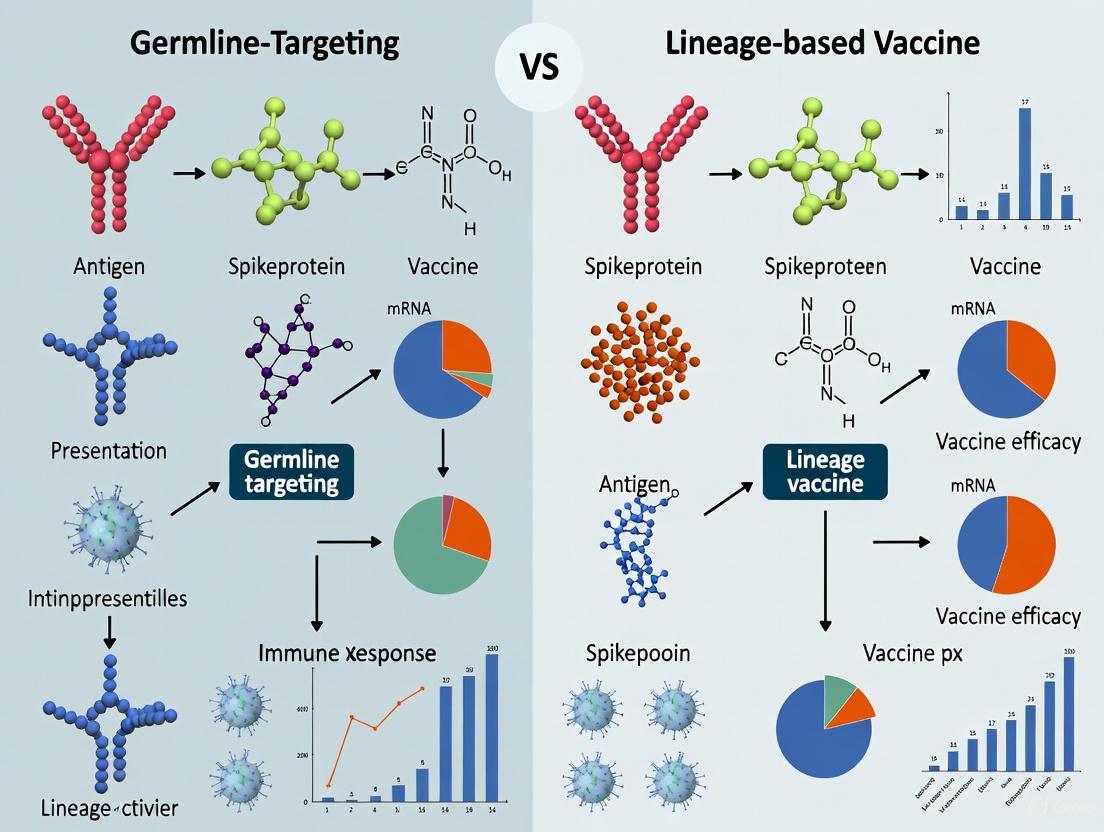

Germline-Targeting vs. Lineage-Based Vaccines: A Comparative Analysis of Next-Generation Immunization Strategies

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of two pioneering vaccine strategies: germline-targeting and lineage-based approaches.

Germline-Targeting vs. Lineage-Based Vaccines: A Comparative Analysis of Next-Generation Immunization Strategies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of two pioneering vaccine strategies: germline-targeting and lineage-based approaches. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles, methodological applications, and current challenges of these platforms. Germline-targeting, exemplified by HIV vaccine trials, uses sequential immunogens to guide B cells toward producing broadly neutralizing antibodies. In contrast, lineage-based strategies, used for rapidly mutating viruses like SARS-CoV-2, adapt vaccine formulations to match circulating viral strains. The scope spans from conceptual frameworks and preclinical design to clinical validation, synthesizing recent data to evaluate the relative effectiveness, advantages, and optimal use cases for each strategy in modern vaccinology.

Conceptual Frameworks: From Empirical Design to Rational Vaccine Engineering

The rapid evolution of pathogens like HIV and influenza presents a monumental challenge for traditional vaccinology. In response, two pioneering strategies have emerged: germline-targeting and lineage-based vaccine design. Both aim to guide the immune system toward generating broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) that can protect against diverse viral variants. While they share this ultimate goal, they are founded on distinct core principles and scientific approaches. Germline-targeting focuses on reverse-engineering immunogens to engage rare, naive B cell precursors with known bNAb potential. In contrast, the lineage-based approach leverages natural infection history, using computational reconstruction of mature bNAb lineages from infected individuals to design immunogens that recapitulate this maturation pathway. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these strategies, examining their theoretical foundations, methodological workflows, and supporting clinical data to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Principle Comparison

The following table summarizes the foundational concepts, objectives, and technological underpinnings of each strategy.

Table 1: Core Principles of Germline-Targeting and Lineage-Based Vaccine Strategies

| Aspect | Germline-Targeting Strategy | Lineage-Based Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Reverse-engineering of immunogens to bind and activate rare naive B cells expressing B cell receptors (BCRs) with bNAb potential [1]. | Computational reconstruction of the natural maturation history of bNAb lineages from infected individuals to identify key mutations [1]. |

| Primary Objective | To "prime" rare bNAb-precursor B cells, initiating an immune response that can be sequentially guided toward breadth [2]. | To design immunogens that selectively promote the acquisition of critical "improbable" mutations required for neutralization breadth during the affinity maturation process [1]. |

| Key Technological Drivers | Structural biology, protein engineering, high-resolution epitope mapping, and next-generation sequencing for B cell repertoire analysis [1] [3]. | Single B cell cloning, deep sequencing, phylogenetic analysis, and in-silico lineage reconstruction [1]. |

| Role of Immunogen Series | A sequence of distinct, rationally designed immunogens administered to shepherd the primed B cell lineage toward broader neutralization [1] [2]. | A series of immunogens designed to mirror the natural evolutionary path of a bNAb lineage, selecting for B cells that acquire desired mutations [1]. |

| Dependency on Human Genetics | High; dependent on an individual's inherited immunoglobulin gene alleles (e.g., IGHV1-2*02 for VRC01-class bNAbs) [4]. | Less dependent on germline genetics; focuses on guiding the somatic hypermutation process after B cell activation. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

The translation of these core principles into effective vaccines requires distinct experimental pipelines. The methodologies below outline the key steps for each strategy, from initial design to clinical evaluation.

Germline-Targeting Workflow

This pipeline involves engineering an immunogen to initiate a desired B cell response.

- Identification of a Target bNAb: Isolate and characterize a potent bNAb from a chronically infected individual. A prominent example is VRC01, which targets the CD4-binding site of HIV Env [1] [5].

- Lineage Analysis and Ancestral Reconstruction: Trace the evolutionary lineage of the mature bNAb back to its inferred germline (unmutated common ancestor) sequence.

- Priming Immunogen Design: Use structural biology (e.g., X-ray crystallography, Cryo-EM) to engineer a immunogen, such as eOD-GT8, that is specifically tailored to have high affinity for the germline-encoded BCR of the target bNAb lineage [1] [2].

- Preclinical Validation: Test the engineered immunogen in animal models, such as knock-in mice expressing humanized BCRs, to confirm its ability to activate the desired naive B cell precursors [3].

- Clinical Trial Evaluation (Priming): Evaluate the immunogen in Phase I trials for safety and its ability to induce targeted B cell responses in humans. Success is measured by the frequency of precursor B cells in blood samples, often using flow cytometry and B cell receptor sequencing [2] [4]. The IAVI G001 and G002 trials are key examples [1] [2].

- Boosting Immunogen Design and Testing: Develop and test a series of distinct, sequentially administered immunogens (e.g., Core-g28v2 and 426c.Mod.Core) designed to bind intermediates of the maturing B cell lineage, guiding them toward broader neutralization [1] [2].

Lineage-Based Workflow

This approach focuses on recapitulating a known successful immune response.

- bNAb Donor Selection: Identify individuals living with HIV (PLWH) who have naturally developed potent bNAb responses after years of infection [1].

- Longitudinal Sampling and Deep Sequencing: Collect blood samples over time to capture the temporal development of the bNAb response. Isolate and sequence the B cell receptors from antigen-specific memory B cells and plasma cells.

- Phylogenetic Lineage Reconstruction: Use computational tools to build a phylogenetic tree from the sequenced BCRs, mapping the evolutionary pathway from the germline ancestor to the mature bNAb [1].

- Identification of Key Mutations: Analyze the lineage to pinpoint critical somatic hypermutations (SHMs) that are essential for conferring neutralization breadth and potency. These are often termed "improbable" mutations [1].

- Intermediate Immunogen Design: Design immunogens that specifically bind to and select for B cell clones that have acquired these key intermediate mutations. The goal is to design a vaccination series that mimics the natural antigenic drive that occurred during infection.

- Preclinical and Clinical Testing: Test the series of immunogens in animal models and subsequently in clinical trials to determine if they can guide developing B cell lineages along a pathway that results in the production of bNAbs.

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and key decision points for the germline-targeting strategy, as demonstrated in recent clinical trials.

Key Experimental Data and Clinical Evidence

Recent clinical trials have provided proof-of-concept for these strategies, yielding critical quantitative data on their immunogenicity and performance.

Germline-Targeting Clinical Trial Data

The IAVI-sponsored trials (G001, G002, and G003) represent a landmark in germline-targeting, using the eOD-GT8 60mer immunogen to prime VRC01-class B cell precursors.

Table 2: Summary of Key Outcomes from Germline-Targeting Clinical Trials

| Trial Identifier | Platform & Population | Intervention | Key Immunological Readout | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IAVI G001 [1] [2] | Protein (eOD-GT8 60mer) with AS01B adjuvant; 48 participants | Two priming doses | Frequency of VRC01-class IgG B cells among memory B cells | 97% response rate (35/36). Median frequency: 0.09% (low dose) and 0.13% (high dose) of MBCs. |

| IAVI G002 [2] | mRNA-LNP (North America); 60 participants | Prime (eOD-GT8) + Heterologous Boost (Core-g28v2) | Development of VRC01-class responses; acquisition of somatic hypermutations (SHMs) | 100% (17/17) in the prime-boost group developed VRC01-class responses. >80% showed "elite" responses with multiple critical SHMs. |

| IAVI G003 [2] | mRNA-LNP (Rwanda & South Africa); 18 participants | Two priming doses | Activation of target naive B cells | 94% response rate (17/18), demonstrating feasibility in key target populations. |

Illustrative Data from a Lineage-Based Approach

While the search results provide more extensive clinical data for germline-targeting, they also describe the rationale and early progress for the lineage-based strategy. One report discussed the use of the BG505 SOSIP GT1.1 native-like trimer immunogen, which is modified to bind both VRC01-class and apex-specific B cell precursors. In infant macaques, three immunizations with this candidate led to expanded VRC01-class B cells that "accumulated several mutations associated with VRC01-class bNAbs," suggesting the antibodies were being guided toward a broad and potent state [1]. This exemplifies the lineage-based goal of using immunogens to promote specific, desirable mutations during the maturation process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The development and evaluation of these advanced vaccine strategies rely on a suite of sophisticated research reagents and assays.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Methods for Germline-Targeting and Lineage-Based Research

| Research Reagent / Assay | Primary Function | Strategic Application |

|---|---|---|

| Stabilized Envelope Trimers (e.g., SOSIP, Native-like) | Antigens that mimic the native structure of viral surface proteins (e.g., HIV Env); key immunogens [1] [6]. | Core component of both strategies; used to focus immune responses on neutralization-sensitive epitopes. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | High-throughput sequencing of B cell receptor (BCR) repertoires from immunized subjects [1]. | Critical for tracking B cell lineage dynamics, measuring SHM, and confirming the engagement of target B cell clones. |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) | High-resolution structural determination of antigen-antibody complexes [1] [6]. | Informs the rational design of immunogens by revealing atomic-level interactions with bNAbs and their precursors. |

| BLI / SPR Biosensors (e.g., Biolayer Interferometry, Surface Plasmon Resonance) | Label-free quantification of binding kinetics (affinity, kon, koff) between antibodies and antigens [1]. | Used to validate immunogen binding to germline and intermediate BCRs, a key parameter in germline-targeting. |

| IGHV Genotyping | Nucleotide-level identification of an individual's inherited immunoglobulin gene alleles [4]. | Essential for patient stratification in germline-targeting trials, as response is dependent on alleles like IGHV1-2*02. |

| Pseudovirus Neutralization Assay | Gold-standard in vitro measurement of antibody function against a panel of diverse viral variants [1] [7]. | The definitive functional assay for determining the breadth and potency of vaccine-elicited neutralizing antibodies. |

The following diagram maps the relationship between these core tools and the specific research questions they help answer within the vaccine development workflow.

Germline-targeting and lineage-based vaccine strategies represent two sophisticated, complementary paradigms in the pursuit of broadly protective immunity. The germline-targeting approach has demonstrated formidable clinical proof-of-concept, with trials like IAVI G002 showing that a prime-boost regimen can successfully initiate and then further mature VRC01-class B cell responses in humans [2]. Its main challenge lies in its inherent dependency on specific human immunoglobulin gene alleles, necessitating careful patient stratification or immunogen designs with broader specificity [4]. In contrast, the lineage-based approach seeks to recapitulate nature's proven path to breadth by guiding B cells through a pre-defined series of mutations, potentially offering a more "agnostic" entry point that is less constrained by germline genetics [1].

The future of vaccine development against highly variable pathogens will likely involve a synergistic integration of both concepts. Germline-targeting immunogens could be used to initiate the response, with subsequent boosts informed by lineage analyses to shepherd the B cells toward full maturity and breadth. As these platforms mature, leveraging mRNA for faster immunogen iteration and advanced adjuvants to shape the immune response, they hold promise not only for HIV but for other antigenically complex pathogens like influenza and future pandemic threats [6].

The development of effective vaccines against highly variable viruses such as HIV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 represents one of the most significant challenges in modern immunology. These pathogens employ sophisticated immune evasion strategies, including rapid genetic mutation, structural mimicry of host antigens, and glycan shielding of conserved epitopes [8] [9]. HIV-1, with its extraordinary global diversity and ability to establish latent reservoirs, has proven particularly recalcitrant to conventional vaccine approaches [10] [9]. Despite nine completed HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trials, only one has demonstrated modest efficacy, highlighting the formidable nature of this challenge [10].

In response to these challenges, the vaccine research community has developed two pioneering strategies: germline-targeting and B-cell lineage vaccine design [10]. Both approaches aim to guide the immune system through complex maturation pathways to generate broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) capable of recognizing diverse viral variants. This review provides a comparative analysis of these strategies, examining their underlying mechanisms, experimental support, and potential for addressing viral diversity and immune evasion.

Theoretical Foundations and Mechanisms

Germline-Targeting Vaccine Strategy

Germline-targeting represents a structure-based reverse engineering approach designed to initiate B-cell responses that can eventually mature into bNAb-producing lineages [10] [11]. This strategy employs engineered immunogens specifically designed to activate rare naive B cells bearing B-cell receptors (BCRs) with potential to develop into bNAbs [12]. The fundamental premise is that the immune system must be deliberately guided through a predefined maturation pathway, as the stochastic natural immune response rarely produces bNAbs even during actual infection [8].

The germline-targeting approach requires sequential immunization with a series of increasingly native-like HIV Envelope immunogens [10]. The process begins with priming immunogens that engage precursor B cells, followed by booster immunogens that shepherd these cells along affinitity maturation pathways toward breadth and potency [12]. As researcher William Schief has described, this approach essentially involves "shepherding" the immune system through multiple shots containing multiple different antigens along a predefined path [12].

Lineage-Based Vaccine Strategy

Lineage-based vaccine design takes a different approach, leveraging computational reconstruction of antibody maturation pathways observed in natural infection [8]. This method analyzes the evolutionary history of bNAbs from HIV-infected individuals and uses this information to design sequential immunogens that recapitulate these pathways in vaccinated individuals [10] [8]. Rather than reverse-engineering from structural biology alone, this approach draws directly from successful antibody lineages that nature has already produced.

The lineage-based approach acknowledges that the antigen stimulating memory B cells during affinity maturation may differ from the antigen that initially activated naive B cells [8]. This insight necessitates using distinct antigens for prime and boost vaccinations to optimize clonal evolution [8]. Additionally, this approach must overcome host immunoregulatory mechanisms that often suppress the development of B cells producing antibodies with "disfavored" characteristics, such as polyreactivity or long heavy-chain third complementarity-determining regions commonly found in bNAbs [8].

Comparative Analysis of Strategic Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of Germline-Targeting and Lineage-Based Vaccine Strategies

| Feature | Germline-Targeting Approach | Lineage-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Structure-based reverse engineering of immunogens to engage precursor B cells [10] [12] | Computational reconstruction of natural antibody maturation pathways from infected individuals [10] [8] |

| Initiation Mechanism | Engineered immunogens bind rare naive B cells with bNAb potential [11] [12] | Immunogens designed based on ancestral antibodies from successful lineages [8] |

| Vaccination Series | Sequential immunization with increasingly native-like envelope immunogens [10] | Prime-boost with antigens representing different stages of lineage development [8] |

| Key Challenges | Engaging extremely rare B cell precursors (~1 in 300,000 naive B cells) [12]; Guiding through complex maturation pathways [11] | Overcoming host regulatory suppression of "disfavored" antibody characteristics; Recapitulating complex maturation pathways [8] |

| Technological Requirements | High-resolution structural biology; Immunogen engineering [12] | High-throughput antibody sequencing; Computational lineage reconstruction [8] |

| Representative Candidates | eOD-GT8 60mer nanoparticle [10] [12] | CH235 lineage-based immunogens [10] |

Synergistic Potential and Combination Approaches

Recent research has explored potential synergies between B-cell and T-cell vaccine approaches to optimize immune responses against HIV [10] [13]. The US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) convened a workshop in 2023 specifically to explore these synergies [10]. Preclinical studies suggest that combining B-cell and T-cell vaccine strategies can establish protection at lower, more attainable concentrations of bNAbs [10] [13].

Studies in non-human primates have demonstrated that combining HIV SOSIP protein vaccines with potent T-cell-inducing viral vectors provided better protection against SHIV challenge than either candidate alone [13]. Importantly, the combination was protective even with sub-optimal titers of neutralizing antibodies [10]. Similarly, vaccine-mediated induction of potent T-cell responses lowered the antibody threshold needed to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection in non-human primates [10]. These findings suggest a promising framework where bNAbs provide sterilizing immunity while T-cell responses control infected cells that escape neutralization [10].

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Key Experimental Models for Vaccine Evaluation

Table 2: Experimental Models for Vaccine Assessment

| Model System | Application | Key Readouts | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Human Primates (NHPs) | SHIV challenge studies [10] [13] | Neutralizing antibody titers; Protection against infection [10] | Physiologically relevant immune system; Mucosal challenge possible [10] | Costly; Limited availability; SHIV not identical to HIV [10] |

| Mouse Models with Humanized Immune Systems | Initial testing of germline-targeting immunogens [12] | Activation of specific B cell precursors; Germinal center responses [12] | Can engraft human B cell precursors; Controlled experimental conditions [12] | Incomplete human immune system reconstitution [12] |

| In Vitro Binding and Neutralization Assays | Screening immunogen-antibody interactions [10] | Binding affinity and kinetics; Neutralization breadth and potency [10] | High-throughput capability; Quantifiable results [10] | Does not capture full immune system complexity [10] |

| Clinical Trials | Evaluation of safety and immunogenicity in humans [10] | bNAb precursor frequency; IgG+ B cells in blood [10] | Direct relevance to human immune responses [10] | Ethical and safety constraints; Costly and time-consuming [10] |

Representative Experimental Protocols

Germline-Targeting Clinical Trial Protocol (IAVI G001)

The IAVI G001 trial represented a landmark proof-of-concept for germline-targeting [12]. This Phase I trial evaluated the eOD-GT8 60mer nanoparticle immunogen, designed to activate naive B cells capable of producing VRC01-class bNAbs targeting the CD4 binding site [12]. The methodology involved:

- Participant Cohort: Healthy adult volunteers without HIV

- Immunization Schedule: Prime and boost vaccinations at designated intervals

- Immunogen: eOD-GT8 60mer nanoparticle administered intramuscularly

- Primary Endpoints: Safety and tolerability of the vaccine regimen

- Key Immunological Assays: Flow cytometry to quantify VRC01-class B cell precursors; ELISA to measure antibody responses; memory B cell characterization [12]

The trial successfully demonstrated that 97% of vaccinees showed VRC01-class bNAb precursors with a median frequency of 0.1% IgG+ B cells in blood, providing critical proof-of-concept for germline-targeting [10] [12].

Lineage-Based Vaccine Assessment in NHPs

A representative preclinical study evaluating lineage-based vaccines involves:

- Immunogen Series: Sequential immunization with immunogens representing different stages of identified bNAb lineages

- Animal Model: Rhesus macaques

- Challenge Model: SHIV challenge via mucosal route

- Immunological Monitoring: Longitudinal assessment of antibody breadth and potency using neutralization panels; B cell sorting and sequencing to track lineage development

- Correlates of Protection: Association between specific antibody responses and protection from infection [10]

Key Research Reagents and Experimental Tools

Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Vaccine Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Engineered Immunogens | eOD-GT8 60mer; SOSIP trimers; CH848 ferritin nanoparticles | Activate specific B cell precursors; Guide antibody maturation | [10] [12] |

| Adjuvant Systems | 3M-052 aqueous formulation; Saponin/MPLA nanoparticles; Alum | Enhance immunogenicity; Modulate immune response quality | [10] |

| Delivery Platforms | mRNA-LNP; Adenovirus vectors; DNA plasmids with electroporation | Present immunogens; Enhance cellular uptake; Promote sustained antigen expression | [10] [12] |

| Animal Models | SHIV in rhesus macaques; Humanized mouse models | Preclinical efficacy assessment; Study of B cell responses in vivo | [10] [13] |

| Analysis Tools | High-throughput B cell sequencing; Neutralization assays; Structural biology techniques | Characterize immune responses; Determine antibody breadth and potency; Guide immunogen design | [10] [8] |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

B Cell Activation and Maturation Pathway

B Cell Maturation to bNAb Producer - This diagram illustrates the sequential process of guiding B cells from naive precursors to bNAb-producing cells through germline-targeting and sequential immunization.

Sequential Immunization Workflow

Sequential Immunization Workflow - This diagram outlines the systematic approach for guiding the immune system through sequential immunizations to generate bNAb responses.

The comparative analysis of germline-targeting and lineage-based vaccine strategies reveals complementary approaches to addressing the fundamental challenges of viral diversity and immune evasion. While both strategies aim to induce bNAbs through sequential immunization, they differ in their starting points and design principles. Germline-targeting begins with structure-based engineering to engage precise B cell precursors, while lineage-based approaches leverage natural antibody evolution from infected individuals.

Recent advances in mRNA delivery platforms and adjuvant technologies have accelerated both strategies, enabling more rapid iteration and optimization of vaccine candidates [10]. The demonstrated success of germline-targeting in priming desired B cell responses in clinical trials provides proof-of-concept for this approach [10] [12]. Meanwhile, lineage-based designs benefit from following nature's blueprint for effective antibody responses.

Future HIV vaccine regimens will likely incorporate elements from both strategies, potentially combined with T-cell vaccine components to create synergistic protection [10] [13]. As the field progresses, the integration of structural biology, computational design, and deep understanding of B cell biology will be essential to develop vaccines capable of overcoming viral diversity and immune evasion mechanisms. The scientific imperative to address these challenges remains critical for controlling not only HIV but other highly variable pathogens with pandemic potential.

The development of a protective HIV vaccine represents one of the most formidable challenges in modern immunology. Traditional vaccine approaches have consistently failed to provide appreciable protection, largely due to the virus's extraordinary genetic diversity and sophisticated immune evasion strategies [1]. In response, researchers have pioneered novel immunization strategies designed to overcome these obstacles through precise engineering of the immune response.

Two leading approaches have emerged: germline-targeting and lineage-based vaccination strategies. While both aim to elicit broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs), they differ fundamentally in their initial mechanisms. Germline-targeting employs reverse-engineered immunogens specifically designed to activate rare naïve B cells possessing genetic signatures characteristic of bNAb precursors [1] [14]. In contrast, lineage-based approaches leverage the reconstructed maturation pathways of known bNAbs to guide B cell development [1].

This review provides a comparative analysis of these strategies, focusing on their mechanistic foundations, clinical validation, and potential for integration into a globally effective HIV vaccine regimen.

Comparative Analysis of Strategic Approaches

Table 1: Core Strategic Comparison Between Germline-Targeting and Lineage-Based Vaccine Approaches

| Feature | Germline-Targeting Strategy | Lineage-Based Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Structure-based immunogen design to activate rare naïve B cell precursors with bNAb potential [1] [14] | Computational reconstruction of bNAb maturation history to design immunogens that promote key mutations [1] |

| Initial Target | Naïve B cells expressing BCRs with specific germline-encoded features (e.g., IGHV1-2*02 for VRC01-class) [4] | Memory B cells, guiding pre-selected lineages toward breadth [1] |

| Immunogen Sequence | Predefined series of immunogens with increasing native-like structure [1] [14] | Immunogens designed to select for specific, critical improbable mutations [1] |

| Key Advantage | Ability to initiate responses from an extremely rare precursor pool [1] [2] | Strategy informed by known, effective bNAb maturation pathways [1] |

Key Experimental Findings and Clinical Validation

Proof-of-Concept Clinical Trials

Recent clinical trials have demonstrated the feasibility of the germline-targeting approach in humans. The IAVI G001 trial used the eOD-GT8 60mer immunogen to prime VRC01-class B cell precursors, achieving a 97% response rate (35 of 36 participants) [1] [2]. Subsequent trials IAVI G002 (North America) and IAVI G003 (Africa) utilized an mRNA platform to deliver the same immunogen, showing similarly high response rates and demonstrating cross-population applicability [2].

A critical finding from these studies was the impact of human genetic variation on vaccine response. Individuals lacking permissive IGHV1-2 alleles (specifically *02 or *04) failed to generate VRC01-class responses, highlighting the necessity of considering population-level immunoglobulin allelic variations in vaccine design [4].

Table 2: Summary of Key Clinical Trial Outcomes for Germline-Targeting Vaccines

| Trial Identifier | Immunogen/Platform | Key Findings | Response Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| IAVI G001 [2] | eOD-GT8 60mer protein + AS01B adjuvant | Successful priming of VRC01-class bnAb precursors; dose-effect observed confounded by IGHV genotype [4] | 35 of 36 participants (97%) [1] |

| IAVI G002 [2] | eOD-GT8 60mer mRNA prime, core-g28v2 60mer mRNA boost | Heterologous boost drove further maturation; "elite" responses with multiple beneficial mutations in >80% of boosted participants [2] | 17 of 17 in prime-boost group (100%) [2] |

| IAVI G003 [2] | eOD-GT8 60mer mRNA (prime only) in African cohorts | Successful priming of VRC01-class B cells in African populations; responses similar to North American trials [2] | 17 of 18 participants (94%) [2] |

| HVTN 301 [1] | 426 c.Mod.Core nanoparticle | Isolation of 38 mAbs with similarities to VRC01-class antibodies; currently under characterization | Data pending |

Preclinical Evidence for Combination Approaches

Beyond targeting single epitopes, research has progressed to evaluating regimens that simultaneously initiate multiple bNAb lineages. A seminal non-human primate study demonstrated that immunization with a combination of three distinct germline-targeting immunogens (targeting the V3-glycan site, V2 Apex, and MPER) could concurrently prime bnAb precursor lineages to all three epitopes without apparent interference [15]. This finding supports the development of multivalent HIV vaccine regimens aiming to elicit a polyclonal bNAb response, which would be critical for overcoming viral diversity and escape mutants.

Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

The advancement of germline-targeting vaccines relies on a specialized toolkit of reagents and analytical techniques.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Germline-Targeting Vaccine Development

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function and Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Engineered Priming Immunogens (e.g., eOD-GT8 60mer, BG505 SOSIP GT1.1) [1] [14] | Activate rare, naïve B cells bearing specific germline-encoded BCRs. | eOD-GT8 60mer used in IAVI G001, G002, and G003 trials to prime VRC01-class precursors [2]. |

| Native-like Env Trimers | Serve as boosting immunogens to guide primed B cells toward broader neutralization. | BG505 SOSIP GT1.1 trimer used to expand and mutate VRC01-class B cells in macaques [1]. |

| mRNA-LNP Vaccine Platform [2] [6] | Enables rapid production and potent delivery of encoded immunogens; can induce strong germinal center responses. | Moderna's mRNA platform used in IAVI G002/G003 trials, found to be at least as effective as protein immunization [1]. |

| IGHV Genotyping & Repertoire Analysis [4] | Identifies permissive immunoglobulin alleles in trial participants and quantifies precursor frequency. | Personalised genotyping in IAVI G001 linked IGHV1-2*02 allele to higher precursor frequency and response [4]. |

| B Cell Isolation & Characterization | Isolate antigen-specific B cells and characterize their antibodies. | 38 vaccine-induced mAbs isolated in HVTN 301 trial for characterization by BLI and cryo-EM [1]. |

Key Experimental Workflow and Signaling

The following diagram visualizes the core experimental workflow and the critical B cell receptor signaling pathway involved in activating rare B cell precursors through a germline-targeting vaccine.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Assessment of Vaccine-Induced VRC01-Class B Cell Responses

This protocol is adapted from the methods used in the IAVI G001, G002, and G003 clinical trials [2].

Sample Collection: Collect peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from trial participants at baseline and at predetermined intervals post-vaccination (e.g., weeks 4, 8, and 10).

B Cell Sorting and Culture:

- Isolate memory B cells or antigen-specific B cells using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). For VRC01-class cells, use labeled eOD-GT8 or related probes.

- Culture sorted B cells and stimulate them to differentiate into antibody-secreting cells.

Antibody Sequencing and Analysis:

- Extract RNA from single B cells and synthesize cDNA.

- Amplify immunoglobulin heavy and light chain variable regions using PCR.

- Sequence the amplified products and analyze the sequences for:

- IGHV1-2 Gene Usage: Confirm use of IGHV1-2*02 or *04 alleles [4].

- Somatic Hypermutation (SHM): Calculate the mutation frequency relative to the inferred germline sequence.

- Lineage Analysis: Track the clonal evolution of B cell lineages over time.

Functional Characterization:

- Express the recombinant monoclonal antibodies from the sequenced pairs.

- Evaluate binding affinity and kinetics to the immunogen using biolayer interferometry (BLI).

- Test neutralization breadth and potency against a panel of diverse HIV pseudoviruses in a TZM-bl neutralization assay.

Protocol: IGHV Genotyping and Naïve B Cell Repertoire Analysis

This protocol is based on the work that revealed the critical role of IGHV1-2 allelic variation [4].

Library Preparation:

- Isulate naïve B cells (e.g., CD19+IgM+IgD+) from participant PBMCs.

- Construct IgM libraries from these cells, incorporating unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) during cDNA synthesis to ensure accurate sequence quantification.

High-Throughput Sequencing: Perform deep sequencing of the immunoglobulin heavy chain loci on a platform such as Illumina.

Germline Allele Inference:

- Use a germline allele inference tool (e.g., IgDiscover) to determine the individual's IGHV genotype with nucleotide-level precision [4].

- Identify all alleles, including single-nucleotide variants.

Repertoire Quantification:

- Map sequence reads to the personalized genotype.

- Calculate the frequency of specific alleles (e.g., IGHV1-2*02 vs. *04) in the naïve repertoire by counting UMIs.

- Count unique heavy chain complementarity-determining region 3 (HCDR3) sequences to estimate the number of unique B cells for each allele.

Germline-targeting vaccines have transitioned from a theoretical concept to a clinically validated strategy for initiating the complex process of eliciting HIV bNAbs. Direct comparative evidence, notably from the IAVI G002 trial, demonstrates that a heterologous prime-boost regimen can drive these early responses toward a more mature state, a key milestone on the path to breadth [2]. The critical influence of human IGHV genotyping on response magnitude underscores the need for personalized vaccinology approaches and the development of a diverse portfolio of immunogens to achieve global coverage [4].

The future of HIV vaccine development likely lies in combination strategies—both in terms of eliciting multiple bNAb classes simultaneously [15] and in potentially integrating germline-targeting and lineage-based approaches in a single regimen. Continued advances in immunogen design, platform delivery (like mRNA), and a deep understanding of human B cell immunology will be essential to guide these rare B cell precursors to become potent, broad, and protective antibody responses.

The field of vaccinology has undergone a revolutionary transformation from empirical discovery to rational, structure-based design. Historically, most successful vaccines were developed empirically through an "isolate, inactivate or attenuate, and inject" approach, without a detailed understanding of the immunological mechanisms underlying protection [16]. While this approach led to tremendous successes against various infectious diseases, it proved inadequate for addressing more complex pathogens such as HIV, influenza, and dengue viruses [16]. The major hurdles included identifying early markers of vaccine efficacy, developing relevant antigens and adjuvants, defining correlates of protection, and understanding mechanisms underlying long-lasting protective immune responses [16].

The rapid emergence of high-throughput 'Omics' methodologies has enabled a comprehensive view of the dynamic responses to vaccines at a cellular and molecular level, giving rise to the field of systems vaccinology [16]. This review traces the historical evolution from empirical approaches to modern structure-based vaccine design, comparing the effectiveness of different strategies and providing the experimental frameworks that have enabled these advances.

Historical Foundations of Empirical Vaccine Development

The Empirical Era

The history of vaccination began long before the understanding of immunology. The earliest documented practices date back to 16th century China and India with variolation against smallpox, which involved inoculation of smallpox pus or scabs through nasal or cutaneous routes [17]. In 1796, Edward Jenner famously demonstrated that inoculation with cowpox lesions could confer immunity against smallpox, leading to the first vaccine (derived from "Vacca," Latin for cow) [17] [18]. For nearly two centuries following this breakthrough, vaccine development proceeded primarily through empirical observation and optimization:

- Late 1800s: Louis Pasteur developed live attenuated vaccines against rabies [17]

- Early 1900s: Chemically inactivated toxins (toxoids) and killed bacteria were introduced for diphtheria and tetanus [18]

- 1920s: Gaston Ramon discovered adjuvants by observing that materials like starch and saponins increased inflammatory responses to diphtheria toxoid [18]

- 1926: Alexander Glenny found that potassium aluminum sulfate (alum) enhanced antibody responses, leading to the most common vaccine adjuvant [18]

- 1930s: Development of viral cultivation techniques enabled influenza and yellow fever vaccines [17]

- 1950s: The golden age of vaccines introduced polio, measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella vaccines [17]

Limitations of the Empirical Approach

While empirically developed vaccines have saved millions of lives, the approach faced significant limitations:

- Mechanistic understanding: The mechanisms of action (MOA) of successful vaccines and adjuvants remained largely unknown [18]

- Development bottlenecks: Difficult-to-target pathogens resisted empirical approaches

- Standardization challenges: Reliable standardized assays to predict protective efficacy were unavailable [16]

- Antigen selection: Identification of protective antigens was time-consuming and labor-intensive

Table 1: Key Milestones in Empirical Vaccine Development

| Time Period | Development | Key Examples | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1796-1900 | Live attenuated vaccines | Smallpox, Rabies | Safety concerns, unknown mechanisms |

| 1920-1950 | Inactivated vaccines & toxoids | Diphtheria, Tetanus, Pertussis | Weaker immune responses, required adjuvants |

| 1950-1980 | Cell culture-based vaccines | Polio, Measles, Mumps, Rubella | Technical challenges in viral cultivation |

| 1980s-present | Polysaccharide conjugate vaccines | Pneumococcal, Meningococcal | Limited to certain pathogen types |

The Transition to Rational Vaccine Design

Technological Enablers of Rational Design

The transition from empirical to rational vaccine design was facilitated by several technological advances:

- High-throughput Omics methodologies: Genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics enabled comprehensive monitoring of systemic changes at molecular, cellular, and organism levels following vaccination [16]

- Structural biology tools: X-ray crystallography and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) allowed determination of 3D structures of viral proteins and antigen-antibody complexes [16]

- Computational capabilities: Advanced algorithms for theoretical predictions of antigen-antibody interactions [16]

- Bioorthogonal chemistry and proteomics: Enabled identification and isolation of cell receptors for adjuvants [18]

Systems Vaccinology Framework

Systems vaccinology has emerged as a key discipline that integrates multiple types of data over time to create predictive models of vaccine-induced immunity [16]. This approach involves:

- Monitoring different components of the biological system in response to vaccination

- Integrating multiple types of Omics data over time

- Creating mathematical models to predict system structure and behavior

- Testing and validating novel hypotheses through iterative experimentation [16]

Key findings from systems vaccinology studies include the identification of molecular signatures of vaccine efficacy. For example, studies of the yellow fever vaccine YF-17D revealed interferon and innate antiviral gene signatures predictive of CD8+ T cell and neutralizing antibody responses [16]. Similarly, transcriptional signatures induced by inactivated trivalent influenza vaccine revealed markers associated with plasmablast expansion that predicted antibody responses [16].

Structure-Based Vaccine Design Strategies

Reverse Vaccinology

Reverse vaccinology represents a fundamental shift from traditional methods. This approach involves:

- Computational mining and analysis of large datasets related to immune responses to pathogens

- Analysis of host-pathogen interactions and genomic data from both host and pathogen

- Prediction of promising antigen candidates through bioinformatic analysis

- Large-scale sampling of potential antigens with down-selection based on affinity for antibodies or MHC molecules [16]

Structural Vaccinology

Structural vaccinology utilizes detailed structural information to design optimized antigens:

- Structure-function analysis: Using structures of viral proteins and antigen-antibody complexes for docking and modeling studies [16]

- Epitope grafting: Transplanting linear and discontinuous epitopes onto computationally designed scaffolds [16]

- Stabilization of native conformations: Engineering antigens to maintain preferred conformations for optimal immune recognition

This approach has been successfully used to develop immunogenic vaccine candidates from respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) glycoprotein and MERS virus spike protein [16].

Germline-Targeting Vaccine Design

For difficult targets like HIV, germline-targeting represents a sophisticated structure-based approach:

- Immunogen design: Creating "germline-targeting" immunogens that can activate rare and low-affinity broadly neutralizing antibody (bnAb) precursor B cells [19]

- Lineage-based design: Guiding the maturation of bnAb precursors through sequential immunization with a series of engineered immunogens [19]

The development of bnAbs against HIV is particularly challenging because these antibodies often exhibit unusual properties including long heavy-chain complementarity-determining region 3 loops and/or autoreactivity, which normally trigger immune tolerance mechanisms [19]. Additionally, mature bnAbs contain a large number of somatic mutations, suggesting that prolonged germinal center reactions are needed for their development [19].

Table 2: Comparison of Vaccine Design Strategies

| Design Strategy | Key Principles | Application Examples | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical | Attenuation, inactivation, observation of natural immunity | Smallpox, Rabies, Polio, Measles | Proven success, straightforward | Limited for complex pathogens, slow |

| Reverse Vaccinology | Genome mining, computational prediction | Meningococcus B | Identifies novel antigens, high-throughput | Limited by prediction accuracy |

| Structural Vaccinology | Structure-based antigen design, epitope scaffolding | RSV, MERS | Precision targeting, rational optimization | Requires detailed structural data |

| Germline-Targeting | Sequential immunization, lineage guidance | HIV clinical trials | Can target difficult epitopes | Complex immunogen series required |

Comparative Analysis: Germline-Targeting vs. Lineage-Based Strategies

Germline-Targeting Approaches

Germline-targeting strategies focus on the initial activation of naive B cells expressing bnAb precursors:

- Immunogen design: Two primary approaches include well-folded native Envs based on transmitted/founder viruses from individuals who eventually generated bnAbs, and proteins engineered to bind unmutated common ancestors (UCAs) to mimic Env neutralizing epitopes [19]

- Affinity considerations: A key consideration is the affinity of the immunogen for B cell receptors expressed by naive bnAb precursor B cells [19]

- Validation tools: Transgenic mice expressing inferred UCA precursor BCRs are used to test immunogens' capacity to activate B cells with bnAb potential [19]

The eOD-GT8 60mer nanoparticle represents a promising germline-targeting immunogen that recently demonstrated success in a phase I clinical trial (NCT03547245, IAVI G001), where 97% of immunized individuals exhibited activated B cells with features of germline precursors of the VRC01 lineage [19].

Lineage-Based Vaccine Strategies

Lineage-based vaccine strategies aim to guide the maturation of bnAb responses through sequential immunization:

- Sequential immunogen series: A sequence of immunogens designed to selectively expand and mature bnAb lineages

- Somatic hypermutation guidance: Encouraging the accumulation of specific mutations required for breadth and potency

- Germinal center engagement: Promoting prolonged germinal center reactions to allow sufficient B cell maturation

Experimental Evidence and Clinical Validation

Recent clinical trials have provided critical insights into both strategies:

Table 3: Clinical Trials of Structure-Based HIV Vaccine Candidates

| Immunogen | Epitope Target | BnAb Lineage Targeted | Clinical Trial | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| eOD-GT8 | CD4 binding site | VRC01 | IAVI G001 (NCT03547245) | 97% of recipients showed activated B cells with germline precursor features [19] |

| BG505 SOSIP.gp140 | V3-glycan | PGT121 | IAVI C101 (NCT04224701) | Ongoing evaluation |

| CH505 TF gp120 | CD4 binding site | CH103 | HVTN 115 (NCT03220724) | Sequential immunization strategy |

| CH848 10.17DT | V3-glycan | DH270.6 | HVTN 3XX | Evaluating germline-targeting and lineage guidance |

The Antibody Mediated Prevention (AMP) trials provided proof-of-concept that bnAb-inducing vaccines could protect against HIV, demonstrating 75% protective efficacy against VRC01-sensitive viruses [19]. However, the lack of overall protection highlighted that high titers of neutralizing antibodies against a wide breadth of HIV isolates will be needed, likely requiring a mixture of bnAbs targeting different epitopes [19].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Structural Biology Techniques

X-ray crystallography and 2D-NMR are essential for determining the spatial interactions between ligand functional groups and their receptors [18]. These techniques provide:

- Atomic-resolution structures of antigen-antibody complexes

- Identification of key residues involved in binding interactions

- Dynamic information about molecular movements (NMR)

- Foundation for structure-based design of improved antigens and adjuvants

Immunological Assays for Vaccine Evaluation

Compprehensive vaccine evaluation requires multiple complementary assays:

- Binding antibody measurements: ELISA, surface plasmon resonance to quantify antibody quantity and affinity [20]

- Neutralization assays: Pseudovirus and live virus neutralization to assess functional antibodies [20]

- T cell responses: ELISpot for IFN-γ production, multiparameter flow cytometry for T cell phenotyping [20]

- Gene expression profiling: Microarray or RNA-seq to identify transcriptional signatures [16]

- B cell repertoire analysis: High-throughput sequencing of B cell receptors [16]

Systems Vaccinology Workflows

The typical systems vaccinology workflow involves:

Diagram 1: Systems Vaccinology Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Technologies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Structure-Based Vaccine Design

| Reagent/Technology | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Protein microarrays | High-throughput mapping of antibody and T cell reactivity to antigens [16] | Antigen discovery, epitope mapping |

| Monoclonal antibodies | Define neutralizing epitopes, provide structural insights [19] | bnAb isolation, passive protection studies |

| Transgenic mouse models | Test immunogens' capacity to activate bnAb precursor B cells [19] | Germline-targeting immunogen validation |

| Pseudovirus systems | Safe measurement of neutralization against dangerous pathogens [20] | Vaccine immunogenicity assessment |

| Mass cytometry (CyTOF) | High-dimensional single-cell analysis of immune responses | Comprehensive immunoprofiling |

| Next-generation sequencing | B cell and T cell receptor repertoire analysis [16] | Immune response characterization |

| Structural biology platforms | Determine atomic-level structures of antigens and complexes [16] [18] | Rational antigen design |

| Bioorthogonal chemistry | Identify and isolate cell receptors for adjuvants [18] | Mechanism of action studies |

Genetic Distance Models for Predicting Vaccine Effectiveness

Recent advances have enabled predictive modeling of vaccine effectiveness based on genetic distance between vaccine strains and circulating variants. Studies of COVID-19 vaccines have established that:

- Genetic distance (GD) in the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of SARS-CoV-2 is highly predictive of vaccine protection, accounting for 86.3-87.9% of VE variation [21]

- For every residue substitution on the RBD, VE decreases by an average of 5.2% for mRNA vaccines, 6.8% for viral vector vaccines, 14.3% for protein subunit vaccines, and 15.8% for inactivated vaccines [21]

- The VE-GD framework enables real-time predictions of vaccine protection against novel variants [21]

This approach demonstrates how structure-based understanding can inform vaccine deployment and public health responses against evolving pathogens.

Diagram 2: Genetic Distance Vaccine Effectiveness Model

The evolution from empirical to structure-based vaccine design represents a fundamental transformation in vaccinology. While empirical approaches successfully controlled many infectious diseases, they reached limitations against complex pathogens. Structure-based strategies, including reverse vaccinology, structural vaccinology, and germline-targeting, leverage detailed molecular understanding to design precision vaccines.

The comparative effectiveness of germline-targeting versus lineage-based vaccine strategies continues to be evaluated in preclinical and clinical studies. Current evidence suggests that successful vaccines against difficult targets will likely require combinations of approaches to elicit broad and potent immune responses. The integration of systems vaccinology with structure-based design provides a powerful framework for addressing remaining challenges in vaccine development, including rapidly evolving pathogens, antigenic variation, and the need for durable protection in diverse populations.

As the field advances, the continued refinement of predictive models based on genetic distance and structural features, coupled with high-resolution monitoring of immune responses, will enable more rational and effective vaccine design against emerging infectious threats.

From Bench to Bedside: Immunogen Design and Clinical Implementation

The development of a broadly effective HIV vaccine represents one of the most formidable challenges in modern immunology. This guide provides a comparative analysis of two pioneering vaccine strategies: germline-targeting versus lineage-based approaches. We focus specifically on the eOD-GT8 60-mer nanoparticle immunogen, examining its design rationale, clinical performance, and mechanistic advantages through structured experimental data, protocol details, and visual schematics. The data presented herein offer researchers a comprehensive resource for evaluating the relative merits of these distinct but complementary immunological strategies.

The quest for an HIV vaccine has evolved through multiple generations of candidates, from early protein subunits to viral vectors and multi-platform regimens [22]. The extraordinary genetic diversity and immune evasion tactics of HIV have necessitated increasingly sophisticated vaccine design strategies [13]. Two principal paradigms have emerged to address these challenges: germline-targeting and lineage-based vaccine approaches [1].

Germline-targeting employs reverse-engineered immunogens designed to bind and activate rare naïve B cells expressing precursors of broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) [1]. This strategy aims to initiate a carefully guided maturation pathway through sequential immunization with increasingly native-like HIV envelope immunogens.

Lineage-based vaccines computationally reconstruct the natural maturation history of bNAbs from HIV-infected individuals, using this roadmap to design sequential immunizations that shepherd B cell development toward bNAb production [1].

This guide objectively compares the performance of the leading germline-targeting candidate—the eOD-GT8 60-mer nanoparticle—against alternative strategies, providing researchers with experimental data and methodological details to inform future vaccine development.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Vaccine Strategies

Table 1: Strategic Comparison of HIV Vaccine Approaches

| Feature | Germline-Targeting (eOD-GT8) | Lineage-Based Approaches | Traditional Empirical Vaccines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Reverse-engineered immunogens to prime rare bNAb precursors [1] | Guide B cell maturation along reconstructed bNAb lineages [1] | Empirical testing of immune responses without precise B cell targeting |

| Target B Cells | Naïve B cells with BCRs having bNAb potential [23] [1] | Developing B cell lineages at various maturation stages | Polyclonal B cell responses without specific guidance |

| Immunogen Design | Structure-based engineering for specific BCR engagement [1] | Immunogens based on ancestral/intermediate sequences in bNAb lineages [1] | Natural pathogen antigens or empirical designs |

| Clinical Validation | Phase 1 trials (IAVI G001, G002) demonstrating precursor activation [23] [1] | Preclinical and early clinical development | Multiple Phase 2b/3 trials with limited efficacy [22] [13] |

| Key Advantage | Precision targeting of desired B cell precursors | Roadmap based on naturally evolved bNAbs | Established development pathway |

Table 2: Quantitative Clinical Trial Outcomes for eOD-GT8

| Trial Identifier | Platform | Dose | Response Rate | Key Immunological Readouts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IAVI G001 [23] [1] | Protein nanoparticle + AS01B adjuvant | 20 µg or 100 µg | 97% (35/36) with VRC01-class precursors; 84-93% with CD4+ T cell responses [23] | Median frequency of 0.1% IgG+ VRC01-class B cells in blood [1] |

| IAVI G002 [13] [1] | mRNA-LNP | Not specified | VRC01-class priming at least equivalent to G001 [1] | Higher number of mutations in IGHV1-2-using VRC01-class mAbs vs. G001 [1] |

eOD-GT8 Nanoparticle Design and Mechanism

The eOD-GT8 immunogen represents a paradigm shift in structure-based vaccine design. This engineered outer domain germline-targeting version 8 (eOD-GT8) is presented as a 60-mer self-assembling nanoparticle that mimics the spatial arrangement of HIV envelope proteins, enhancing B cell receptor cross-linking and activation [23] [1].

The immunogen is co-administered with AS01B adjuvant, which contains MPL (a TLR4 agonist) and QS-21 (a saponin derivative) to enhance innate immune activation and promote robust T follicular helper (Tfh) cell responses [23]. These Tfh cells are crucial for providing the necessary help to B cells during germinal center reactions, ultimately supporting the affinity maturation required for bNAb development.

Diagram Title: eOD-GT8 Germline-Targeting Mechanism

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

IAVI G001 Clinical Trial Protocol

Objective: Evaluate safety and immunogenicity of eOD-GT8 60-mer nanoparticle with AS01B adjuvant in healthy adults [23] [1].

Methodology:

- Study Design: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 1 trial

- Participants: 48 healthy HIV-negative adults

- Vaccination: Intramuscular injection at 0 and 2 months

- Doses: 20 µg or 100 µg eOD-GT8 with AS01B adjuvant

- Immunogenicity Assessment:

- Flow Cytometry: Detection of antigen-specific memory B cells

- ELISPOT: Quantification of antibody-secreting cells

- Luminex: Serum antibody binding to eOD-GT8 and LumSyn

- T Cell Assays: Intracellular cytokine staining for polyfunctional CD4+ T cell responses

Key Analysis: Frequencies of VRC01-class IgG+ B cells were quantified using fluorescently labeled eOD-GT8 probes. T cell epitope "hotspots" were mapped within both eOD-GT8 and lumazine synthase (LumSyn) proteins [23].

Antigen-Specific B Cell Analysis

Objective: Isolate and characterize monoclonal antibodies from vaccine-elicited B cells [1].

Methodology:

- B Cell Sorting: Single-cell sorting of antigen-specific memory B cells using fluorophore-conjugated eOD-GT8

- Antibody Cloning: Amplification of immunoglobulin heavy and light chain variable regions by RT-PCR

- Recombinant Expression: Production of monoclonal antibodies in HEK293T cells

- Binding Analysis: Biolayer interferometry (BLI) to determine antibody affinity and kinetics

- Neutralization Assessment: TZM-bl cell-based assays against HIV pseudoviruses

Key Analysis: 38 monoclonal antibodies from HVTN 301 trial recipients were characterized by BLI, neutralization assays, and cryo-electron microscopy to determine VRC01-class similarity [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Germline-Targeting HIV Vaccine Research

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| eOD-GT8 60-mer Nanoparticle | Prime immunogen for VRC01-class bNAb precursors [23] [1] | IAVI G001 and G002 clinical trials |

| AS01B Adjuvant | Enhance innate immunity and Tfh cell responses [23] | Administered with eOD-GT8 in IAVI G001 |

| mRNA-LNP Platform | Delivery system for encoded immunogens [13] [1] | IAVI G002 and G003 trials |

| Fluorophore-Labeled eOD-GT8 | Probe for identifying antigen-specific B cells [1] | Flow cytometry sorting of B cell precursors |

| Stabilized Env Trimers (SOSIP) | Boost immunogens to guide affinity maturation [13] [1] | Sequential immunization after prime |

| Biolayer Interferometry (BLI) | Measure antibody binding kinetics and affinity [1] | Characterization of isolated mAbs |

| Alhydrogel + CpG ODN | Adjuvant system for protein subunit vaccines [24] | Preclinical studies with various immunogens |

Diagram Title: Research Platforms and Assay Workflow

Discussion: Strategic Implications for Vaccine Development

The comparative data demonstrate that germline-targeting with eOD-GT8 successfully primes rare VRC01-class B cell precursors in most vaccine recipients, achieving a 97% response rate with a median frequency of 0.1% IgG+ B cells in peripheral blood [1]. This represents a significant milestone in structure-based vaccine design.

The mRNA platform (IAVI G002) appears to induce at least equivalent priming efficiency compared to the protein nanoparticle, with the potential advantage of driving greater somatic hypermutation in VRC01-class antibodies [1]. This suggests platform selection may influence the quality of the immune response.

Future development requires optimizing sequential immunization regimens to shepherd these primed B cells toward broad neutralization capacity. Combination approaches that engage both B cell and T cell immunity may lower the antibody titers required for protection, as demonstrated in preclinical models [13].

The germline-targeting strategy exemplified by eOD-GT8 provides a robust foundation for iterative vaccine improvement. As additional clinical data emerge from ongoing trials, the comparative effectiveness of this approach against lineage-based and other strategies will become increasingly clear, potentially heralding a new era in precision vaccinology.

Sequential immunization regimens, often termed "prime-boost" strategies, represent a cornerstone of modern vaccinology, particularly in the fight against complex pathogens. A heterologous prime-boost approach involves administering two different vaccine types or formulations targeting the same pathogen in sequence. This strategy has gained significant traction for its ability to elicit more robust and durable immune responses compared to homologous regimens (using the same vaccine for all doses). The immunological rationale stems from the ability of different vaccine platforms to engage the immune system through distinct mechanisms, thereby overcoming limitations associated with repeated administration of identical vectors or antigens. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of heterologous prime-boost strategies, examining their performance across various disease targets, with a specific focus on the comparative context of germline-targeting versus lineage-based vaccine strategies.

The fundamental advantage of heterologous regimens lies in their capacity to avert the inhibitory effects of vector-specific immune responses. When the same viral vector is used for multiple vaccinations, immune responses against the vector itself can dampen the response to the target antigen in subsequent doses. By switching vaccine platforms between prime and boost, heterologous strategies circumvent this issue, potentially enhancing both cellular and humoral immunity against the pathogen of interest [25]. Furthermore, introducing new antigens into boost inoculations can be advantageous, demonstrating that the effect of 'original antigenic sin'—where the immune system preferentially recalls responses to the initially encountered strain—is not absolute [25].

Comparative Performance of Vaccine Platforms

Quantitative Comparison of Immune Responses

Table 1: Comparison of Immune Responses in Heterologous vs. Homologous SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination

| Vaccine Regimen | Neutralizing Antibody Titers | CD8+ T Cell Responses | CD4+ T Cell Responses | Mucosal Immunity | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenovirus (Prime) + mRNA (Boost) | 6-73-fold increase [26] | Significantly enhanced [26] | Significantly enhanced [26] | Moderate (systemic focus) | Superior neutralizing antibodies and T cell responses against variants [26] |

| mRNA (Prime) + Adenovirus (Boost) | Enhanced compared to homologous | Enhanced compared to homologous | Enhanced compared to homologous | Moderate (systemic focus) | Platform sequence influences immune polarization |

| Adenovirus (Prime) + Protein Subunit (Boost) | Enhanced breadth | Moderate enhancement | Strong CD4+ helper response | Limited | Focus on antibody quality over quantity |

| Homologous mRNA | 4-20-fold increase [26] | Moderate | Strong | Limited | High initial antibody titers but potentially limited breadth |

| Homologous Adenovirus | Lower than heterologous | Moderate | Moderate | Limited | Potentially hampered by anti-vector immunity |

Table 2: HIV-Specific Vaccine Approaches and Outcomes

| Vaccine Strategy | Target | Immune Response | Efficacy/Status | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germline-Targeting (e.g., eOD-GT8 60mer) | Naïve B cells with bnAb potential | Precursor B cell activation: 97% response rate in Phase I [10] | Early clinical trials (IAVI G001) | Requires multiple sequential immunogens to achieve maturity [12] |

| Lineage-Based Design | Evolving B cell lineages | Guided antibody maturation | Preclinical optimization | Complex immunogen design requiring reconstruction of maturation history [10] |

| Adenovirus/Mosaic (Imbokodo, Mosaico) | T cells and non-neutralizing antibodies | CD8+ T cell responses | Efficacy trials completed (HVTN 705/706) | Limited bnAb induction [12] |

| Fusion Peptide Approach | Conserved fusion epitope | Multiple bnAb lineages targeting single epitope | Preclinical/early clinical | Achieving sufficient neutralizing potency [12] |

| Passive bNAb Administration (AMP Trials) | Virus neutralization | Direct virus neutralization | Proof-of-concept: protection at high titers (>1:500) [10] | High antibody titers required for protection |

Mechanisms of Enhanced Immunogenicity

The superior performance of heterologous prime-boost regimens can be attributed to several interconnected immunological mechanisms. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of injection-site tissues in mouse models has revealed that adenoviral priming establishes a pre-conditioned innate immune environment that is further amplified upon mRNA boosting, particularly through fibroblast-driven chemokine responses that promote immune cell recruitment [26]. This creates a favorable microenvironment for the generation of adaptive immunity.

Additionally, adenovirus-based vaccines may contribute to heterologous efficacy through trained immunity—a memory-like state within the innate immune system where innate cells (particularly monocytes and macrophages) are epigenetically and metabolically reprogrammed to respond more robustly to future challenges [26]. This prolonged activation of monocytes, lasting up to three months post-vaccination, enhances cytokine production and antigen presentation capabilities, thereby priming the immune system for more effective responses to subsequent exposures [26].

The route of administration further modulates efficacy. Recent research demonstrates that mucosal delivery of heterologous boost vaccines can overcome deleterious prime-derived immunological imprinting—a phenomenon where preexisting immunity to an antigen negatively impacts responses to related antigens [27]. Intranasal boosting engages different compartments of the immune system, generating robust mucosal immunity while bypassing the suppressive effects of serum antibodies, resulting in enhanced T and B cell responses in respiratory tissues [27].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Preclinical Evaluation of Heterologous Regimens

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Prime-Boost Studies

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| ChAdOx1 vectors | Adenoviral vaccine vector | SARS-CoV-2, HIV, cancer vaccine studies [27] [28] |

| mRNA-LNP | Lipid nanoparticle-formulated mRNA | COVID-19 vaccines, HIV immunogen delivery [10] [26] |

| SOSIP trimers | Stabilized envelope trimers | HIV bnAb induction studies [10] |

| TLR7/8 agonists (3M-052) | Vaccine adjuvant | Enhancing antibody responses in protein vaccines [10] |

| eOD-GT8 60mer | Germline-targeting nanoparticle | Priming HIV bnAb precursors [10] [12] |

Protocol 1: Evaluating Heterologous Regimens in Mouse Models

- Immunization: Female BALB/c mice (4-6 weeks old) are immunized intramuscularly in the hind limb. Prime and booster vaccinations are typically administered 3 weeks apart [26].

- Sample Collection: Blood is collected via facial vein puncture under anesthesia. Spleens and lungs are harvested post-euthanasia for cellular analysis. For mucosal immunity assessment, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and nasal-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT) fluid are collected [27].

- Immune Monitoring: Serum antibodies are analyzed by ELISA for antigen-specific IgG, IgA, and IgM. Neutralizing capacity is assessed using pseudovirus neutralization assays or ACE-2 competition assays. T cell responses are evaluated via intracellular cytokine staining or ELISpot after antigen res stimulation [27] [26].

- Single-Cell Analysis: Injection-site tissues are processed for single-cell RNA sequencing 16 hours post-vaccination to characterize innate immune activation and chemokine responses [26].

Clinical Evaluation of Heterologous Regimens

Protocol 2: Clinical Trial Design for Heterologous COVID-19 Vaccines

- Study Population: Healthcare workers or general adult population without prior SARS-CoV-2 infection (confirmed by serological testing) [29].

- Vaccination Groups: Participants are randomized to receive homologous regimens (e.g., ChAdOx1/ChAdOx1) or heterologous regimens (e.g., CoronaVac/ChAdOx1, ChAdOx1/mRNA) with appropriate intervals between doses [29].

- Serological Assessment: Blood samples are collected at predefined intervals (e.g., 2, 4, 12 weeks post-each dose). A multiplex microsphere assay is employed to measure IgG, IgM, and IgA isotypes against various SARS-CoV-2 antigens (Spike trimer, RBD variants, nucleoprotein) [29].

- Data Analysis: Antibody levels are compared across groups. Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs) can cluster immune responses to differentiate between vaccination types and identify breakthrough infections based on distinct serological profiles [29].

Germline-Targeting vs. Lineage-Based Strategies: A Comparative Framework

The development of HIV vaccines has catalyzed the advancement of two sophisticated immunization strategies: germline-targeting and lineage-based vaccine design. Both approaches represent structured heterologous regimens aimed at solving the unique challenges posed by highly variable pathogens.

Germline-Targeting Approach

Germline targeting employs structure-based design to reverse engineer HIV immunogens that can initiate bnAb development by engaging naïve B cells with bnAb potential [10]. This approach involves a sequential immunization strategy:

The initial prime immunogen is designed to activate rare B cells (approximately 1 in 300,000 naïve B cells) that have the potential to develop into bnAb-producing cells [12]. Successive booster immunogens with increasingly native-like HIV Envelope proteins then shepherd these B cell lineages toward bnAb development through multiple rounds of somatic hypermutation and selection [10]. Clinical trials of the eOD-GT8 60mer immunogen have demonstrated that this initial step is feasible, with 97% of vaccinees showing targeted bnAb precursor responses [10].

Lineage-Based Design

Lineage-based approaches computationally reconstruct the maturation history of a known bnAb from an HIV-infected individual and use this as a blueprint for sequential immunizations [10]. Rather than starting with germline precursors, this strategy aims to recapitulate the natural evolution of bnAbs by presenting a series of immunogens that correspond to sequential stages in the bnAb development pathway.

Comparative Effectiveness

Table 4: Germline-Targeting vs. Lineage-Based Vaccine Strategies

| Parameter | Germline-Targeting Approach | Lineage-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Reverse-engineered immunogens to bind germline B cells [10] | Mature bnAbs from infected individuals [10] |

| Design Basis | Structure-based immunogen engineering [12] | Computational reconstruction of bnAb lineages [10] |

| Immunization Sequence | Predefined path from germline to mature bnAbs [12] | Recapitulation of natural bnAb evolution [10] |

| Clinical Validation | Early-stage clinical trials (IAVI G001) [10] | Preclinical optimization [10] |

| Key Challenge | Engaging extremely rare B cell precursors [12] | Accurately reconstructing evolutionary pathways [10] |

| Advantage | Rational design from first principles | Based on empirically successful bnAb pathways |

Applications Across Disease Targets

SARS-CoV-2 and Respiratory Viruses

For SARS-CoV-2, heterologous prime-boost strategies have demonstrated superior efficacy against variants of concern. Heterologous vaccination (adenoviral prime, mRNA boost) elicits higher neutralizing antibody titers and stronger CD8+ T cell responses against Delta and Omicron variants compared to homologous regimens [26]. This enhanced breadth is particularly valuable for addressing continued viral evolution.

Mucosal delivery of heterologous boosts represents a promising advancement for respiratory viruses. Intranasal administration of omicron vaccine boosters overcame the limitations of immunological imprinting from ancestral strain priming, generating de novo B cell responses in the lungs and recruiting cross-reactive T cells to respiratory tissues [27]. This "prime-pull" strategy enhances protection at the primary site of viral entry, representing a significant improvement over intramuscular vaccination alone.

HIV Vaccine Development

HIV vaccine development has been at the forefront of sophisticated heterologous regimen design. The extraordinary global diversity of HIV and its immune evasion tactics necessitate strategies that can induce broad and potent immune responses [10]. The combination of B cell and T cell vaccine strategies appears particularly promising, with preclinical studies demonstrating that combining an HIV SOSIP protein vaccine that induces autologous neutralizing antibodies with potent T cell-inducing viral vectors provided better protection against SHIV challenge than either candidate alone [10]. Notably, vaccine-mediated induction of potent T cell responses lowered the antibody threshold needed to prevent infection, suggesting important synergies between these arms of immunity [10].

Cancer Immunotherapy

Heterologous prime-boost strategies are also being explored in cancer immunotherapy. A regimen combining a self-assembling peptide nanoparticle TLR-7/8 agonist (SNP) vaccine prime with a chimp adenovirus (ChAdOx1) boost administered intravenously elicited potent CD8+ T cell responses and promoted tumor regression in mouse models [28]. Intravenous administration of the boost generated 4-fold higher antigen-specific CD8+ T cell responses compared to intramuscular boosting and mediated tumor regression through type I IFN-dependent remodeling of the tumor microenvironment [28]. This approach demonstrates how heterologous regimens can be optimized for specific therapeutic applications through route and platform selection.

Heterologous prime-boost vaccination strategies represent a powerful tool in modern vaccinology, offering enhanced immunogenicity and broader protection compared to homologous regimens across multiple disease targets. The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that the strategic combination of different vaccine platforms can overcome limitations associated with single-platform approaches, including vector-specific immunity, antigenic imprinting, and restricted immune breadth.

The ongoing development of both germline-targeting and lineage-based strategies for HIV vaccination illustrates how heterologous regimens can be rationally designed to address specific immunological challenges. As vaccine science advances, the intentional selection and sequencing of vaccine platforms based on their complementary immunological properties will likely play an increasingly important role in combating complex pathogens, with implications for infectious diseases, cancer immunotherapy, and beyond. The experimental data and methodologies compiled in this guide provide researchers with a framework for evaluating and optimizing sequential immunization regimens for specific applications.

Messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines represent a fundamental shift in vaccinology, moving from traditional biological-based production to a programmable platform technology that leverages the body's own cellular machinery. Unlike conventional vaccines that require the production of antigens in complex biological systems (e.g., chicken eggs or cell cultures), mRNA vaccines deliver genetic instructions that direct human cells to temporarily produce specific antigenic proteins, thereby eliciting protective immune responses [30] [31]. This core difference in mechanism enables unprecedented speed and flexibility in vaccine development, which was dramatically demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic when mRNA vaccines were developed, tested, and authorized in less than a year – a process that traditionally takes 5-10 years [32] [31].

The technological underpinnings of mRNA vaccines were established through decades of research addressing key challenges such as mRNA instability, inefficient delivery, and excessive inflammatory responses [33] [32]. Critical breakthroughs include the incorporation of modified nucleosides to reduce immunogenicity and improve stability, sequence engineering to optimize protein expression, and the development of lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) as efficient delivery vehicles that protect mRNA and facilitate its cellular uptake [30] [33] [32]. These advances have created a versatile platform that can be rapidly adapted to target various pathogens, with current research extending to influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and even non-infectious diseases like cancer [30] [33].