Hydrogen Bonding in Primer Dimers: A Scientific Guide to Mechanisms, Detection, and Prevention

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical role hydrogen bonding plays in the formation and prevention of primer dimers, a common obstacle in molecular biology and diagnostic assay...

Hydrogen Bonding in Primer Dimers: A Scientific Guide to Mechanisms, Detection, and Prevention

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the critical role hydrogen bonding plays in the formation and prevention of primer dimers, a common obstacle in molecular biology and diagnostic assay development. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content explores the fundamental biophysical principles governing these non-specific interactions. It further details advanced methodological strategies for detection and mitigation, presents comparative data on troubleshooting and optimization techniques, and validates innovative approaches like Self-Avoiding Molecular Recognition Systems (SAMRS). By synthesizing foundational knowledge with practical applications, this guide aims to empower professionals in designing more robust and reliable molecular assays.

The Hydrogen Bond Blueprint: Deconstructing the Biophysics of Primer Dimers

In nucleic acid amplification technologies, primer dimers represent a significant challenge to assay specificity and efficiency. These unintended artifacts are short, aberrant DNA fragments generated when primers anneal to each other rather than to the target template DNA, becoming substrates for polymerase-mediated extension [1]. The formation of these structures is governed fundamentally by Watson-Crick hydrogen bonding between complementary bases, the same force that facilitates specific primer-template interactions [2]. While high-fidelity replicative DNA polymerases rely primarily on geometric constraints for fidelity, studies demonstrate that Y-family polymerases involved in lesion bypass depend critically on Watson-Crick hydrogen bonding to localize nascent base pairs in their active sites [2]. This dependency underscores the dual role of hydrogen bonding in molecular biology: it is essential for desired specific amplification yet equally capable of facilitating undesirable primer-primer interactions when complementarity exists. This technical guide examines the classification, formation mechanisms, detection, and mitigation of primer dimers within the broader context of hydrogen bonding energetics in nucleic acid biochemistry.

Classification and Formation Mechanisms

Structural Classification of Primer Dimers

Primer dimers are systematically categorized based on the interacting primers involved:

Self-Dimers (Homodimers): Formed when two identical primers anneal to each other through intermolecular bonding [3]. This occurs when a single primer sequence contains regions of self-complementarity.

Cross-Dimers (Heterodimers): Formed when forward and reverse primers with complementary sequences anneal to each other instead of the target template [1] [3].

The thermodynamic driving force for dimer formation is the Gibbs free energy (ΔG) released when complementary sequences hybridize. More negative ΔG values indicate stronger, more stable dimer formations that are increasingly problematic in amplification reactions [4].

Molecular Mechanisms of Dimer Formation

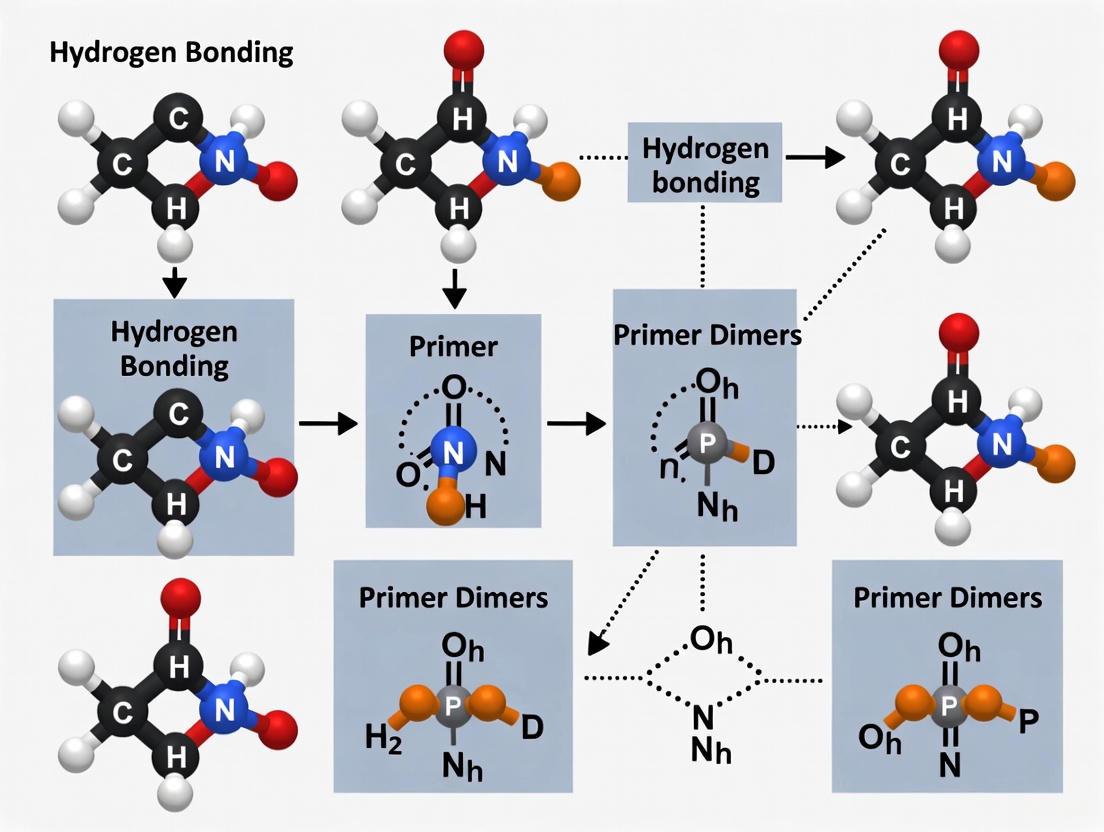

The process of primer dimer formation follows a predictable pathway, illustrated below, which initiates with hydrogen bonding between complementary primer regions and culminates in polymerase-mediated extension:

The diagram illustrates the two-phase process of primer dimer formation. The initial hydrogen bonding phase relies on Watson-Crick base pairing between complementary regions of primers, typically involving 3 or more complementary bases [4]. This creates short double-stranded regions with free 3' hydroxyl ends. During the subsequent polymerase extension phase, DNA polymerase recognizes these free 3' ends as legitimate initiation points and extends the primers, effectively "cementing" the dimer into a stable, amplifiable product [1] [3]. This extension process is particularly efficient when complementarity occurs at the 3' ends of primers, where polymerase binding initiates [3].

Quantitative Impact on Assay Performance

Effects on PCR and qPCR Efficiency

Primer dimers impact molecular assays through multiple mechanisms, with particularly severe consequences in quantitative applications:

Reduced Amplification Efficiency: Primer dimers sequester primers into non-productive complexes, effectively reducing the concentration of primers available for target amplification [5]. This leads to diminished target amplicon yield and reduced assay sensitivity.

qPCR Artifacts: In quantitative PCR using intercalating dyes, primer dimers generate false fluorescent signals as the dyes bind to double-stranded dimer products [6]. This is particularly problematic during later amplification cycles, potentially leading to inaccurate quantification [7].

Inhibition of Target Amplification: The presence of amplifiable primer dimers creates competition for essential reaction components, including primers, nucleotides, and DNA polymerase [3]. This resource partitioning can completely suppress target amplification in severe cases.

The table below summarizes the quantitative impacts of primer dimers on key assay parameters:

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Primer Dimers on Assay Performance

| Assay Parameter | Impact of Primer Dimers | Experimental Manifestation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amplification Efficiency | Decreased by 10-30% | Higher Cq values, reduced slope in standard curve | [7] |

| Detection Sensitivity | 1-3 log10 reduction in sensitivity | Increased limit of detection | [5] |

| Reaction Resources | Up to 50% primer sequestration | Reduced yield of desired product | [1] |

| qPCR Accuracy | False positive signals, efficiency >100% | Incorrect quantification, elevated baseline | [7] |

Special Considerations for Isothermal Amplification

Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) presents unique vulnerabilities to primer dimer formation due to its structural complexity:

- Increased Primer Load: LAMP utilizes 4-6 primers targeting 6-8 regions, substantially increasing the probability of primer-primer interactions [5].

- Complex Primer Structures: Inner primers (FIP/BIP) in LAMP are typically 40-45 bases long, making them particularly prone to stable hairpin formation and self-dimerization [5].

- High Primer Concentrations: Standard LAMP protocols use inner primer concentrations of 1.6 µM, approximately 10-fold higher than conventional PCR, increasing interaction probabilities [5].

Research demonstrates that primer sets with strong 3' complementarity can generate a slowly rising baseline in real-time LAMP assays due to amplifiable primer dimers and hairpin structures, significantly compromising endpoint detection clarity [5].

Detection and Characterization Methods

Electrophoretic and Analytical Techniques

Multiple experimental approaches enable detection and characterization of primer dimers:

Gel Electrophoresis: Primer dimers typically appear as fuzzy, smeary bands below 100 bp, distinct from the well-defined bands of specific amplicons [1]. Running gels for extended time helps separate primer dimers from desired products.

No-Template Controls (NTC): Essential diagnostic reactions containing all PCR components except template DNA. Amplification in NTCs indicates primer-derived artifacts rather than target-specific products [1].

Melting Curve Analysis: Following qPCR with intercalating dyes, melting curves reveal primer dimers through distinct melting temperatures (Tm) that are typically lower than specific amplicons [6].

Thermodynamic Prediction Tools: Software such as OligoAnalyzer and Multiple Prime Analyzer calculates ΔG values for potential dimer formations, with structures exceeding -9 kcal/mol considered problematic [8].

The experimental workflow below outlines a comprehensive approach to primer dimer detection and validation:

This workflow emphasizes the importance of combining computational prediction with experimental validation. The computational phase identifies potential dimerization risks through thermodynamic modeling, while the experimental phase confirms actual dimer formation under reaction conditions. Research demonstrates that primer sets passing in silico screening may still produce problematic dimers in amplification reactions, necessitating empirical validation [5].

Experimental Mitigation Strategies

Primer Design Optimization

Strategic primer design represents the most effective approach to minimizing primer dimer formation:

3' End Complementarity Analysis: Scrutinize the last 3-5 bases at the 3' end for complementarity between primers, as this region most significantly influences dimer formation [4].

Gibbs Free Energy Thresholds: Avoid primer pairs with ΔG values below -9 kcal/mol for cross-dimers and below -2 kcal/mol for 3' end hairpins [8] [4].

GC Clamp Implementation: Include 1-2 G or C bases at the 3' end to enhance specific binding, but avoid more than 3 G/C in the final five bases to prevent non-specific priming [8].

Length Optimization: Design primers between 18-24 nucleotides to balance specificity and binding efficiency while minimizing secondary structure risk [8].

The table below outlines essential computational tools for primer design and dimer prediction:

Table 2: Computational Tools for Primer Dimer Prediction and Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Dimer-Related Parameters | Access Platform |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primer-BLAST | Integrated primer design with specificity checking | Off-target binding prediction, dimer flags | NCBI Web Portal |

| OligoAnalyzer | Thermodynamic analysis of oligonucleotides | ΔG calculation for dimers and hairpins | IDT Web Portal |

| Multiple Prime Analyzer | Multi-primer interaction analysis | Comprehensive dimer network prediction | Thermo Fisher Web Portal |

| mFold | Secondary structure prediction | Stability analysis of hairpin formations | Web-based application |

Reaction Condition Optimization

When primer redesign is not feasible, reaction condition adjustments can suppress dimer formation:

Hot-Start DNA Polymerase: Employ polymerases that remain inactive until elevated temperatures are reached, preventing primer dimer formation during reaction setup [1] [9].

Increased Annealing Temperature: Raise annealing temperature 2-5°C above the calculated Tm to reduce non-specific interactions while maintaining specific binding [1].

Primer Concentration Titration: Lower primer concentrations (50-200 nM for qPCR) to reduce interaction probabilities while maintaining amplification efficiency [1].

Magnesium Concentration Optimization: Titrate Mg²⁺ concentrations, as excess magnesium can stabilize non-specific primer interactions [3].

Recent research demonstrates that incorporating modified nucleotides such as digoxigenin-labeled dUTP can selectively prevent primer dimer detection in lateral flow assays, as dimers contain only one label and fail to generate signal despite their presence [10].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and tools represent essential components for effective primer dimer management in molecular assays:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Primer Dimer Management

| Reagent/Tool | Specific Function | Dimer-Related Application | Example Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Thermal activation prevents pre-PCR activity | Suppresses dimer formation during reaction setup | Bst 2.0 WarmStart, Taq Hot Start |

| Thermodynamic Prediction Software | Calculates interaction energies | Identifies problematic primer pairs pre-synthesis | OligoAnalyzer, mFold |

| No-Template Control Reagents | Validates reaction specificity | Detects primer-derived amplification artifacts | Molecular biology grade water |

| Intercalating Dyes | Binds double-stranded DNA | Enables dimer detection in real-time and melt curves | SYTO 9, SYBR Green |

| Modified Nucleotides | Incorporates non-standard bases | Prevents dimer detection in endpoint assays | Digoxigenin-dUTP, Biotin-dATP |

Primer dimer formation represents a fundamental challenge in nucleic acid amplification technologies, rooted in the same Watson-Crick hydrogen bonding principles that enable specific target recognition. The competitive binding between desired primer-template interactions and undesirable primer-primer interactions directly impacts assay sensitivity, specificity, and quantification accuracy. Effective management requires integrated computational and experimental strategies, from careful primer design with thermodynamic considerations to optimized reaction conditions that favor specific amplification. As molecular diagnostics advance toward point-of-care applications and isothermal methods, understanding and controlling primer dimer formation becomes increasingly critical for assay reliability. The strategies outlined in this guide provide a framework for diagnosing and addressing primer dimer issues across various amplification platforms, emphasizing the continuous balance between harnessing and controlling hydrogen bonding energetics in molecular biology.

The specific pairing of nitrogenous bases—guanine with cytosine (G-C) and adenine with thymine (A-T) or uracil (A-U in RNA)—through hydrogen bonds constitutes a foundational principle of molecular biology [11] [12]. This complementary base pairing, first elucidated by Watson and Crick, is essential for the storage and replication of genetic information in DNA and RNA [13]. While the overall stability of the DNA double helix is significantly influenced by base-stacking interactions between adjacent nucleotide pairs, hydrogen bonding plays a critical role in defining the specificity and fidelity of base pairing [14] [11]. This specificity is not only crucial for in vivo processes like DNA replication and transcription but also forms the basis of numerous in vitro molecular techniques. Among these, the phenomenon of primer dimer formation in amplification reactions like PCR and LAMP represents a significant challenge where unintended hydrogen bonding between primers themselves, rather than with the target template, leads to non-specific amplification and potential false-positive results [5] [3]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of the hydrogen bonding patterns that govern natural base pairing, their quantitative energetic contributions, and their direct implications for the design and optimization of molecular assays, with a particular focus on troubleshooting primer dimer artifacts.

The Molecular Anatomy of Hydrogen Bonds in Base Pairs

Fundamental Hydrogen Bonding Patterns

Hydrogen bonds in base pairs form between hydrogen bond donors (atoms bearing a hydrogen, typically N-H or O-H groups) and hydrogen bond acceptors (electronegative atoms with lone electron pairs, such as nitrogen or oxygen) [15]. The specific patterns of donors and acceptors dictate which bases can form stable, complementary pairs.

- G-C Base Pair: The guanine-cytosine pair forms three hydrogen bonds. Guanine provides a hydrogen bond donor from its N1-H group and an acceptor from its O6 carbonyl group. It also provides an acceptor from the N7 position in its five-membered ring. Cytosine complements this with a donor from its N4-H₂ group and an acceptor from its N3 atom. The canonical pairing involves the N1-H⋯O2, N2-H⋯N3, and O6⋯H4-N4 interactions, creating a robust, thermodynamically stable pair [15] [11].

- A-T Base Pair: The adenine-thymine pair forms two hydrogen bonds. Adenine provides a donor from its N6-H₂ group and an acceptor from its N1 atom. Thymine complements this with an acceptor from its O4 carbonyl oxygen and a donor from its N3-H group. The standard pairing is N1⋯H-N3 and N6-H⋯O4 [15] [13].

The purine-pyrimidine pairing (A-T and G-C) is geometrically optimal. Pyrimidine-pyrimidine pairs are too short to bridge the inter-sugar distance, while purine-purine pairs are too long, leading to steric clash and inefficient overlap repulsion [11]. The distance from sugar linkage to sugar linkage is nearly identical for A-T and G-C pairs, allowing the DNA backbone to maintain a regular helical structure [13].

Table 1: Hydrogen Bond Donors and Acceptors in Natural Base Pairs

| Base | Hydrogen Bond Donors | Hydrogen Bond Acceptors | Complementary Base | Total H-Bonds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guanine (G) | N1-H, N2-H₂ | O6, N7 | Cytosine (C) | 3 |

| Cytosine (C) | N4-H₂ | N3, O2 | Guanine (G) | 3 |

| Adenine (A) | N6-H₂ | N1, N3, N7 | Thymine (T) | 2 |

| Thymine (T) | N3-H | O2, O4 | Adenine (A) | 2 |

| Uracil (U) | N3-H | O2, O4 | Adenine (A) | 2 |

Relative Strength and Energetic Contributions

The stability of a base pair is directly related to its number of hydrogen bonds, with the G-C pair being stronger than the A-T pair. This difference is a primary reason why DNA stability and melting temperature (Tₘ) are dependent on GC content [11]. DNA with high GC-content is more stable and has a higher melting point than DNA with low GC-content.

However, the simplistic view that three hydrogen bonds automatically make G-C much stronger than A-T is nuanced by advanced computational studies. Quantum chemical analyses reveal that the intrinsic strength of individual hydrogen bonds varies. One study found that the most favorable hydrogen bond in both natural and unnatural base pairs is N-H⋯N, while O-H⋯N/O bonds are less favorable [16]. Furthermore, non-classical C-H⋯O/N bonds, particularly C-H⋯O bonds in Watson-Crick base pairs, play a significant and previously underappreciated role in stabilization [16]. When studied in a DNA environment using a QM/MM approach, the strength of the central N-H⋯N bond and the C-H⋯O bonds increases, while the strength of the N-H⋯O bond decreases, though the overall trends remain [16].

Critically, while hydrogen bonding is essential for specificity, π-π stacking interactions between adjacent base pairs in the double helix are primarily responsible for the overall stabilisation of the structure; the contribution of Watson-Crick base pairing to global structural stability is minimal in comparison to stacking [14] [11]. The interplay between these forces is complex, with studies showing that stacking can reinforce hydrogen bonding and vice versa, a phenomenon known as cooperativity [14].

Quantitative Analysis of Base Pair Stability

Thermodynamic Parameters

The stability of base pairs can be quantified using thermodynamic parameters derived from computational chemistry and experimental data. Energy decomposition analyses based on Kohn-Sham molecular orbital theory provide detailed insight into the various interactions that contribute to the stability of stacked base pairs in B-DNA [14]. These analyses break down the total interaction energy (ΔEint) into several components:

- ΔVelstat: The classical electrostatic interaction between the unperturbed charge distributions of the fragments.

- ΔEPauli: The Pauli repulsion, comprising destabilizing interactions between occupied orbitals, responsible for steric repulsion.

- ΔEoi: The orbital interaction, accounting for charge transfer and polarization.

- ΔEdisp: The dispersion interaction, accounting for correlation effects.

Table 2: Energy Decomposition Analysis (kcal mol⁻¹) for Selected Stacked Base Pairs (BP86-D/TZ2P level, Twist Angle = 36°)

| Stacked Base Pair System | ΔEint | ΔVelstat | ΔEPauli | ΔEoi | ΔEdisp | Hydrogen Bonding Contribution | Stacking Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (G-C)/(G-C) | -64.5 | -90.1 | 117.0 | -49.7 | -41.7 | ~40% | ~60% |

| (A-T)/(A-T) | -41.2 | -63.8 | 94.2 | -32.9 | -38.7 | ~30% | ~70% |

| Mismatched Pair | ~ -20 to -35 | Varies | Varies | Varies | Varies | Lower | Lower |

This analysis reveals that stacking interactions (π-π) contribute more to the overall stability of the double helix than the hydrogen bonds within individual base pairs [14]. For instance, in the (G-C)/(G-C) stack, stacking can account for approximately 60% of the stabilisation. The twist angle between stacked base pairs is also a critical factor, with studies showing that twisting from 0° to the canonical 36° provides an additional stabilization of 6 to 12 kcal mol⁻¹ across different base pair stacks [14].

Impact of Solvation

The aqueous environment profoundly impacts hydrogen bonding. In the condensed phase (e.g., water), all hydrogen bonds of the base pairs become weaker and most bonds elongate [14]. This is because the lone pairs on atoms involved in hydrogen bonding are stabilized by the solvent, reducing their energy and availability for interaction. The solvent competes for hydrogen bonding sites, which can weaken the intramolecular base pairing. This desolvation penalty must be paid for hydrogen bonds to form in an aqueous environment, a key consideration for reactions like PCR that occur in solution [14].

Hydrogen Bonding in the Context of Primer Dimers

The Primer Dimer Problem

In molecular techniques such as the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP), synthetic oligonucleotide primers must bind specifically to a target DNA template. Primer dimers are artifacts formed when these primers bind to each other via complementary base pairing instead of to the target template [3]. This occurs due to unintended hydrogen bonding between primers.

- Homodimers vs. Heterodimers: A homodimer is formed when two identical primers bind, while a heterodimer is formed when forward and reverse primers with complementary sequences bind [3].

- Consequences: Once formed, primer dimers can be extended by DNA polymerase, leading to nonspecific amplification. This depletes reaction reagents (primers, nucleotides, enzyme) and generates non-target products, which can cause false-positive signals, reduce amplification efficiency, and lower assay sensitivity [5] [3].

The problem is exacerbated in techniques like LAMP, which uses 4-6 primers targeting 6-8 regions simultaneously. The high primer concentration and the long length of inner primers (FIP and BIP, typically 40-45 bases) increase the probability of primer-primer hybridization and the formation of stable secondary structures like hairpins [5] [3].

Hydrogen Bonding as the Root Cause

The formation of primer dimers is a direct consequence of predictable hydrogen bonding between short, complementary sequences within the primers themselves.

- 3'-End Complementarity: If the 3' ends of two primers have complementary sequences, even as short as 2-3 bases, they can anneal. DNA polymerase can then bind and extend the annealed primers in both directions, creating a short, double-stranded "primer dimer" product that amplifies efficiently [3] [17].

- Inter-Primer Homology: Complementary sequences anywhere within the primers can lead to hybridization. If the 3' ends are involved, extension is efficient; if binding occurs at the 5' end or middle, the polymerase may not extend efficiently, but the hybridized primers are still sequestered and unable to participate in target amplification [3] [17].

- GC Clamps and Repetitive Sequences: Primers with high GC content, especially at the 3' end (a design feature sometimes used to enhance binding, known as a GC clamp), have stronger hydrogen bonding. This can be beneficial for specific binding but also increases the risk of dimer formation if complementarity exists. Similarly, runs of a single base (e.g., AAAA or CCCC) or dinucleotide repeats (e.g., ATATAT) increase the chance of mispriming [17].

Experimental Protocols and Mitigation Strategies

In Silico Primer Analysis and Design

Preventing primer dimers begins with careful primer design and analysis using thermodynamic tools.

Protocol: Analyzing Primers for Secondary Structures

- Sequence Input: Obtain the nucleotide sequences (5' to 3') for all primers to be used in the assay.

- Dimer Analysis: Use oligonucleotide analysis software (e.g., Thermo Fisher's Multiple Prime Analyzer, IDT's OligoAnalyzer) to check for inter-primer homology (complementarity between forward and reverse primers) and intra-primer homology (self-complementarity) [5] [17].

- Parameter Screening:

- Check for complementary regions of 3 or more bases, especially at the 3' ends.

- Calculate the Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of potential dimer formations. More negative ΔG values indicate more stable, and therefore more problematic, dimers.

- Analyze potential hairpin formation within long primers (e.g., LAMP FIP/BIP primers) using tools like mFold [5].

- Iterative Redesign: If stable dimers or hairpins (e.g., ΔG < -5 kcal/mol) are predicted, modify the primer sequences by shifting a few nucleotides upstream or downstream while maintaining a melting temperature (Tₘ) within 65°C–75°C and a GC content between 40%–60% [17].

Protocol: Thermodynamic Evaluation of Dimer Stability

- Apply the Nearest-Neighbor (NN) Model: This model estimates the stability of nucleic acid duplexes based on the identity and orientation of neighboring base pairs. It is the standard for predicting hybridization thermodynamics [5].

- Input Parameters: The model requires the dimer sequence, monovalent salt concentration (e.g., [Na⁺]), and total oligonucleotide strand concentration.

- Calculate ΔG and Tₘ: The software will compute the overall ΔG and Tₘ for the putative dimer. This quantitative data allows for the comparison of different primer sequences and the selection of sets with minimal propensity for interaction [5].

Empirical Validation and Optimization

Theoretical predictions must be confirmed experimentally.

Protocol: Gel Electrophoresis for Dimer Detection

- Run the Amplification Reaction: Perform a no-template control (NTC) reaction containing all components (primers, buffer, polymerase, dNTPs) except the target DNA/RNA.

- Post-Amplification Analysis: Resolve the NTC reaction products on a 2-4% high-resolution agarose or polyacrylamide gel alongside a DNA ladder.

- Visualization: Stain the gel with an intercalating dye like ethidium bromide or SYBR Safe and visualize under UV light.

- Interpretation: The presence of a low molecular weight band (typically smaller than the expected amplicon) in the NTC lane indicates primer dimer formation. The intensity of the band correlates with the efficiency of dimer amplification [3].

Protocol: Real-Time Monitoring with Intercalating Dyes

- Reaction Setup: Set up the NTC reaction in the presence of a fluorescent double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) intercalating dye, such as SYTO 9, SYBR Green, or EvaGreen.

- Real-Time Monitoring: Run the amplification on a real-time PCR instrument, monitoring fluorescence throughout the cycling process.

- Data Interpretation: A slowly rising fluorescent baseline in the NTC, or an amplification curve with a high Cq value, is indicative of non-specific amplification, including primer dimer formation [5]. This is a highly sensitive method for detecting low levels of dimerization.

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Studying Hydrogen Bonding and Primer Dimers

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Bst 2.0 WarmStart DNA Polymerase | A common enzyme used in isothermal amplification (e.g., LAMP). Its strand-displacing activity is essential for these techniques [5]. |

| SYTO 9 / SYBR Green Dyes | Fluorescent dsDNA intercalating dyes. Used for real-time monitoring of DNA amplification, allowing detection of both specific and non-specific (e.g., primer dimer) products [5]. |

| AMV Reverse Transcriptase | Used in RT-LAMP to first convert target RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) before amplification [5]. |

| Betaine | A reagent added to LAMP and PCR buffers to reduce secondary structure in DNA and improve amplification efficiency, especially of GC-rich targets [5]. |

| dNTPs (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) | The building blocks (deoxynucleotide triphosphates) used by DNA polymerase to synthesize new DNA strands [5] [3]. |

| MgSO₄ | A source of Magnesium ions (Mg²⁺), which is a essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity. Its concentration must be optimized, as high levels can promote non-specific priming [5] [3]. |

| Quencher Probes (for QUASR) | Short oligonucleotides with a quencher molecule used in the QUASR detection method. They quench fluorescence of unincorporated labeled primers, reducing background and improving signal-to-noise for specific amplicons [5]. |

Hydrogen bonding provides the specific molecular recognition code that governs G-C and A-T base pairing, a principle that is as fundamental to modern molecular diagnostics as it is to the central dogma of biology. While G-C pairs, with their three hydrogen bonds, confer greater thermodynamic stability than two-bonded A-T pairs, the reality is more complex, with stacking interactions and solvation playing dominant roles in overall duplex stability. In the context of primer design, an over-reliance on simple GC content for predicting stability can be misleading. A thorough thermodynamic analysis, including the evaluation of inter-primer complementarity and secondary structure, is imperative. By applying the quantitative principles and experimental protocols outlined in this guide—from in silico ΔG calculations to empirical validation with NTCs—researchers can systematically design robust assays. Mastering the chemistry of hydrogen bonding enables scientists to harness its power for specificity while mitigating its potential to create artifacts, thereby ensuring the fidelity and reliability of genetic analysis.

Primer-dimer formation represents a significant impediment to the efficiency and specificity of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, a cornerstone of modern molecular biology and diagnostic applications. This whitepaper delineates the fundamental role of hydrogen bonding in the molecular architecture of primer-dimers, with a specific focus on the contributions of guanine (G) and cytosine (C) nucleotide content. The strength of hydrogen bonding, which is markedly greater in G-C pairs (three bonds) than in A-T pairs (two bonds), directly influences the stability of these aberrant primer-primer interactions [18]. We explore how excessive GC content and improperly configured GC clamps at the 3' end of primers can inadvertently promote dimerization, leading to false-positive results and reduced amplification yield. This technical guide provides a detailed examination of the underlying mechanisms, summarizes optimal design parameters in structured tables, and outlines robust experimental protocols for in silico and empirical validation of primer sets to mitigate these issues, thereby enhancing the fidelity of PCR-based research and diagnostics.

The polymerase chain reaction is an indispensable technique across biomedical research, clinical diagnostics, and forensic science. Its success, however, is critically dependent on the specific annealing of oligonucleotide primers to their intended target sequences. A pervasive challenge in PCR optimization is the formation of primer-dimers, which are spurious amplification products generated when primers anneal to each other or to themselves instead of the target DNA template [17] [18]. These artifacts consume reaction reagents, compete with the desired amplification product, and can lead to erroneous interpretations, particularly in sensitive applications like real-time PCR [19].

The formation of primer-dimers is fundamentally governed by the thermodynamics of hydrogen bonding between complementary nucleotide bases. The differential strength between G-C and A-T base pairing is a primary structural culprit in this process. Each G-C pair forms three hydrogen bonds, conferring significantly greater stability to the duplex than an A-T pair, which forms only two [18] [20]. Consequently, primers with high overall GC content or localized regions rich in G and C bases, particularly at the 3' end, possess a heightened propensity for stable, non-specific interactions. This whitepaper examines the precise mechanisms by which GC content and the design of the GC clamp influence dimer formation, framing the discussion within the broader context of hydrogen bonding energetics. The objective is to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for designing and validating primers that minimize these detrimental interactions.

Molecular Mechanisms: Hydrogen Bonding and Dimer Energetics

The Biochemistry of Base Pairing

The stability of any nucleic acid duplex, whether a correctly annealed primer-template complex or an erroneous primer-dimer, is predominantly determined by the cumulative strength of hydrogen bonds between opposing bases and the stabilizing effect of base stacking. The hydrogen bond is a key intermolecular force where a hydrogen atom covalently bonded to an electronegative atom (such as nitrogen or oxygen in DNA bases) experiences an attractive force with another electronegative atom. In the context of primer binding, this translates to a direct relationship between base composition and duplex melting temperature (Tm): the temperature at which 50% of the duplex dissociates into single strands [18].

The following dot code illustrates the fundamental relationship between base pairing, hydrogen bonding, and the subsequent risk of primer-dimer formation.

GC Clamp: A Double-Edged Sword

A GC clamp refers to the strategic placement of G or C bases within the last five nucleotides at the 3' end of a primer. The rationale for its use is sound: promoting strong, specific binding at the primer's 3' terminus, which is crucial for enzymatic elongation by DNA polymerase [17] [21]. The stronger hydrogen bonding of a GC clamp helps ensure the primer's 3' end remains securely annealed to the template.

However, this very feature becomes a liability when primers engage in off-target interactions. A strong GC clamp at the 3' end can facilitate the initiation and stabilization of primer-dimer complexes. If the 3' ends of two primers contain complementary sequences with high GC content, the strong hydrogen bonding can effectively "lock" them in place, allowing DNA polymerase to extend them into a dimer product [20]. This is why it is recommended to avoid more than three G or C bases in the last five bases at the 3' end, as this significantly increases the risk of non-specific binding and false-positive results [17] [18] [21].

Quantitative Design Parameters for Optimal Primer Specificity

Adherence to established quantitative parameters during primer design is the most effective strategy for preemptively minimizing dimer formation. The following table consolidates critical design criteria based on widely accepted principles and experimental validations [17] [18] [20].

Table 1: Optimal Primer Design Parameters to Minimize Dimer Formation

| Parameter | Recommended Range | Rationale and Impact on Dimer Formation |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Length | 18-30 nucleotides [17] | Shorter primers (<18 bp) bind more efficiently but may lack specificity; longer primers can increase chances of inter-primer homology. |

| GC Content | 40-60% [17] [18] | Content below 40% results in weak binding; above 60% promotes overly stable non-specific interactions and dimers. |

| GC Clamp (3' end) | 1-3 G/C bases in the last 5 bases [17] [21] | Fewer than 1 reduces binding efficiency; more than 3 G/C bases drastically increases stability of primer-dimers. |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | 65-75°C for primers in a pair, within 5°C of each other [17] | Ensures both primers anneal efficiently at the same temperature, preventing single-primer artifacts that can lead to dimers. |

| Self-Complementarity | Minimize; avoid runs of 4+ identical bases or dinucleotide repeats (e.g., ACCCC, ATATAT) [17] [22] | Repetitive sequences and mononucleotide runs increase the potential for intra- and inter-primer homology, facilitating dimerization. |

The strategic application of these parameters requires the use of sophisticated bioinformatics tools. These tools perform critical in silico checks for self-complementarity and hairpin formation, parameters that are quantitatively represented as "self-complementarity" and "self 3'-complementarity" scores. The guiding principle for these scores is that lower values are superior, indicating a reduced potential for secondary structure formation [18].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

In Silico Design and Specificity Workflow

Prior to synthesizing primers, a rigorous computational validation workflow is essential. This multi-step process leverages specialized software to preemptively identify and eliminate primers with a high propensity for dimerization [19].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Primer Design and Validation

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Preventing Primer-Dimers |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Design Algorithms | Primer3 (integrated into Primer-BLAST) [23], PrimerMapper [22] | Automates the application of design parameters from Table 1, calculating Tm, GC%, and filtering primers with high self-complementarity. |

| Specificity Checking Tools | NCBI Primer-BLAST [23] | Checks candidate primer pairs for specificity against a selected database (e.g., RefSeq mRNA) to ensure they will not anneal to non-target sequences. |

| Post-Hoc Analysis Tools | URAdime [24] | Analyzes sequencing data from a multiplex PCR to identify the specific primers responsible for generating primer-dimer and super-amplicon artifacts. |

| Dimer Prediction Algorithms | Simulated Annealing Design using Dimer Likelihood Estimation (SADDLE) [24], PrimerMapper's "Multiplex PCR dimer scores" [22] | Systematically calculates cross-complementarity scores between all possible primer pairs in a multiplex set to flag potential dimers before ordering. |

Empirical Optimization and Troubleshooting

Even the most rigorous in silico design requires empirical validation. The following protocol outlines a systematic approach for testing and optimizing primer pairs, with a focus on eliminating spurious amplification [19].

Protocol: Empirical Validation and Optimization of Primer Sets

Reaction Setup: Prepare a standard PCR reaction mix, including all components (polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, Mg²⁺) and the forward and reverse primers. It is critical to include a no-template control (NTC) containing all components except the DNA template. The NTC is essential for detecting primer-dimer formation.

Annealing Temperature Gradient: Perform a thermal cycling reaction using a gradient PCR instrument. Set a range of annealing temperatures (e.g., from 5°C below to 5°C above the calculated Tm of the primers). This helps determine the optimal temperature for specific primer binding.

Primer Concentration Titration: If dimer persistence is observed, titrate the primer concentrations. Testing a range from 50 nM to 500 nM final concentration can identify a concentration that supports efficient amplification while minimizing dimer artifacts. A balanced concentration of both primers is crucial [18].

Analysis: Analyze the PCR products using agarose gel electrophoresis. A successful reaction should show a single, sharp band of the expected amplicon size in the sample lanes, with a clear NTC. A smear or a low molecular weight band (~50 bp or below) in the NTC indicates significant primer-dimer formation.

Troubleshooting: If dimers persist:

- Increase Annealing Temperature: Raise the temperature in 1-2°C increments to disrupt the weaker hydrogen bonding in dimer complexes without significantly affecting specific binding.

- Redesign Primers: If optimization fails, the most reliable solution is to redesign the primers, strictly adhering to the guidelines in Table 1 and avoiding 3' ends with high GC clamps or self-complementary sequences [19].

The intricate role of hydrogen bonding in nucleic acid interactions positions GC content and GC clamp design as critical structural determinants in the formation of primer-dimers. The triple-bonded strength of G-C base pairs, while beneficial for specific target annealing, can readily become a driver of assay failure when primers engage in off-target interactions. A comprehensive strategy that integrates disciplined in silico design, adhering to quantitative parameters for GC distribution and 3' end sequence, with systematic empirical validation is paramount. For the research and drug development community, mastering the hydrogen bonding principles that underpin these artifacts is not merely a technical exercise but a prerequisite for achieving the robust, reliable, and reproducible results demanded in modern molecular biology. As PCR continues to evolve and be applied in increasingly complex multiplexed and diagnostic formats, a deep understanding of these structural culprits will remain essential.

Within the context of primer dimer research, the formation of non-specific amplification artifacts is a critical challenge. These dimers are primarily stabilized by inter-primer hydrogen bonds. This whitepaper examines the underappreciated role of water molecules as direct competitors in these hydrogen bond interactions. The thermodynamic stability of a primer dimer is not merely a function of primer-primer affinity but is a result of a competitive equilibrium between primer-primer, primer-water, and water-water hydrogen bonds. Understanding this solvation shell competition is essential for optimizing assay specificity in molecular diagnostics and drug development targeting nucleic acid interactions.

Quantitative Data on Hydrogen Bond Energetics

The stability of hydrogen-bonded complexes in aqueous solution is governed by the net free energy change, which accounts for the competition between bond formation and the associated (de)solvation penalties.

Table 1: Energetic Contributions to Hydrogen Bond Formation in Aqueous Solution

| Interaction Type | Enthalpy (ΔH, kJ/mol) | Entropy (TΔS, kJ/mol) | Free Energy (ΔG, kJ/mol) | Context in Primer Dimers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base Pair (e.g., A-T) | -15 to -25 (Favorable) | -10 to -20 (Unfavorable) | -4 to -8 (Net Favorable) | Direct stabilization of the dimer complex. |

| Water-Water (Bulk) | ~ -20 (Favorable) | + (Favorable) | ~ -10 (Net Favorable) | Represents the stable reference state for displaced water. |

| Polar Group Hydration | -20 to -40 (Favorable) | -15 to -30 (Unfavorable) | -5 to -10 (Net Favorable) | Energy cost to dehydrate primer bases before dimer formation. |

| Net Dimer Formation | ~0 to -10 (Slightly Favorable) | -15 to -30 (Highly Unfavorable) | +5 to +20 (Net Unfavorable) | Overall process including dehydration and base pairing. |

Experimental Protocols for Probing Water Competition

3.1. Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) for Thermodynamic Profiling

Objective: To directly measure the enthalpy (ΔH), stoichiometry (N), and equilibrium constant (Ka) of primer-primer binding, thereby deriving the full thermodynamic profile (ΔG, ΔS).

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve the forward and reverse primers in an identical, degassed buffer (e.g., 10 mM Sodium Phosphate, pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl). The concentration of the primer in the syringe (typically 100-200 µM) should be 10-20 times higher than the concentration in the cell (typically 10 µM).

- Instrument Setup: Thoroughly clean and dry the ITC sample cell and syringe. Load the reverse primer solution into the 1.4 mL sample cell and the forward primer into the 250 µL syringe. Set the reference cell to degassed, pure water.

- Titration Parameters:

- Temperature: 25°C

- Number of Injections: 19

- Injection Volume: 2 µL (first injection of 0.4 µL discarded from data analysis)

- Duration: 4 seconds per injection

- Spacing: 180 seconds between injections

- Stirring Speed: 750 rpm

- Control Experiment: Perform an identical titration of the forward primer into buffer alone to measure and subtract the heat of dilution.

- Data Analysis: Fit the corrected isotherm (heat per mole of injectant vs. molar ratio) using a suitable binding model (e.g., "One Set of Sites") to obtain ΔH, Ka, and N. Calculate ΔG using ΔG = -RT lnKa and ΔS using ΔG = ΔH - TΔS.

3.2. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations with Explicit Solvent

Objective: To visualize and quantify the dynamics of water molecules in the solvation shell of primers and during dimer formation.

Protocol:

- System Setup:

- Construct a model of a primer dimer using nucleic acid building blocks or extract a structure from a relevant PDB file.

- Place the dimer in a simulation box (e.g., a rhombic dodecahedron) with a minimum 1.0 nm distance between the solute and the box edge.

- Solvate the system with explicit water models (e.g., TIP3P, SPC/E).

- Add ions (e.g., Na+, Cl-) to neutralize the system and achieve a physiologically relevant salt concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl).

- Energy Minimization: Perform steepest descent energy minimization to remove steric clashes and bad contacts.

- Equilibration:

- Run a 100 ps simulation in the NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) using a thermostat (e.g., V-rescale) to stabilize the temperature at 300 K.

- Follow with a 100 ps simulation in the NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) using a barostat (e.g., Berendsen) to stabilize the pressure at 1 bar.

- Production Run: Execute a long-term MD simulation (e.g., 100-500 ns) in the NPT ensemble, saving atomic coordinates every 10 ps.

- Trajectory Analysis:

- Hydrogen Bond Analysis: Use tools like

gmx hbond(GROMACS) to calculate the lifetime and occupancy of hydrogen bonds between primers and between primers and water. - Radial Distribution Function (RDF): Calculate g(r) between primer atoms and water oxygen to understand solvation structure.

- Energetics: Decompose interaction energies to quantify the contribution of water displacement to dimer stability.

- Hydrogen Bond Analysis: Use tools like

Visualizations

Title: Water Competition in Dimer Formation

Title: ITC Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Ultra-Pure DNase/RNase-Free Water | Eliminates nuclease contamination and ensures a consistent, pure aqueous environment for studying hydrogen bonding. |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimeter (ITC) | The gold-standard for label-free, in-solution measurement of binding thermodynamics, directly quantifying the heat changes from competitive interactions. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER) | Enables atomistic simulation of primer-water and primer-primer interactions with explicit solvent models over time. |

| Explicit Solvent Force Fields (e.g., OPC, TIP4P-Ew) | Advanced water models that provide a more accurate representation of hydrogen bond geometry and energetics compared to simpler models. |

| Controlled Atmosphere Glove Box | Allows for the preparation of samples in a water vapor-free environment (e.g., using N₂ gas) to study the effects of controlled re-hydration. |

| High-Performance Salt Solutions (e.g., NaCl, MgCl₂) | Used to systematically investigate the ionic strength's effect on water structure and its competition for phosphate backbone interactions. |

In molecular biology, the efficacy of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and related amplification techniques is fundamentally dependent on the precise binding of primers to their target DNA sequences. The formation of primer secondary structures, particularly hairpins, represents a significant challenge to assay performance. These structures are stabilized primarily by intramolecular hydrogen bonding, which can sequester primer sequences into inactive conformations [5]. When primers form stable hairpins, they are unable to anneal to the template DNA, leading to reduced amplification efficiency, false negatives, or non-specific amplification [25] [4]. Within the broader context of hydrogen bonding research in primer-dimers, understanding hairpin formation is paramount, as these intramolecular interactions follow the same thermodynamic principles that govern intermolecular primer-dimer artifacts.

The propensity for hairpin formation is intrinsically linked to the molecular composition of the primer. Hydrogen bonds between complementary base pairs within a single oligonucleotide strand facilitate the folding of the molecule onto itself. Guanine-cytosine (G-C) base pairs, connected by three hydrogen bonds, confer greater stability to these secondary structures than adenine-thymine (A-T) pairs, which are connected by only two hydrogen bonds [18]. Consequently, primers with high GC content, especially in self-complementary regions, are particularly prone to forming stable hairpins that can withstand the annealing temperature of a PCR reaction, thereby compromising the experiment's success [4].

Molecular Mechanisms of Hairpin Formation and Stabilization

Thermodynamic Principles and Hydrogen Bonding

Hairpin formation is a spontaneous process driven by a negative change in Gibbs free energy (ΔG), which indicates the stability of the formed structure [4]. The overall stability of a hairpin is determined by the sum of favorable and unfavorable energy contributions. The favorable energy gain comes from the hydrogen bonds formed between complementary bases and the stacking interactions between adjacent base pairs in the stem region. Conversely, the main unfavorable energy component is the loop entropy, which is required to bring the complementary regions together to form the stem [5]. The nearest-neighbor model is widely used to predict the thermodynamic stability of these secondary structures by considering the sequence context and interactions between adjacent nucleotide pairs [5].

The role of intramolecular hydrogen bonding in shaping molecular conformation extends beyond nucleic acids and is a critical factor in drug design and bioavailability. Research on small drug molecules like piracetam has demonstrated that the formation of intramolecular hydrogen bonds (IMHBs) can significantly alter a compound's properties, facilitating passive diffusion across lipid membranes by reducing the polarity and desolvation penalty [26]. This principle of conformational control via internal hydrogen bonding is analogous to its role in primer biochemistry, where IMHBs dictate the folding and functional availability of the oligonucleotide.

Structural Types and Classification

Hairpin structures are primarily categorized based on the location of the self-complementary region, which determines their potential impact on amplification:

- 3' End Hairpins: Formed when the first and last few bases at the 3' end of a primer are complementary. These are the most detrimental to PCR efficiency because they can prevent the DNA polymerase from binding and initiating extension [4]. A stable 3' end hairpin effectively blocks the primer from functioning.

- Internal Hairpins: Occur when complementary sequences are located within the internal regions of the primer. While generally less catastrophic than 3' end hairpins, stable internal structures can still sequester a significant portion of the primer molecule, reducing the effective concentration of available primers and lowering the reaction yield [4].

Table 1: Characteristics and Impacts of Different Hairpin Types.

| Hairpin Type | Structural Feature | Potential Impact on PCR |

|---|---|---|

| 3' End Hairpin | Complementarity between the first and last 3-4 bases at the 3' end. | Prevents polymerase binding and extension; most severe impact. |

| Internal Hairpin | Complementarity between two internal regions, creating a loop. | Reduces primer availability and efficiency; can cause failure. |

| Stable Hairpin | ΔG value more negative than -3 kcal/mol [4]. | May not denature at PCR annealing temperature. |

| Unstable Hairpin | ΔG value less negative than -3 kcal/mol [4]. | Likely to denature during PCR, minimal impact. |

Experimental Detection and Analysis Methodologies

In Silico Prediction and Analysis Workflow

Computational tools are the first line of defense against hairpin formation in primer design. The following workflow outlines a standard protocol for analyzing potential secondary structures.

Title: In Silico Primer Analysis Workflow

Protocol Steps:

- Sequence Input and Hairpin Prediction: Input the candidate primer sequence (typically 18-24 nucleotides) into a dedicated analysis tool such as IDT's OligoAnalyzer or mFold [5] [4]. These programs simulate the folding of the single-stranded DNA and identify regions with intra-primer homology capable of forming hairpin loops.

- Thermodynamic Stability Assessment: The software calculates the Gibbs free energy (ΔG) for all possible secondary structures using the nearest-neighbor model [5]. As a general rule, hairpins with a ΔG value more negative than -3 kcal/mol for internal hairpins or -2 kcal/mol for 3' end hairpins are considered stable and likely to interfere with the PCR reaction [4].

- 3' End Complementarity Check: A critical step is to manually inspect the prediction results for any complementarity at the 3' terminus. Even one or two complementary bases at the 3' end can form a self-amplifying structure, leading to primer extension and significant non-specific background amplification [5].

- Cross-homology and Dimer Analysis: Use tools like the Thermo Fisher Scientific Multiple Primer Analyzer to check for inter-primer homology that could lead to primer-dimer formation between forward and reverse primers [27] [4]. Furthermore, test primer specificity by performing a BLAST search against the relevant genomic database to ensure the primer binds uniquely to the intended target [25] [4].

Empirical Validation Protocols

While in silico analysis is powerful, empirical validation is essential for confirming primer performance in actual reaction conditions.

Protocol: Gradient PCR with Melt Curve Analysis

Reaction Setup:

- Prepare a standard PCR master mix containing buffer, dNTPs, DNA polymerase (e.g., Bst 2.0 WarmStart for LAMP), and a fluorescent intercalating dye like SYTO 9 or SYBR Green [5] [4].

- Add the forward and reverse primers at their working concentrations (typically 0.1-0.5 µM each for standard PCR) [5].

- Include a no-template control (NTC) to detect amplification arising from primer artifacts alone.

Thermal Cycling:

- Perform a temperature gradient PCR, setting the annealing temperature (Ta) to a range from 5°C below to 5°C above the calculated theoretical Ta [25] [4].

- Following amplification, conduct a high-resolution melt curve analysis by gradually increasing the temperature from 60°C to 95°C while continuously monitoring fluorescence.

Data Interpretation:

- Analyze the amplification curves. A slowly rising baseline in the NTC, or early amplification in the NTC, indicates non-specific amplification potentially due to hairpins or primer-dimers [5].

- Examine the melt curve. A single, sharp peak corresponds to the specific PCR product. Multiple or broad peaks suggest the presence of non-specific products or primer artifacts, which may stem from primers with stable secondary structures [4].

Quantitative Data and Design Parameters

Adherence to established primer design parameters is the most effective strategy to minimize the risk of hairpin formation. The following table summarizes the optimal values for key design characteristics based on current research and best practices.

Table 2: Optimal Primer Design Parameters to Minimize Secondary Structures [25] [4] [18].

| Design Parameter | Optimal Value or Range | Rationale and Impact on Hairpins |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Length | 18 - 24 bp | Balances specificity and binding efficiency; overly long primers (>30 bp) increase the chance of intra-primer homology. |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | 50 - 65 °C; within 5 °C for a pair | Ensures both primers anneal simultaneously. A very low Tm can permit hairpin stability during annealing. |

| GC Content | 40 - 60% | Provides sufficient stability without promoting overly stable G-C rich hairpins (G-C bonds have 3 H-bonds vs. A-T's 2). |

| GC Clamp | 2-3 G/C bases in last 5 bases at 3' end | Stabilizes primer-template binding but more than 3 can cause non-specific binding and increase risk of 3' end hairpins. |

| Self-Complementarity | As low as possible | Directly measures the potential for a primer to form hairpins or self-dimers. |

| ΔG of Hairpins | > -3 kcal/mol (internal), > -2 kcal/mol (3' end) | A less negative ΔG ensures the hairpin is unstable and will denature at the reaction temperature. |

Case Study: Troubleshooting Hairpins in Complex Assays

The impact of hairpins is particularly pronounced in techniques involving multiple long primers, such as Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP). A study on RT-LAMP detection of dengue and yellow fever viruses provides a compelling case study [5].

Experimental Observation: Previously published primer sets displayed a slowly rising baseline in real-time fluorescence curves and poor endpoint signal in the QUASR detection technique. This was hypothesized to be due to amplifiable primer dimers and self-amplifying hairpin structures in the FIP and BIP primers, which are typically 40-45 bases long [5].

Methodology and Intervention:

- The researchers performed a thorough thermodynamic analysis of the original primers using the nearest-neighbor model to identify regions of high self-complementarity.

- Minor sequence modifications were introduced to these regions to disrupt the stable secondary structures, particularly those with 3' complementarity, while preserving target specificity.

- The performance of the original and modified primer sets was compared using real-time RT-LAMP with intercalating dyes and the QUASR endpoint technique.

Results: The modified primers, designed to eliminate amplifiable hairpins, demonstrated significantly improved performance. The non-specific background amplification was dramatically reduced, leading to clearer positive-negative discrimination and more reliable assay outcomes [5]. This study quantitatively demonstrates that even hairpins with complementarity one or two bases away from the 3' end can self-amplify and that their elimination is critical for robust assay performance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Analyzing Primer Secondary Structures.

| Reagent / Tool | Function and Application |

|---|---|

| Bst 2.0 WarmStart DNA Polymerase | An enzyme commonly used in LAMP assays. Its strand-displacing activity is sensitive to primer secondary structures, making it a good tool for testing functional primer performance [5]. |

| SYTO 9 / SYBR Green Dyes | Fluorescent intercalating dyes that bind double-stranded DNA. They are used in real-time PCR/LAMP to monitor amplification kinetics and identify non-specific amplification from primer artifacts [5] [4]. |

| IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool Suite | A web-based suite for in silico primer analysis. It calculates Tm, ΔG for hairpins and self-dimers, and visualizes potential secondary structures [5] [4]. |

| Thermo Fisher Multiple Primer Analyzer | A tool for checking cross-dimer formation between forward and reverse primers, as well as self-dimerization, which often co-occurs with hairpin problems [27] [4]. |

| mFold Software | A tool for predicting the secondary structure formation of nucleic acids, used for advanced folding simulations and stability assessments [5]. |

The formation of hairpin structures through intramolecular hydrogen bonding is a fundamental phenomenon that can critically undermine the success of nucleic acid amplification experiments. The thermodynamic principles that govern these interactions are well-characterized, enabling robust in silico prediction methods. By integrating computational design adhering to strict parameters, such as optimizing length, Tm, and GC content, with empirical validation techniques like gradient PCR, researchers can effectively mitigate the risks posed by primer secondary structures. As demonstrated in advanced applications like LAMP, a meticulous approach to primer design—paying particular attention to 3' end stability—is not merely a preliminary step but a central component in the development of specific, sensitive, and reliable molecular assays. Future research into the dynamics of intramolecular hydrogen bonding will continue to refine our understanding and control of these crucial molecular interactions.

From Theory to Bench: Strategic Primer Design and Dimer Detection Methods

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) stands as one of the most pivotal inventions in molecular biology, enabling the amplification of small amounts of genetic material for identification, manipulation, and detection [28]. At the heart of every successful PCR experiment lies a critical component: well-designed primers. The quality of these primers directly governs the specificity, efficiency, and overall success of the amplification reaction [29]. In the context of drug development and advanced research, where reproducibility and accuracy are paramount, adhering to gold-standard design rules transcends mere recommendation and becomes an absolute necessity. The exquisite specificity and sensitivity that make PCR uniquely powerful are controlled predominantly by primer properties [30]. Consequently, poor design combined with failure to optimize reaction conditions frequently results in reduced technical precision, false positives, or false negative detection of amplification targets.

The foundational principles of primer design extend beyond simple sequence selection to encompass a deep understanding of molecular interactions, particularly hydrogen bonding dynamics. These interactions not only facilitate the specific binding of primers to their target sequences but also govern undesirable side reactions such as primer-dimer formation. When primers interact with each other instead of the target template, they form primer-dimers through hydrogen bonding between complementary bases, effectively competing for precious reaction resources and compromising assay sensitivity [31] [32]. This comprehensive guide details the gold-standard parameters for primer design, with particular emphasis on how the rules governing length, melting temperature (Tm), and GC content directly influence hydrogen bonding stability and specificity, ultimately determining experimental outcomes in research and diagnostic applications.

Core Parameters for Gold-Standard Primer Design

Optimal Primer Length

Primer length fundamentally determines the balance between specificity and binding efficiency. Excessively short primers lack the sequence complexity required for unique targeting, while overly long primers exhibit slower hybridization rates and can create unnecessarily high melting temperatures that hinder polymerase function.

- Optimal Range: The consensus across multiple authoritative sources recommends maintaining primer lengths between 18 and 30 nucleotides [31] [17] [33]. The most frequently utilized and recommended range narrows this to 18–24 bases [18] [28]. This length provides sufficient sequence for unique binding within complex genomes while ensuring efficient annealing during thermal cycling.

- Impact of Deviations: Primers shorter than 18 bases risk insufficient specificity and may anneal to multiple non-target sites, leading to nonspecific amplification [29]. Conversely, primers exceeding 30 bases hybridize more slowly to their target sequence, potentially reducing amplification yield and efficiency [18]. Long primers also tend to form more stable secondary structures, further complicating the reaction dynamics.

Melting Temperature (Tm)

The melting temperature (Tm) of a primer is defined as the temperature at which half of the DNA duplex dissociates into single strands, providing a quantitative measure of duplex stability [28]. Accurate Tm calculation and synchronization between primer pairs is arguably the most critical factor in successful PCR design.

- Optimal T

mRange: While specific recommended values vary slightly, the general consensus falls within a 55–65°C range [34] [31]. For standard PCR, primers with Tmvalues of 52–58°C often produce excellent results, while for qPCR applications, an optimal Tmof 60–64°C is frequently advised [33] [28]. - Primer Pair Matching: Perhaps the most critical rule is that the forward and reverse primers in a pair should have closely matched T

mvalues, ideally within ≤2°C of each other [33] [18]. A mismatch of 5°C or more can lead to failed amplification, as one primer will anneal efficiently while the other does not [28]. - Calculation Methods: Two primary methods exist for T

mcalculation:- Basic GC% Formula: T

m= 4(G + C) + 2(A + T). This method provides a rough estimate but is less accurate as it ignores sequence context [18]. - Nearest-Neighbor Thermodynamics: This is the gold-standard method based on SantaLucia's unified parameters (1998). It accounts for dinucleotide stacking energies and sequence context, achieving prediction accuracy of ±1–2°C [34]. It requires specialized software but is incorporated into all modern primer design tools.

- Basic GC% Formula: T

Table 1: Comparison of Melting Temperature Calculation Methods

| Method | Accuracy | Complexity | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nearest-Neighbor Thermodynamics | Highest (±1–2°C) [34] | High | Accounts for dinucleotide stacking, sequence context, and salt effects; the gold standard for design [34]. |

| GC% Approximation | Low (±5–10°C) [34] | Low | Considers only GC content, ignoring sequence context; suitable for quick estimates only [34]. |

| Salt-Adjusted Formulas | High | Medium | Incorporates Owczarzy et al. (2008) corrections for mixed ion solutions, essential for PCR with Mg²⁺ [34]. |

GC Content and GC Clamp

The GC content—the percentage of guanine (G) and cytosine (C) bases in the primer—directly influences binding stability through hydrogen bonding. GC base pairs form three hydrogen bonds, while AT pairs form only two [18]. This differential bonding energy is the physical basis for several design rules.

- Optimal GC Content: Primers should have a GC content between 40% and 60%, with an ideal target of 50% [34] [33] [29]. This range provides stable primer-template binding without promoting mispriming or secondary structure formation.

- Consequences of Extreme GC Content:

- Low GC (<40%): Results in overly weak priming sites due to insufficient hydrogen bonding, leading to unstable hybrids and potentially low product yield [34].

- High GC (>60%): Promotes stable non-specific binding and increases the risk of secondary structures (e.g., hairpins) because of the stronger hydrogen bonding, which can halt the reaction [34] [29].

- The GC Clamp: The presence of G or C bases within the last five bases at the 3' end of the primer is known as a GC clamp. This promotes stronger binding at the 3' terminus due to the extra hydrogen bonds, ensuring the polymerase extension site is securely anchored [17] [28]. However, more than three G or C bases in the last five should be avoided, as this can encourage non-specific initiation [28].

Advanced Considerations and Troubleshooting

Avoiding Secondary Structures and Primer Dimers

The same hydrogen bonding forces that facilitate specific primer-template annealing can also lead to detrimental intra-primer and inter-primer interactions. Preventing these is crucial for assay efficiency.

- Hairpins: Formed by intramolecular hybridization within a single primer, where two regions of three or more nucleotides complement each other [18] [28]. Hairpins, especially those at the 3' end, can prevent the primer from binding to its template. Stability is measured by Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG); larger negative values indicate more stable, problematic structures. Hairpins with a ΔG < -3 kcal/mol should generally be avoided [34] [28].

- Self-Dimers and Cross-Dimers: Self-dimers occur when two copies of the same primer hybridize, while cross-dimers form between the forward and reverse primers [18]. These interactions consume primers and polymerase resources, drastically reducing the yield of the desired product. The ΔG of any dimer should be weaker (more positive) than -9.0 kcal/mol [33], with 3' end dimers more critical than internal ones.

Table 2: Summary of Critical Parameters to Avoid in Primer Sequences

| Parameter | Description | Maximum Tolerable Threshold | Impact of Violation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Runs (Homopolymers) | Consecutive identical bases (e.g., AAAA or GGGG) [17]. | 4 contiguous bases [17] [28]. | Mispriming due to slippage, non-specific binding. |

| Dinucleotide Repeats | Short, tandem repeats (e.g., ATATAT) [17]. | 4 di-nucleotides [28]. | Mispriming, poor specificity. |

| Self 3'-Complementarity | Complementarity at the 3' end leading to hairpins [18]. | ΔG > -2 kcal/mol [28]. | Failure of primer extension, no product. |

| Inter-Primer 3'-Complementarity | Complementarity between the 3' ends of forward and reverse primers [31]. | ≤3 contiguous bases, especially at 3'-ends [31]. | Primer-dimer formation, reduced target yield. |

| Intra-Primer Homology | Self-complementarity within a single primer [17]. | ≤3 contiguous bases [31]. | Hairpin formation. |

The Critical Role of the 3' End

The 3' terminus of the primer is where DNA synthesis initiates, making its configuration and stability paramount. A lower ΔG (less negative) at the 3' end is desirable as it facilitates specific binding and reduces the likelihood of non-specific initiation from mismatched primers [29] [28]. Some advanced strategies involve covalently modifying the 3' end with stable alkyl groups attached to the exocyclic amines of adenine or cytosine. These bulky groups are believed to poorly extend from misprimed structures, thereby enhancing specificity by chemically suppressing primer-dimer propagation [32].

Experimental Condition Considerations

Theoretical primer design must be translated into practical reaction environments, which significantly influence hybridization behavior.

- Salt Concentrations: Cations shield the negative charges on the DNA phosphate backbone. Both monovalent (Na⁺, K⁺) and divalent (Mg²⁺) ions stabilize the duplex, increasing the observed T

m.- Mg²⁺ has a stronger effect than Na⁺ and is a critical cofactor for polymerase activity. However, it also binds to dNTPs, reducing its effective concentration. The Owczarzy (2008) salt correction formula is recommended for accurate T

mprediction under standard PCR conditions (1.5–2.5 mM Mg²⁺) [34]. - Impact: Doubling Na⁺ from 50 mM to 100 mM can increase T

mby ~5°C, while adding 2 mM Mg²⁺ can boost Tmby 5–8°C [34].

- Mg²⁺ has a stronger effect than Na⁺ and is a critical cofactor for polymerase activity. However, it also binds to dNTPs, reducing its effective concentration. The Owczarzy (2008) salt correction formula is recommended for accurate T

- Annealing Temperature (T

a) is critically derived from the primer Tm. A common and robust formula is the Rychlik method: TaOpt = 0.3 x Tm(primer) + 0.7 x Tm(product) – 14.9, where Tm(primer) is for the less stable primer [28]. A good starting point is to set Ta2–5°C below the calculated Tmof the primers [18]. If Tais too low, non-specific amplification occurs; if too high, product yield plummets [33]. - Additives: DMSO is often added to disrupt secondary structures, particularly in GC-rich templates. It lowers the T

mby approximately 0.5–0.7°C per 1% concentration and should be accounted for in calculations [34].

Essential Tools and Verification Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Modern primer design and validation rely on a suite of sophisticated software tools and reagents.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Primer Design and Analysis

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Design Software | Primer3 [31], Primer-BLAST [23], Primer Express (Applied Biosystems) [31], Primer Premier [28] | Automates primer design based on user-defined parameters and template sequence. |

| Oligo Analysis Tools | OligoAnalyzer Tool (IDT) [33], UNAFold Tool [33], Netprimer [31] | Analyzes Tm, secondary structures (hairpins, dimers), and ΔG values for pre-designed oligos. |

| Specificity Check Tools | NCBI BLAST [33] [29], Primer-BLAST [23] | Verifies primer uniqueness against genomic databases to ensure target-specific binding. |

| Hot-Start Polymerases | Antibody-bound or chemically modified Taq polymerases [32] | Reduces non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup by inhibiting polymerase activity at low temperatures. |

| Chemically Modified Primers | 3'-end alkyl-modified primers [32], 2'-O-methyl RNA, LNA residues [32] | Enhances PCR specificity by sterically hindering the extension of mis-annealed primers. |

Primer Design and Validation Workflow

The following diagram visualizes the systematic, gold-standard workflow for designing and validating PCR primers, integrating both in silico and experimental steps.

Diagram Title: Primer Design and Validation Workflow

A critical final step in the design process is specificity verification. Before synthesizing primers, their sequences must be checked using a BLAST search against the appropriate genomic database (e.g., Refseq mRNA) to ensure they are unique to the intended target [23] [29]. This in silico step prevents costly experimental failures due to off-target amplification.

Adherence to the gold-standard rules of primer design—length (18–30 bp), melting temperature (55–65°C with ≤2°C difference between pairs), and GC content (40–60%)—is non-negotiable for robust, reproducible PCR in research and drug development. These parameters are not arbitrary but are fundamentally rooted in the thermodynamics of hydrogen bonding, which governs the stability of the primer-template duplex and the propensity for aberrant structures like primer-dimers. By meticulously applying these guidelines, leveraging modern design and analysis software, and validating designs experimentally, researchers can ensure that their assays achieve the highest levels of specificity and efficiency, thereby generating reliable and meaningful scientific data.

Leveraging Computational Tools for Predicting Primer-Primer Interactions

In polymerase chain reaction (PCR) experiments, the undesired formation of primer-dimers through hydrogen bonding between primers represents a significant challenge, often leading to reduced amplification efficiency and false results. Primer-dimers are formed due to the presence of complementary sequences within a single primer or between forward and reverse primers, leading to inter-primer homology that enables hydrogen bonding between them [18]. This comprehensive technical guide explores the sophisticated computational tools and methodologies developed to predict and prevent these detrimental interactions, with particular focus on the fundamental role of hydrogen bonding in stabilizing these non-productive complexes. By framing this discussion within the context of molecular interactions, we provide researchers with a detailed roadmap for leveraging computational predictions to enhance experimental outcomes, ultimately improving the reliability of diagnostic assays, research applications, and drug development processes.

The Molecular Basis of Primer-Dimer Formation

Hydrogen Bonding in Nucleic Acid Interactions

The formation of primer-dimers is fundamentally governed by hydrogen bonding between complementary nucleotide bases, with GC base pairs forming three hydrogen bonds and AT base pairs forming two hydrogen bonds [18] [4]. This differential bonding strength directly influences the stability of primer-dimers, with GC-rich regions contributing disproportionately to dimer stability due to their additional hydrogen bond. The Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of these interactions quantifies the spontaneity of dimer formation, with more negative ΔG values indicating stronger, more stable interactions that are more likely to interfere with PCR amplification [4].

When primers fold back on themselves or bind to each other instead of the target template, they create secondary structures that fall into two primary categories [4]:

- Intra-primer homology: A region of 3 or more bases that are complementary to another region within the same primer, causing intramolecular bonding and hairpin formation.

- Inter-primer homology: Forward and reverse primers that have complementary sequences, causing intermolecular bonding and primer-dimer formation.

These interactions are particularly problematic when they occur near the 3' end of primers, as this positioning can lead to extension by DNA polymerase, effectively amplifying the dimerized primers themselves rather than the target template [4].

Table 1: Types of Primer Secondary Structures and Their Characteristics

| Structure Type | Formation Mechanism | ΔG Tolerance (kcal/mol) | Primary Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hairpins | Intra-primer homology; primer folds on itself | > -2 (3' end), > -3 (internal) | Prevents binding to template; reduces efficiency |

| Self-Dimers | Inter-primer homology between identical primers | > -5.0 | Reduces primer availability; competes with target |

| Cross-Dimers | Inter-primer homology between forward and reverse primers | > -5.0 | Creates alternative amplification products; reduces yield |

Experimental Evidence of Hydrogen Bonding Effects