13] | Impaired dendrite elimination specificity | RABI-1/Rabin8, RAB-11.2 with SAX-1 | Developmental neuronal remodeling |

| Signaling pathway studies [4] | Altered NDR kinase activity | MOB2 competition with Class I Mobs | Hippo-like pathway regulation |

MOB2 represents a crucial adaptor protein that regulates NDR kinase function in fundamental cellular processes, particularly in neuronal development and cellular morphogenesis. The yeast two-hybrid system provides a powerful platform for identifying novel MOB2 binding partners and characterizing their functional relationships. Recent technical advances, including next-generation sequencing integration and specialized systems for membrane-associated proteins, have significantly enhanced the resolution and applicability of Y2H for MOB2 research.

Future investigations should leverage these advanced Y2H methodologies to comprehensively map the MOB2 interactome under different physiological conditions, identify context-dependent interactions, and discover small molecule modulators of MOB2-protein interactions. These approaches will continue to illuminate the multifaceted roles of MOB2 in cellular signaling and its potential implications for therapeutic development in neurological disorders and cancer.

MOB kinase activator 2 (MOB2) is an evolutionarily conserved adaptor protein belonging to the seven-member MOB family, which function as critical regulators of intracellular signaling pathways [4]. As a non-catalytic scaffold protein, MOB2 mediates its biological effects primarily through protein-protein interactions (PPIs), positioning it as a key node in cellular homeostasis [24]. Recent research has established compelling connections between disrupted MOB2 function and human diseases, particularly cancer, highlighting its role as a potential tumor suppressor [25]. The identification and characterization of MOB2 binding partners is therefore essential for understanding its mechanism of action in both normal physiology and disease states. Yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) screening methodologies provide powerful tools for mapping these interactions, offering insights that could inform therapeutic strategies targeting MOB2-mediated pathways [15] [26].

MOB2 Protein Structure and Classification

MOB2 is classified as a Class II MOB protein based on phylogenetic analysis [4]. Structurally, it shares the conserved Mob family fold—a globular structure with a core consisting of a four alpha-helix bundle [4]. Unlike Class I MOB proteins (MOB1A/B) that activate both Warts/LATS and Tricornered/STK38 classes of Nuclear Dbf2-related (NDR) kinases, MOB2 exhibits binding specificity primarily for the NDR1/2 kinases and does not interact with LATS1/2 kinases [25] [4]. This selective binding capacity underscores MOB2's unique functional role in specific signaling cascades distinct from the canonical Hippo pathway.

MOB2 as a Tumor Suppressor: Evidence from Cancer Studies

Expression and Clinical Significance in Glioblastoma

Substantial clinical evidence demonstrates MOB2's role as a tumor suppressor in glioblastoma (GBM). Immunohistochemical analyses reveal that MOB2 expression is markedly decreased or undetectable in GBM patient samples compared to low-grade gliomas and normal brain tissues [25]. Bioinformatic analyses of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data consistently show significant downregulation of MOB2 mRNA in GBM samples compared to lower-grade gliomas and normal brain tissues [25]. This reduced expression carries clinical significance, as Kaplan-Meier survival analyses indicate that low MOB2 expression correlates significantly with poor prognosis in glioma patients [25].

Table 1: MOB2 Expression in Glioma Patient Samples

| Sample Type | MOB2 Protein Level | MOB2 mRNA Level | Clinical Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal brain tissue | High | High | N/A |

| Low-grade glioma (WHO I-II) | Moderate to high | Moderate | Better prognosis |

| Glioblastoma (WHO IV) | Low to undetectable | Significantly downregulated | Poor survival |

Functional Role in Cancer Phenotypes

Functional studies provide compelling mechanistic insights into MOB2's tumor suppressive activities. Ectopic MOB2 expression suppresses malignant phenotypes in GBM cells, including clonogenic growth, migration, and invasion, while MOB2 depletion enhances these phenotypes [25]. In vivo studies using chick chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) and mouse xenograft models confirm that MOB2 overexpression reduces tumor invasion and growth, establishing its functional significance in cancer progression [25].

MOB2 Interaction Partners and Signaling Pathways

Protein-Protein Interaction Landscape

Recent proximity-dependent biotin identification (BioID) screens have substantially expanded our understanding of the MOB2 interactome, revealing over 200 interactions with at least 70% representing previously unreported associations [24]. This comprehensive mapping reliably recalls MOB2's established interaction with NDR kinases (STK38 and STK38L) while identifying novel potential partners that illuminate MOB2's diverse cellular functions [24].

Table 2: Key MOB2 Protein-Protein Interactions and Functional Consequences

| Interaction Partner | Interaction Type/ Domain | Functional Consequence | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| NDR1/2 (STK38/STK38L) | Direct binding | Regulation of cell cycle, morphogenesis | Y2H, BioID, co-IP [24] [25] [4] |

| RAD50 | DNA damage response domain | Homologous recombination repair | Genetic and cellular assays [27] |

| FAK/Akt pathway components | Indirect via integrin signaling | Suppression of migration and invasion | Phosphoprotein arrays, IB analysis [25] |

| PKA signaling components | cAMP-dependent interaction | Regulation of cell migration | Pharmacological inhibition studies [25] |

MOB2 in DNA Damage Response

Beyond its established roles in cell proliferation and migration, MOB2 plays a critical role in genome maintenance through the DNA damage response (DDR). MOB2 deficiency impairs homologous recombination (HR)-mediated DNA double-strand break repair by compromising the stabilization of RAD51 on damaged chromatin [27]. This function appears independent of its role in NDR kinase signaling, revealing a previously unappreciated facet of MOB2 biology [25] [27]. The physiological significance of this role is substantial—cancer cells with reduced MOB2 expression show enhanced sensitivity to PARP inhibitors, suggesting MOB2 expression may serve as a predictive biomarker for stratified cancer therapies [27].

Experimental Protocols for MOB2 Interaction Studies

Yeast Two-Hybrid Screening for MOB2 Binding Partners

Principle: The yeast two-hybrid system detects protein-protein interactions through reconstitution of a functional transcription factor when bait (MOB2) and prey proteins interact [15] [14].

Protocol:

- Strain Construction: Use the ABC9Δ yeast strain with enhanced permeability for small-molecule studies [15].

- Plasmid Design:

- Clone full-length MOB2 into pGBKT7 (Gal4 DNA-BD vector) as bait

- Clone candidate interacting partners or library into pGADT7 (Gal4 AD vector) as prey

- Transformation: Co-transform bait and prey plasmids into yeast reporter strain AH109 using the lithium acetate method [15].

- Selection: Plate transformations on SD/-Leu/-Trp medium to select for plasmid maintenance.

- Interaction Screening: Replate on SD/-Ade/-His/-Leu/-Trp medium to select for protein interactions.

- Validation: Confirm interactions by β-galactosidase assay for additional reporter activation [14].

Troubleshooting Notes: For screening small-molecule inhibitors of MOB2 interactions, use the ABC9Δ strain which lacks nine ABC transporters, enhancing compound permeability [15]. Include controls with empty vectors and known non-interacting proteins to eliminate false positives.

Functional Validation of MOB2 Interactions in Cancer Models

Principle: Validate MOB2 interactions in disease-relevant contexts using glioblastoma cell models [25].

Protocol:

- Cell Culture: Maintain GBM cell lines (e.g., LN-229, T98G, SF-539, SF-767) under standard conditions.

- Genetic Manipulation:

- For knockdown: Use lentiviral shMOB2 constructs

- For overexpression: Use pCDH-MOB2-V5 constructs

- Functional Assays:

- Migration: Transwell migration assay (24-48 hours)

- Invasion: Matrigel-coated Transwell invasion assay (48 hours)

- Proliferation: BrdU incorporation assay (24 hours)

- Anoikis resistance: Culture on poly-HEMA coated plates (72 hours)

- Pathway Analysis:

- Monitor FAK/Akt pathway activity by Western blot for p-FAK (Tyr397) and p-Akt (Ser473)

- Assess cAMP/PKA signaling using forskolin (activator) and H89 (inhibitor)

- In vivo Validation: Use chick chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) model for invasion studies or mouse xenografts for tumor growth analysis [25].

MOB2-Mediated Signaling Pathways: Visualization

MOB2 Signaling in Cancer and Cellular Homeostasis

Research Reagent Solutions for MOB2 Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MOB2 Interaction Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast Two-Hybrid System | AH109 yeast strain, pGBKT7, pGADT7 vectors | Detection of binary protein-protein interactions | [15] [14] |

| Enhanced Permeability Strain | ABC9Δ yeast (deleted 9 ABC transporters) | Small-molecule inhibitor screening | [15] |

| Cell Line Models | LN-229, T98G, SF-539, SF-767 GBM cells | Functional validation in disease context | [25] |

| Genetic Manipulation | shMOB2 lentiviral constructs, pCDH-MOB2-V5 | Knockdown and overexpression studies | [25] |

| Pathway Modulators | Forskolin (cAMP activator), H89 (PKA inhibitor) | Dissecting cAMP/PKA signaling | [25] |

| Interaction Validation | Co-IP, Western blot, BioID proximity labeling | Confirmation of protein complexes | [24] [25] |

The comprehensive mapping of MOB2 interactions through yeast two-hybrid and complementary approaches reveals a multifaceted tumor suppressor protein that integrates signals from diverse cellular pathways. MOB2 emerges as a critical node regulating key cancer hallmarks including proliferation, invasion, and DNA repair fidelity. Its deregulation in glioblastoma and other cancers underscores its clinical relevance, while its role in determining PARP inhibitor sensitivity positions MOB2 as a potential predictive biomarker for targeted therapies. Further exploration of the MOB2 interactome will likely yield additional insights into its mechanisms of action and may uncover novel therapeutic opportunities for cancers characterized by MOB2 dysregulation. The experimental frameworks outlined herein provide robust methodologies for continuing this investigation, with particular promise in identifying small-molecule compounds that modulate MOB2 interactions for therapeutic benefit.

Monopolar spindle-one-binder protein 2 (MOB2) is a highly conserved adaptor protein belonging to the MOB family, which functions as critical regulators in intracellular signaling pathways [4]. MOB proteins serve as kinase activators and scaffolds that mediate the assembly of multiprotein complexes, primarily through interactions with Nuclear Dbf2-related (NDR) kinases [4]. Mammalian MOB2 specifically interacts with NDR1/2 kinases but not with LATS1/2 kinases, positioning it uniquely within the Hippo and Hippo-like signaling networks [28] [4]. Despite its discovery over two decades ago, the full spectrum of MOB2-binding partners and its diverse cellular functions remain incompletely characterized, creating a significant knowledge gap in our understanding of this crucial signaling regulator.

Table 1: MOB Protein Family Classification and Characteristics

| Class | Representative Members | Primary Kinase Partners | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | MOB1A, MOB1B | LATS1/2, NDR1/2 | Core Hippo pathway regulation, growth control |

| Class II | MOB2 | NDR1/2 | Cell morphogenesis, migration, cycle progression |

| Class III | MOB3A, MOB3B, MOB3C | Not well-defined | Poorly characterized; MOB3C associates with RNase P |

| Class IV | MOB4 (Phocein) | STRIPAK complex (phosphatase) | Antagonizes Hippo signaling, cell differentiation |

The Biological and Clinical Significance of MOB2

MOB2 in Cell Signaling and Morphogenesis

MOB2 plays a fundamental role in regulating cell motility, morphogenesis, and cycle progression. In filamentous fungi such as Neurospora crassa, MOB2 proteins interact with the NDR kinase COT1 to control polar tip extension and branching [29]. Genetic deletion studies demonstrate that MOB2 is essential for proper hyphal growth and development, with Δmob-2 strains exhibiting significantly reduced growth rates and altered aerial hyphae formation [29]. This evolutionarily conserved function extends to mammalian systems, where MOB2 regulates cellular processes through its interaction with NDR kinases.

MOB2 as a Tumor Suppressor in Human Cancers

Emerging clinical evidence has established MOB2 as a potential tumor suppressor in various cancers, particularly in glioblastoma (GBM). Immunohistochemical analyses reveal that MOB2 expression is markedly downregulated in GBM patient samples compared to low-grade gliomas and normal brain tissues [30]. Bioinformatic analyses of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) dataset confirm that MOB2 mRNA levels are significantly reduced in GBM samples, and low MOB2 expression correlates with poor patient prognosis [30]. Functional studies demonstrate that MOB2 overexpression suppresses, while its depletion enhances, malignant phenotypes of GBM cells including clonogenic growth, anoikis resistance, migration, and invasion [30]. These findings highlight the clinical relevance of MOB2 and underscore the need to comprehensively understand its binding network.

MOB2 in Hepatocellular Carcinoma

In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), MOB2 inhibits cancer cell motility by regulating the Hippo signaling pathway. Mechanistically, MOB2 competes with MOB1 for binding to NDR1/2, which influences the subsequent interaction of MOB1 with LATS1 [28]. This competition ultimately leads to increased phosphorylation of LATS1 and inactivation of YAP, resulting in inhibition of cell migration and invasion [28]. This regulatory mechanism positions MOB2 as a critical modulator of the Hippo pathway with significant implications for cancer biology.

The MOB2 Knowledge Gap

Limitations of Current MOB2 Interactome Studies

Recent proximity-dependent biotin identification (BioID) screens aimed at mapping the global interactome of all seven human MOB proteins have revealed significant gaps in our understanding of MOB2 partnerships [24]. While these studies successfully recalled established MOB1 and MOB4 interactors, they uncovered that at least 70% of the >200 identified interactions were previously unreported in the BioGrid database [24]. Notably, this systematic comparison highlighted the particularly poor characterization of the MOB3 subfamily, for which no interactions were previously documented [24]. Although MOB2 was included in this analysis, the specialized functional roles of different MOB proteins suggest that unique, cell-type-specific interaction partners for MOB2 remain to be discovered.

Technical Limitations of Existing Methods

While proximity labeling techniques like BioID have advanced interactome mapping, they possess inherent limitations in capturing direct physical interactions. BioID identifies proteins within a ~10 nm radius of the bait protein, which may include both direct binding partners and proximal proteins [24]. This approach cannot distinguish between direct and indirect interactions, potentially obscuring the precise molecular relationships involving MOB2. Furthermore, the transient nature of some MOB2 interactions and its role as an adaptor protein may render certain complexes difficult to capture using standard affinity purification methods.

Table 2: Current Evidence for MOB2 Interactions and Functions

| Evidence Type | Key Findings | Limitations/Gaps |

|---|---|---|

| BioID Proximity Labeling [24] | Identified >200 MOB protein interactions; 70% novel; recalled bona fide MOB1/4 partners | Cannot distinguish direct vs. indirect interactions; MOB2-specific network not focused |

| Functional Studies [30] [28] | MOB2 suppresses GBM migration/invasion; inhibits HCC motility via Hippo pathway | Limited to specific cellular contexts; complete signaling mechanisms unknown |

| Genetic Evidence [29] | MOB2-NDR complexes form distinct modules in fungi | Evolutionary conservation of specific interactions not fully mapped |

| Clinical Correlations [30] | MOB2 downregulated in GBM; correlates with poor survival | Comprehensive mechanistic link between interactions and tumor suppression unclear |

Experimental Approach: Y2H Screen for MOB2 Partners

The yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) system is a powerful molecular biology technique for detecting direct protein-protein interactions in vivo [14]. The classic Y2H approach relies on the functional reconstitution of a transcription factor when two proteins interact. The bait protein (MOB2) is fused to a DNA-binding domain (DBD), while prey proteins are fused to an activation domain (AD). Upon bait-prey interaction, the reconstituted transcription factor activates reporter gene expression, enabling selection and identification of interacting partners [14]. Modern Y2H systems, such as the ULTImate Y2H platform, employ cell-to-cell mating processes that permit testing of approximately 83 million interactions per screen, ensuring exhaustive coverage and identification of rare binding partners [31].

Y2H-SCORES Computational Framework

Next-generation interaction screening (NGIS) protocols that combine Y2H with deep sequencing require sophisticated computational frameworks for data analysis. The Y2H-SCORES system implements three quantitative ranking scores to identify high-confidence interacting partners: (1) significant enrichment under selection for positive interactions, (2) degree of interaction specificity among multi-bait comparisons, and (3) selection of in-frame interactors [32]. This framework maximizes the detection of true interactors while minimizing false positives, which is essential for building reliable interaction networks [32].

Diagram 1: Y2H screening workflow for MOB2 partners. This diagram illustrates the key steps in a comprehensive yeast two-hybrid screen to identify novel MOB2-binding proteins.

Detailed Y2H Protocol for MOB2 Screening

Bait Construction and Validation

- Amplify MOB2 coding sequence using high-fidelity PCR with gene-specific primers containing appropriate restriction sites.

- Clone MOB2 into Y2H bait vector (e.g., pGBKT7) to generate an in-frame fusion with the GAL4 DNA-binding domain.

- Verify bait plasmid sequence by Sanger sequencing to ensure no mutations have been introduced during cloning.

- Test for autoactivation by transforming the MOB2 bait plasmid into yeast reporter strains (e.g., Y2HGold) and plating on dropout media lacking histidine and adenine. A valid bait should not activate reporter gene expression in the absence of a prey protein.

Library Screening

- Transform MOB2 bait plasmid into yeast mating type α strain (e.g., Y187).

- Mate bait strain with prey library (e.g., human cDNA library in mating type a strain) by combining cultures and incubating in rich medium for 24 hours.

- Plate diploid yeast on stringent dropout media (SD/-Ade/-His/-Leu/-Trp) to select for interacting clones.

- Incubate plates at 30°C for 5-7 days and monitor for colony formation.

Interaction Confirmation and Analysis

- Isolate positive colonies and rescue prey plasmids for sequence identification.

- Confirm interactions through pairwise retransformation and growth assays.

- Sequence prey inserts to identify MOB2-binding partners using Sanger or next-generation sequencing.

- Analyze interaction domains by comparing overlapping regions in prey fragments to determine minimal binding domains.

Anticipated Outcomes and Applications

Expected Results and Impact

A comprehensive Y2H screen for MOB2 binding partners is expected to identify both known and novel interactors, potentially including:

- Kinase partners beyond the established NDR1/2 interactions

- Regulatory proteins that modulate MOB2 stability, localization, or function

- Cell type-specific binding partners that explain tissue-specific MOB2 functions

- Disease-associated proteins that link MOB2 to pathological processes beyond cancer

These discoveries would significantly advance our understanding of MOB2's role in cellular signaling and its potential as a therapeutic target.

Technical Considerations and Optimization

To maximize screening success, several technical aspects require careful optimization:

- Bait design: Both full-length MOB2 and functional domains should be screened to identify structured interaction domains.

- Library selection: High-complexity, domain-enriched cDNA libraries from multiple tissue sources increase the probability of identifying relevant partners.

- Selection stringency: Varying selection pressure using competitive inhibitors like 3-AT can help optimize the balance between sensitivity and specificity [14].

- Control experiments: Including both positive and negative control baits is essential for assessing screening quality and identifying nonspecific interactions.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for MOB2 Y2H Screening

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| ULTImate Y2H Platform [31] | High-throughput interaction screening | Tests ~83 million interactions; identifies weak/rare partners |

| Domain-Enriched cDNA Libraries [31] | Source of potential binding partners | >10 million clones; insert size 800-1000 bp (domain-sized) |

| Y2H-SCORES [32] | Computational analysis of NGIS data | Three quantitative scores for ranking interactors by confidence |

| MBmate Y2H System [31] | Screening membrane protein interactions | Validates proper localization of membrane-associated baits |

| pGBKT7 Vector | Bait plasmid for GAL4-DBD fusion | Contains TRP1 selection marker for yeast |

| Prey cDNA Libraries | Collection of potential MOB2 partners | Normalized libraries reduce abundant transcript representation |

Diagram 2: MOB2 signaling network and knowledge gaps. This diagram illustrates established MOB2 interactions (solid lines) and potential novel interactions that could be discovered through Y2H screening (dashed red line), particularly connections to RNA processing machinery suggested by MOB3C findings.

The proposed Y2H screen for MOB2 binding partners addresses a critical knowledge gap in our understanding of this important signaling regulator. By systematically identifying direct protein interactions, this approach will illuminate novel aspects of MOB2 function in both normal physiology and disease states, particularly in cancer biology. The integration of modern Y2H methodologies with advanced computational analysis tools provides an unprecedented opportunity to comprehensively map the MOB2 interactome, potentially revealing new therapeutic targets and regulatory mechanisms in cell signaling pathways.

Executing a MOB2 Y2H Screen: From Vector Design to High-Throughput Sequencing

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) are fundamental to virtually every cellular process, and the yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) system remains a cornerstone technique for their discovery. This application note provides a structured framework for researchers investigating PPIs, with a specific focus on selecting between the canonical GAL4-based system and modern alternative frameworks. Using the characterization of MOB2 binding partners as a thematic example, we detail experimental protocols, compare system performance parameters, and provide visualization tools to guide assay development for researchers and drug development professionals. The emphasis is on practical implementation, from library screening to quantitative validation, within the context of contemporary functional proteomics.

The yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) system, pioneered by Fields and Song in 1989, exploits the modular nature of eukaryotic transcription factors to detect PPIs in vivo [33] [14]. The core principle involves splitting a transcription factor into two discrete domains: a DNA-Binding Domain (DBD) and an Activation Domain (AD). The DBD is fused to a "bait" protein (e.g., MOB2), and the AD is fused to a "prey" protein (e.g., a library of coding sequences). A physical interaction between bait and prey reconstitutes the transcription factor, driving the expression of reporter genes [34] [14].

This technique has been instrumental in saturating protein interaction maps, a pursuit accelerated by genome sequencing projects [33]. Its application to the study of Mps one binder (MOB) proteins, key signal transducers, has been particularly fruitful. MOB proteins are highly conserved regulators of the NDR/LATS kinase family, with MOB2 playing specific roles in cell cycle progression and the DNA Damage Response (DDR) [7]. A Y2H screen, for instance, was successfully used to identify RAD50, a component of the MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 (MRN) DNA damage sensor complex, as a novel MOB2 binding partner [7]. This discovery highlighted MOB2's role in DDR signaling and cell cycle checkpoints, underscoring the functional importance of its interactome.

The following diagram illustrates the core conceptual workflow of a two-hybrid system applied to a signaling pathway like MOB2's:

Figure 1. Logical flow of MOB2 signaling and key Y2H discovery. MOB2 regulates NDR1/2 kinases and was found via Y2H to bind RAD50, linking it to DNA Damage Response (DDR).

Available Two-Hybrid Systems: A Quantitative Comparison

The classic GAL4-based Y2H has been adapted and improved to overcome its limitations, leading to a suite of options for researchers.

Core GAL4-Based Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H)

The classic system uses the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a host. The bait is fused to the GAL4-DBD, and the prey is fused to the GAL4-AD. Interaction is detected by the activation of reporter genes, which are often auxotrophic markers (e.g., HIS3, ADE2) that allow growth on selective media or enzymes that produce a colorimetric signal [33] [34] [14].

Advanced and Alternative Systems

- Quantitative Y2H (qY2H): Replaces auxotrophic reporters with fluorescent or luminescent proteins. This allows for quantitative measurement of interaction strength and faster, more objective readouts. For example, replacing

ADE2with NanoLuc luciferase enables quantitative screening in 96-well plates with high sensitivity [35]. - Fluorescent Two-Hybrid (F2H): Conducted in mammalian cells, this system uses fluorescent protein tags to visualize the co-localization of bait and prey at a defined nuclear spot upon interaction. It is ideal for studying PPIs in a more native cellular environment and for screening inhibitors in live cells [17].

- Mammalian Two-Hybrid (M2H): Similar in principle to Y2H but performed in mammalian cells. This is crucial for proteins requiring post-translational modifications specific to higher eukaryotes. High-throughput versions like the Cell Array Protein-Protein Interaction Assay (CAPPIA) enable screening of thousands of combinations [36].

- Split-Ubiquitin System: An alternative to the transcription-based readout, designed for screening membrane protein interactions [14].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Two-Hybrid System Frameworks

| System Feature | GAL4-based Y2H | Quantitative Y2H (e.g., NanoLuc) | Mammalian / F2H |

|---|---|---|---|

| Host Organism | Yeast (S. cerevisiae) | Yeast | Mammalian Cells |

| Readout Type | Growth (e.g., HIS3), Colorimetric |

Luminescence, Fluorescence | Fluorescence Microscopy |

| Quantification | Semi-quantitative | Fully quantitative, calculates affinity | Semi- to Fully Quantitative |

| Time to Result | Several days | ~2 hours for initial signal [37] | 1-2 days |

| Key Advantage | Well-established, flexible, low cost | Objective, high-throughput, fast | Relevant PTMs, live-cell dynamics |

| Key Disadvantage | High false positives/negatives | Requires specialized equipment/l reagents | Lower throughput, higher cost |

| Ideal for MOB2 | Initial library screening | Validating & ranking interaction affinity [37] | Confirming physiological relevance |

Table 2: Advantages and Disadvantages of the GAL4 Two-Hybrid System

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| In vivo environment (closer to reality than in vitro) [33] | Auto-activation: Bait alone may activate transcription [33] [38] |

| Flexibility & rapid isolation of interacting proteins [38] | Misfolding: Fusion proteins may alter conformation [33] [38] |

| Low cost & less time than protein purification methods [38] | False positives/negatives rate can be high [38] |

| Functional screen: Identifies and clones the gene simultaneously [38] | Post-translational modifications may not occur in yeast [33] [38] |

| Can analyze known interactions (e.g., critical residues) [38] | Toxicity: Expression of some proteins (e.g., cyclins) can be toxic to yeast [38] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Initial Screening with GAL4-Based Y2H for MOB2 Partners

This protocol is adapted for identifying novel binding partners for MOB2 from a cDNA library.

I. Research Reagent Solutions Table 3: Essential Reagents for GAL4-Based Y2H

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| pGBKT7 (Bait Vector) | GAL4-DBD fusion vector; contains TRP1 selectable marker. |

| pGADT7 (Prey Vector) | GAL4-AD fusion vector; contains LEU2 selectable marker. |

| Y2H Gold Yeast Strain | Genetically engineered strain with multiple reporter genes (HIS3, ADE2, AUR1-C, MEL1). |

| cDNA Library | Prey library cloned into pGADT7; represents genes from a relevant tissue or cell line. |

| SD/-Trp/-Leu Media | Selective medium to maintain both bait and prey plasmids. |

| SD/-Trp/-Leu/-His/-Ade (QDO) | Stringent selective medium for interaction screening. |

| X-α-Gal | Substrate added to QDO medium; turns blue if MEL1 reporter is activated. |

II. Step-by-Step Workflow

Figure 2. GAL4 Y2H workflow for MOB2 partner screening.

- Bait Preparation and Validation: Clone the full-length MOB2 gene into the pGBKT7 vector to create an in-frame fusion with the GAL4-DBD. Transform this construct into the Y2H Gold yeast strain and plate on SD/-Trp to select for bait-containing cells.

- Critical Auto-activation Test: Plate the bait strain on stringent media (SD/-His and SD/-Ade/-His supplemented with X-α-Gal). Lack of growth and no blue color formation is essential to proceed, confirming that MOB2 does not autonomously activate transcription [33] [38].

- Library Transformation: Mate the validated bait strain with a pre-transformed cDNA library in the Y2H Gold strain, or co-transform the library plasmid (pGADT7-based) directly into the bait strain. Plate the mixture on SD/-Trp/-Leu to select for diploid yeast or co-transformants containing both bait and prey plasmids.

- Interaction Selection and Screening: After 3-5 days of growth, replica-plate the colonies onto the most stringent selection medium: SD/-Ade/-His/-Leu/-Trp (QDO) supplemented with X-α-Gal. True protein-protein interactions will support growth and produce a blue pigment due to

MEL1reporter activation. - Isolation and Identification of Prey: Isolate the pGADT7 prey plasmid from positive (growing, blue) colonies, typically by bacterial amplification. Sequence the plasmid insert using primers flanking the cloning site to identify the MOB2-interacting protein.

Protocol 2: Quantitative Validation with a Tri-Fluorescent Y2H System

This protocol is for validating hits from the primary screen and quantitatively assessing their binding affinity to MOB2.

I. Research Reagent Solutions Table 4: Essential Reagents for Quantitative Tri-Fluorescent Y2H

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Quantitative Y2H Vectors | Set of plasmids for expressing Bait-FP1, Prey-FP2, and a reporter (e.g., NanoLuc). |

| Fluorescent Protein (FP) Tags | e.g., GFP, mCherry; for quantifying bait and prey expression levels at single-cell level. |

| NanoLuc Luciferase Reporter | Extremely bright, quantitative reporter for the interaction [35]. |

| Flow Cytometer | For simultaneous detection of FP signals (bait/prey levels) and luminescence (interaction strength). |

| Affinity Ladder | A set of control PPIs with known dissociation constants (KD), used for calibration [37]. |

II. Step-by-Step Workflow

- Vector Construction: Subclone the gene for a validated hit (e.g., RAD50 or a fragment) and MOB2 into the quantitative Y2H vectors to create fusions with distinct fluorescent proteins (e.g., Bait-MOB2-FP1 and Prey-RAD50-FP2).

- Co-transformation and Induction: Co-transform the bait and prey constructs, along with the NanoLuc reporter plasmid, into the appropriate yeast strain. Induce protein expression for a short period (as little as 2 hours may be sufficient) [37].

- Flow Cytometry Analysis: Analyze the yeast population using a flow cytometer capable of detecting fluorescence and luminescence.

- Use fluorescence channels to gate on cells expressing similar levels of both Bait-MOB2 and Prey-RAD50. This standardizes expression and ensures a fair comparison.

- Within this gated population, measure the NanoLuc luminescence signal, which is directly proportional to the interaction strength.

- Affinity Estimation: Compare the mean luminescence value of the MOB2-prey pair to the "affinity ladder" created from control PPIs with known KD values. This allows for the ranking and estimation of the dissociation constant for the novel interaction [37].

Selecting the Optimal Framework for MOB2 Research

The choice of system depends on the research question's stage and the specific biochemical characteristics of MOB2 and its partners.

For Discovery Screening: Use Classic GAL4-Y2H. Its well-established protocols, low cost, and flexibility make it ideal for the initial, high-throughput identification of potential MOB2 binding partners from complex cDNA libraries [33] [38]. The discovery of MOB2-RAD50 via a Y2H screen is a testament to its power [7].

For Validation and Affinity Measurement: Use Quantitative Y2H. When you have a defined set of candidate interactors, a quantitative system (e.g., NanoLuc-based) is superior. It provides an objective, numerical measure of interaction strength, helping to prioritize the most biologically relevant partners for MOB2 [35] [37].

For Physiologically Relevant Confirmation: Use Mammalian/F2H Systems. Since MOB2 function is linked to NDR kinase regulation and DDR in human cells, confirming interactions in a mammalian context is critical. The F2H or M2H systems ensure that any post-translational modifications necessary for MOB2's function are present, providing higher confidence in the biological relevance of the finding [7] [17] [36]. This is crucial for downstream drug discovery efforts targeting these interactions.

Common Pitfalls and Solutions:

- High Background (False Positives): Increase stringency by using higher concentrations of 3-AT (a competitive inhibitor of the